User login

HER2 status differed between primary tumor and CTCs in 18.8% of women with MBC

Discordance in HER2 status between the primary breast tumor and circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in women with HER2-negative metastatic disease was 18.8% in a prospective cohort of patients.

The probability of discordance decreased with increasing age but increased with primary tumors that were hormone-receptor positive, higher grade, and of lobular histology, Amelie De Gregorio, MD, and associates reported in JCO Precision Oncology.

The investigators evaluated the HER2 status of CTCs obtained from women with HER2-negative breast cancer screened in the ongoing German DETECT III trial, which is aimed at determining the efficacy of lapatinib in patients with initially HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer but HER2-positive CTCs. HER2 discordance was defined as the presence of a single CTC or more within 7.5 mL of peripheral blood that showed a strong immunohistochemical (IHC) staining intensity (IHC score 3+).

Out of 1,123 women screened, at least one CTC was detected in blood samples from 711 women (63.3%; 95% confidence interval, 60.4%-66.1%). The median number of CTCs detected was seven (interquartile range, 2-30; range, 1-35,078 CTCs), and discordance in HER2 phenotype between primary tumor and CTCs was found in 134 patients (18.8%), Dr. De Gregorio of University Hospital Ulm (Germany) and associates reported (JCO Precis Oncol. 2017 Sep 28. doi: 10.1200/PO.17.00023).

In a multivariable analysis, histologic type (lobular vs. ductal; odds ratio, 2.67; P less than .001), hormone receptor status (positive vs. negative; OR, 2.84; P = .024), and CTC number (greater than 5 vs. 1-4 CTCs; OR, 7.64; P less than .001) significantly and independently predicted discordance in HER2 phenotype between primary tumor and CTCs. There was also a significant effect of age, with the probability of discordance decreasing with increasing age, the investigators noted.

“The knowledge of factors associated with discordance in HER2 status may be incorporated into today’s clinical practice by guiding the decision process for performing biopsy to characterize metastatic relapse,” the investigators wrote.

“Moreover, the concept of liquid biopsy using CTCs as a real-time noninvasive monitoring tool to evaluate tumor biology, progression, and heterogeneity as a basis for more personalized treatment decisions should be tested in prospective randomized clinical trials,” they added.

The DETECT study program is supported by the Investigator-Initiated Study Program of Janssen Diagnostics, with clinical trials also supported by Pierre Fabre Pharma, TEVA Pharmaceuticals Industries, Amgen, Novartis Pharma, and Eisai. Dr. De Gregorio disclosed an advisory role with Roche Pharma AG; several coauthors disclosed consultancy and funding from various pharmaceutical companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @nikolaideslaura

Discordance in HER2 status between the primary breast tumor and circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in women with HER2-negative metastatic disease was 18.8% in a prospective cohort of patients.

The probability of discordance decreased with increasing age but increased with primary tumors that were hormone-receptor positive, higher grade, and of lobular histology, Amelie De Gregorio, MD, and associates reported in JCO Precision Oncology.

The investigators evaluated the HER2 status of CTCs obtained from women with HER2-negative breast cancer screened in the ongoing German DETECT III trial, which is aimed at determining the efficacy of lapatinib in patients with initially HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer but HER2-positive CTCs. HER2 discordance was defined as the presence of a single CTC or more within 7.5 mL of peripheral blood that showed a strong immunohistochemical (IHC) staining intensity (IHC score 3+).

Out of 1,123 women screened, at least one CTC was detected in blood samples from 711 women (63.3%; 95% confidence interval, 60.4%-66.1%). The median number of CTCs detected was seven (interquartile range, 2-30; range, 1-35,078 CTCs), and discordance in HER2 phenotype between primary tumor and CTCs was found in 134 patients (18.8%), Dr. De Gregorio of University Hospital Ulm (Germany) and associates reported (JCO Precis Oncol. 2017 Sep 28. doi: 10.1200/PO.17.00023).

In a multivariable analysis, histologic type (lobular vs. ductal; odds ratio, 2.67; P less than .001), hormone receptor status (positive vs. negative; OR, 2.84; P = .024), and CTC number (greater than 5 vs. 1-4 CTCs; OR, 7.64; P less than .001) significantly and independently predicted discordance in HER2 phenotype between primary tumor and CTCs. There was also a significant effect of age, with the probability of discordance decreasing with increasing age, the investigators noted.

“The knowledge of factors associated with discordance in HER2 status may be incorporated into today’s clinical practice by guiding the decision process for performing biopsy to characterize metastatic relapse,” the investigators wrote.

“Moreover, the concept of liquid biopsy using CTCs as a real-time noninvasive monitoring tool to evaluate tumor biology, progression, and heterogeneity as a basis for more personalized treatment decisions should be tested in prospective randomized clinical trials,” they added.

The DETECT study program is supported by the Investigator-Initiated Study Program of Janssen Diagnostics, with clinical trials also supported by Pierre Fabre Pharma, TEVA Pharmaceuticals Industries, Amgen, Novartis Pharma, and Eisai. Dr. De Gregorio disclosed an advisory role with Roche Pharma AG; several coauthors disclosed consultancy and funding from various pharmaceutical companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @nikolaideslaura

Discordance in HER2 status between the primary breast tumor and circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in women with HER2-negative metastatic disease was 18.8% in a prospective cohort of patients.

The probability of discordance decreased with increasing age but increased with primary tumors that were hormone-receptor positive, higher grade, and of lobular histology, Amelie De Gregorio, MD, and associates reported in JCO Precision Oncology.

The investigators evaluated the HER2 status of CTCs obtained from women with HER2-negative breast cancer screened in the ongoing German DETECT III trial, which is aimed at determining the efficacy of lapatinib in patients with initially HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer but HER2-positive CTCs. HER2 discordance was defined as the presence of a single CTC or more within 7.5 mL of peripheral blood that showed a strong immunohistochemical (IHC) staining intensity (IHC score 3+).

Out of 1,123 women screened, at least one CTC was detected in blood samples from 711 women (63.3%; 95% confidence interval, 60.4%-66.1%). The median number of CTCs detected was seven (interquartile range, 2-30; range, 1-35,078 CTCs), and discordance in HER2 phenotype between primary tumor and CTCs was found in 134 patients (18.8%), Dr. De Gregorio of University Hospital Ulm (Germany) and associates reported (JCO Precis Oncol. 2017 Sep 28. doi: 10.1200/PO.17.00023).

In a multivariable analysis, histologic type (lobular vs. ductal; odds ratio, 2.67; P less than .001), hormone receptor status (positive vs. negative; OR, 2.84; P = .024), and CTC number (greater than 5 vs. 1-4 CTCs; OR, 7.64; P less than .001) significantly and independently predicted discordance in HER2 phenotype between primary tumor and CTCs. There was also a significant effect of age, with the probability of discordance decreasing with increasing age, the investigators noted.

“The knowledge of factors associated with discordance in HER2 status may be incorporated into today’s clinical practice by guiding the decision process for performing biopsy to characterize metastatic relapse,” the investigators wrote.

“Moreover, the concept of liquid biopsy using CTCs as a real-time noninvasive monitoring tool to evaluate tumor biology, progression, and heterogeneity as a basis for more personalized treatment decisions should be tested in prospective randomized clinical trials,” they added.

The DETECT study program is supported by the Investigator-Initiated Study Program of Janssen Diagnostics, with clinical trials also supported by Pierre Fabre Pharma, TEVA Pharmaceuticals Industries, Amgen, Novartis Pharma, and Eisai. Dr. De Gregorio disclosed an advisory role with Roche Pharma AG; several coauthors disclosed consultancy and funding from various pharmaceutical companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @nikolaideslaura

FROM JCO PRECISION ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Histologic type (lobular vs. ductal; odds ratio, 2.67; P less than .001), hormone receptor status (positive vs. negative; OR, 2.84; P = .024), and CTC number (more than 5 vs. 1-4 CTCs; OR, 7.64; P less than .001) significantly predicted HER2 discordance between primary tumor and CTCs.

Data source: A prospective cohort of 1,123 women with metastatic breast cancer screened for the ongoing DETECT III trial in Germany.

