User login

Relationship Between Red Blood Cells and Protein Levels in Cerebrospinal Fluid in Young Infants Defined

Clinical question: What is the association between cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) red blood cell (RBC) counts and protein concentrations in infants younger than 57 days of age?

Background: Lumbar puncture (LP) is commonly performed in young infants to evaluate for meningitis in the clinical scenario of fever without source. Traumatic LP is common in children, and higher RBC counts are associated with increased CSF protein concentrations. The dynamic nature of CSF composition in young infants makes determination of the exact relationship between RBC counts and protein concentration challenging, which then complicates interpretation of CSF.

Study design: Retrospective, cross-sectional study.

Setting: Tertiary-care children's hospital.

Synopsis: Over a four-year period, 1,241 infants younger than 57 days of age that underwent LP were studied, excluding infants with conditions known to increase CSF protein concentrations: ventricular shunt, serious bacterial infection, congenital infection, herpes simplex virus or enterovirus positive PCR in CSF, seizure, or elevated serum bilirubin. Grossly bloody specimens with RBC counts >150,000 cells/mm3 were also excluded. Linear regression was used to determine relationship between CSF RBCs and protein, with protein increasing at a rate of 1.9 mg/dL per 1,000 CSF RBCs.

This ratio is different from a more traditional correction factor of approximately 1 mg/dL CSF protein increase per 1,000 CSF RBCs, which is derived from older populations of children.

However, this study is limited by the exclusion of grossly bloody specimens, which if included would have resulted in a ratio similar to the more traditional values. Additionally, application of this specific correction factor to prediction rules for bacterial meningitis has not been studied. Nonetheless, this study provides a baseline by which clinicians may interpret protein concentrations in traumatically bloody CSF specimens in young infants.

Bottom line: CSF protein concentrations increase at roughly 2 mg/dL per 1,000 CSF RBCs.

Citation: Hines BA, Nigrovic LE, Neuman MI, Shah SS. Adjustment of cerebrospinal fluid protein for red blood cells in neonates and young infants. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:325-328.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Clinical question: What is the association between cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) red blood cell (RBC) counts and protein concentrations in infants younger than 57 days of age?

Background: Lumbar puncture (LP) is commonly performed in young infants to evaluate for meningitis in the clinical scenario of fever without source. Traumatic LP is common in children, and higher RBC counts are associated with increased CSF protein concentrations. The dynamic nature of CSF composition in young infants makes determination of the exact relationship between RBC counts and protein concentration challenging, which then complicates interpretation of CSF.

Study design: Retrospective, cross-sectional study.

Setting: Tertiary-care children's hospital.

Synopsis: Over a four-year period, 1,241 infants younger than 57 days of age that underwent LP were studied, excluding infants with conditions known to increase CSF protein concentrations: ventricular shunt, serious bacterial infection, congenital infection, herpes simplex virus or enterovirus positive PCR in CSF, seizure, or elevated serum bilirubin. Grossly bloody specimens with RBC counts >150,000 cells/mm3 were also excluded. Linear regression was used to determine relationship between CSF RBCs and protein, with protein increasing at a rate of 1.9 mg/dL per 1,000 CSF RBCs.

This ratio is different from a more traditional correction factor of approximately 1 mg/dL CSF protein increase per 1,000 CSF RBCs, which is derived from older populations of children.

However, this study is limited by the exclusion of grossly bloody specimens, which if included would have resulted in a ratio similar to the more traditional values. Additionally, application of this specific correction factor to prediction rules for bacterial meningitis has not been studied. Nonetheless, this study provides a baseline by which clinicians may interpret protein concentrations in traumatically bloody CSF specimens in young infants.

Bottom line: CSF protein concentrations increase at roughly 2 mg/dL per 1,000 CSF RBCs.

Citation: Hines BA, Nigrovic LE, Neuman MI, Shah SS. Adjustment of cerebrospinal fluid protein for red blood cells in neonates and young infants. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:325-328.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Clinical question: What is the association between cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) red blood cell (RBC) counts and protein concentrations in infants younger than 57 days of age?

Background: Lumbar puncture (LP) is commonly performed in young infants to evaluate for meningitis in the clinical scenario of fever without source. Traumatic LP is common in children, and higher RBC counts are associated with increased CSF protein concentrations. The dynamic nature of CSF composition in young infants makes determination of the exact relationship between RBC counts and protein concentration challenging, which then complicates interpretation of CSF.

Study design: Retrospective, cross-sectional study.

Setting: Tertiary-care children's hospital.

Synopsis: Over a four-year period, 1,241 infants younger than 57 days of age that underwent LP were studied, excluding infants with conditions known to increase CSF protein concentrations: ventricular shunt, serious bacterial infection, congenital infection, herpes simplex virus or enterovirus positive PCR in CSF, seizure, or elevated serum bilirubin. Grossly bloody specimens with RBC counts >150,000 cells/mm3 were also excluded. Linear regression was used to determine relationship between CSF RBCs and protein, with protein increasing at a rate of 1.9 mg/dL per 1,000 CSF RBCs.

This ratio is different from a more traditional correction factor of approximately 1 mg/dL CSF protein increase per 1,000 CSF RBCs, which is derived from older populations of children.

However, this study is limited by the exclusion of grossly bloody specimens, which if included would have resulted in a ratio similar to the more traditional values. Additionally, application of this specific correction factor to prediction rules for bacterial meningitis has not been studied. Nonetheless, this study provides a baseline by which clinicians may interpret protein concentrations in traumatically bloody CSF specimens in young infants.

Bottom line: CSF protein concentrations increase at roughly 2 mg/dL per 1,000 CSF RBCs.

Citation: Hines BA, Nigrovic LE, Neuman MI, Shah SS. Adjustment of cerebrospinal fluid protein for red blood cells in neonates and young infants. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:325-328.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

How is Acute Pericarditis Diagnosed and Treated?

Case

A 32-year-old female with no significant past medical history is evaluated for sharp, left-sided chest pain for five days. Her pain is intermittent, worse with deep inspiration and in the supine position. She denies any shortness of breath. Her temperature is 100.8ºF, but otherwise her vital signs are normal. The physical exam and chest radiograph are unremarkable, but an electrocardiogram shows diffuse ST-segment elevations. The initial troponin is mildly elevated at 0.35 ng/ml.

Could this patient have acute pericarditis? If so, how should she be managed?

Background

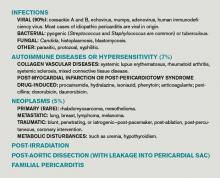

Pericarditis is the most common pericardial disease encountered by hospitalists. As many as 5% of chest pain cases unattributable to myocardial infarction (MI) are diagnosed with pericarditis.1 In immunocompetent individuals, as many as 90% of acute pericarditis cases are viral or idiopathic in etiology.1,2 Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and tuberculosis are common culprits in developing countries and immunocompromised hosts.3 Other specific etiologies of acute pericarditis include autoimmune diseases, neoplasms, chest irradiation, trauma, and metabolic disturbances (e.g. uremia). An etiologic classification of acute pericarditis is shown in Table 2 (p. 16).

Pericarditis primarily is a clinical diagnosis. Most patients present with chest pain.4 A pericardial friction rub may or may not be heard (sensitivity 16% to 85%), but when present is nearly 100% specific for pericarditis.2,5 Diffuse ST-segment elevation on electrocardiogram (EKG) is present in 60% to 90% of cases, but it can be difficult to differentiate from ST-segment elevations in acute MI.4,6

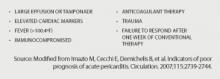

Uncomplicated acute pericarditis often is treated successfully as an outpatient.4 However, patients with high-risk features (see Table 1, right) should be hospitalized for identification and treatment of specific underlying etiology and for monitoring of complications, such as tamponade.7

Our patient has features consistent with pericarditis. In the following sections, we will review the diagnosis and treatment of acute pericarditis.

Review of the Data

How is acute pericarditis diagnosed?

