User login

Is There a Relationship Between Facility Peer Review Findings and Quality in the Veterans Health Administration?

Hospital leaders report the most common aim of peer review (PR) is to improve quality and patient safety, thus it is a potentially powerful quality improvement (QI) driver.1 “When conducted systematically and credibly, peer review for quality management can result in both short-term and long-term improvements in patient care by revealing areas for improvement in the provision of care,” Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Directive 1190 states. “This ultimately contributes to organizational improvements.” At the same time, there are anecdotal concerns that PR may be used punitively and driven by case outcomes rather than by accepted best practices supporting QI.

Studies of the PR process suggest these concerns are valid. A key tenet of QI is standardization. PR is problematic in that regard; studies show poor interrater reliability for judgments on care, as well as hindsight bias—the fact that raters are strongly influenced by the outcome of care, not the process of care.2-5 There are concerns that case selection or review process when not standardized may be wielded as punitive too.6 In this study, we sought to identify the relationship between PR findings and subsequent institution quality metrics. If PR does lead to an improvement in quality, or if quality concerns are managed within the PR committee, it should be possible to identify a measurable relationship between the PR process and a facility’s subsequent quality measures.

A handful of studies describe the association between PR and quality of care. Itri and colleagues noted that random, not standardized PR in radiology does not achieve reductions in diagnostic error rate.7 However, adoption of just culture principles in PR resulted in a significant improvement in facility leaders’ self-reports of quality measures at surveyed institutions.8 The same author reported that increases in PR standardization and integration with performance improvement activities could explain up to 18% of objective quality measure variation.9

We sought to determine whether a specific aspect of the PR process, the PR committee judgment of quality of care by clinicians, was related to medical center quality in a cross-sectional study of 136 Veterans Health Administration (VHA) medical centers. The VHA is a good source of study because there are standardized PR processes and training for committee members and reviewers. Our hypothesis was that medical centers with a higher number of Level 2 (“most experienced and competent clinicians might have managed the case differently”) and Level 3 (“most experienced and competent providers would have managed the case differently”) PR findings would also have lower quality metric scores for processes and outcomes of care.

Methods

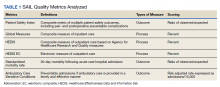

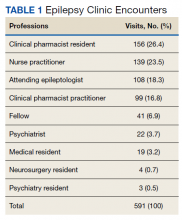

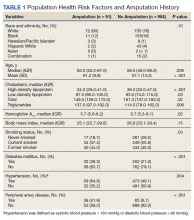

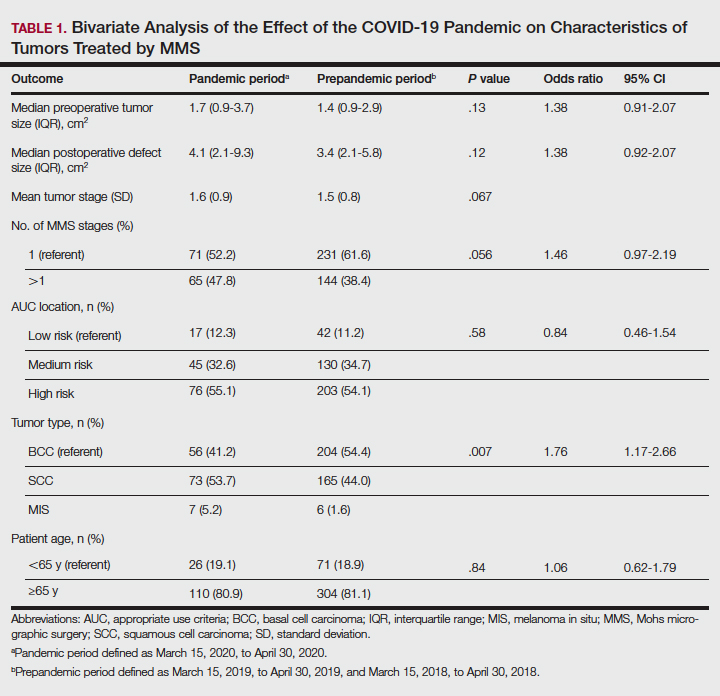

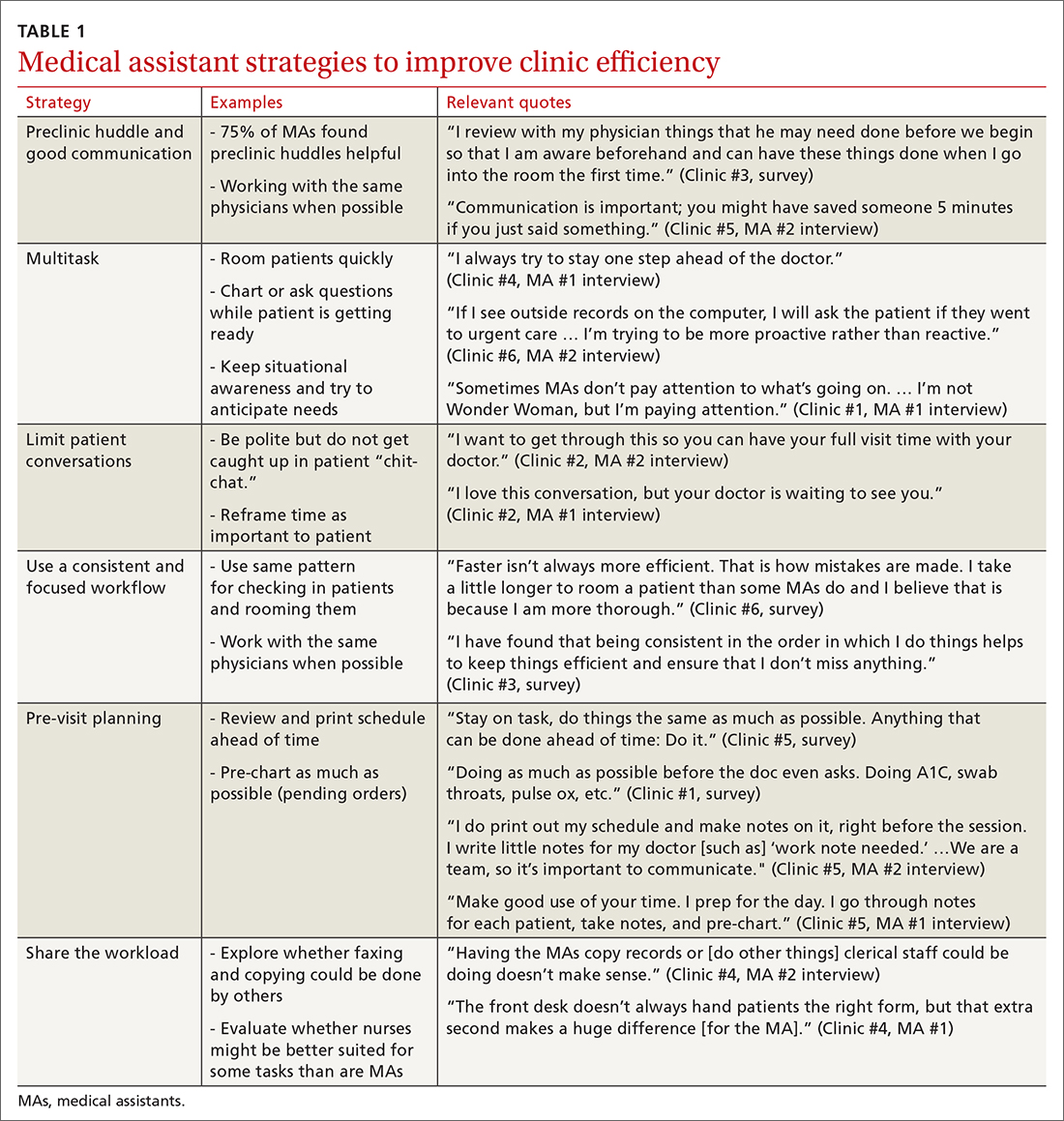

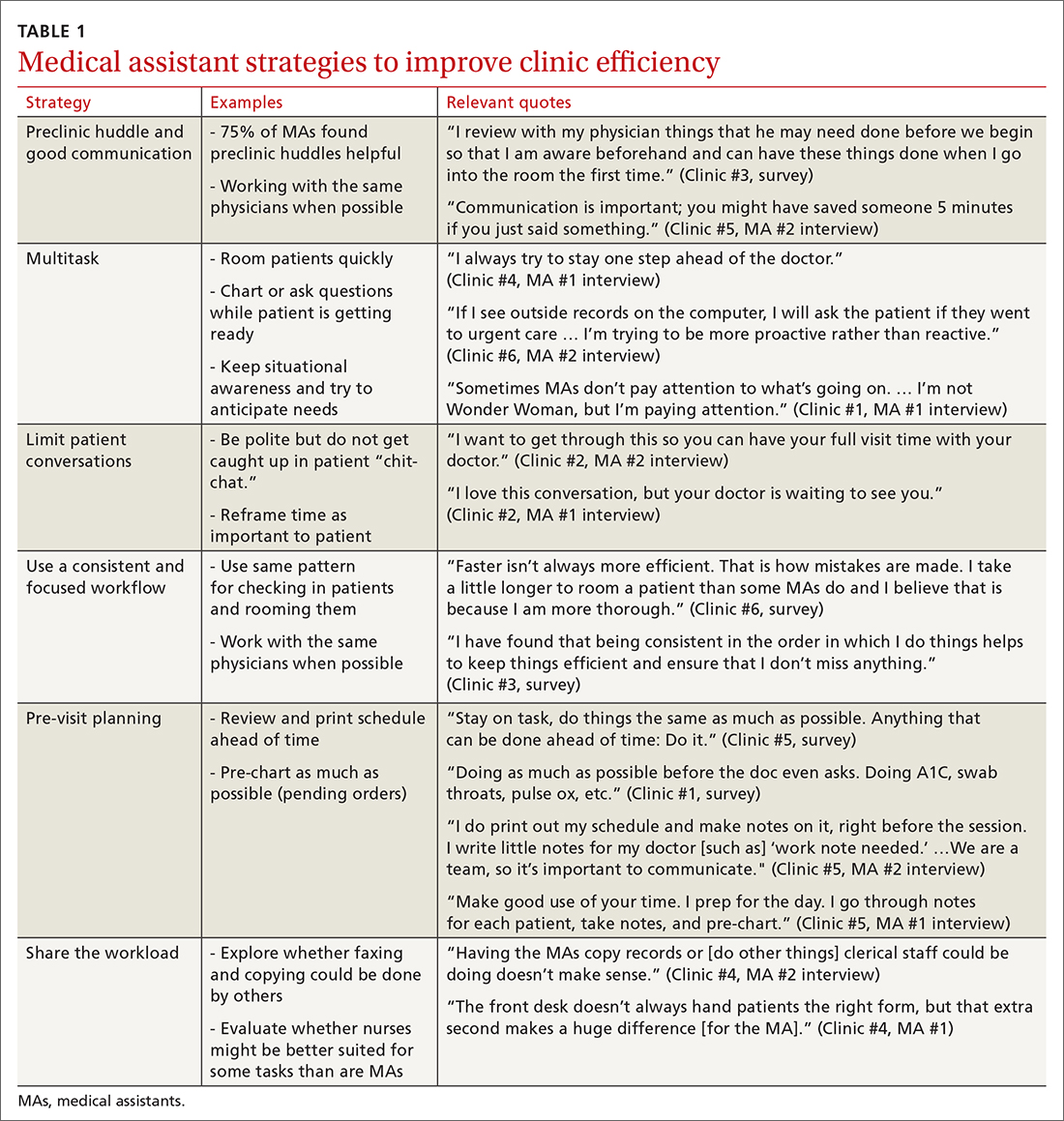

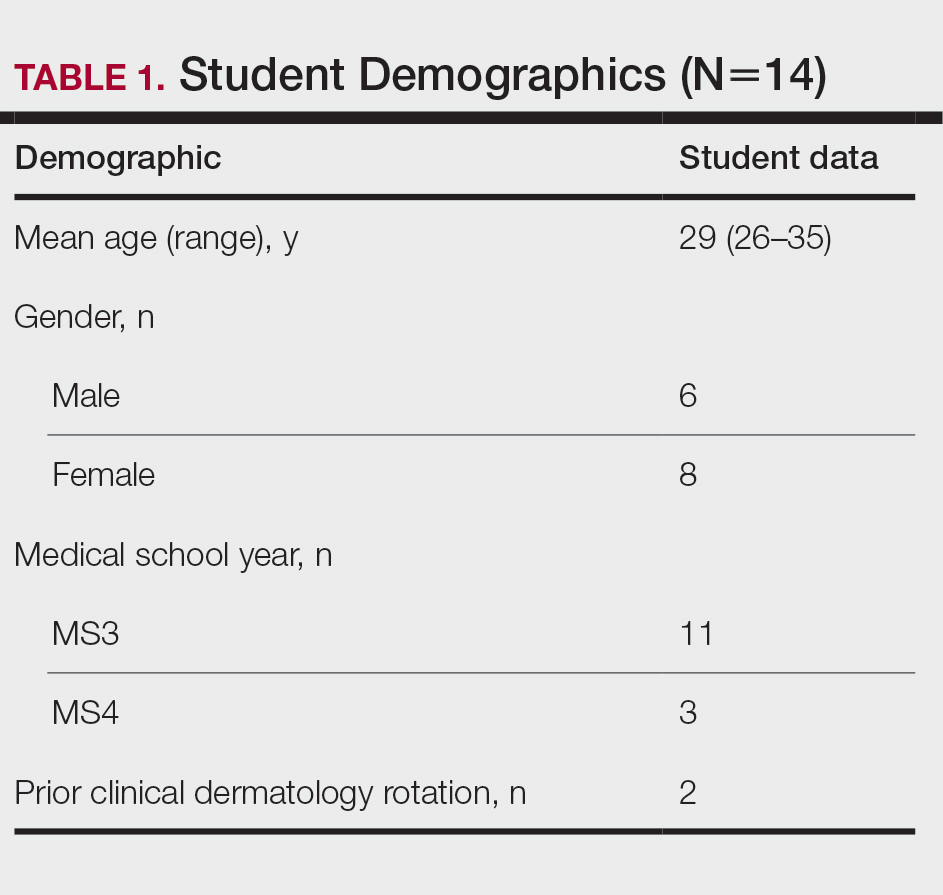

We used PR data from fiscal year 2018 and 2019. VHA PR data are available quarterly and are self-reported by each facility to the VHA Office of Clinical Risk Management. These data are broken down by facility. The following data, when available in both fiscal years 2018 and 2019, were used for this analysis: percent and number of PR that are ranked as level 1, 2, or 3; medical center group (MCG) acuity measure assigned by the VHA (1 is highest, 3 is lowest); and number of PR per 100,000 unique veteran encounters in 2019. Measures of facility quality are drawn from Strategic Analytics for Improvement and Learning (SAIL) data from 2019, which are available quarterly by facility and are rolling for 12 months. SAIL measures processes and outcomes of care. Table 1 indicates which measures are focused on outcomes vs quality processes.

