User login

Psychosis in borderline personality disorder: How assessment and treatment differs from a psychotic disorder

Psychotic symptoms in patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) are common, distressing to patients, and challenging to treat. Issues of comorbidities and misdiagnoses in BPD patients further complicate matters and could lead to iatrogenic harm. The dissociation that patients with BPD experience could be confused with psychosis and exacerbate treatment and diagnostic confusion. Furthermore, BPD patients with unstable identity and who are sensitive to rejection could present in a bizarre, disorganized, or agitated manner when under stress.

Although pitfalls occur when managing psychotic symptoms in patients with BPD, there are trends and clues to help clinicians navigate diagnostic and treatment challenges. This article will review the literature, propose how to distinguish psychotic symptoms in BPD from those in primary psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia, and explore reasonable treatment options.

The scope of the problem

The DSM-5 criteria for BPD states that “during periods of extreme stress, transient paranoid ideation or dissociative symptoms may occur.”1 The term “borderline” originated from the idea that symptoms bordered on the intersection of neurosis and psychosis.2 However, psychotic symptoms in BPD are more varied and frequent than what DSM-5 criteria suggests.

The prevalence of psychotic symptoms in patients with BPD has been estimated between 20% to 50%.3 There also is evidence of frequent auditory and visual hallucinations in patients with BPD, and a recent study using structured psychiatric interviews demonstrated that most BPD patients report at least 1 symptom of psychosis.4 Considering that psychiatric comorbidities are the rule rather than the exception in BPD, the presence of psychotic symptoms further complicates the diagnostic picture. Recognizing the symptoms of BPD is essential for understanding the course of the symptoms and predicting response to treatment.5

Treatment of BPD is strikingly different than that of a primary psychotic disorder. There is some evidence that low-dosage antipsychotics could ease mood instability and perceptual disturbances in patients with BPD.6 Antipsychotic dosages used to treat hallucinations and delusions in a primary psychotic disorder are unlikely to be as effective for a patient with BPD, and are associated with significant adverse effects. Furthermore, these adverse effects—such as weight gain, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes—could become new sources of distress. Clinicians also might miss an opportunity to engage a BPD patient in psychotherapy if the focus is on the anticipated effect of a medication. The mainstay treatment of BPD is an evidence-based psychotherapy, such as dialectical behavioral therapy, transference-focused psychotherapy, mentalization-based therapy, or good psychiatric management.7

CASE Hallucinations during times of stress

Ms. K, a 20-year-old single college student, presents to the psychiatric emergency room with worsening mood swings, anxiety, and hallucinations. Her mood swings are brief and intense, lasting minutes to hours. Anxiety often is triggered by feelings of emptiness and fear of abandonment. She describes herself as a “social chameleon” and notes that she changes how she behaves depending on who she spends time with.

She often hears the voice of her ex-boyfriend instructing her to kill herself and saying that she is a “terrible person.” Their relationship was intense, with many break-ups and reunions. She also reports feeling disconnected from herself at times as though she is being controlled by an outside entity. To relieve her emotional suffering, she cuts herself superficially. Although she has no family history of psychiatric illness, she fears that she may have schizophrenia.

Ms. K’s outpatient psychiatrist prescribes antipsychotics at escalating dosages over a few months (she now takes olanzapine, 40 mg/d, aripiprazole, 30 mg/d, clonazepam, 3 mg/d, and escitalopram, 30 mg/d), but the hallucinations remain. These symptoms worsen during stressful situations, and she notices that they almost are constant as she studies for final exams, prompting her psychiatrist to discuss a clozapine trial. Ms. K is not in psychotherapy, and recognizes that she does not deal with stress well. Despite her symptoms, she is organized in her thought process, has excellent grooming and hygiene, has many social connections, and performs well in school.

How does one approach a patient such as Ms. K?

A chief concern of hallucinations, particularly in a young adult at an age when psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia often emerge, can contribute to a diagnostic quandary. What evidence can guide the clinician? There are some key features to consider:

- Her “mood swings” are notable in their intensity and brevity, making a primary mood disorder with psychotic features less likely.

- Hallucinations are present in the absence of a prodromal period of functional decline or negative symptoms, making a primary psychotic disorder less likely.

- She does not have a family history of psychiatric illness, particularly a primary psychotic disorder.

- She maintains social connections, although her relationships are intense and tumultuous.

- Psychotic symptoms have not changed with higher dosages of antipsychotics.

- Complaints of feeling “disconnected from herself” and “empty” are common symptoms of BPD and necessitate further exploration.

- Psychotic symptoms are largely transient and stress-related, with an overwhelmingly negative tone.

- Techniques that individuals with schizophrenia use, such as distraction or trying to tune out voices, are not being employed. Instead, Ms. K attends to the voices and is anxiously focused on them.

- The relationship of her symptoms to interpersonal stress is key.

When evaluating a patient such as Ms. K, it is important to explore both the nature and timing of the psychotic symptoms and any other related psychiatric symptoms. This helps to determine a less ambiguous diagnosis and clearer treatment plan. Understanding the patient’s perspective about the psychotic symptoms also is useful to gauge the patient’s level of distress and her impression of what the symptoms mean.

Diagnostic considerations

BPD is characterized by a chaotic emotional climate with impulsivity and instability of self-image, affect, and relationships. Most BPD symptoms, including psychosis, often are exacerbated by the perception of abandonment or rejection and other interpersonal stressors.1 Both BPD and schizophrenia are estimated to affect at least 1% of the general population.8,9 Patients with BPD frequently meet criteria for comorbid mental illnesses, including major depressive disorder, substance use disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and eating disorders.10 Because psychotic symptoms can present in some of these disorders, the context and time course of these symptoms are crucial to consider.

Misdiagnosis is common with BPD, and patients can receive the wrong treatment for years before BPD is considered, likely because of the stigma surrounding the diagnosis.5 One also must keep in mind that, although rare, a patient can have both BPD and a primary psychotic disorder.11 Although a patient with schizophrenia could be prone to social isolation because of delusions or paranoia, BPD patients are more apt to experience intense interpersonal relationships driven by the need to avoid abandonment. Manipulation, anger, and neediness in relationships with both peers and health care providers are common—stark contrasts to typical negative symptoms, blunted affect, and a lack of social drive characteristic of schizophrenia.12

Distinguishing between psychosis in BPD and a psychotic disorder

Studies have sought to explore the quality of psychotic symptoms in BPD vs primary psychotic disorders, which can be challenging to differentiate (Table 1). Some have found that transient symptoms, such as non-delusional paranoia, are more prevalent in BPD, and “true” psychotic symptoms that are long-lasting and bizarre are indicative of schizophrenia.13,14 Also, there is evidence that the lower levels of interpersonal functioning often found in BPD are predictive of psychotic symptoms in that disorder but not in schizophrenia.15

Auditory hallucinations in patients with BPD predominantly are negative and critical in tone.4 However, there is no consistent evidence that the quality of auditory hallucinations in BPD vs schizophrenia is different in any meaningful way.16 Because of the frequency of dissociative symptoms in BPD, it is likely that clinicians could misinterpret these symptoms to indicate disorganized behavior associated with a primary psychotic disorder. In one study, 50% of individuals with BPD experienced auditory hallucinations.11 Differentiating between “internal” or “external” voices did not help to clarify the diagnosis, and paranoid delusions occurred in less than one-third of patients with BPD, but in approximately two-third of those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

The McLean Study of Adult Development, a longitudinal study of BPD patients, found that the prevalence of psychotic symptoms diminished over time. It is unclear whether this was due to the spontaneus remission rate of BPD symptoms in general or because of effective treatment.13

Psychotic symptoms in BPD seem to react to stress and increase in intensity when patients are in crisis.17 Nonetheless, because of the prevalence of psychosis in BPD patients and the distress it causes, clinicians should be cautioned against using terms that imply that the symptoms are not “true” or “real.”3

Treatment recommendations

When considering pharmacologic management of psychotic symptoms in BPD, aim to limit antipsychotic medications to low dosages because of adverse effects and the limited evidence that escalating dosages—and especially using >1 antipsychotic concurrently—are more effective.18 Educate patients that in BPD medications are, at best, considered adjunctive treatments. Blaming psychotic symptoms on a purely biological process in BPD, not only is harmful because medications are unlikely to significantly or consistently help, but also because they can undermine patient autonomy and reinforce the need for an outside entity (ie, medication) to fix their problems.

