User login

CPAP Underperforms: The Sequel

A few months ago, I posted a column on continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) with the title, “CPAP Oversells and Underperforms.” To date, it has 299 likes and 90 comments, which are almost all negative. I’m glad to see that it’s generated interest, and I’d like to address some of the themes expressed in the posts.

Most comments were personal testimonies to the miracles of CPAP. These are important, and the point deserves emphasis. CPAP can provide significant improvements in daytime sleepiness and quality of life. I closed the original piece by acknowledging this important fact. Readers can be forgiven for missing it given that the title and text were otherwise disparaging of CPAP.

But several comments warrant a more in-depth discussion. The original piece focuses on CPAP and cardiovascular (CV) outcomes but made no mention of atrial fibrillation (AF) or ejection fraction (EF). The effects of CPAP on each are touted by cardiologists and PAP-pushers alike and are drivers of frequent referrals. It›s my fault for omitting them from the discussion.

AF is easy. The data is identical to all other things CPAP and CV. Based on biologic plausibility alone, the likelihood of a relationship between AF and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is similar to the odds that the Celtics raise an 18th banner come June. There’s hypoxia, intrathoracic pressure swings, sympathetic surges, and sleep state disruptions. It’s easy to get from there to arrhythmogenesis. There’s lots of observational noise, too, but no randomized proof that CPAP alters this relationship.

I found four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that tested CPAP’s effect on AF. I’ll save you the suspense; they were all negative. One even found a signal for more adverse events in the CPAP group. These studies have several positive qualities: They enrolled patients with moderate to severe sleep apnea and high oxygen desaturation indices, adherence averaged more than 4 hours across all groups in all trials, and the methods for assessing the AF outcomes differed slightly. There’s also a lot not to like: The sample sizes were small, only one trial enrolled “sleepy” patients (as assessed by the Epworth Sleepiness Score), and follow-up was short.

To paraphrase Carl Sagan, “absence of evidence does not equal evidence of absence.” As a statistician would say, type II error cannot be excluded by these RCTs. In medicine, however, the burden of proof falls on demonstrating efficacy. If we treat before concluding that a therapy works, we risk wasting time, money, medical resources, and the most precious of patient commodities: the energy required for behavior change. In their response to letters to the editor, the authors of the third RCT summarize the CPAP, AF, and CV disease data far better than I ever could. They sound the same words of caution and come out against screening patients with AF for OSA.

The story for CPAP’s effects on EF is similar though muddier. The American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for heart failure cite a meta-analysis showing that CPAP improves left ventricular EF. In 2019, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) CPAP guidelines included a systematic review and meta-analysis that found that CPAP has no effect on left ventricular EF in patients with or without heart failure.

There are a million reasons why two systematic reviews on the same topic might come to different conclusions. In this case, the included studies only partially overlap, and broadly speaking, it appears the authors made trade-offs. The review cited by the ACC/AHA had broader inclusion and significantly more patients and paid for it in heterogeneity (I2 in the 80%-90% range). The AASM analysis achieved 0% heterogeneity but limited inclusion to fewer than 100 patients. Across both, the improvement in EF was 2%- 5% at a minimally clinically important difference of 4%. Hardly convincing.

In summary, the road to negative trials and patient harm has always been paved with observational signal and biologic plausibility. Throw in some intellectual and academic bias, and you’ve created the perfect storm of therapeutic overconfidence.

Dr. Holley is a professor in the department of medicine, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland, and a physician at Pulmonary/Sleep and Critical Care Medicine, MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Washington. He disclosed ties to Metapharm Inc., CHEST College, and WebMD.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

A few months ago, I posted a column on continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) with the title, “CPAP Oversells and Underperforms.” To date, it has 299 likes and 90 comments, which are almost all negative. I’m glad to see that it’s generated interest, and I’d like to address some of the themes expressed in the posts.

Most comments were personal testimonies to the miracles of CPAP. These are important, and the point deserves emphasis. CPAP can provide significant improvements in daytime sleepiness and quality of life. I closed the original piece by acknowledging this important fact. Readers can be forgiven for missing it given that the title and text were otherwise disparaging of CPAP.

But several comments warrant a more in-depth discussion. The original piece focuses on CPAP and cardiovascular (CV) outcomes but made no mention of atrial fibrillation (AF) or ejection fraction (EF). The effects of CPAP on each are touted by cardiologists and PAP-pushers alike and are drivers of frequent referrals. It›s my fault for omitting them from the discussion.

AF is easy. The data is identical to all other things CPAP and CV. Based on biologic plausibility alone, the likelihood of a relationship between AF and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is similar to the odds that the Celtics raise an 18th banner come June. There’s hypoxia, intrathoracic pressure swings, sympathetic surges, and sleep state disruptions. It’s easy to get from there to arrhythmogenesis. There’s lots of observational noise, too, but no randomized proof that CPAP alters this relationship.

I found four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that tested CPAP’s effect on AF. I’ll save you the suspense; they were all negative. One even found a signal for more adverse events in the CPAP group. These studies have several positive qualities: They enrolled patients with moderate to severe sleep apnea and high oxygen desaturation indices, adherence averaged more than 4 hours across all groups in all trials, and the methods for assessing the AF outcomes differed slightly. There’s also a lot not to like: The sample sizes were small, only one trial enrolled “sleepy” patients (as assessed by the Epworth Sleepiness Score), and follow-up was short.

To paraphrase Carl Sagan, “absence of evidence does not equal evidence of absence.” As a statistician would say, type II error cannot be excluded by these RCTs. In medicine, however, the burden of proof falls on demonstrating efficacy. If we treat before concluding that a therapy works, we risk wasting time, money, medical resources, and the most precious of patient commodities: the energy required for behavior change. In their response to letters to the editor, the authors of the third RCT summarize the CPAP, AF, and CV disease data far better than I ever could. They sound the same words of caution and come out against screening patients with AF for OSA.

The story for CPAP’s effects on EF is similar though muddier. The American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for heart failure cite a meta-analysis showing that CPAP improves left ventricular EF. In 2019, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) CPAP guidelines included a systematic review and meta-analysis that found that CPAP has no effect on left ventricular EF in patients with or without heart failure.

There are a million reasons why two systematic reviews on the same topic might come to different conclusions. In this case, the included studies only partially overlap, and broadly speaking, it appears the authors made trade-offs. The review cited by the ACC/AHA had broader inclusion and significantly more patients and paid for it in heterogeneity (I2 in the 80%-90% range). The AASM analysis achieved 0% heterogeneity but limited inclusion to fewer than 100 patients. Across both, the improvement in EF was 2%- 5% at a minimally clinically important difference of 4%. Hardly convincing.

In summary, the road to negative trials and patient harm has always been paved with observational signal and biologic plausibility. Throw in some intellectual and academic bias, and you’ve created the perfect storm of therapeutic overconfidence.

Dr. Holley is a professor in the department of medicine, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland, and a physician at Pulmonary/Sleep and Critical Care Medicine, MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Washington. He disclosed ties to Metapharm Inc., CHEST College, and WebMD.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

A few months ago, I posted a column on continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) with the title, “CPAP Oversells and Underperforms.” To date, it has 299 likes and 90 comments, which are almost all negative. I’m glad to see that it’s generated interest, and I’d like to address some of the themes expressed in the posts.

Most comments were personal testimonies to the miracles of CPAP. These are important, and the point deserves emphasis. CPAP can provide significant improvements in daytime sleepiness and quality of life. I closed the original piece by acknowledging this important fact. Readers can be forgiven for missing it given that the title and text were otherwise disparaging of CPAP.

But several comments warrant a more in-depth discussion. The original piece focuses on CPAP and cardiovascular (CV) outcomes but made no mention of atrial fibrillation (AF) or ejection fraction (EF). The effects of CPAP on each are touted by cardiologists and PAP-pushers alike and are drivers of frequent referrals. It›s my fault for omitting them from the discussion.

AF is easy. The data is identical to all other things CPAP and CV. Based on biologic plausibility alone, the likelihood of a relationship between AF and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is similar to the odds that the Celtics raise an 18th banner come June. There’s hypoxia, intrathoracic pressure swings, sympathetic surges, and sleep state disruptions. It’s easy to get from there to arrhythmogenesis. There’s lots of observational noise, too, but no randomized proof that CPAP alters this relationship.

I found four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that tested CPAP’s effect on AF. I’ll save you the suspense; they were all negative. One even found a signal for more adverse events in the CPAP group. These studies have several positive qualities: They enrolled patients with moderate to severe sleep apnea and high oxygen desaturation indices, adherence averaged more than 4 hours across all groups in all trials, and the methods for assessing the AF outcomes differed slightly. There’s also a lot not to like: The sample sizes were small, only one trial enrolled “sleepy” patients (as assessed by the Epworth Sleepiness Score), and follow-up was short.

To paraphrase Carl Sagan, “absence of evidence does not equal evidence of absence.” As a statistician would say, type II error cannot be excluded by these RCTs. In medicine, however, the burden of proof falls on demonstrating efficacy. If we treat before concluding that a therapy works, we risk wasting time, money, medical resources, and the most precious of patient commodities: the energy required for behavior change. In their response to letters to the editor, the authors of the third RCT summarize the CPAP, AF, and CV disease data far better than I ever could. They sound the same words of caution and come out against screening patients with AF for OSA.

The story for CPAP’s effects on EF is similar though muddier. The American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for heart failure cite a meta-analysis showing that CPAP improves left ventricular EF. In 2019, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) CPAP guidelines included a systematic review and meta-analysis that found that CPAP has no effect on left ventricular EF in patients with or without heart failure.

There are a million reasons why two systematic reviews on the same topic might come to different conclusions. In this case, the included studies only partially overlap, and broadly speaking, it appears the authors made trade-offs. The review cited by the ACC/AHA had broader inclusion and significantly more patients and paid for it in heterogeneity (I2 in the 80%-90% range). The AASM analysis achieved 0% heterogeneity but limited inclusion to fewer than 100 patients. Across both, the improvement in EF was 2%- 5% at a minimally clinically important difference of 4%. Hardly convincing.

In summary, the road to negative trials and patient harm has always been paved with observational signal and biologic plausibility. Throw in some intellectual and academic bias, and you’ve created the perfect storm of therapeutic overconfidence.

Dr. Holley is a professor in the department of medicine, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland, and a physician at Pulmonary/Sleep and Critical Care Medicine, MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Washington. He disclosed ties to Metapharm Inc., CHEST College, and WebMD.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Unplanned Pregnancy With Weight Loss Drugs: Fact or Fiction?

Claudia* was a charming 27-year-old newlywed. She and her husband wanted to start a family — with one small catch. She had recently gained 30 pounds. During COVID, she and her husband spent 18 months camped out in her parents’ guest room in upstate New York and had eaten their emotions with abandon. They ate when they were happy and ate more when they were sad. They ate when they felt isolated and again when they felt anxious. It didn’t help that her mother was a Culinary Institute–trained amateur chef. They both worked from home and logged long hours on Zoom calls. Because there was no home gym, they replaced their usual fitness club workouts in the city with leisurely strolls around the local lake. When I met her, Claudia categorically refused to entertain the notion of pregnancy until she reached her pre-COVID weight.

At the time, this all seemed quite reasonable to me. We outlined a plan including semaglutide (Wegovy) until she reached her target weight and then a minimum of 2 months off Wegovy prior to conception. We also lined up sessions with a dietitian and trainer and renewed her birth control pill. There was one detail I failed to mention to her: Birth control pills are less effective while on incretin hormones like semaglutide. The reason for my omission is that the medical community at large wasn’t yet aware of this issue.

About 12 weeks into treatment, Claudia had lost 20 of the 30 pounds. She had canceled several appointments with the trainer and dietitian due to work conflicts. She messaged me over the weekend in a panic. Her period was late, and her pregnancy test was positive.

She had three pressing questions for me:

Q: How had this happened while she had taken the birth control pills faithfully?

A: I answered that the scientific reasons for the decrease in efficacy of birth control pills while on semaglutide medications are threefold:

- Weight loss can improve menstrual cycle irregularities and improve fertility. In fact, I have been using semaglutide-like medications to treat polycystic ovary syndrome for decades, well before these medications became mainstream.

- The delayed gastric emptying inherent to incretins leads to decreased absorption of birth control pills.

- Finally, while this did not apply to Claudia, no medicine is particularly efficacious if vomited up shortly after taking. Wegovy is known to cause nausea and vomiting in a sizable percentage of patients.

Q: Would she have a healthy pregnancy given the lingering effects of Wegovy?

A: The short answer is: most likely yes. A review of the package insert revealed something fascinating. It was not strictly contraindicated. It advised doctors to weigh the risks and benefits of the medication during pregnancy. Animal studies have shown that semaglutide increases the risk for fetal death, birth defects, and growth issues, but this is probably due to restrictive eating patterns rather than a direct effect of the medication. A recent study of health records of more than 50,000 women with diabetes who had been inadvertently taking these medications in early pregnancy showed no increase in birth defects when compared with women who took insulin.

Q: What would happen to her weight loss efforts?

