User login

Beauty sleep: Sleep deprivation and the skin

There are many, many, short-term and long-term consequences of sleep deprivation. The most clinically apparent ones – swollen, sunken eyes; dark circles; and pale, dehydrated skin – are obvious. However the subclinical consequences are not so obvious. Sleep deprivation affects wound healing, collagen growth, skin hydration, and skin texture. Inflammation is also higher in sleep-deprived patients, causing outbreaks of acne, eczema, psoriasis, and skin allergies.

The reduction of sleep time affects the composition and integrity of the skin. Sleep deprivation increases glucocorticoid production. The elevation of cortisol inhibits fibroblast function and increases matrix metalloproteinases (collagenase, gelatinase). Matrix metalloproteinases accelerate collagen and elastin breakdown, which is essential to skin integrity, and hastens the aging process by increasing wrinkles, decreasing skin thickness, inhibiting growth factors, and decreasing skin elasticity.

Are there treatments to reverse these signs? Yes. Treatments to help increase skin collagen production include microneedling, radiofrequency devices, fractionated lasers, and topical agents such as retinoids. However, we cannot readily reverse the impact inflammatory processes, skin barrier dysfunction, or the disruption of the skin biome has on our skin. Beauty sleep is both necessary and irreplaceable.

References

1. Am J Physiol. 1993 Nov;265(5 Pt 2):R1148-54.

2. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000 Apr;278(4):R905-16.

3. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005 Feb;288(2):R374-83.

4. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007 Jul;293(1):R504-9.

5. Med Hypotheses. 2010 Dec;75(6):535-7.

6. Sleep. 2013 Sep 1;36(9):1355-60.

7. BMJ. 2010 Dec 14;341:c6614.

8. Brain Behav Immun. 2009 Nov;23(8):1089-95.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley and are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected].

There are many, many, short-term and long-term consequences of sleep deprivation. The most clinically apparent ones – swollen, sunken eyes; dark circles; and pale, dehydrated skin – are obvious. However the subclinical consequences are not so obvious. Sleep deprivation affects wound healing, collagen growth, skin hydration, and skin texture. Inflammation is also higher in sleep-deprived patients, causing outbreaks of acne, eczema, psoriasis, and skin allergies.

The reduction of sleep time affects the composition and integrity of the skin. Sleep deprivation increases glucocorticoid production. The elevation of cortisol inhibits fibroblast function and increases matrix metalloproteinases (collagenase, gelatinase). Matrix metalloproteinases accelerate collagen and elastin breakdown, which is essential to skin integrity, and hastens the aging process by increasing wrinkles, decreasing skin thickness, inhibiting growth factors, and decreasing skin elasticity.

Are there treatments to reverse these signs? Yes. Treatments to help increase skin collagen production include microneedling, radiofrequency devices, fractionated lasers, and topical agents such as retinoids. However, we cannot readily reverse the impact inflammatory processes, skin barrier dysfunction, or the disruption of the skin biome has on our skin. Beauty sleep is both necessary and irreplaceable.

References

1. Am J Physiol. 1993 Nov;265(5 Pt 2):R1148-54.

2. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000 Apr;278(4):R905-16.

3. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005 Feb;288(2):R374-83.

4. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007 Jul;293(1):R504-9.

5. Med Hypotheses. 2010 Dec;75(6):535-7.

6. Sleep. 2013 Sep 1;36(9):1355-60.

7. BMJ. 2010 Dec 14;341:c6614.

8. Brain Behav Immun. 2009 Nov;23(8):1089-95.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley and are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected].

There are many, many, short-term and long-term consequences of sleep deprivation. The most clinically apparent ones – swollen, sunken eyes; dark circles; and pale, dehydrated skin – are obvious. However the subclinical consequences are not so obvious. Sleep deprivation affects wound healing, collagen growth, skin hydration, and skin texture. Inflammation is also higher in sleep-deprived patients, causing outbreaks of acne, eczema, psoriasis, and skin allergies.

The reduction of sleep time affects the composition and integrity of the skin. Sleep deprivation increases glucocorticoid production. The elevation of cortisol inhibits fibroblast function and increases matrix metalloproteinases (collagenase, gelatinase). Matrix metalloproteinases accelerate collagen and elastin breakdown, which is essential to skin integrity, and hastens the aging process by increasing wrinkles, decreasing skin thickness, inhibiting growth factors, and decreasing skin elasticity.

Are there treatments to reverse these signs? Yes. Treatments to help increase skin collagen production include microneedling, radiofrequency devices, fractionated lasers, and topical agents such as retinoids. However, we cannot readily reverse the impact inflammatory processes, skin barrier dysfunction, or the disruption of the skin biome has on our skin. Beauty sleep is both necessary and irreplaceable.

References

1. Am J Physiol. 1993 Nov;265(5 Pt 2):R1148-54.

2. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000 Apr;278(4):R905-16.

3. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005 Feb;288(2):R374-83.

4. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007 Jul;293(1):R504-9.

5. Med Hypotheses. 2010 Dec;75(6):535-7.

6. Sleep. 2013 Sep 1;36(9):1355-60.

7. BMJ. 2010 Dec 14;341:c6614.

8. Brain Behav Immun. 2009 Nov;23(8):1089-95.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley and are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected].

Audiocast: Hysteroscopic tubal occlusion: How new product labeling can be a resource for patient counseling

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Resources

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Resources

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Resources

Clinical rating scales

The New Opioid Epidemic and the Law of Unintended Consequences

In this issue of EM, EP-toxicologists Rama Rao, MD, and Lewis Nelson, MD, review the salient features of the current opioid epidemic in the United States. The authors differentiate this epidemic from prior patterns of heroin and opioid abuse partly by the clinical features that now make timely diagnosis and treatment in the ED more difficult.

According to the CDC, between 2000 and 2015, the number of opioid overdose deaths in this country quadrupled to half a million, or 91 deaths a day (

The road to the current epidemic began to be paved with good intentions in the late 1990s when, soon after the FDA approved the controlled-release form of oxycodone (Oxycontin), the American Pain Society introduced the phrase “pain as the fifth vital sign.” In 1999, the Department of Veterans Affairs embraced the statement, as did other organizations. The Joint Commission standards for pain management in 2001 stated “pain is assessed in all patients” (all was dropped in 2009) and contained a passing reference to pain as the fifth vital sign. In 2012, CMS added to its ED performance core measures timely pain treatment for long bone fractures, emphasizing parenteral medications.

By 2010, the problems created by emphasizing effective pain management had become evident, and measures began to be introduced to restrict the prescribing and availability of pharmaceutical opioids. The restrictions sent many patients to EDs seeking pain meds. Others sought substitutes on the street and ultimately ended up in EDs as overdoses from very potent synthetics. Many EPs began to limit opioid prescriptions to 3 days for acute painful conditions, though not all patients were able to obtain follow-up appointments with PCPs within that time period.

In April 2016, the Joint Commission issued a statement claiming it was not responsible for “pain as the fifth vital sign” or for suggesting that pain be treated with opioids. In June 2016, the AMA urged dropping “pain-as-the-fifth-vital-sign” policies, and in 2014, CMS modified its core measure emphasis on parenteral medication in the timely treatment of long bone fractures. But the damage has been done, leaving many people requiring help managing their pain and others suffering the consequences of opioid dependence.

EPs must continue to deal with victims of overdoses without denying pain treatment to those with acute, acute-on-chronic, and recurrent pain. Increased use of effective non-opioid pain meds such as NSAIDs may help, although not everyone can tolerate them and there are long-term risks. For large, overcrowded, urban EDs where treatment of pain is not always timely or consistent, 24/7 ED pain management teams working with EPs could be a tremendous asset, just as 24/7 ED pharmacists have proven to be. Until both effective pain treatment and the resultant opioid dependence and overdoses can be successfully addressed, regulatory agencies should deemphasize, without completely eliminating, pain treatment questions in scoring patient satisfaction.

In this issue of EM, EP-toxicologists Rama Rao, MD, and Lewis Nelson, MD, review the salient features of the current opioid epidemic in the United States. The authors differentiate this epidemic from prior patterns of heroin and opioid abuse partly by the clinical features that now make timely diagnosis and treatment in the ED more difficult.

According to the CDC, between 2000 and 2015, the number of opioid overdose deaths in this country quadrupled to half a million, or 91 deaths a day (

The road to the current epidemic began to be paved with good intentions in the late 1990s when, soon after the FDA approved the controlled-release form of oxycodone (Oxycontin), the American Pain Society introduced the phrase “pain as the fifth vital sign.” In 1999, the Department of Veterans Affairs embraced the statement, as did other organizations. The Joint Commission standards for pain management in 2001 stated “pain is assessed in all patients” (all was dropped in 2009) and contained a passing reference to pain as the fifth vital sign. In 2012, CMS added to its ED performance core measures timely pain treatment for long bone fractures, emphasizing parenteral medications.

By 2010, the problems created by emphasizing effective pain management had become evident, and measures began to be introduced to restrict the prescribing and availability of pharmaceutical opioids. The restrictions sent many patients to EDs seeking pain meds. Others sought substitutes on the street and ultimately ended up in EDs as overdoses from very potent synthetics. Many EPs began to limit opioid prescriptions to 3 days for acute painful conditions, though not all patients were able to obtain follow-up appointments with PCPs within that time period.

In April 2016, the Joint Commission issued a statement claiming it was not responsible for “pain as the fifth vital sign” or for suggesting that pain be treated with opioids. In June 2016, the AMA urged dropping “pain-as-the-fifth-vital-sign” policies, and in 2014, CMS modified its core measure emphasis on parenteral medication in the timely treatment of long bone fractures. But the damage has been done, leaving many people requiring help managing their pain and others suffering the consequences of opioid dependence.

