User login

A new standard of care for rel/ref MM?

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—Adding the oral proteasome inhibitor ixazomib to treatment with lenalidomide and dexamethasone can prolong progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma (MM), according to interim results of the phase 3 TOURMALINE-MM1 trial.

It is not yet clear if the 3-drug combination can prolong overall survival when compared to treatment with lenalidomide and dexamethasone.

However, researchers believe the triplet shows promise and could become a new standard of care for relapsed/refractory MM.

Philippe Moreau, MD, of the University of Nantes in France, discussed this possibility while presenting results from TOURMALINE-MM1 at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 727*). The study was sponsored by Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

The trial included 722 MM patients enrolled at 147 centers in 26 countries. Patients were randomized to receive ixazomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (IRd, n=360) or placebo, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (Rd, n=362).

Baseline patient characteristics were similar between the arms. The median age was 66 in both arms (overall range, 30-91), and nearly 60% of patients in both arms were male.

Fifty percent of patients in the IRd arm and 47% in the Rd arm had an ECOG performance status of 0. Forty-three percent and 45%, respectively, had a status of 1, and 5% and 7%, respectively, had a status of 2.

Eighty-seven percent and 88%, respectively, had an ISS stage of I or II. Fifty-five percent of patients in the IRd arm had standard-risk cytogenetics, as did 60% in the Rd arm.

Fifty-nine percent of patients in both arms had received 1 prior line of therapy, and 41% in both arms had 2 or 3 prior lines.

Response and survival

“Ixazomib, when combined with len-dex . . . , was associated with a significant and meaningful improvement in progression-free survival, improved time to progression, and [higher] response rate as well,” Dr Moreau said.

At a median follow-up of about 15 months, the median PFS was 20.6 months in the IRd arm and 14.7 months in the Rd arm. The hazard ratio was 0.742 (P=0.012).

Dr Moreau said the PFS benefit was consistent across pre-specified subgroups. So the benefit was present regardless of age, ISS stage, cytogenetic risk, number of prior therapies, prior exposure to a proteasome inhibitor, prior immunomodulatory therapy, whether the patient was refractory to his last therapy, and whether the patient had relapsed or refractory disease.

Dr Moreau also pointed out that, in the IRd arm, the median PFS in high-risk patients was similar to that in the overall patient population and in patients with standard-risk cytogenetics. This suggests ixazomib may overcome the negative impact of cytogenetic alterations.

Whether IRd confers an overall survival benefit is not clear, as those data are not yet mature. At a median follow-up of about 23 months, the median overall survival was not reached in either treatment arm.

The researchers conducted a non-inferential PFS analysis at the same time point (23 months) and found the median PFS was 20 months in the IRd arm and 15.9 months in the Rd arm. The hazard ratio was 0.82.

As for other efficacy endpoints, the overall response rate was 78.3% in the IRd arm and 71.5% in the Rd arm (P=0.035). The rates of complete response were 11.7% and 6.6%, respectively (P=0.019). And the rates of very good partial response or greater were 48.1% and 39%, respectively (P=0.014).

The median time to response was 1.1 months in the IRd arm and 1.9 months in the Rd arm. The median duration of response was 20.5 months and 15 months, respectively. And the median time to progression was 21.4 months and 15.7 months, respectively.

Adverse events

At a median follow-up of about 23 months, patients had received a median of 17 cycles of IRd and a median of 15 cycles of Rd.

The incidence of any adverse event (AE) was 98% in the IRd arm and 99% in the Rd arm. The incidence of grade 3 or higher AEs was 74% and 69%, respectively. The incidence of serious AEs was 47% and 49%, respectively.

The incidence of AEs resulting in discontinuation was 17% and 14%, respectively. And the incidence of on-study deaths (occurring within 30 days of the last dose) was 4% and 6%, respectively.

Common AEs in the IRd and Rd arms, respectively, were diarrhea (45% vs 39%), constipation (35% vs 26%), nausea (29% vs 22%), vomiting (23% vs 12%), rash (36% vs 23%), back pain (24% vs 17%), upper respiratory tract infection (23% vs 19%), thrombocytopenia (31% vs 16%), peripheral neuropathy (27% vs 22%), peripheral edema (28% vs 20%), thromboembolism (8% vs 11%), and neutropenia (33% vs 31%).

“Ixazomib is adding limited toxicity to lenalidomide and dex, with a very low rate of peripheral neuropathy and no cardiovascular or renal adverse signals,” Dr Moreau said.

“This all-oral triplet regimen may become one of the new standards of care in the relapsed setting. [It has] a very safe profile, [is] a very effective combination, [and is] simple and convenient.” ![]()

*Data in the abstract differ from the presentation.

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—Adding the oral proteasome inhibitor ixazomib to treatment with lenalidomide and dexamethasone can prolong progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma (MM), according to interim results of the phase 3 TOURMALINE-MM1 trial.

It is not yet clear if the 3-drug combination can prolong overall survival when compared to treatment with lenalidomide and dexamethasone.

However, researchers believe the triplet shows promise and could become a new standard of care for relapsed/refractory MM.

Philippe Moreau, MD, of the University of Nantes in France, discussed this possibility while presenting results from TOURMALINE-MM1 at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 727*). The study was sponsored by Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

The trial included 722 MM patients enrolled at 147 centers in 26 countries. Patients were randomized to receive ixazomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (IRd, n=360) or placebo, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (Rd, n=362).

Baseline patient characteristics were similar between the arms. The median age was 66 in both arms (overall range, 30-91), and nearly 60% of patients in both arms were male.

Fifty percent of patients in the IRd arm and 47% in the Rd arm had an ECOG performance status of 0. Forty-three percent and 45%, respectively, had a status of 1, and 5% and 7%, respectively, had a status of 2.

Eighty-seven percent and 88%, respectively, had an ISS stage of I or II. Fifty-five percent of patients in the IRd arm had standard-risk cytogenetics, as did 60% in the Rd arm.

Fifty-nine percent of patients in both arms had received 1 prior line of therapy, and 41% in both arms had 2 or 3 prior lines.

Response and survival

“Ixazomib, when combined with len-dex . . . , was associated with a significant and meaningful improvement in progression-free survival, improved time to progression, and [higher] response rate as well,” Dr Moreau said.

At a median follow-up of about 15 months, the median PFS was 20.6 months in the IRd arm and 14.7 months in the Rd arm. The hazard ratio was 0.742 (P=0.012).

Dr Moreau said the PFS benefit was consistent across pre-specified subgroups. So the benefit was present regardless of age, ISS stage, cytogenetic risk, number of prior therapies, prior exposure to a proteasome inhibitor, prior immunomodulatory therapy, whether the patient was refractory to his last therapy, and whether the patient had relapsed or refractory disease.

Dr Moreau also pointed out that, in the IRd arm, the median PFS in high-risk patients was similar to that in the overall patient population and in patients with standard-risk cytogenetics. This suggests ixazomib may overcome the negative impact of cytogenetic alterations.

Whether IRd confers an overall survival benefit is not clear, as those data are not yet mature. At a median follow-up of about 23 months, the median overall survival was not reached in either treatment arm.

The researchers conducted a non-inferential PFS analysis at the same time point (23 months) and found the median PFS was 20 months in the IRd arm and 15.9 months in the Rd arm. The hazard ratio was 0.82.

As for other efficacy endpoints, the overall response rate was 78.3% in the IRd arm and 71.5% in the Rd arm (P=0.035). The rates of complete response were 11.7% and 6.6%, respectively (P=0.019). And the rates of very good partial response or greater were 48.1% and 39%, respectively (P=0.014).

The median time to response was 1.1 months in the IRd arm and 1.9 months in the Rd arm. The median duration of response was 20.5 months and 15 months, respectively. And the median time to progression was 21.4 months and 15.7 months, respectively.

Adverse events

At a median follow-up of about 23 months, patients had received a median of 17 cycles of IRd and a median of 15 cycles of Rd.

The incidence of any adverse event (AE) was 98% in the IRd arm and 99% in the Rd arm. The incidence of grade 3 or higher AEs was 74% and 69%, respectively. The incidence of serious AEs was 47% and 49%, respectively.

The incidence of AEs resulting in discontinuation was 17% and 14%, respectively. And the incidence of on-study deaths (occurring within 30 days of the last dose) was 4% and 6%, respectively.

Common AEs in the IRd and Rd arms, respectively, were diarrhea (45% vs 39%), constipation (35% vs 26%), nausea (29% vs 22%), vomiting (23% vs 12%), rash (36% vs 23%), back pain (24% vs 17%), upper respiratory tract infection (23% vs 19%), thrombocytopenia (31% vs 16%), peripheral neuropathy (27% vs 22%), peripheral edema (28% vs 20%), thromboembolism (8% vs 11%), and neutropenia (33% vs 31%).