A: To address her third concern, I tried to offset the risk for rebound weight gain by stopping Wegovy and giving her metformin in the second and third trimesters. Considered a safe medication in pregnancy, metformin is thought to support weight loss, but it proved to be ineffective against the rebound weight gain from stopping Wegovy. Claudia had not resumed regular exercise and quickly fell into the age-old eating-for-two trap. She gained nearly 50 pounds over the course of her pregnancy.

After a short and unfulfilling attempt at nursing, Claudia restarted Wegovy, this time in conjunction with a Mediterranean meal plan and regular sessions at a fitness club. After losing the pregnancy weight, she has been able to successfully maintain her ideal body weight for the past year, and her baby is perfectly healthy and beautiful.

*Patient’s name changed.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Claudia* was a charming 27-year-old newlywed. She and her husband wanted to start a family — with one small catch. She had recently gained 30 pounds. During COVID, she and her husband spent 18 months camped out in her parents’ guest room in upstate New York and had eaten their emotions with abandon. They ate when they were happy and ate more when they were sad. They ate when they felt isolated and again when they felt anxious. It didn’t help that her mother was a Culinary Institute–trained amateur chef. They both worked from home and logged long hours on Zoom calls. Because there was no home gym, they replaced their usual fitness club workouts in the city with leisurely strolls around the local lake. When I met her, Claudia categorically refused to entertain the notion of pregnancy until she reached her pre-COVID weight.

At the time, this all seemed quite reasonable to me. We outlined a plan including semaglutide (Wegovy) until she reached her target weight and then a minimum of 2 months off Wegovy prior to conception. We also lined up sessions with a dietitian and trainer and renewed her birth control pill. There was one detail I failed to mention to her: Birth control pills are less effective while on incretin hormones like semaglutide. The reason for my omission is that the medical community at large wasn’t yet aware of this issue.

About 12 weeks into treatment, Claudia had lost 20 of the 30 pounds. She had canceled several appointments with the trainer and dietitian due to work conflicts. She messaged me over the weekend in a panic. Her period was late, and her pregnancy test was positive.

She had three pressing questions for me:

Q: How had this happened while she had taken the birth control pills faithfully?

A: I answered that the scientific reasons for the decrease in efficacy of birth control pills while on semaglutide medications are threefold:

- Weight loss can improve menstrual cycle irregularities and improve fertility. In fact, I have been using semaglutide-like medications to treat polycystic ovary syndrome for decades, well before these medications became mainstream.

- The delayed gastric emptying inherent to incretins leads to decreased absorption of birth control pills.

- Finally, while this did not apply to Claudia, no medicine is particularly efficacious if vomited up shortly after taking. Wegovy is known to cause nausea and vomiting in a sizable percentage of patients.

Q: Would she have a healthy pregnancy given the lingering effects of Wegovy?

A: The short answer is: most likely yes. A review of the package insert revealed something fascinating. It was not strictly contraindicated. It advised doctors to weigh the risks and benefits of the medication during pregnancy. Animal studies have shown that semaglutide increases the risk for fetal death, birth defects, and growth issues, but this is probably due to restrictive eating patterns rather than a direct effect of the medication. A recent study of health records of more than 50,000 women with diabetes who had been inadvertently taking these medications in early pregnancy showed no increase in birth defects when compared with women who took insulin.

Q: What would happen to her weight loss efforts?

A: To address her third concern, I tried to offset the risk for rebound weight gain by stopping Wegovy and giving her metformin in the second and third trimesters. Considered a safe medication in pregnancy, metformin is thought to support weight loss, but it proved to be ineffective against the rebound weight gain from stopping Wegovy. Claudia had not resumed regular exercise and quickly fell into the age-old eating-for-two trap. She gained nearly 50 pounds over the course of her pregnancy.

After a short and unfulfilling attempt at nursing, Claudia restarted Wegovy, this time in conjunction with a Mediterranean meal plan and regular sessions at a fitness club. After losing the pregnancy weight, she has been able to successfully maintain her ideal body weight for the past year, and her baby is perfectly healthy and beautiful.

*Patient’s name changed.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Claudia* was a charming 27-year-old newlywed. She and her husband wanted to start a family — with one small catch. She had recently gained 30 pounds. During COVID, she and her husband spent 18 months camped out in her parents’ guest room in upstate New York and had eaten their emotions with abandon. They ate when they were happy and ate more when they were sad. They ate when they felt isolated and again when they felt anxious. It didn’t help that her mother was a Culinary Institute–trained amateur chef. They both worked from home and logged long hours on Zoom calls. Because there was no home gym, they replaced their usual fitness club workouts in the city with leisurely strolls around the local lake. When I met her, Claudia categorically refused to entertain the notion of pregnancy until she reached her pre-COVID weight.

At the time, this all seemed quite reasonable to me. We outlined a plan including semaglutide (Wegovy) until she reached her target weight and then a minimum of 2 months off Wegovy prior to conception. We also lined up sessions with a dietitian and trainer and renewed her birth control pill. There was one detail I failed to mention to her: Birth control pills are less effective while on incretin hormones like semaglutide. The reason for my omission is that the medical community at large wasn’t yet aware of this issue.

About 12 weeks into treatment, Claudia had lost 20 of the 30 pounds. She had canceled several appointments with the trainer and dietitian due to work conflicts. She messaged me over the weekend in a panic. Her period was late, and her pregnancy test was positive.

She had three pressing questions for me:

Q: How had this happened while she had taken the birth control pills faithfully?

A: I answered that the scientific reasons for the decrease in efficacy of birth control pills while on semaglutide medications are threefold:

- Weight loss can improve menstrual cycle irregularities and improve fertility. In fact, I have been using semaglutide-like medications to treat polycystic ovary syndrome for decades, well before these medications became mainstream.

- The delayed gastric emptying inherent to incretins leads to decreased absorption of birth control pills.

- Finally, while this did not apply to Claudia, no medicine is particularly efficacious if vomited up shortly after taking. Wegovy is known to cause nausea and vomiting in a sizable percentage of patients.

Q: Would she have a healthy pregnancy given the lingering effects of Wegovy?

A: The short answer is: most likely yes. A review of the package insert revealed something fascinating. It was not strictly contraindicated. It advised doctors to weigh the risks and benefits of the medication during pregnancy. Animal studies have shown that semaglutide increases the risk for fetal death, birth defects, and growth issues, but this is probably due to restrictive eating patterns rather than a direct effect of the medication. A recent study of health records of more than 50,000 women with diabetes who had been inadvertently taking these medications in early pregnancy showed no increase in birth defects when compared with women who took insulin.

Q: What would happen to her weight loss efforts?

A: To address her third concern, I tried to offset the risk for rebound weight gain by stopping Wegovy and giving her metformin in the second and third trimesters. Considered a safe medication in pregnancy, metformin is thought to support weight loss, but it proved to be ineffective against the rebound weight gain from stopping Wegovy. Claudia had not resumed regular exercise and quickly fell into the age-old eating-for-two trap. She gained nearly 50 pounds over the course of her pregnancy.

After a short and unfulfilling attempt at nursing, Claudia restarted Wegovy, this time in conjunction with a Mediterranean meal plan and regular sessions at a fitness club. After losing the pregnancy weight, she has been able to successfully maintain her ideal body weight for the past year, and her baby is perfectly healthy and beautiful.

*Patient’s name changed.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Why Cardiac Biomarkers Don’t Help Predict Heart Disease

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It’s the counterintuitive stuff in epidemiology that always really interests me. One intuition many of us have is that if a risk factor is significantly associated with an outcome, knowledge of that risk factor would help to predict that outcome. Makes sense. Feels right.

But it’s not right. Not always.

