User login

Understanding the brexpiprazole therapeutic window: Why more isn’t always better

Dosage windows could be difficult to understand pharmacologically, but for a partial agonist the presumed mechanism could be more evident. Clinicians should be aware that more is not always better, meaning that with partial agonist drugs a higher dosage might not lead to greater patient response. With brexpiprazole, a dopamine D2 partial agonist FDA-approved for schizophrenia and an adjunct for major depressive disorder (MDD),1 moderation is best because of

Recommended dosage

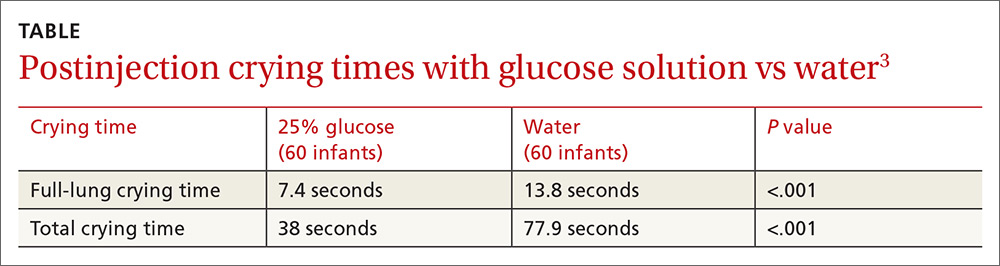

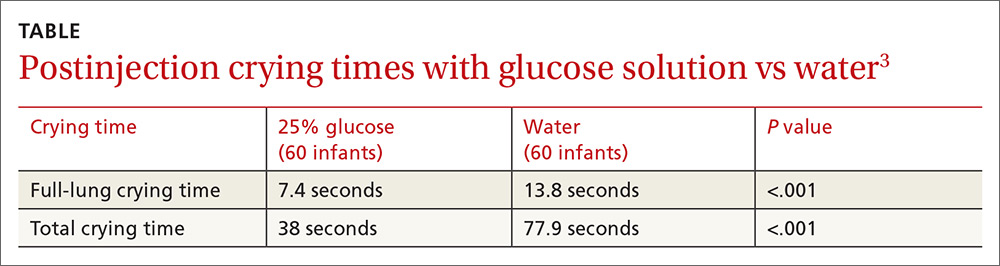

Two placebo-controlled studies2,3 examined brexpiprazole dosages of 1, 2, and 3 mg/d. The recommended dosage of 2 mg/d for MDD was determined by changes in Montgomery-Åsburg Depression Rating Scale scores (Figure).4 Lower dosages of 1 mg/d did not reach statistical significance, and 3 mg/d were less effective than the intermediate dosage of 2 mg/d. This result suggests a window of efficacy for brexpiprazole for MDD. This therapeutic window likely applies to most patients; however, patient-specific variables could alter the optimum dosage.

Dosage window

Brexpiprazole has high affinity for dopamine D2, D3, serotonin 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, norepinephrine α1B, and α2 Creceptors. At relatively low drug concentrations, brexpiprazole achieves high receptor occupancy. At receptors for which brexpiprazole is a partial agonist (5-HT1A, D2, D3) the drug blocks the receptor and stimulates it at a fraction of the endogenous neurotransmitter. With a very high affinity agent, the endogenous neurotransmitter could be completely excluded from interacting with these receptors if brexpiprazole occupancy is high. At lower dosages, the drug occupies only a fraction of the receptors, allowing the endogenous neurotransmitters to continue interacting with their receptors, thereby magnifying the signal of that receptor above baseline.

1. FDA approves Rexulti (brexpiprazole) as adjunctive treatment for adults with major depressive disorder and as a treatment for adults with schizophrenia [news release]. Valby, Denmark; Tokyo, Japan: H. Lundbeck A/S (Lundbeck); Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd; July 11, 2015. http://investor.lundbeck.com/ releasedetail.cfm?Release ID=921621. Accessed October 3, 2015.

2. Thase ME, Youakim JM, Skuban A, et al. Adjunctive brexpiprazole 1 and 3 mg for patients with major depressive disorder following inadequate response to antidepressants: a phase 3, randomized, double-blind study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(9): 1232-1240.

3. Thase ME, Youakim JM, Skuban A, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive brexpiprazole 2 mg in major depressive disorder: a phase 3, randomized, placebocontrolled study in patients with inadequate response to antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(9):1224-1231.

4. Rexulti [package insert]. Rockville, MD: Otsuka; 2015.

Dosage windows could be difficult to understand pharmacologically, but for a partial agonist the presumed mechanism could be more evident. Clinicians should be aware that more is not always better, meaning that with partial agonist drugs a higher dosage might not lead to greater patient response. With brexpiprazole, a dopamine D2 partial agonist FDA-approved for schizophrenia and an adjunct for major depressive disorder (MDD),1 moderation is best because of

Recommended dosage

Two placebo-controlled studies2,3 examined brexpiprazole dosages of 1, 2, and 3 mg/d. The recommended dosage of 2 mg/d for MDD was determined by changes in Montgomery-Åsburg Depression Rating Scale scores (Figure).4 Lower dosages of 1 mg/d did not reach statistical significance, and 3 mg/d were less effective than the intermediate dosage of 2 mg/d. This result suggests a window of efficacy for brexpiprazole for MDD. This therapeutic window likely applies to most patients; however, patient-specific variables could alter the optimum dosage.

Dosage window

Brexpiprazole has high affinity for dopamine D2, D3, serotonin 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, norepinephrine α1B, and α2 Creceptors. At relatively low drug concentrations, brexpiprazole achieves high receptor occupancy. At receptors for which brexpiprazole is a partial agonist (5-HT1A, D2, D3) the drug blocks the receptor and stimulates it at a fraction of the endogenous neurotransmitter. With a very high affinity agent, the endogenous neurotransmitter could be completely excluded from interacting with these receptors if brexpiprazole occupancy is high. At lower dosages, the drug occupies only a fraction of the receptors, allowing the endogenous neurotransmitters to continue interacting with their receptors, thereby magnifying the signal of that receptor above baseline.

Dosage windows could be difficult to understand pharmacologically, but for a partial agonist the presumed mechanism could be more evident. Clinicians should be aware that more is not always better, meaning that with partial agonist drugs a higher dosage might not lead to greater patient response. With brexpiprazole, a dopamine D2 partial agonist FDA-approved for schizophrenia and an adjunct for major depressive disorder (MDD),1 moderation is best because of

Recommended dosage

Two placebo-controlled studies2,3 examined brexpiprazole dosages of 1, 2, and 3 mg/d. The recommended dosage of 2 mg/d for MDD was determined by changes in Montgomery-Åsburg Depression Rating Scale scores (Figure).4 Lower dosages of 1 mg/d did not reach statistical significance, and 3 mg/d were less effective than the intermediate dosage of 2 mg/d. This result suggests a window of efficacy for brexpiprazole for MDD. This therapeutic window likely applies to most patients; however, patient-specific variables could alter the optimum dosage.

Dosage window

Brexpiprazole has high affinity for dopamine D2, D3, serotonin 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, norepinephrine α1B, and α2 Creceptors. At relatively low drug concentrations, brexpiprazole achieves high receptor occupancy. At receptors for which brexpiprazole is a partial agonist (5-HT1A, D2, D3) the drug blocks the receptor and stimulates it at a fraction of the endogenous neurotransmitter. With a very high affinity agent, the endogenous neurotransmitter could be completely excluded from interacting with these receptors if brexpiprazole occupancy is high. At lower dosages, the drug occupies only a fraction of the receptors, allowing the endogenous neurotransmitters to continue interacting with their receptors, thereby magnifying the signal of that receptor above baseline.

1. FDA approves Rexulti (brexpiprazole) as adjunctive treatment for adults with major depressive disorder and as a treatment for adults with schizophrenia [news release]. Valby, Denmark; Tokyo, Japan: H. Lundbeck A/S (Lundbeck); Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd; July 11, 2015. http://investor.lundbeck.com/ releasedetail.cfm?Release ID=921621. Accessed October 3, 2015.

2. Thase ME, Youakim JM, Skuban A, et al. Adjunctive brexpiprazole 1 and 3 mg for patients with major depressive disorder following inadequate response to antidepressants: a phase 3, randomized, double-blind study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(9): 1232-1240.

3. Thase ME, Youakim JM, Skuban A, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive brexpiprazole 2 mg in major depressive disorder: a phase 3, randomized, placebocontrolled study in patients with inadequate response to antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(9):1224-1231.

4. Rexulti [package insert]. Rockville, MD: Otsuka; 2015.

1. FDA approves Rexulti (brexpiprazole) as adjunctive treatment for adults with major depressive disorder and as a treatment for adults with schizophrenia [news release]. Valby, Denmark; Tokyo, Japan: H. Lundbeck A/S (Lundbeck); Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd; July 11, 2015. http://investor.lundbeck.com/ releasedetail.cfm?Release ID=921621. Accessed October 3, 2015.

2. Thase ME, Youakim JM, Skuban A, et al. Adjunctive brexpiprazole 1 and 3 mg for patients with major depressive disorder following inadequate response to antidepressants: a phase 3, randomized, double-blind study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(9): 1232-1240.

3. Thase ME, Youakim JM, Skuban A, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive brexpiprazole 2 mg in major depressive disorder: a phase 3, randomized, placebocontrolled study in patients with inadequate response to antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(9):1224-1231.

4. Rexulti [package insert]. Rockville, MD: Otsuka; 2015.

Hepatitis C among the mentally ill: Review and treatment update

At approximately 3 to 4 million patients, hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the most common viral hepatitis in the United States. Patients with mental illness are disproportionately affected by HCV and the management of their disease poses particular challenges.

HCV is commonly transmitted via IV drug use and blood transfusions; transmission through sexual contact is rare. Most patients with HCV are asymptomatic, although some do develop symptoms of acute hepatitis. Most HCV infections become chronic, with a high incidence of liver failure requiring liver transplantation.

