User login

‘No Pulse’: An MD’s First Night Off in 2 Weeks Turns Grave

Emergencies happen anywhere, anytime, and sometimes, medical professionals find themselves in situations where they are the only ones who can help. Is There a Doctor in the House? is a series by this news organization that tells these stories.

It was my first night off after 12 days. It was a Friday night, and I went to a bar in Naples to get a beer with some friends. As it turned out, it wasn’t a night off after all.

As soon as we got inside, we heard over the speaker that they needed medical personnel and to please go to the left side of the bar. I thought it would be syncope or something like that.

I went over there and saw a woman holding up a man. He was basically leaning all over her. The light was low, and the music was pounding. I started to assess him and tried to get him to answer me. No response. I checked for pulses — nothing.

The woman helped me lower him to the floor. I checked again for a pulse. Still nothing. I said, “Call 911,” and started compressions.

The difficult part was the place was completely dark. I knew where his body was on the floor. I could see his chest. But I couldn’t see his face at all.

It was also extremely loud with the music thumping. After a while, they finally shut it off.

Pretty soon, the security personnel from the bar brought me an automated external defibrillator, and it showed the man was having V-fib arrest. I shocked him. Still no pulse. I continued with cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

I hadn’t noticed, but lots of people were crowding around us. Somebody came up and said, “He’s my friend. He has a 9-year-old daughter. He can’t die. Let me help with the compressions.” I was like, “Go for it.”

The guy started kind of pushing on the man’s abdomen. He had no idea how to do compressions. I said, “Okay, let me take over again.”

Out of the crowd, nobody else volunteered to help. No one asked me, “Hey, what can I do?” Meanwhile, I found out later that someone was filming the whole thing on their phone.

But what the guy said about the man’s young daughter stayed in my brain. I thought, we need to keep going.

I did more compressions and shocked him again. Still no pulse. At that point, the police and emergency medical services showed up. They checked, nothing had changed, so they got him into the ambulance.

I asked one of the paramedics, “Where are you taking him? I can call ahead.”

But he said, “That’s HIPAA. We can’t tell you.” They also wouldn’t let me go with him in the ambulance.

“I have an active Florida license, and I work in the ICU [intensive care unit],” I said.

“No, we need to follow our protocol,” he replied.

I understood that, but I just wanted to help.

It was around 10:30 PM by then, and I was drenched in sweat. I had to go home. The first thing I did after taking a shower was open the computer and check my system. I needed to find out what happened to the guy.

I was looking for admissions, and I didn’t see him. I called the main hospital downtown and the one in North Naples. I couldn’t find him anywhere. I stayed up until almost 1:00 AM checking for his name. At that point I thought, okay, maybe he died.

The next night, Saturday, I was home and got a call from one of my colleagues. “Hey, were you in a bar yesterday? Did you do CPR on somebody?”

“How did you know?” I said.

He said the paramedics had described me — “a tall doctor with glasses who was a nice guy.” It was funny that he knew that was me.

He told me, “The guy’s alive. He’s sick and needs to be put on dialysis, but he’s alive.”

Apparently, the guy had gone to the emergency department at North Naples, and the doctors in the emergency room (ER) worked on him for over an hour. They did continuous CPR and shocked him for close to 40 minutes. They finally got his pulse back, and after that, he was transferred to the main hospital ICU. They didn’t admit him at the ER, which was why I couldn’t find his name.

On Sunday, I was checking my patients’ charts for the ICU that coming week. And there he was. I saw his name and the documentation by the ED that CPR was provided by a critical care doctor in the field. He was still alive. That gave me so much joy.

So, the man I had helped became my patient. When I saw him on Monday, he was intubated and needed dialysis. I finally saw his face and thought, Oh, so that’s what you look like. I hadn’t realized he was only 39 years old.

When he was awake, I explained to him I was the doctor that provided CPR at the bar. He was very grateful, but of course, he didn’t remember anything.

Eventually, I met his daughter, and she just said, “Thank you for allowing me to have my dad.”

The funny part is that he broke his leg. Well, that’s not funny, but no one had any idea how it happened. That was his only complaint. He was asking me, “Doctor, how did you break my leg?”

“Hey, I have no idea how you broke your leg,” I replied. “I was trying to save your life.”

He was in the hospital for almost a month but made a full recovery. The amazing part: After all the evaluations, he has no neurological deficits. He’s back to a normal life now.

They never found a cause for the cardiac arrest. I mean, he had an ejection fraction of 10%. All my money was on something drug related, but that wasn’t the case. They’d done a cardiac cut, and there was no obstruction. They couldn’t find a reason.

We’ve become friends. He still works as a DJ at the bar. He changed his name to “DJ the Survivor” or something like that.

Sometimes, he’ll text me: “Doctor, what are you doing? You want to come down to the bar?”

I’m like, “No. I don’t.”

It’s been more than a year, but I remember every detail. When you go into medicine, you dream that one day you’ll be able to say, “I saved somebody.”

He texted me a year later and told me he’s celebrating two birthdays now. He said, “I’m turning 1 year old today!”

I think about the value of life. How we can take it for granted. We think, I’m young, nothing is going to happen to me. But this guy was 39. He went to work and died that night.

I was able to help bring him back. That makes me thankful for every day.

Jose Valle Giler, MD, is a pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine physician at NCH Healthcare System in Naples, Florida.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Emergencies happen anywhere, anytime, and sometimes, medical professionals find themselves in situations where they are the only ones who can help. Is There a Doctor in the House? is a series by this news organization that tells these stories.

It was my first night off after 12 days. It was a Friday night, and I went to a bar in Naples to get a beer with some friends. As it turned out, it wasn’t a night off after all.

As soon as we got inside, we heard over the speaker that they needed medical personnel and to please go to the left side of the bar. I thought it would be syncope or something like that.

I went over there and saw a woman holding up a man. He was basically leaning all over her. The light was low, and the music was pounding. I started to assess him and tried to get him to answer me. No response. I checked for pulses — nothing.

The woman helped me lower him to the floor. I checked again for a pulse. Still nothing. I said, “Call 911,” and started compressions.

The difficult part was the place was completely dark. I knew where his body was on the floor. I could see his chest. But I couldn’t see his face at all.

It was also extremely loud with the music thumping. After a while, they finally shut it off.

Pretty soon, the security personnel from the bar brought me an automated external defibrillator, and it showed the man was having V-fib arrest. I shocked him. Still no pulse. I continued with cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

I hadn’t noticed, but lots of people were crowding around us. Somebody came up and said, “He’s my friend. He has a 9-year-old daughter. He can’t die. Let me help with the compressions.” I was like, “Go for it.”

The guy started kind of pushing on the man’s abdomen. He had no idea how to do compressions. I said, “Okay, let me take over again.”

Out of the crowd, nobody else volunteered to help. No one asked me, “Hey, what can I do?” Meanwhile, I found out later that someone was filming the whole thing on their phone.

But what the guy said about the man’s young daughter stayed in my brain. I thought, we need to keep going.

I did more compressions and shocked him again. Still no pulse. At that point, the police and emergency medical services showed up. They checked, nothing had changed, so they got him into the ambulance.

I asked one of the paramedics, “Where are you taking him? I can call ahead.”

But he said, “That’s HIPAA. We can’t tell you.” They also wouldn’t let me go with him in the ambulance.

“I have an active Florida license, and I work in the ICU [intensive care unit],” I said.

“No, we need to follow our protocol,” he replied.

I understood that, but I just wanted to help.

It was around 10:30 PM by then, and I was drenched in sweat. I had to go home. The first thing I did after taking a shower was open the computer and check my system. I needed to find out what happened to the guy.

