User login

Are overweight children likely to become overweight adults?

Yes. Overweight children (body mass index [BMI] ≥85th to <95th percentile) are likely to become overweight or obese adults with a BMI ≥25 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, systematic review of high-quality prospective longitudinal studies).

Obese adolescents are significantly more likely to develop severe obesity than normal weight or overweight adolescents (SOR: B, prospective cohort study). (See “Definition of terms” below.)

The trend to overweight and obesity in adulthood is clear

A systematic review of 20 prospective and 5 retrospective trials tracked 179,303 overweight and obese children into adulthood.1 Investigators included studies for evaluation if they were written in English, prospective or retrospective longitudinal in design, described at least one anthropometric measurement, and included odds ratios or risk ratios in the results. The results were not pooled because of heterogeneity among studies.

In high-quality trials, the percentages of overweight or obese children and adolescents who became overweight or obese adults varied: overweight children (76% to 83%), obese children (18% to 60%), overweight adolescents (22% to 58%) and obese adolescents (24% to 90%). Limitations of the review included an inadequate description of the anthropometric measurement protocol, use of self-reported weight and height, and the fact that all studies were conducted in high-income countries.

Obesity in adolescence often progresses to severe obesity later on

A prospective cohort trial followed 8834 nonobese and obese individuals, ages 12 to 21, for 13 years to assess risk of adult obesity.2 Patients were drawn from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, which is a representative sample of United States schools from 1994 to 1995 with respect to region, urbanicity, school size, school type, and ethnicity.

Researchers observed a total of 703 incident cases of severe obesity in adulthood, indicating a total incidence rate of 7.9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 7.4%-8.5%). Obese adolescents were significantly more likely to develop severe obesity than nonobese adolescents who were normal weight or overweight (hazard ratio [HR]=16; 95% CI, 12-21).

A significant proportion of obese adolescents became severely obese by their early 30s, with an incidence of 37% in men (95% CI, 31%-44%) and 51% in women (95% CI, 45%-58%). Black women had the highest incidence at 52% (95% CI, 41%-64%). Fewer than 5% of patients (across sex and race) who were normal weight in adolescence became severely obese in adulthood.

Normal weight: Body mass index (BMI) ≥5th to <85th percentile for individuals <20 years old or BMI ≥18.5 to <25 for individuals >20 years.

Overweight: BMI ≥85th to <95th percentile or BMI ≥25 to <30.

Obesity: BMI ≥95th to <120% of 95th percentile or BMI ≥30 to <40.

Severe obesity: BMI ≥120% of 95th percentile; BMI ≥40.

1. Singh AS, Mulder C, Twisk WR, et al. Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: a systemic review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2008;9:474-488.

2. The NS, Suchindran C, North KE, et al. Association of adolescent obesity with risk of severe obesity in adulthood. JAMA. 2010;304:2042-2047.

Yes. Overweight children (body mass index [BMI] ≥85th to <95th percentile) are likely to become overweight or obese adults with a BMI ≥25 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, systematic review of high-quality prospective longitudinal studies).

Obese adolescents are significantly more likely to develop severe obesity than normal weight or overweight adolescents (SOR: B, prospective cohort study). (See “Definition of terms” below.)

The trend to overweight and obesity in adulthood is clear

A systematic review of 20 prospective and 5 retrospective trials tracked 179,303 overweight and obese children into adulthood.1 Investigators included studies for evaluation if they were written in English, prospective or retrospective longitudinal in design, described at least one anthropometric measurement, and included odds ratios or risk ratios in the results. The results were not pooled because of heterogeneity among studies.

In high-quality trials, the percentages of overweight or obese children and adolescents who became overweight or obese adults varied: overweight children (76% to 83%), obese children (18% to 60%), overweight adolescents (22% to 58%) and obese adolescents (24% to 90%). Limitations of the review included an inadequate description of the anthropometric measurement protocol, use of self-reported weight and height, and the fact that all studies were conducted in high-income countries.

Obesity in adolescence often progresses to severe obesity later on

A prospective cohort trial followed 8834 nonobese and obese individuals, ages 12 to 21, for 13 years to assess risk of adult obesity.2 Patients were drawn from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, which is a representative sample of United States schools from 1994 to 1995 with respect to region, urbanicity, school size, school type, and ethnicity.

Researchers observed a total of 703 incident cases of severe obesity in adulthood, indicating a total incidence rate of 7.9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 7.4%-8.5%). Obese adolescents were significantly more likely to develop severe obesity than nonobese adolescents who were normal weight or overweight (hazard ratio [HR]=16; 95% CI, 12-21).

A significant proportion of obese adolescents became severely obese by their early 30s, with an incidence of 37% in men (95% CI, 31%-44%) and 51% in women (95% CI, 45%-58%). Black women had the highest incidence at 52% (95% CI, 41%-64%). Fewer than 5% of patients (across sex and race) who were normal weight in adolescence became severely obese in adulthood.

Normal weight: Body mass index (BMI) ≥5th to <85th percentile for individuals <20 years old or BMI ≥18.5 to <25 for individuals >20 years.

Overweight: BMI ≥85th to <95th percentile or BMI ≥25 to <30.

Obesity: BMI ≥95th to <120% of 95th percentile or BMI ≥30 to <40.

Severe obesity: BMI ≥120% of 95th percentile; BMI ≥40.

Yes. Overweight children (body mass index [BMI] ≥85th to <95th percentile) are likely to become overweight or obese adults with a BMI ≥25 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, systematic review of high-quality prospective longitudinal studies).

Obese adolescents are significantly more likely to develop severe obesity than normal weight or overweight adolescents (SOR: B, prospective cohort study). (See “Definition of terms” below.)

The trend to overweight and obesity in adulthood is clear

A systematic review of 20 prospective and 5 retrospective trials tracked 179,303 overweight and obese children into adulthood.1 Investigators included studies for evaluation if they were written in English, prospective or retrospective longitudinal in design, described at least one anthropometric measurement, and included odds ratios or risk ratios in the results. The results were not pooled because of heterogeneity among studies.

In high-quality trials, the percentages of overweight or obese children and adolescents who became overweight or obese adults varied: overweight children (76% to 83%), obese children (18% to 60%), overweight adolescents (22% to 58%) and obese adolescents (24% to 90%). Limitations of the review included an inadequate description of the anthropometric measurement protocol, use of self-reported weight and height, and the fact that all studies were conducted in high-income countries.

Obesity in adolescence often progresses to severe obesity later on

A prospective cohort trial followed 8834 nonobese and obese individuals, ages 12 to 21, for 13 years to assess risk of adult obesity.2 Patients were drawn from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, which is a representative sample of United States schools from 1994 to 1995 with respect to region, urbanicity, school size, school type, and ethnicity.

Researchers observed a total of 703 incident cases of severe obesity in adulthood, indicating a total incidence rate of 7.9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 7.4%-8.5%). Obese adolescents were significantly more likely to develop severe obesity than nonobese adolescents who were normal weight or overweight (hazard ratio [HR]=16; 95% CI, 12-21).

A significant proportion of obese adolescents became severely obese by their early 30s, with an incidence of 37% in men (95% CI, 31%-44%) and 51% in women (95% CI, 45%-58%). Black women had the highest incidence at 52% (95% CI, 41%-64%). Fewer than 5% of patients (across sex and race) who were normal weight in adolescence became severely obese in adulthood.

Normal weight: Body mass index (BMI) ≥5th to <85th percentile for individuals <20 years old or BMI ≥18.5 to <25 for individuals >20 years.

Overweight: BMI ≥85th to <95th percentile or BMI ≥25 to <30.

Obesity: BMI ≥95th to <120% of 95th percentile or BMI ≥30 to <40.

Severe obesity: BMI ≥120% of 95th percentile; BMI ≥40.

1. Singh AS, Mulder C, Twisk WR, et al. Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: a systemic review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2008;9:474-488.

2. The NS, Suchindran C, North KE, et al. Association of adolescent obesity with risk of severe obesity in adulthood. JAMA. 2010;304:2042-2047.

1. Singh AS, Mulder C, Twisk WR, et al. Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: a systemic review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2008;9:474-488.

