User login

The practice of caring

“To look deep into your child’s eyes and see in him both yourself and something utterly strange, and then to develop a zealous attachment to every aspect of him, is to achieve parenthood’s self-regarding, yet unselfish, abandon. It is astonishing how often such mutuality had been realized – how frequently parents who had supposed that they couldn’t care for an exceptional child discover that they can. The parental predisposition to love prevails in the most harrowing of circumstances. There is more imagination in the world than one might think.”

Andrew Solomon, “Far from the Tree: Parents, Children, and the Search for Identity” (New York: Scribner, 2012).

In his most recent book, writer and lecturer Andrew Solomon describes a deep love that leads to redemption. His case histories describe parents becoming virtuous through the practice of caring. Solomon records both their loving and their suffering. He does not see caring, necessarily, as an inherent trait but rather sees virtue emerging from the act of caring. The philosophical study of caring and virtue is known as the “ethics of care.” This column considers the ethics of care in relation to our patients and their families.

‘Ethics of care’ origins

Care ethics emerged as a distinct moral theory when psychologist Carol Gilligan, Ph.D., and philosopher Nel Noddings, Ph.D., labeled traditional moral theory as biased toward the male gender. They asserted the “voice of care” as a female alternative to Lawrence Kohlberg’s male “voice of justice.”

Originally, therefore, care ethics were described as a feminist ethic. To drive home this point, the suffragettes argued that granting voting rights to (white) women would lead to moral, social improvements! The naive assumption was that women by nature had traits of compassion, empathy, nurturance, and kindness, as exemplified by the good mother. This is known as feminist essentialism. Taking this gendered view further, Nel Noddings states that the domestic sphere is the originator and nurturer of justice, in the sense that the best social policies are identified, modeled, and sustained by practices in the “best families.” This is a difficult position: Who decides on the characteristics of “best families?”

Practice of caring vs. ethics

The practice of caring can be described as actions performed by the carer, or as a value, or as a disposition or virtue that resides in the person who is caring. The following points summarize the current positions of philosophers who identify themselves as care ethicists.

• Care reflects a specific type of moral reasoning. This is the Kohlberg-Gilligan argument of male vs. female reasoning. Although care and justice have evolved as distinct ethical practices and ideals, they are not necessarily incompatible. As gender roles soften and gender as a concept becomes more blurry, care and justice can be intertwined. Reasoning does not have to be either justice based or care based.

• Care is the practice of caring for someone (Andrew Solomon’s case histories). This stance does not romanticize the practice of caring. This stance does not consider caring as a trait or disposition. This stance acknowledges the suffering and hardship in caring that can coexist with love. This stance points to the potential for individual spiritual and personal growth that can accompany caregiving. Andrew Solomon would agree to the notion of stages of caring (“Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care,” New York: Routledge, 1994). These stages are: (1) attentiveness, becoming aware of need; (2) responsibility, a willingness to respond and take care of need; (3) competence, the skill of providing good and successful care; and (4) responsiveness, consideration of the position of others as they see it and recognition of the potential for abuse in care. The practice of caring is more of a daily reality than the abstract virtue.

• Care is an inherent virtue. This stance includes both feminist essentialism and feminist care ethics. In feminist essentialism, the process of moral development follows gender roles. The prototypical caregiving mother and a care-receiving child romanticize and elevate motherhood to the ideal practice of care. Feminist care ethicists avoid this essentialism by situating caring practices in place and time. They describe care as the symbolic practice rather than actual practice of women. Feminist care ethicists explore care as a gender neutral activity, advancing a utopian vision of care as a gender-neutral activity and virtue. Cognitive capacities and virtues associated with mothering, (better described as being associated with parenting), are seen as essential to the concept of care. These virtues are preservative love (work of protection with cheerfulness and humility), fostering growth (sponsoring or nurturing a child’s unfolding), and training for social acceptability (a process of socialization that requires conscience and a struggle for authenticity). This position also is reflected in Solomon’s ethics of care.

• Care is an inherent character trait or disposition. This stance understands care ethics as a form of virtue ethics, with care being a central virtue. There is an emphasis on relationship as fundamental to being, and the parent-child relationship as paramount. Virtue ethics views emotions such as empathy, compassion, and sensitivity as prerequisites for moral development and the ethics of care.

• Care as social justice and political imperative. One of the earliest objections to an ethics of care was that it valorized the oppression of women. Nietzsche held that those who are oppressed develop moral theories that reaffirm subservient traits as virtues. Women who perform the work of care often perform this care to their own economic disadvantage. A social justice perspective implies that the voice of care is the voice of an oppressed person, and eschews the idea that moral maturity means self-sacrifice and self-effacement. Care ethics informed by a social justice perspective asks who is caring for whom and whether this relationship is just.

When care ethics are applied to domestic politics, economic justice, international relations, and culture, interesting ideas emerge. Governments and businesses become responsible for support in sickness, disability, old age, bad luck, and reversal of fortune, for providing protection, health care, and clean environments, and for upholding the rights of individuals. A focus on autonomy, independence, and self-determination, which traditionally are seen as male traits, devalues interdependence and relatedness, which traditionally are seen as female values. Care ethics suggest that we replace hierarchy and domination that is based on gender, class, race, and ethnicity with cooperation and attention to interdependency. Interdependency is ubiquitous, and care ethics is a political theory with universal application. The practice of caring has no political affiliation; however, if we had founding mothers instead of founding fathers, would the United States be based more on ethics of care?

•The caring professions. The practice of caring is a practice that helps individuals meet their basic needs, maintain capabilities, and alleviate pain and suffering, so they can survive and function in society. Using this definition, the practice of care does not require any emotional attachment. Using this definition, the activity itself is a virtuous moral position. The health care professions mostly provide “services” rather than “care.” Is empathy a necessary ingredient for the practice of care? Many people believe so, and organizations such as the Watson Caring Science Institute (watsoncaringscience.org) are dedicated to putting the caring back into health care.

Meaning for the psychiatrist

When caregivers of patients with dementia were asked how they felt about caregiving, they responded positively. Caregiving felt good. Here is a listing of some their responses:

“Feeling needed and responsible.”

“Feeling good inside, doing for someone what you want for yourself and knowing I’ve done my best.”

“Being able to help.”

“To brighten her days.”

“I know he is being cared for the way he is used to.”

“I feel that she is loved and not alone.”

These caregivers were mostly spouses (61%), with an average of 3.1 caregiving years. Caregivers reported that their relatives were moderately disabled, but they perceived more reward than burden (Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry, 2004;19:533-7). The caregivers’ quality of life also proved similar to those in an age-controlled normal community sample. So if caregiving can be carried out without significantly affecting quality of life, caregiving can be more rewarding than burdensome.

Questions for the family psychiatrist:

• How am I caring for my patients and their families?

• What does it mean to care rather than provide a service?

• How has my psychiatric training changed how I perceive caring? Do I now care in a different way?

• Has the way I care developed through my practice of caring?

• Where am I in the stages of caring?

• When does caring mean advocacy?

Questions to ask patients and their families:

• Do you experience reward in caregiving?

• Are there ways to sustain and enhance the satisfaction and reward of caring?

• How might you explore the practice of caring?

• Has caring been redeeming for you?

• Has caring brought individual growth for you, despite the hardships?

Dr. Heru is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of the recently published book, “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (New York: Routledge, 2013). Some of the research for this article came from The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

“To look deep into your child’s eyes and see in him both yourself and something utterly strange, and then to develop a zealous attachment to every aspect of him, is to achieve parenthood’s self-regarding, yet unselfish, abandon. It is astonishing how often such mutuality had been realized – how frequently parents who had supposed that they couldn’t care for an exceptional child discover that they can. The parental predisposition to love prevails in the most harrowing of circumstances. There is more imagination in the world than one might think.”

Andrew Solomon, “Far from the Tree: Parents, Children, and the Search for Identity” (New York: Scribner, 2012).

