User login

A Game for All Seasons

Sports and sports figures provide both a welcome relief from the stress of dealing with life and death in the ED and memorable ways of characterizing serious health care issues. When the Institute of Medicine issued its 2006 report “Hospital-Based Emergency Care: At the Breaking Point,” we thought that a quote about a popular restaurant by the late, great New York Yankees catcher Yogi Berra better described the severely overcrowded EDs and ambulance diversion: “Nobody goes there anymore—it’s too crowded.”

In late winter and early spring of this year, after vigorous attempts to repeal/revise the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA), a replacement bill was withdrawn immediately prior to a Congressional vote on March 24 due to a lack of support. Seven years earlier, when President Obama also seemed to have little chance of getting the ACA through Congress, we thought that there would be “many more balks before the president and Congress finally pitched a viable health care package to the nation.” Only a month later, however, with the ACA now the law, we suggested that our erroneous prediction was similar to that of “a father who convinces his son to leave for the parking lot during the bottom of the ninth inning of a 3-0 game only to hear the roar of the crowd from the exit ramp as the rookie batter hits a grand-slam home run to win the game.”

In June 2012, when the Supreme Court ruled on the constitutionality of the ACA, many reporters quickly read the Court’s rejection of the first two arguments defending the ACA, and rushed to report that it was dead, without considering that the government had “one more out to go…[the one] casting ACA as a tax—considered to be the weakest player in the lineup—[which] managed to score the winning run to uphold ACA. Game over. Final score: ACA wins 5 to 4.”

But with the 2017 baseball season finally underway, it is a recent football game that provides the perfect paradigm for emergency medicine (EM) and emergency physicians (EPs). The New England Patriots were slight favorites to win Super Bowl 51 over the Atlanta Falcons on February 5,and the first quarter ended with no score. But by halftime, Atlanta was leading 21-3. In 50 years of Super Bowls, no team had ever overcome more than a 10-point deficit to win the game, and with a little over 8 minutes left in the third quarter, the deficit had widened even further to 28-3. Then the Patriots began to turn things around. Though the Patriots never led during regulation play, and no Super Bowl had ever gone into overtime, the fourth quarter ended in a 28-28 tie, and the Patriots went on to win 34-28 in overtime.

Coming out of the locker room to play the second half of that game in front of over 111 million viewers must have been a daunting experience for the Patriots, but no more so than the experience depicted in EP/cinematographer Ryan McGarry’s award-winning documentary “Code Black,” in which he shows young EM residents walking through a packed waiting room to begin their shift, realizing that in the next 12 hours, they could never treat all of the ill patients waiting to be seen. But the young residents proceeded to treat one patient after another without ever giving up or losing their idealism, until in the end, they, too, had won the game against all odds.

Many patients arrive in EDs so ill that there is no reasonable expectation any intervention can save them, but we nevertheless try and sometimes succeed in doing the seemingly impossible. It is the type of medicine we have chosen to devote our careers to, and we are no less heroes than were the Patriots on February 5, 2017. Each time we go out to “play ball” in our overcrowded EDs, it is worth remembering another famous Yogi Berra quote: “It ain’t over till it’s over.”

Sports and sports figures provide both a welcome relief from the stress of dealing with life and death in the ED and memorable ways of characterizing serious health care issues. When the Institute of Medicine issued its 2006 report “Hospital-Based Emergency Care: At the Breaking Point,” we thought that a quote about a popular restaurant by the late, great New York Yankees catcher Yogi Berra better described the severely overcrowded EDs and ambulance diversion: “Nobody goes there anymore—it’s too crowded.”

In late winter and early spring of this year, after vigorous attempts to repeal/revise the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA), a replacement bill was withdrawn immediately prior to a Congressional vote on March 24 due to a lack of support. Seven years earlier, when President Obama also seemed to have little chance of getting the ACA through Congress, we thought that there would be “many more balks before the president and Congress finally pitched a viable health care package to the nation.” Only a month later, however, with the ACA now the law, we suggested that our erroneous prediction was similar to that of “a father who convinces his son to leave for the parking lot during the bottom of the ninth inning of a 3-0 game only to hear the roar of the crowd from the exit ramp as the rookie batter hits a grand-slam home run to win the game.”

In June 2012, when the Supreme Court ruled on the constitutionality of the ACA, many reporters quickly read the Court’s rejection of the first two arguments defending the ACA, and rushed to report that it was dead, without considering that the government had “one more out to go…[the one] casting ACA as a tax—considered to be the weakest player in the lineup—[which] managed to score the winning run to uphold ACA. Game over. Final score: ACA wins 5 to 4.”

But with the 2017 baseball season finally underway, it is a recent football game that provides the perfect paradigm for emergency medicine (EM) and emergency physicians (EPs). The New England Patriots were slight favorites to win Super Bowl 51 over the Atlanta Falcons on February 5,and the first quarter ended with no score. But by halftime, Atlanta was leading 21-3. In 50 years of Super Bowls, no team had ever overcome more than a 10-point deficit to win the game, and with a little over 8 minutes left in the third quarter, the deficit had widened even further to 28-3. Then the Patriots began to turn things around. Though the Patriots never led during regulation play, and no Super Bowl had ever gone into overtime, the fourth quarter ended in a 28-28 tie, and the Patriots went on to win 34-28 in overtime.

Coming out of the locker room to play the second half of that game in front of over 111 million viewers must have been a daunting experience for the Patriots, but no more so than the experience depicted in EP/cinematographer Ryan McGarry’s award-winning documentary “Code Black,” in which he shows young EM residents walking through a packed waiting room to begin their shift, realizing that in the next 12 hours, they could never treat all of the ill patients waiting to be seen. But the young residents proceeded to treat one patient after another without ever giving up or losing their idealism, until in the end, they, too, had won the game against all odds.

Many patients arrive in EDs so ill that there is no reasonable expectation any intervention can save them, but we nevertheless try and sometimes succeed in doing the seemingly impossible. It is the type of medicine we have chosen to devote our careers to, and we are no less heroes than were the Patriots on February 5, 2017. Each time we go out to “play ball” in our overcrowded EDs, it is worth remembering another famous Yogi Berra quote: “It ain’t over till it’s over.”

Sports and sports figures provide both a welcome relief from the stress of dealing with life and death in the ED and memorable ways of characterizing serious health care issues. When the Institute of Medicine issued its 2006 report “Hospital-Based Emergency Care: At the Breaking Point,” we thought that a quote about a popular restaurant by the late, great New York Yankees catcher Yogi Berra better described the severely overcrowded EDs and ambulance diversion: “Nobody goes there anymore—it’s too crowded.”

In late winter and early spring of this year, after vigorous attempts to repeal/revise the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA), a replacement bill was withdrawn immediately prior to a Congressional vote on March 24 due to a lack of support. Seven years earlier, when President Obama also seemed to have little chance of getting the ACA through Congress, we thought that there would be “many more balks before the president and Congress finally pitched a viable health care package to the nation.” Only a month later, however, with the ACA now the law, we suggested that our erroneous prediction was similar to that of “a father who convinces his son to leave for the parking lot during the bottom of the ninth inning of a 3-0 game only to hear the roar of the crowd from the exit ramp as the rookie batter hits a grand-slam home run to win the game.”

In June 2012, when the Supreme Court ruled on the constitutionality of the ACA, many reporters quickly read the Court’s rejection of the first two arguments defending the ACA, and rushed to report that it was dead, without considering that the government had “one more out to go…[the one] casting ACA as a tax—considered to be the weakest player in the lineup—[which] managed to score the winning run to uphold ACA. Game over. Final score: ACA wins 5 to 4.”

But with the 2017 baseball season finally underway, it is a recent football game that provides the perfect paradigm for emergency medicine (EM) and emergency physicians (EPs). The New England Patriots were slight favorites to win Super Bowl 51 over the Atlanta Falcons on February 5,and the first quarter ended with no score. But by halftime, Atlanta was leading 21-3. In 50 years of Super Bowls, no team had ever overcome more than a 10-point deficit to win the game, and with a little over 8 minutes left in the third quarter, the deficit had widened even further to 28-3. Then the Patriots began to turn things around. Though the Patriots never led during regulation play, and no Super Bowl had ever gone into overtime, the fourth quarter ended in a 28-28 tie, and the Patriots went on to win 34-28 in overtime.

Coming out of the locker room to play the second half of that game in front of over 111 million viewers must have been a daunting experience for the Patriots, but no more so than the experience depicted in EP/cinematographer Ryan McGarry’s award-winning documentary “Code Black,” in which he shows young EM residents walking through a packed waiting room to begin their shift, realizing that in the next 12 hours, they could never treat all of the ill patients waiting to be seen. But the young residents proceeded to treat one patient after another without ever giving up or losing their idealism, until in the end, they, too, had won the game against all odds.

