User login

The VA Cannot Be Privatized

As usual, it was a hectic Monday on the psychiatry consult service. All the trainees, from medical student to fellow, were seeing other patients when the call came from the surgery clinic. One of the pleasures of being a VA clinician is the ability to teach and supervise medical students and residents. The attending in that busy clinic said, “There is a patient down here who is refusing care for a gangrenous leg, but he is also talking about his life not being worth living. Could someone evaluate him?” That patient, Mr. S, declined to go to either the emergency department or the urgent care psychiatry clinic, so I went to see him. I realized that I had seen this patient in the hospital several times before.

One of the great clinical benefits of working in the VA, as opposed to in academic or community hospitals, is continuity. In my nearly 20 years at the same medical center, I have had the privilege of following many patients through multiple courses of treatment. This continuity is a huge advantage when there is what Hippocrates called a “critical day,” as on that Monday in the surgery clinic.2 Also, in many cases the continuity allows me to have a reservoir of trust that I can draw on for challenging consultations, like that of Mr. S.

The surgery resident and attending had spent more than an hour talking to Mr. S when I arrived but still they joined me for the conversation. Mr. S was a veteran in his sixties, and after a few minutes of listening to him, it was clear he was talking about ending his life because of its poor quality. He told us that he had acquired the infection in his leg secondary to unsanitary living conditions. The veteran was quite a storyteller, intelligent, and had a wry sense of humor, which only made his point that his living conditions were intolerable more poignant. He apparently had tried to talk to someone about his situation but felt frustrated that he had not obtained more help.

The surgery attending had already told Mr. S that he would respect his right to refuse the amputation but he feared that Mr. S’s refusal was an expression of his depression and hopelessness, hence, the psychiatry consult. Although Mr. S was not acutely suicidal, something about the combination of his despair and deliberation worried me.

The surgery attending offered to admit Mr. S to do a further workup of his leg. I encouraged him to accept this option and added that I would make sure a social worker saw him and the psychiatry service department also would follow him. Mr. S declined even a 24-hour admission, saying that he had just moved to a new apartment and “everything I have in the world is there and I don’t want to lose it.” This comment suggested to me that he was ambivalent about his wish to die and provided an opening to reduce his risk of harming himself either directly or indirectly.

After the discussion, Mr. S seemed to believe we cared about him and was more willing to participate in treatment planning. He agreed to let the surgeons draw blood and to pick up oral antibiotics from the pharmacy. I promised him that if he would come back to clinic that week, I would make sure a social worker met with him and that my team would talk with him more about his depression. Mr. S picked Friday for his return and assured me that now that he knew we were going to try and improve his situation, he would not hurt himself. Obviously, this was a risk on my part—but the show of compassion combined with flexibility had created a therapeutic alliance that I believed was sufficient to protect Mr. S until we met again.

I returned to my office and called the chief of social work: The dedication of career VA employees forges effective working relationships that can be leveraged for the benefit of the patients. At my facility and many others, many of the staff members who are now in positions of leadership rose through the ranks together, giving us a solidarity of purpose and mutual reliance that are rare in community health care settings. The chief of social work looked at the patient’s chart with me on the phone while I explained the circumstances and within a few minutes said, “We can help him. It looks like he is eligible for an increased pension, and I think we can find him better housing.”

I admit to some anxiety on Friday. One of the psychiatry residents on the service had volunteered to see Mr. S after studying his chart in the morning. Most of us are aware that the aging VA electronic health record system is due to be replaced. But having access to more than 20 years of medical history from episodes of inpatient, outpatient, and residential care all over the country is an unrivaled asset that brings a unique breadth that sharpens, deepens, and humanizes diagnosis and treatment planning.

Sure enough at 10

The social worker arranged new housing for Mr. S that day and help to move into his new place. The paperwork was submitted for the pension increase, and help for shopping and meals as well as transportation was either put in place or applied for. As he left to pack, Mr. S told the surgeon he might not want hospice just yet.

The coda to this narrative is equally uplifting. Several weeks after Mr. S was seen in the surgery clinic, I received a call from a midlevel psychiatric practitioner in the urgent care clinic who had been on leave for several weeks. He too had seen Mr. S before and shared my concern about his state of mind and well-being. He thanked me for having the consult service see him and remarked that it was a relief to know Mr. S had been taken care of and was in a better place in every sense of the word.

In response to a rising media tide of concern about the direction VA care is headed, Congress and the VA have issued a strong statements, “debunking” what they called the “myth” of privatization.3 Yet for the first time in my career, many thoughtful people discern a constellation of forces that could eventuate in this reality in our lifetimes. The title and message of this column is that the VA cannot be privatized, not that it will not be privatized. Also, I did not say that it should not be privatized. As I have written in other columns, that is because ethically I do not believe this is even a question.4 Privatization breaks President Abraham Lincoln’s promise to veterans, “to care for him who has borne the battle.” A promise that was kept for Mr. S and is fulfilled for thousands of other veterans every day all over this nation. A promise that far exceeds payments for medical services.

I also do not mean the title to be a rejection of the Veterans Choice Program. The VA has always provided—and should continue to offer—community-based care for veterans that complements VA care. For example, I live in one of the most rural states in the union and recognize that a patient should not have to drive 300 miles to get a routine colonoscopy.

The VA cannot be privatized because of the comprehensive care that it provides: the degree of integration; the wealth of resources; and the level of expertise in caring for the complex medical, psychiatric, and psychosocial problems of veterans cannot be replicated. Nor is this just my opinion—a recent RAND Corporation study documents the evidence.5 There are many medical services in the private sector that may be delivered more efficiently, and Congress has just passed the Mission Act to allocate the funds needed to ensure our veterans have wider and easier access to private care resources.6 Yet someone must coordinate, monitor, and center all these services on the veteran. It is not likely Mr. S’s story would have had this kind of ending in the community. The continuity of care, the access to staff with the knowledge of veterans benefits and health care needs, and the ability to listen and follow up without time or performance constraints is just not possible outside VA.

The other evening in the parking lot of the hospital, I encountered a physician who had left the VA to work in several other large health care organizations. He had some good things to say about their business processes and the volume of patients they saw. He came back to the VA, he said, because “No one else can provide this quality of care for the individual veteran.”

1. Conway E, Batalden P. Like magic? (“Every system is perfectly designed…”). http://www.ihi.org/communities/blogs/o rigin-of-every-system-is-perfectly-designed-quote. Published August 21, 2015. Accessed May 29, 2018.

2. Lloyd GER, ed. Hippocratic Writings . London: Penguin Books ; 1983.

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. Debunking the VA privatization myth [press release]. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=4034. Published April 5, 2018. Accessed June 4, 2018.

4. Geppert CMA. Lessons from history: the ethical foundation of VA health care. Fed Pract. 2016;33(4):6-7.

5. Tanielian T, Farmer CM, Burns RM, Duffy EL, Messan Setodji C. Ready or Not? Assessing the Capacity of New York State Health Care Providers to Meet the Needs of Veterans. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2018.

6. VA MISSION Act of 2018, S 2372, 115th Congress, 2nd Sess (2018).

As usual, it was a hectic Monday on the psychiatry consult service. All the trainees, from medical student to fellow, were seeing other patients when the call came from the surgery clinic. One of the pleasures of being a VA clinician is the ability to teach and supervise medical students and residents. The attending in that busy clinic said, “There is a patient down here who is refusing care for a gangrenous leg, but he is also talking about his life not being worth living. Could someone evaluate him?” That patient, Mr. S, declined to go to either the emergency department or the urgent care psychiatry clinic, so I went to see him. I realized that I had seen this patient in the hospital several times before.

One of the great clinical benefits of working in the VA, as opposed to in academic or community hospitals, is continuity. In my nearly 20 years at the same medical center, I have had the privilege of following many patients through multiple courses of treatment. This continuity is a huge advantage when there is what Hippocrates called a “critical day,” as on that Monday in the surgery clinic.2 Also, in many cases the continuity allows me to have a reservoir of trust that I can draw on for challenging consultations, like that of Mr. S.