Acute pericarditis is a clinical diagnosis supported by EKG and echocardiogram. At least two of the following four criteria must be present for the diagnosis: pleuritic chest pain, pericardial rub, diffuse ST-segment elevation on EKG, and pericardial effusion.8

History. Patients may report fever (46% in one small study of 69 patients) or a recent history of respiratory or gastrointestinal infection (40%).5 Most patients will report pleuritic chest pain. Typically, the pain is improved when sitting up and leaning forward, and gets worse when lying supine.4 Pain might radiate to the trapezius muscle ridge due to the common phrenic nerve innervation of pericardium and trapezius.9 However, pain might be minimal or absent in patients with uremic, neoplastic, tuberculous, or post-irradiation pericarditis.

Physical exam. A pericardial friction rub is nearly 100% specific for a pericarditis diagnosis, but sensitivity can vary (16% to 85%) depending on the frequency of auscultation and underlying etiology.2,5 It is thought to be caused by friction between the parietal and visceral layers of inflamed pericardium. A pericardial rub classically is described as a superficial, high-pitched, scratchy, or squeaking sound best heard with the diaphragm of the stethoscope at the lower left sternal border with the patient leaning forward.

Laboratory data. A complete blood count, metabolic panel, and cardiac enzymes should be checked in all patients with suspected acute pericarditis. Troponin values are elevated in up to one-third of patients, indicating cardiac muscle injury or myopericarditis, but have not been shown to adversely impact hospital length of stay, readmission, or complication rates.5,10 Markers of inflammation (e.g. erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein) are frequently elevated but do not point to a specific underlying etiology. Routine viral cultures and antibody titers are not useful.11

Most cases of pericarditis are presumed idiopathic (viral); however, finding a specific etiology should be considered in patients who do not respond after one week of therapy. Anti-nuclear antibody, complement levels, and rheumatoid factor can serve as screening tests for autoimmune disease. Purified protein derivative or quantiferon testing and HIV testing might be indicated in patients with appropriate risk factors. In cases of suspected tuberculous or neoplastic pericarditis, pericardial fluid analysis and biopsy could be warranted.

Electrocardiography. The EKG is the most useful test in diagnosing acute pericarditis. EKG changes in acute pericarditis can progress over four stages:

- Stage 1: diffuse ST elevations with or without PR depressions, initially;

- Stage 2: normalization of ST and PR segments, typically after several days;

- Stage 3: diffuse T-wave inversions; and

- Stage 4: normalization of T-waves, typically after weeks or months.

While all four stages are unlikely to be present in a given case, 80% of patients with pericarditis will demonstrate diffuse ST-segment elevations and PR-segment depression (see Figure 2, above).12

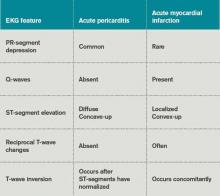

Table 3 lists EKG features helpful in differentiating acute pericarditis from acute myocardial infarction.

Chest radiography. Because a pericardial effusion often accompanies pericarditis, a chest radiograph (CXR) should be performed in all suspected cases. The CXR might show enlargement of the cardiac silhouette if more than 250 ml of pericardial fluid is present.3 A CXR also is helpful to diagnose concomitant pulmonary infection, pleural effusion, or mediastinal mass—all findings that could point to an underlying specific etiology of pericarditis and/or pericardial effusion.

Echocardiography. An echocardiogram should be performed in all patients with suspected pericarditis to detect effusion, associated myocardial, or paracardial disease.13 The echocardiogram frequently is normal but could show an effusion in 60%, and tamponade (see Figure 1, p. 15) in 5%, of cases.4

Computed tomography (CT) and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR).CT or CMR are the imaging modalities of choice when an echocardiogram is inconclusive or in cases of pericarditis complicated by a hemorrhagic or localized effusion, pericardial thickening, or pericardial mass.14 They also help in precise imaging of neighboring structures, such as lungs or mediastinum.

Pericardial fluid analysis and pericardial biopsy. In cases of refractory pericarditis with effusion, pericardial fluid analysis might provide clues to the underlying etiology. Routine chemistry, cell count, gram and acid fast staining, culture, and cytology should be sent. In addition, acid-fast bacillus staining and culture, adenosine deaminase, and interferon-gamma testing should be ordered when tuberculous pericarditis is suspected. A pericardial biopsy may show granulomas or neoplastic cells. Overall, pericardial fluid analysis and biopsy reveal a diagnosis in roughly 20% of cases.11

How is acute pericarditis treated?

Most cases of uncomplicated acute pericarditis are viral and respond well to NSAID plus colchicine therapy.2,4 Failure to respond to NSAIDs plus colchicine—evidenced by persistent fever, pericardial chest pain, new pericardial effusion, or worsening of general illness—within a week of treatment should prompt a search for an underlying systemic illness. If found, treatment should be aimed at the causative illness.

Bacterial pericarditis usually requires surgical drainage in addition to treatment with appropriate antibiotics.11 Tuberculous pericarditis is treated with multidrug therapy; when underlying HIV is present, patients should receive highly active anti-retroviral therapy as well. Steroids and immunosuppressants should be considered in addition to NSAIDs and colchicine in autoimmune pericarditis.10 Neoplastic pericarditis may resolve with chemotherapy but it has a high recurrence rate.13 Uremic pericarditis requires intensified dialysis.

Treatment options for uncomplicated idiopathic or viral pericarditis include:

NSAIDs. It is important to adequately dose NSAIDs when treating acute pericarditis. Initial treatment options include ibuprofen (1,600 to 3,200 mg daily), indomethacin (75 to 150 mg daily) or aspirin (2 to 4 gm daily) for one week.11,15 Aspirin is preferred in patients with ischemic heart disease. For patients with symptoms that persist longer than a week, NSAIDS may be continued, but investigation for an underlying etiology is indicated. Concomitant proton-pump-inhibitor therapy should be considered in patients at high risk for peptic ulcer disease to minimize gastric side effects.

Colchicine. Colchicine has a favorable risk-benefit profile as an adjunct treatment for acute and recurrent pericarditis. Patients experience better symptom relief when treated with both colchicine and an NSAID, compared with NSAIDs alone (88% versus 63%). Recurrence rates are lower with combined therapy (11% versus 32%).16 Colchicine treatment (0.6 mg twice daily after a loading dose of up to 2 mg) is recommended for several months to greater than one year.13,16,17

Glucocorticoids. Routine glucocorticoid use should be avoided in the treatment of acute pericarditis, as it has been associated with an increased risk for recurrence (OR 4.3).16,18 Glucocorticoid use should be considered in cases of pericarditis refractory to NSAIDs and colchicine, cases in which NSAIDs and or colchicine are contraindicated, and in autoimmune or connective-tissue-disease-related pericarditis. Prednisone should be dosed up to 1 mg/kg/day for at least one month, depending on symptom resolution, then tapered after either NSAIDs or colchicine have been started.13 Smaller prednisone doses of up to 0.5 mg/kg/day could be as effective, with the added benefit of reduced side effects and recurrences.19

Invasive treatment. Pericardiocentesis and/or pericardiectomy should be considered when pericarditis is complicated by a large effusion or tamponade, constrictive physiology, or recurrent effusion.11 Pericardiocentesis is the least invasive option and helps provide immediate relief in cases of tamponade or large symptomatic effusions. It is the preferred modality for obtaining pericardial fluid for diagnostic analysis. However, effusions can recur and in those cases pericardial window is preferred, as it provides continued outflow of pericardial fluid. Pericardiectomy is recommended in cases of symptomatic constrictive pericarditis unresponsive to medical therapy.15

Back to the Case

The patient’s presentation—prodrome followed by fever and pleuritic chest pain—is characteristic of acute idiopathic pericarditis. No pericardial rub was heard, but EKG findings were typical. Troponin I elevation suggested underlying myopericarditis. An echocardiogram was unremarkable. Given the likely viral or idiopathic etiology, no further diagnostic tests were ordered to explore the possibility of an underlying systemic illness.

The patient was started on ibuprofen 600 mg every eight hours. She had significant relief of her symptoms within two days. A routine fever workup was negative. She was discharged the following day.

The patient was readmitted three months later with recurrent pleuritic chest pain, which did not improve with resumption of NSAID therapy. Initial troponin I was 0.22 ng/ml, electrocardiogram was unchanged, and an echocardiogram showed small effusion. She was started on ibuprofen 800 mg every eight hours, as well as colchicine 0.6 mg twice daily. Her symptoms resolved the next day and she was discharged with prescriptions for ibuprofen and colchicine. She was instructed to follow up with a primary-care doctor in one week.

