User login

ID Blog: The waters of death

Diseases of the American Civil War, Part I

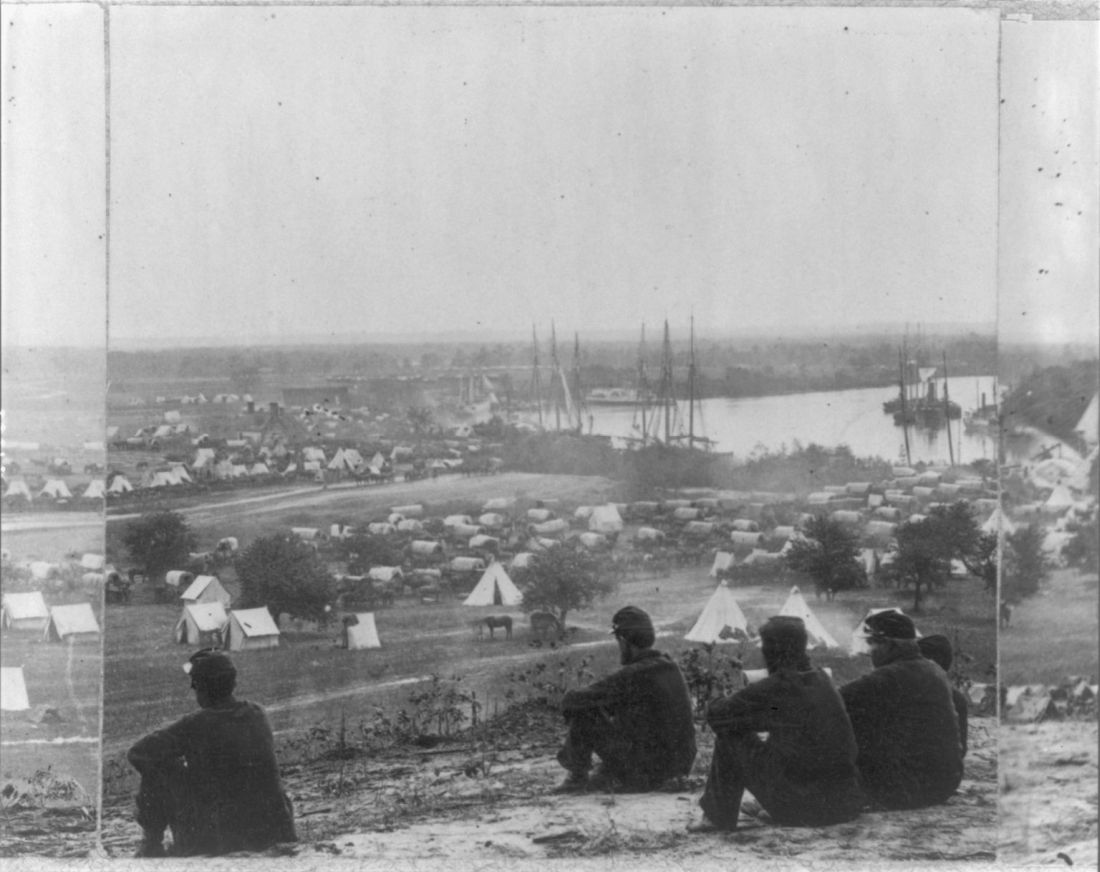

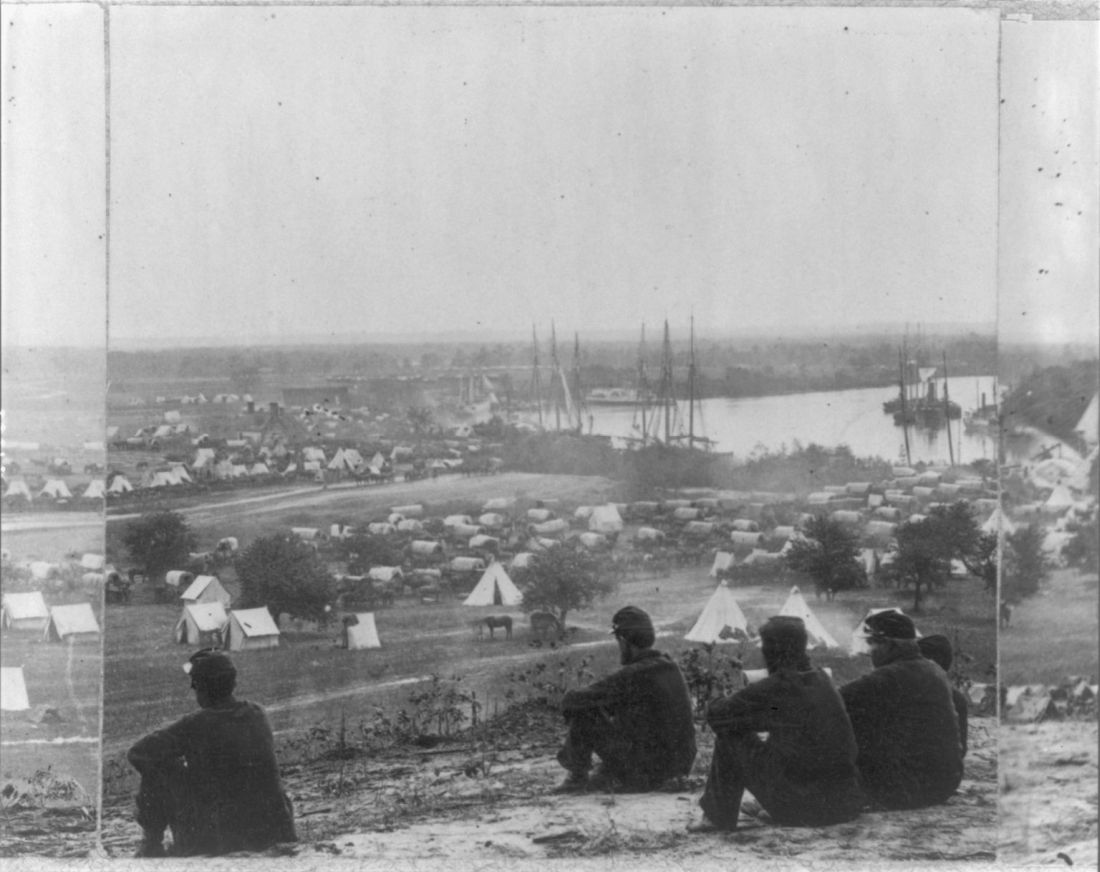

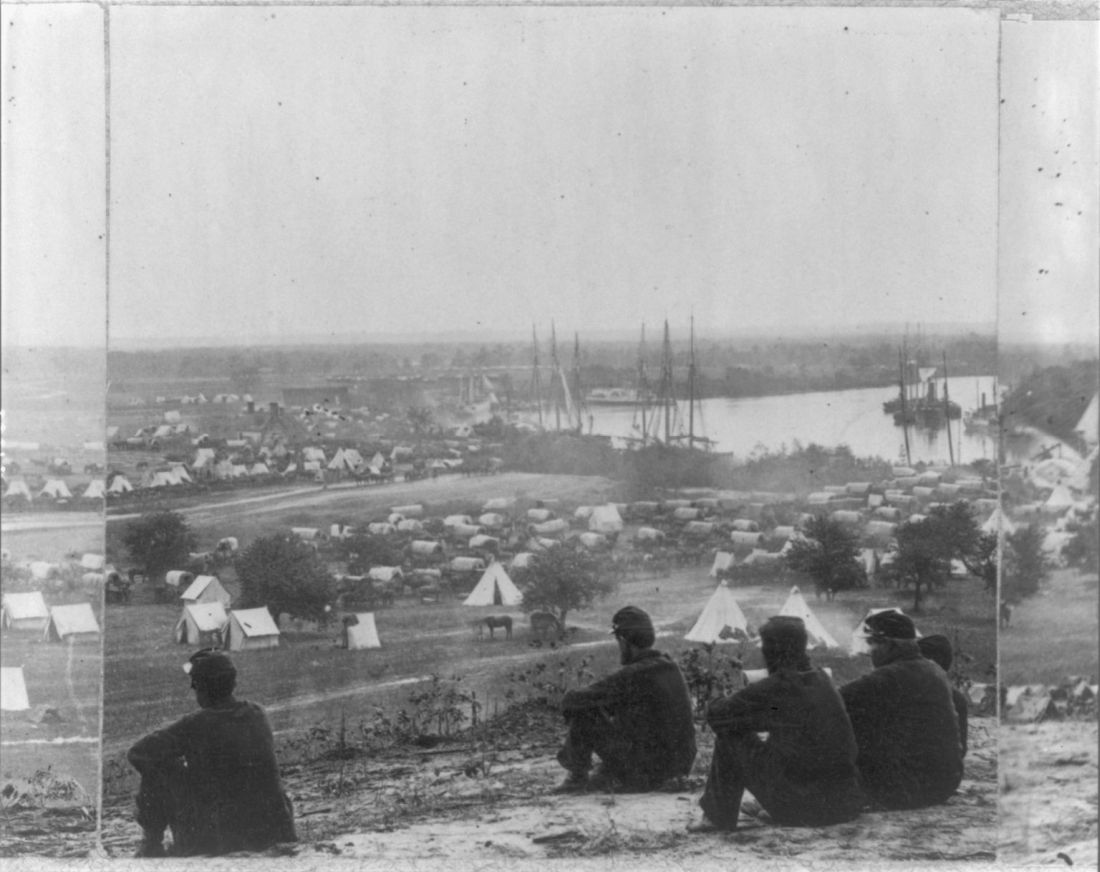

If cleanliness is next to godliness, then the average soldier in the American Civil War lived just down the street from hell. In a land at war, before the formal tenets of germ theory had spread beyond the confines of Louis Pasteur’s laboratory in France, the lack of basic hygiene, both cultural and situational, coupled to an almost complete lack of curative therapies created an appalling death toll. Waterborne diseases in particular spared neither general nor private, and neither doctor nor nurse.