I was looking for admissions, and I didn’t see him. I called the main hospital downtown and the one in North Naples. I couldn’t find him anywhere. I stayed up until almost 1:00 AM checking for his name. At that point I thought, okay, maybe he died.

The next night, Saturday, I was home and got a call from one of my colleagues. “Hey, were you in a bar yesterday? Did you do CPR on somebody?”

“How did you know?” I said.

He said the paramedics had described me — “a tall doctor with glasses who was a nice guy.” It was funny that he knew that was me.

He told me, “The guy’s alive. He’s sick and needs to be put on dialysis, but he’s alive.”

Apparently, the guy had gone to the emergency department at North Naples, and the doctors in the emergency room (ER) worked on him for over an hour. They did continuous CPR and shocked him for close to 40 minutes. They finally got his pulse back, and after that, he was transferred to the main hospital ICU. They didn’t admit him at the ER, which was why I couldn’t find his name.

On Sunday, I was checking my patients’ charts for the ICU that coming week. And there he was. I saw his name and the documentation by the ED that CPR was provided by a critical care doctor in the field. He was still alive. That gave me so much joy.

So, the man I had helped became my patient. When I saw him on Monday, he was intubated and needed dialysis. I finally saw his face and thought, Oh, so that’s what you look like. I hadn’t realized he was only 39 years old.

When he was awake, I explained to him I was the doctor that provided CPR at the bar. He was very grateful, but of course, he didn’t remember anything.

Eventually, I met his daughter, and she just said, “Thank you for allowing me to have my dad.”

The funny part is that he broke his leg. Well, that’s not funny, but no one had any idea how it happened. That was his only complaint. He was asking me, “Doctor, how did you break my leg?”

“Hey, I have no idea how you broke your leg,” I replied. “I was trying to save your life.”

He was in the hospital for almost a month but made a full recovery. The amazing part: After all the evaluations, he has no neurological deficits. He’s back to a normal life now.

They never found a cause for the cardiac arrest. I mean, he had an ejection fraction of 10%. All my money was on something drug related, but that wasn’t the case. They’d done a cardiac cut, and there was no obstruction. They couldn’t find a reason.

We’ve become friends. He still works as a DJ at the bar. He changed his name to “DJ the Survivor” or something like that.

Sometimes, he’ll text me: “Doctor, what are you doing? You want to come down to the bar?”

I’m like, “No. I don’t.”

It’s been more than a year, but I remember every detail. When you go into medicine, you dream that one day you’ll be able to say, “I saved somebody.”

He texted me a year later and told me he’s celebrating two birthdays now. He said, “I’m turning 1 year old today!”

I think about the value of life. How we can take it for granted. We think, I’m young, nothing is going to happen to me. But this guy was 39. He went to work and died that night.

I was able to help bring him back. That makes me thankful for every day.

Jose Valle Giler, MD, is a pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine physician at NCH Healthcare System in Naples, Florida.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Emergencies happen anywhere, anytime, and sometimes, medical professionals find themselves in situations where they are the only ones who can help. Is There a Doctor in the House? is a series by this news organization that tells these stories.

It was my first night off after 12 days. It was a Friday night, and I went to a bar in Naples to get a beer with some friends. As it turned out, it wasn’t a night off after all.

As soon as we got inside, we heard over the speaker that they needed medical personnel and to please go to the left side of the bar. I thought it would be syncope or something like that.

I went over there and saw a woman holding up a man. He was basically leaning all over her. The light was low, and the music was pounding. I started to assess him and tried to get him to answer me. No response. I checked for pulses — nothing.

The woman helped me lower him to the floor. I checked again for a pulse. Still nothing. I said, “Call 911,” and started compressions.

The difficult part was the place was completely dark. I knew where his body was on the floor. I could see his chest. But I couldn’t see his face at all.

It was also extremely loud with the music thumping. After a while, they finally shut it off.

Pretty soon, the security personnel from the bar brought me an automated external defibrillator, and it showed the man was having V-fib arrest. I shocked him. Still no pulse. I continued with cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

I hadn’t noticed, but lots of people were crowding around us. Somebody came up and said, “He’s my friend. He has a 9-year-old daughter. He can’t die. Let me help with the compressions.” I was like, “Go for it.”

The guy started kind of pushing on the man’s abdomen. He had no idea how to do compressions. I said, “Okay, let me take over again.”

Out of the crowd, nobody else volunteered to help. No one asked me, “Hey, what can I do?” Meanwhile, I found out later that someone was filming the whole thing on their phone.

But what the guy said about the man’s young daughter stayed in my brain. I thought, we need to keep going.

I did more compressions and shocked him again. Still no pulse. At that point, the police and emergency medical services showed up. They checked, nothing had changed, so they got him into the ambulance.

I asked one of the paramedics, “Where are you taking him? I can call ahead.”

But he said, “That’s HIPAA. We can’t tell you.” They also wouldn’t let me go with him in the ambulance.

“I have an active Florida license, and I work in the ICU [intensive care unit],” I said.

“No, we need to follow our protocol,” he replied.

I understood that, but I just wanted to help.

It was around 10:30 PM by then, and I was drenched in sweat. I had to go home. The first thing I did after taking a shower was open the computer and check my system. I needed to find out what happened to the guy.

I was looking for admissions, and I didn’t see him. I called the main hospital downtown and the one in North Naples. I couldn’t find him anywhere. I stayed up until almost 1:00 AM checking for his name. At that point I thought, okay, maybe he died.

The next night, Saturday, I was home and got a call from one of my colleagues. “Hey, were you in a bar yesterday? Did you do CPR on somebody?”

“How did you know?” I said.

He said the paramedics had described me — “a tall doctor with glasses who was a nice guy.” It was funny that he knew that was me.

He told me, “The guy’s alive. He’s sick and needs to be put on dialysis, but he’s alive.”

Apparently, the guy had gone to the emergency department at North Naples, and the doctors in the emergency room (ER) worked on him for over an hour. They did continuous CPR and shocked him for close to 40 minutes. They finally got his pulse back, and after that, he was transferred to the main hospital ICU. They didn’t admit him at the ER, which was why I couldn’t find his name.

On Sunday, I was checking my patients’ charts for the ICU that coming week. And there he was. I saw his name and the documentation by the ED that CPR was provided by a critical care doctor in the field. He was still alive. That gave me so much joy.

So, the man I had helped became my patient. When I saw him on Monday, he was intubated and needed dialysis. I finally saw his face and thought, Oh, so that’s what you look like. I hadn’t realized he was only 39 years old.

When he was awake, I explained to him I was the doctor that provided CPR at the bar. He was very grateful, but of course, he didn’t remember anything.

Eventually, I met his daughter, and she just said, “Thank you for allowing me to have my dad.”

The funny part is that he broke his leg. Well, that’s not funny, but no one had any idea how it happened. That was his only complaint. He was asking me, “Doctor, how did you break my leg?”

“Hey, I have no idea how you broke your leg,” I replied. “I was trying to save your life.”

He was in the hospital for almost a month but made a full recovery. The amazing part: After all the evaluations, he has no neurological deficits. He’s back to a normal life now.

They never found a cause for the cardiac arrest. I mean, he had an ejection fraction of 10%. All my money was on something drug related, but that wasn’t the case. They’d done a cardiac cut, and there was no obstruction. They couldn’t find a reason.

We’ve become friends. He still works as a DJ at the bar. He changed his name to “DJ the Survivor” or something like that.

Sometimes, he’ll text me: “Doctor, what are you doing? You want to come down to the bar?”

I’m like, “No. I don’t.”

It’s been more than a year, but I remember every detail. When you go into medicine, you dream that one day you’ll be able to say, “I saved somebody.”

