User login

Multiple Myeloma: New Treatments Aid Patient Subgroups

“The introduction of treatments such as elranatamab (Elrexfio) is allowing patients with multiple myeloma, which is still incurable for now, to have different options and achieve long periods of remission, thus improving their survival,” she added. “This therapeutic innovation is highly effective and well tolerated in patients with relapse or refractory multiple myeloma.” The overall response rate is “up to 61%, early, deep, and long-lasting.”

In an interview with El Médico Interactivo, Dr. Mateos explained the new approaches to multiple myeloma. She highlighted the effectiveness of new treatments and reviewed the latest data on this disease, which were presented at the recent European Hematology Association Congress.

What is the incidence rate of multiple myeloma in the Spanish population?

Multiple myeloma has an incidence of approximately 4-5 new cases per 100,000 inhabitants per year. This means that around 3000 new cases are diagnosed each year in Spain. As with most tumors, multiple myeloma is generally slightly more common in males than females. It is the third most frequent hematologic cancer in men (1757 new cases) and women (1325 new cases), behind lymphoma and leukemias.

At what age is it most often diagnosed?

It affects older people, with recent reports indicating around 68-69 years as the median age. Although more young people are being diagnosed with multiple myeloma, analyses of how this hematologic cancer affects the general population show that it generally impacts patients over age 65 years.

What is the typical survival prognosis?

Thanks to research and therapeutic innovation, the prognosis has changed significantly over the past 20-25 years. Today, if a patient with multiple myeloma receives a diagnosis and does not exhibit poor prognostic characteristics (and this description fits approximately 70%-80% of patients with multiple myeloma), it is realistic to expect a survival exceeding 10 years. A few years ago, this outcome was unimaginable, but a significant amount of therapeutic innovation has made it possible. That’s why I emphasize that it is realistic to provide these data with such a positive outlook.

Is multiple myeloma a refractory type of cancer?

It was a refractory type of cancer. Twenty years ago, there were no treatment options, and therefore survival was around 2-3 years, because treatment mainly consisted of using alkylating agents and corticosteroids. This is what made it refractory.

With the emergence of new therapeutic innovations, patients have been responding better and their responses are lasting longer. Although there is still a group of patients, about 10%-15%, with a poor prognosis and refractory disease, those with standard risk are responding better to different therapies.

Although most patients will eventually exhaust the treatments, which until now were primarily triple-drug regimens (such as proteasome inhibitors, immunomodulators, and antiCD38 antibodies), the introduction of new therapies is extending the duration of responses.

Is the risk for relapse high?

It is very high, in the sense that almost all patients with multiple myeloma eventually relapse. However, we hope that there soon will be some patients who do not relapse.

What are the typical pathologic manifestations of this cancer? Does it affect everyone equally, or in specific ways in each person?

In multiple myeloma, we often say there are multiple myelomas. Clinically, the disease presents in most patients, around 80%, with two clinical manifestations: anemia and bone lesions. Less frequently, patients may also have kidney failure, hypercalcemia, and a higher tendency toward infection. Behind this rather common symptomatology, from a molecular and genetic perspective, each myeloma is practically unique, adding complexity to its treatment. Therefore, ultimately, myelomas end up being refractory.

Elranatamab is a new therapeutic tool. For which patients is it recommended?

It is a bispecific monoclonal antibody that corresponds to the new monotherapy strategies we have for treating patients with multiple myeloma. On the one hand, it targets damaged plasma cells, which are the patient’s tumor cells, and on the other, it binds the patient’s T cells and redirects them to the tumor niche. When this happens, the T cell activates and destroys the tumor cell.

This medication has been approved for patients with relapsed myeloma who have received traditional drugs for their treatment. We know well that patients who have already received proteasome inhibitors, immunomodulators, and anti-CD38 antibodies typically need something new after treatment. Before, there were no other options, and we would reuse what had been previously used. Now we have elranatamab, a bispecific monoclonal antibody targeting a new receptor that has shown significant responses as monotherapy.

More than 60% of patients respond, and more than 30% achieve complete remission. The key is the response duration and progression-free survival of almost a year and a half. This is the longest progression-free survival we have seen to date in previous lines. Therefore, it fills the needs we had for these relapsed or refractory myeloma patients.

What advantages does this new treatment offer?

It represents a therapeutic innovation because, as mentioned, it achieves a response in more than 60% of patients, and around 35% achieve complete remission. The median response duration has not been reached yet. Progression-free survival is 17.2 months, almost a year and a half, and overall survival is almost two years.

Furthermore, it is administered as subcutaneous monotherapy weekly for the first six cycles and then every 15 days. It has a good safety profile, although some adverse events are known, so we have strategies to combat or mitigate them, making the treatment generally well tolerated.

What side effects are being observed?

They are manageable. When the drug is first administered, patients may experience what we call a cytokine release syndrome, which is a result of the treatment’s mechanism. However, we can predict very well when it occurs, usually 2 days after the first doses, and we have strategies to mitigate it.

The second most common adverse event we need to be cautious about is infection. Nowadays, before starting treatment, patients update their vaccination schedule, receive antiviral prophylaxis, and receive prophylaxis against certain germs, resulting in reduced infections. However, infections are probably the adverse events we need to be most careful about when treating the patient.

We must ensure that prophylaxis is performed, and if fever occurs and an infection is suspected, cultures and all kinds of studies must be done to identify and treat it properly.

How does elranatamab change the treatment of an incurable disease? Does it bring us closer to a cure or to making multiple myeloma a manageable chronic disease?

With the already approved elranatamab, the most important aspect is that it adds another treatment option for patients with myeloma. With the progression-free survival data I indicated, life expectancy is increased, with a good quality of life and acceptable safety.

Obviously, elranatamab is still under study and development, even in early lines, including in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma. When we are choosing first-line therapy, we select the best patients by combining traditional drugs with these new immunotherapies, such as elranatamab, it is likely that we are much closer to offering a cure to specific subgroups.

Although it won’t happen in all cases, I believe it will be applicable to a significant subgroup of patients, making chronicity of the disease a reality we are already approaching. Each day, we encounter more patients receiving different lines of treatment and ultimately meeting their life expectancy with myeloma. Even though some may die, it is often due to causes not related to myeloma. This is the most important contribution of these innovations, such as elranatamab.

Dr. Mateos reported receiving honoraria from Janssen, Celgene, Takeda, Amgen, GSK, AbbVie, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi, Stemline, Oncopeptides, and Kite for delivering lectures and for participating in advisory boards.

This story was translated from El Médico Interactivo, which is part of the Medscape professional network, using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

“The introduction of treatments such as elranatamab (Elrexfio) is allowing patients with multiple myeloma, which is still incurable for now, to have different options and achieve long periods of remission, thus improving their survival,” she added. “This therapeutic innovation is highly effective and well tolerated in patients with relapse or refractory multiple myeloma.” The overall response rate is “up to 61%, early, deep, and long-lasting.”

In an interview with El Médico Interactivo, Dr. Mateos explained the new approaches to multiple myeloma. She highlighted the effectiveness of new treatments and reviewed the latest data on this disease, which were presented at the recent European Hematology Association Congress.

What is the incidence rate of multiple myeloma in the Spanish population?

Multiple myeloma has an incidence of approximately 4-5 new cases per 100,000 inhabitants per year. This means that around 3000 new cases are diagnosed each year in Spain. As with most tumors, multiple myeloma is generally slightly more common in males than females. It is the third most frequent hematologic cancer in men (1757 new cases) and women (1325 new cases), behind lymphoma and leukemias.

At what age is it most often diagnosed?

It affects older people, with recent reports indicating around 68-69 years as the median age. Although more young people are being diagnosed with multiple myeloma, analyses of how this hematologic cancer affects the general population show that it generally impacts patients over age 65 years.

What is the typical survival prognosis?