At the clinic visit, ibuprofen was tapered but colchicine was continued for another six months. She remained asymptomatic at her six-month clinic follow-up.

Bottom Line

Acute pericarditis is a clinical diagnosis supported by EKG findings. Most cases are idiopathic or viral, and can be treated successfully with NSAIDs and colchicine. For cases that do not respond to initial therapy, or cases that present with high-risk features, a specific etiology should be sought.

Dr. Southern is chief of the division of hospital medicine at Montefiore Medical Center in Bronx, N.Y. Dr. Galhorta is an instructor and Drs. Martin, Korcak, and Stehlihova are assistant professors in the department of medicine at Albert Einstein.

References

- Lange RA, Hillis LD. Clinical practice. Acute pericarditis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2195-2202.

- Zayas R, Anguita M, Torres F, et al. Incidence of specific etiology and role of methods for specific etiologic diagnosis of primary acute pericarditis. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:378-382.

- Troughton RW, Asher CR, Klein AL. Pericarditis. Lancet. 2004;363:717-727.

- Imazio M, Demichelis B, Parrini I, et al. Day-hospital treatment of acute pericarditis: a management program for outpatient therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1042-1046.

- Bonnefoy E, Godon P, Kirkorian G, et al. Serum cardiac troponin I and ST-segment elevation in patients with acute pericarditis. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:832-836.

- Salisbury AC, Olalla-Gomez C, Rihal CS, et al. Frequency and predictors of urgent coronary angiography in patients with acute pericarditis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(1):11-15.

- Imazio M, Cecchi E, Demichelis B, et al. Indicators of poor prognosis of acute pericarditis. Circulation. 2007;115:2739-2744.

- Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, et al. Diagnostic issues in the clinical management of pericarditis. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64(10):1384-1392.

- Spodick DH. Acute pericarditis: current concepts and practice. JAMA. 2003;289:1150-1153.

- Imazio M, Demichelis B, Cecchi E. Cardiac troponin I in acute pericarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(12):2144-2148.

- Sagristà Sauleda J, Permanyer Miralda G, Soler Soler J. Diagnosis and management of pericardial syndromes. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2005;58(7):830-841.

- Bruce MA, Spodick DH. Atypical electrocardiogram in acute pericarditis: characteristics and prevalence. J Electrocardiol. 1980;13:61-66.

- Maisch B, Seferovic PM, Ristic AD, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases executive summary; the task force on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2004; 25(7):587-610.

- Verhaert D, Gabriel RS, Johnston D, et al. The role of multimodality imaging in the management of pericardial disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:333-343.

- Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, et al. Controversial issues in the management of pericardial diseases. Circulation. 2010;121:916-928.

- Imazio M, Bobbio M, Cecchi E, et al. Colchicine in addition to conventional therapy for acute pericarditis: results of the colchicine for acute pericarditis (COPE) trial. Circulation. 2005;112(13):2012-2016.

- Adler Y, Finkelstein Y, Guindo J, et al. Colchicine treatment for recurrent pericarditis: a decade of experience. Circulation. 1998;97:2183-185.

- Imazio M, Bobbio M, Cecchi E, et al. Colchicine as first-choice therapy for recurrent pericarditis: results of the colchicine for recurrent pericarditis (CORE) trial. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1987-1991.

- Imazio M, Brucato A, Cumetti D, et al. Corticosteroids for recurrent pericarditis: high versus low doses: a nonrandomized observation. Circulation. 2008;118:667-771.

Case

A 32-year-old female with no significant past medical history is evaluated for sharp, left-sided chest pain for five days. Her pain is intermittent, worse with deep inspiration and in the supine position. She denies any shortness of breath. Her temperature is 100.8ºF, but otherwise her vital signs are normal. The physical exam and chest radiograph are unremarkable, but an electrocardiogram shows diffuse ST-segment elevations. The initial troponin is mildly elevated at 0.35 ng/ml.

Could this patient have acute pericarditis? If so, how should she be managed?

Background

Pericarditis is the most common pericardial disease encountered by hospitalists. As many as 5% of chest pain cases unattributable to myocardial infarction (MI) are diagnosed with pericarditis.1 In immunocompetent individuals, as many as 90% of acute pericarditis cases are viral or idiopathic in etiology.1,2 Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and tuberculosis are common culprits in developing countries and immunocompromised hosts.3 Other specific etiologies of acute pericarditis include autoimmune diseases, neoplasms, chest irradiation, trauma, and metabolic disturbances (e.g. uremia). An etiologic classification of acute pericarditis is shown in Table 2 (p. 16).

Pericarditis primarily is a clinical diagnosis. Most patients present with chest pain.4 A pericardial friction rub may or may not be heard (sensitivity 16% to 85%), but when present is nearly 100% specific for pericarditis.2,5 Diffuse ST-segment elevation on electrocardiogram (EKG) is present in 60% to 90% of cases, but it can be difficult to differentiate from ST-segment elevations in acute MI.4,6

Uncomplicated acute pericarditis often is treated successfully as an outpatient.4 However, patients with high-risk features (see Table 1, right) should be hospitalized for identification and treatment of specific underlying etiology and for monitoring of complications, such as tamponade.7

Our patient has features consistent with pericarditis. In the following sections, we will review the diagnosis and treatment of acute pericarditis.

Review of the Data

How is acute pericarditis diagnosed?

Acute pericarditis is a clinical diagnosis supported by EKG and echocardiogram. At least two of the following four criteria must be present for the diagnosis: pleuritic chest pain, pericardial rub, diffuse ST-segment elevation on EKG, and pericardial effusion.8

History. Patients may report fever (46% in one small study of 69 patients) or a recent history of respiratory or gastrointestinal infection (40%).5 Most patients will report pleuritic chest pain. Typically, the pain is improved when sitting up and leaning forward, and gets worse when lying supine.4 Pain might radiate to the trapezius muscle ridge due to the common phrenic nerve innervation of pericardium and trapezius.9 However, pain might be minimal or absent in patients with uremic, neoplastic, tuberculous, or post-irradiation pericarditis.

Physical exam. A pericardial friction rub is nearly 100% specific for a pericarditis diagnosis, but sensitivity can vary (16% to 85%) depending on the frequency of auscultation and underlying etiology.2,5 It is thought to be caused by friction between the parietal and visceral layers of inflamed pericardium. A pericardial rub classically is described as a superficial, high-pitched, scratchy, or squeaking sound best heard with the diaphragm of the stethoscope at the lower left sternal border with the patient leaning forward.

Laboratory data. A complete blood count, metabolic panel, and cardiac enzymes should be checked in all patients with suspected acute pericarditis. Troponin values are elevated in up to one-third of patients, indicating cardiac muscle injury or myopericarditis, but have not been shown to adversely impact hospital length of stay, readmission, or complication rates.5,10 Markers of inflammation (e.g. erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein) are frequently elevated but do not point to a specific underlying etiology. Routine viral cultures and antibody titers are not useful.11

Most cases of pericarditis are presumed idiopathic (viral); however, finding a specific etiology should be considered in patients who do not respond after one week of therapy. Anti-nuclear antibody, complement levels, and rheumatoid factor can serve as screening tests for autoimmune disease. Purified protein derivative or quantiferon testing and HIV testing might be indicated in patients with appropriate risk factors. In cases of suspected tuberculous or neoplastic pericarditis, pericardial fluid analysis and biopsy could be warranted.

Electrocardiography. The EKG is the most useful test in diagnosing acute pericarditis. EKG changes in acute pericarditis can progress over four stages:

- Stage 1: diffuse ST elevations with or without PR depressions, initially;

- Stage 2: normalization of ST and PR segments, typically after several days;

- Stage 3: diffuse T-wave inversions; and

- Stage 4: normalization of T-waves, typically after weeks or months.

While all four stages are unlikely to be present in a given case, 80% of patients with pericarditis will demonstrate diffuse ST-segment elevations and PR-segment depression (see Figure 2, above).12

Table 3 lists EKG features helpful in differentiating acute pericarditis from acute myocardial infarction.