Many patients arrive in EDs so ill that there is no reasonable expectation any intervention can save them, but we nevertheless try and sometimes succeed in doing the seemingly impossible. It is the type of medicine we have chosen to devote our careers to, and we are no less heroes than were the Patriots on February 5, 2017. Each time we go out to “play ball” in our overcrowded EDs, it is worth remembering another famous Yogi Berra quote: “It ain’t over till it’s over.”

How would repeal of the Affordable Care Act affect mental health care?

With the changing political landscape in Washington, there has been much talk about health care in the United States. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) is at risk for repeal or, at least, substantial change. As the debate heats up, many psychiatric clinicians wonder what repeal could mean for mental health care and treatment of substance use disorders.

To examine this issue, we need to understand what the ACA has accomplished so far. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act—known as “Obamacare”—was enacted on March 23, 2010. From 2010 to 2014, various provisions were implemented; more provisions are slated for completion by 2017 if the law remains in place. These provisions are at the heart of how those with mental illness or substance use disorders could be affected by repeal of the ACA.

Since the ACA’s implementation, an estimated 20 million Americans have gained health insurance.1 The ACA includes several provisions that made this number possible, such as the expansion of Medicaid in some states. In addition to plans offered through the Health Insurance Marketplace, private insurers are required to provide insurance to some who previously fell into non-coverage gaps.1 Young adults can remain on a parent’s plan until age 26, which is significant to mental health care because many psychiatric disorders emerge in young adulthood, and this age group is vulnerable to developing substance use disorders.

The ACA also requires private insurance plans to cover those with preexisting health conditions. This has been crucial for persons with mental illness because before the ACA, mental health disorders were the second most common preexisting condition that precipitated either an increase in the cost of a plan or coverage denial.2

These provisions have helped ensure coverage for the approximately 20% of adults in the United States who have a mental illness.3 Before the ACA, 18% of individuals who purchased their own insurance did not have mental health coverage, and more than one-third of insurers did not cover substance use disorders.4 According to the CDC, the uninsured rate for those with serious mental health disorders fell from 28.1% in 2012 to 19.5% in 2015.5 Likewise, the number of adults with mental illness who could not afford needed care decreased during the same years.5 A University of Minnesota study found that persons with mental illness are disproportionately represented among the uninsured.6 Before the ACA, 18% of individual health plans did not cover prescriptions, including those indicated for psychiatric illness.7 Simply put, the ACA has allowed people to seek assessment and treatment for mental health, whereas it would not have been as accessible before the legislation.

What does the ACA cover?

The ACA required health plans to cover Essential Health Benefits starting January 1, 2014. These include:

- medical services such as doctor visits

- emergency and urgent care services

- hospital physician and facility services

- prenatal, delivery, and postnatal care

- evaluation and treatment of mental health conditions

- services to address substance use including behavioral health treatment

- coverage of prescription medications

- rehabilitation services

- diagnostic tests and imaging

- preventive and wellness care and management of chronic diseases

- pediatric care.

As of March 2013, only 2% of existing health plans in the United States provided all of these benefits required by the ACA.7

Required coverage of mental health care and substance use disorders increases patient access to those services. Including preventive care extends the reach of mental health screening to primary care providers, who can screen for mood disorders and substance use in adults and adolescents and for autism and behavioral issues in children.8

The ACA provides further expansion and enforcement of mental health parity. In 2008, the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act was passed with the intent of providing behavioral health benefits at the same level as medical care. Although this law was beneficial in theory, it did not require insurers to cover behavioral health treatment. Rather, it only required parity if large group plans already provided behavioral health coverage; parity laws did not apply to individual or small group plans. The Essential Health Benefits of the ACA specify that insurers must provide mental health and substance use treatment. Essentially, the ACA gave the parity law teeth. The law would matter very little if low-income patients, who often suffer from mental health symptoms, have no insurance coverage.

Perhaps more concerning are the implications for those battling substance use disorders. If the ACA is repealed without appropriate replacement measures, it is unclear how those with limited income or preexisting substance use disorders would access evidence-based treatment.

Opioid use disorder affects >2 million individuals in the United States and caused 33,000 overdose deaths in 2015.9 The Opioid Initiative, established in 2015 by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), has worked to improve prescribing practices, increase use of naloxone to treat overdose, and expand access to medication-assisted treatment and psychosocial support. The success of this initiative relies on accessible health insurance coverage. Medication-assisted treatment and psychosocial support services would be threatened most by repeal of the ACA.9 In 2016, the HHS provided $94 million in grants, through the ACA, for free clinics to screen and treat patients for substance use disorders.10 Continued funding for these programs would be jeopardized if the ACA was repealed without replacement.

Repair rather than replace

The ACA is not without its flaws, but perhaps the best approach is to build on its successes while repairing its weaknesses. Researcher Peter Phalen, MA, looked at changes in rates, usage, affordability, and satisfaction with services for those with moderate and severe mental illness after implementation of the ACA.11 Using a nationally representative sample (N = 35,602), he discovered that those with moderate mental illness, as measured by psychological distress scales, experienced greater gains in finding affordable coverage than those without mental illness.11 However, individuals with severe mental illness showed no improvement on these measures, with the exception of increased satisfaction with current coverage and care. There were no reported increases in health care use or affordability for either group.11

Although the ACA requires prescription coverage, there is no regulation of what insurers choose to include in their formularies, and often brand name drugs, particularly antipsychotics, are not covered. The National Alliance on Mental Illness released a report in 2015 noting that, even with the ACA, individuals continue to experience difficulty accessing behavioral health providers in a timely manner, especially in rural areas. The report also described a lack of parity enforcement for behavioral health coverage.12

What if?

If the ACA is repealed, other legislative acts could continue, in some way, to address the needs of those with mental illness. The 21st Century Cures Act, which has bipartisan support, was passed in 2016 in the hope of reforming national mental health care. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) president, Maria Oquendo, MD, PhD, indicated that the bill enhances parity laws and provides better coordination for national agencies involved in treating psychiatric illness.13 The APA applauded this effort and highlighted these provisions:

- reauthorizing grants to support integrated care models

- reauthorizing grants to train school staff to identify students who need mental health care

- requiring the HHS to develop a plan to enforce parity laws

- providing $1 billion in state grants to address the opioid epidemic.13

The APA has voiced its concern about repealing the ACA without replacement. The APA issued a letter to Congressional leadership stating the organization’s concerns, emphasizing that current law has eased the burden for Americans to access “appropriate and evidence-based mental health care.”14 The APA requested that, in considering reforms to health care law, Congress does not “undo the gains which have been made over the past several years for individuals with mental illness.”14 The APA noted that the proposed ACA replacement bill, released on March 3, 2017, would “negatively impact care for people with mental illness and substance use disorders.”15

Since the ACA was implemented, we have taken for granted many provisions as permanent fixtures of our nation’s health care system. Who now can imagine a denial of coverage for a preexisting condition? How many young adults are ready to purchase their own insurance plans immediately after high school or college if employment is not readily available? Is it reasonable that an insurance plan does not provide prescription coverage or behavioral health services? How will those with mental illness or substance use disorders have reliable access to assessment and treatment?

Repealing, replacing, or enhancing the ACA is a complicated balancing act. We must be vigilant and vocal in asking Congress to continue considering the needs of those with mental illness and substance use disorders.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 20 million people have gained health insurance coverage because of the Affordable Care Act, new estimates show. http://wayback.archive-it.org/3926/20170127190440/https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2016/03/03/20-million-people-have-gained-health-insurance-coverage-because-affordable-care-act-new-estimates. Published March 16, 2016. Accessed February 15, 2017.

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Health insurance coverage for Americans with pre-existing conditions: the impact of the Affordable Care Act. https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/health-insurance-coverage-americans-pre-existing-conditions-impact-affordable-care-act. Published January 5, 2017. Accessed February 20, 2017.

3. National Alliance on Mental Illness. Mental health by the numbers. http://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-By-the-Numbers. Accessed February 20, 2017.

4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Essential health benefits: individual market place. https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/essential-health-benefits-individual-market-coverage. Published December 16, 2011. Accessed February 18, 2017.

5. Cohen R, Zammitti EP. Access to care among adults aged 18-64 with serious psychological distress: early release of estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2012-September 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/er_spd_access_2015_f_auer.pdf. Published May 2016. Accessed February 1, 2017.

6. Rowan K, McAlpine DD, Blewett LA. Access and cost barriers to mental health care by insurance status, 1999-2010. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(10):1723-1730.

7. Health Pocket. Almost no existing health plans meet new ACA essential health benefit standards. https://www.healthpocket.com/healthcare-research/infostat/few-existing-health-plans-meet-new-aca-essential-health-benefit-standards/#.WLSSdqPMxmC. Published March 7, 2013. Accessed February 20, 2017.

8. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Health benefits and coverage: preventive health services. https://www.healthcare.gov/coverage/preventive-care-benefits. Accessed February 26, 2017.

9. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Continuing progress on the opioid epidemic: the role of the Affordable Care Act. https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/continuing-progress-opioid-epidemic-role-affordable-care-act. Published January 11, 2017. Accessed February 15, 2017.

10. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. HHS awards 94 million to health centers help treat the prescription opioid abuse and heroin epidemic in America. http://wayback.archive-it.org/3926/20170127185615/https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2016/03/11/hhs-awards-94-million-to-health-centers.html. Published March 11, 2016. Accessed February 1, 2017.

11. Phalen P. Psychological distress and rates of health insurance coverage and use and affordability of mental health services, 2013-2014 [published online December 15, 2016]. Psychiatr Serv. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201500544.

12. National Alliance on Mental Illness. A long road ahead: achieving true parity in mental health and substance use care. https://www.nami.org/About-NAMI/Publications-Reports/Public-Policy-Reports/A-Long-Road-Ahead/2015-ALongRoadAhead.pdf. Published April 2015. Accessed February 15, 2017.

13. American Psychiatric Association. APA commends house for approving mental health reform bill. https://www.psychiatry.org/newsroom/news-releases/apa-commends-house-for-approving-mental-health-reform-bill?_ga=1.239819267.1833283241.1466442827. Published November 30, 2016. Accessed February 26, 2017.

14. American Psychiatric Association. APA calls on Congress to protect patient access to healthcare. https://www.psychiatry.org/newsroom/news-releases/apa-calls-on-congress-to-protect-patient-access-to-health-care?_ga=1.240843011.1833283241.1466442827. Published January 5, 2017. Accessed February 15, 2017.

15. American Psychiatric Association. APA concerned about proposed ACA replacement bill. https://www.psychiatry.org/newsroom/news-releases/apa-concerned-about-proposed-aca-replacement-bill. Published March 7, 2017. Accessed March 17, 2017.

With the changing political landscape in Washington, there has been much talk about health care in the United States. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) is at risk for repeal or, at least, substantial change. As the debate heats up, many psychiatric clinicians wonder what repeal could mean for mental health care and treatment of substance use disorders.

To examine this issue, we need to understand what the ACA has accomplished so far. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act—known as “Obamacare”—was enacted on March 23, 2010. From 2010 to 2014, various provisions were implemented; more provisions are slated for completion by 2017 if the law remains in place. These provisions are at the heart of how those with mental illness or substance use disorders could be affected by repeal of the ACA.

Since the ACA’s implementation, an estimated 20 million Americans have gained health insurance.1 The ACA includes several provisions that made this number possible, such as the expansion of Medicaid in some states. In addition to plans offered through the Health Insurance Marketplace, private insurers are required to provide insurance to some who previously fell into non-coverage gaps.1 Young adults can remain on a parent’s plan until age 26, which is significant to mental health care because many psychiatric disorders emerge in young adulthood, and this age group is vulnerable to developing substance use disorders.

The ACA also requires private insurance plans to cover those with preexisting health conditions. This has been crucial for persons with mental illness because before the ACA, mental health disorders were the second most common preexisting condition that precipitated either an increase in the cost of a plan or coverage denial.2

These provisions have helped ensure coverage for the approximately 20% of adults in the United States who have a mental illness.3 Before the ACA, 18% of individuals who purchased their own insurance did not have mental health coverage, and more than one-third of insurers did not cover substance use disorders.4 According to the CDC, the uninsured rate for those with serious mental health disorders fell from 28.1% in 2012 to 19.5% in 2015.5 Likewise, the number of adults with mental illness who could not afford needed care decreased during the same years.5 A University of Minnesota study found that persons with mental illness are disproportionately represented among the uninsured.6 Before the ACA, 18% of individual health plans did not cover prescriptions, including those indicated for psychiatric illness.7 Simply put, the ACA has allowed people to seek assessment and treatment for mental health, whereas it would not have been as accessible before the legislation.

What does the ACA cover?

The ACA required health plans to cover Essential Health Benefits starting January 1, 2014. These include:

- medical services such as doctor visits

- emergency and urgent care services

- hospital physician and facility services

- prenatal, delivery, and postnatal care

- evaluation and treatment of mental health conditions

- services to address substance use including behavioral health treatment

- coverage of prescription medications

- rehabilitation services

- diagnostic tests and imaging

- preventive and wellness care and management of chronic diseases

- pediatric care.

As of March 2013, only 2% of existing health plans in the United States provided all of these benefits required by the ACA.7

Required coverage of mental health care and substance use disorders increases patient access to those services. Including preventive care extends the reach of mental health screening to primary care providers, who can screen for mood disorders and substance use in adults and adolescents and for autism and behavioral issues in children.8

The ACA provides further expansion and enforcement of mental health parity. In 2008, the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act was passed with the intent of providing behavioral health benefits at the same level as medical care. Although this law was beneficial in theory, it did not require insurers to cover behavioral health treatment. Rather, it only required parity if large group plans already provided behavioral health coverage; parity laws did not apply to individual or small group plans. The Essential Health Benefits of the ACA specify that insurers must provide mental health and substance use treatment. Essentially, the ACA gave the parity law teeth. The law would matter very little if low-income patients, who often suffer from mental health symptoms, have no insurance coverage.

Perhaps more concerning are the implications for those battling substance use disorders. If the ACA is repealed without appropriate replacement measures, it is unclear how those with limited income or preexisting substance use disorders would access evidence-based treatment.

Opioid use disorder affects >2 million individuals in the United States and caused 33,000 overdose deaths in 2015.9 The Opioid Initiative, established in 2015 by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), has worked to improve prescribing practices, increase use of naloxone to treat overdose, and expand access to medication-assisted treatment and psychosocial support. The success of this initiative relies on accessible health insurance coverage. Medication-assisted treatment and psychosocial support services would be threatened most by repeal of the ACA.9 In 2016, the HHS provided $94 million in grants, through the ACA, for free clinics to screen and treat patients for substance use disorders.10 Continued funding for these programs would be jeopardized if the ACA was repealed without replacement.

Repair rather than replace

The ACA is not without its flaws, but perhaps the best approach is to build on its successes while repairing its weaknesses. Researcher Peter Phalen, MA, looked at changes in rates, usage, affordability, and satisfaction with services for those with moderate and severe mental illness after implementation of the ACA.11 Using a nationally representative sample (N = 35,602), he discovered that those with moderate mental illness, as measured by psychological distress scales, experienced greater gains in finding affordable coverage than those without mental illness.11 However, individuals with severe mental illness showed no improvement on these measures, with the exception of increased satisfaction with current coverage and care. There were no reported increases in health care use or affordability for either group.11

Although the ACA requires prescription coverage, there is no regulation of what insurers choose to include in their formularies, and often brand name drugs, particularly antipsychotics, are not covered. The National Alliance on Mental Illness released a report in 2015 noting that, even with the ACA, individuals continue to experience difficulty accessing behavioral health providers in a timely manner, especially in rural areas. The report also described a lack of parity enforcement for behavioral health coverage.12

What if?

If the ACA is repealed, other legislative acts could continue, in some way, to address the needs of those with mental illness. The 21st Century Cures Act, which has bipartisan support, was passed in 2016 in the hope of reforming national mental health care. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) president, Maria Oquendo, MD, PhD, indicated that the bill enhances parity laws and provides better coordination for national agencies involved in treating psychiatric illness.13 The APA applauded this effort and highlighted these provisions:

- reauthorizing grants to support integrated care models

- reauthorizing grants to train school staff to identify students who need mental health care

- requiring the HHS to develop a plan to enforce parity laws

- providing $1 billion in state grants to address the opioid epidemic.13

The APA has voiced its concern about repealing the ACA without replacement. The APA issued a letter to Congressional leadership stating the organization’s concerns, emphasizing that current law has eased the burden for Americans to access “appropriate and evidence-based mental health care.”14 The APA requested that, in considering reforms to health care law, Congress does not “undo the gains which have been made over the past several years for individuals with mental illness.”14 The APA noted that the proposed ACA replacement bill, released on March 3, 2017, would “negatively impact care for people with mental illness and substance use disorders.”15

Since the ACA was implemented, we have taken for granted many provisions as permanent fixtures of our nation’s health care system. Who now can imagine a denial of coverage for a preexisting condition? How many young adults are ready to purchase their own insurance plans immediately after high school or college if employment is not readily available? Is it reasonable that an insurance plan does not provide prescription coverage or behavioral health services? How will those with mental illness or substance use disorders have reliable access to assessment and treatment?

Repealing, replacing, or enhancing the ACA is a complicated balancing act. We must be vigilant and vocal in asking Congress to continue considering the needs of those with mental illness and substance use disorders.

