User login

Mid-Atlantic Hospital Medicine Symposium Delivers Practice Pearls for Hospitalists

What do Clostridium difficile, Staphylococcus aureus, and acute pulmonary embolism have in common? They were all topics of discussion at the 2015 Mid-Atlantic Hospital Medicine Symposium, held at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City.

Vikas Saini, MD, FACC, president of the Lown Institute in Brookline, Mass., and associate physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, gave the keynote address on high-value care.

“We’re asking you to do hard things: to be kind to complete strangers, to feel their pain, to be compassionate when you’re on the run,” Dr. Saini said as he urged his fellow physicians to be more personable with patients. “Pull up a chair and sit down. It takes you 30 seconds, but for the patient, it feels like an eternity.” Dr. Saini, a guest lecturer at the symposium, also stressed the importance of being collaborative and encouraged clinicians to join their colleagues in implementing RightCare Rounds.

Following the keynote address, Louis DePalo, MD, an associate professor of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep at Icahn School of Medicine, gave a 30-minute presentation on the management of acute pulmonary embolism (PE).

Dr. DePalo said that in his early days of practicing medicine, PE patients were usually hospitalized without debate. Today, thanks to indices such as the Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index, there are algorithms to determine the severity of PE in patients, allowing doctors to determine whether patients should be discharged or hospitalized. Still, Dr. DePalo added, “Discussions about sending a patient home are complicated.”

If a patient has severe PE, Dr. DePalo advised doctors to analyze studies such as the Pulmonary Embolism Thrombolysis (PEITHO) trial and the Moderate Pulmonary Embolism Treated with Thrombolysis (MOPPETT) trial to determine when to use advanced treatments. “One study may not be sufficient for administering advanced therapies,” Dr. DePalo said. “One study doesn’t make us feel good, so get a lot of data.”

After Dr. DePalo’s presentation, physicians gave presentations on common healthcare-associated infections. Gopi Patel, MD, an assistant professor of infectious diseases at Icahn School of Medicine, discussed Clostridium difficile infection (CDI). “CDI is the most common [healthcare-associated infection] in the United States,” Dr. Patel said as she urged physicians to “be a role model” by practicing good hand hygiene.

Using the updated practice guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America, Tim Sullivan, MD, an assistant professor of infectious diseases at Icahn School of Medicine, discussed skin and soft tissue infections, particularly methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The guidelines “make a very important distinction between purulent and nonpurulent infections,” Dr. Sullivan said. “The majority of nonpurulent infections are caused by strep, [and] treating for strep seems to be sufficient to cure the infection … Adding extra coverage for MRSA is either not helpful or may actually be harmful to patients.”

Purulent infections, which require drainage, “are mostly caused by Staph aureus, including MRSA,” Dr. Sullivan said. “You don’t always have to give antibiotics, but they are recommended when the patient is sick.”

Dr. Sullivan said although “it can be sort of confusing trying to choose the right antibiotics for your patient … almost everyone should just receive vancomycin.” The drug is well-studied, inexpensive at $2.80 per dose for a five-day treatment, and well-tolerated by patients, he added. Yet vancomycin should not be administered to everyone as some patients experience devastating adverse reactions, and vancomycin could potentially cause irreversible hearing loss, he said.

Dr. Sullivan mentioned three new antibiotic treatments for MRSA: telavancin, which the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved in 2009, costs 75 times more than vancomycin; dalbavancin, which was approved last May, costs $5,300 for two doses; and oritavancin, which was approved last August, costs $3,400 for one dose.

The arguments for using these newer drugs “may be that you can discharge the patient home, assuming they’ll have an active antibiotic in their system for a week, and maybe that will be more cost-effective,” Dr. Sullivan said. “The role that these should play in the management of your inpatients is still not clear, but they’re very new and interesting developments in treatment.” TH

Visit our website for more information on antibiotic stewardship and hospitalists.

What do Clostridium difficile, Staphylococcus aureus, and acute pulmonary embolism have in common? They were all topics of discussion at the 2015 Mid-Atlantic Hospital Medicine Symposium, held at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City.

Vikas Saini, MD, FACC, president of the Lown Institute in Brookline, Mass., and associate physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, gave the keynote address on high-value care.

“We’re asking you to do hard things: to be kind to complete strangers, to feel their pain, to be compassionate when you’re on the run,” Dr. Saini said as he urged his fellow physicians to be more personable with patients. “Pull up a chair and sit down. It takes you 30 seconds, but for the patient, it feels like an eternity.” Dr. Saini, a guest lecturer at the symposium, also stressed the importance of being collaborative and encouraged clinicians to join their colleagues in implementing RightCare Rounds.

Following the keynote address, Louis DePalo, MD, an associate professor of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep at Icahn School of Medicine, gave a 30-minute presentation on the management of acute pulmonary embolism (PE).

Dr. DePalo said that in his early days of practicing medicine, PE patients were usually hospitalized without debate. Today, thanks to indices such as the Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index, there are algorithms to determine the severity of PE in patients, allowing doctors to determine whether patients should be discharged or hospitalized. Still, Dr. DePalo added, “Discussions about sending a patient home are complicated.”

If a patient has severe PE, Dr. DePalo advised doctors to analyze studies such as the Pulmonary Embolism Thrombolysis (PEITHO) trial and the Moderate Pulmonary Embolism Treated with Thrombolysis (MOPPETT) trial to determine when to use advanced treatments. “One study may not be sufficient for administering advanced therapies,” Dr. DePalo said. “One study doesn’t make us feel good, so get a lot of data.”

After Dr. DePalo’s presentation, physicians gave presentations on common healthcare-associated infections. Gopi Patel, MD, an assistant professor of infectious diseases at Icahn School of Medicine, discussed Clostridium difficile infection (CDI). “CDI is the most common [healthcare-associated infection] in the United States,” Dr. Patel said as she urged physicians to “be a role model” by practicing good hand hygiene.

Using the updated practice guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America, Tim Sullivan, MD, an assistant professor of infectious diseases at Icahn School of Medicine, discussed skin and soft tissue infections, particularly methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The guidelines “make a very important distinction between purulent and nonpurulent infections,” Dr. Sullivan said. “The majority of nonpurulent infections are caused by strep, [and] treating for strep seems to be sufficient to cure the infection … Adding extra coverage for MRSA is either not helpful or may actually be harmful to patients.”

Purulent infections, which require drainage, “are mostly caused by Staph aureus, including MRSA,” Dr. Sullivan said. “You don’t always have to give antibiotics, but they are recommended when the patient is sick.”

Dr. Sullivan said although “it can be sort of confusing trying to choose the right antibiotics for your patient … almost everyone should just receive vancomycin.” The drug is well-studied, inexpensive at $2.80 per dose for a five-day treatment, and well-tolerated by patients, he added. Yet vancomycin should not be administered to everyone as some patients experience devastating adverse reactions, and vancomycin could potentially cause irreversible hearing loss, he said.

Dr. Sullivan mentioned three new antibiotic treatments for MRSA: telavancin, which the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved in 2009, costs 75 times more than vancomycin; dalbavancin, which was approved last May, costs $5,300 for two doses; and oritavancin, which was approved last August, costs $3,400 for one dose.

The arguments for using these newer drugs “may be that you can discharge the patient home, assuming they’ll have an active antibiotic in their system for a week, and maybe that will be more cost-effective,” Dr. Sullivan said. “The role that these should play in the management of your inpatients is still not clear, but they’re very new and interesting developments in treatment.” TH

Visit our website for more information on antibiotic stewardship and hospitalists.

What do Clostridium difficile, Staphylococcus aureus, and acute pulmonary embolism have in common? They were all topics of discussion at the 2015 Mid-Atlantic Hospital Medicine Symposium, held at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City.

Vikas Saini, MD, FACC, president of the Lown Institute in Brookline, Mass., and associate physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, gave the keynote address on high-value care.

“We’re asking you to do hard things: to be kind to complete strangers, to feel their pain, to be compassionate when you’re on the run,” Dr. Saini said as he urged his fellow physicians to be more personable with patients. “Pull up a chair and sit down. It takes you 30 seconds, but for the patient, it feels like an eternity.” Dr. Saini, a guest lecturer at the symposium, also stressed the importance of being collaborative and encouraged clinicians to join their colleagues in implementing RightCare Rounds.

Following the keynote address, Louis DePalo, MD, an associate professor of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep at Icahn School of Medicine, gave a 30-minute presentation on the management of acute pulmonary embolism (PE).

Dr. DePalo said that in his early days of practicing medicine, PE patients were usually hospitalized without debate. Today, thanks to indices such as the Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index, there are algorithms to determine the severity of PE in patients, allowing doctors to determine whether patients should be discharged or hospitalized. Still, Dr. DePalo added, “Discussions about sending a patient home are complicated.”

If a patient has severe PE, Dr. DePalo advised doctors to analyze studies such as the Pulmonary Embolism Thrombolysis (PEITHO) trial and the Moderate Pulmonary Embolism Treated with Thrombolysis (MOPPETT) trial to determine when to use advanced treatments. “One study may not be sufficient for administering advanced therapies,” Dr. DePalo said. “One study doesn’t make us feel good, so get a lot of data.”

After Dr. DePalo’s presentation, physicians gave presentations on common healthcare-associated infections. Gopi Patel, MD, an assistant professor of infectious diseases at Icahn School of Medicine, discussed Clostridium difficile infection (CDI). “CDI is the most common [healthcare-associated infection] in the United States,” Dr. Patel said as she urged physicians to “be a role model” by practicing good hand hygiene.

Using the updated practice guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America, Tim Sullivan, MD, an assistant professor of infectious diseases at Icahn School of Medicine, discussed skin and soft tissue infections, particularly methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The guidelines “make a very important distinction between purulent and nonpurulent infections,” Dr. Sullivan said. “The majority of nonpurulent infections are caused by strep, [and] treating for strep seems to be sufficient to cure the infection … Adding extra coverage for MRSA is either not helpful or may actually be harmful to patients.”

