User login

New kids on the block for migraine treatment and prophylaxis

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Dear colleagues, I’m Hans-Christoph Diener from the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany.

CGRP receptor agonists

Let me start with the treatment of acute migraine attacks. Until recently, we had analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like ibuprofen, ergot alkaloids, and triptans. There are new developments, which are small molecules that are antagonists at the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor. At the moment, we have three of them: rimegepant 75 mg, ubrogepant 50 mg or 100 mg, and zavegepant (a nasal spray) 10 mg.

These are all effective and superior to placebo. The 2-hour pain-free rate is somewhere between 25% and 30%. They have very few side effects; these include a little bit of nausea, somnolence, nasopharyngitis, and for zavegepant, the nasal spray, taste disturbance. In indirect comparisons, the so-called gepants are about as effective as ibuprofen and aspirin, and they seem to be less effective than sumatriptan 100 mg.

Unfortunately, until now, we have no direct comparison with triptans and we have no data demonstrating whether they are effective in people where triptans do not work. The major shortcoming is the cost in the United States. The cost per tablet or nasal spray is somewhere between $80 and $200. This means we definitely need more studies for these gepants.

Migraine prophylaxis

Let me move to the prophylaxis of migraine with drugs. Previously and still, we have all medications like beta-blockers, flunarizine, topiramate, valproic acid, amitriptyline, and candesartan, and for chronic migraine, onabotulinumtoxinA. We have now 5 years’ experience with the monoclonal antibodies against CGRP or the CGRP receptor like eptinezumab, erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab.

These are all equally effective. They reduce migraine-days between 3 and 7 per month. They are effective both in episodic and chronic migraine, and most importantly, they are effective in people with medication overuse headaches. The 50% responder rates are somewhere between 40% and 60%, and there are no significant differences between the four monoclonal antibodies.

The major advantage is a very good tolerability profile; very few patients terminate treatment because of adverse events. There has been, with one exception, no direct comparison of the monoclonal antibodies with traditional migraine preventive drugs or onabotulinumtoxinA. The only exception is a trial that compared topiramate and erenumab, showing that erenumab was definitely more effective and better tolerated.

At the moment, the recommendation is to use these monoclonal antibodies for 12 months in episodic migraine and 24 months in chronic migraine and then pause. It usually turns out that between 50% and 70% of these patients need to continue the treatment. If they are not working, there is a possibility to switch between the monoclonal antibodies, and the success rate after this is somewhere between 15% and 30%.

Gepants were also developed for the prevention of migraine. Here, we have rimegepant 75 mg every other day or atogepant 60 mg daily. They are effective, but in indirect comparisons, they are less effective than the monoclonal antibodies. At present, we have no comparative trials with monoclonal antibodies or the traditional migraine preventive drugs.

Potential patients are those who have needle phobia or patients who do not respond to monoclonal antibodies. Again, the biggest shortcoming is cost in the United States. The cost per year for migraine prevention or prophylaxis is between $12,000 and $20,000.

Finally, we also had very exciting news. There is a new therapeutic approach via PACAP. PACAP is pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide, which has similar biological actions as CGRP but with additional actions. It could very well be that people who do not respond to a monoclonal antibody would respond to a monoclonal antibody against PACAP.

At the congress, the first randomized, placebo-controlled trial with a monoclonal antibody against PACAP was presented. This monoclonal antibody was effective in a population of people in whom prior preventive therapy had failed. A phase 3 study is planned, and most probably the PACAP monoclonal could work in people who do not respond to monoclonal antibodies against CGRP.

Dear colleagues, we have now many choices for the acute treatment of migraine and migraine prophylaxis. We have new kids on the block, and we have to learn more about how to use these drugs, their benefits, and their shortcomings.

He has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:Received honoraria for participation in clinical trials, contribution to advisory boards or oral presentations from: Abbott; Addex Pharma; Alder; Allergan; Almirall; Amgen; Autonomic Technology; AstraZeneca; Bayer Vital; Berlin Chemie; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Boehringer Ingelheim; Chordate; CoAxia; Corimmun; Covidien; Coherex; CoLucid; Daiichi-Sankyo; D-Pharm; Electrocore; Fresenius; GlaxoSmithKline; Grunenthal; Janssen-Cilag; Labrys Biologics Lilly; La Roche; 3M Medica; MSD; Medtronic; Menarini; MindFrame; Minster; Neuroscore; Neurobiological Technologies; Novartis; Novo Nordisk; Johnson & Johnson; Knoll; Paion; Parke-Davis; Pierre Fabre; Pfizer; Schaper and Brummer; Sanofi-Aventis; Schering-Plough; Servier; Solvay; Syngis; St. Jude; Talecris; Thrombogenics; WebMD Global; Weber and Weber; Wyeth; and Yamanouchi.

Dr. Diener is professor, department of neurology, Stroke Center-Headache Center, University Duisburg-Essen (Germany).

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Dear colleagues, I’m Hans-Christoph Diener from the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany.

CGRP receptor agonists

Let me start with the treatment of acute migraine attacks. Until recently, we had analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like ibuprofen, ergot alkaloids, and triptans. There are new developments, which are small molecules that are antagonists at the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor. At the moment, we have three of them: rimegepant 75 mg, ubrogepant 50 mg or 100 mg, and zavegepant (a nasal spray) 10 mg.

These are all effective and superior to placebo. The 2-hour pain-free rate is somewhere between 25% and 30%. They have very few side effects; these include a little bit of nausea, somnolence, nasopharyngitis, and for zavegepant, the nasal spray, taste disturbance. In indirect comparisons, the so-called gepants are about as effective as ibuprofen and aspirin, and they seem to be less effective than sumatriptan 100 mg.

Unfortunately, until now, we have no direct comparison with triptans and we have no data demonstrating whether they are effective in people where triptans do not work. The major shortcoming is the cost in the United States. The cost per tablet or nasal spray is somewhere between $80 and $200. This means we definitely need more studies for these gepants.

Migraine prophylaxis

Let me move to the prophylaxis of migraine with drugs. Previously and still, we have all medications like beta-blockers, flunarizine, topiramate, valproic acid, amitriptyline, and candesartan, and for chronic migraine, onabotulinumtoxinA. We have now 5 years’ experience with the monoclonal antibodies against CGRP or the CGRP receptor like eptinezumab, erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab.

These are all equally effective. They reduce migraine-days between 3 and 7 per month. They are effective both in episodic and chronic migraine, and most importantly, they are effective in people with medication overuse headaches. The 50% responder rates are somewhere between 40% and 60%, and there are no significant differences between the four monoclonal antibodies.

The major advantage is a very good tolerability profile; very few patients terminate treatment because of adverse events. There has been, with one exception, no direct comparison of the monoclonal antibodies with traditional migraine preventive drugs or onabotulinumtoxinA. The only exception is a trial that compared topiramate and erenumab, showing that erenumab was definitely more effective and better tolerated.

At the moment, the recommendation is to use these monoclonal antibodies for 12 months in episodic migraine and 24 months in chronic migraine and then pause. It usually turns out that between 50% and 70% of these patients need to continue the treatment. If they are not working, there is a possibility to switch between the monoclonal antibodies, and the success rate after this is somewhere between 15% and 30%.

Gepants were also developed for the prevention of migraine. Here, we have rimegepant 75 mg every other day or atogepant 60 mg daily. They are effective, but in indirect comparisons, they are less effective than the monoclonal antibodies. At present, we have no comparative trials with monoclonal antibodies or the traditional migraine preventive drugs.

Potential patients are those who have needle phobia or patients who do not respond to monoclonal antibodies. Again, the biggest shortcoming is cost in the United States. The cost per year for migraine prevention or prophylaxis is between $12,000 and $20,000.

Finally, we also had very exciting news. There is a new therapeutic approach via PACAP. PACAP is pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide, which has similar biological actions as CGRP but with additional actions. It could very well be that people who do not respond to a monoclonal antibody would respond to a monoclonal antibody against PACAP.

At the congress, the first randomized, placebo-controlled trial with a monoclonal antibody against PACAP was presented. This monoclonal antibody was effective in a population of people in whom prior preventive therapy had failed. A phase 3 study is planned, and most probably the PACAP monoclonal could work in people who do not respond to monoclonal antibodies against CGRP.

Dear colleagues, we have now many choices for the acute treatment of migraine and migraine prophylaxis. We have new kids on the block, and we have to learn more about how to use these drugs, their benefits, and their shortcomings.

