User login

Adenomyosis increasingly is a concern

“WHY ARE THERE DELAYS IN THE DIAGNOSIS OF ENDOMETRIOSIS?”

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD (EDITORIAL; MARCH 2017)

Adenomyosis increasingly is a concern

Dr. Barbieri’s article on delay in diagnosis of endometriosis is timely and important. I agree that family history is very important, but often the mother had a hysterectomy at a relatively young age for heavy bleeding that was blamed on fibroids.

Adenomyosis seems to be increasing in prevalence and may be suggested by cystic changes in the endometrium on 3D ultrasonography. The patient often reports dark brown spotting before or after periods. The second day of the period is very heavy, and cramping may precede the period. Sometimes you can note punctate lesions on the cervix that cause a very friable cervix that is likely to bleed after the patient has coitus or a Pap smear. Adenomyosis may cause much of the troublesome bleeding seen after medroxyprogesterone acetate injection, insertion of a levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine device, etonogestrel implant placement, and even birth control pills, and it is often dismissed as dysfunctional uterine bleeding. The dark brown blood may represent blood exiting the crypts of the endometrium.

It is concerning that patients who are treated aggressively for adenomyosis in order to get pregnant seem to be at increased risk for retained placenta and decreased uterine tone in the third stage of labor. Certainly this makes intuitive sense if one surmises that the endometrium is abnormally deep into the myometrium, allowing for microscopic placental invasion and myometrial dysfunction.

Most troubling is the warning from the public health community regarding endocrine disruptors. Could BPA (bisphenol A) be contaminating our plastic water bottles and be causing an epidemic of younger-onset adenomyosis? It is certainly something worth studying.

John Lewis, MD

Waterbury, Connecticut

Endometriosis patients receive delayed diagnosis, ineffective treatments

Several points came to mind reading Dr. Barbieri’s article. First, with the surge in deep infiltrating endometriosis as reported in the literature, one has to ask about treating mild disease with hormones initially. Disease can and does progress with hormonal suppression, I assume because endometriosis makes its own estrogen. Yet when the surge is noticed, the recommendation, at least in Europe, is that we should look at pollution.

Second, I have to wonder why it is not reported that older women have endometriosis. I manage a 20,000-member education board for endometriosis patients and many of those seeking help are older and often already castrated. When I can find them access to advanced surgical skill, they are found to have active endometriosis.

The patients seeking more information (gaining 300 a week) have failed all that gynecology has to offer except expert surgical excision of their disease. In my view, gynecology in general has failed this patient population. I have worked with endometriosis patients for 32 years, and 75% of them have been dismissed as neurotic, with average time to diagnosis 9 years after symptoms appear.

It seems that the symptom profile found in endometriosis patients is not well known, and once the disease is diagnosed, the treatment options are ineffective.

Nancy Petersen, RN

Portland, Oregon

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

“WHY ARE THERE DELAYS IN THE DIAGNOSIS OF ENDOMETRIOSIS?”

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD (EDITORIAL; MARCH 2017)

Adenomyosis increasingly is a concern

Dr. Barbieri’s article on delay in diagnosis of endometriosis is timely and important. I agree that family history is very important, but often the mother had a hysterectomy at a relatively young age for heavy bleeding that was blamed on fibroids.

Adenomyosis seems to be increasing in prevalence and may be suggested by cystic changes in the endometrium on 3D ultrasonography. The patient often reports dark brown spotting before or after periods. The second day of the period is very heavy, and cramping may precede the period. Sometimes you can note punctate lesions on the cervix that cause a very friable cervix that is likely to bleed after the patient has coitus or a Pap smear. Adenomyosis may cause much of the troublesome bleeding seen after medroxyprogesterone acetate injection, insertion of a levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine device, etonogestrel implant placement, and even birth control pills, and it is often dismissed as dysfunctional uterine bleeding. The dark brown blood may represent blood exiting the crypts of the endometrium.

It is concerning that patients who are treated aggressively for adenomyosis in order to get pregnant seem to be at increased risk for retained placenta and decreased uterine tone in the third stage of labor. Certainly this makes intuitive sense if one surmises that the endometrium is abnormally deep into the myometrium, allowing for microscopic placental invasion and myometrial dysfunction.

Most troubling is the warning from the public health community regarding endocrine disruptors. Could BPA (bisphenol A) be contaminating our plastic water bottles and be causing an epidemic of younger-onset adenomyosis? It is certainly something worth studying.

John Lewis, MD

Waterbury, Connecticut

Endometriosis patients receive delayed diagnosis, ineffective treatments

Several points came to mind reading Dr. Barbieri’s article. First, with the surge in deep infiltrating endometriosis as reported in the literature, one has to ask about treating mild disease with hormones initially. Disease can and does progress with hormonal suppression, I assume because endometriosis makes its own estrogen. Yet when the surge is noticed, the recommendation, at least in Europe, is that we should look at pollution.

Second, I have to wonder why it is not reported that older women have endometriosis. I manage a 20,000-member education board for endometriosis patients and many of those seeking help are older and often already castrated. When I can find them access to advanced surgical skill, they are found to have active endometriosis.

The patients seeking more information (gaining 300 a week) have failed all that gynecology has to offer except expert surgical excision of their disease. In my view, gynecology in general has failed this patient population. I have worked with endometriosis patients for 32 years, and 75% of them have been dismissed as neurotic, with average time to diagnosis 9 years after symptoms appear.

It seems that the symptom profile found in endometriosis patients is not well known, and once the disease is diagnosed, the treatment options are ineffective.

Nancy Petersen, RN

Portland, Oregon

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

“WHY ARE THERE DELAYS IN THE DIAGNOSIS OF ENDOMETRIOSIS?”

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD (EDITORIAL; MARCH 2017)

Adenomyosis increasingly is a concern

Dr. Barbieri’s article on delay in diagnosis of endometriosis is timely and important. I agree that family history is very important, but often the mother had a hysterectomy at a relatively young age for heavy bleeding that was blamed on fibroids.

Adenomyosis seems to be increasing in prevalence and may be suggested by cystic changes in the endometrium on 3D ultrasonography. The patient often reports dark brown spotting before or after periods. The second day of the period is very heavy, and cramping may precede the period. Sometimes you can note punctate lesions on the cervix that cause a very friable cervix that is likely to bleed after the patient has coitus or a Pap smear. Adenomyosis may cause much of the troublesome bleeding seen after medroxyprogesterone acetate injection, insertion of a levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine device, etonogestrel implant placement, and even birth control pills, and it is often dismissed as dysfunctional uterine bleeding. The dark brown blood may represent blood exiting the crypts of the endometrium.

It is concerning that patients who are treated aggressively for adenomyosis in order to get pregnant seem to be at increased risk for retained placenta and decreased uterine tone in the third stage of labor. Certainly this makes intuitive sense if one surmises that the endometrium is abnormally deep into the myometrium, allowing for microscopic placental invasion and myometrial dysfunction.

Most troubling is the warning from the public health community regarding endocrine disruptors. Could BPA (bisphenol A) be contaminating our plastic water bottles and be causing an epidemic of younger-onset adenomyosis? It is certainly something worth studying.

John Lewis, MD

Waterbury, Connecticut

Endometriosis patients receive delayed diagnosis, ineffective treatments

Several points came to mind reading Dr. Barbieri’s article. First, with the surge in deep infiltrating endometriosis as reported in the literature, one has to ask about treating mild disease with hormones initially. Disease can and does progress with hormonal suppression, I assume because endometriosis makes its own estrogen. Yet when the surge is noticed, the recommendation, at least in Europe, is that we should look at pollution.

Second, I have to wonder why it is not reported that older women have endometriosis. I manage a 20,000-member education board for endometriosis patients and many of those seeking help are older and often already castrated. When I can find them access to advanced surgical skill, they are found to have active endometriosis.

The patients seeking more information (gaining 300 a week) have failed all that gynecology has to offer except expert surgical excision of their disease. In my view, gynecology in general has failed this patient population. I have worked with endometriosis patients for 32 years, and 75% of them have been dismissed as neurotic, with average time to diagnosis 9 years after symptoms appear.

