User login

Diversity – We’re not one size fits all

The United States has often been described as a “melting pot,” defined as diverse cultures and ethnicities coming together to form the rich fabric of our nation. These days, it seems that our fabric is a bit frayed.

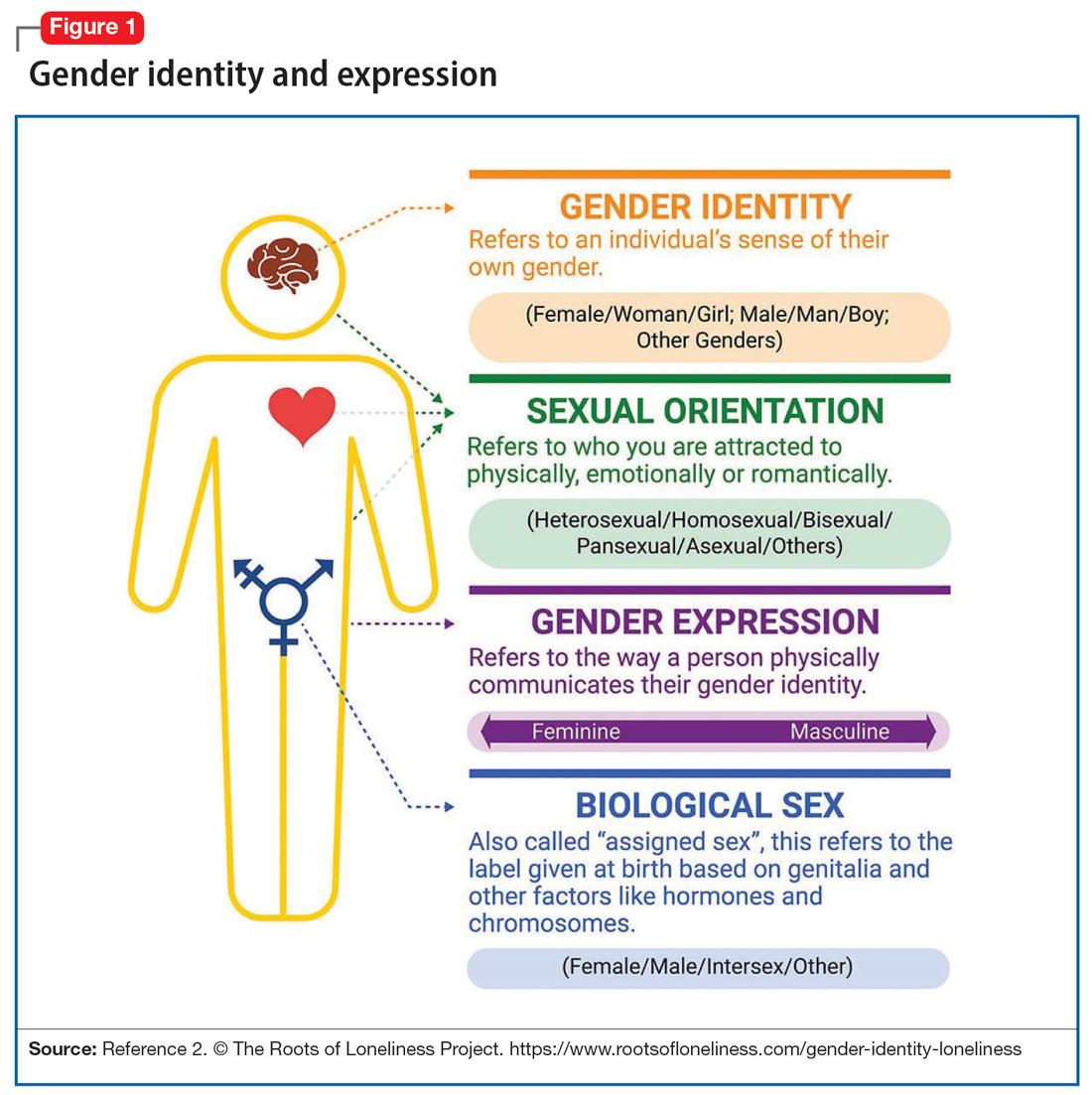

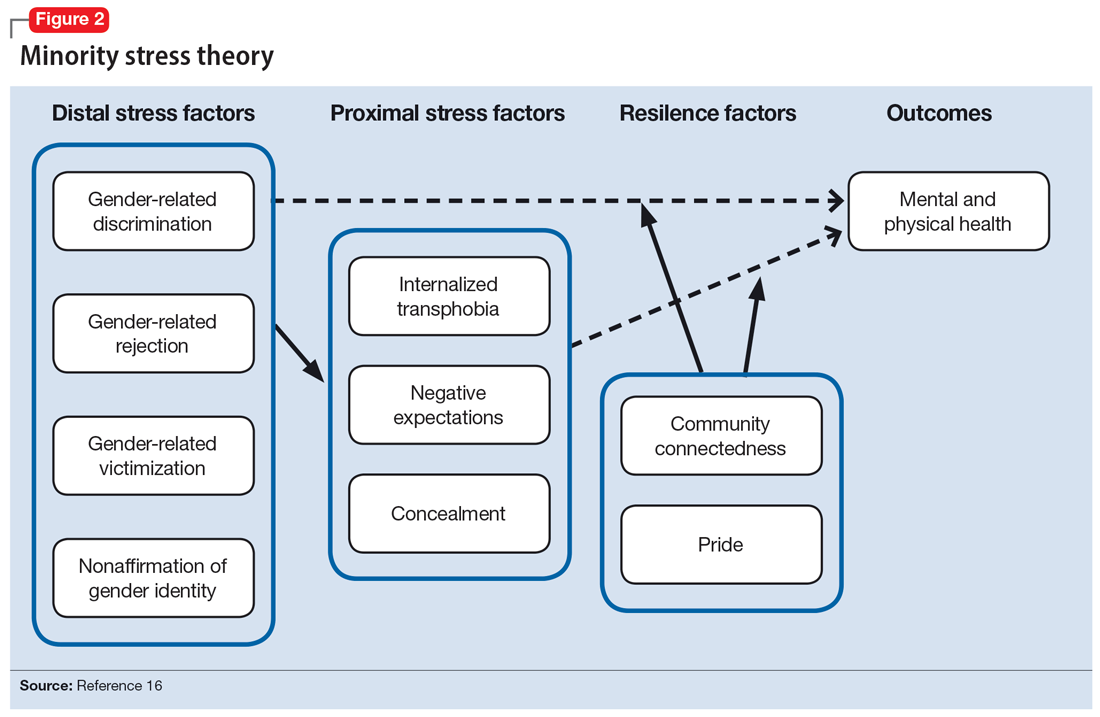

DEIB (diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging) is dawning as a significant conversation. Each and every one of us is unique by age, gender, culture/ethnicity, religion, socioeconomic status, geographical location, race, and sexual identity – to name just a few aspects of our identity. Keeping these differences in mind, it is evident that none of us fits a “one size fits all” mold.

Some of these differences, such as cross-cultural cuisine and holidays, are enjoyed and celebrated as wonderful opportunities to learn from others, embrace our distinctions, and have them beneficially contribute to our lives. Other differences, however, are not understood or embraced and are, in fact, belittled and stigmatized. Sexual identity falls into this category. It behooves us as a country to become more aware and educated about this category in our identities, in order to understand it, quell our unfounded fear, learn to support one another, and improve our collective mental health.

Recent reports have shown that exposing students and teachers to sexual identity diversity education has sparked some backlash from parents and communities alike. Those opposed are citing concerns over introducing children to LGBTQ+ information, either embedded in the school curriculum or made available in school library reading materials. “Children should remain innocent” seems to be the message. Perhaps parents prefer to discuss this topic privately, at home. Either way, teaching about diversity does not damage one’s innocence or deprive parents of private conversations. In fact, it educates children by improving their awareness, tolerance, and acceptance of others’ differences, and can serve as a catalyst to further parental conversation.

There are kids everywhere who are starting to develop and understand their identities. Wouldn’t it be wonderful for them to know that whichever way they identify is okay, that they are not ‘weird’ or ‘different,’ but that in fact we are all different? Wouldn’t it be great for them to be able to explore and discuss their identities and journeys openly, and not have to hide for fear of retribution or bullying?

It is important for these children to know that they are not alone, that they have options, and that they don’t need to contemplate suicide because they believe that their identity makes them not worthy of being in this world.

Starting the conversation early on in life can empower our youth by planting the seed that people are not “one size fits all,” which is the element responsible for our being unique and human. Diversity can be woven into the rich fabric that defines our nation, rather than be a factor that unravels it.

April was National Diversity Awareness Month and we took time to celebrate our country’s cultural melting pot. By embracing our differences, we can show our children and ourselves how to better navigate diversity, which can help us all fit in.

Dr. Jarkon is a psychiatrist and director of the Center for Behavioral Health at the New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine in Old Westbury, N.Y.

The United States has often been described as a “melting pot,” defined as diverse cultures and ethnicities coming together to form the rich fabric of our nation. These days, it seems that our fabric is a bit frayed.

DEIB (diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging) is dawning as a significant conversation. Each and every one of us is unique by age, gender, culture/ethnicity, religion, socioeconomic status, geographical location, race, and sexual identity – to name just a few aspects of our identity. Keeping these differences in mind, it is evident that none of us fits a “one size fits all” mold.

Some of these differences, such as cross-cultural cuisine and holidays, are enjoyed and celebrated as wonderful opportunities to learn from others, embrace our distinctions, and have them beneficially contribute to our lives. Other differences, however, are not understood or embraced and are, in fact, belittled and stigmatized. Sexual identity falls into this category. It behooves us as a country to become more aware and educated about this category in our identities, in order to understand it, quell our unfounded fear, learn to support one another, and improve our collective mental health.

Recent reports have shown that exposing students and teachers to sexual identity diversity education has sparked some backlash from parents and communities alike. Those opposed are citing concerns over introducing children to LGBTQ+ information, either embedded in the school curriculum or made available in school library reading materials. “Children should remain innocent” seems to be the message. Perhaps parents prefer to discuss this topic privately, at home. Either way, teaching about diversity does not damage one’s innocence or deprive parents of private conversations. In fact, it educates children by improving their awareness, tolerance, and acceptance of others’ differences, and can serve as a catalyst to further parental conversation.

