User login

Elder abuse: Strong social support prevents associated psychopathology

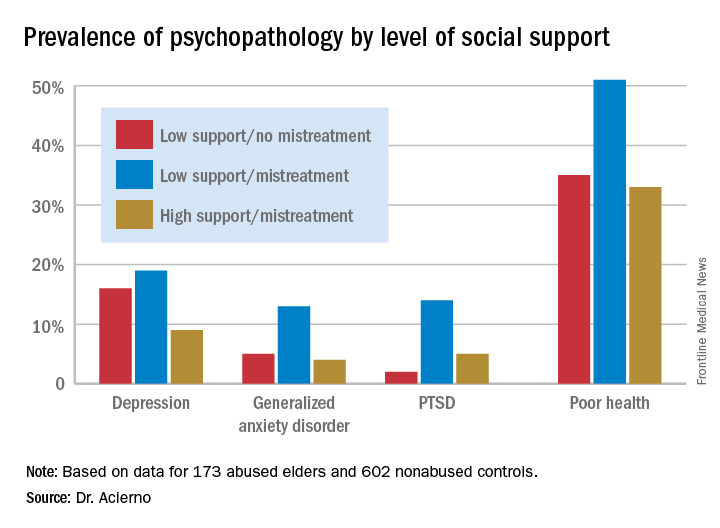

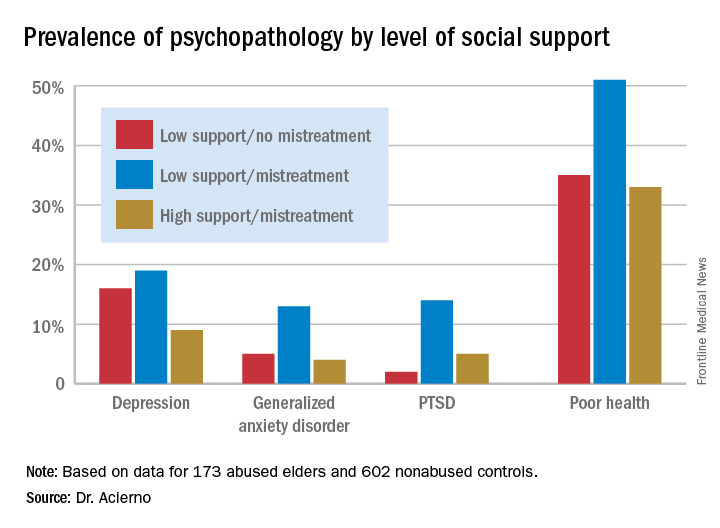

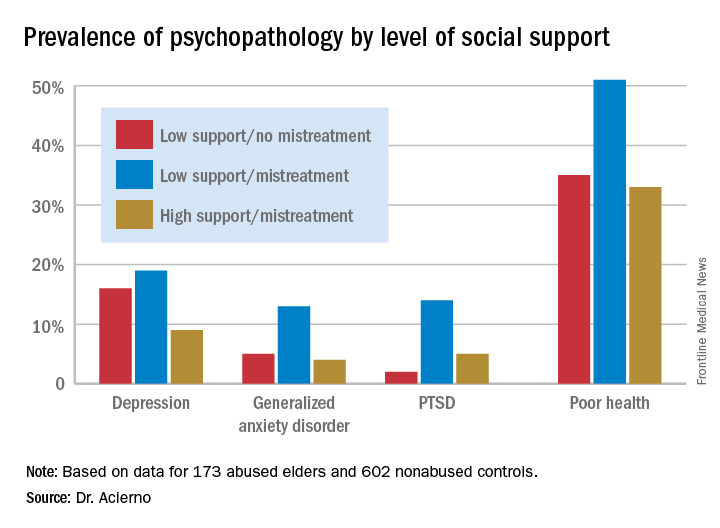

SAN FRANCISCO – Victims of elder abuse who have perceived strong social support from family or friends are “completely inoculated” against the otherwise dramatically increased risk of trauma-related psychopathology that pertains to mistreated seniors who lack such support, according to Ron Acierno, PhD.

Dr. Acierno, professor of nursing at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, presented 8-year follow-up data from the National Elder Mistreatment Study, the largest study of elder abuse ever conducted in the United States.

The National Elder Mistreatment Study involved 5,777 randomly selected community-dwelling older adults who, in 2008, participated in structured interviews assessing whether they had experienced physical, psychological, sexual, or neglectful mistreatment. The study made headlines by documenting an unexpectedly high 11% rate of elder mistreatment within the previous 12 months (Am J Public Health. 2010 Feb;100[2]:292-7).

Eight years later, Dr. Acierno and his coinvestigators were able to recontact 173 of the original 684 abused elders, as well as 602 nonabused controls for structured interviews assessing their current mental health. At that point, the participants averaged 84.9 years of age.

Striking differences in mental health status based on elder abuse history were documented. The prevalences of depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder were 13%, 7%, and 8%, respectively, in the elder abuse group, compared with 5%, 1%, and 1% in the nonabused controls. Of the group subjected to abuse 8 years earlier, 40% were categorized at follow-up as “in poor health,” compared with 23% of controls.

More importantly, high social support essentially erased the elder abuse group’s increased risk (see graphic), Dr. Acierno said.

The National Elder Mistreatment Study was funded by the National Institute of Justice, the National Institute on Aging, and the Archstone Foundation. Dr. Acierno reported having no financial conflicts.

SAN FRANCISCO – Victims of elder abuse who have perceived strong social support from family or friends are “completely inoculated” against the otherwise dramatically increased risk of trauma-related psychopathology that pertains to mistreated seniors who lack such support, according to Ron Acierno, PhD.

Dr. Acierno, professor of nursing at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, presented 8-year follow-up data from the National Elder Mistreatment Study, the largest study of elder abuse ever conducted in the United States.

The National Elder Mistreatment Study involved 5,777 randomly selected community-dwelling older adults who, in 2008, participated in structured interviews assessing whether they had experienced physical, psychological, sexual, or neglectful mistreatment. The study made headlines by documenting an unexpectedly high 11% rate of elder mistreatment within the previous 12 months (Am J Public Health. 2010 Feb;100[2]:292-7).

Eight years later, Dr. Acierno and his coinvestigators were able to recontact 173 of the original 684 abused elders, as well as 602 nonabused controls for structured interviews assessing their current mental health. At that point, the participants averaged 84.9 years of age.

Striking differences in mental health status based on elder abuse history were documented. The prevalences of depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder were 13%, 7%, and 8%, respectively, in the elder abuse group, compared with 5%, 1%, and 1% in the nonabused controls. Of the group subjected to abuse 8 years earlier, 40% were categorized at follow-up as “in poor health,” compared with 23% of controls.

More importantly, high social support essentially erased the elder abuse group’s increased risk (see graphic), Dr. Acierno said.

The National Elder Mistreatment Study was funded by the National Institute of Justice, the National Institute on Aging, and the Archstone Foundation. Dr. Acierno reported having no financial conflicts.

SAN FRANCISCO – Victims of elder abuse who have perceived strong social support from family or friends are “completely inoculated” against the otherwise dramatically increased risk of trauma-related psychopathology that pertains to mistreated seniors who lack such support, according to Ron Acierno, PhD.

Dr. Acierno, professor of nursing at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, presented 8-year follow-up data from the National Elder Mistreatment Study, the largest study of elder abuse ever conducted in the United States.

The National Elder Mistreatment Study involved 5,777 randomly selected community-dwelling older adults who, in 2008, participated in structured interviews assessing whether they had experienced physical, psychological, sexual, or neglectful mistreatment. The study made headlines by documenting an unexpectedly high 11% rate of elder mistreatment within the previous 12 months (Am J Public Health. 2010 Feb;100[2]:292-7).

Eight years later, Dr. Acierno and his coinvestigators were able to recontact 173 of the original 684 abused elders, as well as 602 nonabused controls for structured interviews assessing their current mental health. At that point, the participants averaged 84.9 years of age.

Striking differences in mental health status based on elder abuse history were documented. The prevalences of depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder were 13%, 7%, and 8%, respectively, in the elder abuse group, compared with 5%, 1%, and 1% in the nonabused controls. Of the group subjected to abuse 8 years earlier, 40% were categorized at follow-up as “in poor health,” compared with 23% of controls.

More importantly, high social support essentially erased the elder abuse group’s increased risk (see graphic), Dr. Acierno said.

The National Elder Mistreatment Study was funded by the National Institute of Justice, the National Institute on Aging, and the Archstone Foundation. Dr. Acierno reported having no financial conflicts.

AT THE ANXIETY AND DEPRESSION CONFERENCE 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Having a strong social support network virtually eliminated the otherwise sharply increased risk of trauma-related psychopathology in victims of elder abuse.

Data source: An 8-year follow-up report on the mental health status of participants in the largest study of elder mistreatment in US history.

