User login

Confirmatory blood typing unnecessary for closed prolapse repairs

SAN ANTONIO – It was safe to skip preoperative blood type and antibody screening before vaginal and robotic apical prolapse surgeries at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, so long as the women didn’t have hemorrhage risk factors.

The rate of blood transfusions was 0.5% for both the 204 women who had vaginal repairs and the 203 women who underwent robotic repairs; the rate of positive antibody tests was 1.6%. Given the 0.4% risk of transfusion reactions in unscreened women, the investigators calculated that the risk of serious transfusion reactions was 1 in 50,000 with closed vaginal prolapse repairs.

“The bottom line for us is that the risk in this situation is very low, even if preop type and screens are not performed, and women hemorrhage. This information provides insight to answer our key clinical question, which was if we should continue to order preop type and screens,” lead investigator Taylor Brueseke, MD, an ob.gyn. fellow at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

That question has been on the minds of gynecologic surgeons, and it’s probably never been parsed out before by route of surgery. The American College of Pathologists recommends two blood type and antibody screens from separate venipunctures before surgery. Often, the second, confirmatory test means that women have to come in even earlier on the morning of surgery and deal with another painful blood draw. It also adds a few hundred dollars to the bill.

Every surgeon needs to draw their own line between risks and benefits, Dr. Brueseke said, but it seems reasonable in many cases to skip the second screening for closed repairs. Even if a woman has a transfusion reaction, “it doesn’t mean that the patient is going to die. It’s something that you can deal with,” he said.

However, the team reached a different conclusion for women who undergo open abdominal repairs. Among the 201 cases they reviewed, 10.5% had a transfusion, which translated to a transfusion reaction risk of 1 in 2,645 for unscreened women undergoing open apical prolapse surgery. The higher hemorrhage rate was probably due to concomitant Burch procedures and other open incontinence operations.

For abdominal cases, and for women who have had prior transfusions, surgeries, or anticoagulation, “consider type and screen,” Dr. Brueseke said at the meeting.

In a separate study presented at the conference, more than 50,000 pelvic floor disorder surgeries in the National Surgery Quality Improvement Program database further defined the hemorrhage risk.

Investigators at Ohio State University, Columbus, found that the overall incidence of blood transfusions was low at 1.26%, but open abdominal procedures again increased the risk. Other factors associated with an increased risk of blood transfusion included preoperative hematocrit less than 30%, an American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status score of 3 or higher, concomitant hysterectomy, body mass index below 18.5 kg/m2, age less than 30 and over 65 years, and a history of bleeding disorders.

In the UNC study, the median Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification was stage III. Patients with bleeding disorders, anticoagulant use, or combined surgery with other services were excluded.

There was no industry funding for the two studies, and the investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

A lot of people automatically order type and screen for vaginal prolapse repairs, but we really need to rethink that if there aren’t risk factors that warrant it. I defer to the anesthesiologists because they are the ones who usually want this, but most of the time we screen but don’t use the results. There’s room to improve clinical practice here.

Robert Gutman, MD, is a gynecologic surgeon in Washington, D.C., and the program chair for the 2017 Society of Gynecologic Surgeons annual scientific meeting. He wasn’t involved in the studies presented.

A lot of people automatically order type and screen for vaginal prolapse repairs, but we really need to rethink that if there aren’t risk factors that warrant it. I defer to the anesthesiologists because they are the ones who usually want this, but most of the time we screen but don’t use the results. There’s room to improve clinical practice here.

Robert Gutman, MD, is a gynecologic surgeon in Washington, D.C., and the program chair for the 2017 Society of Gynecologic Surgeons annual scientific meeting. He wasn’t involved in the studies presented.

A lot of people automatically order type and screen for vaginal prolapse repairs, but we really need to rethink that if there aren’t risk factors that warrant it. I defer to the anesthesiologists because they are the ones who usually want this, but most of the time we screen but don’t use the results. There’s room to improve clinical practice here.

Robert Gutman, MD, is a gynecologic surgeon in Washington, D.C., and the program chair for the 2017 Society of Gynecologic Surgeons annual scientific meeting. He wasn’t involved in the studies presented.

SAN ANTONIO – It was safe to skip preoperative blood type and antibody screening before vaginal and robotic apical prolapse surgeries at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, so long as the women didn’t have hemorrhage risk factors.

The rate of blood transfusions was 0.5% for both the 204 women who had vaginal repairs and the 203 women who underwent robotic repairs; the rate of positive antibody tests was 1.6%. Given the 0.4% risk of transfusion reactions in unscreened women, the investigators calculated that the risk of serious transfusion reactions was 1 in 50,000 with closed vaginal prolapse repairs.

“The bottom line for us is that the risk in this situation is very low, even if preop type and screens are not performed, and women hemorrhage. This information provides insight to answer our key clinical question, which was if we should continue to order preop type and screens,” lead investigator Taylor Brueseke, MD, an ob.gyn. fellow at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

That question has been on the minds of gynecologic surgeons, and it’s probably never been parsed out before by route of surgery. The American College of Pathologists recommends two blood type and antibody screens from separate venipunctures before surgery. Often, the second, confirmatory test means that women have to come in even earlier on the morning of surgery and deal with another painful blood draw. It also adds a few hundred dollars to the bill.

Every surgeon needs to draw their own line between risks and benefits, Dr. Brueseke said, but it seems reasonable in many cases to skip the second screening for closed repairs. Even if a woman has a transfusion reaction, “it doesn’t mean that the patient is going to die. It’s something that you can deal with,” he said.

However, the team reached a different conclusion for women who undergo open abdominal repairs. Among the 201 cases they reviewed, 10.5% had a transfusion, which translated to a transfusion reaction risk of 1 in 2,645 for unscreened women undergoing open apical prolapse surgery. The higher hemorrhage rate was probably due to concomitant Burch procedures and other open incontinence operations.

For abdominal cases, and for women who have had prior transfusions, surgeries, or anticoagulation, “consider type and screen,” Dr. Brueseke said at the meeting.

In a separate study presented at the conference, more than 50,000 pelvic floor disorder surgeries in the National Surgery Quality Improvement Program database further defined the hemorrhage risk.

Investigators at Ohio State University, Columbus, found that the overall incidence of blood transfusions was low at 1.26%, but open abdominal procedures again increased the risk. Other factors associated with an increased risk of blood transfusion included preoperative hematocrit less than 30%, an American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status score of 3 or higher, concomitant hysterectomy, body mass index below 18.5 kg/m2, age less than 30 and over 65 years, and a history of bleeding disorders.

In the UNC study, the median Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification was stage III. Patients with bleeding disorders, anticoagulant use, or combined surgery with other services were excluded.

There was no industry funding for the two studies, and the investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

SAN ANTONIO – It was safe to skip preoperative blood type and antibody screening before vaginal and robotic apical prolapse surgeries at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, so long as the women didn’t have hemorrhage risk factors.

The rate of blood transfusions was 0.5% for both the 204 women who had vaginal repairs and the 203 women who underwent robotic repairs; the rate of positive antibody tests was 1.6%. Given the 0.4% risk of transfusion reactions in unscreened women, the investigators calculated that the risk of serious transfusion reactions was 1 in 50,000 with closed vaginal prolapse repairs.

“The bottom line for us is that the risk in this situation is very low, even if preop type and screens are not performed, and women hemorrhage. This information provides insight to answer our key clinical question, which was if we should continue to order preop type and screens,” lead investigator Taylor Brueseke, MD, an ob.gyn. fellow at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

That question has been on the minds of gynecologic surgeons, and it’s probably never been parsed out before by route of surgery. The American College of Pathologists recommends two blood type and antibody screens from separate venipunctures before surgery. Often, the second, confirmatory test means that women have to come in even earlier on the morning of surgery and deal with another painful blood draw. It also adds a few hundred dollars to the bill.

Every surgeon needs to draw their own line between risks and benefits, Dr. Brueseke said, but it seems reasonable in many cases to skip the second screening for closed repairs. Even if a woman has a transfusion reaction, “it doesn’t mean that the patient is going to die. It’s something that you can deal with,” he said.

However, the team reached a different conclusion for women who undergo open abdominal repairs. Among the 201 cases they reviewed, 10.5% had a transfusion, which translated to a transfusion reaction risk of 1 in 2,645 for unscreened women undergoing open apical prolapse surgery. The higher hemorrhage rate was probably due to concomitant Burch procedures and other open incontinence operations.

For abdominal cases, and for women who have had prior transfusions, surgeries, or anticoagulation, “consider type and screen,” Dr. Brueseke said at the meeting.

In a separate study presented at the conference, more than 50,000 pelvic floor disorder surgeries in the National Surgery Quality Improvement Program database further defined the hemorrhage risk.

Investigators at Ohio State University, Columbus, found that the overall incidence of blood transfusions was low at 1.26%, but open abdominal procedures again increased the risk. Other factors associated with an increased risk of blood transfusion included preoperative hematocrit less than 30%, an American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status score of 3 or higher, concomitant hysterectomy, body mass index below 18.5 kg/m2, age less than 30 and over 65 years, and a history of bleeding disorders.

In the UNC study, the median Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification was stage III. Patients with bleeding disorders, anticoagulant use, or combined surgery with other services were excluded.

There was no industry funding for the two studies, and the investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Given the 0.4% risk of transfusion reactions in unscreened women, the risk of serious transfusion reactions was 1 in 50,000 women with closed apical prolapse repairs.

Data source: A review of more than 600 cases of apical prolapse surgery at a single center.

Disclosures: There was no industry funding, and the investigators reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy induces mutational, molecular shifts in ovarian cancers

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Treatment of high-grade serous ovarian carcinomas with platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy led to significant changes in the expression of genes encoding “canonical” cell cycle and DNA damage pathways, said Rebecca C. Arend, MD.

Analyses of cell-free (plasma) DNA also revealed mutations that matched those in tumor specimens obtained before and after platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy, Dr. Arend reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. “Understanding the effect of chemotherapy on gene expression profiles may help guide therapy, and plasma cfDNA could provide a noninvasive approach for monitoring tumor mutations,” said Dr. Arend of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

High-grade serous ovarian carcinoma is genetically heterogeneous, and chemotherapy further alters gene expression profiles and causes molecular derangement, Dr. Arend noted. “Neoadjuvant chemotherapy provides a unique opportunity to evaluate biospecimens before and afterward,” she added.

Both gene expression and mutational profiles have been used to characterize HGSC, but researchers lack solid methods to evaluate tumor heterogeneity and clonal evolution. To begin filling this gap, Dr. Arend and her associates analyzed plasma and tumor specimens from 19 patients with stage 3 or 4 high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma before and after they underwent three to six cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Biopsies yielded the baseline tumor specimens, and follow-up specimens were obtained during interval debulking.