There are kids everywhere who are starting to develop and understand their identities. Wouldn’t it be wonderful for them to know that whichever way they identify is okay, that they are not ‘weird’ or ‘different,’ but that in fact we are all different? Wouldn’t it be great for them to be able to explore and discuss their identities and journeys openly, and not have to hide for fear of retribution or bullying?

It is important for these children to know that they are not alone, that they have options, and that they don’t need to contemplate suicide because they believe that their identity makes them not worthy of being in this world.

Starting the conversation early on in life can empower our youth by planting the seed that people are not “one size fits all,” which is the element responsible for our being unique and human. Diversity can be woven into the rich fabric that defines our nation, rather than be a factor that unravels it.

April was National Diversity Awareness Month and we took time to celebrate our country’s cultural melting pot. By embracing our differences, we can show our children and ourselves how to better navigate diversity, which can help us all fit in.

Dr. Jarkon is a psychiatrist and director of the Center for Behavioral Health at the New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine in Old Westbury, N.Y.

The United States has often been described as a “melting pot,” defined as diverse cultures and ethnicities coming together to form the rich fabric of our nation. These days, it seems that our fabric is a bit frayed.

DEIB (diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging) is dawning as a significant conversation. Each and every one of us is unique by age, gender, culture/ethnicity, religion, socioeconomic status, geographical location, race, and sexual identity – to name just a few aspects of our identity. Keeping these differences in mind, it is evident that none of us fits a “one size fits all” mold.

Some of these differences, such as cross-cultural cuisine and holidays, are enjoyed and celebrated as wonderful opportunities to learn from others, embrace our distinctions, and have them beneficially contribute to our lives. Other differences, however, are not understood or embraced and are, in fact, belittled and stigmatized. Sexual identity falls into this category. It behooves us as a country to become more aware and educated about this category in our identities, in order to understand it, quell our unfounded fear, learn to support one another, and improve our collective mental health.

Recent reports have shown that exposing students and teachers to sexual identity diversity education has sparked some backlash from parents and communities alike. Those opposed are citing concerns over introducing children to LGBTQ+ information, either embedded in the school curriculum or made available in school library reading materials. “Children should remain innocent” seems to be the message. Perhaps parents prefer to discuss this topic privately, at home. Either way, teaching about diversity does not damage one’s innocence or deprive parents of private conversations. In fact, it educates children by improving their awareness, tolerance, and acceptance of others’ differences, and can serve as a catalyst to further parental conversation.

There are kids everywhere who are starting to develop and understand their identities. Wouldn’t it be wonderful for them to know that whichever way they identify is okay, that they are not ‘weird’ or ‘different,’ but that in fact we are all different? Wouldn’t it be great for them to be able to explore and discuss their identities and journeys openly, and not have to hide for fear of retribution or bullying?

It is important for these children to know that they are not alone, that they have options, and that they don’t need to contemplate suicide because they believe that their identity makes them not worthy of being in this world.

Starting the conversation early on in life can empower our youth by planting the seed that people are not “one size fits all,” which is the element responsible for our being unique and human. Diversity can be woven into the rich fabric that defines our nation, rather than be a factor that unravels it.

April was National Diversity Awareness Month and we took time to celebrate our country’s cultural melting pot. By embracing our differences, we can show our children and ourselves how to better navigate diversity, which can help us all fit in.

Dr. Jarkon is a psychiatrist and director of the Center for Behavioral Health at the New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine in Old Westbury, N.Y.

Why the approval of MiniMed 780G is a ‘quantum leap’ forward

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

There is wonderful news in the field of hybrid closed-loop pump technology because the Medtronic 780G system was just approved. I can’t tell you how happy this makes me because we’ve all been waiting for this seemingly forever and ever. This isn’t just a small upgrade from the 770G. It’s a quantum leap from the 770G to the 780G. The 780G has newer algorithms, a new sensor, and a longer-lasting infusion set.

It’s been used since 2020 in Europe, so we have good data on how well it works. Frankly, I think it works really well. We’ve seen nice improvements in [hemoglobin] A1c, time in range, other glycemic metrics, and patient satisfaction in studies done in Europe.

Now, I’ve never had the system to use in one of my patients. I always say I never know a system until I see it in use in my own patients, but let me tell you what I’ve read.

First, it has something called meal-detection technology with autocorrection boluses every 5 minutes. If this works, it can be a huge win for our patients because the problem my patients have is with mealtime dosing. They often dose late, or they may not dose enough insulin for the carbohydrates. That’s where the issues are.

All these hybrid closed-loop systems, this one included, show that the best improvements in glycemia are overnight. I’m hoping that this one shows some nice improvements in daytime glycemia as well. Stay tuned and I’ll let you know once I’ve been using it.

Next, it has adjustable targets down to 100. This is the lowest target for any hybrid closed-loop system. It has an extended-wear infusion set that lasts for 7 days. This infusion set is already available but works with this new system.

Finally, it has a new sensor. It looks like the old sensors, but it’s the Guardian 4, which requires much fewer finger sticks. Now, I’m not entirely sure about how often one has to do a finger stick. I know one has to do with finger sticking to initiate auto mode, or what they call SmartGuard, but I don’t know whether you ever have to do it again. I know for sure that you have to do it again if you fall out of the automated mode into manual mode. Once you’re in SmartGuard, I believe there are no further finger-stick calibrations required.

If people are already on the 770G system, this is just a software update that is presumably easy to upgrade to the 780G. Now, the physical pieces ... If someone doesn’t already have the Guardian 4 sensor or the extended-wear infusion set, they’ll have to get those. The software update to make the 770G increase to the 780G should just come through the cloud. I don’t know when that’s going to happen.

I do know that preorders for this system, if you want to buy the new physical system, start on May 15. The shipping of the new 780G system should occur in the United States toward the end of this summer.

I’m so excited. I think this is really going to benefit my patients. I can’t wait to start using it and letting patients see how these algorithms work and how they really help patients improve their glucose control.

Anne L. Peters, MD, is a professor of medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and director of the USC clinical diabetes programs. She reported conflicts of interest with Abbott Diabetes Care, Becton Dickinson, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Livongo, Medscape, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Omada Health, OptumHealth, Sanofi, Zafgen, Dexcom, MannKind, and AstraZeneca.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

There is wonderful news in the field of hybrid closed-loop pump technology because the Medtronic 780G system was just approved. I can’t tell you how happy this makes me because we’ve all been waiting for this seemingly forever and ever. This isn’t just a small upgrade from the 770G. It’s a quantum leap from the 770G to the 780G. The 780G has newer algorithms, a new sensor, and a longer-lasting infusion set.

It’s been used since 2020 in Europe, so we have good data on how well it works. Frankly, I think it works really well. We’ve seen nice improvements in [hemoglobin] A1c, time in range, other glycemic metrics, and patient satisfaction in studies done in Europe.

Now, I’ve never had the system to use in one of my patients. I always say I never know a system until I see it in use in my own patients, but let me tell you what I’ve read.

First, it has something called meal-detection technology with autocorrection boluses every 5 minutes. If this works, it can be a huge win for our patients because the problem my patients have is with mealtime dosing. They often dose late, or they may not dose enough insulin for the carbohydrates. That’s where the issues are.

All these hybrid closed-loop systems, this one included, show that the best improvements in glycemia are overnight. I’m hoping that this one shows some nice improvements in daytime glycemia as well. Stay tuned and I’ll let you know once I’ve been using it.

Next, it has adjustable targets down to 100. This is the lowest target for any hybrid closed-loop system. It has an extended-wear infusion set that lasts for 7 days. This infusion set is already available but works with this new system.

Finally, it has a new sensor. It looks like the old sensors, but it’s the Guardian 4, which requires much fewer finger sticks. Now, I’m not entirely sure about how often one has to do a finger stick. I know one has to do with finger sticking to initiate auto mode, or what they call SmartGuard, but I don’t know whether you ever have to do it again. I know for sure that you have to do it again if you fall out of the automated mode into manual mode. Once you’re in SmartGuard, I believe there are no further finger-stick calibrations required.

If people are already on the 770G system, this is just a software update that is presumably easy to upgrade to the 780G. Now, the physical pieces ... If someone doesn’t already have the Guardian 4 sensor or the extended-wear infusion set, they’ll have to get those. The software update to make the 770G increase to the 780G should just come through the cloud. I don’t know when that’s going to happen.

I do know that preorders for this system, if you want to buy the new physical system, start on May 15. The shipping of the new 780G system should occur in the United States toward the end of this summer.

I’m so excited. I think this is really going to benefit my patients. I can’t wait to start using it and letting patients see how these algorithms work and how they really help patients improve their glucose control.

Anne L. Peters, MD, is a professor of medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and director of the USC clinical diabetes programs. She reported conflicts of interest with Abbott Diabetes Care, Becton Dickinson, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Livongo, Medscape, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Omada Health, OptumHealth, Sanofi, Zafgen, Dexcom, MannKind, and AstraZeneca.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

There is wonderful news in the field of hybrid closed-loop pump technology because the Medtronic 780G system was just approved. I can’t tell you how happy this makes me because we’ve all been waiting for this seemingly forever and ever. This isn’t just a small upgrade from the 770G. It’s a quantum leap from the 770G to the 780G. The 780G has newer algorithms, a new sensor, and a longer-lasting infusion set.

It’s been used since 2020 in Europe, so we have good data on how well it works. Frankly, I think it works really well. We’ve seen nice improvements in [hemoglobin] A1c, time in range, other glycemic metrics, and patient satisfaction in studies done in Europe.

Now, I’ve never had the system to use in one of my patients. I always say I never know a system until I see it in use in my own patients, but let me tell you what I’ve read.

First, it has something called meal-detection technology with autocorrection boluses every 5 minutes. If this works, it can be a huge win for our patients because the problem my patients have is with mealtime dosing. They often dose late, or they may not dose enough insulin for the carbohydrates. That’s where the issues are.

All these hybrid closed-loop systems, this one included, show that the best improvements in glycemia are overnight. I’m hoping that this one shows some nice improvements in daytime glycemia as well. Stay tuned and I’ll let you know once I’ve been using it.

Next, it has adjustable targets down to 100. This is the lowest target for any hybrid closed-loop system. It has an extended-wear infusion set that lasts for 7 days. This infusion set is already available but works with this new system.

Finally, it has a new sensor. It looks like the old sensors, but it’s the Guardian 4, which requires much fewer finger sticks. Now, I’m not entirely sure about how often one has to do a finger stick. I know one has to do with finger sticking to initiate auto mode, or what they call SmartGuard, but I don’t know whether you ever have to do it again. I know for sure that you have to do it again if you fall out of the automated mode into manual mode. Once you’re in SmartGuard, I believe there are no further finger-stick calibrations required.

