User login

Fellows and Awards of Excellence

Vineet Arora, MD, understands the unique value of being named one of this year’s three Masters in Hospital Medicine. It’s an honor bestowed for hospitalists, by hospitalists.

“I take a lot of pride in an honor determined by peers,” said Dr. Arora, an academic hospitalist at University of Chicago Medicine. “While peers are often the biggest support you receive in your professional career, because they are in the trenches with you, they can also be your best critics. That is especially true of the type of work that I do, which relies on the buy-in of frontline clinicians – including hospitalists and trainees – to achieve better patient care and education.”

The designation of new Masters in Hospital Medicine is a major moment at SHM’s annual meeting. The 2017 list of awardees is headlined by Dr. Arora and the other MHM designees: former SHM President Burke Kealey, MD, and Richard Slataper, MD, who was heavily involved with the National Association of Inpatient Physicians, a predecessor to SHM. The three new masters bring to 24 the number of MHMs the society has named since unveiling the honor in 2010.

Dr. Arora understands that after 20 years as a specialty, just two dozen practitioners have reached hospital medicine’s highest professional distinction.

“I think of ‘mastery’ as someone who has achieved the highest level of expertise in a field, so an honor like Master in Hospital Medicine definitely means a lot to me,” she said. “Especially given the prior recipients of this honor, and the importance of SHM in my own professional growth and development since I was a trainee.”

In addition to the top honor, HM17 will see the induction of 159 Fellows in Hospital Medicine (FHM) and 58 Senior Fellows in Hospital Medicine (SFHM). This year’s fellows join the thousands of physicians and nonphysician providers (NPPs) that have attained the distinction.

SHM also bestows its annual Awards of Excellence (past winners listed here include Dr. Arora and Dr. Kealey) that recognize practitioners across skill sets. The awards are meant to honor SHM members “whose exemplary contributions to the hospital medicine movement deserve acknowledgment and respect,” according to the society’s website.

The 2017 Award winners include:

• Excellence in Teamwork in Quality Improvement: Johnston Memorial Hospital in Abingdon, Va.

• Excellence in Research: Jeffrey Barsuk, MD, MS, SFHM.

• Excellence in Teaching: Steven Cohn, MD, FACP, SFHM.

• Excellence in Hospital Medicine for Non-Physicians: Michael McFall.

• Outstanding Service in Hospital Medicine: Jeffrey Greenwald, MD, SFHM.

• Clinical Excellence: Barbara Slawski, MD.

• Excellence in Humanitarian Services: Jonathan Crocker, MD, FHM.

Dr. Arora, who has served on the SHM committee that analyzes all nominees for the annual awards, recognizes the value of honoring these high-achieving clinicians.

“There is great value to having our specialty society recognize members in different ways,” she said “The awards of excellence serve as a wonderful reminder of the incredible impact that hospitalists have in many diverse ways … while having the distinction of a fellow or senior fellow serves as a nice benchmark to which new hospitalists can aspire and gain recognition as they emerge as leaders in the field.”

Vineet Arora, MD, understands the unique value of being named one of this year’s three Masters in Hospital Medicine. It’s an honor bestowed for hospitalists, by hospitalists.

“I take a lot of pride in an honor determined by peers,” said Dr. Arora, an academic hospitalist at University of Chicago Medicine. “While peers are often the biggest support you receive in your professional career, because they are in the trenches with you, they can also be your best critics. That is especially true of the type of work that I do, which relies on the buy-in of frontline clinicians – including hospitalists and trainees – to achieve better patient care and education.”

The designation of new Masters in Hospital Medicine is a major moment at SHM’s annual meeting. The 2017 list of awardees is headlined by Dr. Arora and the other MHM designees: former SHM President Burke Kealey, MD, and Richard Slataper, MD, who was heavily involved with the National Association of Inpatient Physicians, a predecessor to SHM. The three new masters bring to 24 the number of MHMs the society has named since unveiling the honor in 2010.

Dr. Arora understands that after 20 years as a specialty, just two dozen practitioners have reached hospital medicine’s highest professional distinction.

“I think of ‘mastery’ as someone who has achieved the highest level of expertise in a field, so an honor like Master in Hospital Medicine definitely means a lot to me,” she said. “Especially given the prior recipients of this honor, and the importance of SHM in my own professional growth and development since I was a trainee.”

In addition to the top honor, HM17 will see the induction of 159 Fellows in Hospital Medicine (FHM) and 58 Senior Fellows in Hospital Medicine (SFHM). This year’s fellows join the thousands of physicians and nonphysician providers (NPPs) that have attained the distinction.

SHM also bestows its annual Awards of Excellence (past winners listed here include Dr. Arora and Dr. Kealey) that recognize practitioners across skill sets. The awards are meant to honor SHM members “whose exemplary contributions to the hospital medicine movement deserve acknowledgment and respect,” according to the society’s website.

The 2017 Award winners include:

• Excellence in Teamwork in Quality Improvement: Johnston Memorial Hospital in Abingdon, Va.

• Excellence in Research: Jeffrey Barsuk, MD, MS, SFHM.

• Excellence in Teaching: Steven Cohn, MD, FACP, SFHM.

• Excellence in Hospital Medicine for Non-Physicians: Michael McFall.

• Outstanding Service in Hospital Medicine: Jeffrey Greenwald, MD, SFHM.

• Clinical Excellence: Barbara Slawski, MD.

• Excellence in Humanitarian Services: Jonathan Crocker, MD, FHM.

Dr. Arora, who has served on the SHM committee that analyzes all nominees for the annual awards, recognizes the value of honoring these high-achieving clinicians.

“There is great value to having our specialty society recognize members in different ways,” she said “The awards of excellence serve as a wonderful reminder of the incredible impact that hospitalists have in many diverse ways … while having the distinction of a fellow or senior fellow serves as a nice benchmark to which new hospitalists can aspire and gain recognition as they emerge as leaders in the field.”

Vineet Arora, MD, understands the unique value of being named one of this year’s three Masters in Hospital Medicine. It’s an honor bestowed for hospitalists, by hospitalists.

“I take a lot of pride in an honor determined by peers,” said Dr. Arora, an academic hospitalist at University of Chicago Medicine. “While peers are often the biggest support you receive in your professional career, because they are in the trenches with you, they can also be your best critics. That is especially true of the type of work that I do, which relies on the buy-in of frontline clinicians – including hospitalists and trainees – to achieve better patient care and education.”

The designation of new Masters in Hospital Medicine is a major moment at SHM’s annual meeting. The 2017 list of awardees is headlined by Dr. Arora and the other MHM designees: former SHM President Burke Kealey, MD, and Richard Slataper, MD, who was heavily involved with the National Association of Inpatient Physicians, a predecessor to SHM. The three new masters bring to 24 the number of MHMs the society has named since unveiling the honor in 2010.

Dr. Arora understands that after 20 years as a specialty, just two dozen practitioners have reached hospital medicine’s highest professional distinction.

“I think of ‘mastery’ as someone who has achieved the highest level of expertise in a field, so an honor like Master in Hospital Medicine definitely means a lot to me,” she said. “Especially given the prior recipients of this honor, and the importance of SHM in my own professional growth and development since I was a trainee.”

In addition to the top honor, HM17 will see the induction of 159 Fellows in Hospital Medicine (FHM) and 58 Senior Fellows in Hospital Medicine (SFHM). This year’s fellows join the thousands of physicians and nonphysician providers (NPPs) that have attained the distinction.

SHM also bestows its annual Awards of Excellence (past winners listed here include Dr. Arora and Dr. Kealey) that recognize practitioners across skill sets. The awards are meant to honor SHM members “whose exemplary contributions to the hospital medicine movement deserve acknowledgment and respect,” according to the society’s website.

The 2017 Award winners include:

• Excellence in Teamwork in Quality Improvement: Johnston Memorial Hospital in Abingdon, Va.

• Excellence in Research: Jeffrey Barsuk, MD, MS, SFHM.

• Excellence in Teaching: Steven Cohn, MD, FACP, SFHM.

• Excellence in Hospital Medicine for Non-Physicians: Michael McFall.

