User login

Dropping the A-bomb

Your first patient of the day is a 2½-year-old who has a runny nose and a cough. His mother has brought him in because his cough is more frequent and persistent than she is accustomed to hearing. He is happy and playful, and has a low-grade fever. You notice that he is slightly tachypneic, and you hear fine wheezes scattered throughout his lung fields. You also recall that at age 6 months, he was diagnosed with bronchiolitis but was never hospitalized.

Will you give him antibiotics and send him home with a nebulizer? Just the nebulizer? Just the antibiotics? Neither? We can debate those answers for hours, and you can plead for more information before you commit to an answer. But let’s skip over the question about what you are going to do and focus on what you are going to say. I want to know what diagnosis you are going to share with this mother.

Or are you going to try a pseudoscientific smoke screen and tell her that her that her son has “reactive airway disease”? You could soften it even further by reassuring her that his diagnosis is so common that it has an abbreviation: “We usually just call it RAD.”

You may not have trouble telling a parent that her child has asthma, but most clinicians struggle with dropping the A-bomb. Why? It may be that we don’t want the family to freak out. You could end up spending the rest of the morning coaxing them back off the ledge because you have diagnosed their child with a chronic illness that could kill him. This kind of exaggerated reaction is far less of a problem now than it was 30 or 40 years ago. Almost every parent knows at least one family with an asthmatic child who seems to be doing just fine. In my opinion, this apparent increase in prevalence of asthma is primarily the result of an improved awareness and a relabeling phenomenon.

Your own experience probably reflects the national statistics that less than a third of preschoolers with recurrent wheezing still have asthma by the time they finish kindergarten. And you may be hesitant to use the asthma diagnosis because you don’t want to be labeled as a clinician who cries wolf.

It may be that subconsciously you are afraid that by raising the asthma red flag you will be committing yourself to the time gobbling task of managing another patient with a chronic disease. You could gamble that he will only have one or two more episodes of wheezing, and you will be able to treat his illnesses simply as a short series of unconnected events.

Is there any harm in dancing around the asthma diagnosis? The authors of a Perspectives article in the January 2017 issue of Pediatrics argue persuasively that vague descriptive and nondiagnostic terms such as “reactive airways disease” are confusing and should be abandoned (“RAD: Reactive Airway Disease or Really Asthma Disease?” Pediatrics. 2017 Jan. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0625). They question why we would treat a condition with asthma medications and not call it asthma just because a child will probably out grow it later.

It’s more than just about sloppy language. Jose A. Castro-Rodriguez, MD, a physician who has pioneered one of the tools than can be used to predict persistent asthma in young children, observes that by failing to signal to parents that the child has a chronic condition, we run the risk that the child will be less adherent to the medication and management program we recommend. (“The Asthma Predictive Index,” Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;11[3]:157-61).

If we are going to tighten up our language and drop the vague substitute terms like RAD, and if we are hesitant to drop the A-bomb because it sounds too much like a lifelong disease when the truth is that most young children will outgrow asthma, what should we tell all those parents of wheezing preschoolers? The authors of the article in Pediatrics have several suggestions. Their favorite and the one that appeals most to me is toddler asthma. As they observe, the term “toddler asthma” implies an endpoint and the need for reevaluation to determine if the child is one of the minority who has “real” asthma.

Although it’s almost always about the money. When it's not about the money, it's usually about the labels we use.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Your first patient of the day is a 2½-year-old who has a runny nose and a cough. His mother has brought him in because his cough is more frequent and persistent than she is accustomed to hearing. He is happy and playful, and has a low-grade fever. You notice that he is slightly tachypneic, and you hear fine wheezes scattered throughout his lung fields. You also recall that at age 6 months, he was diagnosed with bronchiolitis but was never hospitalized.

Will you give him antibiotics and send him home with a nebulizer? Just the nebulizer? Just the antibiotics? Neither? We can debate those answers for hours, and you can plead for more information before you commit to an answer. But let’s skip over the question about what you are going to do and focus on what you are going to say. I want to know what diagnosis you are going to share with this mother.

Or are you going to try a pseudoscientific smoke screen and tell her that her that her son has “reactive airway disease”? You could soften it even further by reassuring her that his diagnosis is so common that it has an abbreviation: “We usually just call it RAD.”

You may not have trouble telling a parent that her child has asthma, but most clinicians struggle with dropping the A-bomb. Why? It may be that we don’t want the family to freak out. You could end up spending the rest of the morning coaxing them back off the ledge because you have diagnosed their child with a chronic illness that could kill him. This kind of exaggerated reaction is far less of a problem now than it was 30 or 40 years ago. Almost every parent knows at least one family with an asthmatic child who seems to be doing just fine. In my opinion, this apparent increase in prevalence of asthma is primarily the result of an improved awareness and a relabeling phenomenon.

Your own experience probably reflects the national statistics that less than a third of preschoolers with recurrent wheezing still have asthma by the time they finish kindergarten. And you may be hesitant to use the asthma diagnosis because you don’t want to be labeled as a clinician who cries wolf.

It may be that subconsciously you are afraid that by raising the asthma red flag you will be committing yourself to the time gobbling task of managing another patient with a chronic disease. You could gamble that he will only have one or two more episodes of wheezing, and you will be able to treat his illnesses simply as a short series of unconnected events.

Is there any harm in dancing around the asthma diagnosis? The authors of a Perspectives article in the January 2017 issue of Pediatrics argue persuasively that vague descriptive and nondiagnostic terms such as “reactive airways disease” are confusing and should be abandoned (“RAD: Reactive Airway Disease or Really Asthma Disease?” Pediatrics. 2017 Jan. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0625). They question why we would treat a condition with asthma medications and not call it asthma just because a child will probably out grow it later.

It’s more than just about sloppy language. Jose A. Castro-Rodriguez, MD, a physician who has pioneered one of the tools than can be used to predict persistent asthma in young children, observes that by failing to signal to parents that the child has a chronic condition, we run the risk that the child will be less adherent to the medication and management program we recommend. (“The Asthma Predictive Index,” Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;11[3]:157-61).

If we are going to tighten up our language and drop the vague substitute terms like RAD, and if we are hesitant to drop the A-bomb because it sounds too much like a lifelong disease when the truth is that most young children will outgrow asthma, what should we tell all those parents of wheezing preschoolers? The authors of the article in Pediatrics have several suggestions. Their favorite and the one that appeals most to me is toddler asthma. As they observe, the term “toddler asthma” implies an endpoint and the need for reevaluation to determine if the child is one of the minority who has “real” asthma.

Although it’s almost always about the money. When it's not about the money, it's usually about the labels we use.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Your first patient of the day is a 2½-year-old who has a runny nose and a cough. His mother has brought him in because his cough is more frequent and persistent than she is accustomed to hearing. He is happy and playful, and has a low-grade fever. You notice that he is slightly tachypneic, and you hear fine wheezes scattered throughout his lung fields. You also recall that at age 6 months, he was diagnosed with bronchiolitis but was never hospitalized.

Will you give him antibiotics and send him home with a nebulizer? Just the nebulizer? Just the antibiotics? Neither? We can debate those answers for hours, and you can plead for more information before you commit to an answer. But let’s skip over the question about what you are going to do and focus on what you are going to say. I want to know what diagnosis you are going to share with this mother.

Or are you going to try a pseudoscientific smoke screen and tell her that her that her son has “reactive airway disease”? You could soften it even further by reassuring her that his diagnosis is so common that it has an abbreviation: “We usually just call it RAD.”

You may not have trouble telling a parent that her child has asthma, but most clinicians struggle with dropping the A-bomb. Why? It may be that we don’t want the family to freak out. You could end up spending the rest of the morning coaxing them back off the ledge because you have diagnosed their child with a chronic illness that could kill him. This kind of exaggerated reaction is far less of a problem now than it was 30 or 40 years ago. Almost every parent knows at least one family with an asthmatic child who seems to be doing just fine. In my opinion, this apparent increase in prevalence of asthma is primarily the result of an improved awareness and a relabeling phenomenon.