The investigators used the NanoString PanCancer 770 gene pathway panel, the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis tool, and nSolver Analysis software to assess changes in gene expression. To quantify mutations, they performed longitudinal next-generation sequencing of 50 genes in tumor and plasma specimens with a 50-gene Ion Torrent panel.

After neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the most up-regulated genes included NR4A1 and NR4A3, which regulate cellular proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis, and SFRP2, which promotes resistance to chemotherapy by modulating Wnt signaling, Dr. Arend said. The most down-regulated genes included E2F1, which helps mediate the cell cycle and the activity of tumor suppressor genes, and BRCA2, the tumor suppressor gene that encodes a DNA repair protein.

Pathway analysis confirmed that the cell cycle pathway was most up-regulated after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and that the DNA damage repair pathway was the most downregulated, Dr. Arend reported. Within the DNA damage repair pathway, no gene was significantly up-regulated, while RAD51C, BRCA1, BRCA2, and the FA core complex genes were down-regulated.

Next-generation sequencing of baseline plasma cfDNA identified 57 mutations, of which 6 persisted after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. In contrast, of 38 mutations in tumor at baseline, 33 persisted after chemotherapy.

Only 15 of the 38 mutations in tumor also appeared in cfDNA before treatment. At the time of interval debulking, tumor specimens yielded 36 mutations, of which 11 were detected in cfDNA.

At baseline and after treatment, all patients had TP53 mutations either tumor alone, or in both tumor and plasma. Among four patients whose cancer recurred, three had mutations in cfDNA that were previously detected in tumor. Implicated genes included PIK3CA, TP53, KIT, and KDR.

Overall, the study suggests that gene expression profiling of ovarian HGSC tumor tissue taken at interval debulking could someday help guide treatment decisions after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, Dr. Arend said. “To be able to use cfDNA as liquid biopsy, more studies like this one, which match tumor and cfDNA from multiple time points, are needed,” she added.

Dr. Arend cited no funding sources and reported having no conflicts of interest.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Treatment of high-grade serous ovarian carcinomas with platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy led to significant changes in the expression of genes encoding “canonical” cell cycle and DNA damage pathways, said Rebecca C. Arend, MD.

Analyses of cell-free (plasma) DNA also revealed mutations that matched those in tumor specimens obtained before and after platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy, Dr. Arend reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. “Understanding the effect of chemotherapy on gene expression profiles may help guide therapy, and plasma cfDNA could provide a noninvasive approach for monitoring tumor mutations,” said Dr. Arend of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

High-grade serous ovarian carcinoma is genetically heterogeneous, and chemotherapy further alters gene expression profiles and causes molecular derangement, Dr. Arend noted. “Neoadjuvant chemotherapy provides a unique opportunity to evaluate biospecimens before and afterward,” she added.

Both gene expression and mutational profiles have been used to characterize HGSC, but researchers lack solid methods to evaluate tumor heterogeneity and clonal evolution. To begin filling this gap, Dr. Arend and her associates analyzed plasma and tumor specimens from 19 patients with stage 3 or 4 high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma before and after they underwent three to six cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Biopsies yielded the baseline tumor specimens, and follow-up specimens were obtained during interval debulking.

The investigators used the NanoString PanCancer 770 gene pathway panel, the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis tool, and nSolver Analysis software to assess changes in gene expression. To quantify mutations, they performed longitudinal next-generation sequencing of 50 genes in tumor and plasma specimens with a 50-gene Ion Torrent panel.

After neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the most up-regulated genes included NR4A1 and NR4A3, which regulate cellular proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis, and SFRP2, which promotes resistance to chemotherapy by modulating Wnt signaling, Dr. Arend said. The most down-regulated genes included E2F1, which helps mediate the cell cycle and the activity of tumor suppressor genes, and BRCA2, the tumor suppressor gene that encodes a DNA repair protein.

Pathway analysis confirmed that the cell cycle pathway was most up-regulated after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and that the DNA damage repair pathway was the most downregulated, Dr. Arend reported. Within the DNA damage repair pathway, no gene was significantly up-regulated, while RAD51C, BRCA1, BRCA2, and the FA core complex genes were down-regulated.

Next-generation sequencing of baseline plasma cfDNA identified 57 mutations, of which 6 persisted after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. In contrast, of 38 mutations in tumor at baseline, 33 persisted after chemotherapy.

Only 15 of the 38 mutations in tumor also appeared in cfDNA before treatment. At the time of interval debulking, tumor specimens yielded 36 mutations, of which 11 were detected in cfDNA.

At baseline and after treatment, all patients had TP53 mutations either tumor alone, or in both tumor and plasma. Among four patients whose cancer recurred, three had mutations in cfDNA that were previously detected in tumor. Implicated genes included PIK3CA, TP53, KIT, and KDR.

Overall, the study suggests that gene expression profiling of ovarian HGSC tumor tissue taken at interval debulking could someday help guide treatment decisions after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, Dr. Arend said. “To be able to use cfDNA as liquid biopsy, more studies like this one, which match tumor and cfDNA from multiple time points, are needed,” she added.

Dr. Arend cited no funding sources and reported having no conflicts of interest.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Treatment of high-grade serous ovarian carcinomas with platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy led to significant changes in the expression of genes encoding “canonical” cell cycle and DNA damage pathways, said Rebecca C. Arend, MD.

Analyses of cell-free (plasma) DNA also revealed mutations that matched those in tumor specimens obtained before and after platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy, Dr. Arend reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. “Understanding the effect of chemotherapy on gene expression profiles may help guide therapy, and plasma cfDNA could provide a noninvasive approach for monitoring tumor mutations,” said Dr. Arend of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

High-grade serous ovarian carcinoma is genetically heterogeneous, and chemotherapy further alters gene expression profiles and causes molecular derangement, Dr. Arend noted. “Neoadjuvant chemotherapy provides a unique opportunity to evaluate biospecimens before and afterward,” she added.

Both gene expression and mutational profiles have been used to characterize HGSC, but researchers lack solid methods to evaluate tumor heterogeneity and clonal evolution. To begin filling this gap, Dr. Arend and her associates analyzed plasma and tumor specimens from 19 patients with stage 3 or 4 high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma before and after they underwent three to six cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Biopsies yielded the baseline tumor specimens, and follow-up specimens were obtained during interval debulking.

The investigators used the NanoString PanCancer 770 gene pathway panel, the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis tool, and nSolver Analysis software to assess changes in gene expression. To quantify mutations, they performed longitudinal next-generation sequencing of 50 genes in tumor and plasma specimens with a 50-gene Ion Torrent panel.

After neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the most up-regulated genes included NR4A1 and NR4A3, which regulate cellular proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis, and SFRP2, which promotes resistance to chemotherapy by modulating Wnt signaling, Dr. Arend said. The most down-regulated genes included E2F1, which helps mediate the cell cycle and the activity of tumor suppressor genes, and BRCA2, the tumor suppressor gene that encodes a DNA repair protein.

Pathway analysis confirmed that the cell cycle pathway was most up-regulated after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and that the DNA damage repair pathway was the most downregulated, Dr. Arend reported. Within the DNA damage repair pathway, no gene was significantly up-regulated, while RAD51C, BRCA1, BRCA2, and the FA core complex genes were down-regulated.

Next-generation sequencing of baseline plasma cfDNA identified 57 mutations, of which 6 persisted after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. In contrast, of 38 mutations in tumor at baseline, 33 persisted after chemotherapy.

Only 15 of the 38 mutations in tumor also appeared in cfDNA before treatment. At the time of interval debulking, tumor specimens yielded 36 mutations, of which 11 were detected in cfDNA.

At baseline and after treatment, all patients had TP53 mutations either tumor alone, or in both tumor and plasma. Among four patients whose cancer recurred, three had mutations in cfDNA that were previously detected in tumor. Implicated genes included PIK3CA, TP53, KIT, and KDR.

Overall, the study suggests that gene expression profiling of ovarian HGSC tumor tissue taken at interval debulking could someday help guide treatment decisions after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, Dr. Arend said. “To be able to use cfDNA as liquid biopsy, more studies like this one, which match tumor and cfDNA from multiple time points, are needed,” she added.

Dr. Arend cited no funding sources and reported having no conflicts of interest.

Key clinical point. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy was associated with changes in gene expression and associated pathways in high-grade serous ovarian carcinomas. Some mutations in tumors were also present in plasma cell-free DNA.

Major finding: Pathway analysis confirmed that the cell cycle and apoptosis pathway was the most up-regulated after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, while the DNA damage repair pathway was the most down-regulated. Among 38 baseline mutations in tumor specimens, 15 of 38 appeared in plasma cell-free DNA. At interval debulking, tumor specimens yielded 36 mutations, of which 11 were detected in cfDNA.

Data source: Gene expression profiling, pathway analysis, and next-generation sequencing of 19 patients with high-grade serous ovarian carcinomas.

Disclosures: Dr. Arend cited no funding sources and reported having no conflicts of interest.

Uptake of new heart failure drugs slow despite guidelines

SNOWMASS, COLO. – As William T. Abraham, MD, speaks to colleagues around the country about heart failure therapy, he has noticed that the first-in-class drug ivabradine remains below the radar of most physicians.

“I’ve found that this is an agent that very few people know about, even though it’s been FDA [Food and Drug Administration] approved for about 3 years. It’s used fairly extensively in Europe because that’s where the pivotal SHIFT trial was done, but not very much in the United States,” according to Dr. Abraham, professor of medicine, physiology, and cell biology and director of the division of cardiovascular medicine at Ohio State University in Columbus.

That’s likely to change as word spreads about the May 2016 update of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure. The update incorporated evidence-based recommendations on the use of two important new heart failure medications: ivabradine (Corlanor), which received a moderate class IIa recommendation, meaning the drug “should be considered,” and sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto), which received the strongest class I recommendation.

In the right patients, these two oral medications improve heart failure morbidity and mortality significantly beyond what’s achievable with what has been the gold standard, guideline-directed medical therapy. Dr. Abraham described how to get started using the two medications at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

Ivabradine

Ivabradine is a selective inhibitor of the sinoatrial pacemaker modulating I(f) current. It acts by slowing the sinus rate without reducing myocardial contractility.

“This agent does one thing and one thing alone: It lowers heart rate,” the cardiologist explained.

And that, he added, was sufficient to significantly reduce the risks of death due to heart failure and recurrent hospitalization for worsening heart failure in the pivotal SHIFT trial.

SHIFT included 6,505 patients with moderate to severe heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and a resting heart rate above 70 bpm despite background guideline-directed medical therapy. Participants were randomized double blind to ivabradine titrated to a maximum of 7.5 mg twice daily or placebo and followed for a median of about 23 months. The rate of death due to heart failure was 3% with ivabradine and 5% with placebo, for a statistically significant 26% relative risk reduction favoring ivabradine.

