User login

SSRI activation in children, adolescents often misdiagnosed as bipolar

SAN FRANCISCO – It’s not uncommon for children to arrive at the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic in Pittsburgh with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor activation that was misdiagnosed as bipolar disorder, according to Boris Birmaher, MD.

“We get many kids into our clinic with a diagnosis of bipolar because of this, and they are not bipolar. You have to be careful,” he said during a talk about pediatric depression at a psychopharmacology update held by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

SSRIs activate about 5%-10% of children. There might be sleep problems, fast speech, hyperactivity, agitation, aggression, and even suicidality, he said.

Younger children and those with autism or developmental disabilities are particularly at risk. Occasionally, a child might be a slow metabolizer so that even low SSRI doses cause problems. “Once in a blue moon,” Dr. Birmaher said he will screen for genetic cytochrome P450 deficiency, especially if a child doesn’t seem able to tolerate medications in general, not just psychiatric ones. He’s found a few slow metabolizers over the years.

Psychiatrists also have to be careful when children and adolescents are tagged as “treatment resistant.” It’s important to teach parents what treatment resistance would actually look like for their child, so they don’t jump to conclusions and misdirect therapy, he said.

For example, when a child has been prescribed an SSRI for anxiety, parents might come in and say it’s not helping, when in fact they’re concerned about homework not getting done and restlessness in class. “There’s no treatment resistance. You teach the parent how to measure improvement of anxiety” and tackle the ADHD if it’s truly a problem, said Dr. Birmaher, also professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh.

If there really is SSRI treatment resistance, he said he first ensures that a maximum dose of the drug has been tried, so long as it’s tolerated. If it doesn’t work after 4-6 weeks, he’ll switch to another SSRI or selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, or combination treatment with, for instance, bupropion (Wellbutrin) or an atypical antipsychotic, which are particularly helpful for irritability, even in small doses. Atypicals seem to take the edge off, he said.

It’s trial and error, since there aren’t much data in children to guide treatment. “The only thing I highly recommend is to make one change at a time. Sometimes we see kids who’ve had two or three changes at the same time.” In those cases, he said, it’s impossible to know what to blame if there are side effects or what to credit if depression improves.

Dr. Birmaher said he had no pharmaceutical industry ties.

SAN FRANCISCO – It’s not uncommon for children to arrive at the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic in Pittsburgh with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor activation that was misdiagnosed as bipolar disorder, according to Boris Birmaher, MD.

“We get many kids into our clinic with a diagnosis of bipolar because of this, and they are not bipolar. You have to be careful,” he said during a talk about pediatric depression at a psychopharmacology update held by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

SSRIs activate about 5%-10% of children. There might be sleep problems, fast speech, hyperactivity, agitation, aggression, and even suicidality, he said.

Younger children and those with autism or developmental disabilities are particularly at risk. Occasionally, a child might be a slow metabolizer so that even low SSRI doses cause problems. “Once in a blue moon,” Dr. Birmaher said he will screen for genetic cytochrome P450 deficiency, especially if a child doesn’t seem able to tolerate medications in general, not just psychiatric ones. He’s found a few slow metabolizers over the years.

Psychiatrists also have to be careful when children and adolescents are tagged as “treatment resistant.” It’s important to teach parents what treatment resistance would actually look like for their child, so they don’t jump to conclusions and misdirect therapy, he said.

For example, when a child has been prescribed an SSRI for anxiety, parents might come in and say it’s not helping, when in fact they’re concerned about homework not getting done and restlessness in class. “There’s no treatment resistance. You teach the parent how to measure improvement of anxiety” and tackle the ADHD if it’s truly a problem, said Dr. Birmaher, also professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh.

If there really is SSRI treatment resistance, he said he first ensures that a maximum dose of the drug has been tried, so long as it’s tolerated. If it doesn’t work after 4-6 weeks, he’ll switch to another SSRI or selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, or combination treatment with, for instance, bupropion (Wellbutrin) or an atypical antipsychotic, which are particularly helpful for irritability, even in small doses. Atypicals seem to take the edge off, he said.

It’s trial and error, since there aren’t much data in children to guide treatment. “The only thing I highly recommend is to make one change at a time. Sometimes we see kids who’ve had two or three changes at the same time.” In those cases, he said, it’s impossible to know what to blame if there are side effects or what to credit if depression improves.

Dr. Birmaher said he had no pharmaceutical industry ties.

SAN FRANCISCO – It’s not uncommon for children to arrive at the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic in Pittsburgh with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor activation that was misdiagnosed as bipolar disorder, according to Boris Birmaher, MD.

“We get many kids into our clinic with a diagnosis of bipolar because of this, and they are not bipolar. You have to be careful,” he said during a talk about pediatric depression at a psychopharmacology update held by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

SSRIs activate about 5%-10% of children. There might be sleep problems, fast speech, hyperactivity, agitation, aggression, and even suicidality, he said.

Younger children and those with autism or developmental disabilities are particularly at risk. Occasionally, a child might be a slow metabolizer so that even low SSRI doses cause problems. “Once in a blue moon,” Dr. Birmaher said he will screen for genetic cytochrome P450 deficiency, especially if a child doesn’t seem able to tolerate medications in general, not just psychiatric ones. He’s found a few slow metabolizers over the years.

Psychiatrists also have to be careful when children and adolescents are tagged as “treatment resistant.” It’s important to teach parents what treatment resistance would actually look like for their child, so they don’t jump to conclusions and misdirect therapy, he said.

For example, when a child has been prescribed an SSRI for anxiety, parents might come in and say it’s not helping, when in fact they’re concerned about homework not getting done and restlessness in class. “There’s no treatment resistance. You teach the parent how to measure improvement of anxiety” and tackle the ADHD if it’s truly a problem, said Dr. Birmaher, also professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh.

If there really is SSRI treatment resistance, he said he first ensures that a maximum dose of the drug has been tried, so long as it’s tolerated. If it doesn’t work after 4-6 weeks, he’ll switch to another SSRI or selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, or combination treatment with, for instance, bupropion (Wellbutrin) or an atypical antipsychotic, which are particularly helpful for irritability, even in small doses. Atypicals seem to take the edge off, he said.

It’s trial and error, since there aren’t much data in children to guide treatment. “The only thing I highly recommend is to make one change at a time. Sometimes we see kids who’ve had two or three changes at the same time.” In those cases, he said, it’s impossible to know what to blame if there are side effects or what to credit if depression improves.

Dr. Birmaher said he had no pharmaceutical industry ties.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT THE PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY UPDATE INSTITUTE

Medical organizations respond to Trump’s immigration order

Organizations representing physicians and medical students have expressed their concern regarding President Trump’s executive order of Jan. 27 that curtails entry into the United States by travelers from seven Muslim-majority countries. The order also suspends for 120 days entry into the United States for all persons seeking refugee status, and it bars refugees from Syria indefinitely.

Following are direct excerpts from statements issued by medical organizations.

American Academy of Family Physicians

“We are deeply concerned that steps your Administration has taken will have a chilling effect on our nation’s physician workforce, biomedical research, and global health. It is often America’s physicians who answer the call to assist people around the world when a public health crisis occurs. Imagine a world where physicians fail to answer the call of the needy because they fear they may not be able to return to their home and families in the United States.