Thanks to research and therapeutic innovation, the prognosis has changed significantly over the past 20-25 years. Today, if a patient with multiple myeloma receives a diagnosis and does not exhibit poor prognostic characteristics (and this description fits approximately 70%-80% of patients with multiple myeloma), it is realistic to expect a survival exceeding 10 years. A few years ago, this outcome was unimaginable, but a significant amount of therapeutic innovation has made it possible. That’s why I emphasize that it is realistic to provide these data with such a positive outlook.

Is multiple myeloma a refractory type of cancer?

It was a refractory type of cancer. Twenty years ago, there were no treatment options, and therefore survival was around 2-3 years, because treatment mainly consisted of using alkylating agents and corticosteroids. This is what made it refractory.

With the emergence of new therapeutic innovations, patients have been responding better and their responses are lasting longer. Although there is still a group of patients, about 10%-15%, with a poor prognosis and refractory disease, those with standard risk are responding better to different therapies.

Although most patients will eventually exhaust the treatments, which until now were primarily triple-drug regimens (such as proteasome inhibitors, immunomodulators, and antiCD38 antibodies), the introduction of new therapies is extending the duration of responses.

Is the risk for relapse high?

It is very high, in the sense that almost all patients with multiple myeloma eventually relapse. However, we hope that there soon will be some patients who do not relapse.

What are the typical pathologic manifestations of this cancer? Does it affect everyone equally, or in specific ways in each person?

In multiple myeloma, we often say there are multiple myelomas. Clinically, the disease presents in most patients, around 80%, with two clinical manifestations: anemia and bone lesions. Less frequently, patients may also have kidney failure, hypercalcemia, and a higher tendency toward infection. Behind this rather common symptomatology, from a molecular and genetic perspective, each myeloma is practically unique, adding complexity to its treatment. Therefore, ultimately, myelomas end up being refractory.

Elranatamab is a new therapeutic tool. For which patients is it recommended?

It is a bispecific monoclonal antibody that corresponds to the new monotherapy strategies we have for treating patients with multiple myeloma. On the one hand, it targets damaged plasma cells, which are the patient’s tumor cells, and on the other, it binds the patient’s T cells and redirects them to the tumor niche. When this happens, the T cell activates and destroys the tumor cell.

This medication has been approved for patients with relapsed myeloma who have received traditional drugs for their treatment. We know well that patients who have already received proteasome inhibitors, immunomodulators, and anti-CD38 antibodies typically need something new after treatment. Before, there were no other options, and we would reuse what had been previously used. Now we have elranatamab, a bispecific monoclonal antibody targeting a new receptor that has shown significant responses as monotherapy.

More than 60% of patients respond, and more than 30% achieve complete remission. The key is the response duration and progression-free survival of almost a year and a half. This is the longest progression-free survival we have seen to date in previous lines. Therefore, it fills the needs we had for these relapsed or refractory myeloma patients.

What advantages does this new treatment offer?

It represents a therapeutic innovation because, as mentioned, it achieves a response in more than 60% of patients, and around 35% achieve complete remission. The median response duration has not been reached yet. Progression-free survival is 17.2 months, almost a year and a half, and overall survival is almost two years.

Furthermore, it is administered as subcutaneous monotherapy weekly for the first six cycles and then every 15 days. It has a good safety profile, although some adverse events are known, so we have strategies to combat or mitigate them, making the treatment generally well tolerated.

What side effects are being observed?

They are manageable. When the drug is first administered, patients may experience what we call a cytokine release syndrome, which is a result of the treatment’s mechanism. However, we can predict very well when it occurs, usually 2 days after the first doses, and we have strategies to mitigate it.

The second most common adverse event we need to be cautious about is infection. Nowadays, before starting treatment, patients update their vaccination schedule, receive antiviral prophylaxis, and receive prophylaxis against certain germs, resulting in reduced infections. However, infections are probably the adverse events we need to be most careful about when treating the patient.

We must ensure that prophylaxis is performed, and if fever occurs and an infection is suspected, cultures and all kinds of studies must be done to identify and treat it properly.

How does elranatamab change the treatment of an incurable disease? Does it bring us closer to a cure or to making multiple myeloma a manageable chronic disease?

With the already approved elranatamab, the most important aspect is that it adds another treatment option for patients with myeloma. With the progression-free survival data I indicated, life expectancy is increased, with a good quality of life and acceptable safety.

Obviously, elranatamab is still under study and development, even in early lines, including in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma. When we are choosing first-line therapy, we select the best patients by combining traditional drugs with these new immunotherapies, such as elranatamab, it is likely that we are much closer to offering a cure to specific subgroups.

Although it won’t happen in all cases, I believe it will be applicable to a significant subgroup of patients, making chronicity of the disease a reality we are already approaching. Each day, we encounter more patients receiving different lines of treatment and ultimately meeting their life expectancy with myeloma. Even though some may die, it is often due to causes not related to myeloma. This is the most important contribution of these innovations, such as elranatamab.

Dr. Mateos reported receiving honoraria from Janssen, Celgene, Takeda, Amgen, GSK, AbbVie, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi, Stemline, Oncopeptides, and Kite for delivering lectures and for participating in advisory boards.

This story was translated from El Médico Interactivo, which is part of the Medscape professional network, using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

“The introduction of treatments such as elranatamab (Elrexfio) is allowing patients with multiple myeloma, which is still incurable for now, to have different options and achieve long periods of remission, thus improving their survival,” she added. “This therapeutic innovation is highly effective and well tolerated in patients with relapse or refractory multiple myeloma.” The overall response rate is “up to 61%, early, deep, and long-lasting.”

In an interview with El Médico Interactivo, Dr. Mateos explained the new approaches to multiple myeloma. She highlighted the effectiveness of new treatments and reviewed the latest data on this disease, which were presented at the recent European Hematology Association Congress.

What is the incidence rate of multiple myeloma in the Spanish population?

Multiple myeloma has an incidence of approximately 4-5 new cases per 100,000 inhabitants per year. This means that around 3000 new cases are diagnosed each year in Spain. As with most tumors, multiple myeloma is generally slightly more common in males than females. It is the third most frequent hematologic cancer in men (1757 new cases) and women (1325 new cases), behind lymphoma and leukemias.

At what age is it most often diagnosed?

It affects older people, with recent reports indicating around 68-69 years as the median age. Although more young people are being diagnosed with multiple myeloma, analyses of how this hematologic cancer affects the general population show that it generally impacts patients over age 65 years.

What is the typical survival prognosis?

Thanks to research and therapeutic innovation, the prognosis has changed significantly over the past 20-25 years. Today, if a patient with multiple myeloma receives a diagnosis and does not exhibit poor prognostic characteristics (and this description fits approximately 70%-80% of patients with multiple myeloma), it is realistic to expect a survival exceeding 10 years. A few years ago, this outcome was unimaginable, but a significant amount of therapeutic innovation has made it possible. That’s why I emphasize that it is realistic to provide these data with such a positive outlook.

Is multiple myeloma a refractory type of cancer?

It was a refractory type of cancer. Twenty years ago, there were no treatment options, and therefore survival was around 2-3 years, because treatment mainly consisted of using alkylating agents and corticosteroids. This is what made it refractory.

With the emergence of new therapeutic innovations, patients have been responding better and their responses are lasting longer. Although there is still a group of patients, about 10%-15%, with a poor prognosis and refractory disease, those with standard risk are responding better to different therapies.

Although most patients will eventually exhaust the treatments, which until now were primarily triple-drug regimens (such as proteasome inhibitors, immunomodulators, and antiCD38 antibodies), the introduction of new therapies is extending the duration of responses.

Is the risk for relapse high?

It is very high, in the sense that almost all patients with multiple myeloma eventually relapse. However, we hope that there soon will be some patients who do not relapse.

What are the typical pathologic manifestations of this cancer? Does it affect everyone equally, or in specific ways in each person?

