User login

Dermatitis in an intestinal transplant candidate

A 36-year-old woman on total parenteral nutrition because of short-bowel syndrome presented with a 2-week history of skin lesions on the face, arms, and legs, but no fever. Examination revealed prominent vesicular lesions on the left arm (Figure 1), face, palms, and soles. Cultures of biopsy specimens were negative for viral, bacterial, and fungal organisms.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Herpes simplex infection

- Varicella zoster infection

- Coxsackievirus infection

- Micronutrient deficiency

- Pemphigus vulgaris

A: Micronutrient deficiency is most likely the cause of her lesions—specifically, severe zinc deficiency, as she was found to have a serum zinc concentration of 12 μg/dL (reference range 55–150). Biopsy specimens showed characteristic intraepidermal blistering with necrosis and minimal inflammation. Serum levels of other micronutrients (iron, copper, selenium) were normal.

Her total parenteral nutrition regimen contained no zinc. Zinc supplementation was started, and a few days later the lesions began to resolve.

Herpes viral infections can cause similar blistering lesions, but this diagnosis was unlikely given the negative viral culture and direct fluorescence antibody test. Coxsackievirus infection is most often seen in children and typically causes fever and mouth sores, which this patient did not have. Lesions of pemphigus vulgaris typically exhibit the Nikolsky sign, ie, they are flaccid, they rupture easily, and the surrounding superficial skin separates from the deeper layers with rubbing or minor trauma. Our patient’s blisters were tense, with a negative Nikolsky sign, and skin biopsy was not consistent with pemphigus vulgaris.

Dermatitis can result from zinc deficiency, which can occur in conditions that cause severe malnutrition due to malabsorption or reduced dietary intake—eg, inflammatory bowel disease, anorexia nervosa, chronic alcoholism, and cystic fibrosis. The lesions can be complicated by secondary bacterial infection, which can cause significant morbidity. Zinc deficiency can also suppress cell-mediated and humoral immunity.

Zinc deficiency can be diagnosed on the basis of clinical findings, skin biopsy, and serum zinc levels. Other micronutrient deficiencies can coexist and should be ruled out. Perioral and acral skin lesions are typically more prominent. Zinc supplementation usually produces rapid resolution of the lesions.

Our patient’s presentation highlights the importance of monitoring micronutrient levels, including zinc, in patients on long-term total parenteral nutrition. Nutritional deficiencies should be considered as a possible cause of dermatitis in such patients.

- Gehrig KA, Dinulos JG. Acrodermatitis due to nutritional deficiency. Curr Opin Pediatr 2010; 22:107–112.

A 36-year-old woman on total parenteral nutrition because of short-bowel syndrome presented with a 2-week history of skin lesions on the face, arms, and legs, but no fever. Examination revealed prominent vesicular lesions on the left arm (Figure 1), face, palms, and soles. Cultures of biopsy specimens were negative for viral, bacterial, and fungal organisms.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Herpes simplex infection

- Varicella zoster infection

- Coxsackievirus infection

- Micronutrient deficiency

- Pemphigus vulgaris

A: Micronutrient deficiency is most likely the cause of her lesions—specifically, severe zinc deficiency, as she was found to have a serum zinc concentration of 12 μg/dL (reference range 55–150). Biopsy specimens showed characteristic intraepidermal blistering with necrosis and minimal inflammation. Serum levels of other micronutrients (iron, copper, selenium) were normal.

Her total parenteral nutrition regimen contained no zinc. Zinc supplementation was started, and a few days later the lesions began to resolve.

Herpes viral infections can cause similar blistering lesions, but this diagnosis was unlikely given the negative viral culture and direct fluorescence antibody test. Coxsackievirus infection is most often seen in children and typically causes fever and mouth sores, which this patient did not have. Lesions of pemphigus vulgaris typically exhibit the Nikolsky sign, ie, they are flaccid, they rupture easily, and the surrounding superficial skin separates from the deeper layers with rubbing or minor trauma. Our patient’s blisters were tense, with a negative Nikolsky sign, and skin biopsy was not consistent with pemphigus vulgaris.

Dermatitis can result from zinc deficiency, which can occur in conditions that cause severe malnutrition due to malabsorption or reduced dietary intake—eg, inflammatory bowel disease, anorexia nervosa, chronic alcoholism, and cystic fibrosis. The lesions can be complicated by secondary bacterial infection, which can cause significant morbidity. Zinc deficiency can also suppress cell-mediated and humoral immunity.

Zinc deficiency can be diagnosed on the basis of clinical findings, skin biopsy, and serum zinc levels. Other micronutrient deficiencies can coexist and should be ruled out. Perioral and acral skin lesions are typically more prominent. Zinc supplementation usually produces rapid resolution of the lesions.

Our patient’s presentation highlights the importance of monitoring micronutrient levels, including zinc, in patients on long-term total parenteral nutrition. Nutritional deficiencies should be considered as a possible cause of dermatitis in such patients.

A 36-year-old woman on total parenteral nutrition because of short-bowel syndrome presented with a 2-week history of skin lesions on the face, arms, and legs, but no fever. Examination revealed prominent vesicular lesions on the left arm (Figure 1), face, palms, and soles. Cultures of biopsy specimens were negative for viral, bacterial, and fungal organisms.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Herpes simplex infection

- Varicella zoster infection

- Coxsackievirus infection

- Micronutrient deficiency

- Pemphigus vulgaris

A: Micronutrient deficiency is most likely the cause of her lesions—specifically, severe zinc deficiency, as she was found to have a serum zinc concentration of 12 μg/dL (reference range 55–150). Biopsy specimens showed characteristic intraepidermal blistering with necrosis and minimal inflammation. Serum levels of other micronutrients (iron, copper, selenium) were normal.

Her total parenteral nutrition regimen contained no zinc. Zinc supplementation was started, and a few days later the lesions began to resolve.

Herpes viral infections can cause similar blistering lesions, but this diagnosis was unlikely given the negative viral culture and direct fluorescence antibody test. Coxsackievirus infection is most often seen in children and typically causes fever and mouth sores, which this patient did not have. Lesions of pemphigus vulgaris typically exhibit the Nikolsky sign, ie, they are flaccid, they rupture easily, and the surrounding superficial skin separates from the deeper layers with rubbing or minor trauma. Our patient’s blisters were tense, with a negative Nikolsky sign, and skin biopsy was not consistent with pemphigus vulgaris.

Dermatitis can result from zinc deficiency, which can occur in conditions that cause severe malnutrition due to malabsorption or reduced dietary intake—eg, inflammatory bowel disease, anorexia nervosa, chronic alcoholism, and cystic fibrosis. The lesions can be complicated by secondary bacterial infection, which can cause significant morbidity. Zinc deficiency can also suppress cell-mediated and humoral immunity.

Zinc deficiency can be diagnosed on the basis of clinical findings, skin biopsy, and serum zinc levels. Other micronutrient deficiencies can coexist and should be ruled out. Perioral and acral skin lesions are typically more prominent. Zinc supplementation usually produces rapid resolution of the lesions.

Our patient’s presentation highlights the importance of monitoring micronutrient levels, including zinc, in patients on long-term total parenteral nutrition. Nutritional deficiencies should be considered as a possible cause of dermatitis in such patients.

- Gehrig KA, Dinulos JG. Acrodermatitis due to nutritional deficiency. Curr Opin Pediatr 2010; 22:107–112.

- Gehrig KA, Dinulos JG. Acrodermatitis due to nutritional deficiency. Curr Opin Pediatr 2010; 22:107–112.

It’s all in the P wave

A 49-year-old man with rheumatic mitral valve stenosis, which had been diagnosed 3 years previously, presented to the outpatient department with worsening exertional dyspnea, fatigue, and cough.

At rest, he appeared comfortable; his pulse rate was 94 bpm and his blood pressure was 117/82 mm Hg. Cardiac auscultation revealed a loud first heart sound, a mid-diastolic murmur with presystolic accentuation at the cardiac apex, and a pansystolic murmur at the left lower sternal border that increased in intensity with inspiration. A prominent left parasternal heave was present.

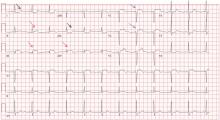

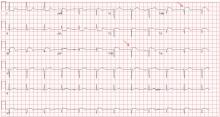

His 12-lead electrocardiogram is shown in Figure 1.

Transthoracic echocardiography confirmed severe mitral stenosis with an estimated mitral valve area of 0.7 cm2 without significant mitral regurgitation. In addition, right ventricular dilatation with moderately severe systolic dysfunction and 4+ (severe) tricuspid regurgitation were present. On the basis of the peak tricuspid regurgitant velocity, the right ventricular systolic pressure was calculated to be 80 mm Hg, consistent with severe pulmonary hypertension. The left ventricular end-diastolic volume was reduced and the ejection fraction was normal.

