User login

Conservative oxygen therapy in critically ill patients

Clinical question: Does a conservative oxygenation strategy improve clinical outcomes, compared with standard clinical practice among critically ill patients?

Background: Supraphysiologic levels of oxygen have been linked to direct cellular injury through generation of reactive oxygen species. Hyperoxia is known to cause airway injury, including diffuse alveolar damage and tracheobronchitis; it also is linked to worse clinical outcomes in various cardiac and surgical patients. ICU patients have not been studied.

Setting: Single-center, academic hospital in Italy.

Synopsis: Investigators randomized 480 adults admitted to the ICU for at least 72 hours to either standard practice (allowing PaO2 up to 150 mmHg, SpO2 97%-100%) or the conservative protocol (PaO2 70-100 mmHg or SpO2 94%-98%). Patients who were pregnant, readmitted, immunosuppressed, neutropenic, with decompensated COPD or acute respiratory distress syndrome were excluded. Outcomes included ICU mortality, hospital mortality, new-onset organ failure, or new infection.

Enrollment was slow, the authors noted, partially due to an earthquake that damaged the facility, and the trial was stopped short of the planned 660 patient sample size.

In an intent-to-treat analysis, there was a statistically significant decrease in ICU and hospital mortality, shock, liver failure, and bacteremia among the conservative group.

Limitations included possible confounding from higher illness severity in the standard practice group, as well as the single-center focus that terminated early due to enrollment challenges.

Bottom line: A conservative oxygen strategy had a statistically significant decrease in ICU and hospital mortality, shock, liver failure, and bacteremia.

Citation: Girardis M, Busani S, Damiani E, et al. Effect of conservative vs conventional oxygen therapy on mortality among patients in an intensive care unit. JAMA. 2016;316(15):1583-9.

Dr. Marr is a clinical instructor at the University of Utah School of Medicine and an academic hospitalist at the University of Utah Hospital.

Clinical question: Does a conservative oxygenation strategy improve clinical outcomes, compared with standard clinical practice among critically ill patients?

Background: Supraphysiologic levels of oxygen have been linked to direct cellular injury through generation of reactive oxygen species. Hyperoxia is known to cause airway injury, including diffuse alveolar damage and tracheobronchitis; it also is linked to worse clinical outcomes in various cardiac and surgical patients. ICU patients have not been studied.

Setting: Single-center, academic hospital in Italy.

Synopsis: Investigators randomized 480 adults admitted to the ICU for at least 72 hours to either standard practice (allowing PaO2 up to 150 mmHg, SpO2 97%-100%) or the conservative protocol (PaO2 70-100 mmHg or SpO2 94%-98%). Patients who were pregnant, readmitted, immunosuppressed, neutropenic, with decompensated COPD or acute respiratory distress syndrome were excluded. Outcomes included ICU mortality, hospital mortality, new-onset organ failure, or new infection.

Enrollment was slow, the authors noted, partially due to an earthquake that damaged the facility, and the trial was stopped short of the planned 660 patient sample size.

In an intent-to-treat analysis, there was a statistically significant decrease in ICU and hospital mortality, shock, liver failure, and bacteremia among the conservative group.

Limitations included possible confounding from higher illness severity in the standard practice group, as well as the single-center focus that terminated early due to enrollment challenges.

Bottom line: A conservative oxygen strategy had a statistically significant decrease in ICU and hospital mortality, shock, liver failure, and bacteremia.

Citation: Girardis M, Busani S, Damiani E, et al. Effect of conservative vs conventional oxygen therapy on mortality among patients in an intensive care unit. JAMA. 2016;316(15):1583-9.

Dr. Marr is a clinical instructor at the University of Utah School of Medicine and an academic hospitalist at the University of Utah Hospital.

Clinical question: Does a conservative oxygenation strategy improve clinical outcomes, compared with standard clinical practice among critically ill patients?

Background: Supraphysiologic levels of oxygen have been linked to direct cellular injury through generation of reactive oxygen species. Hyperoxia is known to cause airway injury, including diffuse alveolar damage and tracheobronchitis; it also is linked to worse clinical outcomes in various cardiac and surgical patients. ICU patients have not been studied.

Setting: Single-center, academic hospital in Italy.

Synopsis: Investigators randomized 480 adults admitted to the ICU for at least 72 hours to either standard practice (allowing PaO2 up to 150 mmHg, SpO2 97%-100%) or the conservative protocol (PaO2 70-100 mmHg or SpO2 94%-98%). Patients who were pregnant, readmitted, immunosuppressed, neutropenic, with decompensated COPD or acute respiratory distress syndrome were excluded. Outcomes included ICU mortality, hospital mortality, new-onset organ failure, or new infection.

Enrollment was slow, the authors noted, partially due to an earthquake that damaged the facility, and the trial was stopped short of the planned 660 patient sample size.

In an intent-to-treat analysis, there was a statistically significant decrease in ICU and hospital mortality, shock, liver failure, and bacteremia among the conservative group.

Limitations included possible confounding from higher illness severity in the standard practice group, as well as the single-center focus that terminated early due to enrollment challenges.

Bottom line: A conservative oxygen strategy had a statistically significant decrease in ICU and hospital mortality, shock, liver failure, and bacteremia.

Citation: Girardis M, Busani S, Damiani E, et al. Effect of conservative vs conventional oxygen therapy on mortality among patients in an intensive care unit. JAMA. 2016;316(15):1583-9.

Dr. Marr is a clinical instructor at the University of Utah School of Medicine and an academic hospitalist at the University of Utah Hospital.

Prevalence of pulmonary embolism among syncope patients

Clinical question: What is the prevalence of acute pulmonary emboli (PE) in patients admitted for syncope?

Background: An acute pulmonary embolism is a differential consideration among patients admitted with syncope. However, current guidelines do not guide evaluation.

Study design: Cross-sectional study.

Setting: Two academic and nine non-academic hospitals in Italy.

Synopsis: Five hundred-sixty patients admitted with a first episode of syncope were evaluated for a PE. Patients with atrial fibrillation, treatment with anticoagulation, recurrent syncope, or who were pregnant were excluded. The simplified Wells score was used to stratify patients into low and high-risk groups, while low-risk groups received D-dimer testing; 230 patients had a positive D-dimer or a high-risk Wells score and received either CT pulmonary angiography or VQ scans.

Ninety-seven of the 230 patients were found to have a PE (42.2%), leading to a prevalence of 17.3% among the entire cohort. The study did not include the 1,867 patients who were discharged from the ED without admission, potentially leading to bias and overestimating the prevalence of pulmonary emboli (PE).

Bottom line: The prevalence of PE in patients with syncope is higher than previously thought, highlighting the importance of considering acute PE in patients hospitalized with syncope.

Citation: Prandoni P, Lensing AWA, Prins MH, et al. Prevalence of pulmonary embolism among patients hospitalized for syncope. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(16):1524-31.

Dr. Marr is a clinical instructor at the University of Utah School of Medicine and an academic hospitalist at the University of Utah Hospital.

Clinical question: What is the prevalence of acute pulmonary emboli (PE) in patients admitted for syncope?

Background: An acute pulmonary embolism is a differential consideration among patients admitted with syncope. However, current guidelines do not guide evaluation.

Study design: Cross-sectional study.

Setting: Two academic and nine non-academic hospitals in Italy.

Synopsis: Five hundred-sixty patients admitted with a first episode of syncope were evaluated for a PE. Patients with atrial fibrillation, treatment with anticoagulation, recurrent syncope, or who were pregnant were excluded. The simplified Wells score was used to stratify patients into low and high-risk groups, while low-risk groups received D-dimer testing; 230 patients had a positive D-dimer or a high-risk Wells score and received either CT pulmonary angiography or VQ scans.

Ninety-seven of the 230 patients were found to have a PE (42.2%), leading to a prevalence of 17.3% among the entire cohort. The study did not include the 1,867 patients who were discharged from the ED without admission, potentially leading to bias and overestimating the prevalence of pulmonary emboli (PE).

Bottom line: The prevalence of PE in patients with syncope is higher than previously thought, highlighting the importance of considering acute PE in patients hospitalized with syncope.

Citation: Prandoni P, Lensing AWA, Prins MH, et al. Prevalence of pulmonary embolism among patients hospitalized for syncope. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(16):1524-31.

Dr. Marr is a clinical instructor at the University of Utah School of Medicine and an academic hospitalist at the University of Utah Hospital.