If people are already on the 770G system, this is just a software update that is presumably easy to upgrade to the 780G. Now, the physical pieces ... If someone doesn’t already have the Guardian 4 sensor or the extended-wear infusion set, they’ll have to get those. The software update to make the 770G increase to the 780G should just come through the cloud. I don’t know when that’s going to happen.

I do know that preorders for this system, if you want to buy the new physical system, start on May 15. The shipping of the new 780G system should occur in the United States toward the end of this summer.

I’m so excited. I think this is really going to benefit my patients. I can’t wait to start using it and letting patients see how these algorithms work and how they really help patients improve their glucose control.

Anne L. Peters, MD, is a professor of medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and director of the USC clinical diabetes programs. She reported conflicts of interest with Abbott Diabetes Care, Becton Dickinson, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Livongo, Medscape, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Omada Health, OptumHealth, Sanofi, Zafgen, Dexcom, MannKind, and AstraZeneca.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Autism and bone health: What you need to know

Many years ago, at the conclusion of a talk I gave on bone health in teens with anorexia nervosa, I was approached by a colleague, Ann Neumeyer, MD, medical director of the Lurie Center for Autism at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who asked about bone health in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

When I explained that there was little information about bone health in this patient population, she suggested that we learn and investigate together. Ann explained that she had observed that some of her patients with ASD had suffered fractures with minimal trauma, raising her concern about their bone health.

This was the beginning of a partnership that led us down the path of many grant submissions, some of which were funded and others that were not, to explore and investigate bone outcomes in children with ASD.

This applies to prepubertal children as well as older children and adolescents. One study showed that 28% and 33% of children with ASD 8-14 years old had very low bone density (z scores of ≤ –2) at the spine and hip, respectively, compared with 0% of typically developing controls.

Studies that have used sophisticated imaging techniques to determine bone strength have shown that it is lower at the forearm and lower leg in children with ASD versus neurotypical children.

These findings are of particular concern during the childhood and teenage years when bone is typically accrued at a rapid rate. A normal rate of bone accrual at this time of life is essential for optimal bone health in later life. While children with ASD gain bone mass at a similar rate as neurotypical controls, they start at a deficit and seem unable to “catch up.”

Further, people with ASD are more prone to certain kinds of fracture than those without the condition. For example, both children and adults with ASD have a high risk for hip fracture, while adult women with ASD have a higher risk for forearm and spine fractures. There is some protection against forearm fractures in children and adult men, probably because of markedly lower levels of physical activity, which would reduce fall risk.

Many of Ann’s patients with ASD had unusual or restricted diets, low levels of physical activity, and were on multiple medications. We have since learned that some factors that contribute to low bone density in ASD include lower levels of weight-bearing physical activity; lower muscle mass; low muscle tone; suboptimal dietary calcium and vitamin D intake; lower vitamin D levels; higher levels of the hormone cortisol, which has deleterious effects on bone; and use of medications that can lower bone density.

In order to mitigate the risk for low bone density and fractures, it is important to optimize physical activity while considering the child’s ability to safely engage in weight-bearing sports.

High-impact sports like gymnastics and jumping, or cross-impact sports like soccer, basketball, field hockey, and lacrosse, are particularly useful in this context, but many patients with ASD are not able to easily engage in typical team sports.

For such children, a prescribed amount of time spent walking, as well as weight and resistance training, could be helpful. The latter would also help increase muscle mass, a key modulator of bone health.

Other strategies include ensuring sufficient intake of calcium and vitamin D through diet and supplements. This can be a particular challenge for children with ASD on specialized diets, such as a gluten-free or dairy-free diet, which are deficient in calcium and vitamin D. Health care providers should check for intake of dairy and dairy products, as well as serum vitamin D levels, and prescribe supplements as needed.

All children should get at least 600 IUs of vitamin D and 1,000-1,300 mg of elemental calcium daily. That said, many with ASD need much higher quantities of vitamin D (1,000-4,000 IUs or more) to maintain levels in the normal range. This is particularly true for dark-skinned children and children with obesity, as well as those who have medical disorders that cause malabsorption.

Higher cortisol levels in the ASD patient population are harder to manage. Efforts to ease anxiety and depression may help reduce cortisol levels. Medications such as protein pump inhibitors and glucocorticosteroids can compromise bone health.

In addition, certain antipsychotics can cause marked elevations in prolactin which, in turn, can lower levels of estrogen and testosterone, which are very important for bone health. In such cases, the clinician should consider switching patients to a different, less detrimental medication or adjust the current medication so that patients receive the lowest possible effective dose.

Obesity is associated with increased fracture risk and with suboptimal bone accrual during childhood, so ensuring a healthy diet is important. This includes avoiding sugary beverages and reducing intake of processed food and juice.

Sometimes, particularly when a child has low bone density and a history of several low-trauma fractures, medications such as bisphosphonates should be considered to increase bone density.

Above all, as physicians who manage ASD, it is essential that we raise awareness about bone health among our colleagues, patients, and their families to help mitigate fracture risk.

Madhusmita Misra, MD, MPH, is chief of the Division of Pediatric Endocrinology at Mass General for Children, Boston.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Many years ago, at the conclusion of a talk I gave on bone health in teens with anorexia nervosa, I was approached by a colleague, Ann Neumeyer, MD, medical director of the Lurie Center for Autism at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who asked about bone health in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

When I explained that there was little information about bone health in this patient population, she suggested that we learn and investigate together. Ann explained that she had observed that some of her patients with ASD had suffered fractures with minimal trauma, raising her concern about their bone health.

This was the beginning of a partnership that led us down the path of many grant submissions, some of which were funded and others that were not, to explore and investigate bone outcomes in children with ASD.

This applies to prepubertal children as well as older children and adolescents. One study showed that 28% and 33% of children with ASD 8-14 years old had very low bone density (z scores of ≤ –2) at the spine and hip, respectively, compared with 0% of typically developing controls.

Studies that have used sophisticated imaging techniques to determine bone strength have shown that it is lower at the forearm and lower leg in children with ASD versus neurotypical children.

These findings are of particular concern during the childhood and teenage years when bone is typically accrued at a rapid rate. A normal rate of bone accrual at this time of life is essential for optimal bone health in later life. While children with ASD gain bone mass at a similar rate as neurotypical controls, they start at a deficit and seem unable to “catch up.”

Further, people with ASD are more prone to certain kinds of fracture than those without the condition. For example, both children and adults with ASD have a high risk for hip fracture, while adult women with ASD have a higher risk for forearm and spine fractures. There is some protection against forearm fractures in children and adult men, probably because of markedly lower levels of physical activity, which would reduce fall risk.

Many of Ann’s patients with ASD had unusual or restricted diets, low levels of physical activity, and were on multiple medications. We have since learned that some factors that contribute to low bone density in ASD include lower levels of weight-bearing physical activity; lower muscle mass; low muscle tone; suboptimal dietary calcium and vitamin D intake; lower vitamin D levels; higher levels of the hormone cortisol, which has deleterious effects on bone; and use of medications that can lower bone density.

In order to mitigate the risk for low bone density and fractures, it is important to optimize physical activity while considering the child’s ability to safely engage in weight-bearing sports.

High-impact sports like gymnastics and jumping, or cross-impact sports like soccer, basketball, field hockey, and lacrosse, are particularly useful in this context, but many patients with ASD are not able to easily engage in typical team sports.

For such children, a prescribed amount of time spent walking, as well as weight and resistance training, could be helpful. The latter would also help increase muscle mass, a key modulator of bone health.

Other strategies include ensuring sufficient intake of calcium and vitamin D through diet and supplements. This can be a particular challenge for children with ASD on specialized diets, such as a gluten-free or dairy-free diet, which are deficient in calcium and vitamin D. Health care providers should check for intake of dairy and dairy products, as well as serum vitamin D levels, and prescribe supplements as needed.

All children should get at least 600 IUs of vitamin D and 1,000-1,300 mg of elemental calcium daily. That said, many with ASD need much higher quantities of vitamin D (1,000-4,000 IUs or more) to maintain levels in the normal range. This is particularly true for dark-skinned children and children with obesity, as well as those who have medical disorders that cause malabsorption.

Higher cortisol levels in the ASD patient population are harder to manage. Efforts to ease anxiety and depression may help reduce cortisol levels. Medications such as protein pump inhibitors and glucocorticosteroids can compromise bone health.

In addition, certain antipsychotics can cause marked elevations in prolactin which, in turn, can lower levels of estrogen and testosterone, which are very important for bone health. In such cases, the clinician should consider switching patients to a different, less detrimental medication or adjust the current medication so that patients receive the lowest possible effective dose.

Obesity is associated with increased fracture risk and with suboptimal bone accrual during childhood, so ensuring a healthy diet is important. This includes avoiding sugary beverages and reducing intake of processed food and juice.

Sometimes, particularly when a child has low bone density and a history of several low-trauma fractures, medications such as bisphosphonates should be considered to increase bone density.

Above all, as physicians who manage ASD, it is essential that we raise awareness about bone health among our colleagues, patients, and their families to help mitigate fracture risk.

Madhusmita Misra, MD, MPH, is chief of the Division of Pediatric Endocrinology at Mass General for Children, Boston.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Many years ago, at the conclusion of a talk I gave on bone health in teens with anorexia nervosa, I was approached by a colleague, Ann Neumeyer, MD, medical director of the Lurie Center for Autism at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who asked about bone health in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

When I explained that there was little information about bone health in this patient population, she suggested that we learn and investigate together. Ann explained that she had observed that some of her patients with ASD had suffered fractures with minimal trauma, raising her concern about their bone health.

This was the beginning of a partnership that led us down the path of many grant submissions, some of which were funded and others that were not, to explore and investigate bone outcomes in children with ASD.

This applies to prepubertal children as well as older children and adolescents. One study showed that 28% and 33% of children with ASD 8-14 years old had very low bone density (z scores of ≤ –2) at the spine and hip, respectively, compared with 0% of typically developing controls.

Studies that have used sophisticated imaging techniques to determine bone strength have shown that it is lower at the forearm and lower leg in children with ASD versus neurotypical children.