He texted me a year later and told me he’s celebrating two birthdays now. He said, “I’m turning 1 year old today!”

I think about the value of life. How we can take it for granted. We think, I’m young, nothing is going to happen to me. But this guy was 39. He went to work and died that night.

I was able to help bring him back. That makes me thankful for every day.

Jose Valle Giler, MD, is a pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine physician at NCH Healthcare System in Naples, Florida.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Moral Injury in Health Care: A Unified Definition and its Relationship to Burnout

Moral injury was identified by health care professionals (HCPs) as a driver of occupational distress prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, but the crisis expanded the appeal and investigation of the term.1 HCPs now consider moral injury an essential component of the framework to describe their distress, because using the term burnout alone fails to capture their full experience and has proven resistant to interventions.2 Moral injury goes beyond the transdiagnostic symptoms of exhaustion and cynicism and beyond operational, demand-resource mismatches that characterize burnout. It describes the frustration, anger, and helplessness associated with relational ruptures and the existential threats to a clinician’s professional identity as business interests erode their ability to put their patients’ needs ahead of corporate and health care system obligations.3

Proper characterization of moral injury in health care—separate from the military environments where it originated—is stymied by an ill-defined relationship between 2 definitions of the term and by an unclear relationship between moral injury and the long-standing body of scholarship in burnout. To clarify the concept, inform research agendas, and open avenues for more effective solutions to the crisis of HCP distress, we propose a unified conceptualization of moral injury and its association with burnout in health care.

CONTEXTUAL DISTINCTIONS

It is important to properly distinguish between the original use of moral injury in the military and its expanded use in civilian circumstances. Health care and the military are both professions whereupon donning the “uniform” of a physician—or soldier, sailor, airman, or marine—members must comport with strict expectations of behavior, including the refusal to engage in illegal actions or those contrary to professional ethics. Individuals in both professions acquire a highly specialized body of knowledge and enter an implied contract to provide critical services to society, specifically healing and protection, respectively. Members of both professions are trained to make complex judgments with integrity under conditions of technical and ethical uncertainty, upon which they take highly skilled action. Medical and military professionals must be free to act on their ethical principles, without confounding demands.4 However, the context of each profession’s commitment to society carries different moral implications.

The risk of moral injury is inherent in military service. The military promises protection with an implicit acknowledgment of the need to use lethal force to uphold the agreement. In contrast, HCPs promise healing and care. The military promises to protect our society, with an implicit acknowledgment of the need to use lethal force to uphold the agreement. Some military actions may inflict harm without the hope of benefitting an individual, and are therefore potentially morally injurious. The health care contract with society, promising healing and care, is devoid of inherent moral injury due to harm without potential individual benefit. Therefore, the presence of moral injury in health care settings are warning signs of a dysfunctional environment.

One complex example of the dysfunctional environments is illustrative. The military and health care are among the few industries where supply creates demand. For example, the more bad state actors there are, the more demand for the military. As we have seen since the 1950s, the more technology and therapeutics we create in health care, coupled with a larger share paid for by third parties, the greater the demand for and use of them.5 In a fee for service environment, corporate greed feeds on this reality. In most other environments, more technological and therapeutic options inevitably pit clinicians against multiple other factions: payers, who do not want to underwrite them; patients, who sometimes demand them without justification or later rail against spiraling health care costs; and administrators, especially in capitated systems, who watch their bottom lines erode. The moral injury risk in this instance demands a collective conversation among stakeholders regarding the structural determinants of health—how we choose to distribute limited resources. The intermediary of moral injury is a useful measure of the harm that results from ignoring or avoiding such challenges.

HARMONIZING DEFINITIONS

Moral injury is inherently nuanced. The 2 dominant definitions arise from work with combat veterans and create additional and perhaps unnecessary complexity. Unifying these 2 definitions eliminates inadvertent confusion, preventing the risk of unbridled interdisciplinary investigation which leads to a lack of precision in the meaning of moral injury and other related concepts, such as burnout.6

The first definition was developed by Jonathan Shay in 1994 and outlines 3 necessarycomponents, viewing the violator as a powerholder: (1) betrayal of what is right, (2) by someone who holds legitimate authority, (3) in a high stakes situation.7 Litz and colleagues describe moral injury another way: “Perpetrating, failing to prevent, bearing witness to, or learning about acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.”8 The violator is posited to be either the self or others.

Rather than representing “self” or “other” imposed moral injury, we propose the 2 definitions are related as exposure (ie, the perceived betrayal) and response (ie, the resulting transgression). An individual who experiences a betrayal by a legitimate authority has an opportunity to choose their response. They may acquiesce and transgress their moral beliefs (eg, their oath to provide ethical health care), or they could refuse, by speaking out, or in some way resisting the authority’s betrayal. The case of Ray Brovont is a useful illustration of reconciling the definitions (Box).9

Myriad factors—known as potentially morally injurious events—drive moral injury, such as resource-constrained decision making, witnessing the behaviors of colleagues that violate deeply held moral beliefs, questionable billing practices, and more. Each begins with a betrayal. Spotlighting the betrayal, refusing to perpetuate it, or taking actions toward change, may reduce the risk of experiencing moral injury.9 Conversely, acquiescing and transgressing one’s oath, the profession’s covenant with society, increases the risk of experiencing moral injury.8

Many HCPs believe they are not always free to resist betrayal, fearing retaliation, job loss, blacklisting, or worse. They feel constrained by debt accrued while receiving their education, being their household’s primary earner, community ties, practicing a niche specialty that requires working for a tertiary referral center, or perhaps believing the situation will be the same elsewhere. To not stand up or speak out is to choose complicity with corporate greed that uses HCPs to undermine their professional duties, which significantly increases the risk of experiencing moral injury.

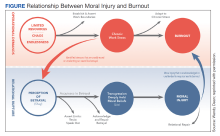

MORAL INJURY AND BURNOUT

In addition to reconciling the definitions of moral injury, the relationship between moral injury and burnout are still being elucidated. We suggest that moral injury and burnout represent independent and potentially interrelated pathways to distress (Figure). Exposure to chronic, inconsonant, and transactional demands, which things like shorter work hours, better self-care, or improved health system operations might mitigate, manifests as burnout. In contrast, moral injury arises when a superior’s actions or a system’s policies and practices—such as justifiable but unnecessary testing, or referral restrictions to prevent revenue leakage—undermine one’s professional obligations to prioritize the patient’s best interest.

If concerns from HCPs about transactional demands are persistently dismissed, such inaction may be perceived as a betrayal, raising the risk of moral injury. Additionally, the resignation or helplessness of moral injury perceived as inescapable may present with emotional exhaustion, ineffectiveness, and depersonalization, all hallmarks of burnout. Both conditions can mediate and moderate the relationship between triggers for workplace distress and resulting psychological, physical, and existential harm.

CONCLUSIONS

Moral injury is increasingly recognized as a source of distress among HCPs, resulting from structural constraints on their ability to deliver optimal care and their own unwillingness to stand up for their patients, their oaths, and their professions.1 Unlike the military, where moral injury is inherent in the contract with society, moral injury in health care (and the relational rupture it connotes) is a signal of systemic dysfunction, fractured trust, and the need for relational repair.

Health care is at a crossroads, experiencing a workforce retention crisis while simultaneously predicting a significant increase in care needs by Baby Boomers over the next 3 decades.

Health care does not have the luxury of experimenting another 30 years with interventions that have limited impact. We must design a new generation of approaches, shaped by lessons learned from the pandemic while acknowledging that prepandemic standards were already failing the workforce. A unified definition of moral injury must be integrated to frame clinician distress alongside burnout, recentering ethical decision making, rather than profit, at the heart of health care. Harmonizing the definitions of moral injury and clarifying the relationship of moral injury with burnout reduces the need for further reinterpretations, allowing for more robust, easily comparable studies focused on identifying risk factors, as well as rapidly implementing effective mitigation strategies.