Chest radiography. Because a pericardial effusion often accompanies pericarditis, a chest radiograph (CXR) should be performed in all suspected cases. The CXR might show enlargement of the cardiac silhouette if more than 250 ml of pericardial fluid is present.3 A CXR also is helpful to diagnose concomitant pulmonary infection, pleural effusion, or mediastinal mass—all findings that could point to an underlying specific etiology of pericarditis and/or pericardial effusion.

Echocardiography. An echocardiogram should be performed in all patients with suspected pericarditis to detect effusion, associated myocardial, or paracardial disease.13 The echocardiogram frequently is normal but could show an effusion in 60%, and tamponade (see Figure 1, p. 15) in 5%, of cases.4

Computed tomography (CT) and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR).CT or CMR are the imaging modalities of choice when an echocardiogram is inconclusive or in cases of pericarditis complicated by a hemorrhagic or localized effusion, pericardial thickening, or pericardial mass.14 They also help in precise imaging of neighboring structures, such as lungs or mediastinum.

Pericardial fluid analysis and pericardial biopsy. In cases of refractory pericarditis with effusion, pericardial fluid analysis might provide clues to the underlying etiology. Routine chemistry, cell count, gram and acid fast staining, culture, and cytology should be sent. In addition, acid-fast bacillus staining and culture, adenosine deaminase, and interferon-gamma testing should be ordered when tuberculous pericarditis is suspected. A pericardial biopsy may show granulomas or neoplastic cells. Overall, pericardial fluid analysis and biopsy reveal a diagnosis in roughly 20% of cases.11

How is acute pericarditis treated?

Most cases of uncomplicated acute pericarditis are viral and respond well to NSAID plus colchicine therapy.2,4 Failure to respond to NSAIDs plus colchicine—evidenced by persistent fever, pericardial chest pain, new pericardial effusion, or worsening of general illness—within a week of treatment should prompt a search for an underlying systemic illness. If found, treatment should be aimed at the causative illness.

Bacterial pericarditis usually requires surgical drainage in addition to treatment with appropriate antibiotics.11 Tuberculous pericarditis is treated with multidrug therapy; when underlying HIV is present, patients should receive highly active anti-retroviral therapy as well. Steroids and immunosuppressants should be considered in addition to NSAIDs and colchicine in autoimmune pericarditis.10 Neoplastic pericarditis may resolve with chemotherapy but it has a high recurrence rate.13 Uremic pericarditis requires intensified dialysis.

Treatment options for uncomplicated idiopathic or viral pericarditis include:

NSAIDs. It is important to adequately dose NSAIDs when treating acute pericarditis. Initial treatment options include ibuprofen (1,600 to 3,200 mg daily), indomethacin (75 to 150 mg daily) or aspirin (2 to 4 gm daily) for one week.11,15 Aspirin is preferred in patients with ischemic heart disease. For patients with symptoms that persist longer than a week, NSAIDS may be continued, but investigation for an underlying etiology is indicated. Concomitant proton-pump-inhibitor therapy should be considered in patients at high risk for peptic ulcer disease to minimize gastric side effects.

Colchicine. Colchicine has a favorable risk-benefit profile as an adjunct treatment for acute and recurrent pericarditis. Patients experience better symptom relief when treated with both colchicine and an NSAID, compared with NSAIDs alone (88% versus 63%). Recurrence rates are lower with combined therapy (11% versus 32%).16 Colchicine treatment (0.6 mg twice daily after a loading dose of up to 2 mg) is recommended for several months to greater than one year.13,16,17

Glucocorticoids. Routine glucocorticoid use should be avoided in the treatment of acute pericarditis, as it has been associated with an increased risk for recurrence (OR 4.3).16,18 Glucocorticoid use should be considered in cases of pericarditis refractory to NSAIDs and colchicine, cases in which NSAIDs and or colchicine are contraindicated, and in autoimmune or connective-tissue-disease-related pericarditis. Prednisone should be dosed up to 1 mg/kg/day for at least one month, depending on symptom resolution, then tapered after either NSAIDs or colchicine have been started.13 Smaller prednisone doses of up to 0.5 mg/kg/day could be as effective, with the added benefit of reduced side effects and recurrences.19

Invasive treatment. Pericardiocentesis and/or pericardiectomy should be considered when pericarditis is complicated by a large effusion or tamponade, constrictive physiology, or recurrent effusion.11 Pericardiocentesis is the least invasive option and helps provide immediate relief in cases of tamponade or large symptomatic effusions. It is the preferred modality for obtaining pericardial fluid for diagnostic analysis. However, effusions can recur and in those cases pericardial window is preferred, as it provides continued outflow of pericardial fluid. Pericardiectomy is recommended in cases of symptomatic constrictive pericarditis unresponsive to medical therapy.15

Back to the Case

The patient’s presentation—prodrome followed by fever and pleuritic chest pain—is characteristic of acute idiopathic pericarditis. No pericardial rub was heard, but EKG findings were typical. Troponin I elevation suggested underlying myopericarditis. An echocardiogram was unremarkable. Given the likely viral or idiopathic etiology, no further diagnostic tests were ordered to explore the possibility of an underlying systemic illness.

The patient was started on ibuprofen 600 mg every eight hours. She had significant relief of her symptoms within two days. A routine fever workup was negative. She was discharged the following day.

The patient was readmitted three months later with recurrent pleuritic chest pain, which did not improve with resumption of NSAID therapy. Initial troponin I was 0.22 ng/ml, electrocardiogram was unchanged, and an echocardiogram showed small effusion. She was started on ibuprofen 800 mg every eight hours, as well as colchicine 0.6 mg twice daily. Her symptoms resolved the next day and she was discharged with prescriptions for ibuprofen and colchicine. She was instructed to follow up with a primary-care doctor in one week.

At the clinic visit, ibuprofen was tapered but colchicine was continued for another six months. She remained asymptomatic at her six-month clinic follow-up.

Bottom Line

Acute pericarditis is a clinical diagnosis supported by EKG findings. Most cases are idiopathic or viral, and can be treated successfully with NSAIDs and colchicine. For cases that do not respond to initial therapy, or cases that present with high-risk features, a specific etiology should be sought.

Dr. Southern is chief of the division of hospital medicine at Montefiore Medical Center in Bronx, N.Y. Dr. Galhorta is an instructor and Drs. Martin, Korcak, and Stehlihova are assistant professors in the department of medicine at Albert Einstein.

References

- Lange RA, Hillis LD. Clinical practice. Acute pericarditis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2195-2202.

- Zayas R, Anguita M, Torres F, et al. Incidence of specific etiology and role of methods for specific etiologic diagnosis of primary acute pericarditis. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:378-382.

- Troughton RW, Asher CR, Klein AL. Pericarditis. Lancet. 2004;363:717-727.

- Imazio M, Demichelis B, Parrini I, et al. Day-hospital treatment of acute pericarditis: a management program for outpatient therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1042-1046.

- Bonnefoy E, Godon P, Kirkorian G, et al. Serum cardiac troponin I and ST-segment elevation in patients with acute pericarditis. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:832-836.

- Salisbury AC, Olalla-Gomez C, Rihal CS, et al. Frequency and predictors of urgent coronary angiography in patients with acute pericarditis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(1):11-15.

- Imazio M, Cecchi E, Demichelis B, et al. Indicators of poor prognosis of acute pericarditis. Circulation. 2007;115:2739-2744.

- Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, et al. Diagnostic issues in the clinical management of pericarditis. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64(10):1384-1392.

- Spodick DH. Acute pericarditis: current concepts and practice. JAMA. 2003;289:1150-1153.

- Imazio M, Demichelis B, Cecchi E. Cardiac troponin I in acute pericarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(12):2144-2148.

- Sagristà Sauleda J, Permanyer Miralda G, Soler Soler J. Diagnosis and management of pericardial syndromes. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2005;58(7):830-841.

- Bruce MA, Spodick DH. Atypical electrocardiogram in acute pericarditis: characteristics and prevalence. J Electrocardiol. 1980;13:61-66.

- Maisch B, Seferovic PM, Ristic AD, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases executive summary; the task force on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2004; 25(7):587-610.

- Verhaert D, Gabriel RS, Johnston D, et al. The role of multimodality imaging in the management of pericardial disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:333-343.

- Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, et al. Controversial issues in the management of pericardial diseases. Circulation. 2010;121:916-928.

- Imazio M, Bobbio M, Cecchi E, et al. Colchicine in addition to conventional therapy for acute pericarditis: results of the colchicine for acute pericarditis (COPE) trial. Circulation. 2005;112(13):2012-2016.

- Adler Y, Finkelstein Y, Guindo J, et al. Colchicine treatment for recurrent pericarditis: a decade of experience. Circulation. 1998;97:2183-185.

- Imazio M, Bobbio M, Cecchi E, et al. Colchicine as first-choice therapy for recurrent pericarditis: results of the colchicine for recurrent pericarditis (CORE) trial. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1987-1991.

- Imazio M, Brucato A, Cumetti D, et al. Corticosteroids for recurrent pericarditis: high versus low doses: a nonrandomized observation. Circulation. 2008;118:667-771.

Case

A 32-year-old female with no significant past medical history is evaluated for sharp, left-sided chest pain for five days. Her pain is intermittent, worse with deep inspiration and in the supine position. She denies any shortness of breath. Her temperature is 100.8ºF, but otherwise her vital signs are normal. The physical exam and chest radiograph are unremarkable, but an electrocardiogram shows diffuse ST-segment elevations. The initial troponin is mildly elevated at 0.35 ng/ml.

Could this patient have acute pericarditis? If so, how should she be managed?

Background

Pericarditis is the most common pericardial disease encountered by hospitalists. As many as 5% of chest pain cases unattributable to myocardial infarction (MI) are diagnosed with pericarditis.1 In immunocompetent individuals, as many as 90% of acute pericarditis cases are viral or idiopathic in etiology.1,2 Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and tuberculosis are common culprits in developing countries and immunocompromised hosts.3 Other specific etiologies of acute pericarditis include autoimmune diseases, neoplasms, chest irradiation, trauma, and metabolic disturbances (e.g. uremia). An etiologic classification of acute pericarditis is shown in Table 2 (p. 16).

Pericarditis primarily is a clinical diagnosis. Most patients present with chest pain.4 A pericardial friction rub may or may not be heard (sensitivity 16% to 85%), but when present is nearly 100% specific for pericarditis.2,5 Diffuse ST-segment elevation on electrocardiogram (EKG) is present in 60% to 90% of cases, but it can be difficult to differentiate from ST-segment elevations in acute MI.4,6

Uncomplicated acute pericarditis often is treated successfully as an outpatient.4 However, patients with high-risk features (see Table 1, right) should be hospitalized for identification and treatment of specific underlying etiology and for monitoring of complications, such as tamponade.7

Our patient has features consistent with pericarditis. In the following sections, we will review the diagnosis and treatment of acute pericarditis.

Review of the Data

How is acute pericarditis diagnosed?

Acute pericarditis is a clinical diagnosis supported by EKG and echocardiogram. At least two of the following four criteria must be present for the diagnosis: pleuritic chest pain, pericardial rub, diffuse ST-segment elevation on EKG, and pericardial effusion.8

History. Patients may report fever (46% in one small study of 69 patients) or a recent history of respiratory or gastrointestinal infection (40%).5 Most patients will report pleuritic chest pain. Typically, the pain is improved when sitting up and leaning forward, and gets worse when lying supine.4 Pain might radiate to the trapezius muscle ridge due to the common phrenic nerve innervation of pericardium and trapezius.9 However, pain might be minimal or absent in patients with uremic, neoplastic, tuberculous, or post-irradiation pericarditis.

Physical exam. A pericardial friction rub is nearly 100% specific for a pericarditis diagnosis, but sensitivity can vary (16% to 85%) depending on the frequency of auscultation and underlying etiology.2,5 It is thought to be caused by friction between the parietal and visceral layers of inflamed pericardium. A pericardial rub classically is described as a superficial, high-pitched, scratchy, or squeaking sound best heard with the diaphragm of the stethoscope at the lower left sternal border with the patient leaning forward.

Laboratory data. A complete blood count, metabolic panel, and cardiac enzymes should be checked in all patients with suspected acute pericarditis. Troponin values are elevated in up to one-third of patients, indicating cardiac muscle injury or myopericarditis, but have not been shown to adversely impact hospital length of stay, readmission, or complication rates.5,10 Markers of inflammation (e.g. erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein) are frequently elevated but do not point to a specific underlying etiology. Routine viral cultures and antibody titers are not useful.11

Most cases of pericarditis are presumed idiopathic (viral); however, finding a specific etiology should be considered in patients who do not respond after one week of therapy. Anti-nuclear antibody, complement levels, and rheumatoid factor can serve as screening tests for autoimmune disease. Purified protein derivative or quantiferon testing and HIV testing might be indicated in patients with appropriate risk factors. In cases of suspected tuberculous or neoplastic pericarditis, pericardial fluid analysis and biopsy could be warranted.

Electrocardiography. The EKG is the most useful test in diagnosing acute pericarditis. EKG changes in acute pericarditis can progress over four stages:

- Stage 1: diffuse ST elevations with or without PR depressions, initially;

- Stage 2: normalization of ST and PR segments, typically after several days;

- Stage 3: diffuse T-wave inversions; and

- Stage 4: normalization of T-waves, typically after weeks or months.

While all four stages are unlikely to be present in a given case, 80% of patients with pericarditis will demonstrate diffuse ST-segment elevations and PR-segment depression (see Figure 2, above).12

Table 3 lists EKG features helpful in differentiating acute pericarditis from acute myocardial infarction.

Chest radiography. Because a pericardial effusion often accompanies pericarditis, a chest radiograph (CXR) should be performed in all suspected cases. The CXR might show enlargement of the cardiac silhouette if more than 250 ml of pericardial fluid is present.3 A CXR also is helpful to diagnose concomitant pulmonary infection, pleural effusion, or mediastinal mass—all findings that could point to an underlying specific etiology of pericarditis and/or pericardial effusion.

Echocardiography. An echocardiogram should be performed in all patients with suspected pericarditis to detect effusion, associated myocardial, or paracardial disease.13 The echocardiogram frequently is normal but could show an effusion in 60%, and tamponade (see Figure 1, p. 15) in 5%, of cases.4

Computed tomography (CT) and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR).CT or CMR are the imaging modalities of choice when an echocardiogram is inconclusive or in cases of pericarditis complicated by a hemorrhagic or localized effusion, pericardial thickening, or pericardial mass.14 They also help in precise imaging of neighboring structures, such as lungs or mediastinum.

Pericardial fluid analysis and pericardial biopsy. In cases of refractory pericarditis with effusion, pericardial fluid analysis might provide clues to the underlying etiology. Routine chemistry, cell count, gram and acid fast staining, culture, and cytology should be sent. In addition, acid-fast bacillus staining and culture, adenosine deaminase, and interferon-gamma testing should be ordered when tuberculous pericarditis is suspected. A pericardial biopsy may show granulomas or neoplastic cells. Overall, pericardial fluid analysis and biopsy reveal a diagnosis in roughly 20% of cases.11

How is acute pericarditis treated?

Most cases of uncomplicated acute pericarditis are viral and respond well to NSAID plus colchicine therapy.2,4 Failure to respond to NSAIDs plus colchicine—evidenced by persistent fever, pericardial chest pain, new pericardial effusion, or worsening of general illness—within a week of treatment should prompt a search for an underlying systemic illness. If found, treatment should be aimed at the causative illness.

Bacterial pericarditis usually requires surgical drainage in addition to treatment with appropriate antibiotics.11 Tuberculous pericarditis is treated with multidrug therapy; when underlying HIV is present, patients should receive highly active anti-retroviral therapy as well. Steroids and immunosuppressants should be considered in addition to NSAIDs and colchicine in autoimmune pericarditis.10 Neoplastic pericarditis may resolve with chemotherapy but it has a high recurrence rate.13 Uremic pericarditis requires intensified dialysis.

