User login

Hepatitis in pregnancy: Sorting through the alphabet

A 27-year-old primigravida at 9 weeks 3 days of gestation tests positive for the hepatitis B surface antigen at her first prenatal appointment. She is completely asymptomatic.

- What additional tests are indicated?

- Does she pose a risk to her sexual partner, and is her newborn at risk for acquiring hepatitis B?

- Can anything be done to protect her partner and newborn from infection?

Meet our perpetrator

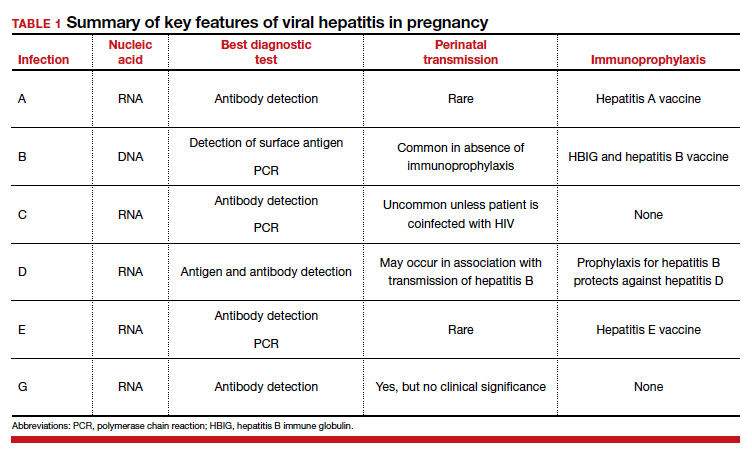

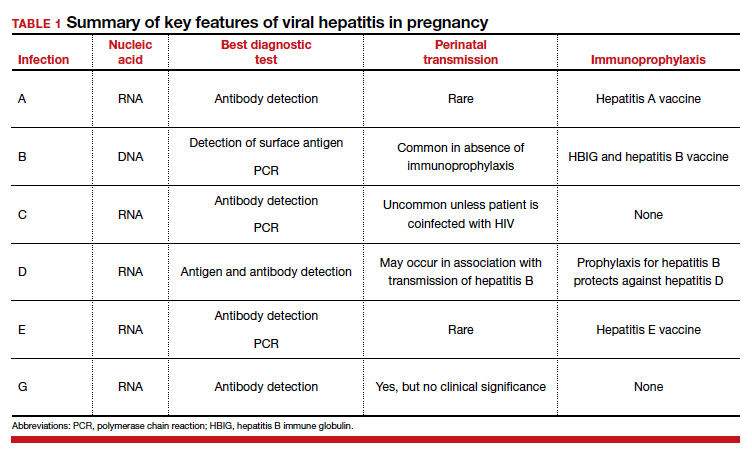

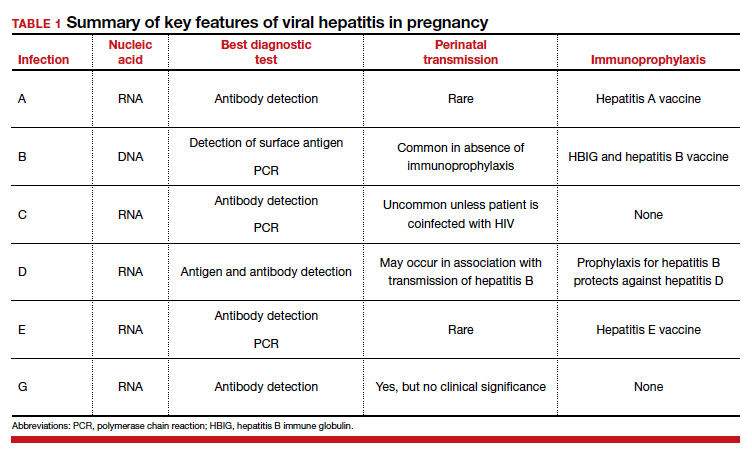

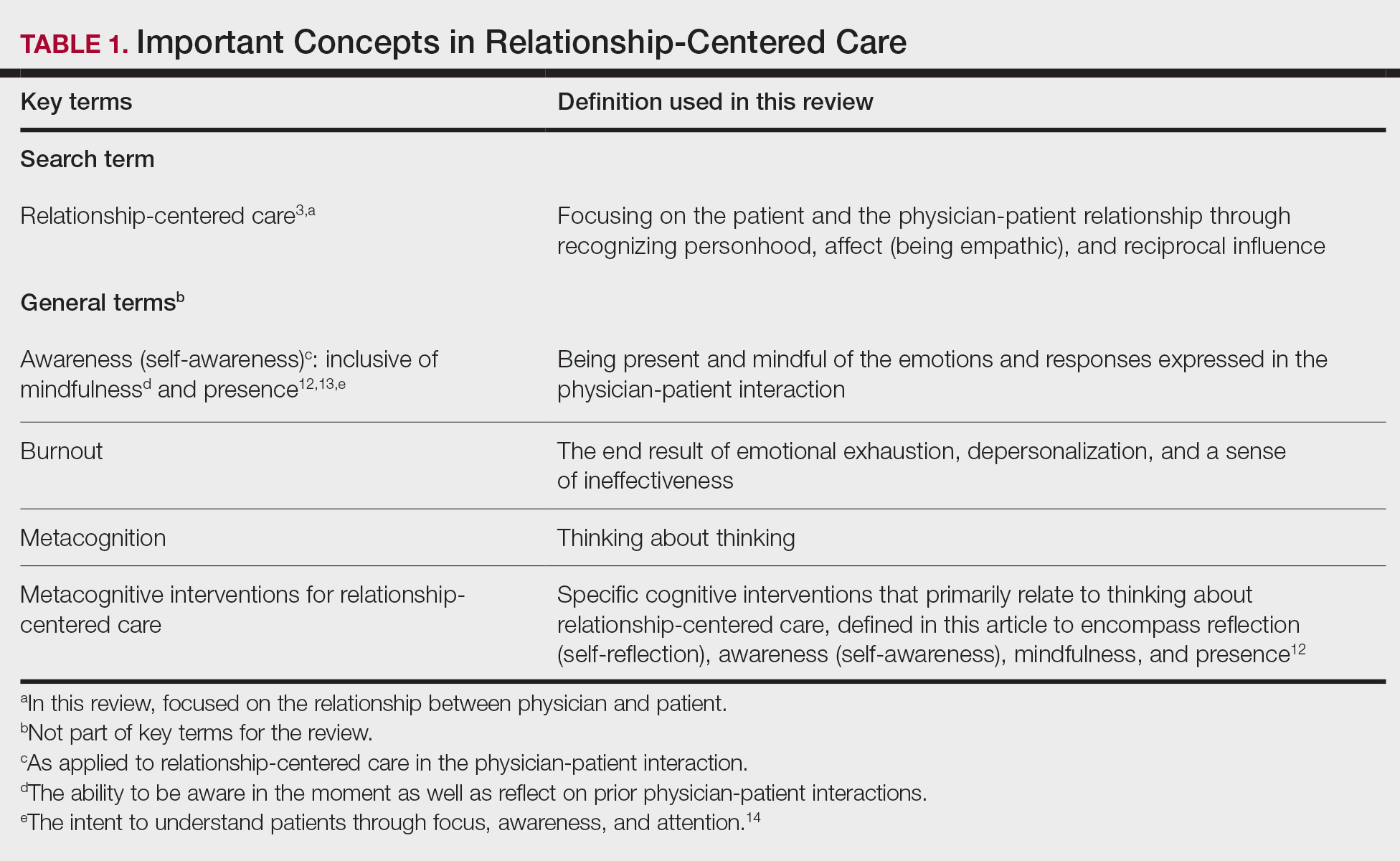

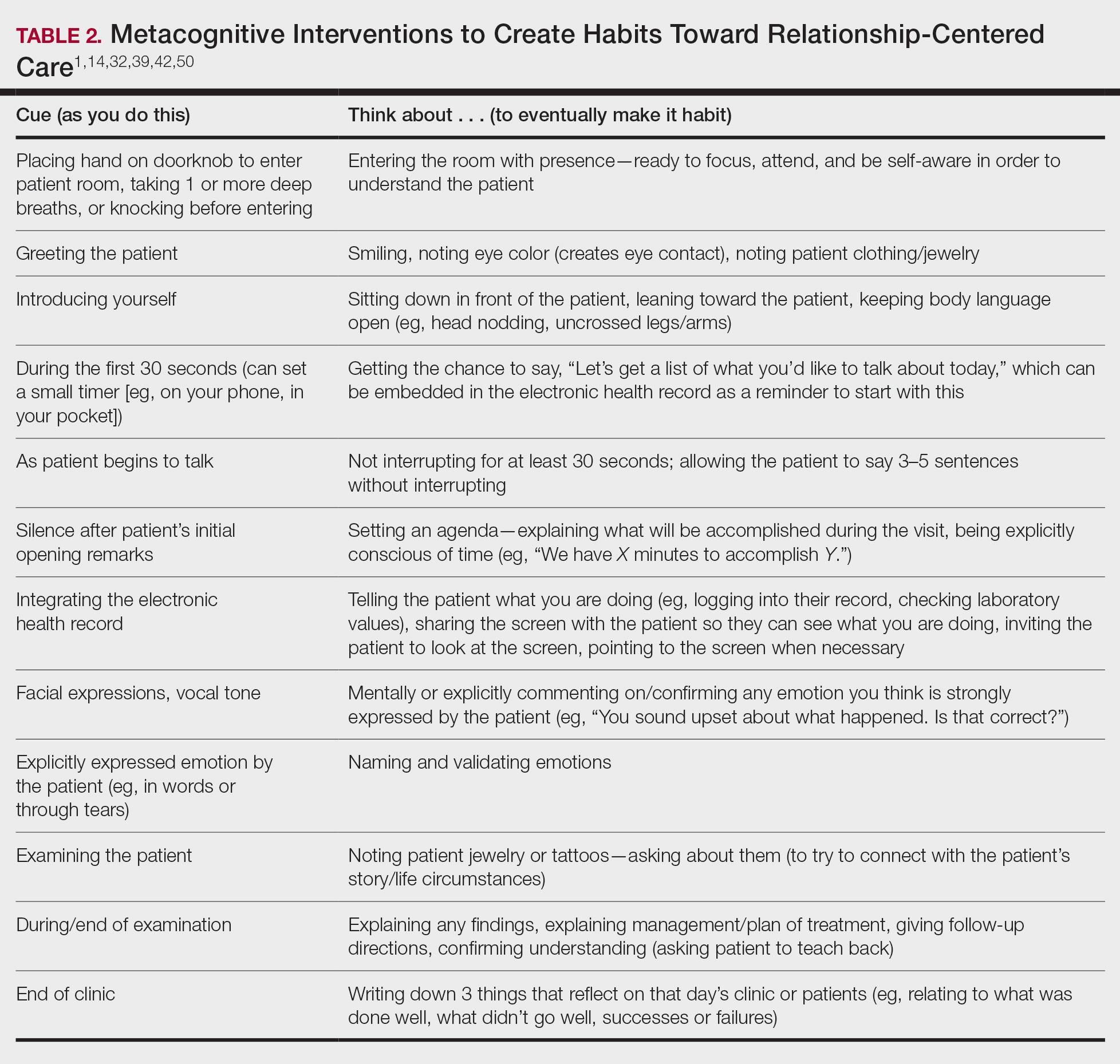

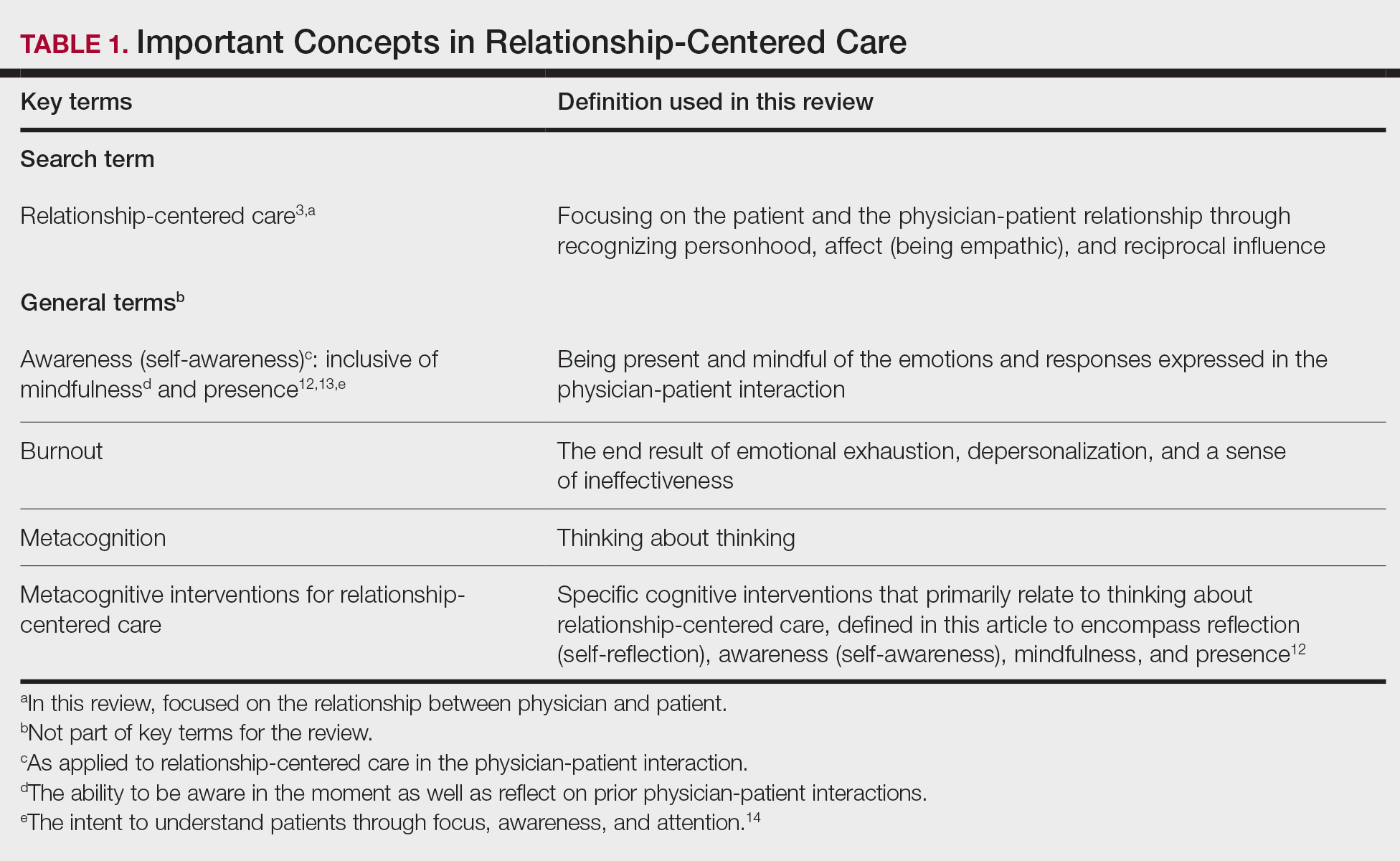

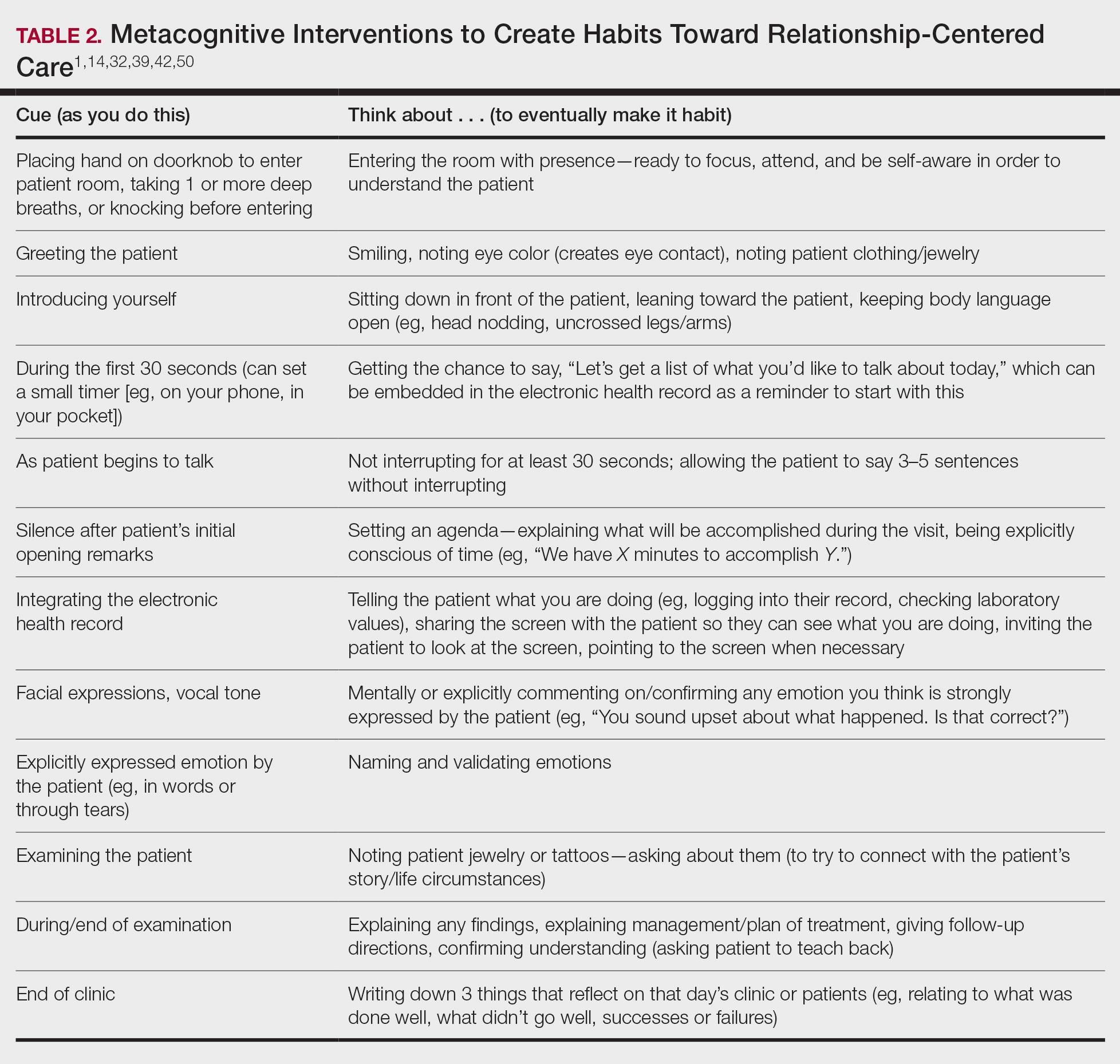

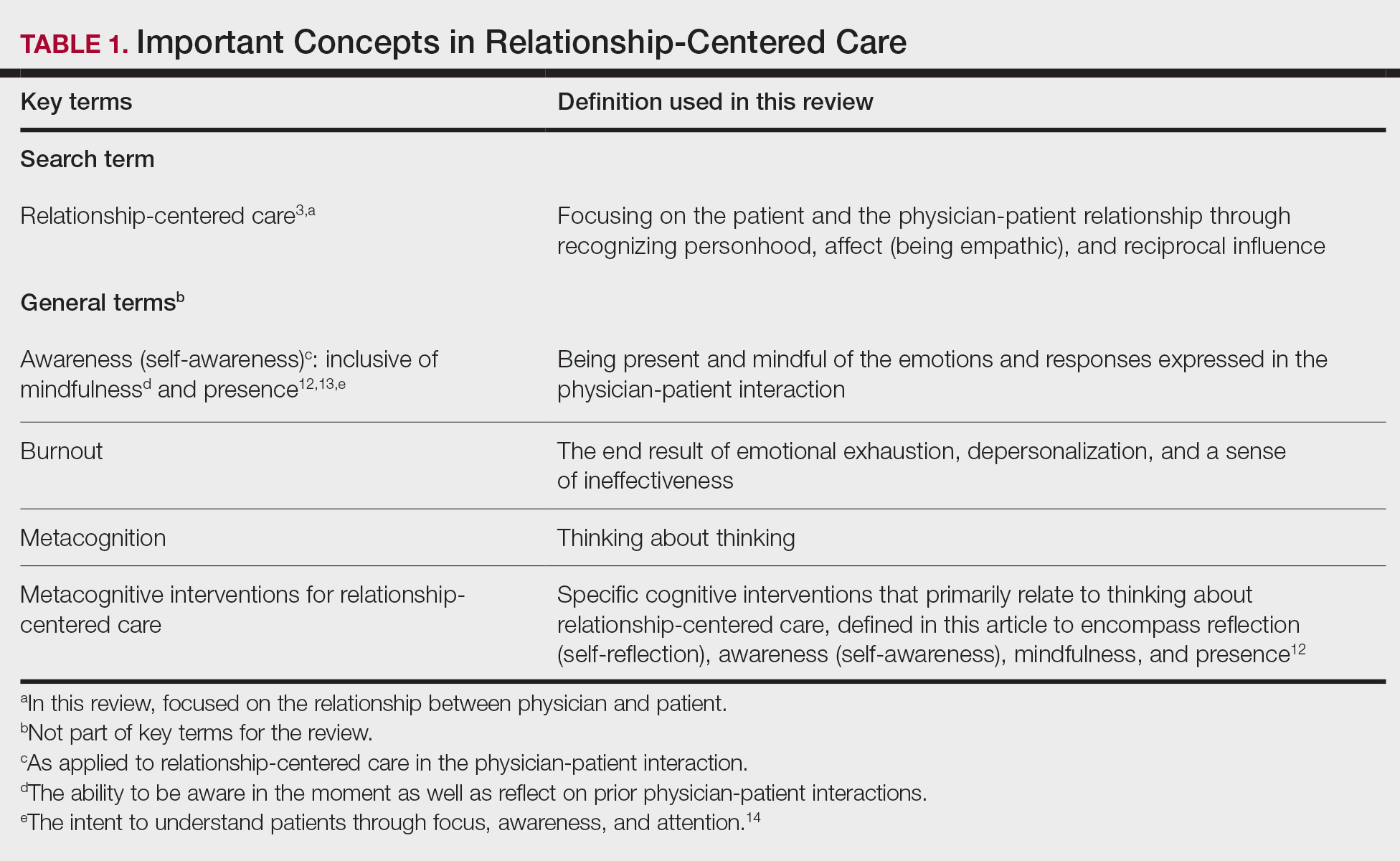

Hepatitis is one of the more common viral infections that may occur during pregnancy. Two forms of hepatitis, notably hepatitis A and E, pose a primary threat to the mother. Three forms (B, C, and D) present dangers for the mother, fetus, and newborn. This article will review the epidemiology, clinical manifestations, perinatal implications, and management of the various forms of viral hepatitis. (TABLE 1).

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A is caused by an RNA virus that is transmitted by fecal-oral contact. The disease is most prevalent in areas with poor sanitation and close living conditions. The incubation period ranges from 15 to 50 days. Most children who acquire this disease are asymptomatic. By contrast, most infected adults are acutely symptomatic. Clinical manifestations typically include low-grade fever, malaise, anorexia, right upper quadrant pain and tenderness, jaundice, and claycolored stools.1,2

The diagnosis of acute hepatitis A infection is best confirmed by detection of immunoglobulin M (IgM)-specific antibodies. The serum transaminase concentrations and the serum bilirubin concentrations usually are significantly elevated. The international normalized ratio, prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time also may be elevated.1,2

