User login

Managing interstitial lung disease detected on CT during lung cancer screening

Primary care physicians are playing a bigger role in evaluating the incidental finding of interstitial lung diseases since the recent publication of guidelines recommending computed tomography (CT) to screen for lung cancer.

In August 2011, the National Cancer Institute published its findings from the National Lung Screening Trial, which demonstrated a 20% reduction in mortality from lung cancer in patients at high risk screened with low-dose CT.1 Based on these results, the American Cancer Society, the American College of Chest Physicians, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommended annual screening for lung cancer with low-dose CT in adults ages 55 to 74 who have a 30-pack-year smoking history and who currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years.2 In December 2013, the US Preventive Services Task Force published similar guidelines but increased the age range to include high-risk patients ages 55 to 80.3

Bach et al4 estimated that, in 2010 in the United States, 8.6 million people met the criteria used in the National Lung Screening Trial for low-dose CT screening. These are the same criteria as in the multisociety recommendations cited above.2 With such large numbers of patients eligible for CT screening, internists and other primary care physicians are undoubtedly encountering the incidental discovery of nonmalignant pulmonary diseases such as interstitial lung disease.

This article reviews the radiographic characteristics of the most common interstitial lung diseases the internist may encounter on screening CT in long-term smokers.

Referral to a specialist has been associated with lower rates of morbidity and death,5 and a diagnosis of interstitial lung disease should be confirmed by a pulmonologist and a radiologist specializing in differentiating the subtypes. But the primary care physician now plays a critical role in recognizing the need for further evaluation.

HOW COMMON IS INTERSTITIAL LUNG DISEASE IN SMOKERS?

Several studies have published data on the prevalence of interstitial lung disease in patients undergoing low-dose CT for lung cancer screening.

A trial at Mayo Clinic in current and former smokers identified “diffuse lung disease” in 9 (0.9%) of 1,049 participants.6

A trial in Ireland identified idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in 6 (1.3%) of 449 current smokers who underwent low-dose CT screening for lung cancer.7

Sverzellati et al8 evaluated 692 participants in the Multicentric Italian Lung Detection CT screening study and reported a respiratory bronchiolitis pattern in 109 (15.7%), a usual interstitial pneumonia pattern in 2 (0.3%), and other patterns of chronic interstitial pneumonia in 26 (3.8%).

The National Lung Screening Trial reported that the frequency of “clinically significant” incidental findings (including pulmonary fibrosis) in all participants was 7.5%.1 A retrospective analysis of 884 participants at a single site in this trial identified interstitial lung abnormalities in 86 participants (9.7%).9 These abnormalities were further categorized as nonfibrotic in 52 (5.9%) of 884, fibrotic in 19 (2.1%) of 884, and mixed fibrotic and nonfibrotic in 15 (1.7%) of 884.

Follow-up CT at 2 years in this trial demonstrated improvement in 50% and progression in 11% of patients who had nonfibrotic abnormalities, while fibrotic abnormalities improved in no cases and progressed in 37%. Interstitial lung abnormalities were more common in those who currently smoked and in those with more pack-years of cigarette smoking.9

In sum, these trials suggest that low-dose CT screening for lung cancer can detect the most common forms of interstitial lung disease in this at-risk population and can characterize them as fibrotic or nonfibrotic, a distinction important for prognosis and subsequent management.

NONFIBROTIC VS FIBROTIC DISEASE

It is important to distinguish between nonfibrotic and fibrotic interstitial lung disease, as fibrotic disease carries a worse prognosis and is treated differently.

Features of nonfibrotic interstitial lung disease:

- Ground-glass opacities

- Nodules

- Mosaic attenuation or consolidation.

Features of fibrotic interstitial lung disease:

- Combination of ground-glass opacities and reticulation

- Reticulation by itself

- Traction bronchiectasis

- Honeycombing

- Loss of lung volume.

NONFIBROTIC INTERSTITIAL LUNG DISEASES

Given the strong likelihood that a patient undergoing screening CT is either a current or former smoker, physicians may encounter, in addition to emphysema and lung cancer, the following smoking-related interstitial lung diseases, which are primarily nonfibrotic and which frequently coexist (Table 1):

- Respiratory bronchiolitis

- Respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease

- Desquamative interstitial pneumonia

- Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

Respiratory bronchiolitis

Respiratory bronchiolitis occurs mostly in smokers and does not necessarily lead to respiratory symptoms in all patients.10 It cannot always be identified radiographically but occasionally appears as predominantly upper-lobe, patchy ground-glass opacities or ill-defined centrilobular nodules without evidence of fibrosis (Figure 1).

Respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease

In rare cases, respiratory bronchiolitis leads to peribronchial fibrosis invading the alveolar walls, which is then classified as respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease.11 The CT findings in respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease are upper-lobe-predominant centrilobular ground-glass nodules, patchy ground-glass opacities, and bronchial wall thickening (Figure 2).10 Occasionally, mild reticulation is noted without honeycombing. Mild air trapping can be seen in the lower lobes, with centrilobular emphysema in the upper lobes.12

The only successful therapy for respiratory bronchiolitis and respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease is smoking cessation. Finding either of these diseases should prompt aggressive counseling by the internist and consideration of referral to a specialist in interstitial lung disease.

Desquamative interstitial pneumonia

Although pathologically different from respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease, desquamative interstitial pneumonia has a similar clinical and radiographic presentation. Because their features significantly overlap, they are considered a pathomorphologic continuum, representing degrees of severity of the same disease process caused by prolonged tobacco inhalation.10,13

Widespread ground-glass opacities are the predominant CT finding. These are bilateral and symmetric in distribution in 86%, basal and peripheral in 60%, patchy in 20%, and diffuse in 20% (Figure 3).14 Other frequent findings are mild reticulation with traction bronchiectasis and coexistent emphysema (Figure 4).15 The small peripheral cystic spaces noted in this disease most likely represent dilated bronchioles and alveolar ducts rather than honeycombing.16

No additional treatment beyond elimination of smoking has been proven effective for desquamative interstitial pneumonia, and patients who manage to quit smoking generally have a favorable prognosis.17,18

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis

The combination of upper-lobe-predominant cysts and nodules in a young heavy smoker are diagnostic of pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. The cysts are bizarrely shaped, thin- or thick-walled, and nonuniform in size (Figure 5). The irregular cavitary nodules are centrilobular. The disease characteristically spares the costophrenic angles.

Spontaneous pneumothorax is the initial clinical presentation in 15% of patients.16 In the early stages of the disease (nodule-predominant disease without cysts), infection and metastatic disease need to be excluded (Figure 6). In the later stages, the cysts become coalescent, making the distinction between this disease and “burned-out” lymphangioleiomyomatosis or severe emphysema extremely difficult (Figure 7).17 Smoking cessation and corticosteroids are the mainstay of medical therapy for pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and about 50% of patients who quit smoking and receive corticosteroids demonstrate partial or complete clearing of the radiographic abnormalities and symptoms (Figure 8).

FIBROTIC INTERSTITIAL LUNG DISEASES

If CT identifies a diffuse fibrotic pattern, the two most common possibilities (Table 2) are:

- Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia

- Usual interstitial pneumonia.

As noted above, these carry a worse prognosis than the nonfibrotic interstitial lung diseases.

Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia

While most frequently idiopathic, the nonspecific interstitial pneumonia pattern can often be seen in connective tissue diseases. It has also been associated with chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, drug toxicity, and slowly resolving diffuse alveolar damage.19 Although it is not the only pathologic pattern in interstitial lung disease associated with connective tissue disease, it is the most common pattern in systemic sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis-polymyositis, and mixed connective tissue disease.20

The parenchymal changes are typically subpleural and symmetric in distribution (Figure 9). In about one-third of cases, there is a peribronchovascular distribution of the abnormalities (Figure 10).