Disclosures: The National Elder Mistreatment Study was funded by the National Institute of Justice, the National Institute on Aging, and the Archstone Foundation. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Study identifies gaps in surgical trainees’ readiness

PHILADELPHIA – The question of how prepared general surgery residents are to operate independently after their training is longstanding, but clear definitions of competency and readiness have been elusive. A consortium of general surgery residencies has developed a metric for assessing surgeon readiness, but what the metric revealed may be a cause for concern for the surgical profession.

Brian C. George, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, reported at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association on results of a study designed to measure the autonomy and readiness for independent practice of residents at 14 general surgery programs.

The study found that in the final 6 months of training, 96% of residents were rated competent by their observers to perform a straightforward appendectomy on their own, but only 71% were rated the same for partial colectomy, Dr. George said.

The participating general surgery attendings rated residents according to three scales (J Surg Educ. 2016;73:e118-130):

•“Performance” scale to measure readiness for independent practice, with competence defined as practice-ready and exceptional performance.

• “Zwisch” scale, named after Jay Zwischenberger, MD, FACS, of the University of Kentucky, to assess the amount of autonomy granted to a resident by the supervising surgical attending.

• “Complexity” scale to measure the patient-related complexity of the case at hand.

The study used a smartphone-based app, SIMPL, to collect data from September 2015 through December 2016. In evaluating performance, 437 observers provided 8,526 different ratings of 522 residents.

In a subset analysis, the study authors focused on the 132 operations the Surgical Council on Resident Education considers the core procedures of general surgery and found that 77% of fifth-year residents were rated as competent. Further restricting the analysis to residents in their final 6 months of training performing the five most commonly rated core procedures – appendectomy, cholecystectomy, ventral hernia repair, inguinal/femoral hernia repair, and partial colectomy – the researchers found that competency ranged from a high of 96% for appendectomy to a low of 71% for partial colectomy.

“If you combine all five procedures into one category, on average the residents are rated competent 84% of the time during the last 6 months of training,” Dr. George said. “But what’s really interesting – and I think this is probably the most important result for this study – is that looking at just the less-frequently rated core procedures and excluding the top five, residents are deemed competent in the last 6 months of training for 74% of those observed procedures.”

According to the Zwisch” scale to measure autonomy, residents in their last 6 months of training displayed what Dr. George termed “meaningful autonomy” in 77% of their observed operations for the core procedures. “Interestingly,” he added, “they were observed to have maximum autonomy, which is the supervision-only level, for 33% of all observed procedures.”

The researchers did an adjusted analysis to account for confounding factors such as the stringency of individual raters and patient complexity. “Using this type of analysis, the likelihood that a typical trainee rated by a typical attendee would be deemed competent by the end of training for a relatively straightforward laparoscopy appendectomy is 97%,” Dr. George said. “For a difficult laparoscopic appendectomy, by the end of training, they’re likely to be deemed competent 92% of time.” In the adjusted analysis, for a straightforward partial colectomy the raters predicted trainees to be competent 91.8% of time, but only 81.8% of the time for a complicated partial colectomy. “For less-frequently performed core procedures, there are many for which residents are likely to be deemed competent at a much lower level,” Dr. George added.

In discussing the study, Ara Darzi, MD, of St. Mary’s Hospital, London, called the methodology “unique and commendable,” and asked “Would you make the case to say we should increase the number of years of trainees from PG5 to PG6 or at least make your fellowships compulsory?”

Dr. George answered that 80% of general surgery residents already go into fellowships. “Whether it’s required or not is above my pay grade,” he said. “I hope not. Five years is already a big ask for a lot of medical students who are considering this profession. If we increase the training requirements, we’re going to have a supply problem that we will then need to address. We will be trading one problem for another.” He later added “The 20,000 hours of surgical residency should be enough to train a general surgeon to competence – its up to us to figure out how.”

The following organizations supported the research: American Board of Surgery, Association for Surgical Education, Association for Program Directors in Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Northwestern University, Indiana University, and the members of the Procedural Learning and Safety Collaborative.

Neither Dr. George nor Dr. Darzi had any relevant financial disclosures.

The complete manuscript of this study and its presentation at the American Surgical Association’s 137th Annual Meeting, April 2017, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, is to be published in Annals of Surgery pending editorial review.

PHILADELPHIA – The question of how prepared general surgery residents are to operate independently after their training is longstanding, but clear definitions of competency and readiness have been elusive. A consortium of general surgery residencies has developed a metric for assessing surgeon readiness, but what the metric revealed may be a cause for concern for the surgical profession.

Brian C. George, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, reported at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association on results of a study designed to measure the autonomy and readiness for independent practice of residents at 14 general surgery programs.

The study found that in the final 6 months of training, 96% of residents were rated competent by their observers to perform a straightforward appendectomy on their own, but only 71% were rated the same for partial colectomy, Dr. George said.

The participating general surgery attendings rated residents according to three scales (J Surg Educ. 2016;73:e118-130):

•“Performance” scale to measure readiness for independent practice, with competence defined as practice-ready and exceptional performance.

• “Zwisch” scale, named after Jay Zwischenberger, MD, FACS, of the University of Kentucky, to assess the amount of autonomy granted to a resident by the supervising surgical attending.

• “Complexity” scale to measure the patient-related complexity of the case at hand.

The study used a smartphone-based app, SIMPL, to collect data from September 2015 through December 2016. In evaluating performance, 437 observers provided 8,526 different ratings of 522 residents.

In a subset analysis, the study authors focused on the 132 operations the Surgical Council on Resident Education considers the core procedures of general surgery and found that 77% of fifth-year residents were rated as competent. Further restricting the analysis to residents in their final 6 months of training performing the five most commonly rated core procedures – appendectomy, cholecystectomy, ventral hernia repair, inguinal/femoral hernia repair, and partial colectomy – the researchers found that competency ranged from a high of 96% for appendectomy to a low of 71% for partial colectomy.

“If you combine all five procedures into one category, on average the residents are rated competent 84% of the time during the last 6 months of training,” Dr. George said. “But what’s really interesting – and I think this is probably the most important result for this study – is that looking at just the less-frequently rated core procedures and excluding the top five, residents are deemed competent in the last 6 months of training for 74% of those observed procedures.”

According to the Zwisch” scale to measure autonomy, residents in their last 6 months of training displayed what Dr. George termed “meaningful autonomy” in 77% of their observed operations for the core procedures. “Interestingly,” he added, “they were observed to have maximum autonomy, which is the supervision-only level, for 33% of all observed procedures.”

The researchers did an adjusted analysis to account for confounding factors such as the stringency of individual raters and patient complexity. “Using this type of analysis, the likelihood that a typical trainee rated by a typical attendee would be deemed competent by the end of training for a relatively straightforward laparoscopy appendectomy is 97%,” Dr. George said. “For a difficult laparoscopic appendectomy, by the end of training, they’re likely to be deemed competent 92% of time.” In the adjusted analysis, for a straightforward partial colectomy the raters predicted trainees to be competent 91.8% of time, but only 81.8% of the time for a complicated partial colectomy. “For less-frequently performed core procedures, there are many for which residents are likely to be deemed competent at a much lower level,” Dr. George added.

In discussing the study, Ara Darzi, MD, of St. Mary’s Hospital, London, called the methodology “unique and commendable,” and asked “Would you make the case to say we should increase the number of years of trainees from PG5 to PG6 or at least make your fellowships compulsory?”

Dr. George answered that 80% of general surgery residents already go into fellowships. “Whether it’s required or not is above my pay grade,” he said. “I hope not. Five years is already a big ask for a lot of medical students who are considering this profession. If we increase the training requirements, we’re going to have a supply problem that we will then need to address. We will be trading one problem for another.” He later added “The 20,000 hours of surgical residency should be enough to train a general surgeon to competence – its up to us to figure out how.”

The following organizations supported the research: American Board of Surgery, Association for Surgical Education, Association for Program Directors in Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Northwestern University, Indiana University, and the members of the Procedural Learning and Safety Collaborative.

Neither Dr. George nor Dr. Darzi had any relevant financial disclosures.

The complete manuscript of this study and its presentation at the American Surgical Association’s 137th Annual Meeting, April 2017, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, is to be published in Annals of Surgery pending editorial review.

PHILADELPHIA – The question of how prepared general surgery residents are to operate independently after their training is longstanding, but clear definitions of competency and readiness have been elusive. A consortium of general surgery residencies has developed a metric for assessing surgeon readiness, but what the metric revealed may be a cause for concern for the surgical profession.

Brian C. George, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, reported at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association on results of a study designed to measure the autonomy and readiness for independent practice of residents at 14 general surgery programs.

The study found that in the final 6 months of training, 96% of residents were rated competent by their observers to perform a straightforward appendectomy on their own, but only 71% were rated the same for partial colectomy, Dr. George said.

The participating general surgery attendings rated residents according to three scales (J Surg Educ. 2016;73:e118-130):

•“Performance” scale to measure readiness for independent practice, with competence defined as practice-ready and exceptional performance.

