User login

Long-term impact of childhood trauma explained

WASHINGTON –

“We already knew childhood trauma is associated with the later development of depressive and anxiety disorders, but it’s been unclear what makes sufferers of early trauma more likely to develop these psychiatric conditions,” study investigator Erika Kuzminskaite, PhD candidate, department of psychiatry, Amsterdam University Medical Center (UMC), the Netherlands, told this news organization.

“The evidence now points to unbalanced stress systems as a possible cause of this vulnerability, and now the most important question is, how we can develop preventive interventions,” she added.

The findings were presented as part of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America Anxiety & Depression conference.

Elevated cortisol, inflammation

The study included 2,779 adults from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). Two thirds of participants were female.

Participants retrospectively reported childhood trauma, defined as emotional, physical, or sexual abuse or emotional or physical neglect, before the age of 18 years. Severe trauma was defined as multiple types or increased frequency of abuse.

Of the total cohort, 48% reported experiencing some childhood trauma – 21% reported severe trauma, 27% reported mild trauma, and 42% reported no childhood trauma.

Among those with trauma, 89% had a current or remitted anxiety or depressive disorder, and 11% had no psychiatric sequelae. Among participants who reported no trauma, 68% had a current or remitted disorder, and 32% had no psychiatric disorders.

At baseline, researchers assessed markers of major bodily stress systems, including the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the immune-inflammatory system, and the autonomic nervous system (ANS). They examined these markers separately and cumulatively.

In one model, investigators found that levels of cortisol and inflammation were significantly elevated in those with severe childhood trauma compared to those with no childhood trauma. The effects were largest for the cumulative markers for HPA-axis, inflammation, and all stress system markers (Cohen’s d = 0.23, 0.12, and 0.25, respectively). There was no association with ANS markers.

The results were partially explained by lifestyle, said Ms. Kuzminskaite, who noted that people with severe childhood trauma tend to have a higher body mass index, smoke more, and have other unhealthy habits that may represent a “coping” mechanism for trauma.

Those who experienced childhood trauma also have higher rates of other disorders, including asthma, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Ms. Kuzminskaite noted that people with childhood trauma have at least double the risk of cancer in later life.

When researchers adjusted for lifestyle factors and chronic conditions, the association for cortisol was reduced and that for inflammation disappeared. However, the cumulative inflammatory markers remained significant.

Another model examined lipopolysaccharide-stimulated (LPS) immune-inflammatory markers by childhood trauma severity. This provides a more “dynamic” measure of stress systems than looking only at static circulating levels in the blood, as was done in the first model, said Ms. Kuzminskaite.

“These levels should theoretically be more affected by experiences such as childhood trauma and they are also less sensitive to lifestyle.”

Here, researchers found significant positive associations with childhood trauma, especially severe trauma, after adjusting for lifestyle and health-related covariates (cumulative index d = 0.19).

“Almost all people with childhood trauma, especially severe trauma, had LPS-stimulated cytokines upregulated,” said Ms. Kuzminskaite. “So again, there is this dysregulation of immune system functioning in these subjects.”

And again, the strongest effect was for the cumulative index of all cytokines, she said.

Personalized interventions

Ms. Kuzminskaite noted the importance of learning the impact of early trauma on stress responses. “The goal is to eventually have personalized interventions for people with depression or anxiety related to childhood trauma, or even preventative interventions. If we know, for example, something is going wrong with a patient’s stress systems, we can suggest some therapeutic targets.”

Investigators in Amsterdam are examining the efficacy of mifepristone, which blocks progesterone and is used along with misoprostol for medication abortions and to treat high blood sugar. “The drug is supposed to reset the stress system functioning,” said Ms. Kuzminskaite.

It’s still important to target unhealthy lifestyle habits “that are really impacting the functioning of the stress systems,” she said. Lifestyle interventions could improve the efficacy of treatments for depression, for example, she added.

Luana Marques, PhD, associate professor, department of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, said such research is important.

“It reveals the potentially extensive and long-lasting impact of childhood trauma on functioning. The findings underscore the importance of equipping at-risk and trauma-exposed youth with evidence-based skills for managing stress,” she said.

No conflicts of interest were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

WASHINGTON –

“We already knew childhood trauma is associated with the later development of depressive and anxiety disorders, but it’s been unclear what makes sufferers of early trauma more likely to develop these psychiatric conditions,” study investigator Erika Kuzminskaite, PhD candidate, department of psychiatry, Amsterdam University Medical Center (UMC), the Netherlands, told this news organization.

“The evidence now points to unbalanced stress systems as a possible cause of this vulnerability, and now the most important question is, how we can develop preventive interventions,” she added.

The findings were presented as part of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America Anxiety & Depression conference.

Elevated cortisol, inflammation

The study included 2,779 adults from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). Two thirds of participants were female.

Participants retrospectively reported childhood trauma, defined as emotional, physical, or sexual abuse or emotional or physical neglect, before the age of 18 years. Severe trauma was defined as multiple types or increased frequency of abuse.

Of the total cohort, 48% reported experiencing some childhood trauma – 21% reported severe trauma, 27% reported mild trauma, and 42% reported no childhood trauma.

Among those with trauma, 89% had a current or remitted anxiety or depressive disorder, and 11% had no psychiatric sequelae. Among participants who reported no trauma, 68% had a current or remitted disorder, and 32% had no psychiatric disorders.

At baseline, researchers assessed markers of major bodily stress systems, including the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the immune-inflammatory system, and the autonomic nervous system (ANS). They examined these markers separately and cumulatively.

In one model, investigators found that levels of cortisol and inflammation were significantly elevated in those with severe childhood trauma compared to those with no childhood trauma. The effects were largest for the cumulative markers for HPA-axis, inflammation, and all stress system markers (Cohen’s d = 0.23, 0.12, and 0.25, respectively). There was no association with ANS markers.

The results were partially explained by lifestyle, said Ms. Kuzminskaite, who noted that people with severe childhood trauma tend to have a higher body mass index, smoke more, and have other unhealthy habits that may represent a “coping” mechanism for trauma.

Those who experienced childhood trauma also have higher rates of other disorders, including asthma, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Ms. Kuzminskaite noted that people with childhood trauma have at least double the risk of cancer in later life.

When researchers adjusted for lifestyle factors and chronic conditions, the association for cortisol was reduced and that for inflammation disappeared. However, the cumulative inflammatory markers remained significant.

Another model examined lipopolysaccharide-stimulated (LPS) immune-inflammatory markers by childhood trauma severity. This provides a more “dynamic” measure of stress systems than looking only at static circulating levels in the blood, as was done in the first model, said Ms. Kuzminskaite.

“These levels should theoretically be more affected by experiences such as childhood trauma and they are also less sensitive to lifestyle.”

Here, researchers found significant positive associations with childhood trauma, especially severe trauma, after adjusting for lifestyle and health-related covariates (cumulative index d = 0.19).

“Almost all people with childhood trauma, especially severe trauma, had LPS-stimulated cytokines upregulated,” said Ms. Kuzminskaite. “So again, there is this dysregulation of immune system functioning in these subjects.”

And again, the strongest effect was for the cumulative index of all cytokines, she said.

Personalized interventions

Ms. Kuzminskaite noted the importance of learning the impact of early trauma on stress responses. “The goal is to eventually have personalized interventions for people with depression or anxiety related to childhood trauma, or even preventative interventions. If we know, for example, something is going wrong with a patient’s stress systems, we can suggest some therapeutic targets.”

Investigators in Amsterdam are examining the efficacy of mifepristone, which blocks progesterone and is used along with misoprostol for medication abortions and to treat high blood sugar. “The drug is supposed to reset the stress system functioning,” said Ms. Kuzminskaite.

It’s still important to target unhealthy lifestyle habits “that are really impacting the functioning of the stress systems,” she said. Lifestyle interventions could improve the efficacy of treatments for depression, for example, she added.

Luana Marques, PhD, associate professor, department of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, said such research is important.

“It reveals the potentially extensive and long-lasting impact of childhood trauma on functioning. The findings underscore the importance of equipping at-risk and trauma-exposed youth with evidence-based skills for managing stress,” she said.

No conflicts of interest were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

WASHINGTON –

“We already knew childhood trauma is associated with the later development of depressive and anxiety disorders, but it’s been unclear what makes sufferers of early trauma more likely to develop these psychiatric conditions,” study investigator Erika Kuzminskaite, PhD candidate, department of psychiatry, Amsterdam University Medical Center (UMC), the Netherlands, told this news organization.

“The evidence now points to unbalanced stress systems as a possible cause of this vulnerability, and now the most important question is, how we can develop preventive interventions,” she added.

The findings were presented as part of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America Anxiety & Depression conference.

Elevated cortisol, inflammation

The study included 2,779 adults from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). Two thirds of participants were female.

Participants retrospectively reported childhood trauma, defined as emotional, physical, or sexual abuse or emotional or physical neglect, before the age of 18 years. Severe trauma was defined as multiple types or increased frequency of abuse.

Of the total cohort, 48% reported experiencing some childhood trauma – 21% reported severe trauma, 27% reported mild trauma, and 42% reported no childhood trauma.

Among those with trauma, 89% had a current or remitted anxiety or depressive disorder, and 11% had no psychiatric sequelae. Among participants who reported no trauma, 68% had a current or remitted disorder, and 32% had no psychiatric disorders.

At baseline, researchers assessed markers of major bodily stress systems, including the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the immune-inflammatory system, and the autonomic nervous system (ANS). They examined these markers separately and cumulatively.