On right heart catheterization, the pulmonary artery pressure was 92/51 mm Hg.

Q: Electrocardiographic findings that support a diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension include which of the following?

- QRS complex axis of +110°

- R/S (QRS complex) ratio greater than 1 in lead V1

- Sum of the amplitudes of the R wave in lead V1 and the S wave in lead V6 greater than 1.0 mV

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is all of the above. Regardless of the cause, patients with long-standing pulmonary hypertension possess varying degrees of right ventricular hypertrophy that may be accompanied by right ventricular enlargement and systolic dysfunction. A QRS complex axis of 110° or more, an R/S (QRS complex) ratio greater than 1 in lead V1, and the sum of the amplitudes of the R wave in lead V1 and the S wave in lead V6 greater than 1.0 mV all support right ventricular hypertrophy.1

As noted in this electrocardiogram, T-wave inversion in leads V1 and V2 supports a right ventricular repolarization abnormality secondary to the hypertrophy.2

Q: Important electrocardiographic findings in this patient that support secondary pulmonary hypertension due to mitral stenosis include which of the following?

- Tall peaked P waves in lead II of at least 0.25 mV and positive P waves in V1 greater than 0.15 mV

- Prolonged P waves of at least 120 ms in lead II and terminal negative P waves in V1 greater than 40 ms

- Right ventricular hypertrophy

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is prolonged P waves of at least 120 ms in lead II and terminal negative P waves in V1 greater than 40 ms.

Abnormal surface electrocardiographic findings reflecting atrial enlargement or slowed atrial conduction are difficult to differentiate and are best characterized as “atrial abnormalities.” On surface electrocardiography, an atrial abnormality is represented by a P wave morphology that is best studied in leads II and V1. In lead II, a tall peaked P wave of at least 0.25 mV supports right atrial abnormality, and a prolonged P wave (≥ 120 ms) supports left atrial abnormality. In lead V1, right atrial abnormality is suggested by a positive P wave in V1 greater than 0.15 mV, and a terminally negative P wave greater than 40 ms in duration and greater than 0.1 mV deep supports left atrial abnormality.3

It is well recognized that the pathophysiology of pulmonary hypertension involves both the right ventricle and the right atrium.4,5 Therefore, irrespective of the cause of pulmonary hypertension, electrocardiography may additionally reveal right atrial abnormality.6

When the findings suggest pulmonary hypertension (ie, right ventricular hypertrophy with or without right atrial abnormality), it is also important to evaluate for concurrent left atrial abnormality. If present, concomitant left atrial abnormality is a valuable, more specific clue that may help characterize secondary pulmonary hypertension from left-sided heart disease, as illustrated in this example with long-standing severe mitral stenosis.2

- Hancock EW, Deal BJ, Mirvis DM, et al; American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part V: electrocardiogram changes associated with cardiac chamber hypertrophy: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society. Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53:992–1002.

- Goldberger AL. Atrial and ventricular enlargement. In: Clinical Electrocardiography: A Simplified Approach. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2006:59–71.

- Bayés-de-Luna A, Goldwasser D, Fiol M, Bayés-Genis A. Surface electrocardiography. In: Hurst’s The Heart. 13th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2011.

- Cioffi G, de Simone G, Mureddu G, Tarantini L, Stefenelli C. Right atrial size and function in patients with pulmonary hypertension associated with disorders of respiratory system or hypoxemia. Eur J Echocardiogr 2007; 8:322–331.

- Raymond RJ, Hinderliter AL, Willis PW, et al. Echocardiographic predictors of adverse outcomes in primary pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39:1214–1219.

- Al-Naamani K, Hijal T, Nguyen V, Andrew S, Nguyen T, Huynh T. Predictive values of the electrocardiogram in diagnosing pulmonary hypertension. Int J Cardiol 2008; 127:214–218.

A 49-year-old man with rheumatic mitral valve stenosis, which had been diagnosed 3 years previously, presented to the outpatient department with worsening exertional dyspnea, fatigue, and cough.

At rest, he appeared comfortable; his pulse rate was 94 bpm and his blood pressure was 117/82 mm Hg. Cardiac auscultation revealed a loud first heart sound, a mid-diastolic murmur with presystolic accentuation at the cardiac apex, and a pansystolic murmur at the left lower sternal border that increased in intensity with inspiration. A prominent left parasternal heave was present.

His 12-lead electrocardiogram is shown in Figure 1.

Transthoracic echocardiography confirmed severe mitral stenosis with an estimated mitral valve area of 0.7 cm2 without significant mitral regurgitation. In addition, right ventricular dilatation with moderately severe systolic dysfunction and 4+ (severe) tricuspid regurgitation were present. On the basis of the peak tricuspid regurgitant velocity, the right ventricular systolic pressure was calculated to be 80 mm Hg, consistent with severe pulmonary hypertension. The left ventricular end-diastolic volume was reduced and the ejection fraction was normal.

On right heart catheterization, the pulmonary artery pressure was 92/51 mm Hg.

Q: Electrocardiographic findings that support a diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension include which of the following?

- QRS complex axis of +110°

- R/S (QRS complex) ratio greater than 1 in lead V1

- Sum of the amplitudes of the R wave in lead V1 and the S wave in lead V6 greater than 1.0 mV

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is all of the above. Regardless of the cause, patients with long-standing pulmonary hypertension possess varying degrees of right ventricular hypertrophy that may be accompanied by right ventricular enlargement and systolic dysfunction. A QRS complex axis of 110° or more, an R/S (QRS complex) ratio greater than 1 in lead V1, and the sum of the amplitudes of the R wave in lead V1 and the S wave in lead V6 greater than 1.0 mV all support right ventricular hypertrophy.1

As noted in this electrocardiogram, T-wave inversion in leads V1 and V2 supports a right ventricular repolarization abnormality secondary to the hypertrophy.2

Q: Important electrocardiographic findings in this patient that support secondary pulmonary hypertension due to mitral stenosis include which of the following?

- Tall peaked P waves in lead II of at least 0.25 mV and positive P waves in V1 greater than 0.15 mV

- Prolonged P waves of at least 120 ms in lead II and terminal negative P waves in V1 greater than 40 ms

- Right ventricular hypertrophy

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is prolonged P waves of at least 120 ms in lead II and terminal negative P waves in V1 greater than 40 ms.

Abnormal surface electrocardiographic findings reflecting atrial enlargement or slowed atrial conduction are difficult to differentiate and are best characterized as “atrial abnormalities.” On surface electrocardiography, an atrial abnormality is represented by a P wave morphology that is best studied in leads II and V1. In lead II, a tall peaked P wave of at least 0.25 mV supports right atrial abnormality, and a prolonged P wave (≥ 120 ms) supports left atrial abnormality. In lead V1, right atrial abnormality is suggested by a positive P wave in V1 greater than 0.15 mV, and a terminally negative P wave greater than 40 ms in duration and greater than 0.1 mV deep supports left atrial abnormality.3

It is well recognized that the pathophysiology of pulmonary hypertension involves both the right ventricle and the right atrium.4,5 Therefore, irrespective of the cause of pulmonary hypertension, electrocardiography may additionally reveal right atrial abnormality.6

When the findings suggest pulmonary hypertension (ie, right ventricular hypertrophy with or without right atrial abnormality), it is also important to evaluate for concurrent left atrial abnormality. If present, concomitant left atrial abnormality is a valuable, more specific clue that may help characterize secondary pulmonary hypertension from left-sided heart disease, as illustrated in this example with long-standing severe mitral stenosis.2

A 49-year-old man with rheumatic mitral valve stenosis, which had been diagnosed 3 years previously, presented to the outpatient department with worsening exertional dyspnea, fatigue, and cough.

At rest, he appeared comfortable; his pulse rate was 94 bpm and his blood pressure was 117/82 mm Hg. Cardiac auscultation revealed a loud first heart sound, a mid-diastolic murmur with presystolic accentuation at the cardiac apex, and a pansystolic murmur at the left lower sternal border that increased in intensity with inspiration. A prominent left parasternal heave was present.

His 12-lead electrocardiogram is shown in Figure 1.

Transthoracic echocardiography confirmed severe mitral stenosis with an estimated mitral valve area of 0.7 cm2 without significant mitral regurgitation. In addition, right ventricular dilatation with moderately severe systolic dysfunction and 4+ (severe) tricuspid regurgitation were present. On the basis of the peak tricuspid regurgitant velocity, the right ventricular systolic pressure was calculated to be 80 mm Hg, consistent with severe pulmonary hypertension. The left ventricular end-diastolic volume was reduced and the ejection fraction was normal.

