User login

Conjoint Sessions With Clinical Pharmacy and Health Psychology for Chronic Pain

Providing comprehensive, integrated, behavioral intervention services to address the prevalent condition of chronic, noncancer pain is a growing concern. Although the biopsychosocial model (BPS) and stepped-care approaches have been understood and discussed for some time, clinician and patient understanding and investment in these approaches continue to face challenges. Moreover, even when resources (eg, staffing, referral options, space) are available, clinicians and patients must engage in meaningful communication to achieve this type of care.

Importantly, engagement means moving beyond diagnosis and assessment and offering interventions that provide psychoeducation related to the chronic pain cycle. These interventions address maladaptive cognitions and beliefs about movement and pain; promote paced, daily physical activity and engagement in life; and help increase coping skills to improve low mood or distress, all fundamental components of the BPS understanding of chronic pain.

Background

Chronic, noncancer pain is a prevalent presentation in primary care settings in the U.S. and even more so for veterans.1 Fifty percent of male veterans and 75% of female veterans report chronic pain as an important condition that impacts their health.2 An important aspect of this prevalence is the focus on opioid pain medication and medical procedures, both of which draw more narrowly on the biomedical model. Additional information on the longer term use of pain procedures and opioid medications is now available,and given some risks and limitations (eg, tolerance, decreasing efficacy, opioid-induced medical complications), the need to study and offer other options is gaining attention.3 Behavioral chronic pain management has a clear historic role that draws on the BPS modeland Gate Control Theory.3-6

More recently, the National Strategy of Chronic Pain collaborative and stepped-care models extended this literature, outlining collaboration and levels of care depending on the chronicity of the pain experience as well as co-occurring conditions and patient presentations.7,8 The Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF), the gold standard in interdisciplinary pain management programs, calls for further resources and coordination of these efforts, including a tertiary level of care representing the highest step in the stepped-care model.8

These interdisciplinary, integrative pain management programs, which include functional restoration and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) interventions, have been effective for the treatment of chronic pain.9-12However, the staffing, resources, clinical access, and coordination of this complex care may not be feasible in many health care settings. For example, a 2005 survey reported that there were only 200 multidisciplinary pain programs in the U.S., and only 84 of them were CARF accredited.13 By 2011 the number of CARF-accredited programs had decreased to 64 (the number of nonaccredited programs was not reported for 2011).13

Furthermore, engagement in behavioral pain management services is a challenge: Studies show that psychosocial interventions are underused, and a majority of studies may not report quantitatively or qualitatively on patient adherence or engagement in these services.14 These realities introduce the idea that coordinated appointments between 2 or 3 different disciplines available in primary care may be a feasible step toward implementing more comprehensive, optimal care models.

Behavioral pain management interventions that uphold the BPS also call on the idea of active self-management. Therefore, effective communication is fundamental at both the provider-patient and interprofessional levels to enhance engagement in health care, receptiveness to interventions, and to self-management of chronic pain.11,15 How clinicians conceptualize, hold assumptions about, and communicate with patients about chronic pain management has received more attention.15,16

Clinician Considerations for Pain Management

On theclinicians’ side, monitoring assumptions about patients and awareness of their beliefs as well as the care itself are foundational in patient interactions, impacting the success of patient engagement. Awareness of the language used in these interactions and how clinicians collaborate with other professionals become salient. Coupled with the reality of high attrition, this discussion lends itself in important ways to the motivational interviewing (MI) approach that aims to meet patients “where they are” by use of open-ended questions and reflective listening to guide the conversation in the direction of contemplating or actual behavior change.17 For example, “What do you think are the best ways to manage your pain?” and “It sounds like sometimes the medicine helps, but you also want more options to feel in control of your pain.”

Given the historic focus on the biomedical approach to chronic pain, including the use of opioid medications and medical procedures as well as traditional challenges to engagement in CBT, researchers have explored whether alternative methods may increase participation and improve outcomes for behavioral self-management.3 Drawing on a history of assessing readiness for change in pain management, Kerns and colleagues offered tailored cognitive strategies or behavioral skills training depending on patient preferences.18,19 These researchers also incorporated motivational enhancement strategies in the tailored interventions and compared engagement with standard CBT for chronic pain protocol. Although they did not find significant differences in engagement between the 2 groups, participation and treatment adherence were associated with posttreatment improvements in both groups.19 Taking a step back from enhancing intervention engagement, first assessing readiness to self-manage becomes another salient exploration and step in the process.

Another element of engagement in services is referral to other clinicians. Dorflinger and colleagues made this point in a conceptual paper that broadly outlined interdisciplinary, integrative, and more comprehensive models of care for chronic pain.15 We know from integrated models that referral-based care may decrease the likelihood of participation in health care services. That is, if a patient needs to make a separate appointment and meet with a new clinician, they are more likely to decline, cancel, or not show, particularly if they are not “ready” for change. Co-located or embedded care and conjoint sessions that include a warm handoff or another clinician who joins the first appointment may reduce stigma and other relevant barriers for introducing a patient to new ideas.20

Using a conjoint session that involves a clinical pharmacy pain specialist and a health psychologist is one way in which veterans can be exposed to more chronic pain-related BPS concepts and behavioral health services than they might be exposed to otherwise. The purpose of this project was to bring awareness to a practical and clinically relevant integrated approach to the dissemination of BPS information for chronic pain management.

In providing this information through effective communication at the patient-provider and interprofessional levels, the clinicians’ intention was to increase patient engagement and use of BPS strategies in the self-management of chronic pain. This project also aimed to enhance engagement and improve the quality of services before acquiring additional positions and funding for a specialized pain management team. These sessions were offered at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System (VAAAHS) in Michigan. Quantitative and qualitative information was examined from the conjoint and subsequent sessions that occurred in this setting.

Methods

With the above concepts in mind, VAAAHS offered veterans conjoint sessions involving a health psychologist and clinical pharmacy specialist during a 3-month period while this resource was available. The conjoint sessions were part of a preexisting pharmacist-run pain medication clinic embedded in primary care. The conjoint session was presented to patients as part of general clinic flow to reduce stigma of engagement in psychological services and allow for the dissemination of BPS information.

Participants

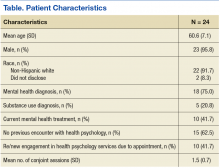

The electronic health records (EHR) of 24 veteran patients with chronic pain, who participated in a conjoint health psychology/pain pharmacy session, were reviewed for the current study. Most of the patients were male (95.8%) and non-Hispanic white (91.7%); the remaining participants did not disclose their ethnicity. The mean age was 60.6 years (SD 7.1; range 50-80). A total of 75% had a mental health diagnosis, and 41.7% were in mental health treatment at the time of the conjoint appointment. Among the sample, 20.8% had a current diagnosis of a substance use disorder (SUD), and no individuals were in treatment for a SUD at the time of the conjoint appointment. Patients received an average of 1.5 conjoint sessions (SD 0.7; range 1-3).

Procedure

The veterans for this project were chosen from a panel of patients followed by the pain medication clinical pharmacy specialist in the primary care pain medication clinic. The selected veterans were offered a joint session with their clinical pharmacy provider and the health psychology resident during their scheduled visit in the pain medication clinic. Each veteran was informed that the goal of the joint visit was to enhance self-directed nonpharmacologic chronic pain management skills as an additional set of tools in the tool kit for particularly difficult pain days. Veterans were assured that their usual care would not be compromised if they declined the session.