Clinical question: What is the prevalence of acute pulmonary emboli (PE) in patients admitted for syncope?

Background: An acute pulmonary embolism is a differential consideration among patients admitted with syncope. However, current guidelines do not guide evaluation.

Study design: Cross-sectional study.

Setting: Two academic and nine non-academic hospitals in Italy.

Synopsis: Five hundred-sixty patients admitted with a first episode of syncope were evaluated for a PE. Patients with atrial fibrillation, treatment with anticoagulation, recurrent syncope, or who were pregnant were excluded. The simplified Wells score was used to stratify patients into low and high-risk groups, while low-risk groups received D-dimer testing; 230 patients had a positive D-dimer or a high-risk Wells score and received either CT pulmonary angiography or VQ scans.

Ninety-seven of the 230 patients were found to have a PE (42.2%), leading to a prevalence of 17.3% among the entire cohort. The study did not include the 1,867 patients who were discharged from the ED without admission, potentially leading to bias and overestimating the prevalence of pulmonary emboli (PE).

Bottom line: The prevalence of PE in patients with syncope is higher than previously thought, highlighting the importance of considering acute PE in patients hospitalized with syncope.

Citation: Prandoni P, Lensing AWA, Prins MH, et al. Prevalence of pulmonary embolism among patients hospitalized for syncope. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(16):1524-31.

Dr. Marr is a clinical instructor at the University of Utah School of Medicine and an academic hospitalist at the University of Utah Hospital.

Evidence suggests fondaparinux is more effective than LMWH in prevention of VTE and total DVT in the postoperative setting

Clinical question: How do pentasaccharides compare to other anticoagulants in postoperative venous thromboembolism prevention?

Background: Venous thromboembolism (VTE) remains a leading cause of preventable hospital related death. Pentasaccharides selectively inhibit factor Xa to inhibit clotting and exhibit a lower risk of heparin induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) compared to low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) and unfractionated heparin. We lack a formal recommendation regarding the pentasaccharides superiority or inferiority, relative to other anticoagulants, in the perioperative setting.

Study design: Cochrane review.

Setting: Hospital and outpatient.

Synopsis: Authors searched randomized controlled trials involving pentasaccharides versus other VTE prophylaxis to obtain 25 studies totaling 21,004 subjects undergoing orthopedic, abdominal, cardiac bypass, thoracic, and bariatric surgery; hospitalized patients, immobilized patients, and those with superficial venous thrombosis. Selected studies pertained to fondaparinux and VTE prevention. Fondaparinux was superior to placebo in prevention of DVT and VTE. Compared to LMWH, fondaparinux reduced total VTE (RR, 0.55, 95% CI, 0.42-0.73) and DVT (RR, 0.54, 95% CI, 0.40-0.71), but carried a higher rate of major bleeding compared to placebo (RR, 2.56, 95% CI, 1.48-4.44) and LMWH (RR, 1.38, 95% CI, 1.09-1.75). The all cause death and major adverse events for fondaparinux versus placebo and LMWH were not statistically significant. Limitations of this review include the predominance of orthopedic patients, variable duration of treatment, and low-moderate quality data.

Bottom line: Fondaparinux demonstrates better perioperative total VTE and DVT reduction compared to LMWH, but it increases the incidence of major bleeding.

Reference: Dong K, Song Y, Li X, Ding J, Gao Z, Lu D, Zhu Y. Pentasaccharides for the prevention of venous thromboembolism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Oct 31;10:CD005134.

Dr. Coleman is an assistant professor of clinical medicine at Cooper Medical School at Rowan University. She works as a hospitalist at Cooper University Hospital in Camden, N.J.

Clinical question: How do pentasaccharides compare to other anticoagulants in postoperative venous thromboembolism prevention?

Background: Venous thromboembolism (VTE) remains a leading cause of preventable hospital related death. Pentasaccharides selectively inhibit factor Xa to inhibit clotting and exhibit a lower risk of heparin induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) compared to low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) and unfractionated heparin. We lack a formal recommendation regarding the pentasaccharides superiority or inferiority, relative to other anticoagulants, in the perioperative setting.

Study design: Cochrane review.

Setting: Hospital and outpatient.

Synopsis: Authors searched randomized controlled trials involving pentasaccharides versus other VTE prophylaxis to obtain 25 studies totaling 21,004 subjects undergoing orthopedic, abdominal, cardiac bypass, thoracic, and bariatric surgery; hospitalized patients, immobilized patients, and those with superficial venous thrombosis. Selected studies pertained to fondaparinux and VTE prevention. Fondaparinux was superior to placebo in prevention of DVT and VTE. Compared to LMWH, fondaparinux reduced total VTE (RR, 0.55, 95% CI, 0.42-0.73) and DVT (RR, 0.54, 95% CI, 0.40-0.71), but carried a higher rate of major bleeding compared to placebo (RR, 2.56, 95% CI, 1.48-4.44) and LMWH (RR, 1.38, 95% CI, 1.09-1.75). The all cause death and major adverse events for fondaparinux versus placebo and LMWH were not statistically significant. Limitations of this review include the predominance of orthopedic patients, variable duration of treatment, and low-moderate quality data.

Bottom line: Fondaparinux demonstrates better perioperative total VTE and DVT reduction compared to LMWH, but it increases the incidence of major bleeding.

Reference: Dong K, Song Y, Li X, Ding J, Gao Z, Lu D, Zhu Y. Pentasaccharides for the prevention of venous thromboembolism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Oct 31;10:CD005134.

Dr. Coleman is an assistant professor of clinical medicine at Cooper Medical School at Rowan University. She works as a hospitalist at Cooper University Hospital in Camden, N.J.

Clinical question: How do pentasaccharides compare to other anticoagulants in postoperative venous thromboembolism prevention?

Background: Venous thromboembolism (VTE) remains a leading cause of preventable hospital related death. Pentasaccharides selectively inhibit factor Xa to inhibit clotting and exhibit a lower risk of heparin induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) compared to low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) and unfractionated heparin. We lack a formal recommendation regarding the pentasaccharides superiority or inferiority, relative to other anticoagulants, in the perioperative setting.

Study design: Cochrane review.

Setting: Hospital and outpatient.

Synopsis: Authors searched randomized controlled trials involving pentasaccharides versus other VTE prophylaxis to obtain 25 studies totaling 21,004 subjects undergoing orthopedic, abdominal, cardiac bypass, thoracic, and bariatric surgery; hospitalized patients, immobilized patients, and those with superficial venous thrombosis. Selected studies pertained to fondaparinux and VTE prevention. Fondaparinux was superior to placebo in prevention of DVT and VTE. Compared to LMWH, fondaparinux reduced total VTE (RR, 0.55, 95% CI, 0.42-0.73) and DVT (RR, 0.54, 95% CI, 0.40-0.71), but carried a higher rate of major bleeding compared to placebo (RR, 2.56, 95% CI, 1.48-4.44) and LMWH (RR, 1.38, 95% CI, 1.09-1.75). The all cause death and major adverse events for fondaparinux versus placebo and LMWH were not statistically significant. Limitations of this review include the predominance of orthopedic patients, variable duration of treatment, and low-moderate quality data.

Bottom line: Fondaparinux demonstrates better perioperative total VTE and DVT reduction compared to LMWH, but it increases the incidence of major bleeding.

Reference: Dong K, Song Y, Li X, Ding J, Gao Z, Lu D, Zhu Y. Pentasaccharides for the prevention of venous thromboembolism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Oct 31;10:CD005134.

Dr. Coleman is an assistant professor of clinical medicine at Cooper Medical School at Rowan University. She works as a hospitalist at Cooper University Hospital in Camden, N.J.

Trending at SHM

Top 10 reasons to attend 2017 Quality and Safety Educators Academy

It’s your last chance to register for the 2017 Quality and Safety Educators Academy (QSEA), which will be held Feb. 26-28 in Tempe, Ariz. Looking for some reasons to attend? Here are the top 10:

- Education. Develop and refine your knowledge in quality and patient safety.

- Desert beauty. Enjoy sunny Tempe, or travel to nearby Phoenix or Scottsdale.

- Curriculum development. Return to your institution with a collection of new educational strategies and curriculum development tactics.

- Professional development. Hone your skills and be the best that you can be to meet the increasing demand for medical educators who are well versed in patient safety and quality.

- Relationships. Build your network with faculty mentors and colleagues who have similar career interests.

- Institutional backing. Engage your institutional leaders to support and implement a quality and patient safety curriculum to meet the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education core competencies and improve patient care.

