User login

Lonely in the middle

Those of us who consider ourselves centrists are feeling pretty lonely right now. It seems everyone else, or at least all of the folks in Washington, have fled to the extreme political poles and left us to search for a patch of middle ground to stand on. It appears that without courageous leadership the silent majority has splintered and gravitated to the tails of what was once a bell-shaped curve.

One issue that might attract support from both sides of the political spectrum emerged from the Nov. 18, 2016, report from the United States Department of Agriculture that listed sweetened drinks as the No. 1 purchase by households participating in SNAP (“Foods Typically Purchased by Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Households”). The data reveal that households in this $74 billion program are spending 5% of their food dollars on soft drinks and almost 10% on sweetened beverages – soft drinks, fruit juices, energy drinks, and sweetened teas.

Several states (including Maine), dozens of other municipalities (most notably New York City under Mayor Michael Bloomberg), and a variety of medical groups have asked the USDA to reconsider its guidelines. Arguing that selectively banning certain items would generate too much red tape and be unfair to food stamp recipients, the department has been resistant to change (“In the Shopping Cart of a Food Stamp Household: Lots of Soda,” by Anahad O’Connor, New York Times, Jan. 13, 2017). One has to wonder how much of the department’s hesitancy is a reflection of the millions of dollars the food and beverage industries have invested in lobbying against change.

There are some ultra liberals (or progressives if you prefer) who feel that no one should be deprived of the privilege of buying unhealthy food simply because he or she is poor. At the other end of the spectrum there are conservatives who would prefer to scrap the whole SNAP program because it is a wasteful frill of the welfare state. However, I have to believe that the vast majority of folks on both sides of the political divide believe that feeding the less fortunate is important, but that spending their tax money on junk food and soft drinks is a bad idea.

While we still are learning that the causes of our obesity epidemic are far more complex than we once imagined, I think most people believe that soft drinks and junk food are playing a significant role – even though these same folks may have found it difficult to change their own behavior. According to the New York Times article mentioned above, Kevin Concannon, the USDA undersecretary for food, nutrition, and consumer services, said that instead of restricting food, the USDA has prioritized incentive programs to encourage participants to purchase more nutritious foods. However, a 2014 study of more than 19,000 SNAP recipients by Stanford researchers determined that an incentive program would not affect obesity rates, while banning sugary drinks would “significantly reduce obesity prevalence and type 2 diabetes incidence” (Health Aff. Jun 2014;33[6]:1032-9).

All we need now are a few courageous senators and congressmen to buck the soft drink lobby and bring this issue to the front burner. I have to believe that there are more than enough people, both liberals and conservatives, who would venture together on the middle ground and support removing sweetened drinks from the SNAP program. If I’m correct, it would be a refreshing example of some much needed legislative cooperation. Or, am I just a lonely dreamer longing for some company here in the center?

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Those of us who consider ourselves centrists are feeling pretty lonely right now. It seems everyone else, or at least all of the folks in Washington, have fled to the extreme political poles and left us to search for a patch of middle ground to stand on. It appears that without courageous leadership the silent majority has splintered and gravitated to the tails of what was once a bell-shaped curve.

One issue that might attract support from both sides of the political spectrum emerged from the Nov. 18, 2016, report from the United States Department of Agriculture that listed sweetened drinks as the No. 1 purchase by households participating in SNAP (“Foods Typically Purchased by Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Households”). The data reveal that households in this $74 billion program are spending 5% of their food dollars on soft drinks and almost 10% on sweetened beverages – soft drinks, fruit juices, energy drinks, and sweetened teas.

Several states (including Maine), dozens of other municipalities (most notably New York City under Mayor Michael Bloomberg), and a variety of medical groups have asked the USDA to reconsider its guidelines. Arguing that selectively banning certain items would generate too much red tape and be unfair to food stamp recipients, the department has been resistant to change (“In the Shopping Cart of a Food Stamp Household: Lots of Soda,” by Anahad O’Connor, New York Times, Jan. 13, 2017). One has to wonder how much of the department’s hesitancy is a reflection of the millions of dollars the food and beverage industries have invested in lobbying against change.

There are some ultra liberals (or progressives if you prefer) who feel that no one should be deprived of the privilege of buying unhealthy food simply because he or she is poor. At the other end of the spectrum there are conservatives who would prefer to scrap the whole SNAP program because it is a wasteful frill of the welfare state. However, I have to believe that the vast majority of folks on both sides of the political divide believe that feeding the less fortunate is important, but that spending their tax money on junk food and soft drinks is a bad idea.

While we still are learning that the causes of our obesity epidemic are far more complex than we once imagined, I think most people believe that soft drinks and junk food are playing a significant role – even though these same folks may have found it difficult to change their own behavior. According to the New York Times article mentioned above, Kevin Concannon, the USDA undersecretary for food, nutrition, and consumer services, said that instead of restricting food, the USDA has prioritized incentive programs to encourage participants to purchase more nutritious foods. However, a 2014 study of more than 19,000 SNAP recipients by Stanford researchers determined that an incentive program would not affect obesity rates, while banning sugary drinks would “significantly reduce obesity prevalence and type 2 diabetes incidence” (Health Aff. Jun 2014;33[6]:1032-9).

All we need now are a few courageous senators and congressmen to buck the soft drink lobby and bring this issue to the front burner. I have to believe that there are more than enough people, both liberals and conservatives, who would venture together on the middle ground and support removing sweetened drinks from the SNAP program. If I’m correct, it would be a refreshing example of some much needed legislative cooperation. Or, am I just a lonely dreamer longing for some company here in the center?

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Those of us who consider ourselves centrists are feeling pretty lonely right now. It seems everyone else, or at least all of the folks in Washington, have fled to the extreme political poles and left us to search for a patch of middle ground to stand on. It appears that without courageous leadership the silent majority has splintered and gravitated to the tails of what was once a bell-shaped curve.

One issue that might attract support from both sides of the political spectrum emerged from the Nov. 18, 2016, report from the United States Department of Agriculture that listed sweetened drinks as the No. 1 purchase by households participating in SNAP (“Foods Typically Purchased by Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Households”). The data reveal that households in this $74 billion program are spending 5% of their food dollars on soft drinks and almost 10% on sweetened beverages – soft drinks, fruit juices, energy drinks, and sweetened teas.

Several states (including Maine), dozens of other municipalities (most notably New York City under Mayor Michael Bloomberg), and a variety of medical groups have asked the USDA to reconsider its guidelines. Arguing that selectively banning certain items would generate too much red tape and be unfair to food stamp recipients, the department has been resistant to change (“In the Shopping Cart of a Food Stamp Household: Lots of Soda,” by Anahad O’Connor, New York Times, Jan. 13, 2017). One has to wonder how much of the department’s hesitancy is a reflection of the millions of dollars the food and beverage industries have invested in lobbying against change.

There are some ultra liberals (or progressives if you prefer) who feel that no one should be deprived of the privilege of buying unhealthy food simply because he or she is poor. At the other end of the spectrum there are conservatives who would prefer to scrap the whole SNAP program because it is a wasteful frill of the welfare state. However, I have to believe that the vast majority of folks on both sides of the political divide believe that feeding the less fortunate is important, but that spending their tax money on junk food and soft drinks is a bad idea.

While we still are learning that the causes of our obesity epidemic are far more complex than we once imagined, I think most people believe that soft drinks and junk food are playing a significant role – even though these same folks may have found it difficult to change their own behavior. According to the New York Times article mentioned above, Kevin Concannon, the USDA undersecretary for food, nutrition, and consumer services, said that instead of restricting food, the USDA has prioritized incentive programs to encourage participants to purchase more nutritious foods. However, a 2014 study of more than 19,000 SNAP recipients by Stanford researchers determined that an incentive program would not affect obesity rates, while banning sugary drinks would “significantly reduce obesity prevalence and type 2 diabetes incidence” (Health Aff. Jun 2014;33[6]:1032-9).