2. The NS, Suchindran C, North KE, et al. Association of adolescent obesity with risk of severe obesity in adulthood. JAMA. 2010;304:2042-2047.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Office visits should be a “dance,” not a dictate

Last month, a group of investigators from the American Academy of Family Physicians and the University of Wisconsin led by Holman1 published a study entitled, “The myth of standardized workflow in primary care.” The researchers directly observed 20 primary care physician (PCP) visits and coded the usual tasks physicians perform during a visit. For some physicians, they observed 2 encounters to see if individual physicians followed a consistent pattern. What they found won’t surprise any of you:

“…We found no consistent workflows when analyzing visits individually or by PCP, or visits conducted at clinics with or without an [electronic medical record (EMR)]. The workflow for tasks is dictated not by the type of chart, the patient, or the physician. Instead, workflow emerges from the interaction between the patient’s and the physician’s agendas.”

This rang true for me. For example, sometimes a patient immediately pulls out her bag of pills, so I do the medication review first. Other times, social chat comes first. Often, asking, “Is there anything else you need today?” leads to another round of history-taking and test-ordering.

The physicians in this study approached patient visits as a conversation rather than adhering to a rigid protocol, as the EMR vendors imply we should do. Frankly, that has never made sense to me. Why shouldn’t the EMR companies adapt their tools to the needs of patients and physicians? It was so heartening to read that experienced family physicians are not kowtowing to EMR experts’ insistence that we change our workflow to adapt to the realities of EMRs. We still approach patient encounters in a patient-centered way, following the thread of the conversation to fully respond to our patients’ needs. (Can the same be said for medical students? See last month’s Guest Editorial, “Med students: Look up from your EMRs”.)

"Workflow" was a foreign concept to me until the advent of EMRs. I never worried much about the order in which I was performing "tasks," and I still don't.

Holman et al1 describe the interplay between physicians and patients during office visits as a “dance” in which patients and physicians take turns leading. Let’s invite EMR vendors to join our dance—and follow our lead.

Reference

1. Holman GT, Beasley JW, Karsh BT, et al. The myth of standardized workflow in primary care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015. [Epub ahead of print].

Last month, a group of investigators from the American Academy of Family Physicians and the University of Wisconsin led by Holman1 published a study entitled, “The myth of standardized workflow in primary care.” The researchers directly observed 20 primary care physician (PCP) visits and coded the usual tasks physicians perform during a visit. For some physicians, they observed 2 encounters to see if individual physicians followed a consistent pattern. What they found won’t surprise any of you:

“…We found no consistent workflows when analyzing visits individually or by PCP, or visits conducted at clinics with or without an [electronic medical record (EMR)]. The workflow for tasks is dictated not by the type of chart, the patient, or the physician. Instead, workflow emerges from the interaction between the patient’s and the physician’s agendas.”

This rang true for me. For example, sometimes a patient immediately pulls out her bag of pills, so I do the medication review first. Other times, social chat comes first. Often, asking, “Is there anything else you need today?” leads to another round of history-taking and test-ordering.

The physicians in this study approached patient visits as a conversation rather than adhering to a rigid protocol, as the EMR vendors imply we should do. Frankly, that has never made sense to me. Why shouldn’t the EMR companies adapt their tools to the needs of patients and physicians? It was so heartening to read that experienced family physicians are not kowtowing to EMR experts’ insistence that we change our workflow to adapt to the realities of EMRs. We still approach patient encounters in a patient-centered way, following the thread of the conversation to fully respond to our patients’ needs. (Can the same be said for medical students? See last month’s Guest Editorial, “Med students: Look up from your EMRs”.)

"Workflow" was a foreign concept to me until the advent of EMRs. I never worried much about the order in which I was performing "tasks," and I still don't.

Holman et al1 describe the interplay between physicians and patients during office visits as a “dance” in which patients and physicians take turns leading. Let’s invite EMR vendors to join our dance—and follow our lead.

Last month, a group of investigators from the American Academy of Family Physicians and the University of Wisconsin led by Holman1 published a study entitled, “The myth of standardized workflow in primary care.” The researchers directly observed 20 primary care physician (PCP) visits and coded the usual tasks physicians perform during a visit. For some physicians, they observed 2 encounters to see if individual physicians followed a consistent pattern. What they found won’t surprise any of you:

“…We found no consistent workflows when analyzing visits individually or by PCP, or visits conducted at clinics with or without an [electronic medical record (EMR)]. The workflow for tasks is dictated not by the type of chart, the patient, or the physician. Instead, workflow emerges from the interaction between the patient’s and the physician’s agendas.”

This rang true for me. For example, sometimes a patient immediately pulls out her bag of pills, so I do the medication review first. Other times, social chat comes first. Often, asking, “Is there anything else you need today?” leads to another round of history-taking and test-ordering.

The physicians in this study approached patient visits as a conversation rather than adhering to a rigid protocol, as the EMR vendors imply we should do. Frankly, that has never made sense to me. Why shouldn’t the EMR companies adapt their tools to the needs of patients and physicians? It was so heartening to read that experienced family physicians are not kowtowing to EMR experts’ insistence that we change our workflow to adapt to the realities of EMRs. We still approach patient encounters in a patient-centered way, following the thread of the conversation to fully respond to our patients’ needs. (Can the same be said for medical students? See last month’s Guest Editorial, “Med students: Look up from your EMRs”.)

"Workflow" was a foreign concept to me until the advent of EMRs. I never worried much about the order in which I was performing "tasks," and I still don't.

Holman et al1 describe the interplay between physicians and patients during office visits as a “dance” in which patients and physicians take turns leading. Let’s invite EMR vendors to join our dance—and follow our lead.

Reference

1. Holman GT, Beasley JW, Karsh BT, et al. The myth of standardized workflow in primary care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015. [Epub ahead of print].

Reference

1. Holman GT, Beasley JW, Karsh BT, et al. The myth of standardized workflow in primary care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015. [Epub ahead of print].

Left subconjunctival hemorrhage • renal dysfunction • international normalized ratio of 4.5 • Dx?

THE CASE

A 71-year-old woman came to our clinic with a left subconjunctival hemorrhage. She had a history of atrial flutter and had received a liver transplant approximately 10 years ago. The patient reported having a procedure 2 weeks before her visit with us to remove a basal cell carcinoma on her lower left eyelid, but had no recent changes in vision or physical damage to the eye.

In the past year, she had been started on dabigatran 150 mg twice daily after developing symptomatic atrial fibrillation. Our patient had also been receiving tacrolimus 3 mg twice daily since her transplant. Other medications she was taking included hydroxychloroquine 200 mg/d for rheumatoid arthritis, propafenone 225 mg twice daily for atrial fibrillation, valsartan 80 mg/d for hypertension, and ranitidine 150 mg/d for reflux.

Venipuncture coagulation tests showed a partial thromboplastin time (PTT) of 75.1 seconds, a prothrombin time (PT) of 46.1 seconds, and an elevated international normalized ratio (INR) of 4.5 (normal range: 0.8-1.2). Point-of-care INR results were not obtained.

A complete blood count (CBC) was unremarkable with the exception of a low platelet count and high red blood cell distribution width (RDW). Our patient’s aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were both within normal limits.

Kidney function tests told another story. The patient’s serum creatinine (SCr) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels were elevated (1.54 mg/dL and 29 mg/dL, respectively) and her creatinine clearance (CrCl; 30.2 mL/min) suggested moderate to severe renal dysfunction.

The patient’s CHADS2 score was calculated as 1, suggesting she had a low-to-moderate risk of stroke.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Our patient had a left subconjunctival hemorrhage and an elevated venipuncture INR. Based on her renal dysfunction, we suspected that her elevated INR was likely due to an excessive dose of dabigatran, as well as an interaction between dabigatran and tacrolimus.

