User login

New Directions in Small-Vessel Vasculitis: ANCA, Target Organs, Treatment, and Beyond

Supplement Editor:

Carol Langford, MD, MHS

Associate Editors:

Leonard Calabrese, DO, and Gary Hoffman, MD

Contents

Diagnosis, ANCA testing, and disease activity

Clinical features and diagnosis of small-vessel vasculitis

Carol Langford, MD, MHS

Controversies in ANCA testing

Ulrich Specks, MD

Defining disease activity and damage in patients with small-vessel vasculitis

Peter A. Merkel, MD, MPH

Impact on individual organs

Upper airway manifestations of granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Daniel S. Alam, MD; Rahul Seth, MD; Raj Sindwani, MD; Erika A. Woodson, MD; and Karthik Rajasekaran, MD

Renal disease in small-vessel vasculitis

Kirsten de Groot, MD

Pulmonary disease in small-vessel vasculitis

Thomas R. Gildea, MD, MS

Ocular manifestations of small-vessel vasculitis

James A. Garrity, MD

Monitoring and safety

Monitoring patients with vasculitis

Alexandra Villa-Forte, MD, MPH

Safety issues in vasculitis: Infections and immunizations in the immunosuppressed host

Carlos M. Isada, MD, FCCP

Treatment considerations

Treating vasculitis with conventional immunosuppressive agents

David Jayne, MD, FRCP

Biologic agents in the treatment of granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Ulrich Specks, MD

Historical perspective

History of vasculitis: The life and work of Adolf Kussmaul

Eric L. Matteson, MD, MPH

Supplement Editor:

Carol Langford, MD, MHS

Associate Editors:

Leonard Calabrese, DO, and Gary Hoffman, MD

Contents

Diagnosis, ANCA testing, and disease activity

Clinical features and diagnosis of small-vessel vasculitis

Carol Langford, MD, MHS

Controversies in ANCA testing

Ulrich Specks, MD

Defining disease activity and damage in patients with small-vessel vasculitis

Peter A. Merkel, MD, MPH

Impact on individual organs

Upper airway manifestations of granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Daniel S. Alam, MD; Rahul Seth, MD; Raj Sindwani, MD; Erika A. Woodson, MD; and Karthik Rajasekaran, MD

Renal disease in small-vessel vasculitis

Kirsten de Groot, MD

Pulmonary disease in small-vessel vasculitis

Thomas R. Gildea, MD, MS

Ocular manifestations of small-vessel vasculitis

James A. Garrity, MD

Monitoring and safety

Monitoring patients with vasculitis

Alexandra Villa-Forte, MD, MPH

Safety issues in vasculitis: Infections and immunizations in the immunosuppressed host

Carlos M. Isada, MD, FCCP

Treatment considerations

Treating vasculitis with conventional immunosuppressive agents

David Jayne, MD, FRCP

Biologic agents in the treatment of granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Ulrich Specks, MD

Historical perspective

History of vasculitis: The life and work of Adolf Kussmaul

Eric L. Matteson, MD, MPH

Supplement Editor:

Carol Langford, MD, MHS

Associate Editors:

Leonard Calabrese, DO, and Gary Hoffman, MD

Contents

Diagnosis, ANCA testing, and disease activity

Clinical features and diagnosis of small-vessel vasculitis

Carol Langford, MD, MHS

Controversies in ANCA testing

Ulrich Specks, MD

Defining disease activity and damage in patients with small-vessel vasculitis

Peter A. Merkel, MD, MPH

Impact on individual organs

Upper airway manifestations of granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Daniel S. Alam, MD; Rahul Seth, MD; Raj Sindwani, MD; Erika A. Woodson, MD; and Karthik Rajasekaran, MD

Renal disease in small-vessel vasculitis

Kirsten de Groot, MD

Pulmonary disease in small-vessel vasculitis

Thomas R. Gildea, MD, MS

Ocular manifestations of small-vessel vasculitis

James A. Garrity, MD

Monitoring and safety

Monitoring patients with vasculitis

Alexandra Villa-Forte, MD, MPH

Safety issues in vasculitis: Infections and immunizations in the immunosuppressed host

Carlos M. Isada, MD, FCCP

Treatment considerations

Treating vasculitis with conventional immunosuppressive agents

David Jayne, MD, FRCP

Biologic agents in the treatment of granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Ulrich Specks, MD

Historical perspective

History of vasculitis: The life and work of Adolf Kussmaul

Eric L. Matteson, MD, MPH

Clinical features and diagnosis of small-vessel vasculitis

Vasculitis refers to inflammation of the blood vessel. This inflammation can cause vessel wall thickening that compromises or occludes the vessel lumen, ultimately resulting in organ ischemia. It also can cause vessel wall attenuation that predisposes to aneurysm formation or breach of the vessel integrity with resultant hemorrhage into the tissue.

Vasculitis can be thought of as a primary or secondary process. Primary vasculitides are unique disease entities without a currently identified underlying cause in which vasculitis forms the pathologic basis of tissue injury. Vasculitis can occur secondary to medication exposure or an underlying illness, including infections, malignancy, cryoglobulinemia, and rheumatic diseases (such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome, or myositis).

Primary vasculitides may differ in epidemiology, such as the age at which they occur and the gender most likely to be affected, their clinical manifestations (including signs, symptoms, and patterns of organ involvement), the diagnostic approach (biopsy, arteriography, and laboratory investigation), treatment (supportive care, glucocorticoids alone, or in combination with other immunosuppressants), and the size of the vessels predominantly affected (large, medium, or small).

Small-vessel vasculitis affects the arteriole, capillary, and venule. An excellent example of small-vessel vasculitis and the one most commonly encountered in clinical practice is cutaneous vasculitis, in which extravasation of erythrocytes from disrupted small vessels is observed histologically, with the clinical sequelae of palpable purpura. Although categorization based on the predominant vessel size that is affected is a helpful way to view these diseases, this is not absolute and each disease has the potential to affect a diverse range of vessels.

This article explores the clinical features and diagnosis of three forms of vasculitis that predominantly affect the small vessels: granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA [Wegener’s granulomatosis]), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), and eosinophilic GPA (Churg-Strauss syndrome, EGPA).

GRANULOMATOSIS WITH POLYANGIITIS

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis is characterized by granulomatous inflammation involving the respiratory tract and by vasculitis affecting small- to medium-sized vessels in which necrotizing glomerulonephritis is common.

Wide range of presentations, manifestations

Approximately 90% of patients with GPA have upper or lower airway involvement or both.1 Upper airway or ear symptoms affect 73% of patients initially and 92% overall.1 Direct inspection of the nasal membranes shows a cobblestoned or ulcerated appearance, and computed tomography reveals mucosal thickening of the sinuses. In some instances, sinus disease can compromise blood supply to the cartilaginous portion of the nasal septum, leading to nasal septum perforations or collapse of the nasal bridge. Another manifestation of upper airway disease and GPA is subglottic stenosis, a narrowing in the subglottic region located just below the vocal cords. The narrowing typically spans about 1 cm and rarely extends or involves the remainder of the trachea.

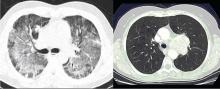

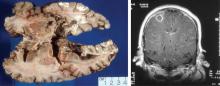

The lungs are involved in 85% of patients.1 Radiographic abnormalities can be diverse and include bilateral pulmonary nodular infiltrates, single or multiple cavities, and bilateral ground glass infiltrates as can be seen in pulmonary hemorrhage (Figure). Bronchoscopy may reveal endobronchial stenosis, and pleural disease can occur rarely.

Approximately 20% of patients with GPA may have glomerulonephritis when they first present for medical attention, but it eventually develops in nearly 80% of patients during the disease course.1 Despite its potential for rapid progression, glomerulonephritis presents a diagnostic challenge because it is asymptomatic. It is detected by evidence of proteinuria and an active urine sediment with dysmorphic red blood cells and red blood cell casts.

Ocular involvement occurs eventually in 52% of patients with GPA.1 Any ocular structure can be affected and ocular involvement can be visually threatening. The more prominent ocular manifestations include scleritis/episcleritis or orbital disease.

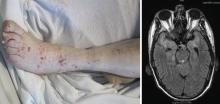

Cutaneous manifestations, observed in 46% of patients, include verrucous-appearing lesions on the elbow and infarctions in the skin and nail folds.1 Other rare manifestations can occur, such as pericarditis and cerebral vasculitis.