During the encounter(s), the health psychologist contributed to the veteran’s care by using MI and CBT for chronic pain skills. The health psychologist further assessed concerns and needs and guided the discussion as appropriate. With veteran readiness, these discussions explored the degree of knowledge and cognitive and behavioral coping skills the patient used. These conjoint sessions also documented the types of discussions and degree of engagement in the encounter(s) as well additional referrals, complementary services, and/or offered follow-up services for either additional conjoint sessions or further health psychology-related services.

A total of 24 EHRs from these conjoint and subsequent encounters were reviewed for evidence of the procedures by a psychology intern involved in chronic pain management services. Of these 24 records, 6 also were reviewed by a board-certified health psychologist for consensus building and agreement on coding (Sidebar, Record Coding).

Using the coding system and SPSS Version 2.1 (IBM, Armonk NY), descriptive statistics were used to examine conjoint session content and new- or re-engagement in health psychology services following the conjoint sessions. For those patients who followed up with additional services, the content, type, and outcome of these services were explored. Next, linear regression was used to determine whether number of conjoint sessions was associated with a qualitative treatment outcome, and 2 logistic regressions were used to determine whether the number of sessions was associated with the likelihood of accepting services and follow-through with services after accepting them. An additional logistic regression examined whether having a mental health diagnosis (yes/no) was associated with whether the individual accepted additional health psychology services. Finally, independent sample t tests examined differences between those who accepted services vs those who declined follow-up services in substance use diagnosis, mental health diagnosis, and previous health psychology services engagement. Of note, given the small sample size, the Levene’s test for equality of variances was conducted and unequal variances were assumed.

Results

All 24 patients agreed to have the conjoint session with the clinical pharmacy specialist and health psychologist. Of the participants, 62.5% had no previous interaction with health psychology services. Among those who had previous encounters with health psychology services, 12.5% had participated in 1 or more group sessions, another 12.5% had participated in 1 or more individual sessions, and an additional 12.5% had been referred for health psychology services but had not followed through. A total of 10 participants represented a new- or re-engagement in health psychology services following the conjoint appointment. Two patients were referred for additional services as a result of their conjoint appointment (1 to specialty mental health and another to Primary Care-Mental Health Integration [PC-MHI]), and 1 of the participants followed through with the referral. Finally, with regard to the content of the initial session, 37.5% of the sessions contained some form of psychoeducation, 54.2% contained a functional assessment, and 41.7% contained an introduction of skills.

Half of the veterans participated in health psychology services beyond the initial conjoint session. Four of these veterans participated in additional conjoint sessions, and the remaining 8 engaged in health psychology services, which took the form of telephone sessions (3), in-person sessions (3), or a combination of both telephone and in-person sessions (2). Twelve veterans participated in an average of 3.4 (SD 3.7) follow-up sessions. In terms of the content of these follow-up sessions, across all formats and types, 3 included some introduction to coping skills, with no documented evidence of follow-through. For 2 of the veterans engaging in some type of follow-up, there was documented use of coping skills, and 2 used the coping skills with self-reported success and benefit. Finally, documentation revealed evidence that 3 of these veterans were not only using the coping skills with benefit, but also reported an improvement in pain management overall. One also was connected with a different service.

Regarding reasons for completion of services, 2 veterans were terminated due to completing treatment/meeting goals, 2 were terminated because they did not follow up after a session, 7 were terminated due to patient declining additional sessions, and 1 veteran was still receiving services at the time of the review. Linear regression indicated that the number of conjoint sessions was not associated with qualitative treatment outcome. Two logistic regressions indicated that number of conjoint sessions was not related to whether the veteran accepted follow-up services or whether the veteran followed through with services after accepting. Of note, logistic regression indicated that having a mental health diagnosiswas associated with a decreased likelihood of accepting health psychology services (P = .03). Regarding the independent samples t tests, veterans who did not accept follow-up services were more likely to have a mental health diagnosis (P = .03). The groups did not differ significantly with regard to substance use diagnosis or previous engagement in health psychology services.

Discussion

Results showed that all 24 veterans who were offered a conjoint session with a clinical pharmacy specialist and health psychologist engaged in at least 1 session. Half the veterans participated in further services as well. Both the initial conjoint and follow-up sessions offered a greater degree of communication related to the cognitive-behavioral and functional restoration components of behavioral pain management. Given that a majority of the sample had not participated in behavioral or mental health services previously, this may represent a greater penetration rate of exposure to mental health service for veterans than would have been available otherwise.

More specifically, qualitative results suggest that in these conjoint sessions, the veterans were exposed to behavioral psychotherapeutic approaches to chronic pain management (eg, health behavior change, motivational enhancement, health-related psychoeducation, and CBT for chronic pain) that again may not have been provided otherwise (ie, via referral and separately scheduled sessions). These findings are supported by theories consistent with the Transtheoretical Model, which indicates that individuals fall in varying degrees of readiness for behavioral change (ie, precontemplative, contemplative, planning, action, maintenance).21,22 Thus, behavioral intervention approaches must be adaptive and adjust format and communication, including the amount and type of psychoeducation offered. Moreover, the integrated theory of health behavior change in the context of chronic pain management calls for fostering awareness, knowledge, and beliefs through effective communication and education for a wide range of individuals who are at varying stages of change.23 In addition to the conjoint session and subsequent service(s) content that were reviewed and coded in this current project, future projects might draw on these theoretical models and code sessions for patients’ stages of change and assess whether a patient made progress across phases of change (eg, the patient shifted from contemplative to the planning stage of change).

Within this project’s conjoint sessions and consistent with MI principles, veterans were offered discussions related to the bidirectional and BPS aspects of their own chronic pain experience. That is, while discussing responses and adjustment to pain medication(s), veterans received reflections with MI and heard feedback related to their current coping strategies, methods to enhance coping, as well as potential psychosocial impacts of their chronic pain experience. With permission, veterans also were introduced to themes that comprised evidence-based CBT for chronic pain (CBT-CP) intervention. Understanding what change means in the context of chronic pain management is critical. That is, tipping the conversation toward consideration of alternative modalities (eg, relaxation, stress management, cognitions, and pain) in conjunction with or in place of the traditional modalities (eg, medication, pain procedures) is paramount.

Clinicians must listen for patient ambivalence related to procedures, interventions, medication changes, and/or the behavioral self-management of chronic pain. This type of active listening and exploration may be more likely when there is collaboration and effective team functioning among clinicians than when clinicians provide care independently. Future quality improvement (QI) or research projects could extend the EHR review and evaluate clinician-patient transcripts for fidelity to the CBT-CP and MI models. Such efforts could assess for associations between clinician MI consistent behaviors and change talk on the part of the patient. Furthermore, clinician communication and patient change talk from transcripts could be evaluated in relation to evidence from the EHR regarding patient use of coping skills and behavior change.

Consistent with behavioral health literature, having a mental health diagnosis was associated with declining additional behavioral health psychology services in this project. Research has shown that individuals with a mental health diagnosis tend to engage less in behavioral health self-management programs, such as chronic headache and weight management.24-26 This phenomenon lends support for the importance of health care professionals (HCPs) to increase access and exposure to mental and behavioral health services, such as the PC-MHI model.20 In fact, chronic pain management program development efforts within the VA system nationwide include collaboration with the PC-MHI services. One of the initial goals for PC-MHI services is to increase penetration rates into the general outpatient medical clinics and enhance engagement in mental health services.