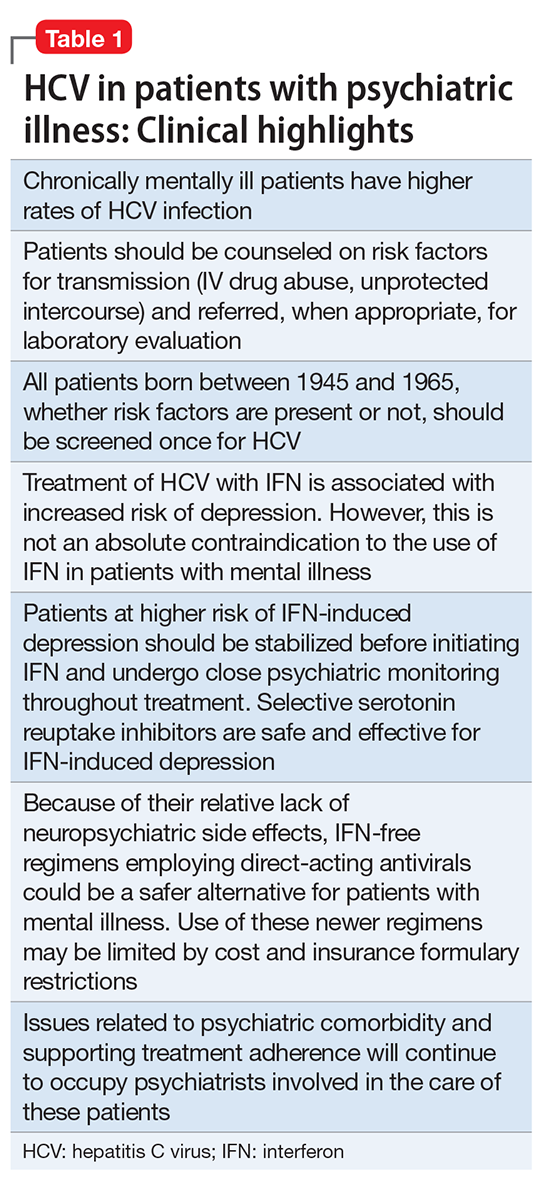

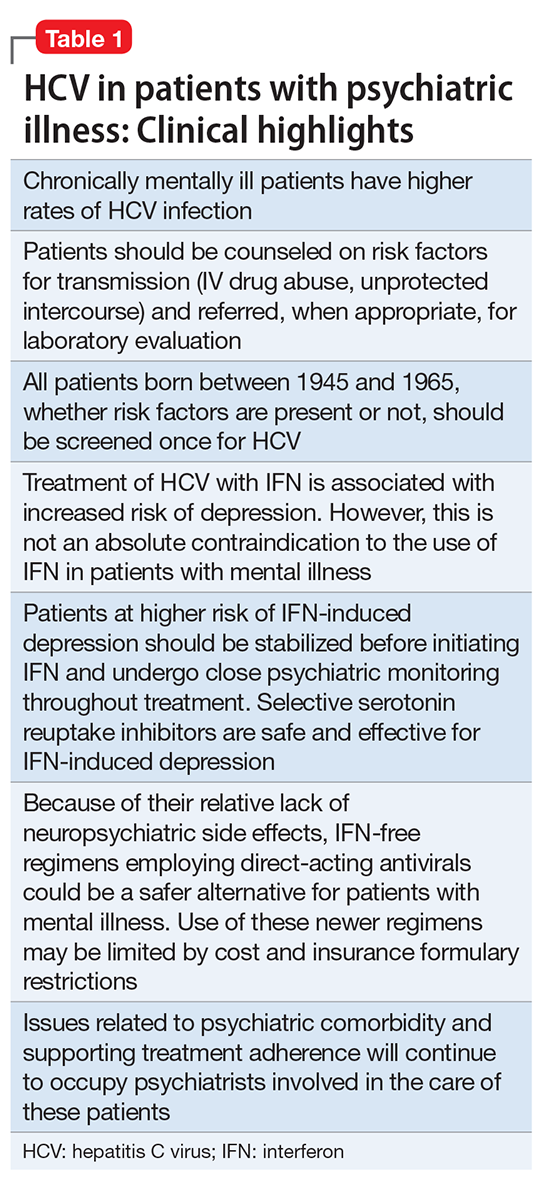

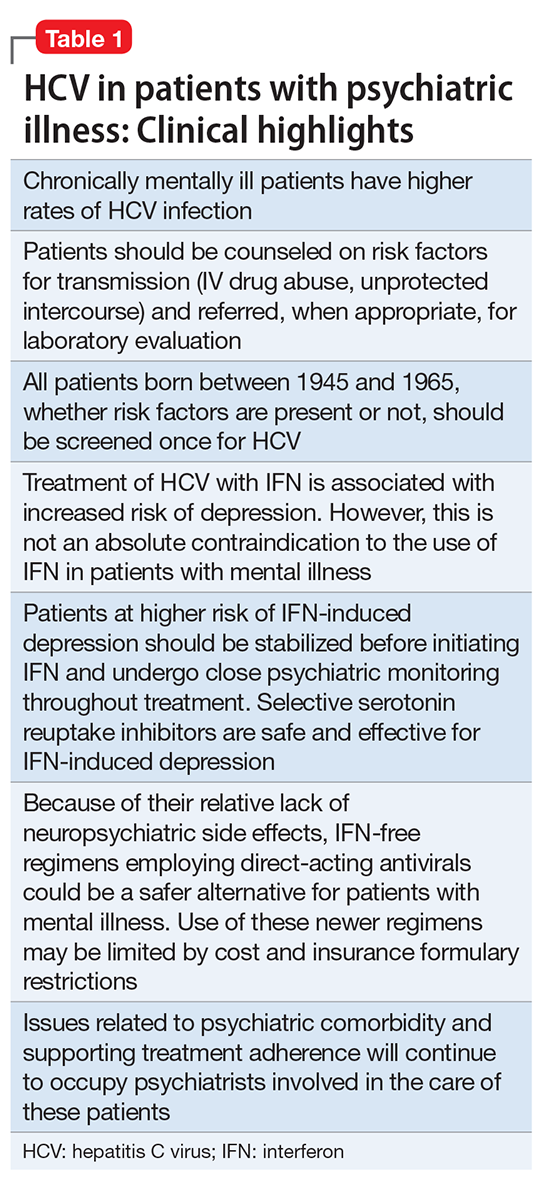

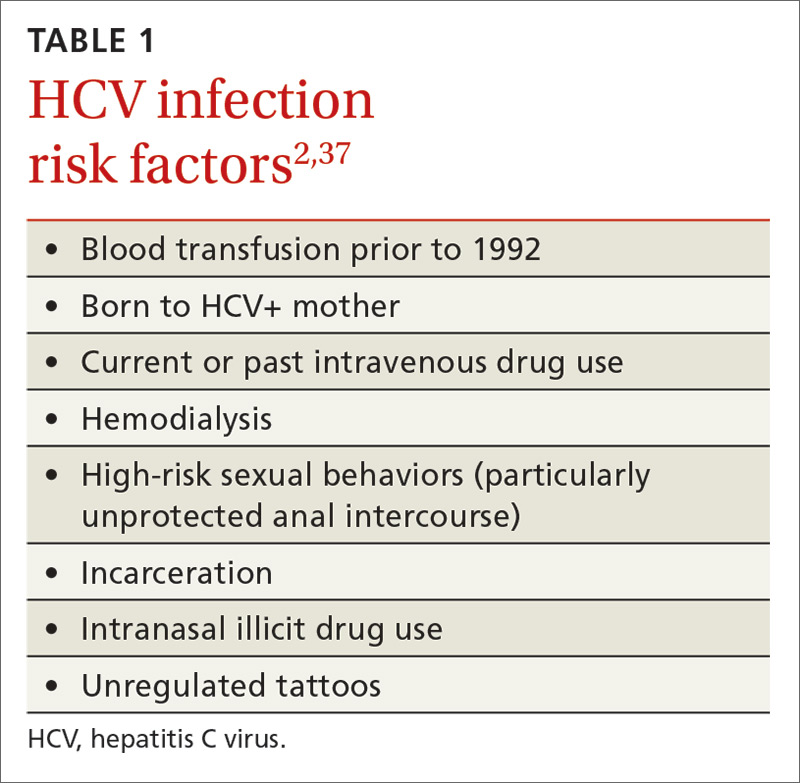

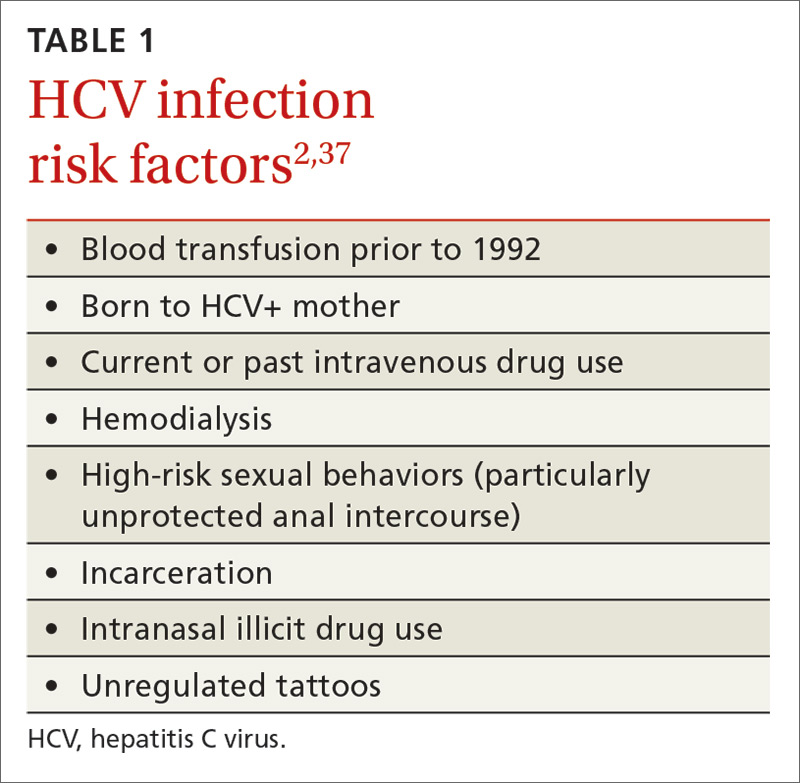

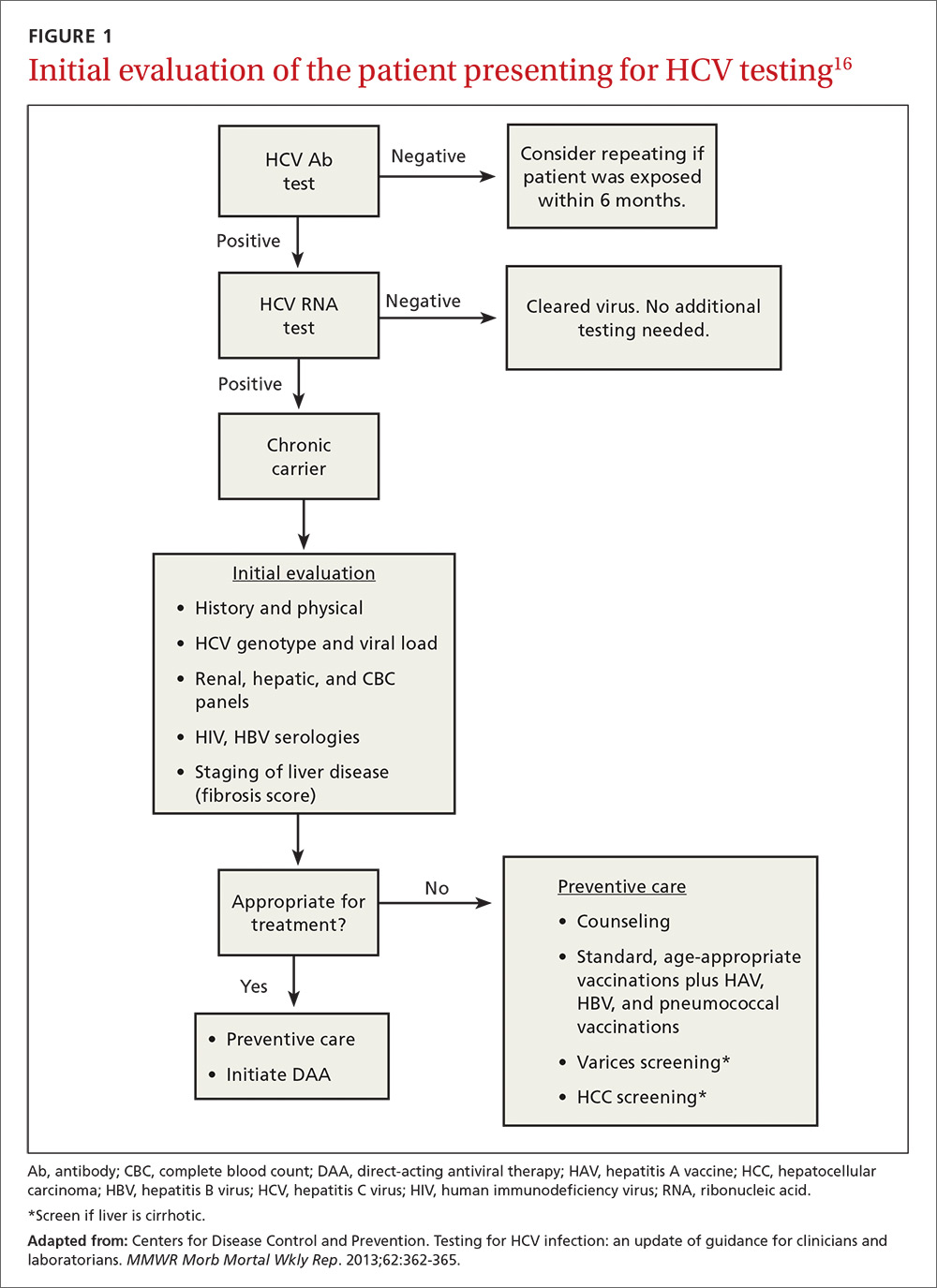

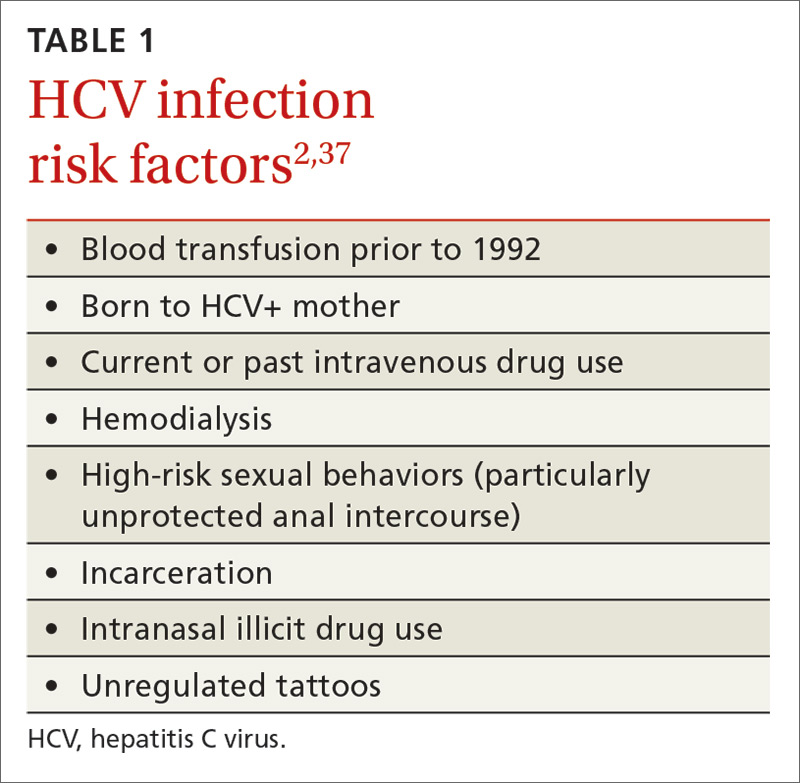

Hepatitis refers to inflammation of the liver, which could have various etiologies, including viral infections, alcohol abuse, or autoimmune disease. Viral hepatitis refers to infection from 5 distinct groups of virus, coined A through E.1 This article will focus on chronic HCV (Table 1).

CASE Bipolar disorder, stress, history of IV drug use

Ms. S, age 48, has bipolar I disorder and has been hospitalized 4 times in the past, including once for a suicide attempt. She has 3 children and works as a cashier. Her psychiatric symptoms have been stable on lurasidone, 80 mg/d, and escitalopram, 10 mg/d. Recently, Ms. S has been under more stress at her job. Sometimes she misses doses of her medication, and then becomes more irritable and impulsive. Her husband, noting that she has used IV heroin in the past, comes with her today and is concerned that she is “not acting right.” What is Ms. S’s risk for HCV?

HCV in mental illness

Compared with the general population, HCV is more prevalent among chronically mentally ill persons. In one study, HCV occurred twice as often in men vs women with chronic mental illness.2 Up to 50% of patients with HCV have a history of mental illness and nearly 90% have a history of substance use disorders.3 Among 668 chronically mentally ill patients at 4 public sector clinics, risk factors for HCV were common and included use of injection drugs (>20%), sharing needles (14%), and crack cocaine use (>20%).4 Higher rates of HCV were reported in hospitalized patients with schizophrenia and comorbid psychoactive substance abuse in Japan.5 Because of the high prevalence in this population, it is essential to assess for substance use disorders. Employing a non-judgmental approach with motivational interviewing techniques can be effective.6

Individuals with mental illness should be screened for HCV risk factors, such as unprotected intercourse with high-risk partners and sharing needles used for illicit drug use. Patients frequently underreport these activities. At-risk individuals should undergo laboratory testing for the HIV-1 antibody, hepatitis C antibodies, and hepatitis B antibodies. Mental health providers should counsel patients about risk reduction (eg, avoiding unprotected sexual intercourse and sharing of drug paraphernalia). Educating patients about complications of viral hepatitis, such as liver failure, could be motivation to change risky behaviors.