With the changing political landscape in Washington, there has been much talk about health care in the United States. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) is at risk for repeal or, at least, substantial change. As the debate heats up, many psychiatric clinicians wonder what repeal could mean for mental health care and treatment of substance use disorders.

To examine this issue, we need to understand what the ACA has accomplished so far. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act—known as “Obamacare”—was enacted on March 23, 2010. From 2010 to 2014, various provisions were implemented; more provisions are slated for completion by 2017 if the law remains in place. These provisions are at the heart of how those with mental illness or substance use disorders could be affected by repeal of the ACA.

Since the ACA’s implementation, an estimated 20 million Americans have gained health insurance.1 The ACA includes several provisions that made this number possible, such as the expansion of Medicaid in some states. In addition to plans offered through the Health Insurance Marketplace, private insurers are required to provide insurance to some who previously fell into non-coverage gaps.1 Young adults can remain on a parent’s plan until age 26, which is significant to mental health care because many psychiatric disorders emerge in young adulthood, and this age group is vulnerable to developing substance use disorders.

The ACA also requires private insurance plans to cover those with preexisting health conditions. This has been crucial for persons with mental illness because before the ACA, mental health disorders were the second most common preexisting condition that precipitated either an increase in the cost of a plan or coverage denial.2

These provisions have helped ensure coverage for the approximately 20% of adults in the United States who have a mental illness.3 Before the ACA, 18% of individuals who purchased their own insurance did not have mental health coverage, and more than one-third of insurers did not cover substance use disorders.4 According to the CDC, the uninsured rate for those with serious mental health disorders fell from 28.1% in 2012 to 19.5% in 2015.5 Likewise, the number of adults with mental illness who could not afford needed care decreased during the same years.5 A University of Minnesota study found that persons with mental illness are disproportionately represented among the uninsured.6 Before the ACA, 18% of individual health plans did not cover prescriptions, including those indicated for psychiatric illness.7 Simply put, the ACA has allowed people to seek assessment and treatment for mental health, whereas it would not have been as accessible before the legislation.

What does the ACA cover?

The ACA required health plans to cover Essential Health Benefits starting January 1, 2014. These include:

- medical services such as doctor visits

- emergency and urgent care services

- hospital physician and facility services

- prenatal, delivery, and postnatal care

- evaluation and treatment of mental health conditions

- services to address substance use including behavioral health treatment

- coverage of prescription medications

- rehabilitation services

- diagnostic tests and imaging

- preventive and wellness care and management of chronic diseases

- pediatric care.

As of March 2013, only 2% of existing health plans in the United States provided all of these benefits required by the ACA.7

Required coverage of mental health care and substance use disorders increases patient access to those services. Including preventive care extends the reach of mental health screening to primary care providers, who can screen for mood disorders and substance use in adults and adolescents and for autism and behavioral issues in children.8

The ACA provides further expansion and enforcement of mental health parity. In 2008, the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act was passed with the intent of providing behavioral health benefits at the same level as medical care. Although this law was beneficial in theory, it did not require insurers to cover behavioral health treatment. Rather, it only required parity if large group plans already provided behavioral health coverage; parity laws did not apply to individual or small group plans. The Essential Health Benefits of the ACA specify that insurers must provide mental health and substance use treatment. Essentially, the ACA gave the parity law teeth. The law would matter very little if low-income patients, who often suffer from mental health symptoms, have no insurance coverage.

Perhaps more concerning are the implications for those battling substance use disorders. If the ACA is repealed without appropriate replacement measures, it is unclear how those with limited income or preexisting substance use disorders would access evidence-based treatment.

Opioid use disorder affects >2 million individuals in the United States and caused 33,000 overdose deaths in 2015.9 The Opioid Initiative, established in 2015 by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), has worked to improve prescribing practices, increase use of naloxone to treat overdose, and expand access to medication-assisted treatment and psychosocial support. The success of this initiative relies on accessible health insurance coverage. Medication-assisted treatment and psychosocial support services would be threatened most by repeal of the ACA.9 In 2016, the HHS provided $94 million in grants, through the ACA, for free clinics to screen and treat patients for substance use disorders.10 Continued funding for these programs would be jeopardized if the ACA was repealed without replacement.

Repair rather than replace

The ACA is not without its flaws, but perhaps the best approach is to build on its successes while repairing its weaknesses. Researcher Peter Phalen, MA, looked at changes in rates, usage, affordability, and satisfaction with services for those with moderate and severe mental illness after implementation of the ACA.11 Using a nationally representative sample (N = 35,602), he discovered that those with moderate mental illness, as measured by psychological distress scales, experienced greater gains in finding affordable coverage than those without mental illness.11 However, individuals with severe mental illness showed no improvement on these measures, with the exception of increased satisfaction with current coverage and care. There were no reported increases in health care use or affordability for either group.11

Although the ACA requires prescription coverage, there is no regulation of what insurers choose to include in their formularies, and often brand name drugs, particularly antipsychotics, are not covered. The National Alliance on Mental Illness released a report in 2015 noting that, even with the ACA, individuals continue to experience difficulty accessing behavioral health providers in a timely manner, especially in rural areas. The report also described a lack of parity enforcement for behavioral health coverage.12

What if?

If the ACA is repealed, other legislative acts could continue, in some way, to address the needs of those with mental illness. The 21st Century Cures Act, which has bipartisan support, was passed in 2016 in the hope of reforming national mental health care. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) president, Maria Oquendo, MD, PhD, indicated that the bill enhances parity laws and provides better coordination for national agencies involved in treating psychiatric illness.13 The APA applauded this effort and highlighted these provisions:

- reauthorizing grants to support integrated care models

- reauthorizing grants to train school staff to identify students who need mental health care

- requiring the HHS to develop a plan to enforce parity laws

- providing $1 billion in state grants to address the opioid epidemic.13

The APA has voiced its concern about repealing the ACA without replacement. The APA issued a letter to Congressional leadership stating the organization’s concerns, emphasizing that current law has eased the burden for Americans to access “appropriate and evidence-based mental health care.”14 The APA requested that, in considering reforms to health care law, Congress does not “undo the gains which have been made over the past several years for individuals with mental illness.”14 The APA noted that the proposed ACA replacement bill, released on March 3, 2017, would “negatively impact care for people with mental illness and substance use disorders.”15

Since the ACA was implemented, we have taken for granted many provisions as permanent fixtures of our nation’s health care system. Who now can imagine a denial of coverage for a preexisting condition? How many young adults are ready to purchase their own insurance plans immediately after high school or college if employment is not readily available? Is it reasonable that an insurance plan does not provide prescription coverage or behavioral health services? How will those with mental illness or substance use disorders have reliable access to assessment and treatment?

Repealing, replacing, or enhancing the ACA is a complicated balancing act. We must be vigilant and vocal in asking Congress to continue considering the needs of those with mental illness and substance use disorders.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 20 million people have gained health insurance coverage because of the Affordable Care Act, new estimates show. http://wayback.archive-it.org/3926/20170127190440/https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2016/03/03/20-million-people-have-gained-health-insurance-coverage-because-affordable-care-act-new-estimates. Published March 16, 2016. Accessed February 15, 2017.

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Health insurance coverage for Americans with pre-existing conditions: the impact of the Affordable Care Act. https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/health-insurance-coverage-americans-pre-existing-conditions-impact-affordable-care-act. Published January 5, 2017. Accessed February 20, 2017.

3. National Alliance on Mental Illness. Mental health by the numbers. http://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-By-the-Numbers. Accessed February 20, 2017.

4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Essential health benefits: individual market place. https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/essential-health-benefits-individual-market-coverage. Published December 16, 2011. Accessed February 18, 2017.

5. Cohen R, Zammitti EP. Access to care among adults aged 18-64 with serious psychological distress: early release of estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2012-September 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/er_spd_access_2015_f_auer.pdf. Published May 2016. Accessed February 1, 2017.

6. Rowan K, McAlpine DD, Blewett LA. Access and cost barriers to mental health care by insurance status, 1999-2010. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(10):1723-1730.

7. Health Pocket. Almost no existing health plans meet new ACA essential health benefit standards. https://www.healthpocket.com/healthcare-research/infostat/few-existing-health-plans-meet-new-aca-essential-health-benefit-standards/#.WLSSdqPMxmC. Published March 7, 2013. Accessed February 20, 2017.

8. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Health benefits and coverage: preventive health services. https://www.healthcare.gov/coverage/preventive-care-benefits. Accessed February 26, 2017.

9. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Continuing progress on the opioid epidemic: the role of the Affordable Care Act. https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/continuing-progress-opioid-epidemic-role-affordable-care-act. Published January 11, 2017. Accessed February 15, 2017.

10. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. HHS awards 94 million to health centers help treat the prescription opioid abuse and heroin epidemic in America. http://wayback.archive-it.org/3926/20170127185615/https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2016/03/11/hhs-awards-94-million-to-health-centers.html. Published March 11, 2016. Accessed February 1, 2017.

11. Phalen P. Psychological distress and rates of health insurance coverage and use and affordability of mental health services, 2013-2014 [published online December 15, 2016]. Psychiatr Serv. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201500544.

12. National Alliance on Mental Illness. A long road ahead: achieving true parity in mental health and substance use care. https://www.nami.org/About-NAMI/Publications-Reports/Public-Policy-Reports/A-Long-Road-Ahead/2015-ALongRoadAhead.pdf. Published April 2015. Accessed February 15, 2017.

13. American Psychiatric Association. APA commends house for approving mental health reform bill. https://www.psychiatry.org/newsroom/news-releases/apa-commends-house-for-approving-mental-health-reform-bill?_ga=1.239819267.1833283241.1466442827. Published November 30, 2016. Accessed February 26, 2017.

14. American Psychiatric Association. APA calls on Congress to protect patient access to healthcare. https://www.psychiatry.org/newsroom/news-releases/apa-calls-on-congress-to-protect-patient-access-to-health-care?_ga=1.240843011.1833283241.1466442827. Published January 5, 2017. Accessed February 15, 2017.

15. American Psychiatric Association. APA concerned about proposed ACA replacement bill. https://www.psychiatry.org/newsroom/news-releases/apa-concerned-about-proposed-aca-replacement-bill. Published March 7, 2017. Accessed March 17, 2017.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 20 million people have gained health insurance coverage because of the Affordable Care Act, new estimates show. http://wayback.archive-it.org/3926/20170127190440/https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2016/03/03/20-million-people-have-gained-health-insurance-coverage-because-affordable-care-act-new-estimates. Published March 16, 2016. Accessed February 15, 2017.

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Health insurance coverage for Americans with pre-existing conditions: the impact of the Affordable Care Act. https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/health-insurance-coverage-americans-pre-existing-conditions-impact-affordable-care-act. Published January 5, 2017. Accessed February 20, 2017.

3. National Alliance on Mental Illness. Mental health by the numbers. http://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-By-the-Numbers. Accessed February 20, 2017.

4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Essential health benefits: individual market place. https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/essential-health-benefits-individual-market-coverage. Published December 16, 2011. Accessed February 18, 2017.

5. Cohen R, Zammitti EP. Access to care among adults aged 18-64 with serious psychological distress: early release of estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2012-September 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/er_spd_access_2015_f_auer.pdf. Published May 2016. Accessed February 1, 2017.

6. Rowan K, McAlpine DD, Blewett LA. Access and cost barriers to mental health care by insurance status, 1999-2010. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(10):1723-1730.

7. Health Pocket. Almost no existing health plans meet new ACA essential health benefit standards. https://www.healthpocket.com/healthcare-research/infostat/few-existing-health-plans-meet-new-aca-essential-health-benefit-standards/#.WLSSdqPMxmC. Published March 7, 2013. Accessed February 20, 2017.

8. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Health benefits and coverage: preventive health services. https://www.healthcare.gov/coverage/preventive-care-benefits. Accessed February 26, 2017.

9. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Continuing progress on the opioid epidemic: the role of the Affordable Care Act. https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/continuing-progress-opioid-epidemic-role-affordable-care-act. Published January 11, 2017. Accessed February 15, 2017.

10. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. HHS awards 94 million to health centers help treat the prescription opioid abuse and heroin epidemic in America. http://wayback.archive-it.org/3926/20170127185615/https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2016/03/11/hhs-awards-94-million-to-health-centers.html. Published March 11, 2016. Accessed February 1, 2017.

11. Phalen P. Psychological distress and rates of health insurance coverage and use and affordability of mental health services, 2013-2014 [published online December 15, 2016]. Psychiatr Serv. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201500544.

12. National Alliance on Mental Illness. A long road ahead: achieving true parity in mental health and substance use care. https://www.nami.org/About-NAMI/Publications-Reports/Public-Policy-Reports/A-Long-Road-Ahead/2015-ALongRoadAhead.pdf. Published April 2015. Accessed February 15, 2017.

13. American Psychiatric Association. APA commends house for approving mental health reform bill. https://www.psychiatry.org/newsroom/news-releases/apa-commends-house-for-approving-mental-health-reform-bill?_ga=1.239819267.1833283241.1466442827. Published November 30, 2016. Accessed February 26, 2017.

14. American Psychiatric Association. APA calls on Congress to protect patient access to healthcare. https://www.psychiatry.org/newsroom/news-releases/apa-calls-on-congress-to-protect-patient-access-to-health-care?_ga=1.240843011.1833283241.1466442827. Published January 5, 2017. Accessed February 15, 2017.

15. American Psychiatric Association. APA concerned about proposed ACA replacement bill. https://www.psychiatry.org/newsroom/news-releases/apa-concerned-about-proposed-aca-replacement-bill. Published March 7, 2017. Accessed March 17, 2017.

Advancing the role of advanced practice psychiatric nurses in today’s psychiatric workforce

The number of psychiatric prescribers per capita is at one of the lowest levels in history.1 Approximately 43.4 million persons (17.9%) in the United States have a diagnosable mental illness2; 9.8 million (4%) are diagnosed with a serious and persistent mental illness, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder (these figures do not include substance use disorders).3

Of the 45,000 licensed psychiatrists, approximately 25,000 are in active practice.4 By comparison, there are approximately 19,000 practicing licensed psychiatric advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs).5 Annually, approximately 1,300 physicians graduate from psychiatric residency programs6 and 700 APRNs from master’s or Doctor of Nursing Practice programs.7 Combining the 2 prescribing workforces (44,000) yields a ratio of 986 patients per licensed prescriber. Seeing each patient only once every 2 months would equate to 25 patients daily considering a 5-day work week. Recognizing that some patients need much more frequent follow-up, this is an impossible task even if these providers and patients were dispersed uniformly across the United States. Currently, ratios are calculated based on the number of psychiatrists per 100,000 individuals, which in the United States is 16.8 Most psychiatrists practice in urban areas,9 whereas psychiatric nurse practitioners are found primarily in rural and less populated urban areas.10

Who can provide care?

Although the growing number of psychiatric APRNs is encouraging for the mental health workforce, their limited role and function remain a battle in the 27 states that do not grant full practice authority. This dispute has become so contentious that the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has stated that the debate over scope of practice represents federal restraint of trade,11 while patients and their families suffer from lack of access to care.

Recognizing that 9 million patients age <65 who were enrolled in Medicaid in 2011 and treated for a mental health disorder (20% of enrollees) accounted for 50% of all Medicaid expenditures prompts the question, “Who is treating these patients?” According to the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 75% of nurse practitioners accept and treat both Medicaid and Medicare patients compared with 43% of psychiatrists who accepted Medicaid and 54% who accepted Medicare in 2011 (these numbers do not include potential overlap).12

Who are APRNs?

The first master’s degree in nursing was created by Hildegard Peplau, EdD, at Rutgers University in 1954, using the title Clinical Specialist in Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing (PMH-CNS). As a master’s prepared clinician, the PMH-CNS could function independently, and many chose to open private practices. Other universities began to create clinical specialty programs in a variety of disciplines. In 1996, 41 states granted prescriptive authority to the PMH-CNS. Psychiatric nurse practitioners were first certified in 2000 to meet the statutory requirements for prescriptive authority of the other 9 states. However this created 4 PMH-APRN roles: Adult and Child/Adolescent CNS and Adult and Family PMHNPs.

Clinical specialists in most areas of health care—except for psychiatry—were primarily working in institutional settings, whereas nurse practitioners were hired principally in primary care community-based settings. The public grew familiar with the term “nurse practitioner,” but these professionals functioned primarily under institutional protocols, while the PMH-CNS had the ability to practice independently. In the mid-1990s, the 4 advanced practice nursing roles of nurse midwife, nurse anesthetist, nurse practitioner, and clinical nurse specialist were encompassed under 1 title: APRN. In 2010 the American Psychiatric Nurses Association endorsed one title for the psychiatric mental health advanced practice registered nurse (PMH-APRN), the psychiatric nurse practitioner, to be educated across the lifespan.

Today, the title PMH-APRN encompasses both the PMHNP and PMH-CNS; the majority specialize in the adult population.

Licensure, accreditation, certification, and education

In 2008, after several years of heated debate among members of >70 nursing organizations, a consensus model governing advanced practice nursing was ratified. This document outlined requirements for licensure, accreditation, certification, and education of the 4 primary advanced practice nursing roles.13 According to the model, the 4 nursing roles would address 1 of 6 major patient populations: neonatal, pediatric, adult-geriatric, family, women’s health/gender-related, and psychiatric. Licensure in each state would be converted to APRN from the existing 26 titles. Each student would have to graduate from a nationally accredited program. In addition to health promotion and advanced roles, educational programs would be required to include advanced courses in pathophysiology, pharmacotherapeutics, and physicalassessment as well as population-specific courses in these same categories. In addition, supervised clinical hour minimums were established for the various population-specific programs.