The surgery resident and attending had spent more than an hour talking to Mr. S when I arrived but still they joined me for the conversation. Mr. S was a veteran in his sixties, and after a few minutes of listening to him, it was clear he was talking about ending his life because of its poor quality. He told us that he had acquired the infection in his leg secondary to unsanitary living conditions. The veteran was quite a storyteller, intelligent, and had a wry sense of humor, which only made his point that his living conditions were intolerable more poignant. He apparently had tried to talk to someone about his situation but felt frustrated that he had not obtained more help.

The surgery attending had already told Mr. S that he would respect his right to refuse the amputation but he feared that Mr. S’s refusal was an expression of his depression and hopelessness, hence, the psychiatry consult. Although Mr. S was not acutely suicidal, something about the combination of his despair and deliberation worried me.

The surgery attending offered to admit Mr. S to do a further workup of his leg. I encouraged him to accept this option and added that I would make sure a social worker saw him and the psychiatry service department also would follow him. Mr. S declined even a 24-hour admission, saying that he had just moved to a new apartment and “everything I have in the world is there and I don’t want to lose it.” This comment suggested to me that he was ambivalent about his wish to die and provided an opening to reduce his risk of harming himself either directly or indirectly.

After the discussion, Mr. S seemed to believe we cared about him and was more willing to participate in treatment planning. He agreed to let the surgeons draw blood and to pick up oral antibiotics from the pharmacy. I promised him that if he would come back to clinic that week, I would make sure a social worker met with him and that my team would talk with him more about his depression. Mr. S picked Friday for his return and assured me that now that he knew we were going to try and improve his situation, he would not hurt himself. Obviously, this was a risk on my part—but the show of compassion combined with flexibility had created a therapeutic alliance that I believed was sufficient to protect Mr. S until we met again.

I returned to my office and called the chief of social work: The dedication of career VA employees forges effective working relationships that can be leveraged for the benefit of the patients. At my facility and many others, many of the staff members who are now in positions of leadership rose through the ranks together, giving us a solidarity of purpose and mutual reliance that are rare in community health care settings. The chief of social work looked at the patient’s chart with me on the phone while I explained the circumstances and within a few minutes said, “We can help him. It looks like he is eligible for an increased pension, and I think we can find him better housing.”

I admit to some anxiety on Friday. One of the psychiatry residents on the service had volunteered to see Mr. S after studying his chart in the morning. Most of us are aware that the aging VA electronic health record system is due to be replaced. But having access to more than 20 years of medical history from episodes of inpatient, outpatient, and residential care all over the country is an unrivaled asset that brings a unique breadth that sharpens, deepens, and humanizes diagnosis and treatment planning.

Sure enough at 10

The social worker arranged new housing for Mr. S that day and help to move into his new place. The paperwork was submitted for the pension increase, and help for shopping and meals as well as transportation was either put in place or applied for. As he left to pack, Mr. S told the surgeon he might not want hospice just yet.

The coda to this narrative is equally uplifting. Several weeks after Mr. S was seen in the surgery clinic, I received a call from a midlevel psychiatric practitioner in the urgent care clinic who had been on leave for several weeks. He too had seen Mr. S before and shared my concern about his state of mind and well-being. He thanked me for having the consult service see him and remarked that it was a relief to know Mr. S had been taken care of and was in a better place in every sense of the word.

In response to a rising media tide of concern about the direction VA care is headed, Congress and the VA have issued a strong statements, “debunking” what they called the “myth” of privatization.3 Yet for the first time in my career, many thoughtful people discern a constellation of forces that could eventuate in this reality in our lifetimes. The title and message of this column is that the VA cannot be privatized, not that it will not be privatized. Also, I did not say that it should not be privatized. As I have written in other columns, that is because ethically I do not believe this is even a question.4 Privatization breaks President Abraham Lincoln’s promise to veterans, “to care for him who has borne the battle.” A promise that was kept for Mr. S and is fulfilled for thousands of other veterans every day all over this nation. A promise that far exceeds payments for medical services.

I also do not mean the title to be a rejection of the Veterans Choice Program. The VA has always provided—and should continue to offer—community-based care for veterans that complements VA care. For example, I live in one of the most rural states in the union and recognize that a patient should not have to drive 300 miles to get a routine colonoscopy.

The VA cannot be privatized because of the comprehensive care that it provides: the degree of integration; the wealth of resources; and the level of expertise in caring for the complex medical, psychiatric, and psychosocial problems of veterans cannot be replicated. Nor is this just my opinion—a recent RAND Corporation study documents the evidence.5 There are many medical services in the private sector that may be delivered more efficiently, and Congress has just passed the Mission Act to allocate the funds needed to ensure our veterans have wider and easier access to private care resources.6 Yet someone must coordinate, monitor, and center all these services on the veteran. It is not likely Mr. S’s story would have had this kind of ending in the community. The continuity of care, the access to staff with the knowledge of veterans benefits and health care needs, and the ability to listen and follow up without time or performance constraints is just not possible outside VA.

The other evening in the parking lot of the hospital, I encountered a physician who had left the VA to work in several other large health care organizations. He had some good things to say about their business processes and the volume of patients they saw. He came back to the VA, he said, because “No one else can provide this quality of care for the individual veteran.”

As usual, it was a hectic Monday on the psychiatry consult service. All the trainees, from medical student to fellow, were seeing other patients when the call came from the surgery clinic. One of the pleasures of being a VA clinician is the ability to teach and supervise medical students and residents. The attending in that busy clinic said, “There is a patient down here who is refusing care for a gangrenous leg, but he is also talking about his life not being worth living. Could someone evaluate him?” That patient, Mr. S, declined to go to either the emergency department or the urgent care psychiatry clinic, so I went to see him. I realized that I had seen this patient in the hospital several times before.

One of the great clinical benefits of working in the VA, as opposed to in academic or community hospitals, is continuity. In my nearly 20 years at the same medical center, I have had the privilege of following many patients through multiple courses of treatment. This continuity is a huge advantage when there is what Hippocrates called a “critical day,” as on that Monday in the surgery clinic.2 Also, in many cases the continuity allows me to have a reservoir of trust that I can draw on for challenging consultations, like that of Mr. S.

The surgery resident and attending had spent more than an hour talking to Mr. S when I arrived but still they joined me for the conversation. Mr. S was a veteran in his sixties, and after a few minutes of listening to him, it was clear he was talking about ending his life because of its poor quality. He told us that he had acquired the infection in his leg secondary to unsanitary living conditions. The veteran was quite a storyteller, intelligent, and had a wry sense of humor, which only made his point that his living conditions were intolerable more poignant. He apparently had tried to talk to someone about his situation but felt frustrated that he had not obtained more help.

The surgery attending had already told Mr. S that he would respect his right to refuse the amputation but he feared that Mr. S’s refusal was an expression of his depression and hopelessness, hence, the psychiatry consult. Although Mr. S was not acutely suicidal, something about the combination of his despair and deliberation worried me.

The surgery attending offered to admit Mr. S to do a further workup of his leg. I encouraged him to accept this option and added that I would make sure a social worker saw him and the psychiatry service department also would follow him. Mr. S declined even a 24-hour admission, saying that he had just moved to a new apartment and “everything I have in the world is there and I don’t want to lose it.” This comment suggested to me that he was ambivalent about his wish to die and provided an opening to reduce his risk of harming himself either directly or indirectly.

After the discussion, Mr. S seemed to believe we cared about him and was more willing to participate in treatment planning. He agreed to let the surgeons draw blood and to pick up oral antibiotics from the pharmacy. I promised him that if he would come back to clinic that week, I would make sure a social worker met with him and that my team would talk with him more about his depression. Mr. S picked Friday for his return and assured me that now that he knew we were going to try and improve his situation, he would not hurt himself. Obviously, this was a risk on my part—but the show of compassion combined with flexibility had created a therapeutic alliance that I believed was sufficient to protect Mr. S until we met again.