These findings are of particular concern during the childhood and teenage years when bone is typically accrued at a rapid rate. A normal rate of bone accrual at this time of life is essential for optimal bone health in later life. While children with ASD gain bone mass at a similar rate as neurotypical controls, they start at a deficit and seem unable to “catch up.”

Further, people with ASD are more prone to certain kinds of fracture than those without the condition. For example, both children and adults with ASD have a high risk for hip fracture, while adult women with ASD have a higher risk for forearm and spine fractures. There is some protection against forearm fractures in children and adult men, probably because of markedly lower levels of physical activity, which would reduce fall risk.

Many of Ann’s patients with ASD had unusual or restricted diets, low levels of physical activity, and were on multiple medications. We have since learned that some factors that contribute to low bone density in ASD include lower levels of weight-bearing physical activity; lower muscle mass; low muscle tone; suboptimal dietary calcium and vitamin D intake; lower vitamin D levels; higher levels of the hormone cortisol, which has deleterious effects on bone; and use of medications that can lower bone density.

In order to mitigate the risk for low bone density and fractures, it is important to optimize physical activity while considering the child’s ability to safely engage in weight-bearing sports.

High-impact sports like gymnastics and jumping, or cross-impact sports like soccer, basketball, field hockey, and lacrosse, are particularly useful in this context, but many patients with ASD are not able to easily engage in typical team sports.

For such children, a prescribed amount of time spent walking, as well as weight and resistance training, could be helpful. The latter would also help increase muscle mass, a key modulator of bone health.

Other strategies include ensuring sufficient intake of calcium and vitamin D through diet and supplements. This can be a particular challenge for children with ASD on specialized diets, such as a gluten-free or dairy-free diet, which are deficient in calcium and vitamin D. Health care providers should check for intake of dairy and dairy products, as well as serum vitamin D levels, and prescribe supplements as needed.

All children should get at least 600 IUs of vitamin D and 1,000-1,300 mg of elemental calcium daily. That said, many with ASD need much higher quantities of vitamin D (1,000-4,000 IUs or more) to maintain levels in the normal range. This is particularly true for dark-skinned children and children with obesity, as well as those who have medical disorders that cause malabsorption.

Higher cortisol levels in the ASD patient population are harder to manage. Efforts to ease anxiety and depression may help reduce cortisol levels. Medications such as protein pump inhibitors and glucocorticosteroids can compromise bone health.

In addition, certain antipsychotics can cause marked elevations in prolactin which, in turn, can lower levels of estrogen and testosterone, which are very important for bone health. In such cases, the clinician should consider switching patients to a different, less detrimental medication or adjust the current medication so that patients receive the lowest possible effective dose.

Obesity is associated with increased fracture risk and with suboptimal bone accrual during childhood, so ensuring a healthy diet is important. This includes avoiding sugary beverages and reducing intake of processed food and juice.

Sometimes, particularly when a child has low bone density and a history of several low-trauma fractures, medications such as bisphosphonates should be considered to increase bone density.

Above all, as physicians who manage ASD, it is essential that we raise awareness about bone health among our colleagues, patients, and their families to help mitigate fracture risk.

Madhusmita Misra, MD, MPH, is chief of the Division of Pediatric Endocrinology at Mass General for Children, Boston.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation during pregnancy: An alternative to antidepressant treatment?

A growing number of women ask about nonpharmacologic approaches for either the treatment of acute perinatal depression or for relapse prevention during pregnancy.

The last several decades have brought an increasing level of comfort with respect to antidepressant use during pregnancy, which derives from several factors.

First, it’s been well described that there’s an increased risk of relapse and morbidity associated with discontinuation of antidepressants proximate to pregnancy, particularly in women with histories of recurrent disease (JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;80[5]:441-50 and JAMA. 2006;295[5]:499-507).

Second, there’s an obvious increased confidence about using antidepressants during pregnancy given the robust reproductive safety data about antidepressants with respect to both teratogenesis and risk for organ malformation. Other studies also fail to demonstrate a relationship between fetal exposure to antidepressants and risk for subsequent development of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism. These latter studies have been reviewed extensively in systematic reviews of meta-analyses addressing this question.

However, there are women who, as they approach the question of antidepressant use during pregnancy, would prefer a nonpharmacologic approach to managing depression in the setting of either a planned pregnancy, or sometimes in the setting of acute onset of depressive symptoms during pregnancy. Other women are more comfortable with the data in hand regarding the reproductive safety of antidepressants and continue antidepressants that have afforded emotional well-being, particularly if the road to well-being or euthymia has been a long one.

Still, we at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Center for Women’s Mental Health along with multidisciplinary colleagues with whom we engage during our weekly Virtual Rounds community have observed a growing number of women asking about nonpharmacologic approaches for either the treatment of acute perinatal depression or for relapse prevention during pregnancy. They ask about these options for personal reasons, regardless of what we may know (and what we may not know) about existing pharmacologic interventions. In these scenarios, it is important to keep in mind that it is not about what we as clinicians necessarily know about these medicines per se that drives treatment, but rather about the private calculus that women and their partners apply about risk and benefit of pharmacologic treatment during pregnancy.

Nonpharmacologic treatment options

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and behavioral activation are therapies all of which have an evidence base with respect to their effectiveness for either the acute treatment of both depression (and perinatal depression specifically) or for mitigating risk for depressive relapse (MBCT). Several investigations are underway evaluating digital apps that utilize MBCT and CBT in these patient populations as well.

New treatments for which we have none or exceedingly sparse data to support use during pregnancy are neurosteroids. We are asked all the time about the use of neurosteroids such as brexanolone or zuranolone during pregnancy. Given the data on effectiveness of these agents for treatment of postpartum depression, the question about use during pregnancy is intuitive. But at this point in time, absent data, their use during pregnancy cannot be recommended.

With respect to newer nonpharmacologic approaches that have been looked at for treatment of major depressive disorder, the Food and Drug Administration has approved transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a noninvasive form of neuromodulating therapy that use magnetic pulses to stimulate specific regions of the brain that have been implicated in psychiatric illness.

While there are no safety concerns that have been noted about use of TMS, the data regarding its use during pregnancy are still relatively limited, but it has been used to treat certain neurologic conditions during pregnancy. We now have a small randomized controlled study using TMS during pregnancy and multiple small case series suggesting a signal of efficacy in women with perinatal major depressive disorder. Side effects of TMS use during pregnancy have included hypotension, which has sometimes required repositioning of subjects, particularly later in pregnancy. Unlike electroconvulsive therapy, (ECT), often used when clinicians have exhausted other treatment options, TMS has no risk of seizure associated with its use.

TMS is now entering into the clinical arena in a more robust way. In certain settings, insurance companies are reimbursing for TMS treatment more often than was the case previously, making it a more viable option for a larger number of patients. There are also several exciting newer protocols, including theta burst stimulation, a new form of TMS treatment with less of a time commitment, and which may be more cost effective. However, data on this modality of treatment remain limited.

Where TMS fits in treating depression during pregnancy

The real question we are getting asked in clinic, both in person and during virtual rounds with multidisciplinary colleagues from across the world, is where TMS might fit into the algorithm for treating of depression during pregnancy. Where is it appropriate to be thinking about TMS in pregnancy, and where should it perhaps be deferred at this moment (and where is it not appropriate)?

It is probably of limited value (and possibly of potential harm) to switch to TMS in patients who have severe recurrent major depression and who are on maintenance antidepressant, and who believe that a switch to TMS will be effective for relapse prevention; there are simply no data currently suggesting that TMS can be used as a relapse prevention tool, unlike certain other nonpharmacologic interventions.

What about managing relapse of major depressive disorder during pregnancy in a patient who had responded to an antidepressant? We have seen patients with histories of severe recurrent disease who are managed well on antidepressants during pregnancy who then have breakthrough symptoms and inquire about using TMS as an augmentation strategy. Although we don’t have clear data supporting the use of TMS as an adjunct in that setting, in those patients, one could argue that a trial of TMS may be appropriate – as opposed to introducing multiple medicines to recapture euthymia during pregnancy where the benefit is unclear and where more exposure is implied by having to do potentially multiple trials.

Other patients with new onset of depression during pregnancy who, for personal reasons, will not take an antidepressant or pursue other nonpharmacologic interventions will frequently ask about TMS. and the increased availability of TMS in the community in various centers – as opposed to previously where it was more restricted to large academic medical centers.

I think it is a time of excitement in reproductive psychiatry where we have a growing number of tools to treat perinatal depression – from medications to digital tools. These tools – either alone or in combination with medicines that we’ve been using for years – are able to afford women a greater number of choices with respect to the treatment of perinatal depression than was available even 5 years ago. That takes us closer to an ability to use interventions that truly combine patient wishes and “precision perinatal psychiatry,” where we can match effective therapies with the individual clinical presentations and wishes with which patients come to us.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

A growing number of women ask about nonpharmacologic approaches for either the treatment of acute perinatal depression or for relapse prevention during pregnancy.

The last several decades have brought an increasing level of comfort with respect to antidepressant use during pregnancy, which derives from several factors.

First, it’s been well described that there’s an increased risk of relapse and morbidity associated with discontinuation of antidepressants proximate to pregnancy, particularly in women with histories of recurrent disease (JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;80[5]:441-50 and JAMA. 2006;295[5]:499-507).

Second, there’s an obvious increased confidence about using antidepressants during pregnancy given the robust reproductive safety data about antidepressants with respect to both teratogenesis and risk for organ malformation. Other studies also fail to demonstrate a relationship between fetal exposure to antidepressants and risk for subsequent development of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism. These latter studies have been reviewed extensively in systematic reviews of meta-analyses addressing this question.

However, there are women who, as they approach the question of antidepressant use during pregnancy, would prefer a nonpharmacologic approach to managing depression in the setting of either a planned pregnancy, or sometimes in the setting of acute onset of depressive symptoms during pregnancy. Other women are more comfortable with the data in hand regarding the reproductive safety of antidepressants and continue antidepressants that have afforded emotional well-being, particularly if the road to well-being or euthymia has been a long one.

Still, we at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Center for Women’s Mental Health along with multidisciplinary colleagues with whom we engage during our weekly Virtual Rounds community have observed a growing number of women asking about nonpharmacologic approaches for either the treatment of acute perinatal depression or for relapse prevention during pregnancy. They ask about these options for personal reasons, regardless of what we may know (and what we may not know) about existing pharmacologic interventions. In these scenarios, it is important to keep in mind that it is not about what we as clinicians necessarily know about these medicines per se that drives treatment, but rather about the private calculus that women and their partners apply about risk and benefit of pharmacologic treatment during pregnancy.