Purulent infections, which require drainage, “are mostly caused by Staph aureus, including MRSA,” Dr. Sullivan said. “You don’t always have to give antibiotics, but they are recommended when the patient is sick.”

Dr. Sullivan said although “it can be sort of confusing trying to choose the right antibiotics for your patient … almost everyone should just receive vancomycin.” The drug is well-studied, inexpensive at $2.80 per dose for a five-day treatment, and well-tolerated by patients, he added. Yet vancomycin should not be administered to everyone as some patients experience devastating adverse reactions, and vancomycin could potentially cause irreversible hearing loss, he said.

Dr. Sullivan mentioned three new antibiotic treatments for MRSA: telavancin, which the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved in 2009, costs 75 times more than vancomycin; dalbavancin, which was approved last May, costs $5,300 for two doses; and oritavancin, which was approved last August, costs $3,400 for one dose.

The arguments for using these newer drugs “may be that you can discharge the patient home, assuming they’ll have an active antibiotic in their system for a week, and maybe that will be more cost-effective,” Dr. Sullivan said. “The role that these should play in the management of your inpatients is still not clear, but they’re very new and interesting developments in treatment.” TH

Visit our website for more information on antibiotic stewardship and hospitalists.

What’s the best way to predict the success of a trial of labor after a previous C-section?