CASE continued

During your interview with Ms. S, she becomes irritable and tells you that you are asking too many questions. It is clear that she is not taking her medications consistently, but she agrees to do so because she does not want to lose custody of her children. She denies current use of heroin but her husband says, “I don’t know what she is doing.” In addition to advising her on reducing risk factors, you order appropriate screening tests, including hepatitis and HIV antibody tests.

Screening guidelines

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and the CDC both recommend a 1-time screening for HCV in asymptomatic or low-risk patients born between 1945 and 1965.1,7 Furthermore, both organizations recommend screening for HCV in persons at high risk, including:

- those with a history of injection drug use

- persons with recognizable exposure, such as needlesticks

- persons who received blood transfusions before 1992

- medical conditions, such as long-term dialysis.

There is no vaccine for HCV; however, patients with HCV should receive vaccination against hepatitis B.

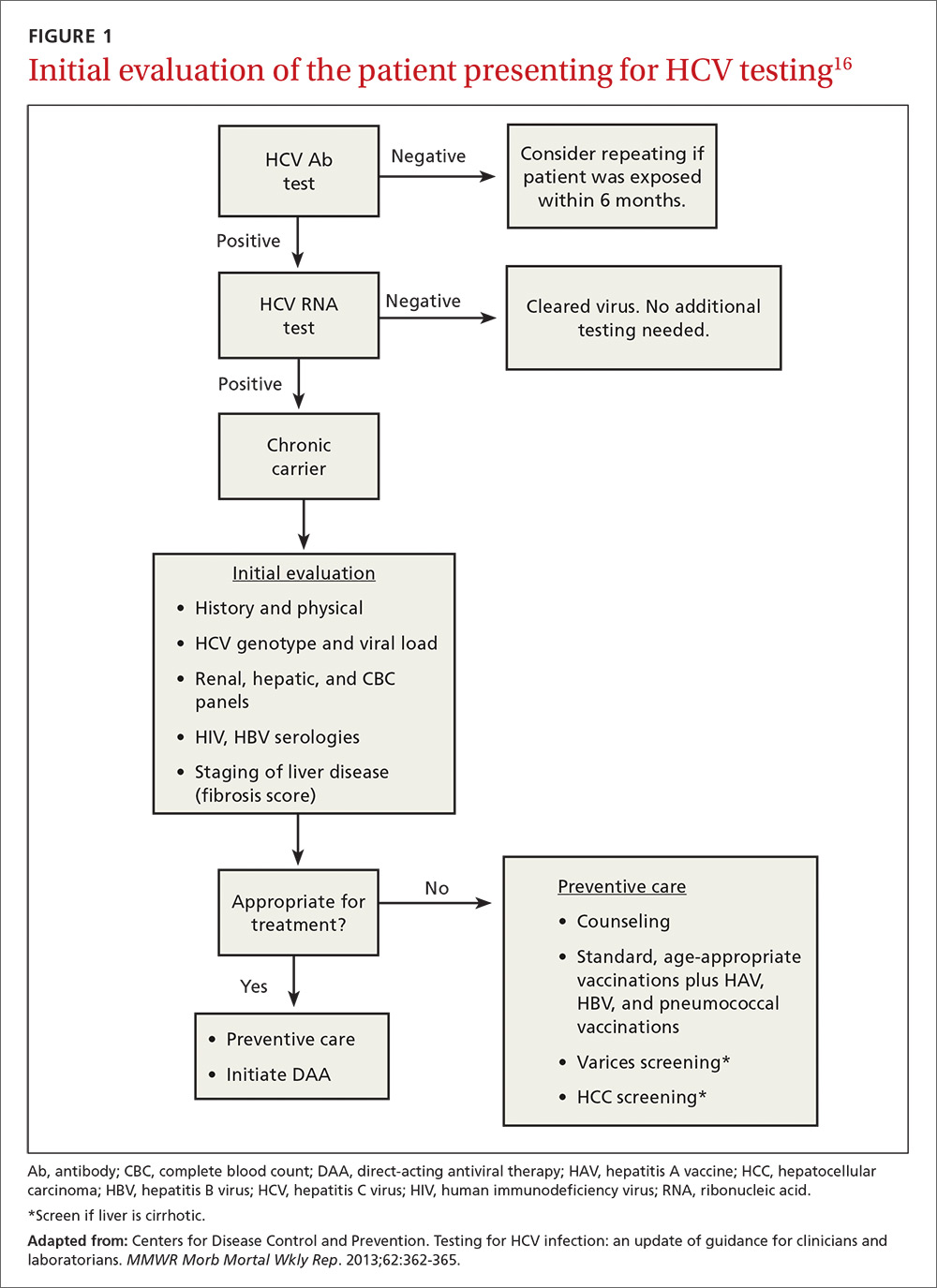

Diagnosis

Acute symptoms include fever, fatigue, headache, cough, nausea, and vomiting. Jaundice could develop, often accompanied by pain in the right upper quadrant. If there is suspicion of viral hepatitis, psychiatrists can initiate the laboratory evaluation. Chronic hepatitis, on the other hand, often is asymptomatic, although stigmata of chronic liver disease (eg, jaundice, ascites, peripheral edema) might be detected on physical exam.8 Elevated serum transaminases are seen with acute viral hepatitis, although levels could vary in chronic cases. Serologic detection of anti-HCV antibodies establishes a HCV diagnosis.

Treatment recommendations

All patients who test positive for HCV should be evaluated and treated by a hepatologist. Goals of therapy are to reduce complications from chronic viral hepatitis, including cirrhosis and hepatic failure. Duration and optimal regimen depends on the HCV genotype.8 Treatment outcomes are measured by virological parameters, including serum aminotransferases, HCV RNA levels, and histology. The most important parameter in treating chronic HCV is the sustained virological response (SVR), which is the absence of HCV RNA 12 weeks after completing therapy.9

Treatment is recommended for all persons with chronic HCV infection, according to current treatment guidelines, which are updated regularly by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.10 Until recently, treatment consisted of IV pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN) in combination with oral ribavirin. Success rates with this regimen are approximately 40% to 50%. The advent of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) has revolutionized treatment of chronic HCV. These agents include simeprevir, sofosbuvir, ledipasvir, and the combination of ombitasvir-paritaprevir-ritonavir plus dasabuvir (brand name, Viekira Pak). Advantages of these agents are oral administration, high treatment success rates (>90%), shorter treatment duration (12 weeks vs up to 48 weeks with older regimens), and few serious adverse effects9-11; drawbacks include the pricing of these regimens, which could cost upward of ≥$100,000 for a 12-week course, and a lack of coverage under some health insurance plans.12 The manufacturers of 2 agents, telaprevir and boceprevir, removed them from the market because of decreased demand related to their unfavorable side-effect profile and the availability of better tolerated agents.

Treatment considerations for interferon in psychiatric patients

Various neuropsychiatric symptoms have been reported with the use of PEG-IFN. The range of reported symptoms include:

- depressed mood

- anxiety

- hostility

- slowness

- fatigue

- sleep disturbance

- lethargy

- irritability

- emotional lability

- social withdrawal

- poor concentration.13,14

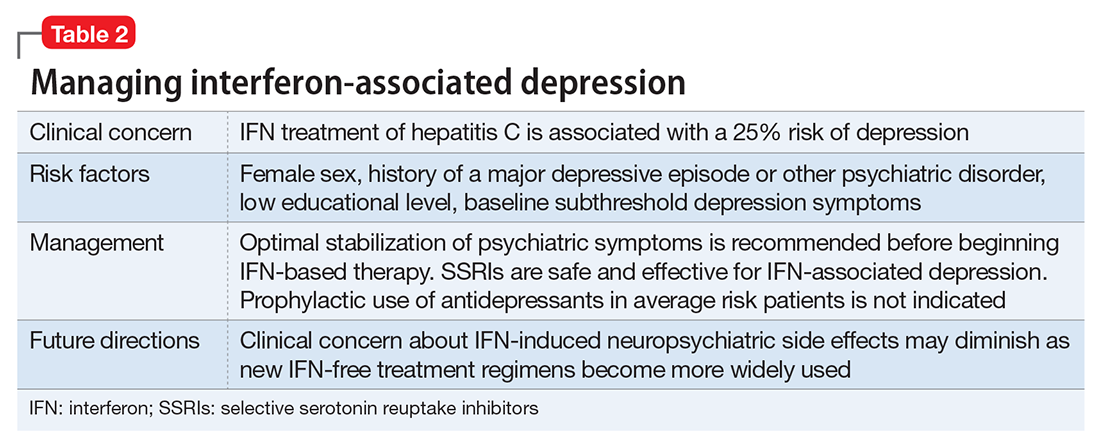

Depressive symptoms can present as early as 1 month after starting treatment, but typically occur at 8 to 12 weeks. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 26 observational studies found a cumulative 25% risk of interferon (IFN)-induced depression in the general HCV population.15 Risk factors for IFN-induced depression include:

- female sex

- history of major depression or other psychiatric disorder

- low educational level

- the presence of baseline subthreshold depressive symptoms.

Because of the risk of inducing depression, there was initial hesitation with providing IFN treatment to patients with psychiatric disorders. However, there is evidence that individuals with chronic psychiatric illness can be treated safely with IFN-based regimens and achieve results similar to non-psychiatric populations.16,17 For example, patients with schizophrenia in a small Veterans Affairs database who received IFN for HCV did not experience higher rates of symptoms of schizophrenia, depression, or mania over 8 years of follow-up.18 Furthermore, those with schizophrenia were just as likely to reach SVR as patients without psychiatric illness.19 Other encouraging results have been reported in depressed patients. One study found similar rates of treatment completion and SVR in patients with a history of major depressive disorder compared with those without depression.20 No difference in frequency of neuropsychiatric side effects was found between the groups.

Presence of a psychiatric disorder is no longer an absolute contraindication to IFN treatment for HCV. Optimal control of psychiatric symptoms should be attained in all patients before starting HCV treatment, and close clinical monitoring is warranted. A review of 9 studies showed benefit of antidepressants for HCV patients with elevated baseline depression or a history of IFN-induced depression.21 The largest body of evidence supports the safety and efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for treating IFN-induced depression. Although no antidepressants are FDA-approved for this indication, the best-studied agents include citalopram, escitalopram, sertraline, and paroxetine.

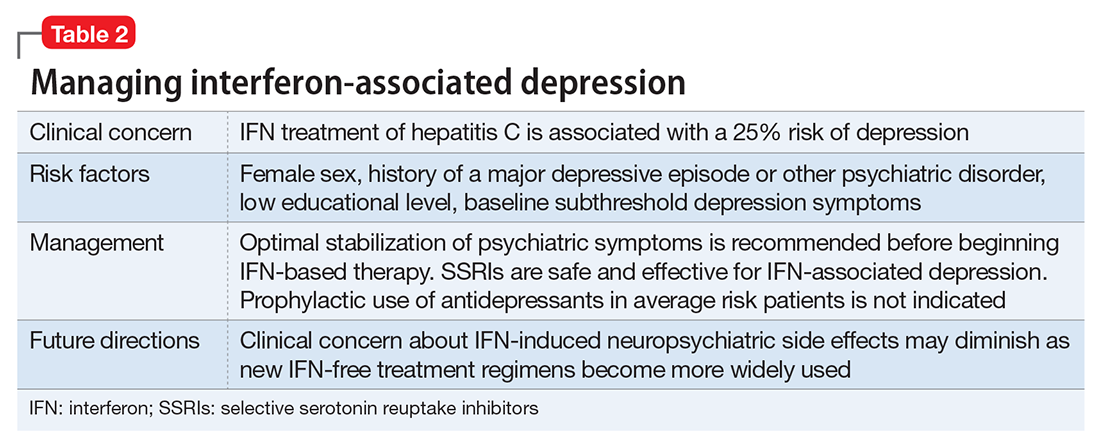

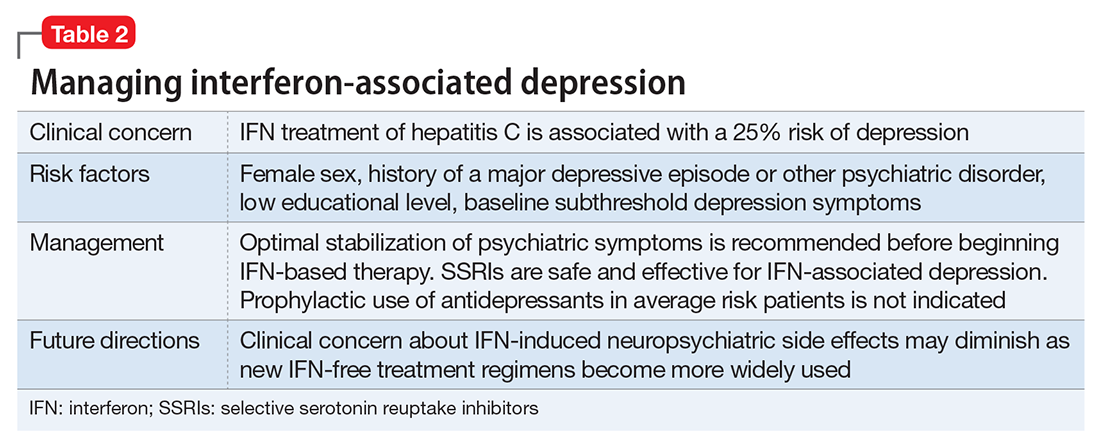

A review of 6 studies on using antidepressants to prevent IFN-induced depression concluded there was inadequate evidence to support this approach in all patients.22 Pretreatment primarily is indicated for those with elevated depressive symptoms at baseline or those with a history of IFN-induced depression. The prevailing approach to IFN-induced depression assessment, prevention, and treatment is summarized in Table 2.

