User login

Afghan Revival

Editors’ note: During 2006 we will publish coverage of hospital practices in other countries. This is the first article in that effort.

Over the past two decades Afghanistan became known to many for its invasion by the Soviets (the war the mujahideen fought against its occupiers), the bloody infighting that followed the Soviet withdrawal, and the horrific rule of the Taliban. The expulsion of the Taliban in 2001 by coalition forces and Afghanistan’s recent steps toward democracy have made it the focus of much world attention.

Afghanistan’s health situation is among the worst in the world.1 The data that emerged in 2002 after the fall of the Taliban reported a maternal mortality ratio of 1,600 per 100,000 women, which translates into a lifetime risk that one in six women will die of complications of pregnancy and delivery.2-3 The same study showed severe inequities in mortality rates between rural and urban areas: Kabul’s maternal mortality ratio is 400 per 100,000, whereas in rural Badakhshan province it is 6,500 per 100,000—the highest recorded rate in the world in modern times.2 Afghanistan is the only country in the world where men outlive women. Twenty-five percent of children die before age five—most of treatable diseases such as diarrhea and pneumonia, and preventable diseases such as measles and pertussis. Children, women, and men face risks from communicable diseases that are among the highest in the world, as well as the risk of death or serious injury from landmines and other unexploded ordnance.

In this setting, the Ministry of Public Health made two major decisions in 2002: All health services would be contracted to nongovernmental organizations and the Ministry would be the steward of the health system, setting policies and regulating services; and the Basic Package of Health Services would be the main policy that all service providers would follow.4-5 This package defines specific services focused on women’s and children’s needs by level and by appropriate intervention.6 The Basic Package also stresses equity by giving priority to rural over urban areas and to women’s participation over men’s. A related policy on hospitals limits spending on hospitals to 40% of the national health budget, with the remaining 60% to be spent on basic health services.7

State of Hospitals

Many health facilities—especially hospitals—had been damaged or destroyed. A survey of all health facilities in the country by Management Sciences for Health (MSH) in 2002, with funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development and other donors, found that 35% of the facilities were severely damaged due to war or natural disasters, and the rest failed to meet current World Health Organization standards.8 A second major concern was the lack of health professionals, many of whom had fled the country during the war years. Finally, the staff remaining, especially physicians, lacked good clinical training and continuing education, which compromised quality of care. The Rural Expansion of Afghanistan’s Community-based Healthcare (REACH) was designed to address all these issues. REACH is a program funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development and implemented by MSH and the Afghan Ministry of Public Health. Partners include the Academy for Educational Development; JHPIEGO (an international health organization affiliated with Johns Hopkins University); Technical Assistance, Inc., and the University of Massachusetts/Amherst.

Hospitals are a critical element of the Afghan health system because they are part of the referral system that plays an essential role in reducing high maternal and early childhood mortality rates. In addition, hospitals use many of the most skilled health workers and the financial resources of the health system. Dramatic improvements in hospital management are needed so hospitals can use these scarce resources effectively and efficiently.9

Challenges

In brief, the key issues facing hospitals in the Afghan health system are:

- Maldistribution of hospitals and hospital beds throughout the country, which means a lack of equitable access to hospital care. People in urban areas have access but semi-urban and rural populations have limited access. For example, Kabul has 1.28 beds per 1,000 people while the provinces have only .22 per 1,000;

- Lack of standards for clinical patient care, resulting in poor quality of care; and

- Lack of hospital management skills, which results in inefficiently run hospitals, poorly managed staff, lack of supplies, and inoperable equipment due to lack of maintenance.10

Response: The Hospital Management Improvement Initiative

REACH began helping to rebuild the health sector in 2003. Initial efforts focused on expanding basic services, and in two years we have moved from 5% to 77% coverage of the population of Afghanistan. In 2004, the contract was amended to include the hospital sector, with a focus on provincial hospitals. REACH developed the Hospital Management Improvement Initiative to build the clinical and management capacity of hospitals so that:

- Health services are delivered more efficiently;

- The quality of services are improved;

- The population has increased access to hospital services; and

- There is a positive impact on health status—especially on the morbidity and mortality of women and children.

Introducing clinical and management improvements, combined with appropriate resources, will improve quality of care, increase access to hospital services, and streamline hospital operations. These improvements will ultimately result in achievement of the goals of improved health status, improved patient and community satisfaction with hospitals, and an improved referral system for Afghanistan.

Although the need was great, it was not possible to train the management team at each hospital in Afghanistan. Instead, clinical and management capacities at the provincial and central hospitals were strengthened through training, mentoring, networking and modeling, and provision of resources.

Training

The Standards Based Management/Performance Quality Improvement approach that JHPIEGO has successfully developed and used to improve the quality of reproductive health services in many resource-poor settings has been expanded and adapted by REACH into a comprehensive approach to improve hospital management in Afghanistan. This process includes all clinical services (surgery, anesthesia, emergency care, pediatrics, infection prevention, and blood transfusion and blood banks) and management systems (governance, facilities and equipment management, pharmacy management, human resource systems) for general hospitals.

Standards were developed in each of these areas, and training modules developed. Eight workshops have been held to train key staff from each hospital, who return to their hospitals to introduce the standards to their medical and administrative staff. Each workshop produces a plan for implementing the standards according to the circumstances of each hospital. The training is incremental. For instance, rather than doing a one- to two-week workshop presenting all the training modules, two modules on standards (usually one clinical and one management area) are presented. Two new modules are presented quarterly thereafter, to prevent information overload, allow trainees to integrate what they have learned with real day-to-day management, and avoid the problem of hospitals being left without leadership for an extended period.

Mentoring

A skilled hospital management advisor visits the hospitals regularly so managers have the opportunity to work with a mentor to apply what they have learned to their hospitals. This practical experience involves applying principles to real-life situations with someone experienced enough to help overcome obstacles not anticipated in the workshops. Mentors from REACH and the Ministry of Public Health visit the provincial hospitals to discuss problems, review progress, talk about problems that prevented achievement of goals, and set goals for the next three-month period.

The first four provincial hospitals selected for this intervention are all in areas formerly controlled by the Taliban, and security issues have added other challenges to this program because of repeated terrorist attacks on non-governmental organizations and people employed by international organizations. The mentors involved must speak Pashto, the local language, and integrate into the culture so they do not attract attention or create local opposition. Mentoring is a necessary but dangerous activity for the success of the program.

Networking and Modeling

As more hospital managers and senior clinicians are trained through this program, networking becomes another important tool. The network uses meetings twice a year for two days in a participating hospital to provide an opportunity for hospital managers to discuss common issues and develop system-wide solutions. Between these meetings, hospital managers in the same region exchange visits to learn from each other. REACH facilitates this networking using e-mail (some of the provincial hospitals have Internet access, which has dramatically increased their participation in evidence-based approaches), dissemination of reports, and passing on requests for communication between hospitals. These formal meetings and informal exchanges permit hospital managers to interact about common problems and learn how other hospitals have solved those problems. This networking will slowly expand to cover more provincial hospitals and will assist in expanding the number of trainers and mentors.

Modeling means trying new systems and methods generated by the trainees to address their self-identified problems. Improvements in five provincial hospitals (in Khost, Paktika, Paktia, Ghazni, and Badakhshan) will provide a model that demonstrates to the public that hospitals can be well run and serve the community. These hospitals can also be used as training grounds for other hospital managers from around the country as the initiative expands to more of the remaining 28 provincial hospitals. The goal is to develop optimism and creativity because one of the main barriers in training is that some managers have difficulty imagining things being different because they feel the system “has always been broken.” When trainees see that other hospitals have successfully tried new approaches, they will consider a broader range of possibilities for their own hospitals.

