User login

Medical identity theft

In his book, “Scam Me If You Can,” fraud expert Frank Abagnale relates the case of a 5-year-old boy whose pediatrician’s computer was hacked, compromising his name, birth date, Social Security number, insurance information, and medical records. The result was a bureaucratic nightmare that may well continue for the rest of that unfortunate young patient’s life. One can only speculate on the difficulties he might have as adult in obtaining a line of credit, or in proving his medical identity to physicians and hospitals.

– your Social Security number, bank account numbers, etc. – sells for about $25 on the black market; add health insurance and medical records, and the price can jump to $1,000 or more. That’s because there is a far greater potential yield from medical identity theft – and once your personal information and medical records are breached, they are in the Cloud for the rest of your life, available to anyone who wants to buy them. Older patients are particularly vulnerable: Medicare billing scams cost taxpayers more than $60 billion a year.

If your office’s computer system does not have effective fraud protection, you could be held liable for any fraud committed with information stolen from it – and if the information is resold years later and reused to commit more fraud, you’ll be liable for that, too. That’s why I strongly recommend that you invest in high-quality security technology and software, so that in the event of a breach, the security company will at least share in the fault and the liability. (As always, I have no financial interest in any product or industry mentioned in this column.)

Even with adequate protection, breaches can still occur, so all medical offices should have a breach response plan in place, covering how to halt security breaches, and how to handle any lost or stolen data. Your computer and security vendors can help with formulating such a plan. Patients affected by a breach need to be contacted as well, so they may put a freeze on accounts or send out fraud alerts.

Patients also need to be aware of the risks. If your EHR includes an online portal to communicate protected information to patients, it may be secure on your end, but patients are unlikely to have similar protection on their home computers. If you offer online patient portal services, you should make your patients aware of measures they can take to protect their data once it arrives on their computers or phones.

Patients should also be warned of the risks that come with sharing medical information with others. If they are asked to reveal medical data via phone or email, they need to ask who is requesting it, and why. Any unsolicited calls inquiring about their medical information, from someone who can’t or won’t confirm their identity, should be considered extremely suspicious.

We tell our patients to protect their insurance numbers as carefully as they guard their Social Security number and other valuable data, and to shred any medical paperwork they no longer need, including labels on prescription bottles. And if they see something on an Explanation of Benefits that doesn’t look right, they should question it immediately. We encourage them to take advantage of the free services at MyMedicare.gov, including Medicare Summary Notices provided every 3 months (if any services or medical supplies are received during that period), to make sure they’re being billed only for services they have received.

Your staff should be made aware of the potential for “friendly fraud,” which is defined as theft of identity and medical information by patients’ friends or family members. (According to some studies, as much as 50% of all medical identity theft may be committed this way.) Staffers should never divulge insurance numbers, diagnoses, lab reports, or any other privileged information to family or friends, whether by phone, fax, mail, or in person, without written permission from the patient. And when callers claiming to be patients request information about themselves, your employees should be alert for “red flags.” For example, legitimate patients won’t stumble over simple questions (such as “What is your birth date?”) or request test results or diagnoses that they should already know about.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

In his book, “Scam Me If You Can,” fraud expert Frank Abagnale relates the case of a 5-year-old boy whose pediatrician’s computer was hacked, compromising his name, birth date, Social Security number, insurance information, and medical records. The result was a bureaucratic nightmare that may well continue for the rest of that unfortunate young patient’s life. One can only speculate on the difficulties he might have as adult in obtaining a line of credit, or in proving his medical identity to physicians and hospitals.

– your Social Security number, bank account numbers, etc. – sells for about $25 on the black market; add health insurance and medical records, and the price can jump to $1,000 or more. That’s because there is a far greater potential yield from medical identity theft – and once your personal information and medical records are breached, they are in the Cloud for the rest of your life, available to anyone who wants to buy them. Older patients are particularly vulnerable: Medicare billing scams cost taxpayers more than $60 billion a year.

If your office’s computer system does not have effective fraud protection, you could be held liable for any fraud committed with information stolen from it – and if the information is resold years later and reused to commit more fraud, you’ll be liable for that, too. That’s why I strongly recommend that you invest in high-quality security technology and software, so that in the event of a breach, the security company will at least share in the fault and the liability. (As always, I have no financial interest in any product or industry mentioned in this column.)

Even with adequate protection, breaches can still occur, so all medical offices should have a breach response plan in place, covering how to halt security breaches, and how to handle any lost or stolen data. Your computer and security vendors can help with formulating such a plan. Patients affected by a breach need to be contacted as well, so they may put a freeze on accounts or send out fraud alerts.

Patients also need to be aware of the risks. If your EHR includes an online portal to communicate protected information to patients, it may be secure on your end, but patients are unlikely to have similar protection on their home computers. If you offer online patient portal services, you should make your patients aware of measures they can take to protect their data once it arrives on their computers or phones.

Patients should also be warned of the risks that come with sharing medical information with others. If they are asked to reveal medical data via phone or email, they need to ask who is requesting it, and why. Any unsolicited calls inquiring about their medical information, from someone who can’t or won’t confirm their identity, should be considered extremely suspicious.

We tell our patients to protect their insurance numbers as carefully as they guard their Social Security number and other valuable data, and to shred any medical paperwork they no longer need, including labels on prescription bottles. And if they see something on an Explanation of Benefits that doesn’t look right, they should question it immediately. We encourage them to take advantage of the free services at MyMedicare.gov, including Medicare Summary Notices provided every 3 months (if any services or medical supplies are received during that period), to make sure they’re being billed only for services they have received.

Your staff should be made aware of the potential for “friendly fraud,” which is defined as theft of identity and medical information by patients’ friends or family members. (According to some studies, as much as 50% of all medical identity theft may be committed this way.) Staffers should never divulge insurance numbers, diagnoses, lab reports, or any other privileged information to family or friends, whether by phone, fax, mail, or in person, without written permission from the patient. And when callers claiming to be patients request information about themselves, your employees should be alert for “red flags.” For example, legitimate patients won’t stumble over simple questions (such as “What is your birth date?”) or request test results or diagnoses that they should already know about.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

In his book, “Scam Me If You Can,” fraud expert Frank Abagnale relates the case of a 5-year-old boy whose pediatrician’s computer was hacked, compromising his name, birth date, Social Security number, insurance information, and medical records. The result was a bureaucratic nightmare that may well continue for the rest of that unfortunate young patient’s life. One can only speculate on the difficulties he might have as adult in obtaining a line of credit, or in proving his medical identity to physicians and hospitals.

– your Social Security number, bank account numbers, etc. – sells for about $25 on the black market; add health insurance and medical records, and the price can jump to $1,000 or more. That’s because there is a far greater potential yield from medical identity theft – and once your personal information and medical records are breached, they are in the Cloud for the rest of your life, available to anyone who wants to buy them. Older patients are particularly vulnerable: Medicare billing scams cost taxpayers more than $60 billion a year.

If your office’s computer system does not have effective fraud protection, you could be held liable for any fraud committed with information stolen from it – and if the information is resold years later and reused to commit more fraud, you’ll be liable for that, too. That’s why I strongly recommend that you invest in high-quality security technology and software, so that in the event of a breach, the security company will at least share in the fault and the liability. (As always, I have no financial interest in any product or industry mentioned in this column.)

Even with adequate protection, breaches can still occur, so all medical offices should have a breach response plan in place, covering how to halt security breaches, and how to handle any lost or stolen data. Your computer and security vendors can help with formulating such a plan. Patients affected by a breach need to be contacted as well, so they may put a freeze on accounts or send out fraud alerts.