EPs must continue to deal with victims of overdoses without denying pain treatment to those with acute, acute-on-chronic, and recurrent pain. Increased use of effective non-opioid pain meds such as NSAIDs may help, although not everyone can tolerate them and there are long-term risks. For large, overcrowded, urban EDs where treatment of pain is not always timely or consistent, 24/7 ED pain management teams working with EPs could be a tremendous asset, just as 24/7 ED pharmacists have proven to be. Until both effective pain treatment and the resultant opioid dependence and overdoses can be successfully addressed, regulatory agencies should deemphasize, without completely eliminating, pain treatment questions in scoring patient satisfaction.

In this issue of EM, EP-toxicologists Rama Rao, MD, and Lewis Nelson, MD, review the salient features of the current opioid epidemic in the United States. The authors differentiate this epidemic from prior patterns of heroin and opioid abuse partly by the clinical features that now make timely diagnosis and treatment in the ED more difficult.

According to the CDC, between 2000 and 2015, the number of opioid overdose deaths in this country quadrupled to half a million, or 91 deaths a day (

The road to the current epidemic began to be paved with good intentions in the late 1990s when, soon after the FDA approved the controlled-release form of oxycodone (Oxycontin), the American Pain Society introduced the phrase “pain as the fifth vital sign.” In 1999, the Department of Veterans Affairs embraced the statement, as did other organizations. The Joint Commission standards for pain management in 2001 stated “pain is assessed in all patients” (all was dropped in 2009) and contained a passing reference to pain as the fifth vital sign. In 2012, CMS added to its ED performance core measures timely pain treatment for long bone fractures, emphasizing parenteral medications.

By 2010, the problems created by emphasizing effective pain management had become evident, and measures began to be introduced to restrict the prescribing and availability of pharmaceutical opioids. The restrictions sent many patients to EDs seeking pain meds. Others sought substitutes on the street and ultimately ended up in EDs as overdoses from very potent synthetics. Many EPs began to limit opioid prescriptions to 3 days for acute painful conditions, though not all patients were able to obtain follow-up appointments with PCPs within that time period.

In April 2016, the Joint Commission issued a statement claiming it was not responsible for “pain as the fifth vital sign” or for suggesting that pain be treated with opioids. In June 2016, the AMA urged dropping “pain-as-the-fifth-vital-sign” policies, and in 2014, CMS modified its core measure emphasis on parenteral medication in the timely treatment of long bone fractures. But the damage has been done, leaving many people requiring help managing their pain and others suffering the consequences of opioid dependence.

EPs must continue to deal with victims of overdoses without denying pain treatment to those with acute, acute-on-chronic, and recurrent pain. Increased use of effective non-opioid pain meds such as NSAIDs may help, although not everyone can tolerate them and there are long-term risks. For large, overcrowded, urban EDs where treatment of pain is not always timely or consistent, 24/7 ED pain management teams working with EPs could be a tremendous asset, just as 24/7 ED pharmacists have proven to be. Until both effective pain treatment and the resultant opioid dependence and overdoses can be successfully addressed, regulatory agencies should deemphasize, without completely eliminating, pain treatment questions in scoring patient satisfaction.

Diagnosis of Severe Acute Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding with CTA

Case

A 31-year-old white man presented to the ED with abdominal and rectal pain accompanied by multiple episodes of bloody diarrhea. He stated he had mild rectal pain the previous night but was pain-free and in his usual state of health the morning of his presentation. Approximately 2 hours before presenting to the ED, however, he began experiencing mild stomach pain, then bloody diarrhea which he described as bright red and “filling the toilet bowl with blood.” He had no history of inflammatory bowel disease or other gastrointestinal (GI) disorder, no recent travel, no complaints of nausea or vomiting, and no infectious symptoms. He described a remote history of external hemorrhoids, and review of his family history was significant for multiple paternal relatives with aortic aneurysms. He was not taking any medications and was a nonsmoker with a normal body mass index (24.3 kg/m2).

Upon arrival at the ED, the patient’s vital signs were: heart rate, 112 beats/min; and blood pressure, 139/102 mm Hg; respiratory rate and temperature were normal, as was the patient’s oxygen saturation on room air. Physical examination was notable for no subjective or objective findings of orthostatic hypotension; increased bowel sounds and diffuse mild abdominal tenderness; and no external hemorrhoids, fissures, or rectal tenderness. Laboratory evaluation was significant for hemoglobin (Hgb), 15.0 g/dL; blood urea nitrogen (BUN)-to-creatinine (Cr) ratio, 11.6; and anion gap, 17 mEq/L.

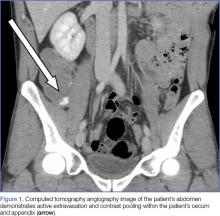

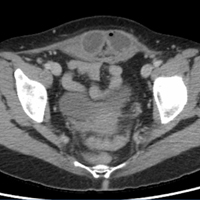

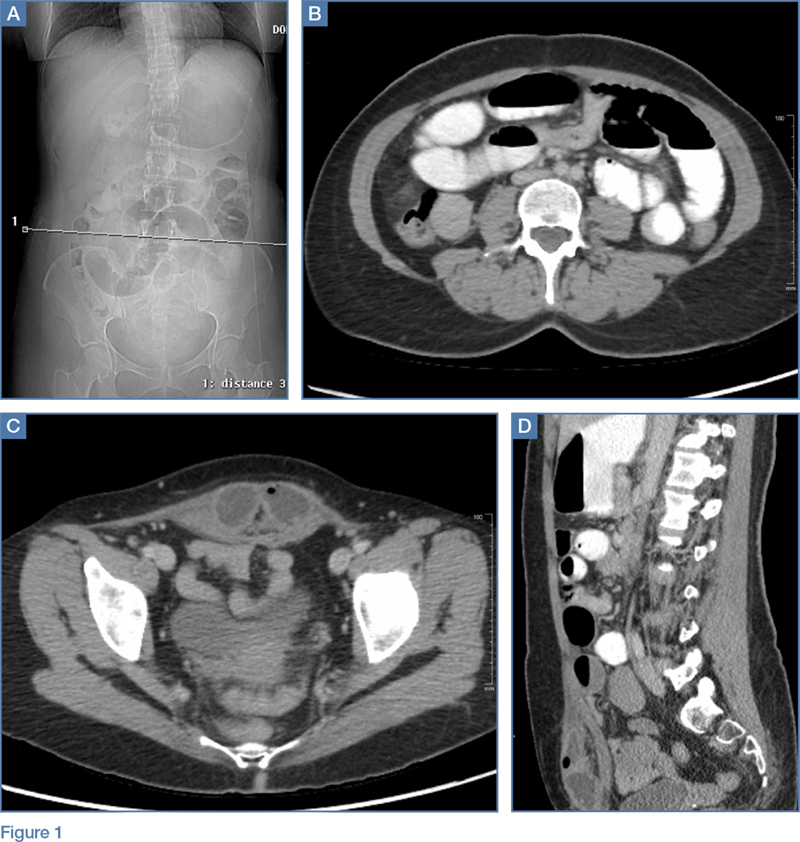

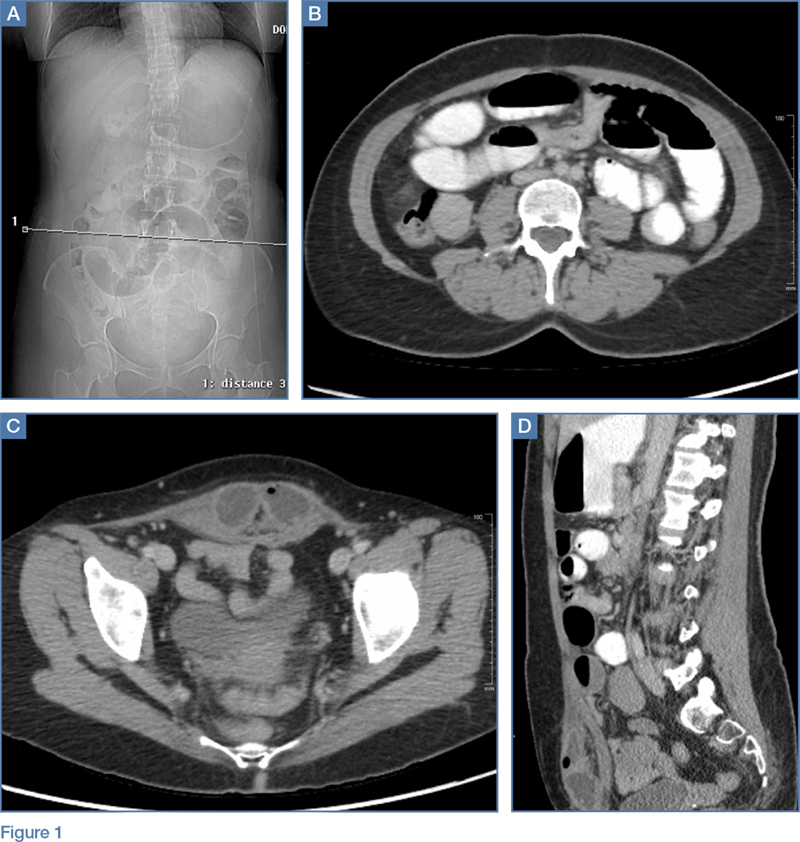

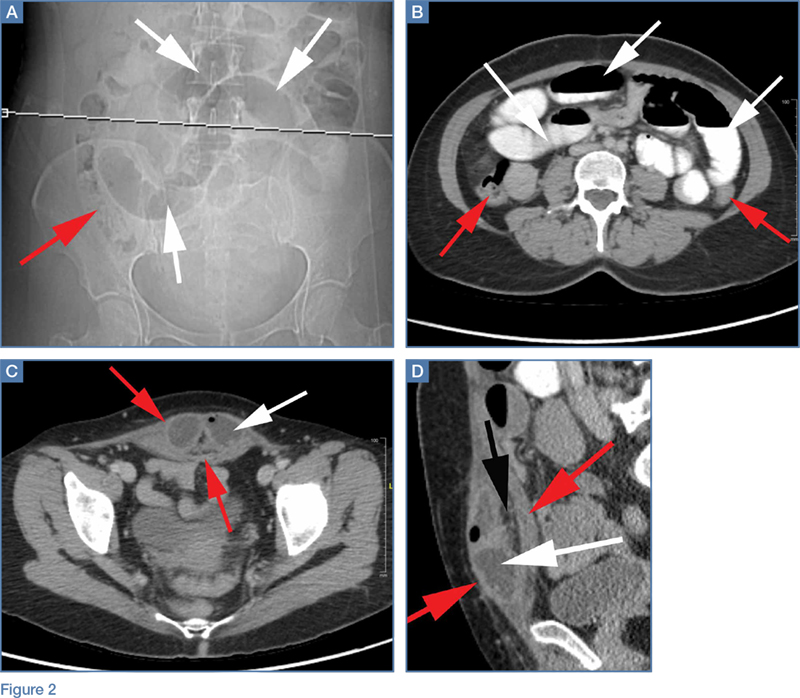

Upon initial presentation, there was some concern for an infection. However, as the patient continued to have bowel movements consisting almost entirely of frank blood and did not have any infectious signs, a vascular etiology was more strongly considered. Given the patient’s relatively stable vital signs, BUN-to-Cr ratio of less than 20, and lack of orthostatic hypotension, there was low concern for an upper GI etiology, and endoscopy was not obtained emergently. The patient instead underwent abdominal computed tomography angiography (CTA), which identified active extravasation and contrast pooling within the cecum and appendix (Figure 1).

