User login

Keeping the doctor-patient relationship at the office

I recently picked up my daughter from summer camp, and on the 5-hour drive home she kept texting people back and forth. I asked her if they were other campers or counselors she’d befriended.

She said yes, they were other campers she’d met, but was horrified that I thought some might be counselors. Counselors, understandably, aren’t allowed to have any contact with kids outside of camp. Not by text, Instagram, Facebook, or any other modern social contrivances.

That probably should have occurred to me before I even asked. It makes sense.

I keep a similar policy with patients.

Nothing against them: The majority are decent people, and there are a few I could easily see being social friends with – meeting for dinner, going to a basketball game ... but I won’t.

Like the kids and counselors at camp, I need to keep a distance between myself and patients. I don’t have any social media accounts, anyway, but I keep the relationship confined to my office.

Keeping an emotional distance with patients makes it easier to do this job. While we may genuinely care about them and are trying to help, it’s important to be objective. Seeing them through the lens of friendship might affect the decision-making process.

The divider of professionalism is there for a good reason, across many fields. It allows us to try and think clearly, to give good and bad news, and make diagnostic and treatment decisions as rationally as possible, based on scientific evidence and each individual’s circumstances.

It’s what makes good medicine possible. I wouldn’t want it to be any other way.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I recently picked up my daughter from summer camp, and on the 5-hour drive home she kept texting people back and forth. I asked her if they were other campers or counselors she’d befriended.

She said yes, they were other campers she’d met, but was horrified that I thought some might be counselors. Counselors, understandably, aren’t allowed to have any contact with kids outside of camp. Not by text, Instagram, Facebook, or any other modern social contrivances.

That probably should have occurred to me before I even asked. It makes sense.

I keep a similar policy with patients.

Nothing against them: The majority are decent people, and there are a few I could easily see being social friends with – meeting for dinner, going to a basketball game ... but I won’t.

Like the kids and counselors at camp, I need to keep a distance between myself and patients. I don’t have any social media accounts, anyway, but I keep the relationship confined to my office.

Keeping an emotional distance with patients makes it easier to do this job. While we may genuinely care about them and are trying to help, it’s important to be objective. Seeing them through the lens of friendship might affect the decision-making process.

The divider of professionalism is there for a good reason, across many fields. It allows us to try and think clearly, to give good and bad news, and make diagnostic and treatment decisions as rationally as possible, based on scientific evidence and each individual’s circumstances.

It’s what makes good medicine possible. I wouldn’t want it to be any other way.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I recently picked up my daughter from summer camp, and on the 5-hour drive home she kept texting people back and forth. I asked her if they were other campers or counselors she’d befriended.

She said yes, they were other campers she’d met, but was horrified that I thought some might be counselors. Counselors, understandably, aren’t allowed to have any contact with kids outside of camp. Not by text, Instagram, Facebook, or any other modern social contrivances.

That probably should have occurred to me before I even asked. It makes sense.

I keep a similar policy with patients.

Nothing against them: The majority are decent people, and there are a few I could easily see being social friends with – meeting for dinner, going to a basketball game ... but I won’t.

Like the kids and counselors at camp, I need to keep a distance between myself and patients. I don’t have any social media accounts, anyway, but I keep the relationship confined to my office.

Keeping an emotional distance with patients makes it easier to do this job. While we may genuinely care about them and are trying to help, it’s important to be objective. Seeing them through the lens of friendship might affect the decision-making process.

The divider of professionalism is there for a good reason, across many fields. It allows us to try and think clearly, to give good and bad news, and make diagnostic and treatment decisions as rationally as possible, based on scientific evidence and each individual’s circumstances.

It’s what makes good medicine possible. I wouldn’t want it to be any other way.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The chief complaint

In medical school, they taught us to learn the patient’s chief complaint.

In dermatology the presenting complaint is on the outside, where the skin is. The chief complaint is often deeper.

Sandra

“How are your parents?”

“Getting older. I’m over their house every day. It’s always something.

“My husband had a stroke this year. Our daughter – she’s a nurse – made him get help. ‘You’re not talking right,’ she said to him. You’re going to the hospital right now.’

“Stan’s at home. He can’t work construction anymore. When I get back from taking care of my parents, I take care of him.”

Sandra’s moles are normal. Who is taking care of her?

Grigoriy

“I’ve had a hard life,” says Grigoriy, apropos of nothing.

“How?”

“My father was important in the Communist party. Stalin purged him in 1938. I was a teenager. “They kept me in a cell of one room for 15 years.”

“Why did they put you in jail?”

“I was my father’s son.”

Phil

Phil is in for his annual. He looks robust, but thinner.

“Sorry I missed last year,” he says. “I was clearing my throat a lot. An ENT doctor found that I had cancer of the vocal cords. I got 39 radiation sessions. They said I would handle them OK, but afterward, I’d feel awful. They were right.

“I lost 20 pounds,” says Phil. “But now I’m getting back to myself.” His smile is broad, but uncertain.

Fred

Fred’s rash is impressive: big, purple blotches all over. Could be a drug eruption, only he takes no drugs.

“It may be viral,” I say.

“Can I visit my Dad in Providence Sunday?” he asks. “It’s Father’s Day.”

“I’m not sure …”

“Dad has cancer of the esophagus. They’re hoping that chemo may buy him a little time.”

I tell Fred to wash carefully. Some things can’t be rescheduled.

Emily

Emily’s Mom has left me a note to read before I see her daughter. It lists Emily’s five psychoactive medications.

Emily is lying on her back and does not sit up. Her gaze is vague and unfocused.

Emily has moderate papular acne on her cheeks. That is her presenting complaint. It is not her chief complaint. As for what her mother goes through, I can barely imagine.

Brenda

Brenda comes for 6-month skin checks. Usually with her husband Glen, but not today.

“Glen’s not so well,” Brenda says. The doctors diagnosed him with MS. They’re vague about how fast it will progress. I guess they don’t know.

“To tell the truth, Glen’s pretty depressed. But he doesn’t want to talk to anyone about it. Do you know a psychiatrist who specializes in MS patients? Glen might take your advice.”

Tom

“It’s been a tough year. Eddie died. You saw him years ago, I think.”

I actually remember Eddie. A troubled kid with terrible acne. He had one visit, never came back.

“I was walking in a mountain field in Cambodia when I got the word,” says Tom. “My ex called me. ‘Tom died,’ she said. ‘Drug overdose. Come home.’

“Every year I walk through Cambodia and Myanmar for a month,” says Tom. “Just to be alone. The people there are nice. They let me be.

“Eddie was a good boy. He hung with the wrong crowd. He made a mistake, and he could never get past it. I think of him every day.”

Frank

Frank doesn’t pick. Frank gouges. He’s been gouging his forearms for years. Intralesional steroids help a little. But he can’t stop.

“I guess it’s stress,” Frank says.

“How about avoiding stress?” I ask, with a smile.

Frank breaks down and weeps.

“I’m sorry,” he says. He gathers himself. “My wife has breast cancer. Mammogram showed a spot 4 years ago. Then it grew. It’s already stage four. Our kids are teenagers.”

Frank breaks down again. He apologizes again. “I’m so sorry for being like this.” Again he weeps, again he apologizes. “I shouldn’t act like this,” he says. “I’m sorry.”

I am sorry, too. Very sorry, indeed. But for patients’ true chief complaints, often incidental to the superficial presenting ones, all I can do is listen. It’s not much, but it’s the best I can do. For many patients, over many years, listening has been the most I’ve had to offer.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

In medical school, they taught us to learn the patient’s chief complaint.

In dermatology the presenting complaint is on the outside, where the skin is. The chief complaint is often deeper.

Sandra

“How are your parents?”

“Getting older. I’m over their house every day. It’s always something.

“My husband had a stroke this year. Our daughter – she’s a nurse – made him get help. ‘You’re not talking right,’ she said to him. You’re going to the hospital right now.’

“Stan’s at home. He can’t work construction anymore. When I get back from taking care of my parents, I take care of him.”

Sandra’s moles are normal. Who is taking care of her?

Grigoriy

“I’ve had a hard life,” says Grigoriy, apropos of nothing.