• Outstanding Service in Hospital Medicine: Jeffrey Greenwald, MD, SFHM.

• Clinical Excellence: Barbara Slawski, MD.

• Excellence in Humanitarian Services: Jonathan Crocker, MD, FHM.

Dr. Arora, who has served on the SHM committee that analyzes all nominees for the annual awards, recognizes the value of honoring these high-achieving clinicians.

“There is great value to having our specialty society recognize members in different ways,” she said “The awards of excellence serve as a wonderful reminder of the incredible impact that hospitalists have in many diverse ways … while having the distinction of a fellow or senior fellow serves as a nice benchmark to which new hospitalists can aspire and gain recognition as they emerge as leaders in the field.”

VIDEO: Occult cancers contribute to GI bleeding in anticoagulated patients

Occult cancers accounted for one in about every 12 major gastrointestinal bleeding events among patients taking warfarin or dabigatran for atrial fibrillation, according to a retrospective analysis of data from a randomized prospective trial reported in the May issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2017. doi: org/10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.011).

These bleeding events caused similarly significant morbidity among patients taking either drug, Kathryn F. Flack, MD, of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York and her associates wrote. “Patients bleeding from cancer required a mean of approximately 10 nights in the hospital, and approximately one-fourth required intensive care, but 0 of 44 died as a direct result of the bleeding,” the researchers reported. They hoped the specific dabigatran reversal agent, idarucizumab (Praxbind), will improve bleeding outcomes in patients receiving dabigatran.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

Major gastrointestinal bleeding (MGIB) is the first sign of occult malignancy in certain patients receiving anticoagulation therapy. Starting an anticoagulant is a type of “stress test” that can reveal an occult cancer, the researchers said. Although dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa) is generally safe and effective, a twice-daily, 150-mg dose of this direct oral anticoagulant slightly increased MGIB, compared with a lower dose in the international, multicenter RE-LY (Randomized Evaluation of Long Term Anticoagulant Therapy) trial (N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139-51). Furthermore, unlike warfarin, dabigatran therapy places active anticoagulant within the luminal gastrointestinal tract, which “might promote bleeding from friable gastrointestinal cancers,” the investigators noted. To explore this possibility, they evaluated 546 unique MGIB events among RE-LY patients.

Medical chart reviews identified 44 (8.1%) MGIB events resulting from occult gastrointestinal cancers. Cancer accounted for similar proportions of MGIB among warfarin and dabigatran recipients (8.5% and 6.8%; P = .6). Nearly all cancers were colorectal or gastric, except for one case each of ampullary cancer, renal cell carcinoma, and melanoma that had metastasized to the luminal gastrointestinal tract. Colorectal cancer accounted for 80% of cancer-related MGIB overall, including 88% in the dabigatran group and 50% in the warfarin group (P = .02). Conversely, warfarin recipients had more MGIB associated with gastric cancer (50%) than did dabigatran recipients (2.9%; P = .001).

Short-term outcomes of MGIB associated with cancer did not vary by anticoagulant, the investigators said. There were no deaths, but two (4.5%) MGIB events required emergency endoscopic treatment, one (2.3%) required emergency surgery, and 33 (75%) required at least one red blood cell transfusion. Compared with patients whose MGIB was unrelated to cancer, those with cancer were more likely to bleed for more than 7 days (27.3% vs. 63.6%; P less than .001). Patients with occult cancer also developed MGIB sooner after starting anticoagulation (223 vs. 343 days; P = .003), but time to bleeding did not significantly vary by type of anticoagulant.

“Most prior studies on cancer bleeding have been case reports and case series in patients receiving warfarin,” the investigators wrote. “Our study is relevant because of the increasing prevalence of atrial fibrillation and anticoagulation in the aging global population, the increasing prescription of direct oral anticoagulants, and the morbidity, mortality, and complex decision making associated with MGIB and especially cancer-related MGIB in patients receiving anticoagulation therapy.”

The RE-LY trial was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim . Dr. Flack reported no conflicts of interest. Senior author James Aisenberg, MD, disclosed advisory board and consulting relationships with Boehringer Ingelheim and Portola Pharmaceuticals. Five other coinvestigators disclosed ties to several pharmaceutical companies, and two coinvestigators reported employment with Boehringer Ingelheim. The other coinvestigators had no conflicts.

Dr. Flack and her colleagues should be congratulated for providing important data as they reviewed 546 major GI bleeding events from a large randomized prospective trial of long-term anticoagulation in subjects with AF. They found that 1 in every 12 major GI bleeding events in patients on warfarin or dabigatran was associated with an occult cancer; colorectal cancer being the most common.

How will these results help us in clinical practice? First, when faced with GI bleeding in AF subjects on anticoagulants, a proactive diagnostic approach is needed for the search for a potential luminal GI malignancy; whether screening for GI malignancy before initiating anticoagulants is beneficial requires prospective studies with cost analysis. Second, cancer-related GI bleeding in dabigatran users occurs earlier than noncancer-related bleeding. Given that a fraction of GI bleeding events were not investigated, one cannot exclude the possibility of undiagnosed luminal GI cancers in the comparator group. Third, cancer-related bleeding is associated with prolonged hospital stay. We should seize the opportunity to study the effects of this double-edged sword; anticoagulants may help us reveal occult malignancy, but more importantly, we need to determine whether dabigatranreversal agent idarucizumab can improve bleeding outcomes in patients on dabigatran presenting with cancer-related bleeding.

Siew C. Ng, MD, PhD, AGAF, is professor at the department of medicine and therapeutics, Institute of Digestive Disease, Chinese University of Hong Kong. She has no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Flack and her colleagues should be congratulated for providing important data as they reviewed 546 major GI bleeding events from a large randomized prospective trial of long-term anticoagulation in subjects with AF. They found that 1 in every 12 major GI bleeding events in patients on warfarin or dabigatran was associated with an occult cancer; colorectal cancer being the most common.

How will these results help us in clinical practice? First, when faced with GI bleeding in AF subjects on anticoagulants, a proactive diagnostic approach is needed for the search for a potential luminal GI malignancy; whether screening for GI malignancy before initiating anticoagulants is beneficial requires prospective studies with cost analysis. Second, cancer-related GI bleeding in dabigatran users occurs earlier than noncancer-related bleeding. Given that a fraction of GI bleeding events were not investigated, one cannot exclude the possibility of undiagnosed luminal GI cancers in the comparator group. Third, cancer-related bleeding is associated with prolonged hospital stay. We should seize the opportunity to study the effects of this double-edged sword; anticoagulants may help us reveal occult malignancy, but more importantly, we need to determine whether dabigatranreversal agent idarucizumab can improve bleeding outcomes in patients on dabigatran presenting with cancer-related bleeding.

Siew C. Ng, MD, PhD, AGAF, is professor at the department of medicine and therapeutics, Institute of Digestive Disease, Chinese University of Hong Kong. She has no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Flack and her colleagues should be congratulated for providing important data as they reviewed 546 major GI bleeding events from a large randomized prospective trial of long-term anticoagulation in subjects with AF. They found that 1 in every 12 major GI bleeding events in patients on warfarin or dabigatran was associated with an occult cancer; colorectal cancer being the most common.

How will these results help us in clinical practice? First, when faced with GI bleeding in AF subjects on anticoagulants, a proactive diagnostic approach is needed for the search for a potential luminal GI malignancy; whether screening for GI malignancy before initiating anticoagulants is beneficial requires prospective studies with cost analysis. Second, cancer-related GI bleeding in dabigatran users occurs earlier than noncancer-related bleeding. Given that a fraction of GI bleeding events were not investigated, one cannot exclude the possibility of undiagnosed luminal GI cancers in the comparator group. Third, cancer-related bleeding is associated with prolonged hospital stay. We should seize the opportunity to study the effects of this double-edged sword; anticoagulants may help us reveal occult malignancy, but more importantly, we need to determine whether dabigatranreversal agent idarucizumab can improve bleeding outcomes in patients on dabigatran presenting with cancer-related bleeding.

Siew C. Ng, MD, PhD, AGAF, is professor at the department of medicine and therapeutics, Institute of Digestive Disease, Chinese University of Hong Kong. She has no conflicts of interest.