SAS Version 9.2 was used to perform statistical analyses. We used Spearman correlation to estimate the PR and quality relationship.

Results

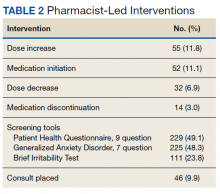

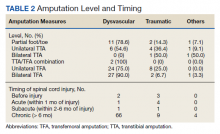

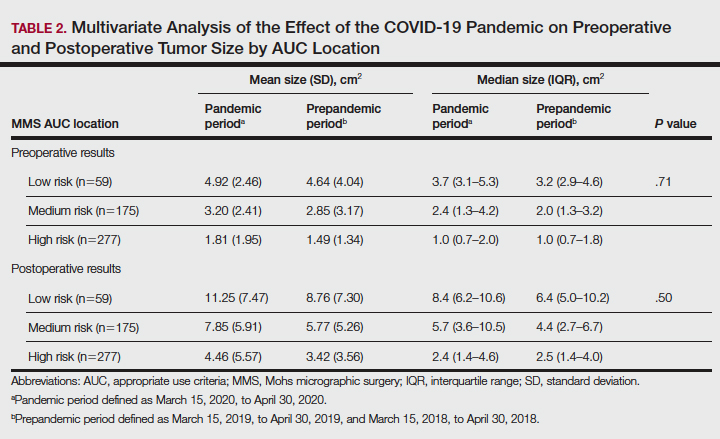

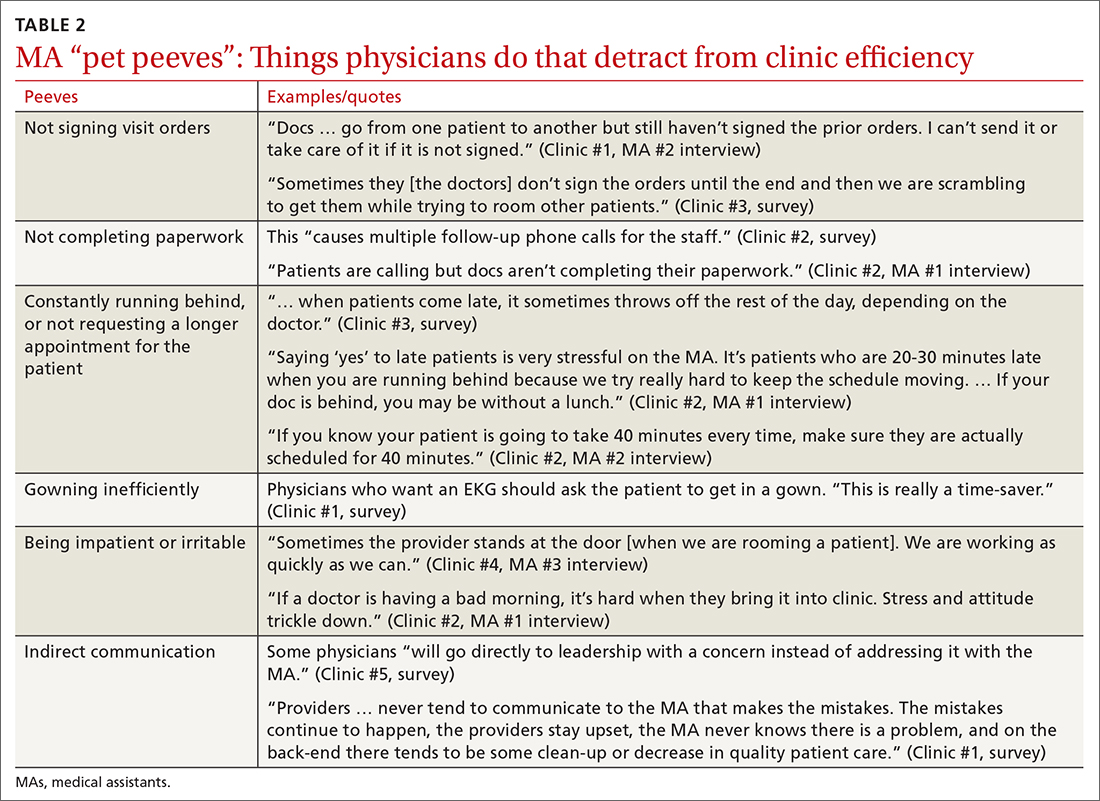

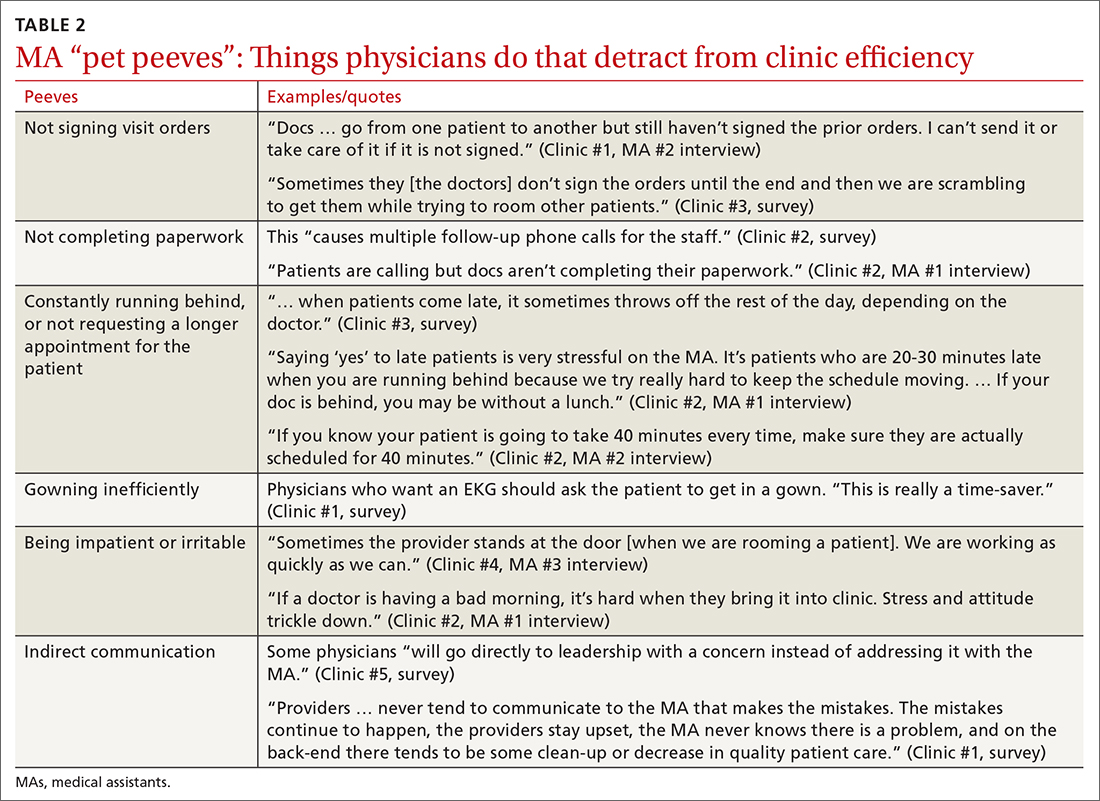

There were 136 facilities with 2 years of PR data available. The majority of these facilities (89) were highest complexity MCG 1 facilities; 19 were MCG 2, and 28 were MCG 3. Of 13,515 PRs, most of the 9555 PR findings were level 1 (70.7%). The between-facility range of level 2 and 3 findings was large, varying from 3.5% to nearly 70% in 2019 (Table 2). Findings were similar in 2018; facilities level 2 and 3 ratings ranged from 3.6% to 73.5% of all PR findings.

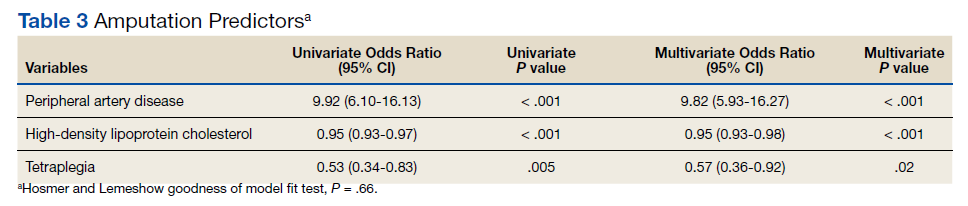

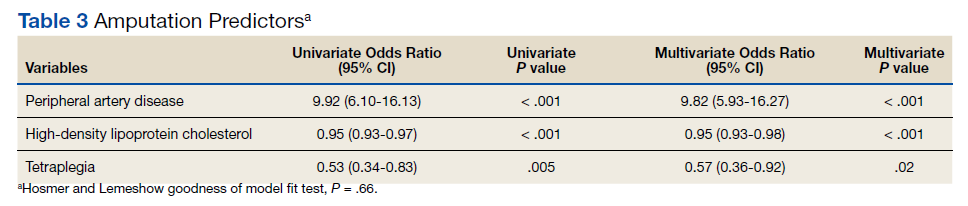

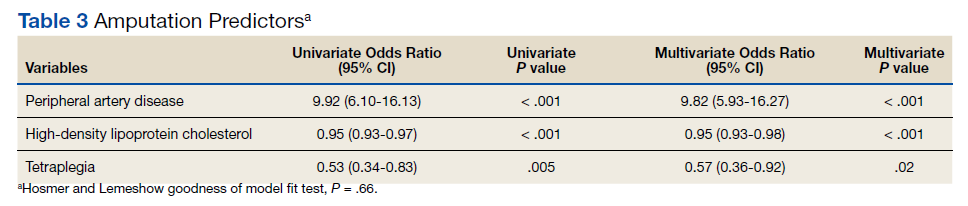

There was no correlation between most quality measures and facility PR findings (Table 3). The only exception was for Global Measures (GM90), an inpatient process of care measure. Unexpectedly, the correlation was positive—facilities with a higher percentage of level 2 and 3 PR findings had better inpatient processes of care SAIL score. The strongest correlation was between 2018 and 2019 PR findings.

Discussion

We hypothesized that a high percentage of level 2 and 3 PR findings would be negatively associated with objective facility measures of care processes in SAIL but we did not see this association. The only quality measure associated with PR findings was GM90, a score of inpatient care processes. However, the association was positive, with better performance associated with more level 2 and 3 PR findings.

The best predictor of the proportion of a facility’s PR findings is the previous year’s PR findings. With an R = 0.59, the previous year findings explain about 35% of the variability in level assignment. Our analysis may describe a new bias in PR, in which committees consistently assign either low or high proportions of level 2 and 3 findings. This correlation could be due to individual PR committee culture or composition, but it does not relate to objective quality measures.

Strengths

For this study we use objective measures of PR processes, the assignment of levels of care.

Limitations

Facilities self-report PR outcomes, so there could be errors in reporting. In addition, this study was cross sectional and not longitudinal and it is possible that change in quality measures over time are correlated with PR findings. Future studies using the VHA PR and SAIL data could evaluate whether changes over time, and perhaps in response to level 2 and 3 findings, would be a more sensitive indicator of the impact of the PR process on quality metrics. Future studies could incorporate the relationship between findings from the All Employee Survey, which is conducted annually, such as psychologic safety, as well as the distance the facility has gone on the high reliability organization journey, with PR findings and SAIL metrics. Finally, PR is focused on the practice of an individual clinician, while SAIL quality metrics reflect facility performance. Interventions possibly stay at the clinician level and do not drive subsequent QI processes.

What does this mean for PR? Since the early 1990s, there have been exhortations from experts to improve PR, by adopting a QI model, or for a deeper integration of PR and QI.1,2,10 Just culture tools, which include QI, are promoted as a means to improve PR.8,11,12 Other studies show PR remains problematic in terms of standardization, incorporation of best practices, redesigning systems of care, or demonstrable improvements to facility safety and care quality.1,4,6,8 Several publications have described interventions to improve PR. Deyo-Svedson discussed a program with standardized training and triggers, much like VHA.13 Itri and colleagues standardized PR in radiology to target areas of known diagnostic error, as well as use the issues assessed in PR to perform QI and education. One example of a successful QI effort involved changing the radiology reporting template to make sure areas that are prone to diagnostic error are addressed.7

Conclusions

Since 35% of PR level variance is correlated with prior year’s results, PR committees should look at increased standardization in reviews and findings. We endorse a strong focus on standardization, application of just culture tools to case reviews, and tighter linkage between process and outcome metrics measured by SAIL and PR case finding. Studies should be performed to pilot interventions to improve the linkage between PR and quality, so that greater and faster gains can be made in quality processes and, leading from this, outcomes. Additionally, future research should investigate why some facilities consistently choose higher or lower PR ratings.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. George “Web” Ross for his helpful edits.