1. Griffin BJ, Weber MC, Hinkson KD, et al. Toward a dimensional contextual model of moral injury: a scoping review on healthcare workers. Curr Treat Options Psych. 2023;10:199-216. doi:10.1007/s40501-023-00296-4

2. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; National Academy of Medicine; Committee on Systems Approaches to Improve Patient Care by Supporting Clinician Well-Being. Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being. The National Academies Press; 2019. doi:10.17226/25521

3. Dean W, Talbot S, Dean A. Reframing clinician distress: moral injury not burnout. Fed Pract. 2019;36(9):400-402.

4. Gardner HE, Schulman LS. The professions in America today: crucial but fragile. Daedalus. 2005;134(3):13-18. doi:10.1162/0011526054622132

5. Fuchs VR. Major trends in the U.S. health economy since 1950. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):973-977. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1200478

6. Molendijk T. Warnings against romanticising moral injury. Br J Psychiatry. 2022;220(1):1-3. doi:10.1192/bjp.2021.114

7. Shay J. Moral injury. Psychoanalytic Psychol. 2014;31(2):182-191. doi:10.1037/a0036090

8. Litz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, et al. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: a preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8):695-706. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003

9. Brovont v KS-I Med. Servs., P.A., 622 SW3d 671 (Mo Ct App 2020).

Moral injury was identified by health care professionals (HCPs) as a driver of occupational distress prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, but the crisis expanded the appeal and investigation of the term.1 HCPs now consider moral injury an essential component of the framework to describe their distress, because using the term burnout alone fails to capture their full experience and has proven resistant to interventions.2 Moral injury goes beyond the transdiagnostic symptoms of exhaustion and cynicism and beyond operational, demand-resource mismatches that characterize burnout. It describes the frustration, anger, and helplessness associated with relational ruptures and the existential threats to a clinician’s professional identity as business interests erode their ability to put their patients’ needs ahead of corporate and health care system obligations.3

Proper characterization of moral injury in health care—separate from the military environments where it originated—is stymied by an ill-defined relationship between 2 definitions of the term and by an unclear relationship between moral injury and the long-standing body of scholarship in burnout. To clarify the concept, inform research agendas, and open avenues for more effective solutions to the crisis of HCP distress, we propose a unified conceptualization of moral injury and its association with burnout in health care.

CONTEXTUAL DISTINCTIONS

It is important to properly distinguish between the original use of moral injury in the military and its expanded use in civilian circumstances. Health care and the military are both professions whereupon donning the “uniform” of a physician—or soldier, sailor, airman, or marine—members must comport with strict expectations of behavior, including the refusal to engage in illegal actions or those contrary to professional ethics. Individuals in both professions acquire a highly specialized body of knowledge and enter an implied contract to provide critical services to society, specifically healing and protection, respectively. Members of both professions are trained to make complex judgments with integrity under conditions of technical and ethical uncertainty, upon which they take highly skilled action. Medical and military professionals must be free to act on their ethical principles, without confounding demands.4 However, the context of each profession’s commitment to society carries different moral implications.

The risk of moral injury is inherent in military service. The military promises protection with an implicit acknowledgment of the need to use lethal force to uphold the agreement. In contrast, HCPs promise healing and care. The military promises to protect our society, with an implicit acknowledgment of the need to use lethal force to uphold the agreement. Some military actions may inflict harm without the hope of benefitting an individual, and are therefore potentially morally injurious. The health care contract with society, promising healing and care, is devoid of inherent moral injury due to harm without potential individual benefit. Therefore, the presence of moral injury in health care settings are warning signs of a dysfunctional environment.

One complex example of the dysfunctional environments is illustrative. The military and health care are among the few industries where supply creates demand. For example, the more bad state actors there are, the more demand for the military. As we have seen since the 1950s, the more technology and therapeutics we create in health care, coupled with a larger share paid for by third parties, the greater the demand for and use of them.5 In a fee for service environment, corporate greed feeds on this reality. In most other environments, more technological and therapeutic options inevitably pit clinicians against multiple other factions: payers, who do not want to underwrite them; patients, who sometimes demand them without justification or later rail against spiraling health care costs; and administrators, especially in capitated systems, who watch their bottom lines erode. The moral injury risk in this instance demands a collective conversation among stakeholders regarding the structural determinants of health—how we choose to distribute limited resources. The intermediary of moral injury is a useful measure of the harm that results from ignoring or avoiding such challenges.

HARMONIZING DEFINITIONS

Moral injury is inherently nuanced. The 2 dominant definitions arise from work with combat veterans and create additional and perhaps unnecessary complexity. Unifying these 2 definitions eliminates inadvertent confusion, preventing the risk of unbridled interdisciplinary investigation which leads to a lack of precision in the meaning of moral injury and other related concepts, such as burnout.6

The first definition was developed by Jonathan Shay in 1994 and outlines 3 necessarycomponents, viewing the violator as a powerholder: (1) betrayal of what is right, (2) by someone who holds legitimate authority, (3) in a high stakes situation.7 Litz and colleagues describe moral injury another way: “Perpetrating, failing to prevent, bearing witness to, or learning about acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.”8 The violator is posited to be either the self or others.

Rather than representing “self” or “other” imposed moral injury, we propose the 2 definitions are related as exposure (ie, the perceived betrayal) and response (ie, the resulting transgression). An individual who experiences a betrayal by a legitimate authority has an opportunity to choose their response. They may acquiesce and transgress their moral beliefs (eg, their oath to provide ethical health care), or they could refuse, by speaking out, or in some way resisting the authority’s betrayal. The case of Ray Brovont is a useful illustration of reconciling the definitions (Box).9

Myriad factors—known as potentially morally injurious events—drive moral injury, such as resource-constrained decision making, witnessing the behaviors of colleagues that violate deeply held moral beliefs, questionable billing practices, and more. Each begins with a betrayal. Spotlighting the betrayal, refusing to perpetuate it, or taking actions toward change, may reduce the risk of experiencing moral injury.9 Conversely, acquiescing and transgressing one’s oath, the profession’s covenant with society, increases the risk of experiencing moral injury.8

Many HCPs believe they are not always free to resist betrayal, fearing retaliation, job loss, blacklisting, or worse. They feel constrained by debt accrued while receiving their education, being their household’s primary earner, community ties, practicing a niche specialty that requires working for a tertiary referral center, or perhaps believing the situation will be the same elsewhere. To not stand up or speak out is to choose complicity with corporate greed that uses HCPs to undermine their professional duties, which significantly increases the risk of experiencing moral injury.

MORAL INJURY AND BURNOUT

In addition to reconciling the definitions of moral injury, the relationship between moral injury and burnout are still being elucidated. We suggest that moral injury and burnout represent independent and potentially interrelated pathways to distress (Figure). Exposure to chronic, inconsonant, and transactional demands, which things like shorter work hours, better self-care, or improved health system operations might mitigate, manifests as burnout. In contrast, moral injury arises when a superior’s actions or a system’s policies and practices—such as justifiable but unnecessary testing, or referral restrictions to prevent revenue leakage—undermine one’s professional obligations to prioritize the patient’s best interest.

If concerns from HCPs about transactional demands are persistently dismissed, such inaction may be perceived as a betrayal, raising the risk of moral injury. Additionally, the resignation or helplessness of moral injury perceived as inescapable may present with emotional exhaustion, ineffectiveness, and depersonalization, all hallmarks of burnout. Both conditions can mediate and moderate the relationship between triggers for workplace distress and resulting psychological, physical, and existential harm.