Resources

Along with the management improvements achieved through training, mentoring, and networking, additional resources are needed to improve hospital services. REACH has been the conduit for U.S. government funding, providing $2.6 million in critical resources to drive improvements in the five provincial hospitals. These funds are channeled through the contracted nongovernmental organizations, which hire staff and pay decent salaries.

The average hospital physician in the Ministry of Public Health is paid $50 a month. In this setting “under-the-table” charges for clinical services are common, and physicians usually leave the hospital by lunch to attend to their private clinics. This initiative pays physicians up to $500 a month with the expectations that they will work a full day, provide 24-hour emergency coverage, and not charge patients. Eighteen months of experience suggest that these expectations are being met. Resources are also used for remodeling facilities, purchasing equipment and supplies, and providing essential medicines. The management standards developed are designed to make rational use of these scarce resources.

Prerequisites for the Initiative

Two key prerequisites for starting the Hospital Management Initiative were:

- Identifying where standards had to be developed: REACH has assisted the Ministry of Public Health to identify the standards that must be developed: responsibilities of hospitals to the community, patient care (clinical care), human resource management, management systems, environmental health, and leadership and management.10 “Areas of Standards for Hospitals in Afghanistan” shows the standards that have been or are to be developed. (See sidebar at left.)

- Essential Package of Hospital Services: To ensure that donor support does not stimulate a proliferation of hospitals and high-tech equipment that are not appropriate or sustainable for Afghanistan, REACH has been helping the Ministry of Public Health define the levels of hospitals (district, provincial, regional), the populations they serve, the services they offer, and the equipment, staff, supplies, and pharmaceuticals they need. The result was the publication of the Essential Package of Hospital Services, which defines these for each of the three levels of hospitals in the country, in 2005. This package will provide guidance for Afghanistan’s hospitals for the coming decade, much as the Basic Package of Health Services has done for primary healthcare services. The hospital package will also support long-term planning and help the Ministry make the best use of donor assistance for redeveloping the hospital sector.

Developing and Implementing Standards

Standards-based management begins by identifying existing clinical guidelines and standards developed by American or international specialty societies. Specialist consultants in each clinical area with many years’ experience in Afghanistan (some of them Afghan-American physicians) are contracted to develop these standards and then adapt them to the Afghan context, in consultation with physicians in Afghanistan.

For example, standards for acute abdominal pain had to be adapted to a situation where CAT scans and ultrasounds are not readily available, and the lack of electrolyte laboratory capacity in hospitals stimulated physicians to adapt standards for shock, and fluid and electrolyte balance that do not rely on knowing electrolyte levels. The standards development teams aimed to raise the standards of Afghan hospitals to a realistic extent but not set the bar so high that improvement was unattainable.

After the standards were developed, clinicians from Afghan hospitals reviewed and revised the standards to ensure that they were appropriate. This review also served as a means of training because the participants were able and eager to question the contracted expert about the standards in developed countries and the evidence supporting those standards. Once the standards are revised, a workshop is held to introduce them to hospital staff. The hospital teams then develop an action plan for introducing the standards into their facilities.

Quality improvement teams at each of the five hospitals take responsibility for shepherding the action plans through implementation. An advisor visits each hospital quarterly to review progress, assess barriers, and help hospital staff develop ways to overcome problems and accelerate standards implementation. During the mentor’s first visit after new standards have been introduced, he performs a baseline assessment of the hospital’s current compliance with the standards. This serves as a benchmark for future measurement of progress in meeting the standards.

The Results

The hospitals have been enthusiastic about this process and the gains they have seen in the quality of care at their facilities. “We have made more progress in four months of the Hospital Management Improvement Initiative than we made in the previous five years with many other donors because this methodology is sound and appropriate for Afghanistan,” said Dr. Mohammed Ismael, the director of Ghazni Provincial Hospital.

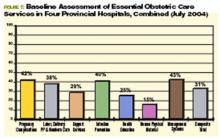

One example of the process and results was the first area in which standards were developed—essential obstetric care. Physicians examined seven components of the quality of emergency obstetric care: handling of pregnancy complications; labor, delivery, and postpartum and newborn care; support services; infection prevention; health education given to families and mothers; human, physical, and material resources; and management systems in the obstetrics/gynecology department. After the standards were established, the first step was to find out where each hospital stood in meeting them. (For the combined results of that first baseline assessment for four hospitals, see Figure 1, p. 20.)

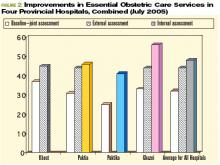

The changes in standards for emergency obstetric care at the hospitals from July 2004 to July 2005 have been impressive. The overall composite scores for emergency obstetric care for the four hospitals have improved from 31% at the baseline assessment to 47%. Here are the average improvements in the same four hospitals over one year:

Lessons Learned

The principal lesson learned through this hospital management improvement initiative is that combining clinical and management improvements can create innovation in a developing country. Improvements are made throughout a hospital—not just in one clinical area. Second, mentoring has proven essential as a follow-up to training. The training alone will not bring about significant positive changes. Only with on-site visitation is there the opportunity to integrate new knowledge with practical implementation issues that have proven troublesome to overcome. Third, setting standards is key to the sustainability of improvements. Training individuals in skills is helpful but is not sustainable if those trained staff depart. Using hospital teams and common standards throughout different hospitals leads to institutionalization of the process.

Staff motivation has also proven to be essential to sustainability. Staff have been motivated because they see that many positive changes are within their control; they do not have to wait for someone else to make an improvement before they can introduce positive change. An ethic of continuous quality improvement is achieved through staff who are proud of the changes they have introduced. The iterative nature of this process has been essential to quality improvement: The standards are continually revisited and revised as needed. At times, new standards for other areas are developed when the hospitals need them. Finally, providing resources to pay adequate salaries, renovate facilities, buy equipment and supplies, and provide essential medicines are all important elements of this success.

This method has proven successful in such a short time that the Minister of Public Health, Dr. Mohammad Amin Fatimie, has expressed his desire to extend it to many other hospitals in the country in an effort to improve the quality of hospital care throughout Afghani-stan. The U.S. Agency for International Development and MSH have agreed to support this request, and the program will expand in future years. TH

Dr. Hartman, is a family physician with subspecialty training in infectious diseases, epidemiology, and public health. He serves as the technical director and deputy chief of party of the REACH Project, based in Kabul. Dr. Newbrander is a health economist who has served in Afghanistan since 2002 as a senior advisor to the Ministry of Health. He is currently Health Financing and Hospital Management Advisor for the USAID-funded REACH Project.

Acknowledgment: Funding for this article was provided by the United States Agency for International Development under the REACH Project, contract number EEE-C-00-03-00015-00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID.

References

- Newbrander W, Ickx P, Leitch GH. Addressing the immediate and long-term health needs in Afghanistan. Harvard Health Pol Rev. 2003;4.

- Ministry of Health Transitional Islamic Government of Afghanistan (TISA), US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United Nations Children’s Fund. Maternal mortality in Afghanistan: magnitude, causes, risk factors and preventability. Kabul: TISA; 2002.

- Bartlett LA, Mawji S, Whitehead S, et al. Where giving birth is a forecast of death: maternal mortality in four districts of Afghanistan, 1999-2002. Lancet. 2005;365:864-870.

- Strong L, Wali A, Sondorp E. Health Policy in Afghanistan: Two Years of Rapid Change: A Review of the Process from 2001 to 2003. London: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; 2005.

