User login

In the Literature: Research You Need to Know

Clinical question: Does the incorporation of bar-code verification technology within an electronic medication-administration system (eMAR) reduce the rate of medication errors?

Background: More than a fourth of medication-related inpatient adverse events are due to errors. Bar-code verification technology reduces the incidence of such errors; however, the quantitative effect of implementing such technology is unknown.

Study design: Before-and-after quasi-experimental study.

Setting: Single academic tertiary-care medical center in Boston.

Synopsis: Investigators directly observed 14,041 medication administrations in patient units that did and did not have bar-code eMAR. They reported a 41.4% relative reduction (RR) in medication administration errors (11.5% error rate before versus 6.8% after adoption of this technology) and 50.8% RR in the rate of potential adverse drug events (3.1% versus 1.6%). Significant reductions in wrong medication, dose, and administration documentation errors were noted. Order transcription errors were completely eliminated (6% versus 0%). Although errors in medication administration timing fell by 27.3%, no significant difference in the number of potential adverse events related to timing errors was found.

The investigators estimated that approximately 145,000 potential adverse drug events would be prevented from amongst an annual 1.69 million medication orders.

Pre-existent computerized physician order entry and bar-code verification technology in the pharmacy at the study hospital might limit the generalization of these results. Additionally, potential, not actual, adverse drug events were reported. Lastly, the study compared early implementers with late implementers.

Bottom line: Bar-code verification technology substantially reduced the number of medication administration errors and associated adverse drug events and completely eliminated the occurrence of transcription errors.

Citation: Poon EG, Keohane CA, Yoon CS, et al. Effect of bar-code technology on the safety of medication administration. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(18):1698-1707.

Reviewed for TH eWire by Robert Chang, MD, Anita Hart, MD, Hae-won Kim, MD, Robert Paretti, MD, Helena Pasieka, MD, and Matt Smitherman, MD, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

For more physician reviews of HM-related research, visit our website.

Clinical question: Does the incorporation of bar-code verification technology within an electronic medication-administration system (eMAR) reduce the rate of medication errors?

Background: More than a fourth of medication-related inpatient adverse events are due to errors. Bar-code verification technology reduces the incidence of such errors; however, the quantitative effect of implementing such technology is unknown.

Study design: Before-and-after quasi-experimental study.

Setting: Single academic tertiary-care medical center in Boston.

Synopsis: Investigators directly observed 14,041 medication administrations in patient units that did and did not have bar-code eMAR. They reported a 41.4% relative reduction (RR) in medication administration errors (11.5% error rate before versus 6.8% after adoption of this technology) and 50.8% RR in the rate of potential adverse drug events (3.1% versus 1.6%). Significant reductions in wrong medication, dose, and administration documentation errors were noted. Order transcription errors were completely eliminated (6% versus 0%). Although errors in medication administration timing fell by 27.3%, no significant difference in the number of potential adverse events related to timing errors was found.

The investigators estimated that approximately 145,000 potential adverse drug events would be prevented from amongst an annual 1.69 million medication orders.

Pre-existent computerized physician order entry and bar-code verification technology in the pharmacy at the study hospital might limit the generalization of these results. Additionally, potential, not actual, adverse drug events were reported. Lastly, the study compared early implementers with late implementers.

Bottom line: Bar-code verification technology substantially reduced the number of medication administration errors and associated adverse drug events and completely eliminated the occurrence of transcription errors.

Citation: Poon EG, Keohane CA, Yoon CS, et al. Effect of bar-code technology on the safety of medication administration. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(18):1698-1707.

Reviewed for TH eWire by Robert Chang, MD, Anita Hart, MD, Hae-won Kim, MD, Robert Paretti, MD, Helena Pasieka, MD, and Matt Smitherman, MD, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

For more physician reviews of HM-related research, visit our website.

Clinical question: Does the incorporation of bar-code verification technology within an electronic medication-administration system (eMAR) reduce the rate of medication errors?

Background: More than a fourth of medication-related inpatient adverse events are due to errors. Bar-code verification technology reduces the incidence of such errors; however, the quantitative effect of implementing such technology is unknown.

Study design: Before-and-after quasi-experimental study.

Setting: Single academic tertiary-care medical center in Boston.

Synopsis: Investigators directly observed 14,041 medication administrations in patient units that did and did not have bar-code eMAR. They reported a 41.4% relative reduction (RR) in medication administration errors (11.5% error rate before versus 6.8% after adoption of this technology) and 50.8% RR in the rate of potential adverse drug events (3.1% versus 1.6%). Significant reductions in wrong medication, dose, and administration documentation errors were noted. Order transcription errors were completely eliminated (6% versus 0%). Although errors in medication administration timing fell by 27.3%, no significant difference in the number of potential adverse events related to timing errors was found.

The investigators estimated that approximately 145,000 potential adverse drug events would be prevented from amongst an annual 1.69 million medication orders.

Pre-existent computerized physician order entry and bar-code verification technology in the pharmacy at the study hospital might limit the generalization of these results. Additionally, potential, not actual, adverse drug events were reported. Lastly, the study compared early implementers with late implementers.

Bottom line: Bar-code verification technology substantially reduced the number of medication administration errors and associated adverse drug events and completely eliminated the occurrence of transcription errors.

Citation: Poon EG, Keohane CA, Yoon CS, et al. Effect of bar-code technology on the safety of medication administration. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(18):1698-1707.

Reviewed for TH eWire by Robert Chang, MD, Anita Hart, MD, Hae-won Kim, MD, Robert Paretti, MD, Helena Pasieka, MD, and Matt Smitherman, MD, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

For more physician reviews of HM-related research, visit our website.

Safety of Inferior Vena Cava Filters Questioned

An Archives of Internal Medicine report and a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) advisory that question the long-term safety of inferior vena cava (IVC) filters should give hospitalists pause, one HM leader says.

The Aug. 9 report (PDF) found that the Bard Recovery and Bard G2 filters “had high prevalences of fracture and embolization, with potentially life-threatening sequelae." An FDA advisory issued the same day as the study cautioned that retrievable filters are not always removed from patients once the risk of pulmonary embolism (PE) has subsided, further increasing the risks.

“We’re going to be thinking more than twice before we recommend when these filters are placed in and then thinking twice about when we get them out,” says Shaker Eid, MD, an instructor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore.

Dr. Eid, however, cautions HM leaders about being too fearful of the data. The Archives report, he notes, was a single-center study. And while the FDA reports that the use of filters grew exponentially from 1979 to 2007, new American College of Chest Physicians guidelines from 2008 have limited their use mostly to patients who cannot receive anticoagulation treatments, Dr. Eid notes.

In cases in which they are necessary to implant, or in instances in which a patient already has a permanent IVC filter implanted, Dr. Eid recommends hospitalists be diligent in working with the filter.

An Archives of Internal Medicine report and a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) advisory that question the long-term safety of inferior vena cava (IVC) filters should give hospitalists pause, one HM leader says.

The Aug. 9 report (PDF) found that the Bard Recovery and Bard G2 filters “had high prevalences of fracture and embolization, with potentially life-threatening sequelae." An FDA advisory issued the same day as the study cautioned that retrievable filters are not always removed from patients once the risk of pulmonary embolism (PE) has subsided, further increasing the risks.

“We’re going to be thinking more than twice before we recommend when these filters are placed in and then thinking twice about when we get them out,” says Shaker Eid, MD, an instructor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore.

Dr. Eid, however, cautions HM leaders about being too fearful of the data. The Archives report, he notes, was a single-center study. And while the FDA reports that the use of filters grew exponentially from 1979 to 2007, new American College of Chest Physicians guidelines from 2008 have limited their use mostly to patients who cannot receive anticoagulation treatments, Dr. Eid notes.

In cases in which they are necessary to implant, or in instances in which a patient already has a permanent IVC filter implanted, Dr. Eid recommends hospitalists be diligent in working with the filter.

An Archives of Internal Medicine report and a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) advisory that question the long-term safety of inferior vena cava (IVC) filters should give hospitalists pause, one HM leader says.

The Aug. 9 report (PDF) found that the Bard Recovery and Bard G2 filters “had high prevalences of fracture and embolization, with potentially life-threatening sequelae." An FDA advisory issued the same day as the study cautioned that retrievable filters are not always removed from patients once the risk of pulmonary embolism (PE) has subsided, further increasing the risks.

“We’re going to be thinking more than twice before we recommend when these filters are placed in and then thinking twice about when we get them out,” says Shaker Eid, MD, an instructor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore.

Dr. Eid, however, cautions HM leaders about being too fearful of the data. The Archives report, he notes, was a single-center study. And while the FDA reports that the use of filters grew exponentially from 1979 to 2007, new American College of Chest Physicians guidelines from 2008 have limited their use mostly to patients who cannot receive anticoagulation treatments, Dr. Eid notes.

In cases in which they are necessary to implant, or in instances in which a patient already has a permanent IVC filter implanted, Dr. Eid recommends hospitalists be diligent in working with the filter.

Hospitalists in the Developing World

Could U.S. hospitals learn from how HM is practiced in developing nations such as Ecuador? David Gaus, MD, MS, founder and director of Andean Health and Development (AHD), thinks so.

Dr. Gaus, who spends half the year as assistant clinical professor of medicine and teaching hospitalist at the University of Wisconsin and the other half with AHD in Ecuador, was inspired to pursue a medical degree by doing development work in Ecuador. When he returned to Ecuador in 1995 to be a doctor to the poor, he discovered a major gap in the healthcare system, between undertrained rural PCPs and the specialist-heavy medical practice in the country’s capital of Quito.

Under his leadership, AHD established a hospital in the rural community of Pedro Vicente Maldonado; it opened in 2000 and now is financially self-sufficient. “The focus was on the need for cost-effective, high-quality hospital services in a country with a dearth of hospitals,” he says.

At the hospital, family-practice physicians serve as hospitalists and deal with a wide spectrum of clinical needs ranging from car accidents and complicated pregnancies to snake bites and toxic organic phosphate herbicide exposure.

“Rural hospitals can’t afford five or six types of attendings, but if you have well-trained family practitioners backed by a general surgeon, they can handle most of the spectrum of clinical needs and the chaos management,” he says. Increasingly, those clinical needs include such chronic degenerative diseases as diabetes, hypertension, and arthritis, for which Ecuador’s cadre of rural PCPs are not trained.