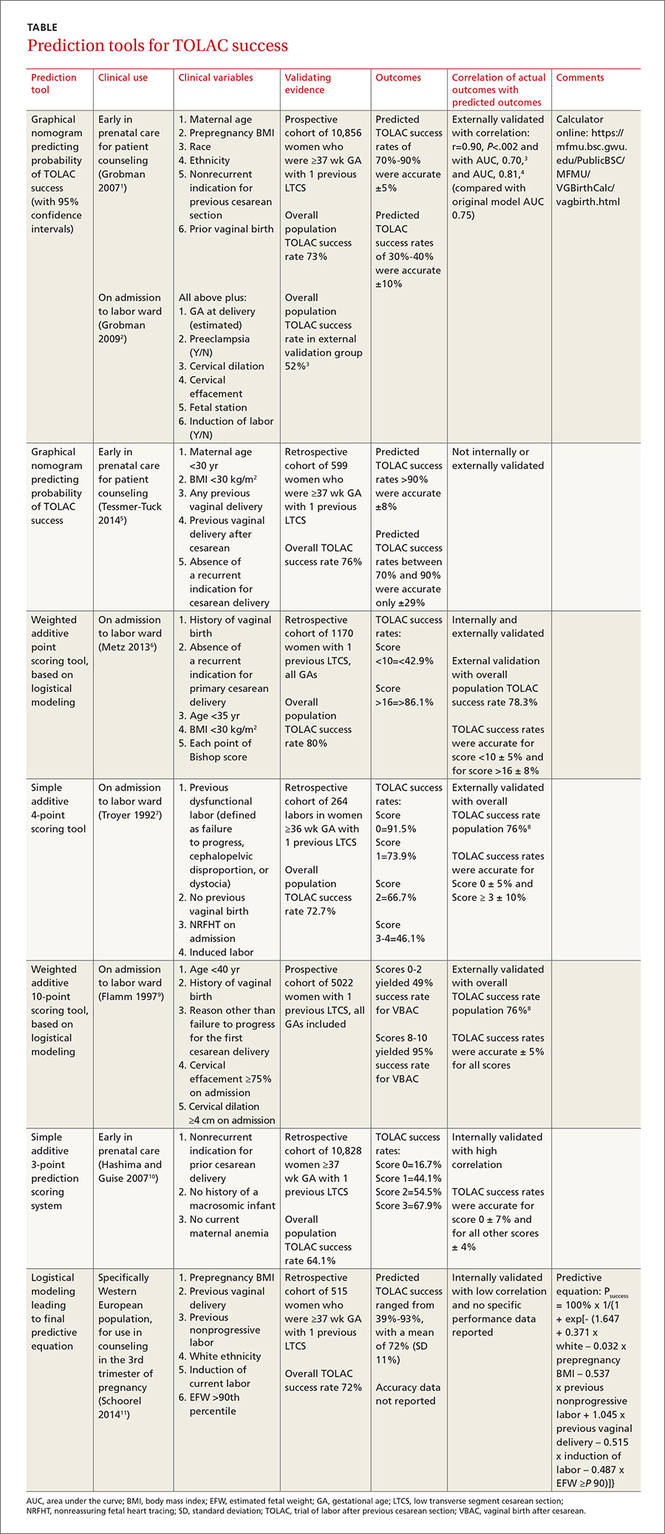

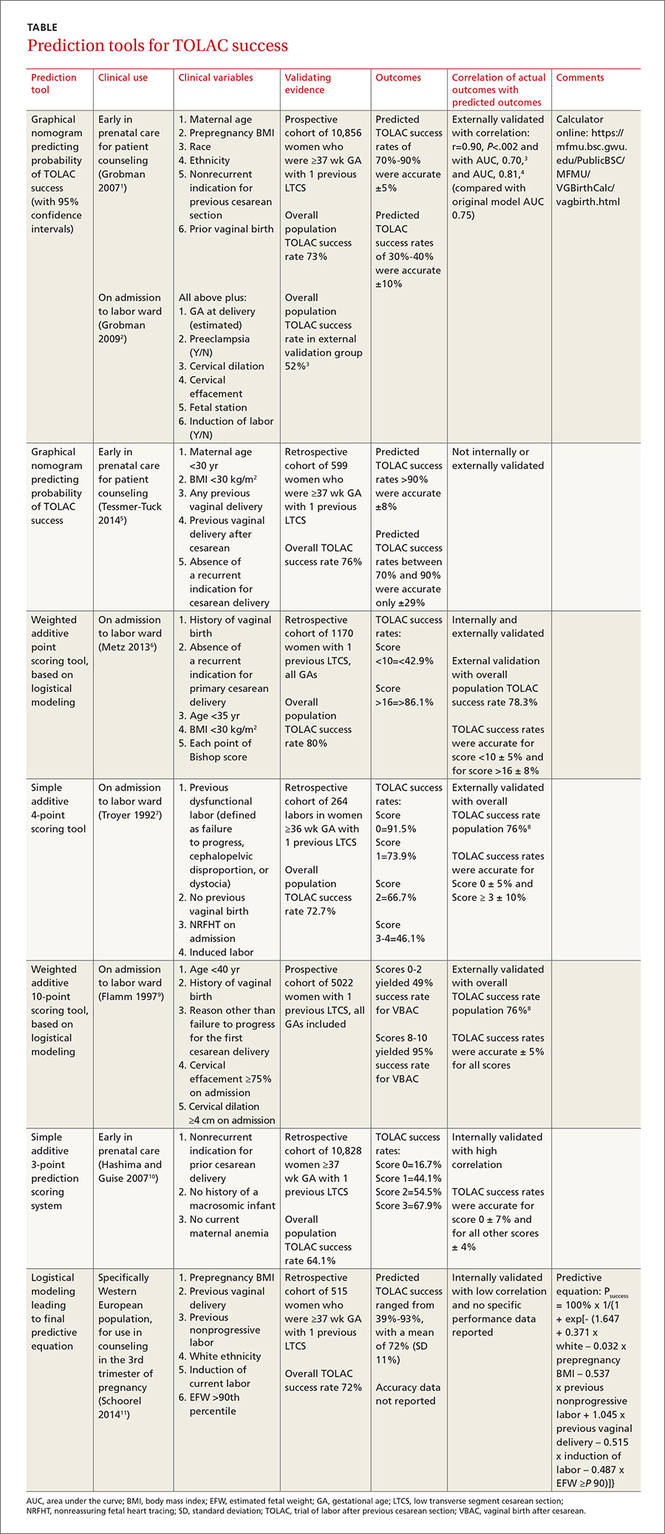

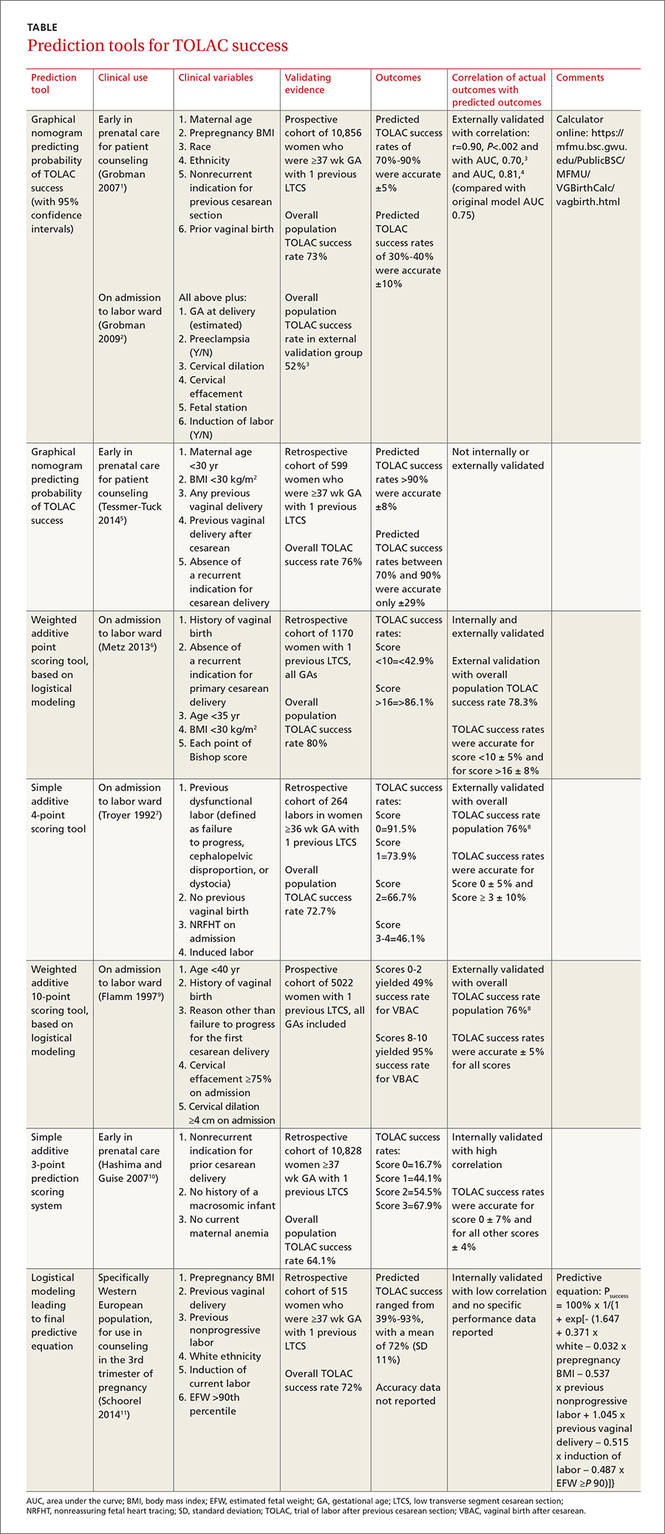

While 8 scoring tools predict success rates for a trial of labor after previous cesarean section (TOLAC), it’s unclear which is the best because no trials have compared prediction tools against each other, and each tool has a unique set of variables.

A “close-to-delivery” scoring nomogram predicting the success rate of TOLAC correlates well (90% accuracy) with actual outcomes (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, prospective and retrospective cohort studies) and has been externally validated with multiple additional cohorts.

All other point-prediction scoring tools are accurate within 10% when predicting the success rate of TOLAC (SOR: B, prospective and retrospective cohort studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Seven validated prospective scoring systems, and one unvalidated system, predict a successful TOLAC based on a variety of clinical factors (TABLE1-11). The systems use different outcome statistics, so their predictive accuracy can’t be directly compared.12

Grobman: Entry-to-care and close-to-delivery nomograms

Grobman et al created 2 prediction models, an “entry-to-care” model (used at the first prenatal visit), and a “close-to-delivery” model (used on admission to the labor ward).1,2 Both models display a graphic nomogram forecasting the probability of TOLAC success (with 95% confidence intervals [CIs]). The authors compared predicted TOLAC outcomes with actual TOLAC outcomes and found that the model predictions most successfully correlated with high-likelihood outcomes (70% to 90% chance of successful TOLAC, plus or minus approximately 5%). Both models were less accurate with low-likelihood outcomes (40% chance of successful TOLAC, plus or minus approximately 10%).

Many independent authors have validated the close-to-delivery model, comparing predicted with actual TOLAC success rates. In a retrospective cohort study of 490 women, Constantine et al found the correlation between the observed and predicted TOLAC rates to have an r of 0.90, P=.002, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.70.3 Yoki et al validated the model in a Japanese cohort of 729 women with an AUC of 0.81, consistent with the AUC of 0.75 reported in the development of the original model.4

Tessmer-Tuck: The close-to-delivery model without the race variable

Tessmer-Tuck et al developed a model similar to Grobman’s close-to-delivery model, but removed race/ethnicity as a variable and compared it to the accuracy of the Grobman nomogram.5 Variables considered in this model were maternal age <30 years (odds ratio [OR]=1.53; 95% CI, 1.00-2.36), body mass index (BMI) <30 kg/m2 (OR=1.82; 95% CI, 1.11-2.97), any previous vaginal delivery (OR=3.17; 95% CI, 1.50-6.80), previous vaginal delivery after cesarean (OR=2.24; 95% CI, 1.25-4.18), and absence of a recurrent indication for cesarean delivery (OR=1.81; 95% CI, 1.18-2.76).

The model provided a successful probability of vaginal birth after cesarean ranging from 38% to 98% with AUC of 0.723 (95% CI, 0.680-0.767). When compared with the Grobman model, the AUC for features in the Tessmer-Tuck model was 0.757 (95% CI, 0.713-0.801), similar to the AUC of 0.75 reported in the development of the original model. The predictive accuracy of TOLAC success between 70% and 90% was quite poor at only ±29%.

Metz: A 5-point scoring tool

Metz et al created a point scoring tool for use on admission to the labor ward, based on 5 variables weighted by degree of correlation with TOLAC success: a history of vaginal birth (OR=2.7; 95% CI, 1.8-4.1), absence of a recurrent indication for initial cesarean delivery (OR=2.0; 95% CI, 1.3-3.1), age <35 years (OR=2.0; 95% CI, 1.1-3.4), BMI <30 kg/m2 (OR=1.6; 95% CI, 1.1-2.4), and each point of Bishop score on admission (OR=1.3; 95% CI, 1.2-1.4).6

The authors internally validated this scoring tool with an AUC of 0.70 (95% CI, 0.67-0.74), then externally validated the tool with an independent cohort of 585 women and found an AUC of 0.80 (95% CI, 0.76-0.84). In the external validation cohort, TOLAC success rates were 37.4% (95% CI, 27.2-47.5) with a score <10 and 94.4% (95% CI, 90.9-97.8) with a score >16, performing within 8% of the prediction model.

Troyer: A simple 4-point tool

Troyer et al created a simple 4-point scoring tool for use on admission to the labor ward.7 The tool’s 4 variables—previous dysfunctional labor, no previous vaginal birth, nonreassuring fetal heart tracing (NRFHT) on admission, and induced labor—were found to reduce the success rate of a trial of labor (P<.05). Dinsmoor et al used this scoring tool in a group of 156 women with an overall TOLAC success rate of 76% (3% higher than Troyer’s group) and found that for labors with a favorable score (0), the tool performed within 5% and for labors with an unfavorable score (≥3), the tool performed within 10%.8

Flamm: 5 variables weighted by correlation with TOLAC success

Flamm et al also created a scoring tool for use on admission to the labor ward, based on 5 variables weighted according to degree of correlation with TOLAC success: age <40 years (OR=2.58; 95% CI, 1.55-4.3), history of a vaginal birth (OR=1.53-9.11 depending on where the vaginal birth fell in the woman’s reproductive history), reason other than failure to progress for the first cesarean delivery (OR=1.93; 95% CI, 1.58-2.35), cervical effacement ≥75% on admission (OR=2.72; 95% CI, 2.00-3.71), and cervical dilation ≥4 cm on admission (OR=2.16; 95% CI, 1.66-2.82).9 Dinsmoor validated this scoring tool as well in 156 women and found 100% TOLAC success for scores ≥7 (within 5% of the original tool) and 56% TOLAC success for scores ≤4 (compared with 49% for scores 0-2 in the original work).8

Hashima and Guise: A 3-point scoring tool

Hashima and Guise evaluated 16 variables and identified 7 associated with TOLAC outcome: indication for cesarean delivery (recurrent vs nonrecurrent), chorioamnionitis, macrosomicinfant, age, anemia, diabetes, and infant sex, from which they created a 3-point scoring tool using the variables most associated with TOLAC outcome. Each variable was assigned a score of 0 or 1, and the likelihood of TOLAC success was calculated.10

They found a relationship between score and TOLAC success. The original study population of 10,828 was randomly divided into a score development and validation group. TOLAC success percentages were most discordant between the tool development and internal validation groups for score 0 at 7%. Scores 1 to 3 were within 4% of each other.

Schoorel: A model designed for Western Europeann women

Finally, Schoorel et al developed and internally validated a prediction model for a Western European population, to be used during counseling in the third trimester of pregnancy.11 Six variables were identified and entered into the model calculations: prepregnancy BMI (entered as a continuous variable), (OR=0.96; 95% CI, 0.92-1.00); previous cesarean for nonprogressive labor (OR=0.50; 95% CI, 0.33-0.76); previous vaginal delivery (OR=3.81; 95% CI, 2.10-6.92); induction of labor (OR=0.52; 95% CI, 0.33-2.10); estimated fetal weight >90th percentile (OR=0.54; 95% CI, 0.14-2.02); and white ethnicity (OR=1.61; 95% CI, 0.97-2.66). The authors noted that the predicted probability of TOLAC success ranged from 39% to 93%, with a mean of 72% (standard deviation, 11%), and only noted the predicted probabilities were well calibrated from 65% upwards without additional data on specific performance.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) lists strong predictors of a successful vaginal birth after cesarean as previous vaginal birth and spontaneous labor. Factors associated with decreased probability of success are recurrent indication for initial cesarean delivery (labor dystocia), increased maternal age, nonwhite ethnicity, gestational age greater than 40 weeks, maternal obesity, preeclampsia, short interpregnancy interval, and increased neonatal birth weight. ACOG does not offer any weighted or risk-based scoring tools for predicting success.13

Neither the American Academy of Family Physicians nor the American College of Nurse Midwives recommend specific scoring tools or success predictors.

1. Grobman WA, Lai Y, Landon MB, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal- Fetal Medicine Units Network (MFMU). Development of a nomogram for prediction of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:806-812.

2. Grobman WA, Lai Y, Landon MB, et al. Does information available at admission for delivery improve prediction of vaginal birth after cesarean? Am J Perinatol. 2009;26:693-701.

3. Costantine MM, Fox KA, Pacheco LD, et al. Does information available at delivery improve the accuracy of predicting vaginal birth after cesarean? Validation of the published models in an independent patient cohort. Am J Perinatol. 2011;28:293-298.

4. Yoki A, Ishikawa K, Miyazaki K, et al. Validation of the prediction model for success of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery in Japanese women. Int J Med Sci. 2012;9:488-491.

5. Tessmer-Tuck JA, El-Nashar SA, Racek AR, et al. Predicting vaginal birth after cesarean section: a cohort study. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2014;77:121-126.