The treatment for acute hepatitis A largely is supportive care: maintaining hydration, optimizing nutrition, and correcting coagulation abnormalities. The appropriate measures for prevention of hepatitis A are adoption of sound sanitation practices, particularly water purification; minimizing overcrowded living conditions; and administering the hepatitis A vaccine for both pre and postexposure prophylaxis.3,4 The hepatitis A vaccine is preferred over administration of immune globulin because it provides lifelong immunity.

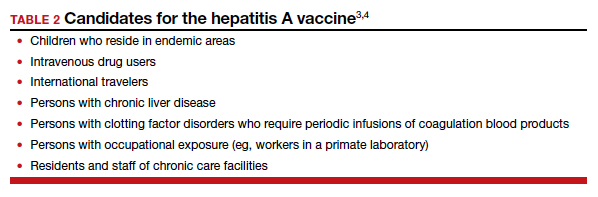

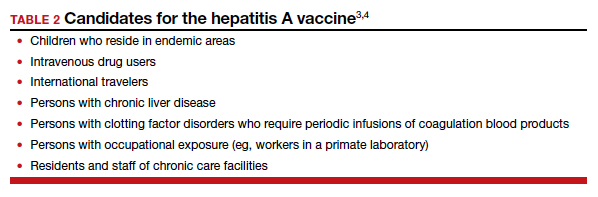

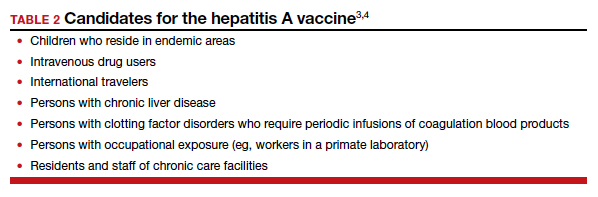

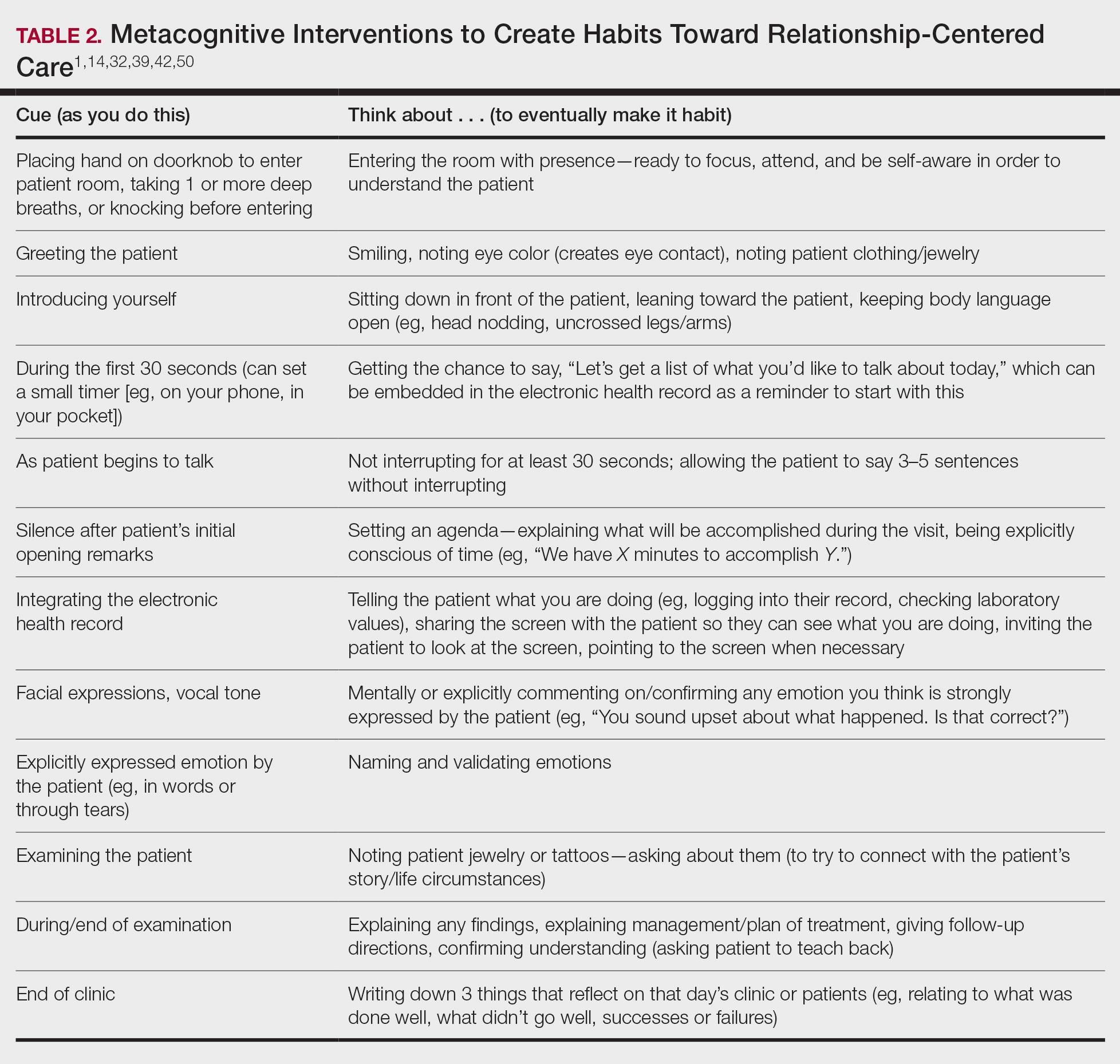

The hepatitis A vaccine is produced in 2 monovalent formulations: Havrix (GlaxoSmithKline) and Vaqta (Merck & Co, Inc). The vaccine should be administered intramuscularly in 2 doses 6 to 12 months apart. The wholesale cost of the vaccine varies from $66 to $119 (according to http://www.goodrx.com). The vaccine also is available in a bivalent form, with recombinant hepatitis B vaccine (Twinrix, GlaxoSmithKline). When used in this form, 3 vaccine administrations are given—at 0, 1, and 6 months apart. The cost of the vaccine is approximately $150 (according to http://www.goodrx.com). TABLE 2 lists the individuals who are appropriate candidates for the hepatitis A vaccine.3,4

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B is caused by a DNA virus that is transmitted parenterally or perinatally or through

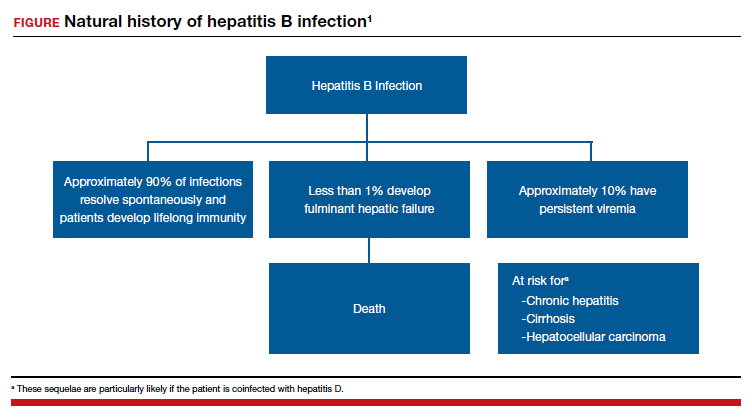

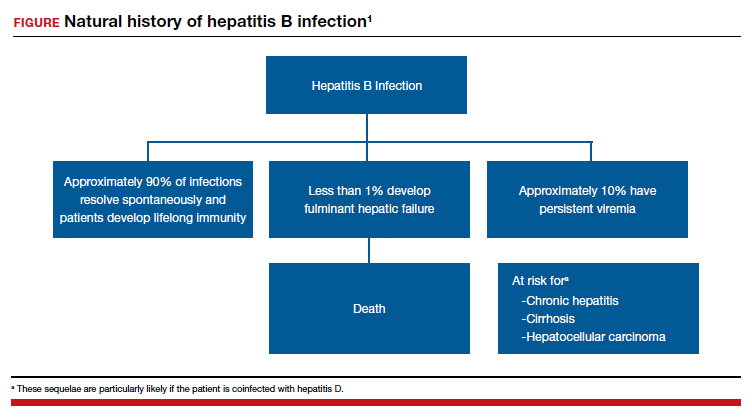

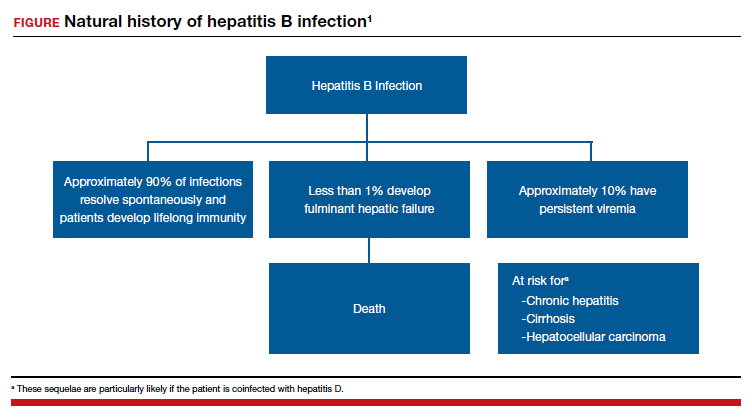

Acute hepatitis B affects 1 to 2 of 1,000 pregnancies in the United States. Approximately 6 to 10 patients per 1,000 pregnancies are asymptomatic but chronically infected.4 The natural history of hepatitis B infection is shown in the FIGURE. The diagnosis of acute and chronic hepatitis B is best established by serology and polymerase chain reaction (PCR; TABLE 3).