Dr. Gaus is planning a second hospital in the larger Ecuadorean city of Santo Domingo (population 400,000), with the support of the Ministry of Public Health and the Social Security system. The new facility, using the same model and hospitalist roles, will open in 12 to 18 months and will increase the number of three-year family-practice residency slots from six to 20.

Could U.S. hospitals learn from how HM is practiced in developing nations such as Ecuador? David Gaus, MD, MS, founder and director of Andean Health and Development (AHD), thinks so.

Dr. Gaus, who spends half the year as assistant clinical professor of medicine and teaching hospitalist at the University of Wisconsin and the other half with AHD in Ecuador, was inspired to pursue a medical degree by doing development work in Ecuador. When he returned to Ecuador in 1995 to be a doctor to the poor, he discovered a major gap in the healthcare system, between undertrained rural PCPs and the specialist-heavy medical practice in the country’s capital of Quito.

Under his leadership, AHD established a hospital in the rural community of Pedro Vicente Maldonado; it opened in 2000 and now is financially self-sufficient. “The focus was on the need for cost-effective, high-quality hospital services in a country with a dearth of hospitals,” he says.

At the hospital, family-practice physicians serve as hospitalists and deal with a wide spectrum of clinical needs ranging from car accidents and complicated pregnancies to snake bites and toxic organic phosphate herbicide exposure.

“Rural hospitals can’t afford five or six types of attendings, but if you have well-trained family practitioners backed by a general surgeon, they can handle most of the spectrum of clinical needs and the chaos management,” he says. Increasingly, those clinical needs include such chronic degenerative diseases as diabetes, hypertension, and arthritis, for which Ecuador’s cadre of rural PCPs are not trained.

Dr. Gaus is planning a second hospital in the larger Ecuadorean city of Santo Domingo (population 400,000), with the support of the Ministry of Public Health and the Social Security system. The new facility, using the same model and hospitalist roles, will open in 12 to 18 months and will increase the number of three-year family-practice residency slots from six to 20.

Could U.S. hospitals learn from how HM is practiced in developing nations such as Ecuador? David Gaus, MD, MS, founder and director of Andean Health and Development (AHD), thinks so.

Dr. Gaus, who spends half the year as assistant clinical professor of medicine and teaching hospitalist at the University of Wisconsin and the other half with AHD in Ecuador, was inspired to pursue a medical degree by doing development work in Ecuador. When he returned to Ecuador in 1995 to be a doctor to the poor, he discovered a major gap in the healthcare system, between undertrained rural PCPs and the specialist-heavy medical practice in the country’s capital of Quito.

Under his leadership, AHD established a hospital in the rural community of Pedro Vicente Maldonado; it opened in 2000 and now is financially self-sufficient. “The focus was on the need for cost-effective, high-quality hospital services in a country with a dearth of hospitals,” he says.

At the hospital, family-practice physicians serve as hospitalists and deal with a wide spectrum of clinical needs ranging from car accidents and complicated pregnancies to snake bites and toxic organic phosphate herbicide exposure.

“Rural hospitals can’t afford five or six types of attendings, but if you have well-trained family practitioners backed by a general surgeon, they can handle most of the spectrum of clinical needs and the chaos management,” he says. Increasingly, those clinical needs include such chronic degenerative diseases as diabetes, hypertension, and arthritis, for which Ecuador’s cadre of rural PCPs are not trained.

Dr. Gaus is planning a second hospital in the larger Ecuadorean city of Santo Domingo (population 400,000), with the support of the Ministry of Public Health and the Social Security system. The new facility, using the same model and hospitalist roles, will open in 12 to 18 months and will increase the number of three-year family-practice residency slots from six to 20.

Sensitivity of Superficial Wound Culture

While a general consensus exists that surface wound cultures have less utility than deeper cultures, surface cultures are nevertheless routinely used to guide empiric antibiotic administration. This is due in part to the ease with which surface cultures are obtained and the delay in obtaining deeper wound and bone cultures. The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommends routine culture of all diabetic infections before initiating empiric antibiotic therapy, despite caveats regarding undebrided wounds.1 Further examination of 2 additional societies, the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases and the Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases, reveals that they also do not describe guidelines on the role of surface wound cultures in skin, and skin structure infection (SSSI) management.2, 3

Surface wound cultures are used to aid in diagnosis and appropriate antibiotic treatment of lower extremity foot ulcers.4 Contaminated cultures from other body locations have shown little utility and may be wasteful of resources.5, 6 We hypothesize that given commensal skin flora, coupled with the additional flora that colonizes (chronic) lower extremity wounds, surface wound cultures provide poor diagnostic accuracy for determining the etiology of acute infection. In contrast, many believe that deep tissue cultures obtained at time of debridement or surgical intervention may provide more relevant information to guide antibiotic therapy, thus serving as a gold standard.13, 7, 8 Nevertheless, with the ease of obtaining these superficial cultures and the promptness of the results, surface wound cultures are still used as a surrogate for the information derived from deeper cultures.

Purpose

The frequency at which superficial wound cultures correlate with the data obtained from deeper cultures is needed to interpret the posttest likelihood of infection. However, the sensitivity and specificity of superficial wound culture as a diagnostic test is unclear. The purpose of this study is to conduct a systematic review of the existing literature in order to investigate the relationship between superficial wound cultures and the etiology of SSSI. Accordingly, we aim to describe any role that surface wound cultures may play in the treatment of lower extremity ulcers.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources

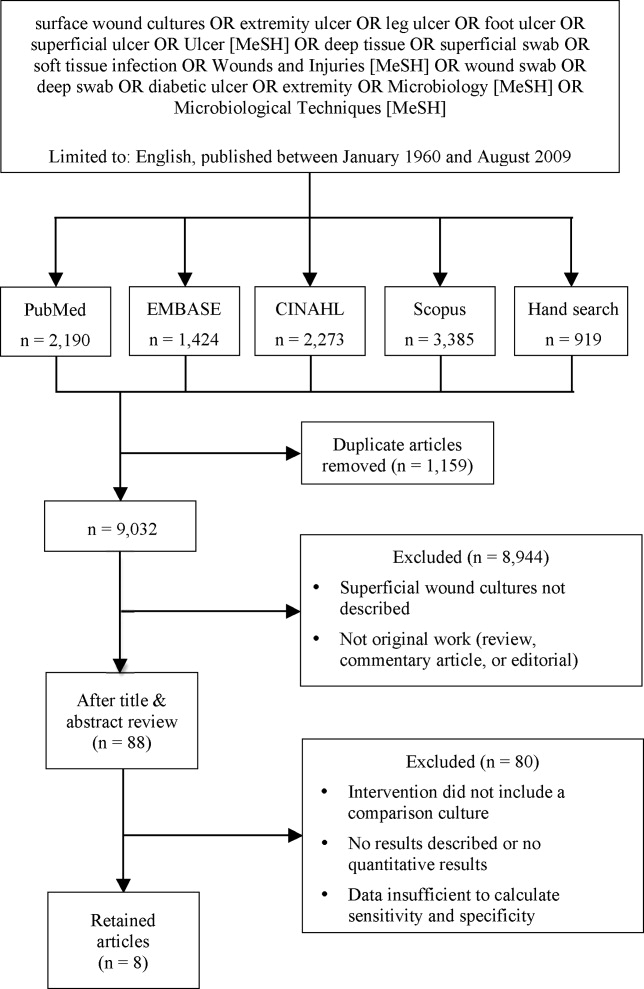

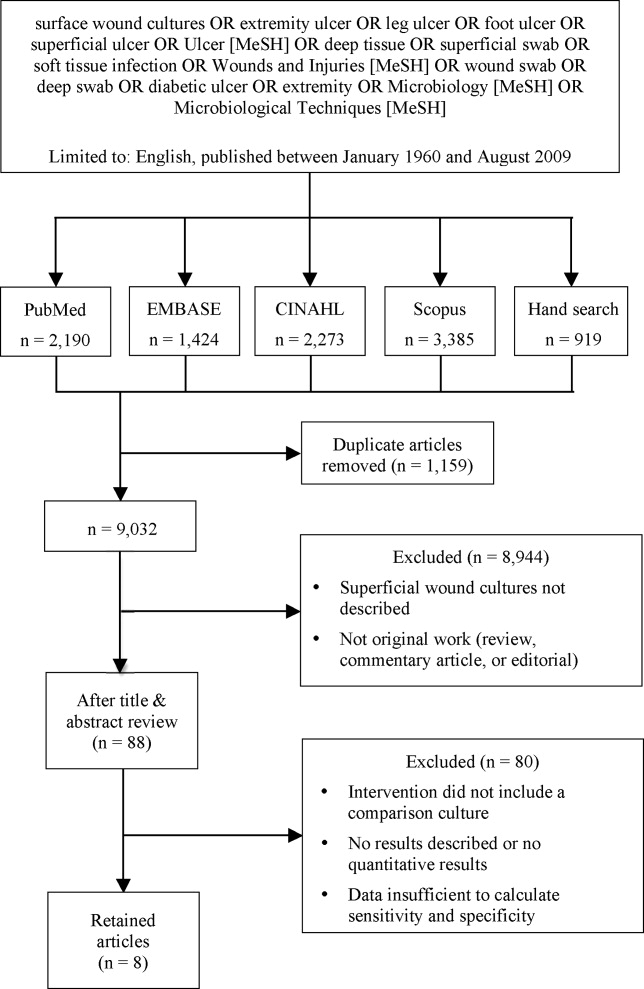

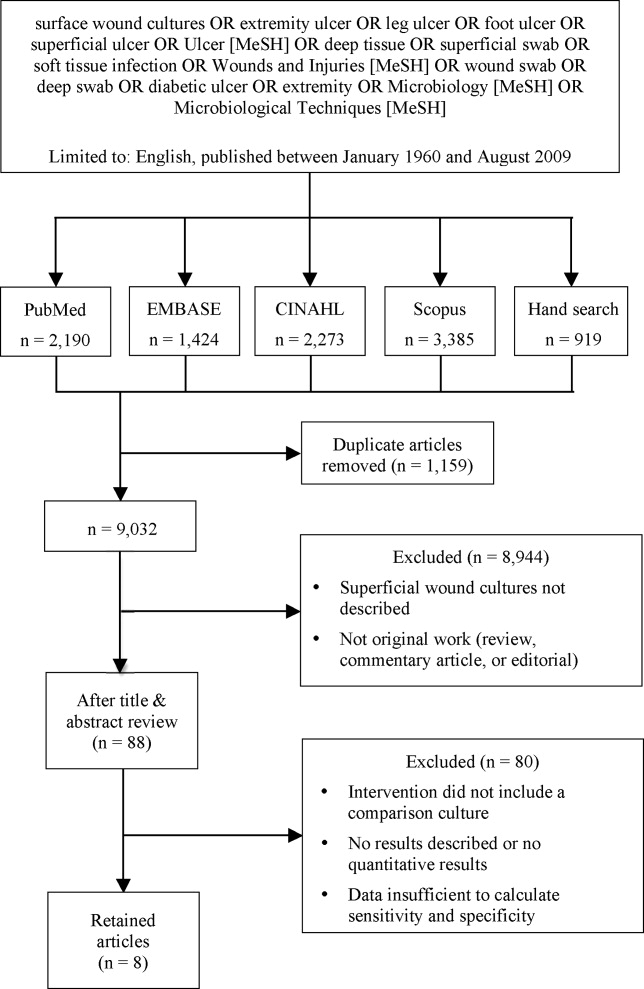

We identified eligible articles through an electronic search of the following databases: Medline through PubMed, Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE), Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Scopus. We also hand searched the reference lists of key review articles identified by the electronic search and the reference lists of all eligible articles (Figure 1).