All we need now are a few courageous senators and congressmen to buck the soft drink lobby and bring this issue to the front burner. I have to believe that there are more than enough people, both liberals and conservatives, who would venture together on the middle ground and support removing sweetened drinks from the SNAP program. If I’m correct, it would be a refreshing example of some much needed legislative cooperation. Or, am I just a lonely dreamer longing for some company here in the center?

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

The power of interaction – Supporting language and play development

Engaging caregivers in the management and treatment of early childhood developmental challenges is a critical component of effective intervention.1 Family-centered care helps to promote positive outcomes with early intervention (across developmental domains), and there’s increasing evidence that parent-training programs can be effective in promoting skill generalization and targeting core impairments in toddlers with autism.2

Furthermore, a 2014 randomized controlled trial revealed that individual Early Social Interaction (ESI) with home coaching using the SCERTS (Social Communication, Emotional Regulation, and Transactional Support) curriculum was associated with improvement of a range of child outcomes, compared with group ESI. The authors commented on the importance of individualized parent coaching in natural environments as a way to improve social components of communication and receptive language for toddlers with autism.3

For many parents and at-home caregivers, however, engaging in home-based and parent-delivered interventions can be overwhelming and anxiety-provoking, as well as complicated by other barriers (competing responsibilities, cultural beliefs, and so on). Additionally, these interventions can themselves be a source of stress for some families.

Case

Jake is a 3-year-old boy with a history of global developmental delays, who presents with particular struggles: relating his expressive communication, ability to engage peers in an age-appropriate manner, and capacity to self-regulate when frustrated. He and his family participated in an comprehensive autism diagnostic assessment. In reviewing the history and presentation, considerable challenges in the two core symptom domains that characterize an autism spectrum disorder were noted. A diagnosis of autism was provided, and treatment recommendations were discussed. “What can I do at home to help Jake learn?” his mother asked, noting that, with one-on-one attention, he does seem to demonstrate increased responsiveness, less use of echolalic language, and improved eye contact.

Discussion

To complement the autism services that Jake would likely qualify for through an Early Education program, in-home interaction and play to ensure skill development was discussed at length with his mother, who readily acknowledged her own care-giving struggles that, in part, are informed by her own mental health troubles.

We openly explored Jake’s mother’s perceived challenges in engaging with her son at home and developed initial recommendations for interaction that didn’t risk overwhelming her. We impressed upon Jake’s mother that, regardless of a child’s developmental profile, toddlers use play to learn and she can be Jake’s “favorite toy.” After all, “play is really the work of childhood,” as Fred Rogers said.

With all children, back-and-forth interactions serve as the foundation for future development. Using scaffolding techniques, parent support is a primary driver of “how children develop cognitive, language, social-emotional, and higher-level thinking skills.”4 In particular, the quality of parental interaction can influence language development, and, when considering children with autism, there are several recommendations for what parents can do to help build social, play, and communication skills.5 The Hanen Program is a great resource for providers and parents to learn more about parent engagement in early learning, the power of building communication through everyday experiences and attention to responsiveness, and the use of a child’s strengths to help make family interactions more meaningful and enjoyable. Additionally, the 2012 book “An Early Start for Your Child with Autism: Using Everyday Activities to Help Kids Connect, Communicate, and Learn” by Sally Rogers, PhD, et al. is an easy-to-read text for parents and caregivers for learning effective and practical strategies for engaging their child with autism.

With Jake and his mother, our team offered the following in-home recommendations:

- Try to keep interaction fun. Be enthusiastic when encouraging Jake’s attempts to communicate.

- Teach Jake song-gesture games. Encourage him to produce routine, predictable gestures to keep the song going (in imitation of mom). Using songs with vowel emphasis is encouraged (for example: Farmer in the Dell with “E I E I OOOOO”).

- Encourage Jake to produce responsive gestures in play and daily routines not involving songs, such as open arms to receive a ball, reaching to mom when about to be tickled, or having his arms up to have his shirt taken off.

- Capitalize on Jake’s natural desires and personal preferences. Activate a wind-up toy, let it deactivate, and then hand it to Jake.

- Initiate a familiar social game with Jake until he expresses pleasure. Then stop the game and wait for him to initiate continuance.

- Adapt the environment so that Jake will need to frequently request objects of assistance to make choices (place favorite toys in clear containers which may be difficult to open so that he must request help).

Clinical pearl

The United States Department of Education recognizes the importance of family engagement in a child’s early years. Their 2015 policy statement notes that “families are their children’s first and most important teachers, advocates, and nurturers. As such, strong family engagement is central – not supplemental – to the success of early childhood systems and programs that promote children’s healthy development, learning, and wellness.”

By recognizing this principle, primary care providers are in a position to talk with parents about how much youth learn through play and regular interaction. This especially holds true for children with autism. Developing in-home strategies to facilitate active engagement, even strategies that may not be a formal component of a home-based intervention program, are instrumental in fostering positive family- and child-based outcomes and wellness.

Dr. Dickerson, a child and adolescent psychiatrist, is assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Vermont, Burlington, where he is director of the autism diagnostic clinic. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6:447-68.

2. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010 Sep;40(9):1045-56.

3. Pediatrics. 2014 Dec;134(6):1084-93.

4. JAMA Pediatr. 2016 Feb;170(2):112-3.

5. Child Dev. 2012 Sep-Oct;83(5):1762-74.

Engaging caregivers in the management and treatment of early childhood developmental challenges is a critical component of effective intervention.1 Family-centered care helps to promote positive outcomes with early intervention (across developmental domains), and there’s increasing evidence that parent-training programs can be effective in promoting skill generalization and targeting core impairments in toddlers with autism.2

Furthermore, a 2014 randomized controlled trial revealed that individual Early Social Interaction (ESI) with home coaching using the SCERTS (Social Communication, Emotional Regulation, and Transactional Support) curriculum was associated with improvement of a range of child outcomes, compared with group ESI. The authors commented on the importance of individualized parent coaching in natural environments as a way to improve social components of communication and receptive language for toddlers with autism.3

For many parents and at-home caregivers, however, engaging in home-based and parent-delivered interventions can be overwhelming and anxiety-provoking, as well as complicated by other barriers (competing responsibilities, cultural beliefs, and so on). Additionally, these interventions can themselves be a source of stress for some families.

Case

Jake is a 3-year-old boy with a history of global developmental delays, who presents with particular struggles: relating his expressive communication, ability to engage peers in an age-appropriate manner, and capacity to self-regulate when frustrated. He and his family participated in an comprehensive autism diagnostic assessment. In reviewing the history and presentation, considerable challenges in the two core symptom domains that characterize an autism spectrum disorder were noted. A diagnosis of autism was provided, and treatment recommendations were discussed. “What can I do at home to help Jake learn?” his mother asked, noting that, with one-on-one attention, he does seem to demonstrate increased responsiveness, less use of echolalic language, and improved eye contact.

Discussion

To complement the autism services that Jake would likely qualify for through an Early Education program, in-home interaction and play to ensure skill development was discussed at length with his mother, who readily acknowledged her own care-giving struggles that, in part, are informed by her own mental health troubles.

We openly explored Jake’s mother’s perceived challenges in engaging with her son at home and developed initial recommendations for interaction that didn’t risk overwhelming her. We impressed upon Jake’s mother that, regardless of a child’s developmental profile, toddlers use play to learn and she can be Jake’s “favorite toy.” After all, “play is really the work of childhood,” as Fred Rogers said.

With all children, back-and-forth interactions serve as the foundation for future development. Using scaffolding techniques, parent support is a primary driver of “how children develop cognitive, language, social-emotional, and higher-level thinking skills.”4 In particular, the quality of parental interaction can influence language development, and, when considering children with autism, there are several recommendations for what parents can do to help build social, play, and communication skills.5 The Hanen Program is a great resource for providers and parents to learn more about parent engagement in early learning, the power of building communication through everyday experiences and attention to responsiveness, and the use of a child’s strengths to help make family interactions more meaningful and enjoyable. Additionally, the 2012 book “An Early Start for Your Child with Autism: Using Everyday Activities to Help Kids Connect, Communicate, and Learn” by Sally Rogers, PhD, et al. is an easy-to-read text for parents and caregivers for learning effective and practical strategies for engaging their child with autism.