Although nearly all patients present with upper or lower airway symptoms, the multisystem nature of GPA explains the wide range of presentations and the varying degrees of disease severity.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis in GPA is varied. Particularly in the setting of isolated lung or sinus disease, infection is foremost in the differential diagnosis. Even in the nonimmunosuppressed host, unusual infections such as mycobacteria, histoplasmosis, and other fungal infections should be considered. Lymphadenopathy, rarely seen in GPA, should raise concern for other causes of disease. Lymphoproliferative processes and other neoplasms, other rheumatic diseases, granulomatous disease (ie, sarcoidosis), and other causes of glomerulonephritis (when present) also merit consideration. Differentiation of these entities from GPA is essential because the treatment differs in many instances.

The differential diagnosis for patients who present with midline destructive lesions must include other causes of collapse of the nasal bridge, nasal septum perforation, and possibly palate destruction. Erosions of the hard palate in particular should raise an immediate red flag for entities other than GPA, such as lymphoproliferative diseases; rare infections, particularly if the patient has studied or worked abroad; and cocaine exposure.

Diagnostic evaluation

A diagnosis of GPA is typically based on the presence of histologic features in a clinically compatible setting. Diagnostic features include necrosis, granulomatous inflammation, vasculitis, and special stains and cultures negative for microorganisms.

Biopsy sites are determined by evidence of clinical disease affecting a target organ and the likelihood of obtaining diagnostically meaningful findings from that site. One challenge is that biopsies are not always diagnostic. The changes tend to be patchy and the likelihood of a positive yield is associated with the amount of tissue that can be obtained. Tissues from the ear, nose, and throat have a yield of about 20%, depending upon the site and the biopsy size. The highest yield comes from radiographically abnormal pulmonary parenchyma. Although transbronchial biopsies are attractive because they are less invasive than open lung biopsy, they are also far less diagnostic, with fewer than 10% having a positive yield. Because cutaneous vasculitis is observed in many settings, its presence is usually insufficient evidence for diagnosis. The renal histologic appearance is a focal, segmental, crescentic, and necrotizing glomerulonephritis that has few to no immune complexes (pauciimmune glomerulonephritis).1–3

Chest imaging should be performed in any patient in whom GPA is part of the differential diagnosis, since up to one-third of patients may be asymptomatic yet have pulmonary radiographic findings.

Laboratory assessment should include serum chemistries to evaluate renal and hepatic function, complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, measurement of C-reactive protein, and urinalysis. If the urinalysis is positive for blood, microscopy should be performed on fresh urine to look for casts. In the setting of pulmonary-renal manifestations, testing for other causes, such as antiglomerular basement antibodies and antinuclear antibodies, should be considered.

Serologic testing for antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) has provided a useful tool in suggesting the diagnosis of GPA. Two forms of ANCA have been identified in patients with vasculitis: ANCA directed against the neutrophil serine protease proteinase-3 (PR3), which results in a cytoplasmic immunofluorescence (cANCA) pattern; and ANCA directed against the neutrophil enzyme myeloperoxidase (MPO), which causes a perinuclear immunofluorescence (pANCA) pattern.4 Approximately 80% to 95% of ANCA found in patients with active severe GPA are detectable PR3-cANCA, while 5% to 20% are MPO-pANCA.5 The predictive value of ANCA for the diagnosis depends on the spectrum of clinical features. As ANCA can be seen in other settings, ANCA as the basis for diagnosis in place of tissue biopsy should be used with caution and only in selected instances where their predictive value would equal that of biopsy. The presence of ANCA is not necessary to establish the diagnosis, as up to 20% of patients with GPA may be ANCA-negative.6

MICROSCOPIC POLYANGIITIS

The history of MPA dates to 1866, with the description of periarteritis nodosa.7 The term “microscopic polyarteritis” was introduced in 1948, when glomerular disease was recognized in some patients.8 In 1994, the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference defined MPA as a necrotizing vasculitis with few or no immune deposits that affects small vessels (ie, capillaries, venules, or arterioles). Necrotizing arteritis of small- and medium-sized arteries may be present. Necrotizing glomerulonephritis and pulmonary capillaritis commonly occur.9 MPA shares many clinical features with GPA and is currently said to be distinguished by the absence of granulomatous inflammation.9

Presentations and manifestations

In one assessment of organ system involvement in 85 patients with MPA, investigators observed glomerular syndrome in 82% of patients.10 They also found a high predilection for involvement of the skin, joints, and lungs. Pulmonary hemorrhage is a particularly important manifestation of MPA because it can be immediately life-threatening.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for MPA is similar to GPA in the inclusion of other causes of classic pulmonary-renal syndromes, such as antiglomerular basement membrane disease and systemic lupus erythematosus. Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis should be considered when the kidney is the predominant organ involved in the absence of lung disease. In the setting of pulmonary infiltrates, infections and neoplasms remain significant in the differential diagnosis.

Diagnostic evaluation

The diagnosis of MPA is based on consistent clinical features and compatible histologic findings. The histologic renal lesion is identical to that seen in GPA. Pulmonary disease typically includes capillaritis and is notable for the absence of evidence of immune deposition, in contrast to antiglomerular basement membrane disease.

Chest imaging is indicated when MPA is part of the differential diagnosis. Computed tomography is the preferred technique, as early alveolar hemorrhage that can occur in MPA may not be visualized on a chest radiograph.

Laboratory assessment should include serum chemistries, complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, measurement of C-reactive protein, and urinalysis. Additional testing should be pursued for other diseases as indicated by the clinical features.

Approximately 40% to 80% of patients with MPA have MPO-pANCA.5 Approximately 15% of patients are MPO-pANCA positive,6 and 0% to 20% are ANCA-negative. As with GPA, ANCA is useful to suggest—but not diagnose—disease in many instances. The absence of ANCA does not rule out MPA.

EOSINOPHILIC GPA

Eosinophilic GPA is a unique entity characterized by eosinophil-rich and granulomatous inflammation involving the respiratory tract and necrotizing vasculitis of small- to medium-size vessels. It is also associated with asthma and eosinophilia.

Different disease phases

Eosinophilic GPA is often thought of as having three phases: prodromal, eosinophilic, and vasculitic.11,12 Although helpful conceptually, these phases may not always be present and may not occur in sequence.

The prodromal phase is characterized by asthma associated with allergic rhinitis with or without polyposis. The eosinophilic phase is characterized by the presence of eosinophilia in the blood and tissue. Eosinophilia is a prominent feature, although accurate detection and assessment can be challenging in the setting of glucocorticoid use for asthma as this normalizes the eosinophil count.

The vasculitic phase distinguishes EGPA from other eosinophilic disorders. Features of vasculitis may occur in multiple organ sites, including the nerves, lungs, heart, gastrointestinal tract, and kidneys. In one series of 96 patients, nearly 100% had asthma, and peripheral nervous system involvement in the form of mononeuritis multiplex was present in 72%.12 Cardiac involvement is of particular importance as it is a prominent cause of disease-related mortality. Cardiac manifestations include myocarditis, pericarditis, endocarditis, valvulitis, and coronary vasculitis.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of EGPA shares similarities with GPA and MPA, but also includes eosino philic disorders such as hypereosinophilic syndrome, eosinophilic leukemia, and parasitic diseases.

Diagnostic evaluation

Diagnosis is often based on the presence of asthma, a finding of peripheral eosinophilia (> 1,500 cells/mm3), and the presence of systemic vasculitis involving, ideally, two or more extrapulmonary organs. While histologic confirmation remains ideal, demonstration of characteristic findings on biopsy can be difficult. Glomerular involvement is far less common than in GPA and MPA, but, when present, the renal lesion is identical. Pulmonary histologic findings can be diverse and include the classic “allergic-granuloma” as originally described by Churg and Strauss, as well as isolated granulomatous inflammation, eosinophilic inflammation, or small-vessel vasculitis. Tissue eosinophilia is a prominent finding that typically is seen on biopsies of skin, nerve, and gastrointestinal tissues.

Chest imaging should be performed when EGPA is part of the differential diagnosis. Because of the potential for cardiac involvement, a baseline echocardiogram should be obtained. Pulmonary function tests may be useful, particularly in patients who have a strong asthmatic component.

Similar to GPA and MPA, laboratory assessment includes serum chemistries, complete blood count with differential to determine the eosinophil count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, measurement of C-reactive protein, and urinalysis. With the allergic and asthmatic components, immunoglobulin E levels are frequently elevated. Additional testing for other eosinophilic diseases should be pursued as indicated by the clinical features.