Study Selection

The search strategy was limited to English articles published between January 1960 and August 2009. A PubMed search identified titles that contained the following keywords combined with OR: surface wound cultures, extremity ulcer, leg ulcer, foot ulcer, superficial ulcer, Ulcer [MeSH], deep tissue, superficial swab, soft tissue infection, Wounds and Injuries [MeSH], wound swab, deep swab, diabetic ulcer, Microbiology [MeSH], Microbiological Techniques [MeSH]. Medical Subject Headings [MeSH] were used as indicated and were exploded to include subheadings and maximize results. This search strategy was adapted to search the other databases.

Data Extraction

Eligible studies were identified in 2 phases. In the first phase, 2 authors (AY and CC) independently reviewed potential titles of citations for eligibility. Citations were returned for adjudication if disagreement occurred. If agreement could not be reached, the article was retained for further review. In the second phase, 2 authors (AY and CC) independently reviewed the abstracts of eligible titles. In situations of disagreement, abstracts were returned for adjudication and if necessary were retained for further review. Once all eligible articles were identified, 2 reviewers (AY and CL) independently abstracted the information within each article using a pre‐defined abstraction tool. A third investigator (CC) reviewed all the abstracted articles for verification.

We initially selected articles that involved lower extremity wounds. Articles were included if they described superficial wound cultures along with an alternative method of culture for comparison. Alternative culture methods were defined as cultures derived from needle aspiration, wound base biopsy, deep tissue biopsy, surgical debridement, or bone biopsy. Further inclusion criteria required that articles have enough microbiology data to calculate sensitivity and specificity values for superficial wound swabs.

For the included articles, 2 reviewers (AY, CC) abstracted information pertaining to microbiology data from superficial wound swabs and alternative comparison cultures as reported in each article in the form of mean number of isolates recovered. Study characteristics and patient demographics were also recorded.

When not reported in the article, calculation of test sensitivity and specificity involved identifying true and false‐positive tests as well as true and false‐negative tests. Articles were excluded if they did not contain sufficient data to calculate true/false‐positive and true/false‐negative tests. For all articles, we used the formulae [(sensitivity) (1‐specificity)] and [(1‐sensitivity) (specificity)] to calculate positive and negative likelihood ratios (LRs), respectively.

Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

Test sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative LR from all articles were pooled using a random‐effects meta‐analysis model (DerSimonian and Laird method). This method considers heterogeneity both within and between studies to calculate the range of possible true effects.9 For situations in which significant heterogeneity is anticipated, the random‐effects model is most conservative and appropriate.9, 10

We also compared the mean number of organisms isolated from wound cultures to the mean number of organisms isolated from alternative culture methods using the nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test. Inter‐rater reliability was assessed using the kappa statistic. We assessed potential publication bias by visually examining a funnel plot as described by Egger et al.11 We report 95% confidence intervals, medians with interquartile ranges, and p‐values where appropriate. All data analyses were performed using Stata 9.2 (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX, 2007).

Results

Of 9032 unique citations, eight studies met all inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Inter‐rater reliability was substantial (Kappa = 0.78).12 Areas of initial disagreement generally involved whether a study adequately described an appropriate alternative culture method for comparison or whether data available in an article was sufficient for sensitivity and specificity calculation. Consensus was achieved once the full article was retrieved, reviewed and discussed.

The 8 studies evaluated in the review included a total number of 615 patients or samples (Table 1). Diabetic wounds were described in four studies.1316 Two studies described wounds associated with peripheral vascular disease,13, 17 while four involved traumatic wounds.13, 1719 One study did not identify the clinical circumstances concerning the wounds.20

| Study ID | n | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive LR | Negative LR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Machowiak et al. (1978)17 | 183* | 0.26 | 0.56 | 0.59 | 1.32 |

| Sharp et al. (1979)15 | 58 | 0.53 | 0.62 | 1.38 | 0.77 |

| Wheat et al. (1986)16 | 26 | 0.35 | 0.32 | 0.51 | 2.06 |

| Zuluaga et al. (2006)19 | 100 | 0.20 | 0.67 | 0.60 | 1.20 |

| Zuluaga et al. (2002)18 | 50 | 0.22 | 0.54 | 0.47 | 1.45 |

| Gardner et al. (2007)13 | 83 | 0.90 | 0.57 | 2.09 | 0.18 |

| Slater et al. (2004)14 | 60 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 23.3 | 0.07 |

| Mousa (1997)20 | 55 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 20.6 | 0.12 |

| Pooled values (95% CI) | 0.49 (0.37‐0.61) | 0.62 (0.51‐0.74) | 1.1 (0.71‐1.5) | 0.67 (0.52‐0.82) | |

The studies used several different methods for obtaining superficial cultures. Six studies obtained purulent wound drainage material through the application of sterile swabs.1316, 18, 19 One study obtained purulent drainage material using needle aspiration.18 Two studies obtained culture material from sinus tracts associated with the wounds, one through sinus tract washings17 and another by obtaining sinus tract discharge material.20

The types of comparison cultures used were equally divided between deep tissue biopsies1316 and bone biopsies,1720 each accounting for 50% (4 of 8) of studies.

In assessing the data from the eight studies, the pooled test sensitivity for superficial wound swabs was 49% (95% confidence interval [CI], 37‐61%) (Figure 2). The pooled specificity for superficial wound swabs was 62% (95% CI, 51‐74%), while the pooled positive and negative LRs were 1.1 (95% CI, 0.71‐1.5) and 0.67 (95% CI, 0.52‐0.82), respectively (Figure 2).

The median number of bacterial isolates reported for each culture type, superficial and comparison culture, was collected from each study (Table 2). The median value for number of bacterial isolates identified by superficial culture was 2.7 (interquartile range [IQR] 1.8‐3.2). The median value for number of bacterial isolates identified by comparison culture was 2.2 (IQR 1.7‐2.9). A Wilcoxon rank sum analysis showed that the number of isolates for surface wound cultures was not significantly different than the number of isolates for comparison cultures (P = 0.75) (Table 1).

| Study ID | # of Isolates (Swab) | # of Isolates (Comparison) | Prior Antibiotics? |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Machowiak et al. (1978)17 | * | * | Treated, but details not reported |

| Sharp et al. (1979)15 | 2.3 | 2.2 | Treated, but details not reported |

| Wheat et al. (1986)16 | 3.3 | 3.4 | Not described |

| Zuluaga et al. (2006)19 | 1.3 | 1.6 | Antibiotics stopped 48 hours prior |

| Zuluaga et al. (2002)18 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 52% on antibiotics, stopped 48 hours prior |

| Gardner et al. (2007)13 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 42% on antibiotics |

| Slater et al. (2004)14 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 27% on prior antibiotics |

| Mousa (1997)20 | 3.6 | 1.9 | Treated, but details not reported |

| Median (IQR) | 2.7 (1.8‐3.2) | 2.2 (1.7‐2.9) | |

Discussion

In performing this review, we discovered ambiguity in the literature regarding the utility of surface wound cultures. Some studies obtained findings to suggest the utility of surface wound cultures,8, 14, 17 while other studies in our review16, 18, 19 provided evidence against them. This variability confirmed the need for a meta‐analytic approach as provided by this review.

While we have tried to minimize bias through a well‐established methodology, we acknowledge that certain methodological limitations should be considered in interpreting the results. There may be publication bias in reviews that include only published articles; a funnel plot of sensitivity vs. sample size showed some asymmetry, suggesting bias. Our search strategy was limited to English‐only articles, which may result in publication bias.

Further, this review included a group of studies that were heterogeneous in several regards. Differences exist in culturing methods and laboratory technology, as exemplified by the variety of superficial culture methods used. We were not able to account for these laboratory differences, as methodologies in obtaining and isolating bacteria were not uniformly well described.

Additionally, the studies classified organisms in different ways. Three studies categorized organisms according to Gram's stain characteristics.13, 16, 18 One study described organisms primarily in terms of aerobic or anaerobic respiration.15 Two studies14, 19 discussed pathogens both in terms of respiration (aerobic/anaerobic) and Gram's stain characteristic, while another 2 studies17, 20 did not describe organisms in either terms. These inconsistencies limited our ability to provide sensitivity and specificity information for specific subclasses of organisms.

The clinical conditions in each study surrounding the wounds were also heterogeneous: most significantly in the issue of prior antibiotic administration. All but 1 study16 indicated that the patients had received antibiotics prior to having cultures obtained. The type of antibiotics (narrow‐spectrum or broad‐spectrum), the route of administration, and the cessation of antibiotics in relation to obtaining swabs and cultures all varied widely or were not well described. This degree of ambiguity will necessarily impact both the reliability of data regarding microbial growth as well as the component flora.

The inclusion of higher quality studies is likely to result in a more reliable meta‐analysis.21 We had hoped that antibiotic trials would contain uniform outcomes and thus strengthen our meta‐analysis through the inclusion of randomized‐controlled studies. Unfortunately, the majority of antibiotic trials did not use superficial wound cultures, did not report mean number of isolates, or did not provide microbiological data in sufficient detail to calculate concordance ratesand therefore, did not meet eligibility criteria. Randomized‐controlled trials were a minority among our included articles; the majority of study designs were retrospective cohorts and case‐controlled studies.