Patients also need to be aware of the risks. If your EHR includes an online portal to communicate protected information to patients, it may be secure on your end, but patients are unlikely to have similar protection on their home computers. If you offer online patient portal services, you should make your patients aware of measures they can take to protect their data once it arrives on their computers or phones.

Patients should also be warned of the risks that come with sharing medical information with others. If they are asked to reveal medical data via phone or email, they need to ask who is requesting it, and why. Any unsolicited calls inquiring about their medical information, from someone who can’t or won’t confirm their identity, should be considered extremely suspicious.

We tell our patients to protect their insurance numbers as carefully as they guard their Social Security number and other valuable data, and to shred any medical paperwork they no longer need, including labels on prescription bottles. And if they see something on an Explanation of Benefits that doesn’t look right, they should question it immediately. We encourage them to take advantage of the free services at MyMedicare.gov, including Medicare Summary Notices provided every 3 months (if any services or medical supplies are received during that period), to make sure they’re being billed only for services they have received.

Your staff should be made aware of the potential for “friendly fraud,” which is defined as theft of identity and medical information by patients’ friends or family members. (According to some studies, as much as 50% of all medical identity theft may be committed this way.) Staffers should never divulge insurance numbers, diagnoses, lab reports, or any other privileged information to family or friends, whether by phone, fax, mail, or in person, without written permission from the patient. And when callers claiming to be patients request information about themselves, your employees should be alert for “red flags.” For example, legitimate patients won’t stumble over simple questions (such as “What is your birth date?”) or request test results or diagnoses that they should already know about.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

Under the influence

I don’t know how successful you have been at getting your adolescent patients to follow your suggestions, but I would guess that my batting average was in the low 100s. Even when I try stepping off my soapbox to involve the patient in a nonjudgmental dialogue, my successes pale in comparison to my failures.

Just looking at our national statistics for obesity, it’s pretty obvious that we are all doing a pretty rotten job of modifying our patients behaviors. You could point to a few encouraging numbers but they are few and far between. You could claim correctly that by the time a child reaches preschool, the die is already cast, throw up your arms, and not even raise the subject of diet with your overweight teenage patients.

A recent article in the journal Appetite hints at a group of strategies for molding patient behavior that so far have gotten very little attention from physicians (“Do perceived norms of social media users eating habits and preferences predict our own food consumption and BMI?” Appetite. 2020 Jan 18. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.104611). Researchers at the department of psychology at Ashton University in Birmingham, England, surveyed more than 350 college-age students asking them about the dietary preference of their Facebook contacts and their own dietary habits. What the investigators found was that respondents who perceived their peers ate a healthy diet ate a healthier diet. Conversely, if the respondents thought their social media contacts ate junk food, they reported eating more of an unhealthy diet themselves.

In other words, it appears that, through social media, we have the potential to influence the eating habits of our patients’ peers. Before we get too excited, it should be pointed out that this study from England wasn’t of a long enough duration to demonstrate an effect on body mass index. And another study of 176 children recently published in Pediatrics found that while influencer marketing of unhealthy foods increased children’s immediate food intake, the equivalent marketing of healthy foods had no effect (“Social influencer marketing and children’s food intake: A randomized trial.” Pediatrics. 2019 Apr 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2554).

Not being terribly aware of the whos, whats, and wheres of influencers, I did a little bit of Internet searching at the Influencer Marketing hub and learned that influencers comes in all shapes and sizes, from “nanoinfluencers” who have acknowledged expertise and a very small Internet following numbering as few as a hundred to “megainfluencers” who have more than a million followers and might charge large entities a million dollars for a single post. The influencer’s content could appear as a blog, a YouTube video, a podcast, or simply a social media post.

The field of influencer marketing is new and growing exponentially. This initiative could come in the form of an office dedicated to Influencer Marketing created by the American Academy of Pediatrics. That group could search for megainfluencers who might be funded by the academy. But it also could develop a handbook for individual practitioners and groups to help them identify nano- and micro- (1,000-40,000 followers) influencers in their own practices.

You probably don’t ask your patients about their social media habits other than to caution them about time management. Maybe it’s time to dig a little deeper. You may find that you have a potent influencer hidden in your practice. She or he might just be willing to spread a good word or two for you.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

I don’t know how successful you have been at getting your adolescent patients to follow your suggestions, but I would guess that my batting average was in the low 100s. Even when I try stepping off my soapbox to involve the patient in a nonjudgmental dialogue, my successes pale in comparison to my failures.

Just looking at our national statistics for obesity, it’s pretty obvious that we are all doing a pretty rotten job of modifying our patients behaviors. You could point to a few encouraging numbers but they are few and far between. You could claim correctly that by the time a child reaches preschool, the die is already cast, throw up your arms, and not even raise the subject of diet with your overweight teenage patients.

A recent article in the journal Appetite hints at a group of strategies for molding patient behavior that so far have gotten very little attention from physicians (“Do perceived norms of social media users eating habits and preferences predict our own food consumption and BMI?” Appetite. 2020 Jan 18. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.104611). Researchers at the department of psychology at Ashton University in Birmingham, England, surveyed more than 350 college-age students asking them about the dietary preference of their Facebook contacts and their own dietary habits. What the investigators found was that respondents who perceived their peers ate a healthy diet ate a healthier diet. Conversely, if the respondents thought their social media contacts ate junk food, they reported eating more of an unhealthy diet themselves.

In other words, it appears that, through social media, we have the potential to influence the eating habits of our patients’ peers. Before we get too excited, it should be pointed out that this study from England wasn’t of a long enough duration to demonstrate an effect on body mass index. And another study of 176 children recently published in Pediatrics found that while influencer marketing of unhealthy foods increased children’s immediate food intake, the equivalent marketing of healthy foods had no effect (“Social influencer marketing and children’s food intake: A randomized trial.” Pediatrics. 2019 Apr 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2554).

Not being terribly aware of the whos, whats, and wheres of influencers, I did a little bit of Internet searching at the Influencer Marketing hub and learned that influencers comes in all shapes and sizes, from “nanoinfluencers” who have acknowledged expertise and a very small Internet following numbering as few as a hundred to “megainfluencers” who have more than a million followers and might charge large entities a million dollars for a single post. The influencer’s content could appear as a blog, a YouTube video, a podcast, or simply a social media post.

The field of influencer marketing is new and growing exponentially. This initiative could come in the form of an office dedicated to Influencer Marketing created by the American Academy of Pediatrics. That group could search for megainfluencers who might be funded by the academy. But it also could develop a handbook for individual practitioners and groups to help them identify nano- and micro- (1,000-40,000 followers) influencers in their own practices.

You probably don’t ask your patients about their social media habits other than to caution them about time management. Maybe it’s time to dig a little deeper. You may find that you have a potent influencer hidden in your practice. She or he might just be willing to spread a good word or two for you.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

I don’t know how successful you have been at getting your adolescent patients to follow your suggestions, but I would guess that my batting average was in the low 100s. Even when I try stepping off my soapbox to involve the patient in a nonjudgmental dialogue, my successes pale in comparison to my failures.

Just looking at our national statistics for obesity, it’s pretty obvious that we are all doing a pretty rotten job of modifying our patients behaviors. You could point to a few encouraging numbers but they are few and far between. You could claim correctly that by the time a child reaches preschool, the die is already cast, throw up your arms, and not even raise the subject of diet with your overweight teenage patients.