CASE continued

Ms. S tests positive for the HCV antibody but negative for HIV and hepatitis B. She immediately receives the hepatitis B vaccine series. Her sister discourages her from receiving treatment for HCV, warning her, “it will make you crazy depressed.” As a result, Ms. S avoids following up with the hepatologist. Her psychiatrist, aware that she now was taking her psychotropic medication and seeing that her mood is stable, educates her about new treatment options for HCV that do not cause depression. Ms. S finally agrees to see a hepatologist to discuss her treatment options.

IFN-free regimens

With the arrival of the DAAs, the potential now exists to use IFN-free treatment regimens,10 which could eliminate concerns about IFN-induced depression.

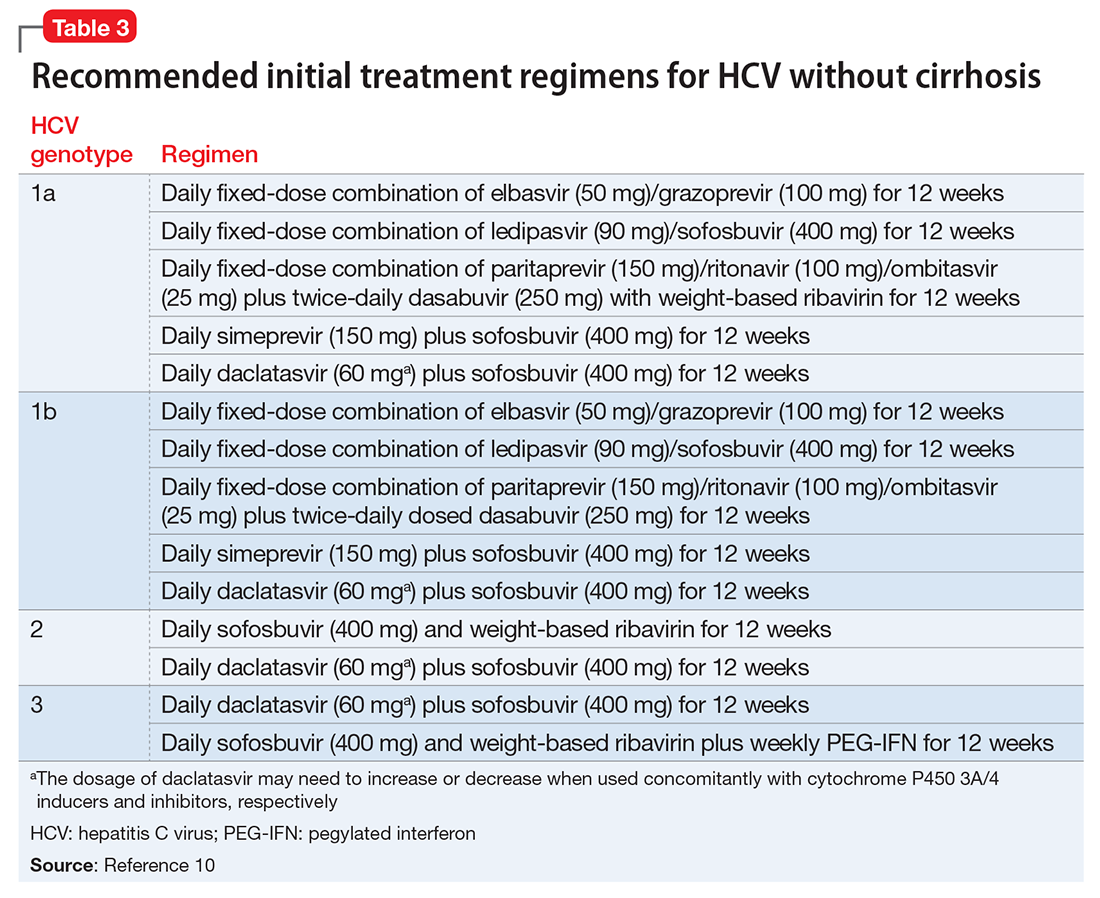

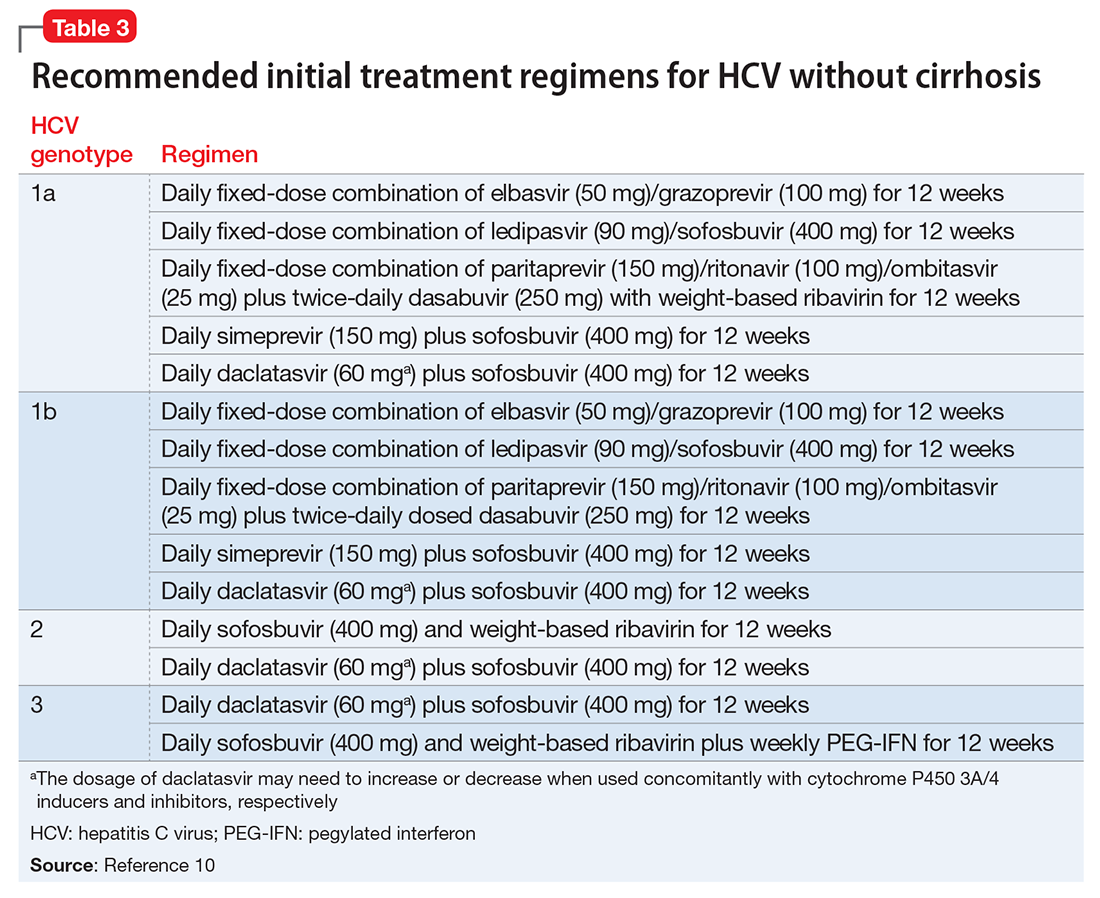

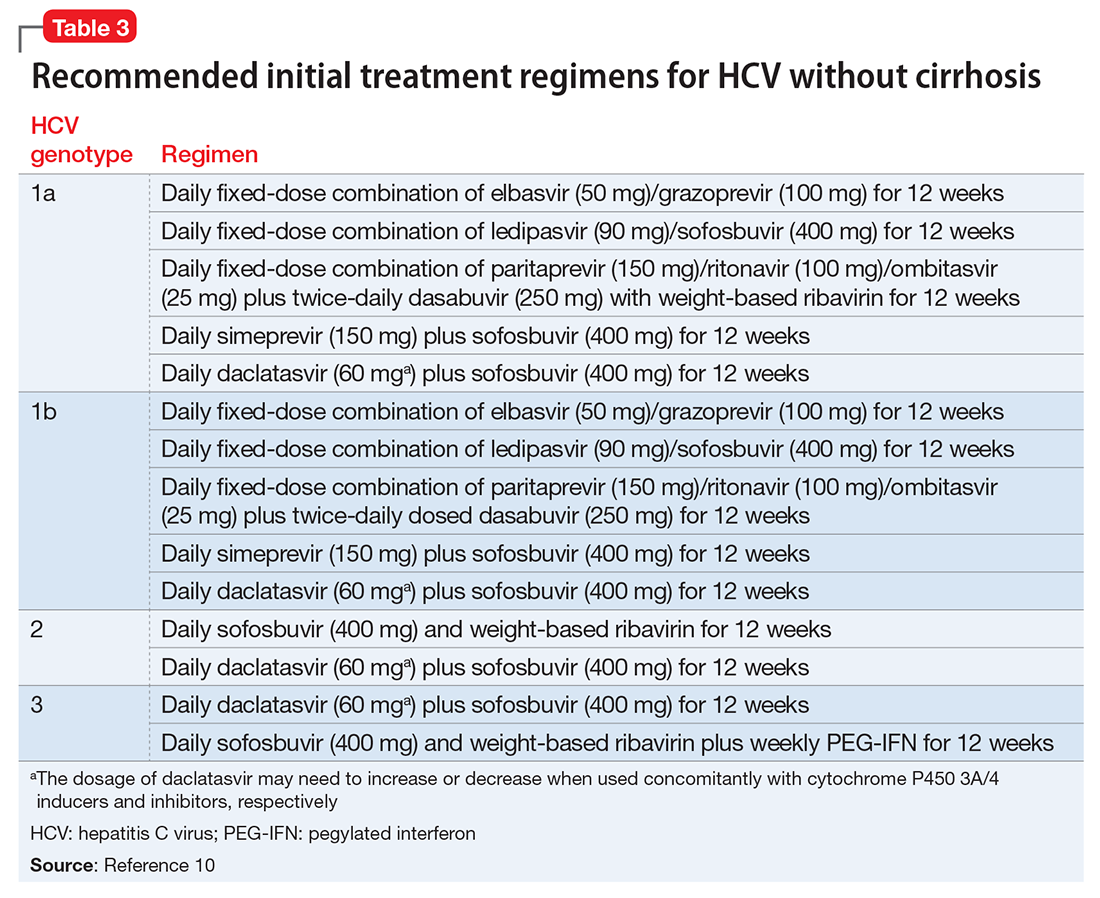

Clinical trials of the DAAs and real-world use so far do not indicate an elevated risk for neuropsychiatric symptoms, including depression.11 As a result, more patients with severe psychiatric illness likely will be eligible to receive treatment for HCV. However, as clinical experience builds with these new agents, it is important to monitor the experience of patients with psychiatric comorbidity. Current treatment guidelines for HCV genotype 1, which is most common in the United States, do not include IFN-based regimens.10 Treatment of genotype 3, which affects 6% of the U.S. population, still includes IFN. Therefore, the risk of IFN-induced depression still exists for some patients with HCV. Table 310 describes current treatment regimens in use for HCV without cirrhosis (see Related Resources for treating HCV with cirrhosis).

Evolving role of the psychiatrist

The availability of shorter, better-tolerated regimens means that the psychiatric contraindications to HCV treatment will be eased. With the emergence of non-IFN treatment regimens, the role of mental health providers could shift toward assisting with treatment adherence, monitoring drug–drug interactions, and managing comorbid substance use disorders.10

The psychiatrist’s role might shift away from the psychosocial assessment of factors affecting treatment eligibility, such as IFN-associated depressive symptoms. Clinical focus will likely shift to supporting adherence to HCV treatment regimens.23 Because depression and substance use disorders are risk factors for non-adherence, mental health providers may be called upon to optimize treatment of these conditions before beginning DAA regimens. A multi-dose regimen might be complicated for those with severe mental illness, and increased psychiatric and community support could be needed in these patients.23 Furthermore, models of care that integrate an HCV specialist with psychiatric care have demonstrated benefits.6,23 Long-term follow-up with a mental health provider will be key to provide ongoing psychiatric support, especially for those who do not achieve SVR.

Psychotropic drug–drug interactions with DAAs

Both sofosbuvir and ledipasvir are substrates of P-glycoprotein and not metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes.24 Therefore, there are no known contraindications with psychotropic medications. However, co-administration of P-glycoprotein inducers, such as St. John’s wort, could reduce sofosbuvir and ledipasvir levels leading to reduced therapeutic efficacy.

Because it has been used for many years as an HIV treatment, drug interactions with ritonavir have been well-described. This agent is a “pan-inhibitor” and inhibits the CYP3A4, 2D6, 2C9, and 2C19 enzymes and could increase levels of any psychotropic metabolized by these enzymes.25 After several weeks of treatment, it also could induce CYP3A4, which could lead to reduced efficacy of oral contraceptives because ethinylestradiol is metabolized by CYP3A4. Ritonavir is primarily metabolized by CYP3A4 (and CYP2D6 to a smaller degree). Carbamazepine induces CYP3A4, which may lead to decreased levels of ritonavir.23 This, in turn, could reduce the likelihood of attaining SVR and successful treatment of HCV.

Boceprevir, telaprevir, and simeprevir inhibit CYP3A4 to varying degrees and therefore could affect psychotropic medications metabolized by this enzyme.23,26,27 These DAAs are metabolized by CYP3A4; therefore CYP3A4 inducers, such as carbamazepine, could lower DAA blood levels, increasing risk of HCV treatment failure and viral resistance.