“How?”

“My father was important in the Communist party. Stalin purged him in 1938. I was a teenager. “They kept me in a cell of one room for 15 years.”

“Why did they put you in jail?”

“I was my father’s son.”

Phil

Phil is in for his annual. He looks robust, but thinner.

“Sorry I missed last year,” he says. “I was clearing my throat a lot. An ENT doctor found that I had cancer of the vocal cords. I got 39 radiation sessions. They said I would handle them OK, but afterward, I’d feel awful. They were right.

“I lost 20 pounds,” says Phil. “But now I’m getting back to myself.” His smile is broad, but uncertain.

Fred

Fred’s rash is impressive: big, purple blotches all over. Could be a drug eruption, only he takes no drugs.

“It may be viral,” I say.

“Can I visit my Dad in Providence Sunday?” he asks. “It’s Father’s Day.”

“I’m not sure …”

“Dad has cancer of the esophagus. They’re hoping that chemo may buy him a little time.”

I tell Fred to wash carefully. Some things can’t be rescheduled.

Emily

Emily’s Mom has left me a note to read before I see her daughter. It lists Emily’s five psychoactive medications.

Emily is lying on her back and does not sit up. Her gaze is vague and unfocused.

Emily has moderate papular acne on her cheeks. That is her presenting complaint. It is not her chief complaint. As for what her mother goes through, I can barely imagine.

Brenda

Brenda comes for 6-month skin checks. Usually with her husband Glen, but not today.

“Glen’s not so well,” Brenda says. The doctors diagnosed him with MS. They’re vague about how fast it will progress. I guess they don’t know.

“To tell the truth, Glen’s pretty depressed. But he doesn’t want to talk to anyone about it. Do you know a psychiatrist who specializes in MS patients? Glen might take your advice.”

Tom

“It’s been a tough year. Eddie died. You saw him years ago, I think.”

I actually remember Eddie. A troubled kid with terrible acne. He had one visit, never came back.

“I was walking in a mountain field in Cambodia when I got the word,” says Tom. “My ex called me. ‘Tom died,’ she said. ‘Drug overdose. Come home.’

“Every year I walk through Cambodia and Myanmar for a month,” says Tom. “Just to be alone. The people there are nice. They let me be.

“Eddie was a good boy. He hung with the wrong crowd. He made a mistake, and he could never get past it. I think of him every day.”

Frank

Frank doesn’t pick. Frank gouges. He’s been gouging his forearms for years. Intralesional steroids help a little. But he can’t stop.

“I guess it’s stress,” Frank says.

“How about avoiding stress?” I ask, with a smile.

Frank breaks down and weeps.

“I’m sorry,” he says. He gathers himself. “My wife has breast cancer. Mammogram showed a spot 4 years ago. Then it grew. It’s already stage four. Our kids are teenagers.”

Frank breaks down again. He apologizes again. “I’m so sorry for being like this.” Again he weeps, again he apologizes. “I shouldn’t act like this,” he says. “I’m sorry.”

I am sorry, too. Very sorry, indeed. But for patients’ true chief complaints, often incidental to the superficial presenting ones, all I can do is listen. It’s not much, but it’s the best I can do. For many patients, over many years, listening has been the most I’ve had to offer.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

In medical school, they taught us to learn the patient’s chief complaint.

In dermatology the presenting complaint is on the outside, where the skin is. The chief complaint is often deeper.

Sandra

“How are your parents?”

“Getting older. I’m over their house every day. It’s always something.

“My husband had a stroke this year. Our daughter – she’s a nurse – made him get help. ‘You’re not talking right,’ she said to him. You’re going to the hospital right now.’

“Stan’s at home. He can’t work construction anymore. When I get back from taking care of my parents, I take care of him.”

Sandra’s moles are normal. Who is taking care of her?

Grigoriy

“I’ve had a hard life,” says Grigoriy, apropos of nothing.

“How?”

“My father was important in the Communist party. Stalin purged him in 1938. I was a teenager. “They kept me in a cell of one room for 15 years.”

“Why did they put you in jail?”

“I was my father’s son.”

Phil

Phil is in for his annual. He looks robust, but thinner.

“Sorry I missed last year,” he says. “I was clearing my throat a lot. An ENT doctor found that I had cancer of the vocal cords. I got 39 radiation sessions. They said I would handle them OK, but afterward, I’d feel awful. They were right.

“I lost 20 pounds,” says Phil. “But now I’m getting back to myself.” His smile is broad, but uncertain.

Fred

Fred’s rash is impressive: big, purple blotches all over. Could be a drug eruption, only he takes no drugs.

“It may be viral,” I say.

“Can I visit my Dad in Providence Sunday?” he asks. “It’s Father’s Day.”

“I’m not sure …”

“Dad has cancer of the esophagus. They’re hoping that chemo may buy him a little time.”

I tell Fred to wash carefully. Some things can’t be rescheduled.

Emily

Emily’s Mom has left me a note to read before I see her daughter. It lists Emily’s five psychoactive medications.

Emily is lying on her back and does not sit up. Her gaze is vague and unfocused.

Emily has moderate papular acne on her cheeks. That is her presenting complaint. It is not her chief complaint. As for what her mother goes through, I can barely imagine.

Brenda

Brenda comes for 6-month skin checks. Usually with her husband Glen, but not today.

“Glen’s not so well,” Brenda says. The doctors diagnosed him with MS. They’re vague about how fast it will progress. I guess they don’t know.

“To tell the truth, Glen’s pretty depressed. But he doesn’t want to talk to anyone about it. Do you know a psychiatrist who specializes in MS patients? Glen might take your advice.”

Tom

“It’s been a tough year. Eddie died. You saw him years ago, I think.”

I actually remember Eddie. A troubled kid with terrible acne. He had one visit, never came back.

“I was walking in a mountain field in Cambodia when I got the word,” says Tom. “My ex called me. ‘Tom died,’ she said. ‘Drug overdose. Come home.’

“Every year I walk through Cambodia and Myanmar for a month,” says Tom. “Just to be alone. The people there are nice. They let me be.

“Eddie was a good boy. He hung with the wrong crowd. He made a mistake, and he could never get past it. I think of him every day.”

Frank

Frank doesn’t pick. Frank gouges. He’s been gouging his forearms for years. Intralesional steroids help a little. But he can’t stop.

“I guess it’s stress,” Frank says.

“How about avoiding stress?” I ask, with a smile.

Frank breaks down and weeps.

“I’m sorry,” he says. He gathers himself. “My wife has breast cancer. Mammogram showed a spot 4 years ago. Then it grew. It’s already stage four. Our kids are teenagers.”

Frank breaks down again. He apologizes again. “I’m so sorry for being like this.” Again he weeps, again he apologizes. “I shouldn’t act like this,” he says. “I’m sorry.”

I am sorry, too. Very sorry, indeed. But for patients’ true chief complaints, often incidental to the superficial presenting ones, all I can do is listen. It’s not much, but it’s the best I can do. For many patients, over many years, listening has been the most I’ve had to offer.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

Am I going to die?

Every cancer diagnosis starts out as anything but. That’s what I was thinking when I met Sue Marcus (not her real name) in the emergency department one Friday afternoon.

“You know,” she said in a matter of fact manner. “I think I might have the flu.”

“Yes,” I said. “You might.”

“I was in Vegas a week ago, and the person next to me was sick.”

“It’s definitely possible. That’s one of the things we’ll test for.”

“I mean ... what else can it be?”

I had information Sue didn’t yet. All her blood counts were disturbingly low. On top of that, the lab had picked up several atypical appearing cells. They could be reactive, in the setting of infection, or they could be blasts – a new diagnosis of leukemia.

I paused.

“I’m going to say this now, so you know what we are looking for. There’s a lot more information we still need.”

“But?”

“But, another possibility is that it is cancer.”

“Cancer?”

“Leukemia, maybe.”

I explained the next steps. We would have flow cytometry by that night, but it’s not a perfect test. We were limited, actually, by logistics. It was a Friday night. We would do a bone marrow biopsy on Monday. It would be several days before we’d know with certainty.