“Of all the adversities that Union and Confederate soldiers confronted, none was more deadly or more prevalent than contaminated water,” according to Jeffrey S. Sartin, MD, in his survey of Civil War diseases.1

The Union Army records list 1,765,000 cases of diarrhea or dysentery with 45,000 deaths and 149,000 cases of typhoid fever with 35,000 deaths. Add to these the 1,316,000 cases of malaria (borne by mosquitoes breeding in the waters) with its 10,000 deaths, and it is easy to see how the battlefield itself took second place in service to the grim reaper. (Overall, there were roughly two deaths from disease for every one from wounds.)

The chief waterborne plague, infectious diarrhea – including bacterial, amoebic, and other parasites – as well as cholera and typhoid, was an all-year-long problem, and, with the typical wry humor of soldiers, these maladies were given popular names, including the “Tennessee trots” and the “Virginia quick-step.”

Unsanitary conditions in the camps were primarily to blame, and this problem of sanitation was obvious to many observers at the time.

Despite a lack of knowledge of germ theory, doctors were fully aware of the relationship of unsanitary conditions to disease, even if they ascribed the link to miasmas or particles of filth.

Hospitals, which were under more strict control than the regular army camps, were meticulous about the placement of latrines and about keeping high standards of cleanliness among the patients, including routine washing. However, this was insufficient for complete protection, because what passed for clean in the absence of the knowledge of bacterial contamination was often totally ineffective. As one Civil War surgeon stated: “We operated in old bloodstained and often pus-stained coats, we used undisinfected instruments from undisinfected plush-lined cases. If a sponge (if they had sponges) or instrument fell on the floor it was washed and squeezed in a basin of water and used as if it was clean.”2

Overall, efforts at what passed for sanitation remained a constant goal and constant struggle in the field.

After the First Battle of Bull Run, Women’s Central Association of Relief President Henry W. Bellows met with Secretary of War Simon Cameron to discuss the abysmal sanitary conditions witnessed by WCAR volunteers. This meeting led to the creation of what would become the U.S. Sanitary Commission, which was approved by President Abraham Lincoln on June 13, 1861.

The U.S. Sanitary Commission served as a means for funneling civilian assistance to the military, with volunteers providing assistance in the organization of military hospitals and camps and aiding in the transportation of the wounded. However, despite these efforts, the setup of army camps and the behavior of the soldiers were not often directed toward proper sanitation. “The principal causes of disease, however, in our camps were the same that we have always to deplore and find it so difficult to remedy, simply because citizens suddenly called to the field cannot comprehend that men in masses require the attention of their officers to enforce certain hygienic conditions without which health cannot be preserved.”3

Breaches of sanitation were common in the confines of the camps, despite regulations designed to protect the soldiers. According to one U.S. Army surgeon of the time: “Especially [needed] was policing of the latrines. The trench is generally too shallow, the daily covering ... with dirt is entirely neglected. Large numbers of the men will not use the sinks [latrines], ... but instead every clump of bushes, every fence border in the vicinity.” Another pointed out that, after the Battle of Seven Pines, “the only water was infiltrated with the decaying animal matter of the battlefield.” Commenting on the placement of latrines in one encampment, another surgeon described how “the sink [latrine] is the ground in the vicinity, which slopes down to the stream, from which all water from the camp is obtained.”4

Treatment for diarrhea and dysentery was varied. Opiates were one of the most common treatments for diarrhea, whether in an alcohol solution as laudanum or in pill form, with belladonna being used to treat intestinal cramps, according to Glenna R. Schroeder-Lein in her book “The Encyclopedia of Civil War Medicine.” However, useless or damaging treatments were also prescribed, including the use of calomel (a mercury compound), turpentine, castor oil, and quinine.5

Acute diarrhea and dysentery illnesses occurred in at least 641/1,000 troops per year in the Union army. And even though the death rate was comparatively low (20/1,000 cases), it frequently led to chronic diarrhea, which was responsible for 288 deaths per 1,000 cases, and was the third highest cause of medical discharge after gunshot wounds and tuberculosis, according to Ms. Schroeder-Lein.

Although the American Civil War was the last major conflict before the spread of the knowledge of germ theory, the struggle to prevent the spread of waterborne diseases under wartime conditions remains ongoing. Hygiene is difficult under conditions of abject poverty and especially under conditions of armed conflict, and until the era of curative antibiotics there was no recourse.

Antibiotics are not the final solution for antibiotic resistance in intestinal disease pathogens, as outlined in a recent CDC report, is an increasing problem.6 For example, nontyphoidal Salmonella causes an estimated 1.35 million infections, 26,500 hospitalizations, and 420 deaths each year in the United States, with 16% of strains being resistant to at least one essential antibiotic. On a global scale, according to the World Health Organization, poor sanitation causes up to 432,000 diarrheal deaths annually and is linked to the transmission of other diseases like cholera, dysentery, typhoid, hepatitis A, and polio.7

With regard to actual epidemics, the world is only a hygienic crisis away from a major outbreak of dysentery (the last occurring between 1969 and 1972, when 20,000 people in Central America died), according to researchers who have detected antibiotic resistance in all but 1% of circulating Shigella dysenteriae strains surveyed since the 1990s. “This bacterium is still in circulation, and could be responsible for future epidemics if conditions should prove favorable – such as a large gathering of people without access to drinking water or treatment of human waste,” wrote François-Xavier Weill of the Pasteur Institute’s Enteric Bacterial Pathogens Unit.8

References

1. Sartin JS. Clin Infec Dis. 1993;16:580-4. (Correction published in 2002).

2. Civil War Battlefield Surgery. eHistory. The Ohio State University.

3. “Myths About Antiseptics and Camp Life – George Wunderlich,” published online Oct. 11, 2011. http://civilwarscholars.com/2011/10/myths-about-antiseptics-and-camp-life-george-wunderlich/

4. Dorwart BB. “Death is in the Breeze: Disease during the American Civil War” (The National Museum of the American Civil War Press, 2009).

5. Glenna R, Schroeder-Lein GR. “The Encyclopedia of Civil War Medicine” (New York: M. E. Sharpe, 2008).

6. “Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States 2019” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

7. “New report exposes horror of working conditions for millions of sanitation workers in the developing world,” World Health Organization. 2019 Nov 14.

8. Grant B. Origins of Dysentery. The Scientist. Published online March 22, 2016.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor of the department of biochemistry and molecular & cellular biology at Georgetown University, Washington.

Diseases of the American Civil War, Part I

Diseases of the American Civil War, Part I

If cleanliness is next to godliness, then the average soldier in the American Civil War lived just down the street from hell. In a land at war, before the formal tenets of germ theory had spread beyond the confines of Louis Pasteur’s laboratory in France, the lack of basic hygiene, both cultural and situational, coupled to an almost complete lack of curative therapies created an appalling death toll. Waterborne diseases in particular spared neither general nor private, and neither doctor nor nurse.

“Of all the adversities that Union and Confederate soldiers confronted, none was more deadly or more prevalent than contaminated water,” according to Jeffrey S. Sartin, MD, in his survey of Civil War diseases.1

The Union Army records list 1,765,000 cases of diarrhea or dysentery with 45,000 deaths and 149,000 cases of typhoid fever with 35,000 deaths. Add to these the 1,316,000 cases of malaria (borne by mosquitoes breeding in the waters) with its 10,000 deaths, and it is easy to see how the battlefield itself took second place in service to the grim reaper. (Overall, there were roughly two deaths from disease for every one from wounds.)

The chief waterborne plague, infectious diarrhea – including bacterial, amoebic, and other parasites – as well as cholera and typhoid, was an all-year-long problem, and, with the typical wry humor of soldiers, these maladies were given popular names, including the “Tennessee trots” and the “Virginia quick-step.”

Unsanitary conditions in the camps were primarily to blame, and this problem of sanitation was obvious to many observers at the time.

Despite a lack of knowledge of germ theory, doctors were fully aware of the relationship of unsanitary conditions to disease, even if they ascribed the link to miasmas or particles of filth.

