User login

‘A huge deal’: Millions have long COVID, and more are expected

with symptoms that have lasted 3 months or longer, according to the latest U.S. government survey done in October. More than a quarter say their condition is severe enough to significantly limit their day-to-day activities – yet the problem is only barely starting to get the attention of employers, the health care system, and policymakers.

With no cure or treatment in sight, long COVID is already burdening not only the health care system, but also the economy – and that burden is set to grow. Many experts worry about the possible long-term ripple effects, from increased spending on medical care costs to lost wages due to not being able to work, as well as the policy implications that come with addressing these issues.

“At this point, anyone who’s looking at this seriously would say this is a huge deal,” says senior Brookings Institution fellow Katie Bach, the author of a study that analyzed long COVID’s impact on the labor market.

“We need a real concerted focus on treating these people, which means both research and the clinical side, and figuring out how to build a labor market that is more inclusive of people with disabilities,” she said.

It’s not only that many people are affected. It’s that they are often affected for months and possibly even years.

The U.S. government figures suggest more than 18 million people could have symptoms of long COVID right now. The latest Household Pulse Survey by the Census Bureau and the National Center for Health Statistics takes data from 41,415 people.

A preprint of a study by researchers from City University of New York, posted on medRxiv in September and based on a similar population survey done between June 30 and July 2, drew comparable results. The study has not been peer reviewed.

More than 7% of all those who answered said they had long COVID at the time of the survey, which the researchers said corresponded to approximately 18.5 million U.S. adults. The same study found that a quarter of those, or an estimated 4.7 million adults, said their daily activities were impacted “a lot.”

This can translate into pain not only for the patients, but for governments and employers, too.

In high-income countries around the world, government surveys and other studies are shedding light on the extent to which post-COVID-19 symptoms – commonly known as long COVID – are affecting populations. While results vary, they generally fall within similar ranges.

The World Health Organization estimates that between 10% and 20% of those with COVID-19 go on to have an array of medium- to long-term post-COVID-19 symptoms that range from mild to debilitating. The U.S. Government Accountability Office puts that estimate at 10% to 30%; one of the latest studies published at the end of October in The Journal of the American Medical Association found that 15% of U.S. adults who had tested positive for COVID-19 reported current long COVID symptoms. Elsewhere, a study from the Netherlands published in The Lancet in August found that one in eight COVID-19 cases, or 12.7%, were likely to become long COVID.

“It’s very clear that the condition is devastating people’s lives and livelihoods,” WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus wrote in an article for The Guardian newspaper in October.

“The world has already lost a significant number of the workforce to illness, death, fatigue, unplanned retirement due to an increase in long-term disability, which not only impacts the health system, but is a hit to the overarching economy … the impact of long COVID for all countries is very serious and needs immediate and sustained action equivalent to its scale.”

Global snapshot: Lasting symptoms, impact on activities

Patients describe a spectrum of persistent issues, with extreme fatigue, brain fog or cognitive problems, and shortness of breath among the most common complaints. Many also have manageable symptoms that worsen significantly after even mild physical or mental exertion.

Women appear almost twice as likely as men to get long COVID. Many patients have other medical conditions and disabilities that make them more vulnerable to the condition. Those who face greater obstacles accessing health care due to discrimination or socioeconomic inequity are at higher risk as well.

While many are older, a large number are also in their prime working age. The Census Bureau data show that people ages 40-49 are more likely than any other group to get long COVID, which has broader implications for labor markets and the global economy. Already, experts have estimated that long COVID is likely to cost the U.S. trillions of dollars and affect multiple industries.

“Whether they’re in the financial world, the medical system, lawyers, they’re telling me they’re sitting at the computer screen and they’re unable to process the data,” said Zachary Schwartz, MD, medical director for Vancouver General Hospital’s Post-COVID-19 Recovery Clinic.

“That is what’s most distressing for people, in that they’re not working, they’re not making money, and they don’t know when, or if, they’re going to get better.”

Nearly a third of respondents in the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey who said they have had COVID-19 reported symptoms that lasted 3 months or longer. People between the ages of 30 and 59 were the most affected, with about 32% reporting symptoms. Across the entire adult U.S. population, the survey found that 1 in 7 adults have had long COVID at some point during the pandemic, with about 1 in 18 saying it limited their activity to some degree, and 1 in 50 saying they have faced “a lot” of limits on their activities. Any way these numbers are dissected, long COVID has impacted a large swath of the population.

Yet research into the causes and possible treatments of long COVID is just getting underway.

“The amount of energy and time devoted to it is way, way less than it should, given how many people are likely affected,” said David Cutler, PhD, professor of economics at Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., who has written about the economic cost of long COVID. “We’re way, way underdoing it here. And I think that’s really a terrible thing.”

Population surveys and studies from around the world show that long COVID lives up to its name, with people reporting serious symptoms for months on end.

In October, Statistics Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada published early results from a questionnaire done between spring and summer 2022 that found just under 15% of adults who had a confirmed or suspected case of COVID-19 went on to have new or continuing symptoms 3 or more months later. Nearly half, or 47.3%, dealt with symptoms that lasted a year or more. More than one in five said their symptoms “often or always” limited their day-to-day activities, which included routine tasks such as preparing meals, doing errands and chores, and basic functions such as personal care and moving around in their homes.

Nearly three-quarters of workers or students said they missed an average of 20 days of work or school.

“We haven’t yet been able to determine exactly when symptoms resolve,” said Rainu Kaushal, MD, the senior associate dean for clinical research at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York. She is co-leading a national study on long COVID in adults and children, funded by the National Institutes of Health RECOVER Initiative.

“But there does seem to be, for many of the milder symptoms, resolution at about 4-6 weeks. There seems to be a second point of resolution around 6 months for certain symptoms, and then some symptoms do seem to be permanent, and those tend to be patients who have underlying conditions,” she said.

Reducing the risk

Given all the data so far, experts recommend urgent policy changes to help people with long COVID.

“The population needs to be prepared, that understanding long COVID is going to be a very long and difficult process,” said Alexander Charney, MD, PhD, associate professor and the lead principal investigator of the RECOVER adult cohort at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. He said the government can do a great deal to help, including setting up a network of connected clinics treating long COVID, standardizing best practices, and sharing information.

“That would go a long way towards making sure that every person feels like they’re not too far away from a clinic where they can get treated for this particular condition,” he said.

But the only known way to prevent long COVID is to prevent COVID-19 infections in the first place, experts say. That means equitable access to tests, therapeutics, and vaccines.

“I will say that avoiding COVID remains the best treatment in the arsenal right now,” said Dr. Kaushal. This means masking, avoiding crowded places with poor ventilation and high exposure risk, and being up to date on vaccinations, she said.

A number of papers – including a large U.K. study published in May 2022, another one from July, and the JAMA study from October – all suggest that vaccinations can help reduce the risk of long COVID.

“I am absolutely of the belief that vaccination has reduced the incidence and overall amount of long COVID … [and is] still by far the best thing the public can do,” said Dr. Schwartz.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

with symptoms that have lasted 3 months or longer, according to the latest U.S. government survey done in October. More than a quarter say their condition is severe enough to significantly limit their day-to-day activities – yet the problem is only barely starting to get the attention of employers, the health care system, and policymakers.

With no cure or treatment in sight, long COVID is already burdening not only the health care system, but also the economy – and that burden is set to grow. Many experts worry about the possible long-term ripple effects, from increased spending on medical care costs to lost wages due to not being able to work, as well as the policy implications that come with addressing these issues.

“At this point, anyone who’s looking at this seriously would say this is a huge deal,” says senior Brookings Institution fellow Katie Bach, the author of a study that analyzed long COVID’s impact on the labor market.

“We need a real concerted focus on treating these people, which means both research and the clinical side, and figuring out how to build a labor market that is more inclusive of people with disabilities,” she said.

It’s not only that many people are affected. It’s that they are often affected for months and possibly even years.

The U.S. government figures suggest more than 18 million people could have symptoms of long COVID right now. The latest Household Pulse Survey by the Census Bureau and the National Center for Health Statistics takes data from 41,415 people.

A preprint of a study by researchers from City University of New York, posted on medRxiv in September and based on a similar population survey done between June 30 and July 2, drew comparable results. The study has not been peer reviewed.