He has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:Received honoraria for participation in clinical trials, contribution to advisory boards or oral presentations from: Abbott; Addex Pharma; Alder; Allergan; Almirall; Amgen; Autonomic Technology; AstraZeneca; Bayer Vital; Berlin Chemie; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Boehringer Ingelheim; Chordate; CoAxia; Corimmun; Covidien; Coherex; CoLucid; Daiichi-Sankyo; D-Pharm; Electrocore; Fresenius; GlaxoSmithKline; Grunenthal; Janssen-Cilag; Labrys Biologics Lilly; La Roche; 3M Medica; MSD; Medtronic; Menarini; MindFrame; Minster; Neuroscore; Neurobiological Technologies; Novartis; Novo Nordisk; Johnson & Johnson; Knoll; Paion; Parke-Davis; Pierre Fabre; Pfizer; Schaper and Brummer; Sanofi-Aventis; Schering-Plough; Servier; Solvay; Syngis; St. Jude; Talecris; Thrombogenics; WebMD Global; Weber and Weber; Wyeth; and Yamanouchi.

Dr. Diener is professor, department of neurology, Stroke Center-Headache Center, University Duisburg-Essen (Germany).

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Dear colleagues, I’m Hans-Christoph Diener from the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany.

CGRP receptor agonists

Let me start with the treatment of acute migraine attacks. Until recently, we had analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like ibuprofen, ergot alkaloids, and triptans. There are new developments, which are small molecules that are antagonists at the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor. At the moment, we have three of them: rimegepant 75 mg, ubrogepant 50 mg or 100 mg, and zavegepant (a nasal spray) 10 mg.

These are all effective and superior to placebo. The 2-hour pain-free rate is somewhere between 25% and 30%. They have very few side effects; these include a little bit of nausea, somnolence, nasopharyngitis, and for zavegepant, the nasal spray, taste disturbance. In indirect comparisons, the so-called gepants are about as effective as ibuprofen and aspirin, and they seem to be less effective than sumatriptan 100 mg.

Unfortunately, until now, we have no direct comparison with triptans and we have no data demonstrating whether they are effective in people where triptans do not work. The major shortcoming is the cost in the United States. The cost per tablet or nasal spray is somewhere between $80 and $200. This means we definitely need more studies for these gepants.

Migraine prophylaxis

Let me move to the prophylaxis of migraine with drugs. Previously and still, we have all medications like beta-blockers, flunarizine, topiramate, valproic acid, amitriptyline, and candesartan, and for chronic migraine, onabotulinumtoxinA. We have now 5 years’ experience with the monoclonal antibodies against CGRP or the CGRP receptor like eptinezumab, erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab.

These are all equally effective. They reduce migraine-days between 3 and 7 per month. They are effective both in episodic and chronic migraine, and most importantly, they are effective in people with medication overuse headaches. The 50% responder rates are somewhere between 40% and 60%, and there are no significant differences between the four monoclonal antibodies.

The major advantage is a very good tolerability profile; very few patients terminate treatment because of adverse events. There has been, with one exception, no direct comparison of the monoclonal antibodies with traditional migraine preventive drugs or onabotulinumtoxinA. The only exception is a trial that compared topiramate and erenumab, showing that erenumab was definitely more effective and better tolerated.

At the moment, the recommendation is to use these monoclonal antibodies for 12 months in episodic migraine and 24 months in chronic migraine and then pause. It usually turns out that between 50% and 70% of these patients need to continue the treatment. If they are not working, there is a possibility to switch between the monoclonal antibodies, and the success rate after this is somewhere between 15% and 30%.

Gepants were also developed for the prevention of migraine. Here, we have rimegepant 75 mg every other day or atogepant 60 mg daily. They are effective, but in indirect comparisons, they are less effective than the monoclonal antibodies. At present, we have no comparative trials with monoclonal antibodies or the traditional migraine preventive drugs.

Potential patients are those who have needle phobia or patients who do not respond to monoclonal antibodies. Again, the biggest shortcoming is cost in the United States. The cost per year for migraine prevention or prophylaxis is between $12,000 and $20,000.

Finally, we also had very exciting news. There is a new therapeutic approach via PACAP. PACAP is pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide, which has similar biological actions as CGRP but with additional actions. It could very well be that people who do not respond to a monoclonal antibody would respond to a monoclonal antibody against PACAP.

At the congress, the first randomized, placebo-controlled trial with a monoclonal antibody against PACAP was presented. This monoclonal antibody was effective in a population of people in whom prior preventive therapy had failed. A phase 3 study is planned, and most probably the PACAP monoclonal could work in people who do not respond to monoclonal antibodies against CGRP.

Dear colleagues, we have now many choices for the acute treatment of migraine and migraine prophylaxis. We have new kids on the block, and we have to learn more about how to use these drugs, their benefits, and their shortcomings.

He has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:Received honoraria for participation in clinical trials, contribution to advisory boards or oral presentations from: Abbott; Addex Pharma; Alder; Allergan; Almirall; Amgen; Autonomic Technology; AstraZeneca; Bayer Vital; Berlin Chemie; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Boehringer Ingelheim; Chordate; CoAxia; Corimmun; Covidien; Coherex; CoLucid; Daiichi-Sankyo; D-Pharm; Electrocore; Fresenius; GlaxoSmithKline; Grunenthal; Janssen-Cilag; Labrys Biologics Lilly; La Roche; 3M Medica; MSD; Medtronic; Menarini; MindFrame; Minster; Neuroscore; Neurobiological Technologies; Novartis; Novo Nordisk; Johnson & Johnson; Knoll; Paion; Parke-Davis; Pierre Fabre; Pfizer; Schaper and Brummer; Sanofi-Aventis; Schering-Plough; Servier; Solvay; Syngis; St. Jude; Talecris; Thrombogenics; WebMD Global; Weber and Weber; Wyeth; and Yamanouchi.

Dr. Diener is professor, department of neurology, Stroke Center-Headache Center, University Duisburg-Essen (Germany).

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Where do you stand on the Middle East conflict?

“What do you think about the whole Israel thing?”

That question came at the end of an otherwise routine appointment.

Maybe she was just chatting. Maybe she wanted something deeper. I have no idea. I just said, “I don’t discuss those things with patients.”

My answer surprised her, but she didn’t push it. She paid her copay, scheduled a follow-up for 3 months, and left.

As I’ve written before, I try to avoid all news except the local weather. The sad reality is that most of it is bad and there’s nothing I can really do about it. It only upsets me, which isn’t good for my mental health and blood pressure, and if I can’t change it, what’s the point of knowing? It falls under the serenity prayer.

Of course, some news stories are too big not to hear something. I pass TVs in the doctors lounge or coffee house, hear others talking as I stand in line for the elevator, or see blurbs go by when checking the weather. It’s not entirely unavoidable.

I’m not trivializing the Middle East. But, to me, it’s not part of the doctor-patient relationship any more than my political views are. You run the risk of driving a wedge between you and the person you’re caring for. If you don’t like their opinion, you may find yourself less interested in them and their care. If they don’t like your opinion on news, they may start to question your ability as a doctor.

That’s not what we strive for, but it can be human nature. For better or worse we often reduce things to “us against them,” and learning someone is on the opposite side may, even subconsciously, alter how you treat them.

That’s not good, so to me it’s best not to know.

Some may think I’m being petty, or aloof, to be unwilling to discuss nonmedical issues of significance, but I don’t see it that way. Time is limited at the appointment and is best spent on medical care. Something unrelated to the visit that may alter my objective opinion of a patient – or theirs of me as a doctor – is best left out of it.

I’m here to be your doctor, and to do the best I can for you. I’m not here to be a debate partner. Whenever a patient asks me a question on politics or news I always think of the Monty Python skit “Argument Clinic.” That’s not why you’re here. There are plenty places to discuss such things. My office isn’t one of them.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

“What do you think about the whole Israel thing?”

That question came at the end of an otherwise routine appointment.

Maybe she was just chatting. Maybe she wanted something deeper. I have no idea. I just said, “I don’t discuss those things with patients.”

My answer surprised her, but she didn’t push it. She paid her copay, scheduled a follow-up for 3 months, and left.

As I’ve written before, I try to avoid all news except the local weather. The sad reality is that most of it is bad and there’s nothing I can really do about it. It only upsets me, which isn’t good for my mental health and blood pressure, and if I can’t change it, what’s the point of knowing? It falls under the serenity prayer.

Of course, some news stories are too big not to hear something. I pass TVs in the doctors lounge or coffee house, hear others talking as I stand in line for the elevator, or see blurbs go by when checking the weather. It’s not entirely unavoidable.

I’m not trivializing the Middle East. But, to me, it’s not part of the doctor-patient relationship any more than my political views are. You run the risk of driving a wedge between you and the person you’re caring for. If you don’t like their opinion, you may find yourself less interested in them and their care. If they don’t like your opinion on news, they may start to question your ability as a doctor.

That’s not what we strive for, but it can be human nature. For better or worse we often reduce things to “us against them,” and learning someone is on the opposite side may, even subconsciously, alter how you treat them.