It seems that the symptom profile found in endometriosis patients is not well known, and once the disease is diagnosed, the treatment options are ineffective.

Nancy Petersen, RN

Portland, Oregon

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Drainage, irrigation, and fibrinolytic therapy held safe, effective for PHVD

SAN FRANCISCO – The 10-year follow-up of neonates treated for posthemorrhagic ventricular dilatation (PHVD) has demonstrated the long-term success of drainage, irrigation, and fibrinolytic therapy (DRIFT), with a cognitive advantage in the now school-age children evident, compared with those neonates who had not received the therapy.

“Children in the DRIFT group had a 23-point cognitive quotient advantage and were nine times more likely to be alive without severe cognitive disability at 10 years,” presenter and DRIFT investigator Karen Luyt, MBChB, PhD, of the University of Bristol and St. Michael’s Hospital, Bristol, England, said at the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting.

PHVD carries a high risk of disabilities in cognition and movement. DRIFT was developed as a way to wash out the ventricles in the brain to clear the effects of bleeding, with the goal of reducing neurodevelopmental disability. In the technique, catheters are inserted into the affected ventricles and are used to deliver an anti-clotting agent (alteplase) and to drain the bloody fluid. The catheters remain in place for a time as a conduit for artificial cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) containing antibiotics.

In the DRIFT trial, 77 preterm infants were randomized to DRIFT (n = 39) or the standard treatment of siphoning off cerebrospinal fluid to restrict brain expansion (n = 38). At 2 years, the DRIFT group displayed fewer cases of severe disability and cognitive disability, and death (Pediatrics. 2010 Apr;125[4]:e852-8).

Dr. Luyt summarized the final 10-year data from 52 school-age children (28 treated using DRIFT and 24 treated in the standard manner). The primary outcomes in the school-age children were cognitive quotient (CQ) and survival without severe cognitive disability. Secondary outcomes included visual function, sensory and motor disabilities, and emotional or behavior problems.

The age at the time of treatment randomization was 19 days in the DRIFT group and 19 days in the standard group. The DRIFT group was composed of more males (79% vs. 63%) and newborns with lower birth weight (336 vs. 535 grams). The gestational age and the prevalence of grade 4 intraventricular hemorrhage were similar between the groups.

DRIFT increased cognitive ability at 10 years (P = .096). Adjustment for gender, birth weight, and grade of intraventricular hemorrhage strengthened this association, with the DRIFT group having an average advantage in CQ score of 23.5 points (P = .009), which translated to a 2.5-year advantage in cognitive ability. When the data was further adjusted by ruling out the three children (two in the DRIFT group and one in the standard treatment group) who died between the 2- and 10-year follow-ups, the CQ score advantage remained (20 points; P = .029).

The other primary outcome of survival without severe cognitive disability also favored DRIFT, with an unadjusted odds ratio (OR) of 3.3 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.1-10.4 (P = .037) and adjusted (as above) OR of 8.9 (95% CI, 1.9-42.3; P = .006). Fewer children in the DRIFT group were attending schools with an expertise in special needs (OR, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.07-1.05; P = .059). No differences between the groups were evident for the secondary outcomes.

The number needed to treat to prevent death or severe cognitive disability was four.

Dr. Luyt’s recommendation that DRIFT become the standard of care for neonatal intraventricular hemorrhage comes with the caveat of increased secondary bleeding, which caused the trial to be halted after a planned external safety monitoring review. Children who already had been treated were followed up, with no further recruitment. In her response to a question from the audience regarding her endorsement of DRIFT despite the trial’s halt, Dr. Luyt pointed to the comparable safety profiles of the two groups, the superior outcomes in the DRIFT group, and the knowledge that modifications made to the technique in the intervening years have reduced the possibility of secondary bleeds.

The sponsor of study was Dr. Birgit Whitman of the University of Bristol. The study was funded by the National Institute of Health’s Health Technology Assessment Programme. Dr. Luyt disclosed the off-label use of alteplase.

SAN FRANCISCO – The 10-year follow-up of neonates treated for posthemorrhagic ventricular dilatation (PHVD) has demonstrated the long-term success of drainage, irrigation, and fibrinolytic therapy (DRIFT), with a cognitive advantage in the now school-age children evident, compared with those neonates who had not received the therapy.

“Children in the DRIFT group had a 23-point cognitive quotient advantage and were nine times more likely to be alive without severe cognitive disability at 10 years,” presenter and DRIFT investigator Karen Luyt, MBChB, PhD, of the University of Bristol and St. Michael’s Hospital, Bristol, England, said at the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting.

PHVD carries a high risk of disabilities in cognition and movement. DRIFT was developed as a way to wash out the ventricles in the brain to clear the effects of bleeding, with the goal of reducing neurodevelopmental disability. In the technique, catheters are inserted into the affected ventricles and are used to deliver an anti-clotting agent (alteplase) and to drain the bloody fluid. The catheters remain in place for a time as a conduit for artificial cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) containing antibiotics.

In the DRIFT trial, 77 preterm infants were randomized to DRIFT (n = 39) or the standard treatment of siphoning off cerebrospinal fluid to restrict brain expansion (n = 38). At 2 years, the DRIFT group displayed fewer cases of severe disability and cognitive disability, and death (Pediatrics. 2010 Apr;125[4]:e852-8).

Dr. Luyt summarized the final 10-year data from 52 school-age children (28 treated using DRIFT and 24 treated in the standard manner). The primary outcomes in the school-age children were cognitive quotient (CQ) and survival without severe cognitive disability. Secondary outcomes included visual function, sensory and motor disabilities, and emotional or behavior problems.

The age at the time of treatment randomization was 19 days in the DRIFT group and 19 days in the standard group. The DRIFT group was composed of more males (79% vs. 63%) and newborns with lower birth weight (336 vs. 535 grams). The gestational age and the prevalence of grade 4 intraventricular hemorrhage were similar between the groups.

DRIFT increased cognitive ability at 10 years (P = .096). Adjustment for gender, birth weight, and grade of intraventricular hemorrhage strengthened this association, with the DRIFT group having an average advantage in CQ score of 23.5 points (P = .009), which translated to a 2.5-year advantage in cognitive ability. When the data was further adjusted by ruling out the three children (two in the DRIFT group and one in the standard treatment group) who died between the 2- and 10-year follow-ups, the CQ score advantage remained (20 points; P = .029).

The other primary outcome of survival without severe cognitive disability also favored DRIFT, with an unadjusted odds ratio (OR) of 3.3 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.1-10.4 (P = .037) and adjusted (as above) OR of 8.9 (95% CI, 1.9-42.3; P = .006). Fewer children in the DRIFT group were attending schools with an expertise in special needs (OR, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.07-1.05; P = .059). No differences between the groups were evident for the secondary outcomes.

The number needed to treat to prevent death or severe cognitive disability was four.

Dr. Luyt’s recommendation that DRIFT become the standard of care for neonatal intraventricular hemorrhage comes with the caveat of increased secondary bleeding, which caused the trial to be halted after a planned external safety monitoring review. Children who already had been treated were followed up, with no further recruitment. In her response to a question from the audience regarding her endorsement of DRIFT despite the trial’s halt, Dr. Luyt pointed to the comparable safety profiles of the two groups, the superior outcomes in the DRIFT group, and the knowledge that modifications made to the technique in the intervening years have reduced the possibility of secondary bleeds.

The sponsor of study was Dr. Birgit Whitman of the University of Bristol. The study was funded by the National Institute of Health’s Health Technology Assessment Programme. Dr. Luyt disclosed the off-label use of alteplase.

SAN FRANCISCO – The 10-year follow-up of neonates treated for posthemorrhagic ventricular dilatation (PHVD) has demonstrated the long-term success of drainage, irrigation, and fibrinolytic therapy (DRIFT), with a cognitive advantage in the now school-age children evident, compared with those neonates who had not received the therapy.

“Children in the DRIFT group had a 23-point cognitive quotient advantage and were nine times more likely to be alive without severe cognitive disability at 10 years,” presenter and DRIFT investigator Karen Luyt, MBChB, PhD, of the University of Bristol and St. Michael’s Hospital, Bristol, England, said at the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting.

