User login

Chronic Hyperpigmented Patches on the Legs

The Diagnosis: Drug-Induced Hyperpigmentation

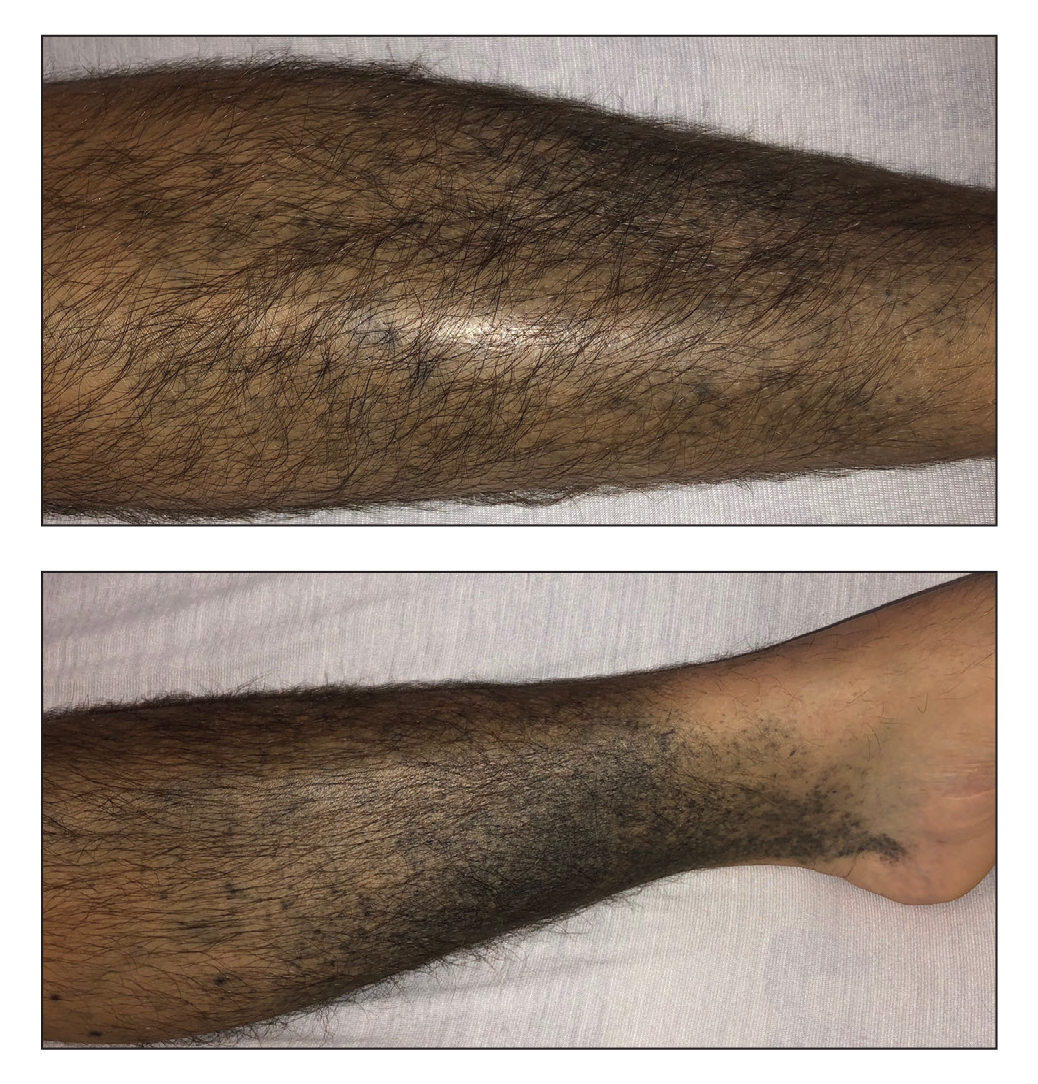

Additional history provided by the patient’s caretaker elucidated an extensive list of medications including chlorpromazine and minocycline, among several others. The caretaker revealed that the patient began treatment for acne vulgaris 2 years prior; despite the acne resolving, therapy was not discontinued. The blue-gray and brown pigmentation on our patient’s shins likely was attributed to a medication he was taking.

Both chlorpromazine and minocycline, among many other medications, are known to cause abnormal pigmentation of the skin.1 Minocycline is a tetracycline antibiotic prescribed for acne and other inflammatory cutaneous conditions. It is highly lipophilic, allowing it to reach high drug concentrations in the skin and nail unit.2 Patients taking minocycline long term and at high doses are at greatest risk for pigment deposition.3,4

Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation is classified into 3 types. Type I describes blue-black deposition of pigment in acne scars and areas of inflammation, typically on facial skin.1,5 Histologically, type I stains positive for Perls Prussian blue, indicating an increased deposition of iron as hemosiderin,1 which likely occurs because minocycline is thought to play a role in defective clearance of hemosiderin from the dermis of injured tissue.5 Type II hyperpigmentation presents as bluegray pigment on the lower legs and occasionally the arms.6,7 Type II stains positive for both Perls Prussian blue and Fontana-Masson, demonstrating hemosiderin and melanin, respectively.6 The third form of hyperpigmentation results in diffuse, dark brown to gray pigmentation with a predilection for sun-exposed areas.8 Histology of type III shows increased pigment in the basal portion of the epidermis and brown-black pigment in macrophages of the dermis. Type III stains positive for Fontana-Masson and negative for Perls Prussian blue. The etiology of hyperpigmentation has been suspected to be caused by minocycline stimulating melanin production and/or deposition of minocycline-melanin complexes in dermal macrophages after a certain drug level; this largely is seen in patients receiving 100 to 200 mg daily as early as 1 year into treatment.8

Chlorpromazine is a typical antipsychotic that causes abnormal skin pigmentation in sun-exposed areas due to increased melanogenesis.9 Similar to type III minocyclineinduced hyperpigmentation, a histologic specimen may stain positive for Fontana-Masson yet negative for Perls Prussian blue. Lal et al10 demonstrated complete resolution of abnormal skin pigmentation within 5 years after stopping chlorpromazine. In contrast, minocyclineinduced hyperpigmentation may be permanent in some cases. There is substantial clinical and histologic overlap for drug-induced hyperpigmentation etiologies; it would behoove the clinician to focus on the most common locations affected and the generalized coloration.

Treatment of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation includes the use of Q-switched lasers, specifically Q-switched ruby and Q-switched alexandrite.11 The use of the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser appears to be ineffective at clearing minocycline-induced pigmentation.7,11 In our patient, minocycline was discontinued immediately. Due to the patient’s critical condition, he deferred all other therapy. Erythema dyschromicum perstans, also referred to as ashy dermatosis, is an idiopathic form of hyperpigmentation.12 Lesions start as blue-gray to ashy gray macules, occasionally surrounded by a slightly erythematous, raised border.

Erythema dyschromicum perstans typically presents on the trunk, face, and arms of patients with Fitzpatrick skin types III and IV; it is considered a variant of lichen planus actinicus.12 Histologically, erythema dyschromicum perstans may mimic lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP); however, subtle differences exist to distinguish the 2 conditions. Erythema dyschromicum perstans demonstrates a mild lichenoid infiltrate, focal basal vacuolization at the dermoepidermal junction, and melanophage deposition.13 In contrast, LPP demonstrates pigmentary incontinence and a more severe inflammatory infiltrate. A perifollicular infiltrate and fibrosis also can be seen in LPP, which may explain the frontal fibrosing alopecia that often precedes LPP.13

Addison disease, also known as primary adrenal insufficiency, can cause diffuse hyperpigmentation in the skin, mucosae, and nail beds. The pigmentation is prominent in regions of naturally increased pigmentation, such as the flexural surfaces and intertriginous areas.14 Patients with adrenal insufficiency will have accompanying weight loss, hypotension, and fatigue, among other symptoms related to deficiency of cortisol and aldosterone. Skin biopsy shows acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, spongiosis, superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, basal melanin deposition, and superficial dermal macrophages.15

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is an uncommon dermatosis that presents with multiple hyperpigmented macules and papules that coalesce to form patches and plaques centrally with reticulation in the periphery.16 Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis commonly presents on the upper trunk, axillae, and neck, though involvement can include flexural surfaces as well as the lower trunk and legs.16,17 Biopsy demonstrates undulating hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, acanthosis, and negative fungal staining.16

Pretibial myxedema most commonly is associated with Graves disease and presents as well-defined thickening and induration with overlying pink or purple-brown papules in the pretibial region.18 An acral surface and mucin deposition within the entire dermis may be appreciated on histology with staining for colloidal iron or Alcian blue.

