User login

Combination Drug Therapy Soothes Scleroderma

A combination of oral methotrexate and pulsed high-dose corticosteroids significantly improved the visible inflammation in 15 adults with severe localized scleroderma, wrote Alexander Kreuter, M.D., of Ruhr-University Bochum (Germany) and his colleagues.

In a prospective, nonrandomized pilot study, nine women and six men received a weekly oral methotrexate dose of 15 mg. They also received an intravenous methylprednisolone sodium succinate dose of 1,000 mg for 3 consecutive days each month.

Patients were treated for at least 6 months, and the mean treatment duration was 9.8 months (Arch. Dermatol. 2005; 141:847–52). The two treatments have shown effectiveness against severe localized scleroderma when used separately, the researchers noted.

On average, the modified skin scores of the patients dropped significantly, from 10.9 to 5.5, and signs of improvement were visible after 2 months. In addition, the visual analog scores (VAS) for tightness improved in 12 patients. On average, the VAS for tightness decreased significantly, from 65.3 to 27.5.

Follow-up visits occurred every 4 weeks, and a modified skin score was used to assess skin involvement. Ultrasonography was performed at the end of the study to confirm the clinical improvement, and it showed a significant decrease in skin thickness between baseline and the study's end.

The patients also demonstrated significant increases in dermal density at the end of the study, and the dermal collagen structure had returned to normal or near normal levels.

The patients' ages ranged from 18 to 73 years, and the duration of illness ranged from 1 to 36 years. Prior to the study, 11 patients had been treated unsuccessfully with other methods.

Adverse effects included mild nausea and headache in three patients, diabetes mellitus in two patients, and weight gain in one patient, but these effects normalized after treatment ended. None of the patients showed signs of relapse over 6 months of follow-up.

Although the study was limited by its small size and lack of placebo controls, the favorable response and moderate side effects suggest that combination therapy for localized scleroderma merits further study and that the treatment may be effective in less severe cases as well.

A combination of oral methotrexate and pulsed high-dose corticosteroids significantly improved the visible inflammation in 15 adults with severe localized scleroderma, wrote Alexander Kreuter, M.D., of Ruhr-University Bochum (Germany) and his colleagues.

In a prospective, nonrandomized pilot study, nine women and six men received a weekly oral methotrexate dose of 15 mg. They also received an intravenous methylprednisolone sodium succinate dose of 1,000 mg for 3 consecutive days each month.

Patients were treated for at least 6 months, and the mean treatment duration was 9.8 months (Arch. Dermatol. 2005; 141:847–52). The two treatments have shown effectiveness against severe localized scleroderma when used separately, the researchers noted.

On average, the modified skin scores of the patients dropped significantly, from 10.9 to 5.5, and signs of improvement were visible after 2 months. In addition, the visual analog scores (VAS) for tightness improved in 12 patients. On average, the VAS for tightness decreased significantly, from 65.3 to 27.5.

Follow-up visits occurred every 4 weeks, and a modified skin score was used to assess skin involvement. Ultrasonography was performed at the end of the study to confirm the clinical improvement, and it showed a significant decrease in skin thickness between baseline and the study's end.

The patients also demonstrated significant increases in dermal density at the end of the study, and the dermal collagen structure had returned to normal or near normal levels.

The patients' ages ranged from 18 to 73 years, and the duration of illness ranged from 1 to 36 years. Prior to the study, 11 patients had been treated unsuccessfully with other methods.

Adverse effects included mild nausea and headache in three patients, diabetes mellitus in two patients, and weight gain in one patient, but these effects normalized after treatment ended. None of the patients showed signs of relapse over 6 months of follow-up.

Although the study was limited by its small size and lack of placebo controls, the favorable response and moderate side effects suggest that combination therapy for localized scleroderma merits further study and that the treatment may be effective in less severe cases as well.

A combination of oral methotrexate and pulsed high-dose corticosteroids significantly improved the visible inflammation in 15 adults with severe localized scleroderma, wrote Alexander Kreuter, M.D., of Ruhr-University Bochum (Germany) and his colleagues.

In a prospective, nonrandomized pilot study, nine women and six men received a weekly oral methotrexate dose of 15 mg. They also received an intravenous methylprednisolone sodium succinate dose of 1,000 mg for 3 consecutive days each month.

Patients were treated for at least 6 months, and the mean treatment duration was 9.8 months (Arch. Dermatol. 2005; 141:847–52). The two treatments have shown effectiveness against severe localized scleroderma when used separately, the researchers noted.

On average, the modified skin scores of the patients dropped significantly, from 10.9 to 5.5, and signs of improvement were visible after 2 months. In addition, the visual analog scores (VAS) for tightness improved in 12 patients. On average, the VAS for tightness decreased significantly, from 65.3 to 27.5.

Follow-up visits occurred every 4 weeks, and a modified skin score was used to assess skin involvement. Ultrasonography was performed at the end of the study to confirm the clinical improvement, and it showed a significant decrease in skin thickness between baseline and the study's end.

The patients also demonstrated significant increases in dermal density at the end of the study, and the dermal collagen structure had returned to normal or near normal levels.

The patients' ages ranged from 18 to 73 years, and the duration of illness ranged from 1 to 36 years. Prior to the study, 11 patients had been treated unsuccessfully with other methods.

Adverse effects included mild nausea and headache in three patients, diabetes mellitus in two patients, and weight gain in one patient, but these effects normalized after treatment ended. None of the patients showed signs of relapse over 6 months of follow-up.

Although the study was limited by its small size and lack of placebo controls, the favorable response and moderate side effects suggest that combination therapy for localized scleroderma merits further study and that the treatment may be effective in less severe cases as well.

Infectious Arthritis of Native and Prosthetic Joints

Introduction

Acute bacterial arthritis is a potentially serious and rapidly progressive infection that may involve native or prosthetic joints. The epidemiology, pathophysiology, repertoire of potential infecting pathogens, clinical presentation and treatment differ for these two forms of infectious arthritis, but both are associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Infectious arthritis of native and prosthetic joints may be caused by viruses, or fungi, but the most common cause is bacteria.

Acute Bacterial Arthritis

Epidemiology

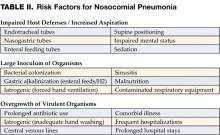

The burden of septic arthritis in the general population is considerable. The incidence of native joint septic arthritis is approximately 5 cases per 100,000 persons per year and is much higher in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (1,2). Between 1% and 5% of joints with indwelling prostheses become infected and the total number of infections per year is increasing due to a rise in the number of patients who have had prosthetic replacement surgery (3). The mortality from joint infection is difficult to estimate due to differing comorbidity in afflicted patients, but is likely between 15% and 30% (4-6). There is substantial morbidity from these infections because of decreased joint function and mobility, and in cases involving joint prostheses from the excisional or exchange arthroplastic surgery that is often required for treatment.

The most common route of infection for native joint infection is hematogenous (1), but may also be a result of direct inoculation of bacteria through trauma or joint surgery (including arthrocentesis, corticosteroid injection, or arthroscopy) (7), or via contiguous spread from adjacent infected soft tissue or bone (1,8). While hematogenous infection of prosthetic joints occurs, the majority of these infections are the result of joint contamination in the course of implantation surgery or post-surgical wound infection (3). Host factors that increase the risk of septic arthritis include pre-existing joint disease (especially rheumatoid arthritis), immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, malignancy, chronic renal failure, intravenous drug use, severe skin diseases, and advanced age (1,2,4,6). The extent of joint injury resulting from infection depends on the virulence of the infecting pathogen and degree of host immune response (9).

Microbiology

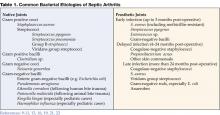

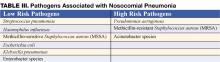

Native Joint

The most common causes of bacterial septic arthritis are outlined in Table 1. In adults, the most frequent etiology is S. aureus (37–65% of cases) (1,4,6,8,12,15,16) followed by Streptococcus sp. (12,15). An increasing percentage of S. aureus isolated from septic joints are resistant to antistaphylococcal penicillins and cephalosporins (methicillin-resistant S. aureus, MRSA). In adults with diabetes, malignancy, and genitourinary structural abnormalities, group B Streptococcus is a frequently isolated pathogen (5,6,17). Gram-negative bacilli are commonly found in neonates, intravenous drug users, and immunocompromised hosts (18). N. gonorrhoeae is a significant cause of bacterial arthritis in sexually active adults and adolescents (19) and Kingella kingae and Haemophilus influenzae are likely pediatric isolates (20,21). Joint infections that follow bite trauma usually are seen in the small joints of the hand and involve Pasteurella multocida in the case of animal bites, and Eikenella corrodens in the case of humans bites (22-24). Polymicrobial floras are found in up to 8% of cases of septic arthritis.