1. Edwards MT. In pursuit of quality and safety: an 8-year study of clinical peer review best practices in US hospitals. Int J Qual Health Care. 2018;30(8):602-607. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzy069

2. Dans PE. Clinical peer Review: burnishing a tarnished icon. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(7):566-568. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-118-7-199304010-00014

3. Goldman RL. The reliability of peer assessments of quality of care. JAMA. 1992;267(7):958-960. doi:10.1001/jama.1992.03480070074034

4. Swaroop R. Disrupting physician clinical practice peer review. Perm J. 2019;23:18-207. doi:10.7812/TPP/18-207

5. Caplan RA, Posner KL, Cheney FW. Effect of outcome on physician judgments of appropriateness of care. JAMA. 1991;265(15):1957–1960. doi:10.1001/jama.1991.03460150061024

6. Vyas D, Hozain AE. Clinical peer review in the United States: history, legal development and subsequent abuse. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(21):6357-6363. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i21.6357

7. Itri JN, Donithan A, Patel SH. Random versus nonrandom peer review: a case for more meaningful peer review. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;15(7):1045-1052. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2018.03.054

8. Edwards MT. An assessment of the impact of just culture on quality and safety in US hospitals. Am J Med Qual. 2018; 33(5):502-508. doi:10.1177/1062860618768057

9. Edwards MT. The objective impact of clinical peer review on hospital quality and safety. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26(2);110-119. doi:10.1177/1062860610380732

10. Berwick DM. Peer review and quality management: are they compatible?. QRB Qual Rev Bull. 1990;16(7):246-251. doi:10.1016/s0097-5990(16)30377-3

11. Volkar JK, Phrampus P, English D, et al. Institution of just culture physician peer review in an academic medical center. J Patient Saf. 2021;17(7):e689-e693. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000449

12. Burns J, Miller T, Weiss JM, Erdfarb A, Silber D, Goldberg-Stein S. Just culture: practical implementation for radiologist peer review. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16(3):384-388. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2018.10.021

13. Deyo-Svendsen ME, Phillips MR, Albright JK, et al. A systematic approach to clinical peer review in a critical access hospital. Qual Manag Health Care. 2016;25(4):213-218. doi:10.1097/QMH.0000000000000113

Hospital leaders report the most common aim of peer review (PR) is to improve quality and patient safety, thus it is a potentially powerful quality improvement (QI) driver.1 “When conducted systematically and credibly, peer review for quality management can result in both short-term and long-term improvements in patient care by revealing areas for improvement in the provision of care,” Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Directive 1190 states. “This ultimately contributes to organizational improvements.” At the same time, there are anecdotal concerns that PR may be used punitively and driven by case outcomes rather than by accepted best practices supporting QI.

Studies of the PR process suggest these concerns are valid. A key tenet of QI is standardization. PR is problematic in that regard; studies show poor interrater reliability for judgments on care, as well as hindsight bias—the fact that raters are strongly influenced by the outcome of care, not the process of care.2-5 There are concerns that case selection or review process when not standardized may be wielded as punitive too.6 In this study, we sought to identify the relationship between PR findings and subsequent institution quality metrics. If PR does lead to an improvement in quality, or if quality concerns are managed within the PR committee, it should be possible to identify a measurable relationship between the PR process and a facility’s subsequent quality measures.

A handful of studies describe the association between PR and quality of care. Itri and colleagues noted that random, not standardized PR in radiology does not achieve reductions in diagnostic error rate.7 However, adoption of just culture principles in PR resulted in a significant improvement in facility leaders’ self-reports of quality measures at surveyed institutions.8 The same author reported that increases in PR standardization and integration with performance improvement activities could explain up to 18% of objective quality measure variation.9

We sought to determine whether a specific aspect of the PR process, the PR committee judgment of quality of care by clinicians, was related to medical center quality in a cross-sectional study of 136 Veterans Health Administration (VHA) medical centers. The VHA is a good source of study because there are standardized PR processes and training for committee members and reviewers. Our hypothesis was that medical centers with a higher number of Level 2 (“most experienced and competent clinicians might have managed the case differently”) and Level 3 (“most experienced and competent providers would have managed the case differently”) PR findings would also have lower quality metric scores for processes and outcomes of care.

Methods

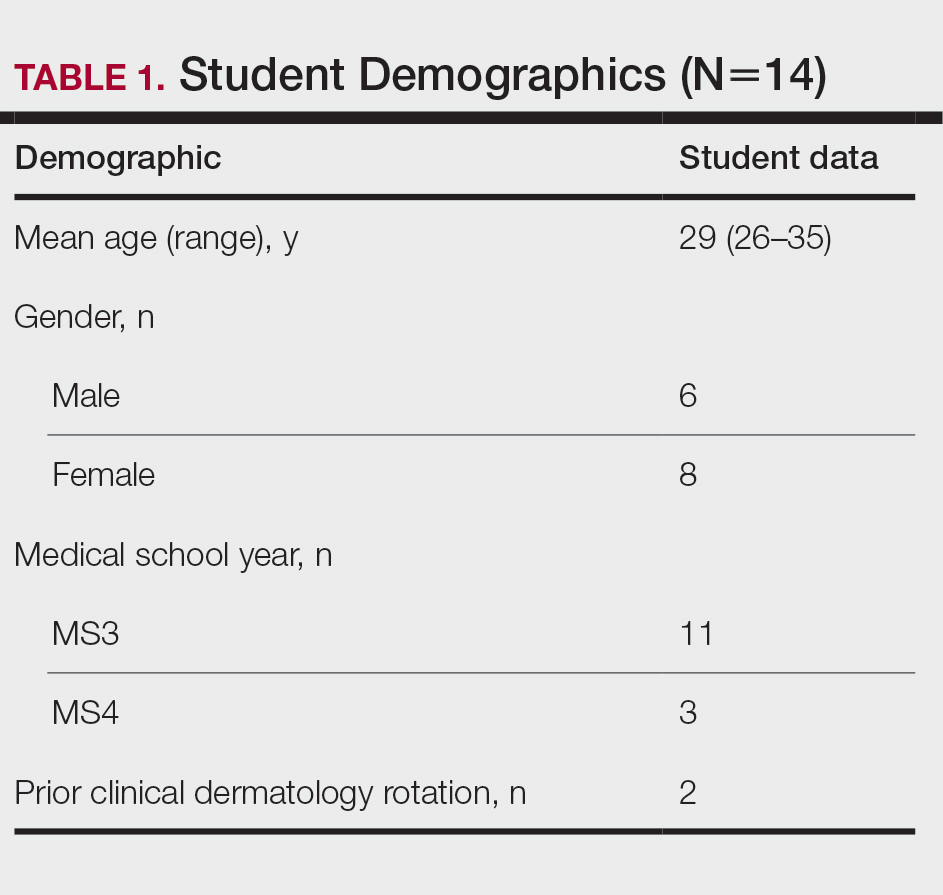

We used PR data from fiscal year 2018 and 2019. VHA PR data are available quarterly and are self-reported by each facility to the VHA Office of Clinical Risk Management. These data are broken down by facility. The following data, when available in both fiscal years 2018 and 2019, were used for this analysis: percent and number of PR that are ranked as level 1, 2, or 3; medical center group (MCG) acuity measure assigned by the VHA (1 is highest, 3 is lowest); and number of PR per 100,000 unique veteran encounters in 2019. Measures of facility quality are drawn from Strategic Analytics for Improvement and Learning (SAIL) data from 2019, which are available quarterly by facility and are rolling for 12 months. SAIL measures processes and outcomes of care. Table 1 indicates which measures are focused on outcomes vs quality processes.

SAS Version 9.2 was used to perform statistical analyses. We used Spearman correlation to estimate the PR and quality relationship.

Results

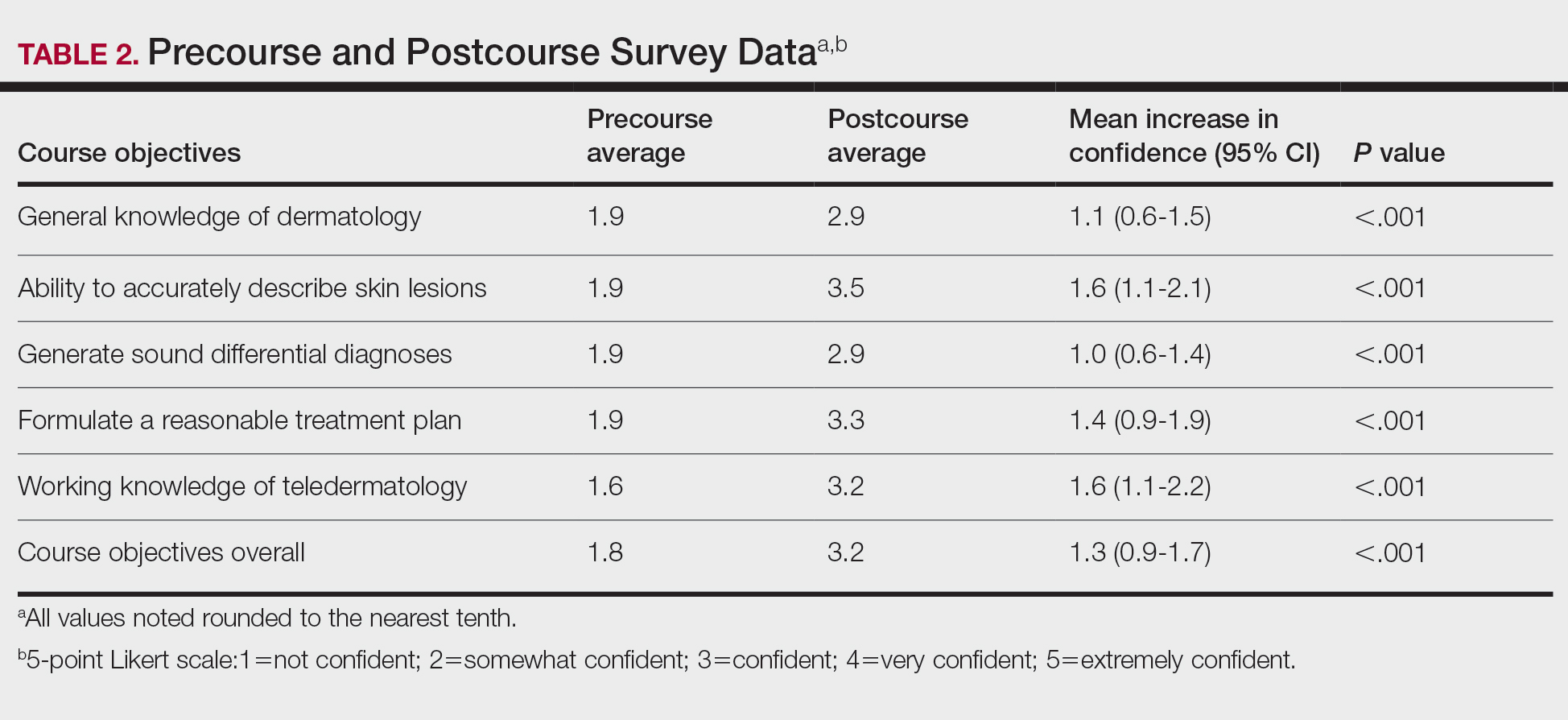

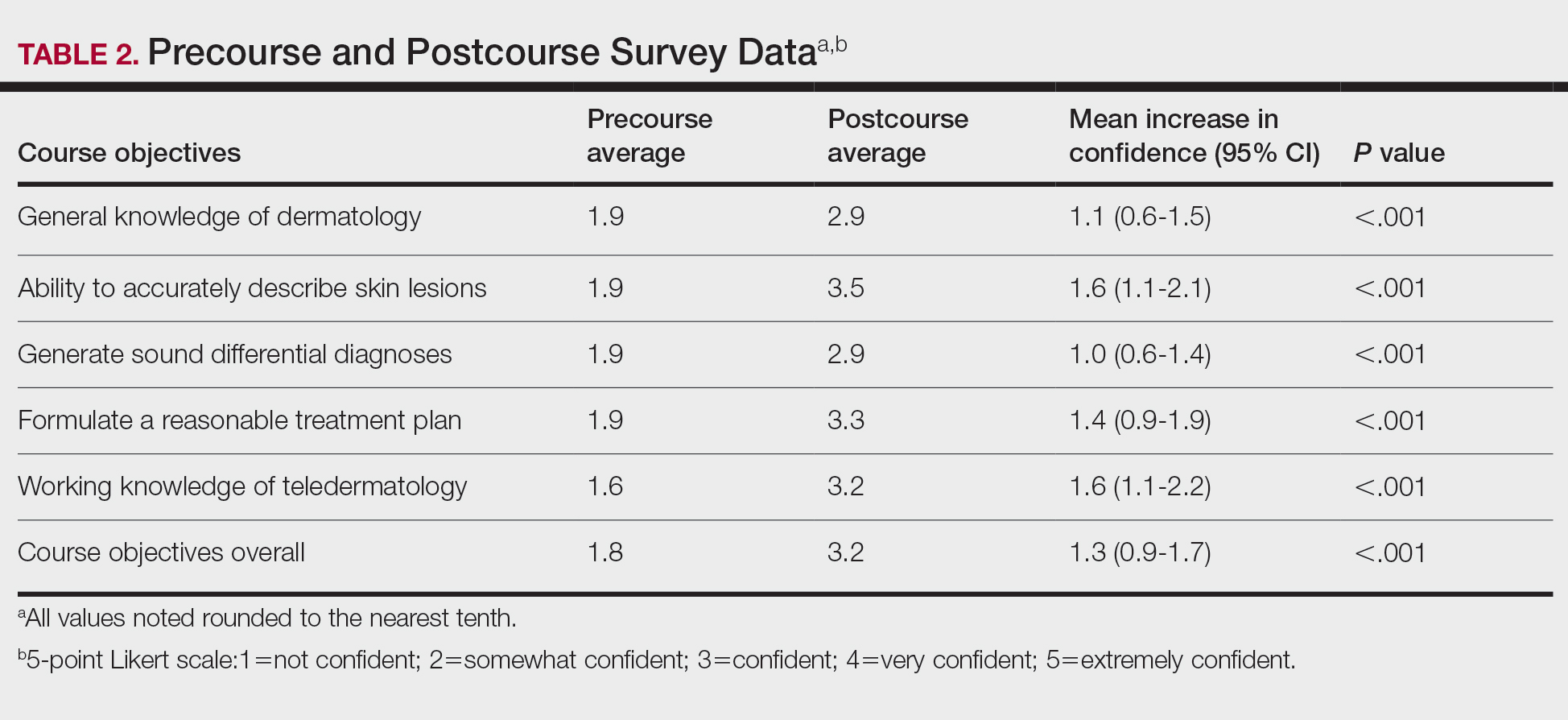

There were 136 facilities with 2 years of PR data available. The majority of these facilities (89) were highest complexity MCG 1 facilities; 19 were MCG 2, and 28 were MCG 3. Of 13,515 PRs, most of the 9555 PR findings were level 1 (70.7%). The between-facility range of level 2 and 3 findings was large, varying from 3.5% to nearly 70% in 2019 (Table 2). Findings were similar in 2018; facilities level 2 and 3 ratings ranged from 3.6% to 73.5% of all PR findings.

