User login

New guidelines say pediatricians should screen for anxiety: Now what?

Recently the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force issued a formal recommendation that adolescents and children as young as 8 should be screened for anxiety.1 The advice was based on a review of the research that concluded that anxiety disorders were common in youth (prevalence around 8%), screening was not overly burdensome or dangerous, and treatments were available and effective.

While pediatricians fully appreciate how common clinically significant anxiety is and its impact on the lives of youth, the reception for the recommendations have been mixed. Some are concerned that it could lead to the overprescribing of medications. Arguably, the biggest pushback, however, relates to the question of what to do when a child screens positive in a time when finding an available child and adolescent psychiatrist or other type of pediatric mental health professional can feel next to impossible. The hope of this article is to fill in some of those gaps.

Screening for anxiety disorders

The recommendations suggest using a rating scale as part of the screen but doesn’t dictate which one. A common instrument that has been employed is the Screen for Child Anxiety and Related Disorders, which is a freely available 41-item instrument that has versions for youth self-report and parent-report. A shorter 7-item rating scale, the General Anxiety Disorder–7, and the even shorter GAD-2 (the first two questions of the GAD-7), are also popular but focus, as the name applies, on general anxiety disorder and not related conditions such as social or separation anxiety that can have some different symptoms. These instruments can be given to patients and families in the waiting room or administered with the help of a nurse, physician, or embedded mental health professional. The recommendations do not include specific guidance on how often the screening should be done but repeated screenings are likely important at some interval.

Confirming the diagnosis

Of course, a screening isn’t a formal diagnosis. The American Academy of Pediatrics has expressed the view that the initial diagnosis and treatment for anxiety disorders is well within a pediatrician’s scope of practice, which means further steps are likely required beyond a referral. Fortunately, going from a positive screen to an initial diagnosis does not have to overly laborious and can focus on reviewing the DSM-5 criteria for key anxiety disorders while also ensuring that there isn’t a nonpsychiatric cause driving the symptoms, such as the often cited but rarely seen pheochromocytoma. More common rule-outs include medication-induced anxiety or substance use, excessive caffeine intake, and cardiac arrhythmias. Assessing for current and past trauma or specific causes of the anxiety such as bullying are also important.

It is important to note that it is the rule rather than the exception that youth with clinical levels of anxiety will frequently endorse a number of criteria that span multiple diagnoses including generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and separation anxiety disorder.2 Spending a lot of effort to narrow things down to a single anxiety diagnosis often is unnecessary, as both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments don’t change all that much between individual diagnoses.

Explaining the diagnosis

In general, I’m a strong proponent of trying to explain any behavioral diagnoses that you make to kids in a way that is accurate but nonstigmatizing. When it comes to anxiety, one parallel I often draw is to our immune system, which most youth understand at least in basic terms. Both our immune system and our anxiety networks are natural and important; as a species, we wouldn’t have lasted long without them. Both are built to assess and respond to threats. Problems can arise, however, if the response is too strong relative to the threat or the response is activated when it doesn’t need to be. Treatment is directed not at ridding ourselves of anxiety but at helping regulate it so it works for us and not against us. Spending a few minutes going through a discussion like this can be very helpful, and perhaps more so than some dry summary of DSM-5 criteria.

Starting treatment

It is important to note that best practice recommendations when it comes to the treatment of anxiety disorder in youth do not suggest medications as the only type of treatment and often urge clinicians to try nonpharmacological interventions first.3 A specific type of psychotherapy called cognitive-behavioral therapy has the strongest scientific support as an effective treatment for anxiety but other modalities, including parenting guidance, can be helpful as well. Consequently, a referral to a good psychotherapist is paramount. For many kids, the key to overcoming anxiety is exposure: which means confronting anxiety slowly, with support, and with specific skills.

If there is a traumatic source of the anxiety, addressing that as much as possible is obviously critical and could involve working with the family or school. For some kids, this may involve frightening things they are seeing online or through other media. Finally, some health promotion activities such as exercise or mindfulness can also be quite useful.

Despite the fact that SSRIs are referred to as antidepressants, there is increasing appreciation that these medications are useful for anxiety, perhaps even more so than for mood. While only one medication, duloxetine, has Food and Drug Administration approval to treat anxiety in children as young as 7, there is good evidence to support the use of many of the most common SSRIs in treating clinical anxiety. Buspirone, beta-blockers, and antihistamine medications like hydroxyzine also can have their place in treatment, while benzodiazepines and antipsychotic medications are generally best avoided for anxious youth, especially in the primary care setting. A short but helpful medication guide with regard to pediatric anxiety has been published by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.4

Conclusions

Clinical levels of anxiety in children and adolescents are both common and quite treatable, which has prompted new recommendations that primary care clinicians screen for them starting at age 8. While this recommendation may at first seem like yet one more task to fit in, following the guidance can be accomplished with the help of short screening tools and a managed multimodal approach to treatment.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist with Lane County Behavioral Health in Eugene, Ore., and Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. You can follow him on Twitter and Facebook @PediPsych.

References

1. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;328(14):1438-44.

2. Strawn JR. Curr Psychiatry. 2012;11(9):16-21.

3. Walter HJ et al. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(10):1107-24.

4. Anxiety Disorders: Parents’ Medication Guide Workgroup. “Anxiety disorders: Parents’ medication guide.” Washington D.C.: American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 2020.

Recently the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force issued a formal recommendation that adolescents and children as young as 8 should be screened for anxiety.1 The advice was based on a review of the research that concluded that anxiety disorders were common in youth (prevalence around 8%), screening was not overly burdensome or dangerous, and treatments were available and effective.

While pediatricians fully appreciate how common clinically significant anxiety is and its impact on the lives of youth, the reception for the recommendations have been mixed. Some are concerned that it could lead to the overprescribing of medications. Arguably, the biggest pushback, however, relates to the question of what to do when a child screens positive in a time when finding an available child and adolescent psychiatrist or other type of pediatric mental health professional can feel next to impossible. The hope of this article is to fill in some of those gaps.

Screening for anxiety disorders

The recommendations suggest using a rating scale as part of the screen but doesn’t dictate which one. A common instrument that has been employed is the Screen for Child Anxiety and Related Disorders, which is a freely available 41-item instrument that has versions for youth self-report and parent-report. A shorter 7-item rating scale, the General Anxiety Disorder–7, and the even shorter GAD-2 (the first two questions of the GAD-7), are also popular but focus, as the name applies, on general anxiety disorder and not related conditions such as social or separation anxiety that can have some different symptoms. These instruments can be given to patients and families in the waiting room or administered with the help of a nurse, physician, or embedded mental health professional. The recommendations do not include specific guidance on how often the screening should be done but repeated screenings are likely important at some interval.

Confirming the diagnosis

Of course, a screening isn’t a formal diagnosis. The American Academy of Pediatrics has expressed the view that the initial diagnosis and treatment for anxiety disorders is well within a pediatrician’s scope of practice, which means further steps are likely required beyond a referral. Fortunately, going from a positive screen to an initial diagnosis does not have to overly laborious and can focus on reviewing the DSM-5 criteria for key anxiety disorders while also ensuring that there isn’t a nonpsychiatric cause driving the symptoms, such as the often cited but rarely seen pheochromocytoma. More common rule-outs include medication-induced anxiety or substance use, excessive caffeine intake, and cardiac arrhythmias. Assessing for current and past trauma or specific causes of the anxiety such as bullying are also important.

It is important to note that it is the rule rather than the exception that youth with clinical levels of anxiety will frequently endorse a number of criteria that span multiple diagnoses including generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and separation anxiety disorder.2 Spending a lot of effort to narrow things down to a single anxiety diagnosis often is unnecessary, as both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments don’t change all that much between individual diagnoses.

Explaining the diagnosis

In general, I’m a strong proponent of trying to explain any behavioral diagnoses that you make to kids in a way that is accurate but nonstigmatizing. When it comes to anxiety, one parallel I often draw is to our immune system, which most youth understand at least in basic terms. Both our immune system and our anxiety networks are natural and important; as a species, we wouldn’t have lasted long without them. Both are built to assess and respond to threats. Problems can arise, however, if the response is too strong relative to the threat or the response is activated when it doesn’t need to be. Treatment is directed not at ridding ourselves of anxiety but at helping regulate it so it works for us and not against us. Spending a few minutes going through a discussion like this can be very helpful, and perhaps more so than some dry summary of DSM-5 criteria.

Starting treatment

It is important to note that best practice recommendations when it comes to the treatment of anxiety disorder in youth do not suggest medications as the only type of treatment and often urge clinicians to try nonpharmacological interventions first.3 A specific type of psychotherapy called cognitive-behavioral therapy has the strongest scientific support as an effective treatment for anxiety but other modalities, including parenting guidance, can be helpful as well. Consequently, a referral to a good psychotherapist is paramount. For many kids, the key to overcoming anxiety is exposure: which means confronting anxiety slowly, with support, and with specific skills.

If there is a traumatic source of the anxiety, addressing that as much as possible is obviously critical and could involve working with the family or school. For some kids, this may involve frightening things they are seeing online or through other media. Finally, some health promotion activities such as exercise or mindfulness can also be quite useful.

Despite the fact that SSRIs are referred to as antidepressants, there is increasing appreciation that these medications are useful for anxiety, perhaps even more so than for mood. While only one medication, duloxetine, has Food and Drug Administration approval to treat anxiety in children as young as 7, there is good evidence to support the use of many of the most common SSRIs in treating clinical anxiety. Buspirone, beta-blockers, and antihistamine medications like hydroxyzine also can have their place in treatment, while benzodiazepines and antipsychotic medications are generally best avoided for anxious youth, especially in the primary care setting. A short but helpful medication guide with regard to pediatric anxiety has been published by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.4

Conclusions

Clinical levels of anxiety in children and adolescents are both common and quite treatable, which has prompted new recommendations that primary care clinicians screen for them starting at age 8. While this recommendation may at first seem like yet one more task to fit in, following the guidance can be accomplished with the help of short screening tools and a managed multimodal approach to treatment.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist with Lane County Behavioral Health in Eugene, Ore., and Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. You can follow him on Twitter and Facebook @PediPsych.

References

1. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;328(14):1438-44.

2. Strawn JR. Curr Psychiatry. 2012;11(9):16-21.

3. Walter HJ et al. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(10):1107-24.

4. Anxiety Disorders: Parents’ Medication Guide Workgroup. “Anxiety disorders: Parents’ medication guide.” Washington D.C.: American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 2020.

Recently the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force issued a formal recommendation that adolescents and children as young as 8 should be screened for anxiety.1 The advice was based on a review of the research that concluded that anxiety disorders were common in youth (prevalence around 8%), screening was not overly burdensome or dangerous, and treatments were available and effective.