“Ixazomib is adding limited toxicity to lenalidomide and dex, with a very low rate of peripheral neuropathy and no cardiovascular or renal adverse signals,” Dr Moreau said.

“This all-oral triplet regimen may become one of the new standards of care in the relapsed setting. [It has] a very safe profile, [is] a very effective combination, [and is] simple and convenient.” ![]()

*Data in the abstract differ from the presentation.

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—Adding the oral proteasome inhibitor ixazomib to treatment with lenalidomide and dexamethasone can prolong progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma (MM), according to interim results of the phase 3 TOURMALINE-MM1 trial.

It is not yet clear if the 3-drug combination can prolong overall survival when compared to treatment with lenalidomide and dexamethasone.

However, researchers believe the triplet shows promise and could become a new standard of care for relapsed/refractory MM.

Philippe Moreau, MD, of the University of Nantes in France, discussed this possibility while presenting results from TOURMALINE-MM1 at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 727*). The study was sponsored by Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

The trial included 722 MM patients enrolled at 147 centers in 26 countries. Patients were randomized to receive ixazomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (IRd, n=360) or placebo, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (Rd, n=362).

Baseline patient characteristics were similar between the arms. The median age was 66 in both arms (overall range, 30-91), and nearly 60% of patients in both arms were male.

Fifty percent of patients in the IRd arm and 47% in the Rd arm had an ECOG performance status of 0. Forty-three percent and 45%, respectively, had a status of 1, and 5% and 7%, respectively, had a status of 2.

Eighty-seven percent and 88%, respectively, had an ISS stage of I or II. Fifty-five percent of patients in the IRd arm had standard-risk cytogenetics, as did 60% in the Rd arm.

Fifty-nine percent of patients in both arms had received 1 prior line of therapy, and 41% in both arms had 2 or 3 prior lines.

Response and survival

“Ixazomib, when combined with len-dex . . . , was associated with a significant and meaningful improvement in progression-free survival, improved time to progression, and [higher] response rate as well,” Dr Moreau said.

At a median follow-up of about 15 months, the median PFS was 20.6 months in the IRd arm and 14.7 months in the Rd arm. The hazard ratio was 0.742 (P=0.012).

Dr Moreau said the PFS benefit was consistent across pre-specified subgroups. So the benefit was present regardless of age, ISS stage, cytogenetic risk, number of prior therapies, prior exposure to a proteasome inhibitor, prior immunomodulatory therapy, whether the patient was refractory to his last therapy, and whether the patient had relapsed or refractory disease.

Dr Moreau also pointed out that, in the IRd arm, the median PFS in high-risk patients was similar to that in the overall patient population and in patients with standard-risk cytogenetics. This suggests ixazomib may overcome the negative impact of cytogenetic alterations.

Whether IRd confers an overall survival benefit is not clear, as those data are not yet mature. At a median follow-up of about 23 months, the median overall survival was not reached in either treatment arm.

The researchers conducted a non-inferential PFS analysis at the same time point (23 months) and found the median PFS was 20 months in the IRd arm and 15.9 months in the Rd arm. The hazard ratio was 0.82.

As for other efficacy endpoints, the overall response rate was 78.3% in the IRd arm and 71.5% in the Rd arm (P=0.035). The rates of complete response were 11.7% and 6.6%, respectively (P=0.019). And the rates of very good partial response or greater were 48.1% and 39%, respectively (P=0.014).

The median time to response was 1.1 months in the IRd arm and 1.9 months in the Rd arm. The median duration of response was 20.5 months and 15 months, respectively. And the median time to progression was 21.4 months and 15.7 months, respectively.

Adverse events

At a median follow-up of about 23 months, patients had received a median of 17 cycles of IRd and a median of 15 cycles of Rd.

The incidence of any adverse event (AE) was 98% in the IRd arm and 99% in the Rd arm. The incidence of grade 3 or higher AEs was 74% and 69%, respectively. The incidence of serious AEs was 47% and 49%, respectively.

The incidence of AEs resulting in discontinuation was 17% and 14%, respectively. And the incidence of on-study deaths (occurring within 30 days of the last dose) was 4% and 6%, respectively.

Common AEs in the IRd and Rd arms, respectively, were diarrhea (45% vs 39%), constipation (35% vs 26%), nausea (29% vs 22%), vomiting (23% vs 12%), rash (36% vs 23%), back pain (24% vs 17%), upper respiratory tract infection (23% vs 19%), thrombocytopenia (31% vs 16%), peripheral neuropathy (27% vs 22%), peripheral edema (28% vs 20%), thromboembolism (8% vs 11%), and neutropenia (33% vs 31%).

“Ixazomib is adding limited toxicity to lenalidomide and dex, with a very low rate of peripheral neuropathy and no cardiovascular or renal adverse signals,” Dr Moreau said.

“This all-oral triplet regimen may become one of the new standards of care in the relapsed setting. [It has] a very safe profile, [is] a very effective combination, [and is] simple and convenient.” ![]()

*Data in the abstract differ from the presentation.

Disease Education

Q) The billing consultant who came to our office said we can increase our reimbursements if we also provide education to our patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Is she right?

In 2010, under an omnibus bill, kidney disease education (KDE) classes were added as a Medicare benefit. These are for patients with stage 4 CKD (glomerular filtration rate, 15-30 mL/min) and are to be taught by a qualified instructor (MD, PA, NP, or CNS).

The classes can be taught on the same day as an evaluation/management visit (ie, a regular office visit) and are compensated by the hour. (Side note: Medicare defines an hour as 31 minutes—yes, 31 minutes; Medicare takes for granted that you will also need time to chart!) You can teach two classes in the same day. Thus, if you wanted to, you could have a patient arrive for an office visit, then teach two 31-minute classes, and bill all three for the same day. The entire visit could be 75 minutes (although this may be exhausting for this population).

You can conduct the classes in a number of settings, including nursing homes, hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, the office, or even the patient’s home. Many PAs and NPs have taught these classes to hospitalized patients who have lost kidney function due to an acute insult (ie, medications, dehydration, contrast).

Each Medicare recipient has a lifetime benefit of six KDE classes. The CPT billing code is G0420 for an individual class and G0421 for a group class. You must make sure you also code for the stage 4 CKD diagnosis (code: 585.4).

Congress stipulated KDE classes must include information on causes, symptoms, and treatments and comprise a posttest at a specific health literacy level. To make it simple, the National Kidney Foundation Council of Advanced Practitioners (NKF-CAP) has developed two free Power-Point slide decks for clinicians to use in KDE classes (available at www.kidney.org/professionals/CAP/sub_resources#kde). References and updated peer-reviewed guidelines are included. You can print the slides for your patients and/or share the program with your colleagues.

Many nephrology practitioners teach the two slide sets over and over, because patients only retain one-third of the info we provide them on a given day. So if you teach each slide set three times, you have six lifetime classes—and hopefully the patient will have retained everything.

One caveat: Before you initiate KDE classes for a specific patient, check with the patient’s nephrology group (we hope at stage 4 the patient has a nephrologist) to see if they are providing the education. —KZ and JD

Kim Zuber, PA-C, MSPS, DFAAPA

American Academy of Nephrology PAs

Jane S. Davis, CRNP, DNP

Division of Nephrology at the University of Alabama

National Kidney Foundation's Council of Advanced Practitioners

Q) The billing consultant who came to our office said we can increase our reimbursements if we also provide education to our patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Is she right?

In 2010, under an omnibus bill, kidney disease education (KDE) classes were added as a Medicare benefit. These are for patients with stage 4 CKD (glomerular filtration rate, 15-30 mL/min) and are to be taught by a qualified instructor (MD, PA, NP, or CNS).

The classes can be taught on the same day as an evaluation/management visit (ie, a regular office visit) and are compensated by the hour. (Side note: Medicare defines an hour as 31 minutes—yes, 31 minutes; Medicare takes for granted that you will also need time to chart!) You can teach two classes in the same day. Thus, if you wanted to, you could have a patient arrive for an office visit, then teach two 31-minute classes, and bill all three for the same day. The entire visit could be 75 minutes (although this may be exhausting for this population).

You can conduct the classes in a number of settings, including nursing homes, hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, the office, or even the patient’s home. Many PAs and NPs have taught these classes to hospitalized patients who have lost kidney function due to an acute insult (ie, medications, dehydration, contrast).