A recent article in the journal Appetite hints at a group of strategies for molding patient behavior that so far have gotten very little attention from physicians (“Do perceived norms of social media users eating habits and preferences predict our own food consumption and BMI?” Appetite. 2020 Jan 18. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.104611). Researchers at the department of psychology at Ashton University in Birmingham, England, surveyed more than 350 college-age students asking them about the dietary preference of their Facebook contacts and their own dietary habits. What the investigators found was that respondents who perceived their peers ate a healthy diet ate a healthier diet. Conversely, if the respondents thought their social media contacts ate junk food, they reported eating more of an unhealthy diet themselves.

In other words, it appears that, through social media, we have the potential to influence the eating habits of our patients’ peers. Before we get too excited, it should be pointed out that this study from England wasn’t of a long enough duration to demonstrate an effect on body mass index. And another study of 176 children recently published in Pediatrics found that while influencer marketing of unhealthy foods increased children’s immediate food intake, the equivalent marketing of healthy foods had no effect (“Social influencer marketing and children’s food intake: A randomized trial.” Pediatrics. 2019 Apr 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2554).

Not being terribly aware of the whos, whats, and wheres of influencers, I did a little bit of Internet searching at the Influencer Marketing hub and learned that influencers comes in all shapes and sizes, from “nanoinfluencers” who have acknowledged expertise and a very small Internet following numbering as few as a hundred to “megainfluencers” who have more than a million followers and might charge large entities a million dollars for a single post. The influencer’s content could appear as a blog, a YouTube video, a podcast, or simply a social media post.

The field of influencer marketing is new and growing exponentially. This initiative could come in the form of an office dedicated to Influencer Marketing created by the American Academy of Pediatrics. That group could search for megainfluencers who might be funded by the academy. But it also could develop a handbook for individual practitioners and groups to help them identify nano- and micro- (1,000-40,000 followers) influencers in their own practices.

You probably don’t ask your patients about their social media habits other than to caution them about time management. Maybe it’s time to dig a little deeper. You may find that you have a potent influencer hidden in your practice. She or he might just be willing to spread a good word or two for you.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

What psychiatrists can do to prepare for the coming pandemic

Coronavirus fever is gripping the world. What I hope to do here is open a discussion of what psychiatrists and other clinicians can do to mitigate the psychological consequences of COVID-19. I am focusing on the right now.

The psychological consequences are fear of the disease, effects of possible quarantine, and the potential effects of the economic slowdown on the world economy.

Fear of the disease is gripping the nation. With invisible diseases, that is not irrational. If you do not know whether you are exposed and/or spreading it to coworkers, children, or aged parents, then the fear of contagion is logical. So I would not “poo-poo” the “worried well.” – especially if you have parents in nursing homes.

The quarantine issue is harder. I have long thought that quarantine would be harder to implement in the United States than in nations like China. But self or home quarantine is currently the de facto solution for those who have been exposed. What are some remedies?

For everybody, having an adequate supply of basic supplies at home is essential. As in preparing for a snowstorm or hurricane, adequate food, water, and yes, toilet paper, is important to relieve anxiety.

Psychiatrists can encourage patients to have an adequate supply of their medications. That may mean that we prescribe more pills. If the patient has suicidal tendencies, we can ask other family members to safeguard those medications.

A salient question is how likely people who are addicted to alcohol or opiates are to stay in place if they are withdrawing. In previous presentations, delivered some 20 years ago, I have (facetiously) suggested horse-drawn wagons of beer to avoid people breaking quarantine in search of the substances they are physically dependent on.

For people in methadone clinics who require daily visits that kind of approach may be harder. I do not have a solution, other than to plan for the eventuality of large-scale withdrawal and the behavioral consequences, which, unfortunately, often involve crime. Telemedicine may be a solution, but we are not yet equipped for it.

The longer-term psychological impacts of a major economic slowdown are not yet known. Based on past epidemics and other disasters, they might include unemployment and the related consequences of domestic violence and suicide.

COVID-19 is spreading fast. As clinicians, we must take steps to protect ourselves and our patients. Because this is a new virus, we have a lot to learn about it. We must be agile, because our actions will need to change over time.

Dr. Ritchie is chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington Hospital Center and professor of psychiatry at Georgetown University, Washington.

Coronavirus fever is gripping the world. What I hope to do here is open a discussion of what psychiatrists and other clinicians can do to mitigate the psychological consequences of COVID-19. I am focusing on the right now.

The psychological consequences are fear of the disease, effects of possible quarantine, and the potential effects of the economic slowdown on the world economy.

Fear of the disease is gripping the nation. With invisible diseases, that is not irrational. If you do not know whether you are exposed and/or spreading it to coworkers, children, or aged parents, then the fear of contagion is logical. So I would not “poo-poo” the “worried well.” – especially if you have parents in nursing homes.

The quarantine issue is harder. I have long thought that quarantine would be harder to implement in the United States than in nations like China. But self or home quarantine is currently the de facto solution for those who have been exposed. What are some remedies?

For everybody, having an adequate supply of basic supplies at home is essential. As in preparing for a snowstorm or hurricane, adequate food, water, and yes, toilet paper, is important to relieve anxiety.

Psychiatrists can encourage patients to have an adequate supply of their medications. That may mean that we prescribe more pills. If the patient has suicidal tendencies, we can ask other family members to safeguard those medications.

A salient question is how likely people who are addicted to alcohol or opiates are to stay in place if they are withdrawing. In previous presentations, delivered some 20 years ago, I have (facetiously) suggested horse-drawn wagons of beer to avoid people breaking quarantine in search of the substances they are physically dependent on.

For people in methadone clinics who require daily visits that kind of approach may be harder. I do not have a solution, other than to plan for the eventuality of large-scale withdrawal and the behavioral consequences, which, unfortunately, often involve crime. Telemedicine may be a solution, but we are not yet equipped for it.

The longer-term psychological impacts of a major economic slowdown are not yet known. Based on past epidemics and other disasters, they might include unemployment and the related consequences of domestic violence and suicide.

COVID-19 is spreading fast. As clinicians, we must take steps to protect ourselves and our patients. Because this is a new virus, we have a lot to learn about it. We must be agile, because our actions will need to change over time.

Dr. Ritchie is chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington Hospital Center and professor of psychiatry at Georgetown University, Washington.

Coronavirus fever is gripping the world. What I hope to do here is open a discussion of what psychiatrists and other clinicians can do to mitigate the psychological consequences of COVID-19. I am focusing on the right now.

The psychological consequences are fear of the disease, effects of possible quarantine, and the potential effects of the economic slowdown on the world economy.

Fear of the disease is gripping the nation. With invisible diseases, that is not irrational. If you do not know whether you are exposed and/or spreading it to coworkers, children, or aged parents, then the fear of contagion is logical. So I would not “poo-poo” the “worried well.” – especially if you have parents in nursing homes.

The quarantine issue is harder. I have long thought that quarantine would be harder to implement in the United States than in nations like China. But self or home quarantine is currently the de facto solution for those who have been exposed. What are some remedies?

For everybody, having an adequate supply of basic supplies at home is essential. As in preparing for a snowstorm or hurricane, adequate food, water, and yes, toilet paper, is important to relieve anxiety.

Psychiatrists can encourage patients to have an adequate supply of their medications. That may mean that we prescribe more pills. If the patient has suicidal tendencies, we can ask other family members to safeguard those medications.