Shortly after the patient returned from imaging, repeat laboratory studies were performed, demonstrating an Hgb drop from 15.0 g/dL to 12.3 g/dL, and surgical services was emergently consulted. The surgeon recommended that embolization first be attempted, with surgery as the option of last resort given the poor localization of the bleed on CTA and the long-term consequences of colonic resection in a young, otherwise healthy man.

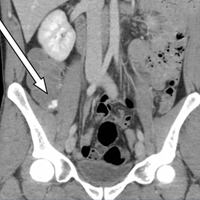

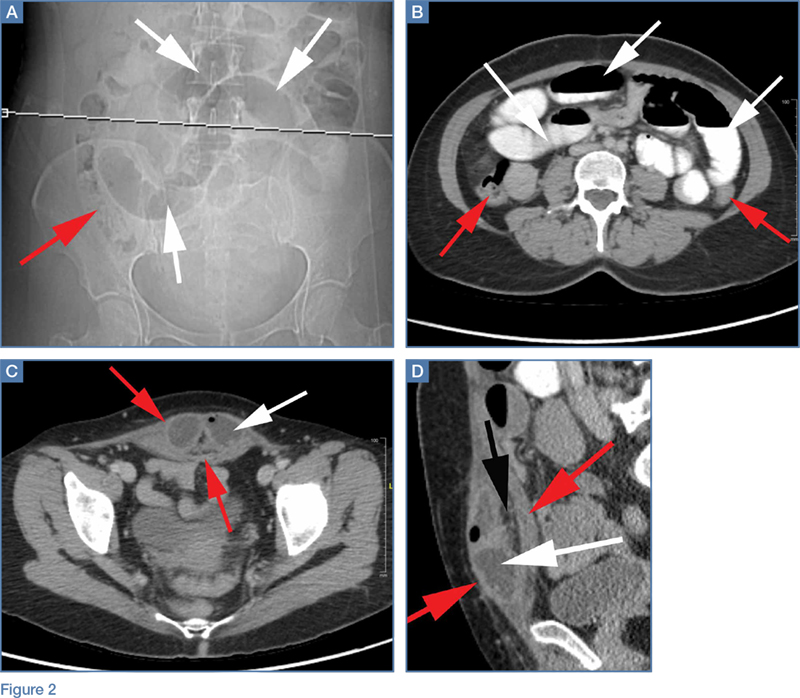

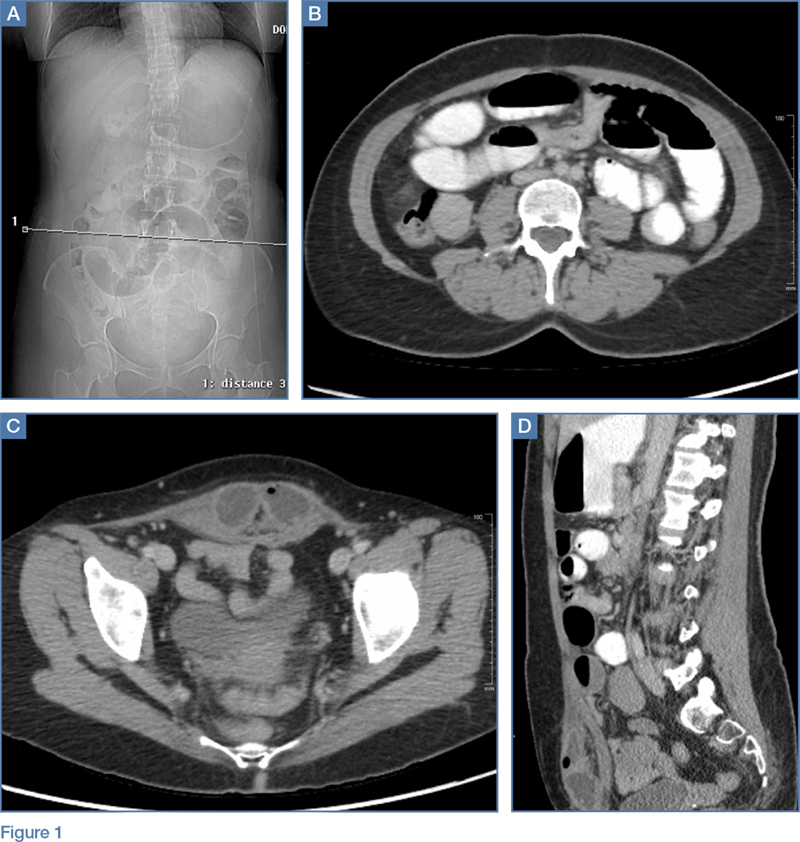

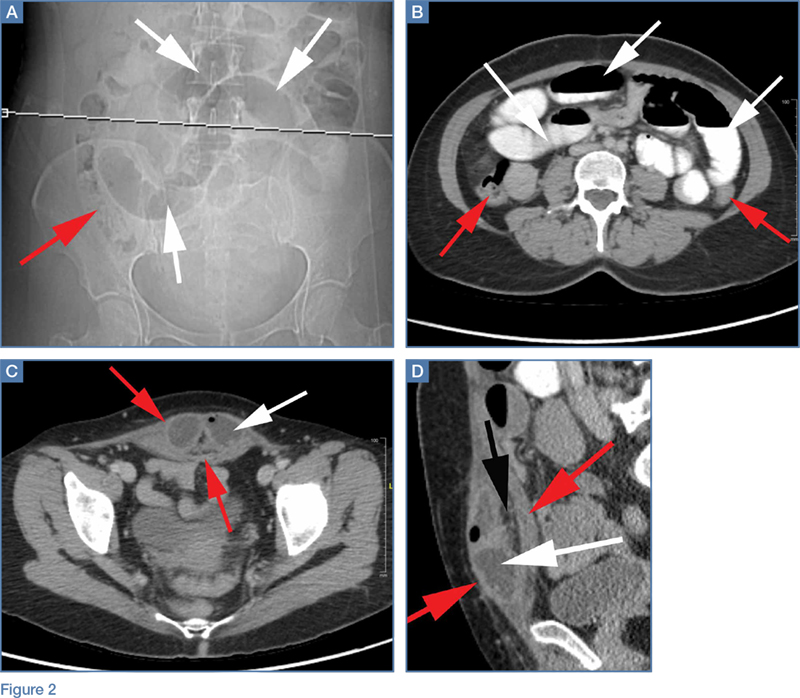

Interventional radiology was consulted, and the patient was brought immediately to the angiography suite, where he was found to have “active extravasation arising from a distal descending branch off the right colic artery” (Figure 2). Coil embolization resulted in complete resolution of the hemorrhage.

Later that evening, the patient’s Hgb continued to drop, reaching nadir at 7.3 g/dL, and he continued to have severe hematochezia. His falling Hgb was thought to be indicative of the degree of hemorrhage he had sustained prior to embolization, and the clearance of such blood as the source of his ongoing hematochezia. Following transfusion of 2 U of packed red blood cells (PRBCs), the patient’s Hgb improved to 12.0 g/dL, and he did not experience any significant bleeding for the remainder of his hospital stay.

The following morning, the patient underwent an extensive colonoscopy (extending 25 cm into the terminal ileum), which was unable to detect any signs of arteriovenous malformations, angiodysplasia, or any other possible source of bleeding. After 24 hours with stable vital signs and Hgb levels, the patient was discharged home with close surgical and gastroenterological follow-up, with possible genetic testing for connective tissue diseases. The diagnosis at discharge was spontaneous mesenteric hemorrhage of unknown etiology.

Discussion

Acute lower GI bleeding has an estimated annual hospitalization rate of 36 patients per 100,000, or about half the rate for upper GI bleeding.1,2 The majority of patients (>80%) will have spontaneous resolution and can be worked up nonemergently.

Etiology and Work-Up

Assessment of the etiology of hematochezia begins with ruling out an upper GI source of the bleed; 10% to 15% of patients presenting with hematochezia without hematemesis are ultimately diagnosed with an upper GI etiology. 4,5

BUN-to-Cr Ratio. In a study of patients presenting with hematochezia but no hematemesis or renal failure, Srygley et al6 found a BUN-to-Cr ratio greater than 93% to be sensitive for an upper GI source, with a likelihood ratio of 7.5. The proposed etiology is some combination of absorption of digested blood products and prerenal azotemia due to hypovolemia.