Each Medicare recipient has a lifetime benefit of six KDE classes. The CPT billing code is G0420 for an individual class and G0421 for a group class. You must make sure you also code for the stage 4 CKD diagnosis (code: 585.4).

Congress stipulated KDE classes must include information on causes, symptoms, and treatments and comprise a posttest at a specific health literacy level. To make it simple, the National Kidney Foundation Council of Advanced Practitioners (NKF-CAP) has developed two free Power-Point slide decks for clinicians to use in KDE classes (available at www.kidney.org/professionals/CAP/sub_resources#kde). References and updated peer-reviewed guidelines are included. You can print the slides for your patients and/or share the program with your colleagues.

Many nephrology practitioners teach the two slide sets over and over, because patients only retain one-third of the info we provide them on a given day. So if you teach each slide set three times, you have six lifetime classes—and hopefully the patient will have retained everything.

One caveat: Before you initiate KDE classes for a specific patient, check with the patient’s nephrology group (we hope at stage 4 the patient has a nephrologist) to see if they are providing the education. —KZ and JD

Kim Zuber, PA-C, MSPS, DFAAPA

American Academy of Nephrology PAs

Jane S. Davis, CRNP, DNP

Division of Nephrology at the University of Alabama

National Kidney Foundation's Council of Advanced Practitioners

Q) The billing consultant who came to our office said we can increase our reimbursements if we also provide education to our patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Is she right?

In 2010, under an omnibus bill, kidney disease education (KDE) classes were added as a Medicare benefit. These are for patients with stage 4 CKD (glomerular filtration rate, 15-30 mL/min) and are to be taught by a qualified instructor (MD, PA, NP, or CNS).

The classes can be taught on the same day as an evaluation/management visit (ie, a regular office visit) and are compensated by the hour. (Side note: Medicare defines an hour as 31 minutes—yes, 31 minutes; Medicare takes for granted that you will also need time to chart!) You can teach two classes in the same day. Thus, if you wanted to, you could have a patient arrive for an office visit, then teach two 31-minute classes, and bill all three for the same day. The entire visit could be 75 minutes (although this may be exhausting for this population).

You can conduct the classes in a number of settings, including nursing homes, hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, the office, or even the patient’s home. Many PAs and NPs have taught these classes to hospitalized patients who have lost kidney function due to an acute insult (ie, medications, dehydration, contrast).

Each Medicare recipient has a lifetime benefit of six KDE classes. The CPT billing code is G0420 for an individual class and G0421 for a group class. You must make sure you also code for the stage 4 CKD diagnosis (code: 585.4).

Congress stipulated KDE classes must include information on causes, symptoms, and treatments and comprise a posttest at a specific health literacy level. To make it simple, the National Kidney Foundation Council of Advanced Practitioners (NKF-CAP) has developed two free Power-Point slide decks for clinicians to use in KDE classes (available at www.kidney.org/professionals/CAP/sub_resources#kde). References and updated peer-reviewed guidelines are included. You can print the slides for your patients and/or share the program with your colleagues.

Many nephrology practitioners teach the two slide sets over and over, because patients only retain one-third of the info we provide them on a given day. So if you teach each slide set three times, you have six lifetime classes—and hopefully the patient will have retained everything.

One caveat: Before you initiate KDE classes for a specific patient, check with the patient’s nephrology group (we hope at stage 4 the patient has a nephrologist) to see if they are providing the education. —KZ and JD

Kim Zuber, PA-C, MSPS, DFAAPA

American Academy of Nephrology PAs

Jane S. Davis, CRNP, DNP

Division of Nephrology at the University of Alabama

National Kidney Foundation's Council of Advanced Practitioners

Advances in Hematology and Oncology (May 2014)

High-risk B-ALL subgroup has ‘outstanding outcomes’

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—A subgroup of young patients with high-risk B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) can have “outstanding outcomes” with contemporary therapy, according to researchers.

Results of a large study suggested that patients ages 1 to 30 who have high-risk B-ALL according to National Cancer Institute (NCI) classification can have high rates of event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) if they have favorable cytogenetic features, have no evidence of CNS disease, and have rapid minimal residual disease (MRD) responses.

The research suggested these patients will not benefit from further chemotherapy intensification.

Elizabeth Raetz, MD, of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, presented these results at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 807).

She and her colleagues analyzed patients enrolled on the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) AALL03B1 classification study at the time of B-ALL diagnosis. From December 2003 to September 2011, there were 11,144 eligible patients enrolled on this trial.

Eighty-nine percent of these patients were also enrolled on a frontline ALL therapeutic trial, and 96% of these patients were evaluable for post-induction treatment assignment. Sixty-five percent of these patients were treated on a trial for NCI standard-risk B-ALL (COG-AALL0331), and 35% were treated on a trial for high-risk B-ALL (COG-AALL0232).

At the end of induction therapy, patients were classified into low-risk (29%), standard-risk (33%), high-risk (34%), and very-high-risk (4%) groups for further treatment allocation. The variables used for risk classification were age, initial white blood cell count, extramedullary disease status, blast cytogenetics, and early treatment response based on bone marrow morphology and day 29 MRD.

Patients with very-high-risk features (BCR-ABL1, hypodiploidy, induction failure, or poor response at day 43) did not continue on AALL0232/AALL0331 post-induction but did have outcome data captured for analysis.

Response and survival

Rapid early response was defined as M1 (<5% blasts) bone marrow by day 15 plus flow cytometry-based MRD <0.1% on day 29 of induction. Patients with either M2/M3 (≥5% blasts) day 15 marrow or MRD ≥0.1% at day 29 were deemed slow early responders.

Eighty-four percent of patients had a rapid early response to induction, and 16% had a slow early response.

For rapid early responders, the 5-year EFS was 89.3%, and the 5-year OS was 95.2%. For slow early responders, the EFS and OS rates were 67.9% and 84.3%, respectively (P<0.0001 for both EFS and OS comparisons).

Survival according to cytogenetics

Having favorable cytogenetic abnormalities (triple trisomies of chromosomes 4, 10, and 17 or ETV6-RUNX1 fusion) was associated with significantly better EFS and OS than having unfavorable cytogenetics (hypodiploidy [DNA index <0.81 or chromosomes < 44], MLL rearrangements, BCR-ABL1, or iAMP21).

And Dr Raetz pointed out that the 5-year OS exceeded 98% for patients with either standard- or high-risk disease who had favorable cytogenetics.

For patients who were ETV6-RUNX1-positive, the EFS was 93.2% and the OS was 98.3%. For patients who were ETV6-RUNX1 negative, the rates were 83.5% and 92%, respectively (P<0.0001).

For patients with triple trisomy, EFS was 94.7% and OS was 98.7%. For those without triple trisomy, the rates were 83.6% and 92.2%, respectively (P<0.0001).

For patients with MLL rearrangement, the EFS was 73.9% and the OS was 83.1%. For patients without MLL rearrangement, the rates were 85.9% and 93.6%, respectively (P<0.0001).

For patients who were positive for iAMP21, the EFS was 69.5% and the OS was 90.1%. For iAMP21-negative patients, the rates were 86.1% and 93.4%, respectively (P<0.0001 for PFS comparison and P=0.0026 for OS comparison).

Survival according to risk group and MRD

The researchers also assessed EFS and OS among patients with favorable cytogenetics according to NCI risk group and MRD at days 8 and 29.

“One thing to point out is that, regardless of having favorable cytogenetics, those individuals who had end-induction MRD values of greater than 0.01% had inferior outcomes, so that was still a prognostic marker,” Dr Raetz said.

“And one thing that we were pleasantly surprised to see was that, among the NCI high-risk patients, those who had very rapid MRD responses—so less than 1% at day 8 in the blood and less than 0.01% in the marrow on day 29—had a 94.9% 5-year event-free survival and 98.1% overall survival.”

The researchers also divided this group according to age—patients younger than 10 and those 10 years or older. There was no significant difference in EFS or OS between the age groups (P=0.126 and P=0.411).

Standard-risk group

Among patients with <1% MRD on day 8 and <0.01% MRD on day 29, the EFS was 95.7% and the OS was 99.1%.

Among patients with ≥1% MRD on day 8 and <0.01% MRD on day 29, the EFS was 91.7% and the OS was 99.4%.

Among patients with any MRD on day 8 and ≥0.01% MRD on day 29, the EFS was 88.1% and the OS was 96.8%.

High-risk group

Among patients with <1% MRD on day 8 and <0.01% MRD on day 29, the EFS was 94.9% and the OS was 98.1%.

Among patients with ≥1% MRD on day 8 and <0.01% MRD on day 29, the EFS was 93.6% and the OS was 95.5%.