More than 7% of all those who answered said they had long COVID at the time of the survey, which the researchers said corresponded to approximately 18.5 million U.S. adults. The same study found that a quarter of those, or an estimated 4.7 million adults, said their daily activities were impacted “a lot.”

This can translate into pain not only for the patients, but for governments and employers, too.

In high-income countries around the world, government surveys and other studies are shedding light on the extent to which post-COVID-19 symptoms – commonly known as long COVID – are affecting populations. While results vary, they generally fall within similar ranges.

The World Health Organization estimates that between 10% and 20% of those with COVID-19 go on to have an array of medium- to long-term post-COVID-19 symptoms that range from mild to debilitating. The U.S. Government Accountability Office puts that estimate at 10% to 30%; one of the latest studies published at the end of October in The Journal of the American Medical Association found that 15% of U.S. adults who had tested positive for COVID-19 reported current long COVID symptoms. Elsewhere, a study from the Netherlands published in The Lancet in August found that one in eight COVID-19 cases, or 12.7%, were likely to become long COVID.

“It’s very clear that the condition is devastating people’s lives and livelihoods,” WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus wrote in an article for The Guardian newspaper in October.

“The world has already lost a significant number of the workforce to illness, death, fatigue, unplanned retirement due to an increase in long-term disability, which not only impacts the health system, but is a hit to the overarching economy … the impact of long COVID for all countries is very serious and needs immediate and sustained action equivalent to its scale.”

Global snapshot: Lasting symptoms, impact on activities

Patients describe a spectrum of persistent issues, with extreme fatigue, brain fog or cognitive problems, and shortness of breath among the most common complaints. Many also have manageable symptoms that worsen significantly after even mild physical or mental exertion.

Women appear almost twice as likely as men to get long COVID. Many patients have other medical conditions and disabilities that make them more vulnerable to the condition. Those who face greater obstacles accessing health care due to discrimination or socioeconomic inequity are at higher risk as well.

While many are older, a large number are also in their prime working age. The Census Bureau data show that people ages 40-49 are more likely than any other group to get long COVID, which has broader implications for labor markets and the global economy. Already, experts have estimated that long COVID is likely to cost the U.S. trillions of dollars and affect multiple industries.

“Whether they’re in the financial world, the medical system, lawyers, they’re telling me they’re sitting at the computer screen and they’re unable to process the data,” said Zachary Schwartz, MD, medical director for Vancouver General Hospital’s Post-COVID-19 Recovery Clinic.

“That is what’s most distressing for people, in that they’re not working, they’re not making money, and they don’t know when, or if, they’re going to get better.”

Nearly a third of respondents in the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey who said they have had COVID-19 reported symptoms that lasted 3 months or longer. People between the ages of 30 and 59 were the most affected, with about 32% reporting symptoms. Across the entire adult U.S. population, the survey found that 1 in 7 adults have had long COVID at some point during the pandemic, with about 1 in 18 saying it limited their activity to some degree, and 1 in 50 saying they have faced “a lot” of limits on their activities. Any way these numbers are dissected, long COVID has impacted a large swath of the population.

Yet research into the causes and possible treatments of long COVID is just getting underway.

“The amount of energy and time devoted to it is way, way less than it should, given how many people are likely affected,” said David Cutler, PhD, professor of economics at Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., who has written about the economic cost of long COVID. “We’re way, way underdoing it here. And I think that’s really a terrible thing.”

Population surveys and studies from around the world show that long COVID lives up to its name, with people reporting serious symptoms for months on end.

In October, Statistics Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada published early results from a questionnaire done between spring and summer 2022 that found just under 15% of adults who had a confirmed or suspected case of COVID-19 went on to have new or continuing symptoms 3 or more months later. Nearly half, or 47.3%, dealt with symptoms that lasted a year or more. More than one in five said their symptoms “often or always” limited their day-to-day activities, which included routine tasks such as preparing meals, doing errands and chores, and basic functions such as personal care and moving around in their homes.

Nearly three-quarters of workers or students said they missed an average of 20 days of work or school.

“We haven’t yet been able to determine exactly when symptoms resolve,” said Rainu Kaushal, MD, the senior associate dean for clinical research at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York. She is co-leading a national study on long COVID in adults and children, funded by the National Institutes of Health RECOVER Initiative.

“But there does seem to be, for many of the milder symptoms, resolution at about 4-6 weeks. There seems to be a second point of resolution around 6 months for certain symptoms, and then some symptoms do seem to be permanent, and those tend to be patients who have underlying conditions,” she said.

Reducing the risk

Given all the data so far, experts recommend urgent policy changes to help people with long COVID.

“The population needs to be prepared, that understanding long COVID is going to be a very long and difficult process,” said Alexander Charney, MD, PhD, associate professor and the lead principal investigator of the RECOVER adult cohort at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. He said the government can do a great deal to help, including setting up a network of connected clinics treating long COVID, standardizing best practices, and sharing information.

“That would go a long way towards making sure that every person feels like they’re not too far away from a clinic where they can get treated for this particular condition,” he said.

But the only known way to prevent long COVID is to prevent COVID-19 infections in the first place, experts say. That means equitable access to tests, therapeutics, and vaccines.

“I will say that avoiding COVID remains the best treatment in the arsenal right now,” said Dr. Kaushal. This means masking, avoiding crowded places with poor ventilation and high exposure risk, and being up to date on vaccinations, she said.

A number of papers – including a large U.K. study published in May 2022, another one from July, and the JAMA study from October – all suggest that vaccinations can help reduce the risk of long COVID.

“I am absolutely of the belief that vaccination has reduced the incidence and overall amount of long COVID … [and is] still by far the best thing the public can do,” said Dr. Schwartz.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

with symptoms that have lasted 3 months or longer, according to the latest U.S. government survey done in October. More than a quarter say their condition is severe enough to significantly limit their day-to-day activities – yet the problem is only barely starting to get the attention of employers, the health care system, and policymakers.

With no cure or treatment in sight, long COVID is already burdening not only the health care system, but also the economy – and that burden is set to grow. Many experts worry about the possible long-term ripple effects, from increased spending on medical care costs to lost wages due to not being able to work, as well as the policy implications that come with addressing these issues.

“At this point, anyone who’s looking at this seriously would say this is a huge deal,” says senior Brookings Institution fellow Katie Bach, the author of a study that analyzed long COVID’s impact on the labor market.

“We need a real concerted focus on treating these people, which means both research and the clinical side, and figuring out how to build a labor market that is more inclusive of people with disabilities,” she said.

It’s not only that many people are affected. It’s that they are often affected for months and possibly even years.

The U.S. government figures suggest more than 18 million people could have symptoms of long COVID right now. The latest Household Pulse Survey by the Census Bureau and the National Center for Health Statistics takes data from 41,415 people.

A preprint of a study by researchers from City University of New York, posted on medRxiv in September and based on a similar population survey done between June 30 and July 2, drew comparable results. The study has not been peer reviewed.

More than 7% of all those who answered said they had long COVID at the time of the survey, which the researchers said corresponded to approximately 18.5 million U.S. adults. The same study found that a quarter of those, or an estimated 4.7 million adults, said their daily activities were impacted “a lot.”

This can translate into pain not only for the patients, but for governments and employers, too.

In high-income countries around the world, government surveys and other studies are shedding light on the extent to which post-COVID-19 symptoms – commonly known as long COVID – are affecting populations. While results vary, they generally fall within similar ranges.

The World Health Organization estimates that between 10% and 20% of those with COVID-19 go on to have an array of medium- to long-term post-COVID-19 symptoms that range from mild to debilitating. The U.S. Government Accountability Office puts that estimate at 10% to 30%; one of the latest studies published at the end of October in The Journal of the American Medical Association found that 15% of U.S. adults who had tested positive for COVID-19 reported current long COVID symptoms. Elsewhere, a study from the Netherlands published in The Lancet in August found that one in eight COVID-19 cases, or 12.7%, were likely to become long COVID.

“It’s very clear that the condition is devastating people’s lives and livelihoods,” WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus wrote in an article for The Guardian newspaper in October.