In his most recent book, writer and lecturer Andrew Solomon describes a deep love that leads to redemption. His case histories describe parents becoming virtuous through the practice of caring. Solomon records both their loving and their suffering. He does not see caring, necessarily, as an inherent trait but rather sees virtue emerging from the act of caring. The philosophical study of caring and virtue is known as the “ethics of care.” This column considers the ethics of care in relation to our patients and their families.

‘Ethics of care’ origins

Care ethics emerged as a distinct moral theory when psychologist Carol Gilligan, Ph.D., and philosopher Nel Noddings, Ph.D., labeled traditional moral theory as biased toward the male gender. They asserted the “voice of care” as a female alternative to Lawrence Kohlberg’s male “voice of justice.”

Originally, therefore, care ethics were described as a feminist ethic. To drive home this point, the suffragettes argued that granting voting rights to (white) women would lead to moral, social improvements! The naive assumption was that women by nature had traits of compassion, empathy, nurturance, and kindness, as exemplified by the good mother. This is known as feminist essentialism. Taking this gendered view further, Nel Noddings states that the domestic sphere is the originator and nurturer of justice, in the sense that the best social policies are identified, modeled, and sustained by practices in the “best families.” This is a difficult position: Who decides on the characteristics of “best families?”

Practice of caring vs. ethics

The practice of caring can be described as actions performed by the carer, or as a value, or as a disposition or virtue that resides in the person who is caring. The following points summarize the current positions of philosophers who identify themselves as care ethicists.

• Care reflects a specific type of moral reasoning. This is the Kohlberg-Gilligan argument of male vs. female reasoning. Although care and justice have evolved as distinct ethical practices and ideals, they are not necessarily incompatible. As gender roles soften and gender as a concept becomes more blurry, care and justice can be intertwined. Reasoning does not have to be either justice based or care based.

• Care is the practice of caring for someone (Andrew Solomon’s case histories). This stance does not romanticize the practice of caring. This stance does not consider caring as a trait or disposition. This stance acknowledges the suffering and hardship in caring that can coexist with love. This stance points to the potential for individual spiritual and personal growth that can accompany caregiving. Andrew Solomon would agree to the notion of stages of caring (“Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care,” New York: Routledge, 1994). These stages are: (1) attentiveness, becoming aware of need; (2) responsibility, a willingness to respond and take care of need; (3) competence, the skill of providing good and successful care; and (4) responsiveness, consideration of the position of others as they see it and recognition of the potential for abuse in care. The practice of caring is more of a daily reality than the abstract virtue.

• Care is an inherent virtue. This stance includes both feminist essentialism and feminist care ethics. In feminist essentialism, the process of moral development follows gender roles. The prototypical caregiving mother and a care-receiving child romanticize and elevate motherhood to the ideal practice of care. Feminist care ethicists avoid this essentialism by situating caring practices in place and time. They describe care as the symbolic practice rather than actual practice of women. Feminist care ethicists explore care as a gender neutral activity, advancing a utopian vision of care as a gender-neutral activity and virtue. Cognitive capacities and virtues associated with mothering, (better described as being associated with parenting), are seen as essential to the concept of care. These virtues are preservative love (work of protection with cheerfulness and humility), fostering growth (sponsoring or nurturing a child’s unfolding), and training for social acceptability (a process of socialization that requires conscience and a struggle for authenticity). This position also is reflected in Solomon’s ethics of care.

• Care is an inherent character trait or disposition. This stance understands care ethics as a form of virtue ethics, with care being a central virtue. There is an emphasis on relationship as fundamental to being, and the parent-child relationship as paramount. Virtue ethics views emotions such as empathy, compassion, and sensitivity as prerequisites for moral development and the ethics of care.

• Care as social justice and political imperative. One of the earliest objections to an ethics of care was that it valorized the oppression of women. Nietzsche held that those who are oppressed develop moral theories that reaffirm subservient traits as virtues. Women who perform the work of care often perform this care to their own economic disadvantage. A social justice perspective implies that the voice of care is the voice of an oppressed person, and eschews the idea that moral maturity means self-sacrifice and self-effacement. Care ethics informed by a social justice perspective asks who is caring for whom and whether this relationship is just.

When care ethics are applied to domestic politics, economic justice, international relations, and culture, interesting ideas emerge. Governments and businesses become responsible for support in sickness, disability, old age, bad luck, and reversal of fortune, for providing protection, health care, and clean environments, and for upholding the rights of individuals. A focus on autonomy, independence, and self-determination, which traditionally are seen as male traits, devalues interdependence and relatedness, which traditionally are seen as female values. Care ethics suggest that we replace hierarchy and domination that is based on gender, class, race, and ethnicity with cooperation and attention to interdependency. Interdependency is ubiquitous, and care ethics is a political theory with universal application. The practice of caring has no political affiliation; however, if we had founding mothers instead of founding fathers, would the United States be based more on ethics of care?

•The caring professions. The practice of caring is a practice that helps individuals meet their basic needs, maintain capabilities, and alleviate pain and suffering, so they can survive and function in society. Using this definition, the practice of care does not require any emotional attachment. Using this definition, the activity itself is a virtuous moral position. The health care professions mostly provide “services” rather than “care.” Is empathy a necessary ingredient for the practice of care? Many people believe so, and organizations such as the Watson Caring Science Institute (watsoncaringscience.org) are dedicated to putting the caring back into health care.

Meaning for the psychiatrist

When caregivers of patients with dementia were asked how they felt about caregiving, they responded positively. Caregiving felt good. Here is a listing of some their responses:

“Feeling needed and responsible.”

“Feeling good inside, doing for someone what you want for yourself and knowing I’ve done my best.”

“Being able to help.”

“To brighten her days.”

“I know he is being cared for the way he is used to.”

“I feel that she is loved and not alone.”

These caregivers were mostly spouses (61%), with an average of 3.1 caregiving years. Caregivers reported that their relatives were moderately disabled, but they perceived more reward than burden (Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry, 2004;19:533-7). The caregivers’ quality of life also proved similar to those in an age-controlled normal community sample. So if caregiving can be carried out without significantly affecting quality of life, caregiving can be more rewarding than burdensome.

Questions for the family psychiatrist:

• How am I caring for my patients and their families?

• What does it mean to care rather than provide a service?

• How has my psychiatric training changed how I perceive caring? Do I now care in a different way?

• Has the way I care developed through my practice of caring?

• Where am I in the stages of caring?

• When does caring mean advocacy?

Questions to ask patients and their families:

• Do you experience reward in caregiving?

• Are there ways to sustain and enhance the satisfaction and reward of caring?

• How might you explore the practice of caring?

• Has caring been redeeming for you?

• Has caring brought individual growth for you, despite the hardships?

Dr. Heru is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of the recently published book, “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (New York: Routledge, 2013). Some of the research for this article came from The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

“To look deep into your child’s eyes and see in him both yourself and something utterly strange, and then to develop a zealous attachment to every aspect of him, is to achieve parenthood’s self-regarding, yet unselfish, abandon. It is astonishing how often such mutuality had been realized – how frequently parents who had supposed that they couldn’t care for an exceptional child discover that they can. The parental predisposition to love prevails in the most harrowing of circumstances. There is more imagination in the world than one might think.”

Andrew Solomon, “Far from the Tree: Parents, Children, and the Search for Identity” (New York: Scribner, 2012).

In his most recent book, writer and lecturer Andrew Solomon describes a deep love that leads to redemption. His case histories describe parents becoming virtuous through the practice of caring. Solomon records both their loving and their suffering. He does not see caring, necessarily, as an inherent trait but rather sees virtue emerging from the act of caring. The philosophical study of caring and virtue is known as the “ethics of care.” This column considers the ethics of care in relation to our patients and their families.

‘Ethics of care’ origins

Care ethics emerged as a distinct moral theory when psychologist Carol Gilligan, Ph.D., and philosopher Nel Noddings, Ph.D., labeled traditional moral theory as biased toward the male gender. They asserted the “voice of care” as a female alternative to Lawrence Kohlberg’s male “voice of justice.”