Prosthetic Joint

The bacteria that cause prosthetic joint arthritis vary depending on the stage of infection as defined by the elapsed time after implantation surgery (Table 1 on page 31). The coagulase negative staphylococci are the most common (30–43% of cases) (3,10), followed by S. aureus (12–23%) (25).

Nonbacterial Pathogens

Nonbacterial pathogens that may cause septic arthritis include viruses, fungi, and mycobacteria. Viral arthritis is often associated with a systemic febrile illness and other manifestations of infection such as rash. Parvovirus B19 is the most common viral arthritide, presenting as a symmetric polyarticular arthritis involving the joints of the hand as well as larger joints (26). The classic red “slapped cheeks” associated with this viral infection in children is usually not present in adults, although a faint lacy reticular rash may be seen.

Fungi and mycobacteria usually cause a subacute or chronic mono- or oligoarticular arthritis (27). Candida species are an increasing cause of both native and prosthetic joint septic arthritis. Risk factors for this infection include loss of skin integrity, diabetes, malignancy, intravenous drug use, and immunosuppressive therapy including glucocorticoids (28). Patients are often chronically ill and have exposure to broad-spectrum antimicrobials, hyperalimentation fluid, and/or indwelling central intravenous catheters. Other fungi, including Cryptococcus, Blastomyces, Histoplasma, Coccidioides, and Sporothrix are rare causes of septic arthritis (29,30). Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the most common cause of mycobacterial arthritis worldwide and should be considered in a patient presenting with chronic arthritis with risk factors for tuberculosis, including being foreign-born (31).

Clinical Features

The clinical manifestations, severity, treatment, and prognosis of septic arthritis are dependent on the identity and virulence of the bacterium, source of joint infection, and underlying host factors. Nongonococcal septic arthritis is monoarticular in 80% to 90% of cases. The knee is usually affected (50% of cases) (27) followed by the hip, wrists, and ankles (2). In adults, the majority of hip infections involve prosthetic or osteosynthetic material (1). Arthritis of the small joints of the foot is most often seen in diabetic patients and is usually secondary to contiguous skin and soft tissue ulcerations or adjacent osteomyelitis.

Gonococcal arthritis may present as febrile monoarticular arthritis, usually of the knees, wrists, and ankles (27), or as one of the manifestations of disseminated gonococcal infection. The latter is characterized by fever, dermatitis, tenosynovitis, and migratory polyarthralgia or polyarthritis (19). Skin lesions are often pustular and occur simultaneously with tenosynovitis, predominately affecting the fingers, hands, wrists, or feet. Concomitant mucosal infection of the urethra or cervix is often present but usually asymptomatic. Urethral and cervical cultures or a nucleic amplification test will frequently yield N. gonorrhoeae (19,32).

Symptoms of acute septic arthritis include pain and loss of joint function. Fever and chills are often present. The acutely infected native joint is usually red, warm, and swollen with an obvious effusion. Range of motion is limited and extremely painful. For deep and axial joint, pain is often the only focal symptom. More subtle symptoms and signs may result in a delay of diagnosis and are particularly seen in patients receiving systemic or intra-articular steroids, and in those with immunocompromised status, advanced comorbidities (including rheumatoid arthritis), and extreme age (33). A thorough physical examination may reveal a distant source of joint infection in up to 50% of patients (27).

Prosthetic joint infection may present acutely as above, particularly in early stage infection, or more indolently with progressive joint pain, minimal swelling or effusion, and absence of fever (34). In late infection a cutaneous draining sinus tract may be present. Rarely, the involved prosthesis may be visible beneath an ulceration or focus of soft-tissue breakdown.

Diseases that can mimic septic arthritis are crystalinduced arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, spondyloarthropathy, Still’s disease, rheumatic fever, and Kawasaki syndrome.

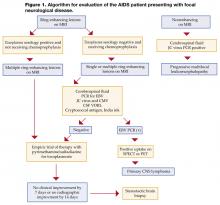

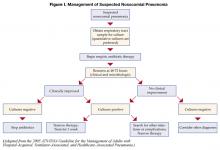

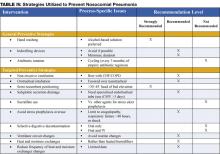

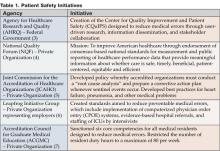

Diagnostic Approach

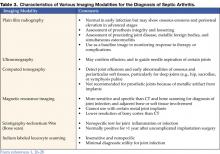

A diagnostic approach to acute native joint arthritis is outlined in Figure 1 on page 32 (35,36). Important aspects include exclusion of other causes of arthritis including trauma, rheumatic diseases, and crystalline arthritis. The most important diagnostic test upon which management hinges is diagnostic arthrocentesis. Fluoroscopic or CT-guided arthrocentesis is indicated for axial and deep joints (e.g., sacroiliac or pubic symphysis) or in the event of a “dry tap” of a peripheral joint. Synovial fluid analysis will often suggest whether an acutely painful joint is due to noninflammatory, sterile inflammatory, or septic causes (Table 2 on page 33). In addition, it will provide fluid for culture and gram stain, a rapid test that can guide early empiric antibiotic therapy. Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures should always be performed in order to direct pathogen-specific antimicrobial therapy, which is often given as a prolonged course. Antimicrobial therapy should be delayed until arthrocentesis and other appropriate diagnostic cultures are obtained unless the patient shows signs of sepsis.

For prosthetic joint infections the diagnostic approach is essentially the same although early radiographic imaging is more important than in native joint infection as it may show signs of prosthesis failure or loosening (seen in many late prosthesis infections). Additionally, the synovial fluid white blood cell (WBC) is often lower than in nativejoint infection, with a diagnostic cutoff suggested as greater than 1,700 cells/mm3 or >65% neutrophils (37).

Nonspecific blood tests such as a white blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, or C-reactive protein argue against joint infection if they are normal, but do not specifically suggest septic arthritis if elevated. Other important diagnostic tests include blood cultures (positive in 50–70% of acute bacterial arthritides) (27), but in only 30% or less of gonococcal arthritis cases) (38), wound cultures (although these often correlate poorly with synovial fluid culture results, except when the pathogen is S. aureus), and serologic testing for B. burgdorferi in selected cases with clinical features of Lyme arthritis in endemic areas. If gonococcal arthritis is suspected urethral and cervical specimens should be sent for N. gonorrhoeae culture and nucleic acid amplification tests. Radiographic and scintillographic imaging may yield additional information that will assist in identifying preexisting joint disease or for confirming a diagnosis of native or prosthetic joint infection or its complications (Table 3 on page 33).

Treatment

Native joint

Prompt joint drainage and antimicrobial therapy are the mainstays of treatment in bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial joint infection. Drainage can be through closed needle aspiration performed daily, or arthroscopy. The former modality allows direct visual inspection of the joint with concomitant irrigation, lysis of adhesions, and removal of necrotic tissue and purulent material (42). Open surgical drainage is recommended for septic arthritis of the hip and when less invasive methods fail to control infection.

Initial antimicrobial therapy should be withheld until synovial fluid has been obtained and should be based on synovial fluid gram staining (Table 4). In the case of a nondiagnostic gram stain, empiric antimicrobial coverage of likely infecting pathogens is indicated. Therapy should be narrowed based on identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing of bacteria cultured from synovial fluid, blood, or in some cases from ancillary cultures. For patients with MRSA-related infection who are allergic to or intolerant of vancomycin, linezolid or daptomycin are potential alternatives, although not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for this indication. Linezolid is a potentially attractive option for treatment as it is available as an oral tablet, but for bone and joint infection treatment experience is limited. For septic arthritis related to animal or human bites ampicillin-sulbactam or amoxicillin-clavulanate (clindamycin plus ciprofloxacin in penicillin-allergic patients) provides activity against Pasteurella multocida and other oral bacteria. Gonococcal arthritis is best treated initially with ceftriaxone or cefotaxime; oral ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin may be substituted in regions without fluoroquinolone resistance as the patient improves (Table 4). Septic arthritis due to Candida sp. should be treated initially with an amphotericin B preparation followed by a prolonged course of fluconazole if susceptibility testing confirms activity against the cultured yeast isolate (43).