All pregnant women should be routinely screened for the hepatitis B surface antigen.5,6 If they are seropositive for the surface antigen alone and receive no immunoprophylaxis, they have a 20% to 30% risk of transmitting infection to their neonate. Subsequently, if they also test positive for the hepatitis Be antigen, the risk of perinatal transmission increases to approximately 90%. Fortunately, 2 forms of immunoprophylaxis are highly effective in preventing perinatal transmission. Infants delivered to seropositive mothers should receive hepatitis B immune globulin within 12 hours of birth. Prior to discharge, the infant also should receive the first dose of the hepatitis B vaccine. Subsequent doses should be administered at 1 and 6 months of age. Infants delivered to seronegative mothers require only the vaccine series.1

Although immunoprophylaxis is highly effective, some neonates still acquire infection perinatally. Pan and colleagues7 and Jourdain et al8 demonstrated that administration of tenofovir 200 mg orally each day from 32 weeks’ gestation until delivery provided further protection against perinatal transmission in patients with a high viral load (defined as >1 million copies/mL). In 2016, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine endorsed the use of tenofovir in women with a high viral load.6

Following delivery, women with chronic hepatitis B infection should be referred to a hepatology specialist for consideration of direct antiviral treatment. Multiple drugs are now available that are highly active against this micro-organism. These drugs include several forms of interferon, lamivudine, adefovir, entecavir, telbivudine, and tenofovir.1

Continue to: Hepatitis C...

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C is caused by an RNA virus that has 6 genotypes. The most common genotype is HCV1, which affects 79% of patients; approximately 13% of patients have HCV2, and 6% have HCV3.9 Of note, the 3 individuals who discovered this virus—Drs. Harvey Alter, Michael Houghton, and Charles Rice—received the 2020 Nobel Prize in Medicine.10

Hepatitis C is transmitted via sexual contact, parenterally, and perinatally. In many patient populations in the United States, hepatitis C is now more prevalent than hepatitis B. Only about half of all infected persons are aware of their infection. If patients go untreated, approximately 15% to 30% eventually develop cirrhosis. Of these individuals, 1% to 3% develop hepatocellular cancer. Chronic hepatitis C is now the most common indication for liver transplantation in the United States.1,9

In the initial stages of infection, hepatitis C usually is asymptomatic. The best screening test is detection of hepatitis C antibody. Because of the increasing prevalence of this disease, the seriousness of the infection, and the recent availability of remarkably effective treatment, routine screening, rather than screening on the basis of risk factors, for hepatitis C in pregnancy is now indicated.11,12

The best tests for confirmation of infection are detection of antibody by enzyme immunoassay and recombinant immuno-blot assay and detection of viral RNA in serum by PCR. Seroconversion may not occur for up to 16 weeks after infection. Therefore, in at-risk patients who initially test negative, retesting is advisable. Patients with positive test results should have tests to identify the specific genotype, determine the viral load, and assess liver function.1

In patients who have undetectable viral loads and who do not have coexisting HIV infection, the risk of perinatal transmission of hepatitis C is less than 5%. If HIV infection is present, the risk of perinatal transmission approaches 20%.1,13,14

If the patient is coinfected with HIV, a scheduled cesarean delivery should be performed at 38 weeks’ gestation.1 If the viral load is undetectable, vaginal delivery is appropriate. If the viral load is high, however (arbitrarily defined as >2.5 millioncopies/mL), the optimal method of delivery is controversial. Several small, nonrandomized noncontrolled cohort studies support elective cesarean delivery in such patients.14

There is no contraindication to breastfeeding in women with hepatitis C unless they are coinfected with HIV. In such a circumstance, formula feeding should be chosen. After delivery, patients with hepatitis C should be referred to a gastroenterology specialist to receive antiviral treatment. Multiple new single-agent and combination regimens have produced cures in more than 90% of patients. These regimens usually require 8 to 12 weeks of treatment, and they are very expensive. They have not been widely tested in pregnant women.1

Hepatitis D

Hepatitis D, or delta hepatitis, is caused by an RNA virus. This virus is unique because it is incapable of independent replication. It must be present in association with hepatitis B to replicate and cause clinical infection. Therefore, the epidemiology of hepatitis D closely mirrors that of hepatitis B.1,2

Patients with hepatitis D typically present in one of two ways. Some individuals are acutely infected with hepatitis D at the same time that they acquire hepatitis B (coinfection). The natural history of this infection usually is spontaneous resolution without sequelae. Other patients have chronic hepatitis D superimposed on chronic hepatitis B (superinfection). Unfortunately, patients with the latter condition are at a notably increased risk for developing severe persistent liver disease.1,2

The diagnosis of hepatitis D may be confirmed by identifying the delta antigen in serum or in liver tissue obtained by biopsy or by identifying IgM- and IgG-specific antibodies in serum. In conjunction with hepatitis B, the delta virus can cause a chronic carrier state. Perinatal transmission is possible but uncommon. Of greatest importance, the immunoprophylaxis described for hepatitis B is almost perfectly protective against perinatal transmission of hepatitis D.1,2

Continue to: Hepatitis E...

Hepatitis E

Hepatitis E is an RNA virus that has 1 serotype and 4 genotypes. Its epidemiology is similar to that of hepatitis A. It is the most common waterborne illness in the world. The incubation period varies from 21 to 56 days. This disease is quite rare in the United States but is endemic in developing nations. In those countries, maternal infection has an alarmingly high mortality rate (5%–25%). For example, in Bangladesh, hepatitis E is responsible for more than 1,000 deaths per year in pregnant women. When hepatitis E is identified in more affluent countries, the individual cases and small outbreaks usually are linked to consumption of undercooked pork or wild game.1,15-17

The clinical presentation of acute hepatitis E also is similar to that of hepatitis A. The usual manifestations are fever, malaise, anorexia, nausea, right upper quadrant pain and tenderness, jaundice, darkened urine, and clay-colored stools. The most useful diagnostic tests are serologic detection of viral-specific antibodies (positive IgM or a 4-fold increase in the prior IgG titer) and PCR-RNA.1,17

Hepatitis E usually does not cause a chronic carrier state, and perinatal transmission is rare. Fortunately, a highly effective vaccine was recently developed (Hecolin, Xiamen Innovax Biotech). This recombinant vaccine is specifically directed against the hepatitis E genotype 1. In the initial efficacy study, healthy adults aged 16 to 65 years were randomly assigned to receive either the hepatitis E vaccine or the hepatitis B vaccine. The vaccine was administered at time point 0, and 1 and 6 months later. Patients were followed for up to 4.5 years to assess efficacy, immunogenicity, and safety. During the study period, 7 cases of hepatitis E occurred in the vaccine group, compared with 53 in the control group. Approximately 56,000 patients were included in each group. The efficacy of the vaccine was 86.8% (P<.001).18

Hepatitis G

Hepatitis G is caused by 2 single-stranded RNA viruses that are virtually identical—hepatitis G virus and GB virus type C. The viruses share approximately 30% homology with hepatitis C virus. The organism is present throughout the world and infects approximately 1.5% to 2.0% of the population. The virus is transmitted by blood and sexual contact. It replicates preferentially in mononuclear cells and the bone marrow rather than in the liver.19-21

Hepatitis G is much less virulent than hepatitis C. Hepatitis G often coexists with hepatitis A, B, and C, as well as with HIV. Coinfection with hepatitis G does not adversely affect the clinical course of the other conditions.22,23

Most patients with hepatitis G are asymptomatic, and no treatment is indicated. The virus can cause a chronic carrier state. Perinatal transmission is distinctly uncommon. When it does occur, however, injury to mother, fetus, or neonate is unlikely.1,24

The diagnosis of hepatitis G can be established by detection of virus with PCR and by the identification of antibody by enzyme immunoassay. Routine screening for this infection in pregnancy is not indicated.1,2

Hepatitis B is highly contagious and can be transmitted from the patient to her sexual partner and neonate. Testing for hepatitis B surface antigen and antibody is indicated in her partner. If these tests are negative, the partner should immediately receive hepatitis B immune globulin and then be started on the 3-dose hepatitis B vaccination series. The patient’s newborn also should receive hepatitis B immune globulin within 12 hours of delivery and should receive the first dose of the hepatitis B vaccine prior to discharge from the hospital. The second and third doses should be administered 1 and 6 months after delivery.

The patient also should have the following tests:

• liver function tests

-serum transaminases

-direct and indirect bilirubin

-coagulation profile

• hepatitis D antigen

• hepatitis B genotype

• hepatitis B viral load

• HIV serology.

If the hepatitis B viral load exceeds 1 million copies/mL, the patient should be treated with tenofovir 200 mg daily from 28 weeks’ gestation until delivery. In addition, she should be referred to a liver disease specialist after delivery for consideration of treatment with directly-acting antiviral agents. ●

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TB, et al, eds. Creasy & Resnik’s MaternalFetal Medicine Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Duff P. Hepatitis in pregnancy. In: Queenan JR, Spong CY, Lockwood CJ, eds. Management of HighRisk Pregnancy. An EvidenceBased Approach. 5th ed. Blackwell; 2007:238-241.

- Duff B, Duff P. Hepatitis A vaccine: ready for prime time. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:468-471.

- Victor JC, Monto AS, Surdina TY, et al. Hepatitis A vaccine versus immune globulin for postexposure prophylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2007;367:1685-1694.

- Dienstag JL. Hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1486-1500.

- Society for MaternalFetal Medicine (SMFM); Dionne-Odom J, Tita ATN, Silverman NS. #38. Hepatitis B in pregnancy: screening, treatment, and prevention of vertical transmission. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214:6-14.

- Pan CQ, Duan Z, Dai E, et al. Tenofovir to prevent hepatitis B transmission in mothers with high viral load. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2324-2334.

- Jourdain G, Huong N, Harrison L, et al. Tenofovir versus placebo to prevent perinatal transmission of hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:911-923.

- Rosen HR. Chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2429-2438.

- Hoofnagle JH, Feinstore SM. The discovery of hepatitis C—the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. N Engl J Med. 2020;384:2297-2299.

- Hughes BL, Page CM, Juller JA. Hepatitis C in pregnancy: screening, treatment, and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:B2-B12.

- Saab S, Kullar R, Gounder P. The urgent need for hepatitis C screening in pregnant women: a call to action. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:773-777.

- Berkley EMF, Leslie KK, Arora S, et al. Chronic hepatitis C in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:304-310.

- Brazel M, Duff P. Considerations on the mode of delivery for pregnant women with hepatitis C infection [published online November 22, 2019]. OBG Manag. 2020;32:39-44.

- Emerson SU, Purcell RH. Hepatitis E virus. Rev Med Virol. 2003;13:145-154.

- Khuroo MS, Teli MR, Skidmore S, et al. Incidence and severity of viral hepatitis in pregnancy. Am J Med. 1981;70:252-255.

- Hoofnangle JH, Nelson KE, Purcell RH. Hepatitis E. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1237-1244.

- Zhang J, Zhang XF, Huang SJ, et al. Longterm efficacy of a hepatitis E vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:914-922.

- Pickering L, ed. Red Book 2000 Report of Committee on Infectious Diseases. 25th ed. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2000.

- Chopra S. GB virus C (hepatitis G) infection. UpToDate website. Updated January 16, 2020. Accessed June 3, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/gb-virus-c-hepatitis-g-infection.

- Reshetnyak VI, Karlovich TI, Ilchenko LU. Hepatitis G virus. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4725-4734.

- Kew MC, Kassianides C. HGV: hepatitis G virus or harmless G virus. Lancet. 1996;348(suppl II):10.

- Jarvis LM, Davidson F, Hanley JP, et al. Infection with hepatitis G virus among recipients of plasma products. Lancet. 1996;348;1352-1355.

- Feucht HH, Zollner B, Polywka S, et al. Vertical transmission of hepatitis G. Lancet. 1996;347;615-616.

A 27-year-old primigravida at 9 weeks 3 days of gestation tests positive for the hepatitis B surface antigen at her first prenatal appointment. She is completely asymptomatic.

- What additional tests are indicated?

- Does she pose a risk to her sexual partner, and is her newborn at risk for acquiring hepatitis B?

- Can anything be done to protect her partner and newborn from infection?

Meet our perpetrator

Hepatitis is one of the more common viral infections that may occur during pregnancy. Two forms of hepatitis, notably hepatitis A and E, pose a primary threat to the mother. Three forms (B, C, and D) present dangers for the mother, fetus, and newborn. This article will review the epidemiology, clinical manifestations, perinatal implications, and management of the various forms of viral hepatitis. (TABLE 1).

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A is caused by an RNA virus that is transmitted by fecal-oral contact. The disease is most prevalent in areas with poor sanitation and close living conditions. The incubation period ranges from 15 to 50 days. Most children who acquire this disease are asymptomatic. By contrast, most infected adults are acutely symptomatic. Clinical manifestations typically include low-grade fever, malaise, anorexia, right upper quadrant pain and tenderness, jaundice, and claycolored stools.1,2

The diagnosis of acute hepatitis A infection is best confirmed by detection of immunoglobulin M (IgM)-specific antibodies. The serum transaminase concentrations and the serum bilirubin concentrations usually are significantly elevated. The international normalized ratio, prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time also may be elevated.1,2

The treatment for acute hepatitis A largely is supportive care: maintaining hydration, optimizing nutrition, and correcting coagulation abnormalities. The appropriate measures for prevention of hepatitis A are adoption of sound sanitation practices, particularly water purification; minimizing overcrowded living conditions; and administering the hepatitis A vaccine for both pre and postexposure prophylaxis.3,4 The hepatitis A vaccine is preferred over administration of immune globulin because it provides lifelong immunity.

