User login

Miss the ear, and you may miss the diagnosis

A 52-year-old woman presented with pain in both ears associated with redness and swelling. The symptoms appeared 3 weeks earlier. The pain had started on one side, then spread to the other over a period of 2 weeks. She denied fever, chills, rigor, rash, or upper respiratory symptoms. She had experienced similar but unilateral ear pain months before. Her medical history included bilateral knee pain and swelling (treated as osteoarthritis), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and hypothyroidism. She also reported progressive bilateral hearing loss, for which she now uses hearing aids. She had no history of conjunctivitis or uveitis.

Physical examination showed swelling and erythema of both ears, sparing the earlobes (Figure 1), as well as bilateral knee-joint tenderness and restricted joint movement. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was elevated at 52 mm/h (reference range 0–20); the complete blood cell count, creatinine, and liver enzyme levels were normal. An autoimmune panel was negative for antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, and rheumatoid factor.

A clinical diagnosis of relapsing polychondritis was made based on the McAdam criteria.1 The patient was initially started on steroids and then was maintained on methotrexate. Her symptoms improved dramatically by 3 weeks.

RELAPSING POLYCHONDRITIS

Relapsing polychondritis is a rare, chronic, and potentially multisystem disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of cartilaginous inflammation that often lead to progressive destruction of the cartilage.2,3

Auricular chondritis is the initial presentation in 43% of cases and eventually develops in 89% of patients.2,4 The earlobes are spared, as they are devoid of cartilage, and this feature helps to differentiate the condition from an infection.

If the condition is not treated, recurrent attacks can result in irreversible cartilage damage and drooping of the pinna (ie, “cauliflower ear”). Biopsy is usually avoided, as it may further damage the ear. The diagnostic criteria for relapsing polychondritis formulated by McAdam et al1 accommodate the different presentations in order to limit the need for biopsy. Systemic involvement may include external eye structures, vasculitis affecting the eighth cranial (vestibulocochlear) nerve, noninflammatory large-joint arthritis, and the trachea. There is also an association with myelodysplasia.

- McAdam LP, O’Hanlan MA, Bluestone R, Pearson CM. Relapsing polychondritis: prospective study of 23 patients and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1976; 55:193–215.

- Mathew SD, Battafarano DF, Morris MJ. Relapsing polychondritis in the Department of Defense population and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2012; 42:70–83.

- Letko E, Zafirakis P, Baltatzis S, Voudouri A, Livir-Rallatos C, Foster CS. Relapsing polychondritis: a clinical review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2002; 31:384–395.

- Kent PD, Michet CJ, Luthra HS. Relapsing polychondritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2004; 16:56–61.

A 52-year-old woman presented with pain in both ears associated with redness and swelling. The symptoms appeared 3 weeks earlier. The pain had started on one side, then spread to the other over a period of 2 weeks. She denied fever, chills, rigor, rash, or upper respiratory symptoms. She had experienced similar but unilateral ear pain months before. Her medical history included bilateral knee pain and swelling (treated as osteoarthritis), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and hypothyroidism. She also reported progressive bilateral hearing loss, for which she now uses hearing aids. She had no history of conjunctivitis or uveitis.

Physical examination showed swelling and erythema of both ears, sparing the earlobes (Figure 1), as well as bilateral knee-joint tenderness and restricted joint movement. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was elevated at 52 mm/h (reference range 0–20); the complete blood cell count, creatinine, and liver enzyme levels were normal. An autoimmune panel was negative for antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, and rheumatoid factor.

A clinical diagnosis of relapsing polychondritis was made based on the McAdam criteria.1 The patient was initially started on steroids and then was maintained on methotrexate. Her symptoms improved dramatically by 3 weeks.

RELAPSING POLYCHONDRITIS

Relapsing polychondritis is a rare, chronic, and potentially multisystem disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of cartilaginous inflammation that often lead to progressive destruction of the cartilage.2,3

Auricular chondritis is the initial presentation in 43% of cases and eventually develops in 89% of patients.2,4 The earlobes are spared, as they are devoid of cartilage, and this feature helps to differentiate the condition from an infection.

If the condition is not treated, recurrent attacks can result in irreversible cartilage damage and drooping of the pinna (ie, “cauliflower ear”). Biopsy is usually avoided, as it may further damage the ear. The diagnostic criteria for relapsing polychondritis formulated by McAdam et al1 accommodate the different presentations in order to limit the need for biopsy. Systemic involvement may include external eye structures, vasculitis affecting the eighth cranial (vestibulocochlear) nerve, noninflammatory large-joint arthritis, and the trachea. There is also an association with myelodysplasia.

A 52-year-old woman presented with pain in both ears associated with redness and swelling. The symptoms appeared 3 weeks earlier. The pain had started on one side, then spread to the other over a period of 2 weeks. She denied fever, chills, rigor, rash, or upper respiratory symptoms. She had experienced similar but unilateral ear pain months before. Her medical history included bilateral knee pain and swelling (treated as osteoarthritis), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and hypothyroidism. She also reported progressive bilateral hearing loss, for which she now uses hearing aids. She had no history of conjunctivitis or uveitis.

Physical examination showed swelling and erythema of both ears, sparing the earlobes (Figure 1), as well as bilateral knee-joint tenderness and restricted joint movement. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was elevated at 52 mm/h (reference range 0–20); the complete blood cell count, creatinine, and liver enzyme levels were normal. An autoimmune panel was negative for antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, and rheumatoid factor.

A clinical diagnosis of relapsing polychondritis was made based on the McAdam criteria.1 The patient was initially started on steroids and then was maintained on methotrexate. Her symptoms improved dramatically by 3 weeks.

RELAPSING POLYCHONDRITIS

Relapsing polychondritis is a rare, chronic, and potentially multisystem disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of cartilaginous inflammation that often lead to progressive destruction of the cartilage.2,3

Auricular chondritis is the initial presentation in 43% of cases and eventually develops in 89% of patients.2,4 The earlobes are spared, as they are devoid of cartilage, and this feature helps to differentiate the condition from an infection.

If the condition is not treated, recurrent attacks can result in irreversible cartilage damage and drooping of the pinna (ie, “cauliflower ear”). Biopsy is usually avoided, as it may further damage the ear. The diagnostic criteria for relapsing polychondritis formulated by McAdam et al1 accommodate the different presentations in order to limit the need for biopsy. Systemic involvement may include external eye structures, vasculitis affecting the eighth cranial (vestibulocochlear) nerve, noninflammatory large-joint arthritis, and the trachea. There is also an association with myelodysplasia.

- McAdam LP, O’Hanlan MA, Bluestone R, Pearson CM. Relapsing polychondritis: prospective study of 23 patients and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1976; 55:193–215.

- Mathew SD, Battafarano DF, Morris MJ. Relapsing polychondritis in the Department of Defense population and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2012; 42:70–83.

- Letko E, Zafirakis P, Baltatzis S, Voudouri A, Livir-Rallatos C, Foster CS. Relapsing polychondritis: a clinical review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2002; 31:384–395.

- Kent PD, Michet CJ, Luthra HS. Relapsing polychondritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2004; 16:56–61.

- McAdam LP, O’Hanlan MA, Bluestone R, Pearson CM. Relapsing polychondritis: prospective study of 23 patients and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1976; 55:193–215.

- Mathew SD, Battafarano DF, Morris MJ. Relapsing polychondritis in the Department of Defense population and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2012; 42:70–83.

- Letko E, Zafirakis P, Baltatzis S, Voudouri A, Livir-Rallatos C, Foster CS. Relapsing polychondritis: a clinical review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2002; 31:384–395.

- Kent PD, Michet CJ, Luthra HS. Relapsing polychondritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2004; 16:56–61.

Terry nails in a patient with chronic alcoholic liver disease

A 45-year-old man with chronic alcoholism for the past 20 years and chronic liver disease for the past 2 years was admitted to the hospital with abdominal distention, yellowish discoloration of the eyes, itching all over the body, decreased appetite, and fresh rectal bleeding.

He had the classic signs of chronic liver disease, including icterus, pallor, parotid swelling, gynecomastia, spider angiomata, sparse axillary and pubic hair, transverse stretched umbilicus, divarication of the rectus abdominis muscles, caput medusae, small testes, and bilateral pedal edema.

Examination of the fingernails revealed a distal thin pink-to-brown transverse band 0.5 to 2.0 mm in width, a white nail bed, and no lunula (Figure 1)—the characteristic findings of Terry nails.

Systemic examination revealed moderate ascites (shifting dullness present), splenomegaly, and external hemorrhoids suggestive of portal hypertension.

TERRY NAILS

In 1954, Dr. Richard Terry first reported the finding of a white nail bed with ground-glass opacity in patients who had hepatic cirrhosis.1 The condition is bilaterally symmetrical, with a tendency to be more marked in the thumb and forefinger.1

In 1984, Holzberg and Walker2 consecutively studied 512 hospitalized patients and observed Terry nails in 25.2% of them. Based on their findings, they redefined the criteria for Terry nail as follows:

- Distal thin pink-to-brown transverse band, 0.5 to 3.0 mm in width

- Decreased venous return not obscuring the distal band

- White or light pink proximal nail

- Lunula possibly absent

- At least 4 of 10 nails with the above criteria.

Patients who do not have the findings on all fingernails commonly have involvement of the thumb and forefinger. Holzberg and Walker confirmed a statistically significant association of Terry nails with cirrhosis, chronic heart failure, and adult-onset diabetes, especially in younger patients.2 Terry nails have also been observed in thyrotoxicosis, pulmonary eosinophilia, malnutrition, actinic keratosis, and advanced age.1–4

Using the updated diagnostic criteria, Park et al5 studied fingernails in 444 medical inpatients with chronic systemic disease, and only 30.6% had Terry nails. There were statistically significant associations with cirrhosis (57%), congestive heart failure (51.5%), and diabetes mellitus (49%); the associations with chronic renal failure (19%) and cancer (18%) were not statistically significant.5 They were more common in older patients. The average number of nails affected per patient tended to be higher in frequency close to the thumb; 28.7% patients had all nails affected.5

Terry nails should alert the clinician to the possibility of an underlying systemic disease, especially advanced liver disease. Possible explanations for the clinical changes observed in Terry nails include abnormal steroid metabolism, abnormal estrogen-androgen ratio, alteration of nail bed-to-nail plate attachment, hypoalbuminemia, increased digital blood flow, and overgrowth of the connective tissue between nail bed and the growth plate. The pathologic study of longitudinal nail biopsy specimens shows telangiectasia in the upper dermis of the distal nail band.3

Important differential diagnoses are Lindsay (half-and-half) nails, associated with chronic renal failure, and Neapolitan nails, associated with aging.3

- Terry R. White nails in hepatic cirrhosis. Lancet 1954; 266:757–759.

- Holzberg M, Walker HK. Terry’s nails: revised definition and new correlations. Lancet 1984; 1:896–899.

- Holzberg M. The nail in systemic disease. In:Baran R, de Berker DAR, Holzberg M, Thomas L, editors. Baran & Dawber’s Diseases of the Nails and Their Management, 4th ed. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.; 2012.

- Nia AM, Ederer S, Dahlem KM, Gassanov N, Er F. Terry’s nails: a window to systemic diseases. Am J Med 2011; 124:602–604.

