User login

Oral and Injectable Medications for Psoriasis: Benefits and Downsides Requiring Patient Support

Approximately three-quarters of respondents indicated that they have used oral or injectable medications (eg, methotrexate, acitretin, cyclosporine, apremilast, biologics) to control their psoriasis, according to a public meeting hosted by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to hear patient perspectives on psoriasis. Approximately 70 psoriasis patients or patient representatives attended the meeting in person and others attended through a live webcast.

Patients universally spoke about the benefits of their current treatments, especially the biologics, but variable experiences regarding the effectiveness of the therapies were reported, ranging from excellent improvement, to improvement that lasted only a few months, to a near-complete clearance. However, limitations to these therapies also were mentioned, which are areas where dermatologists can provide counseling and alternatives. For example, treatments were reported to be effective in clearing cutaneous psoriasis symptoms such as flaking and scaling, but pruritus, burning, and pain were still problematic and mostly limited to areas where the cutaneous symptoms had been located.

Other treatment downsides that dermatologists should discuss with patients are side effects, including fatigue, nausea, fluctuations in weight, increased facial hair growth, nosebleeds, increased blood pressure, headaches, and palpitations, according to the patients present at the meeting. Patients also expressed concern about immune compromise from the biologics. Others reported concerns that the treatments addressed specific psoriasis symptoms but led to worsening of other symptoms or development of new conditions such as uveitis and psoriatic arthritis. The burden of treatment infusions or required blood work also were discussed. These are areas in which dermatologists may be best suited to provide more patient education or support when prescribing these therapies. The National Psoriasis Foundation’s Patient Navigation Center is a tool for patients to access information and interact with members of the psoriasis patient community.

The psoriasis public meeting in March 2016 was the FDA’s 18th patient-focused drug development meeting. The FDA sought this information to have a greater understanding of the burden of psoriasis on patients and the treatments currently used to treat psoriasis and its symptoms. This information will help guide the FDA as they consider future drug approvals.

Approximately three-quarters of respondents indicated that they have used oral or injectable medications (eg, methotrexate, acitretin, cyclosporine, apremilast, biologics) to control their psoriasis, according to a public meeting hosted by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to hear patient perspectives on psoriasis. Approximately 70 psoriasis patients or patient representatives attended the meeting in person and others attended through a live webcast.

Patients universally spoke about the benefits of their current treatments, especially the biologics, but variable experiences regarding the effectiveness of the therapies were reported, ranging from excellent improvement, to improvement that lasted only a few months, to a near-complete clearance. However, limitations to these therapies also were mentioned, which are areas where dermatologists can provide counseling and alternatives. For example, treatments were reported to be effective in clearing cutaneous psoriasis symptoms such as flaking and scaling, but pruritus, burning, and pain were still problematic and mostly limited to areas where the cutaneous symptoms had been located.

Other treatment downsides that dermatologists should discuss with patients are side effects, including fatigue, nausea, fluctuations in weight, increased facial hair growth, nosebleeds, increased blood pressure, headaches, and palpitations, according to the patients present at the meeting. Patients also expressed concern about immune compromise from the biologics. Others reported concerns that the treatments addressed specific psoriasis symptoms but led to worsening of other symptoms or development of new conditions such as uveitis and psoriatic arthritis. The burden of treatment infusions or required blood work also were discussed. These are areas in which dermatologists may be best suited to provide more patient education or support when prescribing these therapies. The National Psoriasis Foundation’s Patient Navigation Center is a tool for patients to access information and interact with members of the psoriasis patient community.

The psoriasis public meeting in March 2016 was the FDA’s 18th patient-focused drug development meeting. The FDA sought this information to have a greater understanding of the burden of psoriasis on patients and the treatments currently used to treat psoriasis and its symptoms. This information will help guide the FDA as they consider future drug approvals.

Approximately three-quarters of respondents indicated that they have used oral or injectable medications (eg, methotrexate, acitretin, cyclosporine, apremilast, biologics) to control their psoriasis, according to a public meeting hosted by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to hear patient perspectives on psoriasis. Approximately 70 psoriasis patients or patient representatives attended the meeting in person and others attended through a live webcast.

Patients universally spoke about the benefits of their current treatments, especially the biologics, but variable experiences regarding the effectiveness of the therapies were reported, ranging from excellent improvement, to improvement that lasted only a few months, to a near-complete clearance. However, limitations to these therapies also were mentioned, which are areas where dermatologists can provide counseling and alternatives. For example, treatments were reported to be effective in clearing cutaneous psoriasis symptoms such as flaking and scaling, but pruritus, burning, and pain were still problematic and mostly limited to areas where the cutaneous symptoms had been located.

Other treatment downsides that dermatologists should discuss with patients are side effects, including fatigue, nausea, fluctuations in weight, increased facial hair growth, nosebleeds, increased blood pressure, headaches, and palpitations, according to the patients present at the meeting. Patients also expressed concern about immune compromise from the biologics. Others reported concerns that the treatments addressed specific psoriasis symptoms but led to worsening of other symptoms or development of new conditions such as uveitis and psoriatic arthritis. The burden of treatment infusions or required blood work also were discussed. These are areas in which dermatologists may be best suited to provide more patient education or support when prescribing these therapies. The National Psoriasis Foundation’s Patient Navigation Center is a tool for patients to access information and interact with members of the psoriasis patient community.

The psoriasis public meeting in March 2016 was the FDA’s 18th patient-focused drug development meeting. The FDA sought this information to have a greater understanding of the burden of psoriasis on patients and the treatments currently used to treat psoriasis and its symptoms. This information will help guide the FDA as they consider future drug approvals.

MACRA Monday: Elder maltreatment screening

If you haven’t started reporting quality data for the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), there’s still time to avoid a 4% cut to your Medicare payments.

Under the Pick Your Pace approach being offered this year, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services allows clinicians to test the system by reporting on one quality measure for one patient through paper-based claims. Be sure to append a Quality Data Code (QDC) to the claim form for care provided up to Dec. 31, 2017, in order to avoid a penalty in payment year 2019.

Consider this measure:

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Measure #181: Elder Maltreatment Screen and Follow-Up Plan

This measure aims to capture the percentage of patients aged 65 years and older who have a documented elder maltreatment screening and a follow-up plan, if appropriate.

What you need to do: Screen your elderly patients for maltreatment using an Elder Maltreatment Screening tool during the visit and if they screen positive, develop and document a follow-up plan at the visit.

Eligible cases include patients who were aged 65 years or older on the date of the encounter and a have patient encounter during the performance period. Applicable codes include (CPT or HCPCS): 90791, 90792, 90832, 90834, 90837, 96116, 96118, 96150, 96151, 96152, 97165, 97166, 97167, 97802, 97803, 99201, 99202, 99203, 99204, 99205, 99212, 99213, 99214, 99215, 99304, 99305, 99306, 99307, 99308, 99309, 99310, 99318, 99324, 99325, 99326, 99327, 99328, 99334, 99335, 99336, 99337, 99341, 99342, 99343, 99344, 99345, 99347, 99348, 99349, 99350, G0101, G0270, G0402, G0438, G0439 without telehealth modifiers GQ or GT.