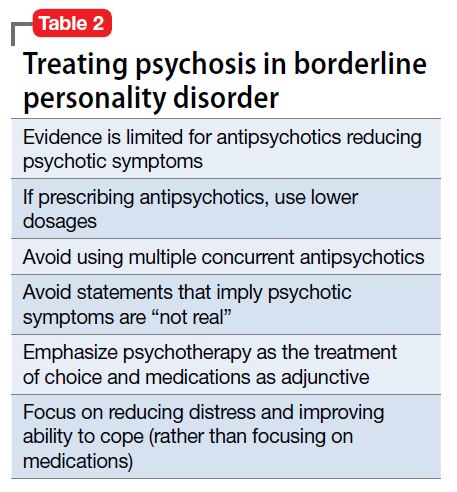

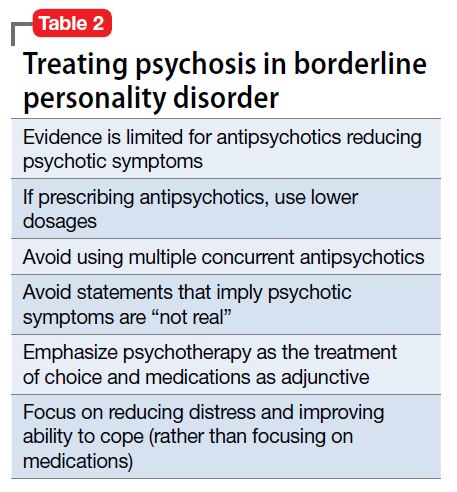

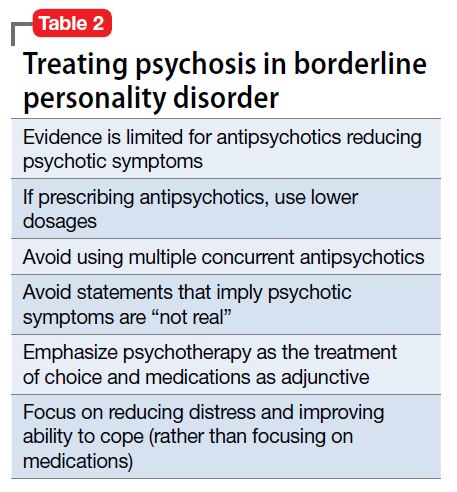

When treatment is ineffective and symptoms do not improve, a patient with BPD likely will experience mounting distress. This, in turn, could exacerbate impulsive, suicidal, and self-injurious behaviors. Emphasize psychotherapy, particularly for those whose psychotic symptoms are transient, stress-related, and present during acute crises (Table 2). With evidence-based psychotherapy, BPD patients can become active participants in treatment, coupling developing insight with concrete skills and teachable principles. This leads to increased interpersonal effectiveness and resilience during times of stress. Challenging the patient’s psychotic symptoms as false or “made up” rarely is helpful and usually harmful, leading to the possible severance of the therapeutic alliance.3

Bottom Line

Psychotic symptoms in patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) could look similar to those in primary psychotic disorders. Factors suggesting BPD include a pattern of worsening psychotic symptoms during stress, long-term symptom instability, lack of delusions, presence of dissociation, and nonresponse to antipsychotics. Although low-dosage antipsychotics could provide some relief of psychotic symptoms in a patient with BPD, they often are not consistently effective and frequently lead to adverse effects. Emphasize evidence-based psychotherapies.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Stern A. Borderline group of neuroses. The Psychoanalytic Quarterly. 1938;7:467-489.

3. Schroeder K, Fisher HL, Schäfer I, et al. Psychotic symptoms in patients with borderline personality disorder: prevalence and clinical management. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26(1):113-119.

4. Pearse LJ, Dibben C, Ziauddeen H, et al. A study of psychotic symptoms in borderline personality disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202(5):368-371.

5. Paris J. Why psychiatrists are reluctant to diagnose: borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2007;4(1):35-

6. Saunders EF, Silk KR. Personality trait dimensions and the pharmacological treatment of borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29(5):461-467.

7. National Education Alliance for Borderline Personality Disorder. Treatments for BPD. http://www.borderlinepersonalitydisorder.com/what-is-bpd/treating-bpd. Accessed September 1, 2016.

8. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, et al. The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system. Epidemiologic catchment area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(2):85-94.

9. Lenzenweger MF, Lane MC, Loranger AW, et al. DSM-IV personality disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(6):553-564.

10. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Dubo ED, et al. Axis I comorbidity of borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(12):1733-1739.

11. Kingdon DG, Ashcroft K, Bhandari B, et al. Schizophrenia and borderline personality disorder: similarities and differences in the experience of auditory hallucinations, paranoia, and childhood trauma. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198(6):399-403.

12. Gunderson JG. Borderline personality disorder. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1984.

13. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Wedig MM, et al. Cognitive experiences reported by patients with borderline personality disorder and Axis II comparison subjects: a 16-year prospective follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(6):671-679.

14. Tschoeke S, Steinert T, Flammer E, et al. Similarities and differences in borderline personality disorder and schizophrenia with voice hearing. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202(7):544-549.

15. Oliva F, Dalmotto M, Pirfo E, et al. A comparison of thought and perception disorders in borderline personality disorder and schizophrenia: psychotic experiences as a reaction to impaired social functioning. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:239.

16. Merrett Z, Rossell SL, Castle DJ, et al. Comparing the experience of voices in borderline personality disorder with the experience of voices in a psychotic disorder: a systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50(7):640-648.

17. Glaser JP, Van Os J, Thewissen V, et al. Psychotic reactivity in borderline personality disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;121(2):125-134.

18. Rosenbluth M, Sinyor M. Off-label use of atypical antipsychotics in personality disorders. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13(11):1575-1585.

Psychotic symptoms in patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) are common, distressing to patients, and challenging to treat. Issues of comorbidities and misdiagnoses in BPD patients further complicate matters and could lead to iatrogenic harm. The dissociation that patients with BPD experience could be confused with psychosis and exacerbate treatment and diagnostic confusion. Furthermore, BPD patients with unstable identity and who are sensitive to rejection could present in a bizarre, disorganized, or agitated manner when under stress.

Although pitfalls occur when managing psychotic symptoms in patients with BPD, there are trends and clues to help clinicians navigate diagnostic and treatment challenges. This article will review the literature, propose how to distinguish psychotic symptoms in BPD from those in primary psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia, and explore reasonable treatment options.

The scope of the problem

The DSM-5 criteria for BPD states that “during periods of extreme stress, transient paranoid ideation or dissociative symptoms may occur.”1 The term “borderline” originated from the idea that symptoms bordered on the intersection of neurosis and psychosis.2 However, psychotic symptoms in BPD are more varied and frequent than what DSM-5 criteria suggests.

The prevalence of psychotic symptoms in patients with BPD has been estimated between 20% to 50%.3 There also is evidence of frequent auditory and visual hallucinations in patients with BPD, and a recent study using structured psychiatric interviews demonstrated that most BPD patients report at least 1 symptom of psychosis.4 Considering that psychiatric comorbidities are the rule rather than the exception in BPD, the presence of psychotic symptoms further complicates the diagnostic picture. Recognizing the symptoms of BPD is essential for understanding the course of the symptoms and predicting response to treatment.5

Treatment of BPD is strikingly different than that of a primary psychotic disorder. There is some evidence that low-dosage antipsychotics could ease mood instability and perceptual disturbances in patients with BPD.6 Antipsychotic dosages used to treat hallucinations and delusions in a primary psychotic disorder are unlikely to be as effective for a patient with BPD, and are associated with significant adverse effects. Furthermore, these adverse effects—such as weight gain, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes—could become new sources of distress. Clinicians also might miss an opportunity to engage a BPD patient in psychotherapy if the focus is on the anticipated effect of a medication. The mainstay treatment of BPD is an evidence-based psychotherapy, such as dialectical behavioral therapy, transference-focused psychotherapy, mentalization-based therapy, or good psychiatric management.7

CASE Hallucinations during times of stress

Ms. K, a 20-year-old single college student, presents to the psychiatric emergency room with worsening mood swings, anxiety, and hallucinations. Her mood swings are brief and intense, lasting minutes to hours. Anxiety often is triggered by feelings of emptiness and fear of abandonment. She describes herself as a “social chameleon” and notes that she changes how she behaves depending on who she spends time with.