Treatment options for uncomplicated idiopathic or viral pericarditis include:

NSAIDs. It is important to adequately dose NSAIDs when treating acute pericarditis. Initial treatment options include ibuprofen (1,600 to 3,200 mg daily), indomethacin (75 to 150 mg daily) or aspirin (2 to 4 gm daily) for one week.11,15 Aspirin is preferred in patients with ischemic heart disease. For patients with symptoms that persist longer than a week, NSAIDS may be continued, but investigation for an underlying etiology is indicated. Concomitant proton-pump-inhibitor therapy should be considered in patients at high risk for peptic ulcer disease to minimize gastric side effects.

Colchicine. Colchicine has a favorable risk-benefit profile as an adjunct treatment for acute and recurrent pericarditis. Patients experience better symptom relief when treated with both colchicine and an NSAID, compared with NSAIDs alone (88% versus 63%). Recurrence rates are lower with combined therapy (11% versus 32%).16 Colchicine treatment (0.6 mg twice daily after a loading dose of up to 2 mg) is recommended for several months to greater than one year.13,16,17

Glucocorticoids. Routine glucocorticoid use should be avoided in the treatment of acute pericarditis, as it has been associated with an increased risk for recurrence (OR 4.3).16,18 Glucocorticoid use should be considered in cases of pericarditis refractory to NSAIDs and colchicine, cases in which NSAIDs and or colchicine are contraindicated, and in autoimmune or connective-tissue-disease-related pericarditis. Prednisone should be dosed up to 1 mg/kg/day for at least one month, depending on symptom resolution, then tapered after either NSAIDs or colchicine have been started.13 Smaller prednisone doses of up to 0.5 mg/kg/day could be as effective, with the added benefit of reduced side effects and recurrences.19

Invasive treatment. Pericardiocentesis and/or pericardiectomy should be considered when pericarditis is complicated by a large effusion or tamponade, constrictive physiology, or recurrent effusion.11 Pericardiocentesis is the least invasive option and helps provide immediate relief in cases of tamponade or large symptomatic effusions. It is the preferred modality for obtaining pericardial fluid for diagnostic analysis. However, effusions can recur and in those cases pericardial window is preferred, as it provides continued outflow of pericardial fluid. Pericardiectomy is recommended in cases of symptomatic constrictive pericarditis unresponsive to medical therapy.15

Back to the Case

The patient’s presentation—prodrome followed by fever and pleuritic chest pain—is characteristic of acute idiopathic pericarditis. No pericardial rub was heard, but EKG findings were typical. Troponin I elevation suggested underlying myopericarditis. An echocardiogram was unremarkable. Given the likely viral or idiopathic etiology, no further diagnostic tests were ordered to explore the possibility of an underlying systemic illness.

The patient was started on ibuprofen 600 mg every eight hours. She had significant relief of her symptoms within two days. A routine fever workup was negative. She was discharged the following day.

The patient was readmitted three months later with recurrent pleuritic chest pain, which did not improve with resumption of NSAID therapy. Initial troponin I was 0.22 ng/ml, electrocardiogram was unchanged, and an echocardiogram showed small effusion. She was started on ibuprofen 800 mg every eight hours, as well as colchicine 0.6 mg twice daily. Her symptoms resolved the next day and she was discharged with prescriptions for ibuprofen and colchicine. She was instructed to follow up with a primary-care doctor in one week.

At the clinic visit, ibuprofen was tapered but colchicine was continued for another six months. She remained asymptomatic at her six-month clinic follow-up.

Bottom Line

Acute pericarditis is a clinical diagnosis supported by EKG findings. Most cases are idiopathic or viral, and can be treated successfully with NSAIDs and colchicine. For cases that do not respond to initial therapy, or cases that present with high-risk features, a specific etiology should be sought.

Dr. Southern is chief of the division of hospital medicine at Montefiore Medical Center in Bronx, N.Y. Dr. Galhorta is an instructor and Drs. Martin, Korcak, and Stehlihova are assistant professors in the department of medicine at Albert Einstein.

References

- Lange RA, Hillis LD. Clinical practice. Acute pericarditis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2195-2202.

- Zayas R, Anguita M, Torres F, et al. Incidence of specific etiology and role of methods for specific etiologic diagnosis of primary acute pericarditis. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:378-382.

- Troughton RW, Asher CR, Klein AL. Pericarditis. Lancet. 2004;363:717-727.

- Imazio M, Demichelis B, Parrini I, et al. Day-hospital treatment of acute pericarditis: a management program for outpatient therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1042-1046.

- Bonnefoy E, Godon P, Kirkorian G, et al. Serum cardiac troponin I and ST-segment elevation in patients with acute pericarditis. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:832-836.

- Salisbury AC, Olalla-Gomez C, Rihal CS, et al. Frequency and predictors of urgent coronary angiography in patients with acute pericarditis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(1):11-15.

- Imazio M, Cecchi E, Demichelis B, et al. Indicators of poor prognosis of acute pericarditis. Circulation. 2007;115:2739-2744.

- Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, et al. Diagnostic issues in the clinical management of pericarditis. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64(10):1384-1392.

- Spodick DH. Acute pericarditis: current concepts and practice. JAMA. 2003;289:1150-1153.

- Imazio M, Demichelis B, Cecchi E. Cardiac troponin I in acute pericarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(12):2144-2148.

- Sagristà Sauleda J, Permanyer Miralda G, Soler Soler J. Diagnosis and management of pericardial syndromes. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2005;58(7):830-841.

- Bruce MA, Spodick DH. Atypical electrocardiogram in acute pericarditis: characteristics and prevalence. J Electrocardiol. 1980;13:61-66.

- Maisch B, Seferovic PM, Ristic AD, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases executive summary; the task force on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2004; 25(7):587-610.

- Verhaert D, Gabriel RS, Johnston D, et al. The role of multimodality imaging in the management of pericardial disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:333-343.

- Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, et al. Controversial issues in the management of pericardial diseases. Circulation. 2010;121:916-928.

- Imazio M, Bobbio M, Cecchi E, et al. Colchicine in addition to conventional therapy for acute pericarditis: results of the colchicine for acute pericarditis (COPE) trial. Circulation. 2005;112(13):2012-2016.

- Adler Y, Finkelstein Y, Guindo J, et al. Colchicine treatment for recurrent pericarditis: a decade of experience. Circulation. 1998;97:2183-185.

- Imazio M, Bobbio M, Cecchi E, et al. Colchicine as first-choice therapy for recurrent pericarditis: results of the colchicine for recurrent pericarditis (CORE) trial. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1987-1991.

- Imazio M, Brucato A, Cumetti D, et al. Corticosteroids for recurrent pericarditis: high versus low doses: a nonrandomized observation. Circulation. 2008;118:667-771.

Surprise patients with the truth about pain and aging

Healthcare Quality Accounting Metrics Need Improvement

—Gregg Meyer, MD, MSc, chief clinical officer and executive vice president for population health for the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health System in Lebanon, N.H.

As healthcare quality reporting continues to evolve in this era of value-based purchasing (VBP), players on both the giving and receiving ends of performance incentives agree on the need to improve the accountability metrics with which providers are measured, ranked, rewarded, and penalized. Many of the measures currently in use—e.g., Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) core process measures and patient satisfaction ratings, the gross outcome metrics of mortality, infection, and readmission rates—are blunt instruments in need of refinement.

Entities such as the National Quality Forum (NQF), the American Medical Association’s Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (PCPI), and the National Quality Measures Clearinghouse (NQMC) recognize the need to develop and endorse more timely, credible, and patient-centered outcome metrics. Largely missing from the current crop of outcome measure sets is a meaningful account of the patient’s perspective.

Enter patient-reported outcomes (PROs), defined as “any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else.”1 PRO tools “measure what patients are able to do and how they feel by asking questions” (see “Types of Patient-Reported Outcomes [PROs],” p. 19).

If successfully adapted for public reporting on a wide scale, PROs could become the next evolutionary step in healthcare quality reporting, integrating health status and patient experience data into outcome metrics that truly matter to patients. They could enable a richer understanding of their clinical experiences and responses to therapy, and help providers target necessary improvements with greater precision.

“As a provider, I care about my patients not developing infections, getting the right medications, and not being readmitted. Patients, however, have a different set of priorities around issues like ‘How quickly will I be able to return to work? When will I be able to chase my grandkids around the yard? How much is this care going to cost me out of pocket?’” says healthcare quality expert Gregg Meyer, MD, MSc, chief clinical officer and executive vice president for population health for the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health System in Lebanon, N.H. “This next generation of accountability will allow us to move from being provider- and payor-centered to becoming truly patient-centered, and will serve as a key reminder that patients are no longer passive participants. They are key partners, in both the delivery of care and the measurement of that care.”