A salient question is how likely people who are addicted to alcohol or opiates are to stay in place if they are withdrawing. In previous presentations, delivered some 20 years ago, I have (facetiously) suggested horse-drawn wagons of beer to avoid people breaking quarantine in search of the substances they are physically dependent on.

For people in methadone clinics who require daily visits that kind of approach may be harder. I do not have a solution, other than to plan for the eventuality of large-scale withdrawal and the behavioral consequences, which, unfortunately, often involve crime. Telemedicine may be a solution, but we are not yet equipped for it.

The longer-term psychological impacts of a major economic slowdown are not yet known. Based on past epidemics and other disasters, they might include unemployment and the related consequences of domestic violence and suicide.

COVID-19 is spreading fast. As clinicians, we must take steps to protect ourselves and our patients. Because this is a new virus, we have a lot to learn about it. We must be agile, because our actions will need to change over time.

Dr. Ritchie is chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington Hospital Center and professor of psychiatry at Georgetown University, Washington.

In the management of cesarean scar defects, is there a superior surgical method for treatment?

He Y, Zhong J, Zhou W, et al. Four surgical strategies for the treatment of cesarean scar defect: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:593-602.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

With the increase in cesarean deliveries performed over the decades, the sequelae of the surgery are now arising. Cesarean scar defects (CSDs) are a complication seen when the endometrium and muscular layers from a prior uterine scar are damaged. This damage in the uterine scar can lead to abnormal uterine bleeding and the implantation of an ectopic pregnancy, which can be life-threatening. Ultrasonography can be used to diagnose this defect, which can appear as a hypoechoic space filled with postmenstrual blood, representing a myometrial tear at the wound site.1 There are several risk factors for CSD, including multiple cesarean deliveries, cesarean delivery during advanced stages of labor, and uterine incisions near the cervix. Elevated body mass index as well as gestational diabetes also have been found to be associated with inadequate healing of the prior cesarean incision.2 Studies have shown that both single- and double-layer closure of the hysterotomy during a cesarean delivery have similar incidences of CSDs.3,4 There are multiple ways to correct a CSD; however, there is no gold standard that has been identified in the literature.

Details about the study

The study by He and colleagues is a meta-analysis aimed at comparing the treatment of CSDs via laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, combined hysteroscopy and laparoscopy, and vaginal repair. The primary outcome measures were reduction in abnormal uterine bleeding and scar defect depth. A total of 10 studies (n = 858) were reviewed: 4 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 6 observational studies. The studies analyzed varied in terms of which techniques were compared.

Patients who underwent uterine scar resection by combined laparoscopy and hysteroscopy had a shorter duration of abnormal uterine bleeding when compared with hysteroscopy alone (standardized mean difference [SMD] = 1.36; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.37−2.36; P = .007) and vaginal repair (SMD = 1.58; 95% CI, 0.97−2.19; P<.0001). Combined laparoscopic and hysteroscopic technique also was found to reduce the diverticulum depth more than in vaginal repair (SMD = 1.57; 95% CI, 0.54−2.61; P = .003).

Continue to: Study strengths and weaknesses...

Study strengths and weaknesses

This is the first meta-analysis to compare the different surgical techniques to correct a CSD. The authors were able to compare many of the characteristics regarding the routes of repair, including hysteroscopy, laparoscopy, and vaginal. The authors were able to analyze the combined laparoscopic and hysteroscopic approach, which facilitates evaluation of the location and satisfaction of defect repair during the procedure.

Some weaknesses of this study include the limited amount of RCTs available for review. All studies were also from China, where the rate of CSDs is higher. Therefore, the results may not be generalizable to all populations. Given that the included studies were done at different sites, it is difficult to determine surgical expertise and surgical technique. Additionally, the studies analyzed varied by which techniques were compared; therefore, indirect analyses were conducted to compare certain techniques. There was limited follow-up for these patients (anywhere from 3 to 6 months), so long-term data and future pregnancy data are needed to determine the efficacy of these procedures.

CSDs are a rising concern due to the increasing cesarean delivery rate. It is critical to be able to identify as well as correct these defects. This is the first systematic review to compare 4 techniques of managing CSDs. Based on this article, there may be some additional benefit from combined hysteroscopic and laparoscopic repair of these defects in terms of decreasing bleeding and decreasing the scar defect depth. However, how these results translate into long-term outcomes for patients and their future pregnancies is still unknown, and further research must be done.

STEPHANIE DELGADO, MD, AND XIAOMING GUAN, MD, PHD

- Woźniak A, Pyra K, Tinto HR, et al. Ultrasonographic criteria of cesarean scar defect evaluation. J Ultrason. 2018;18: 162-165.

- Antila-Långsjö RM, Mäenpää JU, Huhtala HS, et al. Cesarean scar defect: a prospective study on risk factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018:219:458e1-e8.

- Di Spiezio Sardo A, Saccone G, McCurdy R, et al. Risk of cesarean scar defect following single- vs double-layer uterine closure: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;50:578-583.

- Roberge S, Demers S, Berghella V, et al. Impact of single- vs double-layer closure on adverse outcomes and uterine scar defect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:453-460.

He Y, Zhong J, Zhou W, et al. Four surgical strategies for the treatment of cesarean scar defect: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:593-602.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

With the increase in cesarean deliveries performed over the decades, the sequelae of the surgery are now arising. Cesarean scar defects (CSDs) are a complication seen when the endometrium and muscular layers from a prior uterine scar are damaged. This damage in the uterine scar can lead to abnormal uterine bleeding and the implantation of an ectopic pregnancy, which can be life-threatening. Ultrasonography can be used to diagnose this defect, which can appear as a hypoechoic space filled with postmenstrual blood, representing a myometrial tear at the wound site.1 There are several risk factors for CSD, including multiple cesarean deliveries, cesarean delivery during advanced stages of labor, and uterine incisions near the cervix. Elevated body mass index as well as gestational diabetes also have been found to be associated with inadequate healing of the prior cesarean incision.2 Studies have shown that both single- and double-layer closure of the hysterotomy during a cesarean delivery have similar incidences of CSDs.3,4 There are multiple ways to correct a CSD; however, there is no gold standard that has been identified in the literature.

Details about the study

The study by He and colleagues is a meta-analysis aimed at comparing the treatment of CSDs via laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, combined hysteroscopy and laparoscopy, and vaginal repair. The primary outcome measures were reduction in abnormal uterine bleeding and scar defect depth. A total of 10 studies (n = 858) were reviewed: 4 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 6 observational studies. The studies analyzed varied in terms of which techniques were compared.

Patients who underwent uterine scar resection by combined laparoscopy and hysteroscopy had a shorter duration of abnormal uterine bleeding when compared with hysteroscopy alone (standardized mean difference [SMD] = 1.36; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.37−2.36; P = .007) and vaginal repair (SMD = 1.58; 95% CI, 0.97−2.19; P<.0001). Combined laparoscopic and hysteroscopic technique also was found to reduce the diverticulum depth more than in vaginal repair (SMD = 1.57; 95% CI, 0.54−2.61; P = .003).

Continue to: Study strengths and weaknesses...

Study strengths and weaknesses

This is the first meta-analysis to compare the different surgical techniques to correct a CSD. The authors were able to compare many of the characteristics regarding the routes of repair, including hysteroscopy, laparoscopy, and vaginal. The authors were able to analyze the combined laparoscopic and hysteroscopic approach, which facilitates evaluation of the location and satisfaction of defect repair during the procedure.