Disclosures: The DETECT study program is supported by the Investigator-Initiated Study Program of Janssen Diagnostics, with clinical trials also supported by Pierre Fabre Pharma, TEVA Pharmaceuticals Industries, Amgen, Novartis Pharma, and Eisai. Dr. De Gregorio disclosed an advisory role with Roche Pharma AG; several coauthors disclosed consultancy and funding from various pharaceutical companies.

Lithium may reduce melanoma risk

Adults with a history of lithium exposure had a 32% lower risk of melanoma than did those who were not exposed in an unadjusted analysis of data from more than 2 million patients.

Microarray gene profiling techniques suggest that Wnt genes, which “encode a family of secreted glycoproteins that activate cellular signaling pathways to control cell differentiation, proliferation, and motility,” may be involved in melanoma development, wrote Maryam M. Asgari, MD, of the department of dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital and the department of population medicine at Harvard University, both in Boston, and her colleagues. In particular, “transcriptional profiling of melanoma cell lines has suggested that Wnt/beta-catenin signaling regulates a transcriptional signature predictive of less aggressive melanoma,” they wrote.

The psychiatric medication lithium activates the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway and has shown an ability to inhibit the proliferation of melanoma cells in a mouse model, but “to our knowledge, no published epidemiologic studies have examined the association of melanoma risk with lithium exposure,” they wrote.

The researchers reviewed data from the Kaiser Permanente Northern California database of 2,213,848 adult white patients who were members during 1997-2012, which included 11,317 with lithium exposure. They evaluated the association between lithium exposure and both incident melanoma risk and melanoma-associated mortality (J Invest Dermatol. 2017 Oct;137[10]:2087-91.).

Individuals exposed to lithium had a 32% reduced risk of melanoma in an unadjusted analysis; in an adjusted analysis, the reduced risk was 23% and was not significant.

However, there was a significant difference in melanoma incidence per 100,000 person-years in lithium-exposed individuals, compared with unexposed individuals (67.4 vs. 92.5, respectively; P = .027).

Among patients with melanoma, those with exposure to lithium had a lower mortality rate than those not exposed (4.68 vs. 7.21 per 1,000 person-years, respectively), but the sample size for this subgroup was too small to determine statistical significance. In addition, lithium exposure was associated with reduced likelihood of developing skin tumors greater than 4 mm and of presenting with extensive disease. Among those exposed to lithium, none presented with a thick tumor (Breslow depth greater than 4 mm), and none had regional or distant disease when they were diagnosed, compared with 2.8% and 6.3%, respectively, of those not exposed to lithium.

The findings were limited by several factors, including reliance on prescription information to determine lithium exposure, a homogeneous study population, and confounding variables, such as sun exposure behaviors, the researchers noted. However, the large study population adds strength to the results, and “our conclusions provide evidence that lithium, a relatively inexpensive and readily available drug, warrants further study in melanoma,” they said.

Lead author Dr. Asgari and one of the other four authors disclosed serving as investigators for studies funded by Valeant Pharmaceuticals and Pfizer. This study was supported by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Asgari is principal investigator in the Patient-Oriented Research in the Epidemiology of Skin Diseases lab at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Adults with a history of lithium exposure had a 32% lower risk of melanoma than did those who were not exposed in an unadjusted analysis of data from more than 2 million patients.

Microarray gene profiling techniques suggest that Wnt genes, which “encode a family of secreted glycoproteins that activate cellular signaling pathways to control cell differentiation, proliferation, and motility,” may be involved in melanoma development, wrote Maryam M. Asgari, MD, of the department of dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital and the department of population medicine at Harvard University, both in Boston, and her colleagues. In particular, “transcriptional profiling of melanoma cell lines has suggested that Wnt/beta-catenin signaling regulates a transcriptional signature predictive of less aggressive melanoma,” they wrote.

The psychiatric medication lithium activates the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway and has shown an ability to inhibit the proliferation of melanoma cells in a mouse model, but “to our knowledge, no published epidemiologic studies have examined the association of melanoma risk with lithium exposure,” they wrote.

The researchers reviewed data from the Kaiser Permanente Northern California database of 2,213,848 adult white patients who were members during 1997-2012, which included 11,317 with lithium exposure. They evaluated the association between lithium exposure and both incident melanoma risk and melanoma-associated mortality (J Invest Dermatol. 2017 Oct;137[10]:2087-91.).

Individuals exposed to lithium had a 32% reduced risk of melanoma in an unadjusted analysis; in an adjusted analysis, the reduced risk was 23% and was not significant.

However, there was a significant difference in melanoma incidence per 100,000 person-years in lithium-exposed individuals, compared with unexposed individuals (67.4 vs. 92.5, respectively; P = .027).

Among patients with melanoma, those with exposure to lithium had a lower mortality rate than those not exposed (4.68 vs. 7.21 per 1,000 person-years, respectively), but the sample size for this subgroup was too small to determine statistical significance. In addition, lithium exposure was associated with reduced likelihood of developing skin tumors greater than 4 mm and of presenting with extensive disease. Among those exposed to lithium, none presented with a thick tumor (Breslow depth greater than 4 mm), and none had regional or distant disease when they were diagnosed, compared with 2.8% and 6.3%, respectively, of those not exposed to lithium.

The findings were limited by several factors, including reliance on prescription information to determine lithium exposure, a homogeneous study population, and confounding variables, such as sun exposure behaviors, the researchers noted. However, the large study population adds strength to the results, and “our conclusions provide evidence that lithium, a relatively inexpensive and readily available drug, warrants further study in melanoma,” they said.

Lead author Dr. Asgari and one of the other four authors disclosed serving as investigators for studies funded by Valeant Pharmaceuticals and Pfizer. This study was supported by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Asgari is principal investigator in the Patient-Oriented Research in the Epidemiology of Skin Diseases lab at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Adults with a history of lithium exposure had a 32% lower risk of melanoma than did those who were not exposed in an unadjusted analysis of data from more than 2 million patients.

Microarray gene profiling techniques suggest that Wnt genes, which “encode a family of secreted glycoproteins that activate cellular signaling pathways to control cell differentiation, proliferation, and motility,” may be involved in melanoma development, wrote Maryam M. Asgari, MD, of the department of dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital and the department of population medicine at Harvard University, both in Boston, and her colleagues. In particular, “transcriptional profiling of melanoma cell lines has suggested that Wnt/beta-catenin signaling regulates a transcriptional signature predictive of less aggressive melanoma,” they wrote.

The psychiatric medication lithium activates the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway and has shown an ability to inhibit the proliferation of melanoma cells in a mouse model, but “to our knowledge, no published epidemiologic studies have examined the association of melanoma risk with lithium exposure,” they wrote.

The researchers reviewed data from the Kaiser Permanente Northern California database of 2,213,848 adult white patients who were members during 1997-2012, which included 11,317 with lithium exposure. They evaluated the association between lithium exposure and both incident melanoma risk and melanoma-associated mortality (J Invest Dermatol. 2017 Oct;137[10]:2087-91.).

Individuals exposed to lithium had a 32% reduced risk of melanoma in an unadjusted analysis; in an adjusted analysis, the reduced risk was 23% and was not significant.

However, there was a significant difference in melanoma incidence per 100,000 person-years in lithium-exposed individuals, compared with unexposed individuals (67.4 vs. 92.5, respectively; P = .027).

Among patients with melanoma, those with exposure to lithium had a lower mortality rate than those not exposed (4.68 vs. 7.21 per 1,000 person-years, respectively), but the sample size for this subgroup was too small to determine statistical significance. In addition, lithium exposure was associated with reduced likelihood of developing skin tumors greater than 4 mm and of presenting with extensive disease. Among those exposed to lithium, none presented with a thick tumor (Breslow depth greater than 4 mm), and none had regional or distant disease when they were diagnosed, compared with 2.8% and 6.3%, respectively, of those not exposed to lithium.

The findings were limited by several factors, including reliance on prescription information to determine lithium exposure, a homogeneous study population, and confounding variables, such as sun exposure behaviors, the researchers noted. However, the large study population adds strength to the results, and “our conclusions provide evidence that lithium, a relatively inexpensive and readily available drug, warrants further study in melanoma,” they said.

Lead author Dr. Asgari and one of the other four authors disclosed serving as investigators for studies funded by Valeant Pharmaceuticals and Pfizer. This study was supported by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Asgari is principal investigator in the Patient-Oriented Research in the Epidemiology of Skin Diseases lab at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF INVESTIGATIVE DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Lithium may reduce the risk of melanoma and melanoma mortality.

