User login

Leadless cardiac pacing: What primary care providers and non-EP cardiologists should know

WHY LEADLESS PACING?

The first clinical implantation of a cardiac pacemaker was performed surgically in 1958 by Drs. Elmvist and Senning via thoracotomy and direct attachment of electrodes to the myocardium. Transvenous pacing was introduced in 1962 by Drs. Lagergren, Parsonnet, and Welti.1,2 The general configuration of transvenous leads connected to a pulse generator situated in a surgical pocket has remained the standard of care ever since. Despite almost 60 years of technological innovation, contemporary permanent transvenous pacing continues to carry significant short- and long-term morbidity. Long-term composite complication rates are estimated at over 10%,3 further stratified as 12% in the 2 months post-implant (short-term) and 9% thereafter (long-term).4 Transvenous pacing complications are associated with an increase in both hospitalization days (hazard ratio 2.3) and unique hospitalizations (hazard ratio 4.4).5

Short-term complications

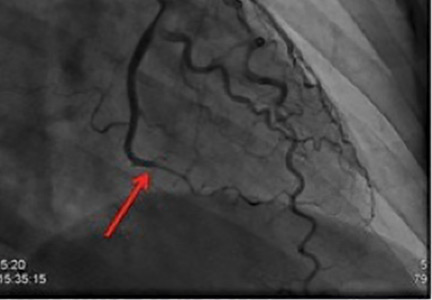

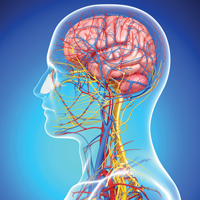

Short-term complications include lead dislodgment, pocket hematoma, pericardial effusion, and pneumothorax (Figure 1). Pocket hematomas are common with concurrent antiplatelet or anticoagulant administration, with incidence estimates varying from 5% to 33% depending on the definition.6 Morbidity associated with pocket hematoma include prolonged hospitalization, need for re-operation,7 and an almost eightfold increase in the rate of device infection over the long term compared with patients without pocket hematoma.8 New pericardial effusions after implant may affect up to 10% of patients; they are generally small, including 90% attributable to pericarditis or contained microperforation not requiring intervention. Overt lead perforation resulting in cardiac tamponade occurs in about 1% of transvenous pacemaker implants, of which 10% (0.1% overall) require open chest surgery, with the remainder treated with percutaneous drainage.9

Long-term complications

Long-term complications are predominantly lead and pocket-related but also include venous occlusive disease and tricuspid valve pathology.4 The development of primary lead failure due to insulation defects, conductor fracture, or dislodgment has been associated with major adverse events in 16% of patients, and an additional 6% if transvenous lead extraction is needed, which can rarely lead to hemorrhagic death by vascular tears involving the heart or superior vena cava.10 Fibrous tissue growth around the indwelling vascular leads can result in venous obstruction present in up to 14% of patients by 6 months after implant.11 This increases to 26% by the time of device replacement or upgrade, which is typically 5 to 10 years after the original implant, including 17% of patients with a complete venous occlusion.12 In addition, worsened tricuspid regurgitation due to lead impingement on the valve is seen in 7% to 40% of patients depending on definitions,13 with post-implant severe tricuspid regurgitation independently associated with increased mortality risk.14 The rate of device infection is 1% to 2% at 1 year,8,15 and 3% over the lifetime of the initial transvenous system; this increases to more than 10% after generator replacement.16

LEADLESS PACING TECHNOLOGY

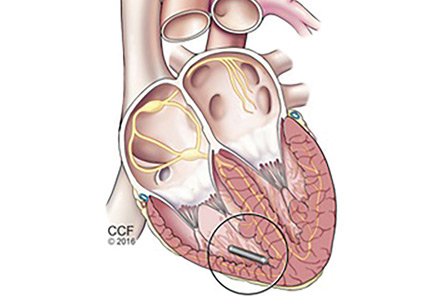

The principal goal of leadless pacing is to reduce short- and long-term pacemaker complications by eliminating the two most common sources of problems: the transvenous leads and the surgical pocket. Discussion of leadless pacing strategies began as early as 1970.17 Although several preclinical studies demonstrated efficacy with leadless prototypes,18–20 clinical implementation of fully leadless technology did not occur until recently. As shown in Figure 2, there are now two commercially available leadless pacing devices: Nanostim (St. Jude Medical Inc., St. Paul, MN) and Micra (Medtronic Inc., Dublin, Ireland). At the time of this writing, both have commercial approval in Europe. In the United States, Micra received commercial approval from the US Food and Drug Administration on April 6, 2016, with a similar decision expected on Nanostim. The current approved indications for leadless pacing are chronic atrial tachyarrhythmia with advanced atrioventricular (AV) block; advanced AV block with low level of physical activity or short expected lifespan; and infrequent pauses or unexplained syncope with abnormal findings at electrophysiologic study. Although differences exist between Nanostim and Micra, as shown in Table 1,21–27 there are fundamental similarities. Both are single-unit designs encapsulating the electrodes and pulse generator with rate-adaptive functionality. Both are delivered via an endovascular femoral venous approach without the need for incisional access, transvenous leads, or surgical pocket (Figures 3 and 4).21–27

Nanostim: Landmark trials

As the world’s first-in-man leadless pacemaker, Nanostim was evaluated in two prospective, non-randomized, multicenter, single-arm trials abbreviated LEADLESS22 and LEADLESS II.24 The first human feasibility study, LEADLESS, enrolled 33 patients with approved indications for ventricular-only pacing while excluding patients with expected pacemaker dependency. The most common indication was bradycardia in the presence of persistent atrial arrhythmias, thereby obviating the need for atrial pacing. The primary outcome was freedom from serious complications at 90 days. The secondary outcomes were implant success rate and device performance at 3 months. The results demonstrated 94% composite safety (31 of 33 patients) at 3 months. There was one cardiac perforation leading to tamponade and eventually death after prolonged hospitalization, and one inadvertent deployment into the left ventricle via patent foramen ovale that was successfully retrieved and redeployed without complication. The implant success rate was 97%, and the electrical parameters involving sensing, pacing thresholds, and impedance were as expected at 3 months. Results of 1-year follow-up were published for the LEADLESS cohort,25 revealing no additional complications from 3 to 12 months, no adverse changes in electrical performance parameters, and 100% effectiveness of rate-responsive programming.

The subsequent LEADLESS II trial enrolled 526 patients but did not exclude patients with expected pacemaker dependency, and its results were reported in a preplanned interim analysis when 300 patients had reached 6 months of follow-up (mean follow-up 6.9 ± 4.2 months).24 The primary efficacy end point involved electrical performance including capture thresholds and sensing. Initial deployment success was 96% with expected electrical parameters at implant that were stable at 6 months of follow-up. The rate of freedom from serious adverse events was 93%, with complications including device dislodgment (1.7%, mean 8 ± 6 days after implant), perforation (1.3%), performance deficiency requiring device retrieval and replacement (1.3%), and groin complications (1.3%). There were no device-related deaths, and all device dislodgments were successfully treated percutaneously.

There was no prospective control arm involving transvenous pacing in either the LEADLESS or LEADLESS II trial. Thus, in an effort to compare Nanostim (n = 718) vs transvenous pacing, complication rates were calculated for a propensity-matched registry cohort of 10,521 transvenous patients, and differences were reported.26 At 1 month, the composite complication rate was 5.8% for Nanostim (1.5% pericardial effusion, 1% dislodgment) and 12.7% for transvenous pacing (7.6% lead-related, 3.9% thoracic trauma, infection 1.9%) (P < .001). Between 1 month and 2 years, complication rates were only 0.6% for Nanostim vs 5.4% for transvenous pacing (P < .001). This lower complication rate at 2 years was driven almost entirely by a 2.6% infection rate and 2.4% lead-complication rate in the transvenous pacemaker group, nonexistent in the leadless group.

Micra: Landmark trials

Micra was evaluated in a prospective, nonrandomized, multicenter, single-arm trial, enrolling 725 patients with indications for ventricular-only pacing; approximately two-thirds of the cohort had bradycardia in the presence of persistent atrial arrhythmias, similar to the Nanostim cohort.27 The efficacy end point was stable capture threshold at 6 months. The safety end point was freedom from major complications resulting in new or prolonged hospitalization at 6 months. The implant success rate was 99%, and 98% of patients met the primary efficacy end point. The safety end point was met in 96% of patients. Complications included perforation or pericardial effusion (1.6%), groin complication (0.7%), elevated threshold (0.3%), venous thromboembolism (0.3%), and others (1.7%). No dislodgments were reported. There was no prospective, randomized control arm to compare Micra and transvenous pacing. A post hoc analysis was performed comparing major complication rates in this study with an unmatched 2,667-patient meta-analysis control cohort.27 The hazard ratio for the leadless pacing strategy was calculated at 0.49 (95% confidence interval 0.33 to 0.75, P = .001) with absolute risk reduction 3.4% at 6 months resulting in a number needed to treat of 29.4 patients. Further broken down, Micra patients compared with the control cohort had reduced rates of both subsequent hospitalizations (3.9% to 2.3%) and device revisions (3.5% to 0.4%).