Among patients with any MRD on day 8 and ≥0.01% MRD on day 29, the EFS was 75.4% and the OS was 90.4%.

In closing, Dr Raetz said this study showed that real‐time classification incorporating clinical features, blast cytogenetics, and early response was feasible in a large group of patients enrolled on COG ALL trials and identified patients with varying outcomes for risk‐based treatment allocation.

She noted that early response by marrow morphology was not prognostic when MRD response was used and is therefore no longer used in COG studies.

And although favorable cytogenetic features were not prognostic in NCI high-risk B‐ALL patients in prior COG studies, the current study indicates that these patients can have “excellent outcomes” if they have no evidence of CNS leukemia and are rapid MRD responders. So these patients will not benefit from further chemotherapy intensification. ![]()

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—A subgroup of young patients with high-risk B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) can have “outstanding outcomes” with contemporary therapy, according to researchers.

Results of a large study suggested that patients ages 1 to 30 who have high-risk B-ALL according to National Cancer Institute (NCI) classification can have high rates of event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) if they have favorable cytogenetic features, have no evidence of CNS disease, and have rapid minimal residual disease (MRD) responses.

The research suggested these patients will not benefit from further chemotherapy intensification.

Elizabeth Raetz, MD, of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, presented these results at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 807).

She and her colleagues analyzed patients enrolled on the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) AALL03B1 classification study at the time of B-ALL diagnosis. From December 2003 to September 2011, there were 11,144 eligible patients enrolled on this trial.

Eighty-nine percent of these patients were also enrolled on a frontline ALL therapeutic trial, and 96% of these patients were evaluable for post-induction treatment assignment. Sixty-five percent of these patients were treated on a trial for NCI standard-risk B-ALL (COG-AALL0331), and 35% were treated on a trial for high-risk B-ALL (COG-AALL0232).

At the end of induction therapy, patients were classified into low-risk (29%), standard-risk (33%), high-risk (34%), and very-high-risk (4%) groups for further treatment allocation. The variables used for risk classification were age, initial white blood cell count, extramedullary disease status, blast cytogenetics, and early treatment response based on bone marrow morphology and day 29 MRD.

Patients with very-high-risk features (BCR-ABL1, hypodiploidy, induction failure, or poor response at day 43) did not continue on AALL0232/AALL0331 post-induction but did have outcome data captured for analysis.

Response and survival

Rapid early response was defined as M1 (<5% blasts) bone marrow by day 15 plus flow cytometry-based MRD <0.1% on day 29 of induction. Patients with either M2/M3 (≥5% blasts) day 15 marrow or MRD ≥0.1% at day 29 were deemed slow early responders.

Eighty-four percent of patients had a rapid early response to induction, and 16% had a slow early response.

For rapid early responders, the 5-year EFS was 89.3%, and the 5-year OS was 95.2%. For slow early responders, the EFS and OS rates were 67.9% and 84.3%, respectively (P<0.0001 for both EFS and OS comparisons).

Survival according to cytogenetics

Having favorable cytogenetic abnormalities (triple trisomies of chromosomes 4, 10, and 17 or ETV6-RUNX1 fusion) was associated with significantly better EFS and OS than having unfavorable cytogenetics (hypodiploidy [DNA index <0.81 or chromosomes < 44], MLL rearrangements, BCR-ABL1, or iAMP21).

And Dr Raetz pointed out that the 5-year OS exceeded 98% for patients with either standard- or high-risk disease who had favorable cytogenetics.

For patients who were ETV6-RUNX1-positive, the EFS was 93.2% and the OS was 98.3%. For patients who were ETV6-RUNX1 negative, the rates were 83.5% and 92%, respectively (P<0.0001).

For patients with triple trisomy, EFS was 94.7% and OS was 98.7%. For those without triple trisomy, the rates were 83.6% and 92.2%, respectively (P<0.0001).

For patients with MLL rearrangement, the EFS was 73.9% and the OS was 83.1%. For patients without MLL rearrangement, the rates were 85.9% and 93.6%, respectively (P<0.0001).

For patients who were positive for iAMP21, the EFS was 69.5% and the OS was 90.1%. For iAMP21-negative patients, the rates were 86.1% and 93.4%, respectively (P<0.0001 for PFS comparison and P=0.0026 for OS comparison).

Survival according to risk group and MRD

The researchers also assessed EFS and OS among patients with favorable cytogenetics according to NCI risk group and MRD at days 8 and 29.

“One thing to point out is that, regardless of having favorable cytogenetics, those individuals who had end-induction MRD values of greater than 0.01% had inferior outcomes, so that was still a prognostic marker,” Dr Raetz said.

“And one thing that we were pleasantly surprised to see was that, among the NCI high-risk patients, those who had very rapid MRD responses—so less than 1% at day 8 in the blood and less than 0.01% in the marrow on day 29—had a 94.9% 5-year event-free survival and 98.1% overall survival.”

The researchers also divided this group according to age—patients younger than 10 and those 10 years or older. There was no significant difference in EFS or OS between the age groups (P=0.126 and P=0.411).

Standard-risk group

Among patients with <1% MRD on day 8 and <0.01% MRD on day 29, the EFS was 95.7% and the OS was 99.1%.

Among patients with ≥1% MRD on day 8 and <0.01% MRD on day 29, the EFS was 91.7% and the OS was 99.4%.

Among patients with any MRD on day 8 and ≥0.01% MRD on day 29, the EFS was 88.1% and the OS was 96.8%.

High-risk group

Among patients with <1% MRD on day 8 and <0.01% MRD on day 29, the EFS was 94.9% and the OS was 98.1%.

Among patients with ≥1% MRD on day 8 and <0.01% MRD on day 29, the EFS was 93.6% and the OS was 95.5%.

Among patients with any MRD on day 8 and ≥0.01% MRD on day 29, the EFS was 75.4% and the OS was 90.4%.

In closing, Dr Raetz said this study showed that real‐time classification incorporating clinical features, blast cytogenetics, and early response was feasible in a large group of patients enrolled on COG ALL trials and identified patients with varying outcomes for risk‐based treatment allocation.

She noted that early response by marrow morphology was not prognostic when MRD response was used and is therefore no longer used in COG studies.

And although favorable cytogenetic features were not prognostic in NCI high-risk B‐ALL patients in prior COG studies, the current study indicates that these patients can have “excellent outcomes” if they have no evidence of CNS leukemia and are rapid MRD responders. So these patients will not benefit from further chemotherapy intensification. ![]()

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—A subgroup of young patients with high-risk B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) can have “outstanding outcomes” with contemporary therapy, according to researchers.

Results of a large study suggested that patients ages 1 to 30 who have high-risk B-ALL according to National Cancer Institute (NCI) classification can have high rates of event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) if they have favorable cytogenetic features, have no evidence of CNS disease, and have rapid minimal residual disease (MRD) responses.

The research suggested these patients will not benefit from further chemotherapy intensification.

Elizabeth Raetz, MD, of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, presented these results at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 807).

She and her colleagues analyzed patients enrolled on the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) AALL03B1 classification study at the time of B-ALL diagnosis. From December 2003 to September 2011, there were 11,144 eligible patients enrolled on this trial.

Eighty-nine percent of these patients were also enrolled on a frontline ALL therapeutic trial, and 96% of these patients were evaluable for post-induction treatment assignment. Sixty-five percent of these patients were treated on a trial for NCI standard-risk B-ALL (COG-AALL0331), and 35% were treated on a trial for high-risk B-ALL (COG-AALL0232).

At the end of induction therapy, patients were classified into low-risk (29%), standard-risk (33%), high-risk (34%), and very-high-risk (4%) groups for further treatment allocation. The variables used for risk classification were age, initial white blood cell count, extramedullary disease status, blast cytogenetics, and early treatment response based on bone marrow morphology and day 29 MRD.

Patients with very-high-risk features (BCR-ABL1, hypodiploidy, induction failure, or poor response at day 43) did not continue on AALL0232/AALL0331 post-induction but did have outcome data captured for analysis.

Response and survival

Rapid early response was defined as M1 (<5% blasts) bone marrow by day 15 plus flow cytometry-based MRD <0.1% on day 29 of induction. Patients with either M2/M3 (≥5% blasts) day 15 marrow or MRD ≥0.1% at day 29 were deemed slow early responders.

Eighty-four percent of patients had a rapid early response to induction, and 16% had a slow early response.

For rapid early responders, the 5-year EFS was 89.3%, and the 5-year OS was 95.2%. For slow early responders, the EFS and OS rates were 67.9% and 84.3%, respectively (P<0.0001 for both EFS and OS comparisons).