Despite these limitations, we were able to conclude that superficial wound culture provides mediocre sensitivity (49%) and specificity (62%). The positive LR of 1.1 is unhelpful in decision making, having a CI that includes 1. Interestingly, the negative LR of 0.67 could be somewhat helpful in medical decision making, modifying the pretest probability and assisting in ruling out a deeper bacterial infection. Although, according to Fagan's nomogram, a negative LR of 0.67 has only a mild effect on pretest odds.22

The bacterial bioburden assessed by the number of isolates obtained by culture method serves as a proxy for reliability of culture results14, 23 by suggesting that fewer organisms isolated from deep tissue or bone samples reflects a less contaminated specimen. Our assessment of the bioburden found that the median number of isolates was slightly higher in surface cultures than deeper cultures, though not to a significant degree (P = 0.75). This indicates that the degree of contamination in superficial cultures was neither significantly worse nor better than deep cultures.

We attempted to define a role for surface wound cultures; however, we found that these did not show any greater utility than deep cultures for identifying the microbiologic etiology of diabetic wound infections. While the negative LR provides some quantitative verification of the common clinical practice that a negative culture argues against infection, the finding is not especially robust.

Although for this meta‐analysis we grouped all organisms in the same way, we recognize that the sensitivity and specificity may differ according to various subclasses of bacteria. Interpretations of culture results also vary (eg, Gram positive vs. negative; aerobic vs. anaerobic); practitioners will not interpret superficial cultures of coagulase‐negative Staphylococcus in the same way as Pseudomonas. However, this study seeks to establish a reasonable starting point for the medical decision‐making process by providing quantitative values in an area with previously conflicting data. We anticipate that as laboratory techniques improve and research into superficial wounds continues, greater sensitivity of superficial wound cultures will result.

Ultimately, physicians use culture data to target therapy in an effort to use the least toxic and most effective antimicrobial agent possible to successfully treat infections. Clinical outcomes were not described in all included articles; in those that did, the endpoints were too dissimilar for meaningful comparison. Limiting our review to studies reporting treatment outcomes would have resulted in too few included studies. Thus, we were unable able to assess whether superficial wound cultures were associated with improved patient‐oriented outcomes in this meta‐analysis.

There is a significant paucity of trials evaluating the accurate concordance of superficial swabs to deep tissue culture. The current data shows poor sensitivity and specificity of superficial culture methods. The presumption that deeper cultures (such as a bone biopsy) should result in a less contaminated sample and more targeted culture results was also not borne out in our review. When presented with a patient with a wound infection, physicians mentally supply a pretest (or a pretreatment) probability as to the microbiologic etiology of the infection. Careful history will, of course, be critical in identifying extenuating circumstance or unusual exposures. From our meta‐analysis, we cannot recommend the routine use of superficial wound cultures to guide initial antibiotic therapy as this may result in poor resource utilization.5 While clinical outcomes from the use of routine superficial cultures are unclear, we suggest greater use of local antibiograms and methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) prevalence data to determine resistance patterns and guide the selection of empiric therapies.

- ,,, et al.Diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infections.Clin Infect Dis.2004;39:885–910.

- AASID,Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases—Standards, Practice Guidelines (Skin and Soft Tissue Infections): Institute for Safe Medication Practices;2006.

- ESCMID,European Society of Clinical Microbiology 2006.

- ,,,.Methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus in community‐acquired skin infections.Emerg Infect Dis.2005;11:928–930.

- ,,.Contaminant blood cultures and resource utilization. The true consequences of false‐positive results.JAMA.1991;265:365–369.

- ,,,,,.Cost‐effectiveness of blood cultures for adult patients with cellulitis.Clin Infect Dis.1999;29:1483–1488.

- ,,,,,.Managing skin and soft tissue infections: expert panel recommendations on key decision points.J Antimicrob Chemother.2003;52 Suppl 1:i3‐i17.

- ,,, et al.Deep tissue biopsy vs. superficial swab culture monitoring in the microbiological assessment of limb‐threatening diabetic foot infection.Diabet Med.2001;18:822–827.

- ,.Meta‐analysis in clinical trials.Control Clin Trials.1986;7:177–188.

- ,,.Quantitative synthesis in systematic reviews.Ann Intern Med.1997;127:820–826.

- ,,,.Bias in meta‐analysis detected by a simple, graphical test.BMJ.1997;315:629–634.

- .Practical statistics for medical research.London, UK:Chapman 1991:403–409.

- ,,,,,.Diagnostic validity of three swab techniques for identifying chronic wound infection.Wound Repair Regen.2006;14(5):548–57.

- ,,, et al.Swab cultures accurately identify bacterial pathogens in diabetic foot wounds not involving bone.Diabet Med.2004;21:705–709.

- ,,,,.Microbiology of superficial and deep tissues in infected diabetic gangrene.Surg Gynecol Obstet.1979;149:217–219.

- ,,, et al.Diabetic foot infections. Bacteriologic analysis.Arch Intern Med.1986;146:1935–1940.

- ,,.Diagnostic value of sinus‐tract cultures in chronic osteomyelitis.JAMA.1978;239:2772–2775.

- ,,,.Lack of microbiological concordance between bone and non‐bone specimens in chronic osteomyelitis: an observational study.BMC Infect Dis.2002;2:8.

- ,,,,,.Etiologic diagnosis of chronic osteomyelitis: a prospective study.Arch Intern Med.2006;166:95–100.

- .Evaluation of sinus‐track cultures in chronic bone infection.J Bone Joint Surg Br.1997;79:567–569.

- ,,, et al.Meta‐analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting.JAMA.2000;283:2008–2012.

- ,Letter: nomogram for Bayes theorem.N Engl J Med.1975;293:257.

- ,,,,,.Quantitative swab culture versus tissue biopsy: a comparison in chronic wounds.Ostomy Wound Manage.2001;47:34–37.

While a general consensus exists that surface wound cultures have less utility than deeper cultures, surface cultures are nevertheless routinely used to guide empiric antibiotic administration. This is due in part to the ease with which surface cultures are obtained and the delay in obtaining deeper wound and bone cultures. The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommends routine culture of all diabetic infections before initiating empiric antibiotic therapy, despite caveats regarding undebrided wounds.1 Further examination of 2 additional societies, the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases and the Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases, reveals that they also do not describe guidelines on the role of surface wound cultures in skin, and skin structure infection (SSSI) management.2, 3

Surface wound cultures are used to aid in diagnosis and appropriate antibiotic treatment of lower extremity foot ulcers.4 Contaminated cultures from other body locations have shown little utility and may be wasteful of resources.5, 6 We hypothesize that given commensal skin flora, coupled with the additional flora that colonizes (chronic) lower extremity wounds, surface wound cultures provide poor diagnostic accuracy for determining the etiology of acute infection. In contrast, many believe that deep tissue cultures obtained at time of debridement or surgical intervention may provide more relevant information to guide antibiotic therapy, thus serving as a gold standard.13, 7, 8 Nevertheless, with the ease of obtaining these superficial cultures and the promptness of the results, surface wound cultures are still used as a surrogate for the information derived from deeper cultures.

Purpose

The frequency at which superficial wound cultures correlate with the data obtained from deeper cultures is needed to interpret the posttest likelihood of infection. However, the sensitivity and specificity of superficial wound culture as a diagnostic test is unclear. The purpose of this study is to conduct a systematic review of the existing literature in order to investigate the relationship between superficial wound cultures and the etiology of SSSI. Accordingly, we aim to describe any role that surface wound cultures may play in the treatment of lower extremity ulcers.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources

We identified eligible articles through an electronic search of the following databases: Medline through PubMed, Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE), Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Scopus. We also hand searched the reference lists of key review articles identified by the electronic search and the reference lists of all eligible articles (Figure 1).

Study Selection

The search strategy was limited to English articles published between January 1960 and August 2009. A PubMed search identified titles that contained the following keywords combined with OR: surface wound cultures, extremity ulcer, leg ulcer, foot ulcer, superficial ulcer, Ulcer [MeSH], deep tissue, superficial swab, soft tissue infection, Wounds and Injuries [MeSH], wound swab, deep swab, diabetic ulcer, Microbiology [MeSH], Microbiological Techniques [MeSH]. Medical Subject Headings [MeSH] were used as indicated and were exploded to include subheadings and maximize results. This search strategy was adapted to search the other databases.

Data Extraction

Eligible studies were identified in 2 phases. In the first phase, 2 authors (AY and CC) independently reviewed potential titles of citations for eligibility. Citations were returned for adjudication if disagreement occurred. If agreement could not be reached, the article was retained for further review. In the second phase, 2 authors (AY and CC) independently reviewed the abstracts of eligible titles. In situations of disagreement, abstracts were returned for adjudication and if necessary were retained for further review. Once all eligible articles were identified, 2 reviewers (AY and CL) independently abstracted the information within each article using a pre‐defined abstraction tool. A third investigator (CC) reviewed all the abstracted articles for verification.

We initially selected articles that involved lower extremity wounds. Articles were included if they described superficial wound cultures along with an alternative method of culture for comparison. Alternative culture methods were defined as cultures derived from needle aspiration, wound base biopsy, deep tissue biopsy, surgical debridement, or bone biopsy. Further inclusion criteria required that articles have enough microbiology data to calculate sensitivity and specificity values for superficial wound swabs.

For the included articles, 2 reviewers (AY, CC) abstracted information pertaining to microbiology data from superficial wound swabs and alternative comparison cultures as reported in each article in the form of mean number of isolates recovered. Study characteristics and patient demographics were also recorded.

When not reported in the article, calculation of test sensitivity and specificity involved identifying true and false‐positive tests as well as true and false‐negative tests. Articles were excluded if they did not contain sufficient data to calculate true/false‐positive and true/false‐negative tests. For all articles, we used the formulae [(sensitivity) (1‐specificity)] and [(1‐sensitivity) (specificity)] to calculate positive and negative likelihood ratios (LRs), respectively.

Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

Test sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative LR from all articles were pooled using a random‐effects meta‐analysis model (DerSimonian and Laird method). This method considers heterogeneity both within and between studies to calculate the range of possible true effects.9 For situations in which significant heterogeneity is anticipated, the random‐effects model is most conservative and appropriate.9, 10

We also compared the mean number of organisms isolated from wound cultures to the mean number of organisms isolated from alternative culture methods using the nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test. Inter‐rater reliability was assessed using the kappa statistic. We assessed potential publication bias by visually examining a funnel plot as described by Egger et al.11 We report 95% confidence intervals, medians with interquartile ranges, and p‐values where appropriate. All data analyses were performed using Stata 9.2 (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX, 2007).

Results

Of 9032 unique citations, eight studies met all inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Inter‐rater reliability was substantial (Kappa = 0.78).12 Areas of initial disagreement generally involved whether a study adequately described an appropriate alternative culture method for comparison or whether data available in an article was sufficient for sensitivity and specificity calculation. Consensus was achieved once the full article was retrieved, reviewed and discussed.

The 8 studies evaluated in the review included a total number of 615 patients or samples (Table 1). Diabetic wounds were described in four studies.1316 Two studies described wounds associated with peripheral vascular disease,13, 17 while four involved traumatic wounds.13, 1719 One study did not identify the clinical circumstances concerning the wounds.20

| Study ID | n | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive LR | Negative LR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Machowiak et al. (1978)17 | 183* | 0.26 | 0.56 | 0.59 | 1.32 |

| Sharp et al. (1979)15 | 58 | 0.53 | 0.62 | 1.38 | 0.77 |

| Wheat et al. (1986)16 | 26 | 0.35 | 0.32 | 0.51 | 2.06 |

| Zuluaga et al. (2006)19 | 100 | 0.20 | 0.67 | 0.60 | 1.20 |

| Zuluaga et al. (2002)18 | 50 | 0.22 | 0.54 | 0.47 | 1.45 |

| Gardner et al. (2007)13 | 83 | 0.90 | 0.57 | 2.09 | 0.18 |

| Slater et al. (2004)14 | 60 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 23.3 | 0.07 |

| Mousa (1997)20 | 55 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 20.6 | 0.12 |

| Pooled values (95% CI) | 0.49 (0.37‐0.61) | 0.62 (0.51‐0.74) | 1.1 (0.71‐1.5) | 0.67 (0.52‐0.82) | |

The studies used several different methods for obtaining superficial cultures. Six studies obtained purulent wound drainage material through the application of sterile swabs.1316, 18, 19 One study obtained purulent drainage material using needle aspiration.18 Two studies obtained culture material from sinus tracts associated with the wounds, one through sinus tract washings17 and another by obtaining sinus tract discharge material.20

The types of comparison cultures used were equally divided between deep tissue biopsies1316 and bone biopsies,1720 each accounting for 50% (4 of 8) of studies.

In assessing the data from the eight studies, the pooled test sensitivity for superficial wound swabs was 49% (95% confidence interval [CI], 37‐61%) (Figure 2). The pooled specificity for superficial wound swabs was 62% (95% CI, 51‐74%), while the pooled positive and negative LRs were 1.1 (95% CI, 0.71‐1.5) and 0.67 (95% CI, 0.52‐0.82), respectively (Figure 2).

The median number of bacterial isolates reported for each culture type, superficial and comparison culture, was collected from each study (Table 2). The median value for number of bacterial isolates identified by superficial culture was 2.7 (interquartile range [IQR] 1.8‐3.2). The median value for number of bacterial isolates identified by comparison culture was 2.2 (IQR 1.7‐2.9). A Wilcoxon rank sum analysis showed that the number of isolates for surface wound cultures was not significantly different than the number of isolates for comparison cultures (P = 0.75) (Table 1).

| Study ID | # of Isolates (Swab) | # of Isolates (Comparison) | Prior Antibiotics? |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Machowiak et al. (1978)17 | * | * | Treated, but details not reported |

| Sharp et al. (1979)15 | 2.3 | 2.2 | Treated, but details not reported |

| Wheat et al. (1986)16 | 3.3 | 3.4 | Not described |

| Zuluaga et al. (2006)19 | 1.3 | 1.6 | Antibiotics stopped 48 hours prior |

| Zuluaga et al. (2002)18 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 52% on antibiotics, stopped 48 hours prior |

| Gardner et al. (2007)13 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 42% on antibiotics |

| Slater et al. (2004)14 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 27% on prior antibiotics |

| Mousa (1997)20 | 3.6 | 1.9 | Treated, but details not reported |

| Median (IQR) | 2.7 (1.8‐3.2) | 2.2 (1.7‐2.9) | |

Discussion

In performing this review, we discovered ambiguity in the literature regarding the utility of surface wound cultures. Some studies obtained findings to suggest the utility of surface wound cultures,8, 14, 17 while other studies in our review16, 18, 19 provided evidence against them. This variability confirmed the need for a meta‐analytic approach as provided by this review.

While we have tried to minimize bias through a well‐established methodology, we acknowledge that certain methodological limitations should be considered in interpreting the results. There may be publication bias in reviews that include only published articles; a funnel plot of sensitivity vs. sample size showed some asymmetry, suggesting bias. Our search strategy was limited to English‐only articles, which may result in publication bias.

Further, this review included a group of studies that were heterogeneous in several regards. Differences exist in culturing methods and laboratory technology, as exemplified by the variety of superficial culture methods used. We were not able to account for these laboratory differences, as methodologies in obtaining and isolating bacteria were not uniformly well described.

Additionally, the studies classified organisms in different ways. Three studies categorized organisms according to Gram's stain characteristics.13, 16, 18 One study described organisms primarily in terms of aerobic or anaerobic respiration.15 Two studies14, 19 discussed pathogens both in terms of respiration (aerobic/anaerobic) and Gram's stain characteristic, while another 2 studies17, 20 did not describe organisms in either terms. These inconsistencies limited our ability to provide sensitivity and specificity information for specific subclasses of organisms.

The clinical conditions in each study surrounding the wounds were also heterogeneous: most significantly in the issue of prior antibiotic administration. All but 1 study16 indicated that the patients had received antibiotics prior to having cultures obtained. The type of antibiotics (narrow‐spectrum or broad‐spectrum), the route of administration, and the cessation of antibiotics in relation to obtaining swabs and cultures all varied widely or were not well described. This degree of ambiguity will necessarily impact both the reliability of data regarding microbial growth as well as the component flora.

The inclusion of higher quality studies is likely to result in a more reliable meta‐analysis.21 We had hoped that antibiotic trials would contain uniform outcomes and thus strengthen our meta‐analysis through the inclusion of randomized‐controlled studies. Unfortunately, the majority of antibiotic trials did not use superficial wound cultures, did not report mean number of isolates, or did not provide microbiological data in sufficient detail to calculate concordance ratesand therefore, did not meet eligibility criteria. Randomized‐controlled trials were a minority among our included articles; the majority of study designs were retrospective cohorts and case‐controlled studies.

Despite these limitations, we were able to conclude that superficial wound culture provides mediocre sensitivity (49%) and specificity (62%). The positive LR of 1.1 is unhelpful in decision making, having a CI that includes 1. Interestingly, the negative LR of 0.67 could be somewhat helpful in medical decision making, modifying the pretest probability and assisting in ruling out a deeper bacterial infection. Although, according to Fagan's nomogram, a negative LR of 0.67 has only a mild effect on pretest odds.22

The bacterial bioburden assessed by the number of isolates obtained by culture method serves as a proxy for reliability of culture results14, 23 by suggesting that fewer organisms isolated from deep tissue or bone samples reflects a less contaminated specimen. Our assessment of the bioburden found that the median number of isolates was slightly higher in surface cultures than deeper cultures, though not to a significant degree (P = 0.75). This indicates that the degree of contamination in superficial cultures was neither significantly worse nor better than deep cultures.

We attempted to define a role for surface wound cultures; however, we found that these did not show any greater utility than deep cultures for identifying the microbiologic etiology of diabetic wound infections. While the negative LR provides some quantitative verification of the common clinical practice that a negative culture argues against infection, the finding is not especially robust.

Although for this meta‐analysis we grouped all organisms in the same way, we recognize that the sensitivity and specificity may differ according to various subclasses of bacteria. Interpretations of culture results also vary (eg, Gram positive vs. negative; aerobic vs. anaerobic); practitioners will not interpret superficial cultures of coagulase‐negative Staphylococcus in the same way as Pseudomonas. However, this study seeks to establish a reasonable starting point for the medical decision‐making process by providing quantitative values in an area with previously conflicting data. We anticipate that as laboratory techniques improve and research into superficial wounds continues, greater sensitivity of superficial wound cultures will result.

Ultimately, physicians use culture data to target therapy in an effort to use the least toxic and most effective antimicrobial agent possible to successfully treat infections. Clinical outcomes were not described in all included articles; in those that did, the endpoints were too dissimilar for meaningful comparison. Limiting our review to studies reporting treatment outcomes would have resulted in too few included studies. Thus, we were unable able to assess whether superficial wound cultures were associated with improved patient‐oriented outcomes in this meta‐analysis.

There is a significant paucity of trials evaluating the accurate concordance of superficial swabs to deep tissue culture. The current data shows poor sensitivity and specificity of superficial culture methods. The presumption that deeper cultures (such as a bone biopsy) should result in a less contaminated sample and more targeted culture results was also not borne out in our review. When presented with a patient with a wound infection, physicians mentally supply a pretest (or a pretreatment) probability as to the microbiologic etiology of the infection. Careful history will, of course, be critical in identifying extenuating circumstance or unusual exposures. From our meta‐analysis, we cannot recommend the routine use of superficial wound cultures to guide initial antibiotic therapy as this may result in poor resource utilization.5 While clinical outcomes from the use of routine superficial cultures are unclear, we suggest greater use of local antibiograms and methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) prevalence data to determine resistance patterns and guide the selection of empiric therapies.