I returned to my office and called the chief of social work: The dedication of career VA employees forges effective working relationships that can be leveraged for the benefit of the patients. At my facility and many others, many of the staff members who are now in positions of leadership rose through the ranks together, giving us a solidarity of purpose and mutual reliance that are rare in community health care settings. The chief of social work looked at the patient’s chart with me on the phone while I explained the circumstances and within a few minutes said, “We can help him. It looks like he is eligible for an increased pension, and I think we can find him better housing.”

I admit to some anxiety on Friday. One of the psychiatry residents on the service had volunteered to see Mr. S after studying his chart in the morning. Most of us are aware that the aging VA electronic health record system is due to be replaced. But having access to more than 20 years of medical history from episodes of inpatient, outpatient, and residential care all over the country is an unrivaled asset that brings a unique breadth that sharpens, deepens, and humanizes diagnosis and treatment planning.

Sure enough at 10

The social worker arranged new housing for Mr. S that day and help to move into his new place. The paperwork was submitted for the pension increase, and help for shopping and meals as well as transportation was either put in place or applied for. As he left to pack, Mr. S told the surgeon he might not want hospice just yet.

The coda to this narrative is equally uplifting. Several weeks after Mr. S was seen in the surgery clinic, I received a call from a midlevel psychiatric practitioner in the urgent care clinic who had been on leave for several weeks. He too had seen Mr. S before and shared my concern about his state of mind and well-being. He thanked me for having the consult service see him and remarked that it was a relief to know Mr. S had been taken care of and was in a better place in every sense of the word.

In response to a rising media tide of concern about the direction VA care is headed, Congress and the VA have issued a strong statements, “debunking” what they called the “myth” of privatization.3 Yet for the first time in my career, many thoughtful people discern a constellation of forces that could eventuate in this reality in our lifetimes. The title and message of this column is that the VA cannot be privatized, not that it will not be privatized. Also, I did not say that it should not be privatized. As I have written in other columns, that is because ethically I do not believe this is even a question.4 Privatization breaks President Abraham Lincoln’s promise to veterans, “to care for him who has borne the battle.” A promise that was kept for Mr. S and is fulfilled for thousands of other veterans every day all over this nation. A promise that far exceeds payments for medical services.

I also do not mean the title to be a rejection of the Veterans Choice Program. The VA has always provided—and should continue to offer—community-based care for veterans that complements VA care. For example, I live in one of the most rural states in the union and recognize that a patient should not have to drive 300 miles to get a routine colonoscopy.

The VA cannot be privatized because of the comprehensive care that it provides: the degree of integration; the wealth of resources; and the level of expertise in caring for the complex medical, psychiatric, and psychosocial problems of veterans cannot be replicated. Nor is this just my opinion—a recent RAND Corporation study documents the evidence.5 There are many medical services in the private sector that may be delivered more efficiently, and Congress has just passed the Mission Act to allocate the funds needed to ensure our veterans have wider and easier access to private care resources.6 Yet someone must coordinate, monitor, and center all these services on the veteran. It is not likely Mr. S’s story would have had this kind of ending in the community. The continuity of care, the access to staff with the knowledge of veterans benefits and health care needs, and the ability to listen and follow up without time or performance constraints is just not possible outside VA.

The other evening in the parking lot of the hospital, I encountered a physician who had left the VA to work in several other large health care organizations. He had some good things to say about their business processes and the volume of patients they saw. He came back to the VA, he said, because “No one else can provide this quality of care for the individual veteran.”

1. Conway E, Batalden P. Like magic? (“Every system is perfectly designed…”). http://www.ihi.org/communities/blogs/o rigin-of-every-system-is-perfectly-designed-quote. Published August 21, 2015. Accessed May 29, 2018.

2. Lloyd GER, ed. Hippocratic Writings . London: Penguin Books ; 1983.

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. Debunking the VA privatization myth [press release]. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=4034. Published April 5, 2018. Accessed June 4, 2018.

4. Geppert CMA. Lessons from history: the ethical foundation of VA health care. Fed Pract. 2016;33(4):6-7.

5. Tanielian T, Farmer CM, Burns RM, Duffy EL, Messan Setodji C. Ready or Not? Assessing the Capacity of New York State Health Care Providers to Meet the Needs of Veterans. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2018.

6. VA MISSION Act of 2018, S 2372, 115th Congress, 2nd Sess (2018).

1. Conway E, Batalden P. Like magic? (“Every system is perfectly designed…”). http://www.ihi.org/communities/blogs/o rigin-of-every-system-is-perfectly-designed-quote. Published August 21, 2015. Accessed May 29, 2018.

2. Lloyd GER, ed. Hippocratic Writings . London: Penguin Books ; 1983.

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. Debunking the VA privatization myth [press release]. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=4034. Published April 5, 2018. Accessed June 4, 2018.

4. Geppert CMA. Lessons from history: the ethical foundation of VA health care. Fed Pract. 2016;33(4):6-7.

5. Tanielian T, Farmer CM, Burns RM, Duffy EL, Messan Setodji C. Ready or Not? Assessing the Capacity of New York State Health Care Providers to Meet the Needs of Veterans. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2018.

6. VA MISSION Act of 2018, S 2372, 115th Congress, 2nd Sess (2018).

Medication management

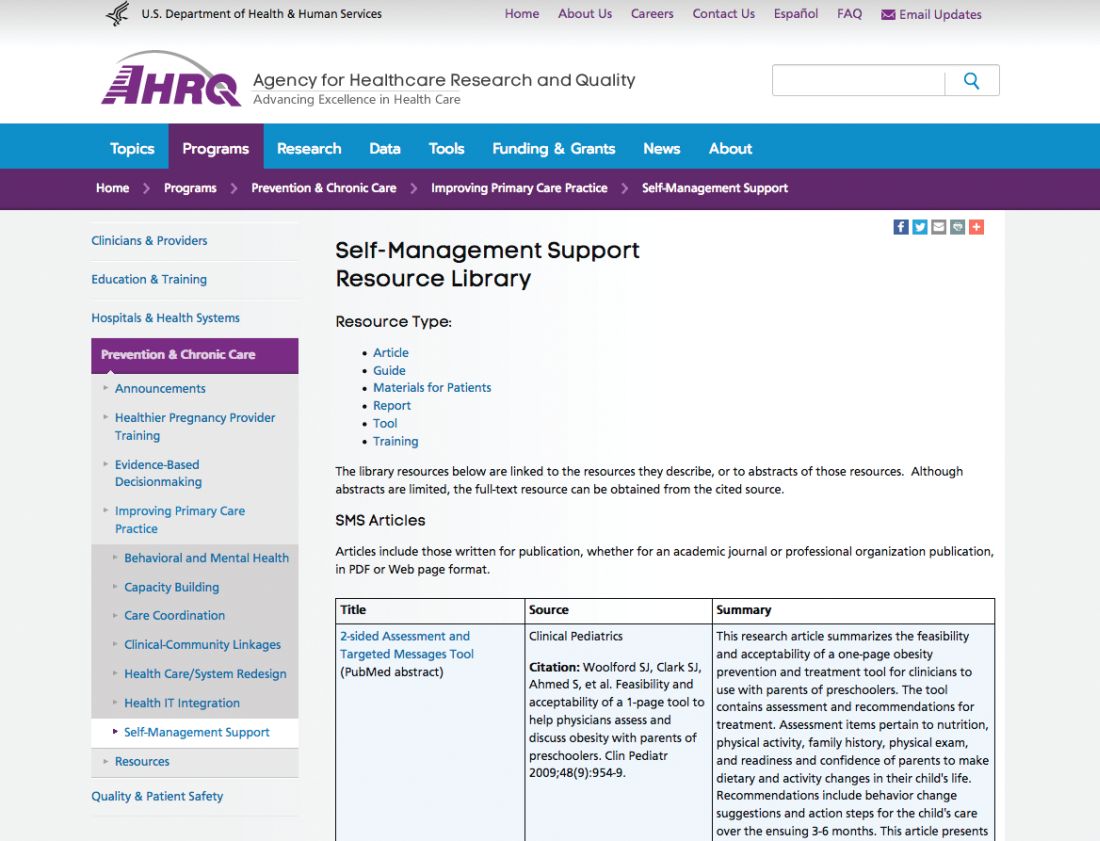

This is the tenth in a series of articles from the National Center for Excellence in Primary Care Research (NCEPCR) in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). This series introduces sets of tools and resources designed to help your practice.