Ground-glass opacities are the dominant imaging findings, seen in 80% of cases.18 In advanced disease (also referred to as fibrotic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia), patients have accompanying fine or coarse reticular opacities, traction bronchiectasis, and consolidation (Figure 11). Honeycombing is seen in 1% to 5% of patients.21

The most specific sign of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia is sparing of the immediate subpleural lung, apparent in 30% to 50% of patients (Figure 12).22 Subpleural sparing with a peribronchovascular distribution of abnormalities, absence of lobular areas with decreased attenuation, and lack of honeycombing are imaging features that increase the diagnostic confidence of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (Table 3).23 Clinically, compared with those who have usual interstitial pneumonia (see below), patients are younger and more of them are female. These patients also present with extrapulmonary manifestations such as joint involvement, rash, and Raynaud phenomenon. Therefore, these associated symptoms on presentation can help distinguish nonspecific interstitial pneumonia or usual interstitial pneumonia related to connective tissue disease from the idiopathic forms.

The first step in managing nonspecific interstitial pneumonia is to remove all potential exposure to inhaled substances or to drugs. Although immunosuppressive therapy has never been studied in a randomized controlled trial in this disease, numerous reports suggest that patients may respond to prednisone and to steroid-sparing immunosuppressants.24

In several studies, survival rates in nonspecific interstitial pneumonia were significantly greater than in usual interstitial pneumonia independent of the treatment strategy. In long-term follow-up of patients with idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia treated with immunosuppressive therapy, two-thirds remained stable or improved.25–27

Although most connective tissue diseases cause a lung pattern of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, some (eg, rheumatoid arthritis) may present with a pattern of usual interstitial pneumonia. In these cases and in those of advanced fibrotic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, the prognosis is worse, as the disease is less responsive to immunosuppressive therapy.20

Usual interstitial pneumonia

Usual interstitial pneumonia is the most severe form of lung fibrosis. Most cases are idiopathic and are termed idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Other causes of the usual interstitial pneumonia pattern include domestic and occupational environmental exposures, connective tissue disease, and drug toxicity.28 An epidemiologic association between smoking and usual interstitial pneumonia is well documented.28

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis typically affects men ages 50 to 70. Because its risk factors coincide with those of lung cancer, there is a high likelihood of detecting idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis early in this screening population. It has an especially poor prognosis, with a mean survival of 2 to 5 years from the time of diagnosis.18

The distribution of disease in usual interstitial pneumonia is characteristically subpleural and basal. CT features include coarse subpleural reticulation and honeycombing combined with traction bronchiectasis or bronchiolectasis and architectural distortion (Figure 13).18 Honeycombing is the most specific and key diagnostic CT finding for establishing a definitive diagnosis of usual interstitial pneumonia.29 However, ground-glass opacities are present in most patients, typically in the region of interstitial fibrosis, and are always less extensive than the reticulation.30 The findings demonstrate morphologic heterogeneity, with areas of fibrosis adjacent to areas of normal lung (Figure 14).

In addition to the aforementioned imaging features, the 2011 American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society joint guidelines for the CT diagnosis of usual interstitial pneumonia patterns require the absence of atypical features that suggest an alternative diagnosis, including those seen in nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, such as an upper, midlung, or peribronchovascular distribution and extensive ground-glass attenuation.28 Mild mediastinal lymphadenopathy (usually < 1.5 cm in the short axis) is common in usual interstitial pneumonia.31

Because other chronic interstitial pneumonias that may resemble usual interstitial pneumonia have a more favorable course and may respond to immunosuppressive therapy, establishing an early and accurate diagnosis is of the utmost importance.5 Additionally, the emergence of possible new therapies for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis makes early referral to a specialist paramount in these cases. Recent studies have demonstrated significant slowing of the progression of disease in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with both pirfenidone and nintedanib.32,33

DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT

The diagnosis of these nonfibrotic and fibrotic lung diseases is complex. In all cases in which interstitial lung disease is detected on screening CT for lung cancer, the internist should strongly consider further evaluation with dedicated high-resolution CT and early referral to a specialist (Figure 15).

Because smoking cessation is the only recommended treatment for nonfibrotic smoking-related interstitial lung diseases, particular emphasis on smoking cessation counseling is essential.

Referral for bronchoscopy with transbronchial lung biopsy is generally not helpful in the diagnosis of the interstitial lung diseases discussed in this article unless there is a need to rule out infection or neoplasm.34 Referral for surgical lung biopsy may be indicated in some cases of suspected pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, desquamative interstitial pneumonia, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, or usual interstitial pneumonia if the diagnosis is uncertain (Tables 1 and 2).35

The American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society guidelines suggest a multidisciplinary team approach that includes a pathologist, radiologist, and clinician.35 This approach more readily determines the correct diagnosis and relies less on invasive methods such as surgical biopsy and more on noninvasive methods such as radiology and clinical history. Overall, this will promote earlier access to appropriate therapies, clinical trial enrollment, and in more severe cases, lung transplant.

Currently, 23% of all lung transplants worldwide are performed in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Other forms of pulmonary fibrosis account for 3% to 4% of lung transplants performed.36

Evidence suggests that early referral reduces rates of morbidity and death in these patients. The results of a single-center study37 of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis demonstrated that a longer delay from the onset of symptoms to evaluation by a specialist at a tertiary care referral center was associated with a higher rate of death from this disease independent of disease severity. Those with the longest delay in referral had a multivariable-adjusted death rate 3.4 times higher than those with the shortest delay.5,37

In summary, with implementation of the new lung cancer screening guidelines, primary care physicians are more often encountering the incidental finding of interstitial lung disease in their patients. Prompt diagnosis of interstitial lung disease helps ensure that patients receive appropriate care and early consideration for clinical trials and lung transplant.

Primary care physicians play a critical role in the initial identification of key characteristics of the interstitial abnormality—namely, whether the pattern is nonfibrotic or fibrotic—and in the correlation of the history and physical findings to expedite the diagnosis. Subsequently, ordering high-resolution CT for more detailed characterization and prompt referral to a specialist in interstitial lung disease allow for a more rapid and accurate diagnosis, specialized therapy, and supportive care.

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team; Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:395–409.

- Detterbeck FC, Lewis SZ, Diekemper R, Addrizzo-Harris D, Alberts WM. Executive summary: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2013; 143(suppl 5):7S–37S.

- Moyer VA; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for lung cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160:330–338.

- Bach PB, Mirkin JN, Oliver TK, et al. Benefits and harms of CT screening for lung cancer: a systematic review. JAMA 2012; 307:2418–2429.

- Lamas DJ, Kawut SM, Bagiella E, Philip N, Arcasoy SM, Lederer DJ. Delayed access and survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 184:842–847.

- Swensen SJ, Jett JR, Hartman TE, et al. Lung cancer screening with CT: Mayo Clinic experience. Radiology 2003; 226:756–761.

- MacRedmond R, Logan PM, Lee M, Kenny D, Foley C, Costello RW. Screening for lung cancer using low dose CT scanning. Thorax 2004; 59:237–241.

- Sverzellati N, Guerci L, Randi G, et al. Interstitial lung diseases in a lung cancer screening trial. Eur Respir J 2011; 38:392–400.

- Jin GY, Lynch D, Chawla A, et al. Interstitial lung abnormalities in a CT lung cancer screening population: prevalence and progression rate. Radiology 2013; 268:563–571.

- Heyneman LE, Ward S, Lynch DA, Remy-Jardin M, Johkoh T, Müller NL. Respiratory bronchiolitis, respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease, and desquamative interstitial pneumonia: different entities or part of the spectrum of the same disease process? AJR Am J Roentgenol 1999; 173:1617–1622.

- Moon J, du Bois RM, Colby TV, Hansell DM, Nicholson AG. Clinical significance of respiratory bronchiolitis on open lung biopsy and its relationship to smoking related interstitial lung disease. Thorax 1999; 54:1009–1014.

- Holt RM, Schmidt RA, Godwin JD, Raghu G. High resolution CT in respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1993; 17:46–50.