ADVANTAGES OF LEADLESS PACING

As discussed above, the major observed benefit with both Nanostim and Micra compared with transvenous cohorts is the elimination of lead and pocket-related complications.25,27 Leadless pacing introduces a new 1% to 2% groin complication rate for both devices not present with transvenous pacing, and also a 1% device dislodgment rate in the case of Nanostim (all dislodgments were treated percutaneously). Data from both clinical trials suggest that the complication rates are largely compressed acutely. In contrast, there are considerable mid-term and long-term complications for transvenous systems.3–5 Indeed, the mid- to long-term window is where leadless pacing is expected to have the most favorable impact. As with any new disruptive technology, operator experience may be important, as evidenced by a near halving of the complication rate observed in the LEADLESS II trial after gaining the experience of 10 implants.25

Other benefits of leadless pacing include a generally quick procedure (average implant time was 30 minutes in LEADLESS and LEADLESS II)22,25 and full shoulder mobility afterwards, so that patients can resume driving once groin soreness has subsided, typically within a few days. (Current studies are investigating whether immediate shoulder mobility with leadless pacing is beneficial to older patients suffering from arthritis.) The lack of an incision allows patients to bathe and shower as soon as they desire, whereas after transvenous pacemaker implant, motion in the affected shoulder is usually restricted for several weeks to avoid lead dislodgment, and showering and bathing are restricted to avoid contamination of the incision with nonsterile tap water. (In some cases, a tightly adherent waterproof dressing can be used.) The leadless systems were designed for compatibility with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), whereas not all transvenous pacemaker generators and leads are MRI compatible.

Leadless devices are not expected to span the tricuspid valve to create incident or worsening tricuspid regurgitation. In a recent small study of 22 patients undergoing Micra implant, there were no new cases of severe tricuspid regurgitation after the procedure, with only a 9% increase in mild and 5% increase in moderate tricuspid regurgitation,28 vs a rate of 40% of worsening tricuspid regurgitation and 10% of new severe tricuspid regurgitation with transvenous pacing.13,14

Transvenous pacemaker implant requires surgery for pulse generator exchange at a mean of 7 years, a procedure carrying significant risk of short- and long-term complications.10

END-OF-SERVICE QUESTIONS: ATTEMPT RETRIEVAL OR NOT?

Both leadless systems have favorable projected in-service battery life: a reported 15.0 years for Nanostim25 and mean 12.5 years for Micra.27 The inevitable question is what to do then. The Nanostim system was designed to be retrievable using a dedicated catheter system. Micra was not designed with an accompanying retrieval system. Pathologic examinations of leadless devices at autopsy or after explant have revealed a range of device endothelialization, from partial at 19 months to full at 4 months.29,30

As of this writing, no extraction complications have been observed with Nanostim explants up to 506 days after implant (n = 12, mean 197 days after implant).31 Needless to say, there is not yet enough experience worldwide with either system to know what the end-of-service will look like in 10 to 15 years. One strategy could involve first attempting percutaneous retrieval and replacement, if retrieval is not possible, abandoning the old device while implanting a new device alongside. Another strategy would be to forgo a retrieval attempt altogether. In the LEADLESS II study,24 the mean patient age was 75. In this cohort, forgoing elective retrieval for those who live to reach the end of pacemaker service between the age of 85 and 90 would seem reasonable assuming the next device provides similar longevity. For younger patients, careful consideration of long-term strategies is needed. It is not known what the replacement technology will look like in another decade with respect to device size or battery longevity. Preclinical studies using swine and human cadaver hearts have demonstrated the feasibility of multiple right-ventricular Micra implants without affecting cardiac function.32,33

OTHER LIMITATIONS AND CAUTIONARY NOTES

At present, leadless pacing is approved for single-chamber right-ventricular pacing. In the developed world, single right-ventricular pacing modes account for only 20% to 30% of new pacemaker implants, which total more than 1 million per year worldwide.34,35 As with any new technology, the up-front cost of leadless pacemaker implant is expected to be significantly higher than transvenous systems, which at this point remains poorly defined, as the field has not caught up in terms of charges, reimbursement, and billing codes. While those concerns fall outside the scope of this review, it is not known if the expected reductions in mid- and long-term complications will make up for an up-front cost difference. However, a cost-efficacy study reported that one complication of a transvenous pacemaker system was more expensive than the initial implant itself.36 The longest-term follow-up data currently available are with Nanostim, showing an absolute complication reduction of 11.7% at 2 years,24 a disparity only expected to widen with prolonged follow-up, particularly after transvenous generator exchange, when complication rates rapidly escalate.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The next horizon of leadless technology will be for right-atrial and dual-chamber pacing to treat the far more pervasive pacing indication of sinus node dysfunction with or without AV block. In the latter application, the two devices will communicate. Prototypes and early nonhuman evaluations are ongoing for both. Leadless pacing is also being investigated for use in tachycardia. Tjong et al37 reported on the safety and feasibility of an entirely leadless pacemaker plus an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) system in two sheep and one human using both Nanostim and subcutaneous ICD. Currently, two important limitations of subcutaneous ICD are its inability to provide backup bradycardia and antitachycardia pacing (it provides only defibrillation). The EMBLEM PACE study will enroll 250 patients to receive a leadless pacemaker and Emblem subcutaneous ICD (Boston Scientific, Boston, MA), with patients subsequently receiving commanded antitachycardia pacing for ventricular arrhythmias and bradycardia pacing provided by the leadless device as indicated.

CONCLUSIONS

Leadless cardiac pacing is a safe and efficacious alternative to standard transvenous pacing systems. Although long-term data are limited, available short- and mid-term data show that the elimination of transvenous leads and the surgical pocket results in significant reductions in complication rates. Currently, leadless pacing is approved only for right-ventricular pacing, but investigation of right-atrial, dual-chamber, and fully leadless pacemaker-defibrillator hybrid systems is ongoing.

- Lagergren H. How it happened: my recollection of early pacing. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1978; 1:140–143.

- Parsonnet V. Permanent transvenous pacing in 1962. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1978; 1:265–268.

- Kirkfeldt RE, Johansen JB, Nohr EA, Jorgensen OD, Nielsen JC. Complications after cardiac implantable electronic device implantations: an analysis of a complete, nationwide cohort in Denmark. Eur Heart J 2014; 35:1186–1194.

- Udo EO, Zuithoff NP, van Hemel NM, et al. Incidence and predictors of short- and long-term complications in pacemaker therapy: the FOLLOWPACE study. Heart Rhythm 2012; 9:728–735.

- Palmisano P, Accogli M, Zaccaria M, et al. Rate, causes, and impact on patient outcome of implantable device complications requiring surgical revision: large population survey from two centres in Italy. Europace 2013; 15:531–540.

- De Sensi F, Miracapillo G, Cresti A, Severi S, Airaksinen KE. Pocket hematoma: a call for definition. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol Aug 2015; 38:909–913.

- Wiegand UK, LeJeune D, Boguschewski F, et al. Pocket hematoma after pacemaker or implantable cardioverter defibrillator surgery: influence of patient morbidity, operation strategy, and perioperative antiplatelet/anticoagulation therapy. Chest 2004; 126:1177–1186.

- Essebag V, Verma A, Healey JS, et al. Clinically significant pocket hematoma increases long-term risk of device infection: Bruise Control Infection Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016; 67:1300–1308.

- Ohlow MA, Lauer B, Brunelli M, Geller JC. Incidence and predictors of pericardial effusion after permanent heart rhythm device implantation: prospective evaluation of 968 consecutive patients. Circ J 2013; 77:975–981.

- Hauser RG, Hayes DL, Kallinen LM, et al. Clinical experience with pacemaker pulse generators and transvenous leads: an 8-year prospective multicenter study. Heart Rhythm 2007; 4:154–160.

- Korkeila P, Nyman K, Ylitalo A, et al. Venous obstruction after pacemaker implantation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2007; 30:199–206.

- Haghjoo M, Nikoo MH, Fazelifar AF, Alizadeh A, Emkanjoo Z, Sadr-Ameli MA. Predictors of venous obstruction following pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation: a contrast venographic study on 100 patients admitted for generator change, lead revision, or device upgrade. Europace 2007; 9:328–332.

- Al-Mohaissen MA, Chan KL. Prevalence and mechanism of tricuspid regurgitation following implantation of endocardial leads for pacemaker or cardioverter-defibrillator. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2012; 25:245–252.