While pediatricians fully appreciate how common clinically significant anxiety is and its impact on the lives of youth, the reception for the recommendations have been mixed. Some are concerned that it could lead to the overprescribing of medications. Arguably, the biggest pushback, however, relates to the question of what to do when a child screens positive in a time when finding an available child and adolescent psychiatrist or other type of pediatric mental health professional can feel next to impossible. The hope of this article is to fill in some of those gaps.

Screening for anxiety disorders

The recommendations suggest using a rating scale as part of the screen but doesn’t dictate which one. A common instrument that has been employed is the Screen for Child Anxiety and Related Disorders, which is a freely available 41-item instrument that has versions for youth self-report and parent-report. A shorter 7-item rating scale, the General Anxiety Disorder–7, and the even shorter GAD-2 (the first two questions of the GAD-7), are also popular but focus, as the name applies, on general anxiety disorder and not related conditions such as social or separation anxiety that can have some different symptoms. These instruments can be given to patients and families in the waiting room or administered with the help of a nurse, physician, or embedded mental health professional. The recommendations do not include specific guidance on how often the screening should be done but repeated screenings are likely important at some interval.

Confirming the diagnosis

Of course, a screening isn’t a formal diagnosis. The American Academy of Pediatrics has expressed the view that the initial diagnosis and treatment for anxiety disorders is well within a pediatrician’s scope of practice, which means further steps are likely required beyond a referral. Fortunately, going from a positive screen to an initial diagnosis does not have to overly laborious and can focus on reviewing the DSM-5 criteria for key anxiety disorders while also ensuring that there isn’t a nonpsychiatric cause driving the symptoms, such as the often cited but rarely seen pheochromocytoma. More common rule-outs include medication-induced anxiety or substance use, excessive caffeine intake, and cardiac arrhythmias. Assessing for current and past trauma or specific causes of the anxiety such as bullying are also important.

It is important to note that it is the rule rather than the exception that youth with clinical levels of anxiety will frequently endorse a number of criteria that span multiple diagnoses including generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and separation anxiety disorder.2 Spending a lot of effort to narrow things down to a single anxiety diagnosis often is unnecessary, as both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments don’t change all that much between individual diagnoses.

Explaining the diagnosis

In general, I’m a strong proponent of trying to explain any behavioral diagnoses that you make to kids in a way that is accurate but nonstigmatizing. When it comes to anxiety, one parallel I often draw is to our immune system, which most youth understand at least in basic terms. Both our immune system and our anxiety networks are natural and important; as a species, we wouldn’t have lasted long without them. Both are built to assess and respond to threats. Problems can arise, however, if the response is too strong relative to the threat or the response is activated when it doesn’t need to be. Treatment is directed not at ridding ourselves of anxiety but at helping regulate it so it works for us and not against us. Spending a few minutes going through a discussion like this can be very helpful, and perhaps more so than some dry summary of DSM-5 criteria.

Starting treatment

It is important to note that best practice recommendations when it comes to the treatment of anxiety disorder in youth do not suggest medications as the only type of treatment and often urge clinicians to try nonpharmacological interventions first.3 A specific type of psychotherapy called cognitive-behavioral therapy has the strongest scientific support as an effective treatment for anxiety but other modalities, including parenting guidance, can be helpful as well. Consequently, a referral to a good psychotherapist is paramount. For many kids, the key to overcoming anxiety is exposure: which means confronting anxiety slowly, with support, and with specific skills.

If there is a traumatic source of the anxiety, addressing that as much as possible is obviously critical and could involve working with the family or school. For some kids, this may involve frightening things they are seeing online or through other media. Finally, some health promotion activities such as exercise or mindfulness can also be quite useful.

Despite the fact that SSRIs are referred to as antidepressants, there is increasing appreciation that these medications are useful for anxiety, perhaps even more so than for mood. While only one medication, duloxetine, has Food and Drug Administration approval to treat anxiety in children as young as 7, there is good evidence to support the use of many of the most common SSRIs in treating clinical anxiety. Buspirone, beta-blockers, and antihistamine medications like hydroxyzine also can have their place in treatment, while benzodiazepines and antipsychotic medications are generally best avoided for anxious youth, especially in the primary care setting. A short but helpful medication guide with regard to pediatric anxiety has been published by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.4

Conclusions

Clinical levels of anxiety in children and adolescents are both common and quite treatable, which has prompted new recommendations that primary care clinicians screen for them starting at age 8. While this recommendation may at first seem like yet one more task to fit in, following the guidance can be accomplished with the help of short screening tools and a managed multimodal approach to treatment.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist with Lane County Behavioral Health in Eugene, Ore., and Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. You can follow him on Twitter and Facebook @PediPsych.

References

1. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;328(14):1438-44.

2. Strawn JR. Curr Psychiatry. 2012;11(9):16-21.

3. Walter HJ et al. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(10):1107-24.

4. Anxiety Disorders: Parents’ Medication Guide Workgroup. “Anxiety disorders: Parents’ medication guide.” Washington D.C.: American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 2020.

Optimal psychiatric treatment: Target the brain and avoid the body

Pharmacotherapy for psychiatric disorders is a mixed blessing. The advent of psychotropic medications since the 1950s (antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, mood stabilizers) has revolutionized the treatment of serious psychiatric brain disorders, allowing certain patients to be discharged to the community after a lifetime of institutionalization.