- Ryu JH, Myers JL, Capizzi SA, Douglas WW, Vassallo R, Decker PA. Desquamative interstitial pneumonia and respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease. Chest 2005; 127:178–184.

- Hartman TE, Primack SL, Swensen SJ, Hansell D, McGuinness G, Müller NL. Desquamative interstitial pneumonia: thin-section CT findings in 22 patients. Radiology 1993; 187:787–790.

- Akira M, Yamamoto S, Hara H, Sakatani M, Ueda E. Serial computed tomographic evaluation in desquamative interstitial pneumonia. Thorax 1997; 52:333–337.

- Lacronique J, Roth C, Battesti JP, Basset F, Chretien J. Chest radiological features of pulmonary histiocytosis X: a report based on 50 adult cases. Thorax 1982; 37:104–109.

- Remy-Jardin M, Edme JL, Boulenguez C, Remy J, Mastora I, Sobaszek A. Longitudinal follow-up study of smoker’s lung with thin-section CT in correlation with pulmonary function tests. Radiology 2002; 222:261–270.

- Mueller-Mang C, Grosse C, Schmid K, Stiebellehner L, Bankier AA. What every radiologist should know about idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Radiographics 2007; 27:595–615.

- Katzenstein AL, Fiorelli RF. Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia/fibrosis. Histologic features and clinical significance. Am J Surg Pathol 1994; 18:136–147.

- Bryson T, Sundaram B, Khanna D, Kazerooni EA. Connective tissue disease-associated interstitial pneumonia and idiopathic interstitial pneumonia: similarity and difference. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2014; 35:29–38.

- Desai SR, Veeraraghavan S, Hansell DM, et al. CT features of lung disease in patients with systemic sclerosis: comparison with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. Radiology 2004; 232:560–567.

- Tsubamoto M, Müller NL, Johkoh T, et al. Pathologic subgroups of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia: differential diagnosis from other idiopathic interstitial pneumonias on high-resolution computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2005; 29:793–800.

- Silva CI, Müller NL, Lynch DA, et al. Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis: differentiation from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia by using thin-section CT. Radiology 2008; 246:288–297.

- Antin-Ozerkis D, Rubinowitz A. An update on nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. Clin Pulm Med 2010; 17:122–128.

- Daniil ZD, Gilchrist FC, Nicholson AG, et al. A histologic pattern of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia is associated with a better prognosis than usual interstitial pneumonia in patients with cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 160:899–905.

- Travis WD, Matsui K, Moss J, Ferrans VJ. Idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia: prognostic significance of cellular and fibrosing patterns: survival comparison with usual interstitial pneumonia and desquamative interstitial pneumonia. Am J Surg Pathol 2000; 24:19–33.

- Riha RL, Duhig EE, Clarke BE, Steele RH, Slaughter RE, Zimmerman PV. Survival of patients with biopsy-proven usual interstitial pneumonia and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2002; 19:1114–1118.

- Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, et al; ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Committee on Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 183:788–824.

- du Bois RM. An earlier and more confident diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir Rev 2012; 21:141–146.

- Nishimura K, Kitaichi M, Izumi T, Nagai S, Kanaoka M, Itoh H. Usual interstitial pneumonia: histologic correlation with high-resolution CT. Radiology 1992; 182:337–342.

- Souza CA, Müller NL, Lee KS, Johkoh T, Mitsuhiro H, Chong S. Idiopathic interstitial pneumonias: prevalence of mediastinal lymph node enlargement in 206 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2006; 186:995–999.

- King TE Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al; ASCEND Study Group. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:2083–2092.

- Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, et al; INPULSIS Trial Investigators. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:2071–2082.

- Bradley B, Branley HM, Egan JJ, et al; British Thoracic Society Interstitial Lung Disease Guideline Group, British Thoracic Society Standards of Care Committee; Thoracic Society of Australia; New Zealand Thoracic Society; Irish Thoracic Society. Interstitial lung disease guideline: the British Thoracic Society in collaboration with the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand and the Irish Thoracic Society. Thorax 2008; 63(suppl 5):v1–v58.

- Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM, et al; ATS/ERS Committee on Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 188:733–748.

- Stehlik J, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, et al; International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: 29th official adult heart transplant report—2012. J Heart Lung Transplant 2012; 31:1052–1064.

- Oldham JM, Noth I. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: early detection and referral. Respir Med 2014; 108:819–829.

Primary care physicians are playing a bigger role in evaluating the incidental finding of interstitial lung diseases since the recent publication of guidelines recommending computed tomography (CT) to screen for lung cancer.

In August 2011, the National Cancer Institute published its findings from the National Lung Screening Trial, which demonstrated a 20% reduction in mortality from lung cancer in patients at high risk screened with low-dose CT.1 Based on these results, the American Cancer Society, the American College of Chest Physicians, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommended annual screening for lung cancer with low-dose CT in adults ages 55 to 74 who have a 30-pack-year smoking history and who currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years.2 In December 2013, the US Preventive Services Task Force published similar guidelines but increased the age range to include high-risk patients ages 55 to 80.3

Bach et al4 estimated that, in 2010 in the United States, 8.6 million people met the criteria used in the National Lung Screening Trial for low-dose CT screening. These are the same criteria as in the multisociety recommendations cited above.2 With such large numbers of patients eligible for CT screening, internists and other primary care physicians are undoubtedly encountering the incidental discovery of nonmalignant pulmonary diseases such as interstitial lung disease.

This article reviews the radiographic characteristics of the most common interstitial lung diseases the internist may encounter on screening CT in long-term smokers.

Referral to a specialist has been associated with lower rates of morbidity and death,5 and a diagnosis of interstitial lung disease should be confirmed by a pulmonologist and a radiologist specializing in differentiating the subtypes. But the primary care physician now plays a critical role in recognizing the need for further evaluation.

HOW COMMON IS INTERSTITIAL LUNG DISEASE IN SMOKERS?

Several studies have published data on the prevalence of interstitial lung disease in patients undergoing low-dose CT for lung cancer screening.

A trial at Mayo Clinic in current and former smokers identified “diffuse lung disease” in 9 (0.9%) of 1,049 participants.6

A trial in Ireland identified idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in 6 (1.3%) of 449 current smokers who underwent low-dose CT screening for lung cancer.7

Sverzellati et al8 evaluated 692 participants in the Multicentric Italian Lung Detection CT screening study and reported a respiratory bronchiolitis pattern in 109 (15.7%), a usual interstitial pneumonia pattern in 2 (0.3%), and other patterns of chronic interstitial pneumonia in 26 (3.8%).

The National Lung Screening Trial reported that the frequency of “clinically significant” incidental findings (including pulmonary fibrosis) in all participants was 7.5%.1 A retrospective analysis of 884 participants at a single site in this trial identified interstitial lung abnormalities in 86 participants (9.7%).9 These abnormalities were further categorized as nonfibrotic in 52 (5.9%) of 884, fibrotic in 19 (2.1%) of 884, and mixed fibrotic and nonfibrotic in 15 (1.7%) of 884.

Follow-up CT at 2 years in this trial demonstrated improvement in 50% and progression in 11% of patients who had nonfibrotic abnormalities, while fibrotic abnormalities improved in no cases and progressed in 37%. Interstitial lung abnormalities were more common in those who currently smoked and in those with more pack-years of cigarette smoking.9

In sum, these trials suggest that low-dose CT screening for lung cancer can detect the most common forms of interstitial lung disease in this at-risk population and can characterize them as fibrotic or nonfibrotic, a distinction important for prognosis and subsequent management.

NONFIBROTIC VS FIBROTIC DISEASE

It is important to distinguish between nonfibrotic and fibrotic interstitial lung disease, as fibrotic disease carries a worse prognosis and is treated differently.

Features of nonfibrotic interstitial lung disease:

- Ground-glass opacities

- Nodules

- Mosaic attenuation or consolidation.