The hepatitis A vaccine is produced in 2 monovalent formulations: Havrix (GlaxoSmithKline) and Vaqta (Merck & Co, Inc). The vaccine should be administered intramuscularly in 2 doses 6 to 12 months apart. The wholesale cost of the vaccine varies from $66 to $119 (according to http://www.goodrx.com). The vaccine also is available in a bivalent form, with recombinant hepatitis B vaccine (Twinrix, GlaxoSmithKline). When used in this form, 3 vaccine administrations are given—at 0, 1, and 6 months apart. The cost of the vaccine is approximately $150 (according to http://www.goodrx.com). TABLE 2 lists the individuals who are appropriate candidates for the hepatitis A vaccine.3,4

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B is caused by a DNA virus that is transmitted parenterally or perinatally or through

Acute hepatitis B affects 1 to 2 of 1,000 pregnancies in the United States. Approximately 6 to 10 patients per 1,000 pregnancies are asymptomatic but chronically infected.4 The natural history of hepatitis B infection is shown in the FIGURE. The diagnosis of acute and chronic hepatitis B is best established by serology and polymerase chain reaction (PCR; TABLE 3).

All pregnant women should be routinely screened for the hepatitis B surface antigen.5,6 If they are seropositive for the surface antigen alone and receive no immunoprophylaxis, they have a 20% to 30% risk of transmitting infection to their neonate. Subsequently, if they also test positive for the hepatitis Be antigen, the risk of perinatal transmission increases to approximately 90%. Fortunately, 2 forms of immunoprophylaxis are highly effective in preventing perinatal transmission. Infants delivered to seropositive mothers should receive hepatitis B immune globulin within 12 hours of birth. Prior to discharge, the infant also should receive the first dose of the hepatitis B vaccine. Subsequent doses should be administered at 1 and 6 months of age. Infants delivered to seronegative mothers require only the vaccine series.1

Although immunoprophylaxis is highly effective, some neonates still acquire infection perinatally. Pan and colleagues7 and Jourdain et al8 demonstrated that administration of tenofovir 200 mg orally each day from 32 weeks’ gestation until delivery provided further protection against perinatal transmission in patients with a high viral load (defined as >1 million copies/mL). In 2016, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine endorsed the use of tenofovir in women with a high viral load.6

Following delivery, women with chronic hepatitis B infection should be referred to a hepatology specialist for consideration of direct antiviral treatment. Multiple drugs are now available that are highly active against this micro-organism. These drugs include several forms of interferon, lamivudine, adefovir, entecavir, telbivudine, and tenofovir.1

Continue to: Hepatitis C...

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C is caused by an RNA virus that has 6 genotypes. The most common genotype is HCV1, which affects 79% of patients; approximately 13% of patients have HCV2, and 6% have HCV3.9 Of note, the 3 individuals who discovered this virus—Drs. Harvey Alter, Michael Houghton, and Charles Rice—received the 2020 Nobel Prize in Medicine.10

Hepatitis C is transmitted via sexual contact, parenterally, and perinatally. In many patient populations in the United States, hepatitis C is now more prevalent than hepatitis B. Only about half of all infected persons are aware of their infection. If patients go untreated, approximately 15% to 30% eventually develop cirrhosis. Of these individuals, 1% to 3% develop hepatocellular cancer. Chronic hepatitis C is now the most common indication for liver transplantation in the United States.1,9

In the initial stages of infection, hepatitis C usually is asymptomatic. The best screening test is detection of hepatitis C antibody. Because of the increasing prevalence of this disease, the seriousness of the infection, and the recent availability of remarkably effective treatment, routine screening, rather than screening on the basis of risk factors, for hepatitis C in pregnancy is now indicated.11,12

The best tests for confirmation of infection are detection of antibody by enzyme immunoassay and recombinant immuno-blot assay and detection of viral RNA in serum by PCR. Seroconversion may not occur for up to 16 weeks after infection. Therefore, in at-risk patients who initially test negative, retesting is advisable. Patients with positive test results should have tests to identify the specific genotype, determine the viral load, and assess liver function.1

In patients who have undetectable viral loads and who do not have coexisting HIV infection, the risk of perinatal transmission of hepatitis C is less than 5%. If HIV infection is present, the risk of perinatal transmission approaches 20%.1,13,14

If the patient is coinfected with HIV, a scheduled cesarean delivery should be performed at 38 weeks’ gestation.1 If the viral load is undetectable, vaginal delivery is appropriate. If the viral load is high, however (arbitrarily defined as >2.5 millioncopies/mL), the optimal method of delivery is controversial. Several small, nonrandomized noncontrolled cohort studies support elective cesarean delivery in such patients.14

There is no contraindication to breastfeeding in women with hepatitis C unless they are coinfected with HIV. In such a circumstance, formula feeding should be chosen. After delivery, patients with hepatitis C should be referred to a gastroenterology specialist to receive antiviral treatment. Multiple new single-agent and combination regimens have produced cures in more than 90% of patients. These regimens usually require 8 to 12 weeks of treatment, and they are very expensive. They have not been widely tested in pregnant women.1

Hepatitis D

Hepatitis D, or delta hepatitis, is caused by an RNA virus. This virus is unique because it is incapable of independent replication. It must be present in association with hepatitis B to replicate and cause clinical infection. Therefore, the epidemiology of hepatitis D closely mirrors that of hepatitis B.1,2

Patients with hepatitis D typically present in one of two ways. Some individuals are acutely infected with hepatitis D at the same time that they acquire hepatitis B (coinfection). The natural history of this infection usually is spontaneous resolution without sequelae. Other patients have chronic hepatitis D superimposed on chronic hepatitis B (superinfection). Unfortunately, patients with the latter condition are at a notably increased risk for developing severe persistent liver disease.1,2

The diagnosis of hepatitis D may be confirmed by identifying the delta antigen in serum or in liver tissue obtained by biopsy or by identifying IgM- and IgG-specific antibodies in serum. In conjunction with hepatitis B, the delta virus can cause a chronic carrier state. Perinatal transmission is possible but uncommon. Of greatest importance, the immunoprophylaxis described for hepatitis B is almost perfectly protective against perinatal transmission of hepatitis D.1,2

Continue to: Hepatitis E...

Hepatitis E

Hepatitis E is an RNA virus that has 1 serotype and 4 genotypes. Its epidemiology is similar to that of hepatitis A. It is the most common waterborne illness in the world. The incubation period varies from 21 to 56 days. This disease is quite rare in the United States but is endemic in developing nations. In those countries, maternal infection has an alarmingly high mortality rate (5%–25%). For example, in Bangladesh, hepatitis E is responsible for more than 1,000 deaths per year in pregnant women. When hepatitis E is identified in more affluent countries, the individual cases and small outbreaks usually are linked to consumption of undercooked pork or wild game.1,15-17

The clinical presentation of acute hepatitis E also is similar to that of hepatitis A. The usual manifestations are fever, malaise, anorexia, nausea, right upper quadrant pain and tenderness, jaundice, darkened urine, and clay-colored stools. The most useful diagnostic tests are serologic detection of viral-specific antibodies (positive IgM or a 4-fold increase in the prior IgG titer) and PCR-RNA.1,17

Hepatitis E usually does not cause a chronic carrier state, and perinatal transmission is rare. Fortunately, a highly effective vaccine was recently developed (Hecolin, Xiamen Innovax Biotech). This recombinant vaccine is specifically directed against the hepatitis E genotype 1. In the initial efficacy study, healthy adults aged 16 to 65 years were randomly assigned to receive either the hepatitis E vaccine or the hepatitis B vaccine. The vaccine was administered at time point 0, and 1 and 6 months later. Patients were followed for up to 4.5 years to assess efficacy, immunogenicity, and safety. During the study period, 7 cases of hepatitis E occurred in the vaccine group, compared with 53 in the control group. Approximately 56,000 patients were included in each group. The efficacy of the vaccine was 86.8% (P<.001).18

Hepatitis G

Hepatitis G is caused by 2 single-stranded RNA viruses that are virtually identical—hepatitis G virus and GB virus type C. The viruses share approximately 30% homology with hepatitis C virus. The organism is present throughout the world and infects approximately 1.5% to 2.0% of the population. The virus is transmitted by blood and sexual contact. It replicates preferentially in mononuclear cells and the bone marrow rather than in the liver.19-21

Hepatitis G is much less virulent than hepatitis C. Hepatitis G often coexists with hepatitis A, B, and C, as well as with HIV. Coinfection with hepatitis G does not adversely affect the clinical course of the other conditions.22,23

Most patients with hepatitis G are asymptomatic, and no treatment is indicated. The virus can cause a chronic carrier state. Perinatal transmission is distinctly uncommon. When it does occur, however, injury to mother, fetus, or neonate is unlikely.1,24

The diagnosis of hepatitis G can be established by detection of virus with PCR and by the identification of antibody by enzyme immunoassay. Routine screening for this infection in pregnancy is not indicated.1,2

Hepatitis B is highly contagious and can be transmitted from the patient to her sexual partner and neonate. Testing for hepatitis B surface antigen and antibody is indicated in her partner. If these tests are negative, the partner should immediately receive hepatitis B immune globulin and then be started on the 3-dose hepatitis B vaccination series. The patient’s newborn also should receive hepatitis B immune globulin within 12 hours of delivery and should receive the first dose of the hepatitis B vaccine prior to discharge from the hospital. The second and third doses should be administered 1 and 6 months after delivery.

The patient also should have the following tests:

• liver function tests

-serum transaminases

-direct and indirect bilirubin

-coagulation profile

• hepatitis D antigen

• hepatitis B genotype

• hepatitis B viral load

• HIV serology.

If the hepatitis B viral load exceeds 1 million copies/mL, the patient should be treated with tenofovir 200 mg daily from 28 weeks’ gestation until delivery. In addition, she should be referred to a liver disease specialist after delivery for consideration of treatment with directly-acting antiviral agents. ●

A 27-year-old primigravida at 9 weeks 3 days of gestation tests positive for the hepatitis B surface antigen at her first prenatal appointment. She is completely asymptomatic.

- What additional tests are indicated?

- Does she pose a risk to her sexual partner, and is her newborn at risk for acquiring hepatitis B?

- Can anything be done to protect her partner and newborn from infection?

Meet our perpetrator

Hepatitis is one of the more common viral infections that may occur during pregnancy. Two forms of hepatitis, notably hepatitis A and E, pose a primary threat to the mother. Three forms (B, C, and D) present dangers for the mother, fetus, and newborn. This article will review the epidemiology, clinical manifestations, perinatal implications, and management of the various forms of viral hepatitis. (TABLE 1).

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A is caused by an RNA virus that is transmitted by fecal-oral contact. The disease is most prevalent in areas with poor sanitation and close living conditions. The incubation period ranges from 15 to 50 days. Most children who acquire this disease are asymptomatic. By contrast, most infected adults are acutely symptomatic. Clinical manifestations typically include low-grade fever, malaise, anorexia, right upper quadrant pain and tenderness, jaundice, and claycolored stools.1,2

The diagnosis of acute hepatitis A infection is best confirmed by detection of immunoglobulin M (IgM)-specific antibodies. The serum transaminase concentrations and the serum bilirubin concentrations usually are significantly elevated. The international normalized ratio, prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time also may be elevated.1,2

The treatment for acute hepatitis A largely is supportive care: maintaining hydration, optimizing nutrition, and correcting coagulation abnormalities. The appropriate measures for prevention of hepatitis A are adoption of sound sanitation practices, particularly water purification; minimizing overcrowded living conditions; and administering the hepatitis A vaccine for both pre and postexposure prophylaxis.3,4 The hepatitis A vaccine is preferred over administration of immune globulin because it provides lifelong immunity.

The hepatitis A vaccine is produced in 2 monovalent formulations: Havrix (GlaxoSmithKline) and Vaqta (Merck & Co, Inc). The vaccine should be administered intramuscularly in 2 doses 6 to 12 months apart. The wholesale cost of the vaccine varies from $66 to $119 (according to http://www.goodrx.com). The vaccine also is available in a bivalent form, with recombinant hepatitis B vaccine (Twinrix, GlaxoSmithKline). When used in this form, 3 vaccine administrations are given—at 0, 1, and 6 months apart. The cost of the vaccine is approximately $150 (according to http://www.goodrx.com). TABLE 2 lists the individuals who are appropriate candidates for the hepatitis A vaccine.3,4

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B is caused by a DNA virus that is transmitted parenterally or perinatally or through

Acute hepatitis B affects 1 to 2 of 1,000 pregnancies in the United States. Approximately 6 to 10 patients per 1,000 pregnancies are asymptomatic but chronically infected.4 The natural history of hepatitis B infection is shown in the FIGURE. The diagnosis of acute and chronic hepatitis B is best established by serology and polymerase chain reaction (PCR; TABLE 3).

All pregnant women should be routinely screened for the hepatitis B surface antigen.5,6 If they are seropositive for the surface antigen alone and receive no immunoprophylaxis, they have a 20% to 30% risk of transmitting infection to their neonate. Subsequently, if they also test positive for the hepatitis Be antigen, the risk of perinatal transmission increases to approximately 90%. Fortunately, 2 forms of immunoprophylaxis are highly effective in preventing perinatal transmission. Infants delivered to seropositive mothers should receive hepatitis B immune globulin within 12 hours of birth. Prior to discharge, the infant also should receive the first dose of the hepatitis B vaccine. Subsequent doses should be administered at 1 and 6 months of age. Infants delivered to seronegative mothers require only the vaccine series.1

Although immunoprophylaxis is highly effective, some neonates still acquire infection perinatally. Pan and colleagues7 and Jourdain et al8 demonstrated that administration of tenofovir 200 mg orally each day from 32 weeks’ gestation until delivery provided further protection against perinatal transmission in patients with a high viral load (defined as >1 million copies/mL). In 2016, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine endorsed the use of tenofovir in women with a high viral load.6

Following delivery, women with chronic hepatitis B infection should be referred to a hepatology specialist for consideration of direct antiviral treatment. Multiple drugs are now available that are highly active against this micro-organism. These drugs include several forms of interferon, lamivudine, adefovir, entecavir, telbivudine, and tenofovir.1

Continue to: Hepatitis C...

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C is caused by an RNA virus that has 6 genotypes. The most common genotype is HCV1, which affects 79% of patients; approximately 13% of patients have HCV2, and 6% have HCV3.9 Of note, the 3 individuals who discovered this virus—Drs. Harvey Alter, Michael Houghton, and Charles Rice—received the 2020 Nobel Prize in Medicine.10

Hepatitis C is transmitted via sexual contact, parenterally, and perinatally. In many patient populations in the United States, hepatitis C is now more prevalent than hepatitis B. Only about half of all infected persons are aware of their infection. If patients go untreated, approximately 15% to 30% eventually develop cirrhosis. Of these individuals, 1% to 3% develop hepatocellular cancer. Chronic hepatitis C is now the most common indication for liver transplantation in the United States.1,9

In the initial stages of infection, hepatitis C usually is asymptomatic. The best screening test is detection of hepatitis C antibody. Because of the increasing prevalence of this disease, the seriousness of the infection, and the recent availability of remarkably effective treatment, routine screening, rather than screening on the basis of risk factors, for hepatitis C in pregnancy is now indicated.11,12

The best tests for confirmation of infection are detection of antibody by enzyme immunoassay and recombinant immuno-blot assay and detection of viral RNA in serum by PCR. Seroconversion may not occur for up to 16 weeks after infection. Therefore, in at-risk patients who initially test negative, retesting is advisable. Patients with positive test results should have tests to identify the specific genotype, determine the viral load, and assess liver function.1

In patients who have undetectable viral loads and who do not have coexisting HIV infection, the risk of perinatal transmission of hepatitis C is less than 5%. If HIV infection is present, the risk of perinatal transmission approaches 20%.1,13,14

If the patient is coinfected with HIV, a scheduled cesarean delivery should be performed at 38 weeks’ gestation.1 If the viral load is undetectable, vaginal delivery is appropriate. If the viral load is high, however (arbitrarily defined as >2.5 millioncopies/mL), the optimal method of delivery is controversial. Several small, nonrandomized noncontrolled cohort studies support elective cesarean delivery in such patients.14

There is no contraindication to breastfeeding in women with hepatitis C unless they are coinfected with HIV. In such a circumstance, formula feeding should be chosen. After delivery, patients with hepatitis C should be referred to a gastroenterology specialist to receive antiviral treatment. Multiple new single-agent and combination regimens have produced cures in more than 90% of patients. These regimens usually require 8 to 12 weeks of treatment, and they are very expensive. They have not been widely tested in pregnant women.1

Hepatitis D

Hepatitis D, or delta hepatitis, is caused by an RNA virus. This virus is unique because it is incapable of independent replication. It must be present in association with hepatitis B to replicate and cause clinical infection. Therefore, the epidemiology of hepatitis D closely mirrors that of hepatitis B.1,2

Patients with hepatitis D typically present in one of two ways. Some individuals are acutely infected with hepatitis D at the same time that they acquire hepatitis B (coinfection). The natural history of this infection usually is spontaneous resolution without sequelae. Other patients have chronic hepatitis D superimposed on chronic hepatitis B (superinfection). Unfortunately, patients with the latter condition are at a notably increased risk for developing severe persistent liver disease.1,2

The diagnosis of hepatitis D may be confirmed by identifying the delta antigen in serum or in liver tissue obtained by biopsy or by identifying IgM- and IgG-specific antibodies in serum. In conjunction with hepatitis B, the delta virus can cause a chronic carrier state. Perinatal transmission is possible but uncommon. Of greatest importance, the immunoprophylaxis described for hepatitis B is almost perfectly protective against perinatal transmission of hepatitis D.1,2

Continue to: Hepatitis E...