- Fenske NA, Millns JL, Greer KE. Minocycline-induced pigmentation at sites of cutaneous inflammation. JAMA. 1980;244:1103-1106. doi:10.1001/jama.1980.03310100021021

- Snodgrass A, Motaparthi K. Systemic antibacterial agents. In: Wolverton SE, Wu JJ, eds. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2020:69-98.

- Eisen D, Hakim MD. Minocycline-induced pigmentation. incidence, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 1998;18:431-440. doi:10.2165/00002018-199818060-00004

- Goulden V, Glass D, Cunliffe WJ. Safety of long-term high-dose minocycline in the treatment of acne. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:693-695. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb06972.x

- Basler RS, Kohnen PW. Localized hemosiderosis as a sequela of acne. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1695-1697.

- Ridgway HA, Sonnex TS, Kennedy CT, et al. Hyperpigmentation associated with oral minocycline. Br J Dermatol. 1982;107:95-102. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1982.tb00296.x

- Nisar MS, Iyer K, Brodell RT, et al. Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation: comparison of 3 Q-switched lasers to reverse its effects. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:159-162. doi:10.2147/CCID.S42166

- Simons JJ, Morales A. Minocycline and generalized cutaneous pigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:244-247. doi:10.1016/s0190 -9622(80)80186-1

- Perry TL, Culling CF, Berry K, et al. 7-Hydroxychlorpromazine: potential toxic drug metabolite in psychiatric patients. Science. 1964;146:81-83. doi:10.1126/science.146.3640.81

- Lal S, Bloom D, Silver B, et al. Replacement of chlorpromazine with other neuroleptics: effect on abnormal skin pigmentation and ocular changes. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1993;18:173-177.

- Tsao H, Busam K, Barnhill RL, et al. Treatment of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation with the Q-switched ruby laser. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1250-1251.

- Knox JM, Dodge BG, Freeman RG. Erythema dyschromicum perstans. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:262-272. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1968.01610090034006

- Rutnin S, Udompanich S, Pratumchart N, et al. Ashy dermatosis and lichen planus pigmentosus: the histopathological differences. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:5829185. doi:10.1155/2019/5829185

- Montgomery H, O’Leary PA. Pigmentation of the skin in Addison’s disease, acanthosis nigricans and hemochromatosis. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1930;21:970-984. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1930.01440120072005

- Fernandez-Flores A, Cassarino DS. Histopathologic findings of cutaneous hyperpigmentation in Addison disease and immunostain of the melanocytic population. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:924-927. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000937

- Davis MD, Weenig RH, Camilleri MJ. Confluent and reticulate papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome): a minocycline-responsive dermatosis without evidence for yeast in pathogenesis. a study of 39 patients and a proposal of diagnostic criteria. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:287-293. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06955.x

- Jo S, Park HS, Cho S, et al. Updated diagnosis criteria for confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: a case report. Ann Dermatol. 2014; 26:409-410. doi:10.5021/ad.2014.26.3.409

- Lause M, Kamboj A, Fernandez Faith E. Dermatologic manifestations of endocrine disorders. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6:300-312. doi:10.21037 /tp.2017.09.08

The Diagnosis: Drug-Induced Hyperpigmentation

Additional history provided by the patient’s caretaker elucidated an extensive list of medications including chlorpromazine and minocycline, among several others. The caretaker revealed that the patient began treatment for acne vulgaris 2 years prior; despite the acne resolving, therapy was not discontinued. The blue-gray and brown pigmentation on our patient’s shins likely was attributed to a medication he was taking.

Both chlorpromazine and minocycline, among many other medications, are known to cause abnormal pigmentation of the skin.1 Minocycline is a tetracycline antibiotic prescribed for acne and other inflammatory cutaneous conditions. It is highly lipophilic, allowing it to reach high drug concentrations in the skin and nail unit.2 Patients taking minocycline long term and at high doses are at greatest risk for pigment deposition.3,4

Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation is classified into 3 types. Type I describes blue-black deposition of pigment in acne scars and areas of inflammation, typically on facial skin.1,5 Histologically, type I stains positive for Perls Prussian blue, indicating an increased deposition of iron as hemosiderin,1 which likely occurs because minocycline is thought to play a role in defective clearance of hemosiderin from the dermis of injured tissue.5 Type II hyperpigmentation presents as bluegray pigment on the lower legs and occasionally the arms.6,7 Type II stains positive for both Perls Prussian blue and Fontana-Masson, demonstrating hemosiderin and melanin, respectively.6 The third form of hyperpigmentation results in diffuse, dark brown to gray pigmentation with a predilection for sun-exposed areas.8 Histology of type III shows increased pigment in the basal portion of the epidermis and brown-black pigment in macrophages of the dermis. Type III stains positive for Fontana-Masson and negative for Perls Prussian blue. The etiology of hyperpigmentation has been suspected to be caused by minocycline stimulating melanin production and/or deposition of minocycline-melanin complexes in dermal macrophages after a certain drug level; this largely is seen in patients receiving 100 to 200 mg daily as early as 1 year into treatment.8

Chlorpromazine is a typical antipsychotic that causes abnormal skin pigmentation in sun-exposed areas due to increased melanogenesis.9 Similar to type III minocyclineinduced hyperpigmentation, a histologic specimen may stain positive for Fontana-Masson yet negative for Perls Prussian blue. Lal et al10 demonstrated complete resolution of abnormal skin pigmentation within 5 years after stopping chlorpromazine. In contrast, minocyclineinduced hyperpigmentation may be permanent in some cases. There is substantial clinical and histologic overlap for drug-induced hyperpigmentation etiologies; it would behoove the clinician to focus on the most common locations affected and the generalized coloration.

Treatment of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation includes the use of Q-switched lasers, specifically Q-switched ruby and Q-switched alexandrite.11 The use of the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser appears to be ineffective at clearing minocycline-induced pigmentation.7,11 In our patient, minocycline was discontinued immediately. Due to the patient’s critical condition, he deferred all other therapy. Erythema dyschromicum perstans, also referred to as ashy dermatosis, is an idiopathic form of hyperpigmentation.12 Lesions start as blue-gray to ashy gray macules, occasionally surrounded by a slightly erythematous, raised border.

Erythema dyschromicum perstans typically presents on the trunk, face, and arms of patients with Fitzpatrick skin types III and IV; it is considered a variant of lichen planus actinicus.12 Histologically, erythema dyschromicum perstans may mimic lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP); however, subtle differences exist to distinguish the 2 conditions. Erythema dyschromicum perstans demonstrates a mild lichenoid infiltrate, focal basal vacuolization at the dermoepidermal junction, and melanophage deposition.13 In contrast, LPP demonstrates pigmentary incontinence and a more severe inflammatory infiltrate. A perifollicular infiltrate and fibrosis also can be seen in LPP, which may explain the frontal fibrosing alopecia that often precedes LPP.13

Addison disease, also known as primary adrenal insufficiency, can cause diffuse hyperpigmentation in the skin, mucosae, and nail beds. The pigmentation is prominent in regions of naturally increased pigmentation, such as the flexural surfaces and intertriginous areas.14 Patients with adrenal insufficiency will have accompanying weight loss, hypotension, and fatigue, among other symptoms related to deficiency of cortisol and aldosterone. Skin biopsy shows acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, spongiosis, superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, basal melanin deposition, and superficial dermal macrophages.15

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is an uncommon dermatosis that presents with multiple hyperpigmented macules and papules that coalesce to form patches and plaques centrally with reticulation in the periphery.16 Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis commonly presents on the upper trunk, axillae, and neck, though involvement can include flexural surfaces as well as the lower trunk and legs.16,17 Biopsy demonstrates undulating hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, acanthosis, and negative fungal staining.16

Pretibial myxedema most commonly is associated with Graves disease and presents as well-defined thickening and induration with overlying pink or purple-brown papules in the pretibial region.18 An acral surface and mucin deposition within the entire dermis may be appreciated on histology with staining for colloidal iron or Alcian blue.