Many family physicians are international medical graduates (IMG), who have completed all or part of their education and training in the United States. They are professionals who dedicate their careers to the service of their patients in communities large and small, urban and rural. In fact, 20% of our membership and over 25% of family medicine residents [comprise] IMGs. The AAFP applauds and supports wholly the contributions of these individual family physicians to their patients and communities and we celebrate their diversity.

We recognize that one of your primary responsibilities as President is to ensure the safety and security of the country and its citizens. This is, without question, a daunting responsibility. But we strongly urge that the methods of doing so be examined carefully, so that the many people who can add so much to our country through immigration have the opportunity to do so, and those who are doing so already are treated with the respect and dignity they deserve.”

American Academy of Pediatrics

“The executive orders signed today are harmful to immigrant children and families throughout our country. Many of the children who will be most affected are the victims of unspeakable violence and have been exposed to trauma. Children do not immigrate, they flee. They are coming to the United States seeking safe haven in our country and they need our compassion and assistance. Broad scale expansion of family detention only exacerbates their suffering ... The AAP is non-partisan and pro-children. We urge President Trump and his administration to ensure that children and families who are fleeing violence and adversity can continue to seek refuge in our country. Immigrant children and families are an integral part of our communities and our nation, and they deserve to be cared for, treated with compassion, and celebrated. Most of all, they deserve to be healthy and safe. Pediatricians stand with the immigrant families we care for and will continue to advocate that their needs are met and prioritized.”

American Association of Medical Colleges

“The United States is facing a serious shortage of physicians. IMGs play an important role in U.S. health care, representing roughly 25% of the workforce. Current immigration pathways – including student, exchange-visitor, and employment visas – provide a balanced solution that improves health care access across the country through programs like the National Interest Waiver and the Conrad 30 J-1 Visa Waiver. In the last decade, Conrad 30 alone has directed nearly 10,000 physicians into rural and urban underserved communities. Impeding these U.S. immigration pathways jeopardizes critical access to high-quality physician care for our nation’s most vulnerable populations.

Our ability to attract top talent from around the world also enriches the research laboratories at medical schools and teaching hospitals that are working toward cures and has helped position the United States as a global leader in medical research, strengthening our economy and bolstering the public’s health. Because disease knows no geographic boundaries, it is essential to ensure that we continue to foster, rather than impede, scientific cooperation with physicians and researchers of all nationalities, as we strive to keep our country healthy.”

American College of Cardiology

“The ability to share ideas and knowledge necessary to address [the global epidemic of cardiovascular disease] is imperative. Policies that impede this free-flow of ideas will have a detrimental impact on scientific discovery, as well as the lives of patients around the world. If we are to realize a future where cardiovascular disease is no longer the number one killer of men and women worldwide we must ensure that our system of scientific exchange allows for health care professionals to learn from each other regardless of their nationality.

Additionally, IMGs, naturalized citizens, and legal residents make up a significant portion of the health care workforce in hospitals and practices across the country. More than 25% of current practicing physicians are IMGs, with cardiology ranking among the top when broken down by medical specialty. Policies that bring the immigration status of those already here into question, while also limiting the ability of others to legally train in the United States going forward, will only serve to exacerbate the already existing cardiovascular workforce shortage, especially in rural America. Such policies also threaten the care continuum of patients who rely on these providers for their medical care.”

American College of Physicians

“The executive order could deny entry or reentry to tens of thousands more persons, including medical students and physicians who are being trained in the United States and/or are delivering direct patient care. ... It also creates a precedent for barring entry of IMGs based on their religion and country of origin. ... Approximately 30% of ACP members are IMGs.”

American Gastroenterological Association

Science and illness ignore borders and political divides. That is why AGA is concerned that the recent U.S. executive order on immigration could limit scientific exchange, delay patient care and impair medical training.

AGA is committed to diversity, which we define as inclusive of race, ethnicity and national origin. Diversity within training programs and laboratories in the United States built today’s practice of gastroenterology. Scientists from around the world publish in our journals, work in our laboratories, train in our programs and present data at Digestive Disease Week. This exchange leads to better patient care, and very sick patients travel to the United States from around the world for the best digestive health care.

AGA adds our support to a growing number of medical institutions urging the administration to consider the devastating impact of the executive order on the health of the nation that will result from turning away patients, health professionals, and researchers. The recent immigration policy is clearly detrimental to America’s leadership role in advancing health care, and to the standing of the United States within the international community.

American Society of Clinical Oncology

ASCO is deeply concerned about the potential impact of the recent executive order on cancer research, patient care, and international scientific collaboration.

Our more than 40,000 members in 148 countries lead the charge to conquer cancer in all its forms and in every nation. Tens of thousands of people from more than 100 countries participate in our scientific meetings to exchange advances and ideas to improve patient care. Millions of cancer survivors are alive today because of the progress made possible by scientific collaboration. Progress against this disease will falter if the close-knit global community of cancer care providers is divided by policies that bar members of certain nationalities from entering the United States to conduct research, care for people with cancer, or participate in scientific and medical conferences.

American Society of Hematology

We express our deep concern about the Administration’s executive order that has denied U.S. entry to people who bring unique expertise to the practice of medicine and the conduct of cancer and biomedical research. Our nation depends on the contributions of the greatest minds from around the world to maintain the high quality of our biomedical research enterprise and health care services.

The benefits of scientific collaborations are amplified by our diversity. Limiting the exchange of ideas, practices, and data across cultures has the potential to significantly retard scientific progress and adversely affect public health. Any loss of researchers and physicians will render the United States less competitive over time, and our traditionally strong research institutions and the patients they serve will be negatively affected.

We remain deeply concerned that restricting travel will prohibit participation in scientific meetings, where cutting-edge science and treatment methods are often first introduced. These in-person meetings and other global exchanges are vitally important because they provide unparalleled opportunities for collaborations and information-sharing. Such scientific and medical meetings are absolutely essential to the conquest of cancer and blood diseases.

(Statement issued on behalf of ASH, American Association for Cancer Research, Association of American Cancer Institutes, American Society for Radiation Oncology, The American Society for Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, and LUNGevity Foundation.)

The text of the executive order can be found on the White House website.

Updated 2/2/17 to include the position of the American Gastroenterological Association.

[email protected]

On Twitter @denisefulton

Organizations representing physicians and medical students have expressed their concern regarding President Trump’s executive order of Jan. 27 that curtails entry into the United States by travelers from seven Muslim-majority countries. The order also suspends for 120 days entry into the United States for all persons seeking refugee status, and it bars refugees from Syria indefinitely.

Following are direct excerpts from statements issued by medical organizations.

American Academy of Family Physicians

“We are deeply concerned that steps your Administration has taken will have a chilling effect on our nation’s physician workforce, biomedical research, and global health. It is often America’s physicians who answer the call to assist people around the world when a public health crisis occurs. Imagine a world where physicians fail to answer the call of the needy because they fear they may not be able to return to their home and families in the United States.

Many family physicians are international medical graduates (IMG), who have completed all or part of their education and training in the United States. They are professionals who dedicate their careers to the service of their patients in communities large and small, urban and rural. In fact, 20% of our membership and over 25% of family medicine residents [comprise] IMGs. The AAFP applauds and supports wholly the contributions of these individual family physicians to their patients and communities and we celebrate their diversity.

We recognize that one of your primary responsibilities as President is to ensure the safety and security of the country and its citizens. This is, without question, a daunting responsibility. But we strongly urge that the methods of doing so be examined carefully, so that the many people who can add so much to our country through immigration have the opportunity to do so, and those who are doing so already are treated with the respect and dignity they deserve.”