Nonpharmacologic treatment options

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and behavioral activation are therapies all of which have an evidence base with respect to their effectiveness for either the acute treatment of both depression (and perinatal depression specifically) or for mitigating risk for depressive relapse (MBCT). Several investigations are underway evaluating digital apps that utilize MBCT and CBT in these patient populations as well.

New treatments for which we have none or exceedingly sparse data to support use during pregnancy are neurosteroids. We are asked all the time about the use of neurosteroids such as brexanolone or zuranolone during pregnancy. Given the data on effectiveness of these agents for treatment of postpartum depression, the question about use during pregnancy is intuitive. But at this point in time, absent data, their use during pregnancy cannot be recommended.

With respect to newer nonpharmacologic approaches that have been looked at for treatment of major depressive disorder, the Food and Drug Administration has approved transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a noninvasive form of neuromodulating therapy that use magnetic pulses to stimulate specific regions of the brain that have been implicated in psychiatric illness.

While there are no safety concerns that have been noted about use of TMS, the data regarding its use during pregnancy are still relatively limited, but it has been used to treat certain neurologic conditions during pregnancy. We now have a small randomized controlled study using TMS during pregnancy and multiple small case series suggesting a signal of efficacy in women with perinatal major depressive disorder. Side effects of TMS use during pregnancy have included hypotension, which has sometimes required repositioning of subjects, particularly later in pregnancy. Unlike electroconvulsive therapy, (ECT), often used when clinicians have exhausted other treatment options, TMS has no risk of seizure associated with its use.

TMS is now entering into the clinical arena in a more robust way. In certain settings, insurance companies are reimbursing for TMS treatment more often than was the case previously, making it a more viable option for a larger number of patients. There are also several exciting newer protocols, including theta burst stimulation, a new form of TMS treatment with less of a time commitment, and which may be more cost effective. However, data on this modality of treatment remain limited.

Where TMS fits in treating depression during pregnancy

The real question we are getting asked in clinic, both in person and during virtual rounds with multidisciplinary colleagues from across the world, is where TMS might fit into the algorithm for treating of depression during pregnancy. Where is it appropriate to be thinking about TMS in pregnancy, and where should it perhaps be deferred at this moment (and where is it not appropriate)?

It is probably of limited value (and possibly of potential harm) to switch to TMS in patients who have severe recurrent major depression and who are on maintenance antidepressant, and who believe that a switch to TMS will be effective for relapse prevention; there are simply no data currently suggesting that TMS can be used as a relapse prevention tool, unlike certain other nonpharmacologic interventions.

What about managing relapse of major depressive disorder during pregnancy in a patient who had responded to an antidepressant? We have seen patients with histories of severe recurrent disease who are managed well on antidepressants during pregnancy who then have breakthrough symptoms and inquire about using TMS as an augmentation strategy. Although we don’t have clear data supporting the use of TMS as an adjunct in that setting, in those patients, one could argue that a trial of TMS may be appropriate – as opposed to introducing multiple medicines to recapture euthymia during pregnancy where the benefit is unclear and where more exposure is implied by having to do potentially multiple trials.

Other patients with new onset of depression during pregnancy who, for personal reasons, will not take an antidepressant or pursue other nonpharmacologic interventions will frequently ask about TMS. and the increased availability of TMS in the community in various centers – as opposed to previously where it was more restricted to large academic medical centers.

I think it is a time of excitement in reproductive psychiatry where we have a growing number of tools to treat perinatal depression – from medications to digital tools. These tools – either alone or in combination with medicines that we’ve been using for years – are able to afford women a greater number of choices with respect to the treatment of perinatal depression than was available even 5 years ago. That takes us closer to an ability to use interventions that truly combine patient wishes and “precision perinatal psychiatry,” where we can match effective therapies with the individual clinical presentations and wishes with which patients come to us.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

A growing number of women ask about nonpharmacologic approaches for either the treatment of acute perinatal depression or for relapse prevention during pregnancy.

The last several decades have brought an increasing level of comfort with respect to antidepressant use during pregnancy, which derives from several factors.

First, it’s been well described that there’s an increased risk of relapse and morbidity associated with discontinuation of antidepressants proximate to pregnancy, particularly in women with histories of recurrent disease (JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;80[5]:441-50 and JAMA. 2006;295[5]:499-507).

Second, there’s an obvious increased confidence about using antidepressants during pregnancy given the robust reproductive safety data about antidepressants with respect to both teratogenesis and risk for organ malformation. Other studies also fail to demonstrate a relationship between fetal exposure to antidepressants and risk for subsequent development of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism. These latter studies have been reviewed extensively in systematic reviews of meta-analyses addressing this question.

However, there are women who, as they approach the question of antidepressant use during pregnancy, would prefer a nonpharmacologic approach to managing depression in the setting of either a planned pregnancy, or sometimes in the setting of acute onset of depressive symptoms during pregnancy. Other women are more comfortable with the data in hand regarding the reproductive safety of antidepressants and continue antidepressants that have afforded emotional well-being, particularly if the road to well-being or euthymia has been a long one.

Still, we at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Center for Women’s Mental Health along with multidisciplinary colleagues with whom we engage during our weekly Virtual Rounds community have observed a growing number of women asking about nonpharmacologic approaches for either the treatment of acute perinatal depression or for relapse prevention during pregnancy. They ask about these options for personal reasons, regardless of what we may know (and what we may not know) about existing pharmacologic interventions. In these scenarios, it is important to keep in mind that it is not about what we as clinicians necessarily know about these medicines per se that drives treatment, but rather about the private calculus that women and their partners apply about risk and benefit of pharmacologic treatment during pregnancy.

Nonpharmacologic treatment options

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and behavioral activation are therapies all of which have an evidence base with respect to their effectiveness for either the acute treatment of both depression (and perinatal depression specifically) or for mitigating risk for depressive relapse (MBCT). Several investigations are underway evaluating digital apps that utilize MBCT and CBT in these patient populations as well.

New treatments for which we have none or exceedingly sparse data to support use during pregnancy are neurosteroids. We are asked all the time about the use of neurosteroids such as brexanolone or zuranolone during pregnancy. Given the data on effectiveness of these agents for treatment of postpartum depression, the question about use during pregnancy is intuitive. But at this point in time, absent data, their use during pregnancy cannot be recommended.

With respect to newer nonpharmacologic approaches that have been looked at for treatment of major depressive disorder, the Food and Drug Administration has approved transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a noninvasive form of neuromodulating therapy that use magnetic pulses to stimulate specific regions of the brain that have been implicated in psychiatric illness.

While there are no safety concerns that have been noted about use of TMS, the data regarding its use during pregnancy are still relatively limited, but it has been used to treat certain neurologic conditions during pregnancy. We now have a small randomized controlled study using TMS during pregnancy and multiple small case series suggesting a signal of efficacy in women with perinatal major depressive disorder. Side effects of TMS use during pregnancy have included hypotension, which has sometimes required repositioning of subjects, particularly later in pregnancy. Unlike electroconvulsive therapy, (ECT), often used when clinicians have exhausted other treatment options, TMS has no risk of seizure associated with its use.

TMS is now entering into the clinical arena in a more robust way. In certain settings, insurance companies are reimbursing for TMS treatment more often than was the case previously, making it a more viable option for a larger number of patients. There are also several exciting newer protocols, including theta burst stimulation, a new form of TMS treatment with less of a time commitment, and which may be more cost effective. However, data on this modality of treatment remain limited.

Where TMS fits in treating depression during pregnancy

The real question we are getting asked in clinic, both in person and during virtual rounds with multidisciplinary colleagues from across the world, is where TMS might fit into the algorithm for treating of depression during pregnancy. Where is it appropriate to be thinking about TMS in pregnancy, and where should it perhaps be deferred at this moment (and where is it not appropriate)?

It is probably of limited value (and possibly of potential harm) to switch to TMS in patients who have severe recurrent major depression and who are on maintenance antidepressant, and who believe that a switch to TMS will be effective for relapse prevention; there are simply no data currently suggesting that TMS can be used as a relapse prevention tool, unlike certain other nonpharmacologic interventions.

What about managing relapse of major depressive disorder during pregnancy in a patient who had responded to an antidepressant? We have seen patients with histories of severe recurrent disease who are managed well on antidepressants during pregnancy who then have breakthrough symptoms and inquire about using TMS as an augmentation strategy. Although we don’t have clear data supporting the use of TMS as an adjunct in that setting, in those patients, one could argue that a trial of TMS may be appropriate – as opposed to introducing multiple medicines to recapture euthymia during pregnancy where the benefit is unclear and where more exposure is implied by having to do potentially multiple trials.

Other patients with new onset of depression during pregnancy who, for personal reasons, will not take an antidepressant or pursue other nonpharmacologic interventions will frequently ask about TMS. and the increased availability of TMS in the community in various centers – as opposed to previously where it was more restricted to large academic medical centers.

I think it is a time of excitement in reproductive psychiatry where we have a growing number of tools to treat perinatal depression – from medications to digital tools. These tools – either alone or in combination with medicines that we’ve been using for years – are able to afford women a greater number of choices with respect to the treatment of perinatal depression than was available even 5 years ago. That takes us closer to an ability to use interventions that truly combine patient wishes and “precision perinatal psychiatry,” where we can match effective therapies with the individual clinical presentations and wishes with which patients come to us.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

Surprising brain activity moments before death

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

All the participants in the study I am going to tell you about this week died. And three of them died twice. But their deaths provide us with a fascinating window into the complex electrochemistry of the dying brain. What we might be looking at, indeed, is the physiologic correlate of the near-death experience.

The concept of the near-death experience is culturally ubiquitous. And though the content seems to track along culture lines – Western Christians are more likely to report seeing guardian angels, while Hindus are more likely to report seeing messengers of the god of death – certain factors seem to transcend culture: an out-of-body experience; a feeling of peace; and, of course, the light at the end of the tunnel.

As a materialist, I won’t discuss the possibility that these commonalities reflect some metaphysical structure to the afterlife. More likely, it seems to me, is that the commonalities result from the fact that the experience is mediated by our brains, and our brains, when dying, may be more alike than different.

We are talking about this study, appearing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, by Jimo Borjigin and her team.