With Jake and his mother, our team offered the following in-home recommendations:

- Try to keep interaction fun. Be enthusiastic when encouraging Jake’s attempts to communicate.

- Teach Jake song-gesture games. Encourage him to produce routine, predictable gestures to keep the song going (in imitation of mom). Using songs with vowel emphasis is encouraged (for example: Farmer in the Dell with “E I E I OOOOO”).

- Encourage Jake to produce responsive gestures in play and daily routines not involving songs, such as open arms to receive a ball, reaching to mom when about to be tickled, or having his arms up to have his shirt taken off.

- Capitalize on Jake’s natural desires and personal preferences. Activate a wind-up toy, let it deactivate, and then hand it to Jake.

- Initiate a familiar social game with Jake until he expresses pleasure. Then stop the game and wait for him to initiate continuance.

- Adapt the environment so that Jake will need to frequently request objects of assistance to make choices (place favorite toys in clear containers which may be difficult to open so that he must request help).

Clinical pearl

The United States Department of Education recognizes the importance of family engagement in a child’s early years. Their 2015 policy statement notes that “families are their children’s first and most important teachers, advocates, and nurturers. As such, strong family engagement is central – not supplemental – to the success of early childhood systems and programs that promote children’s healthy development, learning, and wellness.”

By recognizing this principle, primary care providers are in a position to talk with parents about how much youth learn through play and regular interaction. This especially holds true for children with autism. Developing in-home strategies to facilitate active engagement, even strategies that may not be a formal component of a home-based intervention program, are instrumental in fostering positive family- and child-based outcomes and wellness.

Dr. Dickerson, a child and adolescent psychiatrist, is assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Vermont, Burlington, where he is director of the autism diagnostic clinic. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6:447-68.

2. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010 Sep;40(9):1045-56.

3. Pediatrics. 2014 Dec;134(6):1084-93.

4. JAMA Pediatr. 2016 Feb;170(2):112-3.

5. Child Dev. 2012 Sep-Oct;83(5):1762-74.

Engaging caregivers in the management and treatment of early childhood developmental challenges is a critical component of effective intervention.1 Family-centered care helps to promote positive outcomes with early intervention (across developmental domains), and there’s increasing evidence that parent-training programs can be effective in promoting skill generalization and targeting core impairments in toddlers with autism.2

Furthermore, a 2014 randomized controlled trial revealed that individual Early Social Interaction (ESI) with home coaching using the SCERTS (Social Communication, Emotional Regulation, and Transactional Support) curriculum was associated with improvement of a range of child outcomes, compared with group ESI. The authors commented on the importance of individualized parent coaching in natural environments as a way to improve social components of communication and receptive language for toddlers with autism.3

For many parents and at-home caregivers, however, engaging in home-based and parent-delivered interventions can be overwhelming and anxiety-provoking, as well as complicated by other barriers (competing responsibilities, cultural beliefs, and so on). Additionally, these interventions can themselves be a source of stress for some families.

Case

Jake is a 3-year-old boy with a history of global developmental delays, who presents with particular struggles: relating his expressive communication, ability to engage peers in an age-appropriate manner, and capacity to self-regulate when frustrated. He and his family participated in an comprehensive autism diagnostic assessment. In reviewing the history and presentation, considerable challenges in the two core symptom domains that characterize an autism spectrum disorder were noted. A diagnosis of autism was provided, and treatment recommendations were discussed. “What can I do at home to help Jake learn?” his mother asked, noting that, with one-on-one attention, he does seem to demonstrate increased responsiveness, less use of echolalic language, and improved eye contact.

Discussion

To complement the autism services that Jake would likely qualify for through an Early Education program, in-home interaction and play to ensure skill development was discussed at length with his mother, who readily acknowledged her own care-giving struggles that, in part, are informed by her own mental health troubles.

We openly explored Jake’s mother’s perceived challenges in engaging with her son at home and developed initial recommendations for interaction that didn’t risk overwhelming her. We impressed upon Jake’s mother that, regardless of a child’s developmental profile, toddlers use play to learn and she can be Jake’s “favorite toy.” After all, “play is really the work of childhood,” as Fred Rogers said.

With all children, back-and-forth interactions serve as the foundation for future development. Using scaffolding techniques, parent support is a primary driver of “how children develop cognitive, language, social-emotional, and higher-level thinking skills.”4 In particular, the quality of parental interaction can influence language development, and, when considering children with autism, there are several recommendations for what parents can do to help build social, play, and communication skills.5 The Hanen Program is a great resource for providers and parents to learn more about parent engagement in early learning, the power of building communication through everyday experiences and attention to responsiveness, and the use of a child’s strengths to help make family interactions more meaningful and enjoyable. Additionally, the 2012 book “An Early Start for Your Child with Autism: Using Everyday Activities to Help Kids Connect, Communicate, and Learn” by Sally Rogers, PhD, et al. is an easy-to-read text for parents and caregivers for learning effective and practical strategies for engaging their child with autism.

With Jake and his mother, our team offered the following in-home recommendations:

- Try to keep interaction fun. Be enthusiastic when encouraging Jake’s attempts to communicate.

- Teach Jake song-gesture games. Encourage him to produce routine, predictable gestures to keep the song going (in imitation of mom). Using songs with vowel emphasis is encouraged (for example: Farmer in the Dell with “E I E I OOOOO”).

- Encourage Jake to produce responsive gestures in play and daily routines not involving songs, such as open arms to receive a ball, reaching to mom when about to be tickled, or having his arms up to have his shirt taken off.

- Capitalize on Jake’s natural desires and personal preferences. Activate a wind-up toy, let it deactivate, and then hand it to Jake.

- Initiate a familiar social game with Jake until he expresses pleasure. Then stop the game and wait for him to initiate continuance.

- Adapt the environment so that Jake will need to frequently request objects of assistance to make choices (place favorite toys in clear containers which may be difficult to open so that he must request help).

Clinical pearl

The United States Department of Education recognizes the importance of family engagement in a child’s early years. Their 2015 policy statement notes that “families are their children’s first and most important teachers, advocates, and nurturers. As such, strong family engagement is central – not supplemental – to the success of early childhood systems and programs that promote children’s healthy development, learning, and wellness.”

By recognizing this principle, primary care providers are in a position to talk with parents about how much youth learn through play and regular interaction. This especially holds true for children with autism. Developing in-home strategies to facilitate active engagement, even strategies that may not be a formal component of a home-based intervention program, are instrumental in fostering positive family- and child-based outcomes and wellness.

Dr. Dickerson, a child and adolescent psychiatrist, is assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Vermont, Burlington, where he is director of the autism diagnostic clinic. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6:447-68.

2. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010 Sep;40(9):1045-56.

3. Pediatrics. 2014 Dec;134(6):1084-93.

4. JAMA Pediatr. 2016 Feb;170(2):112-3.

5. Child Dev. 2012 Sep-Oct;83(5):1762-74.

Update on malpractice trends

Question: Recent developments in malpractice include the following:

A. Severity and frequency rates continue to rise.

B. Apology laws appear to be very effective in reducing claims.

C. Litigation surrounds whether an assistant may obtain a patient’s informed consent on behalf of the doctor.

D. A and B.

E. A, B, and C.

Answer: C. Over the past decade, malpractice claims have in fact diminished, accompanied by a leveling or reduction in premiums.1 Rates have plummeted to roughly half of previous levels, averaging six claims per 100 doctors in 2016.

According to The Doctors Company, internists paid an average premium of $15,853, compared with an average of $19,900 in 2006, general surgeons $52,905 instead of $68,186, and obstetricians $72,999, a drop from $93,230. Even claims-plagued Florida’s Dade County has seen a dramatic drop in internist premiums by some $27,000, down to $47,707.2

The latest attack on MICRA, in 2015, concerned a wrongful death suit brought by a woman whose mother died from hemorrhagic complications related to Coumadin use following heart surgery.4 Her constitutional challenges included violation of equal protection, due process, and the right to a jury trial. But these were essentially all grounded on an entitlement to recover additional noneconomic damages sufficient to cover attorney fees. The trial court had reduced her $1 million noneconomic damages to $250,000 as required by MICRA. A California appeals court rejected her claim as being “contrary to many well-established legal principles.”