Occult cancers accounted for one in about every 12 major gastrointestinal bleeding events among patients taking warfarin or dabigatran for atrial fibrillation, according to a retrospective analysis of data from a randomized prospective trial reported in the May issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2017. doi: org/10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.011).

These bleeding events caused similarly significant morbidity among patients taking either drug, Kathryn F. Flack, MD, of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York and her associates wrote. “Patients bleeding from cancer required a mean of approximately 10 nights in the hospital, and approximately one-fourth required intensive care, but 0 of 44 died as a direct result of the bleeding,” the researchers reported. They hoped the specific dabigatran reversal agent, idarucizumab (Praxbind), will improve bleeding outcomes in patients receiving dabigatran.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

Major gastrointestinal bleeding (MGIB) is the first sign of occult malignancy in certain patients receiving anticoagulation therapy. Starting an anticoagulant is a type of “stress test” that can reveal an occult cancer, the researchers said. Although dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa) is generally safe and effective, a twice-daily, 150-mg dose of this direct oral anticoagulant slightly increased MGIB, compared with a lower dose in the international, multicenter RE-LY (Randomized Evaluation of Long Term Anticoagulant Therapy) trial (N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139-51). Furthermore, unlike warfarin, dabigatran therapy places active anticoagulant within the luminal gastrointestinal tract, which “might promote bleeding from friable gastrointestinal cancers,” the investigators noted. To explore this possibility, they evaluated 546 unique MGIB events among RE-LY patients.

Medical chart reviews identified 44 (8.1%) MGIB events resulting from occult gastrointestinal cancers. Cancer accounted for similar proportions of MGIB among warfarin and dabigatran recipients (8.5% and 6.8%; P = .6). Nearly all cancers were colorectal or gastric, except for one case each of ampullary cancer, renal cell carcinoma, and melanoma that had metastasized to the luminal gastrointestinal tract. Colorectal cancer accounted for 80% of cancer-related MGIB overall, including 88% in the dabigatran group and 50% in the warfarin group (P = .02). Conversely, warfarin recipients had more MGIB associated with gastric cancer (50%) than did dabigatran recipients (2.9%; P = .001).

Short-term outcomes of MGIB associated with cancer did not vary by anticoagulant, the investigators said. There were no deaths, but two (4.5%) MGIB events required emergency endoscopic treatment, one (2.3%) required emergency surgery, and 33 (75%) required at least one red blood cell transfusion. Compared with patients whose MGIB was unrelated to cancer, those with cancer were more likely to bleed for more than 7 days (27.3% vs. 63.6%; P less than .001). Patients with occult cancer also developed MGIB sooner after starting anticoagulation (223 vs. 343 days; P = .003), but time to bleeding did not significantly vary by type of anticoagulant.

“Most prior studies on cancer bleeding have been case reports and case series in patients receiving warfarin,” the investigators wrote. “Our study is relevant because of the increasing prevalence of atrial fibrillation and anticoagulation in the aging global population, the increasing prescription of direct oral anticoagulants, and the morbidity, mortality, and complex decision making associated with MGIB and especially cancer-related MGIB in patients receiving anticoagulation therapy.”

The RE-LY trial was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim . Dr. Flack reported no conflicts of interest. Senior author James Aisenberg, MD, disclosed advisory board and consulting relationships with Boehringer Ingelheim and Portola Pharmaceuticals. Five other coinvestigators disclosed ties to several pharmaceutical companies, and two coinvestigators reported employment with Boehringer Ingelheim. The other coinvestigators had no conflicts.

Occult cancers accounted for one in about every 12 major gastrointestinal bleeding events among patients taking warfarin or dabigatran for atrial fibrillation, according to a retrospective analysis of data from a randomized prospective trial reported in the May issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2017. doi: org/10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.011).

These bleeding events caused similarly significant morbidity among patients taking either drug, Kathryn F. Flack, MD, of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York and her associates wrote. “Patients bleeding from cancer required a mean of approximately 10 nights in the hospital, and approximately one-fourth required intensive care, but 0 of 44 died as a direct result of the bleeding,” the researchers reported. They hoped the specific dabigatran reversal agent, idarucizumab (Praxbind), will improve bleeding outcomes in patients receiving dabigatran.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

Major gastrointestinal bleeding (MGIB) is the first sign of occult malignancy in certain patients receiving anticoagulation therapy. Starting an anticoagulant is a type of “stress test” that can reveal an occult cancer, the researchers said. Although dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa) is generally safe and effective, a twice-daily, 150-mg dose of this direct oral anticoagulant slightly increased MGIB, compared with a lower dose in the international, multicenter RE-LY (Randomized Evaluation of Long Term Anticoagulant Therapy) trial (N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139-51). Furthermore, unlike warfarin, dabigatran therapy places active anticoagulant within the luminal gastrointestinal tract, which “might promote bleeding from friable gastrointestinal cancers,” the investigators noted. To explore this possibility, they evaluated 546 unique MGIB events among RE-LY patients.

Medical chart reviews identified 44 (8.1%) MGIB events resulting from occult gastrointestinal cancers. Cancer accounted for similar proportions of MGIB among warfarin and dabigatran recipients (8.5% and 6.8%; P = .6). Nearly all cancers were colorectal or gastric, except for one case each of ampullary cancer, renal cell carcinoma, and melanoma that had metastasized to the luminal gastrointestinal tract. Colorectal cancer accounted for 80% of cancer-related MGIB overall, including 88% in the dabigatran group and 50% in the warfarin group (P = .02). Conversely, warfarin recipients had more MGIB associated with gastric cancer (50%) than did dabigatran recipients (2.9%; P = .001).

Short-term outcomes of MGIB associated with cancer did not vary by anticoagulant, the investigators said. There were no deaths, but two (4.5%) MGIB events required emergency endoscopic treatment, one (2.3%) required emergency surgery, and 33 (75%) required at least one red blood cell transfusion. Compared with patients whose MGIB was unrelated to cancer, those with cancer were more likely to bleed for more than 7 days (27.3% vs. 63.6%; P less than .001). Patients with occult cancer also developed MGIB sooner after starting anticoagulation (223 vs. 343 days; P = .003), but time to bleeding did not significantly vary by type of anticoagulant.

“Most prior studies on cancer bleeding have been case reports and case series in patients receiving warfarin,” the investigators wrote. “Our study is relevant because of the increasing prevalence of atrial fibrillation and anticoagulation in the aging global population, the increasing prescription of direct oral anticoagulants, and the morbidity, mortality, and complex decision making associated with MGIB and especially cancer-related MGIB in patients receiving anticoagulation therapy.”

The RE-LY trial was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim . Dr. Flack reported no conflicts of interest. Senior author James Aisenberg, MD, disclosed advisory board and consulting relationships with Boehringer Ingelheim and Portola Pharmaceuticals. Five other coinvestigators disclosed ties to several pharmaceutical companies, and two coinvestigators reported employment with Boehringer Ingelheim. The other coinvestigators had no conflicts.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Occult cancers accounted for about 1 in every 12 major gastrointestinal bleeding events among patients receiving warfarin or dabigatran for atrial fibrillation.

Major finding: A total of 44 (8.1%) major gastrointestinal bleeds were associated with occult cancers.Data source: A retrospective analysis of 546 unique major gastrointestinal bleeding events from the Randomized Evaluation of Long Term Anticoagulant Therapy (RE-LY) trial.

Disclosures: RE-LY was sponsored by Boehringer Ingleheim. Dr. Flack had no conflicts of interest. Senior author James Aisenberg, MD, disclosed advisory board and consulting relationships with Boehringer Ingelheim and Portola Pharmaceuticals. Five other coinvestigators disclosed ties to several pharmaceutical companies, and two coinvestigators reported employment with Boehringer Ingelheim. The other coinvestigators had no conflicts.

Adapting to change: Dr. Robert Wachter

Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, has given the final plenary address at every SHM annual meeting since 2007. His talks are peppered with his one-of-a-kind take on the confluence of medicine, politics, and policy – and at least once he broke into an Elton John parody.