But the drug’s main benefit was in reducing recurrent hospitalizations for heart failure, an endpoint of particular interest to health policy officials given that heart failure hospitalizations chew up a substantial proportion of the Medicare budget. Ivabradine reduced first hospitalizations for heart failure during the study period by 25%, second hospitalizations by 34%, and third hospitalizations by 29% (Eur Heart J. 2012 Nov;33[22]:2813-20).

The ACC/AHA guideline update stresses the importance of reserving ivabradine for heart failure patients whose resting heart rate exceeds 70 bpm, despite being on their maximum tolerated dose of a beta-blocker, Dr. Abraham noted.

Ivabradine is contraindicated in the setting of acute decompensated heart failure, severe liver disease, or hypotension, in patients on any of the numerous agents that strongly inhibit the enzyme cytochrome P450 3A4, and in those who have sick sinus syndrome, have sinoatrial block, or are pacemaker dependent.

Sacubitril/valsartan

Sacubitril inhibits neprilysin, an enzyme that blocks the action of endogenous vasoactive peptides including bradykinin, substance P, and natriuretic peptides, all of which counter important maladaptive mechanisms in heart failure. Sacubitril has been combined with the angiotensin receptor blocker valsartan to form the first-in-class angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor, or ARNI, formerly known as LCZ696 and now marketed as Entresto.

In the pivotal double-blind PARADIGM-HF trial, 8,442 patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction were randomized to the ARNI at 200 mg b.i.d. or to enalapril at 10 mg b.i.d. on top of background guideline-directed medical therapy. The trial was stopped early because of evidence of overwhelming benefit: a 20% relative risk reduction in cardiovascular death and a 21% decrease in the risk of heart failure hospitalizations in the sacubitril/valsartan group, as well as significant reductions in heart failure symptoms and physical limitations (N Engl J Med. 2014 Sep 11;371[11]:993-1004).

The updated heart failure guidelines strongly recommend that patients with heart failure should be treated with either an ACE inhibitor, an angiotensin receptor blocker, or an ARNI. Further, patients who remain symptomatic on an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker should be switched to an ARNI; that’s a class Ib recommendation based upon the results of PARADIGM-HF.

In getting started using the ARNI, Dr. Abraham said it’s important to understand as background the selective nature of the PARADIGM-HF study design. During the single-blind run-in period of 5-8 weeks, roughly 10% of patients dropped out because they couldn’t tolerate enalapril at 10 mg b.i.d., and a similar percentage dropped out during the ARNI run-in. Thus, patients who couldn’t tolerate a low dose of an ACE inhibitor weren’t in the study. And patients capable of tolerating guideline-recommended full-dose ACE inhibitor therapy were not specifically sought for participation.

“So there are some unanswered questions about the ARNI. If you’re just getting started with this compound in treating your heart failure patients, my own feeling is you should maybe aim for the type of patient that was included in this trial: patients who could tolerate a moderate dose of an ACE inhibitor and had generally good blood pressure. That’s a great way to begin to get experience with this agent in heart failure,” the cardiologist advised.

He reported serving as a consultant to Abbott Vascular, Medtronic, Novartis, and St. Jude Medical.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – As William T. Abraham, MD, speaks to colleagues around the country about heart failure therapy, he has noticed that the first-in-class drug ivabradine remains below the radar of most physicians.

“I’ve found that this is an agent that very few people know about, even though it’s been FDA [Food and Drug Administration] approved for about 3 years. It’s used fairly extensively in Europe because that’s where the pivotal SHIFT trial was done, but not very much in the United States,” according to Dr. Abraham, professor of medicine, physiology, and cell biology and director of the division of cardiovascular medicine at Ohio State University in Columbus.

That’s likely to change as word spreads about the May 2016 update of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure. The update incorporated evidence-based recommendations on the use of two important new heart failure medications: ivabradine (Corlanor), which received a moderate class IIa recommendation, meaning the drug “should be considered,” and sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto), which received the strongest class I recommendation.

In the right patients, these two oral medications improve heart failure morbidity and mortality significantly beyond what’s achievable with what has been the gold standard, guideline-directed medical therapy. Dr. Abraham described how to get started using the two medications at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

Ivabradine

Ivabradine is a selective inhibitor of the sinoatrial pacemaker modulating I(f) current. It acts by slowing the sinus rate without reducing myocardial contractility.

“This agent does one thing and one thing alone: It lowers heart rate,” the cardiologist explained.

And that, he added, was sufficient to significantly reduce the risks of death due to heart failure and recurrent hospitalization for worsening heart failure in the pivotal SHIFT trial.

SHIFT included 6,505 patients with moderate to severe heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and a resting heart rate above 70 bpm despite background guideline-directed medical therapy. Participants were randomized double blind to ivabradine titrated to a maximum of 7.5 mg twice daily or placebo and followed for a median of about 23 months. The rate of death due to heart failure was 3% with ivabradine and 5% with placebo, for a statistically significant 26% relative risk reduction favoring ivabradine.

But the drug’s main benefit was in reducing recurrent hospitalizations for heart failure, an endpoint of particular interest to health policy officials given that heart failure hospitalizations chew up a substantial proportion of the Medicare budget. Ivabradine reduced first hospitalizations for heart failure during the study period by 25%, second hospitalizations by 34%, and third hospitalizations by 29% (Eur Heart J. 2012 Nov;33[22]:2813-20).

The ACC/AHA guideline update stresses the importance of reserving ivabradine for heart failure patients whose resting heart rate exceeds 70 bpm, despite being on their maximum tolerated dose of a beta-blocker, Dr. Abraham noted.

Ivabradine is contraindicated in the setting of acute decompensated heart failure, severe liver disease, or hypotension, in patients on any of the numerous agents that strongly inhibit the enzyme cytochrome P450 3A4, and in those who have sick sinus syndrome, have sinoatrial block, or are pacemaker dependent.

Sacubitril/valsartan

Sacubitril inhibits neprilysin, an enzyme that blocks the action of endogenous vasoactive peptides including bradykinin, substance P, and natriuretic peptides, all of which counter important maladaptive mechanisms in heart failure. Sacubitril has been combined with the angiotensin receptor blocker valsartan to form the first-in-class angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor, or ARNI, formerly known as LCZ696 and now marketed as Entresto.

In the pivotal double-blind PARADIGM-HF trial, 8,442 patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction were randomized to the ARNI at 200 mg b.i.d. or to enalapril at 10 mg b.i.d. on top of background guideline-directed medical therapy. The trial was stopped early because of evidence of overwhelming benefit: a 20% relative risk reduction in cardiovascular death and a 21% decrease in the risk of heart failure hospitalizations in the sacubitril/valsartan group, as well as significant reductions in heart failure symptoms and physical limitations (N Engl J Med. 2014 Sep 11;371[11]:993-1004).

The updated heart failure guidelines strongly recommend that patients with heart failure should be treated with either an ACE inhibitor, an angiotensin receptor blocker, or an ARNI. Further, patients who remain symptomatic on an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker should be switched to an ARNI; that’s a class Ib recommendation based upon the results of PARADIGM-HF.

In getting started using the ARNI, Dr. Abraham said it’s important to understand as background the selective nature of the PARADIGM-HF study design. During the single-blind run-in period of 5-8 weeks, roughly 10% of patients dropped out because they couldn’t tolerate enalapril at 10 mg b.i.d., and a similar percentage dropped out during the ARNI run-in. Thus, patients who couldn’t tolerate a low dose of an ACE inhibitor weren’t in the study. And patients capable of tolerating guideline-recommended full-dose ACE inhibitor therapy were not specifically sought for participation.

“So there are some unanswered questions about the ARNI. If you’re just getting started with this compound in treating your heart failure patients, my own feeling is you should maybe aim for the type of patient that was included in this trial: patients who could tolerate a moderate dose of an ACE inhibitor and had generally good blood pressure. That’s a great way to begin to get experience with this agent in heart failure,” the cardiologist advised.

He reported serving as a consultant to Abbott Vascular, Medtronic, Novartis, and St. Jude Medical.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – As William T. Abraham, MD, speaks to colleagues around the country about heart failure therapy, he has noticed that the first-in-class drug ivabradine remains below the radar of most physicians.

“I’ve found that this is an agent that very few people know about, even though it’s been FDA [Food and Drug Administration] approved for about 3 years. It’s used fairly extensively in Europe because that’s where the pivotal SHIFT trial was done, but not very much in the United States,” according to Dr. Abraham, professor of medicine, physiology, and cell biology and director of the division of cardiovascular medicine at Ohio State University in Columbus.

That’s likely to change as word spreads about the May 2016 update of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure. The update incorporated evidence-based recommendations on the use of two important new heart failure medications: ivabradine (Corlanor), which received a moderate class IIa recommendation, meaning the drug “should be considered,” and sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto), which received the strongest class I recommendation.

In the right patients, these two oral medications improve heart failure morbidity and mortality significantly beyond what’s achievable with what has been the gold standard, guideline-directed medical therapy. Dr. Abraham described how to get started using the two medications at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

Ivabradine

Ivabradine is a selective inhibitor of the sinoatrial pacemaker modulating I(f) current. It acts by slowing the sinus rate without reducing myocardial contractility.

“This agent does one thing and one thing alone: It lowers heart rate,” the cardiologist explained.

And that, he added, was sufficient to significantly reduce the risks of death due to heart failure and recurrent hospitalization for worsening heart failure in the pivotal SHIFT trial.

SHIFT included 6,505 patients with moderate to severe heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and a resting heart rate above 70 bpm despite background guideline-directed medical therapy. Participants were randomized double blind to ivabradine titrated to a maximum of 7.5 mg twice daily or placebo and followed for a median of about 23 months. The rate of death due to heart failure was 3% with ivabradine and 5% with placebo, for a statistically significant 26% relative risk reduction favoring ivabradine.

But the drug’s main benefit was in reducing recurrent hospitalizations for heart failure, an endpoint of particular interest to health policy officials given that heart failure hospitalizations chew up a substantial proportion of the Medicare budget. Ivabradine reduced first hospitalizations for heart failure during the study period by 25%, second hospitalizations by 34%, and third hospitalizations by 29% (Eur Heart J. 2012 Nov;33[22]:2813-20).

The ACC/AHA guideline update stresses the importance of reserving ivabradine for heart failure patients whose resting heart rate exceeds 70 bpm, despite being on their maximum tolerated dose of a beta-blocker, Dr. Abraham noted.

Ivabradine is contraindicated in the setting of acute decompensated heart failure, severe liver disease, or hypotension, in patients on any of the numerous agents that strongly inhibit the enzyme cytochrome P450 3A4, and in those who have sick sinus syndrome, have sinoatrial block, or are pacemaker dependent.