That evening, the hematology fellow and I looked at the slide under the microscope. We agreed with the lab.

“That’s a blast, isn’t it?”

“Yes, I think it is.”

But they were not completely classic, and they were sporadic. It wasn’t enough to say for sure. Meanwhile, Sue, understandably, wanted answers.

“What did you see? Is it cancer, or not?”

There was flow cytometry that night, showing an abnormal population of cells. And then, finally, there was a bone marrow biopsy clinching the diagnosis.

We explained what the path ahead looked like: Hospitalization for a month. Chemotherapy, then a repeat bone marrow biopsy to look for response. Then more chemotherapy. Chances of remission. Long-term implications.

As we gathered more information, Sue’s questions evolved.

“Is it curable?”

“Can I go back to work?”

And one day, a week into treatment, she asked, “Am I going to die?”

Over my last 3 years as an internal medicine resident, I’ve been humbled by how often patients turned to me for answers to some of the most difficult questions I could imagine. Sometimes, the questions seemed purely factual, but often, they took a more existential bent: How should I spend my last months? What should I do now? Patients have asked me if they are going to die, along with when, how, and even why.

I’ve wrestled with how to communicate candidly, treading a delicate balance between being as up-front as possible while also recognizing the uncertainty inherent in predicting. I’ve struggled with walking the tightrope of delivering bad news while also emphasizing compassion and support.

I chose hematology and oncology in part because of the gravity of these interactions. I enjoy being a primary doctor for a complex, sick, patient population who are grappling with physically and emotionally challenging illness. I value longitudinal relationships with patients I know well. I found the medicine of hematology and oncology interdisciplinary, the details high stakes, and the big questions always at play. If it was meaningful work I sought, cancer became the ultimate question that mattered.

The changing landscape of cancer care is making these conversations substantially more difficult. A central tenet of medicine is truthfulness: setting the stage for what is going on and what to anticipate. It’s explaining the nuances of the upcoming treatment options, while also addressing what a person’s life may look like down the road. It’s understanding what matters most to a patient, understanding what therapeutic choices we can offer – and then trying to reconcile them, as best as we can.

This has always been hard. But it’s getting harder. The options we have to treat cancer are expanding rapidly as immunotherapy competes with the basics of chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery. We work alongside researchers looking to change the paradigm, collecting information on outcomes and side effects as we go along. We are learning and we are applying what we learn – in real time – on real people willing to try.

How can we speak honestly about a prognosis when our data are limited and our tools are in continuous flux? How can we prepare someone for what lies ahead when we are still trying to grasp what today looks like?

All the while, medical uncertainties are amplified by a complex system with many moving parts. It’s a system in which some patients cannot afford care, in which insurance companies may deny necessary treatment, and where families may come together or fall apart in the face of incredible adversity. There are factors outside the scope of pure medicine that make the path ahead all the hazier and navigating it all the more challenging.

In July, I began my hematology and oncology fellowship. I am caring for patients with a range of cancers, and all of that goes along with the weight of those diagnoses. Learning the most up-to-date management in a constantly evolving landscape will be an ongoing skill. That my patients allow me into their most vulnerable moments – and trust me with them – is a gift.

For patients like Sue, there sometimes remain more questions than answers. She recently underwent her third round of chemotherapy and endured multiple blood clots. With her insurance covering only limited interventions, she is deciding what to focus on and where to receive her care. Her story, like many others, continues to be written.

I am deeply aware of the difficulties that are a part of the world of cancer – and the heartbreak. How can we hold up scans triumphantly showing no recurrence in some patients while others suffer one failed treatment after another? When should we push for more therapy and when should we shift our efforts toward comfort? What should we prioritize – medically and personally – if time is limited?

These questions are hard, but I cannot think of any that are more meaningful.

This is a column about patients and uncertainty as I pursue my hematology and oncology fellowship and grapple with these questions. I look forward to sharing them with you each month.

Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University. Follow her on Twitter @ilanayurkiewicz.

Every cancer diagnosis starts out as anything but. That’s what I was thinking when I met Sue Marcus (not her real name) in the emergency department one Friday afternoon.

“You know,” she said in a matter of fact manner. “I think I might have the flu.”

“Yes,” I said. “You might.”

“I was in Vegas a week ago, and the person next to me was sick.”

“It’s definitely possible. That’s one of the things we’ll test for.”

“I mean ... what else can it be?”

I had information Sue didn’t yet. All her blood counts were disturbingly low. On top of that, the lab had picked up several atypical appearing cells. They could be reactive, in the setting of infection, or they could be blasts – a new diagnosis of leukemia.

I paused.

“I’m going to say this now, so you know what we are looking for. There’s a lot more information we still need.”

“But?”

“But, another possibility is that it is cancer.”

“Cancer?”

“Leukemia, maybe.”

I explained the next steps. We would have flow cytometry by that night, but it’s not a perfect test. We were limited, actually, by logistics. It was a Friday night. We would do a bone marrow biopsy on Monday. It would be several days before we’d know with certainty.

That evening, the hematology fellow and I looked at the slide under the microscope. We agreed with the lab.

“That’s a blast, isn’t it?”

“Yes, I think it is.”

But they were not completely classic, and they were sporadic. It wasn’t enough to say for sure. Meanwhile, Sue, understandably, wanted answers.

“What did you see? Is it cancer, or not?”

There was flow cytometry that night, showing an abnormal population of cells. And then, finally, there was a bone marrow biopsy clinching the diagnosis.

We explained what the path ahead looked like: Hospitalization for a month. Chemotherapy, then a repeat bone marrow biopsy to look for response. Then more chemotherapy. Chances of remission. Long-term implications.

As we gathered more information, Sue’s questions evolved.

“Is it curable?”

“Can I go back to work?”

And one day, a week into treatment, she asked, “Am I going to die?”

Over my last 3 years as an internal medicine resident, I’ve been humbled by how often patients turned to me for answers to some of the most difficult questions I could imagine. Sometimes, the questions seemed purely factual, but often, they took a more existential bent: How should I spend my last months? What should I do now? Patients have asked me if they are going to die, along with when, how, and even why.

I’ve wrestled with how to communicate candidly, treading a delicate balance between being as up-front as possible while also recognizing the uncertainty inherent in predicting. I’ve struggled with walking the tightrope of delivering bad news while also emphasizing compassion and support.

I chose hematology and oncology in part because of the gravity of these interactions. I enjoy being a primary doctor for a complex, sick, patient population who are grappling with physically and emotionally challenging illness. I value longitudinal relationships with patients I know well. I found the medicine of hematology and oncology interdisciplinary, the details high stakes, and the big questions always at play. If it was meaningful work I sought, cancer became the ultimate question that mattered.

The changing landscape of cancer care is making these conversations substantially more difficult. A central tenet of medicine is truthfulness: setting the stage for what is going on and what to anticipate. It’s explaining the nuances of the upcoming treatment options, while also addressing what a person’s life may look like down the road. It’s understanding what matters most to a patient, understanding what therapeutic choices we can offer – and then trying to reconcile them, as best as we can.

This has always been hard. But it’s getting harder. The options we have to treat cancer are expanding rapidly as immunotherapy competes with the basics of chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery. We work alongside researchers looking to change the paradigm, collecting information on outcomes and side effects as we go along. We are learning and we are applying what we learn – in real time – on real people willing to try.

How can we speak honestly about a prognosis when our data are limited and our tools are in continuous flux? How can we prepare someone for what lies ahead when we are still trying to grasp what today looks like?

All the while, medical uncertainties are amplified by a complex system with many moving parts. It’s a system in which some patients cannot afford care, in which insurance companies may deny necessary treatment, and where families may come together or fall apart in the face of incredible adversity. There are factors outside the scope of pure medicine that make the path ahead all the hazier and navigating it all the more challenging.

In July, I began my hematology and oncology fellowship. I am caring for patients with a range of cancers, and all of that goes along with the weight of those diagnoses. Learning the most up-to-date management in a constantly evolving landscape will be an ongoing skill. That my patients allow me into their most vulnerable moments – and trust me with them – is a gift.