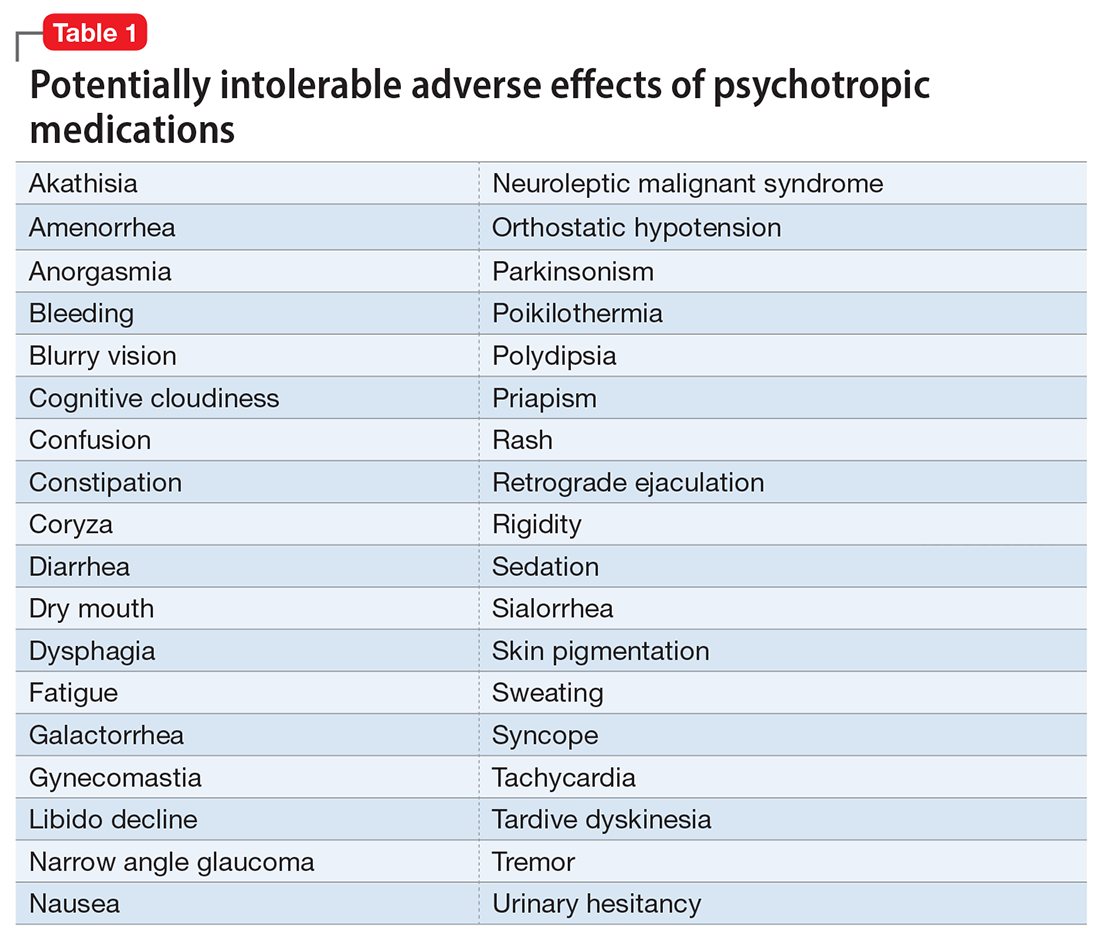

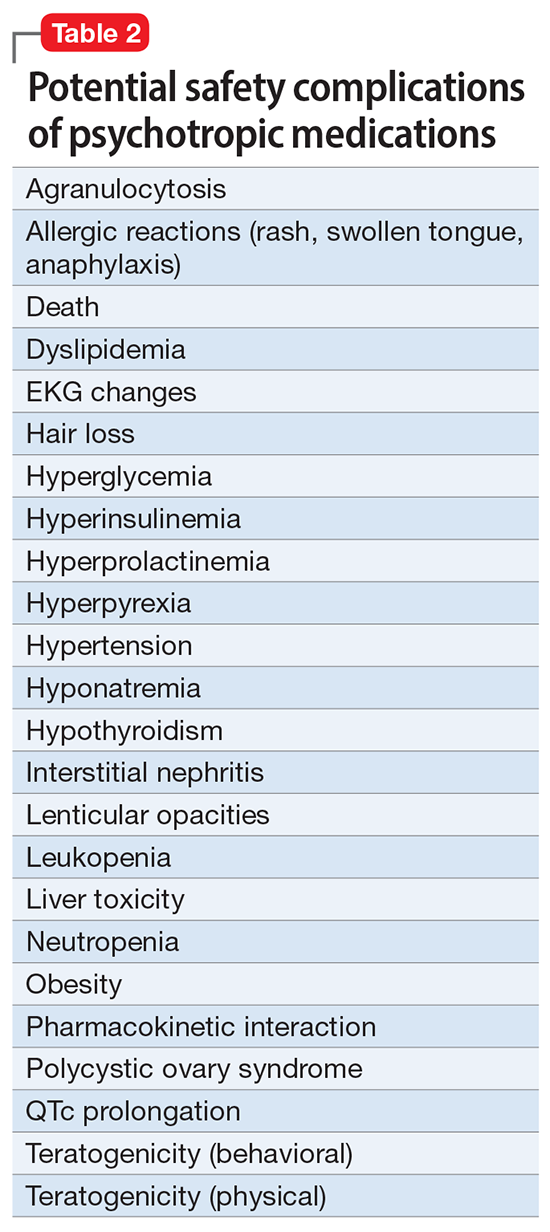

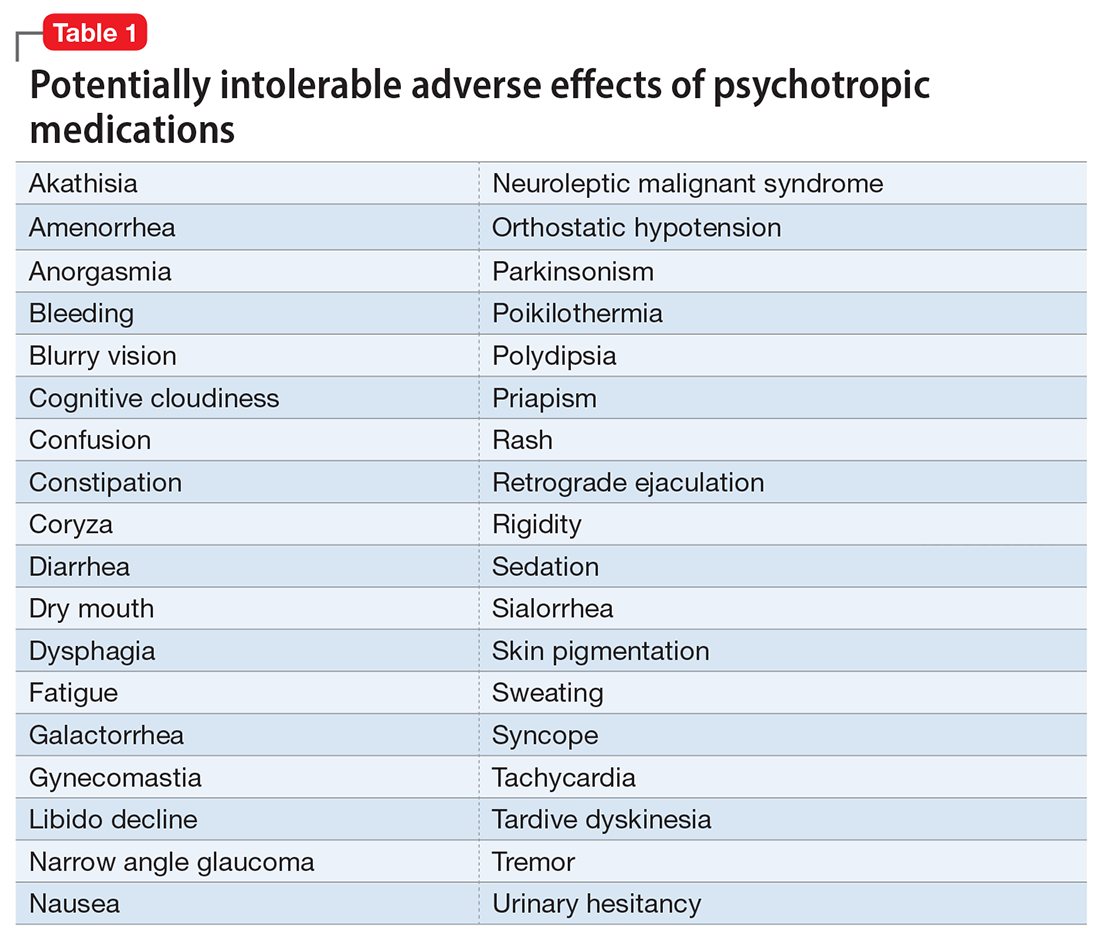

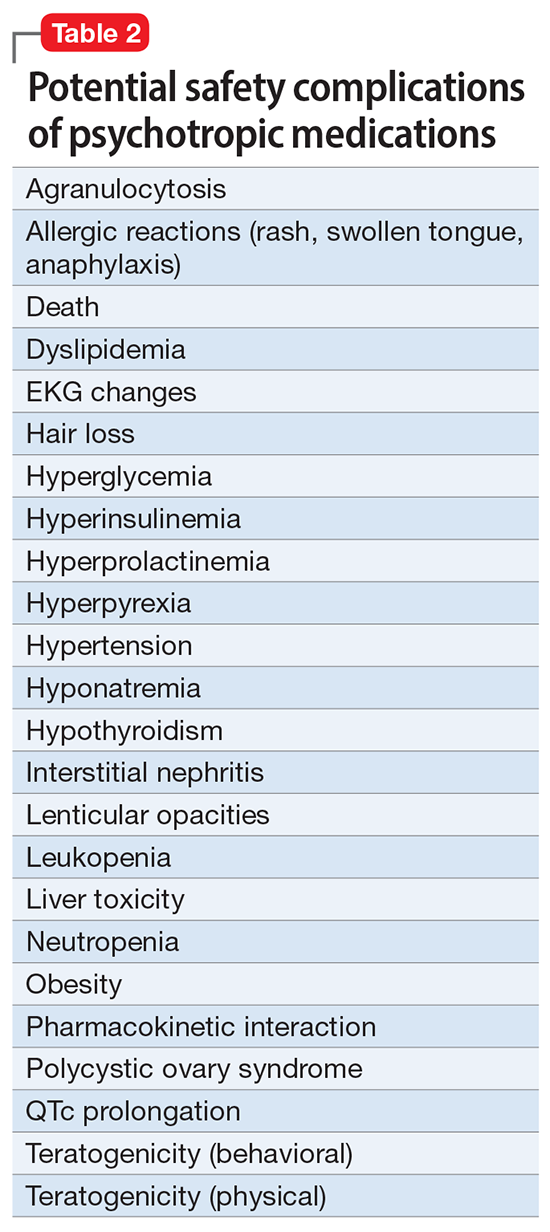

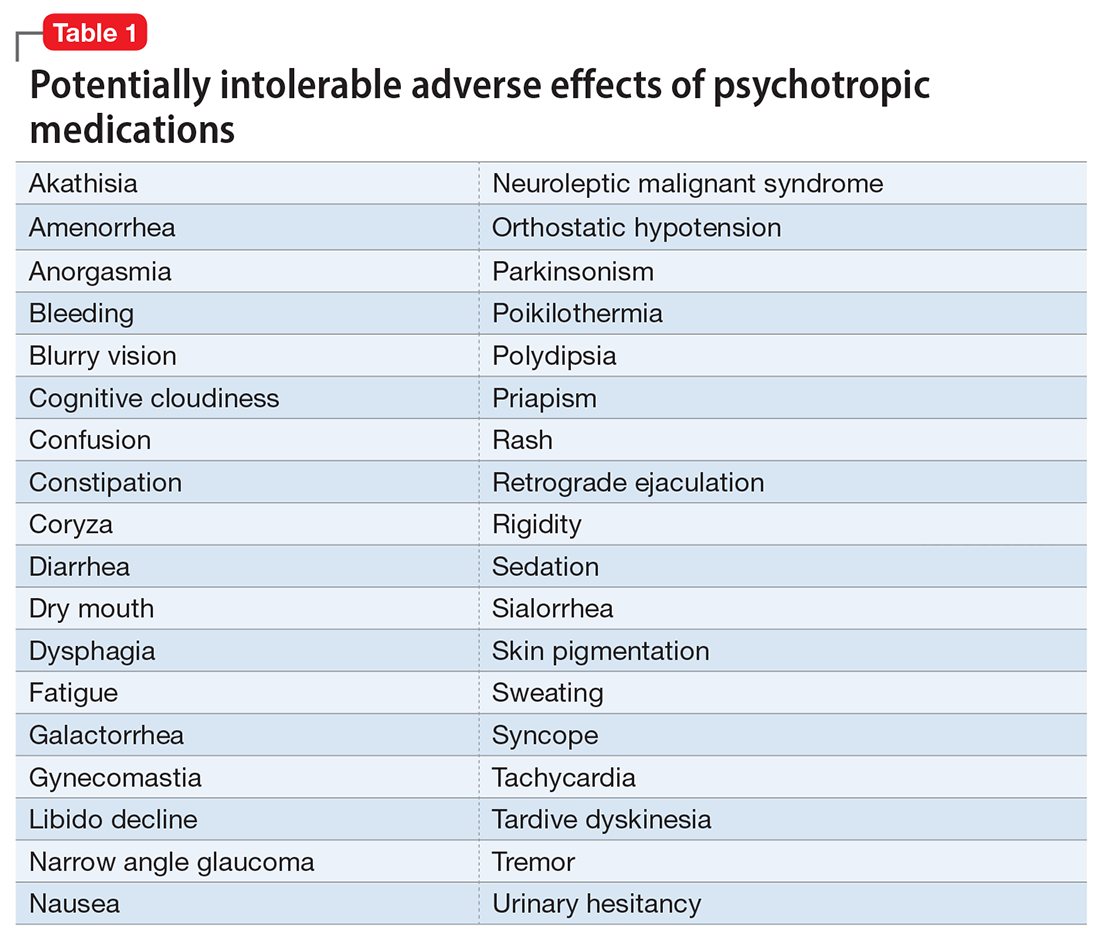

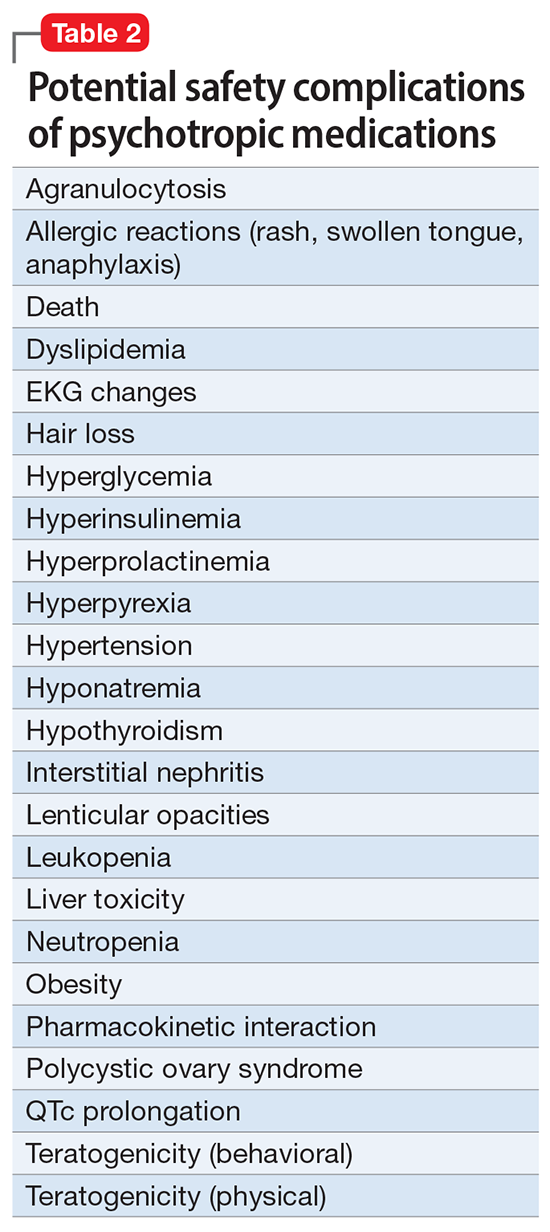

However, like all medications, psychotropic agents are often associated with various potentially intolerable symptoms (Table 1) or safety complications (Table 2) because they interact with every organ in the body besides their intended target, the brain, and its neurochemical circuitry.