Daclatasvir is a substrate of CYP3A4 and an inhibitor of P-glycoprotein.28 Concomitant buprenorphine or buprenorphine/naloxone levels may be increased, although the manufacturer does not recommend dosage adjustment. Elbasvir and grazoprevir are metabolized by CYP3A4.29 Drug–drug interactions therefore may result when administered with either CYP3A4 inducers or inhibitors.

CASE Conclusion

Ms. S sees her new hepatologist, Dr. Smith. She decides to try a 12-week course of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. Dr. Smith collaborates frequently with Ms. S’s psychiatrist to discuss her case and to help monitor her psychiatric symptoms. She follows up closely with her psychiatrist for symptom monitoring and to help ensure treatment compliance. Ms. S does well with the IFN-free treatment regimen and experiences no worsening of her psychiatric symptoms during treatment.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral hepatitis. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis. Updated December 9, 2016. Accessed February 9, 2017.

2. Butterfield MI, Bosworth HB, Meador KG, et al. Five-Site Health and Risk Study Research Committee. Gender differences in hepatitis C infection and risks among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(6):848-853.

3. Rifai MA, Gleason OC, Sabouni D. Psychiatric care of the patient with hepatitis C: a review of the literature. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(6):PCC.09r00877. doi: 10.4088/PCC.09r00877whi.

4. Dinwiddie SH, Shicker L, Newman T. Prevalence of hepatitis C among psychiatric patients in the public sector. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):172-174.

5. Nakamura Y, Koh M, Miyoshi E, et al. High prevalence of the hepatitis C virus infection among the inpatients of schizophrenia and psychoactive substance abuse in Japan. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2004;28(3):591-597.

6. Sockalingam S, Blank D, Banga CA, et al. A novel program for treating patients with trimorbidity: hepatitis C, serious mental illness, and substance abuse. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25(12):1377-1384.

7. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for hepatitis C virus infection: recommendation summary. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/hepatitis-c-screening. Published June 2013. Accessed February 9, 2017.

8. Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

9. Belousova V, Abd-Rabou AA, Mousa SA. Recent advances and future directions in the management of hepatitis C infections. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;145:92-102.

10. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD); The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. http://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed February 9, 2017.

11. Rowan PJ, Bhulani N. Psychosocial assessment and monitoring in the new era of non-interferon-alpha hepatitis C treatments. World J Hepatol. 2015;7(19):2209-2213.

12. Good Rx, Inc. http://www.goodrx.com. Accessed October 9, 2015.

13. Raison CL, Borisov AS, Broadwell SD, et al. Depression during pegylated interferon-alpha plus ribavirin therapy: prevalence and prediction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(1):41-48.

14. Lotrich FE, Rabinovitz M, Gironda P, et al. Depression following pegylated interferon-alpha: characteristics and vulnerability. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63(2):131-135.

15. Udina M, Castellví P, Moreno-España J, et al. Interferon-induced depression in chronic hepatitis C: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(8):1128-1138.

16. Mustafa MZ, Schofield J, Mills PR, et al. The efficacy and safety of treating hepatitis C in patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. J Viral Hepat. 2014;21(7):e48-e51.

17. Huckans M, Mitchell A, Pavawalla S, et al. The influence of antiviral therapy on psychiatric symptoms among patients with hepatitis C and schizophrenia. Antivir Ther. 2010;15(1):111-119.

18. Huckans MS, Blackwell AD, Harms TA, et al. Management of hepatitis C disease among VA patients with schizophrenia and substance use disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(3):403-406.

19. Huckans M, Mitchell A, Ruimy S, et al. Antiviral therapy completion and response rates among hepatitis C patients with and without schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):165-172.

20. Hauser P, Morasco BJ, Linke A, et al. Antiviral completion rates and sustained viral response in hepatitis C patient with and without preexisting major depressive disorder. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(5):500-505.

21. Sockalingam S, Abbey SE. Managing depression during hepatitis C treatment. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(9):614-625.

22. Galvão-de Almeida A, Guindalini C, Batista-Neves S, et al. Can antidepressants prevent interferon-alpha-induced depression? A review of the literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):401-405.

23. Sockalingam S, Sheehan K, Feld JJ, et al. Psychiatric care during hepatitis c treatment: the changing role of psychiatrists in the era of direct-acting antivirals. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(6):512-516.

24. Harvoni [package insert]. Foster City, CA: Gilead Sciences, Inc.; 2016.

25. Wynn GH, Oesterheld, JR, Cozza KL, et al. Clinical manual of drug interactions principles for medical practice. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2009.

26. Olysio [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Therapeutics; 2016.

27. Victrelis [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co.; 2017.

28. Daklinza [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb; 2016.

29. Zepatier [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co.; 2017.

At approximately 3 to 4 million patients, hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the most common viral hepatitis in the United States. Patients with mental illness are disproportionately affected by HCV and the management of their disease poses particular challenges.

HCV is commonly transmitted via IV drug use and blood transfusions; transmission through sexual contact is rare. Most patients with HCV are asymptomatic, although some do develop symptoms of acute hepatitis. Most HCV infections become chronic, with a high incidence of liver failure requiring liver transplantation.

Hepatitis refers to inflammation of the liver, which could have various etiologies, including viral infections, alcohol abuse, or autoimmune disease. Viral hepatitis refers to infection from 5 distinct groups of virus, coined A through E.1 This article will focus on chronic HCV (Table 1).

CASE Bipolar disorder, stress, history of IV drug use

Ms. S, age 48, has bipolar I disorder and has been hospitalized 4 times in the past, including once for a suicide attempt. She has 3 children and works as a cashier. Her psychiatric symptoms have been stable on lurasidone, 80 mg/d, and escitalopram, 10 mg/d. Recently, Ms. S has been under more stress at her job. Sometimes she misses doses of her medication, and then becomes more irritable and impulsive. Her husband, noting that she has used IV heroin in the past, comes with her today and is concerned that she is “not acting right.” What is Ms. S’s risk for HCV?

HCV in mental illness

Compared with the general population, HCV is more prevalent among chronically mentally ill persons. In one study, HCV occurred twice as often in men vs women with chronic mental illness.2 Up to 50% of patients with HCV have a history of mental illness and nearly 90% have a history of substance use disorders.3 Among 668 chronically mentally ill patients at 4 public sector clinics, risk factors for HCV were common and included use of injection drugs (>20%), sharing needles (14%), and crack cocaine use (>20%).4 Higher rates of HCV were reported in hospitalized patients with schizophrenia and comorbid psychoactive substance abuse in Japan.5 Because of the high prevalence in this population, it is essential to assess for substance use disorders. Employing a non-judgmental approach with motivational interviewing techniques can be effective.6

Individuals with mental illness should be screened for HCV risk factors, such as unprotected intercourse with high-risk partners and sharing needles used for illicit drug use. Patients frequently underreport these activities. At-risk individuals should undergo laboratory testing for the HIV-1 antibody, hepatitis C antibodies, and hepatitis B antibodies. Mental health providers should counsel patients about risk reduction (eg, avoiding unprotected sexual intercourse and sharing of drug paraphernalia). Educating patients about complications of viral hepatitis, such as liver failure, could be motivation to change risky behaviors.

CASE continued

During your interview with Ms. S, she becomes irritable and tells you that you are asking too many questions. It is clear that she is not taking her medications consistently, but she agrees to do so because she does not want to lose custody of her children. She denies current use of heroin but her husband says, “I don’t know what she is doing.” In addition to advising her on reducing risk factors, you order appropriate screening tests, including hepatitis and HIV antibody tests.

Screening guidelines

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and the CDC both recommend a 1-time screening for HCV in asymptomatic or low-risk patients born between 1945 and 1965.1,7 Furthermore, both organizations recommend screening for HCV in persons at high risk, including:

- those with a history of injection drug use

- persons with recognizable exposure, such as needlesticks

- persons who received blood transfusions before 1992

- medical conditions, such as long-term dialysis.

There is no vaccine for HCV; however, patients with HCV should receive vaccination against hepatitis B.

Diagnosis

Acute symptoms include fever, fatigue, headache, cough, nausea, and vomiting. Jaundice could develop, often accompanied by pain in the right upper quadrant. If there is suspicion of viral hepatitis, psychiatrists can initiate the laboratory evaluation. Chronic hepatitis, on the other hand, often is asymptomatic, although stigmata of chronic liver disease (eg, jaundice, ascites, peripheral edema) might be detected on physical exam.8 Elevated serum transaminases are seen with acute viral hepatitis, although levels could vary in chronic cases. Serologic detection of anti-HCV antibodies establishes a HCV diagnosis.

Treatment recommendations

All patients who test positive for HCV should be evaluated and treated by a hepatologist. Goals of therapy are to reduce complications from chronic viral hepatitis, including cirrhosis and hepatic failure. Duration and optimal regimen depends on the HCV genotype.8 Treatment outcomes are measured by virological parameters, including serum aminotransferases, HCV RNA levels, and histology. The most important parameter in treating chronic HCV is the sustained virological response (SVR), which is the absence of HCV RNA 12 weeks after completing therapy.9

Treatment is recommended for all persons with chronic HCV infection, according to current treatment guidelines, which are updated regularly by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.10 Until recently, treatment consisted of IV pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN) in combination with oral ribavirin. Success rates with this regimen are approximately 40% to 50%. The advent of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) has revolutionized treatment of chronic HCV. These agents include simeprevir, sofosbuvir, ledipasvir, and the combination of ombitasvir-paritaprevir-ritonavir plus dasabuvir (brand name, Viekira Pak). Advantages of these agents are oral administration, high treatment success rates (>90%), shorter treatment duration (12 weeks vs up to 48 weeks with older regimens), and few serious adverse effects9-11; drawbacks include the pricing of these regimens, which could cost upward of ≥$100,000 for a 12-week course, and a lack of coverage under some health insurance plans.12 The manufacturers of 2 agents, telaprevir and boceprevir, removed them from the market because of decreased demand related to their unfavorable side-effect profile and the availability of better tolerated agents.

Treatment considerations for interferon in psychiatric patients

Various neuropsychiatric symptoms have been reported with the use of PEG-IFN. The range of reported symptoms include:

- depressed mood

- anxiety

- hostility

- slowness

- fatigue

- sleep disturbance

- lethargy

- irritability

- emotional lability

- social withdrawal

- poor concentration.13,14

Depressive symptoms can present as early as 1 month after starting treatment, but typically occur at 8 to 12 weeks. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 26 observational studies found a cumulative 25% risk of interferon (IFN)-induced depression in the general HCV population.15 Risk factors for IFN-induced depression include:

- female sex

- history of major depression or other psychiatric disorder

- low educational level

- the presence of baseline subthreshold depressive symptoms.

Because of the risk of inducing depression, there was initial hesitation with providing IFN treatment to patients with psychiatric disorders. However, there is evidence that individuals with chronic psychiatric illness can be treated safely with IFN-based regimens and achieve results similar to non-psychiatric populations.16,17 For example, patients with schizophrenia in a small Veterans Affairs database who received IFN for HCV did not experience higher rates of symptoms of schizophrenia, depression, or mania over 8 years of follow-up.18 Furthermore, those with schizophrenia were just as likely to reach SVR as patients without psychiatric illness.19 Other encouraging results have been reported in depressed patients. One study found similar rates of treatment completion and SVR in patients with a history of major depressive disorder compared with those without depression.20 No difference in frequency of neuropsychiatric side effects was found between the groups.

Presence of a psychiatric disorder is no longer an absolute contraindication to IFN treatment for HCV. Optimal control of psychiatric symptoms should be attained in all patients before starting HCV treatment, and close clinical monitoring is warranted. A review of 9 studies showed benefit of antidepressants for HCV patients with elevated baseline depression or a history of IFN-induced depression.21 The largest body of evidence supports the safety and efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for treating IFN-induced depression. Although no antidepressants are FDA-approved for this indication, the best-studied agents include citalopram, escitalopram, sertraline, and paroxetine.

A review of 6 studies on using antidepressants to prevent IFN-induced depression concluded there was inadequate evidence to support this approach in all patients.22 Pretreatment primarily is indicated for those with elevated depressive symptoms at baseline or those with a history of IFN-induced depression. The prevailing approach to IFN-induced depression assessment, prevention, and treatment is summarized in Table 2.

CASE continued

Ms. S tests positive for the HCV antibody but negative for HIV and hepatitis B. She immediately receives the hepatitis B vaccine series. Her sister discourages her from receiving treatment for HCV, warning her, “it will make you crazy depressed.” As a result, Ms. S avoids following up with the hepatologist. Her psychiatrist, aware that she now was taking her psychotropic medication and seeing that her mood is stable, educates her about new treatment options for HCV that do not cause depression. Ms. S finally agrees to see a hepatologist to discuss her treatment options.

IFN-free regimens

With the arrival of the DAAs, the potential now exists to use IFN-free treatment regimens,10 which could eliminate concerns about IFN-induced depression.

Clinical trials of the DAAs and real-world use so far do not indicate an elevated risk for neuropsychiatric symptoms, including depression.11 As a result, more patients with severe psychiatric illness likely will be eligible to receive treatment for HCV. However, as clinical experience builds with these new agents, it is important to monitor the experience of patients with psychiatric comorbidity. Current treatment guidelines for HCV genotype 1, which is most common in the United States, do not include IFN-based regimens.10 Treatment of genotype 3, which affects 6% of the U.S. population, still includes IFN. Therefore, the risk of IFN-induced depression still exists for some patients with HCV. Table 310 describes current treatment regimens in use for HCV without cirrhosis (see Related Resources for treating HCV with cirrhosis).