American Academy of Pediatrics

“The executive orders signed today are harmful to immigrant children and families throughout our country. Many of the children who will be most affected are the victims of unspeakable violence and have been exposed to trauma. Children do not immigrate, they flee. They are coming to the United States seeking safe haven in our country and they need our compassion and assistance. Broad scale expansion of family detention only exacerbates their suffering ... The AAP is non-partisan and pro-children. We urge President Trump and his administration to ensure that children and families who are fleeing violence and adversity can continue to seek refuge in our country. Immigrant children and families are an integral part of our communities and our nation, and they deserve to be cared for, treated with compassion, and celebrated. Most of all, they deserve to be healthy and safe. Pediatricians stand with the immigrant families we care for and will continue to advocate that their needs are met and prioritized.”

American Association of Medical Colleges

“The United States is facing a serious shortage of physicians. IMGs play an important role in U.S. health care, representing roughly 25% of the workforce. Current immigration pathways – including student, exchange-visitor, and employment visas – provide a balanced solution that improves health care access across the country through programs like the National Interest Waiver and the Conrad 30 J-1 Visa Waiver. In the last decade, Conrad 30 alone has directed nearly 10,000 physicians into rural and urban underserved communities. Impeding these U.S. immigration pathways jeopardizes critical access to high-quality physician care for our nation’s most vulnerable populations.

Our ability to attract top talent from around the world also enriches the research laboratories at medical schools and teaching hospitals that are working toward cures and has helped position the United States as a global leader in medical research, strengthening our economy and bolstering the public’s health. Because disease knows no geographic boundaries, it is essential to ensure that we continue to foster, rather than impede, scientific cooperation with physicians and researchers of all nationalities, as we strive to keep our country healthy.”

American College of Cardiology

“The ability to share ideas and knowledge necessary to address [the global epidemic of cardiovascular disease] is imperative. Policies that impede this free-flow of ideas will have a detrimental impact on scientific discovery, as well as the lives of patients around the world. If we are to realize a future where cardiovascular disease is no longer the number one killer of men and women worldwide we must ensure that our system of scientific exchange allows for health care professionals to learn from each other regardless of their nationality.

Additionally, IMGs, naturalized citizens, and legal residents make up a significant portion of the health care workforce in hospitals and practices across the country. More than 25% of current practicing physicians are IMGs, with cardiology ranking among the top when broken down by medical specialty. Policies that bring the immigration status of those already here into question, while also limiting the ability of others to legally train in the United States going forward, will only serve to exacerbate the already existing cardiovascular workforce shortage, especially in rural America. Such policies also threaten the care continuum of patients who rely on these providers for their medical care.”

American College of Physicians

“The executive order could deny entry or reentry to tens of thousands more persons, including medical students and physicians who are being trained in the United States and/or are delivering direct patient care. ... It also creates a precedent for barring entry of IMGs based on their religion and country of origin. ... Approximately 30% of ACP members are IMGs.”

American Gastroenterological Association

Science and illness ignore borders and political divides. That is why AGA is concerned that the recent U.S. executive order on immigration could limit scientific exchange, delay patient care and impair medical training.

AGA is committed to diversity, which we define as inclusive of race, ethnicity and national origin. Diversity within training programs and laboratories in the United States built today’s practice of gastroenterology. Scientists from around the world publish in our journals, work in our laboratories, train in our programs and present data at Digestive Disease Week. This exchange leads to better patient care, and very sick patients travel to the United States from around the world for the best digestive health care.

AGA adds our support to a growing number of medical institutions urging the administration to consider the devastating impact of the executive order on the health of the nation that will result from turning away patients, health professionals, and researchers. The recent immigration policy is clearly detrimental to America’s leadership role in advancing health care, and to the standing of the United States within the international community.

American Society of Clinical Oncology

ASCO is deeply concerned about the potential impact of the recent executive order on cancer research, patient care, and international scientific collaboration.

Our more than 40,000 members in 148 countries lead the charge to conquer cancer in all its forms and in every nation. Tens of thousands of people from more than 100 countries participate in our scientific meetings to exchange advances and ideas to improve patient care. Millions of cancer survivors are alive today because of the progress made possible by scientific collaboration. Progress against this disease will falter if the close-knit global community of cancer care providers is divided by policies that bar members of certain nationalities from entering the United States to conduct research, care for people with cancer, or participate in scientific and medical conferences.

American Society of Hematology

We express our deep concern about the Administration’s executive order that has denied U.S. entry to people who bring unique expertise to the practice of medicine and the conduct of cancer and biomedical research. Our nation depends on the contributions of the greatest minds from around the world to maintain the high quality of our biomedical research enterprise and health care services.

The benefits of scientific collaborations are amplified by our diversity. Limiting the exchange of ideas, practices, and data across cultures has the potential to significantly retard scientific progress and adversely affect public health. Any loss of researchers and physicians will render the United States less competitive over time, and our traditionally strong research institutions and the patients they serve will be negatively affected.

We remain deeply concerned that restricting travel will prohibit participation in scientific meetings, where cutting-edge science and treatment methods are often first introduced. These in-person meetings and other global exchanges are vitally important because they provide unparalleled opportunities for collaborations and information-sharing. Such scientific and medical meetings are absolutely essential to the conquest of cancer and blood diseases.

(Statement issued on behalf of ASH, American Association for Cancer Research, Association of American Cancer Institutes, American Society for Radiation Oncology, The American Society for Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, and LUNGevity Foundation.)

The text of the executive order can be found on the White House website.

Updated 2/2/17 to include the position of the American Gastroenterological Association.

[email protected]

On Twitter @denisefulton

Organizations representing physicians and medical students have expressed their concern regarding President Trump’s executive order of Jan. 27 that curtails entry into the United States by travelers from seven Muslim-majority countries. The order also suspends for 120 days entry into the United States for all persons seeking refugee status, and it bars refugees from Syria indefinitely.

Following are direct excerpts from statements issued by medical organizations.

American Academy of Family Physicians

“We are deeply concerned that steps your Administration has taken will have a chilling effect on our nation’s physician workforce, biomedical research, and global health. It is often America’s physicians who answer the call to assist people around the world when a public health crisis occurs. Imagine a world where physicians fail to answer the call of the needy because they fear they may not be able to return to their home and families in the United States.

Many family physicians are international medical graduates (IMG), who have completed all or part of their education and training in the United States. They are professionals who dedicate their careers to the service of their patients in communities large and small, urban and rural. In fact, 20% of our membership and over 25% of family medicine residents [comprise] IMGs. The AAFP applauds and supports wholly the contributions of these individual family physicians to their patients and communities and we celebrate their diversity.

We recognize that one of your primary responsibilities as President is to ensure the safety and security of the country and its citizens. This is, without question, a daunting responsibility. But we strongly urge that the methods of doing so be examined carefully, so that the many people who can add so much to our country through immigration have the opportunity to do so, and those who are doing so already are treated with the respect and dignity they deserve.”

American Academy of Pediatrics

“The executive orders signed today are harmful to immigrant children and families throughout our country. Many of the children who will be most affected are the victims of unspeakable violence and have been exposed to trauma. Children do not immigrate, they flee. They are coming to the United States seeking safe haven in our country and they need our compassion and assistance. Broad scale expansion of family detention only exacerbates their suffering ... The AAP is non-partisan and pro-children. We urge President Trump and his administration to ensure that children and families who are fleeing violence and adversity can continue to seek refuge in our country. Immigrant children and families are an integral part of our communities and our nation, and they deserve to be cared for, treated with compassion, and celebrated. Most of all, they deserve to be healthy and safe. Pediatricians stand with the immigrant families we care for and will continue to advocate that their needs are met and prioritized.”