• “Zwisch” scale, named after Jay Zwischenberger, MD, FACS, of the University of Kentucky, to assess the amount of autonomy granted to a resident by the supervising surgical attending.

• “Complexity” scale to measure the patient-related complexity of the case at hand.

The study used a smartphone-based app, SIMPL, to collect data from September 2015 through December 2016. In evaluating performance, 437 observers provided 8,526 different ratings of 522 residents.

In a subset analysis, the study authors focused on the 132 operations the Surgical Council on Resident Education considers the core procedures of general surgery and found that 77% of fifth-year residents were rated as competent. Further restricting the analysis to residents in their final 6 months of training performing the five most commonly rated core procedures – appendectomy, cholecystectomy, ventral hernia repair, inguinal/femoral hernia repair, and partial colectomy – the researchers found that competency ranged from a high of 96% for appendectomy to a low of 71% for partial colectomy.

“If you combine all five procedures into one category, on average the residents are rated competent 84% of the time during the last 6 months of training,” Dr. George said. “But what’s really interesting – and I think this is probably the most important result for this study – is that looking at just the less-frequently rated core procedures and excluding the top five, residents are deemed competent in the last 6 months of training for 74% of those observed procedures.”

According to the Zwisch” scale to measure autonomy, residents in their last 6 months of training displayed what Dr. George termed “meaningful autonomy” in 77% of their observed operations for the core procedures. “Interestingly,” he added, “they were observed to have maximum autonomy, which is the supervision-only level, for 33% of all observed procedures.”

The researchers did an adjusted analysis to account for confounding factors such as the stringency of individual raters and patient complexity. “Using this type of analysis, the likelihood that a typical trainee rated by a typical attendee would be deemed competent by the end of training for a relatively straightforward laparoscopy appendectomy is 97%,” Dr. George said. “For a difficult laparoscopic appendectomy, by the end of training, they’re likely to be deemed competent 92% of time.” In the adjusted analysis, for a straightforward partial colectomy the raters predicted trainees to be competent 91.8% of time, but only 81.8% of the time for a complicated partial colectomy. “For less-frequently performed core procedures, there are many for which residents are likely to be deemed competent at a much lower level,” Dr. George added.

In discussing the study, Ara Darzi, MD, of St. Mary’s Hospital, London, called the methodology “unique and commendable,” and asked “Would you make the case to say we should increase the number of years of trainees from PG5 to PG6 or at least make your fellowships compulsory?”

Dr. George answered that 80% of general surgery residents already go into fellowships. “Whether it’s required or not is above my pay grade,” he said. “I hope not. Five years is already a big ask for a lot of medical students who are considering this profession. If we increase the training requirements, we’re going to have a supply problem that we will then need to address. We will be trading one problem for another.” He later added “The 20,000 hours of surgical residency should be enough to train a general surgeon to competence – its up to us to figure out how.”

The following organizations supported the research: American Board of Surgery, Association for Surgical Education, Association for Program Directors in Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Northwestern University, Indiana University, and the members of the Procedural Learning and Safety Collaborative.

Neither Dr. George nor Dr. Darzi had any relevant financial disclosures.

The complete manuscript of this study and its presentation at the American Surgical Association’s 137th Annual Meeting, April 2017, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, is to be published in Annals of Surgery pending editorial review.

AT THE ASA ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: General surgery residents are often but not universally ready to independently perform core surgical procedures upon completion of surgical training.

Major finding: In the last 6 months of training, residents were rated competent 84% of the time in performing the five leading core procedures and 64% of the time for less-frequently performed procedures.

Data source: Ratings of 437 of 8,526 different observations of 522 residents at 14 institutions of the Procedural Learning and Safety Collaborative.

Disclosures: Dr. George and his coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

How Often Is Optic Neuritis Misdiagnosed?

BOSTON—Misdiagnosing optic neuritis may expose patients to risks associated with undergoing MRI with a contrast agent, lumbar puncture, and high-dose steroid treatment. It also costs patients and hospitals time and money. Leanne Stunkel, MD, a neurology resident at Washington University in St. Louis, and her colleagues observed a 60% misdiagnosis rate of optic neuritis among patients who were referred to their neuro-ophthalmology clinic, according to a study presented at the 69th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

“The most common [diagnostic] errors were overreliance on a single item of history and failure to consider alternative diagnoses,” said Dr. Stunkel.

Optic neuritis is an acute inflammatory demyelinating condition of the optic nerve. Presenting symptoms include acute or subacute vision loss, pain with eye movement, and changes in color vision, especially affecting the color red, said Dr. Stunkel. Many patients who were referred to their tertiary care clinic for optic neuritis turned out to have other conditions, which prompted the researchers to find out more about optic neuritis misdiagnosis.

Previous studies found a misdiagnosis rate of between 10% and 40%, but none of these studies examined which errors led to these misdiagnoses. To determine how often optic neuritis is misdiagnosed and which diagnostic errors play a role, and to identify diagnoses commonly mistaken for optic neuritis, Dr. Stunkel and colleagues performed a retrospective chart review.

The researchers reviewed new patient encounters between January 2014 and October 2016 to identify patients referred with a diagnosis of optic neuritis. Experienced neuro-ophthalmologists determined the final diagnosis. The researchers then applied the Diagnosis Error Evaluation and Research (DEER) taxonomy tool to identify diagnostic errors in cases in which the patient did not have optic neuritis.

A total of 122 patients were referred for optic neuritis during the study period. Only 40% of these patients were diagnosed with optic neuritis, and 60% of patients had alternative diagnoses. The most common alternative diagnoses were headache with eye pain and visual symptoms (22%), functional visual loss (19%), and other optic neuropathies (16%).

In addition, 15% of patients had retinal or macular problems rather than pathology of the optic nerve. Other diagnoses included neoplasms, congenital disk abnormalities, and inflammatory conditions that affected other parts of the eye.

The most common diagnostic errors were from problems eliciting or interpreting the history (33%). “We saw an overreliance on history of risk factors such as multiple sclerosis or other inflammatory disorders and some failure to elicit the fact that these were brief stereotyped episodes of vision loss, like in a migraine aura,” said Dr. Stunkel.

Twenty-one percent of diagnostic errors were due to errors interpreting physical exam findings, and 14% of errors were due to misinterpretation of diagnostic tests. Finally, 32% of diagnostic errors resulted from failure to consider alternative diagnoses. Of patients who did not have optic neuritis, 17% had already received a lumbar puncture, 17% had received a contrast MRI that turned out to be negative, and 11 patients had inappropriately received IV steroids, said Dr. Stunkel.

Some of the study limitations include that the DEER category assignments were subjective, and that not every referral for optic neuritis was included in the study due to limitations of the clinic’s electronic medical records system, said Dr. Stunkel.

—Erica Tricarico

BOSTON—Misdiagnosing optic neuritis may expose patients to risks associated with undergoing MRI with a contrast agent, lumbar puncture, and high-dose steroid treatment. It also costs patients and hospitals time and money. Leanne Stunkel, MD, a neurology resident at Washington University in St. Louis, and her colleagues observed a 60% misdiagnosis rate of optic neuritis among patients who were referred to their neuro-ophthalmology clinic, according to a study presented at the 69th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

“The most common [diagnostic] errors were overreliance on a single item of history and failure to consider alternative diagnoses,” said Dr. Stunkel.

Optic neuritis is an acute inflammatory demyelinating condition of the optic nerve. Presenting symptoms include acute or subacute vision loss, pain with eye movement, and changes in color vision, especially affecting the color red, said Dr. Stunkel. Many patients who were referred to their tertiary care clinic for optic neuritis turned out to have other conditions, which prompted the researchers to find out more about optic neuritis misdiagnosis.

Previous studies found a misdiagnosis rate of between 10% and 40%, but none of these studies examined which errors led to these misdiagnoses. To determine how often optic neuritis is misdiagnosed and which diagnostic errors play a role, and to identify diagnoses commonly mistaken for optic neuritis, Dr. Stunkel and colleagues performed a retrospective chart review.

The researchers reviewed new patient encounters between January 2014 and October 2016 to identify patients referred with a diagnosis of optic neuritis. Experienced neuro-ophthalmologists determined the final diagnosis. The researchers then applied the Diagnosis Error Evaluation and Research (DEER) taxonomy tool to identify diagnostic errors in cases in which the patient did not have optic neuritis.

A total of 122 patients were referred for optic neuritis during the study period. Only 40% of these patients were diagnosed with optic neuritis, and 60% of patients had alternative diagnoses. The most common alternative diagnoses were headache with eye pain and visual symptoms (22%), functional visual loss (19%), and other optic neuropathies (16%).

In addition, 15% of patients had retinal or macular problems rather than pathology of the optic nerve. Other diagnoses included neoplasms, congenital disk abnormalities, and inflammatory conditions that affected other parts of the eye.