Tachycardia and Orthostatic Hypotension. There have been discussions in the literature about other findings to rule in/out upper GI bleeding. While some studies have found statistically significant results between upper and lower GI bleeding for tachycardia and orthostatic hypotension (increased percentage of both in upper GI bleeding), there is disagreement about whether these findings are clinically significant.7-9

Nasogastric Lavage. Although nasogastric (NG) lavage is no longer the standard of care in the ED due to poor sensitivity and marked discomfort to the patient, most current gastroenterology guidelines still recommend its use; therefore, NG may be requested by the GI consultant.10-12

Diagnosis

Once an upper GI source has been ruled out, identification of the lesion is the next step. The differential diagnosis includes common sources such as diverticular disease, angiodysplasia, colitis, anorectal sources, and neoplasm.5 Less common, but associated with a high risk of mortality, is aortoenteric fistula (100% mortality without surgical intervention).5

Colonoscopy. Emergent colonoscopy can be used for both diagnosis and (potential) therapeutic intervention and is therefore the first option of choice.1,3,4,9 However, as seen in our case, some patients experience such profound hemorrhage that visualization of the colon may be difficult or impossible; patients may also be too unstable to await bowel preparation or undergo a procedure.

Computed Tomography Angiography. For patients in whom colonoscopy is contraindicated, CTA is the imaging modality of choice, and has a 91% to 92% sensitivity in identifying active bleeding (>0.35 mL/min).13-16

Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast alone, as opposed to CTA, is insufficient for detecting GI bleeding, as it is timed so that imaging is obtained when the contrast is in the portal venous capillary beds, rather than in the arteries or arterioles. By protocol, though, many institutions require abdominal and pelvic CTA to include both arterial phase and venous phase images, allowing for assessment of both active arterial bleeding and alternative lower GI sources of hematochezia (eg, mesenteric ischemia).

When ordering a CT study, an awareness of local practice is important in understanding the information that will be obtained from the study. Protocols for lower GI bleed that include CTA have reported accuracy and efficiency without worsening of renal function, despite the increased contrast load.17

Triphasic CT Enterography. Another CT modality to consider is triphasic CT enterography, which uses IV and oral contrast. In a preliminary trial, this modality achieved a specificity of 100% (sensitivity 42%) in detecting GI bleeding.18

Red Blood Cell Scintigraphy. An additional imaging modality that has been the subject of much debate in the GI literature is tagged RBC scintigraphy with Technetium-99m. Various studies have found bleeding-site confirmation in 24% to 97% of patients, and correct localization in 41% to 100% of patients. Given the extensive variability within the literature on selection criteria, localization, site confirmation, and other variables, as well as evidence from one prospective trial by Zink et al19 that found a significant disagreement between CTA and scintigraphy, RBC scintigraphy is not recommended as an alternative imaging modality for the rapid diagnosis of an acute lower GI bleed.

Conclusion

Severe hematochezia is a potential surgical emergency with a broad differential diagnosis. While emergent colonoscopy is an excellent first option, in patients with severe hematochezia, there may be too much blood in the colon to obtain adequate visual images; additionally, depending on practice setting, emergency colonoscopy may not be immediately available. In either case, CTA—a readily available, noninvasive, rapid, and repeatable diagnostic tool—should be considered as an alternate to colonoscopy, particularly in patients with brisk hematochezia.

If a patient with severe hematochezia presents to the ED, the emergency physician (EP) must recognize that the degree of hemorrhage may not correlate with the patient’s vital signs or initial laboratory values. For this reason, the EP must have a high index of suspicion, and consider CTA to allow for a rapid definitive diagnosis and prompt discussion between surgical, interventional radiology, and/or gastroenterology teams to improve clinical outcomes and decrease morbidity and mortality.20

1. Ghassemi K, Jensen D. Lower GI bleeding: epidemiology and management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;15(7):333. doi:10.1007/s11894-013-0333-5.

2. Strate LL, Ayanian JZ, Kotler G, Syngal S. Risk factors for mortality in lower intestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(9):1004-1010. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2008.03.021.

3. Qayad E, Dagar G, Nanchal R. Lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Crit Care Clin. 2016;32(2):241-254. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2015.12.004.

4. Strate LL. Lower GI bleeding: epidemiology and diagnosis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34(4):643-664.

5. Goralnick E, Meguerdichian D. Gastrointestinal bleeding. In: Marx J, Hockberger R, Walls R. (Eds.). Rosen’s Emergency Medicine, 8th Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 2014;248-253.

6. Srygley FD, Gerando CJ, Tran T, Fisher DA. Does this patient have a severe upper gastrointestinal bleed? JAMA. 2012;307(10):1072-1079. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.253.

7. Whelen C, Chen C, Kaboli P, Siddique J, Prochaska M, Meltzer DO. Upper versus lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a direct comparison of clinical presentation, outcomes, and resource utilization. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(3):141-147. doi:10.1002/jhm.606.

8. Sittichanbunch Y, Senasu S, Thongkrau T, Keeratiksikorn C, Sawanyawisuth K. How to differentiate sites of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with hematochezia by using clinical factors? Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:265076. doi:10.1155/2013/265076.

9. Velayos F, Williamson A, Sousa KH, et al. Early predictors of severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding and adverse outcomes: a prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(6):485-490.

10. Palamidessi N, Sinert R, Falzon L, Zehtabchi S. Nasogastric aspiration and lavage in emergency department patients with hematochezia or melena without hematemesis. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(2):126-132. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00609.x.

11. Singer AJ, Richman PB, Kowalska A, Thode HC Jr. Comparison of patient and practitioner assessments of pain from commonly performed emergency department procedures. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33(6):652-658.

12. Strate L, Gralnek I. ACG clinical guideline: management of patients with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(4):459-474. doi:10.1038/ajg.2016.41.

13. Wu LM, Xu JR, Yin Y, Qu XH. Usefulness of CT angiography in diagnosing acute gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(31):3957-3963.

14. Geffroy Y, Rodallec MH, Boulay-Coletta I, Julles MC, Ridereau-Zins C, Zins M. Multidetector CT angiography in acute gastrointestinal bleeding: why, when, and how. Radiographics. 2011;31(3):E35-E46.

15. Reis F, Cardia P, D’Ippolito G. Computed tomography angiography in patients with active gastrointestinal bleeding. Radiol Bras. 2015;48(6):381-390. doi:10.1590/0100-3984.2014.0014.

16. Chan V, Tse D, Dixon S, et al. Outcome following a negative CT angiogram for gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2015;38(2):329-335. doi:10.1007/s00270-014-0928-8.

17. Jacovides T, Nadolski G, Allen S, et al. Arteriography for lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: role of preceding abdominal computed tomographic angiogram in diagnosis and localization. JAMA Surgery. 2015;150(7):650-656. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.97.

18. Hara AK, Walker FB, Silva AC, Leighton JA. Preliminary estimate of triphasic CT enterography performance in hemodynamically stable patients with suspected gastrointestinal bleeding. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(5):1252-1260. doi:10.2214/AJR.08.1494.

19. Zink SI, Ohki SK, Stein B, et al. Noninvasive evaluation of active lower gastrointestinal bleeding: comparison between contrast-enhanced MDCT and 99mTc-labeled RBC scintigraphy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;91(4):1107-1114. doi:10.2214/AJR.07.3642.

20. Nable J, Graham A. Gastrointestinal bleeding. Emerg Med Clin N Am. 2016;34(2):309-325. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2015.12.001.

Case

A 31-year-old white man presented to the ED with abdominal and rectal pain accompanied by multiple episodes of bloody diarrhea. He stated he had mild rectal pain the previous night but was pain-free and in his usual state of health the morning of his presentation. Approximately 2 hours before presenting to the ED, however, he began experiencing mild stomach pain, then bloody diarrhea which he described as bright red and “filling the toilet bowl with blood.” He had no history of inflammatory bowel disease or other gastrointestinal (GI) disorder, no recent travel, no complaints of nausea or vomiting, and no infectious symptoms. He described a remote history of external hemorrhoids, and review of his family history was significant for multiple paternal relatives with aortic aneurysms. He was not taking any medications and was a nonsmoker with a normal body mass index (24.3 kg/m2).

Upon arrival at the ED, the patient’s vital signs were: heart rate, 112 beats/min; and blood pressure, 139/102 mm Hg; respiratory rate and temperature were normal, as was the patient’s oxygen saturation on room air. Physical examination was notable for no subjective or objective findings of orthostatic hypotension; increased bowel sounds and diffuse mild abdominal tenderness; and no external hemorrhoids, fissures, or rectal tenderness. Laboratory evaluation was significant for hemoglobin (Hgb), 15.0 g/dL; blood urea nitrogen (BUN)-to-creatinine (Cr) ratio, 11.6; and anion gap, 17 mEq/L.

Upon initial presentation, there was some concern for an infection. However, as the patient continued to have bowel movements consisting almost entirely of frank blood and did not have any infectious signs, a vascular etiology was more strongly considered. Given the patient’s relatively stable vital signs, BUN-to-Cr ratio of less than 20, and lack of orthostatic hypotension, there was low concern for an upper GI etiology, and endoscopy was not obtained emergently. The patient instead underwent abdominal computed tomography angiography (CTA), which identified active extravasation and contrast pooling within the cecum and appendix (Figure 1).

Shortly after the patient returned from imaging, repeat laboratory studies were performed, demonstrating an Hgb drop from 15.0 g/dL to 12.3 g/dL, and surgical services was emergently consulted. The surgeon recommended that embolization first be attempted, with surgery as the option of last resort given the poor localization of the bleed on CTA and the long-term consequences of colonic resection in a young, otherwise healthy man.

Interventional radiology was consulted, and the patient was brought immediately to the angiography suite, where he was found to have “active extravasation arising from a distal descending branch off the right colic artery” (Figure 2). Coil embolization resulted in complete resolution of the hemorrhage.

Later that evening, the patient’s Hgb continued to drop, reaching nadir at 7.3 g/dL, and he continued to have severe hematochezia. His falling Hgb was thought to be indicative of the degree of hemorrhage he had sustained prior to embolization, and the clearance of such blood as the source of his ongoing hematochezia. Following transfusion of 2 U of packed red blood cells (PRBCs), the patient’s Hgb improved to 12.0 g/dL, and he did not experience any significant bleeding for the remainder of his hospital stay.