Some weaknesses of this study include the limited amount of RCTs available for review. All studies were also from China, where the rate of CSDs is higher. Therefore, the results may not be generalizable to all populations. Given that the included studies were done at different sites, it is difficult to determine surgical expertise and surgical technique. Additionally, the studies analyzed varied by which techniques were compared; therefore, indirect analyses were conducted to compare certain techniques. There was limited follow-up for these patients (anywhere from 3 to 6 months), so long-term data and future pregnancy data are needed to determine the efficacy of these procedures.

CSDs are a rising concern due to the increasing cesarean delivery rate. It is critical to be able to identify as well as correct these defects. This is the first systematic review to compare 4 techniques of managing CSDs. Based on this article, there may be some additional benefit from combined hysteroscopic and laparoscopic repair of these defects in terms of decreasing bleeding and decreasing the scar defect depth. However, how these results translate into long-term outcomes for patients and their future pregnancies is still unknown, and further research must be done.

STEPHANIE DELGADO, MD, AND XIAOMING GUAN, MD, PHD

He Y, Zhong J, Zhou W, et al. Four surgical strategies for the treatment of cesarean scar defect: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:593-602.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

With the increase in cesarean deliveries performed over the decades, the sequelae of the surgery are now arising. Cesarean scar defects (CSDs) are a complication seen when the endometrium and muscular layers from a prior uterine scar are damaged. This damage in the uterine scar can lead to abnormal uterine bleeding and the implantation of an ectopic pregnancy, which can be life-threatening. Ultrasonography can be used to diagnose this defect, which can appear as a hypoechoic space filled with postmenstrual blood, representing a myometrial tear at the wound site.1 There are several risk factors for CSD, including multiple cesarean deliveries, cesarean delivery during advanced stages of labor, and uterine incisions near the cervix. Elevated body mass index as well as gestational diabetes also have been found to be associated with inadequate healing of the prior cesarean incision.2 Studies have shown that both single- and double-layer closure of the hysterotomy during a cesarean delivery have similar incidences of CSDs.3,4 There are multiple ways to correct a CSD; however, there is no gold standard that has been identified in the literature.

Details about the study

The study by He and colleagues is a meta-analysis aimed at comparing the treatment of CSDs via laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, combined hysteroscopy and laparoscopy, and vaginal repair. The primary outcome measures were reduction in abnormal uterine bleeding and scar defect depth. A total of 10 studies (n = 858) were reviewed: 4 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 6 observational studies. The studies analyzed varied in terms of which techniques were compared.

Patients who underwent uterine scar resection by combined laparoscopy and hysteroscopy had a shorter duration of abnormal uterine bleeding when compared with hysteroscopy alone (standardized mean difference [SMD] = 1.36; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.37−2.36; P = .007) and vaginal repair (SMD = 1.58; 95% CI, 0.97−2.19; P<.0001). Combined laparoscopic and hysteroscopic technique also was found to reduce the diverticulum depth more than in vaginal repair (SMD = 1.57; 95% CI, 0.54−2.61; P = .003).

Continue to: Study strengths and weaknesses...

Study strengths and weaknesses

This is the first meta-analysis to compare the different surgical techniques to correct a CSD. The authors were able to compare many of the characteristics regarding the routes of repair, including hysteroscopy, laparoscopy, and vaginal. The authors were able to analyze the combined laparoscopic and hysteroscopic approach, which facilitates evaluation of the location and satisfaction of defect repair during the procedure.

Some weaknesses of this study include the limited amount of RCTs available for review. All studies were also from China, where the rate of CSDs is higher. Therefore, the results may not be generalizable to all populations. Given that the included studies were done at different sites, it is difficult to determine surgical expertise and surgical technique. Additionally, the studies analyzed varied by which techniques were compared; therefore, indirect analyses were conducted to compare certain techniques. There was limited follow-up for these patients (anywhere from 3 to 6 months), so long-term data and future pregnancy data are needed to determine the efficacy of these procedures.

CSDs are a rising concern due to the increasing cesarean delivery rate. It is critical to be able to identify as well as correct these defects. This is the first systematic review to compare 4 techniques of managing CSDs. Based on this article, there may be some additional benefit from combined hysteroscopic and laparoscopic repair of these defects in terms of decreasing bleeding and decreasing the scar defect depth. However, how these results translate into long-term outcomes for patients and their future pregnancies is still unknown, and further research must be done.

STEPHANIE DELGADO, MD, AND XIAOMING GUAN, MD, PHD

- Woźniak A, Pyra K, Tinto HR, et al. Ultrasonographic criteria of cesarean scar defect evaluation. J Ultrason. 2018;18: 162-165.

- Antila-Långsjö RM, Mäenpää JU, Huhtala HS, et al. Cesarean scar defect: a prospective study on risk factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018:219:458e1-e8.

- Di Spiezio Sardo A, Saccone G, McCurdy R, et al. Risk of cesarean scar defect following single- vs double-layer uterine closure: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;50:578-583.

- Roberge S, Demers S, Berghella V, et al. Impact of single- vs double-layer closure on adverse outcomes and uterine scar defect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:453-460.

- Woźniak A, Pyra K, Tinto HR, et al. Ultrasonographic criteria of cesarean scar defect evaluation. J Ultrason. 2018;18: 162-165.

- Antila-Långsjö RM, Mäenpää JU, Huhtala HS, et al. Cesarean scar defect: a prospective study on risk factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018:219:458e1-e8.

- Di Spiezio Sardo A, Saccone G, McCurdy R, et al. Risk of cesarean scar defect following single- vs double-layer uterine closure: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;50:578-583.

- Roberge S, Demers S, Berghella V, et al. Impact of single- vs double-layer closure on adverse outcomes and uterine scar defect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:453-460.

Is there empathy erosion?

You learned a lot of things in medical school. But there must have been some things that you unlearned on the way to your degree. For instance, you unlearned that you could catch a cold by playing outside on a cold damp day without your jacket. You unlearned that handling a toad would give you warts.

The authors of a recent study suggest that over your 4 years in medical school you also unlearned how to be empathetic (“Does Empathy Decline in the Clinical Phase of Medical Education? A Nationwide, Multi-institutional, Cross-Sectional Study of Students at DO-Granting Medical Schools,” Acad Med. 2020 Jan 21. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003175). The researchers surveyed more than 10,000 medical students at nearly 50 DO-granting medical schools using standardized questionnaire called the Jefferson Scale of Empathy. They discovered that the students in the clinical phase (years 3 and 4) had lower “empathy scores” than the students in the preclinical phase of their education (years 1 and 2). This decline was statistically significant but “negligible” in magnitude. One wonders why they even chose to publish their results, particularly when the number of respondents to the web-based survey declined with each successive year in medical school. Having looked at the a sample of some of the questions being asked, I can understand why third- and fourth-year students couldn’t be bothered to respond. They were too busy to answer a few dozen “lame” questions.

There may be a decline in empathy over the course our medical training, but I’m not sure that this study can speak to it. An older study found that although medical students scores on a self-administered scale declined between the second and third year, the observed empathetic behavior actually increased. If I had to choose, I would lean more heavily on the results of the behavioral observations.

Certainly, we all changed over the course of our medical education. Including postgraduate training, it may have lasted a decade or more. We saw hundreds of patients, observed life and death on a scale and with an intensity that most of us previously had never experienced. Our perspective changed from being a naive observer to playing the role of an active participant. Did that change include a decline in our capacity for empathy?