Only about 40% of patients are ANCA-positive.13 Most of these are MPO-pANCA, with PR3-cANCA occurring less commonly. Although some reports have suggested differing clinical patterns of EGPA based on ANCA positivity, the presence or absence of ANCA is less helpful in the diagnosis.13

DIFFERENTIATION

A key histologic difference between GPA and MPA is the presence of granulomatous inflammation in GPA and its absence in MPA under the current nomenclature system.9 Granulomatous inflammation can be seen in EGPA, but it is usually accompanied by eosinophils, which are less likely to be present in GPA and MPA.

The predominance of the ANCA immunofluorescence pattern and target antigen differs between GPA and MPA, with ANCA positivity occurring in 38% of patients with EGPA.13

SUMMARY

Conceptualizing vasculitic disease based on vessel size can be useful, but it is not an absolute definition. Although GPA, MPA, and EGPA predominantly affect small- to medium-sized vessels, these disease entities are phenotypically unique, with both shared features and differences. Common to all three entities is the potential for organ- and life-threatening manifestations, particularly involving the lungs, kidneys, nerves, gastrointestinal tract, and heart. All three entities need aggressive immuno suppression for severe disease. Recognition of these entities and the distinctions among them can guide the approach to diagnosis, treatment, and future outcomes.

- Hoffman GS, Kerr GS, Leavitt RY, et al Wegener granulomatosis: an analysis of 158 patients. Ann Intern Med 1992; 116:488–498.

- Travis WD, Hoffman GS, Leavitt RY, Pass HI, Fauci AS. Surgical pathology of the lung in Wegener’s granulomatosis: review of 87 open lung biopsies from 67 patients. Am J Surg Pathol 1991; 15:315–333.

- Devaney KO, Travis WD, Hoffman G, Leavitt R, Lebovics R, Fauci AS. Interpretation of head and neck biopsies in Wegener’s granulomatosis: a pathologic study of 126 biopsies in 70 patients. Am J Surg Pathol 1990; 14:555–564.

- Bosch X, Guilabert A, Font J. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Lancet 2006; 368:404–418.

- Hoffman GS, Specks U. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Arthritis Rheum 1998;1521–1537.

- Wiik A. What you should know about PR3-ANCA. An introduction. Arthritis Res 2000; 2:252–254.

- Kussmaul A, Maier R. Über eine bisher nicht beschriebene eigenthümliche Arterienerkrankung (Periarteritis nodosa), die mit Morbus Brightii und rapid fortschreitender allgemeiner Muskellähmung einhergeht. Dtsch Arch Klin Med 1866; 1:484–518.

- Davson J, Ball J, Platt R. The kidney in periarteritis nodosa. Q J Med 1948; 17:175–202.

- Jennette C, Falk RJ, Andrassy K, et al Nomenclature of systemic vasculitides: proposal of an international consensus conference. Arthritis Rheum 1994; 37:187–192.

- Guillevin L, Durand-Gasselin B, Cevallos R, et al Microscopic polyangiitis: clinical and laboratory findings in eighty-five patients. Arthritis Rheum 1999; 42:421–430.

- Keogh KA, Specks U. Churg-Strauss syndrome. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 27:148–157.

- Guillevin L, Cohen P, Gayraud M, Lhote F, Jarrousse B, Casassus P. Churg-Strauss syndrome: clinical study and long-term follow-up of 96 patients. Medicine 1999; 78:26–37.

- Sablé-Fourtassou R, Cohen P, Mahr A, et al., for the French Vasculitis Study Group. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and the Churg-Strauss syndrome. Ann Intern Med 2005; 143:632–638.

Vasculitis refers to inflammation of the blood vessel. This inflammation can cause vessel wall thickening that compromises or occludes the vessel lumen, ultimately resulting in organ ischemia. It also can cause vessel wall attenuation that predisposes to aneurysm formation or breach of the vessel integrity with resultant hemorrhage into the tissue.

Vasculitis can be thought of as a primary or secondary process. Primary vasculitides are unique disease entities without a currently identified underlying cause in which vasculitis forms the pathologic basis of tissue injury. Vasculitis can occur secondary to medication exposure or an underlying illness, including infections, malignancy, cryoglobulinemia, and rheumatic diseases (such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome, or myositis).

Primary vasculitides may differ in epidemiology, such as the age at which they occur and the gender most likely to be affected, their clinical manifestations (including signs, symptoms, and patterns of organ involvement), the diagnostic approach (biopsy, arteriography, and laboratory investigation), treatment (supportive care, glucocorticoids alone, or in combination with other immunosuppressants), and the size of the vessels predominantly affected (large, medium, or small).

Small-vessel vasculitis affects the arteriole, capillary, and venule. An excellent example of small-vessel vasculitis and the one most commonly encountered in clinical practice is cutaneous vasculitis, in which extravasation of erythrocytes from disrupted small vessels is observed histologically, with the clinical sequelae of palpable purpura. Although categorization based on the predominant vessel size that is affected is a helpful way to view these diseases, this is not absolute and each disease has the potential to affect a diverse range of vessels.

This article explores the clinical features and diagnosis of three forms of vasculitis that predominantly affect the small vessels: granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA [Wegener’s granulomatosis]), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), and eosinophilic GPA (Churg-Strauss syndrome, EGPA).

GRANULOMATOSIS WITH POLYANGIITIS

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis is characterized by granulomatous inflammation involving the respiratory tract and by vasculitis affecting small- to medium-sized vessels in which necrotizing glomerulonephritis is common.

Wide range of presentations, manifestations

Approximately 90% of patients with GPA have upper or lower airway involvement or both.1 Upper airway or ear symptoms affect 73% of patients initially and 92% overall.1 Direct inspection of the nasal membranes shows a cobblestoned or ulcerated appearance, and computed tomography reveals mucosal thickening of the sinuses. In some instances, sinus disease can compromise blood supply to the cartilaginous portion of the nasal septum, leading to nasal septum perforations or collapse of the nasal bridge. Another manifestation of upper airway disease and GPA is subglottic stenosis, a narrowing in the subglottic region located just below the vocal cords. The narrowing typically spans about 1 cm and rarely extends or involves the remainder of the trachea.

The lungs are involved in 85% of patients.1 Radiographic abnormalities can be diverse and include bilateral pulmonary nodular infiltrates, single or multiple cavities, and bilateral ground glass infiltrates as can be seen in pulmonary hemorrhage (Figure). Bronchoscopy may reveal endobronchial stenosis, and pleural disease can occur rarely.

Approximately 20% of patients with GPA may have glomerulonephritis when they first present for medical attention, but it eventually develops in nearly 80% of patients during the disease course.1 Despite its potential for rapid progression, glomerulonephritis presents a diagnostic challenge because it is asymptomatic. It is detected by evidence of proteinuria and an active urine sediment with dysmorphic red blood cells and red blood cell casts.

Ocular involvement occurs eventually in 52% of patients with GPA.1 Any ocular structure can be affected and ocular involvement can be visually threatening. The more prominent ocular manifestations include scleritis/episcleritis or orbital disease.

Cutaneous manifestations, observed in 46% of patients, include verrucous-appearing lesions on the elbow and infarctions in the skin and nail folds.1 Other rare manifestations can occur, such as pericarditis and cerebral vasculitis.

Although nearly all patients present with upper or lower airway symptoms, the multisystem nature of GPA explains the wide range of presentations and the varying degrees of disease severity.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis in GPA is varied. Particularly in the setting of isolated lung or sinus disease, infection is foremost in the differential diagnosis. Even in the nonimmunosuppressed host, unusual infections such as mycobacteria, histoplasmosis, and other fungal infections should be considered. Lymphadenopathy, rarely seen in GPA, should raise concern for other causes of disease. Lymphoproliferative processes and other neoplasms, other rheumatic diseases, granulomatous disease (ie, sarcoidosis), and other causes of glomerulonephritis (when present) also merit consideration. Differentiation of these entities from GPA is essential because the treatment differs in many instances.

The differential diagnosis for patients who present with midline destructive lesions must include other causes of collapse of the nasal bridge, nasal septum perforation, and possibly palate destruction. Erosions of the hard palate in particular should raise an immediate red flag for entities other than GPA, such as lymphoproliferative diseases; rare infections, particularly if the patient has studied or worked abroad; and cocaine exposure.

Diagnostic evaluation

A diagnosis of GPA is typically based on the presence of histologic features in a clinically compatible setting. Diagnostic features include necrosis, granulomatous inflammation, vasculitis, and special stains and cultures negative for microorganisms.