- Afghanistan’s health challenge. Lancet. 2003;362:841.

- Ministry of Health Transitional Islamic Government of Afghanistan (TISA). The Basic Package of Health Services for Afghanistan. Kabul: TISA; 2003.

- Ministry of Health Transitional Islamic Government of Afghanistan (TISA). Hospital Policy for Afghanistan’s Health System. Kabul: TISA; 2004.

- Ministry of Health Transitional Islamic Government of Afghanistan (TISA), Management Sciences for Health. Afghanistan national health resources assessment: Preliminary results. Kabul: TISA; 2002.

- A crucial time for Afghanistan’s fledgling health system. Lancet. 2005; 365:819-820.

- Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. The Essential Package of Hospital Services for Afghanistan. Kabul: MOPH; 2005.

Editors’ note: During 2006 we will publish coverage of hospital practices in other countries. This is the first article in that effort.

Over the past two decades Afghanistan became known to many for its invasion by the Soviets (the war the mujahideen fought against its occupiers), the bloody infighting that followed the Soviet withdrawal, and the horrific rule of the Taliban. The expulsion of the Taliban in 2001 by coalition forces and Afghanistan’s recent steps toward democracy have made it the focus of much world attention.

Afghanistan’s health situation is among the worst in the world.1 The data that emerged in 2002 after the fall of the Taliban reported a maternal mortality ratio of 1,600 per 100,000 women, which translates into a lifetime risk that one in six women will die of complications of pregnancy and delivery.2-3 The same study showed severe inequities in mortality rates between rural and urban areas: Kabul’s maternal mortality ratio is 400 per 100,000, whereas in rural Badakhshan province it is 6,500 per 100,000—the highest recorded rate in the world in modern times.2 Afghanistan is the only country in the world where men outlive women. Twenty-five percent of children die before age five—most of treatable diseases such as diarrhea and pneumonia, and preventable diseases such as measles and pertussis. Children, women, and men face risks from communicable diseases that are among the highest in the world, as well as the risk of death or serious injury from landmines and other unexploded ordnance.

In this setting, the Ministry of Public Health made two major decisions in 2002: All health services would be contracted to nongovernmental organizations and the Ministry would be the steward of the health system, setting policies and regulating services; and the Basic Package of Health Services would be the main policy that all service providers would follow.4-5 This package defines specific services focused on women’s and children’s needs by level and by appropriate intervention.6 The Basic Package also stresses equity by giving priority to rural over urban areas and to women’s participation over men’s. A related policy on hospitals limits spending on hospitals to 40% of the national health budget, with the remaining 60% to be spent on basic health services.7

State of Hospitals

Many health facilities—especially hospitals—had been damaged or destroyed. A survey of all health facilities in the country by Management Sciences for Health (MSH) in 2002, with funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development and other donors, found that 35% of the facilities were severely damaged due to war or natural disasters, and the rest failed to meet current World Health Organization standards.8 A second major concern was the lack of health professionals, many of whom had fled the country during the war years. Finally, the staff remaining, especially physicians, lacked good clinical training and continuing education, which compromised quality of care. The Rural Expansion of Afghanistan’s Community-based Healthcare (REACH) was designed to address all these issues. REACH is a program funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development and implemented by MSH and the Afghan Ministry of Public Health. Partners include the Academy for Educational Development; JHPIEGO (an international health organization affiliated with Johns Hopkins University); Technical Assistance, Inc., and the University of Massachusetts/Amherst.

Hospitals are a critical element of the Afghan health system because they are part of the referral system that plays an essential role in reducing high maternal and early childhood mortality rates. In addition, hospitals use many of the most skilled health workers and the financial resources of the health system. Dramatic improvements in hospital management are needed so hospitals can use these scarce resources effectively and efficiently.9

Challenges

In brief, the key issues facing hospitals in the Afghan health system are:

- Maldistribution of hospitals and hospital beds throughout the country, which means a lack of equitable access to hospital care. People in urban areas have access but semi-urban and rural populations have limited access. For example, Kabul has 1.28 beds per 1,000 people while the provinces have only .22 per 1,000;

- Lack of standards for clinical patient care, resulting in poor quality of care; and

- Lack of hospital management skills, which results in inefficiently run hospitals, poorly managed staff, lack of supplies, and inoperable equipment due to lack of maintenance.10

Response: The Hospital Management Improvement Initiative

REACH began helping to rebuild the health sector in 2003. Initial efforts focused on expanding basic services, and in two years we have moved from 5% to 77% coverage of the population of Afghanistan. In 2004, the contract was amended to include the hospital sector, with a focus on provincial hospitals. REACH developed the Hospital Management Improvement Initiative to build the clinical and management capacity of hospitals so that:

- Health services are delivered more efficiently;

- The quality of services are improved;

- The population has increased access to hospital services; and

- There is a positive impact on health status—especially on the morbidity and mortality of women and children.

Introducing clinical and management improvements, combined with appropriate resources, will improve quality of care, increase access to hospital services, and streamline hospital operations. These improvements will ultimately result in achievement of the goals of improved health status, improved patient and community satisfaction with hospitals, and an improved referral system for Afghanistan.

Although the need was great, it was not possible to train the management team at each hospital in Afghanistan. Instead, clinical and management capacities at the provincial and central hospitals were strengthened through training, mentoring, networking and modeling, and provision of resources.

Training

The Standards Based Management/Performance Quality Improvement approach that JHPIEGO has successfully developed and used to improve the quality of reproductive health services in many resource-poor settings has been expanded and adapted by REACH into a comprehensive approach to improve hospital management in Afghanistan. This process includes all clinical services (surgery, anesthesia, emergency care, pediatrics, infection prevention, and blood transfusion and blood banks) and management systems (governance, facilities and equipment management, pharmacy management, human resource systems) for general hospitals.

Standards were developed in each of these areas, and training modules developed. Eight workshops have been held to train key staff from each hospital, who return to their hospitals to introduce the standards to their medical and administrative staff. Each workshop produces a plan for implementing the standards according to the circumstances of each hospital. The training is incremental. For instance, rather than doing a one- to two-week workshop presenting all the training modules, two modules on standards (usually one clinical and one management area) are presented. Two new modules are presented quarterly thereafter, to prevent information overload, allow trainees to integrate what they have learned with real day-to-day management, and avoid the problem of hospitals being left without leadership for an extended period.

Mentoring

A skilled hospital management advisor visits the hospitals regularly so managers have the opportunity to work with a mentor to apply what they have learned to their hospitals. This practical experience involves applying principles to real-life situations with someone experienced enough to help overcome obstacles not anticipated in the workshops. Mentors from REACH and the Ministry of Public Health visit the provincial hospitals to discuss problems, review progress, talk about problems that prevented achievement of goals, and set goals for the next three-month period.

The first four provincial hospitals selected for this intervention are all in areas formerly controlled by the Taliban, and security issues have added other challenges to this program because of repeated terrorist attacks on non-governmental organizations and people employed by international organizations. The mentors involved must speak Pashto, the local language, and integrate into the culture so they do not attract attention or create local opposition. Mentoring is a necessary but dangerous activity for the success of the program.

Networking and Modeling

As more hospital managers and senior clinicians are trained through this program, networking becomes another important tool. The network uses meetings twice a year for two days in a participating hospital to provide an opportunity for hospital managers to discuss common issues and develop system-wide solutions. Between these meetings, hospital managers in the same region exchange visits to learn from each other. REACH facilitates this networking using e-mail (some of the provincial hospitals have Internet access, which has dramatically increased their participation in evidence-based approaches), dissemination of reports, and passing on requests for communication between hospitals. These formal meetings and informal exchanges permit hospital managers to interact about common problems and learn how other hospitals have solved those problems. This networking will slowly expand to cover more provincial hospitals and will assist in expanding the number of trainers and mentors.