Concomitantly, graduate educational programs were wrestling with the 2005 statement from the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) that all advanced practice nursing education should be at the doctoral level by 2015. Because of the knowledge explosion, nurses needed more than what could be achieved in a master’s program to meet practice requirements as well as leadership, systems evaluation, quality improvement, research, and program development. Currently, there are 264 Doctor of Nursing Practice programs in the United States with less than one-half having a PMHNP program.14

Nursing education at the collegiate level has been evolving, which is fostered and supported by the 2010 Institute of Medicine (IOM) Report on the Future of Nursing that identified 4 key recommendations to promote a workforce at capacity to help care for our nation’s growing population:

- Remove scope of practice barriers

- Expand opportunities for nurses to lead and diffuse collaborative improvement efforts

- Implement nurse residency programs

- Increase the proportion of nurses with a baccalaureate degree to 80% by 2020.

The current status of advanced practice nursing

Each of the 50 states is in varying levels of compliance with the 2015 mandates from the consensus model and the AACN. From the psychiatric workforce perspective, many state boards of nursing are concerned because titles often are linked to legislative statute or rules. Despite the 2010 IOM recommendations and the FTC, the American Medical Association (AMA) has stationed AMA lobbyists in the legislatures that are poised to open the nurse practice act to comply with the consensus model. The sole purpose of these lobbyists is to block independent practice for APRNs in the 26 states that are seeking this status and to remove independent practice from the states where it already exists. For example, in Washington the title is ARNP but to change it to APRN will require opening the state’s legislative action. The AMA is eager to remove the autonomy that has existed in that state since 1978. One of the reasons is because where the APRN is required to be in a collaborative or supervisory relationship with a physician, the physician can charge the APRN to be compliant with state regulations. (In some states, the APRN cannot see patients or be on call if the collaborator is on vacation).

This has turned into a cottage industry for many physicians. However, there are many who do not charge because they are able to add additional patients to the practice by adding an APRN and generate more revenue. Others do not charge because they are supportive and committed to the APRN role.

Some thoughts about our mutual field

Can we move past the guild issue and come together to respect our given scopes of practice? I see psychiatry far ahead of the curve compared with APRNs in other specialties. The PMH-APRN is a highly educated nurse with a specific scope of practice that provides skilled psychiatric care (assessment, diagnosis, prescribing, psychotherapy) from a nursing perspective. Independent practice certainly does not imply that we do not collaborate with one another in a professional manner.