Biopsy sites are determined by evidence of clinical disease affecting a target organ and the likelihood of obtaining diagnostically meaningful findings from that site. One challenge is that biopsies are not always diagnostic. The changes tend to be patchy and the likelihood of a positive yield is associated with the amount of tissue that can be obtained. Tissues from the ear, nose, and throat have a yield of about 20%, depending upon the site and the biopsy size. The highest yield comes from radiographically abnormal pulmonary parenchyma. Although transbronchial biopsies are attractive because they are less invasive than open lung biopsy, they are also far less diagnostic, with fewer than 10% having a positive yield. Because cutaneous vasculitis is observed in many settings, its presence is usually insufficient evidence for diagnosis. The renal histologic appearance is a focal, segmental, crescentic, and necrotizing glomerulonephritis that has few to no immune complexes (pauciimmune glomerulonephritis).1–3

Chest imaging should be performed in any patient in whom GPA is part of the differential diagnosis, since up to one-third of patients may be asymptomatic yet have pulmonary radiographic findings.

Laboratory assessment should include serum chemistries to evaluate renal and hepatic function, complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, measurement of C-reactive protein, and urinalysis. If the urinalysis is positive for blood, microscopy should be performed on fresh urine to look for casts. In the setting of pulmonary-renal manifestations, testing for other causes, such as antiglomerular basement antibodies and antinuclear antibodies, should be considered.

Serologic testing for antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) has provided a useful tool in suggesting the diagnosis of GPA. Two forms of ANCA have been identified in patients with vasculitis: ANCA directed against the neutrophil serine protease proteinase-3 (PR3), which results in a cytoplasmic immunofluorescence (cANCA) pattern; and ANCA directed against the neutrophil enzyme myeloperoxidase (MPO), which causes a perinuclear immunofluorescence (pANCA) pattern.4 Approximately 80% to 95% of ANCA found in patients with active severe GPA are detectable PR3-cANCA, while 5% to 20% are MPO-pANCA.5 The predictive value of ANCA for the diagnosis depends on the spectrum of clinical features. As ANCA can be seen in other settings, ANCA as the basis for diagnosis in place of tissue biopsy should be used with caution and only in selected instances where their predictive value would equal that of biopsy. The presence of ANCA is not necessary to establish the diagnosis, as up to 20% of patients with GPA may be ANCA-negative.6

MICROSCOPIC POLYANGIITIS

The history of MPA dates to 1866, with the description of periarteritis nodosa.7 The term “microscopic polyarteritis” was introduced in 1948, when glomerular disease was recognized in some patients.8 In 1994, the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference defined MPA as a necrotizing vasculitis with few or no immune deposits that affects small vessels (ie, capillaries, venules, or arterioles). Necrotizing arteritis of small- and medium-sized arteries may be present. Necrotizing glomerulonephritis and pulmonary capillaritis commonly occur.9 MPA shares many clinical features with GPA and is currently said to be distinguished by the absence of granulomatous inflammation.9

Presentations and manifestations

In one assessment of organ system involvement in 85 patients with MPA, investigators observed glomerular syndrome in 82% of patients.10 They also found a high predilection for involvement of the skin, joints, and lungs. Pulmonary hemorrhage is a particularly important manifestation of MPA because it can be immediately life-threatening.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for MPA is similar to GPA in the inclusion of other causes of classic pulmonary-renal syndromes, such as antiglomerular basement membrane disease and systemic lupus erythematosus. Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis should be considered when the kidney is the predominant organ involved in the absence of lung disease. In the setting of pulmonary infiltrates, infections and neoplasms remain significant in the differential diagnosis.

Diagnostic evaluation

The diagnosis of MPA is based on consistent clinical features and compatible histologic findings. The histologic renal lesion is identical to that seen in GPA. Pulmonary disease typically includes capillaritis and is notable for the absence of evidence of immune deposition, in contrast to antiglomerular basement membrane disease.

Chest imaging is indicated when MPA is part of the differential diagnosis. Computed tomography is the preferred technique, as early alveolar hemorrhage that can occur in MPA may not be visualized on a chest radiograph.

Laboratory assessment should include serum chemistries, complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, measurement of C-reactive protein, and urinalysis. Additional testing should be pursued for other diseases as indicated by the clinical features.

Approximately 40% to 80% of patients with MPA have MPO-pANCA.5 Approximately 15% of patients are MPO-pANCA positive,6 and 0% to 20% are ANCA-negative. As with GPA, ANCA is useful to suggest—but not diagnose—disease in many instances. The absence of ANCA does not rule out MPA.

EOSINOPHILIC GPA

Eosinophilic GPA is a unique entity characterized by eosinophil-rich and granulomatous inflammation involving the respiratory tract and necrotizing vasculitis of small- to medium-size vessels. It is also associated with asthma and eosinophilia.

Different disease phases

Eosinophilic GPA is often thought of as having three phases: prodromal, eosinophilic, and vasculitic.11,12 Although helpful conceptually, these phases may not always be present and may not occur in sequence.

The prodromal phase is characterized by asthma associated with allergic rhinitis with or without polyposis. The eosinophilic phase is characterized by the presence of eosinophilia in the blood and tissue. Eosinophilia is a prominent feature, although accurate detection and assessment can be challenging in the setting of glucocorticoid use for asthma as this normalizes the eosinophil count.

The vasculitic phase distinguishes EGPA from other eosinophilic disorders. Features of vasculitis may occur in multiple organ sites, including the nerves, lungs, heart, gastrointestinal tract, and kidneys. In one series of 96 patients, nearly 100% had asthma, and peripheral nervous system involvement in the form of mononeuritis multiplex was present in 72%.12 Cardiac involvement is of particular importance as it is a prominent cause of disease-related mortality. Cardiac manifestations include myocarditis, pericarditis, endocarditis, valvulitis, and coronary vasculitis.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of EGPA shares similarities with GPA and MPA, but also includes eosino philic disorders such as hypereosinophilic syndrome, eosinophilic leukemia, and parasitic diseases.

Diagnostic evaluation

Diagnosis is often based on the presence of asthma, a finding of peripheral eosinophilia (> 1,500 cells/mm3), and the presence of systemic vasculitis involving, ideally, two or more extrapulmonary organs. While histologic confirmation remains ideal, demonstration of characteristic findings on biopsy can be difficult. Glomerular involvement is far less common than in GPA and MPA, but, when present, the renal lesion is identical. Pulmonary histologic findings can be diverse and include the classic “allergic-granuloma” as originally described by Churg and Strauss, as well as isolated granulomatous inflammation, eosinophilic inflammation, or small-vessel vasculitis. Tissue eosinophilia is a prominent finding that typically is seen on biopsies of skin, nerve, and gastrointestinal tissues.

Chest imaging should be performed when EGPA is part of the differential diagnosis. Because of the potential for cardiac involvement, a baseline echocardiogram should be obtained. Pulmonary function tests may be useful, particularly in patients who have a strong asthmatic component.

Similar to GPA and MPA, laboratory assessment includes serum chemistries, complete blood count with differential to determine the eosinophil count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, measurement of C-reactive protein, and urinalysis. With the allergic and asthmatic components, immunoglobulin E levels are frequently elevated. Additional testing for other eosinophilic diseases should be pursued as indicated by the clinical features.

Only about 40% of patients are ANCA-positive.13 Most of these are MPO-pANCA, with PR3-cANCA occurring less commonly. Although some reports have suggested differing clinical patterns of EGPA based on ANCA positivity, the presence or absence of ANCA is less helpful in the diagnosis.13

DIFFERENTIATION

A key histologic difference between GPA and MPA is the presence of granulomatous inflammation in GPA and its absence in MPA under the current nomenclature system.9 Granulomatous inflammation can be seen in EGPA, but it is usually accompanied by eosinophils, which are less likely to be present in GPA and MPA.

The predominance of the ANCA immunofluorescence pattern and target antigen differs between GPA and MPA, with ANCA positivity occurring in 38% of patients with EGPA.13

SUMMARY

Conceptualizing vasculitic disease based on vessel size can be useful, but it is not an absolute definition. Although GPA, MPA, and EGPA predominantly affect small- to medium-sized vessels, these disease entities are phenotypically unique, with both shared features and differences. Common to all three entities is the potential for organ- and life-threatening manifestations, particularly involving the lungs, kidneys, nerves, gastrointestinal tract, and heart. All three entities need aggressive immuno suppression for severe disease. Recognition of these entities and the distinctions among them can guide the approach to diagnosis, treatment, and future outcomes.

Vasculitis refers to inflammation of the blood vessel. This inflammation can cause vessel wall thickening that compromises or occludes the vessel lumen, ultimately resulting in organ ischemia. It also can cause vessel wall attenuation that predisposes to aneurysm formation or breach of the vessel integrity with resultant hemorrhage into the tissue.