On right heart catheterization, the pulmonary artery pressure was 92/51 mm Hg.

Q: Electrocardiographic findings that support a diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension include which of the following?

- QRS complex axis of +110°

- R/S (QRS complex) ratio greater than 1 in lead V1

- Sum of the amplitudes of the R wave in lead V1 and the S wave in lead V6 greater than 1.0 mV

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is all of the above. Regardless of the cause, patients with long-standing pulmonary hypertension possess varying degrees of right ventricular hypertrophy that may be accompanied by right ventricular enlargement and systolic dysfunction. A QRS complex axis of 110° or more, an R/S (QRS complex) ratio greater than 1 in lead V1, and the sum of the amplitudes of the R wave in lead V1 and the S wave in lead V6 greater than 1.0 mV all support right ventricular hypertrophy.1

As noted in this electrocardiogram, T-wave inversion in leads V1 and V2 supports a right ventricular repolarization abnormality secondary to the hypertrophy.2

Q: Important electrocardiographic findings in this patient that support secondary pulmonary hypertension due to mitral stenosis include which of the following?

- Tall peaked P waves in lead II of at least 0.25 mV and positive P waves in V1 greater than 0.15 mV

- Prolonged P waves of at least 120 ms in lead II and terminal negative P waves in V1 greater than 40 ms

- Right ventricular hypertrophy

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is prolonged P waves of at least 120 ms in lead II and terminal negative P waves in V1 greater than 40 ms.

Abnormal surface electrocardiographic findings reflecting atrial enlargement or slowed atrial conduction are difficult to differentiate and are best characterized as “atrial abnormalities.” On surface electrocardiography, an atrial abnormality is represented by a P wave morphology that is best studied in leads II and V1. In lead II, a tall peaked P wave of at least 0.25 mV supports right atrial abnormality, and a prolonged P wave (≥ 120 ms) supports left atrial abnormality. In lead V1, right atrial abnormality is suggested by a positive P wave in V1 greater than 0.15 mV, and a terminally negative P wave greater than 40 ms in duration and greater than 0.1 mV deep supports left atrial abnormality.3

It is well recognized that the pathophysiology of pulmonary hypertension involves both the right ventricle and the right atrium.4,5 Therefore, irrespective of the cause of pulmonary hypertension, electrocardiography may additionally reveal right atrial abnormality.6

When the findings suggest pulmonary hypertension (ie, right ventricular hypertrophy with or without right atrial abnormality), it is also important to evaluate for concurrent left atrial abnormality. If present, concomitant left atrial abnormality is a valuable, more specific clue that may help characterize secondary pulmonary hypertension from left-sided heart disease, as illustrated in this example with long-standing severe mitral stenosis.2

- Hancock EW, Deal BJ, Mirvis DM, et al; American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part V: electrocardiogram changes associated with cardiac chamber hypertrophy: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society. Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53:992–1002.

- Goldberger AL. Atrial and ventricular enlargement. In: Clinical Electrocardiography: A Simplified Approach. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2006:59–71.

- Bayés-de-Luna A, Goldwasser D, Fiol M, Bayés-Genis A. Surface electrocardiography. In: Hurst’s The Heart. 13th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2011.

- Cioffi G, de Simone G, Mureddu G, Tarantini L, Stefenelli C. Right atrial size and function in patients with pulmonary hypertension associated with disorders of respiratory system or hypoxemia. Eur J Echocardiogr 2007; 8:322–331.

- Raymond RJ, Hinderliter AL, Willis PW, et al. Echocardiographic predictors of adverse outcomes in primary pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39:1214–1219.

- Al-Naamani K, Hijal T, Nguyen V, Andrew S, Nguyen T, Huynh T. Predictive values of the electrocardiogram in diagnosing pulmonary hypertension. Int J Cardiol 2008; 127:214–218.

- Hancock EW, Deal BJ, Mirvis DM, et al; American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part V: electrocardiogram changes associated with cardiac chamber hypertrophy: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society. Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53:992–1002.

- Goldberger AL. Atrial and ventricular enlargement. In: Clinical Electrocardiography: A Simplified Approach. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2006:59–71.

- Bayés-de-Luna A, Goldwasser D, Fiol M, Bayés-Genis A. Surface electrocardiography. In: Hurst’s The Heart. 13th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2011.

- Cioffi G, de Simone G, Mureddu G, Tarantini L, Stefenelli C. Right atrial size and function in patients with pulmonary hypertension associated with disorders of respiratory system or hypoxemia. Eur J Echocardiogr 2007; 8:322–331.

- Raymond RJ, Hinderliter AL, Willis PW, et al. Echocardiographic predictors of adverse outcomes in primary pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39:1214–1219.

- Al-Naamani K, Hijal T, Nguyen V, Andrew S, Nguyen T, Huynh T. Predictive values of the electrocardiogram in diagnosing pulmonary hypertension. Int J Cardiol 2008; 127:214–218.

Odynophagia, peripheral facial nerve paralysis, mucocutaneous lesions

A 54-year-old woman presented with a 7-day history of odynophagia, pharyngeal swelling, and painful skin lesions on her left ear. She had been on antiretroviral therapy for human immunodeficiency virus infection but had not been fully compliant with the treatment.

On examination, she had painful erythematous vesicles and pustules on the left auricle and in the external auditory canal (Figure 1), as well as small vesicles and circumscribed erosions on the left anterior twothirds of her tongue (Figure 2) and left palate. Facial sensory function was normal; however, she had lagophthalmos, a flattened nasolabial fold, ptosis of the oral commissure, and a loss of the forehead wrinkles on the left side of her face—all signs of peripheral facial nerve paralysis.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Ramsay Hunt syndrome

- Herpes simplex

- Contact dermatitis

- Malignant external otitis

- Erysipelas

A: This patient had Ramsay Hunt syndrome, also known as herpes zoster oticus. It is a rare complication of herpes zoster in which the reactivation of latent varicella-zoster virus infection in the geniculate ganglion causes the triad of ipsilateral facial paralysis, ear pain, and vesicles in the auditory canal and auricle. Taste perception, hearing (eg, tinnitus, hyperacusis), and lacrimation can be affected.1

Ramsay Hunt syndrome is generally considered a polycranial neuropathy of cranial nerves VII (facial) and VIII (acoustic). In some cases other cranial neuropathies may be present and may involve cranial nerves V (trigeminal), IX (glossopharyngeal), and X (vagus). Vestibular disturbances such as vertigo are also often reported. It is more severe in patients with immune deficiency. Because the classic symptoms are not always present at the onset, the syndrome can be misdiagnosed.

DIAGNOSIS

Once the vesicular rash caused by herpes zoster has appeared, the diagnosis is usually readily apparent. The other main disease to consider in the differential diagnosis is herpes simplex. Herpes zoster infection is characterized by a painful sensory prodrome, dermatomal distribution, and lack of a history of a similar rash. However, if the patient has had a similar vesicular rash in the same location, then recurrent zosteriform herpes simplex should be considered. A noninfectious cause to consider is contact dermatitis. However, contact dermatitis usually produces intense itch rather than pain.

If the clinical presentation is uncertain, then viral culture, direct immunofluorescence testing, and a polymerase chain reaction assay is indicated to confirm the diagnosis. Polymerase chain reaction testing is the most sensitive test.3

TREATMENT

The rapid start of antiviral therapy is particularly critical in immunocompromised patients,4 even if the vesicles have been present for 72 hours. Immunocompromised patients with Ramsay Hunt syndrome and other forms of complicated herpes zoster infection should be hospitalized for intravenous acyclovir therapy.

Corticosteroids and oral acyclovir (10 mg/kg three times daily for 7 days) are commonly used in Ramsay Hunt syndrome. In a recent review,5 combination therapy with a corticosteroid and intravenous acyclovir did not show a benefit over corticosteroids alone in promoting resolution of facial neuropathy after 6 months.5 However, randomized clinical trials are needed to evaluate both therapies.

Although antiviral therapy reduces pain associated with acute neuritis, pain syndromes associated with herpes zoster can still be severe. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and acetaminophen are useful for mild pain, either alone or in combination with a weak opioid analgesic (eg, tramadol, codeine). For moderate to severe pain that disturbs sleep, a stronger opioid analgesic (eg, oxycodone, morphine) may be necessary.6

Vestibular suppressants may be helpful if vestibular symptoms are severe. Temporary relief of otalgia may be achieved by applying a local anesthetic to the trigger point, if in the external auditory canal. Carbamazepine may be helpful, especially in cases of idiopathic geniculate neuralgia.7

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

Once drug therapy is started, the patient should be seen at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, and 3 months to monitor the evolution of nerve paralysis.8

- Mishell JH, Applebaum EL. Ramsay-Hunt syndrome in a patient with HIV infection. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1990; 102:177–179.