Hospitals, which were under more strict control than the regular army camps, were meticulous about the placement of latrines and about keeping high standards of cleanliness among the patients, including routine washing. However, this was insufficient for complete protection, because what passed for clean in the absence of the knowledge of bacterial contamination was often totally ineffective. As one Civil War surgeon stated: “We operated in old bloodstained and often pus-stained coats, we used undisinfected instruments from undisinfected plush-lined cases. If a sponge (if they had sponges) or instrument fell on the floor it was washed and squeezed in a basin of water and used as if it was clean.”2

Overall, efforts at what passed for sanitation remained a constant goal and constant struggle in the field.

After the First Battle of Bull Run, Women’s Central Association of Relief President Henry W. Bellows met with Secretary of War Simon Cameron to discuss the abysmal sanitary conditions witnessed by WCAR volunteers. This meeting led to the creation of what would become the U.S. Sanitary Commission, which was approved by President Abraham Lincoln on June 13, 1861.

The U.S. Sanitary Commission served as a means for funneling civilian assistance to the military, with volunteers providing assistance in the organization of military hospitals and camps and aiding in the transportation of the wounded. However, despite these efforts, the setup of army camps and the behavior of the soldiers were not often directed toward proper sanitation. “The principal causes of disease, however, in our camps were the same that we have always to deplore and find it so difficult to remedy, simply because citizens suddenly called to the field cannot comprehend that men in masses require the attention of their officers to enforce certain hygienic conditions without which health cannot be preserved.”3

Breaches of sanitation were common in the confines of the camps, despite regulations designed to protect the soldiers. According to one U.S. Army surgeon of the time: “Especially [needed] was policing of the latrines. The trench is generally too shallow, the daily covering ... with dirt is entirely neglected. Large numbers of the men will not use the sinks [latrines], ... but instead every clump of bushes, every fence border in the vicinity.” Another pointed out that, after the Battle of Seven Pines, “the only water was infiltrated with the decaying animal matter of the battlefield.” Commenting on the placement of latrines in one encampment, another surgeon described how “the sink [latrine] is the ground in the vicinity, which slopes down to the stream, from which all water from the camp is obtained.”4

Treatment for diarrhea and dysentery was varied. Opiates were one of the most common treatments for diarrhea, whether in an alcohol solution as laudanum or in pill form, with belladonna being used to treat intestinal cramps, according to Glenna R. Schroeder-Lein in her book “The Encyclopedia of Civil War Medicine.” However, useless or damaging treatments were also prescribed, including the use of calomel (a mercury compound), turpentine, castor oil, and quinine.5

Acute diarrhea and dysentery illnesses occurred in at least 641/1,000 troops per year in the Union army. And even though the death rate was comparatively low (20/1,000 cases), it frequently led to chronic diarrhea, which was responsible for 288 deaths per 1,000 cases, and was the third highest cause of medical discharge after gunshot wounds and tuberculosis, according to Ms. Schroeder-Lein.

Although the American Civil War was the last major conflict before the spread of the knowledge of germ theory, the struggle to prevent the spread of waterborne diseases under wartime conditions remains ongoing. Hygiene is difficult under conditions of abject poverty and especially under conditions of armed conflict, and until the era of curative antibiotics there was no recourse.

Antibiotics are not the final solution for antibiotic resistance in intestinal disease pathogens, as outlined in a recent CDC report, is an increasing problem.6 For example, nontyphoidal Salmonella causes an estimated 1.35 million infections, 26,500 hospitalizations, and 420 deaths each year in the United States, with 16% of strains being resistant to at least one essential antibiotic. On a global scale, according to the World Health Organization, poor sanitation causes up to 432,000 diarrheal deaths annually and is linked to the transmission of other diseases like cholera, dysentery, typhoid, hepatitis A, and polio.7

With regard to actual epidemics, the world is only a hygienic crisis away from a major outbreak of dysentery (the last occurring between 1969 and 1972, when 20,000 people in Central America died), according to researchers who have detected antibiotic resistance in all but 1% of circulating Shigella dysenteriae strains surveyed since the 1990s. “This bacterium is still in circulation, and could be responsible for future epidemics if conditions should prove favorable – such as a large gathering of people without access to drinking water or treatment of human waste,” wrote François-Xavier Weill of the Pasteur Institute’s Enteric Bacterial Pathogens Unit.8

References

1. Sartin JS. Clin Infec Dis. 1993;16:580-4. (Correction published in 2002).

2. Civil War Battlefield Surgery. eHistory. The Ohio State University.

3. “Myths About Antiseptics and Camp Life – George Wunderlich,” published online Oct. 11, 2011. http://civilwarscholars.com/2011/10/myths-about-antiseptics-and-camp-life-george-wunderlich/

4. Dorwart BB. “Death is in the Breeze: Disease during the American Civil War” (The National Museum of the American Civil War Press, 2009).

5. Glenna R, Schroeder-Lein GR. “The Encyclopedia of Civil War Medicine” (New York: M. E. Sharpe, 2008).

6. “Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States 2019” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

7. “New report exposes horror of working conditions for millions of sanitation workers in the developing world,” World Health Organization. 2019 Nov 14.

8. Grant B. Origins of Dysentery. The Scientist. Published online March 22, 2016.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor of the department of biochemistry and molecular & cellular biology at Georgetown University, Washington.

If cleanliness is next to godliness, then the average soldier in the American Civil War lived just down the street from hell. In a land at war, before the formal tenets of germ theory had spread beyond the confines of Louis Pasteur’s laboratory in France, the lack of basic hygiene, both cultural and situational, coupled to an almost complete lack of curative therapies created an appalling death toll. Waterborne diseases in particular spared neither general nor private, and neither doctor nor nurse.

“Of all the adversities that Union and Confederate soldiers confronted, none was more deadly or more prevalent than contaminated water,” according to Jeffrey S. Sartin, MD, in his survey of Civil War diseases.1

The Union Army records list 1,765,000 cases of diarrhea or dysentery with 45,000 deaths and 149,000 cases of typhoid fever with 35,000 deaths. Add to these the 1,316,000 cases of malaria (borne by mosquitoes breeding in the waters) with its 10,000 deaths, and it is easy to see how the battlefield itself took second place in service to the grim reaper. (Overall, there were roughly two deaths from disease for every one from wounds.)

The chief waterborne plague, infectious diarrhea – including bacterial, amoebic, and other parasites – as well as cholera and typhoid, was an all-year-long problem, and, with the typical wry humor of soldiers, these maladies were given popular names, including the “Tennessee trots” and the “Virginia quick-step.”

Unsanitary conditions in the camps were primarily to blame, and this problem of sanitation was obvious to many observers at the time.

Despite a lack of knowledge of germ theory, doctors were fully aware of the relationship of unsanitary conditions to disease, even if they ascribed the link to miasmas or particles of filth.

Hospitals, which were under more strict control than the regular army camps, were meticulous about the placement of latrines and about keeping high standards of cleanliness among the patients, including routine washing. However, this was insufficient for complete protection, because what passed for clean in the absence of the knowledge of bacterial contamination was often totally ineffective. As one Civil War surgeon stated: “We operated in old bloodstained and often pus-stained coats, we used undisinfected instruments from undisinfected plush-lined cases. If a sponge (if they had sponges) or instrument fell on the floor it was washed and squeezed in a basin of water and used as if it was clean.”2

Overall, efforts at what passed for sanitation remained a constant goal and constant struggle in the field.

After the First Battle of Bull Run, Women’s Central Association of Relief President Henry W. Bellows met with Secretary of War Simon Cameron to discuss the abysmal sanitary conditions witnessed by WCAR volunteers. This meeting led to the creation of what would become the U.S. Sanitary Commission, which was approved by President Abraham Lincoln on June 13, 1861.

The U.S. Sanitary Commission served as a means for funneling civilian assistance to the military, with volunteers providing assistance in the organization of military hospitals and camps and aiding in the transportation of the wounded. However, despite these efforts, the setup of army camps and the behavior of the soldiers were not often directed toward proper sanitation. “The principal causes of disease, however, in our camps were the same that we have always to deplore and find it so difficult to remedy, simply because citizens suddenly called to the field cannot comprehend that men in masses require the attention of their officers to enforce certain hygienic conditions without which health cannot be preserved.”3

Breaches of sanitation were common in the confines of the camps, despite regulations designed to protect the soldiers. According to one U.S. Army surgeon of the time: “Especially [needed] was policing of the latrines. The trench is generally too shallow, the daily covering ... with dirt is entirely neglected. Large numbers of the men will not use the sinks [latrines], ... but instead every clump of bushes, every fence border in the vicinity.” Another pointed out that, after the Battle of Seven Pines, “the only water was infiltrated with the decaying animal matter of the battlefield.” Commenting on the placement of latrines in one encampment, another surgeon described how “the sink [latrine] is the ground in the vicinity, which slopes down to the stream, from which all water from the camp is obtained.”4

Treatment for diarrhea and dysentery was varied. Opiates were one of the most common treatments for diarrhea, whether in an alcohol solution as laudanum or in pill form, with belladonna being used to treat intestinal cramps, according to Glenna R. Schroeder-Lein in her book “The Encyclopedia of Civil War Medicine.” However, useless or damaging treatments were also prescribed, including the use of calomel (a mercury compound), turpentine, castor oil, and quinine.5

Acute diarrhea and dysentery illnesses occurred in at least 641/1,000 troops per year in the Union army. And even though the death rate was comparatively low (20/1,000 cases), it frequently led to chronic diarrhea, which was responsible for 288 deaths per 1,000 cases, and was the third highest cause of medical discharge after gunshot wounds and tuberculosis, according to Ms. Schroeder-Lein.