Vasculitis can be thought of as a primary or secondary process. Primary vasculitides are unique disease entities without a currently identified underlying cause in which vasculitis forms the pathologic basis of tissue injury. Vasculitis can occur secondary to medication exposure or an underlying illness, including infections, malignancy, cryoglobulinemia, and rheumatic diseases (such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome, or myositis).

Primary vasculitides may differ in epidemiology, such as the age at which they occur and the gender most likely to be affected, their clinical manifestations (including signs, symptoms, and patterns of organ involvement), the diagnostic approach (biopsy, arteriography, and laboratory investigation), treatment (supportive care, glucocorticoids alone, or in combination with other immunosuppressants), and the size of the vessels predominantly affected (large, medium, or small).

Small-vessel vasculitis affects the arteriole, capillary, and venule. An excellent example of small-vessel vasculitis and the one most commonly encountered in clinical practice is cutaneous vasculitis, in which extravasation of erythrocytes from disrupted small vessels is observed histologically, with the clinical sequelae of palpable purpura. Although categorization based on the predominant vessel size that is affected is a helpful way to view these diseases, this is not absolute and each disease has the potential to affect a diverse range of vessels.

This article explores the clinical features and diagnosis of three forms of vasculitis that predominantly affect the small vessels: granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA [Wegener’s granulomatosis]), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), and eosinophilic GPA (Churg-Strauss syndrome, EGPA).

GRANULOMATOSIS WITH POLYANGIITIS

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis is characterized by granulomatous inflammation involving the respiratory tract and by vasculitis affecting small- to medium-sized vessels in which necrotizing glomerulonephritis is common.

Wide range of presentations, manifestations

Approximately 90% of patients with GPA have upper or lower airway involvement or both.1 Upper airway or ear symptoms affect 73% of patients initially and 92% overall.1 Direct inspection of the nasal membranes shows a cobblestoned or ulcerated appearance, and computed tomography reveals mucosal thickening of the sinuses. In some instances, sinus disease can compromise blood supply to the cartilaginous portion of the nasal septum, leading to nasal septum perforations or collapse of the nasal bridge. Another manifestation of upper airway disease and GPA is subglottic stenosis, a narrowing in the subglottic region located just below the vocal cords. The narrowing typically spans about 1 cm and rarely extends or involves the remainder of the trachea.

The lungs are involved in 85% of patients.1 Radiographic abnormalities can be diverse and include bilateral pulmonary nodular infiltrates, single or multiple cavities, and bilateral ground glass infiltrates as can be seen in pulmonary hemorrhage (Figure). Bronchoscopy may reveal endobronchial stenosis, and pleural disease can occur rarely.

Approximately 20% of patients with GPA may have glomerulonephritis when they first present for medical attention, but it eventually develops in nearly 80% of patients during the disease course.1 Despite its potential for rapid progression, glomerulonephritis presents a diagnostic challenge because it is asymptomatic. It is detected by evidence of proteinuria and an active urine sediment with dysmorphic red blood cells and red blood cell casts.

Ocular involvement occurs eventually in 52% of patients with GPA.1 Any ocular structure can be affected and ocular involvement can be visually threatening. The more prominent ocular manifestations include scleritis/episcleritis or orbital disease.

Cutaneous manifestations, observed in 46% of patients, include verrucous-appearing lesions on the elbow and infarctions in the skin and nail folds.1 Other rare manifestations can occur, such as pericarditis and cerebral vasculitis.

Although nearly all patients present with upper or lower airway symptoms, the multisystem nature of GPA explains the wide range of presentations and the varying degrees of disease severity.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis in GPA is varied. Particularly in the setting of isolated lung or sinus disease, infection is foremost in the differential diagnosis. Even in the nonimmunosuppressed host, unusual infections such as mycobacteria, histoplasmosis, and other fungal infections should be considered. Lymphadenopathy, rarely seen in GPA, should raise concern for other causes of disease. Lymphoproliferative processes and other neoplasms, other rheumatic diseases, granulomatous disease (ie, sarcoidosis), and other causes of glomerulonephritis (when present) also merit consideration. Differentiation of these entities from GPA is essential because the treatment differs in many instances.

The differential diagnosis for patients who present with midline destructive lesions must include other causes of collapse of the nasal bridge, nasal septum perforation, and possibly palate destruction. Erosions of the hard palate in particular should raise an immediate red flag for entities other than GPA, such as lymphoproliferative diseases; rare infections, particularly if the patient has studied or worked abroad; and cocaine exposure.

Diagnostic evaluation

A diagnosis of GPA is typically based on the presence of histologic features in a clinically compatible setting. Diagnostic features include necrosis, granulomatous inflammation, vasculitis, and special stains and cultures negative for microorganisms.

Biopsy sites are determined by evidence of clinical disease affecting a target organ and the likelihood of obtaining diagnostically meaningful findings from that site. One challenge is that biopsies are not always diagnostic. The changes tend to be patchy and the likelihood of a positive yield is associated with the amount of tissue that can be obtained. Tissues from the ear, nose, and throat have a yield of about 20%, depending upon the site and the biopsy size. The highest yield comes from radiographically abnormal pulmonary parenchyma. Although transbronchial biopsies are attractive because they are less invasive than open lung biopsy, they are also far less diagnostic, with fewer than 10% having a positive yield. Because cutaneous vasculitis is observed in many settings, its presence is usually insufficient evidence for diagnosis. The renal histologic appearance is a focal, segmental, crescentic, and necrotizing glomerulonephritis that has few to no immune complexes (pauciimmune glomerulonephritis).1–3

Chest imaging should be performed in any patient in whom GPA is part of the differential diagnosis, since up to one-third of patients may be asymptomatic yet have pulmonary radiographic findings.

Laboratory assessment should include serum chemistries to evaluate renal and hepatic function, complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, measurement of C-reactive protein, and urinalysis. If the urinalysis is positive for blood, microscopy should be performed on fresh urine to look for casts. In the setting of pulmonary-renal manifestations, testing for other causes, such as antiglomerular basement antibodies and antinuclear antibodies, should be considered.

Serologic testing for antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) has provided a useful tool in suggesting the diagnosis of GPA. Two forms of ANCA have been identified in patients with vasculitis: ANCA directed against the neutrophil serine protease proteinase-3 (PR3), which results in a cytoplasmic immunofluorescence (cANCA) pattern; and ANCA directed against the neutrophil enzyme myeloperoxidase (MPO), which causes a perinuclear immunofluorescence (pANCA) pattern.4 Approximately 80% to 95% of ANCA found in patients with active severe GPA are detectable PR3-cANCA, while 5% to 20% are MPO-pANCA.5 The predictive value of ANCA for the diagnosis depends on the spectrum of clinical features. As ANCA can be seen in other settings, ANCA as the basis for diagnosis in place of tissue biopsy should be used with caution and only in selected instances where their predictive value would equal that of biopsy. The presence of ANCA is not necessary to establish the diagnosis, as up to 20% of patients with GPA may be ANCA-negative.6

MICROSCOPIC POLYANGIITIS

The history of MPA dates to 1866, with the description of periarteritis nodosa.7 The term “microscopic polyarteritis” was introduced in 1948, when glomerular disease was recognized in some patients.8 In 1994, the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference defined MPA as a necrotizing vasculitis with few or no immune deposits that affects small vessels (ie, capillaries, venules, or arterioles). Necrotizing arteritis of small- and medium-sized arteries may be present. Necrotizing glomerulonephritis and pulmonary capillaritis commonly occur.9 MPA shares many clinical features with GPA and is currently said to be distinguished by the absence of granulomatous inflammation.9

Presentations and manifestations

In one assessment of organ system involvement in 85 patients with MPA, investigators observed glomerular syndrome in 82% of patients.10 They also found a high predilection for involvement of the skin, joints, and lungs. Pulmonary hemorrhage is a particularly important manifestation of MPA because it can be immediately life-threatening.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for MPA is similar to GPA in the inclusion of other causes of classic pulmonary-renal syndromes, such as antiglomerular basement membrane disease and systemic lupus erythematosus. Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis should be considered when the kidney is the predominant organ involved in the absence of lung disease. In the setting of pulmonary infiltrates, infections and neoplasms remain significant in the differential diagnosis.

Diagnostic evaluation

The diagnosis of MPA is based on consistent clinical features and compatible histologic findings. The histologic renal lesion is identical to that seen in GPA. Pulmonary disease typically includes capillaritis and is notable for the absence of evidence of immune deposition, in contrast to antiglomerular basement membrane disease.

Chest imaging is indicated when MPA is part of the differential diagnosis. Computed tomography is the preferred technique, as early alveolar hemorrhage that can occur in MPA may not be visualized on a chest radiograph.