Features of fibrotic interstitial lung disease:

- Combination of ground-glass opacities and reticulation

- Reticulation by itself

- Traction bronchiectasis

- Honeycombing

- Loss of lung volume.

NONFIBROTIC INTERSTITIAL LUNG DISEASES

Given the strong likelihood that a patient undergoing screening CT is either a current or former smoker, physicians may encounter, in addition to emphysema and lung cancer, the following smoking-related interstitial lung diseases, which are primarily nonfibrotic and which frequently coexist (Table 1):

- Respiratory bronchiolitis

- Respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease

- Desquamative interstitial pneumonia

- Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

Respiratory bronchiolitis

Respiratory bronchiolitis occurs mostly in smokers and does not necessarily lead to respiratory symptoms in all patients.10 It cannot always be identified radiographically but occasionally appears as predominantly upper-lobe, patchy ground-glass opacities or ill-defined centrilobular nodules without evidence of fibrosis (Figure 1).

Respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease

In rare cases, respiratory bronchiolitis leads to peribronchial fibrosis invading the alveolar walls, which is then classified as respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease.11 The CT findings in respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease are upper-lobe-predominant centrilobular ground-glass nodules, patchy ground-glass opacities, and bronchial wall thickening (Figure 2).10 Occasionally, mild reticulation is noted without honeycombing. Mild air trapping can be seen in the lower lobes, with centrilobular emphysema in the upper lobes.12

The only successful therapy for respiratory bronchiolitis and respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease is smoking cessation. Finding either of these diseases should prompt aggressive counseling by the internist and consideration of referral to a specialist in interstitial lung disease.

Desquamative interstitial pneumonia

Although pathologically different from respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease, desquamative interstitial pneumonia has a similar clinical and radiographic presentation. Because their features significantly overlap, they are considered a pathomorphologic continuum, representing degrees of severity of the same disease process caused by prolonged tobacco inhalation.10,13

Widespread ground-glass opacities are the predominant CT finding. These are bilateral and symmetric in distribution in 86%, basal and peripheral in 60%, patchy in 20%, and diffuse in 20% (Figure 3).14 Other frequent findings are mild reticulation with traction bronchiectasis and coexistent emphysema (Figure 4).15 The small peripheral cystic spaces noted in this disease most likely represent dilated bronchioles and alveolar ducts rather than honeycombing.16

No additional treatment beyond elimination of smoking has been proven effective for desquamative interstitial pneumonia, and patients who manage to quit smoking generally have a favorable prognosis.17,18

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis

The combination of upper-lobe-predominant cysts and nodules in a young heavy smoker are diagnostic of pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. The cysts are bizarrely shaped, thin- or thick-walled, and nonuniform in size (Figure 5). The irregular cavitary nodules are centrilobular. The disease characteristically spares the costophrenic angles.

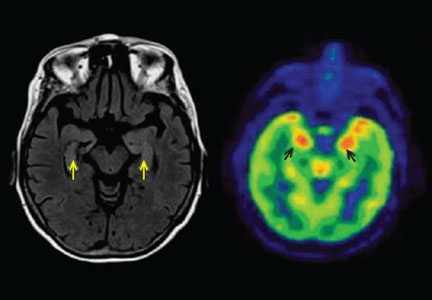

Spontaneous pneumothorax is the initial clinical presentation in 15% of patients.16 In the early stages of the disease (nodule-predominant disease without cysts), infection and metastatic disease need to be excluded (Figure 6). In the later stages, the cysts become coalescent, making the distinction between this disease and “burned-out” lymphangioleiomyomatosis or severe emphysema extremely difficult (Figure 7).17 Smoking cessation and corticosteroids are the mainstay of medical therapy for pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and about 50% of patients who quit smoking and receive corticosteroids demonstrate partial or complete clearing of the radiographic abnormalities and symptoms (Figure 8).

FIBROTIC INTERSTITIAL LUNG DISEASES

If CT identifies a diffuse fibrotic pattern, the two most common possibilities (Table 2) are:

- Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia

- Usual interstitial pneumonia.

As noted above, these carry a worse prognosis than the nonfibrotic interstitial lung diseases.

Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia

While most frequently idiopathic, the nonspecific interstitial pneumonia pattern can often be seen in connective tissue diseases. It has also been associated with chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, drug toxicity, and slowly resolving diffuse alveolar damage.19 Although it is not the only pathologic pattern in interstitial lung disease associated with connective tissue disease, it is the most common pattern in systemic sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis-polymyositis, and mixed connective tissue disease.20

The parenchymal changes are typically subpleural and symmetric in distribution (Figure 9). In about one-third of cases, there is a peribronchovascular distribution of the abnormalities (Figure 10).

Ground-glass opacities are the dominant imaging findings, seen in 80% of cases.18 In advanced disease (also referred to as fibrotic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia), patients have accompanying fine or coarse reticular opacities, traction bronchiectasis, and consolidation (Figure 11). Honeycombing is seen in 1% to 5% of patients.21

The most specific sign of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia is sparing of the immediate subpleural lung, apparent in 30% to 50% of patients (Figure 12).22 Subpleural sparing with a peribronchovascular distribution of abnormalities, absence of lobular areas with decreased attenuation, and lack of honeycombing are imaging features that increase the diagnostic confidence of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (Table 3).23 Clinically, compared with those who have usual interstitial pneumonia (see below), patients are younger and more of them are female. These patients also present with extrapulmonary manifestations such as joint involvement, rash, and Raynaud phenomenon. Therefore, these associated symptoms on presentation can help distinguish nonspecific interstitial pneumonia or usual interstitial pneumonia related to connective tissue disease from the idiopathic forms.

The first step in managing nonspecific interstitial pneumonia is to remove all potential exposure to inhaled substances or to drugs. Although immunosuppressive therapy has never been studied in a randomized controlled trial in this disease, numerous reports suggest that patients may respond to prednisone and to steroid-sparing immunosuppressants.24

In several studies, survival rates in nonspecific interstitial pneumonia were significantly greater than in usual interstitial pneumonia independent of the treatment strategy. In long-term follow-up of patients with idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia treated with immunosuppressive therapy, two-thirds remained stable or improved.25–27

Although most connective tissue diseases cause a lung pattern of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, some (eg, rheumatoid arthritis) may present with a pattern of usual interstitial pneumonia. In these cases and in those of advanced fibrotic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, the prognosis is worse, as the disease is less responsive to immunosuppressive therapy.20

Usual interstitial pneumonia

Usual interstitial pneumonia is the most severe form of lung fibrosis. Most cases are idiopathic and are termed idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Other causes of the usual interstitial pneumonia pattern include domestic and occupational environmental exposures, connective tissue disease, and drug toxicity.28 An epidemiologic association between smoking and usual interstitial pneumonia is well documented.28

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis typically affects men ages 50 to 70. Because its risk factors coincide with those of lung cancer, there is a high likelihood of detecting idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis early in this screening population. It has an especially poor prognosis, with a mean survival of 2 to 5 years from the time of diagnosis.18

The distribution of disease in usual interstitial pneumonia is characteristically subpleural and basal. CT features include coarse subpleural reticulation and honeycombing combined with traction bronchiectasis or bronchiolectasis and architectural distortion (Figure 13).18 Honeycombing is the most specific and key diagnostic CT finding for establishing a definitive diagnosis of usual interstitial pneumonia.29 However, ground-glass opacities are present in most patients, typically in the region of interstitial fibrosis, and are always less extensive than the reticulation.30 The findings demonstrate morphologic heterogeneity, with areas of fibrosis adjacent to areas of normal lung (Figure 14).