To get credit under MIPS, be sure to include a QDC that shows that you successfully performed the measure or had a good reason for not doing so. For instance, G8733 indicates that an elder maltreatment screen was documented as positive and a follow-up plan was documented, while G8734 indicates that the screen was negative and a follow-up plan is not required. Use exception code G8535 if the screening was not documented because the patient is not eligible. For example, a patient is not eligible if they require urgent medical care during the visit and the screening would delay treatment.

CMS has a full list measures available for claims-based reporting at qpp.cms.gov. The American Medical Association has also created a step-by-step guide for reporting on one quality measure.

Certain clinicians are exempt from reporting and do not face a penalty under MIPS:

- Those who enrolled in Medicare for the first time during a performance period.

- Those who have Medicare Part B allowed charges of $30,000 or less.

- Those who have 100 or fewer Medicare Part B patients.

- Those who are significantly participating in an Advanced Alternative Payment Model (APM).

If you haven’t started reporting quality data for the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), there’s still time to avoid a 4% cut to your Medicare payments.

Under the Pick Your Pace approach being offered this year, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services allows clinicians to test the system by reporting on one quality measure for one patient through paper-based claims. Be sure to append a Quality Data Code (QDC) to the claim form for care provided up to Dec. 31, 2017, in order to avoid a penalty in payment year 2019.

Consider this measure:

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Measure #181: Elder Maltreatment Screen and Follow-Up Plan

This measure aims to capture the percentage of patients aged 65 years and older who have a documented elder maltreatment screening and a follow-up plan, if appropriate.

What you need to do: Screen your elderly patients for maltreatment using an Elder Maltreatment Screening tool during the visit and if they screen positive, develop and document a follow-up plan at the visit.

Eligible cases include patients who were aged 65 years or older on the date of the encounter and a have patient encounter during the performance period. Applicable codes include (CPT or HCPCS): 90791, 90792, 90832, 90834, 90837, 96116, 96118, 96150, 96151, 96152, 97165, 97166, 97167, 97802, 97803, 99201, 99202, 99203, 99204, 99205, 99212, 99213, 99214, 99215, 99304, 99305, 99306, 99307, 99308, 99309, 99310, 99318, 99324, 99325, 99326, 99327, 99328, 99334, 99335, 99336, 99337, 99341, 99342, 99343, 99344, 99345, 99347, 99348, 99349, 99350, G0101, G0270, G0402, G0438, G0439 without telehealth modifiers GQ or GT.

To get credit under MIPS, be sure to include a QDC that shows that you successfully performed the measure or had a good reason for not doing so. For instance, G8733 indicates that an elder maltreatment screen was documented as positive and a follow-up plan was documented, while G8734 indicates that the screen was negative and a follow-up plan is not required. Use exception code G8535 if the screening was not documented because the patient is not eligible. For example, a patient is not eligible if they require urgent medical care during the visit and the screening would delay treatment.

CMS has a full list measures available for claims-based reporting at qpp.cms.gov. The American Medical Association has also created a step-by-step guide for reporting on one quality measure.

Certain clinicians are exempt from reporting and do not face a penalty under MIPS:

- Those who enrolled in Medicare for the first time during a performance period.

- Those who have Medicare Part B allowed charges of $30,000 or less.

- Those who have 100 or fewer Medicare Part B patients.

- Those who are significantly participating in an Advanced Alternative Payment Model (APM).

If you haven’t started reporting quality data for the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), there’s still time to avoid a 4% cut to your Medicare payments.

Under the Pick Your Pace approach being offered this year, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services allows clinicians to test the system by reporting on one quality measure for one patient through paper-based claims. Be sure to append a Quality Data Code (QDC) to the claim form for care provided up to Dec. 31, 2017, in order to avoid a penalty in payment year 2019.

Consider this measure:

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Measure #181: Elder Maltreatment Screen and Follow-Up Plan

This measure aims to capture the percentage of patients aged 65 years and older who have a documented elder maltreatment screening and a follow-up plan, if appropriate.

What you need to do: Screen your elderly patients for maltreatment using an Elder Maltreatment Screening tool during the visit and if they screen positive, develop and document a follow-up plan at the visit.

Eligible cases include patients who were aged 65 years or older on the date of the encounter and a have patient encounter during the performance period. Applicable codes include (CPT or HCPCS): 90791, 90792, 90832, 90834, 90837, 96116, 96118, 96150, 96151, 96152, 97165, 97166, 97167, 97802, 97803, 99201, 99202, 99203, 99204, 99205, 99212, 99213, 99214, 99215, 99304, 99305, 99306, 99307, 99308, 99309, 99310, 99318, 99324, 99325, 99326, 99327, 99328, 99334, 99335, 99336, 99337, 99341, 99342, 99343, 99344, 99345, 99347, 99348, 99349, 99350, G0101, G0270, G0402, G0438, G0439 without telehealth modifiers GQ or GT.

To get credit under MIPS, be sure to include a QDC that shows that you successfully performed the measure or had a good reason for not doing so. For instance, G8733 indicates that an elder maltreatment screen was documented as positive and a follow-up plan was documented, while G8734 indicates that the screen was negative and a follow-up plan is not required. Use exception code G8535 if the screening was not documented because the patient is not eligible. For example, a patient is not eligible if they require urgent medical care during the visit and the screening would delay treatment.

CMS has a full list measures available for claims-based reporting at qpp.cms.gov. The American Medical Association has also created a step-by-step guide for reporting on one quality measure.

Certain clinicians are exempt from reporting and do not face a penalty under MIPS:

- Those who enrolled in Medicare for the first time during a performance period.

- Those who have Medicare Part B allowed charges of $30,000 or less.

- Those who have 100 or fewer Medicare Part B patients.

- Those who are significantly participating in an Advanced Alternative Payment Model (APM).

Technique may predict treatment outcomes in MM

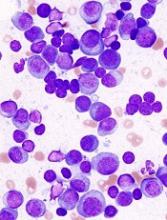

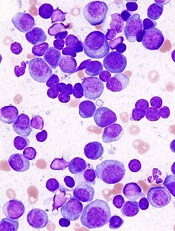

A cell-measuring technique can help predict how multiple myeloma (MM) patients will respond to different therapies, according to research published in Nature Communications.

The technique involves a microfluidic device known as a serial suspended microchannel resonator (sSMR).

The sSMR measures cell mass and allows researchers to calculate growth rates of single cells over short periods of time.

The device consists of a series of sensors that weigh cells as they flow through tiny channels.

The sSMR can measure 50 to 100 cells per hour.

Over a 20-minute period, each cell is weighed 10 times. This is enough to get an accurate mass accumulation rate (MAR), which is a measurement of the rate at which the cells gain mass.

With previous work, researchers showed that MAR can reveal drug susceptibility. A decrease in MAR following drug treatment means cells are sensitive to the drug. If cells are resistant, there is no change in MAR.

For the current study, Scott Manalis, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, and his colleagues tested drugs on cells from MM patients.

The team compared MAR results obtained via sSMR to outcomes of treatment in 9 patients.

For each patient, the researchers tracked the cells’ response to 3 different drugs—bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone—plus combinations of those drugs.

In all 9 cases, the sSMR results matched the outcomes seen in patients, as measured by clinical biomarkers in the bloodstream.