In multiple myeloma, we often say there are multiple myelomas. Clinically, the disease presents in most patients, around 80%, with two clinical manifestations: anemia and bone lesions. Less frequently, patients may also have kidney failure, hypercalcemia, and a higher tendency toward infection. Behind this rather common symptomatology, from a molecular and genetic perspective, each myeloma is practically unique, adding complexity to its treatment. Therefore, ultimately, myelomas end up being refractory.

Elranatamab is a new therapeutic tool. For which patients is it recommended?

It is a bispecific monoclonal antibody that corresponds to the new monotherapy strategies we have for treating patients with multiple myeloma. On the one hand, it targets damaged plasma cells, which are the patient’s tumor cells, and on the other, it binds the patient’s T cells and redirects them to the tumor niche. When this happens, the T cell activates and destroys the tumor cell.

This medication has been approved for patients with relapsed myeloma who have received traditional drugs for their treatment. We know well that patients who have already received proteasome inhibitors, immunomodulators, and anti-CD38 antibodies typically need something new after treatment. Before, there were no other options, and we would reuse what had been previously used. Now we have elranatamab, a bispecific monoclonal antibody targeting a new receptor that has shown significant responses as monotherapy.

More than 60% of patients respond, and more than 30% achieve complete remission. The key is the response duration and progression-free survival of almost a year and a half. This is the longest progression-free survival we have seen to date in previous lines. Therefore, it fills the needs we had for these relapsed or refractory myeloma patients.

What advantages does this new treatment offer?

It represents a therapeutic innovation because, as mentioned, it achieves a response in more than 60% of patients, and around 35% achieve complete remission. The median response duration has not been reached yet. Progression-free survival is 17.2 months, almost a year and a half, and overall survival is almost two years.

Furthermore, it is administered as subcutaneous monotherapy weekly for the first six cycles and then every 15 days. It has a good safety profile, although some adverse events are known, so we have strategies to combat or mitigate them, making the treatment generally well tolerated.

What side effects are being observed?

They are manageable. When the drug is first administered, patients may experience what we call a cytokine release syndrome, which is a result of the treatment’s mechanism. However, we can predict very well when it occurs, usually 2 days after the first doses, and we have strategies to mitigate it.

The second most common adverse event we need to be cautious about is infection. Nowadays, before starting treatment, patients update their vaccination schedule, receive antiviral prophylaxis, and receive prophylaxis against certain germs, resulting in reduced infections. However, infections are probably the adverse events we need to be most careful about when treating the patient.

We must ensure that prophylaxis is performed, and if fever occurs and an infection is suspected, cultures and all kinds of studies must be done to identify and treat it properly.

How does elranatamab change the treatment of an incurable disease? Does it bring us closer to a cure or to making multiple myeloma a manageable chronic disease?

With the already approved elranatamab, the most important aspect is that it adds another treatment option for patients with myeloma. With the progression-free survival data I indicated, life expectancy is increased, with a good quality of life and acceptable safety.

Obviously, elranatamab is still under study and development, even in early lines, including in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma. When we are choosing first-line therapy, we select the best patients by combining traditional drugs with these new immunotherapies, such as elranatamab, it is likely that we are much closer to offering a cure to specific subgroups.

Although it won’t happen in all cases, I believe it will be applicable to a significant subgroup of patients, making chronicity of the disease a reality we are already approaching. Each day, we encounter more patients receiving different lines of treatment and ultimately meeting their life expectancy with myeloma. Even though some may die, it is often due to causes not related to myeloma. This is the most important contribution of these innovations, such as elranatamab.

Dr. Mateos reported receiving honoraria from Janssen, Celgene, Takeda, Amgen, GSK, AbbVie, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi, Stemline, Oncopeptides, and Kite for delivering lectures and for participating in advisory boards.

This story was translated from El Médico Interactivo, which is part of the Medscape professional network, using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

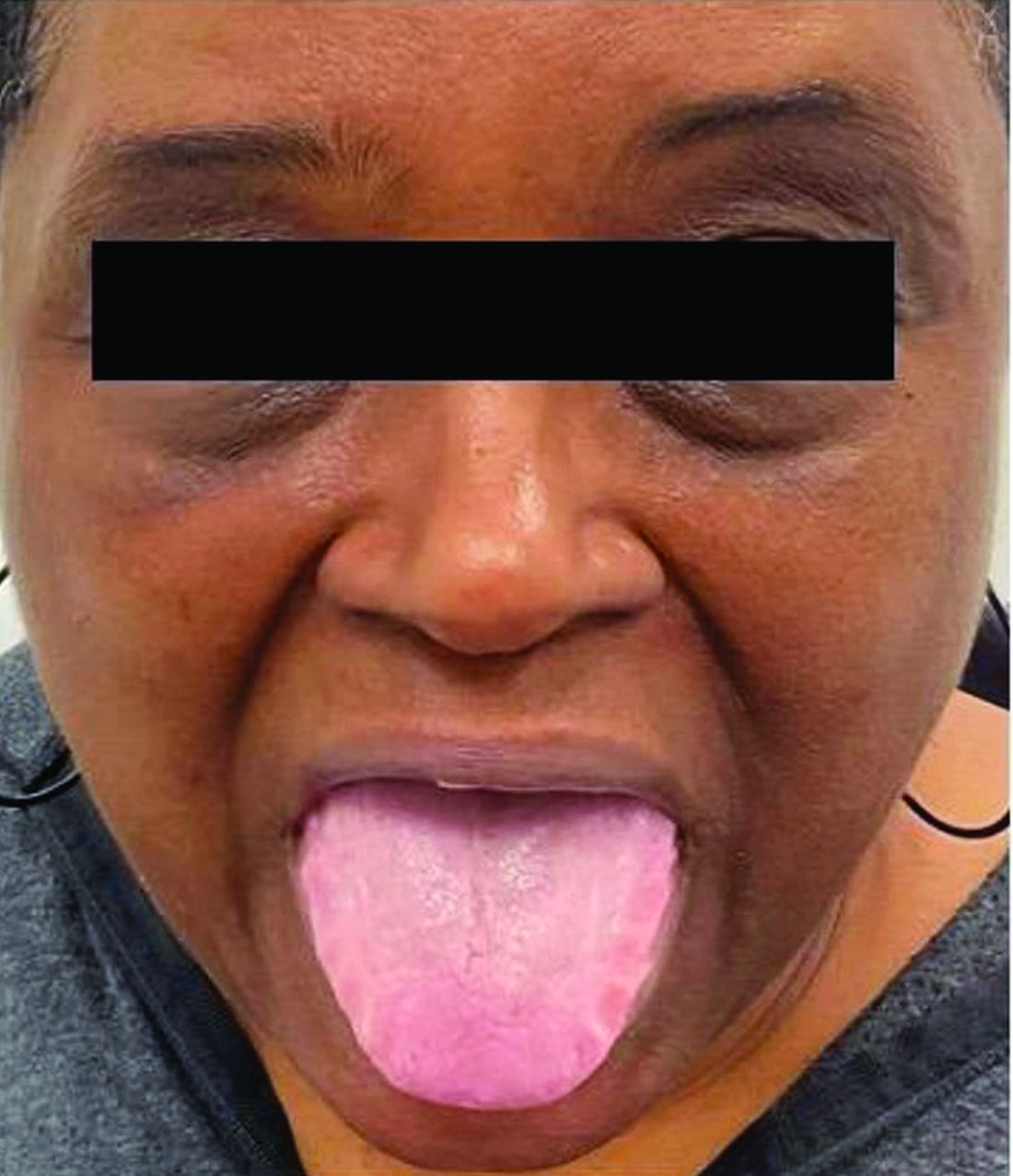

A 62-year-old Black female presented with an epidermal inclusion cyst on her left upper back

This heterogeneous disorder can present with a wide range of clinical manifestations, including dermatological symptoms that may be the first or predominant feature. Systemic amyloidosis is characterized by macroglossia, periorbital purpura, and waxy skin plaques. Lateral scalloping of the tongue may be seen due to impingement of the teeth. Cutaneous amyloidosis occurs when amyloid is deposited in the skin, without internal organ involvement. Variants of cutaneous amyloidosis include macular, lichen, nodular and biphasic.