For patients like Sue, there sometimes remain more questions than answers. She recently underwent her third round of chemotherapy and endured multiple blood clots. With her insurance covering only limited interventions, she is deciding what to focus on and where to receive her care. Her story, like many others, continues to be written.

I am deeply aware of the difficulties that are a part of the world of cancer – and the heartbreak. How can we hold up scans triumphantly showing no recurrence in some patients while others suffer one failed treatment after another? When should we push for more therapy and when should we shift our efforts toward comfort? What should we prioritize – medically and personally – if time is limited?

These questions are hard, but I cannot think of any that are more meaningful.

This is a column about patients and uncertainty as I pursue my hematology and oncology fellowship and grapple with these questions. I look forward to sharing them with you each month.

Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University. Follow her on Twitter @ilanayurkiewicz.

Every cancer diagnosis starts out as anything but. That’s what I was thinking when I met Sue Marcus (not her real name) in the emergency department one Friday afternoon.

“You know,” she said in a matter of fact manner. “I think I might have the flu.”

“Yes,” I said. “You might.”

“I was in Vegas a week ago, and the person next to me was sick.”

“It’s definitely possible. That’s one of the things we’ll test for.”

“I mean ... what else can it be?”

I had information Sue didn’t yet. All her blood counts were disturbingly low. On top of that, the lab had picked up several atypical appearing cells. They could be reactive, in the setting of infection, or they could be blasts – a new diagnosis of leukemia.

I paused.

“I’m going to say this now, so you know what we are looking for. There’s a lot more information we still need.”

“But?”

“But, another possibility is that it is cancer.”

“Cancer?”

“Leukemia, maybe.”

I explained the next steps. We would have flow cytometry by that night, but it’s not a perfect test. We were limited, actually, by logistics. It was a Friday night. We would do a bone marrow biopsy on Monday. It would be several days before we’d know with certainty.

That evening, the hematology fellow and I looked at the slide under the microscope. We agreed with the lab.

“That’s a blast, isn’t it?”

“Yes, I think it is.”

But they were not completely classic, and they were sporadic. It wasn’t enough to say for sure. Meanwhile, Sue, understandably, wanted answers.

“What did you see? Is it cancer, or not?”

There was flow cytometry that night, showing an abnormal population of cells. And then, finally, there was a bone marrow biopsy clinching the diagnosis.

We explained what the path ahead looked like: Hospitalization for a month. Chemotherapy, then a repeat bone marrow biopsy to look for response. Then more chemotherapy. Chances of remission. Long-term implications.

As we gathered more information, Sue’s questions evolved.

“Is it curable?”

“Can I go back to work?”

And one day, a week into treatment, she asked, “Am I going to die?”

Over my last 3 years as an internal medicine resident, I’ve been humbled by how often patients turned to me for answers to some of the most difficult questions I could imagine. Sometimes, the questions seemed purely factual, but often, they took a more existential bent: How should I spend my last months? What should I do now? Patients have asked me if they are going to die, along with when, how, and even why.

I’ve wrestled with how to communicate candidly, treading a delicate balance between being as up-front as possible while also recognizing the uncertainty inherent in predicting. I’ve struggled with walking the tightrope of delivering bad news while also emphasizing compassion and support.

I chose hematology and oncology in part because of the gravity of these interactions. I enjoy being a primary doctor for a complex, sick, patient population who are grappling with physically and emotionally challenging illness. I value longitudinal relationships with patients I know well. I found the medicine of hematology and oncology interdisciplinary, the details high stakes, and the big questions always at play. If it was meaningful work I sought, cancer became the ultimate question that mattered.

The changing landscape of cancer care is making these conversations substantially more difficult. A central tenet of medicine is truthfulness: setting the stage for what is going on and what to anticipate. It’s explaining the nuances of the upcoming treatment options, while also addressing what a person’s life may look like down the road. It’s understanding what matters most to a patient, understanding what therapeutic choices we can offer – and then trying to reconcile them, as best as we can.

This has always been hard. But it’s getting harder. The options we have to treat cancer are expanding rapidly as immunotherapy competes with the basics of chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery. We work alongside researchers looking to change the paradigm, collecting information on outcomes and side effects as we go along. We are learning and we are applying what we learn – in real time – on real people willing to try.

How can we speak honestly about a prognosis when our data are limited and our tools are in continuous flux? How can we prepare someone for what lies ahead when we are still trying to grasp what today looks like?

All the while, medical uncertainties are amplified by a complex system with many moving parts. It’s a system in which some patients cannot afford care, in which insurance companies may deny necessary treatment, and where families may come together or fall apart in the face of incredible adversity. There are factors outside the scope of pure medicine that make the path ahead all the hazier and navigating it all the more challenging.

In July, I began my hematology and oncology fellowship. I am caring for patients with a range of cancers, and all of that goes along with the weight of those diagnoses. Learning the most up-to-date management in a constantly evolving landscape will be an ongoing skill. That my patients allow me into their most vulnerable moments – and trust me with them – is a gift.

For patients like Sue, there sometimes remain more questions than answers. She recently underwent her third round of chemotherapy and endured multiple blood clots. With her insurance covering only limited interventions, she is deciding what to focus on and where to receive her care. Her story, like many others, continues to be written.

I am deeply aware of the difficulties that are a part of the world of cancer – and the heartbreak. How can we hold up scans triumphantly showing no recurrence in some patients while others suffer one failed treatment after another? When should we push for more therapy and when should we shift our efforts toward comfort? What should we prioritize – medically and personally – if time is limited?

These questions are hard, but I cannot think of any that are more meaningful.

This is a column about patients and uncertainty as I pursue my hematology and oncology fellowship and grapple with these questions. I look forward to sharing them with you each month.

Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University. Follow her on Twitter @ilanayurkiewicz.

Education: The Mediating Factor in Gun Violence?

I read “Up In Arms About Gun Violence” in the May/June issue of Clinician Reviews with great interest. My response is drawn from research, professional experience, and three particularly formative experiences:

- The birth of a child with learning and behavioral differences requiring an individualized education program and temporary placement in an alternative school.

- Co-leading a parent workshop for my clinical Capstone project.

- A nonclinical position at a public alternative school for children with emotional and behavioral disorders.

In nursing, as in all human services, we strive to be holistic, drawing from science, research, ethics, human development, sociology, anthropology, etc, to function in our roles. Many in nursing have come to value and function well in multidisciplinary teams for the management of individuals with complex needs.

What I have learned in my life—a fact supported by my professional preparation—is that the cycle of poverty, poor health, and quality of life are greatly influenced by education. During my pediatrics rotation and clinical, I learned you must consider family to be the vehicle by which the child may benefit from your clinical services. Therefore, you must reach beyond your setting in an effective and consistent way to engage, connect the home, and then follow up for response. My colleagues are aware of the need to document and the processes currently available for health, social service, and school professionals to report concerns. Too often, obstacles and other influences stand in the way of our ethical duty as professionals; we must find a way to overcome them, both individually and as a group.

We have processes for adolescents aging out of foster care and the developmentally delayed transitioning to sheltered work; can these be expanded?

My experience in a public school district’s alternative school for children in grades 6-12 opened my eyes to the need for the public to understand how these schools function. I likened these schools to the intensive care unit in the acute care setting. Smaller population, high needs, high cost, and dedicated staff but high burnout and turnover. Children in my school came from foster care or struggling homes and often had experienced trauma. Underfunded school districts cut nurses and social workers, cannot attract professional support staff, and choose to distribute money and efforts on the general population in neighborhood schools.

My “professional health care” mindset was embedded in an environment of wounded children, amazing educators, and support staff; powerless to do our best, we held on. But it is not enough to just hold on, sequestering at-risk children out of sight. We can do better.

Continue to: Some ideas to turn this belief into reality

Some ideas to turn this belief into reality:

- Create position statements and recommendations for our licensing and professional certifying bodies to share with their membership.

- Include mandates for communicating those recommendations during certification and relicensing.

- Employ district staff or contracted consulting medical and psychologic evaluators for review of public school students with health and behavioral diagnoses.

- Partner better with schools from the community health, pediatrician, behavioral health, and primary care settings. Kennedy Krieger Institute has partnered with schools in Baltimore—can this be replicated elsewhere?