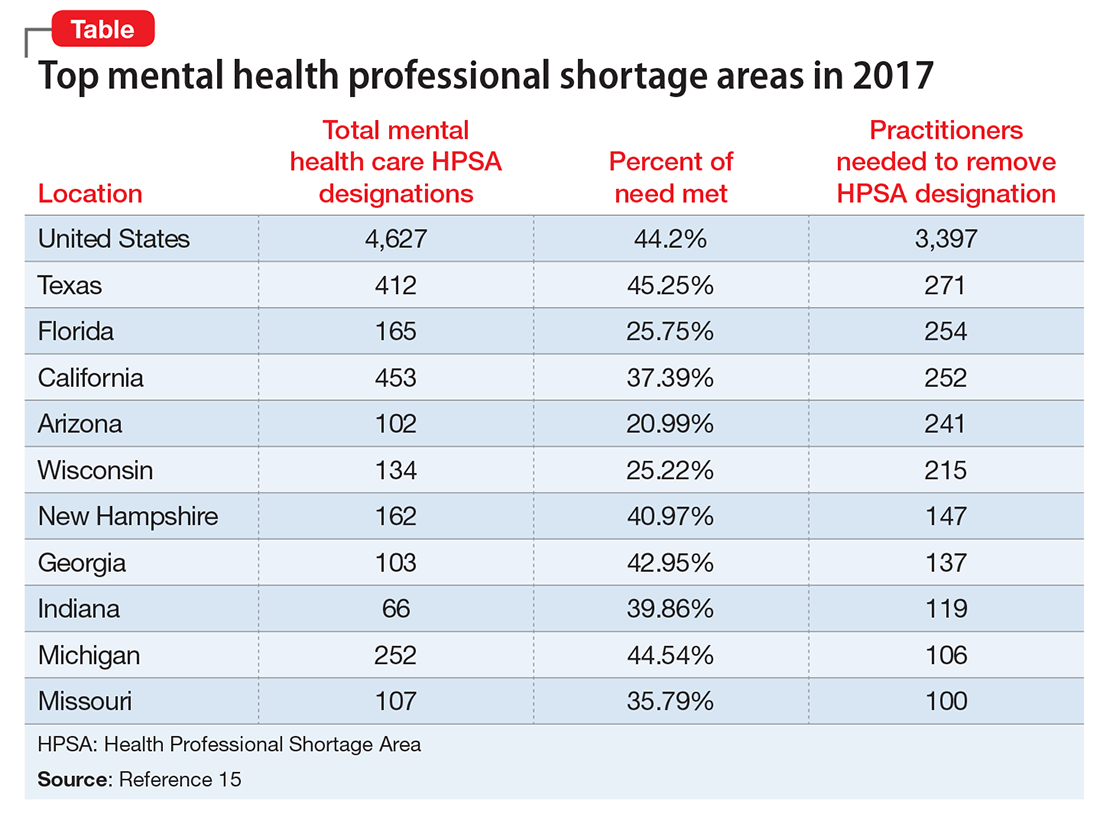

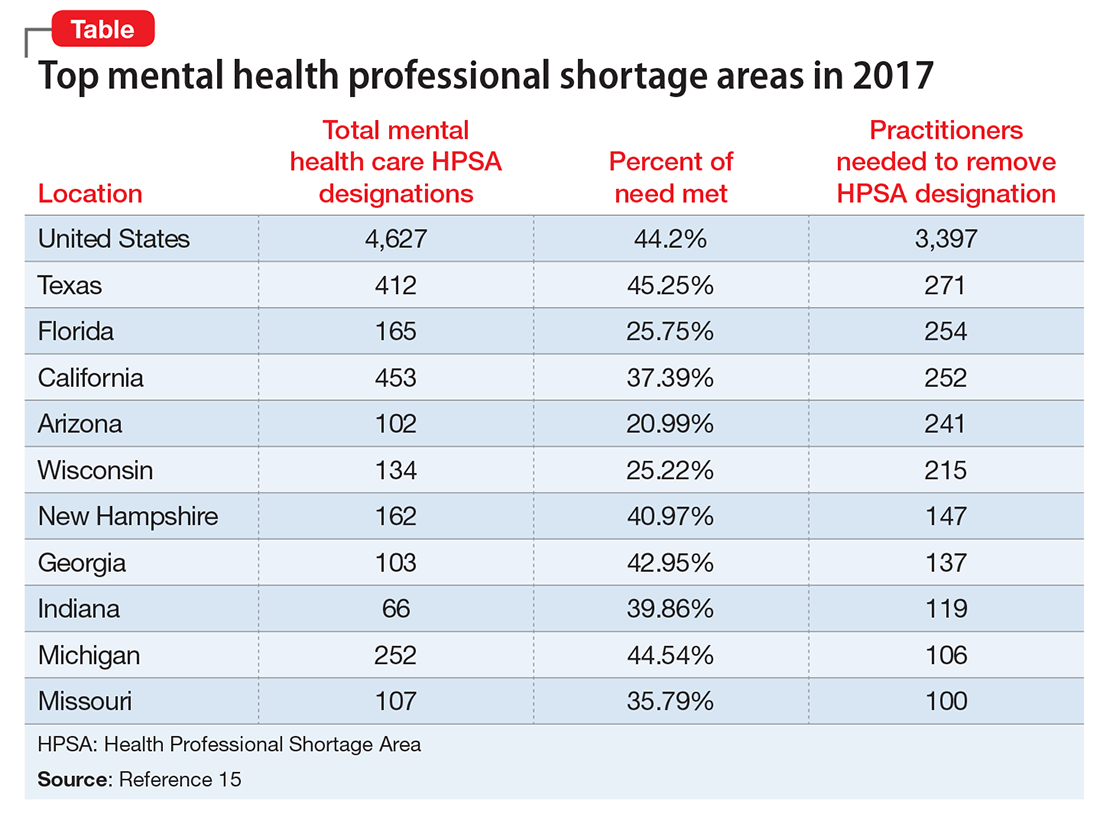

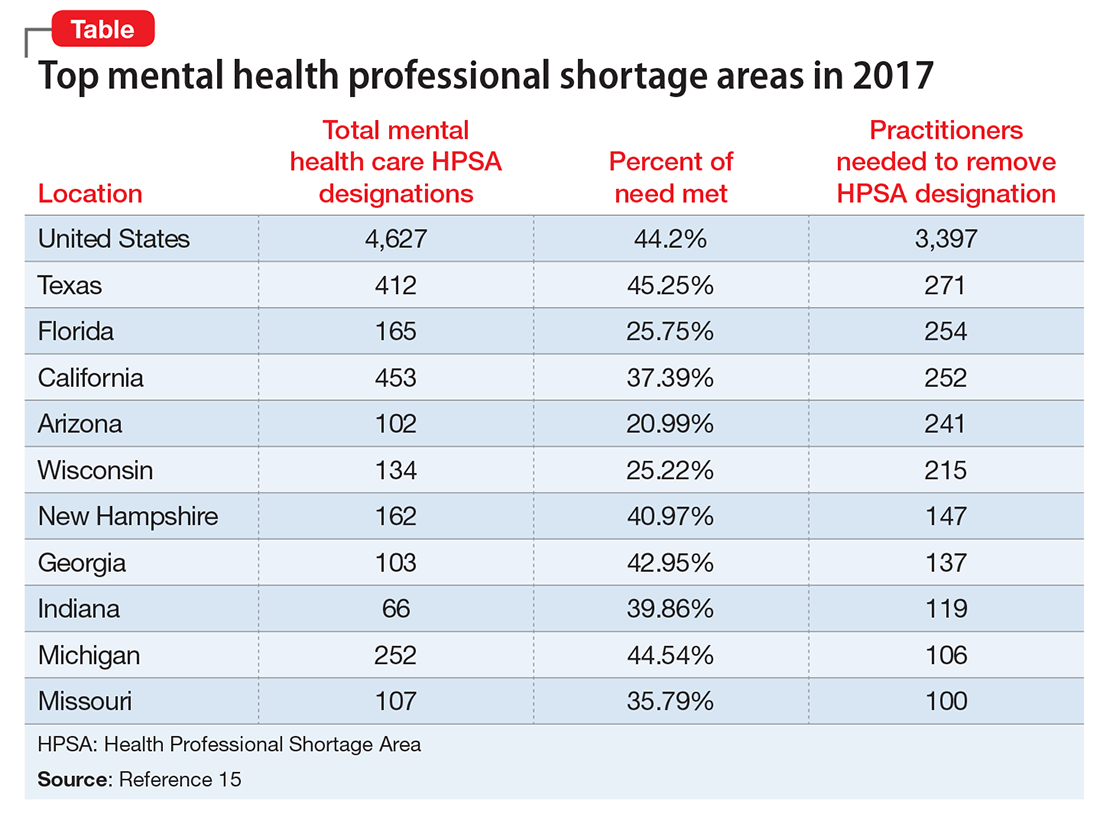

Mental Health Professional Shortage Areas

As of January 1, 2017, there are 4,627 Mental Health Professional Shortage Areas (MHPSA) in the United States and Territories (Table), which translates to only 44.2% of the need for psychiatric practitioners being met.15 To eliminate the designation of a MHSPA there must be a population to psychiatric provider ratio of at least 30,000 to 1 (20,000 to 1 if there are unusually high needs in the community). Currently 3,397 practitioners are needed to remove the designation across the United States. The state in most need of providers is Texas with 271 clinicians required to meet the need.

Considering that approximately 700 PMH-APRNs graduate each year16 and 1,317 psychiatry residents17 entered PGY-1 residency in 2016, it will be decades—or longer—before there are enough new providers to eliminate MHPSAs, particularly because the current workforce is aging (average age of the PMH-APRN is 55).

Because there are more than enough patients to go around, I encourage the APA to take a stand against the AMA and unite with the psychiatric APRNs to remove unnecessary barriers to practice and promote a unified and collegial workforce. This will transmit a strong message to the most underserved of our communities that psychiatrists and psychiatric nurse practitioners can emulate the therapeutic relationship by virtue of presenting a unified force. Imagine psychiatrists and psychiatric nurse practitioners going arm in arm to lobby county commissioners, state legislators, and Congressional Representatives and Senators. Together we could be a true force to be reckoned with.

1. Heisler EJ, Bagalman E. The mental health workforce: a primer. http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/key_workplace/1410. Published April 16, 2015. Accessed March 13, 2017.

2. National Institute of Mental Health. Any mental illness (AMI) among U.S. adults. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/prevalence/any-mental-illness-ami-among-us-adults.shtml. Accessed March 13, 2017.

3. National Institute of Mental Health. Serious mental illness (SMI) among U.S. adults. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/prevalence/serious-mental-illness-smi-among-us-adults.shtml. Accessed March 13, 2017.

4. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational employment and wages, May 2015. https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291066.htm. Updated March 30, 2016. Accessed March 13, 2017.

5. American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Program directory. http://www.aacn.nche.edu/dnp/program-directory. Accessed March 13, 2017.

7. Fang D, Li Y, Stauffer DC, et al. 2015-2016 Enrollment and graduations in baccalaureate and graduate programs in nursing. http://www.nonpf.org/resource/resmgr/docs/NPTables15-16.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed March 13, 2017.

8. Tasman A. Too few psychiatrists for too many. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/cultural-psychiatry/too-few-psychiatrists-too-many. Published April 16, 2015. Accessed March 15, 2017.

9. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National projections of supply and demand for selected behavioral health practitioners: 2013-2025. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/health-workforce-analysis/research/projections/behavioral-health2013-2025.pdf. Published November 2016. Accessed March 13, 2017.

10. Hanrahan NP, Hartley D. Employment of advanced-practice psychiatric nurses to stem rural mental health workforce shortages. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(1):109-111.

11. Koslov T. The doctor (or nurse practitioner) will see you now: competition and the regulation of advanced practice nurses. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/blogs/competition-matters/2014/03/doctor-or-nurse-practitioner-will-see-you-now. Published March 7, 2014. Accessed March 14, 2017.

12. Bishop TF, Press MJ, Keyhani S, et al. Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):176-181.

13. National Council of State Boards of Nursing. APRN consensus model. The consensus model for APRN regulation, licensure, accreditation, certification and education. https://www.ncsbn.org/736.htm. Accessed March 13, 2017.

14. National Council of State Boards of Nursing. APRN title map. NCSBN’s APRN campaign for consensus: State progress toward uniformity. https://www.ncsbn.org/5398.htm. Accessed March 13, 2017.

15. Kaiser Family Foundation. Mental health care health professional shortage areas (HPSAs). http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/mental-health-care-health-professional-shortage-areas-hpsas/?activeTab=map¤tTimeframe=0&selectedDistributions=total-mental-health-care-hpsa-designations&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D. Accessed March 13, 2017.

16. Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education. CCNE-Accredited Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) Programs. http://directory.ccnecommunity.org/reports/rptAccreditedPrograms_New.asp?sort=state&sProgramType=3. Accessed March 15, 2017.

17. National Residency Match Program. 2016 match results by state, specialty, and applicant type. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Main-Match-Results-by-State-and-Specialty-2016.pdf. Accessed March 13, 2017.

The number of psychiatric prescribers per capita is at one of the lowest levels in history.1 Approximately 43.4 million persons (17.9%) in the United States have a diagnosable mental illness2; 9.8 million (4%) are diagnosed with a serious and persistent mental illness, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder (these figures do not include substance use disorders).3

Of the 45,000 licensed psychiatrists, approximately 25,000 are in active practice.4 By comparison, there are approximately 19,000 practicing licensed psychiatric advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs).5 Annually, approximately 1,300 physicians graduate from psychiatric residency programs6 and 700 APRNs from master’s or Doctor of Nursing Practice programs.7 Combining the 2 prescribing workforces (44,000) yields a ratio of 986 patients per licensed prescriber. Seeing each patient only once every 2 months would equate to 25 patients daily considering a 5-day work week. Recognizing that some patients need much more frequent follow-up, this is an impossible task even if these providers and patients were dispersed uniformly across the United States. Currently, ratios are calculated based on the number of psychiatrists per 100,000 individuals, which in the United States is 16.8 Most psychiatrists practice in urban areas,9 whereas psychiatric nurse practitioners are found primarily in rural and less populated urban areas.10

Who can provide care?

Although the growing number of psychiatric APRNs is encouraging for the mental health workforce, their limited role and function remain a battle in the 27 states that do not grant full practice authority. This dispute has become so contentious that the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has stated that the debate over scope of practice represents federal restraint of trade,11 while patients and their families suffer from lack of access to care.