Laboratory assessment should include serum chemistries, complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, measurement of C-reactive protein, and urinalysis. Additional testing should be pursued for other diseases as indicated by the clinical features.

Approximately 40% to 80% of patients with MPA have MPO-pANCA.5 Approximately 15% of patients are MPO-pANCA positive,6 and 0% to 20% are ANCA-negative. As with GPA, ANCA is useful to suggest—but not diagnose—disease in many instances. The absence of ANCA does not rule out MPA.

EOSINOPHILIC GPA

Eosinophilic GPA is a unique entity characterized by eosinophil-rich and granulomatous inflammation involving the respiratory tract and necrotizing vasculitis of small- to medium-size vessels. It is also associated with asthma and eosinophilia.

Different disease phases

Eosinophilic GPA is often thought of as having three phases: prodromal, eosinophilic, and vasculitic.11,12 Although helpful conceptually, these phases may not always be present and may not occur in sequence.

The prodromal phase is characterized by asthma associated with allergic rhinitis with or without polyposis. The eosinophilic phase is characterized by the presence of eosinophilia in the blood and tissue. Eosinophilia is a prominent feature, although accurate detection and assessment can be challenging in the setting of glucocorticoid use for asthma as this normalizes the eosinophil count.

The vasculitic phase distinguishes EGPA from other eosinophilic disorders. Features of vasculitis may occur in multiple organ sites, including the nerves, lungs, heart, gastrointestinal tract, and kidneys. In one series of 96 patients, nearly 100% had asthma, and peripheral nervous system involvement in the form of mononeuritis multiplex was present in 72%.12 Cardiac involvement is of particular importance as it is a prominent cause of disease-related mortality. Cardiac manifestations include myocarditis, pericarditis, endocarditis, valvulitis, and coronary vasculitis.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of EGPA shares similarities with GPA and MPA, but also includes eosino philic disorders such as hypereosinophilic syndrome, eosinophilic leukemia, and parasitic diseases.

Diagnostic evaluation

Diagnosis is often based on the presence of asthma, a finding of peripheral eosinophilia (> 1,500 cells/mm3), and the presence of systemic vasculitis involving, ideally, two or more extrapulmonary organs. While histologic confirmation remains ideal, demonstration of characteristic findings on biopsy can be difficult. Glomerular involvement is far less common than in GPA and MPA, but, when present, the renal lesion is identical. Pulmonary histologic findings can be diverse and include the classic “allergic-granuloma” as originally described by Churg and Strauss, as well as isolated granulomatous inflammation, eosinophilic inflammation, or small-vessel vasculitis. Tissue eosinophilia is a prominent finding that typically is seen on biopsies of skin, nerve, and gastrointestinal tissues.

Chest imaging should be performed when EGPA is part of the differential diagnosis. Because of the potential for cardiac involvement, a baseline echocardiogram should be obtained. Pulmonary function tests may be useful, particularly in patients who have a strong asthmatic component.

Similar to GPA and MPA, laboratory assessment includes serum chemistries, complete blood count with differential to determine the eosinophil count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, measurement of C-reactive protein, and urinalysis. With the allergic and asthmatic components, immunoglobulin E levels are frequently elevated. Additional testing for other eosinophilic diseases should be pursued as indicated by the clinical features.

Only about 40% of patients are ANCA-positive.13 Most of these are MPO-pANCA, with PR3-cANCA occurring less commonly. Although some reports have suggested differing clinical patterns of EGPA based on ANCA positivity, the presence or absence of ANCA is less helpful in the diagnosis.13

DIFFERENTIATION

A key histologic difference between GPA and MPA is the presence of granulomatous inflammation in GPA and its absence in MPA under the current nomenclature system.9 Granulomatous inflammation can be seen in EGPA, but it is usually accompanied by eosinophils, which are less likely to be present in GPA and MPA.

The predominance of the ANCA immunofluorescence pattern and target antigen differs between GPA and MPA, with ANCA positivity occurring in 38% of patients with EGPA.13

SUMMARY

Conceptualizing vasculitic disease based on vessel size can be useful, but it is not an absolute definition. Although GPA, MPA, and EGPA predominantly affect small- to medium-sized vessels, these disease entities are phenotypically unique, with both shared features and differences. Common to all three entities is the potential for organ- and life-threatening manifestations, particularly involving the lungs, kidneys, nerves, gastrointestinal tract, and heart. All three entities need aggressive immuno suppression for severe disease. Recognition of these entities and the distinctions among them can guide the approach to diagnosis, treatment, and future outcomes.

- Hoffman GS, Kerr GS, Leavitt RY, et al Wegener granulomatosis: an analysis of 158 patients. Ann Intern Med 1992; 116:488–498.

- Travis WD, Hoffman GS, Leavitt RY, Pass HI, Fauci AS. Surgical pathology of the lung in Wegener’s granulomatosis: review of 87 open lung biopsies from 67 patients. Am J Surg Pathol 1991; 15:315–333.

- Devaney KO, Travis WD, Hoffman G, Leavitt R, Lebovics R, Fauci AS. Interpretation of head and neck biopsies in Wegener’s granulomatosis: a pathologic study of 126 biopsies in 70 patients. Am J Surg Pathol 1990; 14:555–564.

- Bosch X, Guilabert A, Font J. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Lancet 2006; 368:404–418.

- Hoffman GS, Specks U. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Arthritis Rheum 1998;1521–1537.

- Wiik A. What you should know about PR3-ANCA. An introduction. Arthritis Res 2000; 2:252–254.

- Kussmaul A, Maier R. Über eine bisher nicht beschriebene eigenthümliche Arterienerkrankung (Periarteritis nodosa), die mit Morbus Brightii und rapid fortschreitender allgemeiner Muskellähmung einhergeht. Dtsch Arch Klin Med 1866; 1:484–518.

- Davson J, Ball J, Platt R. The kidney in periarteritis nodosa. Q J Med 1948; 17:175–202.

- Jennette C, Falk RJ, Andrassy K, et al Nomenclature of systemic vasculitides: proposal of an international consensus conference. Arthritis Rheum 1994; 37:187–192.

- Guillevin L, Durand-Gasselin B, Cevallos R, et al Microscopic polyangiitis: clinical and laboratory findings in eighty-five patients. Arthritis Rheum 1999; 42:421–430.

- Keogh KA, Specks U. Churg-Strauss syndrome. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 27:148–157.

- Guillevin L, Cohen P, Gayraud M, Lhote F, Jarrousse B, Casassus P. Churg-Strauss syndrome: clinical study and long-term follow-up of 96 patients. Medicine 1999; 78:26–37.

- Sablé-Fourtassou R, Cohen P, Mahr A, et al., for the French Vasculitis Study Group. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and the Churg-Strauss syndrome. Ann Intern Med 2005; 143:632–638.

- Hoffman GS, Kerr GS, Leavitt RY, et al Wegener granulomatosis: an analysis of 158 patients. Ann Intern Med 1992; 116:488–498.

- Travis WD, Hoffman GS, Leavitt RY, Pass HI, Fauci AS. Surgical pathology of the lung in Wegener’s granulomatosis: review of 87 open lung biopsies from 67 patients. Am J Surg Pathol 1991; 15:315–333.

- Devaney KO, Travis WD, Hoffman G, Leavitt R, Lebovics R, Fauci AS. Interpretation of head and neck biopsies in Wegener’s granulomatosis: a pathologic study of 126 biopsies in 70 patients. Am J Surg Pathol 1990; 14:555–564.

- Bosch X, Guilabert A, Font J. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Lancet 2006; 368:404–418.

- Hoffman GS, Specks U. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Arthritis Rheum 1998;1521–1537.

- Wiik A. What you should know about PR3-ANCA. An introduction. Arthritis Res 2000; 2:252–254.

- Kussmaul A, Maier R. Über eine bisher nicht beschriebene eigenthümliche Arterienerkrankung (Periarteritis nodosa), die mit Morbus Brightii und rapid fortschreitender allgemeiner Muskellähmung einhergeht. Dtsch Arch Klin Med 1866; 1:484–518.

- Davson J, Ball J, Platt R. The kidney in periarteritis nodosa. Q J Med 1948; 17:175–202.

- Jennette C, Falk RJ, Andrassy K, et al Nomenclature of systemic vasculitides: proposal of an international consensus conference. Arthritis Rheum 1994; 37:187–192.

- Guillevin L, Durand-Gasselin B, Cevallos R, et al Microscopic polyangiitis: clinical and laboratory findings in eighty-five patients. Arthritis Rheum 1999; 42:421–430.

