User login

Compliance with HAI policies varies across US

Credit: Rhoda Baer

An analysis of US intensive care units (ICUs) shows uneven compliance with policies for preventing healthcare-associated infections (HAIs).

The survey of more than 1500 ICUs showed that a majority of hospitals had prevention policies in place for central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs). But adherence to these policies ranged from 37% to 71%.

And both the prevalence of and adherence to policies was even lower for 2 other common HAIs.

Patricia W. Stone PhD, of the Columbia University School of Nursing in New York, and her colleagues shared these results in the American Journal of Infection Control.

The researchers surveyed 1534 ICUs at 975 hospitals. They assessed the implementation of 16 prescribed infection-prevention measures, as well as clinician adherence to these policies for the prevention of CLABSIs, ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), and catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs).

The survey revealed that most hospitals had policies in place to prevent CLABSIs. Prevalence ranged from 87% for checking lines daily to 97% for applying chlorhexidine at catheter insertion sites.

This was followed by VAP prevention policies, which ranged from 69% for providing chlorhexidine mouth care to 91% for raising the head of the bed.

And finally, the presence of CAUTI policies ranged from 27% for nurse-initiated urinary catheterization to 68% for portable bladder ultrasounds. The researchers said it was surprising that evidence-based practices related to CAUTI prevention have not been well implemented, as CAUTIs are the most frequent HAI.

The survey also showed that many of the ICUs fell short in adhering to infection-prevention policies. Adherence ranged from 37% to 71% for CLABSIs, 45% to 55% for VAP, and 6% to 27% for CAUTIs.

The researchers analyzed other characteristics of the hospitals and their infection-prevention programs as well. The hospitals had an average of 52,578 annual patient-days, with 11,377 admissions, 32 ICU beds, 12 specialty beds, and 182 other beds.

Roughly a third of the departments (34%) had an electronic surveillance system, and most were commercially developed (86%).

Eighty-four percent of the institutions used hospitalists, 49% used intensivists, and 50% had a physician hospital epidemiologist. The average number of infection preventionists per 100 beds was 1.2, but certification of these staff members varied.

Having gained new insight into infection-prevention policies at hospitals across the US, the researchers are now planning to analyze the associations between HAI rates and characteristics of infection-prevention programs. They also plan to look at the relationship between HAI rates and adherence to evidence-based policies. ![]()

Credit: Rhoda Baer

An analysis of US intensive care units (ICUs) shows uneven compliance with policies for preventing healthcare-associated infections (HAIs).

The survey of more than 1500 ICUs showed that a majority of hospitals had prevention policies in place for central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs). But adherence to these policies ranged from 37% to 71%.

And both the prevalence of and adherence to policies was even lower for 2 other common HAIs.

Patricia W. Stone PhD, of the Columbia University School of Nursing in New York, and her colleagues shared these results in the American Journal of Infection Control.

The researchers surveyed 1534 ICUs at 975 hospitals. They assessed the implementation of 16 prescribed infection-prevention measures, as well as clinician adherence to these policies for the prevention of CLABSIs, ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), and catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs).

The survey revealed that most hospitals had policies in place to prevent CLABSIs. Prevalence ranged from 87% for checking lines daily to 97% for applying chlorhexidine at catheter insertion sites.

This was followed by VAP prevention policies, which ranged from 69% for providing chlorhexidine mouth care to 91% for raising the head of the bed.

And finally, the presence of CAUTI policies ranged from 27% for nurse-initiated urinary catheterization to 68% for portable bladder ultrasounds. The researchers said it was surprising that evidence-based practices related to CAUTI prevention have not been well implemented, as CAUTIs are the most frequent HAI.

The survey also showed that many of the ICUs fell short in adhering to infection-prevention policies. Adherence ranged from 37% to 71% for CLABSIs, 45% to 55% for VAP, and 6% to 27% for CAUTIs.

The researchers analyzed other characteristics of the hospitals and their infection-prevention programs as well. The hospitals had an average of 52,578 annual patient-days, with 11,377 admissions, 32 ICU beds, 12 specialty beds, and 182 other beds.

Roughly a third of the departments (34%) had an electronic surveillance system, and most were commercially developed (86%).

Eighty-four percent of the institutions used hospitalists, 49% used intensivists, and 50% had a physician hospital epidemiologist. The average number of infection preventionists per 100 beds was 1.2, but certification of these staff members varied.

Having gained new insight into infection-prevention policies at hospitals across the US, the researchers are now planning to analyze the associations between HAI rates and characteristics of infection-prevention programs. They also plan to look at the relationship between HAI rates and adherence to evidence-based policies. ![]()

Credit: Rhoda Baer

An analysis of US intensive care units (ICUs) shows uneven compliance with policies for preventing healthcare-associated infections (HAIs).

The survey of more than 1500 ICUs showed that a majority of hospitals had prevention policies in place for central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs). But adherence to these policies ranged from 37% to 71%.

And both the prevalence of and adherence to policies was even lower for 2 other common HAIs.

Patricia W. Stone PhD, of the Columbia University School of Nursing in New York, and her colleagues shared these results in the American Journal of Infection Control.

The researchers surveyed 1534 ICUs at 975 hospitals. They assessed the implementation of 16 prescribed infection-prevention measures, as well as clinician adherence to these policies for the prevention of CLABSIs, ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), and catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs).

The survey revealed that most hospitals had policies in place to prevent CLABSIs. Prevalence ranged from 87% for checking lines daily to 97% for applying chlorhexidine at catheter insertion sites.

This was followed by VAP prevention policies, which ranged from 69% for providing chlorhexidine mouth care to 91% for raising the head of the bed.

And finally, the presence of CAUTI policies ranged from 27% for nurse-initiated urinary catheterization to 68% for portable bladder ultrasounds. The researchers said it was surprising that evidence-based practices related to CAUTI prevention have not been well implemented, as CAUTIs are the most frequent HAI.

The survey also showed that many of the ICUs fell short in adhering to infection-prevention policies. Adherence ranged from 37% to 71% for CLABSIs, 45% to 55% for VAP, and 6% to 27% for CAUTIs.

The researchers analyzed other characteristics of the hospitals and their infection-prevention programs as well. The hospitals had an average of 52,578 annual patient-days, with 11,377 admissions, 32 ICU beds, 12 specialty beds, and 182 other beds.

Roughly a third of the departments (34%) had an electronic surveillance system, and most were commercially developed (86%).

Eighty-four percent of the institutions used hospitalists, 49% used intensivists, and 50% had a physician hospital epidemiologist. The average number of infection preventionists per 100 beds was 1.2, but certification of these staff members varied.

Having gained new insight into infection-prevention policies at hospitals across the US, the researchers are now planning to analyze the associations between HAI rates and characteristics of infection-prevention programs. They also plan to look at the relationship between HAI rates and adherence to evidence-based policies. ![]()

von Willebrand Disease: Approach to Diagnosis and Management

von Willebrand disease (VWD) is an inherited bleeding disorder caused by deficient or defective plasma von Willebrand factor (VWF). VWF is an adhesive multimeric plasma glycoprotein that performs 2 major functions in hemostasis: it mediates platelet adhesion to injured subendothelium via glycoprotein 1bα (GPIbα), and it binds and stabilizes factor VIII (FVIII) in circulation, protecting it from proteolytic degradation by enzymes. The current VWD classification recognizes 3 types. In order to understand the role of the numerous laboratory investigations as well as the classification of VWD, it is important to review the structure and function of the VWF subunit. Bleeding symptoms reflect the defect in primary hemostasis: mucocutaneous bleeding and excessive bleeding after surgery or trauma. Treatment focuses on increasing VWF levels with desmopressin (1-deamino-8-D-arginine vasopressin, DDAVP) or clotting factor concentrates containing both VWF and FVIII (VWF/FVIII concentrate). Nonspecific treatment options include antifibrinolytic agents (tranexamic acid) and hormone therapy (oral contraceptive pill).

To read the full article in PDF:

von Willebrand disease (VWD) is an inherited bleeding disorder caused by deficient or defective plasma von Willebrand factor (VWF). VWF is an adhesive multimeric plasma glycoprotein that performs 2 major functions in hemostasis: it mediates platelet adhesion to injured subendothelium via glycoprotein 1bα (GPIbα), and it binds and stabilizes factor VIII (FVIII) in circulation, protecting it from proteolytic degradation by enzymes. The current VWD classification recognizes 3 types. In order to understand the role of the numerous laboratory investigations as well as the classification of VWD, it is important to review the structure and function of the VWF subunit. Bleeding symptoms reflect the defect in primary hemostasis: mucocutaneous bleeding and excessive bleeding after surgery or trauma. Treatment focuses on increasing VWF levels with desmopressin (1-deamino-8-D-arginine vasopressin, DDAVP) or clotting factor concentrates containing both VWF and FVIII (VWF/FVIII concentrate). Nonspecific treatment options include antifibrinolytic agents (tranexamic acid) and hormone therapy (oral contraceptive pill).