Modeling means trying new systems and methods generated by the trainees to address their self-identified problems. Improvements in five provincial hospitals (in Khost, Paktika, Paktia, Ghazni, and Badakhshan) will provide a model that demonstrates to the public that hospitals can be well run and serve the community. These hospitals can also be used as training grounds for other hospital managers from around the country as the initiative expands to more of the remaining 28 provincial hospitals. The goal is to develop optimism and creativity because one of the main barriers in training is that some managers have difficulty imagining things being different because they feel the system “has always been broken.” When trainees see that other hospitals have successfully tried new approaches, they will consider a broader range of possibilities for their own hospitals.

Resources

Along with the management improvements achieved through training, mentoring, and networking, additional resources are needed to improve hospital services. REACH has been the conduit for U.S. government funding, providing $2.6 million in critical resources to drive improvements in the five provincial hospitals. These funds are channeled through the contracted nongovernmental organizations, which hire staff and pay decent salaries.

The average hospital physician in the Ministry of Public Health is paid $50 a month. In this setting “under-the-table” charges for clinical services are common, and physicians usually leave the hospital by lunch to attend to their private clinics. This initiative pays physicians up to $500 a month with the expectations that they will work a full day, provide 24-hour emergency coverage, and not charge patients. Eighteen months of experience suggest that these expectations are being met. Resources are also used for remodeling facilities, purchasing equipment and supplies, and providing essential medicines. The management standards developed are designed to make rational use of these scarce resources.

Prerequisites for the Initiative

Two key prerequisites for starting the Hospital Management Initiative were:

- Identifying where standards had to be developed: REACH has assisted the Ministry of Public Health to identify the standards that must be developed: responsibilities of hospitals to the community, patient care (clinical care), human resource management, management systems, environmental health, and leadership and management.10 “Areas of Standards for Hospitals in Afghanistan” shows the standards that have been or are to be developed. (See sidebar at left.)

- Essential Package of Hospital Services: To ensure that donor support does not stimulate a proliferation of hospitals and high-tech equipment that are not appropriate or sustainable for Afghanistan, REACH has been helping the Ministry of Public Health define the levels of hospitals (district, provincial, regional), the populations they serve, the services they offer, and the equipment, staff, supplies, and pharmaceuticals they need. The result was the publication of the Essential Package of Hospital Services, which defines these for each of the three levels of hospitals in the country, in 2005. This package will provide guidance for Afghanistan’s hospitals for the coming decade, much as the Basic Package of Health Services has done for primary healthcare services. The hospital package will also support long-term planning and help the Ministry make the best use of donor assistance for redeveloping the hospital sector.

Developing and Implementing Standards

Standards-based management begins by identifying existing clinical guidelines and standards developed by American or international specialty societies. Specialist consultants in each clinical area with many years’ experience in Afghanistan (some of them Afghan-American physicians) are contracted to develop these standards and then adapt them to the Afghan context, in consultation with physicians in Afghanistan.

For example, standards for acute abdominal pain had to be adapted to a situation where CAT scans and ultrasounds are not readily available, and the lack of electrolyte laboratory capacity in hospitals stimulated physicians to adapt standards for shock, and fluid and electrolyte balance that do not rely on knowing electrolyte levels. The standards development teams aimed to raise the standards of Afghan hospitals to a realistic extent but not set the bar so high that improvement was unattainable.

After the standards were developed, clinicians from Afghan hospitals reviewed and revised the standards to ensure that they were appropriate. This review also served as a means of training because the participants were able and eager to question the contracted expert about the standards in developed countries and the evidence supporting those standards. Once the standards are revised, a workshop is held to introduce them to hospital staff. The hospital teams then develop an action plan for introducing the standards into their facilities.

Quality improvement teams at each of the five hospitals take responsibility for shepherding the action plans through implementation. An advisor visits each hospital quarterly to review progress, assess barriers, and help hospital staff develop ways to overcome problems and accelerate standards implementation. During the mentor’s first visit after new standards have been introduced, he performs a baseline assessment of the hospital’s current compliance with the standards. This serves as a benchmark for future measurement of progress in meeting the standards.

The Results

The hospitals have been enthusiastic about this process and the gains they have seen in the quality of care at their facilities. “We have made more progress in four months of the Hospital Management Improvement Initiative than we made in the previous five years with many other donors because this methodology is sound and appropriate for Afghanistan,” said Dr. Mohammed Ismael, the director of Ghazni Provincial Hospital.

One example of the process and results was the first area in which standards were developed—essential obstetric care. Physicians examined seven components of the quality of emergency obstetric care: handling of pregnancy complications; labor, delivery, and postpartum and newborn care; support services; infection prevention; health education given to families and mothers; human, physical, and material resources; and management systems in the obstetrics/gynecology department. After the standards were established, the first step was to find out where each hospital stood in meeting them. (For the combined results of that first baseline assessment for four hospitals, see Figure 1, p. 20.)

The changes in standards for emergency obstetric care at the hospitals from July 2004 to July 2005 have been impressive. The overall composite scores for emergency obstetric care for the four hospitals have improved from 31% at the baseline assessment to 47%. Here are the average improvements in the same four hospitals over one year:

Lessons Learned

The principal lesson learned through this hospital management improvement initiative is that combining clinical and management improvements can create innovation in a developing country. Improvements are made throughout a hospital—not just in one clinical area. Second, mentoring has proven essential as a follow-up to training. The training alone will not bring about significant positive changes. Only with on-site visitation is there the opportunity to integrate new knowledge with practical implementation issues that have proven troublesome to overcome. Third, setting standards is key to the sustainability of improvements. Training individuals in skills is helpful but is not sustainable if those trained staff depart. Using hospital teams and common standards throughout different hospitals leads to institutionalization of the process.

Staff motivation has also proven to be essential to sustainability. Staff have been motivated because they see that many positive changes are within their control; they do not have to wait for someone else to make an improvement before they can introduce positive change. An ethic of continuous quality improvement is achieved through staff who are proud of the changes they have introduced. The iterative nature of this process has been essential to quality improvement: The standards are continually revisited and revised as needed. At times, new standards for other areas are developed when the hospitals need them. Finally, providing resources to pay adequate salaries, renovate facilities, buy equipment and supplies, and provide essential medicines are all important elements of this success.

This method has proven successful in such a short time that the Minister of Public Health, Dr. Mohammad Amin Fatimie, has expressed his desire to extend it to many other hospitals in the country in an effort to improve the quality of hospital care throughout Afghani-stan. The U.S. Agency for International Development and MSH have agreed to support this request, and the program will expand in future years. TH

Dr. Hartman, is a family physician with subspecialty training in infectious diseases, epidemiology, and public health. He serves as the technical director and deputy chief of party of the REACH Project, based in Kabul. Dr. Newbrander is a health economist who has served in Afghanistan since 2002 as a senior advisor to the Ministry of Health. He is currently Health Financing and Hospital Management Advisor for the USAID-funded REACH Project.

Acknowledgment: Funding for this article was provided by the United States Agency for International Development under the REACH Project, contract number EEE-C-00-03-00015-00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID.

References

- Newbrander W, Ickx P, Leitch GH. Addressing the immediate and long-term health needs in Afghanistan. Harvard Health Pol Rev. 2003;4.