- Every child enters school with a need for health clearance and a “Guardian Permission Contact Card.” Perhaps we can expand this to develop a process for results of routine assessments to be shared, for the safety and welfare of the child.

- Teach individuals to cope effectively with the anxiety and distress fed by constant exposure to the Internet and social media. This can—and should—be done through multiple venues: religious and social groups and the workplace.

- Inform the public with PowerPoint presentations and seminars, advertising what to look for and where to get help for concerning behaviors; again, this can be done through multiple portals. This, I believe, may also help defuse tensions between parents and schools surrounding children with health and educational differences.

- Have professional health associations deliver a cohesive message to our legislators for gun control, funding for research, and mental and public health.

Dr. Onieal, you are correct in saying that this epidemic of mass shootings is a public health issue. It is a threat as serious as HIV, cancer, lead poisoning, hypertension, and diabetes. We must find a way to stop this epidemic.

Diane Page, RN, MSN, ARNP-C

Sanford, FL

I read “Up In Arms About Gun Violence” in the May/June issue of Clinician Reviews with great interest. My response is drawn from research, professional experience, and three particularly formative experiences:

- The birth of a child with learning and behavioral differences requiring an individualized education program and temporary placement in an alternative school.

- Co-leading a parent workshop for my clinical Capstone project.

- A nonclinical position at a public alternative school for children with emotional and behavioral disorders.

In nursing, as in all human services, we strive to be holistic, drawing from science, research, ethics, human development, sociology, anthropology, etc, to function in our roles. Many in nursing have come to value and function well in multidisciplinary teams for the management of individuals with complex needs.

What I have learned in my life—a fact supported by my professional preparation—is that the cycle of poverty, poor health, and quality of life are greatly influenced by education. During my pediatrics rotation and clinical, I learned you must consider family to be the vehicle by which the child may benefit from your clinical services. Therefore, you must reach beyond your setting in an effective and consistent way to engage, connect the home, and then follow up for response. My colleagues are aware of the need to document and the processes currently available for health, social service, and school professionals to report concerns. Too often, obstacles and other influences stand in the way of our ethical duty as professionals; we must find a way to overcome them, both individually and as a group.

We have processes for adolescents aging out of foster care and the developmentally delayed transitioning to sheltered work; can these be expanded?

My experience in a public school district’s alternative school for children in grades 6-12 opened my eyes to the need for the public to understand how these schools function. I likened these schools to the intensive care unit in the acute care setting. Smaller population, high needs, high cost, and dedicated staff but high burnout and turnover. Children in my school came from foster care or struggling homes and often had experienced trauma. Underfunded school districts cut nurses and social workers, cannot attract professional support staff, and choose to distribute money and efforts on the general population in neighborhood schools.

My “professional health care” mindset was embedded in an environment of wounded children, amazing educators, and support staff; powerless to do our best, we held on. But it is not enough to just hold on, sequestering at-risk children out of sight. We can do better.

Continue to: Some ideas to turn this belief into reality

Some ideas to turn this belief into reality:

- Create position statements and recommendations for our licensing and professional certifying bodies to share with their membership.

- Include mandates for communicating those recommendations during certification and relicensing.

- Employ district staff or contracted consulting medical and psychologic evaluators for review of public school students with health and behavioral diagnoses.

- Partner better with schools from the community health, pediatrician, behavioral health, and primary care settings. Kennedy Krieger Institute has partnered with schools in Baltimore—can this be replicated elsewhere?

- Every child enters school with a need for health clearance and a “Guardian Permission Contact Card.” Perhaps we can expand this to develop a process for results of routine assessments to be shared, for the safety and welfare of the child.

- Teach individuals to cope effectively with the anxiety and distress fed by constant exposure to the Internet and social media. This can—and should—be done through multiple venues: religious and social groups and the workplace.

- Inform the public with PowerPoint presentations and seminars, advertising what to look for and where to get help for concerning behaviors; again, this can be done through multiple portals. This, I believe, may also help defuse tensions between parents and schools surrounding children with health and educational differences.

- Have professional health associations deliver a cohesive message to our legislators for gun control, funding for research, and mental and public health.

Dr. Onieal, you are correct in saying that this epidemic of mass shootings is a public health issue. It is a threat as serious as HIV, cancer, lead poisoning, hypertension, and diabetes. We must find a way to stop this epidemic.

Diane Page, RN, MSN, ARNP-C

Sanford, FL

I read “Up In Arms About Gun Violence” in the May/June issue of Clinician Reviews with great interest. My response is drawn from research, professional experience, and three particularly formative experiences:

- The birth of a child with learning and behavioral differences requiring an individualized education program and temporary placement in an alternative school.

- Co-leading a parent workshop for my clinical Capstone project.

- A nonclinical position at a public alternative school for children with emotional and behavioral disorders.

In nursing, as in all human services, we strive to be holistic, drawing from science, research, ethics, human development, sociology, anthropology, etc, to function in our roles. Many in nursing have come to value and function well in multidisciplinary teams for the management of individuals with complex needs.

What I have learned in my life—a fact supported by my professional preparation—is that the cycle of poverty, poor health, and quality of life are greatly influenced by education. During my pediatrics rotation and clinical, I learned you must consider family to be the vehicle by which the child may benefit from your clinical services. Therefore, you must reach beyond your setting in an effective and consistent way to engage, connect the home, and then follow up for response. My colleagues are aware of the need to document and the processes currently available for health, social service, and school professionals to report concerns. Too often, obstacles and other influences stand in the way of our ethical duty as professionals; we must find a way to overcome them, both individually and as a group.

We have processes for adolescents aging out of foster care and the developmentally delayed transitioning to sheltered work; can these be expanded?

My experience in a public school district’s alternative school for children in grades 6-12 opened my eyes to the need for the public to understand how these schools function. I likened these schools to the intensive care unit in the acute care setting. Smaller population, high needs, high cost, and dedicated staff but high burnout and turnover. Children in my school came from foster care or struggling homes and often had experienced trauma. Underfunded school districts cut nurses and social workers, cannot attract professional support staff, and choose to distribute money and efforts on the general population in neighborhood schools.

My “professional health care” mindset was embedded in an environment of wounded children, amazing educators, and support staff; powerless to do our best, we held on. But it is not enough to just hold on, sequestering at-risk children out of sight. We can do better.

Continue to: Some ideas to turn this belief into reality

Some ideas to turn this belief into reality:

- Create position statements and recommendations for our licensing and professional certifying bodies to share with their membership.

- Include mandates for communicating those recommendations during certification and relicensing.

- Employ district staff or contracted consulting medical and psychologic evaluators for review of public school students with health and behavioral diagnoses.

- Partner better with schools from the community health, pediatrician, behavioral health, and primary care settings. Kennedy Krieger Institute has partnered with schools in Baltimore—can this be replicated elsewhere?

- Every child enters school with a need for health clearance and a “Guardian Permission Contact Card.” Perhaps we can expand this to develop a process for results of routine assessments to be shared, for the safety and welfare of the child.

- Teach individuals to cope effectively with the anxiety and distress fed by constant exposure to the Internet and social media. This can—and should—be done through multiple venues: religious and social groups and the workplace.

- Inform the public with PowerPoint presentations and seminars, advertising what to look for and where to get help for concerning behaviors; again, this can be done through multiple portals. This, I believe, may also help defuse tensions between parents and schools surrounding children with health and educational differences.

- Have professional health associations deliver a cohesive message to our legislators for gun control, funding for research, and mental and public health.

Dr. Onieal, you are correct in saying that this epidemic of mass shootings is a public health issue. It is a threat as serious as HIV, cancer, lead poisoning, hypertension, and diabetes. We must find a way to stop this epidemic.

Diane Page, RN, MSN, ARNP-C

Sanford, FL

Screening for osteoporosis to prevent fractures: USPSTF recommendation statement

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force commissioned a systematic evidence review of 168 fair-good quality articles to examine newer evidence on screening for and treatment of osteoporotic fracture in women and men and update its 2011 guideline. For postmenopausal women older than 65 years and those younger than 65 years with increased risk of osteoporosis, USPSTF found convincing evidence that screening can detect osteoporosis and that treatment can provide at least a moderate benefit in preventing fractures (grade B). For men, they report inadequate evidence on the benefits and harms of screening for osteoporosis to reduce the risk of fractures (I statement).