Major finding: The incidence of melanoma was significantly lower among adults exposed to lithium (67/100,000 person-years) than those not exposed (93/100,000 person-years).

Data source: The data come from a population-based, retrospective cohort study of 11,317 white adults in Northern California.

Disclosures: The lead author and one of the other four authors disclosed serving as investigators for studies funded by Valeant Pharmaceuticals and Pfizer. The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute.

FDA offers 2 tools to snuff out risk for e-cigarette fires and explosions

The Food and Drug Administration is concerned about incidents of overheating, fires, and explosions of e-cigarettes, or “vapes,” which in some cases have resulted in serious injuries. The agency is reviewing these types of incidents and has taken steps to protect the public.

The FDA recently developed resources for consumers, including tips to help avoid e-cigarette overheating and explosions, as well as social media tools to help spread the word about protective steps. The agency also has a reporting system to collect information about adverse experiences associated with e-cigarettes and other tobacco products. Comprehensive and accurate reports could provide evidence to help inform future actions to protect the public.

For e-cigarette users: Tips to help prevent fires and explosions

Learn about your device.

The best protection against battery explosions may be knowing about your device and how to handle and charge its batteries appropriately. Read and follow the manufacturer’s use and care recommendations. If the e-cigarette did not come with instructions or you have additional questions, contact the manufacturer.

Consider using e-cigarettes with protective features.

Some e-cigarettes have features such as firing button locks, vent holes, and protection against overcharging. These features are designed to prevent battery overheating and explosions, so do not remove or disable them.

Choose batteries carefully and replace them if necessary:

• Use only the batteries recommended for your device. Do not mix different brands, different charge levels, or old and new batteries in the same device.

• Replace the batteries if they get damaged or wet. If your e-cigarette is damaged and the batteries are not replaceable, contact the manufacturer.

• Stop using the device under certain circumstances. Although battery explosions can occur with no warning, you should immediately stop using your e-cigarette and get a safe distance from it if you notice any of these during use or while charging: strange noises; unusual smells; a leaking battery; the e-cigarette becoming unusually hot; or the device beginning to smoke, spark, emit flashes, or catch fire.

Be aware when charging your e-cigarette:

• Use only the charger that came with your device, and never charge it with a phone or tablet charger.

• Charge the device on a clean, flat surface, in a place you can clearly see it, and away from anything that can easily catch fire. Do not leave the e-cigarette charging on a surface such as a couch or pillow, where it may be more likely to overheat or turn on unintentionally.

• Do not charge the device overnight or leave it charging unattended.

Know this about carrying and storing your e-cigarette:

• Keep your e-cigarette covered. If you are carrying it in your pocket, avoid having it come in contact with coins or loose batteries.

• Protect the e-cigarette from extreme temperatures. Do not leave it in direct sunlight or in your car in extremely cold or hot temperatures.

Report any problems.

If something goes wrong with an e-cigarette, please submit a report to https://www.safetyreporting.hhs.gov

To make it easy to share the FDA’s top tips, the agency has developed a 5 Tips to Help Avoid “Vape” Battery Explosion infographic.

This infographic and other public-health resources can be found on a dedicated CTP webpage, which offers shareable and downloadable content to help spread the word about e-cigarette battery issues, as well as a video on how to report adverse experiences related to tobacco products to the FDA.

When a fire or explosion does occur: The Safety Reporting Portal

The CTP identified 143 reported incidents of e-cigarette overheating, fires, and explosions during 2009-2015, and 20 additional reports during 2016. Based on the FDA’s experience with underreporting of adverse events for other regulated products, the number of actual events is probably higher.

The FDA is working to collect more information to identify the true number of events and why these incidents are occurring. The agency has a Safety Reporting Portal (SRP) dedicated to receiving reports of issues associated with FDA-regulated products, including e-cigarettes and other tobacco products.

The FDA strongly encourages any physicians, other health care professionals, or those with firsthand knowledge about an unexpected e-cigarette incident to report it through the SRP. Family physicians can play a valuable reporting role by informing patients about the reporting system, helping people submit complete information about incidents related to e-cigarettes, or providing information about an incident on a patient’s behalf.

To report an e-cigarette failure or other tobacco-related adverse event, please go to the SRP and follow the instructions in each section. Those unable to use the SRP to submit a report can call 877-CTP-1373 or email [email protected].

The more complete and accurate a report is, the more helpful it can be to the FDA and, in turn, to public health. When submitting a report about an e-cigarette, please include:

• E-cigarette manufacturer’s name.

• E-cigarette’s brand name, model, and serial number.

• Battery’s brand name and model.

• Place the e-cigarette was purchased.

• Whether, and how, the product was being used at the time of the incident.

• Whether the product was used differently than intended by the manufacturer.

• Whether the product was modified in any way.

To collect as much detail as possible, the FDA encourages those submitting reports to upload photos or other files, such as police or hospital reports. They also appreciate submission of contact information, such as a phone number or email address, which will help the agency follow up with any questions related to the report. Personal information will not be shared or used for any additional matter and is protected by security practices. The HHS Privacy Policy contains more information.

Ongoing public health protection efforts

The FDA continues to evaluate possible ways to protect the public from device-related fires and explosions. During a public workshop in April, the FDA heard from experts including scientists, engineers, and e-cigarette manufacturers and retailers, as well as from the general public, about hazards and possible solutions related to batteries in e-cigarettes and other electronic nicotine delivery systems. Also, the agency’s premarket review process for electronic nicotine delivery systems includes an assessment of device operation and any features that may reduce the risks associated with product use, including testing related to overheating and exploding batteries.

Through these and other measures, the FDA is committed to identifying and addressing factors leading to e-cigarette overheating and any subsequent injuries. Health care professionals can help by spreading the word about the agency’s user tips and reporting portal.

To learn more broadly about the FDA’s ongoing efforts to protect the public health by regulating the manufacture, marketing, and distribution of tobacco products, please visit the Center for Tobacco Products website.

Dr. Holman is director of the office of science at the FDA’s Center for Tobacco Products.

The Food and Drug Administration is concerned about incidents of overheating, fires, and explosions of e-cigarettes, or “vapes,” which in some cases have resulted in serious injuries. The agency is reviewing these types of incidents and has taken steps to protect the public.

The FDA recently developed resources for consumers, including tips to help avoid e-cigarette overheating and explosions, as well as social media tools to help spread the word about protective steps. The agency also has a reporting system to collect information about adverse experiences associated with e-cigarettes and other tobacco products. Comprehensive and accurate reports could provide evidence to help inform future actions to protect the public.

For e-cigarette users: Tips to help prevent fires and explosions

Learn about your device.

The best protection against battery explosions may be knowing about your device and how to handle and charge its batteries appropriately. Read and follow the manufacturer’s use and care recommendations. If the e-cigarette did not come with instructions or you have additional questions, contact the manufacturer.

Consider using e-cigarettes with protective features.

Some e-cigarettes have features such as firing button locks, vent holes, and protection against overcharging. These features are designed to prevent battery overheating and explosions, so do not remove or disable them.

Choose batteries carefully and replace them if necessary:

• Use only the batteries recommended for your device. Do not mix different brands, different charge levels, or old and new batteries in the same device.

• Replace the batteries if they get damaged or wet. If your e-cigarette is damaged and the batteries are not replaceable, contact the manufacturer.

• Stop using the device under certain circumstances. Although battery explosions can occur with no warning, you should immediately stop using your e-cigarette and get a safe distance from it if you notice any of these during use or while charging: strange noises; unusual smells; a leaking battery; the e-cigarette becoming unusually hot; or the device beginning to smoke, spark, emit flashes, or catch fire.

Be aware when charging your e-cigarette:

• Use only the charger that came with your device, and never charge it with a phone or tablet charger.

• Charge the device on a clean, flat surface, in a place you can clearly see it, and away from anything that can easily catch fire. Do not leave the e-cigarette charging on a surface such as a couch or pillow, where it may be more likely to overheat or turn on unintentionally.

• Do not charge the device overnight or leave it charging unattended.

Know this about carrying and storing your e-cigarette:

• Keep your e-cigarette covered. If you are carrying it in your pocket, avoid having it come in contact with coins or loose batteries.