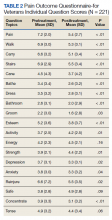

There was no correlation between most quality measures and facility PR findings (Table 3). The only exception was for Global Measures (GM90), an inpatient process of care measure. Unexpectedly, the correlation was positive—facilities with a higher percentage of level 2 and 3 PR findings had better inpatient processes of care SAIL score. The strongest correlation was between 2018 and 2019 PR findings.

Discussion

We hypothesized that a high percentage of level 2 and 3 PR findings would be negatively associated with objective facility measures of care processes in SAIL but we did not see this association. The only quality measure associated with PR findings was GM90, a score of inpatient care processes. However, the association was positive, with better performance associated with more level 2 and 3 PR findings.

The best predictor of the proportion of a facility’s PR findings is the previous year’s PR findings. With an R = 0.59, the previous year findings explain about 35% of the variability in level assignment. Our analysis may describe a new bias in PR, in which committees consistently assign either low or high proportions of level 2 and 3 findings. This correlation could be due to individual PR committee culture or composition, but it does not relate to objective quality measures.

Strengths

For this study we use objective measures of PR processes, the assignment of levels of care.

Limitations

Facilities self-report PR outcomes, so there could be errors in reporting. In addition, this study was cross sectional and not longitudinal and it is possible that change in quality measures over time are correlated with PR findings. Future studies using the VHA PR and SAIL data could evaluate whether changes over time, and perhaps in response to level 2 and 3 findings, would be a more sensitive indicator of the impact of the PR process on quality metrics. Future studies could incorporate the relationship between findings from the All Employee Survey, which is conducted annually, such as psychologic safety, as well as the distance the facility has gone on the high reliability organization journey, with PR findings and SAIL metrics. Finally, PR is focused on the practice of an individual clinician, while SAIL quality metrics reflect facility performance. Interventions possibly stay at the clinician level and do not drive subsequent QI processes.

What does this mean for PR? Since the early 1990s, there have been exhortations from experts to improve PR, by adopting a QI model, or for a deeper integration of PR and QI.1,2,10 Just culture tools, which include QI, are promoted as a means to improve PR.8,11,12 Other studies show PR remains problematic in terms of standardization, incorporation of best practices, redesigning systems of care, or demonstrable improvements to facility safety and care quality.1,4,6,8 Several publications have described interventions to improve PR. Deyo-Svedson discussed a program with standardized training and triggers, much like VHA.13 Itri and colleagues standardized PR in radiology to target areas of known diagnostic error, as well as use the issues assessed in PR to perform QI and education. One example of a successful QI effort involved changing the radiology reporting template to make sure areas that are prone to diagnostic error are addressed.7

Conclusions

Since 35% of PR level variance is correlated with prior year’s results, PR committees should look at increased standardization in reviews and findings. We endorse a strong focus on standardization, application of just culture tools to case reviews, and tighter linkage between process and outcome metrics measured by SAIL and PR case finding. Studies should be performed to pilot interventions to improve the linkage between PR and quality, so that greater and faster gains can be made in quality processes and, leading from this, outcomes. Additionally, future research should investigate why some facilities consistently choose higher or lower PR ratings.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. George “Web” Ross for his helpful edits.

Hospital leaders report the most common aim of peer review (PR) is to improve quality and patient safety, thus it is a potentially powerful quality improvement (QI) driver.1 “When conducted systematically and credibly, peer review for quality management can result in both short-term and long-term improvements in patient care by revealing areas for improvement in the provision of care,” Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Directive 1190 states. “This ultimately contributes to organizational improvements.” At the same time, there are anecdotal concerns that PR may be used punitively and driven by case outcomes rather than by accepted best practices supporting QI.

Studies of the PR process suggest these concerns are valid. A key tenet of QI is standardization. PR is problematic in that regard; studies show poor interrater reliability for judgments on care, as well as hindsight bias—the fact that raters are strongly influenced by the outcome of care, not the process of care.2-5 There are concerns that case selection or review process when not standardized may be wielded as punitive too.6 In this study, we sought to identify the relationship between PR findings and subsequent institution quality metrics. If PR does lead to an improvement in quality, or if quality concerns are managed within the PR committee, it should be possible to identify a measurable relationship between the PR process and a facility’s subsequent quality measures.

A handful of studies describe the association between PR and quality of care. Itri and colleagues noted that random, not standardized PR in radiology does not achieve reductions in diagnostic error rate.7 However, adoption of just culture principles in PR resulted in a significant improvement in facility leaders’ self-reports of quality measures at surveyed institutions.8 The same author reported that increases in PR standardization and integration with performance improvement activities could explain up to 18% of objective quality measure variation.9

We sought to determine whether a specific aspect of the PR process, the PR committee judgment of quality of care by clinicians, was related to medical center quality in a cross-sectional study of 136 Veterans Health Administration (VHA) medical centers. The VHA is a good source of study because there are standardized PR processes and training for committee members and reviewers. Our hypothesis was that medical centers with a higher number of Level 2 (“most experienced and competent clinicians might have managed the case differently”) and Level 3 (“most experienced and competent providers would have managed the case differently”) PR findings would also have lower quality metric scores for processes and outcomes of care.

Methods

We used PR data from fiscal year 2018 and 2019. VHA PR data are available quarterly and are self-reported by each facility to the VHA Office of Clinical Risk Management. These data are broken down by facility. The following data, when available in both fiscal years 2018 and 2019, were used for this analysis: percent and number of PR that are ranked as level 1, 2, or 3; medical center group (MCG) acuity measure assigned by the VHA (1 is highest, 3 is lowest); and number of PR per 100,000 unique veteran encounters in 2019. Measures of facility quality are drawn from Strategic Analytics for Improvement and Learning (SAIL) data from 2019, which are available quarterly by facility and are rolling for 12 months. SAIL measures processes and outcomes of care. Table 1 indicates which measures are focused on outcomes vs quality processes.

SAS Version 9.2 was used to perform statistical analyses. We used Spearman correlation to estimate the PR and quality relationship.

Results

There were 136 facilities with 2 years of PR data available. The majority of these facilities (89) were highest complexity MCG 1 facilities; 19 were MCG 2, and 28 were MCG 3. Of 13,515 PRs, most of the 9555 PR findings were level 1 (70.7%). The between-facility range of level 2 and 3 findings was large, varying from 3.5% to nearly 70% in 2019 (Table 2). Findings were similar in 2018; facilities level 2 and 3 ratings ranged from 3.6% to 73.5% of all PR findings.

There was no correlation between most quality measures and facility PR findings (Table 3). The only exception was for Global Measures (GM90), an inpatient process of care measure. Unexpectedly, the correlation was positive—facilities with a higher percentage of level 2 and 3 PR findings had better inpatient processes of care SAIL score. The strongest correlation was between 2018 and 2019 PR findings.

Discussion

We hypothesized that a high percentage of level 2 and 3 PR findings would be negatively associated with objective facility measures of care processes in SAIL but we did not see this association. The only quality measure associated with PR findings was GM90, a score of inpatient care processes. However, the association was positive, with better performance associated with more level 2 and 3 PR findings.

The best predictor of the proportion of a facility’s PR findings is the previous year’s PR findings. With an R = 0.59, the previous year findings explain about 35% of the variability in level assignment. Our analysis may describe a new bias in PR, in which committees consistently assign either low or high proportions of level 2 and 3 findings. This correlation could be due to individual PR committee culture or composition, but it does not relate to objective quality measures.

Strengths

For this study we use objective measures of PR processes, the assignment of levels of care.

Limitations

Facilities self-report PR outcomes, so there could be errors in reporting. In addition, this study was cross sectional and not longitudinal and it is possible that change in quality measures over time are correlated with PR findings. Future studies using the VHA PR and SAIL data could evaluate whether changes over time, and perhaps in response to level 2 and 3 findings, would be a more sensitive indicator of the impact of the PR process on quality metrics. Future studies could incorporate the relationship between findings from the All Employee Survey, which is conducted annually, such as psychologic safety, as well as the distance the facility has gone on the high reliability organization journey, with PR findings and SAIL metrics. Finally, PR is focused on the practice of an individual clinician, while SAIL quality metrics reflect facility performance. Interventions possibly stay at the clinician level and do not drive subsequent QI processes.

What does this mean for PR? Since the early 1990s, there have been exhortations from experts to improve PR, by adopting a QI model, or for a deeper integration of PR and QI.1,2,10 Just culture tools, which include QI, are promoted as a means to improve PR.8,11,12 Other studies show PR remains problematic in terms of standardization, incorporation of best practices, redesigning systems of care, or demonstrable improvements to facility safety and care quality.1,4,6,8 Several publications have described interventions to improve PR. Deyo-Svedson discussed a program with standardized training and triggers, much like VHA.13 Itri and colleagues standardized PR in radiology to target areas of known diagnostic error, as well as use the issues assessed in PR to perform QI and education. One example of a successful QI effort involved changing the radiology reporting template to make sure areas that are prone to diagnostic error are addressed.7

Conclusions

Since 35% of PR level variance is correlated with prior year’s results, PR committees should look at increased standardization in reviews and findings. We endorse a strong focus on standardization, application of just culture tools to case reviews, and tighter linkage between process and outcome metrics measured by SAIL and PR case finding. Studies should be performed to pilot interventions to improve the linkage between PR and quality, so that greater and faster gains can be made in quality processes and, leading from this, outcomes. Additionally, future research should investigate why some facilities consistently choose higher or lower PR ratings.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. George “Web” Ross for his helpful edits.

1. Edwards MT. In pursuit of quality and safety: an 8-year study of clinical peer review best practices in US hospitals. Int J Qual Health Care. 2018;30(8):602-607. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzy069

2. Dans PE. Clinical peer Review: burnishing a tarnished icon. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(7):566-568. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-118-7-199304010-00014

3. Goldman RL. The reliability of peer assessments of quality of care. JAMA. 1992;267(7):958-960. doi:10.1001/jama.1992.03480070074034

4. Swaroop R. Disrupting physician clinical practice peer review. Perm J. 2019;23:18-207. doi:10.7812/TPP/18-207

5. Caplan RA, Posner KL, Cheney FW. Effect of outcome on physician judgments of appropriateness of care. JAMA. 1991;265(15):1957–1960. doi:10.1001/jama.1991.03460150061024

6. Vyas D, Hozain AE. Clinical peer review in the United States: history, legal development and subsequent abuse. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(21):6357-6363. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i21.6357

7. Itri JN, Donithan A, Patel SH. Random versus nonrandom peer review: a case for more meaningful peer review. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;15(7):1045-1052. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2018.03.054

8. Edwards MT. An assessment of the impact of just culture on quality and safety in US hospitals. Am J Med Qual. 2018; 33(5):502-508. doi:10.1177/1062860618768057

9. Edwards MT. The objective impact of clinical peer review on hospital quality and safety. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26(2);110-119. doi:10.1177/1062860610380732

10. Berwick DM. Peer review and quality management: are they compatible?. QRB Qual Rev Bull. 1990;16(7):246-251. doi:10.1016/s0097-5990(16)30377-3

11. Volkar JK, Phrampus P, English D, et al. Institution of just culture physician peer review in an academic medical center. J Patient Saf. 2021;17(7):e689-e693. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000449

12. Burns J, Miller T, Weiss JM, Erdfarb A, Silber D, Goldberg-Stein S. Just culture: practical implementation for radiologist peer review. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16(3):384-388. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2018.10.021

13. Deyo-Svendsen ME, Phillips MR, Albright JK, et al. A systematic approach to clinical peer review in a critical access hospital. Qual Manag Health Care. 2016;25(4):213-218. doi:10.1097/QMH.0000000000000113

1. Edwards MT. In pursuit of quality and safety: an 8-year study of clinical peer review best practices in US hospitals. Int J Qual Health Care. 2018;30(8):602-607. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzy069

2. Dans PE. Clinical peer Review: burnishing a tarnished icon. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(7):566-568. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-118-7-199304010-00014

3. Goldman RL. The reliability of peer assessments of quality of care. JAMA. 1992;267(7):958-960. doi:10.1001/jama.1992.03480070074034

4. Swaroop R. Disrupting physician clinical practice peer review. Perm J. 2019;23:18-207. doi:10.7812/TPP/18-207

5. Caplan RA, Posner KL, Cheney FW. Effect of outcome on physician judgments of appropriateness of care. JAMA. 1991;265(15):1957–1960. doi:10.1001/jama.1991.03460150061024

6. Vyas D, Hozain AE. Clinical peer review in the United States: history, legal development and subsequent abuse. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(21):6357-6363. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i21.6357