Disclosure of medical errors is a relative newcomer as an ethical and effective way of thwarting potential malpractice claims. Many states have enacted so-called “apology laws,” an outgrowth of the communication and resolution programs popularized by the Lexington (Ky.) VA Medical Center, University of Michigan Health System, Harvard’s affiliated institutions, and Colorado’s COPIC Insurance.

Apology laws disallow statements of sympathy from being admitted into evidence. In some cases, these laws may assist the physician. For example, the Ohio Supreme Court has ruled that a surgeon’s comments and alleged admission of guilt (“I take full responsibility for this” regarding accidentally sectioning the common bile duct) were properly shielded from discovery by the state’s apology statute, even though the incident took place before the law went into effect.5

However, apology laws do vary from state to state, and some do not shield admissions regarding causation of error or fault.

A recent study suggests that apology laws don’t work. A Vanderbilt University study published online used a unique dataset covering all malpractice claims for 90% of physicians practicing in a single specialty across the country.6 The findings revealed that, for physicians who do not regularly perform surgery, apology laws actually increased the probability of facing a lawsuit. For surgeons, apology laws do not have a substantial effect on the probability of facing a claim or the average payment made to resolve a claim.

The study’s authors concluded that “apology laws are not substitutes for specific physician disclosure programs, and that the experiences of these types of programs are not generalizable to the physician population at large. In other words, simply being allowed to apologize is not enough to reduce malpractice risk.”

In the informed consent arena, the latest development in the law revolves around whether a physician assistant, in lieu of the surgeon himself, can obtain informed consent from a patient.

In Shinal v. Toms,7 Megan Shinal underwent surgery to remove a craniopharyngioma, but it regrew and required re-exploration by Dr. Steven Toms. Dr. Toms testified that Ms. Shinal had agreed that he would determine during the surgery whether he should remove the entire tumor or perform a partial resection. The operation was complicated by a carotid artery perforation, which left the patient with impaired vision and ambulation.

The complaint asserted that Dr. Toms’s physician assistant, not Dr. Toms himself, had provided the actual discussion during the informed consent process, and thus the patient’s consent was invalid.

The jury was allowed to consider the information provided by the doctor’s support staff, and the Superior Court of Pennsylvania affirmed the validity of the patient’s consent, holding that consent is based on the scope of information relayed rather than the identity of the individual communicating the information. This carefully watched case is now on final appeal before the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania.

At a personal level, physicians dread the stress surrounding medical malpractice litigation. The process frontally attacks their competence and consumes much time and energy, notwithstanding there being little or no exposure of personal assets because of insurance protection. Virtually all doctors practice defensive medicine, which has been defined as “deviation from sound medical practice that is induced primarily by a threat of liability.”

At a societal level, defensive medicine is reported to add substantially to the nation’s medical bill. The figure tossed around is $12 billion to $50 billion a year, based mostly on estimates by the American Medical Association and an older study extrapolating potential Medicare savings from litigation over heart disease.8

A more recent report continues to emphasize the high cost of defensive medicine.9 Jackson Healthcare invited 138,686 physicians to participate in a confidential online survey to quantify the costs and impact of defensive medicine. More than 3,000 physicians spanning all states and medical specialties completed the survey; however, this represented only a 2.21% response rate.

The authors concluded that defensive medicine is a significant force driving the high cost of health care in the United States, and that physicians estimate the cost of defensive medicine to be in the $650 billion to $850 billion range, or between 26% and 34% of annual health care costs.

Skeptics question the way the profession defines defensive medicine, pointing out that malpractice concerns may not be the primary reason, as most interventions add some marginal value to patient care. There may also be conflicting motivations of physicians, such as financial or other personal rewards.

Above all, there is no acceptable method for measuring the extent and use of defensive medicine, and survey reports are apt to be misleading because of bias and the lack of controls and baseline data.

Looking ahead, what can we expect for malpractice law under the Trump administration? Tom Price, MD, a former Republican congressman from Georgia, is an orthopedic surgeon and the new secretary of the Department of Health & Human Services. He has previously spoken passionately about tort reforms such as defensive medicine, damage caps, health tribunals, and practice guidelines. Many states have already incorporated some of these measures into their own tort reforms – with salutary results. It remains to be seen whether HHS will deem any omnibus federal legislation necessary at this point.

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some of the materials have been taken from my earlier columns in Internal Medicine News. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

References

1. JAMA. 2014 Nov 26;312(20):2146-55.

2. “Malpractice 2017: Do We Need Reform?” Internal Medicine News, March 1, 2017, page 1.

3. Fein v. Permanente, 38 Cal.3d 137 (1985).

4. Chan v. Curran, 237 CA 4th 601 (2015).

5. Estate of Johnson v. Randall Smith, Inc., 135 Ohio St.3d 440 (2013).

6. Available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers2.cfm?abstract_id=2883693.

7. Shinal v. Toms, 122 A. 3d 1066 (Pa. Super. Ct. 2015).

8. Q J Econ. (1996) 111 (2): 353-390.

9. Available at www.jacksonhealthcare.com/media/8968/defensivemedicine_ebook_final.pdf.

Question: Recent developments in malpractice include the following:

A. Severity and frequency rates continue to rise.

B. Apology laws appear to be very effective in reducing claims.

C. Litigation surrounds whether an assistant may obtain a patient’s informed consent on behalf of the doctor.

D. A and B.

E. A, B, and C.

Answer: C. Over the past decade, malpractice claims have in fact diminished, accompanied by a leveling or reduction in premiums.1 Rates have plummeted to roughly half of previous levels, averaging six claims per 100 doctors in 2016.

According to The Doctors Company, internists paid an average premium of $15,853, compared with an average of $19,900 in 2006, general surgeons $52,905 instead of $68,186, and obstetricians $72,999, a drop from $93,230. Even claims-plagued Florida’s Dade County has seen a dramatic drop in internist premiums by some $27,000, down to $47,707.2

The latest attack on MICRA, in 2015, concerned a wrongful death suit brought by a woman whose mother died from hemorrhagic complications related to Coumadin use following heart surgery.4 Her constitutional challenges included violation of equal protection, due process, and the right to a jury trial. But these were essentially all grounded on an entitlement to recover additional noneconomic damages sufficient to cover attorney fees. The trial court had reduced her $1 million noneconomic damages to $250,000 as required by MICRA. A California appeals court rejected her claim as being “contrary to many well-established legal principles.”

Disclosure of medical errors is a relative newcomer as an ethical and effective way of thwarting potential malpractice claims. Many states have enacted so-called “apology laws,” an outgrowth of the communication and resolution programs popularized by the Lexington (Ky.) VA Medical Center, University of Michigan Health System, Harvard’s affiliated institutions, and Colorado’s COPIC Insurance.

Apology laws disallow statements of sympathy from being admitted into evidence. In some cases, these laws may assist the physician. For example, the Ohio Supreme Court has ruled that a surgeon’s comments and alleged admission of guilt (“I take full responsibility for this” regarding accidentally sectioning the common bile duct) were properly shielded from discovery by the state’s apology statute, even though the incident took place before the law went into effect.5

However, apology laws do vary from state to state, and some do not shield admissions regarding causation of error or fault.

A recent study suggests that apology laws don’t work. A Vanderbilt University study published online used a unique dataset covering all malpractice claims for 90% of physicians practicing in a single specialty across the country.6 The findings revealed that, for physicians who do not regularly perform surgery, apology laws actually increased the probability of facing a lawsuit. For surgeons, apology laws do not have a substantial effect on the probability of facing a claim or the average payment made to resolve a claim.

The study’s authors concluded that “apology laws are not substitutes for specific physician disclosure programs, and that the experiences of these types of programs are not generalizable to the physician population at large. In other words, simply being allowed to apologize is not enough to reduce malpractice risk.”

In the informed consent arena, the latest development in the law revolves around whether a physician assistant, in lieu of the surgeon himself, can obtain informed consent from a patient.