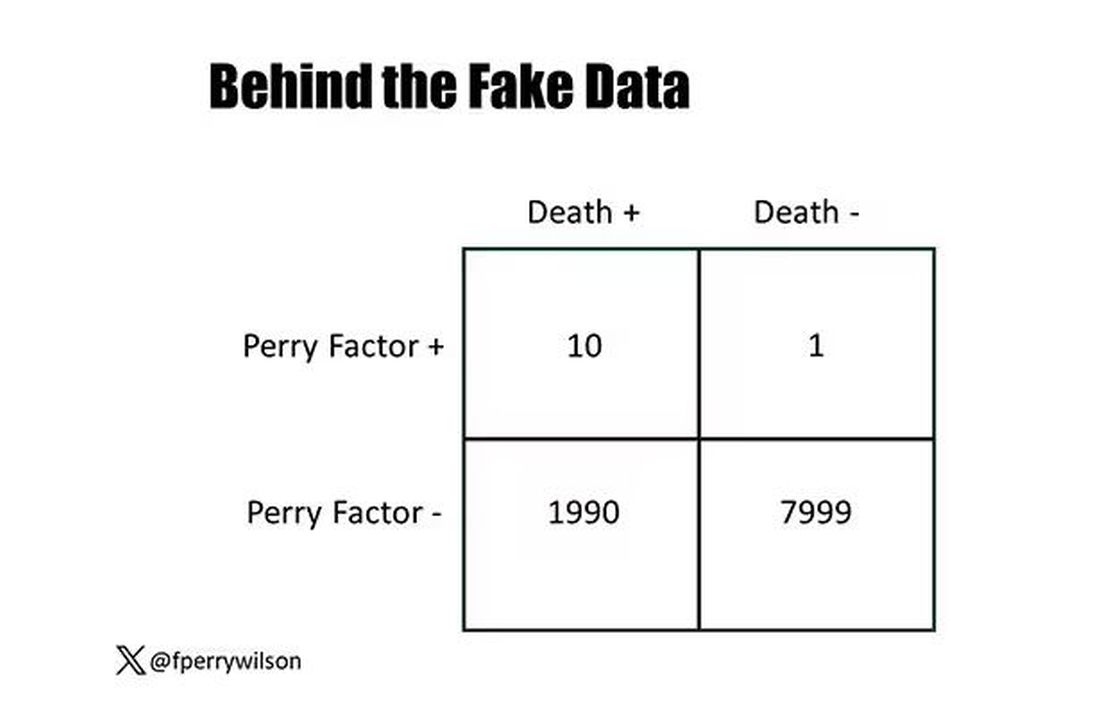

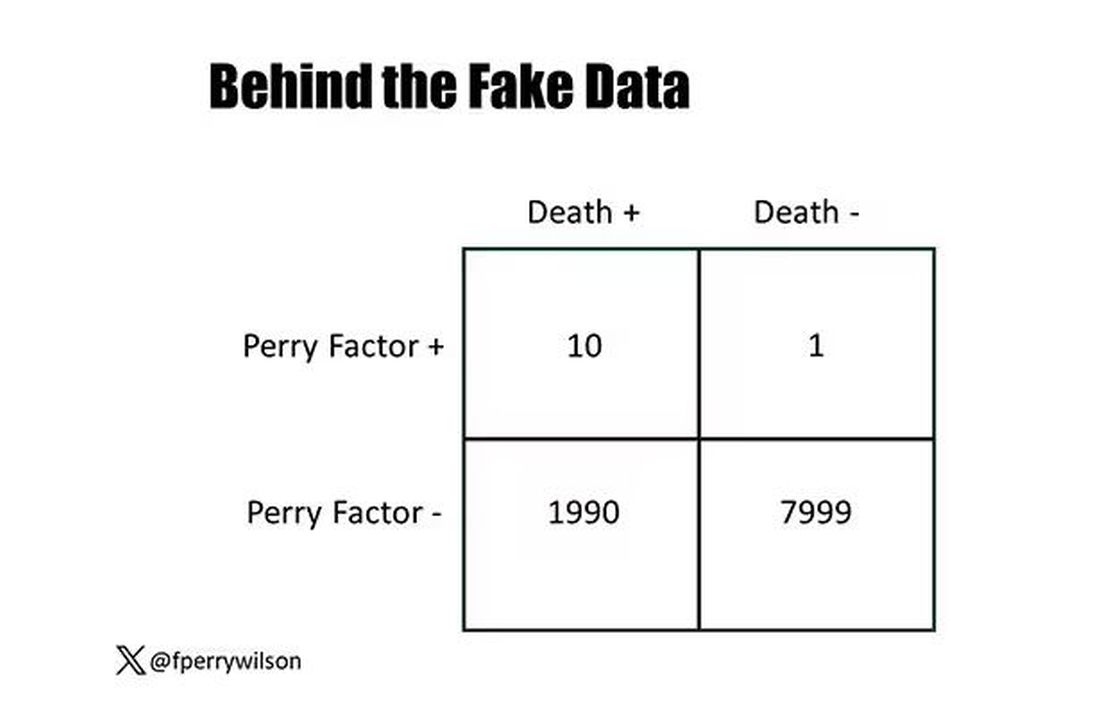

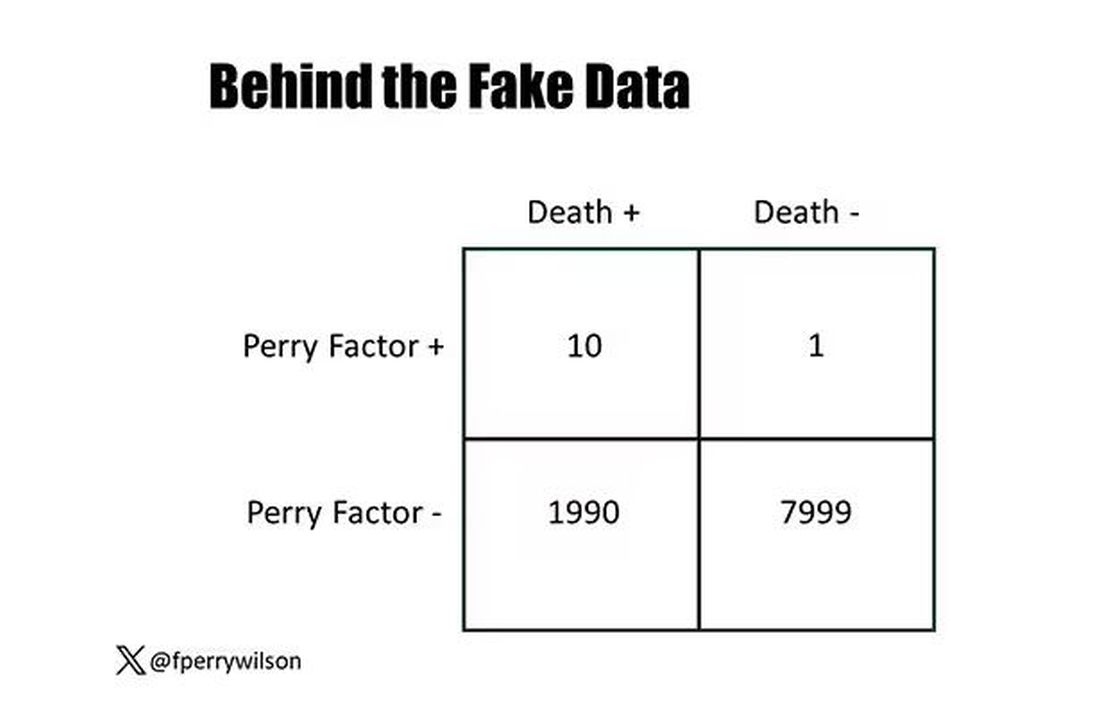

Here’s a fake example to illustrate my point. Let’s say we have 10,000 individuals who we follow for 10 years and 2000 of them die. (It’s been a rough decade.) At baseline, I measured a novel biomarker, the Perry Factor, in everyone. To keep it simple, the Perry Factor has only two values: 0 or 1.

I then do a standard associational analysis and find that individuals who are positive for the Perry Factor have a 40-fold higher odds of death than those who are negative for it. I am beginning to reconsider ascribing my good name to this biomarker. This is a highly statistically significant result — a P value <.001.

Clearly, knowledge of the Perry Factor should help me predict who will die in the cohort. I evaluate predictive power using a metric called the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC, referred to as the C-statistic in time-to-event studies). It tells you, given two people — one who dies and one who doesn’t — how frequently you “pick” the right person, given the knowledge of their Perry Factor.

A C-statistic of 0.5, or 50%, would mean the Perry Factor gives you no better results than a coin flip; it’s chance. A C-statistic of 1 is perfect prediction. So, what will the C-statistic be, given the incredibly strong association of the Perry Factor with outcomes? 0.9? 0.95?

0.5024. Almost useless.

Let’s figure out why strength of association and usefulness for prediction are not always the same thing.

I constructed my fake Perry Factor dataset quite carefully to illustrate this point. Let me show you what happened. What you see here is a breakdown of the patients in my fake study. You can see that just 11 of them were Perry Factor positive, but 10 of those 11 ended up dying.

That’s quite unlikely by chance alone. It really does appear that if you have Perry Factor, your risk for death is much higher. But the reason that Perry Factor is a bad predictor is because it is so rare in the population. Sure, you can use it to correctly predict the outcome of 10 of the 11 people who have it, but the vast majority of people don’t have Perry Factor. It’s useless to distinguish who will die vs who will live in that population.

Why have I spent so much time trying to reverse our intuition that strength of association and strength of predictive power must be related? Because it helps to explain this paper, “Prognostic Value of Cardiovascular Biomarkers in the Population,” appearing in JAMA, which is a very nice piece of work trying to help us better predict cardiovascular disease.

I don’t need to tell you that cardiovascular disease is the number-one killer in this country and most of the world. I don’t need to tell you that we have really good preventive therapies and lifestyle interventions that can reduce the risk. But it would be nice to know in whom, specifically, we should use those interventions.

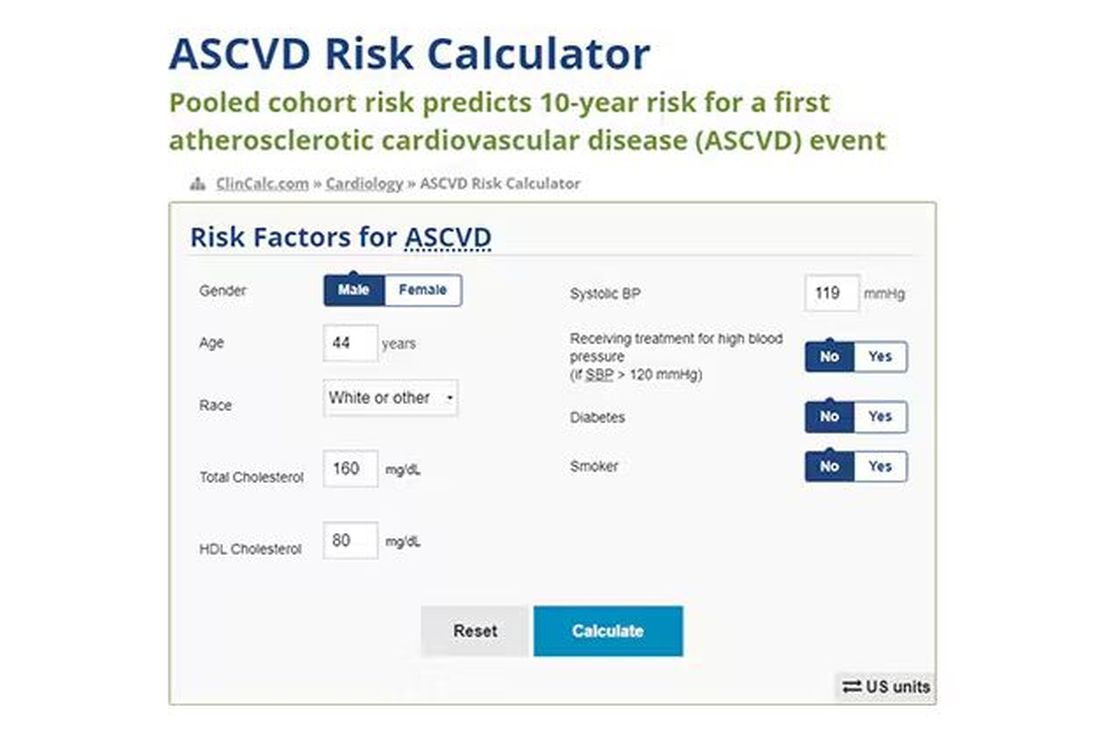

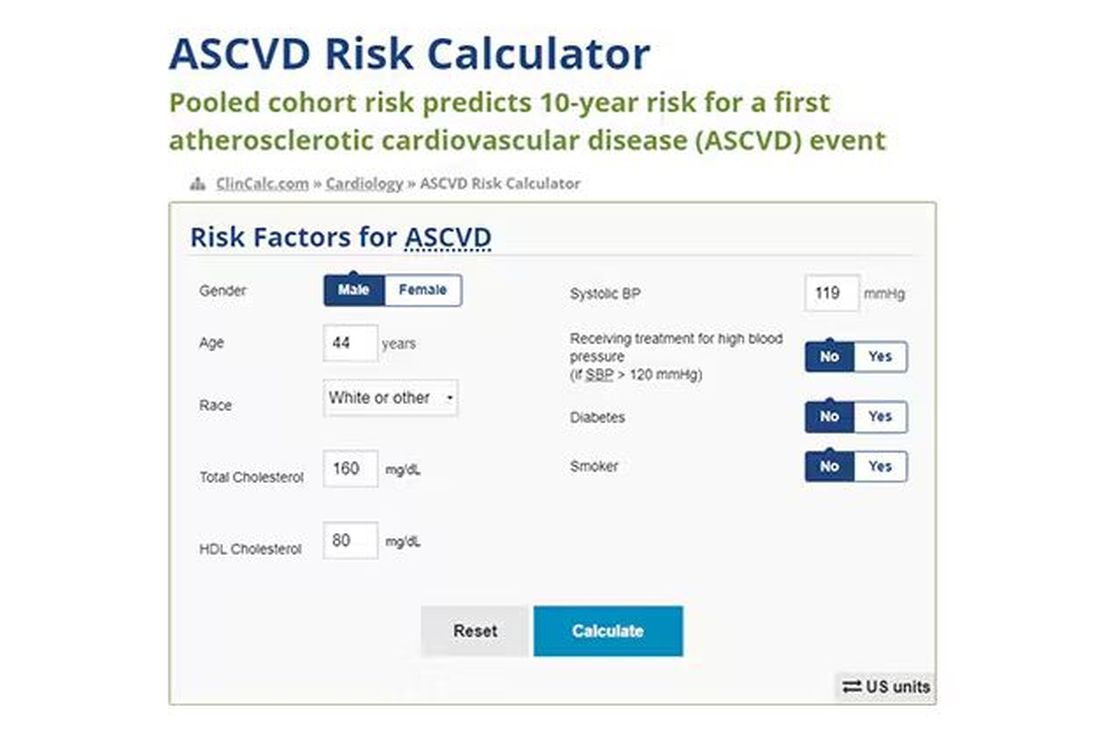

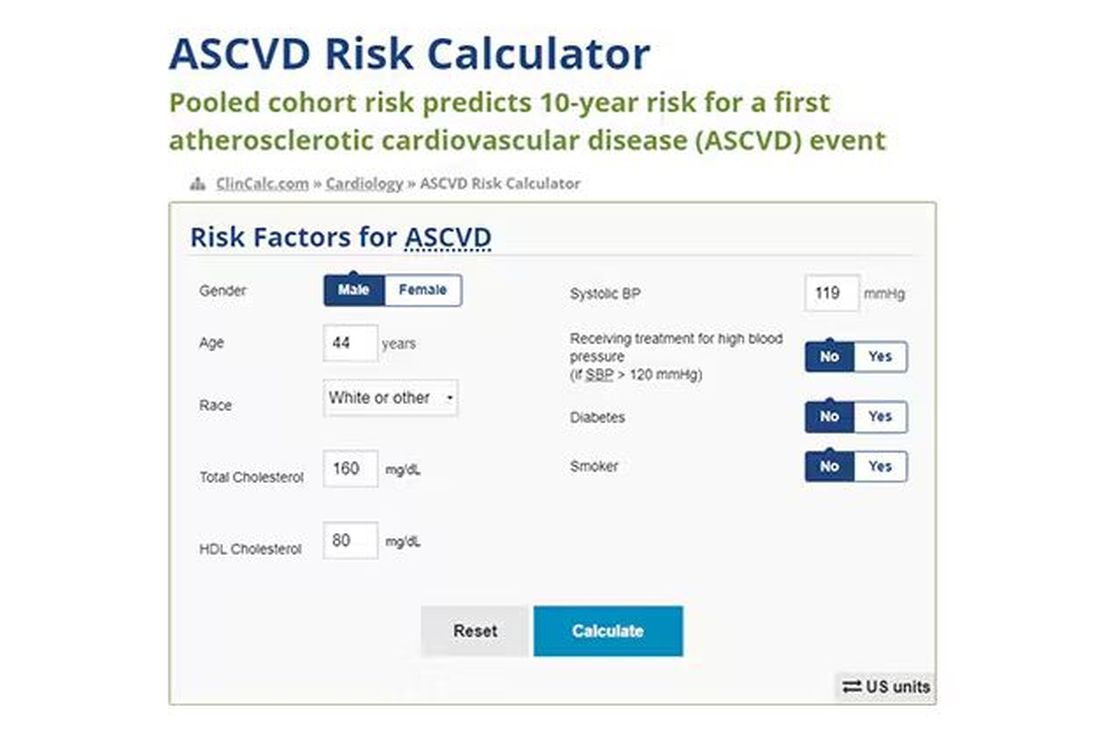

Cardiovascular risk scores, to date, are pretty simple. The most common one in use in the United States, the pooled cohort risk equation, has nine variables, two of which require a cholesterol panel and one a blood pressure test. It’s easy and it’s pretty accurate.

Using the score from the pooled cohort risk calculator, you get a C-statistic as high as 0.82 when applied to Black women, a low of 0.71 when applied to Black men. Non-Black individuals are in the middle. Not bad. But, clearly, not perfect.

And aren’t we in the era of big data, the era of personalized medicine? We have dozens, maybe hundreds, of quantifiable biomarkers that are associated with subsequent heart disease. Surely, by adding these biomarkers into the risk equation, we can improve prediction. Right?

The JAMA study includes 164,054 patients pooled from 28 cohort studies from 12 countries. All the studies measured various key biomarkers at baseline and followed their participants for cardiovascular events like heart attack, stroke, coronary revascularization, and so on.