Your own experience probably reflects the national statistics that less than a third of preschoolers with recurrent wheezing still have asthma by the time they finish kindergarten. And you may be hesitant to use the asthma diagnosis because you don’t want to be labeled as a clinician who cries wolf.

It may be that subconsciously you are afraid that by raising the asthma red flag you will be committing yourself to the time gobbling task of managing another patient with a chronic disease. You could gamble that he will only have one or two more episodes of wheezing, and you will be able to treat his illnesses simply as a short series of unconnected events.

Is there any harm in dancing around the asthma diagnosis? The authors of a Perspectives article in the January 2017 issue of Pediatrics argue persuasively that vague descriptive and nondiagnostic terms such as “reactive airways disease” are confusing and should be abandoned (“RAD: Reactive Airway Disease or Really Asthma Disease?” Pediatrics. 2017 Jan. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0625). They question why we would treat a condition with asthma medications and not call it asthma just because a child will probably out grow it later.

It’s more than just about sloppy language. Jose A. Castro-Rodriguez, MD, a physician who has pioneered one of the tools than can be used to predict persistent asthma in young children, observes that by failing to signal to parents that the child has a chronic condition, we run the risk that the child will be less adherent to the medication and management program we recommend. (“The Asthma Predictive Index,” Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;11[3]:157-61).

If we are going to tighten up our language and drop the vague substitute terms like RAD, and if we are hesitant to drop the A-bomb because it sounds too much like a lifelong disease when the truth is that most young children will outgrow asthma, what should we tell all those parents of wheezing preschoolers? The authors of the article in Pediatrics have several suggestions. Their favorite and the one that appeals most to me is toddler asthma. As they observe, the term “toddler asthma” implies an endpoint and the need for reevaluation to determine if the child is one of the minority who has “real” asthma.

Although it’s almost always about the money. When it's not about the money, it's usually about the labels we use.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Essential tips to diagnose and intervene early in hair loss

MIAMI – and watch for a new trend – man bun traction alopecia.

These and other clinical pearls on hair loss come courtesy of Wendy E. Roberts, MD.

“Hair loss can be scary,” but if physicians diagnose the underlying cause and treat early, a number of existing and upcoming treatments can be effective, said Dr. Roberts, a dermatologist in private practice in Rancho Mirage, Calif. “Timing is very critical.”

A dermatology full body examination is a perfect opportunity to ask patients about their hair because “you’re checking them from head to toe,” Dr. Roberts said. She recommends asking: “How is your hair doing?” This advice prompted a bit of uproar from the ODAC audience, suggesting this may be too sensitive a subject for some to broach with patients. Dr. Roberts responded, “No, not at all. Your patients will be glad you asked.

“That simple question will open up doors of opportunity” for dermatologists, she said. The condition remains very common: About 80 million people in the United States are affected by its No. 1 cause, hereditary hair loss. An Internet search for “hair loss,” in fact, reveals an overwhelming amount of consumer interest in hair loss treatment and management, yielding approximately 35 million results.

Paying attention to hair loss is not just question of appearance or aesthetics; hair loss can also indicate declining health, Dr. Roberts said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

Suggest supplements backed by science

Given the millions of online searches, it’s apparent that people continue to look for the latest solutions to treat or prevent further hair loss. But as with many “treatments” and “cures” touted online, caution is warranted – not every claim is backed by solid research, she said. “Go with supplements that do have peer review literature.”

For this reason, Dr. Roberts suggests considering the following three supplements for patients with hair loss:

• Nutrafol – “What I like about this supplement is it has ashwagandha, an Indian herb that reduces stress,” she said.

• Viviscal – This supplement has the marine extract AminoMar, which includes shark cartilage and oyster extract powder.

• Vitalize Hair – Its active ingredient, Redensyl, contains two molecules, Dr. Roberts said, one to boost metabolism of the hair follicle and the other to increase hair volume over time.

Application of platelet rich plasma is another option showing promise for hair loss. It works by activating hair bulb cells. “It kind of whispers to the hair: ‘Be young again.’ Many times it comes in at the original hair color – tell your patients to be prepared to see their hair color from childhood.” Dr. Roberts said.

Man bun alert

There is a new consideration in male hair loss based on changing hairstyles. “One thing that is trending: man bun traction alopecia. We see a lot of this in Southern California where I practice,” Dr. Roberts said. She showed meeting attendees the photo of a man with a tight hair bun whose hairline was starting to recede.

Basics to remember: differential diagnosis

When a patient presents with hair loss, things to consider in a differential diagnosis include chemical hair treatments, hairstyles that can cause traction alopecia, and behaviors such as compulsive hair pulling. Trichotillomania is on the increase. It affects approximately 2% of the population, but 90% of those are women, Dr. Roberts said. To diagnose, “look at the scalp and lower area near the nape of neck, especially in younger patients.”

She suggested that dermatologists show male patients the Norwood Scale illustrations of hair loss. The illustrations can help them understand when their hair loss is progressing over time, she added. For female patients with hair loss, the Ludwig Scale for hair loss in women can be very illustrative.

In the work-up of the patient, conduct a physical exam and consider overall health and nutritional status. Ask about family history as well, because relatives are the best window for insight into hair loss caused by genetics and aging, Dr. Roberts said.

Review patient medications. Older patients, in particular, often take multiple medications, which increases the likelihood for interactions or side effects leading to hair loss.

In addition, she had a few specific recommendations. “When you have male patient with hair loss taking Propecia [finasteride], talk to them about the dangers of exposure to a female partner and pregnancy in particular.” Also ask patients to bring in any supplements they are taking. Watch out for keratin supplements in patients with renal disease, she added, because elevated levels can be associated with kidney problems.

In terms of laboratory testing, consider checking for thyroid function, hormonal imbalance, and anemia. “The most overlooked is hemoglobin levels,” Dr. Roberts said, although anemia can cause hair loss in some patients.

Dr. Roberts is a speaker, consultant, investigator for and/or receives honoraria from Allergan, Colorescience, Galderma, Lytera, MDRejuvena, Restorsea, SkinMedica, Theraplex, Top MD Skincare, Valeant Pharmaceutical International, and Viviscal.

MIAMI – and watch for a new trend – man bun traction alopecia.

These and other clinical pearls on hair loss come courtesy of Wendy E. Roberts, MD.

“Hair loss can be scary,” but if physicians diagnose the underlying cause and treat early, a number of existing and upcoming treatments can be effective, said Dr. Roberts, a dermatologist in private practice in Rancho Mirage, Calif. “Timing is very critical.”

A dermatology full body examination is a perfect opportunity to ask patients about their hair because “you’re checking them from head to toe,” Dr. Roberts said. She recommends asking: “How is your hair doing?” This advice prompted a bit of uproar from the ODAC audience, suggesting this may be too sensitive a subject for some to broach with patients. Dr. Roberts responded, “No, not at all. Your patients will be glad you asked.

“That simple question will open up doors of opportunity” for dermatologists, she said. The condition remains very common: About 80 million people in the United States are affected by its No. 1 cause, hereditary hair loss. An Internet search for “hair loss,” in fact, reveals an overwhelming amount of consumer interest in hair loss treatment and management, yielding approximately 35 million results.

Paying attention to hair loss is not just question of appearance or aesthetics; hair loss can also indicate declining health, Dr. Roberts said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

Suggest supplements backed by science

Given the millions of online searches, it’s apparent that people continue to look for the latest solutions to treat or prevent further hair loss. But as with many “treatments” and “cures” touted online, caution is warranted – not every claim is backed by solid research, she said. “Go with supplements that do have peer review literature.”