- Hands-on learning. Engage in an interactive learning environment, with a 10:1 student to faculty ratio, including facilitated large-group sessions, small-group exercises, and panel discussions.

- Variety. Each day has its own topic that breaks down into subtopics, covering the breadth of information you need to know to succeed.

- Faculty. All sessions are led by experienced physicians known for their ability to practice and teach quality improvement and patient safety, mentor junior faculty, and guide educators in curriculum development.

- Resources. Leave with a toolkit of educational resources and curricular tools for quality and safety education.

Reserve your spot today before the meeting sells out at www.shmqsea.org.

SHM committees address practice management topics

SHM’s Practice Management Committee has been researching, deliberating case studies, and authoring timely content to further define HM’s role in key health care innovations. As the specialty has grown and evolved, so have hospitalists’ involvement in comanagement relationships.

The committee recently released a white paper addressing the evolution of comanagement in hospital medicine. Be on the lookout for that in early 2017.

Similarly, telemedicine is rapidly expanding, and the committee found it imperative to clarify the who, what, when, where, why, and how of telemedicine programs in hospital medicine. You can also expect this white paper in early 2017.

The committee also has created guidelines on how to raise awareness of cultural humility in your HM group. Deemed the “5 R’s of Cultural Humility,” look for a campaign around the guidelines to launch at HM17 in May in Las Vegas.

SHM’s Health Information Technology Committee has been diligently analyzing and reporting on survey results that captured hospitalists’ attitudes toward electronic health records. The purpose of this white paper is to effect change on EHR systems by informing conversations with decision makers, and to provide HM a definitive voice in the landscape of the tumultuous world of EHRs. More information is coming soon.

Make a difference with SHM

Grow professionally, expand your curriculum vitae, and get involved in work you are passionate about with colleagues across the country with SHM’s volunteer experiences. New opportunities are constantly being added that will bolster your strengths, sharpen your professional acumen and enhance your profile in the hospital medicine community at www.hospitalmedicine.org/getinvolved.

Leadership Academy 2017 has a new look

Don’t miss out on the only leadership program designed specifically for hospitalists. SHM Leadership Academy 2017 will be at the JW Marriott Camelback Inn in Scottsdale, Ariz., on Oct. 23-26.

For the first time, the Leadership Academy prerequisite of attendance in the first-level, Foundations course has been removed. Essential Strategies (formerly Leadership Foundations), Influential Management, and Mastering Teamwork courses are available to all attendees, regardless of previous attendance. Prior participants have made recommendations to help interested registrants determine which course fits them best in their leadership journey.

All three courses run concurrently over the span of 4 days. This expanded meeting will provide attendees with world-class networking opportunities, creating opportunities for a more engaging, impactful educational experience.

Learn more about SHM’s Leadership Academy at www.shmleadershipacademy.org.

Earn dues credits with the Membership Ambassador Program

Help SHM grow its network of hospitalists and continue to provide education, networking, and career advancement for its members. Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/refer today.

Brett Radler is SHM's communications specialist.

Top 10 reasons to attend 2017 Quality and Safety Educators Academy

It’s your last chance to register for the 2017 Quality and Safety Educators Academy (QSEA), which will be held Feb. 26-28 in Tempe, Ariz. Looking for some reasons to attend? Here are the top 10:

- Education. Develop and refine your knowledge in quality and patient safety.

- Desert beauty. Enjoy sunny Tempe, or travel to nearby Phoenix or Scottsdale.

- Curriculum development. Return to your institution with a collection of new educational strategies and curriculum development tactics.

- Professional development. Hone your skills and be the best that you can be to meet the increasing demand for medical educators who are well versed in patient safety and quality.

- Relationships. Build your network with faculty mentors and colleagues who have similar career interests.

- Institutional backing. Engage your institutional leaders to support and implement a quality and patient safety curriculum to meet the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education core competencies and improve patient care.

- Hands-on learning. Engage in an interactive learning environment, with a 10:1 student to faculty ratio, including facilitated large-group sessions, small-group exercises, and panel discussions.

- Variety. Each day has its own topic that breaks down into subtopics, covering the breadth of information you need to know to succeed.

- Faculty. All sessions are led by experienced physicians known for their ability to practice and teach quality improvement and patient safety, mentor junior faculty, and guide educators in curriculum development.

- Resources. Leave with a toolkit of educational resources and curricular tools for quality and safety education.

Reserve your spot today before the meeting sells out at www.shmqsea.org.

SHM committees address practice management topics

SHM’s Practice Management Committee has been researching, deliberating case studies, and authoring timely content to further define HM’s role in key health care innovations. As the specialty has grown and evolved, so have hospitalists’ involvement in comanagement relationships.

The committee recently released a white paper addressing the evolution of comanagement in hospital medicine. Be on the lookout for that in early 2017.

Similarly, telemedicine is rapidly expanding, and the committee found it imperative to clarify the who, what, when, where, why, and how of telemedicine programs in hospital medicine. You can also expect this white paper in early 2017.

The committee also has created guidelines on how to raise awareness of cultural humility in your HM group. Deemed the “5 R’s of Cultural Humility,” look for a campaign around the guidelines to launch at HM17 in May in Las Vegas.

SHM’s Health Information Technology Committee has been diligently analyzing and reporting on survey results that captured hospitalists’ attitudes toward electronic health records. The purpose of this white paper is to effect change on EHR systems by informing conversations with decision makers, and to provide HM a definitive voice in the landscape of the tumultuous world of EHRs. More information is coming soon.

Make a difference with SHM

Grow professionally, expand your curriculum vitae, and get involved in work you are passionate about with colleagues across the country with SHM’s volunteer experiences. New opportunities are constantly being added that will bolster your strengths, sharpen your professional acumen and enhance your profile in the hospital medicine community at www.hospitalmedicine.org/getinvolved.

Leadership Academy 2017 has a new look

Don’t miss out on the only leadership program designed specifically for hospitalists. SHM Leadership Academy 2017 will be at the JW Marriott Camelback Inn in Scottsdale, Ariz., on Oct. 23-26.

For the first time, the Leadership Academy prerequisite of attendance in the first-level, Foundations course has been removed. Essential Strategies (formerly Leadership Foundations), Influential Management, and Mastering Teamwork courses are available to all attendees, regardless of previous attendance. Prior participants have made recommendations to help interested registrants determine which course fits them best in their leadership journey.

All three courses run concurrently over the span of 4 days. This expanded meeting will provide attendees with world-class networking opportunities, creating opportunities for a more engaging, impactful educational experience.

Learn more about SHM’s Leadership Academy at www.shmleadershipacademy.org.

Earn dues credits with the Membership Ambassador Program

Help SHM grow its network of hospitalists and continue to provide education, networking, and career advancement for its members. Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/refer today.

Brett Radler is SHM's communications specialist.

Top 10 reasons to attend 2017 Quality and Safety Educators Academy

It’s your last chance to register for the 2017 Quality and Safety Educators Academy (QSEA), which will be held Feb. 26-28 in Tempe, Ariz. Looking for some reasons to attend? Here are the top 10:

- Education. Develop and refine your knowledge in quality and patient safety.

- Desert beauty. Enjoy sunny Tempe, or travel to nearby Phoenix or Scottsdale.

- Curriculum development. Return to your institution with a collection of new educational strategies and curriculum development tactics.

- Professional development. Hone your skills and be the best that you can be to meet the increasing demand for medical educators who are well versed in patient safety and quality.

- Relationships. Build your network with faculty mentors and colleagues who have similar career interests.

- Institutional backing. Engage your institutional leaders to support and implement a quality and patient safety curriculum to meet the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education core competencies and improve patient care.

- Hands-on learning. Engage in an interactive learning environment, with a 10:1 student to faculty ratio, including facilitated large-group sessions, small-group exercises, and panel discussions.

- Variety. Each day has its own topic that breaks down into subtopics, covering the breadth of information you need to know to succeed.

- Faculty. All sessions are led by experienced physicians known for their ability to practice and teach quality improvement and patient safety, mentor junior faculty, and guide educators in curriculum development.

- Resources. Leave with a toolkit of educational resources and curricular tools for quality and safety education.

Reserve your spot today before the meeting sells out at www.shmqsea.org.

SHM committees address practice management topics

SHM’s Practice Management Committee has been researching, deliberating case studies, and authoring timely content to further define HM’s role in key health care innovations. As the specialty has grown and evolved, so have hospitalists’ involvement in comanagement relationships.