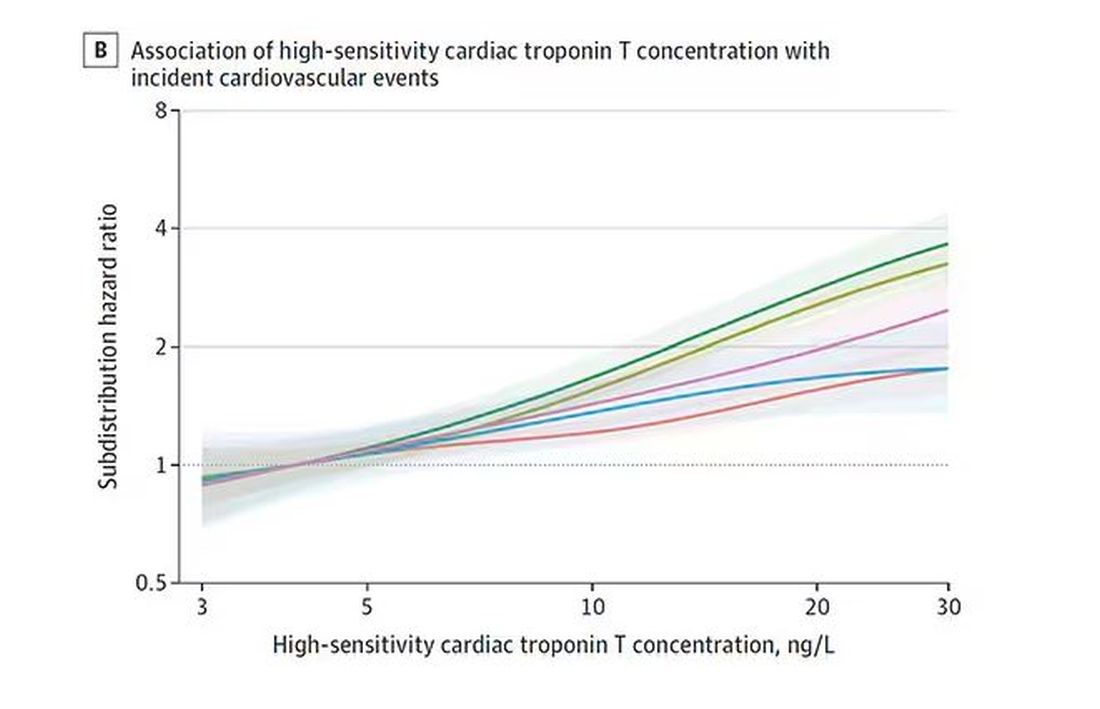

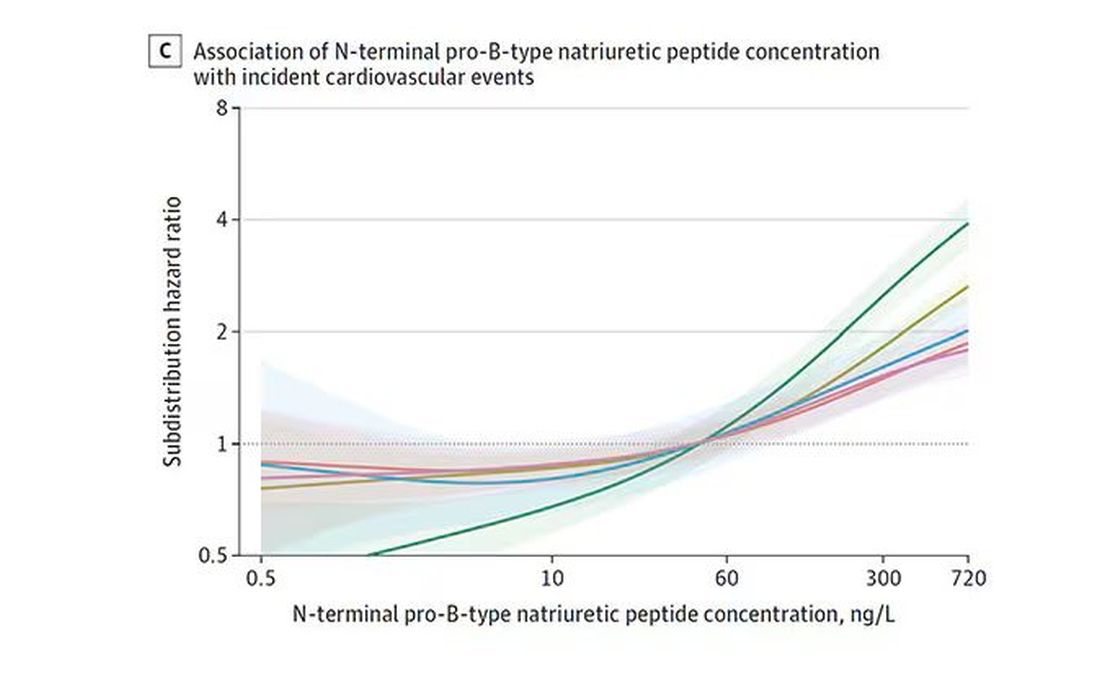

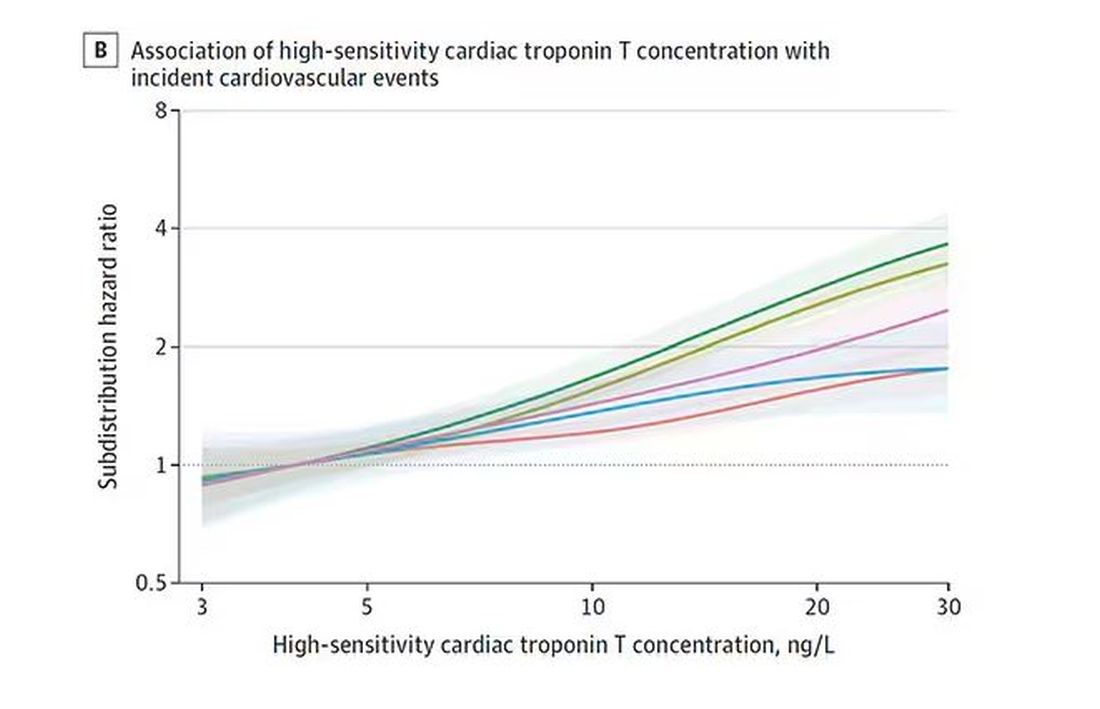

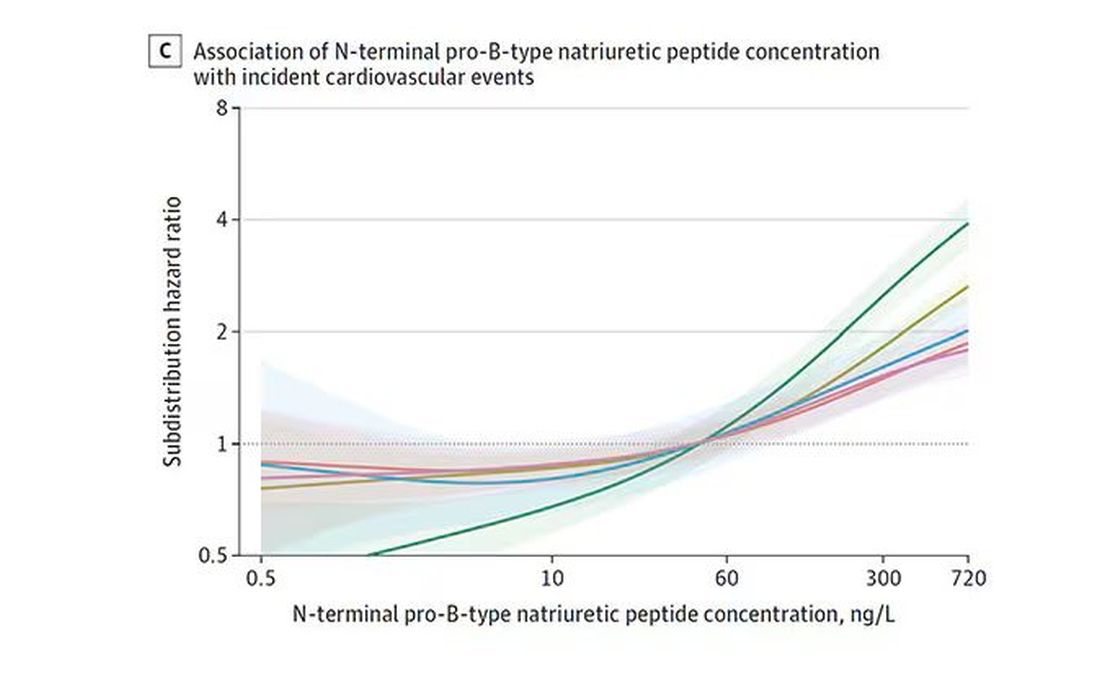

The biomarkers in question are really the big guns in this space: troponin, a marker of stress on the heart muscle; NT-proBNP, a marker of stretch on the heart muscle; and C-reactive protein, a marker of inflammation. In every case, higher levels of these markers at baseline were associated with a higher risk for cardiovascular disease in the future.

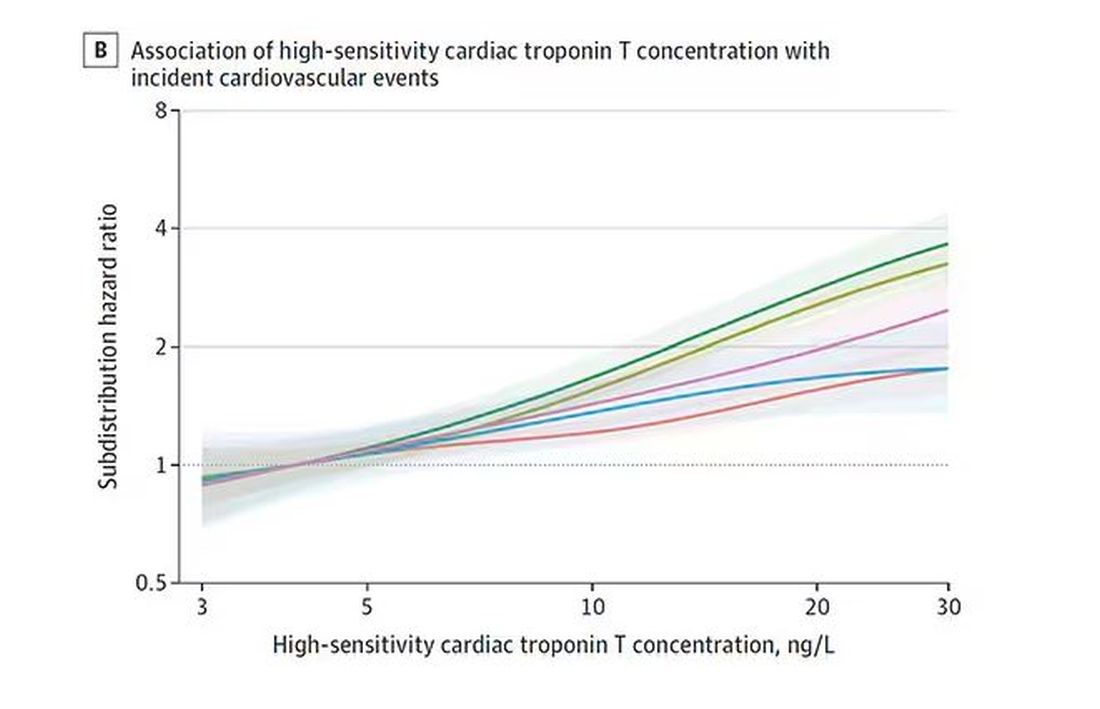

Troponin T, shown here, has a basically linear risk with subsequent cardiovascular disease.