Imagine if we could treat our psychiatric patients while bypassing the body and achieve response, remission, and ultimately recovery without any systemic adverse effects. Adherence would dramatically improve, our patients’ quality of life would be enhanced, and the overall effectiveness (defined as the complex package of efficacy, safety, and tolerability) would be superior to current pharmacotherapies. This is important because most psychiatric medications must be taken daily for years, even a lifetime, to avoid a relapse of the illness. Psychiatrists frequently must manage adverse effects or switch the patient to a different medication if a tolerability or safety issue emerges, which is very common in psychiatric practice. A significant part of psychopharmacologic management includes ordering various laboratory tests to monitor adverse reactions in major organs, especially the liver, kidney, and heart. Additionally, psychiatric physicians must be constantly cognizant of medications prescribed by other clinicians for comorbid medical conditions to successfully navigate the turbulent seas of pharmacokinetic interactions.

I am sure you have noticed that whenever you watch a direct-to-consumer commercial for any medication, 90% of the advertisement is a background voice listing the various tolerability and safety complications of the medication as required by the FDA. Interestingly, these ads frequently contain colorful scenery and joyful clips, which I suspect are cleverly designed to distract the audience from focusing on the list of adverse effects.

Benefits of nonpharmacologic treatments

No wonder I am a fan of psychotherapy, a well-established psychiatric treatment modality that completely avoids body tissues. It directly targets the brain without needlessly interacting with any other organ. Psychotherapy’s many benefits (improving insight, enhancing adherence, improving self-esteem, reducing risky behaviors, guiding stress management and coping skills, modifying unhealthy beliefs, and ultimately relieving symptoms such as anxiety and depression) are achieved without any somatic adverse effects! Psychotherapy has also been shown to induce neuroplasticity and reduce inflammatory biomarkers.1 Unlike FDA-approved medications, psychotherapy does not include a “package insert,” 10 to 20 pages (in small print) that mostly focus on warnings, precautions, and sundry physical adverse effects. Even the dosing of psychotherapy is left entirely up to the treating clinician!

Although I have had many gratifying results with pharmacotherapy in my practice, especially in combination with psychotherapy,2 I also have observed excellent outcomes with nonpharmacologic approaches, especially neuromodulation therapies. The best antidepressant I have ever used since my residency training days is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). My experience is consistent with a large meta-analysis3showing a huge effect size (Cohen d = .91) in contrast to the usual effect size of .3 to .5 for standard antidepressants (except IV ketamine). A recent study showed ECT is even better than the vaunted rapid-acting ketamine,4 which is further evidence of its remarkable efficacy in depression. Neuroimaging studies report that ECT rapidly increases the volume of the hippocampus,5,6 which shrinks in size in patients with unipolar or bipolar depression.

Neuromodulation may very well be the future of psychiatric therapeutics. It targets the brain and avoids the body, thus achieving efficacy with minimal systemic tolerability (ie, patient complaints) (Table 1) or safety (abnormal laboratory test results) issues (Table 2). This sounds ideal, and it is arguably an optimal approach to repairing the brain and healing the mind.

Continue to: ECT is the oldest...