CONCLUSIONS

Moral injury is increasingly recognized as a source of distress among HCPs, resulting from structural constraints on their ability to deliver optimal care and their own unwillingness to stand up for their patients, their oaths, and their professions.1 Unlike the military, where moral injury is inherent in the contract with society, moral injury in health care (and the relational rupture it connotes) is a signal of systemic dysfunction, fractured trust, and the need for relational repair.

Health care is at a crossroads, experiencing a workforce retention crisis while simultaneously predicting a significant increase in care needs by Baby Boomers over the next 3 decades.

Health care does not have the luxury of experimenting another 30 years with interventions that have limited impact. We must design a new generation of approaches, shaped by lessons learned from the pandemic while acknowledging that prepandemic standards were already failing the workforce. A unified definition of moral injury must be integrated to frame clinician distress alongside burnout, recentering ethical decision making, rather than profit, at the heart of health care. Harmonizing the definitions of moral injury and clarifying the relationship of moral injury with burnout reduces the need for further reinterpretations, allowing for more robust, easily comparable studies focused on identifying risk factors, as well as rapidly implementing effective mitigation strategies.

Moral injury was identified by health care professionals (HCPs) as a driver of occupational distress prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, but the crisis expanded the appeal and investigation of the term.1 HCPs now consider moral injury an essential component of the framework to describe their distress, because using the term burnout alone fails to capture their full experience and has proven resistant to interventions.2 Moral injury goes beyond the transdiagnostic symptoms of exhaustion and cynicism and beyond operational, demand-resource mismatches that characterize burnout. It describes the frustration, anger, and helplessness associated with relational ruptures and the existential threats to a clinician’s professional identity as business interests erode their ability to put their patients’ needs ahead of corporate and health care system obligations.3

Proper characterization of moral injury in health care—separate from the military environments where it originated—is stymied by an ill-defined relationship between 2 definitions of the term and by an unclear relationship between moral injury and the long-standing body of scholarship in burnout. To clarify the concept, inform research agendas, and open avenues for more effective solutions to the crisis of HCP distress, we propose a unified conceptualization of moral injury and its association with burnout in health care.

CONTEXTUAL DISTINCTIONS

It is important to properly distinguish between the original use of moral injury in the military and its expanded use in civilian circumstances. Health care and the military are both professions whereupon donning the “uniform” of a physician—or soldier, sailor, airman, or marine—members must comport with strict expectations of behavior, including the refusal to engage in illegal actions or those contrary to professional ethics. Individuals in both professions acquire a highly specialized body of knowledge and enter an implied contract to provide critical services to society, specifically healing and protection, respectively. Members of both professions are trained to make complex judgments with integrity under conditions of technical and ethical uncertainty, upon which they take highly skilled action. Medical and military professionals must be free to act on their ethical principles, without confounding demands.4 However, the context of each profession’s commitment to society carries different moral implications.

The risk of moral injury is inherent in military service. The military promises protection with an implicit acknowledgment of the need to use lethal force to uphold the agreement. In contrast, HCPs promise healing and care. The military promises to protect our society, with an implicit acknowledgment of the need to use lethal force to uphold the agreement. Some military actions may inflict harm without the hope of benefitting an individual, and are therefore potentially morally injurious. The health care contract with society, promising healing and care, is devoid of inherent moral injury due to harm without potential individual benefit. Therefore, the presence of moral injury in health care settings are warning signs of a dysfunctional environment.

One complex example of the dysfunctional environments is illustrative. The military and health care are among the few industries where supply creates demand. For example, the more bad state actors there are, the more demand for the military. As we have seen since the 1950s, the more technology and therapeutics we create in health care, coupled with a larger share paid for by third parties, the greater the demand for and use of them.5 In a fee for service environment, corporate greed feeds on this reality. In most other environments, more technological and therapeutic options inevitably pit clinicians against multiple other factions: payers, who do not want to underwrite them; patients, who sometimes demand them without justification or later rail against spiraling health care costs; and administrators, especially in capitated systems, who watch their bottom lines erode. The moral injury risk in this instance demands a collective conversation among stakeholders regarding the structural determinants of health—how we choose to distribute limited resources. The intermediary of moral injury is a useful measure of the harm that results from ignoring or avoiding such challenges.

HARMONIZING DEFINITIONS

Moral injury is inherently nuanced. The 2 dominant definitions arise from work with combat veterans and create additional and perhaps unnecessary complexity. Unifying these 2 definitions eliminates inadvertent confusion, preventing the risk of unbridled interdisciplinary investigation which leads to a lack of precision in the meaning of moral injury and other related concepts, such as burnout.6

The first definition was developed by Jonathan Shay in 1994 and outlines 3 necessarycomponents, viewing the violator as a powerholder: (1) betrayal of what is right, (2) by someone who holds legitimate authority, (3) in a high stakes situation.7 Litz and colleagues describe moral injury another way: “Perpetrating, failing to prevent, bearing witness to, or learning about acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.”8 The violator is posited to be either the self or others.

Rather than representing “self” or “other” imposed moral injury, we propose the 2 definitions are related as exposure (ie, the perceived betrayal) and response (ie, the resulting transgression). An individual who experiences a betrayal by a legitimate authority has an opportunity to choose their response. They may acquiesce and transgress their moral beliefs (eg, their oath to provide ethical health care), or they could refuse, by speaking out, or in some way resisting the authority’s betrayal. The case of Ray Brovont is a useful illustration of reconciling the definitions (Box).9

Myriad factors—known as potentially morally injurious events—drive moral injury, such as resource-constrained decision making, witnessing the behaviors of colleagues that violate deeply held moral beliefs, questionable billing practices, and more. Each begins with a betrayal. Spotlighting the betrayal, refusing to perpetuate it, or taking actions toward change, may reduce the risk of experiencing moral injury.9 Conversely, acquiescing and transgressing one’s oath, the profession’s covenant with society, increases the risk of experiencing moral injury.8

Many HCPs believe they are not always free to resist betrayal, fearing retaliation, job loss, blacklisting, or worse. They feel constrained by debt accrued while receiving their education, being their household’s primary earner, community ties, practicing a niche specialty that requires working for a tertiary referral center, or perhaps believing the situation will be the same elsewhere. To not stand up or speak out is to choose complicity with corporate greed that uses HCPs to undermine their professional duties, which significantly increases the risk of experiencing moral injury.

MORAL INJURY AND BURNOUT

In addition to reconciling the definitions of moral injury, the relationship between moral injury and burnout are still being elucidated. We suggest that moral injury and burnout represent independent and potentially interrelated pathways to distress (Figure). Exposure to chronic, inconsonant, and transactional demands, which things like shorter work hours, better self-care, or improved health system operations might mitigate, manifests as burnout. In contrast, moral injury arises when a superior’s actions or a system’s policies and practices—such as justifiable but unnecessary testing, or referral restrictions to prevent revenue leakage—undermine one’s professional obligations to prioritize the patient’s best interest.

If concerns from HCPs about transactional demands are persistently dismissed, such inaction may be perceived as a betrayal, raising the risk of moral injury. Additionally, the resignation or helplessness of moral injury perceived as inescapable may present with emotional exhaustion, ineffectiveness, and depersonalization, all hallmarks of burnout. Both conditions can mediate and moderate the relationship between triggers for workplace distress and resulting psychological, physical, and existential harm.

CONCLUSIONS

Moral injury is increasingly recognized as a source of distress among HCPs, resulting from structural constraints on their ability to deliver optimal care and their own unwillingness to stand up for their patients, their oaths, and their professions.1 Unlike the military, where moral injury is inherent in the contract with society, moral injury in health care (and the relational rupture it connotes) is a signal of systemic dysfunction, fractured trust, and the need for relational repair.