Duration of intravenous antimicrobials for bacterial joint infections is usually 2 to 4 weeks, while for gonococcal arthritis 2 weeks is sufficient. Antimicrobial therapy that continues for 2 weeks or longer should have weekly followup and laboratory monitoring for hematologic, renal, and liver toxicity.

Prosthetic Joint

Treatment of prosthetic joint septic arthritis is complex, and early consultation with an orthopedic surgeon and infectious diseases physician is recommended. Extensive surgical debridement of the afflicted joint and effective, prolonged antimicrobial therapy is necessary in almost all cases. In order to achieve an optimal synovial fluid and tissue culture yield, antimicrobial therapy should be delayed until the time of debridement surgery unless the patient is septic or exhibiting serious systemic complications of infection. Suggestions for early empiric therapy while awaiting culture results are given in Table 4. Final antimicrobial choices should be based on culture results with assistance from an infectious diseases consultant.

Carefully selected cases of prosthetic joint infection may be treated with simple surgical debridement of the joint with prosthesis retention and at least 3 months of antimicrobial therapy that includes rifampin if the organism is gram positive (44). Patients who present with a short duration of symptoms within 1 month of joint implantation, or those with acute hematogenous infection, are the best candidates for such a treatment strategy. Unfortunately, relapse is common in these cases, particularly if the infection is due to S. aureus, gram-negative bacilli, or drug-resistant pathogens. Thus, the optimal treatment protocols involve surgical excision of the infected prosthesis and prolonged antimicrobial therapy.

Surgical prosthesis extraction and reimplantation can be performed in either a one- or two-stage approach. The two-stage procedure is the more successful strategy and involves removal of the prosthesis and cement followed by a 6-week course of bactericidal antimicrobial therapy. Subsequently a new prosthesis is reimplanted. Using this approach, a 90% to 96% success rate in total hip replacement infections and a 97% success rate in total knee infections has been realized (45-47). An alternative tactic is a one-stage surgical procedure that excises the infected prosthesis with immediate reimplantation of a new joint using antibiotic-impregnated methacrylate cement. This method is effective in 77% to 83% of cases (48-50). Higher failure rates are observed for S. aureus and gram-negative bacillary infections (51). One-stage procedures are often used for elderly or infirm patients who might not tolerate protracted bed rest and a second major operation (52). A recent review article by Zimmerli et al. provides an excellent overview of antimicrobial and surgical treatment options for prosthetic joint infections (34).

Suppressive Antibiotic Therapy

Lifelong oral antimicrobial therapy plays a limited role for definitive therapy but is useful when a surgical approach is not possible because of medical or surgical contraindications. The goal of suppressive therapy is to control the infection and retain prosthesis function. It is important that patients and their families understand that the intention of such treatment is not to cure but to suppress the infection. Generally, oral suppressive therapy is initiated after a course of intravenous therapy. Goulet et al. (53) demonstrated a 63% success rate in maintaining function of hip arthroplasty in patients who met 5 criteria: 1) prostheses removal is not possible, 2) the pathogen is avirulent, 3) the pathogen is sensitive to oral antibiotics, 4) the patient is adherent to and tolerates antibiotics, and 5) the prosthesis is not loose. Patients being treated with lifelong suppressive therapy are at risk for the development of antibiotic resistance (in either the joint infecting pathogen or other commensal organism), local or systemic progression of infection, and adverse effects from chronic antibiotic usage.

Antimicrobial Prophylaxis to Prevent Joint Prosthesis Infection

Patients undergoing elective total joint replacement surgery should be evaluated for symptoms or signs of local infection that predispose to occult or overt bacteremia (particularly odontogenic, urologic, and dermatologic). Surgery should be delayed until such infections and coexisting medical conditions have been treated. Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis has been shown to reduce deep wound infection and prosthetic joint infection in joint reimplant surgery but should not be continued for more than 24 hours after the preoperative dose (54,55). In order to decrease the risk of hematogenous seeding of established implants, early recognition and treatment of overt infection is crucial. The use of prophylactic antibiotics for patients with joint implants prior to or after dental or other procedures such as colonoscopy or cystoscopy is controversial. The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons recommends that a single dose of prophylactic antibiotic be given to certain patients undergoing urologic instrumentation or dental procedures that are accompanied by significant bleeding (56,57). Patients who are candidates for such prophylaxis include those with rheumatoid arthritis or other inflammatory arthropathy, immunosuppression, diabetes, malnutrition, hemophilia, or who have had a previous joint infection.

Dr. Ohl can be contacted at [email protected].

References

- Kaandorp CJ, Dinant HJ, van de Laar MA, Moens HJ, Prins AP, Dijkmans BA. Incidence and sources of native and prosthetic joint infection: a community based prospective survey. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56:470-5.

- Ohl C. Infectious arthritis of native joints. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2005:1311-1322.

- Brause B. Infections with prostheses in bones and joints. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Principles and Practices of Infectious Diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2005:1332-7.

- Gupta MN, Sturrock RD, Field M. A prospective 2-year study of 75 patients with adult-onset septic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2001;40:24-30.

- Nolla JM, Gomez-Vaquero C, Fiter J, et al. Pyarthrosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a detailed analysis of 10 cases and literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2000;30: 121-6.

- Weston VC, Jones AC, Bradbury N, Fawthrop F, Doherty M. Clinical features and outcome of septic arthritis in a single UK Health District 1982-1991. Ann Rheum Dis 1999;58:214-219.

- Kuzmanova SI, Atanassov AN, Andreev SA, Solakov PT. Minor and major complications of arthroscopic synovectomy of the knee joint performed by rheumatologist. Folia Med (Plovdiv). 2003;45:55-9.

- Morgan DS, Fisher D, Merianos A, Currie BJ. An 18 year clinical review of septic arthritis from tropical Australia. Epidemiol Infect 1996;117:423-8.

- Mader JT, Shirtliff M, Calhoun JH. The host and the skeletal infection: classification and pathogenesis of acute bacterial bone and joint sepsis. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 1999;13:1-20.

- Berendt A. Infections of prosthetic joints and related problems. In: Cohen J, Powderly W, eds. Infectious Diseases. Edinburgh: Mosby, 2005: 583-589.

- Raymond NJ, Henry J, Workowski KA. Enterococcal arthritis: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21: 516-522.

- Ross JJ, Saltzman CL, Carling P, Shapiro DS. Pneumococcal septic arthritis: review of 190 cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:319-27.

- Kortekangas P, Aro HT, Tuominen J, Toivanen A. Synovial fluid leukocytosis in bacterial arthritis vs. reactive arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis in the adult knee. Scand J Rheumatol. 1992;21:283-8.

- Sack K. Monarthritis: differential diagnosis. Am J Med. 1997; 102(1A):30S-34S.

- Dubost JJ, Soubrier M, De Champs C, Ristori JM, Bussiere JL, Sauvezie B. No changes in the distribution of organisms responsible for septic arthritis over a 20 year period. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:267-9.

- Ryan MJ, Kavanagh R, Wall PG, Hazleman BL. Bacterial joint infections in England and Wales: analysis of bacterial isolates over a four year period. Br J Rheumatol. 1997;36:370-3.

- Nolla JM, Gomez-Vaquero C, Corbella X, et al. Group B streptococcus (Streptococcus agalactiae) pyogenic arthritis in nonpregnant adults. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003;82: 119-28.

- Shirtliff ME, Mader JT. Acute septic arthritis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:527-44.

- Bardin T. Gonococcal arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2003;17:201-8.

- Yagupsky P, Dagan R. Kingella kingae: an emerging cause of invasive infections in young children. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:860-66.

- Bowerman SG, Green NE, Mencio GA. Decline of bone and joint infections attributable to haemophilus influenzae type b. Clin Orthop. 1997;(341):128-33.

- Ewing R, Fainstein V, Musher DM, Lidsky M, Clarridge J. Articular and skeletal infections caused by Pasteurella multocida. South Med J. 1980;73:1349-52.

- Murray PM. Septic arthritis of the hand and wrist. Hand Clin. 1998;14:579-87, viii.

- Resnick D, Pineda CJ, Weisman MH, Kerr R. Osteomyelitis and septic arthritis of the hand following human bites. Skeletal Radiol. 1985;14:263-6.

- Murdoch DR, Roberts SA, Fowler JV Jr, et al. Infection of orthopedic prostheses after Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:647-9.

- Woolf AD, Campion GV, Chishick A, et al. Clinical manifestations of human parvovirus B19 in adults. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:1153-6.

- Goldenberg DL. Septic arthritis. Lancet 1998; 351:197-202.

- Silveira LH, Cuellar ML, Citera G, Cabrera GE, Scopelitis E, Espinoza LR. Candida arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1993;19:427-37.