To read the full article in PDF:

von Willebrand disease (VWD) is an inherited bleeding disorder caused by deficient or defective plasma von Willebrand factor (VWF). VWF is an adhesive multimeric plasma glycoprotein that performs 2 major functions in hemostasis: it mediates platelet adhesion to injured subendothelium via glycoprotein 1bα (GPIbα), and it binds and stabilizes factor VIII (FVIII) in circulation, protecting it from proteolytic degradation by enzymes. The current VWD classification recognizes 3 types. In order to understand the role of the numerous laboratory investigations as well as the classification of VWD, it is important to review the structure and function of the VWF subunit. Bleeding symptoms reflect the defect in primary hemostasis: mucocutaneous bleeding and excessive bleeding after surgery or trauma. Treatment focuses on increasing VWF levels with desmopressin (1-deamino-8-D-arginine vasopressin, DDAVP) or clotting factor concentrates containing both VWF and FVIII (VWF/FVIII concentrate). Nonspecific treatment options include antifibrinolytic agents (tranexamic acid) and hormone therapy (oral contraceptive pill).

To read the full article in PDF:

Anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy in acute coronary syndromes

Antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs are a cornerstone of the medical treatment of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), reducing the rates of both morbidity and death.1–4 However, reductions in ischemic events with these drugs have uniformly been accompanied by increases in bleeding complications, which reduce the net benefit.5 Thus, clinical research has been exploring ways to maximize the benefit while minimizing the risk.

Here, we review the guidelines and evidence supporting the use of antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs in ACS.

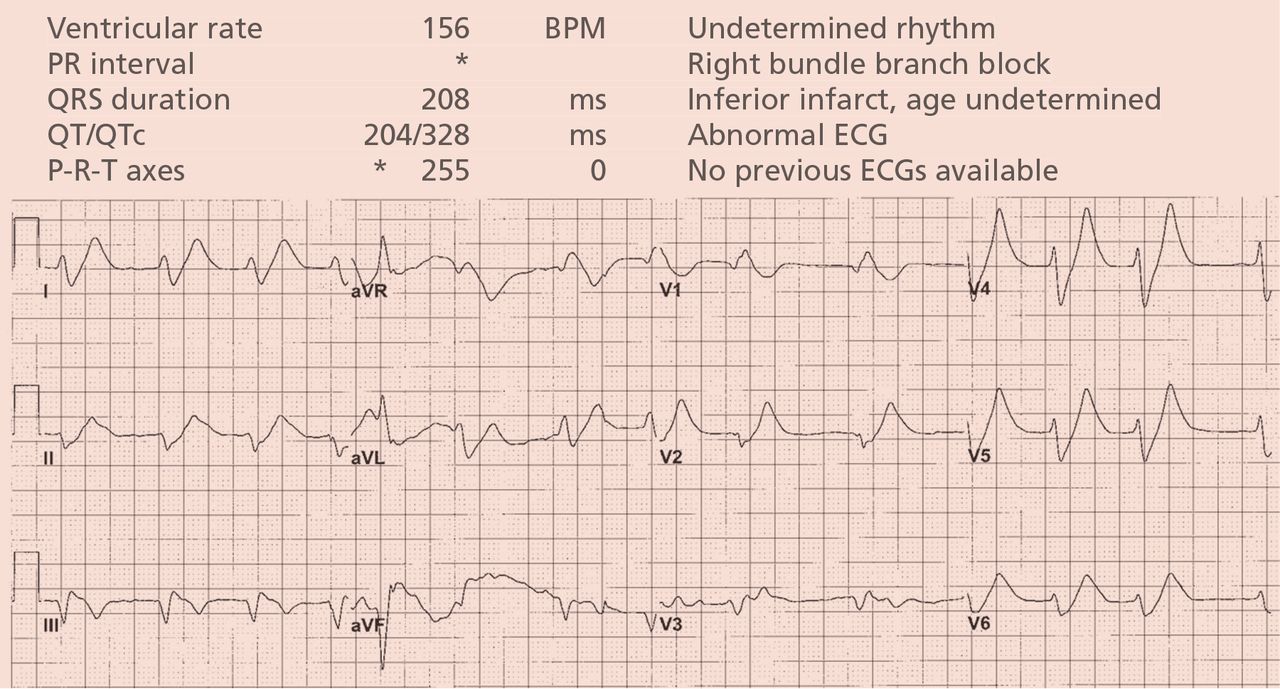

ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROMES WITH OR WITHOUT ST ELEVATION

A key distinction when treating ACS is whether the electrocardiogram shows ST-segment elevation. In cases of non-ST-elevation ACS (ie, unstable angina or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction), a second key question is whether the initial strategy will be invasive (with angiography performed urgently) or conservative (with angiography performed later). In ST-elevation myocardial infarction, another distinction is how perfusion is to be restored, ie, with primary percutaneous coronary intervention or with thrombolysis. All these questions affect the choice of antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy.

Figure 1 and Figure 2 summarize the guidelines of the American College of Cardiology Foundation and American Heart Association.1,2,6,7

ANTIPLATELET THERAPY

Aspirin for all

Aspirin irreversibly acetylates the enzyme cyclooxygenase-1, blocking intraplatelet formation of thromboxane A2 (Figure 3), a potent platelet aggregator and endothelial vasoconstrictor. Large clinical trials have confirmed that aspirin reduces morbidity and mortality rates by as much as 50% in patients with ACS.8

The ISIS-2 trial9 found that giving aspirin early in the emergency department significantly reduced the mortality rate.

The Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration,10 in a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing different doses of aspirin in high-risk ACS patients, found no greater benefit for doses of aspirin higher than 162 mg per day when used long-term.

How to use. During an ACS, the patient should receive one dose of aspirin 325 mg (the standard high-dose pill in the United States). This dose should be chewed, as buccal absorption results in more rapid systemic effects.11

Thereafter, the patient should take 81 mg per day, continued indefinitely. The 81-mg dose also applies to patients who undergo a percutaneous coronary intervention with a drug-eluting stent.7 Previous recommendations called for higher doses, but studies have shown that higher doses pose a higher risk of bleeding without additional clinical benefit. The use of enteric-coated aspirin does not reduce this risk,12 and its delayed release may in fact cause aspirin “pseudoresistance.”13

The concurrent use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should be avoided, as NSAIDs reversibly bind to platelets, thus preventing aspirin from binding.14 As aspirin washes out of the body, NSAIDs may then become unbound from platelets, leaving platelets activated.

P2Y12 receptor inhibitors: Clopidogrel, prasugrel, ticagrelor

These agents bind to P2Y12 receptors on platelets to inhibit adenosine diphosphate-mediated platelet activation (Figure 3). Clopidogrel and prasugrel are irreversible prodrugs, whereas ticagrelor binds reversibly.

Clopidogrel, a prodrug

Clopidogrel has a half-life of 8 hours and a time to peak concentration of 4 hours. Eighty-five percent of a dose is inactivated by gut esterases. The remainder is metabolized primarily by the cytochrome P4502C19 enzyme system into its active metabolite.

How to use. The recommended dosage is a 600-mg bolus early in the course of ACS. This is associated with a lower rate of cardiovascular events than a 300-mg dose,2,15 although no trial has rigorously compared 300-mg vs 600-mg doses using major clinical end points. In patients presenting with ACS who cannot tolerate aspirin because of hypersensitivity or major gastrointestinal contraindication, clopidogrel is an alternative.1

The CURE trial16 randomized 12,526 patients with non-ST-elevation ACS to receive clopidogrel or placebo in addition to standard therapy. Clopidogrel was associated with a 20% lower rate of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke in both low- and high-risk patients regardless of whether an invasive or conservative strategy was pursued.

However, patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) had a 53% higher risk of bleeding (an absolute risk of 3.3%) if they received clopidogrel within 5 days of the surgery. This has led to the practice in some centers of delaying giving clopidogrel until after the coronary anatomy has been defined. This deprives the patient of the anti-ischemic benefits conferred by giving clopidogrel early and remains a contentious issue, with most suggesting that the risk-benefit ratio still favors giving clopidogrel early, before angiography, unless there is a high likelihood that surgery will ultimately be required.17 Alternatively, one could consider using a shorter-acting intravenous glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor such as eptifibatide as a “bridge” until a definitive reperfusion strategy is chosen.