In addition to the aforementioned imaging features, the 2011 American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society joint guidelines for the CT diagnosis of usual interstitial pneumonia patterns require the absence of atypical features that suggest an alternative diagnosis, including those seen in nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, such as an upper, midlung, or peribronchovascular distribution and extensive ground-glass attenuation.28 Mild mediastinal lymphadenopathy (usually < 1.5 cm in the short axis) is common in usual interstitial pneumonia.31

Because other chronic interstitial pneumonias that may resemble usual interstitial pneumonia have a more favorable course and may respond to immunosuppressive therapy, establishing an early and accurate diagnosis is of the utmost importance.5 Additionally, the emergence of possible new therapies for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis makes early referral to a specialist paramount in these cases. Recent studies have demonstrated significant slowing of the progression of disease in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with both pirfenidone and nintedanib.32,33

DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT

The diagnosis of these nonfibrotic and fibrotic lung diseases is complex. In all cases in which interstitial lung disease is detected on screening CT for lung cancer, the internist should strongly consider further evaluation with dedicated high-resolution CT and early referral to a specialist (Figure 15).

Because smoking cessation is the only recommended treatment for nonfibrotic smoking-related interstitial lung diseases, particular emphasis on smoking cessation counseling is essential.

Referral for bronchoscopy with transbronchial lung biopsy is generally not helpful in the diagnosis of the interstitial lung diseases discussed in this article unless there is a need to rule out infection or neoplasm.34 Referral for surgical lung biopsy may be indicated in some cases of suspected pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, desquamative interstitial pneumonia, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, or usual interstitial pneumonia if the diagnosis is uncertain (Tables 1 and 2).35

The American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society guidelines suggest a multidisciplinary team approach that includes a pathologist, radiologist, and clinician.35 This approach more readily determines the correct diagnosis and relies less on invasive methods such as surgical biopsy and more on noninvasive methods such as radiology and clinical history. Overall, this will promote earlier access to appropriate therapies, clinical trial enrollment, and in more severe cases, lung transplant.

Currently, 23% of all lung transplants worldwide are performed in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Other forms of pulmonary fibrosis account for 3% to 4% of lung transplants performed.36

Evidence suggests that early referral reduces rates of morbidity and death in these patients. The results of a single-center study37 of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis demonstrated that a longer delay from the onset of symptoms to evaluation by a specialist at a tertiary care referral center was associated with a higher rate of death from this disease independent of disease severity. Those with the longest delay in referral had a multivariable-adjusted death rate 3.4 times higher than those with the shortest delay.5,37

In summary, with implementation of the new lung cancer screening guidelines, primary care physicians are more often encountering the incidental finding of interstitial lung disease in their patients. Prompt diagnosis of interstitial lung disease helps ensure that patients receive appropriate care and early consideration for clinical trials and lung transplant.

Primary care physicians play a critical role in the initial identification of key characteristics of the interstitial abnormality—namely, whether the pattern is nonfibrotic or fibrotic—and in the correlation of the history and physical findings to expedite the diagnosis. Subsequently, ordering high-resolution CT for more detailed characterization and prompt referral to a specialist in interstitial lung disease allow for a more rapid and accurate diagnosis, specialized therapy, and supportive care.

Primary care physicians are playing a bigger role in evaluating the incidental finding of interstitial lung diseases since the recent publication of guidelines recommending computed tomography (CT) to screen for lung cancer.

In August 2011, the National Cancer Institute published its findings from the National Lung Screening Trial, which demonstrated a 20% reduction in mortality from lung cancer in patients at high risk screened with low-dose CT.1 Based on these results, the American Cancer Society, the American College of Chest Physicians, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommended annual screening for lung cancer with low-dose CT in adults ages 55 to 74 who have a 30-pack-year smoking history and who currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years.2 In December 2013, the US Preventive Services Task Force published similar guidelines but increased the age range to include high-risk patients ages 55 to 80.3

Bach et al4 estimated that, in 2010 in the United States, 8.6 million people met the criteria used in the National Lung Screening Trial for low-dose CT screening. These are the same criteria as in the multisociety recommendations cited above.2 With such large numbers of patients eligible for CT screening, internists and other primary care physicians are undoubtedly encountering the incidental discovery of nonmalignant pulmonary diseases such as interstitial lung disease.

This article reviews the radiographic characteristics of the most common interstitial lung diseases the internist may encounter on screening CT in long-term smokers.

Referral to a specialist has been associated with lower rates of morbidity and death,5 and a diagnosis of interstitial lung disease should be confirmed by a pulmonologist and a radiologist specializing in differentiating the subtypes. But the primary care physician now plays a critical role in recognizing the need for further evaluation.

HOW COMMON IS INTERSTITIAL LUNG DISEASE IN SMOKERS?

Several studies have published data on the prevalence of interstitial lung disease in patients undergoing low-dose CT for lung cancer screening.

A trial at Mayo Clinic in current and former smokers identified “diffuse lung disease” in 9 (0.9%) of 1,049 participants.6

A trial in Ireland identified idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in 6 (1.3%) of 449 current smokers who underwent low-dose CT screening for lung cancer.7

Sverzellati et al8 evaluated 692 participants in the Multicentric Italian Lung Detection CT screening study and reported a respiratory bronchiolitis pattern in 109 (15.7%), a usual interstitial pneumonia pattern in 2 (0.3%), and other patterns of chronic interstitial pneumonia in 26 (3.8%).

The National Lung Screening Trial reported that the frequency of “clinically significant” incidental findings (including pulmonary fibrosis) in all participants was 7.5%.1 A retrospective analysis of 884 participants at a single site in this trial identified interstitial lung abnormalities in 86 participants (9.7%).9 These abnormalities were further categorized as nonfibrotic in 52 (5.9%) of 884, fibrotic in 19 (2.1%) of 884, and mixed fibrotic and nonfibrotic in 15 (1.7%) of 884.

Follow-up CT at 2 years in this trial demonstrated improvement in 50% and progression in 11% of patients who had nonfibrotic abnormalities, while fibrotic abnormalities improved in no cases and progressed in 37%. Interstitial lung abnormalities were more common in those who currently smoked and in those with more pack-years of cigarette smoking.9

In sum, these trials suggest that low-dose CT screening for lung cancer can detect the most common forms of interstitial lung disease in this at-risk population and can characterize them as fibrotic or nonfibrotic, a distinction important for prognosis and subsequent management.

NONFIBROTIC VS FIBROTIC DISEASE

It is important to distinguish between nonfibrotic and fibrotic interstitial lung disease, as fibrotic disease carries a worse prognosis and is treated differently.

Features of nonfibrotic interstitial lung disease:

- Ground-glass opacities

- Nodules

- Mosaic attenuation or consolidation.

Features of fibrotic interstitial lung disease:

- Combination of ground-glass opacities and reticulation

- Reticulation by itself

- Traction bronchiectasis

- Honeycombing

- Loss of lung volume.

NONFIBROTIC INTERSTITIAL LUNG DISEASES

Given the strong likelihood that a patient undergoing screening CT is either a current or former smoker, physicians may encounter, in addition to emphysema and lung cancer, the following smoking-related interstitial lung diseases, which are primarily nonfibrotic and which frequently coexist (Table 1):

- Respiratory bronchiolitis

- Respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease

- Desquamative interstitial pneumonia

- Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

Respiratory bronchiolitis

Respiratory bronchiolitis occurs mostly in smokers and does not necessarily lead to respiratory symptoms in all patients.10 It cannot always be identified radiographically but occasionally appears as predominantly upper-lobe, patchy ground-glass opacities or ill-defined centrilobular nodules without evidence of fibrosis (Figure 1).

Respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease

In rare cases, respiratory bronchiolitis leads to peribronchial fibrosis invading the alveolar walls, which is then classified as respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease.11 The CT findings in respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease are upper-lobe-predominant centrilobular ground-glass nodules, patchy ground-glass opacities, and bronchial wall thickening (Figure 2).10 Occasionally, mild reticulation is noted without honeycombing. Mild air trapping can be seen in the lower lobes, with centrilobular emphysema in the upper lobes.12

The only successful therapy for respiratory bronchiolitis and respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease is smoking cessation. Finding either of these diseases should prompt aggressive counseling by the internist and consideration of referral to a specialist in interstitial lung disease.