Something had to change. We found quickly that we didn’t have the time or emotional energy to learn as much about the person hiding behind every complaint as we once thought we should. We had to cut corners. Sometimes we cut too many. On the other hand, as we saw more patients we may have learned more efficient ways of discovering what we needed to know about them to become an effective and caring physician. If we found ourselves in a specialty in which patients have a high mortality, we were forced to learn ways of protecting ourselves from the emotional damage.

What would you call this process? Was it empathy erosion? Was it a hardening or toughening? Or was it simply maturation? Whatever term you use, it was an obligatory process if we hoped to survive. However, not all of us have done it well. Some of us have narrowed our focus to see only the complaint and the diagnosis, and we too often fail to see the human hiding in plain sight.

For those of us who completed our training with our empathy intact, was this the result of a genetic gift or the atmosphere our parents had created at home? I suspect that in most cases our capacity for empathy as physicians was nurtured and enhanced by the role models we encountered during our training. The mentors we most revered were those who had already been through the annealing process of medical school and specialty training and become even more skilled at caring than when they left college. It is an intangible that can’t be taught. Sadly, there is no way of guaranteeing that everyone who enters medical school will be exposed to or benefit from even one of these master physicians.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

You learned a lot of things in medical school. But there must have been some things that you unlearned on the way to your degree. For instance, you unlearned that you could catch a cold by playing outside on a cold damp day without your jacket. You unlearned that handling a toad would give you warts.

The authors of a recent study suggest that over your 4 years in medical school you also unlearned how to be empathetic (“Does Empathy Decline in the Clinical Phase of Medical Education? A Nationwide, Multi-institutional, Cross-Sectional Study of Students at DO-Granting Medical Schools,” Acad Med. 2020 Jan 21. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003175). The researchers surveyed more than 10,000 medical students at nearly 50 DO-granting medical schools using standardized questionnaire called the Jefferson Scale of Empathy. They discovered that the students in the clinical phase (years 3 and 4) had lower “empathy scores” than the students in the preclinical phase of their education (years 1 and 2). This decline was statistically significant but “negligible” in magnitude. One wonders why they even chose to publish their results, particularly when the number of respondents to the web-based survey declined with each successive year in medical school. Having looked at the a sample of some of the questions being asked, I can understand why third- and fourth-year students couldn’t be bothered to respond. They were too busy to answer a few dozen “lame” questions.

There may be a decline in empathy over the course our medical training, but I’m not sure that this study can speak to it. An older study found that although medical students scores on a self-administered scale declined between the second and third year, the observed empathetic behavior actually increased. If I had to choose, I would lean more heavily on the results of the behavioral observations.

Certainly, we all changed over the course of our medical education. Including postgraduate training, it may have lasted a decade or more. We saw hundreds of patients, observed life and death on a scale and with an intensity that most of us previously had never experienced. Our perspective changed from being a naive observer to playing the role of an active participant. Did that change include a decline in our capacity for empathy?

Something had to change. We found quickly that we didn’t have the time or emotional energy to learn as much about the person hiding behind every complaint as we once thought we should. We had to cut corners. Sometimes we cut too many. On the other hand, as we saw more patients we may have learned more efficient ways of discovering what we needed to know about them to become an effective and caring physician. If we found ourselves in a specialty in which patients have a high mortality, we were forced to learn ways of protecting ourselves from the emotional damage.

What would you call this process? Was it empathy erosion? Was it a hardening or toughening? Or was it simply maturation? Whatever term you use, it was an obligatory process if we hoped to survive. However, not all of us have done it well. Some of us have narrowed our focus to see only the complaint and the diagnosis, and we too often fail to see the human hiding in plain sight.

For those of us who completed our training with our empathy intact, was this the result of a genetic gift or the atmosphere our parents had created at home? I suspect that in most cases our capacity for empathy as physicians was nurtured and enhanced by the role models we encountered during our training. The mentors we most revered were those who had already been through the annealing process of medical school and specialty training and become even more skilled at caring than when they left college. It is an intangible that can’t be taught. Sadly, there is no way of guaranteeing that everyone who enters medical school will be exposed to or benefit from even one of these master physicians.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

You learned a lot of things in medical school. But there must have been some things that you unlearned on the way to your degree. For instance, you unlearned that you could catch a cold by playing outside on a cold damp day without your jacket. You unlearned that handling a toad would give you warts.

The authors of a recent study suggest that over your 4 years in medical school you also unlearned how to be empathetic (“Does Empathy Decline in the Clinical Phase of Medical Education? A Nationwide, Multi-institutional, Cross-Sectional Study of Students at DO-Granting Medical Schools,” Acad Med. 2020 Jan 21. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003175). The researchers surveyed more than 10,000 medical students at nearly 50 DO-granting medical schools using standardized questionnaire called the Jefferson Scale of Empathy. They discovered that the students in the clinical phase (years 3 and 4) had lower “empathy scores” than the students in the preclinical phase of their education (years 1 and 2). This decline was statistically significant but “negligible” in magnitude. One wonders why they even chose to publish their results, particularly when the number of respondents to the web-based survey declined with each successive year in medical school. Having looked at the a sample of some of the questions being asked, I can understand why third- and fourth-year students couldn’t be bothered to respond. They were too busy to answer a few dozen “lame” questions.

There may be a decline in empathy over the course our medical training, but I’m not sure that this study can speak to it. An older study found that although medical students scores on a self-administered scale declined between the second and third year, the observed empathetic behavior actually increased. If I had to choose, I would lean more heavily on the results of the behavioral observations.

Certainly, we all changed over the course of our medical education. Including postgraduate training, it may have lasted a decade or more. We saw hundreds of patients, observed life and death on a scale and with an intensity that most of us previously had never experienced. Our perspective changed from being a naive observer to playing the role of an active participant. Did that change include a decline in our capacity for empathy?

Something had to change. We found quickly that we didn’t have the time or emotional energy to learn as much about the person hiding behind every complaint as we once thought we should. We had to cut corners. Sometimes we cut too many. On the other hand, as we saw more patients we may have learned more efficient ways of discovering what we needed to know about them to become an effective and caring physician. If we found ourselves in a specialty in which patients have a high mortality, we were forced to learn ways of protecting ourselves from the emotional damage.

What would you call this process? Was it empathy erosion? Was it a hardening or toughening? Or was it simply maturation? Whatever term you use, it was an obligatory process if we hoped to survive. However, not all of us have done it well. Some of us have narrowed our focus to see only the complaint and the diagnosis, and we too often fail to see the human hiding in plain sight.

For those of us who completed our training with our empathy intact, was this the result of a genetic gift or the atmosphere our parents had created at home? I suspect that in most cases our capacity for empathy as physicians was nurtured and enhanced by the role models we encountered during our training. The mentors we most revered were those who had already been through the annealing process of medical school and specialty training and become even more skilled at caring than when they left college. It is an intangible that can’t be taught. Sadly, there is no way of guaranteeing that everyone who enters medical school will be exposed to or benefit from even one of these master physicians.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

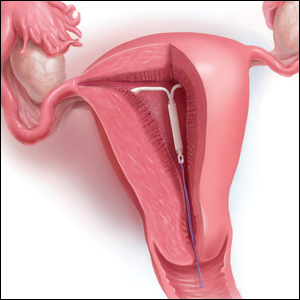

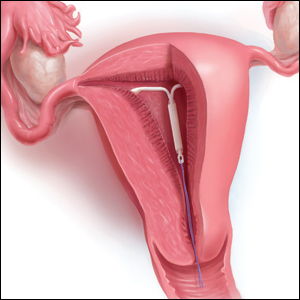

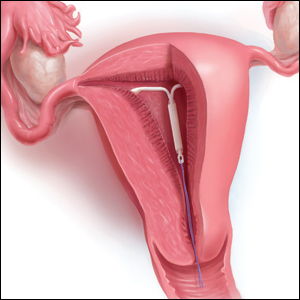

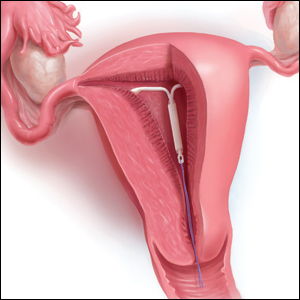

The IUD string check: Benefit or burden?