Using conjoint sessions as was offered in the current project is one step in the development of more comprehensive interdisciplinary teams through interprofessional collaboration and the use of effective clinical communication. In turn, it will be important to directly explore the communication skills and attitudes of these HCPs with regard to interdisciplinary program development and collaboration as teams continue to integrate more broadly into the medical system and enhance chronic pain management services.11 Similarly, measuring the perceptions of clinical pharmacy specialists, physicians, health psychologists, or other clinical disciplines involved in chronic pain management could be another area to explore. More specific to MI, clinician confidence in the use of effective communication and MI skills represents still another area for future study.16

Limitations

Some limitations and suggested future directions found as part of this QI project have been outlined earlier. Other limitations include the used of a retrospective review of information available in patient medical charts. More developed measurement-based care or research could collect self-reports of patient satisfaction with care, functioning, knowledge, readiness for change, and mood in addition to what is noted and documented in clinical observations. Second, the sample was small and did not include any female and few younger veterans, even though these are important subpopulations when examining pain management services. When resources are available for a larger sample size, some exploratory analyses could be conducted for differences in engagement among subgroups. Third, this project may have further confounding variables as this was not an experimental or a controlled study, which could directly compare conjoint sessions with referral-based care and/or those not offered conjoint sessions.

Conclusion

The optimal method of behavioral pain management suggests the need for an interdisciplinary, coordinated team approach, in which the gold standard programs meet requirements set by CARF. However, on a practical level, optimal behavioral pain management may not be feasible at all health care facilities. Furthermore, in an effort to provide best practices to individuals with chronic pain, clinicians must be adaptive and skilled in using effective communication and specialized interventions, such as CBT and MI.

Approaching the more optimal behavioral self-management of chronic pain from a multimodal interdisciplinary perspective and further engaging veterans in this care is paramount. This project is merely one step in this effort that can shed light on the function and logistic outcomes of using a practical, integrated approach to chronic pain. It demonstrates that implementing best practices founded in sound theoretical models despite staffing and resource constraints is possible. Thus, continuing to explore the utility of alternate modalities may offer important applied and translational information to help disseminate and improve chronic pain management services.

Future research could focus on important subpopulations and enhance experimental design with pre- and postmeasures, controlling for possible confounding variables and if possible a controlled design.

Acknowledgments

This quality improvement project was unfunded, and approval was confirmed with the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System Institutional Review Board and Research & Development committees. The authors also thank Associate Chief of Staff, Ambulatory Care, Clinton Greenstone, MD, and Chief of Primary Care Adam Tremblay, MD, for their leadership and support of these integrative services and quality improvement efforts. The authors especially recognize the veterans for whom they aim to provide the highest quality of services possible.

1. Brooks PM. The burden of musculoskeletal disease—a global perspective. Clin Rheumatol. 2006;25(6):778-781.

2. Haskell SG, Heapy A, Reid MC, Papas RK, Kerns RD. The prevalence and age-related characteristics of pain in a sample of women veterans receiving primary care. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2006;15(7):862-869.

3. Roth RS, Geisser ME, Williams DA. Interventional pain medicine: retreat from the biopsychosocial model of pain. Transl Behav Med. 2012;2(1):106-116.

4. Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129-136.

5. Borrell-Carrió F, Suchman AL, Epstein RM. The biopsychosocial model 25 years later: principles, practice, and scientific inquiry. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(6):576-582.

6. Wall PD. The gate control theory of pain mechanisms: a re-examination and re-statement. Brain. 1978;101(1):1-18.

7. Dobscha SK, Corson K, Perrin NA, et al. Collaborative care for chronic pain in primary care: a cluster randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;301(12):1242-1252.

8. Von Korff, Moore JC. Stepped care for back pain: activating approaches for primary care. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(9, pt 2):911-917.

9. Oslund S, Robinson RC, Clark TC, et al. Long-term effectiveness of a comprehensive pain management program: strengthening the case for interdisciplinary care. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2009;22(3):211-214.

10. Scascighini L, Toma V, Dober-Spielmann S, Sprott H. Multidisciplinary treatment for chronic pain: a systematic review of interventions and outcomes. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47(5):670-678.

11. Gatchel RJ, McGeary DD, McGeary CA, Lippe B. Interdisciplinary chronic pain management: past, present, and future. Am Psychol. 2014;69(2):119-130.

12. McCracken LM, Turk DC. Behavioral and cognitive-behavioral treatment for chronic pain: outcome, predictors of outcome, and treatment process. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27(22): 2564-2573.

13. Jeffery MM, Butler M, Stark A, Kane RL. Multidisciplinary Pain Programs for Chronic Noncancer Pain. Comparative Effectiveness Technical Briefs, No 8. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011.

14. Ehde DM, Dilworth TM, Turner JA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for individuals with chronic pain: efficacy, innovations, and directions for research. Am Psychol. 2014;69(2):153-166.

15. Dorflinger L, Kerns RD, Auerbach SM. Providers’ roles in enhancing patients’ adherence to pain self management. Transl Behav Med. 2013;3(1):39-46.

16. Pellico LH, Gilliam WP, Lee AW, Kerns RD. Hearing new voices: registered nurses and health technicians experience caring for chronic pain patients in primary care clinics. Open Nurs J. 2014;8:25-33.

17. Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler CC, eds. Motivational Interviewing in Health Care: Helping Patients Change Behavior. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2008.

18. Kerns RD, Habib S. A critical review of the pain readiness to change model. J Pain. 2004;5(7):357-367.19. Kerns RD, Burns JW, Shulman M, et al. Can we improve cognitive-behavior therapy for chronic back pain treatment engagement and adherence? A controlled trial of tailored versus standard therapy. Health Psychol. 2014;33(9):938-947.

20. Kearney LK, Post EP, Zeiss A, Goldstein MG, Dundon M. The role of mental and behavioral health in the application of the patient-centered medical home in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1(4):624-628.

21. Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51(3):390-395.

22. Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change. Applications to addictive behaviors. Am Psychol. 1992;47(9):1102-1114.

23. Ryan P. Integrated theory of health behavior change: background and intervention development. Clin Nurse Spec. 2009;23(3):161-172.

24. Evans DD , Blanchard EB. Prediction of early termination from the self-regulatory treatment of chronic headache. Biofeedback Self Regul. 1988;13(3):245-256.

25. Maguen S, Hoerster KD, Littman AJ, et al. Iraq and Afghanistan veterans with PTSD participate less in VA’s weight loss program than those without PTSD. J Affect Disord. 2016;193:289-294.

26. Bloor LE. Improving weight management services for female veterans: design and participation factors with a women only program, and comparisons with gender neutral services. Med Res Arch. 2015;2.

Providing comprehensive, integrated, behavioral intervention services to address the prevalent condition of chronic, noncancer pain is a growing concern. Although the biopsychosocial model (BPS) and stepped-care approaches have been understood and discussed for some time, clinician and patient understanding and investment in these approaches continue to face challenges. Moreover, even when resources (eg, staffing, referral options, space) are available, clinicians and patients must engage in meaningful communication to achieve this type of care.

Importantly, engagement means moving beyond diagnosis and assessment and offering interventions that provide psychoeducation related to the chronic pain cycle. These interventions address maladaptive cognitions and beliefs about movement and pain; promote paced, daily physical activity and engagement in life; and help increase coping skills to improve low mood or distress, all fundamental components of the BPS understanding of chronic pain.