The most common diagnostic errors were from problems eliciting or interpreting the history (33%). “We saw an overreliance on history of risk factors such as multiple sclerosis or other inflammatory disorders and some failure to elicit the fact that these were brief stereotyped episodes of vision loss, like in a migraine aura,” said Dr. Stunkel.

Twenty-one percent of diagnostic errors were due to errors interpreting physical exam findings, and 14% of errors were due to misinterpretation of diagnostic tests. Finally, 32% of diagnostic errors resulted from failure to consider alternative diagnoses. Of patients who did not have optic neuritis, 17% had already received a lumbar puncture, 17% had received a contrast MRI that turned out to be negative, and 11 patients had inappropriately received IV steroids, said Dr. Stunkel.

Some of the study limitations include that the DEER category assignments were subjective, and that not every referral for optic neuritis was included in the study due to limitations of the clinic’s electronic medical records system, said Dr. Stunkel.

—Erica Tricarico

BOSTON—Misdiagnosing optic neuritis may expose patients to risks associated with undergoing MRI with a contrast agent, lumbar puncture, and high-dose steroid treatment. It also costs patients and hospitals time and money. Leanne Stunkel, MD, a neurology resident at Washington University in St. Louis, and her colleagues observed a 60% misdiagnosis rate of optic neuritis among patients who were referred to their neuro-ophthalmology clinic, according to a study presented at the 69th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

“The most common [diagnostic] errors were overreliance on a single item of history and failure to consider alternative diagnoses,” said Dr. Stunkel.

Optic neuritis is an acute inflammatory demyelinating condition of the optic nerve. Presenting symptoms include acute or subacute vision loss, pain with eye movement, and changes in color vision, especially affecting the color red, said Dr. Stunkel. Many patients who were referred to their tertiary care clinic for optic neuritis turned out to have other conditions, which prompted the researchers to find out more about optic neuritis misdiagnosis.

Previous studies found a misdiagnosis rate of between 10% and 40%, but none of these studies examined which errors led to these misdiagnoses. To determine how often optic neuritis is misdiagnosed and which diagnostic errors play a role, and to identify diagnoses commonly mistaken for optic neuritis, Dr. Stunkel and colleagues performed a retrospective chart review.

The researchers reviewed new patient encounters between January 2014 and October 2016 to identify patients referred with a diagnosis of optic neuritis. Experienced neuro-ophthalmologists determined the final diagnosis. The researchers then applied the Diagnosis Error Evaluation and Research (DEER) taxonomy tool to identify diagnostic errors in cases in which the patient did not have optic neuritis.

A total of 122 patients were referred for optic neuritis during the study period. Only 40% of these patients were diagnosed with optic neuritis, and 60% of patients had alternative diagnoses. The most common alternative diagnoses were headache with eye pain and visual symptoms (22%), functional visual loss (19%), and other optic neuropathies (16%).

In addition, 15% of patients had retinal or macular problems rather than pathology of the optic nerve. Other diagnoses included neoplasms, congenital disk abnormalities, and inflammatory conditions that affected other parts of the eye.

The most common diagnostic errors were from problems eliciting or interpreting the history (33%). “We saw an overreliance on history of risk factors such as multiple sclerosis or other inflammatory disorders and some failure to elicit the fact that these were brief stereotyped episodes of vision loss, like in a migraine aura,” said Dr. Stunkel.

Twenty-one percent of diagnostic errors were due to errors interpreting physical exam findings, and 14% of errors were due to misinterpretation of diagnostic tests. Finally, 32% of diagnostic errors resulted from failure to consider alternative diagnoses. Of patients who did not have optic neuritis, 17% had already received a lumbar puncture, 17% had received a contrast MRI that turned out to be negative, and 11 patients had inappropriately received IV steroids, said Dr. Stunkel.

Some of the study limitations include that the DEER category assignments were subjective, and that not every referral for optic neuritis was included in the study due to limitations of the clinic’s electronic medical records system, said Dr. Stunkel.

—Erica Tricarico

Hot Threads in ACS Communities

Here are the top discussion threads in ACS Communities just prior to press time (all of these threads are from the General Surgery community):

1. Potential Florida legislation prohibiting maintenance of certification requirements

2. My proposal for changing MOC

3. Surgical training and ethics in the ’50s/’60s

4. Timing of cholecystectomy in severe gallstone pancreatitis

5. GOO (Gastric Outlet Obstruction) – What would you do?

6. Transv colon cancer, abdominal aortic aneurysm

7. Catheter migration

8. Cholecystectomy after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for choledocholithiasis

9. Cecal mass and concomitant distal sigmoid large polyp

10. Feeding after perforated ulcer/Graham patch

To join communities, log in to ACS Communities at http://acscommunities.facs.org/home, go to “Browse All Communities” near the top of any page, and click the blue “Join” button next to the community you’d like to join. If you have any questions, please send them to [email protected].

Here are the top discussion threads in ACS Communities just prior to press time (all of these threads are from the General Surgery community):

1. Potential Florida legislation prohibiting maintenance of certification requirements

2. My proposal for changing MOC

3. Surgical training and ethics in the ’50s/’60s

4. Timing of cholecystectomy in severe gallstone pancreatitis

5. GOO (Gastric Outlet Obstruction) – What would you do?

6. Transv colon cancer, abdominal aortic aneurysm

7. Catheter migration

8. Cholecystectomy after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for choledocholithiasis

9. Cecal mass and concomitant distal sigmoid large polyp

10. Feeding after perforated ulcer/Graham patch

To join communities, log in to ACS Communities at http://acscommunities.facs.org/home, go to “Browse All Communities” near the top of any page, and click the blue “Join” button next to the community you’d like to join. If you have any questions, please send them to [email protected].

Here are the top discussion threads in ACS Communities just prior to press time (all of these threads are from the General Surgery community):

1. Potential Florida legislation prohibiting maintenance of certification requirements

2. My proposal for changing MOC

3. Surgical training and ethics in the ’50s/’60s

4. Timing of cholecystectomy in severe gallstone pancreatitis

5. GOO (Gastric Outlet Obstruction) – What would you do?

6. Transv colon cancer, abdominal aortic aneurysm

7. Catheter migration

8. Cholecystectomy after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for choledocholithiasis

9. Cecal mass and concomitant distal sigmoid large polyp

10. Feeding after perforated ulcer/Graham patch

To join communities, log in to ACS Communities at http://acscommunities.facs.org/home, go to “Browse All Communities” near the top of any page, and click the blue “Join” button next to the community you’d like to join. If you have any questions, please send them to [email protected].