- Al-Bawardy R, Krishnaswamy A, Rajeswaran J, et al. Tricuspid regurgitation and implantable devices. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2015; 38:259–266.

- Klug D, Balde M, Pavin D, et al. Risk factors related to infections of implanted pacemakers and cardioverter-defibrillators: results of a large prospective study. Circulation 2007; 116:1349–1355.

- Johansen JB, Jorgensen OD, Moller M, Arnsbo P, Mortensen PT, Nielsen JC. Infection after pacemaker implantation: infection rates and risk factors associated with infection in a population-based cohort study of 46,299 consecutive patients. Eur Heart J 2011; 32:991–998.

- Lown B, Kosowsky BD. Artificial cardiac pacemakers. I. N Engl J Med 1970; 283:907–916.

- Spickler JW, Rasor NS, Kezdi P, Misra SN, Robins KE, LeBoeuf C. Totally self-contained intracardiac pacemaker. J Electrocardiol 1970; 3:325–331.

- Sutton R. The first European journal on cardiac electrophysiology and pacing, the European Journal of Cardiac Pacing and Electrophysiology. Europace 2011; 13:1663–1664.

- Vardas PE, Politopoulous C, Manios E, Parthenakis F, Tsagarkis C. A miniature pacemaker introduced intravenously and implanted endocardially. Preliminary findings from an experimental study. Eur J Card Pacing Electrophysiol 1991; 1:27–30.

- Eggen MD, Grubac V, Bonner MD. Design and evaluation of a novel fixation mechanism for a transcatheter pacemaker. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2015; 62:2316–2323.

- Reddy VY, Knops RE, Sperzel J, et al. Permanent leadless cardiac pacing: results of the LEADLESS trial. Circulation 2014; 129:1466–1471.

- Ritter P, Duray GZ, Steinwender C, et al. Early performance of a miniaturized leadless cardiac pacemaker: the Micra Transcatheter Pacing Study. Eur Heart J 2015; 36:2510–2519.

- Reddy VY, Exner DV, Cantillon DJ, et al. Percutaneous implantation of an entirely intracardiac leadless pacemaker. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:1125–1135.

- Knops RE, Tjong FV, Neuzil P, et al. Chronic performance of a leadless cardiac pacemaker: 1-year follow-up of the LEADLESS trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 65:1497–1504.

- Reddy VY, Cantillon DJ, Ip J, et al. A comparative study of acute and mid-term complications of leadless versus transvenous pacemakers. Heart Rhythm 2016 July. [Epub ahead of print].

- Reynolds D, Duray GZ, Omar R, et al. A leadless intracardiac transcatheter pacing system. N Engl J Med 2016; 374:533–541.

- Garikipati NV, Karve A, Okabe T, et al. Tricuspid regurgitation after leadless pacemaker implantation. Abstract presented at Heart Rhythm Society Scientific Sessions, May 4–7, 2016, San Francisco, CA.

- Tjong FV, Stam OC, van der Wal AC, et al. Postmortem histopathological examination of a leadless pacemaker shows partial encapsulation after 19 months. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2015; 8:1293–1295.

- Borgquist R, Ljungstrom E, Koul B, Hoijer CJ. Leadless Medtronic Micra pacemaker almost completely endothelialized already after 4 months: first clinical experience from an explanted heart. Eur Heart J 2016; 37:2503.

- Reddy VY, Knops RE, Defaye P, et al. Worldwide clinical experience of the retrieval of leadless cardiac pacemakers. Abstract presented at Heart Rhythm Society Scientific Sessions, May 4–7, 2016, San Francisco, CA.

- Chen K, Zheng X, Dai Y, et al. Multiple leadless pacemakers implanted in the right ventricle of swine. Europace 2016 January 31. pii: euv418. [Epub ahead of print].

- Omdahl P, Eggen MD, Bonner MD, Iaizzo PA, Wika K. Right ventricular anatomy can accommodate multiple micra transcatheter pacemakers. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2016; 39:393–397.

- Mond HG, Proclemer A. The 11th world survey of cardiac pacing and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: calendar year 2009—a World Society of Arrhythmia’s project. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2011; 34:1013–1027.

- Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Heart Rhythm Society. 2012 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update incorporated into the ACCF/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2013; 127:e283–352.

- Tobin K, Stewart J, Westveer D, Frumin H. Acute complications of permanent pacemaker implantation: their financial implication and relation to volume and operator experience. Am J Cardiol 2000; 85:774–776, A9.

- Tjong FV, Brouwer TF, Smeding L, et al. Combined leadless pacemaker and subcutaneous implantable defibrillator therapy: feasibility, safety, and performance. Europace 2016 March 3. [Epub ahead of print].

WHY LEADLESS PACING?

The first clinical implantation of a cardiac pacemaker was performed surgically in 1958 by Drs. Elmvist and Senning via thoracotomy and direct attachment of electrodes to the myocardium. Transvenous pacing was introduced in 1962 by Drs. Lagergren, Parsonnet, and Welti.1,2 The general configuration of transvenous leads connected to a pulse generator situated in a surgical pocket has remained the standard of care ever since. Despite almost 60 years of technological innovation, contemporary permanent transvenous pacing continues to carry significant short- and long-term morbidity. Long-term composite complication rates are estimated at over 10%,3 further stratified as 12% in the 2 months post-implant (short-term) and 9% thereafter (long-term).4 Transvenous pacing complications are associated with an increase in both hospitalization days (hazard ratio 2.3) and unique hospitalizations (hazard ratio 4.4).5

Short-term complications

Short-term complications include lead dislodgment, pocket hematoma, pericardial effusion, and pneumothorax (Figure 1). Pocket hematomas are common with concurrent antiplatelet or anticoagulant administration, with incidence estimates varying from 5% to 33% depending on the definition.6 Morbidity associated with pocket hematoma include prolonged hospitalization, need for re-operation,7 and an almost eightfold increase in the rate of device infection over the long term compared with patients without pocket hematoma.8 New pericardial effusions after implant may affect up to 10% of patients; they are generally small, including 90% attributable to pericarditis or contained microperforation not requiring intervention. Overt lead perforation resulting in cardiac tamponade occurs in about 1% of transvenous pacemaker implants, of which 10% (0.1% overall) require open chest surgery, with the remainder treated with percutaneous drainage.9

Long-term complications

Long-term complications are predominantly lead and pocket-related but also include venous occlusive disease and tricuspid valve pathology.4 The development of primary lead failure due to insulation defects, conductor fracture, or dislodgment has been associated with major adverse events in 16% of patients, and an additional 6% if transvenous lead extraction is needed, which can rarely lead to hemorrhagic death by vascular tears involving the heart or superior vena cava.10 Fibrous tissue growth around the indwelling vascular leads can result in venous obstruction present in up to 14% of patients by 6 months after implant.11 This increases to 26% by the time of device replacement or upgrade, which is typically 5 to 10 years after the original implant, including 17% of patients with a complete venous occlusion.12 In addition, worsened tricuspid regurgitation due to lead impingement on the valve is seen in 7% to 40% of patients depending on definitions,13 with post-implant severe tricuspid regurgitation independently associated with increased mortality risk.14 The rate of device infection is 1% to 2% at 1 year,8,15 and 3% over the lifetime of the initial transvenous system; this increases to more than 10% after generator replacement.16

LEADLESS PACING TECHNOLOGY

The principal goal of leadless pacing is to reduce short- and long-term pacemaker complications by eliminating the two most common sources of problems: the transvenous leads and the surgical pocket. Discussion of leadless pacing strategies began as early as 1970.17 Although several preclinical studies demonstrated efficacy with leadless prototypes,18–20 clinical implementation of fully leadless technology did not occur until recently. As shown in Figure 2, there are now two commercially available leadless pacing devices: Nanostim (St. Jude Medical Inc., St. Paul, MN) and Micra (Medtronic Inc., Dublin, Ireland). At the time of this writing, both have commercial approval in Europe. In the United States, Micra received commercial approval from the US Food and Drug Administration on April 6, 2016, with a similar decision expected on Nanostim. The current approved indications for leadless pacing are chronic atrial tachyarrhythmia with advanced atrioventricular (AV) block; advanced AV block with low level of physical activity or short expected lifespan; and infrequent pauses or unexplained syncope with abnormal findings at electrophysiologic study. Although differences exist between Nanostim and Micra, as shown in Table 1,21–27 there are fundamental similarities. Both are single-unit designs encapsulating the electrodes and pulse generator with rate-adaptive functionality. Both are delivered via an endovascular femoral venous approach without the need for incisional access, transvenous leads, or surgical pocket (Figures 3 and 4).21–27

Nanostim: Landmark trials

As the world’s first-in-man leadless pacemaker, Nanostim was evaluated in two prospective, non-randomized, multicenter, single-arm trials abbreviated LEADLESS22 and LEADLESS II.24 The first human feasibility study, LEADLESS, enrolled 33 patients with approved indications for ventricular-only pacing while excluding patients with expected pacemaker dependency. The most common indication was bradycardia in the presence of persistent atrial arrhythmias, thereby obviating the need for atrial pacing. The primary outcome was freedom from serious complications at 90 days. The secondary outcomes were implant success rate and device performance at 3 months. The results demonstrated 94% composite safety (31 of 33 patients) at 3 months. There was one cardiac perforation leading to tamponade and eventually death after prolonged hospitalization, and one inadvertent deployment into the left ventricle via patent foramen ovale that was successfully retrieved and redeployed without complication. The implant success rate was 97%, and the electrical parameters involving sensing, pacing thresholds, and impedance were as expected at 3 months. Results of 1-year follow-up were published for the LEADLESS cohort,25 revealing no additional complications from 3 to 12 months, no adverse changes in electrical performance parameters, and 100% effectiveness of rate-responsive programming.