PHVD carries a high risk of disabilities in cognition and movement. DRIFT was developed as a way to wash out the ventricles in the brain to clear the effects of bleeding, with the goal of reducing neurodevelopmental disability. In the technique, catheters are inserted into the affected ventricles and are used to deliver an anti-clotting agent (alteplase) and to drain the bloody fluid. The catheters remain in place for a time as a conduit for artificial cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) containing antibiotics.

In the DRIFT trial, 77 preterm infants were randomized to DRIFT (n = 39) or the standard treatment of siphoning off cerebrospinal fluid to restrict brain expansion (n = 38). At 2 years, the DRIFT group displayed fewer cases of severe disability and cognitive disability, and death (Pediatrics. 2010 Apr;125[4]:e852-8).

Dr. Luyt summarized the final 10-year data from 52 school-age children (28 treated using DRIFT and 24 treated in the standard manner). The primary outcomes in the school-age children were cognitive quotient (CQ) and survival without severe cognitive disability. Secondary outcomes included visual function, sensory and motor disabilities, and emotional or behavior problems.

The age at the time of treatment randomization was 19 days in the DRIFT group and 19 days in the standard group. The DRIFT group was composed of more males (79% vs. 63%) and newborns with lower birth weight (336 vs. 535 grams). The gestational age and the prevalence of grade 4 intraventricular hemorrhage were similar between the groups.

DRIFT increased cognitive ability at 10 years (P = .096). Adjustment for gender, birth weight, and grade of intraventricular hemorrhage strengthened this association, with the DRIFT group having an average advantage in CQ score of 23.5 points (P = .009), which translated to a 2.5-year advantage in cognitive ability. When the data was further adjusted by ruling out the three children (two in the DRIFT group and one in the standard treatment group) who died between the 2- and 10-year follow-ups, the CQ score advantage remained (20 points; P = .029).

The other primary outcome of survival without severe cognitive disability also favored DRIFT, with an unadjusted odds ratio (OR) of 3.3 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.1-10.4 (P = .037) and adjusted (as above) OR of 8.9 (95% CI, 1.9-42.3; P = .006). Fewer children in the DRIFT group were attending schools with an expertise in special needs (OR, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.07-1.05; P = .059). No differences between the groups were evident for the secondary outcomes.

The number needed to treat to prevent death or severe cognitive disability was four.

Dr. Luyt’s recommendation that DRIFT become the standard of care for neonatal intraventricular hemorrhage comes with the caveat of increased secondary bleeding, which caused the trial to be halted after a planned external safety monitoring review. Children who already had been treated were followed up, with no further recruitment. In her response to a question from the audience regarding her endorsement of DRIFT despite the trial’s halt, Dr. Luyt pointed to the comparable safety profiles of the two groups, the superior outcomes in the DRIFT group, and the knowledge that modifications made to the technique in the intervening years have reduced the possibility of secondary bleeds.

The sponsor of study was Dr. Birgit Whitman of the University of Bristol. The study was funded by the National Institute of Health’s Health Technology Assessment Programme. Dr. Luyt disclosed the off-label use of alteplase.

AT PAS 17

Key clinical point: The 10-year follow-up data from the Drainage, Irrigation, and Fibrinolytic Therapy (DRIFT) study has confirmed the long-term safety and effectiveness of the intervention in treatment of preterm intraventricular hemorrhage.

Major finding: The DRIFT group had an average advantage in cognitive quotient score of 23.5 points (P = .009), translating to a 2.5 year advantage in cognitive ability.

Data source: Randomized controlled trial of 52 10-year-old children from the DRIFT study.

Disclosures: The sponsor of study was Dr. Birgit Whitman of the University of Bristol. The study was funded by the National Institute of Health’s Health Technology Assessment Programme. Dr. Luyt disclosed the off-label use of alteplase.

A Pathway to Full Practice Authority for Physician Assistants in the VA

On December 13, 2016, the VA announced a change in its medical regulations to permit full practice authority for all VA advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) when they are acting within the scope of their VA employment.This amendment removed the stipulation requiring physician supervision or collaboration for APRNs. Many states across the U.S. have similar statutes for APRNs.

Not surprisingly, the regulatorychange was met with resistance fromof the physician establishment. “TheAmerican Medical Association (AMA) is disappointed by the Department of Veterans Affairs’ unprecedented proposal to allow advanced practice nurses within the VA to practice independently of a physician’s clinical oversight, regardless of individual state law,” Stephen R. Permut, MD, JD, AMA immediate past-chair wrote in a statement.

The American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) then announced that it was “actively working with senior officials at the VA to institute a similar rule for PAs (physician assistants).” The well-intentioned AAPA statement seems misguided. It implies that PAs should be granted full practice authority because APRNs were granted the authority.

No matter the rational for granting APRNs full practice authority, the VA should not pursue similar regulations for PAs only because APRNs were granted the privilege. If the VA should institute a new amendment granting full practice authority to PAs, this action should be done independent of actions taken by any other nonphysician profession. Full practice authority for PAs should be based on training, clinical experience, and competency. Rather than adjusting the previously established threshold to obtain full practice authority to meet current PA standards, PAs should pursue further training and certification to earn this privilege. Physician assistant didactic and clinical training is based on the same model as training for medical doctors.

Physician assistant programs generally have 1 year of didactic training and 1 year of clinical training before trainees are eligible to take the Physician Assistant National Certifying Exam. Many schools, such as my alma mater, George Washington University School of Medicine, have PA students in the same lecture hall training side by side with medical students.

Medical doctor training generally includes 2 years of didactic training, 2 years of clinical training in medical school, and 3 years of clinical training in residency (for internal medicine) before trainees are eligible to take the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) exam. The didactic training in PA programs mirrors that of medical doctor programs. The real difference in education and preparation is the duration of clinical training; 1 year of clinical training for PAs vs 5 years of clinical training for MDs.

Therefore, my suggestion would be that leaders within the PA profession should work with the ABIM to create a pathway in which PAs who work in the VA could take the ABIM exam after 4 years of clinical experience. If a PA employed by the VA passes the ABIM exam, they would be granted full practice authority within their scope of practice at the VA. This requirement would validate that these PAs warrant this privilege and subsequently satisfy physician concerns by showing that they have passed the same exam required of physicians. Moreover, this additional level of preparation and testing would increase the competency of PAs and the quality of care they provide to the veterans they serve.

On December 13, 2016, the VA announced a change in its medical regulations to permit full practice authority for all VA advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) when they are acting within the scope of their VA employment.This amendment removed the stipulation requiring physician supervision or collaboration for APRNs. Many states across the U.S. have similar statutes for APRNs.

Not surprisingly, the regulatorychange was met with resistance fromof the physician establishment. “TheAmerican Medical Association (AMA) is disappointed by the Department of Veterans Affairs’ unprecedented proposal to allow advanced practice nurses within the VA to practice independently of a physician’s clinical oversight, regardless of individual state law,” Stephen R. Permut, MD, JD, AMA immediate past-chair wrote in a statement.

The American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) then announced that it was “actively working with senior officials at the VA to institute a similar rule for PAs (physician assistants).” The well-intentioned AAPA statement seems misguided. It implies that PAs should be granted full practice authority because APRNs were granted the authority.

No matter the rational for granting APRNs full practice authority, the VA should not pursue similar regulations for PAs only because APRNs were granted the privilege. If the VA should institute a new amendment granting full practice authority to PAs, this action should be done independent of actions taken by any other nonphysician profession. Full practice authority for PAs should be based on training, clinical experience, and competency. Rather than adjusting the previously established threshold to obtain full practice authority to meet current PA standards, PAs should pursue further training and certification to earn this privilege. Physician assistant didactic and clinical training is based on the same model as training for medical doctors.

Physician assistant programs generally have 1 year of didactic training and 1 year of clinical training before trainees are eligible to take the Physician Assistant National Certifying Exam. Many schools, such as my alma mater, George Washington University School of Medicine, have PA students in the same lecture hall training side by side with medical students.