Sacubitril/valsartan

Sacubitril inhibits neprilysin, an enzyme that blocks the action of endogenous vasoactive peptides including bradykinin, substance P, and natriuretic peptides, all of which counter important maladaptive mechanisms in heart failure. Sacubitril has been combined with the angiotensin receptor blocker valsartan to form the first-in-class angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor, or ARNI, formerly known as LCZ696 and now marketed as Entresto.

In the pivotal double-blind PARADIGM-HF trial, 8,442 patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction were randomized to the ARNI at 200 mg b.i.d. or to enalapril at 10 mg b.i.d. on top of background guideline-directed medical therapy. The trial was stopped early because of evidence of overwhelming benefit: a 20% relative risk reduction in cardiovascular death and a 21% decrease in the risk of heart failure hospitalizations in the sacubitril/valsartan group, as well as significant reductions in heart failure symptoms and physical limitations (N Engl J Med. 2014 Sep 11;371[11]:993-1004).

The updated heart failure guidelines strongly recommend that patients with heart failure should be treated with either an ACE inhibitor, an angiotensin receptor blocker, or an ARNI. Further, patients who remain symptomatic on an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker should be switched to an ARNI; that’s a class Ib recommendation based upon the results of PARADIGM-HF.

In getting started using the ARNI, Dr. Abraham said it’s important to understand as background the selective nature of the PARADIGM-HF study design. During the single-blind run-in period of 5-8 weeks, roughly 10% of patients dropped out because they couldn’t tolerate enalapril at 10 mg b.i.d., and a similar percentage dropped out during the ARNI run-in. Thus, patients who couldn’t tolerate a low dose of an ACE inhibitor weren’t in the study. And patients capable of tolerating guideline-recommended full-dose ACE inhibitor therapy were not specifically sought for participation.

“So there are some unanswered questions about the ARNI. If you’re just getting started with this compound in treating your heart failure patients, my own feeling is you should maybe aim for the type of patient that was included in this trial: patients who could tolerate a moderate dose of an ACE inhibitor and had generally good blood pressure. That’s a great way to begin to get experience with this agent in heart failure,” the cardiologist advised.

He reported serving as a consultant to Abbott Vascular, Medtronic, Novartis, and St. Jude Medical.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

Boston - Rich History, Lively Cultural Scene

There is history around every corner in Boston. This vibrant city is rich with art, music, and dance institutions, theatre and cultural attractions, distinguished dining and nightlife venues, world-class shopping and championship sports teams that attract millions of visitors each year.

The city’s downtown neighborhoods, each with its own personality, offer endless unique experiences, and Boston’s proximity to other must-see sites all around New England make it one of the country’s most diverse and exciting locales.Each of the city’s neighborhoods has a remarkably different style and tone. From the Back Bay’s cosmopolitan streets and ornate Victorian townhouses to the aromas spilling into the narrow and jumbled 17th-century streets of Boston’s North End to the spirited and funky neighborhood squares of Cambridge – all within easy distance from one another.Boston is “America’s Walking City.” Even though it is one of the largest cities in the country, its accessibility is unparalleled. And while sightseeing on foot is easy, Boston also has an excellent public transportation system to help you get around.

Boston is also known as the mecca of medicine. Boston is home to some of the most prestigious hospitals and medical schools, physicians, and medical scientists in the world. Thoralf M. Sundt, III, MD, and the AATS Centennial Committee have organized an engaging social program for the AATS Centennial.

Tour 1: ITALIAN GASTRONOMY NORTH END MARKET TOUR

Sunday, April 30, 2017

10:30 a.m.– 1:15 p.m.

Cost: $95 per person

Tour 2: A VISIT TO THE ISABELLA STEWART GARDNER MUSEUM

Monday, May 1, 2017

12:15 p.m. – 2:45 p.m.

Cost: $85 per person

Enjoy the Gardners’ compilation of tapestries, exquisite antique furniture, and famous collections while hearing wonderful anecdotes about Mrs. Gardner’s sophisticated and eclectic life and the famous heist. A docent will be available to guidevisitors.

Tour 3: BEACON HILL CIRCLE “BEHIND THE BRAHMIN DOORS”

Tuesday, May 2, 2017

9:15 a.m. – 11:45 a.m.

Cost: $110 per person

*Preregistration for social events and tours are required. Tours require a minimum number of participants. All tours will depart from the Hynes Convention Center.

For additional visit information and things to do in Boston, go to https://www.bostonusa.com/things-to-do.

There is history around every corner in Boston. This vibrant city is rich with art, music, and dance institutions, theatre and cultural attractions, distinguished dining and nightlife venues, world-class shopping and championship sports teams that attract millions of visitors each year.

The city’s downtown neighborhoods, each with its own personality, offer endless unique experiences, and Boston’s proximity to other must-see sites all around New England make it one of the country’s most diverse and exciting locales.Each of the city’s neighborhoods has a remarkably different style and tone. From the Back Bay’s cosmopolitan streets and ornate Victorian townhouses to the aromas spilling into the narrow and jumbled 17th-century streets of Boston’s North End to the spirited and funky neighborhood squares of Cambridge – all within easy distance from one another.Boston is “America’s Walking City.” Even though it is one of the largest cities in the country, its accessibility is unparalleled. And while sightseeing on foot is easy, Boston also has an excellent public transportation system to help you get around.

Boston is also known as the mecca of medicine. Boston is home to some of the most prestigious hospitals and medical schools, physicians, and medical scientists in the world. Thoralf M. Sundt, III, MD, and the AATS Centennial Committee have organized an engaging social program for the AATS Centennial.

Tour 1: ITALIAN GASTRONOMY NORTH END MARKET TOUR

Sunday, April 30, 2017

10:30 a.m.– 1:15 p.m.

Cost: $95 per person

Tour 2: A VISIT TO THE ISABELLA STEWART GARDNER MUSEUM

Monday, May 1, 2017

12:15 p.m. – 2:45 p.m.

Cost: $85 per person

Enjoy the Gardners’ compilation of tapestries, exquisite antique furniture, and famous collections while hearing wonderful anecdotes about Mrs. Gardner’s sophisticated and eclectic life and the famous heist. A docent will be available to guidevisitors.

Tour 3: BEACON HILL CIRCLE “BEHIND THE BRAHMIN DOORS”

Tuesday, May 2, 2017

9:15 a.m. – 11:45 a.m.

Cost: $110 per person

*Preregistration for social events and tours are required. Tours require a minimum number of participants. All tours will depart from the Hynes Convention Center.

For additional visit information and things to do in Boston, go to https://www.bostonusa.com/things-to-do.

There is history around every corner in Boston. This vibrant city is rich with art, music, and dance institutions, theatre and cultural attractions, distinguished dining and nightlife venues, world-class shopping and championship sports teams that attract millions of visitors each year.

The city’s downtown neighborhoods, each with its own personality, offer endless unique experiences, and Boston’s proximity to other must-see sites all around New England make it one of the country’s most diverse and exciting locales.Each of the city’s neighborhoods has a remarkably different style and tone. From the Back Bay’s cosmopolitan streets and ornate Victorian townhouses to the aromas spilling into the narrow and jumbled 17th-century streets of Boston’s North End to the spirited and funky neighborhood squares of Cambridge – all within easy distance from one another.Boston is “America’s Walking City.” Even though it is one of the largest cities in the country, its accessibility is unparalleled. And while sightseeing on foot is easy, Boston also has an excellent public transportation system to help you get around.

Boston is also known as the mecca of medicine. Boston is home to some of the most prestigious hospitals and medical schools, physicians, and medical scientists in the world. Thoralf M. Sundt, III, MD, and the AATS Centennial Committee have organized an engaging social program for the AATS Centennial.

Tour 1: ITALIAN GASTRONOMY NORTH END MARKET TOUR

Sunday, April 30, 2017

10:30 a.m.– 1:15 p.m.

Cost: $95 per person

Tour 2: A VISIT TO THE ISABELLA STEWART GARDNER MUSEUM

Monday, May 1, 2017

12:15 p.m. – 2:45 p.m.

Cost: $85 per person

Enjoy the Gardners’ compilation of tapestries, exquisite antique furniture, and famous collections while hearing wonderful anecdotes about Mrs. Gardner’s sophisticated and eclectic life and the famous heist. A docent will be available to guidevisitors.

Tour 3: BEACON HILL CIRCLE “BEHIND THE BRAHMIN DOORS”

Tuesday, May 2, 2017

9:15 a.m. – 11:45 a.m.

Cost: $110 per person

*Preregistration for social events and tours are required. Tours require a minimum number of participants. All tours will depart from the Hynes Convention Center.

For additional visit information and things to do in Boston, go to https://www.bostonusa.com/things-to-do.

Off-the-shelf T cells an option for post-HCT viral infections

ORLANDO – Infusions of banked multivirus-specific T lymphocytes were associated with complete or partial responses in 93% of 42 patients who had undergone hematopoietic cell transplants and had drug-refractory viral illnesses. Further, these patients experienced minimal new or reactivated graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

Viral infections cause nearly 40% of deaths after alternative donor hematopoietic cell transfer (HCT), Ifigeneia Tzannou, MD, said at the combined annual meetings of the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research and the American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Banked, “off-the-shelf” donor virus-resistant T cells can be an alternative to antiviral drugs, which are far from universally effective and may have serious side effects.

“Traditionally, we have generated T cells for infusion from the stem cell donor” by isolating and then stimulating and expanding the peripheral blood mononuclear cells for about 10 days ex vivo, said Dr. Tzannou. At that point, the clonal multivirus-resistant T cells can then be transferred to the recipient.

Donor-derived T cells have been used to prevent and treat Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), adenovirus (AdV), BK virus (BKV), and human herpes virus 6 (HHV6) infections. The approach has been safe, reconstituting antiviral immunity and clearing disease effectively, with a 94% response rate reported in one recent study. However, said Dr. Tzannou, donor-derived virus-specific T cells (VSTs) have their limitations. Donors are increasingly younger and cord blood is being used more commonly, so there are growing numbers of donors who are seronegative for pathogenic viruses. In addition, the 10 days of production time and the additional week or 10 days required for release means that donor-derived VSTs can’t be urgently used.

The concept of banked third party VST therapy came about to address those limitations, said Dr. Tzannou of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

In a banked VST scenario, donor T cells with specific multiviral immunity are human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typed, expanded, and cryopreserved. A post-HCT patient with drug-refractory viral illness can receive T cells that are partially matched at HLA –A, HLA-B, or HLA-DR. Dr. Tzannou said that her group has now generated a bank of 59 VST lines to use in clinical testing of the third party approach.