The following morning, the patient underwent an extensive colonoscopy (extending 25 cm into the terminal ileum), which was unable to detect any signs of arteriovenous malformations, angiodysplasia, or any other possible source of bleeding. After 24 hours with stable vital signs and Hgb levels, the patient was discharged home with close surgical and gastroenterological follow-up, with possible genetic testing for connective tissue diseases. The diagnosis at discharge was spontaneous mesenteric hemorrhage of unknown etiology.

Discussion

Acute lower GI bleeding has an estimated annual hospitalization rate of 36 patients per 100,000, or about half the rate for upper GI bleeding.1,2 The majority of patients (>80%) will have spontaneous resolution and can be worked up nonemergently.

Etiology and Work-Up

Assessment of the etiology of hematochezia begins with ruling out an upper GI source of the bleed; 10% to 15% of patients presenting with hematochezia without hematemesis are ultimately diagnosed with an upper GI etiology. 4,5

BUN-to-Cr Ratio. In a study of patients presenting with hematochezia but no hematemesis or renal failure, Srygley et al6 found a BUN-to-Cr ratio greater than 93% to be sensitive for an upper GI source, with a likelihood ratio of 7.5. The proposed etiology is some combination of absorption of digested blood products and prerenal azotemia due to hypovolemia.

Tachycardia and Orthostatic Hypotension. There have been discussions in the literature about other findings to rule in/out upper GI bleeding. While some studies have found statistically significant results between upper and lower GI bleeding for tachycardia and orthostatic hypotension (increased percentage of both in upper GI bleeding), there is disagreement about whether these findings are clinically significant.7-9

Nasogastric Lavage. Although nasogastric (NG) lavage is no longer the standard of care in the ED due to poor sensitivity and marked discomfort to the patient, most current gastroenterology guidelines still recommend its use; therefore, NG may be requested by the GI consultant.10-12

Diagnosis

Once an upper GI source has been ruled out, identification of the lesion is the next step. The differential diagnosis includes common sources such as diverticular disease, angiodysplasia, colitis, anorectal sources, and neoplasm.5 Less common, but associated with a high risk of mortality, is aortoenteric fistula (100% mortality without surgical intervention).5

Colonoscopy. Emergent colonoscopy can be used for both diagnosis and (potential) therapeutic intervention and is therefore the first option of choice.1,3,4,9 However, as seen in our case, some patients experience such profound hemorrhage that visualization of the colon may be difficult or impossible; patients may also be too unstable to await bowel preparation or undergo a procedure.

Computed Tomography Angiography. For patients in whom colonoscopy is contraindicated, CTA is the imaging modality of choice, and has a 91% to 92% sensitivity in identifying active bleeding (>0.35 mL/min).13-16

Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast alone, as opposed to CTA, is insufficient for detecting GI bleeding, as it is timed so that imaging is obtained when the contrast is in the portal venous capillary beds, rather than in the arteries or arterioles. By protocol, though, many institutions require abdominal and pelvic CTA to include both arterial phase and venous phase images, allowing for assessment of both active arterial bleeding and alternative lower GI sources of hematochezia (eg, mesenteric ischemia).

When ordering a CT study, an awareness of local practice is important in understanding the information that will be obtained from the study. Protocols for lower GI bleed that include CTA have reported accuracy and efficiency without worsening of renal function, despite the increased contrast load.17

Triphasic CT Enterography. Another CT modality to consider is triphasic CT enterography, which uses IV and oral contrast. In a preliminary trial, this modality achieved a specificity of 100% (sensitivity 42%) in detecting GI bleeding.18

Red Blood Cell Scintigraphy. An additional imaging modality that has been the subject of much debate in the GI literature is tagged RBC scintigraphy with Technetium-99m. Various studies have found bleeding-site confirmation in 24% to 97% of patients, and correct localization in 41% to 100% of patients. Given the extensive variability within the literature on selection criteria, localization, site confirmation, and other variables, as well as evidence from one prospective trial by Zink et al19 that found a significant disagreement between CTA and scintigraphy, RBC scintigraphy is not recommended as an alternative imaging modality for the rapid diagnosis of an acute lower GI bleed.

Conclusion

Severe hematochezia is a potential surgical emergency with a broad differential diagnosis. While emergent colonoscopy is an excellent first option, in patients with severe hematochezia, there may be too much blood in the colon to obtain adequate visual images; additionally, depending on practice setting, emergency colonoscopy may not be immediately available. In either case, CTA—a readily available, noninvasive, rapid, and repeatable diagnostic tool—should be considered as an alternate to colonoscopy, particularly in patients with brisk hematochezia.

If a patient with severe hematochezia presents to the ED, the emergency physician (EP) must recognize that the degree of hemorrhage may not correlate with the patient’s vital signs or initial laboratory values. For this reason, the EP must have a high index of suspicion, and consider CTA to allow for a rapid definitive diagnosis and prompt discussion between surgical, interventional radiology, and/or gastroenterology teams to improve clinical outcomes and decrease morbidity and mortality.20

Case

A 31-year-old white man presented to the ED with abdominal and rectal pain accompanied by multiple episodes of bloody diarrhea. He stated he had mild rectal pain the previous night but was pain-free and in his usual state of health the morning of his presentation. Approximately 2 hours before presenting to the ED, however, he began experiencing mild stomach pain, then bloody diarrhea which he described as bright red and “filling the toilet bowl with blood.” He had no history of inflammatory bowel disease or other gastrointestinal (GI) disorder, no recent travel, no complaints of nausea or vomiting, and no infectious symptoms. He described a remote history of external hemorrhoids, and review of his family history was significant for multiple paternal relatives with aortic aneurysms. He was not taking any medications and was a nonsmoker with a normal body mass index (24.3 kg/m2).

Upon arrival at the ED, the patient’s vital signs were: heart rate, 112 beats/min; and blood pressure, 139/102 mm Hg; respiratory rate and temperature were normal, as was the patient’s oxygen saturation on room air. Physical examination was notable for no subjective or objective findings of orthostatic hypotension; increased bowel sounds and diffuse mild abdominal tenderness; and no external hemorrhoids, fissures, or rectal tenderness. Laboratory evaluation was significant for hemoglobin (Hgb), 15.0 g/dL; blood urea nitrogen (BUN)-to-creatinine (Cr) ratio, 11.6; and anion gap, 17 mEq/L.

Upon initial presentation, there was some concern for an infection. However, as the patient continued to have bowel movements consisting almost entirely of frank blood and did not have any infectious signs, a vascular etiology was more strongly considered. Given the patient’s relatively stable vital signs, BUN-to-Cr ratio of less than 20, and lack of orthostatic hypotension, there was low concern for an upper GI etiology, and endoscopy was not obtained emergently. The patient instead underwent abdominal computed tomography angiography (CTA), which identified active extravasation and contrast pooling within the cecum and appendix (Figure 1).

Shortly after the patient returned from imaging, repeat laboratory studies were performed, demonstrating an Hgb drop from 15.0 g/dL to 12.3 g/dL, and surgical services was emergently consulted. The surgeon recommended that embolization first be attempted, with surgery as the option of last resort given the poor localization of the bleed on CTA and the long-term consequences of colonic resection in a young, otherwise healthy man.

Interventional radiology was consulted, and the patient was brought immediately to the angiography suite, where he was found to have “active extravasation arising from a distal descending branch off the right colic artery” (Figure 2). Coil embolization resulted in complete resolution of the hemorrhage.

Later that evening, the patient’s Hgb continued to drop, reaching nadir at 7.3 g/dL, and he continued to have severe hematochezia. His falling Hgb was thought to be indicative of the degree of hemorrhage he had sustained prior to embolization, and the clearance of such blood as the source of his ongoing hematochezia. Following transfusion of 2 U of packed red blood cells (PRBCs), the patient’s Hgb improved to 12.0 g/dL, and he did not experience any significant bleeding for the remainder of his hospital stay.

The following morning, the patient underwent an extensive colonoscopy (extending 25 cm into the terminal ileum), which was unable to detect any signs of arteriovenous malformations, angiodysplasia, or any other possible source of bleeding. After 24 hours with stable vital signs and Hgb levels, the patient was discharged home with close surgical and gastroenterological follow-up, with possible genetic testing for connective tissue diseases. The diagnosis at discharge was spontaneous mesenteric hemorrhage of unknown etiology.

Discussion

Acute lower GI bleeding has an estimated annual hospitalization rate of 36 patients per 100,000, or about half the rate for upper GI bleeding.1,2 The majority of patients (>80%) will have spontaneous resolution and can be worked up nonemergently.

Etiology and Work-Up

Assessment of the etiology of hematochezia begins with ruling out an upper GI source of the bleed; 10% to 15% of patients presenting with hematochezia without hematemesis are ultimately diagnosed with an upper GI etiology. 4,5

BUN-to-Cr Ratio. In a study of patients presenting with hematochezia but no hematemesis or renal failure, Srygley et al6 found a BUN-to-Cr ratio greater than 93% to be sensitive for an upper GI source, with a likelihood ratio of 7.5. The proposed etiology is some combination of absorption of digested blood products and prerenal azotemia due to hypovolemia.

Tachycardia and Orthostatic Hypotension. There have been discussions in the literature about other findings to rule in/out upper GI bleeding. While some studies have found statistically significant results between upper and lower GI bleeding for tachycardia and orthostatic hypotension (increased percentage of both in upper GI bleeding), there is disagreement about whether these findings are clinically significant.7-9

Nasogastric Lavage. Although nasogastric (NG) lavage is no longer the standard of care in the ED due to poor sensitivity and marked discomfort to the patient, most current gastroenterology guidelines still recommend its use; therefore, NG may be requested by the GI consultant.10-12

Diagnosis

Once an upper GI source has been ruled out, identification of the lesion is the next step. The differential diagnosis includes common sources such as diverticular disease, angiodysplasia, colitis, anorectal sources, and neoplasm.5 Less common, but associated with a high risk of mortality, is aortoenteric fistula (100% mortality without surgical intervention).5

Colonoscopy. Emergent colonoscopy can be used for both diagnosis and (potential) therapeutic intervention and is therefore the first option of choice.1,3,4,9 However, as seen in our case, some patients experience such profound hemorrhage that visualization of the colon may be difficult or impossible; patients may also be too unstable to await bowel preparation or undergo a procedure.