Survival according to cytogenetics

Having favorable cytogenetic abnormalities (triple trisomies of chromosomes 4, 10, and 17 or ETV6-RUNX1 fusion) was associated with significantly better EFS and OS than having unfavorable cytogenetics (hypodiploidy [DNA index <0.81 or chromosomes < 44], MLL rearrangements, BCR-ABL1, or iAMP21).

And Dr Raetz pointed out that the 5-year OS exceeded 98% for patients with either standard- or high-risk disease who had favorable cytogenetics.

For patients who were ETV6-RUNX1-positive, the EFS was 93.2% and the OS was 98.3%. For patients who were ETV6-RUNX1 negative, the rates were 83.5% and 92%, respectively (P<0.0001).

For patients with triple trisomy, EFS was 94.7% and OS was 98.7%. For those without triple trisomy, the rates were 83.6% and 92.2%, respectively (P<0.0001).

For patients with MLL rearrangement, the EFS was 73.9% and the OS was 83.1%. For patients without MLL rearrangement, the rates were 85.9% and 93.6%, respectively (P<0.0001).

For patients who were positive for iAMP21, the EFS was 69.5% and the OS was 90.1%. For iAMP21-negative patients, the rates were 86.1% and 93.4%, respectively (P<0.0001 for PFS comparison and P=0.0026 for OS comparison).

Survival according to risk group and MRD

The researchers also assessed EFS and OS among patients with favorable cytogenetics according to NCI risk group and MRD at days 8 and 29.

“One thing to point out is that, regardless of having favorable cytogenetics, those individuals who had end-induction MRD values of greater than 0.01% had inferior outcomes, so that was still a prognostic marker,” Dr Raetz said.

“And one thing that we were pleasantly surprised to see was that, among the NCI high-risk patients, those who had very rapid MRD responses—so less than 1% at day 8 in the blood and less than 0.01% in the marrow on day 29—had a 94.9% 5-year event-free survival and 98.1% overall survival.”

The researchers also divided this group according to age—patients younger than 10 and those 10 years or older. There was no significant difference in EFS or OS between the age groups (P=0.126 and P=0.411).

Standard-risk group

Among patients with <1% MRD on day 8 and <0.01% MRD on day 29, the EFS was 95.7% and the OS was 99.1%.

Among patients with ≥1% MRD on day 8 and <0.01% MRD on day 29, the EFS was 91.7% and the OS was 99.4%.

Among patients with any MRD on day 8 and ≥0.01% MRD on day 29, the EFS was 88.1% and the OS was 96.8%.

High-risk group

Among patients with <1% MRD on day 8 and <0.01% MRD on day 29, the EFS was 94.9% and the OS was 98.1%.

Among patients with ≥1% MRD on day 8 and <0.01% MRD on day 29, the EFS was 93.6% and the OS was 95.5%.

Among patients with any MRD on day 8 and ≥0.01% MRD on day 29, the EFS was 75.4% and the OS was 90.4%.

In closing, Dr Raetz said this study showed that real‐time classification incorporating clinical features, blast cytogenetics, and early response was feasible in a large group of patients enrolled on COG ALL trials and identified patients with varying outcomes for risk‐based treatment allocation.

She noted that early response by marrow morphology was not prognostic when MRD response was used and is therefore no longer used in COG studies.

And although favorable cytogenetic features were not prognostic in NCI high-risk B‐ALL patients in prior COG studies, the current study indicates that these patients can have “excellent outcomes” if they have no evidence of CNS leukemia and are rapid MRD responders. So these patients will not benefit from further chemotherapy intensification. ![]()

Pulmonary nodule on x-ray: An algorithmic approach

› Order a computed tomography chest scan, preferably with thin sections through the nodule, to help characterize an indeterminate pulmonary nodule identified on x-ray. B

› Estimate the pretest probability of malignancy for a patient with a pulmonary nodule using your clinical judgment and/or by using a validated model. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE 1 › George D is a 67-year-old patient who has never smoked and who has no history of malignancy. An x-ray of his ribs performed after a fall shows a 13-mm solitary nodule in his right upper lung.

CASE 2 › Cathy B is a healthy 80-year-old with no history of smoking. During a trip to the emergency department for chest pain, she had a computed tomography (CT) scan of her chest. While the chest pain was subsequently attributed to gastroesophageal reflux, the CT revealed a 9-mm part solid nodule that was 75% solid.

How should the physicians caring for each of these patients proceed with their care?

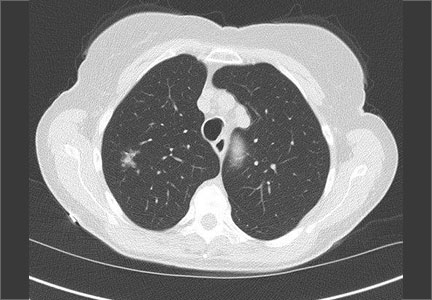

The widespread use of sensitive imaging techniques often leads to the incidental discovery of unrelated—but possibly significant—pulmonary findings. Pulmonary nodules are incidentally discovered on an estimated 0.09% to 0.2% of all chest x-rays, 13% of all chest CT angiograms,1 31% of all cardiac CTs performed for coronary calcium scoring,2 and up to 50% of thin-section chest CT scans.1

The widespread implementation of the US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations on lung cancer screening has further expanded the number of patients in whom asymptomatic pulmonary nodules will be detected. As a result, family physicians (FPs) will frequently encounter this challenging clinical dilemma and will need to:

- assess the patient’s risk profile

- address the patient’s concerns about malignancy while eliciting his or her preference for management

- minimize the risks of surveillance testing

- minimize patient distress while ensuring compliance with a follow-up that may extend up to 4 years

- determine when it’s appropriate to refer the patient to a pulmonologist and/or pulmonary nodule clinic or registry.

Taking these steps, however, can be challenging. In interviews, 15 primary care clinicians who care for patients with pulmonary nodules expressed concerns about limitations in time, knowledge, and resources, as well as a fear about such patients “falling through the cracks.”3 Familiarity with current evidence-based guidelines such as those from the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) and knowledge of emerging data on the management of various types of nodules are imperative.

To that end, this review will fill in the information gaps and provide guidance on how best to communicate what is known about a particular type of nodule with the patient who has one. (See “What to say to improve joint decision-making.”4-7) But first, a word about terminology.

What to say to improve joint decision-making4-7

Diagnosis and follow-up of a pulmonary nodule takes an emotional toll on patients, who often have a poor sense of what the presence of a nodule signifies. When caring for a patient with a pulmonary nodule, it’s essential to have an effective communication strategy to ensure that he or she is a well-informed partner in decision-making.

Specifically, you'll need to describe the type of nodule that the patient has, how fast it might grow and its malignancy potential, steps that will need to be taken, and the importance of smoking cessation (if the patient smokes).

Ask the patient about any concerns/fears he or she may have, and provide resources to reduce them. Emphasize shared decision-making and discuss the rationale for various management plans and the limitations of diagnostic tests. Do not minimize the issue; emphasize the need for, and importance of, prolonged follow-up—even for a patient who has a small, low-risk nodule.

Solid vs subsolid pulmonary nodules

Solid pulmonary nodules. Traditionally, the term “solitary pulmonary nodule” has been used to describe a single, well-circumscribed, radiographic opacity that measures up to 3 cm in diameter and is completely surrounded by aerated lung.1,8 The term “solitary” is now less useful because increasingly sensitive imaging techniques often reveal more than one nodule. In the absence of evidence of features that strongly suggest a benign etiology, these are now commonly referred to as indeterminate solid nodules.

Subsolid nodules are pulmonary nodules that have unique characteristics and require separate guidelines for management. Subsolid nodules include pure ground glass nodules (GGNs) and part solid nodules. GGNs are focal nodular areas of increased lung attenuation through which normal parenchymal structures such as airways, vessels, and interlobular septa can be visualized.1,8 Part solid nodules have a solid component. They are usually, but not necessarily, >50% ground glass in appearance.

Lung masses. Focal pulmonary lesions >3 cm in diameter are called lung masses and are presumed to be malignant (bronchogenic carcinoma) unless proven otherwise.1,8

The specific approach to evaluating and monitoring a pulmonary nodule varies depending on whether the nodule is solid or subsolid and other factors, including the nodule’s size.