- Park KY, Kim SW, Cho JS. Research on the frequency of Terry’s nail in the medical inpatients with chronic illnesses. Korean J Dermatol 1992; 30:864–870.

A 45-year-old man with chronic alcoholism for the past 20 years and chronic liver disease for the past 2 years was admitted to the hospital with abdominal distention, yellowish discoloration of the eyes, itching all over the body, decreased appetite, and fresh rectal bleeding.

He had the classic signs of chronic liver disease, including icterus, pallor, parotid swelling, gynecomastia, spider angiomata, sparse axillary and pubic hair, transverse stretched umbilicus, divarication of the rectus abdominis muscles, caput medusae, small testes, and bilateral pedal edema.

Examination of the fingernails revealed a distal thin pink-to-brown transverse band 0.5 to 2.0 mm in width, a white nail bed, and no lunula (Figure 1)—the characteristic findings of Terry nails.

Systemic examination revealed moderate ascites (shifting dullness present), splenomegaly, and external hemorrhoids suggestive of portal hypertension.

TERRY NAILS

In 1954, Dr. Richard Terry first reported the finding of a white nail bed with ground-glass opacity in patients who had hepatic cirrhosis.1 The condition is bilaterally symmetrical, with a tendency to be more marked in the thumb and forefinger.1

In 1984, Holzberg and Walker2 consecutively studied 512 hospitalized patients and observed Terry nails in 25.2% of them. Based on their findings, they redefined the criteria for Terry nail as follows:

- Distal thin pink-to-brown transverse band, 0.5 to 3.0 mm in width

- Decreased venous return not obscuring the distal band

- White or light pink proximal nail

- Lunula possibly absent

- At least 4 of 10 nails with the above criteria.

Patients who do not have the findings on all fingernails commonly have involvement of the thumb and forefinger. Holzberg and Walker confirmed a statistically significant association of Terry nails with cirrhosis, chronic heart failure, and adult-onset diabetes, especially in younger patients.2 Terry nails have also been observed in thyrotoxicosis, pulmonary eosinophilia, malnutrition, actinic keratosis, and advanced age.1–4

Using the updated diagnostic criteria, Park et al5 studied fingernails in 444 medical inpatients with chronic systemic disease, and only 30.6% had Terry nails. There were statistically significant associations with cirrhosis (57%), congestive heart failure (51.5%), and diabetes mellitus (49%); the associations with chronic renal failure (19%) and cancer (18%) were not statistically significant.5 They were more common in older patients. The average number of nails affected per patient tended to be higher in frequency close to the thumb; 28.7% patients had all nails affected.5

Terry nails should alert the clinician to the possibility of an underlying systemic disease, especially advanced liver disease. Possible explanations for the clinical changes observed in Terry nails include abnormal steroid metabolism, abnormal estrogen-androgen ratio, alteration of nail bed-to-nail plate attachment, hypoalbuminemia, increased digital blood flow, and overgrowth of the connective tissue between nail bed and the growth plate. The pathologic study of longitudinal nail biopsy specimens shows telangiectasia in the upper dermis of the distal nail band.3

Important differential diagnoses are Lindsay (half-and-half) nails, associated with chronic renal failure, and Neapolitan nails, associated with aging.3

A 45-year-old man with chronic alcoholism for the past 20 years and chronic liver disease for the past 2 years was admitted to the hospital with abdominal distention, yellowish discoloration of the eyes, itching all over the body, decreased appetite, and fresh rectal bleeding.

He had the classic signs of chronic liver disease, including icterus, pallor, parotid swelling, gynecomastia, spider angiomata, sparse axillary and pubic hair, transverse stretched umbilicus, divarication of the rectus abdominis muscles, caput medusae, small testes, and bilateral pedal edema.

Examination of the fingernails revealed a distal thin pink-to-brown transverse band 0.5 to 2.0 mm in width, a white nail bed, and no lunula (Figure 1)—the characteristic findings of Terry nails.

Systemic examination revealed moderate ascites (shifting dullness present), splenomegaly, and external hemorrhoids suggestive of portal hypertension.

TERRY NAILS

In 1954, Dr. Richard Terry first reported the finding of a white nail bed with ground-glass opacity in patients who had hepatic cirrhosis.1 The condition is bilaterally symmetrical, with a tendency to be more marked in the thumb and forefinger.1

In 1984, Holzberg and Walker2 consecutively studied 512 hospitalized patients and observed Terry nails in 25.2% of them. Based on their findings, they redefined the criteria for Terry nail as follows:

- Distal thin pink-to-brown transverse band, 0.5 to 3.0 mm in width

- Decreased venous return not obscuring the distal band

- White or light pink proximal nail

- Lunula possibly absent

- At least 4 of 10 nails with the above criteria.

Patients who do not have the findings on all fingernails commonly have involvement of the thumb and forefinger. Holzberg and Walker confirmed a statistically significant association of Terry nails with cirrhosis, chronic heart failure, and adult-onset diabetes, especially in younger patients.2 Terry nails have also been observed in thyrotoxicosis, pulmonary eosinophilia, malnutrition, actinic keratosis, and advanced age.1–4

Using the updated diagnostic criteria, Park et al5 studied fingernails in 444 medical inpatients with chronic systemic disease, and only 30.6% had Terry nails. There were statistically significant associations with cirrhosis (57%), congestive heart failure (51.5%), and diabetes mellitus (49%); the associations with chronic renal failure (19%) and cancer (18%) were not statistically significant.5 They were more common in older patients. The average number of nails affected per patient tended to be higher in frequency close to the thumb; 28.7% patients had all nails affected.5

Terry nails should alert the clinician to the possibility of an underlying systemic disease, especially advanced liver disease. Possible explanations for the clinical changes observed in Terry nails include abnormal steroid metabolism, abnormal estrogen-androgen ratio, alteration of nail bed-to-nail plate attachment, hypoalbuminemia, increased digital blood flow, and overgrowth of the connective tissue between nail bed and the growth plate. The pathologic study of longitudinal nail biopsy specimens shows telangiectasia in the upper dermis of the distal nail band.3

Important differential diagnoses are Lindsay (half-and-half) nails, associated with chronic renal failure, and Neapolitan nails, associated with aging.3

- Terry R. White nails in hepatic cirrhosis. Lancet 1954; 266:757–759.

- Holzberg M, Walker HK. Terry’s nails: revised definition and new correlations. Lancet 1984; 1:896–899.

- Holzberg M. The nail in systemic disease. In:Baran R, de Berker DAR, Holzberg M, Thomas L, editors. Baran & Dawber’s Diseases of the Nails and Their Management, 4th ed. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.; 2012.

- Nia AM, Ederer S, Dahlem KM, Gassanov N, Er F. Terry’s nails: a window to systemic diseases. Am J Med 2011; 124:602–604.

- Park KY, Kim SW, Cho JS. Research on the frequency of Terry’s nail in the medical inpatients with chronic illnesses. Korean J Dermatol 1992; 30:864–870.

- Terry R. White nails in hepatic cirrhosis. Lancet 1954; 266:757–759.

- Holzberg M, Walker HK. Terry’s nails: revised definition and new correlations. Lancet 1984; 1:896–899.

- Holzberg M. The nail in systemic disease. In:Baran R, de Berker DAR, Holzberg M, Thomas L, editors. Baran & Dawber’s Diseases of the Nails and Their Management, 4th ed. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.; 2012.

- Nia AM, Ederer S, Dahlem KM, Gassanov N, Er F. Terry’s nails: a window to systemic diseases. Am J Med 2011; 124:602–604.

- Park KY, Kim SW, Cho JS. Research on the frequency of Terry’s nail in the medical inpatients with chronic illnesses. Korean J Dermatol 1992; 30:864–870.

Erythema and atrophy on the tongue

A 26-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology department with a 6-month history of a painful burning sensation on the tongue. Examination revealed a reddish, atrophic area on the dorsum of the tongue (Figure 1).

She had been treated unsuccessfully with topical antifungal drugs (clotrimazole and nystatin) for a presumed diagnosis of oral candidiasis. Otherwise, her medical history was notable only for occasional episodes of epigastric pain. She did not smoke or drink alcohol.

Fungal culture and oral exfoliative cytology studies were negative.

Laboratory results:

- Red blood cell count 3.9 × 1012/L (reference range 4.2–5.4)

- Hemoglobin 11.3 g/dL (12–16)

- Mean corpuscular volume 92 fL (80–99)

- Mean corpuscular hemoglobin 29 pg (27–34)

- Iron 14 μg/dL (37–145),

- Vitamin B12 119 pg/dL (250–900)

- Zinc 33 μg/dL (66–110)

- Serum gastric parietal cell antibody positive

- Serum creatinine and liver enzyme tests were normal.

Biopsy of the gastric mucosa revealed severe atrophic gastritis, so the possibility of atrophy related to gastroesophageal reflux was considered. But the laboratory results and the patient’s presentation pointed to iron deficiency and pernicious anemia (due to deficiency of vitamin B12). Zinc deficiency is associated with oral burning but not atrophic glossitis.

Based on the patient’s symptoms and the testing results, she was given the diagnosis of atrophic glossitis. She was treated with oral iron supplementation, intramuscular injections of vitamin B12, and oral zinc supplementation. The glossitis resolved, and the gastric symptoms improved within 2 months, thus supporting our diagnosis of atrophic glossitis.

ATROPHIC GLOSSITIS

The diagnosis of abnormalities of the tongue requires a thorough history, including onset and duration, antecedent symptoms, and tobacco and alcohol use. Examination of tongue morphology is also important.1 Tongue abnormalities related to tobacco use and to alcohol use include leukoplakia, erythroplakia, oral submucosal fibrosis, lichen planus, and oral squamous cell carcinoma.

Atrophic glossitis is often linked to an underlying nutritional deficiency of iron, folic acid, vitamin B12, riboflavin, or niacin, although other nutritional deficiencies can be implicated. As noted, zinc deficiency can cause oral burning but not atrophic glossitis, and it resolves with correction of the underlying deficiency.2 Cobalamin deficiency is the main cause of atrophic glossitis.

As our patient’s presentation illustrated, oral symptoms can be multifactorial. Oral conditions may be an early clinical manifestation of a nutritional deficiency, but they can also reflect an alteration of the gastric mucosa3; a bacterial, viral, or fungal infection; neoplastic disease; autoimmune disease; endocrine disorder; local mechanical trauma; exposure to an irritant; or an allergic reaction.2

- Reamy BV, Derby R, Bunt CW. Common tongue conditions in primary care. Am Fam Physician 2010; 81:627–634.

- Chi AC, Neville BW, Krayer JW, Gonsalves WC. Oral manifestations of systemic disease. Am Fam Physician 2010; 82:1381–1388.

- Sun A, Lin HP, Wang YP, Chiang CP. Significant association of deficiency of hemoglobin, iron and vitamin B12, high homocysteine level, and gastric parietal cell antibody positivity with atrophic glossitis. J Oral Pathol Med 2012; 41:500–504.

A 26-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology department with a 6-month history of a painful burning sensation on the tongue. Examination revealed a reddish, atrophic area on the dorsum of the tongue (Figure 1).

She had been treated unsuccessfully with topical antifungal drugs (clotrimazole and nystatin) for a presumed diagnosis of oral candidiasis. Otherwise, her medical history was notable only for occasional episodes of epigastric pain. She did not smoke or drink alcohol.