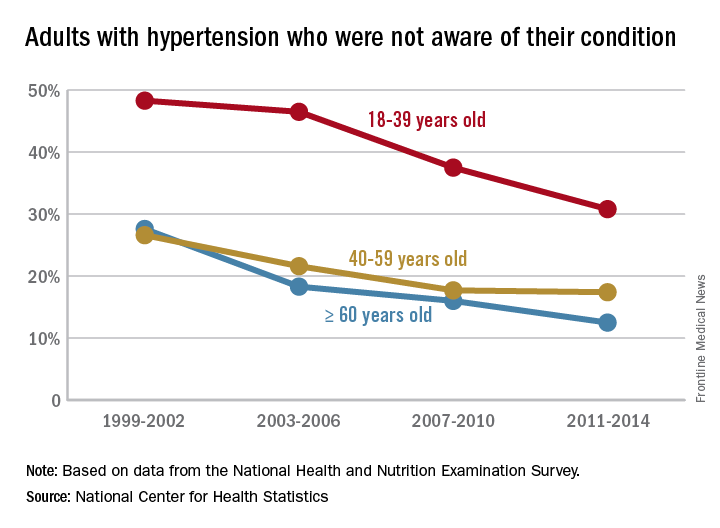

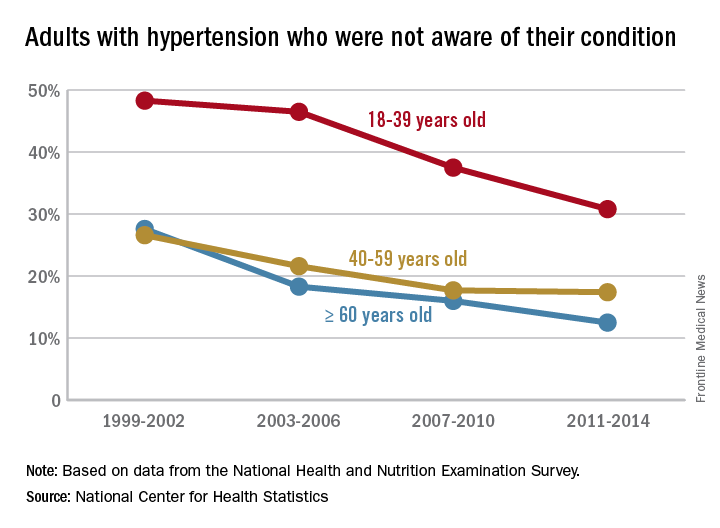

Fewer adults unaware of their hypertension

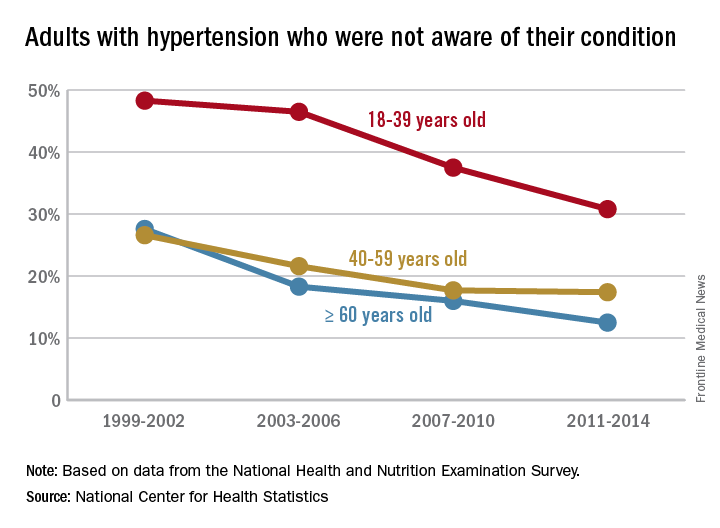

Hypertension awareness has improved significantly in adults since 2002, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

The percentage of adults aged 18-39 years who had hypertension but reported not being told about it by a health care provider dropped 36% from 1999-2002, when it was 48.3%, to 2011-2014, when it was down to 30.8%. For adults aged 40-59 years, 26.6% were unaware of their hypertension in 1999-2002, compared with 17.4% in 2011-2014, a relative decrease of almost 35%. The decline was an even larger 55% for those aged 60 years and over – from 27.6% in 1999-2002 to 12.5% in 2011-2014, the NCHS reported.

Hypertension awareness has improved significantly in adults since 2002, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

The percentage of adults aged 18-39 years who had hypertension but reported not being told about it by a health care provider dropped 36% from 1999-2002, when it was 48.3%, to 2011-2014, when it was down to 30.8%. For adults aged 40-59 years, 26.6% were unaware of their hypertension in 1999-2002, compared with 17.4% in 2011-2014, a relative decrease of almost 35%. The decline was an even larger 55% for those aged 60 years and over – from 27.6% in 1999-2002 to 12.5% in 2011-2014, the NCHS reported.

Hypertension awareness has improved significantly in adults since 2002, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

The percentage of adults aged 18-39 years who had hypertension but reported not being told about it by a health care provider dropped 36% from 1999-2002, when it was 48.3%, to 2011-2014, when it was down to 30.8%. For adults aged 40-59 years, 26.6% were unaware of their hypertension in 1999-2002, compared with 17.4% in 2011-2014, a relative decrease of almost 35%. The decline was an even larger 55% for those aged 60 years and over – from 27.6% in 1999-2002 to 12.5% in 2011-2014, the NCHS reported.

Bacterial vaginosis: Meet patients' needs with effective diagnosis and treatment

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Editorial Note

The first Skin of Color column, "Diversity in Dermatology: A Society Devoted to Skin of Color," produced in collaboration with the Skin of Color Society appears on page 322. This column will be published quarterly and will serve to increase the knowledge available to dermatologists to help improve delivery of care to this underserved population.

Look for Skin of Color columns in upcoming issues of Cutis.

The first Skin of Color column, "Diversity in Dermatology: A Society Devoted to Skin of Color," produced in collaboration with the Skin of Color Society appears on page 322. This column will be published quarterly and will serve to increase the knowledge available to dermatologists to help improve delivery of care to this underserved population.

Look for Skin of Color columns in upcoming issues of Cutis.

The first Skin of Color column, "Diversity in Dermatology: A Society Devoted to Skin of Color," produced in collaboration with the Skin of Color Society appears on page 322. This column will be published quarterly and will serve to increase the knowledge available to dermatologists to help improve delivery of care to this underserved population.

Look for Skin of Color columns in upcoming issues of Cutis.

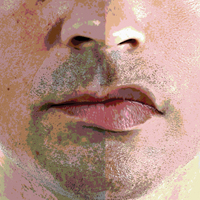

Skin Cancer Mortality in Patients With Skin of Color

Skin cancers in patients with skin of color are less prevalent but have a higher morbidity and mortality compared to white patients. Challenges to early detection, including clinical differences in presentation, low public awareness, lower index of suspicion among health care providers, and access to specialty care, likely contribute to observed differences in prognosis between skin of color and white populations.

Skin cancer is the most common malignancy in the United States, accounting for approximately 40% of all neoplasms in white patients but only 1% to 4% in Asian American and black patients.1,2 Largely due to the photoprotective effects of increased constitutive epidermal melanin, melanoma is approximately 10 to 20 times less frequent in black patients and 3 to 7 times less common in Hispanics than age-matched whites.1 Nonmelanoma skin cancers including squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and basal cell carcinoma also are less prevalent in darker skin types.3,4

In the United States, Hispanic, American Indian

Similar to melanoma, the mortality from SCC is disproportionately increased in skin of color populations, ranging from 18% to 29% in black patients.3,10,11 There is a paucity of population-based studies in the United States looking at mortality rates of nonmelanoma skin cancers and their trends over time, but a 1993 study suggests that mortality rates are declining less consistently in black patients than white patients.11

Factors that may contribute to higher mortality rates in patients with skin of color include a greater propensity for inherently aggressive skin cancers (eg, higher risk of SCC) and delays in diagnosis (eg, late-stage diagnosis of melanoma).1,4 For melanoma, increased mortality has been attributed to a predominance of acral lentiginous melanomas, which are more frequently diagnosed at more advanced stages than other melanoma subtypes.6,12,13 Black patients, Hispanics, Asians, and Pacific Islanders are all more likely to present with thicker tumors and metastases on initial presentation than their white counterparts (P<.001).2,8,9,12-14 The higher risk of death from SCC results from the predominance of lesions on non–sun-exposed areas, particularly the legs and anogenital areas, and within sites of chronic scarring or inflammation.4 Unlike sun-induced SCC, the most commonly observed type of SCC in lighter skin types, SCCs that develop in association with chronic inflammatory or ulcerative processes are aggressive and invasive, and they metastasize to distant sites in 20% to 40% of cases (versus 1%–4% in sun-induced SCC).1,3,4 For all skin cancers, poor access to medical care, patients’ unawareness of their skin cancer risk, lack of adequate skin examinations, and prevalence of lesions on uncommon sites that may be inconspicuous or overlooked have all been suggested to delay diagnosis.1,15,16 Given that more advanced disease is associated with worse outcomes, the implications of this delay are enormous and remain a cause for concern.

The alarming skin cancer mortality rates in patients with skin of color are a call to action for the medical community. The consistent use of full-body skin examinations including close inspection of mucosal, acral, and genital areas for all patients independent of skin type and racial/ethnic background is paramount. Advancing skin cancer education in skin of color populations, such as through distribution of patient-directed educational materials produced by organizations such as the American Academy of Dermatology, Skin Cancer Foundation, and Skin of Color Society, is an important step toward increased public awareness.16 Use of social and traditional media outlets as well as community-directed health outreach campaigns also are important strategies to change the common misconception that darker-skinned individuals do not get skin cancer. We hope that with a multipronged approach, disparities in skin cancer mortality will steadily be eliminated.

- Gloster HM Jr, Neal K. Skin cancer in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:741-760; quiz 761-764.

- Cormier JN, Xing Y, Ding M, et al. Ethnic differences among patients with cutaneous melanoma. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1907-1914.

- Mora RG, Perniciaro C. Cancer of the skin in blacks: I. a review of 163 black patients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:535-543.

- Halder RM, Bridgeman-Shah S. Skin cancer in African Americans. Cancer. 1995;75:667-673.

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2013. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; April 2016. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2013/. Updated September 12, 2016. Accessed April 7, 2017.

- Bellows CF, Belafsky P, Fortgang IS, et al. Melanoma in African-Americans: trends in biological behavior and clinical characteristics over two decades. J Surg Oncol. 2001;78:10-16.

- Chen L, Jin S. Trends in mortality rates of cutaneous melanoma in East Asian populations. Peer J. 2014;4:e2809.

- Cress RD, Holly EA. Incidence of cutaneous melanoma among non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, Asians, and blacks: an analysis of California Cancer Registry data. Cancer Causes Control. 1997;8:246-252.

- Johnson DS, Yamane S, Morita S, et al. Malignant melanoma in non-Caucasians: experience from Hawaii. Surg Clin N Am. 2003;83:275-282.

- Fleming ID, Barnawell JR, Burlison PE, et al. Skin cancer in black patients. Cancer. 1975;35:600-605.

- Weinstock MA. Nonmelanoma skin cancer mortality in the United States, 1969 through 1988. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:1286-1290.