For this reason, Dr. Roberts suggests considering the following three supplements for patients with hair loss:

• Nutrafol – “What I like about this supplement is it has ashwagandha, an Indian herb that reduces stress,” she said.

• Viviscal – This supplement has the marine extract AminoMar, which includes shark cartilage and oyster extract powder.

• Vitalize Hair – Its active ingredient, Redensyl, contains two molecules, Dr. Roberts said, one to boost metabolism of the hair follicle and the other to increase hair volume over time.

Application of platelet rich plasma is another option showing promise for hair loss. It works by activating hair bulb cells. “It kind of whispers to the hair: ‘Be young again.’ Many times it comes in at the original hair color – tell your patients to be prepared to see their hair color from childhood.” Dr. Roberts said.

Man bun alert

There is a new consideration in male hair loss based on changing hairstyles. “One thing that is trending: man bun traction alopecia. We see a lot of this in Southern California where I practice,” Dr. Roberts said. She showed meeting attendees the photo of a man with a tight hair bun whose hairline was starting to recede.

Basics to remember: differential diagnosis

When a patient presents with hair loss, things to consider in a differential diagnosis include chemical hair treatments, hairstyles that can cause traction alopecia, and behaviors such as compulsive hair pulling. Trichotillomania is on the increase. It affects approximately 2% of the population, but 90% of those are women, Dr. Roberts said. To diagnose, “look at the scalp and lower area near the nape of neck, especially in younger patients.”

She suggested that dermatologists show male patients the Norwood Scale illustrations of hair loss. The illustrations can help them understand when their hair loss is progressing over time, she added. For female patients with hair loss, the Ludwig Scale for hair loss in women can be very illustrative.

In the work-up of the patient, conduct a physical exam and consider overall health and nutritional status. Ask about family history as well, because relatives are the best window for insight into hair loss caused by genetics and aging, Dr. Roberts said.

Review patient medications. Older patients, in particular, often take multiple medications, which increases the likelihood for interactions or side effects leading to hair loss.

In addition, she had a few specific recommendations. “When you have male patient with hair loss taking Propecia [finasteride], talk to them about the dangers of exposure to a female partner and pregnancy in particular.” Also ask patients to bring in any supplements they are taking. Watch out for keratin supplements in patients with renal disease, she added, because elevated levels can be associated with kidney problems.

In terms of laboratory testing, consider checking for thyroid function, hormonal imbalance, and anemia. “The most overlooked is hemoglobin levels,” Dr. Roberts said, although anemia can cause hair loss in some patients.

Dr. Roberts is a speaker, consultant, investigator for and/or receives honoraria from Allergan, Colorescience, Galderma, Lytera, MDRejuvena, Restorsea, SkinMedica, Theraplex, Top MD Skincare, Valeant Pharmaceutical International, and Viviscal.

MIAMI – and watch for a new trend – man bun traction alopecia.

These and other clinical pearls on hair loss come courtesy of Wendy E. Roberts, MD.

“Hair loss can be scary,” but if physicians diagnose the underlying cause and treat early, a number of existing and upcoming treatments can be effective, said Dr. Roberts, a dermatologist in private practice in Rancho Mirage, Calif. “Timing is very critical.”

A dermatology full body examination is a perfect opportunity to ask patients about their hair because “you’re checking them from head to toe,” Dr. Roberts said. She recommends asking: “How is your hair doing?” This advice prompted a bit of uproar from the ODAC audience, suggesting this may be too sensitive a subject for some to broach with patients. Dr. Roberts responded, “No, not at all. Your patients will be glad you asked.

“That simple question will open up doors of opportunity” for dermatologists, she said. The condition remains very common: About 80 million people in the United States are affected by its No. 1 cause, hereditary hair loss. An Internet search for “hair loss,” in fact, reveals an overwhelming amount of consumer interest in hair loss treatment and management, yielding approximately 35 million results.

Paying attention to hair loss is not just question of appearance or aesthetics; hair loss can also indicate declining health, Dr. Roberts said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

Suggest supplements backed by science

Given the millions of online searches, it’s apparent that people continue to look for the latest solutions to treat or prevent further hair loss. But as with many “treatments” and “cures” touted online, caution is warranted – not every claim is backed by solid research, she said. “Go with supplements that do have peer review literature.”

For this reason, Dr. Roberts suggests considering the following three supplements for patients with hair loss:

• Nutrafol – “What I like about this supplement is it has ashwagandha, an Indian herb that reduces stress,” she said.

• Viviscal – This supplement has the marine extract AminoMar, which includes shark cartilage and oyster extract powder.

• Vitalize Hair – Its active ingredient, Redensyl, contains two molecules, Dr. Roberts said, one to boost metabolism of the hair follicle and the other to increase hair volume over time.

Application of platelet rich plasma is another option showing promise for hair loss. It works by activating hair bulb cells. “It kind of whispers to the hair: ‘Be young again.’ Many times it comes in at the original hair color – tell your patients to be prepared to see their hair color from childhood.” Dr. Roberts said.

Man bun alert

There is a new consideration in male hair loss based on changing hairstyles. “One thing that is trending: man bun traction alopecia. We see a lot of this in Southern California where I practice,” Dr. Roberts said. She showed meeting attendees the photo of a man with a tight hair bun whose hairline was starting to recede.

Basics to remember: differential diagnosis

When a patient presents with hair loss, things to consider in a differential diagnosis include chemical hair treatments, hairstyles that can cause traction alopecia, and behaviors such as compulsive hair pulling. Trichotillomania is on the increase. It affects approximately 2% of the population, but 90% of those are women, Dr. Roberts said. To diagnose, “look at the scalp and lower area near the nape of neck, especially in younger patients.”

She suggested that dermatologists show male patients the Norwood Scale illustrations of hair loss. The illustrations can help them understand when their hair loss is progressing over time, she added. For female patients with hair loss, the Ludwig Scale for hair loss in women can be very illustrative.

In the work-up of the patient, conduct a physical exam and consider overall health and nutritional status. Ask about family history as well, because relatives are the best window for insight into hair loss caused by genetics and aging, Dr. Roberts said.

Review patient medications. Older patients, in particular, often take multiple medications, which increases the likelihood for interactions or side effects leading to hair loss.

In addition, she had a few specific recommendations. “When you have male patient with hair loss taking Propecia [finasteride], talk to them about the dangers of exposure to a female partner and pregnancy in particular.” Also ask patients to bring in any supplements they are taking. Watch out for keratin supplements in patients with renal disease, she added, because elevated levels can be associated with kidney problems.

In terms of laboratory testing, consider checking for thyroid function, hormonal imbalance, and anemia. “The most overlooked is hemoglobin levels,” Dr. Roberts said, although anemia can cause hair loss in some patients.

Dr. Roberts is a speaker, consultant, investigator for and/or receives honoraria from Allergan, Colorescience, Galderma, Lytera, MDRejuvena, Restorsea, SkinMedica, Theraplex, Top MD Skincare, Valeant Pharmaceutical International, and Viviscal.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ODAC 2017

Dual fractional laser offers advantages for facial rejuvenation

MIAMI – A device that combines nonablative and ablative laser energies can promote mild to moderate facial photo rejuvenation and improve the appearance of fine lines and wrinkles, according to Jason Pozner, MD.

Clinicians can tailor the depth for the 1470 nm nonablative diode and the 2940 nm Er:YAG lasers for each individual patient, Dr. Pozner said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference. Advantages of resurfacing with the device, the HALO laser, include a cost-effective disposable tip and the ability to combine treatment with other therapies, he noted.

Before treatment begins, clinicians use the device to take facial measurements. Many patients find this precision reassuring, Dr. Pozner said during a live patient demonstration. Also, the device uses the information to help clinicians deliver the appropriate duration of therapy.

At this stage, it is a simple procedure, said Dr. Pozner, a plastic surgeon in a group practice in Boca Raton, Fla. Suction is turned on and the probe is then slowly advanced back and forth until the zone is finished, and “the laser beeps at you and you know you’re done,” he explained.