In the study, Dr. Tzannou and her colleagues included both pediatric and adult post-allo-HCT patients with refractory EBV, CMV, AdV, BKV, and/or HHV6 infections. All had either failed a 14-day trial of antiviral therapy or could not tolerate antivirals. Patients could not be on more than 0.5 mg/kg per day of prednisone; they had to have an absolute neutrophil count above 500 per microliter and hemoglobin greater than 8 g/dL. Patients were excluded if they had acute GVHD of grade 2 or higher. There had to be a compatible VST line available that matched both the patient’s illness and HLA typing.

Patients initially received 20,000,000 VST cells per square meter of body surface area. If the investigators saw a partial response, patients could receive additional VST doses every 2 weeks.

Of the 42 patients infused, 23 received one infusion and 19 required two or more infusions. Seven study participants had two viral infections; 18 had CMV, 2 had EBV, 9 had AdV, 17 had BKV, and 3 had HHV6.

Dr. Tzannou and her colleagues tracked the virus-specific T cells and viral load for particular viruses. Virus-specific peripheral T cell counts also rose measurably and viral load plummeted within 2 weeks of VST infusions for most patients.

Overall, 93% of patients met the primary outcome measure of achieving complete or partial response; a partial response was defined as a 50% or better decrease in the viral load and/or clinical improvement.

All of the 17 BKV patients treated to date had tissue disease; 15 had hemorrhagic cystitis and 2 had nephritis. All responded to VSTs, and all of those with hemorrhagic cystitis had symptomatic improvement or resolution.

Overall, the safety profile for VST was good, said Dr. Tzannou. Four patients developed grade 1 acute cutaneous GVHD within 45 days of infusion; one of these developed de novo, but resolved with topical steroids. Another patient had a flare of gastrointestinal GVHD when immunosuppresion was being tapered. One more patient had a transient fever post infusion that resolved spontaneously, said Dr. Tzannou.

Next steps include a multicenter registration study, said Dr. Tzannou, who reports being a consultant for ViraCyte, which helped fund the study.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

ORLANDO – Infusions of banked multivirus-specific T lymphocytes were associated with complete or partial responses in 93% of 42 patients who had undergone hematopoietic cell transplants and had drug-refractory viral illnesses. Further, these patients experienced minimal new or reactivated graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

Viral infections cause nearly 40% of deaths after alternative donor hematopoietic cell transfer (HCT), Ifigeneia Tzannou, MD, said at the combined annual meetings of the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research and the American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Banked, “off-the-shelf” donor virus-resistant T cells can be an alternative to antiviral drugs, which are far from universally effective and may have serious side effects.

“Traditionally, we have generated T cells for infusion from the stem cell donor” by isolating and then stimulating and expanding the peripheral blood mononuclear cells for about 10 days ex vivo, said Dr. Tzannou. At that point, the clonal multivirus-resistant T cells can then be transferred to the recipient.

Donor-derived T cells have been used to prevent and treat Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), adenovirus (AdV), BK virus (BKV), and human herpes virus 6 (HHV6) infections. The approach has been safe, reconstituting antiviral immunity and clearing disease effectively, with a 94% response rate reported in one recent study. However, said Dr. Tzannou, donor-derived virus-specific T cells (VSTs) have their limitations. Donors are increasingly younger and cord blood is being used more commonly, so there are growing numbers of donors who are seronegative for pathogenic viruses. In addition, the 10 days of production time and the additional week or 10 days required for release means that donor-derived VSTs can’t be urgently used.

The concept of banked third party VST therapy came about to address those limitations, said Dr. Tzannou of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

In a banked VST scenario, donor T cells with specific multiviral immunity are human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typed, expanded, and cryopreserved. A post-HCT patient with drug-refractory viral illness can receive T cells that are partially matched at HLA –A, HLA-B, or HLA-DR. Dr. Tzannou said that her group has now generated a bank of 59 VST lines to use in clinical testing of the third party approach.

In the study, Dr. Tzannou and her colleagues included both pediatric and adult post-allo-HCT patients with refractory EBV, CMV, AdV, BKV, and/or HHV6 infections. All had either failed a 14-day trial of antiviral therapy or could not tolerate antivirals. Patients could not be on more than 0.5 mg/kg per day of prednisone; they had to have an absolute neutrophil count above 500 per microliter and hemoglobin greater than 8 g/dL. Patients were excluded if they had acute GVHD of grade 2 or higher. There had to be a compatible VST line available that matched both the patient’s illness and HLA typing.

Patients initially received 20,000,000 VST cells per square meter of body surface area. If the investigators saw a partial response, patients could receive additional VST doses every 2 weeks.

Of the 42 patients infused, 23 received one infusion and 19 required two or more infusions. Seven study participants had two viral infections; 18 had CMV, 2 had EBV, 9 had AdV, 17 had BKV, and 3 had HHV6.

Dr. Tzannou and her colleagues tracked the virus-specific T cells and viral load for particular viruses. Virus-specific peripheral T cell counts also rose measurably and viral load plummeted within 2 weeks of VST infusions for most patients.

Overall, 93% of patients met the primary outcome measure of achieving complete or partial response; a partial response was defined as a 50% or better decrease in the viral load and/or clinical improvement.

All of the 17 BKV patients treated to date had tissue disease; 15 had hemorrhagic cystitis and 2 had nephritis. All responded to VSTs, and all of those with hemorrhagic cystitis had symptomatic improvement or resolution.

Overall, the safety profile for VST was good, said Dr. Tzannou. Four patients developed grade 1 acute cutaneous GVHD within 45 days of infusion; one of these developed de novo, but resolved with topical steroids. Another patient had a flare of gastrointestinal GVHD when immunosuppresion was being tapered. One more patient had a transient fever post infusion that resolved spontaneously, said Dr. Tzannou.

Next steps include a multicenter registration study, said Dr. Tzannou, who reports being a consultant for ViraCyte, which helped fund the study.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

ORLANDO – Infusions of banked multivirus-specific T lymphocytes were associated with complete or partial responses in 93% of 42 patients who had undergone hematopoietic cell transplants and had drug-refractory viral illnesses. Further, these patients experienced minimal new or reactivated graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

Viral infections cause nearly 40% of deaths after alternative donor hematopoietic cell transfer (HCT), Ifigeneia Tzannou, MD, said at the combined annual meetings of the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research and the American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Banked, “off-the-shelf” donor virus-resistant T cells can be an alternative to antiviral drugs, which are far from universally effective and may have serious side effects.

“Traditionally, we have generated T cells for infusion from the stem cell donor” by isolating and then stimulating and expanding the peripheral blood mononuclear cells for about 10 days ex vivo, said Dr. Tzannou. At that point, the clonal multivirus-resistant T cells can then be transferred to the recipient.

Donor-derived T cells have been used to prevent and treat Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), adenovirus (AdV), BK virus (BKV), and human herpes virus 6 (HHV6) infections. The approach has been safe, reconstituting antiviral immunity and clearing disease effectively, with a 94% response rate reported in one recent study. However, said Dr. Tzannou, donor-derived virus-specific T cells (VSTs) have their limitations. Donors are increasingly younger and cord blood is being used more commonly, so there are growing numbers of donors who are seronegative for pathogenic viruses. In addition, the 10 days of production time and the additional week or 10 days required for release means that donor-derived VSTs can’t be urgently used.

The concept of banked third party VST therapy came about to address those limitations, said Dr. Tzannou of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

In a banked VST scenario, donor T cells with specific multiviral immunity are human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typed, expanded, and cryopreserved. A post-HCT patient with drug-refractory viral illness can receive T cells that are partially matched at HLA –A, HLA-B, or HLA-DR. Dr. Tzannou said that her group has now generated a bank of 59 VST lines to use in clinical testing of the third party approach.

In the study, Dr. Tzannou and her colleagues included both pediatric and adult post-allo-HCT patients with refractory EBV, CMV, AdV, BKV, and/or HHV6 infections. All had either failed a 14-day trial of antiviral therapy or could not tolerate antivirals. Patients could not be on more than 0.5 mg/kg per day of prednisone; they had to have an absolute neutrophil count above 500 per microliter and hemoglobin greater than 8 g/dL. Patients were excluded if they had acute GVHD of grade 2 or higher. There had to be a compatible VST line available that matched both the patient’s illness and HLA typing.

Patients initially received 20,000,000 VST cells per square meter of body surface area. If the investigators saw a partial response, patients could receive additional VST doses every 2 weeks.

Of the 42 patients infused, 23 received one infusion and 19 required two or more infusions. Seven study participants had two viral infections; 18 had CMV, 2 had EBV, 9 had AdV, 17 had BKV, and 3 had HHV6.

Dr. Tzannou and her colleagues tracked the virus-specific T cells and viral load for particular viruses. Virus-specific peripheral T cell counts also rose measurably and viral load plummeted within 2 weeks of VST infusions for most patients.

Overall, 93% of patients met the primary outcome measure of achieving complete or partial response; a partial response was defined as a 50% or better decrease in the viral load and/or clinical improvement.

All of the 17 BKV patients treated to date had tissue disease; 15 had hemorrhagic cystitis and 2 had nephritis. All responded to VSTs, and all of those with hemorrhagic cystitis had symptomatic improvement or resolution.

Overall, the safety profile for VST was good, said Dr. Tzannou. Four patients developed grade 1 acute cutaneous GVHD within 45 days of infusion; one of these developed de novo, but resolved with topical steroids. Another patient had a flare of gastrointestinal GVHD when immunosuppresion was being tapered. One more patient had a transient fever post infusion that resolved spontaneously, said Dr. Tzannou.

Next steps include a multicenter registration study, said Dr. Tzannou, who reports being a consultant for ViraCyte, which helped fund the study.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

AT THE 2017 BMT TANDEM MEETINGS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: With banked multivirus-specific T cells, viral illnesses either improved or resolved in 93% of 42 patients.

Data source: Clinical trial of 42 postallogeneic hematopoietic cell transfer patients who had any of five viral illnesses and had either failed a 14-day trial of antiviral therapy or could not tolerate antivirals.

Disclosures: Dr. Tzannou is a consultant for Incyte, which partially funded the trial and is developing third-party VSTs.