- Adour KK. Otological complications of herpes zoster. Ann Neurol 1994; 35(suppl):S62–S64.

- Stránská R, Schuurman R, de Vos M, van Loon AM. Routine use of a highly automated and internally controlled real-time PCR assay for the diagnosis of herpes simplex and varicella-zoster virus infections. J Clin Virol 2004; 30:39–44.

- Miller GG, Dummer JS. Herpes simplex and varicella zoster viruses: forgotten but not gone. Am J Transplant 2007; 7:741–747.

- Uscategui T, Dorée C, Chamberlain IJ, Burton MJ. Antiviral therapy for Ramsay Hunt syndrome (herpes zoster oticus with facial palsy) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;(4):CD006851.

- Dworkin RH, Barbano RL, Tyring SK, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of oxycodone and of gabapentin for acute pain in herpes zoster. Pain 2009; 142:209–217.

- Edelsberg JS, Lord C, Oster G. Systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy, safety, and tolerability data from randomized controlled trials of drugs used to treat postherpetic neuralgia. Ann Pharmacother 2011; 45:1483–1490.

- Ryu EW, Lee HY, Lee SY, Park MS, Yeo SG. Clinical manifestations and prognosis of patients with Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Am J Otolaryngol 2012; 33:313–318.

A 54-year-old woman presented with a 7-day history of odynophagia, pharyngeal swelling, and painful skin lesions on her left ear. She had been on antiretroviral therapy for human immunodeficiency virus infection but had not been fully compliant with the treatment.

On examination, she had painful erythematous vesicles and pustules on the left auricle and in the external auditory canal (Figure 1), as well as small vesicles and circumscribed erosions on the left anterior twothirds of her tongue (Figure 2) and left palate. Facial sensory function was normal; however, she had lagophthalmos, a flattened nasolabial fold, ptosis of the oral commissure, and a loss of the forehead wrinkles on the left side of her face—all signs of peripheral facial nerve paralysis.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Ramsay Hunt syndrome

- Herpes simplex

- Contact dermatitis

- Malignant external otitis

- Erysipelas

A: This patient had Ramsay Hunt syndrome, also known as herpes zoster oticus. It is a rare complication of herpes zoster in which the reactivation of latent varicella-zoster virus infection in the geniculate ganglion causes the triad of ipsilateral facial paralysis, ear pain, and vesicles in the auditory canal and auricle. Taste perception, hearing (eg, tinnitus, hyperacusis), and lacrimation can be affected.1

Ramsay Hunt syndrome is generally considered a polycranial neuropathy of cranial nerves VII (facial) and VIII (acoustic). In some cases other cranial neuropathies may be present and may involve cranial nerves V (trigeminal), IX (glossopharyngeal), and X (vagus). Vestibular disturbances such as vertigo are also often reported. It is more severe in patients with immune deficiency. Because the classic symptoms are not always present at the onset, the syndrome can be misdiagnosed.

DIAGNOSIS

Once the vesicular rash caused by herpes zoster has appeared, the diagnosis is usually readily apparent. The other main disease to consider in the differential diagnosis is herpes simplex. Herpes zoster infection is characterized by a painful sensory prodrome, dermatomal distribution, and lack of a history of a similar rash. However, if the patient has had a similar vesicular rash in the same location, then recurrent zosteriform herpes simplex should be considered. A noninfectious cause to consider is contact dermatitis. However, contact dermatitis usually produces intense itch rather than pain.

If the clinical presentation is uncertain, then viral culture, direct immunofluorescence testing, and a polymerase chain reaction assay is indicated to confirm the diagnosis. Polymerase chain reaction testing is the most sensitive test.3

TREATMENT

The rapid start of antiviral therapy is particularly critical in immunocompromised patients,4 even if the vesicles have been present for 72 hours. Immunocompromised patients with Ramsay Hunt syndrome and other forms of complicated herpes zoster infection should be hospitalized for intravenous acyclovir therapy.

Corticosteroids and oral acyclovir (10 mg/kg three times daily for 7 days) are commonly used in Ramsay Hunt syndrome. In a recent review,5 combination therapy with a corticosteroid and intravenous acyclovir did not show a benefit over corticosteroids alone in promoting resolution of facial neuropathy after 6 months.5 However, randomized clinical trials are needed to evaluate both therapies.

Although antiviral therapy reduces pain associated with acute neuritis, pain syndromes associated with herpes zoster can still be severe. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and acetaminophen are useful for mild pain, either alone or in combination with a weak opioid analgesic (eg, tramadol, codeine). For moderate to severe pain that disturbs sleep, a stronger opioid analgesic (eg, oxycodone, morphine) may be necessary.6

Vestibular suppressants may be helpful if vestibular symptoms are severe. Temporary relief of otalgia may be achieved by applying a local anesthetic to the trigger point, if in the external auditory canal. Carbamazepine may be helpful, especially in cases of idiopathic geniculate neuralgia.7

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

Once drug therapy is started, the patient should be seen at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, and 3 months to monitor the evolution of nerve paralysis.8

A 54-year-old woman presented with a 7-day history of odynophagia, pharyngeal swelling, and painful skin lesions on her left ear. She had been on antiretroviral therapy for human immunodeficiency virus infection but had not been fully compliant with the treatment.

On examination, she had painful erythematous vesicles and pustules on the left auricle and in the external auditory canal (Figure 1), as well as small vesicles and circumscribed erosions on the left anterior twothirds of her tongue (Figure 2) and left palate. Facial sensory function was normal; however, she had lagophthalmos, a flattened nasolabial fold, ptosis of the oral commissure, and a loss of the forehead wrinkles on the left side of her face—all signs of peripheral facial nerve paralysis.

Q: Which is the most likely diagnosis?

- Ramsay Hunt syndrome

- Herpes simplex

- Contact dermatitis

- Malignant external otitis

- Erysipelas

A: This patient had Ramsay Hunt syndrome, also known as herpes zoster oticus. It is a rare complication of herpes zoster in which the reactivation of latent varicella-zoster virus infection in the geniculate ganglion causes the triad of ipsilateral facial paralysis, ear pain, and vesicles in the auditory canal and auricle. Taste perception, hearing (eg, tinnitus, hyperacusis), and lacrimation can be affected.1

Ramsay Hunt syndrome is generally considered a polycranial neuropathy of cranial nerves VII (facial) and VIII (acoustic). In some cases other cranial neuropathies may be present and may involve cranial nerves V (trigeminal), IX (glossopharyngeal), and X (vagus). Vestibular disturbances such as vertigo are also often reported. It is more severe in patients with immune deficiency. Because the classic symptoms are not always present at the onset, the syndrome can be misdiagnosed.

DIAGNOSIS

Once the vesicular rash caused by herpes zoster has appeared, the diagnosis is usually readily apparent. The other main disease to consider in the differential diagnosis is herpes simplex. Herpes zoster infection is characterized by a painful sensory prodrome, dermatomal distribution, and lack of a history of a similar rash. However, if the patient has had a similar vesicular rash in the same location, then recurrent zosteriform herpes simplex should be considered. A noninfectious cause to consider is contact dermatitis. However, contact dermatitis usually produces intense itch rather than pain.

If the clinical presentation is uncertain, then viral culture, direct immunofluorescence testing, and a polymerase chain reaction assay is indicated to confirm the diagnosis. Polymerase chain reaction testing is the most sensitive test.3

TREATMENT

The rapid start of antiviral therapy is particularly critical in immunocompromised patients,4 even if the vesicles have been present for 72 hours. Immunocompromised patients with Ramsay Hunt syndrome and other forms of complicated herpes zoster infection should be hospitalized for intravenous acyclovir therapy.

Corticosteroids and oral acyclovir (10 mg/kg three times daily for 7 days) are commonly used in Ramsay Hunt syndrome. In a recent review,5 combination therapy with a corticosteroid and intravenous acyclovir did not show a benefit over corticosteroids alone in promoting resolution of facial neuropathy after 6 months.5 However, randomized clinical trials are needed to evaluate both therapies.