American Association of Medical Colleges

“The United States is facing a serious shortage of physicians. IMGs play an important role in U.S. health care, representing roughly 25% of the workforce. Current immigration pathways – including student, exchange-visitor, and employment visas – provide a balanced solution that improves health care access across the country through programs like the National Interest Waiver and the Conrad 30 J-1 Visa Waiver. In the last decade, Conrad 30 alone has directed nearly 10,000 physicians into rural and urban underserved communities. Impeding these U.S. immigration pathways jeopardizes critical access to high-quality physician care for our nation’s most vulnerable populations.

Our ability to attract top talent from around the world also enriches the research laboratories at medical schools and teaching hospitals that are working toward cures and has helped position the United States as a global leader in medical research, strengthening our economy and bolstering the public’s health. Because disease knows no geographic boundaries, it is essential to ensure that we continue to foster, rather than impede, scientific cooperation with physicians and researchers of all nationalities, as we strive to keep our country healthy.”

American College of Cardiology

“The ability to share ideas and knowledge necessary to address [the global epidemic of cardiovascular disease] is imperative. Policies that impede this free-flow of ideas will have a detrimental impact on scientific discovery, as well as the lives of patients around the world. If we are to realize a future where cardiovascular disease is no longer the number one killer of men and women worldwide we must ensure that our system of scientific exchange allows for health care professionals to learn from each other regardless of their nationality.

Additionally, IMGs, naturalized citizens, and legal residents make up a significant portion of the health care workforce in hospitals and practices across the country. More than 25% of current practicing physicians are IMGs, with cardiology ranking among the top when broken down by medical specialty. Policies that bring the immigration status of those already here into question, while also limiting the ability of others to legally train in the United States going forward, will only serve to exacerbate the already existing cardiovascular workforce shortage, especially in rural America. Such policies also threaten the care continuum of patients who rely on these providers for their medical care.”

American College of Physicians

“The executive order could deny entry or reentry to tens of thousands more persons, including medical students and physicians who are being trained in the United States and/or are delivering direct patient care. ... It also creates a precedent for barring entry of IMGs based on their religion and country of origin. ... Approximately 30% of ACP members are IMGs.”

American Gastroenterological Association

Science and illness ignore borders and political divides. That is why AGA is concerned that the recent U.S. executive order on immigration could limit scientific exchange, delay patient care and impair medical training.

AGA is committed to diversity, which we define as inclusive of race, ethnicity and national origin. Diversity within training programs and laboratories in the United States built today’s practice of gastroenterology. Scientists from around the world publish in our journals, work in our laboratories, train in our programs and present data at Digestive Disease Week. This exchange leads to better patient care, and very sick patients travel to the United States from around the world for the best digestive health care.

AGA adds our support to a growing number of medical institutions urging the administration to consider the devastating impact of the executive order on the health of the nation that will result from turning away patients, health professionals, and researchers. The recent immigration policy is clearly detrimental to America’s leadership role in advancing health care, and to the standing of the United States within the international community.

American Society of Clinical Oncology

ASCO is deeply concerned about the potential impact of the recent executive order on cancer research, patient care, and international scientific collaboration.

Our more than 40,000 members in 148 countries lead the charge to conquer cancer in all its forms and in every nation. Tens of thousands of people from more than 100 countries participate in our scientific meetings to exchange advances and ideas to improve patient care. Millions of cancer survivors are alive today because of the progress made possible by scientific collaboration. Progress against this disease will falter if the close-knit global community of cancer care providers is divided by policies that bar members of certain nationalities from entering the United States to conduct research, care for people with cancer, or participate in scientific and medical conferences.

American Society of Hematology

We express our deep concern about the Administration’s executive order that has denied U.S. entry to people who bring unique expertise to the practice of medicine and the conduct of cancer and biomedical research. Our nation depends on the contributions of the greatest minds from around the world to maintain the high quality of our biomedical research enterprise and health care services.

The benefits of scientific collaborations are amplified by our diversity. Limiting the exchange of ideas, practices, and data across cultures has the potential to significantly retard scientific progress and adversely affect public health. Any loss of researchers and physicians will render the United States less competitive over time, and our traditionally strong research institutions and the patients they serve will be negatively affected.

We remain deeply concerned that restricting travel will prohibit participation in scientific meetings, where cutting-edge science and treatment methods are often first introduced. These in-person meetings and other global exchanges are vitally important because they provide unparalleled opportunities for collaborations and information-sharing. Such scientific and medical meetings are absolutely essential to the conquest of cancer and blood diseases.

(Statement issued on behalf of ASH, American Association for Cancer Research, Association of American Cancer Institutes, American Society for Radiation Oncology, The American Society for Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, and LUNGevity Foundation.)

The text of the executive order can be found on the White House website.

Updated 2/2/17 to include the position of the American Gastroenterological Association.

[email protected]

On Twitter @denisefulton

February 2017 Quiz 2

Q2: Answer: B

Objective: Recognize the features of CVID-associated noninfectious gastrointestinal manifestations.

Explanation: This patient has gastrointestinal manifestations of common variable immune deficiency (CVID), which can present similarly to celiac disease or inflammatory bowel disease. Histologically, intestinal biopsies will reveal villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, and intraepithelial lymphocytosis similar to celiac disease. However, while plasma cells are increased in celiac disease, they are absent in CVID.

The initial treatment strategy for CVID typically includes oral corticosteroids, either prednisone or budesonide, with other immunosuppressants such as the thiopurines or anti–tumor necrosis factor agents reserved for steroid-dependent or refractory disease.

Gluten-free diet is ineffective for the treatment of CVID-associated enteropathy. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy reduces the frequency of infections associated with CVID, but does not affect the noninfectious GI symptoms. While bacterial overgrowth can occur in CVID, it is typically the consequence of the luminal changes, not the cause.

Reference

1. Agarwal S., Mayer L. Gastrointestinal manifestations in primary immune disorders. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:703-11.

Q2: Answer: B

Objective: Recognize the features of CVID-associated noninfectious gastrointestinal manifestations.

Explanation: This patient has gastrointestinal manifestations of common variable immune deficiency (CVID), which can present similarly to celiac disease or inflammatory bowel disease. Histologically, intestinal biopsies will reveal villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, and intraepithelial lymphocytosis similar to celiac disease. However, while plasma cells are increased in celiac disease, they are absent in CVID.

The initial treatment strategy for CVID typically includes oral corticosteroids, either prednisone or budesonide, with other immunosuppressants such as the thiopurines or anti–tumor necrosis factor agents reserved for steroid-dependent or refractory disease.

Gluten-free diet is ineffective for the treatment of CVID-associated enteropathy. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy reduces the frequency of infections associated with CVID, but does not affect the noninfectious GI symptoms. While bacterial overgrowth can occur in CVID, it is typically the consequence of the luminal changes, not the cause.

Reference

1. Agarwal S., Mayer L. Gastrointestinal manifestations in primary immune disorders. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:703-11.

Q2: Answer: B

Objective: Recognize the features of CVID-associated noninfectious gastrointestinal manifestations.

Explanation: This patient has gastrointestinal manifestations of common variable immune deficiency (CVID), which can present similarly to celiac disease or inflammatory bowel disease. Histologically, intestinal biopsies will reveal villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, and intraepithelial lymphocytosis similar to celiac disease. However, while plasma cells are increased in celiac disease, they are absent in CVID.