That’s not good, so to me it’s best not to know.

Some may think I’m being petty, or aloof, to be unwilling to discuss nonmedical issues of significance, but I don’t see it that way. Time is limited at the appointment and is best spent on medical care. Something unrelated to the visit that may alter my objective opinion of a patient – or theirs of me as a doctor – is best left out of it.

I’m here to be your doctor, and to do the best I can for you. I’m not here to be a debate partner. Whenever a patient asks me a question on politics or news I always think of the Monty Python skit “Argument Clinic.” That’s not why you’re here. There are plenty places to discuss such things. My office isn’t one of them.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

“What do you think about the whole Israel thing?”

That question came at the end of an otherwise routine appointment.

Maybe she was just chatting. Maybe she wanted something deeper. I have no idea. I just said, “I don’t discuss those things with patients.”

My answer surprised her, but she didn’t push it. She paid her copay, scheduled a follow-up for 3 months, and left.

As I’ve written before, I try to avoid all news except the local weather. The sad reality is that most of it is bad and there’s nothing I can really do about it. It only upsets me, which isn’t good for my mental health and blood pressure, and if I can’t change it, what’s the point of knowing? It falls under the serenity prayer.

Of course, some news stories are too big not to hear something. I pass TVs in the doctors lounge or coffee house, hear others talking as I stand in line for the elevator, or see blurbs go by when checking the weather. It’s not entirely unavoidable.

I’m not trivializing the Middle East. But, to me, it’s not part of the doctor-patient relationship any more than my political views are. You run the risk of driving a wedge between you and the person you’re caring for. If you don’t like their opinion, you may find yourself less interested in them and their care. If they don’t like your opinion on news, they may start to question your ability as a doctor.

That’s not what we strive for, but it can be human nature. For better or worse we often reduce things to “us against them,” and learning someone is on the opposite side may, even subconsciously, alter how you treat them.

That’s not good, so to me it’s best not to know.

Some may think I’m being petty, or aloof, to be unwilling to discuss nonmedical issues of significance, but I don’t see it that way. Time is limited at the appointment and is best spent on medical care. Something unrelated to the visit that may alter my objective opinion of a patient – or theirs of me as a doctor – is best left out of it.

I’m here to be your doctor, and to do the best I can for you. I’m not here to be a debate partner. Whenever a patient asks me a question on politics or news I always think of the Monty Python skit “Argument Clinic.” That’s not why you’re here. There are plenty places to discuss such things. My office isn’t one of them.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

AI in medicine has a major Cassandra problem

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Today I’m going to talk to you about a study at the cutting edge of modern medicine, one that uses an artificial intelligence (AI) model to guide care. But before I do, I need to take you back to the late Bronze Age, to a city located on the coast of what is now Turkey.

Troy’s towering walls made it seem unassailable, but that would not stop the Achaeans and their fleet of black ships from making landfall, and, after a siege, destroying the city. The destruction of Troy, as told in the Iliad and the Aeneid, was foretold by Cassandra, the daughter of King Priam and Priestess of Troy.

Cassandra had been given the gift of prophecy by the god Apollo in exchange for her favors. But after the gift was bestowed, she rejected the bright god and, in his rage, he added a curse to her blessing: that no one would ever believe her prophecies.

Thus it was that when her brother Paris set off to Sparta to abduct Helen, she warned him that his actions would lead to the downfall of their great city. He, of course, ignored her.

And you know the rest of the story.

Why am I telling you the story of Cassandra of Troy when we’re supposed to be talking about AI in medicine? Because AI has a major Cassandra problem.

The recent history of AI, and particularly the subset of AI known as machine learning in medicine, has been characterized by an accuracy arms race.

The electronic health record allows for the collection of volumes of data orders of magnitude greater than what we have ever been able to collect before. And all that data can be crunched by various algorithms to make predictions about, well, anything – whether a patient will be transferred to the intensive care unit, whether a GI bleed will need an intervention, whether someone will die in the next year.

Studies in this area tend to rely on retrospective datasets, and as time has gone on, better algorithms and more data have led to better and better predictions. In some simpler cases, machine-learning models have achieved near-perfect accuracy – Cassandra-level accuracy – as in the reading of chest x-rays for pneumonia, for example.

But as Cassandra teaches us, even perfect prediction is useless if no one believes you, if they don’t change their behavior. And this is the central problem of AI in medicine today. Many people are focusing on accuracy of the prediction but have forgotten that high accuracy is just table stakes for an AI model to be useful. It has to not only be accurate, but its use also has to change outcomes for patients. We need to be able to save Troy.

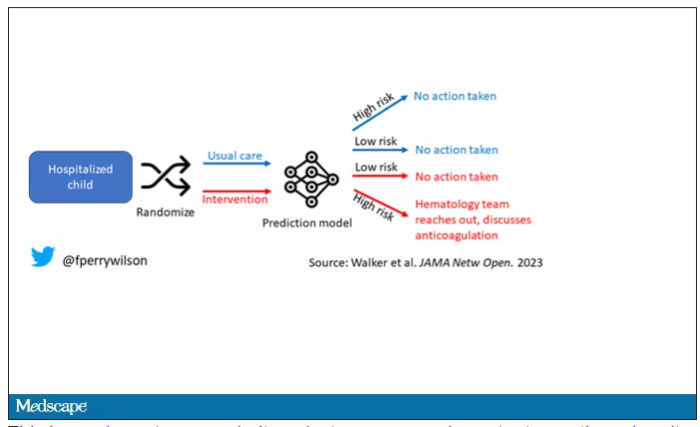

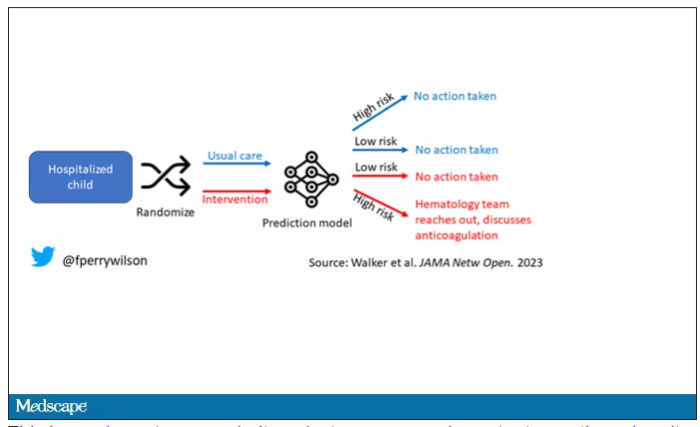

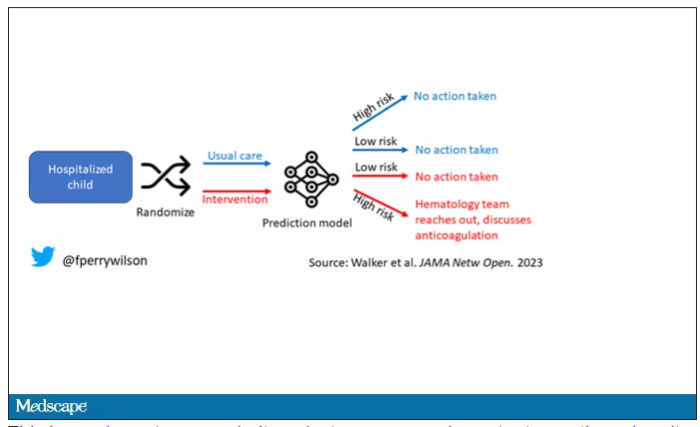

The best way to determine whether an AI model will help patients is to treat a model like we treat a new medication and evaluate it through a randomized trial. That’s what researchers, led by Shannon Walker of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., did in a paper appearing in JAMA Network Open.

The model in question was one that predicted venous thromboembolism – blood clots – in hospitalized children. The model took in a variety of data points from the health record: a history of blood clot, history of cancer, presence of a central line, a variety of lab values. And the predictive model was very good – maybe not Cassandra good, but it achieved an AUC of 0.90, which means it had very high accuracy.

But again, accuracy is just table stakes.

The authors deployed the model in the live health record and recorded the results. For half of the kids, that was all that happened; no one actually saw the predictions. For those randomized to the intervention, the hematology team would be notified when the risk for clot was calculated to be greater than 2.5%. The hematology team would then contact the primary team to discuss prophylactic anticoagulation.

This is an elegant approach.