Hepatitis E

Hepatitis E is an RNA virus that has 1 serotype and 4 genotypes. Its epidemiology is similar to that of hepatitis A. It is the most common waterborne illness in the world. The incubation period varies from 21 to 56 days. This disease is quite rare in the United States but is endemic in developing nations. In those countries, maternal infection has an alarmingly high mortality rate (5%–25%). For example, in Bangladesh, hepatitis E is responsible for more than 1,000 deaths per year in pregnant women. When hepatitis E is identified in more affluent countries, the individual cases and small outbreaks usually are linked to consumption of undercooked pork or wild game.1,15-17

The clinical presentation of acute hepatitis E also is similar to that of hepatitis A. The usual manifestations are fever, malaise, anorexia, nausea, right upper quadrant pain and tenderness, jaundice, darkened urine, and clay-colored stools. The most useful diagnostic tests are serologic detection of viral-specific antibodies (positive IgM or a 4-fold increase in the prior IgG titer) and PCR-RNA.1,17

Hepatitis E usually does not cause a chronic carrier state, and perinatal transmission is rare. Fortunately, a highly effective vaccine was recently developed (Hecolin, Xiamen Innovax Biotech). This recombinant vaccine is specifically directed against the hepatitis E genotype 1. In the initial efficacy study, healthy adults aged 16 to 65 years were randomly assigned to receive either the hepatitis E vaccine or the hepatitis B vaccine. The vaccine was administered at time point 0, and 1 and 6 months later. Patients were followed for up to 4.5 years to assess efficacy, immunogenicity, and safety. During the study period, 7 cases of hepatitis E occurred in the vaccine group, compared with 53 in the control group. Approximately 56,000 patients were included in each group. The efficacy of the vaccine was 86.8% (P<.001).18

Hepatitis G

Hepatitis G is caused by 2 single-stranded RNA viruses that are virtually identical—hepatitis G virus and GB virus type C. The viruses share approximately 30% homology with hepatitis C virus. The organism is present throughout the world and infects approximately 1.5% to 2.0% of the population. The virus is transmitted by blood and sexual contact. It replicates preferentially in mononuclear cells and the bone marrow rather than in the liver.19-21

Hepatitis G is much less virulent than hepatitis C. Hepatitis G often coexists with hepatitis A, B, and C, as well as with HIV. Coinfection with hepatitis G does not adversely affect the clinical course of the other conditions.22,23

Most patients with hepatitis G are asymptomatic, and no treatment is indicated. The virus can cause a chronic carrier state. Perinatal transmission is distinctly uncommon. When it does occur, however, injury to mother, fetus, or neonate is unlikely.1,24

The diagnosis of hepatitis G can be established by detection of virus with PCR and by the identification of antibody by enzyme immunoassay. Routine screening for this infection in pregnancy is not indicated.1,2

Hepatitis B is highly contagious and can be transmitted from the patient to her sexual partner and neonate. Testing for hepatitis B surface antigen and antibody is indicated in her partner. If these tests are negative, the partner should immediately receive hepatitis B immune globulin and then be started on the 3-dose hepatitis B vaccination series. The patient’s newborn also should receive hepatitis B immune globulin within 12 hours of delivery and should receive the first dose of the hepatitis B vaccine prior to discharge from the hospital. The second and third doses should be administered 1 and 6 months after delivery.

The patient also should have the following tests:

• liver function tests

-serum transaminases

-direct and indirect bilirubin

-coagulation profile

• hepatitis D antigen

• hepatitis B genotype

• hepatitis B viral load

• HIV serology.

If the hepatitis B viral load exceeds 1 million copies/mL, the patient should be treated with tenofovir 200 mg daily from 28 weeks’ gestation until delivery. In addition, she should be referred to a liver disease specialist after delivery for consideration of treatment with directly-acting antiviral agents. ●

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TB, et al, eds. Creasy & Resnik’s MaternalFetal Medicine Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Duff P. Hepatitis in pregnancy. In: Queenan JR, Spong CY, Lockwood CJ, eds. Management of HighRisk Pregnancy. An EvidenceBased Approach. 5th ed. Blackwell; 2007:238-241.

- Duff B, Duff P. Hepatitis A vaccine: ready for prime time. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:468-471.

- Victor JC, Monto AS, Surdina TY, et al. Hepatitis A vaccine versus immune globulin for postexposure prophylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2007;367:1685-1694.

- Dienstag JL. Hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1486-1500.

- Society for MaternalFetal Medicine (SMFM); Dionne-Odom J, Tita ATN, Silverman NS. #38. Hepatitis B in pregnancy: screening, treatment, and prevention of vertical transmission. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214:6-14.

- Pan CQ, Duan Z, Dai E, et al. Tenofovir to prevent hepatitis B transmission in mothers with high viral load. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2324-2334.

- Jourdain G, Huong N, Harrison L, et al. Tenofovir versus placebo to prevent perinatal transmission of hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:911-923.

- Rosen HR. Chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2429-2438.

- Hoofnagle JH, Feinstore SM. The discovery of hepatitis C—the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. N Engl J Med. 2020;384:2297-2299.

- Hughes BL, Page CM, Juller JA. Hepatitis C in pregnancy: screening, treatment, and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:B2-B12.

- Saab S, Kullar R, Gounder P. The urgent need for hepatitis C screening in pregnant women: a call to action. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:773-777.

- Berkley EMF, Leslie KK, Arora S, et al. Chronic hepatitis C in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:304-310.

- Brazel M, Duff P. Considerations on the mode of delivery for pregnant women with hepatitis C infection [published online November 22, 2019]. OBG Manag. 2020;32:39-44.

- Emerson SU, Purcell RH. Hepatitis E virus. Rev Med Virol. 2003;13:145-154.

- Khuroo MS, Teli MR, Skidmore S, et al. Incidence and severity of viral hepatitis in pregnancy. Am J Med. 1981;70:252-255.

- Hoofnangle JH, Nelson KE, Purcell RH. Hepatitis E. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1237-1244.

- Zhang J, Zhang XF, Huang SJ, et al. Longterm efficacy of a hepatitis E vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:914-922.

- Pickering L, ed. Red Book 2000 Report of Committee on Infectious Diseases. 25th ed. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2000.

- Chopra S. GB virus C (hepatitis G) infection. UpToDate website. Updated January 16, 2020. Accessed June 3, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/gb-virus-c-hepatitis-g-infection.

- Reshetnyak VI, Karlovich TI, Ilchenko LU. Hepatitis G virus. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4725-4734.

- Kew MC, Kassianides C. HGV: hepatitis G virus or harmless G virus. Lancet. 1996;348(suppl II):10.

- Jarvis LM, Davidson F, Hanley JP, et al. Infection with hepatitis G virus among recipients of plasma products. Lancet. 1996;348;1352-1355.

- Feucht HH, Zollner B, Polywka S, et al. Vertical transmission of hepatitis G. Lancet. 1996;347;615-616.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TB, et al, eds. Creasy & Resnik’s MaternalFetal Medicine Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Duff P. Hepatitis in pregnancy. In: Queenan JR, Spong CY, Lockwood CJ, eds. Management of HighRisk Pregnancy. An EvidenceBased Approach. 5th ed. Blackwell; 2007:238-241.

- Duff B, Duff P. Hepatitis A vaccine: ready for prime time. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:468-471.

- Victor JC, Monto AS, Surdina TY, et al. Hepatitis A vaccine versus immune globulin for postexposure prophylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2007;367:1685-1694.

- Dienstag JL. Hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1486-1500.

- Society for MaternalFetal Medicine (SMFM); Dionne-Odom J, Tita ATN, Silverman NS. #38. Hepatitis B in pregnancy: screening, treatment, and prevention of vertical transmission. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214:6-14.

- Pan CQ, Duan Z, Dai E, et al. Tenofovir to prevent hepatitis B transmission in mothers with high viral load. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2324-2334.

- Jourdain G, Huong N, Harrison L, et al. Tenofovir versus placebo to prevent perinatal transmission of hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:911-923.

- Rosen HR. Chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2429-2438.

- Hoofnagle JH, Feinstore SM. The discovery of hepatitis C—the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. N Engl J Med. 2020;384:2297-2299.

- Hughes BL, Page CM, Juller JA. Hepatitis C in pregnancy: screening, treatment, and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:B2-B12.

- Saab S, Kullar R, Gounder P. The urgent need for hepatitis C screening in pregnant women: a call to action. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:773-777.

- Berkley EMF, Leslie KK, Arora S, et al. Chronic hepatitis C in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:304-310.

- Brazel M, Duff P. Considerations on the mode of delivery for pregnant women with hepatitis C infection [published online November 22, 2019]. OBG Manag. 2020;32:39-44.

- Emerson SU, Purcell RH. Hepatitis E virus. Rev Med Virol. 2003;13:145-154.

- Khuroo MS, Teli MR, Skidmore S, et al. Incidence and severity of viral hepatitis in pregnancy. Am J Med. 1981;70:252-255.

- Hoofnangle JH, Nelson KE, Purcell RH. Hepatitis E. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1237-1244.

- Zhang J, Zhang XF, Huang SJ, et al. Longterm efficacy of a hepatitis E vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:914-922.

- Pickering L, ed. Red Book 2000 Report of Committee on Infectious Diseases. 25th ed. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2000.

- Chopra S. GB virus C (hepatitis G) infection. UpToDate website. Updated January 16, 2020. Accessed June 3, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/gb-virus-c-hepatitis-g-infection.

- Reshetnyak VI, Karlovich TI, Ilchenko LU. Hepatitis G virus. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4725-4734.

- Kew MC, Kassianides C. HGV: hepatitis G virus or harmless G virus. Lancet. 1996;348(suppl II):10.

- Jarvis LM, Davidson F, Hanley JP, et al. Infection with hepatitis G virus among recipients of plasma products. Lancet. 1996;348;1352-1355.

- Feucht HH, Zollner B, Polywka S, et al. Vertical transmission of hepatitis G. Lancet. 1996;347;615-616.

Dynamic ultrasonography: An idea whose time has come

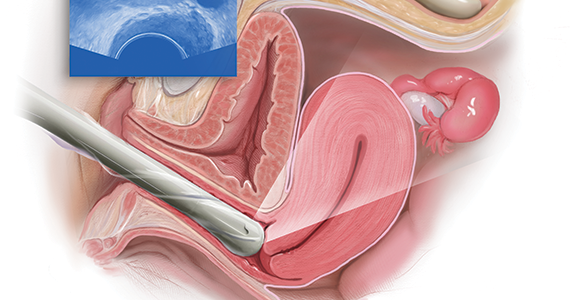

Ultrasonography truly has revolutionized the practice of obstetrics and gynecology. Initially, transabdominal ultrasonography was mainly a tool of the obstetrician. Early linear array, real-time equipment had barely enough resolution to perform very limited assessments, such as measure biparietal diameter and identify vertex versus breech presentation, and anterior versus posterior placenta location. The introduction of transvaginal probes, which employ higher frequency and provide closer proximity to structures, yielded a degree of image magnification that was dubbed sonomicroscopy.1 In other words, we are seeing things with our naked eye that we could not see if we could hold them in our hand at arm’s length and squint at them. An example of this is the cardiac activity clearly visible in a 3-mm embryo at 45 days from the last menstrual period. One would not appreciate this without the low power magnification of the vaginal probe.

The concept of dynamic imaging

As early as 1990, I realized that there is a difference between an ultrasound “examination” performed because of referral for imaging, which generated a report back to the referring health care provider, and “examining” one’s own patient with ultrasonography at the time of bimanual exam. I coined the phrase “the ultrasound-enhanced bimanual exam,” and I believed it should become a routine part of gynecologic care. I put forth this thesis in an article entitled, “Incorporating endovaginal ultrasonography into the overall gynecologic examination.”2 The idea is based on thinking: What exactly are we are trying to discern from a bimanual exam?

Clinicians perform the bimanual exam thousands of times. The bimanual examination consists of 2 components, an objective portion and a subjective portion. The objective component attempts to discern information that is totally objective, such as, Is the ovary enlarged? If so, is it cystic or solid? Is this uterus normal in shape and contour? If so, does it feel like leiomyomas or is it globularly enlarged as with adenomyosis? The subjective component of the bimanual examination attempts to determine whether or not tenderness is present or if there is normal mobility of the pelvic organs.

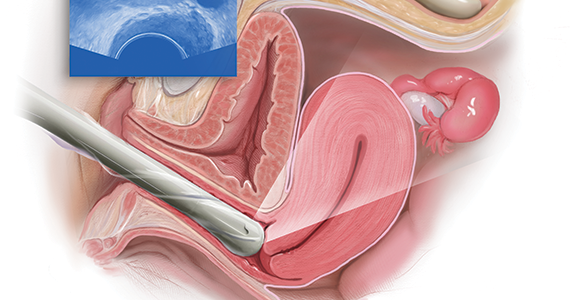

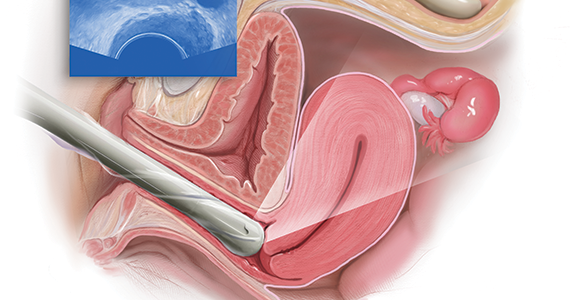

The objective component can be replaced by an image in very little time if the examiner has the equipment and the knowledge and skill. The subjective component, however, depends on the experience and often the nuance of the examiner. That was my original thought process. I wanted, and still want, the examining clinician to use imaging as part of the overall exam. But now, I want the imager to use examination as part of the overall imaging. (VIDEOS 1A and 1B.) This is the concept of dynamic imaging. It involves the liberal use of the abdominal hand as well as an in-and-out motion of the vaginal probe to ascertain aspects of the examination that in the past I deemed “subjective.” Mainly, this involves the aspects of mobility and/or tenderness.

Continue to: Guidelines concerning pelvic ultrasound do not consider dynamic imaging...