- Cuellar ML, Silveira LH, Espinoza LR. Fungal arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992;51:690-7.

- Cuellar ML, Silveira LH, Citera G, Cabrera GE, Valle R. Other fungal arthritides. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1993;19:439-55.

- Malaviya AN, Kotwal PP. Arthritis associated with tuberculosis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2003;17:319-43.

- Van Der PB, Ferrero DV, Buck-Barrington L, et al. Multicenter evaluation of the BDProbeTec ET System for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in urine specimens, female endocervical swabs, and male urethral swabs. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:1008-16.

- Kaandorp CJ, van Schaardenburg D, Krijnen P, Habbema JD, van de Laar MA. Risk factors for septic arthritis in patients with joint disease: a prospective study. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1819-25.

- Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner PE. Prosthetic-joint infections. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1645-54.

- Guidelines for the initial evaluation of the adult patient with acute musculoskeletal symptoms. American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on Clinical Guidelines. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:1-8.

- Siva C, Velazquez C, Mody A, Brasington R. Diagnosing acute monoarthritis in adults: a practical approach for the family physician. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:83-90.

- Trampuz A, Hanssen AD, Osmon DR, Mandrekar J, Steckelberg JM, Patel R. Synovial fluid leukocyte count and differential for the diagnosis of prosthetic knee infection. Am J Med. 2004; 117:556-62.

- Cucurull E, Espinoza LR. Gonococcal arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1998; 24:305-22.

- Chhem RK, Kaplan PA, Dussault RG. Ultrasonography of the musculoskeletal system. Radiol Clin North Am. 1994;32:275-289.

- Learch TJ, Farooki S. Magnetic resonance imaging of septic arthritis. Clin Imaging. 2000;24:236-42.

- Mohana-Borges AV, Chung CB, Resnick D. Monoarticular arthritis. Radiol Clin North Am. 2004;42:135-49.

- Donatto KC. Orthopedic management of septic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1998;24:275-86.

- Pappas PG, Rex JH, Sobel JD, et al. Guidelines for treatment of candidiasis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:161-89.

- Zimmerli W, Widmer AF, Blatter M, Frei R, Ochsner PE. Role of rifampin for treatment of orthopedic implant-related staphylococcal infections: a randomized controlled trial. Foreign-Body Infection (FBI) Study Group. JAMA. 1998;279:1537-41.

- Garvin KL, Salvati EA, Brause BD. Role of gentamicin-impregnated cement in total joint arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 1988;19:605-10.

- Lieberman JR, Callaway GH, Salvati EA, Pellicci PM, Brause BD. Treatment of the infected total hip arthroplasty with a two-stage reimplantation protocol. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;205-12.

- Windsor RE, Insall JN, Urs WK, Miller DV, Brause BD. Twostage reimplantation for the salvage of total knee arthroplasty complicated by infection. Further follow-up and refinement of indications. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:272-8.

- Buchholz HW, Elson RA, Engelbrecht E, Lodenkamper H, Rottger J, Siegel A. Management of deep infection of total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1981; 63-B(3):342-53.

- Carlsson AS, Josefsson G, Lindberg L. Revision with gentamicin-impregnated cement for deep infections in total hip arthroplasties. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60:1059-64.

- Jackson WO, Schmalzried TP. Limited role of direct exchange arthroplasty in the treatment of infected total hip replacements. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;(381):101-5.

- Fitzgerald RH Jr, Jones DR. Hip implant infection. Treatment with resection arthroplasty and late total hip arthroplasty. Am J Med. 1985; 78(6B):225-8.

- Garvin KL, Hanssen AD. Infection after total hip arthroplasty. Past, present, and future. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:1576-88.

- Goulet JA, Pellicci PM, Brause BD, Salvati EM. Prolonged suppression of infection in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1988; 3:109-16.

- Engesaeter LB, Lie SA, Espehaug B, Furnes O, Vollset SE, Havelin LI. Antibiotic prophylaxis in total hip arthroplasty: effects of antibiotic prophylaxis systemically and in bone cement on the revision rate of 22,170 primary hip replacements followed 0-14 years in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop Scand. 2003; 74:644-51.

- Norden CW. A critical review of antibiotic prophylaxis in orthopedic surgery. Rev Infect Dis 1983;5:928-32.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis for urological patients with total joint replacements. J Urol. 2003; 169:1796-7.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis for dental patients with total joint replacements. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003; 134:895-9.

Introduction

Acute bacterial arthritis is a potentially serious and rapidly progressive infection that may involve native or prosthetic joints. The epidemiology, pathophysiology, repertoire of potential infecting pathogens, clinical presentation and treatment differ for these two forms of infectious arthritis, but both are associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Infectious arthritis of native and prosthetic joints may be caused by viruses, or fungi, but the most common cause is bacteria.

Acute Bacterial Arthritis

Epidemiology

The burden of septic arthritis in the general population is considerable. The incidence of native joint septic arthritis is approximately 5 cases per 100,000 persons per year and is much higher in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (1,2). Between 1% and 5% of joints with indwelling prostheses become infected and the total number of infections per year is increasing due to a rise in the number of patients who have had prosthetic replacement surgery (3). The mortality from joint infection is difficult to estimate due to differing comorbidity in afflicted patients, but is likely between 15% and 30% (4-6). There is substantial morbidity from these infections because of decreased joint function and mobility, and in cases involving joint prostheses from the excisional or exchange arthroplastic surgery that is often required for treatment.

The most common route of infection for native joint infection is hematogenous (1), but may also be a result of direct inoculation of bacteria through trauma or joint surgery (including arthrocentesis, corticosteroid injection, or arthroscopy) (7), or via contiguous spread from adjacent infected soft tissue or bone (1,8). While hematogenous infection of prosthetic joints occurs, the majority of these infections are the result of joint contamination in the course of implantation surgery or post-surgical wound infection (3). Host factors that increase the risk of septic arthritis include pre-existing joint disease (especially rheumatoid arthritis), immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, malignancy, chronic renal failure, intravenous drug use, severe skin diseases, and advanced age (1,2,4,6). The extent of joint injury resulting from infection depends on the virulence of the infecting pathogen and degree of host immune response (9).

Microbiology

Native Joint

The most common causes of bacterial septic arthritis are outlined in Table 1. In adults, the most frequent etiology is S. aureus (37–65% of cases) (1,4,6,8,12,15,16) followed by Streptococcus sp. (12,15). An increasing percentage of S. aureus isolated from septic joints are resistant to antistaphylococcal penicillins and cephalosporins (methicillin-resistant S. aureus, MRSA). In adults with diabetes, malignancy, and genitourinary structural abnormalities, group B Streptococcus is a frequently isolated pathogen (5,6,17). Gram-negative bacilli are commonly found in neonates, intravenous drug users, and immunocompromised hosts (18). N. gonorrhoeae is a significant cause of bacterial arthritis in sexually active adults and adolescents (19) and Kingella kingae and Haemophilus influenzae are likely pediatric isolates (20,21). Joint infections that follow bite trauma usually are seen in the small joints of the hand and involve Pasteurella multocida in the case of animal bites, and Eikenella corrodens in the case of humans bites (22-24). Polymicrobial floras are found in up to 8% of cases of septic arthritis.

Prosthetic Joint

The bacteria that cause prosthetic joint arthritis vary depending on the stage of infection as defined by the elapsed time after implantation surgery (Table 1 on page 31). The coagulase negative staphylococci are the most common (30–43% of cases) (3,10), followed by S. aureus (12–23%) (25).

Nonbacterial Pathogens

Nonbacterial pathogens that may cause septic arthritis include viruses, fungi, and mycobacteria. Viral arthritis is often associated with a systemic febrile illness and other manifestations of infection such as rash. Parvovirus B19 is the most common viral arthritide, presenting as a symmetric polyarticular arthritis involving the joints of the hand as well as larger joints (26). The classic red “slapped cheeks” associated with this viral infection in children is usually not present in adults, although a faint lacy reticular rash may be seen.

Fungi and mycobacteria usually cause a subacute or chronic mono- or oligoarticular arthritis (27). Candida species are an increasing cause of both native and prosthetic joint septic arthritis. Risk factors for this infection include loss of skin integrity, diabetes, malignancy, intravenous drug use, and immunosuppressive therapy including glucocorticoids (28). Patients are often chronically ill and have exposure to broad-spectrum antimicrobials, hyperalimentation fluid, and/or indwelling central intravenous catheters. Other fungi, including Cryptococcus, Blastomyces, Histoplasma, Coccidioides, and Sporothrix are rare causes of septic arthritis (29,30). Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the most common cause of mycobacterial arthritis worldwide and should be considered in a patient presenting with chronic arthritis with risk factors for tuberculosis, including being foreign-born (31).