DISCUSSION

Dabigatran is an oral direct thrombin inhibitor approved for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. An important advantage of dabigatran compared to warfarin is that the fixed-dose regimen does not require routine anticoagulation monitoring. In cases where anticoagulation monitoring is needed, PTT is the preferred method.1

While PT and INR have generally not been shown to accurately reflect the degree of anticoagulation with dabigatran at therapeutic doses, there have been in vitro reports of elevated INRs with supratherapeutic dabigatran levels.2,3 At a typical peak therapeutic dabigatran concentration of approximately 184 ng/mL, the INR generally ranged from 1.1 to 1.7.2 However, at a dabigatran concentration of 1000 ng/mL, the INR was elevated to 4.5,2,3 which is the same venipuncture INR recorded in our patient. While there have been published reports of falsely elevated point-of-care INR results compared to corresponding venipuncture INR results in patients taking dabigatran,4,5 a literature review found only a case of an elevated venipuncture INR in an end-stage renal disease patient receiving hemodialysis.6

In the case noted above, as well as our patient, an accumulation of dabigatran due to the patient’s renal dysfunction likely resulted in high plasma concentrations and therefore an elevated venipuncture INR. The elimination half-life for dabigatran is approximately 14 hours in patients with normal renal function; in a patient with severe renal impairment, the half-life can be up to 28 hours.7 Our patient’s CrCl at the time of presentation was 30.2 mL/min, which indicated moderate to severe renal dysfunction. Based on dabigatran prescribing recommendations, a dose adjustment to 75 mg bid might be appropriate.1 (Our patient was taking 150 mg bid.)

We do not believe our patient’s elevated INR was due to her liver transplant because there were no clinical signs of liver dysfunction. A more likely contributing factor was a drug interaction with tacrolimus. Dabigatran is a moderate affinity P-glycoprotein (P-gp) substrate and tacrolimus is both a P-gp substrate and inhibitor. While an interaction between tacrolimus and dabigatran has not been studied directly, concurrent use of any P-gp inhibitor and dabigatran is contraindicated in patients with severe renal dysfunction (CrCl: 15-30 mL/min).1 For these theoretical interactions, the Drug Interaction Probability Scale (DIPS) has been developed.8 In our patient’s case, the calculated DIPS score of 5 suggests a probable interaction, likely due to P-gp inhibition. The other medications our patient was taking did not have this interaction and were unlikely to contribute to the elevated INR and subconjunctival hemorrhage.

Our patient was instructed to stop taking dabigatran and return in 3 days for additional lab tests. At her follow-up visit, the lab results were PTT, 34.3 seconds; PT, 11.6 seconds; and venipuncture INR, 1.1. Her CBC was unremarkable and unchanged. Shortly after the follow-up visit, our patient was assessed by her cardiologist. Due to her renal dysfunction, risk of bleeding, and relatively low CHADS2 score, the cardiologist decided to discontinue dabigatran and start her on aspirin.

THE TAKEAWAY

Dabigatran may cause elevated INR levels in patients with renal dysfunction and/or those taking other medications that could interact with dabigatran. Concurrent use of any P-gp inhibitor (such as tacrolimus) and dabigatran is contraindicated in patients with severe renal dysfunction. Despite the lack of required routine laboratory monitoring, renal function and drug interactions associated with dabigatran therapy should be monitored closely.

1. Praxada [package insert]. Ridgefield, CT: Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals; 2015.

2. van Ryn J, Stangier J, Haertter S, et al. Dabigatran etexilate—a novel, reversible, oral direct thrombin inhibitor: interpretation of coagulation assays and reversal of anticoagulant activity. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103:1116-1127.

3. Lindahl TL, Baghaei F, Blixter IF, et al; Expert Group on Coagulation of the External Quality Assurance in Laboratory Medicine in Sweden. Effects of the oral, direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran on five common coagulation assays. Thromb Haemost. 2011;105:371-378.

4. Baruch L, Sherman O. Potential inaccuracy of point-of-care INR in dabigatran-treated patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45:e40.

5. van Ryn J, Baruch L, Clemens A. Interpretation of point-ofcare INR results in patients treated with dabigatran. Am J Med. 2012;125:417-420.

6. Kim J, Yadava M, An IC, et al. Coagulopathy and extremely elevated PT/INR after dabigatran etexilate use in a patient with end-stage renal disease. Case Rep Med. 2013;2013:131395.

7. Stangier J, Rathgen K, Stähle H, et al. Influence of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral dabigatran etexilate: an open-label, parallel-group, single-centre study. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010;49:259-268.

8. Horn JR, Hansten PD, Chan LN. Proposal for a new tool to evaluate drug interaction cases. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:674-680.

THE CASE

A 71-year-old woman came to our clinic with a left subconjunctival hemorrhage. She had a history of atrial flutter and had received a liver transplant approximately 10 years ago. The patient reported having a procedure 2 weeks before her visit with us to remove a basal cell carcinoma on her lower left eyelid, but had no recent changes in vision or physical damage to the eye.

In the past year, she had been started on dabigatran 150 mg twice daily after developing symptomatic atrial fibrillation. Our patient had also been receiving tacrolimus 3 mg twice daily since her transplant. Other medications she was taking included hydroxychloroquine 200 mg/d for rheumatoid arthritis, propafenone 225 mg twice daily for atrial fibrillation, valsartan 80 mg/d for hypertension, and ranitidine 150 mg/d for reflux.

Venipuncture coagulation tests showed a partial thromboplastin time (PTT) of 75.1 seconds, a prothrombin time (PT) of 46.1 seconds, and an elevated international normalized ratio (INR) of 4.5 (normal range: 0.8-1.2). Point-of-care INR results were not obtained.

A complete blood count (CBC) was unremarkable with the exception of a low platelet count and high red blood cell distribution width (RDW). Our patient’s aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were both within normal limits.

Kidney function tests told another story. The patient’s serum creatinine (SCr) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels were elevated (1.54 mg/dL and 29 mg/dL, respectively) and her creatinine clearance (CrCl; 30.2 mL/min) suggested moderate to severe renal dysfunction.

The patient’s CHADS2 score was calculated as 1, suggesting she had a low-to-moderate risk of stroke.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Our patient had a left subconjunctival hemorrhage and an elevated venipuncture INR. Based on her renal dysfunction, we suspected that her elevated INR was likely due to an excessive dose of dabigatran, as well as an interaction between dabigatran and tacrolimus.

DISCUSSION

Dabigatran is an oral direct thrombin inhibitor approved for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. An important advantage of dabigatran compared to warfarin is that the fixed-dose regimen does not require routine anticoagulation monitoring. In cases where anticoagulation monitoring is needed, PTT is the preferred method.1

While PT and INR have generally not been shown to accurately reflect the degree of anticoagulation with dabigatran at therapeutic doses, there have been in vitro reports of elevated INRs with supratherapeutic dabigatran levels.2,3 At a typical peak therapeutic dabigatran concentration of approximately 184 ng/mL, the INR generally ranged from 1.1 to 1.7.2 However, at a dabigatran concentration of 1000 ng/mL, the INR was elevated to 4.5,2,3 which is the same venipuncture INR recorded in our patient. While there have been published reports of falsely elevated point-of-care INR results compared to corresponding venipuncture INR results in patients taking dabigatran,4,5 a literature review found only a case of an elevated venipuncture INR in an end-stage renal disease patient receiving hemodialysis.6

In the case noted above, as well as our patient, an accumulation of dabigatran due to the patient’s renal dysfunction likely resulted in high plasma concentrations and therefore an elevated venipuncture INR. The elimination half-life for dabigatran is approximately 14 hours in patients with normal renal function; in a patient with severe renal impairment, the half-life can be up to 28 hours.7 Our patient’s CrCl at the time of presentation was 30.2 mL/min, which indicated moderate to severe renal dysfunction. Based on dabigatran prescribing recommendations, a dose adjustment to 75 mg bid might be appropriate.1 (Our patient was taking 150 mg bid.)

We do not believe our patient’s elevated INR was due to her liver transplant because there were no clinical signs of liver dysfunction. A more likely contributing factor was a drug interaction with tacrolimus. Dabigatran is a moderate affinity P-glycoprotein (P-gp) substrate and tacrolimus is both a P-gp substrate and inhibitor. While an interaction between tacrolimus and dabigatran has not been studied directly, concurrent use of any P-gp inhibitor and dabigatran is contraindicated in patients with severe renal dysfunction (CrCl: 15-30 mL/min).1 For these theoretical interactions, the Drug Interaction Probability Scale (DIPS) has been developed.8 In our patient’s case, the calculated DIPS score of 5 suggests a probable interaction, likely due to P-gp inhibition. The other medications our patient was taking did not have this interaction and were unlikely to contribute to the elevated INR and subconjunctival hemorrhage.