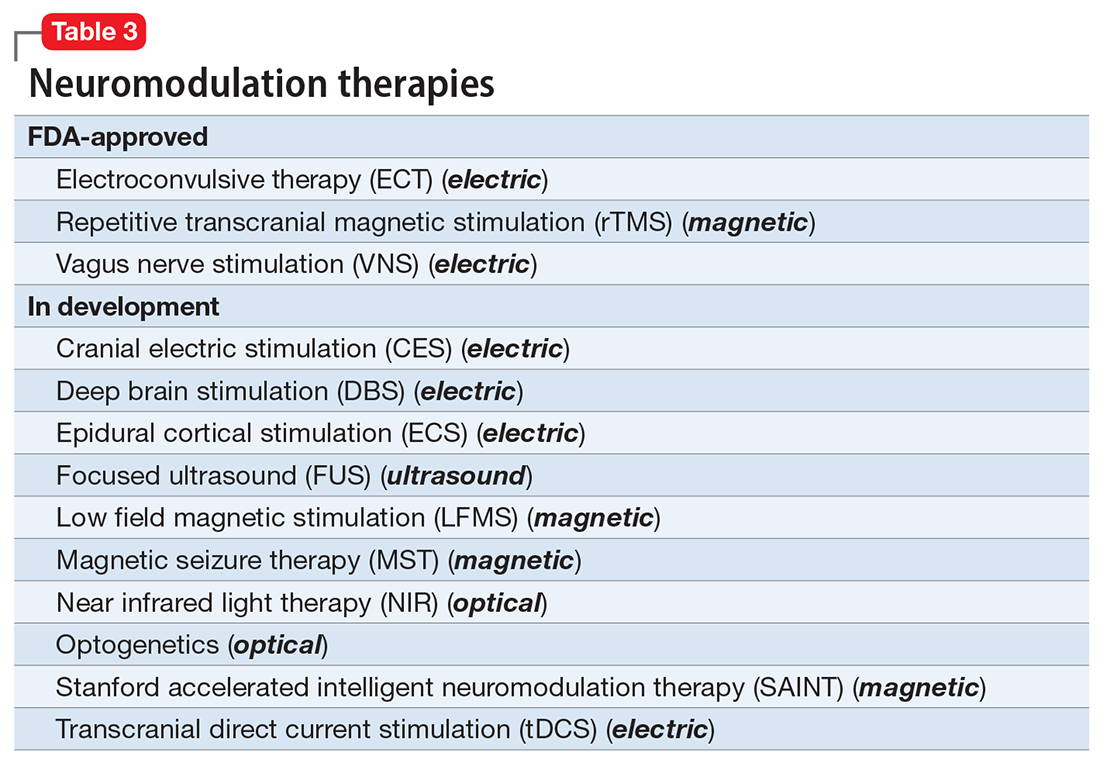

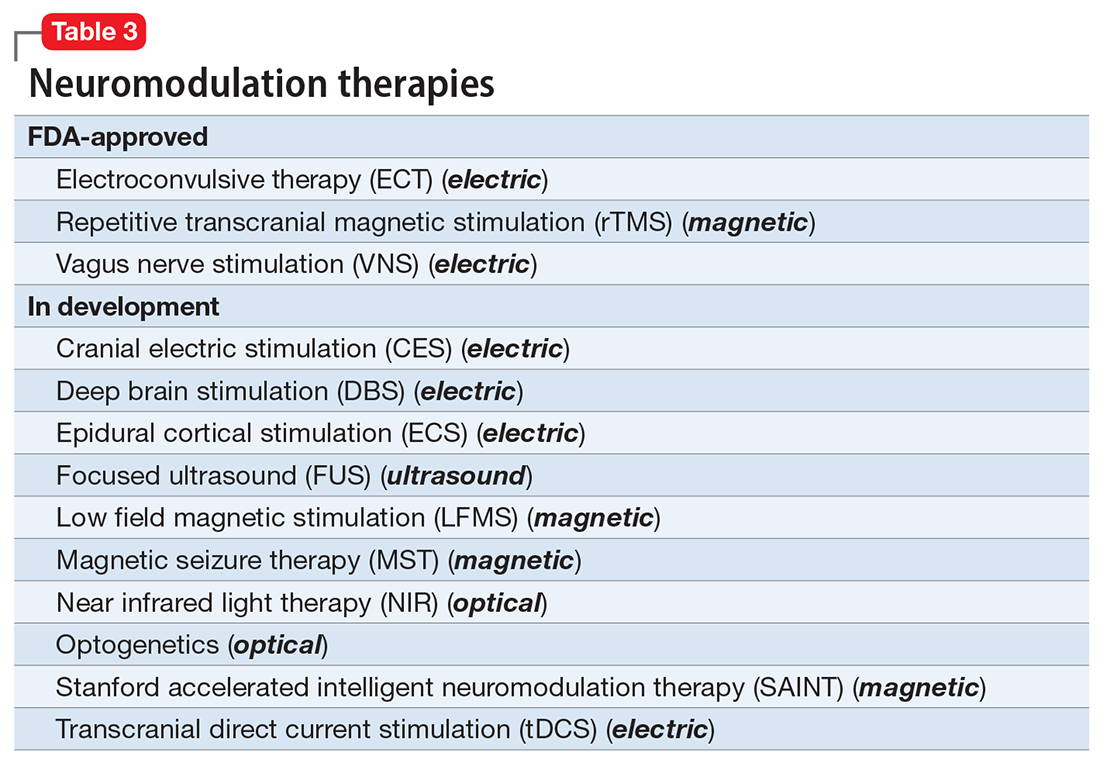

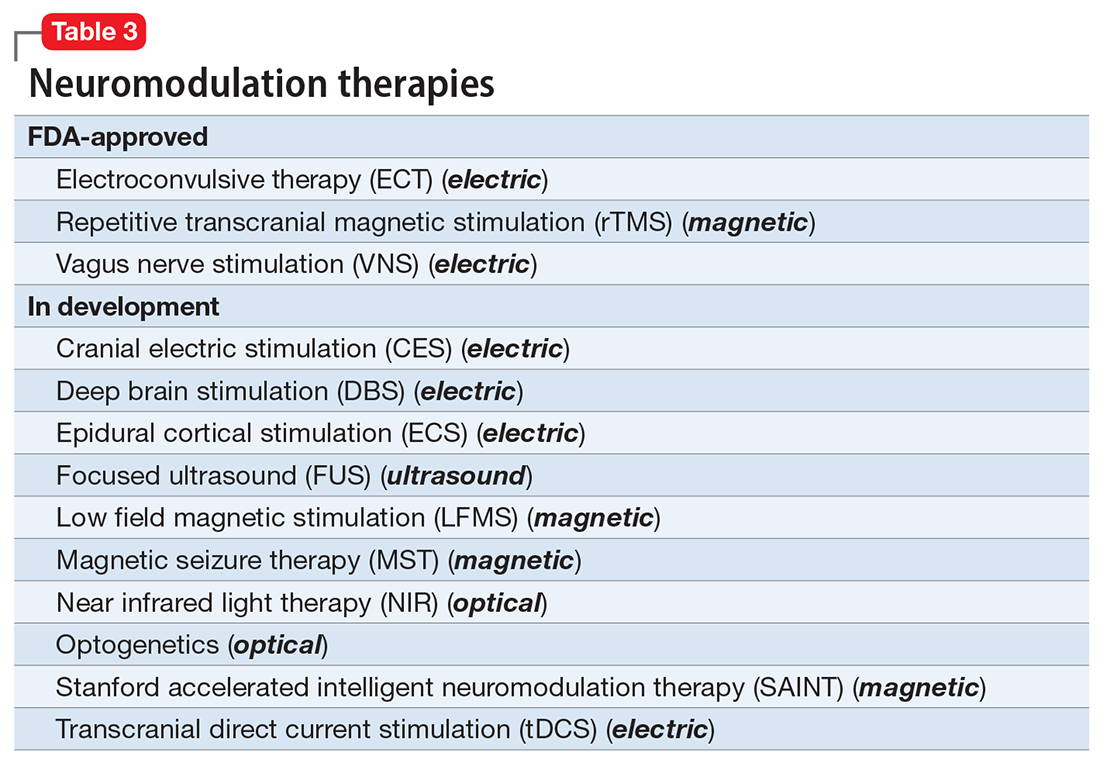

ECT is the oldest neuromodulation technique (developed almost 100 years ago and significantly refined since then). Newer FDA-approved neuromodulation therapies include repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), which was approved for depression in 2013, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in 2018, smoking cessation in 2020, and anxious depression in 2021.7 Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) is used for drug-resistant epilepsy and was later approved for treatment-resistant depression,8,9 but some studies report it can be helpful for fear and anxiety in autism spectrum disorder10 and primary insomnia.11

There are many other neuromodulation therapies in development12 that have not yet been FDA approved (Table 3). The most prominent of these is deep brain stimulation (DBS), which is approved for Parkinson disease and has been reported in many studies to improve treatment-resistant depression13,14 and OCD.15 Another promising neuromodulation therapy is transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), which has promising results in schizophrenia16 similar to ECT’s effects in treatment-resistant schizophrenia.17

A particularly exciting neuromodulation approach published by Stanford University researchers is Stanford accelerated intelligent neuromodulation therapy (SAINT),18 which uses intermittent theta-burst stimulation (iTBS) daily for 5 days, targeted at the subgenual anterior cingulate gyrus (Brodman area 25). Remarkably, efficacy was rapid, with a very high remission rate (absence of symptoms) in approximately 90% of patients with severe depression.18

The future is bright for neuromodulation therapies, and for a good reason. Why send a chemical agent to every cell and organ in the body when the brain can be targeted directly? As psychiatric neuroscience advances to a point where we can localize the abnormal neurologic circuit in a specific brain region for each psychiatric disorder, it will be possible to treat almost all psychiatric disorders without burdening patients with the intolerable symptoms or safety adverse effects of medications. Psychiatrists should modulate their perspective about the future of psychiatric treatments. And finally, I propose that psychotherapy should be reclassified as a “verbal neuromodulation” technique.

1. Nasrallah HA. Repositioning psychotherapy as a neurobiological intervention. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(12):18-19.

2. Nasrallah HA. Bipolar disorder: clinical questions beg for answers. Current Psychiatry. 2006;5(12):11-12.

3. UK ECT Review Group. Efficacy and safety of electroconvulsive therapy in depressive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2003;361(9360):799-808.

4. Rhee TG, Shim SR, Forester BP, et al. Efficacy and safety of ketamine vs electroconvulsive therapy among patients with major depressive episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022:e223352. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.3352

5. Nuninga JO, Mandl RCW, Boks MP, et al. Volume increase in the dentate gyrus after electroconvulsive therapy in depressed patients as measured with 7T. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(7):1559-1568.

6. Joshi SH, Espinoza RT, Pirnia T, et al. Structural plasticity of the hippocampus and amygdala induced by electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):282-292.

7. Rhee TG, Olfson M, Nierenberg AA, et al. 20-year trends in the pharmacologic treatment of bipolar disorder by psychiatrists in outpatient care settings. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(8):706-715.

8. Hilz MJ. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation - a brief introduction and overview. Auton Neurosci. 2022;243:103038. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2022.103038

9. Pigato G, Rosson S, Bresolin N, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation in treatment-resistant depression: a case series of long-term follow-up. J ECT. 2022. doi:10.1097/YCT.0000000000000869

10. Shivaswamy T, Souza RR, Engineer CT, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation as a treatment for fear and anxiety in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. J Psychiatr Brain Sci. 2022;7(4):e220007. doi:10.20900/jpbs.20220007

11. Wu Y, Song L, Wang X, et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation could improve the effective rate on the quality of sleep in the treatment of primary insomnia: a randomized control trial. Brain Sci. 2022;12(10):1296. doi:10.3390/brainsci12101296

12. Rosa MA, Lisanby SH. Somatic treatments for mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(1):102-116.

13. Mayberg HS, Lozano AM, Voon V, et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron. 2005;45(5):651-660.

14. Choi KS, Mayberg H. Connectomic DBS in major depression. In: Horn A, ed. Connectomic Deep Brain Stimulation. Academic Press; 2022:433-447.

15. Cruz S, Gutiérrez-Rojas L, González-Domenech P, et al. Deep brain stimulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder: results from meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317:114869. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114869

16. Lisoni J, Baldacci G, Nibbio G, et al. Effects of bilateral, bipolar-nonbalanced, frontal transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on negative symptoms and neurocognition in a sample of patients living with schizophrenia: results of a randomized double-blind sham-controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;155:430-442.

17. Sinclair DJ, Zhao S, Qi F, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3(3):CD011847. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011847.pub2

18. Cole EJ, Stimpson KH, Bentzley BS, et al. Stanford accelerated intelligent neuromodulation therapy for treatment-resistant depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(8):716-726.

Pharmacotherapy for psychiatric disorders is a mixed blessing. The advent of psychotropic medications since the 1950s (antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, mood stabilizers) has revolutionized the treatment of serious psychiatric brain disorders, allowing certain patients to be discharged to the community after a lifetime of institutionalization.

However, like all medications, psychotropic agents are often associated with various potentially intolerable symptoms (Table 1) or safety complications (Table 2) because they interact with every organ in the body besides their intended target, the brain, and its neurochemical circuitry.

Imagine if we could treat our psychiatric patients while bypassing the body and achieve response, remission, and ultimately recovery without any systemic adverse effects. Adherence would dramatically improve, our patients’ quality of life would be enhanced, and the overall effectiveness (defined as the complex package of efficacy, safety, and tolerability) would be superior to current pharmacotherapies. This is important because most psychiatric medications must be taken daily for years, even a lifetime, to avoid a relapse of the illness. Psychiatrists frequently must manage adverse effects or switch the patient to a different medication if a tolerability or safety issue emerges, which is very common in psychiatric practice. A significant part of psychopharmacologic management includes ordering various laboratory tests to monitor adverse reactions in major organs, especially the liver, kidney, and heart. Additionally, psychiatric physicians must be constantly cognizant of medications prescribed by other clinicians for comorbid medical conditions to successfully navigate the turbulent seas of pharmacokinetic interactions.

I am sure you have noticed that whenever you watch a direct-to-consumer commercial for any medication, 90% of the advertisement is a background voice listing the various tolerability and safety complications of the medication as required by the FDA. Interestingly, these ads frequently contain colorful scenery and joyful clips, which I suspect are cleverly designed to distract the audience from focusing on the list of adverse effects.

Benefits of nonpharmacologic treatments

No wonder I am a fan of psychotherapy, a well-established psychiatric treatment modality that completely avoids body tissues. It directly targets the brain without needlessly interacting with any other organ. Psychotherapy’s many benefits (improving insight, enhancing adherence, improving self-esteem, reducing risky behaviors, guiding stress management and coping skills, modifying unhealthy beliefs, and ultimately relieving symptoms such as anxiety and depression) are achieved without any somatic adverse effects! Psychotherapy has also been shown to induce neuroplasticity and reduce inflammatory biomarkers.1 Unlike FDA-approved medications, psychotherapy does not include a “package insert,” 10 to 20 pages (in small print) that mostly focus on warnings, precautions, and sundry physical adverse effects. Even the dosing of psychotherapy is left entirely up to the treating clinician!

Although I have had many gratifying results with pharmacotherapy in my practice, especially in combination with psychotherapy,2 I also have observed excellent outcomes with nonpharmacologic approaches, especially neuromodulation therapies. The best antidepressant I have ever used since my residency training days is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). My experience is consistent with a large meta-analysis3showing a huge effect size (Cohen d = .91) in contrast to the usual effect size of .3 to .5 for standard antidepressants (except IV ketamine). A recent study showed ECT is even better than the vaunted rapid-acting ketamine,4 which is further evidence of its remarkable efficacy in depression. Neuroimaging studies report that ECT rapidly increases the volume of the hippocampus,5,6 which shrinks in size in patients with unipolar or bipolar depression.

Neuromodulation may very well be the future of psychiatric therapeutics. It targets the brain and avoids the body, thus achieving efficacy with minimal systemic tolerability (ie, patient complaints) (Table 1) or safety (abnormal laboratory test results) issues (Table 2). This sounds ideal, and it is arguably an optimal approach to repairing the brain and healing the mind.

Continue to: ECT is the oldest...

ECT is the oldest neuromodulation technique (developed almost 100 years ago and significantly refined since then). Newer FDA-approved neuromodulation therapies include repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), which was approved for depression in 2013, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in 2018, smoking cessation in 2020, and anxious depression in 2021.7 Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) is used for drug-resistant epilepsy and was later approved for treatment-resistant depression,8,9 but some studies report it can be helpful for fear and anxiety in autism spectrum disorder10 and primary insomnia.11

There are many other neuromodulation therapies in development12 that have not yet been FDA approved (Table 3). The most prominent of these is deep brain stimulation (DBS), which is approved for Parkinson disease and has been reported in many studies to improve treatment-resistant depression13,14 and OCD.15 Another promising neuromodulation therapy is transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), which has promising results in schizophrenia16 similar to ECT’s effects in treatment-resistant schizophrenia.17

A particularly exciting neuromodulation approach published by Stanford University researchers is Stanford accelerated intelligent neuromodulation therapy (SAINT),18 which uses intermittent theta-burst stimulation (iTBS) daily for 5 days, targeted at the subgenual anterior cingulate gyrus (Brodman area 25). Remarkably, efficacy was rapid, with a very high remission rate (absence of symptoms) in approximately 90% of patients with severe depression.18

The future is bright for neuromodulation therapies, and for a good reason. Why send a chemical agent to every cell and organ in the body when the brain can be targeted directly? As psychiatric neuroscience advances to a point where we can localize the abnormal neurologic circuit in a specific brain region for each psychiatric disorder, it will be possible to treat almost all psychiatric disorders without burdening patients with the intolerable symptoms or safety adverse effects of medications. Psychiatrists should modulate their perspective about the future of psychiatric treatments. And finally, I propose that psychotherapy should be reclassified as a “verbal neuromodulation” technique.