While a general consensus exists that surface wound cultures have less utility than deeper cultures, surface cultures are nevertheless routinely used to guide empiric antibiotic administration. This is due in part to the ease with which surface cultures are obtained and the delay in obtaining deeper wound and bone cultures. The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommends routine culture of all diabetic infections before initiating empiric antibiotic therapy, despite caveats regarding undebrided wounds.1 Further examination of 2 additional societies, the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases and the Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases, reveals that they also do not describe guidelines on the role of surface wound cultures in skin, and skin structure infection (SSSI) management.2, 3

Surface wound cultures are used to aid in diagnosis and appropriate antibiotic treatment of lower extremity foot ulcers.4 Contaminated cultures from other body locations have shown little utility and may be wasteful of resources.5, 6 We hypothesize that given commensal skin flora, coupled with the additional flora that colonizes (chronic) lower extremity wounds, surface wound cultures provide poor diagnostic accuracy for determining the etiology of acute infection. In contrast, many believe that deep tissue cultures obtained at time of debridement or surgical intervention may provide more relevant information to guide antibiotic therapy, thus serving as a gold standard.13, 7, 8 Nevertheless, with the ease of obtaining these superficial cultures and the promptness of the results, surface wound cultures are still used as a surrogate for the information derived from deeper cultures.

Purpose

The frequency at which superficial wound cultures correlate with the data obtained from deeper cultures is needed to interpret the posttest likelihood of infection. However, the sensitivity and specificity of superficial wound culture as a diagnostic test is unclear. The purpose of this study is to conduct a systematic review of the existing literature in order to investigate the relationship between superficial wound cultures and the etiology of SSSI. Accordingly, we aim to describe any role that surface wound cultures may play in the treatment of lower extremity ulcers.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources

We identified eligible articles through an electronic search of the following databases: Medline through PubMed, Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE), Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Scopus. We also hand searched the reference lists of key review articles identified by the electronic search and the reference lists of all eligible articles (Figure 1).

Study Selection

The search strategy was limited to English articles published between January 1960 and August 2009. A PubMed search identified titles that contained the following keywords combined with OR: surface wound cultures, extremity ulcer, leg ulcer, foot ulcer, superficial ulcer, Ulcer [MeSH], deep tissue, superficial swab, soft tissue infection, Wounds and Injuries [MeSH], wound swab, deep swab, diabetic ulcer, Microbiology [MeSH], Microbiological Techniques [MeSH]. Medical Subject Headings [MeSH] were used as indicated and were exploded to include subheadings and maximize results. This search strategy was adapted to search the other databases.

Data Extraction

Eligible studies were identified in 2 phases. In the first phase, 2 authors (AY and CC) independently reviewed potential titles of citations for eligibility. Citations were returned for adjudication if disagreement occurred. If agreement could not be reached, the article was retained for further review. In the second phase, 2 authors (AY and CC) independently reviewed the abstracts of eligible titles. In situations of disagreement, abstracts were returned for adjudication and if necessary were retained for further review. Once all eligible articles were identified, 2 reviewers (AY and CL) independently abstracted the information within each article using a pre‐defined abstraction tool. A third investigator (CC) reviewed all the abstracted articles for verification.

We initially selected articles that involved lower extremity wounds. Articles were included if they described superficial wound cultures along with an alternative method of culture for comparison. Alternative culture methods were defined as cultures derived from needle aspiration, wound base biopsy, deep tissue biopsy, surgical debridement, or bone biopsy. Further inclusion criteria required that articles have enough microbiology data to calculate sensitivity and specificity values for superficial wound swabs.

For the included articles, 2 reviewers (AY, CC) abstracted information pertaining to microbiology data from superficial wound swabs and alternative comparison cultures as reported in each article in the form of mean number of isolates recovered. Study characteristics and patient demographics were also recorded.

When not reported in the article, calculation of test sensitivity and specificity involved identifying true and false‐positive tests as well as true and false‐negative tests. Articles were excluded if they did not contain sufficient data to calculate true/false‐positive and true/false‐negative tests. For all articles, we used the formulae [(sensitivity) (1‐specificity)] and [(1‐sensitivity) (specificity)] to calculate positive and negative likelihood ratios (LRs), respectively.

Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

Test sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative LR from all articles were pooled using a random‐effects meta‐analysis model (DerSimonian and Laird method). This method considers heterogeneity both within and between studies to calculate the range of possible true effects.9 For situations in which significant heterogeneity is anticipated, the random‐effects model is most conservative and appropriate.9, 10

We also compared the mean number of organisms isolated from wound cultures to the mean number of organisms isolated from alternative culture methods using the nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test. Inter‐rater reliability was assessed using the kappa statistic. We assessed potential publication bias by visually examining a funnel plot as described by Egger et al.11 We report 95% confidence intervals, medians with interquartile ranges, and p‐values where appropriate. All data analyses were performed using Stata 9.2 (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX, 2007).

Results

Of 9032 unique citations, eight studies met all inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Inter‐rater reliability was substantial (Kappa = 0.78).12 Areas of initial disagreement generally involved whether a study adequately described an appropriate alternative culture method for comparison or whether data available in an article was sufficient for sensitivity and specificity calculation. Consensus was achieved once the full article was retrieved, reviewed and discussed.

The 8 studies evaluated in the review included a total number of 615 patients or samples (Table 1). Diabetic wounds were described in four studies.1316 Two studies described wounds associated with peripheral vascular disease,13, 17 while four involved traumatic wounds.13, 1719 One study did not identify the clinical circumstances concerning the wounds.20

| Study ID | n | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive LR | Negative LR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Machowiak et al. (1978)17 | 183* | 0.26 | 0.56 | 0.59 | 1.32 |

| Sharp et al. (1979)15 | 58 | 0.53 | 0.62 | 1.38 | 0.77 |

| Wheat et al. (1986)16 | 26 | 0.35 | 0.32 | 0.51 | 2.06 |

| Zuluaga et al. (2006)19 | 100 | 0.20 | 0.67 | 0.60 | 1.20 |

| Zuluaga et al. (2002)18 | 50 | 0.22 | 0.54 | 0.47 | 1.45 |

| Gardner et al. (2007)13 | 83 | 0.90 | 0.57 | 2.09 | 0.18 |

| Slater et al. (2004)14 | 60 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 23.3 | 0.07 |

| Mousa (1997)20 | 55 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 20.6 | 0.12 |

| Pooled values (95% CI) | 0.49 (0.37‐0.61) | 0.62 (0.51‐0.74) | 1.1 (0.71‐1.5) | 0.67 (0.52‐0.82) | |

The studies used several different methods for obtaining superficial cultures. Six studies obtained purulent wound drainage material through the application of sterile swabs.1316, 18, 19 One study obtained purulent drainage material using needle aspiration.18 Two studies obtained culture material from sinus tracts associated with the wounds, one through sinus tract washings17 and another by obtaining sinus tract discharge material.20

The types of comparison cultures used were equally divided between deep tissue biopsies1316 and bone biopsies,1720 each accounting for 50% (4 of 8) of studies.

In assessing the data from the eight studies, the pooled test sensitivity for superficial wound swabs was 49% (95% confidence interval [CI], 37‐61%) (Figure 2). The pooled specificity for superficial wound swabs was 62% (95% CI, 51‐74%), while the pooled positive and negative LRs were 1.1 (95% CI, 0.71‐1.5) and 0.67 (95% CI, 0.52‐0.82), respectively (Figure 2).

The median number of bacterial isolates reported for each culture type, superficial and comparison culture, was collected from each study (Table 2). The median value for number of bacterial isolates identified by superficial culture was 2.7 (interquartile range [IQR] 1.8‐3.2). The median value for number of bacterial isolates identified by comparison culture was 2.2 (IQR 1.7‐2.9). A Wilcoxon rank sum analysis showed that the number of isolates for surface wound cultures was not significantly different than the number of isolates for comparison cultures (P = 0.75) (Table 1).

| Study ID | # of Isolates (Swab) | # of Isolates (Comparison) | Prior Antibiotics? |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Machowiak et al. (1978)17 | * | * | Treated, but details not reported |

| Sharp et al. (1979)15 | 2.3 | 2.2 | Treated, but details not reported |

| Wheat et al. (1986)16 | 3.3 | 3.4 | Not described |

| Zuluaga et al. (2006)19 | 1.3 | 1.6 | Antibiotics stopped 48 hours prior |

| Zuluaga et al. (2002)18 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 52% on antibiotics, stopped 48 hours prior |

| Gardner et al. (2007)13 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 42% on antibiotics |

| Slater et al. (2004)14 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 27% on prior antibiotics |

| Mousa (1997)20 | 3.6 | 1.9 | Treated, but details not reported |

| Median (IQR) | 2.7 (1.8‐3.2) | 2.2 (1.7‐2.9) | |

Discussion

In performing this review, we discovered ambiguity in the literature regarding the utility of surface wound cultures. Some studies obtained findings to suggest the utility of surface wound cultures,8, 14, 17 while other studies in our review16, 18, 19 provided evidence against them. This variability confirmed the need for a meta‐analytic approach as provided by this review.

While we have tried to minimize bias through a well‐established methodology, we acknowledge that certain methodological limitations should be considered in interpreting the results. There may be publication bias in reviews that include only published articles; a funnel plot of sensitivity vs. sample size showed some asymmetry, suggesting bias. Our search strategy was limited to English‐only articles, which may result in publication bias.

Further, this review included a group of studies that were heterogeneous in several regards. Differences exist in culturing methods and laboratory technology, as exemplified by the variety of superficial culture methods used. We were not able to account for these laboratory differences, as methodologies in obtaining and isolating bacteria were not uniformly well described.

Additionally, the studies classified organisms in different ways. Three studies categorized organisms according to Gram's stain characteristics.13, 16, 18 One study described organisms primarily in terms of aerobic or anaerobic respiration.15 Two studies14, 19 discussed pathogens both in terms of respiration (aerobic/anaerobic) and Gram's stain characteristic, while another 2 studies17, 20 did not describe organisms in either terms. These inconsistencies limited our ability to provide sensitivity and specificity information for specific subclasses of organisms.

The clinical conditions in each study surrounding the wounds were also heterogeneous: most significantly in the issue of prior antibiotic administration. All but 1 study16 indicated that the patients had received antibiotics prior to having cultures obtained. The type of antibiotics (narrow‐spectrum or broad‐spectrum), the route of administration, and the cessation of antibiotics in relation to obtaining swabs and cultures all varied widely or were not well described. This degree of ambiguity will necessarily impact both the reliability of data regarding microbial growth as well as the component flora.

The inclusion of higher quality studies is likely to result in a more reliable meta‐analysis.21 We had hoped that antibiotic trials would contain uniform outcomes and thus strengthen our meta‐analysis through the inclusion of randomized‐controlled studies. Unfortunately, the majority of antibiotic trials did not use superficial wound cultures, did not report mean number of isolates, or did not provide microbiological data in sufficient detail to calculate concordance ratesand therefore, did not meet eligibility criteria. Randomized‐controlled trials were a minority among our included articles; the majority of study designs were retrospective cohorts and case‐controlled studies.