Effect of CYP2C19 variants. The CLOVIS-2 study18 assessed the effects of genetic variants on the clopidogrel concentration in 106 patients who had had a myocardial infarction. The study confirmed that patients who carry certain variants of the CYP2C19 gene attain lower plasma concentrations of clopidogrel after receiving this drug.19 This accounts for its delayed onset of action as well as its variability in response in patients who have reduced expression or inhibition of this enzyme system. Doubling the standard dose in patients who carry these variants does not appear to provide clinical benefit.20

Thus, the thought is emerging that one should consider using prasugrel or ticagrelor instead of clopidogrel in patients who have these polymorphisms, though this is yet to be backed by robust clinical evidence.

Possible interaction with proton pump inhibitors. Controversy exists about whether proton pump inhibitors inhibit clopidogrel’s action. Although the US Food and Drug Administration continues to warn against the concurrent use of omeprazole and clopidogrel,21 an analysis of the PLATO trial22 concluded that patients with ACS who were taking proton pump inhibitors were at higher risk of ischemic events regardless of whether they had been randomized to clopidogrel or ticagrelor (a drug that acts independently of the cytochrome P450 system). This observation suggests that patients on proton pump inhibitors are generally sicker and at higher risk of ischemic events regardless of the choice of antiplatelet therapy. The use of other gastroprotective agents did not appear to mitigate these risks.

Prasugrel: Faster metabolism to active drug

Prasugrel is an irreversible P2Y12 receptor antagonist (Figure 3) that is metabolized into its active metabolite faster and in a more predictable fashion than clopidogrel.23

The TRITON-TIMI 38 study24 included 13,608 ACS patients in whom an early invasive strategy was planned and who were pretreated with prasugrel or clopidogrel in addition to standard treatment. The rate of the primary efficacy end point of death, myocardial infarction, or stroke was 19% lower in the prasugrel group. In those who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention, the incidence of in-stent thrombosis was more than 50% lower in the prasugrel group regardless of whether bare metal stents or drug-eluting stents were used.

Greater platelet inhibition came at the price of a higher incidence of serious bleeding, particularly in the subgroups of patients who were over age 75, had a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack, or weighed less than 60 kg. Prasugrel is therefore contraindicated in patients with a history of transient ischemic attack or stroke. Some suggest that a 5-mg dose can be used with caution (rather than the usual 10-mg dose) in patients over age 75 years or those who have low body weight.

The TRILOGY-ACS trial25 compared prasugrel and clopidogrel in medically managed patients with high-risk non-ST-elevation ACS. It found no difference in the rates of the primary end points of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke at 1 year. In the prespecified subset of patients over age 75 years, the rate of bleeding end points was no higher with prasugrel 5 mg once daily than with clopidogrel.

Prasugrel’s half-life is 7 hours, and its peak antiplatelet effect is within 30 minutes after an oral dose, compared with 4 hours with clopidogrel. Therefore, if a patient with non-ST-elevation ACS is going to go to the catheterization laboratory soon, he or she should not receive prasugrel beforehand, and should receive it later only if the results of angiography indicate that CABG will not be needed urgently. This is an important consideration when using prasugrel, as the rate of surgery-related bleeding was four times higher than with clopidogrel. If possible, this drug should be withheld for at least 7 days before CABG.

Ticagrelor, a direct P2Y12 receptor inhibitor

Ticagrelor, a reversible direct inhibitor of the P2Y12 receptor, inhibits adenosine diphosphate-mediated activation and aggregation (Figure 3). It has a median time to peak concentration of 1.3 to 2 hours and a half-life of 9 hours.

The PLATO trial26 enrolled 18,624 patients with ACS who were given either ticagrelor or clopidogrel in addition to standard therapy. At 12 months, the composite primary end point of myocardial infarction, death, or stroke had occurred in 16% fewer patients receiving ticagrelor than in the clopidogrel group. Analyzed separately, there were 16% fewer myocardial infarctions, 21% fewer cardiovascular deaths, and 22% fewer deaths from any cause, regardless of whether an invasive or conservative strategy was used, and with or without prior clopidogrel use. Fewer cases of stent thrombosis occurred in the ticagrelor group, and the rate of major bleeding was the same.

In a prospectively defined subgroup analysis,27 ticagrelor was beneficial only in patients who received lower doses of aspirin (< 100 mg daily): the hazard ratio for the primary end point was 0.79 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.71–0.88) in ticagrelor recipients who received low-dose aspirin and 1.45 (95% CI 1.01–2.09) in those who received high-dose aspirin.

Although this analysis is underpowered and controversial, the current evidence suggests that when used in combination with ticagrelor, the aspirin dose should be 81 mg.

Ticagrelor was also associated with a 19% higher incidence of non-CABG- or procedure-related major bleeding, more nonfatal and fatal intracranial bleeding, a higher incidence of dyspnea, and significantly more ventricular pauses.

Although ticagrelor carries no black-box warning about its use in patients with prior stroke or transient ischemic attack, the number of such patients in PLATO was small. Thus, caution should still be used in these patients.28

Ticagrelor should preferably be discontinued 5 days before CABG.

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors: Eptifibatide, tirofiban, abciximab

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors are intravenous agents that act by inhibiting fibrinogen-and von Willebrand factor-mediated platelet-to-platelet cross-linkage, the final pathway of platelet aggregation (Figure 3).

Use of these agents in ACS has been decreasing, as evidence supporting their use was largely established before the era of dual antiplatelet therapy.

A meta-analysis29 of 46,374 patients with non-ST-elevation ACS found that routinely adding a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor “upstream” as a third agent in patients receiving dual antiplatelet therapy bought only a modest (11%) reduction in death or myocardial infarction at 30 days, at the price of a 23% increase in major bleeding and no decrease in the overall rate of death. Roughly 70% of the patients were receiving dual antiplatelet therapy before cardiac catheterization.

These agents can be considered in high-risk ACS patients, such as those with ST-segment changes or elevated troponin concentrations, and in diabetic patients, on the assumption that these patients likely have a high intracoronary thrombus burden and are at higher risk of microvascular embolization.6,30 They can also be considered at the time of primary percutaneous coronary intervention in selected patients receiving heparin.7

Eptifibatide

Eptifibatide is a small-molecule, short-acting glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor with a half-life of 2.5 hours. Its inhibition of platelet aggregation is reversible by stopping the drug infusion and is thought to be a result of dissociation of the drug from platelets.

The PURSUIT trial31 studied 10,948 patients presenting with non-ST-elevation ACS randomized to placebo, eptifibatide in a 180-μg/kg bolus followed by a 2.0-μg/kg/min infusion, or eptifibatide in a 180-μg/kg bolus followed by a 1.3-μg/kg/min infusion. Both eptifibatide groups had a 1.5% absolute reduction in the incidence of the primary end point of death or myocardial infarction, a benefit that was apparent at 96 hours and that persisted through 30 days. Bleeding was more common in the eptifibatide groups, but there was no increase in the rate of hemorrhagic stroke.

The ACUITY trial32 found that early use of eptifibatide or tirofiban had no effect on the primary outcome. (See the section below on bivalirudin for more information about the ACUITY trial.)

PARENTERAL ANTICOAGULANTS

Unfractionated heparin: A declining role

Heparin binds to antithrombin and induces a conformational change, causing rapid inhibition of factor IIa (thrombin), factor IXa, and factor Xa, thus preventing further thrombus propagation (Figure 4). An intravenous bolus of 60 units/kg produces a time to peak of 5 to 10 minutes and a half-life of 30 to 60 minutes.

Heparin can be reversed by giving protamine sulfate (1 mg per 100 units of heparin). For ACS, it is given in a bolus of 60 units/kg not exceeding 4,000 units, followed by an infusion of 12 units/kg/hour, with monitoring of the activated partial thromboplastin time every 6 hours with a goal value of 50 to 70 seconds or 1.5 to 2.5 times control.

Side effects include thrombocytopenia, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (a distinct condition), and bleeding.

The use of unfractionated heparin was tested in ACS in the early 1990s. Oler et al33 performed a meta-analysis of six randomized trials and found a 33% lower rate of death in patients treated with heparin in addition to aspirin in ACS, as well less reported ischemic pain.

Advantages of unfractionated heparin are that it has stood the test of time, is inexpensive, and can be rapidly reversed. The disadvantages are that it can have serious side effects, including heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and is more likely to cause bleeding than the newer intravenous anticoagulants discussed below. Thus, its position as the main anticoagulant in ACS is being challenged.

