User login

Ibrutinib ‘treatment of choice’ in rel/ref MCL

Annual Meeting

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—The BTK inhibitor ibrutinib should be considered the treatment of choice for patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), according to a speaker at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting.

Results of the phase 3 RAY trial showed that ibrutinib can prolong progression-free survival (PFS) when compared to the mTOR inhibitor temsirolimus.

There was no significant difference in overall survival (OS) between the treatment arms, but this outcome was influenced by the fact that patients were allowed to cross over from the temsirolimus arm to the ibrutinib arm after they progressed.

A majority of patients in both arms experienced adverse events (AEs), and the incidence of grade 3 or higher AEs was high—about 70% with ibrutinib and 90% with temsirolimus.

Simon Rule, MD, of Derriford Hospital in Plymouth, UK, presented these results at the meeting as abstract 469. The study has been published in The Lancet as well.

The research was sponsored by Janssen Biotech, Inc., which is jointly developing and commercializing ibrutinib with Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie company.

Study design

The trial included 280 patients with relapsed or refractory MCL. They were enrolled from December 2012 to November 2013.

The patients were randomized to receive oral ibrutinib (n=139) at 560 mg or intravenous temsirolimus (n=141) at 175 mg on days 1, 8, and 15 of cycle 1 and 75 mg on days 1, 8, and 15 of all subsequent 21-day cycles until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Starting July 2014, patients were allowed to cross over from the ibrutinib arm to the temsirolimus arm if they had progressive disease, as confirmed by an independent review committee. Thirty-two patients ultimately crossed over.

Patient characteristics

Baseline characteristics were similar between the treatment arms. The median age was 67 (range, 39-84) in the ibrutinib arm and 68 (range, 34-88) in the temsirolimus arm. Most patients had an ECOG performance status of 0 (48.2% and 47.5%, respectively) or 1 (51.1% in both arms).

The median number of prior therapies was 2 in both arms (range, 1-9). A majority of patients had 1 to 2 prior lines of therapy—68.3% in the ibrutinib arm and 66% in the temsirolimus arm.

The median time from the end of last therapy was 8.25 months for the ibrutinib arm and 7.03 months for the temsirolimus arm. And about 30% of patients in each arm were refractory to their last therapy—25.9% and 33.3%, respectively.

About half of patients in each arm had intermediate-risk disease (46.8% in the ibrutinib arm and 48.9% in the temsirolimus arm), followed by low-risk (31.7% and 29.8%, respectively) and high-risk disease (21.6% and 21.3%, respectively).

Most patients had stage IV disease—80.6% in the ibrutinib arm and 85.1% in the temsirolimus arm.

PFS

The study’s primary endpoint was PFS, as assessed by an independent review committee.

At a median follow-up of 20 months, the median PFS was 14.6 months for patients in the ibrutinib arm and 6.2 months for patients in the temsirolimus arm (hazard ratio=0.43, P<0.0001). At 2 years, the PFS was 41% in the ibrutinib arm and 7% in the temsirolimus arm.

Dr Rule noted that, looking at these data, people might question the validity of temsirolimus as a comparator to ibrutinib for this patient population.

“If you look at the median PFS for temsirolimus here, it’s 6.2 months,” he said. “In the registration study for Velcade—bortezomib—in the US, PFS was 6.5 months. If you look at the median PFS in the lenalidomide study that got registration, it was 4 months. So [the PFS for temsirolimus] is very representative of an oral novel agent in the context of mantle cell lymphoma.”

Dr Rule also pointed out that the improvement in PFS with ibrutinib was consistent across subgroups (ie, older age, risk score, tumor bulk, refractory disease). The only exception was patients with blastoid histology, but this was a very small group.

Secondary endpoints

The median OS was not reached in the ibrutinib arm but was 21.3 months in the temsirolimus arm.

This difference was not statistically significant, but Dr Rule noted that the trial was not powered for OS, and the analysis is confounded by the crossover. Twenty-three percent of patients in the temsirolimus arm ultimately received ibrutinib.

The overall response rate (ORR) was 71.9% in the ibrutinib arm and 40.4% in the temsirolimus arm (P<0.0001), according to the independent review committee. The complete response rates were 18.7% (n=26) and 1.4% (n=2), respectively.

The median duration of response was not reached with ibrutinib but was 7 months for temsirolimus. The median time to next treatment was not reached with ibrutinib, but it was 11.6 months in the temsirolimus arm (P<0.0001).

And the median duration of study treatment was 14.4 months in the ibrutinib arm and 3 months in the temsirolimus arm.

Timing counts

Dr Rule also presented response and PFS data according to the number of prior therapies patients received.

He noted that patients were more likely to respond to temsirolimus if they had received fewer prior therapies, but this was not the case with ibrutinib. Ibrutinib produced consistent ORRs regardless of when it was given.

In the ibrutinib arm, the ORR was 71.9% for patients who had received 1 prior line of therapy, 68.4% for those who received 2 prior therapies, and 75% for those who received 3 prior therapies. In the temsirolimus arm, the ORRs were 48%, 39.5%, and 33.3%, respectively.

Conversely, patients had a greater PFS benefit if they received ibrutinib earlier in their treatment course, but this was not true for temsirolimus.

At the median follow-up of 20 months, PFS was more than 60% for ibrutinib-treated patients who had received 1 prior line of therapy and less than 30% for ibrutinib-treated patients who received 2 or more prior lines of therapy. PFS was less than 15% for patients in the temsirolimus arm, regardless of their number of prior therapies.

“So that’s perhaps the first hint that, if we’re going to be using [ibrutinib], we should be using it earlier on,” Dr Rule said. “And I also suspect that, with further follow-up with this study, if this holds up, there will be, indeed, a survival benefit observed.”

Safety

“Despite patients on the ibrutinib arm being exposed to drug more than 4 times longer than those with temsirolimus, the frequency of most cumulative adverse events was lower in the ibrutinib arm,” Dr Rule said.

Still, he noted that most patients had some adverse events. And grade 3 or higher adverse events were reported in 67.6% of patients on ibrutinib and 87.1% of patients on temsirolimus.

Grade 3 or higher AEs included atrial fibrillation (AFib) and major bleeding. AFib occurred in 4.3% of patients in the ibrutinib arm and 1.4% in the temsirolimus arm. Major bleeding occurred in 10.1% and 6.5%, respectively.

Five of the 6 patients with AFib in the ibrutinib arm and all 3 patients who developed AFib in the temsirolimus arm had risk factors for AFib prior to treatment. None of these patients discontinued treatment due to AFib.

Dr Rule said there was no evidence to suggest that either drug increases the risk of second primary malignancies, although 3.6% of patients in the ibrutinib arm and 2.9% in the temsirolimus arm were diagnosed with second primary malignancies (mostly non-melanoma skin cancers).

The most common treatment-emergent AEs (≥20%) of any grade for the ibrutinib arm were diarrhea (28.8%), cough (22.3%), and fatigue (22.3%).

The most common treatment-emergent AEs (>20%) of any grade for the temsirolimus arm were thrombocytopenia (56.1%), anemia (43.2%), diarrhea (30.9%), fatigue (28.8%), neutropenia (25.9%), epistaxis (23.7%), cough (22.3%), peripheral edema (22.3%), nausea (21.6%), pyrexia (20.9%), and stomatitis (20.9%).

The most common hematologic AEs (≥10%) in the ibrutinib and temsirolimus arms, respectively, were thrombocytopenia (18% vs 56.1%), anemia (18% vs 43.2%), and neutropenia (15.8% vs 25.9%).

Six percent of patients in the ibrutinib arm and 26% in the temsirolimus arm discontinued treatment due to AEs.

At a median follow-up of 20 months, 42% of patients in the ibrutinib arm and 45% in the temsirolimus arm had died. The most common cause of death associated with ibrutinib was disease progression, and deaths in the temsirolimus arm were primarily attributed to AEs. ![]()

Annual Meeting

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—The BTK inhibitor ibrutinib should be considered the treatment of choice for patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), according to a speaker at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting.

Results of the phase 3 RAY trial showed that ibrutinib can prolong progression-free survival (PFS) when compared to the mTOR inhibitor temsirolimus.