Originally, therefore, care ethics were described as a feminist ethic. To drive home this point, the suffragettes argued that granting voting rights to (white) women would lead to moral, social improvements! The naive assumption was that women by nature had traits of compassion, empathy, nurturance, and kindness, as exemplified by the good mother. This is known as feminist essentialism. Taking this gendered view further, Nel Noddings states that the domestic sphere is the originator and nurturer of justice, in the sense that the best social policies are identified, modeled, and sustained by practices in the “best families.” This is a difficult position: Who decides on the characteristics of “best families?”

Practice of caring vs. ethics

The practice of caring can be described as actions performed by the carer, or as a value, or as a disposition or virtue that resides in the person who is caring. The following points summarize the current positions of philosophers who identify themselves as care ethicists.

• Care reflects a specific type of moral reasoning. This is the Kohlberg-Gilligan argument of male vs. female reasoning. Although care and justice have evolved as distinct ethical practices and ideals, they are not necessarily incompatible. As gender roles soften and gender as a concept becomes more blurry, care and justice can be intertwined. Reasoning does not have to be either justice based or care based.

• Care is the practice of caring for someone (Andrew Solomon’s case histories). This stance does not romanticize the practice of caring. This stance does not consider caring as a trait or disposition. This stance acknowledges the suffering and hardship in caring that can coexist with love. This stance points to the potential for individual spiritual and personal growth that can accompany caregiving. Andrew Solomon would agree to the notion of stages of caring (“Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care,” New York: Routledge, 1994). These stages are: (1) attentiveness, becoming aware of need; (2) responsibility, a willingness to respond and take care of need; (3) competence, the skill of providing good and successful care; and (4) responsiveness, consideration of the position of others as they see it and recognition of the potential for abuse in care. The practice of caring is more of a daily reality than the abstract virtue.

• Care is an inherent virtue. This stance includes both feminist essentialism and feminist care ethics. In feminist essentialism, the process of moral development follows gender roles. The prototypical caregiving mother and a care-receiving child romanticize and elevate motherhood to the ideal practice of care. Feminist care ethicists avoid this essentialism by situating caring practices in place and time. They describe care as the symbolic practice rather than actual practice of women. Feminist care ethicists explore care as a gender neutral activity, advancing a utopian vision of care as a gender-neutral activity and virtue. Cognitive capacities and virtues associated with mothering, (better described as being associated with parenting), are seen as essential to the concept of care. These virtues are preservative love (work of protection with cheerfulness and humility), fostering growth (sponsoring or nurturing a child’s unfolding), and training for social acceptability (a process of socialization that requires conscience and a struggle for authenticity). This position also is reflected in Solomon’s ethics of care.

• Care is an inherent character trait or disposition. This stance understands care ethics as a form of virtue ethics, with care being a central virtue. There is an emphasis on relationship as fundamental to being, and the parent-child relationship as paramount. Virtue ethics views emotions such as empathy, compassion, and sensitivity as prerequisites for moral development and the ethics of care.

• Care as social justice and political imperative. One of the earliest objections to an ethics of care was that it valorized the oppression of women. Nietzsche held that those who are oppressed develop moral theories that reaffirm subservient traits as virtues. Women who perform the work of care often perform this care to their own economic disadvantage. A social justice perspective implies that the voice of care is the voice of an oppressed person, and eschews the idea that moral maturity means self-sacrifice and self-effacement. Care ethics informed by a social justice perspective asks who is caring for whom and whether this relationship is just.

When care ethics are applied to domestic politics, economic justice, international relations, and culture, interesting ideas emerge. Governments and businesses become responsible for support in sickness, disability, old age, bad luck, and reversal of fortune, for providing protection, health care, and clean environments, and for upholding the rights of individuals. A focus on autonomy, independence, and self-determination, which traditionally are seen as male traits, devalues interdependence and relatedness, which traditionally are seen as female values. Care ethics suggest that we replace hierarchy and domination that is based on gender, class, race, and ethnicity with cooperation and attention to interdependency. Interdependency is ubiquitous, and care ethics is a political theory with universal application. The practice of caring has no political affiliation; however, if we had founding mothers instead of founding fathers, would the United States be based more on ethics of care?

•The caring professions. The practice of caring is a practice that helps individuals meet their basic needs, maintain capabilities, and alleviate pain and suffering, so they can survive and function in society. Using this definition, the practice of care does not require any emotional attachment. Using this definition, the activity itself is a virtuous moral position. The health care professions mostly provide “services” rather than “care.” Is empathy a necessary ingredient for the practice of care? Many people believe so, and organizations such as the Watson Caring Science Institute (watsoncaringscience.org) are dedicated to putting the caring back into health care.

Meaning for the psychiatrist

When caregivers of patients with dementia were asked how they felt about caregiving, they responded positively. Caregiving felt good. Here is a listing of some their responses:

“Feeling needed and responsible.”

“Feeling good inside, doing for someone what you want for yourself and knowing I’ve done my best.”

“Being able to help.”

“To brighten her days.”

“I know he is being cared for the way he is used to.”

“I feel that she is loved and not alone.”

These caregivers were mostly spouses (61%), with an average of 3.1 caregiving years. Caregivers reported that their relatives were moderately disabled, but they perceived more reward than burden (Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry, 2004;19:533-7). The caregivers’ quality of life also proved similar to those in an age-controlled normal community sample. So if caregiving can be carried out without significantly affecting quality of life, caregiving can be more rewarding than burdensome.

Questions for the family psychiatrist:

• How am I caring for my patients and their families?

• What does it mean to care rather than provide a service?

• How has my psychiatric training changed how I perceive caring? Do I now care in a different way?

• Has the way I care developed through my practice of caring?

• Where am I in the stages of caring?

• When does caring mean advocacy?

Questions to ask patients and their families:

• Do you experience reward in caregiving?

• Are there ways to sustain and enhance the satisfaction and reward of caring?

• How might you explore the practice of caring?

• Has caring been redeeming for you?

• Has caring brought individual growth for you, despite the hardships?

Dr. Heru is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of the recently published book, “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (New York: Routledge, 2013). Some of the research for this article came from The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Rapid INR reversal key in oral anticoagulant–associated intracerebral hemorrhage

Rapid reversal of international normalized ratio, along with systolic blood pressure reduction, in patients with oral anticoagulant–associated intracerebral hemorrhage can significantly reduce the rates of hematoma enlargement and in-hospital mortality, a retrospective cohort study has found.

In the German study of 1,176 patients with oral anticoagulant–associated intracerebral hemorrhage, patients whose INR was reduced below 1.3 with use of vitamin K agonists and whose systolic BP was reduced below 160 mm Hg within 4 hours of admission had a 72% reduction in the rates of hematoma enlargement and 40% reduction in in-hospital mortality, compared with patients who did not achieve those reductions in that time frame.

Researchers also showed that there were no significant increases in hemorrhagic complications, but fewer ischemic complications, among patients who resumed oral anticoagulation, according to the study published online Feb. 24 in JAMA.

“Consensus exists that elevated international normalized ratio (INR) levels should be reversed to minimize hematoma enlargement, yet mode, timing, and extent of INR reversal are unclear [and] valid data on safety and clinical benefit of [oral anticoagulant] resumption are missing and remain to be established,” wrote Dr. Joji B. Kuramatsu of the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany, and coauthors (JAMA 2015;313:824-836 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.0846]).

The study was supported by the Johannes and Frieda Marohn Foundation. Authors declared a range of funding, grants, fees, and honoraria from the pharmaceutical industry.

Rapid reversal of international normalized ratio, along with systolic blood pressure reduction, in patients with oral anticoagulant–associated intracerebral hemorrhage can significantly reduce the rates of hematoma enlargement and in-hospital mortality, a retrospective cohort study has found.

In the German study of 1,176 patients with oral anticoagulant–associated intracerebral hemorrhage, patients whose INR was reduced below 1.3 with use of vitamin K agonists and whose systolic BP was reduced below 160 mm Hg within 4 hours of admission had a 72% reduction in the rates of hematoma enlargement and 40% reduction in in-hospital mortality, compared with patients who did not achieve those reductions in that time frame.