Medical doctor training generally includes 2 years of didactic training, 2 years of clinical training in medical school, and 3 years of clinical training in residency (for internal medicine) before trainees are eligible to take the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) exam. The didactic training in PA programs mirrors that of medical doctor programs. The real difference in education and preparation is the duration of clinical training; 1 year of clinical training for PAs vs 5 years of clinical training for MDs.

Therefore, my suggestion would be that leaders within the PA profession should work with the ABIM to create a pathway in which PAs who work in the VA could take the ABIM exam after 4 years of clinical experience. If a PA employed by the VA passes the ABIM exam, they would be granted full practice authority within their scope of practice at the VA. This requirement would validate that these PAs warrant this privilege and subsequently satisfy physician concerns by showing that they have passed the same exam required of physicians. Moreover, this additional level of preparation and testing would increase the competency of PAs and the quality of care they provide to the veterans they serve.

On December 13, 2016, the VA announced a change in its medical regulations to permit full practice authority for all VA advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) when they are acting within the scope of their VA employment.This amendment removed the stipulation requiring physician supervision or collaboration for APRNs. Many states across the U.S. have similar statutes for APRNs.

Not surprisingly, the regulatorychange was met with resistance fromof the physician establishment. “TheAmerican Medical Association (AMA) is disappointed by the Department of Veterans Affairs’ unprecedented proposal to allow advanced practice nurses within the VA to practice independently of a physician’s clinical oversight, regardless of individual state law,” Stephen R. Permut, MD, JD, AMA immediate past-chair wrote in a statement.

The American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) then announced that it was “actively working with senior officials at the VA to institute a similar rule for PAs (physician assistants).” The well-intentioned AAPA statement seems misguided. It implies that PAs should be granted full practice authority because APRNs were granted the authority.

No matter the rational for granting APRNs full practice authority, the VA should not pursue similar regulations for PAs only because APRNs were granted the privilege. If the VA should institute a new amendment granting full practice authority to PAs, this action should be done independent of actions taken by any other nonphysician profession. Full practice authority for PAs should be based on training, clinical experience, and competency. Rather than adjusting the previously established threshold to obtain full practice authority to meet current PA standards, PAs should pursue further training and certification to earn this privilege. Physician assistant didactic and clinical training is based on the same model as training for medical doctors.

Physician assistant programs generally have 1 year of didactic training and 1 year of clinical training before trainees are eligible to take the Physician Assistant National Certifying Exam. Many schools, such as my alma mater, George Washington University School of Medicine, have PA students in the same lecture hall training side by side with medical students.

Medical doctor training generally includes 2 years of didactic training, 2 years of clinical training in medical school, and 3 years of clinical training in residency (for internal medicine) before trainees are eligible to take the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) exam. The didactic training in PA programs mirrors that of medical doctor programs. The real difference in education and preparation is the duration of clinical training; 1 year of clinical training for PAs vs 5 years of clinical training for MDs.

Therefore, my suggestion would be that leaders within the PA profession should work with the ABIM to create a pathway in which PAs who work in the VA could take the ABIM exam after 4 years of clinical experience. If a PA employed by the VA passes the ABIM exam, they would be granted full practice authority within their scope of practice at the VA. This requirement would validate that these PAs warrant this privilege and subsequently satisfy physician concerns by showing that they have passed the same exam required of physicians. Moreover, this additional level of preparation and testing would increase the competency of PAs and the quality of care they provide to the veterans they serve.

Phase II Data Show Safety and Efficacy of Ozanimod for Relapsing MS

NEW ORLEANS—Ozanimod demonstrated durable efficacy with a favorable safety profile in patients continuing ozanimod for 120 weeks or switching from placebo to ozanimod for 96 weeks, according to results of a phase II study presented at the 31st Annual Meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. “These data support the ongoing RADIANCE and SUNBEAM phase III studies,” said Brett E. Skolnick, PhD, on behalf of his study collaborators. Dr. Skolnick is an employee of Receptos, a wholly owned subsidiary of Celgene, in San Diego.

Ozanimod, an oral, once-daily immunomodulator selectively targeting sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptor-1 and -5 , is in development for relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS). “The increased receptor selectivity of ozanimod and additional pharmaceutical properties may result in a more favorable safety profile versus other nonselective and selective S1P receptor modulators,” said Dr. Skolnick.

In the completed RADIANCE Part A phase II trial, patients with relapsing MS were randomized (1:1:1) to once-daily ozanimod 0.5 mg or 1.0 mg or to placebo for 24 weeks. At week 24, patients could enter a 96-week, blinded extension phase. Patients randomized to ozanimod continued their assigned dose; 85 patients received 0.5 mg, and 81 patients received 1.0 mg. Patients administered placebo were re-randomized (1:1) to ozanimod 0.5 mg (n = 41) or 1.0 mg (n = 42). Ozanimod was dose-escalated over seven days to attenuate first-dose effects.

A total of 89% of patients taking the 0.5 mg dose and 90% of patients taking the 1.0 mg dose completed the extension study. At week 120, 89% to 91% of patients were free of gadolinium-enhancing lesions. Unadjusted annualized relapse rates were 0.31 in the 0.5 mg group and 0.18 in the 1.0 mg group. One or more treatment-emergent adverse events were seen in 79% of patients taking the 0.5 mg dose and in 76% of those taking the 1.0 mg dose. The most common adverse events were increased alanine aminotransferases, nasopharyngitis, and upper respiratory tract infection. Serious treatment-emergent adverse events were seen in 12 patients in the 0.5 mg group and in nine patients in the 1.0 mg group. Mild blunting of the normal diurnal heart rate was observed. The largest mean decrease in heart rate relative to pre-dose was 3.5 bpm at hour 6 on day 1, with no associated symptoms. No type II or 2:1 atrioventricular block was reported.

At week 120, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were three or more times upper limit of normal in 6% of the 0.5 mg group and in 7% of the 1.0 mg group. In the 0.5 mg group, 2% of patients discontinued ozanimod due to increased liver transaminases. Less than 1% of patients in the 1.0 mg group discontinued ozanimod for the same reason. Between baseline and week 120, three patients in the 1.0 mg group had absolute lymphocyte counts below 200 cells/μL; none was associated with severe or serious infection. There were no notable cases of pulmonary adverse events and no cases of macular edema, malignancy-related adverse events, or serious opportunistic infections.

This study was supported by Celgene.

Suggested Reading

Cohen JA, Arnold DL, Comi G, et al. Safety and efficacy of the selective sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulator ozanimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis (RADIANCE): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(4):373-381.

NEW ORLEANS—Ozanimod demonstrated durable efficacy with a favorable safety profile in patients continuing ozanimod for 120 weeks or switching from placebo to ozanimod for 96 weeks, according to results of a phase II study presented at the 31st Annual Meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. “These data support the ongoing RADIANCE and SUNBEAM phase III studies,” said Brett E. Skolnick, PhD, on behalf of his study collaborators. Dr. Skolnick is an employee of Receptos, a wholly owned subsidiary of Celgene, in San Diego.

Ozanimod, an oral, once-daily immunomodulator selectively targeting sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptor-1 and -5 , is in development for relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS). “The increased receptor selectivity of ozanimod and additional pharmaceutical properties may result in a more favorable safety profile versus other nonselective and selective S1P receptor modulators,” said Dr. Skolnick.

In the completed RADIANCE Part A phase II trial, patients with relapsing MS were randomized (1:1:1) to once-daily ozanimod 0.5 mg or 1.0 mg or to placebo for 24 weeks. At week 24, patients could enter a 96-week, blinded extension phase. Patients randomized to ozanimod continued their assigned dose; 85 patients received 0.5 mg, and 81 patients received 1.0 mg. Patients administered placebo were re-randomized (1:1) to ozanimod 0.5 mg (n = 41) or 1.0 mg (n = 42). Ozanimod was dose-escalated over seven days to attenuate first-dose effects.