She often hears the voice of her ex-boyfriend instructing her to kill herself and saying that she is a “terrible person.” Their relationship was intense, with many break-ups and reunions. She also reports feeling disconnected from herself at times as though she is being controlled by an outside entity. To relieve her emotional suffering, she cuts herself superficially. Although she has no family history of psychiatric illness, she fears that she may have schizophrenia.

Ms. K’s outpatient psychiatrist prescribes antipsychotics at escalating dosages over a few months (she now takes olanzapine, 40 mg/d, aripiprazole, 30 mg/d, clonazepam, 3 mg/d, and escitalopram, 30 mg/d), but the hallucinations remain. These symptoms worsen during stressful situations, and she notices that they almost are constant as she studies for final exams, prompting her psychiatrist to discuss a clozapine trial. Ms. K is not in psychotherapy, and recognizes that she does not deal with stress well. Despite her symptoms, she is organized in her thought process, has excellent grooming and hygiene, has many social connections, and performs well in school.

How does one approach a patient such as Ms. K?

A chief concern of hallucinations, particularly in a young adult at an age when psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia often emerge, can contribute to a diagnostic quandary. What evidence can guide the clinician? There are some key features to consider:

- Her “mood swings” are notable in their intensity and brevity, making a primary mood disorder with psychotic features less likely.

- Hallucinations are present in the absence of a prodromal period of functional decline or negative symptoms, making a primary psychotic disorder less likely.

- She does not have a family history of psychiatric illness, particularly a primary psychotic disorder.

- She maintains social connections, although her relationships are intense and tumultuous.

- Psychotic symptoms have not changed with higher dosages of antipsychotics.

- Complaints of feeling “disconnected from herself” and “empty” are common symptoms of BPD and necessitate further exploration.

- Psychotic symptoms are largely transient and stress-related, with an overwhelmingly negative tone.

- Techniques that individuals with schizophrenia use, such as distraction or trying to tune out voices, are not being employed. Instead, Ms. K attends to the voices and is anxiously focused on them.

- The relationship of her symptoms to interpersonal stress is key.

When evaluating a patient such as Ms. K, it is important to explore both the nature and timing of the psychotic symptoms and any other related psychiatric symptoms. This helps to determine a less ambiguous diagnosis and clearer treatment plan. Understanding the patient’s perspective about the psychotic symptoms also is useful to gauge the patient’s level of distress and her impression of what the symptoms mean.

Diagnostic considerations

BPD is characterized by a chaotic emotional climate with impulsivity and instability of self-image, affect, and relationships. Most BPD symptoms, including psychosis, often are exacerbated by the perception of abandonment or rejection and other interpersonal stressors.1 Both BPD and schizophrenia are estimated to affect at least 1% of the general population.8,9 Patients with BPD frequently meet criteria for comorbid mental illnesses, including major depressive disorder, substance use disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and eating disorders.10 Because psychotic symptoms can present in some of these disorders, the context and time course of these symptoms are crucial to consider.

Misdiagnosis is common with BPD, and patients can receive the wrong treatment for years before BPD is considered, likely because of the stigma surrounding the diagnosis.5 One also must keep in mind that, although rare, a patient can have both BPD and a primary psychotic disorder.11 Although a patient with schizophrenia could be prone to social isolation because of delusions or paranoia, BPD patients are more apt to experience intense interpersonal relationships driven by the need to avoid abandonment. Manipulation, anger, and neediness in relationships with both peers and health care providers are common—stark contrasts to typical negative symptoms, blunted affect, and a lack of social drive characteristic of schizophrenia.12

Distinguishing between psychosis in BPD and a psychotic disorder

Studies have sought to explore the quality of psychotic symptoms in BPD vs primary psychotic disorders, which can be challenging to differentiate (Table 1). Some have found that transient symptoms, such as non-delusional paranoia, are more prevalent in BPD, and “true” psychotic symptoms that are long-lasting and bizarre are indicative of schizophrenia.13,14 Also, there is evidence that the lower levels of interpersonal functioning often found in BPD are predictive of psychotic symptoms in that disorder but not in schizophrenia.15

Auditory hallucinations in patients with BPD predominantly are negative and critical in tone.4 However, there is no consistent evidence that the quality of auditory hallucinations in BPD vs schizophrenia is different in any meaningful way.16 Because of the frequency of dissociative symptoms in BPD, it is likely that clinicians could misinterpret these symptoms to indicate disorganized behavior associated with a primary psychotic disorder. In one study, 50% of individuals with BPD experienced auditory hallucinations.11 Differentiating between “internal” or “external” voices did not help to clarify the diagnosis, and paranoid delusions occurred in less than one-third of patients with BPD, but in approximately two-third of those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

The McLean Study of Adult Development, a longitudinal study of BPD patients, found that the prevalence of psychotic symptoms diminished over time. It is unclear whether this was due to the spontaneus remission rate of BPD symptoms in general or because of effective treatment.13

Psychotic symptoms in BPD seem to react to stress and increase in intensity when patients are in crisis.17 Nonetheless, because of the prevalence of psychosis in BPD patients and the distress it causes, clinicians should be cautioned against using terms that imply that the symptoms are not “true” or “real.”3

Treatment recommendations

When considering pharmacologic management of psychotic symptoms in BPD, aim to limit antipsychotic medications to low dosages because of adverse effects and the limited evidence that escalating dosages—and especially using >1 antipsychotic concurrently—are more effective.18 Educate patients that in BPD medications are, at best, considered adjunctive treatments. Blaming psychotic symptoms on a purely biological process in BPD, not only is harmful because medications are unlikely to significantly or consistently help, but also because they can undermine patient autonomy and reinforce the need for an outside entity (ie, medication) to fix their problems.

When treatment is ineffective and symptoms do not improve, a patient with BPD likely will experience mounting distress. This, in turn, could exacerbate impulsive, suicidal, and self-injurious behaviors. Emphasize psychotherapy, particularly for those whose psychotic symptoms are transient, stress-related, and present during acute crises (Table 2). With evidence-based psychotherapy, BPD patients can become active participants in treatment, coupling developing insight with concrete skills and teachable principles. This leads to increased interpersonal effectiveness and resilience during times of stress. Challenging the patient’s psychotic symptoms as false or “made up” rarely is helpful and usually harmful, leading to the possible severance of the therapeutic alliance.3

Bottom Line

Psychotic symptoms in patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) could look similar to those in primary psychotic disorders. Factors suggesting BPD include a pattern of worsening psychotic symptoms during stress, long-term symptom instability, lack of delusions, presence of dissociation, and nonresponse to antipsychotics. Although low-dosage antipsychotics could provide some relief of psychotic symptoms in a patient with BPD, they often are not consistently effective and frequently lead to adverse effects. Emphasize evidence-based psychotherapies.

Psychotic symptoms in patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) are common, distressing to patients, and challenging to treat. Issues of comorbidities and misdiagnoses in BPD patients further complicate matters and could lead to iatrogenic harm. The dissociation that patients with BPD experience could be confused with psychosis and exacerbate treatment and diagnostic confusion. Furthermore, BPD patients with unstable identity and who are sensitive to rejection could present in a bizarre, disorganized, or agitated manner when under stress.

Although pitfalls occur when managing psychotic symptoms in patients with BPD, there are trends and clues to help clinicians navigate diagnostic and treatment challenges. This article will review the literature, propose how to distinguish psychotic symptoms in BPD from those in primary psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia, and explore reasonable treatment options.

The scope of the problem

The DSM-5 criteria for BPD states that “during periods of extreme stress, transient paranoid ideation or dissociative symptoms may occur.”1 The term “borderline” originated from the idea that symptoms bordered on the intersection of neurosis and psychosis.2 However, psychotic symptoms in BPD are more varied and frequent than what DSM-5 criteria suggests.