Desquamative interstitial pneumonia

Although pathologically different from respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease, desquamative interstitial pneumonia has a similar clinical and radiographic presentation. Because their features significantly overlap, they are considered a pathomorphologic continuum, representing degrees of severity of the same disease process caused by prolonged tobacco inhalation.10,13

Widespread ground-glass opacities are the predominant CT finding. These are bilateral and symmetric in distribution in 86%, basal and peripheral in 60%, patchy in 20%, and diffuse in 20% (Figure 3).14 Other frequent findings are mild reticulation with traction bronchiectasis and coexistent emphysema (Figure 4).15 The small peripheral cystic spaces noted in this disease most likely represent dilated bronchioles and alveolar ducts rather than honeycombing.16

No additional treatment beyond elimination of smoking has been proven effective for desquamative interstitial pneumonia, and patients who manage to quit smoking generally have a favorable prognosis.17,18

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis

The combination of upper-lobe-predominant cysts and nodules in a young heavy smoker are diagnostic of pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. The cysts are bizarrely shaped, thin- or thick-walled, and nonuniform in size (Figure 5). The irregular cavitary nodules are centrilobular. The disease characteristically spares the costophrenic angles.

Spontaneous pneumothorax is the initial clinical presentation in 15% of patients.16 In the early stages of the disease (nodule-predominant disease without cysts), infection and metastatic disease need to be excluded (Figure 6). In the later stages, the cysts become coalescent, making the distinction between this disease and “burned-out” lymphangioleiomyomatosis or severe emphysema extremely difficult (Figure 7).17 Smoking cessation and corticosteroids are the mainstay of medical therapy for pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and about 50% of patients who quit smoking and receive corticosteroids demonstrate partial or complete clearing of the radiographic abnormalities and symptoms (Figure 8).

FIBROTIC INTERSTITIAL LUNG DISEASES

If CT identifies a diffuse fibrotic pattern, the two most common possibilities (Table 2) are:

- Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia

- Usual interstitial pneumonia.

As noted above, these carry a worse prognosis than the nonfibrotic interstitial lung diseases.

Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia

While most frequently idiopathic, the nonspecific interstitial pneumonia pattern can often be seen in connective tissue diseases. It has also been associated with chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, drug toxicity, and slowly resolving diffuse alveolar damage.19 Although it is not the only pathologic pattern in interstitial lung disease associated with connective tissue disease, it is the most common pattern in systemic sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis-polymyositis, and mixed connective tissue disease.20

The parenchymal changes are typically subpleural and symmetric in distribution (Figure 9). In about one-third of cases, there is a peribronchovascular distribution of the abnormalities (Figure 10).

Ground-glass opacities are the dominant imaging findings, seen in 80% of cases.18 In advanced disease (also referred to as fibrotic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia), patients have accompanying fine or coarse reticular opacities, traction bronchiectasis, and consolidation (Figure 11). Honeycombing is seen in 1% to 5% of patients.21

The most specific sign of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia is sparing of the immediate subpleural lung, apparent in 30% to 50% of patients (Figure 12).22 Subpleural sparing with a peribronchovascular distribution of abnormalities, absence of lobular areas with decreased attenuation, and lack of honeycombing are imaging features that increase the diagnostic confidence of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (Table 3).23 Clinically, compared with those who have usual interstitial pneumonia (see below), patients are younger and more of them are female. These patients also present with extrapulmonary manifestations such as joint involvement, rash, and Raynaud phenomenon. Therefore, these associated symptoms on presentation can help distinguish nonspecific interstitial pneumonia or usual interstitial pneumonia related to connective tissue disease from the idiopathic forms.

The first step in managing nonspecific interstitial pneumonia is to remove all potential exposure to inhaled substances or to drugs. Although immunosuppressive therapy has never been studied in a randomized controlled trial in this disease, numerous reports suggest that patients may respond to prednisone and to steroid-sparing immunosuppressants.24

In several studies, survival rates in nonspecific interstitial pneumonia were significantly greater than in usual interstitial pneumonia independent of the treatment strategy. In long-term follow-up of patients with idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia treated with immunosuppressive therapy, two-thirds remained stable or improved.25–27

Although most connective tissue diseases cause a lung pattern of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, some (eg, rheumatoid arthritis) may present with a pattern of usual interstitial pneumonia. In these cases and in those of advanced fibrotic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, the prognosis is worse, as the disease is less responsive to immunosuppressive therapy.20

Usual interstitial pneumonia

Usual interstitial pneumonia is the most severe form of lung fibrosis. Most cases are idiopathic and are termed idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Other causes of the usual interstitial pneumonia pattern include domestic and occupational environmental exposures, connective tissue disease, and drug toxicity.28 An epidemiologic association between smoking and usual interstitial pneumonia is well documented.28

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis typically affects men ages 50 to 70. Because its risk factors coincide with those of lung cancer, there is a high likelihood of detecting idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis early in this screening population. It has an especially poor prognosis, with a mean survival of 2 to 5 years from the time of diagnosis.18

The distribution of disease in usual interstitial pneumonia is characteristically subpleural and basal. CT features include coarse subpleural reticulation and honeycombing combined with traction bronchiectasis or bronchiolectasis and architectural distortion (Figure 13).18 Honeycombing is the most specific and key diagnostic CT finding for establishing a definitive diagnosis of usual interstitial pneumonia.29 However, ground-glass opacities are present in most patients, typically in the region of interstitial fibrosis, and are always less extensive than the reticulation.30 The findings demonstrate morphologic heterogeneity, with areas of fibrosis adjacent to areas of normal lung (Figure 14).

In addition to the aforementioned imaging features, the 2011 American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society joint guidelines for the CT diagnosis of usual interstitial pneumonia patterns require the absence of atypical features that suggest an alternative diagnosis, including those seen in nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, such as an upper, midlung, or peribronchovascular distribution and extensive ground-glass attenuation.28 Mild mediastinal lymphadenopathy (usually < 1.5 cm in the short axis) is common in usual interstitial pneumonia.31

Because other chronic interstitial pneumonias that may resemble usual interstitial pneumonia have a more favorable course and may respond to immunosuppressive therapy, establishing an early and accurate diagnosis is of the utmost importance.5 Additionally, the emergence of possible new therapies for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis makes early referral to a specialist paramount in these cases. Recent studies have demonstrated significant slowing of the progression of disease in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with both pirfenidone and nintedanib.32,33

DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT

The diagnosis of these nonfibrotic and fibrotic lung diseases is complex. In all cases in which interstitial lung disease is detected on screening CT for lung cancer, the internist should strongly consider further evaluation with dedicated high-resolution CT and early referral to a specialist (Figure 15).

Because smoking cessation is the only recommended treatment for nonfibrotic smoking-related interstitial lung diseases, particular emphasis on smoking cessation counseling is essential.

Referral for bronchoscopy with transbronchial lung biopsy is generally not helpful in the diagnosis of the interstitial lung diseases discussed in this article unless there is a need to rule out infection or neoplasm.34 Referral for surgical lung biopsy may be indicated in some cases of suspected pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, desquamative interstitial pneumonia, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, or usual interstitial pneumonia if the diagnosis is uncertain (Tables 1 and 2).35

The American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society guidelines suggest a multidisciplinary team approach that includes a pathologist, radiologist, and clinician.35 This approach more readily determines the correct diagnosis and relies less on invasive methods such as surgical biopsy and more on noninvasive methods such as radiology and clinical history. Overall, this will promote earlier access to appropriate therapies, clinical trial enrollment, and in more severe cases, lung transplant.