Pharmacotherapy for psychiatric disorders is a mixed blessing. The advent of psychotropic medications since the 1950s (antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, mood stabilizers) has revolutionized the treatment of serious psychiatric brain disorders, allowing certain patients to be discharged to the community after a lifetime of institutionalization.

However, like all medications, psychotropic agents are often associated with various potentially intolerable symptoms (Table 1) or safety complications (Table 2) because they interact with every organ in the body besides their intended target, the brain, and its neurochemical circuitry.

Imagine if we could treat our psychiatric patients while bypassing the body and achieve response, remission, and ultimately recovery without any systemic adverse effects. Adherence would dramatically improve, our patients’ quality of life would be enhanced, and the overall effectiveness (defined as the complex package of efficacy, safety, and tolerability) would be superior to current pharmacotherapies. This is important because most psychiatric medications must be taken daily for years, even a lifetime, to avoid a relapse of the illness. Psychiatrists frequently must manage adverse effects or switch the patient to a different medication if a tolerability or safety issue emerges, which is very common in psychiatric practice. A significant part of psychopharmacologic management includes ordering various laboratory tests to monitor adverse reactions in major organs, especially the liver, kidney, and heart. Additionally, psychiatric physicians must be constantly cognizant of medications prescribed by other clinicians for comorbid medical conditions to successfully navigate the turbulent seas of pharmacokinetic interactions.

I am sure you have noticed that whenever you watch a direct-to-consumer commercial for any medication, 90% of the advertisement is a background voice listing the various tolerability and safety complications of the medication as required by the FDA. Interestingly, these ads frequently contain colorful scenery and joyful clips, which I suspect are cleverly designed to distract the audience from focusing on the list of adverse effects.

Benefits of nonpharmacologic treatments

No wonder I am a fan of psychotherapy, a well-established psychiatric treatment modality that completely avoids body tissues. It directly targets the brain without needlessly interacting with any other organ. Psychotherapy’s many benefits (improving insight, enhancing adherence, improving self-esteem, reducing risky behaviors, guiding stress management and coping skills, modifying unhealthy beliefs, and ultimately relieving symptoms such as anxiety and depression) are achieved without any somatic adverse effects! Psychotherapy has also been shown to induce neuroplasticity and reduce inflammatory biomarkers.1 Unlike FDA-approved medications, psychotherapy does not include a “package insert,” 10 to 20 pages (in small print) that mostly focus on warnings, precautions, and sundry physical adverse effects. Even the dosing of psychotherapy is left entirely up to the treating clinician!

Although I have had many gratifying results with pharmacotherapy in my practice, especially in combination with psychotherapy,2 I also have observed excellent outcomes with nonpharmacologic approaches, especially neuromodulation therapies. The best antidepressant I have ever used since my residency training days is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). My experience is consistent with a large meta-analysis3showing a huge effect size (Cohen d = .91) in contrast to the usual effect size of .3 to .5 for standard antidepressants (except IV ketamine). A recent study showed ECT is even better than the vaunted rapid-acting ketamine,4 which is further evidence of its remarkable efficacy in depression. Neuroimaging studies report that ECT rapidly increases the volume of the hippocampus,5,6 which shrinks in size in patients with unipolar or bipolar depression.

Neuromodulation may very well be the future of psychiatric therapeutics. It targets the brain and avoids the body, thus achieving efficacy with minimal systemic tolerability (ie, patient complaints) (Table 1) or safety (abnormal laboratory test results) issues (Table 2). This sounds ideal, and it is arguably an optimal approach to repairing the brain and healing the mind.

Continue to: ECT is the oldest...

ECT is the oldest neuromodulation technique (developed almost 100 years ago and significantly refined since then). Newer FDA-approved neuromodulation therapies include repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), which was approved for depression in 2013, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in 2018, smoking cessation in 2020, and anxious depression in 2021.7 Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) is used for drug-resistant epilepsy and was later approved for treatment-resistant depression,8,9 but some studies report it can be helpful for fear and anxiety in autism spectrum disorder10 and primary insomnia.11

There are many other neuromodulation therapies in development12 that have not yet been FDA approved (Table 3). The most prominent of these is deep brain stimulation (DBS), which is approved for Parkinson disease and has been reported in many studies to improve treatment-resistant depression13,14 and OCD.15 Another promising neuromodulation therapy is transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), which has promising results in schizophrenia16 similar to ECT’s effects in treatment-resistant schizophrenia.17

A particularly exciting neuromodulation approach published by Stanford University researchers is Stanford accelerated intelligent neuromodulation therapy (SAINT),18 which uses intermittent theta-burst stimulation (iTBS) daily for 5 days, targeted at the subgenual anterior cingulate gyrus (Brodman area 25). Remarkably, efficacy was rapid, with a very high remission rate (absence of symptoms) in approximately 90% of patients with severe depression.18

The future is bright for neuromodulation therapies, and for a good reason. Why send a chemical agent to every cell and organ in the body when the brain can be targeted directly? As psychiatric neuroscience advances to a point where we can localize the abnormal neurologic circuit in a specific brain region for each psychiatric disorder, it will be possible to treat almost all psychiatric disorders without burdening patients with the intolerable symptoms or safety adverse effects of medications. Psychiatrists should modulate their perspective about the future of psychiatric treatments. And finally, I propose that psychotherapy should be reclassified as a “verbal neuromodulation” technique.

1. Nasrallah HA. Repositioning psychotherapy as a neurobiological intervention. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(12):18-19.

2. Nasrallah HA. Bipolar disorder: clinical questions beg for answers. Current Psychiatry. 2006;5(12):11-12.

3. UK ECT Review Group. Efficacy and safety of electroconvulsive therapy in depressive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2003;361(9360):799-808.

4. Rhee TG, Shim SR, Forester BP, et al. Efficacy and safety of ketamine vs electroconvulsive therapy among patients with major depressive episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022:e223352. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.3352

5. Nuninga JO, Mandl RCW, Boks MP, et al. Volume increase in the dentate gyrus after electroconvulsive therapy in depressed patients as measured with 7T. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(7):1559-1568.

6. Joshi SH, Espinoza RT, Pirnia T, et al. Structural plasticity of the hippocampus and amygdala induced by electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):282-292.

7. Rhee TG, Olfson M, Nierenberg AA, et al. 20-year trends in the pharmacologic treatment of bipolar disorder by psychiatrists in outpatient care settings. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(8):706-715.

8. Hilz MJ. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation - a brief introduction and overview. Auton Neurosci. 2022;243:103038. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2022.103038

9. Pigato G, Rosson S, Bresolin N, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation in treatment-resistant depression: a case series of long-term follow-up. J ECT. 2022. doi:10.1097/YCT.0000000000000869

10. Shivaswamy T, Souza RR, Engineer CT, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation as a treatment for fear and anxiety in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. J Psychiatr Brain Sci. 2022;7(4):e220007. doi:10.20900/jpbs.20220007

11. Wu Y, Song L, Wang X, et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation could improve the effective rate on the quality of sleep in the treatment of primary insomnia: a randomized control trial. Brain Sci. 2022;12(10):1296. doi:10.3390/brainsci12101296

12. Rosa MA, Lisanby SH. Somatic treatments for mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(1):102-116.

13. Mayberg HS, Lozano AM, Voon V, et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron. 2005;45(5):651-660.

14. Choi KS, Mayberg H. Connectomic DBS in major depression. In: Horn A, ed. Connectomic Deep Brain Stimulation. Academic Press; 2022:433-447.

15. Cruz S, Gutiérrez-Rojas L, González-Domenech P, et al. Deep brain stimulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder: results from meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317:114869. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114869

16. Lisoni J, Baldacci G, Nibbio G, et al. Effects of bilateral, bipolar-nonbalanced, frontal transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on negative symptoms and neurocognition in a sample of patients living with schizophrenia: results of a randomized double-blind sham-controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;155:430-442.

17. Sinclair DJ, Zhao S, Qi F, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3(3):CD011847. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011847.pub2

18. Cole EJ, Stimpson KH, Bentzley BS, et al. Stanford accelerated intelligent neuromodulation therapy for treatment-resistant depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(8):716-726.

1. Nasrallah HA. Repositioning psychotherapy as a neurobiological intervention. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(12):18-19.

2. Nasrallah HA. Bipolar disorder: clinical questions beg for answers. Current Psychiatry. 2006;5(12):11-12.

3. UK ECT Review Group. Efficacy and safety of electroconvulsive therapy in depressive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2003;361(9360):799-808.

4. Rhee TG, Shim SR, Forester BP, et al. Efficacy and safety of ketamine vs electroconvulsive therapy among patients with major depressive episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022:e223352. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.3352

5. Nuninga JO, Mandl RCW, Boks MP, et al. Volume increase in the dentate gyrus after electroconvulsive therapy in depressed patients as measured with 7T. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(7):1559-1568.

6. Joshi SH, Espinoza RT, Pirnia T, et al. Structural plasticity of the hippocampus and amygdala induced by electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):282-292.

7. Rhee TG, Olfson M, Nierenberg AA, et al. 20-year trends in the pharmacologic treatment of bipolar disorder by psychiatrists in outpatient care settings. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(8):706-715.

8. Hilz MJ. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation - a brief introduction and overview. Auton Neurosci. 2022;243:103038. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2022.103038

9. Pigato G, Rosson S, Bresolin N, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation in treatment-resistant depression: a case series of long-term follow-up. J ECT. 2022. doi:10.1097/YCT.0000000000000869

10. Shivaswamy T, Souza RR, Engineer CT, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation as a treatment for fear and anxiety in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. J Psychiatr Brain Sci. 2022;7(4):e220007. doi:10.20900/jpbs.20220007

11. Wu Y, Song L, Wang X, et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation could improve the effective rate on the quality of sleep in the treatment of primary insomnia: a randomized control trial. Brain Sci. 2022;12(10):1296. doi:10.3390/brainsci12101296

12. Rosa MA, Lisanby SH. Somatic treatments for mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(1):102-116.

13. Mayberg HS, Lozano AM, Voon V, et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron. 2005;45(5):651-660.

14. Choi KS, Mayberg H. Connectomic DBS in major depression. In: Horn A, ed. Connectomic Deep Brain Stimulation. Academic Press; 2022:433-447.