In one model, investigators found that levels of cortisol and inflammation were significantly elevated in those with severe childhood trauma compared to those with no childhood trauma. The effects were largest for the cumulative markers for HPA-axis, inflammation, and all stress system markers (Cohen’s d = 0.23, 0.12, and 0.25, respectively). There was no association with ANS markers.

The results were partially explained by lifestyle, said Ms. Kuzminskaite, who noted that people with severe childhood trauma tend to have a higher body mass index, smoke more, and have other unhealthy habits that may represent a “coping” mechanism for trauma.

Those who experienced childhood trauma also have higher rates of other disorders, including asthma, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Ms. Kuzminskaite noted that people with childhood trauma have at least double the risk of cancer in later life.

When researchers adjusted for lifestyle factors and chronic conditions, the association for cortisol was reduced and that for inflammation disappeared. However, the cumulative inflammatory markers remained significant.

Another model examined lipopolysaccharide-stimulated (LPS) immune-inflammatory markers by childhood trauma severity. This provides a more “dynamic” measure of stress systems than looking only at static circulating levels in the blood, as was done in the first model, said Ms. Kuzminskaite.

“These levels should theoretically be more affected by experiences such as childhood trauma and they are also less sensitive to lifestyle.”

Here, researchers found significant positive associations with childhood trauma, especially severe trauma, after adjusting for lifestyle and health-related covariates (cumulative index d = 0.19).

“Almost all people with childhood trauma, especially severe trauma, had LPS-stimulated cytokines upregulated,” said Ms. Kuzminskaite. “So again, there is this dysregulation of immune system functioning in these subjects.”

And again, the strongest effect was for the cumulative index of all cytokines, she said.

Personalized interventions

Ms. Kuzminskaite noted the importance of learning the impact of early trauma on stress responses. “The goal is to eventually have personalized interventions for people with depression or anxiety related to childhood trauma, or even preventative interventions. If we know, for example, something is going wrong with a patient’s stress systems, we can suggest some therapeutic targets.”

Investigators in Amsterdam are examining the efficacy of mifepristone, which blocks progesterone and is used along with misoprostol for medication abortions and to treat high blood sugar. “The drug is supposed to reset the stress system functioning,” said Ms. Kuzminskaite.

It’s still important to target unhealthy lifestyle habits “that are really impacting the functioning of the stress systems,” she said. Lifestyle interventions could improve the efficacy of treatments for depression, for example, she added.

Luana Marques, PhD, associate professor, department of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, said such research is important.

“It reveals the potentially extensive and long-lasting impact of childhood trauma on functioning. The findings underscore the importance of equipping at-risk and trauma-exposed youth with evidence-based skills for managing stress,” she said.

No conflicts of interest were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ADAA 2023

Normal CRP during RA flares: An ‘underappreciated, persistent phenotype’

MANCHESTER, England – Even when C-reactive protein (CRP) levels are normal, patients with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis (RA) could still be experiencing significant disease that persists over time, researchers from University College London have found.

Similar levels of joint erosion and disease activity were observed over a 5-year period; researchers compared patients who had high CRP levels (> 5 mg/L)* with patients whose CRP levels were consistently normal (< 5 mg/L) at the time of an ultrasound-proven disease flare.

“Our data suggests that the phenotype of normal CRP represents at least 5% of our cohort,” Bhavika Sethi, MBChB, reported in a virtual poster presentation at the annual meeting of the British Society for Rheumatology.

“They are more likely to require biologic treatment, and this continues on even though they have equivalent DAS28 [disease activity score in 28 joints] and risk of joint damage” to high-CRP patients, she said.

These patients are a significant minority, Dr. Sethi added, and “we need to think about how we provide care for them and allocate resources.”

Diagnostic delay and poor outcomes previously seen

The study is a continuation of a larger project, the corresponding author for the poster, Matthew Hutchinson, MBChB, told this news organization.

A few years ago, Dr. Hutchinson explained, a subset of patients with normal CRP levels during RA flares were identified and were found to be more likely to have experienced diagnostic delay and worse outcomes than did those with high CRP levels.

The aim of the current study was to see whether those findings persisted by longitudinally assessing patient records and seeing what happened 1, 2, and 5 years later. They evaluated 312 patients with seropositive RA, of whom 28 had CRP < 5 mg/L as well as active disease, which was determined on the basis of a DAS28 > 4.5. Of those 28 patients, 16 had persistently low CRP (< 5 mg/L) despite active disease. All patients who were taking tocilizumab were excluded from the study because of its CRP-lowering properties.

“Our project was showing that this group of people exist, trying to characterize them a little better” and that the study serves as a “jumping-off point” for future research, Dr. Hutchinson said.

The study was also conducted to “make people more aware of [patients with normal CRP during flare], because treating clinicians could be falsely reassured by a normal CRP,” he added. “Patients in front of them could actually be undertreated and have worse outcomes if [it is] not picked up,” Dr. Hutchinson suggested.

In comparison with those with high CRP levels, those with normal CRP levels were more likely to be receiving biologic treatment at 5 years (76.6% vs. 44.4%; P = .0323).

At 5 years, DAS28 was similar (P = .9615) among patients with normal CRP levels and those with high CRP levels, at a median of 2.8 and 3.2, respectively. A similar percentage of patients in these two groups also had joint damage (63.3% vs. 71.4%; P = .7384).

Don’t rely only on CRP to diagnose and manage RA flares

“CRP is a generic inflammatory marker in most people,” Dr. Hutchinson said. “In the majority of situations when either there is inflammation or an infection, certainly if it’s systemic infection or inflammation, you will find CRP being elevated on the blood tests.”

For someone presenting with joint pain, high CRP can be a useful indicator that it’s more of an inflammatory process than physical injury, he added. CRP is also frequently used to calculate DAS28 to monitor disease activity.

“This study highlights that CRP may be normal during flares in some people with RA,” Jeffrey A. Sparks, MD, told this news organization.

“These patients may still require advanced therapies and can accrue damage,” the rheumatologist from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard University, Boston, added.

“Clinicians should not only rely on CRP to diagnose and manage RA flares,” said Dr. Sparks, who was not involved in the study.

The study was independently supported. Dr. Hutchinson and Dr. Sethi report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Sparks is supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the R. Bruce and Joan M. Mickey Research Scholar Fund, and the Llura Gund Award for Rheumatoid Arthritis Research and Care; he has received research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb and has performed consultancy for AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Inova Diagnostics, Janssen, Optum, and Pfizer.

*Correction, 5/9/2023: This article has been updated to correct the units for C-reactive protein from mg/dL to mg/L.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MANCHESTER, England – Even when C-reactive protein (CRP) levels are normal, patients with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis (RA) could still be experiencing significant disease that persists over time, researchers from University College London have found.

Similar levels of joint erosion and disease activity were observed over a 5-year period; researchers compared patients who had high CRP levels (> 5 mg/L)* with patients whose CRP levels were consistently normal (< 5 mg/L) at the time of an ultrasound-proven disease flare.

“Our data suggests that the phenotype of normal CRP represents at least 5% of our cohort,” Bhavika Sethi, MBChB, reported in a virtual poster presentation at the annual meeting of the British Society for Rheumatology.

“They are more likely to require biologic treatment, and this continues on even though they have equivalent DAS28 [disease activity score in 28 joints] and risk of joint damage” to high-CRP patients, she said.

These patients are a significant minority, Dr. Sethi added, and “we need to think about how we provide care for them and allocate resources.”

Diagnostic delay and poor outcomes previously seen

The study is a continuation of a larger project, the corresponding author for the poster, Matthew Hutchinson, MBChB, told this news organization.

A few years ago, Dr. Hutchinson explained, a subset of patients with normal CRP levels during RA flares were identified and were found to be more likely to have experienced diagnostic delay and worse outcomes than did those with high CRP levels.

The aim of the current study was to see whether those findings persisted by longitudinally assessing patient records and seeing what happened 1, 2, and 5 years later. They evaluated 312 patients with seropositive RA, of whom 28 had CRP < 5 mg/L as well as active disease, which was determined on the basis of a DAS28 > 4.5. Of those 28 patients, 16 had persistently low CRP (< 5 mg/L) despite active disease. All patients who were taking tocilizumab were excluded from the study because of its CRP-lowering properties.

“Our project was showing that this group of people exist, trying to characterize them a little better” and that the study serves as a “jumping-off point” for future research, Dr. Hutchinson said.

The study was also conducted to “make people more aware of [patients with normal CRP during flare], because treating clinicians could be falsely reassured by a normal CRP,” he added. “Patients in front of them could actually be undertreated and have worse outcomes if [it is] not picked up,” Dr. Hutchinson suggested.

In comparison with those with high CRP levels, those with normal CRP levels were more likely to be receiving biologic treatment at 5 years (76.6% vs. 44.4%; P = .0323).

At 5 years, DAS28 was similar (P = .9615) among patients with normal CRP levels and those with high CRP levels, at a median of 2.8 and 3.2, respectively. A similar percentage of patients in these two groups also had joint damage (63.3% vs. 71.4%; P = .7384).

Don’t rely only on CRP to diagnose and manage RA flares

“CRP is a generic inflammatory marker in most people,” Dr. Hutchinson said. “In the majority of situations when either there is inflammation or an infection, certainly if it’s systemic infection or inflammation, you will find CRP being elevated on the blood tests.”