Although the American Civil War was the last major conflict before the spread of the knowledge of germ theory, the struggle to prevent the spread of waterborne diseases under wartime conditions remains ongoing. Hygiene is difficult under conditions of abject poverty and especially under conditions of armed conflict, and until the era of curative antibiotics there was no recourse.

Antibiotics are not the final solution for antibiotic resistance in intestinal disease pathogens, as outlined in a recent CDC report, is an increasing problem.6 For example, nontyphoidal Salmonella causes an estimated 1.35 million infections, 26,500 hospitalizations, and 420 deaths each year in the United States, with 16% of strains being resistant to at least one essential antibiotic. On a global scale, according to the World Health Organization, poor sanitation causes up to 432,000 diarrheal deaths annually and is linked to the transmission of other diseases like cholera, dysentery, typhoid, hepatitis A, and polio.7

With regard to actual epidemics, the world is only a hygienic crisis away from a major outbreak of dysentery (the last occurring between 1969 and 1972, when 20,000 people in Central America died), according to researchers who have detected antibiotic resistance in all but 1% of circulating Shigella dysenteriae strains surveyed since the 1990s. “This bacterium is still in circulation, and could be responsible for future epidemics if conditions should prove favorable – such as a large gathering of people without access to drinking water or treatment of human waste,” wrote François-Xavier Weill of the Pasteur Institute’s Enteric Bacterial Pathogens Unit.8

References

1. Sartin JS. Clin Infec Dis. 1993;16:580-4. (Correction published in 2002).

2. Civil War Battlefield Surgery. eHistory. The Ohio State University.

3. “Myths About Antiseptics and Camp Life – George Wunderlich,” published online Oct. 11, 2011. http://civilwarscholars.com/2011/10/myths-about-antiseptics-and-camp-life-george-wunderlich/

4. Dorwart BB. “Death is in the Breeze: Disease during the American Civil War” (The National Museum of the American Civil War Press, 2009).

5. Glenna R, Schroeder-Lein GR. “The Encyclopedia of Civil War Medicine” (New York: M. E. Sharpe, 2008).

6. “Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States 2019” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

7. “New report exposes horror of working conditions for millions of sanitation workers in the developing world,” World Health Organization. 2019 Nov 14.

8. Grant B. Origins of Dysentery. The Scientist. Published online March 22, 2016.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor of the department of biochemistry and molecular & cellular biology at Georgetown University, Washington.

OTC hormonal contraception: An important goal in the fight for reproductive justice

A new American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) committee opinion addresses how contraception access can be improved through over-the-counter (OTC) hormonal contraception for people of all ages—including oral contraceptive pills (OCPs), progesterone-only pills, the patch, vaginal rings, and depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA). Although ACOG endorses OTC contraception, some health care providers may be hesitant to support the increase in accessibility for a variety of reasons. We are hopeful that we address these concerns and that all clinicians can move to support ACOG’s position.

Easing access to hormonal contraception is a first step

OCPs are the most widely used contraception among teens and women of reproductive age in the United States.1 Although the Affordable Care Act (ACA) mandated health insurance coverage for contraception, many barriers continue to exist, including obtaining a prescription. Only 13 states have made it legal to obtain hormonal contraception through a pharmacist.2 There also has been an increase in the number of telemedicine and online services that deliver contraceptives to individuals’ homes. While these efforts have helped to decrease barriers to hormonal contraception access for some patients, they only reach a small segment of the population. As clinicians, we should strive to make contraception universally accessible and affordable to everyone who desires to use it. OTC provision can bring us closer to this goal.

Addressing the misconceptions about contraception

Adverse events with hormonal contraception are rarer than one may think. There are few risks associated with hormonal contraception. Venous thromboembolus (VTE) is a serious, although rare, adverse effect (AE) of hormonal contraception. The rate of VTE with combined oral contraception is estimated at 3 to 8 events per 10,000 patient-years, and VTE is even less common with progestin-only contraception (1 to 5 per 10,000 patient-years). For both types of hormonal contraception, the risk of VTE is smaller than with pregnancy, which is 5 to 20 per 10,000 patient-years.3 There are comorbidities that increase the risk of VTE and other AEs of hormonal contraception. In the setting of OTC hormonal contraception, individuals would self-screen for contraindications in order to reduce these complications.

Patients have the aptitude to self-screen for contraindications. Studies looking at the ability of patients over the age of 18 to self-screen for contraindications to hormonal contraception have found that patients do appropriately screen themselves. In fact, they are often more conservative than a physician in avoiding hormonal contraceptive methods.4 Patients younger than age 18 rarely have contraindications to hormonal contraception, but limited studies have shown that they too are able to successfully self-screen.5 ACOG recommends self-screening tools be provided with all OTC combined hormonal contraceptive methods to aid an individual’s contraceptive choice.

Most patients continue their well person care. Some opponents to ACOG’s position also have expressed concern that people who access their contraception OTC will forego their annual exam with their provider. However, studies have shown that the majority of people will continue to make their preventative health care visits.6,7

We need to invest in preventing unplanned pregnancy

Currently, hormonal contraception is covered by health insurance under the ACA, with some caveats. Without a prescription, patients may have to pay full price for their contraception. However, one can find generic OCPs for less than $10 per pack out of pocket. Any cost can be prohibitive to many patients; thus, transition to OTC access to contraception also should ensure limiting the cost to the patient. One possible solution to mitigate costs is to require insurance companies to cover the cost of OTC hormonal contraceptives. (See action item below.)

Reduction in unplanned pregnancies improves public health and public expense, and broadening access to effective forms of contraception is imperative in reducing unplanned pregnancies. Every $1 invested in contraception access realizes $7.09 in savings.8 By making hormonal contraception widely available OTC, access could be improved dramatically—although pharmacist provision of hormonal contraception may be a necessary intermediate step. ACOG’s most recent committee opinion encourages all reproductive health care providers to be strong advocates for this improvement in access. As women’s health providers, we should work to decrease access barriers for our patients; working toward OTC contraception is a critical step in equal access to birth control methods for all of our patients.

Action items

Remember, before a pill can move to OTC access, the manufacturing (pharmaceutical) company must submit an application to the US Food and Drug Administration to obtain this status. Once submitted, the process may take 3 to 4 years to be completed. Currently, no company has submitted an OTC application and no hormonal birth control is available OTC. Find resources for OTC birth control access here: http://ocsotc.org/ and www.freethepill.org.

- Talk to your state representatives about why both OTC birth control access and direct pharmacy availability are important to increasing access and decreasing disparities in reproductive health care. Find your local and federal representatives here and check the status of OCP access in your state here.

- Representative Ayanna Pressley (D-MA) and Senator Patty Murray (D-WA) both have introduced legislation—the Affordability is Access Act (HR 3296/S1847)—to ensure insurance coverage for OTC contraception. Call your representative and ask them to cosponsor this legislation.

- Be mindful of legislation that promotes OTC OCPs but limits access to some populations (minors) and increases cost sharing to the patient. This type of legislation can create harmful barriers to access for some of our patients

- Jones J, Mosher W, Daniels K. Current contraceptive use in the United States, 2006-2010, and changes in patterns of use since 1995. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2012;(60):1-25.

- Free the pill. What’s the law in your state? Ibis Reproductive Health website. http://freethepill.org/statepolicies. Accessed November 15, 2019.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: updated information about the risk of blood clots in women taking birth control pills containing drospirenone. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm299305.htm. Accessed November 15, 2019.

- Grossman D, Fernandez L, Hopkins K, et al. Accuracy of self-screening for contraindications to combined oral contraceptive use. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:572e8.

- Williams R, Hensel D, Lehmann A, et al. Adolescent self-screening for contraindications to combined oral contraceptive pills [abstract]. Contraception. 2015;92:380.

- Hopkins K, Grossman D, White K, et al. Reproductive health preventive screening among clinic vs. over-the-counter oral contraceptive users. Contraception. 2012;86:376-382.

- Grindlay K, Grossman D. Interest in over-the-counter access to a progestin-only pill among women in the United States. Womens Health Issues. 2018;28:144-151.

- Frost JJ, Sonfield A, Zolna MR, et al. Return on investment: a fuller assessment of the benefits and cost savings of the US publicly funded family planning program. Milbank Q. 2014;92:696-749.