- Ministry of Health Transitional Islamic Government of Afghanistan (TISA), US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United Nations Children’s Fund. Maternal mortality in Afghanistan: magnitude, causes, risk factors and preventability. Kabul: TISA; 2002.

- Bartlett LA, Mawji S, Whitehead S, et al. Where giving birth is a forecast of death: maternal mortality in four districts of Afghanistan, 1999-2002. Lancet. 2005;365:864-870.

- Strong L, Wali A, Sondorp E. Health Policy in Afghanistan: Two Years of Rapid Change: A Review of the Process from 2001 to 2003. London: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; 2005.

- Afghanistan’s health challenge. Lancet. 2003;362:841.

- Ministry of Health Transitional Islamic Government of Afghanistan (TISA). The Basic Package of Health Services for Afghanistan. Kabul: TISA; 2003.

- Ministry of Health Transitional Islamic Government of Afghanistan (TISA). Hospital Policy for Afghanistan’s Health System. Kabul: TISA; 2004.

- Ministry of Health Transitional Islamic Government of Afghanistan (TISA), Management Sciences for Health. Afghanistan national health resources assessment: Preliminary results. Kabul: TISA; 2002.

- A crucial time for Afghanistan’s fledgling health system. Lancet. 2005; 365:819-820.

- Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. The Essential Package of Hospital Services for Afghanistan. Kabul: MOPH; 2005.

Editors’ note: During 2006 we will publish coverage of hospital practices in other countries. This is the first article in that effort.

Over the past two decades Afghanistan became known to many for its invasion by the Soviets (the war the mujahideen fought against its occupiers), the bloody infighting that followed the Soviet withdrawal, and the horrific rule of the Taliban. The expulsion of the Taliban in 2001 by coalition forces and Afghanistan’s recent steps toward democracy have made it the focus of much world attention.

Afghanistan’s health situation is among the worst in the world.1 The data that emerged in 2002 after the fall of the Taliban reported a maternal mortality ratio of 1,600 per 100,000 women, which translates into a lifetime risk that one in six women will die of complications of pregnancy and delivery.2-3 The same study showed severe inequities in mortality rates between rural and urban areas: Kabul’s maternal mortality ratio is 400 per 100,000, whereas in rural Badakhshan province it is 6,500 per 100,000—the highest recorded rate in the world in modern times.2 Afghanistan is the only country in the world where men outlive women. Twenty-five percent of children die before age five—most of treatable diseases such as diarrhea and pneumonia, and preventable diseases such as measles and pertussis. Children, women, and men face risks from communicable diseases that are among the highest in the world, as well as the risk of death or serious injury from landmines and other unexploded ordnance.

In this setting, the Ministry of Public Health made two major decisions in 2002: All health services would be contracted to nongovernmental organizations and the Ministry would be the steward of the health system, setting policies and regulating services; and the Basic Package of Health Services would be the main policy that all service providers would follow.4-5 This package defines specific services focused on women’s and children’s needs by level and by appropriate intervention.6 The Basic Package also stresses equity by giving priority to rural over urban areas and to women’s participation over men’s. A related policy on hospitals limits spending on hospitals to 40% of the national health budget, with the remaining 60% to be spent on basic health services.7

State of Hospitals

Many health facilities—especially hospitals—had been damaged or destroyed. A survey of all health facilities in the country by Management Sciences for Health (MSH) in 2002, with funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development and other donors, found that 35% of the facilities were severely damaged due to war or natural disasters, and the rest failed to meet current World Health Organization standards.8 A second major concern was the lack of health professionals, many of whom had fled the country during the war years. Finally, the staff remaining, especially physicians, lacked good clinical training and continuing education, which compromised quality of care. The Rural Expansion of Afghanistan’s Community-based Healthcare (REACH) was designed to address all these issues. REACH is a program funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development and implemented by MSH and the Afghan Ministry of Public Health. Partners include the Academy for Educational Development; JHPIEGO (an international health organization affiliated with Johns Hopkins University); Technical Assistance, Inc., and the University of Massachusetts/Amherst.

Hospitals are a critical element of the Afghan health system because they are part of the referral system that plays an essential role in reducing high maternal and early childhood mortality rates. In addition, hospitals use many of the most skilled health workers and the financial resources of the health system. Dramatic improvements in hospital management are needed so hospitals can use these scarce resources effectively and efficiently.9

Challenges

In brief, the key issues facing hospitals in the Afghan health system are:

- Maldistribution of hospitals and hospital beds throughout the country, which means a lack of equitable access to hospital care. People in urban areas have access but semi-urban and rural populations have limited access. For example, Kabul has 1.28 beds per 1,000 people while the provinces have only .22 per 1,000;

- Lack of standards for clinical patient care, resulting in poor quality of care; and

- Lack of hospital management skills, which results in inefficiently run hospitals, poorly managed staff, lack of supplies, and inoperable equipment due to lack of maintenance.10

Response: The Hospital Management Improvement Initiative

REACH began helping to rebuild the health sector in 2003. Initial efforts focused on expanding basic services, and in two years we have moved from 5% to 77% coverage of the population of Afghanistan. In 2004, the contract was amended to include the hospital sector, with a focus on provincial hospitals. REACH developed the Hospital Management Improvement Initiative to build the clinical and management capacity of hospitals so that:

- Health services are delivered more efficiently;

- The quality of services are improved;

- The population has increased access to hospital services; and

- There is a positive impact on health status—especially on the morbidity and mortality of women and children.

Introducing clinical and management improvements, combined with appropriate resources, will improve quality of care, increase access to hospital services, and streamline hospital operations. These improvements will ultimately result in achievement of the goals of improved health status, improved patient and community satisfaction with hospitals, and an improved referral system for Afghanistan.

Although the need was great, it was not possible to train the management team at each hospital in Afghanistan. Instead, clinical and management capacities at the provincial and central hospitals were strengthened through training, mentoring, networking and modeling, and provision of resources.

Training

The Standards Based Management/Performance Quality Improvement approach that JHPIEGO has successfully developed and used to improve the quality of reproductive health services in many resource-poor settings has been expanded and adapted by REACH into a comprehensive approach to improve hospital management in Afghanistan. This process includes all clinical services (surgery, anesthesia, emergency care, pediatrics, infection prevention, and blood transfusion and blood banks) and management systems (governance, facilities and equipment management, pharmacy management, human resource systems) for general hospitals.

Standards were developed in each of these areas, and training modules developed. Eight workshops have been held to train key staff from each hospital, who return to their hospitals to introduce the standards to their medical and administrative staff. Each workshop produces a plan for implementing the standards according to the circumstances of each hospital. The training is incremental. For instance, rather than doing a one- to two-week workshop presenting all the training modules, two modules on standards (usually one clinical and one management area) are presented. Two new modules are presented quarterly thereafter, to prevent information overload, allow trainees to integrate what they have learned with real day-to-day management, and avoid the problem of hospitals being left without leadership for an extended period.

Mentoring

A skilled hospital management advisor visits the hospitals regularly so managers have the opportunity to work with a mentor to apply what they have learned to their hospitals. This practical experience involves applying principles to real-life situations with someone experienced enough to help overcome obstacles not anticipated in the workshops. Mentors from REACH and the Ministry of Public Health visit the provincial hospitals to discuss problems, review progress, talk about problems that prevented achievement of goals, and set goals for the next three-month period.

The first four provincial hospitals selected for this intervention are all in areas formerly controlled by the Taliban, and security issues have added other challenges to this program because of repeated terrorist attacks on non-governmental organizations and people employed by international organizations. The mentors involved must speak Pashto, the local language, and integrate into the culture so they do not attract attention or create local opposition. Mentoring is a necessary but dangerous activity for the success of the program.