• Protect the e-cigarette from extreme temperatures. Do not leave it in direct sunlight or in your car in extremely cold or hot temperatures.

Report any problems.

If something goes wrong with an e-cigarette, please submit a report to https://www.safetyreporting.hhs.gov

To make it easy to share the FDA’s top tips, the agency has developed a 5 Tips to Help Avoid “Vape” Battery Explosion infographic.

This infographic and other public-health resources can be found on a dedicated CTP webpage, which offers shareable and downloadable content to help spread the word about e-cigarette battery issues, as well as a video on how to report adverse experiences related to tobacco products to the FDA.

When a fire or explosion does occur: The Safety Reporting Portal

The CTP identified 143 reported incidents of e-cigarette overheating, fires, and explosions during 2009-2015, and 20 additional reports during 2016. Based on the FDA’s experience with underreporting of adverse events for other regulated products, the number of actual events is probably higher.

The FDA is working to collect more information to identify the true number of events and why these incidents are occurring. The agency has a Safety Reporting Portal (SRP) dedicated to receiving reports of issues associated with FDA-regulated products, including e-cigarettes and other tobacco products.

The FDA strongly encourages any physicians, other health care professionals, or those with firsthand knowledge about an unexpected e-cigarette incident to report it through the SRP. Family physicians can play a valuable reporting role by informing patients about the reporting system, helping people submit complete information about incidents related to e-cigarettes, or providing information about an incident on a patient’s behalf.

To report an e-cigarette failure or other tobacco-related adverse event, please go to the SRP and follow the instructions in each section. Those unable to use the SRP to submit a report can call 877-CTP-1373 or email [email protected].

The more complete and accurate a report is, the more helpful it can be to the FDA and, in turn, to public health. When submitting a report about an e-cigarette, please include:

• E-cigarette manufacturer’s name.

• E-cigarette’s brand name, model, and serial number.

• Battery’s brand name and model.

• Place the e-cigarette was purchased.

• Whether, and how, the product was being used at the time of the incident.

• Whether the product was used differently than intended by the manufacturer.

• Whether the product was modified in any way.

To collect as much detail as possible, the FDA encourages those submitting reports to upload photos or other files, such as police or hospital reports. They also appreciate submission of contact information, such as a phone number or email address, which will help the agency follow up with any questions related to the report. Personal information will not be shared or used for any additional matter and is protected by security practices. The HHS Privacy Policy contains more information.

Ongoing public health protection efforts

The FDA continues to evaluate possible ways to protect the public from device-related fires and explosions. During a public workshop in April, the FDA heard from experts including scientists, engineers, and e-cigarette manufacturers and retailers, as well as from the general public, about hazards and possible solutions related to batteries in e-cigarettes and other electronic nicotine delivery systems. Also, the agency’s premarket review process for electronic nicotine delivery systems includes an assessment of device operation and any features that may reduce the risks associated with product use, including testing related to overheating and exploding batteries.

Through these and other measures, the FDA is committed to identifying and addressing factors leading to e-cigarette overheating and any subsequent injuries. Health care professionals can help by spreading the word about the agency’s user tips and reporting portal.

To learn more broadly about the FDA’s ongoing efforts to protect the public health by regulating the manufacture, marketing, and distribution of tobacco products, please visit the Center for Tobacco Products website.

Dr. Holman is director of the office of science at the FDA’s Center for Tobacco Products.

The Food and Drug Administration is concerned about incidents of overheating, fires, and explosions of e-cigarettes, or “vapes,” which in some cases have resulted in serious injuries. The agency is reviewing these types of incidents and has taken steps to protect the public.

The FDA recently developed resources for consumers, including tips to help avoid e-cigarette overheating and explosions, as well as social media tools to help spread the word about protective steps. The agency also has a reporting system to collect information about adverse experiences associated with e-cigarettes and other tobacco products. Comprehensive and accurate reports could provide evidence to help inform future actions to protect the public.

For e-cigarette users: Tips to help prevent fires and explosions

Learn about your device.

The best protection against battery explosions may be knowing about your device and how to handle and charge its batteries appropriately. Read and follow the manufacturer’s use and care recommendations. If the e-cigarette did not come with instructions or you have additional questions, contact the manufacturer.

Consider using e-cigarettes with protective features.

Some e-cigarettes have features such as firing button locks, vent holes, and protection against overcharging. These features are designed to prevent battery overheating and explosions, so do not remove or disable them.

Choose batteries carefully and replace them if necessary:

• Use only the batteries recommended for your device. Do not mix different brands, different charge levels, or old and new batteries in the same device.

• Replace the batteries if they get damaged or wet. If your e-cigarette is damaged and the batteries are not replaceable, contact the manufacturer.

• Stop using the device under certain circumstances. Although battery explosions can occur with no warning, you should immediately stop using your e-cigarette and get a safe distance from it if you notice any of these during use or while charging: strange noises; unusual smells; a leaking battery; the e-cigarette becoming unusually hot; or the device beginning to smoke, spark, emit flashes, or catch fire.

Be aware when charging your e-cigarette:

• Use only the charger that came with your device, and never charge it with a phone or tablet charger.

• Charge the device on a clean, flat surface, in a place you can clearly see it, and away from anything that can easily catch fire. Do not leave the e-cigarette charging on a surface such as a couch or pillow, where it may be more likely to overheat or turn on unintentionally.

• Do not charge the device overnight or leave it charging unattended.

Know this about carrying and storing your e-cigarette:

• Keep your e-cigarette covered. If you are carrying it in your pocket, avoid having it come in contact with coins or loose batteries.

• Protect the e-cigarette from extreme temperatures. Do not leave it in direct sunlight or in your car in extremely cold or hot temperatures.

Report any problems.

If something goes wrong with an e-cigarette, please submit a report to https://www.safetyreporting.hhs.gov

To make it easy to share the FDA’s top tips, the agency has developed a 5 Tips to Help Avoid “Vape” Battery Explosion infographic.

This infographic and other public-health resources can be found on a dedicated CTP webpage, which offers shareable and downloadable content to help spread the word about e-cigarette battery issues, as well as a video on how to report adverse experiences related to tobacco products to the FDA.

When a fire or explosion does occur: The Safety Reporting Portal

The CTP identified 143 reported incidents of e-cigarette overheating, fires, and explosions during 2009-2015, and 20 additional reports during 2016. Based on the FDA’s experience with underreporting of adverse events for other regulated products, the number of actual events is probably higher.

The FDA is working to collect more information to identify the true number of events and why these incidents are occurring. The agency has a Safety Reporting Portal (SRP) dedicated to receiving reports of issues associated with FDA-regulated products, including e-cigarettes and other tobacco products.

The FDA strongly encourages any physicians, other health care professionals, or those with firsthand knowledge about an unexpected e-cigarette incident to report it through the SRP. Family physicians can play a valuable reporting role by informing patients about the reporting system, helping people submit complete information about incidents related to e-cigarettes, or providing information about an incident on a patient’s behalf.

To report an e-cigarette failure or other tobacco-related adverse event, please go to the SRP and follow the instructions in each section. Those unable to use the SRP to submit a report can call 877-CTP-1373 or email [email protected].

The more complete and accurate a report is, the more helpful it can be to the FDA and, in turn, to public health. When submitting a report about an e-cigarette, please include:

• E-cigarette manufacturer’s name.

• E-cigarette’s brand name, model, and serial number.

• Battery’s brand name and model.

• Place the e-cigarette was purchased.

• Whether, and how, the product was being used at the time of the incident.

• Whether the product was used differently than intended by the manufacturer.

• Whether the product was modified in any way.

To collect as much detail as possible, the FDA encourages those submitting reports to upload photos or other files, such as police or hospital reports. They also appreciate submission of contact information, such as a phone number or email address, which will help the agency follow up with any questions related to the report. Personal information will not be shared or used for any additional matter and is protected by security practices. The HHS Privacy Policy contains more information.

Ongoing public health protection efforts

The FDA continues to evaluate possible ways to protect the public from device-related fires and explosions. During a public workshop in April, the FDA heard from experts including scientists, engineers, and e-cigarette manufacturers and retailers, as well as from the general public, about hazards and possible solutions related to batteries in e-cigarettes and other electronic nicotine delivery systems. Also, the agency’s premarket review process for electronic nicotine delivery systems includes an assessment of device operation and any features that may reduce the risks associated with product use, including testing related to overheating and exploding batteries.