Background

Chronic, noncancer pain is a prevalent presentation in primary care settings in the U.S. and even more so for veterans.1 Fifty percent of male veterans and 75% of female veterans report chronic pain as an important condition that impacts their health.2 An important aspect of this prevalence is the focus on opioid pain medication and medical procedures, both of which draw more narrowly on the biomedical model. Additional information on the longer term use of pain procedures and opioid medications is now available,and given some risks and limitations (eg, tolerance, decreasing efficacy, opioid-induced medical complications), the need to study and offer other options is gaining attention.3 Behavioral chronic pain management has a clear historic role that draws on the BPS modeland Gate Control Theory.3-6

More recently, the National Strategy of Chronic Pain collaborative and stepped-care models extended this literature, outlining collaboration and levels of care depending on the chronicity of the pain experience as well as co-occurring conditions and patient presentations.7,8 The Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF), the gold standard in interdisciplinary pain management programs, calls for further resources and coordination of these efforts, including a tertiary level of care representing the highest step in the stepped-care model.8

These interdisciplinary, integrative pain management programs, which include functional restoration and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) interventions, have been effective for the treatment of chronic pain.9-12However, the staffing, resources, clinical access, and coordination of this complex care may not be feasible in many health care settings. For example, a 2005 survey reported that there were only 200 multidisciplinary pain programs in the U.S., and only 84 of them were CARF accredited.13 By 2011 the number of CARF-accredited programs had decreased to 64 (the number of nonaccredited programs was not reported for 2011).13

Furthermore, engagement in behavioral pain management services is a challenge: Studies show that psychosocial interventions are underused, and a majority of studies may not report quantitatively or qualitatively on patient adherence or engagement in these services.14 These realities introduce the idea that coordinated appointments between 2 or 3 different disciplines available in primary care may be a feasible step toward implementing more comprehensive, optimal care models.

Behavioral pain management interventions that uphold the BPS also call on the idea of active self-management. Therefore, effective communication is fundamental at both the provider-patient and interprofessional levels to enhance engagement in health care, receptiveness to interventions, and to self-management of chronic pain.11,15 How clinicians conceptualize, hold assumptions about, and communicate with patients about chronic pain management has received more attention.15,16

Clinician Considerations for Pain Management

On theclinicians’ side, monitoring assumptions about patients and awareness of their beliefs as well as the care itself are foundational in patient interactions, impacting the success of patient engagement. Awareness of the language used in these interactions and how clinicians collaborate with other professionals become salient. Coupled with the reality of high attrition, this discussion lends itself in important ways to the motivational interviewing (MI) approach that aims to meet patients “where they are” by use of open-ended questions and reflective listening to guide the conversation in the direction of contemplating or actual behavior change.17 For example, “What do you think are the best ways to manage your pain?” and “It sounds like sometimes the medicine helps, but you also want more options to feel in control of your pain.”

Given the historic focus on the biomedical approach to chronic pain, including the use of opioid medications and medical procedures as well as traditional challenges to engagement in CBT, researchers have explored whether alternative methods may increase participation and improve outcomes for behavioral self-management.3 Drawing on a history of assessing readiness for change in pain management, Kerns and colleagues offered tailored cognitive strategies or behavioral skills training depending on patient preferences.18,19 These researchers also incorporated motivational enhancement strategies in the tailored interventions and compared engagement with standard CBT for chronic pain protocol. Although they did not find significant differences in engagement between the 2 groups, participation and treatment adherence were associated with posttreatment improvements in both groups.19 Taking a step back from enhancing intervention engagement, first assessing readiness to self-manage becomes another salient exploration and step in the process.

Another element of engagement in services is referral to other clinicians. Dorflinger and colleagues made this point in a conceptual paper that broadly outlined interdisciplinary, integrative, and more comprehensive models of care for chronic pain.15 We know from integrated models that referral-based care may decrease the likelihood of participation in health care services. That is, if a patient needs to make a separate appointment and meet with a new clinician, they are more likely to decline, cancel, or not show, particularly if they are not “ready” for change. Co-located or embedded care and conjoint sessions that include a warm handoff or another clinician who joins the first appointment may reduce stigma and other relevant barriers for introducing a patient to new ideas.20

Using a conjoint session that involves a clinical pharmacy pain specialist and a health psychologist is one way in which veterans can be exposed to more chronic pain-related BPS concepts and behavioral health services than they might be exposed to otherwise. The purpose of this project was to bring awareness to a practical and clinically relevant integrated approach to the dissemination of BPS information for chronic pain management.

In providing this information through effective communication at the patient-provider and interprofessional levels, the clinicians’ intention was to increase patient engagement and use of BPS strategies in the self-management of chronic pain. This project also aimed to enhance engagement and improve the quality of services before acquiring additional positions and funding for a specialized pain management team. These sessions were offered at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System (VAAAHS) in Michigan. Quantitative and qualitative information was examined from the conjoint and subsequent sessions that occurred in this setting.

Methods

With the above concepts in mind, VAAAHS offered veterans conjoint sessions involving a health psychologist and clinical pharmacy specialist during a 3-month period while this resource was available. The conjoint sessions were part of a preexisting pharmacist-run pain medication clinic embedded in primary care. The conjoint session was presented to patients as part of general clinic flow to reduce stigma of engagement in psychological services and allow for the dissemination of BPS information.

Participants

The electronic health records (EHR) of 24 veteran patients with chronic pain, who participated in a conjoint health psychology/pain pharmacy session, were reviewed for the current study. Most of the patients were male (95.8%) and non-Hispanic white (91.7%); the remaining participants did not disclose their ethnicity. The mean age was 60.6 years (SD 7.1; range 50-80). A total of 75% had a mental health diagnosis, and 41.7% were in mental health treatment at the time of the conjoint appointment. Among the sample, 20.8% had a current diagnosis of a substance use disorder (SUD), and no individuals were in treatment for a SUD at the time of the conjoint appointment. Patients received an average of 1.5 conjoint sessions (SD 0.7; range 1-3).

Procedure

The veterans for this project were chosen from a panel of patients followed by the pain medication clinical pharmacy specialist in the primary care pain medication clinic. The selected veterans were offered a joint session with their clinical pharmacy provider and the health psychology resident during their scheduled visit in the pain medication clinic. Each veteran was informed that the goal of the joint visit was to enhance self-directed nonpharmacologic chronic pain management skills as an additional set of tools in the tool kit for particularly difficult pain days. Veterans were assured that their usual care would not be compromised if they declined the session.

During the encounter(s), the health psychologist contributed to the veteran’s care by using MI and CBT for chronic pain skills. The health psychologist further assessed concerns and needs and guided the discussion as appropriate. With veteran readiness, these discussions explored the degree of knowledge and cognitive and behavioral coping skills the patient used. These conjoint sessions also documented the types of discussions and degree of engagement in the encounter(s) as well additional referrals, complementary services, and/or offered follow-up services for either additional conjoint sessions or further health psychology-related services.

A total of 24 EHRs from these conjoint and subsequent encounters were reviewed for evidence of the procedures by a psychology intern involved in chronic pain management services. Of these 24 records, 6 also were reviewed by a board-certified health psychologist for consensus building and agreement on coding (Sidebar, Record Coding).