Health care is at a crossroads, experiencing a workforce retention crisis while simultaneously predicting a significant increase in care needs by Baby Boomers over the next 3 decades.

Health care does not have the luxury of experimenting another 30 years with interventions that have limited impact. We must design a new generation of approaches, shaped by lessons learned from the pandemic while acknowledging that prepandemic standards were already failing the workforce. A unified definition of moral injury must be integrated to frame clinician distress alongside burnout, recentering ethical decision making, rather than profit, at the heart of health care. Harmonizing the definitions of moral injury and clarifying the relationship of moral injury with burnout reduces the need for further reinterpretations, allowing for more robust, easily comparable studies focused on identifying risk factors, as well as rapidly implementing effective mitigation strategies.

1. Griffin BJ, Weber MC, Hinkson KD, et al. Toward a dimensional contextual model of moral injury: a scoping review on healthcare workers. Curr Treat Options Psych. 2023;10:199-216. doi:10.1007/s40501-023-00296-4

2. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; National Academy of Medicine; Committee on Systems Approaches to Improve Patient Care by Supporting Clinician Well-Being. Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being. The National Academies Press; 2019. doi:10.17226/25521

3. Dean W, Talbot S, Dean A. Reframing clinician distress: moral injury not burnout. Fed Pract. 2019;36(9):400-402.

4. Gardner HE, Schulman LS. The professions in America today: crucial but fragile. Daedalus. 2005;134(3):13-18. doi:10.1162/0011526054622132

5. Fuchs VR. Major trends in the U.S. health economy since 1950. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):973-977. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1200478

6. Molendijk T. Warnings against romanticising moral injury. Br J Psychiatry. 2022;220(1):1-3. doi:10.1192/bjp.2021.114

7. Shay J. Moral injury. Psychoanalytic Psychol. 2014;31(2):182-191. doi:10.1037/a0036090

8. Litz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, et al. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: a preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8):695-706. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003

9. Brovont v KS-I Med. Servs., P.A., 622 SW3d 671 (Mo Ct App 2020).

1. Griffin BJ, Weber MC, Hinkson KD, et al. Toward a dimensional contextual model of moral injury: a scoping review on healthcare workers. Curr Treat Options Psych. 2023;10:199-216. doi:10.1007/s40501-023-00296-4

2. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; National Academy of Medicine; Committee on Systems Approaches to Improve Patient Care by Supporting Clinician Well-Being. Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being. The National Academies Press; 2019. doi:10.17226/25521

3. Dean W, Talbot S, Dean A. Reframing clinician distress: moral injury not burnout. Fed Pract. 2019;36(9):400-402.

4. Gardner HE, Schulman LS. The professions in America today: crucial but fragile. Daedalus. 2005;134(3):13-18. doi:10.1162/0011526054622132

5. Fuchs VR. Major trends in the U.S. health economy since 1950. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):973-977. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1200478

6. Molendijk T. Warnings against romanticising moral injury. Br J Psychiatry. 2022;220(1):1-3. doi:10.1192/bjp.2021.114

7. Shay J. Moral injury. Psychoanalytic Psychol. 2014;31(2):182-191. doi:10.1037/a0036090

8. Litz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, et al. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: a preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8):695-706. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003

9. Brovont v KS-I Med. Servs., P.A., 622 SW3d 671 (Mo Ct App 2020).

How to Cure Hedonic Eating?

Logan is a 62-year-old woman who has reached the pinnacle of professional success. She started a $50 million consumer products company and, after selling it, managed to develop another successful brand. She is healthy and happily married, with four adult children. And yet, despite all her achievements and stable family life, Logan was always bothered by her inability to lose weight.

Despite peddling in beauty, she felt perpetually overweight and, frankly, unattractive. She has no family history of obesity, drinks minimal alcohol, and follows an (allegedly) healthy diet. Logan had tried “everything” to lose weight — human growth hormone injections (not prescribed by me), Ozempic-like medications, Belviq, etc. — all to no avail.

Here’s the catch: After she finished with her busy days of meetings and spreadsheets, Logan sat down to read through countless emails and rewarded herself with all her favorite foods. Without realizing it, she often doubled her daily caloric intake in one sitting. She wasn’t hungry in these moments, rather just a little worn out and perhaps a little careless. She then proceeded to email her doctor (me) to report on this endless cycle of unwanted behavior.

In January 2024, a novel study from Turkey examined the relationship between hedonic eating, self-condemnation, and self-esteem. Surprising to no one, the study determined that higher hedonic hunger scores were associated with lower self-esteem and an increased propensity to self-stigmatize.

Oprah could have handily predicted this conclusion. Many years ago, she described food as a fake friend: Perhaps you’ve had a long and difficult day. While you’re busy eating your feelings, the heaping plate of pasta feels like your best buddy in the world. However, the moment the plate is empty, you realize that you feel worse than before. Not only do you have to unbutton your new jeans, but you also realize that you have just lost your ability to self-regulate.

While the positive association between hedonic eating and low self-esteem may seem self-evident, the solution is less obvious. Mindfulness is one possible approach to this issue. Mindfulness has been described as “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally” and has existed for thousands of years. Mindful eating, in particular, involves paying close attention to our food choices and how they affect our emotions, and typically includes some combination of:

- Slowing down eating/chewing thoroughly

- Eliminating distractions such as TV, computers, and phones — perhaps even eating in silence

- Eating only until physically satiated

- Distinguishing between true hunger and cravings

- Noticing the texture, flavors, and smell of food

- Paying attention to the effect of food on your mood

- Appreciating food

In our society, where processed food is so readily available and stress is so ubiquitous, eating can become a hedonic and fast-paced activity. Our brains don’t have time to process our bodies’ signals of fullness and, as a result, we often ingest many more calories than we need for a healthy lifestyle.

If mindless eating is part of the problem, mindful eating is part of the solution. Indeed, a meta-review of 10 scientific studies showed that mindful eating is as effective as conventional weight loss programs in regard to body mass index and waist circumference. On the basis of these studies — as well as some good old-fashioned common sense — intuitive eating is an important component of sustainable weight reduction.

Eventually, I convinced Logan to meet up with the psychologist in our group who specializes in emotional eating. Through weekly cognitive-behavioral therapy sessions, Logan was able to understand the impetus behind her self-defeating behavior and has finally been able to reverse some of her lifelong habits. Once she started practicing mindful eating, I was able to introduce Ozempic, and now Logan is happily shedding several pounds a week.

Dr. Messer has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Messer is clinical assistant professor, Mount Sinai School of Medicine and associate professor, Hofstra School of Medicine, both in New York City.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Logan is a 62-year-old woman who has reached the pinnacle of professional success. She started a $50 million consumer products company and, after selling it, managed to develop another successful brand. She is healthy and happily married, with four adult children. And yet, despite all her achievements and stable family life, Logan was always bothered by her inability to lose weight.

Despite peddling in beauty, she felt perpetually overweight and, frankly, unattractive. She has no family history of obesity, drinks minimal alcohol, and follows an (allegedly) healthy diet. Logan had tried “everything” to lose weight — human growth hormone injections (not prescribed by me), Ozempic-like medications, Belviq, etc. — all to no avail.

Here’s the catch: After she finished with her busy days of meetings and spreadsheets, Logan sat down to read through countless emails and rewarded herself with all her favorite foods. Without realizing it, she often doubled her daily caloric intake in one sitting. She wasn’t hungry in these moments, rather just a little worn out and perhaps a little careless. She then proceeded to email her doctor (me) to report on this endless cycle of unwanted behavior.