A total of 89% of patients taking the 0.5 mg dose and 90% of patients taking the 1.0 mg dose completed the extension study. At week 120, 89% to 91% of patients were free of gadolinium-enhancing lesions. Unadjusted annualized relapse rates were 0.31 in the 0.5 mg group and 0.18 in the 1.0 mg group. One or more treatment-emergent adverse events were seen in 79% of patients taking the 0.5 mg dose and in 76% of those taking the 1.0 mg dose. The most common adverse events were increased alanine aminotransferases, nasopharyngitis, and upper respiratory tract infection. Serious treatment-emergent adverse events were seen in 12 patients in the 0.5 mg group and in nine patients in the 1.0 mg group. Mild blunting of the normal diurnal heart rate was observed. The largest mean decrease in heart rate relative to pre-dose was 3.5 bpm at hour 6 on day 1, with no associated symptoms. No type II or 2:1 atrioventricular block was reported.

At week 120, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were three or more times upper limit of normal in 6% of the 0.5 mg group and in 7% of the 1.0 mg group. In the 0.5 mg group, 2% of patients discontinued ozanimod due to increased liver transaminases. Less than 1% of patients in the 1.0 mg group discontinued ozanimod for the same reason. Between baseline and week 120, three patients in the 1.0 mg group had absolute lymphocyte counts below 200 cells/μL; none was associated with severe or serious infection. There were no notable cases of pulmonary adverse events and no cases of macular edema, malignancy-related adverse events, or serious opportunistic infections.

This study was supported by Celgene.

Suggested Reading

Cohen JA, Arnold DL, Comi G, et al. Safety and efficacy of the selective sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulator ozanimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis (RADIANCE): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(4):373-381.

NEW ORLEANS—Ozanimod demonstrated durable efficacy with a favorable safety profile in patients continuing ozanimod for 120 weeks or switching from placebo to ozanimod for 96 weeks, according to results of a phase II study presented at the 31st Annual Meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. “These data support the ongoing RADIANCE and SUNBEAM phase III studies,” said Brett E. Skolnick, PhD, on behalf of his study collaborators. Dr. Skolnick is an employee of Receptos, a wholly owned subsidiary of Celgene, in San Diego.

Ozanimod, an oral, once-daily immunomodulator selectively targeting sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptor-1 and -5 , is in development for relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS). “The increased receptor selectivity of ozanimod and additional pharmaceutical properties may result in a more favorable safety profile versus other nonselective and selective S1P receptor modulators,” said Dr. Skolnick.

In the completed RADIANCE Part A phase II trial, patients with relapsing MS were randomized (1:1:1) to once-daily ozanimod 0.5 mg or 1.0 mg or to placebo for 24 weeks. At week 24, patients could enter a 96-week, blinded extension phase. Patients randomized to ozanimod continued their assigned dose; 85 patients received 0.5 mg, and 81 patients received 1.0 mg. Patients administered placebo were re-randomized (1:1) to ozanimod 0.5 mg (n = 41) or 1.0 mg (n = 42). Ozanimod was dose-escalated over seven days to attenuate first-dose effects.

A total of 89% of patients taking the 0.5 mg dose and 90% of patients taking the 1.0 mg dose completed the extension study. At week 120, 89% to 91% of patients were free of gadolinium-enhancing lesions. Unadjusted annualized relapse rates were 0.31 in the 0.5 mg group and 0.18 in the 1.0 mg group. One or more treatment-emergent adverse events were seen in 79% of patients taking the 0.5 mg dose and in 76% of those taking the 1.0 mg dose. The most common adverse events were increased alanine aminotransferases, nasopharyngitis, and upper respiratory tract infection. Serious treatment-emergent adverse events were seen in 12 patients in the 0.5 mg group and in nine patients in the 1.0 mg group. Mild blunting of the normal diurnal heart rate was observed. The largest mean decrease in heart rate relative to pre-dose was 3.5 bpm at hour 6 on day 1, with no associated symptoms. No type II or 2:1 atrioventricular block was reported.

At week 120, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were three or more times upper limit of normal in 6% of the 0.5 mg group and in 7% of the 1.0 mg group. In the 0.5 mg group, 2% of patients discontinued ozanimod due to increased liver transaminases. Less than 1% of patients in the 1.0 mg group discontinued ozanimod for the same reason. Between baseline and week 120, three patients in the 1.0 mg group had absolute lymphocyte counts below 200 cells/μL; none was associated with severe or serious infection. There were no notable cases of pulmonary adverse events and no cases of macular edema, malignancy-related adverse events, or serious opportunistic infections.

This study was supported by Celgene.

Suggested Reading

Cohen JA, Arnold DL, Comi G, et al. Safety and efficacy of the selective sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulator ozanimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis (RADIANCE): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(4):373-381.

As government-funded cancer research sags, scientists fear U.S. is ‘losing its edge’

Less and less of the research presented at a prominent cancer conference is supported by the National Institutes of Health, a development that some of the country’s top scientists see as a worrisome trend.

The number of studies fully funded by the NIH at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) – the world’s largest gathering of cancer researchers – has fallen 75% in the past decade, from 575 papers in 2008 to 144 this year, according to the society, which meets June 2-6 in Chicago.

American researchers typically dominate the meeting’s press conferences – designed to feature the most important and newsworthy research. This year, there are 14 studies led by international scientists versus 12 led by U.S.-based research teams. That’s a big shift from just 5 years ago, when 15 studies in the “press program” were led by Americans versus 9 by international researchers.

Several of the studies on this weekend’s press program come from Europe and Canada, along with two from China.

President Donald Trump has proposed cutting the NIH budget for 2018 from $31.8 billion to $26 billion, a decline that many worry would jeopardize the fight against cancer and other diseases. Those cuts include $1 billion less for the National Cancer Institute.

On its website, the NCI notes that its purchasing power already has declined by 25% since 2003, because its budget – while growing – hasn’t kept up with inflation. Congress gave the NCI nearly $5.4 billion in fiscal year 2017, an increase of $174.6 million over last year. The NCI also received $300 million for the Beau Biden Cancer Moonshot through the 21st Century Cures Act in December 2016.

“America may be losing its edge in medical research,” said Otis Brawley, MD, chief medical officer at the American Cancer Society. The brightest young scientists are having trouble finding funding for their research, leading them to look for jobs not at universities but at drug companies “or even Wall Street,” he said. “I fear we are losing a generation of young, talented biomedical scientists.”

Some see America’s leading role in science as a point of national pride.

“Do we want the U.S. to remain at the center of biomedical innovation, or do we want to cede that to China or other countries?” said Dr. Stephan Grupp, director of the Cancer Immunotherapy Frontier Program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “If you don’t push to stay in front, you don’t stay in front.”

But more than pride is at stake.

Public funding is critical, because it allows researchers to answer questions that don’t interest drug companies, said Richard Schilsky, senior vice president and chief medical officer at ASCO.

While drug companies fund studies that help them get their medications approved, they tend not to pay for studies that focus on cancer prevention, screening, or quality of life, Mr. Schilsky said. The NIH also funds head-to-head comparisons of cancer drugs, which allow patients and doctors to select the most effective treatments.

“If the NIH-funded studies continue to decline, we simply won’t get the answers that patients are looking for,” he said.

While government research often addresses areas of greatest need, “industry research is geared toward marketable products,” Dr. Brawley said.

To help make up the deficit, the American Cancer Society will double its research budget to $240 million by 2021, he added.

But Dr. Grupp notes that charities and the drug industry are often reluctant to cover the indirect costs of research, such as labs. Without steady, predictable support from government grants, Dr. Grupp said he wouldn’t “have a building to do my research in or a way to keep the lights on.”

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Less and less of the research presented at a prominent cancer conference is supported by the National Institutes of Health, a development that some of the country’s top scientists see as a worrisome trend.

The number of studies fully funded by the NIH at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) – the world’s largest gathering of cancer researchers – has fallen 75% in the past decade, from 575 papers in 2008 to 144 this year, according to the society, which meets June 2-6 in Chicago.

American researchers typically dominate the meeting’s press conferences – designed to feature the most important and newsworthy research. This year, there are 14 studies led by international scientists versus 12 led by U.S.-based research teams. That’s a big shift from just 5 years ago, when 15 studies in the “press program” were led by Americans versus 9 by international researchers.

Several of the studies on this weekend’s press program come from Europe and Canada, along with two from China.