A new American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) committee opinion addresses how contraception access can be improved through over-the-counter (OTC) hormonal contraception for people of all ages—including oral contraceptive pills (OCPs), progesterone-only pills, the patch, vaginal rings, and depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA). Although ACOG endorses OTC contraception, some health care providers may be hesitant to support the increase in accessibility for a variety of reasons. We are hopeful that we address these concerns and that all clinicians can move to support ACOG’s position.

Easing access to hormonal contraception is a first step

OCPs are the most widely used contraception among teens and women of reproductive age in the United States.1 Although the Affordable Care Act (ACA) mandated health insurance coverage for contraception, many barriers continue to exist, including obtaining a prescription. Only 13 states have made it legal to obtain hormonal contraception through a pharmacist.2 There also has been an increase in the number of telemedicine and online services that deliver contraceptives to individuals’ homes. While these efforts have helped to decrease barriers to hormonal contraception access for some patients, they only reach a small segment of the population. As clinicians, we should strive to make contraception universally accessible and affordable to everyone who desires to use it. OTC provision can bring us closer to this goal.

Addressing the misconceptions about contraception

Adverse events with hormonal contraception are rarer than one may think. There are few risks associated with hormonal contraception. Venous thromboembolus (VTE) is a serious, although rare, adverse effect (AE) of hormonal contraception. The rate of VTE with combined oral contraception is estimated at 3 to 8 events per 10,000 patient-years, and VTE is even less common with progestin-only contraception (1 to 5 per 10,000 patient-years). For both types of hormonal contraception, the risk of VTE is smaller than with pregnancy, which is 5 to 20 per 10,000 patient-years.3 There are comorbidities that increase the risk of VTE and other AEs of hormonal contraception. In the setting of OTC hormonal contraception, individuals would self-screen for contraindications in order to reduce these complications.

Patients have the aptitude to self-screen for contraindications. Studies looking at the ability of patients over the age of 18 to self-screen for contraindications to hormonal contraception have found that patients do appropriately screen themselves. In fact, they are often more conservative than a physician in avoiding hormonal contraceptive methods.4 Patients younger than age 18 rarely have contraindications to hormonal contraception, but limited studies have shown that they too are able to successfully self-screen.5 ACOG recommends self-screening tools be provided with all OTC combined hormonal contraceptive methods to aid an individual’s contraceptive choice.

Most patients continue their well person care. Some opponents to ACOG’s position also have expressed concern that people who access their contraception OTC will forego their annual exam with their provider. However, studies have shown that the majority of people will continue to make their preventative health care visits.6,7

We need to invest in preventing unplanned pregnancy

Currently, hormonal contraception is covered by health insurance under the ACA, with some caveats. Without a prescription, patients may have to pay full price for their contraception. However, one can find generic OCPs for less than $10 per pack out of pocket. Any cost can be prohibitive to many patients; thus, transition to OTC access to contraception also should ensure limiting the cost to the patient. One possible solution to mitigate costs is to require insurance companies to cover the cost of OTC hormonal contraceptives. (See action item below.)

Reduction in unplanned pregnancies improves public health and public expense, and broadening access to effective forms of contraception is imperative in reducing unplanned pregnancies. Every $1 invested in contraception access realizes $7.09 in savings.8 By making hormonal contraception widely available OTC, access could be improved dramatically—although pharmacist provision of hormonal contraception may be a necessary intermediate step. ACOG’s most recent committee opinion encourages all reproductive health care providers to be strong advocates for this improvement in access. As women’s health providers, we should work to decrease access barriers for our patients; working toward OTC contraception is a critical step in equal access to birth control methods for all of our patients.

Action items

Remember, before a pill can move to OTC access, the manufacturing (pharmaceutical) company must submit an application to the US Food and Drug Administration to obtain this status. Once submitted, the process may take 3 to 4 years to be completed. Currently, no company has submitted an OTC application and no hormonal birth control is available OTC. Find resources for OTC birth control access here: http://ocsotc.org/ and www.freethepill.org.

- Talk to your state representatives about why both OTC birth control access and direct pharmacy availability are important to increasing access and decreasing disparities in reproductive health care. Find your local and federal representatives here and check the status of OCP access in your state here.

- Representative Ayanna Pressley (D-MA) and Senator Patty Murray (D-WA) both have introduced legislation—the Affordability is Access Act (HR 3296/S1847)—to ensure insurance coverage for OTC contraception. Call your representative and ask them to cosponsor this legislation.

- Be mindful of legislation that promotes OTC OCPs but limits access to some populations (minors) and increases cost sharing to the patient. This type of legislation can create harmful barriers to access for some of our patients

A new American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) committee opinion addresses how contraception access can be improved through over-the-counter (OTC) hormonal contraception for people of all ages—including oral contraceptive pills (OCPs), progesterone-only pills, the patch, vaginal rings, and depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA). Although ACOG endorses OTC contraception, some health care providers may be hesitant to support the increase in accessibility for a variety of reasons. We are hopeful that we address these concerns and that all clinicians can move to support ACOG’s position.

Easing access to hormonal contraception is a first step

OCPs are the most widely used contraception among teens and women of reproductive age in the United States.1 Although the Affordable Care Act (ACA) mandated health insurance coverage for contraception, many barriers continue to exist, including obtaining a prescription. Only 13 states have made it legal to obtain hormonal contraception through a pharmacist.2 There also has been an increase in the number of telemedicine and online services that deliver contraceptives to individuals’ homes. While these efforts have helped to decrease barriers to hormonal contraception access for some patients, they only reach a small segment of the population. As clinicians, we should strive to make contraception universally accessible and affordable to everyone who desires to use it. OTC provision can bring us closer to this goal.

Addressing the misconceptions about contraception

Adverse events with hormonal contraception are rarer than one may think. There are few risks associated with hormonal contraception. Venous thromboembolus (VTE) is a serious, although rare, adverse effect (AE) of hormonal contraception. The rate of VTE with combined oral contraception is estimated at 3 to 8 events per 10,000 patient-years, and VTE is even less common with progestin-only contraception (1 to 5 per 10,000 patient-years). For both types of hormonal contraception, the risk of VTE is smaller than with pregnancy, which is 5 to 20 per 10,000 patient-years.3 There are comorbidities that increase the risk of VTE and other AEs of hormonal contraception. In the setting of OTC hormonal contraception, individuals would self-screen for contraindications in order to reduce these complications.

Patients have the aptitude to self-screen for contraindications. Studies looking at the ability of patients over the age of 18 to self-screen for contraindications to hormonal contraception have found that patients do appropriately screen themselves. In fact, they are often more conservative than a physician in avoiding hormonal contraceptive methods.4 Patients younger than age 18 rarely have contraindications to hormonal contraception, but limited studies have shown that they too are able to successfully self-screen.5 ACOG recommends self-screening tools be provided with all OTC combined hormonal contraceptive methods to aid an individual’s contraceptive choice.

Most patients continue their well person care. Some opponents to ACOG’s position also have expressed concern that people who access their contraception OTC will forego their annual exam with their provider. However, studies have shown that the majority of people will continue to make their preventative health care visits.6,7

We need to invest in preventing unplanned pregnancy

Currently, hormonal contraception is covered by health insurance under the ACA, with some caveats. Without a prescription, patients may have to pay full price for their contraception. However, one can find generic OCPs for less than $10 per pack out of pocket. Any cost can be prohibitive to many patients; thus, transition to OTC access to contraception also should ensure limiting the cost to the patient. One possible solution to mitigate costs is to require insurance companies to cover the cost of OTC hormonal contraceptives. (See action item below.)

Reduction in unplanned pregnancies improves public health and public expense, and broadening access to effective forms of contraception is imperative in reducing unplanned pregnancies. Every $1 invested in contraception access realizes $7.09 in savings.8 By making hormonal contraception widely available OTC, access could be improved dramatically—although pharmacist provision of hormonal contraception may be a necessary intermediate step. ACOG’s most recent committee opinion encourages all reproductive health care providers to be strong advocates for this improvement in access. As women’s health providers, we should work to decrease access barriers for our patients; working toward OTC contraception is a critical step in equal access to birth control methods for all of our patients.

Action items

Remember, before a pill can move to OTC access, the manufacturing (pharmaceutical) company must submit an application to the US Food and Drug Administration to obtain this status. Once submitted, the process may take 3 to 4 years to be completed. Currently, no company has submitted an OTC application and no hormonal birth control is available OTC. Find resources for OTC birth control access here: http://ocsotc.org/ and www.freethepill.org.

- Talk to your state representatives about why both OTC birth control access and direct pharmacy availability are important to increasing access and decreasing disparities in reproductive health care. Find your local and federal representatives here and check the status of OCP access in your state here.

- Representative Ayanna Pressley (D-MA) and Senator Patty Murray (D-WA) both have introduced legislation—the Affordability is Access Act (HR 3296/S1847)—to ensure insurance coverage for OTC contraception. Call your representative and ask them to cosponsor this legislation.