Evolving role of the psychiatrist

The availability of shorter, better-tolerated regimens means that the psychiatric contraindications to HCV treatment will be eased. With the emergence of non-IFN treatment regimens, the role of mental health providers could shift toward assisting with treatment adherence, monitoring drug–drug interactions, and managing comorbid substance use disorders.10

The psychiatrist’s role might shift away from the psychosocial assessment of factors affecting treatment eligibility, such as IFN-associated depressive symptoms. Clinical focus will likely shift to supporting adherence to HCV treatment regimens.23 Because depression and substance use disorders are risk factors for non-adherence, mental health providers may be called upon to optimize treatment of these conditions before beginning DAA regimens. A multi-dose regimen might be complicated for those with severe mental illness, and increased psychiatric and community support could be needed in these patients.23 Furthermore, models of care that integrate an HCV specialist with psychiatric care have demonstrated benefits.6,23 Long-term follow-up with a mental health provider will be key to provide ongoing psychiatric support, especially for those who do not achieve SVR.

Psychotropic drug–drug interactions with DAAs

Both sofosbuvir and ledipasvir are substrates of P-glycoprotein and not metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes.24 Therefore, there are no known contraindications with psychotropic medications. However, co-administration of P-glycoprotein inducers, such as St. John’s wort, could reduce sofosbuvir and ledipasvir levels leading to reduced therapeutic efficacy.

Because it has been used for many years as an HIV treatment, drug interactions with ritonavir have been well-described. This agent is a “pan-inhibitor” and inhibits the CYP3A4, 2D6, 2C9, and 2C19 enzymes and could increase levels of any psychotropic metabolized by these enzymes.25 After several weeks of treatment, it also could induce CYP3A4, which could lead to reduced efficacy of oral contraceptives because ethinylestradiol is metabolized by CYP3A4. Ritonavir is primarily metabolized by CYP3A4 (and CYP2D6 to a smaller degree). Carbamazepine induces CYP3A4, which may lead to decreased levels of ritonavir.23 This, in turn, could reduce the likelihood of attaining SVR and successful treatment of HCV.

Boceprevir, telaprevir, and simeprevir inhibit CYP3A4 to varying degrees and therefore could affect psychotropic medications metabolized by this enzyme.23,26,27 These DAAs are metabolized by CYP3A4; therefore CYP3A4 inducers, such as carbamazepine, could lower DAA blood levels, increasing risk of HCV treatment failure and viral resistance.

Daclatasvir is a substrate of CYP3A4 and an inhibitor of P-glycoprotein.28 Concomitant buprenorphine or buprenorphine/naloxone levels may be increased, although the manufacturer does not recommend dosage adjustment. Elbasvir and grazoprevir are metabolized by CYP3A4.29 Drug–drug interactions therefore may result when administered with either CYP3A4 inducers or inhibitors.

CASE Conclusion

Ms. S sees her new hepatologist, Dr. Smith. She decides to try a 12-week course of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. Dr. Smith collaborates frequently with Ms. S’s psychiatrist to discuss her case and to help monitor her psychiatric symptoms. She follows up closely with her psychiatrist for symptom monitoring and to help ensure treatment compliance. Ms. S does well with the IFN-free treatment regimen and experiences no worsening of her psychiatric symptoms during treatment.

At approximately 3 to 4 million patients, hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the most common viral hepatitis in the United States. Patients with mental illness are disproportionately affected by HCV and the management of their disease poses particular challenges.

HCV is commonly transmitted via IV drug use and blood transfusions; transmission through sexual contact is rare. Most patients with HCV are asymptomatic, although some do develop symptoms of acute hepatitis. Most HCV infections become chronic, with a high incidence of liver failure requiring liver transplantation.

Hepatitis refers to inflammation of the liver, which could have various etiologies, including viral infections, alcohol abuse, or autoimmune disease. Viral hepatitis refers to infection from 5 distinct groups of virus, coined A through E.1 This article will focus on chronic HCV (Table 1).

CASE Bipolar disorder, stress, history of IV drug use

Ms. S, age 48, has bipolar I disorder and has been hospitalized 4 times in the past, including once for a suicide attempt. She has 3 children and works as a cashier. Her psychiatric symptoms have been stable on lurasidone, 80 mg/d, and escitalopram, 10 mg/d. Recently, Ms. S has been under more stress at her job. Sometimes she misses doses of her medication, and then becomes more irritable and impulsive. Her husband, noting that she has used IV heroin in the past, comes with her today and is concerned that she is “not acting right.” What is Ms. S’s risk for HCV?

HCV in mental illness

Compared with the general population, HCV is more prevalent among chronically mentally ill persons. In one study, HCV occurred twice as often in men vs women with chronic mental illness.2 Up to 50% of patients with HCV have a history of mental illness and nearly 90% have a history of substance use disorders.3 Among 668 chronically mentally ill patients at 4 public sector clinics, risk factors for HCV were common and included use of injection drugs (>20%), sharing needles (14%), and crack cocaine use (>20%).4 Higher rates of HCV were reported in hospitalized patients with schizophrenia and comorbid psychoactive substance abuse in Japan.5 Because of the high prevalence in this population, it is essential to assess for substance use disorders. Employing a non-judgmental approach with motivational interviewing techniques can be effective.6

Individuals with mental illness should be screened for HCV risk factors, such as unprotected intercourse with high-risk partners and sharing needles used for illicit drug use. Patients frequently underreport these activities. At-risk individuals should undergo laboratory testing for the HIV-1 antibody, hepatitis C antibodies, and hepatitis B antibodies. Mental health providers should counsel patients about risk reduction (eg, avoiding unprotected sexual intercourse and sharing of drug paraphernalia). Educating patients about complications of viral hepatitis, such as liver failure, could be motivation to change risky behaviors.

CASE continued

During your interview with Ms. S, she becomes irritable and tells you that you are asking too many questions. It is clear that she is not taking her medications consistently, but she agrees to do so because she does not want to lose custody of her children. She denies current use of heroin but her husband says, “I don’t know what she is doing.” In addition to advising her on reducing risk factors, you order appropriate screening tests, including hepatitis and HIV antibody tests.

Screening guidelines

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and the CDC both recommend a 1-time screening for HCV in asymptomatic or low-risk patients born between 1945 and 1965.1,7 Furthermore, both organizations recommend screening for HCV in persons at high risk, including:

- those with a history of injection drug use

- persons with recognizable exposure, such as needlesticks

- persons who received blood transfusions before 1992

- medical conditions, such as long-term dialysis.

There is no vaccine for HCV; however, patients with HCV should receive vaccination against hepatitis B.

Diagnosis

Acute symptoms include fever, fatigue, headache, cough, nausea, and vomiting. Jaundice could develop, often accompanied by pain in the right upper quadrant. If there is suspicion of viral hepatitis, psychiatrists can initiate the laboratory evaluation. Chronic hepatitis, on the other hand, often is asymptomatic, although stigmata of chronic liver disease (eg, jaundice, ascites, peripheral edema) might be detected on physical exam.8 Elevated serum transaminases are seen with acute viral hepatitis, although levels could vary in chronic cases. Serologic detection of anti-HCV antibodies establishes a HCV diagnosis.

Treatment recommendations

All patients who test positive for HCV should be evaluated and treated by a hepatologist. Goals of therapy are to reduce complications from chronic viral hepatitis, including cirrhosis and hepatic failure. Duration and optimal regimen depends on the HCV genotype.8 Treatment outcomes are measured by virological parameters, including serum aminotransferases, HCV RNA levels, and histology. The most important parameter in treating chronic HCV is the sustained virological response (SVR), which is the absence of HCV RNA 12 weeks after completing therapy.9

Treatment is recommended for all persons with chronic HCV infection, according to current treatment guidelines, which are updated regularly by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.10 Until recently, treatment consisted of IV pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN) in combination with oral ribavirin. Success rates with this regimen are approximately 40% to 50%. The advent of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) has revolutionized treatment of chronic HCV. These agents include simeprevir, sofosbuvir, ledipasvir, and the combination of ombitasvir-paritaprevir-ritonavir plus dasabuvir (brand name, Viekira Pak). Advantages of these agents are oral administration, high treatment success rates (>90%), shorter treatment duration (12 weeks vs up to 48 weeks with older regimens), and few serious adverse effects9-11; drawbacks include the pricing of these regimens, which could cost upward of ≥$100,000 for a 12-week course, and a lack of coverage under some health insurance plans.12 The manufacturers of 2 agents, telaprevir and boceprevir, removed them from the market because of decreased demand related to their unfavorable side-effect profile and the availability of better tolerated agents.

Treatment considerations for interferon in psychiatric patients

Various neuropsychiatric symptoms have been reported with the use of PEG-IFN. The range of reported symptoms include:

- depressed mood

- anxiety

- hostility

- slowness

- fatigue

- sleep disturbance

- lethargy

- irritability

- emotional lability

- social withdrawal

- poor concentration.13,14

Depressive symptoms can present as early as 1 month after starting treatment, but typically occur at 8 to 12 weeks. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 26 observational studies found a cumulative 25% risk of interferon (IFN)-induced depression in the general HCV population.15 Risk factors for IFN-induced depression include:

- female sex

- history of major depression or other psychiatric disorder

- low educational level

- the presence of baseline subthreshold depressive symptoms.

Because of the risk of inducing depression, there was initial hesitation with providing IFN treatment to patients with psychiatric disorders. However, there is evidence that individuals with chronic psychiatric illness can be treated safely with IFN-based regimens and achieve results similar to non-psychiatric populations.16,17 For example, patients with schizophrenia in a small Veterans Affairs database who received IFN for HCV did not experience higher rates of symptoms of schizophrenia, depression, or mania over 8 years of follow-up.18 Furthermore, those with schizophrenia were just as likely to reach SVR as patients without psychiatric illness.19 Other encouraging results have been reported in depressed patients. One study found similar rates of treatment completion and SVR in patients with a history of major depressive disorder compared with those without depression.20 No difference in frequency of neuropsychiatric side effects was found between the groups.

Presence of a psychiatric disorder is no longer an absolute contraindication to IFN treatment for HCV. Optimal control of psychiatric symptoms should be attained in all patients before starting HCV treatment, and close clinical monitoring is warranted. A review of 9 studies showed benefit of antidepressants for HCV patients with elevated baseline depression or a history of IFN-induced depression.21 The largest body of evidence supports the safety and efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for treating IFN-induced depression. Although no antidepressants are FDA-approved for this indication, the best-studied agents include citalopram, escitalopram, sertraline, and paroxetine.

A review of 6 studies on using antidepressants to prevent IFN-induced depression concluded there was inadequate evidence to support this approach in all patients.22 Pretreatment primarily is indicated for those with elevated depressive symptoms at baseline or those with a history of IFN-induced depression. The prevailing approach to IFN-induced depression assessment, prevention, and treatment is summarized in Table 2.

CASE continued

Ms. S tests positive for the HCV antibody but negative for HIV and hepatitis B. She immediately receives the hepatitis B vaccine series. Her sister discourages her from receiving treatment for HCV, warning her, “it will make you crazy depressed.” As a result, Ms. S avoids following up with the hepatologist. Her psychiatrist, aware that she now was taking her psychotropic medication and seeing that her mood is stable, educates her about new treatment options for HCV that do not cause depression. Ms. S finally agrees to see a hepatologist to discuss her treatment options.

IFN-free regimens

With the arrival of the DAAs, the potential now exists to use IFN-free treatment regimens,10 which could eliminate concerns about IFN-induced depression.

Clinical trials of the DAAs and real-world use so far do not indicate an elevated risk for neuropsychiatric symptoms, including depression.11 As a result, more patients with severe psychiatric illness likely will be eligible to receive treatment for HCV. However, as clinical experience builds with these new agents, it is important to monitor the experience of patients with psychiatric comorbidity. Current treatment guidelines for HCV genotype 1, which is most common in the United States, do not include IFN-based regimens.10 Treatment of genotype 3, which affects 6% of the U.S. population, still includes IFN. Therefore, the risk of IFN-induced depression still exists for some patients with HCV. Table 310 describes current treatment regimens in use for HCV without cirrhosis (see Related Resources for treating HCV with cirrhosis).

Evolving role of the psychiatrist

The availability of shorter, better-tolerated regimens means that the psychiatric contraindications to HCV treatment will be eased. With the emergence of non-IFN treatment regimens, the role of mental health providers could shift toward assisting with treatment adherence, monitoring drug–drug interactions, and managing comorbid substance use disorders.10

The psychiatrist’s role might shift away from the psychosocial assessment of factors affecting treatment eligibility, such as IFN-associated depressive symptoms. Clinical focus will likely shift to supporting adherence to HCV treatment regimens.23 Because depression and substance use disorders are risk factors for non-adherence, mental health providers may be called upon to optimize treatment of these conditions before beginning DAA regimens. A multi-dose regimen might be complicated for those with severe mental illness, and increased psychiatric and community support could be needed in these patients.23 Furthermore, models of care that integrate an HCV specialist with psychiatric care have demonstrated benefits.6,23 Long-term follow-up with a mental health provider will be key to provide ongoing psychiatric support, especially for those who do not achieve SVR.

Psychotropic drug–drug interactions with DAAs

Both sofosbuvir and ledipasvir are substrates of P-glycoprotein and not metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes.24 Therefore, there are no known contraindications with psychotropic medications. However, co-administration of P-glycoprotein inducers, such as St. John’s wort, could reduce sofosbuvir and ledipasvir levels leading to reduced therapeutic efficacy.

Because it has been used for many years as an HIV treatment, drug interactions with ritonavir have been well-described. This agent is a “pan-inhibitor” and inhibits the CYP3A4, 2D6, 2C9, and 2C19 enzymes and could increase levels of any psychotropic metabolized by these enzymes.25 After several weeks of treatment, it also could induce CYP3A4, which could lead to reduced efficacy of oral contraceptives because ethinylestradiol is metabolized by CYP3A4. Ritonavir is primarily metabolized by CYP3A4 (and CYP2D6 to a smaller degree). Carbamazepine induces CYP3A4, which may lead to decreased levels of ritonavir.23 This, in turn, could reduce the likelihood of attaining SVR and successful treatment of HCV.