This condition requires a thorough diagnostic workup, including serum and urine protein electrophoresis and biopsy of the affected tissue. Biopsy of a cutaneous amyloidosis lesion will show fractured, amorphous, eosinophilic material in the dermis. Pigment and epidermal changes are often found with cutaneous amyloidosis, including hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, hypergranulosis, parakeratosis, and epidermal atrophy. Stains that may be used include Congo red showing apple-green birefringence, thioflavin T, and crystal violet.

If untreated, the prognosis is generally poor, related to the extent of organ involvement. Cardiac involvement, a common feature of systemic amyloidosis, can lead to restrictive cardiomyopathy, heart failure, and arrhythmias. Management strategies include steroids, chemotherapy, and stem cell transplantation. Medications include dexamethasone, cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and melphalan.

This patient went undiagnosed for several years until she began experiencing cardiac issues, including syncope, angina, and restrictive cardiomyopathy with heart failure. A cardiac biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of systemic amyloidosis. This patient is currently awaiting a heart transplant. Early diagnosis of amyloidosis is vital, as it can help prevent severe complications such as heart involvement, significantly impacting the patient’s prognosis and quality of life. When amyloidosis is suspected based on dermatological findings, it is essential to distinguish it from other conditions, such as chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, scleromyxedema, and lipoid proteinosis. Early identification of characteristic skin lesions and systemic features can lead to timely interventions, more favorable outcomes, and reduction in the risk of advanced organ damage.

The case and photo were submitted by Ms. Cael Aoki and Mr. Shapiro of Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Davie, Florida, and Dr. Bartos, of Imperial Dermatology, Hollywood, Florida. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Florida. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Brunt EM, Tiniakos DG. Clin Liver Dis. 2004 Nov;8(4):915-30, x. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2004.06.009.

2. Bolognia JL et al. (2017). Dermatology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences.

3. Mehrotra K et al. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017 Aug;11(8):WC01-WC05. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/24273.10334.

4. Banypersad SM et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012 Apr;1(2):e000364. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.111.000364.

5. Bustamante JG, Zaidi SRH. Amyloidosis. [Updated 2023 Jul 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

This heterogeneous disorder can present with a wide range of clinical manifestations, including dermatological symptoms that may be the first or predominant feature. Systemic amyloidosis is characterized by macroglossia, periorbital purpura, and waxy skin plaques. Lateral scalloping of the tongue may be seen due to impingement of the teeth. Cutaneous amyloidosis occurs when amyloid is deposited in the skin, without internal organ involvement. Variants of cutaneous amyloidosis include macular, lichen, nodular and biphasic.

This condition requires a thorough diagnostic workup, including serum and urine protein electrophoresis and biopsy of the affected tissue. Biopsy of a cutaneous amyloidosis lesion will show fractured, amorphous, eosinophilic material in the dermis. Pigment and epidermal changes are often found with cutaneous amyloidosis, including hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, hypergranulosis, parakeratosis, and epidermal atrophy. Stains that may be used include Congo red showing apple-green birefringence, thioflavin T, and crystal violet.

If untreated, the prognosis is generally poor, related to the extent of organ involvement. Cardiac involvement, a common feature of systemic amyloidosis, can lead to restrictive cardiomyopathy, heart failure, and arrhythmias. Management strategies include steroids, chemotherapy, and stem cell transplantation. Medications include dexamethasone, cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and melphalan.

This patient went undiagnosed for several years until she began experiencing cardiac issues, including syncope, angina, and restrictive cardiomyopathy with heart failure. A cardiac biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of systemic amyloidosis. This patient is currently awaiting a heart transplant. Early diagnosis of amyloidosis is vital, as it can help prevent severe complications such as heart involvement, significantly impacting the patient’s prognosis and quality of life. When amyloidosis is suspected based on dermatological findings, it is essential to distinguish it from other conditions, such as chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, scleromyxedema, and lipoid proteinosis. Early identification of characteristic skin lesions and systemic features can lead to timely interventions, more favorable outcomes, and reduction in the risk of advanced organ damage.

The case and photo were submitted by Ms. Cael Aoki and Mr. Shapiro of Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Davie, Florida, and Dr. Bartos, of Imperial Dermatology, Hollywood, Florida. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Florida. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Brunt EM, Tiniakos DG. Clin Liver Dis. 2004 Nov;8(4):915-30, x. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2004.06.009.

2. Bolognia JL et al. (2017). Dermatology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences.

3. Mehrotra K et al. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017 Aug;11(8):WC01-WC05. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/24273.10334.

4. Banypersad SM et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012 Apr;1(2):e000364. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.111.000364.

5. Bustamante JG, Zaidi SRH. Amyloidosis. [Updated 2023 Jul 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

This heterogeneous disorder can present with a wide range of clinical manifestations, including dermatological symptoms that may be the first or predominant feature. Systemic amyloidosis is characterized by macroglossia, periorbital purpura, and waxy skin plaques. Lateral scalloping of the tongue may be seen due to impingement of the teeth. Cutaneous amyloidosis occurs when amyloid is deposited in the skin, without internal organ involvement. Variants of cutaneous amyloidosis include macular, lichen, nodular and biphasic.

This condition requires a thorough diagnostic workup, including serum and urine protein electrophoresis and biopsy of the affected tissue. Biopsy of a cutaneous amyloidosis lesion will show fractured, amorphous, eosinophilic material in the dermis. Pigment and epidermal changes are often found with cutaneous amyloidosis, including hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, hypergranulosis, parakeratosis, and epidermal atrophy. Stains that may be used include Congo red showing apple-green birefringence, thioflavin T, and crystal violet.

If untreated, the prognosis is generally poor, related to the extent of organ involvement. Cardiac involvement, a common feature of systemic amyloidosis, can lead to restrictive cardiomyopathy, heart failure, and arrhythmias. Management strategies include steroids, chemotherapy, and stem cell transplantation. Medications include dexamethasone, cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and melphalan.

This patient went undiagnosed for several years until she began experiencing cardiac issues, including syncope, angina, and restrictive cardiomyopathy with heart failure. A cardiac biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of systemic amyloidosis. This patient is currently awaiting a heart transplant. Early diagnosis of amyloidosis is vital, as it can help prevent severe complications such as heart involvement, significantly impacting the patient’s prognosis and quality of life. When amyloidosis is suspected based on dermatological findings, it is essential to distinguish it from other conditions, such as chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, scleromyxedema, and lipoid proteinosis. Early identification of characteristic skin lesions and systemic features can lead to timely interventions, more favorable outcomes, and reduction in the risk of advanced organ damage.

The case and photo were submitted by Ms. Cael Aoki and Mr. Shapiro of Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Davie, Florida, and Dr. Bartos, of Imperial Dermatology, Hollywood, Florida. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Florida. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Brunt EM, Tiniakos DG. Clin Liver Dis. 2004 Nov;8(4):915-30, x. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2004.06.009.

2. Bolognia JL et al. (2017). Dermatology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences.

3. Mehrotra K et al. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017 Aug;11(8):WC01-WC05. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/24273.10334.

4. Banypersad SM et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012 Apr;1(2):e000364. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.111.000364.

5. Bustamante JG, Zaidi SRH. Amyloidosis. [Updated 2023 Jul 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

Low HPV Vaccination in the United States Is a Public Health ‘Failure’

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I would like to briefly discuss what I consider to be a very discouraging report and one that I believe we as an oncology society and, quite frankly, as a medical community need to deal with.

The manuscript I’m referring to is from the United States Department of Health and Human Services, titled, “Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Coverage in Children Ages 9-17 Years: United States, 2022.” This particular analysis looked at the coverage of both men and women — young boys and young girls, I would say — receiving at least one dose of the recommended human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination.