President Donald Trump has proposed cutting the NIH budget for 2018 from $31.8 billion to $26 billion, a decline that many worry would jeopardize the fight against cancer and other diseases. Those cuts include $1 billion less for the National Cancer Institute.

On its website, the NCI notes that its purchasing power already has declined by 25% since 2003, because its budget – while growing – hasn’t kept up with inflation. Congress gave the NCI nearly $5.4 billion in fiscal year 2017, an increase of $174.6 million over last year. The NCI also received $300 million for the Beau Biden Cancer Moonshot through the 21st Century Cures Act in December 2016.

“America may be losing its edge in medical research,” said Otis Brawley, MD, chief medical officer at the American Cancer Society. The brightest young scientists are having trouble finding funding for their research, leading them to look for jobs not at universities but at drug companies “or even Wall Street,” he said. “I fear we are losing a generation of young, talented biomedical scientists.”

Some see America’s leading role in science as a point of national pride.

“Do we want the U.S. to remain at the center of biomedical innovation, or do we want to cede that to China or other countries?” said Dr. Stephan Grupp, director of the Cancer Immunotherapy Frontier Program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “If you don’t push to stay in front, you don’t stay in front.”

But more than pride is at stake.

Public funding is critical, because it allows researchers to answer questions that don’t interest drug companies, said Richard Schilsky, senior vice president and chief medical officer at ASCO.

While drug companies fund studies that help them get their medications approved, they tend not to pay for studies that focus on cancer prevention, screening, or quality of life, Mr. Schilsky said. The NIH also funds head-to-head comparisons of cancer drugs, which allow patients and doctors to select the most effective treatments.

“If the NIH-funded studies continue to decline, we simply won’t get the answers that patients are looking for,” he said.

While government research often addresses areas of greatest need, “industry research is geared toward marketable products,” Dr. Brawley said.

To help make up the deficit, the American Cancer Society will double its research budget to $240 million by 2021, he added.

But Dr. Grupp notes that charities and the drug industry are often reluctant to cover the indirect costs of research, such as labs. Without steady, predictable support from government grants, Dr. Grupp said he wouldn’t “have a building to do my research in or a way to keep the lights on.”

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Less and less of the research presented at a prominent cancer conference is supported by the National Institutes of Health, a development that some of the country’s top scientists see as a worrisome trend.

The number of studies fully funded by the NIH at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) – the world’s largest gathering of cancer researchers – has fallen 75% in the past decade, from 575 papers in 2008 to 144 this year, according to the society, which meets June 2-6 in Chicago.

American researchers typically dominate the meeting’s press conferences – designed to feature the most important and newsworthy research. This year, there are 14 studies led by international scientists versus 12 led by U.S.-based research teams. That’s a big shift from just 5 years ago, when 15 studies in the “press program” were led by Americans versus 9 by international researchers.

Several of the studies on this weekend’s press program come from Europe and Canada, along with two from China.

President Donald Trump has proposed cutting the NIH budget for 2018 from $31.8 billion to $26 billion, a decline that many worry would jeopardize the fight against cancer and other diseases. Those cuts include $1 billion less for the National Cancer Institute.

On its website, the NCI notes that its purchasing power already has declined by 25% since 2003, because its budget – while growing – hasn’t kept up with inflation. Congress gave the NCI nearly $5.4 billion in fiscal year 2017, an increase of $174.6 million over last year. The NCI also received $300 million for the Beau Biden Cancer Moonshot through the 21st Century Cures Act in December 2016.

“America may be losing its edge in medical research,” said Otis Brawley, MD, chief medical officer at the American Cancer Society. The brightest young scientists are having trouble finding funding for their research, leading them to look for jobs not at universities but at drug companies “or even Wall Street,” he said. “I fear we are losing a generation of young, talented biomedical scientists.”

Some see America’s leading role in science as a point of national pride.

“Do we want the U.S. to remain at the center of biomedical innovation, or do we want to cede that to China or other countries?” said Dr. Stephan Grupp, director of the Cancer Immunotherapy Frontier Program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “If you don’t push to stay in front, you don’t stay in front.”

But more than pride is at stake.

Public funding is critical, because it allows researchers to answer questions that don’t interest drug companies, said Richard Schilsky, senior vice president and chief medical officer at ASCO.

While drug companies fund studies that help them get their medications approved, they tend not to pay for studies that focus on cancer prevention, screening, or quality of life, Mr. Schilsky said. The NIH also funds head-to-head comparisons of cancer drugs, which allow patients and doctors to select the most effective treatments.

“If the NIH-funded studies continue to decline, we simply won’t get the answers that patients are looking for,” he said.

While government research often addresses areas of greatest need, “industry research is geared toward marketable products,” Dr. Brawley said.

To help make up the deficit, the American Cancer Society will double its research budget to $240 million by 2021, he added.

But Dr. Grupp notes that charities and the drug industry are often reluctant to cover the indirect costs of research, such as labs. Without steady, predictable support from government grants, Dr. Grupp said he wouldn’t “have a building to do my research in or a way to keep the lights on.”

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

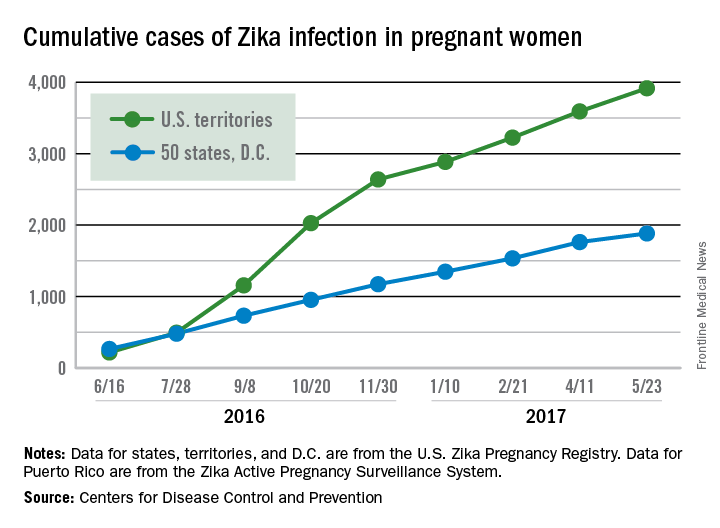

Zika-related birth defects up in recent weeks

Zika virus infection has been occurring in pregnant women at a slow but steady clip over the last couple of months, but cases of liveborn infants with Zika-related birth defects have jumped in recent weeks, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Eight liveborn infants with Zika-related birth defects were reported to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry during the 2 weeks ending May 23, more than any other 2-week period this year, and that was after six such infants were reported for the 2 weeks ending May 9. The total for the 50 states and the District of Columbia is now 72 for 2016-2017. No new pregnancy losses with birth defects were reported over the same 4-week span, so the 50 state/D.C. total remained at eight for 2016-2017, CDC data show.

The CDC notes that these are not real-time data and reflect only pregnancy outcomes for women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, although it is not known if Zika virus was the cause of the poor outcomes. Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, or termination with evidence of birth defects.

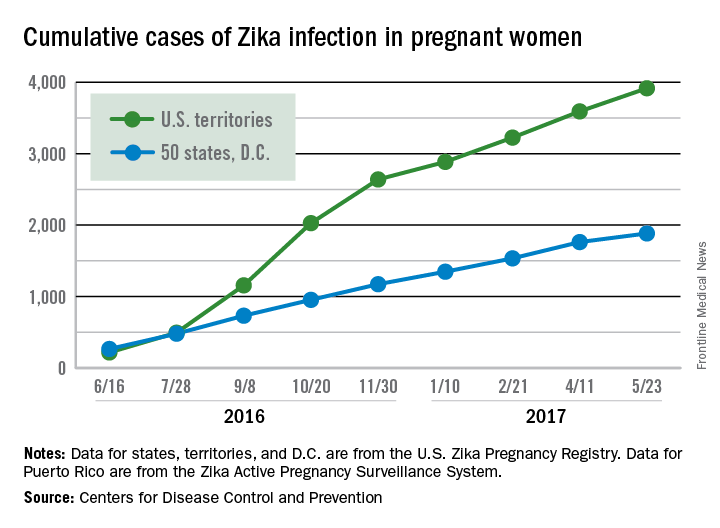

Zika virus infection has been occurring in pregnant women at a slow but steady clip over the last couple of months, but cases of liveborn infants with Zika-related birth defects have jumped in recent weeks, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Eight liveborn infants with Zika-related birth defects were reported to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry during the 2 weeks ending May 23, more than any other 2-week period this year, and that was after six such infants were reported for the 2 weeks ending May 9. The total for the 50 states and the District of Columbia is now 72 for 2016-2017. No new pregnancy losses with birth defects were reported over the same 4-week span, so the 50 state/D.C. total remained at eight for 2016-2017, CDC data show.