15. Cruz S, Gutiérrez-Rojas L, González-Domenech P, et al. Deep brain stimulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder: results from meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317:114869. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114869

16. Lisoni J, Baldacci G, Nibbio G, et al. Effects of bilateral, bipolar-nonbalanced, frontal transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on negative symptoms and neurocognition in a sample of patients living with schizophrenia: results of a randomized double-blind sham-controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;155:430-442.

17. Sinclair DJ, Zhao S, Qi F, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3(3):CD011847. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011847.pub2

18. Cole EJ, Stimpson KH, Bentzley BS, et al. Stanford accelerated intelligent neuromodulation therapy for treatment-resistant depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(8):716-726.

More on social entropy

As leaders of the American Psychiatric Association, we received dozens of communications from members who were shocked by the discriminatory and transphobic commentary in the recent editorial “The accelerating societal entropy undermines mental health” (

Specifically, citing “lack of certainty about gender identity in children and adults” as an indicator of societal turmoil that undermines mental health is contrary to the scientific understanding of gender identity. Physicians have professional obligations to advance patients’ well-being and do no harm.

The medical profession, including psychiatry, is at a critical juncture in coming to terms with and dismantling its longstanding history of systemic racism and discrimination. Authors and editors must be aware that harmful and divisive language negatively affects mental health, especially for people who have been subject to discrimination individually and/or as members of historically excluded and/or minoritized groups.

In publishing this editorial,

Rebecca W. Brendel, MD, JD, DFAPA

President

American Psychiatric Association

Saul Levin, MD, MPA, FRCP-E, FRCPsych

CEO and Medical Director

American Psychiatric Association

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this letter, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Nasrallah responds

I regret that the sentence about gender identity in my October editorial was regarded as transphobic and harmful. While the phrasing reflected my patients’ comments to me, I realize my unfortunate choice of words deeply offended individuals who are transgender, who have been subjected to ongoing discrimination and prejudice.

I apologize to our readers; to my American Psychiatric Association LGBTQAI+ friends, colleagues, and relatives; and to the LGBTQAI+ community at large. The sentence has been deleted from the online version of my editorial. This has been a teachable moment for me.

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Editor-In-Chief

Continue to: More on psychiatric documentation

More on psychiatric documentation

Dr. Joshi’s helpful discussion of clinical documentation strategies (“Medical record documentation: What to do, and what to avoid,”

The mental health record may not always be as confidential as psychiatrists think (or hope) it is. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule, for example, generally does not distinguish between medical and mental health information, nor does it provide special rules for the latter (although certain state laws may do so). HIPAA provides added protections for “psychotherapy notes,” but this category explicitly excludes progress notes that discuss treatment modalities, diagnosis, and clinical milestones. To retain their protected status, psychotherapists’ private, “desk-drawer memory joggers” must never be comingled with the patient chart.1 For mental health professionals, this distinction underscores the importance of keeping personal details broad in the progress note; scandalous or embarrassing narratives recounted in the medical record itself are routinely accessible to the patient and may be lawfully disclosed to others under specified circumstances.

In addition to avoiding speculation and including patient quotes when appropriate, documenting objectively and nonjudgmentally means annotating facts and observations that helped the clinician arrive at their conclusion. For example, “patient appears intoxicated” is less helpful than noting the patient’s slurred speech, impaired gait and/or coordination, and alcohol odor.

Clinical care and its associated documentation are so intertwined that they can become virtually indistinguishable. In a medical malpractice case, the burden is on the plaintiff to prove their injury resulted from substandard care. Some courts, however, have held that missing or incomplete records can effectively shift the burden from the recipient to the provider of care to show that the treatment at issue was rendered non-negligently.2 Statutes of limitations restricting the amount of time in which a patient can sue after an adverse event are sometimes triggered by the date on which they knew or should have known of the alleged malpractice.3 One of the best ways of ascertaining this date, and starting the statute of limitations clock, can be a clear annotation in the medical record that the patient was apprised of an unanticipated outcome or iatrogenic harm. In this way, a timely and thorough note can be critical not just to defending the physician’s quality of care, but potentially to precluding a cognizable lawsuit altogether.

Charles G. Kels, JD

Defense Health Agency

San Antonio, Texas

Disclosures

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of any government agency, nor do they constitute individualized legal advice. The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this letter, or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. 45 CFR Parts 160 and 164, Subparts A and E.

2. Valcin v Public Health Trust, 473 So. 2d 1297 (1984).

3. US v Kubrick, 444 US 111 (1979).

As leaders of the American Psychiatric Association, we received dozens of communications from members who were shocked by the discriminatory and transphobic commentary in the recent editorial “The accelerating societal entropy undermines mental health” (

Specifically, citing “lack of certainty about gender identity in children and adults” as an indicator of societal turmoil that undermines mental health is contrary to the scientific understanding of gender identity. Physicians have professional obligations to advance patients’ well-being and do no harm.

The medical profession, including psychiatry, is at a critical juncture in coming to terms with and dismantling its longstanding history of systemic racism and discrimination. Authors and editors must be aware that harmful and divisive language negatively affects mental health, especially for people who have been subject to discrimination individually and/or as members of historically excluded and/or minoritized groups.

In publishing this editorial,

Rebecca W. Brendel, MD, JD, DFAPA

President

American Psychiatric Association

Saul Levin, MD, MPA, FRCP-E, FRCPsych

CEO and Medical Director

American Psychiatric Association

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this letter, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Nasrallah responds

I regret that the sentence about gender identity in my October editorial was regarded as transphobic and harmful. While the phrasing reflected my patients’ comments to me, I realize my unfortunate choice of words deeply offended individuals who are transgender, who have been subjected to ongoing discrimination and prejudice.

I apologize to our readers; to my American Psychiatric Association LGBTQAI+ friends, colleagues, and relatives; and to the LGBTQAI+ community at large. The sentence has been deleted from the online version of my editorial. This has been a teachable moment for me.

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Editor-In-Chief

Continue to: More on psychiatric documentation

More on psychiatric documentation

Dr. Joshi’s helpful discussion of clinical documentation strategies (“Medical record documentation: What to do, and what to avoid,”

The mental health record may not always be as confidential as psychiatrists think (or hope) it is. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule, for example, generally does not distinguish between medical and mental health information, nor does it provide special rules for the latter (although certain state laws may do so). HIPAA provides added protections for “psychotherapy notes,” but this category explicitly excludes progress notes that discuss treatment modalities, diagnosis, and clinical milestones. To retain their protected status, psychotherapists’ private, “desk-drawer memory joggers” must never be comingled with the patient chart.1 For mental health professionals, this distinction underscores the importance of keeping personal details broad in the progress note; scandalous or embarrassing narratives recounted in the medical record itself are routinely accessible to the patient and may be lawfully disclosed to others under specified circumstances.

In addition to avoiding speculation and including patient quotes when appropriate, documenting objectively and nonjudgmentally means annotating facts and observations that helped the clinician arrive at their conclusion. For example, “patient appears intoxicated” is less helpful than noting the patient’s slurred speech, impaired gait and/or coordination, and alcohol odor.

Clinical care and its associated documentation are so intertwined that they can become virtually indistinguishable. In a medical malpractice case, the burden is on the plaintiff to prove their injury resulted from substandard care. Some courts, however, have held that missing or incomplete records can effectively shift the burden from the recipient to the provider of care to show that the treatment at issue was rendered non-negligently.2 Statutes of limitations restricting the amount of time in which a patient can sue after an adverse event are sometimes triggered by the date on which they knew or should have known of the alleged malpractice.3 One of the best ways of ascertaining this date, and starting the statute of limitations clock, can be a clear annotation in the medical record that the patient was apprised of an unanticipated outcome or iatrogenic harm. In this way, a timely and thorough note can be critical not just to defending the physician’s quality of care, but potentially to precluding a cognizable lawsuit altogether.

Charles G. Kels, JD

Defense Health Agency

San Antonio, Texas

Disclosures

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of any government agency, nor do they constitute individualized legal advice. The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this letter, or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. 45 CFR Parts 160 and 164, Subparts A and E.

2. Valcin v Public Health Trust, 473 So. 2d 1297 (1984).

3. US v Kubrick, 444 US 111 (1979).

As leaders of the American Psychiatric Association, we received dozens of communications from members who were shocked by the discriminatory and transphobic commentary in the recent editorial “The accelerating societal entropy undermines mental health” (

Specifically, citing “lack of certainty about gender identity in children and adults” as an indicator of societal turmoil that undermines mental health is contrary to the scientific understanding of gender identity. Physicians have professional obligations to advance patients’ well-being and do no harm.

The medical profession, including psychiatry, is at a critical juncture in coming to terms with and dismantling its longstanding history of systemic racism and discrimination. Authors and editors must be aware that harmful and divisive language negatively affects mental health, especially for people who have been subject to discrimination individually and/or as members of historically excluded and/or minoritized groups.

In publishing this editorial,

Rebecca W. Brendel, MD, JD, DFAPA

President

American Psychiatric Association

Saul Levin, MD, MPA, FRCP-E, FRCPsych

CEO and Medical Director

American Psychiatric Association

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this letter, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Nasrallah responds

I regret that the sentence about gender identity in my October editorial was regarded as transphobic and harmful. While the phrasing reflected my patients’ comments to me, I realize my unfortunate choice of words deeply offended individuals who are transgender, who have been subjected to ongoing discrimination and prejudice.

I apologize to our readers; to my American Psychiatric Association LGBTQAI+ friends, colleagues, and relatives; and to the LGBTQAI+ community at large. The sentence has been deleted from the online version of my editorial. This has been a teachable moment for me.

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Editor-In-Chief

Continue to: More on psychiatric documentation

More on psychiatric documentation

Dr. Joshi’s helpful discussion of clinical documentation strategies (“Medical record documentation: What to do, and what to avoid,”

The mental health record may not always be as confidential as psychiatrists think (or hope) it is. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule, for example, generally does not distinguish between medical and mental health information, nor does it provide special rules for the latter (although certain state laws may do so). HIPAA provides added protections for “psychotherapy notes,” but this category explicitly excludes progress notes that discuss treatment modalities, diagnosis, and clinical milestones. To retain their protected status, psychotherapists’ private, “desk-drawer memory joggers” must never be comingled with the patient chart.1 For mental health professionals, this distinction underscores the importance of keeping personal details broad in the progress note; scandalous or embarrassing narratives recounted in the medical record itself are routinely accessible to the patient and may be lawfully disclosed to others under specified circumstances.