Clinical Features

The clinical manifestations, severity, treatment, and prognosis of septic arthritis are dependent on the identity and virulence of the bacterium, source of joint infection, and underlying host factors. Nongonococcal septic arthritis is monoarticular in 80% to 90% of cases. The knee is usually affected (50% of cases) (27) followed by the hip, wrists, and ankles (2). In adults, the majority of hip infections involve prosthetic or osteosynthetic material (1). Arthritis of the small joints of the foot is most often seen in diabetic patients and is usually secondary to contiguous skin and soft tissue ulcerations or adjacent osteomyelitis.

Gonococcal arthritis may present as febrile monoarticular arthritis, usually of the knees, wrists, and ankles (27), or as one of the manifestations of disseminated gonococcal infection. The latter is characterized by fever, dermatitis, tenosynovitis, and migratory polyarthralgia or polyarthritis (19). Skin lesions are often pustular and occur simultaneously with tenosynovitis, predominately affecting the fingers, hands, wrists, or feet. Concomitant mucosal infection of the urethra or cervix is often present but usually asymptomatic. Urethral and cervical cultures or a nucleic amplification test will frequently yield N. gonorrhoeae (19,32).

Symptoms of acute septic arthritis include pain and loss of joint function. Fever and chills are often present. The acutely infected native joint is usually red, warm, and swollen with an obvious effusion. Range of motion is limited and extremely painful. For deep and axial joint, pain is often the only focal symptom. More subtle symptoms and signs may result in a delay of diagnosis and are particularly seen in patients receiving systemic or intra-articular steroids, and in those with immunocompromised status, advanced comorbidities (including rheumatoid arthritis), and extreme age (33). A thorough physical examination may reveal a distant source of joint infection in up to 50% of patients (27).

Prosthetic joint infection may present acutely as above, particularly in early stage infection, or more indolently with progressive joint pain, minimal swelling or effusion, and absence of fever (34). In late infection a cutaneous draining sinus tract may be present. Rarely, the involved prosthesis may be visible beneath an ulceration or focus of soft-tissue breakdown.

Diseases that can mimic septic arthritis are crystalinduced arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, spondyloarthropathy, Still’s disease, rheumatic fever, and Kawasaki syndrome.

Diagnostic Approach

A diagnostic approach to acute native joint arthritis is outlined in Figure 1 on page 32 (35,36). Important aspects include exclusion of other causes of arthritis including trauma, rheumatic diseases, and crystalline arthritis. The most important diagnostic test upon which management hinges is diagnostic arthrocentesis. Fluoroscopic or CT-guided arthrocentesis is indicated for axial and deep joints (e.g., sacroiliac or pubic symphysis) or in the event of a “dry tap” of a peripheral joint. Synovial fluid analysis will often suggest whether an acutely painful joint is due to noninflammatory, sterile inflammatory, or septic causes (Table 2 on page 33). In addition, it will provide fluid for culture and gram stain, a rapid test that can guide early empiric antibiotic therapy. Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures should always be performed in order to direct pathogen-specific antimicrobial therapy, which is often given as a prolonged course. Antimicrobial therapy should be delayed until arthrocentesis and other appropriate diagnostic cultures are obtained unless the patient shows signs of sepsis.

For prosthetic joint infections the diagnostic approach is essentially the same although early radiographic imaging is more important than in native joint infection as it may show signs of prosthesis failure or loosening (seen in many late prosthesis infections). Additionally, the synovial fluid white blood cell (WBC) is often lower than in nativejoint infection, with a diagnostic cutoff suggested as greater than 1,700 cells/mm3 or >65% neutrophils (37).

Nonspecific blood tests such as a white blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, or C-reactive protein argue against joint infection if they are normal, but do not specifically suggest septic arthritis if elevated. Other important diagnostic tests include blood cultures (positive in 50–70% of acute bacterial arthritides) (27), but in only 30% or less of gonococcal arthritis cases) (38), wound cultures (although these often correlate poorly with synovial fluid culture results, except when the pathogen is S. aureus), and serologic testing for B. burgdorferi in selected cases with clinical features of Lyme arthritis in endemic areas. If gonococcal arthritis is suspected urethral and cervical specimens should be sent for N. gonorrhoeae culture and nucleic acid amplification tests. Radiographic and scintillographic imaging may yield additional information that will assist in identifying preexisting joint disease or for confirming a diagnosis of native or prosthetic joint infection or its complications (Table 3 on page 33).

Treatment

Native joint

Prompt joint drainage and antimicrobial therapy are the mainstays of treatment in bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial joint infection. Drainage can be through closed needle aspiration performed daily, or arthroscopy. The former modality allows direct visual inspection of the joint with concomitant irrigation, lysis of adhesions, and removal of necrotic tissue and purulent material (42). Open surgical drainage is recommended for septic arthritis of the hip and when less invasive methods fail to control infection.

Initial antimicrobial therapy should be withheld until synovial fluid has been obtained and should be based on synovial fluid gram staining (Table 4). In the case of a nondiagnostic gram stain, empiric antimicrobial coverage of likely infecting pathogens is indicated. Therapy should be narrowed based on identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing of bacteria cultured from synovial fluid, blood, or in some cases from ancillary cultures. For patients with MRSA-related infection who are allergic to or intolerant of vancomycin, linezolid or daptomycin are potential alternatives, although not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for this indication. Linezolid is a potentially attractive option for treatment as it is available as an oral tablet, but for bone and joint infection treatment experience is limited. For septic arthritis related to animal or human bites ampicillin-sulbactam or amoxicillin-clavulanate (clindamycin plus ciprofloxacin in penicillin-allergic patients) provides activity against Pasteurella multocida and other oral bacteria. Gonococcal arthritis is best treated initially with ceftriaxone or cefotaxime; oral ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin may be substituted in regions without fluoroquinolone resistance as the patient improves (Table 4). Septic arthritis due to Candida sp. should be treated initially with an amphotericin B preparation followed by a prolonged course of fluconazole if susceptibility testing confirms activity against the cultured yeast isolate (43).

Duration of intravenous antimicrobials for bacterial joint infections is usually 2 to 4 weeks, while for gonococcal arthritis 2 weeks is sufficient. Antimicrobial therapy that continues for 2 weeks or longer should have weekly followup and laboratory monitoring for hematologic, renal, and liver toxicity.

Prosthetic Joint

Treatment of prosthetic joint septic arthritis is complex, and early consultation with an orthopedic surgeon and infectious diseases physician is recommended. Extensive surgical debridement of the afflicted joint and effective, prolonged antimicrobial therapy is necessary in almost all cases. In order to achieve an optimal synovial fluid and tissue culture yield, antimicrobial therapy should be delayed until the time of debridement surgery unless the patient is septic or exhibiting serious systemic complications of infection. Suggestions for early empiric therapy while awaiting culture results are given in Table 4. Final antimicrobial choices should be based on culture results with assistance from an infectious diseases consultant.

Carefully selected cases of prosthetic joint infection may be treated with simple surgical debridement of the joint with prosthesis retention and at least 3 months of antimicrobial therapy that includes rifampin if the organism is gram positive (44). Patients who present with a short duration of symptoms within 1 month of joint implantation, or those with acute hematogenous infection, are the best candidates for such a treatment strategy. Unfortunately, relapse is common in these cases, particularly if the infection is due to S. aureus, gram-negative bacilli, or drug-resistant pathogens. Thus, the optimal treatment protocols involve surgical excision of the infected prosthesis and prolonged antimicrobial therapy.

Surgical prosthesis extraction and reimplantation can be performed in either a one- or two-stage approach. The two-stage procedure is the more successful strategy and involves removal of the prosthesis and cement followed by a 6-week course of bactericidal antimicrobial therapy. Subsequently a new prosthesis is reimplanted. Using this approach, a 90% to 96% success rate in total hip replacement infections and a 97% success rate in total knee infections has been realized (45-47). An alternative tactic is a one-stage surgical procedure that excises the infected prosthesis with immediate reimplantation of a new joint using antibiotic-impregnated methacrylate cement. This method is effective in 77% to 83% of cases (48-50). Higher failure rates are observed for S. aureus and gram-negative bacillary infections (51). One-stage procedures are often used for elderly or infirm patients who might not tolerate protracted bed rest and a second major operation (52). A recent review article by Zimmerli et al. provides an excellent overview of antimicrobial and surgical treatment options for prosthetic joint infections (34).