The HALO laser is useful for rejuvenation with little downtime. Most women treated with the device can wear makeup the same day, although more aggressively treated patients generally wait 1 additional day, Dr. Pozner said.

“I’ve never seen anything in our practice that gives this good a clinical result with this little downtime,” he added. He initially expected results to fall in between those associated with typical nonablative and ablative fractional laser treatments. But “in our experience, we get better results than ablative fractional [laser therapy], a story of one plus one equals three,” he said. “No matter what laser setting you use, patients are better by 5 days.”

When combined with intense pulsed light (IPL) treatment you can get a “double whammy effect,” Dr. Pozner said.

A meeting attendee asked about the appropriate order of IPL and HALO treatments. “When you combine the BBL (IPL) and HALO, yes, you do the IPL first,” Joel L. Cohen, MD, a private practice aesthetic dermatologist and Mohs surgeon in Denver who moderated the session at the meeting and also gave his own lecture on resurfacing options for the face.

Aside from the laser itself, the HALO system contains two tubes integrated into the handpiece, one of which is a Zimmer to deliver cooling during the procedure and the other is an air evacuator, he explained. “By having all of this integrated into the handpiece itself, it makes it much easier for the nurse who is circulating in the room to assist.”

Patients may feel warm for about 90 minutes post procedure, Dr. Cohen said. Make sure patients’ hands are clean and that the circulating nurse has given them an ice pack to minimize discomfort. “Even though I practice in Denver, where it is freezing cold right now, I’ve had patients drive home with the air conditioning on – just to try to cool down in the hour or so immediately following the laser treatment.”

Dr. Pozner said that a decrease in pore counts was an unexpected effect of HALO treatment, and he estimated that patients end up with about 20% fewer pores in treated areas, which can be advantage because “nothing else works on pores.” In his experience, most of the pore reduction persists over time.

A HALO disposal tip costs approximately $50, which he said was inexpensive, compared with other devices.

Dr. Cohen said that in his practice, using HALO, “We can give patients a significant improvement in overall photodamage and mild improvement in wrinkles with only about 5 days of redness and swelling, and on the last few days, some coffee-ground appearance.” The nonablative component can promote coagulation, so there is less bleeding when you turn up the erbium component, “offering synergistic results for the patient,” he added.

Dr. Pozner has received equipment, consulting fees, and honoraria from Halo manufacturer Sciton and is a member of the company’s advisory board and speakers bureau. Dr. Cohen is a consultant for Sciton.

MIAMI – A device that combines nonablative and ablative laser energies can promote mild to moderate facial photo rejuvenation and improve the appearance of fine lines and wrinkles, according to Jason Pozner, MD.

Clinicians can tailor the depth for the 1470 nm nonablative diode and the 2940 nm Er:YAG lasers for each individual patient, Dr. Pozner said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference. Advantages of resurfacing with the device, the HALO laser, include a cost-effective disposable tip and the ability to combine treatment with other therapies, he noted.

Before treatment begins, clinicians use the device to take facial measurements. Many patients find this precision reassuring, Dr. Pozner said during a live patient demonstration. Also, the device uses the information to help clinicians deliver the appropriate duration of therapy.

At this stage, it is a simple procedure, said Dr. Pozner, a plastic surgeon in a group practice in Boca Raton, Fla. Suction is turned on and the probe is then slowly advanced back and forth until the zone is finished, and “the laser beeps at you and you know you’re done,” he explained.

The HALO laser is useful for rejuvenation with little downtime. Most women treated with the device can wear makeup the same day, although more aggressively treated patients generally wait 1 additional day, Dr. Pozner said.

“I’ve never seen anything in our practice that gives this good a clinical result with this little downtime,” he added. He initially expected results to fall in between those associated with typical nonablative and ablative fractional laser treatments. But “in our experience, we get better results than ablative fractional [laser therapy], a story of one plus one equals three,” he said. “No matter what laser setting you use, patients are better by 5 days.”

When combined with intense pulsed light (IPL) treatment you can get a “double whammy effect,” Dr. Pozner said.

A meeting attendee asked about the appropriate order of IPL and HALO treatments. “When you combine the BBL (IPL) and HALO, yes, you do the IPL first,” Joel L. Cohen, MD, a private practice aesthetic dermatologist and Mohs surgeon in Denver who moderated the session at the meeting and also gave his own lecture on resurfacing options for the face.

Aside from the laser itself, the HALO system contains two tubes integrated into the handpiece, one of which is a Zimmer to deliver cooling during the procedure and the other is an air evacuator, he explained. “By having all of this integrated into the handpiece itself, it makes it much easier for the nurse who is circulating in the room to assist.”

Patients may feel warm for about 90 minutes post procedure, Dr. Cohen said. Make sure patients’ hands are clean and that the circulating nurse has given them an ice pack to minimize discomfort. “Even though I practice in Denver, where it is freezing cold right now, I’ve had patients drive home with the air conditioning on – just to try to cool down in the hour or so immediately following the laser treatment.”

Dr. Pozner said that a decrease in pore counts was an unexpected effect of HALO treatment, and he estimated that patients end up with about 20% fewer pores in treated areas, which can be advantage because “nothing else works on pores.” In his experience, most of the pore reduction persists over time.

A HALO disposal tip costs approximately $50, which he said was inexpensive, compared with other devices.

Dr. Cohen said that in his practice, using HALO, “We can give patients a significant improvement in overall photodamage and mild improvement in wrinkles with only about 5 days of redness and swelling, and on the last few days, some coffee-ground appearance.” The nonablative component can promote coagulation, so there is less bleeding when you turn up the erbium component, “offering synergistic results for the patient,” he added.

Dr. Pozner has received equipment, consulting fees, and honoraria from Halo manufacturer Sciton and is a member of the company’s advisory board and speakers bureau. Dr. Cohen is a consultant for Sciton.

MIAMI – A device that combines nonablative and ablative laser energies can promote mild to moderate facial photo rejuvenation and improve the appearance of fine lines and wrinkles, according to Jason Pozner, MD.

Clinicians can tailor the depth for the 1470 nm nonablative diode and the 2940 nm Er:YAG lasers for each individual patient, Dr. Pozner said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference. Advantages of resurfacing with the device, the HALO laser, include a cost-effective disposable tip and the ability to combine treatment with other therapies, he noted.

Before treatment begins, clinicians use the device to take facial measurements. Many patients find this precision reassuring, Dr. Pozner said during a live patient demonstration. Also, the device uses the information to help clinicians deliver the appropriate duration of therapy.

At this stage, it is a simple procedure, said Dr. Pozner, a plastic surgeon in a group practice in Boca Raton, Fla. Suction is turned on and the probe is then slowly advanced back and forth until the zone is finished, and “the laser beeps at you and you know you’re done,” he explained.

The HALO laser is useful for rejuvenation with little downtime. Most women treated with the device can wear makeup the same day, although more aggressively treated patients generally wait 1 additional day, Dr. Pozner said.

“I’ve never seen anything in our practice that gives this good a clinical result with this little downtime,” he added. He initially expected results to fall in between those associated with typical nonablative and ablative fractional laser treatments. But “in our experience, we get better results than ablative fractional [laser therapy], a story of one plus one equals three,” he said. “No matter what laser setting you use, patients are better by 5 days.”

When combined with intense pulsed light (IPL) treatment you can get a “double whammy effect,” Dr. Pozner said.

A meeting attendee asked about the appropriate order of IPL and HALO treatments. “When you combine the BBL (IPL) and HALO, yes, you do the IPL first,” Joel L. Cohen, MD, a private practice aesthetic dermatologist and Mohs surgeon in Denver who moderated the session at the meeting and also gave his own lecture on resurfacing options for the face.