An important part of self-management (last month’s article) is medication management, often augmented by the use of a portal and always cognizant of the importance of medication reconciliation and drug interactions. These latter issues can be addressed with health information technology (health IT), which will be discussed the next two columns. This month, we examine some of AHRQ’s other tools and resources to assist with medication management.

Patient understanding of the medications and medication schedule is important, and therefore health literacy key. The AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit – 2nd edition can help primary care practices reduce the complexity of health care, increase patient understanding of health information, and enhance support for patients of all health literacy levels. Also available are the companion guide, Implementing the AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit: Practical Ideas for Primary Care Practices, and a crosswalk showing how implementing health literacy tools can help meet standards for patient-centered medical home certification or recognition or meet Accreditation Canada standards.

Finally, How to Create a Pill Card helps users create an easy-to-use “pill card” for anyone who has a hard time keeping track of their medicines. Step-by-step instructions, sample clip art, and suggestions for design and use will help to customize a reminder card.

These and other tools can be found at the NCEPCR Web site: www.ahrq.gov/ncepcr.

Dr. Ganiats is director of the National Center for Excellence in Primary Care Research at AHRQ, Rockville, Md.

This is the tenth in a series of articles from the National Center for Excellence in Primary Care Research (NCEPCR) in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). This series introduces sets of tools and resources designed to help your practice.

An important part of self-management (last month’s article) is medication management, often augmented by the use of a portal and always cognizant of the importance of medication reconciliation and drug interactions. These latter issues can be addressed with health information technology (health IT), which will be discussed the next two columns. This month, we examine some of AHRQ’s other tools and resources to assist with medication management.

Patient understanding of the medications and medication schedule is important, and therefore health literacy key. The AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit – 2nd edition can help primary care practices reduce the complexity of health care, increase patient understanding of health information, and enhance support for patients of all health literacy levels. Also available are the companion guide, Implementing the AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit: Practical Ideas for Primary Care Practices, and a crosswalk showing how implementing health literacy tools can help meet standards for patient-centered medical home certification or recognition or meet Accreditation Canada standards.

Finally, How to Create a Pill Card helps users create an easy-to-use “pill card” for anyone who has a hard time keeping track of their medicines. Step-by-step instructions, sample clip art, and suggestions for design and use will help to customize a reminder card.

These and other tools can be found at the NCEPCR Web site: www.ahrq.gov/ncepcr.

Dr. Ganiats is director of the National Center for Excellence in Primary Care Research at AHRQ, Rockville, Md.

This is the tenth in a series of articles from the National Center for Excellence in Primary Care Research (NCEPCR) in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). This series introduces sets of tools and resources designed to help your practice.

An important part of self-management (last month’s article) is medication management, often augmented by the use of a portal and always cognizant of the importance of medication reconciliation and drug interactions. These latter issues can be addressed with health information technology (health IT), which will be discussed the next two columns. This month, we examine some of AHRQ’s other tools and resources to assist with medication management.

Patient understanding of the medications and medication schedule is important, and therefore health literacy key. The AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit – 2nd edition can help primary care practices reduce the complexity of health care, increase patient understanding of health information, and enhance support for patients of all health literacy levels. Also available are the companion guide, Implementing the AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit: Practical Ideas for Primary Care Practices, and a crosswalk showing how implementing health literacy tools can help meet standards for patient-centered medical home certification or recognition or meet Accreditation Canada standards.

Finally, How to Create a Pill Card helps users create an easy-to-use “pill card” for anyone who has a hard time keeping track of their medicines. Step-by-step instructions, sample clip art, and suggestions for design and use will help to customize a reminder card.

These and other tools can be found at the NCEPCR Web site: www.ahrq.gov/ncepcr.

Dr. Ganiats is director of the National Center for Excellence in Primary Care Research at AHRQ, Rockville, Md.

Updated Guidelines on Peanut Allergy Prevention in Infants With Atopic Dermatitis

It has been said that “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.”1 In the pursuit of evidence-based medicine, we are encouraged to follow a similar standard, with an emphasis on waiting for multiple studies with good-quality data and high levels of agreement before changing any aspect of our clinical practice. The ostensible purpose is that studies can be flawed, conclusions can be incorrect, or biases can be overlooked. In such cases, acting on questionable results could imperil patients. It is for this reason that so many review articles sometimes frustratingly seem to conclude that further evidence is needed.2

Based on this standard, recently published addendum guidelines from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases for prevention of peanut allergy in the United States3 are somewhat striking in that they make fairly bold recommendations based on results from the 2015 Learning Early about Peanut Allergy (LEAP) study,4 a randomized trial evaluating early peanut introduction as a preventive strategy for peanut allergy. Of note, this study was not placebo controlled, was conducted at only 1 site in the United Kingdom, and only included 640 children, though the number of participants was admittedly large for this type of study.4 Arguably, the LEAP study alone does not provide enough evidence upon which to base what essentially amounts to an about-face in the official recommendations for prevention of peanut and other food allergies, which emphasized delayed introduction of high-risk foods, especially in high-risk individuals.5-7 To better understand this shift, we need to briefly explore the context of the addendum guidelines.

As many as one-third of pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) have food allergies, thus diet often is invoked by patients and providers alike as an underlying cause of the disease.8 Many patients in my practice are so focused on potential food allergies that actual treatment of the affected skin is marginalized and often dismissed as a stopgap that does not address the root of the problem. A 2004 study of 100 children with AD found that diet was manipulated by the parents in 75% of patients in an attempt to manage the disease.9

Patients are not the only ones who consider food allergies to be a driving force in AD. The medical literature indicates that this theory has existed for centuries; for instance, with regard to the relationship between diet and AD, the author of an article from 1830 quipped, “There is probably no subject in which more deeply rooted convictions have been held . . . than the connection between diet and disease, both as regards the causation and treatment of the latter . . .”10 More apropos perhaps is a statement from the 2010 National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases guidelines on food allergy management, which noted that while the expert group “does not mean to imply that AD results from [food allergies], the role of [food allergies] in the pathogenesis and severity of this condition remains controversial.”11

Prior to the LEAP study, food allergy recommendations for clinical practice in the United Kingdom in 199812 and the United States in 200013 recommended excluding allergenic foods (eg, peanuts, tree nuts, soy, milk, eggs) from the diet in infants with a family history of atopy until 3 years of age. However, those recommendations did not seem to be working, when in fact just the opposite was happening. From 1997 until the LEAP study was conducted in 2015, the prevalence of peanut allergy more than quadrupled and became the leading cause of anaphylaxis and death related to food allergy.14 Additionally, study after study concluded that elimination diets did not seem to help most patients with AD.15 As is required in good scientific thinking, when a hypothesis is proven false, other approaches must be considered.

The idea arose that perhaps delaying introduction of allergenic foods was the opposite of the answer.4 The LEAP study tested the notion that peanut allergies are rare in countries where peanuts are introduced early and if telling families to delay introduction of peanuts in infants might actually be causing development of a peanut allergy, and the tests bore fruit. It was found that giving infants peanut-containing foods resulted in a more than 80% reduction in peanut allergy at 5 years of age (P<.001).4 What was perhaps even more interesting was the connection between AD and peanut allergy. An important idea articulated in the LEAP study is in some ways revolutionary: Rather than foods causing AD, it could be that “early environmental exposure (through the skin) to peanut may account for early sensitization, whereas early oral exposure may lead to immune tolerance.”4 This concept—that impaired eczematous skin may actually lead to the development of food allergies—turns the whole thing upside down.