- Keogh KA, Specks U. Churg-Strauss syndrome. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 27:148–157.

- Guillevin L, Cohen P, Gayraud M, Lhote F, Jarrousse B, Casassus P. Churg-Strauss syndrome: clinical study and long-term follow-up of 96 patients. Medicine 1999; 78:26–37.

- Sablé-Fourtassou R, Cohen P, Mahr A, et al., for the French Vasculitis Study Group. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and the Churg-Strauss syndrome. Ann Intern Med 2005; 143:632–638.

Controversies in ANCA testing

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) detection is a valuable tool for diagnosing small-vessel vasculitis,1 but measuring and interpreting ANCA levels is an inexact science. There is no single perfect ANCA test, and even a perfect test would not provide definitive clinical answers. The diagnostic utility of ANCA testing depends on the methodologic accuracy of the test and the appropriate ordering of testing in the right clinical setting. This article examines three important questions about this technology:

- What is the best ANCA test methodology?

- What is the prognostic value of serial ANCA testing?

- What is the clinical implication of ANCA type?

WHAT IS THE BEST ANCA TEST METHODOLOGY?

The diagnostic utility of ANCA testing depends on both the methodologic accuracy of the test and the appropriate ordering of tests. Methodologic accuracy comprises the analytic sensitivity and specificity of the test. Analytic sensitivity refers to the accurate identification of the presence of ANCA, and analytic specificity refers to measurement of only the entity in question (ANCA), not confounded by the presence of other entities (antibodies).

Equally as important as analytic accuracy is the appropriate ordering of the tests in the right clinical setting. Using a test that is sensitive to the presence of a specific ANCA type accurately identifies the presence of either proteinase-3 (PR3)- or myeloperoxidase (MPO)-ANCA. Once obtained, test results must be evaluated in terms of their relationship to the diagnosis being considered. If the tests are deemed diagnostically useful based on the results, the data can be used to assess the positive and negative predictive value of the tests.

Immunofluorescence or antigen-specific testing—or both?

A definitive diagnosis is more likely if an immunofluorescence staining pattern of cANCA is paired with the antigen specificity of PR3-ANCA, for example, or a perinuclear immunofluorescence pattern (pANCA) is paired with a positive MPO-ANCA. When positive test pairings have been obtained and the patient’s antigen ANCA reactivity is known, subsequent serial ANCA testing with an antigen-specific assay alone may be indicated, because the ANCA types of patients with vasculitis are unlikely to switch between PR3 and MPO during the course of their disease. If matching pairings are not obtained, the diagnostic utility of the tests remains unconfirmed.

Antigen type (PR3 or MPO) is determined through antigen-specific methods that include solid-phase assays and other methods of bringing the specific antigen in contact with the specific antibody in question. There are two categories of solid-phase assays: the enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assay (ELISA) and the capture ELISA. In the ELISA methodology, the antigen is directly coated to a plastic plate; in the capture ELISA, an anchor, usually a monoclonal antibody or combination of antibodies, captures the target antigen on the plate. In both ELISA and capture ELISA assays, ANCA contained in the serum sample subjected to testing bind to the immobilized antigen. The amount of ANCA bound to the antigen can then be detected by a secondary antibody that is conjugated with an enzyme that can elicit a color reaction. The intensity of the color reaction is proportional to the amount of ANCA bound to the immobilized antigen.

The ELISA methodology tends to trade off analytic sensitivity for specificity, since the antigen purification process (which allows the ELISA system to increase its specificity) can cause conformational changes to the antigen being bound to the plate. This, in turn, causes a loss of some recognition of the conformationally sensitive ANCA.

In capture ELISA, a specific antibody captures the antigen; this stabilizes the conformation, boosts the analytic sensitivity, and allows a gentler purification process because it only captures the antigen in question and then binds it to the plate. This process decreases false-positive test results caused by residual contaminants in the antigen preparation. Analytic sensitivity issues may come into play if the anchoring monoclonal antibody competes for the epitope on the antigen being recognized by the serum antibody in question (ANCA), causing occasional false-negative results.

Another method now applied to commercial ANCA testing involves bead-based multiplex assays. These assays are based on principles similar to the ELISA or capture ELISA methods. In multiplex microsphere technology, the purified antigen is bound to a polystyrene microsphere instead of a plate. The microsphere is then presented to the antibody in question. The bead is then introduced to a secondary antibody labeled with a fluorescent marker (instead of an enzyme) for detection of the antibody. One advantage of this system is that various beads containing different antigens can be introduced to the same serum sample, and then different color reactions can be measured for each bead. Because only one antigen is bound to each microsphere (eg, PR3-ANCA, MPOANCA or other specific autoantibodies), only specific antibodies will react to each bead of a specific color. If there is no MPO antibody in the sample, there will be no reaction against the MPO antigen bead; however, if PR3-ANCA is present in the sample, it would react with the PR3 antigen beads. Using this methodology, a single serum sample can be tested for a multitude of autoantibodies at the same time (see “Interpreting ANCA results: Accurate tests, appropriate orders,”2–10 above).

WHAT IS THE PROGNOSTIC VALUE OF SERIAL ANCA TESTING?

Persistent changes in ANCA levels in relapsing disease may have some value in predicting outcome. The issues to consider include the methodology used to determine serial ANCA levels, correlations between ANCA and disease activity, and the use of ANCA changes to guide treatment.

Does methodology matter when determining serial ANCA levels?

Methodology in serial ANCA testing is probably unimportant as long as the same method is used serially. Analysis of large groups of ANCA-positive patients show a statistically highly significant correlation among results obtained with different detection methods, including immunofluorescence, direct ELISA, or capture ELISA. However, at the individual patient level there is some variability.

Do ANCA levels correlate with disease activity?

In a prospective study, serial ANCA samples obtained during the Wegener’s Granulomatosis Etanercept Trial (WGET)11 were processed in the same manner (collected every 3 months, mean follow-up of 22 months, uniform handling of samples). All samples were analyzed by capture ELISA, and disease activity was measured by the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score for Wegener’s Granulomatosis (BVAS/WG). The results indicated that an increase in PR3-ANCA levels was not a significant predictor of relapse. The frequency of a relapse within 1 year of an increase in PR3-ANCA levels was found to be approximately 50%,11 a result similar to that reported in several smaller studies of different design and methodology.

Should ANCA changes guide treatment?

The available data regarding serial ANCA testing are limited mostly to PR3-ANCA. Serial ANCA testing has limited value as a guide to treatment and, in general, changes in ANCA levels alone should not be used to guide treatment decisions. In new patients without documented serial ANCA level associations, an increase in PR3-ANCA levels has no reliable predictive value. The existing literature suggests that this lack of association is not dependent on the method used for ANCA detection. For individual patients in whom long-term serial ANCA testing has been performed and a relationship between PR3-ANCA levels and disease activity has been established, serial ANCA testing can have some predictive value and can be used to guide treatment. For example, when remission is achieved by depleting B cells in patients with chronically relapsing GPA, ANCA levels usually go down. After B-cell reconstitution, the ANCA level rises in most patients, and this rise is usually associated with a flare shortly thereafter. A flare can be preempted when this pattern is determined in a specific patient, and preemptive treatment is applied accordingly.12

WHAT IS THE IMPLICATION OF ANCA TYPE?

Available reports consistently suggest that PR3-ANCA is associated with a higher mortality than MPO-ANCA (relative risk [RR], 3.78),13 and a higher relapse rate.14,15 A more rapid loss of renal function among patients with glomerulonephritis and PR3-ANCA than those with MPO-ANCA has also been reported.16 Using remission as the starting point, the number of days from complete remission to first disease flare was plotted for patients with MPO- versus PR3-ANCA in an analysis of long-term data from the Rituximab in ANCA-Associated Vasculitis (RAVE) trial.17 The resulting curve demonstrated a divergence in the probability of remaining in remission, confirming that remission maintenance is clearly greater in patients with MPO-ANCA than in patients with PR3-ANCA.

The primary end point of the RAVE trial was remission of disease without the use of prednisone at 6 months. There was little difference in end point achieved based on comparison of diagnosis (microscopic polyangiitis or granulomatosis) or treatment arms (rituximab versus cyclophosphamide); however, an analysis of end point data separating the patients by ANCA type showed that the treatment response to rituximab was superior to that of cyclophosphamide among patients with PR3-ANCA, whereas in patients with MPO-ANCA, there was little difference in response associated with either treatment. Regarding the likelihood of attaining an ANCA-negative status after 6 months, again MPO-ANCA patients showed no difference in frequency on either treatment. Among PR3-ANCA–positive patients, 50% in the rituximab arm attained ANCA-negative status compared with only 17% in the cyclophosphamide arm.17

SUMMARY

Diagnostic utility of ANCA testing depends on the methodology and clinical setting. Only cANCA/PR3-ANCA and pANCA/MPO-ANCA pairings have positive predictive value for diagnosis of small-vessel vasculitis. Mismatches in results, findings of human neutrophil elastase–ANCA, or identification of multiple positive antigens should be considered in cases of cocaine or drug use.