Where does that point of view come from? As the “dean” of hospital medicine says in his ever-popular Twitter bio, he is “what happens when a poli sci major becomes an academic physician.”

That’s a needed perspective this year, as the level of political upheaval in the United States ups the ante on the tumult the health care field has experienced over the past few years. Questions surrounding the implementation of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) and the continued struggles experienced by clinicians using electronic health records (EHR) are among the topics to be addressed.

“While [President] Trump brings massive uncertainty, the shift to value and the increasing importance of building a strong culture, a method to continuously improve, and a way to use the EHR to make things better is unlikely to go away,” Dr. Wachter said. His closing plenary is titled, “Mergers, MACRA, and Mission-Creep: Can Hospitalists Thrive in the New World of Health Care?”

In an email interview with The Hospitalist, Dr. Wachter, chair of the department of medicine at the University of California San Francisco, said the Trump administration is a once-in-a-lifetime anomaly that has both physicians and patients nervous, especially at a time when health care reform seemed to be stabilizing.

The new president “adds an amazing wild card, at every level,” he said. “If it weren’t for his administration, I think we’d be on a fairly stable, predictable path. Not that that path didn’t include a ton of change, but at least it was a predictable path.”

Dr. Wachter, who famously helped coin the term “hospitalist” in a 1996 New England Journal of Medicine paper, said that one of the biggest challenges to hospital medicine in the future is how hospitals will be paid – and how they pay their employees.

“The business model for hospitals will be massively challenged, and it could get worse if a lot of your patients lose insurance or their payments go way down,” he said.

But if the past decade of Dr. Wachter’s insights delivered at SHM annual meetings are any indication, his message of trepidation and concern will end on a high note.

The veteran doctor in him says “don’t get too distracted by all of the zigs and zags.” The utopian politico in him says “don’t ever forget the core values and imperatives remain.”

Perhaps that really is what happens when a political science major becomes an academic physician.

Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, has given the final plenary address at every SHM annual meeting since 2007. His talks are peppered with his one-of-a-kind take on the confluence of medicine, politics, and policy – and at least once he broke into an Elton John parody.

Where does that point of view come from? As the “dean” of hospital medicine says in his ever-popular Twitter bio, he is “what happens when a poli sci major becomes an academic physician.”

That’s a needed perspective this year, as the level of political upheaval in the United States ups the ante on the tumult the health care field has experienced over the past few years. Questions surrounding the implementation of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) and the continued struggles experienced by clinicians using electronic health records (EHR) are among the topics to be addressed.

“While [President] Trump brings massive uncertainty, the shift to value and the increasing importance of building a strong culture, a method to continuously improve, and a way to use the EHR to make things better is unlikely to go away,” Dr. Wachter said. His closing plenary is titled, “Mergers, MACRA, and Mission-Creep: Can Hospitalists Thrive in the New World of Health Care?”

In an email interview with The Hospitalist, Dr. Wachter, chair of the department of medicine at the University of California San Francisco, said the Trump administration is a once-in-a-lifetime anomaly that has both physicians and patients nervous, especially at a time when health care reform seemed to be stabilizing.

The new president “adds an amazing wild card, at every level,” he said. “If it weren’t for his administration, I think we’d be on a fairly stable, predictable path. Not that that path didn’t include a ton of change, but at least it was a predictable path.”

Dr. Wachter, who famously helped coin the term “hospitalist” in a 1996 New England Journal of Medicine paper, said that one of the biggest challenges to hospital medicine in the future is how hospitals will be paid – and how they pay their employees.

“The business model for hospitals will be massively challenged, and it could get worse if a lot of your patients lose insurance or their payments go way down,” he said.

But if the past decade of Dr. Wachter’s insights delivered at SHM annual meetings are any indication, his message of trepidation and concern will end on a high note.

The veteran doctor in him says “don’t get too distracted by all of the zigs and zags.” The utopian politico in him says “don’t ever forget the core values and imperatives remain.”

Perhaps that really is what happens when a political science major becomes an academic physician.

Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, has given the final plenary address at every SHM annual meeting since 2007. His talks are peppered with his one-of-a-kind take on the confluence of medicine, politics, and policy – and at least once he broke into an Elton John parody.

Where does that point of view come from? As the “dean” of hospital medicine says in his ever-popular Twitter bio, he is “what happens when a poli sci major becomes an academic physician.”

That’s a needed perspective this year, as the level of political upheaval in the United States ups the ante on the tumult the health care field has experienced over the past few years. Questions surrounding the implementation of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) and the continued struggles experienced by clinicians using electronic health records (EHR) are among the topics to be addressed.

“While [President] Trump brings massive uncertainty, the shift to value and the increasing importance of building a strong culture, a method to continuously improve, and a way to use the EHR to make things better is unlikely to go away,” Dr. Wachter said. His closing plenary is titled, “Mergers, MACRA, and Mission-Creep: Can Hospitalists Thrive in the New World of Health Care?”

In an email interview with The Hospitalist, Dr. Wachter, chair of the department of medicine at the University of California San Francisco, said the Trump administration is a once-in-a-lifetime anomaly that has both physicians and patients nervous, especially at a time when health care reform seemed to be stabilizing.

The new president “adds an amazing wild card, at every level,” he said. “If it weren’t for his administration, I think we’d be on a fairly stable, predictable path. Not that that path didn’t include a ton of change, but at least it was a predictable path.”

Dr. Wachter, who famously helped coin the term “hospitalist” in a 1996 New England Journal of Medicine paper, said that one of the biggest challenges to hospital medicine in the future is how hospitals will be paid – and how they pay their employees.

“The business model for hospitals will be massively challenged, and it could get worse if a lot of your patients lose insurance or their payments go way down,” he said.

But if the past decade of Dr. Wachter’s insights delivered at SHM annual meetings are any indication, his message of trepidation and concern will end on a high note.

The veteran doctor in him says “don’t get too distracted by all of the zigs and zags.” The utopian politico in him says “don’t ever forget the core values and imperatives remain.”

Perhaps that really is what happens when a political science major becomes an academic physician.

Networking: A skill worth learning

Ivan Misner once spent one week on Necker Island – the tony 74-acre island in the British Virgin Islands that is entirely owned by billionaire Sir Richard Branson – because he met a guy at a convention.

And Misner is really good at networking.

“I stayed in touch with the person, and when there was an opportunity, I got invited to this incredible ethics program on Necker where I had a chance to meet Sir Richard. It all comes from building relationships with people,” said Misner, founder and chairman of BNI (Business Network International), a 32-year-old global business networking platform based in Charlotte, N.C., that has led CNN to call him “the father of modern networking.”

The why doesn’t matter most, Misner said. A person’s approach to networking, regardless of the hoped-for outcome, should always remain the same.

“The two key themes that I would address would be the mindset and the skill set,” he said.

The mindset is making sure one’s approach doesn’t “feel artificial,” Misner said.

“A lot of people, when they go to some kind of networking environment, they feel like they need to get a shower afterwards and think, ‘Ick, I don’t like that,’” Misner said. “The best way to become an effective networker is to go to networking events with the idea of being willing to help people and really believe in that and practice that. I’ve been doing this a long time and where I see it done wrong is when people use face-to-face networking as a cold-calling opportunity.”

Instead, Misner suggests, approach networking like it is “more about farming than it is about hunting.” Cultivate relationships with time and tenacity and don’t just expect them to be instant. Once the approach is set, Misner has a process he calls VCP – visibility, credibility, and profitability.

“Credibility is what takes time,” he said. “You really want to build credibility with somebody. It doesn’t happen overnight. People have to get to know, like, and trust you. It is the most time consuming portion of the VCP process... then, and only then, can you get to profitability. Where people know who you are, they know what you do, they know you’re good at it, and they’re willing to refer a business to you. They’re willing to put you in touch with other people.”

But even when a relationship gets struck early on, networking must be more than a few minutes at an SHM conference, a local chapter mixer, or a medical school reunion.

It’s the follow-up that makes all the impact. Misner calls that process 24/7/30.

Within 24 hours, send the person a note. An email, or even the seemingly lost art of a hand-written card. (If your handwriting is sloppy, Misner often recommends services that will send out legible notes on your behalf.)