Computed Tomography Angiography. For patients in whom colonoscopy is contraindicated, CTA is the imaging modality of choice, and has a 91% to 92% sensitivity in identifying active bleeding (>0.35 mL/min).13-16

Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast alone, as opposed to CTA, is insufficient for detecting GI bleeding, as it is timed so that imaging is obtained when the contrast is in the portal venous capillary beds, rather than in the arteries or arterioles. By protocol, though, many institutions require abdominal and pelvic CTA to include both arterial phase and venous phase images, allowing for assessment of both active arterial bleeding and alternative lower GI sources of hematochezia (eg, mesenteric ischemia).

When ordering a CT study, an awareness of local practice is important in understanding the information that will be obtained from the study. Protocols for lower GI bleed that include CTA have reported accuracy and efficiency without worsening of renal function, despite the increased contrast load.17

Triphasic CT Enterography. Another CT modality to consider is triphasic CT enterography, which uses IV and oral contrast. In a preliminary trial, this modality achieved a specificity of 100% (sensitivity 42%) in detecting GI bleeding.18

Red Blood Cell Scintigraphy. An additional imaging modality that has been the subject of much debate in the GI literature is tagged RBC scintigraphy with Technetium-99m. Various studies have found bleeding-site confirmation in 24% to 97% of patients, and correct localization in 41% to 100% of patients. Given the extensive variability within the literature on selection criteria, localization, site confirmation, and other variables, as well as evidence from one prospective trial by Zink et al19 that found a significant disagreement between CTA and scintigraphy, RBC scintigraphy is not recommended as an alternative imaging modality for the rapid diagnosis of an acute lower GI bleed.

Conclusion

Severe hematochezia is a potential surgical emergency with a broad differential diagnosis. While emergent colonoscopy is an excellent first option, in patients with severe hematochezia, there may be too much blood in the colon to obtain adequate visual images; additionally, depending on practice setting, emergency colonoscopy may not be immediately available. In either case, CTA—a readily available, noninvasive, rapid, and repeatable diagnostic tool—should be considered as an alternate to colonoscopy, particularly in patients with brisk hematochezia.

If a patient with severe hematochezia presents to the ED, the emergency physician (EP) must recognize that the degree of hemorrhage may not correlate with the patient’s vital signs or initial laboratory values. For this reason, the EP must have a high index of suspicion, and consider CTA to allow for a rapid definitive diagnosis and prompt discussion between surgical, interventional radiology, and/or gastroenterology teams to improve clinical outcomes and decrease morbidity and mortality.20

1. Ghassemi K, Jensen D. Lower GI bleeding: epidemiology and management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;15(7):333. doi:10.1007/s11894-013-0333-5.

2. Strate LL, Ayanian JZ, Kotler G, Syngal S. Risk factors for mortality in lower intestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(9):1004-1010. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2008.03.021.

3. Qayad E, Dagar G, Nanchal R. Lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Crit Care Clin. 2016;32(2):241-254. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2015.12.004.

4. Strate LL. Lower GI bleeding: epidemiology and diagnosis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34(4):643-664.

5. Goralnick E, Meguerdichian D. Gastrointestinal bleeding. In: Marx J, Hockberger R, Walls R. (Eds.). Rosen’s Emergency Medicine, 8th Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 2014;248-253.

6. Srygley FD, Gerando CJ, Tran T, Fisher DA. Does this patient have a severe upper gastrointestinal bleed? JAMA. 2012;307(10):1072-1079. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.253.

7. Whelen C, Chen C, Kaboli P, Siddique J, Prochaska M, Meltzer DO. Upper versus lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a direct comparison of clinical presentation, outcomes, and resource utilization. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(3):141-147. doi:10.1002/jhm.606.

8. Sittichanbunch Y, Senasu S, Thongkrau T, Keeratiksikorn C, Sawanyawisuth K. How to differentiate sites of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with hematochezia by using clinical factors? Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:265076. doi:10.1155/2013/265076.

9. Velayos F, Williamson A, Sousa KH, et al. Early predictors of severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding and adverse outcomes: a prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(6):485-490.

10. Palamidessi N, Sinert R, Falzon L, Zehtabchi S. Nasogastric aspiration and lavage in emergency department patients with hematochezia or melena without hematemesis. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(2):126-132. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00609.x.

11. Singer AJ, Richman PB, Kowalska A, Thode HC Jr. Comparison of patient and practitioner assessments of pain from commonly performed emergency department procedures. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33(6):652-658.

12. Strate L, Gralnek I. ACG clinical guideline: management of patients with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(4):459-474. doi:10.1038/ajg.2016.41.

13. Wu LM, Xu JR, Yin Y, Qu XH. Usefulness of CT angiography in diagnosing acute gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(31):3957-3963.

14. Geffroy Y, Rodallec MH, Boulay-Coletta I, Julles MC, Ridereau-Zins C, Zins M. Multidetector CT angiography in acute gastrointestinal bleeding: why, when, and how. Radiographics. 2011;31(3):E35-E46.

15. Reis F, Cardia P, D’Ippolito G. Computed tomography angiography in patients with active gastrointestinal bleeding. Radiol Bras. 2015;48(6):381-390. doi:10.1590/0100-3984.2014.0014.

16. Chan V, Tse D, Dixon S, et al. Outcome following a negative CT angiogram for gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2015;38(2):329-335. doi:10.1007/s00270-014-0928-8.

17. Jacovides T, Nadolski G, Allen S, et al. Arteriography for lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: role of preceding abdominal computed tomographic angiogram in diagnosis and localization. JAMA Surgery. 2015;150(7):650-656. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.97.

18. Hara AK, Walker FB, Silva AC, Leighton JA. Preliminary estimate of triphasic CT enterography performance in hemodynamically stable patients with suspected gastrointestinal bleeding. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(5):1252-1260. doi:10.2214/AJR.08.1494.

19. Zink SI, Ohki SK, Stein B, et al. Noninvasive evaluation of active lower gastrointestinal bleeding: comparison between contrast-enhanced MDCT and 99mTc-labeled RBC scintigraphy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;91(4):1107-1114. doi:10.2214/AJR.07.3642.

20. Nable J, Graham A. Gastrointestinal bleeding. Emerg Med Clin N Am. 2016;34(2):309-325. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2015.12.001.

1. Ghassemi K, Jensen D. Lower GI bleeding: epidemiology and management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;15(7):333. doi:10.1007/s11894-013-0333-5.

2. Strate LL, Ayanian JZ, Kotler G, Syngal S. Risk factors for mortality in lower intestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(9):1004-1010. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2008.03.021.

3. Qayad E, Dagar G, Nanchal R. Lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Crit Care Clin. 2016;32(2):241-254. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2015.12.004.

4. Strate LL. Lower GI bleeding: epidemiology and diagnosis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34(4):643-664.

5. Goralnick E, Meguerdichian D. Gastrointestinal bleeding. In: Marx J, Hockberger R, Walls R. (Eds.). Rosen’s Emergency Medicine, 8th Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 2014;248-253.

6. Srygley FD, Gerando CJ, Tran T, Fisher DA. Does this patient have a severe upper gastrointestinal bleed? JAMA. 2012;307(10):1072-1079. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.253.

7. Whelen C, Chen C, Kaboli P, Siddique J, Prochaska M, Meltzer DO. Upper versus lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a direct comparison of clinical presentation, outcomes, and resource utilization. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(3):141-147. doi:10.1002/jhm.606.

8. Sittichanbunch Y, Senasu S, Thongkrau T, Keeratiksikorn C, Sawanyawisuth K. How to differentiate sites of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with hematochezia by using clinical factors? Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:265076. doi:10.1155/2013/265076.

9. Velayos F, Williamson A, Sousa KH, et al. Early predictors of severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding and adverse outcomes: a prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(6):485-490.

10. Palamidessi N, Sinert R, Falzon L, Zehtabchi S. Nasogastric aspiration and lavage in emergency department patients with hematochezia or melena without hematemesis. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(2):126-132. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00609.x.

11. Singer AJ, Richman PB, Kowalska A, Thode HC Jr. Comparison of patient and practitioner assessments of pain from commonly performed emergency department procedures. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33(6):652-658.

12. Strate L, Gralnek I. ACG clinical guideline: management of patients with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(4):459-474. doi:10.1038/ajg.2016.41.

13. Wu LM, Xu JR, Yin Y, Qu XH. Usefulness of CT angiography in diagnosing acute gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(31):3957-3963.

14. Geffroy Y, Rodallec MH, Boulay-Coletta I, Julles MC, Ridereau-Zins C, Zins M. Multidetector CT angiography in acute gastrointestinal bleeding: why, when, and how. Radiographics. 2011;31(3):E35-E46.

15. Reis F, Cardia P, D’Ippolito G. Computed tomography angiography in patients with active gastrointestinal bleeding. Radiol Bras. 2015;48(6):381-390. doi:10.1590/0100-3984.2014.0014.

16. Chan V, Tse D, Dixon S, et al. Outcome following a negative CT angiogram for gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2015;38(2):329-335. doi:10.1007/s00270-014-0928-8.

17. Jacovides T, Nadolski G, Allen S, et al. Arteriography for lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: role of preceding abdominal computed tomographic angiogram in diagnosis and localization. JAMA Surgery. 2015;150(7):650-656. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.97.