Aside from the laser itself, the HALO system contains two tubes integrated into the handpiece, one of which is a Zimmer to deliver cooling during the procedure and the other is an air evacuator, he explained. “By having all of this integrated into the handpiece itself, it makes it much easier for the nurse who is circulating in the room to assist.”

Patients may feel warm for about 90 minutes post procedure, Dr. Cohen said. Make sure patients’ hands are clean and that the circulating nurse has given them an ice pack to minimize discomfort. “Even though I practice in Denver, where it is freezing cold right now, I’ve had patients drive home with the air conditioning on – just to try to cool down in the hour or so immediately following the laser treatment.”

Dr. Pozner said that a decrease in pore counts was an unexpected effect of HALO treatment, and he estimated that patients end up with about 20% fewer pores in treated areas, which can be advantage because “nothing else works on pores.” In his experience, most of the pore reduction persists over time.

A HALO disposal tip costs approximately $50, which he said was inexpensive, compared with other devices.

Dr. Cohen said that in his practice, using HALO, “We can give patients a significant improvement in overall photodamage and mild improvement in wrinkles with only about 5 days of redness and swelling, and on the last few days, some coffee-ground appearance.” The nonablative component can promote coagulation, so there is less bleeding when you turn up the erbium component, “offering synergistic results for the patient,” he added.

Dr. Pozner has received equipment, consulting fees, and honoraria from Halo manufacturer Sciton and is a member of the company’s advisory board and speakers bureau. Dr. Cohen is a consultant for Sciton.

AT THE ODAC CONFERENCE

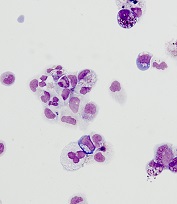

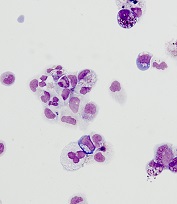

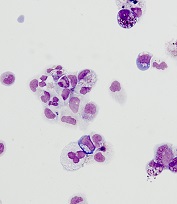

In active CLL with deletion 17p, consider trial enrollment

NEW YORK – Outside of clinical trials, therapy for early stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia in patients with deletion of the short arm of chromosome 17 (del[17]p) and/or mutation of the tumor suppressor gene TP53 requires the presence of active disease, according to Neil E. Kay, MD.

“Right now, we would propose that patients with del[17]p should have additional prognostic work-up. It’s very important to know if they are unmutated or mutated for the IgVH gene,” he said, adding that stimulated karyotype is also important to perform in those with del[17]p.

“The median overall survivorship in many phase II and phase III trials appears to be around 2 to 3 years,” he said.

Those with a chromosome 17 (del[17]p) and/or mutation of the tumor suppressor gene TP53 who receive chemoimmunotherapy very rarely achieve a complete response, or if they do they have a short duration of response, he added.

In treated patients, 17p deletion and p53 mutation are the most common abnormalities acquired during the course of the disease.

“Unfortunately there appears to be a selection pressure, and [in treated patients] the incidence of 17p and the p53 mutation has been reported up to 23%-44%. No one understands completely the biology of this, but it may be that subclones are present and expand, or that new mutations occur due to selection pressure of [chemoimmunotherapy] and the overgrowth of these subclones,” he said.

Importantly, not all patients with del[17]p or p53 mutation have bad outcomes; there are patients with indolent disease, he noted, adding that various criteria have been shown to help identify which patients are at risk for poor outcomes and to classify them according to risk. In general, lower-risk patients have mutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable gene status, early stage disease, younger age, good performance status, and normal serum lactate dehydrogenase. These criteria could be used to identify low-risk patients who can be followed, he said.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) evaluation of patients is a useful tool when there is no access to sequencing and other tests, Dr. Kay said, describing a recent multinational CLL Research Consortium study of nearly 1,600 patients (Br J Haematol. 2016 Apr;173[1]:105-13).

In that study, he and his colleagues found that patients with less than 50% 17p did not have such poor outcomes, but at 50%-plus they did much worse in terms of time to first treatment.

Based on the available data, Dr. Kay said that treatment is unnecessary in asymptomatic patients, except, perhaps, in high-risk patients identified using recently published risk models, for whom clinical trial enrollment may be considered.

“We do advocate having a discussion about allogeneic stem cell transplant since this may still be the only curative approach,” he added.

In patients with del[17]p and/or p53 mutation who have progressive disease, Dr. Kay said his take on the available data is that patients should first be categorized by age, then by whether they are fit or frail, and finally by whether or not they have del[17]p. Those under age 70 years without del[17]p and who have a mutated IgVH status should be considered for a clinical trial, and are also good candidates for chemoimmunotherapy. If they do have del[17]p or p53 mutation, consider clinical trial enrollment or treatment with ibrutinib, he said.

Fit patients in a complete response can be referred for transplant evaluation, but while the other treatments can be considered in frail patients or those aged 70 years or older, transplant is not advised, he added.

For relapsed or refractory patients, FISH testing should be performed or repeated, because such patients are at high risk of progression to develop del[17]p or mutation, he noted.

Those who are asymptomatic can be observed or enrolled in a clinical trial, and those who are symptomatic can be enrolled in a clinical trial or treated with various novel agents, including ibrutinib, idelalisib/rituximab, venetoclax, or combination therapies with methylpred–anti-CD20, or alemtuzumab with or without rituximab. Referral for transplant may be warranted in these patients if they are fit.

“Progressive CLL patients with 17p deletion/p53 mutations are much less likely to do well with chemoimmunotherapy, and novel inhibitors are effective, but we still need to enhance complete response rates and minimal residual disease-negative status for these high-risk patients,” he said.

Dr. Kay reported consulting for or receiving grant/research support from Acerta, Celgene, Gilead, Infinity, MorphoSys, Pharmacyclics, and Tolero.

NEW YORK – Outside of clinical trials, therapy for early stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia in patients with deletion of the short arm of chromosome 17 (del[17]p) and/or mutation of the tumor suppressor gene TP53 requires the presence of active disease, according to Neil E. Kay, MD.

“Right now, we would propose that patients with del[17]p should have additional prognostic work-up. It’s very important to know if they are unmutated or mutated for the IgVH gene,” he said, adding that stimulated karyotype is also important to perform in those with del[17]p.

“The median overall survivorship in many phase II and phase III trials appears to be around 2 to 3 years,” he said.

Those with a chromosome 17 (del[17]p) and/or mutation of the tumor suppressor gene TP53 who receive chemoimmunotherapy very rarely achieve a complete response, or if they do they have a short duration of response, he added.

In treated patients, 17p deletion and p53 mutation are the most common abnormalities acquired during the course of the disease.

“Unfortunately there appears to be a selection pressure, and [in treated patients] the incidence of 17p and the p53 mutation has been reported up to 23%-44%. No one understands completely the biology of this, but it may be that subclones are present and expand, or that new mutations occur due to selection pressure of [chemoimmunotherapy] and the overgrowth of these subclones,” he said.

Importantly, not all patients with del[17]p or p53 mutation have bad outcomes; there are patients with indolent disease, he noted, adding that various criteria have been shown to help identify which patients are at risk for poor outcomes and to classify them according to risk. In general, lower-risk patients have mutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable gene status, early stage disease, younger age, good performance status, and normal serum lactate dehydrogenase. These criteria could be used to identify low-risk patients who can be followed, he said.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) evaluation of patients is a useful tool when there is no access to sequencing and other tests, Dr. Kay said, describing a recent multinational CLL Research Consortium study of nearly 1,600 patients (Br J Haematol. 2016 Apr;173[1]:105-13).

In that study, he and his colleagues found that patients with less than 50% 17p did not have such poor outcomes, but at 50%-plus they did much worse in terms of time to first treatment.

Based on the available data, Dr. Kay said that treatment is unnecessary in asymptomatic patients, except, perhaps, in high-risk patients identified using recently published risk models, for whom clinical trial enrollment may be considered.