The committee recently released a white paper addressing the evolution of comanagement in hospital medicine. Be on the lookout for that in early 2017.

Similarly, telemedicine is rapidly expanding, and the committee found it imperative to clarify the who, what, when, where, why, and how of telemedicine programs in hospital medicine. You can also expect this white paper in early 2017.

The committee also has created guidelines on how to raise awareness of cultural humility in your HM group. Deemed the “5 R’s of Cultural Humility,” look for a campaign around the guidelines to launch at HM17 in May in Las Vegas.

SHM’s Health Information Technology Committee has been diligently analyzing and reporting on survey results that captured hospitalists’ attitudes toward electronic health records. The purpose of this white paper is to effect change on EHR systems by informing conversations with decision makers, and to provide HM a definitive voice in the landscape of the tumultuous world of EHRs. More information is coming soon.

Make a difference with SHM

Grow professionally, expand your curriculum vitae, and get involved in work you are passionate about with colleagues across the country with SHM’s volunteer experiences. New opportunities are constantly being added that will bolster your strengths, sharpen your professional acumen and enhance your profile in the hospital medicine community at www.hospitalmedicine.org/getinvolved.

Leadership Academy 2017 has a new look

Don’t miss out on the only leadership program designed specifically for hospitalists. SHM Leadership Academy 2017 will be at the JW Marriott Camelback Inn in Scottsdale, Ariz., on Oct. 23-26.

For the first time, the Leadership Academy prerequisite of attendance in the first-level, Foundations course has been removed. Essential Strategies (formerly Leadership Foundations), Influential Management, and Mastering Teamwork courses are available to all attendees, regardless of previous attendance. Prior participants have made recommendations to help interested registrants determine which course fits them best in their leadership journey.

All three courses run concurrently over the span of 4 days. This expanded meeting will provide attendees with world-class networking opportunities, creating opportunities for a more engaging, impactful educational experience.

Learn more about SHM’s Leadership Academy at www.shmleadershipacademy.org.

Earn dues credits with the Membership Ambassador Program

Help SHM grow its network of hospitalists and continue to provide education, networking, and career advancement for its members. Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/refer today.

Brett Radler is SHM's communications specialist.

From the Washington Office: Navigating MIPS in 2017

2017 is here and the new Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) is now in effect. MIPS has taken a number of steps to streamline reporting and make it easier to avoid penalties and achieve positive updates. However, over time penalties for non-participation or poor performance will grow. Therefore, it is critically important that all surgeons make a plan for how they can best participate in order to succeed. Knowing what options are available is vital to navigating the new reporting requirements and achieving the best possible financial outcome.

Background on MIPS and its components

MIPS began measuring performance in January 2017. The data reported in 2017 will be used to adjust payments in 2019. MIPS took the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), the Value Based Modifier (VM), and the EHR Incentive Program commonly referred to as Meaningful Use (EHR-MU), added a new component that provides credit for Improvement Activities and combined them to derive a composite MIPS Final Score. The components of the Final Score are known as Quality, (formerly PQRS), Cost, (formerly VM), Advancing Care Information (ACI), (formerly EHR-MU), and Improvement Activities. The weights for the individual components of the final score for the first year of the MIPS program are represented in the chart above.

Though CMS has chosen not to provide any weight to the Cost component during the first year of the program, those who report Quality data will receive feedback reports on their performance in the Cost component.

2017: The transition year

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) designated 2017 as a transition year and has provided a clear pathway to avoid penalties. In addition, CMS has reduced the reporting requirements in 2017 for those who wish to fully participate in preparation for the future or those practices whose goal is the achievement of a positive payment update. It is important to note that the funds available for positive payment updates are derived from the penalties assessed on those who choose NOT to participate. Accordingly, by making it easier to avoid penalties in the first year, CMS has also reduced the amount of funds available for positive incentives.

Participating to avoid penalties

For 2017, CMS instituted options to allow surgeons to “Pick Your Pace” for participation in MIPS. Those who choose not to participate at any level will receive the full negative payment adjustment of 4% in 2019. However, it is noteworthy that a 4% negative payment adjustment is less than half of the negative adjustments associated with the PQRS, VM, and Meaningful Use programs in 2016.

To avoid the 4% penalty, CMS only requires that surgeons test their ability to report data in any of three reporting components, namely Quality, ACI or Improvement Activities. Information for the Cost component is derived automatically and has no reporting requirement. To avoid a penalty, surgeons must simply report one Quality measure for a single patient, attest to participating in an approved Improvement Activity for at least 90 consecutive days or complete the Base score requirements for ACI.

Participating to prepare for future success

Those who wish to attempt to achieve a higher score must report data for 50% of all patients seen (for ALL payors) for any consecutive 90 day period. Accordingly, one could begin as late as October 2, 2017. How data is reported depends upon the circumstances of an individual’s practice as there are multiple methods (electronic health record, registry, or qualified clinical data registry) for submitting data to CMS. It should be noted that data can also be submitted either on an individual basis or as a group.

Reporting pathway toward potentially receiving a positive payment update: Reporting for Quality

To receive the full potential Quality score, data must be submitted for 50% of all patients seen (for ALL payors) for any consecutive 90 day period on a minimum of 6 measures including one Outcome measure. Alternatively, one can choose to use a specialty measure set to report on 50% of all patients seen (for ALL payors) for any consecutive 90 day period. Those who do meet the reporting requirement and perform well on the measures will receive up to 60 points toward their MIPS Final Score. For those who intend to simply avoid penalties for the first year of the MIPS program, reporting a single measure for a single patient will earn the 3 points necessary to meet the threshold prescribed by CMS to avoid a penalty.

Reporting for ACI

The ACI component is worth 25 percent of the MIPS Final Score. The assessment for ACI is a composite score composed of two parts, a Base score and a Performance score. To receive credit for the ACI component 2017, one must have either 2014 or 2015 Edition CEHRT.

The Base score is an “all-or-nothing” threshold and accounts for 50 percent of the total score for the ACI component. Achievement of the Base score is required before any score can be accrued for the Performance portion. Achieving the Base score is also one of the options prescribed by CMS sufficient to avoid MIPS penalties in the first year and if the Base Score is achieved, one will not receive a penalty for 2017. The ACI measures are intended to ensure that certified EHRs are being used for core tasks such as providing patients with online access to their medical records, exchanging health information with patients and other providers, electronic prescribing and protecting sensitive patient health information.

Once all of the measures for the Base score have been met, clinicians are eligible to receive credit for performance on both a subset of the Base score measures and on a set of additional optional measures. Bonus points are also available by reporting certain Improvement Activities via a certified EHR.

Reporting for Improvement Activities

While the Improvement Activities (IA) is a new category, surgeons are familiar with many of the activities including maintenance of certification, use of the ACS Surgical Risk Calculator, participation in a QCDR and registry with their state’s prescription drug monitoring program. Each activity is assigned a point value of either 20 points (high value) or 10 points (medium value). The reporting requirement for the IA is fulfilled by simple attestation via either a registry, qualified clinical data registry, or a portal on the CMS website. To receive full credit, most surgeons must select and attest to having completed between two and four activities for a total of 40 points. Some surgeons in rural or small practices will only need to complete one high value or two medium value activities to achieve full credit. Those who fulfill the requirement will receive 15 points toward the MIPS Final Score. For those whose goal is simply to avoid a penalty in the first reporting year of MIPS, reporting a single activity for 90 days is enough to avoid any MIPS penalties for 2017

For those seeking further information, the ACS website (www.facs.org/qpp) has additional fact sheets and informational videos on the MIPS program.

Until next month …

Dr. Bailey is a pediatric surgeon, and Medical Director, Advocacy, for the Division of Advocacy and Health Policy in the ACS offices in Washington, D.C.

2017 is here and the new Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) is now in effect. MIPS has taken a number of steps to streamline reporting and make it easier to avoid penalties and achieve positive updates. However, over time penalties for non-participation or poor performance will grow. Therefore, it is critically important that all surgeons make a plan for how they can best participate in order to succeed. Knowing what options are available is vital to navigating the new reporting requirements and achieving the best possible financial outcome.

Background on MIPS and its components

MIPS began measuring performance in January 2017. The data reported in 2017 will be used to adjust payments in 2019. MIPS took the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), the Value Based Modifier (VM), and the EHR Incentive Program commonly referred to as Meaningful Use (EHR-MU), added a new component that provides credit for Improvement Activities and combined them to derive a composite MIPS Final Score. The components of the Final Score are known as Quality, (formerly PQRS), Cost, (formerly VM), Advancing Care Information (ACI), (formerly EHR-MU), and Improvement Activities. The weights for the individual components of the final score for the first year of the MIPS program are represented in the chart above.