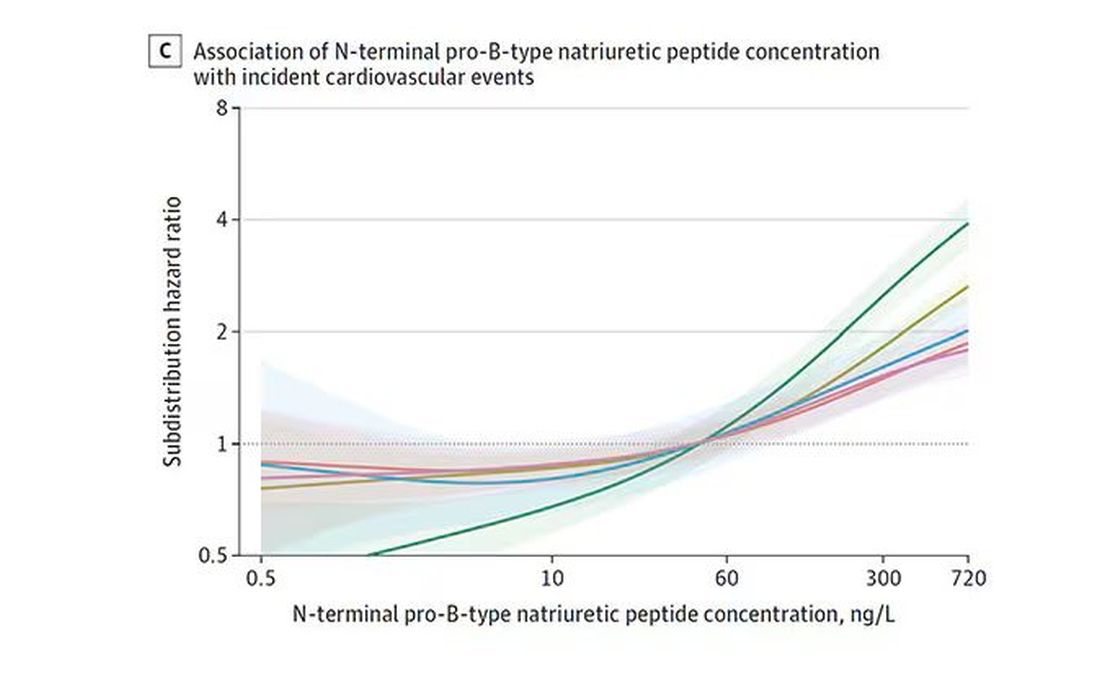

BNP seems to demonstrate more of a threshold effect, where levels above 60 start to associate with problems.

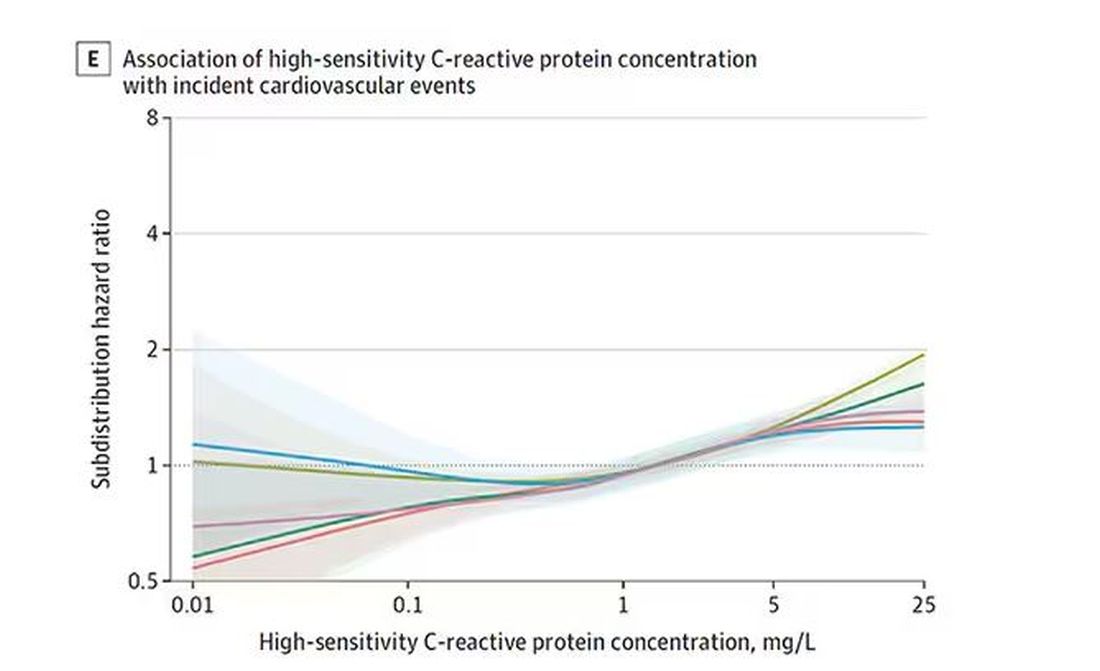

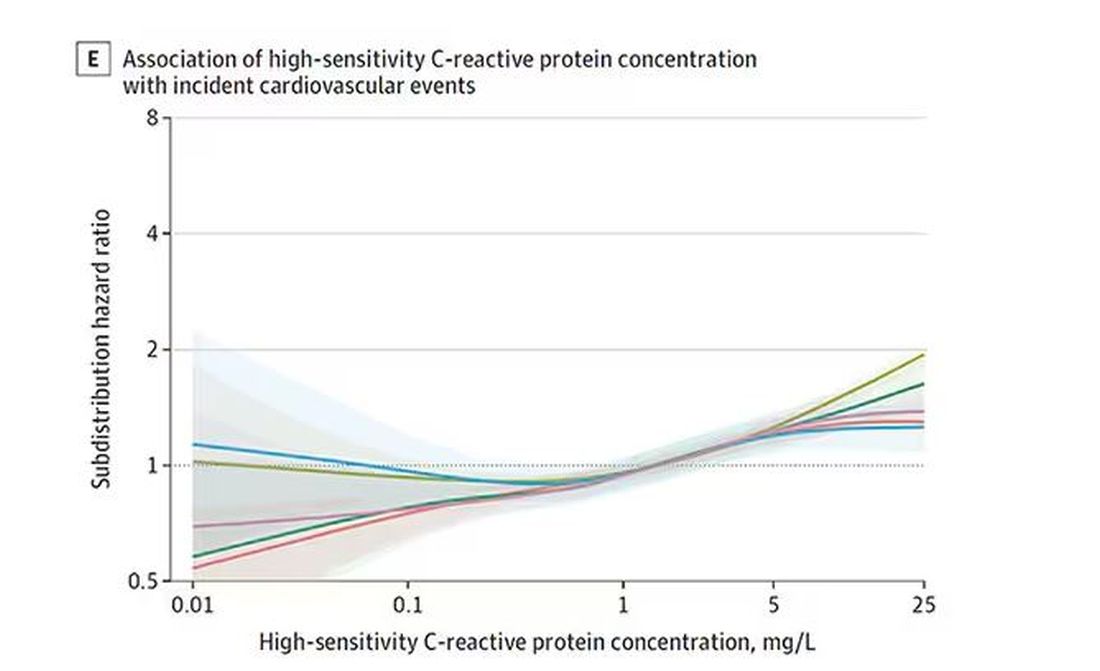

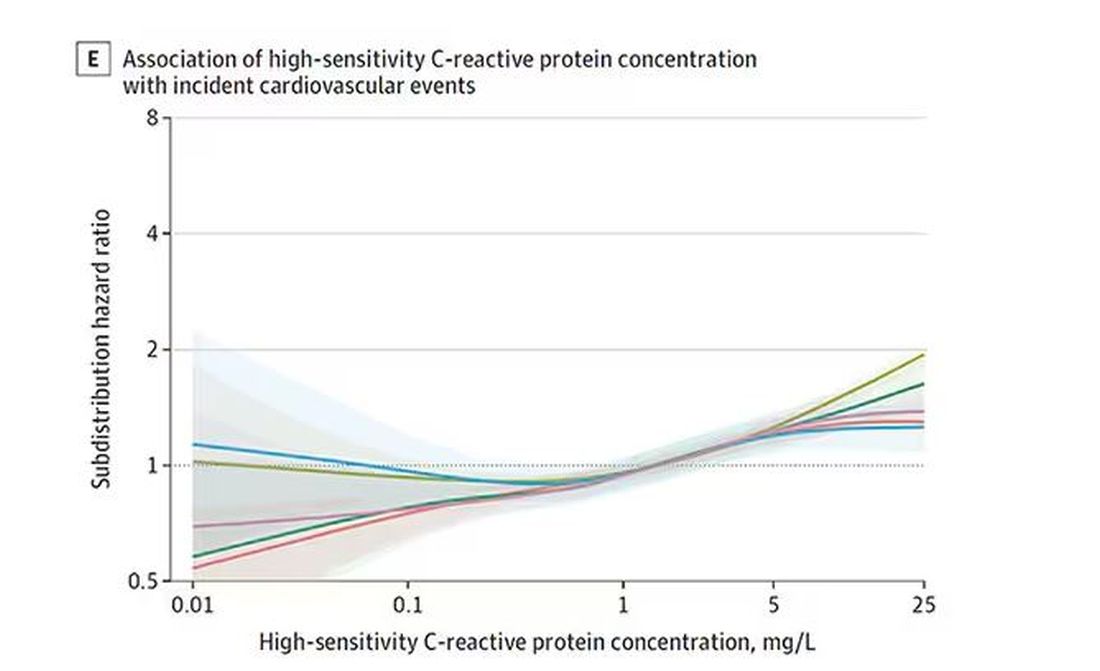

And CRP does a similar thing, with levels above 1.

All of these findings were statistically significant. If you have higher levels of one or more of these biomarkers, you are more likely to have cardiovascular disease in the future.

Of course, our old friend the pooled cohort risk equation is still here — in the background — requiring just that one blood test and measurement of blood pressure. Let’s talk about predictive power.