Importance

Osteoporosis leads to increased bone fragility and risk of fractures, specifically hip fractures, that are associated with limitations in ambulation, chronic pain, disability and loss of independence, and decreased quality of life: 21%-30% of those who suffer hip fractures die within 1 year. Osteoporosis is usually asymptomatic until a fracture occurs, thus preventing fractures is the main goal of an osteoporosis screening strategy. With the increasing life expectancy of the U.S. population, the potential preventable burden is likely to increase in future years.

Screening tests

The most commonly used test is central dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), which provides measurement of bone mineral density (BMD) of the hip and lumbar spine. Most treatment guidelines already use central DXA BMD to define osteoporosis and the threshold at which to start drug therapies for prevention. Other lower-cost and more accessible alternatives include peripheral DXA, which measures BMD at lower forearm and heel, and quantitative ultrasound (QUS), which also evaluates peripheral sites like the calcaneus. QUS does not measure BMD. USPSTF found that the harms associated with screening were small (mainly radiation exposure from DXA and opportunity costs).

Population and risk assessment

The review included adults older than 40 years of age, mostly postmenopausal women, without a history of previous low-trauma fractures, without conditions or medications that may cause secondary osteoporosis, and without increased risk of falls.

Patients at increased risk of osteoporotic fractures include those with parental history of hip fractures, low body weight, excessive alcohol consumption, and smokers. For postmenopausal women younger than 65 years of age with at least one risk factor, a reasonable approach to determine who should be screened with BMD is to use one of the various clinical risk assessment tools available. The most frequently studied tools in women are the Osteoporosis Risk Assessment Instrument (ORAI), Osteoporosis Index of Risk (OSIRIS), Osteoporosis Self-Assessment Tool (OST), and Simple Calculated Osteoporosis Risk Estimation (SCORE). The Fracture Risk Assessment (FRAX) tool calculates the 10-year risk of a major osteoporotic fracture (MOF) using clinical risk factors. For example, one approach is to perform BMD in women younger than 65 years with a FRAX risk greater than 8.4% (the FRAX risk of a 65-year-old woman of mean height and weight without major risk factors).

In men, the prevalence of osteoporosis (4.3%) is generally lower than in women (15.4%). In the absence of other risk factors, it is not till age 80 that the prevalence of osteoporosis in white men starts to reach that of a 65-year-old white woman. While men have similar risk factors as women described above, men with hypogonadism, history of cerebrovascular accident, and history of diabetes are also at increased risk of fracture.

Preventative measures to reduce osteoporotic fractures

Approved drug therapies. The majority of studies were conducted in postmenopausal women. Bisphosphonates, most commonly used and studied, significantly reduced vertebral and nonvertebral fractures but not hip fractures (possibly because of underpowered studies). Raloxifene and parathyroid hormone reduced vertebral fractures but not nonvertebral fractures. Denosumab significantly reduced all three types of fractures. A 2011 review identified that estrogen reduced vertebral fractures, but no new studies were identified for the current review. Data from the Women’s Health Initiative show that women receiving estrogen with or without progesterone had an elevated risk of stroke, venous thromboembolism, and gallbladder disease; their risk for urinary incontinence was increased during the first year of follow-up. In addition, women receiving estrogen plus progestin had a higher risk of invasive breast cancer, coronary heart disease, and probable dementia. The risk of serious adverse events, upper-gastrointestinal events, or cardiovascular events associated with the most common class of medications used, bisphosphonates, is small. Evidence on the effectiveness of medications to treat osteoporosis in men is lacking (only two studies conducted).

Exercise. Engagement in 120-300 minutes of weekly moderate-intensity aerobic activity can reduce the risk of hip fractures, and performance of weekly balance and muscle-strengthening activities can help prevent falls in older adults.

Supplements. In a separate recommendation, USPSTF recommends against daily supplementation with less than 400 IU of vitamin D and less than 1,000 mg of calcium for the primary prevention of fractures in community-dwelling, postmenopausal women. They found insufficient evidence on supplementation with higher doses of vitamin D and calcium in postmenopausal women, or at any dose in men and premenopausal women.

Recommendations from others

The National Osteoporosis Foundation and the International Society for Clinical Densitometry recommend BMD testing in all women older than 65 years, all men over 70 years, postmenopausal women younger than 65 years, and men aged 50-69 years with increased risk factors. The American Academy of Family Physicians recommends against DXA screening in women younger than 65 years and men younger than 70 years with no risk factors.

The bottom line

For all women older than 65 years and postmenopausal women younger than 65 years who are at increased risk, screen for and treat osteoporosis to prevent fractures. For men, there is insufficient evidence to screen.

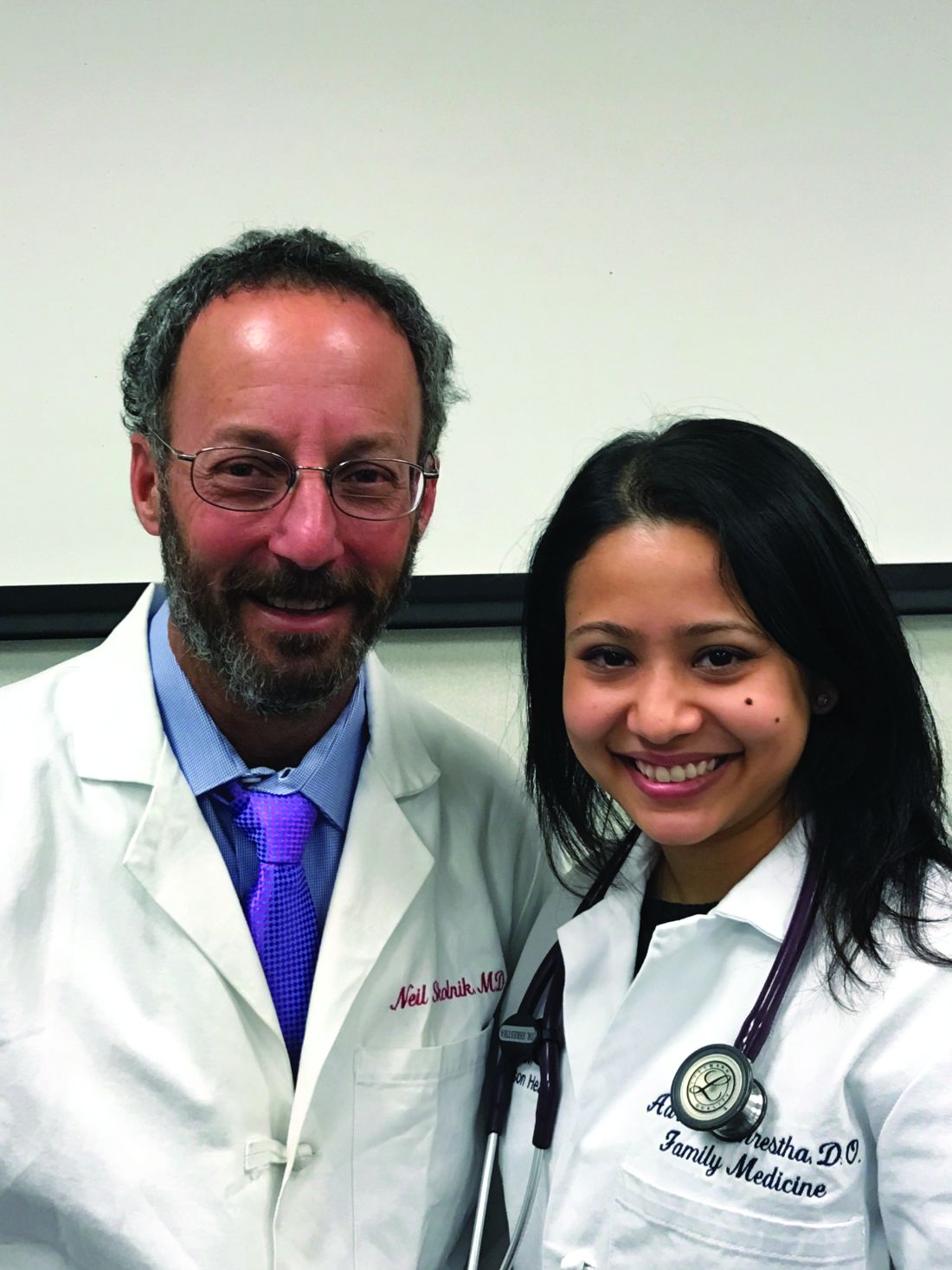

Dr. Shrestha is a second-year resident in the Family Medicine Residency Program at Abington (Pa.) - Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington - Jefferson Health.