Though CMS has chosen not to provide any weight to the Cost component during the first year of the program, those who report Quality data will receive feedback reports on their performance in the Cost component.

2017: The transition year

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) designated 2017 as a transition year and has provided a clear pathway to avoid penalties. In addition, CMS has reduced the reporting requirements in 2017 for those who wish to fully participate in preparation for the future or those practices whose goal is the achievement of a positive payment update. It is important to note that the funds available for positive payment updates are derived from the penalties assessed on those who choose NOT to participate. Accordingly, by making it easier to avoid penalties in the first year, CMS has also reduced the amount of funds available for positive incentives.

Participating to avoid penalties

For 2017, CMS instituted options to allow surgeons to “Pick Your Pace” for participation in MIPS. Those who choose not to participate at any level will receive the full negative payment adjustment of 4% in 2019. However, it is noteworthy that a 4% negative payment adjustment is less than half of the negative adjustments associated with the PQRS, VM, and Meaningful Use programs in 2016.

To avoid the 4% penalty, CMS only requires that surgeons test their ability to report data in any of three reporting components, namely Quality, ACI or Improvement Activities. Information for the Cost component is derived automatically and has no reporting requirement. To avoid a penalty, surgeons must simply report one Quality measure for a single patient, attest to participating in an approved Improvement Activity for at least 90 consecutive days or complete the Base score requirements for ACI.

Participating to prepare for future success

Those who wish to attempt to achieve a higher score must report data for 50% of all patients seen (for ALL payors) for any consecutive 90 day period. Accordingly, one could begin as late as October 2, 2017. How data is reported depends upon the circumstances of an individual’s practice as there are multiple methods (electronic health record, registry, or qualified clinical data registry) for submitting data to CMS. It should be noted that data can also be submitted either on an individual basis or as a group.

Reporting pathway toward potentially receiving a positive payment update: Reporting for Quality

To receive the full potential Quality score, data must be submitted for 50% of all patients seen (for ALL payors) for any consecutive 90 day period on a minimum of 6 measures including one Outcome measure. Alternatively, one can choose to use a specialty measure set to report on 50% of all patients seen (for ALL payors) for any consecutive 90 day period. Those who do meet the reporting requirement and perform well on the measures will receive up to 60 points toward their MIPS Final Score. For those who intend to simply avoid penalties for the first year of the MIPS program, reporting a single measure for a single patient will earn the 3 points necessary to meet the threshold prescribed by CMS to avoid a penalty.

Reporting for ACI

The ACI component is worth 25 percent of the MIPS Final Score. The assessment for ACI is a composite score composed of two parts, a Base score and a Performance score. To receive credit for the ACI component 2017, one must have either 2014 or 2015 Edition CEHRT.

The Base score is an “all-or-nothing” threshold and accounts for 50 percent of the total score for the ACI component. Achievement of the Base score is required before any score can be accrued for the Performance portion. Achieving the Base score is also one of the options prescribed by CMS sufficient to avoid MIPS penalties in the first year and if the Base Score is achieved, one will not receive a penalty for 2017. The ACI measures are intended to ensure that certified EHRs are being used for core tasks such as providing patients with online access to their medical records, exchanging health information with patients and other providers, electronic prescribing and protecting sensitive patient health information.

Once all of the measures for the Base score have been met, clinicians are eligible to receive credit for performance on both a subset of the Base score measures and on a set of additional optional measures. Bonus points are also available by reporting certain Improvement Activities via a certified EHR.

Reporting for Improvement Activities

While the Improvement Activities (IA) is a new category, surgeons are familiar with many of the activities including maintenance of certification, use of the ACS Surgical Risk Calculator, participation in a QCDR and registry with their state’s prescription drug monitoring program. Each activity is assigned a point value of either 20 points (high value) or 10 points (medium value). The reporting requirement for the IA is fulfilled by simple attestation via either a registry, qualified clinical data registry, or a portal on the CMS website. To receive full credit, most surgeons must select and attest to having completed between two and four activities for a total of 40 points. Some surgeons in rural or small practices will only need to complete one high value or two medium value activities to achieve full credit. Those who fulfill the requirement will receive 15 points toward the MIPS Final Score. For those whose goal is simply to avoid a penalty in the first reporting year of MIPS, reporting a single activity for 90 days is enough to avoid any MIPS penalties for 2017

For those seeking further information, the ACS website (www.facs.org/qpp) has additional fact sheets and informational videos on the MIPS program.

Until next month …

Dr. Bailey is a pediatric surgeon, and Medical Director, Advocacy, for the Division of Advocacy and Health Policy in the ACS offices in Washington, D.C.

2017 is here and the new Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) is now in effect. MIPS has taken a number of steps to streamline reporting and make it easier to avoid penalties and achieve positive updates. However, over time penalties for non-participation or poor performance will grow. Therefore, it is critically important that all surgeons make a plan for how they can best participate in order to succeed. Knowing what options are available is vital to navigating the new reporting requirements and achieving the best possible financial outcome.

Background on MIPS and its components

MIPS began measuring performance in January 2017. The data reported in 2017 will be used to adjust payments in 2019. MIPS took the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), the Value Based Modifier (VM), and the EHR Incentive Program commonly referred to as Meaningful Use (EHR-MU), added a new component that provides credit for Improvement Activities and combined them to derive a composite MIPS Final Score. The components of the Final Score are known as Quality, (formerly PQRS), Cost, (formerly VM), Advancing Care Information (ACI), (formerly EHR-MU), and Improvement Activities. The weights for the individual components of the final score for the first year of the MIPS program are represented in the chart above.

Though CMS has chosen not to provide any weight to the Cost component during the first year of the program, those who report Quality data will receive feedback reports on their performance in the Cost component.

2017: The transition year

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) designated 2017 as a transition year and has provided a clear pathway to avoid penalties. In addition, CMS has reduced the reporting requirements in 2017 for those who wish to fully participate in preparation for the future or those practices whose goal is the achievement of a positive payment update. It is important to note that the funds available for positive payment updates are derived from the penalties assessed on those who choose NOT to participate. Accordingly, by making it easier to avoid penalties in the first year, CMS has also reduced the amount of funds available for positive incentives.

Participating to avoid penalties

For 2017, CMS instituted options to allow surgeons to “Pick Your Pace” for participation in MIPS. Those who choose not to participate at any level will receive the full negative payment adjustment of 4% in 2019. However, it is noteworthy that a 4% negative payment adjustment is less than half of the negative adjustments associated with the PQRS, VM, and Meaningful Use programs in 2016.

To avoid the 4% penalty, CMS only requires that surgeons test their ability to report data in any of three reporting components, namely Quality, ACI or Improvement Activities. Information for the Cost component is derived automatically and has no reporting requirement. To avoid a penalty, surgeons must simply report one Quality measure for a single patient, attest to participating in an approved Improvement Activity for at least 90 consecutive days or complete the Base score requirements for ACI.

Participating to prepare for future success

Those who wish to attempt to achieve a higher score must report data for 50% of all patients seen (for ALL payors) for any consecutive 90 day period. Accordingly, one could begin as late as October 2, 2017. How data is reported depends upon the circumstances of an individual’s practice as there are multiple methods (electronic health record, registry, or qualified clinical data registry) for submitting data to CMS. It should be noted that data can also be submitted either on an individual basis or as a group.

Reporting pathway toward potentially receiving a positive payment update: Reporting for Quality

To receive the full potential Quality score, data must be submitted for 50% of all patients seen (for ALL payors) for any consecutive 90 day period on a minimum of 6 measures including one Outcome measure. Alternatively, one can choose to use a specialty measure set to report on 50% of all patients seen (for ALL payors) for any consecutive 90 day period. Those who do meet the reporting requirement and perform well on the measures will receive up to 60 points toward their MIPS Final Score. For those who intend to simply avoid penalties for the first year of the MIPS program, reporting a single measure for a single patient will earn the 3 points necessary to meet the threshold prescribed by CMS to avoid a penalty.

Reporting for ACI

The ACI component is worth 25 percent of the MIPS Final Score. The assessment for ACI is a composite score composed of two parts, a Base score and a Performance score. To receive credit for the ACI component 2017, one must have either 2014 or 2015 Edition CEHRT.