Fungal culture and oral exfoliative cytology studies were negative.

Laboratory results:

- Red blood cell count 3.9 × 1012/L (reference range 4.2–5.4)

- Hemoglobin 11.3 g/dL (12–16)

- Mean corpuscular volume 92 fL (80–99)

- Mean corpuscular hemoglobin 29 pg (27–34)

- Iron 14 μg/dL (37–145),

- Vitamin B12 119 pg/dL (250–900)

- Zinc 33 μg/dL (66–110)

- Serum gastric parietal cell antibody positive

- Serum creatinine and liver enzyme tests were normal.

Biopsy of the gastric mucosa revealed severe atrophic gastritis, so the possibility of atrophy related to gastroesophageal reflux was considered. But the laboratory results and the patient’s presentation pointed to iron deficiency and pernicious anemia (due to deficiency of vitamin B12). Zinc deficiency is associated with oral burning but not atrophic glossitis.

Based on the patient’s symptoms and the testing results, she was given the diagnosis of atrophic glossitis. She was treated with oral iron supplementation, intramuscular injections of vitamin B12, and oral zinc supplementation. The glossitis resolved, and the gastric symptoms improved within 2 months, thus supporting our diagnosis of atrophic glossitis.

ATROPHIC GLOSSITIS

The diagnosis of abnormalities of the tongue requires a thorough history, including onset and duration, antecedent symptoms, and tobacco and alcohol use. Examination of tongue morphology is also important.1 Tongue abnormalities related to tobacco use and to alcohol use include leukoplakia, erythroplakia, oral submucosal fibrosis, lichen planus, and oral squamous cell carcinoma.

Atrophic glossitis is often linked to an underlying nutritional deficiency of iron, folic acid, vitamin B12, riboflavin, or niacin, although other nutritional deficiencies can be implicated. As noted, zinc deficiency can cause oral burning but not atrophic glossitis, and it resolves with correction of the underlying deficiency.2 Cobalamin deficiency is the main cause of atrophic glossitis.

As our patient’s presentation illustrated, oral symptoms can be multifactorial. Oral conditions may be an early clinical manifestation of a nutritional deficiency, but they can also reflect an alteration of the gastric mucosa3; a bacterial, viral, or fungal infection; neoplastic disease; autoimmune disease; endocrine disorder; local mechanical trauma; exposure to an irritant; or an allergic reaction.2

A 26-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology department with a 6-month history of a painful burning sensation on the tongue. Examination revealed a reddish, atrophic area on the dorsum of the tongue (Figure 1).

She had been treated unsuccessfully with topical antifungal drugs (clotrimazole and nystatin) for a presumed diagnosis of oral candidiasis. Otherwise, her medical history was notable only for occasional episodes of epigastric pain. She did not smoke or drink alcohol.

Fungal culture and oral exfoliative cytology studies were negative.

Laboratory results:

- Red blood cell count 3.9 × 1012/L (reference range 4.2–5.4)

- Hemoglobin 11.3 g/dL (12–16)

- Mean corpuscular volume 92 fL (80–99)

- Mean corpuscular hemoglobin 29 pg (27–34)

- Iron 14 μg/dL (37–145),

- Vitamin B12 119 pg/dL (250–900)

- Zinc 33 μg/dL (66–110)

- Serum gastric parietal cell antibody positive

- Serum creatinine and liver enzyme tests were normal.

Biopsy of the gastric mucosa revealed severe atrophic gastritis, so the possibility of atrophy related to gastroesophageal reflux was considered. But the laboratory results and the patient’s presentation pointed to iron deficiency and pernicious anemia (due to deficiency of vitamin B12). Zinc deficiency is associated with oral burning but not atrophic glossitis.

Based on the patient’s symptoms and the testing results, she was given the diagnosis of atrophic glossitis. She was treated with oral iron supplementation, intramuscular injections of vitamin B12, and oral zinc supplementation. The glossitis resolved, and the gastric symptoms improved within 2 months, thus supporting our diagnosis of atrophic glossitis.

ATROPHIC GLOSSITIS

The diagnosis of abnormalities of the tongue requires a thorough history, including onset and duration, antecedent symptoms, and tobacco and alcohol use. Examination of tongue morphology is also important.1 Tongue abnormalities related to tobacco use and to alcohol use include leukoplakia, erythroplakia, oral submucosal fibrosis, lichen planus, and oral squamous cell carcinoma.

Atrophic glossitis is often linked to an underlying nutritional deficiency of iron, folic acid, vitamin B12, riboflavin, or niacin, although other nutritional deficiencies can be implicated. As noted, zinc deficiency can cause oral burning but not atrophic glossitis, and it resolves with correction of the underlying deficiency.2 Cobalamin deficiency is the main cause of atrophic glossitis.

As our patient’s presentation illustrated, oral symptoms can be multifactorial. Oral conditions may be an early clinical manifestation of a nutritional deficiency, but they can also reflect an alteration of the gastric mucosa3; a bacterial, viral, or fungal infection; neoplastic disease; autoimmune disease; endocrine disorder; local mechanical trauma; exposure to an irritant; or an allergic reaction.2

- Reamy BV, Derby R, Bunt CW. Common tongue conditions in primary care. Am Fam Physician 2010; 81:627–634.

- Chi AC, Neville BW, Krayer JW, Gonsalves WC. Oral manifestations of systemic disease. Am Fam Physician 2010; 82:1381–1388.

- Sun A, Lin HP, Wang YP, Chiang CP. Significant association of deficiency of hemoglobin, iron and vitamin B12, high homocysteine level, and gastric parietal cell antibody positivity with atrophic glossitis. J Oral Pathol Med 2012; 41:500–504.

- Reamy BV, Derby R, Bunt CW. Common tongue conditions in primary care. Am Fam Physician 2010; 81:627–634.

- Chi AC, Neville BW, Krayer JW, Gonsalves WC. Oral manifestations of systemic disease. Am Fam Physician 2010; 82:1381–1388.

- Sun A, Lin HP, Wang YP, Chiang CP. Significant association of deficiency of hemoglobin, iron and vitamin B12, high homocysteine level, and gastric parietal cell antibody positivity with atrophic glossitis. J Oral Pathol Med 2012; 41:500–504.

'Allergic to the sun'

A 54-year-old white man presents to the emergency department with burning pain in his left upper arm for the past 2 to 3 days. His medical history includes seizure disorder, for which he takes levetiracetam (Keppra); hypertension, for which he takes metoprolol succinate (Toprol); and in the remote past, a gunshot wound to the head that left his right arm with residual contracture and weakness.

He says he is homeless, has been “allergic to the sun for a while,” and has had dark-colored urine and intermittent abdominal pain. He states that he does not use illicit substances but that he drinks 6 to 12 beers per night and smokes 1 pack of cigarettes per day.

Initial vital signs:

- Temperature 37.7°C (99.9°F)

- Blood pressure 217/114 mm Hg

- Heart rate 82 bpm

- Respiratory rate 18 per minute

- Capillary oxygen saturation 98% while breathing room air.

On examination, his right arm is significantly weak and contracted. His left arm has decreased sensation to pinprick and light touch from elbow to fingers. His face and both arms show hyperpigmentation alternating with atrophic scarring, which also affects his lips. There is no overt mucosal involvement. His hands and forearms have a sclerotic texture and patchy hair loss. Several small bullae are present on the dorsum of the left forearm and hand. There is a 6-inch, irregular, open lesion on the left forearm and a 1-inch lesion on the left hand (Figure 1).

Initial laboratory studies show:

- Chemistries and complete blood cell count within normal limits

- Platelet count 305 × 109/L (reference range 150–350)

- Orange-colored urine

- Hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibody positive (new finding)

- Human immunodeficiency virus antibody, hepatitis B surface antigen, and antinuclear antibody negative

- Phenytoin and urine drug screen negative

- Aspartate aminotransferase 70 U/L (reference range 5–34)

- Alanine aminotransferase 73 U/L (reference range 0–55)

- Prothrombin time 10.8 seconds (reference range 8.3–13.0), international normalized ratio 0.98 (reference range 0.8–1.2)

- Iron studies within normal limits.

The patient is admitted to the hospital and is started on cefazolin and clindamycin. Urine is collected for a porphyrin screen, and punch-biopsy samples from the forearms are sent for study. Ultrasonography shows splenomegaly, as well as increased echogenicity of the liver without structural abnormalities. Blood and urine cultures, drawn upon admission, are negative by discharge.

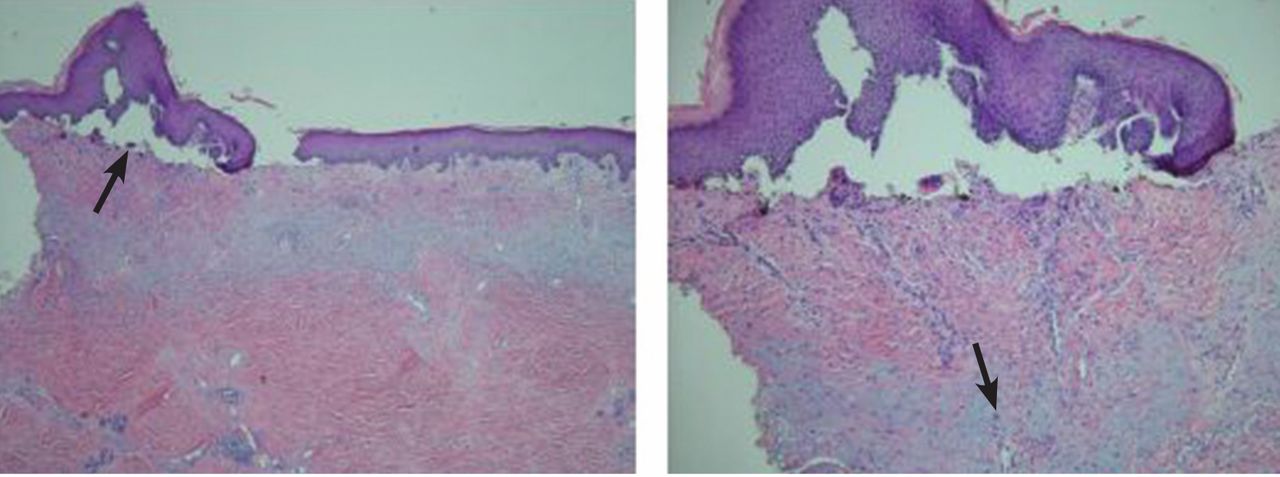

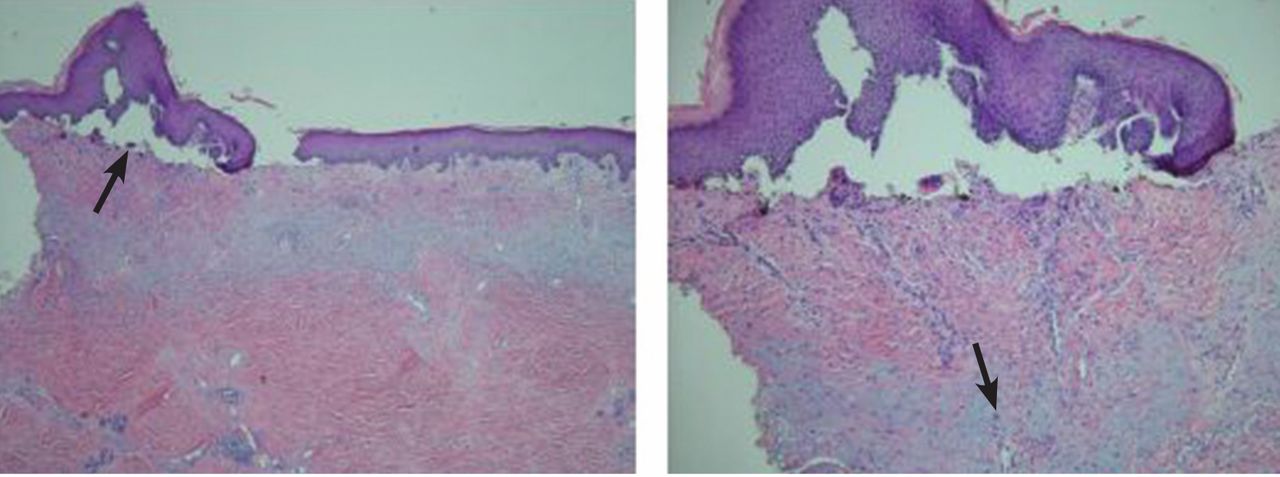

Pathologic study of the punch-biopsy specimens (Figure 2) shows the formation of subepidermal vesicles with extensive reticular and dermal fibrosis.