Since 2006, girls have been recommended to receive HPV vaccination; for boys, it’s been since 2011. Certainly, the time period that we’re considering falls within the recommendations based on overwhelmingly positive data. Now, today, still, the recommendation is for more than one vaccine. Obviously, there may be evidence in the future that a single vaccination may be acceptable or appropriate. But today, it’s more than one.

In this particular analysis, they were looking at just a single vaccination. The vaccines have targeted young individuals, both male and female children aged 11-12 years, but it’s certainly acceptable to look starting at age 9.

What is the bottom line? At least one dose of the HPV vaccination was given to 38.6% of children aged 9-17 years in 2022. We are talking about a cancer-preventive vaccine, which on the basis of population-based data in the United States, but also in other countries, is incredibly effective in preventing HPV-associated cancers. This not only includes cervical cancer, but also a large percentage of head and neck cancers.

For this vaccine, which is incredibly safe and incredibly effective, in this country, only 38.6% have received even a single dose. It is noted that the individuals with private insurance had a higher rate, at 41.5%, than individuals with no insurance, at only 20.7%.

In my opinion, this is clearly a failure of our public health establishment at all levels. My own focus has been in gynecologic cancers. I’ve seen young women with advanced cervical cancer, and this is a disease we can prevent. Yet, this is where we are.

For those of you who are interested in cancer prevention or public health, I think this is a very sobering statistic. It’s my plea and my hope that we can, as a society, somehow do something about it.

I thank you for listening. I would encourage you to think about this question if you’re in this area.

Dr. Markman, professor, Department of Medical Oncology and Therapeutics Research, City of Hope, Duarte, California, and president of Medicine & Science, City of Hope Atlanta, Chicago, and Phoenix, disclosed ties with GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I would like to briefly discuss what I consider to be a very discouraging report and one that I believe we as an oncology society and, quite frankly, as a medical community need to deal with.

The manuscript I’m referring to is from the United States Department of Health and Human Services, titled, “Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Coverage in Children Ages 9-17 Years: United States, 2022.” This particular analysis looked at the coverage of both men and women — young boys and young girls, I would say — receiving at least one dose of the recommended human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination.

Since 2006, girls have been recommended to receive HPV vaccination; for boys, it’s been since 2011. Certainly, the time period that we’re considering falls within the recommendations based on overwhelmingly positive data. Now, today, still, the recommendation is for more than one vaccine. Obviously, there may be evidence in the future that a single vaccination may be acceptable or appropriate. But today, it’s more than one.

In this particular analysis, they were looking at just a single vaccination. The vaccines have targeted young individuals, both male and female children aged 11-12 years, but it’s certainly acceptable to look starting at age 9.

What is the bottom line? At least one dose of the HPV vaccination was given to 38.6% of children aged 9-17 years in 2022. We are talking about a cancer-preventive vaccine, which on the basis of population-based data in the United States, but also in other countries, is incredibly effective in preventing HPV-associated cancers. This not only includes cervical cancer, but also a large percentage of head and neck cancers.

For this vaccine, which is incredibly safe and incredibly effective, in this country, only 38.6% have received even a single dose. It is noted that the individuals with private insurance had a higher rate, at 41.5%, than individuals with no insurance, at only 20.7%.

In my opinion, this is clearly a failure of our public health establishment at all levels. My own focus has been in gynecologic cancers. I’ve seen young women with advanced cervical cancer, and this is a disease we can prevent. Yet, this is where we are.

For those of you who are interested in cancer prevention or public health, I think this is a very sobering statistic. It’s my plea and my hope that we can, as a society, somehow do something about it.

I thank you for listening. I would encourage you to think about this question if you’re in this area.

Dr. Markman, professor, Department of Medical Oncology and Therapeutics Research, City of Hope, Duarte, California, and president of Medicine & Science, City of Hope Atlanta, Chicago, and Phoenix, disclosed ties with GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I would like to briefly discuss what I consider to be a very discouraging report and one that I believe we as an oncology society and, quite frankly, as a medical community need to deal with.

The manuscript I’m referring to is from the United States Department of Health and Human Services, titled, “Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Coverage in Children Ages 9-17 Years: United States, 2022.” This particular analysis looked at the coverage of both men and women — young boys and young girls, I would say — receiving at least one dose of the recommended human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination.

Since 2006, girls have been recommended to receive HPV vaccination; for boys, it’s been since 2011. Certainly, the time period that we’re considering falls within the recommendations based on overwhelmingly positive data. Now, today, still, the recommendation is for more than one vaccine. Obviously, there may be evidence in the future that a single vaccination may be acceptable or appropriate. But today, it’s more than one.

In this particular analysis, they were looking at just a single vaccination. The vaccines have targeted young individuals, both male and female children aged 11-12 years, but it’s certainly acceptable to look starting at age 9.

What is the bottom line? At least one dose of the HPV vaccination was given to 38.6% of children aged 9-17 years in 2022. We are talking about a cancer-preventive vaccine, which on the basis of population-based data in the United States, but also in other countries, is incredibly effective in preventing HPV-associated cancers. This not only includes cervical cancer, but also a large percentage of head and neck cancers.

For this vaccine, which is incredibly safe and incredibly effective, in this country, only 38.6% have received even a single dose. It is noted that the individuals with private insurance had a higher rate, at 41.5%, than individuals with no insurance, at only 20.7%.

In my opinion, this is clearly a failure of our public health establishment at all levels. My own focus has been in gynecologic cancers. I’ve seen young women with advanced cervical cancer, and this is a disease we can prevent. Yet, this is where we are.

For those of you who are interested in cancer prevention or public health, I think this is a very sobering statistic. It’s my plea and my hope that we can, as a society, somehow do something about it.

I thank you for listening. I would encourage you to think about this question if you’re in this area.

Dr. Markman, professor, Department of Medical Oncology and Therapeutics Research, City of Hope, Duarte, California, and president of Medicine & Science, City of Hope Atlanta, Chicago, and Phoenix, disclosed ties with GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s Never Too Late to Convince Patients to Quit Smoking

An estimated 450,000 US deaths are expected this year from conditions attributed to cigarette smoking. Although the percentage of adults who smoke declined from 21% in 2005 to 11% in 2022, the annual death toll has been stable since 2005 and isn’t expected to decline until 2030, owing to an aging population of current and former smokers.

In 2022, based on a national survey, two thirds of the 28.8 million US adult smokers wanted to quit, and more than half tried quitting on their own or with the help of clinicians, but less than 9% succeeded in kicking the habit. The health benefits of quitting, summarized in a patient education handout from the American Cancer Society, include a lower risk for cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, the handout states, “quitting smoking can add as much as 10 years to your life, compared to if you continued to smoke.”

For my patients older than age 50 who are lifelong smokers, the qualifier “as much as” can be a sticking point. Although most recognize that continuing to smoke exposes them to greater health risks and are willing to undergo lung cancer screening and receive pneumococcal vaccines, a kind of fatalism frequently sets in. I’ve heard more times than I can recall some version of the declaration, “It’s too late for quitting to make much difference for me.” Many smokers think that once they reach middle age, gains in life expectancy will be too small to be worth the intense effort and multiple failed attempts that are typically required to quit permanently. Until recently, there were few data I could call on to persuade them they were wrong.

In February 2024, Dr. Eo Rin Cho and colleagues pooled data from four national cohort studies (United States, United Kingdom, Norway, and Canada) to calculate mortality differences among current, former, and never smokers aged 20-79 years. Compared with never smokers, lifelong smokers died an average of 12-13 years earlier. However, quitting before age 50 nearly eliminated the excess mortality associated with smoking, and in the 50- to 59-year-old age group, cessation eventually reduced excess mortality by 92%-95%. Better yet, more than half of the benefits occurred within the first 3 years after cessation.

At first glance, these estimates may seem too good to be true. A few months later, though, a different research group, using data from a large cancer prevention study and 2018 US population census and mortality rates, largely confirmed their findings. Dr. Thuy Le and colleagues found that quitting at age 35, 45, 55, 65, or 75 years resulted in average life gains of 8, 5.6, 3.5, 1.7, and 0.7 years, respectively, relative to continuing to smoke. Because no patient is average, the analysis also presented some helpful probabilities. For example, a smoker who quits at age 65 has about a 1 in 4 chance of gaining at least 1 full year of life and a 1 in 6 chance of gaining at least 4 years. In other words, from a life expectancy perspective alone, it’s almost never too late to quit smoking.