“The world has already lost a significant number of the workforce to illness, death, fatigue, unplanned retirement due to an increase in long-term disability, which not only impacts the health system, but is a hit to the overarching economy … the impact of long COVID for all countries is very serious and needs immediate and sustained action equivalent to its scale.”

Global snapshot: Lasting symptoms, impact on activities

Patients describe a spectrum of persistent issues, with extreme fatigue, brain fog or cognitive problems, and shortness of breath among the most common complaints. Many also have manageable symptoms that worsen significantly after even mild physical or mental exertion.

Women appear almost twice as likely as men to get long COVID. Many patients have other medical conditions and disabilities that make them more vulnerable to the condition. Those who face greater obstacles accessing health care due to discrimination or socioeconomic inequity are at higher risk as well.

While many are older, a large number are also in their prime working age. The Census Bureau data show that people ages 40-49 are more likely than any other group to get long COVID, which has broader implications for labor markets and the global economy. Already, experts have estimated that long COVID is likely to cost the U.S. trillions of dollars and affect multiple industries.

“Whether they’re in the financial world, the medical system, lawyers, they’re telling me they’re sitting at the computer screen and they’re unable to process the data,” said Zachary Schwartz, MD, medical director for Vancouver General Hospital’s Post-COVID-19 Recovery Clinic.

“That is what’s most distressing for people, in that they’re not working, they’re not making money, and they don’t know when, or if, they’re going to get better.”

Nearly a third of respondents in the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey who said they have had COVID-19 reported symptoms that lasted 3 months or longer. People between the ages of 30 and 59 were the most affected, with about 32% reporting symptoms. Across the entire adult U.S. population, the survey found that 1 in 7 adults have had long COVID at some point during the pandemic, with about 1 in 18 saying it limited their activity to some degree, and 1 in 50 saying they have faced “a lot” of limits on their activities. Any way these numbers are dissected, long COVID has impacted a large swath of the population.

Yet research into the causes and possible treatments of long COVID is just getting underway.

“The amount of energy and time devoted to it is way, way less than it should, given how many people are likely affected,” said David Cutler, PhD, professor of economics at Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., who has written about the economic cost of long COVID. “We’re way, way underdoing it here. And I think that’s really a terrible thing.”

Population surveys and studies from around the world show that long COVID lives up to its name, with people reporting serious symptoms for months on end.

In October, Statistics Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada published early results from a questionnaire done between spring and summer 2022 that found just under 15% of adults who had a confirmed or suspected case of COVID-19 went on to have new or continuing symptoms 3 or more months later. Nearly half, or 47.3%, dealt with symptoms that lasted a year or more. More than one in five said their symptoms “often or always” limited their day-to-day activities, which included routine tasks such as preparing meals, doing errands and chores, and basic functions such as personal care and moving around in their homes.

Nearly three-quarters of workers or students said they missed an average of 20 days of work or school.

“We haven’t yet been able to determine exactly when symptoms resolve,” said Rainu Kaushal, MD, the senior associate dean for clinical research at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York. She is co-leading a national study on long COVID in adults and children, funded by the National Institutes of Health RECOVER Initiative.

“But there does seem to be, for many of the milder symptoms, resolution at about 4-6 weeks. There seems to be a second point of resolution around 6 months for certain symptoms, and then some symptoms do seem to be permanent, and those tend to be patients who have underlying conditions,” she said.

Reducing the risk

Given all the data so far, experts recommend urgent policy changes to help people with long COVID.

“The population needs to be prepared, that understanding long COVID is going to be a very long and difficult process,” said Alexander Charney, MD, PhD, associate professor and the lead principal investigator of the RECOVER adult cohort at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. He said the government can do a great deal to help, including setting up a network of connected clinics treating long COVID, standardizing best practices, and sharing information.

“That would go a long way towards making sure that every person feels like they’re not too far away from a clinic where they can get treated for this particular condition,” he said.

But the only known way to prevent long COVID is to prevent COVID-19 infections in the first place, experts say. That means equitable access to tests, therapeutics, and vaccines.

“I will say that avoiding COVID remains the best treatment in the arsenal right now,” said Dr. Kaushal. This means masking, avoiding crowded places with poor ventilation and high exposure risk, and being up to date on vaccinations, she said.

A number of papers – including a large U.K. study published in May 2022, another one from July, and the JAMA study from October – all suggest that vaccinations can help reduce the risk of long COVID.

“I am absolutely of the belief that vaccination has reduced the incidence and overall amount of long COVID … [and is] still by far the best thing the public can do,” said Dr. Schwartz.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

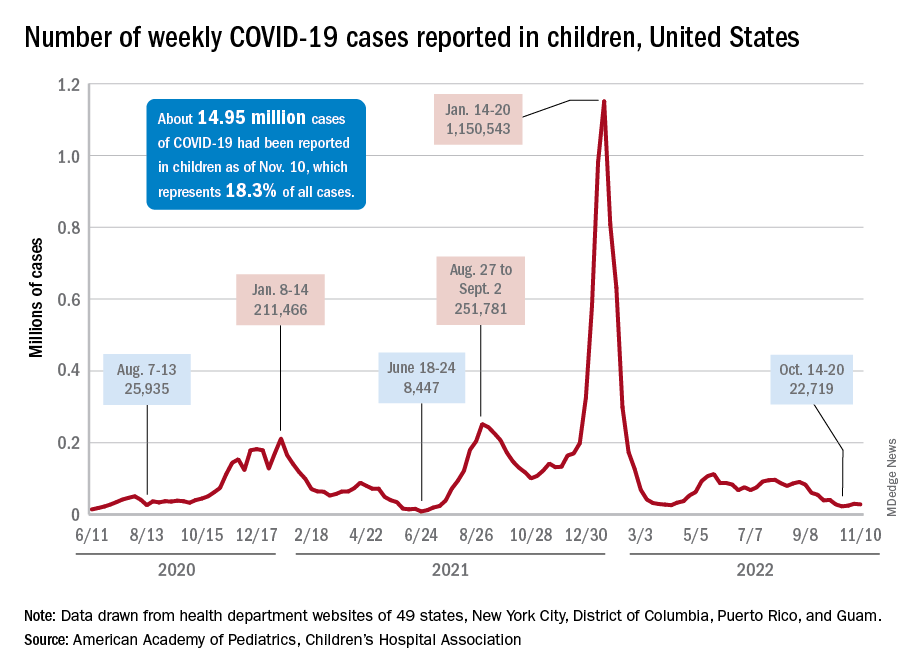

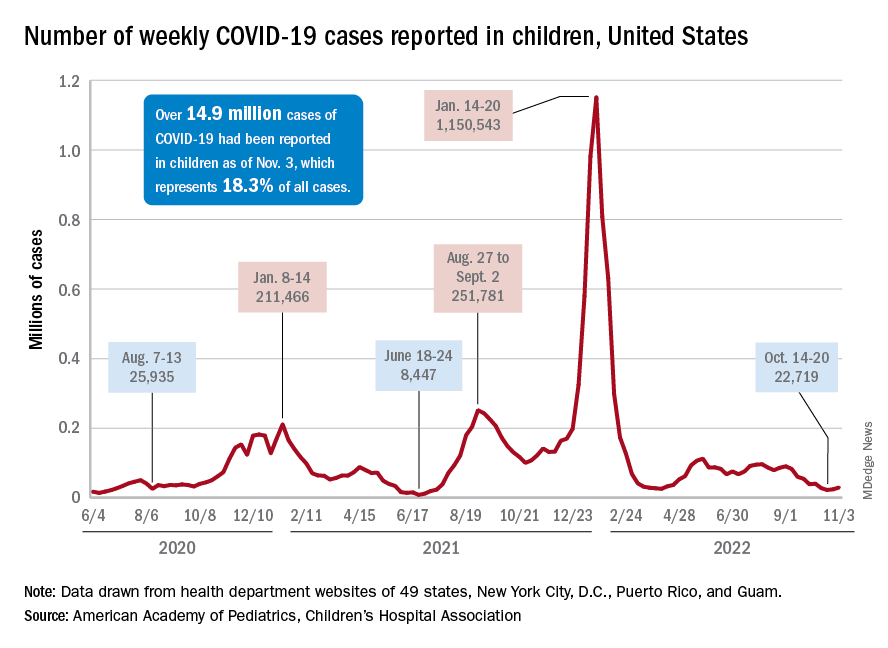

Children and COVID: Weekly cases continue to hold fairly steady

The incidence of new COVID-19 cases in children seems to have stabilized as the national count remained under 30,000 for the fifth consecutive week, but hospitalization data may indicate some possible turbulence.