The initial treatment strategy for CVID typically includes oral corticosteroids, either prednisone or budesonide, with other immunosuppressants such as the thiopurines or anti–tumor necrosis factor agents reserved for steroid-dependent or refractory disease.

Gluten-free diet is ineffective for the treatment of CVID-associated enteropathy. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy reduces the frequency of infections associated with CVID, but does not affect the noninfectious GI symptoms. While bacterial overgrowth can occur in CVID, it is typically the consequence of the luminal changes, not the cause.

Reference

1. Agarwal S., Mayer L. Gastrointestinal manifestations in primary immune disorders. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:703-11.

Q2: A 34-year-old woman presents with a 3-year history of watery, nonbloody diarrhea with associated weight loss, and recurrent bacterial bronchitis and pneumonias. Laboratory studies show iron deficiency anemia, low 25-OH vitamin D, and a slightly elevated INR. Celiac serologies were negative, and small bowel biopsies revealed near total villous atrophy, increased intraepithelial lymphocytes, and crypt hyperplasia with absent plasma cells.

February 2017 Quiz 1

Q1: Answer: D

Current recommendations suggest H. pylori testing for patients with active or a documented history of peptic ulcer disease, gastric MALT lymphoma, or gastric carcinoma. The H. pylori test-and-treat strategy is also recommended for patients less than 55 years of age who present with dyspepsia symptoms without “alarm features.”

There is currently no recommendation for asymptomatic family members of patients diagnosed with H. pylori infection to be tested, unless there are known factors that may increase the patient’s risk for gastric malignancy (e.g., family history of gastric carcinoma, and ethnic background from areas with high prevalence of H. pylori and gastric cancer such as East Asia, Latin America, and Eastern Europe).

References

1. Chey W.D., Wong B.C. Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1808-25.

2. Talley N.J., Vakil N.B., Moayyedi P. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the evaluation of dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 2005;129:1756-80.

3. Suerbaum S., Michetti P. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1175-86.

4. Everhart J.E., Kruszon-Moran D., Perez-Perez G.I., et al. Seroprevalence and ethnic differences in Helicobacter pylori infection among adults in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1359-63.

Q1: Answer: D

Current recommendations suggest H. pylori testing for patients with active or a documented history of peptic ulcer disease, gastric MALT lymphoma, or gastric carcinoma. The H. pylori test-and-treat strategy is also recommended for patients less than 55 years of age who present with dyspepsia symptoms without “alarm features.”

There is currently no recommendation for asymptomatic family members of patients diagnosed with H. pylori infection to be tested, unless there are known factors that may increase the patient’s risk for gastric malignancy (e.g., family history of gastric carcinoma, and ethnic background from areas with high prevalence of H. pylori and gastric cancer such as East Asia, Latin America, and Eastern Europe).

References

1. Chey W.D., Wong B.C. Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1808-25.

2. Talley N.J., Vakil N.B., Moayyedi P. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the evaluation of dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 2005;129:1756-80.

3. Suerbaum S., Michetti P. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1175-86.

4. Everhart J.E., Kruszon-Moran D., Perez-Perez G.I., et al. Seroprevalence and ethnic differences in Helicobacter pylori infection among adults in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1359-63.

Q1: Answer: D

Current recommendations suggest H. pylori testing for patients with active or a documented history of peptic ulcer disease, gastric MALT lymphoma, or gastric carcinoma. The H. pylori test-and-treat strategy is also recommended for patients less than 55 years of age who present with dyspepsia symptoms without “alarm features.”

There is currently no recommendation for asymptomatic family members of patients diagnosed with H. pylori infection to be tested, unless there are known factors that may increase the patient’s risk for gastric malignancy (e.g., family history of gastric carcinoma, and ethnic background from areas with high prevalence of H. pylori and gastric cancer such as East Asia, Latin America, and Eastern Europe).

References

1. Chey W.D., Wong B.C. Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1808-25.

2. Talley N.J., Vakil N.B., Moayyedi P. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the evaluation of dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 2005;129:1756-80.

3. Suerbaum S., Michetti P. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1175-86.

4. Everhart J.E., Kruszon-Moran D., Perez-Perez G.I., et al. Seroprevalence and ethnic differences in Helicobacter pylori infection among adults in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1359-63.

A Primary Hospital Antimicrobial Stewardship Intervention on Pneumonia Treatment Duration

The safety and the efficacy of shorter durations of antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated pneumonia have been clearly established in the past decade.1,2 Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Thoracic Society have been available since 2007. These expert consensus statements recommend that uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) should be treated for 5 to 7 days, as long as the patient exhibits signs and symptoms of clinical stability.3 Similarly, recently updated guidelines for hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonias call for short-course therapy.4 Despite this guidance, pneumonia treatment duration is often discordant.5 Unnecessary antimicrobial use is associated with greater selection pressure on pathogens, increased risk of adverse events (AEs), and elevated treatment costs.6 The growing burden of antibiotic resistance coupled with limited availability of new antibiotics requires judicious use of these agents.

The IDSA guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) note that exposure to antimicrobial agents is the most important modifiable risk factor for the development of CDI.7 Longer durations of antibiotics increase the risk of CDI compared with shorter durations.8,9 Antibiotics are a frequent cause of drug-associated AEs and likely are underestimated.10 To decrease the unwanted effects of excessive therapy, IDSA and CDC suggest that antimicrobial stewardship interventions should be implemented.11-13

Antimicrobial stewardship efforts in small community hospitals (also known as district, rural, general, and primary hospitals) are varied and can be challenging due to limited staff and resources.14,15 The World Health Organization defines a primary care facility as having few specialties, mainly internal medicine and general surgery with limited laboratory services for general (but not specialized) pathologic analysis, and bed size ranging from 30 to 200 beds.16 Although guidance is available for effective intervention strategies in smaller hospitals, there are limited data in the literature regarding successful outcomes.17-22

The purpose of this study was to establish the need and evaluate the impact of a pharmacy-initiated 3-part intervention targeting treatment duration in patients hospitalized with uncomplicated pneumonia in a primary hospital setting. The Veterans Health Care System of the Ozarks (VHSO) in Fayetteville, Arkansas, has 50 acute care beds, including 7 intensive care unit beds and excluding 15 mental health beds. The pharmacy is staffed 24 hours a day. Acute-care providers consist of 7 full-time hospitalists, not including nocturnists and contract physicians. The VHSO does not have an infectious disease physician on staff.

The antimicrobial stewardship committee consists of 3 clinical pharmacists, a pulmonologist, a pathologist, and 2 infection-control nurses. There is 1 full-time equivalent allotted for inpatient clinical pharmacy activities in the acute care areas, including enforcement of all antimicrobial stewardship policies, which are conducted by a single pharmacist.

Methods

This was a retrospective chart review of two 12-month periods using a before and after study design. Medical records were reviewed during October 2012 through September 2013 (before the stewardship implementation) and December 2014 through November 2015 (after implementation). Inclusion criteria consisted of a primary discharge diagnosis of pneumonia as documented by the provider (or secondary diagnosis if sepsis was primary), hospitalization for at least 48 hours, administration of antibiotics for a minimum of 24 hours, and survival to discharge.