Bivalirudin, a direct thrombin inhibitor

Bivalirudin is a synthetic direct thrombin inhibitor of fluid-phase and clot-bound thrombin (Figure 4). It also inhibits platelets directly.

The ACUITY trial32 randomized 13,819 patients with moderate to high-risk ACS scheduled for invasive treatment into three treatment groups:

- Heparin (either unfractionated heparin or enoxaparin) plus a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor (either eptifibatide, tirofiban, or abciximab)

- Bivalirudin plus a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor

- Bivalirudin alone.

The bivalirudin-alone treatment was as sociated with noninferior rates of composite ischemia end points and significantly lower rates of major bleeding, adding up to a significant reduction in the net clinical outcome end point. An important caveat is that bivalirudin’s noninferiority was mostly in the group of patients already receiving a thienopyridine before angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention (RR 0.97 vs 1.27, P = .054). There was less major, nonmajor, minor, CABG-related, and non-CABG-related bleeding as well as need for transfusion in the bivalirudin-alone group, making bivalirudin monotherapy an attractive option in ACS patients with or without ST-segment elevation undergoing a percutaneous coronary intervention.1,31

The ISAR-REACT trial34 later compared bivalirudin alone vs unfractionated heparin and abciximab in patients with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention pretreated with aspirin and clopidogrel. The composite rate of ischemia was similar in the two treatment groups, with significantly lower rates of bleeding in the bivalirudin group.

HORIZONS-AMI35 randomized 3,602 patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction receiving aspirin and clopidogrel either to unfractionated heparin and a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor or to bivalirudin. As in the ACUITY trial, there was no difference in ischemic end points and a 40% to 45% lower rate of major bleeding end points in the bivalirudin group, translating into an overall lower rate of death.

Enoxaparin, a low-molecular weight heparin

Enoxaparin is a low-molecular-weight heparin that inhibits factor IIa and factor Xa via antithrombin, roughly in a ratio of 1:3 (Figure 4). It has a time to peak effect of 10 minutes when given intravenously36 and 3 to 5 hours when given subcutaneously.37 Its half-life is 4.5 hours, but it is longer in patients with renal dysfunction, requiring dose adjustments in this population.

Its anticoagulant effect is partially reversible. If it is to be reversed between 0 and 8 hours after dosing, the recommended reversal regimen is 1 mg of protamine sulfate for every 1 mg of enoxaparin used. At 8 to 12 hours, it is 0.5 mg of protamine for every 1 mg of enoxaparin. After 12 hours, no protamine is required.

Compared with unfractionated heparin, enoxaparin has less plasma protein binding and a more consistent anticoagulant effect. Its high bioavailability also allows for subcutaneous dosing. Its greater anti-Xa activity inhibits thrombin generation more effectively, and it causes lower rates of thrombocytopenia and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

de Lemos et al38 found that, in ACS patients in whom an early conservative approach of medical management was planned, enoxaparin was more efficacious than unfractionated heparin and caused a similar rate of bleeding.

Murphy et al,39 in a meta-analysis of 12 trials in 49,088 ACS patients, also found that enoxaparin had a net clinical benefit compared with unfractionated heparin in reducing rates of myocardial infarction and death despite more bleeding.

The ESSENCE trial40 compared enoxaparin vs unfractionated heparin in 3,171 patients with ACS. It found fewer ischemic events with enoxaparin in the early phase, more minor bleeding, but no increase in major bleeding.

The SYNERGY trial,41 in 10,027 patients with high-risk non-ST-elevation ACS undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention, compared subcutaneous enoxaparin with intravenous heparin. Enoxaparin was found to be noninferior to heparin but caused more bleeding, including major bleeding, drops in hemoglobin, and intracranial hemorrhage.

The EXTRACT-TIMI 25 trial.42 In patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction, enoxaparin has been shown to be beneficial both in patients treated with fibrinolysis and in those who underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention. The EXTRACT-TIMI 25 trial randomized 20,749 patients to receive either enoxaparin (an intravenous bolus and maintenance subcutaneous dosing based on renal function) or intravenous heparin in addition to thrombolysis within 6 hours of the diagnosis of ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Although the enoxaparin group had more bleeding end points, they had fewer primary and secondary efficacy end points, translating into an overall net clinical benefit in favor of enoxaparin.

The ATOLL trial43 examined the use of enoxaparin (0.5 mg/kg intravenously) or unfractionated heparin in 910 patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention (via the radial artery in 66% to 69%). Although there was a trend towards benefit in terms of the primary end point of death, myocardial infarction complications, procedure failure, and major bleeding favoring enoxaparin, it was not statistically significant (95% CI 0.68–1.01, P = .06).

However, there was a 37% to 42% lower rate of the secondary end point of death, recurrent myocardial infarction or ACS, or urgent target-vessel revascularization in the enoxaparin group, with a 40% reduction in death from any cause, death from a cardiac cause, or shock. The safety profiles of the two drugs were similar, and the net clinical benefit significantly favored enoxaparin.

Fondaparinux, a factor Xa inhibitor

Fondaparinux is a synthetic pentasaccharide that indirectly inhibits factor Xa through the action of antithrombin (Figure 4). After a 2.5-mg subcutaneous dose, it has a time to peak concentration of 2 hours and a half-life of 17 to 21 hours.

The OASIS-5 trial44 compared fondaparinux and enoxaparin in 20,078 patients treated for non-ST-elevation ACS. Although the rates of death, myocardial infarction, and refractory ischemia at 9 days were similar for both drugs, the fondaparinux group had a significantly (almost 50%) lower rate of bleeding at 30 days, translating into significantly fewer deaths at 30 days. However, patients receiving fondaparinux who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention had a threefold higher rate of catheter-related thrombosis.

The OASIS-6 trial45 compared fondaparinux vs usual care (placebo in those in whom unfractionated heparin was not indicated or unfractionated heparin for up to 48 hours followed by placebo for up to 8 days) in 12,092 patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. There was a 1.5% absolute risk reduction in death and reinfarction without an increase in bleeding at 30 days, with trends persisting 6 months into the study. However, fondaparinux was not superior to heparin in the 3% of patients who underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention. As in OASIS-5, there was more catheter-related thrombosis in the fondaparinux group.

Although the use of supplemental unfractionated heparin appears to have mitigated this risk, fondaparinux remains a less-than-ideal option in the era of primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction and has therefore found limited use in this group of patients. It should, however, be considered in patients for whom a conservative strategy is planned, especially if bleeding risk is deemed to be high.

ORAL ANTICOAGULANTS

Oral anticoagulants provide ischemic benefit in selected patients with ACS—at the price of a higher risk of significant bleeding.

Warfarin

Warfarin was investigated after myocardial infarction in the WARIS II,46 CARS,47 and CHAMP48 trials.

WARIS II46 looked at the use of aspirin alone, warfarin alone, and aspirin and warfarin in combination. The rates of the primary end points of stroke, nonfatal infarction, and death were lower in the warfarin group.

CARS47 found no difference in the rate of the primary end point of fatal infarction, nonfatal ischemic stroke, or cardiovascular death with aspirin vs warfarin plus aspirin.

CHAMP48 saw similar trends, ie, no difference in the rate of death, recurrent myocardial infarction, or stroke with warfarin plus aspirin vs aspirin alone.

All three studies showed increases in major bleeding with warfarin use.

Putting these trials into context, the significant net clinical benefit of dual antiplatelet therapy in the current era compared with the significant bleeding and questionable conflicting evidence supporting benefit with warfarin has limited its use in ACS patients.

Rivaroxaban, an oral factor Xa inhibitor

Rivaroxaban is a novel oral direct reversible factor Xa inhibitor.

The ATLAS ACS 2-TIMI 51 trial49 found rivaroxaban 2.5 mg or 5 mg to yield a significantly lower rate of the primary outcome of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and in-stent thrombosis compared with placebo, but significantly more major non-CABG bleeding and intracranial hemorrhage.

The dose used in this trial was much lower than the dose used in trials investigating the role of this drug in stroke prophylaxis in atrial fibrillation.

Apixaban, an oral factor Xa inhibitor

Apixaban is another direct factor Xa inhibitor.

The APPRAISE-2 trial50 compared apixaban 5 mg twice daily vs placebo in ACS. There was no difference in the rate of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke, but there was significantly more bleeding in the apixaban group, prompting early termination of this study.

Dabigatran, an oral thrombin inhibitor

Dabigatran is an oral direct thrombin inhibitor.

The RE-DEEM trial51 compared four doses of dabigatran (50, 75, 110, and 150 mg twice daily) and placebo in ACS patients. The dabigatran groups had more major and minor bleeding, and the higher the dose, the higher the incidence of bleeding. In addition, the rates of ischemic end points were no lower with dabigatran, although this trial was not powered to show differences in clinical events.