The subsequent LEADLESS II trial enrolled 526 patients but did not exclude patients with expected pacemaker dependency, and its results were reported in a preplanned interim analysis when 300 patients had reached 6 months of follow-up (mean follow-up 6.9 ± 4.2 months).24 The primary efficacy end point involved electrical performance including capture thresholds and sensing. Initial deployment success was 96% with expected electrical parameters at implant that were stable at 6 months of follow-up. The rate of freedom from serious adverse events was 93%, with complications including device dislodgment (1.7%, mean 8 ± 6 days after implant), perforation (1.3%), performance deficiency requiring device retrieval and replacement (1.3%), and groin complications (1.3%). There were no device-related deaths, and all device dislodgments were successfully treated percutaneously.

There was no prospective control arm involving transvenous pacing in either the LEADLESS or LEADLESS II trial. Thus, in an effort to compare Nanostim (n = 718) vs transvenous pacing, complication rates were calculated for a propensity-matched registry cohort of 10,521 transvenous patients, and differences were reported.26 At 1 month, the composite complication rate was 5.8% for Nanostim (1.5% pericardial effusion, 1% dislodgment) and 12.7% for transvenous pacing (7.6% lead-related, 3.9% thoracic trauma, infection 1.9%) (P < .001). Between 1 month and 2 years, complication rates were only 0.6% for Nanostim vs 5.4% for transvenous pacing (P < .001). This lower complication rate at 2 years was driven almost entirely by a 2.6% infection rate and 2.4% lead-complication rate in the transvenous pacemaker group, nonexistent in the leadless group.

Micra: Landmark trials

Micra was evaluated in a prospective, nonrandomized, multicenter, single-arm trial, enrolling 725 patients with indications for ventricular-only pacing; approximately two-thirds of the cohort had bradycardia in the presence of persistent atrial arrhythmias, similar to the Nanostim cohort.27 The efficacy end point was stable capture threshold at 6 months. The safety end point was freedom from major complications resulting in new or prolonged hospitalization at 6 months. The implant success rate was 99%, and 98% of patients met the primary efficacy end point. The safety end point was met in 96% of patients. Complications included perforation or pericardial effusion (1.6%), groin complication (0.7%), elevated threshold (0.3%), venous thromboembolism (0.3%), and others (1.7%). No dislodgments were reported. There was no prospective, randomized control arm to compare Micra and transvenous pacing. A post hoc analysis was performed comparing major complication rates in this study with an unmatched 2,667-patient meta-analysis control cohort.27 The hazard ratio for the leadless pacing strategy was calculated at 0.49 (95% confidence interval 0.33 to 0.75, P = .001) with absolute risk reduction 3.4% at 6 months resulting in a number needed to treat of 29.4 patients. Further broken down, Micra patients compared with the control cohort had reduced rates of both subsequent hospitalizations (3.9% to 2.3%) and device revisions (3.5% to 0.4%).

ADVANTAGES OF LEADLESS PACING

As discussed above, the major observed benefit with both Nanostim and Micra compared with transvenous cohorts is the elimination of lead and pocket-related complications.25,27 Leadless pacing introduces a new 1% to 2% groin complication rate for both devices not present with transvenous pacing, and also a 1% device dislodgment rate in the case of Nanostim (all dislodgments were treated percutaneously). Data from both clinical trials suggest that the complication rates are largely compressed acutely. In contrast, there are considerable mid-term and long-term complications for transvenous systems.3–5 Indeed, the mid- to long-term window is where leadless pacing is expected to have the most favorable impact. As with any new disruptive technology, operator experience may be important, as evidenced by a near halving of the complication rate observed in the LEADLESS II trial after gaining the experience of 10 implants.25

Other benefits of leadless pacing include a generally quick procedure (average implant time was 30 minutes in LEADLESS and LEADLESS II)22,25 and full shoulder mobility afterwards, so that patients can resume driving once groin soreness has subsided, typically within a few days. (Current studies are investigating whether immediate shoulder mobility with leadless pacing is beneficial to older patients suffering from arthritis.) The lack of an incision allows patients to bathe and shower as soon as they desire, whereas after transvenous pacemaker implant, motion in the affected shoulder is usually restricted for several weeks to avoid lead dislodgment, and showering and bathing are restricted to avoid contamination of the incision with nonsterile tap water. (In some cases, a tightly adherent waterproof dressing can be used.) The leadless systems were designed for compatibility with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), whereas not all transvenous pacemaker generators and leads are MRI compatible.

Leadless devices are not expected to span the tricuspid valve to create incident or worsening tricuspid regurgitation. In a recent small study of 22 patients undergoing Micra implant, there were no new cases of severe tricuspid regurgitation after the procedure, with only a 9% increase in mild and 5% increase in moderate tricuspid regurgitation,28 vs a rate of 40% of worsening tricuspid regurgitation and 10% of new severe tricuspid regurgitation with transvenous pacing.13,14

Transvenous pacemaker implant requires surgery for pulse generator exchange at a mean of 7 years, a procedure carrying significant risk of short- and long-term complications.10

END-OF-SERVICE QUESTIONS: ATTEMPT RETRIEVAL OR NOT?

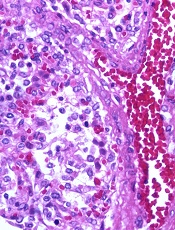

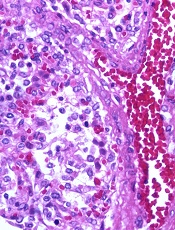

Both leadless systems have favorable projected in-service battery life: a reported 15.0 years for Nanostim25 and mean 12.5 years for Micra.27 The inevitable question is what to do then. The Nanostim system was designed to be retrievable using a dedicated catheter system. Micra was not designed with an accompanying retrieval system. Pathologic examinations of leadless devices at autopsy or after explant have revealed a range of device endothelialization, from partial at 19 months to full at 4 months.29,30

As of this writing, no extraction complications have been observed with Nanostim explants up to 506 days after implant (n = 12, mean 197 days after implant).31 Needless to say, there is not yet enough experience worldwide with either system to know what the end-of-service will look like in 10 to 15 years. One strategy could involve first attempting percutaneous retrieval and replacement, if retrieval is not possible, abandoning the old device while implanting a new device alongside. Another strategy would be to forgo a retrieval attempt altogether. In the LEADLESS II study,24 the mean patient age was 75. In this cohort, forgoing elective retrieval for those who live to reach the end of pacemaker service between the age of 85 and 90 would seem reasonable assuming the next device provides similar longevity. For younger patients, careful consideration of long-term strategies is needed. It is not known what the replacement technology will look like in another decade with respect to device size or battery longevity. Preclinical studies using swine and human cadaver hearts have demonstrated the feasibility of multiple right-ventricular Micra implants without affecting cardiac function.32,33

OTHER LIMITATIONS AND CAUTIONARY NOTES

At present, leadless pacing is approved for single-chamber right-ventricular pacing. In the developed world, single right-ventricular pacing modes account for only 20% to 30% of new pacemaker implants, which total more than 1 million per year worldwide.34,35 As with any new technology, the up-front cost of leadless pacemaker implant is expected to be significantly higher than transvenous systems, which at this point remains poorly defined, as the field has not caught up in terms of charges, reimbursement, and billing codes. While those concerns fall outside the scope of this review, it is not known if the expected reductions in mid- and long-term complications will make up for an up-front cost difference. However, a cost-efficacy study reported that one complication of a transvenous pacemaker system was more expensive than the initial implant itself.36 The longest-term follow-up data currently available are with Nanostim, showing an absolute complication reduction of 11.7% at 2 years,24 a disparity only expected to widen with prolonged follow-up, particularly after transvenous generator exchange, when complication rates rapidly escalate.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The next horizon of leadless technology will be for right-atrial and dual-chamber pacing to treat the far more pervasive pacing indication of sinus node dysfunction with or without AV block. In the latter application, the two devices will communicate. Prototypes and early nonhuman evaluations are ongoing for both. Leadless pacing is also being investigated for use in tachycardia. Tjong et al37 reported on the safety and feasibility of an entirely leadless pacemaker plus an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) system in two sheep and one human using both Nanostim and subcutaneous ICD. Currently, two important limitations of subcutaneous ICD are its inability to provide backup bradycardia and antitachycardia pacing (it provides only defibrillation). The EMBLEM PACE study will enroll 250 patients to receive a leadless pacemaker and Emblem subcutaneous ICD (Boston Scientific, Boston, MA), with patients subsequently receiving commanded antitachycardia pacing for ventricular arrhythmias and bradycardia pacing provided by the leadless device as indicated.