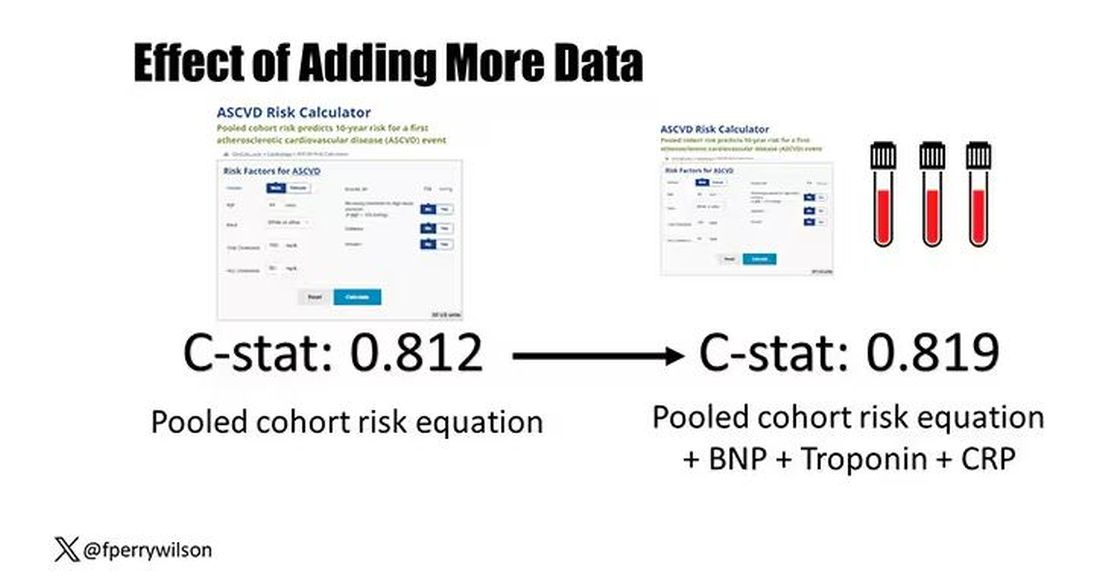

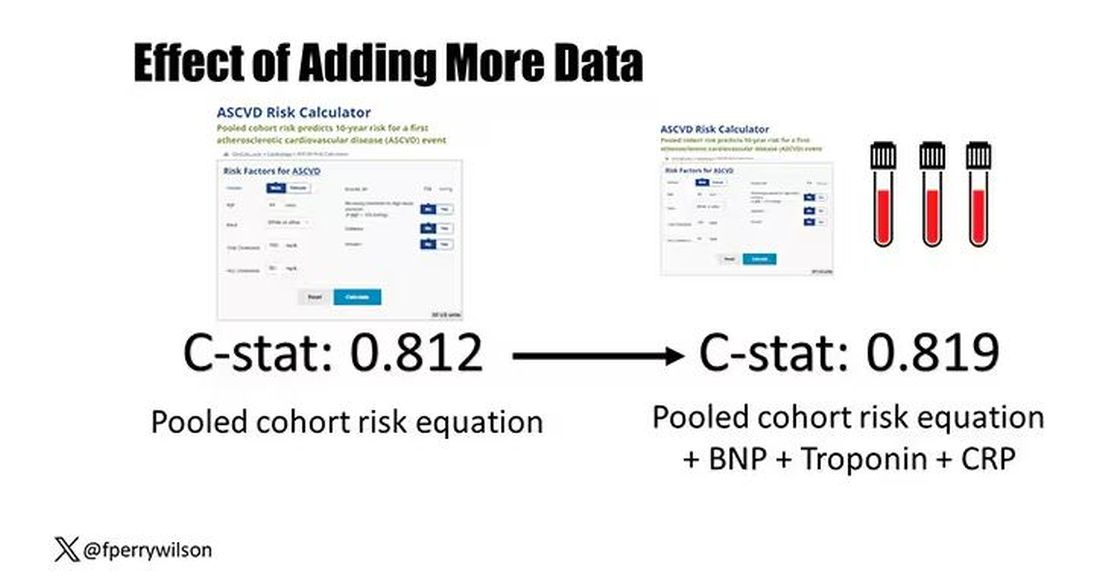

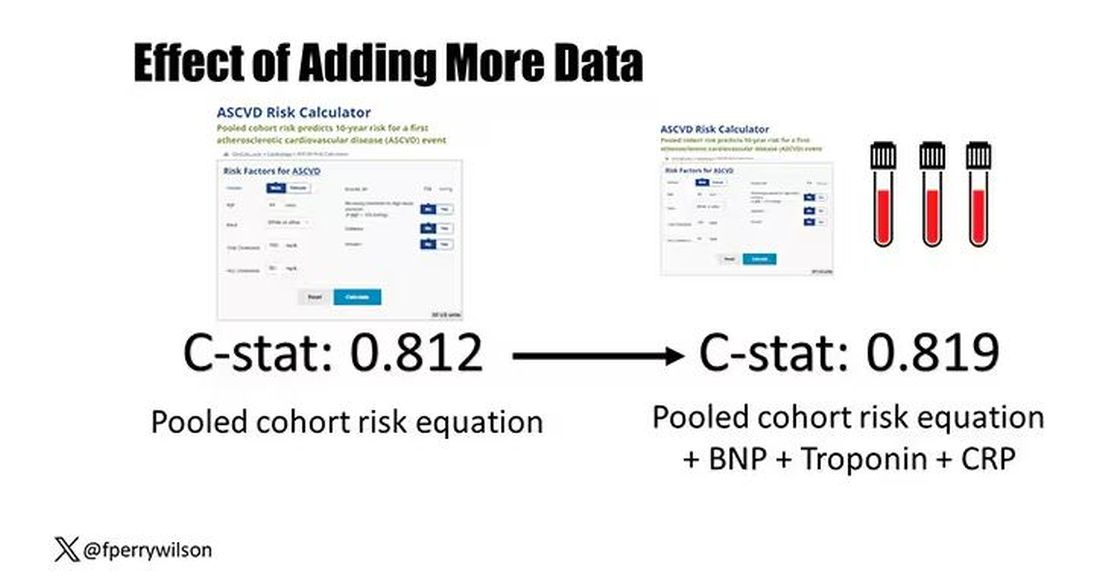

The pooled cohort risk equation score, in this study, had a C-statistic of 0.812.

By adding troponin, BNP, and CRP to the equation, the new C-statistic is 0.819. Barely any change.

Now, the authors looked at different types of prediction here. The greatest improvement in the AUC was seen when they tried to predict heart failure within 1 year of measurement; there the AUC improved by 0.04. But the presence of BNP as a biomarker and the short time window of 1 year makes me wonder whether this is really prediction at all or whether they were essentially just diagnosing people with existing heart failure.

Why does this happen? Why do these promising biomarkers, clearly associated with bad outcomes, fail to improve our ability to predict the future? I already gave one example, which has to do with how the markers are distributed in the population. But even more relevant here is that the new markers will only improve prediction insofar as they are not already represented in the old predictive model.

Of course, BNP, for example, wasn’t in the old model. But smoking was. Diabetes was. Blood pressure was. All of that data might actually tell you something about the patient’s BNP through their mutual correlation. And improvement in prediction requires new information.

This is actually why I consider this a really successful study. We need to do studies like this to help us find what those new sources of information might be.

We will never get to a C-statistic of 1. Perfect prediction is the domain of palm readers and astrophysicists. But better prediction is always possible through data. The big question, of course, is which data?

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It’s the counterintuitive stuff in epidemiology that always really interests me. One intuition many of us have is that if a risk factor is significantly associated with an outcome, knowledge of that risk factor would help to predict that outcome. Makes sense. Feels right.

But it’s not right. Not always.

Here’s a fake example to illustrate my point. Let’s say we have 10,000 individuals who we follow for 10 years and 2000 of them die. (It’s been a rough decade.) At baseline, I measured a novel biomarker, the Perry Factor, in everyone. To keep it simple, the Perry Factor has only two values: 0 or 1.

I then do a standard associational analysis and find that individuals who are positive for the Perry Factor have a 40-fold higher odds of death than those who are negative for it. I am beginning to reconsider ascribing my good name to this biomarker. This is a highly statistically significant result — a P value <.001.

Clearly, knowledge of the Perry Factor should help me predict who will die in the cohort. I evaluate predictive power using a metric called the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC, referred to as the C-statistic in time-to-event studies). It tells you, given two people — one who dies and one who doesn’t — how frequently you “pick” the right person, given the knowledge of their Perry Factor.

A C-statistic of 0.5, or 50%, would mean the Perry Factor gives you no better results than a coin flip; it’s chance. A C-statistic of 1 is perfect prediction. So, what will the C-statistic be, given the incredibly strong association of the Perry Factor with outcomes? 0.9? 0.95?

0.5024. Almost useless.

Let’s figure out why strength of association and usefulness for prediction are not always the same thing.

I constructed my fake Perry Factor dataset quite carefully to illustrate this point. Let me show you what happened. What you see here is a breakdown of the patients in my fake study. You can see that just 11 of them were Perry Factor positive, but 10 of those 11 ended up dying.

That’s quite unlikely by chance alone. It really does appear that if you have Perry Factor, your risk for death is much higher. But the reason that Perry Factor is a bad predictor is because it is so rare in the population. Sure, you can use it to correctly predict the outcome of 10 of the 11 people who have it, but the vast majority of people don’t have Perry Factor. It’s useless to distinguish who will die vs who will live in that population.

Why have I spent so much time trying to reverse our intuition that strength of association and strength of predictive power must be related? Because it helps to explain this paper, “Prognostic Value of Cardiovascular Biomarkers in the Population,” appearing in JAMA, which is a very nice piece of work trying to help us better predict cardiovascular disease.

I don’t need to tell you that cardiovascular disease is the number-one killer in this country and most of the world. I don’t need to tell you that we have really good preventive therapies and lifestyle interventions that can reduce the risk. But it would be nice to know in whom, specifically, we should use those interventions.

Cardiovascular risk scores, to date, are pretty simple. The most common one in use in the United States, the pooled cohort risk equation, has nine variables, two of which require a cholesterol panel and one a blood pressure test. It’s easy and it’s pretty accurate.

Using the score from the pooled cohort risk calculator, you get a C-statistic as high as 0.82 when applied to Black women, a low of 0.71 when applied to Black men. Non-Black individuals are in the middle. Not bad. But, clearly, not perfect.

And aren’t we in the era of big data, the era of personalized medicine? We have dozens, maybe hundreds, of quantifiable biomarkers that are associated with subsequent heart disease. Surely, by adding these biomarkers into the risk equation, we can improve prediction. Right?

The JAMA study includes 164,054 patients pooled from 28 cohort studies from 12 countries. All the studies measured various key biomarkers at baseline and followed their participants for cardiovascular events like heart attack, stroke, coronary revascularization, and so on.

The biomarkers in question are really the big guns in this space: troponin, a marker of stress on the heart muscle; NT-proBNP, a marker of stretch on the heart muscle; and C-reactive protein, a marker of inflammation. In every case, higher levels of these markers at baseline were associated with a higher risk for cardiovascular disease in the future.

Troponin T, shown here, has a basically linear risk with subsequent cardiovascular disease.

BNP seems to demonstrate more of a threshold effect, where levels above 60 start to associate with problems.

And CRP does a similar thing, with levels above 1.

All of these findings were statistically significant. If you have higher levels of one or more of these biomarkers, you are more likely to have cardiovascular disease in the future.

Of course, our old friend the pooled cohort risk equation is still here — in the background — requiring just that one blood test and measurement of blood pressure. Let’s talk about predictive power.

The pooled cohort risk equation score, in this study, had a C-statistic of 0.812.

By adding troponin, BNP, and CRP to the equation, the new C-statistic is 0.819. Barely any change.

Now, the authors looked at different types of prediction here. The greatest improvement in the AUC was seen when they tried to predict heart failure within 1 year of measurement; there the AUC improved by 0.04. But the presence of BNP as a biomarker and the short time window of 1 year makes me wonder whether this is really prediction at all or whether they were essentially just diagnosing people with existing heart failure.

Why does this happen? Why do these promising biomarkers, clearly associated with bad outcomes, fail to improve our ability to predict the future? I already gave one example, which has to do with how the markers are distributed in the population. But even more relevant here is that the new markers will only improve prediction insofar as they are not already represented in the old predictive model.

Of course, BNP, for example, wasn’t in the old model. But smoking was. Diabetes was. Blood pressure was. All of that data might actually tell you something about the patient’s BNP through their mutual correlation. And improvement in prediction requires new information.

This is actually why I consider this a really successful study. We need to do studies like this to help us find what those new sources of information might be.

We will never get to a C-statistic of 1. Perfect prediction is the domain of palm readers and astrophysicists. But better prediction is always possible through data. The big question, of course, is which data?

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It’s the counterintuitive stuff in epidemiology that always really interests me. One intuition many of us have is that if a risk factor is significantly associated with an outcome, knowledge of that risk factor would help to predict that outcome. Makes sense. Feels right.

But it’s not right. Not always.

Here’s a fake example to illustrate my point. Let’s say we have 10,000 individuals who we follow for 10 years and 2000 of them die. (It’s been a rough decade.) At baseline, I measured a novel biomarker, the Perry Factor, in everyone. To keep it simple, the Perry Factor has only two values: 0 or 1.

I then do a standard associational analysis and find that individuals who are positive for the Perry Factor have a 40-fold higher odds of death than those who are negative for it. I am beginning to reconsider ascribing my good name to this biomarker. This is a highly statistically significant result — a P value <.001.

Clearly, knowledge of the Perry Factor should help me predict who will die in the cohort. I evaluate predictive power using a metric called the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC, referred to as the C-statistic in time-to-event studies). It tells you, given two people — one who dies and one who doesn’t — how frequently you “pick” the right person, given the knowledge of their Perry Factor.

A C-statistic of 0.5, or 50%, would mean the Perry Factor gives you no better results than a coin flip; it’s chance. A C-statistic of 1 is perfect prediction. So, what will the C-statistic be, given the incredibly strong association of the Perry Factor with outcomes? 0.9? 0.95?

0.5024. Almost useless.

Let’s figure out why strength of association and usefulness for prediction are not always the same thing.

I constructed my fake Perry Factor dataset quite carefully to illustrate this point. Let me show you what happened. What you see here is a breakdown of the patients in my fake study. You can see that just 11 of them were Perry Factor positive, but 10 of those 11 ended up dying.

That’s quite unlikely by chance alone. It really does appear that if you have Perry Factor, your risk for death is much higher. But the reason that Perry Factor is a bad predictor is because it is so rare in the population. Sure, you can use it to correctly predict the outcome of 10 of the 11 people who have it, but the vast majority of people don’t have Perry Factor. It’s useless to distinguish who will die vs who will live in that population.

Why have I spent so much time trying to reverse our intuition that strength of association and strength of predictive power must be related? Because it helps to explain this paper, “Prognostic Value of Cardiovascular Biomarkers in the Population,” appearing in JAMA, which is a very nice piece of work trying to help us better predict cardiovascular disease.

I don’t need to tell you that cardiovascular disease is the number-one killer in this country and most of the world. I don’t need to tell you that we have really good preventive therapies and lifestyle interventions that can reduce the risk. But it would be nice to know in whom, specifically, we should use those interventions.

Cardiovascular risk scores, to date, are pretty simple. The most common one in use in the United States, the pooled cohort risk equation, has nine variables, two of which require a cholesterol panel and one a blood pressure test. It’s easy and it’s pretty accurate.

Using the score from the pooled cohort risk calculator, you get a C-statistic as high as 0.82 when applied to Black women, a low of 0.71 when applied to Black men. Non-Black individuals are in the middle. Not bad. But, clearly, not perfect.

And aren’t we in the era of big data, the era of personalized medicine? We have dozens, maybe hundreds, of quantifiable biomarkers that are associated with subsequent heart disease. Surely, by adding these biomarkers into the risk equation, we can improve prediction. Right?

The JAMA study includes 164,054 patients pooled from 28 cohort studies from 12 countries. All the studies measured various key biomarkers at baseline and followed their participants for cardiovascular events like heart attack, stroke, coronary revascularization, and so on.