Although antiviral therapy reduces pain associated with acute neuritis, pain syndromes associated with herpes zoster can still be severe. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and acetaminophen are useful for mild pain, either alone or in combination with a weak opioid analgesic (eg, tramadol, codeine). For moderate to severe pain that disturbs sleep, a stronger opioid analgesic (eg, oxycodone, morphine) may be necessary.6

Vestibular suppressants may be helpful if vestibular symptoms are severe. Temporary relief of otalgia may be achieved by applying a local anesthetic to the trigger point, if in the external auditory canal. Carbamazepine may be helpful, especially in cases of idiopathic geniculate neuralgia.7

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

Once drug therapy is started, the patient should be seen at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, and 3 months to monitor the evolution of nerve paralysis.8

- Mishell JH, Applebaum EL. Ramsay-Hunt syndrome in a patient with HIV infection. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1990; 102:177–179.

- Adour KK. Otological complications of herpes zoster. Ann Neurol 1994; 35(suppl):S62–S64.

- Stránská R, Schuurman R, de Vos M, van Loon AM. Routine use of a highly automated and internally controlled real-time PCR assay for the diagnosis of herpes simplex and varicella-zoster virus infections. J Clin Virol 2004; 30:39–44.

- Miller GG, Dummer JS. Herpes simplex and varicella zoster viruses: forgotten but not gone. Am J Transplant 2007; 7:741–747.

- Uscategui T, Dorée C, Chamberlain IJ, Burton MJ. Antiviral therapy for Ramsay Hunt syndrome (herpes zoster oticus with facial palsy) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;(4):CD006851.

- Dworkin RH, Barbano RL, Tyring SK, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of oxycodone and of gabapentin for acute pain in herpes zoster. Pain 2009; 142:209–217.

- Edelsberg JS, Lord C, Oster G. Systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy, safety, and tolerability data from randomized controlled trials of drugs used to treat postherpetic neuralgia. Ann Pharmacother 2011; 45:1483–1490.

- Ryu EW, Lee HY, Lee SY, Park MS, Yeo SG. Clinical manifestations and prognosis of patients with Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Am J Otolaryngol 2012; 33:313–318.

- Mishell JH, Applebaum EL. Ramsay-Hunt syndrome in a patient with HIV infection. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1990; 102:177–179.

- Adour KK. Otological complications of herpes zoster. Ann Neurol 1994; 35(suppl):S62–S64.

- Stránská R, Schuurman R, de Vos M, van Loon AM. Routine use of a highly automated and internally controlled real-time PCR assay for the diagnosis of herpes simplex and varicella-zoster virus infections. J Clin Virol 2004; 30:39–44.

- Miller GG, Dummer JS. Herpes simplex and varicella zoster viruses: forgotten but not gone. Am J Transplant 2007; 7:741–747.

- Uscategui T, Dorée C, Chamberlain IJ, Burton MJ. Antiviral therapy for Ramsay Hunt syndrome (herpes zoster oticus with facial palsy) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;(4):CD006851.

- Dworkin RH, Barbano RL, Tyring SK, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of oxycodone and of gabapentin for acute pain in herpes zoster. Pain 2009; 142:209–217.

- Edelsberg JS, Lord C, Oster G. Systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy, safety, and tolerability data from randomized controlled trials of drugs used to treat postherpetic neuralgia. Ann Pharmacother 2011; 45:1483–1490.

- Ryu EW, Lee HY, Lee SY, Park MS, Yeo SG. Clinical manifestations and prognosis of patients with Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Am J Otolaryngol 2012; 33:313–318.

Right upper-abdominal pain in a 97-year-old

A 97-year-old man has had right upper-abdominal pain intermittently for 2 weeks. He has hypertension, stage IV chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and constipation. He has never had abdominal surgery.

He describes his pain as mild and dull. It does not radiate to the right lower quadrant or the back and is not aggravated by eating. He reports no fever or changes in appetite or bowel habits during the last 2 weeks. His body temperature is 36.8°C, blood pressure 114/68 mm Hg, heart rate 86 beats per minute, and respiratory rate 16 times per minute.

On physical examination, his abdomen is soft with no guarding and with hypoactive bowel sounds. No Murphy sign is noted. Hemography shows a normal white blood cell count of 7.8 × 109/L) (reference range 4.5–11.0). Serum biochemistry studies show an alanine transaminase level of 23 U/L (5–50) and a lipase level of 40 U/L (12–70); the C-reactive protein level is 0.5 mg/dL (0.0–1.0). A sitting chest radiograph shows a focal gas collection over the right subdiaphragmatic area (Figure 1).

Q: Based on the information above, which is most likely the cause of this man’s upper-abdominal pain?

- Perforated viscera

- Diverticulitis

- Chilaiditi syndrome

- Subdiaphragmatic abscess

- Emphysematous cholecystitis

A: The workup of this patient did not indicate active disease, so the subphrenic gas on the radiograph most likely is the Chilaiditi sign. This is a benign finding that, in a patient with gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting, constipation, upper-abdominal pain), is labeled Chilaiditi syndrome.

CHILAIDITI SIGN AND SYNDROME

The Chilaiditi sign1 describes a benign, incidental radiologic finding of subphrenic gas caused by interposition of colonic segments (or small intestine in rare cases) between the liver and the diaphragm. The radiologic finding is called the Chilaiditi sign if the patient is asymptomatic or Chilaiditi syndrome if the patient has gastrointestinal symptoms, as our patient did. The Chilaiditi sign is reportedly found in 0.02% to 0.2% of all chest and abdominal films.

Chilaiditi syndrome has a male predominance.2 Predisposing factors include an atrophic liver, laxity of the hepatic or the transverse colon suspension ligament, abnormal fixation of the mesointestine, and diaphragmatic weakness. Other factors include advanced age; a history of abdominal surgery, adhesion, or intestinal obstruction3; chronic lung disease; and cirrhosis.4

Management is usually conservative, with a prokinetic agent or enema for constipation, and bed-rest or bowel decompression as needed, unless complications occur. Our patient’s extreme age, underlying chronic pulmonary disease, and constipation predisposed him to this rare gastrointestinal disorder.

In this patient, pain in the right upper quadrant initially suggested an inflammatory disorder involving the liver, gallbladder, and transverse or ascending colon. Right upper-quadrant pain with radiologic evidence of subphrenic air collection further raises suspicion of pneumoperitoneum from diverticulitis, bowel perforation, or gas-forming abscess. However, this patient’s normal transaminase level, low C-reactive protein value, and prolonged symptom course made hepatitis, cholecystitis, diverticulitis, and subdiaphragmatic abscess less likely. Nonetheless, severe intra-abdominal pathology can sometimes manifest with only minor symptoms in very elderly patients. Consequently, the main concern in this scenario was whether he had minor and undetected perforated viscera causing pneumoperitoneum with an indolent course, or rather a benign condition such as Chilaiditi syndrome causing pain and subphrenic air.

IS IT CHILAIDITI SYNDROME OR PNEUMOPERITONEUM?

Chilaiditi syndrome and perforated viscera both involve subphrenic air, but they differ radiologically and clinically. Radiologically, identification of haustra or plicae circulares within the gas collection or fixed subphrenic air upon postural change indicates the Chilaiditi sign and favors Chilaiditi syndrome as the origin of the symptoms. Pneumoperitoneum from perforated viscera is more likely if the abnormal gas collection changes its position upon postural change. Abdominal ultrasonography can also assist in diagnosis by showing a fixed air collection around the hepatic surface in the Chilaiditi sign. Definite radiologic diagnosis can be reached through abdominal computed tomography. Clinically, these two disorders may manifest different severity, as perforated viscera often mandate surgical attention, whereas Chilaiditi syndrome seldom requires surgical treatment (25% of cases).2

Patients with the Chilaiditi sign also may develop abdominal pathology other than Chilaiditi syndrome per se. In our patient, the subphrenic air displayed a faint contour of bowel segments. His symptom course, benign physical examination, and the lack of laboratory evidence of other intra-abdominal pathology led us to suspect Chilaiditi syndrome as the cause of his abdominal pain. A normal leukocyte count and stable vital signs made the diagnosis of a major life-threatening condition extremely unlikely. Subsequently, abdominal sonography done at the bedside disclosed fixed colonic segments between the liver and the diaphragm. No hepatic or gallbladder lesions were detected. Chilaiditi syndrome was confirmed.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

As seen in this case, the accurate diagnosis rests on a careful physical examination and laboratory evaluation but, most importantly, on sound clinical judgment. Right upper-quadrant pain is often encountered in primary care practice and has many diagnostic possibilities, including benign, self-limited conditions such as Chilaiditi syndrome. It is vital to distinguish between benign conditions and severe life-threatening disorders such as hollow organ perforation so as not to operate on patients who can be managed conservatively.

- Chilaiditi D. Zur Frage der Hepatoptose und Ptose in allegemeinen in Anschluss an drei Fälle von temporärer, partieller Lebersverlagerung. Fortschr Geb Röntgenstr Nuklearmed Erganzungsband 1910; 16:173–208.