7. Itri JN, Donithan A, Patel SH. Random versus nonrandom peer review: a case for more meaningful peer review. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;15(7):1045-1052. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2018.03.054

8. Edwards MT. An assessment of the impact of just culture on quality and safety in US hospitals. Am J Med Qual. 2018; 33(5):502-508. doi:10.1177/1062860618768057

9. Edwards MT. The objective impact of clinical peer review on hospital quality and safety. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26(2);110-119. doi:10.1177/1062860610380732

10. Berwick DM. Peer review and quality management: are they compatible?. QRB Qual Rev Bull. 1990;16(7):246-251. doi:10.1016/s0097-5990(16)30377-3

11. Volkar JK, Phrampus P, English D, et al. Institution of just culture physician peer review in an academic medical center. J Patient Saf. 2021;17(7):e689-e693. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000449

12. Burns J, Miller T, Weiss JM, Erdfarb A, Silber D, Goldberg-Stein S. Just culture: practical implementation for radiologist peer review. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16(3):384-388. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2018.10.021

13. Deyo-Svendsen ME, Phillips MR, Albright JK, et al. A systematic approach to clinical peer review in a critical access hospital. Qual Manag Health Care. 2016;25(4):213-218. doi:10.1097/QMH.0000000000000113

BRAF V600E Expression in Primary Melanoma and Its Association With Death: A Population-Based, Retrospective, Cross-Sectional Study

Approximately 50% of melanomas contain BRAF mutations, which occur in a greater proportion of melanomas found on sites of intermittent sun exposure.1BRAF-mutated melanomas have been associated with high levels of early-life ambient UV exposure, especially between ages 0 and 20 years.2 In addition, studies have shown that BRAF-mutated melanomas commonly are found on the trunk and extremities.1-3BRAF mutations also have been associated with younger age, superficial spreading subtype and low tumor thickness, absence of dermal melanocyte mitosis, low Ki-67 score, low phospho-histone H3 score, pigmented melanoma, advanced melanoma stage, and conjunctival melanoma.4-7BRAF mutations are found more frequently in metastatic melanoma lesions than primary melanomas, suggesting that BRAF mutations may be acquired during metastasis.8 Studies have shown different conclusions on the effect of BRAF mutation on melanoma-related death.5,9,10

The aim of this study was to identify trends in BRAF V600E–mutated melanoma according to age, sex, and melanoma-specific survival among Olmsted County, Minnesota, residents with a first diagnosis of melanoma at 18 to 60 years of age.

Methods

In total, 638 patients aged 18 to 60 years who resided in Olmsted County and had a first lifetime diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma between 1970 and 2009 were retrospectively identified as a part of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP). The REP is a health records linkage system that encompasses almost all sources of medical care available to the local population of Olmsted County.11 This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (Rochester, Minnesota).

Of the 638 individuals identified in the REP, 536 had been seen at Mayo Clinic and thus potentially had tissue blocks available for the study of BRAF mutation expression. Of these 536 patients, 156 did not have sufficient residual tissue available. As a result, 380 (60%) of the original 638 patients had available blocks with sufficient tissue for immunohistochemical analysis of BRAF expression. Only primary cutaneous melanomas were included in the present study.

All specimens were reviewed by a board-certified dermatopathologist (J.S.L.) for appropriateness of inclusion, which involved confirmation of the diagnosis of melanoma, histologic type of melanoma, and presence of sufficient residual tissue for immunohistochemical stains.

All specimens were originally diagnosed as malignant melanoma at the time of clinical care by at least 2 board-certified dermatopathologists. For the purposes of this study, all specimens were rereviewed for diagnostic accuracy. We required that specimens exhibit severe cytologic and architectural atypia as well as other features favoring melanoma, such as consumption of rete pegs, pagetosis, confluence of junctional melanocytes, evidence of regression, lack of maturation of melanocytes with descent into the dermis, or mitotic figures among the dermal melanocyte population.

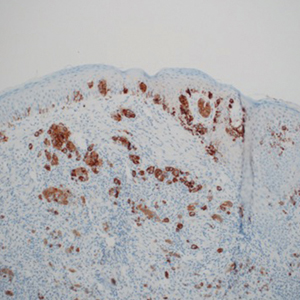

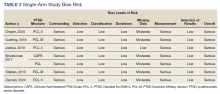

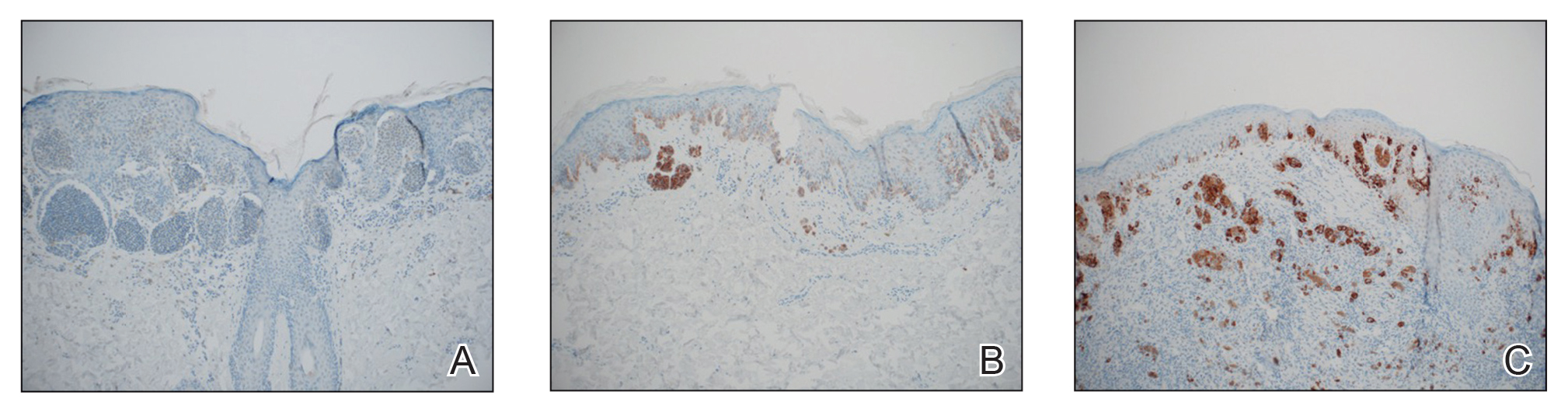

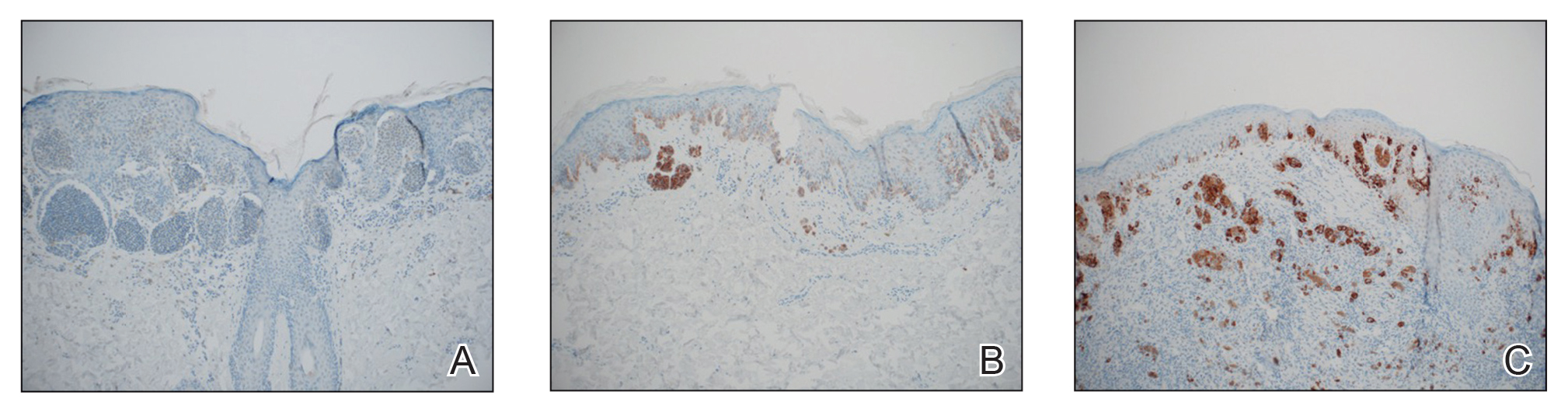

The available tissue blocks were retrieved, sectioned, confirmed as melanoma, and stained with a mouse antihuman BRAF V600E monoclonal antibody (clone VE1; Spring Bioscience) to determine the presence of a BRAF V600E mutation. BRAF staining was evaluated in conjunction with a review of the associated slides stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Cytoplasmic staining of melanocytes for BRAF was graded as negative, focal or partial positive (<50% of tumor), or diffuse positive (>50% of tumor)(Figure 1). When a melanoma arose in association with a nevus, we considered only the melanoma component for BRAF staining. We categorized the histologic type as superficial spreading, nodular, or lentigo maligna, and the location as head and neck, trunk, or extremities.

Patient characteristics and survival outcomes were gathered through the health record and included age, Breslow thickness, location, decade of diagnosis, histologic type, stage (ie, noninvasive, invasive, or advanced), and follow-up. Pathologic stage 0 was considered noninvasive; stages IA and IB, invasive; and stages IIA or higher, advanced.

Statistical Analysis—Comparisons between the group of patients in the study (n=380) and the group of patients excluded for the reasons stated above (n=258) as well as associations of mutant BRAF status (positive [partial positive and diffuse positive] vs negative) with patient age (young adults [age range, 18–39 years] and middle-aged adults [age range, 40–60 years]), sex, decade of diagnosis, location, histologic type, and stage were evaluated with Wilcoxon rank sum, χ2, Fisher exact, or Cochran-Armitage trend tests. Disease-specific survival and overall survival rates were estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method, and the duration of follow-up was calculated from the date of melanoma diagnosis to the date of death or the last follow-up. Associations of mutant BRAF expression status with death from melanoma and death from any cause were evaluated with Cox proportional hazard regression models and summarized with hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI. Survival analyses were limited to patients with invasive or advanced disease. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS statistical software (SAS version 9.4). All tests were 2-sided, and P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical and Tumor Characteristics—Of the 380 tissue specimens that underwent BRAF V600E analysis, 247 had negative staining; 106 had diffuse strong staining; and 27 had focal or partial staining. In total, 133 (35%) were positive, either partially or diffusely. The median age for patients who had negative staining was 45 years; for those with positive staining, it was 41 years (P=.07).

The patients who met inclusion criteria (n=380) were compared with those who were excluded (n=258)(eTable 1). The groups were similar on the basis of sex; age; and melanoma location, stage, and histologic subtype. However, some evidence showed that patients included in the study received the diagnosis of melanoma more recently (1970-1989, 13.2%; 1990-1999, 28.7%; 2000-2009, 58.2%) than those who were excluded (1970-1989, 24.7%; 1990-1999, 23.5%; 2000-2009, 51.8%)(P=.02).

BRAF V600E expression was more commonly found in superficial spreading (37.7%) and nodular melanomas (35.0%) than in situ melanomas (17.1%)(P=.01). Other characteristics of BRAF V600E expression are described in eTable 2. Overall, invasive and advanced melanomas were significantly more likely to harbor BRAF V600E expression than noninvasive melanomas (39.6% and 37.9%, respectively, vs 17.9%; P=.003). However, advanced melanomas more commonly expressed BRAF positivity among women, and invasive melanomas more commonly expressed BRAF positivity among men (eTable 2).

Survival—Survival analyses were limited to 297 patients with confirmed invasive or advanced disease. Of these, 180 (61%) had no BRAF V600E staining; 25 (8%) had partial staining; and 92 (31%) had diffuse positive staining. In total, 117 patients (39%) had a BRAF-mutated melanoma.

Among the patients still alive, the median (interquartile range [IQR]) duration of follow-up was 10.2 (7.0-16.8) years. Thirty-nine patients with invasive or advanced disease had died of any cause at a median (IQR) of 3.0 (1.3-10.2) years after diagnosis. In total, 26 patients died of melanoma at a median (IQR) follow-up of 2.5 (1.3-7.4) years after diagnosis. Eight women and 18 men died of malignant melanoma. Five deaths occurred because of malignant melanoma among patients aged 18 to 39 years, and 21 occurred among patients aged 40 to 60 years. In the 18- to 39-year-old group, all 5 deaths were among patients with a BRAF-positive melanoma. Estimated disease-specific survival rate (95% CI; number still at risk) at 5, 10, 15, and 20 years after diagnosis was 94% (91%-97%; 243), 91% (87%-95%; 142), 89% (85%-94%; 87), and 88% (83%-93%; 45), respectively.