Researchers also showed that there were no significant increases in hemorrhagic complications, but fewer ischemic complications, among patients who resumed oral anticoagulation, according to the study published online Feb. 24 in JAMA.

“Consensus exists that elevated international normalized ratio (INR) levels should be reversed to minimize hematoma enlargement, yet mode, timing, and extent of INR reversal are unclear [and] valid data on safety and clinical benefit of [oral anticoagulant] resumption are missing and remain to be established,” wrote Dr. Joji B. Kuramatsu of the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany, and coauthors (JAMA 2015;313:824-836 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.0846]).

The study was supported by the Johannes and Frieda Marohn Foundation. Authors declared a range of funding, grants, fees, and honoraria from the pharmaceutical industry.

Rapid reversal of international normalized ratio, along with systolic blood pressure reduction, in patients with oral anticoagulant–associated intracerebral hemorrhage can significantly reduce the rates of hematoma enlargement and in-hospital mortality, a retrospective cohort study has found.

In the German study of 1,176 patients with oral anticoagulant–associated intracerebral hemorrhage, patients whose INR was reduced below 1.3 with use of vitamin K agonists and whose systolic BP was reduced below 160 mm Hg within 4 hours of admission had a 72% reduction in the rates of hematoma enlargement and 40% reduction in in-hospital mortality, compared with patients who did not achieve those reductions in that time frame.

Researchers also showed that there were no significant increases in hemorrhagic complications, but fewer ischemic complications, among patients who resumed oral anticoagulation, according to the study published online Feb. 24 in JAMA.

“Consensus exists that elevated international normalized ratio (INR) levels should be reversed to minimize hematoma enlargement, yet mode, timing, and extent of INR reversal are unclear [and] valid data on safety and clinical benefit of [oral anticoagulant] resumption are missing and remain to be established,” wrote Dr. Joji B. Kuramatsu of the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany, and coauthors (JAMA 2015;313:824-836 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.0846]).

The study was supported by the Johannes and Frieda Marohn Foundation. Authors declared a range of funding, grants, fees, and honoraria from the pharmaceutical industry.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Rapid INR reversal and systolic blood pressure reduction in patients lowers the rates of hematoma enlargement and in-hospital mortality from oral anticoagulant–associated intracerebral hemorrhage.

Major finding: Patients whose INR was reduced below 1.3 and systolic blood pressure reduced below 160 mm Hg within 4 hours of admission had a 72% reduction in the rates of hematoma enlargement and 40% reduction in in-hospital mortality.

Data source: Retrospective cohort study of 1,176 patients with oral anticoagulant–associated intracerebral hemorrhage .

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Johannes and Frieda Marohn Foundation. Authors declared a range of funding, grants, fees, and honoraria from the pharmaceutical industry.

An Incidental Finding During Neuro Evaluation

ANSWER

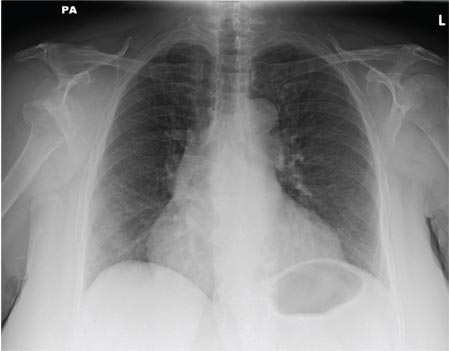

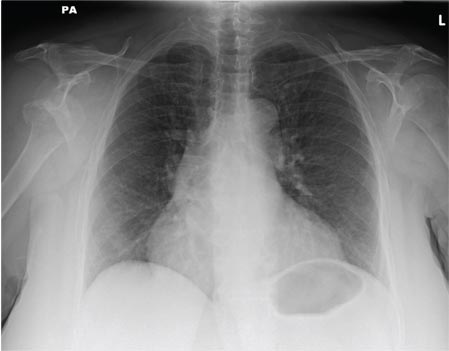

The radiograph shows a normal-appearing chest. Of note, though, is an anterior dislocation of the right shoulder. In addition, there is a fracture within the greater tuberosity of the right humerus.

Prompt orthopedic evaluation is obtained. In further discussion with the family, it was revealed that the patient had been experiencing falls recently; this injury was most likely the result of one.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows a normal-appearing chest. Of note, though, is an anterior dislocation of the right shoulder. In addition, there is a fracture within the greater tuberosity of the right humerus.

Prompt orthopedic evaluation is obtained. In further discussion with the family, it was revealed that the patient had been experiencing falls recently; this injury was most likely the result of one.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows a normal-appearing chest. Of note, though, is an anterior dislocation of the right shoulder. In addition, there is a fracture within the greater tuberosity of the right humerus.

Prompt orthopedic evaluation is obtained. In further discussion with the family, it was revealed that the patient had been experiencing falls recently; this injury was most likely the result of one.

A 65-year-old woman is transferred to your facility from an outlying hospital for evaluation of a brain tumor. Family members found the patient sitting on the sofa, with a decreased level of consciousness. There was reported “seizure-type activity.” When she arrived at the outlying hospital, the patient was noted to have right-side weakness. Stat CT of the head demonstrated a fairly large parasagittal mass, and the patient was urgently transferred to your facility for neurosurgical evaluation. Primary survey on arrival shows an older female who is awake, alert, and in no obvious distress. Vital signs are normal. She has fairly pronounced right upper extremity weakness, more proximally than distally. Otherwise, the exam grossly appears normal. The patient’s initial imaging studies were sent with her on a CD. As you are trying to view the images of the brain, a chest radiograph pops up on your screen. What is your impression?

What Does This Man Need (Besides Milk & Cookies)?

ANSWER

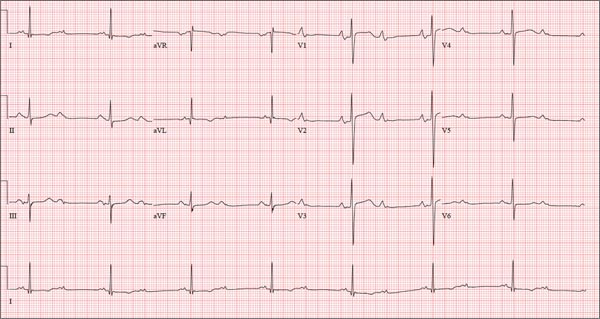

This ECG is representative of sinus rhythm with second-degree atrioventricular block with 2:1 conduction; possible left atrial enlargement; and ST-T wave abnormalities suspicious for lateral ischemia.

Sinus rhythm is evidenced by the P waves that march through at a rate that is consistently double that of the QRS rate (82 beats/min). The PR interval in the conducted beats remains constant, with every other P wave blocked from conducting into the ventricles.

The biphasic P wave seen in lead V1 does not meet criteria for left atrial enlargement (P wave in lead I ≥ 110 ms, terminal negative P wave in lead V1 ≥ 1 mm2) but is suspicious. Finally, ST-T wave elevations in leads V2-V4 are suspicious for ventricular septal ischemia.

The patient underwent placement of a dual-chamber permanent pacemaker. He has done well since.

ANSWER

This ECG is representative of sinus rhythm with second-degree atrioventricular block with 2:1 conduction; possible left atrial enlargement; and ST-T wave abnormalities suspicious for lateral ischemia.

Sinus rhythm is evidenced by the P waves that march through at a rate that is consistently double that of the QRS rate (82 beats/min). The PR interval in the conducted beats remains constant, with every other P wave blocked from conducting into the ventricles.

The biphasic P wave seen in lead V1 does not meet criteria for left atrial enlargement (P wave in lead I ≥ 110 ms, terminal negative P wave in lead V1 ≥ 1 mm2) but is suspicious. Finally, ST-T wave elevations in leads V2-V4 are suspicious for ventricular septal ischemia.