There was no significant difference in overall survival (OS) between the treatment arms, but this outcome was influenced by the fact that patients were allowed to cross over from the temsirolimus arm to the ibrutinib arm after they progressed.

A majority of patients in both arms experienced adverse events (AEs), and the incidence of grade 3 or higher AEs was high—about 70% with ibrutinib and 90% with temsirolimus.

Simon Rule, MD, of Derriford Hospital in Plymouth, UK, presented these results at the meeting as abstract 469. The study has been published in The Lancet as well.

The research was sponsored by Janssen Biotech, Inc., which is jointly developing and commercializing ibrutinib with Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie company.

Study design

The trial included 280 patients with relapsed or refractory MCL. They were enrolled from December 2012 to November 2013.

The patients were randomized to receive oral ibrutinib (n=139) at 560 mg or intravenous temsirolimus (n=141) at 175 mg on days 1, 8, and 15 of cycle 1 and 75 mg on days 1, 8, and 15 of all subsequent 21-day cycles until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Starting July 2014, patients were allowed to cross over from the ibrutinib arm to the temsirolimus arm if they had progressive disease, as confirmed by an independent review committee. Thirty-two patients ultimately crossed over.

Patient characteristics

Baseline characteristics were similar between the treatment arms. The median age was 67 (range, 39-84) in the ibrutinib arm and 68 (range, 34-88) in the temsirolimus arm. Most patients had an ECOG performance status of 0 (48.2% and 47.5%, respectively) or 1 (51.1% in both arms).

The median number of prior therapies was 2 in both arms (range, 1-9). A majority of patients had 1 to 2 prior lines of therapy—68.3% in the ibrutinib arm and 66% in the temsirolimus arm.

The median time from the end of last therapy was 8.25 months for the ibrutinib arm and 7.03 months for the temsirolimus arm. And about 30% of patients in each arm were refractory to their last therapy—25.9% and 33.3%, respectively.

About half of patients in each arm had intermediate-risk disease (46.8% in the ibrutinib arm and 48.9% in the temsirolimus arm), followed by low-risk (31.7% and 29.8%, respectively) and high-risk disease (21.6% and 21.3%, respectively).

Most patients had stage IV disease—80.6% in the ibrutinib arm and 85.1% in the temsirolimus arm.

PFS

The study’s primary endpoint was PFS, as assessed by an independent review committee.

At a median follow-up of 20 months, the median PFS was 14.6 months for patients in the ibrutinib arm and 6.2 months for patients in the temsirolimus arm (hazard ratio=0.43, P<0.0001). At 2 years, the PFS was 41% in the ibrutinib arm and 7% in the temsirolimus arm.

Dr Rule noted that, looking at these data, people might question the validity of temsirolimus as a comparator to ibrutinib for this patient population.

“If you look at the median PFS for temsirolimus here, it’s 6.2 months,” he said. “In the registration study for Velcade—bortezomib—in the US, PFS was 6.5 months. If you look at the median PFS in the lenalidomide study that got registration, it was 4 months. So [the PFS for temsirolimus] is very representative of an oral novel agent in the context of mantle cell lymphoma.”

Dr Rule also pointed out that the improvement in PFS with ibrutinib was consistent across subgroups (ie, older age, risk score, tumor bulk, refractory disease). The only exception was patients with blastoid histology, but this was a very small group.

Secondary endpoints

The median OS was not reached in the ibrutinib arm but was 21.3 months in the temsirolimus arm.

This difference was not statistically significant, but Dr Rule noted that the trial was not powered for OS, and the analysis is confounded by the crossover. Twenty-three percent of patients in the temsirolimus arm ultimately received ibrutinib.

The overall response rate (ORR) was 71.9% in the ibrutinib arm and 40.4% in the temsirolimus arm (P<0.0001), according to the independent review committee. The complete response rates were 18.7% (n=26) and 1.4% (n=2), respectively.

The median duration of response was not reached with ibrutinib but was 7 months for temsirolimus. The median time to next treatment was not reached with ibrutinib, but it was 11.6 months in the temsirolimus arm (P<0.0001).

And the median duration of study treatment was 14.4 months in the ibrutinib arm and 3 months in the temsirolimus arm.

Timing counts

Dr Rule also presented response and PFS data according to the number of prior therapies patients received.

He noted that patients were more likely to respond to temsirolimus if they had received fewer prior therapies, but this was not the case with ibrutinib. Ibrutinib produced consistent ORRs regardless of when it was given.

In the ibrutinib arm, the ORR was 71.9% for patients who had received 1 prior line of therapy, 68.4% for those who received 2 prior therapies, and 75% for those who received 3 prior therapies. In the temsirolimus arm, the ORRs were 48%, 39.5%, and 33.3%, respectively.

Conversely, patients had a greater PFS benefit if they received ibrutinib earlier in their treatment course, but this was not true for temsirolimus.

At the median follow-up of 20 months, PFS was more than 60% for ibrutinib-treated patients who had received 1 prior line of therapy and less than 30% for ibrutinib-treated patients who received 2 or more prior lines of therapy. PFS was less than 15% for patients in the temsirolimus arm, regardless of their number of prior therapies.

“So that’s perhaps the first hint that, if we’re going to be using [ibrutinib], we should be using it earlier on,” Dr Rule said. “And I also suspect that, with further follow-up with this study, if this holds up, there will be, indeed, a survival benefit observed.”

Safety

“Despite patients on the ibrutinib arm being exposed to drug more than 4 times longer than those with temsirolimus, the frequency of most cumulative adverse events was lower in the ibrutinib arm,” Dr Rule said.

Still, he noted that most patients had some adverse events. And grade 3 or higher adverse events were reported in 67.6% of patients on ibrutinib and 87.1% of patients on temsirolimus.

Grade 3 or higher AEs included atrial fibrillation (AFib) and major bleeding. AFib occurred in 4.3% of patients in the ibrutinib arm and 1.4% in the temsirolimus arm. Major bleeding occurred in 10.1% and 6.5%, respectively.

Five of the 6 patients with AFib in the ibrutinib arm and all 3 patients who developed AFib in the temsirolimus arm had risk factors for AFib prior to treatment. None of these patients discontinued treatment due to AFib.

Dr Rule said there was no evidence to suggest that either drug increases the risk of second primary malignancies, although 3.6% of patients in the ibrutinib arm and 2.9% in the temsirolimus arm were diagnosed with second primary malignancies (mostly non-melanoma skin cancers).

The most common treatment-emergent AEs (≥20%) of any grade for the ibrutinib arm were diarrhea (28.8%), cough (22.3%), and fatigue (22.3%).

The most common treatment-emergent AEs (>20%) of any grade for the temsirolimus arm were thrombocytopenia (56.1%), anemia (43.2%), diarrhea (30.9%), fatigue (28.8%), neutropenia (25.9%), epistaxis (23.7%), cough (22.3%), peripheral edema (22.3%), nausea (21.6%), pyrexia (20.9%), and stomatitis (20.9%).

The most common hematologic AEs (≥10%) in the ibrutinib and temsirolimus arms, respectively, were thrombocytopenia (18% vs 56.1%), anemia (18% vs 43.2%), and neutropenia (15.8% vs 25.9%).

Six percent of patients in the ibrutinib arm and 26% in the temsirolimus arm discontinued treatment due to AEs.

At a median follow-up of 20 months, 42% of patients in the ibrutinib arm and 45% in the temsirolimus arm had died. The most common cause of death associated with ibrutinib was disease progression, and deaths in the temsirolimus arm were primarily attributed to AEs. ![]()

Annual Meeting

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—The BTK inhibitor ibrutinib should be considered the treatment of choice for patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), according to a speaker at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting.

Results of the phase 3 RAY trial showed that ibrutinib can prolong progression-free survival (PFS) when compared to the mTOR inhibitor temsirolimus.

There was no significant difference in overall survival (OS) between the treatment arms, but this outcome was influenced by the fact that patients were allowed to cross over from the temsirolimus arm to the ibrutinib arm after they progressed.

A majority of patients in both arms experienced adverse events (AEs), and the incidence of grade 3 or higher AEs was high—about 70% with ibrutinib and 90% with temsirolimus.