Just over 28,000 pediatric cases were reported during the week of Nov. 4-10, a drop of 5.4% from the previous week, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report involving data from state and territorial health departments, several of which are no longer updating their websites.

The stability in weekly cases, however, comes in contrast to a very recent and considerable increase in new hospital admissions of children aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID-19. That rate, which was 0.18 hospitalizations per 100,000 population on Nov. 7 and 0.19 per 100,000 on Nov. 8 and 9, jumped all the way to 0.34 on Nov. 10 and 0.48 on Nov. 11, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That is the highest rate since the closing days of the Omicron surge in February.

The rate for Nov. 12, the most recent one available, was down slightly to 0.47 admissions per 100,000. There doesn’t seem to be any evidence in the CDC’s data of a similar sudden increase in new hospitalizations among any other age group, and no age group, including children, shows any sign of a recent increase in emergency department visits with diagnosed COVID. (The CDC has not yet responded to our inquiry about this development.)

The two most recent 7-day averages for new admissions in children aged 0-17 show a small increase, but they cover the periods of Oct. 15 to Oct. 31, when there were 126 admissions per day, and Nov. 1 to Nov. 7, when the average went up to 133 per day, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The CDC does not publish a weekly count of new COVID cases, but its latest data on the rate of incident cases seem to agree with the AAP/CHA figures: A gradual decline in all age groups, including children, since the beginning of September.

Vaccinations, on the other hand, bucked their recent trend and increased in the last week. About 43,000 children under age 5 years received their initial dose of COVID vaccine during Nov. 3-9, compared with 30,000 and 33,000 the 2 previous weeks, while 5- to 11-year-olds hit their highest weekly mark (31,000) since late August and 12- to 17-year-olds had their biggest week (27,000) since mid-August, the AAP reported based on CDC data.

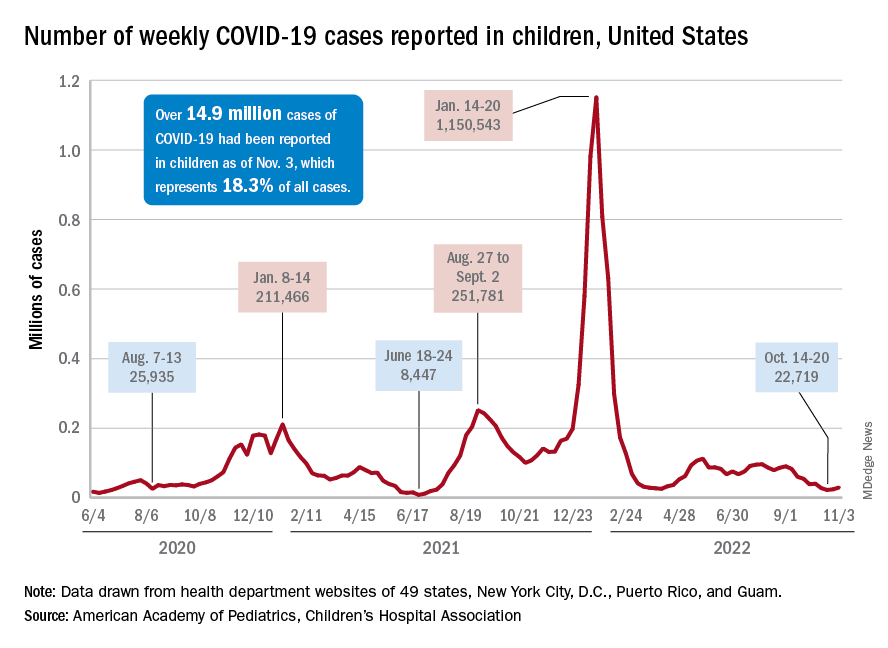

The incidence of new COVID-19 cases in children seems to have stabilized as the national count remained under 30,000 for the fifth consecutive week, but hospitalization data may indicate some possible turbulence.

Just over 28,000 pediatric cases were reported during the week of Nov. 4-10, a drop of 5.4% from the previous week, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report involving data from state and territorial health departments, several of which are no longer updating their websites.

The stability in weekly cases, however, comes in contrast to a very recent and considerable increase in new hospital admissions of children aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID-19. That rate, which was 0.18 hospitalizations per 100,000 population on Nov. 7 and 0.19 per 100,000 on Nov. 8 and 9, jumped all the way to 0.34 on Nov. 10 and 0.48 on Nov. 11, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That is the highest rate since the closing days of the Omicron surge in February.

The rate for Nov. 12, the most recent one available, was down slightly to 0.47 admissions per 100,000. There doesn’t seem to be any evidence in the CDC’s data of a similar sudden increase in new hospitalizations among any other age group, and no age group, including children, shows any sign of a recent increase in emergency department visits with diagnosed COVID. (The CDC has not yet responded to our inquiry about this development.)

The two most recent 7-day averages for new admissions in children aged 0-17 show a small increase, but they cover the periods of Oct. 15 to Oct. 31, when there were 126 admissions per day, and Nov. 1 to Nov. 7, when the average went up to 133 per day, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The CDC does not publish a weekly count of new COVID cases, but its latest data on the rate of incident cases seem to agree with the AAP/CHA figures: A gradual decline in all age groups, including children, since the beginning of September.

Vaccinations, on the other hand, bucked their recent trend and increased in the last week. About 43,000 children under age 5 years received their initial dose of COVID vaccine during Nov. 3-9, compared with 30,000 and 33,000 the 2 previous weeks, while 5- to 11-year-olds hit their highest weekly mark (31,000) since late August and 12- to 17-year-olds had their biggest week (27,000) since mid-August, the AAP reported based on CDC data.

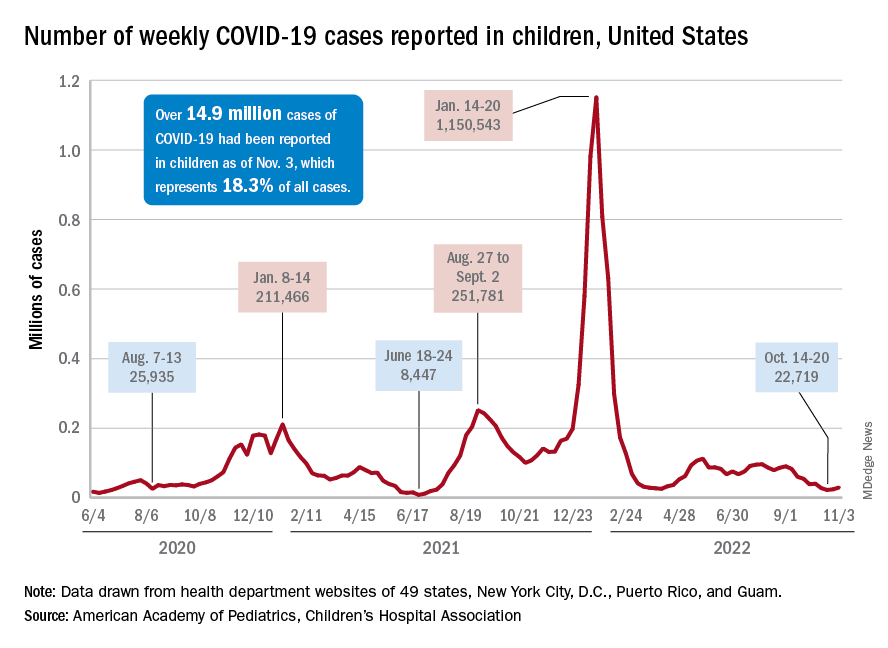

The incidence of new COVID-19 cases in children seems to have stabilized as the national count remained under 30,000 for the fifth consecutive week, but hospitalization data may indicate some possible turbulence.

Just over 28,000 pediatric cases were reported during the week of Nov. 4-10, a drop of 5.4% from the previous week, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report involving data from state and territorial health departments, several of which are no longer updating their websites.