The patient underwent placement of a dual-chamber permanent pacemaker. He has done well since.

ANSWER

This ECG is representative of sinus rhythm with second-degree atrioventricular block with 2:1 conduction; possible left atrial enlargement; and ST-T wave abnormalities suspicious for lateral ischemia.

Sinus rhythm is evidenced by the P waves that march through at a rate that is consistently double that of the QRS rate (82 beats/min). The PR interval in the conducted beats remains constant, with every other P wave blocked from conducting into the ventricles.

The biphasic P wave seen in lead V1 does not meet criteria for left atrial enlargement (P wave in lead I ≥ 110 ms, terminal negative P wave in lead V1 ≥ 1 mm2) but is suspicious. Finally, ST-T wave elevations in leads V2-V4 are suspicious for ventricular septal ischemia.

The patient underwent placement of a dual-chamber permanent pacemaker. He has done well since.

A 74-year-old man has been a resident of a skilled nursing facility for seven years and is well known to the staff. This morning, when the medical assistant performed a routine vital sign check, she noticed the patient’s heart rate was in the 40s. This newly discovered bradycardia, coupled with a four-day history of lethargy, prompts the facility to transfer the patient to your emergency department for evaluation. The patient has a history of hypertension, hypothyroidism, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, GERD, osteoarthritis, and dementia. Surgical history includes appendectomy, cholecystectomy, and left hip replacement. The patient’s multiple chronic conditions are well managed with medications, including a b-blocker, hydrochlorothiazide, levothyroxine, and an inhaler. He receives protein and vitamin supplements daily and is allergic to penicillin. There is a remote history of smoking (from his youth and tour of duty in the Korean War), although the patient says he hasn’t smoked in 30 years. He has “never touched” alcohol, because his father died of complications from alcoholism at age 45. The patient’s wife died of a stroke 11 years ago. His son (and family) visit him twice weekly, bringing chocolate milk and cookies that the patient anxiously awaits. The review of systems is remarkable for a recent cold (resolved), urinary retention, and loose stools. The patient’s appetite is intact. He also exhibits evidence of short-term memory loss; however, this is sporadic. Vital signs on arrival include a blood pressure of 158/88 mm Hg; pulse, 48 beats/min and regular; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min; and temperature, 97.6°F. His weight is 174 lb and his height, 69 in. Pertinent findings on the physical exam include mild cataracts bilaterally, a right carotid bruit, no evidence of elevated neck veins, and late expiratory wheezes in both bases. The cardiac exam is remarkable for a regular rhythm with a heart rate of 42 beats/min. There is a grade II/VI early systolic murmur at the left upper sternal border but no radiation, extra heart sounds, or rubs. The abdomen is soft and nontender, with old surgical scars, and the abdominal aorta is easily palpable. The extremities exhibit full range of motion without peripheral edema, and osteoarthritic changes are evident in both hands. An ECG shows a ventricular rate of 43 beats/min; PR interval, 198 ms; QRS duration, 96 ms; QT/QTc interval, 464/392 ms; P axis, 60°; R axis, 4°; and T axis, 107°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Boy Has Had “Bald Spot” Since Birth

ANSWER

The answer is temporal triangular alopecia (choice “d”), an unusual form of permanent hair loss preferentially affecting the exact area depicted in this case.

Alopecia areata (choice “a”) involves localized hair loss. By contrast, this patient never had hair in this area to lose.

Nevus sebaceous (choice “b”) is a congenital hamartoma that is typically hairless; there are no follicles, and the bumpy, rough surface is composed of sebaceous globules.

Cutis aplasia (choice “c”) manifests with hairless lesions, but there is marked aplasia of the skin as well and no surface adnexae, let alone hairs or follicles.

DISCUSSION

Temporal triangular alopecia (TTA) is an unusual type of alopecia. Of unknown origin, it usually affects this area of the scalp—and usually unilaterally. Approximately one-third of TTA patients are born with the condition; the rest develop it in the first two to three years of life. As in this case, it is often wrongly attributed to the use of forceps but has nothing to do with trauma. One school of thought holds that TTA is probably an inherited condition—but others disagree.

TTA was originally known as congenital triangular alopecia. However, when enough cases had been accumulated to accurately determine the nature of the condition, it was realized that TTA is not always congenital or triangular. Thus, a new name was bestowed.

The hallmark of TTA is the normal number of hair follicles that only grow vellus hairs. The solitary peripheral tuft of terminal dark hairs is typical of TTA and thus a confirmatory finding.

TREATMENT/PROGNOSIS

TTA is by definition permanent. Since there’s no inflammation (a key difference from alopecia areata), steroids are useless. The only successful treatment for TTA, if any is attempted, is hair transplantation. As of this writing, the family is mulling this treatment option.

ANSWER

The answer is temporal triangular alopecia (choice “d”), an unusual form of permanent hair loss preferentially affecting the exact area depicted in this case.

Alopecia areata (choice “a”) involves localized hair loss. By contrast, this patient never had hair in this area to lose.

Nevus sebaceous (choice “b”) is a congenital hamartoma that is typically hairless; there are no follicles, and the bumpy, rough surface is composed of sebaceous globules.

Cutis aplasia (choice “c”) manifests with hairless lesions, but there is marked aplasia of the skin as well and no surface adnexae, let alone hairs or follicles.

DISCUSSION

Temporal triangular alopecia (TTA) is an unusual type of alopecia. Of unknown origin, it usually affects this area of the scalp—and usually unilaterally. Approximately one-third of TTA patients are born with the condition; the rest develop it in the first two to three years of life. As in this case, it is often wrongly attributed to the use of forceps but has nothing to do with trauma. One school of thought holds that TTA is probably an inherited condition—but others disagree.

TTA was originally known as congenital triangular alopecia. However, when enough cases had been accumulated to accurately determine the nature of the condition, it was realized that TTA is not always congenital or triangular. Thus, a new name was bestowed.

The hallmark of TTA is the normal number of hair follicles that only grow vellus hairs. The solitary peripheral tuft of terminal dark hairs is typical of TTA and thus a confirmatory finding.

TREATMENT/PROGNOSIS

TTA is by definition permanent. Since there’s no inflammation (a key difference from alopecia areata), steroids are useless. The only successful treatment for TTA, if any is attempted, is hair transplantation. As of this writing, the family is mulling this treatment option.

ANSWER

The answer is temporal triangular alopecia (choice “d”), an unusual form of permanent hair loss preferentially affecting the exact area depicted in this case.

Alopecia areata (choice “a”) involves localized hair loss. By contrast, this patient never had hair in this area to lose.

Nevus sebaceous (choice “b”) is a congenital hamartoma that is typically hairless; there are no follicles, and the bumpy, rough surface is composed of sebaceous globules.

Cutis aplasia (choice “c”) manifests with hairless lesions, but there is marked aplasia of the skin as well and no surface adnexae, let alone hairs or follicles.

DISCUSSION

Temporal triangular alopecia (TTA) is an unusual type of alopecia. Of unknown origin, it usually affects this area of the scalp—and usually unilaterally. Approximately one-third of TTA patients are born with the condition; the rest develop it in the first two to three years of life. As in this case, it is often wrongly attributed to the use of forceps but has nothing to do with trauma. One school of thought holds that TTA is probably an inherited condition—but others disagree.

TTA was originally known as congenital triangular alopecia. However, when enough cases had been accumulated to accurately determine the nature of the condition, it was realized that TTA is not always congenital or triangular. Thus, a new name was bestowed.

The hallmark of TTA is the normal number of hair follicles that only grow vellus hairs. The solitary peripheral tuft of terminal dark hairs is typical of TTA and thus a confirmatory finding.

TREATMENT/PROGNOSIS

TTA is by definition permanent. Since there’s no inflammation (a key difference from alopecia areata), steroids are useless. The only successful treatment for TTA, if any is attempted, is hair transplantation. As of this writing, the family is mulling this treatment option.