In Shinal v. Toms,7 Megan Shinal underwent surgery to remove a craniopharyngioma, but it regrew and required re-exploration by Dr. Steven Toms. Dr. Toms testified that Ms. Shinal had agreed that he would determine during the surgery whether he should remove the entire tumor or perform a partial resection. The operation was complicated by a carotid artery perforation, which left the patient with impaired vision and ambulation.

The complaint asserted that Dr. Toms’s physician assistant, not Dr. Toms himself, had provided the actual discussion during the informed consent process, and thus the patient’s consent was invalid.

The jury was allowed to consider the information provided by the doctor’s support staff, and the Superior Court of Pennsylvania affirmed the validity of the patient’s consent, holding that consent is based on the scope of information relayed rather than the identity of the individual communicating the information. This carefully watched case is now on final appeal before the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania.

At a personal level, physicians dread the stress surrounding medical malpractice litigation. The process frontally attacks their competence and consumes much time and energy, notwithstanding there being little or no exposure of personal assets because of insurance protection. Virtually all doctors practice defensive medicine, which has been defined as “deviation from sound medical practice that is induced primarily by a threat of liability.”

At a societal level, defensive medicine is reported to add substantially to the nation’s medical bill. The figure tossed around is $12 billion to $50 billion a year, based mostly on estimates by the American Medical Association and an older study extrapolating potential Medicare savings from litigation over heart disease.8

A more recent report continues to emphasize the high cost of defensive medicine.9 Jackson Healthcare invited 138,686 physicians to participate in a confidential online survey to quantify the costs and impact of defensive medicine. More than 3,000 physicians spanning all states and medical specialties completed the survey; however, this represented only a 2.21% response rate.

The authors concluded that defensive medicine is a significant force driving the high cost of health care in the United States, and that physicians estimate the cost of defensive medicine to be in the $650 billion to $850 billion range, or between 26% and 34% of annual health care costs.

Skeptics question the way the profession defines defensive medicine, pointing out that malpractice concerns may not be the primary reason, as most interventions add some marginal value to patient care. There may also be conflicting motivations of physicians, such as financial or other personal rewards.

Above all, there is no acceptable method for measuring the extent and use of defensive medicine, and survey reports are apt to be misleading because of bias and the lack of controls and baseline data.

Looking ahead, what can we expect for malpractice law under the Trump administration? Tom Price, MD, a former Republican congressman from Georgia, is an orthopedic surgeon and the new secretary of the Department of Health & Human Services. He has previously spoken passionately about tort reforms such as defensive medicine, damage caps, health tribunals, and practice guidelines. Many states have already incorporated some of these measures into their own tort reforms – with salutary results. It remains to be seen whether HHS will deem any omnibus federal legislation necessary at this point.

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some of the materials have been taken from my earlier columns in Internal Medicine News. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

References

1. JAMA. 2014 Nov 26;312(20):2146-55.

2. “Malpractice 2017: Do We Need Reform?” Internal Medicine News, March 1, 2017, page 1.

3. Fein v. Permanente, 38 Cal.3d 137 (1985).

4. Chan v. Curran, 237 CA 4th 601 (2015).

5. Estate of Johnson v. Randall Smith, Inc., 135 Ohio St.3d 440 (2013).

6. Available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers2.cfm?abstract_id=2883693.

7. Shinal v. Toms, 122 A. 3d 1066 (Pa. Super. Ct. 2015).

8. Q J Econ. (1996) 111 (2): 353-390.

9. Available at www.jacksonhealthcare.com/media/8968/defensivemedicine_ebook_final.pdf.

Question: Recent developments in malpractice include the following:

A. Severity and frequency rates continue to rise.

B. Apology laws appear to be very effective in reducing claims.

C. Litigation surrounds whether an assistant may obtain a patient’s informed consent on behalf of the doctor.

D. A and B.

E. A, B, and C.

Answer: C. Over the past decade, malpractice claims have in fact diminished, accompanied by a leveling or reduction in premiums.1 Rates have plummeted to roughly half of previous levels, averaging six claims per 100 doctors in 2016.

According to The Doctors Company, internists paid an average premium of $15,853, compared with an average of $19,900 in 2006, general surgeons $52,905 instead of $68,186, and obstetricians $72,999, a drop from $93,230. Even claims-plagued Florida’s Dade County has seen a dramatic drop in internist premiums by some $27,000, down to $47,707.2

The latest attack on MICRA, in 2015, concerned a wrongful death suit brought by a woman whose mother died from hemorrhagic complications related to Coumadin use following heart surgery.4 Her constitutional challenges included violation of equal protection, due process, and the right to a jury trial. But these were essentially all grounded on an entitlement to recover additional noneconomic damages sufficient to cover attorney fees. The trial court had reduced her $1 million noneconomic damages to $250,000 as required by MICRA. A California appeals court rejected her claim as being “contrary to many well-established legal principles.”

Disclosure of medical errors is a relative newcomer as an ethical and effective way of thwarting potential malpractice claims. Many states have enacted so-called “apology laws,” an outgrowth of the communication and resolution programs popularized by the Lexington (Ky.) VA Medical Center, University of Michigan Health System, Harvard’s affiliated institutions, and Colorado’s COPIC Insurance.

Apology laws disallow statements of sympathy from being admitted into evidence. In some cases, these laws may assist the physician. For example, the Ohio Supreme Court has ruled that a surgeon’s comments and alleged admission of guilt (“I take full responsibility for this” regarding accidentally sectioning the common bile duct) were properly shielded from discovery by the state’s apology statute, even though the incident took place before the law went into effect.5

However, apology laws do vary from state to state, and some do not shield admissions regarding causation of error or fault.

A recent study suggests that apology laws don’t work. A Vanderbilt University study published online used a unique dataset covering all malpractice claims for 90% of physicians practicing in a single specialty across the country.6 The findings revealed that, for physicians who do not regularly perform surgery, apology laws actually increased the probability of facing a lawsuit. For surgeons, apology laws do not have a substantial effect on the probability of facing a claim or the average payment made to resolve a claim.

The study’s authors concluded that “apology laws are not substitutes for specific physician disclosure programs, and that the experiences of these types of programs are not generalizable to the physician population at large. In other words, simply being allowed to apologize is not enough to reduce malpractice risk.”

In the informed consent arena, the latest development in the law revolves around whether a physician assistant, in lieu of the surgeon himself, can obtain informed consent from a patient.

In Shinal v. Toms,7 Megan Shinal underwent surgery to remove a craniopharyngioma, but it regrew and required re-exploration by Dr. Steven Toms. Dr. Toms testified that Ms. Shinal had agreed that he would determine during the surgery whether he should remove the entire tumor or perform a partial resection. The operation was complicated by a carotid artery perforation, which left the patient with impaired vision and ambulation.

The complaint asserted that Dr. Toms’s physician assistant, not Dr. Toms himself, had provided the actual discussion during the informed consent process, and thus the patient’s consent was invalid.

The jury was allowed to consider the information provided by the doctor’s support staff, and the Superior Court of Pennsylvania affirmed the validity of the patient’s consent, holding that consent is based on the scope of information relayed rather than the identity of the individual communicating the information. This carefully watched case is now on final appeal before the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania.

At a personal level, physicians dread the stress surrounding medical malpractice litigation. The process frontally attacks their competence and consumes much time and energy, notwithstanding there being little or no exposure of personal assets because of insurance protection. Virtually all doctors practice defensive medicine, which has been defined as “deviation from sound medical practice that is induced primarily by a threat of liability.”

At a societal level, defensive medicine is reported to add substantially to the nation’s medical bill. The figure tossed around is $12 billion to $50 billion a year, based mostly on estimates by the American Medical Association and an older study extrapolating potential Medicare savings from litigation over heart disease.8

A more recent report continues to emphasize the high cost of defensive medicine.9 Jackson Healthcare invited 138,686 physicians to participate in a confidential online survey to quantify the costs and impact of defensive medicine. More than 3,000 physicians spanning all states and medical specialties completed the survey; however, this represented only a 2.21% response rate.