The idea of PROs is one whose “time has finally arrived,” according to medical outcomes researcher David Cella, PhD, professor and chair of the Department of Medical Social Sciences at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

“The case for inclusion of outcomes that matter most to patients, like the effect of treatment upon their symptoms, function, and overall well-being, has always been compelling as an ideal to strive toward,” Cella adds. “PROs can and should be considered as true treatment outcome measures, and their ability to capture quality information efficiently make them well-suited for this role.”

The FDA even permits PROs (i.e. pain, anxiety, depression, sleep, and physical and social functioning) to be used as experimental endpoints for clinical trials to support claims in medical product labeling.2

The Patient Voice

The Department Health and Human Services (HHS) is searching for ways to fill current gaps in outcome measures, and has funded a patient outcomes project by the NQF to help ramp up patient-focused measure development activities within the federal government. In a recent report stemming from that project, the NQF states: “The patient’s voice is not readily captured in traditional health records and data systems, yet the beneficiary of healthcare services is often in the best position to evaluate the effectiveness of those services.”3

The NQF also is conducting foundational work to evaluate the most promising and viable PROs for quality measurement use and methodological issues involved in collecting and aggregating PRO data for provider performance assessment, says Helen Burstin, MD, MPH, NQF’s senior vice president for performance measures.

“PROs provide the opportunity to hear about the outcome of a clinician’s intervention directly from the patient—for example, visual improvement after cataract surgery, relief from nausea after chemotherapy, and mobility enhancement and pain relief after a hip or knee replacement,” she says. “The goal is to develop reliable and valid PRO performance measures that are applicable across multiple settings of care and/or multiple conditions, which the NQF can endorse for accountability and quality-improvement purposes.”

Specific NQF recommendations regarding PROs and performance measurement are expected to be available for review and comment this month, with a 30-day public and member comment period.

A wide variety of patient-level instruments to measure PROs have been used for clinical research purposes, many of which have been evaluated and catalogued within a system of assessment tools known as the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS), Dr. Burstin says. PROMIS questionnaires prompt patients to measure such outcomes as how much difficulty they experience when walking a block on flat ground, getting in and out of bed, or doing strenuous activities, such as bicycling or jogging. NIH-funded studies using PROMIS tools are taking place at 12 sites across the country (http://nihpromis.org/default).

“PROMIS provides two distinct advantages to the PRO performance metric landscape,” argues Cella, who is principal investigator of the Statistical Center for PROMIS. “It has a computerized adaptive testing option, so efficient and accurate assessment is now possible at the individual patient level, with just a few questions per area. It also standardizes its scoring and reporting, such that many other similar measures can be used and their scores reported on a common, PROMIS metric.”

HM Applications

“The voice of the clinician is also needed during this PRO development process,” Dr. Burstin says. “We welcome hospitalists to engage in our projects and weigh in about the most meaningful and actionable patient outcomes that are relevant to their practice.”

“Taking PROs and applying them to hospital medicine is really doable if you take into account the lessons learned from providers who have already used PROs successfully in clinical settings,” says Pat Courneya, MD, medical director for HealthPartners Health Plan in Minnesota.

HealthPartners recently began using PROs in a quality measurement and reward program, offering financial bonuses to physical therapists who achieve a high PRO score relative to resource use (number of PT sessions required). “Having objective PRO measurements allows clinicians to create benchmarks for their patients regarding how much functional improvement they expect to achieve, and how many PT sessions are required to achieve that degree of improvement,” Dr. Courneya says. Using an interactive, Web-based PRO assessment tool, the program has helped tailor care to the expectations of patients while also significantly reducing the overall number of PT visits, especially by medically complex, post-operative patients.

HealthPartners has successfully used PROs as part of an innovative care model for managing patients with depression. At the outset of treatment, patients are administered the PHQ-9, a nine-item patient health questionnaire designed to assess depression symptoms and functional impairment, and derive a severity score. Patients receive care by a team composed of a primary-care physician, a care manager, and a consulting psychiatrist, after which their degree of symptom improvement is again measured. With this program, HealthPartners has achieved significantly more patients with depression into remission by six months compared with typical primary-care treatment, Dr. Courneya says. This model of care has since garnered a CMS Innovation Grant, managed by the HealthPartners Institute for Education and Research and directed by Minnesota’s Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, aimed at spreading the model to five other states.

“PROs are potentially as useful for hospital medicine as for any other type of medical practice,” says Shaun Frost, MD, SFHM, SHM president and associate medical director of care delivery systems for HealthPartners Health Plan. “There is a big opportunity for hospitalists to incorporate shared decision-making to learn patients’ preferences, such as expectations of when they will be discharged, and understanding of therapeutic options.”

Peri-surgical care is a particularly important opportunity for hospitalists to demonstrate their value by leveraging PROs, according to Dr. Frost. “Patients sometimes come to the table with unrealistic prior expectations that physicians can make pain go away completely. We need to clarify their expectations preoperatively, when we meet them for the very first time, so that they establish a realistic baseline,” he says. “We then need to have a diligent conversation with them immediately after their operation to discuss their pain-management goals, a realistic physical therapy schedule, and post-discharge expectations.”

By clearly understanding patient objectives, hospitalists can “adjust the therapy they’re getting to their expectations, maximizing its effectiveness while minimizing delays in care and transitions to other care settings,” Dr. Frost says.

Chris Guadagnino is a freelance medical writer in Philadelphia.

References

- National Quality Forum. Patient-reported outcomes. National Quality Forum website. Available at: http://www.qualityforum.org/Projects/n-r/Patient-Reported_Outcomes/Patient-Reported_Outcomes.aspx. Accessed Oct. 2, 2012.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Consortium. U.S. Food and Drug Administration website. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/PartnershipsCollaborations/PublicPrivatePartnershipProgram/ucm231129.htm. Accessed Oct. 2, 2012.

- National Quality Forum. National voluntary consensus standards for patient outcomes 2009.National Quality Forum website. Available at: http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2011/07/National_Voluntary_Consensus_Standards_for_Patient_Outcomes_2009.aspx. Accessed Oct. 2, 2012.

—Gregg Meyer, MD, MSc, chief clinical officer and executive vice president for population health for the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health System in Lebanon, N.H.

As healthcare quality reporting continues to evolve in this era of value-based purchasing (VBP), players on both the giving and receiving ends of performance incentives agree on the need to improve the accountability metrics with which providers are measured, ranked, rewarded, and penalized. Many of the measures currently in use—e.g., Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) core process measures and patient satisfaction ratings, the gross outcome metrics of mortality, infection, and readmission rates—are blunt instruments in need of refinement.

Entities such as the National Quality Forum (NQF), the American Medical Association’s Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (PCPI), and the National Quality Measures Clearinghouse (NQMC) recognize the need to develop and endorse more timely, credible, and patient-centered outcome metrics. Largely missing from the current crop of outcome measure sets is a meaningful account of the patient’s perspective.

Enter patient-reported outcomes (PROs), defined as “any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else.”1 PRO tools “measure what patients are able to do and how they feel by asking questions” (see “Types of Patient-Reported Outcomes [PROs],” p. 19).

If successfully adapted for public reporting on a wide scale, PROs could become the next evolutionary step in healthcare quality reporting, integrating health status and patient experience data into outcome metrics that truly matter to patients. They could enable a richer understanding of their clinical experiences and responses to therapy, and help providers target necessary improvements with greater precision.

“As a provider, I care about my patients not developing infections, getting the right medications, and not being readmitted. Patients, however, have a different set of priorities around issues like ‘How quickly will I be able to return to work? When will I be able to chase my grandkids around the yard? How much is this care going to cost me out of pocket?’” says healthcare quality expert Gregg Meyer, MD, MSc, chief clinical officer and executive vice president for population health for the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health System in Lebanon, N.H. “This next generation of accountability will allow us to move from being provider- and payor-centered to becoming truly patient-centered, and will serve as a key reminder that patients are no longer passive participants. They are key partners, in both the delivery of care and the measurement of that care.”