Currently, 23% of all lung transplants worldwide are performed in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Other forms of pulmonary fibrosis account for 3% to 4% of lung transplants performed.36

Evidence suggests that early referral reduces rates of morbidity and death in these patients. The results of a single-center study37 of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis demonstrated that a longer delay from the onset of symptoms to evaluation by a specialist at a tertiary care referral center was associated with a higher rate of death from this disease independent of disease severity. Those with the longest delay in referral had a multivariable-adjusted death rate 3.4 times higher than those with the shortest delay.5,37

In summary, with implementation of the new lung cancer screening guidelines, primary care physicians are more often encountering the incidental finding of interstitial lung disease in their patients. Prompt diagnosis of interstitial lung disease helps ensure that patients receive appropriate care and early consideration for clinical trials and lung transplant.

Primary care physicians play a critical role in the initial identification of key characteristics of the interstitial abnormality—namely, whether the pattern is nonfibrotic or fibrotic—and in the correlation of the history and physical findings to expedite the diagnosis. Subsequently, ordering high-resolution CT for more detailed characterization and prompt referral to a specialist in interstitial lung disease allow for a more rapid and accurate diagnosis, specialized therapy, and supportive care.

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team; Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:395–409.

- Detterbeck FC, Lewis SZ, Diekemper R, Addrizzo-Harris D, Alberts WM. Executive summary: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2013; 143(suppl 5):7S–37S.

- Moyer VA; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for lung cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160:330–338.

- Bach PB, Mirkin JN, Oliver TK, et al. Benefits and harms of CT screening for lung cancer: a systematic review. JAMA 2012; 307:2418–2429.

- Lamas DJ, Kawut SM, Bagiella E, Philip N, Arcasoy SM, Lederer DJ. Delayed access and survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 184:842–847.

- Swensen SJ, Jett JR, Hartman TE, et al. Lung cancer screening with CT: Mayo Clinic experience. Radiology 2003; 226:756–761.

- MacRedmond R, Logan PM, Lee M, Kenny D, Foley C, Costello RW. Screening for lung cancer using low dose CT scanning. Thorax 2004; 59:237–241.

- Sverzellati N, Guerci L, Randi G, et al. Interstitial lung diseases in a lung cancer screening trial. Eur Respir J 2011; 38:392–400.

- Jin GY, Lynch D, Chawla A, et al. Interstitial lung abnormalities in a CT lung cancer screening population: prevalence and progression rate. Radiology 2013; 268:563–571.

- Heyneman LE, Ward S, Lynch DA, Remy-Jardin M, Johkoh T, Müller NL. Respiratory bronchiolitis, respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease, and desquamative interstitial pneumonia: different entities or part of the spectrum of the same disease process? AJR Am J Roentgenol 1999; 173:1617–1622.

- Moon J, du Bois RM, Colby TV, Hansell DM, Nicholson AG. Clinical significance of respiratory bronchiolitis on open lung biopsy and its relationship to smoking related interstitial lung disease. Thorax 1999; 54:1009–1014.

- Holt RM, Schmidt RA, Godwin JD, Raghu G. High resolution CT in respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1993; 17:46–50.

- Ryu JH, Myers JL, Capizzi SA, Douglas WW, Vassallo R, Decker PA. Desquamative interstitial pneumonia and respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease. Chest 2005; 127:178–184.

- Hartman TE, Primack SL, Swensen SJ, Hansell D, McGuinness G, Müller NL. Desquamative interstitial pneumonia: thin-section CT findings in 22 patients. Radiology 1993; 187:787–790.

- Akira M, Yamamoto S, Hara H, Sakatani M, Ueda E. Serial computed tomographic evaluation in desquamative interstitial pneumonia. Thorax 1997; 52:333–337.

- Lacronique J, Roth C, Battesti JP, Basset F, Chretien J. Chest radiological features of pulmonary histiocytosis X: a report based on 50 adult cases. Thorax 1982; 37:104–109.

- Remy-Jardin M, Edme JL, Boulenguez C, Remy J, Mastora I, Sobaszek A. Longitudinal follow-up study of smoker’s lung with thin-section CT in correlation with pulmonary function tests. Radiology 2002; 222:261–270.

- Mueller-Mang C, Grosse C, Schmid K, Stiebellehner L, Bankier AA. What every radiologist should know about idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Radiographics 2007; 27:595–615.

- Katzenstein AL, Fiorelli RF. Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia/fibrosis. Histologic features and clinical significance. Am J Surg Pathol 1994; 18:136–147.

- Bryson T, Sundaram B, Khanna D, Kazerooni EA. Connective tissue disease-associated interstitial pneumonia and idiopathic interstitial pneumonia: similarity and difference. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2014; 35:29–38.

- Desai SR, Veeraraghavan S, Hansell DM, et al. CT features of lung disease in patients with systemic sclerosis: comparison with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. Radiology 2004; 232:560–567.

- Tsubamoto M, Müller NL, Johkoh T, et al. Pathologic subgroups of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia: differential diagnosis from other idiopathic interstitial pneumonias on high-resolution computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2005; 29:793–800.

- Silva CI, Müller NL, Lynch DA, et al. Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis: differentiation from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia by using thin-section CT. Radiology 2008; 246:288–297.

- Antin-Ozerkis D, Rubinowitz A. An update on nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. Clin Pulm Med 2010; 17:122–128.

- Daniil ZD, Gilchrist FC, Nicholson AG, et al. A histologic pattern of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia is associated with a better prognosis than usual interstitial pneumonia in patients with cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 160:899–905.

- Travis WD, Matsui K, Moss J, Ferrans VJ. Idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia: prognostic significance of cellular and fibrosing patterns: survival comparison with usual interstitial pneumonia and desquamative interstitial pneumonia. Am J Surg Pathol 2000; 24:19–33.

- Riha RL, Duhig EE, Clarke BE, Steele RH, Slaughter RE, Zimmerman PV. Survival of patients with biopsy-proven usual interstitial pneumonia and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2002; 19:1114–1118.

- Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, et al; ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Committee on Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 183:788–824.

- du Bois RM. An earlier and more confident diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir Rev 2012; 21:141–146.

- Nishimura K, Kitaichi M, Izumi T, Nagai S, Kanaoka M, Itoh H. Usual interstitial pneumonia: histologic correlation with high-resolution CT. Radiology 1992; 182:337–342.

- Souza CA, Müller NL, Lee KS, Johkoh T, Mitsuhiro H, Chong S. Idiopathic interstitial pneumonias: prevalence of mediastinal lymph node enlargement in 206 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2006; 186:995–999.

- King TE Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al; ASCEND Study Group. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:2083–2092.

- Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, et al; INPULSIS Trial Investigators. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:2071–2082.

- Bradley B, Branley HM, Egan JJ, et al; British Thoracic Society Interstitial Lung Disease Guideline Group, British Thoracic Society Standards of Care Committee; Thoracic Society of Australia; New Zealand Thoracic Society; Irish Thoracic Society. Interstitial lung disease guideline: the British Thoracic Society in collaboration with the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand and the Irish Thoracic Society. Thorax 2008; 63(suppl 5):v1–v58.

- Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM, et al; ATS/ERS Committee on Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 188:733–748.

- Stehlik J, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, et al; International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: 29th official adult heart transplant report—2012. J Heart Lung Transplant 2012; 31:1052–1064.

- Oldham JM, Noth I. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: early detection and referral. Respir Med 2014; 108:819–829.

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team; Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:395–409.

- Detterbeck FC, Lewis SZ, Diekemper R, Addrizzo-Harris D, Alberts WM. Executive summary: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2013; 143(suppl 5):7S–37S.

- Moyer VA; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for lung cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160:330–338.

- Bach PB, Mirkin JN, Oliver TK, et al. Benefits and harms of CT screening for lung cancer: a systematic review. JAMA 2012; 307:2418–2429.

- Lamas DJ, Kawut SM, Bagiella E, Philip N, Arcasoy SM, Lederer DJ. Delayed access and survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 184:842–847.

- Swensen SJ, Jett JR, Hartman TE, et al. Lung cancer screening with CT: Mayo Clinic experience. Radiology 2003; 226:756–761.

- MacRedmond R, Logan PM, Lee M, Kenny D, Foley C, Costello RW. Screening for lung cancer using low dose CT scanning. Thorax 2004; 59:237–241.