CASE A patient experiences unnessary inconvenience, distress, and cost following IUD placement

Ms. J had a levonorgestrel intrauterine device (IUD) placed at her postpartum visit. Her physician asked her to return for a string check in 4 to 6 weeks. She was dismayed at the prospect of re-presenting for care, as she is losing the Medicaid coverage that paid for her pregnancy care. One month later, she arranged for a babysitter so she could obtain the recommended string check. The physician told her the strings seemed longer than expected and ordered ultrasonography. Ms. J is distressed because of the mounting cost of care but is anxious to ensure that the IUD will prevent future pregnancy.

Should the routine IUD string check be reconsidered?

The string check dissension

Intrauterine devices offer reliable contraception with a high rate of satisfaction and a remarkably low rate of complications.1-3 With the increased uptake of IUDs, the value of “string checks” is being debated, with myriad responses from professional groups, manufacturers, and individual clinicians. For many practicing ObGyns, the question remains: Should patients be counseled about presenting for or doing their own IUD string checks?

Indeed, all IUD manufacturers recommend monthly self-examination to evaluate string presence.4-8 Manufacturers’ websites prominently display this information in material directed toward current or potential users, so many patients may be familiar already with this recommendation before their clinician visit. Yet, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention state that no routine follow-up or monitoring is needed.9

In our case scenario, follow-up is clearly burdensome and ultimately costly. Instead, clinicians can advise patients to return with rare but important to recognize complications (such as perforation, expulsion, infection), adverse effects, or desire for change. While no data are available to support in-office or at-home string checks, data do show that women reliably present when intervention is needed.

Here, we explore 5 questions relevant to IUD string checks and discuss why it is time to rethink this practice habit.

What is the purpose of a string check?

String checks serve as a surrogate for assessing an IUD’s position and function. A string check can be performed by a clinician, who observes the IUD strings on speculum exam or palpates the strings on bimanual exam, or by the patient doing a self-exam. A positive string check purportedly assures both the IUD user and the health care provider that an IUD remains in a fundal, intrauterine position, thus providing an ongoing reliable contraceptive effect.

However, string check reliability in detecting contraceptive effectiveness is uncertain. Strings that subjectively feel or appear longer than anticipated can lead to unnecessary additional evaluation and emotional distress: These are harms. By contrast, when an expulsion occurs, it often is a partial expulsion or displacement, with unclear effect on patient or physician perception of the strings on examination. One retrospective review identified women with a history of IUD placement and a positive pregnancy test; those with an intrauterine pregnancy (74%) frequently also had a malpositioned IUD (55%) and rarely identifiable string issues (16%).10 Before asking patients and clinicians to use resources for performing string evaluations, the association between this action and outcomes of interest must be elucidated.

If not for assessing risk of expulsion, IUD follow-up allows the clinician to evaluate for other complications or adverse effects and to address patient concerns. This practice often is performed when the patient is starting a new medication or medical intervention. However, a systematic review involving 4 studies of IUD follow-up visits or phone calls after contraceptive initiation generated limited data, with no notable impact on contraceptive continuation or indicated use.11

Most important, data show that patients present to their clinician when issues arise with IUD use. One prospective study of 280 women compared multiple follow-up visits with a single 6-week follow-up visit after IUD placement; 10 expulsions were identified, and 8 of these were noted at unscheduled visits when patients presented with symptoms.12 This study suggests that there is little benefit in scheduled follow-up or set self-checks.

Furthermore, in a study in Finland of more than 17,000 IUD users, the rare participants who became pregnant during IUD use promptly presented for care because of a change in menses, pain, or symptoms of pregnancy.13 While IUDs are touted as user independent, this overlooks the reality: Data show that device failure, although rare, is rapidly and appropriately addressed by the user.

Continue to: Does the risk of IUD expulsion warrant string checks?...

Does the risk of IUD expulsion warrant string checks?

The risk of IUD expulsion is estimated to be 1% at 1 month and 4% at 1 year, with a contraceptive failure rate of 0.4% at 1 year. The risk of expulsion does not differ by age group, including adolescents, or parity, but it is higher with use of the copper IUD (2% at 1 month, 6% at 1 year) and with prior expulsion (14%, limited by small numbers).1 Furthermore, risk of expulsion is higher with postplacental placement and second trimester abortion.14,15 Despite this risk, the contraceptive failure rate of all types of IUDs remains consistently lower than all other reversible methods besides the contraceptive implant.16

Furthermore, while IUD expulsion is rare, unnoticed expulsion is even more rare. In one study with more than 58,000 person-years of use, 132 pregnancies were noted, and 7 of these occurred in the setting of an unnoticed expulsion.13 Notably, a higher risk threshold is held for other medications. For example, statins are associated with a 3% risk of irreversible hepatic injury, yet serial liver function tests are not performed in patients without baseline liver dysfunction.17 A less than 0.1% risk of a non–life-threatening complication—unnoticed expulsion—does not warrant routine follow-up. Instead, the patient gauges the tolerability of that risk in making a follow-up plan, particularly given the varied individual preferences in patients’ management of the associated outcome of unintended pregnancy.

Are women interested in and able to perform their own string checks?

Recommendations to perform IUD string self-checks should consider whether women are willing and able to do so. In a study of 126 IUD users, 59% of women had attempted to check their IUD strings at home, and one-third were unable to do so successfully; all participants had visible strings on subsequent speculum exam.18 The women also were given the opportunity to perform a string self-check at the study visit. Overall, only 46% of participants found the exercise acceptable and were able to palpate the IUD strings.18 The authors aptly stated, “A universal recommendation for practice that is meant to identify a rare complication has no clinical utility if at least half of the women are unable to follow it.”

In which scenarios might a string check have clear utility?

The most important reason for follow-up after IUD placement or for patients to perform string self-checks is patient preference. At least anecdotally, some patients take comfort, particularly in the absence of menses, in palpating IUD strings regularly; these individuals should know that there is no necessity for but also no harm in this practice. In addition, patients may desire a string check or follow-up visit to discuss their new contraceptive’s goodness-of-fit.

While limited data show that routinely scheduling such visits does not improve contraceptive continuation, it is difficult to extrapolate these data to the select individuals who independently desire follow-up. (In addition, contraceptive continuance is hardly a metric of success, as clinicians and patients can agree that discontinuation in the setting of patient dissatisfaction is always appropriate.)

Clinicians should share with patients differing risks of IUD expulsion, and this may prompt more nuanced decisions about string checks and/or follow-up. Patients with postplacental or postabortion (second trimester) IUD placement or placement following prior expulsion may opt to perform string checks given the relatively higher risk of expulsion despite the maintained, absolutely low risk that such an event is unnoticed.