Dr. Lin is a family physician and Associate Director, Family Medicine Residency Program, Lancaster General Hospital, Lancaster, Pennsylvania. He blogs at Common Sense Family Doctor. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An estimated 450,000 US deaths are expected this year from conditions attributed to cigarette smoking. Although the percentage of adults who smoke declined from 21% in 2005 to 11% in 2022, the annual death toll has been stable since 2005 and isn’t expected to decline until 2030, owing to an aging population of current and former smokers.

In 2022, based on a national survey, two thirds of the 28.8 million US adult smokers wanted to quit, and more than half tried quitting on their own or with the help of clinicians, but less than 9% succeeded in kicking the habit. The health benefits of quitting, summarized in a patient education handout from the American Cancer Society, include a lower risk for cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, the handout states, “quitting smoking can add as much as 10 years to your life, compared to if you continued to smoke.”

For my patients older than age 50 who are lifelong smokers, the qualifier “as much as” can be a sticking point. Although most recognize that continuing to smoke exposes them to greater health risks and are willing to undergo lung cancer screening and receive pneumococcal vaccines, a kind of fatalism frequently sets in. I’ve heard more times than I can recall some version of the declaration, “It’s too late for quitting to make much difference for me.” Many smokers think that once they reach middle age, gains in life expectancy will be too small to be worth the intense effort and multiple failed attempts that are typically required to quit permanently. Until recently, there were few data I could call on to persuade them they were wrong.

In February 2024, Dr. Eo Rin Cho and colleagues pooled data from four national cohort studies (United States, United Kingdom, Norway, and Canada) to calculate mortality differences among current, former, and never smokers aged 20-79 years. Compared with never smokers, lifelong smokers died an average of 12-13 years earlier. However, quitting before age 50 nearly eliminated the excess mortality associated with smoking, and in the 50- to 59-year-old age group, cessation eventually reduced excess mortality by 92%-95%. Better yet, more than half of the benefits occurred within the first 3 years after cessation.

At first glance, these estimates may seem too good to be true. A few months later, though, a different research group, using data from a large cancer prevention study and 2018 US population census and mortality rates, largely confirmed their findings. Dr. Thuy Le and colleagues found that quitting at age 35, 45, 55, 65, or 75 years resulted in average life gains of 8, 5.6, 3.5, 1.7, and 0.7 years, respectively, relative to continuing to smoke. Because no patient is average, the analysis also presented some helpful probabilities. For example, a smoker who quits at age 65 has about a 1 in 4 chance of gaining at least 1 full year of life and a 1 in 6 chance of gaining at least 4 years. In other words, from a life expectancy perspective alone, it’s almost never too late to quit smoking.

Dr. Lin is a family physician and Associate Director, Family Medicine Residency Program, Lancaster General Hospital, Lancaster, Pennsylvania. He blogs at Common Sense Family Doctor. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An estimated 450,000 US deaths are expected this year from conditions attributed to cigarette smoking. Although the percentage of adults who smoke declined from 21% in 2005 to 11% in 2022, the annual death toll has been stable since 2005 and isn’t expected to decline until 2030, owing to an aging population of current and former smokers.

In 2022, based on a national survey, two thirds of the 28.8 million US adult smokers wanted to quit, and more than half tried quitting on their own or with the help of clinicians, but less than 9% succeeded in kicking the habit. The health benefits of quitting, summarized in a patient education handout from the American Cancer Society, include a lower risk for cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, the handout states, “quitting smoking can add as much as 10 years to your life, compared to if you continued to smoke.”

For my patients older than age 50 who are lifelong smokers, the qualifier “as much as” can be a sticking point. Although most recognize that continuing to smoke exposes them to greater health risks and are willing to undergo lung cancer screening and receive pneumococcal vaccines, a kind of fatalism frequently sets in. I’ve heard more times than I can recall some version of the declaration, “It’s too late for quitting to make much difference for me.” Many smokers think that once they reach middle age, gains in life expectancy will be too small to be worth the intense effort and multiple failed attempts that are typically required to quit permanently. Until recently, there were few data I could call on to persuade them they were wrong.

In February 2024, Dr. Eo Rin Cho and colleagues pooled data from four national cohort studies (United States, United Kingdom, Norway, and Canada) to calculate mortality differences among current, former, and never smokers aged 20-79 years. Compared with never smokers, lifelong smokers died an average of 12-13 years earlier. However, quitting before age 50 nearly eliminated the excess mortality associated with smoking, and in the 50- to 59-year-old age group, cessation eventually reduced excess mortality by 92%-95%. Better yet, more than half of the benefits occurred within the first 3 years after cessation.

At first glance, these estimates may seem too good to be true. A few months later, though, a different research group, using data from a large cancer prevention study and 2018 US population census and mortality rates, largely confirmed their findings. Dr. Thuy Le and colleagues found that quitting at age 35, 45, 55, 65, or 75 years resulted in average life gains of 8, 5.6, 3.5, 1.7, and 0.7 years, respectively, relative to continuing to smoke. Because no patient is average, the analysis also presented some helpful probabilities. For example, a smoker who quits at age 65 has about a 1 in 4 chance of gaining at least 1 full year of life and a 1 in 6 chance of gaining at least 4 years. In other words, from a life expectancy perspective alone, it’s almost never too late to quit smoking.

Dr. Lin is a family physician and Associate Director, Family Medicine Residency Program, Lancaster General Hospital, Lancaster, Pennsylvania. He blogs at Common Sense Family Doctor. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Is There a Role for GLP-1s in Neurology and Psychiatry?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I usually report five or six studies in the field of neurology that were published in the last months, but July was a vacation month.

I decided to cover another topic, which is the role of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptor agonists beyond diabetes and obesity, and in particular, for the field of neurology and psychiatry. Until a few years ago, the treatment of diabetes with traditional antidiabetic drugs was frustrating for vascular neurologists.

These drugs would lower glucose and had an impact on small-vessel disease, but they had no impact on large-vessel disease, stroke, and vascular mortality. This changed with the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 antagonists because these drugs were not only effective for diabetes, but they also lowered cardiac mortality, in particular, in patients with cardiac failure.

The next generation of antidiabetic drugs were the GLP-1 receptor agonists and the combined GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists. These two polypeptides and their receptors play a very important role in diabetes and in obesity. The receptors are found not only in the pancreas but also in the intestinal system, the liver, and the central nervous system.

We have a number of preclinical models, mostly in transgenic mice, which show that these drugs are not effective only in diabetes and obesity, but also in liver disease, kidney failure, and neurodegenerative diseases. GLP-1 receptor agonists also have powerful anti-inflammatory properties. These drugs reduce body weight, and they have positive effects on blood pressure and lipid metabolism.

In the studies on the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists in diabetes, a meta-analysis with more than 58,000 patients showed a significant risk reduction for stroke compared with placebo, and this risk reduction was in the range of 80%.

Stroke, Smoking, and Alcohol

A meta-analysis on the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists in over 30,000 nondiabetic patients with obesity found a significant reduction in blood pressure, mortality, and the risk of myocardial infarction. There was no significant decrease in the risk of stroke, but most probably this is due to the fact that strokes are much less frequent in obesity than in diabetes.

You all know that obesity is also a major risk factor for sleep apnea syndrome. Recently, two large studies with the GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide found a significant improvement in sleep apnea syndrome compared to placebo, regardless of whether patients needed continuous positive airway pressure therapy or not.

In the therapy studies on diabetes and obesity, there were indications that some smokers in the studies stopped their nicotine consumption. A small pilot study with exenatide in 84 overweight patients who were smokers showed that 46% of patients on exenatide stopped smoking compared with 27% in the placebo group. This could be an indication that GLP-1 receptor agonists have activity on the reward system in the brain. Currently, there are a number of larger placebo-controlled trials ongoing.