Monitoring solid nodules

Monitoring of an indeterminate solid nodule is largely determined by the patient’s risk profile and the characteristics of the identified nodule.1 Independent patient predictors of malignancy include older age, smoking status, and history of prior malignancy (>5 years ago). Less established predictors are the presence of moderate or severe obstructive lung disease and exposure to particulate or sulfur oxide-related pollution.9

Patients who have an indeterminate nodule identified on chest x-ray should undergo a chest CT scan, preferably with thin sections through the nodule to help characterize it.1 Nodule characteristics that can help predict a patient’s risk of malignancy include the size (>8 mm confers higher risk), malignant rate of growth, edge characteristics (spiculation or irregular edges), thickness of the wall of a cavitary pulmonary nodule (≥16 mm has a likelihood ratio [LR] 37.97 of malignancy), and the location of the nodule (upper or middle lobe [LR=1.2 to 1.6]). 10 A lack of growth over 2 years and a benign pattern of calcification eliminate the need for further evaluation.

Validated tools to help guide decision-making. Although many physicians estimate pretest probability of malignancy intuitively, validated tools are readily available and can help in clinical decision-making.11 One such tool is the Mayo model, which is available at http://reference.medscape.com/calculator/solitary-pulmonary-nodule-risk. This model takes into account the patient’s age, smoking status, history of cancer, and characteristics of the nodule.

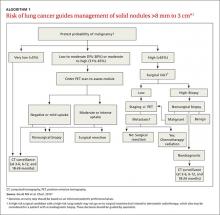

Solid nodules >8 mm to 3 cm

For a patient with a solid nodule >8 mm to 3 cm, ACCP guidelines suggest that physicians estimate the pretest probability of malignancy qualitatively using their clinical judgment and/or quantitatively by using a validated model, such as the Mayo model described above.

Based on the patient’s probability of malignancy, management options include continued CT surveillance, positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, CT-guided needle lung biopsy, bronchoscopy with biopsy, or surgical wedge resection (ALGORITHM 1).1

CT surveillance is recommended for individuals:

- with very low (<5%) probability of malignancy

- with low to moderate (5% to 30%) or moderate to high (31% to 65%) probability of malignancy with negative functional imaging (PET)

- with high probability of malignancy (>65%) when needle biopsy is nondiagnostic and the lesion is not hypermetabolic on PET scan.

Surveillance is also recommended when a fully informed patient prefers nonaggressive management. The intervals for serial CT in this population are at 3 to 6 months, 9 to 12 months, and 18 to 24 months.

In an individual with a solid indeterminate nodule with a high probability of malignancy (>65%), functional imaging should not be performed to characterize the nodule. It may, however, be performed for staging.

Time for biopsy or resection? If a nodule shows evidence of malignant growth on serial imaging, nonsurgical biopsy (CT scan-guided transthoracic needle biopsy, bronchoscopy guided by fluoroscopy, endobronchial ultrasound, electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy, or virtual bronchoscopy navigation) or surgical resection is recommended.

Nonsurgical biopsy is also recommended when the patient’s pretest probability and imaging test results are discordant, when a benign diagnosis requires specific medical treatment, or if a fully informed patient desires proof of diagnosis prior to surgery.

Thoracoscopy with wedge resection is the gold standard for diagnosis of a malignant nodule. It is recommended:

- when the clinical probability of malignancy is high (>65%)

- when the nodule is intensely hypermetabolic by PET scan or positive by other functional imaging tests

- when nonsurgical biopsy is suggestive of malignancy

- when a fully informed patient prefers a definitive diagnostic procedure.

CASE 1 › The FP contacts Mr. D and advises that he get a chest CT to better characterize his pulmonary nodule. A thin-slice CT of the lung reveals that the 13-mm solid nodule in the right upper lobe has spiculated margins. According to the Mayo risk calculator, Mr. D is at moderate risk of malignancy (32.5%). Mr. D and his physician discuss the findings and possible management options, and Mr. D opts to have a PET scan. The FP gives Mr. D literature on pulmonary nodules and contact information for the provider team. A PET scan shows negative uptake. Mr. D and his physician discuss CT surveillance and nonsurgical biopsy. He opts for CT surveillance. The next CT is scheduled for 3 months.

Solid nodules ≤8 mm

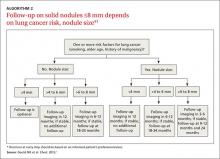

Management of these lesions generally follows the consensus-based guidelines that were first published by the Fleischner Society and subsequently endorsed by the ACCP.1 The 2 main determinants that guide management of nodules ≤8 mm are the patient’s risk factors for cancer and nodule size (ALGORITHM 2).1 The Fleischner guidelines pertain only to patients older than age 35 with no current extra pulmonary malignancy or unexplained fevers. The ACCP guidelines, although similar, do not include these limitations. Patient risk factors include history of smoking, older age, and a history of malignancy.1

Patients with no risk factors for malignancy. The frequency of surveillance CT is determined by the size of the nodule. Nodules ≤4 mm do not need to be followed. For nodules >4 mm to 6 mm, a repeat CT in 12 months is recommended with no follow-up if stable. For nodules >6 to <8 mm, repeat CT is recommended at 6 to 12 months, and again between 18 and 24 months if unchanged.1Patients with one or more risk factors for malignancy. Nodules ≤4 mm should be reevaluated at 12 months in patients with one or more risk factors; no additional follow-up is needed if unchanged. For nodules >4 mm to 6 mm, CT should be repeated between 6 and 12 months and again between 18 and 24 months. Nodules >6 mm to <8 mm should be followed initially between 3 to 6 months, then between 9 and 12 months and again at 24 months if unchanged.1

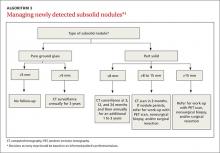

Subsolid nodules require a different approach

Subsolid nodules have a high prevalence of premalignant and malignant disease (adenocarcinoma in situ, minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, and adenocarcinoma). Studies have reported subsolid nodule malignancy rates ranging from 20% to 75%.11-15 This wide range may be a function of different nodule sizes or rates of biopsy. The prevalence increases even further in nodules with a part solid component.

These factors, plus challenges in measuring serial growth on CT and the uncertain prognosis of untreated premalignant disease, make it necessary to have separate guidelines for managing subsolid nodules. The Fleischner Society, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and the American College of Radiology (LungRads) each have differing recommendations on the frequency of follow-up for different-sized subsolid nodules. Newer studies favor a more conservative approach.16 Here we describe the current ACCP guidelines for managing subsolid nodules (ALGORITHM 3).1

GGNs. In an individual with a pure GGN ≤5 mm in diameter, no further evaluation is recommended. In an individual with a pure GGN >5 mm in diameter, annual surveillance with chest CT for at least 3 years is recommended.1

Part solid nodules. In an individual with a part solid nodule ≤8 mm, conduct CT surveillance at 3, 12, and 24 months and then annually for an additional one to 3 years. In a patient with a part solid nodule >8 mm to 15 mm, repeat chest CT at 3 months followed by a PET scan, nonsurgical biopsy, and/or surgical resection if the nodule persists. A patient with a part solid nodule >15 mm should undergo a PET scan, nonsurgical biopsy, and/or surgical resection.

CASE 2 › Ms. G is seen in the office by her FP, and they discuss management options. A repeat CT is done in 3 months and shows a persistent, unchanged nodule. Ms. G opts for a transthoracic biopsy, which reveals adenocarcinoma. Following a PET scan, which shows no evidence of metastasis, curative surgical wedge resection is done.

Multiple subsolid nodules. In a patient who has a dominant nodule and one or more additional nodules, each nodule should be evaluated individually, according to recommendations from the Fleischner Society (the ACCP currently does not have guidelines for managing multiple subsolid nodules). An individual with multiple GGNs that all measure ≤5 mm should receive CT exams at 2 and 4 years.13 A patient with multiple GGNs that include at least one nodule >5 mm but no dominant nodule should undergo follow-up CT at 3 months and annual CT surveillance for at least 3 years.13

CORRESPONDENCE

Samina Yunus, MD, MPH, Cleveland Clinic, Family Medicine, 551 East Washington Street, Chagrin Falls, OH 44022; [email protected].

1. Gould MK, Donington J, Lynch WR, et al. Evaluation of individuals with pulmonary nodules: when is it lung cancer? Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143:e93S-e120S.

2. Burt JR, Iribarren C, Fair JM, et al; Atherosclerotic Disease, Vascular Function, and Genetic Epidemiology (ADVANCE) Study. Incidental findings on cardiac multidetector row computed tomography among healthy older adults: prevalence and clinical correlates. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:756-761.

3. Golden SE, Wiener RS, Sullivan D, et al. Primary care providers and a system problem: A qualitative study of clinicians caring for patients with incidental pulmonary nodules. Chest. 2015;148:1422-1429.

4. Sullivan DR, Golden SE, Ganzini L, et al. ‘I still don’t know diddly’: a longitudinal qualitative study of patients’ knowledge and distress while undergoing evaluation of incidental pulmonary nodules. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2015;25:15028.