The Diagnosis: Drug-Induced Hyperpigmentation

Additional history provided by the patient’s caretaker elucidated an extensive list of medications including chlorpromazine and minocycline, among several others. The caretaker revealed that the patient began treatment for acne vulgaris 2 years prior; despite the acne resolving, therapy was not discontinued. The blue-gray and brown pigmentation on our patient’s shins likely was attributed to a medication he was taking.

Both chlorpromazine and minocycline, among many other medications, are known to cause abnormal pigmentation of the skin.1 Minocycline is a tetracycline antibiotic prescribed for acne and other inflammatory cutaneous conditions. It is highly lipophilic, allowing it to reach high drug concentrations in the skin and nail unit.2 Patients taking minocycline long term and at high doses are at greatest risk for pigment deposition.3,4

Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation is classified into 3 types. Type I describes blue-black deposition of pigment in acne scars and areas of inflammation, typically on facial skin.1,5 Histologically, type I stains positive for Perls Prussian blue, indicating an increased deposition of iron as hemosiderin,1 which likely occurs because minocycline is thought to play a role in defective clearance of hemosiderin from the dermis of injured tissue.5 Type II hyperpigmentation presents as bluegray pigment on the lower legs and occasionally the arms.6,7 Type II stains positive for both Perls Prussian blue and Fontana-Masson, demonstrating hemosiderin and melanin, respectively.6 The third form of hyperpigmentation results in diffuse, dark brown to gray pigmentation with a predilection for sun-exposed areas.8 Histology of type III shows increased pigment in the basal portion of the epidermis and brown-black pigment in macrophages of the dermis. Type III stains positive for Fontana-Masson and negative for Perls Prussian blue. The etiology of hyperpigmentation has been suspected to be caused by minocycline stimulating melanin production and/or deposition of minocycline-melanin complexes in dermal macrophages after a certain drug level; this largely is seen in patients receiving 100 to 200 mg daily as early as 1 year into treatment.8

Chlorpromazine is a typical antipsychotic that causes abnormal skin pigmentation in sun-exposed areas due to increased melanogenesis.9 Similar to type III minocyclineinduced hyperpigmentation, a histologic specimen may stain positive for Fontana-Masson yet negative for Perls Prussian blue. Lal et al10 demonstrated complete resolution of abnormal skin pigmentation within 5 years after stopping chlorpromazine. In contrast, minocyclineinduced hyperpigmentation may be permanent in some cases. There is substantial clinical and histologic overlap for drug-induced hyperpigmentation etiologies; it would behoove the clinician to focus on the most common locations affected and the generalized coloration.

Treatment of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation includes the use of Q-switched lasers, specifically Q-switched ruby and Q-switched alexandrite.11 The use of the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser appears to be ineffective at clearing minocycline-induced pigmentation.7,11 In our patient, minocycline was discontinued immediately. Due to the patient’s critical condition, he deferred all other therapy. Erythema dyschromicum perstans, also referred to as ashy dermatosis, is an idiopathic form of hyperpigmentation.12 Lesions start as blue-gray to ashy gray macules, occasionally surrounded by a slightly erythematous, raised border.

Erythema dyschromicum perstans typically presents on the trunk, face, and arms of patients with Fitzpatrick skin types III and IV; it is considered a variant of lichen planus actinicus.12 Histologically, erythema dyschromicum perstans may mimic lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP); however, subtle differences exist to distinguish the 2 conditions. Erythema dyschromicum perstans demonstrates a mild lichenoid infiltrate, focal basal vacuolization at the dermoepidermal junction, and melanophage deposition.13 In contrast, LPP demonstrates pigmentary incontinence and a more severe inflammatory infiltrate. A perifollicular infiltrate and fibrosis also can be seen in LPP, which may explain the frontal fibrosing alopecia that often precedes LPP.13

Addison disease, also known as primary adrenal insufficiency, can cause diffuse hyperpigmentation in the skin, mucosae, and nail beds. The pigmentation is prominent in regions of naturally increased pigmentation, such as the flexural surfaces and intertriginous areas.14 Patients with adrenal insufficiency will have accompanying weight loss, hypotension, and fatigue, among other symptoms related to deficiency of cortisol and aldosterone. Skin biopsy shows acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, spongiosis, superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, basal melanin deposition, and superficial dermal macrophages.15

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is an uncommon dermatosis that presents with multiple hyperpigmented macules and papules that coalesce to form patches and plaques centrally with reticulation in the periphery.16 Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis commonly presents on the upper trunk, axillae, and neck, though involvement can include flexural surfaces as well as the lower trunk and legs.16,17 Biopsy demonstrates undulating hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, acanthosis, and negative fungal staining.16

Pretibial myxedema most commonly is associated with Graves disease and presents as well-defined thickening and induration with overlying pink or purple-brown papules in the pretibial region.18 An acral surface and mucin deposition within the entire dermis may be appreciated on histology with staining for colloidal iron or Alcian blue.

- Fenske NA, Millns JL, Greer KE. Minocycline-induced pigmentation at sites of cutaneous inflammation. JAMA. 1980;244:1103-1106. doi:10.1001/jama.1980.03310100021021

- Snodgrass A, Motaparthi K. Systemic antibacterial agents. In: Wolverton SE, Wu JJ, eds. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2020:69-98.

- Eisen D, Hakim MD. Minocycline-induced pigmentation. incidence, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 1998;18:431-440. doi:10.2165/00002018-199818060-00004

- Goulden V, Glass D, Cunliffe WJ. Safety of long-term high-dose minocycline in the treatment of acne. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:693-695. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb06972.x

- Basler RS, Kohnen PW. Localized hemosiderosis as a sequela of acne. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1695-1697.

- Ridgway HA, Sonnex TS, Kennedy CT, et al. Hyperpigmentation associated with oral minocycline. Br J Dermatol. 1982;107:95-102. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1982.tb00296.x

- Nisar MS, Iyer K, Brodell RT, et al. Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation: comparison of 3 Q-switched lasers to reverse its effects. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:159-162. doi:10.2147/CCID.S42166

- Simons JJ, Morales A. Minocycline and generalized cutaneous pigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:244-247. doi:10.1016/s0190 -9622(80)80186-1

- Perry TL, Culling CF, Berry K, et al. 7-Hydroxychlorpromazine: potential toxic drug metabolite in psychiatric patients. Science. 1964;146:81-83. doi:10.1126/science.146.3640.81

- Lal S, Bloom D, Silver B, et al. Replacement of chlorpromazine with other neuroleptics: effect on abnormal skin pigmentation and ocular changes. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1993;18:173-177.

- Tsao H, Busam K, Barnhill RL, et al. Treatment of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation with the Q-switched ruby laser. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1250-1251.