References

1. U.S. Preventative Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018 Jun 26;319(24):2521-31.

2. U.S. Preventative Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018 Jun 26;319(24):2532-51.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force commissioned a systematic evidence review of 168 fair-good quality articles to examine newer evidence on screening for and treatment of osteoporotic fracture in women and men and update its 2011 guideline. For postmenopausal women older than 65 years and those younger than 65 years with increased risk of osteoporosis, USPSTF found convincing evidence that screening can detect osteoporosis and that treatment can provide at least a moderate benefit in preventing fractures (grade B). For men, they report inadequate evidence on the benefits and harms of screening for osteoporosis to reduce the risk of fractures (I statement).

Importance

Osteoporosis leads to increased bone fragility and risk of fractures, specifically hip fractures, that are associated with limitations in ambulation, chronic pain, disability and loss of independence, and decreased quality of life: 21%-30% of those who suffer hip fractures die within 1 year. Osteoporosis is usually asymptomatic until a fracture occurs, thus preventing fractures is the main goal of an osteoporosis screening strategy. With the increasing life expectancy of the U.S. population, the potential preventable burden is likely to increase in future years.

Screening tests

The most commonly used test is central dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), which provides measurement of bone mineral density (BMD) of the hip and lumbar spine. Most treatment guidelines already use central DXA BMD to define osteoporosis and the threshold at which to start drug therapies for prevention. Other lower-cost and more accessible alternatives include peripheral DXA, which measures BMD at lower forearm and heel, and quantitative ultrasound (QUS), which also evaluates peripheral sites like the calcaneus. QUS does not measure BMD. USPSTF found that the harms associated with screening were small (mainly radiation exposure from DXA and opportunity costs).

Population and risk assessment

The review included adults older than 40 years of age, mostly postmenopausal women, without a history of previous low-trauma fractures, without conditions or medications that may cause secondary osteoporosis, and without increased risk of falls.

Patients at increased risk of osteoporotic fractures include those with parental history of hip fractures, low body weight, excessive alcohol consumption, and smokers. For postmenopausal women younger than 65 years of age with at least one risk factor, a reasonable approach to determine who should be screened with BMD is to use one of the various clinical risk assessment tools available. The most frequently studied tools in women are the Osteoporosis Risk Assessment Instrument (ORAI), Osteoporosis Index of Risk (OSIRIS), Osteoporosis Self-Assessment Tool (OST), and Simple Calculated Osteoporosis Risk Estimation (SCORE). The Fracture Risk Assessment (FRAX) tool calculates the 10-year risk of a major osteoporotic fracture (MOF) using clinical risk factors. For example, one approach is to perform BMD in women younger than 65 years with a FRAX risk greater than 8.4% (the FRAX risk of a 65-year-old woman of mean height and weight without major risk factors).

In men, the prevalence of osteoporosis (4.3%) is generally lower than in women (15.4%). In the absence of other risk factors, it is not till age 80 that the prevalence of osteoporosis in white men starts to reach that of a 65-year-old white woman. While men have similar risk factors as women described above, men with hypogonadism, history of cerebrovascular accident, and history of diabetes are also at increased risk of fracture.

Preventative measures to reduce osteoporotic fractures

Approved drug therapies. The majority of studies were conducted in postmenopausal women. Bisphosphonates, most commonly used and studied, significantly reduced vertebral and nonvertebral fractures but not hip fractures (possibly because of underpowered studies). Raloxifene and parathyroid hormone reduced vertebral fractures but not nonvertebral fractures. Denosumab significantly reduced all three types of fractures. A 2011 review identified that estrogen reduced vertebral fractures, but no new studies were identified for the current review. Data from the Women’s Health Initiative show that women receiving estrogen with or without progesterone had an elevated risk of stroke, venous thromboembolism, and gallbladder disease; their risk for urinary incontinence was increased during the first year of follow-up. In addition, women receiving estrogen plus progestin had a higher risk of invasive breast cancer, coronary heart disease, and probable dementia. The risk of serious adverse events, upper-gastrointestinal events, or cardiovascular events associated with the most common class of medications used, bisphosphonates, is small. Evidence on the effectiveness of medications to treat osteoporosis in men is lacking (only two studies conducted).

Exercise. Engagement in 120-300 minutes of weekly moderate-intensity aerobic activity can reduce the risk of hip fractures, and performance of weekly balance and muscle-strengthening activities can help prevent falls in older adults.

Supplements. In a separate recommendation, USPSTF recommends against daily supplementation with less than 400 IU of vitamin D and less than 1,000 mg of calcium for the primary prevention of fractures in community-dwelling, postmenopausal women. They found insufficient evidence on supplementation with higher doses of vitamin D and calcium in postmenopausal women, or at any dose in men and premenopausal women.

Recommendations from others

The National Osteoporosis Foundation and the International Society for Clinical Densitometry recommend BMD testing in all women older than 65 years, all men over 70 years, postmenopausal women younger than 65 years, and men aged 50-69 years with increased risk factors. The American Academy of Family Physicians recommends against DXA screening in women younger than 65 years and men younger than 70 years with no risk factors.

The bottom line

For all women older than 65 years and postmenopausal women younger than 65 years who are at increased risk, screen for and treat osteoporosis to prevent fractures. For men, there is insufficient evidence to screen.

Dr. Shrestha is a second-year resident in the Family Medicine Residency Program at Abington (Pa.) - Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington - Jefferson Health.

References

1. U.S. Preventative Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018 Jun 26;319(24):2521-31.

2. U.S. Preventative Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018 Jun 26;319(24):2532-51.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force commissioned a systematic evidence review of 168 fair-good quality articles to examine newer evidence on screening for and treatment of osteoporotic fracture in women and men and update its 2011 guideline. For postmenopausal women older than 65 years and those younger than 65 years with increased risk of osteoporosis, USPSTF found convincing evidence that screening can detect osteoporosis and that treatment can provide at least a moderate benefit in preventing fractures (grade B). For men, they report inadequate evidence on the benefits and harms of screening for osteoporosis to reduce the risk of fractures (I statement).

Importance

Osteoporosis leads to increased bone fragility and risk of fractures, specifically hip fractures, that are associated with limitations in ambulation, chronic pain, disability and loss of independence, and decreased quality of life: 21%-30% of those who suffer hip fractures die within 1 year. Osteoporosis is usually asymptomatic until a fracture occurs, thus preventing fractures is the main goal of an osteoporosis screening strategy. With the increasing life expectancy of the U.S. population, the potential preventable burden is likely to increase in future years.

Screening tests

The most commonly used test is central dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), which provides measurement of bone mineral density (BMD) of the hip and lumbar spine. Most treatment guidelines already use central DXA BMD to define osteoporosis and the threshold at which to start drug therapies for prevention. Other lower-cost and more accessible alternatives include peripheral DXA, which measures BMD at lower forearm and heel, and quantitative ultrasound (QUS), which also evaluates peripheral sites like the calcaneus. QUS does not measure BMD. USPSTF found that the harms associated with screening were small (mainly radiation exposure from DXA and opportunity costs).

Population and risk assessment

The review included adults older than 40 years of age, mostly postmenopausal women, without a history of previous low-trauma fractures, without conditions or medications that may cause secondary osteoporosis, and without increased risk of falls.