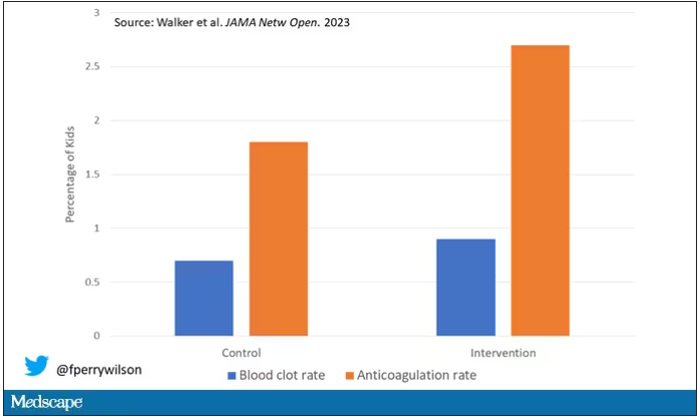

Let’s start with those table stakes – accuracy. The predictions were, by and large, pretty accurate in this trial. Of the 135 kids who developed blood clots, 121 had been flagged by the model in advance. That’s about 90%. The model flagged about 10% of kids who didn’t get a blood clot as well, but that’s not entirely surprising since the threshold for flagging was a 2.5% risk.

Given that the model preidentified almost every kid who would go on to develop a blood clot, it would make sense that kids randomized to the intervention would do better; after all, Cassandra was calling out her warnings.

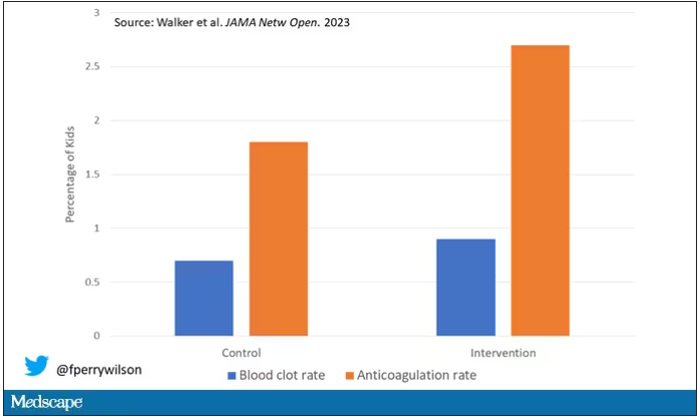

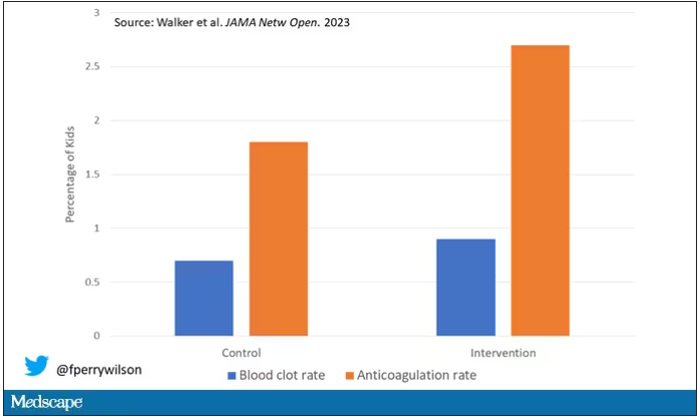

But those kids didn’t do better. The rate of blood clot was no different between the group that used the accurate prediction model and the group that did not.

Why? Why does the use of an accurate model not necessarily improve outcomes?

First of all, a warning must lead to some change in management. Indeed, the kids in the intervention group were more likely to receive anticoagulation, but barely so. There were lots of reasons for this: physician preference, imminent discharge, active bleeding, and so on.

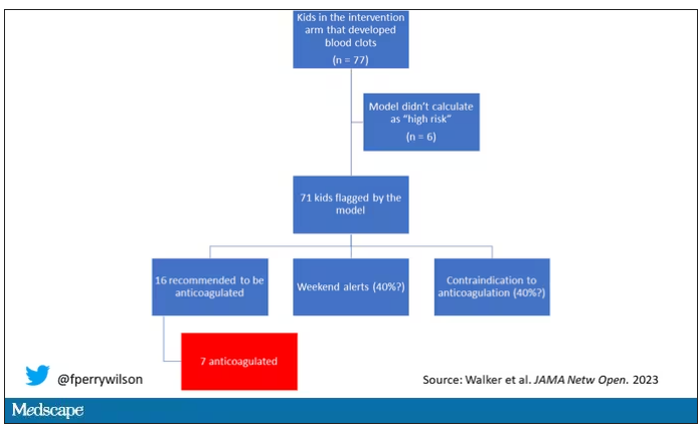

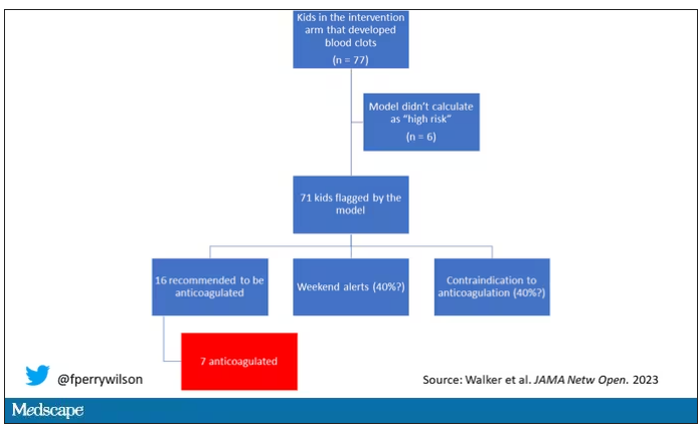

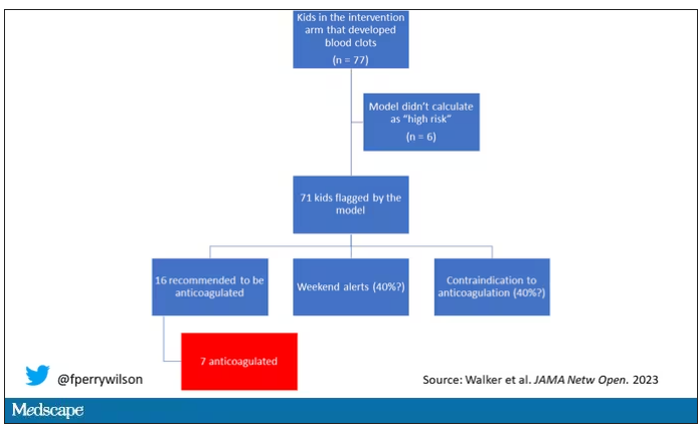

But let’s take a look at the 77 kids in the intervention arm who developed blood clots, because I think this is an instructive analysis.

Six of them did not meet the 2.5% threshold criteria, a case where the model missed its mark. Again, accuracy is table stakes.

Of the remaining 71, only 16 got a recommendation from the hematologist to start anticoagulation. Why not more? Well, the model identified some of the high-risk kids on the weekend, and it seems that the study team did not contact treatment teams during that time. That may account for about 40% of these cases. The remainder had some contraindication to anticoagulation.

Most tellingly, of the 16 who did get a recommendation to start anticoagulation, the recommendation was followed in only seven patients.

This is the gap between accurate prediction and the ability to change outcomes for patients. A prediction is useless if it is wrong, for sure. But it’s also useless if you don’t tell anyone about it. It’s useless if you tell someone but they can’t do anything about it. And it’s useless if they could do something about it but choose not to.

That’s the gulf that these models need to cross at this point. So, the next time some slick company tells you how accurate their AI model is, ask them if accuracy is really the most important thing. If they say, “Well, yes, of course,” then tell them about Cassandra.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Today I’m going to talk to you about a study at the cutting edge of modern medicine, one that uses an artificial intelligence (AI) model to guide care. But before I do, I need to take you back to the late Bronze Age, to a city located on the coast of what is now Turkey.

Troy’s towering walls made it seem unassailable, but that would not stop the Achaeans and their fleet of black ships from making landfall, and, after a siege, destroying the city. The destruction of Troy, as told in the Iliad and the Aeneid, was foretold by Cassandra, the daughter of King Priam and Priestess of Troy.

Cassandra had been given the gift of prophecy by the god Apollo in exchange for her favors. But after the gift was bestowed, she rejected the bright god and, in his rage, he added a curse to her blessing: that no one would ever believe her prophecies.

Thus it was that when her brother Paris set off to Sparta to abduct Helen, she warned him that his actions would lead to the downfall of their great city. He, of course, ignored her.

And you know the rest of the story.

Why am I telling you the story of Cassandra of Troy when we’re supposed to be talking about AI in medicine? Because AI has a major Cassandra problem.

The recent history of AI, and particularly the subset of AI known as machine learning in medicine, has been characterized by an accuracy arms race.

The electronic health record allows for the collection of volumes of data orders of magnitude greater than what we have ever been able to collect before. And all that data can be crunched by various algorithms to make predictions about, well, anything – whether a patient will be transferred to the intensive care unit, whether a GI bleed will need an intervention, whether someone will die in the next year.