The prevalence of psychotic symptoms in patients with BPD has been estimated between 20% to 50%.3 There also is evidence of frequent auditory and visual hallucinations in patients with BPD, and a recent study using structured psychiatric interviews demonstrated that most BPD patients report at least 1 symptom of psychosis.4 Considering that psychiatric comorbidities are the rule rather than the exception in BPD, the presence of psychotic symptoms further complicates the diagnostic picture. Recognizing the symptoms of BPD is essential for understanding the course of the symptoms and predicting response to treatment.5

Treatment of BPD is strikingly different than that of a primary psychotic disorder. There is some evidence that low-dosage antipsychotics could ease mood instability and perceptual disturbances in patients with BPD.6 Antipsychotic dosages used to treat hallucinations and delusions in a primary psychotic disorder are unlikely to be as effective for a patient with BPD, and are associated with significant adverse effects. Furthermore, these adverse effects—such as weight gain, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes—could become new sources of distress. Clinicians also might miss an opportunity to engage a BPD patient in psychotherapy if the focus is on the anticipated effect of a medication. The mainstay treatment of BPD is an evidence-based psychotherapy, such as dialectical behavioral therapy, transference-focused psychotherapy, mentalization-based therapy, or good psychiatric management.7

CASE Hallucinations during times of stress

Ms. K, a 20-year-old single college student, presents to the psychiatric emergency room with worsening mood swings, anxiety, and hallucinations. Her mood swings are brief and intense, lasting minutes to hours. Anxiety often is triggered by feelings of emptiness and fear of abandonment. She describes herself as a “social chameleon” and notes that she changes how she behaves depending on who she spends time with.

She often hears the voice of her ex-boyfriend instructing her to kill herself and saying that she is a “terrible person.” Their relationship was intense, with many break-ups and reunions. She also reports feeling disconnected from herself at times as though she is being controlled by an outside entity. To relieve her emotional suffering, she cuts herself superficially. Although she has no family history of psychiatric illness, she fears that she may have schizophrenia.

Ms. K’s outpatient psychiatrist prescribes antipsychotics at escalating dosages over a few months (she now takes olanzapine, 40 mg/d, aripiprazole, 30 mg/d, clonazepam, 3 mg/d, and escitalopram, 30 mg/d), but the hallucinations remain. These symptoms worsen during stressful situations, and she notices that they almost are constant as she studies for final exams, prompting her psychiatrist to discuss a clozapine trial. Ms. K is not in psychotherapy, and recognizes that she does not deal with stress well. Despite her symptoms, she is organized in her thought process, has excellent grooming and hygiene, has many social connections, and performs well in school.

How does one approach a patient such as Ms. K?

A chief concern of hallucinations, particularly in a young adult at an age when psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia often emerge, can contribute to a diagnostic quandary. What evidence can guide the clinician? There are some key features to consider:

- Her “mood swings” are notable in their intensity and brevity, making a primary mood disorder with psychotic features less likely.

- Hallucinations are present in the absence of a prodromal period of functional decline or negative symptoms, making a primary psychotic disorder less likely.

- She does not have a family history of psychiatric illness, particularly a primary psychotic disorder.

- She maintains social connections, although her relationships are intense and tumultuous.

- Psychotic symptoms have not changed with higher dosages of antipsychotics.

- Complaints of feeling “disconnected from herself” and “empty” are common symptoms of BPD and necessitate further exploration.

- Psychotic symptoms are largely transient and stress-related, with an overwhelmingly negative tone.

- Techniques that individuals with schizophrenia use, such as distraction or trying to tune out voices, are not being employed. Instead, Ms. K attends to the voices and is anxiously focused on them.

- The relationship of her symptoms to interpersonal stress is key.

When evaluating a patient such as Ms. K, it is important to explore both the nature and timing of the psychotic symptoms and any other related psychiatric symptoms. This helps to determine a less ambiguous diagnosis and clearer treatment plan. Understanding the patient’s perspective about the psychotic symptoms also is useful to gauge the patient’s level of distress and her impression of what the symptoms mean.

Diagnostic considerations

BPD is characterized by a chaotic emotional climate with impulsivity and instability of self-image, affect, and relationships. Most BPD symptoms, including psychosis, often are exacerbated by the perception of abandonment or rejection and other interpersonal stressors.1 Both BPD and schizophrenia are estimated to affect at least 1% of the general population.8,9 Patients with BPD frequently meet criteria for comorbid mental illnesses, including major depressive disorder, substance use disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and eating disorders.10 Because psychotic symptoms can present in some of these disorders, the context and time course of these symptoms are crucial to consider.

Misdiagnosis is common with BPD, and patients can receive the wrong treatment for years before BPD is considered, likely because of the stigma surrounding the diagnosis.5 One also must keep in mind that, although rare, a patient can have both BPD and a primary psychotic disorder.11 Although a patient with schizophrenia could be prone to social isolation because of delusions or paranoia, BPD patients are more apt to experience intense interpersonal relationships driven by the need to avoid abandonment. Manipulation, anger, and neediness in relationships with both peers and health care providers are common—stark contrasts to typical negative symptoms, blunted affect, and a lack of social drive characteristic of schizophrenia.12

Distinguishing between psychosis in BPD and a psychotic disorder

Studies have sought to explore the quality of psychotic symptoms in BPD vs primary psychotic disorders, which can be challenging to differentiate (Table 1). Some have found that transient symptoms, such as non-delusional paranoia, are more prevalent in BPD, and “true” psychotic symptoms that are long-lasting and bizarre are indicative of schizophrenia.13,14 Also, there is evidence that the lower levels of interpersonal functioning often found in BPD are predictive of psychotic symptoms in that disorder but not in schizophrenia.15

Auditory hallucinations in patients with BPD predominantly are negative and critical in tone.4 However, there is no consistent evidence that the quality of auditory hallucinations in BPD vs schizophrenia is different in any meaningful way.16 Because of the frequency of dissociative symptoms in BPD, it is likely that clinicians could misinterpret these symptoms to indicate disorganized behavior associated with a primary psychotic disorder. In one study, 50% of individuals with BPD experienced auditory hallucinations.11 Differentiating between “internal” or “external” voices did not help to clarify the diagnosis, and paranoid delusions occurred in less than one-third of patients with BPD, but in approximately two-third of those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

The McLean Study of Adult Development, a longitudinal study of BPD patients, found that the prevalence of psychotic symptoms diminished over time. It is unclear whether this was due to the spontaneus remission rate of BPD symptoms in general or because of effective treatment.13

Psychotic symptoms in BPD seem to react to stress and increase in intensity when patients are in crisis.17 Nonetheless, because of the prevalence of psychosis in BPD patients and the distress it causes, clinicians should be cautioned against using terms that imply that the symptoms are not “true” or “real.”3

Treatment recommendations

When considering pharmacologic management of psychotic symptoms in BPD, aim to limit antipsychotic medications to low dosages because of adverse effects and the limited evidence that escalating dosages—and especially using >1 antipsychotic concurrently—are more effective.18 Educate patients that in BPD medications are, at best, considered adjunctive treatments. Blaming psychotic symptoms on a purely biological process in BPD, not only is harmful because medications are unlikely to significantly or consistently help, but also because they can undermine patient autonomy and reinforce the need for an outside entity (ie, medication) to fix their problems.

When treatment is ineffective and symptoms do not improve, a patient with BPD likely will experience mounting distress. This, in turn, could exacerbate impulsive, suicidal, and self-injurious behaviors. Emphasize psychotherapy, particularly for those whose psychotic symptoms are transient, stress-related, and present during acute crises (Table 2). With evidence-based psychotherapy, BPD patients can become active participants in treatment, coupling developing insight with concrete skills and teachable principles. This leads to increased interpersonal effectiveness and resilience during times of stress. Challenging the patient’s psychotic symptoms as false or “made up” rarely is helpful and usually harmful, leading to the possible severance of the therapeutic alliance.3

Bottom Line

Psychotic symptoms in patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) could look similar to those in primary psychotic disorders. Factors suggesting BPD include a pattern of worsening psychotic symptoms during stress, long-term symptom instability, lack of delusions, presence of dissociation, and nonresponse to antipsychotics. Although low-dosage antipsychotics could provide some relief of psychotic symptoms in a patient with BPD, they often are not consistently effective and frequently lead to adverse effects. Emphasize evidence-based psychotherapies.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Stern A. Borderline group of neuroses. The Psychoanalytic Quarterly. 1938;7:467-489.

3. Schroeder K, Fisher HL, Schäfer I, et al. Psychotic symptoms in patients with borderline personality disorder: prevalence and clinical management. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26(1):113-119.