Simon Rule, MD, of Derriford Hospital in Plymouth, UK, presented these results at the meeting as abstract 469. The study has been published in The Lancet as well.

The research was sponsored by Janssen Biotech, Inc., which is jointly developing and commercializing ibrutinib with Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie company.

Study design

The trial included 280 patients with relapsed or refractory MCL. They were enrolled from December 2012 to November 2013.

The patients were randomized to receive oral ibrutinib (n=139) at 560 mg or intravenous temsirolimus (n=141) at 175 mg on days 1, 8, and 15 of cycle 1 and 75 mg on days 1, 8, and 15 of all subsequent 21-day cycles until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Starting July 2014, patients were allowed to cross over from the ibrutinib arm to the temsirolimus arm if they had progressive disease, as confirmed by an independent review committee. Thirty-two patients ultimately crossed over.

Patient characteristics

Baseline characteristics were similar between the treatment arms. The median age was 67 (range, 39-84) in the ibrutinib arm and 68 (range, 34-88) in the temsirolimus arm. Most patients had an ECOG performance status of 0 (48.2% and 47.5%, respectively) or 1 (51.1% in both arms).

The median number of prior therapies was 2 in both arms (range, 1-9). A majority of patients had 1 to 2 prior lines of therapy—68.3% in the ibrutinib arm and 66% in the temsirolimus arm.

The median time from the end of last therapy was 8.25 months for the ibrutinib arm and 7.03 months for the temsirolimus arm. And about 30% of patients in each arm were refractory to their last therapy—25.9% and 33.3%, respectively.

About half of patients in each arm had intermediate-risk disease (46.8% in the ibrutinib arm and 48.9% in the temsirolimus arm), followed by low-risk (31.7% and 29.8%, respectively) and high-risk disease (21.6% and 21.3%, respectively).

Most patients had stage IV disease—80.6% in the ibrutinib arm and 85.1% in the temsirolimus arm.

PFS

The study’s primary endpoint was PFS, as assessed by an independent review committee.

At a median follow-up of 20 months, the median PFS was 14.6 months for patients in the ibrutinib arm and 6.2 months for patients in the temsirolimus arm (hazard ratio=0.43, P<0.0001). At 2 years, the PFS was 41% in the ibrutinib arm and 7% in the temsirolimus arm.

Dr Rule noted that, looking at these data, people might question the validity of temsirolimus as a comparator to ibrutinib for this patient population.

“If you look at the median PFS for temsirolimus here, it’s 6.2 months,” he said. “In the registration study for Velcade—bortezomib—in the US, PFS was 6.5 months. If you look at the median PFS in the lenalidomide study that got registration, it was 4 months. So [the PFS for temsirolimus] is very representative of an oral novel agent in the context of mantle cell lymphoma.”

Dr Rule also pointed out that the improvement in PFS with ibrutinib was consistent across subgroups (ie, older age, risk score, tumor bulk, refractory disease). The only exception was patients with blastoid histology, but this was a very small group.

Secondary endpoints

The median OS was not reached in the ibrutinib arm but was 21.3 months in the temsirolimus arm.

This difference was not statistically significant, but Dr Rule noted that the trial was not powered for OS, and the analysis is confounded by the crossover. Twenty-three percent of patients in the temsirolimus arm ultimately received ibrutinib.

The overall response rate (ORR) was 71.9% in the ibrutinib arm and 40.4% in the temsirolimus arm (P<0.0001), according to the independent review committee. The complete response rates were 18.7% (n=26) and 1.4% (n=2), respectively.

The median duration of response was not reached with ibrutinib but was 7 months for temsirolimus. The median time to next treatment was not reached with ibrutinib, but it was 11.6 months in the temsirolimus arm (P<0.0001).

And the median duration of study treatment was 14.4 months in the ibrutinib arm and 3 months in the temsirolimus arm.

Timing counts

Dr Rule also presented response and PFS data according to the number of prior therapies patients received.

He noted that patients were more likely to respond to temsirolimus if they had received fewer prior therapies, but this was not the case with ibrutinib. Ibrutinib produced consistent ORRs regardless of when it was given.

In the ibrutinib arm, the ORR was 71.9% for patients who had received 1 prior line of therapy, 68.4% for those who received 2 prior therapies, and 75% for those who received 3 prior therapies. In the temsirolimus arm, the ORRs were 48%, 39.5%, and 33.3%, respectively.

Conversely, patients had a greater PFS benefit if they received ibrutinib earlier in their treatment course, but this was not true for temsirolimus.

At the median follow-up of 20 months, PFS was more than 60% for ibrutinib-treated patients who had received 1 prior line of therapy and less than 30% for ibrutinib-treated patients who received 2 or more prior lines of therapy. PFS was less than 15% for patients in the temsirolimus arm, regardless of their number of prior therapies.

“So that’s perhaps the first hint that, if we’re going to be using [ibrutinib], we should be using it earlier on,” Dr Rule said. “And I also suspect that, with further follow-up with this study, if this holds up, there will be, indeed, a survival benefit observed.”

Safety

“Despite patients on the ibrutinib arm being exposed to drug more than 4 times longer than those with temsirolimus, the frequency of most cumulative adverse events was lower in the ibrutinib arm,” Dr Rule said.

Still, he noted that most patients had some adverse events. And grade 3 or higher adverse events were reported in 67.6% of patients on ibrutinib and 87.1% of patients on temsirolimus.

Grade 3 or higher AEs included atrial fibrillation (AFib) and major bleeding. AFib occurred in 4.3% of patients in the ibrutinib arm and 1.4% in the temsirolimus arm. Major bleeding occurred in 10.1% and 6.5%, respectively.

Five of the 6 patients with AFib in the ibrutinib arm and all 3 patients who developed AFib in the temsirolimus arm had risk factors for AFib prior to treatment. None of these patients discontinued treatment due to AFib.

Dr Rule said there was no evidence to suggest that either drug increases the risk of second primary malignancies, although 3.6% of patients in the ibrutinib arm and 2.9% in the temsirolimus arm were diagnosed with second primary malignancies (mostly non-melanoma skin cancers).

The most common treatment-emergent AEs (≥20%) of any grade for the ibrutinib arm were diarrhea (28.8%), cough (22.3%), and fatigue (22.3%).

The most common treatment-emergent AEs (>20%) of any grade for the temsirolimus arm were thrombocytopenia (56.1%), anemia (43.2%), diarrhea (30.9%), fatigue (28.8%), neutropenia (25.9%), epistaxis (23.7%), cough (22.3%), peripheral edema (22.3%), nausea (21.6%), pyrexia (20.9%), and stomatitis (20.9%).

The most common hematologic AEs (≥10%) in the ibrutinib and temsirolimus arms, respectively, were thrombocytopenia (18% vs 56.1%), anemia (18% vs 43.2%), and neutropenia (15.8% vs 25.9%).

Six percent of patients in the ibrutinib arm and 26% in the temsirolimus arm discontinued treatment due to AEs.

At a median follow-up of 20 months, 42% of patients in the ibrutinib arm and 45% in the temsirolimus arm had died. The most common cause of death associated with ibrutinib was disease progression, and deaths in the temsirolimus arm were primarily attributed to AEs. ![]()

ALL patients over-report their 6MP compliance, researchers say

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—A study comparing subjective versus objective reporting of treatment compliance in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) has shown that about a fourth of patients over-report how compliant they are with taking 6-mercaptopurine (6MP) as part of their maintenance therapy.

An earlier analysis of the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) AALL03N1 compliance study showed that adherence rates of less than 95% were associated with a 3.7-fold increased risk of relapse.

And about 40% of patients were non-adherent. Yet patients indicate they are taking their medication when questioned.

“We ask our patients if they are taking their meds,” said Wendy Landier, PhD, “and they tell us they are.”

“Even in this cohort who were being closely monitored and knew that they were being closely monitored electronically and were asked to self-report, we found over-reporting.”

Dr Landier, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, reported these findings comparing self-reported adherence with electronic monitoring of 6MP intake at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 82).

The investigators collected data over 6 months from 416 ALL patients who were 21 years at diagnosis or younger and were receiving 6MP as part of their maintenance therapy.