- Byrd KM, Wilson DC, Hoyler SS. Advanced presentation of melanoma in African Americans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:142-143.

- Hu S, Parmet Y, Allen G, et al. Disparity in melanoma: a trend analysis of melanoma incidence and stage at diagnosis among whites, Hispanics, and blacks in Florida. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1369-1374.

- Black WC, Goldhahn RT, Wiggins C. Melanoma within a southwestern Hispanic population. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1331-1334.

- Harvey VM, Oldfield CW, Chen JT, et al. Melanoma disparities among US Hispanics: use of the social ecological model to contextualize reasons for inequitable outcomes and frame a research agenda [published online August 29, 2016]. J Skin Cancer. 2016;2016:4635740.

- Robinson JK, Joshi KM, Ortiz S, et al. Melanoma knowledge, perception, and awareness in ethnic minorities in Chicago: recommendations regarding education. Psychooncology. 2011;20:313-320.

Skin cancers in patients with skin of color are less prevalent but have a higher morbidity and mortality compared to white patients. Challenges to early detection, including clinical differences in presentation, low public awareness, lower index of suspicion among health care providers, and access to specialty care, likely contribute to observed differences in prognosis between skin of color and white populations.

Skin cancer is the most common malignancy in the United States, accounting for approximately 40% of all neoplasms in white patients but only 1% to 4% in Asian American and black patients.1,2 Largely due to the photoprotective effects of increased constitutive epidermal melanin, melanoma is approximately 10 to 20 times less frequent in black patients and 3 to 7 times less common in Hispanics than age-matched whites.1 Nonmelanoma skin cancers including squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and basal cell carcinoma also are less prevalent in darker skin types.3,4

In the United States, Hispanic, American Indian

Similar to melanoma, the mortality from SCC is disproportionately increased in skin of color populations, ranging from 18% to 29% in black patients.3,10,11 There is a paucity of population-based studies in the United States looking at mortality rates of nonmelanoma skin cancers and their trends over time, but a 1993 study suggests that mortality rates are declining less consistently in black patients than white patients.11

Factors that may contribute to higher mortality rates in patients with skin of color include a greater propensity for inherently aggressive skin cancers (eg, higher risk of SCC) and delays in diagnosis (eg, late-stage diagnosis of melanoma).1,4 For melanoma, increased mortality has been attributed to a predominance of acral lentiginous melanomas, which are more frequently diagnosed at more advanced stages than other melanoma subtypes.6,12,13 Black patients, Hispanics, Asians, and Pacific Islanders are all more likely to present with thicker tumors and metastases on initial presentation than their white counterparts (P<.001).2,8,9,12-14 The higher risk of death from SCC results from the predominance of lesions on non–sun-exposed areas, particularly the legs and anogenital areas, and within sites of chronic scarring or inflammation.4 Unlike sun-induced SCC, the most commonly observed type of SCC in lighter skin types, SCCs that develop in association with chronic inflammatory or ulcerative processes are aggressive and invasive, and they metastasize to distant sites in 20% to 40% of cases (versus 1%–4% in sun-induced SCC).1,3,4 For all skin cancers, poor access to medical care, patients’ unawareness of their skin cancer risk, lack of adequate skin examinations, and prevalence of lesions on uncommon sites that may be inconspicuous or overlooked have all been suggested to delay diagnosis.1,15,16 Given that more advanced disease is associated with worse outcomes, the implications of this delay are enormous and remain a cause for concern.

The alarming skin cancer mortality rates in patients with skin of color are a call to action for the medical community. The consistent use of full-body skin examinations including close inspection of mucosal, acral, and genital areas for all patients independent of skin type and racial/ethnic background is paramount. Advancing skin cancer education in skin of color populations, such as through distribution of patient-directed educational materials produced by organizations such as the American Academy of Dermatology, Skin Cancer Foundation, and Skin of Color Society, is an important step toward increased public awareness.16 Use of social and traditional media outlets as well as community-directed health outreach campaigns also are important strategies to change the common misconception that darker-skinned individuals do not get skin cancer. We hope that with a multipronged approach, disparities in skin cancer mortality will steadily be eliminated.

Skin cancers in patients with skin of color are less prevalent but have a higher morbidity and mortality compared to white patients. Challenges to early detection, including clinical differences in presentation, low public awareness, lower index of suspicion among health care providers, and access to specialty care, likely contribute to observed differences in prognosis between skin of color and white populations.

Skin cancer is the most common malignancy in the United States, accounting for approximately 40% of all neoplasms in white patients but only 1% to 4% in Asian American and black patients.1,2 Largely due to the photoprotective effects of increased constitutive epidermal melanin, melanoma is approximately 10 to 20 times less frequent in black patients and 3 to 7 times less common in Hispanics than age-matched whites.1 Nonmelanoma skin cancers including squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and basal cell carcinoma also are less prevalent in darker skin types.3,4

In the United States, Hispanic, American Indian

Similar to melanoma, the mortality from SCC is disproportionately increased in skin of color populations, ranging from 18% to 29% in black patients.3,10,11 There is a paucity of population-based studies in the United States looking at mortality rates of nonmelanoma skin cancers and their trends over time, but a 1993 study suggests that mortality rates are declining less consistently in black patients than white patients.11

Factors that may contribute to higher mortality rates in patients with skin of color include a greater propensity for inherently aggressive skin cancers (eg, higher risk of SCC) and delays in diagnosis (eg, late-stage diagnosis of melanoma).1,4 For melanoma, increased mortality has been attributed to a predominance of acral lentiginous melanomas, which are more frequently diagnosed at more advanced stages than other melanoma subtypes.6,12,13 Black patients, Hispanics, Asians, and Pacific Islanders are all more likely to present with thicker tumors and metastases on initial presentation than their white counterparts (P<.001).2,8,9,12-14 The higher risk of death from SCC results from the predominance of lesions on non–sun-exposed areas, particularly the legs and anogenital areas, and within sites of chronic scarring or inflammation.4 Unlike sun-induced SCC, the most commonly observed type of SCC in lighter skin types, SCCs that develop in association with chronic inflammatory or ulcerative processes are aggressive and invasive, and they metastasize to distant sites in 20% to 40% of cases (versus 1%–4% in sun-induced SCC).1,3,4 For all skin cancers, poor access to medical care, patients’ unawareness of their skin cancer risk, lack of adequate skin examinations, and prevalence of lesions on uncommon sites that may be inconspicuous or overlooked have all been suggested to delay diagnosis.1,15,16 Given that more advanced disease is associated with worse outcomes, the implications of this delay are enormous and remain a cause for concern.

The alarming skin cancer mortality rates in patients with skin of color are a call to action for the medical community. The consistent use of full-body skin examinations including close inspection of mucosal, acral, and genital areas for all patients independent of skin type and racial/ethnic background is paramount. Advancing skin cancer education in skin of color populations, such as through distribution of patient-directed educational materials produced by organizations such as the American Academy of Dermatology, Skin Cancer Foundation, and Skin of Color Society, is an important step toward increased public awareness.16 Use of social and traditional media outlets as well as community-directed health outreach campaigns also are important strategies to change the common misconception that darker-skinned individuals do not get skin cancer. We hope that with a multipronged approach, disparities in skin cancer mortality will steadily be eliminated.

- Gloster HM Jr, Neal K. Skin cancer in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:741-760; quiz 761-764.

- Cormier JN, Xing Y, Ding M, et al. Ethnic differences among patients with cutaneous melanoma. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1907-1914.

- Mora RG, Perniciaro C. Cancer of the skin in blacks: I. a review of 163 black patients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:535-543.

- Halder RM, Bridgeman-Shah S. Skin cancer in African Americans. Cancer. 1995;75:667-673.

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2013. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; April 2016. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2013/. Updated September 12, 2016. Accessed April 7, 2017.

- Bellows CF, Belafsky P, Fortgang IS, et al. Melanoma in African-Americans: trends in biological behavior and clinical characteristics over two decades. J Surg Oncol. 2001;78:10-16.

- Chen L, Jin S. Trends in mortality rates of cutaneous melanoma in East Asian populations. Peer J. 2014;4:e2809.

- Cress RD, Holly EA. Incidence of cutaneous melanoma among non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, Asians, and blacks: an analysis of California Cancer Registry data. Cancer Causes Control. 1997;8:246-252.

- Johnson DS, Yamane S, Morita S, et al. Malignant melanoma in non-Caucasians: experience from Hawaii. Surg Clin N Am. 2003;83:275-282.

- Fleming ID, Barnawell JR, Burlison PE, et al. Skin cancer in black patients. Cancer. 1975;35:600-605.

- Weinstock MA. Nonmelanoma skin cancer mortality in the United States, 1969 through 1988. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:1286-1290.

- Byrd KM, Wilson DC, Hoyler SS. Advanced presentation of melanoma in African Americans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:142-143.