CONCLUSIONS

Leadless cardiac pacing is a safe and efficacious alternative to standard transvenous pacing systems. Although long-term data are limited, available short- and mid-term data show that the elimination of transvenous leads and the surgical pocket results in significant reductions in complication rates. Currently, leadless pacing is approved only for right-ventricular pacing, but investigation of right-atrial, dual-chamber, and fully leadless pacemaker-defibrillator hybrid systems is ongoing.

WHY LEADLESS PACING?

The first clinical implantation of a cardiac pacemaker was performed surgically in 1958 by Drs. Elmvist and Senning via thoracotomy and direct attachment of electrodes to the myocardium. Transvenous pacing was introduced in 1962 by Drs. Lagergren, Parsonnet, and Welti.1,2 The general configuration of transvenous leads connected to a pulse generator situated in a surgical pocket has remained the standard of care ever since. Despite almost 60 years of technological innovation, contemporary permanent transvenous pacing continues to carry significant short- and long-term morbidity. Long-term composite complication rates are estimated at over 10%,3 further stratified as 12% in the 2 months post-implant (short-term) and 9% thereafter (long-term).4 Transvenous pacing complications are associated with an increase in both hospitalization days (hazard ratio 2.3) and unique hospitalizations (hazard ratio 4.4).5

Short-term complications

Short-term complications include lead dislodgment, pocket hematoma, pericardial effusion, and pneumothorax (Figure 1). Pocket hematomas are common with concurrent antiplatelet or anticoagulant administration, with incidence estimates varying from 5% to 33% depending on the definition.6 Morbidity associated with pocket hematoma include prolonged hospitalization, need for re-operation,7 and an almost eightfold increase in the rate of device infection over the long term compared with patients without pocket hematoma.8 New pericardial effusions after implant may affect up to 10% of patients; they are generally small, including 90% attributable to pericarditis or contained microperforation not requiring intervention. Overt lead perforation resulting in cardiac tamponade occurs in about 1% of transvenous pacemaker implants, of which 10% (0.1% overall) require open chest surgery, with the remainder treated with percutaneous drainage.9

Long-term complications

Long-term complications are predominantly lead and pocket-related but also include venous occlusive disease and tricuspid valve pathology.4 The development of primary lead failure due to insulation defects, conductor fracture, or dislodgment has been associated with major adverse events in 16% of patients, and an additional 6% if transvenous lead extraction is needed, which can rarely lead to hemorrhagic death by vascular tears involving the heart or superior vena cava.10 Fibrous tissue growth around the indwelling vascular leads can result in venous obstruction present in up to 14% of patients by 6 months after implant.11 This increases to 26% by the time of device replacement or upgrade, which is typically 5 to 10 years after the original implant, including 17% of patients with a complete venous occlusion.12 In addition, worsened tricuspid regurgitation due to lead impingement on the valve is seen in 7% to 40% of patients depending on definitions,13 with post-implant severe tricuspid regurgitation independently associated with increased mortality risk.14 The rate of device infection is 1% to 2% at 1 year,8,15 and 3% over the lifetime of the initial transvenous system; this increases to more than 10% after generator replacement.16

LEADLESS PACING TECHNOLOGY

The principal goal of leadless pacing is to reduce short- and long-term pacemaker complications by eliminating the two most common sources of problems: the transvenous leads and the surgical pocket. Discussion of leadless pacing strategies began as early as 1970.17 Although several preclinical studies demonstrated efficacy with leadless prototypes,18–20 clinical implementation of fully leadless technology did not occur until recently. As shown in Figure 2, there are now two commercially available leadless pacing devices: Nanostim (St. Jude Medical Inc., St. Paul, MN) and Micra (Medtronic Inc., Dublin, Ireland). At the time of this writing, both have commercial approval in Europe. In the United States, Micra received commercial approval from the US Food and Drug Administration on April 6, 2016, with a similar decision expected on Nanostim. The current approved indications for leadless pacing are chronic atrial tachyarrhythmia with advanced atrioventricular (AV) block; advanced AV block with low level of physical activity or short expected lifespan; and infrequent pauses or unexplained syncope with abnormal findings at electrophysiologic study. Although differences exist between Nanostim and Micra, as shown in Table 1,21–27 there are fundamental similarities. Both are single-unit designs encapsulating the electrodes and pulse generator with rate-adaptive functionality. Both are delivered via an endovascular femoral venous approach without the need for incisional access, transvenous leads, or surgical pocket (Figures 3 and 4).21–27

Nanostim: Landmark trials

As the world’s first-in-man leadless pacemaker, Nanostim was evaluated in two prospective, non-randomized, multicenter, single-arm trials abbreviated LEADLESS22 and LEADLESS II.24 The first human feasibility study, LEADLESS, enrolled 33 patients with approved indications for ventricular-only pacing while excluding patients with expected pacemaker dependency. The most common indication was bradycardia in the presence of persistent atrial arrhythmias, thereby obviating the need for atrial pacing. The primary outcome was freedom from serious complications at 90 days. The secondary outcomes were implant success rate and device performance at 3 months. The results demonstrated 94% composite safety (31 of 33 patients) at 3 months. There was one cardiac perforation leading to tamponade and eventually death after prolonged hospitalization, and one inadvertent deployment into the left ventricle via patent foramen ovale that was successfully retrieved and redeployed without complication. The implant success rate was 97%, and the electrical parameters involving sensing, pacing thresholds, and impedance were as expected at 3 months. Results of 1-year follow-up were published for the LEADLESS cohort,25 revealing no additional complications from 3 to 12 months, no adverse changes in electrical performance parameters, and 100% effectiveness of rate-responsive programming.

The subsequent LEADLESS II trial enrolled 526 patients but did not exclude patients with expected pacemaker dependency, and its results were reported in a preplanned interim analysis when 300 patients had reached 6 months of follow-up (mean follow-up 6.9 ± 4.2 months).24 The primary efficacy end point involved electrical performance including capture thresholds and sensing. Initial deployment success was 96% with expected electrical parameters at implant that were stable at 6 months of follow-up. The rate of freedom from serious adverse events was 93%, with complications including device dislodgment (1.7%, mean 8 ± 6 days after implant), perforation (1.3%), performance deficiency requiring device retrieval and replacement (1.3%), and groin complications (1.3%). There were no device-related deaths, and all device dislodgments were successfully treated percutaneously.

There was no prospective control arm involving transvenous pacing in either the LEADLESS or LEADLESS II trial. Thus, in an effort to compare Nanostim (n = 718) vs transvenous pacing, complication rates were calculated for a propensity-matched registry cohort of 10,521 transvenous patients, and differences were reported.26 At 1 month, the composite complication rate was 5.8% for Nanostim (1.5% pericardial effusion, 1% dislodgment) and 12.7% for transvenous pacing (7.6% lead-related, 3.9% thoracic trauma, infection 1.9%) (P < .001). Between 1 month and 2 years, complication rates were only 0.6% for Nanostim vs 5.4% for transvenous pacing (P < .001). This lower complication rate at 2 years was driven almost entirely by a 2.6% infection rate and 2.4% lead-complication rate in the transvenous pacemaker group, nonexistent in the leadless group.

Micra: Landmark trials

Micra was evaluated in a prospective, nonrandomized, multicenter, single-arm trial, enrolling 725 patients with indications for ventricular-only pacing; approximately two-thirds of the cohort had bradycardia in the presence of persistent atrial arrhythmias, similar to the Nanostim cohort.27 The efficacy end point was stable capture threshold at 6 months. The safety end point was freedom from major complications resulting in new or prolonged hospitalization at 6 months. The implant success rate was 99%, and 98% of patients met the primary efficacy end point. The safety end point was met in 96% of patients. Complications included perforation or pericardial effusion (1.6%), groin complication (0.7%), elevated threshold (0.3%), venous thromboembolism (0.3%), and others (1.7%). No dislodgments were reported. There was no prospective, randomized control arm to compare Micra and transvenous pacing. A post hoc analysis was performed comparing major complication rates in this study with an unmatched 2,667-patient meta-analysis control cohort.27 The hazard ratio for the leadless pacing strategy was calculated at 0.49 (95% confidence interval 0.33 to 0.75, P = .001) with absolute risk reduction 3.4% at 6 months resulting in a number needed to treat of 29.4 patients. Further broken down, Micra patients compared with the control cohort had reduced rates of both subsequent hospitalizations (3.9% to 2.3%) and device revisions (3.5% to 0.4%).