Investigators measured subjective self-reporting by a patient questionnaire, which included patient demographic information in addition to the number of days the patient took 6MP over the past month.

For the objective medication event-monitoring system (MEMS), patients received a 6MP bottle that was fitted with a TrackCapTM. The cap had a microprocessor chip that recorded the date and time of each bottle opening.

Investigators downloaded the data at the end of the study. They then compared the MEMS with the self-reported data.

The investigators classified perfect reporters as those whose self-report corresponded to their MEMS.

They classified over-reporters as those whose self-report was greater than their MEMS data for 5 days or more and 50% of the months.

The rest they classified as others.

Patients were a median age of 6.0 years, and 277 (66.6%) were male. Parents completed the survey for patients younger than 12.

Two hundred forty-two patients (60.9%) had fathers whose education was less than some college, 159 (38.4%) had NCI high-risk disease, and 168 (40.4%) were non-adherent to 6MP as determined by earlier analysis of the COG AALL03N1 study.

Thirty-six percent were non-Hispanic white, 37% were Hispanic, 14% Asian, and 13% African American.

The investigators monitored the patients’ 6MP intake for a total of 1344 patient-months at 87 COG sites.

And the correlation between subjective and objective reporting was moderate, Dr Landier said, with the correlation ranging from 0.36 to 0.58.

Twelve percent of the patients were perfect reporters, with no difference between the reporting methods.

Twenty-four percent over-reported their intake, 1% under-reported their intake, and 64% were other.

The investigators analyzed variables associated with over-reporting and found that age 12 years or older (P=0.02), being Hispanic (P=0.02), Asian (P=0.02), or African American (P<0.001), paternal education less than college (P=0.02), and being classified as 6MP non-adherent (P<0.001) were all significant.

“Over-reporting of 6MP ingestion is common,” Dr Landier said, with 88% of patients or parents over-reporting the number of days 6MP was taken.

“What we’ve learned from this study is that we cannot rely on patients’ self-report in the clinic,” she said. “What we found is that only 12% of our patients are perfect, so to speak, and that the others mainly over-estimate, and I don’t believe intentionally.”

“[W]e need to have a better way of identifying which patients are at risk for over-reporting their intake, whether they’re aware of it or not,” she added. ![]()

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—A study comparing subjective versus objective reporting of treatment compliance in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) has shown that about a fourth of patients over-report how compliant they are with taking 6-mercaptopurine (6MP) as part of their maintenance therapy.

An earlier analysis of the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) AALL03N1 compliance study showed that adherence rates of less than 95% were associated with a 3.7-fold increased risk of relapse.

And about 40% of patients were non-adherent. Yet patients indicate they are taking their medication when questioned.

“We ask our patients if they are taking their meds,” said Wendy Landier, PhD, “and they tell us they are.”

“Even in this cohort who were being closely monitored and knew that they were being closely monitored electronically and were asked to self-report, we found over-reporting.”

Dr Landier, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, reported these findings comparing self-reported adherence with electronic monitoring of 6MP intake at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 82).

The investigators collected data over 6 months from 416 ALL patients who were 21 years at diagnosis or younger and were receiving 6MP as part of their maintenance therapy.

Investigators measured subjective self-reporting by a patient questionnaire, which included patient demographic information in addition to the number of days the patient took 6MP over the past month.

For the objective medication event-monitoring system (MEMS), patients received a 6MP bottle that was fitted with a TrackCapTM. The cap had a microprocessor chip that recorded the date and time of each bottle opening.

Investigators downloaded the data at the end of the study. They then compared the MEMS with the self-reported data.

The investigators classified perfect reporters as those whose self-report corresponded to their MEMS.

They classified over-reporters as those whose self-report was greater than their MEMS data for 5 days or more and 50% of the months.

The rest they classified as others.

Patients were a median age of 6.0 years, and 277 (66.6%) were male. Parents completed the survey for patients younger than 12.

Two hundred forty-two patients (60.9%) had fathers whose education was less than some college, 159 (38.4%) had NCI high-risk disease, and 168 (40.4%) were non-adherent to 6MP as determined by earlier analysis of the COG AALL03N1 study.

Thirty-six percent were non-Hispanic white, 37% were Hispanic, 14% Asian, and 13% African American.

The investigators monitored the patients’ 6MP intake for a total of 1344 patient-months at 87 COG sites.

And the correlation between subjective and objective reporting was moderate, Dr Landier said, with the correlation ranging from 0.36 to 0.58.

Twelve percent of the patients were perfect reporters, with no difference between the reporting methods.

Twenty-four percent over-reported their intake, 1% under-reported their intake, and 64% were other.

The investigators analyzed variables associated with over-reporting and found that age 12 years or older (P=0.02), being Hispanic (P=0.02), Asian (P=0.02), or African American (P<0.001), paternal education less than college (P=0.02), and being classified as 6MP non-adherent (P<0.001) were all significant.

“Over-reporting of 6MP ingestion is common,” Dr Landier said, with 88% of patients or parents over-reporting the number of days 6MP was taken.

“What we’ve learned from this study is that we cannot rely on patients’ self-report in the clinic,” she said. “What we found is that only 12% of our patients are perfect, so to speak, and that the others mainly over-estimate, and I don’t believe intentionally.”

“[W]e need to have a better way of identifying which patients are at risk for over-reporting their intake, whether they’re aware of it or not,” she added. ![]()

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—A study comparing subjective versus objective reporting of treatment compliance in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) has shown that about a fourth of patients over-report how compliant they are with taking 6-mercaptopurine (6MP) as part of their maintenance therapy.

An earlier analysis of the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) AALL03N1 compliance study showed that adherence rates of less than 95% were associated with a 3.7-fold increased risk of relapse.

And about 40% of patients were non-adherent. Yet patients indicate they are taking their medication when questioned.

“We ask our patients if they are taking their meds,” said Wendy Landier, PhD, “and they tell us they are.”

“Even in this cohort who were being closely monitored and knew that they were being closely monitored electronically and were asked to self-report, we found over-reporting.”

Dr Landier, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, reported these findings comparing self-reported adherence with electronic monitoring of 6MP intake at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 82).

The investigators collected data over 6 months from 416 ALL patients who were 21 years at diagnosis or younger and were receiving 6MP as part of their maintenance therapy.

Investigators measured subjective self-reporting by a patient questionnaire, which included patient demographic information in addition to the number of days the patient took 6MP over the past month.

For the objective medication event-monitoring system (MEMS), patients received a 6MP bottle that was fitted with a TrackCapTM. The cap had a microprocessor chip that recorded the date and time of each bottle opening.

Investigators downloaded the data at the end of the study. They then compared the MEMS with the self-reported data.

The investigators classified perfect reporters as those whose self-report corresponded to their MEMS.

They classified over-reporters as those whose self-report was greater than their MEMS data for 5 days or more and 50% of the months.

The rest they classified as others.

Patients were a median age of 6.0 years, and 277 (66.6%) were male. Parents completed the survey for patients younger than 12.

Two hundred forty-two patients (60.9%) had fathers whose education was less than some college, 159 (38.4%) had NCI high-risk disease, and 168 (40.4%) were non-adherent to 6MP as determined by earlier analysis of the COG AALL03N1 study.

Thirty-six percent were non-Hispanic white, 37% were Hispanic, 14% Asian, and 13% African American.

The investigators monitored the patients’ 6MP intake for a total of 1344 patient-months at 87 COG sites.

And the correlation between subjective and objective reporting was moderate, Dr Landier said, with the correlation ranging from 0.36 to 0.58.

Twelve percent of the patients were perfect reporters, with no difference between the reporting methods.

Twenty-four percent over-reported their intake, 1% under-reported their intake, and 64% were other.

The investigators analyzed variables associated with over-reporting and found that age 12 years or older (P=0.02), being Hispanic (P=0.02), Asian (P=0.02), or African American (P<0.001), paternal education less than college (P=0.02), and being classified as 6MP non-adherent (P<0.001) were all significant.

“Over-reporting of 6MP ingestion is common,” Dr Landier said, with 88% of patients or parents over-reporting the number of days 6MP was taken.

“What we’ve learned from this study is that we cannot rely on patients’ self-report in the clinic,” she said. “What we found is that only 12% of our patients are perfect, so to speak, and that the others mainly over-estimate, and I don’t believe intentionally.”