Pruritic Rash on the Buttock

Cutaneous Larva Migrans

Cutaneous larva migrans (CLM) is caused by the larval migration of animal hookworms. Ancylostoma braziliense, Ancylostoma ceylanicum, and Ancylostoma caninum are the species most commonly associated with the disease. The hookworm is endemic to tropical and subtropical climates in areas such as Africa, Southeast Asia, South America, and the southeastern United States.1 Although cats and dogs are most commonly affected, humans can be infected if they are exposed to sand or soil containing hookworm larvae, often due to contamination from animal feces.2 Cutaneous larva migrans is characterized by pruritic erythematous papules and linear or serpiginous, reddish brown, elevated tracks most commonly appearing on the feet, buttocks, thighs, and lower legs; however, lesions can appear anywhere. In human hosts, the larvae travel in the epidermis and are unable to invade the dermis; it is speculated that they lack the collagenase enzymes required to penetrate the basement membrane before invading the dermis.2

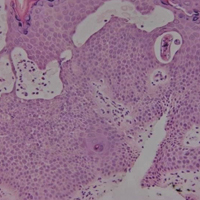

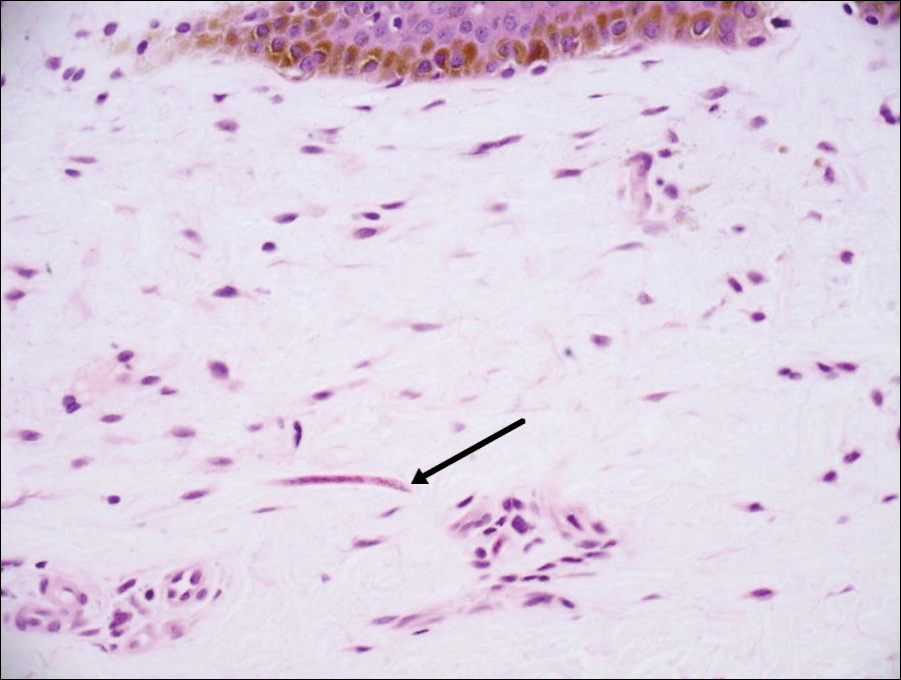

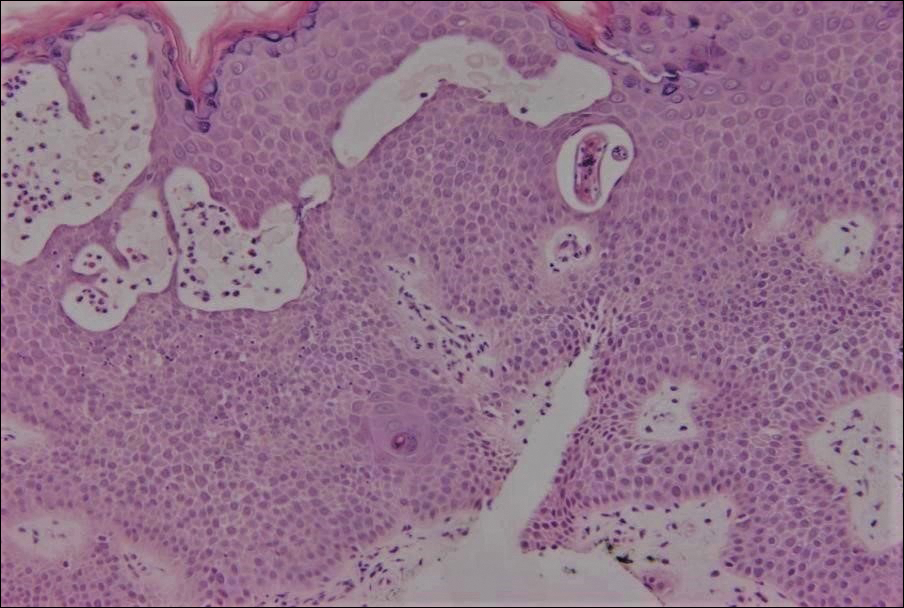

On histopathology, there typically are small cavities in the epidermis corresponding to the track of the larvae.3 There often is a spongiotic dermatitis with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate following the larvae with scattered eosinophils. The migrating larvae may be up to 1 mm in size and have bilateral double alae, or winglike projections, on the side of the body (Figure 1).4 The larvae are difficult to find on histopathology because they often travel beyond the areas that demonstrate clinical findings. The diagnosis of CLM is mostly clinical, but if a biopsy is performed, the specimen should be taken ahead of the track.