Through these and other measures, the FDA is committed to identifying and addressing factors leading to e-cigarette overheating and any subsequent injuries. Health care professionals can help by spreading the word about the agency’s user tips and reporting portal.

To learn more broadly about the FDA’s ongoing efforts to protect the public health by regulating the manufacture, marketing, and distribution of tobacco products, please visit the Center for Tobacco Products website.

Dr. Holman is director of the office of science at the FDA’s Center for Tobacco Products.

PRIDE study supports novel approach to ECT for geriatric depression

PARIS – Results of the randomized phase 2 portion of the landmark PRIDE study of electroconvulsive therapy for severe unipolar depression in geriatric patients hold a key message for clinicians, according to Charles H. Kellner, MD.

“The clinical take-home message is that practitioners should be liberal in prescribing additional ECT past the acute course. So our recommendation is that tapering ECT courses and being liberal with continuation and maintenance ECT should be adopted in clinical practice more widely with the aim of preventing full syndromic relapse and its catastrophic consequences,” Dr. Kellner said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

PRIDE (Prolonging Remission in Depressed Elderly) was a National Institute of Mental Health–sponsored nine-center study of right unilateral ultrabrief pulse ECT at 0.25 msec plus supportive pharmacotherapy for treatment of geriatric depression.

Phase 1 of the study involved 240 affected patients, 62% of whom achieved remission after receiving this form of ECT at six times the seizure threshold thrice weekly for up to 1 month coupled with low- or medium-dose venlafaxine. A mean of 7.3 ECT sessions were needed to attain remission as defined by a score of 10 or less on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D24) on two consecutive occasions, down from a mean baseline score of 31.2. The scale was administered three times per week. Safety and tolerability of the ECT regimen were excellent, according to Dr. Kellner, chief of electroconvulsive therapy at New York Community Hospital and a psychiatrist at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York.

The PRIDE phase 1 data confirmed several points previously made in earlier studies. One is that the older patients are, the more ECT-responsive they are, even within an all-geriatric cohort such as PRIDE. Indeed, the remission rate was 55% in the 60- to 69-year-olds, compared with 72% in the 70- to 79-year-olds.

Another finding consistent with other studies: Patients with psychotic depression do particularly well with ECT. All PRIDE participants with psychotic depression achieved remission.

Also, ECT had a very rapid antisuicidal effect. At baseline, 24% of patients had a score of 1 on HAM-D24 item 3, which rates suicidality. An additional 34% had a baseline score of 2, 14% scored 3, and only 23% had a score of 0. After only a few weeks of ECT, however, 84% of patients had a score of 0 and 9% scored a 1.

“That’s one of the compelling clinical reasons to refer patients for ECT: This type of ECT is really good for treating suicidality,” Dr. Kellner noted.

Phase 2 was the more interesting part of the PRIDE study, he continued, because it evaluated in randomized fashion the efficacy and tolerability of a novel flexible, individualized strategy for as-needed maintenance ECT to sustain the mood improvement once remission was achieved. Dr. Kellner stressed that some form of maintenance therapy is essential post ECT-induced remission.

“It’s unreasonable to expect that ECT could cure the patients’ underlying illness and protect them from getting sick again for the rest of their lives. One has to understand this is a recurrent episodic illness that we’re treating. What ECT does is treat the current episode, and it does it better and more thoroughly than any other treatment in psychiatry,” Dr. Kellner said.

Post-ECT relapse rates are clearly higher in the modern era, which makes a compelling case for developing safe and effective maintenance strategies.

“We don’t quite understand why relapse rates are higher today. My belief is that for patients who come to ECT, their illness has been destabilized by having been on multiple trials of antidepressant medications beforehand. It may also be that the forms of ECT that we’re using today are somewhat less potent than the ones used in previous decades,” Dr. Kellner conceded.

He and his coinvestigators named their investigational maintenance ECT strategy STABLE, for Symptom-Titrated, Algorithm-Based Longitudinal ECT. It’s a complex algorithm described in detail in a published report (Am J Psychiatry. 2016 Nov 1; 173[11]:1110-18). Basically, it consisted of four mandatory additional ECT sessions administered once weekly for the first month post remission, followed by either one, two, or no ECT sessions per week based upon evidence of deterioration as expressed in HAM-D24 scores.

In phase 2 of PRIDE, 128 remitters from phase 1 were continued on venlafaxine at a mean dose of 192 mg/day. In addition, they were placed on lithium, achieving a mean lithium level of 0.53 mEq/L, which Dr. Kellner deemed “low but reasonable.” These 128 patients were then randomized to the STABLE arm of flexibly administered ECT or to medication only and were followed prospectively for 6 months.

The primary endpoint was change in HAM-D24 score over the course of 6 months. From a baseline mean total score of 6, the mean score climbed to 8.4 in the medication-only group while dropping to 4.2 in the STABLE arm.

“At every time point along the way in the 6-month course of phase 2 of the illness, patients who were in the STABLE arm were less symptomatic and doing better than patients in the medication-only arm,” Dr. Kellner observed.

The key secondary efficacy outcome was change in the Clinical Global Impressions Severity scale. At follow-up, the patients in the flexible ECT plus medication arm were 5.2 times more likely to be rated “not ill at all” than were those on pharmacotherapy only.

In addition, relapse occurred in 20% of the medication-only group versus 13% in the STABLE group.

Global cognitive functioning as assessed by the Mini-Mental State Examination – crudely, in Dr. Kellner’s view – did not differ between the two groups at follow-up. Results of more sophisticated tests of multiple specific domains of cognition will be forthcoming.

Of note, two-thirds of patients in the STABLE arm required no additional ECT after their four continuation ECTs during the first month.

A swipe at ECT’s critics

Dr. Kellner called ECT “a fabulous therapy,” albeit one with a serious image problem.

“I think the problem with ECT is not that we don’t know all the details of how it works or what it does clinically, it’s really a sociopolitical issue about ECT not being adequately accepted. I break down this lack of acceptance into two forms: The first is passive lack of acceptance based on our profession not having embraced ECT and continuing to fail to embrace it. The other is the active propaganda against ECT that is promulgated by the Church of Scientology, which has taken on a life of its own now because of the Internet. ECT is still fought by the Church of Scientology. They fund lots of people to say incorrect nasty things about ECT to inappropriately frighten our patients,” Dr. Kellner charged.

He cautioned that proposed new Food and Drug Administration regulations governing ECT devices would greatly limit the use of ECT, restricting it to adults with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder or who require a rapid response. Other currently cleared indications would become off-label uses.

“With off-label ECT, the potential problem is practitioners may not be covered by their malpractice insurance. And the bigger issue is health insurers may not pay for it unless the ECT is for an on-label indication,” Dr. Kellner said.

He shared that he has found extremely helpful a colleague’s advice to demystify ECT by inviting a family member to witness a patient’s treatment session. That witness can then testify to others that what goes on bears no resemblance to what happens to Jack Nicholson in the classic film “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.”

The PRIDE study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Kellner reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

PARIS – Results of the randomized phase 2 portion of the landmark PRIDE study of electroconvulsive therapy for severe unipolar depression in geriatric patients hold a key message for clinicians, according to Charles H. Kellner, MD.

“The clinical take-home message is that practitioners should be liberal in prescribing additional ECT past the acute course. So our recommendation is that tapering ECT courses and being liberal with continuation and maintenance ECT should be adopted in clinical practice more widely with the aim of preventing full syndromic relapse and its catastrophic consequences,” Dr. Kellner said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

PRIDE (Prolonging Remission in Depressed Elderly) was a National Institute of Mental Health–sponsored nine-center study of right unilateral ultrabrief pulse ECT at 0.25 msec plus supportive pharmacotherapy for treatment of geriatric depression.

Phase 1 of the study involved 240 affected patients, 62% of whom achieved remission after receiving this form of ECT at six times the seizure threshold thrice weekly for up to 1 month coupled with low- or medium-dose venlafaxine. A mean of 7.3 ECT sessions were needed to attain remission as defined by a score of 10 or less on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D24) on two consecutive occasions, down from a mean baseline score of 31.2. The scale was administered three times per week. Safety and tolerability of the ECT regimen were excellent, according to Dr. Kellner, chief of electroconvulsive therapy at New York Community Hospital and a psychiatrist at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York.