Boceprevir, telaprevir, and simeprevir inhibit CYP3A4 to varying degrees and therefore could affect psychotropic medications metabolized by this enzyme.23,26,27 These DAAs are metabolized by CYP3A4; therefore CYP3A4 inducers, such as carbamazepine, could lower DAA blood levels, increasing risk of HCV treatment failure and viral resistance.

Daclatasvir is a substrate of CYP3A4 and an inhibitor of P-glycoprotein.28 Concomitant buprenorphine or buprenorphine/naloxone levels may be increased, although the manufacturer does not recommend dosage adjustment. Elbasvir and grazoprevir are metabolized by CYP3A4.29 Drug–drug interactions therefore may result when administered with either CYP3A4 inducers or inhibitors.

CASE Conclusion

Ms. S sees her new hepatologist, Dr. Smith. She decides to try a 12-week course of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. Dr. Smith collaborates frequently with Ms. S’s psychiatrist to discuss her case and to help monitor her psychiatric symptoms. She follows up closely with her psychiatrist for symptom monitoring and to help ensure treatment compliance. Ms. S does well with the IFN-free treatment regimen and experiences no worsening of her psychiatric symptoms during treatment.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral hepatitis. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis. Updated December 9, 2016. Accessed February 9, 2017.

2. Butterfield MI, Bosworth HB, Meador KG, et al. Five-Site Health and Risk Study Research Committee. Gender differences in hepatitis C infection and risks among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(6):848-853.

3. Rifai MA, Gleason OC, Sabouni D. Psychiatric care of the patient with hepatitis C: a review of the literature. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(6):PCC.09r00877. doi: 10.4088/PCC.09r00877whi.

4. Dinwiddie SH, Shicker L, Newman T. Prevalence of hepatitis C among psychiatric patients in the public sector. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):172-174.

5. Nakamura Y, Koh M, Miyoshi E, et al. High prevalence of the hepatitis C virus infection among the inpatients of schizophrenia and psychoactive substance abuse in Japan. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2004;28(3):591-597.

6. Sockalingam S, Blank D, Banga CA, et al. A novel program for treating patients with trimorbidity: hepatitis C, serious mental illness, and substance abuse. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25(12):1377-1384.

7. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for hepatitis C virus infection: recommendation summary. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/hepatitis-c-screening. Published June 2013. Accessed February 9, 2017.

8. Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

9. Belousova V, Abd-Rabou AA, Mousa SA. Recent advances and future directions in the management of hepatitis C infections. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;145:92-102.

10. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD); The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. http://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed February 9, 2017.

11. Rowan PJ, Bhulani N. Psychosocial assessment and monitoring in the new era of non-interferon-alpha hepatitis C treatments. World J Hepatol. 2015;7(19):2209-2213.

12. Good Rx, Inc. http://www.goodrx.com. Accessed October 9, 2015.

13. Raison CL, Borisov AS, Broadwell SD, et al. Depression during pegylated interferon-alpha plus ribavirin therapy: prevalence and prediction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(1):41-48.

14. Lotrich FE, Rabinovitz M, Gironda P, et al. Depression following pegylated interferon-alpha: characteristics and vulnerability. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63(2):131-135.

15. Udina M, Castellví P, Moreno-España J, et al. Interferon-induced depression in chronic hepatitis C: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(8):1128-1138.

16. Mustafa MZ, Schofield J, Mills PR, et al. The efficacy and safety of treating hepatitis C in patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. J Viral Hepat. 2014;21(7):e48-e51.

17. Huckans M, Mitchell A, Pavawalla S, et al. The influence of antiviral therapy on psychiatric symptoms among patients with hepatitis C and schizophrenia. Antivir Ther. 2010;15(1):111-119.

18. Huckans MS, Blackwell AD, Harms TA, et al. Management of hepatitis C disease among VA patients with schizophrenia and substance use disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(3):403-406.

19. Huckans M, Mitchell A, Ruimy S, et al. Antiviral therapy completion and response rates among hepatitis C patients with and without schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):165-172.

20. Hauser P, Morasco BJ, Linke A, et al. Antiviral completion rates and sustained viral response in hepatitis C patient with and without preexisting major depressive disorder. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(5):500-505.

21. Sockalingam S, Abbey SE. Managing depression during hepatitis C treatment. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(9):614-625.

22. Galvão-de Almeida A, Guindalini C, Batista-Neves S, et al. Can antidepressants prevent interferon-alpha-induced depression? A review of the literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):401-405.

23. Sockalingam S, Sheehan K, Feld JJ, et al. Psychiatric care during hepatitis c treatment: the changing role of psychiatrists in the era of direct-acting antivirals. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(6):512-516.

24. Harvoni [package insert]. Foster City, CA: Gilead Sciences, Inc.; 2016.

25. Wynn GH, Oesterheld, JR, Cozza KL, et al. Clinical manual of drug interactions principles for medical practice. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2009.

26. Olysio [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Therapeutics; 2016.

27. Victrelis [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co.; 2017.

28. Daklinza [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb; 2016.

29. Zepatier [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co.; 2017.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral hepatitis. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis. Updated December 9, 2016. Accessed February 9, 2017.

2. Butterfield MI, Bosworth HB, Meador KG, et al. Five-Site Health and Risk Study Research Committee. Gender differences in hepatitis C infection and risks among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(6):848-853.

3. Rifai MA, Gleason OC, Sabouni D. Psychiatric care of the patient with hepatitis C: a review of the literature. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(6):PCC.09r00877. doi: 10.4088/PCC.09r00877whi.

4. Dinwiddie SH, Shicker L, Newman T. Prevalence of hepatitis C among psychiatric patients in the public sector. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):172-174.

5. Nakamura Y, Koh M, Miyoshi E, et al. High prevalence of the hepatitis C virus infection among the inpatients of schizophrenia and psychoactive substance abuse in Japan. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2004;28(3):591-597.

6. Sockalingam S, Blank D, Banga CA, et al. A novel program for treating patients with trimorbidity: hepatitis C, serious mental illness, and substance abuse. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25(12):1377-1384.

7. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for hepatitis C virus infection: recommendation summary. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/hepatitis-c-screening. Published June 2013. Accessed February 9, 2017.

8. Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

9. Belousova V, Abd-Rabou AA, Mousa SA. Recent advances and future directions in the management of hepatitis C infections. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;145:92-102.

10. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD); The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. http://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed February 9, 2017.

11. Rowan PJ, Bhulani N. Psychosocial assessment and monitoring in the new era of non-interferon-alpha hepatitis C treatments. World J Hepatol. 2015;7(19):2209-2213.

12. Good Rx, Inc. http://www.goodrx.com. Accessed October 9, 2015.

13. Raison CL, Borisov AS, Broadwell SD, et al. Depression during pegylated interferon-alpha plus ribavirin therapy: prevalence and prediction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(1):41-48.

14. Lotrich FE, Rabinovitz M, Gironda P, et al. Depression following pegylated interferon-alpha: characteristics and vulnerability. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63(2):131-135.

15. Udina M, Castellví P, Moreno-España J, et al. Interferon-induced depression in chronic hepatitis C: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(8):1128-1138.

16. Mustafa MZ, Schofield J, Mills PR, et al. The efficacy and safety of treating hepatitis C in patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. J Viral Hepat. 2014;21(7):e48-e51.

17. Huckans M, Mitchell A, Pavawalla S, et al. The influence of antiviral therapy on psychiatric symptoms among patients with hepatitis C and schizophrenia. Antivir Ther. 2010;15(1):111-119.

18. Huckans MS, Blackwell AD, Harms TA, et al. Management of hepatitis C disease among VA patients with schizophrenia and substance use disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(3):403-406.

19. Huckans M, Mitchell A, Ruimy S, et al. Antiviral therapy completion and response rates among hepatitis C patients with and without schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):165-172.

20. Hauser P, Morasco BJ, Linke A, et al. Antiviral completion rates and sustained viral response in hepatitis C patient with and without preexisting major depressive disorder. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(5):500-505.

21. Sockalingam S, Abbey SE. Managing depression during hepatitis C treatment. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(9):614-625.

22. Galvão-de Almeida A, Guindalini C, Batista-Neves S, et al. Can antidepressants prevent interferon-alpha-induced depression? A review of the literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):401-405.

23. Sockalingam S, Sheehan K, Feld JJ, et al. Psychiatric care during hepatitis c treatment: the changing role of psychiatrists in the era of direct-acting antivirals. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(6):512-516.

24. Harvoni [package insert]. Foster City, CA: Gilead Sciences, Inc.; 2016.

25. Wynn GH, Oesterheld, JR, Cozza KL, et al. Clinical manual of drug interactions principles for medical practice. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2009.

26. Olysio [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Therapeutics; 2016.

27. Victrelis [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co.; 2017.

28. Daklinza [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb; 2016.

29. Zepatier [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co.; 2017.

Social withdrawal and confusion in an inmate with schizoaffective disorder

CASE Withdrawn and confused

Mr. J, age 54, is brought to the emergency department from a correctional treatment facility where he is reported to be displaying new, unusual behavior. He has a history of schizoaffective disorder, which has been stable with haloperidol, 10 mg/d, for more than a year.

Although previously Mr. J openly discussed his long-standing delusions about the FBI coming to release him from prison, he no longer mentions this or any other delusional beliefs, and has become less communicative with staff and peers. Mr. J no longer accompanies the other patients to the cafeteria for meals and eats in his room alone and appears to be losing weight. He says, “I do not feel good,” but otherwise does not communicate spontaneously. Intermittently, he is irritable, without known triggers. The staff notices that Mr. J often lays on his bed, sometimes in a fetal position. Over time, he becomes confused and is seen attempting to open his room door with a toothbrush. His personal hygiene is poor, and he often urinates through his clothes, on the floor, and in his bed. Recently, Mr. J’s eczema has worsened. His gait has become unsteady, and he has orthostasis.

What could be causing these new symptoms?

a) worsening schizoaffective disorder

b) illicit drug use in the prison

c) atypical dementia

d) cardiac etiology

The author’s observations

The differential diagnosis for Mr. J appeared to be wide and without specific etiology. Because of the complex types of symptoms that Mr. J was experiencing, the emergency department managed his care and specialty clinic referrals were ordered.

It was reported that Mr. J started complaining of lightheadedness a few months ago, which worsened (unsteady gait, near falls). In the context of Mr. J’s history of lightheadedness and orthostasis, the cardiology clinic ordered a tilt table test, which was within normal limits:

- 70º head-up tilt: blood pressure, 91/67 to 102/62 mm Hg, and pulse, 70 to 79 beats per minute (bpm)

- with isoproterenol, 1 μg/minute: blood pressure, 90/66 to 110/70 mm Hg, and pulse, 77 to 124 bpm

- with isoproterenol, 2 μg/minute: blood pressure, 98/58 to 111/66 mm Hg, and pulse, 121 to 134 bpm.

The neurologist’s diagnostic impression was atypical dementia; however, Mr. J showed no memory deficits. Parkinsonism also was considered, but Mr. J had no unilateral tremor, masked facies, or micrographia. Mr. J showed some restriction in his movement, but he was not bradykinetic. The team suspected haloperidol could be causing his stiff movement.

Although it was possible that Mr. J’s schizoaffective disorder was worsening and led to the new symptoms, Mr. J appeared to be less delusional because he was no longer talking to the staff about his delusions. There seemed to be no outward evidence of progression of psychotic symptoms.

Mr. J had a history of substance abuse, including alcohol, cocaine, and Cannabis. Although prison inmates have been known to manufacture and drink “hooch,” the new symptoms Mr. J was experiencing were severe enough that his social interactions with other inmates diminished substantially. Because Mr. J had not been communicating with the other inmates and had no recent visitors, the team felt that it was unlikely that drugs were causing these symptoms. Also, a urine drug screen for cocaine, amphetamines, benzodiazepines, Cannabis, and opioids was negative.

HISTORY Substance use, violence

Mr. J was diagnosed with bipolar disorder at age 18. After later hospitalizations, his diagnosis was changed to schizoaffective disorder as a matter of diagnostic clarification. He has a long history of non-compliance with treatment, homelessness, and drug abuse.

Mr. J is serving a 20-year sentence for first-degree reckless homicide. A year after he was incarcerated, Mr. J was sent to a specialized mental health facility for inmates whose illness cannot be managed in a typical correctional setting. While at the treatment facility, Mr. J was non-compliant with medications and because of concerns about dangerousness and psychosis, the court found probable cause for involuntary commitment.

His medication regimen is trihexyphenidyl, 2 mg/d, for extrapyramidal symptoms; haloperidol, 10 mg/d, for psychosis; trazodone, 150 mg/d, for insomnia; vitamin D3, 2,000 IU/d; vitamin E, 400 IU/d, for symptoms of tardive dyskinesia; IM ziprasidone, 20 mg, because he refused oral haliperidol; and hydrocortisone cream 1% for eczema.

EVALUATION Additional tests

Mr. J’s blood pressure is 124/72 mm Hg, and pulse, 104 bpm, laying down; blood pressure, 110/84 mm Hg, and pulse, 112 bpm, sitting; and blood pressure, 108/82 mm Hg, and pulse, 129 bpm, standing. With repeated readings: blood pressure, 128/84 mm Hg, and pulse, 98 bpm, laying down; blood pressure, 125/86 mm Hg, and pulse, 113 bpm, sitting; and blood pressure, 105/76 mm Hg, and pulse, 130 bpm, standing.

Laboratory tests, including complete blood count, chemistry panel, thyroid-stimulating hormone, are within normal limits. The team feels that the investigation for an etiology for Mr. J’s symptoms needs to be more exhaustive and additional tests are ordered, including vitamin levels (C, B1, B12, B6), rapid plasma reagin for syphilis, and arbovirus testing (eastern equine encephalitis virus, western equine encephalitis, West Nile virus, La Crosse encephalitis, St. Louis encephalitis), which are negative.