“[W]e need to have a better way of identifying which patients are at risk for over-reporting their intake, whether they’re aware of it or not,” she added. ![]()

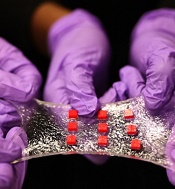

Engineers create ‘smart wound dressing’

a matrix of polymer islands

(red) that can encapsulate

electronic components

Photo by Melanie Gonick/MIT

Engineers say they have designed “smart wound dressing,” a sticky, stretchy, gel-like material that can incorporate temperature sensors, LED lights, and other electronics, as well as tiny, drug-delivering reservoirs and channels.

The dressing releases medicine in response to changes in skin temperature and can be designed to light up if, say, medicine is running low.

When the dressing is applied to a highly flexible area, such as the elbow or knee, it stretches with the body, keeping the embedded electronics functional and intact.

The key to the design is a hydrogel matrix designed by Xuanhe Zhao, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge.

The hydrogel, which was describe in Nature Materials last month, is a rubbery material, mostly composed of water, designed to bond strongly to surfaces such as gold, titanium, aluminum, silicon, glass, and ceramic.

In a paper published in Advanced Materials, Dr Zhao and his colleagues described embedding various electronics within the hydrogel, such as conductive wires, semiconductor chips, LED lights, and temperature sensors.

Dr Zhao said electronics coated in hydrogel may be used not just on the surface of the skin but also inside the body; for example, as implanted, biocompatible glucose sensors, or even soft, compliant neural probes.

“Electronics are usually hard and dry, but the human body is soft and wet,” Dr Zhao said. “These two systems have drastically different properties. If you want to put electronics in close contact with the human body for applications such as healthcare monitoring and drug delivery, it is highly desirable to make the electronic devices soft and stretchable to fit the environment of the human body. That’s the motivation for stretchable hydrogel electronics.”

A strong and stretchy bond

Typical synthetic hydrogels are brittle, barely stretchable, and adhere weakly to other surfaces.

“They’re often used as degradable biomaterials at the current stage,” Dr Zhao said. “If you want to make an electronic device out of hydrogels, you need to think of long-term stability of the hydrogels and interfaces.”

To get around these challenges, his team came up with a design strategy for robust hydrogels, mixing water with a small amount of selected biopolymers to create soft, stretchy materials with a stiffness of 10 to 100 kilopascals—about the range of human soft tissues. The researchers also devised a method to strongly bond the hydrogel to various nonporous surfaces.

In the new study, the researchers applied their techniques to demonstrate several uses for the hydrogel, including encapsulating a titanium wire to form a transparent, stretchable conductor. In experiments, they stretched the encapsulated wire multiple times and found it maintained constant electrical conductivity.

Dr Zhao also created an array of LED lights embedded in a sheet of hydrogel. When attached to different regions of the body, the array continued working, even when stretched across highly deformable areas such as the knee and elbow.

A versatile matrix

Finally, the group embedded various electronic components within a sheet of hydrogel to create a “smart wound dressing,” comprising regularly spaced temperature sensors and tiny drug reservoirs.

The researchers also created pathways for drugs to flow through the hydrogel, by either inserting patterned tubes or drilling tiny holes through the matrix. They placed the dressing over various regions of the body and found that, even when highly stretched, the dressing continued to monitor skin temperature and release drugs according to the sensor readings.

An immediate application of the technology may be as a stretchable, on-demand treatment for burns or other skin conditions, said Hyunwoo Yuk, a graduate student at MIT.

“It’s a very versatile matrix,” Yuk said. “The unique capability here is, when a sensor senses something different, like an abnormal increase in temperature, the device can, on demand, release drugs to that specific location and select a specific drug from one of the reservoirs, which can diffuse in the hydrogel matrix for sustained release over time.”

Delving deeper, Dr Zhao envisions hydrogel to be an ideal, biocompatible vehicle for delivering electronics inside the body. He is currently exploring hydrogel’s potential as a carrier for glucose sensors as well as neural probes. ![]()

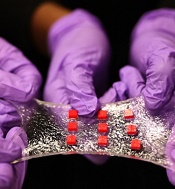

a matrix of polymer islands

(red) that can encapsulate

electronic components

Photo by Melanie Gonick/MIT

Engineers say they have designed “smart wound dressing,” a sticky, stretchy, gel-like material that can incorporate temperature sensors, LED lights, and other electronics, as well as tiny, drug-delivering reservoirs and channels.

The dressing releases medicine in response to changes in skin temperature and can be designed to light up if, say, medicine is running low.

When the dressing is applied to a highly flexible area, such as the elbow or knee, it stretches with the body, keeping the embedded electronics functional and intact.

The key to the design is a hydrogel matrix designed by Xuanhe Zhao, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge.

The hydrogel, which was describe in Nature Materials last month, is a rubbery material, mostly composed of water, designed to bond strongly to surfaces such as gold, titanium, aluminum, silicon, glass, and ceramic.

In a paper published in Advanced Materials, Dr Zhao and his colleagues described embedding various electronics within the hydrogel, such as conductive wires, semiconductor chips, LED lights, and temperature sensors.

Dr Zhao said electronics coated in hydrogel may be used not just on the surface of the skin but also inside the body; for example, as implanted, biocompatible glucose sensors, or even soft, compliant neural probes.

“Electronics are usually hard and dry, but the human body is soft and wet,” Dr Zhao said. “These two systems have drastically different properties. If you want to put electronics in close contact with the human body for applications such as healthcare monitoring and drug delivery, it is highly desirable to make the electronic devices soft and stretchable to fit the environment of the human body. That’s the motivation for stretchable hydrogel electronics.”

A strong and stretchy bond

Typical synthetic hydrogels are brittle, barely stretchable, and adhere weakly to other surfaces.

“They’re often used as degradable biomaterials at the current stage,” Dr Zhao said. “If you want to make an electronic device out of hydrogels, you need to think of long-term stability of the hydrogels and interfaces.”

To get around these challenges, his team came up with a design strategy for robust hydrogels, mixing water with a small amount of selected biopolymers to create soft, stretchy materials with a stiffness of 10 to 100 kilopascals—about the range of human soft tissues. The researchers also devised a method to strongly bond the hydrogel to various nonporous surfaces.

In the new study, the researchers applied their techniques to demonstrate several uses for the hydrogel, including encapsulating a titanium wire to form a transparent, stretchable conductor. In experiments, they stretched the encapsulated wire multiple times and found it maintained constant electrical conductivity.

Dr Zhao also created an array of LED lights embedded in a sheet of hydrogel. When attached to different regions of the body, the array continued working, even when stretched across highly deformable areas such as the knee and elbow.

A versatile matrix

Finally, the group embedded various electronic components within a sheet of hydrogel to create a “smart wound dressing,” comprising regularly spaced temperature sensors and tiny drug reservoirs.

The researchers also created pathways for drugs to flow through the hydrogel, by either inserting patterned tubes or drilling tiny holes through the matrix. They placed the dressing over various regions of the body and found that, even when highly stretched, the dressing continued to monitor skin temperature and release drugs according to the sensor readings.

An immediate application of the technology may be as a stretchable, on-demand treatment for burns or other skin conditions, said Hyunwoo Yuk, a graduate student at MIT.

“It’s a very versatile matrix,” Yuk said. “The unique capability here is, when a sensor senses something different, like an abnormal increase in temperature, the device can, on demand, release drugs to that specific location and select a specific drug from one of the reservoirs, which can diffuse in the hydrogel matrix for sustained release over time.”

Delving deeper, Dr Zhao envisions hydrogel to be an ideal, biocompatible vehicle for delivering electronics inside the body. He is currently exploring hydrogel’s potential as a carrier for glucose sensors as well as neural probes. ![]()

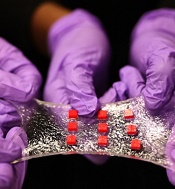

a matrix of polymer islands

(red) that can encapsulate

electronic components

Photo by Melanie Gonick/MIT

Engineers say they have designed “smart wound dressing,” a sticky, stretchy, gel-like material that can incorporate temperature sensors, LED lights, and other electronics, as well as tiny, drug-delivering reservoirs and channels.