4. Pearse LJ, Dibben C, Ziauddeen H, et al. A study of psychotic symptoms in borderline personality disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202(5):368-371.

5. Paris J. Why psychiatrists are reluctant to diagnose: borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2007;4(1):35-

6. Saunders EF, Silk KR. Personality trait dimensions and the pharmacological treatment of borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29(5):461-467.

7. National Education Alliance for Borderline Personality Disorder. Treatments for BPD. http://www.borderlinepersonalitydisorder.com/what-is-bpd/treating-bpd. Accessed September 1, 2016.

8. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, et al. The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system. Epidemiologic catchment area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(2):85-94.

9. Lenzenweger MF, Lane MC, Loranger AW, et al. DSM-IV personality disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(6):553-564.

10. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Dubo ED, et al. Axis I comorbidity of borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(12):1733-1739.

11. Kingdon DG, Ashcroft K, Bhandari B, et al. Schizophrenia and borderline personality disorder: similarities and differences in the experience of auditory hallucinations, paranoia, and childhood trauma. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198(6):399-403.

12. Gunderson JG. Borderline personality disorder. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1984.

13. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Wedig MM, et al. Cognitive experiences reported by patients with borderline personality disorder and Axis II comparison subjects: a 16-year prospective follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(6):671-679.

14. Tschoeke S, Steinert T, Flammer E, et al. Similarities and differences in borderline personality disorder and schizophrenia with voice hearing. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202(7):544-549.

15. Oliva F, Dalmotto M, Pirfo E, et al. A comparison of thought and perception disorders in borderline personality disorder and schizophrenia: psychotic experiences as a reaction to impaired social functioning. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:239.

16. Merrett Z, Rossell SL, Castle DJ, et al. Comparing the experience of voices in borderline personality disorder with the experience of voices in a psychotic disorder: a systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50(7):640-648.

17. Glaser JP, Van Os J, Thewissen V, et al. Psychotic reactivity in borderline personality disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;121(2):125-134.

18. Rosenbluth M, Sinyor M. Off-label use of atypical antipsychotics in personality disorders. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13(11):1575-1585.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Stern A. Borderline group of neuroses. The Psychoanalytic Quarterly. 1938;7:467-489.

3. Schroeder K, Fisher HL, Schäfer I, et al. Psychotic symptoms in patients with borderline personality disorder: prevalence and clinical management. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26(1):113-119.

4. Pearse LJ, Dibben C, Ziauddeen H, et al. A study of psychotic symptoms in borderline personality disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202(5):368-371.

5. Paris J. Why psychiatrists are reluctant to diagnose: borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2007;4(1):35-

6. Saunders EF, Silk KR. Personality trait dimensions and the pharmacological treatment of borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29(5):461-467.

7. National Education Alliance for Borderline Personality Disorder. Treatments for BPD. http://www.borderlinepersonalitydisorder.com/what-is-bpd/treating-bpd. Accessed September 1, 2016.

8. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, et al. The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system. Epidemiologic catchment area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(2):85-94.

9. Lenzenweger MF, Lane MC, Loranger AW, et al. DSM-IV personality disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(6):553-564.

10. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Dubo ED, et al. Axis I comorbidity of borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(12):1733-1739.

11. Kingdon DG, Ashcroft K, Bhandari B, et al. Schizophrenia and borderline personality disorder: similarities and differences in the experience of auditory hallucinations, paranoia, and childhood trauma. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198(6):399-403.

12. Gunderson JG. Borderline personality disorder. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1984.

13. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Wedig MM, et al. Cognitive experiences reported by patients with borderline personality disorder and Axis II comparison subjects: a 16-year prospective follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(6):671-679.

14. Tschoeke S, Steinert T, Flammer E, et al. Similarities and differences in borderline personality disorder and schizophrenia with voice hearing. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202(7):544-549.

15. Oliva F, Dalmotto M, Pirfo E, et al. A comparison of thought and perception disorders in borderline personality disorder and schizophrenia: psychotic experiences as a reaction to impaired social functioning. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:239.

16. Merrett Z, Rossell SL, Castle DJ, et al. Comparing the experience of voices in borderline personality disorder with the experience of voices in a psychotic disorder: a systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50(7):640-648.

17. Glaser JP, Van Os J, Thewissen V, et al. Psychotic reactivity in borderline personality disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;121(2):125-134.

18. Rosenbluth M, Sinyor M. Off-label use of atypical antipsychotics in personality disorders. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13(11):1575-1585.

Superior Mesenteric Artery Syndrome as a Complication of Scoliosis Surgery

Take-Home Points

- Adolescent growth spurt, height-to-weight ratio, and perioperative weight loss are risk factors associated with SMA syndrome following pediatric spine surgery.

- Must recognize nonspecific symptoms such as abdominal pain, tenderness, distention, bilious or projectile vomiting, hypoactive bowel sounds, and anorexia postoperatively.

- Complications of SMA syndrome can potentially lead to aspiration pneumonia, acute gastric rupture, or cardiovascular collapse and death.

Superior mesenteric artery (SMA) syndrome resulting from surgical treatment of scoliosis has been recognized in the medical literature since 1752.1 Throughout the literature, SMA syndrome variably has been referred to as cast syndrome, Wilkie syndrome, arteriomesenteric duodenal obstruction, and chronic duodenal ileus.2 We now recognize numerous etiologies of SMA syndrome, as several sources can externally compress the duodenum. Classic acute symptoms of bowel obstruction include bilious vomiting, nausea, and epigastric pain. Chronic manifestations of SMA syndrome may include weight loss and decreased appetite. Our literature review revealed that adolescent growth spurt, height-to-weight ratio, and perioperative weight loss are risk factors associated with SMA syndrome after pediatric spine surgery.

We report the case of a 14-year-old boy who developed SMA syndrome after undergoing scoliosis surgery. The patient and his mother provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 14-year-old boy with a history of idiopathic scoliosis presented to Cohen Children’s Hospital (Long Island Jewish Medical Center) with bilious vomiting that had persisted for 7 days after posterior T9–L4 fusion with instrumentation.

Discussion

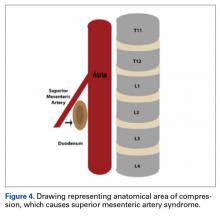

SMA syndrome is attributed to the anatomical orientation of the third part of the duodenum, which passes between the aorta and the SMA (Figure 4).

Adolescents are particularly vulnerable to this condition. Faster adolescent bone growth relative to visceral growth is accompanied by a decrease in SMA angle.3 Occasionally, body casts are used after surgery to immobilize the vertebrae and augment healing. Cast syndrome occurs when pressure from a body cast causes a bowel obstruction secondary to spinal hyperextension and amplified spinal lordosis.2 This finding, dating to the 19th century, was reported by Willet4 when a patient died 48 hours after application of a body cast. In 1950, the term cast syndrome was coined after a motorcyclist’s injuries were treated with a hip spica cast and the patient died of cardiovascular collapse secondary to persistent vomiting.5

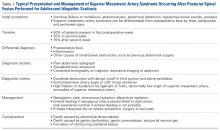

Table 1 summarizes various evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment algorithms designed to optimize nutrition and weight in patients developing signs and symptoms of SMA syndrome after posterior spinal instrumentation and fusion for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS).

The third unique feature in this case is electrocardiogram findings. Although some cases briefly discussed electrolyte abnormalities, none presented evidence that these abnormalities caused cardiac changes.6,16,18 The overall clinical significance of the QT prolongation in our patient’s case is unknown, as this finding was improved with correction of the electrolyte abnormalities and appropriate fluid replenishment.

Early recognition of nonspecific symptoms (eg, abdominal pain, tenderness, distension, bilious or projectile vomiting, hypoactive bowel sounds, anorexia) plays a key role in preventing severe morbidity and mortality from SMA syndrome after scoliosis surgery. Although many patients present in the semiclassic obstructed pattern, notable reasons for diagnostic delay include normal appetite and bowel sounds.3 For example, SMA syndrome may be misdiagnosed as stomach flu because of unfamiliarity with disease diagnosis and management.20 Complications of SMA syndrome can potentially lead to aspiration pneumonia, acute gastric rupture, and cardiovascular collapse and death.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(2):E124-E130. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Evarts CM, Winter RB, Hall JE. Vascular compression of the duodenum associated with the treatment of scoliosis. Review of the literature and report of eighteen cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971;53(3):431-444.