Guidelines concerning pelvic ultrasound do not consider dynamic imaging

Until now, most imagers take a myriad of pictures, mostly still snapshots, to illustrate anatomy. Most imaging physicians then look at a series of such pictures and may never even hold the transducer. This is increasingly true in instances of remote teleradiology. Even for the minority of imagers who utilize video clips (VIDEOS 2A–2C), these are still representations of anatomy .

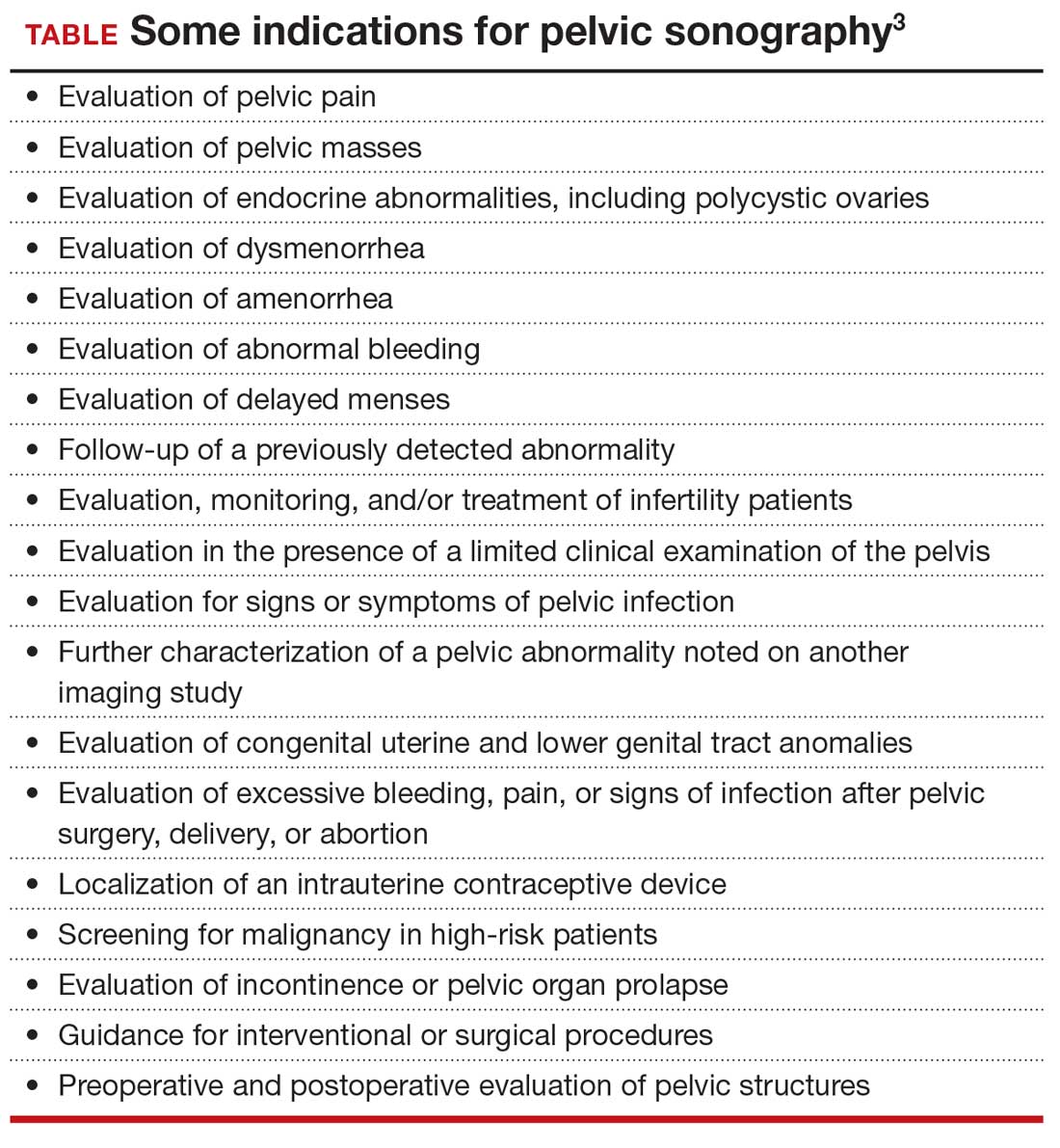

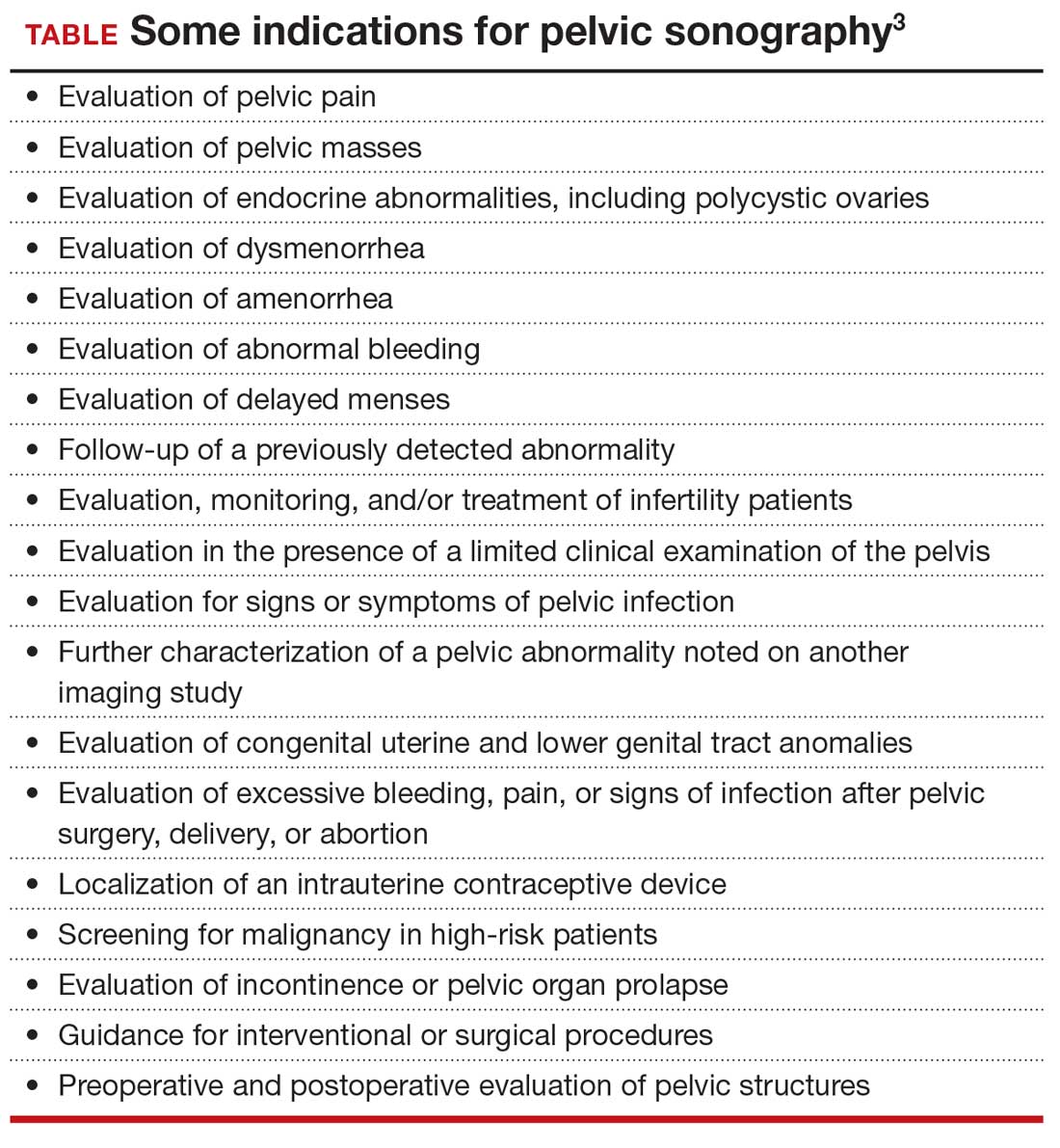

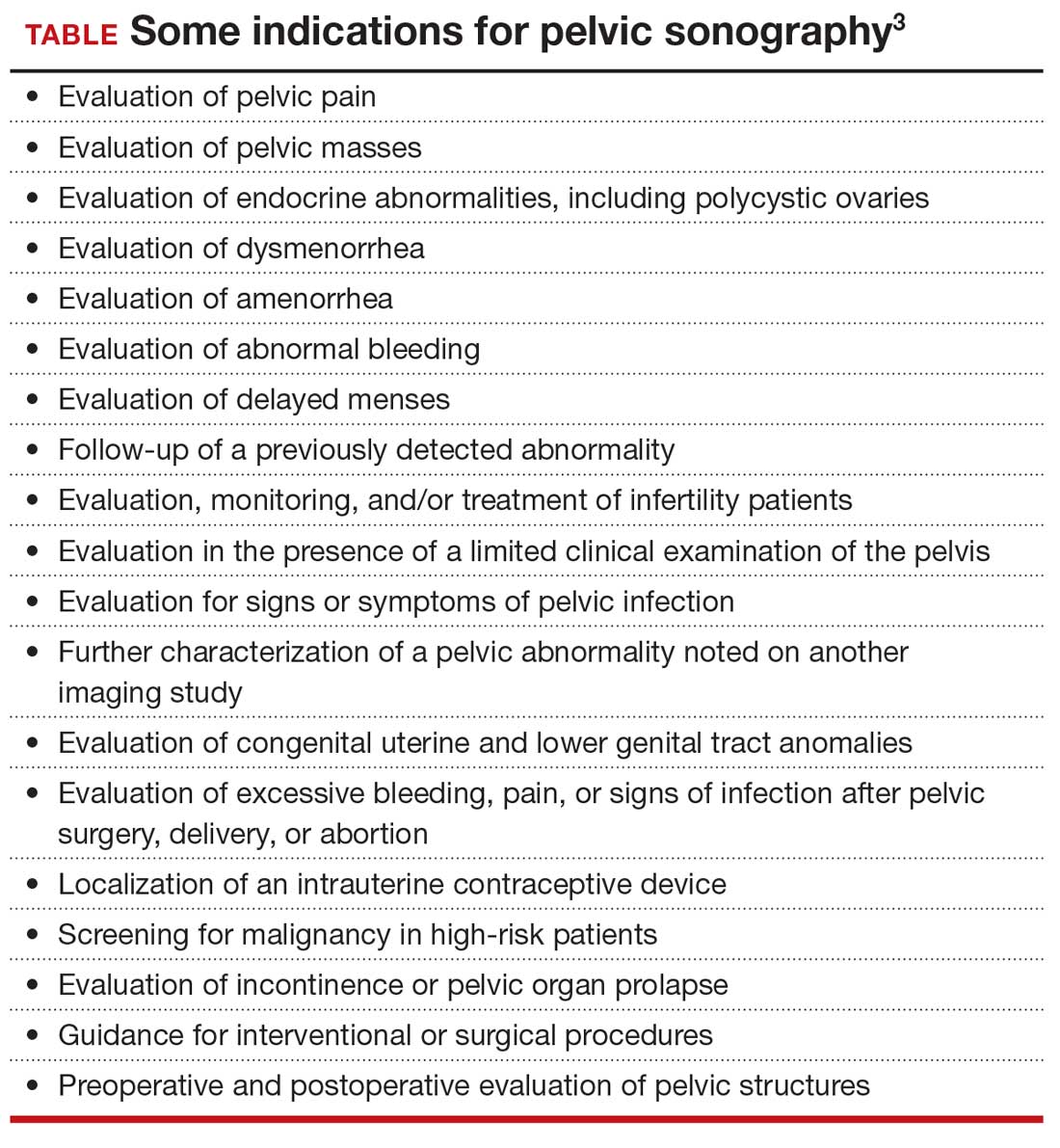

One need look no further than the guidelines that underpin the expectation of those who scan the female pelvis. The American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM) published a practice parameter for the performance of ultrasonography of the female pelvis, developed in collaboration with the American College of Radiology, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Society for Pediatric Radiology, and Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound. 3 Nowhere does this document mention anything other than what images to obtain, where to look, and how to measure. Nowhere is there any mention of dynamic imaging—the concept of using one’s other hand on the abdomen, eliciting pain with the vaginal probe, checking for mobility, asking the patient to bear down. The document lists indications for pelvic sonography that include but are not limited to 19 different indications, such as pelvic pain, evaluation of dysmenorrhea, evaluation for signs or symptoms of pelvic infection, and evaluation of incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse (TABLE). 3

Dynamic ultrasonography can aid in the diagnosis of certain conditions

Specifically, what can dynamic ultrasonography add to anatomic imaging? The main considerations are pain, adhesions, endometriosis, and pelvic organ prolapse.