What do these updated guidelines actually suggest? The first guideline focuses on infants with severe AD, egg allergy, or both, who therefore are thought to be at the highest risk for developing peanut allergy.3 Because of the higher baseline risk in this subgroup, measurement of the peanut-specific IgE (peanut sIgE) level, skin prick testing (SPT), or both is strongly recommended before introducing peanut protein into the diet. This testing can be performed by qualified providers as a screening measure, but if positive (≥0.35 kUA/L for peanut sIgE or >2 mm on the peanut SPT), referral to an allergy specialist is warranted. If these studies are negative, it is thought the likelihood of peanut allergy is low, and it is recommended that caregivers introduce age-appropriate peanut-containing foods (eg, peanut butter snack puffs, diluted peanut butter) as early as 4 to 6 months of age. The second guideline recommends that peanut-containing foods should be introduced into the diets of infants with mild or moderate AD at approximately 6 months of age without the need for prior screening via peanut sIgE or SPT. Lastly, the third guideline recommends that caregivers freely introduce peanut-containing foods together with other solid foods in infants without AD or food allergies in accordance with family preference.3

The results of the LEAP study are certainly exciting, and although the theoretical basis makes good scientific sense and the updated guidelines truly address an important and growing problem, there are several issues with this update that are worth considering. Given the constraints of the LEAP study, it certainly seems possible that the results will not be applicable to all populations or foods. More research is needed to ensure that this robust finding applies to other children and to explore the introduction of other allergenic foods, which the LEAP study investigators also emphasized.4

In fairness, the updated guidelines clearly state the quality of evidence of their recommendations and make it clear that expert opinion is playing a large role.3 For the first guideline regarding recommendations for those with severe AD and/or egg allergy, the quality of evidence is deemed moderate, while the contribution of expert opinion is listed as significant. For the second and third guidelines regarding recommendations for mild to moderate AD and those without AD, respectively, the quality of evidence is low and expert opinion is again listed as significant.3

Importantly, delineating severe AD from moderate disease—which is necessary because only severe AD warrants evaluation with peanut sIgE and/or SPT—can be difficult, as the distinction relies on a degree of subjectivity that may vary between specialists. Indeed, 2 publications suggest extending the definition of severe AD to include infants with early-onset AD (<3 months of age) and those with moderate AD not responding to treatment.16,17

Despite these reservations, the updated guidelines represent a breakthrough in understanding in an area truly in need of advancement. Although the evidence may not be exactly extraordinary, the context for these developments and our deeper understanding suggest that we do indeed live in extraordinary times.

- Encyclopaedia Galactica [television transcript]. Cosmos: A Personal Voyage. Public Broadcasting Service. December 14, 1980.

- Ezzo J, Bausell B, Moerman DE, et al. Reviewing the reviews: how strong is the evidence? how clear are the conclusions? Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2001;17:457-466.

- Togias A, Cooper SF, Acebal ML, et al. Addendum guidelines for the prevention of peanut allergy in the United States: report of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases–sponsored expert panel.J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:29-44.

- Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, et al. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:803-813.

- Høst A, Koletzko B, Dreborg S, et al. Dietary products used in infants for treatment and prevention of food allergy. joint statement of the European Society for Paediatric Allergology and Clinical Immunology (ESPACI) Committee on Hypoallergenic Formulas and the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) Committee on Nutrition. Arch Dis Child. 1999;81:80-84.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Nutrition. hypoallergenic infant formulas. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2, pt 1):346-349.

- Fiocchi A, Assa’ad A, Bahna S; Adverse Reactions to Foods Committee; American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Food allergy and the introduction of solid foods to infants: a consensus document. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97:10-20.

- Thompson MM, Hanifin JM. Effective therapy of childhood atopic dermatitis allays food allergy concerns. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(2 suppl 2):S214-S219.

- Johnston GA, Bilbao RM, Graham-Brown RA. The use of dietary manipulation by parents of children with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:1186-1189.

- Mackenzie S. The inaugural address on the advantages to be derived from the study of dermatology. BMJ. 1830;1:193-197.

- Boyce JA, Assa’ad A, Burks AW, et al; NIAID-Sponsored Expert Panel. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(6 suppl):S1-S58.

- Committee on Toxicity of Chemicals in Food, Consumer Products and the Environment. Peanut Allergy. London, England: Department of Health; 1998.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. Hypoallergenic infant formulas. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2, pt 1):346-349.

- Gruchalla RS, Sampson HA. Preventing peanut allergy through early consumption—ready for prime time? N Engl J Med. 2015;372:875-877.

- Lim NR, Lohman ME, Lio PA. The role of elimination diets in atopic dermatitis: a comprehensive review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:516-527.

- Wong CC, Allen KJ, Orchard D. Changes to infant feeding guidelines: relevance to dermatologists. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:e171-e175.

- Martin PE, Eckert JK, Koplin JJ, et al. Which infants with eczema are at risk of food allergy? results from a population-based cohort. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45:255-264.

It has been said that “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.”1 In the pursuit of evidence-based medicine, we are encouraged to follow a similar standard, with an emphasis on waiting for multiple studies with good-quality data and high levels of agreement before changing any aspect of our clinical practice. The ostensible purpose is that studies can be flawed, conclusions can be incorrect, or biases can be overlooked. In such cases, acting on questionable results could imperil patients. It is for this reason that so many review articles sometimes frustratingly seem to conclude that further evidence is needed.2

Based on this standard, recently published addendum guidelines from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases for prevention of peanut allergy in the United States3 are somewhat striking in that they make fairly bold recommendations based on results from the 2015 Learning Early about Peanut Allergy (LEAP) study,4 a randomized trial evaluating early peanut introduction as a preventive strategy for peanut allergy. Of note, this study was not placebo controlled, was conducted at only 1 site in the United Kingdom, and only included 640 children, though the number of participants was admittedly large for this type of study.4 Arguably, the LEAP study alone does not provide enough evidence upon which to base what essentially amounts to an about-face in the official recommendations for prevention of peanut and other food allergies, which emphasized delayed introduction of high-risk foods, especially in high-risk individuals.5-7 To better understand this shift, we need to briefly explore the context of the addendum guidelines.

As many as one-third of pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) have food allergies, thus diet often is invoked by patients and providers alike as an underlying cause of the disease.8 Many patients in my practice are so focused on potential food allergies that actual treatment of the affected skin is marginalized and often dismissed as a stopgap that does not address the root of the problem. A 2004 study of 100 children with AD found that diet was manipulated by the parents in 75% of patients in an attempt to manage the disease.9

Patients are not the only ones who consider food allergies to be a driving force in AD. The medical literature indicates that this theory has existed for centuries; for instance, with regard to the relationship between diet and AD, the author of an article from 1830 quipped, “There is probably no subject in which more deeply rooted convictions have been held . . . than the connection between diet and disease, both as regards the causation and treatment of the latter . . .”10 More apropos perhaps is a statement from the 2010 National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases guidelines on food allergy management, which noted that while the expert group “does not mean to imply that AD results from [food allergies], the role of [food allergies] in the pathogenesis and severity of this condition remains controversial.”11

Prior to the LEAP study, food allergy recommendations for clinical practice in the United Kingdom in 199812 and the United States in 200013 recommended excluding allergenic foods (eg, peanuts, tree nuts, soy, milk, eggs) from the diet in infants with a family history of atopy until 3 years of age. However, those recommendations did not seem to be working, when in fact just the opposite was happening. From 1997 until the LEAP study was conducted in 2015, the prevalence of peanut allergy more than quadrupled and became the leading cause of anaphylaxis and death related to food allergy.14 Additionally, study after study concluded that elimination diets did not seem to help most patients with AD.15 As is required in good scientific thinking, when a hypothesis is proven false, other approaches must be considered.