The idea of PROs is one whose “time has finally arrived,” according to medical outcomes researcher David Cella, PhD, professor and chair of the Department of Medical Social Sciences at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

“The case for inclusion of outcomes that matter most to patients, like the effect of treatment upon their symptoms, function, and overall well-being, has always been compelling as an ideal to strive toward,” Cella adds. “PROs can and should be considered as true treatment outcome measures, and their ability to capture quality information efficiently make them well-suited for this role.”

The FDA even permits PROs (i.e. pain, anxiety, depression, sleep, and physical and social functioning) to be used as experimental endpoints for clinical trials to support claims in medical product labeling.2

The Patient Voice

The Department Health and Human Services (HHS) is searching for ways to fill current gaps in outcome measures, and has funded a patient outcomes project by the NQF to help ramp up patient-focused measure development activities within the federal government. In a recent report stemming from that project, the NQF states: “The patient’s voice is not readily captured in traditional health records and data systems, yet the beneficiary of healthcare services is often in the best position to evaluate the effectiveness of those services.”3

The NQF also is conducting foundational work to evaluate the most promising and viable PROs for quality measurement use and methodological issues involved in collecting and aggregating PRO data for provider performance assessment, says Helen Burstin, MD, MPH, NQF’s senior vice president for performance measures.

“PROs provide the opportunity to hear about the outcome of a clinician’s intervention directly from the patient—for example, visual improvement after cataract surgery, relief from nausea after chemotherapy, and mobility enhancement and pain relief after a hip or knee replacement,” she says. “The goal is to develop reliable and valid PRO performance measures that are applicable across multiple settings of care and/or multiple conditions, which the NQF can endorse for accountability and quality-improvement purposes.”

Specific NQF recommendations regarding PROs and performance measurement are expected to be available for review and comment this month, with a 30-day public and member comment period.

A wide variety of patient-level instruments to measure PROs have been used for clinical research purposes, many of which have been evaluated and catalogued within a system of assessment tools known as the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS), Dr. Burstin says. PROMIS questionnaires prompt patients to measure such outcomes as how much difficulty they experience when walking a block on flat ground, getting in and out of bed, or doing strenuous activities, such as bicycling or jogging. NIH-funded studies using PROMIS tools are taking place at 12 sites across the country (http://nihpromis.org/default).

“PROMIS provides two distinct advantages to the PRO performance metric landscape,” argues Cella, who is principal investigator of the Statistical Center for PROMIS. “It has a computerized adaptive testing option, so efficient and accurate assessment is now possible at the individual patient level, with just a few questions per area. It also standardizes its scoring and reporting, such that many other similar measures can be used and their scores reported on a common, PROMIS metric.”

HM Applications

“The voice of the clinician is also needed during this PRO development process,” Dr. Burstin says. “We welcome hospitalists to engage in our projects and weigh in about the most meaningful and actionable patient outcomes that are relevant to their practice.”

“Taking PROs and applying them to hospital medicine is really doable if you take into account the lessons learned from providers who have already used PROs successfully in clinical settings,” says Pat Courneya, MD, medical director for HealthPartners Health Plan in Minnesota.

HealthPartners recently began using PROs in a quality measurement and reward program, offering financial bonuses to physical therapists who achieve a high PRO score relative to resource use (number of PT sessions required). “Having objective PRO measurements allows clinicians to create benchmarks for their patients regarding how much functional improvement they expect to achieve, and how many PT sessions are required to achieve that degree of improvement,” Dr. Courneya says. Using an interactive, Web-based PRO assessment tool, the program has helped tailor care to the expectations of patients while also significantly reducing the overall number of PT visits, especially by medically complex, post-operative patients.

HealthPartners has successfully used PROs as part of an innovative care model for managing patients with depression. At the outset of treatment, patients are administered the PHQ-9, a nine-item patient health questionnaire designed to assess depression symptoms and functional impairment, and derive a severity score. Patients receive care by a team composed of a primary-care physician, a care manager, and a consulting psychiatrist, after which their degree of symptom improvement is again measured. With this program, HealthPartners has achieved significantly more patients with depression into remission by six months compared with typical primary-care treatment, Dr. Courneya says. This model of care has since garnered a CMS Innovation Grant, managed by the HealthPartners Institute for Education and Research and directed by Minnesota’s Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, aimed at spreading the model to five other states.

“PROs are potentially as useful for hospital medicine as for any other type of medical practice,” says Shaun Frost, MD, SFHM, SHM president and associate medical director of care delivery systems for HealthPartners Health Plan. “There is a big opportunity for hospitalists to incorporate shared decision-making to learn patients’ preferences, such as expectations of when they will be discharged, and understanding of therapeutic options.”

Peri-surgical care is a particularly important opportunity for hospitalists to demonstrate their value by leveraging PROs, according to Dr. Frost. “Patients sometimes come to the table with unrealistic prior expectations that physicians can make pain go away completely. We need to clarify their expectations preoperatively, when we meet them for the very first time, so that they establish a realistic baseline,” he says. “We then need to have a diligent conversation with them immediately after their operation to discuss their pain-management goals, a realistic physical therapy schedule, and post-discharge expectations.”

By clearly understanding patient objectives, hospitalists can “adjust the therapy they’re getting to their expectations, maximizing its effectiveness while minimizing delays in care and transitions to other care settings,” Dr. Frost says.

Chris Guadagnino is a freelance medical writer in Philadelphia.

References

- National Quality Forum. Patient-reported outcomes. National Quality Forum website. Available at: http://www.qualityforum.org/Projects/n-r/Patient-Reported_Outcomes/Patient-Reported_Outcomes.aspx. Accessed Oct. 2, 2012.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Consortium. U.S. Food and Drug Administration website. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/PartnershipsCollaborations/PublicPrivatePartnershipProgram/ucm231129.htm. Accessed Oct. 2, 2012.

- National Quality Forum. National voluntary consensus standards for patient outcomes 2009.National Quality Forum website. Available at: http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2011/07/National_Voluntary_Consensus_Standards_for_Patient_Outcomes_2009.aspx. Accessed Oct. 2, 2012.

—Gregg Meyer, MD, MSc, chief clinical officer and executive vice president for population health for the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health System in Lebanon, N.H.

As healthcare quality reporting continues to evolve in this era of value-based purchasing (VBP), players on both the giving and receiving ends of performance incentives agree on the need to improve the accountability metrics with which providers are measured, ranked, rewarded, and penalized. Many of the measures currently in use—e.g., Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) core process measures and patient satisfaction ratings, the gross outcome metrics of mortality, infection, and readmission rates—are blunt instruments in need of refinement.

Entities such as the National Quality Forum (NQF), the American Medical Association’s Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (PCPI), and the National Quality Measures Clearinghouse (NQMC) recognize the need to develop and endorse more timely, credible, and patient-centered outcome metrics. Largely missing from the current crop of outcome measure sets is a meaningful account of the patient’s perspective.

Enter patient-reported outcomes (PROs), defined as “any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else.”1 PRO tools “measure what patients are able to do and how they feel by asking questions” (see “Types of Patient-Reported Outcomes [PROs],” p. 19).

If successfully adapted for public reporting on a wide scale, PROs could become the next evolutionary step in healthcare quality reporting, integrating health status and patient experience data into outcome metrics that truly matter to patients. They could enable a richer understanding of their clinical experiences and responses to therapy, and help providers target necessary improvements with greater precision.

“As a provider, I care about my patients not developing infections, getting the right medications, and not being readmitted. Patients, however, have a different set of priorities around issues like ‘How quickly will I be able to return to work? When will I be able to chase my grandkids around the yard? How much is this care going to cost me out of pocket?’” says healthcare quality expert Gregg Meyer, MD, MSc, chief clinical officer and executive vice president for population health for the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health System in Lebanon, N.H. “This next generation of accountability will allow us to move from being provider- and payor-centered to becoming truly patient-centered, and will serve as a key reminder that patients are no longer passive participants. They are key partners, in both the delivery of care and the measurement of that care.”

The idea of PROs is one whose “time has finally arrived,” according to medical outcomes researcher David Cella, PhD, professor and chair of the Department of Medical Social Sciences at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.