- Be mindful of legislation that promotes OTC OCPs but limits access to some populations (minors) and increases cost sharing to the patient. This type of legislation can create harmful barriers to access for some of our patients

- Jones J, Mosher W, Daniels K. Current contraceptive use in the United States, 2006-2010, and changes in patterns of use since 1995. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2012;(60):1-25.

- Free the pill. What’s the law in your state? Ibis Reproductive Health website. http://freethepill.org/statepolicies. Accessed November 15, 2019.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: updated information about the risk of blood clots in women taking birth control pills containing drospirenone. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm299305.htm. Accessed November 15, 2019.

- Grossman D, Fernandez L, Hopkins K, et al. Accuracy of self-screening for contraindications to combined oral contraceptive use. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:572e8.

- Williams R, Hensel D, Lehmann A, et al. Adolescent self-screening for contraindications to combined oral contraceptive pills [abstract]. Contraception. 2015;92:380.

- Hopkins K, Grossman D, White K, et al. Reproductive health preventive screening among clinic vs. over-the-counter oral contraceptive users. Contraception. 2012;86:376-382.

- Grindlay K, Grossman D. Interest in over-the-counter access to a progestin-only pill among women in the United States. Womens Health Issues. 2018;28:144-151.

- Frost JJ, Sonfield A, Zolna MR, et al. Return on investment: a fuller assessment of the benefits and cost savings of the US publicly funded family planning program. Milbank Q. 2014;92:696-749.

- Jones J, Mosher W, Daniels K. Current contraceptive use in the United States, 2006-2010, and changes in patterns of use since 1995. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2012;(60):1-25.

- Free the pill. What’s the law in your state? Ibis Reproductive Health website. http://freethepill.org/statepolicies. Accessed November 15, 2019.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: updated information about the risk of blood clots in women taking birth control pills containing drospirenone. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm299305.htm. Accessed November 15, 2019.

- Grossman D, Fernandez L, Hopkins K, et al. Accuracy of self-screening for contraindications to combined oral contraceptive use. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:572e8.

- Williams R, Hensel D, Lehmann A, et al. Adolescent self-screening for contraindications to combined oral contraceptive pills [abstract]. Contraception. 2015;92:380.

- Hopkins K, Grossman D, White K, et al. Reproductive health preventive screening among clinic vs. over-the-counter oral contraceptive users. Contraception. 2012;86:376-382.

- Grindlay K, Grossman D. Interest in over-the-counter access to a progestin-only pill among women in the United States. Womens Health Issues. 2018;28:144-151.

- Frost JJ, Sonfield A, Zolna MR, et al. Return on investment: a fuller assessment of the benefits and cost savings of the US publicly funded family planning program. Milbank Q. 2014;92:696-749.

Newer IL-17 inhibitors make their case in phase 3 nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis trials

A major gap in interleukin-17 inhibitor (IL-17i) therapy for axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) was evidence of efficacy in nonradiographic axSpA. At ACR 2019, we saw two different IL-17i studies showing efficacy in nr-axSpA patients. Now we know that both secukinumab and ixekizumab are effective in the full spectrum of axSpA patients (ankylosing spondylitis [AS] and nr-axSpA).

The majority of clinicians would consider both AS and nr-axSpA to be driven by common processes and so drugs that are effective on one should have the same effect in the other as well. Hence the results are not a big surprise. In certain places, an approved indication for use may be important especially for reimbursement purposes. These results are likely to have maximal impact there.

The COAST-X study on ixekizumab was designed in a way similar to that of the C-axSpAnd study with certolizumab pegol. There was an extended 52-week placebo arm to study the natural history of nr-axSpA patients who are not actively treated with biologics. This design was necessary to respond to the Food and Drug Administration’s concern that, in the absence of this prolonged observation on placebo, we cannot be sure that nr-axSpA patients are not spontaneously remitting (not due to biologics).

However, the results here did surprise me. Unlike in the C-axSpAnd trial where only 13% of actively treated patients (on certolizumab pegol) switched to open-label treatment, in the COAST-X study 40% of patients on both doses of ixekizumab opted for open-label treatment. The number of patients moving out of the placebo arm was around 60% (similar in both studies). There are no straightforward factors evidently explaining this discrepancy. Between 15% and 25% of patients who switched had achieved the primary endpoint of ASAS40. Does this reflect that ASAS40 is not acceptable to patients? As the results show responses plateaued after week 16, it could be that the patients who switched might have done so well into the 52-week observation period.

Patients in the COAST-X study had slightly longer disease duration and marginally lower HLA-B27 prevalence (both factors may indicate lower chance of treatment response).

The primary endpoint of ASAS40 was met at weeks 16 and 52 with significantly higher rates seen with ixekizumab than with placebo. Again the response seems to plateau around 16 weeks with minimal gain up to week 52.

The results from the secukinumab PREVENT study are very similar to those of the COAST-X study showing the superiority of secukinumab over placebo in treating nr-axSpA patients. Interestingly, if we do not use the loading dose for secukinumab, there does not seem to be any difference from standard treatment with loading. This may have economic and administrative implications on the decision to use loading doses of secukinumab. We should carefully consider the MEASURE 4 trial results before making decisions on the utility of loading doses. In the MEASURE 4 study on AS patients, although there was no difference between load and no load arms of secukinumab (around 60% ASAS20 response in both arms), there was no significant gain above placebo with both doses. (The primary endpoint was not met.) This is likely due to the high placebo response (47% ASAS20 response). Similarly, we see a high placebo response in the COAST-X study as well, with an ASAS40 response rate of about 40% in active secukinumab arms vs. 30% in the placebo arm.

The number of patients dropping out over the 52-week follow-up period was not discussed in the PREVENT trial presentation.

There is not much here to favor one IL-17i over the other.

Dr. Haroon is codirector of the Spondylitis Program at University Health Network and associate professor of medicine and rheumatology at the University of Toronto. He is chair of the scientific committee of the Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network. He disclosed serving as a consultant for Amgen, AbbVie, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, and UCB.

A major gap in interleukin-17 inhibitor (IL-17i) therapy for axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) was evidence of efficacy in nonradiographic axSpA. At ACR 2019, we saw two different IL-17i studies showing efficacy in nr-axSpA patients. Now we know that both secukinumab and ixekizumab are effective in the full spectrum of axSpA patients (ankylosing spondylitis [AS] and nr-axSpA).

The majority of clinicians would consider both AS and nr-axSpA to be driven by common processes and so drugs that are effective on one should have the same effect in the other as well. Hence the results are not a big surprise. In certain places, an approved indication for use may be important especially for reimbursement purposes. These results are likely to have maximal impact there.

The COAST-X study on ixekizumab was designed in a way similar to that of the C-axSpAnd study with certolizumab pegol. There was an extended 52-week placebo arm to study the natural history of nr-axSpA patients who are not actively treated with biologics. This design was necessary to respond to the Food and Drug Administration’s concern that, in the absence of this prolonged observation on placebo, we cannot be sure that nr-axSpA patients are not spontaneously remitting (not due to biologics).

However, the results here did surprise me. Unlike in the C-axSpAnd trial where only 13% of actively treated patients (on certolizumab pegol) switched to open-label treatment, in the COAST-X study 40% of patients on both doses of ixekizumab opted for open-label treatment. The number of patients moving out of the placebo arm was around 60% (similar in both studies). There are no straightforward factors evidently explaining this discrepancy. Between 15% and 25% of patients who switched had achieved the primary endpoint of ASAS40. Does this reflect that ASAS40 is not acceptable to patients? As the results show responses plateaued after week 16, it could be that the patients who switched might have done so well into the 52-week observation period.

Patients in the COAST-X study had slightly longer disease duration and marginally lower HLA-B27 prevalence (both factors may indicate lower chance of treatment response).

The primary endpoint of ASAS40 was met at weeks 16 and 52 with significantly higher rates seen with ixekizumab than with placebo. Again the response seems to plateau around 16 weeks with minimal gain up to week 52.

The results from the secukinumab PREVENT study are very similar to those of the COAST-X study showing the superiority of secukinumab over placebo in treating nr-axSpA patients. Interestingly, if we do not use the loading dose for secukinumab, there does not seem to be any difference from standard treatment with loading. This may have economic and administrative implications on the decision to use loading doses of secukinumab. We should carefully consider the MEASURE 4 trial results before making decisions on the utility of loading doses. In the MEASURE 4 study on AS patients, although there was no difference between load and no load arms of secukinumab (around 60% ASAS20 response in both arms), there was no significant gain above placebo with both doses. (The primary endpoint was not met.) This is likely due to the high placebo response (47% ASAS20 response). Similarly, we see a high placebo response in the COAST-X study as well, with an ASAS40 response rate of about 40% in active secukinumab arms vs. 30% in the placebo arm.

The number of patients dropping out over the 52-week follow-up period was not discussed in the PREVENT trial presentation.

There is not much here to favor one IL-17i over the other.

Dr. Haroon is codirector of the Spondylitis Program at University Health Network and associate professor of medicine and rheumatology at the University of Toronto. He is chair of the scientific committee of the Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network. He disclosed serving as a consultant for Amgen, AbbVie, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, and UCB.