The authors concluded that defensive medicine is a significant force driving the high cost of health care in the United States, and that physicians estimate the cost of defensive medicine to be in the $650 billion to $850 billion range, or between 26% and 34% of annual health care costs.

Skeptics question the way the profession defines defensive medicine, pointing out that malpractice concerns may not be the primary reason, as most interventions add some marginal value to patient care. There may also be conflicting motivations of physicians, such as financial or other personal rewards.

Above all, there is no acceptable method for measuring the extent and use of defensive medicine, and survey reports are apt to be misleading because of bias and the lack of controls and baseline data.

Looking ahead, what can we expect for malpractice law under the Trump administration? Tom Price, MD, a former Republican congressman from Georgia, is an orthopedic surgeon and the new secretary of the Department of Health & Human Services. He has previously spoken passionately about tort reforms such as defensive medicine, damage caps, health tribunals, and practice guidelines. Many states have already incorporated some of these measures into their own tort reforms – with salutary results. It remains to be seen whether HHS will deem any omnibus federal legislation necessary at this point.

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. Some of the materials have been taken from my earlier columns in Internal Medicine News. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

References

1. JAMA. 2014 Nov 26;312(20):2146-55.

2. “Malpractice 2017: Do We Need Reform?” Internal Medicine News, March 1, 2017, page 1.

3. Fein v. Permanente, 38 Cal.3d 137 (1985).

4. Chan v. Curran, 237 CA 4th 601 (2015).

5. Estate of Johnson v. Randall Smith, Inc., 135 Ohio St.3d 440 (2013).

6. Available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers2.cfm?abstract_id=2883693.

7. Shinal v. Toms, 122 A. 3d 1066 (Pa. Super. Ct. 2015).

8. Q J Econ. (1996) 111 (2): 353-390.

9. Available at www.jacksonhealthcare.com/media/8968/defensivemedicine_ebook_final.pdf.

Hold your breath

“Exercising my ‘reasoned judgment,’ I have no doubt that the right to a climate system capable of sustaining human life is fundamental to a free and ordered society.”

– U.S. District Judge Ann Aiken in Kelsey Cascadia Rose Juliana vs. United States of America, et al.

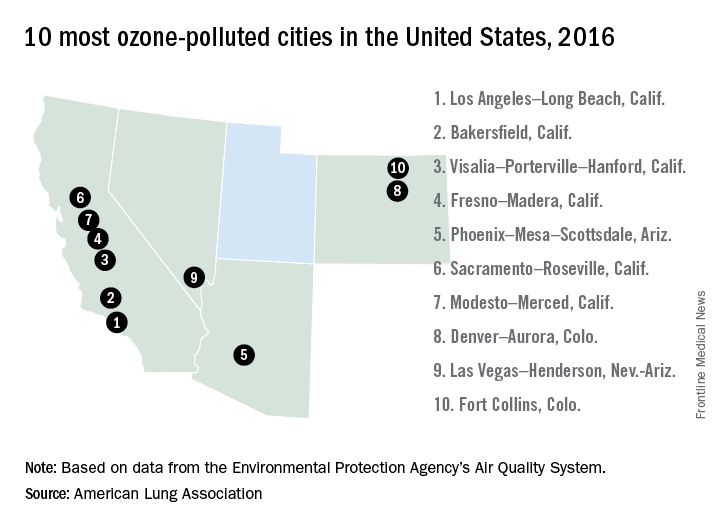

In many areas of the world, the simple act of breathing has become hazardous to people’s health.

According to the World Health Organization, more people die every day from air pollution than from HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and road injuries combined. In China, more than 1 million deaths annually are linked to polluted air (76/100,000); in India the number of deaths is more than 600,000 annually (49/100,000); and in the United States, that figure comes to more than 38,000 (12/100,000).

And yet, nonpolluting, alternative options – such as sun and wind power – are readily available.

Dirty air is visible on a hot summer day – when, mixed with other substances, it forms smog. Higher temperatures can then speed up the chemical reactions that form smog. We breathe in that polluted air, especially on days when the air is stagnant or there is temperature inversion.

The health effects of climate change

Black carbon found in air pollution leads to drug-resistant bacteria and alters antibiotic tolerance.1 The pollution also is associated with multiple cancers: lung, liver, ovarian, and, possibly, breast.2,3,4,5 It causes inflammation linked to the development of coronary artery disease (seen even in children!) and plaque formation leading to heart attacks and cardiac arrhythmias – including atrial fibrillation. Air pollution causes, triggers, or worsens respiratory illnesses – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, asthma, infections – and is responsible for lifelong diminished lung volume in children (a reason families are leaving Beijing.) Exponentially increased rates of autism are linked to bad air quality, as are autoimmune diseases, which also are on the rise.6,7 Polluted air causes brain inflammation – living near sources of air pollution increases the risk of dementia – and other neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.8 The blood brain barrier protects the brain from most foreign matter, but particulate matter, especially ultrafine particulate matter of less than 1 mcm such as magnetite, can cross directly into the brain via the olfactory nerve. (Magnetite has been identified in the brain tissue of residents living in areas where the substance is produced as a result of industrial waste.) While particulate matter of 2.5 mcmis measured in the United States, ultrafine particulate matter is not.

Psychiatric symptoms and chronic psychiatric disorders also are associated with polluted air: On days with poor air quality, a statistically significant increase is seen in suicide threats and visits to emergency departments for panic attacks.9,10

A rise in aggression occurs when there are abnormally high temperatures and significant changes in rainfall. More assaults, murders, suicides, domestic violence, and child abuse can be expected, and a rise in unrest around the world should come as no surprise.

As a consequence of increased CO2 in the atmosphere, temperatures have already risen by 2° F: Sixteen of the hottest years on record have occurred in the last 17 years, with 2016 as the hottest year ever recorded. In Iraq and Kuwait, the temperature last summer reached 129.2° F.

We are experiencing more frequent and extreme weather events, chronic climate conditions, and the cascading disruption of ecosystems. Drought and sea level rise are leading to physical and psychological impacts – both direct and indirect. Some regions of the world have become destabilized, triggering migrations and the refugee crisis.

Along with these psychological impacts, CO2 affects cognition: A recent study by the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, shows that the indoor levels of CO2 to which American workers typically are exposed impair cognitive functioning, particularly in the areas of strategic thinking, information processing, and crisis management.11

What do we do about it?

As mental health professionals, we know that aggression can be overt or passive (from inaction). Overwhelming evidence shows harm to public health from burning fossil fuels, and yet, though we are making progress, resistance still exists in the transition to clean, renewable energy critical for the health of our families and communities. When political will is what stands between us and getting back on a path to breathing clean air, how can inaction be understood as anything but an act of aggression?

This issue has reached U.S. courts: In a landmark case, 21 youths aged 9-20 years represented by “Our Children’s Trust” are suing the U.S. government in the Oregon U.S. District Court for failure to act on climate. The case, heard by Judge Ann Aiken, is now headed to trial.

All of us have a duty to collectively, repeatedly, and forcefully call on policy makers to take action.

That leads me to what we can do as doctors. In this effort to quickly transition to safe, clean renewable energy, we all have a role to play. The notion that we can’t do anything as individuals is no more credible than saying “my vote doesn’t matter.” Just as our actions as voters in a democracy demonstrate the collective civic responsibility we owe one another, so too do our actions on climate. As global citizens, all actions that we take to help us live within the planet’s means are opportunities to restore balance.

What we do collectively drives markets and determines the social norms that powerfully influence the decisions of others – sometimes even unconsciously.

As doctors, we have a unique role to play in the places we work – urging hospitals, clinics, academic centers, and other organizations and facilities to lead by example, become role models for energy efficiency, and choose clean renewable energy sources over the ones harming our health. We can start by choosing wind and solar to power our homes and influencing others to do the same.

We are the voices because this is a health message.