Despite these limitations, we were able to conclude that superficial wound culture provides mediocre sensitivity (49%) and specificity (62%). The positive LR of 1.1 is unhelpful in decision making, having a CI that includes 1. Interestingly, the negative LR of 0.67 could be somewhat helpful in medical decision making, modifying the pretest probability and assisting in ruling out a deeper bacterial infection. Although, according to Fagan's nomogram, a negative LR of 0.67 has only a mild effect on pretest odds.22

The bacterial bioburden assessed by the number of isolates obtained by culture method serves as a proxy for reliability of culture results14, 23 by suggesting that fewer organisms isolated from deep tissue or bone samples reflects a less contaminated specimen. Our assessment of the bioburden found that the median number of isolates was slightly higher in surface cultures than deeper cultures, though not to a significant degree (P = 0.75). This indicates that the degree of contamination in superficial cultures was neither significantly worse nor better than deep cultures.

We attempted to define a role for surface wound cultures; however, we found that these did not show any greater utility than deep cultures for identifying the microbiologic etiology of diabetic wound infections. While the negative LR provides some quantitative verification of the common clinical practice that a negative culture argues against infection, the finding is not especially robust.

Although for this meta‐analysis we grouped all organisms in the same way, we recognize that the sensitivity and specificity may differ according to various subclasses of bacteria. Interpretations of culture results also vary (eg, Gram positive vs. negative; aerobic vs. anaerobic); practitioners will not interpret superficial cultures of coagulase‐negative Staphylococcus in the same way as Pseudomonas. However, this study seeks to establish a reasonable starting point for the medical decision‐making process by providing quantitative values in an area with previously conflicting data. We anticipate that as laboratory techniques improve and research into superficial wounds continues, greater sensitivity of superficial wound cultures will result.

Ultimately, physicians use culture data to target therapy in an effort to use the least toxic and most effective antimicrobial agent possible to successfully treat infections. Clinical outcomes were not described in all included articles; in those that did, the endpoints were too dissimilar for meaningful comparison. Limiting our review to studies reporting treatment outcomes would have resulted in too few included studies. Thus, we were unable able to assess whether superficial wound cultures were associated with improved patient‐oriented outcomes in this meta‐analysis.

There is a significant paucity of trials evaluating the accurate concordance of superficial swabs to deep tissue culture. The current data shows poor sensitivity and specificity of superficial culture methods. The presumption that deeper cultures (such as a bone biopsy) should result in a less contaminated sample and more targeted culture results was also not borne out in our review. When presented with a patient with a wound infection, physicians mentally supply a pretest (or a pretreatment) probability as to the microbiologic etiology of the infection. Careful history will, of course, be critical in identifying extenuating circumstance or unusual exposures. From our meta‐analysis, we cannot recommend the routine use of superficial wound cultures to guide initial antibiotic therapy as this may result in poor resource utilization.5 While clinical outcomes from the use of routine superficial cultures are unclear, we suggest greater use of local antibiograms and methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) prevalence data to determine resistance patterns and guide the selection of empiric therapies.

- ,,, et al.Diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infections.Clin Infect Dis.2004;39:885–910.

- AASID,Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases—Standards, Practice Guidelines (Skin and Soft Tissue Infections): Institute for Safe Medication Practices;2006.

- ESCMID,European Society of Clinical Microbiology 2006.

- ,,,.Methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus in community‐acquired skin infections.Emerg Infect Dis.2005;11:928–930.

- ,,.Contaminant blood cultures and resource utilization. The true consequences of false‐positive results.JAMA.1991;265:365–369.

- ,,,,,.Cost‐effectiveness of blood cultures for adult patients with cellulitis.Clin Infect Dis.1999;29:1483–1488.

- ,,,,,.Managing skin and soft tissue infections: expert panel recommendations on key decision points.J Antimicrob Chemother.2003;52 Suppl 1:i3‐i17.

- ,,, et al.Deep tissue biopsy vs. superficial swab culture monitoring in the microbiological assessment of limb‐threatening diabetic foot infection.Diabet Med.2001;18:822–827.

- ,.Meta‐analysis in clinical trials.Control Clin Trials.1986;7:177–188.

- ,,.Quantitative synthesis in systematic reviews.Ann Intern Med.1997;127:820–826.

- ,,,.Bias in meta‐analysis detected by a simple, graphical test.BMJ.1997;315:629–634.

- .Practical statistics for medical research.London, UK:Chapman 1991:403–409.

- ,,,,,.Diagnostic validity of three swab techniques for identifying chronic wound infection.Wound Repair Regen.2006;14(5):548–57.

- ,,, et al.Swab cultures accurately identify bacterial pathogens in diabetic foot wounds not involving bone.Diabet Med.2004;21:705–709.

- ,,,,.Microbiology of superficial and deep tissues in infected diabetic gangrene.Surg Gynecol Obstet.1979;149:217–219.

- ,,, et al.Diabetic foot infections. Bacteriologic analysis.Arch Intern Med.1986;146:1935–1940.

- ,,.Diagnostic value of sinus‐tract cultures in chronic osteomyelitis.JAMA.1978;239:2772–2775.

- ,,,.Lack of microbiological concordance between bone and non‐bone specimens in chronic osteomyelitis: an observational study.BMC Infect Dis.2002;2:8.

- ,,,,,.Etiologic diagnosis of chronic osteomyelitis: a prospective study.Arch Intern Med.2006;166:95–100.

- .Evaluation of sinus‐track cultures in chronic bone infection.J Bone Joint Surg Br.1997;79:567–569.

- ,,, et al.Meta‐analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting.JAMA.2000;283:2008–2012.

- ,Letter: nomogram for Bayes theorem.N Engl J Med.1975;293:257.

- ,,,,,.Quantitative swab culture versus tissue biopsy: a comparison in chronic wounds.Ostomy Wound Manage.2001;47:34–37.

- ,,, et al.Diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infections.Clin Infect Dis.2004;39:885–910.

- AASID,Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases—Standards, Practice Guidelines (Skin and Soft Tissue Infections): Institute for Safe Medication Practices;2006.

- ESCMID,European Society of Clinical Microbiology 2006.

- ,,,.Methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus in community‐acquired skin infections.Emerg Infect Dis.2005;11:928–930.

- ,,.Contaminant blood cultures and resource utilization. The true consequences of false‐positive results.JAMA.1991;265:365–369.

- ,,,,,.Cost‐effectiveness of blood cultures for adult patients with cellulitis.Clin Infect Dis.1999;29:1483–1488.

- ,,,,,.Managing skin and soft tissue infections: expert panel recommendations on key decision points.J Antimicrob Chemother.2003;52 Suppl 1:i3‐i17.

- ,,, et al.Deep tissue biopsy vs. superficial swab culture monitoring in the microbiological assessment of limb‐threatening diabetic foot infection.Diabet Med.2001;18:822–827.

- ,.Meta‐analysis in clinical trials.Control Clin Trials.1986;7:177–188.

- ,,.Quantitative synthesis in systematic reviews.Ann Intern Med.1997;127:820–826.

- ,,,.Bias in meta‐analysis detected by a simple, graphical test.BMJ.1997;315:629–634.

- .Practical statistics for medical research.London, UK:Chapman 1991:403–409.

- ,,,,,.Diagnostic validity of three swab techniques for identifying chronic wound infection.Wound Repair Regen.2006;14(5):548–57.

- ,,, et al.Swab cultures accurately identify bacterial pathogens in diabetic foot wounds not involving bone.Diabet Med.2004;21:705–709.

- ,,,,.Microbiology of superficial and deep tissues in infected diabetic gangrene.Surg Gynecol Obstet.1979;149:217–219.

- ,,, et al.Diabetic foot infections. Bacteriologic analysis.Arch Intern Med.1986;146:1935–1940.

- ,,.Diagnostic value of sinus‐tract cultures in chronic osteomyelitis.JAMA.1978;239:2772–2775.

- ,,,.Lack of microbiological concordance between bone and non‐bone specimens in chronic osteomyelitis: an observational study.BMC Infect Dis.2002;2:8.

- ,,,,,.Etiologic diagnosis of chronic osteomyelitis: a prospective study.Arch Intern Med.2006;166:95–100.

- .Evaluation of sinus‐track cultures in chronic bone infection.J Bone Joint Surg Br.1997;79:567–569.

- ,,, et al.Meta‐analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting.JAMA.2000;283:2008–2012.

- ,Letter: nomogram for Bayes theorem.N Engl J Med.1975;293:257.

- ,,,,,.Quantitative swab culture versus tissue biopsy: a comparison in chronic wounds.Ostomy Wound Manage.2001;47:34–37.