The idea arose that perhaps delaying introduction of allergenic foods was the opposite of the answer.4 The LEAP study tested the notion that peanut allergies are rare in countries where peanuts are introduced early and if telling families to delay introduction of peanuts in infants might actually be causing development of a peanut allergy, and the tests bore fruit. It was found that giving infants peanut-containing foods resulted in a more than 80% reduction in peanut allergy at 5 years of age (P<.001).4 What was perhaps even more interesting was the connection between AD and peanut allergy. An important idea articulated in the LEAP study is in some ways revolutionary: Rather than foods causing AD, it could be that “early environmental exposure (through the skin) to peanut may account for early sensitization, whereas early oral exposure may lead to immune tolerance.”4 This concept—that impaired eczematous skin may actually lead to the development of food allergies—turns the whole thing upside down.

What do these updated guidelines actually suggest? The first guideline focuses on infants with severe AD, egg allergy, or both, who therefore are thought to be at the highest risk for developing peanut allergy.3 Because of the higher baseline risk in this subgroup, measurement of the peanut-specific IgE (peanut sIgE) level, skin prick testing (SPT), or both is strongly recommended before introducing peanut protein into the diet. This testing can be performed by qualified providers as a screening measure, but if positive (≥0.35 kUA/L for peanut sIgE or >2 mm on the peanut SPT), referral to an allergy specialist is warranted. If these studies are negative, it is thought the likelihood of peanut allergy is low, and it is recommended that caregivers introduce age-appropriate peanut-containing foods (eg, peanut butter snack puffs, diluted peanut butter) as early as 4 to 6 months of age. The second guideline recommends that peanut-containing foods should be introduced into the diets of infants with mild or moderate AD at approximately 6 months of age without the need for prior screening via peanut sIgE or SPT. Lastly, the third guideline recommends that caregivers freely introduce peanut-containing foods together with other solid foods in infants without AD or food allergies in accordance with family preference.3

The results of the LEAP study are certainly exciting, and although the theoretical basis makes good scientific sense and the updated guidelines truly address an important and growing problem, there are several issues with this update that are worth considering. Given the constraints of the LEAP study, it certainly seems possible that the results will not be applicable to all populations or foods. More research is needed to ensure that this robust finding applies to other children and to explore the introduction of other allergenic foods, which the LEAP study investigators also emphasized.4

In fairness, the updated guidelines clearly state the quality of evidence of their recommendations and make it clear that expert opinion is playing a large role.3 For the first guideline regarding recommendations for those with severe AD and/or egg allergy, the quality of evidence is deemed moderate, while the contribution of expert opinion is listed as significant. For the second and third guidelines regarding recommendations for mild to moderate AD and those without AD, respectively, the quality of evidence is low and expert opinion is again listed as significant.3

Importantly, delineating severe AD from moderate disease—which is necessary because only severe AD warrants evaluation with peanut sIgE and/or SPT—can be difficult, as the distinction relies on a degree of subjectivity that may vary between specialists. Indeed, 2 publications suggest extending the definition of severe AD to include infants with early-onset AD (<3 months of age) and those with moderate AD not responding to treatment.16,17

Despite these reservations, the updated guidelines represent a breakthrough in understanding in an area truly in need of advancement. Although the evidence may not be exactly extraordinary, the context for these developments and our deeper understanding suggest that we do indeed live in extraordinary times.

It has been said that “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.”1 In the pursuit of evidence-based medicine, we are encouraged to follow a similar standard, with an emphasis on waiting for multiple studies with good-quality data and high levels of agreement before changing any aspect of our clinical practice. The ostensible purpose is that studies can be flawed, conclusions can be incorrect, or biases can be overlooked. In such cases, acting on questionable results could imperil patients. It is for this reason that so many review articles sometimes frustratingly seem to conclude that further evidence is needed.2

Based on this standard, recently published addendum guidelines from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases for prevention of peanut allergy in the United States3 are somewhat striking in that they make fairly bold recommendations based on results from the 2015 Learning Early about Peanut Allergy (LEAP) study,4 a randomized trial evaluating early peanut introduction as a preventive strategy for peanut allergy. Of note, this study was not placebo controlled, was conducted at only 1 site in the United Kingdom, and only included 640 children, though the number of participants was admittedly large for this type of study.4 Arguably, the LEAP study alone does not provide enough evidence upon which to base what essentially amounts to an about-face in the official recommendations for prevention of peanut and other food allergies, which emphasized delayed introduction of high-risk foods, especially in high-risk individuals.5-7 To better understand this shift, we need to briefly explore the context of the addendum guidelines.

As many as one-third of pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) have food allergies, thus diet often is invoked by patients and providers alike as an underlying cause of the disease.8 Many patients in my practice are so focused on potential food allergies that actual treatment of the affected skin is marginalized and often dismissed as a stopgap that does not address the root of the problem. A 2004 study of 100 children with AD found that diet was manipulated by the parents in 75% of patients in an attempt to manage the disease.9

Patients are not the only ones who consider food allergies to be a driving force in AD. The medical literature indicates that this theory has existed for centuries; for instance, with regard to the relationship between diet and AD, the author of an article from 1830 quipped, “There is probably no subject in which more deeply rooted convictions have been held . . . than the connection between diet and disease, both as regards the causation and treatment of the latter . . .”10 More apropos perhaps is a statement from the 2010 National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases guidelines on food allergy management, which noted that while the expert group “does not mean to imply that AD results from [food allergies], the role of [food allergies] in the pathogenesis and severity of this condition remains controversial.”11

Prior to the LEAP study, food allergy recommendations for clinical practice in the United Kingdom in 199812 and the United States in 200013 recommended excluding allergenic foods (eg, peanuts, tree nuts, soy, milk, eggs) from the diet in infants with a family history of atopy until 3 years of age. However, those recommendations did not seem to be working, when in fact just the opposite was happening. From 1997 until the LEAP study was conducted in 2015, the prevalence of peanut allergy more than quadrupled and became the leading cause of anaphylaxis and death related to food allergy.14 Additionally, study after study concluded that elimination diets did not seem to help most patients with AD.15 As is required in good scientific thinking, when a hypothesis is proven false, other approaches must be considered.

The idea arose that perhaps delaying introduction of allergenic foods was the opposite of the answer.4 The LEAP study tested the notion that peanut allergies are rare in countries where peanuts are introduced early and if telling families to delay introduction of peanuts in infants might actually be causing development of a peanut allergy, and the tests bore fruit. It was found that giving infants peanut-containing foods resulted in a more than 80% reduction in peanut allergy at 5 years of age (P<.001).4 What was perhaps even more interesting was the connection between AD and peanut allergy. An important idea articulated in the LEAP study is in some ways revolutionary: Rather than foods causing AD, it could be that “early environmental exposure (through the skin) to peanut may account for early sensitization, whereas early oral exposure may lead to immune tolerance.”4 This concept—that impaired eczematous skin may actually lead to the development of food allergies—turns the whole thing upside down.

What do these updated guidelines actually suggest? The first guideline focuses on infants with severe AD, egg allergy, or both, who therefore are thought to be at the highest risk for developing peanut allergy.3 Because of the higher baseline risk in this subgroup, measurement of the peanut-specific IgE (peanut sIgE) level, skin prick testing (SPT), or both is strongly recommended before introducing peanut protein into the diet. This testing can be performed by qualified providers as a screening measure, but if positive (≥0.35 kUA/L for peanut sIgE or >2 mm on the peanut SPT), referral to an allergy specialist is warranted. If these studies are negative, it is thought the likelihood of peanut allergy is low, and it is recommended that caregivers introduce age-appropriate peanut-containing foods (eg, peanut butter snack puffs, diluted peanut butter) as early as 4 to 6 months of age. The second guideline recommends that peanut-containing foods should be introduced into the diets of infants with mild or moderate AD at approximately 6 months of age without the need for prior screening via peanut sIgE or SPT. Lastly, the third guideline recommends that caregivers freely introduce peanut-containing foods together with other solid foods in infants without AD or food allergies in accordance with family preference.3

The results of the LEAP study are certainly exciting, and although the theoretical basis makes good scientific sense and the updated guidelines truly address an important and growing problem, there are several issues with this update that are worth considering. Given the constraints of the LEAP study, it certainly seems possible that the results will not be applicable to all populations or foods. More research is needed to ensure that this robust finding applies to other children and to explore the introduction of other allergenic foods, which the LEAP study investigators also emphasized.4

In fairness, the updated guidelines clearly state the quality of evidence of their recommendations and make it clear that expert opinion is playing a large role.3 For the first guideline regarding recommendations for those with severe AD and/or egg allergy, the quality of evidence is deemed moderate, while the contribution of expert opinion is listed as significant. For the second and third guidelines regarding recommendations for mild to moderate AD and those without AD, respectively, the quality of evidence is low and expert opinion is again listed as significant.3

Importantly, delineating severe AD from moderate disease—which is necessary because only severe AD warrants evaluation with peanut sIgE and/or SPT—can be difficult, as the distinction relies on a degree of subjectivity that may vary between specialists. Indeed, 2 publications suggest extending the definition of severe AD to include infants with early-onset AD (<3 months of age) and those with moderate AD not responding to treatment.16,17

Despite these reservations, the updated guidelines represent a breakthrough in understanding in an area truly in need of advancement. Although the evidence may not be exactly extraordinary, the context for these developments and our deeper understanding suggest that we do indeed live in extraordinary times.