“When the clinical biomarkers showed that the patients should be sensitive to a drug, we also saw sensitivity by our measurement,” said study author Mark Stevens, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

“[I]n cases where the patients were resistant, we saw that in the clinical biomarkers as well as our measurement.”

The researchers believe their device could potentially be used in MM patients at the time of relapse when the disease may have developed resistance to specific therapies.

“At this time of relapse, we would take a bone marrow biopsy from a patient, and we would test each therapy individually or in combinations that are typically used in the clinic,” Dr Stevens said. “At that point, we’d be able to inform the clinician as to which therapy or combinations of therapies this patient seems to be most sensitive or most resistant to.”

Now, the researchers are planning to conduct a larger clinical study to validate this approach. They also aim to investigate the possibility of using this technology for other cancers.

Some of the researchers involved in this study are cofounders of Travera and Affinity Biosensors, 2 companies that develop techniques relevant to this research. ![]()

A cell-measuring technique can help predict how multiple myeloma (MM) patients will respond to different therapies, according to research published in Nature Communications.

The technique involves a microfluidic device known as a serial suspended microchannel resonator (sSMR).

The sSMR measures cell mass and allows researchers to calculate growth rates of single cells over short periods of time.

The device consists of a series of sensors that weigh cells as they flow through tiny channels.

The sSMR can measure 50 to 100 cells per hour.

Over a 20-minute period, each cell is weighed 10 times. This is enough to get an accurate mass accumulation rate (MAR), which is a measurement of the rate at which the cells gain mass.

With previous work, researchers showed that MAR can reveal drug susceptibility. A decrease in MAR following drug treatment means cells are sensitive to the drug. If cells are resistant, there is no change in MAR.

For the current study, Scott Manalis, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, and his colleagues tested drugs on cells from MM patients.

The team compared MAR results obtained via sSMR to outcomes of treatment in 9 patients.

For each patient, the researchers tracked the cells’ response to 3 different drugs—bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone—plus combinations of those drugs.

In all 9 cases, the sSMR results matched the outcomes seen in patients, as measured by clinical biomarkers in the bloodstream.

“When the clinical biomarkers showed that the patients should be sensitive to a drug, we also saw sensitivity by our measurement,” said study author Mark Stevens, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

“[I]n cases where the patients were resistant, we saw that in the clinical biomarkers as well as our measurement.”

The researchers believe their device could potentially be used in MM patients at the time of relapse when the disease may have developed resistance to specific therapies.

“At this time of relapse, we would take a bone marrow biopsy from a patient, and we would test each therapy individually or in combinations that are typically used in the clinic,” Dr Stevens said. “At that point, we’d be able to inform the clinician as to which therapy or combinations of therapies this patient seems to be most sensitive or most resistant to.”

Now, the researchers are planning to conduct a larger clinical study to validate this approach. They also aim to investigate the possibility of using this technology for other cancers.

Some of the researchers involved in this study are cofounders of Travera and Affinity Biosensors, 2 companies that develop techniques relevant to this research. ![]()

A cell-measuring technique can help predict how multiple myeloma (MM) patients will respond to different therapies, according to research published in Nature Communications.

The technique involves a microfluidic device known as a serial suspended microchannel resonator (sSMR).

The sSMR measures cell mass and allows researchers to calculate growth rates of single cells over short periods of time.

The device consists of a series of sensors that weigh cells as they flow through tiny channels.

The sSMR can measure 50 to 100 cells per hour.

Over a 20-minute period, each cell is weighed 10 times. This is enough to get an accurate mass accumulation rate (MAR), which is a measurement of the rate at which the cells gain mass.

With previous work, researchers showed that MAR can reveal drug susceptibility. A decrease in MAR following drug treatment means cells are sensitive to the drug. If cells are resistant, there is no change in MAR.

For the current study, Scott Manalis, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, and his colleagues tested drugs on cells from MM patients.

The team compared MAR results obtained via sSMR to outcomes of treatment in 9 patients.

For each patient, the researchers tracked the cells’ response to 3 different drugs—bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone—plus combinations of those drugs.

In all 9 cases, the sSMR results matched the outcomes seen in patients, as measured by clinical biomarkers in the bloodstream.

“When the clinical biomarkers showed that the patients should be sensitive to a drug, we also saw sensitivity by our measurement,” said study author Mark Stevens, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

“[I]n cases where the patients were resistant, we saw that in the clinical biomarkers as well as our measurement.”

The researchers believe their device could potentially be used in MM patients at the time of relapse when the disease may have developed resistance to specific therapies.

“At this time of relapse, we would take a bone marrow biopsy from a patient, and we would test each therapy individually or in combinations that are typically used in the clinic,” Dr Stevens said. “At that point, we’d be able to inform the clinician as to which therapy or combinations of therapies this patient seems to be most sensitive or most resistant to.”

Now, the researchers are planning to conduct a larger clinical study to validate this approach. They also aim to investigate the possibility of using this technology for other cancers.

Some of the researchers involved in this study are cofounders of Travera and Affinity Biosensors, 2 companies that develop techniques relevant to this research. ![]()

Monitoring HIV and Kidney Disease in Aging Asians

More people who are HIV-1 positive are living longer and better managing comorbidities—especially those associated with kidney disease. This becomes critical since the medications patients with HIV must take can be nephrotoxic with long-term use. Researchers from the AIDS Clinical Center, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, in Tokyo, Japan note that Asian patients may be at higher risk because of their generally smaller body weight and metabolism differences, compared with whites and blacks.

Few studies in Asia had assessed the prevalence and factors associated with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ERSD) in patients with HIV-1, the researchers say, so they conducted the first, to their knowledge, with a cross-sectional study of 1,990 patients.

One third of the patients were aged ≥ 50 years. Nearly all (94%) had HIV-load < 50 copies/mL. The median time from diagnosis to study enrollment was 9.1 years; the median duration of antiretroviral therapy (ART) was 7.35 years. Of the study patients, 256 (13%) had chronic kidney disease and 9 (0.5%) had ESRD. It is noteworthy, the researchers say, that 5 of those 9 developed ESRD long after the diagnosis of HIV infection and that the age of the ESRD patients varied from 30s to 60s.

The incidence of CKD rose from 18.6% among those aged 50-59 years to 47% for those aged > 70 years. Heavier body weight, diabetes, hypertension, and longer duration of ART also were associated with CKD. Duration of exposure to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), however, was not associated with CKD. Of all the patients, 61% had a history of TDF use. At the time of the study, 774 patients were taking TDF; 69 in the group with CKD and 705 in the group without CKD.

Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate nephrotoxicity had been well publicized by 2016, when the data were collected for this study, the researchers note, which is why they used “duration of TDF exposure” in their logistic regression model. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate may have been discontinued early on for the patients at risk for CKD in their study cohort. However, they note that while TDF will be replaced with its prodrug tenofovir alafenamide, other antiretroviral drugs that inhibit excretion of creatinine in the renal proximal tubules and increase serum creatinine value, such as dolutegravir, cobicistat, rilpivirine, raltegravir, and ritonavir, will still be widely used.