The biomarkers in question are really the big guns in this space: troponin, a marker of stress on the heart muscle; NT-proBNP, a marker of stretch on the heart muscle; and C-reactive protein, a marker of inflammation. In every case, higher levels of these markers at baseline were associated with a higher risk for cardiovascular disease in the future.

Troponin T, shown here, has a basically linear risk with subsequent cardiovascular disease.

BNP seems to demonstrate more of a threshold effect, where levels above 60 start to associate with problems.

And CRP does a similar thing, with levels above 1.

All of these findings were statistically significant. If you have higher levels of one or more of these biomarkers, you are more likely to have cardiovascular disease in the future.

Of course, our old friend the pooled cohort risk equation is still here — in the background — requiring just that one blood test and measurement of blood pressure. Let’s talk about predictive power.

The pooled cohort risk equation score, in this study, had a C-statistic of 0.812.

By adding troponin, BNP, and CRP to the equation, the new C-statistic is 0.819. Barely any change.

Now, the authors looked at different types of prediction here. The greatest improvement in the AUC was seen when they tried to predict heart failure within 1 year of measurement; there the AUC improved by 0.04. But the presence of BNP as a biomarker and the short time window of 1 year makes me wonder whether this is really prediction at all or whether they were essentially just diagnosing people with existing heart failure.

Why does this happen? Why do these promising biomarkers, clearly associated with bad outcomes, fail to improve our ability to predict the future? I already gave one example, which has to do with how the markers are distributed in the population. But even more relevant here is that the new markers will only improve prediction insofar as they are not already represented in the old predictive model.

Of course, BNP, for example, wasn’t in the old model. But smoking was. Diabetes was. Blood pressure was. All of that data might actually tell you something about the patient’s BNP through their mutual correlation. And improvement in prediction requires new information.

This is actually why I consider this a really successful study. We need to do studies like this to help us find what those new sources of information might be.

We will never get to a C-statistic of 1. Perfect prediction is the domain of palm readers and astrophysicists. But better prediction is always possible through data. The big question, of course, is which data?

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Vacationing Doctors Fight to Revive a Drowned Child

Emergencies happen anywhere, anytime, and sometimes, medical professionals find themselves in situations where they are the only ones who can help. Is There a Doctor in the House? is a series telling these stories.

Jennifer Suders, DO: We were in Florida with our 1-year-old daughter visiting my parents. They moved to an area called Hallandale Beach and live in a high-rise community with a few different pools and spas.

Dan and I were in the spa area at the gym. He was getting me to hurry up because we were supposed to meet my parents who were with our daughter. I was sort of moseying and taking my time.

We were walking by one of the pool decks to get into the building when I heard what sounded like a slap. My first thought was that maybe somebody was choking and someone was hitting their back. Choking has always been my biggest fear with our daughter.

I turned and saw some people who seemed frantic. I looked at Dan and started to ask, “Do you think they need help?” I don’t even think I got the whole sentence out before this mom whipped her head around. I’ll never forget her dark brown hair flying. She screamed, “HELP!”

Dan and I just ran. I let go of my backpack and iPad and water bottle. They scattered across the pool deck. I instantly had my phone in my hand dialing 911.

Daniel Suders, DO: That’s what they teach us, to call 911 first. I didn’t think of it in the moment, but Jenny did.

Jennifer Suders:

Dan and I got down on either side of the boy and checked for a pulse. We couldn’t feel anything. Dan started chest compressions. I was talking to the 911 operator, and then I gave two rescue breaths. We did a sternal rub.

I was kind of yelling in the boy’s face, trying to get him to respond. I tried English and Russian because there’s a big Russian community there, and my family speaks Russian. The grandma asked us if we knew what we were doing.

Daniel Suders: I think she asked if Jenny was a nurse.

Jennifer Suders: Common misconception. Suddenly, the boy started vomiting, and so much water poured out. We turned him on his side, and he had two or three more episodes of spitting up the water. After that, we could see the color start to come back into his face. His eyes started fluttering.

We thought he was probably coming back. But we were too scared to say that in case we were wrong, and he went back under. So, we just held him steady. We didn’t know what had happened, if he might have hit his head, so we needed to keep him still.

Daniel Suders: It was amazing when those eyes opened, and he started to wake up.

Jennifer Suders: It felt like my heart had stopped while I was waiting for his to start.

Daniel Suders: He was clutching his chest like it hurt and started calling for his mom. He was crying and wanting to get in his mom’s arms. We had to keep him from standing up and walking.

Jennifer Suders: He was clearly scared. There were all these strange faces around him. I kept looking at my phone, anxiously waiting for EMS to come. They got there about 8 or 9 minutes later.

At some point, the father walked in with their daughter, a baby under a year old. He was in shock, not knowing what was going on. The grandma explained that the boy had been jumping into the pool over and over with his brother. All of a sudden, they looked over, and he was just lying there, floating, face down. They were right there; they were watching him. It was just that quick.

Daniel Suders: They pulled him out right away, and that was a big thing on his side that it was caught so quickly. He didn’t have to wait long to start resuscitation.

Jennifer Suders: Once EMS got there and assessed him, they put him and his mom on the stretcher. I remember watching them wheel it through the double doors to get to the elevator. As soon as they were gone, I just turned around and broke down. I had been in doctor mode if you will. Straight to the point. No nonsense. Suddenly, I went back into civilian mode, and my emotions just bubbled up.

After we left, we went to meet my parents who had our kid. Dan just beelined toward her and scooped her up and wouldn’t let her go.

For the rest of the day, it was all I could think about. It took me a while to fall asleep that night, and it was the first thing I thought when I woke up the next morning. We were hopeful that the boy was going to be okay, but you never know. We didn’t call the hospital because with HIPAA, I didn’t know if they could tell us anything.

And then the next day — there they were. The family was back at the pool. The little boy was running around like nothing had happened. We were a little surprised. But I would hate for him to be scared of the pool for the rest of his life. His family was watching him like a hawk.

They told us that the boy and his mom had stayed overnight in the ER, but only as a precaution. He didn’t have any more vomiting. He was absolutely fine. They were incredibly grateful.

We got their names and exchanged numbers and took a picture. That’s all I wanted — a photo to remember them.

A day or so later, we saw them again at a nearby park. The boy was climbing trees and seemed completely normal. It was the best outcome we could have hoped for.

Daniel Suders: My biggest worry was any harm to his chest from the resuscitation, or of course how long he was without oxygen. But everyone says that kids are really resilient. I work with adults, so I don’t have a lot of experience.

As a hospitalist, we don’t always see a lot of success with CPR. It’s often an elderly person who just doesn’t have much of a chance. That same week before our vacation, I had lost a 90-year-old in the hospital. It was such a juxtaposition — a 3-year-old with their whole life in front of them. We were able to preserve that, and it was incredible.

Jennifer Suders: I’m a nephrologist, so my field is pretty calm. No big emergencies. We have patients on the floor, but if a code gets called, there’s a team that comes in from the intensive care unit. I always kind of wondered what I would do if I was presented with a scenario like this.

Daniel Suders: We have a lot of friends that do ER medicine, and I felt like those were the guys that really understood when we told them the story. One friend said to me, “By the time they get to us, they’re either in bad shape or they’re better already.” A lot depends on what happens in the field.

Jennifer Suders: I’m even more vigilant about pool safety now. I want to make sure parents know that drowning doesn›t look like flailing theatrics. It can be soundless. Three adults were right next to this little boy and didn›t realize until they looked down and saw him.

If we hadn’t been there, I don’t know if anyone would’ve been able to step in. No one else was medically trained. But I think the message is — you don’t have to be. Anyone can take a CPR class.

When I told my parents, my dad said, “Oh my gosh, I would’ve laid right down there next to that kid and passed out.” Without any training, it’s petrifying to see something like that.

I think about how we could have stayed in the gym longer and been too late. Or we could have gotten on the elevator earlier and been gone. Two minutes, and it would’ve been a story we heard later, not one we were a part of. It feels like we were at a true crossroads in that moment where that boy could have lived or died. And the stars aligned perfectly.

We had no medicine, no monitors, nothing but our hands and our breaths. And we helped a family continue their vacation rather than plan a funeral.

Jennifer Suders, DO, is a nephrologist at West Virginia University Medicine Wheeling Clinic. Daniel Suders, DO, is a hospitalist at West Virginia University Medicine Reynolds Memorial Hospital.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Emergencies happen anywhere, anytime, and sometimes, medical professionals find themselves in situations where they are the only ones who can help. Is There a Doctor in the House? is a series telling these stories.

Jennifer Suders, DO: We were in Florida with our 1-year-old daughter visiting my parents. They moved to an area called Hallandale Beach and live in a high-rise community with a few different pools and spas.

Dan and I were in the spa area at the gym. He was getting me to hurry up because we were supposed to meet my parents who were with our daughter. I was sort of moseying and taking my time.

We were walking by one of the pool decks to get into the building when I heard what sounded like a slap. My first thought was that maybe somebody was choking and someone was hitting their back. Choking has always been my biggest fear with our daughter.

I turned and saw some people who seemed frantic. I looked at Dan and started to ask, “Do you think they need help?” I don’t even think I got the whole sentence out before this mom whipped her head around. I’ll never forget her dark brown hair flying. She screamed, “HELP!”

Dan and I just ran. I let go of my backpack and iPad and water bottle. They scattered across the pool deck. I instantly had my phone in my hand dialing 911.

Daniel Suders, DO: That’s what they teach us, to call 911 first. I didn’t think of it in the moment, but Jenny did.

Jennifer Suders:

Dan and I got down on either side of the boy and checked for a pulse. We couldn’t feel anything. Dan started chest compressions. I was talking to the 911 operator, and then I gave two rescue breaths. We did a sternal rub.

I was kind of yelling in the boy’s face, trying to get him to respond. I tried English and Russian because there’s a big Russian community there, and my family speaks Russian. The grandma asked us if we knew what we were doing.

Daniel Suders: I think she asked if Jenny was a nurse.

Jennifer Suders: Common misconception. Suddenly, the boy started vomiting, and so much water poured out. We turned him on his side, and he had two or three more episodes of spitting up the water. After that, we could see the color start to come back into his face. His eyes started fluttering.

We thought he was probably coming back. But we were too scared to say that in case we were wrong, and he went back under. So, we just held him steady. We didn’t know what had happened, if he might have hit his head, so we needed to keep him still.

Daniel Suders: It was amazing when those eyes opened, and he started to wake up.

Jennifer Suders: It felt like my heart had stopped while I was waiting for his to start.

Daniel Suders: He was clutching his chest like it hurt and started calling for his mom. He was crying and wanting to get in his mom’s arms. We had to keep him from standing up and walking.

Jennifer Suders: He was clearly scared. There were all these strange faces around him. I kept looking at my phone, anxiously waiting for EMS to come. They got there about 8 or 9 minutes later.

At some point, the father walked in with their daughter, a baby under a year old. He was in shock, not knowing what was going on. The grandma explained that the boy had been jumping into the pool over and over with his brother. All of a sudden, they looked over, and he was just lying there, floating, face down. They were right there; they were watching him. It was just that quick.

Daniel Suders: They pulled him out right away, and that was a big thing on his side that it was caught so quickly. He didn’t have to wait long to start resuscitation.

Jennifer Suders: Once EMS got there and assessed him, they put him and his mom on the stretcher. I remember watching them wheel it through the double doors to get to the elevator. As soon as they were gone, I just turned around and broke down. I had been in doctor mode if you will. Straight to the point. No nonsense. Suddenly, I went back into civilian mode, and my emotions just bubbled up.

After we left, we went to meet my parents who had our kid. Dan just beelined toward her and scooped her up and wouldn’t let her go.

For the rest of the day, it was all I could think about. It took me a while to fall asleep that night, and it was the first thing I thought when I woke up the next morning. We were hopeful that the boy was going to be okay, but you never know. We didn’t call the hospital because with HIPAA, I didn’t know if they could tell us anything.

And then the next day — there they were. The family was back at the pool. The little boy was running around like nothing had happened. We were a little surprised. But I would hate for him to be scared of the pool for the rest of his life. His family was watching him like a hawk.

They told us that the boy and his mom had stayed overnight in the ER, but only as a precaution. He didn’t have any more vomiting. He was absolutely fine. They were incredibly grateful.

We got their names and exchanged numbers and took a picture. That’s all I wanted — a photo to remember them.

A day or so later, we saw them again at a nearby park. The boy was climbing trees and seemed completely normal. It was the best outcome we could have hoped for.

Daniel Suders: My biggest worry was any harm to his chest from the resuscitation, or of course how long he was without oxygen. But everyone says that kids are really resilient. I work with adults, so I don’t have a lot of experience.

As a hospitalist, we don’t always see a lot of success with CPR. It’s often an elderly person who just doesn’t have much of a chance. That same week before our vacation, I had lost a 90-year-old in the hospital. It was such a juxtaposition — a 3-year-old with their whole life in front of them. We were able to preserve that, and it was incredible.

Jennifer Suders: I’m a nephrologist, so my field is pretty calm. No big emergencies. We have patients on the floor, but if a code gets called, there’s a team that comes in from the intensive care unit. I always kind of wondered what I would do if I was presented with a scenario like this.