“We do advocate having a discussion about allogeneic stem cell transplant since this may still be the only curative approach,” he added.

In patients with del[17]p and/or p53 mutation who have progressive disease, Dr. Kay said his take on the available data is that patients should first be categorized by age, then by whether they are fit or frail, and finally by whether or not they have del[17]p. Those under age 70 years without del[17]p and who have a mutated IgVH status should be considered for a clinical trial, and are also good candidates for chemoimmunotherapy. If they do have del[17]p or p53 mutation, consider clinical trial enrollment or treatment with ibrutinib, he said.

Fit patients in a complete response can be referred for transplant evaluation, but while the other treatments can be considered in frail patients or those aged 70 years or older, transplant is not advised, he added.

For relapsed or refractory patients, FISH testing should be performed or repeated, because such patients are at high risk of progression to develop del[17]p or mutation, he noted.

Those who are asymptomatic can be observed or enrolled in a clinical trial, and those who are symptomatic can be enrolled in a clinical trial or treated with various novel agents, including ibrutinib, idelalisib/rituximab, venetoclax, or combination therapies with methylpred–anti-CD20, or alemtuzumab with or without rituximab. Referral for transplant may be warranted in these patients if they are fit.

“Progressive CLL patients with 17p deletion/p53 mutations are much less likely to do well with chemoimmunotherapy, and novel inhibitors are effective, but we still need to enhance complete response rates and minimal residual disease-negative status for these high-risk patients,” he said.

Dr. Kay reported consulting for or receiving grant/research support from Acerta, Celgene, Gilead, Infinity, MorphoSys, Pharmacyclics, and Tolero.

NEW YORK – Outside of clinical trials, therapy for early stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia in patients with deletion of the short arm of chromosome 17 (del[17]p) and/or mutation of the tumor suppressor gene TP53 requires the presence of active disease, according to Neil E. Kay, MD.

“Right now, we would propose that patients with del[17]p should have additional prognostic work-up. It’s very important to know if they are unmutated or mutated for the IgVH gene,” he said, adding that stimulated karyotype is also important to perform in those with del[17]p.

“The median overall survivorship in many phase II and phase III trials appears to be around 2 to 3 years,” he said.

Those with a chromosome 17 (del[17]p) and/or mutation of the tumor suppressor gene TP53 who receive chemoimmunotherapy very rarely achieve a complete response, or if they do they have a short duration of response, he added.

In treated patients, 17p deletion and p53 mutation are the most common abnormalities acquired during the course of the disease.

“Unfortunately there appears to be a selection pressure, and [in treated patients] the incidence of 17p and the p53 mutation has been reported up to 23%-44%. No one understands completely the biology of this, but it may be that subclones are present and expand, or that new mutations occur due to selection pressure of [chemoimmunotherapy] and the overgrowth of these subclones,” he said.

Importantly, not all patients with del[17]p or p53 mutation have bad outcomes; there are patients with indolent disease, he noted, adding that various criteria have been shown to help identify which patients are at risk for poor outcomes and to classify them according to risk. In general, lower-risk patients have mutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable gene status, early stage disease, younger age, good performance status, and normal serum lactate dehydrogenase. These criteria could be used to identify low-risk patients who can be followed, he said.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) evaluation of patients is a useful tool when there is no access to sequencing and other tests, Dr. Kay said, describing a recent multinational CLL Research Consortium study of nearly 1,600 patients (Br J Haematol. 2016 Apr;173[1]:105-13).

In that study, he and his colleagues found that patients with less than 50% 17p did not have such poor outcomes, but at 50%-plus they did much worse in terms of time to first treatment.

Based on the available data, Dr. Kay said that treatment is unnecessary in asymptomatic patients, except, perhaps, in high-risk patients identified using recently published risk models, for whom clinical trial enrollment may be considered.

“We do advocate having a discussion about allogeneic stem cell transplant since this may still be the only curative approach,” he added.

In patients with del[17]p and/or p53 mutation who have progressive disease, Dr. Kay said his take on the available data is that patients should first be categorized by age, then by whether they are fit or frail, and finally by whether or not they have del[17]p. Those under age 70 years without del[17]p and who have a mutated IgVH status should be considered for a clinical trial, and are also good candidates for chemoimmunotherapy. If they do have del[17]p or p53 mutation, consider clinical trial enrollment or treatment with ibrutinib, he said.

Fit patients in a complete response can be referred for transplant evaluation, but while the other treatments can be considered in frail patients or those aged 70 years or older, transplant is not advised, he added.

For relapsed or refractory patients, FISH testing should be performed or repeated, because such patients are at high risk of progression to develop del[17]p or mutation, he noted.

Those who are asymptomatic can be observed or enrolled in a clinical trial, and those who are symptomatic can be enrolled in a clinical trial or treated with various novel agents, including ibrutinib, idelalisib/rituximab, venetoclax, or combination therapies with methylpred–anti-CD20, or alemtuzumab with or without rituximab. Referral for transplant may be warranted in these patients if they are fit.

“Progressive CLL patients with 17p deletion/p53 mutations are much less likely to do well with chemoimmunotherapy, and novel inhibitors are effective, but we still need to enhance complete response rates and minimal residual disease-negative status for these high-risk patients,” he said.

Dr. Kay reported consulting for or receiving grant/research support from Acerta, Celgene, Gilead, Infinity, MorphoSys, Pharmacyclics, and Tolero.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM LYMPHOMA & MYELOMA

Antibiotics have a role in PANS even with no infection

SAN FRANCISCO – Antibiotics might help in pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS) even if there’s no apparent infection, according to Kiki Chang, MD, director of PANS research at Stanford (Calif.) University.

The first step at Stanford is to look for an active infection, and knock it out with antibiotics. Dr. Chang has seen remarkable turnarounds in some of those cases, but even if there’s no infection, “we still do use antibiotics.” There are positive data, “although not a lot,” indicating that they can help. Some kids even seem to need to be on long-term antibiotics, and flair if taken off long after infections should have been cleared.

“We don’t know what’s going on. We try to stop antibiotics if we can; if patients relapse, we think the benefit [of ongoing treatment] outweighs the risks. Some kids just have to be on antibiotics for a long time, and that’s an issue.” Perhaps it has something to do with the anti-inflammatory properties of antibiotics like azithromycin and amoxicillin, or there might be a lingering infection, he said at a psychopharmacology update held by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

PANS is a recently coined term for the sudden onset of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) within a few days of an infection, metabolic disturbance, or other inflammatory insult. Anxiety, mood problems, and tics are common. There might be severe food restriction – only eating white foods, for instance – that are not related to body image.

PANS broadened the concept of pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS), which was first described in 1998, although it’s been known for generations that acute streptococcus infections can lead to abrupt psychiatric symptoms.

PANS is the topic of ongoing investigation, and Dr. Chang and many others are working to define the syndrome and its treatment, and trying especially to determine how PANS differs from typical OCD and other problems with more insidious onset. The idea is that inflammation in the patient’s brain, whatever the source, triggers an OCD mechanism in susceptible patients. As a concept, “we believe it’s true,” he said.

For now, it’s best to refer suspected cases to one of several academic PANS programs in the United States, as diagnosis and treatment isn’t ready for general practice, he said.

If more than antibiotics are needed, Stanford considers targeting inflammation. Some children respond to easy options such as ibuprofen. Dr. Chang has seen some helped with prednisone, but treatment is tricky. There might be an occult infection, and PANS can present with psychiatric issues that prednisone can make worse, including depression and mania. Intravenous immunoglobulin is another of the many options, “but we really need about four treatments” to see if it helps.

Cognitive behavioral therapy and family support also helps. As for psychotropic medication, “we often use them, but they rarely take away the acute symptoms,” and PANS children seem especially sensitive to side effects. “I’ve seen many of them become manic on SSRIs. I’ve seen some of them have very strong [extrapyramidal symptoms] with atypical antipsychotics. You have to be very careful; we don’t have any good studies” of psychiatric drugs in this population, he said.