Source:

Nishijima T, Kawasaki Y, Mutoh Y, et al. Sci Rep. 2017;7(14565) doi:10.1038/s41598-017-15214-x

More people who are HIV-1 positive are living longer and better managing comorbidities—especially those associated with kidney disease. This becomes critical since the medications patients with HIV must take can be nephrotoxic with long-term use. Researchers from the AIDS Clinical Center, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, in Tokyo, Japan note that Asian patients may be at higher risk because of their generally smaller body weight and metabolism differences, compared with whites and blacks.

Few studies in Asia had assessed the prevalence and factors associated with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ERSD) in patients with HIV-1, the researchers say, so they conducted the first, to their knowledge, with a cross-sectional study of 1,990 patients.

One third of the patients were aged ≥ 50 years. Nearly all (94%) had HIV-load < 50 copies/mL. The median time from diagnosis to study enrollment was 9.1 years; the median duration of antiretroviral therapy (ART) was 7.35 years. Of the study patients, 256 (13%) had chronic kidney disease and 9 (0.5%) had ESRD. It is noteworthy, the researchers say, that 5 of those 9 developed ESRD long after the diagnosis of HIV infection and that the age of the ESRD patients varied from 30s to 60s.

The incidence of CKD rose from 18.6% among those aged 50-59 years to 47% for those aged > 70 years. Heavier body weight, diabetes, hypertension, and longer duration of ART also were associated with CKD. Duration of exposure to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), however, was not associated with CKD. Of all the patients, 61% had a history of TDF use. At the time of the study, 774 patients were taking TDF; 69 in the group with CKD and 705 in the group without CKD.

Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate nephrotoxicity had been well publicized by 2016, when the data were collected for this study, the researchers note, which is why they used “duration of TDF exposure” in their logistic regression model. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate may have been discontinued early on for the patients at risk for CKD in their study cohort. However, they note that while TDF will be replaced with its prodrug tenofovir alafenamide, other antiretroviral drugs that inhibit excretion of creatinine in the renal proximal tubules and increase serum creatinine value, such as dolutegravir, cobicistat, rilpivirine, raltegravir, and ritonavir, will still be widely used.

Source:

Nishijima T, Kawasaki Y, Mutoh Y, et al. Sci Rep. 2017;7(14565) doi:10.1038/s41598-017-15214-x

More people who are HIV-1 positive are living longer and better managing comorbidities—especially those associated with kidney disease. This becomes critical since the medications patients with HIV must take can be nephrotoxic with long-term use. Researchers from the AIDS Clinical Center, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, in Tokyo, Japan note that Asian patients may be at higher risk because of their generally smaller body weight and metabolism differences, compared with whites and blacks.

Few studies in Asia had assessed the prevalence and factors associated with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ERSD) in patients with HIV-1, the researchers say, so they conducted the first, to their knowledge, with a cross-sectional study of 1,990 patients.

One third of the patients were aged ≥ 50 years. Nearly all (94%) had HIV-load < 50 copies/mL. The median time from diagnosis to study enrollment was 9.1 years; the median duration of antiretroviral therapy (ART) was 7.35 years. Of the study patients, 256 (13%) had chronic kidney disease and 9 (0.5%) had ESRD. It is noteworthy, the researchers say, that 5 of those 9 developed ESRD long after the diagnosis of HIV infection and that the age of the ESRD patients varied from 30s to 60s.

The incidence of CKD rose from 18.6% among those aged 50-59 years to 47% for those aged > 70 years. Heavier body weight, diabetes, hypertension, and longer duration of ART also were associated with CKD. Duration of exposure to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), however, was not associated with CKD. Of all the patients, 61% had a history of TDF use. At the time of the study, 774 patients were taking TDF; 69 in the group with CKD and 705 in the group without CKD.

Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate nephrotoxicity had been well publicized by 2016, when the data were collected for this study, the researchers note, which is why they used “duration of TDF exposure” in their logistic regression model. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate may have been discontinued early on for the patients at risk for CKD in their study cohort. However, they note that while TDF will be replaced with its prodrug tenofovir alafenamide, other antiretroviral drugs that inhibit excretion of creatinine in the renal proximal tubules and increase serum creatinine value, such as dolutegravir, cobicistat, rilpivirine, raltegravir, and ritonavir, will still be widely used.

Source:

Nishijima T, Kawasaki Y, Mutoh Y, et al. Sci Rep. 2017;7(14565) doi:10.1038/s41598-017-15214-x

Enteroendocrine System and Cardio-Pulmonary Health

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Parents have diverse reasons for refusing HPV vaccine for their child

, so health care providers have much work to do to educate parents about this anticancer vaccine, said Frances DiAnna Kinder, PhD, RN, CPNP-PC, of the La Salle University, Philadelphia.

Pediatricians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants from numerous private pediatric settings in Philadelphia discussed HPV vaccination during a well-child visit with parents and children who were eligible for the vaccine, which generally starts at age 9 years. After a health visit in which the HPV vaccine was refused, the parent was asked to complete a survey in a private room. Of 72 surveys by 63 mothers, 8 fathers, and 1 grandparent of children who were mostly female and mostly between ages 11-16 years, 58% said the vaccine was too new, and 50% said there was not enough research. However, 63% said they believed in the HPV vaccine’s efficacy, and all reported their child was up to date with other recommended vaccines.

There was an open-ended question for parents to indicate other reasons for refusal; some themes of refusal included fear, anxiety, and misunderstanding the facts of the HPV vaccine; 21 parents whose children were aged 11-13 years said their child was too young to be vaccinated with the HPV vaccine. Three parents said that they had “witnessed severe side effects such as becoming paralyzed” or “acquiring an autoimmune disease after the vaccine was administered” to either a family member or friend’s child, Dr. Kinder noted. One parent said, “this vaccine was a money maker for the pharmaceutical companies” and there was “too much controversy for her to be comfortable giving this to her child.”

Read more at (J Pediatr Health Care. 2017. 10.1016/j.pedhc.2017.09.003).

, so health care providers have much work to do to educate parents about this anticancer vaccine, said Frances DiAnna Kinder, PhD, RN, CPNP-PC, of the La Salle University, Philadelphia.

Pediatricians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants from numerous private pediatric settings in Philadelphia discussed HPV vaccination during a well-child visit with parents and children who were eligible for the vaccine, which generally starts at age 9 years. After a health visit in which the HPV vaccine was refused, the parent was asked to complete a survey in a private room. Of 72 surveys by 63 mothers, 8 fathers, and 1 grandparent of children who were mostly female and mostly between ages 11-16 years, 58% said the vaccine was too new, and 50% said there was not enough research. However, 63% said they believed in the HPV vaccine’s efficacy, and all reported their child was up to date with other recommended vaccines.

There was an open-ended question for parents to indicate other reasons for refusal; some themes of refusal included fear, anxiety, and misunderstanding the facts of the HPV vaccine; 21 parents whose children were aged 11-13 years said their child was too young to be vaccinated with the HPV vaccine. Three parents said that they had “witnessed severe side effects such as becoming paralyzed” or “acquiring an autoimmune disease after the vaccine was administered” to either a family member or friend’s child, Dr. Kinder noted. One parent said, “this vaccine was a money maker for the pharmaceutical companies” and there was “too much controversy for her to be comfortable giving this to her child.”

Read more at (J Pediatr Health Care. 2017. 10.1016/j.pedhc.2017.09.003).