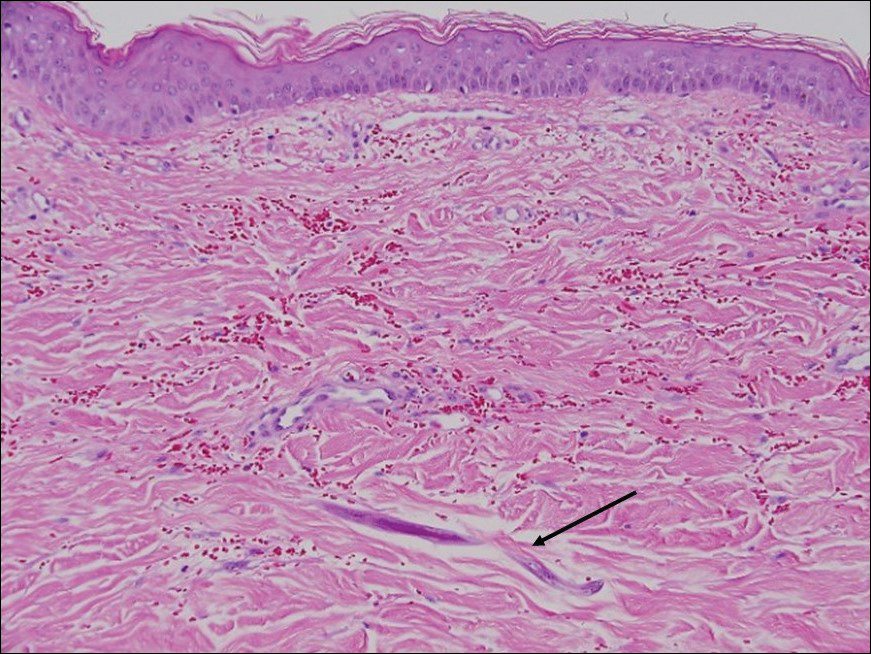

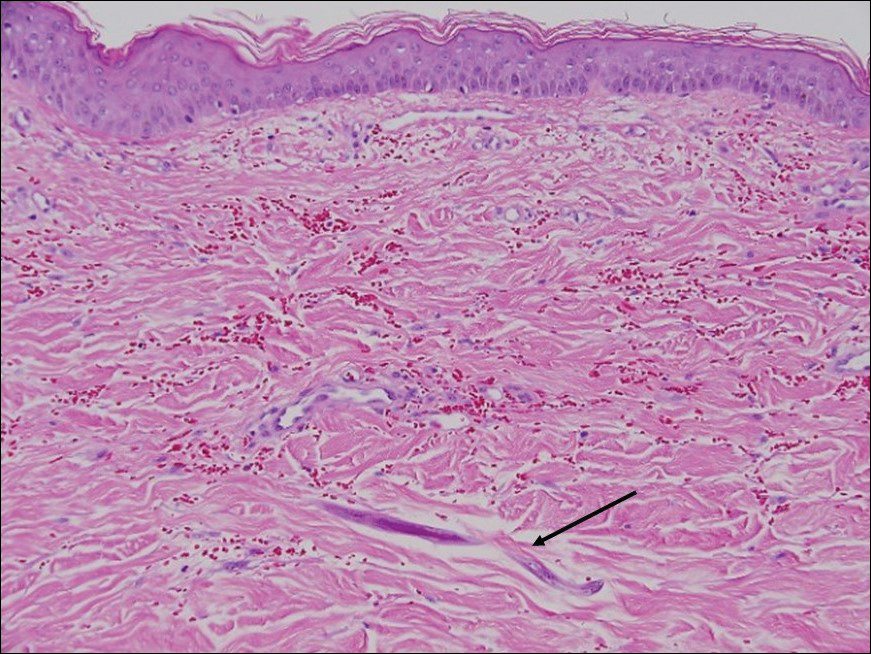

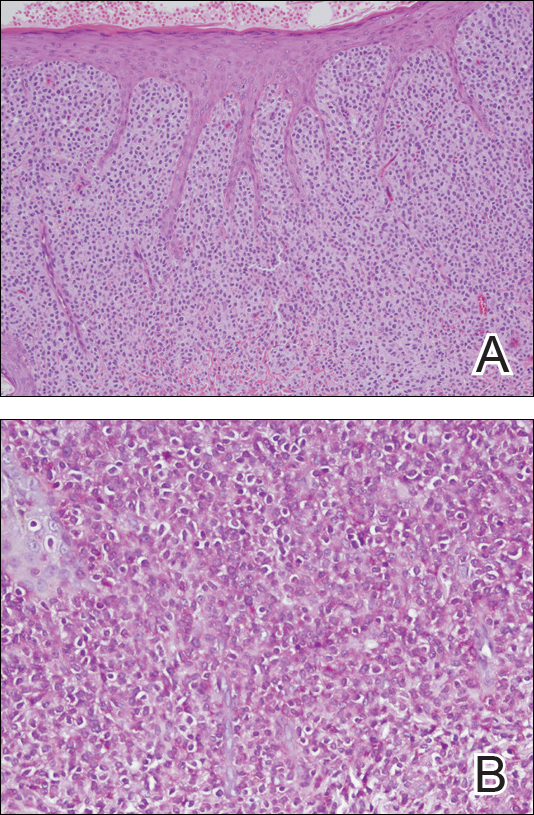

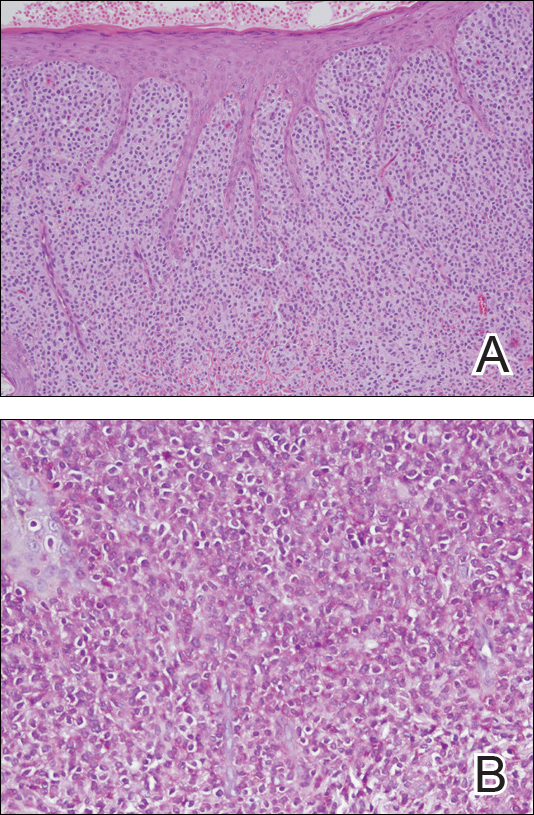

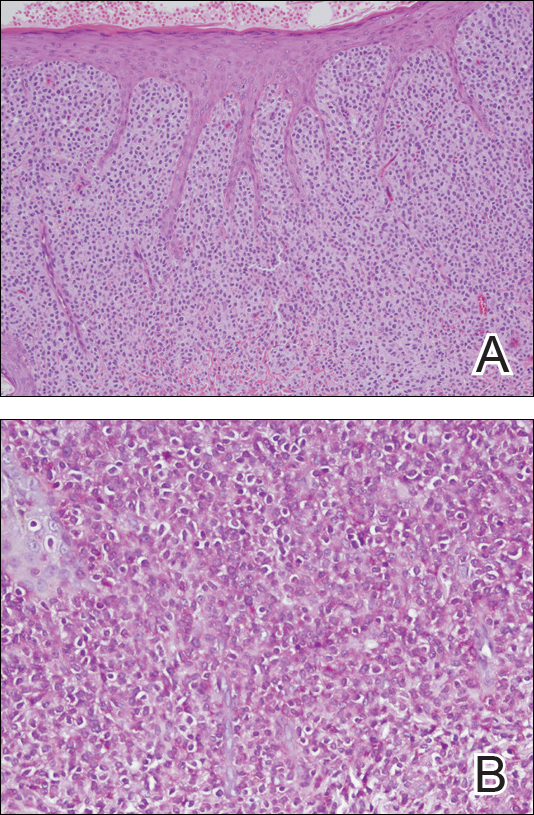

Disseminated strongyloidiasis is caused by Strongyloides stercoralis. When filariform larvae migrate out of the intestinal tract into the skin, they can cause an urticarial rash and serpiginous patterns on the skin that can move 5 to 15 cm per hour, a clinical condition known as larva currens. In immunocompromised individuals, there can be hyperinfection with diffuse petechial thumbprint purpura seen clinically, which characteristically radiate from the periumbilical area.1 On pathology, there may be numerous larvae found between the dermal collagen bundles, measuring 9 to 15 µm in diameter. Rarely, they also can be found in small blood vessels.3 They often are accompanied by extravasated red blood cells in the tissues (Figure 2).

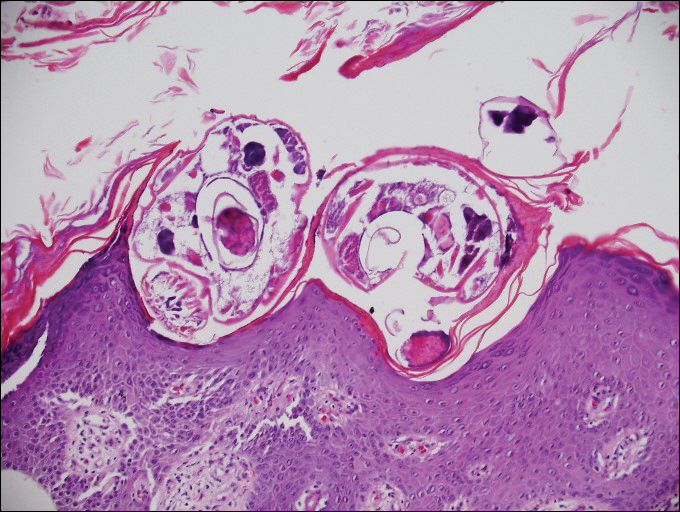

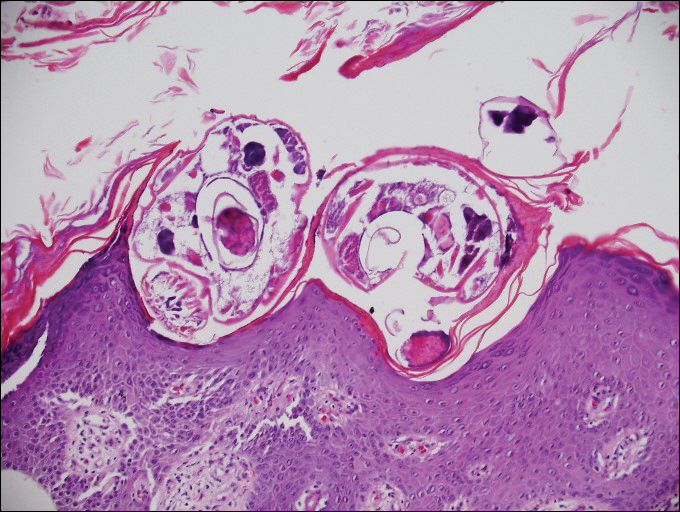

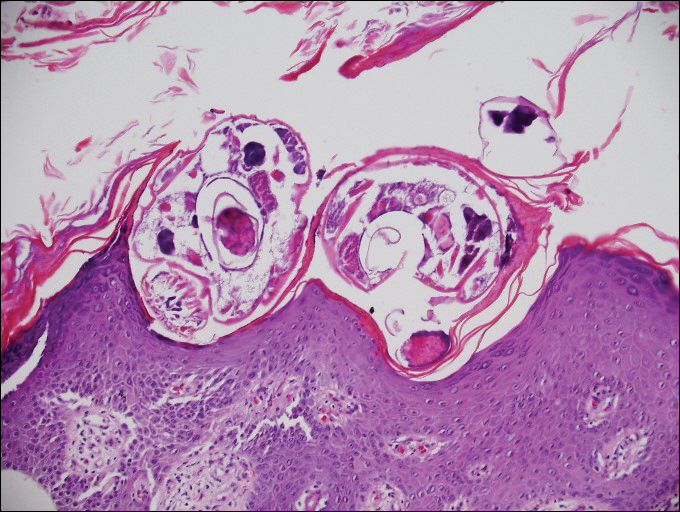

Myiasis represents the largest pathogen in the differential diagnosis for CLM. In myiasis, fly larvae will infest human tissue, usually by forming a small cavity in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue. The larvae are visible to the human eye and can be up to several centimeters in length. In the skin, the histology of myiasis usually is accompanied by a heavy mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate with many eosinophils. Fragments of the larvae are seen encased by a thick chitinous cuticle with widely spaced spines or pigmented setae (Figure 3) on the surface of the cuticle.5 Layers of striated muscle and internal organs may be seen beneath the cuticle.3