For someone presenting with joint pain, high CRP can be a useful indicator that it’s more of an inflammatory process than physical injury, he added. CRP is also frequently used to calculate DAS28 to monitor disease activity.

“This study highlights that CRP may be normal during flares in some people with RA,” Jeffrey A. Sparks, MD, told this news organization.

“These patients may still require advanced therapies and can accrue damage,” the rheumatologist from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard University, Boston, added.

“Clinicians should not only rely on CRP to diagnose and manage RA flares,” said Dr. Sparks, who was not involved in the study.

The study was independently supported. Dr. Hutchinson and Dr. Sethi report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Sparks is supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the R. Bruce and Joan M. Mickey Research Scholar Fund, and the Llura Gund Award for Rheumatoid Arthritis Research and Care; he has received research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb and has performed consultancy for AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Inova Diagnostics, Janssen, Optum, and Pfizer.

*Correction, 5/9/2023: This article has been updated to correct the units for C-reactive protein from mg/dL to mg/L.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MANCHESTER, England – Even when C-reactive protein (CRP) levels are normal, patients with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis (RA) could still be experiencing significant disease that persists over time, researchers from University College London have found.

Similar levels of joint erosion and disease activity were observed over a 5-year period; researchers compared patients who had high CRP levels (> 5 mg/L)* with patients whose CRP levels were consistently normal (< 5 mg/L) at the time of an ultrasound-proven disease flare.

“Our data suggests that the phenotype of normal CRP represents at least 5% of our cohort,” Bhavika Sethi, MBChB, reported in a virtual poster presentation at the annual meeting of the British Society for Rheumatology.

“They are more likely to require biologic treatment, and this continues on even though they have equivalent DAS28 [disease activity score in 28 joints] and risk of joint damage” to high-CRP patients, she said.

These patients are a significant minority, Dr. Sethi added, and “we need to think about how we provide care for them and allocate resources.”

Diagnostic delay and poor outcomes previously seen

The study is a continuation of a larger project, the corresponding author for the poster, Matthew Hutchinson, MBChB, told this news organization.

A few years ago, Dr. Hutchinson explained, a subset of patients with normal CRP levels during RA flares were identified and were found to be more likely to have experienced diagnostic delay and worse outcomes than did those with high CRP levels.

The aim of the current study was to see whether those findings persisted by longitudinally assessing patient records and seeing what happened 1, 2, and 5 years later. They evaluated 312 patients with seropositive RA, of whom 28 had CRP < 5 mg/L as well as active disease, which was determined on the basis of a DAS28 > 4.5. Of those 28 patients, 16 had persistently low CRP (< 5 mg/L) despite active disease. All patients who were taking tocilizumab were excluded from the study because of its CRP-lowering properties.

“Our project was showing that this group of people exist, trying to characterize them a little better” and that the study serves as a “jumping-off point” for future research, Dr. Hutchinson said.

The study was also conducted to “make people more aware of [patients with normal CRP during flare], because treating clinicians could be falsely reassured by a normal CRP,” he added. “Patients in front of them could actually be undertreated and have worse outcomes if [it is] not picked up,” Dr. Hutchinson suggested.

In comparison with those with high CRP levels, those with normal CRP levels were more likely to be receiving biologic treatment at 5 years (76.6% vs. 44.4%; P = .0323).

At 5 years, DAS28 was similar (P = .9615) among patients with normal CRP levels and those with high CRP levels, at a median of 2.8 and 3.2, respectively. A similar percentage of patients in these two groups also had joint damage (63.3% vs. 71.4%; P = .7384).

Don’t rely only on CRP to diagnose and manage RA flares

“CRP is a generic inflammatory marker in most people,” Dr. Hutchinson said. “In the majority of situations when either there is inflammation or an infection, certainly if it’s systemic infection or inflammation, you will find CRP being elevated on the blood tests.”

For someone presenting with joint pain, high CRP can be a useful indicator that it’s more of an inflammatory process than physical injury, he added. CRP is also frequently used to calculate DAS28 to monitor disease activity.

“This study highlights that CRP may be normal during flares in some people with RA,” Jeffrey A. Sparks, MD, told this news organization.

“These patients may still require advanced therapies and can accrue damage,” the rheumatologist from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard University, Boston, added.

“Clinicians should not only rely on CRP to diagnose and manage RA flares,” said Dr. Sparks, who was not involved in the study.

The study was independently supported. Dr. Hutchinson and Dr. Sethi report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Sparks is supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the R. Bruce and Joan M. Mickey Research Scholar Fund, and the Llura Gund Award for Rheumatoid Arthritis Research and Care; he has received research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb and has performed consultancy for AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Inova Diagnostics, Janssen, Optum, and Pfizer.

*Correction, 5/9/2023: This article has been updated to correct the units for C-reactive protein from mg/dL to mg/L.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT BSR 2023

LAA closure outcomes improve with CCTA: Swiss-Apero subanalysis

The largest multicenter randomized trial to date of CT angiography before left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) to treat atrial fibrillation has added to the evidence that the imaging technique on top of transesophageal echocardiography achieves a higher degree of short- and long-term success than TEE alone.

The results are from a subanalysis of the Swiss-Apero trial, a randomized comparative trial of the Watchman and Amulet devices for LAAC, which published results in Circulation.

“Our observational data support to use of CT for LAAC procedure planning,” senior investigator Lorenz Räber, MD, PhD, said in an interview. “This is not very surprising given the high variability of the LAA anatomy and the associated complexity of the procedure.” Dr. Räber is director of the catheterization laboratory at Inselspital, Bern (Switzerland) University Hospital.

The study, published online in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions, included 219 LAAC procedures in which the operators performed coronary CT angiography (CTTA) beforehand. When the investigators designed the study, LAAC procedures were typically planned using TEE alone, and so participating operators were blinded to preprocedural CCTA imaging. Soon after the study launch, European cardiology societies issued a consensus statement that included CCTA as an option for procedure planning. So the Swiss-Apero investigators changed the subanalysis protocol to unblind the operators – that is, they were permitted to plan LAAC procedures with CCTA imaging in addition to TEE. In this subanalysis, most patients had implantation with blinding to CCTA (57.9% vs. 41.2%).

Study results

The subanalysis determined that operator unblinding to preprocedural CCTA resulted in better success with LAAC, both in the short term, at 93.5% vs. 81.1% (P = .009; adjusted odds ratio, 2.76; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-7.29; P = .40) and the long term, at 83.7% vs. 72.4% (P = .050; aOR, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.03-4.35; P = .041).

Dr. Räber noted that this is only the third study to date that examined the potential impact of preprocedural CCTA plus TEE. One was a small study of 24 consecutive LAAC procedures with the Watchman device that compared TEE alone and CCTA plus TEE, finding better outcomes in the group that had both imaging modalities . A larger, single-center cohort study of 485 LAAC Watchman procedures found that CCTA resulted in faster operation times and higher successful device implantation rates, but no significant difference in procedural complications.

Dr. Räber explained why his group’s subanalysis may have found a clinical benefit with CCTA on top of TEE. “Our study was much larger, as compared to the randomized clinical trial, and there was no selection bias as in the second study mentioned before, as operators did not have the option to decide whether or not to assess the CCTA prior to the procedure,” he said. “Finally, in the previous studies there was no random allocation of device type” – that is, Amulet versus Watchman.

One study limitation Dr. Räber noted was that significantly more patients in the blinded group were discharged with dual-antiplatelet therapy. “The lower rate of procedure complications observed in unblinded procedures was mostly driven by a lower number of major bleedings and in particular of pericardial tamponade,” he said. “We cannot therefore exclude that the higher percentage of patients under dual-antiplatelet therapy in the CCTA-blinded group might have favored this difference.”

However, he noted the investigators corrected their analysis to account for differences between the groups. “Importantly, the numerical excess in major procedural bleeding was observed within both the single-antiplatelet therapy and dual-antiplatelet therapy subgroups of the TEE-only group.”

In an accompanying editorial, coauthors Brian O’Neill, MD, and Dee Dee Wang, MD, both with the Center for Structural Heard Disease at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, noted that the Swiss-Apero subanalysis “reinforced” the benefit of CCTA before LAAC.

“This study demonstrated, for the first time, improved short- and long-term procedural success using CT in addition to TEE for left atrial appendage occlusion,” Dr. O’Neill said in an interview. “This particular study may serve as a guide to an adequately powered randomized trial of CT versus TEE in left atrial appendage occlusion.” Future LAAC trials should incorporate preprocedural CCTA.

Dr. O’Neill noted that, as a subanalysis of a randomized trial, the “results are hypothesis generating.” However, he added, “the results are in line with several previous studies of CT versus TEE in left atrial appendage occlusion.”

Dr Räber disclosed financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Infraredx, Heartflow, Sanofi, Regeneron, Amgen, AstraZeneca, CSL Behring, Canon, Occlutech, and Vifor. Dr. O’Neill disclosed financial relationships with Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, and Abbott Vascular.

The largest multicenter randomized trial to date of CT angiography before left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) to treat atrial fibrillation has added to the evidence that the imaging technique on top of transesophageal echocardiography achieves a higher degree of short- and long-term success than TEE alone.

The results are from a subanalysis of the Swiss-Apero trial, a randomized comparative trial of the Watchman and Amulet devices for LAAC, which published results in Circulation.