Networking and Modeling

As more hospital managers and senior clinicians are trained through this program, networking becomes another important tool. The network uses meetings twice a year for two days in a participating hospital to provide an opportunity for hospital managers to discuss common issues and develop system-wide solutions. Between these meetings, hospital managers in the same region exchange visits to learn from each other. REACH facilitates this networking using e-mail (some of the provincial hospitals have Internet access, which has dramatically increased their participation in evidence-based approaches), dissemination of reports, and passing on requests for communication between hospitals. These formal meetings and informal exchanges permit hospital managers to interact about common problems and learn how other hospitals have solved those problems. This networking will slowly expand to cover more provincial hospitals and will assist in expanding the number of trainers and mentors.

Modeling means trying new systems and methods generated by the trainees to address their self-identified problems. Improvements in five provincial hospitals (in Khost, Paktika, Paktia, Ghazni, and Badakhshan) will provide a model that demonstrates to the public that hospitals can be well run and serve the community. These hospitals can also be used as training grounds for other hospital managers from around the country as the initiative expands to more of the remaining 28 provincial hospitals. The goal is to develop optimism and creativity because one of the main barriers in training is that some managers have difficulty imagining things being different because they feel the system “has always been broken.” When trainees see that other hospitals have successfully tried new approaches, they will consider a broader range of possibilities for their own hospitals.

Resources

Along with the management improvements achieved through training, mentoring, and networking, additional resources are needed to improve hospital services. REACH has been the conduit for U.S. government funding, providing $2.6 million in critical resources to drive improvements in the five provincial hospitals. These funds are channeled through the contracted nongovernmental organizations, which hire staff and pay decent salaries.

The average hospital physician in the Ministry of Public Health is paid $50 a month. In this setting “under-the-table” charges for clinical services are common, and physicians usually leave the hospital by lunch to attend to their private clinics. This initiative pays physicians up to $500 a month with the expectations that they will work a full day, provide 24-hour emergency coverage, and not charge patients. Eighteen months of experience suggest that these expectations are being met. Resources are also used for remodeling facilities, purchasing equipment and supplies, and providing essential medicines. The management standards developed are designed to make rational use of these scarce resources.

Prerequisites for the Initiative

Two key prerequisites for starting the Hospital Management Initiative were:

- Identifying where standards had to be developed: REACH has assisted the Ministry of Public Health to identify the standards that must be developed: responsibilities of hospitals to the community, patient care (clinical care), human resource management, management systems, environmental health, and leadership and management.10 “Areas of Standards for Hospitals in Afghanistan” shows the standards that have been or are to be developed. (See sidebar at left.)

- Essential Package of Hospital Services: To ensure that donor support does not stimulate a proliferation of hospitals and high-tech equipment that are not appropriate or sustainable for Afghanistan, REACH has been helping the Ministry of Public Health define the levels of hospitals (district, provincial, regional), the populations they serve, the services they offer, and the equipment, staff, supplies, and pharmaceuticals they need. The result was the publication of the Essential Package of Hospital Services, which defines these for each of the three levels of hospitals in the country, in 2005. This package will provide guidance for Afghanistan’s hospitals for the coming decade, much as the Basic Package of Health Services has done for primary healthcare services. The hospital package will also support long-term planning and help the Ministry make the best use of donor assistance for redeveloping the hospital sector.

Developing and Implementing Standards

Standards-based management begins by identifying existing clinical guidelines and standards developed by American or international specialty societies. Specialist consultants in each clinical area with many years’ experience in Afghanistan (some of them Afghan-American physicians) are contracted to develop these standards and then adapt them to the Afghan context, in consultation with physicians in Afghanistan.

For example, standards for acute abdominal pain had to be adapted to a situation where CAT scans and ultrasounds are not readily available, and the lack of electrolyte laboratory capacity in hospitals stimulated physicians to adapt standards for shock, and fluid and electrolyte balance that do not rely on knowing electrolyte levels. The standards development teams aimed to raise the standards of Afghan hospitals to a realistic extent but not set the bar so high that improvement was unattainable.

After the standards were developed, clinicians from Afghan hospitals reviewed and revised the standards to ensure that they were appropriate. This review also served as a means of training because the participants were able and eager to question the contracted expert about the standards in developed countries and the evidence supporting those standards. Once the standards are revised, a workshop is held to introduce them to hospital staff. The hospital teams then develop an action plan for introducing the standards into their facilities.

Quality improvement teams at each of the five hospitals take responsibility for shepherding the action plans through implementation. An advisor visits each hospital quarterly to review progress, assess barriers, and help hospital staff develop ways to overcome problems and accelerate standards implementation. During the mentor’s first visit after new standards have been introduced, he performs a baseline assessment of the hospital’s current compliance with the standards. This serves as a benchmark for future measurement of progress in meeting the standards.

The Results

The hospitals have been enthusiastic about this process and the gains they have seen in the quality of care at their facilities. “We have made more progress in four months of the Hospital Management Improvement Initiative than we made in the previous five years with many other donors because this methodology is sound and appropriate for Afghanistan,” said Dr. Mohammed Ismael, the director of Ghazni Provincial Hospital.

One example of the process and results was the first area in which standards were developed—essential obstetric care. Physicians examined seven components of the quality of emergency obstetric care: handling of pregnancy complications; labor, delivery, and postpartum and newborn care; support services; infection prevention; health education given to families and mothers; human, physical, and material resources; and management systems in the obstetrics/gynecology department. After the standards were established, the first step was to find out where each hospital stood in meeting them. (For the combined results of that first baseline assessment for four hospitals, see Figure 1, p. 20.)

The changes in standards for emergency obstetric care at the hospitals from July 2004 to July 2005 have been impressive. The overall composite scores for emergency obstetric care for the four hospitals have improved from 31% at the baseline assessment to 47%. Here are the average improvements in the same four hospitals over one year:

Lessons Learned

The principal lesson learned through this hospital management improvement initiative is that combining clinical and management improvements can create innovation in a developing country. Improvements are made throughout a hospital—not just in one clinical area. Second, mentoring has proven essential as a follow-up to training. The training alone will not bring about significant positive changes. Only with on-site visitation is there the opportunity to integrate new knowledge with practical implementation issues that have proven troublesome to overcome. Third, setting standards is key to the sustainability of improvements. Training individuals in skills is helpful but is not sustainable if those trained staff depart. Using hospital teams and common standards throughout different hospitals leads to institutionalization of the process.

Staff motivation has also proven to be essential to sustainability. Staff have been motivated because they see that many positive changes are within their control; they do not have to wait for someone else to make an improvement before they can introduce positive change. An ethic of continuous quality improvement is achieved through staff who are proud of the changes they have introduced. The iterative nature of this process has been essential to quality improvement: The standards are continually revisited and revised as needed. At times, new standards for other areas are developed when the hospitals need them. Finally, providing resources to pay adequate salaries, renovate facilities, buy equipment and supplies, and provide essential medicines are all important elements of this success.

This method has proven successful in such a short time that the Minister of Public Health, Dr. Mohammad Amin Fatimie, has expressed his desire to extend it to many other hospitals in the country in an effort to improve the quality of hospital care throughout Afghani-stan. The U.S. Agency for International Development and MSH have agreed to support this request, and the program will expand in future years. TH

Dr. Hartman, is a family physician with subspecialty training in infectious diseases, epidemiology, and public health. He serves as the technical director and deputy chief of party of the REACH Project, based in Kabul. Dr. Newbrander is a health economist who has served in Afghanistan since 2002 as a senior advisor to the Ministry of Health. He is currently Health Financing and Hospital Management Advisor for the USAID-funded REACH Project.