Our patient was instructed to stop taking dabigatran and return in 3 days for additional lab tests. At her follow-up visit, the lab results were PTT, 34.3 seconds; PT, 11.6 seconds; and venipuncture INR, 1.1. Her CBC was unremarkable and unchanged. Shortly after the follow-up visit, our patient was assessed by her cardiologist. Due to her renal dysfunction, risk of bleeding, and relatively low CHADS2 score, the cardiologist decided to discontinue dabigatran and start her on aspirin.

THE TAKEAWAY

Dabigatran may cause elevated INR levels in patients with renal dysfunction and/or those taking other medications that could interact with dabigatran. Concurrent use of any P-gp inhibitor (such as tacrolimus) and dabigatran is contraindicated in patients with severe renal dysfunction. Despite the lack of required routine laboratory monitoring, renal function and drug interactions associated with dabigatran therapy should be monitored closely.

THE CASE

A 71-year-old woman came to our clinic with a left subconjunctival hemorrhage. She had a history of atrial flutter and had received a liver transplant approximately 10 years ago. The patient reported having a procedure 2 weeks before her visit with us to remove a basal cell carcinoma on her lower left eyelid, but had no recent changes in vision or physical damage to the eye.

In the past year, she had been started on dabigatran 150 mg twice daily after developing symptomatic atrial fibrillation. Our patient had also been receiving tacrolimus 3 mg twice daily since her transplant. Other medications she was taking included hydroxychloroquine 200 mg/d for rheumatoid arthritis, propafenone 225 mg twice daily for atrial fibrillation, valsartan 80 mg/d for hypertension, and ranitidine 150 mg/d for reflux.

Venipuncture coagulation tests showed a partial thromboplastin time (PTT) of 75.1 seconds, a prothrombin time (PT) of 46.1 seconds, and an elevated international normalized ratio (INR) of 4.5 (normal range: 0.8-1.2). Point-of-care INR results were not obtained.

A complete blood count (CBC) was unremarkable with the exception of a low platelet count and high red blood cell distribution width (RDW). Our patient’s aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were both within normal limits.

Kidney function tests told another story. The patient’s serum creatinine (SCr) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels were elevated (1.54 mg/dL and 29 mg/dL, respectively) and her creatinine clearance (CrCl; 30.2 mL/min) suggested moderate to severe renal dysfunction.

The patient’s CHADS2 score was calculated as 1, suggesting she had a low-to-moderate risk of stroke.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Our patient had a left subconjunctival hemorrhage and an elevated venipuncture INR. Based on her renal dysfunction, we suspected that her elevated INR was likely due to an excessive dose of dabigatran, as well as an interaction between dabigatran and tacrolimus.

DISCUSSION

Dabigatran is an oral direct thrombin inhibitor approved for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. An important advantage of dabigatran compared to warfarin is that the fixed-dose regimen does not require routine anticoagulation monitoring. In cases where anticoagulation monitoring is needed, PTT is the preferred method.1

While PT and INR have generally not been shown to accurately reflect the degree of anticoagulation with dabigatran at therapeutic doses, there have been in vitro reports of elevated INRs with supratherapeutic dabigatran levels.2,3 At a typical peak therapeutic dabigatran concentration of approximately 184 ng/mL, the INR generally ranged from 1.1 to 1.7.2 However, at a dabigatran concentration of 1000 ng/mL, the INR was elevated to 4.5,2,3 which is the same venipuncture INR recorded in our patient. While there have been published reports of falsely elevated point-of-care INR results compared to corresponding venipuncture INR results in patients taking dabigatran,4,5 a literature review found only a case of an elevated venipuncture INR in an end-stage renal disease patient receiving hemodialysis.6

In the case noted above, as well as our patient, an accumulation of dabigatran due to the patient’s renal dysfunction likely resulted in high plasma concentrations and therefore an elevated venipuncture INR. The elimination half-life for dabigatran is approximately 14 hours in patients with normal renal function; in a patient with severe renal impairment, the half-life can be up to 28 hours.7 Our patient’s CrCl at the time of presentation was 30.2 mL/min, which indicated moderate to severe renal dysfunction. Based on dabigatran prescribing recommendations, a dose adjustment to 75 mg bid might be appropriate.1 (Our patient was taking 150 mg bid.)

We do not believe our patient’s elevated INR was due to her liver transplant because there were no clinical signs of liver dysfunction. A more likely contributing factor was a drug interaction with tacrolimus. Dabigatran is a moderate affinity P-glycoprotein (P-gp) substrate and tacrolimus is both a P-gp substrate and inhibitor. While an interaction between tacrolimus and dabigatran has not been studied directly, concurrent use of any P-gp inhibitor and dabigatran is contraindicated in patients with severe renal dysfunction (CrCl: 15-30 mL/min).1 For these theoretical interactions, the Drug Interaction Probability Scale (DIPS) has been developed.8 In our patient’s case, the calculated DIPS score of 5 suggests a probable interaction, likely due to P-gp inhibition. The other medications our patient was taking did not have this interaction and were unlikely to contribute to the elevated INR and subconjunctival hemorrhage.

Our patient was instructed to stop taking dabigatran and return in 3 days for additional lab tests. At her follow-up visit, the lab results were PTT, 34.3 seconds; PT, 11.6 seconds; and venipuncture INR, 1.1. Her CBC was unremarkable and unchanged. Shortly after the follow-up visit, our patient was assessed by her cardiologist. Due to her renal dysfunction, risk of bleeding, and relatively low CHADS2 score, the cardiologist decided to discontinue dabigatran and start her on aspirin.

THE TAKEAWAY

Dabigatran may cause elevated INR levels in patients with renal dysfunction and/or those taking other medications that could interact with dabigatran. Concurrent use of any P-gp inhibitor (such as tacrolimus) and dabigatran is contraindicated in patients with severe renal dysfunction. Despite the lack of required routine laboratory monitoring, renal function and drug interactions associated with dabigatran therapy should be monitored closely.

1. Praxada [package insert]. Ridgefield, CT: Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals; 2015.

2. van Ryn J, Stangier J, Haertter S, et al. Dabigatran etexilate—a novel, reversible, oral direct thrombin inhibitor: interpretation of coagulation assays and reversal of anticoagulant activity. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103:1116-1127.

3. Lindahl TL, Baghaei F, Blixter IF, et al; Expert Group on Coagulation of the External Quality Assurance in Laboratory Medicine in Sweden. Effects of the oral, direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran on five common coagulation assays. Thromb Haemost. 2011;105:371-378.

4. Baruch L, Sherman O. Potential inaccuracy of point-of-care INR in dabigatran-treated patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45:e40.

5. van Ryn J, Baruch L, Clemens A. Interpretation of point-ofcare INR results in patients treated with dabigatran. Am J Med. 2012;125:417-420.

6. Kim J, Yadava M, An IC, et al. Coagulopathy and extremely elevated PT/INR after dabigatran etexilate use in a patient with end-stage renal disease. Case Rep Med. 2013;2013:131395.

7. Stangier J, Rathgen K, Stähle H, et al. Influence of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral dabigatran etexilate: an open-label, parallel-group, single-centre study. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010;49:259-268.

8. Horn JR, Hansten PD, Chan LN. Proposal for a new tool to evaluate drug interaction cases. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:674-680.

1. Praxada [package insert]. Ridgefield, CT: Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals; 2015.

2. van Ryn J, Stangier J, Haertter S, et al. Dabigatran etexilate—a novel, reversible, oral direct thrombin inhibitor: interpretation of coagulation assays and reversal of anticoagulant activity. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103:1116-1127.

3. Lindahl TL, Baghaei F, Blixter IF, et al; Expert Group on Coagulation of the External Quality Assurance in Laboratory Medicine in Sweden. Effects of the oral, direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran on five common coagulation assays. Thromb Haemost. 2011;105:371-378.