Studies in this area tend to rely on retrospective datasets, and as time has gone on, better algorithms and more data have led to better and better predictions. In some simpler cases, machine-learning models have achieved near-perfect accuracy – Cassandra-level accuracy – as in the reading of chest x-rays for pneumonia, for example.

But as Cassandra teaches us, even perfect prediction is useless if no one believes you, if they don’t change their behavior. And this is the central problem of AI in medicine today. Many people are focusing on accuracy of the prediction but have forgotten that high accuracy is just table stakes for an AI model to be useful. It has to not only be accurate, but its use also has to change outcomes for patients. We need to be able to save Troy.

The best way to determine whether an AI model will help patients is to treat a model like we treat a new medication and evaluate it through a randomized trial. That’s what researchers, led by Shannon Walker of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., did in a paper appearing in JAMA Network Open.

The model in question was one that predicted venous thromboembolism – blood clots – in hospitalized children. The model took in a variety of data points from the health record: a history of blood clot, history of cancer, presence of a central line, a variety of lab values. And the predictive model was very good – maybe not Cassandra good, but it achieved an AUC of 0.90, which means it had very high accuracy.

But again, accuracy is just table stakes.

The authors deployed the model in the live health record and recorded the results. For half of the kids, that was all that happened; no one actually saw the predictions. For those randomized to the intervention, the hematology team would be notified when the risk for clot was calculated to be greater than 2.5%. The hematology team would then contact the primary team to discuss prophylactic anticoagulation.

This is an elegant approach.

Let’s start with those table stakes – accuracy. The predictions were, by and large, pretty accurate in this trial. Of the 135 kids who developed blood clots, 121 had been flagged by the model in advance. That’s about 90%. The model flagged about 10% of kids who didn’t get a blood clot as well, but that’s not entirely surprising since the threshold for flagging was a 2.5% risk.

Given that the model preidentified almost every kid who would go on to develop a blood clot, it would make sense that kids randomized to the intervention would do better; after all, Cassandra was calling out her warnings.

But those kids didn’t do better. The rate of blood clot was no different between the group that used the accurate prediction model and the group that did not.

Why? Why does the use of an accurate model not necessarily improve outcomes?

First of all, a warning must lead to some change in management. Indeed, the kids in the intervention group were more likely to receive anticoagulation, but barely so. There were lots of reasons for this: physician preference, imminent discharge, active bleeding, and so on.

But let’s take a look at the 77 kids in the intervention arm who developed blood clots, because I think this is an instructive analysis.

Six of them did not meet the 2.5% threshold criteria, a case where the model missed its mark. Again, accuracy is table stakes.

Of the remaining 71, only 16 got a recommendation from the hematologist to start anticoagulation. Why not more? Well, the model identified some of the high-risk kids on the weekend, and it seems that the study team did not contact treatment teams during that time. That may account for about 40% of these cases. The remainder had some contraindication to anticoagulation.

Most tellingly, of the 16 who did get a recommendation to start anticoagulation, the recommendation was followed in only seven patients.

This is the gap between accurate prediction and the ability to change outcomes for patients. A prediction is useless if it is wrong, for sure. But it’s also useless if you don’t tell anyone about it. It’s useless if you tell someone but they can’t do anything about it. And it’s useless if they could do something about it but choose not to.

That’s the gulf that these models need to cross at this point. So, the next time some slick company tells you how accurate their AI model is, ask them if accuracy is really the most important thing. If they say, “Well, yes, of course,” then tell them about Cassandra.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Today I’m going to talk to you about a study at the cutting edge of modern medicine, one that uses an artificial intelligence (AI) model to guide care. But before I do, I need to take you back to the late Bronze Age, to a city located on the coast of what is now Turkey.

Troy’s towering walls made it seem unassailable, but that would not stop the Achaeans and their fleet of black ships from making landfall, and, after a siege, destroying the city. The destruction of Troy, as told in the Iliad and the Aeneid, was foretold by Cassandra, the daughter of King Priam and Priestess of Troy.

Cassandra had been given the gift of prophecy by the god Apollo in exchange for her favors. But after the gift was bestowed, she rejected the bright god and, in his rage, he added a curse to her blessing: that no one would ever believe her prophecies.

Thus it was that when her brother Paris set off to Sparta to abduct Helen, she warned him that his actions would lead to the downfall of their great city. He, of course, ignored her.

And you know the rest of the story.

Why am I telling you the story of Cassandra of Troy when we’re supposed to be talking about AI in medicine? Because AI has a major Cassandra problem.

The recent history of AI, and particularly the subset of AI known as machine learning in medicine, has been characterized by an accuracy arms race.

The electronic health record allows for the collection of volumes of data orders of magnitude greater than what we have ever been able to collect before. And all that data can be crunched by various algorithms to make predictions about, well, anything – whether a patient will be transferred to the intensive care unit, whether a GI bleed will need an intervention, whether someone will die in the next year.

Studies in this area tend to rely on retrospective datasets, and as time has gone on, better algorithms and more data have led to better and better predictions. In some simpler cases, machine-learning models have achieved near-perfect accuracy – Cassandra-level accuracy – as in the reading of chest x-rays for pneumonia, for example.

But as Cassandra teaches us, even perfect prediction is useless if no one believes you, if they don’t change their behavior. And this is the central problem of AI in medicine today. Many people are focusing on accuracy of the prediction but have forgotten that high accuracy is just table stakes for an AI model to be useful. It has to not only be accurate, but its use also has to change outcomes for patients. We need to be able to save Troy.

The best way to determine whether an AI model will help patients is to treat a model like we treat a new medication and evaluate it through a randomized trial. That’s what researchers, led by Shannon Walker of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., did in a paper appearing in JAMA Network Open.

The model in question was one that predicted venous thromboembolism – blood clots – in hospitalized children. The model took in a variety of data points from the health record: a history of blood clot, history of cancer, presence of a central line, a variety of lab values. And the predictive model was very good – maybe not Cassandra good, but it achieved an AUC of 0.90, which means it had very high accuracy.

But again, accuracy is just table stakes.

The authors deployed the model in the live health record and recorded the results. For half of the kids, that was all that happened; no one actually saw the predictions. For those randomized to the intervention, the hematology team would be notified when the risk for clot was calculated to be greater than 2.5%. The hematology team would then contact the primary team to discuss prophylactic anticoagulation.

This is an elegant approach.

Let’s start with those table stakes – accuracy. The predictions were, by and large, pretty accurate in this trial. Of the 135 kids who developed blood clots, 121 had been flagged by the model in advance. That’s about 90%. The model flagged about 10% of kids who didn’t get a blood clot as well, but that’s not entirely surprising since the threshold for flagging was a 2.5% risk.

Given that the model preidentified almost every kid who would go on to develop a blood clot, it would make sense that kids randomized to the intervention would do better; after all, Cassandra was calling out her warnings.

But those kids didn’t do better. The rate of blood clot was no different between the group that used the accurate prediction model and the group that did not.

Why? Why does the use of an accurate model not necessarily improve outcomes?

First of all, a warning must lead to some change in management. Indeed, the kids in the intervention group were more likely to receive anticoagulation, but barely so. There were lots of reasons for this: physician preference, imminent discharge, active bleeding, and so on.

But let’s take a look at the 77 kids in the intervention arm who developed blood clots, because I think this is an instructive analysis.

Six of them did not meet the 2.5% threshold criteria, a case where the model missed its mark. Again, accuracy is table stakes.

Of the remaining 71, only 16 got a recommendation from the hematologist to start anticoagulation. Why not more? Well, the model identified some of the high-risk kids on the weekend, and it seems that the study team did not contact treatment teams during that time. That may account for about 40% of these cases. The remainder had some contraindication to anticoagulation.

Most tellingly, of the 16 who did get a recommendation to start anticoagulation, the recommendation was followed in only seven patients.

This is the gap between accurate prediction and the ability to change outcomes for patients. A prediction is useless if it is wrong, for sure. But it’s also useless if you don’t tell anyone about it. It’s useless if you tell someone but they can’t do anything about it. And it’s useless if they could do something about it but choose not to.

That’s the gulf that these models need to cross at this point. So, the next time some slick company tells you how accurate their AI model is, ask them if accuracy is really the most important thing. If they say, “Well, yes, of course,” then tell them about Cassandra.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Debate: Is lasting remission of type 2 diabetes feasible in the real-world setting?

The prospect of remission of type 2 diabetes (T2D) has captured the hearts and minds of many patients with T2D and health care professionals, including myself.

I have changed my narrative when supporting my patients with T2D. I used to say that T2D is a progressive condition, but considering seminal recent evidence like the DiRECT trial, I now say that T2D can be a progressive condition. Through significant weight loss, patients can reverse it and achieve remission of T2D. This has given my patients hope that their T2D is no longer an inexorable condition. And hope, of course, is a powerful enabler of change.