Patients at increased risk of osteoporotic fractures include those with parental history of hip fractures, low body weight, excessive alcohol consumption, and smokers. For postmenopausal women younger than 65 years of age with at least one risk factor, a reasonable approach to determine who should be screened with BMD is to use one of the various clinical risk assessment tools available. The most frequently studied tools in women are the Osteoporosis Risk Assessment Instrument (ORAI), Osteoporosis Index of Risk (OSIRIS), Osteoporosis Self-Assessment Tool (OST), and Simple Calculated Osteoporosis Risk Estimation (SCORE). The Fracture Risk Assessment (FRAX) tool calculates the 10-year risk of a major osteoporotic fracture (MOF) using clinical risk factors. For example, one approach is to perform BMD in women younger than 65 years with a FRAX risk greater than 8.4% (the FRAX risk of a 65-year-old woman of mean height and weight without major risk factors).

In men, the prevalence of osteoporosis (4.3%) is generally lower than in women (15.4%). In the absence of other risk factors, it is not till age 80 that the prevalence of osteoporosis in white men starts to reach that of a 65-year-old white woman. While men have similar risk factors as women described above, men with hypogonadism, history of cerebrovascular accident, and history of diabetes are also at increased risk of fracture.

Preventative measures to reduce osteoporotic fractures

Approved drug therapies. The majority of studies were conducted in postmenopausal women. Bisphosphonates, most commonly used and studied, significantly reduced vertebral and nonvertebral fractures but not hip fractures (possibly because of underpowered studies). Raloxifene and parathyroid hormone reduced vertebral fractures but not nonvertebral fractures. Denosumab significantly reduced all three types of fractures. A 2011 review identified that estrogen reduced vertebral fractures, but no new studies were identified for the current review. Data from the Women’s Health Initiative show that women receiving estrogen with or without progesterone had an elevated risk of stroke, venous thromboembolism, and gallbladder disease; their risk for urinary incontinence was increased during the first year of follow-up. In addition, women receiving estrogen plus progestin had a higher risk of invasive breast cancer, coronary heart disease, and probable dementia. The risk of serious adverse events, upper-gastrointestinal events, or cardiovascular events associated with the most common class of medications used, bisphosphonates, is small. Evidence on the effectiveness of medications to treat osteoporosis in men is lacking (only two studies conducted).

Exercise. Engagement in 120-300 minutes of weekly moderate-intensity aerobic activity can reduce the risk of hip fractures, and performance of weekly balance and muscle-strengthening activities can help prevent falls in older adults.

Supplements. In a separate recommendation, USPSTF recommends against daily supplementation with less than 400 IU of vitamin D and less than 1,000 mg of calcium for the primary prevention of fractures in community-dwelling, postmenopausal women. They found insufficient evidence on supplementation with higher doses of vitamin D and calcium in postmenopausal women, or at any dose in men and premenopausal women.

Recommendations from others

The National Osteoporosis Foundation and the International Society for Clinical Densitometry recommend BMD testing in all women older than 65 years, all men over 70 years, postmenopausal women younger than 65 years, and men aged 50-69 years with increased risk factors. The American Academy of Family Physicians recommends against DXA screening in women younger than 65 years and men younger than 70 years with no risk factors.

The bottom line

For all women older than 65 years and postmenopausal women younger than 65 years who are at increased risk, screen for and treat osteoporosis to prevent fractures. For men, there is insufficient evidence to screen.

Dr. Shrestha is a second-year resident in the Family Medicine Residency Program at Abington (Pa.) - Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington - Jefferson Health.

References

1. U.S. Preventative Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018 Jun 26;319(24):2521-31.

2. U.S. Preventative Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018 Jun 26;319(24):2532-51.

Denial of science isn’t fiction

Summer is often a time when we can take a break from our usual frenetic schedules. It is a time to catch up on nonurgent reading. I just completed 3 books of interest, including Bad Blood, by John Carreyrou, What the Eyes Don’t See, by Mona Hanna-Attisha, and Overcharged, by Charles Silver and David Hyman.

The common thread among them is their focus on the interplay among American medicine, politics, money, and denial of science. Carreyrou is a Wall Street Journal investigative reporter who describes the spectacular rise and ignominious fall of Theranos, a privately held company in the business of blood testing and diagnostics. Theranos claimed to have a secret process enabling them to run over 200 diagnostic blood tests on blood derived from a finger prick. At its peak, the company was valued at $10 billion but their secret process proved to be false science. They are now subject to multiple lawsuits and their leaders are under criminal investigation.

Dr. Attisha’s book describes the decisions made by Michigan political and administrative leaders that resulted in high levels of lead in Flint’s water supply. Dr. Attisha is a pediatrician in Flint who documented elevated lead levels in her small patients. When she tried to bring this to public attention, her data was met with enormous backlash by leaders who tried to deny facts and discredit her personally. Neurological damage from childhood lead poisoning is not reversible.

Hyman and Silver’s book (published by the Cato Institute) asserts that politics, third-party payers, and the health care industry, together, have devised a system of wealth transfer from taxpayers to health care providers. It provides examples where this system (that separates payment from health value) does real harm to individual people and the nation. Reading this book makes us think about who should hold the assets from which first-dollar medical payments derive. It reminded me of the famous saying by James Madison, “If all men were angels, there would be no need for government.”

In some circles, science, data, and the scientific method are not valued. In the end, as these books point out, everyone can be entitled to their opinion, but no one has the power to alter facts.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Summer is often a time when we can take a break from our usual frenetic schedules. It is a time to catch up on nonurgent reading. I just completed 3 books of interest, including Bad Blood, by John Carreyrou, What the Eyes Don’t See, by Mona Hanna-Attisha, and Overcharged, by Charles Silver and David Hyman.

The common thread among them is their focus on the interplay among American medicine, politics, money, and denial of science. Carreyrou is a Wall Street Journal investigative reporter who describes the spectacular rise and ignominious fall of Theranos, a privately held company in the business of blood testing and diagnostics. Theranos claimed to have a secret process enabling them to run over 200 diagnostic blood tests on blood derived from a finger prick. At its peak, the company was valued at $10 billion but their secret process proved to be false science. They are now subject to multiple lawsuits and their leaders are under criminal investigation.

Dr. Attisha’s book describes the decisions made by Michigan political and administrative leaders that resulted in high levels of lead in Flint’s water supply. Dr. Attisha is a pediatrician in Flint who documented elevated lead levels in her small patients. When she tried to bring this to public attention, her data was met with enormous backlash by leaders who tried to deny facts and discredit her personally. Neurological damage from childhood lead poisoning is not reversible.

Hyman and Silver’s book (published by the Cato Institute) asserts that politics, third-party payers, and the health care industry, together, have devised a system of wealth transfer from taxpayers to health care providers. It provides examples where this system (that separates payment from health value) does real harm to individual people and the nation. Reading this book makes us think about who should hold the assets from which first-dollar medical payments derive. It reminded me of the famous saying by James Madison, “If all men were angels, there would be no need for government.”

In some circles, science, data, and the scientific method are not valued. In the end, as these books point out, everyone can be entitled to their opinion, but no one has the power to alter facts.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Summer is often a time when we can take a break from our usual frenetic schedules. It is a time to catch up on nonurgent reading. I just completed 3 books of interest, including Bad Blood, by John Carreyrou, What the Eyes Don’t See, by Mona Hanna-Attisha, and Overcharged, by Charles Silver and David Hyman.

The common thread among them is their focus on the interplay among American medicine, politics, money, and denial of science. Carreyrou is a Wall Street Journal investigative reporter who describes the spectacular rise and ignominious fall of Theranos, a privately held company in the business of blood testing and diagnostics. Theranos claimed to have a secret process enabling them to run over 200 diagnostic blood tests on blood derived from a finger prick. At its peak, the company was valued at $10 billion but their secret process proved to be false science. They are now subject to multiple lawsuits and their leaders are under criminal investigation.

Dr. Attisha’s book describes the decisions made by Michigan political and administrative leaders that resulted in high levels of lead in Flint’s water supply. Dr. Attisha is a pediatrician in Flint who documented elevated lead levels in her small patients. When she tried to bring this to public attention, her data was met with enormous backlash by leaders who tried to deny facts and discredit her personally. Neurological damage from childhood lead poisoning is not reversible.