The stability in weekly cases, however, comes in contrast to a very recent and considerable increase in new hospital admissions of children aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID-19. That rate, which was 0.18 hospitalizations per 100,000 population on Nov. 7 and 0.19 per 100,000 on Nov. 8 and 9, jumped all the way to 0.34 on Nov. 10 and 0.48 on Nov. 11, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That is the highest rate since the closing days of the Omicron surge in February.

The rate for Nov. 12, the most recent one available, was down slightly to 0.47 admissions per 100,000. There doesn’t seem to be any evidence in the CDC’s data of a similar sudden increase in new hospitalizations among any other age group, and no age group, including children, shows any sign of a recent increase in emergency department visits with diagnosed COVID. (The CDC has not yet responded to our inquiry about this development.)

The two most recent 7-day averages for new admissions in children aged 0-17 show a small increase, but they cover the periods of Oct. 15 to Oct. 31, when there were 126 admissions per day, and Nov. 1 to Nov. 7, when the average went up to 133 per day, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The CDC does not publish a weekly count of new COVID cases, but its latest data on the rate of incident cases seem to agree with the AAP/CHA figures: A gradual decline in all age groups, including children, since the beginning of September.

Vaccinations, on the other hand, bucked their recent trend and increased in the last week. About 43,000 children under age 5 years received their initial dose of COVID vaccine during Nov. 3-9, compared with 30,000 and 33,000 the 2 previous weeks, while 5- to 11-year-olds hit their highest weekly mark (31,000) since late August and 12- to 17-year-olds had their biggest week (27,000) since mid-August, the AAP reported based on CDC data.

Love them or hate them, masks in schools work

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

On March 26, 2022, Hawaii became the last state in the United States to lift its indoor mask mandate. By the time the current school year started, there were essentially no public school mask mandates either.

Whether you viewed the mask as an emblem of stalwart defiance against a rampaging virus, or a scarlet letter emblematic of the overreaches of public policy, you probably aren’t seeing them much anymore.

And yet, the debate about masks still rages. Who was right, who was wrong? Who trusted science, and what does the science even say? If we brought our country into marriage counseling, would we be told it is time to move on? To look forward, not backward? To plan for our bright future together?

Perhaps. But this question isn’t really moot just because masks have largely disappeared in the United States. Variants may emerge that lead to more infection waves – and other pandemics may occur in the future. And so I think it is important to discuss a study that, with quite rigorous analysis, attempts to answer the following question: Did masking in schools lower students’ and teachers’ risk of COVID?

We are talking about this study, appearing in the New England Journal of Medicine. The short version goes like this.

Researchers had access to two important sources of data. One – an accounting of all the teachers and students (more than 300,000 of them) in 79 public, noncharter school districts in Eastern Massachusetts who tested positive for COVID every week. Two – the date that each of those school districts lifted their mask mandates or (in the case of two districts) didn’t.

Right away, I’m sure you’re thinking of potential issues. Districts that kept masks even when the statewide ban was lifted are likely quite a bit different from districts that dropped masks right away. You’re right, of course – hold on to that thought; we’ll get there.

But first – the big question – would districts that kept their masks on longer do better when it comes to the rate of COVID infection?

When everyone was masking, COVID case rates were pretty similar. Statewide mandates are lifted in late February – and most school districts remove their mandates within a few weeks – the black line are the two districts (Boston and Chelsea) where mask mandates remained in place.

Prior to the mask mandate lifting, you see very similar COVID rates in districts that would eventually remove the mandate and those that would not, with a bit of noise around the initial Omicron wave which saw just a huge amount of people get infected.

And then, after the mandate was lifted, separation. Districts that held on to masks longer had lower rates of COVID infection.

In all, over the 15-weeks of the study, there were roughly 12,000 extra cases of COVID in the mask-free school districts, which corresponds to about 35% of the total COVID burden during that time. And, yes, kids do well with COVID – on average. But 12,000 extra cases is enough to translate into a significant number of important clinical outcomes – think hospitalizations and post-COVID syndromes. And of course, maybe most importantly, missed school days. Positive kids were not allowed in class no matter what district they were in.

Okay – I promised we’d address confounders. This was not a cluster-randomized trial, where some school districts had their mandates removed based on the vicissitudes of a virtual coin flip, as much as many of us would have been interested to see that. The decision to remove masks was up to the various school boards – and they had a lot of pressure on them from many different directions. But all we need to worry about is whether any of those things that pressure a school board to keep masks on would ALSO lead to fewer COVID cases. That’s how confounders work, and how you can get false results in a study like this.

And yes – districts that kept the masks on longer were different than those who took them right off. But check out how they were different.

The districts that kept masks on longer had more low-income students. More Black and Latino students. More students per classroom. These are all risk factors that increase the risk of COVID infection. In other words, the confounding here goes in the opposite direction of the results. If anything, these factors should make you more certain that masking works.

The authors also adjusted for other factors – the community transmission of COVID-19, vaccination rates, school district sizes, and so on. No major change in the results.

One concern I addressed to Dr. Ellie Murray, the biostatistician on the study – could districts that removed masks simply have been testing more to compensate, leading to increased capturing of cases?

If anything, the schools that kept masks on were testing more than the schools that took them off – again that would tend to imply that the results are even stronger than what was reported.

Is this a perfect study? Of course not – it’s one study, it’s from one state. And the relatively large effects from keeping masks on for one or 2 weeks require us to really embrace the concept of exponential growth of infections, but, if COVID has taught us anything, it is that small changes in initial conditions can have pretty big effects.

My daughter, who goes to a public school here in Connecticut, unmasked, was home with COVID this past week. She’s fine. But you know what? She missed a week of school. I worked from home to be with her – though I didn’t test positive. And that is a real cost to both of us that I think we need to consider when we consider the value of masks. Yes, they’re annoying – but if they keep kids in school, might they be worth it? Perhaps not for now, as cases aren’t surging. But in the future, be it a particularly concerning variant, or a whole new pandemic, we should not discount the simple, cheap, and apparently beneficial act of wearing masks to decrease transmission.

Dr. Perry Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

On March 26, 2022, Hawaii became the last state in the United States to lift its indoor mask mandate. By the time the current school year started, there were essentially no public school mask mandates either.

Whether you viewed the mask as an emblem of stalwart defiance against a rampaging virus, or a scarlet letter emblematic of the overreaches of public policy, you probably aren’t seeing them much anymore.

And yet, the debate about masks still rages. Who was right, who was wrong? Who trusted science, and what does the science even say? If we brought our country into marriage counseling, would we be told it is time to move on? To look forward, not backward? To plan for our bright future together?

Perhaps. But this question isn’t really moot just because masks have largely disappeared in the United States. Variants may emerge that lead to more infection waves – and other pandemics may occur in the future. And so I think it is important to discuss a study that, with quite rigorous analysis, attempts to answer the following question: Did masking in schools lower students’ and teachers’ risk of COVID?

We are talking about this study, appearing in the New England Journal of Medicine. The short version goes like this.

Researchers had access to two important sources of data. One – an accounting of all the teachers and students (more than 300,000 of them) in 79 public, noncharter school districts in Eastern Massachusetts who tested positive for COVID every week. Two – the date that each of those school districts lifted their mask mandates or (in the case of two districts) didn’t.

Right away, I’m sure you’re thinking of potential issues. Districts that kept masks even when the statewide ban was lifted are likely quite a bit different from districts that dropped masks right away. You’re right, of course – hold on to that thought; we’ll get there.

But first – the big question – would districts that kept their masks on longer do better when it comes to the rate of COVID infection?

When everyone was masking, COVID case rates were pretty similar. Statewide mandates are lifted in late February – and most school districts remove their mandates within a few weeks – the black line are the two districts (Boston and Chelsea) where mask mandates remained in place.

Prior to the mask mandate lifting, you see very similar COVID rates in districts that would eventually remove the mandate and those that would not, with a bit of noise around the initial Omicron wave which saw just a huge amount of people get infected.

And then, after the mandate was lifted, separation. Districts that held on to masks longer had lower rates of COVID infection.

In all, over the 15-weeks of the study, there were roughly 12,000 extra cases of COVID in the mask-free school districts, which corresponds to about 35% of the total COVID burden during that time. And, yes, kids do well with COVID – on average. But 12,000 extra cases is enough to translate into a significant number of important clinical outcomes – think hospitalizations and post-COVID syndromes. And of course, maybe most importantly, missed school days. Positive kids were not allowed in class no matter what district they were in.