- Knox JM, Dodge BG, Freeman RG. Erythema dyschromicum perstans. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:262-272. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1968.01610090034006

- Rutnin S, Udompanich S, Pratumchart N, et al. Ashy dermatosis and lichen planus pigmentosus: the histopathological differences. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:5829185. doi:10.1155/2019/5829185

- Montgomery H, O’Leary PA. Pigmentation of the skin in Addison’s disease, acanthosis nigricans and hemochromatosis. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1930;21:970-984. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1930.01440120072005

- Fernandez-Flores A, Cassarino DS. Histopathologic findings of cutaneous hyperpigmentation in Addison disease and immunostain of the melanocytic population. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:924-927. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000937

- Davis MD, Weenig RH, Camilleri MJ. Confluent and reticulate papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome): a minocycline-responsive dermatosis without evidence for yeast in pathogenesis. a study of 39 patients and a proposal of diagnostic criteria. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:287-293. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06955.x

- Jo S, Park HS, Cho S, et al. Updated diagnosis criteria for confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: a case report. Ann Dermatol. 2014; 26:409-410. doi:10.5021/ad.2014.26.3.409

- Lause M, Kamboj A, Fernandez Faith E. Dermatologic manifestations of endocrine disorders. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6:300-312. doi:10.21037 /tp.2017.09.08

- Fenske NA, Millns JL, Greer KE. Minocycline-induced pigmentation at sites of cutaneous inflammation. JAMA. 1980;244:1103-1106. doi:10.1001/jama.1980.03310100021021

- Snodgrass A, Motaparthi K. Systemic antibacterial agents. In: Wolverton SE, Wu JJ, eds. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2020:69-98.

- Eisen D, Hakim MD. Minocycline-induced pigmentation. incidence, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 1998;18:431-440. doi:10.2165/00002018-199818060-00004

- Goulden V, Glass D, Cunliffe WJ. Safety of long-term high-dose minocycline in the treatment of acne. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:693-695. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb06972.x

- Basler RS, Kohnen PW. Localized hemosiderosis as a sequela of acne. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1695-1697.

- Ridgway HA, Sonnex TS, Kennedy CT, et al. Hyperpigmentation associated with oral minocycline. Br J Dermatol. 1982;107:95-102. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1982.tb00296.x

- Nisar MS, Iyer K, Brodell RT, et al. Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation: comparison of 3 Q-switched lasers to reverse its effects. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:159-162. doi:10.2147/CCID.S42166

- Simons JJ, Morales A. Minocycline and generalized cutaneous pigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:244-247. doi:10.1016/s0190 -9622(80)80186-1

- Perry TL, Culling CF, Berry K, et al. 7-Hydroxychlorpromazine: potential toxic drug metabolite in psychiatric patients. Science. 1964;146:81-83. doi:10.1126/science.146.3640.81

- Lal S, Bloom D, Silver B, et al. Replacement of chlorpromazine with other neuroleptics: effect on abnormal skin pigmentation and ocular changes. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1993;18:173-177.

- Tsao H, Busam K, Barnhill RL, et al. Treatment of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation with the Q-switched ruby laser. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1250-1251.

- Knox JM, Dodge BG, Freeman RG. Erythema dyschromicum perstans. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:262-272. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1968.01610090034006

- Rutnin S, Udompanich S, Pratumchart N, et al. Ashy dermatosis and lichen planus pigmentosus: the histopathological differences. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:5829185. doi:10.1155/2019/5829185

- Montgomery H, O’Leary PA. Pigmentation of the skin in Addison’s disease, acanthosis nigricans and hemochromatosis. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1930;21:970-984. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1930.01440120072005

- Fernandez-Flores A, Cassarino DS. Histopathologic findings of cutaneous hyperpigmentation in Addison disease and immunostain of the melanocytic population. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:924-927. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000937

- Davis MD, Weenig RH, Camilleri MJ. Confluent and reticulate papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome): a minocycline-responsive dermatosis without evidence for yeast in pathogenesis. a study of 39 patients and a proposal of diagnostic criteria. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:287-293. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06955.x

- Jo S, Park HS, Cho S, et al. Updated diagnosis criteria for confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: a case report. Ann Dermatol. 2014; 26:409-410. doi:10.5021/ad.2014.26.3.409

- Lause M, Kamboj A, Fernandez Faith E. Dermatologic manifestations of endocrine disorders. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6:300-312. doi:10.21037 /tp.2017.09.08

A 37-year-old man with a history of cerebral palsy, bipolar disorder, and impulse control disorder presented to the emergency department with breathing difficulty and worsening malaise. The patient subsequently was intubated due to hypoxic respiratory failure and was found to be positive for SARS-CoV-2. He was admitted to the intensive care unit, and dermatology was consulted due to concern that the cutaneous findings were demonstrative of a vasculitic process. Physical examination revealed diffuse, symmetric, dark brown to blue-gray macules coalescing into patches on the anterior tibia (top) and covering the entire lower leg (bottom). The patches were mottled and did not blanch with pressure. According to the patient’s caretaker, the leg hyperpigmentation had been present for 2 years.

Acid series: Lactic acid

One of the most commonly used organic acids used on the skin, lactic acid, has been used for over 3 decades. Originally derived from milk or plant-derived sugars, this gentle exfoliating acid can be used in peels, serums, masks, and toners, and has the additional benefit of hydrating the skin. Lactic acid is formulated in concentrations from 2% to 50%; however, because of its large molecular size, it doesn’t penetrate the deeper layers of the dermis to the same extent as the other alpha-hydroxy acids (AHAs), such as glycolic acid. Thus, it is one of the gentler exfoliants and one that can be used in sensitive skin or darker skin types.

Despite its mild peeling effects, lactic acid is best used to treat xerotic skin because of its function as a humectant, drawing moisture into the stratum corneum. Similar to the other AHAs, lactic acid has also been shown to decrease melanogenesis and is a gentle treatment for skin hyperpigmentation, particularly in skin of color. Side effects include peeling, stinging, erythema, photosensitivity, and hyperpigmentation when improperly used.

Very little clinical research has been reported in the last 20 years as to the uses and benefits of lactic acid in skincare. In my clinical experience, daily use of lactic acid is more effective and has more long-term benefits for hydration and rejuvenation of the skin than the other AHAs. Concentrations of 10%-15% used daily on the skin as a mild exfoliant and humectant have shown to improve texture, decrease pigmentation and improve fine lines – without thinning of the skin seen with the deeper dermal penetrating acids.

Confusion in the market has also risen as many over-the-counter brands have included ammonium lactate in their portfolio of moisturizers. Ammonium lactate is a combination of ammonium hydroxide and lactic acid, or the salt of lactic acid. A comparative study evaluating the difference between 5% lactic acid and 12% ammonium lactate for the treatment of xerosis showed that ammonium lactate was significantly more effective at reducing xerosis. It is widely used in the treatment of keratosis pilaris, calluses, xerosis, and ichthyosis.

Widespread use of lactic acid has not gotten as much glory as that of glycolic acid. However, in clinical practice, its functions are more widespread. It is a much safer acid to use, and its added benefit of increasing hydration of the skin is crucial in its long-term use for both photoaging and the prevention of wrinkles. With any acid, the exfoliating properties must be treated with adequate hydration and barrier repair.

The intrinsic moisturizing effect of lactic acid makes it a much more well-rounded acid and that can be used for longer periods of time in a broader spectrum of patients.

Dr. Lily Talakoub and Dr. Naissan O. Wesley are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

One of the most commonly used organic acids used on the skin, lactic acid, has been used for over 3 decades. Originally derived from milk or plant-derived sugars, this gentle exfoliating acid can be used in peels, serums, masks, and toners, and has the additional benefit of hydrating the skin. Lactic acid is formulated in concentrations from 2% to 50%; however, because of its large molecular size, it doesn’t penetrate the deeper layers of the dermis to the same extent as the other alpha-hydroxy acids (AHAs), such as glycolic acid. Thus, it is one of the gentler exfoliants and one that can be used in sensitive skin or darker skin types.

Despite its mild peeling effects, lactic acid is best used to treat xerotic skin because of its function as a humectant, drawing moisture into the stratum corneum. Similar to the other AHAs, lactic acid has also been shown to decrease melanogenesis and is a gentle treatment for skin hyperpigmentation, particularly in skin of color. Side effects include peeling, stinging, erythema, photosensitivity, and hyperpigmentation when improperly used.