DIAGNOSIS: PORPHYRIA CUTANEA TARDA

Because of the patient’s history, examination, and pathology results, he was preliminarily diagnosed with porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT).1,2 The diagnosis was confirmed after he was discharged when his urine uroporphyrin level was found to be 157.5 μmol/mol of creatinine (reference range < 4) and his urine heptacarboxylporphyrin level was 118.0 μmol/mol of creatinine (reference range < 2).

This patient’s clinical presentation is classic for sporadic (ie, type 1) PCT. Sporadic PCT is an acquired deficiency of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase, an enzyme that catalyzes the fifth step in heme metabolism.3 The deficiency of this enzyme is exclusively hepatic and is strongly associated with chronic hepatitis C infection. Mutations of the hemochromatosis gene (HFE), human immunodeficiency virus infection, alcohol use, and smoking are also risk factors.4 The prevalence in the United States is about 1:25,000; nearly 80% of cases are sporadic (type 1), and 20% are familial (type 2).5

Manifestations of PCT include photosensitive dermatitis, facial hypertrichosis, and orange urine.3 The photosensitivity dermatitis heals slowly and leads to sclerosis and hyperpigmentation.

Repeated phlebotomy is the first-line treatment, and hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) is the second-line treatment.6 Patients with PCT and hepatitis C should be considered for antiviral therapy according to standard guidelines. Treatment of hepatitis C may reduce the symptoms of PCT, even without a sustained viral response. However, not enough evidence exists to make treatment recommendations for this group.7

Because we were uncertain that the patient would return for follow-up, we did not start phlebotomy or treatment for hepatitis C. However, we did prescribe hydroxychloroquine 100 mg three times a week and instructed him to cover his skin when outside and to use effective sunblock. An outpatient visit was scheduled prior to discharge. Unfortunately, the patient was lost to follow-up.

Acknowledgment: The authors would like to personally thank Dr. Karen DeSouza from the University of Tennessee, Graduate School of Medicine, Department of Pathology, for her clinical expertise and kind advice.

- The University of Iowa, Department of Pathology, Laboratory Services Handbook. Porphyrins & Porphobilinogen, Urine (24 hr or random). www.healthcare.uiowa.edu/path_handbook/handbook/test2893.html. Accessed August 8, 2014.

- Maynard B, Peters MS. Histologic and immunofluorescence study of cutaneous porphyrias. J Cutan Pathol 1992; 19:40–47.

- Thunell S, Harper P. Porphyrins, porphyrin metabolism, porphyrias. III. Diagnosis, care and monitoring in porphyria cutanea tarda—suggestions for a handling programme. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2000; 60:561–579.

- Lambrecht RW, Thapar M, Bonkovsky HL. Genetic aspects of porphyria cutanea tarda. Semin Liver Dis 2007; 27:99–108.

- Kushner JP, Barbuto AJ, Lee GR. An inherited enzymatic defect in porphyria cutanea tarda: decreased uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase activity. J Clin Invest 1976; 58:1089–1097.

- Singal AK, Kormos-Hallberg C, Lee C, et al. Low-dose hydroxychloroquine is as effective as phlebotomy in treatment of patients with porphyria cutanea tarda. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 10:1402–1409.

- Ryan Caballes F, Sendi H, Bonkovsky HL. Hepatitis C, porphyria cutanea tarda and liver iron: an update. Liver Int 2012; 32:880–893.

A 54-year-old white man presents to the emergency department with burning pain in his left upper arm for the past 2 to 3 days. His medical history includes seizure disorder, for which he takes levetiracetam (Keppra); hypertension, for which he takes metoprolol succinate (Toprol); and in the remote past, a gunshot wound to the head that left his right arm with residual contracture and weakness.

He says he is homeless, has been “allergic to the sun for a while,” and has had dark-colored urine and intermittent abdominal pain. He states that he does not use illicit substances but that he drinks 6 to 12 beers per night and smokes 1 pack of cigarettes per day.

Initial vital signs:

- Temperature 37.7°C (99.9°F)

- Blood pressure 217/114 mm Hg

- Heart rate 82 bpm

- Respiratory rate 18 per minute

- Capillary oxygen saturation 98% while breathing room air.

On examination, his right arm is significantly weak and contracted. His left arm has decreased sensation to pinprick and light touch from elbow to fingers. His face and both arms show hyperpigmentation alternating with atrophic scarring, which also affects his lips. There is no overt mucosal involvement. His hands and forearms have a sclerotic texture and patchy hair loss. Several small bullae are present on the dorsum of the left forearm and hand. There is a 6-inch, irregular, open lesion on the left forearm and a 1-inch lesion on the left hand (Figure 1).

Initial laboratory studies show:

- Chemistries and complete blood cell count within normal limits

- Platelet count 305 × 109/L (reference range 150–350)

- Orange-colored urine

- Hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibody positive (new finding)

- Human immunodeficiency virus antibody, hepatitis B surface antigen, and antinuclear antibody negative

- Phenytoin and urine drug screen negative

- Aspartate aminotransferase 70 U/L (reference range 5–34)

- Alanine aminotransferase 73 U/L (reference range 0–55)

- Prothrombin time 10.8 seconds (reference range 8.3–13.0), international normalized ratio 0.98 (reference range 0.8–1.2)

- Iron studies within normal limits.

The patient is admitted to the hospital and is started on cefazolin and clindamycin. Urine is collected for a porphyrin screen, and punch-biopsy samples from the forearms are sent for study. Ultrasonography shows splenomegaly, as well as increased echogenicity of the liver without structural abnormalities. Blood and urine cultures, drawn upon admission, are negative by discharge.

Pathologic study of the punch-biopsy specimens (Figure 2) shows the formation of subepidermal vesicles with extensive reticular and dermal fibrosis.

DIAGNOSIS: PORPHYRIA CUTANEA TARDA

Because of the patient’s history, examination, and pathology results, he was preliminarily diagnosed with porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT).1,2 The diagnosis was confirmed after he was discharged when his urine uroporphyrin level was found to be 157.5 μmol/mol of creatinine (reference range < 4) and his urine heptacarboxylporphyrin level was 118.0 μmol/mol of creatinine (reference range < 2).

This patient’s clinical presentation is classic for sporadic (ie, type 1) PCT. Sporadic PCT is an acquired deficiency of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase, an enzyme that catalyzes the fifth step in heme metabolism.3 The deficiency of this enzyme is exclusively hepatic and is strongly associated with chronic hepatitis C infection. Mutations of the hemochromatosis gene (HFE), human immunodeficiency virus infection, alcohol use, and smoking are also risk factors.4 The prevalence in the United States is about 1:25,000; nearly 80% of cases are sporadic (type 1), and 20% are familial (type 2).5

Manifestations of PCT include photosensitive dermatitis, facial hypertrichosis, and orange urine.3 The photosensitivity dermatitis heals slowly and leads to sclerosis and hyperpigmentation.

Repeated phlebotomy is the first-line treatment, and hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) is the second-line treatment.6 Patients with PCT and hepatitis C should be considered for antiviral therapy according to standard guidelines. Treatment of hepatitis C may reduce the symptoms of PCT, even without a sustained viral response. However, not enough evidence exists to make treatment recommendations for this group.7

Because we were uncertain that the patient would return for follow-up, we did not start phlebotomy or treatment for hepatitis C. However, we did prescribe hydroxychloroquine 100 mg three times a week and instructed him to cover his skin when outside and to use effective sunblock. An outpatient visit was scheduled prior to discharge. Unfortunately, the patient was lost to follow-up.

Acknowledgment: The authors would like to personally thank Dr. Karen DeSouza from the University of Tennessee, Graduate School of Medicine, Department of Pathology, for her clinical expertise and kind advice.

A 54-year-old white man presents to the emergency department with burning pain in his left upper arm for the past 2 to 3 days. His medical history includes seizure disorder, for which he takes levetiracetam (Keppra); hypertension, for which he takes metoprolol succinate (Toprol); and in the remote past, a gunshot wound to the head that left his right arm with residual contracture and weakness.

He says he is homeless, has been “allergic to the sun for a while,” and has had dark-colored urine and intermittent abdominal pain. He states that he does not use illicit substances but that he drinks 6 to 12 beers per night and smokes 1 pack of cigarettes per day.

Initial vital signs:

- Temperature 37.7°C (99.9°F)

- Blood pressure 217/114 mm Hg

- Heart rate 82 bpm

- Respiratory rate 18 per minute

- Capillary oxygen saturation 98% while breathing room air.

On examination, his right arm is significantly weak and contracted. His left arm has decreased sensation to pinprick and light touch from elbow to fingers. His face and both arms show hyperpigmentation alternating with atrophic scarring, which also affects his lips. There is no overt mucosal involvement. His hands and forearms have a sclerotic texture and patchy hair loss. Several small bullae are present on the dorsum of the left forearm and hand. There is a 6-inch, irregular, open lesion on the left forearm and a 1-inch lesion on the left hand (Figure 1).

Initial laboratory studies show:

- Chemistries and complete blood cell count within normal limits

- Platelet count 305 × 109/L (reference range 150–350)

- Orange-colored urine

- Hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibody positive (new finding)

- Human immunodeficiency virus antibody, hepatitis B surface antigen, and antinuclear antibody negative

- Phenytoin and urine drug screen negative

- Aspartate aminotransferase 70 U/L (reference range 5–34)

- Alanine aminotransferase 73 U/L (reference range 0–55)

- Prothrombin time 10.8 seconds (reference range 8.3–13.0), international normalized ratio 0.98 (reference range 0.8–1.2)

- Iron studies within normal limits.

The patient is admitted to the hospital and is started on cefazolin and clindamycin. Urine is collected for a porphyrin screen, and punch-biopsy samples from the forearms are sent for study. Ultrasonography shows splenomegaly, as well as increased echogenicity of the liver without structural abnormalities. Blood and urine cultures, drawn upon admission, are negative by discharge.