Okay – I promised we’d address confounders. This was not a cluster-randomized trial, where some school districts had their mandates removed based on the vicissitudes of a virtual coin flip, as much as many of us would have been interested to see that. The decision to remove masks was up to the various school boards – and they had a lot of pressure on them from many different directions. But all we need to worry about is whether any of those things that pressure a school board to keep masks on would ALSO lead to fewer COVID cases. That’s how confounders work, and how you can get false results in a study like this.

And yes – districts that kept the masks on longer were different than those who took them right off. But check out how they were different.

The districts that kept masks on longer had more low-income students. More Black and Latino students. More students per classroom. These are all risk factors that increase the risk of COVID infection. In other words, the confounding here goes in the opposite direction of the results. If anything, these factors should make you more certain that masking works.

The authors also adjusted for other factors – the community transmission of COVID-19, vaccination rates, school district sizes, and so on. No major change in the results.

One concern I addressed to Dr. Ellie Murray, the biostatistician on the study – could districts that removed masks simply have been testing more to compensate, leading to increased capturing of cases?

If anything, the schools that kept masks on were testing more than the schools that took them off – again that would tend to imply that the results are even stronger than what was reported.

Is this a perfect study? Of course not – it’s one study, it’s from one state. And the relatively large effects from keeping masks on for one or 2 weeks require us to really embrace the concept of exponential growth of infections, but, if COVID has taught us anything, it is that small changes in initial conditions can have pretty big effects.

My daughter, who goes to a public school here in Connecticut, unmasked, was home with COVID this past week. She’s fine. But you know what? She missed a week of school. I worked from home to be with her – though I didn’t test positive. And that is a real cost to both of us that I think we need to consider when we consider the value of masks. Yes, they’re annoying – but if they keep kids in school, might they be worth it? Perhaps not for now, as cases aren’t surging. But in the future, be it a particularly concerning variant, or a whole new pandemic, we should not discount the simple, cheap, and apparently beneficial act of wearing masks to decrease transmission.

Dr. Perry Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

On March 26, 2022, Hawaii became the last state in the United States to lift its indoor mask mandate. By the time the current school year started, there were essentially no public school mask mandates either.

Whether you viewed the mask as an emblem of stalwart defiance against a rampaging virus, or a scarlet letter emblematic of the overreaches of public policy, you probably aren’t seeing them much anymore.

And yet, the debate about masks still rages. Who was right, who was wrong? Who trusted science, and what does the science even say? If we brought our country into marriage counseling, would we be told it is time to move on? To look forward, not backward? To plan for our bright future together?

Perhaps. But this question isn’t really moot just because masks have largely disappeared in the United States. Variants may emerge that lead to more infection waves – and other pandemics may occur in the future. And so I think it is important to discuss a study that, with quite rigorous analysis, attempts to answer the following question: Did masking in schools lower students’ and teachers’ risk of COVID?

We are talking about this study, appearing in the New England Journal of Medicine. The short version goes like this.

Researchers had access to two important sources of data. One – an accounting of all the teachers and students (more than 300,000 of them) in 79 public, noncharter school districts in Eastern Massachusetts who tested positive for COVID every week. Two – the date that each of those school districts lifted their mask mandates or (in the case of two districts) didn’t.

Right away, I’m sure you’re thinking of potential issues. Districts that kept masks even when the statewide ban was lifted are likely quite a bit different from districts that dropped masks right away. You’re right, of course – hold on to that thought; we’ll get there.

But first – the big question – would districts that kept their masks on longer do better when it comes to the rate of COVID infection?

When everyone was masking, COVID case rates were pretty similar. Statewide mandates are lifted in late February – and most school districts remove their mandates within a few weeks – the black line are the two districts (Boston and Chelsea) where mask mandates remained in place.

Prior to the mask mandate lifting, you see very similar COVID rates in districts that would eventually remove the mandate and those that would not, with a bit of noise around the initial Omicron wave which saw just a huge amount of people get infected.

And then, after the mandate was lifted, separation. Districts that held on to masks longer had lower rates of COVID infection.

In all, over the 15-weeks of the study, there were roughly 12,000 extra cases of COVID in the mask-free school districts, which corresponds to about 35% of the total COVID burden during that time. And, yes, kids do well with COVID – on average. But 12,000 extra cases is enough to translate into a significant number of important clinical outcomes – think hospitalizations and post-COVID syndromes. And of course, maybe most importantly, missed school days. Positive kids were not allowed in class no matter what district they were in.

Okay – I promised we’d address confounders. This was not a cluster-randomized trial, where some school districts had their mandates removed based on the vicissitudes of a virtual coin flip, as much as many of us would have been interested to see that. The decision to remove masks was up to the various school boards – and they had a lot of pressure on them from many different directions. But all we need to worry about is whether any of those things that pressure a school board to keep masks on would ALSO lead to fewer COVID cases. That’s how confounders work, and how you can get false results in a study like this.

And yes – districts that kept the masks on longer were different than those who took them right off. But check out how they were different.

The districts that kept masks on longer had more low-income students. More Black and Latino students. More students per classroom. These are all risk factors that increase the risk of COVID infection. In other words, the confounding here goes in the opposite direction of the results. If anything, these factors should make you more certain that masking works.

The authors also adjusted for other factors – the community transmission of COVID-19, vaccination rates, school district sizes, and so on. No major change in the results.

One concern I addressed to Dr. Ellie Murray, the biostatistician on the study – could districts that removed masks simply have been testing more to compensate, leading to increased capturing of cases?

If anything, the schools that kept masks on were testing more than the schools that took them off – again that would tend to imply that the results are even stronger than what was reported.

Is this a perfect study? Of course not – it’s one study, it’s from one state. And the relatively large effects from keeping masks on for one or 2 weeks require us to really embrace the concept of exponential growth of infections, but, if COVID has taught us anything, it is that small changes in initial conditions can have pretty big effects.

My daughter, who goes to a public school here in Connecticut, unmasked, was home with COVID this past week. She’s fine. But you know what? She missed a week of school. I worked from home to be with her – though I didn’t test positive. And that is a real cost to both of us that I think we need to consider when we consider the value of masks. Yes, they’re annoying – but if they keep kids in school, might they be worth it? Perhaps not for now, as cases aren’t surging. But in the future, be it a particularly concerning variant, or a whole new pandemic, we should not discount the simple, cheap, and apparently beneficial act of wearing masks to decrease transmission.

Dr. Perry Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The body of evidence for Paxlovid therapy

Dear Colleagues,

We have a mismatch. The evidence supporting treatment for Paxlovid is compelling for people aged 60 or over, but the older patients in the United States are much less likely to be treated. Not only was there a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of high-risk patients which showed 89% reduction of hospitalizations and deaths (median age, 45), but there have been multiple real-world effectiveness studies subsequently published that have partitioned the benefit for age 65 or older, such as the ones from Israel and Hong Kong (age 60+). Overall, the real-world effectiveness in the first month after treatment is at least as good, if not better, than in the high-risk randomized trial.

We’re doing the current survey to find out, but the most likely reasons include (1) lack of confidence of benefit; (2) medication interactions; and (3) concerns over rebound.

Let me address each of these briefly. The lack of confidence in benefit stems from the fact that the initial high-risk trial was in unvaccinated individuals. That concern can now be put aside because all of the several real-world studies confirming the protective benefit against hospitalizations and deaths are in people who have been vaccinated, and a significant proportion received booster shots.

The potential medication interactions due to the ritonavir component of the Paxlovid drug combination, attributable to its cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibition, have been unduly emphasized. There are many drug-interaction checkers for Paxlovid, but this one from the University of Liverpool is user friendly, color- and icon-coded, and shows that the vast majority of interactions can be sidestepped by discontinuing the medication of concern for the length of the Paxlovid treatment, 5 days. The simple chart is provided in my recent substack newsletter.

As far as rebound, this problem has unfortunately been exaggerated because of lack of prospective systematic studies and appreciation that a positive test of clinical symptom rebound can occur without Paxlovid. There are soon to be multiple reports that the incidence of Paxlovid rebound is fairly low, in the range of 10%. That concern should not be a reason to withhold treatment.