, so health care providers have much work to do to educate parents about this anticancer vaccine, said Frances DiAnna Kinder, PhD, RN, CPNP-PC, of the La Salle University, Philadelphia.

Pediatricians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants from numerous private pediatric settings in Philadelphia discussed HPV vaccination during a well-child visit with parents and children who were eligible for the vaccine, which generally starts at age 9 years. After a health visit in which the HPV vaccine was refused, the parent was asked to complete a survey in a private room. Of 72 surveys by 63 mothers, 8 fathers, and 1 grandparent of children who were mostly female and mostly between ages 11-16 years, 58% said the vaccine was too new, and 50% said there was not enough research. However, 63% said they believed in the HPV vaccine’s efficacy, and all reported their child was up to date with other recommended vaccines.

There was an open-ended question for parents to indicate other reasons for refusal; some themes of refusal included fear, anxiety, and misunderstanding the facts of the HPV vaccine; 21 parents whose children were aged 11-13 years said their child was too young to be vaccinated with the HPV vaccine. Three parents said that they had “witnessed severe side effects such as becoming paralyzed” or “acquiring an autoimmune disease after the vaccine was administered” to either a family member or friend’s child, Dr. Kinder noted. One parent said, “this vaccine was a money maker for the pharmaceutical companies” and there was “too much controversy for her to be comfortable giving this to her child.”

Read more at (J Pediatr Health Care. 2017. 10.1016/j.pedhc.2017.09.003).

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRIC HEALTH CARE

Safety-net hospitals would be hurt by hospital-wide 30-day readmission penalties

Considering all readmissions within 30 days of discharge in the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program would modestly increase the number of hospitals eligible for penalties and would have a bigger impact on safety-net hospitals, based on a study of two years of Medicare claims data from 3,443 hospitals.

“Transition to a hospital-wide measure would require an adjustment in the penalty formula to keep penalties in the same range for most hospitals and without a change in procedures would have a deleterious effect on safety-net hospitals,” according to Rachael B. Zuckerman, PhD, from the Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, and her co-authors.

Analyzing 6,807,899 admissions for hospital-wide readmission measures and 4,392,658 admissions for condition-specific measures, the researchers found that a condition-specific approach would result in 3,238 hospitals being eligible for penalties for at least one condition. A hospital-wide measure of readmissions would result in 76 additional hospitals being eligible for penalties based on one year of admissions data, and 128 additional hospitals based on 3 years of admissions data (NEJM 2017, 377:1551-58. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMsa1701791).

Moving to a hospital-wide measure of readmissions also would significantly increase mean annual penalty rates across all hospitals by 0.89% of base diagnosis-related group (DRG) payments or $393,000; 43% of hospitals would be penalized under this standard.

“Moving to the hospital-wide readmission measure would also substantially increase the disparity between safety-net and other hospitals: the mean penalty as a percentage of base DRG payments would be 0.41 percentage points ($198,000) higher among safety net hospitals,” the authors wrote.

“Since safety-net hospitals tend to perform slightly worse on the hospital-wide measure, they are more likely to receive a penalty, which would increase the disparity in penalties between the two groups.”

The study was supported by the Department of Health and Human Services. One author declared grants from funding bodies and universities outside the submitted work. One author is an associate editor of the New England Journal of Medicine. One author was an employee of the Department of Health and Human Services at the time of the study. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

Considering all readmissions within 30 days of discharge in the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program would modestly increase the number of hospitals eligible for penalties and would have a bigger impact on safety-net hospitals, based on a study of two years of Medicare claims data from 3,443 hospitals.

“Transition to a hospital-wide measure would require an adjustment in the penalty formula to keep penalties in the same range for most hospitals and without a change in procedures would have a deleterious effect on safety-net hospitals,” according to Rachael B. Zuckerman, PhD, from the Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, and her co-authors.

Analyzing 6,807,899 admissions for hospital-wide readmission measures and 4,392,658 admissions for condition-specific measures, the researchers found that a condition-specific approach would result in 3,238 hospitals being eligible for penalties for at least one condition. A hospital-wide measure of readmissions would result in 76 additional hospitals being eligible for penalties based on one year of admissions data, and 128 additional hospitals based on 3 years of admissions data (NEJM 2017, 377:1551-58. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMsa1701791).

Moving to a hospital-wide measure of readmissions also would significantly increase mean annual penalty rates across all hospitals by 0.89% of base diagnosis-related group (DRG) payments or $393,000; 43% of hospitals would be penalized under this standard.

“Moving to the hospital-wide readmission measure would also substantially increase the disparity between safety-net and other hospitals: the mean penalty as a percentage of base DRG payments would be 0.41 percentage points ($198,000) higher among safety net hospitals,” the authors wrote.

“Since safety-net hospitals tend to perform slightly worse on the hospital-wide measure, they are more likely to receive a penalty, which would increase the disparity in penalties between the two groups.”

The study was supported by the Department of Health and Human Services. One author declared grants from funding bodies and universities outside the submitted work. One author is an associate editor of the New England Journal of Medicine. One author was an employee of the Department of Health and Human Services at the time of the study. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

Considering all readmissions within 30 days of discharge in the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program would modestly increase the number of hospitals eligible for penalties and would have a bigger impact on safety-net hospitals, based on a study of two years of Medicare claims data from 3,443 hospitals.

“Transition to a hospital-wide measure would require an adjustment in the penalty formula to keep penalties in the same range for most hospitals and without a change in procedures would have a deleterious effect on safety-net hospitals,” according to Rachael B. Zuckerman, PhD, from the Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, and her co-authors.

Analyzing 6,807,899 admissions for hospital-wide readmission measures and 4,392,658 admissions for condition-specific measures, the researchers found that a condition-specific approach would result in 3,238 hospitals being eligible for penalties for at least one condition. A hospital-wide measure of readmissions would result in 76 additional hospitals being eligible for penalties based on one year of admissions data, and 128 additional hospitals based on 3 years of admissions data (NEJM 2017, 377:1551-58. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMsa1701791).

Moving to a hospital-wide measure of readmissions also would significantly increase mean annual penalty rates across all hospitals by 0.89% of base diagnosis-related group (DRG) payments or $393,000; 43% of hospitals would be penalized under this standard.

“Moving to the hospital-wide readmission measure would also substantially increase the disparity between safety-net and other hospitals: the mean penalty as a percentage of base DRG payments would be 0.41 percentage points ($198,000) higher among safety net hospitals,” the authors wrote.

“Since safety-net hospitals tend to perform slightly worse on the hospital-wide measure, they are more likely to receive a penalty, which would increase the disparity in penalties between the two groups.”

The study was supported by the Department of Health and Human Services. One author declared grants from funding bodies and universities outside the submitted work. One author is an associate editor of the New England Journal of Medicine. One author was an employee of the Department of Health and Human Services at the time of the study. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM NEJM

Key clinical point: Adopting a hospital-wide measure of 30-day readmissions for the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program would modestly increase the number of hospitals eligible for penalties and would have a bigger impact on safety-net hospitals.

Major finding: With a hospital-wide measure of readmissions in the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, the mean penalty as a percentage of base DRG payments would be 0.41 percentage points ($198,000) higher among safety net hospitals.