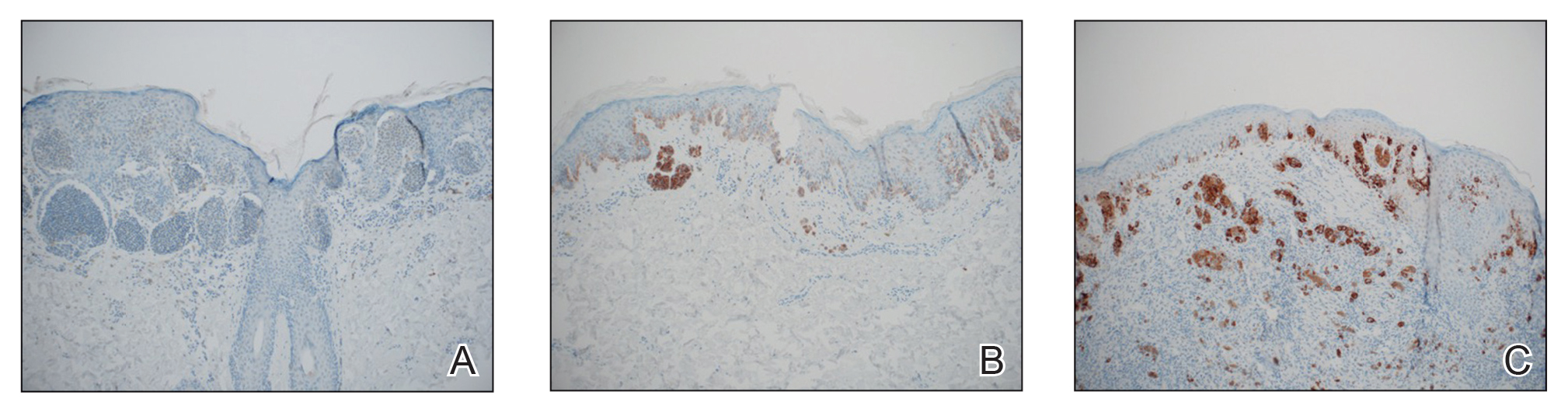

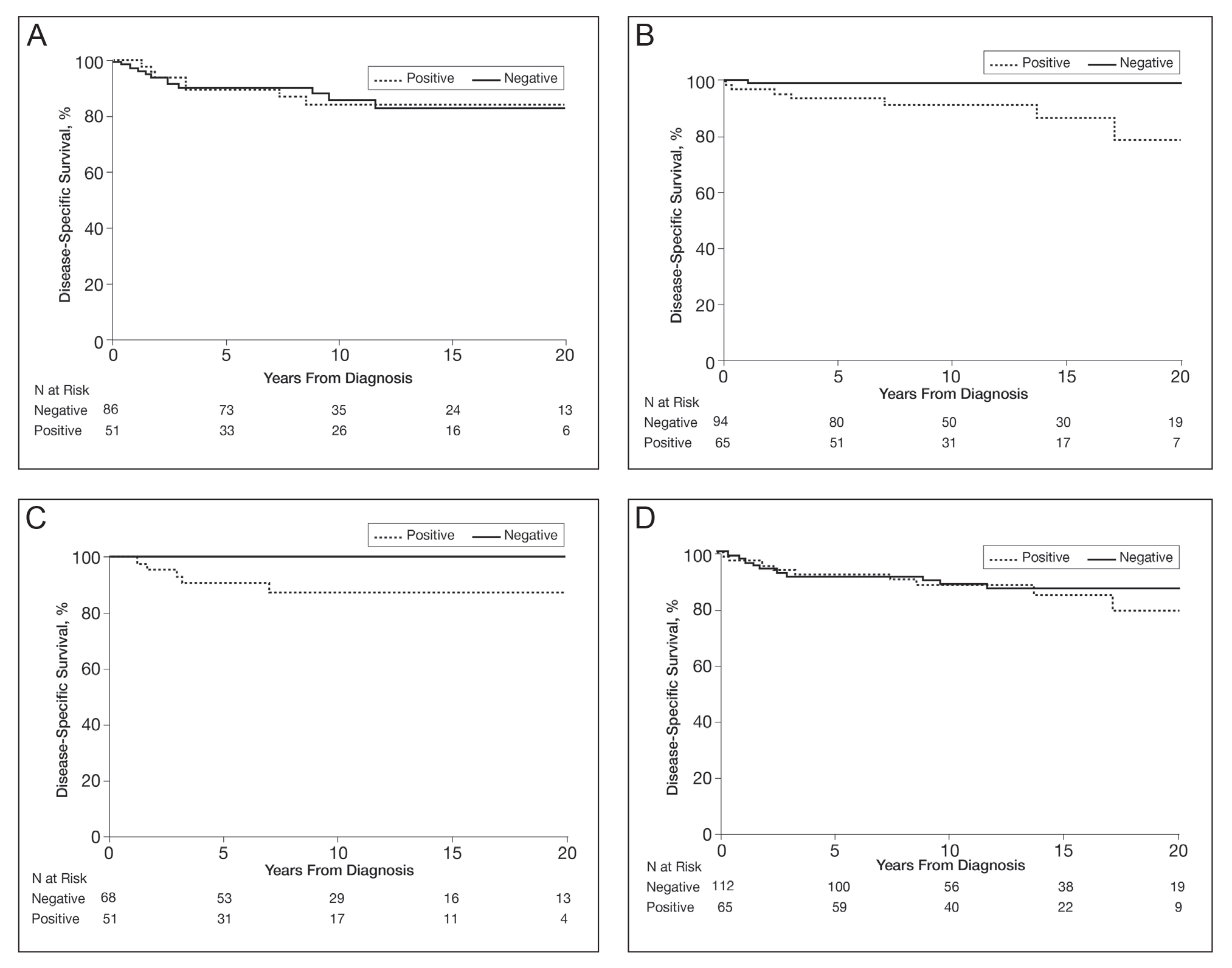

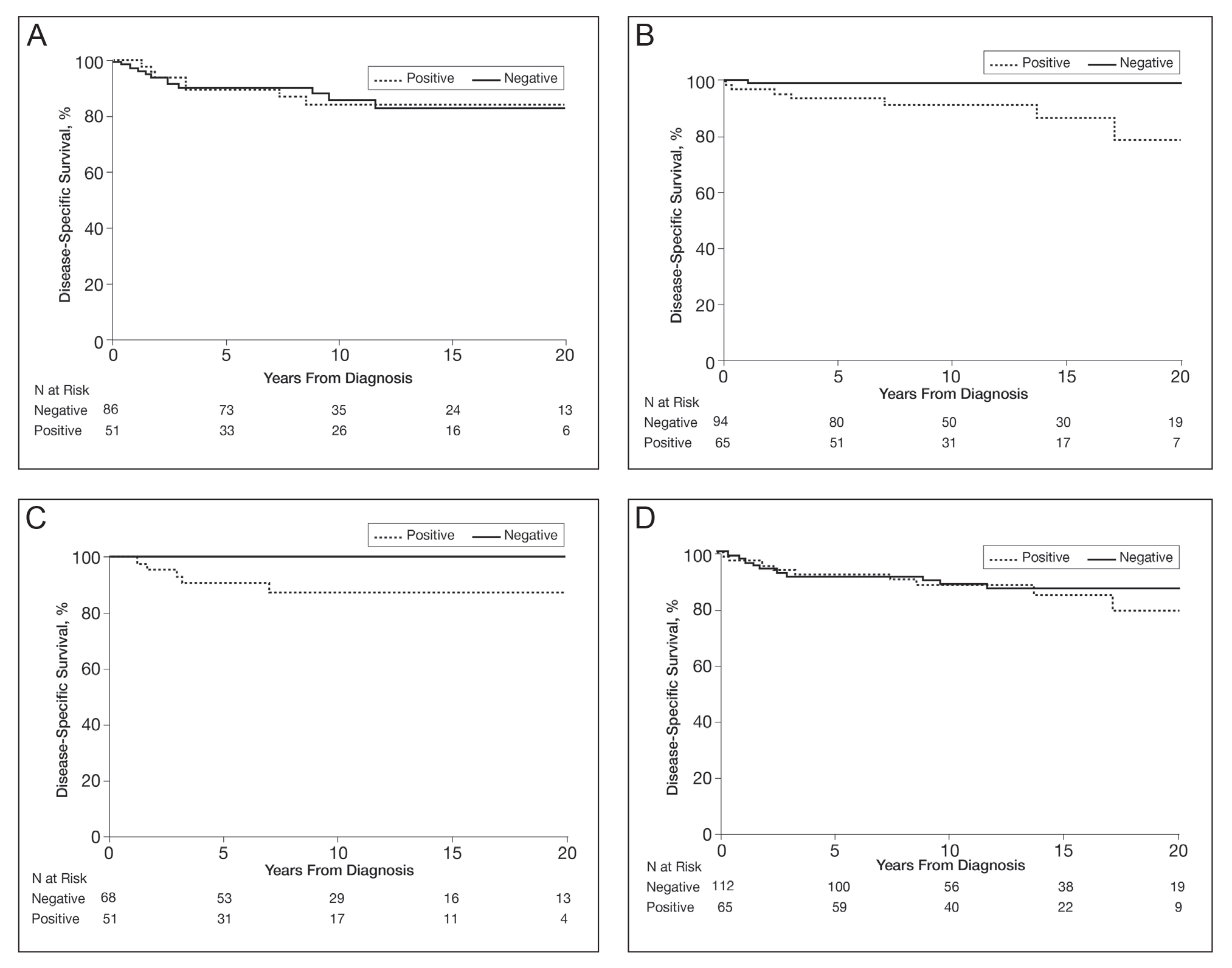

In a univariable analysis, the HR for association of positive mutant BRAF expression with death of malignant melanoma was 1.84 (95% CI, 0.85-3.98; P=.12). No statistically significant interaction was observed between decade of diagnosis and BRAF expression (P=.60). However, the interaction between sex and BRAF expression was significant (P=.04), with increased risk of death from melanoma among women with BRAF-mutated melanoma (HR, 10.88; 95% CI, 1.34-88.41; P=.026) but not among men (HR 1.02; 95% CI, 0.40-2.64; P=.97)(Figures 2A and 2B). The HR for death from malignant melanoma among young adults aged 18 to 39 years with a BRAF-mutated melanoma was 16.4 (95% CI, 0.81-330.10; P=.068), whereas the HR among adults aged 40 to 60 years with a BRAF-mutated melanoma was 1.24 (95% CI, 0.52-2.98; P=.63)(Figures 2C and 2D).

BRAF V600E expression was not significantly associated with death from any cause (HR, 1.39; 95% CI, 0.74-2.61; P=.31) or with decade of diagnosis (P=.13). Similarly, BRAF expression was not associated with death from any cause according to sex (P=.31). However, a statistically significant interaction was seen between age at diagnosis and BRAF expression (P=.003). BRAF expression was significantly associated with death from any cause for adults aged 18 to 39 years (HR, 9.60; 95% CI, 1.15-80.00; P=.04). In comparison, no association of BRAF expression with death was observed for adults aged 40 to 60 years (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.48-2.03; P=.98).

Comment

We found that melanomas with BRAF mutations were more likely in advanced and invasive melanoma. The frequency of BRAF mutations among melanomas that were considered advanced was higher in women than men. Although the number of deaths was limited, women with a melanoma with BRAF expression were more likely to die of melanoma, young adults with a BRAF-mutated melanoma had an almost 10-fold increased risk of dying from any cause, and middle-aged adults showed no increased risk of death. These findings suggest that young adults who are genetically prone to a BRAF-mutated melanoma could be at a disadvantage for all-cause mortality. Although this finding was significant, the 95% CI was large, and further studies would be warranted before sound conclusions could be made.

Melanoma has been increasing in incidence across all age groups in Olmsted County over the last 4 decades.12-14 However, our results show that the percentage of BRAF-mutated melanomas in this population has been stable over time, with no statistically significant difference by age or sex. Other confounding factors may have an influence, such as increased rates of early detection and diagnosis of melanoma in contemporary times. Our data suggest that patients included in the BRAF-mutation analysis study had received the diagnosis of melanoma more recently than those who were excluded from the study, which could be due to older melanomas being less likely to have adequate tissue specimens available for immunohistochemical staining/evaluation.

Prior research has shown that BRAF-mutated melanomas typically occur on the trunk and are more likely in individuals with more than 14 nevi on the back.2 In the present cohort, BRAF-positive melanomas had a predisposition toward the trunk but also were found on the head, neck, and extremities—areas that are more likely to have long-term sun damage. One suggestion is that 2 distinct pathways for melanoma development exist: one associated with a large number of melanocytic nevi (that is more prone to genetic mutations in melanocytes) and the other associated with long-term sun exposure.15,16 The combination of these hypotheses suggests that individuals who are prone to the development of large numbers of nevi may require sun exposure for the initial insult, but the development of melanoma may be carried out by other factors after this initial sun exposure insult, whereas individuals without large numbers of nevi who may have less genetic risk may require continued long-term sun exposure for melanoma to develop.17

Our study had limitations, including the small numbers of deaths overall and cause-specific deaths of metastatic melanoma, which limited our ability to conduct more extensive multivariable modeling. Also, the retrospective nature and time frame of looking back 4 decades did not allow us to have information sufficient to categorize some patients as having dysplastic nevus syndrome or not, which would be a potentially interesting variable to include in the analysis. Because the number of deaths in the 18- to 39-year-old cohort was only 5, further statistical comparison regarding tumor type and other variables pertaining to BRAF positivity were not possible. In addition, our data were collected from patients residing in a single geographic county (Olmsted County, Minnesota), which may limit generalizability. Lastly, BRAF V600E mutations were identified through immunostaining only, not molecular data, so it is possible some patients had false-negative immunohistochemistry findings and thus were not identified.

Conclusion

BRAF-mutated melanomas were found in 35% of our cohort, with no significant change in the percentage of melanomas with BRAF V600E mutations over the last 4 decades in this population. In addition, no differences or significant trends existed according to sex and BRAF-mutated melanoma development. Women with BRAF-mutated melanomas were more likely to die of metastatic melanoma than men, and young adults with BRAF-mutated melanomas had a higher all-cause mortality risk. Further research is needed to decipher what effect BRAF-mutated melanomas have on metastasis and cause-specific death in women as well as all-cause mortality in young adults.

Acknowledgment—The authors are indebted to Scientific Publications, Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota).

- Grimaldi AM, Cassidy PB, Leachmann S, et al. Novel approaches in melanoma prevention and therapy. Cancer Treat Res. 2014;159: 443-455.

- Thomas NE, Edmiston SN, Alexander A, et al. Number of nevi and early-life ambient UV exposure are associated with BRAF-mutant melanoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:991-997.

- Curtin JA, Fridlyand J, Kageshita T, et al. Distinct sets of genetic alterations in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2135-2147.

- Thomas NE, Edmiston SN, Alexander A, et al. Association between NRAS and BRAF mutational status and melanoma-specific survival among patients with higher-risk primary melanoma. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:359-368.

- Liu W, Kelly JW, Trivett M, et al. Distinct clinical and pathological features are associated with the BRAF(T1799A(V600E)) mutation in primary melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:900-905.