4. Baruch L, Sherman O. Potential inaccuracy of point-of-care INR in dabigatran-treated patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45:e40.

5. van Ryn J, Baruch L, Clemens A. Interpretation of point-ofcare INR results in patients treated with dabigatran. Am J Med. 2012;125:417-420.

6. Kim J, Yadava M, An IC, et al. Coagulopathy and extremely elevated PT/INR after dabigatran etexilate use in a patient with end-stage renal disease. Case Rep Med. 2013;2013:131395.

7. Stangier J, Rathgen K, Stähle H, et al. Influence of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral dabigatran etexilate: an open-label, parallel-group, single-centre study. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010;49:259-268.

8. Horn JR, Hansten PD, Chan LN. Proposal for a new tool to evaluate drug interaction cases. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:674-680.

Diagnosing and Managing Depressive Episodes in the DSM-5 Era

Man Collapses While Playing Basketball

ANSWER

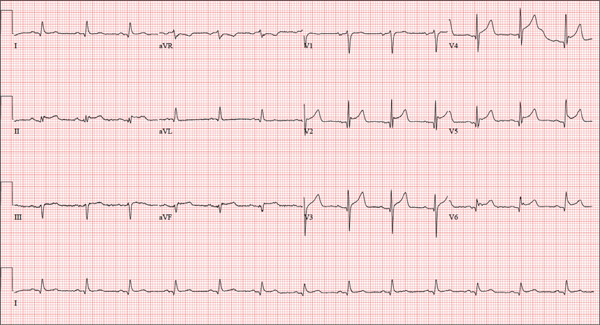

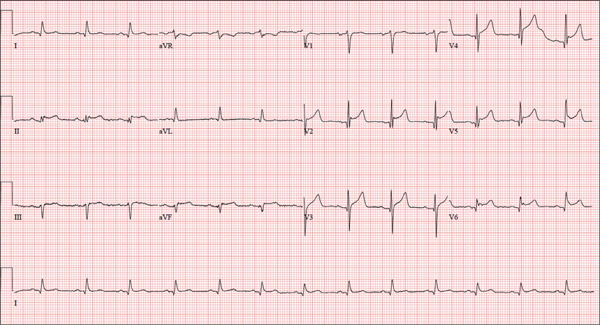

The correct interpretation is normal sinus rhythm with an acute anterior MI (STEMI) and inferolateral injury. In the absence of left ventricular hypertrophy and left bundle-branch block, an acute anterior MI manifests with new ST elevations ≥ 0.1 mV, measured at the J point in leads V2-V3. Inferolateral injury is indicated by ST elevations in leads II, III, and aVF, as well as ST elevations in leads V4-V6.

Laboratory findings confirmed the diagnosis of a new infarction, and cardiac catheterization revealed significant blockage in the proximal left anterior descending and circumflex coronary arteries. These were treated percutaneously, and the patient recovered without sequelae.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation is normal sinus rhythm with an acute anterior MI (STEMI) and inferolateral injury. In the absence of left ventricular hypertrophy and left bundle-branch block, an acute anterior MI manifests with new ST elevations ≥ 0.1 mV, measured at the J point in leads V2-V3. Inferolateral injury is indicated by ST elevations in leads II, III, and aVF, as well as ST elevations in leads V4-V6.

Laboratory findings confirmed the diagnosis of a new infarction, and cardiac catheterization revealed significant blockage in the proximal left anterior descending and circumflex coronary arteries. These were treated percutaneously, and the patient recovered without sequelae.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation is normal sinus rhythm with an acute anterior MI (STEMI) and inferolateral injury. In the absence of left ventricular hypertrophy and left bundle-branch block, an acute anterior MI manifests with new ST elevations ≥ 0.1 mV, measured at the J point in leads V2-V3. Inferolateral injury is indicated by ST elevations in leads II, III, and aVF, as well as ST elevations in leads V4-V6.

Laboratory findings confirmed the diagnosis of a new infarction, and cardiac catheterization revealed significant blockage in the proximal left anterior descending and circumflex coronary arteries. These were treated percutaneously, and the patient recovered without sequelae.

A 46-year-old man is playing intramural basketball when he suddenly collapses on the court. Bystander CPR is begun; the patient is revived immediately without need for cardioversion or defibrillation. He regains consciousness before EMS arrives and, although he does not recall collapsing, he is able to tell them that he has been experiencing chest discomfort all morning (but didn’t mention it to anyone). The patient is transported in stable condition to the emergency department (ED) via BLS ambulance. The total time from his collapse to hospital arrival is 77 minutes, due to the rural location of the high school where he was playing. When you see the patient in the ED, you learn that he has no prior history of cardiac symptoms. He specifically denies chest pain, shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion, or peripheral edema, although with additional questioning, he admits to having ongoing substernal pressure. There is no history of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or thyroid disorder. Surgical history is remarkable for a left anterior cruciate repair that he underwent while in high school. He is employed as an assistant principal at a local high school, is married with two children, and is active in his community—a fact borne out by the volume of well-wishers in the waiting area, inquiring about his status. He does not smoke, drinks two or three beers on the weekend, and does not use recreational drugs, although he admits he tried marijuana in college and didn’t care for it. He is not taking any routine prescription or holistic medications and has no known drug allergies. He reports taking ibuprofen on occasion but adds that he hasn’t taken any in the past three weeks. Review of systems is remarkable for a recent cold. He says he has a residual cough and runny nose but does not feel like he’s currently sick. He considers himself to be very healthy and a role model for the students and faculty at his school. Physical exam reveals a blood pressure of 142/84 mm Hg; pulse, 84 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; and O2 saturation, 99% on 2 L of oxygen. His weight is 189 lb and his height, 74 in. He appears anxious and apprehensive but is alert and cooperative. Pertinent physical findings include a regular rate and rhythm, clear lungs, a soft, nontender abdomen, and no peripheral edema or jugular venous distention. The neurologic exam is intact. Specimens are drawn and sent to the lab for processing. While awaiting the results, you review the ECG taken at the time of arrival. It shows a ventricular rate of 80 beats/min; PR interval, 162 ms; QRS duration, 106 ms; QT/QTc interval, 370/426 ms; P axis, 51°; R axis, –20°; and T axis, 70°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

What you can do to improve adult immunization rates

› Recommend immunization to patients routinely. Most adults believe vaccines are important and are likely to get them if recommended by their health care professionals. C

› Consider implementing standing orders that authorize nurses, pharmacists, or other trained health care personnel to assess a patient’s immunization status and administer vaccinations according to a protocol. C

› Explore the use of Web-based patient portals or other new-media communication formats to engage patients. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Vaccines have been proven effective in preventing disease and are one of the most cost-effective and successful public health initiatives of the 20th century. Nevertheless, adult vaccination rates in the United States for vaccine-preventable diseases are low for most routinely recommended vaccines.1 In 2013 alone, there were an estimated 3700 deaths in the United States (95% of which were adults) from pneumococcal infections—a vaccine-preventable disorder.2

Consider the threat posed by the flu. Annually, most people who die of influenza and its complications are adults, with estimates ranging from a low of 3000 to a high of 49,000 based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data from the 1976-1977 flu season to the 2006-2007 season.3 Vaccination during the 2013-2014 season resulted in an estimated 7.2 million fewer cases of influenza, 90,000 fewer hospitalizations, and 3.1 million fewer medically attended cases than would have been expected without vaccination.4 If vaccination levels had reached the Healthy People 2020 target of 70%, an additional 5.9 million illnesses, 2.3 million medically attended illnesses, and 42,000 hospitalizations might have been averted.4

How are we doing with other vaccines? Based on the 2013 National Health Interview Survey, the CDC assessed vaccination coverage among adults ages ≥19 years for selected vaccines: pneumococcal vaccine, tetanus toxoid-containing vaccines (tetanus and diphtheria vaccine [Td] or tetanus and diphtheria with acellular pertussis vaccine [Tdap]), and vaccines for hepatitis A, hepatitis B, herpes zoster, and human papillomavirus (HPV). (With the exception of influenza vaccination, which is recommended annually for all adults, other vaccinations are directed at specific populations based on age, health conditions, behavioral risk factors, occupation, or travel conditions.)