ADVANTAGES OF LEADLESS PACING

As discussed above, the major observed benefit with both Nanostim and Micra compared with transvenous cohorts is the elimination of lead and pocket-related complications.25,27 Leadless pacing introduces a new 1% to 2% groin complication rate for both devices not present with transvenous pacing, and also a 1% device dislodgment rate in the case of Nanostim (all dislodgments were treated percutaneously). Data from both clinical trials suggest that the complication rates are largely compressed acutely. In contrast, there are considerable mid-term and long-term complications for transvenous systems.3–5 Indeed, the mid- to long-term window is where leadless pacing is expected to have the most favorable impact. As with any new disruptive technology, operator experience may be important, as evidenced by a near halving of the complication rate observed in the LEADLESS II trial after gaining the experience of 10 implants.25

Other benefits of leadless pacing include a generally quick procedure (average implant time was 30 minutes in LEADLESS and LEADLESS II)22,25 and full shoulder mobility afterwards, so that patients can resume driving once groin soreness has subsided, typically within a few days. (Current studies are investigating whether immediate shoulder mobility with leadless pacing is beneficial to older patients suffering from arthritis.) The lack of an incision allows patients to bathe and shower as soon as they desire, whereas after transvenous pacemaker implant, motion in the affected shoulder is usually restricted for several weeks to avoid lead dislodgment, and showering and bathing are restricted to avoid contamination of the incision with nonsterile tap water. (In some cases, a tightly adherent waterproof dressing can be used.) The leadless systems were designed for compatibility with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), whereas not all transvenous pacemaker generators and leads are MRI compatible.

Leadless devices are not expected to span the tricuspid valve to create incident or worsening tricuspid regurgitation. In a recent small study of 22 patients undergoing Micra implant, there were no new cases of severe tricuspid regurgitation after the procedure, with only a 9% increase in mild and 5% increase in moderate tricuspid regurgitation,28 vs a rate of 40% of worsening tricuspid regurgitation and 10% of new severe tricuspid regurgitation with transvenous pacing.13,14

Transvenous pacemaker implant requires surgery for pulse generator exchange at a mean of 7 years, a procedure carrying significant risk of short- and long-term complications.10

END-OF-SERVICE QUESTIONS: ATTEMPT RETRIEVAL OR NOT?

Both leadless systems have favorable projected in-service battery life: a reported 15.0 years for Nanostim25 and mean 12.5 years for Micra.27 The inevitable question is what to do then. The Nanostim system was designed to be retrievable using a dedicated catheter system. Micra was not designed with an accompanying retrieval system. Pathologic examinations of leadless devices at autopsy or after explant have revealed a range of device endothelialization, from partial at 19 months to full at 4 months.29,30

As of this writing, no extraction complications have been observed with Nanostim explants up to 506 days after implant (n = 12, mean 197 days after implant).31 Needless to say, there is not yet enough experience worldwide with either system to know what the end-of-service will look like in 10 to 15 years. One strategy could involve first attempting percutaneous retrieval and replacement, if retrieval is not possible, abandoning the old device while implanting a new device alongside. Another strategy would be to forgo a retrieval attempt altogether. In the LEADLESS II study,24 the mean patient age was 75. In this cohort, forgoing elective retrieval for those who live to reach the end of pacemaker service between the age of 85 and 90 would seem reasonable assuming the next device provides similar longevity. For younger patients, careful consideration of long-term strategies is needed. It is not known what the replacement technology will look like in another decade with respect to device size or battery longevity. Preclinical studies using swine and human cadaver hearts have demonstrated the feasibility of multiple right-ventricular Micra implants without affecting cardiac function.32,33

OTHER LIMITATIONS AND CAUTIONARY NOTES

At present, leadless pacing is approved for single-chamber right-ventricular pacing. In the developed world, single right-ventricular pacing modes account for only 20% to 30% of new pacemaker implants, which total more than 1 million per year worldwide.34,35 As with any new technology, the up-front cost of leadless pacemaker implant is expected to be significantly higher than transvenous systems, which at this point remains poorly defined, as the field has not caught up in terms of charges, reimbursement, and billing codes. While those concerns fall outside the scope of this review, it is not known if the expected reductions in mid- and long-term complications will make up for an up-front cost difference. However, a cost-efficacy study reported that one complication of a transvenous pacemaker system was more expensive than the initial implant itself.36 The longest-term follow-up data currently available are with Nanostim, showing an absolute complication reduction of 11.7% at 2 years,24 a disparity only expected to widen with prolonged follow-up, particularly after transvenous generator exchange, when complication rates rapidly escalate.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The next horizon of leadless technology will be for right-atrial and dual-chamber pacing to treat the far more pervasive pacing indication of sinus node dysfunction with or without AV block. In the latter application, the two devices will communicate. Prototypes and early nonhuman evaluations are ongoing for both. Leadless pacing is also being investigated for use in tachycardia. Tjong et al37 reported on the safety and feasibility of an entirely leadless pacemaker plus an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) system in two sheep and one human using both Nanostim and subcutaneous ICD. Currently, two important limitations of subcutaneous ICD are its inability to provide backup bradycardia and antitachycardia pacing (it provides only defibrillation). The EMBLEM PACE study will enroll 250 patients to receive a leadless pacemaker and Emblem subcutaneous ICD (Boston Scientific, Boston, MA), with patients subsequently receiving commanded antitachycardia pacing for ventricular arrhythmias and bradycardia pacing provided by the leadless device as indicated.

CONCLUSIONS

Leadless cardiac pacing is a safe and efficacious alternative to standard transvenous pacing systems. Although long-term data are limited, available short- and mid-term data show that the elimination of transvenous leads and the surgical pocket results in significant reductions in complication rates. Currently, leadless pacing is approved only for right-ventricular pacing, but investigation of right-atrial, dual-chamber, and fully leadless pacemaker-defibrillator hybrid systems is ongoing.

- Lagergren H. How it happened: my recollection of early pacing. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1978; 1:140–143.

- Parsonnet V. Permanent transvenous pacing in 1962. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1978; 1:265–268.

- Kirkfeldt RE, Johansen JB, Nohr EA, Jorgensen OD, Nielsen JC. Complications after cardiac implantable electronic device implantations: an analysis of a complete, nationwide cohort in Denmark. Eur Heart J 2014; 35:1186–1194.

- Udo EO, Zuithoff NP, van Hemel NM, et al. Incidence and predictors of short- and long-term complications in pacemaker therapy: the FOLLOWPACE study. Heart Rhythm 2012; 9:728–735.

- Palmisano P, Accogli M, Zaccaria M, et al. Rate, causes, and impact on patient outcome of implantable device complications requiring surgical revision: large population survey from two centres in Italy. Europace 2013; 15:531–540.

- De Sensi F, Miracapillo G, Cresti A, Severi S, Airaksinen KE. Pocket hematoma: a call for definition. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol Aug 2015; 38:909–913.

- Wiegand UK, LeJeune D, Boguschewski F, et al. Pocket hematoma after pacemaker or implantable cardioverter defibrillator surgery: influence of patient morbidity, operation strategy, and perioperative antiplatelet/anticoagulation therapy. Chest 2004; 126:1177–1186.

- Essebag V, Verma A, Healey JS, et al. Clinically significant pocket hematoma increases long-term risk of device infection: Bruise Control Infection Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016; 67:1300–1308.

- Ohlow MA, Lauer B, Brunelli M, Geller JC. Incidence and predictors of pericardial effusion after permanent heart rhythm device implantation: prospective evaluation of 968 consecutive patients. Circ J 2013; 77:975–981.

- Hauser RG, Hayes DL, Kallinen LM, et al. Clinical experience with pacemaker pulse generators and transvenous leads: an 8-year prospective multicenter study. Heart Rhythm 2007; 4:154–160.

- Korkeila P, Nyman K, Ylitalo A, et al. Venous obstruction after pacemaker implantation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2007; 30:199–206.

- Haghjoo M, Nikoo MH, Fazelifar AF, Alizadeh A, Emkanjoo Z, Sadr-Ameli MA. Predictors of venous obstruction following pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation: a contrast venographic study on 100 patients admitted for generator change, lead revision, or device upgrade. Europace 2007; 9:328–332.