Pott's Puffy Tumor

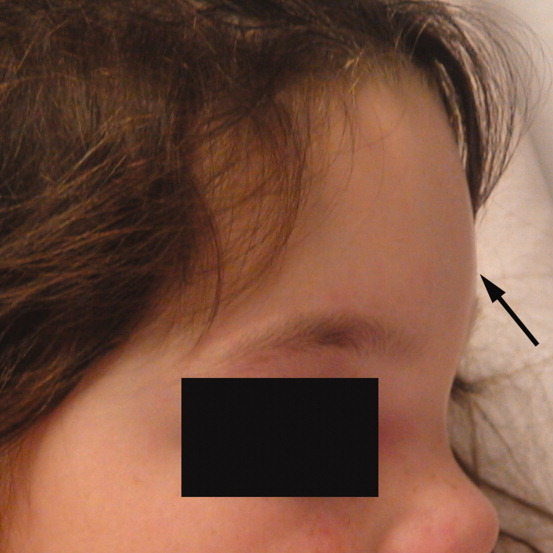

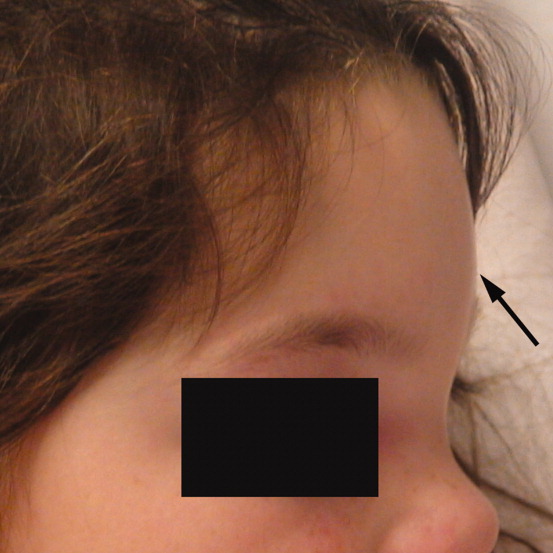

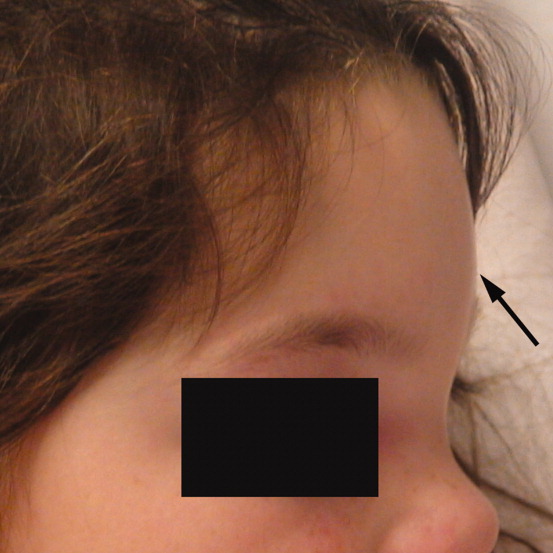

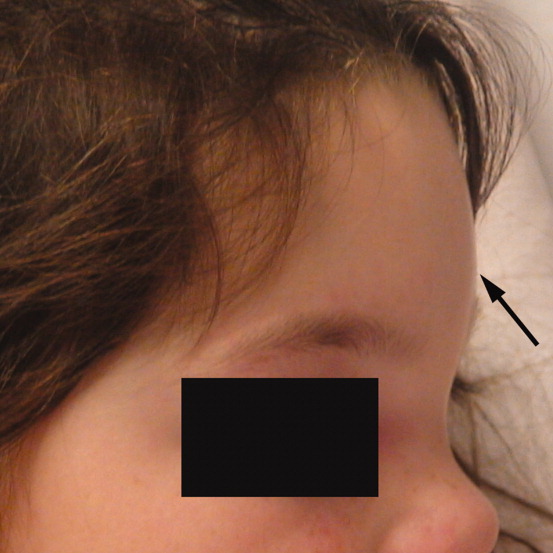

A 6‐year‐old girl with a history of bilateral myringotomies, tonsillectomy, and adenoidectomy 6 and 8 months prior, presented with forehead swelling. Eight days prior, she developed right ear pain, sore throat and fever followed by eye pain and headache for which she was evaluated and diagnosed with viral illness. On the day of presentation she awoke with forehead swelling, persistent headache, and recurrent fever.

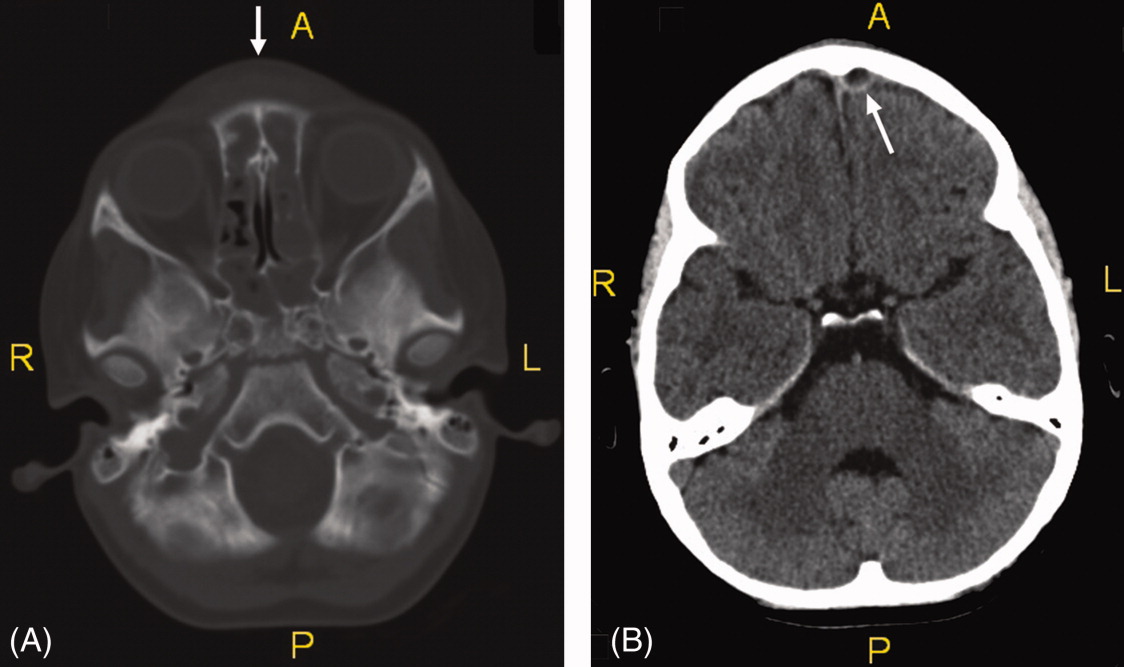

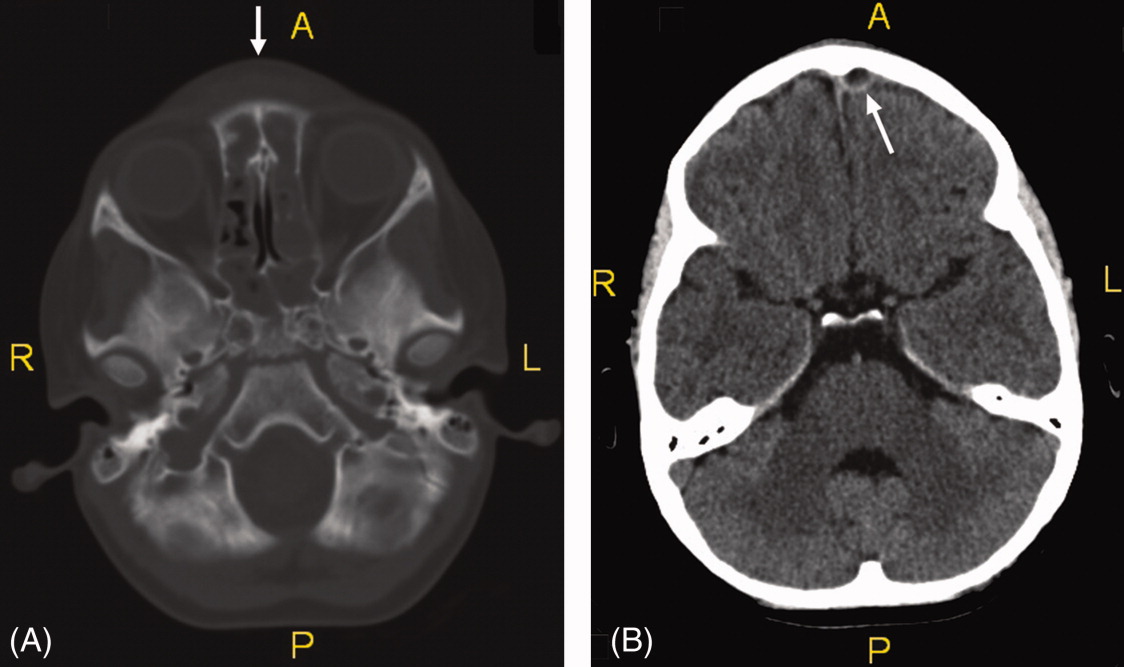

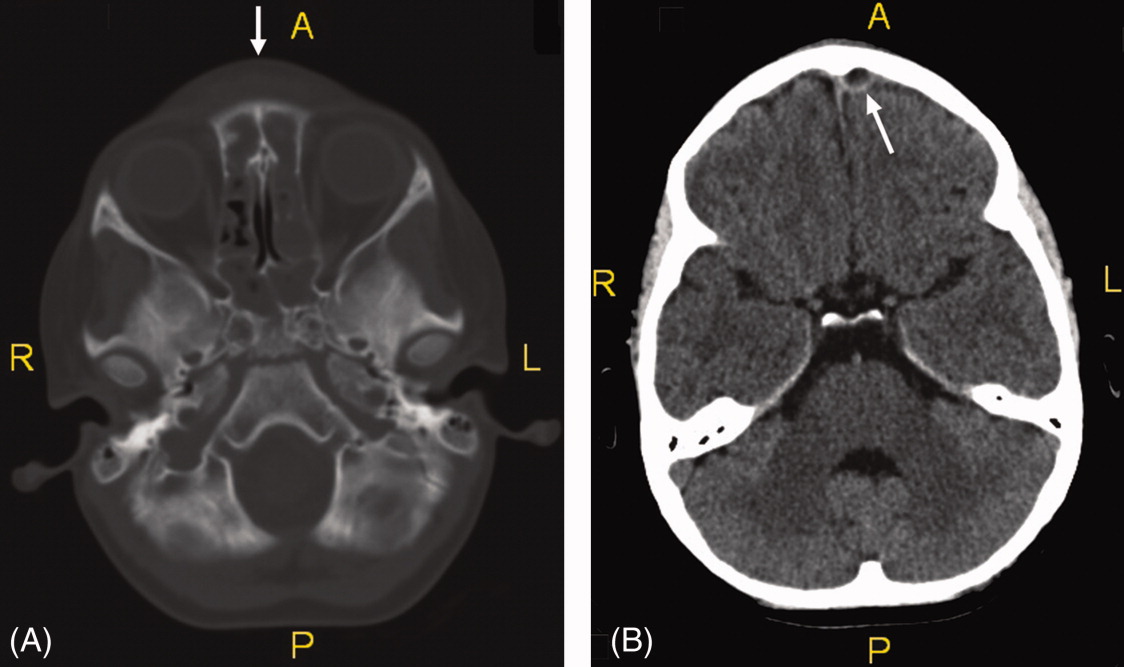

On exam she was afebrile. Central forehead swelling was noted without overlying erythema or fluctulence (Figure 1). Neurologic exam was normal. Noncontrast computed tomography (CT) scan of the head showed pan sinusitis with an extra‐axial fluid collection in the left frontal region (Figure 2).