At the moment, PANS seems to be more common in boys than girls, and most patients have a relapsing/remitting course and a family history of autoimmune disease. Suicidal and homicidal ideation can be part of the condition.

Dr. Chang believes PANS could be part of the overall increase in autoimmune disease and psychiatric disorders in children over the past few decades.

“We have more kids who have special needs than ever before,” large, objective increases in bipolar, autism, and other psychiatric problems, as well as increases in psoriasis, nut allergies, and other autoimmune issues. “What causes it is harder to say, but there has been a change for sure in kids and their immune system development that does affect the brain, and has probably led to more neuropsychiatric disturbances,” he said.

“No one talks about it. Everyone thinks that it’s some sort of pharmaceutical industry conspiracy” to sell more drugs by increasing scrutiny of children. “I think it’s caused by something in the environment interacting with genetics,” whether it’s infections, toxins, or something else. “We don’t know. Any kind of inflammation can be a trigger” and “we know inflammation” is key to “many psychiatric symptoms. I do think there’s something going on with kids over the last 30 years,” he said.

Dr. Chang is a consultant for and/or has received research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Lilly, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, and other companies.

SAN FRANCISCO – Antibiotics might help in pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS) even if there’s no apparent infection, according to Kiki Chang, MD, director of PANS research at Stanford (Calif.) University.

The first step at Stanford is to look for an active infection, and knock it out with antibiotics. Dr. Chang has seen remarkable turnarounds in some of those cases, but even if there’s no infection, “we still do use antibiotics.” There are positive data, “although not a lot,” indicating that they can help. Some kids even seem to need to be on long-term antibiotics, and flair if taken off long after infections should have been cleared.

“We don’t know what’s going on. We try to stop antibiotics if we can; if patients relapse, we think the benefit [of ongoing treatment] outweighs the risks. Some kids just have to be on antibiotics for a long time, and that’s an issue.” Perhaps it has something to do with the anti-inflammatory properties of antibiotics like azithromycin and amoxicillin, or there might be a lingering infection, he said at a psychopharmacology update held by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

PANS is a recently coined term for the sudden onset of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) within a few days of an infection, metabolic disturbance, or other inflammatory insult. Anxiety, mood problems, and tics are common. There might be severe food restriction – only eating white foods, for instance – that are not related to body image.

PANS broadened the concept of pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS), which was first described in 1998, although it’s been known for generations that acute streptococcus infections can lead to abrupt psychiatric symptoms.

PANS is the topic of ongoing investigation, and Dr. Chang and many others are working to define the syndrome and its treatment, and trying especially to determine how PANS differs from typical OCD and other problems with more insidious onset. The idea is that inflammation in the patient’s brain, whatever the source, triggers an OCD mechanism in susceptible patients. As a concept, “we believe it’s true,” he said.

For now, it’s best to refer suspected cases to one of several academic PANS programs in the United States, as diagnosis and treatment isn’t ready for general practice, he said.

If more than antibiotics are needed, Stanford considers targeting inflammation. Some children respond to easy options such as ibuprofen. Dr. Chang has seen some helped with prednisone, but treatment is tricky. There might be an occult infection, and PANS can present with psychiatric issues that prednisone can make worse, including depression and mania. Intravenous immunoglobulin is another of the many options, “but we really need about four treatments” to see if it helps.

Cognitive behavioral therapy and family support also helps. As for psychotropic medication, “we often use them, but they rarely take away the acute symptoms,” and PANS children seem especially sensitive to side effects. “I’ve seen many of them become manic on SSRIs. I’ve seen some of them have very strong [extrapyramidal symptoms] with atypical antipsychotics. You have to be very careful; we don’t have any good studies” of psychiatric drugs in this population, he said.

At the moment, PANS seems to be more common in boys than girls, and most patients have a relapsing/remitting course and a family history of autoimmune disease. Suicidal and homicidal ideation can be part of the condition.

Dr. Chang believes PANS could be part of the overall increase in autoimmune disease and psychiatric disorders in children over the past few decades.

“We have more kids who have special needs than ever before,” large, objective increases in bipolar, autism, and other psychiatric problems, as well as increases in psoriasis, nut allergies, and other autoimmune issues. “What causes it is harder to say, but there has been a change for sure in kids and their immune system development that does affect the brain, and has probably led to more neuropsychiatric disturbances,” he said.

“No one talks about it. Everyone thinks that it’s some sort of pharmaceutical industry conspiracy” to sell more drugs by increasing scrutiny of children. “I think it’s caused by something in the environment interacting with genetics,” whether it’s infections, toxins, or something else. “We don’t know. Any kind of inflammation can be a trigger” and “we know inflammation” is key to “many psychiatric symptoms. I do think there’s something going on with kids over the last 30 years,” he said.

Dr. Chang is a consultant for and/or has received research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Lilly, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, and other companies.

SAN FRANCISCO – Antibiotics might help in pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS) even if there’s no apparent infection, according to Kiki Chang, MD, director of PANS research at Stanford (Calif.) University.

The first step at Stanford is to look for an active infection, and knock it out with antibiotics. Dr. Chang has seen remarkable turnarounds in some of those cases, but even if there’s no infection, “we still do use antibiotics.” There are positive data, “although not a lot,” indicating that they can help. Some kids even seem to need to be on long-term antibiotics, and flair if taken off long after infections should have been cleared.

“We don’t know what’s going on. We try to stop antibiotics if we can; if patients relapse, we think the benefit [of ongoing treatment] outweighs the risks. Some kids just have to be on antibiotics for a long time, and that’s an issue.” Perhaps it has something to do with the anti-inflammatory properties of antibiotics like azithromycin and amoxicillin, or there might be a lingering infection, he said at a psychopharmacology update held by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

PANS is a recently coined term for the sudden onset of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) within a few days of an infection, metabolic disturbance, or other inflammatory insult. Anxiety, mood problems, and tics are common. There might be severe food restriction – only eating white foods, for instance – that are not related to body image.

PANS broadened the concept of pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS), which was first described in 1998, although it’s been known for generations that acute streptococcus infections can lead to abrupt psychiatric symptoms.

PANS is the topic of ongoing investigation, and Dr. Chang and many others are working to define the syndrome and its treatment, and trying especially to determine how PANS differs from typical OCD and other problems with more insidious onset. The idea is that inflammation in the patient’s brain, whatever the source, triggers an OCD mechanism in susceptible patients. As a concept, “we believe it’s true,” he said.

For now, it’s best to refer suspected cases to one of several academic PANS programs in the United States, as diagnosis and treatment isn’t ready for general practice, he said.

If more than antibiotics are needed, Stanford considers targeting inflammation. Some children respond to easy options such as ibuprofen. Dr. Chang has seen some helped with prednisone, but treatment is tricky. There might be an occult infection, and PANS can present with psychiatric issues that prednisone can make worse, including depression and mania. Intravenous immunoglobulin is another of the many options, “but we really need about four treatments” to see if it helps.

Cognitive behavioral therapy and family support also helps. As for psychotropic medication, “we often use them, but they rarely take away the acute symptoms,” and PANS children seem especially sensitive to side effects. “I’ve seen many of them become manic on SSRIs. I’ve seen some of them have very strong [extrapyramidal symptoms] with atypical antipsychotics. You have to be very careful; we don’t have any good studies” of psychiatric drugs in this population, he said.

At the moment, PANS seems to be more common in boys than girls, and most patients have a relapsing/remitting course and a family history of autoimmune disease. Suicidal and homicidal ideation can be part of the condition.

Dr. Chang believes PANS could be part of the overall increase in autoimmune disease and psychiatric disorders in children over the past few decades.