A major gap in interleukin-17 inhibitor (IL-17i) therapy for axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) was evidence of efficacy in nonradiographic axSpA. At ACR 2019, we saw two different IL-17i studies showing efficacy in nr-axSpA patients. Now we know that both secukinumab and ixekizumab are effective in the full spectrum of axSpA patients (ankylosing spondylitis [AS] and nr-axSpA).

The majority of clinicians would consider both AS and nr-axSpA to be driven by common processes and so drugs that are effective on one should have the same effect in the other as well. Hence the results are not a big surprise. In certain places, an approved indication for use may be important especially for reimbursement purposes. These results are likely to have maximal impact there.

The COAST-X study on ixekizumab was designed in a way similar to that of the C-axSpAnd study with certolizumab pegol. There was an extended 52-week placebo arm to study the natural history of nr-axSpA patients who are not actively treated with biologics. This design was necessary to respond to the Food and Drug Administration’s concern that, in the absence of this prolonged observation on placebo, we cannot be sure that nr-axSpA patients are not spontaneously remitting (not due to biologics).

However, the results here did surprise me. Unlike in the C-axSpAnd trial where only 13% of actively treated patients (on certolizumab pegol) switched to open-label treatment, in the COAST-X study 40% of patients on both doses of ixekizumab opted for open-label treatment. The number of patients moving out of the placebo arm was around 60% (similar in both studies). There are no straightforward factors evidently explaining this discrepancy. Between 15% and 25% of patients who switched had achieved the primary endpoint of ASAS40. Does this reflect that ASAS40 is not acceptable to patients? As the results show responses plateaued after week 16, it could be that the patients who switched might have done so well into the 52-week observation period.

Patients in the COAST-X study had slightly longer disease duration and marginally lower HLA-B27 prevalence (both factors may indicate lower chance of treatment response).

The primary endpoint of ASAS40 was met at weeks 16 and 52 with significantly higher rates seen with ixekizumab than with placebo. Again the response seems to plateau around 16 weeks with minimal gain up to week 52.

The results from the secukinumab PREVENT study are very similar to those of the COAST-X study showing the superiority of secukinumab over placebo in treating nr-axSpA patients. Interestingly, if we do not use the loading dose for secukinumab, there does not seem to be any difference from standard treatment with loading. This may have economic and administrative implications on the decision to use loading doses of secukinumab. We should carefully consider the MEASURE 4 trial results before making decisions on the utility of loading doses. In the MEASURE 4 study on AS patients, although there was no difference between load and no load arms of secukinumab (around 60% ASAS20 response in both arms), there was no significant gain above placebo with both doses. (The primary endpoint was not met.) This is likely due to the high placebo response (47% ASAS20 response). Similarly, we see a high placebo response in the COAST-X study as well, with an ASAS40 response rate of about 40% in active secukinumab arms vs. 30% in the placebo arm.

The number of patients dropping out over the 52-week follow-up period was not discussed in the PREVENT trial presentation.

There is not much here to favor one IL-17i over the other.

Dr. Haroon is codirector of the Spondylitis Program at University Health Network and associate professor of medicine and rheumatology at the University of Toronto. He is chair of the scientific committee of the Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network. He disclosed serving as a consultant for Amgen, AbbVie, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, and UCB.

An alarming number of bipolar disorder diagnoses or something else?

During a particularly busy day in my inpatient and outpatient practice, I realized that nearly every one of the patients had been given the diagnosis of bipolar disorder at one point or another. The interesting thing is this wasn’t an unusual day.

Nearly all of my patients and their family members have been given the diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Because prevalence of bipolar affective disorders is a little over 2%, this seemed a little odd. Could there be an epidemic of bipolar disorder in the area? Should someone sound the alarm on this unique cluster and get Julia Roberts ready? Unfortunately, the story behind this mystery is a little less sexy but nevertheless interesting.

When I probe more into what symptoms might have led to the diagnosis of bipolar disorder, I most often get some sort of answer about being easily angered (“I’m fine 1 minute and the next minute I’m yelling at my mom”) or mood changing from 1 minute to the next. Rarely do they tell me about sleeping less, increased energy, change in mood (elation, anger, irritability), increase in activity level, and increased pleasurable though dangerous activities all happening around the same time(s). So what is going on?

Beginning in the 1990s, a debate about the phenotypic presentation of pediatric bipolar disorder polarized the field. It was theorized that mania could present with severe nonepisodic irritability with extended periods of very rapid mood cycling within the day as opposed to discrete episodic mood cycles in children and adolescents. With this broader conceptualization in the United States, the rate of bipolar diagnosis increased by over 40 times in less than a decade.1 Similarly, the use of mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics in children also rose substantially.2

To help assess if severe nonepisodic irritability belongs in the spectrum of bipolar disorders, the National Institutes of Mental Health proposed a syndrome called “Severe Mood Dysregulation” or SMD, to promote the study of children with this phenotype. In longitudinal studies, Stringaris et al. compared rates of manic episodes in youth with SMD versus bipolar disorder over 2 years and found only one youth (1%) with SMD who presented with manic, hypomanic, or mixed episodes, compared with 58 (62%) with bipolar disorder.3 Leibenluft et al.showed that chronic irritability during early adolescence predicted ADHD at late adolescence and major depressive disorder in early adulthood whereas episodic irritability predicted mania.4 Twenty-year follow-up of the same sample showed chronic irritability in adolescence predicted dysthymia, generalized anxiety disorders, and major depressive disorder.5 Other longitudinal studies essentially have shown the same results.6

At this point, the question of whether chronic irritability is a part of the bipolar spectrum disorder is largely resolved – 7 The diagnosis emphasizes the episodic nature of the illness, and that irritability would wax and wane with other manic symptoms such as changes in energy and sleep. And the ultrarapid mood changes (mood changes within the day) appear to describe mood fluctuations within a manic episode as opposed to each change being a separate episode.

So, most likely, my patients were caught in a time of uncertainty before data were able to clarify their phenotype.

Dr. Chung is a child and adolescent psychiatrist at the University of Vermont Medical Center, Burlington, and practices at Champlain Valley Physician’s Hospital in Plattsburgh, N.Y. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Biol Psychiatry. 2007 Jul 15;62(2):107–14.

2. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015 Sep;72(9):859-60.

3. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010 Apr;49(4):397-405.

4. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2006;16(4):456-66.

5. Am J Psychiatry. 2009 Sep;166(9):1048-54.

6. Biol Psychiatry. 2006 Nov 1;60(9):991-7.

7. Bipolar Disord. 2017 Nov;19(7):524-43.

During a particularly busy day in my inpatient and outpatient practice, I realized that nearly every one of the patients had been given the diagnosis of bipolar disorder at one point or another. The interesting thing is this wasn’t an unusual day.

Nearly all of my patients and their family members have been given the diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Because prevalence of bipolar affective disorders is a little over 2%, this seemed a little odd. Could there be an epidemic of bipolar disorder in the area? Should someone sound the alarm on this unique cluster and get Julia Roberts ready? Unfortunately, the story behind this mystery is a little less sexy but nevertheless interesting.

When I probe more into what symptoms might have led to the diagnosis of bipolar disorder, I most often get some sort of answer about being easily angered (“I’m fine 1 minute and the next minute I’m yelling at my mom”) or mood changing from 1 minute to the next. Rarely do they tell me about sleeping less, increased energy, change in mood (elation, anger, irritability), increase in activity level, and increased pleasurable though dangerous activities all happening around the same time(s). So what is going on?

Beginning in the 1990s, a debate about the phenotypic presentation of pediatric bipolar disorder polarized the field. It was theorized that mania could present with severe nonepisodic irritability with extended periods of very rapid mood cycling within the day as opposed to discrete episodic mood cycles in children and adolescents. With this broader conceptualization in the United States, the rate of bipolar diagnosis increased by over 40 times in less than a decade.1 Similarly, the use of mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics in children also rose substantially.2

To help assess if severe nonepisodic irritability belongs in the spectrum of bipolar disorders, the National Institutes of Mental Health proposed a syndrome called “Severe Mood Dysregulation” or SMD, to promote the study of children with this phenotype. In longitudinal studies, Stringaris et al. compared rates of manic episodes in youth with SMD versus bipolar disorder over 2 years and found only one youth (1%) with SMD who presented with manic, hypomanic, or mixed episodes, compared with 58 (62%) with bipolar disorder.3 Leibenluft et al.showed that chronic irritability during early adolescence predicted ADHD at late adolescence and major depressive disorder in early adulthood whereas episodic irritability predicted mania.4 Twenty-year follow-up of the same sample showed chronic irritability in adolescence predicted dysthymia, generalized anxiety disorders, and major depressive disorder.5 Other longitudinal studies essentially have shown the same results.6

At this point, the question of whether chronic irritability is a part of the bipolar spectrum disorder is largely resolved – 7 The diagnosis emphasizes the episodic nature of the illness, and that irritability would wax and wane with other manic symptoms such as changes in energy and sleep. And the ultrarapid mood changes (mood changes within the day) appear to describe mood fluctuations within a manic episode as opposed to each change being a separate episode.