Using the coding system and SPSS Version 2.1 (IBM, Armonk NY), descriptive statistics were used to examine conjoint session content and new- or re-engagement in health psychology services following the conjoint sessions. For those patients who followed up with additional services, the content, type, and outcome of these services were explored. Next, linear regression was used to determine whether number of conjoint sessions was associated with a qualitative treatment outcome, and 2 logistic regressions were used to determine whether the number of sessions was associated with the likelihood of accepting services and follow-through with services after accepting them. An additional logistic regression examined whether having a mental health diagnosis (yes/no) was associated with whether the individual accepted additional health psychology services. Finally, independent sample t tests examined differences between those who accepted services vs those who declined follow-up services in substance use diagnosis, mental health diagnosis, and previous health psychology services engagement. Of note, given the small sample size, the Levene’s test for equality of variances was conducted and unequal variances were assumed.

Results

All 24 patients agreed to have the conjoint session with the clinical pharmacy specialist and health psychologist. Of the participants, 62.5% had no previous interaction with health psychology services. Among those who had previous encounters with health psychology services, 12.5% had participated in 1 or more group sessions, another 12.5% had participated in 1 or more individual sessions, and an additional 12.5% had been referred for health psychology services but had not followed through. A total of 10 participants represented a new- or re-engagement in health psychology services following the conjoint appointment. Two patients were referred for additional services as a result of their conjoint appointment (1 to specialty mental health and another to Primary Care-Mental Health Integration [PC-MHI]), and 1 of the participants followed through with the referral. Finally, with regard to the content of the initial session, 37.5% of the sessions contained some form of psychoeducation, 54.2% contained a functional assessment, and 41.7% contained an introduction of skills.

Half of the veterans participated in health psychology services beyond the initial conjoint session. Four of these veterans participated in additional conjoint sessions, and the remaining 8 engaged in health psychology services, which took the form of telephone sessions (3), in-person sessions (3), or a combination of both telephone and in-person sessions (2). Twelve veterans participated in an average of 3.4 (SD 3.7) follow-up sessions. In terms of the content of these follow-up sessions, across all formats and types, 3 included some introduction to coping skills, with no documented evidence of follow-through. For 2 of the veterans engaging in some type of follow-up, there was documented use of coping skills, and 2 used the coping skills with self-reported success and benefit. Finally, documentation revealed evidence that 3 of these veterans were not only using the coping skills with benefit, but also reported an improvement in pain management overall. One also was connected with a different service.

Regarding reasons for completion of services, 2 veterans were terminated due to completing treatment/meeting goals, 2 were terminated because they did not follow up after a session, 7 were terminated due to patient declining additional sessions, and 1 veteran was still receiving services at the time of the review. Linear regression indicated that the number of conjoint sessions was not associated with qualitative treatment outcome. Two logistic regressions indicated that number of conjoint sessions was not related to whether the veteran accepted follow-up services or whether the veteran followed through with services after accepting. Of note, logistic regression indicated that having a mental health diagnosiswas associated with a decreased likelihood of accepting health psychology services (P = .03). Regarding the independent samples t tests, veterans who did not accept follow-up services were more likely to have a mental health diagnosis (P = .03). The groups did not differ significantly with regard to substance use diagnosis or previous engagement in health psychology services.

Discussion

Results showed that all 24 veterans who were offered a conjoint session with a clinical pharmacy specialist and health psychologist engaged in at least 1 session. Half the veterans participated in further services as well. Both the initial conjoint and follow-up sessions offered a greater degree of communication related to the cognitive-behavioral and functional restoration components of behavioral pain management. Given that a majority of the sample had not participated in behavioral or mental health services previously, this may represent a greater penetration rate of exposure to mental health service for veterans than would have been available otherwise.

More specifically, qualitative results suggest that in these conjoint sessions, the veterans were exposed to behavioral psychotherapeutic approaches to chronic pain management (eg, health behavior change, motivational enhancement, health-related psychoeducation, and CBT for chronic pain) that again may not have been provided otherwise (ie, via referral and separately scheduled sessions). These findings are supported by theories consistent with the Transtheoretical Model, which indicates that individuals fall in varying degrees of readiness for behavioral change (ie, precontemplative, contemplative, planning, action, maintenance).21,22 Thus, behavioral intervention approaches must be adaptive and adjust format and communication, including the amount and type of psychoeducation offered. Moreover, the integrated theory of health behavior change in the context of chronic pain management calls for fostering awareness, knowledge, and beliefs through effective communication and education for a wide range of individuals who are at varying stages of change.23 In addition to the conjoint session and subsequent service(s) content that were reviewed and coded in this current project, future projects might draw on these theoretical models and code sessions for patients’ stages of change and assess whether a patient made progress across phases of change (eg, the patient shifted from contemplative to the planning stage of change).

Within this project’s conjoint sessions and consistent with MI principles, veterans were offered discussions related to the bidirectional and BPS aspects of their own chronic pain experience. That is, while discussing responses and adjustment to pain medication(s), veterans received reflections with MI and heard feedback related to their current coping strategies, methods to enhance coping, as well as potential psychosocial impacts of their chronic pain experience. With permission, veterans also were introduced to themes that comprised evidence-based CBT for chronic pain (CBT-CP) intervention. Understanding what change means in the context of chronic pain management is critical. That is, tipping the conversation toward consideration of alternative modalities (eg, relaxation, stress management, cognitions, and pain) in conjunction with or in place of the traditional modalities (eg, medication, pain procedures) is paramount.

Clinicians must listen for patient ambivalence related to procedures, interventions, medication changes, and/or the behavioral self-management of chronic pain. This type of active listening and exploration may be more likely when there is collaboration and effective team functioning among clinicians than when clinicians provide care independently. Future quality improvement (QI) or research projects could extend the EHR review and evaluate clinician-patient transcripts for fidelity to the CBT-CP and MI models. Such efforts could assess for associations between clinician MI consistent behaviors and change talk on the part of the patient. Furthermore, clinician communication and patient change talk from transcripts could be evaluated in relation to evidence from the EHR regarding patient use of coping skills and behavior change.

Consistent with behavioral health literature, having a mental health diagnosis was associated with declining additional behavioral health psychology services in this project. Research has shown that individuals with a mental health diagnosis tend to engage less in behavioral health self-management programs, such as chronic headache and weight management.24-26 This phenomenon lends support for the importance of health care professionals (HCPs) to increase access and exposure to mental and behavioral health services, such as the PC-MHI model.20 In fact, chronic pain management program development efforts within the VA system nationwide include collaboration with the PC-MHI services. One of the initial goals for PC-MHI services is to increase penetration rates into the general outpatient medical clinics and enhance engagement in mental health services.

Using conjoint sessions as was offered in the current project is one step in the development of more comprehensive interdisciplinary teams through interprofessional collaboration and the use of effective clinical communication. In turn, it will be important to directly explore the communication skills and attitudes of these HCPs with regard to interdisciplinary program development and collaboration as teams continue to integrate more broadly into the medical system and enhance chronic pain management services.11 Similarly, measuring the perceptions of clinical pharmacy specialists, physicians, health psychologists, or other clinical disciplines involved in chronic pain management could be another area to explore. More specific to MI, clinician confidence in the use of effective communication and MI skills represents still another area for future study.16

Limitations

Some limitations and suggested future directions found as part of this QI project have been outlined earlier. Other limitations include the used of a retrospective review of information available in patient medical charts. More developed measurement-based care or research could collect self-reports of patient satisfaction with care, functioning, knowledge, readiness for change, and mood in addition to what is noted and documented in clinical observations. Second, the sample was small and did not include any female and few younger veterans, even though these are important subpopulations when examining pain management services. When resources are available for a larger sample size, some exploratory analyses could be conducted for differences in engagement among subgroups. Third, this project may have further confounding variables as this was not an experimental or a controlled study, which could directly compare conjoint sessions with referral-based care and/or those not offered conjoint sessions.