“Our observational data support to use of CT for LAAC procedure planning,” senior investigator Lorenz Räber, MD, PhD, said in an interview. “This is not very surprising given the high variability of the LAA anatomy and the associated complexity of the procedure.” Dr. Räber is director of the catheterization laboratory at Inselspital, Bern (Switzerland) University Hospital.

The study, published online in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions, included 219 LAAC procedures in which the operators performed coronary CT angiography (CTTA) beforehand. When the investigators designed the study, LAAC procedures were typically planned using TEE alone, and so participating operators were blinded to preprocedural CCTA imaging. Soon after the study launch, European cardiology societies issued a consensus statement that included CCTA as an option for procedure planning. So the Swiss-Apero investigators changed the subanalysis protocol to unblind the operators – that is, they were permitted to plan LAAC procedures with CCTA imaging in addition to TEE. In this subanalysis, most patients had implantation with blinding to CCTA (57.9% vs. 41.2%).

Study results

The subanalysis determined that operator unblinding to preprocedural CCTA resulted in better success with LAAC, both in the short term, at 93.5% vs. 81.1% (P = .009; adjusted odds ratio, 2.76; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-7.29; P = .40) and the long term, at 83.7% vs. 72.4% (P = .050; aOR, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.03-4.35; P = .041).

Dr. Räber noted that this is only the third study to date that examined the potential impact of preprocedural CCTA plus TEE. One was a small study of 24 consecutive LAAC procedures with the Watchman device that compared TEE alone and CCTA plus TEE, finding better outcomes in the group that had both imaging modalities . A larger, single-center cohort study of 485 LAAC Watchman procedures found that CCTA resulted in faster operation times and higher successful device implantation rates, but no significant difference in procedural complications.

Dr. Räber explained why his group’s subanalysis may have found a clinical benefit with CCTA on top of TEE. “Our study was much larger, as compared to the randomized clinical trial, and there was no selection bias as in the second study mentioned before, as operators did not have the option to decide whether or not to assess the CCTA prior to the procedure,” he said. “Finally, in the previous studies there was no random allocation of device type” – that is, Amulet versus Watchman.

One study limitation Dr. Räber noted was that significantly more patients in the blinded group were discharged with dual-antiplatelet therapy. “The lower rate of procedure complications observed in unblinded procedures was mostly driven by a lower number of major bleedings and in particular of pericardial tamponade,” he said. “We cannot therefore exclude that the higher percentage of patients under dual-antiplatelet therapy in the CCTA-blinded group might have favored this difference.”

However, he noted the investigators corrected their analysis to account for differences between the groups. “Importantly, the numerical excess in major procedural bleeding was observed within both the single-antiplatelet therapy and dual-antiplatelet therapy subgroups of the TEE-only group.”

In an accompanying editorial, coauthors Brian O’Neill, MD, and Dee Dee Wang, MD, both with the Center for Structural Heard Disease at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, noted that the Swiss-Apero subanalysis “reinforced” the benefit of CCTA before LAAC.

“This study demonstrated, for the first time, improved short- and long-term procedural success using CT in addition to TEE for left atrial appendage occlusion,” Dr. O’Neill said in an interview. “This particular study may serve as a guide to an adequately powered randomized trial of CT versus TEE in left atrial appendage occlusion.” Future LAAC trials should incorporate preprocedural CCTA.

Dr. O’Neill noted that, as a subanalysis of a randomized trial, the “results are hypothesis generating.” However, he added, “the results are in line with several previous studies of CT versus TEE in left atrial appendage occlusion.”

Dr Räber disclosed financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Infraredx, Heartflow, Sanofi, Regeneron, Amgen, AstraZeneca, CSL Behring, Canon, Occlutech, and Vifor. Dr. O’Neill disclosed financial relationships with Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, and Abbott Vascular.

The largest multicenter randomized trial to date of CT angiography before left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) to treat atrial fibrillation has added to the evidence that the imaging technique on top of transesophageal echocardiography achieves a higher degree of short- and long-term success than TEE alone.

The results are from a subanalysis of the Swiss-Apero trial, a randomized comparative trial of the Watchman and Amulet devices for LAAC, which published results in Circulation.

“Our observational data support to use of CT for LAAC procedure planning,” senior investigator Lorenz Räber, MD, PhD, said in an interview. “This is not very surprising given the high variability of the LAA anatomy and the associated complexity of the procedure.” Dr. Räber is director of the catheterization laboratory at Inselspital, Bern (Switzerland) University Hospital.

The study, published online in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions, included 219 LAAC procedures in which the operators performed coronary CT angiography (CTTA) beforehand. When the investigators designed the study, LAAC procedures were typically planned using TEE alone, and so participating operators were blinded to preprocedural CCTA imaging. Soon after the study launch, European cardiology societies issued a consensus statement that included CCTA as an option for procedure planning. So the Swiss-Apero investigators changed the subanalysis protocol to unblind the operators – that is, they were permitted to plan LAAC procedures with CCTA imaging in addition to TEE. In this subanalysis, most patients had implantation with blinding to CCTA (57.9% vs. 41.2%).

Study results

The subanalysis determined that operator unblinding to preprocedural CCTA resulted in better success with LAAC, both in the short term, at 93.5% vs. 81.1% (P = .009; adjusted odds ratio, 2.76; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-7.29; P = .40) and the long term, at 83.7% vs. 72.4% (P = .050; aOR, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.03-4.35; P = .041).

Dr. Räber noted that this is only the third study to date that examined the potential impact of preprocedural CCTA plus TEE. One was a small study of 24 consecutive LAAC procedures with the Watchman device that compared TEE alone and CCTA plus TEE, finding better outcomes in the group that had both imaging modalities . A larger, single-center cohort study of 485 LAAC Watchman procedures found that CCTA resulted in faster operation times and higher successful device implantation rates, but no significant difference in procedural complications.

Dr. Räber explained why his group’s subanalysis may have found a clinical benefit with CCTA on top of TEE. “Our study was much larger, as compared to the randomized clinical trial, and there was no selection bias as in the second study mentioned before, as operators did not have the option to decide whether or not to assess the CCTA prior to the procedure,” he said. “Finally, in the previous studies there was no random allocation of device type” – that is, Amulet versus Watchman.

One study limitation Dr. Räber noted was that significantly more patients in the blinded group were discharged with dual-antiplatelet therapy. “The lower rate of procedure complications observed in unblinded procedures was mostly driven by a lower number of major bleedings and in particular of pericardial tamponade,” he said. “We cannot therefore exclude that the higher percentage of patients under dual-antiplatelet therapy in the CCTA-blinded group might have favored this difference.”

However, he noted the investigators corrected their analysis to account for differences between the groups. “Importantly, the numerical excess in major procedural bleeding was observed within both the single-antiplatelet therapy and dual-antiplatelet therapy subgroups of the TEE-only group.”

In an accompanying editorial, coauthors Brian O’Neill, MD, and Dee Dee Wang, MD, both with the Center for Structural Heard Disease at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, noted that the Swiss-Apero subanalysis “reinforced” the benefit of CCTA before LAAC.

“This study demonstrated, for the first time, improved short- and long-term procedural success using CT in addition to TEE for left atrial appendage occlusion,” Dr. O’Neill said in an interview. “This particular study may serve as a guide to an adequately powered randomized trial of CT versus TEE in left atrial appendage occlusion.” Future LAAC trials should incorporate preprocedural CCTA.

Dr. O’Neill noted that, as a subanalysis of a randomized trial, the “results are hypothesis generating.” However, he added, “the results are in line with several previous studies of CT versus TEE in left atrial appendage occlusion.”

Dr Räber disclosed financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Infraredx, Heartflow, Sanofi, Regeneron, Amgen, AstraZeneca, CSL Behring, Canon, Occlutech, and Vifor. Dr. O’Neill disclosed financial relationships with Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, and Abbott Vascular.

FROM JACC: CARDIOVASCULAR INTERVENTIONS

Controlled hyperthermia: Novel treatment of BCCs without surgery continues to be refined

PHOENIX – .

“For 2,000 years, it’s been known that heat can kill cancers,” an apoptotic reaction “rather than a destructive reaction coming from excessive heat,” Christopher B. Zachary, MD, said at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, where the study was presented during an abstract session.

Dr. Zachary, professor and chair emeritus of the department of dermatology at the University of California, Irvine, and colleagues, evaluated a novel, noninvasive technique of controlled hyperthermia and mapping protocol (CHAMP) designed to help clinicians with margin assessment and treatment of superficial and nodular BCCs. For this prospective study, which was first described at the 2022 ASLMS annual conference and is being conducted at three centers, 73 patients with biopsy-proven superficial and nodular BCCs have been scanned with the VivoSight Dx optical coherence tomography (OCT) device to map BCC tumor margins.

The BCCs were treated with the Sciton 1,064-nm Er:YAG laser equipped with a 4-mm beam diameter scan pattern with no overlap and an 8-millisecond pulse duration, randomized to either standard 120-140 J/cm2 pulses until tissue graying and contraction was observed, or the CHAMP controlled hyperthermia technique using repeated 25 J/cm2 pulses under thermal camera imaging to maintain a consistent temperature of 55º C for 60 seconds. Patients were rescanned by OCT at 3 to 12 months for any signs of residual tumor and if positive, were retreated. Finally, lesions were excised for evidence of histological clearance.

To date, 48 patients have completed the study. Among the 26 patients treated with the CHAMP method, 22 (84.6%) were histologically clear, as were 19 of the 22 (86.4%) in the standard treatment group. Ulceration was uncommon with the CHAMP method, and patients healed with modest erythema, Dr. Zachary said.