6. Metz TD, Stoddard GJ, Henry E, et al. Simple, validated vaginal birth after cesarean delivery prediction model for use at the time of admission. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:571-578.

7. Troyer LR, Parisi VM. Obstetric parameters affecting success in a trial of labor: designation of a scoring system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167(4 pt 1):1099-1104.

8. Dinsmoor MJ, Brock EL. Predicting failed trial of labor after primary cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:282-286.

9. Flamm BL, Geiger AM. Vaginal birth after cesarean delivery: an admission scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:907-910.

10. Hashima JN, Guise JM. Vaginal birth after cesarean: a prenatal scoring tool. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:e22-e23.

11. Schoorel ENC, van Kuijk SMJ, Melman S, et al. Vaginal birth after a caesarean section: the development of a Western European population-based prediction model for deliveries at term. BJOG. 2014;121:194-201.

12. Guise JM, Eden K, Emeis C, et al. Vaginal birth after cesarean: New insights. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 191. AHRQ Publication No. 10-E003. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010.

13. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice bulletin no. 115: Vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(2 pt 1):450-463.

While 8 scoring tools predict success rates for a trial of labor after previous cesarean section (TOLAC), it’s unclear which is the best because no trials have compared prediction tools against each other, and each tool has a unique set of variables.

A “close-to-delivery” scoring nomogram predicting the success rate of TOLAC correlates well (90% accuracy) with actual outcomes (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, prospective and retrospective cohort studies) and has been externally validated with multiple additional cohorts.

All other point-prediction scoring tools are accurate within 10% when predicting the success rate of TOLAC (SOR: B, prospective and retrospective cohort studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Seven validated prospective scoring systems, and one unvalidated system, predict a successful TOLAC based on a variety of clinical factors (TABLE1-11). The systems use different outcome statistics, so their predictive accuracy can’t be directly compared.12

Grobman: Entry-to-care and close-to-delivery nomograms

Grobman et al created 2 prediction models, an “entry-to-care” model (used at the first prenatal visit), and a “close-to-delivery” model (used on admission to the labor ward).1,2 Both models display a graphic nomogram forecasting the probability of TOLAC success (with 95% confidence intervals [CIs]). The authors compared predicted TOLAC outcomes with actual TOLAC outcomes and found that the model predictions most successfully correlated with high-likelihood outcomes (70% to 90% chance of successful TOLAC, plus or minus approximately 5%). Both models were less accurate with low-likelihood outcomes (40% chance of successful TOLAC, plus or minus approximately 10%).

Many independent authors have validated the close-to-delivery model, comparing predicted with actual TOLAC success rates. In a retrospective cohort study of 490 women, Constantine et al found the correlation between the observed and predicted TOLAC rates to have an r of 0.90, P=.002, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.70.3 Yoki et al validated the model in a Japanese cohort of 729 women with an AUC of 0.81, consistent with the AUC of 0.75 reported in the development of the original model.4

Tessmer-Tuck: The close-to-delivery model without the race variable

Tessmer-Tuck et al developed a model similar to Grobman’s close-to-delivery model, but removed race/ethnicity as a variable and compared it to the accuracy of the Grobman nomogram.5 Variables considered in this model were maternal age <30 years (odds ratio [OR]=1.53; 95% CI, 1.00-2.36), body mass index (BMI) <30 kg/m2 (OR=1.82; 95% CI, 1.11-2.97), any previous vaginal delivery (OR=3.17; 95% CI, 1.50-6.80), previous vaginal delivery after cesarean (OR=2.24; 95% CI, 1.25-4.18), and absence of a recurrent indication for cesarean delivery (OR=1.81; 95% CI, 1.18-2.76).

The model provided a successful probability of vaginal birth after cesarean ranging from 38% to 98% with AUC of 0.723 (95% CI, 0.680-0.767). When compared with the Grobman model, the AUC for features in the Tessmer-Tuck model was 0.757 (95% CI, 0.713-0.801), similar to the AUC of 0.75 reported in the development of the original model. The predictive accuracy of TOLAC success between 70% and 90% was quite poor at only ±29%.

Metz: A 5-point scoring tool

Metz et al created a point scoring tool for use on admission to the labor ward, based on 5 variables weighted by degree of correlation with TOLAC success: a history of vaginal birth (OR=2.7; 95% CI, 1.8-4.1), absence of a recurrent indication for initial cesarean delivery (OR=2.0; 95% CI, 1.3-3.1), age <35 years (OR=2.0; 95% CI, 1.1-3.4), BMI <30 kg/m2 (OR=1.6; 95% CI, 1.1-2.4), and each point of Bishop score on admission (OR=1.3; 95% CI, 1.2-1.4).6

The authors internally validated this scoring tool with an AUC of 0.70 (95% CI, 0.67-0.74), then externally validated the tool with an independent cohort of 585 women and found an AUC of 0.80 (95% CI, 0.76-0.84). In the external validation cohort, TOLAC success rates were 37.4% (95% CI, 27.2-47.5) with a score <10 and 94.4% (95% CI, 90.9-97.8) with a score >16, performing within 8% of the prediction model.

Troyer: A simple 4-point tool

Troyer et al created a simple 4-point scoring tool for use on admission to the labor ward.7 The tool’s 4 variables—previous dysfunctional labor, no previous vaginal birth, nonreassuring fetal heart tracing (NRFHT) on admission, and induced labor—were found to reduce the success rate of a trial of labor (P<.05). Dinsmoor et al used this scoring tool in a group of 156 women with an overall TOLAC success rate of 76% (3% higher than Troyer’s group) and found that for labors with a favorable score (0), the tool performed within 5% and for labors with an unfavorable score (≥3), the tool performed within 10%.8

Flamm: 5 variables weighted by correlation with TOLAC success

Flamm et al also created a scoring tool for use on admission to the labor ward, based on 5 variables weighted according to degree of correlation with TOLAC success: age <40 years (OR=2.58; 95% CI, 1.55-4.3), history of a vaginal birth (OR=1.53-9.11 depending on where the vaginal birth fell in the woman’s reproductive history), reason other than failure to progress for the first cesarean delivery (OR=1.93; 95% CI, 1.58-2.35), cervical effacement ≥75% on admission (OR=2.72; 95% CI, 2.00-3.71), and cervical dilation ≥4 cm on admission (OR=2.16; 95% CI, 1.66-2.82).9 Dinsmoor validated this scoring tool as well in 156 women and found 100% TOLAC success for scores ≥7 (within 5% of the original tool) and 56% TOLAC success for scores ≤4 (compared with 49% for scores 0-2 in the original work).8

Hashima and Guise: A 3-point scoring tool

Hashima and Guise evaluated 16 variables and identified 7 associated with TOLAC outcome: indication for cesarean delivery (recurrent vs nonrecurrent), chorioamnionitis, macrosomicinfant, age, anemia, diabetes, and infant sex, from which they created a 3-point scoring tool using the variables most associated with TOLAC outcome. Each variable was assigned a score of 0 or 1, and the likelihood of TOLAC success was calculated.10

They found a relationship between score and TOLAC success. The original study population of 10,828 was randomly divided into a score development and validation group. TOLAC success percentages were most discordant between the tool development and internal validation groups for score 0 at 7%. Scores 1 to 3 were within 4% of each other.

Schoorel: A model designed for Western Europeann women

Finally, Schoorel et al developed and internally validated a prediction model for a Western European population, to be used during counseling in the third trimester of pregnancy.11 Six variables were identified and entered into the model calculations: prepregnancy BMI (entered as a continuous variable), (OR=0.96; 95% CI, 0.92-1.00); previous cesarean for nonprogressive labor (OR=0.50; 95% CI, 0.33-0.76); previous vaginal delivery (OR=3.81; 95% CI, 2.10-6.92); induction of labor (OR=0.52; 95% CI, 0.33-2.10); estimated fetal weight >90th percentile (OR=0.54; 95% CI, 0.14-2.02); and white ethnicity (OR=1.61; 95% CI, 0.97-2.66). The authors noted that the predicted probability of TOLAC success ranged from 39% to 93%, with a mean of 72% (standard deviation, 11%), and only noted the predicted probabilities were well calibrated from 65% upwards without additional data on specific performance.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) lists strong predictors of a successful vaginal birth after cesarean as previous vaginal birth and spontaneous labor. Factors associated with decreased probability of success are recurrent indication for initial cesarean delivery (labor dystocia), increased maternal age, nonwhite ethnicity, gestational age greater than 40 weeks, maternal obesity, preeclampsia, short interpregnancy interval, and increased neonatal birth weight. ACOG does not offer any weighted or risk-based scoring tools for predicting success.13

Neither the American Academy of Family Physicians nor the American College of Nurse Midwives recommend specific scoring tools or success predictors.

While 8 scoring tools predict success rates for a trial of labor after previous cesarean section (TOLAC), it’s unclear which is the best because no trials have compared prediction tools against each other, and each tool has a unique set of variables.

A “close-to-delivery” scoring nomogram predicting the success rate of TOLAC correlates well (90% accuracy) with actual outcomes (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, prospective and retrospective cohort studies) and has been externally validated with multiple additional cohorts.

All other point-prediction scoring tools are accurate within 10% when predicting the success rate of TOLAC (SOR: B, prospective and retrospective cohort studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Seven validated prospective scoring systems, and one unvalidated system, predict a successful TOLAC based on a variety of clinical factors (TABLE1-11). The systems use different outcome statistics, so their predictive accuracy can’t be directly compared.12

Grobman: Entry-to-care and close-to-delivery nomograms

Grobman et al created 2 prediction models, an “entry-to-care” model (used at the first prenatal visit), and a “close-to-delivery” model (used on admission to the labor ward).1,2 Both models display a graphic nomogram forecasting the probability of TOLAC success (with 95% confidence intervals [CIs]). The authors compared predicted TOLAC outcomes with actual TOLAC outcomes and found that the model predictions most successfully correlated with high-likelihood outcomes (70% to 90% chance of successful TOLAC, plus or minus approximately 5%). Both models were less accurate with low-likelihood outcomes (40% chance of successful TOLAC, plus or minus approximately 10%).