However,

I therefore relished the opportunity to attend a debate on this topic at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes in Hamburg, Germany, between Roy Taylor, MD, principal investigator for the DiRECT study and professor of medicine and metabolism at the University of Newcastle, England, and Kamlesh Khunti, MD, PhD, professor of primary care diabetes at the University of Leicester, England.

Remarkable weight loss

Dr. Taylor powerfully recapitulated the initial results of the DiRECT study. T2D remission was achieved in 46% of participants who underwent a low-energy formula diet (around 850 calories daily) for 3-5 months. After 2 years’ follow-up, an impressive 36% of participants were still in remission. Dr. Taylor then discussed unpublished 5-year extension follow-up data of the DiRECT study. Average weight loss in the remaining intervention group was 6.1 kg. I echo Taylor’s sentiment that this finding is remarkable in the context of a dietary study.

Overall, 13% of participants were still in remission, and this cohort maintained an average weight loss of 8.9 kg. Dr. Taylor concluded that lasting remission of T2D is indeed feasible in a primary care setting.

Yet he acknowledged that although remission appears feasible in the longer term, it was not necessarily easy, or indeed possible, for everyone. He used a wonderful analogy about climbing Mount Everest: It is feasible, but not everyone can or wants to climb it. And even if you try, you might not reach the top.

This analogy perfectly encapsulates the challenges I have observed when my patients have striven for T2D remission. In my opinion, intensive weight management with a low-energy formula diet is not a panacea for T2D but another tool in our toolbox to offer patients.

He also described some “jaw-dropping” results regarding incidence of cancer: There were no cases of cancer in the intervention group during the 5-year period, but there were eight cases of cancer in the control group. The latter figure is consistent with published data for cancer incidence in patients with T2D and the body mass index (BMI) inclusion criteria for the DiRECT study (a BMI of 27-45 kg/m2). Obesity is an established risk factor for 13 types of cancer, and excess body fat entails an approximately 17% increased risk for cancer-specific mortality. This indeed is a powerful motivator to facilitate meaningful lifestyle change.

In primary care, we also need to be aware that most weight regain usually occurs secondary to a life event (for example, financial, family, or illness). We should reiterate to our patients that weight regain is not a failure; it is just part of life. Once the life event has passed, rapid weight loss can be attempted again. In the “rescue plans” that were integral to the DiRECT study, participants were offered further periods of total diet replacement, depending on quantity of weight gain. In fact, 50% of participants in DiRECT required rescue therapy, and their outcomes, reassuringly, were the same as the other 50%.

Dr. Taylor also quoted data from the ReTUNE study suggesting that weight regain was less of an issue for those with initial BMI of 21-27, and there is “more bang for your buck” in approaching remission of T2D in patients with lower BMI. The fact that people with normal or near-normal BMI can also reverse their T2D was also a game changer for my clinical practice; the concept of an individual or personal fat threshold that results in T2D offers a pragmatic explanation to patients with T2D who are frustrated by the lack of improvements in cardiometabolic parameters despite significant weight loss.

Finally, Dr. Taylor acknowledged the breadth of the definition of T2D remission: A1c < 48 mmol/mol at least 2 months off all antidiabetic medication. This definition includes A1c values within the “prediabetes” range: 42-47 mmol/mol.

He cited 10-year cardiovascular risk data driven by hypertension and dyslipidemia before significant weight loss and compared it with 10-year cardiovascular risk data after significant weight loss. Cardiovascular risk profile was more favorable after weight loss, compared with controls with prediabetes without weight loss, even though some of the intervention group who lost significant weight still had an A1c of 42-47 mmol/mol. Dr. Taylor suggested that we not label these individuals who have lost significant weight as having prediabetes. Instead “postdiabetes” should be preferred, because these patients had more favorable cardiovascular profiles.

This is a very important take-home message for primary care: prediabetes is more than just dysglycemia.

New terminology proposed

Dr. Khunti outlined a recent large, systematic review that concluded that the definition of T2D remission encompassed substantial heterogeneity. This heterogeneity complicates the interpretation of previous research on T2D remission and complicates the implementation of remission pathways into routine clinical practice. Furthermore, Dr. Khunti highlighted a recent consensus report on the definition and interpretation of remission in T2D that explicitly stated that the underlying pathophysiology of T2D is rarely normalized completely by interventions, thus reducing the possibility of lasting remission.

Dr. Khunti also challenged the cardiovascular benefits seen after T2D remission. Recent Danish registry data were presented, demonstrating a twofold increased risk for major adverse cardiovascular events over 5 years in individuals who achieved remission of T2D, but not on glucose-lowering drug therapy.

Adherence to strict dietary interventions in the longer term was also addressed. Diet-induced weight loss causes changes in circulating hormones such as ghrelin, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), and leptin, which mediate appetite and drive hunger and an increased preference for energy-dense foods (that is, high-fat or sugary foods), all of which encourage weight regain. Dr. Khunti suggested that other interventions, such as glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists or bariatric surgery, specifically target some of these hormonal responses.

The challenges in recruitment and retention for lifestyle studies were also discussed; they reflect the challenges of behavioral programs in primary care. The DiRECT study had 20% participation of screened candidates and an attrition rate approaching 30%. The seminal Diabetes Prevention Program study and Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study had similar results. At a population level, individuals do not appear to want to participate in behavioral programs.

Dr. Khunti also warned that the review of annual care processes for diabetes is declining for patients who had achieved remission, possibly because of a false sense of reassurance among health care professionals. It is essential that all those in remission remain under at least annual follow-up, because there is still a risk for future microvascular and macrovascular complications, especially in the event of weight regain.

Dr. Khunti concluded by proposing new terminology for remission: remission of hyperglycemia or euglycemia, aiming for A1c < 48 mmol/mol with or without glucose-lowering therapy. I do agree with this; it reflects the zeitgeist of cardiorenal protective diabetes therapies and is analogous to rheumatoid arthritis, where remission is defined as no disease activity while on therapy. But one size does not fit all.

Sir William Osler’s words provide a fitting conclusion: “If it were not for the great variability among individuals, medicine might as well be a science and not an art.”

Dr. Fernando has disclosed that he has received speakers’ fees from Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk.

Dr. Fernando is a general practitioner near Edinburgh, with a specialist interest in diabetes; cardiovascular, renal, and metabolic diseases; and medical education.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The prospect of remission of type 2 diabetes (T2D) has captured the hearts and minds of many patients with T2D and health care professionals, including myself.

I have changed my narrative when supporting my patients with T2D. I used to say that T2D is a progressive condition, but considering seminal recent evidence like the DiRECT trial, I now say that T2D can be a progressive condition. Through significant weight loss, patients can reverse it and achieve remission of T2D. This has given my patients hope that their T2D is no longer an inexorable condition. And hope, of course, is a powerful enabler of change.

However,

I therefore relished the opportunity to attend a debate on this topic at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes in Hamburg, Germany, between Roy Taylor, MD, principal investigator for the DiRECT study and professor of medicine and metabolism at the University of Newcastle, England, and Kamlesh Khunti, MD, PhD, professor of primary care diabetes at the University of Leicester, England.

Remarkable weight loss

Dr. Taylor powerfully recapitulated the initial results of the DiRECT study. T2D remission was achieved in 46% of participants who underwent a low-energy formula diet (around 850 calories daily) for 3-5 months. After 2 years’ follow-up, an impressive 36% of participants were still in remission. Dr. Taylor then discussed unpublished 5-year extension follow-up data of the DiRECT study. Average weight loss in the remaining intervention group was 6.1 kg. I echo Taylor’s sentiment that this finding is remarkable in the context of a dietary study.

Overall, 13% of participants were still in remission, and this cohort maintained an average weight loss of 8.9 kg. Dr. Taylor concluded that lasting remission of T2D is indeed feasible in a primary care setting.

Yet he acknowledged that although remission appears feasible in the longer term, it was not necessarily easy, or indeed possible, for everyone. He used a wonderful analogy about climbing Mount Everest: It is feasible, but not everyone can or wants to climb it. And even if you try, you might not reach the top.

This analogy perfectly encapsulates the challenges I have observed when my patients have striven for T2D remission. In my opinion, intensive weight management with a low-energy formula diet is not a panacea for T2D but another tool in our toolbox to offer patients.

He also described some “jaw-dropping” results regarding incidence of cancer: There were no cases of cancer in the intervention group during the 5-year period, but there were eight cases of cancer in the control group. The latter figure is consistent with published data for cancer incidence in patients with T2D and the body mass index (BMI) inclusion criteria for the DiRECT study (a BMI of 27-45 kg/m2). Obesity is an established risk factor for 13 types of cancer, and excess body fat entails an approximately 17% increased risk for cancer-specific mortality. This indeed is a powerful motivator to facilitate meaningful lifestyle change.