- Al-Mohaissen MA, Chan KL. Prevalence and mechanism of tricuspid regurgitation following implantation of endocardial leads for pacemaker or cardioverter-defibrillator. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2012; 25:245–252.

- Al-Bawardy R, Krishnaswamy A, Rajeswaran J, et al. Tricuspid regurgitation and implantable devices. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2015; 38:259–266.

- Klug D, Balde M, Pavin D, et al. Risk factors related to infections of implanted pacemakers and cardioverter-defibrillators: results of a large prospective study. Circulation 2007; 116:1349–1355.

- Johansen JB, Jorgensen OD, Moller M, Arnsbo P, Mortensen PT, Nielsen JC. Infection after pacemaker implantation: infection rates and risk factors associated with infection in a population-based cohort study of 46,299 consecutive patients. Eur Heart J 2011; 32:991–998.

- Lown B, Kosowsky BD. Artificial cardiac pacemakers. I. N Engl J Med 1970; 283:907–916.

- Spickler JW, Rasor NS, Kezdi P, Misra SN, Robins KE, LeBoeuf C. Totally self-contained intracardiac pacemaker. J Electrocardiol 1970; 3:325–331.

- Sutton R. The first European journal on cardiac electrophysiology and pacing, the European Journal of Cardiac Pacing and Electrophysiology. Europace 2011; 13:1663–1664.

- Vardas PE, Politopoulous C, Manios E, Parthenakis F, Tsagarkis C. A miniature pacemaker introduced intravenously and implanted endocardially. Preliminary findings from an experimental study. Eur J Card Pacing Electrophysiol 1991; 1:27–30.

- Eggen MD, Grubac V, Bonner MD. Design and evaluation of a novel fixation mechanism for a transcatheter pacemaker. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2015; 62:2316–2323.

- Reddy VY, Knops RE, Sperzel J, et al. Permanent leadless cardiac pacing: results of the LEADLESS trial. Circulation 2014; 129:1466–1471.

- Ritter P, Duray GZ, Steinwender C, et al. Early performance of a miniaturized leadless cardiac pacemaker: the Micra Transcatheter Pacing Study. Eur Heart J 2015; 36:2510–2519.

- Reddy VY, Exner DV, Cantillon DJ, et al. Percutaneous implantation of an entirely intracardiac leadless pacemaker. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:1125–1135.

- Knops RE, Tjong FV, Neuzil P, et al. Chronic performance of a leadless cardiac pacemaker: 1-year follow-up of the LEADLESS trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 65:1497–1504.

- Reddy VY, Cantillon DJ, Ip J, et al. A comparative study of acute and mid-term complications of leadless versus transvenous pacemakers. Heart Rhythm 2016 July. [Epub ahead of print].

- Reynolds D, Duray GZ, Omar R, et al. A leadless intracardiac transcatheter pacing system. N Engl J Med 2016; 374:533–541.

- Garikipati NV, Karve A, Okabe T, et al. Tricuspid regurgitation after leadless pacemaker implantation. Abstract presented at Heart Rhythm Society Scientific Sessions, May 4–7, 2016, San Francisco, CA.

- Tjong FV, Stam OC, van der Wal AC, et al. Postmortem histopathological examination of a leadless pacemaker shows partial encapsulation after 19 months. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2015; 8:1293–1295.

- Borgquist R, Ljungstrom E, Koul B, Hoijer CJ. Leadless Medtronic Micra pacemaker almost completely endothelialized already after 4 months: first clinical experience from an explanted heart. Eur Heart J 2016; 37:2503.

- Reddy VY, Knops RE, Defaye P, et al. Worldwide clinical experience of the retrieval of leadless cardiac pacemakers. Abstract presented at Heart Rhythm Society Scientific Sessions, May 4–7, 2016, San Francisco, CA.

- Chen K, Zheng X, Dai Y, et al. Multiple leadless pacemakers implanted in the right ventricle of swine. Europace 2016 January 31. pii: euv418. [Epub ahead of print].

- Omdahl P, Eggen MD, Bonner MD, Iaizzo PA, Wika K. Right ventricular anatomy can accommodate multiple micra transcatheter pacemakers. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2016; 39:393–397.

- Mond HG, Proclemer A. The 11th world survey of cardiac pacing and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: calendar year 2009—a World Society of Arrhythmia’s project. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2011; 34:1013–1027.

- Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Heart Rhythm Society. 2012 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update incorporated into the ACCF/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2013; 127:e283–352.

- Tobin K, Stewart J, Westveer D, Frumin H. Acute complications of permanent pacemaker implantation: their financial implication and relation to volume and operator experience. Am J Cardiol 2000; 85:774–776, A9.

- Tjong FV, Brouwer TF, Smeding L, et al. Combined leadless pacemaker and subcutaneous implantable defibrillator therapy: feasibility, safety, and performance. Europace 2016 March 3. [Epub ahead of print].

- Lagergren H. How it happened: my recollection of early pacing. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1978; 1:140–143.

- Parsonnet V. Permanent transvenous pacing in 1962. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1978; 1:265–268.

- Kirkfeldt RE, Johansen JB, Nohr EA, Jorgensen OD, Nielsen JC. Complications after cardiac implantable electronic device implantations: an analysis of a complete, nationwide cohort in Denmark. Eur Heart J 2014; 35:1186–1194.

- Udo EO, Zuithoff NP, van Hemel NM, et al. Incidence and predictors of short- and long-term complications in pacemaker therapy: the FOLLOWPACE study. Heart Rhythm 2012; 9:728–735.

- Palmisano P, Accogli M, Zaccaria M, et al. Rate, causes, and impact on patient outcome of implantable device complications requiring surgical revision: large population survey from two centres in Italy. Europace 2013; 15:531–540.

- De Sensi F, Miracapillo G, Cresti A, Severi S, Airaksinen KE. Pocket hematoma: a call for definition. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol Aug 2015; 38:909–913.

- Wiegand UK, LeJeune D, Boguschewski F, et al. Pocket hematoma after pacemaker or implantable cardioverter defibrillator surgery: influence of patient morbidity, operation strategy, and perioperative antiplatelet/anticoagulation therapy. Chest 2004; 126:1177–1186.

- Essebag V, Verma A, Healey JS, et al. Clinically significant pocket hematoma increases long-term risk of device infection: Bruise Control Infection Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016; 67:1300–1308.

- Ohlow MA, Lauer B, Brunelli M, Geller JC. Incidence and predictors of pericardial effusion after permanent heart rhythm device implantation: prospective evaluation of 968 consecutive patients. Circ J 2013; 77:975–981.

- Hauser RG, Hayes DL, Kallinen LM, et al. Clinical experience with pacemaker pulse generators and transvenous leads: an 8-year prospective multicenter study. Heart Rhythm 2007; 4:154–160.

- Korkeila P, Nyman K, Ylitalo A, et al. Venous obstruction after pacemaker implantation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2007; 30:199–206.

- Haghjoo M, Nikoo MH, Fazelifar AF, Alizadeh A, Emkanjoo Z, Sadr-Ameli MA. Predictors of venous obstruction following pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation: a contrast venographic study on 100 patients admitted for generator change, lead revision, or device upgrade. Europace 2007; 9:328–332.

- Al-Mohaissen MA, Chan KL. Prevalence and mechanism of tricuspid regurgitation following implantation of endocardial leads for pacemaker or cardioverter-defibrillator. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2012; 25:245–252.

- Al-Bawardy R, Krishnaswamy A, Rajeswaran J, et al. Tricuspid regurgitation and implantable devices. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2015; 38:259–266.

- Klug D, Balde M, Pavin D, et al. Risk factors related to infections of implanted pacemakers and cardioverter-defibrillators: results of a large prospective study. Circulation 2007; 116:1349–1355.

- Johansen JB, Jorgensen OD, Moller M, Arnsbo P, Mortensen PT, Nielsen JC. Infection after pacemaker implantation: infection rates and risk factors associated with infection in a population-based cohort study of 46,299 consecutive patients. Eur Heart J 2011; 32:991–998.

- Lown B, Kosowsky BD. Artificial cardiac pacemakers. I. N Engl J Med 1970; 283:907–916.

- Spickler JW, Rasor NS, Kezdi P, Misra SN, Robins KE, LeBoeuf C. Totally self-contained intracardiac pacemaker. J Electrocardiol 1970; 3:325–331.

- Sutton R. The first European journal on cardiac electrophysiology and pacing, the European Journal of Cardiac Pacing and Electrophysiology. Europace 2011; 13:1663–1664.

- Vardas PE, Politopoulous C, Manios E, Parthenakis F, Tsagarkis C. A miniature pacemaker introduced intravenously and implanted endocardially. Preliminary findings from an experimental study. Eur J Card Pacing Electrophysiol 1991; 1:27–30.