Pretreatment OCT mapping of BCCs indicated that tumors extended beyond their 5-mm clinical margins in 11 cases (15%). “This will be of interest to those who treat BCCs by Mohs or standard excision,” he said. Increased vascularity measured by dynamic OCT was noted in most CHAMP patients immediately after irradiation, which suggests that apoptosis was the primary mechanism of tumor response instead of vascular destruction.

“The traditional technique for using the long pulsed 1,064-nm Er:YAG laser to cause damage and destruction of BCC is 120-140 J/cm2 at one or two passes until you get to an endpoint of graying and contraction of tissue,” Dr. Zachary said. “That’s opposed to the ‘Low and Slow’ approach [where you use] multiple pulses at 25 J/cm2 until you achieve an optimal time and temperature. If you treat above 60º C, you tend to get epidermal blistering, prolonged healing, and interestingly, absence of pain. I think that’s because you kill off the nerve fibers. With the low fluence multiple scan technique, you’re going for an even flat-top heating.”

Currently, he and his colleagues consider 55 degrees at 60 seconds as “the optimal parameters,” he said, but “it could be 45 degrees at 90 seconds or two minutes. We don’t know yet.”

In an interview at the meeting, one of the abstract session moderators, Mathew M. Avram, MD, JD, director of laser, cosmetics, and dermatologic surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said that he was encouraged by the study results as investigations into effective, noninvasive treatment of BCC continue to move forward. “Details matter such as the temperature [of energy delivery] and noninvasive imaging to delineate the appropriate margins,” said Dr. Avram, who has conducted research on the 1,064-nm long-pulsed Nd:YAG laser as an alternative treatment for nonfacial BCCs in patients who are poor surgical candidates.

“Hopefully, at some point,” he said, such approaches will “become the standard of care for many BCCs that we are now treating surgically. I don’t think this will happen in the next 3 years, but I think in the long term, it will emerge as the treatment of choice.”

The study is being funded by Michelson Diagnostics. Sciton provided the long-pulsed 1,064-nm lasers devices being used in the trial. Dr. Zachary reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Avram disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Sciton.

PHOENIX – .

“For 2,000 years, it’s been known that heat can kill cancers,” an apoptotic reaction “rather than a destructive reaction coming from excessive heat,” Christopher B. Zachary, MD, said at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, where the study was presented during an abstract session.

Dr. Zachary, professor and chair emeritus of the department of dermatology at the University of California, Irvine, and colleagues, evaluated a novel, noninvasive technique of controlled hyperthermia and mapping protocol (CHAMP) designed to help clinicians with margin assessment and treatment of superficial and nodular BCCs. For this prospective study, which was first described at the 2022 ASLMS annual conference and is being conducted at three centers, 73 patients with biopsy-proven superficial and nodular BCCs have been scanned with the VivoSight Dx optical coherence tomography (OCT) device to map BCC tumor margins.

The BCCs were treated with the Sciton 1,064-nm Er:YAG laser equipped with a 4-mm beam diameter scan pattern with no overlap and an 8-millisecond pulse duration, randomized to either standard 120-140 J/cm2 pulses until tissue graying and contraction was observed, or the CHAMP controlled hyperthermia technique using repeated 25 J/cm2 pulses under thermal camera imaging to maintain a consistent temperature of 55º C for 60 seconds. Patients were rescanned by OCT at 3 to 12 months for any signs of residual tumor and if positive, were retreated. Finally, lesions were excised for evidence of histological clearance.

To date, 48 patients have completed the study. Among the 26 patients treated with the CHAMP method, 22 (84.6%) were histologically clear, as were 19 of the 22 (86.4%) in the standard treatment group. Ulceration was uncommon with the CHAMP method, and patients healed with modest erythema, Dr. Zachary said.

Pretreatment OCT mapping of BCCs indicated that tumors extended beyond their 5-mm clinical margins in 11 cases (15%). “This will be of interest to those who treat BCCs by Mohs or standard excision,” he said. Increased vascularity measured by dynamic OCT was noted in most CHAMP patients immediately after irradiation, which suggests that apoptosis was the primary mechanism of tumor response instead of vascular destruction.

“The traditional technique for using the long pulsed 1,064-nm Er:YAG laser to cause damage and destruction of BCC is 120-140 J/cm2 at one or two passes until you get to an endpoint of graying and contraction of tissue,” Dr. Zachary said. “That’s opposed to the ‘Low and Slow’ approach [where you use] multiple pulses at 25 J/cm2 until you achieve an optimal time and temperature. If you treat above 60º C, you tend to get epidermal blistering, prolonged healing, and interestingly, absence of pain. I think that’s because you kill off the nerve fibers. With the low fluence multiple scan technique, you’re going for an even flat-top heating.”

Currently, he and his colleagues consider 55 degrees at 60 seconds as “the optimal parameters,” he said, but “it could be 45 degrees at 90 seconds or two minutes. We don’t know yet.”

In an interview at the meeting, one of the abstract session moderators, Mathew M. Avram, MD, JD, director of laser, cosmetics, and dermatologic surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said that he was encouraged by the study results as investigations into effective, noninvasive treatment of BCC continue to move forward. “Details matter such as the temperature [of energy delivery] and noninvasive imaging to delineate the appropriate margins,” said Dr. Avram, who has conducted research on the 1,064-nm long-pulsed Nd:YAG laser as an alternative treatment for nonfacial BCCs in patients who are poor surgical candidates.

“Hopefully, at some point,” he said, such approaches will “become the standard of care for many BCCs that we are now treating surgically. I don’t think this will happen in the next 3 years, but I think in the long term, it will emerge as the treatment of choice.”

The study is being funded by Michelson Diagnostics. Sciton provided the long-pulsed 1,064-nm lasers devices being used in the trial. Dr. Zachary reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Avram disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Sciton.

PHOENIX – .

“For 2,000 years, it’s been known that heat can kill cancers,” an apoptotic reaction “rather than a destructive reaction coming from excessive heat,” Christopher B. Zachary, MD, said at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, where the study was presented during an abstract session.

Dr. Zachary, professor and chair emeritus of the department of dermatology at the University of California, Irvine, and colleagues, evaluated a novel, noninvasive technique of controlled hyperthermia and mapping protocol (CHAMP) designed to help clinicians with margin assessment and treatment of superficial and nodular BCCs. For this prospective study, which was first described at the 2022 ASLMS annual conference and is being conducted at three centers, 73 patients with biopsy-proven superficial and nodular BCCs have been scanned with the VivoSight Dx optical coherence tomography (OCT) device to map BCC tumor margins.

The BCCs were treated with the Sciton 1,064-nm Er:YAG laser equipped with a 4-mm beam diameter scan pattern with no overlap and an 8-millisecond pulse duration, randomized to either standard 120-140 J/cm2 pulses until tissue graying and contraction was observed, or the CHAMP controlled hyperthermia technique using repeated 25 J/cm2 pulses under thermal camera imaging to maintain a consistent temperature of 55º C for 60 seconds. Patients were rescanned by OCT at 3 to 12 months for any signs of residual tumor and if positive, were retreated. Finally, lesions were excised for evidence of histological clearance.

To date, 48 patients have completed the study. Among the 26 patients treated with the CHAMP method, 22 (84.6%) were histologically clear, as were 19 of the 22 (86.4%) in the standard treatment group. Ulceration was uncommon with the CHAMP method, and patients healed with modest erythema, Dr. Zachary said.

Pretreatment OCT mapping of BCCs indicated that tumors extended beyond their 5-mm clinical margins in 11 cases (15%). “This will be of interest to those who treat BCCs by Mohs or standard excision,” he said. Increased vascularity measured by dynamic OCT was noted in most CHAMP patients immediately after irradiation, which suggests that apoptosis was the primary mechanism of tumor response instead of vascular destruction.

“The traditional technique for using the long pulsed 1,064-nm Er:YAG laser to cause damage and destruction of BCC is 120-140 J/cm2 at one or two passes until you get to an endpoint of graying and contraction of tissue,” Dr. Zachary said. “That’s opposed to the ‘Low and Slow’ approach [where you use] multiple pulses at 25 J/cm2 until you achieve an optimal time and temperature. If you treat above 60º C, you tend to get epidermal blistering, prolonged healing, and interestingly, absence of pain. I think that’s because you kill off the nerve fibers. With the low fluence multiple scan technique, you’re going for an even flat-top heating.”

Currently, he and his colleagues consider 55 degrees at 60 seconds as “the optimal parameters,” he said, but “it could be 45 degrees at 90 seconds or two minutes. We don’t know yet.”

In an interview at the meeting, one of the abstract session moderators, Mathew M. Avram, MD, JD, director of laser, cosmetics, and dermatologic surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said that he was encouraged by the study results as investigations into effective, noninvasive treatment of BCC continue to move forward. “Details matter such as the temperature [of energy delivery] and noninvasive imaging to delineate the appropriate margins,” said Dr. Avram, who has conducted research on the 1,064-nm long-pulsed Nd:YAG laser as an alternative treatment for nonfacial BCCs in patients who are poor surgical candidates.

“Hopefully, at some point,” he said, such approaches will “become the standard of care for many BCCs that we are now treating surgically. I don’t think this will happen in the next 3 years, but I think in the long term, it will emerge as the treatment of choice.”

The study is being funded by Michelson Diagnostics. Sciton provided the long-pulsed 1,064-nm lasers devices being used in the trial. Dr. Zachary reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Avram disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Sciton.