REDUCING THE RISK OF BLEEDING

In the treatment of ACS, the benefits of restoring perfusion by preventing further propagation of thrombus and platelet aggregation come at a significant price of higher bleeding risk. This in turn increases the risk of death through various mechanisms, including shock, worsening ischemia, discontinuation of antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapy causing stent thrombosis, and anemia leading to transfusion, which propagates the underlying inflammatory milieu.52

Giugliano and Braunwald53 provide practical suggestions to reduce this risk, advising physicians to:

- Avoid inappropriately high dosing, particularly in patients with renal insufficiency

- Preferentially use agents that cause less bleeding (eg, bivalirudin, fondaparinux) without compromising anti-ischemic efficacy

- Minimize the concomitant use of other drugs that cause bleeding (eg, NSAIDs)

- Use drugs that protect against bleeding (eg, proton pump inhibitors) in patients at high risk

- Prevent access-site bleeding by using the radial artery, smaller sheaths, and appropriate sheath and closure device management. Indeed, the use of radial interventions in ACS has been shown to reduce access-site-related bleeding, even in patients at high risk.54

The reduction in bleeding risk may provide future trials the opportunity to increase antithrombotic efficacy of different agents with goals of reducing ischemic end points.

- Wright RS, Anderson JL, Adams CD, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2011 ACCF/AHA focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57:e215–e367.

- Jneid H, Anderson JL, Wright RS, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2007 guideline and replacing the 2011 focused update): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 60:645–681.

- CAPRIE Steering Committee. A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). CAPRIE Steering Committee. Lancet 1996; 348:1329–1339.

- Cohen M, Adams PC, Parry G, et al. Combination antithrombotic therapy in unstable rest angina and non-Q-wave infarction in nonprior aspirin users. Primary end points analysis from the ATACS trial. Antithrombotic Therapy in Acute Coronary Syndromes Research Group. Circulation 1994; 89:81–88.

- Moscucci M, Fox KA, Cannon CP, et al. Predictors of major bleeding in acute coronary syndromes: the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE). Eur Heart J 2003; 24:1815–1823.

- Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58:e44–e122.

- American College of Emergency Physicians; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 61:485–510.

- Lewis HD, Davis JW, Archibald DG, et al. Protective effects of aspirin against acute myocardial infarction and death in men with unstable angina. Results of a Veterans Administration Cooperative Study. N Engl J Med 1983; 309:396–403.

- ISIS-2 (Second International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of intravenous streptokinase, oral aspirin, both, or neither among 17,187 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction: ISIS-2. Lancet 1988; 2:349–360.

- Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ 2002; 324:71–86.

- Sweeny JM, Gorog DA, Fuster V. Antiplatelet drug ‘resistance’. Part 1: mechanisms and clinical measurements. Nat Rev Cardiol 2009; 6:273–282.

- Kelly JP, Kaufman DW, Jurgelon JM, Sheehan J, Koff RS, Shapiro S. Risk of aspirin-associated major upper-gastrointestinal bleeding with enteric-coated or buffered product. Lancet 1996; 348:1413–1416.

- Grosser T, Fries S, Lawson JA, Kapoor SC, Grant GR, FitzGerald GA. Drug resistance and pseudoresistance: an unintended consequence of enteric coating aspirin. Circulation 2013; 127:377–385.

- US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Concomitant use of ibuprofen and aspirin: potential for attenuation of the anti-platelet effect of aspirin. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/drugsafety/postmarketdrugsafetyinformationforpatientsandproviders/ucm161282.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2013.

- Patti G, Colonna G, Pasceri V, Pepe LL, Montinaro A, Di Sciascio G. Randomized trial of high loading dose of clopidogrel for reduction of periprocedural myocardial infarction in patients undergoing coronary intervention: results from the ARMYDA-2 (Antiplatelet therapy for Reduction of MYocardial Damage during Angioplasty) study. Circulation 2005; 111:2099–2106.

- Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, Tognoni G, Fox KK; Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events Trial Investigators. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:494–502.

- Bavry AA, Lincoff AM. Is clopidogrel cardiovascular medicine’s double-edged sword? Circulation 2006; 113:1638–1640.

- Collet JP, Hulot JS, Anzaha G, et al; CLOVIS-2 Investigators. High doses of clopidogrel to overcome genetic resistance: the randomized crossover CLOVIS-2 (Clopidogrel and Response Variability Investigation Study 2). JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2011; 4:392–402.

- Hulot JS, Collet JP, Cayla G, et al. CYP2C19 but not PON1 genetic variants influence clopidogrel pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and clinical efficacy in post-myocardial infarction patients. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2011; 4:422–428.

- Cuisset T, Quilici J, Cohen W, et al. Usefulness of high clopidogrel maintenance dose according to CYP2C19 genotypes in clopidogrel low responders undergoing coronary stenting for non ST elevation acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol 2011; 108:760–765.

- US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). FDA reminder to avoid concomitant use of Plavix (clopidogrel) and omeprazole. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm231161.htm. Accessed November 30, 2013.

- Goodman SG, Clare R, Pieper KS, et al; Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes Trial Investigators. Association of proton pump inhibitor use on cardiovascular outcomes with clopidogrel and ticagrelor: insights from the platelet inhibition and patient outcomes trial. Circulation 2012; 125:978–986.

- Solomon S, Vacek JL. Reducing cardiac ischemic events in patients with ACS: prasugrel versus clopidogrel. Commentary. Postgrad Med 2010; 122:198–200.

- Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al; TRITON-TIMI 38 Investigators. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:2001–2015.

- Roe MT, Armstrong PW, Fox KA, et al; TRILOGY ACS Investigators. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel for acute coronary syndromes without revascularization. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:1297–1309.

- Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, et al; PLATO Investigators. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:1045–1057.

- Mahaffey KW, Wojdyla DM, Carroll K, et al; PLATO Investigators. Ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel by geographic region in the Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial. Circulation 2011; 124:544–554.

- Verheugt FW. Beware of novel antiplatelet therapy in acute coronary syndrome patients with previous stroke. Circulation 2012; 125:2821–2823.

- Tricoci P, Newby LK, Hasselblad V, et al. Upstream use of small-molecule glycoprotein iib/iiia inhibitors in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: a systematic overview of randomized clinical trials. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2011; 4:448–458.

- Kastrati A, Mehilli J, Neumann FJ, et al; Intracoronary Stenting and Antithrombotic: Regimen Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment 2 (ISAR-REACT 2) Trial Investigators. Abciximab in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention after clopidogrel pretreatment: the ISAR-REACT 2 randomized trial. JAMA 2006; 295:1531–1538.

- Inhibition of platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa with eptifibatide in patients with acute coronary syndromes. The PURSUIT Trial Investigators. Platelet Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa in Unstable Angina: Receptor Suppression Using Integrilin Therapy. N Engl J Med 1998; 339:436–443.

- Stone GW, McLaurin BT, Cox DA, et al; ACUITY Investigators. Bivalirudin for patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2006; 355:2203–2216.

- Oler A, Whooley MA, Oler J, Grady D. Adding heparin to aspirin reduces the incidence of myocardial infarction and death in patients with unstable angina. A meta-analysis. JAMA 1996; 276:811–815.

- Kastrati A, Neumann FJ, Schulz S, et al; ISAR-REACT 4 Trial Investigators. Abciximab and heparin versus bivalirudin for non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:1980–1989.

- Stone GW, Witzenbichler B, Guagliumi G, et al; HORIZONS-AMI Trial Investigators. Bivalirudin during primary PCI in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:2218–2230.

- Aslam MS, Sundberg S, Sabri MN, Cooke D, Lakier JB. Pharmacokinetics of intravenous/subcutaneous enoxaparin in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2002; 57:187–190.

- Sanofi-Aventis US. Lovenox (enoxaparin sodium injection) product information. http://www.lovenox.com/hcp/clinical-data.aspx. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- de Lemos JA, Blazing MA, Wiviott SD, et al. Enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin in patients treated with tirofiban, aspirin and an early conservative initial management strategy: results from the A phase of the A-to-Z trial. Eur Heart J 2004; 25:1688–1694.

- Murphy SA, Gibson CM, Morrow DA, et al. Efficacy and safety of the low-molecular weight heparin enoxaparin compared with unfractionated heparin across the acute coronary syndrome spectrum: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 2007; 28:2077–2086.