Many independent authors have validated the close-to-delivery model, comparing predicted with actual TOLAC success rates. In a retrospective cohort study of 490 women, Constantine et al found the correlation between the observed and predicted TOLAC rates to have an r of 0.90, P=.002, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.70.3 Yoki et al validated the model in a Japanese cohort of 729 women with an AUC of 0.81, consistent with the AUC of 0.75 reported in the development of the original model.4

Tessmer-Tuck: The close-to-delivery model without the race variable

Tessmer-Tuck et al developed a model similar to Grobman’s close-to-delivery model, but removed race/ethnicity as a variable and compared it to the accuracy of the Grobman nomogram.5 Variables considered in this model were maternal age <30 years (odds ratio [OR]=1.53; 95% CI, 1.00-2.36), body mass index (BMI) <30 kg/m2 (OR=1.82; 95% CI, 1.11-2.97), any previous vaginal delivery (OR=3.17; 95% CI, 1.50-6.80), previous vaginal delivery after cesarean (OR=2.24; 95% CI, 1.25-4.18), and absence of a recurrent indication for cesarean delivery (OR=1.81; 95% CI, 1.18-2.76).

The model provided a successful probability of vaginal birth after cesarean ranging from 38% to 98% with AUC of 0.723 (95% CI, 0.680-0.767). When compared with the Grobman model, the AUC for features in the Tessmer-Tuck model was 0.757 (95% CI, 0.713-0.801), similar to the AUC of 0.75 reported in the development of the original model. The predictive accuracy of TOLAC success between 70% and 90% was quite poor at only ±29%.

Metz: A 5-point scoring tool

Metz et al created a point scoring tool for use on admission to the labor ward, based on 5 variables weighted by degree of correlation with TOLAC success: a history of vaginal birth (OR=2.7; 95% CI, 1.8-4.1), absence of a recurrent indication for initial cesarean delivery (OR=2.0; 95% CI, 1.3-3.1), age <35 years (OR=2.0; 95% CI, 1.1-3.4), BMI <30 kg/m2 (OR=1.6; 95% CI, 1.1-2.4), and each point of Bishop score on admission (OR=1.3; 95% CI, 1.2-1.4).6

The authors internally validated this scoring tool with an AUC of 0.70 (95% CI, 0.67-0.74), then externally validated the tool with an independent cohort of 585 women and found an AUC of 0.80 (95% CI, 0.76-0.84). In the external validation cohort, TOLAC success rates were 37.4% (95% CI, 27.2-47.5) with a score <10 and 94.4% (95% CI, 90.9-97.8) with a score >16, performing within 8% of the prediction model.

Troyer: A simple 4-point tool

Troyer et al created a simple 4-point scoring tool for use on admission to the labor ward.7 The tool’s 4 variables—previous dysfunctional labor, no previous vaginal birth, nonreassuring fetal heart tracing (NRFHT) on admission, and induced labor—were found to reduce the success rate of a trial of labor (P<.05). Dinsmoor et al used this scoring tool in a group of 156 women with an overall TOLAC success rate of 76% (3% higher than Troyer’s group) and found that for labors with a favorable score (0), the tool performed within 5% and for labors with an unfavorable score (≥3), the tool performed within 10%.8

Flamm: 5 variables weighted by correlation with TOLAC success

Flamm et al also created a scoring tool for use on admission to the labor ward, based on 5 variables weighted according to degree of correlation with TOLAC success: age <40 years (OR=2.58; 95% CI, 1.55-4.3), history of a vaginal birth (OR=1.53-9.11 depending on where the vaginal birth fell in the woman’s reproductive history), reason other than failure to progress for the first cesarean delivery (OR=1.93; 95% CI, 1.58-2.35), cervical effacement ≥75% on admission (OR=2.72; 95% CI, 2.00-3.71), and cervical dilation ≥4 cm on admission (OR=2.16; 95% CI, 1.66-2.82).9 Dinsmoor validated this scoring tool as well in 156 women and found 100% TOLAC success for scores ≥7 (within 5% of the original tool) and 56% TOLAC success for scores ≤4 (compared with 49% for scores 0-2 in the original work).8

Hashima and Guise: A 3-point scoring tool

Hashima and Guise evaluated 16 variables and identified 7 associated with TOLAC outcome: indication for cesarean delivery (recurrent vs nonrecurrent), chorioamnionitis, macrosomicinfant, age, anemia, diabetes, and infant sex, from which they created a 3-point scoring tool using the variables most associated with TOLAC outcome. Each variable was assigned a score of 0 or 1, and the likelihood of TOLAC success was calculated.10

They found a relationship between score and TOLAC success. The original study population of 10,828 was randomly divided into a score development and validation group. TOLAC success percentages were most discordant between the tool development and internal validation groups for score 0 at 7%. Scores 1 to 3 were within 4% of each other.

Schoorel: A model designed for Western Europeann women

Finally, Schoorel et al developed and internally validated a prediction model for a Western European population, to be used during counseling in the third trimester of pregnancy.11 Six variables were identified and entered into the model calculations: prepregnancy BMI (entered as a continuous variable), (OR=0.96; 95% CI, 0.92-1.00); previous cesarean for nonprogressive labor (OR=0.50; 95% CI, 0.33-0.76); previous vaginal delivery (OR=3.81; 95% CI, 2.10-6.92); induction of labor (OR=0.52; 95% CI, 0.33-2.10); estimated fetal weight >90th percentile (OR=0.54; 95% CI, 0.14-2.02); and white ethnicity (OR=1.61; 95% CI, 0.97-2.66). The authors noted that the predicted probability of TOLAC success ranged from 39% to 93%, with a mean of 72% (standard deviation, 11%), and only noted the predicted probabilities were well calibrated from 65% upwards without additional data on specific performance.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) lists strong predictors of a successful vaginal birth after cesarean as previous vaginal birth and spontaneous labor. Factors associated with decreased probability of success are recurrent indication for initial cesarean delivery (labor dystocia), increased maternal age, nonwhite ethnicity, gestational age greater than 40 weeks, maternal obesity, preeclampsia, short interpregnancy interval, and increased neonatal birth weight. ACOG does not offer any weighted or risk-based scoring tools for predicting success.13

Neither the American Academy of Family Physicians nor the American College of Nurse Midwives recommend specific scoring tools or success predictors.

1. Grobman WA, Lai Y, Landon MB, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal- Fetal Medicine Units Network (MFMU). Development of a nomogram for prediction of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:806-812.

2. Grobman WA, Lai Y, Landon MB, et al. Does information available at admission for delivery improve prediction of vaginal birth after cesarean? Am J Perinatol. 2009;26:693-701.

3. Costantine MM, Fox KA, Pacheco LD, et al. Does information available at delivery improve the accuracy of predicting vaginal birth after cesarean? Validation of the published models in an independent patient cohort. Am J Perinatol. 2011;28:293-298.

4. Yoki A, Ishikawa K, Miyazaki K, et al. Validation of the prediction model for success of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery in Japanese women. Int J Med Sci. 2012;9:488-491.

5. Tessmer-Tuck JA, El-Nashar SA, Racek AR, et al. Predicting vaginal birth after cesarean section: a cohort study. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2014;77:121-126.

6. Metz TD, Stoddard GJ, Henry E, et al. Simple, validated vaginal birth after cesarean delivery prediction model for use at the time of admission. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:571-578.

7. Troyer LR, Parisi VM. Obstetric parameters affecting success in a trial of labor: designation of a scoring system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167(4 pt 1):1099-1104.

8. Dinsmoor MJ, Brock EL. Predicting failed trial of labor after primary cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:282-286.

9. Flamm BL, Geiger AM. Vaginal birth after cesarean delivery: an admission scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:907-910.

10. Hashima JN, Guise JM. Vaginal birth after cesarean: a prenatal scoring tool. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:e22-e23.

11. Schoorel ENC, van Kuijk SMJ, Melman S, et al. Vaginal birth after a caesarean section: the development of a Western European population-based prediction model for deliveries at term. BJOG. 2014;121:194-201.

12. Guise JM, Eden K, Emeis C, et al. Vaginal birth after cesarean: New insights. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 191. AHRQ Publication No. 10-E003. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010.

13. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice bulletin no. 115: Vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(2 pt 1):450-463.

1. Grobman WA, Lai Y, Landon MB, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal- Fetal Medicine Units Network (MFMU). Development of a nomogram for prediction of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:806-812.

2. Grobman WA, Lai Y, Landon MB, et al. Does information available at admission for delivery improve prediction of vaginal birth after cesarean? Am J Perinatol. 2009;26:693-701.

3. Costantine MM, Fox KA, Pacheco LD, et al. Does information available at delivery improve the accuracy of predicting vaginal birth after cesarean? Validation of the published models in an independent patient cohort. Am J Perinatol. 2011;28:293-298.

4. Yoki A, Ishikawa K, Miyazaki K, et al. Validation of the prediction model for success of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery in Japanese women. Int J Med Sci. 2012;9:488-491.

5. Tessmer-Tuck JA, El-Nashar SA, Racek AR, et al. Predicting vaginal birth after cesarean section: a cohort study. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2014;77:121-126.

6. Metz TD, Stoddard GJ, Henry E, et al. Simple, validated vaginal birth after cesarean delivery prediction model for use at the time of admission. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:571-578.

7. Troyer LR, Parisi VM. Obstetric parameters affecting success in a trial of labor: designation of a scoring system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167(4 pt 1):1099-1104.

8. Dinsmoor MJ, Brock EL. Predicting failed trial of labor after primary cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:282-286.