Conclusion

The optimal method of behavioral pain management suggests the need for an interdisciplinary, coordinated team approach, in which the gold standard programs meet requirements set by CARF. However, on a practical level, optimal behavioral pain management may not be feasible at all health care facilities. Furthermore, in an effort to provide best practices to individuals with chronic pain, clinicians must be adaptive and skilled in using effective communication and specialized interventions, such as CBT and MI.

Approaching the more optimal behavioral self-management of chronic pain from a multimodal interdisciplinary perspective and further engaging veterans in this care is paramount. This project is merely one step in this effort that can shed light on the function and logistic outcomes of using a practical, integrated approach to chronic pain. It demonstrates that implementing best practices founded in sound theoretical models despite staffing and resource constraints is possible. Thus, continuing to explore the utility of alternate modalities may offer important applied and translational information to help disseminate and improve chronic pain management services.

Future research could focus on important subpopulations and enhance experimental design with pre- and postmeasures, controlling for possible confounding variables and if possible a controlled design.

Acknowledgments

This quality improvement project was unfunded, and approval was confirmed with the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System Institutional Review Board and Research & Development committees. The authors also thank Associate Chief of Staff, Ambulatory Care, Clinton Greenstone, MD, and Chief of Primary Care Adam Tremblay, MD, for their leadership and support of these integrative services and quality improvement efforts. The authors especially recognize the veterans for whom they aim to provide the highest quality of services possible.

Providing comprehensive, integrated, behavioral intervention services to address the prevalent condition of chronic, noncancer pain is a growing concern. Although the biopsychosocial model (BPS) and stepped-care approaches have been understood and discussed for some time, clinician and patient understanding and investment in these approaches continue to face challenges. Moreover, even when resources (eg, staffing, referral options, space) are available, clinicians and patients must engage in meaningful communication to achieve this type of care.

Importantly, engagement means moving beyond diagnosis and assessment and offering interventions that provide psychoeducation related to the chronic pain cycle. These interventions address maladaptive cognitions and beliefs about movement and pain; promote paced, daily physical activity and engagement in life; and help increase coping skills to improve low mood or distress, all fundamental components of the BPS understanding of chronic pain.

Background

Chronic, noncancer pain is a prevalent presentation in primary care settings in the U.S. and even more so for veterans.1 Fifty percent of male veterans and 75% of female veterans report chronic pain as an important condition that impacts their health.2 An important aspect of this prevalence is the focus on opioid pain medication and medical procedures, both of which draw more narrowly on the biomedical model. Additional information on the longer term use of pain procedures and opioid medications is now available,and given some risks and limitations (eg, tolerance, decreasing efficacy, opioid-induced medical complications), the need to study and offer other options is gaining attention.3 Behavioral chronic pain management has a clear historic role that draws on the BPS modeland Gate Control Theory.3-6

More recently, the National Strategy of Chronic Pain collaborative and stepped-care models extended this literature, outlining collaboration and levels of care depending on the chronicity of the pain experience as well as co-occurring conditions and patient presentations.7,8 The Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF), the gold standard in interdisciplinary pain management programs, calls for further resources and coordination of these efforts, including a tertiary level of care representing the highest step in the stepped-care model.8

These interdisciplinary, integrative pain management programs, which include functional restoration and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) interventions, have been effective for the treatment of chronic pain.9-12However, the staffing, resources, clinical access, and coordination of this complex care may not be feasible in many health care settings. For example, a 2005 survey reported that there were only 200 multidisciplinary pain programs in the U.S., and only 84 of them were CARF accredited.13 By 2011 the number of CARF-accredited programs had decreased to 64 (the number of nonaccredited programs was not reported for 2011).13

Furthermore, engagement in behavioral pain management services is a challenge: Studies show that psychosocial interventions are underused, and a majority of studies may not report quantitatively or qualitatively on patient adherence or engagement in these services.14 These realities introduce the idea that coordinated appointments between 2 or 3 different disciplines available in primary care may be a feasible step toward implementing more comprehensive, optimal care models.

Behavioral pain management interventions that uphold the BPS also call on the idea of active self-management. Therefore, effective communication is fundamental at both the provider-patient and interprofessional levels to enhance engagement in health care, receptiveness to interventions, and to self-management of chronic pain.11,15 How clinicians conceptualize, hold assumptions about, and communicate with patients about chronic pain management has received more attention.15,16

Clinician Considerations for Pain Management

On theclinicians’ side, monitoring assumptions about patients and awareness of their beliefs as well as the care itself are foundational in patient interactions, impacting the success of patient engagement. Awareness of the language used in these interactions and how clinicians collaborate with other professionals become salient. Coupled with the reality of high attrition, this discussion lends itself in important ways to the motivational interviewing (MI) approach that aims to meet patients “where they are” by use of open-ended questions and reflective listening to guide the conversation in the direction of contemplating or actual behavior change.17 For example, “What do you think are the best ways to manage your pain?” and “It sounds like sometimes the medicine helps, but you also want more options to feel in control of your pain.”

Given the historic focus on the biomedical approach to chronic pain, including the use of opioid medications and medical procedures as well as traditional challenges to engagement in CBT, researchers have explored whether alternative methods may increase participation and improve outcomes for behavioral self-management.3 Drawing on a history of assessing readiness for change in pain management, Kerns and colleagues offered tailored cognitive strategies or behavioral skills training depending on patient preferences.18,19 These researchers also incorporated motivational enhancement strategies in the tailored interventions and compared engagement with standard CBT for chronic pain protocol. Although they did not find significant differences in engagement between the 2 groups, participation and treatment adherence were associated with posttreatment improvements in both groups.19 Taking a step back from enhancing intervention engagement, first assessing readiness to self-manage becomes another salient exploration and step in the process.

Another element of engagement in services is referral to other clinicians. Dorflinger and colleagues made this point in a conceptual paper that broadly outlined interdisciplinary, integrative, and more comprehensive models of care for chronic pain.15 We know from integrated models that referral-based care may decrease the likelihood of participation in health care services. That is, if a patient needs to make a separate appointment and meet with a new clinician, they are more likely to decline, cancel, or not show, particularly if they are not “ready” for change. Co-located or embedded care and conjoint sessions that include a warm handoff or another clinician who joins the first appointment may reduce stigma and other relevant barriers for introducing a patient to new ideas.20

Using a conjoint session that involves a clinical pharmacy pain specialist and a health psychologist is one way in which veterans can be exposed to more chronic pain-related BPS concepts and behavioral health services than they might be exposed to otherwise. The purpose of this project was to bring awareness to a practical and clinically relevant integrated approach to the dissemination of BPS information for chronic pain management.

In providing this information through effective communication at the patient-provider and interprofessional levels, the clinicians’ intention was to increase patient engagement and use of BPS strategies in the self-management of chronic pain. This project also aimed to enhance engagement and improve the quality of services before acquiring additional positions and funding for a specialized pain management team. These sessions were offered at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System (VAAAHS) in Michigan. Quantitative and qualitative information was examined from the conjoint and subsequent sessions that occurred in this setting.