Dr. Borjigin studies the neural correlates of consciousness, perhaps one of the biggest questions in all of science today. To wit,

The study in question follows four unconscious patients –comatose patients, really – as life-sustaining support was withdrawn, up until the moment of death. Three had suffered severe anoxic brain injury in the setting of prolonged cardiac arrest. Though the heart was restarted, the brain damage was severe. The fourth had a large brain hemorrhage. All four patients were thus comatose and, though not brain-dead, unresponsive – with the lowest possible Glasgow Coma Scale score. No response to outside stimuli.

The families had made the decision to withdraw life support – to remove the breathing tube – but agreed to enroll their loved one in the study.

The team applied EEG leads to the head, EKG leads to the chest, and other monitoring equipment to observe the physiologic changes that occurred as the comatose and unresponsive patient died.

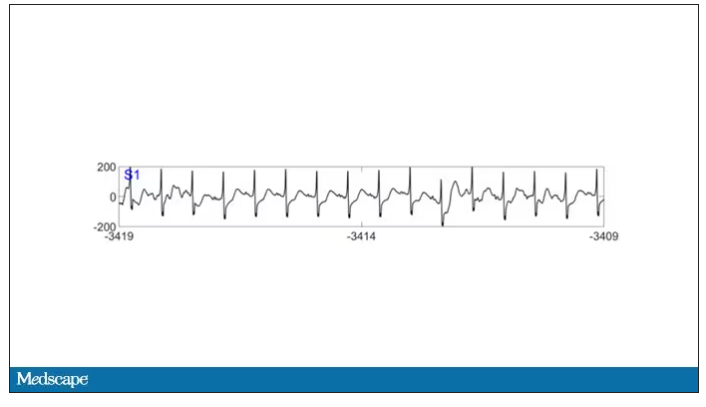

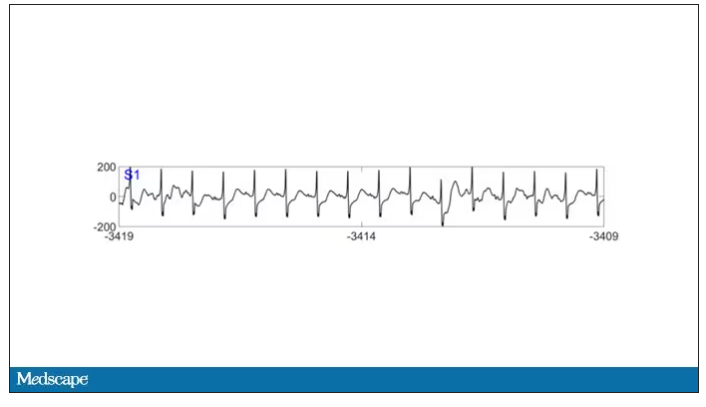

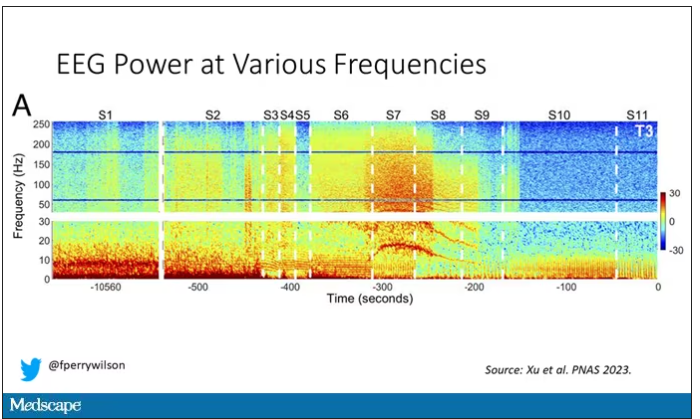

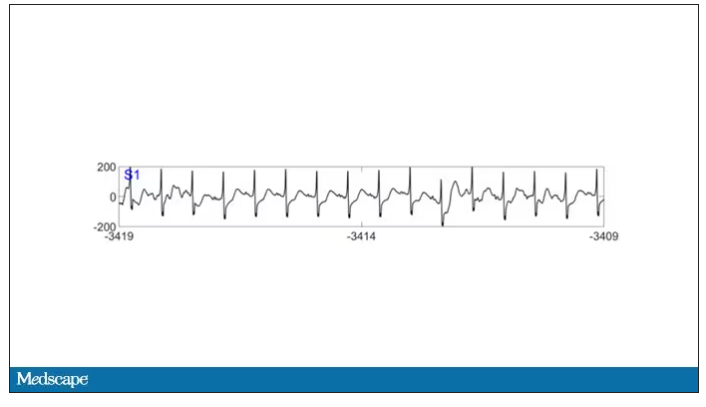

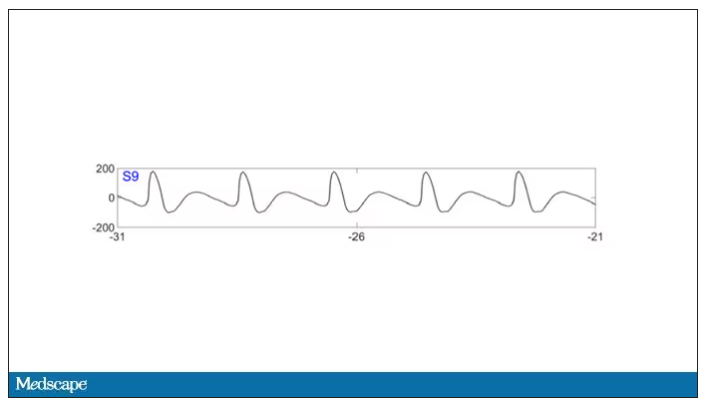

As the heart rhythm evolved from this:

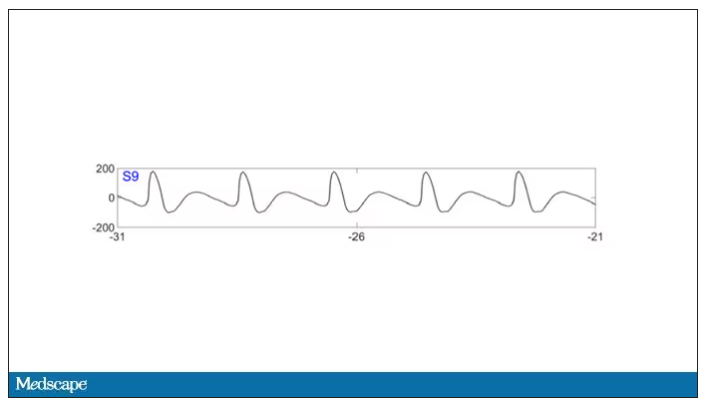

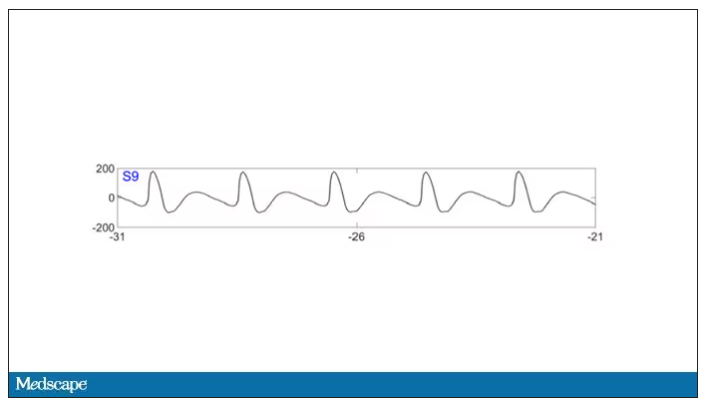

To this:

And eventually stopped.

But this is a study about the brain, not the heart.