Recognizing that 9 million patients age <65 who were enrolled in Medicaid in 2011 and treated for a mental health disorder (20% of enrollees) accounted for 50% of all Medicaid expenditures prompts the question, “Who is treating these patients?” According to the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 75% of nurse practitioners accept and treat both Medicaid and Medicare patients compared with 43% of psychiatrists who accepted Medicaid and 54% who accepted Medicare in 2011 (these numbers do not include potential overlap).12

Who are APRNs?

The first master’s degree in nursing was created by Hildegard Peplau, EdD, at Rutgers University in 1954, using the title Clinical Specialist in Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing (PMH-CNS). As a master’s prepared clinician, the PMH-CNS could function independently, and many chose to open private practices. Other universities began to create clinical specialty programs in a variety of disciplines. In 1996, 41 states granted prescriptive authority to the PMH-CNS. Psychiatric nurse practitioners were first certified in 2000 to meet the statutory requirements for prescriptive authority of the other 9 states. However this created 4 PMH-APRN roles: Adult and Child/Adolescent CNS and Adult and Family PMHNPs.

Clinical specialists in most areas of health care—except for psychiatry—were primarily working in institutional settings, whereas nurse practitioners were hired principally in primary care community-based settings. The public grew familiar with the term “nurse practitioner,” but these professionals functioned primarily under institutional protocols, while the PMH-CNS had the ability to practice independently. In the mid-1990s, the 4 advanced practice nursing roles of nurse midwife, nurse anesthetist, nurse practitioner, and clinical nurse specialist were encompassed under 1 title: APRN. In 2010 the American Psychiatric Nurses Association endorsed one title for the psychiatric mental health advanced practice registered nurse (PMH-APRN), the psychiatric nurse practitioner, to be educated across the lifespan.

Today, the title PMH-APRN encompasses both the PMHNP and PMH-CNS; the majority specialize in the adult population.

Licensure, accreditation, certification, and education

In 2008, after several years of heated debate among members of >70 nursing organizations, a consensus model governing advanced practice nursing was ratified. This document outlined requirements for licensure, accreditation, certification, and education of the 4 primary advanced practice nursing roles.13 According to the model, the 4 nursing roles would address 1 of 6 major patient populations: neonatal, pediatric, adult-geriatric, family, women’s health/gender-related, and psychiatric. Licensure in each state would be converted to APRN from the existing 26 titles. Each student would have to graduate from a nationally accredited program. In addition to health promotion and advanced roles, educational programs would be required to include advanced courses in pathophysiology, pharmacotherapeutics, and physicalassessment as well as population-specific courses in these same categories. In addition, supervised clinical hour minimums were established for the various population-specific programs.

Concomitantly, graduate educational programs were wrestling with the 2005 statement from the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) that all advanced practice nursing education should be at the doctoral level by 2015. Because of the knowledge explosion, nurses needed more than what could be achieved in a master’s program to meet practice requirements as well as leadership, systems evaluation, quality improvement, research, and program development. Currently, there are 264 Doctor of Nursing Practice programs in the United States with less than one-half having a PMHNP program.14

Nursing education at the collegiate level has been evolving, which is fostered and supported by the 2010 Institute of Medicine (IOM) Report on the Future of Nursing that identified 4 key recommendations to promote a workforce at capacity to help care for our nation’s growing population:

- Remove scope of practice barriers

- Expand opportunities for nurses to lead and diffuse collaborative improvement efforts

- Implement nurse residency programs

- Increase the proportion of nurses with a baccalaureate degree to 80% by 2020.

The current status of advanced practice nursing

Each of the 50 states is in varying levels of compliance with the 2015 mandates from the consensus model and the AACN. From the psychiatric workforce perspective, many state boards of nursing are concerned because titles often are linked to legislative statute or rules. Despite the 2010 IOM recommendations and the FTC, the American Medical Association (AMA) has stationed AMA lobbyists in the legislatures that are poised to open the nurse practice act to comply with the consensus model. The sole purpose of these lobbyists is to block independent practice for APRNs in the 26 states that are seeking this status and to remove independent practice from the states where it already exists. For example, in Washington the title is ARNP but to change it to APRN will require opening the state’s legislative action. The AMA is eager to remove the autonomy that has existed in that state since 1978. One of the reasons is because where the APRN is required to be in a collaborative or supervisory relationship with a physician, the physician can charge the APRN to be compliant with state regulations. (In some states, the APRN cannot see patients or be on call if the collaborator is on vacation).

This has turned into a cottage industry for many physicians. However, there are many who do not charge because they are able to add additional patients to the practice by adding an APRN and generate more revenue. Others do not charge because they are supportive and committed to the APRN role.

Some thoughts about our mutual field

Can we move past the guild issue and come together to respect our given scopes of practice? I see psychiatry far ahead of the curve compared with APRNs in other specialties. The PMH-APRN is a highly educated nurse with a specific scope of practice that provides skilled psychiatric care (assessment, diagnosis, prescribing, psychotherapy) from a nursing perspective. Independent practice certainly does not imply that we do not collaborate with one another in a professional manner.

Mental Health Professional Shortage Areas

As of January 1, 2017, there are 4,627 Mental Health Professional Shortage Areas (MHPSA) in the United States and Territories (Table), which translates to only 44.2% of the need for psychiatric practitioners being met.15 To eliminate the designation of a MHSPA there must be a population to psychiatric provider ratio of at least 30,000 to 1 (20,000 to 1 if there are unusually high needs in the community). Currently 3,397 practitioners are needed to remove the designation across the United States. The state in most need of providers is Texas with 271 clinicians required to meet the need.

Considering that approximately 700 PMH-APRNs graduate each year16 and 1,317 psychiatry residents17 entered PGY-1 residency in 2016, it will be decades—or longer—before there are enough new providers to eliminate MHPSAs, particularly because the current workforce is aging (average age of the PMH-APRN is 55).

Because there are more than enough patients to go around, I encourage the APA to take a stand against the AMA and unite with the psychiatric APRNs to remove unnecessary barriers to practice and promote a unified and collegial workforce. This will transmit a strong message to the most underserved of our communities that psychiatrists and psychiatric nurse practitioners can emulate the therapeutic relationship by virtue of presenting a unified force. Imagine psychiatrists and psychiatric nurse practitioners going arm in arm to lobby county commissioners, state legislators, and Congressional Representatives and Senators. Together we could be a true force to be reckoned with.

The number of psychiatric prescribers per capita is at one of the lowest levels in history.1 Approximately 43.4 million persons (17.9%) in the United States have a diagnosable mental illness2; 9.8 million (4%) are diagnosed with a serious and persistent mental illness, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder (these figures do not include substance use disorders).3

Of the 45,000 licensed psychiatrists, approximately 25,000 are in active practice.4 By comparison, there are approximately 19,000 practicing licensed psychiatric advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs).5 Annually, approximately 1,300 physicians graduate from psychiatric residency programs6 and 700 APRNs from master’s or Doctor of Nursing Practice programs.7 Combining the 2 prescribing workforces (44,000) yields a ratio of 986 patients per licensed prescriber. Seeing each patient only once every 2 months would equate to 25 patients daily considering a 5-day work week. Recognizing that some patients need much more frequent follow-up, this is an impossible task even if these providers and patients were dispersed uniformly across the United States. Currently, ratios are calculated based on the number of psychiatrists per 100,000 individuals, which in the United States is 16.8 Most psychiatrists practice in urban areas,9 whereas psychiatric nurse practitioners are found primarily in rural and less populated urban areas.10

Who can provide care?

Although the growing number of psychiatric APRNs is encouraging for the mental health workforce, their limited role and function remain a battle in the 27 states that do not grant full practice authority. This dispute has become so contentious that the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has stated that the debate over scope of practice represents federal restraint of trade,11 while patients and their families suffer from lack of access to care.

Recognizing that 9 million patients age <65 who were enrolled in Medicaid in 2011 and treated for a mental health disorder (20% of enrollees) accounted for 50% of all Medicaid expenditures prompts the question, “Who is treating these patients?” According to the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 75% of nurse practitioners accept and treat both Medicaid and Medicare patients compared with 43% of psychiatrists who accepted Medicaid and 54% who accepted Medicare in 2011 (these numbers do not include potential overlap).12

Who are APRNs?

The first master’s degree in nursing was created by Hildegard Peplau, EdD, at Rutgers University in 1954, using the title Clinical Specialist in Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing (PMH-CNS). As a master’s prepared clinician, the PMH-CNS could function independently, and many chose to open private practices. Other universities began to create clinical specialty programs in a variety of disciplines. In 1996, 41 states granted prescriptive authority to the PMH-CNS. Psychiatric nurse practitioners were first certified in 2000 to meet the statutory requirements for prescriptive authority of the other 9 states. However this created 4 PMH-APRN roles: Adult and Child/Adolescent CNS and Adult and Family PMHNPs.