Within a week, connect on social media. Focus on whatever platform that person has on their business card, or email signature. Connect where they like to connect to show the person you’re willing to make the effort.

Within a month, reach out to the person and set a time to talk, either face-to-face or via a telecommunication service like Skype.

“It’s these touch points that you make with people that build the relationship,” Misner said. “Without building a real relationship, there is almost no value in the networking effort because you basically are just waiting to stumble upon opportunities as opposed to building relationships and opportunities. It has to be more than just bumping into somebody at a meeting... otherwise you’re really wasting your time.”

Misner also notes that the point of networking is collaboration at some point. That partnership could be working on a research paper or a pilot project. Or just even getting a phone call returned to talk about something important to you.

“It’s not what you know or who you know, it’s how well you know each other that really counts,” he added. “And meeting people at events like HM17 is only the start of the process. It’s not the end of the process by any means, if you want to do this well.”

Ivan Misner once spent one week on Necker Island – the tony 74-acre island in the British Virgin Islands that is entirely owned by billionaire Sir Richard Branson – because he met a guy at a convention.

And Misner is really good at networking.

“I stayed in touch with the person, and when there was an opportunity, I got invited to this incredible ethics program on Necker where I had a chance to meet Sir Richard. It all comes from building relationships with people,” said Misner, founder and chairman of BNI (Business Network International), a 32-year-old global business networking platform based in Charlotte, N.C., that has led CNN to call him “the father of modern networking.”

The why doesn’t matter most, Misner said. A person’s approach to networking, regardless of the hoped-for outcome, should always remain the same.

“The two key themes that I would address would be the mindset and the skill set,” he said.

The mindset is making sure one’s approach doesn’t “feel artificial,” Misner said.

“A lot of people, when they go to some kind of networking environment, they feel like they need to get a shower afterwards and think, ‘Ick, I don’t like that,’” Misner said. “The best way to become an effective networker is to go to networking events with the idea of being willing to help people and really believe in that and practice that. I’ve been doing this a long time and where I see it done wrong is when people use face-to-face networking as a cold-calling opportunity.”

Instead, Misner suggests, approach networking like it is “more about farming than it is about hunting.” Cultivate relationships with time and tenacity and don’t just expect them to be instant. Once the approach is set, Misner has a process he calls VCP – visibility, credibility, and profitability.

“Credibility is what takes time,” he said. “You really want to build credibility with somebody. It doesn’t happen overnight. People have to get to know, like, and trust you. It is the most time consuming portion of the VCP process... then, and only then, can you get to profitability. Where people know who you are, they know what you do, they know you’re good at it, and they’re willing to refer a business to you. They’re willing to put you in touch with other people.”

But even when a relationship gets struck early on, networking must be more than a few minutes at an SHM conference, a local chapter mixer, or a medical school reunion.

It’s the follow-up that makes all the impact. Misner calls that process 24/7/30.

Within 24 hours, send the person a note. An email, or even the seemingly lost art of a hand-written card. (If your handwriting is sloppy, Misner often recommends services that will send out legible notes on your behalf.)

Within a week, connect on social media. Focus on whatever platform that person has on their business card, or email signature. Connect where they like to connect to show the person you’re willing to make the effort.

Within a month, reach out to the person and set a time to talk, either face-to-face or via a telecommunication service like Skype.

“It’s these touch points that you make with people that build the relationship,” Misner said. “Without building a real relationship, there is almost no value in the networking effort because you basically are just waiting to stumble upon opportunities as opposed to building relationships and opportunities. It has to be more than just bumping into somebody at a meeting... otherwise you’re really wasting your time.”

Misner also notes that the point of networking is collaboration at some point. That partnership could be working on a research paper or a pilot project. Or just even getting a phone call returned to talk about something important to you.

“It’s not what you know or who you know, it’s how well you know each other that really counts,” he added. “And meeting people at events like HM17 is only the start of the process. It’s not the end of the process by any means, if you want to do this well.”

Ivan Misner once spent one week on Necker Island – the tony 74-acre island in the British Virgin Islands that is entirely owned by billionaire Sir Richard Branson – because he met a guy at a convention.

And Misner is really good at networking.

“I stayed in touch with the person, and when there was an opportunity, I got invited to this incredible ethics program on Necker where I had a chance to meet Sir Richard. It all comes from building relationships with people,” said Misner, founder and chairman of BNI (Business Network International), a 32-year-old global business networking platform based in Charlotte, N.C., that has led CNN to call him “the father of modern networking.”

The why doesn’t matter most, Misner said. A person’s approach to networking, regardless of the hoped-for outcome, should always remain the same.

“The two key themes that I would address would be the mindset and the skill set,” he said.

The mindset is making sure one’s approach doesn’t “feel artificial,” Misner said.

“A lot of people, when they go to some kind of networking environment, they feel like they need to get a shower afterwards and think, ‘Ick, I don’t like that,’” Misner said. “The best way to become an effective networker is to go to networking events with the idea of being willing to help people and really believe in that and practice that. I’ve been doing this a long time and where I see it done wrong is when people use face-to-face networking as a cold-calling opportunity.”

Instead, Misner suggests, approach networking like it is “more about farming than it is about hunting.” Cultivate relationships with time and tenacity and don’t just expect them to be instant. Once the approach is set, Misner has a process he calls VCP – visibility, credibility, and profitability.

“Credibility is what takes time,” he said. “You really want to build credibility with somebody. It doesn’t happen overnight. People have to get to know, like, and trust you. It is the most time consuming portion of the VCP process... then, and only then, can you get to profitability. Where people know who you are, they know what you do, they know you’re good at it, and they’re willing to refer a business to you. They’re willing to put you in touch with other people.”

But even when a relationship gets struck early on, networking must be more than a few minutes at an SHM conference, a local chapter mixer, or a medical school reunion.

It’s the follow-up that makes all the impact. Misner calls that process 24/7/30.

Within 24 hours, send the person a note. An email, or even the seemingly lost art of a hand-written card. (If your handwriting is sloppy, Misner often recommends services that will send out legible notes on your behalf.)

Within a week, connect on social media. Focus on whatever platform that person has on their business card, or email signature. Connect where they like to connect to show the person you’re willing to make the effort.

Within a month, reach out to the person and set a time to talk, either face-to-face or via a telecommunication service like Skype.

“It’s these touch points that you make with people that build the relationship,” Misner said. “Without building a real relationship, there is almost no value in the networking effort because you basically are just waiting to stumble upon opportunities as opposed to building relationships and opportunities. It has to be more than just bumping into somebody at a meeting... otherwise you’re really wasting your time.”

Misner also notes that the point of networking is collaboration at some point. That partnership could be working on a research paper or a pilot project. Or just even getting a phone call returned to talk about something important to you.

“It’s not what you know or who you know, it’s how well you know each other that really counts,” he added. “And meeting people at events like HM17 is only the start of the process. It’s not the end of the process by any means, if you want to do this well.”

Automating venous thromboembolism risk calculation using electronic health record data upon hospital admission: The automated Padua Prediction Score

Hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism (VTE) continues to be a critical quality challenge for U.S. hospitals,1 and high-risk patients are often not adequately prophylaxed. Use of VTE prophylaxis (VTEP) varies as widely as 26% to 85% of patients in various studies, as does patient outcomes and care expenditures.2-6 The 9th edition of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) guidelines7 recommend the Padua Prediction Score (PPS) to select individual patients who may be at high risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE) and could benefit from thromboprophylaxis. Use of the manually calculated PPS to select patients for thromboprophylaxis has been shown to help decrease 30-day and 90-day mortality associated with VTE events after hospitalization to medical services.8 However, the PPS requires time-consuming manual calculation by a provider, who may be focused on more immediate aspects of patient care and several other risk scores competing for his attention, potentially decreasing its use.