Acknowledgment: Funding for this article was provided by the United States Agency for International Development under the REACH Project, contract number EEE-C-00-03-00015-00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID.

References

- Newbrander W, Ickx P, Leitch GH. Addressing the immediate and long-term health needs in Afghanistan. Harvard Health Pol Rev. 2003;4.

- Ministry of Health Transitional Islamic Government of Afghanistan (TISA), US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United Nations Children’s Fund. Maternal mortality in Afghanistan: magnitude, causes, risk factors and preventability. Kabul: TISA; 2002.

- Bartlett LA, Mawji S, Whitehead S, et al. Where giving birth is a forecast of death: maternal mortality in four districts of Afghanistan, 1999-2002. Lancet. 2005;365:864-870.

- Strong L, Wali A, Sondorp E. Health Policy in Afghanistan: Two Years of Rapid Change: A Review of the Process from 2001 to 2003. London: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; 2005.

- Afghanistan’s health challenge. Lancet. 2003;362:841.

- Ministry of Health Transitional Islamic Government of Afghanistan (TISA). The Basic Package of Health Services for Afghanistan. Kabul: TISA; 2003.

- Ministry of Health Transitional Islamic Government of Afghanistan (TISA). Hospital Policy for Afghanistan’s Health System. Kabul: TISA; 2004.

- Ministry of Health Transitional Islamic Government of Afghanistan (TISA), Management Sciences for Health. Afghanistan national health resources assessment: Preliminary results. Kabul: TISA; 2002.

- A crucial time for Afghanistan’s fledgling health system. Lancet. 2005; 365:819-820.

- Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. The Essential Package of Hospital Services for Afghanistan. Kabul: MOPH; 2005.

Familial hypercholesterolemia: A challenge of diagnosis and therapy

Abdominal aortic aneurysms: What we don't seek we won't find

Should we screen for abdominal aortic aneurysms?

Treating HIV Lipodystrophy

Syringomatous Carcinoma in a Young Patient Treated With Mohs Micrographic Surgery

Syringomatous carcinoma (SC), considered by some to be a variant of microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC),1 is a rare malignant neoplasm of sweat gland origin. SC encompasses a range of neoplasms with different degrees of differentiation, and its nomenclature has varied over the years. SC also has been referred to as syringoid eccrine carcinoma,2 basal cell tumor with eccrine differentiation,3 malignant syringoma,4 and sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma.5 Its diagnosis has been a dilemma in a number of reported cases, probably due to the combination of its rarity and thus limited clinical and histopathologic information, microscopic similarities to other benign and malignant neoplasms, and characteristic histologic features that may only be apparent in surgical excisions containing deeper tissue. We report a case of SC that masqueraded as an epidermoid cyst in an unusually young patient.

Case Report

A 23-year-old Asian man, who was otherwise healthy, presented with an asymptomatic slowly enlarging nodule of one year's duration on the right medial eyebrow. Prior treatment with intralesional steroid injections resulted in minimal improvement. The patient had no personal or family history of skin cancers. Physical examination results demonstrated a well-demarcated, mobile, nontender subcutaneous nodule measuring 7 mm in diameter. The clinical presentation favored a diagnosis of an epidermal inclusion cyst, and the patient underwent surgical excision of the lesion. Results of the histopathologic examination revealed a neoplasm in the dermis consisting of bands and nests of pale staining basaloid cells extending between the collagen fibers (Figure 1). There were focal areas of ductal differentiation, scattered individual necrotic cells, moderate dermal fibrosis, and chronic inflammation with numerous eo-sinophils. Moderate nuclear atypia also was present (Figure 2). Perineural involvement was not seen. Results of immunohistochemical analysis revealed positive staining for high—and low—molecular-weight cytokeratins, as well as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)(Figure 3). There was scattered positivity with S-100 protein in occasional cells lining lumina and in dendritic cells (Figure 4). The histopathologic findings supported the diagnosis of SC. Because the neoplasm extended to the surgical margins of the specimen, repeat surgical excision with continuous microscopic control under the Mohs micrographic technique was performed to prevent local recurrence and spare normal tissue. At the 18-month follow-up visit, no local recurrence was seen.

Comment SC is a rare, malignant sweat gland neoplasm that usually occurs in the fourth and fifth decades of life.4-8 SC typically presents as a slow-growing, solitary, painless nodule or indurated plaque on the head or neck region.6-8 It has been frequently found on the upper and lower lips; however, it also has been reported to occur on the finger and breast.9,10 Predisposing factors for the development of SC are unclear11 but may include previous radiation to the face and history of receiving an organ transplant with immunosuppressive drug therapy.12-17 Histopathologically, SC is characterized by asymmetric and deep dermal invasion of tumor cells, perineural involvement, ductal formation, keratin-filled cysts, multiple nests of basaloid or squamous cells, and desmoplasia of the surrounding dermal stroma (Table 1).5,6 Some authors consider SC to be closely related to MAC but generally describe SC as more basaloid with larger tubules and a more sclerotic stroma than MAC.18-26 If histologic examination of SC is limited to the superficial dermis, SC demonstrates similarities to other neoplasms, including syringomas, trichoadenomas, trichoepitheliomas, basal cell carcinomas, or squamous cell carcinomas. In the reported cases in which SC was initially misdiagnosed as another benign or malignant neoplasm, many misdiagnoses were due to either a benign clinical appearance of the lesion or biopsy specimens that were too superficial to contain the deeper characteristic histologic features of SC.8,9,11,27-30

Immunohistochemical studies can facilitate the diagnosis of SC and differentiate it from other neoplasms. SC stains positively for CEA, S-100 protein, epithelial membrane antigen, cyto-keratin, and gross cystic disease fluid protein 15,31 all of which aid in the confirmation of a sweat gland neoplasm (Table 2).8,32,33,39 Positivity for CEA in the ductal lining cells and the luminal contents of tumor ducts confirms sweat gland differentiation.25,33,34 This ductal immunoreactivity to CEA appears to be one of the most reliable findings to differentiate SC and MAC from other adnexal tumors, especially desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, which may be one of the more challenging histo-pathologic differential diagnoses.35 In addition, epithelial membrane antigen positivity can be found in the areas showing glandular features.35 This can assist in distinguishing SC from a desmoplastic trichoepithelioma or sclerosing type basal cell carcinoma, both of which demonstrate negativity to epithelial membrane antigen.35 S-100 protein positivity in dendritic cells, as well as in some cords and ducts in SC, further verifies dendritic differentiation toward sweat gland structures and is useful as an adjunct in the confirmation of glandular differentiation.25,33,34,36