The PRIDE phase 1 data confirmed several points previously made in earlier studies. One is that the older patients are, the more ECT-responsive they are, even within an all-geriatric cohort such as PRIDE. Indeed, the remission rate was 55% in the 60- to 69-year-olds, compared with 72% in the 70- to 79-year-olds.

Another finding consistent with other studies: Patients with psychotic depression do particularly well with ECT. All PRIDE participants with psychotic depression achieved remission.

Also, ECT had a very rapid antisuicidal effect. At baseline, 24% of patients had a score of 1 on HAM-D24 item 3, which rates suicidality. An additional 34% had a baseline score of 2, 14% scored 3, and only 23% had a score of 0. After only a few weeks of ECT, however, 84% of patients had a score of 0 and 9% scored a 1.

“That’s one of the compelling clinical reasons to refer patients for ECT: This type of ECT is really good for treating suicidality,” Dr. Kellner noted.

Phase 2 was the more interesting part of the PRIDE study, he continued, because it evaluated in randomized fashion the efficacy and tolerability of a novel flexible, individualized strategy for as-needed maintenance ECT to sustain the mood improvement once remission was achieved. Dr. Kellner stressed that some form of maintenance therapy is essential post ECT-induced remission.

“It’s unreasonable to expect that ECT could cure the patients’ underlying illness and protect them from getting sick again for the rest of their lives. One has to understand this is a recurrent episodic illness that we’re treating. What ECT does is treat the current episode, and it does it better and more thoroughly than any other treatment in psychiatry,” Dr. Kellner said.

Post-ECT relapse rates are clearly higher in the modern era, which makes a compelling case for developing safe and effective maintenance strategies.

“We don’t quite understand why relapse rates are higher today. My belief is that for patients who come to ECT, their illness has been destabilized by having been on multiple trials of antidepressant medications beforehand. It may also be that the forms of ECT that we’re using today are somewhat less potent than the ones used in previous decades,” Dr. Kellner conceded.

He and his coinvestigators named their investigational maintenance ECT strategy STABLE, for Symptom-Titrated, Algorithm-Based Longitudinal ECT. It’s a complex algorithm described in detail in a published report (Am J Psychiatry. 2016 Nov 1; 173[11]:1110-18). Basically, it consisted of four mandatory additional ECT sessions administered once weekly for the first month post remission, followed by either one, two, or no ECT sessions per week based upon evidence of deterioration as expressed in HAM-D24 scores.

In phase 2 of PRIDE, 128 remitters from phase 1 were continued on venlafaxine at a mean dose of 192 mg/day. In addition, they were placed on lithium, achieving a mean lithium level of 0.53 mEq/L, which Dr. Kellner deemed “low but reasonable.” These 128 patients were then randomized to the STABLE arm of flexibly administered ECT or to medication only and were followed prospectively for 6 months.

The primary endpoint was change in HAM-D24 score over the course of 6 months. From a baseline mean total score of 6, the mean score climbed to 8.4 in the medication-only group while dropping to 4.2 in the STABLE arm.

“At every time point along the way in the 6-month course of phase 2 of the illness, patients who were in the STABLE arm were less symptomatic and doing better than patients in the medication-only arm,” Dr. Kellner observed.

The key secondary efficacy outcome was change in the Clinical Global Impressions Severity scale. At follow-up, the patients in the flexible ECT plus medication arm were 5.2 times more likely to be rated “not ill at all” than were those on pharmacotherapy only.

In addition, relapse occurred in 20% of the medication-only group versus 13% in the STABLE group.

Global cognitive functioning as assessed by the Mini-Mental State Examination – crudely, in Dr. Kellner’s view – did not differ between the two groups at follow-up. Results of more sophisticated tests of multiple specific domains of cognition will be forthcoming.

Of note, two-thirds of patients in the STABLE arm required no additional ECT after their four continuation ECTs during the first month.

A swipe at ECT’s critics

Dr. Kellner called ECT “a fabulous therapy,” albeit one with a serious image problem.

“I think the problem with ECT is not that we don’t know all the details of how it works or what it does clinically, it’s really a sociopolitical issue about ECT not being adequately accepted. I break down this lack of acceptance into two forms: The first is passive lack of acceptance based on our profession not having embraced ECT and continuing to fail to embrace it. The other is the active propaganda against ECT that is promulgated by the Church of Scientology, which has taken on a life of its own now because of the Internet. ECT is still fought by the Church of Scientology. They fund lots of people to say incorrect nasty things about ECT to inappropriately frighten our patients,” Dr. Kellner charged.

He cautioned that proposed new Food and Drug Administration regulations governing ECT devices would greatly limit the use of ECT, restricting it to adults with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder or who require a rapid response. Other currently cleared indications would become off-label uses.

“With off-label ECT, the potential problem is practitioners may not be covered by their malpractice insurance. And the bigger issue is health insurers may not pay for it unless the ECT is for an on-label indication,” Dr. Kellner said.

He shared that he has found extremely helpful a colleague’s advice to demystify ECT by inviting a family member to witness a patient’s treatment session. That witness can then testify to others that what goes on bears no resemblance to what happens to Jack Nicholson in the classic film “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.”

The PRIDE study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Kellner reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

PARIS – Results of the randomized phase 2 portion of the landmark PRIDE study of electroconvulsive therapy for severe unipolar depression in geriatric patients hold a key message for clinicians, according to Charles H. Kellner, MD.

“The clinical take-home message is that practitioners should be liberal in prescribing additional ECT past the acute course. So our recommendation is that tapering ECT courses and being liberal with continuation and maintenance ECT should be adopted in clinical practice more widely with the aim of preventing full syndromic relapse and its catastrophic consequences,” Dr. Kellner said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

PRIDE (Prolonging Remission in Depressed Elderly) was a National Institute of Mental Health–sponsored nine-center study of right unilateral ultrabrief pulse ECT at 0.25 msec plus supportive pharmacotherapy for treatment of geriatric depression.

Phase 1 of the study involved 240 affected patients, 62% of whom achieved remission after receiving this form of ECT at six times the seizure threshold thrice weekly for up to 1 month coupled with low- or medium-dose venlafaxine. A mean of 7.3 ECT sessions were needed to attain remission as defined by a score of 10 or less on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D24) on two consecutive occasions, down from a mean baseline score of 31.2. The scale was administered three times per week. Safety and tolerability of the ECT regimen were excellent, according to Dr. Kellner, chief of electroconvulsive therapy at New York Community Hospital and a psychiatrist at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York.

The PRIDE phase 1 data confirmed several points previously made in earlier studies. One is that the older patients are, the more ECT-responsive they are, even within an all-geriatric cohort such as PRIDE. Indeed, the remission rate was 55% in the 60- to 69-year-olds, compared with 72% in the 70- to 79-year-olds.

Another finding consistent with other studies: Patients with psychotic depression do particularly well with ECT. All PRIDE participants with psychotic depression achieved remission.

Also, ECT had a very rapid antisuicidal effect. At baseline, 24% of patients had a score of 1 on HAM-D24 item 3, which rates suicidality. An additional 34% had a baseline score of 2, 14% scored 3, and only 23% had a score of 0. After only a few weeks of ECT, however, 84% of patients had a score of 0 and 9% scored a 1.

“That’s one of the compelling clinical reasons to refer patients for ECT: This type of ECT is really good for treating suicidality,” Dr. Kellner noted.

Phase 2 was the more interesting part of the PRIDE study, he continued, because it evaluated in randomized fashion the efficacy and tolerability of a novel flexible, individualized strategy for as-needed maintenance ECT to sustain the mood improvement once remission was achieved. Dr. Kellner stressed that some form of maintenance therapy is essential post ECT-induced remission.

“It’s unreasonable to expect that ECT could cure the patients’ underlying illness and protect them from getting sick again for the rest of their lives. One has to understand this is a recurrent episodic illness that we’re treating. What ECT does is treat the current episode, and it does it better and more thoroughly than any other treatment in psychiatry,” Dr. Kellner said.

Post-ECT relapse rates are clearly higher in the modern era, which makes a compelling case for developing safe and effective maintenance strategies.