Now the plot thickens. A new preprint report from the Veterans Health Administration, the largest health care system in the United States, looks at 90-day outcomes of about 9,000 Paxlovid-treated patients and approximately 47,000 controls. Not only was there a 26% reduction in long COVID, but of the breakdown of 12 organs/systems and symptoms, 10 of 12 were significantly reduced with Paxlovid, including pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, and neurocognitive impairment. There was also a 48% reduction in death and a 30% reduction in hospitalizations after the first 30 days. I have reviewed all of these data and put them in context in a recent newsletter. A key point is that the magnitude of benefit was unaffected by vaccination or booster status, or prior COVID infections, or unvaccinated status. Also, it was the same for men and women, as well as for age > 70 and age < 60. These findings all emphasize a new reason to be using Paxlovid therapy, and if replicated, Paxlovid may even be indicated for younger patients (who are at low risk for hospitalizations and deaths but at increased risk for long COVID).

In summary, for older patients, we should be thinking of why we should be using Paxlovid rather than the reason not to treat. We’ll be interested in the survey results to understand the mismatch better, and we look forward to your ideas and feedback to make better use of this treatment for the people who need it the most.

Sincerely yours, Eric J. Topol, MD

Dr. Topol reports no conflicts of interest with Pfizer; he receives no honoraria or speaker fees, does not serve in an advisory role, and has no financial association with the company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dear Colleagues,

We have a mismatch. The evidence supporting treatment for Paxlovid is compelling for people aged 60 or over, but the older patients in the United States are much less likely to be treated. Not only was there a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of high-risk patients which showed 89% reduction of hospitalizations and deaths (median age, 45), but there have been multiple real-world effectiveness studies subsequently published that have partitioned the benefit for age 65 or older, such as the ones from Israel and Hong Kong (age 60+). Overall, the real-world effectiveness in the first month after treatment is at least as good, if not better, than in the high-risk randomized trial.

We’re doing the current survey to find out, but the most likely reasons include (1) lack of confidence of benefit; (2) medication interactions; and (3) concerns over rebound.

Let me address each of these briefly. The lack of confidence in benefit stems from the fact that the initial high-risk trial was in unvaccinated individuals. That concern can now be put aside because all of the several real-world studies confirming the protective benefit against hospitalizations and deaths are in people who have been vaccinated, and a significant proportion received booster shots.

The potential medication interactions due to the ritonavir component of the Paxlovid drug combination, attributable to its cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibition, have been unduly emphasized. There are many drug-interaction checkers for Paxlovid, but this one from the University of Liverpool is user friendly, color- and icon-coded, and shows that the vast majority of interactions can be sidestepped by discontinuing the medication of concern for the length of the Paxlovid treatment, 5 days. The simple chart is provided in my recent substack newsletter.

As far as rebound, this problem has unfortunately been exaggerated because of lack of prospective systematic studies and appreciation that a positive test of clinical symptom rebound can occur without Paxlovid. There are soon to be multiple reports that the incidence of Paxlovid rebound is fairly low, in the range of 10%. That concern should not be a reason to withhold treatment.

Now the plot thickens. A new preprint report from the Veterans Health Administration, the largest health care system in the United States, looks at 90-day outcomes of about 9,000 Paxlovid-treated patients and approximately 47,000 controls. Not only was there a 26% reduction in long COVID, but of the breakdown of 12 organs/systems and symptoms, 10 of 12 were significantly reduced with Paxlovid, including pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, and neurocognitive impairment. There was also a 48% reduction in death and a 30% reduction in hospitalizations after the first 30 days. I have reviewed all of these data and put them in context in a recent newsletter. A key point is that the magnitude of benefit was unaffected by vaccination or booster status, or prior COVID infections, or unvaccinated status. Also, it was the same for men and women, as well as for age > 70 and age < 60. These findings all emphasize a new reason to be using Paxlovid therapy, and if replicated, Paxlovid may even be indicated for younger patients (who are at low risk for hospitalizations and deaths but at increased risk for long COVID).

In summary, for older patients, we should be thinking of why we should be using Paxlovid rather than the reason not to treat. We’ll be interested in the survey results to understand the mismatch better, and we look forward to your ideas and feedback to make better use of this treatment for the people who need it the most.

Sincerely yours, Eric J. Topol, MD

Dr. Topol reports no conflicts of interest with Pfizer; he receives no honoraria or speaker fees, does not serve in an advisory role, and has no financial association with the company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dear Colleagues,

We have a mismatch. The evidence supporting treatment for Paxlovid is compelling for people aged 60 or over, but the older patients in the United States are much less likely to be treated. Not only was there a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of high-risk patients which showed 89% reduction of hospitalizations and deaths (median age, 45), but there have been multiple real-world effectiveness studies subsequently published that have partitioned the benefit for age 65 or older, such as the ones from Israel and Hong Kong (age 60+). Overall, the real-world effectiveness in the first month after treatment is at least as good, if not better, than in the high-risk randomized trial.

We’re doing the current survey to find out, but the most likely reasons include (1) lack of confidence of benefit; (2) medication interactions; and (3) concerns over rebound.

Let me address each of these briefly. The lack of confidence in benefit stems from the fact that the initial high-risk trial was in unvaccinated individuals. That concern can now be put aside because all of the several real-world studies confirming the protective benefit against hospitalizations and deaths are in people who have been vaccinated, and a significant proportion received booster shots.

The potential medication interactions due to the ritonavir component of the Paxlovid drug combination, attributable to its cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibition, have been unduly emphasized. There are many drug-interaction checkers for Paxlovid, but this one from the University of Liverpool is user friendly, color- and icon-coded, and shows that the vast majority of interactions can be sidestepped by discontinuing the medication of concern for the length of the Paxlovid treatment, 5 days. The simple chart is provided in my recent substack newsletter.

As far as rebound, this problem has unfortunately been exaggerated because of lack of prospective systematic studies and appreciation that a positive test of clinical symptom rebound can occur without Paxlovid. There are soon to be multiple reports that the incidence of Paxlovid rebound is fairly low, in the range of 10%. That concern should not be a reason to withhold treatment.

Now the plot thickens. A new preprint report from the Veterans Health Administration, the largest health care system in the United States, looks at 90-day outcomes of about 9,000 Paxlovid-treated patients and approximately 47,000 controls. Not only was there a 26% reduction in long COVID, but of the breakdown of 12 organs/systems and symptoms, 10 of 12 were significantly reduced with Paxlovid, including pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, and neurocognitive impairment. There was also a 48% reduction in death and a 30% reduction in hospitalizations after the first 30 days. I have reviewed all of these data and put them in context in a recent newsletter. A key point is that the magnitude of benefit was unaffected by vaccination or booster status, or prior COVID infections, or unvaccinated status. Also, it was the same for men and women, as well as for age > 70 and age < 60. These findings all emphasize a new reason to be using Paxlovid therapy, and if replicated, Paxlovid may even be indicated for younger patients (who are at low risk for hospitalizations and deaths but at increased risk for long COVID).

In summary, for older patients, we should be thinking of why we should be using Paxlovid rather than the reason not to treat. We’ll be interested in the survey results to understand the mismatch better, and we look forward to your ideas and feedback to make better use of this treatment for the people who need it the most.

Sincerely yours, Eric J. Topol, MD

Dr. Topol reports no conflicts of interest with Pfizer; he receives no honoraria or speaker fees, does not serve in an advisory role, and has no financial association with the company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Repeat COVID infection doubles mortality risk

Getting COVID-19 a second time doubles a person’s chance of dying and triples the likelihood of being hospitalized in the next 6 months, a new study found.

Vaccination and booster status did not improve survival or hospitalization rates among people who were infected more than once.

“Reinfection with COVID-19 increases the risk of both acute outcomes and long COVID,” study author Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, told Reuters. “This was evident in unvaccinated, vaccinated and boosted people.”

The study was published in the journal Nature Medicine.

Researchers analyzed U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs data, including 443,588 people with a first infection of SARS-CoV-2, 40,947 people who were infected two or more times, and 5.3 million people who had not been infected with coronavirus, whose data served as the control group.