9. Flamm BL, Geiger AM. Vaginal birth after cesarean delivery: an admission scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:907-910.

10. Hashima JN, Guise JM. Vaginal birth after cesarean: a prenatal scoring tool. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:e22-e23.

11. Schoorel ENC, van Kuijk SMJ, Melman S, et al. Vaginal birth after a caesarean section: the development of a Western European population-based prediction model for deliveries at term. BJOG. 2014;121:194-201.

12. Guise JM, Eden K, Emeis C, et al. Vaginal birth after cesarean: New insights. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 191. AHRQ Publication No. 10-E003. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010.

13. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice bulletin no. 115: Vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(2 pt 1):450-463.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Prevention, recognition, and management of complications associated with sacrospinous colpopexy

For more videos from the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, click here

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

For more videos from the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, click here

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

For more videos from the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, click here

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

This video is brought to you by ![]()

I will click those boxes, but first, I will care for my patient

I am a member of a large primary care group certified as a level 3 patient-centered medical home; we are in the midst of certifying for Meaningful Use Stage 2. Recently, my first patient of the day was a 65-year-old widowed man who used tobacco, had diabetes, hypertension, and elevated lipid levels, and hadn’t seen me in 2 years. He came in for a Medicare Advantage comprehensive physical examination.

To meet all Meaningful Use Stage 2 expectations during his physical exam, I had to:

• check the box to document discussion of body mass index (his was 26 kg/m2),

• check the box for functional status assessment,

• check the box to indicate that his blood pressure was under 140/90 mm Hg (the threshold for a previously diagnosed hypertensive patient),

• generate annual care guides for the “clinically important conditions” of hypertension with diabetes, tobacco use, and hyperlipidemia,

• review the quality information stoplight for lab tests to be ordered,

• remind the patient to complete his annual eye examination,

• identify hierarchical categorical coding to maximize the accurate morbidity determination of my patient and, therefore, funding for our medical group,

• click on the code for annual prostate examination screening,

• click on the code to bill for tobacco cessation counseling, and

• generate a visit summary.

Naturally, all of this was in addition to giving my patient my full, undivided attention, providing him with the opportunity to express his concerns, and then pursuing a careful examination of his health problems.

Documentation expectations, coding, billing, and the like degrade the clinician-patient relationship, and I’m not going to redirect my attention away from the patient’s concerns and toward these activities. I will continue to listen and respect what my patients have to say and engage with them, and not my keyboard. I will strive to identify and meet their health needs.

Click the boxes? Yes, I will click all the right boxes; my livelihood and my medical group’s future success depend on that. But how much congruence will there be between what I “click” and what I “do”? Well …

We are challenged by good intentions but crushingly poor execution—and it’s taking its toll.

H. Andrew Selinger, MD

Bristol, Conn

I am a member of a large primary care group certified as a level 3 patient-centered medical home; we are in the midst of certifying for Meaningful Use Stage 2. Recently, my first patient of the day was a 65-year-old widowed man who used tobacco, had diabetes, hypertension, and elevated lipid levels, and hadn’t seen me in 2 years. He came in for a Medicare Advantage comprehensive physical examination.

To meet all Meaningful Use Stage 2 expectations during his physical exam, I had to:

• check the box to document discussion of body mass index (his was 26 kg/m2),

• check the box for functional status assessment,

• check the box to indicate that his blood pressure was under 140/90 mm Hg (the threshold for a previously diagnosed hypertensive patient),

• generate annual care guides for the “clinically important conditions” of hypertension with diabetes, tobacco use, and hyperlipidemia,

• review the quality information stoplight for lab tests to be ordered,

• remind the patient to complete his annual eye examination,

• identify hierarchical categorical coding to maximize the accurate morbidity determination of my patient and, therefore, funding for our medical group,

• click on the code for annual prostate examination screening,

• click on the code to bill for tobacco cessation counseling, and

• generate a visit summary.

Naturally, all of this was in addition to giving my patient my full, undivided attention, providing him with the opportunity to express his concerns, and then pursuing a careful examination of his health problems.

Documentation expectations, coding, billing, and the like degrade the clinician-patient relationship, and I’m not going to redirect my attention away from the patient’s concerns and toward these activities. I will continue to listen and respect what my patients have to say and engage with them, and not my keyboard. I will strive to identify and meet their health needs.

Click the boxes? Yes, I will click all the right boxes; my livelihood and my medical group’s future success depend on that. But how much congruence will there be between what I “click” and what I “do”? Well …

We are challenged by good intentions but crushingly poor execution—and it’s taking its toll.

H. Andrew Selinger, MD

Bristol, Conn

I am a member of a large primary care group certified as a level 3 patient-centered medical home; we are in the midst of certifying for Meaningful Use Stage 2. Recently, my first patient of the day was a 65-year-old widowed man who used tobacco, had diabetes, hypertension, and elevated lipid levels, and hadn’t seen me in 2 years. He came in for a Medicare Advantage comprehensive physical examination.

To meet all Meaningful Use Stage 2 expectations during his physical exam, I had to:

• check the box to document discussion of body mass index (his was 26 kg/m2),

• check the box for functional status assessment,

• check the box to indicate that his blood pressure was under 140/90 mm Hg (the threshold for a previously diagnosed hypertensive patient),

• generate annual care guides for the “clinically important conditions” of hypertension with diabetes, tobacco use, and hyperlipidemia,

• review the quality information stoplight for lab tests to be ordered,

• remind the patient to complete his annual eye examination,

• identify hierarchical categorical coding to maximize the accurate morbidity determination of my patient and, therefore, funding for our medical group,

• click on the code for annual prostate examination screening,

• click on the code to bill for tobacco cessation counseling, and

• generate a visit summary.

Naturally, all of this was in addition to giving my patient my full, undivided attention, providing him with the opportunity to express his concerns, and then pursuing a careful examination of his health problems.

Documentation expectations, coding, billing, and the like degrade the clinician-patient relationship, and I’m not going to redirect my attention away from the patient’s concerns and toward these activities. I will continue to listen and respect what my patients have to say and engage with them, and not my keyboard. I will strive to identify and meet their health needs.

Click the boxes? Yes, I will click all the right boxes; my livelihood and my medical group’s future success depend on that. But how much congruence will there be between what I “click” and what I “do”? Well …

We are challenged by good intentions but crushingly poor execution—and it’s taking its toll.

H. Andrew Selinger, MD

Bristol, Conn

Sleep apnea treatments: Helping patients explore options

If you’re looking for a resource to provide to your patients with sleep apnea, you may want to consider this one from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. “How Is Sleep Apnea Treated?” discusses lifestyle changes, mouthpieces, breathing devices, and surgery, and explains which work options work best for which patients. The resource can be found at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/sleepapnea/treatment.

If you’re looking for a resource to provide to your patients with sleep apnea, you may want to consider this one from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. “How Is Sleep Apnea Treated?” discusses lifestyle changes, mouthpieces, breathing devices, and surgery, and explains which work options work best for which patients. The resource can be found at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/sleepapnea/treatment.

If you’re looking for a resource to provide to your patients with sleep apnea, you may want to consider this one from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. “How Is Sleep Apnea Treated?” discusses lifestyle changes, mouthpieces, breathing devices, and surgery, and explains which work options work best for which patients. The resource can be found at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/sleepapnea/treatment.

Helping patients who are newly diagnosed with hepatitis C

Patients who are newly diagnosed with hepatitis C are likely to feel overwhelmed—but this detailed brochure from the American Liver Foundation provides answers to questions that patients are likely to have. The brochure, available at http://www.liverfoundation.org/downloads/alf_download_901.pdf, addresses issues such as available treatments and steps to take to prevent the transmission of hepatitis C to others.

Patients who are newly diagnosed with hepatitis C are likely to feel overwhelmed—but this detailed brochure from the American Liver Foundation provides answers to questions that patients are likely to have. The brochure, available at http://www.liverfoundation.org/downloads/alf_download_901.pdf, addresses issues such as available treatments and steps to take to prevent the transmission of hepatitis C to others.

Patients who are newly diagnosed with hepatitis C are likely to feel overwhelmed—but this detailed brochure from the American Liver Foundation provides answers to questions that patients are likely to have. The brochure, available at http://www.liverfoundation.org/downloads/alf_download_901.pdf, addresses issues such as available treatments and steps to take to prevent the transmission of hepatitis C to others.

Should newborns at 22 or 23 weeks’ gestational age be aggressively resuscitated?

For many decades the limit of viability was believed to be approximately 24 weeks of gestation. In many medical centers, newborns delivered at less than 25 weeks are evaluated in the delivery room and the decision to resuscitate is based on the infant’s clinical response. In the past, aggressive and extended resuscitation of newborns at 22 and 23 weeks was not common because the prognosis was bleak and clinicians did not want to inflict unnecessary pain when the chances for survival were limited. Recent advances in obstetric and pediatric care, however, have resulted in the survival of some infants born at 22 weeks’ gestation, calling into question long-held beliefs about the limits of viability.