Another aspect is alcohol consumption. An epidemiologic study in Denmark using data from the National Health Registry showed that the incidence of alcohol-related events decreased significantly in almost 40,000 patients with diabetes when they were treated with GLP-1 receptor agonists compared with other antidiabetic drugs.

A retrospective cohort study from the United States with over 80,000 patients with obesity showed that treatment with GLP-1 receptor agonists was associated with a 50%-60% lower risk for occurrence or recurrence of high alcohol consumption. There is only one small study with exenatide, which was not really informative.

There are a number of studies underway for GLP-1 receptor agonists compared with placebo in patients with alcohol dependence or alcohol consumption. Preclinical models also indicate that these drugs might be effective in cocaine abuse, and there is one placebo-controlled study ongoing.

Parkinson’s Disease

Let’s come to neurology. Preclinical models of Parkinson’s disease have shown neuroprotective activities of GLP-1. Until now, we have three randomized placebo-controlled trials with exenatide, NLY01, and lixisenatide. Two of these studies were positive, showing that the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease were stable over time and deteriorated with placebo. One study was neutral. This means we need more large-scale placebo-controlled studies in the early phases of Parkinson’s disease.

Another potential use of GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists is in dementia. These substances, as you know, have positive effects on high blood pressure and vascular risk factors.

A working group in China analyzed 27 studies on the treatment of diabetes. A small number of randomized studies and a large number of cohort studies showed that modern antidiabetic drugs reduce the risk for dementia. The risk reduction for dementia for the GLP-1 receptor agonists was 75%. At the moment, there are only small prospective studies and they are not conclusive. Again, we need large-scale placebo-controlled studies.

The most important limitation at the moment beyond the cost is the other adverse drug reactions with the GLP-1 receptor agonists; these include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation. There might be a slightly increased risk for pancreatitis. The US Food and Drug Administration recently reported there is no increased risk for suicide. Another potential adverse drug reaction is nonatherosclerotic anterior optic neuropathy.

These drugs, GLP-1 receptor agonists and GIP agonists, are also investigated in a variety of other non-neurologic diseases. The focus here is on metabolic liver disease, such as fatty liver and kidney diseases. Smaller, positive studies have been conducted in this area, and large placebo-controlled trials for both indications are currently underway.

If these diverse therapeutic properties would turn out to be really the case with GLP-1 receptor agonists, this would lead to a significant expansion of the range of indications. If we consider cost, this would be the end of our healthcare systems because we cannot afford this. In addition, the new antidiabetic drugs and the treatment of obesity are available only to a limited extent.

Finally, at least for neurology, it’s unclear whether the impact of these diseases is in the brain or whether it’s indirect, due to the effectiveness on vascular risk factors and concomitant diseases.

Dr. Diener is Professor in the Department of Neurology, Stroke Center-Headache Center, University Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany; he has disclosed conflicts of interest with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I usually report five or six studies in the field of neurology that were published in the last months, but July was a vacation month.

I decided to cover another topic, which is the role of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptor agonists beyond diabetes and obesity, and in particular, for the field of neurology and psychiatry. Until a few years ago, the treatment of diabetes with traditional antidiabetic drugs was frustrating for vascular neurologists.

These drugs would lower glucose and had an impact on small-vessel disease, but they had no impact on large-vessel disease, stroke, and vascular mortality. This changed with the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 antagonists because these drugs were not only effective for diabetes, but they also lowered cardiac mortality, in particular, in patients with cardiac failure.

The next generation of antidiabetic drugs were the GLP-1 receptor agonists and the combined GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists. These two polypeptides and their receptors play a very important role in diabetes and in obesity. The receptors are found not only in the pancreas but also in the intestinal system, the liver, and the central nervous system.

We have a number of preclinical models, mostly in transgenic mice, which show that these drugs are not effective only in diabetes and obesity, but also in liver disease, kidney failure, and neurodegenerative diseases. GLP-1 receptor agonists also have powerful anti-inflammatory properties. These drugs reduce body weight, and they have positive effects on blood pressure and lipid metabolism.

In the studies on the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists in diabetes, a meta-analysis with more than 58,000 patients showed a significant risk reduction for stroke compared with placebo, and this risk reduction was in the range of 80%.

Stroke, Smoking, and Alcohol

A meta-analysis on the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists in over 30,000 nondiabetic patients with obesity found a significant reduction in blood pressure, mortality, and the risk of myocardial infarction. There was no significant decrease in the risk of stroke, but most probably this is due to the fact that strokes are much less frequent in obesity than in diabetes.

You all know that obesity is also a major risk factor for sleep apnea syndrome. Recently, two large studies with the GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide found a significant improvement in sleep apnea syndrome compared to placebo, regardless of whether patients needed continuous positive airway pressure therapy or not.

In the therapy studies on diabetes and obesity, there were indications that some smokers in the studies stopped their nicotine consumption. A small pilot study with exenatide in 84 overweight patients who were smokers showed that 46% of patients on exenatide stopped smoking compared with 27% in the placebo group. This could be an indication that GLP-1 receptor agonists have activity on the reward system in the brain. Currently, there are a number of larger placebo-controlled trials ongoing.

Another aspect is alcohol consumption. An epidemiologic study in Denmark using data from the National Health Registry showed that the incidence of alcohol-related events decreased significantly in almost 40,000 patients with diabetes when they were treated with GLP-1 receptor agonists compared with other antidiabetic drugs.

A retrospective cohort study from the United States with over 80,000 patients with obesity showed that treatment with GLP-1 receptor agonists was associated with a 50%-60% lower risk for occurrence or recurrence of high alcohol consumption. There is only one small study with exenatide, which was not really informative.

There are a number of studies underway for GLP-1 receptor agonists compared with placebo in patients with alcohol dependence or alcohol consumption. Preclinical models also indicate that these drugs might be effective in cocaine abuse, and there is one placebo-controlled study ongoing.

Parkinson’s Disease

Let’s come to neurology. Preclinical models of Parkinson’s disease have shown neuroprotective activities of GLP-1. Until now, we have three randomized placebo-controlled trials with exenatide, NLY01, and lixisenatide. Two of these studies were positive, showing that the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease were stable over time and deteriorated with placebo. One study was neutral. This means we need more large-scale placebo-controlled studies in the early phases of Parkinson’s disease.

Another potential use of GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists is in dementia. These substances, as you know, have positive effects on high blood pressure and vascular risk factors.

A working group in China analyzed 27 studies on the treatment of diabetes. A small number of randomized studies and a large number of cohort studies showed that modern antidiabetic drugs reduce the risk for dementia. The risk reduction for dementia for the GLP-1 receptor agonists was 75%. At the moment, there are only small prospective studies and they are not conclusive. Again, we need large-scale placebo-controlled studies.

The most important limitation at the moment beyond the cost is the other adverse drug reactions with the GLP-1 receptor agonists; these include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation. There might be a slightly increased risk for pancreatitis. The US Food and Drug Administration recently reported there is no increased risk for suicide. Another potential adverse drug reaction is nonatherosclerotic anterior optic neuropathy.

These drugs, GLP-1 receptor agonists and GIP agonists, are also investigated in a variety of other non-neurologic diseases. The focus here is on metabolic liver disease, such as fatty liver and kidney diseases. Smaller, positive studies have been conducted in this area, and large placebo-controlled trials for both indications are currently underway.

If these diverse therapeutic properties would turn out to be really the case with GLP-1 receptor agonists, this would lead to a significant expansion of the range of indications. If we consider cost, this would be the end of our healthcare systems because we cannot afford this. In addition, the new antidiabetic drugs and the treatment of obesity are available only to a limited extent.

Finally, at least for neurology, it’s unclear whether the impact of these diseases is in the brain or whether it’s indirect, due to the effectiveness on vascular risk factors and concomitant diseases.