Without proper and timely diagnosis and management, SC can cause severe patient morbidity. Although SC rarely metastasizes and can have an indolent course, it can be locally de-structive and lead to potentially disfiguring outcomes.5-7 SC can invade deeply and infiltrate into the dermis, subcutaneous fat tissue, muscle, perichondrium, periosteum, and galea.8 Goto et al9 reported a case of an SC that was initially misdiagnosed as a basal cell carcinoma of the left middle finger. The deeper, characteristic features of SC were not recognized until after the affected finger required amputation due to erosion of the bone. Hoppenreijs et al11 described an aggressive case of an SC arising at a site of previously irradiated squamous cell carcinoma of the lower eyelid. Extensive involvement of the SC in the orbit led to the recommendation of an orbital exenter-ation; however, it was not performed because of the poor clinical condition of the patient. Treatments for SC have included wide local excision and Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS). SC treatment with wide local excision often resulted in incomplete excision of the neoplasm despite having taken an adequate margin around the clinically assessable tumor.5 Cases of SC treated with wide local excision had a recurrence rate of 47%.5 The positive surgical margins following wide local excision may be due to the deep infiltration of SC, which frequently exceeds the clinically predicted size of the tumor.5 Due to the close relationship of MAC and SC, we feel that MMS treatment of SC will reduce recurrences as it has for MAC. Currently, there is strong support for the treatment of MAC with MMS as a gold standard to ensure complete clearance of the neoplasm and to reduce the local recurrence rate.12,13,17,21,22,37,38 In a study of MAC by Chiller et al,37 the authors demonstrated a median 4-fold increase in defect size when they compared the clinically estimated pretreatment size of the lesion with the MMS-determined posttreatment size of the lesion. The authors therefore suggest that, similar to the MMS-treated lesions, the lesions completely treated with wide local excision also would produce a defect size that is at least 4 times greater than the predicted pretreatment size of the lesion. Because wide local excision relies on predicted margins of the lesion, which the authors have shown can be greatly underestimated, Chiller et al37 argue that the use of MMS, which does not rely on predicted margins, is a reasonable first-line therapeutic modality for effectively treating patients with MAC. Furthermore, MMS allows for the examination of the entire peripheral and deep margins of the lesion, which is critical when considering the deep infiltrative nature of MAC. The reported local recurrence rate of MAC treated with MMS is 0% to 5%,12,13,21,26,38 which is much lower than the reported local recurrence rate following treatment with wide local excision. This reduced recurrence rate found in MAC cases treated with MMS is probably due to the ability to confirm complete removal of the neoplasm with MMS.

Conclusion To our knowledge, this case report describes the occurrence of SC, a rare sweat gland neoplasm, in the youngest reported patient and is only the second reported case of SC treated with MMS. Adequate sampling of tissue with an excisional biopsy allowed for appropriate evaluation with histologic and immunohistochemical studies to arrive at the diagnosis that could easily have been missed with a superficial biopsy. In our patient, histopathologic evaluation showed typical nests of basaloid cells, ductal differentiation, and ductal fibrosis seen in SC. However, perineural involvement that is particularly characteristic of SC was not present. This may portend a better prognosis for our patient whose tumor was completely excised after one stage of MMS and has not shown evidence of recurrence at the 18-month follow-up visit. MMS allowed for evaluation of the entire surgical margin and decreased risk of local recurrence resulting from an incomplete excision. In addition, it also allowed for sparing of normal tissue in a cosmetically sensitive area where SC commonly occurs. In summary, this case highlights the importance of including SC in the differential diagnosis of an enlarging cystic lesion in a younger patient and its successful treatment with MMS.

- Weedon D. Tumors of cutaneous appendages. In: Weedon D, ed. Skin Pathology. 2nd ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:897.

- Sanchez Yus E, Requena Caballero L, Garcia Salazar I, et al. Clear cell syringoid eccrine carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1987;9:225-231.

- Freeman RG, Winkelmann RK. Basal cell tumor with eccrine differentiation (eccrine epithelioma). Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:234-242.

- Glatt HJ, Proia AD, Tsoy EA, et al. Malignant syringoma of the eyelid. Ophthalmology. 1984;91:987-990.

- Cooper PH, Mills SE, Leonard DD, et al. Sclerosing sweat duct (syringomatous) carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9:422-433.

- Mehregan AH, Hashimoto K, Rahbari H. Eccrine adenocarcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 35 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:104-114.

- Wick MR, Goellner JR, Wolfe JT III, et al. Adnexal carcinomas of the skin, I: eccrine carcinomas. Cancer. 1985;56:1147-1162.

- Abenoza P, Ackerman AB. Syringomatous carcinomas. In: Abenoza P, Ackerman AB, eds. Neoplasms with Eccrine Differentiation. Philadelphia, Pa: Lea & Febiger; 1990:371-412.

- Goto M, Sonoda T, Shibuya H, et al. Digital syringomatous carcinoma mimicking basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:438-439.

- Urso C. Syringomatous breast carcinoma and correlated lesions. Pathologica. 1996;88:196-199.

- Hoppenreijs VP, Reuser TT, Mooy CM, et al. Syringomatous carcinoma of the eyelid and orbit: a clinical and histopathological challenge. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;81:668-672.

- Snow S, Madjar DD, Hardy S, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: report of 13 cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:401-408.

- Friedman PM, Friedman RH, Jiang SB, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: collaborative series review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:225-231.

- Antley CA, Carney M, Smoller BR. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma arising in the setting of previous radiation therapy. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:48-50.

- Borenstein A, Seidman DS, Trau H, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma following radiotherapy in childhood. Am J Med Sci. 1991;301:259-261.

- Fleischmann HE, Roth RJ, Wood C, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma treated by microscopically controlled excision. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1984;10:873-875.

- Schwarze HP, Loche F, Lamant L, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma induced by multiple radiation therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:369-372.

- Cooper PH, Mills SE. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:908-914.

- Hamm JC, Argenta LC, Swanson NA. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: an unpredictable aggressive neoplasm. Ann Plast Surg. 1987;19:173-180.

- Birkby CS, Argenyi ZB, Whitaker DC. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma with mandibular invasion and bone marrow replacement. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15:308-312.

- Leibovitch I, Huilgol SC, Selva D, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:295-300.

- Gardner ES, Goldb

Syringomatous carcinoma (SC), considered by some to be a variant of microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC),1 is a rare malignant neoplasm of sweat gland origin. SC encompasses a range of neoplasms with different degrees of differentiation, and its nomenclature has varied over the years. SC also has been referred to as syringoid eccrine carcinoma,2 basal cell tumor with eccrine differentiation,3 malignant syringoma,4 and sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma.5 Its diagnosis has been a dilemma in a number of reported cases, probably due to the combination of its rarity and thus limited clinical and histopathologic information, microscopic similarities to other benign and malignant neoplasms, and characteristic histologic features that may only be apparent in surgical excisions containing deeper tissue. We report a case of SC that masqueraded as an epidermoid cyst in an unusually young patient.

Case Report

A 23-year-old Asian man, who was otherwise healthy, presented with an asymptomatic slowly enlarging nodule of one year's duration on the right medial eyebrow. Prior treatment with intralesional steroid injections resulted in minimal improvement. The patient had no personal or family history of skin cancers. Physical examination results demonstrated a well-demarcated, mobile, nontender subcutaneous nodule measuring 7 mm in diameter. The clinical presentation favored a diagnosis of an epidermal inclusion cyst, and the patient underwent surgical excision of the lesion. Results of the histopathologic examination revealed a neoplasm in the dermis consisting of bands and nests of pale staining basaloid cells extending between the collagen fibers (Figure 1). There were focal areas of ductal differentiation, scattered individual necrotic cells, moderate dermal fibrosis, and chronic inflammation with numerous eo-sinophils. Moderate nuclear atypia also was present (Figure 2). Perineural involvement was not seen. Results of immunohistochemical analysis revealed positive staining for high—and low—molecular-weight cytokeratins, as well as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)(Figure 3). There was scattered positivity with S-100 protein in occasional cells lining lumina and in dendritic cells (Figure 4). The histopathologic findings supported the diagnosis of SC. Because the neoplasm extended to the surgical margins of the specimen, repeat surgical excision with continuous microscopic control under the Mohs micrographic technique was performed to prevent local recurrence and spare normal tissue. At the 18-month follow-up visit, no local recurrence was seen.