Overall, coverage rates for hepatitis A and B, pneumococcal, Td, and human papillomavirus (HPV) for all adults did not improve from 2012 to 2013; rates increased only modestly for Tdap among adults ≥19 years, for herpes zoster among adults ≥60 years, and for HPV among men ages 19 to 26. Furthermore, racial and ethnic gaps in coverage are seen in all vaccines, and these gaps widened since 2012 for Tdap, herpes zoster, and HPV vaccination.1

Commonly cited barriers to improved vaccine uptake in adults include lack of regular assessment of vaccine status; lack of physician and other health care provider knowledge on current vaccine recommendations; cost; insufficient stocking of some vaccines; financial disincentives for vaccination in the primary care setting; limited use of electronic records, tools, and immunization registries; missed opportunities; and patient hesitancy and vaccine refusal.5

Removing barriers to immunization. Several recommendations on ways to improve adult vaccination rates are made by many federal organizations as well as by The Community Preventive Services Task Force (Task Force), an independent, nonfederal, unpaid panel of public health and prevention experts. The Task Force—which makes recommendations based on systematic reviews of the evidence of effectiveness, the applicability of the evidence, economic evaluations, and barriers to implementation of interventions6—advocates a 3-pronged approach to improve adult vaccination rates: 1) enhance access to vaccination services; 2) increase community demand for vaccinations; and 3) incorporate physician- or system-based interventions into practice.7

The CDC and other groups such as the National Vaccine Advisory Committee (NVAC) recommend that every routine adult office visit include a vaccination needs assessment, recommendation, and offer of vaccination.8 Additionally, the Task Force recommends 3 means of enhancing adult access to vaccination services: make home visits, reduce patient costs, and offer vaccination programs in the community.7

This article describes a number of simple steps physicians can take to increase the likelihood that adults will get their vaccines and reviews the literature on using new media such as smartphones and other Internet-based tools to improve immunization coverage.9

Increasing community demands for vaccinations

Physicians and other healthcare providers can increase community demand for vaccinations by improving their own knowledge on the subject, recommending vaccination to patients, and increasing their community and political involvement to strengthen or change laws to better support immunization uptake.

To increase awareness and education, keep abreast of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommendations and guidelines, which are updated annually and reported on in this journal’s Practice Alert column. Consider taking advantage of free immunization apps that are available from the CDC (“CDC Vaccine Schedules” http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/schedule-app.html), the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM; “Shots Immunizations” http://www.immunizationed.org/Shots-Mobile-App), and the American College of Physicians (“ACP Immunization Advisor” http://immunization.acponline.org/app/).

Take steps to put guidelines into practice. Despite wide promulgation, clinical practice guidelines alone have had limited effect on changing physician behavior and improving patient outcomes. Interactive techniques are more effective than guidelines and didactic presentations alone at changing physician care and patient outcomes. Such techniques include audit/feedback (the reporting of an individual clinician’s vaccination rates compared with desired or target rates, for example), academic detailing/outreach, and reminders by way of electronic or other alerts.10,11

Promote immunization to patients. Physicians are highly influential in determining a patient’s decision to vaccinate, and it is well documented that a strong recommendation about the importance of immunizations makes a difference to patients.12,13

What you say and how you say it matters. A halfhearted recommendation for vaccination may result in the patient remaining unvaccinated.14 For example, “If you want, you can get your pneumonia shot today” is much less persuasive than, “I recommend you get your pneumonia vaccine today to prevent a potentially serious disease that affects thousands of adults each year.” Most adults believe that vaccines are important and are likely to get them if recommended by their health care professionals.15

The CDC recommends that physicians encourage patients to make an informed decision about vaccination by sharing critical information highlighting the importance of vaccinations and reminding patients what vaccines protect against while addressing their concerns (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/adultstandards). Free educational materials for patients can be found at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/AdultPatientEd.

Draw on community resources. Laws and policies that require vaccinations as a prerequisite for attending childcare, school, or college increase coverage. Community and faith-based organizations are likely to play an important role in reducing racial and ethnic disparities in adult immunizations because they can deliver education that is culturally sensitive and tailored to specific subpopulations.16,17 Physicians and other health care providers can get involved with community and faith-based groups and local and federal legislative efforts to improve immunization rates.

Consider implementing these system-based interventions

The following 6 system-based interventions can help improve adult immunization rates:

1. Develop a practice team. The practice team, based on the Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH), includes physicians, midlevel providers, nurses, medical assistants, pharmacists, social workers, and other staff. The PCMH team model can facilitate a shift of responsibilities among individuals to better orient the practice toward patients’ health and preventive services.18,19 While physicians have traditionally held all of the responsibility for patient care, including screening for disease and prevention, shifting the responsibility of vaccine screening to nurses or medical assistants can free up time for longer physician/patient interactions.18

The creation of a practice champion within the PCMH team—a physician, midlevel provider, or nurse—to oversee quality improvement for vaccine rates and work to generate support and cooperation from coworkers has also been shown to improve vaccination rates.20 The vaccine champion should keep abreast of new vaccine recommendations and relay that information to the practice through regular staff meetings, announcements, and office postings. The champion can also supervise pre-visit planning for immunizations.19

2. Use electronic immunization information systems (IIS). All states except New Hampshire have an IIS.21 Accurate tracking of adult immunizations in a registry provides a complete record and is essential to improving adult immunization rates,22 as does the use of chart notes, computerized alerts, checklists, and other tools that remind health care providers when patients are due for vaccinations.18 NVAC recommends that all physicians use their state IIS and create a process in their practice to include its use.

3. Incorporate physician feedback. Many health care systems and payers are using benchmarking and incentives to provide physician feedback on vaccination performance.23 Using achievable benchmarks enhances the effectiveness of physician performance feedback.24 The Task Force conducted a systematic review of the evidence on the effectiveness of health care provider assessment and feedback for increasing coverage rates and found that this strategy remains an effective means to increase vaccination rates.25

4. Use reminders/alerts. Even though you may intend to routinely recommend immunizations, remembering to do so at the time of each visit can be difficult when there are so many other issues to address. Reminders at the time of the visit can help. Some electronic records have reminder prompts, or “best practice alerts” (BPAs), programmed into their systems.26 These BPAs will prompt for needed immunizations whether the patient is being seen for a well, acute, or routine follow-up visit. These reminder/recall activities can be greatly simplified by participation in a population-based IIS.

Practices that don’t have an electronic health record can still improve vaccination rates by conveying the reminder with a brightly colored paper form attached to the front of a patient’s chart during the check-in process. One recent study showed that this approach increased rates of influenza vaccination in an urban practice by 12 percentage points.27

Furthermore, simply reminding patients to vaccinate increases the vaccination rate.28 Patient reminder/recall systems using telephone calls or mailings (phone calls are more effective than mailings) improve both childhood and adult vaccinations in all medical settings. More intensive systems using multiple reminders appear to be more effective than single reminders, and while costly, the benefits of increasing preventive visits/services and vaccine uptake help offset this cost.28

5. Implement standing orders. Standing orders—which allow nurses and other appropriately trained health care personnel to assess immunization status and administer vaccinations according to protocol—help improve immunization rates.29 ACIP advises that standing order programs be used in long-term care facilities under the supervision of a medical director to ensure the administration of recommended vaccinations for adults, and in inpatient and outpatient facilities. Because of the societal burden of influenza and pneumococcal disease, implementation of standing orders programs to improve adult vaccination coverage for these diseases is considered a national public health priority.30

6. Develop an encouraging communication style. Studies show that how one communicates with patients is just as important as what one communicates. Certain communication styles and techniques may be more or less effective when discussing vaccination needs with some patients, especially those with vaccine hesitancy or low confidence in vaccine safety or effectiveness. For example, styles that are “directing” are usually unhelpful in addressing concerns about vaccination. These styles typically use information and persuasion to achieve change and may be perceived as confrontational. This approach can lead to cues being missed, jargon being used, and vaccine safety being overstated.