5. van den Bergh KA, Essink-Bot ML, Borsboom GJ, et al. Long-term effects of lung cancer computed tomography screening on health-related quality of life: the NELSON trial. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:154-161.

6. Wiener RS, Gould MK, Woloshin S, et al. What do you mean, a spot?: A qualitative analysis of patients’ reactions to discussions with their physicians about pulmonary nodules. Chest. 2013;143:672-677.

7. Wiener RS, Gould MK, Woloshin S, et al. ‘The thing is not knowing’: patients’ perspectives on surveillance of an indeterminate pulmonary nodule. Health Expect. 2015;18:355-365.

8. Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, et al. Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology. 2008;246:697-722.

9. Pope CA 3rd, Burnett RT, Thun MJ, et al. Lung cancer, cardiopulmonary mortality, and long-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution. JAMA. 2002;287:1132-1141.

10. Winer-Muram HT. The solitary pulmonary nodule. Radiology. 2006;239:34-49.

11. Gould MK, Ananth L, Barnett PG; Veterans Affairs SNAP Cooperative Study Group. A clinical model to estimate the pretest probability of lung cancer in patients with solitary pulmonary nodules. Chest. 2007;131:383-388.

12. Seidelman JL, Myers JL, Quint LE. Incidental, subsolid pulmonary nodules at CT: etiology and management. Cancer Imaging. 2013;13:365-373.

13. Naidich DP, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, et al. Recommendations for the management of subsolid pulmonary nodules detected at CT: a statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2013;266:304-317.

14. Oh JY, Kwon SY, Yoon HI, et al. Clinical significance of a solitary ground-glass opacity (GGO) lesion of the lung detected by chest CT. Lung Cancer. 2007;55:67-73.

15. Park CM, Goo JM, Lee HJ, et al. Nodular ground-glass opacity at thin-section CT: histologic correlation and evaluation of change at follow-up. Radiographics. 2007;27:391-408.

16. Heuvelmans MA, Oudkerk M. Management of subsolid pulmonary nodules in CT lung cancer screening. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7:1103-1106.

› Order a computed tomography chest scan, preferably with thin sections through the nodule, to help characterize an indeterminate pulmonary nodule identified on x-ray. B

› Estimate the pretest probability of malignancy for a patient with a pulmonary nodule using your clinical judgment and/or by using a validated model. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE 1 › George D is a 67-year-old patient who has never smoked and who has no history of malignancy. An x-ray of his ribs performed after a fall shows a 13-mm solitary nodule in his right upper lung.

CASE 2 › Cathy B is a healthy 80-year-old with no history of smoking. During a trip to the emergency department for chest pain, she had a computed tomography (CT) scan of her chest. While the chest pain was subsequently attributed to gastroesophageal reflux, the CT revealed a 9-mm part solid nodule that was 75% solid.

How should the physicians caring for each of these patients proceed with their care?

The widespread use of sensitive imaging techniques often leads to the incidental discovery of unrelated—but possibly significant—pulmonary findings. Pulmonary nodules are incidentally discovered on an estimated 0.09% to 0.2% of all chest x-rays, 13% of all chest CT angiograms,1 31% of all cardiac CTs performed for coronary calcium scoring,2 and up to 50% of thin-section chest CT scans.1

The widespread implementation of the US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations on lung cancer screening has further expanded the number of patients in whom asymptomatic pulmonary nodules will be detected. As a result, family physicians (FPs) will frequently encounter this challenging clinical dilemma and will need to:

- assess the patient’s risk profile

- address the patient’s concerns about malignancy while eliciting his or her preference for management

- minimize the risks of surveillance testing

- minimize patient distress while ensuring compliance with a follow-up that may extend up to 4 years

- determine when it’s appropriate to refer the patient to a pulmonologist and/or pulmonary nodule clinic or registry.

Taking these steps, however, can be challenging. In interviews, 15 primary care clinicians who care for patients with pulmonary nodules expressed concerns about limitations in time, knowledge, and resources, as well as a fear about such patients “falling through the cracks.”3 Familiarity with current evidence-based guidelines such as those from the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) and knowledge of emerging data on the management of various types of nodules are imperative.

To that end, this review will fill in the information gaps and provide guidance on how best to communicate what is known about a particular type of nodule with the patient who has one. (See “What to say to improve joint decision-making.”4-7) But first, a word about terminology.

What to say to improve joint decision-making4-7

Diagnosis and follow-up of a pulmonary nodule takes an emotional toll on patients, who often have a poor sense of what the presence of a nodule signifies. When caring for a patient with a pulmonary nodule, it’s essential to have an effective communication strategy to ensure that he or she is a well-informed partner in decision-making.

Specifically, you'll need to describe the type of nodule that the patient has, how fast it might grow and its malignancy potential, steps that will need to be taken, and the importance of smoking cessation (if the patient smokes).

Ask the patient about any concerns/fears he or she may have, and provide resources to reduce them. Emphasize shared decision-making and discuss the rationale for various management plans and the limitations of diagnostic tests. Do not minimize the issue; emphasize the need for, and importance of, prolonged follow-up—even for a patient who has a small, low-risk nodule.

Solid vs subsolid pulmonary nodules

Solid pulmonary nodules. Traditionally, the term “solitary pulmonary nodule” has been used to describe a single, well-circumscribed, radiographic opacity that measures up to 3 cm in diameter and is completely surrounded by aerated lung.1,8 The term “solitary” is now less useful because increasingly sensitive imaging techniques often reveal more than one nodule. In the absence of evidence of features that strongly suggest a benign etiology, these are now commonly referred to as indeterminate solid nodules.

Subsolid nodules are pulmonary nodules that have unique characteristics and require separate guidelines for management. Subsolid nodules include pure ground glass nodules (GGNs) and part solid nodules. GGNs are focal nodular areas of increased lung attenuation through which normal parenchymal structures such as airways, vessels, and interlobular septa can be visualized.1,8 Part solid nodules have a solid component. They are usually, but not necessarily, >50% ground glass in appearance.

Lung masses. Focal pulmonary lesions >3 cm in diameter are called lung masses and are presumed to be malignant (bronchogenic carcinoma) unless proven otherwise.1,8

The specific approach to evaluating and monitoring a pulmonary nodule varies depending on whether the nodule is solid or subsolid and other factors, including the nodule’s size.

Monitoring solid nodules

Monitoring of an indeterminate solid nodule is largely determined by the patient’s risk profile and the characteristics of the identified nodule.1 Independent patient predictors of malignancy include older age, smoking status, and history of prior malignancy (>5 years ago). Less established predictors are the presence of moderate or severe obstructive lung disease and exposure to particulate or sulfur oxide-related pollution.9

Patients who have an indeterminate nodule identified on chest x-ray should undergo a chest CT scan, preferably with thin sections through the nodule to help characterize it.1 Nodule characteristics that can help predict a patient’s risk of malignancy include the size (>8 mm confers higher risk), malignant rate of growth, edge characteristics (spiculation or irregular edges), thickness of the wall of a cavitary pulmonary nodule (≥16 mm has a likelihood ratio [LR] 37.97 of malignancy), and the location of the nodule (upper or middle lobe [LR=1.2 to 1.6]). 10 A lack of growth over 2 years and a benign pattern of calcification eliminate the need for further evaluation.

Validated tools to help guide decision-making. Although many physicians estimate pretest probability of malignancy intuitively, validated tools are readily available and can help in clinical decision-making.11 One such tool is the Mayo model, which is available at http://reference.medscape.com/calculator/solitary-pulmonary-nodule-risk. This model takes into account the patient’s age, smoking status, history of cancer, and characteristics of the nodule.

Solid nodules >8 mm to 3 cm

For a patient with a solid nodule >8 mm to 3 cm, ACCP guidelines suggest that physicians estimate the pretest probability of malignancy qualitatively using their clinical judgment and/or quantitatively by using a validated model, such as the Mayo model described above.

Based on the patient’s probability of malignancy, management options include continued CT surveillance, positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, CT-guided needle lung biopsy, bronchoscopy with biopsy, or surgical wedge resection (ALGORITHM 1).1

CT surveillance is recommended for individuals:

- with very low (<5%) probability of malignancy

- with low to moderate (5% to 30%) or moderate to high (31% to 65%) probability of malignancy with negative functional imaging (PET)

- with high probability of malignancy (>65%) when needle biopsy is nondiagnostic and the lesion is not hypermetabolic on PET scan.