- Eggen MD, Grubac V, Bonner MD. Design and evaluation of a novel fixation mechanism for a transcatheter pacemaker. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2015; 62:2316–2323.

- Reddy VY, Knops RE, Sperzel J, et al. Permanent leadless cardiac pacing: results of the LEADLESS trial. Circulation 2014; 129:1466–1471.

- Ritter P, Duray GZ, Steinwender C, et al. Early performance of a miniaturized leadless cardiac pacemaker: the Micra Transcatheter Pacing Study. Eur Heart J 2015; 36:2510–2519.

- Reddy VY, Exner DV, Cantillon DJ, et al. Percutaneous implantation of an entirely intracardiac leadless pacemaker. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:1125–1135.

- Knops RE, Tjong FV, Neuzil P, et al. Chronic performance of a leadless cardiac pacemaker: 1-year follow-up of the LEADLESS trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 65:1497–1504.

- Reddy VY, Cantillon DJ, Ip J, et al. A comparative study of acute and mid-term complications of leadless versus transvenous pacemakers. Heart Rhythm 2016 July. [Epub ahead of print].

- Reynolds D, Duray GZ, Omar R, et al. A leadless intracardiac transcatheter pacing system. N Engl J Med 2016; 374:533–541.

- Garikipati NV, Karve A, Okabe T, et al. Tricuspid regurgitation after leadless pacemaker implantation. Abstract presented at Heart Rhythm Society Scientific Sessions, May 4–7, 2016, San Francisco, CA.

- Tjong FV, Stam OC, van der Wal AC, et al. Postmortem histopathological examination of a leadless pacemaker shows partial encapsulation after 19 months. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2015; 8:1293–1295.

- Borgquist R, Ljungstrom E, Koul B, Hoijer CJ. Leadless Medtronic Micra pacemaker almost completely endothelialized already after 4 months: first clinical experience from an explanted heart. Eur Heart J 2016; 37:2503.

- Reddy VY, Knops RE, Defaye P, et al. Worldwide clinical experience of the retrieval of leadless cardiac pacemakers. Abstract presented at Heart Rhythm Society Scientific Sessions, May 4–7, 2016, San Francisco, CA.

- Chen K, Zheng X, Dai Y, et al. Multiple leadless pacemakers implanted in the right ventricle of swine. Europace 2016 January 31. pii: euv418. [Epub ahead of print].

- Omdahl P, Eggen MD, Bonner MD, Iaizzo PA, Wika K. Right ventricular anatomy can accommodate multiple micra transcatheter pacemakers. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2016; 39:393–397.

- Mond HG, Proclemer A. The 11th world survey of cardiac pacing and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: calendar year 2009—a World Society of Arrhythmia’s project. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2011; 34:1013–1027.

- Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Heart Rhythm Society. 2012 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update incorporated into the ACCF/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2013; 127:e283–352.

- Tobin K, Stewart J, Westveer D, Frumin H. Acute complications of permanent pacemaker implantation: their financial implication and relation to volume and operator experience. Am J Cardiol 2000; 85:774–776, A9.

- Tjong FV, Brouwer TF, Smeding L, et al. Combined leadless pacemaker and subcutaneous implantable defibrillator therapy: feasibility, safety, and performance. Europace 2016 March 3. [Epub ahead of print].

KEY POINTS

- Leadless cardiac pacing has emerged as a safe and effective alternative involving catheter-based delivery of a self-contained device directly into the right ventricle without incisional access, leads, or a surgical pocket. The procedure typically can be performed in 30 minutes or less, with fewer postprocedure restrictions.

- Leadless pacing is showing promising results, but it is currently limited to single-chamber pacing.

- Future directions include atrial and dual-chamber pacing and combining the procedure with a subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.

PCSK9 inhibition: A promise fulfilled?

Statin therapy has been shown to substantially reduce adverse events associated with low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and cardiovascular disease (CVD). Statins alone are often not adequate to achieve treatment goals, and residual CVD risk remains high. Combination therapies of statins with ezetimibe and resins to further lower LDL-C, fibrates and omega 3 fatty acids to lower triglycerides, and niacin to lower both and raise high-density-liproprotein cholesterol are available, but additional risk reduction has not been consistently demonstrated in clinical trials.

The link between atherogenic lipoproteins and CVD is strong, and the need to develop therapies in addition to statins to substantially and safely reduce LDL-C is a priority. The association of reduced proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) activity with reduced LDL-C and CVD events has led to the rapid development and approval of monoclonal antibody therapies to inhibit PCSK9.

In this review, we discuss trials of these therapies that have shown durable reductions in LDL-C of more than 50%, with acceptable tolerability. Now that PCSK9 inhibitors are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), extended data are needed as to long-term tolerability, safety, and efficacy of these agents and, most importantly, demonstration of additional reduction in CVD events.

A CASE FOR ADDITIONAL THERAPIES

CVD is the leading cause of morbidity and death in the United States, responsible for one in four deaths. Hyperlipidemia and, specifically, elevated LDL-C have been found to be important drivers of atherosclerosis and, in turn, adverse cardiovascular (CV) events. Likewise, numerous observational and clinical trials have shown that reducing LDL-C, particularly with statins, decreases CVD events.1–4 More aggressive lowering with higher doses or more intensive statin therapy further reduces rates of adverse outcomes.3,4 In addition, the pleiotropic effects of statins imply that not all of their benefits are derived from LDL-C lowering alone.5 Consequently, it is now standard practice to use statins at the highest tolerable dose to reach target LDL-C levels and prevent CV events in high-risk patients with CVD or multiple coronary artery disease risk factors, regardless of the LDL-C levels.6,7

The American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association released cholesterol guidelines in 2013 that recommend a risk-based approach for statin therapy rather than targeting specific LDL-C levels.6 Although this evidence-based approach may better conform to clinical trials, the debate that lower LDL-C targets will further prevent CVD continues.

Indeed, it appears that lower is better, as demonstrated by the IMPROVE-IT trial.8 Although the control group receiving simvastatin monotherapy had low LDL-C levels (mean, 69.9 mg/dL; 1.8 mmol/L), the experimental group receiving simvastatin plus ezetimibe achieved even lower levels (mean, 53.2 mg/dL;1.4 mmol/L) after 1 year of therapy and had a significantly lower composite primary end point of CV death, major coronary event, or nonfatal stroke at 7 years (34.7% for simvastatin monotherapy vs 32.7% for combined therapy).9 Furthermore, the event-rate reduction with the addition of ezetimibe was the same as the average predicted by the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ meta-analysis: an LDL-C reduction of 1 mmol/L (38.6 mg/dL) yields a 23% risk reduction in major coronary events over 5 years.10 Although only a modest absolute reduction in outcomes, it supports the notion that further reduction of LDL-C levels by more potent therapies may offer greater benefit.

There is strong evidence that statin therapy reduces the risk of developing CVD in patients with or without a previous atherosclerotic event; however, residual CVD risk remains even for those on therapy. A contributing factor to this residual risk is that many statin-treated patients have insufficient response or intolerance and do not achieve adequate LDL-C reductions.

There are three clinically important patient populations who are inadequately managed with current therapies and remain at high risk of subsequent CV events; these are patients who would benefit from additional therapies.

1. Patients with familial hypercholesterolemia (FH). This is the most common genetic disorder in the world, yet it is frequently undiagnosed and untreated. Due to high baseline cholesterol levels, achieving LDL-C treatment goals is challenging.

- The prevalence may be closer to 1:200 to 1:250 rather than the often quoted 1:500.11

- Fewer than 12% of patients with heterzygous FH achieve the LDL-C goal of < 100 mg/dL with maximal statin treatment alone or with a second agent.12

2. Patients with hyperlipidemia not due to FH who are at elevated CV risk and undertreated. In US and European surveys, between 50% and 60% of patients receiving statins with or without other therapies failed to reach LDL-C reduction goals.13

- Variation in response to statin treatment between individuals may be considerable.

- Poor adherence to statin therapy is common.

3. Patients with side effects to statins, particularly muscle symptoms that prevent statin use or substantially limit the dose.

- Although the incidence of myopathy is low (< 0.1%) and rhabdomyolysis is even less common, observational studies suggest that 10% to 20% of patients may limit statin use due to muscle-associated complaints including muscle aching, cramps, or weakness.14

- Side effects may be dose-dependent, limiting the use of the high-intensity statin doses that are frequently necessary to achieve LDL-C goals.

Consequently, there is great interest in developing therapies beyond statins that may further reduce CV events. However, treatments other than ezetimibe for further management of hyperlipidemia and risk reduction have failed to demonstrate consistent benefit when added to statin therapy.15–19 The largest studies were with niacin and fibrates. Unfortunately, most trials demonstrated no overall outcomes benefit or only benefits in subgroup analyses, leaving the door open to other pharmacologic interventions.