- Kim SY, Kim SN, Hahn HJ, et al. Metaanalysis of BRAF mutations and clinicopathologic characteristics in primary melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:1036-1046.e2.

- Larsen AC, Dahl C, Dahmcke CM, et al. BRAF mutations in conjunctival melanoma: investigation of incidence, clinicopathological features, prognosis and paired premalignant lesions. Acta Ophthalmol. 2016;94:463-470.

- Shinozaki M, Fujimoto A, Morton DL, et al. Incidence of BRAF oncogene mutation and clinical relevance for primary cutaneous melanomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1753-1757.

- Heppt MV, Siepmann T, Engel J, et al. Prognostic significance of BRAF and NRAS mutations in melanoma: a German study from routine care. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:536.

- Mar VJ, Liu W, Devitt B, et al. The role of BRAF mutations in primary melanoma growth rate and survival. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:76-82.

- Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, et al. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:1202-1213.

- Reed KB, Brewer JD, Lohse CM, et al. Increasing incidence of melanoma among young adults: an epidemiological study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:328-334.

- Olazagasti Lourido JM, Ma JE, Lohse CM, et al. Increasing incidence of melanoma in the elderly: an epidemiological study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:1555-1562.

- Lowe GC, Saavedra A, Reed KB, et al. Increasing incidence of melanoma among middle-aged adults: an epidemiologic study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:52-59.

- Whiteman DC, Parsons PG, Green AC. p53 expression and risk factors for cutaneous melanoma: a case-control study. Int J Cancer. 1998;77:843-848.

- Whiteman DC, Watt P, Purdie DM, et al. Melanocytic nevi, solar keratoses, and divergent pathways to cutaneous melanoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:806-812.

- Olsen CM, Zens MS, Green AC, et al. Biologic markers of sun exposure and melanoma risk in women: pooled case-control analysis. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:713-723.

Approximately 50% of melanomas contain BRAF mutations, which occur in a greater proportion of melanomas found on sites of intermittent sun exposure.1BRAF-mutated melanomas have been associated with high levels of early-life ambient UV exposure, especially between ages 0 and 20 years.2 In addition, studies have shown that BRAF-mutated melanomas commonly are found on the trunk and extremities.1-3BRAF mutations also have been associated with younger age, superficial spreading subtype and low tumor thickness, absence of dermal melanocyte mitosis, low Ki-67 score, low phospho-histone H3 score, pigmented melanoma, advanced melanoma stage, and conjunctival melanoma.4-7BRAF mutations are found more frequently in metastatic melanoma lesions than primary melanomas, suggesting that BRAF mutations may be acquired during metastasis.8 Studies have shown different conclusions on the effect of BRAF mutation on melanoma-related death.5,9,10

The aim of this study was to identify trends in BRAF V600E–mutated melanoma according to age, sex, and melanoma-specific survival among Olmsted County, Minnesota, residents with a first diagnosis of melanoma at 18 to 60 years of age.

Methods

In total, 638 patients aged 18 to 60 years who resided in Olmsted County and had a first lifetime diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma between 1970 and 2009 were retrospectively identified as a part of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP). The REP is a health records linkage system that encompasses almost all sources of medical care available to the local population of Olmsted County.11 This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (Rochester, Minnesota).

Of the 638 individuals identified in the REP, 536 had been seen at Mayo Clinic and thus potentially had tissue blocks available for the study of BRAF mutation expression. Of these 536 patients, 156 did not have sufficient residual tissue available. As a result, 380 (60%) of the original 638 patients had available blocks with sufficient tissue for immunohistochemical analysis of BRAF expression. Only primary cutaneous melanomas were included in the present study.

All specimens were reviewed by a board-certified dermatopathologist (J.S.L.) for appropriateness of inclusion, which involved confirmation of the diagnosis of melanoma, histologic type of melanoma, and presence of sufficient residual tissue for immunohistochemical stains.

All specimens were originally diagnosed as malignant melanoma at the time of clinical care by at least 2 board-certified dermatopathologists. For the purposes of this study, all specimens were rereviewed for diagnostic accuracy. We required that specimens exhibit severe cytologic and architectural atypia as well as other features favoring melanoma, such as consumption of rete pegs, pagetosis, confluence of junctional melanocytes, evidence of regression, lack of maturation of melanocytes with descent into the dermis, or mitotic figures among the dermal melanocyte population.

The available tissue blocks were retrieved, sectioned, confirmed as melanoma, and stained with a mouse antihuman BRAF V600E monoclonal antibody (clone VE1; Spring Bioscience) to determine the presence of a BRAF V600E mutation. BRAF staining was evaluated in conjunction with a review of the associated slides stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Cytoplasmic staining of melanocytes for BRAF was graded as negative, focal or partial positive (<50% of tumor), or diffuse positive (>50% of tumor)(Figure 1). When a melanoma arose in association with a nevus, we considered only the melanoma component for BRAF staining. We categorized the histologic type as superficial spreading, nodular, or lentigo maligna, and the location as head and neck, trunk, or extremities.

Patient characteristics and survival outcomes were gathered through the health record and included age, Breslow thickness, location, decade of diagnosis, histologic type, stage (ie, noninvasive, invasive, or advanced), and follow-up. Pathologic stage 0 was considered noninvasive; stages IA and IB, invasive; and stages IIA or higher, advanced.

Statistical Analysis—Comparisons between the group of patients in the study (n=380) and the group of patients excluded for the reasons stated above (n=258) as well as associations of mutant BRAF status (positive [partial positive and diffuse positive] vs negative) with patient age (young adults [age range, 18–39 years] and middle-aged adults [age range, 40–60 years]), sex, decade of diagnosis, location, histologic type, and stage were evaluated with Wilcoxon rank sum, χ2, Fisher exact, or Cochran-Armitage trend tests. Disease-specific survival and overall survival rates were estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method, and the duration of follow-up was calculated from the date of melanoma diagnosis to the date of death or the last follow-up. Associations of mutant BRAF expression status with death from melanoma and death from any cause were evaluated with Cox proportional hazard regression models and summarized with hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI. Survival analyses were limited to patients with invasive or advanced disease. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS statistical software (SAS version 9.4). All tests were 2-sided, and P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical and Tumor Characteristics—Of the 380 tissue specimens that underwent BRAF V600E analysis, 247 had negative staining; 106 had diffuse strong staining; and 27 had focal or partial staining. In total, 133 (35%) were positive, either partially or diffusely. The median age for patients who had negative staining was 45 years; for those with positive staining, it was 41 years (P=.07).

The patients who met inclusion criteria (n=380) were compared with those who were excluded (n=258)(eTable 1). The groups were similar on the basis of sex; age; and melanoma location, stage, and histologic subtype. However, some evidence showed that patients included in the study received the diagnosis of melanoma more recently (1970-1989, 13.2%; 1990-1999, 28.7%; 2000-2009, 58.2%) than those who were excluded (1970-1989, 24.7%; 1990-1999, 23.5%; 2000-2009, 51.8%)(P=.02).

BRAF V600E expression was more commonly found in superficial spreading (37.7%) and nodular melanomas (35.0%) than in situ melanomas (17.1%)(P=.01). Other characteristics of BRAF V600E expression are described in eTable 2. Overall, invasive and advanced melanomas were significantly more likely to harbor BRAF V600E expression than noninvasive melanomas (39.6% and 37.9%, respectively, vs 17.9%; P=.003). However, advanced melanomas more commonly expressed BRAF positivity among women, and invasive melanomas more commonly expressed BRAF positivity among men (eTable 2).

Survival—Survival analyses were limited to 297 patients with confirmed invasive or advanced disease. Of these, 180 (61%) had no BRAF V600E staining; 25 (8%) had partial staining; and 92 (31%) had diffuse positive staining. In total, 117 patients (39%) had a BRAF-mutated melanoma.

Among the patients still alive, the median (interquartile range [IQR]) duration of follow-up was 10.2 (7.0-16.8) years. Thirty-nine patients with invasive or advanced disease had died of any cause at a median (IQR) of 3.0 (1.3-10.2) years after diagnosis. In total, 26 patients died of melanoma at a median (IQR) follow-up of 2.5 (1.3-7.4) years after diagnosis. Eight women and 18 men died of malignant melanoma. Five deaths occurred because of malignant melanoma among patients aged 18 to 39 years, and 21 occurred among patients aged 40 to 60 years. In the 18- to 39-year-old group, all 5 deaths were among patients with a BRAF-positive melanoma. Estimated disease-specific survival rate (95% CI; number still at risk) at 5, 10, 15, and 20 years after diagnosis was 94% (91%-97%; 243), 91% (87%-95%; 142), 89% (85%-94%; 87), and 88% (83%-93%; 45), respectively.

In a univariable analysis, the HR for association of positive mutant BRAF expression with death of malignant melanoma was 1.84 (95% CI, 0.85-3.98; P=.12). No statistically significant interaction was observed between decade of diagnosis and BRAF expression (P=.60). However, the interaction between sex and BRAF expression was significant (P=.04), with increased risk of death from melanoma among women with BRAF-mutated melanoma (HR, 10.88; 95% CI, 1.34-88.41; P=.026) but not among men (HR 1.02; 95% CI, 0.40-2.64; P=.97)(Figures 2A and 2B). The HR for death from malignant melanoma among young adults aged 18 to 39 years with a BRAF-mutated melanoma was 16.4 (95% CI, 0.81-330.10; P=.068), whereas the HR among adults aged 40 to 60 years with a BRAF-mutated melanoma was 1.24 (95% CI, 0.52-2.98; P=.63)(Figures 2C and 2D).

BRAF V600E expression was not significantly associated with death from any cause (HR, 1.39; 95% CI, 0.74-2.61; P=.31) or with decade of diagnosis (P=.13). Similarly, BRAF expression was not associated with death from any cause according to sex (P=.31). However, a statistically significant interaction was seen between age at diagnosis and BRAF expression (P=.003). BRAF expression was significantly associated with death from any cause for adults aged 18 to 39 years (HR, 9.60; 95% CI, 1.15-80.00; P=.04). In comparison, no association of BRAF expression with death was observed for adults aged 40 to 60 years (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.48-2.03; P=.98).

Comment

We found that melanomas with BRAF mutations were more likely in advanced and invasive melanoma. The frequency of BRAF mutations among melanomas that were considered advanced was higher in women than men. Although the number of deaths was limited, women with a melanoma with BRAF expression were more likely to die of melanoma, young adults with a BRAF-mutated melanoma had an almost 10-fold increased risk of dying from any cause, and middle-aged adults showed no increased risk of death. These findings suggest that young adults who are genetically prone to a BRAF-mutated melanoma could be at a disadvantage for all-cause mortality. Although this finding was significant, the 95% CI was large, and further studies would be warranted before sound conclusions could be made.

Melanoma has been increasing in incidence across all age groups in Olmsted County over the last 4 decades.12-14 However, our results show that the percentage of BRAF-mutated melanomas in this population has been stable over time, with no statistically significant difference by age or sex. Other confounding factors may have an influence, such as increased rates of early detection and diagnosis of melanoma in contemporary times. Our data suggest that patients included in the BRAF-mutation analysis study had received the diagnosis of melanoma more recently than those who were excluded from the study, which could be due to older melanomas being less likely to have adequate tissue specimens available for immunohistochemical staining/evaluation.

Prior research has shown that BRAF-mutated melanomas typically occur on the trunk and are more likely in individuals with more than 14 nevi on the back.2 In the present cohort, BRAF-positive melanomas had a predisposition toward the trunk but also were found on the head, neck, and extremities—areas that are more likely to have long-term sun damage. One suggestion is that 2 distinct pathways for melanoma development exist: one associated with a large number of melanocytic nevi (that is more prone to genetic mutations in melanocytes) and the other associated with long-term sun exposure.15,16 The combination of these hypotheses suggests that individuals who are prone to the development of large numbers of nevi may require sun exposure for the initial insult, but the development of melanoma may be carried out by other factors after this initial sun exposure insult, whereas individuals without large numbers of nevi who may have less genetic risk may require continued long-term sun exposure for melanoma to develop.17

Our study had limitations, including the small numbers of deaths overall and cause-specific deaths of metastatic melanoma, which limited our ability to conduct more extensive multivariable modeling. Also, the retrospective nature and time frame of looking back 4 decades did not allow us to have information sufficient to categorize some patients as having dysplastic nevus syndrome or not, which would be a potentially interesting variable to include in the analysis. Because the number of deaths in the 18- to 39-year-old cohort was only 5, further statistical comparison regarding tumor type and other variables pertaining to BRAF positivity were not possible. In addition, our data were collected from patients residing in a single geographic county (Olmsted County, Minnesota), which may limit generalizability. Lastly, BRAF V600E mutations were identified through immunostaining only, not molecular data, so it is possible some patients had false-negative immunohistochemistry findings and thus were not identified.

Conclusion

BRAF-mutated melanomas were found in 35% of our cohort, with no significant change in the percentage of melanomas with BRAF V600E mutations over the last 4 decades in this population. In addition, no differences or significant trends existed according to sex and BRAF-mutated melanoma development. Women with BRAF-mutated melanomas were more likely to die of metastatic melanoma than men, and young adults with BRAF-mutated melanomas had a higher all-cause mortality risk. Further research is needed to decipher what effect BRAF-mutated melanomas have on metastasis and cause-specific death in women as well as all-cause mortality in young adults.

Acknowledgment—The authors are indebted to Scientific Publications, Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota).