Exclusion criteria consisted of direct transfer from another facility, inappropriate empiric therapy as evidenced by culture data (isolated pathogens not covered by prescribed antibiotics), pneumonia that developed 48 hours after admission, extrapulmonary sources of infection, hospitalization > 14 days, discharge without a known duration of outpatient antibiotics, discharge for pneumonia within 28 days prior to admission, documented infection caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa or other nonlactose fermenting Gram-negative rod, and complicated pneumonias defined as lung abscess, empyema, or severe immunosuppression (eg, cancer with chemotherapy within the previous 30 days, transplant recipients, HIV infection, acquired or congenital immunodeficiency, or absolute neutrophil count 1,500 cell/mm3 within past 28 days).

Patients were designated with health care-associated pneumonia (HCAP) if they were hospitalized ≥ 2 days or resided in a skilled nursing or extended-care facility within the previous 90 days; on chronic dialysis; or had wound care, tracheostomy care, or ventilator care from a health care professional within the previous 28 days. Criteria for clinical stability were defined as ≤ 100.4º F temperature, ≤ 100 beats/min heart rate, ≤ 24 breaths/min respiratory rate, ≥ 90 mm Hg systolic blood pressure, ≥ 90% or PaO2 ≥ 60 mm Hg oxygen saturation on room air (or baseline oxygen requirements), and return to baseline mental status. To compare groups, researchers tabulated the pneumonia severity index on hospital day 1.

The intervention consisted of a 3-part process. First, hospitalists were educated on VHSO’s baseline treatment duration data, and these were compared with current IDSA recommendations. The education was followed by an open-discussion component to solicit feedback from providers on perceived barriers to following guidelines. Provider feedback was used to tailor an antimicrobial stewardship intervention to address perceived barriers to optimal antibiotic treatment duration.

After the education component, prospective intervention and feedback were provided for hospitalized patients by a single clinical pharmacist. This pharmacist interacted verbally and in writing with the patients’ providers, discussing antimicrobial appropriateness, de-escalation, duration of therapy, and intravenous to oral switching. Finally, a stewardship note for the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) was generated and included a template with reminders of clinical stability, duration of current therapy, and a request to discontinue therapy if the patient met criteria. For patients who remained hospitalized, this note was entered into CPRS on or about day 7 of antibiotic therapy; this required an electronic signature from the provider.

The VHSO Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee approved both the provider education and the stewardship note in November 2014, and implementation of the stewardship intervention occurred immediately afterward. The pharmacy staff also was educated on the VHSO baseline data and stewardship efforts.

The primary outcome of the study was the change in days of total antibiotic treatment. Secondary outcomes included days of intravenous antibiotic therapy, days of inpatient oral therapy, mean length of stay (LOS), and number of outpatient antibiotic days once discharged. Incidence of CDI and 28-day readmissions were also evaluated. The VHSO Institutional Review Board approved these methods and the procedures that followed were in accord with the ethical standards of the VHSO Committee on Human Experimentation.

Statistical Analysis

All continuous variables are reported as mean ± standard deviation. Data analysis for significance was performed using a Student t test for continuous variables and a χ2 test (or Fisher exact test) for categorical variables in R Foundation for Statistical Computing version 3.1.0. All samples were 2-tailed. A P value < .05 was considered statistically significant. Using the smaller of the 2 study populations, the investigators calculated that the given sample size of 88 in each group would provide 99% power to detect a 2-day difference in the primary endpoint at a 2-sided significance level of 5%.

Results

During the baseline assessment (group 1), 192 cases were reviewed with 103 meeting the inclusion criteria. Group 1 consisted of 85 cases of CAP and 18 cases of HCAP (mean age, 70.7 years). During the follow-up assessment (group 2), 168 cases were reviewed with 88 meeting the inclusion criteria. Group 2 consisted of 68 cases of CAP and 20 cases of HCAP (mean age, 70.8 years).

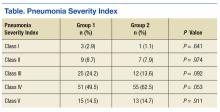

There was no difference in inpatient mortality rates between groups (3.1% vs 3.0%, P = .99). This mortality rate is consistent with published reports.23 Empiric antibiotic selection was appropriate because there were no exclusions for drug/pathogen mismatch. Pneumonia severity was similar in both groups (Table).

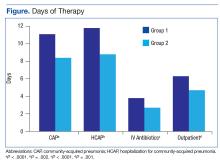

The total duration of antibiotic treatment decreased significantly for CAP and HCAP (Figure). The observed median treatment days for groups 1 and 2 were 11 days and 8 days, respectively. Outpatient antibiotic days also decreased. Mean LOS was shorter in the follow-up group (4.9 ± 2.6 days vs 4.0 ± 2.6 days, P = .02). Length of IV antibiotic duration decreased. Oral antibiotic days while inpatient were not statistically different (1.5 ± 1.8 days vs 1.1 ± 1.5 days, P = .15). During the follow-up period, 26 stewardship notes were entered into CPRS; antibiotics were stopped in 65% of cases.

There were no recorded cases of CDI in either group. There were eleven 28-day readmissions in group 1, only 3 of which were due to infectious causes. One patient had a primary diagnosis of necrotizing pneumonia, 1 had Pseudomonas pneumonia, and 1 patient had a new lung mass and was diagnosed with postobstructive pneumonia. Of eight 28-day readmissions in group 2, only 2 resulted from infectious causes. One readmission primary diagnosis was sinusitis and 1 was recurrent pneumonia (of note, this patient received a 10-day treatment course for pneumonia on initial admission). Two patients died within 28 days of discharge in each group.

Discussion

Other multifaceted single-center interventions have been shown to be effective in large, teaching hospitals,24,25 and it has been suggested that smaller, rural hospitals may be underserved in antimicrobial stewardship activities.26,27 In the global struggle with antimicrobial resistance, McGregor and colleagues highlighted the importance of evaluating successful stewardship methods in an array of clinical settings to help tailor an approach for a specific type of facility.28 To the authors knowledge, this is the first publication showing efficacy of such antimicrobial stewardship interventions specific to pneumonia therapy in a small, primary facility.

The intervention methods used at VHSO are supported by recent IDSA and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America guidelines for effective stewardship implementation.29 Prospective audit and feedback is considered a core recommendation, whereas didactic education is recommended only in conjunction with other stewardship activities. Additionally, the guidelines recommend evaluating specific infectious disease syndromes, in this case uncomplicated pneumonia, to focus on specific treatment guidelines. Last, the results of the 3-part intervention can be used to aid in demonstrating facility improvement and encourage continued success.

Of note, VHSO has had established inpatient and outpatient clinical pharmacy roles for several years. Stewardship interventions already in place included an intravenous-to-oral antibiotic switch policy, automatic antibiotic stop dates, as well as pharmacist-driven vancomycin and aminoglycoside dosing. Prior to this multifaceted intervention specific to pneumonia duration, prospective audit and feedback interventions (verbal and written) also were common. The number of interventions specific to this study outside of the stewardship note was not recorded. Using rapid diagnostic testing and biomarkers to aid in stewardship activities at VHSO have been considered, but these tools are not available due to a lab personnel shortage.

Soliciting feedback from providers on their preferred stewardship strategy and perceived barriers was a key component of the educational intervention. Of equal importance was presenting providers with their baseline prescribing data to provide objective evidence of a problem. While all were familiar with existing treatment guidelines, some feedback indicated that it can be difficult to determine accurate antibiotic duration in CPRS. Prescribers reported that identifying antibiotic duration was especially challenging when antibiotics as well as providers change during an admission. Also frequently overlooked were antibiotics given in the emergency department. This could be a key area for clinical pharmacists’ intervention given their familiarity with the CPRS medication sections.