“We don’t quite understand why relapse rates are higher today. My belief is that for patients who come to ECT, their illness has been destabilized by having been on multiple trials of antidepressant medications beforehand. It may also be that the forms of ECT that we’re using today are somewhat less potent than the ones used in previous decades,” Dr. Kellner conceded.

He and his coinvestigators named their investigational maintenance ECT strategy STABLE, for Symptom-Titrated, Algorithm-Based Longitudinal ECT. It’s a complex algorithm described in detail in a published report (Am J Psychiatry. 2016 Nov 1; 173[11]:1110-18). Basically, it consisted of four mandatory additional ECT sessions administered once weekly for the first month post remission, followed by either one, two, or no ECT sessions per week based upon evidence of deterioration as expressed in HAM-D24 scores.

In phase 2 of PRIDE, 128 remitters from phase 1 were continued on venlafaxine at a mean dose of 192 mg/day. In addition, they were placed on lithium, achieving a mean lithium level of 0.53 mEq/L, which Dr. Kellner deemed “low but reasonable.” These 128 patients were then randomized to the STABLE arm of flexibly administered ECT or to medication only and were followed prospectively for 6 months.

The primary endpoint was change in HAM-D24 score over the course of 6 months. From a baseline mean total score of 6, the mean score climbed to 8.4 in the medication-only group while dropping to 4.2 in the STABLE arm.

“At every time point along the way in the 6-month course of phase 2 of the illness, patients who were in the STABLE arm were less symptomatic and doing better than patients in the medication-only arm,” Dr. Kellner observed.

The key secondary efficacy outcome was change in the Clinical Global Impressions Severity scale. At follow-up, the patients in the flexible ECT plus medication arm were 5.2 times more likely to be rated “not ill at all” than were those on pharmacotherapy only.

In addition, relapse occurred in 20% of the medication-only group versus 13% in the STABLE group.

Global cognitive functioning as assessed by the Mini-Mental State Examination – crudely, in Dr. Kellner’s view – did not differ between the two groups at follow-up. Results of more sophisticated tests of multiple specific domains of cognition will be forthcoming.

Of note, two-thirds of patients in the STABLE arm required no additional ECT after their four continuation ECTs during the first month.

A swipe at ECT’s critics

Dr. Kellner called ECT “a fabulous therapy,” albeit one with a serious image problem.

“I think the problem with ECT is not that we don’t know all the details of how it works or what it does clinically, it’s really a sociopolitical issue about ECT not being adequately accepted. I break down this lack of acceptance into two forms: The first is passive lack of acceptance based on our profession not having embraced ECT and continuing to fail to embrace it. The other is the active propaganda against ECT that is promulgated by the Church of Scientology, which has taken on a life of its own now because of the Internet. ECT is still fought by the Church of Scientology. They fund lots of people to say incorrect nasty things about ECT to inappropriately frighten our patients,” Dr. Kellner charged.

He cautioned that proposed new Food and Drug Administration regulations governing ECT devices would greatly limit the use of ECT, restricting it to adults with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder or who require a rapid response. Other currently cleared indications would become off-label uses.

“With off-label ECT, the potential problem is practitioners may not be covered by their malpractice insurance. And the bigger issue is health insurers may not pay for it unless the ECT is for an on-label indication,” Dr. Kellner said.

He shared that he has found extremely helpful a colleague’s advice to demystify ECT by inviting a family member to witness a patient’s treatment session. That witness can then testify to others that what goes on bears no resemblance to what happens to Jack Nicholson in the classic film “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.”

The PRIDE study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Kellner reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AT THE ECNP CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: At 6 months follow-up, the mean score on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression was 4.2 points lower in the flexible maintenance ECT group than in the medication-only group, from a baseline score of 6.

Data source: Phase 2 of the PRIDE study randomized 128 elderly patients whose severe depression remitted in response to ECT to one of two maintenance treatment strategies.

Disclosures: The PRIDE study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

FDA approves first non–finger-stick glucose monitoring system

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the FreeStyle Libre Flash Glucose Monitoring System for the continuous monitoring of glucose in adults with diabetes, the first system of its type that does not require blood samples for calibration, according to a press release.

Instead of using a more standard finger stick with which patients must draw blood samples multiple times a day to measure glucose levels, the FreeStyle Libre Flash Glucose Monitoring System uses a thin wire less than 0.4-mm thick inserted underneath the skin in the back of the upper arm to continually monitor glucose. Blood glucose levels are read by swiping a mobile reader over the wire. After a 12-hour start-up period, the wire can be worn for 10 days.

FDA approval was based on results from a study of diabetes patients older than 18 years, as well as a performance review comparing readings obtained by the device with readings obtained in a traditional laboratory method utilizing blood samples.

“This system allows people with diabetes to avoid the additional step of finger-stick calibration, which can sometimes be painful, but still provides necessary information for treating their diabetes – with a wave of the mobile reader,” Donald St. Pierre, acting director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health and deputy director of new product evaluation in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the FreeStyle Libre Flash Glucose Monitoring System for the continuous monitoring of glucose in adults with diabetes, the first system of its type that does not require blood samples for calibration, according to a press release.

Instead of using a more standard finger stick with which patients must draw blood samples multiple times a day to measure glucose levels, the FreeStyle Libre Flash Glucose Monitoring System uses a thin wire less than 0.4-mm thick inserted underneath the skin in the back of the upper arm to continually monitor glucose. Blood glucose levels are read by swiping a mobile reader over the wire. After a 12-hour start-up period, the wire can be worn for 10 days.

FDA approval was based on results from a study of diabetes patients older than 18 years, as well as a performance review comparing readings obtained by the device with readings obtained in a traditional laboratory method utilizing blood samples.

“This system allows people with diabetes to avoid the additional step of finger-stick calibration, which can sometimes be painful, but still provides necessary information for treating their diabetes – with a wave of the mobile reader,” Donald St. Pierre, acting director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health and deputy director of new product evaluation in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the FreeStyle Libre Flash Glucose Monitoring System for the continuous monitoring of glucose in adults with diabetes, the first system of its type that does not require blood samples for calibration, according to a press release.

Instead of using a more standard finger stick with which patients must draw blood samples multiple times a day to measure glucose levels, the FreeStyle Libre Flash Glucose Monitoring System uses a thin wire less than 0.4-mm thick inserted underneath the skin in the back of the upper arm to continually monitor glucose. Blood glucose levels are read by swiping a mobile reader over the wire. After a 12-hour start-up period, the wire can be worn for 10 days.

FDA approval was based on results from a study of diabetes patients older than 18 years, as well as a performance review comparing readings obtained by the device with readings obtained in a traditional laboratory method utilizing blood samples.

“This system allows people with diabetes to avoid the additional step of finger-stick calibration, which can sometimes be painful, but still provides necessary information for treating their diabetes – with a wave of the mobile reader,” Donald St. Pierre, acting director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health and deputy director of new product evaluation in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

A spike in syphilis puts prenatal care in focus

Fifteen years ago, reported cases of syphilis in the United States were so infrequent that public health officials thought it might join the ranks of malaria, polio, and smallpox as an eradicated disease. That turned out to be wishful thinking.

According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, between 2012 and 2015, the overall rates of syphilis in the United States increased by 48%, while the rates of primary and secondary infection among women spiked by 56%. That was a compelling enough rise, but fresh data from the agency indicate that the overall rates of syphilis increased by 17.6% between 2015 and 2016, and by 74% between 2012 and 2016.

These trends prompted the CDC to launch a “call to action” educational campaign in an effort to curb the rising syphilis rates. The United States Preventive Services Task Force also is taking action. It recently posted a research plan on screening pregnant women for syphilis that will form the basis of a forthcoming evidence review and, potentially, new recommendations.