AT ASLMS 2023

Teriflunomide delays MS symptoms in radiologically isolated syndrome

BOSTON – , according to a double-blind, phase 3 trial presented in the Emerging Science session of the 2023 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

“These data add to the evidence that early immunomodulation offers clinical benefit even in the presymptomatic phase of MS,” reported Christine Lebrun-Frenay, MD, PhD, head of inflammatory neurological disorders research unit, University of Nice, France. This is the second study to show a benefit from a disease-modifying therapy in asymptomatic RIS patients. The ARISE study, which was presented at the 2022 European Committee for Treatment and Research in MS and has now been published, compared 240 mg of twice-daily dimethyl fumarate with placebo. Dimethyl fumarate was associated with an 82% (hazard ratio, 0.18; P = .007) reduction in the risk of a first demyelinating event after 96 weeks of follow-up.

TERIS trial data

In the new study, called TERIS, the design and outcomes were similar to the ARISE study. Eighty-nine patients meeting standard criteria for RIS were randomized to 14 mg of once-daily teriflunomide or placebo. The majority (71%) were female, and the mean age was 39.8 years. At the time of RIS diagnosis, the mean age was 38 years. At study entry, standardized MRI studies were performed of the brain and spinal cord.

During 2 years of follow-up, 8 of 28 demyelinating events were observed in the active treatment group. The remaining 20 occurred in the placebo group. This translated to a 63% reduction (HR, 0.37; P = .018) in favor of teriflunomide. When graphed, the curves separated at about 6 months and then widened progressively over time.

Distinct from clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), which describes individuals who have a symptomatic episode consistent with a demyelinating event, RIS is based primarily on an MRI that shows lesions highly suggestive of MS. Neither confirms the MS diagnosis, but both are associated with a high likelihood of eventually meeting MS diagnostic criteria. The ARISE and TERIS studies now support therapy to delay demyelinating events.

“With more and more people having brain scans for various reasons, such as headache or head trauma, more of these cases are being discovered,” Dr. Lebrun-Frenay said.

Caution warranted when interpreting the findings

The data support the theory that treatment should begin early in patients with a high likelihood of developing symptomatic MS on the basis of brain lesions. It is logical to assume that preventing damage to the myelin will reduce or delay permanent symptoms and permanent neurologic impairment, but Dr. Lebrun-Frenay suggested that the available data from ARISE and TERIS are not practice changing even though both were multicenter double-blind trials.

“More data from larger groups of patients are needed to confirm the findings,” she said. She expressed concern about not adhering to strict criteria to diagnosis RIS.

“It is important that medical professionals are cautious,” she said, citing the risk of misdiagnosis of pathology of MRI that leads to treatment of patients with a low risk of developing symptomatic MS.

Teriflunomide and dimethyl fumarate, which have long been available as first-line therapies in relapsing-remitting MS, are generally well tolerated. In the TERIS and ARISE studies, mild or moderate events occurred more commonly in the active treatment than the placebo arms, but there were no serious adverse events. However, both can produce more serious adverse events, which, in the case of teriflunomide, include liver toxicity leading to injury and liver failure.

Challenging the traditional definition of MS

The author of the ARISE study, Darin T. Okuda, MD, a professor of neurology at the UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, indicated that his study, now reinforced by the TERIS study, challenges the definition of MS.

“Both ARISE and TERIS demonstrated a significant reduction in seminal clinical event rates related to inflammatory demyelination,” Dr. Okuda said in an interview. They provide evidence that patients are at high risk of the demyelinating events that characterize MS. Given the potential difficulty for accessing therapies of benefit, “how we define multiple sclerosis is highly important.”

“Individuals of younger age with abnormal spinal cord MRI studies along with other paraclinical features related to risk for a first event may be the most ideal group to treat,” he said. However, he agreed with Dr. Lebrun-Frenay that it is not yet clear which RIS patients are the most appropriate candidates.

“Gaining a more refined sense of who we should treat will require more work,” he said.

These data are likely to change the orientation toward RIS, according to Melina Hosseiny, MD, department of radiology, University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center. She noted that the relationship between RIS and increased risk of MS has long been recognized, and the risk increases with specific features on imaging.

“Studies have shown that spinal cord lesions are associated with a greater than 50% chance of converting to MS,” said Dr. Hosseiny, who was the lead author of a review article on RIS. “Identifying such imaging findings can help identify patients who may benefit from disease-modifying medications.”

Dr. Lebrun-Frenay reports no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Okuda has financial relationships with Alexion, Biogen, Celgene, EMD Serono, Genzyme, TG Therapeutics, and VielaBio. Dr. Hosseiny reports no potential conflicts of interest.

BOSTON – , according to a double-blind, phase 3 trial presented in the Emerging Science session of the 2023 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

“These data add to the evidence that early immunomodulation offers clinical benefit even in the presymptomatic phase of MS,” reported Christine Lebrun-Frenay, MD, PhD, head of inflammatory neurological disorders research unit, University of Nice, France. This is the second study to show a benefit from a disease-modifying therapy in asymptomatic RIS patients. The ARISE study, which was presented at the 2022 European Committee for Treatment and Research in MS and has now been published, compared 240 mg of twice-daily dimethyl fumarate with placebo. Dimethyl fumarate was associated with an 82% (hazard ratio, 0.18; P = .007) reduction in the risk of a first demyelinating event after 96 weeks of follow-up.

TERIS trial data

In the new study, called TERIS, the design and outcomes were similar to the ARISE study. Eighty-nine patients meeting standard criteria for RIS were randomized to 14 mg of once-daily teriflunomide or placebo. The majority (71%) were female, and the mean age was 39.8 years. At the time of RIS diagnosis, the mean age was 38 years. At study entry, standardized MRI studies were performed of the brain and spinal cord.

During 2 years of follow-up, 8 of 28 demyelinating events were observed in the active treatment group. The remaining 20 occurred in the placebo group. This translated to a 63% reduction (HR, 0.37; P = .018) in favor of teriflunomide. When graphed, the curves separated at about 6 months and then widened progressively over time.

Distinct from clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), which describes individuals who have a symptomatic episode consistent with a demyelinating event, RIS is based primarily on an MRI that shows lesions highly suggestive of MS. Neither confirms the MS diagnosis, but both are associated with a high likelihood of eventually meeting MS diagnostic criteria. The ARISE and TERIS studies now support therapy to delay demyelinating events.

“With more and more people having brain scans for various reasons, such as headache or head trauma, more of these cases are being discovered,” Dr. Lebrun-Frenay said.

Caution warranted when interpreting the findings

The data support the theory that treatment should begin early in patients with a high likelihood of developing symptomatic MS on the basis of brain lesions. It is logical to assume that preventing damage to the myelin will reduce or delay permanent symptoms and permanent neurologic impairment, but Dr. Lebrun-Frenay suggested that the available data from ARISE and TERIS are not practice changing even though both were multicenter double-blind trials.

“More data from larger groups of patients are needed to confirm the findings,” she said. She expressed concern about not adhering to strict criteria to diagnosis RIS.

“It is important that medical professionals are cautious,” she said, citing the risk of misdiagnosis of pathology of MRI that leads to treatment of patients with a low risk of developing symptomatic MS.

Teriflunomide and dimethyl fumarate, which have long been available as first-line therapies in relapsing-remitting MS, are generally well tolerated. In the TERIS and ARISE studies, mild or moderate events occurred more commonly in the active treatment than the placebo arms, but there were no serious adverse events. However, both can produce more serious adverse events, which, in the case of teriflunomide, include liver toxicity leading to injury and liver failure.

Challenging the traditional definition of MS

The author of the ARISE study, Darin T. Okuda, MD, a professor of neurology at the UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, indicated that his study, now reinforced by the TERIS study, challenges the definition of MS.

“Both ARISE and TERIS demonstrated a significant reduction in seminal clinical event rates related to inflammatory demyelination,” Dr. Okuda said in an interview. They provide evidence that patients are at high risk of the demyelinating events that characterize MS. Given the potential difficulty for accessing therapies of benefit, “how we define multiple sclerosis is highly important.”

“Individuals of younger age with abnormal spinal cord MRI studies along with other paraclinical features related to risk for a first event may be the most ideal group to treat,” he said. However, he agreed with Dr. Lebrun-Frenay that it is not yet clear which RIS patients are the most appropriate candidates.

“Gaining a more refined sense of who we should treat will require more work,” he said.

These data are likely to change the orientation toward RIS, according to Melina Hosseiny, MD, department of radiology, University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center. She noted that the relationship between RIS and increased risk of MS has long been recognized, and the risk increases with specific features on imaging.

“Studies have shown that spinal cord lesions are associated with a greater than 50% chance of converting to MS,” said Dr. Hosseiny, who was the lead author of a review article on RIS. “Identifying such imaging findings can help identify patients who may benefit from disease-modifying medications.”

Dr. Lebrun-Frenay reports no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Okuda has financial relationships with Alexion, Biogen, Celgene, EMD Serono, Genzyme, TG Therapeutics, and VielaBio. Dr. Hosseiny reports no potential conflicts of interest.