Charani and colleagues suggest that recognizing barriers to implementing best practices and adapting to the local facility culture is paramount for changing prescribing behaviors and developing a successful stewardship intervention.30 At VHSO, the providers were presented with multiple stewardship options but agreed to the new note and template. This process gave providers a voice in selecting their own stewardship intervention. In a culture with no infectious disease physician to champion initiatives, the investigators felt that provider involvement in the intervention selection was unique and may have encouraged provider concurrence.

Although not directly targeted by the intervention strategies, average LOS was shorter in the follow-up group. According to investigators, frequent reminders of clinical stability in the stewardship notes may have influenced this. Even though the note was used only in patients who remained hospitalized for their entire treatment course, investigators felt that it still served as a reminder for prescribing habits as they were also able to show a decrease in outpatient prescription duration.

Limitations

Potential weaknesses of the study include changes in providers. During the transition between group 1 and group 2, 2 hospitalists left and 2 new hospitalists arrived. Given the small size of the staff, this could significantly impact prescribing trends. Another potential weakness is the high exclusion rate, although these rates were similar in both groups (46% group 1, 47% group 2). Furthermore, similar exclusion rates have been reported elsewhere.24,25,31 The most common reasons for exclusion were complicated pneumonias (36%) and immunocompromised patients (18%). These patient populations were not evaluated in the current study, and optimal treatment durations are unknown. Hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonias also were excluded. Therefore, limitations in applicability of the results should be noted.

The authors acknowledge that, prior to this publication, the IDSA guidelines have removed the designation of HCAP as a separate clinical entity.4 However, this should not affect the significance of the intervention for treatment duration.

The study facility experienced a hiring freeze resulting in a 9.3% decrease in overall admissions from fiscal year 2013 to fiscal year 2015. This is likely why there were fewer admissions for pneumonia in group 2. Regardless, power analysis revealed the study was of adequate sample size to detect its primary outcome. It is possible that patients in either group could have sought health care at other facilities, making the CDI and readmission endpoints less inclusive.

The study was not of a scale to detect changes in antimicrobial resistance pressure or clinical outcomes. Cost savings were not analyzed. However, this study adds to the growing body of evidence that a structured intervention can result in positive outcomes at the facility level. This study shows that interventions targeting pneumonia treatment duration could feasibly be added to the menu of stewardship options available to smaller facilities.

Like other stewardship studies in the literature, the follow-up treatment duration, while improved, still exceeded those recommended in the IDSA guidelines. The investigators noted that not all providers were equal regarding change in prescribing habits, perhaps making the average duration longer. Additionally, the request to discontinue antibiotic therapy through the stewardship note could have been entered earlier (eg, as early as day 5 of therapy) to target the shortest effective date as recommended in the recent stewardship guidelines.29 Future steps include continued feedback to providers on their progress in this area and encouragement to document day of antibiotic treatment in their daily progress notes.

Conclusion

This study showed a significant decrease in antibiotic duration for the treatment of uncomplicated pneumonia using a 3-part pharmacy intervention in a primary hospital setting. The investigators feel that each arm of the strategy was equally important and fewer interventions were not likely to be as effective.32 Although data collection for baseline prescribing and follow-up on outcomes may be a time-consuming task, it can be a valuable component of successful stewardship interventions.

1. Li JZ, Winston LG, Moore DH, Bent S. Efficacy of short-course antibiotic regimens for community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2007;120(9):783-790.

2. Dimopoulos G, Matthaiou DK, Karageorgopoulos DE, Grammatikos AP, Athanassa Z, Falagas ME. Short- versus long-course antibacterial therapy of community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Drugs. 2008;68(13):1841-1854.

3. Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America; American Thoracic Society. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(suppl 2):S27-S72.

4. Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator associated pneumonia: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(5):e61-e111.

5. Jenkins TC, Stella SA, Cervantes L, et al. Targets for antibiotic and healthcare resource stewardship in inpatient community-acquired pneumonia: a comparison of management practices with National Guideline Recommendations. Infection. 2013; 41(1):135-144.

6. Shlaes DM, Gerding DN, John JF Jr, et al. Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, and Infectious Diseases Society of America Joint Committee on the Prevention of Antimicrobial Resistance: guidelines for the prevention of antimicrobial resistance in hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25(3):584-599.

7. Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(5):431-455.

8. Brown E, Talbot GH, Axelrod P, Provencher M, Hoegg C. Risk factors for Clostridium-difficile toxin-associated diarrhea. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1990;11(6):283-290.

9. McFarland LV, Surawicz CM, Stamm WE. Risk factors for Clostridium-difficile carriage and C. difficile-associated diarrhea in a cohort of hospitalized patients. J Infect Dis. 1990;162(3):678-684.

10. Shehab N, Patel PR, Srinivasan A, Budnitz DS. Emergency department visits for antibiotic-associated adverse events. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(6):735-743.

11. Dellit TH, Owens RC, McGowan JE Jr, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America Guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(2):159-177.

12. Fridkin S, Baggs J, Fagan R, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: improving antibiotic use among hospitalized patients. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(9):194-200.

13. Nussenblatt V, Avdic E, Cosgrove S. What is the role of antimicrobial stewardship in improving outcomes of patients with CAP? Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2013;27(1):211-228.

14. Septimus EJ, Owens RC Jr. Need and potential of antimicrobial stewardship in community hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(suppl 1):S8-S14.

15. Hensher M, Price M, Adomakoh S. Referral hospitals. In Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, eds, et al. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006:1230.

16. Mulligan J, Fox-Rushby JA, Adam T, Johns B, Mills A. Unit costs of health care inputs in low and middle income regions. 2003. Working Paper 9, Disease Control Priorities Project. Published September 2003. Revised June 2005.

17. Ohl CA, Dodds Ashley ES. Antimicrobial stewardship programs in community hospitals: the evidence base and case studies. Clin Infect Dis 2011;53(suppl 1):S23-S28.

18. Trevidi KK, Kuper K. Hospital antimicrobial stewardship in the nonuniversity setting. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2014;28(2):281-289.

19. Yam P, Fales D, Jemison J, Gillum M, Bernstein M. Implementation of an antimicrobial stewardship program in a rural hospital. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012;69(13);1142-1148.

20. LaRocco A Jr. Concurrent antibiotic review programs—a role for infectious diseases specialists at small community hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(5):742-743.

21. Bartlett JM, Siola PL. Implementation and first-year results of an antimicrobial stewardship program at a community hospital. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(11):943-949.

22. Storey DF, Pate PG, Nguyen AT, Chang F. Implementation of an antimicrobial stewardship program on the medical-surgical service of a 100-bed community hospital. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2012;1(1):32.

23. Fine MJ, Smith MA, Carson CA, et al. Prognosis and outcomes of patients with community-acquired pneumonia. A meta-analysis. JAMA. 1996;275(2):134-141.

24. Advic E, Cushinotto LA, Hughes AH, et al. Impact of an antimicrobial stewardship intervention on shortening the duration of therapy for community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(11):1581-1587.

25. Carratallà J, Garcia-Vidal C, Ortega L, et al. Effect of a 3-step critical pathway to reduce duration of intravenous antibiotic therapy and length of stay in community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(12):922-928.

26. Stevenson KB, Samore M, Barbera J, et al. Pharmacist involvement in antimicrobial use at rural community hospitals in four Western states. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(8):787-792.