Other risk scores that use only discrete scalar data, such as vital signs and lab results to predict early recognition of sepsis, have been successfully automated and implemented within electronic health records (EHRs).9-11 Successful automation of scores requiring input of diagnoses, recent medical events, and current clinical status such as the PPS remains difficult.12 Data representing these characteristics are more prone to error, and harder to translate clearly into a single data field than discrete elements like heart rate, potentially impacting validity of the calculated result.13 To improve usage of guideline based VTE risk assessment and decrease physician burden, we developed an algorithm called Automated Padua Prediction Score (APPS) that automatically calculates the PPS using only EHR data available within prior encounters and the first 4 hours of admission, a similar timeframe to when admitting providers would be entering orders. Our goal was to assess if an automatically calculated version of the PPS, a score that depends on criteria more complex than vital signs and labs, would accurately assess risk for hospital-acquired VTE when compared to traditional manual calculation of the Padua Prediction Score by a provider.

METHODS

Site Description and Ethics

The study was conducted at University of California, San Francisco Medical Center, a 790-bed academic hospital; its Institutional Review Board approved the study and collection of data via chart review. Handling of patient information complied with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996.

Patient Inclusion

Adult patients admitted to a medical or surgical service between July 1, 2012 and April 1, 2014 were included in the study if they were candidates for VTEP, defined as: length of stay (LOS) greater than 2 days, not on hospice care, not pregnant at admission, no present on admission VTE diagnosis, no known contraindications to prophylaxis (eg, gastrointestinal bleed), and were not receiving therapeutic doses of warfarin, low molecular weight heparins, heparin, or novel anticoagulants prior to admission.

Data Sources

Clinical variables were extracted from the EHR’s enterprise data warehouse (EDW) by SQL Server query (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington) and deposited in a secure database. Chart review was conducted by a trained researcher (Mr. Jacolbia) using the EHR and a standardized protocol. Findings were recorded using REDCap (REDCap Consortium, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee). The specific ICD-9, procedure, and lab codes used to determine each criterion of APPS are available in the Appendix.

Creation of the Automated Padua Prediction Score (APPS)

We developed APPS from the original 11 criteria that comprise the Padua Prediction Score: active cancer, previous VTE (excluding superficial vein thrombosis), reduced mobility, known thrombophilic condition, recent (1 month or less) trauma and/or surgery, age 70 years or older, heart and/or respiratory failure, acute myocardial infarction and/or ischemic stroke, acute infection and/or rheumatologic disorder, body mass index (BMI) 30 or higher, and ongoing hormonal treatment.13 APPS has the same scoring methodology as PPS: criteria are weighted from 1 to 3 points and summed with a maximum score of 20, representing highest risk of VTE. To automate the score calculation from data routinely available in the EHR, APPS checks pre-selected structured data fields for specific values within laboratory results, orders, nursing flowsheets and claims. Claims data included all ICD-9 and procedure codes used for billing purposes. If any of the predetermined data elements are found, then the specific criterion is considered positive; otherwise, it is scored as negative. The creators of the PPS were consulted in the generation of these data queries to replicate the original standards for deeming a criterion positive. The automated calculation required no use of natural language processing.

Characterization of Study Population

We recorded patient demographics (age, race, gender, BMI), LOS, and rate of hospital-acquired VTE. These patients were separated into 2 cohorts determined by the VTE prophylaxis they received. The risk profile of patients who received pharmacologic prophylaxis was hypothesized to be inherently different from those who had not. To evaluate APPS within this heterogeneous cohort, patients were divided into 2 major categories: pharmacologic vs. no pharmacologic prophylaxis. If they had a completed order or medication administration record on the institution’s approved formulary for pharmacologic VTEP, they were considered to have received pharmacologic prophylaxis. If they had only a completed order for usage of mechanical prophylaxis (sequential compression devices) or no evidence of any form of VTEP, they were considered to have received no pharmacologic prophylaxis. Patients with evidence of both pharmacologic and mechanical were placed in the pharmacologic prophylaxis group. To ensure that automated designation of prophylaxis group was accurate, we reviewed 40 randomly chosen charts because prior researchers were able to achieve sensitivity and specificity greater than 90% with that sample size.14

The primary outcome of hospital-acquired VTE was defined as an ICD-9 code for VTE (specific codes are found in the Appendix) paired with a “present on admission = no” flag on that encounter’s hospital billing data, abstracted from the EDW. A previous study at this institution used the same methodology and found 212/226 (94%) of patients with a VTE ICD-9 code on claim had evidence of a hospital-acquired VTE event upon chart review.14 Chart review was also completed to ensure that the primary outcome of newly discovered hospital-acquired VTE was differentiated from chronic VTE or history of VTE. Theoretically, ICD-9 codes and other data elements treat chronic VTE, history of VTE, and hospital-acquired VTE as distinct diagnoses, but it was unclear if this was true in our dataset. For 75 randomly selected cases of presumed hospital-acquired VTE, charts were reviewed for evidence that confirmed newly found VTE during that encounter.

Validation of APPS through Comparison to Manual Calculation of the Original PPS

To compare our automated calculation to standard clinical practice, we manually calculated the PPS through chart review within the first 2 days of admission on 300 random patients, a subsample of the entire study cohort. The largest study we could find had manually calculated the PPS of 1,080 hospitalized patients with a mean PPS of 4.86 (standard deviation [SD], 2.26).15 One researcher (Mr. Jacolbia) accessed the EHR with all patient information available to physicians, including admission notes, orders, labs, flowsheets, past medical history, and all prior encounters to calculate and record the PPS. To limit potential score bias, 2 authors (Drs. Elias and Davies) assessed 30 randomly selected charts from the cohort of 300. The standardized chart review protocol mimicked a physician’s approach to determine if a patient met a criterion, such as concluding if he/she had active cancer by examining medication lists for chemotherapy, procedure notes for radiation, and recent diagnoses on problem lists. After the original PPS was manually calculated, APPS was automatically calculated for the same 300 patients. We intended to characterize similarities and differences between APPS and manual calculation prior to investigating APPS’ predictive capacity for the entire study population, because it would not be feasible to manually calculate the PPS for all 30,726 patients.

Statistical Analysis

For the 75 randomly selected cases of presumed hospital-acquired VTE, the number of cases was chosen by powering our analysis to find a difference in proportion of 20% with 90% power, α = 0.05 (two-sided). We conducted χ2 tests on the entire study cohort to determine if there were significant differences in demographics, LOS, and incidence of hospital-acquired VTE by prophylaxis received. For both the pharmacologic and the no pharmacologic prophylaxis groups, we conducted 2-sample Student t tests to determine significant differences in demographics and LOS between patients who experienced a hospital-acquired VTE and those who did not.

For the comparison of our automated calculation to standard clinical practice, we manually calculated the PPS through chart review within the first 2 days of admission on a subsample of 300 random patients. We powered our analysis to detect a difference in mean PPS from 4.86 to 4.36, enough to alter the point value, with 90% power and α = 0.05 (two-sided) and found 300 patients to be comfortably above the required sample size. We compared APPS and manual calculation in the 300-patient cohort using: 2-sample Student t tests to compare mean scores, χ2 tests to compare the frequency with which criteria were positive, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves to determine capacity to predict a hospital-acquired VTE event. Pearson’s correlation was also completed to assess score agreement between APPS and manual calculation on a per-patient basis. After comparing automated calculation of APPS to manual chart review on the same 300 patients, we used APPS to calculate scores for the entire study cohort (n = 30,726). We calculated the mean of APPS by prophylaxis group and whether hospital-acquired VTE had occurred. We analyzed APPS’ ROC curve statistics by prophylaxis group to determine its overall predictive capacity in our study population. Lastly, we computed the time required to calculate APPS per patient. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics (IBM, Armonk, New York) and Python 2.7 (Python Software Foundation, Beaverton, Oregon); 95% confidence intervals (CI) and (SD) were reported when appropriate.