“We have more kids who have special needs than ever before,” large, objective increases in bipolar, autism, and other psychiatric problems, as well as increases in psoriasis, nut allergies, and other autoimmune issues. “What causes it is harder to say, but there has been a change for sure in kids and their immune system development that does affect the brain, and has probably led to more neuropsychiatric disturbances,” he said.

“No one talks about it. Everyone thinks that it’s some sort of pharmaceutical industry conspiracy” to sell more drugs by increasing scrutiny of children. “I think it’s caused by something in the environment interacting with genetics,” whether it’s infections, toxins, or something else. “We don’t know. Any kind of inflammation can be a trigger” and “we know inflammation” is key to “many psychiatric symptoms. I do think there’s something going on with kids over the last 30 years,” he said.

Dr. Chang is a consultant for and/or has received research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Lilly, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, and other companies.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY UPDATE INSTITUTE

Thigh muscle weakness predicts knee osteoarthritis in women only

Weakness in the lower thigh muscles is a stronger risk factor for knee osteoarthritis in women than in men, possibly because of the greater influence that high body mass index has on thigh muscle strength in women, according to new case-control study findings.

The findings, published online Feb. 8 in Arthritis Care & Research (doi: 10.1002/acr.23182), come from a study enrolling 161 patients with radiographic knee osteoarthritis and 186 controls without arthritis at baseline who were observed over a 4-year period in the ongoing multicenter Osteoarthritis Initiative cohort study. About 60% of patients and controls were women.

They found that lower muscle-specific strength in these areas significantly increased the risk of incident knee osteoarthritis in women, with odds ratios of 1.47 (95% confidence interval, 1.10-1.96) for knee flexors and 1.41 (95% CI, 1.06-1.89) for extensors. This relationship was not significant in men, and in women, the relationship lost statistical significance after adjustment for high body mass index (BMI). Lower specific strength was associated with higher BMI in women (r = –0.29, P less than .001), but not in men.

“The lower muscle-specific strength in the presence of higher BMI in women (possibly driven by greater intramuscular adiposity), but not in men, may provide a possible explanation” for the differences in knee osteoarthritis incidence in men and women with muscle strength deficits, Dr. Culvenor and colleagues wrote in their analysis.

“The response of thigh muscle to variations in BMI differed between men and women, with apparently more contractile tissue (and strength) being present in men with greater BMI, and apparently more noncontractile (adipose) tissue in women with greater BMI,” the researchers concluded.

The Osteoarthritis Initiative is cofunded by the National Institutes of Health and a consortium of pharmacological manufacturers. The work for this analysis also received funding from Paracelsus Medical University and the European Union Seventh Framework Programme. Three of the study’s seven coauthors disclosed extensive financial relationships, including employment, with Chondrometrics GmbH, a company that provides MRI analysis services, among other firms, while four disclosed no commercial conflicts.

Weakness in the lower thigh muscles is a stronger risk factor for knee osteoarthritis in women than in men, possibly because of the greater influence that high body mass index has on thigh muscle strength in women, according to new case-control study findings.

The findings, published online Feb. 8 in Arthritis Care & Research (doi: 10.1002/acr.23182), come from a study enrolling 161 patients with radiographic knee osteoarthritis and 186 controls without arthritis at baseline who were observed over a 4-year period in the ongoing multicenter Osteoarthritis Initiative cohort study. About 60% of patients and controls were women.

They found that lower muscle-specific strength in these areas significantly increased the risk of incident knee osteoarthritis in women, with odds ratios of 1.47 (95% confidence interval, 1.10-1.96) for knee flexors and 1.41 (95% CI, 1.06-1.89) for extensors. This relationship was not significant in men, and in women, the relationship lost statistical significance after adjustment for high body mass index (BMI). Lower specific strength was associated with higher BMI in women (r = –0.29, P less than .001), but not in men.

“The lower muscle-specific strength in the presence of higher BMI in women (possibly driven by greater intramuscular adiposity), but not in men, may provide a possible explanation” for the differences in knee osteoarthritis incidence in men and women with muscle strength deficits, Dr. Culvenor and colleagues wrote in their analysis.

“The response of thigh muscle to variations in BMI differed between men and women, with apparently more contractile tissue (and strength) being present in men with greater BMI, and apparently more noncontractile (adipose) tissue in women with greater BMI,” the researchers concluded.

The Osteoarthritis Initiative is cofunded by the National Institutes of Health and a consortium of pharmacological manufacturers. The work for this analysis also received funding from Paracelsus Medical University and the European Union Seventh Framework Programme. Three of the study’s seven coauthors disclosed extensive financial relationships, including employment, with Chondrometrics GmbH, a company that provides MRI analysis services, among other firms, while four disclosed no commercial conflicts.

Weakness in the lower thigh muscles is a stronger risk factor for knee osteoarthritis in women than in men, possibly because of the greater influence that high body mass index has on thigh muscle strength in women, according to new case-control study findings.

The findings, published online Feb. 8 in Arthritis Care & Research (doi: 10.1002/acr.23182), come from a study enrolling 161 patients with radiographic knee osteoarthritis and 186 controls without arthritis at baseline who were observed over a 4-year period in the ongoing multicenter Osteoarthritis Initiative cohort study. About 60% of patients and controls were women.

They found that lower muscle-specific strength in these areas significantly increased the risk of incident knee osteoarthritis in women, with odds ratios of 1.47 (95% confidence interval, 1.10-1.96) for knee flexors and 1.41 (95% CI, 1.06-1.89) for extensors. This relationship was not significant in men, and in women, the relationship lost statistical significance after adjustment for high body mass index (BMI). Lower specific strength was associated with higher BMI in women (r = –0.29, P less than .001), but not in men.

“The lower muscle-specific strength in the presence of higher BMI in women (possibly driven by greater intramuscular adiposity), but not in men, may provide a possible explanation” for the differences in knee osteoarthritis incidence in men and women with muscle strength deficits, Dr. Culvenor and colleagues wrote in their analysis.

“The response of thigh muscle to variations in BMI differed between men and women, with apparently more contractile tissue (and strength) being present in men with greater BMI, and apparently more noncontractile (adipose) tissue in women with greater BMI,” the researchers concluded.

The Osteoarthritis Initiative is cofunded by the National Institutes of Health and a consortium of pharmacological manufacturers. The work for this analysis also received funding from Paracelsus Medical University and the European Union Seventh Framework Programme. Three of the study’s seven coauthors disclosed extensive financial relationships, including employment, with Chondrometrics GmbH, a company that provides MRI analysis services, among other firms, while four disclosed no commercial conflicts.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Weaker thigh muscle significantly increased the risk of incident knee osteoarthritis in women, but after adjusting for BMI the relationship lost significance.

Data source: Men and women (n = 161) with knee osteoarthritis and matched controls (n = 186) without osteoarthritis at baseline who were recruited from a multisite longitudinal cohort.

Disclosures: The Osteoarthritis Initiative is cofunded by the National Institutes of Health and a consortium of pharmacological manufacturers. The work for this analysis also received funding from Paracelsus Medical University and the European Union Seventh Framework Programme. Three of the study’s seven coauthors disclosed extensive financial relationships, including employment, with Chondrometrics GmbH, a company that provides MRI analysis services, among other firms, while four disclosed no commercial conflicts.

Nicardipine okay to use after pediatric cardiac surgery

HOUSTON – The use of nicardipine following cardiac surgery in children appears to be safe and effective, results from a single-center study suggest.

“There has been a traditional hesitation to use calcium channel blockers, particularly in infants, due to underdevelopment of their calcium channels,” study investigator Matthew L. Stone, MD, PhD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

“Further, these agents have commonly lacked selectivity to the vascular smooth muscles affecting both the blood vessels and the heart. Nicardipine offers a unique advantage over other calcium channel blockers in that it has more direct effects on vascular smooth muscles than it does on the actual myocardium.”