Pathologic study of the punch-biopsy specimens (Figure 2) shows the formation of subepidermal vesicles with extensive reticular and dermal fibrosis.

DIAGNOSIS: PORPHYRIA CUTANEA TARDA

Because of the patient’s history, examination, and pathology results, he was preliminarily diagnosed with porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT).1,2 The diagnosis was confirmed after he was discharged when his urine uroporphyrin level was found to be 157.5 μmol/mol of creatinine (reference range < 4) and his urine heptacarboxylporphyrin level was 118.0 μmol/mol of creatinine (reference range < 2).

This patient’s clinical presentation is classic for sporadic (ie, type 1) PCT. Sporadic PCT is an acquired deficiency of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase, an enzyme that catalyzes the fifth step in heme metabolism.3 The deficiency of this enzyme is exclusively hepatic and is strongly associated with chronic hepatitis C infection. Mutations of the hemochromatosis gene (HFE), human immunodeficiency virus infection, alcohol use, and smoking are also risk factors.4 The prevalence in the United States is about 1:25,000; nearly 80% of cases are sporadic (type 1), and 20% are familial (type 2).5

Manifestations of PCT include photosensitive dermatitis, facial hypertrichosis, and orange urine.3 The photosensitivity dermatitis heals slowly and leads to sclerosis and hyperpigmentation.

Repeated phlebotomy is the first-line treatment, and hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) is the second-line treatment.6 Patients with PCT and hepatitis C should be considered for antiviral therapy according to standard guidelines. Treatment of hepatitis C may reduce the symptoms of PCT, even without a sustained viral response. However, not enough evidence exists to make treatment recommendations for this group.7

Because we were uncertain that the patient would return for follow-up, we did not start phlebotomy or treatment for hepatitis C. However, we did prescribe hydroxychloroquine 100 mg three times a week and instructed him to cover his skin when outside and to use effective sunblock. An outpatient visit was scheduled prior to discharge. Unfortunately, the patient was lost to follow-up.

Acknowledgment: The authors would like to personally thank Dr. Karen DeSouza from the University of Tennessee, Graduate School of Medicine, Department of Pathology, for her clinical expertise and kind advice.

- The University of Iowa, Department of Pathology, Laboratory Services Handbook. Porphyrins & Porphobilinogen, Urine (24 hr or random). www.healthcare.uiowa.edu/path_handbook/handbook/test2893.html. Accessed August 8, 2014.

- Maynard B, Peters MS. Histologic and immunofluorescence study of cutaneous porphyrias. J Cutan Pathol 1992; 19:40–47.

- Thunell S, Harper P. Porphyrins, porphyrin metabolism, porphyrias. III. Diagnosis, care and monitoring in porphyria cutanea tarda—suggestions for a handling programme. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2000; 60:561–579.

- Lambrecht RW, Thapar M, Bonkovsky HL. Genetic aspects of porphyria cutanea tarda. Semin Liver Dis 2007; 27:99–108.

- Kushner JP, Barbuto AJ, Lee GR. An inherited enzymatic defect in porphyria cutanea tarda: decreased uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase activity. J Clin Invest 1976; 58:1089–1097.

- Singal AK, Kormos-Hallberg C, Lee C, et al. Low-dose hydroxychloroquine is as effective as phlebotomy in treatment of patients with porphyria cutanea tarda. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 10:1402–1409.

- Ryan Caballes F, Sendi H, Bonkovsky HL. Hepatitis C, porphyria cutanea tarda and liver iron: an update. Liver Int 2012; 32:880–893.

- The University of Iowa, Department of Pathology, Laboratory Services Handbook. Porphyrins & Porphobilinogen, Urine (24 hr or random). www.healthcare.uiowa.edu/path_handbook/handbook/test2893.html. Accessed August 8, 2014.

- Maynard B, Peters MS. Histologic and immunofluorescence study of cutaneous porphyrias. J Cutan Pathol 1992; 19:40–47.

- Thunell S, Harper P. Porphyrins, porphyrin metabolism, porphyrias. III. Diagnosis, care and monitoring in porphyria cutanea tarda—suggestions for a handling programme. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2000; 60:561–579.

- Lambrecht RW, Thapar M, Bonkovsky HL. Genetic aspects of porphyria cutanea tarda. Semin Liver Dis 2007; 27:99–108.

- Kushner JP, Barbuto AJ, Lee GR. An inherited enzymatic defect in porphyria cutanea tarda: decreased uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase activity. J Clin Invest 1976; 58:1089–1097.

- Singal AK, Kormos-Hallberg C, Lee C, et al. Low-dose hydroxychloroquine is as effective as phlebotomy in treatment of patients with porphyria cutanea tarda. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 10:1402–1409.

- Ryan Caballes F, Sendi H, Bonkovsky HL. Hepatitis C, porphyria cutanea tarda and liver iron: an update. Liver Int 2012; 32:880–893.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy apical variant

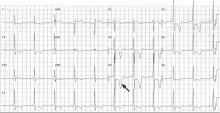

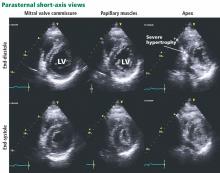

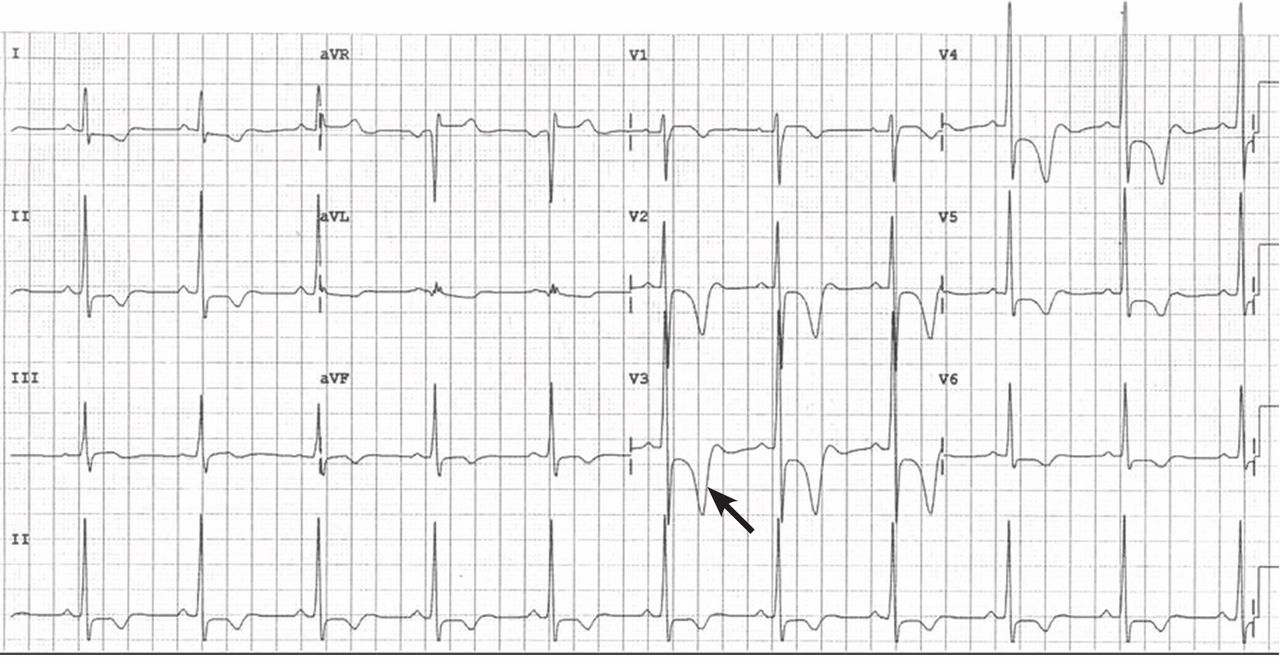

He had had an isolated syncopal episode while intensely training a year ago, but his medical history was otherwise unremarkable.

On examination, he appeared fit. His vital signs were normal. The apical pulse was sustained on palpation and was not displaced. Auscultation revealed an S4 heart sound.

HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY: THE APICAL VARIANT

In typical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, the left ventricle, especially the interventricular septum, is thickened, but the left ventricular chamber size is normal or small. In severe cases, the left ventricular outflow tract can become very narrowed, resulting in accelerated blood flow, which may further increase in the presence of hypovolemia, peripheral vasodilation, and increased cardiac contractility. The Venturi effect thus created may entrain a typically malformed anterior mitral valve leaflet toward the aortic valve (systolic anterior motion), causing mitral insufficiency and exacerbating obstruction of the left ventricular outflow tract. Systolic anterior motion may play an important role in exercise-induced syncope and sudden death in young people with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.4

In the apical variant, hypertrophy is confined to the left ventricular apex.1–3 There is no dynamic outflow tract obstruction. Still, unexplained syncope has been reported, and recent data challenge the conventional wisdom that the apical variant of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy has a benign prognosis.2 In patients without a history of recurrent syncope, chest pain, or heart failure, perioperative risk is probably not significantly increased. The differential diagnosis includes myocardial ischemia or infarction, electrolyte disturbances, effects of drugs (eg, digoxin), and subarachnoid hemorrhage.1–3,5 Plain or contrast-enhanced echocardiography or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, or both, can help confirm the diagnosis. Long-term management should be guided by the patient’s symptoms.

- Eriksson MJ, Sonnenberg B, Woo A, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39:638–645.

- Kasirye Y, Manne JR, Epperla N, Bapani S, Garcia-Montilla R. Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy presenting as recurrent unexplained syncope. Clin Med Res 2012; 10:26–31.

- Lee CH, Liu PY, Lin LJ, Chen JH, Tsai LM. Clinical features and outcome of patients with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Taiwan. Cardiology 2006; 106:29–35.

- Nishimura RA, Holmes DR Clinical practice. Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2004; 350:1320–1327.

- Lin CS, Chen CH, Ding PY. Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 1998; 64:305–307.

He had had an isolated syncopal episode while intensely training a year ago, but his medical history was otherwise unremarkable.

On examination, he appeared fit. His vital signs were normal. The apical pulse was sustained on palpation and was not displaced. Auscultation revealed an S4 heart sound.

HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY: THE APICAL VARIANT

In typical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, the left ventricle, especially the interventricular septum, is thickened, but the left ventricular chamber size is normal or small. In severe cases, the left ventricular outflow tract can become very narrowed, resulting in accelerated blood flow, which may further increase in the presence of hypovolemia, peripheral vasodilation, and increased cardiac contractility. The Venturi effect thus created may entrain a typically malformed anterior mitral valve leaflet toward the aortic valve (systolic anterior motion), causing mitral insufficiency and exacerbating obstruction of the left ventricular outflow tract. Systolic anterior motion may play an important role in exercise-induced syncope and sudden death in young people with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.4

In the apical variant, hypertrophy is confined to the left ventricular apex.1–3 There is no dynamic outflow tract obstruction. Still, unexplained syncope has been reported, and recent data challenge the conventional wisdom that the apical variant of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy has a benign prognosis.2 In patients without a history of recurrent syncope, chest pain, or heart failure, perioperative risk is probably not significantly increased. The differential diagnosis includes myocardial ischemia or infarction, electrolyte disturbances, effects of drugs (eg, digoxin), and subarachnoid hemorrhage.1–3,5 Plain or contrast-enhanced echocardiography or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, or both, can help confirm the diagnosis. Long-term management should be guided by the patient’s symptoms.