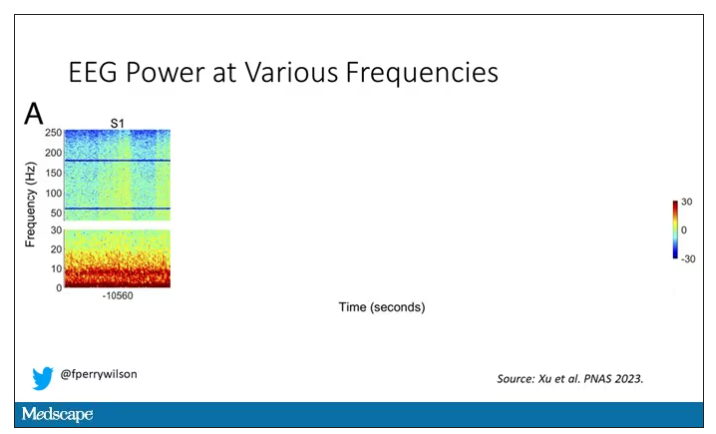

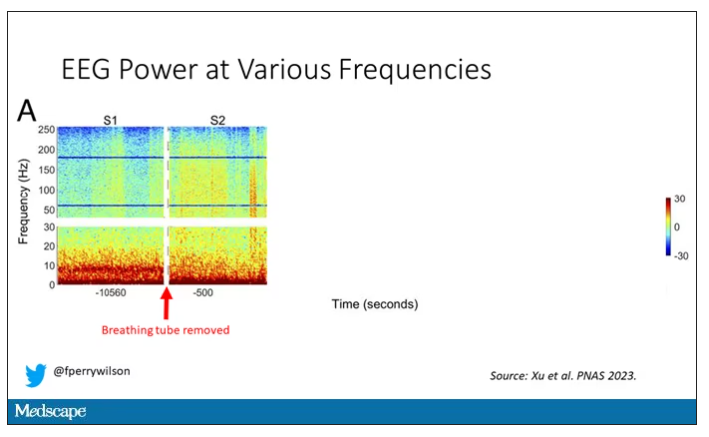

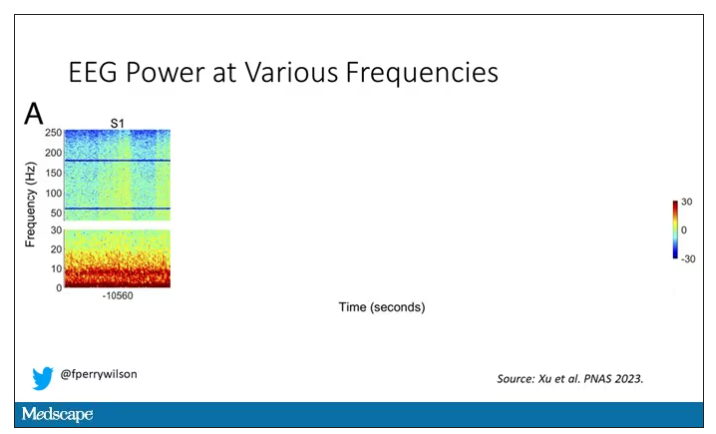

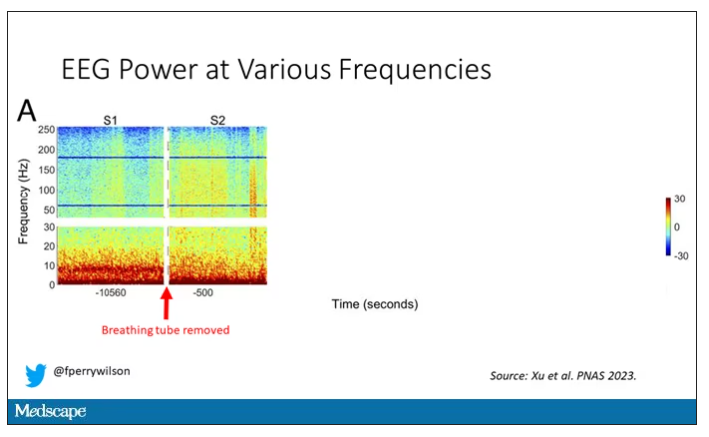

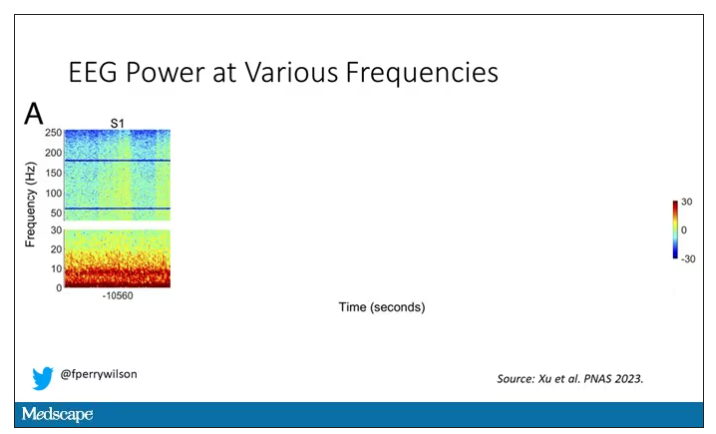

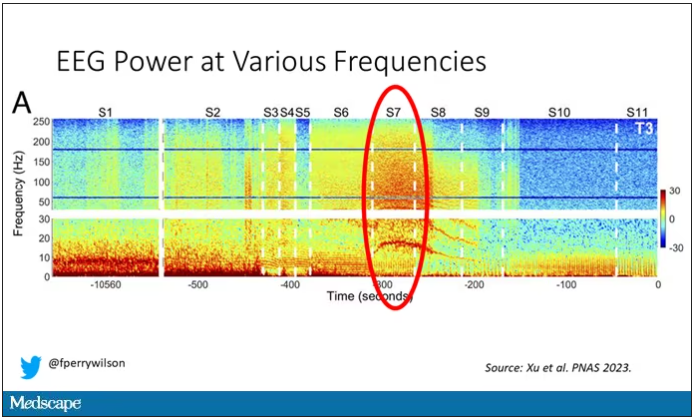

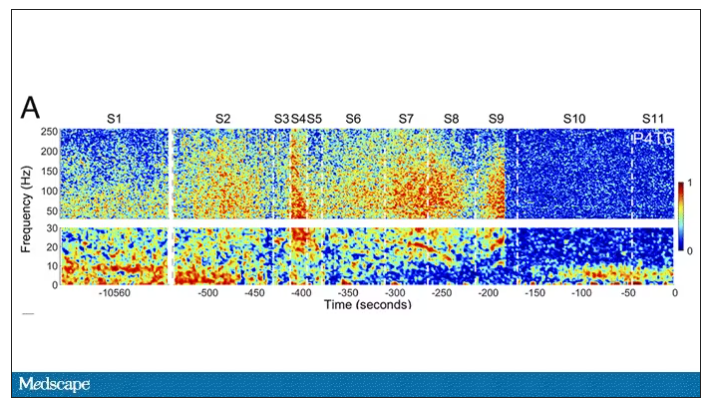

Prior to the withdrawal of life support, the brain electrical signals looked like this:

What you see is the EEG power at various frequencies, with red being higher. All the red was down at the low frequencies. Consciousness, at least as we understand it, is a higher-frequency phenomenon.

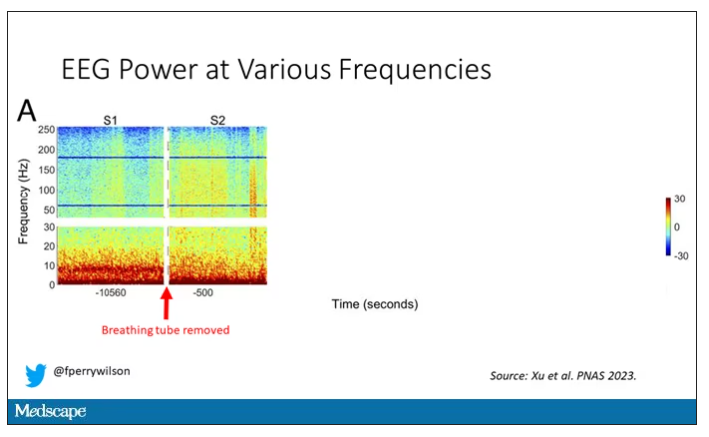

Right after the breathing tube was removed, the power didn’t change too much, but you can see some increased activity at the higher frequencies.

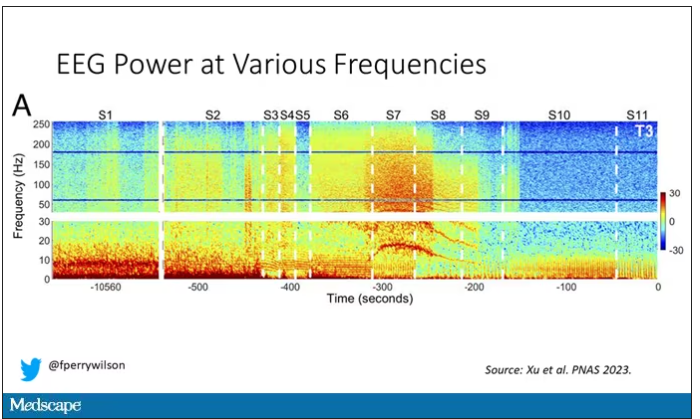

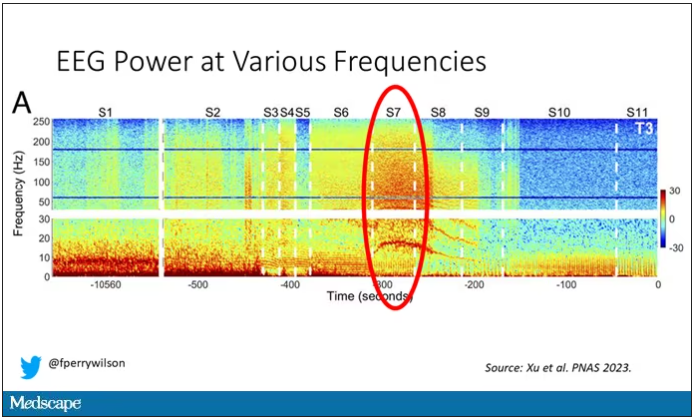

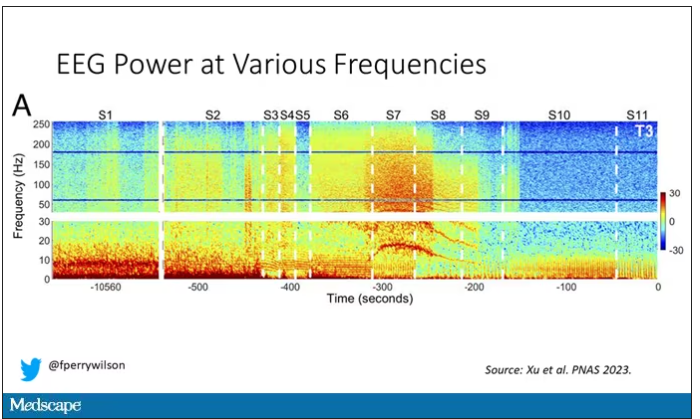

But in two of the four patients, something really surprising happened. Watch what happens as the brain gets closer and closer to death.

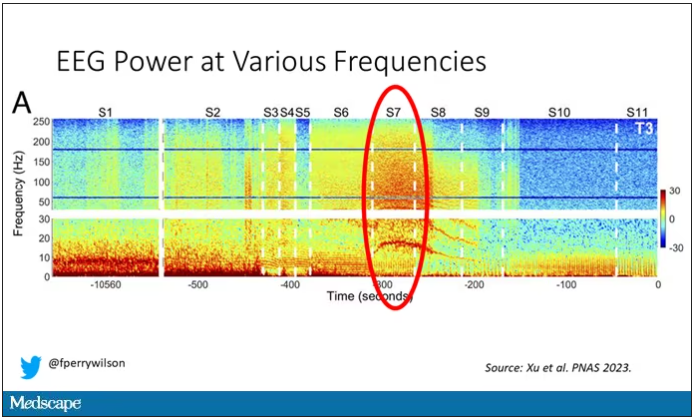

Here, about 300 seconds before death, there was a power surge at the high gamma frequencies.

This spike in power occurred in the somatosensory cortex and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, areas that are associated with conscious experience. It seems that this patient, 5 minutes before death, was experiencing something.

But I know what you’re thinking. This is a brain that is not receiving oxygen. Cells are going to become disordered quickly and start firing randomly – a last gasp, so to speak, before the end. Meaningless noise.