The dressing releases medicine in response to changes in skin temperature and can be designed to light up if, say, medicine is running low.

When the dressing is applied to a highly flexible area, such as the elbow or knee, it stretches with the body, keeping the embedded electronics functional and intact.

The key to the design is a hydrogel matrix designed by Xuanhe Zhao, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge.

The hydrogel, which was describe in Nature Materials last month, is a rubbery material, mostly composed of water, designed to bond strongly to surfaces such as gold, titanium, aluminum, silicon, glass, and ceramic.

In a paper published in Advanced Materials, Dr Zhao and his colleagues described embedding various electronics within the hydrogel, such as conductive wires, semiconductor chips, LED lights, and temperature sensors.

Dr Zhao said electronics coated in hydrogel may be used not just on the surface of the skin but also inside the body; for example, as implanted, biocompatible glucose sensors, or even soft, compliant neural probes.

“Electronics are usually hard and dry, but the human body is soft and wet,” Dr Zhao said. “These two systems have drastically different properties. If you want to put electronics in close contact with the human body for applications such as healthcare monitoring and drug delivery, it is highly desirable to make the electronic devices soft and stretchable to fit the environment of the human body. That’s the motivation for stretchable hydrogel electronics.”

A strong and stretchy bond

Typical synthetic hydrogels are brittle, barely stretchable, and adhere weakly to other surfaces.

“They’re often used as degradable biomaterials at the current stage,” Dr Zhao said. “If you want to make an electronic device out of hydrogels, you need to think of long-term stability of the hydrogels and interfaces.”

To get around these challenges, his team came up with a design strategy for robust hydrogels, mixing water with a small amount of selected biopolymers to create soft, stretchy materials with a stiffness of 10 to 100 kilopascals—about the range of human soft tissues. The researchers also devised a method to strongly bond the hydrogel to various nonporous surfaces.

In the new study, the researchers applied their techniques to demonstrate several uses for the hydrogel, including encapsulating a titanium wire to form a transparent, stretchable conductor. In experiments, they stretched the encapsulated wire multiple times and found it maintained constant electrical conductivity.

Dr Zhao also created an array of LED lights embedded in a sheet of hydrogel. When attached to different regions of the body, the array continued working, even when stretched across highly deformable areas such as the knee and elbow.

A versatile matrix

Finally, the group embedded various electronic components within a sheet of hydrogel to create a “smart wound dressing,” comprising regularly spaced temperature sensors and tiny drug reservoirs.

The researchers also created pathways for drugs to flow through the hydrogel, by either inserting patterned tubes or drilling tiny holes through the matrix. They placed the dressing over various regions of the body and found that, even when highly stretched, the dressing continued to monitor skin temperature and release drugs according to the sensor readings.

An immediate application of the technology may be as a stretchable, on-demand treatment for burns or other skin conditions, said Hyunwoo Yuk, a graduate student at MIT.

“It’s a very versatile matrix,” Yuk said. “The unique capability here is, when a sensor senses something different, like an abnormal increase in temperature, the device can, on demand, release drugs to that specific location and select a specific drug from one of the reservoirs, which can diffuse in the hydrogel matrix for sustained release over time.”

Delving deeper, Dr Zhao envisions hydrogel to be an ideal, biocompatible vehicle for delivering electronics inside the body. He is currently exploring hydrogel’s potential as a carrier for glucose sensors as well as neural probes. ![]()

VIDEO: Top-line results from Tourmaline in multiple myeloma, plus ongoing trials and treatment selection

ORLANDO – The combination of the oral proteasome inhibitor ixazomib (Ninlaro, recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration) with lenalidomide and dexamethasone was associated with a 35% improvement in progression free survival in the Tourmaline trial.

In a video interview, Tourmaline investigator Dr. Shaji Kumar, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., discussed the top-line study results, the status of ongoing trials with ixazomib in other combination regimens, and the decision rationales that will need to be considered in selecting one of the newly approved multiple myeloma therapies.

Dr. Kumar has received funding from Takeda, the makers of ixazomib; he has also received funding from Celgene, Onyx, Janssen, and Sanofi.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

ORLANDO – The combination of the oral proteasome inhibitor ixazomib (Ninlaro, recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration) with lenalidomide and dexamethasone was associated with a 35% improvement in progression free survival in the Tourmaline trial.

In a video interview, Tourmaline investigator Dr. Shaji Kumar, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., discussed the top-line study results, the status of ongoing trials with ixazomib in other combination regimens, and the decision rationales that will need to be considered in selecting one of the newly approved multiple myeloma therapies.

Dr. Kumar has received funding from Takeda, the makers of ixazomib; he has also received funding from Celgene, Onyx, Janssen, and Sanofi.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

ORLANDO – The combination of the oral proteasome inhibitor ixazomib (Ninlaro, recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration) with lenalidomide and dexamethasone was associated with a 35% improvement in progression free survival in the Tourmaline trial.

In a video interview, Tourmaline investigator Dr. Shaji Kumar, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., discussed the top-line study results, the status of ongoing trials with ixazomib in other combination regimens, and the decision rationales that will need to be considered in selecting one of the newly approved multiple myeloma therapies.

Dr. Kumar has received funding from Takeda, the makers of ixazomib; he has also received funding from Celgene, Onyx, Janssen, and Sanofi.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT ASH 2015

ASH: Rituximab add-on therapy ‘new standard’ in BCP-ALL

ORLANDO – Adding rituximab to standard intensive chemotherapy significantly improved event-free survival in adults with Philadelphia-negative, CD20-positive B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the phase III GRAALL-R 2005 study.

Rituximab (Rituxan) is already being used to improve outcomes in patients with lymphoma, and non-randomized data support addition of the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody to chemotherapy in B-cell precursor (BCP) ALL, where the CD20 antigen is expressed in 30% to 40% of patients at diagnosis.

In the randomized GRAALL-R 2005, 2-year event-free survival (EFS) was 65% in the rituximab arm vs. 52% in the control arm (hazard ratio, 0.66; P = .038).

This difference is not explained by the early response rates, which were very close in both arms after one or two induction courses (92% vs. 90%; P = .63), Dr. Sébastien Maury, Hôpital Henri Mondor in Créteil, France, said during the plenary session at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology (Ab. 1).

The beneficial effect of rituximab, however, was clearly related to the cumulative incidence of relapse at 18% with vs. 32% without rituximab (HR, 0.52; P = .017).

Despite this advantage, overall survival was similar between patients given chemotherapy with and without rituximab (71% vs. 64%; HR, 0.70; P = .095), he said.

After censoring for patients not receiving allogeneic stem cell transplant in first complete remission, however, rituximab significantly prolonged 2-year EFS (HR, 0.59; P = .021) as well as overall survival (HR, 0.55; P = .018), Dr. Maury said.

“We thus recommend that the addition of rituximab become a new standard of care for these patients, although some aspects including the definition of the optimal dose needs to be determined in further studies,” he concluded.

Dr. Adele Fielding of University College London, who introduced the study at the meeting, said, “For me, the prior knowledge that the drug can be safely already added to chemotherapy in other settings provides profound comfort in a disease in which so many people are already damaged by the current therapies we offer.”

Also, of importance is the potential relevance of rituximab in patients in whom CD20 is present on fewer than 20% of blasts at diagnosis.

Key questions that remain in rituximab therapy of ALL beyond overall benefit include early and late toxicities and how best to judge response and when, she said. Synergies with other agents and the mechanism of action will also require clarification, especially which effector cells are relevant to ensure that agents are not used with rituximab that destroy the optimal chance for response.

“Finally, the cost of introducing novel agents cannot be ignored, even in well-developed economies, and I am hopeful that the cost of this drug will be variable for many countries and many patients.” Dr. Fielding said.