BOSTON – , according to a double-blind, phase 3 trial presented in the Emerging Science session of the 2023 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

“These data add to the evidence that early immunomodulation offers clinical benefit even in the presymptomatic phase of MS,” reported Christine Lebrun-Frenay, MD, PhD, head of inflammatory neurological disorders research unit, University of Nice, France. This is the second study to show a benefit from a disease-modifying therapy in asymptomatic RIS patients. The ARISE study, which was presented at the 2022 European Committee for Treatment and Research in MS and has now been published, compared 240 mg of twice-daily dimethyl fumarate with placebo. Dimethyl fumarate was associated with an 82% (hazard ratio, 0.18; P = .007) reduction in the risk of a first demyelinating event after 96 weeks of follow-up.

TERIS trial data

In the new study, called TERIS, the design and outcomes were similar to the ARISE study. Eighty-nine patients meeting standard criteria for RIS were randomized to 14 mg of once-daily teriflunomide or placebo. The majority (71%) were female, and the mean age was 39.8 years. At the time of RIS diagnosis, the mean age was 38 years. At study entry, standardized MRI studies were performed of the brain and spinal cord.

During 2 years of follow-up, 8 of 28 demyelinating events were observed in the active treatment group. The remaining 20 occurred in the placebo group. This translated to a 63% reduction (HR, 0.37; P = .018) in favor of teriflunomide. When graphed, the curves separated at about 6 months and then widened progressively over time.

Distinct from clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), which describes individuals who have a symptomatic episode consistent with a demyelinating event, RIS is based primarily on an MRI that shows lesions highly suggestive of MS. Neither confirms the MS diagnosis, but both are associated with a high likelihood of eventually meeting MS diagnostic criteria. The ARISE and TERIS studies now support therapy to delay demyelinating events.

“With more and more people having brain scans for various reasons, such as headache or head trauma, more of these cases are being discovered,” Dr. Lebrun-Frenay said.

Caution warranted when interpreting the findings

The data support the theory that treatment should begin early in patients with a high likelihood of developing symptomatic MS on the basis of brain lesions. It is logical to assume that preventing damage to the myelin will reduce or delay permanent symptoms and permanent neurologic impairment, but Dr. Lebrun-Frenay suggested that the available data from ARISE and TERIS are not practice changing even though both were multicenter double-blind trials.

“More data from larger groups of patients are needed to confirm the findings,” she said. She expressed concern about not adhering to strict criteria to diagnosis RIS.

“It is important that medical professionals are cautious,” she said, citing the risk of misdiagnosis of pathology of MRI that leads to treatment of patients with a low risk of developing symptomatic MS.

Teriflunomide and dimethyl fumarate, which have long been available as first-line therapies in relapsing-remitting MS, are generally well tolerated. In the TERIS and ARISE studies, mild or moderate events occurred more commonly in the active treatment than the placebo arms, but there were no serious adverse events. However, both can produce more serious adverse events, which, in the case of teriflunomide, include liver toxicity leading to injury and liver failure.

Challenging the traditional definition of MS

The author of the ARISE study, Darin T. Okuda, MD, a professor of neurology at the UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, indicated that his study, now reinforced by the TERIS study, challenges the definition of MS.

“Both ARISE and TERIS demonstrated a significant reduction in seminal clinical event rates related to inflammatory demyelination,” Dr. Okuda said in an interview. They provide evidence that patients are at high risk of the demyelinating events that characterize MS. Given the potential difficulty for accessing therapies of benefit, “how we define multiple sclerosis is highly important.”

“Individuals of younger age with abnormal spinal cord MRI studies along with other paraclinical features related to risk for a first event may be the most ideal group to treat,” he said. However, he agreed with Dr. Lebrun-Frenay that it is not yet clear which RIS patients are the most appropriate candidates.

“Gaining a more refined sense of who we should treat will require more work,” he said.

These data are likely to change the orientation toward RIS, according to Melina Hosseiny, MD, department of radiology, University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center. She noted that the relationship between RIS and increased risk of MS has long been recognized, and the risk increases with specific features on imaging.

“Studies have shown that spinal cord lesions are associated with a greater than 50% chance of converting to MS,” said Dr. Hosseiny, who was the lead author of a review article on RIS. “Identifying such imaging findings can help identify patients who may benefit from disease-modifying medications.”

Dr. Lebrun-Frenay reports no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Okuda has financial relationships with Alexion, Biogen, Celgene, EMD Serono, Genzyme, TG Therapeutics, and VielaBio. Dr. Hosseiny reports no potential conflicts of interest.

AT AAN 2023

Miliarial Gout in an Immunocompromised Patient

To the Editor:

Miliarial gout is a rare intradermal manifestation of tophaceous gout. It was first described in 2007 when a patient presented with multiple small papules with a red base containing a white- to cream-colored substance,1 which has rarely been reported,1-6 according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE from 2007 to 2023 using the term miliarial gout. We describe a case of miliarial gout in a patient with a history of gout, uric acid levels within reference range, and immunocompromised status due to a prior orthotopic heart transplant.