- Saber AA, Boros MJ. Chilaiditi’s syndrome: what should every surgeon know? Am Surg 2005; 71:261–263.

- Lo BM. Radiographic look-alikes: distinguishing between pneumoperitoneum and pseudopneumoperitoneum. J Emerg Med 2010; 38:36–39.

- Fisher AA, Davis MW. An elderly man with chest pain, shortness of breath, and constipation. Postgrad Med J 2003; 79:180,183–184.

A 97-year-old man has had right upper-abdominal pain intermittently for 2 weeks. He has hypertension, stage IV chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and constipation. He has never had abdominal surgery.

He describes his pain as mild and dull. It does not radiate to the right lower quadrant or the back and is not aggravated by eating. He reports no fever or changes in appetite or bowel habits during the last 2 weeks. His body temperature is 36.8°C, blood pressure 114/68 mm Hg, heart rate 86 beats per minute, and respiratory rate 16 times per minute.

On physical examination, his abdomen is soft with no guarding and with hypoactive bowel sounds. No Murphy sign is noted. Hemography shows a normal white blood cell count of 7.8 × 109/L) (reference range 4.5–11.0). Serum biochemistry studies show an alanine transaminase level of 23 U/L (5–50) and a lipase level of 40 U/L (12–70); the C-reactive protein level is 0.5 mg/dL (0.0–1.0). A sitting chest radiograph shows a focal gas collection over the right subdiaphragmatic area (Figure 1).

Q: Based on the information above, which is most likely the cause of this man’s upper-abdominal pain?

- Perforated viscera

- Diverticulitis

- Chilaiditi syndrome

- Subdiaphragmatic abscess

- Emphysematous cholecystitis

A: The workup of this patient did not indicate active disease, so the subphrenic gas on the radiograph most likely is the Chilaiditi sign. This is a benign finding that, in a patient with gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting, constipation, upper-abdominal pain), is labeled Chilaiditi syndrome.

CHILAIDITI SIGN AND SYNDROME

The Chilaiditi sign1 describes a benign, incidental radiologic finding of subphrenic gas caused by interposition of colonic segments (or small intestine in rare cases) between the liver and the diaphragm. The radiologic finding is called the Chilaiditi sign if the patient is asymptomatic or Chilaiditi syndrome if the patient has gastrointestinal symptoms, as our patient did. The Chilaiditi sign is reportedly found in 0.02% to 0.2% of all chest and abdominal films.

Chilaiditi syndrome has a male predominance.2 Predisposing factors include an atrophic liver, laxity of the hepatic or the transverse colon suspension ligament, abnormal fixation of the mesointestine, and diaphragmatic weakness. Other factors include advanced age; a history of abdominal surgery, adhesion, or intestinal obstruction3; chronic lung disease; and cirrhosis.4

Management is usually conservative, with a prokinetic agent or enema for constipation, and bed-rest or bowel decompression as needed, unless complications occur. Our patient’s extreme age, underlying chronic pulmonary disease, and constipation predisposed him to this rare gastrointestinal disorder.

In this patient, pain in the right upper quadrant initially suggested an inflammatory disorder involving the liver, gallbladder, and transverse or ascending colon. Right upper-quadrant pain with radiologic evidence of subphrenic air collection further raises suspicion of pneumoperitoneum from diverticulitis, bowel perforation, or gas-forming abscess. However, this patient’s normal transaminase level, low C-reactive protein value, and prolonged symptom course made hepatitis, cholecystitis, diverticulitis, and subdiaphragmatic abscess less likely. Nonetheless, severe intra-abdominal pathology can sometimes manifest with only minor symptoms in very elderly patients. Consequently, the main concern in this scenario was whether he had minor and undetected perforated viscera causing pneumoperitoneum with an indolent course, or rather a benign condition such as Chilaiditi syndrome causing pain and subphrenic air.

IS IT CHILAIDITI SYNDROME OR PNEUMOPERITONEUM?

Chilaiditi syndrome and perforated viscera both involve subphrenic air, but they differ radiologically and clinically. Radiologically, identification of haustra or plicae circulares within the gas collection or fixed subphrenic air upon postural change indicates the Chilaiditi sign and favors Chilaiditi syndrome as the origin of the symptoms. Pneumoperitoneum from perforated viscera is more likely if the abnormal gas collection changes its position upon postural change. Abdominal ultrasonography can also assist in diagnosis by showing a fixed air collection around the hepatic surface in the Chilaiditi sign. Definite radiologic diagnosis can be reached through abdominal computed tomography. Clinically, these two disorders may manifest different severity, as perforated viscera often mandate surgical attention, whereas Chilaiditi syndrome seldom requires surgical treatment (25% of cases).2

Patients with the Chilaiditi sign also may develop abdominal pathology other than Chilaiditi syndrome per se. In our patient, the subphrenic air displayed a faint contour of bowel segments. His symptom course, benign physical examination, and the lack of laboratory evidence of other intra-abdominal pathology led us to suspect Chilaiditi syndrome as the cause of his abdominal pain. A normal leukocyte count and stable vital signs made the diagnosis of a major life-threatening condition extremely unlikely. Subsequently, abdominal sonography done at the bedside disclosed fixed colonic segments between the liver and the diaphragm. No hepatic or gallbladder lesions were detected. Chilaiditi syndrome was confirmed.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

As seen in this case, the accurate diagnosis rests on a careful physical examination and laboratory evaluation but, most importantly, on sound clinical judgment. Right upper-quadrant pain is often encountered in primary care practice and has many diagnostic possibilities, including benign, self-limited conditions such as Chilaiditi syndrome. It is vital to distinguish between benign conditions and severe life-threatening disorders such as hollow organ perforation so as not to operate on patients who can be managed conservatively.

A 97-year-old man has had right upper-abdominal pain intermittently for 2 weeks. He has hypertension, stage IV chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and constipation. He has never had abdominal surgery.

He describes his pain as mild and dull. It does not radiate to the right lower quadrant or the back and is not aggravated by eating. He reports no fever or changes in appetite or bowel habits during the last 2 weeks. His body temperature is 36.8°C, blood pressure 114/68 mm Hg, heart rate 86 beats per minute, and respiratory rate 16 times per minute.

On physical examination, his abdomen is soft with no guarding and with hypoactive bowel sounds. No Murphy sign is noted. Hemography shows a normal white blood cell count of 7.8 × 109/L) (reference range 4.5–11.0). Serum biochemistry studies show an alanine transaminase level of 23 U/L (5–50) and a lipase level of 40 U/L (12–70); the C-reactive protein level is 0.5 mg/dL (0.0–1.0). A sitting chest radiograph shows a focal gas collection over the right subdiaphragmatic area (Figure 1).

Q: Based on the information above, which is most likely the cause of this man’s upper-abdominal pain?

- Perforated viscera

- Diverticulitis

- Chilaiditi syndrome

- Subdiaphragmatic abscess

- Emphysematous cholecystitis

A: The workup of this patient did not indicate active disease, so the subphrenic gas on the radiograph most likely is the Chilaiditi sign. This is a benign finding that, in a patient with gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting, constipation, upper-abdominal pain), is labeled Chilaiditi syndrome.

CHILAIDITI SIGN AND SYNDROME

The Chilaiditi sign1 describes a benign, incidental radiologic finding of subphrenic gas caused by interposition of colonic segments (or small intestine in rare cases) between the liver and the diaphragm. The radiologic finding is called the Chilaiditi sign if the patient is asymptomatic or Chilaiditi syndrome if the patient has gastrointestinal symptoms, as our patient did. The Chilaiditi sign is reportedly found in 0.02% to 0.2% of all chest and abdominal films.

Chilaiditi syndrome has a male predominance.2 Predisposing factors include an atrophic liver, laxity of the hepatic or the transverse colon suspension ligament, abnormal fixation of the mesointestine, and diaphragmatic weakness. Other factors include advanced age; a history of abdominal surgery, adhesion, or intestinal obstruction3; chronic lung disease; and cirrhosis.4

Management is usually conservative, with a prokinetic agent or enema for constipation, and bed-rest or bowel decompression as needed, unless complications occur. Our patient’s extreme age, underlying chronic pulmonary disease, and constipation predisposed him to this rare gastrointestinal disorder.

In this patient, pain in the right upper quadrant initially suggested an inflammatory disorder involving the liver, gallbladder, and transverse or ascending colon. Right upper-quadrant pain with radiologic evidence of subphrenic air collection further raises suspicion of pneumoperitoneum from diverticulitis, bowel perforation, or gas-forming abscess. However, this patient’s normal transaminase level, low C-reactive protein value, and prolonged symptom course made hepatitis, cholecystitis, diverticulitis, and subdiaphragmatic abscess less likely. Nonetheless, severe intra-abdominal pathology can sometimes manifest with only minor symptoms in very elderly patients. Consequently, the main concern in this scenario was whether he had minor and undetected perforated viscera causing pneumoperitoneum with an indolent course, or rather a benign condition such as Chilaiditi syndrome causing pain and subphrenic air.