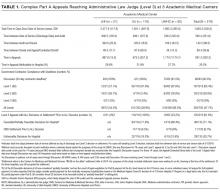

RESULTS

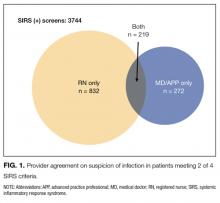

Among the 30,726 unique patients in our entire cohort (all patients admitted during the time period who met the study criteria), we found 6574 (21.4%) on pharmacologic (with or without mechanical) prophylaxis, 13,511 (44.0%) on mechanical only, and 10,641 (34.6%) on no prophylaxis. χ2 tests found no significant differences in demographics, LOS, or incidence of hospital-acquired VTE between the patients who received mechanical prophylaxis only and those who received no prophylaxis (Table 1). Similarly, there were no differences in these characteristics in patients receiving pharmacologic prophylaxis with or without the addition of mechanical prophylaxis. Designation of prophylaxis group by manual chart review vs. our automated process was found to agree in categorization for 39/40 (97.5%) sampled encounters. When comparing the cohort that received pharmacologic prophylaxis against the cohort that did not, there were significant differences in racial distribution, sex, BMI, and average LOS as shown in Table 1. Those who received pharmacologic prophylaxis were found to be significantly older than those who did not (62.7 years versus 53.2 years, P < 0.001), more likely to be male (50.6% vs, 42.4%, P < 0.001), more likely to have hospital-acquired VTE (2.2% vs. 0.5%, P < 0.001), and to have a shorter LOS (7.1 days vs. 9.8, P < 0.001).

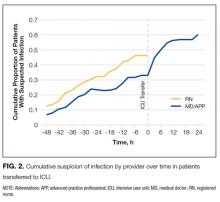

Within the cohort group receiving pharmacologic prophylaxis (n = 6574), hospital-acquired VTE occurred in patients who were significantly younger (58.2 years vs. 62.8 years, P = 0.003) with a greater LOS (23.8 days vs. 6.7, P < 0.001) than those without. Within the group receiving no pharmacologic prophylaxis (n = 24,152), hospital-acquired VTE occurred in patients who were significantly older (57.1 years vs. 53.2 years, P = 0.014) with more than twice the LOS (20.2 days vs. 9.7 days, P < 0.001) compared to those without. Sixty-six of 75 (88%) randomly selected patients in which new VTE was identified by the automated electronic query had this diagnosis confirmed during manual chart review.

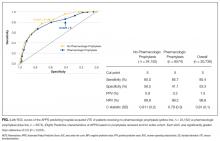

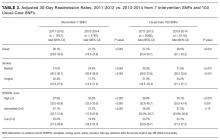

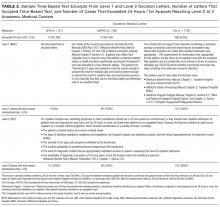

As shown in Table 2, automated calculation on a subsample of 300 randomly selected patients using APPS had a mean of 5.5 (SD, 2.9) while manual calculation of the original PPS on the same patients had a mean of 5.1 (SD, 2.6). There was no significant difference in mean between manual calculation and APPS (P = 0.073). There were, however, significant differences in how often individual criteria were considered present. The largest contributors to the difference in scores between APPS and manual calculation were “prior VTE” (positive, 16% vs. 8.3%, respectively) and “reduced mobility” (positive, 74.3% vs. 66%, respectively) as shown in Table 2. In the subsample, there were a total of 6 (2.0%) hospital-acquired VTE events. APPS’ automated calculation had an AUC = 0.79 (CI, 0.63-0.95) that was significant (P = 0.016) with a cutoff value of 5. Chart review’s manual calculation of the PPS had an AUC = 0.76 (CI 0.61-0.91) that was also significant (P = 0.029).

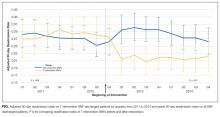

Distribution of Patient Characteristics in Cohort

Our entire cohort of 30,726 unique patients admitted during the study period included 260 (0.8%) who experienced hospital-acquired VTEs (Table 3). In patients receiving no pharmacologic prophylaxis, the average APPS was 4.0 (SD, 2.4) for those without VTE and 7.1 (SD, 2.3) for those with VTE. In patients who had received pharmacologic prophylaxis, those without hospital-acquired VTE had an average APPS of 4.9 (SD, 2.6) and those with hospital-acquired VTE averaged 7.7 (SD, 2.6). APPS’ ROC curves for “no pharmacologic prophylaxis” had an AUC = 0.81 (CI, 0.79 – 0.83) that was significant (P < 0.001) with a cutoff value of 5. There was similar performance in the pharmacologic prophylaxis group with an AUC = 0.79 (CI, 0.76 – 0.82) and cutoff value of 5, as shown in the Figure. Over the entire cohort, APPS had a sensitivity of 85.4%, specificity of 53.3%, positive predictive value (PPV) of 1.5%, and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 99.8% when using a cutoff of 5. The average APPS calculation time was 0.03 seconds per encounter. Additional information on individual criteria can be found in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

Automated calculation of APPS using EHR data from prior encounters and the first 4 hours of admission was predictive of in-hospital VTE. APPS performed as well as traditional manual score calculation of the PPS. It was able to do so with no physician input, significantly lessening the burden of calculation and potentially increasing frequency of data-driven VTE risk assessment.

While automated calculation of certain scores is becoming more common, risk calculators that require data beyond vital signs and lab results have lagged,16-19 in part because of uncertainty about 2 issues. The first is whether EHR data accurately represent the current clinical picture. The second is if a machine-interpretable algorithm to determine a clinical status (eg, “active cancer”) would be similar to a doctor’s perception of that same concept. We attempted to better understand these 2 challenges through developing APPS. Concerning accuracy, EHR data correctly represent the clinical scenario: designations of VTEP and hospital-acquired VTE were accurate in approximately 90% of reviewed cases. Regarding the second concern, when comparing APPS to manual calculation, we found significant differences (P < 0.001) in how often 8 of the 11 criteria were positive, yet no significant difference in overall score and similar predictive capacity. Manual calculation appeared more likely to find data in the index encounter or in structured data. For example, “active cancer” may be documented only in a physician’s note, easily accounted for during a physician’s calculation but missed by APPS looking only for structured data. In contrast, automated calculation found historic criteria, such as “prior VTE” or “known thrombophilic condition,” positive more often. If the patient is being admitted for a problem unrelated to blood clots, the physician may have little time or interest to look through hundreds of EHR documents to discover a 2-year-old VTE. As patients’ records become larger and denser, more historic data can become buried and forgotten. While the 2 scores differ on individual criteria, they are similarly predictive and able to bifurcate the at-risk population to those who should and should not receive pharmacologic prophylaxis.

The APPS was found to have near-equal performance in the pharmacologic vs. no pharmacologic prophylaxis cohorts. This finding agrees with a study that found no significant difference in predicting 90-day VTE when looking at 86 risk factors vs. the most significant 4, none of which related to prescribed prophylaxis.18 The original PPS had a reported sensitivity of 94.6%, specificity 62%, PPV 7.5%, and NPV 99.7% in its derivation cohort.13 We matched APPS to the ratio of sensitivity to specificity, using 5 as the cutoff value. APPS performed slightly worse with sensitivity of 85.4%, specificity 53.3%, PPV 1.5%, and NPV 99.8%. This difference may have resulted from the original PPS study’s use of 90-day follow-up to determine VTE occurrence, whereas we looked only until the end of current hospitalization, an average of 9.2 days. Furthermore, the PPS had significantly poorer performance (AUC = 0.62) than that seen in the original derivation cohort in a separate study that manually calculated the score on more than 1000 patients.15

There are important limitations to our study. It was done at a single academic institution using a dataset of VTE-associated, validated research that was well-known to the researchers.20 Another major limitation is the dependence of the algorithm on data available within the first 4 hours of admission and earlier; thus, previous encounters may frequently play an important role. Patients presenting to our health system for the first time would have significantly fewer data available at the time of calculation. Additionally, our data could not reliably tell us the total doses of pharmacologic prophylaxis that a patient received. While most patients will maintain a consistent VTEP regimen once initiated in the hospital, 2 patients with the same LOS may have received differing amounts of pharmacologic prophylaxis. This research study did not assess how much time automatic calculation of VTE risk might save providers, because we did not record the time for each manual abstraction; however, from discussion with the main abstracter, chart review and manual calculation for this study took from 2 to 14 minutes per patient, depending on the number of previous interactions with the health system. Finally, although we chose data elements that are likely to exist at most institutions using an EHR, many institutions’ EHRs do not have EDW capabilities nor programmers who can assist with an automated risk score.