In January 2024, a novel study from Turkey examined the relationship between hedonic eating, self-condemnation, and self-esteem. Surprising to no one, the study determined that higher hedonic hunger scores were associated with lower self-esteem and an increased propensity to self-stigmatize.

Oprah could have handily predicted this conclusion. Many years ago, she described food as a fake friend: Perhaps you’ve had a long and difficult day. While you’re busy eating your feelings, the heaping plate of pasta feels like your best buddy in the world. However, the moment the plate is empty, you realize that you feel worse than before. Not only do you have to unbutton your new jeans, but you also realize that you have just lost your ability to self-regulate.

While the positive association between hedonic eating and low self-esteem may seem self-evident, the solution is less obvious. Mindfulness is one possible approach to this issue. Mindfulness has been described as “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally” and has existed for thousands of years. Mindful eating, in particular, involves paying close attention to our food choices and how they affect our emotions, and typically includes some combination of:

- Slowing down eating/chewing thoroughly

- Eliminating distractions such as TV, computers, and phones — perhaps even eating in silence

- Eating only until physically satiated

- Distinguishing between true hunger and cravings

- Noticing the texture, flavors, and smell of food

- Paying attention to the effect of food on your mood

- Appreciating food

In our society, where processed food is so readily available and stress is so ubiquitous, eating can become a hedonic and fast-paced activity. Our brains don’t have time to process our bodies’ signals of fullness and, as a result, we often ingest many more calories than we need for a healthy lifestyle.

If mindless eating is part of the problem, mindful eating is part of the solution. Indeed, a meta-review of 10 scientific studies showed that mindful eating is as effective as conventional weight loss programs in regard to body mass index and waist circumference. On the basis of these studies — as well as some good old-fashioned common sense — intuitive eating is an important component of sustainable weight reduction.

Eventually, I convinced Logan to meet up with the psychologist in our group who specializes in emotional eating. Through weekly cognitive-behavioral therapy sessions, Logan was able to understand the impetus behind her self-defeating behavior and has finally been able to reverse some of her lifelong habits. Once she started practicing mindful eating, I was able to introduce Ozempic, and now Logan is happily shedding several pounds a week.

Dr. Messer has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Messer is clinical assistant professor, Mount Sinai School of Medicine and associate professor, Hofstra School of Medicine, both in New York City.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Logan is a 62-year-old woman who has reached the pinnacle of professional success. She started a $50 million consumer products company and, after selling it, managed to develop another successful brand. She is healthy and happily married, with four adult children. And yet, despite all her achievements and stable family life, Logan was always bothered by her inability to lose weight.

Despite peddling in beauty, she felt perpetually overweight and, frankly, unattractive. She has no family history of obesity, drinks minimal alcohol, and follows an (allegedly) healthy diet. Logan had tried “everything” to lose weight — human growth hormone injections (not prescribed by me), Ozempic-like medications, Belviq, etc. — all to no avail.

Here’s the catch: After she finished with her busy days of meetings and spreadsheets, Logan sat down to read through countless emails and rewarded herself with all her favorite foods. Without realizing it, she often doubled her daily caloric intake in one sitting. She wasn’t hungry in these moments, rather just a little worn out and perhaps a little careless. She then proceeded to email her doctor (me) to report on this endless cycle of unwanted behavior.

In January 2024, a novel study from Turkey examined the relationship between hedonic eating, self-condemnation, and self-esteem. Surprising to no one, the study determined that higher hedonic hunger scores were associated with lower self-esteem and an increased propensity to self-stigmatize.

Oprah could have handily predicted this conclusion. Many years ago, she described food as a fake friend: Perhaps you’ve had a long and difficult day. While you’re busy eating your feelings, the heaping plate of pasta feels like your best buddy in the world. However, the moment the plate is empty, you realize that you feel worse than before. Not only do you have to unbutton your new jeans, but you also realize that you have just lost your ability to self-regulate.

While the positive association between hedonic eating and low self-esteem may seem self-evident, the solution is less obvious. Mindfulness is one possible approach to this issue. Mindfulness has been described as “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally” and has existed for thousands of years. Mindful eating, in particular, involves paying close attention to our food choices and how they affect our emotions, and typically includes some combination of:

- Slowing down eating/chewing thoroughly

- Eliminating distractions such as TV, computers, and phones — perhaps even eating in silence

- Eating only until physically satiated

- Distinguishing between true hunger and cravings

- Noticing the texture, flavors, and smell of food

- Paying attention to the effect of food on your mood

- Appreciating food

In our society, where processed food is so readily available and stress is so ubiquitous, eating can become a hedonic and fast-paced activity. Our brains don’t have time to process our bodies’ signals of fullness and, as a result, we often ingest many more calories than we need for a healthy lifestyle.

If mindless eating is part of the problem, mindful eating is part of the solution. Indeed, a meta-review of 10 scientific studies showed that mindful eating is as effective as conventional weight loss programs in regard to body mass index and waist circumference. On the basis of these studies — as well as some good old-fashioned common sense — intuitive eating is an important component of sustainable weight reduction.

Eventually, I convinced Logan to meet up with the psychologist in our group who specializes in emotional eating. Through weekly cognitive-behavioral therapy sessions, Logan was able to understand the impetus behind her self-defeating behavior and has finally been able to reverse some of her lifelong habits. Once she started practicing mindful eating, I was able to introduce Ozempic, and now Logan is happily shedding several pounds a week.

Dr. Messer has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Messer is clinical assistant professor, Mount Sinai School of Medicine and associate professor, Hofstra School of Medicine, both in New York City.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Why We Need to Know About Our Patients’ History of Trauma

This case is a little out of the ordinary, but we would love to find out how readers would handle it.

Diana is a 51-year-old woman with a history of depression, obesity, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and coronary artery disease. She has come in for a routine visit for her chronic illnesses. She seems very distant and has a flat affect during the initial interview. When you ask about any recent stressful events, she begins crying and explains that her daughter was just deported, leaving behind a child and boyfriend.

Their country of origin suffers from chronic instability and violence. Diana’s father was murdered there, and Diana was the victim of sexual assault. “I escaped when I was 18, and I tried to never look back. Until now.” Diana is very worried about her daughter’s return to that country. “I don’t want her to have to endure what I have endured.”

You spend some time discussing the patient’s mental health burden and identify a counselor and online resources that might help. You wonder if Diana’s adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) might have contributed to some of her physical illnesses.

ACEs and Adult Health

One of the most pronounced and straightforward links is that between ACEs and depression. In the Southern Community Cohort Study of more than 38,200 US adults, the highest odds ratio between ACEs and chronic disease was for depression. Persons who reported more than three ACEs had about a twofold increase in the risk for depression compared with persons without ACEs. There was a monotonic increase in the risk for depression and other chronic illnesses as the burden of ACEs increased.

In another study from the United Kingdom, each additional ACE was associated with a significant 11% increase in the risk for incident diabetes during adulthood. Researchers found that both depression symptoms and cardiometabolic dysfunction mediated the effects of ACEs in promoting higher rates of diabetes.

Depression and diabetes are significant risk factors for coronary artery disease, so it is not surprising that ACEs are also associated with a higher risk for coronary events. A review by Godoy and colleagues described how ACEs promote neuroendocrine, autonomic, and inflammatory dysfunction, which in turn leads to higher rates of traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes and obesity. Ultimately, the presence of four or more ACEs is associated with more than a twofold higher risk for cardiovascular disease compared with no ACEs.