He had had an isolated syncopal episode while intensely training a year ago, but his medical history was otherwise unremarkable.

On examination, he appeared fit. His vital signs were normal. The apical pulse was sustained on palpation and was not displaced. Auscultation revealed an S4 heart sound.

HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY: THE APICAL VARIANT

In typical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, the left ventricle, especially the interventricular septum, is thickened, but the left ventricular chamber size is normal or small. In severe cases, the left ventricular outflow tract can become very narrowed, resulting in accelerated blood flow, which may further increase in the presence of hypovolemia, peripheral vasodilation, and increased cardiac contractility. The Venturi effect thus created may entrain a typically malformed anterior mitral valve leaflet toward the aortic valve (systolic anterior motion), causing mitral insufficiency and exacerbating obstruction of the left ventricular outflow tract. Systolic anterior motion may play an important role in exercise-induced syncope and sudden death in young people with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.4

In the apical variant, hypertrophy is confined to the left ventricular apex.1–3 There is no dynamic outflow tract obstruction. Still, unexplained syncope has been reported, and recent data challenge the conventional wisdom that the apical variant of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy has a benign prognosis.2 In patients without a history of recurrent syncope, chest pain, or heart failure, perioperative risk is probably not significantly increased. The differential diagnosis includes myocardial ischemia or infarction, electrolyte disturbances, effects of drugs (eg, digoxin), and subarachnoid hemorrhage.1–3,5 Plain or contrast-enhanced echocardiography or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, or both, can help confirm the diagnosis. Long-term management should be guided by the patient’s symptoms.

- Eriksson MJ, Sonnenberg B, Woo A, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39:638–645.

- Kasirye Y, Manne JR, Epperla N, Bapani S, Garcia-Montilla R. Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy presenting as recurrent unexplained syncope. Clin Med Res 2012; 10:26–31.

- Lee CH, Liu PY, Lin LJ, Chen JH, Tsai LM. Clinical features and outcome of patients with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Taiwan. Cardiology 2006; 106:29–35.

- Nishimura RA, Holmes DR Clinical practice. Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2004; 350:1320–1327.

- Lin CS, Chen CH, Ding PY. Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 1998; 64:305–307.

- Eriksson MJ, Sonnenberg B, Woo A, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39:638–645.

- Kasirye Y, Manne JR, Epperla N, Bapani S, Garcia-Montilla R. Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy presenting as recurrent unexplained syncope. Clin Med Res 2012; 10:26–31.

- Lee CH, Liu PY, Lin LJ, Chen JH, Tsai LM. Clinical features and outcome of patients with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Taiwan. Cardiology 2006; 106:29–35.

- Nishimura RA, Holmes DR Clinical practice. Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2004; 350:1320–1327.

- Lin CS, Chen CH, Ding PY. Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 1998; 64:305–307.

A 78-year-old smoker with an incidental pulmonary mass

When a 78-year-old man underwent magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine because of back pain, the scan revealed a mass in the right lung. He had no respiratory symptoms but had a 40-pack-year smoking history. Physical examination and routine blood tests were unremarkable.

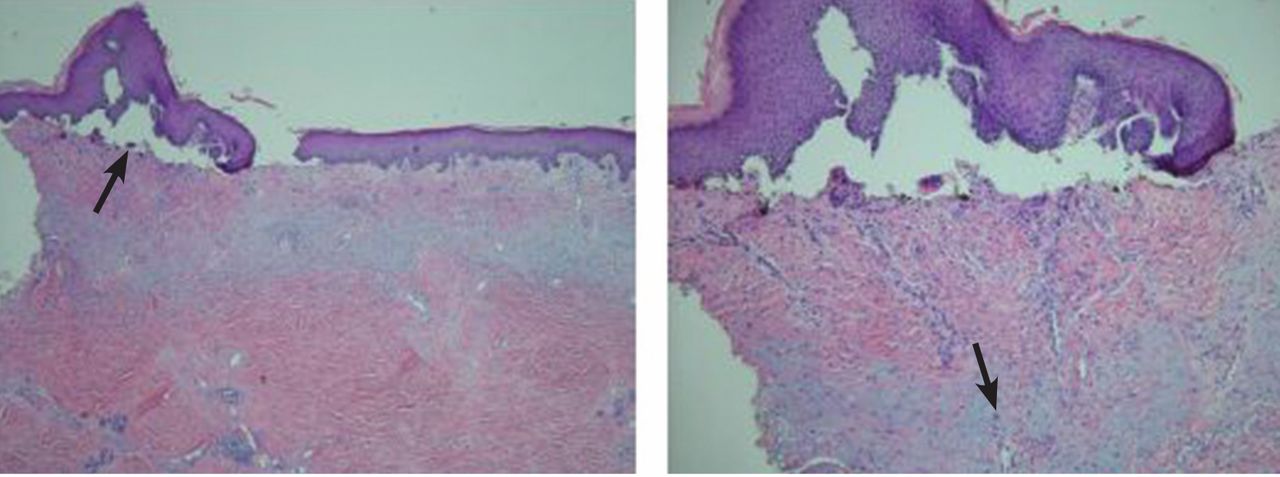

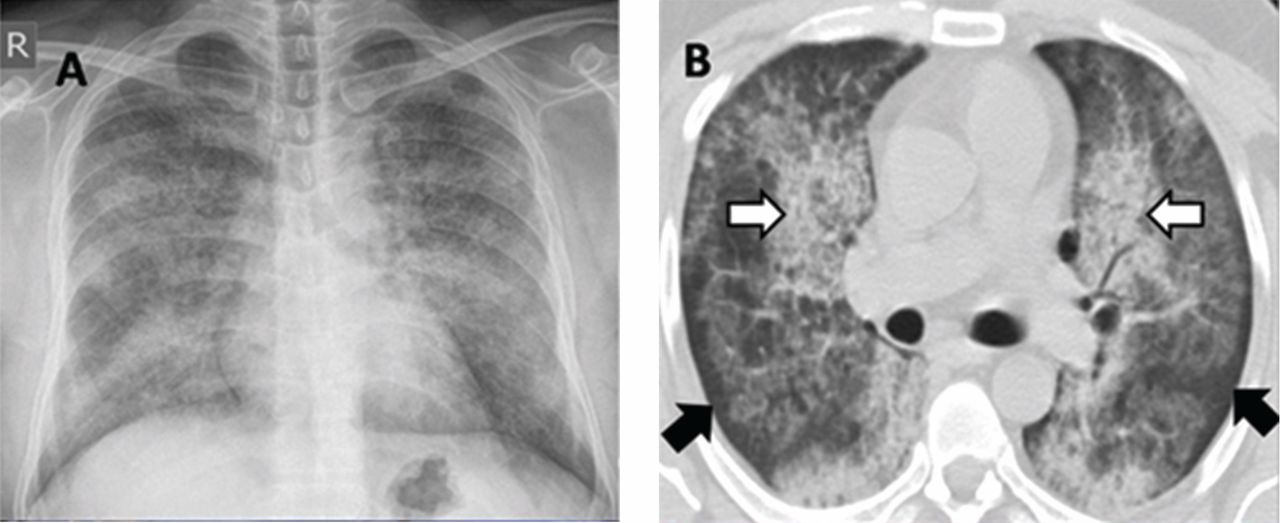

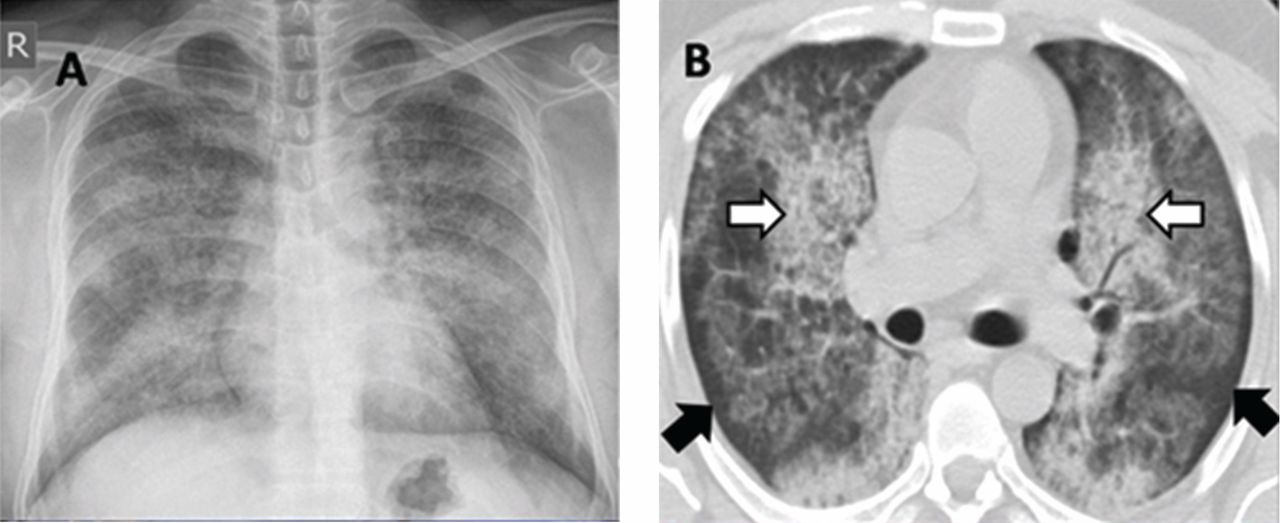

Radiography (Figure 1) showed a large rounded opacity in the right lower lobe. The patient’s age, smoking history, and imaging findings raised concern for lung cancer, so computed tomography (CT) was performed (Figure 2).

DIAGNOSIS: PULMONARY HAMARTOMA

The findings of a well-circumscribed solitary pulmonary nodule or mass containing areas of fat, either as focal islands or more generally distributed, and chondroid “popcorn” calcification are virtually pathognomonic for pulmonary hamartoma.1,2 Unfortunately, although this pattern of calcification is strongly diagnostic, it is present in only a minority of cases of hamartoma.

Pulmonary hamartoma is the most common benign tumor of the lung, accounting for approximately 75% of benign neoplasms and 6% to 8% of all focal lung parenchymal masses.3

Like hamartoma elsewhere in the body, pulmonary hamartoma consists of disorganized overgrowth and aberrant arrangement of normal tissues, including cartilage (which may calcify), smooth muscle, epithelium, and fibrostroma. Pulmonary hamartoma is twice as common in men as in women, and it has a peak incidence in the seventh decade of life.4

Although size ranged from 0.2 to 6 cm in a large case series,4 hamartomas are usually less than 2.5 cm in diameter. As noted in Figure 1, our patient’s lesion was 5 cm.

Pulmonary hamartomas grow slowly and are often asymptomatic, although up to 39% of patients may have symptoms such as cough, dyspnea, and chest tightness.5 The nonspecific nature of these symptoms makes it difficult to be certain that they are caused by the hamartoma; in many cases, they are likely to be coincidental. Lesions tend to occur in the periphery of the lobe and do not favor a particular lobe. Endobronchial lesions can occur but are uncommon.