- Hu S, Parmet Y, Allen G, et al. Disparity in melanoma: a trend analysis of melanoma incidence and stage at diagnosis among whites, Hispanics, and blacks in Florida. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1369-1374.

- Black WC, Goldhahn RT, Wiggins C. Melanoma within a southwestern Hispanic population. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1331-1334.

- Harvey VM, Oldfield CW, Chen JT, et al. Melanoma disparities among US Hispanics: use of the social ecological model to contextualize reasons for inequitable outcomes and frame a research agenda [published online August 29, 2016]. J Skin Cancer. 2016;2016:4635740.

- Robinson JK, Joshi KM, Ortiz S, et al. Melanoma knowledge, perception, and awareness in ethnic minorities in Chicago: recommendations regarding education. Psychooncology. 2011;20:313-320.

- Gloster HM Jr, Neal K. Skin cancer in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:741-760; quiz 761-764.

- Cormier JN, Xing Y, Ding M, et al. Ethnic differences among patients with cutaneous melanoma. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1907-1914.

- Mora RG, Perniciaro C. Cancer of the skin in blacks: I. a review of 163 black patients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:535-543.

- Halder RM, Bridgeman-Shah S. Skin cancer in African Americans. Cancer. 1995;75:667-673.

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2013. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; April 2016. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2013/. Updated September 12, 2016. Accessed April 7, 2017.

- Bellows CF, Belafsky P, Fortgang IS, et al. Melanoma in African-Americans: trends in biological behavior and clinical characteristics over two decades. J Surg Oncol. 2001;78:10-16.

- Chen L, Jin S. Trends in mortality rates of cutaneous melanoma in East Asian populations. Peer J. 2014;4:e2809.

- Cress RD, Holly EA. Incidence of cutaneous melanoma among non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, Asians, and blacks: an analysis of California Cancer Registry data. Cancer Causes Control. 1997;8:246-252.

- Johnson DS, Yamane S, Morita S, et al. Malignant melanoma in non-Caucasians: experience from Hawaii. Surg Clin N Am. 2003;83:275-282.

- Fleming ID, Barnawell JR, Burlison PE, et al. Skin cancer in black patients. Cancer. 1975;35:600-605.

- Weinstock MA. Nonmelanoma skin cancer mortality in the United States, 1969 through 1988. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:1286-1290.

- Byrd KM, Wilson DC, Hoyler SS. Advanced presentation of melanoma in African Americans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:142-143.

- Hu S, Parmet Y, Allen G, et al. Disparity in melanoma: a trend analysis of melanoma incidence and stage at diagnosis among whites, Hispanics, and blacks in Florida. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1369-1374.

- Black WC, Goldhahn RT, Wiggins C. Melanoma within a southwestern Hispanic population. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1331-1334.

- Harvey VM, Oldfield CW, Chen JT, et al. Melanoma disparities among US Hispanics: use of the social ecological model to contextualize reasons for inequitable outcomes and frame a research agenda [published online August 29, 2016]. J Skin Cancer. 2016;2016:4635740.

- Robinson JK, Joshi KM, Ortiz S, et al. Melanoma knowledge, perception, and awareness in ethnic minorities in Chicago: recommendations regarding education. Psychooncology. 2011;20:313-320.

Recognizing and Managing Elder Abuse in the Emergency Department

Case

An 85-year-old right-handed woman who recently had been diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment arrived at the ED via emergency medical services (EMS) for evaluation of a reported fall. She was accompanied by her daughter, who resided with the patient and was her primary caregiver. The patient stated that she had tripped on a wet rug in the bathroom of her home, striking her head and face on the edge of the sink without losing consciousness. Her daughter reported that she was not assisting her mother when the fall occurred, but had witnessed the fall from the hallway and called EMS. At the patient’s home, EMS found the patient to be alert, oriented, and ambulatory with normal vital signs that remained stable throughout prehospital transport.

The remainder of the patient’s history was provided almost entirely by her daughter, who constantly interrupted her mother whenever she attempted to directly answer a question or provide information. On physical examination, the patient had bilateral tenderness, edema, and periorbital ecchymoses, and a left eye that was nearly swollen shut. Extraocular movements were normal, visual acuity was intact, and sclerae were noninjected. The patient had tenderness over both maxillary sinuses, and edema and ecchymosis of her left cheek. There was also tenderness, ecchymoses, and edema on the lateral aspects of both forearms, and decreased range of motion of her right lower arm and wrist. With the exception of the patient not knowing the date during the orientation part of the thorough neurological examination, the remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Radiological evaluation found no evidence of traumatic brain injury, but did reveal an acute fracture of the left zygomatic arch, an acute displaced nasal bone fracture, an age-indeterminate fracture of the right zygomatic arch, and an acute right ulnar fracture. Considering all of these findings, particularly the pattern of acute injuries, the emergency physician (EP) considered elder abuse as the possible etiology of the patient’s acute and chronic injuries.

Although the patient had initially agreed with her daughter’s description of the events—including her claim that she had fallen—when the EP questioned the patient alone, she related a history of frequent verbal and less frequent physical abuse by her daughter. The patient further noted that immediately before sustaining the injuries that brought her to the ED, her daughter had been insisting that she sign documents to give her control of her banking and finances. After refusing to sign the papers, the patient said that she and her daughter got into an argument, which she noted “they tended to do frequently.” The patient admitted that during this argument, her daughter struck her in the face repeatedly with the cane that the daughter had grabbed with her right hand.

The EP admitted the patient to the hospital for management of her orthopedic injuries and related pain, and to formulate a safe discharge plan. During admission, additional diagnostic testing revealed multiple old rib fractures, anemia, and a low-serum albumin, which suggested poor nutritional status.

Epidemiology

The term elder abuse refers to harm or the risk of harm to an older adult from either action or negligence committed by someone in a relationship of trust, or when a victim has been targeted because of age or disability. Elder abuse encompasses physical, sexual, or psychological abuse, neglect, and financial exploitation.1-5 Identified victims of elder abuse typically suffer from multiple forms of abuse.1-5

At present, elder abuse annually affects 5% to 10% of community-dwelling older adults,1-6 and nursing-home residents are at increased risk of abuse.7-10 Poor medical outcomes, including depression and dementia,11 and much higher mortality6,12,13 have been linked to victims of elder abuse.

Etiology

When treating older adults, it is critically important for EPs and the ED staff to consider and identify elder abuse in the differential diagnosis.14,15 Presently, only an estimated 1 in 24 cases of abuse is recognized and reported to the authorities,2 and much of the subsequent morbidity and mortality of elder abuse results from poor detection. A visit to the ED for an acute injury or illness may be the only time socially isolated older adults leave their homes.15-17 Additionally, the ED setting is uniquely suited to identify mistreatment, as a patient typically may be evaluated for several hours by providers from multiple disciplines who are able to observe, interact with, and examine the patient.15 The ED already exercises a similar essential role in the identification and initial intervention for both child abuse18,19 and intimate partner violence among younger adults.20,21

Recognition

Unfortunately, at present, ED providers rarely recognize and report elder abuse.22-24 Though the reasons for this are not entirely understood, inadequate training, lack of time and space to conduct complete evaluations, reluctance to become involved with the legal system, and challenges to distinguishing intentional from unintentional injuries may be contributing factors.24,25 A focus on improving EP and ED staff approaches to elder abuse is relevant and timely given the growing elderly population.

Risk Factors

When evaluating elderly patients, providers should consider research suggesting that some older adults may be at particularly high risk for abuse.4,26-29 Notably, individuals who have cognitive impairment are more likely to be victims of abuse.30-32 Health-related demographic characteristics such as poor physical and mental health, substance abuse, low income/socioeconomic status, and social isolation all may increase the potential for mistreatment.

Family History

Similar to situations resulting in intimate partner violence, a family history of abuse and exposure to traumatic events may increase risk, and those responsible for elder abuse often turn out to be spouses, romantic partners, or an adult child living with the elderly parent—though paid caregivers also can be abusive.

Suspicion of abuse should be increased when individuals in caregiving roles have a history or show signs of mental illness, substance abuse, financial dependence on the victim, or caregiver stress. Considering that a caregiver may be overwhelmed is particularly relevant when an elderly patient exhibits behavioral issues.

Medical History

Obtaining a clear and thorough medical history from the patient and caregiver, both together and alone, is paramount to assessing the potential for abuse. Many indicators from the history may suggest the possibility of mistreatment (Table 1)33-37 and although challenging in a busy ED, a comprehensive head-to-toe examination is crucial to adequately assess abuse. Suspicious physical findings and injury patterns of physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect are listed in Table 2.33-37 Ongoing research is aimed at improving ED providers’ ability to differentiate accidental injuries, such as fall injuries, from injuries caused by physical elder abuse.