The CDC notes that these are not real-time data and reflect only pregnancy outcomes for women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, although it is not known if Zika virus was the cause of the poor outcomes. Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, or termination with evidence of birth defects.

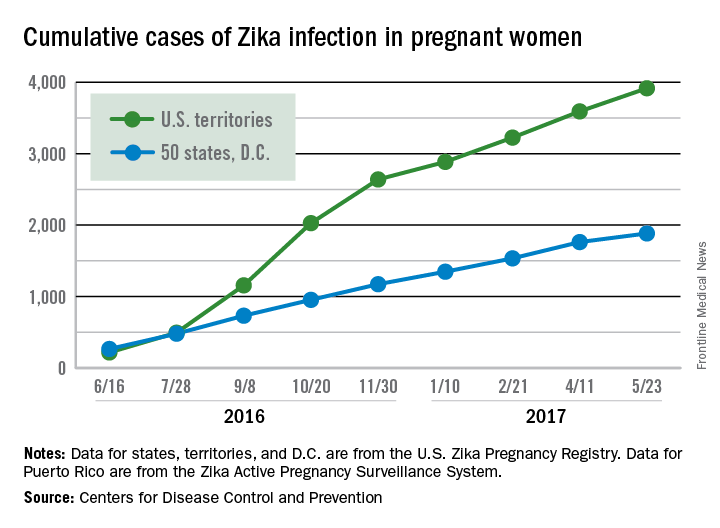

Zika virus infection has been occurring in pregnant women at a slow but steady clip over the last couple of months, but cases of liveborn infants with Zika-related birth defects have jumped in recent weeks, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Eight liveborn infants with Zika-related birth defects were reported to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry during the 2 weeks ending May 23, more than any other 2-week period this year, and that was after six such infants were reported for the 2 weeks ending May 9. The total for the 50 states and the District of Columbia is now 72 for 2016-2017. No new pregnancy losses with birth defects were reported over the same 4-week span, so the 50 state/D.C. total remained at eight for 2016-2017, CDC data show.

The CDC notes that these are not real-time data and reflect only pregnancy outcomes for women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, although it is not known if Zika virus was the cause of the poor outcomes. Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, or termination with evidence of birth defects.

Program for Maintenance of Certification by the American Board of Dermatology

Maintenance of Certification (MOC) was adopted by the 24 certifying boards constituting the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) in 2000. The American Board of Dermatology (ABD) granted its first time-limited certificates in 1991 with the first cohort of diplomates entering MOC in 2006. The rationale for MOC centered on 2 propositions: First, continuing medical education (CME) alone was insufficient to assure the public that physicians were remaining up-to-date with an expanding knowledge base and offered little opportunity to engage in meaningful self-assessment and practice improvement. Second, parties external to the medical profession were focusing increased attention on physician error and quality assurance in medical practice. Maintenance of Certification, therefore, provided a mechanism of physician self-regulation in meeting public scrutiny.1,2

The basic framework of MOC remains unchanged since its inception, though notable effort has been expended in simplifying the tools available. All MOC components offered directly by ABD including the MOC examination are covered by the $150 annual fee.

Professional Standing

Diplomates attest to the status of all state medical licenses and level of clinical activity. All licenses must be unrestricted. “Clinically active” is defined as any patient care delivered within the prior 12 months. Having a restricted license or being clinically inactive does not automatically trigger loss of certification but does result in an ABD review.

Self-assessment

Diplomates complete 300 credits (1 question=1 credit) over 10 years and complete, or attest to prior completion of, a foundational course in patient safety. Self-assessment questions are widely available from various sources, including the Question of the Week offered by the American Academy of Dermatology, Clinicopathologic Correlation and CME-designated articles offered by JAMA Dermatology, and Photo Challenges and Dermatopathology Diagnosis quizzes offered by Cutis. The ABD recognizes patient safety education satisfied as part of medical school and residency as well as various other venues. Online courses offering CME and MOC credit also are available. Credit is accrued whether the item is answered correctly or not.

Cognitive Expertise

Dermatologists take a general dermatology module and choose one subspecialty module composed of questions directed to the clinical practitioner. The general module consists of 100 image items, most of which ask for a diagnosis. The list of entities potentially included on the assessment is made available in advance for self-study. The subspecialty module consists of 50 questions targeting the specific content area selected: medical dermatology, surgical dermatology, pediatric dermatology, and dermatopathology. The actual questions also are made available in advance for self-study. Board-certified pediatric dermatologists and dermatopathologists are offered a second 50-question set of items in their specialty to allow maintenance of the second certificate. Venues include Pearson VUE testing centers and at-home or in-office tests by remote proctoring.

The ABD is considering participation in the longitudinal assessment program developed by the ABMS. If adopted, it will offer questions distributed over a many-year span in small packets, on mobile devices, and on personal computers. Diplomates will have the ability to select content and pace, including opt-out periods as life events dictate. A minimum number of correctly answered items over time will form the basis for summative assessment.

Practice Improvement

A critical element of MOC, practice improvement affords the physician the opportunity to study how patients receive care in a wide range of settings. Beginning in 2015, the ABD developed focused practice improvement modules, now totaling 21, with many more coming in the future. The free modules are offered on an online platform (https://secure.dataharborsolutions.com/ABDermOrg/Default.aspx) and target narrow content areas. The broad range of offerings allows diplomates to choose an area of specific interest. The participant is asked to read an overview and rationale for the module, consider reading selected references that provide the evidence base, and perform 5 chart abstractions consisting of yes or no answers to no more than 5 questions narrowly focused on the chosen topic. If a first round shows no room for improvement, the participant is finished. If a deficiency is identified, the diplomate can reflect on and implement any necessary changes in process of care and pursue a second round. These modules have been very well received, with typical diplomates’ comments expressing appreciation for the ease of use and relevance to practice. Unedited and unselected reviews can be found online (https://www.abderm.org/diplomates/fulfilling-moc-requirements/resource-vendor-list/practice-improvement/american-board-of-dermatology-focused-pi-modules-free.aspx).

Future Direction

The ABD continuously communicates with diplomates about changes and new opportunities in its MOC program with a goal of maximizing value and minimizing cost in terms of dollars and time.3 The directors of the ABD continue to seek feedback about the MOC program and are committed to further refinements to achieve this goal. A critical feature of the redesigned website (http://www.abderm.org/) allows diplomates to submit and read anonymous reviews of all tools available to fulfill MOC requirements. This thoughtful diplomate feedback informs MOC developmental efforts.

All directors and executive staff of the ABD, regardless of certificate status, pay the annual fee and participate in MOC. Active participation in MOC is made public on the ABMS website. This acknowledgment is an assurance to patients that the physician’s professional standing is sound, that the physician periodically self-assesses what he/she knows, that this knowledge meets psychometrically valid standards set by dermatologists, and that physicians explore the quality of care delivered in specific practice settings. It’s the right thing to do!

- Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000.

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001:337.

- American Board of Dermatology. We are simplifying maintenance of certification. here’s how. http://eepurl.com/bLd9vz. Published January 3, 2016. Accessed May 11, 2017.