Methods

With the above concepts in mind, VAAAHS offered veterans conjoint sessions involving a health psychologist and clinical pharmacy specialist during a 3-month period while this resource was available. The conjoint sessions were part of a preexisting pharmacist-run pain medication clinic embedded in primary care. The conjoint session was presented to patients as part of general clinic flow to reduce stigma of engagement in psychological services and allow for the dissemination of BPS information.

Participants

The electronic health records (EHR) of 24 veteran patients with chronic pain, who participated in a conjoint health psychology/pain pharmacy session, were reviewed for the current study. Most of the patients were male (95.8%) and non-Hispanic white (91.7%); the remaining participants did not disclose their ethnicity. The mean age was 60.6 years (SD 7.1; range 50-80). A total of 75% had a mental health diagnosis, and 41.7% were in mental health treatment at the time of the conjoint appointment. Among the sample, 20.8% had a current diagnosis of a substance use disorder (SUD), and no individuals were in treatment for a SUD at the time of the conjoint appointment. Patients received an average of 1.5 conjoint sessions (SD 0.7; range 1-3).

Procedure

The veterans for this project were chosen from a panel of patients followed by the pain medication clinical pharmacy specialist in the primary care pain medication clinic. The selected veterans were offered a joint session with their clinical pharmacy provider and the health psychology resident during their scheduled visit in the pain medication clinic. Each veteran was informed that the goal of the joint visit was to enhance self-directed nonpharmacologic chronic pain management skills as an additional set of tools in the tool kit for particularly difficult pain days. Veterans were assured that their usual care would not be compromised if they declined the session.

During the encounter(s), the health psychologist contributed to the veteran’s care by using MI and CBT for chronic pain skills. The health psychologist further assessed concerns and needs and guided the discussion as appropriate. With veteran readiness, these discussions explored the degree of knowledge and cognitive and behavioral coping skills the patient used. These conjoint sessions also documented the types of discussions and degree of engagement in the encounter(s) as well additional referrals, complementary services, and/or offered follow-up services for either additional conjoint sessions or further health psychology-related services.

A total of 24 EHRs from these conjoint and subsequent encounters were reviewed for evidence of the procedures by a psychology intern involved in chronic pain management services. Of these 24 records, 6 also were reviewed by a board-certified health psychologist for consensus building and agreement on coding (Sidebar, Record Coding).

Using the coding system and SPSS Version 2.1 (IBM, Armonk NY), descriptive statistics were used to examine conjoint session content and new- or re-engagement in health psychology services following the conjoint sessions. For those patients who followed up with additional services, the content, type, and outcome of these services were explored. Next, linear regression was used to determine whether number of conjoint sessions was associated with a qualitative treatment outcome, and 2 logistic regressions were used to determine whether the number of sessions was associated with the likelihood of accepting services and follow-through with services after accepting them. An additional logistic regression examined whether having a mental health diagnosis (yes/no) was associated with whether the individual accepted additional health psychology services. Finally, independent sample t tests examined differences between those who accepted services vs those who declined follow-up services in substance use diagnosis, mental health diagnosis, and previous health psychology services engagement. Of note, given the small sample size, the Levene’s test for equality of variances was conducted and unequal variances were assumed.

Results

All 24 patients agreed to have the conjoint session with the clinical pharmacy specialist and health psychologist. Of the participants, 62.5% had no previous interaction with health psychology services. Among those who had previous encounters with health psychology services, 12.5% had participated in 1 or more group sessions, another 12.5% had participated in 1 or more individual sessions, and an additional 12.5% had been referred for health psychology services but had not followed through. A total of 10 participants represented a new- or re-engagement in health psychology services following the conjoint appointment. Two patients were referred for additional services as a result of their conjoint appointment (1 to specialty mental health and another to Primary Care-Mental Health Integration [PC-MHI]), and 1 of the participants followed through with the referral. Finally, with regard to the content of the initial session, 37.5% of the sessions contained some form of psychoeducation, 54.2% contained a functional assessment, and 41.7% contained an introduction of skills.

Half of the veterans participated in health psychology services beyond the initial conjoint session. Four of these veterans participated in additional conjoint sessions, and the remaining 8 engaged in health psychology services, which took the form of telephone sessions (3), in-person sessions (3), or a combination of both telephone and in-person sessions (2). Twelve veterans participated in an average of 3.4 (SD 3.7) follow-up sessions. In terms of the content of these follow-up sessions, across all formats and types, 3 included some introduction to coping skills, with no documented evidence of follow-through. For 2 of the veterans engaging in some type of follow-up, there was documented use of coping skills, and 2 used the coping skills with self-reported success and benefit. Finally, documentation revealed evidence that 3 of these veterans were not only using the coping skills with benefit, but also reported an improvement in pain management overall. One also was connected with a different service.

Regarding reasons for completion of services, 2 veterans were terminated due to completing treatment/meeting goals, 2 were terminated because they did not follow up after a session, 7 were terminated due to patient declining additional sessions, and 1 veteran was still receiving services at the time of the review. Linear regression indicated that the number of conjoint sessions was not associated with qualitative treatment outcome. Two logistic regressions indicated that number of conjoint sessions was not related to whether the veteran accepted follow-up services or whether the veteran followed through with services after accepting. Of note, logistic regression indicated that having a mental health diagnosiswas associated with a decreased likelihood of accepting health psychology services (P = .03). Regarding the independent samples t tests, veterans who did not accept follow-up services were more likely to have a mental health diagnosis (P = .03). The groups did not differ significantly with regard to substance use diagnosis or previous engagement in health psychology services.

Discussion

Results showed that all 24 veterans who were offered a conjoint session with a clinical pharmacy specialist and health psychologist engaged in at least 1 session. Half the veterans participated in further services as well. Both the initial conjoint and follow-up sessions offered a greater degree of communication related to the cognitive-behavioral and functional restoration components of behavioral pain management. Given that a majority of the sample had not participated in behavioral or mental health services previously, this may represent a greater penetration rate of exposure to mental health service for veterans than would have been available otherwise.

More specifically, qualitative results suggest that in these conjoint sessions, the veterans were exposed to behavioral psychotherapeutic approaches to chronic pain management (eg, health behavior change, motivational enhancement, health-related psychoeducation, and CBT for chronic pain) that again may not have been provided otherwise (ie, via referral and separately scheduled sessions). These findings are supported by theories consistent with the Transtheoretical Model, which indicates that individuals fall in varying degrees of readiness for behavioral change (ie, precontemplative, contemplative, planning, action, maintenance).21,22 Thus, behavioral intervention approaches must be adaptive and adjust format and communication, including the amount and type of psychoeducation offered. Moreover, the integrated theory of health behavior change in the context of chronic pain management calls for fostering awareness, knowledge, and beliefs through effective communication and education for a wide range of individuals who are at varying stages of change.23 In addition to the conjoint session and subsequent service(s) content that were reviewed and coded in this current project, future projects might draw on these theoretical models and code sessions for patients’ stages of change and assess whether a patient made progress across phases of change (eg, the patient shifted from contemplative to the planning stage of change).

Within this project’s conjoint sessions and consistent with MI principles, veterans were offered discussions related to the bidirectional and BPS aspects of their own chronic pain experience. That is, while discussing responses and adjustment to pain medication(s), veterans received reflections with MI and heard feedback related to their current coping strategies, methods to enhance coping, as well as potential psychosocial impacts of their chronic pain experience. With permission, veterans also were introduced to themes that comprised evidence-based CBT for chronic pain (CBT-CP) intervention. Understanding what change means in the context of chronic pain management is critical. That is, tipping the conversation toward consideration of alternative modalities (eg, relaxation, stress management, cognitions, and pain) in conjunction with or in place of the traditional modalities (eg, medication, pain procedures) is paramount.