- Cohen M, Demers C, Gurfinkel EP, et al. A comparison of low-molecular-weight heparin with unfractionated heparin for unstable coronary artery disease. Efficacy and Safety of Subcutaneous Enoxaparin in Non-Q-Wave Coronary Events Study Group. N Engl J Med 1997; 337:447–452.

- Ferguson JJ, Califf RM, Antman EM, et al; SYNERGY Trial Investigators. Enoxaparin vs unfractionated heparin in high-risk patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes managed with an intended early invasive strategy: primary results of the SYNERGY randomized trial. JAMA 2004; 292:45–54.

- Antman EM, Morrow DA, McCabe CH, et al; ExTRACT-TIMI 25 Investigators. Enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin with fibrinolysis for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:1477–1488.

- Montalescot G, Zeymer U, Silvain J, et al; ATOLL Investigators. Intravenous enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin in primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the international randomised open-label ATOLL trial. Lancet 2011; 378:693–703.

- Yusuf S, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, et al; Fifth Organization to Assess Strategies in Acute Ischemic Syndromes Investigators. Comparison of fondaparinux and enoxaparin in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:1464–1476.

- Yusuf S, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, et al; OASIS-6 Trial Group. Effects of fondaparinux on mortality and reinfarction in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: the OASIS-6 randomized trial. JAMA 2006; 295:1519–1530.

- Hurlen M, Abdelnoor M, Smith P, Erikssen J, Arnesen H. Warfarin, aspirin, or both after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2002; 347:969–974.

- Coumadin Aspirin Reinfarction Study (CARS) Investigators. Randomised double-blind trial of fixed low-dose warfarin with aspirin after myocardial infarction. Lancet 1997; 350:389–396.

- Fiore LD, Ezekowitz MD, Brophy MT, Lu D, Sacco J, Peduzzi P; Combination Hemotherapy and Mortality Prevention (CHAMP) Study Group. Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program Clinical Trial comparing combined warfarin and aspirin with aspirin alone in survivors of acute myocardial infarction: primary results of the CHAMP study. Circulation 2002; 105:557–563.

- Mega JL, Braunwald E, Wiviott SD, et al; ATLAS ACS 2–TIMI 51 Investigators. Rivaroxaban in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:9–19.

- Alexander JH, Lopes RD, James S, et al; APPRAISE-2 Investigators. Apixaban with antiplatelet therapy after acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:699–708.

- Oldgren J, Budaj A, Granger CB, et al; RE-DEEM Investigators. Dabigatran vs placebo in patients with acute coronary syndromes on dual antiplatelet therapy: a randomized, double-blind, phase II trial. Eur Heart J 2011; 32:2781–2789.

- Steg PG, Huber K, Andreotti F, et al. Bleeding in acute coronary syndromes and percutaneous coronary interventions: position paper by the Working Group on Thrombosis of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2011; 32:1854–1864.

- Giugliano RP, Braunwald E. The year in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 60:2127–039.

- Rao SV, Ou FS, Wang TY, et al. Trends in the prevalence and outcomes of radial and femoral approaches to percutaneous coronary intervention: a report from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2008; 1:379–386.

Antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs are a cornerstone of the medical treatment of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), reducing the rates of both morbidity and death.1–4 However, reductions in ischemic events with these drugs have uniformly been accompanied by increases in bleeding complications, which reduce the net benefit.5 Thus, clinical research has been exploring ways to maximize the benefit while minimizing the risk.

Here, we review the guidelines and evidence supporting the use of antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs in ACS.

ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROMES WITH OR WITHOUT ST ELEVATION

A key distinction when treating ACS is whether the electrocardiogram shows ST-segment elevation. In cases of non-ST-elevation ACS (ie, unstable angina or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction), a second key question is whether the initial strategy will be invasive (with angiography performed urgently) or conservative (with angiography performed later). In ST-elevation myocardial infarction, another distinction is how perfusion is to be restored, ie, with primary percutaneous coronary intervention or with thrombolysis. All these questions affect the choice of antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy.

Figure 1 and Figure 2 summarize the guidelines of the American College of Cardiology Foundation and American Heart Association.1,2,6,7

ANTIPLATELET THERAPY

Aspirin for all

Aspirin irreversibly acetylates the enzyme cyclooxygenase-1, blocking intraplatelet formation of thromboxane A2 (Figure 3), a potent platelet aggregator and endothelial vasoconstrictor. Large clinical trials have confirmed that aspirin reduces morbidity and mortality rates by as much as 50% in patients with ACS.8

The ISIS-2 trial9 found that giving aspirin early in the emergency department significantly reduced the mortality rate.

The Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration,10 in a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing different doses of aspirin in high-risk ACS patients, found no greater benefit for doses of aspirin higher than 162 mg per day when used long-term.

How to use. During an ACS, the patient should receive one dose of aspirin 325 mg (the standard high-dose pill in the United States). This dose should be chewed, as buccal absorption results in more rapid systemic effects.11

Thereafter, the patient should take 81 mg per day, continued indefinitely. The 81-mg dose also applies to patients who undergo a percutaneous coronary intervention with a drug-eluting stent.7 Previous recommendations called for higher doses, but studies have shown that higher doses pose a higher risk of bleeding without additional clinical benefit. The use of enteric-coated aspirin does not reduce this risk,12 and its delayed release may in fact cause aspirin “pseudoresistance.”13

The concurrent use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should be avoided, as NSAIDs reversibly bind to platelets, thus preventing aspirin from binding.14 As aspirin washes out of the body, NSAIDs may then become unbound from platelets, leaving platelets activated.

P2Y12 receptor inhibitors: Clopidogrel, prasugrel, ticagrelor

These agents bind to P2Y12 receptors on platelets to inhibit adenosine diphosphate-mediated platelet activation (Figure 3). Clopidogrel and prasugrel are irreversible prodrugs, whereas ticagrelor binds reversibly.

Clopidogrel, a prodrug

Clopidogrel has a half-life of 8 hours and a time to peak concentration of 4 hours. Eighty-five percent of a dose is inactivated by gut esterases. The remainder is metabolized primarily by the cytochrome P4502C19 enzyme system into its active metabolite.

How to use. The recommended dosage is a 600-mg bolus early in the course of ACS. This is associated with a lower rate of cardiovascular events than a 300-mg dose,2,15 although no trial has rigorously compared 300-mg vs 600-mg doses using major clinical end points. In patients presenting with ACS who cannot tolerate aspirin because of hypersensitivity or major gastrointestinal contraindication, clopidogrel is an alternative.1

The CURE trial16 randomized 12,526 patients with non-ST-elevation ACS to receive clopidogrel or placebo in addition to standard therapy. Clopidogrel was associated with a 20% lower rate of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke in both low- and high-risk patients regardless of whether an invasive or conservative strategy was pursued.

However, patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) had a 53% higher risk of bleeding (an absolute risk of 3.3%) if they received clopidogrel within 5 days of the surgery. This has led to the practice in some centers of delaying giving clopidogrel until after the coronary anatomy has been defined. This deprives the patient of the anti-ischemic benefits conferred by giving clopidogrel early and remains a contentious issue, with most suggesting that the risk-benefit ratio still favors giving clopidogrel early, before angiography, unless there is a high likelihood that surgery will ultimately be required.17 Alternatively, one could consider using a shorter-acting intravenous glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor such as eptifibatide as a “bridge” until a definitive reperfusion strategy is chosen.

Effect of CYP2C19 variants. The CLOVIS-2 study18 assessed the effects of genetic variants on the clopidogrel concentration in 106 patients who had had a myocardial infarction. The study confirmed that patients who carry certain variants of the CYP2C19 gene attain lower plasma concentrations of clopidogrel after receiving this drug.19 This accounts for its delayed onset of action as well as its variability in response in patients who have reduced expression or inhibition of this enzyme system. Doubling the standard dose in patients who carry these variants does not appear to provide clinical benefit.20

Thus, the thought is emerging that one should consider using prasugrel or ticagrelor instead of clopidogrel in patients who have these polymorphisms, though this is yet to be backed by robust clinical evidence.

Possible interaction with proton pump inhibitors. Controversy exists about whether proton pump inhibitors inhibit clopidogrel’s action. Although the US Food and Drug Administration continues to warn against the concurrent use of omeprazole and clopidogrel,21 an analysis of the PLATO trial22 concluded that patients with ACS who were taking proton pump inhibitors were at higher risk of ischemic events regardless of whether they had been randomized to clopidogrel or ticagrelor (a drug that acts independently of the cytochrome P450 system). This observation suggests that patients on proton pump inhibitors are generally sicker and at higher risk of ischemic events regardless of the choice of antiplatelet therapy. The use of other gastroprotective agents did not appear to mitigate these risks.