- Encyclopaedia Galactica [television transcript]. Cosmos: A Personal Voyage. Public Broadcasting Service. December 14, 1980.

- Ezzo J, Bausell B, Moerman DE, et al. Reviewing the reviews: how strong is the evidence? how clear are the conclusions? Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2001;17:457-466.

- Togias A, Cooper SF, Acebal ML, et al. Addendum guidelines for the prevention of peanut allergy in the United States: report of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases–sponsored expert panel.J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:29-44.

- Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, et al. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:803-813.

- Høst A, Koletzko B, Dreborg S, et al. Dietary products used in infants for treatment and prevention of food allergy. joint statement of the European Society for Paediatric Allergology and Clinical Immunology (ESPACI) Committee on Hypoallergenic Formulas and the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) Committee on Nutrition. Arch Dis Child. 1999;81:80-84.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Nutrition. hypoallergenic infant formulas. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2, pt 1):346-349.

- Fiocchi A, Assa’ad A, Bahna S; Adverse Reactions to Foods Committee; American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Food allergy and the introduction of solid foods to infants: a consensus document. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97:10-20.

- Thompson MM, Hanifin JM. Effective therapy of childhood atopic dermatitis allays food allergy concerns. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(2 suppl 2):S214-S219.

- Johnston GA, Bilbao RM, Graham-Brown RA. The use of dietary manipulation by parents of children with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:1186-1189.

- Mackenzie S. The inaugural address on the advantages to be derived from the study of dermatology. BMJ. 1830;1:193-197.

- Boyce JA, Assa’ad A, Burks AW, et al; NIAID-Sponsored Expert Panel. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(6 suppl):S1-S58.

- Committee on Toxicity of Chemicals in Food, Consumer Products and the Environment. Peanut Allergy. London, England: Department of Health; 1998.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. Hypoallergenic infant formulas. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2, pt 1):346-349.

- Gruchalla RS, Sampson HA. Preventing peanut allergy through early consumption—ready for prime time? N Engl J Med. 2015;372:875-877.

- Lim NR, Lohman ME, Lio PA. The role of elimination diets in atopic dermatitis: a comprehensive review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:516-527.

- Wong CC, Allen KJ, Orchard D. Changes to infant feeding guidelines: relevance to dermatologists. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:e171-e175.

- Martin PE, Eckert JK, Koplin JJ, et al. Which infants with eczema are at risk of food allergy? results from a population-based cohort. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45:255-264.

- Encyclopaedia Galactica [television transcript]. Cosmos: A Personal Voyage. Public Broadcasting Service. December 14, 1980.

- Ezzo J, Bausell B, Moerman DE, et al. Reviewing the reviews: how strong is the evidence? how clear are the conclusions? Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2001;17:457-466.

- Togias A, Cooper SF, Acebal ML, et al. Addendum guidelines for the prevention of peanut allergy in the United States: report of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases–sponsored expert panel.J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:29-44.

- Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, et al. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:803-813.

- Høst A, Koletzko B, Dreborg S, et al. Dietary products used in infants for treatment and prevention of food allergy. joint statement of the European Society for Paediatric Allergology and Clinical Immunology (ESPACI) Committee on Hypoallergenic Formulas and the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) Committee on Nutrition. Arch Dis Child. 1999;81:80-84.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Nutrition. hypoallergenic infant formulas. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2, pt 1):346-349.

- Fiocchi A, Assa’ad A, Bahna S; Adverse Reactions to Foods Committee; American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Food allergy and the introduction of solid foods to infants: a consensus document. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97:10-20.

- Thompson MM, Hanifin JM. Effective therapy of childhood atopic dermatitis allays food allergy concerns. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(2 suppl 2):S214-S219.

- Johnston GA, Bilbao RM, Graham-Brown RA. The use of dietary manipulation by parents of children with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:1186-1189.

- Mackenzie S. The inaugural address on the advantages to be derived from the study of dermatology. BMJ. 1830;1:193-197.

- Boyce JA, Assa’ad A, Burks AW, et al; NIAID-Sponsored Expert Panel. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(6 suppl):S1-S58.

- Committee on Toxicity of Chemicals in Food, Consumer Products and the Environment. Peanut Allergy. London, England: Department of Health; 1998.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. Hypoallergenic infant formulas. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2, pt 1):346-349.

- Gruchalla RS, Sampson HA. Preventing peanut allergy through early consumption—ready for prime time? N Engl J Med. 2015;372:875-877.

- Lim NR, Lohman ME, Lio PA. The role of elimination diets in atopic dermatitis: a comprehensive review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:516-527.

- Wong CC, Allen KJ, Orchard D. Changes to infant feeding guidelines: relevance to dermatologists. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:e171-e175.

- Martin PE, Eckert JK, Koplin JJ, et al. Which infants with eczema are at risk of food allergy? results from a population-based cohort. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45:255-264.

What is causing my patients’ macrocytosis?

A 56-year-old man presents for his annual physical. He brings in blood work done for all employees in his workplace (he is an aerospace engineer), and wants to talk about the lab that has an asterisk by it. All his labs are normal, except that his mean corpuscular volume (MCV) is 101. His hematocrit (HCT) is 42. He has no symptoms and a normal physical exam.

What test or tests would most likely be abnormal?

A. Thyroid-stimulating hormone.

B. Vitamin B12/folate.

C. Testosterone.

D. Gamma-glutamyl-transferase (GGT).

The finding of macrocytosis is fairly common in primary care, estimated to be found in 3% of complete blood count results.1 Most students in medical school quickly learn that vitamin B12 and folate deficiency can cause macrocytic anemias. The standard workups for patients with macrocytosis began and ended with checking vitamin B12 and folate levels, which are usually normal in the vast majority of patients with macrocytosis.

For this patient, the correct answer would be an abnormal GGT, because chronic moderate to heavy alcohol use can raise GGT levels, as well as MCVs.

Dr. David Savage and colleagues evaluated the etiology of macrocytosis in 300 consecutive hospitalized patients with macrocytosis.2 They found that the most common causes were medications, alcohol, liver disease, and reticulocytosis. The study was done in New York and was published in 2000, so zidovudine (AZT) was a common medication cause of the macrocytosis. This medication is much less commonly used today. Zidovudine causes macrocytosis in more than 80% of patients who take it. They also found in the study that very high MCVs (> 120) were most commonly associated with vitamin B12 deficiency.

Dr. Kaija Seppä and colleagues looked at all outpatients who had a blood count done over an 8-month period. A total of 9,527 blood counts were ordered, and 287 (3%) had macrocytosis.1 Further workup was done for 113 of the patients. The most common cause found for macrocytosis was alcohol abuse, in 74 (65%) of the patients (80% of the men and 36% of the women). No cause of the macrocytosis was found in 24 (21%) of the patients.

Dr. A. Wymer and colleagues looked at 2,800 adult outpatients who had complete blood counts. A total of 138 (3.7%) had macrocytosis, with 128 of these patients having charts that could be reviewed.3 A total of 73 patients had a workup for their macrocytosis. Alcohol was the diagnostic cause of the macrocytosis in 47 (64%). Only five of the patients had B12 deficiency (7%).