Styles shown to be helpful are those that elicit patient concerns, ask permission to discuss, acknowledge/listen/empathize, determine readiness to change, inform about benefits and risks, and give appropriate resources. These helpful forms of communication are more of a “May I help you?” style vs a “This is what you should do” style of communication.31

Assure patients that recommendations are based on the best interest of their health and on the best available science. Listen to a patient’s concerns and acknowledge them in a nonconfrontational manner, allowing patients to express their concerns and thereby increase their willingness to listen.32 Saying that there is “absolutely no need to worry—vaccines are safe and you are silly not to get yours” is not as effective as saying, “What are your concerns regarding vaccines? Let’s talk about them.”

For the vaccine-hesitant group, building trust is essential through a respectful, nonjudgmental approach that aims to elicit and address specific concerns. For those who refuse vaccines, keep the consultation brief, keep the door open for further discussion, and provide appropriate resources if the patient wants them.33

Increase use of new media

Mass communication through smartphones and other Internet-based tools such as Facebook and Twitter brings a new dimension to health care, allowing patients and health professionals to communicate about health issues and possibly improve health outcomes.34 The number of people using social media increased by almost 570% worldwide between 2000 and 2012 and surpassed 2.75 billion in 2013.35

Sixty-one percent of adults in the United States look online for health information.36 In a survey conducted in September 2014, the Pew Research Center found that Facebook is the most popular social media site in the United States. Seventy-one percent of online-knowledgeable adults use Facebook, and multiplatform use is on the rise: 52% of adult Internet users now use 2 or more social media sites, a significant increase from 2013, when it stood at 42%. (Other platforms such as Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest, and LinkedIn saw significant increases over the past year in the proportion of online adults who use them).37

Health information provided by social media can answer medical questions and concerns and enhance health promotion and education.35 A recent review of 98 research studies provided evidence that social media can create a space to share, comment, and discuss health information.34 Compared with traditional communication methods, the widespread availability of social media makes health information more accessible, broadening access to various population groups, regardless of age, education, race, ethnicity, and locale.

New media platforms are proving effective. The first systematic assessment of available evidence on the use of new media to increase vaccine uptake and immunization coverage (a review of 7 randomized controlled trials [RCTs], 5 non-RCTs, 3 cross-sectional studies, one case-control study and 3 operational research studies published between 2000-2013) found that text messaging, accessing immunization campaign Web sites, using patient-held Web-based portals, computerized reminders, and standing orders increased immunization coverage rates.35 However, evidence was insufficient in this regard on the value of social networks, email communication, and smartphone applications.

One RCT showed that having access to a personalized Web-based portal where patients could manage health records as well as interact with both health care providers and other members of the community through social forums and messaging tools increased influenza vaccination rates.35

CORRESPONDENCE

Pamela G. Rockwell, DO, Department of Family Medicine, University of Michigan, 24 Frank Lloyd Wright Drive, P.O. Box 431, Ann Arbor, MI 48106-0795; [email protected].

1. Williams WW, Lu PJ, O’Halloran A, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vaccination coverage among adults, excluding influenza vaccination - United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:95-102.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Active bacterial core surveillance (ABCs) report, emerging infections program network, Streptococcus pneumoniae, 2013. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/abcs/reports-findings/survreports/spneu13.pdf. Accessed August 20, 2015.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Estimates of deaths associated with seasonal influenza --- United States, 1976-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1057-1062.

4. Reed C, Kim IK, Singleton JA, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Estimated influenza illnesses and hospitalizations averted by vaccination--United States, 2013-14 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:1151-1154.

5. Kimmel SR, Burns IT, Wolfe RM, et al. Addressing immunization barriers, benefits, and risks. J Fam Pract. 2007;56:S61-S69.

6. Briss PA, Zaza S, Pappaioanou M, et al. Developing an evidence-based Guide to Community Preventive Services—methods. The Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18:35-43.

7. The Guide to Community Preventive Services. Increasing appropriate vaccination. The Community Guide Web site. Available at: http://www.thecommunityguide.org/vaccines/index.html. Accessed August 20, 2015.

8. National Vaccine Advisory Committee. Recommendations from the National Vaccine Advisory committee: standards for adult immunization practice. Public Health Rep. 2014;129:115-123.

9. Househ M. The use of social media in healthcare: organizational, clinical, and patient perspectives. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2013;183:244-248.

10. Bloom BS. Effects of continuing medical education on improving physician clinical care and patient health: a review of systematic reviews. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21:380-385.

11. Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282:1458-1465.

12. Rosenthal SL, Weiss TW, Zimet GD, et al. Predictors of HPV vaccine uptake among women aged 19-26: importance of a physician’s recommendation. Vaccine. 2011;29:890-895.

13. Zimmerman RK, Santibanez TA, Janosky JE, et al. What affects influenza vaccination rates among older patients? An analysis from inner-city, suburban, rural, and Veterans Affairs practices. Am J Med. 2003;114:31-38.

14. American Academy of Family Physicians. Strong recommendation to vaccinate against HPV is key to boosting uptake. American Academy of Family Physicians Web site. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/news/health-of-the-public/20140212hpv-vaccltr.html. Accessed August 20, 2015.

15. National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. Survey: adults do not recognize infectious disease risks. National Foundation for Infectious Diseases Web site. Available at: http://www.adultvaccination.org/newsroom/events/2009-vaccination-news-conference/NFID-Survey-Fact-Sheet.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2015.

16. Wang E, Clymer J, Davis-Hayes C, et al. Nonmedical exemptions from school immunization requirements: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:e62-e84.

17. National Vaccine Advisory Committee. A pathway to leadership for adult immunization: recommendations of the National Vaccine Advisory Committee: approved by the National Vaccine Advisory Committee on June 14, 2011. Public Health Rep. 2012;127:1-42.

18. Gannon M, Qaseem A, Snooks Q, et al. Improving adult immunization practices using a team approach in the primary care setting. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:e46-e52.

19. Bottino CJ, Cox JE, Kahlon PS, et al. Improving immunization rates in a hospital-based primary care practice. Pediatrics. 2014;133:e1047-e1054.

20. Hainer BL. Vaccine administration: making the process more efficient in your practice. Fam Pract Manag. 2007;14:48-53.

21. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Progress in immunization information systems - United States, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:1005-1008.

22. Jones KL, Hammer AL, Swenson C, et al. Improving adult immunization rates in primary care clinics. Nurs Econ. 2008;26:404-407.

23. Kerr EA, McGlynn EA, Adams J, et al. Profiling the quality of care in twelve communities: results from the CQI study. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;23:247-256.

24. Kiefe CI, Allison JJ, Williams OD, et al. Improving quality improvement using achievable benchmarks for physician feedback: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:2871-2879.

25. National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. General recommendations on immunization --- recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60:1-64.

26. Klatt TE, Hopp E. Effect of a best-practice alert on the rate of influenza vaccination of pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:301-305.

27. Pierson RC, Malone AM, Haas DM. Increasing influenza vaccination rates in a busy urban clinic. J Nat Sci. 2015;1.

28. Jacobson Vann JC, Szilagyi P. Patient reminder and patient recall systems to improve immunization rates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;CD003941.

29. Recommendations regarding interventions to improve vaccination coverage in children, adolescents, and adults. Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18:92-96.

30. McKibben LJ, Stange PV, Sneller VP, et al; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Use of standing orders programs to increase adult vaccination rates. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2000;49:15-16.

31. Leask J, Kinnersley P, Jackson C, et al. Communicating with parents about vaccination: a framework for health professionals. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:154.

32. Kimmel SR, Wolfe RM. Communicating the benefits and risks of vaccines. J Fam Pract. 2005;54:S51-S57.

33. Danchin M, Nolan T. A positive approach to parents with concerns about vaccination for the family physician. Aust Fam Physician. 2014;43:690-694.

34. Moorhead SA, Hazlett DE, Harrison L, et al. A new dimension of health care: systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social media for health communication. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e85.

35. Odone A, Ferrari A, Spagnoli F, et al. Effectiveness of interventions that apply new media to improve vaccine uptake and vaccine coverage. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11:72-82.

36. Pew Research Center. Fox S. The Social Life of Health Information, 2011. Pew Research Center Web site. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/2011/05/12/the-social-life-of-health-information-2011/. Accessed August 20, 2015.