Since birth, this 8-year-old boy has had a “bald spot” on his scalp. The pediatrician who attended the birth suggested trauma as the cause, since forceps were used to facilitate delivery. But the problem has failed to resolve, leaving the boy an object of ridicule among his classmates. According to the patient’s parents, there has never been any broken skin or hair growth in the area. There is no family history of similar problems, and the child’s health history is unremarkable. The child’s current pediatrician, who made the referral to dermatology, suggested the lesion might be a form of nevus sebaceous. The affected site is roughly triangular, measures about 3 cm on each side, and is located just inside the temporal scalp. The hair loss in this sharply circumscribed area is almost complete, with a lone tuft of darker terminal hairs on the inferior aspect of the site. No redness or epidermal disturbance (eg, scaling) is noted. Dermatoscopic examination (with 10x magnification) reveals a normal number of follicles and hairs. The latter are vellus hairs, except for the aforementioned solitary tuft. The rest of the scalp, including the same location on the opposite side, is free of any significant changes.

Nanoparticles destroy blood clots faster

iron oxide (red), albumin

(gray), and tPA (green)

Image courtesy of

Paolo Decuzzi lab

Results of preclinical experiments suggest that nanoparticles made of iron oxide and coated with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and albumin can directly target blood clots and destroy them faster than free tPA injected into the bloodstream.

Researchers found these nanoparticles could destroy blood clots 100 times faster than free tPA. And when the nanoparticles were heated using alternating magnetic fields, they destroyed clots 1000 times faster than free tPA.

Paolo Decuzzi, PhD, of Fondazione Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia in Genoa, Italy, and his colleagues described these experiments in Advanced Functional Materials.

The researchers created iron oxide nanoparticles and coated them with tPA. Typically, a small volume of concentrated tPA is injected into a patient’s blood upstream of a confirmed or suspected clot. From there, some of the tPA reaches the clot, but much of it may travel past or around the clot, potentially ending up anywhere in the circulatory system.

“We have designed the nanoparticles so that they trap themselves at the site of the clot, which means they can quickly deliver a burst of the commonly used, clot-busting drug tPA where it is most needed,” Dr Decuzzi said.

He and his colleagues used iron oxide as the nanoparticles’ core so the particles can be used for magnetic resonance imaging, remote guidance with external magnetic fields, and for further accelerating clot dissolution with localized magnetic heating.

“We think it is possible to use a static magnetic field first to help guide the nanoparticles to the clot, then alternate the orientation of the field to increase the nanoparticles’ efficiency in dissolving clots,” Dr Decuzzi said.

The team also coated the nanoparticles in albumin, which provides a sort of camouflage. It gives the nanoparticles time to reach a clot before the immune system recognizes the particles as invaders and attacks them.

“The nanoparticle protects the drug from the body’s defenses, giving the tPA time to work,” said Alan Lumsden, MD, of Houston Methodist Hospital in Texas.

“But it also allows us to use less tPA, which could make hemorrhage less likely. We are excited to see if the technique works as phenomenally well for our patients as what we saw in these experiments.”

The researchers tested the nanoparticles using human tissue cultures to see where the tPA landed and how long it took to destroy fibrin-rich clots. They also introduced blood clots in mice, injected the nanoparticles into the bloodstream, and used optical microscopy to follow the dissolution of the clots.

The nanoparticles destroyed clots about 100 times faster than free tPA.

Although free tPA is usually injected at room temperature, a number of studies have suggested the drug is most effective at higher temperatures (40° C or about 104° F). The same seems to be true for tPA delivered via the iron oxide nanoparticles.

By exposing the nanoparticles to external, alternating magnetic fields, the researchers created friction and heat. Warmer tPA (42° C or about 108° F) was released faster and increased the rate of clot dissolution 10-fold (to 1000 times greater than free tPA).

Dr Decuzzi said the next steps with this research will be testing the nanoparticles’ safety and effectiveness in other animal models, with the ultimate goal of clinical trials. He said his group will continue to examine the feasibility of using magnetic fields to guide and heat the nanoparticles.

“We are optimistic because the [US Food and Drug Administration] has already approved the use of iron oxide as a contrast agent in MRIs,” Dr Decuzzi said. “And we do not anticipate needing to use as much of the iron oxide at concentrations higher than what’s already been approved. The other chemical aspects of the nanoparticles are natural substances you already find in the bloodstream.” ![]()

iron oxide (red), albumin

(gray), and tPA (green)

Image courtesy of

Paolo Decuzzi lab

Results of preclinical experiments suggest that nanoparticles made of iron oxide and coated with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and albumin can directly target blood clots and destroy them faster than free tPA injected into the bloodstream.

Researchers found these nanoparticles could destroy blood clots 100 times faster than free tPA. And when the nanoparticles were heated using alternating magnetic fields, they destroyed clots 1000 times faster than free tPA.

Paolo Decuzzi, PhD, of Fondazione Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia in Genoa, Italy, and his colleagues described these experiments in Advanced Functional Materials.

The researchers created iron oxide nanoparticles and coated them with tPA. Typically, a small volume of concentrated tPA is injected into a patient’s blood upstream of a confirmed or suspected clot. From there, some of the tPA reaches the clot, but much of it may travel past or around the clot, potentially ending up anywhere in the circulatory system.

“We have designed the nanoparticles so that they trap themselves at the site of the clot, which means they can quickly deliver a burst of the commonly used, clot-busting drug tPA where it is most needed,” Dr Decuzzi said.

He and his colleagues used iron oxide as the nanoparticles’ core so the particles can be used for magnetic resonance imaging, remote guidance with external magnetic fields, and for further accelerating clot dissolution with localized magnetic heating.

“We think it is possible to use a static magnetic field first to help guide the nanoparticles to the clot, then alternate the orientation of the field to increase the nanoparticles’ efficiency in dissolving clots,” Dr Decuzzi said.

The team also coated the nanoparticles in albumin, which provides a sort of camouflage. It gives the nanoparticles time to reach a clot before the immune system recognizes the particles as invaders and attacks them.

“The nanoparticle protects the drug from the body’s defenses, giving the tPA time to work,” said Alan Lumsden, MD, of Houston Methodist Hospital in Texas.

“But it also allows us to use less tPA, which could make hemorrhage less likely. We are excited to see if the technique works as phenomenally well for our patients as what we saw in these experiments.”

The researchers tested the nanoparticles using human tissue cultures to see where the tPA landed and how long it took to destroy fibrin-rich clots. They also introduced blood clots in mice, injected the nanoparticles into the bloodstream, and used optical microscopy to follow the dissolution of the clots.

The nanoparticles destroyed clots about 100 times faster than free tPA.

Although free tPA is usually injected at room temperature, a number of studies have suggested the drug is most effective at higher temperatures (40° C or about 104° F). The same seems to be true for tPA delivered via the iron oxide nanoparticles.

By exposing the nanoparticles to external, alternating magnetic fields, the researchers created friction and heat. Warmer tPA (42° C or about 108° F) was released faster and increased the rate of clot dissolution 10-fold (to 1000 times greater than free tPA).

Dr Decuzzi said the next steps with this research will be testing the nanoparticles’ safety and effectiveness in other animal models, with the ultimate goal of clinical trials. He said his group will continue to examine the feasibility of using magnetic fields to guide and heat the nanoparticles.

“We are optimistic because the [US Food and Drug Administration] has already approved the use of iron oxide as a contrast agent in MRIs,” Dr Decuzzi said. “And we do not anticipate needing to use as much of the iron oxide at concentrations higher than what’s already been approved. The other chemical aspects of the nanoparticles are natural substances you already find in the bloodstream.” ![]()

iron oxide (red), albumin

(gray), and tPA (green)

Image courtesy of

Paolo Decuzzi lab

Results of preclinical experiments suggest that nanoparticles made of iron oxide and coated with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and albumin can directly target blood clots and destroy them faster than free tPA injected into the bloodstream.

Researchers found these nanoparticles could destroy blood clots 100 times faster than free tPA. And when the nanoparticles were heated using alternating magnetic fields, they destroyed clots 1000 times faster than free tPA.