27. Reese SM, Gilmartin H, Rich KL, Price CS. Infection prevention needs assessment in Colorado hospitals: rural and urban settings. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42(6):597-601.

28. McGregor JC, Furuno JP. Optimizing research methods used for the evaluation of antimicrobial stewardship programs. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(suppl 3):S185-S192.

29. Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, et al. Implementing an antibiotic stewardship program: Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(10):e51-e77.

30. Charani E, Castro-Sánchez E, Holmes A. The role of behavior change in antimicrobial stewardship. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2014;28(2):169-175.

31. Attridge RT, Frei CR, Restrepo MI, et al. Guideline-concordant therapy and outcomes in healthcare-associated pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2011;38(4):878-887.

32. MacDougal C, Polk RE. Antimicrobial stewardship programs in health care systems. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18(4):638-656.

The safety and the efficacy of shorter durations of antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated pneumonia have been clearly established in the past decade.1,2 Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Thoracic Society have been available since 2007. These expert consensus statements recommend that uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) should be treated for 5 to 7 days, as long as the patient exhibits signs and symptoms of clinical stability.3 Similarly, recently updated guidelines for hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonias call for short-course therapy.4 Despite this guidance, pneumonia treatment duration is often discordant.5 Unnecessary antimicrobial use is associated with greater selection pressure on pathogens, increased risk of adverse events (AEs), and elevated treatment costs.6 The growing burden of antibiotic resistance coupled with limited availability of new antibiotics requires judicious use of these agents.

The IDSA guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) note that exposure to antimicrobial agents is the most important modifiable risk factor for the development of CDI.7 Longer durations of antibiotics increase the risk of CDI compared with shorter durations.8,9 Antibiotics are a frequent cause of drug-associated AEs and likely are underestimated.10 To decrease the unwanted effects of excessive therapy, IDSA and CDC suggest that antimicrobial stewardship interventions should be implemented.11-13

Antimicrobial stewardship efforts in small community hospitals (also known as district, rural, general, and primary hospitals) are varied and can be challenging due to limited staff and resources.14,15 The World Health Organization defines a primary care facility as having few specialties, mainly internal medicine and general surgery with limited laboratory services for general (but not specialized) pathologic analysis, and bed size ranging from 30 to 200 beds.16 Although guidance is available for effective intervention strategies in smaller hospitals, there are limited data in the literature regarding successful outcomes.17-22

The purpose of this study was to establish the need and evaluate the impact of a pharmacy-initiated 3-part intervention targeting treatment duration in patients hospitalized with uncomplicated pneumonia in a primary hospital setting. The Veterans Health Care System of the Ozarks (VHSO) in Fayetteville, Arkansas, has 50 acute care beds, including 7 intensive care unit beds and excluding 15 mental health beds. The pharmacy is staffed 24 hours a day. Acute-care providers consist of 7 full-time hospitalists, not including nocturnists and contract physicians. The VHSO does not have an infectious disease physician on staff.

The antimicrobial stewardship committee consists of 3 clinical pharmacists, a pulmonologist, a pathologist, and 2 infection-control nurses. There is 1 full-time equivalent allotted for inpatient clinical pharmacy activities in the acute care areas, including enforcement of all antimicrobial stewardship policies, which are conducted by a single pharmacist.

Methods

This was a retrospective chart review of two 12-month periods using a before and after study design. Medical records were reviewed during October 2012 through September 2013 (before the stewardship implementation) and December 2014 through November 2015 (after implementation). Inclusion criteria consisted of a primary discharge diagnosis of pneumonia as documented by the provider (or secondary diagnosis if sepsis was primary), hospitalization for at least 48 hours, administration of antibiotics for a minimum of 24 hours, and survival to discharge.

Exclusion criteria consisted of direct transfer from another facility, inappropriate empiric therapy as evidenced by culture data (isolated pathogens not covered by prescribed antibiotics), pneumonia that developed 48 hours after admission, extrapulmonary sources of infection, hospitalization > 14 days, discharge without a known duration of outpatient antibiotics, discharge for pneumonia within 28 days prior to admission, documented infection caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa or other nonlactose fermenting Gram-negative rod, and complicated pneumonias defined as lung abscess, empyema, or severe immunosuppression (eg, cancer with chemotherapy within the previous 30 days, transplant recipients, HIV infection, acquired or congenital immunodeficiency, or absolute neutrophil count 1,500 cell/mm3 within past 28 days).

Patients were designated with health care-associated pneumonia (HCAP) if they were hospitalized ≥ 2 days or resided in a skilled nursing or extended-care facility within the previous 90 days; on chronic dialysis; or had wound care, tracheostomy care, or ventilator care from a health care professional within the previous 28 days. Criteria for clinical stability were defined as ≤ 100.4º F temperature, ≤ 100 beats/min heart rate, ≤ 24 breaths/min respiratory rate, ≥ 90 mm Hg systolic blood pressure, ≥ 90% or PaO2 ≥ 60 mm Hg oxygen saturation on room air (or baseline oxygen requirements), and return to baseline mental status. To compare groups, researchers tabulated the pneumonia severity index on hospital day 1.

The intervention consisted of a 3-part process. First, hospitalists were educated on VHSO’s baseline treatment duration data, and these were compared with current IDSA recommendations. The education was followed by an open-discussion component to solicit feedback from providers on perceived barriers to following guidelines. Provider feedback was used to tailor an antimicrobial stewardship intervention to address perceived barriers to optimal antibiotic treatment duration.

After the education component, prospective intervention and feedback were provided for hospitalized patients by a single clinical pharmacist. This pharmacist interacted verbally and in writing with the patients’ providers, discussing antimicrobial appropriateness, de-escalation, duration of therapy, and intravenous to oral switching. Finally, a stewardship note for the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) was generated and included a template with reminders of clinical stability, duration of current therapy, and a request to discontinue therapy if the patient met criteria. For patients who remained hospitalized, this note was entered into CPRS on or about day 7 of antibiotic therapy; this required an electronic signature from the provider.

The VHSO Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee approved both the provider education and the stewardship note in November 2014, and implementation of the stewardship intervention occurred immediately afterward. The pharmacy staff also was educated on the VHSO baseline data and stewardship efforts.

The primary outcome of the study was the change in days of total antibiotic treatment. Secondary outcomes included days of intravenous antibiotic therapy, days of inpatient oral therapy, mean length of stay (LOS), and number of outpatient antibiotic days once discharged. Incidence of CDI and 28-day readmissions were also evaluated. The VHSO Institutional Review Board approved these methods and the procedures that followed were in accord with the ethical standards of the VHSO Committee on Human Experimentation.

Statistical Analysis

All continuous variables are reported as mean ± standard deviation. Data analysis for significance was performed using a Student t test for continuous variables and a χ2 test (or Fisher exact test) for categorical variables in R Foundation for Statistical Computing version 3.1.0. All samples were 2-tailed. A P value < .05 was considered statistically significant. Using the smaller of the 2 study populations, the investigators calculated that the given sample size of 88 in each group would provide 99% power to detect a 2-day difference in the primary endpoint at a 2-sided significance level of 5%.

Results

During the baseline assessment (group 1), 192 cases were reviewed with 103 meeting the inclusion criteria. Group 1 consisted of 85 cases of CAP and 18 cases of HCAP (mean age, 70.7 years). During the follow-up assessment (group 2), 168 cases were reviewed with 88 meeting the inclusion criteria. Group 2 consisted of 68 cases of CAP and 20 cases of HCAP (mean age, 70.8 years).