Data source: Analysis of two years of Medicare claims data from 3,443 hospitals.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Department of Health and Human Services. One author declared grants from funding bodies and universities outside the submitted work. One author is an associated editor of the New England Journal of Medicine. One author was an employee of the Department of Health and Human Services at the time of the study. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

Robotic Nissen fundoplication has teaching advantages

Training level affected operative time for laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication, but not for the robotic procedure, according to Maureen D. Moore, MD, and her associates.

Further, in laparoscopic and robotic procedures, junior and senior assistant cohorts had similar outcome measures for estimated blood loss, length of stay, postoperative complications, and 30-day readmission rate.

“The robotic technique offers unique advantages as an educational platform and potentially allows for increased trainee participation without compromising perioperative outcomes,” researchers concluded.

They evaluated surgical times and outcomes for 105 patients; junior assistants (postgraduate year-3 surgery residents) were present in 29 laparoscopic and 44 robotic procedures and senior assistants (minimally invasive surgery fellows) assisted in 18 laparoscopic and 14 robotic procedures.

Median operative time was significantly shorter for the laparoscopic procedures, 112 minutes vs. 157 minutes for the robotic procedures (P less than 0.001). Plus, the median operative time was significantly lower when senior assistants were involved in the laparoscopic procedures, 85 minutes vs. 129 minutes for the junior assistants (P = 0.02).

For the robotic procedures, the median operative times were not significantly different based on the assistant’s level of training, 154 minutes vs. 158 minutes.

Read the full study in the Journal of Surgical Research (doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2017.05.127).

Training level affected operative time for laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication, but not for the robotic procedure, according to Maureen D. Moore, MD, and her associates.

Further, in laparoscopic and robotic procedures, junior and senior assistant cohorts had similar outcome measures for estimated blood loss, length of stay, postoperative complications, and 30-day readmission rate.

“The robotic technique offers unique advantages as an educational platform and potentially allows for increased trainee participation without compromising perioperative outcomes,” researchers concluded.

They evaluated surgical times and outcomes for 105 patients; junior assistants (postgraduate year-3 surgery residents) were present in 29 laparoscopic and 44 robotic procedures and senior assistants (minimally invasive surgery fellows) assisted in 18 laparoscopic and 14 robotic procedures.

Median operative time was significantly shorter for the laparoscopic procedures, 112 minutes vs. 157 minutes for the robotic procedures (P less than 0.001). Plus, the median operative time was significantly lower when senior assistants were involved in the laparoscopic procedures, 85 minutes vs. 129 minutes for the junior assistants (P = 0.02).

For the robotic procedures, the median operative times were not significantly different based on the assistant’s level of training, 154 minutes vs. 158 minutes.

Read the full study in the Journal of Surgical Research (doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2017.05.127).

Training level affected operative time for laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication, but not for the robotic procedure, according to Maureen D. Moore, MD, and her associates.

Further, in laparoscopic and robotic procedures, junior and senior assistant cohorts had similar outcome measures for estimated blood loss, length of stay, postoperative complications, and 30-day readmission rate.

“The robotic technique offers unique advantages as an educational platform and potentially allows for increased trainee participation without compromising perioperative outcomes,” researchers concluded.

They evaluated surgical times and outcomes for 105 patients; junior assistants (postgraduate year-3 surgery residents) were present in 29 laparoscopic and 44 robotic procedures and senior assistants (minimally invasive surgery fellows) assisted in 18 laparoscopic and 14 robotic procedures.

Median operative time was significantly shorter for the laparoscopic procedures, 112 minutes vs. 157 minutes for the robotic procedures (P less than 0.001). Plus, the median operative time was significantly lower when senior assistants were involved in the laparoscopic procedures, 85 minutes vs. 129 minutes for the junior assistants (P = 0.02).

For the robotic procedures, the median operative times were not significantly different based on the assistant’s level of training, 154 minutes vs. 158 minutes.

Read the full study in the Journal of Surgical Research (doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2017.05.127).

FROM THE JOURNAL OF SURGICAL RESEARCH

Antimalarial might fight Zika virus

Preclinical research suggests a drug used to prevent and treat malaria may also be effective against Zika virus.

Investigators found that chloroquine can protect human neural progenitors from infection with Zika virus.

The drug also decreased Zika-induced mortality in one mouse model and hindered transmission of Zika virus from mother to fetus in another mouse model.

Alexey Terskikh, PhD, of Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute in La Jolla, California, and his colleagues conducted this research and disclosed the results in Scientific Reports.

“There is still an urgent need to bolster our preparedness and capacity to respond to the next Zika outbreak,” Dr Terskikh said. “Our latest research suggests the antimalaria drug chloroquine may be an effective drug to treat and prevent Zika infections.”

The investigators first found that chloroquine reduced Zika infection in primary human fetal neural precursor cells.

The team also discovered that chloroquine reduced the percentage of Zika-positive cells and the level of apoptosis in neurospheres derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells.

The investigators then tested chloroquine in AG129 mice, which lack receptors for type I and II interferons and have been used to model Zika virus infection.

Some of these mice received chloroquine (50 mg/kg/day) in their drinking water for 2 days and were then infected with Zika virus. The mice continued to receive chloroquine at the same dose for 5 days and then received 5 mg/kg/day until the end of the experiment.

Control AG129 mice were infected with Zika virus and received regular drinking water.

Compared to controls, chloroquine-treated mice had significantly prolonged survival and a significant reduction in Zika-induced weight loss (P<0.01 for both).

Next, the investigators used SJL mice to study horizontal and vertical transmission of Zika. They observed successful transmission of the virus from males to females and from mothers to pups.

The team then analyzed the effects of chloroquine on fetal transmission of Zika. Pregnant SJL mice were infected with Zika and given drinking water containing chloroquine (30 mg/kg/day) starting on day E13.5. The mice were euthanized on E18.5, and maternal blood and fetal brain samples were collected.

Chloroquine treatment resulted in a roughly 20-fold reduction in Zika virus titers in the maternal blood and fetal brain.

“Although chloroquine didn’t completely clear Zika from infected mice, it did reduce the viral load, suggesting it could limit the neurological damage found in newborns infected by the virus,” Dr Terskikh said.

“Chloroquine has a long history of successfully treating malaria, and there are no reports of it causing birth defects. Additional studies are certainly needed to determine the precise details of how it works. But given its low cost, availability, and safety history, further study in a clinical trial to test its effectiveness against Zika virus in humans is merited.” ![]()

Preclinical research suggests a drug used to prevent and treat malaria may also be effective against Zika virus.

Investigators found that chloroquine can protect human neural progenitors from infection with Zika virus.

The drug also decreased Zika-induced mortality in one mouse model and hindered transmission of Zika virus from mother to fetus in another mouse model.

Alexey Terskikh, PhD, of Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute in La Jolla, California, and his colleagues conducted this research and disclosed the results in Scientific Reports.

“There is still an urgent need to bolster our preparedness and capacity to respond to the next Zika outbreak,” Dr Terskikh said. “Our latest research suggests the antimalaria drug chloroquine may be an effective drug to treat and prevent Zika infections.”

The investigators first found that chloroquine reduced Zika infection in primary human fetal neural precursor cells.

The team also discovered that chloroquine reduced the percentage of Zika-positive cells and the level of apoptosis in neurospheres derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells.