Suppressive Antibiotic Therapy

Lifelong oral antimicrobial therapy plays a limited role for definitive therapy but is useful when a surgical approach is not possible because of medical or surgical contraindications. The goal of suppressive therapy is to control the infection and retain prosthesis function. It is important that patients and their families understand that the intention of such treatment is not to cure but to suppress the infection. Generally, oral suppressive therapy is initiated after a course of intravenous therapy. Goulet et al. (53) demonstrated a 63% success rate in maintaining function of hip arthroplasty in patients who met 5 criteria: 1) prostheses removal is not possible, 2) the pathogen is avirulent, 3) the pathogen is sensitive to oral antibiotics, 4) the patient is adherent to and tolerates antibiotics, and 5) the prosthesis is not loose. Patients being treated with lifelong suppressive therapy are at risk for the development of antibiotic resistance (in either the joint infecting pathogen or other commensal organism), local or systemic progression of infection, and adverse effects from chronic antibiotic usage.

Antimicrobial Prophylaxis to Prevent Joint Prosthesis Infection

Patients undergoing elective total joint replacement surgery should be evaluated for symptoms or signs of local infection that predispose to occult or overt bacteremia (particularly odontogenic, urologic, and dermatologic). Surgery should be delayed until such infections and coexisting medical conditions have been treated. Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis has been shown to reduce deep wound infection and prosthetic joint infection in joint reimplant surgery but should not be continued for more than 24 hours after the preoperative dose (54,55). In order to decrease the risk of hematogenous seeding of established implants, early recognition and treatment of overt infection is crucial. The use of prophylactic antibiotics for patients with joint implants prior to or after dental or other procedures such as colonoscopy or cystoscopy is controversial. The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons recommends that a single dose of prophylactic antibiotic be given to certain patients undergoing urologic instrumentation or dental procedures that are accompanied by significant bleeding (56,57). Patients who are candidates for such prophylaxis include those with rheumatoid arthritis or other inflammatory arthropathy, immunosuppression, diabetes, malnutrition, hemophilia, or who have had a previous joint infection.

Dr. Ohl can be contacted at [email protected].

References

- Kaandorp CJ, Dinant HJ, van de Laar MA, Moens HJ, Prins AP, Dijkmans BA. Incidence and sources of native and prosthetic joint infection: a community based prospective survey. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56:470-5.

- Ohl C. Infectious arthritis of native joints. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2005:1311-1322.

- Brause B. Infections with prostheses in bones and joints. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Principles and Practices of Infectious Diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2005:1332-7.

- Gupta MN, Sturrock RD, Field M. A prospective 2-year study of 75 patients with adult-onset septic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2001;40:24-30.

- Nolla JM, Gomez-Vaquero C, Fiter J, et al. Pyarthrosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a detailed analysis of 10 cases and literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2000;30: 121-6.

- Weston VC, Jones AC, Bradbury N, Fawthrop F, Doherty M. Clinical features and outcome of septic arthritis in a single UK Health District 1982-1991. Ann Rheum Dis 1999;58:214-219.

- Kuzmanova SI, Atanassov AN, Andreev SA, Solakov PT. Minor and major complications of arthroscopic synovectomy of the knee joint performed by rheumatologist. Folia Med (Plovdiv). 2003;45:55-9.

- Morgan DS, Fisher D, Merianos A, Currie BJ. An 18 year clinical review of septic arthritis from tropical Australia. Epidemiol Infect 1996;117:423-8.

- Mader JT, Shirtliff M, Calhoun JH. The host and the skeletal infection: classification and pathogenesis of acute bacterial bone and joint sepsis. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 1999;13:1-20.

- Berendt A. Infections of prosthetic joints and related problems. In: Cohen J, Powderly W, eds. Infectious Diseases. Edinburgh: Mosby, 2005: 583-589.

- Raymond NJ, Henry J, Workowski KA. Enterococcal arthritis: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21: 516-522.

- Ross JJ, Saltzman CL, Carling P, Shapiro DS. Pneumococcal septic arthritis: review of 190 cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:319-27.

- Kortekangas P, Aro HT, Tuominen J, Toivanen A. Synovial fluid leukocytosis in bacterial arthritis vs. reactive arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis in the adult knee. Scand J Rheumatol. 1992;21:283-8.

- Sack K. Monarthritis: differential diagnosis. Am J Med. 1997; 102(1A):30S-34S.

- Dubost JJ, Soubrier M, De Champs C, Ristori JM, Bussiere JL, Sauvezie B. No changes in the distribution of organisms responsible for septic arthritis over a 20 year period. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:267-9.

- Ryan MJ, Kavanagh R, Wall PG, Hazleman BL. Bacterial joint infections in England and Wales: analysis of bacterial isolates over a four year period. Br J Rheumatol. 1997;36:370-3.

- Nolla JM, Gomez-Vaquero C, Corbella X, et al. Group B streptococcus (Streptococcus agalactiae) pyogenic arthritis in nonpregnant adults. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003;82: 119-28.

- Shirtliff ME, Mader JT. Acute septic arthritis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:527-44.

- Bardin T. Gonococcal arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2003;17:201-8.

- Yagupsky P, Dagan R. Kingella kingae: an emerging cause of invasive infections in young children. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:860-66.

- Bowerman SG, Green NE, Mencio GA. Decline of bone and joint infections attributable to haemophilus influenzae type b. Clin Orthop. 1997;(341):128-33.

- Ewing R, Fainstein V, Musher DM, Lidsky M, Clarridge J. Articular and skeletal infections caused by Pasteurella multocida. South Med J. 1980;73:1349-52.

- Murray PM. Septic arthritis of the hand and wrist. Hand Clin. 1998;14:579-87, viii.

- Resnick D, Pineda CJ, Weisman MH, Kerr R. Osteomyelitis and septic arthritis of the hand following human bites. Skeletal Radiol. 1985;14:263-6.

- Murdoch DR, Roberts SA, Fowler JV Jr, et al. Infection of orthopedic prostheses after Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:647-9.

- Woolf AD, Campion GV, Chishick A, et al. Clinical manifestations of human parvovirus B19 in adults. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:1153-6.

- Goldenberg DL. Septic arthritis. Lancet 1998; 351:197-202.

- Silveira LH, Cuellar ML, Citera G, Cabrera GE, Scopelitis E, Espinoza LR. Candida arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1993;19:427-37.

- Cuellar ML, Silveira LH, Espinoza LR. Fungal arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992;51:690-7.

- Cuellar ML, Silveira LH, Citera G, Cabrera GE, Valle R. Other fungal arthritides. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1993;19:439-55.

- Malaviya AN, Kotwal PP. Arthritis associated with tuberculosis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2003;17:319-43.

- Van Der PB, Ferrero DV, Buck-Barrington L, et al. Multicenter evaluation of the BDProbeTec ET System for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in urine specimens, female endocervical swabs, and male urethral swabs. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:1008-16.

- Kaandorp CJ, van Schaardenburg D, Krijnen P, Habbema JD, van de Laar MA. Risk factors for septic arthritis in patients with joint disease: a prospective study. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1819-25.

- Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner PE. Prosthetic-joint infections. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1645-54.

- Guidelines for the initial evaluation of the adult patient with acute musculoskeletal symptoms. American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on Clinical Guidelines. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:1-8.

- Siva C, Velazquez C, Mody A, Brasington R. Diagnosing acute monoarthritis in adults: a practical approach for the family physician. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:83-90.

- Trampuz A, Hanssen AD, Osmon DR, Mandrekar J, Steckelberg JM, Patel R. Synovial fluid leukocyte count and differential for the diagnosis of prosthetic knee infection. Am J Med. 2004; 117:556-62.

- Cucurull E, Espinoza LR. Gonococcal arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1998; 24:305-22.

- Chhem RK, Kaplan PA, Dussault RG. Ultrasonography of the musculoskeletal system. Radiol Clin North Am. 1994;32:275-289.

- Learch TJ, Farooki S. Magnetic resonance imaging of septic arthritis. Clin Imaging. 2000;24:236-42.

- Mohana-Borges AV, Chung CB, Resnick D. Monoarticular arthritis. Radiol Clin North Am. 2004;42:135-49.

- Donatto KC. Orthopedic management of septic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1998;24:275-86.

- Pappas PG, Rex JH, Sobel JD, et al. Guidelines for treatment of candidiasis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:161-89.