Dr. Diener is Professor in the Department of Neurology, Stroke Center-Headache Center, University Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany; he has disclosed conflicts of interest with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I usually report five or six studies in the field of neurology that were published in the last months, but July was a vacation month.

I decided to cover another topic, which is the role of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptor agonists beyond diabetes and obesity, and in particular, for the field of neurology and psychiatry. Until a few years ago, the treatment of diabetes with traditional antidiabetic drugs was frustrating for vascular neurologists.

These drugs would lower glucose and had an impact on small-vessel disease, but they had no impact on large-vessel disease, stroke, and vascular mortality. This changed with the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 antagonists because these drugs were not only effective for diabetes, but they also lowered cardiac mortality, in particular, in patients with cardiac failure.

The next generation of antidiabetic drugs were the GLP-1 receptor agonists and the combined GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists. These two polypeptides and their receptors play a very important role in diabetes and in obesity. The receptors are found not only in the pancreas but also in the intestinal system, the liver, and the central nervous system.

We have a number of preclinical models, mostly in transgenic mice, which show that these drugs are not effective only in diabetes and obesity, but also in liver disease, kidney failure, and neurodegenerative diseases. GLP-1 receptor agonists also have powerful anti-inflammatory properties. These drugs reduce body weight, and they have positive effects on blood pressure and lipid metabolism.

In the studies on the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists in diabetes, a meta-analysis with more than 58,000 patients showed a significant risk reduction for stroke compared with placebo, and this risk reduction was in the range of 80%.

Stroke, Smoking, and Alcohol

A meta-analysis on the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists in over 30,000 nondiabetic patients with obesity found a significant reduction in blood pressure, mortality, and the risk of myocardial infarction. There was no significant decrease in the risk of stroke, but most probably this is due to the fact that strokes are much less frequent in obesity than in diabetes.

You all know that obesity is also a major risk factor for sleep apnea syndrome. Recently, two large studies with the GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide found a significant improvement in sleep apnea syndrome compared to placebo, regardless of whether patients needed continuous positive airway pressure therapy or not.

In the therapy studies on diabetes and obesity, there were indications that some smokers in the studies stopped their nicotine consumption. A small pilot study with exenatide in 84 overweight patients who were smokers showed that 46% of patients on exenatide stopped smoking compared with 27% in the placebo group. This could be an indication that GLP-1 receptor agonists have activity on the reward system in the brain. Currently, there are a number of larger placebo-controlled trials ongoing.

Another aspect is alcohol consumption. An epidemiologic study in Denmark using data from the National Health Registry showed that the incidence of alcohol-related events decreased significantly in almost 40,000 patients with diabetes when they were treated with GLP-1 receptor agonists compared with other antidiabetic drugs.

A retrospective cohort study from the United States with over 80,000 patients with obesity showed that treatment with GLP-1 receptor agonists was associated with a 50%-60% lower risk for occurrence or recurrence of high alcohol consumption. There is only one small study with exenatide, which was not really informative.

There are a number of studies underway for GLP-1 receptor agonists compared with placebo in patients with alcohol dependence or alcohol consumption. Preclinical models also indicate that these drugs might be effective in cocaine abuse, and there is one placebo-controlled study ongoing.

Parkinson’s Disease

Let’s come to neurology. Preclinical models of Parkinson’s disease have shown neuroprotective activities of GLP-1. Until now, we have three randomized placebo-controlled trials with exenatide, NLY01, and lixisenatide. Two of these studies were positive, showing that the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease were stable over time and deteriorated with placebo. One study was neutral. This means we need more large-scale placebo-controlled studies in the early phases of Parkinson’s disease.

Another potential use of GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists is in dementia. These substances, as you know, have positive effects on high blood pressure and vascular risk factors.

A working group in China analyzed 27 studies on the treatment of diabetes. A small number of randomized studies and a large number of cohort studies showed that modern antidiabetic drugs reduce the risk for dementia. The risk reduction for dementia for the GLP-1 receptor agonists was 75%. At the moment, there are only small prospective studies and they are not conclusive. Again, we need large-scale placebo-controlled studies.

The most important limitation at the moment beyond the cost is the other adverse drug reactions with the GLP-1 receptor agonists; these include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation. There might be a slightly increased risk for pancreatitis. The US Food and Drug Administration recently reported there is no increased risk for suicide. Another potential adverse drug reaction is nonatherosclerotic anterior optic neuropathy.

These drugs, GLP-1 receptor agonists and GIP agonists, are also investigated in a variety of other non-neurologic diseases. The focus here is on metabolic liver disease, such as fatty liver and kidney diseases. Smaller, positive studies have been conducted in this area, and large placebo-controlled trials for both indications are currently underway.

If these diverse therapeutic properties would turn out to be really the case with GLP-1 receptor agonists, this would lead to a significant expansion of the range of indications. If we consider cost, this would be the end of our healthcare systems because we cannot afford this. In addition, the new antidiabetic drugs and the treatment of obesity are available only to a limited extent.

Finally, at least for neurology, it’s unclear whether the impact of these diseases is in the brain or whether it’s indirect, due to the effectiveness on vascular risk factors and concomitant diseases.

Dr. Diener is Professor in the Department of Neurology, Stroke Center-Headache Center, University Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany; he has disclosed conflicts of interest with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

What Every Provider Should Know About Type 1 Diabetes

In July 2024, a 33-year-old woman with type 1 diabetes was boating on a hot day when her insulin delivery device slipped off. By the time she was able to exit the river, she was clearly ill, and an ambulance was called. The hospital was at capacity. Lying in the hallway, she was treated with fluids but not insulin, despite her boyfriend repeatedly telling the staff she had diabetes. She was released while still vomiting. The next morning, her boyfriend found her dead.

This story was shared by a friend of the woman in a Facebook group for people with type 1 diabetes and later confirmed by the boyfriend in a separate heartbreaking post. While it may be an extreme case,

In my 50+ years of living with the condition, I’ve lost track of the number of times I’ve had to speak up for myself, correct errors, raise issues that haven’t been considered, and educate nonspecialist healthcare professionals about even some of the basics.

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune condition in which the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas are destroyed, necessitating lifelong insulin treatment. Type 2, in contrast, arises from a combination of insulin resistance and decreased insulin production. Type 1 accounts for just 5% of all people with diabetes, but at a prevalence of about 1 in 200, it’s not rare. And that’s not even counting the adults who have been misdiagnosed as having type 2 but who actually have type 1.

As a general rule, people with type 1 diabetes are more insulin sensitive than those with type 2 and more prone to both hyper- and hypoglycemia. Blood sugar levels tend to be more labile and less predictable, even under normal circumstances. Recent advances in hybrid closed-loop technology have been extremely helpful in reducing the swings, but the systems aren’t foolproof yet. They still require user input (ie, guesswork), so there’s still room for error.

Managing type 1 diabetes is challenging even for endocrinologists. But here are some very important basics that every healthcare provider should know.

We Need Insulin 24/7

Never, ever withhold insulin from a person with type 1 diabetes, for any reason. Even when not eating — or when vomiting — we still need basal (background) insulin, either via long-acting analog or a pump infusion. The dose may need to be lowered to avoid hypoglycemia, but if insulin is stopped, diabetic ketoacidosis will result. And if that continues, death will follow.

This should be basic knowledge, but I’ve read and heard far too many stories of insulin being withheld from people with type 1 in various settings, including emergency departments, psychiatric facilities, and jails. On Facebook, people with type 1 diabetes often report being told not to take their insulin the morning before a procedure, while more than one has described “sneaking” their own insulin while hospitalized because they weren’t receiving any or not receiving enough.

On the flip side, although insulin needs are very individual, the amount needed for someone with type 1 is typically considerably less than for a person with type 2. Too much can result in severe hypoglycemia. There are lots of stories from people with type 1 diabetes who had to battle with hospital staff who tried to give them much higher doses than they knew they needed.