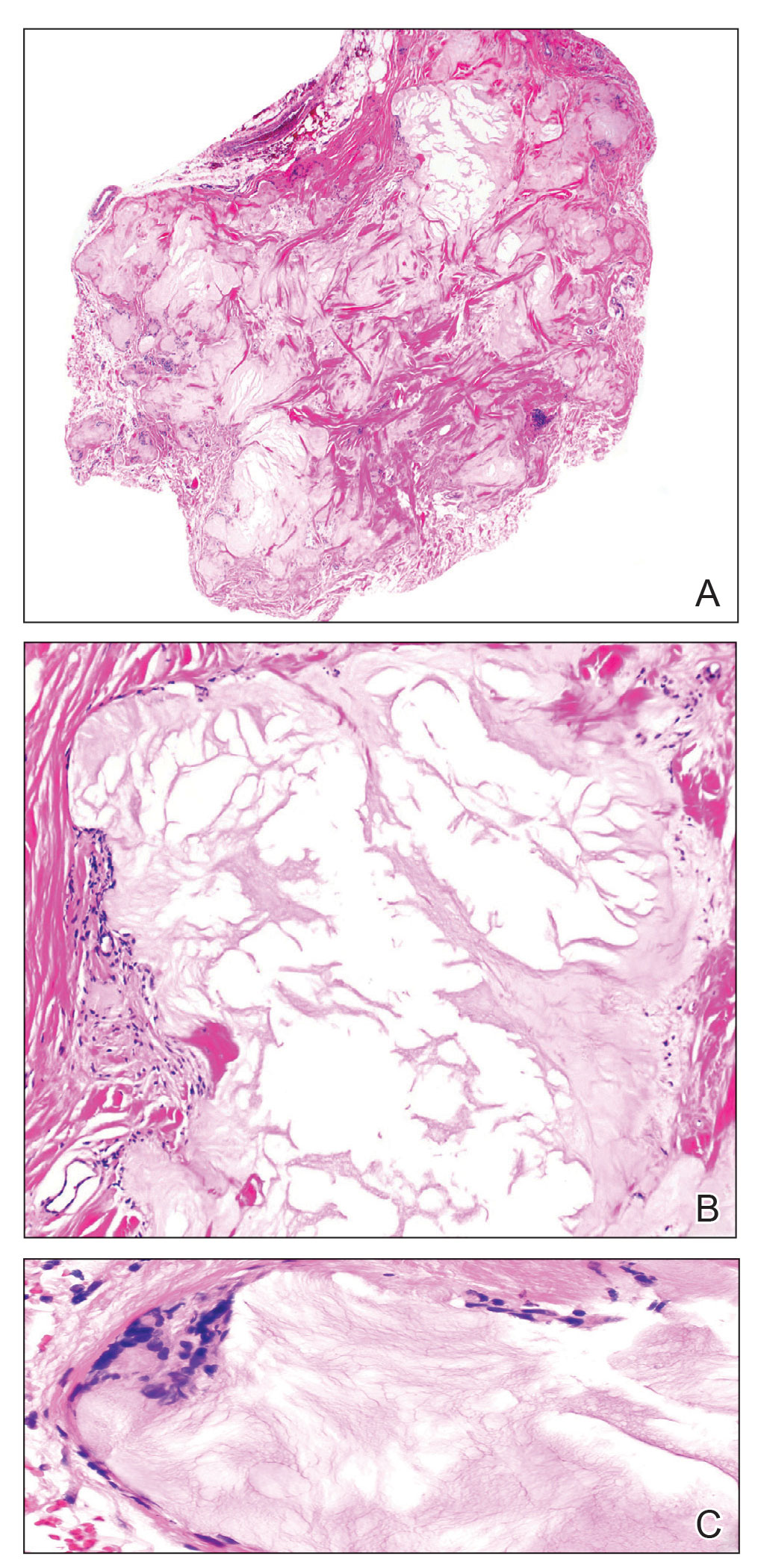

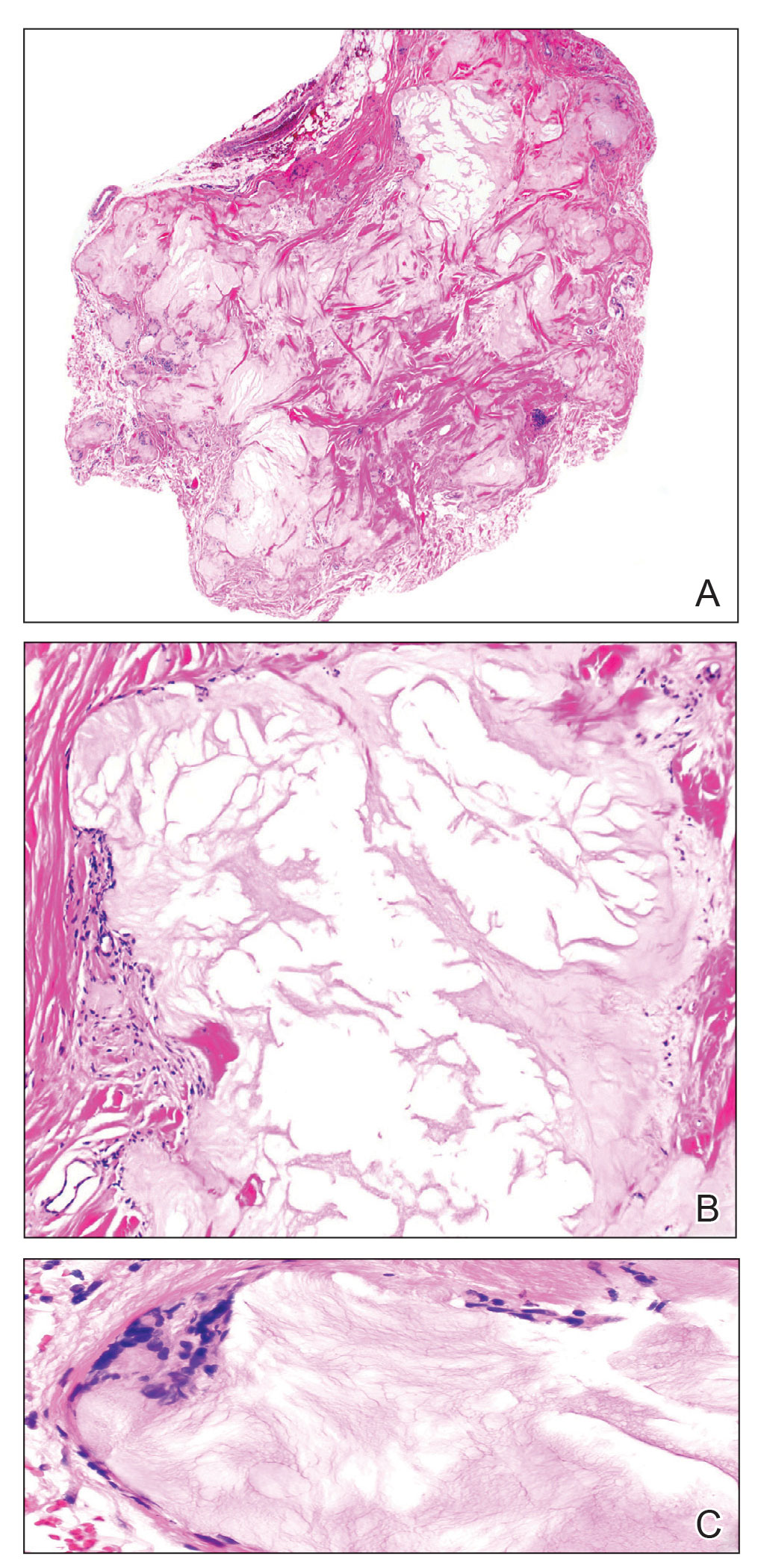

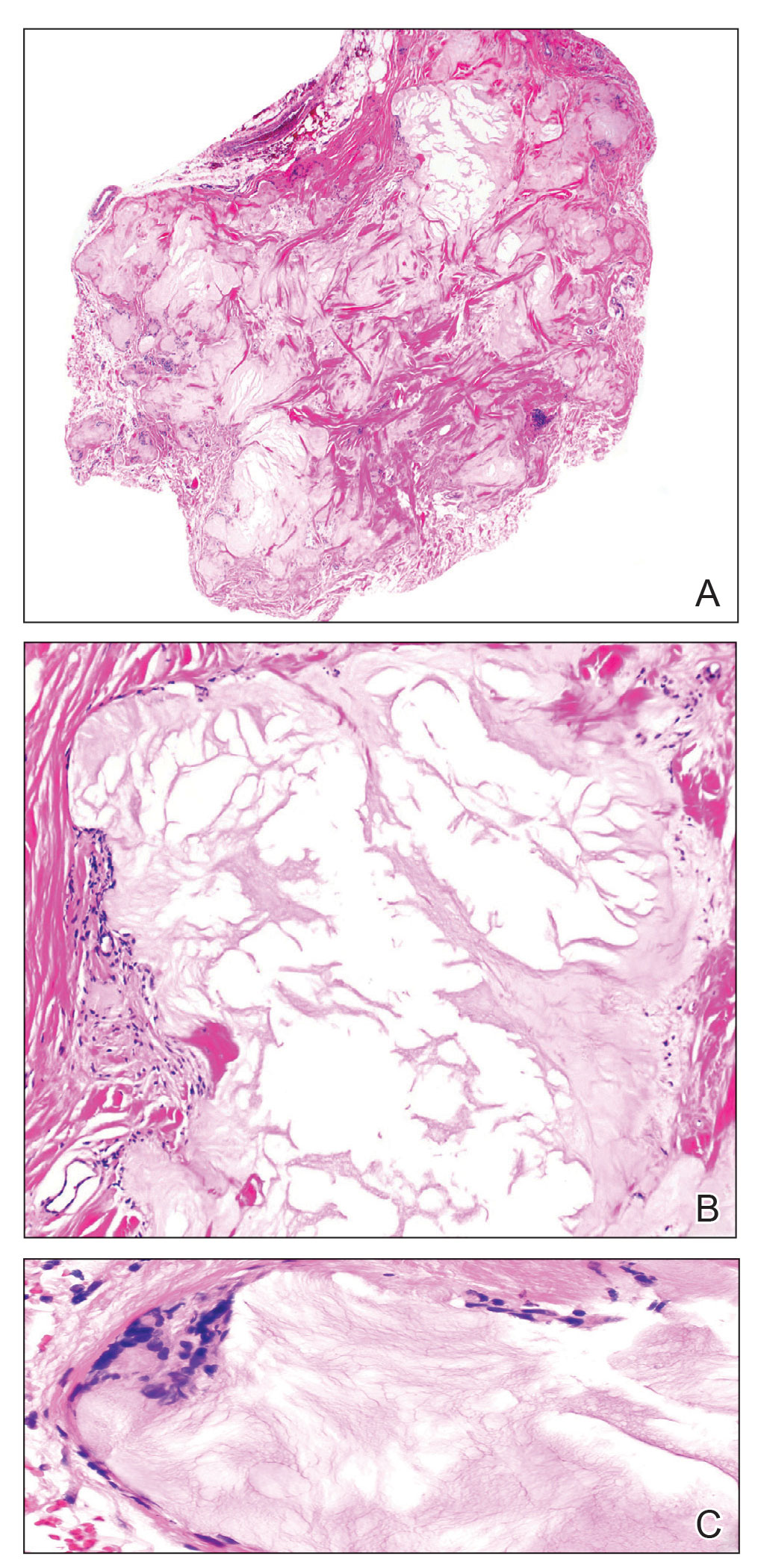

A 59-year-old man presented with innumerable subcutaneous, firm, popcornlike clustered papules on the posterior surfaces of the upper arms and thighs of 5 years’ duration (Figure 1). The involved areas were sometimes painful on manipulation, but the patient was otherwise asymptomatic. His medical history was notable for tophaceous gout of more than 10 years’ duration, calcinosis cutis, adrenal insufficiency, essential hypertension, and an orthotopic heart transplant 2 years prior to the current presentation. At the current presentation he was taking tacrolimus, colchicine, febuxostat, and low-dose prednisone. The patient denied any other skin changes such as ulceration or bullae. In addition to the innumerable subcutaneous papules, he had much larger firm deep nodules bilaterally on the elbow (Figure 2). A complete blood cell count with differential and comprehensive metabolic panel results were within reference range. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the right posterior arm revealed dermal deposits consistent with gout on hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 3) but no calcium deposits on von Kossa staining, consistent with miliarial gout.

He was treated with 0.6 mg of colchicine daily, 80 mg of febuxostat twice daily, and 2.5 mg of prednisone daily. Unfortunately, the patient had difficulty affording his medications and therefore experienced frequent flares.

Gout is caused by inflammation that occurs from deposition of monosodium urate crystals in tissues, most commonly occurring in the skin and joints. Gout affects8.3 million individuals and is one of the most common rheumatic diseases of adulthood. The classic presentation of the acute form is monoarticular with associated swelling, erythema, and pain. The chronic form (also known as tophaceous gout) affects soft tissue and presents with smooth or multilobulated nodules.2 Miliarial gout is a rare variant of chronic tophaceous gout, and the diagnosis is based on atypical location, size, and distribution of tophi deposition.

In the updated American College of Rheumatology criteria for gout published in 2020, tophi are defined as draining or chalklike subcutaneous nodules that typically are located in joints, ears, olecranon bursae, finger pads, and tendons.3 The term miliarial gout, which is not universally defined, is used to describe the morphology and distribution of tophi deposition in areas outside of the typical locations defined by the American College of Rheumatology criteria. Miliarial refers to the small, multilobulated, and disseminated presentation of tophi. The involvement of atypical locations distinguishes miliarial gout from chronic tophaceous gout.

The cause of tophi deposition in atypical locations is unknown. It is thought that patients with a history of sustained hyperuricemia have a much greater burden of urate crystal deposition, which can lead to involvement of atypical locations. Our patient had innumerable, discrete, 1- to 5-mm, multilobulated tophi located on the posterior upper arms and thighs even though his uric acid levels were within reference range over the last 5 years.