2. Zhu ZZ, Qiu Y. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome following scoliosis surgery: its risk indicators and treatment strategy. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(21):3307-3310.

3. Hutchinson DT, Bassett GS. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome in pediatric orthopedic patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;(250):250-257.

4. Willet A. Fatal vomiting following application of plaster-of-Paris bandage in case of spinal curvature. St Barth Hosp Rep. 1878;14:333-335.

5. Dorph MH. The cast syndrome; review of the literature and report of a case. N Engl J Med. 1950;243(12):440-442.

6. Lam DJ, Lee JZ, Chua JH, Lee YT, Lim KB. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome following surgery for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a case series, review of the literature, and an algorithm for management. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2014;23(4):312-318.

7. Tsirikos AI, Anakwe RE, Baker AD. Late presentation of superior mesenteric artery syndrome following scoliosis surgery: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:9.

8. Akin JT Jr, Skandalakis JE, Gray SW. The anatomic basis of vascular compression of the duodenum. Surg Clin North Am. 1974;54(6):1361-1370.

9. Amy BW, Priebe CJ Jr, King A. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome associated with scoliosis treated by a modified Ladd procedure. J Pediatr Orthop. 1985;5(3):361-363.

10. Richardson WS, Surowiec WJ. Laparoscopic repair of superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Am J Surg. 2001;181(4):377-378.

11. Lenke LG, Betz RR, Harms J, et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a new classification to determine extent of spinal arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(8):1169-1181.

12. Braun SV, Hedden DM, Howard AW. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome following spinal deformity correction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(10):2252-2257.

13. Smith BG, Hakim-Zargar M, Thomson JD. Low body mass index: a risk factor for superior mesenteric artery syndrome in adolescents undergoing spinal fusion for scoliosis. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2009;22(2):144-148.

14. Pan CH, Tzeng ST, Chen CS, Chen PQ. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome complicating staged corrective surgery for scoliosis. J Formos Med Assoc. 2007;106(2 suppl):S37-S45.

15. Kennedy RH, Cooper MJ. An unusually severe case of the cast syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 1983;59(694):539-540.

16. Keskin M, Akgül T, Bayraktar A, Dikici F, Balik E. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: an infrequent complication of scoliosis surgery. Case Rep Surg. 2014;2014:263431.

17. Amarawickrama H, Harikrishnan A, Krijgsman B. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome in a young girl following spinal surgery for scoliosis. Br J Hosp Med. 2005;66(12):700-701.

18. Crowther MA, Webb PJ, Eyre-Brook IA. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome following surgery for scoliosis. Spine. 2002;27(24):E528-E533.

19. Moskovich R, Cheong-Leen P. Vascular compression of the duodenum. J R Soc Med. 1986;79(8):465-467.

20. Shah MA, Albright MB, Vogt MT, Moreland MS. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome in scoliosis surgery: weight percentile for height as an indicator of risk. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23(5):665-668.

Take-Home Points

- Adolescent growth spurt, height-to-weight ratio, and perioperative weight loss are risk factors associated with SMA syndrome following pediatric spine surgery.

- Must recognize nonspecific symptoms such as abdominal pain, tenderness, distention, bilious or projectile vomiting, hypoactive bowel sounds, and anorexia postoperatively.

- Complications of SMA syndrome can potentially lead to aspiration pneumonia, acute gastric rupture, or cardiovascular collapse and death.

Superior mesenteric artery (SMA) syndrome resulting from surgical treatment of scoliosis has been recognized in the medical literature since 1752.1 Throughout the literature, SMA syndrome variably has been referred to as cast syndrome, Wilkie syndrome, arteriomesenteric duodenal obstruction, and chronic duodenal ileus.2 We now recognize numerous etiologies of SMA syndrome, as several sources can externally compress the duodenum. Classic acute symptoms of bowel obstruction include bilious vomiting, nausea, and epigastric pain. Chronic manifestations of SMA syndrome may include weight loss and decreased appetite. Our literature review revealed that adolescent growth spurt, height-to-weight ratio, and perioperative weight loss are risk factors associated with SMA syndrome after pediatric spine surgery.

We report the case of a 14-year-old boy who developed SMA syndrome after undergoing scoliosis surgery. The patient and his mother provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 14-year-old boy with a history of idiopathic scoliosis presented to Cohen Children’s Hospital (Long Island Jewish Medical Center) with bilious vomiting that had persisted for 7 days after posterior T9–L4 fusion with instrumentation.

Discussion

SMA syndrome is attributed to the anatomical orientation of the third part of the duodenum, which passes between the aorta and the SMA (Figure 4).

Adolescents are particularly vulnerable to this condition. Faster adolescent bone growth relative to visceral growth is accompanied by a decrease in SMA angle.3 Occasionally, body casts are used after surgery to immobilize the vertebrae and augment healing. Cast syndrome occurs when pressure from a body cast causes a bowel obstruction secondary to spinal hyperextension and amplified spinal lordosis.2 This finding, dating to the 19th century, was reported by Willet4 when a patient died 48 hours after application of a body cast. In 1950, the term cast syndrome was coined after a motorcyclist’s injuries were treated with a hip spica cast and the patient died of cardiovascular collapse secondary to persistent vomiting.5

Table 1 summarizes various evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment algorithms designed to optimize nutrition and weight in patients developing signs and symptoms of SMA syndrome after posterior spinal instrumentation and fusion for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS).

The third unique feature in this case is electrocardiogram findings. Although some cases briefly discussed electrolyte abnormalities, none presented evidence that these abnormalities caused cardiac changes.6,16,18 The overall clinical significance of the QT prolongation in our patient’s case is unknown, as this finding was improved with correction of the electrolyte abnormalities and appropriate fluid replenishment.

Early recognition of nonspecific symptoms (eg, abdominal pain, tenderness, distension, bilious or projectile vomiting, hypoactive bowel sounds, anorexia) plays a key role in preventing severe morbidity and mortality from SMA syndrome after scoliosis surgery. Although many patients present in the semiclassic obstructed pattern, notable reasons for diagnostic delay include normal appetite and bowel sounds.3 For example, SMA syndrome may be misdiagnosed as stomach flu because of unfamiliarity with disease diagnosis and management.20 Complications of SMA syndrome can potentially lead to aspiration pneumonia, acute gastric rupture, and cardiovascular collapse and death.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(2):E124-E130. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

Take-Home Points

- Adolescent growth spurt, height-to-weight ratio, and perioperative weight loss are risk factors associated with SMA syndrome following pediatric spine surgery.

- Must recognize nonspecific symptoms such as abdominal pain, tenderness, distention, bilious or projectile vomiting, hypoactive bowel sounds, and anorexia postoperatively.

- Complications of SMA syndrome can potentially lead to aspiration pneumonia, acute gastric rupture, or cardiovascular collapse and death.

Superior mesenteric artery (SMA) syndrome resulting from surgical treatment of scoliosis has been recognized in the medical literature since 1752.1 Throughout the literature, SMA syndrome variably has been referred to as cast syndrome, Wilkie syndrome, arteriomesenteric duodenal obstruction, and chronic duodenal ileus.2 We now recognize numerous etiologies of SMA syndrome, as several sources can externally compress the duodenum. Classic acute symptoms of bowel obstruction include bilious vomiting, nausea, and epigastric pain. Chronic manifestations of SMA syndrome may include weight loss and decreased appetite. Our literature review revealed that adolescent growth spurt, height-to-weight ratio, and perioperative weight loss are risk factors associated with SMA syndrome after pediatric spine surgery.

We report the case of a 14-year-old boy who developed SMA syndrome after undergoing scoliosis surgery. The patient and his mother provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 14-year-old boy with a history of idiopathic scoliosis presented to Cohen Children’s Hospital (Long Island Jewish Medical Center) with bilious vomiting that had persisted for 7 days after posterior T9–L4 fusion with instrumentation.

Discussion

SMA syndrome is attributed to the anatomical orientation of the third part of the duodenum, which passes between the aorta and the SMA (Figure 4).