The Base score is an “all-or-nothing” threshold and accounts for 50 percent of the total score for the ACI component. Achievement of the Base score is required before any score can be accrued for the Performance portion. Achieving the Base score is also one of the options prescribed by CMS sufficient to avoid MIPS penalties in the first year and if the Base Score is achieved, one will not receive a penalty for 2017. The ACI measures are intended to ensure that certified EHRs are being used for core tasks such as providing patients with online access to their medical records, exchanging health information with patients and other providers, electronic prescribing and protecting sensitive patient health information.

Once all of the measures for the Base score have been met, clinicians are eligible to receive credit for performance on both a subset of the Base score measures and on a set of additional optional measures. Bonus points are also available by reporting certain Improvement Activities via a certified EHR.

Reporting for Improvement Activities

While the Improvement Activities (IA) is a new category, surgeons are familiar with many of the activities including maintenance of certification, use of the ACS Surgical Risk Calculator, participation in a QCDR and registry with their state’s prescription drug monitoring program. Each activity is assigned a point value of either 20 points (high value) or 10 points (medium value). The reporting requirement for the IA is fulfilled by simple attestation via either a registry, qualified clinical data registry, or a portal on the CMS website. To receive full credit, most surgeons must select and attest to having completed between two and four activities for a total of 40 points. Some surgeons in rural or small practices will only need to complete one high value or two medium value activities to achieve full credit. Those who fulfill the requirement will receive 15 points toward the MIPS Final Score. For those whose goal is simply to avoid a penalty in the first reporting year of MIPS, reporting a single activity for 90 days is enough to avoid any MIPS penalties for 2017

For those seeking further information, the ACS website (www.facs.org/qpp) has additional fact sheets and informational videos on the MIPS program.

Until next month …

Dr. Bailey is a pediatric surgeon, and Medical Director, Advocacy, for the Division of Advocacy and Health Policy in the ACS offices in Washington, D.C.

Chikungunya arthritis symptoms reduced with immunomodulatory drugs

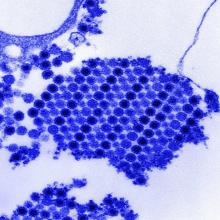

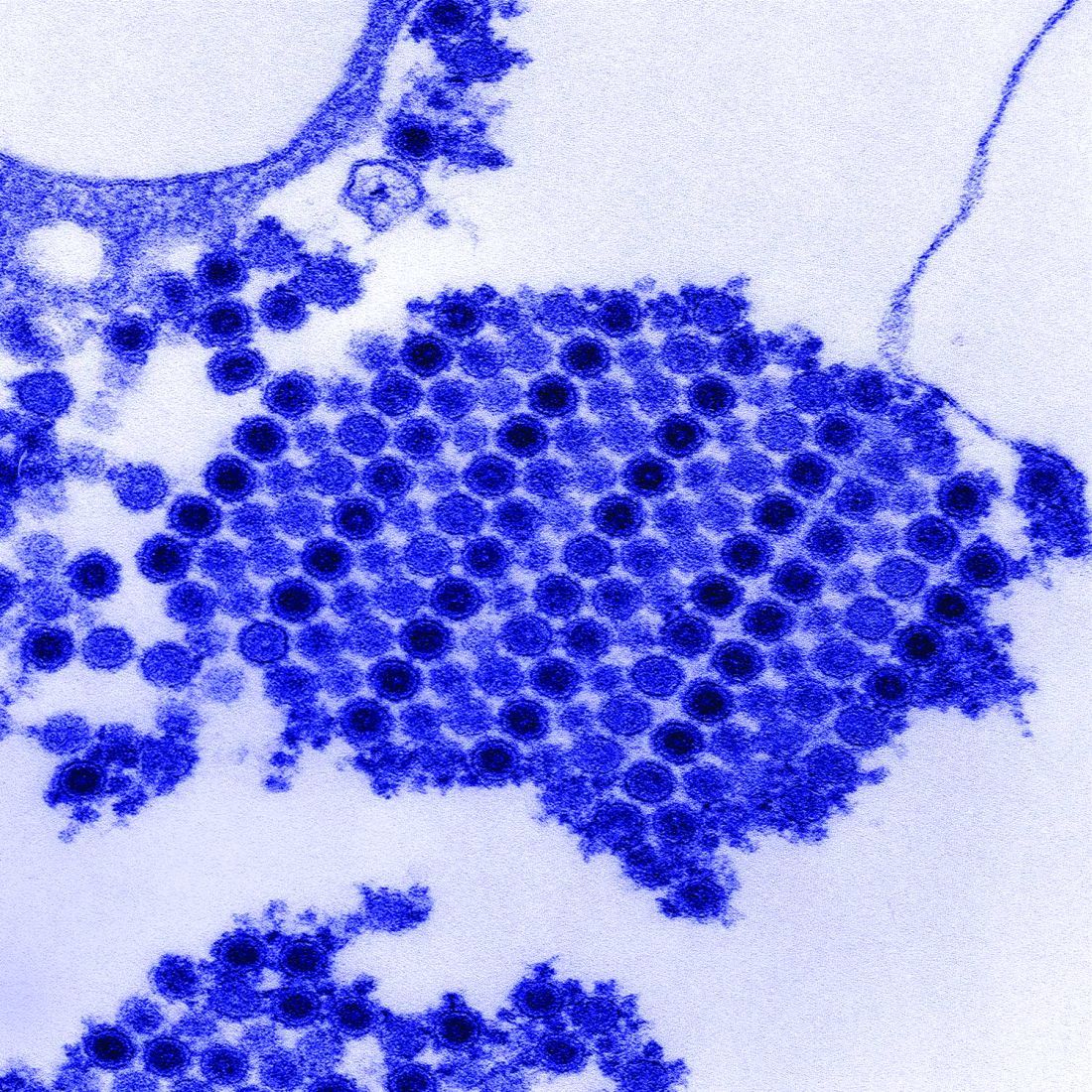

Several different currently approved immunomodulatory therapies ameliorated arthritis symptoms in chikungunya-infected mice in two studies that separate teams of researchers published online Feb. 1 in Science Translational Medicine.

The first team, led by Jonathan J. Miner, MD, PhD, of Washington University in St. Louis tested six different approved oral and biologic antirheumatic agents (along with control agents) in chikungunya virus-infected mice with acute arthritis and foot swelling (Sci Transl Med. 2017;9:eaah3438).

When the researchers paired abatacept with an antiviral therapy (monoclonal anti-CHIKV human antibody) the combination “was highly effective at reducing joint inflammation, periarticular swelling, migration of inflammatory leukocytes, and infection, even when administered several days after virus inoculation,” Dr. Miner and his colleagues wrote.

The researchers concluded that a combination of anti-inflammatory and antibody-based antiviral therapy “may serve as a model for treating humans with arthritis caused by CHIKV or other related viruses.”

In the second study, researchers led by Teck-Hui Teo, PhD, of the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) in Singapore, further elucidated the mechanisms by which CHIKV proteins act on T cells (Sci Transl Med. 2017;9:eaal1333). They also found that CHIKV-infected mice treated with fingolimod (Gilenya), a drug that blocks T-cell migration from the lymph nodes to the joints and is approved for the treatment of multiple sclerosis, saw reduced arthritis symptoms even without reduction of viral replication.

Infection with the chikungunya virus can produce arthritis that mimics symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis and may in some cases lead to joint damage. Though the mechanisms driving chikungunya-related arthritis are not well understood, preliminary studies have suggested a T-cell–mediated adverse response.

The Singapore team received funding from its own agency, A*STAR, while the Washington University researchers received grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Rheumatology Research Foundation. Two coauthors on the U.S. study reported extensive commercial conflicts, including consulting and advisory relationships with pharmaceutical and vaccine manufacturers, and one patent.

The studies by Dr. Miner and his colleagues and Dr. Teo and his associates demonstrate the potential value of combination therapies for ameliorating heightened T-cell responses and their pathogenic role in joint inflammation. They explored how T-cell responses could be blunted during ongoing viral replication to control overt inflammation, an approach that also may be valuable for treating immune-mediated tissue damage associated with other infectious agents.

Selective T-cell immunomodulatory therapies that offset damaging immune responses offer an attractive option for future pharmacologic interventions for treating chikungunya virus–induced inflammatory disease. The small market size and the rapid sporadic nature of outbreaks could be major obstacles to the development and deployment of virus-specific interventions such as therapeutic antiviral neutralizing monoclonal antibodies or even vaccines. Targeted drug and immunotherapy treatments are likely to offer practical and beneficial options for most patients with chikungunya.