Dr. Seppä and colleagues also reported on hematologic morphologic features in nonanemic patients with macrocytosis due to alcohol abuse or vitamin B12 deficiency.4 They studied 136 patients with alcohol abuse and normal B12 levels, and 18 patients with pernicious anemia. The combination of a low red cell count or a high red cell distribution width with a normal platelet count was found in 94.4% of the vitamin-deficient patients but in only 14.6% of the abusers.

Pearl:

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the university. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. J Stud Alcohol. 1996 Jan;57(1):97-100.

2. Am J Med Sci. 2000 Jun;319(6):343-52.

3. J Gen Intern Med. 1990 May-Jun;5(3):192-7.

4. Alcohol. 1993 Sep-Oct;10(5):343-7.

5. South Med J. 2013 Feb;106(2):121-5.

A 56-year-old man presents for his annual physical. He brings in blood work done for all employees in his workplace (he is an aerospace engineer), and wants to talk about the lab that has an asterisk by it. All his labs are normal, except that his mean corpuscular volume (MCV) is 101. His hematocrit (HCT) is 42. He has no symptoms and a normal physical exam.

What test or tests would most likely be abnormal?

A. Thyroid-stimulating hormone.

B. Vitamin B12/folate.

C. Testosterone.

D. Gamma-glutamyl-transferase (GGT).

The finding of macrocytosis is fairly common in primary care, estimated to be found in 3% of complete blood count results.1 Most students in medical school quickly learn that vitamin B12 and folate deficiency can cause macrocytic anemias. The standard workups for patients with macrocytosis began and ended with checking vitamin B12 and folate levels, which are usually normal in the vast majority of patients with macrocytosis.

For this patient, the correct answer would be an abnormal GGT, because chronic moderate to heavy alcohol use can raise GGT levels, as well as MCVs.

Dr. David Savage and colleagues evaluated the etiology of macrocytosis in 300 consecutive hospitalized patients with macrocytosis.2 They found that the most common causes were medications, alcohol, liver disease, and reticulocytosis. The study was done in New York and was published in 2000, so zidovudine (AZT) was a common medication cause of the macrocytosis. This medication is much less commonly used today. Zidovudine causes macrocytosis in more than 80% of patients who take it. They also found in the study that very high MCVs (> 120) were most commonly associated with vitamin B12 deficiency.

Dr. Kaija Seppä and colleagues looked at all outpatients who had a blood count done over an 8-month period. A total of 9,527 blood counts were ordered, and 287 (3%) had macrocytosis.1 Further workup was done for 113 of the patients. The most common cause found for macrocytosis was alcohol abuse, in 74 (65%) of the patients (80% of the men and 36% of the women). No cause of the macrocytosis was found in 24 (21%) of the patients.

Dr. A. Wymer and colleagues looked at 2,800 adult outpatients who had complete blood counts. A total of 138 (3.7%) had macrocytosis, with 128 of these patients having charts that could be reviewed.3 A total of 73 patients had a workup for their macrocytosis. Alcohol was the diagnostic cause of the macrocytosis in 47 (64%). Only five of the patients had B12 deficiency (7%).

Dr. Seppä and colleagues also reported on hematologic morphologic features in nonanemic patients with macrocytosis due to alcohol abuse or vitamin B12 deficiency.4 They studied 136 patients with alcohol abuse and normal B12 levels, and 18 patients with pernicious anemia. The combination of a low red cell count or a high red cell distribution width with a normal platelet count was found in 94.4% of the vitamin-deficient patients but in only 14.6% of the abusers.

Pearl:

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the university. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. J Stud Alcohol. 1996 Jan;57(1):97-100.

2. Am J Med Sci. 2000 Jun;319(6):343-52.

3. J Gen Intern Med. 1990 May-Jun;5(3):192-7.

4. Alcohol. 1993 Sep-Oct;10(5):343-7.

5. South Med J. 2013 Feb;106(2):121-5.

A 56-year-old man presents for his annual physical. He brings in blood work done for all employees in his workplace (he is an aerospace engineer), and wants to talk about the lab that has an asterisk by it. All his labs are normal, except that his mean corpuscular volume (MCV) is 101. His hematocrit (HCT) is 42. He has no symptoms and a normal physical exam.

What test or tests would most likely be abnormal?

A. Thyroid-stimulating hormone.

B. Vitamin B12/folate.

C. Testosterone.

D. Gamma-glutamyl-transferase (GGT).

The finding of macrocytosis is fairly common in primary care, estimated to be found in 3% of complete blood count results.1 Most students in medical school quickly learn that vitamin B12 and folate deficiency can cause macrocytic anemias. The standard workups for patients with macrocytosis began and ended with checking vitamin B12 and folate levels, which are usually normal in the vast majority of patients with macrocytosis.

For this patient, the correct answer would be an abnormal GGT, because chronic moderate to heavy alcohol use can raise GGT levels, as well as MCVs.

Dr. David Savage and colleagues evaluated the etiology of macrocytosis in 300 consecutive hospitalized patients with macrocytosis.2 They found that the most common causes were medications, alcohol, liver disease, and reticulocytosis. The study was done in New York and was published in 2000, so zidovudine (AZT) was a common medication cause of the macrocytosis. This medication is much less commonly used today. Zidovudine causes macrocytosis in more than 80% of patients who take it. They also found in the study that very high MCVs (> 120) were most commonly associated with vitamin B12 deficiency.

Dr. Kaija Seppä and colleagues looked at all outpatients who had a blood count done over an 8-month period. A total of 9,527 blood counts were ordered, and 287 (3%) had macrocytosis.1 Further workup was done for 113 of the patients. The most common cause found for macrocytosis was alcohol abuse, in 74 (65%) of the patients (80% of the men and 36% of the women). No cause of the macrocytosis was found in 24 (21%) of the patients.

Dr. A. Wymer and colleagues looked at 2,800 adult outpatients who had complete blood counts. A total of 138 (3.7%) had macrocytosis, with 128 of these patients having charts that could be reviewed.3 A total of 73 patients had a workup for their macrocytosis. Alcohol was the diagnostic cause of the macrocytosis in 47 (64%). Only five of the patients had B12 deficiency (7%).

Dr. Seppä and colleagues also reported on hematologic morphologic features in nonanemic patients with macrocytosis due to alcohol abuse or vitamin B12 deficiency.4 They studied 136 patients with alcohol abuse and normal B12 levels, and 18 patients with pernicious anemia. The combination of a low red cell count or a high red cell distribution width with a normal platelet count was found in 94.4% of the vitamin-deficient patients but in only 14.6% of the abusers.

Pearl:

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the university. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. J Stud Alcohol. 1996 Jan;57(1):97-100.

2. Am J Med Sci. 2000 Jun;319(6):343-52.

3. J Gen Intern Med. 1990 May-Jun;5(3):192-7.

4. Alcohol. 1993 Sep-Oct;10(5):343-7.

5. South Med J. 2013 Feb;106(2):121-5.

Anorectal Evaluations: Are You Willing to Look?

Just over a year ago, I established a solo colorectal surgery clinic within a comprehensive academic medical center hospital system and have since seen a variety of cases: benign anorectal conditions, acute and chronic diseases, complex defecatory dysfunction, and colorectal surgery pre- and postop patients. I also manage a colorectal cancer survivorship clinic. As a PA in this field, I very much appreciated the November 2017 CE/CME, “Anorectal Evaluations: Diagnosing & Treating Benign Conditions” (Clinician Reviews. 2017;27[11]:28-37). The article offered useful highlights and clinical pearls for diagnosing common anorectal conditions. It supplied corresponding images for quick reference, discussed the need for a thorough history, and detailed the finesse of the often-dreaded-yet-so-important physical exam, reassuring providers that the majority of anorectal complaints are, indeed, benign and often treatable on first visit. However, the latter is contingent on one key factor: Are you willing to look?