The investigators then tested chloroquine in AG129 mice, which lack receptors for type I and II interferons and have been used to model Zika virus infection.

Some of these mice received chloroquine (50 mg/kg/day) in their drinking water for 2 days and were then infected with Zika virus. The mice continued to receive chloroquine at the same dose for 5 days and then received 5 mg/kg/day until the end of the experiment.

Control AG129 mice were infected with Zika virus and received regular drinking water.

Compared to controls, chloroquine-treated mice had significantly prolonged survival and a significant reduction in Zika-induced weight loss (P<0.01 for both).

Next, the investigators used SJL mice to study horizontal and vertical transmission of Zika. They observed successful transmission of the virus from males to females and from mothers to pups.

The team then analyzed the effects of chloroquine on fetal transmission of Zika. Pregnant SJL mice were infected with Zika and given drinking water containing chloroquine (30 mg/kg/day) starting on day E13.5. The mice were euthanized on E18.5, and maternal blood and fetal brain samples were collected.

Chloroquine treatment resulted in a roughly 20-fold reduction in Zika virus titers in the maternal blood and fetal brain.

“Although chloroquine didn’t completely clear Zika from infected mice, it did reduce the viral load, suggesting it could limit the neurological damage found in newborns infected by the virus,” Dr Terskikh said.

“Chloroquine has a long history of successfully treating malaria, and there are no reports of it causing birth defects. Additional studies are certainly needed to determine the precise details of how it works. But given its low cost, availability, and safety history, further study in a clinical trial to test its effectiveness against Zika virus in humans is merited.” ![]()

Preclinical research suggests a drug used to prevent and treat malaria may also be effective against Zika virus.

Investigators found that chloroquine can protect human neural progenitors from infection with Zika virus.

The drug also decreased Zika-induced mortality in one mouse model and hindered transmission of Zika virus from mother to fetus in another mouse model.

Alexey Terskikh, PhD, of Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute in La Jolla, California, and his colleagues conducted this research and disclosed the results in Scientific Reports.

“There is still an urgent need to bolster our preparedness and capacity to respond to the next Zika outbreak,” Dr Terskikh said. “Our latest research suggests the antimalaria drug chloroquine may be an effective drug to treat and prevent Zika infections.”

The investigators first found that chloroquine reduced Zika infection in primary human fetal neural precursor cells.

The team also discovered that chloroquine reduced the percentage of Zika-positive cells and the level of apoptosis in neurospheres derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells.

The investigators then tested chloroquine in AG129 mice, which lack receptors for type I and II interferons and have been used to model Zika virus infection.

Some of these mice received chloroquine (50 mg/kg/day) in their drinking water for 2 days and were then infected with Zika virus. The mice continued to receive chloroquine at the same dose for 5 days and then received 5 mg/kg/day until the end of the experiment.

Control AG129 mice were infected with Zika virus and received regular drinking water.

Compared to controls, chloroquine-treated mice had significantly prolonged survival and a significant reduction in Zika-induced weight loss (P<0.01 for both).

Next, the investigators used SJL mice to study horizontal and vertical transmission of Zika. They observed successful transmission of the virus from males to females and from mothers to pups.

The team then analyzed the effects of chloroquine on fetal transmission of Zika. Pregnant SJL mice were infected with Zika and given drinking water containing chloroquine (30 mg/kg/day) starting on day E13.5. The mice were euthanized on E18.5, and maternal blood and fetal brain samples were collected.

Chloroquine treatment resulted in a roughly 20-fold reduction in Zika virus titers in the maternal blood and fetal brain.

“Although chloroquine didn’t completely clear Zika from infected mice, it did reduce the viral load, suggesting it could limit the neurological damage found in newborns infected by the virus,” Dr Terskikh said.

“Chloroquine has a long history of successfully treating malaria, and there are no reports of it causing birth defects. Additional studies are certainly needed to determine the precise details of how it works. But given its low cost, availability, and safety history, further study in a clinical trial to test its effectiveness against Zika virus in humans is merited.” ![]()

Educational innovation

My son’s in medical school,” Fred told me. “First year.”

“Which school?”

Fred named a newly-chartered one.

“Really innovative curriculum,” he said.

“He got into a different school, too,” he said, “but he didn’t like how that school had canceled all lectures. Students just watch the lecture videos on their devices, so they scratched all the live ones.”

“Now that they don’t need lecturers, did they cut tuition?” I asked.

We both chuckled.

I was exposed to educational innovation on Day One of medical school, in the fall of 1968. (Go ahead, do the math.) The Dean addressed our entering class. “We’ve abolished tests,” he said. “We cut preclinical study from 2 years to 18 months, followed by one comprehensive exam.

"We want to get you into the clinic right away," he said, "because you chose to be doctors to help people. Even during the preclinical period, you’ll be getting not just dry frontal teaching but exposure to actual patients.”

We guessed that sounded good, especially the part about no tests. Less day-to-day studying. A lot less.

We still had lectures, of course, on biochemistry, anatomy, and so forth (they ran out of time and did all four extremities in 1 hour), but we felt little need to pay close attention. After all, any details we’d have to memorize would be diluted over three semesters, and 18 months was so far away.

As to the lectures themselves, I’ve never been diagnosed with actual narcolepsy, but when they turned out the lights and started showing slides, I fell fast asleep. Always have.

Most of us passed the comprehensive exam and moved on to the clinic. (We didn’t get into med school without knowing how to take tests, did we?)

The basic science faculty hated this educational innovation and recognized – correctly – that without tests we would take their classes less seriously. A couple of years later, the students themselves demanded that the tests be reinstated; lack of regular, numerical feedback made them anxious. So it was back to exams every 2 weeks. Poor devils.

Fast forward 40 years. Over lunch at a friend’s house, I recently met a young woman in her second year at a medical school in Chicago. “The school has an exciting, innovative curriculum,” she told me.

“No kidding,” I said. “What’s that?”

“They want to get us into the clinic as soon as possible,” she replied. “So they cut preclinical years to 18 months. And no regular tests. Just a comprehensive exam at the end. Much less day-to-day pressure.”

“Very innovative,” I observed.

***

Once in practice, I joined the clinical faculty of a local medical school. For 35 years, I hosted senior medical students for a month-long elective. During that time, I tried to pass on some of the things that weren’t on the standard academic curriculum. For instance, that patients have their own ideas about what is wrong with them, how it got that way, and what to do about it. That medical advice is less an order than a negotiation. Students seemed to find such notions – and their daily illustrations in the office – of some interest.

I put these and related deep thoughts between the covers of a book and sent a copy to the medical school registrar, from whom I had heard little over the years unless my student evaluations were 2 days late. My cover letter suggested that the school’s educators might be curious about what I’d been teaching their charges for 35 years.

The registrar replied by e-mail. “Thank you for your book,” she wrote. “I showed it to our dean of education, who told me that we would definitely not be changing our curriculum on the basis of your book. You might contact the medical librarian to see if they want to display it.”

I didn’t recall thinking, much less saying, that my ruminations ought to overturn the medical curriculum. I just thought they might be of some passing interest, coming as they did from an outside perspective.

Not so much, it turns out.