Preliminary reports in humans have suggested that methotrexate may be effective for treating chikungunya virus–induced arthritis. In Dr. Miner and colleagues’ study, a low dose of methotrexate (0.3 mg/kg) was ineffective at treating acute joint swelling in mice. It remains to be addressed whether a higher dose of methotrexate for a longer time period could be of benefit in the setting of chronic chikungunya virus–induced arthritis.

Philippe Gasque, MD, PhD, is with the Université de La Réunion, Saint-Denis, Réunion, and Marie Christine Jaffar-Bandjee, MD, PhD, is with the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Félix Guyon, Saint-Denis, Réunion. They made these remarks in an editorial (Sci Transl Med. 2017;9:eaam6567).

The studies by Dr. Miner and his colleagues and Dr. Teo and his associates demonstrate the potential value of combination therapies for ameliorating heightened T-cell responses and their pathogenic role in joint inflammation. They explored how T-cell responses could be blunted during ongoing viral replication to control overt inflammation, an approach that also may be valuable for treating immune-mediated tissue damage associated with other infectious agents.

Selective T-cell immunomodulatory therapies that offset damaging immune responses offer an attractive option for future pharmacologic interventions for treating chikungunya virus–induced inflammatory disease. The small market size and the rapid sporadic nature of outbreaks could be major obstacles to the development and deployment of virus-specific interventions such as therapeutic antiviral neutralizing monoclonal antibodies or even vaccines. Targeted drug and immunotherapy treatments are likely to offer practical and beneficial options for most patients with chikungunya.

Preliminary reports in humans have suggested that methotrexate may be effective for treating chikungunya virus–induced arthritis. In Dr. Miner and colleagues’ study, a low dose of methotrexate (0.3 mg/kg) was ineffective at treating acute joint swelling in mice. It remains to be addressed whether a higher dose of methotrexate for a longer time period could be of benefit in the setting of chronic chikungunya virus–induced arthritis.

Philippe Gasque, MD, PhD, is with the Université de La Réunion, Saint-Denis, Réunion, and Marie Christine Jaffar-Bandjee, MD, PhD, is with the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Félix Guyon, Saint-Denis, Réunion. They made these remarks in an editorial (Sci Transl Med. 2017;9:eaam6567).

The studies by Dr. Miner and his colleagues and Dr. Teo and his associates demonstrate the potential value of combination therapies for ameliorating heightened T-cell responses and their pathogenic role in joint inflammation. They explored how T-cell responses could be blunted during ongoing viral replication to control overt inflammation, an approach that also may be valuable for treating immune-mediated tissue damage associated with other infectious agents.

Selective T-cell immunomodulatory therapies that offset damaging immune responses offer an attractive option for future pharmacologic interventions for treating chikungunya virus–induced inflammatory disease. The small market size and the rapid sporadic nature of outbreaks could be major obstacles to the development and deployment of virus-specific interventions such as therapeutic antiviral neutralizing monoclonal antibodies or even vaccines. Targeted drug and immunotherapy treatments are likely to offer practical and beneficial options for most patients with chikungunya.

Preliminary reports in humans have suggested that methotrexate may be effective for treating chikungunya virus–induced arthritis. In Dr. Miner and colleagues’ study, a low dose of methotrexate (0.3 mg/kg) was ineffective at treating acute joint swelling in mice. It remains to be addressed whether a higher dose of methotrexate for a longer time period could be of benefit in the setting of chronic chikungunya virus–induced arthritis.

Philippe Gasque, MD, PhD, is with the Université de La Réunion, Saint-Denis, Réunion, and Marie Christine Jaffar-Bandjee, MD, PhD, is with the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Félix Guyon, Saint-Denis, Réunion. They made these remarks in an editorial (Sci Transl Med. 2017;9:eaam6567).

Several different currently approved immunomodulatory therapies ameliorated arthritis symptoms in chikungunya-infected mice in two studies that separate teams of researchers published online Feb. 1 in Science Translational Medicine.

The first team, led by Jonathan J. Miner, MD, PhD, of Washington University in St. Louis tested six different approved oral and biologic antirheumatic agents (along with control agents) in chikungunya virus-infected mice with acute arthritis and foot swelling (Sci Transl Med. 2017;9:eaah3438).

When the researchers paired abatacept with an antiviral therapy (monoclonal anti-CHIKV human antibody) the combination “was highly effective at reducing joint inflammation, periarticular swelling, migration of inflammatory leukocytes, and infection, even when administered several days after virus inoculation,” Dr. Miner and his colleagues wrote.

The researchers concluded that a combination of anti-inflammatory and antibody-based antiviral therapy “may serve as a model for treating humans with arthritis caused by CHIKV or other related viruses.”

In the second study, researchers led by Teck-Hui Teo, PhD, of the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) in Singapore, further elucidated the mechanisms by which CHIKV proteins act on T cells (Sci Transl Med. 2017;9:eaal1333). They also found that CHIKV-infected mice treated with fingolimod (Gilenya), a drug that blocks T-cell migration from the lymph nodes to the joints and is approved for the treatment of multiple sclerosis, saw reduced arthritis symptoms even without reduction of viral replication.

Infection with the chikungunya virus can produce arthritis that mimics symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis and may in some cases lead to joint damage. Though the mechanisms driving chikungunya-related arthritis are not well understood, preliminary studies have suggested a T-cell–mediated adverse response.

The Singapore team received funding from its own agency, A*STAR, while the Washington University researchers received grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Rheumatology Research Foundation. Two coauthors on the U.S. study reported extensive commercial conflicts, including consulting and advisory relationships with pharmaceutical and vaccine manufacturers, and one patent.

Several different currently approved immunomodulatory therapies ameliorated arthritis symptoms in chikungunya-infected mice in two studies that separate teams of researchers published online Feb. 1 in Science Translational Medicine.

The first team, led by Jonathan J. Miner, MD, PhD, of Washington University in St. Louis tested six different approved oral and biologic antirheumatic agents (along with control agents) in chikungunya virus-infected mice with acute arthritis and foot swelling (Sci Transl Med. 2017;9:eaah3438).

When the researchers paired abatacept with an antiviral therapy (monoclonal anti-CHIKV human antibody) the combination “was highly effective at reducing joint inflammation, periarticular swelling, migration of inflammatory leukocytes, and infection, even when administered several days after virus inoculation,” Dr. Miner and his colleagues wrote.

The researchers concluded that a combination of anti-inflammatory and antibody-based antiviral therapy “may serve as a model for treating humans with arthritis caused by CHIKV or other related viruses.”

In the second study, researchers led by Teck-Hui Teo, PhD, of the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) in Singapore, further elucidated the mechanisms by which CHIKV proteins act on T cells (Sci Transl Med. 2017;9:eaal1333). They also found that CHIKV-infected mice treated with fingolimod (Gilenya), a drug that blocks T-cell migration from the lymph nodes to the joints and is approved for the treatment of multiple sclerosis, saw reduced arthritis symptoms even without reduction of viral replication.

Infection with the chikungunya virus can produce arthritis that mimics symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis and may in some cases lead to joint damage. Though the mechanisms driving chikungunya-related arthritis are not well understood, preliminary studies have suggested a T-cell–mediated adverse response.

The Singapore team received funding from its own agency, A*STAR, while the Washington University researchers received grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Rheumatology Research Foundation. Two coauthors on the U.S. study reported extensive commercial conflicts, including consulting and advisory relationships with pharmaceutical and vaccine manufacturers, and one patent.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Abatacept, tofacitinib, and fingolimod all reduced arthritis symptoms, compared with controls.

Data source: Two studies testing multiple immunomodulatory or antirheumatic agents in chikungunya virus–infected mice.

Disclosures: The Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) funded the Singapore researchers, while grants from the NIH and the Rheumatology Research Foundation funded the U.S. team. Two coauthors on the U.S. study disclosed extensive financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical and vaccine manufacturers.

Smaller, intrapericardial LVAD noninferior to HeartMate II

A smaller, centrifugal-flow left ventricular assist device that lies entirely within the pericardial space was found noninferior to the HeartMate II axial-flow device in patients with advanced heart failure who weren’t eligible for heart transplant, according to a report published online Feb. 2 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The two LVADs were compared in ENDURANCE (A Clinical Trial to Evaluate the HeartWare Ventricular Assist System), a prospective, randomized trial in 445 patients who were treated at 48 U.S. sites and followed for 2 years. The study participants had an LV ejection fraction of 25% or less and high prevalences of abnormal renal function and dependence on intravenous inotropic support, said Joseph G. Rogers, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and his associates.