The internal heterogeneous elements are difficult to see on radiography; CT is usually required to further characterize the lesion and to exclude more sinister differential diagnoses. In some cases the characteristic features of fat and calcification are absent, making a certain diagnosis difficult or impossible radiologically; in such cases, biopsy or resection may be required.

Hamartomas usually do not take up fluorodeoxyglucose avidly on positron-emission tomography CT. However, nuclear medicine studies such as this are superfluous if the classic features are present on CT.

FOLLOW-UP AND TREATMENT

Given the benign nature, slow growth, and usually incidental detection of pulmonary hamartoma in patients without symptoms, no follow-up imaging or treatment is usually required. In the few cases in which symptoms are attributable to the lesion, the lesion can be resected.5 Resection is also an option when the patient is very anxious about the mass, or when imaging studies do not provide a clear diagnosis and tissue needs to be obtained for study.

Because patients often present to different institutions during their lifetime, it is important to counsel them about the natural history of pulmonary hamartomas. Giving them a copy of their imaging may help avoid unnecessary repetition.

- Erasmus JJ, Connolly JE, McAdams HP, Roggli VL. Solitary pulmonary nodules: Part I. Morphologic evaluation for differentiation of benign and malignant lesions. Radiographics 2000; 20:43–58.

- Khan AN, Al-Jahdali HH, Allen CM, Irion KL, Al Ghanem S, Koteyar SS. The calcified lung nodule: what does it mean? Ann Thorac Med 2010; 5:67–79.

- Siegelman SS, Khouri NF, Scott WW, et al. Pulmonary hamartoma: CT findings. Radiology 1986; 160:313–317.

- Gjevre JA, Myers JL, Prakash UB. Pulmonary hamartomas. Mayo Clin Proc 1996; 71:14–20.

- Hansen CP, Holtveg H, Francis D, Rasch L, Bertelsen S. Pulmonary hamartoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1992; 104:674–678.

When a 78-year-old man underwent magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine because of back pain, the scan revealed a mass in the right lung. He had no respiratory symptoms but had a 40-pack-year smoking history. Physical examination and routine blood tests were unremarkable.

Radiography (Figure 1) showed a large rounded opacity in the right lower lobe. The patient’s age, smoking history, and imaging findings raised concern for lung cancer, so computed tomography (CT) was performed (Figure 2).

DIAGNOSIS: PULMONARY HAMARTOMA

The findings of a well-circumscribed solitary pulmonary nodule or mass containing areas of fat, either as focal islands or more generally distributed, and chondroid “popcorn” calcification are virtually pathognomonic for pulmonary hamartoma.1,2 Unfortunately, although this pattern of calcification is strongly diagnostic, it is present in only a minority of cases of hamartoma.

Pulmonary hamartoma is the most common benign tumor of the lung, accounting for approximately 75% of benign neoplasms and 6% to 8% of all focal lung parenchymal masses.3

Like hamartoma elsewhere in the body, pulmonary hamartoma consists of disorganized overgrowth and aberrant arrangement of normal tissues, including cartilage (which may calcify), smooth muscle, epithelium, and fibrostroma. Pulmonary hamartoma is twice as common in men as in women, and it has a peak incidence in the seventh decade of life.4

Although size ranged from 0.2 to 6 cm in a large case series,4 hamartomas are usually less than 2.5 cm in diameter. As noted in Figure 1, our patient’s lesion was 5 cm.

Pulmonary hamartomas grow slowly and are often asymptomatic, although up to 39% of patients may have symptoms such as cough, dyspnea, and chest tightness.5 The nonspecific nature of these symptoms makes it difficult to be certain that they are caused by the hamartoma; in many cases, they are likely to be coincidental. Lesions tend to occur in the periphery of the lobe and do not favor a particular lobe. Endobronchial lesions can occur but are uncommon.

The internal heterogeneous elements are difficult to see on radiography; CT is usually required to further characterize the lesion and to exclude more sinister differential diagnoses. In some cases the characteristic features of fat and calcification are absent, making a certain diagnosis difficult or impossible radiologically; in such cases, biopsy or resection may be required.

Hamartomas usually do not take up fluorodeoxyglucose avidly on positron-emission tomography CT. However, nuclear medicine studies such as this are superfluous if the classic features are present on CT.

FOLLOW-UP AND TREATMENT

Given the benign nature, slow growth, and usually incidental detection of pulmonary hamartoma in patients without symptoms, no follow-up imaging or treatment is usually required. In the few cases in which symptoms are attributable to the lesion, the lesion can be resected.5 Resection is also an option when the patient is very anxious about the mass, or when imaging studies do not provide a clear diagnosis and tissue needs to be obtained for study.

Because patients often present to different institutions during their lifetime, it is important to counsel them about the natural history of pulmonary hamartomas. Giving them a copy of their imaging may help avoid unnecessary repetition.

When a 78-year-old man underwent magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine because of back pain, the scan revealed a mass in the right lung. He had no respiratory symptoms but had a 40-pack-year smoking history. Physical examination and routine blood tests were unremarkable.

Radiography (Figure 1) showed a large rounded opacity in the right lower lobe. The patient’s age, smoking history, and imaging findings raised concern for lung cancer, so computed tomography (CT) was performed (Figure 2).

DIAGNOSIS: PULMONARY HAMARTOMA

The findings of a well-circumscribed solitary pulmonary nodule or mass containing areas of fat, either as focal islands or more generally distributed, and chondroid “popcorn” calcification are virtually pathognomonic for pulmonary hamartoma.1,2 Unfortunately, although this pattern of calcification is strongly diagnostic, it is present in only a minority of cases of hamartoma.

Pulmonary hamartoma is the most common benign tumor of the lung, accounting for approximately 75% of benign neoplasms and 6% to 8% of all focal lung parenchymal masses.3

Like hamartoma elsewhere in the body, pulmonary hamartoma consists of disorganized overgrowth and aberrant arrangement of normal tissues, including cartilage (which may calcify), smooth muscle, epithelium, and fibrostroma. Pulmonary hamartoma is twice as common in men as in women, and it has a peak incidence in the seventh decade of life.4

Although size ranged from 0.2 to 6 cm in a large case series,4 hamartomas are usually less than 2.5 cm in diameter. As noted in Figure 1, our patient’s lesion was 5 cm.

Pulmonary hamartomas grow slowly and are often asymptomatic, although up to 39% of patients may have symptoms such as cough, dyspnea, and chest tightness.5 The nonspecific nature of these symptoms makes it difficult to be certain that they are caused by the hamartoma; in many cases, they are likely to be coincidental. Lesions tend to occur in the periphery of the lobe and do not favor a particular lobe. Endobronchial lesions can occur but are uncommon.

The internal heterogeneous elements are difficult to see on radiography; CT is usually required to further characterize the lesion and to exclude more sinister differential diagnoses. In some cases the characteristic features of fat and calcification are absent, making a certain diagnosis difficult or impossible radiologically; in such cases, biopsy or resection may be required.

Hamartomas usually do not take up fluorodeoxyglucose avidly on positron-emission tomography CT. However, nuclear medicine studies such as this are superfluous if the classic features are present on CT.

FOLLOW-UP AND TREATMENT

Given the benign nature, slow growth, and usually incidental detection of pulmonary hamartoma in patients without symptoms, no follow-up imaging or treatment is usually required. In the few cases in which symptoms are attributable to the lesion, the lesion can be resected.5 Resection is also an option when the patient is very anxious about the mass, or when imaging studies do not provide a clear diagnosis and tissue needs to be obtained for study.

Because patients often present to different institutions during their lifetime, it is important to counsel them about the natural history of pulmonary hamartomas. Giving them a copy of their imaging may help avoid unnecessary repetition.

- Erasmus JJ, Connolly JE, McAdams HP, Roggli VL. Solitary pulmonary nodules: Part I. Morphologic evaluation for differentiation of benign and malignant lesions. Radiographics 2000; 20:43–58.

- Khan AN, Al-Jahdali HH, Allen CM, Irion KL, Al Ghanem S, Koteyar SS. The calcified lung nodule: what does it mean? Ann Thorac Med 2010; 5:67–79.

- Siegelman SS, Khouri NF, Scott WW, et al. Pulmonary hamartoma: CT findings. Radiology 1986; 160:313–317.

- Gjevre JA, Myers JL, Prakash UB. Pulmonary hamartomas. Mayo Clin Proc 1996; 71:14–20.

- Hansen CP, Holtveg H, Francis D, Rasch L, Bertelsen S. Pulmonary hamartoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1992; 104:674–678.

- Erasmus JJ, Connolly JE, McAdams HP, Roggli VL. Solitary pulmonary nodules: Part I. Morphologic evaluation for differentiation of benign and malignant lesions. Radiographics 2000; 20:43–58.

- Khan AN, Al-Jahdali HH, Allen CM, Irion KL, Al Ghanem S, Koteyar SS. The calcified lung nodule: what does it mean? Ann Thorac Med 2010; 5:67–79.

- Siegelman SS, Khouri NF, Scott WW, et al. Pulmonary hamartoma: CT findings. Radiology 1986; 160:313–317.

- Gjevre JA, Myers JL, Prakash UB. Pulmonary hamartomas. Mayo Clin Proc 1996; 71:14–20.

- Hansen CP, Holtveg H, Francis D, Rasch L, Bertelsen S. Pulmonary hamartoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1992; 104:674–678.

Alveolar proteinosis: A slow drowning in mud

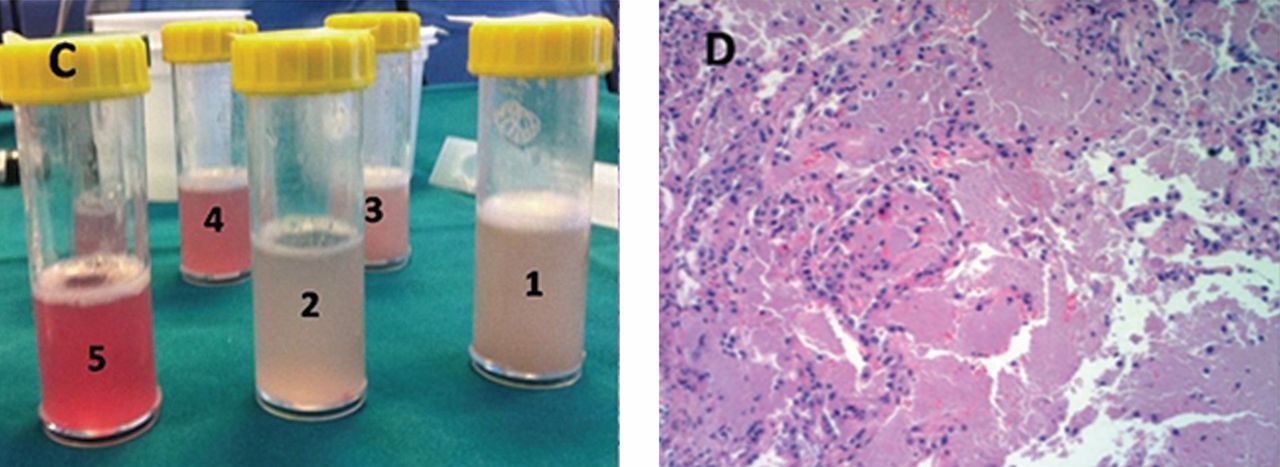

A 30-year-old man presented with progressive dyspnea and dry cough, which had developed over the last 6 months. His oxygen saturation was 88% on room air, and he had diffuse bilateral crackles on auscultation. Imaging showed a mixture of diffuse airspace and interstitial abnormalities (Figure 1).