Clinicians must listen for patient ambivalence related to procedures, interventions, medication changes, and/or the behavioral self-management of chronic pain. This type of active listening and exploration may be more likely when there is collaboration and effective team functioning among clinicians than when clinicians provide care independently. Future quality improvement (QI) or research projects could extend the EHR review and evaluate clinician-patient transcripts for fidelity to the CBT-CP and MI models. Such efforts could assess for associations between clinician MI consistent behaviors and change talk on the part of the patient. Furthermore, clinician communication and patient change talk from transcripts could be evaluated in relation to evidence from the EHR regarding patient use of coping skills and behavior change.

Consistent with behavioral health literature, having a mental health diagnosis was associated with declining additional behavioral health psychology services in this project. Research has shown that individuals with a mental health diagnosis tend to engage less in behavioral health self-management programs, such as chronic headache and weight management.24-26 This phenomenon lends support for the importance of health care professionals (HCPs) to increase access and exposure to mental and behavioral health services, such as the PC-MHI model.20 In fact, chronic pain management program development efforts within the VA system nationwide include collaboration with the PC-MHI services. One of the initial goals for PC-MHI services is to increase penetration rates into the general outpatient medical clinics and enhance engagement in mental health services.

Using conjoint sessions as was offered in the current project is one step in the development of more comprehensive interdisciplinary teams through interprofessional collaboration and the use of effective clinical communication. In turn, it will be important to directly explore the communication skills and attitudes of these HCPs with regard to interdisciplinary program development and collaboration as teams continue to integrate more broadly into the medical system and enhance chronic pain management services.11 Similarly, measuring the perceptions of clinical pharmacy specialists, physicians, health psychologists, or other clinical disciplines involved in chronic pain management could be another area to explore. More specific to MI, clinician confidence in the use of effective communication and MI skills represents still another area for future study.16

Limitations

Some limitations and suggested future directions found as part of this QI project have been outlined earlier. Other limitations include the used of a retrospective review of information available in patient medical charts. More developed measurement-based care or research could collect self-reports of patient satisfaction with care, functioning, knowledge, readiness for change, and mood in addition to what is noted and documented in clinical observations. Second, the sample was small and did not include any female and few younger veterans, even though these are important subpopulations when examining pain management services. When resources are available for a larger sample size, some exploratory analyses could be conducted for differences in engagement among subgroups. Third, this project may have further confounding variables as this was not an experimental or a controlled study, which could directly compare conjoint sessions with referral-based care and/or those not offered conjoint sessions.

Conclusion

The optimal method of behavioral pain management suggests the need for an interdisciplinary, coordinated team approach, in which the gold standard programs meet requirements set by CARF. However, on a practical level, optimal behavioral pain management may not be feasible at all health care facilities. Furthermore, in an effort to provide best practices to individuals with chronic pain, clinicians must be adaptive and skilled in using effective communication and specialized interventions, such as CBT and MI.

Approaching the more optimal behavioral self-management of chronic pain from a multimodal interdisciplinary perspective and further engaging veterans in this care is paramount. This project is merely one step in this effort that can shed light on the function and logistic outcomes of using a practical, integrated approach to chronic pain. It demonstrates that implementing best practices founded in sound theoretical models despite staffing and resource constraints is possible. Thus, continuing to explore the utility of alternate modalities may offer important applied and translational information to help disseminate and improve chronic pain management services.

Future research could focus on important subpopulations and enhance experimental design with pre- and postmeasures, controlling for possible confounding variables and if possible a controlled design.

Acknowledgments

This quality improvement project was unfunded, and approval was confirmed with the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System Institutional Review Board and Research & Development committees. The authors also thank Associate Chief of Staff, Ambulatory Care, Clinton Greenstone, MD, and Chief of Primary Care Adam Tremblay, MD, for their leadership and support of these integrative services and quality improvement efforts. The authors especially recognize the veterans for whom they aim to provide the highest quality of services possible.

1. Brooks PM. The burden of musculoskeletal disease—a global perspective. Clin Rheumatol. 2006;25(6):778-781.

2. Haskell SG, Heapy A, Reid MC, Papas RK, Kerns RD. The prevalence and age-related characteristics of pain in a sample of women veterans receiving primary care. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2006;15(7):862-869.

3. Roth RS, Geisser ME, Williams DA. Interventional pain medicine: retreat from the biopsychosocial model of pain. Transl Behav Med. 2012;2(1):106-116.

4. Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129-136.

5. Borrell-Carrió F, Suchman AL, Epstein RM. The biopsychosocial model 25 years later: principles, practice, and scientific inquiry. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(6):576-582.

6. Wall PD. The gate control theory of pain mechanisms: a re-examination and re-statement. Brain. 1978;101(1):1-18.

7. Dobscha SK, Corson K, Perrin NA, et al. Collaborative care for chronic pain in primary care: a cluster randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;301(12):1242-1252.

8. Von Korff, Moore JC. Stepped care for back pain: activating approaches for primary care. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(9, pt 2):911-917.

9. Oslund S, Robinson RC, Clark TC, et al. Long-term effectiveness of a comprehensive pain management program: strengthening the case for interdisciplinary care. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2009;22(3):211-214.

10. Scascighini L, Toma V, Dober-Spielmann S, Sprott H. Multidisciplinary treatment for chronic pain: a systematic review of interventions and outcomes. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47(5):670-678.

11. Gatchel RJ, McGeary DD, McGeary CA, Lippe B. Interdisciplinary chronic pain management: past, present, and future. Am Psychol. 2014;69(2):119-130.

12. McCracken LM, Turk DC. Behavioral and cognitive-behavioral treatment for chronic pain: outcome, predictors of outcome, and treatment process. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27(22): 2564-2573.

13. Jeffery MM, Butler M, Stark A, Kane RL. Multidisciplinary Pain Programs for Chronic Noncancer Pain. Comparative Effectiveness Technical Briefs, No 8. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011.

14. Ehde DM, Dilworth TM, Turner JA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for individuals with chronic pain: efficacy, innovations, and directions for research. Am Psychol. 2014;69(2):153-166.

15. Dorflinger L, Kerns RD, Auerbach SM. Providers’ roles in enhancing patients’ adherence to pain self management. Transl Behav Med. 2013;3(1):39-46.

16. Pellico LH, Gilliam WP, Lee AW, Kerns RD. Hearing new voices: registered nurses and health technicians experience caring for chronic pain patients in primary care clinics. Open Nurs J. 2014;8:25-33.

17. Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler CC, eds. Motivational Interviewing in Health Care: Helping Patients Change Behavior. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2008.

18. Kerns RD, Habib S. A critical review of the pain readiness to change model. J Pain. 2004;5(7):357-367.19. Kerns RD, Burns JW, Shulman M, et al. Can we improve cognitive-behavior therapy for chronic back pain treatment engagement and adherence? A controlled trial of tailored versus standard therapy. Health Psychol. 2014;33(9):938-947.

20. Kearney LK, Post EP, Zeiss A, Goldstein MG, Dundon M. The role of mental and behavioral health in the application of the patient-centered medical home in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1(4):624-628.