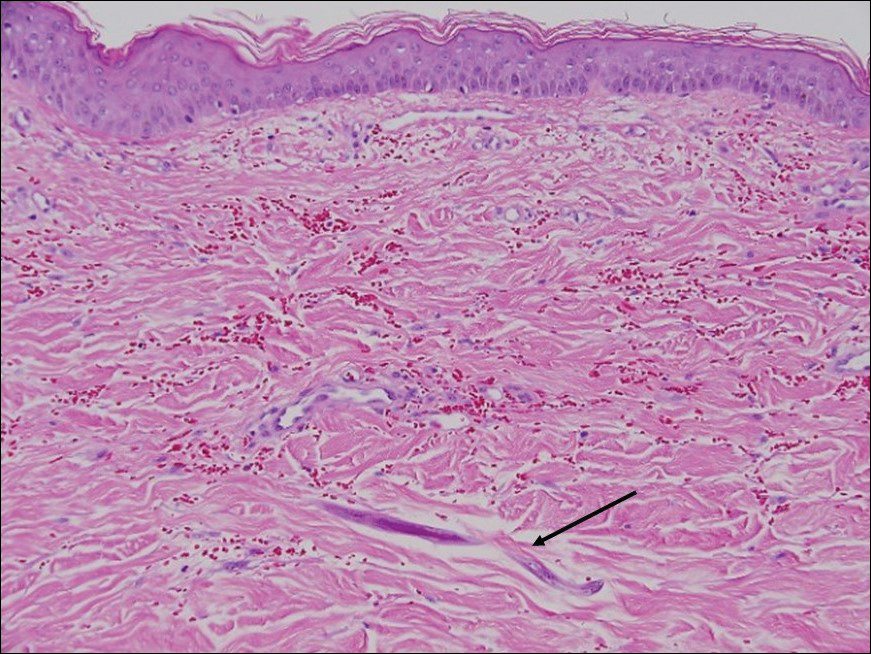

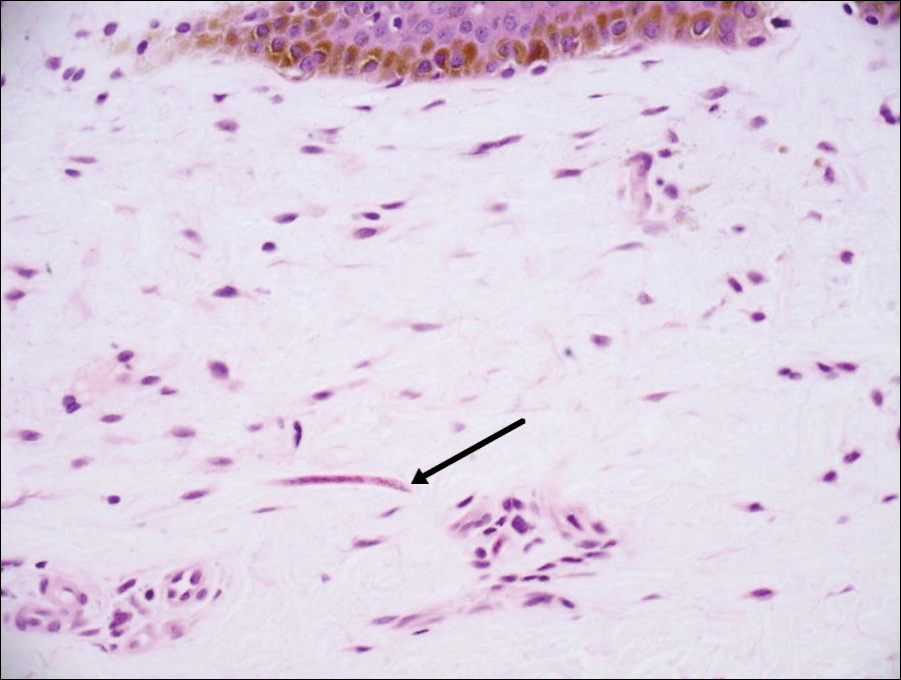

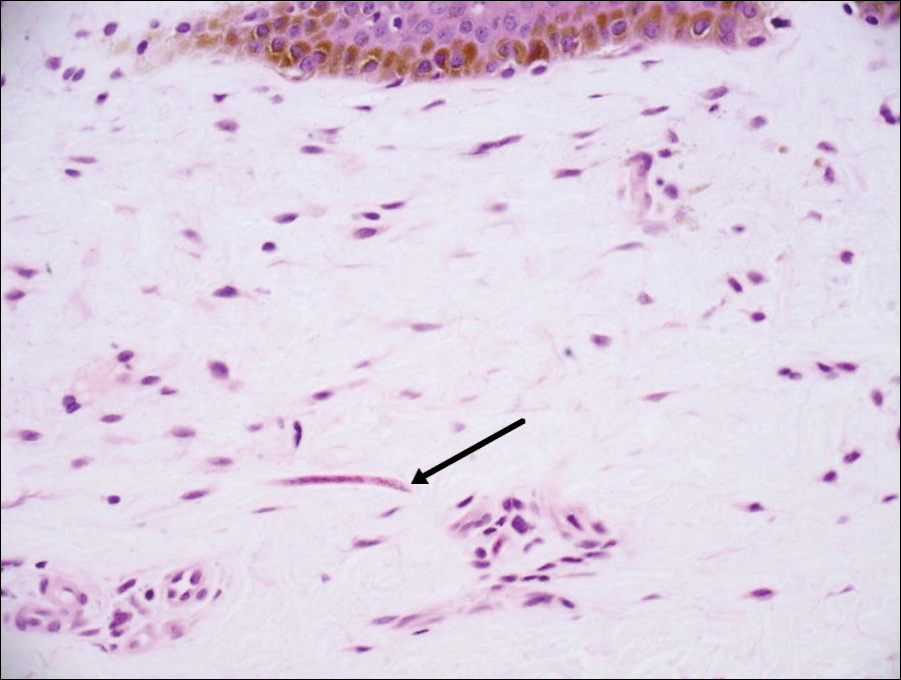

Onchocerciasis, or river blindness, is a parasitic disease caused by Onchocerca volvulus that is most often seen in sub-Saharan Africa. It may cause the skin finding of an onchocercoma, a subcutaneous nodule made up of Onchocerca nematodes. However, when the filaria disseminate, it may cause onchocerciasis with cutaneous findings of an eczematous dermatitis with itching and lichenification.1 In onchocercal dermatitis, microfilariae may be found in the dermis and there may be a mild dermal chronic inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils.3 These microfilariae are smaller than Strongyloides larvae (Figure 4).

Sarcoptes scabiei are mites that are pathologically found limited to the stratum corneum. There often is a spongiotic dermatitis as the mite travels with an accompanying mixed cell inflammatory infiltrate with many eosinophils. One or more mites may be seen with or without eggs and excreta or scybala (Figure 5). Pink pigtails may be seen connected to the stratum corneum, representing egg fragments or casings left behind after the mite hatches.3 The female mite measures up to 0.4 mm in length.3

- Lupi O, Downing C, Lee M, et al. Mucocutaneous manifestations of helminth infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:929-944.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

- Patterson J. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

- Milner D. Diagnostic Pathology: Infectious Diseases. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Ferringer T, Peckham S, Ko CJ, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013.

Cutaneous Larva Migrans

Cutaneous larva migrans (CLM) is caused by the larval migration of animal hookworms. Ancylostoma braziliense, Ancylostoma ceylanicum, and Ancylostoma caninum are the species most commonly associated with the disease. The hookworm is endemic to tropical and subtropical climates in areas such as Africa, Southeast Asia, South America, and the southeastern United States.1 Although cats and dogs are most commonly affected, humans can be infected if they are exposed to sand or soil containing hookworm larvae, often due to contamination from animal feces.2 Cutaneous larva migrans is characterized by pruritic erythematous papules and linear or serpiginous, reddish brown, elevated tracks most commonly appearing on the feet, buttocks, thighs, and lower legs; however, lesions can appear anywhere. In human hosts, the larvae travel in the epidermis and are unable to invade the dermis; it is speculated that they lack the collagenase enzymes required to penetrate the basement membrane before invading the dermis.2

On histopathology, there typically are small cavities in the epidermis corresponding to the track of the larvae.3 There often is a spongiotic dermatitis with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate following the larvae with scattered eosinophils. The migrating larvae may be up to 1 mm in size and have bilateral double alae, or winglike projections, on the side of the body (Figure 1).4 The larvae are difficult to find on histopathology because they often travel beyond the areas that demonstrate clinical findings. The diagnosis of CLM is mostly clinical, but if a biopsy is performed, the specimen should be taken ahead of the track.

Disseminated strongyloidiasis is caused by Strongyloides stercoralis. When filariform larvae migrate out of the intestinal tract into the skin, they can cause an urticarial rash and serpiginous patterns on the skin that can move 5 to 15 cm per hour, a clinical condition known as larva currens. In immunocompromised individuals, there can be hyperinfection with diffuse petechial thumbprint purpura seen clinically, which characteristically radiate from the periumbilical area.1 On pathology, there may be numerous larvae found between the dermal collagen bundles, measuring 9 to 15 µm in diameter. Rarely, they also can be found in small blood vessels.3 They often are accompanied by extravasated red blood cells in the tissues (Figure 2).

Myiasis represents the largest pathogen in the differential diagnosis for CLM. In myiasis, fly larvae will infest human tissue, usually by forming a small cavity in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue. The larvae are visible to the human eye and can be up to several centimeters in length. In the skin, the histology of myiasis usually is accompanied by a heavy mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate with many eosinophils. Fragments of the larvae are seen encased by a thick chitinous cuticle with widely spaced spines or pigmented setae (Figure 3) on the surface of the cuticle.5 Layers of striated muscle and internal organs may be seen beneath the cuticle.3

Onchocerciasis, or river blindness, is a parasitic disease caused by Onchocerca volvulus that is most often seen in sub-Saharan Africa. It may cause the skin finding of an onchocercoma, a subcutaneous nodule made up of Onchocerca nematodes. However, when the filaria disseminate, it may cause onchocerciasis with cutaneous findings of an eczematous dermatitis with itching and lichenification.1 In onchocercal dermatitis, microfilariae may be found in the dermis and there may be a mild dermal chronic inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils.3 These microfilariae are smaller than Strongyloides larvae (Figure 4).

Sarcoptes scabiei are mites that are pathologically found limited to the stratum corneum. There often is a spongiotic dermatitis as the mite travels with an accompanying mixed cell inflammatory infiltrate with many eosinophils. One or more mites may be seen with or without eggs and excreta or scybala (Figure 5). Pink pigtails may be seen connected to the stratum corneum, representing egg fragments or casings left behind after the mite hatches.3 The female mite measures up to 0.4 mm in length.3

Cutaneous Larva Migrans

Cutaneous larva migrans (CLM) is caused by the larval migration of animal hookworms. Ancylostoma braziliense, Ancylostoma ceylanicum, and Ancylostoma caninum are the species most commonly associated with the disease. The hookworm is endemic to tropical and subtropical climates in areas such as Africa, Southeast Asia, South America, and the southeastern United States.1 Although cats and dogs are most commonly affected, humans can be infected if they are exposed to sand or soil containing hookworm larvae, often due to contamination from animal feces.2 Cutaneous larva migrans is characterized by pruritic erythematous papules and linear or serpiginous, reddish brown, elevated tracks most commonly appearing on the feet, buttocks, thighs, and lower legs; however, lesions can appear anywhere. In human hosts, the larvae travel in the epidermis and are unable to invade the dermis; it is speculated that they lack the collagenase enzymes required to penetrate the basement membrane before invading the dermis.2

On histopathology, there typically are small cavities in the epidermis corresponding to the track of the larvae.3 There often is a spongiotic dermatitis with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate following the larvae with scattered eosinophils. The migrating larvae may be up to 1 mm in size and have bilateral double alae, or winglike projections, on the side of the body (Figure 1).4 The larvae are difficult to find on histopathology because they often travel beyond the areas that demonstrate clinical findings. The diagnosis of CLM is mostly clinical, but if a biopsy is performed, the specimen should be taken ahead of the track.

Disseminated strongyloidiasis is caused by Strongyloides stercoralis. When filariform larvae migrate out of the intestinal tract into the skin, they can cause an urticarial rash and serpiginous patterns on the skin that can move 5 to 15 cm per hour, a clinical condition known as larva currens. In immunocompromised individuals, there can be hyperinfection with diffuse petechial thumbprint purpura seen clinically, which characteristically radiate from the periumbilical area.1 On pathology, there may be numerous larvae found between the dermal collagen bundles, measuring 9 to 15 µm in diameter. Rarely, they also can be found in small blood vessels.3 They often are accompanied by extravasated red blood cells in the tissues (Figure 2).

Myiasis represents the largest pathogen in the differential diagnosis for CLM. In myiasis, fly larvae will infest human tissue, usually by forming a small cavity in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue. The larvae are visible to the human eye and can be up to several centimeters in length. In the skin, the histology of myiasis usually is accompanied by a heavy mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate with many eosinophils. Fragments of the larvae are seen encased by a thick chitinous cuticle with widely spaced spines or pigmented setae (Figure 3) on the surface of the cuticle.5 Layers of striated muscle and internal organs may be seen beneath the cuticle.3

Onchocerciasis, or river blindness, is a parasitic disease caused by Onchocerca volvulus that is most often seen in sub-Saharan Africa. It may cause the skin finding of an onchocercoma, a subcutaneous nodule made up of Onchocerca nematodes. However, when the filaria disseminate, it may cause onchocerciasis with cutaneous findings of an eczematous dermatitis with itching and lichenification.1 In onchocercal dermatitis, microfilariae may be found in the dermis and there may be a mild dermal chronic inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils.3 These microfilariae are smaller than Strongyloides larvae (Figure 4).

Sarcoptes scabiei are mites that are pathologically found limited to the stratum corneum. There often is a spongiotic dermatitis as the mite travels with an accompanying mixed cell inflammatory infiltrate with many eosinophils. One or more mites may be seen with or without eggs and excreta or scybala (Figure 5). Pink pigtails may be seen connected to the stratum corneum, representing egg fragments or casings left behind after the mite hatches.3 The female mite measures up to 0.4 mm in length.3

- Lupi O, Downing C, Lee M, et al. Mucocutaneous manifestations of helminth infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:929-944.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

- Patterson J. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

- Milner D. Diagnostic Pathology: Infectious Diseases. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.