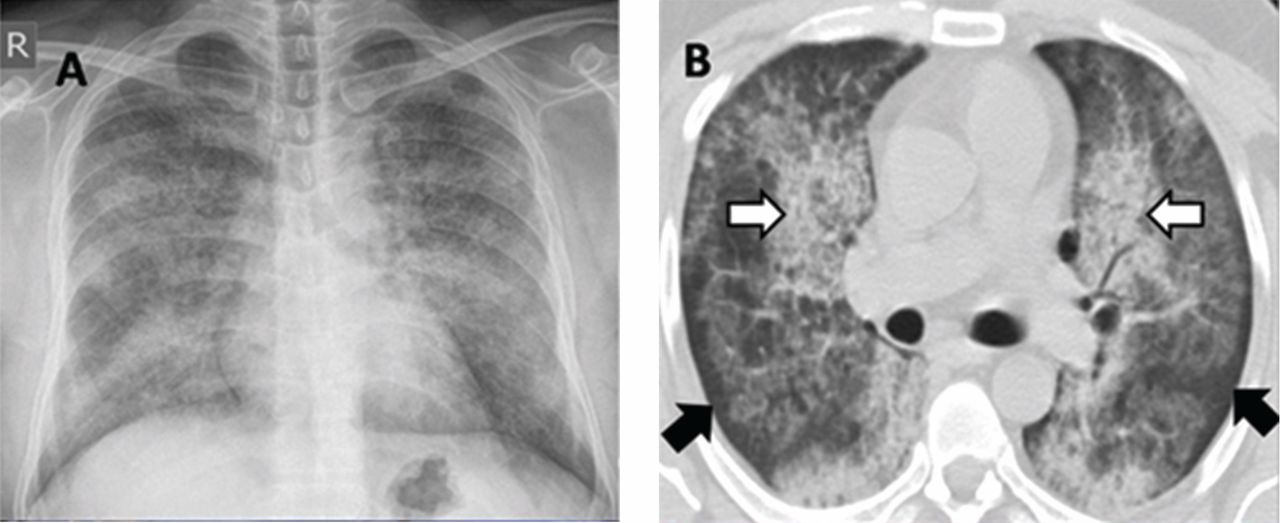

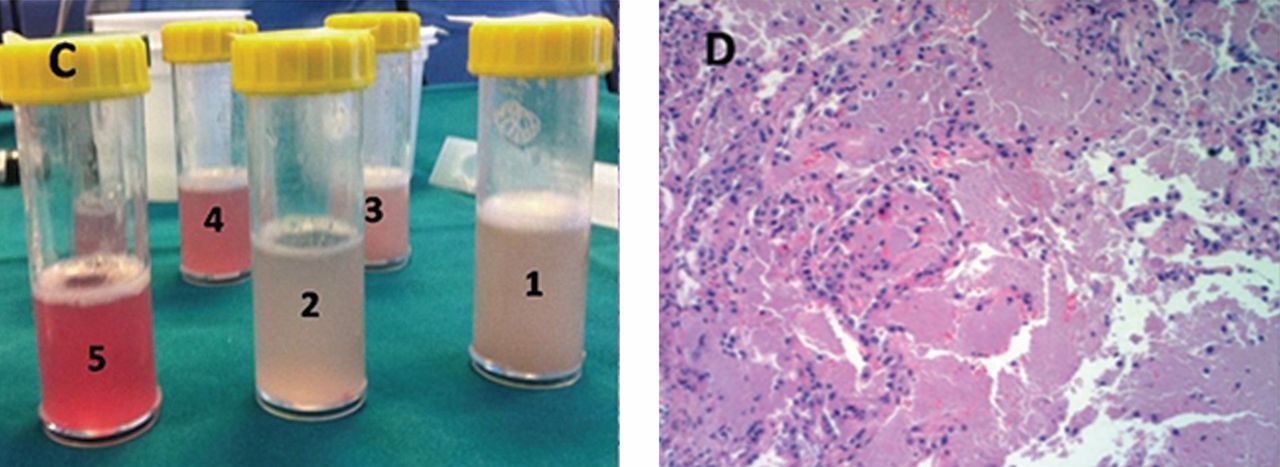

He underwent bronchoscopy. The bronchoalveolar lavage fluid had a turbid appearance that gradually cleared with successive aliquots. Transbronchial biopsy studies confirmed the diagnosis of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (Figure 2). Sequential whole-lung lavage recovered significant amounts of thick, proteinaceous effluent that slowly cleared. After the procedure, the patient’s symptoms, oxygen saturation, and chest radiographic appearance (Figure 3) improved markedly, with no recurrence at 1 year of follow-up.

ALVEOLAR PROTEINOSIS

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis is a rare disease characterized by the accumulation of lipoproteinaceous material in the alveolar space secondary to alveolar macrophage dysfunction. The condition can be congenital, secondary, or acquired. Patients typically present with progressive exertional dyspnea, nonproductive cough, variable restrictive ventilatory defects, and diffusion limitation on pulmonary function testing.

Plain chest radiographs usually resemble those seen in pulmonary edema but without features of heart failure, ie, cardiomegaly, Kerley B lines, and effusion.

A “crazy-paving” pattern on computed tomography—a combination of geographic ground-glass appearance and interseptal thickening—suggests alveolar proteinosis, but is not specific for it. Other differential diagnoses for the crazy-paving pattern include Pneumocystis jirovecii infection, invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma, cardiogenic pulmonary edema, alveolar hemorrhage, sarcoidosis, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, exogenous lipoid pneumonia, drug-induced lung disease, acute radiation pneumonitis, and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia.1

Laboratory testing is not very helpful in the diagnosis, although the serum lactate dehydrogenase level may be mildly elevated. Circulating antibodies to granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor may support the diagnosis, but they are only present in the acquired form. Communication with a research laboratory is usually needed to test for these antibodies.

The bronchoalveolar lavage fluid typically has an opaque, milky, or muddy appearance. The diagnosis is confirmed by demonstration of alveolar filling with material that is periodic acid-Schiff-positive and that is amorphous, eosinophilic, and granular.

Whole-lung lavage2 is the physical removal of surfactant by repeated flooding of the lungs with warmed saline, done under general anesthesia with single-lung ventilation. It remains the standard of care and is indicated in patients with the confirmed diagnosis and one of the following: severe dyspnea, resting hypoxemia (Pao2 < 60 mm Hg at sea level), alveolar-arterial gradient > 40 mm Hg, or a shunt fraction of more than 10%. Successful bronchoscopic lavage has also been reported.3

Other treatments include granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, rituximab (Rituxan, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody), plasmapheresis, and lung transplantation. Systemic corticosteroids are usually ineffective unless indicated for secondary types of alveolar proteinosis.

Inhalation rather than subcutaneous administration of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor seems preferred as it ensures a high concentration in the target organ, avoids systemic complications (injection-site edema, erythema, neutropenia, malaise, and shortness of breath) and achieves lower levels of autoantibodies in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, which correlates with disease activity.

Data are sparse as to the recurrence of autoimmune pulmonary alveolar proteinosis after whole-lung lavage, yet about 40% of patients require a repeat procedure within 18 months. Recurrence has also been reported after double-lung transplantation.4

Adjuvant therapy with rituximab or, to a lesser extent, with inhaled granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor has recently been shown to diminish the need for repeated lavage.5 These treatments can also be used when whole-lung lavage cannot be performed or proves to be ineffective.5

Acknowledgment: I would like to thank Dr. Kamelia Velikova for providing the pathology image.

- Rossi SE, Erasmus JJ, Volpacchio M, Franquet T, Castiglioni T, McAdams HP. ‘Crazy-paving’ pattern at thin-section CT of the lungs: radiologic-pathologic overview. Radiographics 2003; 23:1509–1519.

- Michaud G, Reddy C, Ernst A. Whole-lung lavage for pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Chest 2009; 136:1678–1681.

- Cheng SL, Chang HT, Lau HP, Lee LN, Yang PC. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: treatment by bronchofiberscopic lobar lavage. Chest 2002; 122:1480–1485.

- Parker LA, Novotny DB. Recurrent alveolar proteinosis following double lung transplantation. Chest 1997; 111:1457–1458.

- Leth S, Bendstrup E, Vestergaard H, Hilberg O. Autoimmune pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: treatment options in year 2013. Respirology 2013; 18:82–91.

SUGGESTED READING

Borie R, Danel C, Debray MP, et al. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis.Eur Respir Rev 2011; 20:98–107.

Carey B, Trapnell BC. The molecular basis of pulmonary alveolarproteinosis. Clin Immunol 2010; 135:223–235.

Ioachimescu OC, Kavuru MS. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis.Chron Respir Dis 2006; 3:149–159.

Luisetti M, Kadija Z, Mariani F, Rodi G, Campo I, Trapnell BC.Therapy options in pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. TherAdv Respir Dis 2010; 4:239–248.

A 30-year-old man presented with progressive dyspnea and dry cough, which had developed over the last 6 months. His oxygen saturation was 88% on room air, and he had diffuse bilateral crackles on auscultation. Imaging showed a mixture of diffuse airspace and interstitial abnormalities (Figure 1).

He underwent bronchoscopy. The bronchoalveolar lavage fluid had a turbid appearance that gradually cleared with successive aliquots. Transbronchial biopsy studies confirmed the diagnosis of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (Figure 2). Sequential whole-lung lavage recovered significant amounts of thick, proteinaceous effluent that slowly cleared. After the procedure, the patient’s symptoms, oxygen saturation, and chest radiographic appearance (Figure 3) improved markedly, with no recurrence at 1 year of follow-up.

ALVEOLAR PROTEINOSIS

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis is a rare disease characterized by the accumulation of lipoproteinaceous material in the alveolar space secondary to alveolar macrophage dysfunction. The condition can be congenital, secondary, or acquired. Patients typically present with progressive exertional dyspnea, nonproductive cough, variable restrictive ventilatory defects, and diffusion limitation on pulmonary function testing.

Plain chest radiographs usually resemble those seen in pulmonary edema but without features of heart failure, ie, cardiomegaly, Kerley B lines, and effusion.

A “crazy-paving” pattern on computed tomography—a combination of geographic ground-glass appearance and interseptal thickening—suggests alveolar proteinosis, but is not specific for it. Other differential diagnoses for the crazy-paving pattern include Pneumocystis jirovecii infection, invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma, cardiogenic pulmonary edema, alveolar hemorrhage, sarcoidosis, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, exogenous lipoid pneumonia, drug-induced lung disease, acute radiation pneumonitis, and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia.1

Laboratory testing is not very helpful in the diagnosis, although the serum lactate dehydrogenase level may be mildly elevated. Circulating antibodies to granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor may support the diagnosis, but they are only present in the acquired form. Communication with a research laboratory is usually needed to test for these antibodies.

The bronchoalveolar lavage fluid typically has an opaque, milky, or muddy appearance. The diagnosis is confirmed by demonstration of alveolar filling with material that is periodic acid-Schiff-positive and that is amorphous, eosinophilic, and granular.