Approximately 50% of melanomas contain BRAF mutations, which occur in a greater proportion of melanomas found on sites of intermittent sun exposure.1BRAF-mutated melanomas have been associated with high levels of early-life ambient UV exposure, especially between ages 0 and 20 years.2 In addition, studies have shown that BRAF-mutated melanomas commonly are found on the trunk and extremities.1-3BRAF mutations also have been associated with younger age, superficial spreading subtype and low tumor thickness, absence of dermal melanocyte mitosis, low Ki-67 score, low phospho-histone H3 score, pigmented melanoma, advanced melanoma stage, and conjunctival melanoma.4-7BRAF mutations are found more frequently in metastatic melanoma lesions than primary melanomas, suggesting that BRAF mutations may be acquired during metastasis.8 Studies have shown different conclusions on the effect of BRAF mutation on melanoma-related death.5,9,10

The aim of this study was to identify trends in BRAF V600E–mutated melanoma according to age, sex, and melanoma-specific survival among Olmsted County, Minnesota, residents with a first diagnosis of melanoma at 18 to 60 years of age.

Methods

In total, 638 patients aged 18 to 60 years who resided in Olmsted County and had a first lifetime diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma between 1970 and 2009 were retrospectively identified as a part of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP). The REP is a health records linkage system that encompasses almost all sources of medical care available to the local population of Olmsted County.11 This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (Rochester, Minnesota).

Of the 638 individuals identified in the REP, 536 had been seen at Mayo Clinic and thus potentially had tissue blocks available for the study of BRAF mutation expression. Of these 536 patients, 156 did not have sufficient residual tissue available. As a result, 380 (60%) of the original 638 patients had available blocks with sufficient tissue for immunohistochemical analysis of BRAF expression. Only primary cutaneous melanomas were included in the present study.

All specimens were reviewed by a board-certified dermatopathologist (J.S.L.) for appropriateness of inclusion, which involved confirmation of the diagnosis of melanoma, histologic type of melanoma, and presence of sufficient residual tissue for immunohistochemical stains.

All specimens were originally diagnosed as malignant melanoma at the time of clinical care by at least 2 board-certified dermatopathologists. For the purposes of this study, all specimens were rereviewed for diagnostic accuracy. We required that specimens exhibit severe cytologic and architectural atypia as well as other features favoring melanoma, such as consumption of rete pegs, pagetosis, confluence of junctional melanocytes, evidence of regression, lack of maturation of melanocytes with descent into the dermis, or mitotic figures among the dermal melanocyte population.

The available tissue blocks were retrieved, sectioned, confirmed as melanoma, and stained with a mouse antihuman BRAF V600E monoclonal antibody (clone VE1; Spring Bioscience) to determine the presence of a BRAF V600E mutation. BRAF staining was evaluated in conjunction with a review of the associated slides stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Cytoplasmic staining of melanocytes for BRAF was graded as negative, focal or partial positive (<50% of tumor), or diffuse positive (>50% of tumor)(Figure 1). When a melanoma arose in association with a nevus, we considered only the melanoma component for BRAF staining. We categorized the histologic type as superficial spreading, nodular, or lentigo maligna, and the location as head and neck, trunk, or extremities.

Patient characteristics and survival outcomes were gathered through the health record and included age, Breslow thickness, location, decade of diagnosis, histologic type, stage (ie, noninvasive, invasive, or advanced), and follow-up. Pathologic stage 0 was considered noninvasive; stages IA and IB, invasive; and stages IIA or higher, advanced.

Statistical Analysis—Comparisons between the group of patients in the study (n=380) and the group of patients excluded for the reasons stated above (n=258) as well as associations of mutant BRAF status (positive [partial positive and diffuse positive] vs negative) with patient age (young adults [age range, 18–39 years] and middle-aged adults [age range, 40–60 years]), sex, decade of diagnosis, location, histologic type, and stage were evaluated with Wilcoxon rank sum, χ2, Fisher exact, or Cochran-Armitage trend tests. Disease-specific survival and overall survival rates were estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method, and the duration of follow-up was calculated from the date of melanoma diagnosis to the date of death or the last follow-up. Associations of mutant BRAF expression status with death from melanoma and death from any cause were evaluated with Cox proportional hazard regression models and summarized with hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI. Survival analyses were limited to patients with invasive or advanced disease. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS statistical software (SAS version 9.4). All tests were 2-sided, and P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical and Tumor Characteristics—Of the 380 tissue specimens that underwent BRAF V600E analysis, 247 had negative staining; 106 had diffuse strong staining; and 27 had focal or partial staining. In total, 133 (35%) were positive, either partially or diffusely. The median age for patients who had negative staining was 45 years; for those with positive staining, it was 41 years (P=.07).

The patients who met inclusion criteria (n=380) were compared with those who were excluded (n=258)(eTable 1). The groups were similar on the basis of sex; age; and melanoma location, stage, and histologic subtype. However, some evidence showed that patients included in the study received the diagnosis of melanoma more recently (1970-1989, 13.2%; 1990-1999, 28.7%; 2000-2009, 58.2%) than those who were excluded (1970-1989, 24.7%; 1990-1999, 23.5%; 2000-2009, 51.8%)(P=.02).

BRAF V600E expression was more commonly found in superficial spreading (37.7%) and nodular melanomas (35.0%) than in situ melanomas (17.1%)(P=.01). Other characteristics of BRAF V600E expression are described in eTable 2. Overall, invasive and advanced melanomas were significantly more likely to harbor BRAF V600E expression than noninvasive melanomas (39.6% and 37.9%, respectively, vs 17.9%; P=.003). However, advanced melanomas more commonly expressed BRAF positivity among women, and invasive melanomas more commonly expressed BRAF positivity among men (eTable 2).

Survival—Survival analyses were limited to 297 patients with confirmed invasive or advanced disease. Of these, 180 (61%) had no BRAF V600E staining; 25 (8%) had partial staining; and 92 (31%) had diffuse positive staining. In total, 117 patients (39%) had a BRAF-mutated melanoma.

Among the patients still alive, the median (interquartile range [IQR]) duration of follow-up was 10.2 (7.0-16.8) years. Thirty-nine patients with invasive or advanced disease had died of any cause at a median (IQR) of 3.0 (1.3-10.2) years after diagnosis. In total, 26 patients died of melanoma at a median (IQR) follow-up of 2.5 (1.3-7.4) years after diagnosis. Eight women and 18 men died of malignant melanoma. Five deaths occurred because of malignant melanoma among patients aged 18 to 39 years, and 21 occurred among patients aged 40 to 60 years. In the 18- to 39-year-old group, all 5 deaths were among patients with a BRAF-positive melanoma. Estimated disease-specific survival rate (95% CI; number still at risk) at 5, 10, 15, and 20 years after diagnosis was 94% (91%-97%; 243), 91% (87%-95%; 142), 89% (85%-94%; 87), and 88% (83%-93%; 45), respectively.

In a univariable analysis, the HR for association of positive mutant BRAF expression with death of malignant melanoma was 1.84 (95% CI, 0.85-3.98; P=.12). No statistically significant interaction was observed between decade of diagnosis and BRAF expression (P=.60). However, the interaction between sex and BRAF expression was significant (P=.04), with increased risk of death from melanoma among women with BRAF-mutated melanoma (HR, 10.88; 95% CI, 1.34-88.41; P=.026) but not among men (HR 1.02; 95% CI, 0.40-2.64; P=.97)(Figures 2A and 2B). The HR for death from malignant melanoma among young adults aged 18 to 39 years with a BRAF-mutated melanoma was 16.4 (95% CI, 0.81-330.10; P=.068), whereas the HR among adults aged 40 to 60 years with a BRAF-mutated melanoma was 1.24 (95% CI, 0.52-2.98; P=.63)(Figures 2C and 2D).

BRAF V600E expression was not significantly associated with death from any cause (HR, 1.39; 95% CI, 0.74-2.61; P=.31) or with decade of diagnosis (P=.13). Similarly, BRAF expression was not associated with death from any cause according to sex (P=.31). However, a statistically significant interaction was seen between age at diagnosis and BRAF expression (P=.003). BRAF expression was significantly associated with death from any cause for adults aged 18 to 39 years (HR, 9.60; 95% CI, 1.15-80.00; P=.04). In comparison, no association of BRAF expression with death was observed for adults aged 40 to 60 years (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.48-2.03; P=.98).

Comment

We found that melanomas with BRAF mutations were more likely in advanced and invasive melanoma. The frequency of BRAF mutations among melanomas that were considered advanced was higher in women than men. Although the number of deaths was limited, women with a melanoma with BRAF expression were more likely to die of melanoma, young adults with a BRAF-mutated melanoma had an almost 10-fold increased risk of dying from any cause, and middle-aged adults showed no increased risk of death. These findings suggest that young adults who are genetically prone to a BRAF-mutated melanoma could be at a disadvantage for all-cause mortality. Although this finding was significant, the 95% CI was large, and further studies would be warranted before sound conclusions could be made.

Melanoma has been increasing in incidence across all age groups in Olmsted County over the last 4 decades.12-14 However, our results show that the percentage of BRAF-mutated melanomas in this population has been stable over time, with no statistically significant difference by age or sex. Other confounding factors may have an influence, such as increased rates of early detection and diagnosis of melanoma in contemporary times. Our data suggest that patients included in the BRAF-mutation analysis study had received the diagnosis of melanoma more recently than those who were excluded from the study, which could be due to older melanomas being less likely to have adequate tissue specimens available for immunohistochemical staining/evaluation.

Prior research has shown that BRAF-mutated melanomas typically occur on the trunk and are more likely in individuals with more than 14 nevi on the back.2 In the present cohort, BRAF-positive melanomas had a predisposition toward the trunk but also were found on the head, neck, and extremities—areas that are more likely to have long-term sun damage. One suggestion is that 2 distinct pathways for melanoma development exist: one associated with a large number of melanocytic nevi (that is more prone to genetic mutations in melanocytes) and the other associated with long-term sun exposure.15,16 The combination of these hypotheses suggests that individuals who are prone to the development of large numbers of nevi may require sun exposure for the initial insult, but the development of melanoma may be carried out by other factors after this initial sun exposure insult, whereas individuals without large numbers of nevi who may have less genetic risk may require continued long-term sun exposure for melanoma to develop.17

Our study had limitations, including the small numbers of deaths overall and cause-specific deaths of metastatic melanoma, which limited our ability to conduct more extensive multivariable modeling. Also, the retrospective nature and time frame of looking back 4 decades did not allow us to have information sufficient to categorize some patients as having dysplastic nevus syndrome or not, which would be a potentially interesting variable to include in the analysis. Because the number of deaths in the 18- to 39-year-old cohort was only 5, further statistical comparison regarding tumor type and other variables pertaining to BRAF positivity were not possible. In addition, our data were collected from patients residing in a single geographic county (Olmsted County, Minnesota), which may limit generalizability. Lastly, BRAF V600E mutations were identified through immunostaining only, not molecular data, so it is possible some patients had false-negative immunohistochemistry findings and thus were not identified.

Conclusion

BRAF-mutated melanomas were found in 35% of our cohort, with no significant change in the percentage of melanomas with BRAF V600E mutations over the last 4 decades in this population. In addition, no differences or significant trends existed according to sex and BRAF-mutated melanoma development. Women with BRAF-mutated melanomas were more likely to die of metastatic melanoma than men, and young adults with BRAF-mutated melanomas had a higher all-cause mortality risk. Further research is needed to decipher what effect BRAF-mutated melanomas have on metastasis and cause-specific death in women as well as all-cause mortality in young adults.

Acknowledgment—The authors are indebted to Scientific Publications, Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota).

- Grimaldi AM, Cassidy PB, Leachmann S, et al. Novel approaches in melanoma prevention and therapy. Cancer Treat Res. 2014;159: 443-455.

- Thomas NE, Edmiston SN, Alexander A, et al. Number of nevi and early-life ambient UV exposure are associated with BRAF-mutant melanoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:991-997.

- Curtin JA, Fridlyand J, Kageshita T, et al. Distinct sets of genetic alterations in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2135-2147.

- Thomas NE, Edmiston SN, Alexander A, et al. Association between NRAS and BRAF mutational status and melanoma-specific survival among patients with higher-risk primary melanoma. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:359-368.

- Liu W, Kelly JW, Trivett M, et al. Distinct clinical and pathological features are associated with the BRAF(T1799A(V600E)) mutation in primary melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:900-905.

- Kim SY, Kim SN, Hahn HJ, et al. Metaanalysis of BRAF mutations and clinicopathologic characteristics in primary melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:1036-1046.e2.

- Larsen AC, Dahl C, Dahmcke CM, et al. BRAF mutations in conjunctival melanoma: investigation of incidence, clinicopathological features, prognosis and paired premalignant lesions. Acta Ophthalmol. 2016;94:463-470.

- Shinozaki M, Fujimoto A, Morton DL, et al. Incidence of BRAF oncogene mutation and clinical relevance for primary cutaneous melanomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1753-1757.

- Heppt MV, Siepmann T, Engel J, et al. Prognostic significance of BRAF and NRAS mutations in melanoma: a German study from routine care. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:536.

- Mar VJ, Liu W, Devitt B, et al. The role of BRAF mutations in primary melanoma growth rate and survival. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:76-82.

- Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, et al. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:1202-1213.

- Reed KB, Brewer JD, Lohse CM, et al. Increasing incidence of melanoma among young adults: an epidemiological study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:328-334.

- Olazagasti Lourido JM, Ma JE, Lohse CM, et al. Increasing incidence of melanoma in the elderly: an epidemiological study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:1555-1562.

- Lowe GC, Saavedra A, Reed KB, et al. Increasing incidence of melanoma among middle-aged adults: an epidemiologic study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:52-59.

- Whiteman DC, Parsons PG, Green AC. p53 expression and risk factors for cutaneous melanoma: a case-control study. Int J Cancer. 1998;77:843-848.

- Whiteman DC, Watt P, Purdie DM, et al. Melanocytic nevi, solar keratoses, and divergent pathways to cutaneous melanoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:806-812.

- Olsen CM, Zens MS, Green AC, et al. Biologic markers of sun exposure and melanoma risk in women: pooled case-control analysis. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:713-723.

- Grimaldi AM, Cassidy PB, Leachmann S, et al. Novel approaches in melanoma prevention and therapy. Cancer Treat Res. 2014;159: 443-455.