The study participants were randomly assigned to receive the HeartWare, an investigational centrifugal-flow LVAD (297 patients) or the standard axial-flow HeartMate II LVAD (148 patients). In the intention-to-treat analysis, the primary endpoint – a composite of survival free from disabling stroke and no removal of the device for malfunction or failure – was 55.4% with the new device and 59.1% in the control group. The results were similar in the per-protocol and the as-treated analyses, demonstrating that the new device was noninferior but not superior to the axial-flow LVAD, the investigators said (N Engl J Med. 2017 Feb 2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602954).

There were significantly more cases of device malfunction or failure requiring urgent surgery in the control group than in the centrifugal-flow group (16.2% vs 8.8%), but significantly more cases of stroke (29.7% vs 12.1%), sepsis, and right heart failure. Rates of major bleeding, cardiac arrhythmia, renal dysfunction, and infection were similar between the two study groups. Overall survival* also was not significantly different (60.2% with the new LVAD and 67.6% in the control group).

Both study groups showed significant and comparable improvement after LVAD implantation. Functional status improved to New York Heart Association class I or II in roughly 80% of patients. Mean 6-minute walk distance improved from 100.2 to 199.4 meters with the new device and from 91.9 to 190.1 meters in the control group, a change that was noted within 3 months of surgery and persisted through the end of follow-up. Similarly, mean scores on the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire improved by 25.8 points and 25.3 points, respectively, and mean scores on the European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions scale improved by 22.5 points and 25.5 points, respectively.

This trial was sponsored by HeartWare, which was also involved in data management and analysis. Dr. Rogers reported having no relevant financial disclosures; his associates reported ties to HeartWare (Medtronic), Thoratec (St. Jude Medical), Novartis, and GE HealthCare.

*Correction 2/2/17: An earlier version of this article misidentified survival rates as mortality rates.

The smaller, fully intrapericardial, centrifugal-flow LVAD met one of its goals: Compared with the existing LVAD, it significantly reduced the need for urgent reoperation due to device malfunction or failure.

However, it did not resolve some of the most important problems with LVAD support. It didn’t reduce stroke risk; in fact, the overall risk of stroke was higher with the new device. It also failed to reduce the risk of bleeding, sepsis, or right heart failure.

It appears that no LVAD is fully superior to the others.

Roland Hetzer, MD, PhD, and Eva M. Delmo Walter, MD, PhD, of Cardio Centrum in Berlin, made these remarks in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2017 Feb 2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1613755). They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The smaller, fully intrapericardial, centrifugal-flow LVAD met one of its goals: Compared with the existing LVAD, it significantly reduced the need for urgent reoperation due to device malfunction or failure.

However, it did not resolve some of the most important problems with LVAD support. It didn’t reduce stroke risk; in fact, the overall risk of stroke was higher with the new device. It also failed to reduce the risk of bleeding, sepsis, or right heart failure.

It appears that no LVAD is fully superior to the others.

Roland Hetzer, MD, PhD, and Eva M. Delmo Walter, MD, PhD, of Cardio Centrum in Berlin, made these remarks in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2017 Feb 2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1613755). They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The smaller, fully intrapericardial, centrifugal-flow LVAD met one of its goals: Compared with the existing LVAD, it significantly reduced the need for urgent reoperation due to device malfunction or failure.

However, it did not resolve some of the most important problems with LVAD support. It didn’t reduce stroke risk; in fact, the overall risk of stroke was higher with the new device. It also failed to reduce the risk of bleeding, sepsis, or right heart failure.

It appears that no LVAD is fully superior to the others.

Roland Hetzer, MD, PhD, and Eva M. Delmo Walter, MD, PhD, of Cardio Centrum in Berlin, made these remarks in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2017 Feb 2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1613755). They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

A smaller, centrifugal-flow left ventricular assist device that lies entirely within the pericardial space was found noninferior to the HeartMate II axial-flow device in patients with advanced heart failure who weren’t eligible for heart transplant, according to a report published online Feb. 2 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The two LVADs were compared in ENDURANCE (A Clinical Trial to Evaluate the HeartWare Ventricular Assist System), a prospective, randomized trial in 445 patients who were treated at 48 U.S. sites and followed for 2 years. The study participants had an LV ejection fraction of 25% or less and high prevalences of abnormal renal function and dependence on intravenous inotropic support, said Joseph G. Rogers, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and his associates.

The study participants were randomly assigned to receive the HeartWare, an investigational centrifugal-flow LVAD (297 patients) or the standard axial-flow HeartMate II LVAD (148 patients). In the intention-to-treat analysis, the primary endpoint – a composite of survival free from disabling stroke and no removal of the device for malfunction or failure – was 55.4% with the new device and 59.1% in the control group. The results were similar in the per-protocol and the as-treated analyses, demonstrating that the new device was noninferior but not superior to the axial-flow LVAD, the investigators said (N Engl J Med. 2017 Feb 2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602954).

There were significantly more cases of device malfunction or failure requiring urgent surgery in the control group than in the centrifugal-flow group (16.2% vs 8.8%), but significantly more cases of stroke (29.7% vs 12.1%), sepsis, and right heart failure. Rates of major bleeding, cardiac arrhythmia, renal dysfunction, and infection were similar between the two study groups. Overall survival* also was not significantly different (60.2% with the new LVAD and 67.6% in the control group).

Both study groups showed significant and comparable improvement after LVAD implantation. Functional status improved to New York Heart Association class I or II in roughly 80% of patients. Mean 6-minute walk distance improved from 100.2 to 199.4 meters with the new device and from 91.9 to 190.1 meters in the control group, a change that was noted within 3 months of surgery and persisted through the end of follow-up. Similarly, mean scores on the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire improved by 25.8 points and 25.3 points, respectively, and mean scores on the European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions scale improved by 22.5 points and 25.5 points, respectively.

This trial was sponsored by HeartWare, which was also involved in data management and analysis. Dr. Rogers reported having no relevant financial disclosures; his associates reported ties to HeartWare (Medtronic), Thoratec (St. Jude Medical), Novartis, and GE HealthCare.

*Correction 2/2/17: An earlier version of this article misidentified survival rates as mortality rates.

A smaller, centrifugal-flow left ventricular assist device that lies entirely within the pericardial space was found noninferior to the HeartMate II axial-flow device in patients with advanced heart failure who weren’t eligible for heart transplant, according to a report published online Feb. 2 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The two LVADs were compared in ENDURANCE (A Clinical Trial to Evaluate the HeartWare Ventricular Assist System), a prospective, randomized trial in 445 patients who were treated at 48 U.S. sites and followed for 2 years. The study participants had an LV ejection fraction of 25% or less and high prevalences of abnormal renal function and dependence on intravenous inotropic support, said Joseph G. Rogers, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and his associates.

The study participants were randomly assigned to receive the HeartWare, an investigational centrifugal-flow LVAD (297 patients) or the standard axial-flow HeartMate II LVAD (148 patients). In the intention-to-treat analysis, the primary endpoint – a composite of survival free from disabling stroke and no removal of the device for malfunction or failure – was 55.4% with the new device and 59.1% in the control group. The results were similar in the per-protocol and the as-treated analyses, demonstrating that the new device was noninferior but not superior to the axial-flow LVAD, the investigators said (N Engl J Med. 2017 Feb 2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602954).

There were significantly more cases of device malfunction or failure requiring urgent surgery in the control group than in the centrifugal-flow group (16.2% vs 8.8%), but significantly more cases of stroke (29.7% vs 12.1%), sepsis, and right heart failure. Rates of major bleeding, cardiac arrhythmia, renal dysfunction, and infection were similar between the two study groups. Overall survival* also was not significantly different (60.2% with the new LVAD and 67.6% in the control group).

Both study groups showed significant and comparable improvement after LVAD implantation. Functional status improved to New York Heart Association class I or II in roughly 80% of patients. Mean 6-minute walk distance improved from 100.2 to 199.4 meters with the new device and from 91.9 to 190.1 meters in the control group, a change that was noted within 3 months of surgery and persisted through the end of follow-up. Similarly, mean scores on the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire improved by 25.8 points and 25.3 points, respectively, and mean scores on the European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions scale improved by 22.5 points and 25.5 points, respectively.