18. Hara AK, Walker FB, Silva AC, Leighton JA. Preliminary estimate of triphasic CT enterography performance in hemodynamically stable patients with suspected gastrointestinal bleeding. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(5):1252-1260. doi:10.2214/AJR.08.1494.

19. Zink SI, Ohki SK, Stein B, et al. Noninvasive evaluation of active lower gastrointestinal bleeding: comparison between contrast-enhanced MDCT and 99mTc-labeled RBC scintigraphy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;91(4):1107-1114. doi:10.2214/AJR.07.3642.

20. Nable J, Graham A. Gastrointestinal bleeding. Emerg Med Clin N Am. 2016;34(2):309-325. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2015.12.001.

Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension in a 24-Year-Old Woman

Case

A 24-year-old woman presented to the ED for evaluation of a 3-week history of worsening headache and a 5-day history of increasingly blurry vision. The patient stated that she had initially contacted her primary care physician, but instead presented to the ED because he had no open appointments until the following week and recommended that she go to the ED.

The patient described her headache as a pulsating and throbbing pain over her entire head, which only mildly improved after taking over-the-counter (OTC) ibuprofen. She further noted that her headache was somewhat worse when lying down, and reported the sensation of hearing her own pulsating heartbeat in her ears.

The patient had no personal or family history of migraines, tension headaches, aneurysms, clotting disorders, bleeding disorders, or renal disease, and stated that she had never experienced this type of headache before. She denied photophobia, phonophobia, neck stiffness, fever, vomiting, cough, numbness or weakness in her extremities, or pain anywhere else in her body.

Over the past 5 days, the patient noticed her vision had become increasingly blurry. She was not on any prescription medications, stating the only medication she used was occasional OTC ibuprofen. She had no known allergy to medications and denied smoking or recreational drug use; she admitted to occasional alcohol consumption.

The patient resided with her husband, who had no similar symptoms. Physical examination showed an obese woman (height, 5 ft 6 in; weight, 195 lb; body mass index, 32 kg/m2), lying supine in apparent discomfort. Vital signs at presentation were all normal, and oxygen saturation was normal on room air.

A bedside ocular examination showed 20/100 in both eyes while using glasses; no visual field cuts or obvious central scotoma was present. The patient was alert and oriented to time and place. The neurological examination showed intact cranial nerves, 5/5 strength in all extremities, intact sensation in all extremities, no pronator drift, negative Romberg test, and a normal gait. Fundoscopic examination revealed mildly blurred medial optic discs bilaterally. The rest of the physical examination was normal.

Discussion

Pseudotumor cerebri, more commonly referred to as idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), is characterized by increased intracranial pressure (ICP) with no explanatory findings on imaging studies or in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, and may be accompanied by symptoms of chronic headache, tinnitus, papilledema and progressive vision loss caused by optic nerve damage.1 Though historically IIH was referred to by several other names, including “benign intracranial hypertension,” the condition is not benign—when untreated, IIH can cause chronic disabling headaches and permanent vision loss.1

Clinical Course

The clinical course of IIH is unpredictable: In some patients, vision loss occurs gradually over the course of several weeks, while in others, loss occurs over a several month period. There are also patients with IIH who do not experience any alteration or loss of vision. Furthermore, some patients will experience permanent resolution of symptoms after a single lumbar puncture (LP); others have symptom recurrence after less than 24 hours; and some patients spontaneously remit on their own with no treatment whatsoever.1-4

Etiology

In the United States, IIH is a rare cause of headache, occurring in just 1 person per 100,000 annually.1 Though 90% of IIH cases occur in obese women of childbearing age, the etiology of IIH is unknown. Lumbar puncture usually alleviates the patient’s headache, but the CSF pressure typically returns to its pre-tap levels after a few hours.4,5 Neither CSF overproduction nor insufficient CSF resorption is responsible for causing IIH. One theory on the etiology of IIH proposes its cause to be due to a congenital malformation of the venous sinuses. This theory would explain why the symptoms so closely mimic those of venous sinus thrombosis, and why some IIH patients experience relief of symptoms after placement of a venous sinus stent.2

Symptoms

As noted previously, the most common symptom of IIH is headache, which patients usually describe as pressure-like and throbbing, and often involving retro-ocular pain. One feature in over half of patients is pulse-synchronous tinnitus (ie, hearing their own heartbeat in their ears). Eye pain, photophobia, blurry vision, and nausea/vomiting are all common symptoms in IIH, but these symptoms are also present in other causes of headache. The IIH headache might be relapsing and remitting, and can last from a few hours to weeks.2-4,6

Diagnosis

Imaging Studies. Noncontrast computed tomography (CT) imaging studies do not typically demonstrate any abnormal findings.1 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies show some inconsistent and subtle findings, such as flattening of the backs of the eyeballs, empty sella, or tortuous optic nerves.1

Lumbar Puncture. On LP, a very high opening pressure is a hallmark of IIH. An opening pressure <20 cm H2O is generally considered normal, 20 cm to 25 cm H2O is “equivocal,” and >25 cm H2O is abnormal.7 Patients presenting with IIH commonly have an opening pressure that exceeds 200 cm H2O.1-3 Extremely high pressures, however, are not required for the diagnosis, but some elevations in opening pressure will always be present.2,5 With the exception of a high opening pressure, the patient’s CSF analysis is normal.

Differential Diagnosis

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension is essentially a diagnosis of exclusion, one that is made after exclusion of all other potential causes of increased ICP (Table). Since contrast CT and MRI can identify subtle anatomical deformities and small lesions, their absence on these studies can help establish a diagnosis of IIH.

Venous Sinus Thrombosis. Venous sinus thrombosis is a rare but devastating condition that also cannot be diagnosed from a noncontrast CT but must always be considered in the differential diagnosis of IIH.8-10 Venous sinus thrombosis is characterized by a clot in one of the large venous sinuses that drain blood from the brain; the clot causes pressure to back up into the smaller cerebral vasculature, eventually inducing either a hemorrhagic stroke from a stressed vessel rupturing, or an ischemic stroke from lack of blood flow to the affected area of the brain. This condition is even more rare than IIH (0.5 cases per 100,000 population), but it can be devastating if missed, carrying a mortality rate as high as 15% in some studies.11

Risk Factors

Risk factors known to cause cerebral venous clots include genetic thrombophilias, pregnancy or recent pregnancy, oral contraceptive use, inflammatory bowel disease, severe dehydration, local infection/trauma, and substance abuse. Regardless of risk factors, the most recent guidelines of the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association recommend imaging studies of the cerebral venous sinuses for any patient presenting with new-onset symptoms suggestive of IIH (Class 1, Level of Evidence C).11 The two imaging options for evaluation of the cerebral venous sinuses are CT venography or MR venography. Since the 2013 American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria do not indicate a preference of one modality over the other, the choice of can be left to your radiologist.12

Patient Disposition

Patients with IIH typically do not require inpatient admission. Only about 3% of IIH patients will have a fulminant course of rapid-onset of vision loss, but even the most severe and acute cases will deteriorate over weeks, not hours or days.13 Nevertheless, close neurology follow-up is essential. If rapid and thorough outpatient neurological care is unavailable, admission is required.

Management

Not every patient with IIH experiences amelioration or resolution of symptoms following an LP; moreover, there is no clear way to differentiate patients who will experience therapeutic effects from LP from those who will not. Serial LPs as treatment for IIH have been discussed in the literature, but a ventriculoperitoneal shunt is a more practical approach in patients who do not respond to an initial LP.2,14

CSF Volume. The volume of CSF that can be removed safely may be 15 to 25 mL or more. A 1974 paper by Johnston and Paterson15 described five pseudotumor patients whose CSF was drained until their pressure had normalized; the amount removed varied from 15 to 25 mL, without adverse effects. A 1975 case series by Weisberg6 described safe removal of up to 30 mL of CSF in pseudotumor patients—the precise amount removed was determined by that which was necessary to lower the CSF pressure into the normal range. In 2007, a case report by Aly and Lawther16 of a pregnant woman with IIH describes twice weekly LP drainage of 30 mL.

There is nothing in the current literature to suggest that removing 10 to 30 mL of CSF instead of the 4 to 8 mL typically drawn in a diagnostic LP is going to pose any risk to the patient. The main complication associated with therapeutic LP is post-LP headache.5,17,18 There are currently no studies documenting outcomes after specific amounts of CSF removal.

Lifestyle Modifications: Weight Loss. No prospective, randomized controlled trials have proven weight loss to be effective in ameliorating the symptoms of IIH; however, several studies have found that rapid weight loss—whether through aggressive dieting or gastric bypass surgery—can improve symptoms dramatically within several months.19,20 One small study by Johnson et al has suggested that a 6% weight reduction is associated with marked improvement in papilledema.21Pharmacotherapy. The accepted first-line medication to alleviate symptoms of IIH is acetazolamide, and its use is supported by a recent randomized controlled trial conducted by the Neuro-Ophthalmology Research Disease Investigator Consortium (NORDIC).22 Most neurologists will administer a starting dose of acetazolamide 500 mg twice a day, and then increase the dose until symptoms are controlled or adverse effects appear (eg, fatigue, nausea/vomiting/diarrhea, electrolyte abnormalities, kidney stones) that contraindicate further dosage increases. In the NORDIC trial, patients were given up to 4 g of acetazolamide daily.22

Other medications, including loop diuretics and corticosteroids, should not be used except under the direct supervision of a neurologist.2,14

Refractory Cases

A patient who fails conservative treatment should be referred to a neurosurgeon for placement of a CSF shunt, optic nerve sheath fenestration, or placement of a venous sinus stent.23

Case Conclusion

After a noncontrast CT of the head was interpreted as completely normal, an LP was performed with the patient in the left lateral recumbent position. The opening CSF pressure exceeded 55 cm H2O (the upper limit of the manometer). The CSF was clear, and opening pressure was rechecked after each 5 mL draw. After 15 mL had been removed, the patient reported a sudden, dramatic disappearance of her headache and clearing of her vision. After 19 mL of CSF had been removed, the CSF pressure had dropped into the normal range (<20 cm H2O), and the procedure was ended.