Study details

A total of 220 patients, aged 18-59 years, with newly diagnosed CD20-positive Ph-negative BCP-ALL were randomized to the pediatric-inspired Group for Research on Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (GRAALL) chemotherapy protocol with or without rituximab 375 mg/m2 given during induction (day 1 and 7), salvage reinduction when needed (day 1 and 7), consolidation blocks (6 infusions), late intensification (day 1 and 7, and the first year of maintenance [6 infusions], for a total of 16-18 infusions. Allogeneic stem cell transplant (SCT) was offered after consolidation blocks 1 or 2 to patients with one or more high-risk criteria and an available donor. CD20-positivity was defined as expression of CD20 in more than 20% of leukemia blasts.

Eleven patients were excluded from the analysis because of non–ineligibility criteria, leaving 209 patients in the modified intent-to-treat analysis. Their median age was 40.2 years and 67% had high-risk ALL.

Rates of postinduction minimal residual disease less than 10–4 were 65% and 61% in the rituximab and control arms among 85 evaluable patients(P = .82), and rates of postconsolidation minimal residual disease less than 10–4 were 91% and 82% among 80 evaluable patients (P = .31), Dr. Maury reported.

Notably, more patients in the rituximab arm received allogeneic SCT in their first complete remission (34% vs. 20%; P = .029).

The cumulative incidence of death in first complete remission was 12% in both arms.

In multivariate analysis, rituximab impacted EFS, together with age, central nervous system involvement, white blood cells, or CD20 expression at diagnosis. A preferential effect with rituximab was seen in patients with high CD20 levels that deserves further evaluation, he observed.

There was no difference in the incidence of adverse events between the rituximab and control arms, although there was a trend for more infectious events with rituximab (71 events vs. 55 events), Dr. Maury said.

Allergic events – all but one from aspergillosis – were significantly more common in the control arm (2 events vs. 14 events; P = .002).

The Group for Research in Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia sponsored the study. Dr. Maury reported having no disclosures.

ORLANDO – Adding rituximab to standard intensive chemotherapy significantly improved event-free survival in adults with Philadelphia-negative, CD20-positive B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the phase III GRAALL-R 2005 study.

Rituximab (Rituxan) is already being used to improve outcomes in patients with lymphoma, and non-randomized data support addition of the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody to chemotherapy in B-cell precursor (BCP) ALL, where the CD20 antigen is expressed in 30% to 40% of patients at diagnosis.

In the randomized GRAALL-R 2005, 2-year event-free survival (EFS) was 65% in the rituximab arm vs. 52% in the control arm (hazard ratio, 0.66; P = .038).

This difference is not explained by the early response rates, which were very close in both arms after one or two induction courses (92% vs. 90%; P = .63), Dr. Sébastien Maury, Hôpital Henri Mondor in Créteil, France, said during the plenary session at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology (Ab. 1).

The beneficial effect of rituximab, however, was clearly related to the cumulative incidence of relapse at 18% with vs. 32% without rituximab (HR, 0.52; P = .017).

Despite this advantage, overall survival was similar between patients given chemotherapy with and without rituximab (71% vs. 64%; HR, 0.70; P = .095), he said.

After censoring for patients not receiving allogeneic stem cell transplant in first complete remission, however, rituximab significantly prolonged 2-year EFS (HR, 0.59; P = .021) as well as overall survival (HR, 0.55; P = .018), Dr. Maury said.

“We thus recommend that the addition of rituximab become a new standard of care for these patients, although some aspects including the definition of the optimal dose needs to be determined in further studies,” he concluded.

Dr. Adele Fielding of University College London, who introduced the study at the meeting, said, “For me, the prior knowledge that the drug can be safely already added to chemotherapy in other settings provides profound comfort in a disease in which so many people are already damaged by the current therapies we offer.”

Also, of importance is the potential relevance of rituximab in patients in whom CD20 is present on fewer than 20% of blasts at diagnosis.

Key questions that remain in rituximab therapy of ALL beyond overall benefit include early and late toxicities and how best to judge response and when, she said. Synergies with other agents and the mechanism of action will also require clarification, especially which effector cells are relevant to ensure that agents are not used with rituximab that destroy the optimal chance for response.

“Finally, the cost of introducing novel agents cannot be ignored, even in well-developed economies, and I am hopeful that the cost of this drug will be variable for many countries and many patients.” Dr. Fielding said.

Study details

A total of 220 patients, aged 18-59 years, with newly diagnosed CD20-positive Ph-negative BCP-ALL were randomized to the pediatric-inspired Group for Research on Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (GRAALL) chemotherapy protocol with or without rituximab 375 mg/m2 given during induction (day 1 and 7), salvage reinduction when needed (day 1 and 7), consolidation blocks (6 infusions), late intensification (day 1 and 7, and the first year of maintenance [6 infusions], for a total of 16-18 infusions. Allogeneic stem cell transplant (SCT) was offered after consolidation blocks 1 or 2 to patients with one or more high-risk criteria and an available donor. CD20-positivity was defined as expression of CD20 in more than 20% of leukemia blasts.

Eleven patients were excluded from the analysis because of non–ineligibility criteria, leaving 209 patients in the modified intent-to-treat analysis. Their median age was 40.2 years and 67% had high-risk ALL.

Rates of postinduction minimal residual disease less than 10–4 were 65% and 61% in the rituximab and control arms among 85 evaluable patients(P = .82), and rates of postconsolidation minimal residual disease less than 10–4 were 91% and 82% among 80 evaluable patients (P = .31), Dr. Maury reported.

Notably, more patients in the rituximab arm received allogeneic SCT in their first complete remission (34% vs. 20%; P = .029).

The cumulative incidence of death in first complete remission was 12% in both arms.

In multivariate analysis, rituximab impacted EFS, together with age, central nervous system involvement, white blood cells, or CD20 expression at diagnosis. A preferential effect with rituximab was seen in patients with high CD20 levels that deserves further evaluation, he observed.

There was no difference in the incidence of adverse events between the rituximab and control arms, although there was a trend for more infectious events with rituximab (71 events vs. 55 events), Dr. Maury said.

Allergic events – all but one from aspergillosis – were significantly more common in the control arm (2 events vs. 14 events; P = .002).

The Group for Research in Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia sponsored the study. Dr. Maury reported having no disclosures.

ORLANDO – Adding rituximab to standard intensive chemotherapy significantly improved event-free survival in adults with Philadelphia-negative, CD20-positive B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the phase III GRAALL-R 2005 study.

Rituximab (Rituxan) is already being used to improve outcomes in patients with lymphoma, and non-randomized data support addition of the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody to chemotherapy in B-cell precursor (BCP) ALL, where the CD20 antigen is expressed in 30% to 40% of patients at diagnosis.

In the randomized GRAALL-R 2005, 2-year event-free survival (EFS) was 65% in the rituximab arm vs. 52% in the control arm (hazard ratio, 0.66; P = .038).

This difference is not explained by the early response rates, which were very close in both arms after one or two induction courses (92% vs. 90%; P = .63), Dr. Sébastien Maury, Hôpital Henri Mondor in Créteil, France, said during the plenary session at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology (Ab. 1).

The beneficial effect of rituximab, however, was clearly related to the cumulative incidence of relapse at 18% with vs. 32% without rituximab (HR, 0.52; P = .017).

Despite this advantage, overall survival was similar between patients given chemotherapy with and without rituximab (71% vs. 64%; HR, 0.70; P = .095), he said.

After censoring for patients not receiving allogeneic stem cell transplant in first complete remission, however, rituximab significantly prolonged 2-year EFS (HR, 0.59; P = .021) as well as overall survival (HR, 0.55; P = .018), Dr. Maury said.

“We thus recommend that the addition of rituximab become a new standard of care for these patients, although some aspects including the definition of the optimal dose needs to be determined in further studies,” he concluded.

Dr. Adele Fielding of University College London, who introduced the study at the meeting, said, “For me, the prior knowledge that the drug can be safely already added to chemotherapy in other settings provides profound comfort in a disease in which so many people are already damaged by the current therapies we offer.”

Also, of importance is the potential relevance of rituximab in patients in whom CD20 is present on fewer than 20% of blasts at diagnosis.

Key questions that remain in rituximab therapy of ALL beyond overall benefit include early and late toxicities and how best to judge response and when, she said. Synergies with other agents and the mechanism of action will also require clarification, especially which effector cells are relevant to ensure that agents are not used with rituximab that destroy the optimal chance for response.