Adolescents are particularly vulnerable to this condition. Faster adolescent bone growth relative to visceral growth is accompanied by a decrease in SMA angle.3 Occasionally, body casts are used after surgery to immobilize the vertebrae and augment healing. Cast syndrome occurs when pressure from a body cast causes a bowel obstruction secondary to spinal hyperextension and amplified spinal lordosis.2 This finding, dating to the 19th century, was reported by Willet4 when a patient died 48 hours after application of a body cast. In 1950, the term cast syndrome was coined after a motorcyclist’s injuries were treated with a hip spica cast and the patient died of cardiovascular collapse secondary to persistent vomiting.5

Table 1 summarizes various evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment algorithms designed to optimize nutrition and weight in patients developing signs and symptoms of SMA syndrome after posterior spinal instrumentation and fusion for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS).

The third unique feature in this case is electrocardiogram findings. Although some cases briefly discussed electrolyte abnormalities, none presented evidence that these abnormalities caused cardiac changes.6,16,18 The overall clinical significance of the QT prolongation in our patient’s case is unknown, as this finding was improved with correction of the electrolyte abnormalities and appropriate fluid replenishment.

Early recognition of nonspecific symptoms (eg, abdominal pain, tenderness, distension, bilious or projectile vomiting, hypoactive bowel sounds, anorexia) plays a key role in preventing severe morbidity and mortality from SMA syndrome after scoliosis surgery. Although many patients present in the semiclassic obstructed pattern, notable reasons for diagnostic delay include normal appetite and bowel sounds.3 For example, SMA syndrome may be misdiagnosed as stomach flu because of unfamiliarity with disease diagnosis and management.20 Complications of SMA syndrome can potentially lead to aspiration pneumonia, acute gastric rupture, and cardiovascular collapse and death.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(2):E124-E130. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Evarts CM, Winter RB, Hall JE. Vascular compression of the duodenum associated with the treatment of scoliosis. Review of the literature and report of eighteen cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971;53(3):431-444.

2. Zhu ZZ, Qiu Y. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome following scoliosis surgery: its risk indicators and treatment strategy. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(21):3307-3310.

3. Hutchinson DT, Bassett GS. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome in pediatric orthopedic patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;(250):250-257.

4. Willet A. Fatal vomiting following application of plaster-of-Paris bandage in case of spinal curvature. St Barth Hosp Rep. 1878;14:333-335.

5. Dorph MH. The cast syndrome; review of the literature and report of a case. N Engl J Med. 1950;243(12):440-442.

6. Lam DJ, Lee JZ, Chua JH, Lee YT, Lim KB. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome following surgery for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a case series, review of the literature, and an algorithm for management. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2014;23(4):312-318.

7. Tsirikos AI, Anakwe RE, Baker AD. Late presentation of superior mesenteric artery syndrome following scoliosis surgery: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:9.

8. Akin JT Jr, Skandalakis JE, Gray SW. The anatomic basis of vascular compression of the duodenum. Surg Clin North Am. 1974;54(6):1361-1370.

9. Amy BW, Priebe CJ Jr, King A. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome associated with scoliosis treated by a modified Ladd procedure. J Pediatr Orthop. 1985;5(3):361-363.

10. Richardson WS, Surowiec WJ. Laparoscopic repair of superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Am J Surg. 2001;181(4):377-378.

11. Lenke LG, Betz RR, Harms J, et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a new classification to determine extent of spinal arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(8):1169-1181.

12. Braun SV, Hedden DM, Howard AW. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome following spinal deformity correction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(10):2252-2257.

13. Smith BG, Hakim-Zargar M, Thomson JD. Low body mass index: a risk factor for superior mesenteric artery syndrome in adolescents undergoing spinal fusion for scoliosis. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2009;22(2):144-148.

14. Pan CH, Tzeng ST, Chen CS, Chen PQ. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome complicating staged corrective surgery for scoliosis. J Formos Med Assoc. 2007;106(2 suppl):S37-S45.

15. Kennedy RH, Cooper MJ. An unusually severe case of the cast syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 1983;59(694):539-540.

16. Keskin M, Akgül T, Bayraktar A, Dikici F, Balik E. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: an infrequent complication of scoliosis surgery. Case Rep Surg. 2014;2014:263431.

17. Amarawickrama H, Harikrishnan A, Krijgsman B. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome in a young girl following spinal surgery for scoliosis. Br J Hosp Med. 2005;66(12):700-701.

18. Crowther MA, Webb PJ, Eyre-Brook IA. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome following surgery for scoliosis. Spine. 2002;27(24):E528-E533.

19. Moskovich R, Cheong-Leen P. Vascular compression of the duodenum. J R Soc Med. 1986;79(8):465-467.

20. Shah MA, Albright MB, Vogt MT, Moreland MS. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome in scoliosis surgery: weight percentile for height as an indicator of risk. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23(5):665-668.

1. Evarts CM, Winter RB, Hall JE. Vascular compression of the duodenum associated with the treatment of scoliosis. Review of the literature and report of eighteen cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971;53(3):431-444.

2. Zhu ZZ, Qiu Y. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome following scoliosis surgery: its risk indicators and treatment strategy. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(21):3307-3310.

3. Hutchinson DT, Bassett GS. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome in pediatric orthopedic patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;(250):250-257.

4. Willet A. Fatal vomiting following application of plaster-of-Paris bandage in case of spinal curvature. St Barth Hosp Rep. 1878;14:333-335.

5. Dorph MH. The cast syndrome; review of the literature and report of a case. N Engl J Med. 1950;243(12):440-442.

6. Lam DJ, Lee JZ, Chua JH, Lee YT, Lim KB. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome following surgery for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a case series, review of the literature, and an algorithm for management. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2014;23(4):312-318.

7. Tsirikos AI, Anakwe RE, Baker AD. Late presentation of superior mesenteric artery syndrome following scoliosis surgery: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:9.

8. Akin JT Jr, Skandalakis JE, Gray SW. The anatomic basis of vascular compression of the duodenum. Surg Clin North Am. 1974;54(6):1361-1370.

9. Amy BW, Priebe CJ Jr, King A. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome associated with scoliosis treated by a modified Ladd procedure. J Pediatr Orthop. 1985;5(3):361-363.

10. Richardson WS, Surowiec WJ. Laparoscopic repair of superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Am J Surg. 2001;181(4):377-378.

11. Lenke LG, Betz RR, Harms J, et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a new classification to determine extent of spinal arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(8):1169-1181.

12. Braun SV, Hedden DM, Howard AW. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome following spinal deformity correction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(10):2252-2257.

13. Smith BG, Hakim-Zargar M, Thomson JD. Low body mass index: a risk factor for superior mesenteric artery syndrome in adolescents undergoing spinal fusion for scoliosis. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2009;22(2):144-148.

14. Pan CH, Tzeng ST, Chen CS, Chen PQ. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome complicating staged corrective surgery for scoliosis. J Formos Med Assoc. 2007;106(2 suppl):S37-S45.

15. Kennedy RH, Cooper MJ. An unusually severe case of the cast syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 1983;59(694):539-540.

16. Keskin M, Akgül T, Bayraktar A, Dikici F, Balik E. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: an infrequent complication of scoliosis surgery. Case Rep Surg. 2014;2014:263431.

17. Amarawickrama H, Harikrishnan A, Krijgsman B. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome in a young girl following spinal surgery for scoliosis. Br J Hosp Med. 2005;66(12):700-701.

18. Crowther MA, Webb PJ, Eyre-Brook IA. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome following surgery for scoliosis. Spine. 2002;27(24):E528-E533.

19. Moskovich R, Cheong-Leen P. Vascular compression of the duodenum. J R Soc Med. 1986;79(8):465-467.

20. Shah MA, Albright MB, Vogt MT, Moreland MS. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome in scoliosis surgery: weight percentile for height as an indicator of risk. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23(5):665-668.

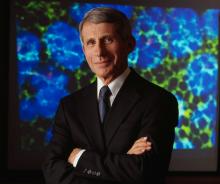

Anthony Fauci faces the ‘perpetual challenge’ of emerging infections

SAN DIEGO – Reflecting on his 33-year career as director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, can say one thing for certain: Emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases in the continental United States are here to stay.

In an article that he and his colleagues published in the Lancet in 2008, they used the term “perpetual challenge” to describe emerging infections, a descriptor that resonates with him to this day.