- Zimmerli W, Widmer AF, Blatter M, Frei R, Ochsner PE. Role of rifampin for treatment of orthopedic implant-related staphylococcal infections: a randomized controlled trial. Foreign-Body Infection (FBI) Study Group. JAMA. 1998;279:1537-41.

- Garvin KL, Salvati EA, Brause BD. Role of gentamicin-impregnated cement in total joint arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 1988;19:605-10.

- Lieberman JR, Callaway GH, Salvati EA, Pellicci PM, Brause BD. Treatment of the infected total hip arthroplasty with a two-stage reimplantation protocol. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;205-12.

- Windsor RE, Insall JN, Urs WK, Miller DV, Brause BD. Twostage reimplantation for the salvage of total knee arthroplasty complicated by infection. Further follow-up and refinement of indications. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:272-8.

- Buchholz HW, Elson RA, Engelbrecht E, Lodenkamper H, Rottger J, Siegel A. Management of deep infection of total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1981; 63-B(3):342-53.

- Carlsson AS, Josefsson G, Lindberg L. Revision with gentamicin-impregnated cement for deep infections in total hip arthroplasties. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60:1059-64.

- Jackson WO, Schmalzried TP. Limited role of direct exchange arthroplasty in the treatment of infected total hip replacements. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;(381):101-5.

- Fitzgerald RH Jr, Jones DR. Hip implant infection. Treatment with resection arthroplasty and late total hip arthroplasty. Am J Med. 1985; 78(6B):225-8.

- Garvin KL, Hanssen AD. Infection after total hip arthroplasty. Past, present, and future. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:1576-88.

- Goulet JA, Pellicci PM, Brause BD, Salvati EM. Prolonged suppression of infection in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1988; 3:109-16.

- Engesaeter LB, Lie SA, Espehaug B, Furnes O, Vollset SE, Havelin LI. Antibiotic prophylaxis in total hip arthroplasty: effects of antibiotic prophylaxis systemically and in bone cement on the revision rate of 22,170 primary hip replacements followed 0-14 years in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop Scand. 2003; 74:644-51.

- Norden CW. A critical review of antibiotic prophylaxis in orthopedic surgery. Rev Infect Dis 1983;5:928-32.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis for urological patients with total joint replacements. J Urol. 2003; 169:1796-7.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis for dental patients with total joint replacements. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003; 134:895-9.

Introduction

Acute bacterial arthritis is a potentially serious and rapidly progressive infection that may involve native or prosthetic joints. The epidemiology, pathophysiology, repertoire of potential infecting pathogens, clinical presentation and treatment differ for these two forms of infectious arthritis, but both are associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Infectious arthritis of native and prosthetic joints may be caused by viruses, or fungi, but the most common cause is bacteria.

Acute Bacterial Arthritis

Epidemiology

The burden of septic arthritis in the general population is considerable. The incidence of native joint septic arthritis is approximately 5 cases per 100,000 persons per year and is much higher in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (1,2). Between 1% and 5% of joints with indwelling prostheses become infected and the total number of infections per year is increasing due to a rise in the number of patients who have had prosthetic replacement surgery (3). The mortality from joint infection is difficult to estimate due to differing comorbidity in afflicted patients, but is likely between 15% and 30% (4-6). There is substantial morbidity from these infections because of decreased joint function and mobility, and in cases involving joint prostheses from the excisional or exchange arthroplastic surgery that is often required for treatment.

The most common route of infection for native joint infection is hematogenous (1), but may also be a result of direct inoculation of bacteria through trauma or joint surgery (including arthrocentesis, corticosteroid injection, or arthroscopy) (7), or via contiguous spread from adjacent infected soft tissue or bone (1,8). While hematogenous infection of prosthetic joints occurs, the majority of these infections are the result of joint contamination in the course of implantation surgery or post-surgical wound infection (3). Host factors that increase the risk of septic arthritis include pre-existing joint disease (especially rheumatoid arthritis), immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, malignancy, chronic renal failure, intravenous drug use, severe skin diseases, and advanced age (1,2,4,6). The extent of joint injury resulting from infection depends on the virulence of the infecting pathogen and degree of host immune response (9).

Microbiology

Native Joint

The most common causes of bacterial septic arthritis are outlined in Table 1. In adults, the most frequent etiology is S. aureus (37–65% of cases) (1,4,6,8,12,15,16) followed by Streptococcus sp. (12,15). An increasing percentage of S. aureus isolated from septic joints are resistant to antistaphylococcal penicillins and cephalosporins (methicillin-resistant S. aureus, MRSA). In adults with diabetes, malignancy, and genitourinary structural abnormalities, group B Streptococcus is a frequently isolated pathogen (5,6,17). Gram-negative bacilli are commonly found in neonates, intravenous drug users, and immunocompromised hosts (18). N. gonorrhoeae is a significant cause of bacterial arthritis in sexually active adults and adolescents (19) and Kingella kingae and Haemophilus influenzae are likely pediatric isolates (20,21). Joint infections that follow bite trauma usually are seen in the small joints of the hand and involve Pasteurella multocida in the case of animal bites, and Eikenella corrodens in the case of humans bites (22-24). Polymicrobial floras are found in up to 8% of cases of septic arthritis.

Prosthetic Joint

The bacteria that cause prosthetic joint arthritis vary depending on the stage of infection as defined by the elapsed time after implantation surgery (Table 1 on page 31). The coagulase negative staphylococci are the most common (30–43% of cases) (3,10), followed by S. aureus (12–23%) (25).

Nonbacterial Pathogens

Nonbacterial pathogens that may cause septic arthritis include viruses, fungi, and mycobacteria. Viral arthritis is often associated with a systemic febrile illness and other manifestations of infection such as rash. Parvovirus B19 is the most common viral arthritide, presenting as a symmetric polyarticular arthritis involving the joints of the hand as well as larger joints (26). The classic red “slapped cheeks” associated with this viral infection in children is usually not present in adults, although a faint lacy reticular rash may be seen.

Fungi and mycobacteria usually cause a subacute or chronic mono- or oligoarticular arthritis (27). Candida species are an increasing cause of both native and prosthetic joint septic arthritis. Risk factors for this infection include loss of skin integrity, diabetes, malignancy, intravenous drug use, and immunosuppressive therapy including glucocorticoids (28). Patients are often chronically ill and have exposure to broad-spectrum antimicrobials, hyperalimentation fluid, and/or indwelling central intravenous catheters. Other fungi, including Cryptococcus, Blastomyces, Histoplasma, Coccidioides, and Sporothrix are rare causes of septic arthritis (29,30). Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the most common cause of mycobacterial arthritis worldwide and should be considered in a patient presenting with chronic arthritis with risk factors for tuberculosis, including being foreign-born (31).

Clinical Features

The clinical manifestations, severity, treatment, and prognosis of septic arthritis are dependent on the identity and virulence of the bacterium, source of joint infection, and underlying host factors. Nongonococcal septic arthritis is monoarticular in 80% to 90% of cases. The knee is usually affected (50% of cases) (27) followed by the hip, wrists, and ankles (2). In adults, the majority of hip infections involve prosthetic or osteosynthetic material (1). Arthritis of the small joints of the foot is most often seen in diabetic patients and is usually secondary to contiguous skin and soft tissue ulcerations or adjacent osteomyelitis.

Gonococcal arthritis may present as febrile monoarticular arthritis, usually of the knees, wrists, and ankles (27), or as one of the manifestations of disseminated gonococcal infection. The latter is characterized by fever, dermatitis, tenosynovitis, and migratory polyarthralgia or polyarthritis (19). Skin lesions are often pustular and occur simultaneously with tenosynovitis, predominately affecting the fingers, hands, wrists, or feet. Concomitant mucosal infection of the urethra or cervix is often present but usually asymptomatic. Urethral and cervical cultures or a nucleic amplification test will frequently yield N. gonorrhoeae (19,32).

Symptoms of acute septic arthritis include pain and loss of joint function. Fever and chills are often present. The acutely infected native joint is usually red, warm, and swollen with an obvious effusion. Range of motion is limited and extremely painful. For deep and axial joint, pain is often the only focal symptom. More subtle symptoms and signs may result in a delay of diagnosis and are particularly seen in patients receiving systemic or intra-articular steroids, and in those with immunocompromised status, advanced comorbidities (including rheumatoid arthritis), and extreme age (33). A thorough physical examination may reveal a distant source of joint infection in up to 50% of patients (27).

Prosthetic joint infection may present acutely as above, particularly in early stage infection, or more indolently with progressive joint pain, minimal swelling or effusion, and absence of fever (34). In late infection a cutaneous draining sinus tract may be present. Rarely, the involved prosthesis may be visible beneath an ulceration or focus of soft-tissue breakdown.