Very little clinical research has been reported in the last 20 years as to the uses and benefits of lactic acid in skincare. In my clinical experience, daily use of lactic acid is more effective and has more long-term benefits for hydration and rejuvenation of the skin than the other AHAs. Concentrations of 10%-15% used daily on the skin as a mild exfoliant and humectant have shown to improve texture, decrease pigmentation and improve fine lines – without thinning of the skin seen with the deeper dermal penetrating acids.

Confusion in the market has also risen as many over-the-counter brands have included ammonium lactate in their portfolio of moisturizers. Ammonium lactate is a combination of ammonium hydroxide and lactic acid, or the salt of lactic acid. A comparative study evaluating the difference between 5% lactic acid and 12% ammonium lactate for the treatment of xerosis showed that ammonium lactate was significantly more effective at reducing xerosis. It is widely used in the treatment of keratosis pilaris, calluses, xerosis, and ichthyosis.

Widespread use of lactic acid has not gotten as much glory as that of glycolic acid. However, in clinical practice, its functions are more widespread. It is a much safer acid to use, and its added benefit of increasing hydration of the skin is crucial in its long-term use for both photoaging and the prevention of wrinkles. With any acid, the exfoliating properties must be treated with adequate hydration and barrier repair.

The intrinsic moisturizing effect of lactic acid makes it a much more well-rounded acid and that can be used for longer periods of time in a broader spectrum of patients.

Dr. Lily Talakoub and Dr. Naissan O. Wesley are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

One of the most commonly used organic acids used on the skin, lactic acid, has been used for over 3 decades. Originally derived from milk or plant-derived sugars, this gentle exfoliating acid can be used in peels, serums, masks, and toners, and has the additional benefit of hydrating the skin. Lactic acid is formulated in concentrations from 2% to 50%; however, because of its large molecular size, it doesn’t penetrate the deeper layers of the dermis to the same extent as the other alpha-hydroxy acids (AHAs), such as glycolic acid. Thus, it is one of the gentler exfoliants and one that can be used in sensitive skin or darker skin types.

Despite its mild peeling effects, lactic acid is best used to treat xerotic skin because of its function as a humectant, drawing moisture into the stratum corneum. Similar to the other AHAs, lactic acid has also been shown to decrease melanogenesis and is a gentle treatment for skin hyperpigmentation, particularly in skin of color. Side effects include peeling, stinging, erythema, photosensitivity, and hyperpigmentation when improperly used.

Very little clinical research has been reported in the last 20 years as to the uses and benefits of lactic acid in skincare. In my clinical experience, daily use of lactic acid is more effective and has more long-term benefits for hydration and rejuvenation of the skin than the other AHAs. Concentrations of 10%-15% used daily on the skin as a mild exfoliant and humectant have shown to improve texture, decrease pigmentation and improve fine lines – without thinning of the skin seen with the deeper dermal penetrating acids.

Confusion in the market has also risen as many over-the-counter brands have included ammonium lactate in their portfolio of moisturizers. Ammonium lactate is a combination of ammonium hydroxide and lactic acid, or the salt of lactic acid. A comparative study evaluating the difference between 5% lactic acid and 12% ammonium lactate for the treatment of xerosis showed that ammonium lactate was significantly more effective at reducing xerosis. It is widely used in the treatment of keratosis pilaris, calluses, xerosis, and ichthyosis.

Widespread use of lactic acid has not gotten as much glory as that of glycolic acid. However, in clinical practice, its functions are more widespread. It is a much safer acid to use, and its added benefit of increasing hydration of the skin is crucial in its long-term use for both photoaging and the prevention of wrinkles. With any acid, the exfoliating properties must be treated with adequate hydration and barrier repair.

The intrinsic moisturizing effect of lactic acid makes it a much more well-rounded acid and that can be used for longer periods of time in a broader spectrum of patients.

Dr. Lily Talakoub and Dr. Naissan O. Wesley are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