The EHR interventions to assist providers in determining appropriate VTEP have been able to increase rates of VTEP and decrease VTE-associated mortality.16,21 In addition to automating the calculation of guideline-adherent risk scores, there is a need for wider adoption for clinical decision support for VTE. For this reason, we chose only structured data fields from some of the most common elements within our EHR’s data warehouse to derive APPS (Appendix 1). Our study supports the idea that automated calculation of scores requiring input of more complex data such as diagnoses, recent medical events, and current clinical status remains predictive of hospital-acquired VTE risk. Because it is calculated automatically in the background while the clinician completes his or her assessment, the APPS holds the potential to significantly reduce the burden on providers while making guideline-adherent risk assessment more readily accessible. Further research is required to determine the exact amount of time automatic calculation saves, and, more important, if the relatively high predictive capacity we observed using APPS would be reproducible across institutions and could reduce incidence of hospital-acquired VTE.

Disclosures

Dr. Auerbach was supported by NHLBI K24HL098372 during the period of this study. Dr. Khanna, who is an implementation scientist at the University of California San Francisco Center for Digital Health Innovation, is the principal inventor of CareWeb, and may benefit financially from its commercialization. The other authors report no financial conflicts of interest.

1. Galson S. The Surgeon General’s call to action to prevent deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. 2008. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44178/. Accessed February 11, 2016. PubMed

2. Borch KH, Nyegaard C, Hansen JB, et al. Joint effects of obesity and body height on the risk of venous thromboembolism: the Tromsø study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31(6):1439-44. PubMed

3. Braekkan SK, Borch KH, Mathiesen EB, Njølstad I, Wilsgaard T, Hansen JB.. Body height and risk of venous thromboembolism: the Tromsø Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(10):1109-1115. PubMed

4. Bounameaux H, Rosendaal FR. Venous thromboembolism: why does ethnicity matter? Circulation. 2011;123(200:2189-2191. PubMed

5. Spyropoulos AC, Anderson FA Jr, Fitzgerald G, et al; IMPROVE Investigators. Predictive and associative models to identify hospitalized medical patients at risk for VTE. Chest. 2011;140(3):706-714. PubMed

6. Rothberg MB, Lindenauer PK, Lahti M, Pekow PS, Selker HP. Risk factor model to predict venous thromboembolism in hospitalized medical patients. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(4):202-209. PubMed

7. Perioperative Management of Antithrombotic Therapy: Prevention of VTE in Nonsurgical Patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(6):1645.

8. Subbe CP, Kruger M, Rutherford P, Gemmel L. Validation of a modified Early Warning Score in medical admissions. QJM. 2001;94(10):521-526. PubMed

9. Alvarez CA, Clark CA, Zhang S, et al. Predicting out of intensive care unit cardiopulmonary arrest or death using electronic medical record data. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13:28. PubMed

10. Escobar GJ, LaGuardia JC, Turk BJ, Ragins A, Kipnis P, Draper D. Early detection of impending physiologic deterioration among patients who are not in intensive care: development of predictive models using data from an automated electronic medical record. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):388-395. PubMed

11. Umscheid CA, Hanish A, Chittams J, Weiner MG, Hecht TE. Effectiveness of a novel and scalable clinical decision support intervention to improve venous thromboembolism prophylaxis: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:92. PubMed

12. Tepas JJ 3rd, Rimar JM, Hsiao AL, Nussbaum MS. Automated analysis of electronic medical record data reflects the pathophysiology of operative complications. Surgery. 2013;154(4):918-924. PubMed

13. Barbar S, Noventa F, Rossetto V, et al. A risk assessment model for the identification of hospitalized medical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism: the Padua Prediction Score. J Thromb Haemost. 2010; 8(11):2450-2457. PubMed

14. Khanna R, Maynard G, Sadeghi B, et al. Incidence of hospital-acquired venous thromboembolic codes in medical patients hospitalized in academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2014; 9(4):221-225. PubMed

15. Vardi M, Ghanem-Zoubi NO, Zidan R, Yurin V, Bitterman H. Venous thromboembolism and the utility of the Padua Prediction Score in patients with sepsis admitted to internal medicine departments. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11(3):467-473. PubMed

16. Samama MM, Dahl OE, Mismetti P, et al. An electronic tool for venous thromboembolism prevention in medical and surgical patients. Haematologica. 2006;91(1):64-70. PubMed

17. Mann DM, Kannry JL, Edonyabo D, et al. Rationale, design, and implementation protocol of an electronic health record integrated clinical prediction rule (iCPR) randomized trial in primary care. Implement Sci. 2011;6:109. PubMed

18. Woller SC, Stevens SM, Jones JP, et al. Derivation and validation of a simple model to identify venous thromboembolism risk in medical patients. Am J Med. 2011;124(10):947-954. PubMed

19. Huang W, Anderson FA, Spencer FA, Gallus A, Goldberg RJ. Risk-assessment models for predicting venous thromboembolism among hospitalized non-surgical patients: a systematic review. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2013;35(1):67-80. PubMed

20. Khanna RR, Kim SB, Jenkins I, et al. Predictive value of the present-on-admission indicator for hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism. Med Care. 2015;53(4):e31-e36. PubMed

21. Kucher N, Koo S, Quiroz R, et al. Electronic alerts to prevent venous thromboembolism a

Hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism (VTE) continues to be a critical quality challenge for U.S. hospitals,1 and high-risk patients are often not adequately prophylaxed. Use of VTE prophylaxis (VTEP) varies as widely as 26% to 85% of patients in various studies, as does patient outcomes and care expenditures.2-6 The 9th edition of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) guidelines7 recommend the Padua Prediction Score (PPS) to select individual patients who may be at high risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE) and could benefit from thromboprophylaxis. Use of the manually calculated PPS to select patients for thromboprophylaxis has been shown to help decrease 30-day and 90-day mortality associated with VTE events after hospitalization to medical services.8 However, the PPS requires time-consuming manual calculation by a provider, who may be focused on more immediate aspects of patient care and several other risk scores competing for his attention, potentially decreasing its use.

Other risk scores that use only discrete scalar data, such as vital signs and lab results to predict early recognition of sepsis, have been successfully automated and implemented within electronic health records (EHRs).9-11 Successful automation of scores requiring input of diagnoses, recent medical events, and current clinical status such as the PPS remains difficult.12 Data representing these characteristics are more prone to error, and harder to translate clearly into a single data field than discrete elements like heart rate, potentially impacting validity of the calculated result.13 To improve usage of guideline based VTE risk assessment and decrease physician burden, we developed an algorithm called Automated Padua Prediction Score (APPS) that automatically calculates the PPS using only EHR data available within prior encounters and the first 4 hours of admission, a similar timeframe to when admitting providers would be entering orders. Our goal was to assess if an automatically calculated version of the PPS, a score that depends on criteria more complex than vital signs and labs, would accurately assess risk for hospital-acquired VTE when compared to traditional manual calculation of the Padua Prediction Score by a provider.

METHODS

Site Description and Ethics

The study was conducted at University of California, San Francisco Medical Center, a 790-bed academic hospital; its Institutional Review Board approved the study and collection of data via chart review. Handling of patient information complied with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996.

Patient Inclusion

Adult patients admitted to a medical or surgical service between July 1, 2012 and April 1, 2014 were included in the study if they were candidates for VTEP, defined as: length of stay (LOS) greater than 2 days, not on hospice care, not pregnant at admission, no present on admission VTE diagnosis, no known contraindications to prophylaxis (eg, gastrointestinal bleed), and were not receiving therapeutic doses of warfarin, low molecular weight heparins, heparin, or novel anticoagulants prior to admission.

Data Sources

Clinical variables were extracted from the EHR’s enterprise data warehouse (EDW) by SQL Server query (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington) and deposited in a secure database. Chart review was conducted by a trained researcher (Mr. Jacolbia) using the EHR and a standardized protocol. Findings were recorded using REDCap (REDCap Consortium, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee). The specific ICD-9, procedure, and lab codes used to determine each criterion of APPS are available in the Appendix.

Creation of the Automated Padua Prediction Score (APPS)