If a patient does present for a string check and strings are not visualized on exam, reasonable attempts should be made to identify the strings at that time. A cytobrush can be used to liberate and identify strings within the cervical canal. If the clinician cannot identify the strings or the patient is unable to tolerate such attempts, ultrasonography should be performed to localize the IUD. The ultrasound scan can be done in the office, if available, which is more cost-effective for women than a referral to radiology. If ultrasonography does not identify an intrauterine IUD, an x-ray is the next step to determine if the IUD has expulsed or perforated.

Continue to: Is a string check worth the cost?...

Is a string check worth the cost?

Health care providers may not be aware of the cost of care from the patient perspective. While the Affordable Care Act of 2010 mandates contraceptive coverage for women with insurance, a string check often is coded as a problem-based visit and thus may require a significant copay or out-of-pocket cost for high-deductible plans—without a proven benefit.19 Women who lack insurance coverage may forgo even necessary care due to the cost.20

The bottom line

The medical community and ObGyns specifically are familiar with a practice of patient self-examination falling by the wayside, as has been the case with breast self-examination.21 While counseling on string checks can complement conversations about risks and patients’ personal preferences regarding follow-up, no data support routine string checks in the clinic or at home. One of the great benefits of IUD use is its lack of barriers and resources for ongoing use. Physicians need not reintroduce burdens without benefits to those who desire this contraceptive method.

- Aoun J, Dines VA, Stovall DW, et al. Effects of age, parity, and device type on complications and discontinuation of intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:585-592.

- Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Allsworth JE, et al. Continuation and satisfaction of reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1105-1113.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecology Practice. Committee opinion No. 672. Clinical challenges of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e69-e77.

- Mirena website. Placement of Mirena. 2019. https://www.mirena-us.com/placement-of-mirena/. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- Kyleena website. Let’s get started. 2019. https://www.kyleena-us.com/lets-get-started/what-to-expect/. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- Skyla website. What to expect. 2019. https://www.skyla-us.com/getting-skyla/index.php. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- Liletta website. What should I expect after Liletta insertion? 2020. https://www.liletta.com/about/what-to-expect-afterinsertion. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- Paragard website. What to expect with Paragard. 2019. https://www.paragard.com/what-can-i-expect-with-paragard/. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. US selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(4):1-66. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/ volumes/65/rr/pdfs/rr6504.pdf. Accessed February 19, 2020.

- Moschos E, Twickler DM. Intrauterine devices in early pregnancy: findings on ultrasound and clinical outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:427.e1-6.

- Steenland MW, Zapata LB, Brahmi D, et al. Appropriate follow up to detect potential adverse events after initiation of select contraceptive methods: a systematic review. Contraception 2013;87:611-624.

- Neuteboom K, de Kroon CD, Dersjant-Roorda M, et al. Follow-up visits after IUD-insertion: sense or nonsense? Contraception. 2003;68:101-104.

- Backman T, Rauramo I, Huhtala S, et al. Pregnancy during the use of levonorgestrel intrauterine system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:50-54.

- Whitaker AK, Chen BA. Society of Family Planning guidelines: postplacental insertion of intrauterine devices. Contraception. 2018;97:2-13.

- Roe AH, Bartz D. Society of Family Planning clinical recommendations: contraception after surgical abortion. Contraception. 2019;99:2-9.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. Practice bulletin No. 186. Long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e251-e269.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: important safety label changes to cholesterol-lowering statin drugs. 2016. https://www .fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drugsafety-communication-important-safety-label-changescholesterol-lowering-statin-drugs. Accessed January 9, 2020.

- Melo J, Tschann M, Soon R, et al. Women’s willingness and ability to feel the strings of their intrauterine device. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;137:309-313.

- Healthcare.gov website. Health benefits & coverage: birth control benefits. 2020. https://www.healthcare.gov/ coverage/birth-control-benefits/. Accessed January 6, 2020.

- NORC at the University of Chicago. Americans’ views of healthcare costs, coverage, and policy. 2018;1-15. https:// www.norc.org/PDFs/WHI%20Healthcare%20Costs%20 Coverage%20and%20Policy/WHI%20Healthcare%20 Costs%20Coverage%20and%20Policy%20Issue%20Brief.pdf. Accessed February 19, 2020.

- Kosters JP, Gotzsche PC. Regular self-examination or clinical examination for early detection of breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003. CD003373.

CASE A patient experiences unnessary inconvenience, distress, and cost following IUD placement

Ms. J had a levonorgestrel intrauterine device (IUD) placed at her postpartum visit. Her physician asked her to return for a string check in 4 to 6 weeks. She was dismayed at the prospect of re-presenting for care, as she is losing the Medicaid coverage that paid for her pregnancy care. One month later, she arranged for a babysitter so she could obtain the recommended string check. The physician told her the strings seemed longer than expected and ordered ultrasonography. Ms. J is distressed because of the mounting cost of care but is anxious to ensure that the IUD will prevent future pregnancy.

Should the routine IUD string check be reconsidered?

The string check dissension

Intrauterine devices offer reliable contraception with a high rate of satisfaction and a remarkably low rate of complications.1-3 With the increased uptake of IUDs, the value of “string checks” is being debated, with myriad responses from professional groups, manufacturers, and individual clinicians. For many practicing ObGyns, the question remains: Should patients be counseled about presenting for or doing their own IUD string checks?

Indeed, all IUD manufacturers recommend monthly self-examination to evaluate string presence.4-8 Manufacturers’ websites prominently display this information in material directed toward current or potential users, so many patients may be familiar already with this recommendation before their clinician visit. Yet, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention state that no routine follow-up or monitoring is needed.9

In our case scenario, follow-up is clearly burdensome and ultimately costly. Instead, clinicians can advise patients to return with rare but important to recognize complications (such as perforation, expulsion, infection), adverse effects, or desire for change. While no data are available to support in-office or at-home string checks, data do show that women reliably present when intervention is needed.

Here, we explore 5 questions relevant to IUD string checks and discuss why it is time to rethink this practice habit.

What is the purpose of a string check?

String checks serve as a surrogate for assessing an IUD’s position and function. A string check can be performed by a clinician, who observes the IUD strings on speculum exam or palpates the strings on bimanual exam, or by the patient doing a self-exam. A positive string check purportedly assures both the IUD user and the health care provider that an IUD remains in a fundal, intrauterine position, thus providing an ongoing reliable contraceptive effect.

However, string check reliability in detecting contraceptive effectiveness is uncertain. Strings that subjectively feel or appear longer than anticipated can lead to unnecessary additional evaluation and emotional distress: These are harms. By contrast, when an expulsion occurs, it often is a partial expulsion or displacement, with unclear effect on patient or physician perception of the strings on examination. One retrospective review identified women with a history of IUD placement and a positive pregnancy test; those with an intrauterine pregnancy (74%) frequently also had a malpositioned IUD (55%) and rarely identifiable string issues (16%).10 Before asking patients and clinicians to use resources for performing string evaluations, the association between this action and outcomes of interest must be elucidated.

If not for assessing risk of expulsion, IUD follow-up allows the clinician to evaluate for other complications or adverse effects and to address patient concerns. This practice often is performed when the patient is starting a new medication or medical intervention. However, a systematic review involving 4 studies of IUD follow-up visits or phone calls after contraceptive initiation generated limited data, with no notable impact on contraceptive continuation or indicated use.11

Most important, data show that patients present to their clinician when issues arise with IUD use. One prospective study of 280 women compared multiple follow-up visits with a single 6-week follow-up visit after IUD placement; 10 expulsions were identified, and 8 of these were noted at unscheduled visits when patients presented with symptoms.12 This study suggests that there is little benefit in scheduled follow-up or set self-checks.