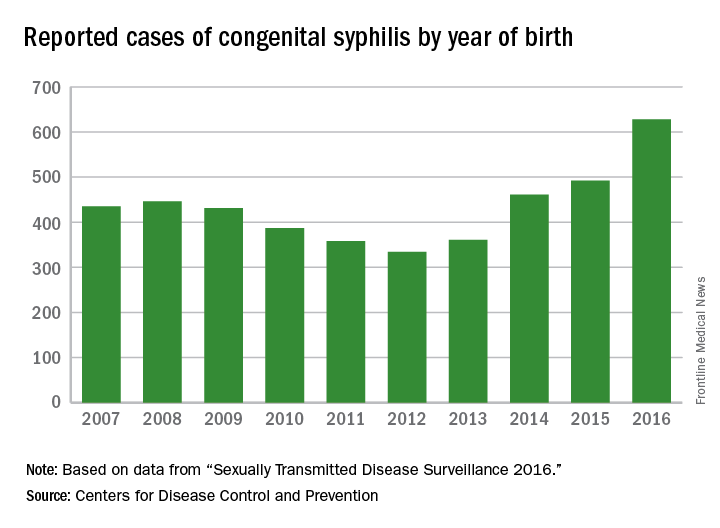

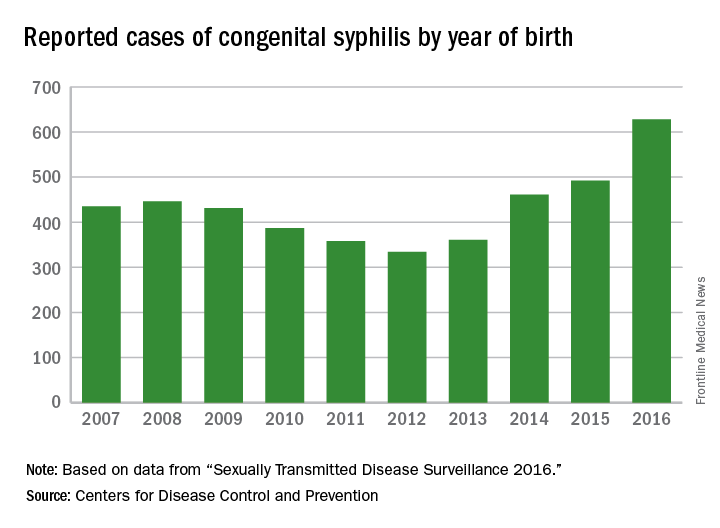

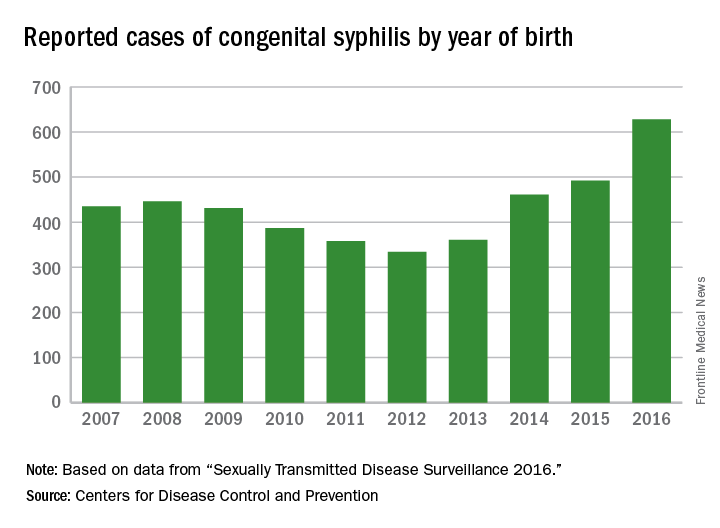

observed in all regions of the United States during the same time period, said Dr. Kidd, who coauthored a 2015 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report on the topic (MMWR. 2015 Nov 13;64[44]:1241-5). That analysis found that during 2012-2014, the number of reported CS cases in the United States increased from 334 to 458, which represents a rate increase from 8.4 to 11.6 cases per 100,000 live births. This contrasted with earlier data, which found that the overall rate of reported CS had decreased from 10.5 to 8.4 cases per 100,000 live births during 2008-2012.

In 2016, there were 628 reported cases of CS, including 41 syphilitic stillbirths, according to the CDC.

“Congenital syphilis rates tend to track female syphilis rates; so as female rates go up, we know we’re going to see a rise in congenital syphilis rates,” Dr. Kidd said. “One way to prevent syphilis is to prevent female syphilis altogether. Another way is to prevent the transmission from mother to infant when you have a pregnant woman with syphilis.”

Lack of prenatal care

CDC guidelines recommend that all pregnant women undergo routine serologic screening for syphilis during their first prenatal visit. Additional testing at 28 weeks’ gestation and again at delivery is warranted for women who are at increased risk or live in communities with increased prevalence of syphilis infection. That approach may seem sensible, but such prevention measures are ineffective when mothers don’t receive any prenatal care or receive it late, which happens in about half of all CS cases, Dr. Kidd said.

Inconsistent, inadequate, or a total absence of prenatal care is “probably the biggest risk factor for vertical transmission, especially among high-risk populations, where there is an increased background prevalence of syphilis in childbearing women,” said Robert Maupin, MD, professor of clinical obstetrics and gynecology in the section of maternal-fetal medicine at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans.

To complicate matters, women who receive no or inconsistent prenatal care face an increased risk for preterm birth, Dr. Maupin noted. So while a clinician might follow CDC recommendations that pregnant women with confirmed or suspected syphilis complete a course of long-acting penicillin G for at least 30 days or longer before the child is born, “the timing of being able to implement effective prevention and treatment prior to that 30-day window can sometimes be compromised by the fact that she ends up delivering prematurely,” he said. “If someone’s not adequately linked to consistent prenatal care, she may not complete that full course of prevention. Additionally, patterns of care are often fragmented, meaning that patients may go to one clinic or one provider, may not return, and may end up switching to a different clinic. That translates into a potential lag in implementing treatment or making a diagnosis in the first place, and that may be disruptive in the context of our attempted prevention measures.”

Precise reasons why some pregnant women in the United States receive no or inadequate prenatal care remain unclear.

“Anecdotally, in the West, I hear that women with drug abuse histories or drug abuse issues [are vulnerable], or they may be homeless or have mental health issues,” Dr. Kidd said. “In other areas of the country, people feel that it’s more of an insurance or access to care issue, but we don’t have data on that here at the CDC.”

Repeat screening

In 2015, a large analysis of women who were commercially-insured or Medicaid-insured found that more than 95% who received prenatal care were screened for syphilis at least once during pregnancy (Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125[5]:1211-6). However, CDC data of CS cases shows that about 15% of their mothers are infected during pregnancy, which would occur after that first screening test.

“That’s where the repeat screening early in the third trimester and at delivery becomes the real issue,” Dr. Kidd said. “For high-risk women, including those who live in the high morbidity areas, they should be screened again later in pregnancy. Many ob.gyns. may not be aware of that recommendation, or may not be aware they’re in an area that does have a high syphilis morbidity, and that the pregnant women who are seeing them may be at increased risk of syphilis.”

Dr. Maupin, who is associate dean of diversity and community engagement at LSU Health Sciences Center, advised clinicians to view CS with the same sense of urgency that existed in previous years with perinatal HIV transmission.

“In the last decade and a half we’ve seen a substantial decline in perinatal HIV transmission because of intensive efforts on the public health side in terms of both screening and use of treatment,” he said. “If we look at this with a similar level of contemporary urgency, it will bear similar fruit over time. Additionally, from a maternal-fetal medicine standpoint, the more effectively we treat and/or control diseases and comorbidities prior to pregnancy, the less likely those things will have an adverse impact on the health and well-being of the newborn.”

Steps you can take to curb CS

In its “call to action” on syphilis, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cited several practical ways that clinicians can combat the spread of congenital syphilis (CS).

1. Complete a sexual history for your patients. The CDC recommends following this with STD counseling for those at risk and contraception counseling for women at risk of unintended pregnancy.

2. Test all pregnant women for syphilis. This should be done at the first prenatal visit, with repeat screening for pregnant women at high risk and in areas of high prevalence at the beginning of the third trimester and again at delivery.

3. Treat women infected with syphilis immediately. If a woman has syphilis or suspected syphilis, she should be treated with long-acting penicillin G, especially if she is pregnant. CDC also calls for testing and treating the infected woman’s sex partner(s) to avoid reinfection.

4. Confirm syphilis testing at delivery. Before discharging the mother or infant from the hospital, check that the mother has been tested for syphilis at least once during pregnancy or at delivery. All women who deliver a stillborn infant should be tested for syphilis.

5. Report CS cases to the local or state health department within 24 hours.