Global examples of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases he discussed include dengue, West Nile virus, chikungunya, and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, “which is becoming a progressively more serious problem in hospitalized patients,” said Dr. Fauci, who is also chief of the NIAID Laboratory of Immunoregulation.

“We had a serious challenge with that at our own clinical center in Bethesda just a few years ago,” he noted. Numerous cases of antimicrobial resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Clostridium difficile, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae have been reported.

Dr. Fauci described the Ebola outbreak as “a globally important disease that had ripple effects in the United States that were unpredicted,” referring to the case of the infected man who traveled from Monrovia to Dallas on Sept. 19, 2014, and developed Ebola symptoms 5 days later. Between 2014 and 2016, there were 28,616 cases and 11,310 deaths combined in the countries of Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia.

“There is virtually no health care system in those three countries,” he said. “There’s a distrust in authority, and anything we tried to do as a global health [effort] made things worse. What we’re trying to do now is built sustainable health care issues in countries that don’t have it.”

Of particular concern to public health officials worldwide is getting a lid on Zika virus, a mosquito-borne illness that can be passed from a pregnant woman to her fetus and cause an increased risk of microcephaly, particularly during the first trimester.

“Not only is there microcephaly, there’s a whole host of abnormalities that involve hearing loss, visual abnormalities, and a variety of other issues,” Dr. Fauci said. “There are about 50 countries in the Americas and the Caribbean that have Zika virus transmission.”

According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, from Jan. 1, 2015, to March 29, 2017, there were 5,182 reported cases of Zika virus disease in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. The majority of those (4,886) were travel associated, 222 were locally acquired mosquito-borne, 45 were sexually transmitted, 27 congenital, 1 was laboratory acquired, and 1 was unknown.

At the same time, there have been 38,303 cases in the U.S. territories. Of those, 38,156 were locally acquired, and 147 were travel associated. “That’s why there’s such an intense effort to develop a Zika vaccine,” he said.

According to the CDC, as of March 15, 2017, there are 265 cases of locally transmitted cases in Florida: 216 by mosquito and the rest by sexual transmission. “Talk about surprises,” Dr. Fauci said. “Zika is the first mosquito-borne infection that can result in a congenital abnormality, the first mosquito-borne infection that can be sexually transmitted, and now we’re learning more about this problem, which is the reason why it’s very important for us to develop a vaccine.”

A phase I trial of a DNA vaccine developed by the NIH Vaccine Research Center has reached its enrollment goal of 80 patients age 18-35 years. Initial results are expected sometime in the first quarter of 2017. A phase II trial in the United States and Puerto Rico is expected to launch soon.

Dr. Fauci closed his presentation by sharing lessons learned from previous pandemics.

The first lesson is that global surveillance is required. “Namely, know what’s going on in real time,” he said. “That has to be linked to transparency and communication. So that if something happens in China, we don’t find out about it months later, but we know about it in real time.”

Infrastructure and capacity building are also important. “The lack of capacity in West Africa can ultimately have an indirect impact on us here in the United States,” he said.

“Finally, we need to coordinate and collaborate; we need adaptable platforms for vaccines,” Dr. Fauci cautioned. “Importantly, we need a stable funding mechanism such as a public health emergency fund so that we do not have to go scrambling before the Congress when we need emergency funds.”

SAN DIEGO – Reflecting on his 33-year career as director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, can say one thing for certain: Emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases in the continental United States are here to stay.

In an article that he and his colleagues published in the Lancet in 2008, they used the term “perpetual challenge” to describe emerging infections, a descriptor that resonates with him to this day.

Global examples of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases he discussed include dengue, West Nile virus, chikungunya, and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, “which is becoming a progressively more serious problem in hospitalized patients,” said Dr. Fauci, who is also chief of the NIAID Laboratory of Immunoregulation.

“We had a serious challenge with that at our own clinical center in Bethesda just a few years ago,” he noted. Numerous cases of antimicrobial resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Clostridium difficile, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae have been reported.

Dr. Fauci described the Ebola outbreak as “a globally important disease that had ripple effects in the United States that were unpredicted,” referring to the case of the infected man who traveled from Monrovia to Dallas on Sept. 19, 2014, and developed Ebola symptoms 5 days later. Between 2014 and 2016, there were 28,616 cases and 11,310 deaths combined in the countries of Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia.

“There is virtually no health care system in those three countries,” he said. “There’s a distrust in authority, and anything we tried to do as a global health [effort] made things worse. What we’re trying to do now is built sustainable health care issues in countries that don’t have it.”

Of particular concern to public health officials worldwide is getting a lid on Zika virus, a mosquito-borne illness that can be passed from a pregnant woman to her fetus and cause an increased risk of microcephaly, particularly during the first trimester.

“Not only is there microcephaly, there’s a whole host of abnormalities that involve hearing loss, visual abnormalities, and a variety of other issues,” Dr. Fauci said. “There are about 50 countries in the Americas and the Caribbean that have Zika virus transmission.”

According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, from Jan. 1, 2015, to March 29, 2017, there were 5,182 reported cases of Zika virus disease in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. The majority of those (4,886) were travel associated, 222 were locally acquired mosquito-borne, 45 were sexually transmitted, 27 congenital, 1 was laboratory acquired, and 1 was unknown.

At the same time, there have been 38,303 cases in the U.S. territories. Of those, 38,156 were locally acquired, and 147 were travel associated. “That’s why there’s such an intense effort to develop a Zika vaccine,” he said.

According to the CDC, as of March 15, 2017, there are 265 cases of locally transmitted cases in Florida: 216 by mosquito and the rest by sexual transmission. “Talk about surprises,” Dr. Fauci said. “Zika is the first mosquito-borne infection that can result in a congenital abnormality, the first mosquito-borne infection that can be sexually transmitted, and now we’re learning more about this problem, which is the reason why it’s very important for us to develop a vaccine.”

A phase I trial of a DNA vaccine developed by the NIH Vaccine Research Center has reached its enrollment goal of 80 patients age 18-35 years. Initial results are expected sometime in the first quarter of 2017. A phase II trial in the United States and Puerto Rico is expected to launch soon.

Dr. Fauci closed his presentation by sharing lessons learned from previous pandemics.

The first lesson is that global surveillance is required. “Namely, know what’s going on in real time,” he said. “That has to be linked to transparency and communication. So that if something happens in China, we don’t find out about it months later, but we know about it in real time.”

Infrastructure and capacity building are also important. “The lack of capacity in West Africa can ultimately have an indirect impact on us here in the United States,” he said.

“Finally, we need to coordinate and collaborate; we need adaptable platforms for vaccines,” Dr. Fauci cautioned. “Importantly, we need a stable funding mechanism such as a public health emergency fund so that we do not have to go scrambling before the Congress when we need emergency funds.”

SAN DIEGO – Reflecting on his 33-year career as director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, can say one thing for certain: Emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases in the continental United States are here to stay.

In an article that he and his colleagues published in the Lancet in 2008, they used the term “perpetual challenge” to describe emerging infections, a descriptor that resonates with him to this day.

Global examples of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases he discussed include dengue, West Nile virus, chikungunya, and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, “which is becoming a progressively more serious problem in hospitalized patients,” said Dr. Fauci, who is also chief of the NIAID Laboratory of Immunoregulation.

“We had a serious challenge with that at our own clinical center in Bethesda just a few years ago,” he noted. Numerous cases of antimicrobial resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Clostridium difficile, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae have been reported.

Dr. Fauci described the Ebola outbreak as “a globally important disease that had ripple effects in the United States that were unpredicted,” referring to the case of the infected man who traveled from Monrovia to Dallas on Sept. 19, 2014, and developed Ebola symptoms 5 days later. Between 2014 and 2016, there were 28,616 cases and 11,310 deaths combined in the countries of Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia.

“There is virtually no health care system in those three countries,” he said. “There’s a distrust in authority, and anything we tried to do as a global health [effort] made things worse. What we’re trying to do now is built sustainable health care issues in countries that don’t have it.”

Of particular concern to public health officials worldwide is getting a lid on Zika virus, a mosquito-borne illness that can be passed from a pregnant woman to her fetus and cause an increased risk of microcephaly, particularly during the first trimester.

“Not only is there microcephaly, there’s a whole host of abnormalities that involve hearing loss, visual abnormalities, and a variety of other issues,” Dr. Fauci said. “There are about 50 countries in the Americas and the Caribbean that have Zika virus transmission.”