So, most likely, my patients were caught in a time of uncertainty before data were able to clarify their phenotype.

Dr. Chung is a child and adolescent psychiatrist at the University of Vermont Medical Center, Burlington, and practices at Champlain Valley Physician’s Hospital in Plattsburgh, N.Y. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Biol Psychiatry. 2007 Jul 15;62(2):107–14.

2. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015 Sep;72(9):859-60.

3. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010 Apr;49(4):397-405.

4. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2006;16(4):456-66.

5. Am J Psychiatry. 2009 Sep;166(9):1048-54.

6. Biol Psychiatry. 2006 Nov 1;60(9):991-7.

7. Bipolar Disord. 2017 Nov;19(7):524-43.

During a particularly busy day in my inpatient and outpatient practice, I realized that nearly every one of the patients had been given the diagnosis of bipolar disorder at one point or another. The interesting thing is this wasn’t an unusual day.

Nearly all of my patients and their family members have been given the diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Because prevalence of bipolar affective disorders is a little over 2%, this seemed a little odd. Could there be an epidemic of bipolar disorder in the area? Should someone sound the alarm on this unique cluster and get Julia Roberts ready? Unfortunately, the story behind this mystery is a little less sexy but nevertheless interesting.

When I probe more into what symptoms might have led to the diagnosis of bipolar disorder, I most often get some sort of answer about being easily angered (“I’m fine 1 minute and the next minute I’m yelling at my mom”) or mood changing from 1 minute to the next. Rarely do they tell me about sleeping less, increased energy, change in mood (elation, anger, irritability), increase in activity level, and increased pleasurable though dangerous activities all happening around the same time(s). So what is going on?

Beginning in the 1990s, a debate about the phenotypic presentation of pediatric bipolar disorder polarized the field. It was theorized that mania could present with severe nonepisodic irritability with extended periods of very rapid mood cycling within the day as opposed to discrete episodic mood cycles in children and adolescents. With this broader conceptualization in the United States, the rate of bipolar diagnosis increased by over 40 times in less than a decade.1 Similarly, the use of mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics in children also rose substantially.2

To help assess if severe nonepisodic irritability belongs in the spectrum of bipolar disorders, the National Institutes of Mental Health proposed a syndrome called “Severe Mood Dysregulation” or SMD, to promote the study of children with this phenotype. In longitudinal studies, Stringaris et al. compared rates of manic episodes in youth with SMD versus bipolar disorder over 2 years and found only one youth (1%) with SMD who presented with manic, hypomanic, or mixed episodes, compared with 58 (62%) with bipolar disorder.3 Leibenluft et al.showed that chronic irritability during early adolescence predicted ADHD at late adolescence and major depressive disorder in early adulthood whereas episodic irritability predicted mania.4 Twenty-year follow-up of the same sample showed chronic irritability in adolescence predicted dysthymia, generalized anxiety disorders, and major depressive disorder.5 Other longitudinal studies essentially have shown the same results.6

At this point, the question of whether chronic irritability is a part of the bipolar spectrum disorder is largely resolved – 7 The diagnosis emphasizes the episodic nature of the illness, and that irritability would wax and wane with other manic symptoms such as changes in energy and sleep. And the ultrarapid mood changes (mood changes within the day) appear to describe mood fluctuations within a manic episode as opposed to each change being a separate episode.

So, most likely, my patients were caught in a time of uncertainty before data were able to clarify their phenotype.

Dr. Chung is a child and adolescent psychiatrist at the University of Vermont Medical Center, Burlington, and practices at Champlain Valley Physician’s Hospital in Plattsburgh, N.Y. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Biol Psychiatry. 2007 Jul 15;62(2):107–14.

2. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015 Sep;72(9):859-60.

3. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010 Apr;49(4):397-405.

4. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2006;16(4):456-66.

5. Am J Psychiatry. 2009 Sep;166(9):1048-54.

6. Biol Psychiatry. 2006 Nov 1;60(9):991-7.

7. Bipolar Disord. 2017 Nov;19(7):524-43.

Proposed RESPONSE Act targets potential shooters

As I’m writing, my Twitter feed announces yet another public shooting, this one at a Walmart in Oklahoma. It’s a problem that gets worse as it gets more attention and the argument over how to approach the issue of mass shootings still continues down two separate and distinct pathways: Is this the result of too-easy access to firearms or is it one of untreated mental illness?

Sen. John Cornyn (R-Tex.) spoke on the Senate floor on Oct. 23, 2019, about new legislation he is cosponsoring in the aftermath of two mass shootings in Texas this past August. The Restoring, Enhancing, Strengthening, and Promoting Our Nation’s Safety Efforts Act of 2019 (S. 2690), or the RESPONSE Act, is designed to “reduce mass violence, strengthen mental health collaboration in communities, improve school safety, and for other purposes.” Sen. Cornyn notes that in the aftermath of those shootings he met with his constituents and he heard a common refrain: Please do something.

“Unfortunately, there is no quick fix, no simple answer, instead we are left to look at the factors that led to these attacks and to try to do something to prevent the sequence of events from playing out again in the future,” Sen. Cornyn said.

“While mental illness is not the prevailing cause of mass violence, enhanced mental health resources are critical to saving lives,” he said, adding that most gun deaths are from suicide. In his speech, he outlined the issues it would address – and despite his statement that mental illness is not the cause of mass violence – he went on to elaborate on the issues that the bill would address.

“First, this legislation takes aim at unlicensed firearms dealers who are breaking the law,” he said. This legislation would create a task force to prosecute those who buy and sell firearms through unlicensed dealers, and he notes that one of the Texas shooters was denied a gun by a licensed firearms dealer before purchasing one from an unlicensed dealer. That Sen. Cornyn’s proposed legislation would not create any new gun legislation is not a surprise: he has an A+ rating from the National Rifle Association and his website’s fun facts include the statement: “Sen. Cornyn owns several firearms and hunts as often as he can.”

The rest of the RESPONSE Act takes aim at those who have or might have psychiatric disorders or a tendency toward violence. Sen. Cornyn noted that the act would expand assisted outpatient treatment (AOT, or outpatient civil commitment). He referenced this as a way for families to get care for their loved ones in the community rather than in a hospital and did not allude to the involuntary nature of the treatment.

Marvin Swartz, MD, is professor of psychiatry at Duke University, Durham, N.C., and lead investigator on outcome studies following the implementation of outpatient civil commitment legislation.

“AOT may be justified in improving treatment adherence and service provision,” Dr. Swartz noted, “but there is no direct line to serious violence. The violence we documented as reduced were mainly minor acts of interpersonal violence – pushing and shoving – what we call minor acts of violence. There is no evidence that AOT is a remedy to serious acts of violence – mass shootings included.”

In addition, Sen. Cornyn noted there would be expanded crisis intervention teams and increased coordination between mental health providers and law enforcement. Furthermore, the bill would make schools safer by identifying students whose behavior indicated a threat of violence and providing those students with the services they need. This would be done “by promoting best practices within our schools and promoting Internet safety.”

Finally, Sen. Cornyn talked about using social media as a means to identify those who might be a danger. “Because so often these shooters advertise on social media ... this legislation includes provisions to [ensure] that law enforcement can receive timely information about threats made online.”

The bill already has garnered both support and opposition. It has been supported by the National Council for Behavioral Health, the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), and the Treatment Advocacy Center. Those opposed to the legislation include the National Disability Rights Network, the American Association of People with Disabilities, the National Council on Independent Living, the Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund, the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, and the Autistic Self Advocacy Network. The American Psychiatric Association has not made a statement on the proposed legislation as of this writing.

The National Council for Behavioral Health posted an endorsement on its website. It notes: “The RESPONSE Act authorizes up to $10 million of existing funds in the Department of Justice for partnership between law enforcement and mental health providers to increase access to long-acting medically assisted treatment. Additionally, it requires the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to develop and disseminate guidance for states to fund mental health programs and crisis intervention teams through Medicaid as well as to issue a report to Congress on best practices to expand the mental health workforce. These provisions aim to divert more individuals from incarceration and will create more opportunities for community-based treatment and recovery.”

There is no question that psychiatric treatment for those with mental illness is underfunded and often inaccessible. But while it is true that some individuals become violent when they are ill, most do not, and targeting those one in five Americans who suffer from a psychiatric disorder each year in an effort to identify, then thwart, the rare mass murderer among us makes no sense.

Acts of mass violence remain rare. In 2018, the year we had a record-breaking number of mass shootings, there were 12 mass murders in the United States, according to the criteria used by Mother Jones, and 27 active shooter incidents using the FBI’s criteria. Approximately half of all mass shooters showed signs of mental illness prior to the shooting and of those, some had never come to the attention of mental health professionals in a way that would have predicted violence. While linking mass violence to mental illness may seem reasonable, the numbers just don’t make sense and targeting this presumed link between mental illness and mass violence is stigmatizing.