Paolo Decuzzi, PhD, of Fondazione Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia in Genoa, Italy, and his colleagues described these experiments in Advanced Functional Materials.

The researchers created iron oxide nanoparticles and coated them with tPA. Typically, a small volume of concentrated tPA is injected into a patient’s blood upstream of a confirmed or suspected clot. From there, some of the tPA reaches the clot, but much of it may travel past or around the clot, potentially ending up anywhere in the circulatory system.

“We have designed the nanoparticles so that they trap themselves at the site of the clot, which means they can quickly deliver a burst of the commonly used, clot-busting drug tPA where it is most needed,” Dr Decuzzi said.

He and his colleagues used iron oxide as the nanoparticles’ core so the particles can be used for magnetic resonance imaging, remote guidance with external magnetic fields, and for further accelerating clot dissolution with localized magnetic heating.

“We think it is possible to use a static magnetic field first to help guide the nanoparticles to the clot, then alternate the orientation of the field to increase the nanoparticles’ efficiency in dissolving clots,” Dr Decuzzi said.

The team also coated the nanoparticles in albumin, which provides a sort of camouflage. It gives the nanoparticles time to reach a clot before the immune system recognizes the particles as invaders and attacks them.

“The nanoparticle protects the drug from the body’s defenses, giving the tPA time to work,” said Alan Lumsden, MD, of Houston Methodist Hospital in Texas.

“But it also allows us to use less tPA, which could make hemorrhage less likely. We are excited to see if the technique works as phenomenally well for our patients as what we saw in these experiments.”

The researchers tested the nanoparticles using human tissue cultures to see where the tPA landed and how long it took to destroy fibrin-rich clots. They also introduced blood clots in mice, injected the nanoparticles into the bloodstream, and used optical microscopy to follow the dissolution of the clots.

The nanoparticles destroyed clots about 100 times faster than free tPA.

Although free tPA is usually injected at room temperature, a number of studies have suggested the drug is most effective at higher temperatures (40° C or about 104° F). The same seems to be true for tPA delivered via the iron oxide nanoparticles.

By exposing the nanoparticles to external, alternating magnetic fields, the researchers created friction and heat. Warmer tPA (42° C or about 108° F) was released faster and increased the rate of clot dissolution 10-fold (to 1000 times greater than free tPA).

Dr Decuzzi said the next steps with this research will be testing the nanoparticles’ safety and effectiveness in other animal models, with the ultimate goal of clinical trials. He said his group will continue to examine the feasibility of using magnetic fields to guide and heat the nanoparticles.

“We are optimistic because the [US Food and Drug Administration] has already approved the use of iron oxide as a contrast agent in MRIs,” Dr Decuzzi said. “And we do not anticipate needing to use as much of the iron oxide at concentrations higher than what’s already been approved. The other chemical aspects of the nanoparticles are natural substances you already find in the bloodstream.” ![]()

Older age doesn’t decrease HRQOL among PBSC donors

Photo courtesy of Canterbury

District Health Board

SAN DIEGO—New research indicates that older stem cell donors have somewhat poorer overall health before they donate, but their health-related quality of life (HRQOL) post-donation is similar to that of younger donors.

In fact, the older donors included in this study actually fared better than their younger counterparts in some respects.

Galen E. Switzer, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania, presented these results at the 2015 BMT Tandem Meetings (abstract 27*).

“[Older donors] may be at greater physical and psychological risk because of their age and comorbid conditions,” Dr Switzer noted. “So it’s critical for us to understand the health-related quality of life experiences of these donors.”

With that in mind, he and his colleagues evaluated 163 subjects who donated peripheral blood stem cells (PBSCs) to relatives in need of a transplant. The team compared donors over the age of 60 (n=104, median age 66 years) to those aged 18 to 60 (n=59, median age 41 years).

The investigators collected data via structured telephone interviews 2 weeks before PBSC donation and at 4 weeks and 1 year post-donation.

A comparison of sociodemographic factors revealed that older PBSC donors were significantly less likely to be employed (P<0.001) but more likely be white (P=0.009), be married (P=0.044), and have children (P<0.001).

Pre- and post-donation HRQOL

Pre-donation, older donors had significantly poorer physical health (P=0.001) and better mental health (P=0.036) than younger donors. But there was no significant difference between the age groups with regard to the incidence of depression or anxiety.

Similarly, there were no significant differences with regard to ambivalence, satisfaction, or medical concerns about donation. However, older donors were more likely to consult their physician about donation (P=0.049), and they had fewer work/family concerns (P=0.049) than younger donors.

At 4 weeks post-donation, there were no significant differences between the age groups with regard to general physical health, mental health, or any of 12 donation-related symptoms. However, younger donors were significantly more likely to report that donation was painful (P=0.025).

Older donors were significantly less likely to report work/family concerns, such as missing work, family worry, or worry about what others would think (P=0.001). They were less likely to have other donation-related concerns as well, such as worrying about who would pay for the procedure (P=0.034). And they were less likely to say they would feel responsible if the transplant did not have a favorable outcome (P=0.022).

At 1 year post-donation, there were no significant differences between the age groups with regard to overall physical and mental health, depression, ambivalence, satisfaction, 11 of 12 donation side effects, physical difficulty, psychological difficulty, or “other concerns.”

However, older donors reported significantly less anxiety, fewer medical concerns, and fewer work/family concerns (P<0.05 for all). They were also less likely to feel responsible for transplant outcomes and less likely to have problems sleeping, which was 1 of the 12 donation side effects (P<0.05 for both).

“So the overall conclusion, I think, is really reassuring,” Dr Switzer said. “Despite having somewhat poorer overall general physical health at pre-donation, older donors experience similar—and, in some domains, better—donation-related health-related quality of life than younger donors. So they seem to be doing at least as well and, in some domains, better than their younger counterparts.” ![]()

*Information in the abstract differs from that presented at the meeting.

Photo courtesy of Canterbury

District Health Board

SAN DIEGO—New research indicates that older stem cell donors have somewhat poorer overall health before they donate, but their health-related quality of life (HRQOL) post-donation is similar to that of younger donors.

In fact, the older donors included in this study actually fared better than their younger counterparts in some respects.

Galen E. Switzer, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania, presented these results at the 2015 BMT Tandem Meetings (abstract 27*).

“[Older donors] may be at greater physical and psychological risk because of their age and comorbid conditions,” Dr Switzer noted. “So it’s critical for us to understand the health-related quality of life experiences of these donors.”

With that in mind, he and his colleagues evaluated 163 subjects who donated peripheral blood stem cells (PBSCs) to relatives in need of a transplant. The team compared donors over the age of 60 (n=104, median age 66 years) to those aged 18 to 60 (n=59, median age 41 years).

The investigators collected data via structured telephone interviews 2 weeks before PBSC donation and at 4 weeks and 1 year post-donation.

A comparison of sociodemographic factors revealed that older PBSC donors were significantly less likely to be employed (P<0.001) but more likely be white (P=0.009), be married (P=0.044), and have children (P<0.001).

Pre- and post-donation HRQOL

Pre-donation, older donors had significantly poorer physical health (P=0.001) and better mental health (P=0.036) than younger donors. But there was no significant difference between the age groups with regard to the incidence of depression or anxiety.

Similarly, there were no significant differences with regard to ambivalence, satisfaction, or medical concerns about donation. However, older donors were more likely to consult their physician about donation (P=0.049), and they had fewer work/family concerns (P=0.049) than younger donors.

At 4 weeks post-donation, there were no significant differences between the age groups with regard to general physical health, mental health, or any of 12 donation-related symptoms. However, younger donors were significantly more likely to report that donation was painful (P=0.025).

Older donors were significantly less likely to report work/family concerns, such as missing work, family worry, or worry about what others would think (P=0.001). They were less likely to have other donation-related concerns as well, such as worrying about who would pay for the procedure (P=0.034). And they were less likely to say they would feel responsible if the transplant did not have a favorable outcome (P=0.022).