Pelvic pain or tenderness

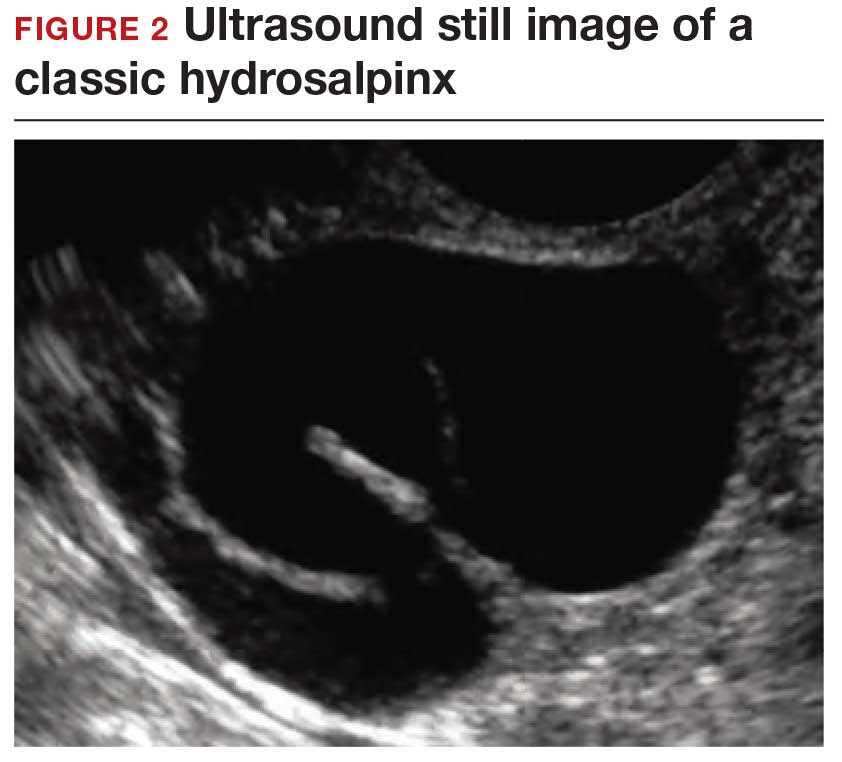

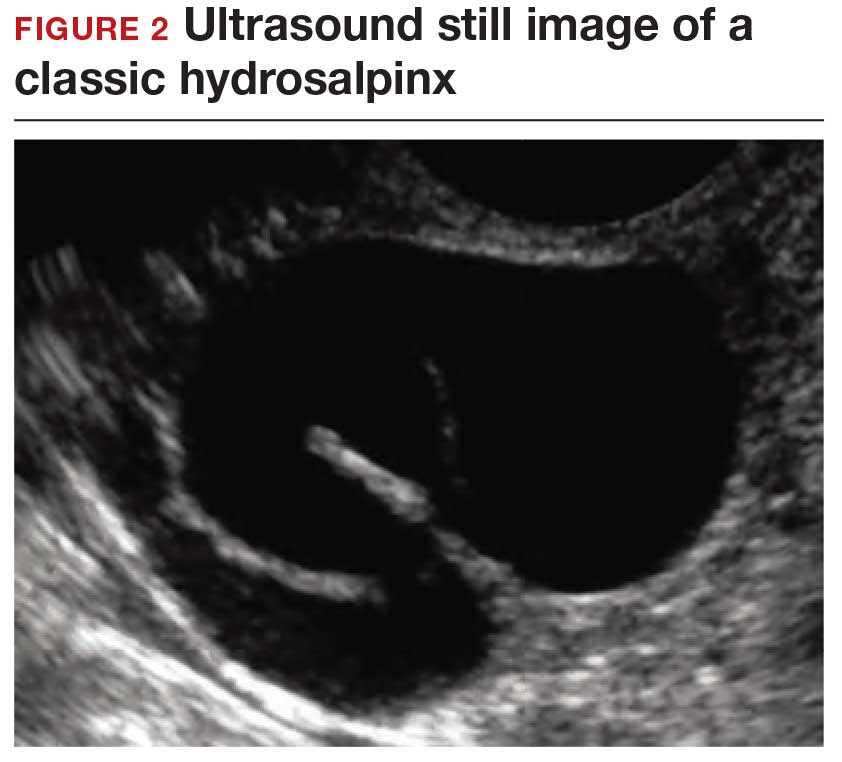

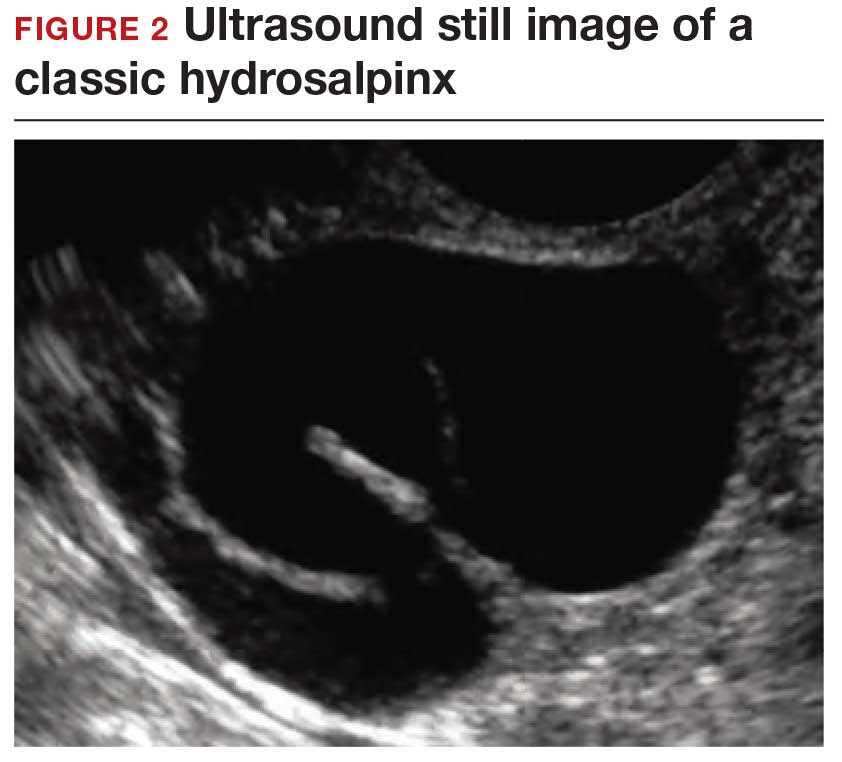

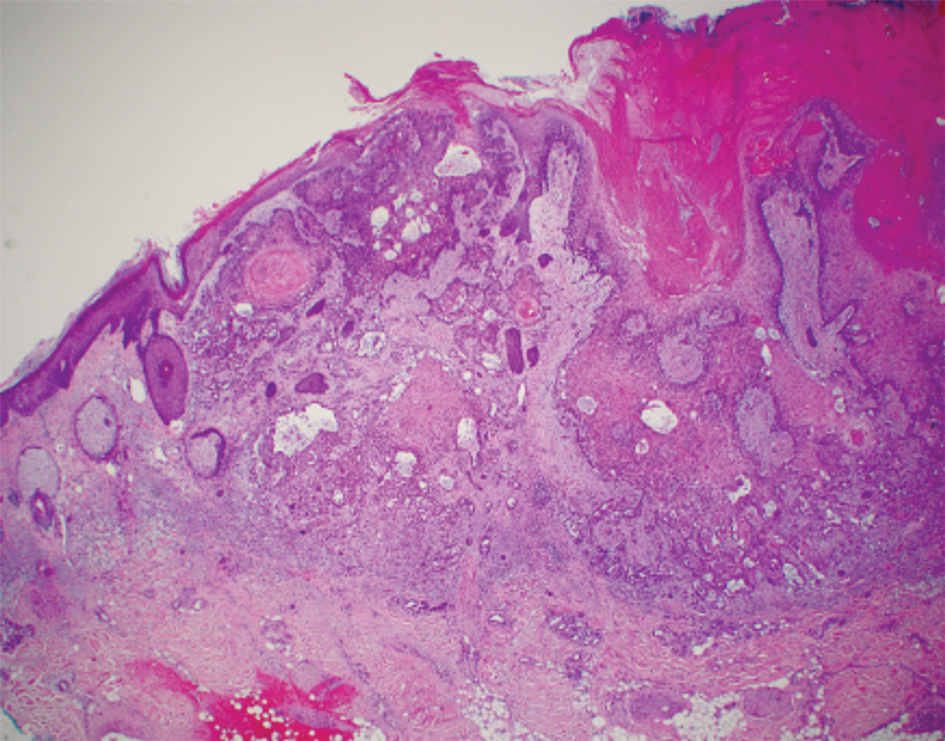

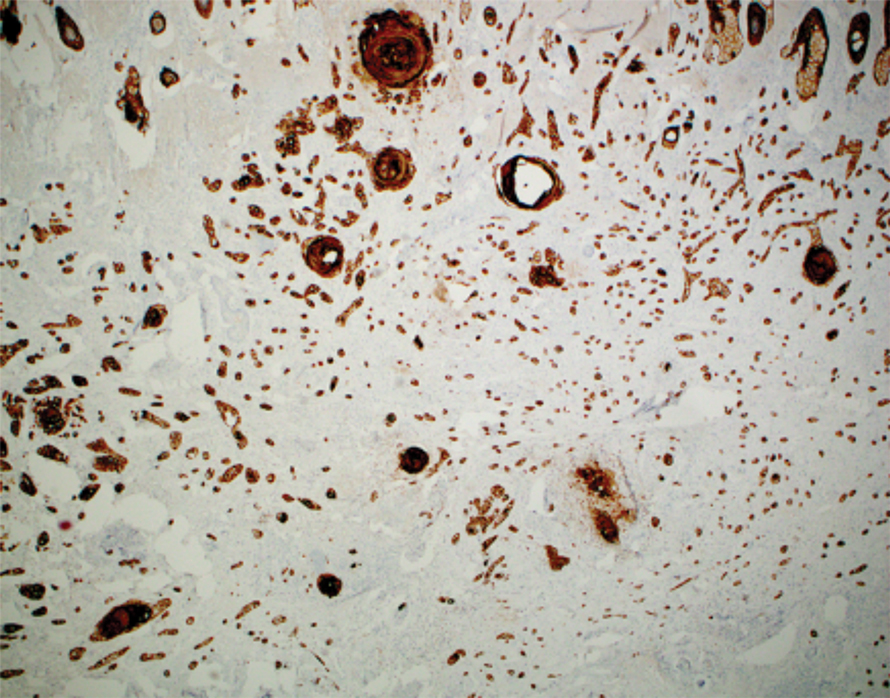

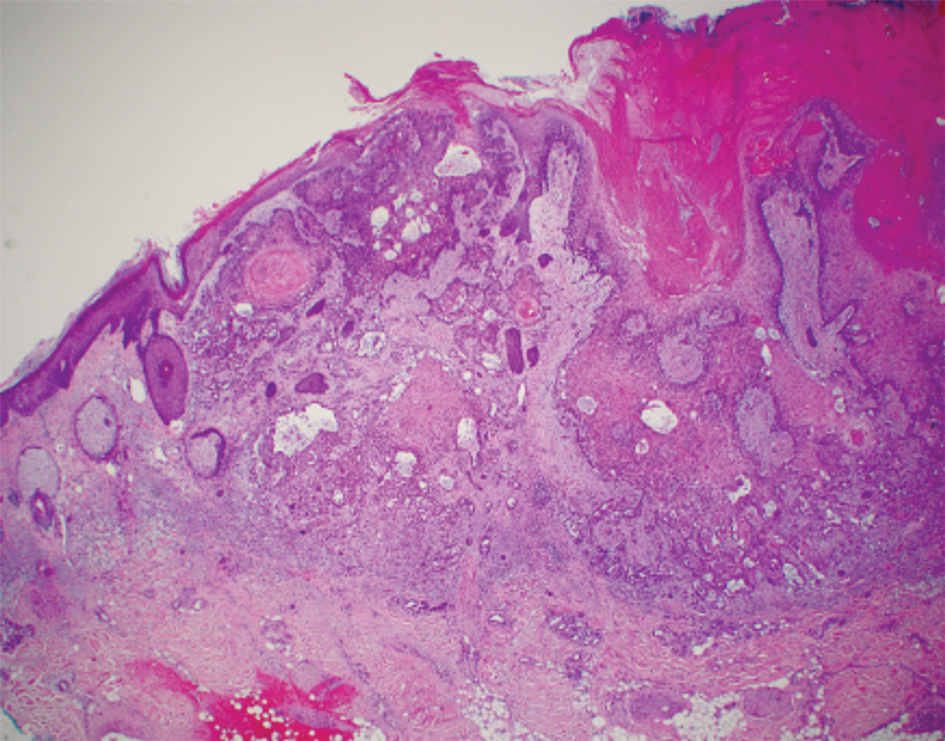

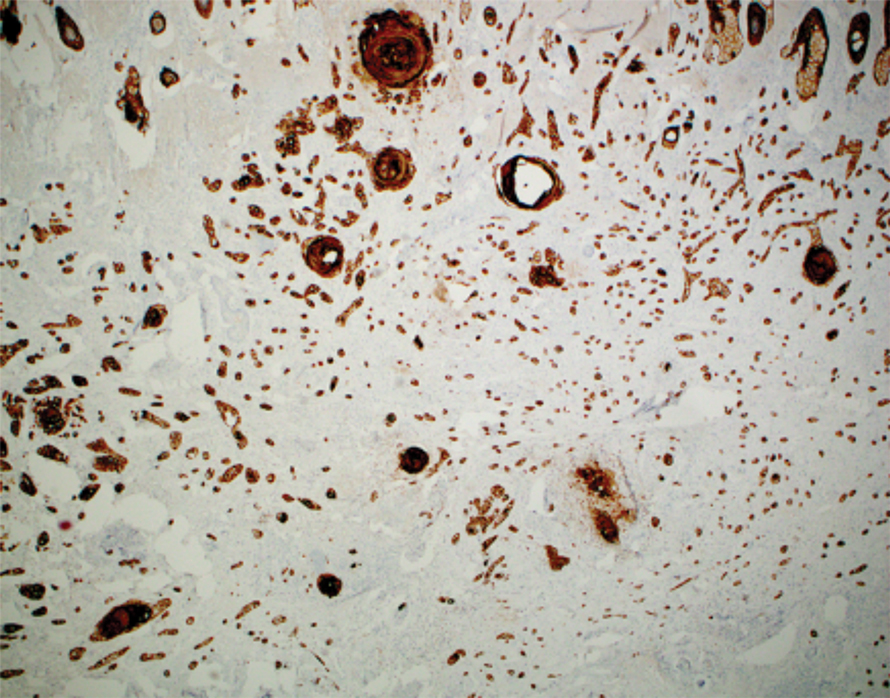

How can you evaluate a patient’s pelvic pain with an anatomic image? Perhaps pain can be corroborated if there is a classic ovarian endometrioma (FIGURE 1) (VIDEOS 3A, 3B) or classic hydrosalpinx (FIGURE 2) (VIDEOS 4A–4C). But can we evaluate pelvic pain with only an anatomic image? No, absolutely not. Evaluating pain requires dynamic assessment. As described above, in a dynamic ultrasound assessment, liberal use of the abdominal hand and the tip of the vaginal probe can elicit where the patient’s pain exists and whether the pain can be recreated.

Adhesions

Pelvic adhesions can be a significant source of pelvic pain and, also, sometimes infertility. The adhesions themselves may not be visible on anatomic imaging. This is where the concept of the sliding organ sign is paramount, a concept first described by Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch in his book Transvaginal Sonography . 4 He stated, “Diagnosis of pelvic adhesions becomes possible by the ‘sliding organ sign.’ The transducer tip is pointed at the uterus, ovaries or any pelvic finding, and a gentle push-pull movement of several centimeters is started. If no adhesions are present, the organs will move freely in the pelvis. This displacement of organs is perceived on the screen as a sliding movement.” 4 Thus, if structures are in fact adherent, they will move in tandem with each other as evidenced by this dynamic assessment. If they are not adherent, they will move slightly but independently of each other ( VIDEOS 5A–5G ).

Continue to: Endometriosis...

Endometriosis

Dynamic ultrasonography can be a significant part of a nonlaparoscopic, presumptive diagnosis of endometriosis when there is no obvious ovarian endometrioma.5 The evidence for this comes from a classic paper by Okaro and colleagues, “The use of ultrasound‐based ‘soft markers’ for the prediction of pelvic pathology in women with chronic pelvic pain–can we reduce the need for laparoscopy?”6 In that study, 120 consecutive women with chronic pelvic pain scheduled for laparoscopy underwent vaginal ultrasonography. Hard markers were defined as structural abnormalities, such as classic endometriomas or hydrosalpinges.

These markers demonstrated a 100% correlation (24 of 24 women) with laparoscopic findings, as one might have suspected. In addition, soft markers (VIDEOS 6A–6C) were defined as reduced ovarian mobility, site-specific pelvic tenderness, and the presence of loculated peritoneal fluid in the pelvis. These were predictive of pelvic pathology in 73% of these women (37 of 51).6

Thus, women who have soft markers on dynamic scanning but no obvious anatomic abnormalities can be treated with a high degree of sensitivity without the need for laparoscopic intervention.

Pelvic organ prolapse and incontinence

With the vaginal probe in place, and even a small amount of urine in the bladder, the patient can be asked to bear down (Valsalva maneuver), and cystocele (VIDEO 7) and/or hypermobility of the urethra (VIDEO 8) is easily discerned with dynamic ultrasonography. This information is not available on static anatomic imaging.