Diseases that can mimic septic arthritis are crystalinduced arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, spondyloarthropathy, Still’s disease, rheumatic fever, and Kawasaki syndrome.

Diagnostic Approach

A diagnostic approach to acute native joint arthritis is outlined in Figure 1 on page 32 (35,36). Important aspects include exclusion of other causes of arthritis including trauma, rheumatic diseases, and crystalline arthritis. The most important diagnostic test upon which management hinges is diagnostic arthrocentesis. Fluoroscopic or CT-guided arthrocentesis is indicated for axial and deep joints (e.g., sacroiliac or pubic symphysis) or in the event of a “dry tap” of a peripheral joint. Synovial fluid analysis will often suggest whether an acutely painful joint is due to noninflammatory, sterile inflammatory, or septic causes (Table 2 on page 33). In addition, it will provide fluid for culture and gram stain, a rapid test that can guide early empiric antibiotic therapy. Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures should always be performed in order to direct pathogen-specific antimicrobial therapy, which is often given as a prolonged course. Antimicrobial therapy should be delayed until arthrocentesis and other appropriate diagnostic cultures are obtained unless the patient shows signs of sepsis.

For prosthetic joint infections the diagnostic approach is essentially the same although early radiographic imaging is more important than in native joint infection as it may show signs of prosthesis failure or loosening (seen in many late prosthesis infections). Additionally, the synovial fluid white blood cell (WBC) is often lower than in nativejoint infection, with a diagnostic cutoff suggested as greater than 1,700 cells/mm3 or >65% neutrophils (37).

Nonspecific blood tests such as a white blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, or C-reactive protein argue against joint infection if they are normal, but do not specifically suggest septic arthritis if elevated. Other important diagnostic tests include blood cultures (positive in 50–70% of acute bacterial arthritides) (27), but in only 30% or less of gonococcal arthritis cases) (38), wound cultures (although these often correlate poorly with synovial fluid culture results, except when the pathogen is S. aureus), and serologic testing for B. burgdorferi in selected cases with clinical features of Lyme arthritis in endemic areas. If gonococcal arthritis is suspected urethral and cervical specimens should be sent for N. gonorrhoeae culture and nucleic acid amplification tests. Radiographic and scintillographic imaging may yield additional information that will assist in identifying preexisting joint disease or for confirming a diagnosis of native or prosthetic joint infection or its complications (Table 3 on page 33).

Treatment

Native joint

Prompt joint drainage and antimicrobial therapy are the mainstays of treatment in bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial joint infection. Drainage can be through closed needle aspiration performed daily, or arthroscopy. The former modality allows direct visual inspection of the joint with concomitant irrigation, lysis of adhesions, and removal of necrotic tissue and purulent material (42). Open surgical drainage is recommended for septic arthritis of the hip and when less invasive methods fail to control infection.

Initial antimicrobial therapy should be withheld until synovial fluid has been obtained and should be based on synovial fluid gram staining (Table 4). In the case of a nondiagnostic gram stain, empiric antimicrobial coverage of likely infecting pathogens is indicated. Therapy should be narrowed based on identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing of bacteria cultured from synovial fluid, blood, or in some cases from ancillary cultures. For patients with MRSA-related infection who are allergic to or intolerant of vancomycin, linezolid or daptomycin are potential alternatives, although not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for this indication. Linezolid is a potentially attractive option for treatment as it is available as an oral tablet, but for bone and joint infection treatment experience is limited. For septic arthritis related to animal or human bites ampicillin-sulbactam or amoxicillin-clavulanate (clindamycin plus ciprofloxacin in penicillin-allergic patients) provides activity against Pasteurella multocida and other oral bacteria. Gonococcal arthritis is best treated initially with ceftriaxone or cefotaxime; oral ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin may be substituted in regions without fluoroquinolone resistance as the patient improves (Table 4). Septic arthritis due to Candida sp. should be treated initially with an amphotericin B preparation followed by a prolonged course of fluconazole if susceptibility testing confirms activity against the cultured yeast isolate (43).

Duration of intravenous antimicrobials for bacterial joint infections is usually 2 to 4 weeks, while for gonococcal arthritis 2 weeks is sufficient. Antimicrobial therapy that continues for 2 weeks or longer should have weekly followup and laboratory monitoring for hematologic, renal, and liver toxicity.

Prosthetic Joint

Treatment of prosthetic joint septic arthritis is complex, and early consultation with an orthopedic surgeon and infectious diseases physician is recommended. Extensive surgical debridement of the afflicted joint and effective, prolonged antimicrobial therapy is necessary in almost all cases. In order to achieve an optimal synovial fluid and tissue culture yield, antimicrobial therapy should be delayed until the time of debridement surgery unless the patient is septic or exhibiting serious systemic complications of infection. Suggestions for early empiric therapy while awaiting culture results are given in Table 4. Final antimicrobial choices should be based on culture results with assistance from an infectious diseases consultant.

Carefully selected cases of prosthetic joint infection may be treated with simple surgical debridement of the joint with prosthesis retention and at least 3 months of antimicrobial therapy that includes rifampin if the organism is gram positive (44). Patients who present with a short duration of symptoms within 1 month of joint implantation, or those with acute hematogenous infection, are the best candidates for such a treatment strategy. Unfortunately, relapse is common in these cases, particularly if the infection is due to S. aureus, gram-negative bacilli, or drug-resistant pathogens. Thus, the optimal treatment protocols involve surgical excision of the infected prosthesis and prolonged antimicrobial therapy.

Surgical prosthesis extraction and reimplantation can be performed in either a one- or two-stage approach. The two-stage procedure is the more successful strategy and involves removal of the prosthesis and cement followed by a 6-week course of bactericidal antimicrobial therapy. Subsequently a new prosthesis is reimplanted. Using this approach, a 90% to 96% success rate in total hip replacement infections and a 97% success rate in total knee infections has been realized (45-47). An alternative tactic is a one-stage surgical procedure that excises the infected prosthesis with immediate reimplantation of a new joint using antibiotic-impregnated methacrylate cement. This method is effective in 77% to 83% of cases (48-50). Higher failure rates are observed for S. aureus and gram-negative bacillary infections (51). One-stage procedures are often used for elderly or infirm patients who might not tolerate protracted bed rest and a second major operation (52). A recent review article by Zimmerli et al. provides an excellent overview of antimicrobial and surgical treatment options for prosthetic joint infections (34).

Suppressive Antibiotic Therapy

Lifelong oral antimicrobial therapy plays a limited role for definitive therapy but is useful when a surgical approach is not possible because of medical or surgical contraindications. The goal of suppressive therapy is to control the infection and retain prosthesis function. It is important that patients and their families understand that the intention of such treatment is not to cure but to suppress the infection. Generally, oral suppressive therapy is initiated after a course of intravenous therapy. Goulet et al. (53) demonstrated a 63% success rate in maintaining function of hip arthroplasty in patients who met 5 criteria: 1) prostheses removal is not possible, 2) the pathogen is avirulent, 3) the pathogen is sensitive to oral antibiotics, 4) the patient is adherent to and tolerates antibiotics, and 5) the prosthesis is not loose. Patients being treated with lifelong suppressive therapy are at risk for the development of antibiotic resistance (in either the joint infecting pathogen or other commensal organism), local or systemic progression of infection, and adverse effects from chronic antibiotic usage.

Antimicrobial Prophylaxis to Prevent Joint Prosthesis Infection

Patients undergoing elective total joint replacement surgery should be evaluated for symptoms or signs of local infection that predispose to occult or overt bacteremia (particularly odontogenic, urologic, and dermatologic). Surgery should be delayed until such infections and coexisting medical conditions have been treated. Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis has been shown to reduce deep wound infection and prosthetic joint infection in joint reimplant surgery but should not be continued for more than 24 hours after the preoperative dose (54,55). In order to decrease the risk of hematogenous seeding of established implants, early recognition and treatment of overt infection is crucial. The use of prophylactic antibiotics for patients with joint implants prior to or after dental or other procedures such as colonoscopy or cystoscopy is controversial. The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons recommends that a single dose of prophylactic antibiotic be given to certain patients undergoing urologic instrumentation or dental procedures that are accompanied by significant bleeding (56,57). Patients who are candidates for such prophylaxis include those with rheumatoid arthritis or other inflammatory arthropathy, immunosuppression, diabetes, malnutrition, hemophilia, or who have had a previous joint infection.

Dr. Ohl can be contacted at [email protected].

References