Prasugrel: Faster metabolism to active drug

Prasugrel is an irreversible P2Y12 receptor antagonist (Figure 3) that is metabolized into its active metabolite faster and in a more predictable fashion than clopidogrel.23

The TRITON-TIMI 38 study24 included 13,608 ACS patients in whom an early invasive strategy was planned and who were pretreated with prasugrel or clopidogrel in addition to standard treatment. The rate of the primary efficacy end point of death, myocardial infarction, or stroke was 19% lower in the prasugrel group. In those who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention, the incidence of in-stent thrombosis was more than 50% lower in the prasugrel group regardless of whether bare metal stents or drug-eluting stents were used.

Greater platelet inhibition came at the price of a higher incidence of serious bleeding, particularly in the subgroups of patients who were over age 75, had a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack, or weighed less than 60 kg. Prasugrel is therefore contraindicated in patients with a history of transient ischemic attack or stroke. Some suggest that a 5-mg dose can be used with caution (rather than the usual 10-mg dose) in patients over age 75 years or those who have low body weight.

The TRILOGY-ACS trial25 compared prasugrel and clopidogrel in medically managed patients with high-risk non-ST-elevation ACS. It found no difference in the rates of the primary end points of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke at 1 year. In the prespecified subset of patients over age 75 years, the rate of bleeding end points was no higher with prasugrel 5 mg once daily than with clopidogrel.

Prasugrel’s half-life is 7 hours, and its peak antiplatelet effect is within 30 minutes after an oral dose, compared with 4 hours with clopidogrel. Therefore, if a patient with non-ST-elevation ACS is going to go to the catheterization laboratory soon, he or she should not receive prasugrel beforehand, and should receive it later only if the results of angiography indicate that CABG will not be needed urgently. This is an important consideration when using prasugrel, as the rate of surgery-related bleeding was four times higher than with clopidogrel. If possible, this drug should be withheld for at least 7 days before CABG.

Ticagrelor, a direct P2Y12 receptor inhibitor

Ticagrelor, a reversible direct inhibitor of the P2Y12 receptor, inhibits adenosine diphosphate-mediated activation and aggregation (Figure 3). It has a median time to peak concentration of 1.3 to 2 hours and a half-life of 9 hours.

The PLATO trial26 enrolled 18,624 patients with ACS who were given either ticagrelor or clopidogrel in addition to standard therapy. At 12 months, the composite primary end point of myocardial infarction, death, or stroke had occurred in 16% fewer patients receiving ticagrelor than in the clopidogrel group. Analyzed separately, there were 16% fewer myocardial infarctions, 21% fewer cardiovascular deaths, and 22% fewer deaths from any cause, regardless of whether an invasive or conservative strategy was used, and with or without prior clopidogrel use. Fewer cases of stent thrombosis occurred in the ticagrelor group, and the rate of major bleeding was the same.

In a prospectively defined subgroup analysis,27 ticagrelor was beneficial only in patients who received lower doses of aspirin (< 100 mg daily): the hazard ratio for the primary end point was 0.79 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.71–0.88) in ticagrelor recipients who received low-dose aspirin and 1.45 (95% CI 1.01–2.09) in those who received high-dose aspirin.

Although this analysis is underpowered and controversial, the current evidence suggests that when used in combination with ticagrelor, the aspirin dose should be 81 mg.

Ticagrelor was also associated with a 19% higher incidence of non-CABG- or procedure-related major bleeding, more nonfatal and fatal intracranial bleeding, a higher incidence of dyspnea, and significantly more ventricular pauses.

Although ticagrelor carries no black-box warning about its use in patients with prior stroke or transient ischemic attack, the number of such patients in PLATO was small. Thus, caution should still be used in these patients.28

Ticagrelor should preferably be discontinued 5 days before CABG.

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors: Eptifibatide, tirofiban, abciximab

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors are intravenous agents that act by inhibiting fibrinogen-and von Willebrand factor-mediated platelet-to-platelet cross-linkage, the final pathway of platelet aggregation (Figure 3).

Use of these agents in ACS has been decreasing, as evidence supporting their use was largely established before the era of dual antiplatelet therapy.

A meta-analysis29 of 46,374 patients with non-ST-elevation ACS found that routinely adding a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor “upstream” as a third agent in patients receiving dual antiplatelet therapy bought only a modest (11%) reduction in death or myocardial infarction at 30 days, at the price of a 23% increase in major bleeding and no decrease in the overall rate of death. Roughly 70% of the patients were receiving dual antiplatelet therapy before cardiac catheterization.

These agents can be considered in high-risk ACS patients, such as those with ST-segment changes or elevated troponin concentrations, and in diabetic patients, on the assumption that these patients likely have a high intracoronary thrombus burden and are at higher risk of microvascular embolization.6,30 They can also be considered at the time of primary percutaneous coronary intervention in selected patients receiving heparin.7

Eptifibatide

Eptifibatide is a small-molecule, short-acting glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor with a half-life of 2.5 hours. Its inhibition of platelet aggregation is reversible by stopping the drug infusion and is thought to be a result of dissociation of the drug from platelets.

The PURSUIT trial31 studied 10,948 patients presenting with non-ST-elevation ACS randomized to placebo, eptifibatide in a 180-μg/kg bolus followed by a 2.0-μg/kg/min infusion, or eptifibatide in a 180-μg/kg bolus followed by a 1.3-μg/kg/min infusion. Both eptifibatide groups had a 1.5% absolute reduction in the incidence of the primary end point of death or myocardial infarction, a benefit that was apparent at 96 hours and that persisted through 30 days. Bleeding was more common in the eptifibatide groups, but there was no increase in the rate of hemorrhagic stroke.

The ACUITY trial32 found that early use of eptifibatide or tirofiban had no effect on the primary outcome. (See the section below on bivalirudin for more information about the ACUITY trial.)

PARENTERAL ANTICOAGULANTS

Unfractionated heparin: A declining role

Heparin binds to antithrombin and induces a conformational change, causing rapid inhibition of factor IIa (thrombin), factor IXa, and factor Xa, thus preventing further thrombus propagation (Figure 4). An intravenous bolus of 60 units/kg produces a time to peak of 5 to 10 minutes and a half-life of 30 to 60 minutes.

Heparin can be reversed by giving protamine sulfate (1 mg per 100 units of heparin). For ACS, it is given in a bolus of 60 units/kg not exceeding 4,000 units, followed by an infusion of 12 units/kg/hour, with monitoring of the activated partial thromboplastin time every 6 hours with a goal value of 50 to 70 seconds or 1.5 to 2.5 times control.

Side effects include thrombocytopenia, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (a distinct condition), and bleeding.

The use of unfractionated heparin was tested in ACS in the early 1990s. Oler et al33 performed a meta-analysis of six randomized trials and found a 33% lower rate of death in patients treated with heparin in addition to aspirin in ACS, as well less reported ischemic pain.

Advantages of unfractionated heparin are that it has stood the test of time, is inexpensive, and can be rapidly reversed. The disadvantages are that it can have serious side effects, including heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and is more likely to cause bleeding than the newer intravenous anticoagulants discussed below. Thus, its position as the main anticoagulant in ACS is being challenged.

Bivalirudin, a direct thrombin inhibitor

Bivalirudin is a synthetic direct thrombin inhibitor of fluid-phase and clot-bound thrombin (Figure 4). It also inhibits platelets directly.

The ACUITY trial32 randomized 13,819 patients with moderate to high-risk ACS scheduled for invasive treatment into three treatment groups:

- Heparin (either unfractionated heparin or enoxaparin) plus a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor (either eptifibatide, tirofiban, or abciximab)

- Bivalirudin plus a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor

- Bivalirudin alone.

The bivalirudin-alone treatment was as sociated with noninferior rates of composite ischemia end points and significantly lower rates of major bleeding, adding up to a significant reduction in the net clinical outcome end point. An important caveat is that bivalirudin’s noninferiority was mostly in the group of patients already receiving a thienopyridine before angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention (RR 0.97 vs 1.27, P = .054). There was less major, nonmajor, minor, CABG-related, and non-CABG-related bleeding as well as need for transfusion in the bivalirudin-alone group, making bivalirudin monotherapy an attractive option in ACS patients with or without ST-segment elevation undergoing a percutaneous coronary intervention.1,31

The ISAR-REACT trial34 later compared bivalirudin alone vs unfractionated heparin and abciximab in patients with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention pretreated with aspirin and clopidogrel. The composite rate of ischemia was similar in the two treatment groups, with significantly lower rates of bleeding in the bivalirudin group.