In addition to avoiding speculation and including patient quotes when appropriate, documenting objectively and nonjudgmentally means annotating facts and observations that helped the clinician arrive at their conclusion. For example, “patient appears intoxicated” is less helpful than noting the patient’s slurred speech, impaired gait and/or coordination, and alcohol odor.

Clinical care and its associated documentation are so intertwined that they can become virtually indistinguishable. In a medical malpractice case, the burden is on the plaintiff to prove their injury resulted from substandard care. Some courts, however, have held that missing or incomplete records can effectively shift the burden from the recipient to the provider of care to show that the treatment at issue was rendered non-negligently.2 Statutes of limitations restricting the amount of time in which a patient can sue after an adverse event are sometimes triggered by the date on which they knew or should have known of the alleged malpractice.3 One of the best ways of ascertaining this date, and starting the statute of limitations clock, can be a clear annotation in the medical record that the patient was apprised of an unanticipated outcome or iatrogenic harm. In this way, a timely and thorough note can be critical not just to defending the physician’s quality of care, but potentially to precluding a cognizable lawsuit altogether.

Charles G. Kels, JD

Defense Health Agency

San Antonio, Texas

Disclosures

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of any government agency, nor do they constitute individualized legal advice. The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this letter, or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. 45 CFR Parts 160 and 164, Subparts A and E.

2. Valcin v Public Health Trust, 473 So. 2d 1297 (1984).

3. US v Kubrick, 444 US 111 (1979).

Should residents be taught how to prescribe monoamine oxidase inhibitors?

What else can I offer this patient?

This thought passed through my mind as the patient’s desperation grew palpable. He had experienced intractable major depressive disorder (MDD) for years and had exhausted multiple classes of antidepressants, trying various combinations without any relief.

The previous resident had arranged for intranasal ketamine treatment, but the patient was unable to receive it due to lack of transportation. As I combed through the list of the dozens of medications the patient previously had been prescribed, I noticed the absence of a certain class of agents: monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs).

My knowledge of MAOIs stemmed from medical school, where the dietary restrictions, potential for hypertensive crisis, and capricious drug-drug interactions were heavily emphasized while their value was minimized. I did not have any practical experience with these medications, and even the attending physician disclosed he had not prescribed an MAOI in more than 30 years. Nonetheless, both the attending physician and patient agreed that the patient would try one.

Following a washout period, the patient began tranylcypromine. After taking tranylcypromine 40 mg/d for 3 months, he reported he felt like a weight had been lifted off his chest. He felt less irritable and depressed, more energetic, and more hopeful for the future. He also felt that his symptoms were improving for the first time in many years.

An older but still potentially helpful class of medications

MDD is one of the leading causes of disability in the United States, affecting millions of people. Its economic burden is estimated to be more than $200 billion, with a large contingent consisting of direct medical cost and suicide-related costs.1 MDD is often recurrent—60% of patients experience another episode within 5 years.2 Most of these patients are classified as having treatment-resistant depression (TRD), which typically is defined as the failure to respond to 2 different medications given at adequate doses for a sufficient duration.3 The Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression trial suggested that after each medication failure, depression becomes increasingly difficult to treat, with many patients developing TRD.4 For some patients with TRD, MAOIs may be a powerful and beneficial option.5,6 Studies have shown that MAOIs (at adequate doses) can be effective in approximately one-half of patients with TRD. Patients with anxious, endogenous, or atypical depression may also respond to MAOIs.7

MAOIs were among the earliest antidepressants on the market, starting in the late 1950s with isocarboxazid, phenelzine, tranylcypromine, and selegiline. The use of MAOIs as a treatment for depression was serendipitously discovered when iproniazid, a tuberculosis drug, was observed to have mood-elevating adverse effects that were explained by its monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitory properties.8 This sparked the hypothesis that a deficiency in serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine played a central role in depressive disorders. MAOs encompass a class of enzymes that metabolize catecholamines, which include the previously mentioned neurotransmitters and the trace amine tyramine. The MAO isoenzymes also inhabit many tissues, including the central and peripheral nervous system, liver, and intestines.

There are 2 subtypes of MAOs: MAO-A and MAO-B. MAO-A inhibits tyramine, serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. MAO-B is mainly responsible for the degradation of dopamine, which makes MAO-B inhibitors (ie, rasagiline) useful in treating Parkinson disease.9

Continue to: For most psychiatrists...

For most psychiatrists, MAOIs have fallen out of favor due to their discomfort with their potential adverse effects and drug-drug interactions, the dietary restrictions patients must face, and the perception that newer medications have fewer adverse effects.10 Prescribing an MAOI requires the clinician to remain vigilant of any new medication the patient is taking that may potentiate intrasynaptic serotonin, which may include certain antibiotics or analgesics, causing serotonin syndrome. Close monitoring of the patient’s diet also is necessary so the patient avoids foods rich in tyramine that may trigger a hypertensive crisis. This is because excess tyramine can precipitate an increase in catecholamine release, causing a dangerous increase in blood pressure. However, many foods have safe levels of tyramine (<6 mg/serving), although the perception of tyramine levels in modern foods remains overestimated.5

Residents need to know how to use MAOIs

Psychiatrists should weigh the risks and benefits prior to prescribing any new medication, and MAOIs should be no exception. A patient’s enduring pain is often overshadowed by the potential for adverse effects, which occasionally is overemphasized. Other treatments for severe psychiatric illnesses (such as lithium and clozapine) are also declining due to these agents’ requirement for cumbersome monitoring and potential for adverse effects despite evidence of their superior efficacy and antisuicidal properties.11,12

Fortunately, there are many novel therapies available that can be effective for patients with TRD, including transcranial magnetic stimulation, ketamine, and vagal nerve stimulation. However, as psychiatrists, especially during training, our armamentarium should be equipped with all modalities of psychopharmacology. Training and teaching residents to prescribe MAOIs safely and effectively may add a glimmer of hope for an otherwise hopeless patient.

1. Greenberg PE, Fournier AA, Sisitsky T, et al. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2010 and 2018). Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39(6):653-665.

2. Hardeveld F, Spijker J, De Graaf R, et al. Prevalence and predictors of recurrence of major depressive disorder in the adult population. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;122(3):184-191.

3. Gaynes BN, Lux L, Gartlehner G, et al. Defining treatment-resistant depression. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37(2):134-145.

4. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):28-40.

5. Fiedorowicz JG, Swartz KL. The role of monoamine oxidase inhibitors in current psychiatric practice. J Psychiatr Pract. 2004;10(4):239-248.

6. Amsterdam JD, Shults J. MAOI efficacy and safety in advanced stage treatment-resistant depression--a retrospective study. J Affect Disord. 2005;89(1-3):183-188.

7. Amsterdam JD, Hornig-Rohan M. Treatment algorithms in treatment-resistant depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1996;19(2):371-386.

8. Ramachandraih CT, Subramanyam N, Bar KJ, et al. Antidepressants: from MAOIs to SSRIs and more. Indian J Psychiatry. 2011;53(2):180-182.

9. Tipton KF. 90 years of monoamine oxidase: some progress and some confusion. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2018;125(11):1519-1551.

10. Gillman PK, Feinberg SS, Fochtmann LJ. Revitalizing monoamine oxidase inhibitors: a call for action. CNS Spectr. 2020;25(4):452-454.

11. Kelly DL, Wehring HJ, Vyas G. Current status of clozapine in the United States. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2012;24(2):110-113.

12. Tibrewal P, Ng T, Bastiampillai T, et al. Why is lithium use declining? Asian J Psychiatr. 2019;43:219-220.

What else can I offer this patient?

This thought passed through my mind as the patient’s desperation grew palpable. He had experienced intractable major depressive disorder (MDD) for years and had exhausted multiple classes of antidepressants, trying various combinations without any relief.

The previous resident had arranged for intranasal ketamine treatment, but the patient was unable to receive it due to lack of transportation. As I combed through the list of the dozens of medications the patient previously had been prescribed, I noticed the absence of a certain class of agents: monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs).

My knowledge of MAOIs stemmed from medical school, where the dietary restrictions, potential for hypertensive crisis, and capricious drug-drug interactions were heavily emphasized while their value was minimized. I did not have any practical experience with these medications, and even the attending physician disclosed he had not prescribed an MAOI in more than 30 years. Nonetheless, both the attending physician and patient agreed that the patient would try one.

Following a washout period, the patient began tranylcypromine. After taking tranylcypromine 40 mg/d for 3 months, he reported he felt like a weight had been lifted off his chest. He felt less irritable and depressed, more energetic, and more hopeful for the future. He also felt that his symptoms were improving for the first time in many years.

An older but still potentially helpful class of medications

MDD is one of the leading causes of disability in the United States, affecting millions of people. Its economic burden is estimated to be more than $200 billion, with a large contingent consisting of direct medical cost and suicide-related costs.1 MDD is often recurrent—60% of patients experience another episode within 5 years.2 Most of these patients are classified as having treatment-resistant depression (TRD), which typically is defined as the failure to respond to 2 different medications given at adequate doses for a sufficient duration.3 The Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression trial suggested that after each medication failure, depression becomes increasingly difficult to treat, with many patients developing TRD.4 For some patients with TRD, MAOIs may be a powerful and beneficial option.5,6 Studies have shown that MAOIs (at adequate doses) can be effective in approximately one-half of patients with TRD. Patients with anxious, endogenous, or atypical depression may also respond to MAOIs.7

MAOIs were among the earliest antidepressants on the market, starting in the late 1950s with isocarboxazid, phenelzine, tranylcypromine, and selegiline. The use of MAOIs as a treatment for depression was serendipitously discovered when iproniazid, a tuberculosis drug, was observed to have mood-elevating adverse effects that were explained by its monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitory properties.8 This sparked the hypothesis that a deficiency in serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine played a central role in depressive disorders. MAOs encompass a class of enzymes that metabolize catecholamines, which include the previously mentioned neurotransmitters and the trace amine tyramine. The MAO isoenzymes also inhabit many tissues, including the central and peripheral nervous system, liver, and intestines.

There are 2 subtypes of MAOs: MAO-A and MAO-B. MAO-A inhibits tyramine, serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. MAO-B is mainly responsible for the degradation of dopamine, which makes MAO-B inhibitors (ie, rasagiline) useful in treating Parkinson disease.9

Continue to: For most psychiatrists...