The clinical utility of serial ANCA testing is unconfirmed. Good data currently exist only for PR3-ANCA, and different drugs may affect ANCA levels in different ways. ANCA type is significant in that PR3-ANCA portends a higher relapse rate and poorer patient outcomes compared with MPO-ANCA.

- Russell KA, Wiegert E, Schroeder DR, Homburger HA, Specks U. Detection of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies under actual clinical testing conditions. Clin Immunol 2002; 103:196–203.

- Langford CA. The diagnostic utility of c-ANCA in Wegener’s granulomatosis. Cleve Clin J Med 1998; 65:135–140.

- Trimarchi M, Gregorini G, Facchetti F, et al. Cocaine-induced midline destructive lesions: clinical, radiographic, histopathologic, and serologic features and their differentiation from Wegener granulomatosis. Medicine 2001; 80:391–404.

- Wiesner O, Russell KA, Lee AS, et al. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies reacting with human neutrophil elastase as a diagnostic marker for cocaine-induced midline destructive lesions but not autoimmune vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50:2954–2965.

- Peikert T, Finkielman JD, Hummel AM, et al. Functional characterization of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in patients with cocaine-induced midline destructive lesions. Arthritis Rheum 2008; 58:1546–1551.

- Knowles L, Buxton JA, Skuridina N, et al. Levamisole tainted cocaine causing severe neutropenia in Alberta and British Columbia. Harm Reduct J 2009; 6 (Nov 17):30. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-6-30.

- Zhu NY, LeGatt DF, Turner AR. Agranulocytosis after consumption of cocaine adulterated with levamisole. Ann Intern Med 2009; 150:287–289.

- Bradford M, Rosenberg B, Moreno J, Dumyati G. Bilateral necrosis of earlobes and cheeks: another complication of cocaine contaminated with levamisole. Ann Intern Med 2010; 152:758–759.

- Waller JM, Feramisco JD, Alberta-Wszolek L, McCalmont TH, Fox LP. Cocaine-associated retiform purpura and neutropenia: is levamisole the culprit [published online ahead of print March 20, 2010]? J Am Acad Dermatol 2010; 63:530–535. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.01.055

- Chang A, Osterloh J, Thomas J. Levamisole: a dangerous new cocaine adulterant [published online ahead of print July 28, 2010]. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2010; 88:408–411. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.156

- Finkielman JD, Merkel PA, Schroeder D, et al. Antiproteinase 3 antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and disease activity in Wegener granulomatosis. Ann Intern Med 2007; 147:611–619.

- Cartin-Ceba R, Golbin J, Keogh KA, et al. Rituximab for remission induction and maintenance in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s): a single-center ten-year experience [published online ahead of print June 21, 2012]. Arthritis Rheum. doi: 10.1002/art.34584

- Hogan SL, Nachman PH, Wilkman AS, Jennette JC, Falk RJ; the Glomerular Disease Collaborative Network. Prognostic markers in patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-associated microscopic polyangiitis and glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 1996; 7:23–32.

- Booth AD, Almond MK, Burns A, et al. Outcome of ANCA-associated renal vasculitis: a 5-year retrospective study. Am J Kidney Dis 2003; 41:776–784.

- Jayne D, Rasmussen N, Andrassy K, et al. A randomized trial of maintenance therapy for vasculitis associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies. N Engl J Med 2003; 349:36–44.

- Franssen CFM, Gans ROB, Arends B, et al. Differences between anti-myeloperoxidase- and anti-proteinase 3-associated renal disease. Kidney Int 1995; 47:193–199.

- Stone JH, Merkel PA, Spiera R, et al; for the RAVE–ITN Research Group. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:221–232.

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) detection is a valuable tool for diagnosing small-vessel vasculitis,1 but measuring and interpreting ANCA levels is an inexact science. There is no single perfect ANCA test, and even a perfect test would not provide definitive clinical answers. The diagnostic utility of ANCA testing depends on the methodologic accuracy of the test and the appropriate ordering of testing in the right clinical setting. This article examines three important questions about this technology:

- What is the best ANCA test methodology?

- What is the prognostic value of serial ANCA testing?

- What is the clinical implication of ANCA type?

WHAT IS THE BEST ANCA TEST METHODOLOGY?

The diagnostic utility of ANCA testing depends on both the methodologic accuracy of the test and the appropriate ordering of tests. Methodologic accuracy comprises the analytic sensitivity and specificity of the test. Analytic sensitivity refers to the accurate identification of the presence of ANCA, and analytic specificity refers to measurement of only the entity in question (ANCA), not confounded by the presence of other entities (antibodies).

Equally as important as analytic accuracy is the appropriate ordering of the tests in the right clinical setting. Using a test that is sensitive to the presence of a specific ANCA type accurately identifies the presence of either proteinase-3 (PR3)- or myeloperoxidase (MPO)-ANCA. Once obtained, test results must be evaluated in terms of their relationship to the diagnosis being considered. If the tests are deemed diagnostically useful based on the results, the data can be used to assess the positive and negative predictive value of the tests.

Immunofluorescence or antigen-specific testing—or both?

A definitive diagnosis is more likely if an immunofluorescence staining pattern of cANCA is paired with the antigen specificity of PR3-ANCA, for example, or a perinuclear immunofluorescence pattern (pANCA) is paired with a positive MPO-ANCA. When positive test pairings have been obtained and the patient’s antigen ANCA reactivity is known, subsequent serial ANCA testing with an antigen-specific assay alone may be indicated, because the ANCA types of patients with vasculitis are unlikely to switch between PR3 and MPO during the course of their disease. If matching pairings are not obtained, the diagnostic utility of the tests remains unconfirmed.

Antigen type (PR3 or MPO) is determined through antigen-specific methods that include solid-phase assays and other methods of bringing the specific antigen in contact with the specific antibody in question. There are two categories of solid-phase assays: the enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assay (ELISA) and the capture ELISA. In the ELISA methodology, the antigen is directly coated to a plastic plate; in the capture ELISA, an anchor, usually a monoclonal antibody or combination of antibodies, captures the target antigen on the plate. In both ELISA and capture ELISA assays, ANCA contained in the serum sample subjected to testing bind to the immobilized antigen. The amount of ANCA bound to the antigen can then be detected by a secondary antibody that is conjugated with an enzyme that can elicit a color reaction. The intensity of the color reaction is proportional to the amount of ANCA bound to the immobilized antigen.

The ELISA methodology tends to trade off analytic sensitivity for specificity, since the antigen purification process (which allows the ELISA system to increase its specificity) can cause conformational changes to the antigen being bound to the plate. This, in turn, causes a loss of some recognition of the conformationally sensitive ANCA.

In capture ELISA, a specific antibody captures the antigen; this stabilizes the conformation, boosts the analytic sensitivity, and allows a gentler purification process because it only captures the antigen in question and then binds it to the plate. This process decreases false-positive test results caused by residual contaminants in the antigen preparation. Analytic sensitivity issues may come into play if the anchoring monoclonal antibody competes for the epitope on the antigen being recognized by the serum antibody in question (ANCA), causing occasional false-negative results.

Another method now applied to commercial ANCA testing involves bead-based multiplex assays. These assays are based on principles similar to the ELISA or capture ELISA methods. In multiplex microsphere technology, the purified antigen is bound to a polystyrene microsphere instead of a plate. The microsphere is then presented to the antibody in question. The bead is then introduced to a secondary antibody labeled with a fluorescent marker (instead of an enzyme) for detection of the antibody. One advantage of this system is that various beads containing different antigens can be introduced to the same serum sample, and then different color reactions can be measured for each bead. Because only one antigen is bound to each microsphere (eg, PR3-ANCA, MPOANCA or other specific autoantibodies), only specific antibodies will react to each bead of a specific color. If there is no MPO antibody in the sample, there will be no reaction against the MPO antigen bead; however, if PR3-ANCA is present in the sample, it would react with the PR3 antigen beads. Using this methodology, a single serum sample can be tested for a multitude of autoantibodies at the same time (see “Interpreting ANCA results: Accurate tests, appropriate orders,”2–10 above).