“Finally, the cost of introducing novel agents cannot be ignored, even in well-developed economies, and I am hopeful that the cost of this drug will be variable for many countries and many patients.” Dr. Fielding said.

Study details

A total of 220 patients, aged 18-59 years, with newly diagnosed CD20-positive Ph-negative BCP-ALL were randomized to the pediatric-inspired Group for Research on Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (GRAALL) chemotherapy protocol with or without rituximab 375 mg/m2 given during induction (day 1 and 7), salvage reinduction when needed (day 1 and 7), consolidation blocks (6 infusions), late intensification (day 1 and 7, and the first year of maintenance [6 infusions], for a total of 16-18 infusions. Allogeneic stem cell transplant (SCT) was offered after consolidation blocks 1 or 2 to patients with one or more high-risk criteria and an available donor. CD20-positivity was defined as expression of CD20 in more than 20% of leukemia blasts.

Eleven patients were excluded from the analysis because of non–ineligibility criteria, leaving 209 patients in the modified intent-to-treat analysis. Their median age was 40.2 years and 67% had high-risk ALL.

Rates of postinduction minimal residual disease less than 10–4 were 65% and 61% in the rituximab and control arms among 85 evaluable patients(P = .82), and rates of postconsolidation minimal residual disease less than 10–4 were 91% and 82% among 80 evaluable patients (P = .31), Dr. Maury reported.

Notably, more patients in the rituximab arm received allogeneic SCT in their first complete remission (34% vs. 20%; P = .029).

The cumulative incidence of death in first complete remission was 12% in both arms.

In multivariate analysis, rituximab impacted EFS, together with age, central nervous system involvement, white blood cells, or CD20 expression at diagnosis. A preferential effect with rituximab was seen in patients with high CD20 levels that deserves further evaluation, he observed.

There was no difference in the incidence of adverse events between the rituximab and control arms, although there was a trend for more infectious events with rituximab (71 events vs. 55 events), Dr. Maury said.

Allergic events – all but one from aspergillosis – were significantly more common in the control arm (2 events vs. 14 events; P = .002).

The Group for Research in Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia sponsored the study. Dr. Maury reported having no disclosures.

AT ASH 2015

Key clinical point: Adding rituximab to standard intensive chemotherapy is a new standard for CD20-positive, Philadelphia-negative, B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Major finding: Event-free survival was 65% in the rituximab arm vs. 52% in the control arm (HR, 0.66; P = .038).

Data source: Phase III study in 220 adults with CD20-positive, Ph-negative, BCP-ALL.

Disclosures: Group for Research in Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia sponsored the study. Dr. Maury reported having no disclosures.

The Changing Landscape of Orthopedic Practice: Challenges and Opportunities

Orthopedic surgery is going through a time of remarkable change. Health care reform, heightened public scrutiny, shifting population demographics, increased reliance on the Internet for information, ongoing metamorphosis of our profession into a business, and lack of consistent high-quality clinical evidence have created a new frontier of challenges and opportunities. At heart are the needs to deliver high-quality education that is in line with new technological media, to reclaim our ability to guide musculoskeletal care at the policymaking level, to fortify our long-held tradition of ethical responsibility, to invest in research and the training of physician-scientists, to maintain unity among the different subspecialties, and to increase female and minority representation. Never before has understanding and applying the key tenets of our philosophy as orthopedic surgeons been more crucial.

The changing landscape of orthopedic practice has been an unsettling topic in many of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) presidential addresses in recent years.1-11 What are the challenges and what can we learn moving forward? In this article, we seek to answer these questions by drawing insights from the combined experience and wisdom of past AAOS presidents since the turn of the 21st century.

Education

Education is the cornerstone of providing quality musculoskeletal care12 and staying up to date with technological advances.13 The modes of education delivery, however, have changed. No longer is orthopedic education confined to tangible textbooks and journal articles, nor is it limited to those of us in the profession. Instead, orthopedic education has shifted toward online learning14 and is available to patients and nonorthopedic providers.12 With more patients gaining access to rapidly growing online resources, a unique challenge has arisen: an abundance of data with variable quality of evidence influencing the decision-making process. This has created what Richard Kyle15 described as the “trap of the new technology war,” where patient misinformation and direct-to-consumer marketing can lead to dangerous musculoskeletal care delivery, including unrealistic patient expectations.3 To compound the problem, our ability to provide orthopedic education in formats compatible with the new learning mediums has not been up to the demand, with issues of cost, accessibility, and efficacy plaguing the current process.3,5 Also, we have yet to unlock the benefits of surgical simulation, which has the potential to provide more effective training at no risk to the patient.4,13 By adapting to the new learning formats, we can provide numerous new opportunities for keeping up to date on evolving practice management principles, which, with added accessibility, will be used more often by orthopedic surgeons and the public.13

Research

Research is vital for quality improvement and the continuation of excellence.5 It is only with research that we can provide groundbreaking advances and measure the outcomes of our interventions.2 Unfortunately, orthopedic research funding continues to be disproportionately low, especially given that musculoskeletal ailments are the leading cause of both physician visits and chronic impairment in the United States.2 For example, the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases receives only 10% of what our country spends on cancer research and 15% of what is spent on heart- and lung-disease research.2 To compound the problem of limited funding, the number of physician-scientists has been dropping at an alarming rate.2 As a result, we must not only refocus our research efforts so that they are efficient and effective, but we must also invest in the training of orthopedic physician-scientists to ensure a continuous stream of groundbreaking discoveries. We owe it to our patients to provide them with proven, effective, and high-quality care.

Industry Relationships

Local and national attention will continue to focus on our relationships with industry. The challenge is twofold: mitigating the negative portrayal of industry relationships and navigating the changes applied to industry funding for research and education.9 Our collaboration with industry is important for the development and advancement of orthopedics,15 but it must be guided by the professional and ethical guidelines established by the AAOS, ensuring that the best interest of patients remains a top priority.8,15 We must maintain the public’s trust by using every opportunity to convey our lone goal in collaborating with industry, ie, improving patient care.9 According to James Beaty,7 any relationship with industry should be “so ethical that it could be printed on the front page of the newspaper and we could face our neighbors with our heads held high.”

Gender and Minority Representation

The racial and ethnic makeup of the United States is undergoing a rapid change. Over the next 4 decades, the white population is projected to become the minority, while women will continue to outnumber men.16 Despite the rapidly changing demographics of the United States, health care disparities persist. As of 2011, minorities and women made up only 22.55% and 14.52%, respectively, of all orthopedic surgery residents.17 This limited diversity in orthopedic training programs is alarming and may lead to suboptimal physician–patient relationships, because patients tend to be more comfortable with and respond better to the care provided by physicians of similar background.3 In addition, if we do not integrate women into orthopedics, the number of female medical students applying to orthopedic residency programs might decline.3

Equating excellent medical care with diversity and cultural competence requires that we bridge the gap that has prevented patients from obtaining high-quality care.8 To achieve this goal, we need to continue recruiting orthopedic surgeons from all segments of our population. Ultimately, health care disparities can be effectively reduced through the delivery of culturally competent care.8

Physician–Patient Relationship

Medical liability has resulted in the development of damaging attitudes among physicians, with many viewing patients as potential adversaries and even avoiding high-risk procedures altogether.6 This deterioration of the physician–patient relationship has been another troubling consequence of managed care that emphasizes quantity and speed.1 As a result, we are perceived by the public as impersonal, poor listeners, and difficult to see on short notice.1

The poor perception of orthopedic surgeons by the general public is not acceptable for a field that places such a high value on excellence. Patient-centered care is at the core of quality improvement, and improving patient relationships starts and ends with us and with each patient we treat.6 In a health care environment in which the average orthopedic surgeon cares for thousands of patients each year, we must make certain to use each opportunity to engage our patients and enhance our relationships with them.6 The basic necessities of patient-centered care include empowerment of the patient through education, better communication, and transparency; providing accurate and evidence-based information; and cooperation among physicians.3,6 The benefits of improving personal relationships with patients are multifold and could have lasting positive effects: increased physician and patient satisfaction, better patient compliance, greater practice efficiency, and fewer malpractice lawsuits.1 We can also benefit from mobilizing a greater constituency to advocate alongside us.6

Unity