Injury Patterns

Preliminary studies have indicated that physical abuse injuries most commonly occur on the head, neck, and upper extremities.38,39 A study comparing abuse victims to accidental injury sufferers found that abuse victims often had large bruises (>5 cm) on the face, lateral right arm, or posterior torso.40 Preliminary results from a study in progress suggest that injuries to the left periorbital area, neck, and ulnar forearm may be much more common in abuse than in accident.

Imaging Studies

Emergency radiologists are contributing additional concerning findings indicative of elder abuse,38,41,42 such as the concomitant presence of old and new fractures, high-energy fractures inconsistent with the purported mechanism, and distal ulnar diaphyseal fractures.41,42 The ultimate goal is to identify pathognomonic injury patterns similar to those found in child abuse cases, to assist ED providers.

Laboratory Studies

Although there are no laboratory tests to definitively identify abuse or neglect, specific findings that may indicate abuse include anemia, dehydration, malnutrition, hypothermia/hyperthermia, and rhabdomyolysis.43 In addition, inappropriately high- or low-medication levels and the presence of illicit drugs, which are not often checked in elderly patients in the ED, may be a sign of abuse.43

Laboratory studies that reveal undetectable levels of a patient’s prescription medications may indicate a caregiver’s intentional or neglectful withholding of such medications—especially diversion of opioid medications prescribed for painful conditions.43 Likewise, elevated levels of prescribed drugs may point to intentional or unintentional overdose, whereas the presence of nonprescribed drugs or toxins may suggest poisoning.43

Screening Tools

To improve identification of elder abuse in the ED, universal or targeted screening tools are under consideration. Though several screening tools for elder abuse are already available, none have been validated in the ED.15,44,45 Research sponsored by the National Institute of Justice to identify an ED-specific screening tool is ongoing.15

Elder Abuse Suspicion Index

The Elder Abuse Suspicion Index (EASI) is a short screening tool that has been validated for cognitively intact patients being treated in family practice and ambulatory care settings, and may be used in EDs.44 The tool comprises six questions: five for patient response, and a sixth question for clinician response. This tool is available at http://www.nicenet.ca/tools-easi-elder-abuse-suspicion-index.46

Interventional Measures

When elder mistreatment is suspected or confirmed, health care providers must first address any acute medical, traumatic, or psychological issues. Bleeding, orthopedic injuries, metabolic abnormalities, infections, and agitation must be treated and/or stabilized, while neglected or inappropriately managed chronic medical conditions may require treatment.

Hospitalization should be considered for an older adult who needs extended treatment or observation and, in cases of immediate or continued danger of abuse, separation from contact with the suspected abuser. These measures present several challenges, particularly if the suspected abuser is the patient’s health care proxy, in which case early involvement of the hospital’s legal department, social services, and administration may be necessary—especially in navigating the guardianship process.

Engaging security also may be necessary if the patient requires one-to-one patient watch or when the perpetrator must be removed from the ED. Social workers, patient services representatives, and law enforcement officials should be informed when such intervention is necessary.

In instances when a patient is not at risk of immediate harm, interventions can be more individualized. Coordination with primary care physicians (PCPs) must also be facilitated prior to discharge, to ensure consistent longitudinal follow-up care, and social workers should provide any needed out-of-hospital resources to the patient—and caregiver—such as Meals-on-Wheels, medical transportation services, adult day care/senior center participation, and substance abuse treatment.

Patient Decision-Making Capacity

When a patient experiencing abuse declines interventions or services, the EP must evaluate the patient’s decision-making capacity. In unclear cases, a psychiatric evaluation can help to assess decision-making capacity. If the victim is deemed to have capacity with regard to care and/or discharge, the patient’s choice of returning to an unsafe environment must be respected, as is true in instances of intimate partner violence among younger adults—but not in child abuse cases. In such situations, the EP should nevertheless discuss safety planning, offer psychoeducation about violence and abuse, suggest appropriate community referrals, and encourage abused patients to return or call a contact person whenever they desire or feel the need to talk further. For a victim who is deemed not to possess capacity, providers should proceed with treatment considered to be in the best interest of the patient.

Reporting Abuse

Emergency department providers should notify the appropriate authorities when elder abuse is suspected or identified. A report may be made to the local Adult Protective Services (APS), but this agency operates much differently than Child Protective Services. Case workers with APS will not open a case while a patient is in the ED or hospital, as it is deemed a safe environment and any investigation they undertake will only commence upon discharge. Because of this, contacting the local police department prior to discharge should be considered.

Mandatory elder abuse-reporting laws vary from state to state. Health care providers should therefore contact their respective state or city department of health to obtain local legislation.

Multidisciplinary Approach

Ideally, a multidisciplinary, ED-based intervention team modeled on child abuse teams18,19 would help to optimize treatment and ensure the safety and treatment of vulnerable older adults. These teams could conduct thorough medical, forensic, and social work assessments, allowing ED providers to attend to other patients. The team could also assist in arranging for appropriate and safe dispositions. An innovative Vulnerable Elder Protection Team was recently launched at New York-Presbyterian Weill Cornell Medical Center to provide these services, and its impact is currently being evaluated.

Case Conclusion

The EP who treated the patient realized that blows from a blunt object held by a right-handed person would tend to land on the left side of the victim’s face and upper torso, and that a right-handed victim who successfully blocked the blows intended for her face would instead sustain an isolated right ulna or radius midshaft fracture. These findings, together with the concomitant presence of both old and new fractures, led the EP to question the patient alone and, after obtaining a different history of the events that led to the injuries, admit her for further evaluation, treatment, and interventions to prevent continuing abuse.

Summary

Elder abuse has the potential to affect an increasing number of older adults in this growing population, and an ED visit may offer the only opportunity to identify victims and provide intervention, in turn reducing morbidity and mortality. The results of ongoing research will improve the ability of EPs and ED staff to accurately assess the presence or risk of elder abuse and respond more effectively. It is essential that EPs always consider elder abuse and neglect as a possible etiology when evaluating injuries in this population. Moreover, when identified, addressing elder mistreatment may dramatically improve quality of life or save the lives of these vulnerable patients.

1. Elder Mistreatment: Abuse, Neglect, and Exploitation in an Aging America. Bonnie RJ, Wallace RB, eds. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003:1-552. https://www.nap.edu/read/10406/chapter/1. Accessed April 4, 2017.

2. Lifespan of Greater Rochester, Inc; Weill Cornell Medical Center of Cornell University; New York City Department for the Aging. Under the radar: New York state elder abuse prevalence study: self-reported prevalence and documented case surveys 2011.http://ocfs.ny.gov/main/reports/Under%20the%20Radar%2005%2012%2011%20final%20report.pdf. Published May 2011. Accessed April 4, 2017.

3. Connolly MT, Brandl B, Breckman R. The Elder Justice Roadmap: A Stakeholder Initiative to Respond to an Emerging Health, Justice, Financial, and Social Crisis. https://www.justice.gov/elderjustice/file/829266/download. National Center for Elder Abuse. Published January 2014. Accessed April 4, 2017.

4. Acierno R, Hernandez MA, Amstadter AB, et al. Prevalence and correlates of emotional, physical, sexual, and financial abuse and potential neglect in the United States: the National Elder Mistreatment Study. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(2):292-297. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.163089.

5. Lachs MS, Pillemer K. Elder abuse. Lancet. 2004;364(9441):1263-1272. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17144-4.

6. Lachs MS, Pillemer KA. Elder abuse. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(20):1947-1956. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1404688.

7. Ortmann C, Fechner G, Bajanowski T, Brinkmann B. Fatal neglect of the elderly. Int J Legal Med. 2001;114(3):191-193.

8. Schiamberg LB, Oehmke J, Zhang Z, et al. Physical abuse of older adults in nursing homes: a random sample survey of adults with an elderly family member in a nursing home. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2012;24(1):65-83. doi:10.1080/08946566.2011.608056.

9. Rosen T, Pillemer K, Lachs M. Resident-to-resident aggression in long-term care facilities: an understudied problem. Aggress Violent Behav. 2008;13(2):77-87. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2007.12.001.

10. Shinoda-Tagawa T, Leonard R, Pontikas J, McDonough JE, Allen D, Dreyer PI. Resident-to-resident violent incidents in nursing homes. JAMA. 2004;291(5):591-598. doi:10.1001/jama.291.5.591.

11. Dyer CB, Pavlik VN, Murphy KP, Hyman DJ. The high prevalence of depression and dementia in elder abuse or neglect. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(2):205-208.

12. Lachs MS, Williams CS, O’Brien S, Pillemer KA, Charlson ME. The mortality of elder mistreatment. JAMA. 1998;280(5):428-432.

13. Dong XQ, Simon MA, Beck TT, et al. Elder abuse and mortality: the role of psychological and social wellbeing. Gerontology. 2011;57(6):549-658. doi:10.1159/000321881.

14. Stevens TB, Richmond NL, Pereira GF, Shenvi CL, Platts-Mills TF. Prevalence of nonmedical problems among older adults presenting to the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(6):651-658. doi:10.1111/acem.12395.