In primary care, we also need to be aware that most weight regain usually occurs secondary to a life event (for example, financial, family, or illness). We should reiterate to our patients that weight regain is not a failure; it is just part of life. Once the life event has passed, rapid weight loss can be attempted again. In the “rescue plans” that were integral to the DiRECT study, participants were offered further periods of total diet replacement, depending on quantity of weight gain. In fact, 50% of participants in DiRECT required rescue therapy, and their outcomes, reassuringly, were the same as the other 50%.

Dr. Taylor also quoted data from the ReTUNE study suggesting that weight regain was less of an issue for those with initial BMI of 21-27, and there is “more bang for your buck” in approaching remission of T2D in patients with lower BMI. The fact that people with normal or near-normal BMI can also reverse their T2D was also a game changer for my clinical practice; the concept of an individual or personal fat threshold that results in T2D offers a pragmatic explanation to patients with T2D who are frustrated by the lack of improvements in cardiometabolic parameters despite significant weight loss.

Finally, Dr. Taylor acknowledged the breadth of the definition of T2D remission: A1c < 48 mmol/mol at least 2 months off all antidiabetic medication. This definition includes A1c values within the “prediabetes” range: 42-47 mmol/mol.

He cited 10-year cardiovascular risk data driven by hypertension and dyslipidemia before significant weight loss and compared it with 10-year cardiovascular risk data after significant weight loss. Cardiovascular risk profile was more favorable after weight loss, compared with controls with prediabetes without weight loss, even though some of the intervention group who lost significant weight still had an A1c of 42-47 mmol/mol. Dr. Taylor suggested that we not label these individuals who have lost significant weight as having prediabetes. Instead “postdiabetes” should be preferred, because these patients had more favorable cardiovascular profiles.

This is a very important take-home message for primary care: prediabetes is more than just dysglycemia.

New terminology proposed

Dr. Khunti outlined a recent large, systematic review that concluded that the definition of T2D remission encompassed substantial heterogeneity. This heterogeneity complicates the interpretation of previous research on T2D remission and complicates the implementation of remission pathways into routine clinical practice. Furthermore, Dr. Khunti highlighted a recent consensus report on the definition and interpretation of remission in T2D that explicitly stated that the underlying pathophysiology of T2D is rarely normalized completely by interventions, thus reducing the possibility of lasting remission.

Dr. Khunti also challenged the cardiovascular benefits seen after T2D remission. Recent Danish registry data were presented, demonstrating a twofold increased risk for major adverse cardiovascular events over 5 years in individuals who achieved remission of T2D, but not on glucose-lowering drug therapy.

Adherence to strict dietary interventions in the longer term was also addressed. Diet-induced weight loss causes changes in circulating hormones such as ghrelin, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), and leptin, which mediate appetite and drive hunger and an increased preference for energy-dense foods (that is, high-fat or sugary foods), all of which encourage weight regain. Dr. Khunti suggested that other interventions, such as glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists or bariatric surgery, specifically target some of these hormonal responses.

The challenges in recruitment and retention for lifestyle studies were also discussed; they reflect the challenges of behavioral programs in primary care. The DiRECT study had 20% participation of screened candidates and an attrition rate approaching 30%. The seminal Diabetes Prevention Program study and Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study had similar results. At a population level, individuals do not appear to want to participate in behavioral programs.

Dr. Khunti also warned that the review of annual care processes for diabetes is declining for patients who had achieved remission, possibly because of a false sense of reassurance among health care professionals. It is essential that all those in remission remain under at least annual follow-up, because there is still a risk for future microvascular and macrovascular complications, especially in the event of weight regain.

Dr. Khunti concluded by proposing new terminology for remission: remission of hyperglycemia or euglycemia, aiming for A1c < 48 mmol/mol with or without glucose-lowering therapy. I do agree with this; it reflects the zeitgeist of cardiorenal protective diabetes therapies and is analogous to rheumatoid arthritis, where remission is defined as no disease activity while on therapy. But one size does not fit all.

Sir William Osler’s words provide a fitting conclusion: “If it were not for the great variability among individuals, medicine might as well be a science and not an art.”

Dr. Fernando has disclosed that he has received speakers’ fees from Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk.

Dr. Fernando is a general practitioner near Edinburgh, with a specialist interest in diabetes; cardiovascular, renal, and metabolic diseases; and medical education.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The prospect of remission of type 2 diabetes (T2D) has captured the hearts and minds of many patients with T2D and health care professionals, including myself.

I have changed my narrative when supporting my patients with T2D. I used to say that T2D is a progressive condition, but considering seminal recent evidence like the DiRECT trial, I now say that T2D can be a progressive condition. Through significant weight loss, patients can reverse it and achieve remission of T2D. This has given my patients hope that their T2D is no longer an inexorable condition. And hope, of course, is a powerful enabler of change.

However,

I therefore relished the opportunity to attend a debate on this topic at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes in Hamburg, Germany, between Roy Taylor, MD, principal investigator for the DiRECT study and professor of medicine and metabolism at the University of Newcastle, England, and Kamlesh Khunti, MD, PhD, professor of primary care diabetes at the University of Leicester, England.

Remarkable weight loss

Dr. Taylor powerfully recapitulated the initial results of the DiRECT study. T2D remission was achieved in 46% of participants who underwent a low-energy formula diet (around 850 calories daily) for 3-5 months. After 2 years’ follow-up, an impressive 36% of participants were still in remission. Dr. Taylor then discussed unpublished 5-year extension follow-up data of the DiRECT study. Average weight loss in the remaining intervention group was 6.1 kg. I echo Taylor’s sentiment that this finding is remarkable in the context of a dietary study.

Overall, 13% of participants were still in remission, and this cohort maintained an average weight loss of 8.9 kg. Dr. Taylor concluded that lasting remission of T2D is indeed feasible in a primary care setting.

Yet he acknowledged that although remission appears feasible in the longer term, it was not necessarily easy, or indeed possible, for everyone. He used a wonderful analogy about climbing Mount Everest: It is feasible, but not everyone can or wants to climb it. And even if you try, you might not reach the top.

This analogy perfectly encapsulates the challenges I have observed when my patients have striven for T2D remission. In my opinion, intensive weight management with a low-energy formula diet is not a panacea for T2D but another tool in our toolbox to offer patients.

He also described some “jaw-dropping” results regarding incidence of cancer: There were no cases of cancer in the intervention group during the 5-year period, but there were eight cases of cancer in the control group. The latter figure is consistent with published data for cancer incidence in patients with T2D and the body mass index (BMI) inclusion criteria for the DiRECT study (a BMI of 27-45 kg/m2). Obesity is an established risk factor for 13 types of cancer, and excess body fat entails an approximately 17% increased risk for cancer-specific mortality. This indeed is a powerful motivator to facilitate meaningful lifestyle change.

In primary care, we also need to be aware that most weight regain usually occurs secondary to a life event (for example, financial, family, or illness). We should reiterate to our patients that weight regain is not a failure; it is just part of life. Once the life event has passed, rapid weight loss can be attempted again. In the “rescue plans” that were integral to the DiRECT study, participants were offered further periods of total diet replacement, depending on quantity of weight gain. In fact, 50% of participants in DiRECT required rescue therapy, and their outcomes, reassuringly, were the same as the other 50%.

Dr. Taylor also quoted data from the ReTUNE study suggesting that weight regain was less of an issue for those with initial BMI of 21-27, and there is “more bang for your buck” in approaching remission of T2D in patients with lower BMI. The fact that people with normal or near-normal BMI can also reverse their T2D was also a game changer for my clinical practice; the concept of an individual or personal fat threshold that results in T2D offers a pragmatic explanation to patients with T2D who are frustrated by the lack of improvements in cardiometabolic parameters despite significant weight loss.

Finally, Dr. Taylor acknowledged the breadth of the definition of T2D remission: A1c < 48 mmol/mol at least 2 months off all antidiabetic medication. This definition includes A1c values within the “prediabetes” range: 42-47 mmol/mol.

He cited 10-year cardiovascular risk data driven by hypertension and dyslipidemia before significant weight loss and compared it with 10-year cardiovascular risk data after significant weight loss. Cardiovascular risk profile was more favorable after weight loss, compared with controls with prediabetes without weight loss, even though some of the intervention group who lost significant weight still had an A1c of 42-47 mmol/mol. Dr. Taylor suggested that we not label these individuals who have lost significant weight as having prediabetes. Instead “postdiabetes” should be preferred, because these patients had more favorable cardiovascular profiles.

This is a very important take-home message for primary care: prediabetes is more than just dysglycemia.