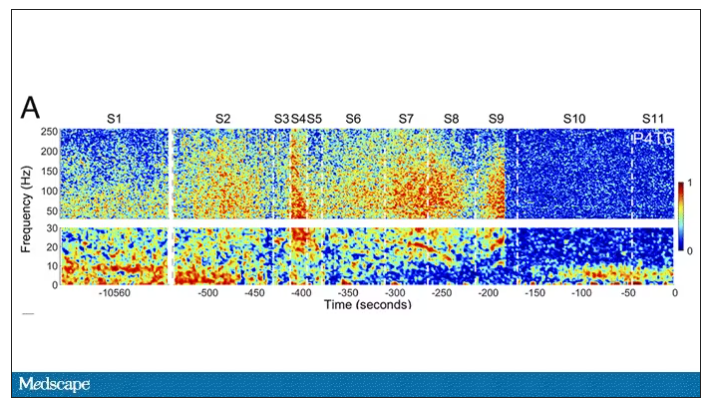

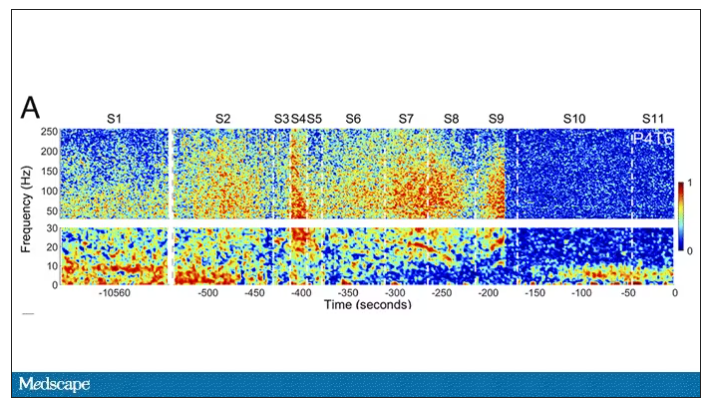

But connectivity mapping tells a different story. The signals seem to have structure.

Those high-frequency power surges increased connectivity in the posterior cortical “hot zone,” an area of the brain many researchers feel is necessary for conscious perception. This figure is not a map of raw brain electrical output like the one I showed before, but of coherence between brain regions in the consciousness hot zone. Those red areas indicate cross-talk – not the disordered scream of dying neurons, but a last set of messages passing back and forth from the parietal and posterior temporal lobes.

In fact, the electrical patterns of the brains in these patients looked very similar to the patterns seen in dreaming humans, as well as in patients with epilepsy who report sensations of out-of-body experiences.

It’s critical to realize two things here. First, these signals of consciousness were not present before life support was withdrawn. These comatose patients had minimal brain activity; there was no evidence that they were experiencing anything before the process of dying began. These brains are behaving fundamentally differently near death.

But second, we must realize that, although the brains of these individuals, in their last moments, appeared to be acting in a way that conscious brains act, we have no way of knowing if the patients were truly having a conscious experience. As I said, all the patients in the study died. Short of those metaphysics I alluded to earlier, we will have no way to ask them how they experienced their final moments.

Let’s be clear: This study doesn’t answer the question of what happens when we die. It says nothing about life after death or the existence or persistence of the soul. But what it does do is shed light on an incredibly difficult problem in neuroscience: the problem of consciousness. And as studies like this move forward, we may discover that the root of consciousness comes not from the breath of God or the energy of a living universe, but from very specific parts of the very complicated machine that is the brain, acting together to produce something transcendent. And to me, that is no less sublime.

Dr. Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now. Dr. Wilson has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

All the participants in the study I am going to tell you about this week died. And three of them died twice. But their deaths provide us with a fascinating window into the complex electrochemistry of the dying brain. What we might be looking at, indeed, is the physiologic correlate of the near-death experience.

The concept of the near-death experience is culturally ubiquitous. And though the content seems to track along culture lines – Western Christians are more likely to report seeing guardian angels, while Hindus are more likely to report seeing messengers of the god of death – certain factors seem to transcend culture: an out-of-body experience; a feeling of peace; and, of course, the light at the end of the tunnel.

As a materialist, I won’t discuss the possibility that these commonalities reflect some metaphysical structure to the afterlife. More likely, it seems to me, is that the commonalities result from the fact that the experience is mediated by our brains, and our brains, when dying, may be more alike than different.

We are talking about this study, appearing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, by Jimo Borjigin and her team.

Dr. Borjigin studies the neural correlates of consciousness, perhaps one of the biggest questions in all of science today. To wit,

The study in question follows four unconscious patients –comatose patients, really – as life-sustaining support was withdrawn, up until the moment of death. Three had suffered severe anoxic brain injury in the setting of prolonged cardiac arrest. Though the heart was restarted, the brain damage was severe. The fourth had a large brain hemorrhage. All four patients were thus comatose and, though not brain-dead, unresponsive – with the lowest possible Glasgow Coma Scale score. No response to outside stimuli.

The families had made the decision to withdraw life support – to remove the breathing tube – but agreed to enroll their loved one in the study.

The team applied EEG leads to the head, EKG leads to the chest, and other monitoring equipment to observe the physiologic changes that occurred as the comatose and unresponsive patient died.

As the heart rhythm evolved from this:

To this:

And eventually stopped.

But this is a study about the brain, not the heart.

Prior to the withdrawal of life support, the brain electrical signals looked like this:

What you see is the EEG power at various frequencies, with red being higher. All the red was down at the low frequencies. Consciousness, at least as we understand it, is a higher-frequency phenomenon.

Right after the breathing tube was removed, the power didn’t change too much, but you can see some increased activity at the higher frequencies.

But in two of the four patients, something really surprising happened. Watch what happens as the brain gets closer and closer to death.

Here, about 300 seconds before death, there was a power surge at the high gamma frequencies.

This spike in power occurred in the somatosensory cortex and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, areas that are associated with conscious experience. It seems that this patient, 5 minutes before death, was experiencing something.

But I know what you’re thinking. This is a brain that is not receiving oxygen. Cells are going to become disordered quickly and start firing randomly – a last gasp, so to speak, before the end. Meaningless noise.

But connectivity mapping tells a different story. The signals seem to have structure.

Those high-frequency power surges increased connectivity in the posterior cortical “hot zone,” an area of the brain many researchers feel is necessary for conscious perception. This figure is not a map of raw brain electrical output like the one I showed before, but of coherence between brain regions in the consciousness hot zone. Those red areas indicate cross-talk – not the disordered scream of dying neurons, but a last set of messages passing back and forth from the parietal and posterior temporal lobes.

In fact, the electrical patterns of the brains in these patients looked very similar to the patterns seen in dreaming humans, as well as in patients with epilepsy who report sensations of out-of-body experiences.

It’s critical to realize two things here. First, these signals of consciousness were not present before life support was withdrawn. These comatose patients had minimal brain activity; there was no evidence that they were experiencing anything before the process of dying began. These brains are behaving fundamentally differently near death.

But second, we must realize that, although the brains of these individuals, in their last moments, appeared to be acting in a way that conscious brains act, we have no way of knowing if the patients were truly having a conscious experience. As I said, all the patients in the study died. Short of those metaphysics I alluded to earlier, we will have no way to ask them how they experienced their final moments.

Let’s be clear: This study doesn’t answer the question of what happens when we die. It says nothing about life after death or the existence or persistence of the soul. But what it does do is shed light on an incredibly difficult problem in neuroscience: the problem of consciousness. And as studies like this move forward, we may discover that the root of consciousness comes not from the breath of God or the energy of a living universe, but from very specific parts of the very complicated machine that is the brain, acting together to produce something transcendent. And to me, that is no less sublime.

Dr. Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now. Dr. Wilson has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

All the participants in the study I am going to tell you about this week died. And three of them died twice. But their deaths provide us with a fascinating window into the complex electrochemistry of the dying brain. What we might be looking at, indeed, is the physiologic correlate of the near-death experience.

The concept of the near-death experience is culturally ubiquitous. And though the content seems to track along culture lines – Western Christians are more likely to report seeing guardian angels, while Hindus are more likely to report seeing messengers of the god of death – certain factors seem to transcend culture: an out-of-body experience; a feeling of peace; and, of course, the light at the end of the tunnel.

As a materialist, I won’t discuss the possibility that these commonalities reflect some metaphysical structure to the afterlife. More likely, it seems to me, is that the commonalities result from the fact that the experience is mediated by our brains, and our brains, when dying, may be more alike than different.

We are talking about this study, appearing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, by Jimo Borjigin and her team.

Dr. Borjigin studies the neural correlates of consciousness, perhaps one of the biggest questions in all of science today. To wit,

The study in question follows four unconscious patients –comatose patients, really – as life-sustaining support was withdrawn, up until the moment of death. Three had suffered severe anoxic brain injury in the setting of prolonged cardiac arrest. Though the heart was restarted, the brain damage was severe. The fourth had a large brain hemorrhage. All four patients were thus comatose and, though not brain-dead, unresponsive – with the lowest possible Glasgow Coma Scale score. No response to outside stimuli.

The families had made the decision to withdraw life support – to remove the breathing tube – but agreed to enroll their loved one in the study.

The team applied EEG leads to the head, EKG leads to the chest, and other monitoring equipment to observe the physiologic changes that occurred as the comatose and unresponsive patient died.

As the heart rhythm evolved from this:

To this:

And eventually stopped.

But this is a study about the brain, not the heart.

Prior to the withdrawal of life support, the brain electrical signals looked like this:

What you see is the EEG power at various frequencies, with red being higher. All the red was down at the low frequencies. Consciousness, at least as we understand it, is a higher-frequency phenomenon.

Right after the breathing tube was removed, the power didn’t change too much, but you can see some increased activity at the higher frequencies.

But in two of the four patients, something really surprising happened. Watch what happens as the brain gets closer and closer to death.

Here, about 300 seconds before death, there was a power surge at the high gamma frequencies.

This spike in power occurred in the somatosensory cortex and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, areas that are associated with conscious experience. It seems that this patient, 5 minutes before death, was experiencing something.

But I know what you’re thinking. This is a brain that is not receiving oxygen. Cells are going to become disordered quickly and start firing randomly – a last gasp, so to speak, before the end. Meaningless noise.

But connectivity mapping tells a different story. The signals seem to have structure.

Those high-frequency power surges increased connectivity in the posterior cortical “hot zone,” an area of the brain many researchers feel is necessary for conscious perception. This figure is not a map of raw brain electrical output like the one I showed before, but of coherence between brain regions in the consciousness hot zone. Those red areas indicate cross-talk – not the disordered scream of dying neurons, but a last set of messages passing back and forth from the parietal and posterior temporal lobes.

In fact, the electrical patterns of the brains in these patients looked very similar to the patterns seen in dreaming humans, as well as in patients with epilepsy who report sensations of out-of-body experiences.

It’s critical to realize two things here. First, these signals of consciousness were not present before life support was withdrawn. These comatose patients had minimal brain activity; there was no evidence that they were experiencing anything before the process of dying began. These brains are behaving fundamentally differently near death.