Maintenance of Certification (MOC) was adopted by the 24 certifying boards constituting the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) in 2000. The American Board of Dermatology (ABD) granted its first time-limited certificates in 1991 with the first cohort of diplomates entering MOC in 2006. The rationale for MOC centered on 2 propositions: First, continuing medical education (CME) alone was insufficient to assure the public that physicians were remaining up-to-date with an expanding knowledge base and offered little opportunity to engage in meaningful self-assessment and practice improvement. Second, parties external to the medical profession were focusing increased attention on physician error and quality assurance in medical practice. Maintenance of Certification, therefore, provided a mechanism of physician self-regulation in meeting public scrutiny.1,2

The basic framework of MOC remains unchanged since its inception, though notable effort has been expended in simplifying the tools available. All MOC components offered directly by ABD including the MOC examination are covered by the $150 annual fee.

Professional Standing

Diplomates attest to the status of all state medical licenses and level of clinical activity. All licenses must be unrestricted. “Clinically active” is defined as any patient care delivered within the prior 12 months. Having a restricted license or being clinically inactive does not automatically trigger loss of certification but does result in an ABD review.

Self-assessment

Diplomates complete 300 credits (1 question=1 credit) over 10 years and complete, or attest to prior completion of, a foundational course in patient safety. Self-assessment questions are widely available from various sources, including the Question of the Week offered by the American Academy of Dermatology, Clinicopathologic Correlation and CME-designated articles offered by JAMA Dermatology, and Photo Challenges and Dermatopathology Diagnosis quizzes offered by Cutis. The ABD recognizes patient safety education satisfied as part of medical school and residency as well as various other venues. Online courses offering CME and MOC credit also are available. Credit is accrued whether the item is answered correctly or not.

Cognitive Expertise

Dermatologists take a general dermatology module and choose one subspecialty module composed of questions directed to the clinical practitioner. The general module consists of 100 image items, most of which ask for a diagnosis. The list of entities potentially included on the assessment is made available in advance for self-study. The subspecialty module consists of 50 questions targeting the specific content area selected: medical dermatology, surgical dermatology, pediatric dermatology, and dermatopathology. The actual questions also are made available in advance for self-study. Board-certified pediatric dermatologists and dermatopathologists are offered a second 50-question set of items in their specialty to allow maintenance of the second certificate. Venues include Pearson VUE testing centers and at-home or in-office tests by remote proctoring.

The ABD is considering participation in the longitudinal assessment program developed by the ABMS. If adopted, it will offer questions distributed over a many-year span in small packets, on mobile devices, and on personal computers. Diplomates will have the ability to select content and pace, including opt-out periods as life events dictate. A minimum number of correctly answered items over time will form the basis for summative assessment.

Practice Improvement

A critical element of MOC, practice improvement affords the physician the opportunity to study how patients receive care in a wide range of settings. Beginning in 2015, the ABD developed focused practice improvement modules, now totaling 21, with many more coming in the future. The free modules are offered on an online platform (https://secure.dataharborsolutions.com/ABDermOrg/Default.aspx) and target narrow content areas. The broad range of offerings allows diplomates to choose an area of specific interest. The participant is asked to read an overview and rationale for the module, consider reading selected references that provide the evidence base, and perform 5 chart abstractions consisting of yes or no answers to no more than 5 questions narrowly focused on the chosen topic. If a first round shows no room for improvement, the participant is finished. If a deficiency is identified, the diplomate can reflect on and implement any necessary changes in process of care and pursue a second round. These modules have been very well received, with typical diplomates’ comments expressing appreciation for the ease of use and relevance to practice. Unedited and unselected reviews can be found online (https://www.abderm.org/diplomates/fulfilling-moc-requirements/resource-vendor-list/practice-improvement/american-board-of-dermatology-focused-pi-modules-free.aspx).

Future Direction

The ABD continuously communicates with diplomates about changes and new opportunities in its MOC program with a goal of maximizing value and minimizing cost in terms of dollars and time.3 The directors of the ABD continue to seek feedback about the MOC program and are committed to further refinements to achieve this goal. A critical feature of the redesigned website (http://www.abderm.org/) allows diplomates to submit and read anonymous reviews of all tools available to fulfill MOC requirements. This thoughtful diplomate feedback informs MOC developmental efforts.

All directors and executive staff of the ABD, regardless of certificate status, pay the annual fee and participate in MOC. Active participation in MOC is made public on the ABMS website. This acknowledgment is an assurance to patients that the physician’s professional standing is sound, that the physician periodically self-assesses what he/she knows, that this knowledge meets psychometrically valid standards set by dermatologists, and that physicians explore the quality of care delivered in specific practice settings. It’s the right thing to do!

Maintenance of Certification (MOC) was adopted by the 24 certifying boards constituting the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) in 2000. The American Board of Dermatology (ABD) granted its first time-limited certificates in 1991 with the first cohort of diplomates entering MOC in 2006. The rationale for MOC centered on 2 propositions: First, continuing medical education (CME) alone was insufficient to assure the public that physicians were remaining up-to-date with an expanding knowledge base and offered little opportunity to engage in meaningful self-assessment and practice improvement. Second, parties external to the medical profession were focusing increased attention on physician error and quality assurance in medical practice. Maintenance of Certification, therefore, provided a mechanism of physician self-regulation in meeting public scrutiny.1,2

The basic framework of MOC remains unchanged since its inception, though notable effort has been expended in simplifying the tools available. All MOC components offered directly by ABD including the MOC examination are covered by the $150 annual fee.

Professional Standing

Diplomates attest to the status of all state medical licenses and level of clinical activity. All licenses must be unrestricted. “Clinically active” is defined as any patient care delivered within the prior 12 months. Having a restricted license or being clinically inactive does not automatically trigger loss of certification but does result in an ABD review.

Self-assessment

Diplomates complete 300 credits (1 question=1 credit) over 10 years and complete, or attest to prior completion of, a foundational course in patient safety. Self-assessment questions are widely available from various sources, including the Question of the Week offered by the American Academy of Dermatology, Clinicopathologic Correlation and CME-designated articles offered by JAMA Dermatology, and Photo Challenges and Dermatopathology Diagnosis quizzes offered by Cutis. The ABD recognizes patient safety education satisfied as part of medical school and residency as well as various other venues. Online courses offering CME and MOC credit also are available. Credit is accrued whether the item is answered correctly or not.

Cognitive Expertise

Dermatologists take a general dermatology module and choose one subspecialty module composed of questions directed to the clinical practitioner. The general module consists of 100 image items, most of which ask for a diagnosis. The list of entities potentially included on the assessment is made available in advance for self-study. The subspecialty module consists of 50 questions targeting the specific content area selected: medical dermatology, surgical dermatology, pediatric dermatology, and dermatopathology. The actual questions also are made available in advance for self-study. Board-certified pediatric dermatologists and dermatopathologists are offered a second 50-question set of items in their specialty to allow maintenance of the second certificate. Venues include Pearson VUE testing centers and at-home or in-office tests by remote proctoring.

The ABD is considering participation in the longitudinal assessment program developed by the ABMS. If adopted, it will offer questions distributed over a many-year span in small packets, on mobile devices, and on personal computers. Diplomates will have the ability to select content and pace, including opt-out periods as life events dictate. A minimum number of correctly answered items over time will form the basis for summative assessment.

Practice Improvement

A critical element of MOC, practice improvement affords the physician the opportunity to study how patients receive care in a wide range of settings. Beginning in 2015, the ABD developed focused practice improvement modules, now totaling 21, with many more coming in the future. The free modules are offered on an online platform (https://secure.dataharborsolutions.com/ABDermOrg/Default.aspx) and target narrow content areas. The broad range of offerings allows diplomates to choose an area of specific interest. The participant is asked to read an overview and rationale for the module, consider reading selected references that provide the evidence base, and perform 5 chart abstractions consisting of yes or no answers to no more than 5 questions narrowly focused on the chosen topic. If a first round shows no room for improvement, the participant is finished. If a deficiency is identified, the diplomate can reflect on and implement any necessary changes in process of care and pursue a second round. These modules have been very well received, with typical diplomates’ comments expressing appreciation for the ease of use and relevance to practice. Unedited and unselected reviews can be found online (https://www.abderm.org/diplomates/fulfilling-moc-requirements/resource-vendor-list/practice-improvement/american-board-of-dermatology-focused-pi-modules-free.aspx).

Future Direction