New terminology proposed

Dr. Khunti outlined a recent large, systematic review that concluded that the definition of T2D remission encompassed substantial heterogeneity. This heterogeneity complicates the interpretation of previous research on T2D remission and complicates the implementation of remission pathways into routine clinical practice. Furthermore, Dr. Khunti highlighted a recent consensus report on the definition and interpretation of remission in T2D that explicitly stated that the underlying pathophysiology of T2D is rarely normalized completely by interventions, thus reducing the possibility of lasting remission.

Dr. Khunti also challenged the cardiovascular benefits seen after T2D remission. Recent Danish registry data were presented, demonstrating a twofold increased risk for major adverse cardiovascular events over 5 years in individuals who achieved remission of T2D, but not on glucose-lowering drug therapy.

Adherence to strict dietary interventions in the longer term was also addressed. Diet-induced weight loss causes changes in circulating hormones such as ghrelin, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), and leptin, which mediate appetite and drive hunger and an increased preference for energy-dense foods (that is, high-fat or sugary foods), all of which encourage weight regain. Dr. Khunti suggested that other interventions, such as glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists or bariatric surgery, specifically target some of these hormonal responses.

The challenges in recruitment and retention for lifestyle studies were also discussed; they reflect the challenges of behavioral programs in primary care. The DiRECT study had 20% participation of screened candidates and an attrition rate approaching 30%. The seminal Diabetes Prevention Program study and Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study had similar results. At a population level, individuals do not appear to want to participate in behavioral programs.

Dr. Khunti also warned that the review of annual care processes for diabetes is declining for patients who had achieved remission, possibly because of a false sense of reassurance among health care professionals. It is essential that all those in remission remain under at least annual follow-up, because there is still a risk for future microvascular and macrovascular complications, especially in the event of weight regain.

Dr. Khunti concluded by proposing new terminology for remission: remission of hyperglycemia or euglycemia, aiming for A1c < 48 mmol/mol with or without glucose-lowering therapy. I do agree with this; it reflects the zeitgeist of cardiorenal protective diabetes therapies and is analogous to rheumatoid arthritis, where remission is defined as no disease activity while on therapy. But one size does not fit all.

Sir William Osler’s words provide a fitting conclusion: “If it were not for the great variability among individuals, medicine might as well be a science and not an art.”

Dr. Fernando has disclosed that he has received speakers’ fees from Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk.

Dr. Fernando is a general practitioner near Edinburgh, with a specialist interest in diabetes; cardiovascular, renal, and metabolic diseases; and medical education.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Making time to care for patients with diabetes

Can busy primary care offices continue to care for patients with diabetes? No one would argue that it is involved and takes effort, and health care providers are bankrupt when it comes to sparing additional time for this chronic disease. With roughly 37 million people living with diabetes and 96 million with prediabetes or early type 2 diabetes, and just over 8,000 practicing endocrinologists in the United States, we all need to make time especially in primary care to provide insight and holistic care. With limited time and budget, how do we do this?

First, decide to be involved in caring for patients with diabetes. Diabetes is best managed by interprofessional care teams, so you’re not going it alone. These teams may include physicians; pharmacists; physician assistants; advanced practice nurses; registered nurses; certified diabetes care and education specialists (CDCES); dietitians; and other professionals such as social workers, behavioral health professionals, medical assistants, and community health workers. Know which professionals are available to serve on your team, either within your clinic or as a consultant, and reach out to them to share the care and ease the burden. Remember to refer to these professionals to reinforce the diabetes intervention message to the patient.

Second, incorporate “diabetes only” appointments into your schedule, allowing time to focus on current comprehensive diabetes treatment goals, barriers/inertia for care. Remember to have short-interval follow-up as needed to keep that patient engaged to achieve their targets. Instruct your office staff to create diabetes appointment templates and reminders to patients to bring diabetes-related technologies, medication lists, and diabetes questions to the appointment. When I implemented this change, my patients welcomed the focus on their diabetes health, and they knew we were prioritizing this disease that they have for a lifetime. These appointments did not take away from their other conditions; rather, they often reminded me to stay focused on their diabetes and associated coconditions.

Taking the time to establish efficient workflows before implementing diabetes care saves countless hours later and immediately maximizes health care provider–patient interactions. Assign specific staff duties and expectations related to diabetes appointments, such as downloading diabetes technology, medication reconciliation, laboratory data, point-of-care hemoglobin A1c, basic foot exam, and patient goals for diabetes care. This allows the prescriber to focus on the glycemic, cardiologic, renal, and metabolic goals and overcome the therapeutic inertia that plagues us all.

Incorporating diabetes-related technology into clinical practice can be a significant time-saver but requires initial onboarding. Set aside a few hours to create a technology clinic flow, and designate at least one team member to be responsible for obtaining patient data before, during, or after encounters. If possible, obtaining data ahead of the visit will enhance efficiency, allowing for meaningful discussion of blood glucose and lifestyle patterns. Diabetes technology reveals the gaps in care and enhances our ability to identify the areas where glycemic intervention is needed. In addition, it reveals the impact of food choices, activity level, stress, and medication adherence to the person living with diabetes.

Finally, be proactive about therapeutic inertia. This is defined as a prescribers’ failure to intensify or deintensify a patient’s treatment when appropriate to do so. Causes of therapeutic inertia can be placed at the primary care physician level, including time constraints or inexperience in treating diabetes; the patient level, such as concerns about side effects or new treatment regimens; or a systemic level, such as availability of medications or their costs. Be real with yourself: We all have inertia and can identify areas to overcome. Never let inertia be traced back to you.

Not all inertia lives with the health care provider. Patients bring apprehension and concerns, have questions, and just want to share the frustrations associated with living their best life with the disease. Don’t assume that you know what your patients’ treatment barriers are; ask them. If you don’t have an answer, then note it and come up with one by the next follow-up. Remember that this is a chronic disease – a marathon, not a sprint. You don’t have to solve everything at one appointment; rather, keep the momentum going.

Let’s put this into clinical practice. For the next patient with diabetes who comes into your office, discuss with them your intention to prioritize their diabetes by having an appointment set aside to specifically focus on their individual goals and targets for their disease. Have the patient list any barriers and treatment goals they would like to review; flag your schedule to indicate it is a diabetes-only visit; and orient your staff to reconcile diabetes medications and record the patient’s last eye exam, urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio, A1c result, and blood glucose data. During this encounter, identify the patient’s personal targets for control, examine their feet, and review or order necessary laboratory metrics. Explore the patient-reported barriers and make inroads to remove or alleviate these. Advance treatment intervention, and schedule follow-up: every 4-6 weeks if the A1c is > 9%, every 2 months if it’s 7% to < 9%, and every 3-6 months if it’s < 7%. Utilize team diabetes care, such as CDCES referrals, dietitians, online resources, and community members, to help reinforce care and enhance engagement.

We need to take steps in our clinical practice to make the necessary space to accommodate this pervasive disease affecting nearly one-third of our population. Take a moment to look up and determine what needs to be in place so that you can take care of the people in your practice with diabetes. Laying the groundwork for implementing diabetes-only appointments can be time-consuming, but establishing consistent procedures, developing efficient workflows, and clearly defining roles and responsibilities is well worth the effort. This solid foundation equips the office, health care providers, and staff to care for persons with diabetes and will be invaluable to ensure that time for this care is available in the day-to-day clinical practice.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Can busy primary care offices continue to care for patients with diabetes? No one would argue that it is involved and takes effort, and health care providers are bankrupt when it comes to sparing additional time for this chronic disease. With roughly 37 million people living with diabetes and 96 million with prediabetes or early type 2 diabetes, and just over 8,000 practicing endocrinologists in the United States, we all need to make time especially in primary care to provide insight and holistic care. With limited time and budget, how do we do this?

First, decide to be involved in caring for patients with diabetes. Diabetes is best managed by interprofessional care teams, so you’re not going it alone. These teams may include physicians; pharmacists; physician assistants; advanced practice nurses; registered nurses; certified diabetes care and education specialists (CDCES); dietitians; and other professionals such as social workers, behavioral health professionals, medical assistants, and community health workers. Know which professionals are available to serve on your team, either within your clinic or as a consultant, and reach out to them to share the care and ease the burden. Remember to refer to these professionals to reinforce the diabetes intervention message to the patient.

Second, incorporate “diabetes only” appointments into your schedule, allowing time to focus on current comprehensive diabetes treatment goals, barriers/inertia for care. Remember to have short-interval follow-up as needed to keep that patient engaged to achieve their targets. Instruct your office staff to create diabetes appointment templates and reminders to patients to bring diabetes-related technologies, medication lists, and diabetes questions to the appointment. When I implemented this change, my patients welcomed the focus on their diabetes health, and they knew we were prioritizing this disease that they have for a lifetime. These appointments did not take away from their other conditions; rather, they often reminded me to stay focused on their diabetes and associated coconditions.