- Sverzellati N, Guerci L, Randi G, et al. Interstitial lung diseases in a lung cancer screening trial. Eur Respir J 2011; 38:392–400.

- Jin GY, Lynch D, Chawla A, et al. Interstitial lung abnormalities in a CT lung cancer screening population: prevalence and progression rate. Radiology 2013; 268:563–571.

- Heyneman LE, Ward S, Lynch DA, Remy-Jardin M, Johkoh T, Müller NL. Respiratory bronchiolitis, respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease, and desquamative interstitial pneumonia: different entities or part of the spectrum of the same disease process? AJR Am J Roentgenol 1999; 173:1617–1622.

- Moon J, du Bois RM, Colby TV, Hansell DM, Nicholson AG. Clinical significance of respiratory bronchiolitis on open lung biopsy and its relationship to smoking related interstitial lung disease. Thorax 1999; 54:1009–1014.

- Holt RM, Schmidt RA, Godwin JD, Raghu G. High resolution CT in respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1993; 17:46–50.

- Ryu JH, Myers JL, Capizzi SA, Douglas WW, Vassallo R, Decker PA. Desquamative interstitial pneumonia and respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease. Chest 2005; 127:178–184.

- Hartman TE, Primack SL, Swensen SJ, Hansell D, McGuinness G, Müller NL. Desquamative interstitial pneumonia: thin-section CT findings in 22 patients. Radiology 1993; 187:787–790.

- Akira M, Yamamoto S, Hara H, Sakatani M, Ueda E. Serial computed tomographic evaluation in desquamative interstitial pneumonia. Thorax 1997; 52:333–337.

- Lacronique J, Roth C, Battesti JP, Basset F, Chretien J. Chest radiological features of pulmonary histiocytosis X: a report based on 50 adult cases. Thorax 1982; 37:104–109.

- Remy-Jardin M, Edme JL, Boulenguez C, Remy J, Mastora I, Sobaszek A. Longitudinal follow-up study of smoker’s lung with thin-section CT in correlation with pulmonary function tests. Radiology 2002; 222:261–270.

- Mueller-Mang C, Grosse C, Schmid K, Stiebellehner L, Bankier AA. What every radiologist should know about idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Radiographics 2007; 27:595–615.

- Katzenstein AL, Fiorelli RF. Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia/fibrosis. Histologic features and clinical significance. Am J Surg Pathol 1994; 18:136–147.

- Bryson T, Sundaram B, Khanna D, Kazerooni EA. Connective tissue disease-associated interstitial pneumonia and idiopathic interstitial pneumonia: similarity and difference. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2014; 35:29–38.

- Desai SR, Veeraraghavan S, Hansell DM, et al. CT features of lung disease in patients with systemic sclerosis: comparison with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. Radiology 2004; 232:560–567.

- Tsubamoto M, Müller NL, Johkoh T, et al. Pathologic subgroups of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia: differential diagnosis from other idiopathic interstitial pneumonias on high-resolution computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2005; 29:793–800.

- Silva CI, Müller NL, Lynch DA, et al. Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis: differentiation from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia by using thin-section CT. Radiology 2008; 246:288–297.

- Antin-Ozerkis D, Rubinowitz A. An update on nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. Clin Pulm Med 2010; 17:122–128.

- Daniil ZD, Gilchrist FC, Nicholson AG, et al. A histologic pattern of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia is associated with a better prognosis than usual interstitial pneumonia in patients with cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 160:899–905.

- Travis WD, Matsui K, Moss J, Ferrans VJ. Idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia: prognostic significance of cellular and fibrosing patterns: survival comparison with usual interstitial pneumonia and desquamative interstitial pneumonia. Am J Surg Pathol 2000; 24:19–33.

- Riha RL, Duhig EE, Clarke BE, Steele RH, Slaughter RE, Zimmerman PV. Survival of patients with biopsy-proven usual interstitial pneumonia and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2002; 19:1114–1118.

- Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, et al; ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Committee on Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 183:788–824.

- du Bois RM. An earlier and more confident diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir Rev 2012; 21:141–146.

- Nishimura K, Kitaichi M, Izumi T, Nagai S, Kanaoka M, Itoh H. Usual interstitial pneumonia: histologic correlation with high-resolution CT. Radiology 1992; 182:337–342.

- Souza CA, Müller NL, Lee KS, Johkoh T, Mitsuhiro H, Chong S. Idiopathic interstitial pneumonias: prevalence of mediastinal lymph node enlargement in 206 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2006; 186:995–999.

- King TE Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al; ASCEND Study Group. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:2083–2092.

- Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, et al; INPULSIS Trial Investigators. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:2071–2082.

- Bradley B, Branley HM, Egan JJ, et al; British Thoracic Society Interstitial Lung Disease Guideline Group, British Thoracic Society Standards of Care Committee; Thoracic Society of Australia; New Zealand Thoracic Society; Irish Thoracic Society. Interstitial lung disease guideline: the British Thoracic Society in collaboration with the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand and the Irish Thoracic Society. Thorax 2008; 63(suppl 5):v1–v58.

- Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM, et al; ATS/ERS Committee on Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 188:733–748.

- Stehlik J, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, et al; International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: 29th official adult heart transplant report—2012. J Heart Lung Transplant 2012; 31:1052–1064.

- Oldham JM, Noth I. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: early detection and referral. Respir Med 2014; 108:819–829.

KEY POINTS

- Smoking-related interstitial lung diseases can broadly be categorized as fibrotic or nonfibrotic on the basis of their appearance on CT. Fibrotic disease generally carries a worse prognosis.

- Nonfibrotic interstitial lung diseases include respiratory bronchiolitis, respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease, desquamative interstitial pneumonia, and pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

- Smoking-related fibrotic interstitial lung diseases include nonspecific interstitial pneumonia and usual interstitial pneumonia. A subset of usual interstitial pneumonia, called idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, carries the worst prognosis of all.

- If CT detects interstitial lung disease during screening for lung cancer, the clinician should strongly consider further evaluation with dedicated high-resolution CT and early referral to a specialist. Smoking cessation is extremely important.

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome in medical patients

Deprived of alcohol while in the hospital, up to 80% of patients who are alcohol-dependent risk developing alcohol withdrawal syndrome,1 a potentially life-threatening condition. Clinicians should anticipate the syndrome and be ready to treat and prevent its complications.

Because alcoholism is common, nearly every provider will encounter its complications and withdrawal symptoms. Each year, an estimated 1.2 million hospital admissions are related to alcohol abuse, and about 500,000 episodes of withdrawal symptoms are severe enough to require clinical attention.1–3 Nearly 50% of patients with alcohol withdrawal syndrome are middle-class, highly functional individuals, making withdrawal difficult to recognize.1

While acute trauma patients or those with alcohol withdrawal delirium are often admitted directly to an intensive care unit (ICU), many others are at risk for or develop alcohol withdrawal syndrome and are managed initially or wholly on the acute medical unit. While specific statistics have not been published on non-ICU patients with alcohol withdrawal syndrome, they are an important group of patients who need to be well managed to prevent the progression of alcohol withdrawal syndrome to alcohol withdrawal delirium, alcohol withdrawal-induced seizure, and other complications.

This article reviews how to identify and manage alcohol withdrawal symptoms in noncritical, acutely ill medical patients, with practical recommendations for diagnosis and management.

CAN LEAD TO DELIRIUM TREMENS

In people who are physiologically dependent on alcohol, symptoms of withdrawal usually occur after abrupt cessation.4 If not addressed early in the hospitalization, alcohol withdrawal syndrome can progress to alcohol withdrawal delirium (also known as delirium tremens or DTs), in which the mortality rate is 5% to 10%.5,6 Potential mechanisms of DTs include increased dopamine release and dopamine receptor activity, hypersensitivity to N-methyl-d-aspartate, and reduced levels of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA).7