Surveillance is also recommended when a fully informed patient prefers nonaggressive management. The intervals for serial CT in this population are at 3 to 6 months, 9 to 12 months, and 18 to 24 months.

In an individual with a solid indeterminate nodule with a high probability of malignancy (>65%), functional imaging should not be performed to characterize the nodule. It may, however, be performed for staging.

Time for biopsy or resection? If a nodule shows evidence of malignant growth on serial imaging, nonsurgical biopsy (CT scan-guided transthoracic needle biopsy, bronchoscopy guided by fluoroscopy, endobronchial ultrasound, electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy, or virtual bronchoscopy navigation) or surgical resection is recommended.

Nonsurgical biopsy is also recommended when the patient’s pretest probability and imaging test results are discordant, when a benign diagnosis requires specific medical treatment, or if a fully informed patient desires proof of diagnosis prior to surgery.

Thoracoscopy with wedge resection is the gold standard for diagnosis of a malignant nodule. It is recommended:

- when the clinical probability of malignancy is high (>65%)

- when the nodule is intensely hypermetabolic by PET scan or positive by other functional imaging tests

- when nonsurgical biopsy is suggestive of malignancy

- when a fully informed patient prefers a definitive diagnostic procedure.

CASE 1 › The FP contacts Mr. D and advises that he get a chest CT to better characterize his pulmonary nodule. A thin-slice CT of the lung reveals that the 13-mm solid nodule in the right upper lobe has spiculated margins. According to the Mayo risk calculator, Mr. D is at moderate risk of malignancy (32.5%). Mr. D and his physician discuss the findings and possible management options, and Mr. D opts to have a PET scan. The FP gives Mr. D literature on pulmonary nodules and contact information for the provider team. A PET scan shows negative uptake. Mr. D and his physician discuss CT surveillance and nonsurgical biopsy. He opts for CT surveillance. The next CT is scheduled for 3 months.

Solid nodules ≤8 mm

Management of these lesions generally follows the consensus-based guidelines that were first published by the Fleischner Society and subsequently endorsed by the ACCP.1 The 2 main determinants that guide management of nodules ≤8 mm are the patient’s risk factors for cancer and nodule size (ALGORITHM 2).1 The Fleischner guidelines pertain only to patients older than age 35 with no current extra pulmonary malignancy or unexplained fevers. The ACCP guidelines, although similar, do not include these limitations. Patient risk factors include history of smoking, older age, and a history of malignancy.1

Patients with no risk factors for malignancy. The frequency of surveillance CT is determined by the size of the nodule. Nodules ≤4 mm do not need to be followed. For nodules >4 mm to 6 mm, a repeat CT in 12 months is recommended with no follow-up if stable. For nodules >6 to <8 mm, repeat CT is recommended at 6 to 12 months, and again between 18 and 24 months if unchanged.1Patients with one or more risk factors for malignancy. Nodules ≤4 mm should be reevaluated at 12 months in patients with one or more risk factors; no additional follow-up is needed if unchanged. For nodules >4 mm to 6 mm, CT should be repeated between 6 and 12 months and again between 18 and 24 months. Nodules >6 mm to <8 mm should be followed initially between 3 to 6 months, then between 9 and 12 months and again at 24 months if unchanged.1

Subsolid nodules require a different approach

Subsolid nodules have a high prevalence of premalignant and malignant disease (adenocarcinoma in situ, minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, and adenocarcinoma). Studies have reported subsolid nodule malignancy rates ranging from 20% to 75%.11-15 This wide range may be a function of different nodule sizes or rates of biopsy. The prevalence increases even further in nodules with a part solid component.

These factors, plus challenges in measuring serial growth on CT and the uncertain prognosis of untreated premalignant disease, make it necessary to have separate guidelines for managing subsolid nodules. The Fleischner Society, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and the American College of Radiology (LungRads) each have differing recommendations on the frequency of follow-up for different-sized subsolid nodules. Newer studies favor a more conservative approach.16 Here we describe the current ACCP guidelines for managing subsolid nodules (ALGORITHM 3).1

GGNs. In an individual with a pure GGN ≤5 mm in diameter, no further evaluation is recommended. In an individual with a pure GGN >5 mm in diameter, annual surveillance with chest CT for at least 3 years is recommended.1

Part solid nodules. In an individual with a part solid nodule ≤8 mm, conduct CT surveillance at 3, 12, and 24 months and then annually for an additional one to 3 years. In a patient with a part solid nodule >8 mm to 15 mm, repeat chest CT at 3 months followed by a PET scan, nonsurgical biopsy, and/or surgical resection if the nodule persists. A patient with a part solid nodule >15 mm should undergo a PET scan, nonsurgical biopsy, and/or surgical resection.

CASE 2 › Ms. G is seen in the office by her FP, and they discuss management options. A repeat CT is done in 3 months and shows a persistent, unchanged nodule. Ms. G opts for a transthoracic biopsy, which reveals adenocarcinoma. Following a PET scan, which shows no evidence of metastasis, curative surgical wedge resection is done.

Multiple subsolid nodules. In a patient who has a dominant nodule and one or more additional nodules, each nodule should be evaluated individually, according to recommendations from the Fleischner Society (the ACCP currently does not have guidelines for managing multiple subsolid nodules). An individual with multiple GGNs that all measure ≤5 mm should receive CT exams at 2 and 4 years.13 A patient with multiple GGNs that include at least one nodule >5 mm but no dominant nodule should undergo follow-up CT at 3 months and annual CT surveillance for at least 3 years.13

CORRESPONDENCE

Samina Yunus, MD, MPH, Cleveland Clinic, Family Medicine, 551 East Washington Street, Chagrin Falls, OH 44022; [email protected].

› Order a computed tomography chest scan, preferably with thin sections through the nodule, to help characterize an indeterminate pulmonary nodule identified on x-ray. B

› Estimate the pretest probability of malignancy for a patient with a pulmonary nodule using your clinical judgment and/or by using a validated model. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE 1 › George D is a 67-year-old patient who has never smoked and who has no history of malignancy. An x-ray of his ribs performed after a fall shows a 13-mm solitary nodule in his right upper lung.

CASE 2 › Cathy B is a healthy 80-year-old with no history of smoking. During a trip to the emergency department for chest pain, she had a computed tomography (CT) scan of her chest. While the chest pain was subsequently attributed to gastroesophageal reflux, the CT revealed a 9-mm part solid nodule that was 75% solid.

How should the physicians caring for each of these patients proceed with their care?

The widespread use of sensitive imaging techniques often leads to the incidental discovery of unrelated—but possibly significant—pulmonary findings. Pulmonary nodules are incidentally discovered on an estimated 0.09% to 0.2% of all chest x-rays, 13% of all chest CT angiograms,1 31% of all cardiac CTs performed for coronary calcium scoring,2 and up to 50% of thin-section chest CT scans.1

The widespread implementation of the US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations on lung cancer screening has further expanded the number of patients in whom asymptomatic pulmonary nodules will be detected. As a result, family physicians (FPs) will frequently encounter this challenging clinical dilemma and will need to:

- assess the patient’s risk profile

- address the patient’s concerns about malignancy while eliciting his or her preference for management

- minimize the risks of surveillance testing

- minimize patient distress while ensuring compliance with a follow-up that may extend up to 4 years

- determine when it’s appropriate to refer the patient to a pulmonologist and/or pulmonary nodule clinic or registry.

Taking these steps, however, can be challenging. In interviews, 15 primary care clinicians who care for patients with pulmonary nodules expressed concerns about limitations in time, knowledge, and resources, as well as a fear about such patients “falling through the cracks.”3 Familiarity with current evidence-based guidelines such as those from the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) and knowledge of emerging data on the management of various types of nodules are imperative.

To that end, this review will fill in the information gaps and provide guidance on how best to communicate what is known about a particular type of nodule with the patient who has one. (See “What to say to improve joint decision-making.”4-7) But first, a word about terminology.

What to say to improve joint decision-making4-7

Diagnosis and follow-up of a pulmonary nodule takes an emotional toll on patients, who often have a poor sense of what the presence of a nodule signifies. When caring for a patient with a pulmonary nodule, it’s essential to have an effective communication strategy to ensure that he or she is a well-informed partner in decision-making.

Specifically, you'll need to describe the type of nodule that the patient has, how fast it might grow and its malignancy potential, steps that will need to be taken, and the importance of smoking cessation (if the patient smokes).

Ask the patient about any concerns/fears he or she may have, and provide resources to reduce them. Emphasize shared decision-making and discuss the rationale for various management plans and the limitations of diagnostic tests. Do not minimize the issue; emphasize the need for, and importance of, prolonged follow-up—even for a patient who has a small, low-risk nodule.