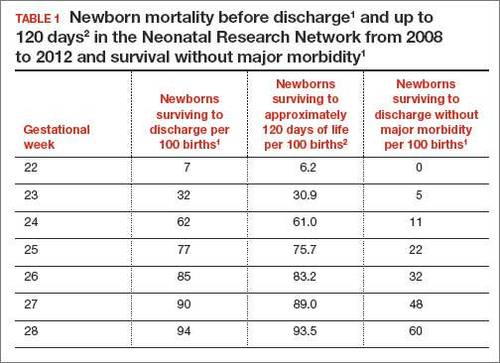

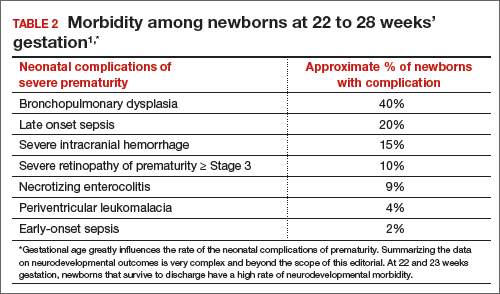

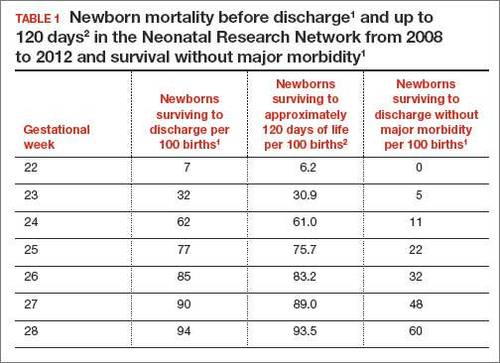

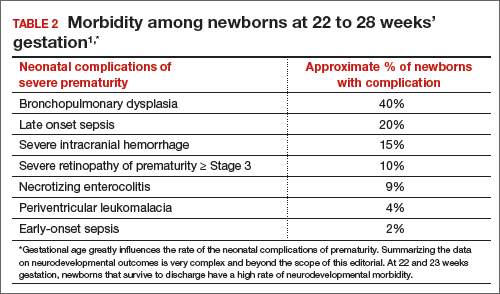

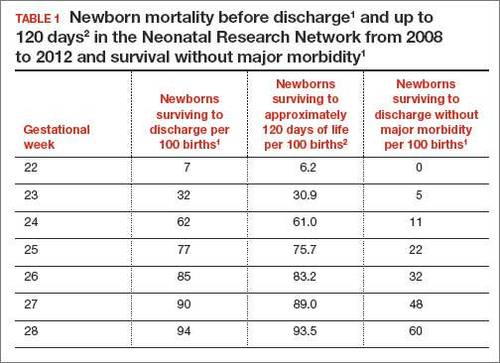

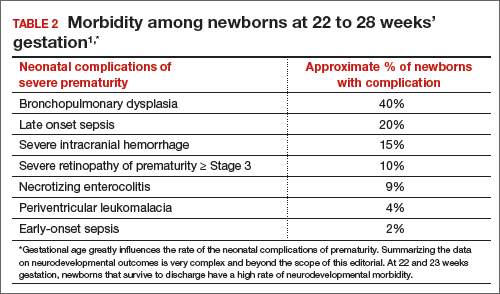

In 2 recent reports, investigators used data from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Neonatal Research Network to acquire detailed information about newborn survival and morbidity at 22 through 28 weeks’ gestation (TABLES 1 and 2).1,2 These data show that the survival of newborns at 23 through 27 weeks’ gestation is increasing, albeit slowly. Survival, without major morbidity, is gradually improving for newborns at 25 through 28 weeks.1,2 But what is the prognosis for a fetus born at 22 or 23 weeks?

There are several aspects of this issue to consider, including accurate dating of the gestational age and current viability outcomes data.

Determining the limit of viability: Accurate dating is essentialThe limit of viability is the milestone in gestation when there is a high probability of extrauterine survival. A major challenge in studies of the limit of viability for newborns is that accurate gestational dating is not always available. For example, in recent reports from the NICHD Neonatal Research Network the gestational age was determined by the best obstetric estimate, or the Ballard or Dubowitz examination, of the newborn.1,2

It is well known that ultrasound dating early in gestation is a better estimate of gestational age than last menstrual period, uterine sizing, or pediatric examination of the newborn. Hence, the available data are limited by the absence of precise gestational dating with early ultrasound. Data on the limit of viability with large numbers of births between 22 and 24 weeks with early ultrasound dating would help to refine our understanding of the limit of viability.

At 23 weeks, each day of in utero development is criticalThe importance of each additional day spent in utero during the 23rd week of gestation was demonstrated in a small cohort in 2001.4 Overall, during the 23rd week of gestation the survival of newborns to discharge was 33%.4 This finding is similar to the survival rate reported by the NICHD Neonatal Research Network in 2012.1 However, survival was vastly different early, compared with later, in the 23rd week4:

- from 23 weeks 0 days to 23 weeks 2 days: no newborn survived

- at 23 weeks 3 days and 23 weeks 4 days: 40% of newborns survived

- at 23 weeks 5 days and 23 weeks 6 days: 63% of newborns survived (a similar survival rate of 24-week gestations was reported by the NICHD Neonatal Research Network1).

The development of the fetus across the 23rd week of gestation appears to be critical to newborn survival. Hence, every day of in utero development during the 23rd week is critically important. A great challenge for obstetricians is how to approach the woman with threatened preterm birth at 22 weeks 0 days’ gestation. If the woman delivers within a few days, the likelihood of survival is minimal. However, if the pregnancy can be extended to 23 weeks and 5 days, survival rates increase significantly.

Aligning the actions of birth team, mother, and familyFactors that influence the limit of viability include:

- gestational age

- gender of the fetus (Females are more likely than males to survive.)

- treatment of the mother with glucocorticoids prior to birth

- newborn weight.

To increase the likelihood of newborn survival, obstetricians need to treat women at risk for preterm birth with antenatal glucocorticoids and antibiotics for rupture of membranes and to limit fetal stress during the birth process. Guidelines have evolved to encourage clinicians to treat women at preterm birth risk with glucocorticoids either at:

- 23 weeks’ gestation or

- 22 weeks’ gestation, if birth is anticipated to occur at 23 weeks or later.5

At birth, pediatricians are then faced with the very difficult decision of whether or not to aggressively resuscitate the severely preterm infant. Complex medical, social, and ethical issues ultimately guide pediatricians’ actions in this challenging situation. It is important for their actions to be in consensus with the obstetrician, the mother, and the mother’s family and for a consensus to be reached. Dissonant plans may increase adverse outcomes for the newborn. In one study when pediatricians and obstetricians were not aligned in their actions, the risk of death of an extremely preterm newborn significantly increased.6

Prior to birth, team meetings that include the obstetricians, pediatricians, mother, and family will help to set expectations about the course of care and, in turn, improve perceived outcomes.5 If feasible, obstetricians and pediatricians should develop joint institutional guidelines about the general approach to pregnant women when birth may occur at 22 or 23 weeks’ gestation.5

A neonatal outcomes predictor

The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development provides a Web-based tool for estimating newborn outcomes based on gestational age (22 to 25 weeks), birth weight, gender, singleton or multiple gestation, and exposure to antenatal glucocorticoid treatment. The outcomes tool provides estimates for survival and survival with severe morbidity. It uses data collected by the Neonatal Research Network to predict outcomes. To access the outcomes data assessment, visit https://www.nichd.nih.gov/about/org/der/branches/ppb/programs/epbo/Pages/epbo_case.aspx.

Is aggressive management of preterm birth and neonatal resuscitation a self-fulfilling prophecy?The beliefs and training of clinicians may influence the outcome of extremely preterm newborns. For example, if obstetricians and pediatricians focus on the fact that birth at 23 weeks is not likely to result in survival without severe morbidity, they may withhold key interventions such as antenatal glucocorticoids, antibiotics for rupture of the membranes, and aggressive newborn resuscitation.7 Consequently the likelihood of survival may be reduced.

If clinicians believe in maximal interventions for all newborns at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation, their actions may result in a small increase in newborn survival—but at the cost of painful and unnecessary interventions in many newborns who are destined to die. Finding the right balance along the broad spectrum from expectant management to aggressive and extended resuscitation is challenging. Clearly there is no “right answer” with these extremely difficult decisions.

Future trends in the limit of viabilityIn 1963, Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, at 34 weeks’ gestation, went into preterm labor and delivered her son Patrick at a community hospital. Patrick developed respiratory distress syndrome and was transferred to the Boston Children’s Hospital. He died shortly thereafter.8 Would Patrick have survived if he had been delivered at an institution capable of providing high-risk obstetric and newborn services? Would such modern interventions as antenatal glucocorticoids, antibiotics for ruptured membranes, liberal use of cesarean delivery, and aggressive neonatal resuscitation have improved his chances for survival?

From our current perspective, it is surprising that a 34-week newborn died shortly after birth. With modern obstetric and pediatric care that scenario is unusual. It is possible that future advances in medical care will push the limit of viability to 22 weeks’ gestation. Future generations of clinicians may be surprised that the medicine we practice today is so limited.

However, given our current resources, it is unlikely that newborns at 22 weeks’ gestation will survive, or survive without severe morbidity. Consequently, routine aggressive resuscitation of newborns at 22 weeks should be approached with caution. At 23 weeks and later, many newborns will survive and a few will survive without severe morbidity. Given the complexity of the issues, the approach to resuscitation of infants at 22 and 23 weeks must account for the perspectives of the birth mother and her family, obstetricians, and pediatricians. Managing threatened preterm birth at 22 and 23 weeks is one of our greatest challenges as obstetricians, and we need to meet this challenge with grace and skill.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, et al; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Trends in care practices, morbidity and mortality of extremely preterm neonates, 1993-2012. JAMA. 2015;314(10):1039–1051.

- Patel RM, Kandefer S, Walsh MC, et al; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Causes and timing of death in extremely premature infants from 2000 through 2011. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(4):331–340.

- Donovan EF, Tyson JE, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Inaccuracy of Ballard scores before 28 weeks’ gestation. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. J Pediatr. 1999;135(2 pt 1):147–152.

- McElrath TF, Robinson JN, Ecker JL, Ringer SA, Norwitz ER. Neonatal outcome of infants born at 23 weeks’ gestation. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(1):49–52.

- Raju TN, Mercer BM, Burchfield DJ, Joseph GF Jr. Periviable birth: executive summary of a joint workshop by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics, and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(5):1083–1096.

- Guinsburg R, Branco de Almeida MF, dos Santos Rodrigues Sadeck L, et al; Brazilian Network on Neonatal Research. Proactive management of extreme prematurity: disagreement between obstetricians and neonatologists. J Perinatol. 2012;32(12):913-919.