What’s the next best step in managing Mr. J’s care?

a) adjust his medication

b) eliminate a mediation

c) order further testing

The author’s observations

To determine if Mr. J’s new-onset symptoms might be related to the progression of his psychiatric illness, the haloperidol dosage was increased to 20 mg/d; however, we saw no positive response to this change. His tardive dyskinesia symptoms (bruxism and other oral buccal movements) worsened. Haloperidol was reduced to 10 mg/d.

Trihexyphenidyl then was suspected to contribute to Mr. J’s confusion. Unfortunately, lowering the dosage of trihexyphenidyl to 1 mg/d, did not affect Mr. J’s current symptoms and exacerbated extrapyramidal symptoms.

The treatment team then questioned if porphyria—known as the “little imitator”—might be considered because of the variety of symptoms without an etiology, despite extensive testing. A 24-hour urine collection was ordered.

What is the correct method of collecting a urine sample for porphyrins?

a) collect a small sample and expose it to light before testing

b) collect a 24-hour sample with the sample kept in ambient temperature and light

c) collect a 24-hour sample with the sample kept on ice in a light-blocking container and frozen when sent to the laboratory

EVALUATION Diagnosis revealed

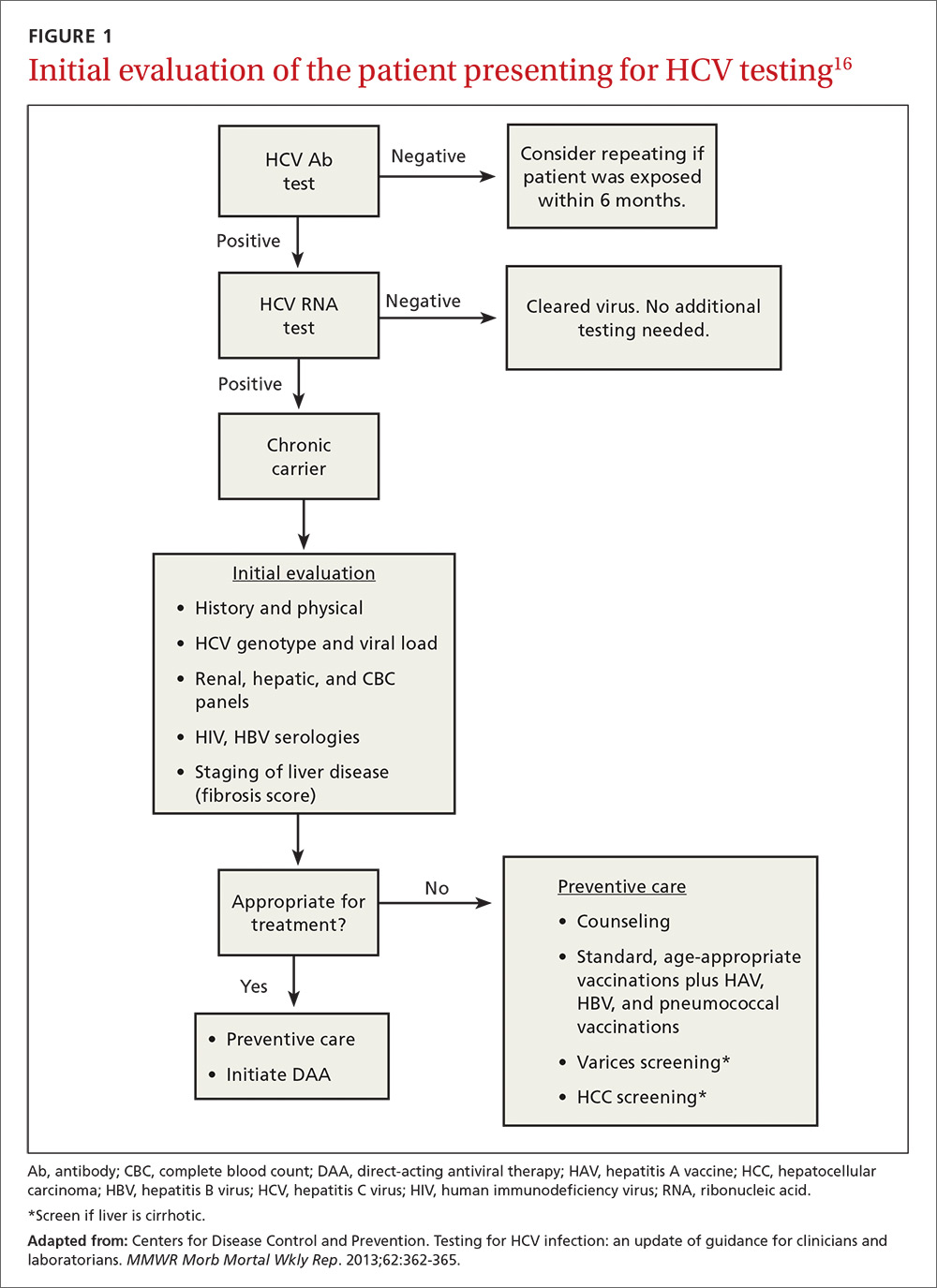

The 24-hour urine collection is obtained. However, it needed to be collected twice, because the first sample was not a full sample. Interestingly, the first sample, which is exposed to light and not kept on ice, turned dark in color. The second sample is obtained properly and sent to the laboratory. When the laboratory results are returned (Figure 1), Mr. J is diagnosed with hereditary coproporphyria (HCP).

The author’s observations

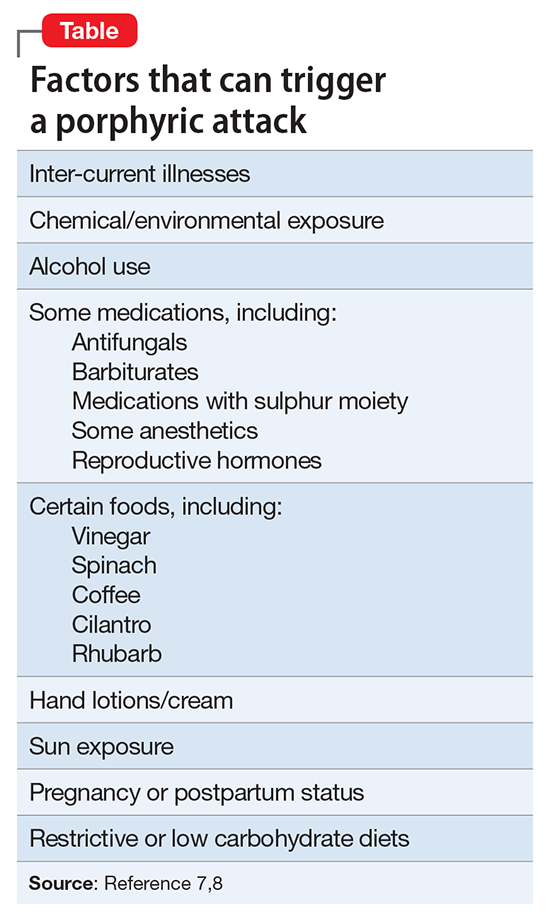

There are several types of porphyria, each associated with a different step in the chain of enzymes associated with synthesis of a heme molecule in the mitochondria. A defect in any single enzyme step will create a build up of porphyrins—a precursor to heme molecules—in erythrocytes or hepatic cells.

It is important to differentiate hepatic from erythropoietic porphyrias. The acute porphyrias (acute intermittent porphyria [AIP], HCP, and variegate porphyria generally are hepatic in origin with neuropsychiatric and neurovisceral symptoms. Cutaneous porphyrias originate in bone marrow and therefore are erythropoietic. However, there are exceptions such as porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT), which is hepatic in origin but the manifestations mainly are cutaneous1 (Figure 2).2

Although acute porphyria originates in the liver, it is a neuropsychiatric illness. In these cases, excess porphyrins cannot cross the blood–brain barrier and are neurotoxic. Clinicians can look for abnormalities in the liver via liver function tests, but liver parenchyma is not damaged by these enzyme precursors. During an acute porphyic attack, patients could experience symptoms such as:

- muscle spasms (commonly abdominal, but can be any muscle group)

- confusion

- disorientation

- autonomic instability

- lightheadness

- disorientation

- diarrhea

- light sensitivity

- dermatologic conditions

- weakness (particularly peripheral weakness)

- hypesthesia

- allodynia

- severe nausea and vomiting

- emotional lability

- psychosis as well as general malaise.

The attack could result in death.

Mr. J had many differing symptoms and was evaluated by several specialty providers. He had a chronic dermatologic condition; he was confused, disoriented, and complained of nausea, weakness, orthostasis, and loose stools. With the variety of possible symptoms that patients such as Mr. J could experience, one can see why it would lead to many different providers being involved in the diagnosis. It is not uncommon for psychiatrists to be the last providers to care for such patients who could have been evaluated by hematology, cardiology, gastroenterology, dermatology, and/or neurology.

Hereditary coproporphyria

The team considered hepatic porphyias because of new-onset symptoms of mood lability, confusion, orthostasis, unsteady gait, weakness, dermatologic conditions on hands not responsive to treatment, and general malaise. Mr. J was diagnosed with HCP, a type of porphyria caused by a defect in coproporphyrinogen oxidase that leads to an accumulation of coproporphyrinogen III. This precursor, as are many porphyrin precursors, is neurotoxic, leading to neurovisceral or neuropsychiatric effects. Although in Mr. J’s case the coproporphyrinogen III value from the 24-hour drug screen was only modestly elevated, it has been noted that levels of excreted prophyrins do not necessarily correlate with symptom severity.3

In the past, porphyria testing was performed using the Watson-Schwartz test, which used Ehrlich’s reagent to precipitate porphyrins in a urine sample,4 and was used as a “bedside” test. Interestingly, porphyrins—not the iron found in the heme molecule—are precipitated in this test and cause the reddish-purple coloration of the urine sample. When quantitative testing was developed, a 24-hour sample of urine—kept on ice and away from ambient light, later to be frozen when sent to the laboratory—became the standard tool for testing for porphyrins. Now DNA testing can be used to diagnose HCP.

OUTCOME Symptoms resolve

Mr. J is started on loxapine, 20 mg at bedtime, and his symptoms resolve within 2 weeks. He maintains some baseline delusional ideation consistent with his history of schizoaffective disorder, but he is more social, his personal hygiene improves, he attends groups, eats in the cafeteria with his peers, and is no longer confused.

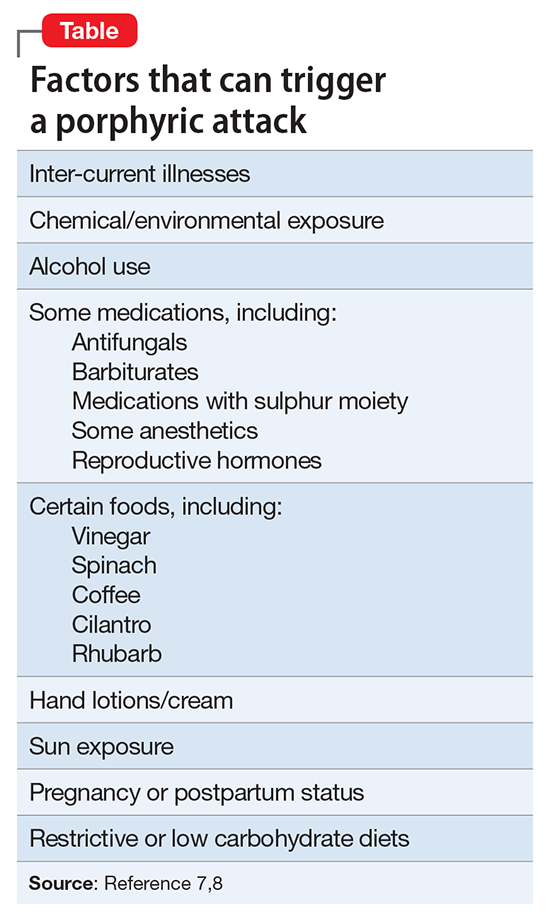

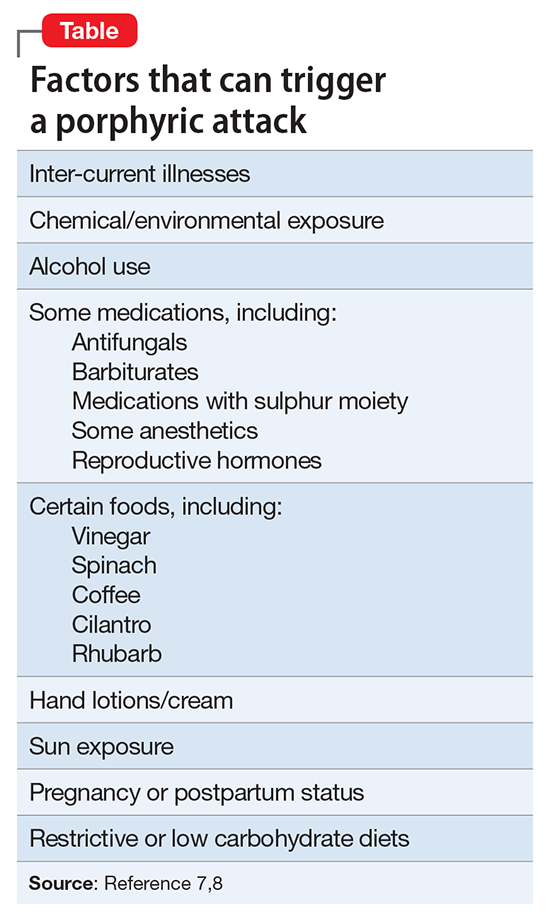

The author’s observations