37. Pew Research Center. Duggan M, Ellison NB, Lampe C, et al. Social Media Update 2014. Pew Research Center Web site. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/01/09/social-media-update-2014/. Accessed August 20, 2015.

› Recommend immunization to patients routinely. Most adults believe vaccines are important and are likely to get them if recommended by their health care professionals. C

› Consider implementing standing orders that authorize nurses, pharmacists, or other trained health care personnel to assess a patient’s immunization status and administer vaccinations according to a protocol. C

› Explore the use of Web-based patient portals or other new-media communication formats to engage patients. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Vaccines have been proven effective in preventing disease and are one of the most cost-effective and successful public health initiatives of the 20th century. Nevertheless, adult vaccination rates in the United States for vaccine-preventable diseases are low for most routinely recommended vaccines.1 In 2013 alone, there were an estimated 3700 deaths in the United States (95% of which were adults) from pneumococcal infections—a vaccine-preventable disorder.2

Consider the threat posed by the flu. Annually, most people who die of influenza and its complications are adults, with estimates ranging from a low of 3000 to a high of 49,000 based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data from the 1976-1977 flu season to the 2006-2007 season.3 Vaccination during the 2013-2014 season resulted in an estimated 7.2 million fewer cases of influenza, 90,000 fewer hospitalizations, and 3.1 million fewer medically attended cases than would have been expected without vaccination.4 If vaccination levels had reached the Healthy People 2020 target of 70%, an additional 5.9 million illnesses, 2.3 million medically attended illnesses, and 42,000 hospitalizations might have been averted.4

How are we doing with other vaccines? Based on the 2013 National Health Interview Survey, the CDC assessed vaccination coverage among adults ages ≥19 years for selected vaccines: pneumococcal vaccine, tetanus toxoid-containing vaccines (tetanus and diphtheria vaccine [Td] or tetanus and diphtheria with acellular pertussis vaccine [Tdap]), and vaccines for hepatitis A, hepatitis B, herpes zoster, and human papillomavirus (HPV). (With the exception of influenza vaccination, which is recommended annually for all adults, other vaccinations are directed at specific populations based on age, health conditions, behavioral risk factors, occupation, or travel conditions.)

Overall, coverage rates for hepatitis A and B, pneumococcal, Td, and human papillomavirus (HPV) for all adults did not improve from 2012 to 2013; rates increased only modestly for Tdap among adults ≥19 years, for herpes zoster among adults ≥60 years, and for HPV among men ages 19 to 26. Furthermore, racial and ethnic gaps in coverage are seen in all vaccines, and these gaps widened since 2012 for Tdap, herpes zoster, and HPV vaccination.1

Commonly cited barriers to improved vaccine uptake in adults include lack of regular assessment of vaccine status; lack of physician and other health care provider knowledge on current vaccine recommendations; cost; insufficient stocking of some vaccines; financial disincentives for vaccination in the primary care setting; limited use of electronic records, tools, and immunization registries; missed opportunities; and patient hesitancy and vaccine refusal.5

Removing barriers to immunization. Several recommendations on ways to improve adult vaccination rates are made by many federal organizations as well as by The Community Preventive Services Task Force (Task Force), an independent, nonfederal, unpaid panel of public health and prevention experts. The Task Force—which makes recommendations based on systematic reviews of the evidence of effectiveness, the applicability of the evidence, economic evaluations, and barriers to implementation of interventions6—advocates a 3-pronged approach to improve adult vaccination rates: 1) enhance access to vaccination services; 2) increase community demand for vaccinations; and 3) incorporate physician- or system-based interventions into practice.7

The CDC and other groups such as the National Vaccine Advisory Committee (NVAC) recommend that every routine adult office visit include a vaccination needs assessment, recommendation, and offer of vaccination.8 Additionally, the Task Force recommends 3 means of enhancing adult access to vaccination services: make home visits, reduce patient costs, and offer vaccination programs in the community.7

This article describes a number of simple steps physicians can take to increase the likelihood that adults will get their vaccines and reviews the literature on using new media such as smartphones and other Internet-based tools to improve immunization coverage.9

Increasing community demands for vaccinations

Physicians and other healthcare providers can increase community demand for vaccinations by improving their own knowledge on the subject, recommending vaccination to patients, and increasing their community and political involvement to strengthen or change laws to better support immunization uptake.

To increase awareness and education, keep abreast of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommendations and guidelines, which are updated annually and reported on in this journal’s Practice Alert column. Consider taking advantage of free immunization apps that are available from the CDC (“CDC Vaccine Schedules” http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/schedule-app.html), the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM; “Shots Immunizations” http://www.immunizationed.org/Shots-Mobile-App), and the American College of Physicians (“ACP Immunization Advisor” http://immunization.acponline.org/app/).

Take steps to put guidelines into practice. Despite wide promulgation, clinical practice guidelines alone have had limited effect on changing physician behavior and improving patient outcomes. Interactive techniques are more effective than guidelines and didactic presentations alone at changing physician care and patient outcomes. Such techniques include audit/feedback (the reporting of an individual clinician’s vaccination rates compared with desired or target rates, for example), academic detailing/outreach, and reminders by way of electronic or other alerts.10,11

Promote immunization to patients. Physicians are highly influential in determining a patient’s decision to vaccinate, and it is well documented that a strong recommendation about the importance of immunizations makes a difference to patients.12,13

What you say and how you say it matters. A halfhearted recommendation for vaccination may result in the patient remaining unvaccinated.14 For example, “If you want, you can get your pneumonia shot today” is much less persuasive than, “I recommend you get your pneumonia vaccine today to prevent a potentially serious disease that affects thousands of adults each year.” Most adults believe that vaccines are important and are likely to get them if recommended by their health care professionals.15

The CDC recommends that physicians encourage patients to make an informed decision about vaccination by sharing critical information highlighting the importance of vaccinations and reminding patients what vaccines protect against while addressing their concerns (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/adultstandards). Free educational materials for patients can be found at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/AdultPatientEd.

Draw on community resources. Laws and policies that require vaccinations as a prerequisite for attending childcare, school, or college increase coverage. Community and faith-based organizations are likely to play an important role in reducing racial and ethnic disparities in adult immunizations because they can deliver education that is culturally sensitive and tailored to specific subpopulations.16,17 Physicians and other health care providers can get involved with community and faith-based groups and local and federal legislative efforts to improve immunization rates.

Consider implementing these system-based interventions

The following 6 system-based interventions can help improve adult immunization rates:

1. Develop a practice team. The practice team, based on the Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH), includes physicians, midlevel providers, nurses, medical assistants, pharmacists, social workers, and other staff. The PCMH team model can facilitate a shift of responsibilities among individuals to better orient the practice toward patients’ health and preventive services.18,19 While physicians have traditionally held all of the responsibility for patient care, including screening for disease and prevention, shifting the responsibility of vaccine screening to nurses or medical assistants can free up time for longer physician/patient interactions.18

The creation of a practice champion within the PCMH team—a physician, midlevel provider, or nurse—to oversee quality improvement for vaccine rates and work to generate support and cooperation from coworkers has also been shown to improve vaccination rates.20 The vaccine champion should keep abreast of new vaccine recommendations and relay that information to the practice through regular staff meetings, announcements, and office postings. The champion can also supervise pre-visit planning for immunizations.19

2. Use electronic immunization information systems (IIS). All states except New Hampshire have an IIS.21 Accurate tracking of adult immunizations in a registry provides a complete record and is essential to improving adult immunization rates,22 as does the use of chart notes, computerized alerts, checklists, and other tools that remind health care providers when patients are due for vaccinations.18 NVAC recommends that all physicians use their state IIS and create a process in their practice to include its use.

3. Incorporate physician feedback. Many health care systems and payers are using benchmarking and incentives to provide physician feedback on vaccination performance.23 Using achievable benchmarks enhances the effectiveness of physician performance feedback.24 The Task Force conducted a systematic review of the evidence on the effectiveness of health care provider assessment and feedback for increasing coverage rates and found that this strategy remains an effective means to increase vaccination rates.25