- Tucker Emonds B, McKenzie F, Farrow V, Raglan G, Schulkin J. A national survey of obstetricians’ attitudes toward and practice of periviable interventions. J Perinatol. 2015;35(5):338–343.

- Altman LK. A Kennedy baby’s life and death. New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/30/health/a-kennedy-babys-life-and-death.html?_r=0. Published July 29, 2013. Accessed November 19, 2015.

For many decades the limit of viability was believed to be approximately 24 weeks of gestation. In many medical centers, newborns delivered at less than 25 weeks are evaluated in the delivery room and the decision to resuscitate is based on the infant’s clinical response. In the past, aggressive and extended resuscitation of newborns at 22 and 23 weeks was not common because the prognosis was bleak and clinicians did not want to inflict unnecessary pain when the chances for survival were limited. Recent advances in obstetric and pediatric care, however, have resulted in the survival of some infants born at 22 weeks’ gestation, calling into question long-held beliefs about the limits of viability.

In 2 recent reports, investigators used data from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Neonatal Research Network to acquire detailed information about newborn survival and morbidity at 22 through 28 weeks’ gestation (TABLES 1 and 2).1,2 These data show that the survival of newborns at 23 through 27 weeks’ gestation is increasing, albeit slowly. Survival, without major morbidity, is gradually improving for newborns at 25 through 28 weeks.1,2 But what is the prognosis for a fetus born at 22 or 23 weeks?

There are several aspects of this issue to consider, including accurate dating of the gestational age and current viability outcomes data.

Determining the limit of viability: Accurate dating is essentialThe limit of viability is the milestone in gestation when there is a high probability of extrauterine survival. A major challenge in studies of the limit of viability for newborns is that accurate gestational dating is not always available. For example, in recent reports from the NICHD Neonatal Research Network the gestational age was determined by the best obstetric estimate, or the Ballard or Dubowitz examination, of the newborn.1,2

It is well known that ultrasound dating early in gestation is a better estimate of gestational age than last menstrual period, uterine sizing, or pediatric examination of the newborn. Hence, the available data are limited by the absence of precise gestational dating with early ultrasound. Data on the limit of viability with large numbers of births between 22 and 24 weeks with early ultrasound dating would help to refine our understanding of the limit of viability.

At 23 weeks, each day of in utero development is criticalThe importance of each additional day spent in utero during the 23rd week of gestation was demonstrated in a small cohort in 2001.4 Overall, during the 23rd week of gestation the survival of newborns to discharge was 33%.4 This finding is similar to the survival rate reported by the NICHD Neonatal Research Network in 2012.1 However, survival was vastly different early, compared with later, in the 23rd week4:

- from 23 weeks 0 days to 23 weeks 2 days: no newborn survived

- at 23 weeks 3 days and 23 weeks 4 days: 40% of newborns survived

- at 23 weeks 5 days and 23 weeks 6 days: 63% of newborns survived (a similar survival rate of 24-week gestations was reported by the NICHD Neonatal Research Network1).

The development of the fetus across the 23rd week of gestation appears to be critical to newborn survival. Hence, every day of in utero development during the 23rd week is critically important. A great challenge for obstetricians is how to approach the woman with threatened preterm birth at 22 weeks 0 days’ gestation. If the woman delivers within a few days, the likelihood of survival is minimal. However, if the pregnancy can be extended to 23 weeks and 5 days, survival rates increase significantly.

Aligning the actions of birth team, mother, and familyFactors that influence the limit of viability include:

- gestational age

- gender of the fetus (Females are more likely than males to survive.)

- treatment of the mother with glucocorticoids prior to birth

- newborn weight.

To increase the likelihood of newborn survival, obstetricians need to treat women at risk for preterm birth with antenatal glucocorticoids and antibiotics for rupture of membranes and to limit fetal stress during the birth process. Guidelines have evolved to encourage clinicians to treat women at preterm birth risk with glucocorticoids either at:

- 23 weeks’ gestation or

- 22 weeks’ gestation, if birth is anticipated to occur at 23 weeks or later.5

At birth, pediatricians are then faced with the very difficult decision of whether or not to aggressively resuscitate the severely preterm infant. Complex medical, social, and ethical issues ultimately guide pediatricians’ actions in this challenging situation. It is important for their actions to be in consensus with the obstetrician, the mother, and the mother’s family and for a consensus to be reached. Dissonant plans may increase adverse outcomes for the newborn. In one study when pediatricians and obstetricians were not aligned in their actions, the risk of death of an extremely preterm newborn significantly increased.6

Prior to birth, team meetings that include the obstetricians, pediatricians, mother, and family will help to set expectations about the course of care and, in turn, improve perceived outcomes.5 If feasible, obstetricians and pediatricians should develop joint institutional guidelines about the general approach to pregnant women when birth may occur at 22 or 23 weeks’ gestation.5

A neonatal outcomes predictor

The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development provides a Web-based tool for estimating newborn outcomes based on gestational age (22 to 25 weeks), birth weight, gender, singleton or multiple gestation, and exposure to antenatal glucocorticoid treatment. The outcomes tool provides estimates for survival and survival with severe morbidity. It uses data collected by the Neonatal Research Network to predict outcomes. To access the outcomes data assessment, visit https://www.nichd.nih.gov/about/org/der/branches/ppb/programs/epbo/Pages/epbo_case.aspx.

Is aggressive management of preterm birth and neonatal resuscitation a self-fulfilling prophecy?The beliefs and training of clinicians may influence the outcome of extremely preterm newborns. For example, if obstetricians and pediatricians focus on the fact that birth at 23 weeks is not likely to result in survival without severe morbidity, they may withhold key interventions such as antenatal glucocorticoids, antibiotics for rupture of the membranes, and aggressive newborn resuscitation.7 Consequently the likelihood of survival may be reduced.

If clinicians believe in maximal interventions for all newborns at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation, their actions may result in a small increase in newborn survival—but at the cost of painful and unnecessary interventions in many newborns who are destined to die. Finding the right balance along the broad spectrum from expectant management to aggressive and extended resuscitation is challenging. Clearly there is no “right answer” with these extremely difficult decisions.

Future trends in the limit of viabilityIn 1963, Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, at 34 weeks’ gestation, went into preterm labor and delivered her son Patrick at a community hospital. Patrick developed respiratory distress syndrome and was transferred to the Boston Children’s Hospital. He died shortly thereafter.8 Would Patrick have survived if he had been delivered at an institution capable of providing high-risk obstetric and newborn services? Would such modern interventions as antenatal glucocorticoids, antibiotics for ruptured membranes, liberal use of cesarean delivery, and aggressive neonatal resuscitation have improved his chances for survival?

From our current perspective, it is surprising that a 34-week newborn died shortly after birth. With modern obstetric and pediatric care that scenario is unusual. It is possible that future advances in medical care will push the limit of viability to 22 weeks’ gestation. Future generations of clinicians may be surprised that the medicine we practice today is so limited.

However, given our current resources, it is unlikely that newborns at 22 weeks’ gestation will survive, or survive without severe morbidity. Consequently, routine aggressive resuscitation of newborns at 22 weeks should be approached with caution. At 23 weeks and later, many newborns will survive and a few will survive without severe morbidity. Given the complexity of the issues, the approach to resuscitation of infants at 22 and 23 weeks must account for the perspectives of the birth mother and her family, obstetricians, and pediatricians. Managing threatened preterm birth at 22 and 23 weeks is one of our greatest challenges as obstetricians, and we need to meet this challenge with grace and skill.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

For many decades the limit of viability was believed to be approximately 24 weeks of gestation. In many medical centers, newborns delivered at less than 25 weeks are evaluated in the delivery room and the decision to resuscitate is based on the infant’s clinical response. In the past, aggressive and extended resuscitation of newborns at 22 and 23 weeks was not common because the prognosis was bleak and clinicians did not want to inflict unnecessary pain when the chances for survival were limited. Recent advances in obstetric and pediatric care, however, have resulted in the survival of some infants born at 22 weeks’ gestation, calling into question long-held beliefs about the limits of viability.

In 2 recent reports, investigators used data from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Neonatal Research Network to acquire detailed information about newborn survival and morbidity at 22 through 28 weeks’ gestation (TABLES 1 and 2).1,2 These data show that the survival of newborns at 23 through 27 weeks’ gestation is increasing, albeit slowly. Survival, without major morbidity, is gradually improving for newborns at 25 through 28 weeks.1,2 But what is the prognosis for a fetus born at 22 or 23 weeks?

There are several aspects of this issue to consider, including accurate dating of the gestational age and current viability outcomes data.

Determining the limit of viability: Accurate dating is essentialThe limit of viability is the milestone in gestation when there is a high probability of extrauterine survival. A major challenge in studies of the limit of viability for newborns is that accurate gestational dating is not always available. For example, in recent reports from the NICHD Neonatal Research Network the gestational age was determined by the best obstetric estimate, or the Ballard or Dubowitz examination, of the newborn.1,2

It is well known that ultrasound dating early in gestation is a better estimate of gestational age than last menstrual period, uterine sizing, or pediatric examination of the newborn. Hence, the available data are limited by the absence of precise gestational dating with early ultrasound. Data on the limit of viability with large numbers of births between 22 and 24 weeks with early ultrasound dating would help to refine our understanding of the limit of viability.

At 23 weeks, each day of in utero development is criticalThe importance of each additional day spent in utero during the 23rd week of gestation was demonstrated in a small cohort in 2001.4 Overall, during the 23rd week of gestation the survival of newborns to discharge was 33%.4 This finding is similar to the survival rate reported by the NICHD Neonatal Research Network in 2012.1 However, survival was vastly different early, compared with later, in the 23rd week4:

- from 23 weeks 0 days to 23 weeks 2 days: no newborn survived

- at 23 weeks 3 days and 23 weeks 4 days: 40% of newborns survived