Many of the pathologic processes that promote cardiovascular disease also increase the risk for dementia. Could the reach of ACEs span decades to promote a higher risk for dementia among older adults? A study by Yuan and colleagues of 7222 Chinese adults suggests that the answer is yes. This study divided the cohort into persons with a history of no ACEs, household dysfunction during childhood, or mistreatment during childhood. Child mistreatment was associated with higher rates of diabetes, depression, and cardiovascular disease, as well as an odds ratio of 1.37 (95% CI, 1.12 to 1.68) for cognitive impairment.

The magnitude of the effects ACEs can have on well-being is reinforced by epidemiologic data surrounding ACEs. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 64% of US adults report at least one ACE and 17% experienced at least four ACEs. Risk factors for ACEs include being female, American Indian or Alaska Native, or unemployed.

How do we reduce the impact of ACEs? Prevention is key. The CDC estimates that nearly 2 million cases of adult heart disease and more than 20 million cases of adult depression could be avoided if ACEs were eliminated.

But what is the best means to pragmatically reduce ACEs in our current practice models? How do we discover a history of ACEs in patients, and what are the best practices in managing persons with a positive history? We will cover these critical subjects in a future article, but for now, please provide your own comments and pearls regarding the prevention and management of ACEs.

Dr. Vega, health sciences clinical professor, family medicine, University of California, Irvine, disclosed ties with GlaxoSmithKline and Johnson and Johnson. Ms. Hurtado, MD candidate, University of California, Irvine School of Medicine, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This case is a little out of the ordinary, but we would love to find out how readers would handle it.

Diana is a 51-year-old woman with a history of depression, obesity, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and coronary artery disease. She has come in for a routine visit for her chronic illnesses. She seems very distant and has a flat affect during the initial interview. When you ask about any recent stressful events, she begins crying and explains that her daughter was just deported, leaving behind a child and boyfriend.

Their country of origin suffers from chronic instability and violence. Diana’s father was murdered there, and Diana was the victim of sexual assault. “I escaped when I was 18, and I tried to never look back. Until now.” Diana is very worried about her daughter’s return to that country. “I don’t want her to have to endure what I have endured.”

You spend some time discussing the patient’s mental health burden and identify a counselor and online resources that might help. You wonder if Diana’s adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) might have contributed to some of her physical illnesses.

ACEs and Adult Health

One of the most pronounced and straightforward links is that between ACEs and depression. In the Southern Community Cohort Study of more than 38,200 US adults, the highest odds ratio between ACEs and chronic disease was for depression. Persons who reported more than three ACEs had about a twofold increase in the risk for depression compared with persons without ACEs. There was a monotonic increase in the risk for depression and other chronic illnesses as the burden of ACEs increased.

In another study from the United Kingdom, each additional ACE was associated with a significant 11% increase in the risk for incident diabetes during adulthood. Researchers found that both depression symptoms and cardiometabolic dysfunction mediated the effects of ACEs in promoting higher rates of diabetes.

Depression and diabetes are significant risk factors for coronary artery disease, so it is not surprising that ACEs are also associated with a higher risk for coronary events. A review by Godoy and colleagues described how ACEs promote neuroendocrine, autonomic, and inflammatory dysfunction, which in turn leads to higher rates of traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes and obesity. Ultimately, the presence of four or more ACEs is associated with more than a twofold higher risk for cardiovascular disease compared with no ACEs.

Many of the pathologic processes that promote cardiovascular disease also increase the risk for dementia. Could the reach of ACEs span decades to promote a higher risk for dementia among older adults? A study by Yuan and colleagues of 7222 Chinese adults suggests that the answer is yes. This study divided the cohort into persons with a history of no ACEs, household dysfunction during childhood, or mistreatment during childhood. Child mistreatment was associated with higher rates of diabetes, depression, and cardiovascular disease, as well as an odds ratio of 1.37 (95% CI, 1.12 to 1.68) for cognitive impairment.

The magnitude of the effects ACEs can have on well-being is reinforced by epidemiologic data surrounding ACEs. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 64% of US adults report at least one ACE and 17% experienced at least four ACEs. Risk factors for ACEs include being female, American Indian or Alaska Native, or unemployed.

How do we reduce the impact of ACEs? Prevention is key. The CDC estimates that nearly 2 million cases of adult heart disease and more than 20 million cases of adult depression could be avoided if ACEs were eliminated.

But what is the best means to pragmatically reduce ACEs in our current practice models? How do we discover a history of ACEs in patients, and what are the best practices in managing persons with a positive history? We will cover these critical subjects in a future article, but for now, please provide your own comments and pearls regarding the prevention and management of ACEs.

Dr. Vega, health sciences clinical professor, family medicine, University of California, Irvine, disclosed ties with GlaxoSmithKline and Johnson and Johnson. Ms. Hurtado, MD candidate, University of California, Irvine School of Medicine, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This case is a little out of the ordinary, but we would love to find out how readers would handle it.

Diana is a 51-year-old woman with a history of depression, obesity, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and coronary artery disease. She has come in for a routine visit for her chronic illnesses. She seems very distant and has a flat affect during the initial interview. When you ask about any recent stressful events, she begins crying and explains that her daughter was just deported, leaving behind a child and boyfriend.

Their country of origin suffers from chronic instability and violence. Diana’s father was murdered there, and Diana was the victim of sexual assault. “I escaped when I was 18, and I tried to never look back. Until now.” Diana is very worried about her daughter’s return to that country. “I don’t want her to have to endure what I have endured.”

You spend some time discussing the patient’s mental health burden and identify a counselor and online resources that might help. You wonder if Diana’s adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) might have contributed to some of her physical illnesses.

ACEs and Adult Health

One of the most pronounced and straightforward links is that between ACEs and depression. In the Southern Community Cohort Study of more than 38,200 US adults, the highest odds ratio between ACEs and chronic disease was for depression. Persons who reported more than three ACEs had about a twofold increase in the risk for depression compared with persons without ACEs. There was a monotonic increase in the risk for depression and other chronic illnesses as the burden of ACEs increased.

In another study from the United Kingdom, each additional ACE was associated with a significant 11% increase in the risk for incident diabetes during adulthood. Researchers found that both depression symptoms and cardiometabolic dysfunction mediated the effects of ACEs in promoting higher rates of diabetes.

Depression and diabetes are significant risk factors for coronary artery disease, so it is not surprising that ACEs are also associated with a higher risk for coronary events. A review by Godoy and colleagues described how ACEs promote neuroendocrine, autonomic, and inflammatory dysfunction, which in turn leads to higher rates of traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes and obesity. Ultimately, the presence of four or more ACEs is associated with more than a twofold higher risk for cardiovascular disease compared with no ACEs.

Many of the pathologic processes that promote cardiovascular disease also increase the risk for dementia. Could the reach of ACEs span decades to promote a higher risk for dementia among older adults? A study by Yuan and colleagues of 7222 Chinese adults suggests that the answer is yes. This study divided the cohort into persons with a history of no ACEs, household dysfunction during childhood, or mistreatment during childhood. Child mistreatment was associated with higher rates of diabetes, depression, and cardiovascular disease, as well as an odds ratio of 1.37 (95% CI, 1.12 to 1.68) for cognitive impairment.

The magnitude of the effects ACEs can have on well-being is reinforced by epidemiologic data surrounding ACEs. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 64% of US adults report at least one ACE and 17% experienced at least four ACEs. Risk factors for ACEs include being female, American Indian or Alaska Native, or unemployed.

How do we reduce the impact of ACEs? Prevention is key. The CDC estimates that nearly 2 million cases of adult heart disease and more than 20 million cases of adult depression could be avoided if ACEs were eliminated.

But what is the best means to pragmatically reduce ACEs in our current practice models? How do we discover a history of ACEs in patients, and what are the best practices in managing persons with a positive history? We will cover these critical subjects in a future article, but for now, please provide your own comments and pearls regarding the prevention and management of ACEs.