Dr. Van Susteren is a practicing general and forensic psychiatrist in Washington. She serves on the advisory board of the Center for Health and the Global Environment at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston. Dr. Van Susteren is a former member of the board of directors of the National Wildlife Federation and coauthor of group’s report, “The Psychological Effects of Global Warming on the United States – Why the U.S. Mental Health System is Not Prepared.” In 2006, Dr. Van Susteren sought the Democratic nomination for a U.S. Senate seat in Maryland. She also founded Lucky Planet Foods, a company that provides plant-based, low carbon foods.

References

1. Environ Microbiol. 2017 Feb 14. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13686.

2. Environ Health Perspect. 2017 Mar;125[3]:378-84.

3. J Hepatol. 2015;63[6]:1397-1404.

4. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2012;75[3]:174-82.

5. Environ Health Perspect. 2012 Nov; 118[11]:1578-83.

6. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016; 57[3]:271-92.

7. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22[2]219-25.

8. Inhal Toxicol. 2008;20[5]:499-506.

9. J Psychiatr Res. 2015 Mar;62:130-5.

10. Schizophr Res. 2016 Oct 5. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.10.003.

11. Environ Health Perspect. 2016 Jun;124[6]:805-12.

“Exercising my ‘reasoned judgment,’ I have no doubt that the right to a climate system capable of sustaining human life is fundamental to a free and ordered society.”

– U.S. District Judge Ann Aiken in Kelsey Cascadia Rose Juliana vs. United States of America, et al.

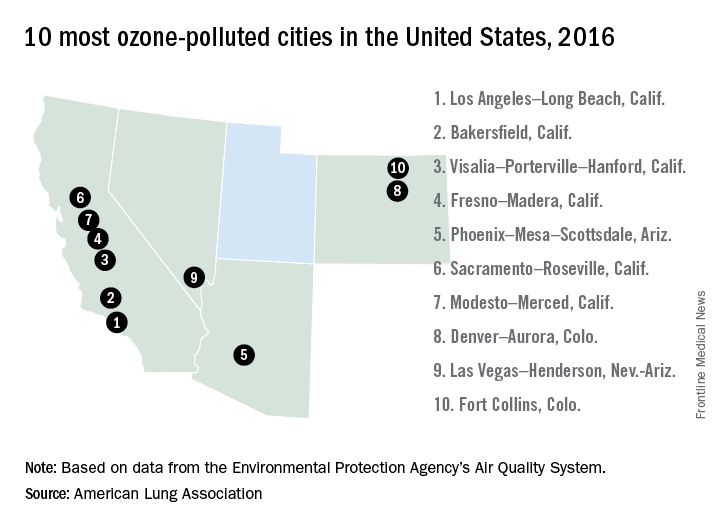

In many areas of the world, the simple act of breathing has become hazardous to people’s health.

According to the World Health Organization, more people die every day from air pollution than from HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and road injuries combined. In China, more than 1 million deaths annually are linked to polluted air (76/100,000); in India the number of deaths is more than 600,000 annually (49/100,000); and in the United States, that figure comes to more than 38,000 (12/100,000).

And yet, nonpolluting, alternative options – such as sun and wind power – are readily available.

Dirty air is visible on a hot summer day – when, mixed with other substances, it forms smog. Higher temperatures can then speed up the chemical reactions that form smog. We breathe in that polluted air, especially on days when the air is stagnant or there is temperature inversion.

The health effects of climate change

Black carbon found in air pollution leads to drug-resistant bacteria and alters antibiotic tolerance.1 The pollution also is associated with multiple cancers: lung, liver, ovarian, and, possibly, breast.2,3,4,5 It causes inflammation linked to the development of coronary artery disease (seen even in children!) and plaque formation leading to heart attacks and cardiac arrhythmias – including atrial fibrillation. Air pollution causes, triggers, or worsens respiratory illnesses – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, asthma, infections – and is responsible for lifelong diminished lung volume in children (a reason families are leaving Beijing.) Exponentially increased rates of autism are linked to bad air quality, as are autoimmune diseases, which also are on the rise.6,7 Polluted air causes brain inflammation – living near sources of air pollution increases the risk of dementia – and other neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.8 The blood brain barrier protects the brain from most foreign matter, but particulate matter, especially ultrafine particulate matter of less than 1 mcm such as magnetite, can cross directly into the brain via the olfactory nerve. (Magnetite has been identified in the brain tissue of residents living in areas where the substance is produced as a result of industrial waste.) While particulate matter of 2.5 mcmis measured in the United States, ultrafine particulate matter is not.

Psychiatric symptoms and chronic psychiatric disorders also are associated with polluted air: On days with poor air quality, a statistically significant increase is seen in suicide threats and visits to emergency departments for panic attacks.9,10

A rise in aggression occurs when there are abnormally high temperatures and significant changes in rainfall. More assaults, murders, suicides, domestic violence, and child abuse can be expected, and a rise in unrest around the world should come as no surprise.

As a consequence of increased CO2 in the atmosphere, temperatures have already risen by 2° F: Sixteen of the hottest years on record have occurred in the last 17 years, with 2016 as the hottest year ever recorded. In Iraq and Kuwait, the temperature last summer reached 129.2° F.

We are experiencing more frequent and extreme weather events, chronic climate conditions, and the cascading disruption of ecosystems. Drought and sea level rise are leading to physical and psychological impacts – both direct and indirect. Some regions of the world have become destabilized, triggering migrations and the refugee crisis.

Along with these psychological impacts, CO2 affects cognition: A recent study by the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, shows that the indoor levels of CO2 to which American workers typically are exposed impair cognitive functioning, particularly in the areas of strategic thinking, information processing, and crisis management.11

What do we do about it?

As mental health professionals, we know that aggression can be overt or passive (from inaction). Overwhelming evidence shows harm to public health from burning fossil fuels, and yet, though we are making progress, resistance still exists in the transition to clean, renewable energy critical for the health of our families and communities. When political will is what stands between us and getting back on a path to breathing clean air, how can inaction be understood as anything but an act of aggression?

This issue has reached U.S. courts: In a landmark case, 21 youths aged 9-20 years represented by “Our Children’s Trust” are suing the U.S. government in the Oregon U.S. District Court for failure to act on climate. The case, heard by Judge Ann Aiken, is now headed to trial.

All of us have a duty to collectively, repeatedly, and forcefully call on policy makers to take action.

That leads me to what we can do as doctors. In this effort to quickly transition to safe, clean renewable energy, we all have a role to play. The notion that we can’t do anything as individuals is no more credible than saying “my vote doesn’t matter.” Just as our actions as voters in a democracy demonstrate the collective civic responsibility we owe one another, so too do our actions on climate. As global citizens, all actions that we take to help us live within the planet’s means are opportunities to restore balance.

What we do collectively drives markets and determines the social norms that powerfully influence the decisions of others – sometimes even unconsciously.

As doctors, we have a unique role to play in the places we work – urging hospitals, clinics, academic centers, and other organizations and facilities to lead by example, become role models for energy efficiency, and choose clean renewable energy sources over the ones harming our health. We can start by choosing wind and solar to power our homes and influencing others to do the same.

We are the voices because this is a health message.

Dr. Van Susteren is a practicing general and forensic psychiatrist in Washington. She serves on the advisory board of the Center for Health and the Global Environment at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston. Dr. Van Susteren is a former member of the board of directors of the National Wildlife Federation and coauthor of group’s report, “The Psychological Effects of Global Warming on the United States – Why the U.S. Mental Health System is Not Prepared.” In 2006, Dr. Van Susteren sought the Democratic nomination for a U.S. Senate seat in Maryland. She also founded Lucky Planet Foods, a company that provides plant-based, low carbon foods.

References

1. Environ Microbiol. 2017 Feb 14. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13686.

2. Environ Health Perspect. 2017 Mar;125[3]:378-84.

3. J Hepatol. 2015;63[6]:1397-1404.

4. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2012;75[3]:174-82.

5. Environ Health Perspect. 2012 Nov; 118[11]:1578-83.

6. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016; 57[3]:271-92.

7. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22[2]219-25.