IS IT CHILAIDITI SYNDROME OR PNEUMOPERITONEUM?

Chilaiditi syndrome and perforated viscera both involve subphrenic air, but they differ radiologically and clinically. Radiologically, identification of haustra or plicae circulares within the gas collection or fixed subphrenic air upon postural change indicates the Chilaiditi sign and favors Chilaiditi syndrome as the origin of the symptoms. Pneumoperitoneum from perforated viscera is more likely if the abnormal gas collection changes its position upon postural change. Abdominal ultrasonography can also assist in diagnosis by showing a fixed air collection around the hepatic surface in the Chilaiditi sign. Definite radiologic diagnosis can be reached through abdominal computed tomography. Clinically, these two disorders may manifest different severity, as perforated viscera often mandate surgical attention, whereas Chilaiditi syndrome seldom requires surgical treatment (25% of cases).2

Patients with the Chilaiditi sign also may develop abdominal pathology other than Chilaiditi syndrome per se. In our patient, the subphrenic air displayed a faint contour of bowel segments. His symptom course, benign physical examination, and the lack of laboratory evidence of other intra-abdominal pathology led us to suspect Chilaiditi syndrome as the cause of his abdominal pain. A normal leukocyte count and stable vital signs made the diagnosis of a major life-threatening condition extremely unlikely. Subsequently, abdominal sonography done at the bedside disclosed fixed colonic segments between the liver and the diaphragm. No hepatic or gallbladder lesions were detected. Chilaiditi syndrome was confirmed.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

As seen in this case, the accurate diagnosis rests on a careful physical examination and laboratory evaluation but, most importantly, on sound clinical judgment. Right upper-quadrant pain is often encountered in primary care practice and has many diagnostic possibilities, including benign, self-limited conditions such as Chilaiditi syndrome. It is vital to distinguish between benign conditions and severe life-threatening disorders such as hollow organ perforation so as not to operate on patients who can be managed conservatively.

- Chilaiditi D. Zur Frage der Hepatoptose und Ptose in allegemeinen in Anschluss an drei Fälle von temporärer, partieller Lebersverlagerung. Fortschr Geb Röntgenstr Nuklearmed Erganzungsband 1910; 16:173–208.

- Saber AA, Boros MJ. Chilaiditi’s syndrome: what should every surgeon know? Am Surg 2005; 71:261–263.

- Lo BM. Radiographic look-alikes: distinguishing between pneumoperitoneum and pseudopneumoperitoneum. J Emerg Med 2010; 38:36–39.

- Fisher AA, Davis MW. An elderly man with chest pain, shortness of breath, and constipation. Postgrad Med J 2003; 79:180,183–184.

- Chilaiditi D. Zur Frage der Hepatoptose und Ptose in allegemeinen in Anschluss an drei Fälle von temporärer, partieller Lebersverlagerung. Fortschr Geb Röntgenstr Nuklearmed Erganzungsband 1910; 16:173–208.

- Saber AA, Boros MJ. Chilaiditi’s syndrome: what should every surgeon know? Am Surg 2005; 71:261–263.

- Lo BM. Radiographic look-alikes: distinguishing between pneumoperitoneum and pseudopneumoperitoneum. J Emerg Med 2010; 38:36–39.

- Fisher AA, Davis MW. An elderly man with chest pain, shortness of breath, and constipation. Postgrad Med J 2003; 79:180,183–184.

A 47-year-old man with chest and neck pain

A 47-year-old man presented with acute shortness of breath and chest and neck pain, which began after he heard popping sounds while boarding a bus. The pain was right-sided, sharp, worse with deep breathing, and associated with a sensation of fullness over the right chest.

His medical conditions included controlled hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The COPD was managed with an albuterol inhaler only. He had a 50-pack-year history of smoking, and he drank alcohol occasionally.

On arrival, he was in mild respiratory distress, but his vital signs were stable. We could hear wheezing on both sides of his chest and feel subcutaneous crepitation on both sides of his chest and neck, the latter more on the right side. The rest of the examination was unremarkable.

Results of a complete blood cell count and metabolic panel were within normal limits. Because of the above findings, nasopharyngeal radiogragraphy was ordered (Figures 1 and 2).

Q: What is the most likely cause of this presentation?

- Esophageal rupture

- Gas gangrene

- Asthma exacerbation

- Ruptured emphysematous bullae

A: This patient had a history of COPD, which put him at risk of developing bullous emphysematous bullae that can rupture and cause subcutaneous emphysema. His nasopharyngeal radiograph (Figure1) showed bilateral extensive subcutaneous emphysema. His lateral nasopharyngeal radiograph (Figure 2) showed air-tracking within the mediastinum and into the retropharyngeal space (arrow). Computed tomography (Figure 3) showed extensive subcutaneous emphysema in the right lateral chest wall (arrow) and large bullae in the right upper lobe (arrow heads). As for the other possibilities:

Esophageal ruptures and tears are iatrogenic in most cases and usually occur after endoscopic procedures, but they can also occur in patients with intractable vomiting. Computed tomography often shows esophageal thickening, periesophageal fluid, mediastinal widening, and extraluminal air. However, in most cases, it is seen as pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema.1

Gas gangrene is a life-threatening soft-tissue and muscle infection caused by Clostridium perfringens in most cases.2 The pain is out of proportion to the findings on physical examination. Patients usually have toxic signs and symptoms such as fever and hypotension. Our patient was hemodynamically stable, with no changes in skin color.

Severe exacerbations of asthma can lead to alveolar rupture, pneumothorax, and subcutaneous emphysema, although this is a rare complication. Air can dissect along the bronchovascular sheaths into the neck and cause subcutaneous emphysema, or into the pleural space and cause pneumothorax. Our patient had no history of asthma and plainly had emphysematous bullae.3

SUBCUTANEOUS EMPHYSEMA

Subcutaneous emphysema is a collection of air within subcutaneous tissues. It usually presents as bloating of the skin around the neck and the chest wall. It is often seen in patients with pneumothorax.

The most common cause of subcutaneous emphysema is traumatic injury to the chest wall, such as from a motor vehicle accident or a stab wound,4 but it can also occur spontaneously in patients who have severe emphysema with large bullae. As the emphysema progresses, the bullae can easily rupture, and this can lead to pneumothorax, which can lead to subcutaneous emphysema. Primary spontaneous pneumothorax and subcutaneous emphysema can occur in people who have unrecognized lung disease and genetic disorders such as Marfan syndrome and Ehler-Danlos syndrome.5 Other causes include iatrogenic injury, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (common in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection), and cystic fibrosis. Pneumothorax occurs in about 30% of cases of P jirovecii pneumonia,6 and in about 6% of patients with cystic fibrosis.7 Bronchocutaneous fistula is an extremely rare complication of lung cancer and can cause subcutaneous emphysema.8 Tuberculosis is another possible cause.9

Subcutaneous emphysema mainly presents with chest or neck pain and wheezing. In severe cases, air can track to the face, causing facial swelling and difficulty breathing due to compression of the larynx. Also, it can track down to the thighs, causing leg pain and swelling.10

On examination, subcutaneous emphysema can be detected by palpating the chest wall, which causes the air bubble to move and produce crackling sounds. Most cases of subcutaneous emphysema are diagnosed clinically. Chest radiography and computed tomography help identify the source of air leak. Ultrasonography is usually used in cases of blunt trauma to the chest as part of the Focal Assessment With Sonography for Trauma protocol.11

Subcutaneous emphysema can resolve spontaneously, requiring only pain management and supplemental oxygen.12 In severe cases, air collection can lead to what is called “massive subcutaneous emphysema,” which requires surgical drainage.

Our patient had large emphysematous bullae in the apical region of the right lung that ruptured and led to subcutaneous emphysema. After placement of a chest tube, he underwent right-sided thoracotomy with bullectomy. His postoperative course was uneventful, and he was discharged a few days later. Three weeks later, repeated chest radiography showed resolution of his subcutaneous emphysema (Figure 4).

- White CS, Templeton PA, Attar S. Esophageal perforation: CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1993; 160:767–770.

- Aggelidakis J, Lasithiotakis K, Topalidou A, Koutroumpas J, Kouvidis G, Katonis P. Limb salvage after gas gangrene: a case report and review of the literature. World J Emerg Surg 2011; 6:28.