Acne Vulgaris

THE COMPARISON

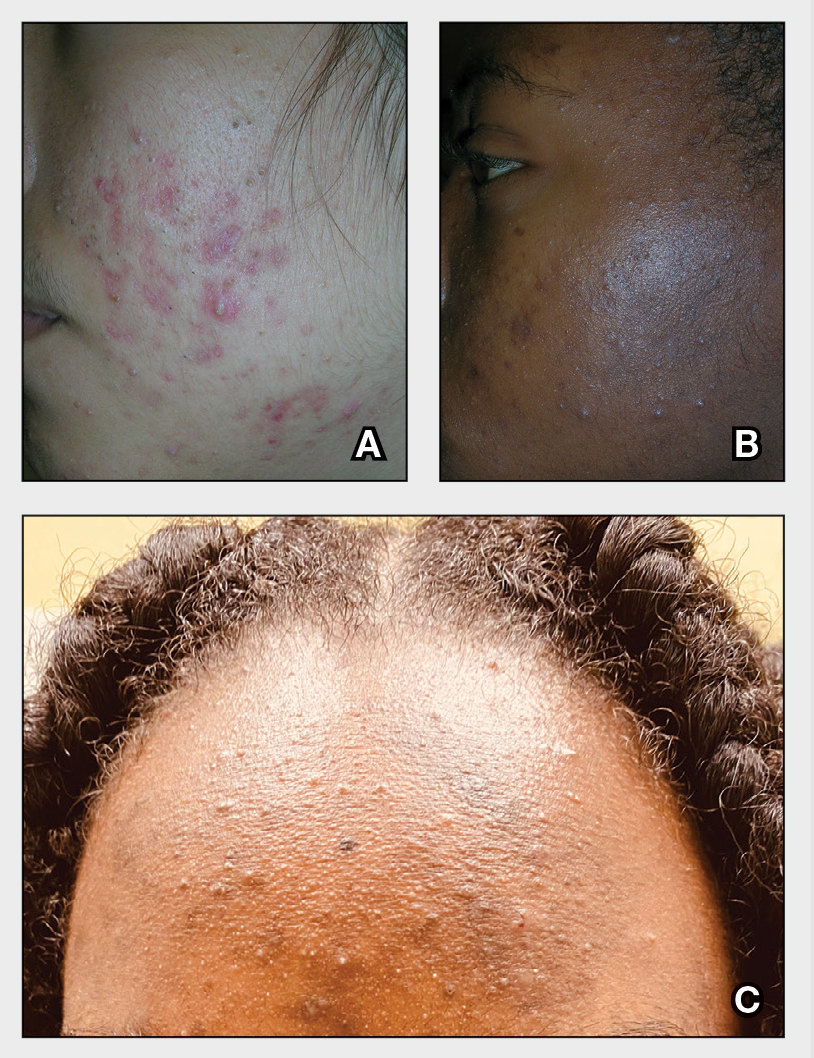

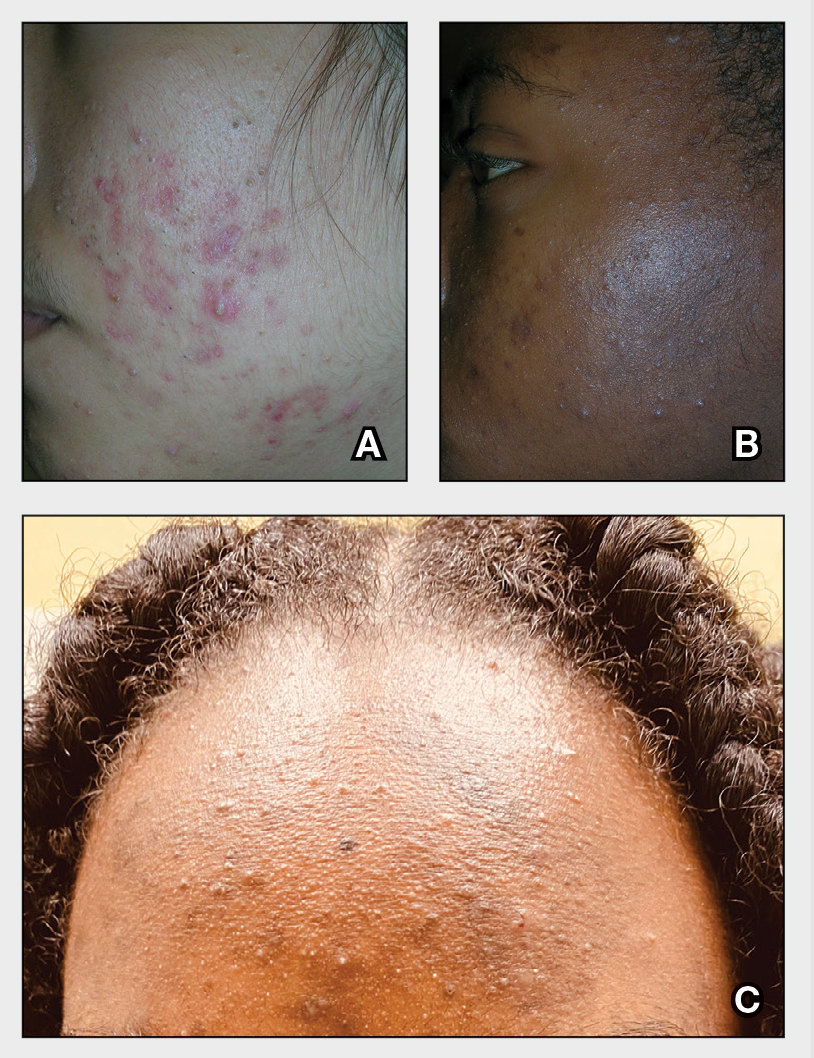

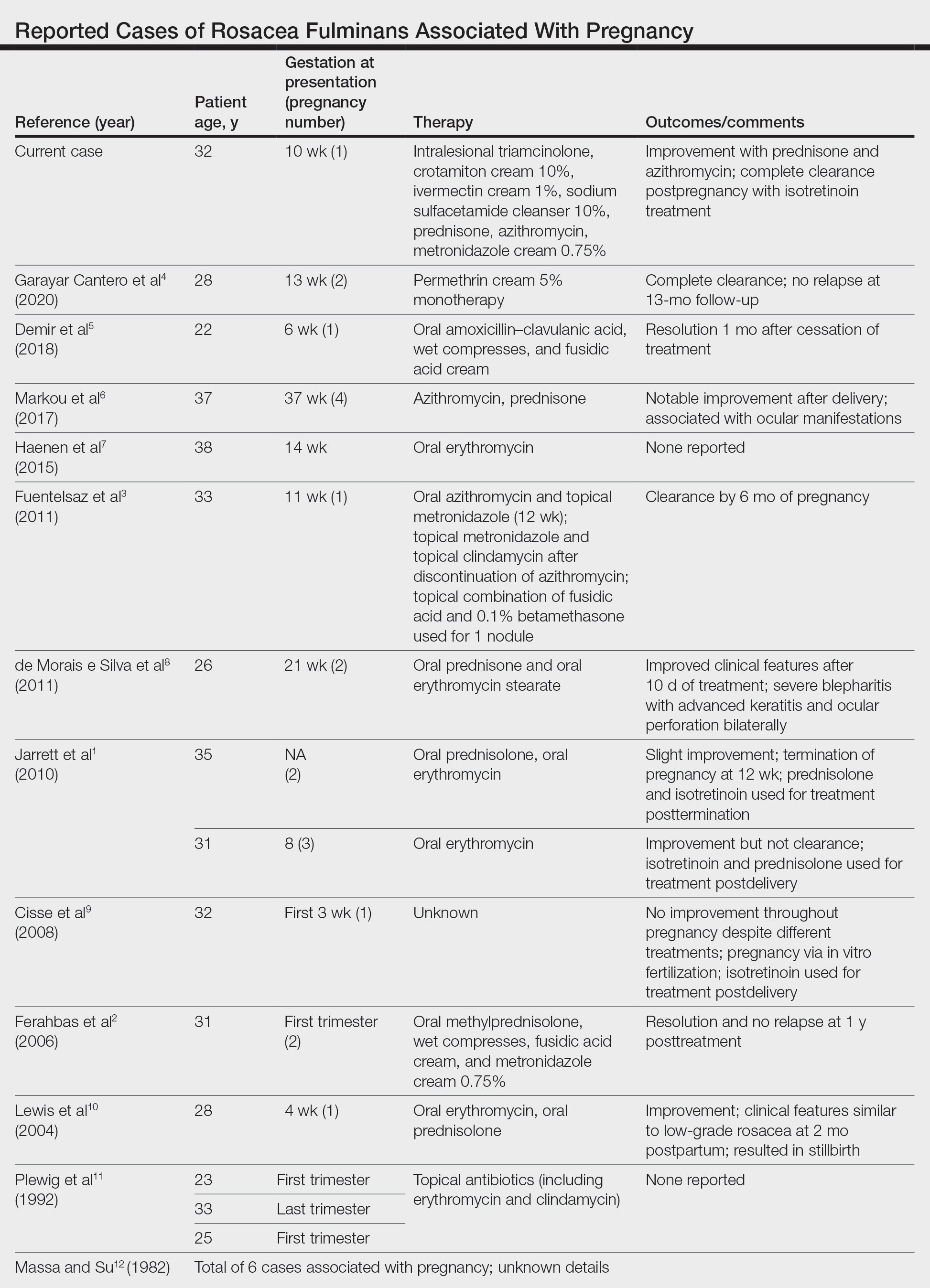

A A 27-year-old Hispanic woman with comedonal and inflammatory acne. Erythema is prominent around the inflammatory lesions. Note the pustule on the cheek surrounded by pink color.

B A teenaged Black boy with acne papules and pustules on the face. There are comedones, hyperpigmented macules, and pustules on the cheek.

C A teenaged Black girl with pomade acne. The patient used various hair care products, which obstructed the pilosebaceous units on the forehead.

Epidemiology

Acne is a leading dermatologic condition in individuals with skin of color in the United States.1

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones include:

- erythematous or hyperpigmented papules or comedones

- hyperpigmented macules and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH)

- increased risk for keloidal scars.2

Worth noting

- Patients with darker skin tones may be more concerned with the dark marks (also referred to as scars or manchas in Spanish) than the acne itself. This PIH may be viewed by patients as the major problem.

- Acne medications such as azelaic acid and some retinoids (when applied appropriately) can treat both acne and PIH.3

- Irritation from topical acne medications, including retinoid dermatitis, may lead to more PIH. Using noncomedogenic moisturizers and applying medication appropriately (ie, a pea-sized amount of topical retinoid per application) may help limit irritation.4,5

- One type of acne seen more commonly, although not exclusively, in Black patients is pomade acne, which principally appears on the forehead and is associated with use of hair care and styling products (Figure, C).

Health disparity highlight

Disparities in access to health care exist for those with dermatologic concerns. According to one study, African American (28.5%) and Hispanic patients (23.9%) were less likely to be seen by a dermatologist solely for the diagnosis of a dermatologic condition compared to Asian and Pacific Islander patients (36.7%) or White patients (43.2%).1

Noting that isotretinoin is the most potent systemic therapy for severe cystic acne vulgaris, Bell et al6 reported that Black patients had lower odds of receiving isotretinoin compared to White patients. Hispanic patients had lower odds of receiving a topical retinoid, tretinoin, than non-Hispanic patients.6

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Alexis AF, Woolery-Lloyd H, Williams K, et al. Racial/ethnic variations in acne: implications for treatment and skin care recommendations for acne patients with skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:716-725.

- Woolery-Lloyd HC, Keri J, Doig S. Retinoids and azelaic acid to treat acne and hyperpigmentation in skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:434-437.

- Grayson C, Heath C. Tips for addressing common conditions affecting pediatric and adolescent patients with skin of color [published online March 2, 2021]. Pediatr Dermatol. doi:10.1111/pde.14525

- Alexis AD, Harper JC, Stein Gold L, et al. Treating acne in patients with skin of color. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2018;37(suppl 3):S71-S73.