At 1 year post-donation, there were no significant differences between the age groups with regard to overall physical and mental health, depression, ambivalence, satisfaction, 11 of 12 donation side effects, physical difficulty, psychological difficulty, or “other concerns.”

However, older donors reported significantly less anxiety, fewer medical concerns, and fewer work/family concerns (P<0.05 for all). They were also less likely to feel responsible for transplant outcomes and less likely to have problems sleeping, which was 1 of the 12 donation side effects (P<0.05 for both).

“So the overall conclusion, I think, is really reassuring,” Dr Switzer said. “Despite having somewhat poorer overall general physical health at pre-donation, older donors experience similar—and, in some domains, better—donation-related health-related quality of life than younger donors. So they seem to be doing at least as well and, in some domains, better than their younger counterparts.” ![]()

*Information in the abstract differs from that presented at the meeting.

Photo courtesy of Canterbury

District Health Board

SAN DIEGO—New research indicates that older stem cell donors have somewhat poorer overall health before they donate, but their health-related quality of life (HRQOL) post-donation is similar to that of younger donors.

In fact, the older donors included in this study actually fared better than their younger counterparts in some respects.

Galen E. Switzer, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania, presented these results at the 2015 BMT Tandem Meetings (abstract 27*).

“[Older donors] may be at greater physical and psychological risk because of their age and comorbid conditions,” Dr Switzer noted. “So it’s critical for us to understand the health-related quality of life experiences of these donors.”

With that in mind, he and his colleagues evaluated 163 subjects who donated peripheral blood stem cells (PBSCs) to relatives in need of a transplant. The team compared donors over the age of 60 (n=104, median age 66 years) to those aged 18 to 60 (n=59, median age 41 years).

The investigators collected data via structured telephone interviews 2 weeks before PBSC donation and at 4 weeks and 1 year post-donation.

A comparison of sociodemographic factors revealed that older PBSC donors were significantly less likely to be employed (P<0.001) but more likely be white (P=0.009), be married (P=0.044), and have children (P<0.001).

Pre- and post-donation HRQOL

Pre-donation, older donors had significantly poorer physical health (P=0.001) and better mental health (P=0.036) than younger donors. But there was no significant difference between the age groups with regard to the incidence of depression or anxiety.

Similarly, there were no significant differences with regard to ambivalence, satisfaction, or medical concerns about donation. However, older donors were more likely to consult their physician about donation (P=0.049), and they had fewer work/family concerns (P=0.049) than younger donors.

At 4 weeks post-donation, there were no significant differences between the age groups with regard to general physical health, mental health, or any of 12 donation-related symptoms. However, younger donors were significantly more likely to report that donation was painful (P=0.025).

Older donors were significantly less likely to report work/family concerns, such as missing work, family worry, or worry about what others would think (P=0.001). They were less likely to have other donation-related concerns as well, such as worrying about who would pay for the procedure (P=0.034). And they were less likely to say they would feel responsible if the transplant did not have a favorable outcome (P=0.022).

At 1 year post-donation, there were no significant differences between the age groups with regard to overall physical and mental health, depression, ambivalence, satisfaction, 11 of 12 donation side effects, physical difficulty, psychological difficulty, or “other concerns.”

However, older donors reported significantly less anxiety, fewer medical concerns, and fewer work/family concerns (P<0.05 for all). They were also less likely to feel responsible for transplant outcomes and less likely to have problems sleeping, which was 1 of the 12 donation side effects (P<0.05 for both).

“So the overall conclusion, I think, is really reassuring,” Dr Switzer said. “Despite having somewhat poorer overall general physical health at pre-donation, older donors experience similar—and, in some domains, better—donation-related health-related quality of life than younger donors. So they seem to be doing at least as well and, in some domains, better than their younger counterparts.” ![]()

*Information in the abstract differs from that presented at the meeting.

Treatment likely doesn’t increase risk of cancer

Pimecrolimus, a topical cream used to treat eczema in children, does not appear to confer an increased risk of hematologic and other cancers, according to researchers.

In 2001 and 2002, respectively, the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency approved pimecrolimus to treat eczema in children 2 years of age and older.

The product was approved with a black box warning describing a potential risk of malignancy.

To investigate this risk, and as part of the post-marketing commitments for the approval of pimecrolimus, researchers initiated the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER) study in 2004.

David J. Margolis, MD, PhD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and his colleagues analyzed data from this study, comparing the incidence of malignancy among PEER subjects to expected cancer rates from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results program.

The team reported their findings in JAMA Dermatology.

The PEER study enrolled 7457 children (26,792 person-years) who used an average of 793 g of pimecrolimus while on study.

As of May 2014, 5 malignancies were reported in these children: 2 leukemias, 2 lymphomas, and 1 osteosarcoma.

No skin cancers were reported, and none of the findings regarding cancer incidence were statistically significant.

The researchers therefore said it’s unlikely that topical pimecrolimus, as it was used in the PEER study, is associated with an increased risk of malignancy.

This research and the PEER study were both funded by Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, makers of pimecrolimus.

In a related editorial in JAMA Dermatology, Jon M. Hanifin, MD, of Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, said he hopes this research will improve the management of eczema by countering any concerns about pimecrolimus use that were raised by the treatment’s black box warning.

“The positive and optimistic report of pimecrolimus post-marketing surveillance by Margolis et al should help reduce the physician and pharmacist concerns that have restricted the use of these effective topical alternatives to corticosteroids,” Dr Hanifin wrote. “The interim results should help bring relief to a larger segment of the many young individuals with [eczema].” ![]()

Pimecrolimus, a topical cream used to treat eczema in children, does not appear to confer an increased risk of hematologic and other cancers, according to researchers.

In 2001 and 2002, respectively, the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency approved pimecrolimus to treat eczema in children 2 years of age and older.

The product was approved with a black box warning describing a potential risk of malignancy.

To investigate this risk, and as part of the post-marketing commitments for the approval of pimecrolimus, researchers initiated the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER) study in 2004.

David J. Margolis, MD, PhD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and his colleagues analyzed data from this study, comparing the incidence of malignancy among PEER subjects to expected cancer rates from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results program.

The team reported their findings in JAMA Dermatology.

The PEER study enrolled 7457 children (26,792 person-years) who used an average of 793 g of pimecrolimus while on study.

As of May 2014, 5 malignancies were reported in these children: 2 leukemias, 2 lymphomas, and 1 osteosarcoma.

No skin cancers were reported, and none of the findings regarding cancer incidence were statistically significant.

The researchers therefore said it’s unlikely that topical pimecrolimus, as it was used in the PEER study, is associated with an increased risk of malignancy.

This research and the PEER study were both funded by Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, makers of pimecrolimus.

In a related editorial in JAMA Dermatology, Jon M. Hanifin, MD, of Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, said he hopes this research will improve the management of eczema by countering any concerns about pimecrolimus use that were raised by the treatment’s black box warning.

“The positive and optimistic report of pimecrolimus post-marketing surveillance by Margolis et al should help reduce the physician and pharmacist concerns that have restricted the use of these effective topical alternatives to corticosteroids,” Dr Hanifin wrote. “The interim results should help bring relief to a larger segment of the many young individuals with [eczema].” ![]()

Pimecrolimus, a topical cream used to treat eczema in children, does not appear to confer an increased risk of hematologic and other cancers, according to researchers.

In 2001 and 2002, respectively, the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency approved pimecrolimus to treat eczema in children 2 years of age and older.

The product was approved with a black box warning describing a potential risk of malignancy.

To investigate this risk, and as part of the post-marketing commitments for the approval of pimecrolimus, researchers initiated the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER) study in 2004.

David J. Margolis, MD, PhD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and his colleagues analyzed data from this study, comparing the incidence of malignancy among PEER subjects to expected cancer rates from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results program.

The team reported their findings in JAMA Dermatology.

The PEER study enrolled 7457 children (26,792 person-years) who used an average of 793 g of pimecrolimus while on study.