- Romero KJ, Trujillo MH. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema in asthma exacerbation: the Macklin effect. Heart Lung 2010; 39:444–447.

- Peart O. Subcutaneous emphysema. Radiol Technol 2006; 77:296.

- Chiu HT, Garcia CK. Familial spontaneous pneumothorax. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2006; 12:268–272.

- Sepkowitz KA, Telzak EE, Gold JW, et al. Pneumothorax in AIDS. Ann Intern Med 1991; 114:455–459.

- Flume PA, Strange C, Ye X, Ebeling M, Hulsey T, Clark LL. Pneumothorax in cystic fibrosis. Chest 2005; 128:720–728.

- Yalçinkaya S, Vural AH, Göncü MT, Özyazicioglu AF. Cavitary lung cancer presenting as subcutaneous emphysema on the contralateral side. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2012; 14:338–339.

- Shamaei M, Tabarsi P, Pojhan S, et al. Tuberculosis-associated secondary pneumothorax: a retrospective study of 53 patients. Respir Care 2011; 56:298–302.

- Sherif HM, Ott DA. The use of subcutaneous drains to manage subcutaneous emphysema. Tex Heart Inst J 1999; 26:129–131.

- Wilkerson RG, Stone MB. Sensitivity of bedside ultrasound and supine anteroposterior chest radiographs for the identification of pneumothorax after blunt trauma. Acad Emerg Med 2010; 17:11–17.

- Mattox KL, Allen MK. Systematic approach to pneumothorax, haemothorax, pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema. Injury 1986; 17:309–312.

A 47-year-old man presented with acute shortness of breath and chest and neck pain, which began after he heard popping sounds while boarding a bus. The pain was right-sided, sharp, worse with deep breathing, and associated with a sensation of fullness over the right chest.

His medical conditions included controlled hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The COPD was managed with an albuterol inhaler only. He had a 50-pack-year history of smoking, and he drank alcohol occasionally.

On arrival, he was in mild respiratory distress, but his vital signs were stable. We could hear wheezing on both sides of his chest and feel subcutaneous crepitation on both sides of his chest and neck, the latter more on the right side. The rest of the examination was unremarkable.

Results of a complete blood cell count and metabolic panel were within normal limits. Because of the above findings, nasopharyngeal radiogragraphy was ordered (Figures 1 and 2).

Q: What is the most likely cause of this presentation?

- Esophageal rupture

- Gas gangrene

- Asthma exacerbation

- Ruptured emphysematous bullae

A: This patient had a history of COPD, which put him at risk of developing bullous emphysematous bullae that can rupture and cause subcutaneous emphysema. His nasopharyngeal radiograph (Figure1) showed bilateral extensive subcutaneous emphysema. His lateral nasopharyngeal radiograph (Figure 2) showed air-tracking within the mediastinum and into the retropharyngeal space (arrow). Computed tomography (Figure 3) showed extensive subcutaneous emphysema in the right lateral chest wall (arrow) and large bullae in the right upper lobe (arrow heads). As for the other possibilities:

Esophageal ruptures and tears are iatrogenic in most cases and usually occur after endoscopic procedures, but they can also occur in patients with intractable vomiting. Computed tomography often shows esophageal thickening, periesophageal fluid, mediastinal widening, and extraluminal air. However, in most cases, it is seen as pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema.1

Gas gangrene is a life-threatening soft-tissue and muscle infection caused by Clostridium perfringens in most cases.2 The pain is out of proportion to the findings on physical examination. Patients usually have toxic signs and symptoms such as fever and hypotension. Our patient was hemodynamically stable, with no changes in skin color.

Severe exacerbations of asthma can lead to alveolar rupture, pneumothorax, and subcutaneous emphysema, although this is a rare complication. Air can dissect along the bronchovascular sheaths into the neck and cause subcutaneous emphysema, or into the pleural space and cause pneumothorax. Our patient had no history of asthma and plainly had emphysematous bullae.3

SUBCUTANEOUS EMPHYSEMA

Subcutaneous emphysema is a collection of air within subcutaneous tissues. It usually presents as bloating of the skin around the neck and the chest wall. It is often seen in patients with pneumothorax.

The most common cause of subcutaneous emphysema is traumatic injury to the chest wall, such as from a motor vehicle accident or a stab wound,4 but it can also occur spontaneously in patients who have severe emphysema with large bullae. As the emphysema progresses, the bullae can easily rupture, and this can lead to pneumothorax, which can lead to subcutaneous emphysema. Primary spontaneous pneumothorax and subcutaneous emphysema can occur in people who have unrecognized lung disease and genetic disorders such as Marfan syndrome and Ehler-Danlos syndrome.5 Other causes include iatrogenic injury, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (common in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection), and cystic fibrosis. Pneumothorax occurs in about 30% of cases of P jirovecii pneumonia,6 and in about 6% of patients with cystic fibrosis.7 Bronchocutaneous fistula is an extremely rare complication of lung cancer and can cause subcutaneous emphysema.8 Tuberculosis is another possible cause.9

Subcutaneous emphysema mainly presents with chest or neck pain and wheezing. In severe cases, air can track to the face, causing facial swelling and difficulty breathing due to compression of the larynx. Also, it can track down to the thighs, causing leg pain and swelling.10

On examination, subcutaneous emphysema can be detected by palpating the chest wall, which causes the air bubble to move and produce crackling sounds. Most cases of subcutaneous emphysema are diagnosed clinically. Chest radiography and computed tomography help identify the source of air leak. Ultrasonography is usually used in cases of blunt trauma to the chest as part of the Focal Assessment With Sonography for Trauma protocol.11

Subcutaneous emphysema can resolve spontaneously, requiring only pain management and supplemental oxygen.12 In severe cases, air collection can lead to what is called “massive subcutaneous emphysema,” which requires surgical drainage.

Our patient had large emphysematous bullae in the apical region of the right lung that ruptured and led to subcutaneous emphysema. After placement of a chest tube, he underwent right-sided thoracotomy with bullectomy. His postoperative course was uneventful, and he was discharged a few days later. Three weeks later, repeated chest radiography showed resolution of his subcutaneous emphysema (Figure 4).

A 47-year-old man presented with acute shortness of breath and chest and neck pain, which began after he heard popping sounds while boarding a bus. The pain was right-sided, sharp, worse with deep breathing, and associated with a sensation of fullness over the right chest.

His medical conditions included controlled hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The COPD was managed with an albuterol inhaler only. He had a 50-pack-year history of smoking, and he drank alcohol occasionally.

On arrival, he was in mild respiratory distress, but his vital signs were stable. We could hear wheezing on both sides of his chest and feel subcutaneous crepitation on both sides of his chest and neck, the latter more on the right side. The rest of the examination was unremarkable.

Results of a complete blood cell count and metabolic panel were within normal limits. Because of the above findings, nasopharyngeal radiogragraphy was ordered (Figures 1 and 2).

Q: What is the most likely cause of this presentation?

- Esophageal rupture

- Gas gangrene

- Asthma exacerbation

- Ruptured emphysematous bullae

A: This patient had a history of COPD, which put him at risk of developing bullous emphysematous bullae that can rupture and cause subcutaneous emphysema. His nasopharyngeal radiograph (Figure1) showed bilateral extensive subcutaneous emphysema. His lateral nasopharyngeal radiograph (Figure 2) showed air-tracking within the mediastinum and into the retropharyngeal space (arrow). Computed tomography (Figure 3) showed extensive subcutaneous emphysema in the right lateral chest wall (arrow) and large bullae in the right upper lobe (arrow heads). As for the other possibilities:

Esophageal ruptures and tears are iatrogenic in most cases and usually occur after endoscopic procedures, but they can also occur in patients with intractable vomiting. Computed tomography often shows esophageal thickening, periesophageal fluid, mediastinal widening, and extraluminal air. However, in most cases, it is seen as pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema.1

Gas gangrene is a life-threatening soft-tissue and muscle infection caused by Clostridium perfringens in most cases.2 The pain is out of proportion to the findings on physical examination. Patients usually have toxic signs and symptoms such as fever and hypotension. Our patient was hemodynamically stable, with no changes in skin color.

Severe exacerbations of asthma can lead to alveolar rupture, pneumothorax, and subcutaneous emphysema, although this is a rare complication. Air can dissect along the bronchovascular sheaths into the neck and cause subcutaneous emphysema, or into the pleural space and cause pneumothorax. Our patient had no history of asthma and plainly had emphysematous bullae.3

SUBCUTANEOUS EMPHYSEMA

Subcutaneous emphysema is a collection of air within subcutaneous tissues. It usually presents as bloating of the skin around the neck and the chest wall. It is often seen in patients with pneumothorax.