- Bell MA, Whang KA, Thomas J, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in access to emerging and frontline therapies in common dermatological conditions: a cross-sectional study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020;112:650-653.

THE COMPARISON

A A 27-year-old Hispanic woman with comedonal and inflammatory acne. Erythema is prominent around the inflammatory lesions. Note the pustule on the cheek surrounded by pink color.

B A teenaged Black boy with acne papules and pustules on the face. There are comedones, hyperpigmented macules, and pustules on the cheek.

C A teenaged Black girl with pomade acne. The patient used various hair care products, which obstructed the pilosebaceous units on the forehead.

Epidemiology

Acne is a leading dermatologic condition in individuals with skin of color in the United States.1

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones include:

- erythematous or hyperpigmented papules or comedones

- hyperpigmented macules and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH)

- increased risk for keloidal scars.2

Worth noting

- Patients with darker skin tones may be more concerned with the dark marks (also referred to as scars or manchas in Spanish) than the acne itself. This PIH may be viewed by patients as the major problem.

- Acne medications such as azelaic acid and some retinoids (when applied appropriately) can treat both acne and PIH.3

- Irritation from topical acne medications, including retinoid dermatitis, may lead to more PIH. Using noncomedogenic moisturizers and applying medication appropriately (ie, a pea-sized amount of topical retinoid per application) may help limit irritation.4,5

- One type of acne seen more commonly, although not exclusively, in Black patients is pomade acne, which principally appears on the forehead and is associated with use of hair care and styling products (Figure, C).

Health disparity highlight

Disparities in access to health care exist for those with dermatologic concerns. According to one study, African American (28.5%) and Hispanic patients (23.9%) were less likely to be seen by a dermatologist solely for the diagnosis of a dermatologic condition compared to Asian and Pacific Islander patients (36.7%) or White patients (43.2%).1

Noting that isotretinoin is the most potent systemic therapy for severe cystic acne vulgaris, Bell et al6 reported that Black patients had lower odds of receiving isotretinoin compared to White patients. Hispanic patients had lower odds of receiving a topical retinoid, tretinoin, than non-Hispanic patients.6

THE COMPARISON

A A 27-year-old Hispanic woman with comedonal and inflammatory acne. Erythema is prominent around the inflammatory lesions. Note the pustule on the cheek surrounded by pink color.

B A teenaged Black boy with acne papules and pustules on the face. There are comedones, hyperpigmented macules, and pustules on the cheek.

C A teenaged Black girl with pomade acne. The patient used various hair care products, which obstructed the pilosebaceous units on the forehead.

Epidemiology

Acne is a leading dermatologic condition in individuals with skin of color in the United States.1

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones include:

- erythematous or hyperpigmented papules or comedones

- hyperpigmented macules and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH)

- increased risk for keloidal scars.2

Worth noting

- Patients with darker skin tones may be more concerned with the dark marks (also referred to as scars or manchas in Spanish) than the acne itself. This PIH may be viewed by patients as the major problem.

- Acne medications such as azelaic acid and some retinoids (when applied appropriately) can treat both acne and PIH.3

- Irritation from topical acne medications, including retinoid dermatitis, may lead to more PIH. Using noncomedogenic moisturizers and applying medication appropriately (ie, a pea-sized amount of topical retinoid per application) may help limit irritation.4,5

- One type of acne seen more commonly, although not exclusively, in Black patients is pomade acne, which principally appears on the forehead and is associated with use of hair care and styling products (Figure, C).

Health disparity highlight

Disparities in access to health care exist for those with dermatologic concerns. According to one study, African American (28.5%) and Hispanic patients (23.9%) were less likely to be seen by a dermatologist solely for the diagnosis of a dermatologic condition compared to Asian and Pacific Islander patients (36.7%) or White patients (43.2%).1

Noting that isotretinoin is the most potent systemic therapy for severe cystic acne vulgaris, Bell et al6 reported that Black patients had lower odds of receiving isotretinoin compared to White patients. Hispanic patients had lower odds of receiving a topical retinoid, tretinoin, than non-Hispanic patients.6

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Alexis AF, Woolery-Lloyd H, Williams K, et al. Racial/ethnic variations in acne: implications for treatment and skin care recommendations for acne patients with skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:716-725.

- Woolery-Lloyd HC, Keri J, Doig S. Retinoids and azelaic acid to treat acne and hyperpigmentation in skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:434-437.

- Grayson C, Heath C. Tips for addressing common conditions affecting pediatric and adolescent patients with skin of color [published online March 2, 2021]. Pediatr Dermatol. doi:10.1111/pde.14525

- Alexis AD, Harper JC, Stein Gold L, et al. Treating acne in patients with skin of color. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2018;37(suppl 3):S71-S73.

- Bell MA, Whang KA, Thomas J, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in access to emerging and frontline therapies in common dermatological conditions: a cross-sectional study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020;112:650-653.

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Alexis AF, Woolery-Lloyd H, Williams K, et al. Racial/ethnic variations in acne: implications for treatment and skin care recommendations for acne patients with skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:716-725.

- Woolery-Lloyd HC, Keri J, Doig S. Retinoids and azelaic acid to treat acne and hyperpigmentation in skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:434-437.

- Grayson C, Heath C. Tips for addressing common conditions affecting pediatric and adolescent patients with skin of color [published online March 2, 2021]. Pediatr Dermatol. doi:10.1111/pde.14525

- Alexis AD, Harper JC, Stein Gold L, et al. Treating acne in patients with skin of color. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2018;37(suppl 3):S71-S73.

- Bell MA, Whang KA, Thomas J, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in access to emerging and frontline therapies in common dermatological conditions: a cross-sectional study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020;112:650-653.

Vetiver: More than a pleasant aroma?

An important ingredient in the contemporary perfume and cosmetics industries, vetiver, is the only grass cultivated throughout the world to retain its essential oil, which contains sesquiterpene alcohols and hydrocarbons.1-3 Field and glasshouse studies have revealed that vetiver grass can tolerate extreme variations in climate well, including protracted drought, floods, submergence, temperature, and soils high in acidity, alkalinity, and various heavy metals. Its heartiness may explain its continuing or even increasing use in fragrances and other products pertinent to skin health as humanity strives to adapt to climate change.4 In a 2017 review of various commercial essential oils as antimicrobial therapy for cutaneous disorders, Orchard and van Vuuren identified vetiver as warranting particular attention for its capacity to confer broad benefits to the skin in addressing acne, cuts, eczema, oiliness, sores, wounds, and aging skin.5 The focus of this column will be the dermatologic potential of vetiver.

Chemical constituents

Vetiver is thought to be one of the most complex of the essential oils owing to the hundreds of sesquiterpene derivatives with large structural diversity that contribute to its composition. 3

In a 2012 analysis of the components of South Indian vetiver oils, Mallavarapu et al. found an abundance of sesquiterpenes and oxygenated sesquiterpenes with cedrane, bisabolane, eudesmane, eremophilane, and zizaane skeletons. The primary constituents identified in the four oils evaluated included eudesma-4,6-diene (delta-selinene) + beta-vetispirene (3.9%-6.1%), beta-vetivenene (0.9%-9.4%), 13-nor-trans-eudesma-4(15),7-dien-11-one + amorph-4-en-10-ol (5.0%-6.4%), trans-eudesma-4(15),7-dien-12-ol (vetiselinenol) + (E)-opposita-4(15),7(11)-dien-12-ol (3.7%-5.9%), eremophila-1 (10),11-dien-2alpha-ol (nootkatol) + ziza-6(13)-en-12-ol (khusimol) (16.1%-19.2%), and eremophila-1(10),7(11)-dien-2alpha-ol (isonootkatol) + (E)-eremophila-1(10),7(11)-12-ol (isovalencenol) (5.6%-6.9%).6