Daniel Suders: We have a lot of friends that do ER medicine, and I felt like those were the guys that really understood when we told them the story. One friend said to me, “By the time they get to us, they’re either in bad shape or they’re better already.” A lot depends on what happens in the field.

Jennifer Suders: I’m even more vigilant about pool safety now. I want to make sure parents know that drowning doesn›t look like flailing theatrics. It can be soundless. Three adults were right next to this little boy and didn›t realize until they looked down and saw him.

If we hadn’t been there, I don’t know if anyone would’ve been able to step in. No one else was medically trained. But I think the message is — you don’t have to be. Anyone can take a CPR class.

When I told my parents, my dad said, “Oh my gosh, I would’ve laid right down there next to that kid and passed out.” Without any training, it’s petrifying to see something like that.

I think about how we could have stayed in the gym longer and been too late. Or we could have gotten on the elevator earlier and been gone. Two minutes, and it would’ve been a story we heard later, not one we were a part of. It feels like we were at a true crossroads in that moment where that boy could have lived or died. And the stars aligned perfectly.

We had no medicine, no monitors, nothing but our hands and our breaths. And we helped a family continue their vacation rather than plan a funeral.

Jennifer Suders, DO, is a nephrologist at West Virginia University Medicine Wheeling Clinic. Daniel Suders, DO, is a hospitalist at West Virginia University Medicine Reynolds Memorial Hospital.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Emergencies happen anywhere, anytime, and sometimes, medical professionals find themselves in situations where they are the only ones who can help. Is There a Doctor in the House? is a series telling these stories.

Jennifer Suders, DO: We were in Florida with our 1-year-old daughter visiting my parents. They moved to an area called Hallandale Beach and live in a high-rise community with a few different pools and spas.

Dan and I were in the spa area at the gym. He was getting me to hurry up because we were supposed to meet my parents who were with our daughter. I was sort of moseying and taking my time.

We were walking by one of the pool decks to get into the building when I heard what sounded like a slap. My first thought was that maybe somebody was choking and someone was hitting their back. Choking has always been my biggest fear with our daughter.

I turned and saw some people who seemed frantic. I looked at Dan and started to ask, “Do you think they need help?” I don’t even think I got the whole sentence out before this mom whipped her head around. I’ll never forget her dark brown hair flying. She screamed, “HELP!”

Dan and I just ran. I let go of my backpack and iPad and water bottle. They scattered across the pool deck. I instantly had my phone in my hand dialing 911.

Daniel Suders, DO: That’s what they teach us, to call 911 first. I didn’t think of it in the moment, but Jenny did.

Jennifer Suders:

Dan and I got down on either side of the boy and checked for a pulse. We couldn’t feel anything. Dan started chest compressions. I was talking to the 911 operator, and then I gave two rescue breaths. We did a sternal rub.

I was kind of yelling in the boy’s face, trying to get him to respond. I tried English and Russian because there’s a big Russian community there, and my family speaks Russian. The grandma asked us if we knew what we were doing.

Daniel Suders: I think she asked if Jenny was a nurse.

Jennifer Suders: Common misconception. Suddenly, the boy started vomiting, and so much water poured out. We turned him on his side, and he had two or three more episodes of spitting up the water. After that, we could see the color start to come back into his face. His eyes started fluttering.

We thought he was probably coming back. But we were too scared to say that in case we were wrong, and he went back under. So, we just held him steady. We didn’t know what had happened, if he might have hit his head, so we needed to keep him still.

Daniel Suders: It was amazing when those eyes opened, and he started to wake up.

Jennifer Suders: It felt like my heart had stopped while I was waiting for his to start.

Daniel Suders: He was clutching his chest like it hurt and started calling for his mom. He was crying and wanting to get in his mom’s arms. We had to keep him from standing up and walking.

Jennifer Suders: He was clearly scared. There were all these strange faces around him. I kept looking at my phone, anxiously waiting for EMS to come. They got there about 8 or 9 minutes later.

At some point, the father walked in with their daughter, a baby under a year old. He was in shock, not knowing what was going on. The grandma explained that the boy had been jumping into the pool over and over with his brother. All of a sudden, they looked over, and he was just lying there, floating, face down. They were right there; they were watching him. It was just that quick.

Daniel Suders: They pulled him out right away, and that was a big thing on his side that it was caught so quickly. He didn’t have to wait long to start resuscitation.

Jennifer Suders: Once EMS got there and assessed him, they put him and his mom on the stretcher. I remember watching them wheel it through the double doors to get to the elevator. As soon as they were gone, I just turned around and broke down. I had been in doctor mode if you will. Straight to the point. No nonsense. Suddenly, I went back into civilian mode, and my emotions just bubbled up.

After we left, we went to meet my parents who had our kid. Dan just beelined toward her and scooped her up and wouldn’t let her go.

For the rest of the day, it was all I could think about. It took me a while to fall asleep that night, and it was the first thing I thought when I woke up the next morning. We were hopeful that the boy was going to be okay, but you never know. We didn’t call the hospital because with HIPAA, I didn’t know if they could tell us anything.

And then the next day — there they were. The family was back at the pool. The little boy was running around like nothing had happened. We were a little surprised. But I would hate for him to be scared of the pool for the rest of his life. His family was watching him like a hawk.

They told us that the boy and his mom had stayed overnight in the ER, but only as a precaution. He didn’t have any more vomiting. He was absolutely fine. They were incredibly grateful.

We got their names and exchanged numbers and took a picture. That’s all I wanted — a photo to remember them.

A day or so later, we saw them again at a nearby park. The boy was climbing trees and seemed completely normal. It was the best outcome we could have hoped for.

Daniel Suders: My biggest worry was any harm to his chest from the resuscitation, or of course how long he was without oxygen. But everyone says that kids are really resilient. I work with adults, so I don’t have a lot of experience.

As a hospitalist, we don’t always see a lot of success with CPR. It’s often an elderly person who just doesn’t have much of a chance. That same week before our vacation, I had lost a 90-year-old in the hospital. It was such a juxtaposition — a 3-year-old with their whole life in front of them. We were able to preserve that, and it was incredible.

Jennifer Suders: I’m a nephrologist, so my field is pretty calm. No big emergencies. We have patients on the floor, but if a code gets called, there’s a team that comes in from the intensive care unit. I always kind of wondered what I would do if I was presented with a scenario like this.

Daniel Suders: We have a lot of friends that do ER medicine, and I felt like those were the guys that really understood when we told them the story. One friend said to me, “By the time they get to us, they’re either in bad shape or they’re better already.” A lot depends on what happens in the field.

Jennifer Suders: I’m even more vigilant about pool safety now. I want to make sure parents know that drowning doesn›t look like flailing theatrics. It can be soundless. Three adults were right next to this little boy and didn›t realize until they looked down and saw him.

If we hadn’t been there, I don’t know if anyone would’ve been able to step in. No one else was medically trained. But I think the message is — you don’t have to be. Anyone can take a CPR class.

When I told my parents, my dad said, “Oh my gosh, I would’ve laid right down there next to that kid and passed out.” Without any training, it’s petrifying to see something like that.

I think about how we could have stayed in the gym longer and been too late. Or we could have gotten on the elevator earlier and been gone. Two minutes, and it would’ve been a story we heard later, not one we were a part of. It feels like we were at a true crossroads in that moment where that boy could have lived or died. And the stars aligned perfectly.

We had no medicine, no monitors, nothing but our hands and our breaths. And we helped a family continue their vacation rather than plan a funeral.

Jennifer Suders, DO, is a nephrologist at West Virginia University Medicine Wheeling Clinic. Daniel Suders, DO, is a hospitalist at West Virginia University Medicine Reynolds Memorial Hospital.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Nocturnal Hot Flashes and Alzheimer’s Risk

In a recent article in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Rebecca C. Thurston, PhD, and Pauline Maki, PhD, leading scientists in the area of menopause’s impact on brain function, presented data from their assessment of 248 late perimenopausal and postmenopausal women who reported hot flashes, also known as vasomotor symptoms (VMS).

Hot flashes are known to be associated with changes in brain white matter, carotid atherosclerosis, brain function, and memory. Dr. Thurston and colleagues objectively measured VMS over 24 hours, using skin conductance monitoring. Plasma concentrations of Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers, including the amyloid beta 42–to–amyloid beta 40 ratio, were assessed. The mean age of study participants was 59 years, and they experienced a mean of five objective VMS daily.

A key finding was that VMS, particularly those occurring during sleep, were associated with a significantly lower amyloid beta 42–to–beta 40 ratio. This finding suggests that nighttime VMS may be a marker of risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

Previous research has found that menopausal hormone therapy is associated with favorable changes in Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers. Likewise, large observational studies have shown a lower incidence of Alzheimer’s disease among women who initiate hormone therapy in their late perimenopausal or early postmenopausal years and continue such therapy long term.

The findings of this important study by Thurston and colleagues provide further evidence to support the tantalizing possibility that agents that reduce nighttime hot flashes (including hormone therapy) may lower the subsequent incidence of Alzheimer’s disease in high-risk women.

Dr. Kaunitz is a tenured professor and associate chair in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville, and medical director and director of menopause and gynecologic ultrasound services at the University of Florida Southside Women’s Health, Jacksonville. He disclosed ties to Sumitomo Pharma America, Mithra, Viatris, Bayer, Merck, Mylan (Viatris), and UpToDate.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

In a recent article in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Rebecca C. Thurston, PhD, and Pauline Maki, PhD, leading scientists in the area of menopause’s impact on brain function, presented data from their assessment of 248 late perimenopausal and postmenopausal women who reported hot flashes, also known as vasomotor symptoms (VMS).

Hot flashes are known to be associated with changes in brain white matter, carotid atherosclerosis, brain function, and memory. Dr. Thurston and colleagues objectively measured VMS over 24 hours, using skin conductance monitoring. Plasma concentrations of Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers, including the amyloid beta 42–to–amyloid beta 40 ratio, were assessed. The mean age of study participants was 59 years, and they experienced a mean of five objective VMS daily.

A key finding was that VMS, particularly those occurring during sleep, were associated with a significantly lower amyloid beta 42–to–beta 40 ratio. This finding suggests that nighttime VMS may be a marker of risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

Previous research has found that menopausal hormone therapy is associated with favorable changes in Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers. Likewise, large observational studies have shown a lower incidence of Alzheimer’s disease among women who initiate hormone therapy in their late perimenopausal or early postmenopausal years and continue such therapy long term.

The findings of this important study by Thurston and colleagues provide further evidence to support the tantalizing possibility that agents that reduce nighttime hot flashes (including hormone therapy) may lower the subsequent incidence of Alzheimer’s disease in high-risk women.

Dr. Kaunitz is a tenured professor and associate chair in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville, and medical director and director of menopause and gynecologic ultrasound services at the University of Florida Southside Women’s Health, Jacksonville. He disclosed ties to Sumitomo Pharma America, Mithra, Viatris, Bayer, Merck, Mylan (Viatris), and UpToDate.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

In a recent article in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Rebecca C. Thurston, PhD, and Pauline Maki, PhD, leading scientists in the area of menopause’s impact on brain function, presented data from their assessment of 248 late perimenopausal and postmenopausal women who reported hot flashes, also known as vasomotor symptoms (VMS).

Hot flashes are known to be associated with changes in brain white matter, carotid atherosclerosis, brain function, and memory. Dr. Thurston and colleagues objectively measured VMS over 24 hours, using skin conductance monitoring. Plasma concentrations of Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers, including the amyloid beta 42–to–amyloid beta 40 ratio, were assessed. The mean age of study participants was 59 years, and they experienced a mean of five objective VMS daily.

A key finding was that VMS, particularly those occurring during sleep, were associated with a significantly lower amyloid beta 42–to–beta 40 ratio. This finding suggests that nighttime VMS may be a marker of risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

Previous research has found that menopausal hormone therapy is associated with favorable changes in Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers. Likewise, large observational studies have shown a lower incidence of Alzheimer’s disease among women who initiate hormone therapy in their late perimenopausal or early postmenopausal years and continue such therapy long term.

The findings of this important study by Thurston and colleagues provide further evidence to support the tantalizing possibility that agents that reduce nighttime hot flashes (including hormone therapy) may lower the subsequent incidence of Alzheimer’s disease in high-risk women.

Dr. Kaunitz is a tenured professor and associate chair in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville, and medical director and director of menopause and gynecologic ultrasound services at the University of Florida Southside Women’s Health, Jacksonville. He disclosed ties to Sumitomo Pharma America, Mithra, Viatris, Bayer, Merck, Mylan (Viatris), and UpToDate.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Molecular Classification of Endometrial Carcinomas

Historically, endometrial cancer has been classified as type I or type II. Type I endometrial cancers are typically estrogen driven, low grade, with endometrioid histology, and have a more favorable prognosis. In contrast, type II endometrial cancers are typically high grade, have more aggressive histologies (eg, serous or clear cell), and have a poorer prognosis.1

While this system provides a helpful schema for understanding endometrial cancers, it fails to represent the immense variation of biologic behavior and outcomes in endometrial cancers and oversimplifies what has come to be understood as a complex and molecularly diverse disease.