A tool that enhances patient care

Dynamic ultrasonography is an important and emerging topic in gynecologic imaging. Static images and even cine clips will yield only anatomic information. Increasingly, whoever holds the transducer—whether it be the gynecologist, radiologist, or sonographer—needs to examine the patient with the probe and include liberal use of the abdominal hand as well. Incorporating this concept will enhance the overall diagnostic input of ultrasound scanning, not just imaging, into better and more accurate patient care. ●

VIDEO 1A Liberal use of your nonscanning hand on dynamic scanning shows “wiggling” of debris classic of a hemorrhagic corpus luteum

VIDEO 1B Liberal use of your nonscanning hand helps identify a small postmenopausal ovary

VIDEO 2A Dynamic scanning can give the correct diagnosis even though clips were used! This clip appears to show a relatively normal uterus

VIDEO 2B Dynamic scanning can give the correct diagnosis even though clips were used! Same patient as in VIDEO 2A showing what appears to be a solid adnexal mass

VIDEO 2C Dynamic scan clearly shows the “mass” to be a pedunculated fibroid

VIDEO 3A Video clip of a classic endometrioma

VIDEO 3B Classic endometrioma showing no Doppler flow internally

VIDEO 4A Video of dynamic assessment in a patient with pain symptoms with a hydrosalpinx

VIDEO 4B Another example of video of dynamic assessment in a patient with pain symptoms with a hydrosalpinx

VIDEO 4C Another example of video of dynamic assessment in a patient with pain symptoms with a hydrosalpinx

VIDEO 5A Sliding organ sign with normal mobility (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

VIDEO 5B Sliding sign showing adherent ovary (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

VIDEO 5C Normal mobility (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

VIDEO 5D Left ovary: Normal mobility (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

VIDEO 5E Right ovary: Normal mobility (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

VIDEO 5F Normal mobility even with a classic endometrioma (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

VIDEO 5G Adherent ovary (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

VIDEO 6A Dynamic scanning shows the ovary to be “stuck” in the cul-de-sac in a patient with endometriosis

VIDEO 6B Dynamic scanning in another patient with endometriosis showing markedly retroverted uterus with adherent bowel posteriorly

VIDEO 6C Dynamic scanning in another patient with endometriosis showing markedly retroverted uterus with adherent bowel posteriorly

VIDEO 7 Cystocele or urethral lengthening are key elements for the diagnosis of incontinence with or without pelvic relaxation

VIDEO 8 Urethral lengthening is a key element for the diagnosis of incontinence with or without pelvic relaxation

- Goldstein SR. Pregnancy I: Embryo. In: Endovaginal Ultrasound. 2nd ed. Wiley-Liss; 1991:58.

- Goldstein SR. Incorporating endovaginal ultrasonography into the overall gynecologic examination. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162:625-632.

- AIUM practice parameter for the performance of an ultrasound examination of the female pelvis. J Ultrasound Med. 2020;39:E17-E23.

- Timor-Tritsch IE, Rottem S, Elgali S. How transvaginal sonography is done. In: Timor-Tritsch IE, Rottem S, eds. Transvaginal Sonography. Elsevier Science Publishing Company, Inc; 1988:24.

- Taylor HS, Adamson GD, Diamond MP, et al. An evidence-based approach to assessing surgical versus clinical diagnosis of symptomatic endometriosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;142:131-142.

- Okaro E, Condous G, Khalid A, et al. The use of ultrasound‐ based ‘soft markers’ for the prediction of pelvic pathology in women with chronic pelvic pain–can we reduce the need for laparoscopy? BJOG. 2006;113:251-256.

Ultrasonography truly has revolutionized the practice of obstetrics and gynecology. Initially, transabdominal ultrasonography was mainly a tool of the obstetrician. Early linear array, real-time equipment had barely enough resolution to perform very limited assessments, such as measure biparietal diameter and identify vertex versus breech presentation, and anterior versus posterior placenta location. The introduction of transvaginal probes, which employ higher frequency and provide closer proximity to structures, yielded a degree of image magnification that was dubbed sonomicroscopy.1 In other words, we are seeing things with our naked eye that we could not see if we could hold them in our hand at arm’s length and squint at them. An example of this is the cardiac activity clearly visible in a 3-mm embryo at 45 days from the last menstrual period. One would not appreciate this without the low power magnification of the vaginal probe.

The concept of dynamic imaging

As early as 1990, I realized that there is a difference between an ultrasound “examination” performed because of referral for imaging, which generated a report back to the referring health care provider, and “examining” one’s own patient with ultrasonography at the time of bimanual exam. I coined the phrase “the ultrasound-enhanced bimanual exam,” and I believed it should become a routine part of gynecologic care. I put forth this thesis in an article entitled, “Incorporating endovaginal ultrasonography into the overall gynecologic examination.”2 The idea is based on thinking: What exactly are we are trying to discern from a bimanual exam?

Clinicians perform the bimanual exam thousands of times. The bimanual examination consists of 2 components, an objective portion and a subjective portion. The objective component attempts to discern information that is totally objective, such as, Is the ovary enlarged? If so, is it cystic or solid? Is this uterus normal in shape and contour? If so, does it feel like leiomyomas or is it globularly enlarged as with adenomyosis? The subjective component of the bimanual examination attempts to determine whether or not tenderness is present or if there is normal mobility of the pelvic organs.

The objective component can be replaced by an image in very little time if the examiner has the equipment and the knowledge and skill. The subjective component, however, depends on the experience and often the nuance of the examiner. That was my original thought process. I wanted, and still want, the examining clinician to use imaging as part of the overall exam. But now, I want the imager to use examination as part of the overall imaging. (VIDEOS 1A and 1B.) This is the concept of dynamic imaging. It involves the liberal use of the abdominal hand as well as an in-and-out motion of the vaginal probe to ascertain aspects of the examination that in the past I deemed “subjective.” Mainly, this involves the aspects of mobility and/or tenderness.

Continue to: Guidelines concerning pelvic ultrasound do not consider dynamic imaging...

Guidelines concerning pelvic ultrasound do not consider dynamic imaging

Until now, most imagers take a myriad of pictures, mostly still snapshots, to illustrate anatomy. Most imaging physicians then look at a series of such pictures and may never even hold the transducer. This is increasingly true in instances of remote teleradiology. Even for the minority of imagers who utilize video clips (VIDEOS 2A–2C), these are still representations of anatomy .

One need look no further than the guidelines that underpin the expectation of those who scan the female pelvis. The American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM) published a practice parameter for the performance of ultrasonography of the female pelvis, developed in collaboration with the American College of Radiology, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Society for Pediatric Radiology, and Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound. 3 Nowhere does this document mention anything other than what images to obtain, where to look, and how to measure. Nowhere is there any mention of dynamic imaging—the concept of using one’s other hand on the abdomen, eliciting pain with the vaginal probe, checking for mobility, asking the patient to bear down. The document lists indications for pelvic sonography that include but are not limited to 19 different indications, such as pelvic pain, evaluation of dysmenorrhea, evaluation for signs or symptoms of pelvic infection, and evaluation of incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse (TABLE). 3

Dynamic ultrasonography can aid in the diagnosis of certain conditions

Specifically, what can dynamic ultrasonography add to anatomic imaging? The main considerations are pain, adhesions, endometriosis, and pelvic organ prolapse.

Pelvic pain or tenderness

How can you evaluate a patient’s pelvic pain with an anatomic image? Perhaps pain can be corroborated if there is a classic ovarian endometrioma (FIGURE 1) (VIDEOS 3A, 3B) or classic hydrosalpinx (FIGURE 2) (VIDEOS 4A–4C). But can we evaluate pelvic pain with only an anatomic image? No, absolutely not. Evaluating pain requires dynamic assessment. As described above, in a dynamic ultrasound assessment, liberal use of the abdominal hand and the tip of the vaginal probe can elicit where the patient’s pain exists and whether the pain can be recreated.

Adhesions

Pelvic adhesions can be a significant source of pelvic pain and, also, sometimes infertility. The adhesions themselves may not be visible on anatomic imaging. This is where the concept of the sliding organ sign is paramount, a concept first described by Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch in his book Transvaginal Sonography . 4 He stated, “Diagnosis of pelvic adhesions becomes possible by the ‘sliding organ sign.’ The transducer tip is pointed at the uterus, ovaries or any pelvic finding, and a gentle push-pull movement of several centimeters is started. If no adhesions are present, the organs will move freely in the pelvis. This displacement of organs is perceived on the screen as a sliding movement.” 4 Thus, if structures are in fact adherent, they will move in tandem with each other as evidenced by this dynamic assessment. If they are not adherent, they will move slightly but independently of each other ( VIDEOS 5A–5G ).

Continue to: Endometriosis...

Endometriosis

Dynamic ultrasonography can be a significant part of a nonlaparoscopic, presumptive diagnosis of endometriosis when there is no obvious ovarian endometrioma.5 The evidence for this comes from a classic paper by Okaro and colleagues, “The use of ultrasound‐based ‘soft markers’ for the prediction of pelvic pathology in women with chronic pelvic pain–can we reduce the need for laparoscopy?”6 In that study, 120 consecutive women with chronic pelvic pain scheduled for laparoscopy underwent vaginal ultrasonography. Hard markers were defined as structural abnormalities, such as classic endometriomas or hydrosalpinges.

These markers demonstrated a 100% correlation (24 of 24 women) with laparoscopic findings, as one might have suspected. In addition, soft markers (VIDEOS 6A–6C) were defined as reduced ovarian mobility, site-specific pelvic tenderness, and the presence of loculated peritoneal fluid in the pelvis. These were predictive of pelvic pathology in 73% of these women (37 of 51).6

Thus, women who have soft markers on dynamic scanning but no obvious anatomic abnormalities can be treated with a high degree of sensitivity without the need for laparoscopic intervention.

Pelvic organ prolapse and incontinence

With the vaginal probe in place, and even a small amount of urine in the bladder, the patient can be asked to bear down (Valsalva maneuver), and cystocele (VIDEO 7) and/or hypermobility of the urethra (VIDEO 8) is easily discerned with dynamic ultrasonography. This information is not available on static anatomic imaging.

A tool that enhances patient care

Dynamic ultrasonography is an important and emerging topic in gynecologic imaging. Static images and even cine clips will yield only anatomic information. Increasingly, whoever holds the transducer—whether it be the gynecologist, radiologist, or sonographer—needs to examine the patient with the probe and include liberal use of the abdominal hand as well. Incorporating this concept will enhance the overall diagnostic input of ultrasound scanning, not just imaging, into better and more accurate patient care. ●

VIDEO 1A Liberal use of your nonscanning hand on dynamic scanning shows “wiggling” of debris classic of a hemorrhagic corpus luteum

VIDEO 1B Liberal use of your nonscanning hand helps identify a small postmenopausal ovary

VIDEO 2A Dynamic scanning can give the correct diagnosis even though clips were used! This clip appears to show a relatively normal uterus

VIDEO 2B Dynamic scanning can give the correct diagnosis even though clips were used! Same patient as in VIDEO 2A showing what appears to be a solid adnexal mass

VIDEO 2C Dynamic scan clearly shows the “mass” to be a pedunculated fibroid

VIDEO 3A Video clip of a classic endometrioma

VIDEO 3B Classic endometrioma showing no Doppler flow internally

VIDEO 4A Video of dynamic assessment in a patient with pain symptoms with a hydrosalpinx

VIDEO 4B Another example of video of dynamic assessment in a patient with pain symptoms with a hydrosalpinx

VIDEO 4C Another example of video of dynamic assessment in a patient with pain symptoms with a hydrosalpinx

VIDEO 5A Sliding organ sign with normal mobility (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

VIDEO 5B Sliding sign showing adherent ovary (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

VIDEO 5C Normal mobility (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

VIDEO 5D Left ovary: Normal mobility (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

VIDEO 5E Right ovary: Normal mobility (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

VIDEO 5F Normal mobility even with a classic endometrioma (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

VIDEO 5G Adherent ovary (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

VIDEO 6A Dynamic scanning shows the ovary to be “stuck” in the cul-de-sac in a patient with endometriosis

VIDEO 6B Dynamic scanning in another patient with endometriosis showing markedly retroverted uterus with adherent bowel posteriorly

VIDEO 6C Dynamic scanning in another patient with endometriosis showing markedly retroverted uterus with adherent bowel posteriorly

VIDEO 7 Cystocele or urethral lengthening are key elements for the diagnosis of incontinence with or without pelvic relaxation

VIDEO 8 Urethral lengthening is a key element for the diagnosis of incontinence with or without pelvic relaxation

Ultrasonography truly has revolutionized the practice of obstetrics and gynecology. Initially, transabdominal ultrasonography was mainly a tool of the obstetrician. Early linear array, real-time equipment had barely enough resolution to perform very limited assessments, such as measure biparietal diameter and identify vertex versus breech presentation, and anterior versus posterior placenta location. The introduction of transvaginal probes, which employ higher frequency and provide closer proximity to structures, yielded a degree of image magnification that was dubbed sonomicroscopy.1 In other words, we are seeing things with our naked eye that we could not see if we could hold them in our hand at arm’s length and squint at them. An example of this is the cardiac activity clearly visible in a 3-mm embryo at 45 days from the last menstrual period. One would not appreciate this without the low power magnification of the vaginal probe.

The concept of dynamic imaging

As early as 1990, I realized that there is a difference between an ultrasound “examination” performed because of referral for imaging, which generated a report back to the referring health care provider, and “examining” one’s own patient with ultrasonography at the time of bimanual exam. I coined the phrase “the ultrasound-enhanced bimanual exam,” and I believed it should become a routine part of gynecologic care. I put forth this thesis in an article entitled, “Incorporating endovaginal ultrasonography into the overall gynecologic examination.”2 The idea is based on thinking: What exactly are we are trying to discern from a bimanual exam?

Clinicians perform the bimanual exam thousands of times. The bimanual examination consists of 2 components, an objective portion and a subjective portion. The objective component attempts to discern information that is totally objective, such as, Is the ovary enlarged? If so, is it cystic or solid? Is this uterus normal in shape and contour? If so, does it feel like leiomyomas or is it globularly enlarged as with adenomyosis? The subjective component of the bimanual examination attempts to determine whether or not tenderness is present or if there is normal mobility of the pelvic organs.

The objective component can be replaced by an image in very little time if the examiner has the equipment and the knowledge and skill. The subjective component, however, depends on the experience and often the nuance of the examiner. That was my original thought process. I wanted, and still want, the examining clinician to use imaging as part of the overall exam. But now, I want the imager to use examination as part of the overall imaging. (VIDEOS 1A and 1B.) This is the concept of dynamic imaging. It involves the liberal use of the abdominal hand as well as an in-and-out motion of the vaginal probe to ascertain aspects of the examination that in the past I deemed “subjective.” Mainly, this involves the aspects of mobility and/or tenderness.

Continue to: Guidelines concerning pelvic ultrasound do not consider dynamic imaging...

Guidelines concerning pelvic ultrasound do not consider dynamic imaging

Until now, most imagers take a myriad of pictures, mostly still snapshots, to illustrate anatomy. Most imaging physicians then look at a series of such pictures and may never even hold the transducer. This is increasingly true in instances of remote teleradiology. Even for the minority of imagers who utilize video clips (VIDEOS 2A–2C), these are still representations of anatomy .

One need look no further than the guidelines that underpin the expectation of those who scan the female pelvis. The American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM) published a practice parameter for the performance of ultrasonography of the female pelvis, developed in collaboration with the American College of Radiology, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Society for Pediatric Radiology, and Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound. 3 Nowhere does this document mention anything other than what images to obtain, where to look, and how to measure. Nowhere is there any mention of dynamic imaging—the concept of using one’s other hand on the abdomen, eliciting pain with the vaginal probe, checking for mobility, asking the patient to bear down. The document lists indications for pelvic sonography that include but are not limited to 19 different indications, such as pelvic pain, evaluation of dysmenorrhea, evaluation for signs or symptoms of pelvic infection, and evaluation of incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse (TABLE). 3

Dynamic ultrasonography can aid in the diagnosis of certain conditions

Specifically, what can dynamic ultrasonography add to anatomic imaging? The main considerations are pain, adhesions, endometriosis, and pelvic organ prolapse.

Pelvic pain or tenderness

How can you evaluate a patient’s pelvic pain with an anatomic image? Perhaps pain can be corroborated if there is a classic ovarian endometrioma (FIGURE 1) (VIDEOS 3A, 3B) or classic hydrosalpinx (FIGURE 2) (VIDEOS 4A–4C). But can we evaluate pelvic pain with only an anatomic image? No, absolutely not. Evaluating pain requires dynamic assessment. As described above, in a dynamic ultrasound assessment, liberal use of the abdominal hand and the tip of the vaginal probe can elicit where the patient’s pain exists and whether the pain can be recreated.

Adhesions