To definitively rule out venous sinus thrombosis, a CT venogram was performed in the ED, and interpreted as normal. All other CSF results (cell count, protein, glucose, and gram stain) were normal. After complete resolution of the patient’s symptoms, she was discharged home with a prescription for acetazolamide 500 mg twice daily and instructions to follow-up with a neurologist within 48 hours. At discharge, the patient also received weight-loss counseling and was instructed to return immediately to the ED if her headache recurred or if she experienced any new neurological symptoms.

Summary

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension, also referred to as pseudotumor cerebri, is a rare but potentially vision-threatening cause of headache. Patients with signs and symptoms of IIH often initially present to the ED for evaluation and management. While the etiology of IIH is poorly understood, its clinical picture is unique: elevated ICP (sometimes markedly so) with no other significant findings on noncontrast head CT or CSF analysis. Venous sinus thrombosis, a life-threatening mimic of IIH, must always be included in the differential diagnosis.

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension is initially treated with rapid weight loss and acetazolamide. Many patients experience instant, though sometimes only transient, symptom relief from LP. No definitive studies to support any specific approach, including “therapeutic lumbar punctures.” The condition is rarely fulminant, and hospital admission is not typically required as long as urgent outpatient neurology follow-up is available.

1. Degnan AJ, Levy LM. Pseudotumor cerebri: brief review of clinical syndrome and imaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32(11):1986-1893. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A2404.

2. Biousse V, Bruce BB, Newman NJ. Update on the pathophysiology and management of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83(5):488-494. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2011-302029. 3. Wall M, George D. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: a prospective study of 50 patients. Brain. 1991;114(Pt 1A):155-180.

4. Wall M. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurol Clin. 2010;28(3):593-617. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2010.03.003.

5. Friedman DI, Rausch EA. Headache diagnoses in patients with treated idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology. 2002;58(10):1551-1553.

6. Weisberg LA. Benign intracranial hypertension. Medicine (Baltimore). 1975;54(3):197-207.

7. Whiteley W, Al-Shahi R, Warlow CP, Zeidler M, Lueck CJ. CSF opening pressure: reference interval and the effect of body mass index. Neurology. 2006;67(9):1690-1691.

8. Biousse V, Ameri A, Bousser MG. Isolated intracranial hypertension as the only sign of cerebral venous thrombosis. Neurology. 1999;53(7):1537-1542.

9. Leker RR, Steiner I. Features of dural sinus thrombosis simulating pseudotumor cerebri. Eur J Neurol. 1999;6(5):601-604.

10. Sylaja PN, Ahsan Moosa NV, Radhakrishnan K, Sankara Sarma P, Pradeep Kumar S. Differential diagnosis of patients with intracranial sinus venous thrombosis related isolated intracranial hypertension from those with idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Neurol Sci. 2003;215(1-2):9-12.

11. Saposnik G, Barinagarrementeria F, Brown RD Jr, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council and the Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Diagnosis and management of cerebral venous thrombosis: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42(4):1158-1192. doi:10.1161/STR.0b013e31820a8364.

12. American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria: Headache. https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69482/Narrative/. Updated 2013. Accessed January 19, 2017.

13. Thambisetty M, Lavin PJ, Newman NJ, Biousse V. Fulminant idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology. 2007;68(3):229-232.

14. Mollan SP, Markey KA, Benzimra JD, et al. A practical approach to, diagnosis, assessment and management of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Pract Neurol. 2014;14(6):380-390. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2014-000821.

15. Johnston I, Paterson A. Benign intracranial hypertension. II. CSF pressure and circulation. Brain. 1974;97(2):301-312.

16. Aly EE, Lawther BK. Anaesthetic management of uncontrolled idiopathic intracranial hypertension during labour and delivery using an intrathecal catheter. Anesthesia. 2007;62(2):178-181.

17. Panikkath R, Welker J, Johnston R, Lado-Abeal J. Intracranial hypertension and intracranial hypotension causing headache in the same patient. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2014;27(3):217-218.

18. Nafiu OO, Monterosso D, Walton SR, Bradin S. Post dural puncture headache in a pediatric patient with idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Paediatr Anaesth. 2005;15(9):778-781. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9592.2004.01529.x.

19. Sinclair AJ, Burdon MA, Nightingale PG, et al. Low energy diet and intracranial pressure in women with idiopathic intracranial hypertension: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2010;341:c2701. doi:10.1136/bmj.c2701.

20. Kupersmith MJ, Gamell L, Turbin R, Peck V, Spiegel P, Wall M. Effects of weight loss on the course of idiopathic intracranial hypertension in women. Neurology. 1998;50(4):1094-1098.

21. Johnson LN, Krohel GB, Madsen RW, March GA Jr. The role of weight loss and acetazolamide in the treatment of idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri) Ophthalmology. 1998;105(12):2313-2317. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(98)91234-9.

22. NORDIC Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Study Group Writing Committee; Wall M, McDermott MP, Kieburtz KD, et al. Effect of acetazolamide on visual function in patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension and mild visual loss: the idiopathic intracranial hypertension treatment trial. JAMA. 2014;311(16):1641-1651. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3312.

23. Fonseca PL, Rigamonti D, Miller NR, Subramanian PS. Visual outcomes of surgical intervention for pseudotumour cerebri: optic nerve sheath fenestration versus cerebrospinal fluid diversion. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98(10):1360-1363. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-304953.

Case

A 24-year-old woman presented to the ED for evaluation of a 3-week history of worsening headache and a 5-day history of increasingly blurry vision. The patient stated that she had initially contacted her primary care physician, but instead presented to the ED because he had no open appointments until the following week and recommended that she go to the ED.

The patient described her headache as a pulsating and throbbing pain over her entire head, which only mildly improved after taking over-the-counter (OTC) ibuprofen. She further noted that her headache was somewhat worse when lying down, and reported the sensation of hearing her own pulsating heartbeat in her ears.

The patient had no personal or family history of migraines, tension headaches, aneurysms, clotting disorders, bleeding disorders, or renal disease, and stated that she had never experienced this type of headache before. She denied photophobia, phonophobia, neck stiffness, fever, vomiting, cough, numbness or weakness in her extremities, or pain anywhere else in her body.

Over the past 5 days, the patient noticed her vision had become increasingly blurry. She was not on any prescription medications, stating the only medication she used was occasional OTC ibuprofen. She had no known allergy to medications and denied smoking or recreational drug use; she admitted to occasional alcohol consumption.

The patient resided with her husband, who had no similar symptoms. Physical examination showed an obese woman (height, 5 ft 6 in; weight, 195 lb; body mass index, 32 kg/m2), lying supine in apparent discomfort. Vital signs at presentation were all normal, and oxygen saturation was normal on room air.

A bedside ocular examination showed 20/100 in both eyes while using glasses; no visual field cuts or obvious central scotoma was present. The patient was alert and oriented to time and place. The neurological examination showed intact cranial nerves, 5/5 strength in all extremities, intact sensation in all extremities, no pronator drift, negative Romberg test, and a normal gait. Fundoscopic examination revealed mildly blurred medial optic discs bilaterally. The rest of the physical examination was normal.

Discussion

Pseudotumor cerebri, more commonly referred to as idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), is characterized by increased intracranial pressure (ICP) with no explanatory findings on imaging studies or in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, and may be accompanied by symptoms of chronic headache, tinnitus, papilledema and progressive vision loss caused by optic nerve damage.1 Though historically IIH was referred to by several other names, including “benign intracranial hypertension,” the condition is not benign—when untreated, IIH can cause chronic disabling headaches and permanent vision loss.1

Clinical Course

The clinical course of IIH is unpredictable: In some patients, vision loss occurs gradually over the course of several weeks, while in others, loss occurs over a several month period. There are also patients with IIH who do not experience any alteration or loss of vision. Furthermore, some patients will experience permanent resolution of symptoms after a single lumbar puncture (LP); others have symptom recurrence after less than 24 hours; and some patients spontaneously remit on their own with no treatment whatsoever.1-4

Etiology

In the United States, IIH is a rare cause of headache, occurring in just 1 person per 100,000 annually.1 Though 90% of IIH cases occur in obese women of childbearing age, the etiology of IIH is unknown. Lumbar puncture usually alleviates the patient’s headache, but the CSF pressure typically returns to its pre-tap levels after a few hours.4,5 Neither CSF overproduction nor insufficient CSF resorption is responsible for causing IIH. One theory on the etiology of IIH proposes its cause to be due to a congenital malformation of the venous sinuses. This theory would explain why the symptoms so closely mimic those of venous sinus thrombosis, and why some IIH patients experience relief of symptoms after placement of a venous sinus stent.2

Symptoms

As noted previously, the most common symptom of IIH is headache, which patients usually describe as pressure-like and throbbing, and often involving retro-ocular pain. One feature in over half of patients is pulse-synchronous tinnitus (ie, hearing their own heartbeat in their ears). Eye pain, photophobia, blurry vision, and nausea/vomiting are all common symptoms in IIH, but these symptoms are also present in other causes of headache. The IIH headache might be relapsing and remitting, and can last from a few hours to weeks.2-4,6

Diagnosis

Imaging Studies. Noncontrast computed tomography (CT) imaging studies do not typically demonstrate any abnormal findings.1 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies show some inconsistent and subtle findings, such as flattening of the backs of the eyeballs, empty sella, or tortuous optic nerves.1

Lumbar Puncture. On LP, a very high opening pressure is a hallmark of IIH. An opening pressure <20 cm H2O is generally considered normal, 20 cm to 25 cm H2O is “equivocal,” and >25 cm H2O is abnormal.7 Patients presenting with IIH commonly have an opening pressure that exceeds 200 cm H2O.1-3 Extremely high pressures, however, are not required for the diagnosis, but some elevations in opening pressure will always be present.2,5 With the exception of a high opening pressure, the patient’s CSF analysis is normal.

Differential Diagnosis