There are, in any event, so many exciting vistas of educational innovation to develop: genomics, precision medicine, and folding doctors into health care teams, and replacing clinical judgment with algorithms. The next generation of physicians, innovatively educated, will surpass all predecessors, just as we did.

Anyhow, they'll be bound to know more about the origins and insertions of the leg muscles. They could hardly know any less.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

My son’s in medical school,” Fred told me. “First year.”

“Which school?”

Fred named a newly-chartered one.

“Really innovative curriculum,” he said.

“He got into a different school, too,” he said, “but he didn’t like how that school had canceled all lectures. Students just watch the lecture videos on their devices, so they scratched all the live ones.”

“Now that they don’t need lecturers, did they cut tuition?” I asked.

We both chuckled.

I was exposed to educational innovation on Day One of medical school, in the fall of 1968. (Go ahead, do the math.) The Dean addressed our entering class. “We’ve abolished tests,” he said. “We cut preclinical study from 2 years to 18 months, followed by one comprehensive exam.

"We want to get you into the clinic right away," he said, "because you chose to be doctors to help people. Even during the preclinical period, you’ll be getting not just dry frontal teaching but exposure to actual patients.”

We guessed that sounded good, especially the part about no tests. Less day-to-day studying. A lot less.

We still had lectures, of course, on biochemistry, anatomy, and so forth (they ran out of time and did all four extremities in 1 hour), but we felt little need to pay close attention. After all, any details we’d have to memorize would be diluted over three semesters, and 18 months was so far away.

As to the lectures themselves, I’ve never been diagnosed with actual narcolepsy, but when they turned out the lights and started showing slides, I fell fast asleep. Always have.

Most of us passed the comprehensive exam and moved on to the clinic. (We didn’t get into med school without knowing how to take tests, did we?)

The basic science faculty hated this educational innovation and recognized – correctly – that without tests we would take their classes less seriously. A couple of years later, the students themselves demanded that the tests be reinstated; lack of regular, numerical feedback made them anxious. So it was back to exams every 2 weeks. Poor devils.

Fast forward 40 years. Over lunch at a friend’s house, I recently met a young woman in her second year at a medical school in Chicago. “The school has an exciting, innovative curriculum,” she told me.

“No kidding,” I said. “What’s that?”

“They want to get us into the clinic as soon as possible,” she replied. “So they cut preclinical years to 18 months. And no regular tests. Just a comprehensive exam at the end. Much less day-to-day pressure.”

“Very innovative,” I observed.

***

Once in practice, I joined the clinical faculty of a local medical school. For 35 years, I hosted senior medical students for a month-long elective. During that time, I tried to pass on some of the things that weren’t on the standard academic curriculum. For instance, that patients have their own ideas about what is wrong with them, how it got that way, and what to do about it. That medical advice is less an order than a negotiation. Students seemed to find such notions – and their daily illustrations in the office – of some interest.

I put these and related deep thoughts between the covers of a book and sent a copy to the medical school registrar, from whom I had heard little over the years unless my student evaluations were 2 days late. My cover letter suggested that the school’s educators might be curious about what I’d been teaching their charges for 35 years.

The registrar replied by e-mail. “Thank you for your book,” she wrote. “I showed it to our dean of education, who told me that we would definitely not be changing our curriculum on the basis of your book. You might contact the medical librarian to see if they want to display it.”

I didn’t recall thinking, much less saying, that my ruminations ought to overturn the medical curriculum. I just thought they might be of some passing interest, coming as they did from an outside perspective.

Not so much, it turns out.

There are, in any event, so many exciting vistas of educational innovation to develop: genomics, precision medicine, and folding doctors into health care teams, and replacing clinical judgment with algorithms. The next generation of physicians, innovatively educated, will surpass all predecessors, just as we did.

Anyhow, they'll be bound to know more about the origins and insertions of the leg muscles. They could hardly know any less.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

My son’s in medical school,” Fred told me. “First year.”

“Which school?”

Fred named a newly-chartered one.

“Really innovative curriculum,” he said.

“He got into a different school, too,” he said, “but he didn’t like how that school had canceled all lectures. Students just watch the lecture videos on their devices, so they scratched all the live ones.”

“Now that they don’t need lecturers, did they cut tuition?” I asked.

We both chuckled.

I was exposed to educational innovation on Day One of medical school, in the fall of 1968. (Go ahead, do the math.) The Dean addressed our entering class. “We’ve abolished tests,” he said. “We cut preclinical study from 2 years to 18 months, followed by one comprehensive exam.

"We want to get you into the clinic right away," he said, "because you chose to be doctors to help people. Even during the preclinical period, you’ll be getting not just dry frontal teaching but exposure to actual patients.”

We guessed that sounded good, especially the part about no tests. Less day-to-day studying. A lot less.

We still had lectures, of course, on biochemistry, anatomy, and so forth (they ran out of time and did all four extremities in 1 hour), but we felt little need to pay close attention. After all, any details we’d have to memorize would be diluted over three semesters, and 18 months was so far away.

As to the lectures themselves, I’ve never been diagnosed with actual narcolepsy, but when they turned out the lights and started showing slides, I fell fast asleep. Always have.

Most of us passed the comprehensive exam and moved on to the clinic. (We didn’t get into med school without knowing how to take tests, did we?)

The basic science faculty hated this educational innovation and recognized – correctly – that without tests we would take their classes less seriously. A couple of years later, the students themselves demanded that the tests be reinstated; lack of regular, numerical feedback made them anxious. So it was back to exams every 2 weeks. Poor devils.

Fast forward 40 years. Over lunch at a friend’s house, I recently met a young woman in her second year at a medical school in Chicago. “The school has an exciting, innovative curriculum,” she told me.

“No kidding,” I said. “What’s that?”

“They want to get us into the clinic as soon as possible,” she replied. “So they cut preclinical years to 18 months. And no regular tests. Just a comprehensive exam at the end. Much less day-to-day pressure.”

“Very innovative,” I observed.

***

Once in practice, I joined the clinical faculty of a local medical school. For 35 years, I hosted senior medical students for a month-long elective. During that time, I tried to pass on some of the things that weren’t on the standard academic curriculum. For instance, that patients have their own ideas about what is wrong with them, how it got that way, and what to do about it. That medical advice is less an order than a negotiation. Students seemed to find such notions – and their daily illustrations in the office – of some interest.

I put these and related deep thoughts between the covers of a book and sent a copy to the medical school registrar, from whom I had heard little over the years unless my student evaluations were 2 days late. My cover letter suggested that the school’s educators might be curious about what I’d been teaching their charges for 35 years.

The registrar replied by e-mail. “Thank you for your book,” she wrote. “I showed it to our dean of education, who told me that we would definitely not be changing our curriculum on the basis of your book. You might contact the medical librarian to see if they want to display it.”

I didn’t recall thinking, much less saying, that my ruminations ought to overturn the medical curriculum. I just thought they might be of some passing interest, coming as they did from an outside perspective.

Not so much, it turns out.

There are, in any event, so many exciting vistas of educational innovation to develop: genomics, precision medicine, and folding doctors into health care teams, and replacing clinical judgment with algorithms. The next generation of physicians, innovatively educated, will surpass all predecessors, just as we did.

Anyhow, they'll be bound to know more about the origins and insertions of the leg muscles. They could hardly know any less.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].