“During the past few months, there’s been an air of invincibility among people who have had COVID-19 or their vaccinations and boosters, and especially among people who have had an infection and also received vaccines; some people started to [refer] to these individuals as having a sort of superimmunity to the virus,” Dr. Al-Aly said in a press release from Washington University in St. Louis. “Without ambiguity, our research showed that getting an infection a second, third or fourth time contributes to additional health risks in the acute phase, meaning the first 30 days after infection, and in the months beyond, meaning the long COVID phase.”

Being infected with COVID-19 more than once also dramatically increased the risk of developing lung problems, heart conditions, or brain conditions. The heightened risks persisted for 6 months.

Researchers said a limitation of their study was that data primarily came from White males.

An expert not involved in the study told Reuters that the Veterans Affairs population does not reflect the general population. Patients at VA health facilities are generally older with more than normal health complications, said John Moore, PhD, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

Dr. Al-Aly encouraged people to be vigilant as they plan for the holiday season, Reuters reported.

“We had started seeing a lot of patients coming to the clinic with an air of invincibility,” he told Reuters. “They wondered, ‘Does getting a reinfection really matter?’ The answer is yes, it absolutely does.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Getting COVID-19 a second time doubles a person’s chance of dying and triples the likelihood of being hospitalized in the next 6 months, a new study found.

Vaccination and booster status did not improve survival or hospitalization rates among people who were infected more than once.

“Reinfection with COVID-19 increases the risk of both acute outcomes and long COVID,” study author Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, told Reuters. “This was evident in unvaccinated, vaccinated and boosted people.”

The study was published in the journal Nature Medicine.

Researchers analyzed U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs data, including 443,588 people with a first infection of SARS-CoV-2, 40,947 people who were infected two or more times, and 5.3 million people who had not been infected with coronavirus, whose data served as the control group.

“During the past few months, there’s been an air of invincibility among people who have had COVID-19 or their vaccinations and boosters, and especially among people who have had an infection and also received vaccines; some people started to [refer] to these individuals as having a sort of superimmunity to the virus,” Dr. Al-Aly said in a press release from Washington University in St. Louis. “Without ambiguity, our research showed that getting an infection a second, third or fourth time contributes to additional health risks in the acute phase, meaning the first 30 days after infection, and in the months beyond, meaning the long COVID phase.”

Being infected with COVID-19 more than once also dramatically increased the risk of developing lung problems, heart conditions, or brain conditions. The heightened risks persisted for 6 months.

Researchers said a limitation of their study was that data primarily came from White males.

An expert not involved in the study told Reuters that the Veterans Affairs population does not reflect the general population. Patients at VA health facilities are generally older with more than normal health complications, said John Moore, PhD, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

Dr. Al-Aly encouraged people to be vigilant as they plan for the holiday season, Reuters reported.

“We had started seeing a lot of patients coming to the clinic with an air of invincibility,” he told Reuters. “They wondered, ‘Does getting a reinfection really matter?’ The answer is yes, it absolutely does.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Getting COVID-19 a second time doubles a person’s chance of dying and triples the likelihood of being hospitalized in the next 6 months, a new study found.

Vaccination and booster status did not improve survival or hospitalization rates among people who were infected more than once.

“Reinfection with COVID-19 increases the risk of both acute outcomes and long COVID,” study author Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, told Reuters. “This was evident in unvaccinated, vaccinated and boosted people.”

The study was published in the journal Nature Medicine.

Researchers analyzed U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs data, including 443,588 people with a first infection of SARS-CoV-2, 40,947 people who were infected two or more times, and 5.3 million people who had not been infected with coronavirus, whose data served as the control group.

“During the past few months, there’s been an air of invincibility among people who have had COVID-19 or their vaccinations and boosters, and especially among people who have had an infection and also received vaccines; some people started to [refer] to these individuals as having a sort of superimmunity to the virus,” Dr. Al-Aly said in a press release from Washington University in St. Louis. “Without ambiguity, our research showed that getting an infection a second, third or fourth time contributes to additional health risks in the acute phase, meaning the first 30 days after infection, and in the months beyond, meaning the long COVID phase.”

Being infected with COVID-19 more than once also dramatically increased the risk of developing lung problems, heart conditions, or brain conditions. The heightened risks persisted for 6 months.

Researchers said a limitation of their study was that data primarily came from White males.

An expert not involved in the study told Reuters that the Veterans Affairs population does not reflect the general population. Patients at VA health facilities are generally older with more than normal health complications, said John Moore, PhD, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

Dr. Al-Aly encouraged people to be vigilant as they plan for the holiday season, Reuters reported.

“We had started seeing a lot of patients coming to the clinic with an air of invincibility,” he told Reuters. “They wondered, ‘Does getting a reinfection really matter?’ The answer is yes, it absolutely does.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM NATURE MEDICINE

Third COVID booster benefits cancer patients

though this population still suffers higher risks than those of the general population, according to a new large-scale observational study out of the United Kingdom.

People living with lymphoma and those who underwent recent systemic anti-cancer treatment or radiotherapy are at the highest risk, according to study author Lennard Y.W. Lee, PhD. “Our study is the largest evaluation of a coronavirus third dose vaccine booster effectiveness in people living with cancer in the world. For the first time we have quantified the benefits of boosters for COVID-19 in cancer patients,” said Dr. Lee, UK COVID Cancer program lead and a medical oncologist at the University of Oxford, England.

The research was published in the November issue of the European Journal of Cancer.

Despite the encouraging numbers, those with cancer continue to have a more than threefold increased risk of both hospitalization and death from coronavirus compared to the general population. “More needs to be done to reduce this excess risk, like prophylactic antibody therapies,” Dr. Lee said.

Third dose efficacy was lower among cancer patients who had been diagnosed within the past 12 months, as well as those with lymphoma, and those who had undergone systemic anti-cancer therapy or radiotherapy within the past 12 months.

The increased vulnerability among individuals with cancer is likely due to compromised immune systems. “Patients with cancer often have impaired B and T cell function and this study provides the largest global clinical study showing the definitive meaningful clinical impact of this,” Dr. Lee said. The greater risk among those with lymphoma likely traces to aberrant white cells or immunosuppressant regimens, he said.

“Vaccination probably should be used in combination with new forms of prevention and in Europe the strategy of using prophylactic antibodies is going to provide additional levels of protection,” Dr. Lee said.

Overall, the study reveals the challenges that cancer patients face in a pandemic that remains a critical health concern, one that can seriously affect quality of life. “Many are still shielding, unable to see family or hug loved ones. Furthermore, looking beyond the direct health risks, there is also the mental health impact. Shielding for nearly 3 years is very difficult. It is important to realize that behind this large-scale study, which is the biggest in the world, there are real people. The pandemic still goes on for them as they remain at higher risk from COVID-19 and we must be aware of the impact on them,” Dr. Lee said.

The study included data from the United Kingdom’s third dose booster vaccine program, representing 361,098 individuals who participated from December 2020 through December 2021. It also include results from all coronavirus tests conducted in the United Kingdom during that period. Among the participants, 97.8% got the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine as a booster, while 1.5% received the Moderna vaccine. Overall, 8,371,139 individuals received a third dose booster, including 230,666 living with cancer. The researchers used a test-negative case-controlled analysis to estimate vaccine efficacy.

The booster shot had a 59.1% efficacy against breakthrough infections, 62.8% efficacy against symptomatic infections, 80.5% efficacy versus coronavirus hospitalization, and 94.5% efficacy against coronavirus death. Patients with solid tumors benefited from higher efficacy versus breakthrough infections 66.0% versus 53.2%) and symptomatic infections (69.6% versus 56.0%).

Patients with lymphoma experienced just a 10.5% efficacy of the primary dose vaccine versus breakthrough infections and 13.6% versus symptomatic infections, and this did not improve with a third dose. The benefit was greater for hospitalization (23.2%) and death (80.1%).

Despite the additional protection of a third dose, patients with cancer had a higher risk than the population control for coronavirus hospitalization (odds ratio, 3.38; P < .000001) and death (odds ratio, 3.01; P < .000001).

Dr. Lee has no relevant financial disclosures.

though this population still suffers higher risks than those of the general population, according to a new large-scale observational study out of the United Kingdom.