8. Inhal Toxicol. 2008;20[5]:499-506.

9. J Psychiatr Res. 2015 Mar;62:130-5.

10. Schizophr Res. 2016 Oct 5. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.10.003.

11. Environ Health Perspect. 2016 Jun;124[6]:805-12.

“Exercising my ‘reasoned judgment,’ I have no doubt that the right to a climate system capable of sustaining human life is fundamental to a free and ordered society.”

– U.S. District Judge Ann Aiken in Kelsey Cascadia Rose Juliana vs. United States of America, et al.

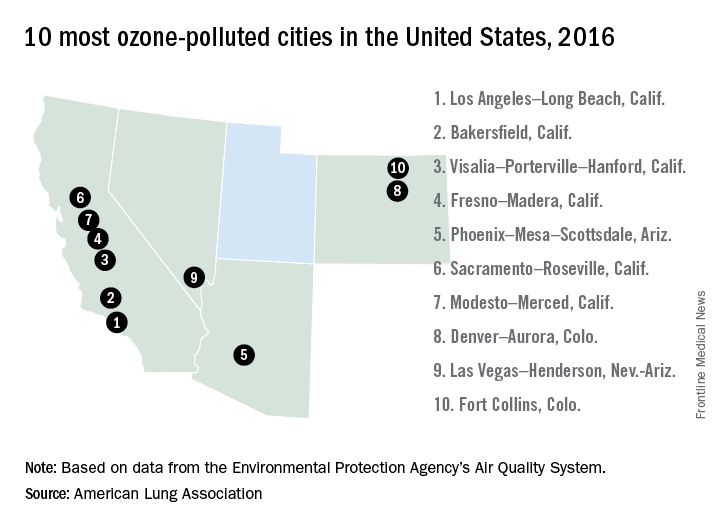

In many areas of the world, the simple act of breathing has become hazardous to people’s health.

According to the World Health Organization, more people die every day from air pollution than from HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and road injuries combined. In China, more than 1 million deaths annually are linked to polluted air (76/100,000); in India the number of deaths is more than 600,000 annually (49/100,000); and in the United States, that figure comes to more than 38,000 (12/100,000).

And yet, nonpolluting, alternative options – such as sun and wind power – are readily available.

Dirty air is visible on a hot summer day – when, mixed with other substances, it forms smog. Higher temperatures can then speed up the chemical reactions that form smog. We breathe in that polluted air, especially on days when the air is stagnant or there is temperature inversion.

The health effects of climate change

Black carbon found in air pollution leads to drug-resistant bacteria and alters antibiotic tolerance.1 The pollution also is associated with multiple cancers: lung, liver, ovarian, and, possibly, breast.2,3,4,5 It causes inflammation linked to the development of coronary artery disease (seen even in children!) and plaque formation leading to heart attacks and cardiac arrhythmias – including atrial fibrillation. Air pollution causes, triggers, or worsens respiratory illnesses – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, asthma, infections – and is responsible for lifelong diminished lung volume in children (a reason families are leaving Beijing.) Exponentially increased rates of autism are linked to bad air quality, as are autoimmune diseases, which also are on the rise.6,7 Polluted air causes brain inflammation – living near sources of air pollution increases the risk of dementia – and other neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.8 The blood brain barrier protects the brain from most foreign matter, but particulate matter, especially ultrafine particulate matter of less than 1 mcm such as magnetite, can cross directly into the brain via the olfactory nerve. (Magnetite has been identified in the brain tissue of residents living in areas where the substance is produced as a result of industrial waste.) While particulate matter of 2.5 mcmis measured in the United States, ultrafine particulate matter is not.

Psychiatric symptoms and chronic psychiatric disorders also are associated with polluted air: On days with poor air quality, a statistically significant increase is seen in suicide threats and visits to emergency departments for panic attacks.9,10

A rise in aggression occurs when there are abnormally high temperatures and significant changes in rainfall. More assaults, murders, suicides, domestic violence, and child abuse can be expected, and a rise in unrest around the world should come as no surprise.

As a consequence of increased CO2 in the atmosphere, temperatures have already risen by 2° F: Sixteen of the hottest years on record have occurred in the last 17 years, with 2016 as the hottest year ever recorded. In Iraq and Kuwait, the temperature last summer reached 129.2° F.

We are experiencing more frequent and extreme weather events, chronic climate conditions, and the cascading disruption of ecosystems. Drought and sea level rise are leading to physical and psychological impacts – both direct and indirect. Some regions of the world have become destabilized, triggering migrations and the refugee crisis.

Along with these psychological impacts, CO2 affects cognition: A recent study by the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, shows that the indoor levels of CO2 to which American workers typically are exposed impair cognitive functioning, particularly in the areas of strategic thinking, information processing, and crisis management.11

What do we do about it?

As mental health professionals, we know that aggression can be overt or passive (from inaction). Overwhelming evidence shows harm to public health from burning fossil fuels, and yet, though we are making progress, resistance still exists in the transition to clean, renewable energy critical for the health of our families and communities. When political will is what stands between us and getting back on a path to breathing clean air, how can inaction be understood as anything but an act of aggression?

This issue has reached U.S. courts: In a landmark case, 21 youths aged 9-20 years represented by “Our Children’s Trust” are suing the U.S. government in the Oregon U.S. District Court for failure to act on climate. The case, heard by Judge Ann Aiken, is now headed to trial.

All of us have a duty to collectively, repeatedly, and forcefully call on policy makers to take action.

That leads me to what we can do as doctors. In this effort to quickly transition to safe, clean renewable energy, we all have a role to play. The notion that we can’t do anything as individuals is no more credible than saying “my vote doesn’t matter.” Just as our actions as voters in a democracy demonstrate the collective civic responsibility we owe one another, so too do our actions on climate. As global citizens, all actions that we take to help us live within the planet’s means are opportunities to restore balance.

What we do collectively drives markets and determines the social norms that powerfully influence the decisions of others – sometimes even unconsciously.

As doctors, we have a unique role to play in the places we work – urging hospitals, clinics, academic centers, and other organizations and facilities to lead by example, become role models for energy efficiency, and choose clean renewable energy sources over the ones harming our health. We can start by choosing wind and solar to power our homes and influencing others to do the same.

We are the voices because this is a health message.

Dr. Van Susteren is a practicing general and forensic psychiatrist in Washington. She serves on the advisory board of the Center for Health and the Global Environment at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston. Dr. Van Susteren is a former member of the board of directors of the National Wildlife Federation and coauthor of group’s report, “The Psychological Effects of Global Warming on the United States – Why the U.S. Mental Health System is Not Prepared.” In 2006, Dr. Van Susteren sought the Democratic nomination for a U.S. Senate seat in Maryland. She also founded Lucky Planet Foods, a company that provides plant-based, low carbon foods.

References

1. Environ Microbiol. 2017 Feb 14. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13686.

2. Environ Health Perspect. 2017 Mar;125[3]:378-84.

3. J Hepatol. 2015;63[6]:1397-1404.

4. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2012;75[3]:174-82.

5. Environ Health Perspect. 2012 Nov; 118[11]:1578-83.

6. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016; 57[3]:271-92.

7. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22[2]219-25.

8. Inhal Toxicol. 2008;20[5]:499-506.

9. J Psychiatr Res. 2015 Mar;62:130-5.

10. Schizophr Res. 2016 Oct 5. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.10.003.

11. Environ Health Perspect. 2016 Jun;124[6]:805-12.

MACRA: Not going away any time soon

MACRA is now a fact of life.

Implementation of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA), the historic Medicare reform law that replaced the Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) formula in 2015, began in January 2017. Patrick V. Bailey, MD, FACS, Medical Director, Advocacy, in the American College of Surgeons (ACS) Division of Advocacy and Health Policy (DAHP) office in Washington DC has, for the past several years, been involved with ensuring that the policy implemented takes into account the interests of surgeons and their patients. He has seen MACRA develop from its beginnings. Dr. Bailey, a pediatric surgeon, has deep knowledge about the program, both from the policy perspective and as a surgeon. We asked Dr. Bailey to share with us his insights on what surgeons can expect and what surgeons can do to avoid penalties.

1) Many surgeons are overwhelmed by the perceived complexity of the new MACRA law. What do you say to those who have so far tuned out much of the information they have been given?