HORIZONS-AMI35 randomized 3,602 patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction receiving aspirin and clopidogrel either to unfractionated heparin and a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor or to bivalirudin. As in the ACUITY trial, there was no difference in ischemic end points and a 40% to 45% lower rate of major bleeding end points in the bivalirudin group, translating into an overall lower rate of death.

Enoxaparin, a low-molecular weight heparin

Enoxaparin is a low-molecular-weight heparin that inhibits factor IIa and factor Xa via antithrombin, roughly in a ratio of 1:3 (Figure 4). It has a time to peak effect of 10 minutes when given intravenously36 and 3 to 5 hours when given subcutaneously.37 Its half-life is 4.5 hours, but it is longer in patients with renal dysfunction, requiring dose adjustments in this population.

Its anticoagulant effect is partially reversible. If it is to be reversed between 0 and 8 hours after dosing, the recommended reversal regimen is 1 mg of protamine sulfate for every 1 mg of enoxaparin used. At 8 to 12 hours, it is 0.5 mg of protamine for every 1 mg of enoxaparin. After 12 hours, no protamine is required.

Compared with unfractionated heparin, enoxaparin has less plasma protein binding and a more consistent anticoagulant effect. Its high bioavailability also allows for subcutaneous dosing. Its greater anti-Xa activity inhibits thrombin generation more effectively, and it causes lower rates of thrombocytopenia and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

de Lemos et al38 found that, in ACS patients in whom an early conservative approach of medical management was planned, enoxaparin was more efficacious than unfractionated heparin and caused a similar rate of bleeding.

Murphy et al,39 in a meta-analysis of 12 trials in 49,088 ACS patients, also found that enoxaparin had a net clinical benefit compared with unfractionated heparin in reducing rates of myocardial infarction and death despite more bleeding.

The ESSENCE trial40 compared enoxaparin vs unfractionated heparin in 3,171 patients with ACS. It found fewer ischemic events with enoxaparin in the early phase, more minor bleeding, but no increase in major bleeding.

The SYNERGY trial,41 in 10,027 patients with high-risk non-ST-elevation ACS undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention, compared subcutaneous enoxaparin with intravenous heparin. Enoxaparin was found to be noninferior to heparin but caused more bleeding, including major bleeding, drops in hemoglobin, and intracranial hemorrhage.

The EXTRACT-TIMI 25 trial.42 In patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction, enoxaparin has been shown to be beneficial both in patients treated with fibrinolysis and in those who underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention. The EXTRACT-TIMI 25 trial randomized 20,749 patients to receive either enoxaparin (an intravenous bolus and maintenance subcutaneous dosing based on renal function) or intravenous heparin in addition to thrombolysis within 6 hours of the diagnosis of ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Although the enoxaparin group had more bleeding end points, they had fewer primary and secondary efficacy end points, translating into an overall net clinical benefit in favor of enoxaparin.

The ATOLL trial43 examined the use of enoxaparin (0.5 mg/kg intravenously) or unfractionated heparin in 910 patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention (via the radial artery in 66% to 69%). Although there was a trend towards benefit in terms of the primary end point of death, myocardial infarction complications, procedure failure, and major bleeding favoring enoxaparin, it was not statistically significant (95% CI 0.68–1.01, P = .06).

However, there was a 37% to 42% lower rate of the secondary end point of death, recurrent myocardial infarction or ACS, or urgent target-vessel revascularization in the enoxaparin group, with a 40% reduction in death from any cause, death from a cardiac cause, or shock. The safety profiles of the two drugs were similar, and the net clinical benefit significantly favored enoxaparin.

Fondaparinux, a factor Xa inhibitor

Fondaparinux is a synthetic pentasaccharide that indirectly inhibits factor Xa through the action of antithrombin (Figure 4). After a 2.5-mg subcutaneous dose, it has a time to peak concentration of 2 hours and a half-life of 17 to 21 hours.

The OASIS-5 trial44 compared fondaparinux and enoxaparin in 20,078 patients treated for non-ST-elevation ACS. Although the rates of death, myocardial infarction, and refractory ischemia at 9 days were similar for both drugs, the fondaparinux group had a significantly (almost 50%) lower rate of bleeding at 30 days, translating into significantly fewer deaths at 30 days. However, patients receiving fondaparinux who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention had a threefold higher rate of catheter-related thrombosis.

The OASIS-6 trial45 compared fondaparinux vs usual care (placebo in those in whom unfractionated heparin was not indicated or unfractionated heparin for up to 48 hours followed by placebo for up to 8 days) in 12,092 patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. There was a 1.5% absolute risk reduction in death and reinfarction without an increase in bleeding at 30 days, with trends persisting 6 months into the study. However, fondaparinux was not superior to heparin in the 3% of patients who underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention. As in OASIS-5, there was more catheter-related thrombosis in the fondaparinux group.

Although the use of supplemental unfractionated heparin appears to have mitigated this risk, fondaparinux remains a less-than-ideal option in the era of primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction and has therefore found limited use in this group of patients. It should, however, be considered in patients for whom a conservative strategy is planned, especially if bleeding risk is deemed to be high.

ORAL ANTICOAGULANTS

Oral anticoagulants provide ischemic benefit in selected patients with ACS—at the price of a higher risk of significant bleeding.

Warfarin

Warfarin was investigated after myocardial infarction in the WARIS II,46 CARS,47 and CHAMP48 trials.

WARIS II46 looked at the use of aspirin alone, warfarin alone, and aspirin and warfarin in combination. The rates of the primary end points of stroke, nonfatal infarction, and death were lower in the warfarin group.

CARS47 found no difference in the rate of the primary end point of fatal infarction, nonfatal ischemic stroke, or cardiovascular death with aspirin vs warfarin plus aspirin.

CHAMP48 saw similar trends, ie, no difference in the rate of death, recurrent myocardial infarction, or stroke with warfarin plus aspirin vs aspirin alone.

All three studies showed increases in major bleeding with warfarin use.

Putting these trials into context, the significant net clinical benefit of dual antiplatelet therapy in the current era compared with the significant bleeding and questionable conflicting evidence supporting benefit with warfarin has limited its use in ACS patients.

Rivaroxaban, an oral factor Xa inhibitor

Rivaroxaban is a novel oral direct reversible factor Xa inhibitor.

The ATLAS ACS 2-TIMI 51 trial49 found rivaroxaban 2.5 mg or 5 mg to yield a significantly lower rate of the primary outcome of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and in-stent thrombosis compared with placebo, but significantly more major non-CABG bleeding and intracranial hemorrhage.

The dose used in this trial was much lower than the dose used in trials investigating the role of this drug in stroke prophylaxis in atrial fibrillation.

Apixaban, an oral factor Xa inhibitor

Apixaban is another direct factor Xa inhibitor.

The APPRAISE-2 trial50 compared apixaban 5 mg twice daily vs placebo in ACS. There was no difference in the rate of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke, but there was significantly more bleeding in the apixaban group, prompting early termination of this study.

Dabigatran, an oral thrombin inhibitor

Dabigatran is an oral direct thrombin inhibitor.

The RE-DEEM trial51 compared four doses of dabigatran (50, 75, 110, and 150 mg twice daily) and placebo in ACS patients. The dabigatran groups had more major and minor bleeding, and the higher the dose, the higher the incidence of bleeding. In addition, the rates of ischemic end points were no lower with dabigatran, although this trial was not powered to show differences in clinical events.

REDUCING THE RISK OF BLEEDING

In the treatment of ACS, the benefits of restoring perfusion by preventing further propagation of thrombus and platelet aggregation come at a significant price of higher bleeding risk. This in turn increases the risk of death through various mechanisms, including shock, worsening ischemia, discontinuation of antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapy causing stent thrombosis, and anemia leading to transfusion, which propagates the underlying inflammatory milieu.52

Giugliano and Braunwald53 provide practical suggestions to reduce this risk, advising physicians to:

- Avoid inappropriately high dosing, particularly in patients with renal insufficiency

- Preferentially use agents that cause less bleeding (eg, bivalirudin, fondaparinux) without compromising anti-ischemic efficacy

- Minimize the concomitant use of other drugs that cause bleeding (eg, NSAIDs)

- Use drugs that protect against bleeding (eg, proton pump inhibitors) in patients at high risk

- Prevent access-site bleeding by using the radial artery, smaller sheaths, and appropriate sheath and closure device management. Indeed, the use of radial interventions in ACS has been shown to reduce access-site-related bleeding, even in patients at high risk.54

The reduction in bleeding risk may provide future trials the opportunity to increase antithrombotic efficacy of different agents with goals of reducing ischemic end points.