Antimicrobial activity

In 2012, Saikia et al. assessed the antimycobacterial activity of Vetiveria zizanioides against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H(37)Rv and H(37)Ra strains. Their results showed that ethanolic extracts and hexane fractions displayed robust antimycobacterial properties, buttressing the traditional medical uses of the plant, as well as consideration of this agent as a modern antituberculosis agent.7

Two years later, Dos Santos et al. showed that Vetiveria zizanioides roots grown in Brazil exhibited notable antimicrobial effects against various pathogenic organisms.8In 2017, Burger et al. showed that vetiver essential oil primarily contributes its scent to cosmetic formulations but also displayed antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive bacterial strains, as well as one strain of Candida glabrata. They suggest that vetiver should be considered for its antimicrobial capacity as an added bonus to cosmetic formulations.2

In a 2018 study to ascertain the antimicrobial activity of 247 essential oil combinations against five reference strains of wound pathogens, Orchard et al. found that 26 combinations exhibited extensive antimicrobial activity. Sandalwood and vetiver were found to contribute most to antimicrobial function when used in combination. The investigators concluded that such combinations warrant consideration for wound therapy.9

Antiacne activity

In 2018, Orchard et al. conducted another study of the efficacy of commercial essential oil combinations against the two pathogens responsible for acne, Propionibacterium acnes and Staphlyococcus epidermidis. They investigated 408 combinations, of which 167 exhibited notable antimicrobial activity. They observed that the combination with the lowest minimum inhibitory concentration value against P. acnes and S. epidermidis was vetiver and cinnamon bark.10 This usage points to the potential of vetiver use as an antiacne ingredient.

Safety

The Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety (SCCS) offered a final opinion on the safety of the fragrance ingredient acetylated vetiver oil in 2019, declaring its use with 1% alpha-tocopherol in cosmetic leave-on and rinse-off products safe at proposed concentration levels. They noted that acetylated vetiver oil has been used for several years without provoking contact allergies.11

Conclusion

Much more research is necessary to determine just what kind of a role this perfumery powerhouse can play in dermatology.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Del Giudice L et al. Environ Microbiol. 2008 Oct;10(10):2824-41.

2. Burger P et al. Medicines (Basel). 2017 Jun 16;4(2):41.

3. Belhassen E et al. Chem Biodivers. 2014 Nov;11(11):1821–42.

4. Danh LT et al. Int J Phytoremediation. 2009 Oct-Dec;11(8):664–91.

5. Orchard A and van Vuuren S. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017;2017:4517971.

6. Mallavarapu GR et al. Nat Prod Commun. 2012 Feb;7(2):223–5.

7. Saikia D et al. Complement Ther Med. 2012 Dec;20(6):434–6.

8. Dos Santos DS et al. Acta Pharm. 2014 Dec;64(4):495-501.

9. Orchard A et al. Chem Biodivers. 2018 Dec;15(12):e1800405.

10. Orchard A et al. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2018 Mar 24. [Epub ahead of print].

11. SCCS members & External experts. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2019 Oct;107:104389.

An important ingredient in the contemporary perfume and cosmetics industries, vetiver, is the only grass cultivated throughout the world to retain its essential oil, which contains sesquiterpene alcohols and hydrocarbons.1-3 Field and glasshouse studies have revealed that vetiver grass can tolerate extreme variations in climate well, including protracted drought, floods, submergence, temperature, and soils high in acidity, alkalinity, and various heavy metals. Its heartiness may explain its continuing or even increasing use in fragrances and other products pertinent to skin health as humanity strives to adapt to climate change.4 In a 2017 review of various commercial essential oils as antimicrobial therapy for cutaneous disorders, Orchard and van Vuuren identified vetiver as warranting particular attention for its capacity to confer broad benefits to the skin in addressing acne, cuts, eczema, oiliness, sores, wounds, and aging skin.5 The focus of this column will be the dermatologic potential of vetiver.

Chemical constituents

Vetiver is thought to be one of the most complex of the essential oils owing to the hundreds of sesquiterpene derivatives with large structural diversity that contribute to its composition. 3

In a 2012 analysis of the components of South Indian vetiver oils, Mallavarapu et al. found an abundance of sesquiterpenes and oxygenated sesquiterpenes with cedrane, bisabolane, eudesmane, eremophilane, and zizaane skeletons. The primary constituents identified in the four oils evaluated included eudesma-4,6-diene (delta-selinene) + beta-vetispirene (3.9%-6.1%), beta-vetivenene (0.9%-9.4%), 13-nor-trans-eudesma-4(15),7-dien-11-one + amorph-4-en-10-ol (5.0%-6.4%), trans-eudesma-4(15),7-dien-12-ol (vetiselinenol) + (E)-opposita-4(15),7(11)-dien-12-ol (3.7%-5.9%), eremophila-1 (10),11-dien-2alpha-ol (nootkatol) + ziza-6(13)-en-12-ol (khusimol) (16.1%-19.2%), and eremophila-1(10),7(11)-dien-2alpha-ol (isonootkatol) + (E)-eremophila-1(10),7(11)-12-ol (isovalencenol) (5.6%-6.9%).6

Antimicrobial activity

In 2012, Saikia et al. assessed the antimycobacterial activity of Vetiveria zizanioides against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H(37)Rv and H(37)Ra strains. Their results showed that ethanolic extracts and hexane fractions displayed robust antimycobacterial properties, buttressing the traditional medical uses of the plant, as well as consideration of this agent as a modern antituberculosis agent.7

Two years later, Dos Santos et al. showed that Vetiveria zizanioides roots grown in Brazil exhibited notable antimicrobial effects against various pathogenic organisms.8In 2017, Burger et al. showed that vetiver essential oil primarily contributes its scent to cosmetic formulations but also displayed antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive bacterial strains, as well as one strain of Candida glabrata. They suggest that vetiver should be considered for its antimicrobial capacity as an added bonus to cosmetic formulations.2

In a 2018 study to ascertain the antimicrobial activity of 247 essential oil combinations against five reference strains of wound pathogens, Orchard et al. found that 26 combinations exhibited extensive antimicrobial activity. Sandalwood and vetiver were found to contribute most to antimicrobial function when used in combination. The investigators concluded that such combinations warrant consideration for wound therapy.9

Antiacne activity

In 2018, Orchard et al. conducted another study of the efficacy of commercial essential oil combinations against the two pathogens responsible for acne, Propionibacterium acnes and Staphlyococcus epidermidis. They investigated 408 combinations, of which 167 exhibited notable antimicrobial activity. They observed that the combination with the lowest minimum inhibitory concentration value against P. acnes and S. epidermidis was vetiver and cinnamon bark.10 This usage points to the potential of vetiver use as an antiacne ingredient.

Safety

The Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety (SCCS) offered a final opinion on the safety of the fragrance ingredient acetylated vetiver oil in 2019, declaring its use with 1% alpha-tocopherol in cosmetic leave-on and rinse-off products safe at proposed concentration levels. They noted that acetylated vetiver oil has been used for several years without provoking contact allergies.11

Conclusion

Much more research is necessary to determine just what kind of a role this perfumery powerhouse can play in dermatology.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Del Giudice L et al. Environ Microbiol. 2008 Oct;10(10):2824-41.

2. Burger P et al. Medicines (Basel). 2017 Jun 16;4(2):41.

3. Belhassen E et al. Chem Biodivers. 2014 Nov;11(11):1821–42.

4. Danh LT et al. Int J Phytoremediation. 2009 Oct-Dec;11(8):664–91.

5. Orchard A and van Vuuren S. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017;2017:4517971.

6. Mallavarapu GR et al. Nat Prod Commun. 2012 Feb;7(2):223–5.

7. Saikia D et al. Complement Ther Med. 2012 Dec;20(6):434–6.

8. Dos Santos DS et al. Acta Pharm. 2014 Dec;64(4):495-501.

9. Orchard A et al. Chem Biodivers. 2018 Dec;15(12):e1800405.

10. Orchard A et al. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2018 Mar 24. [Epub ahead of print].

11. SCCS members & External experts. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2019 Oct;107:104389.

An important ingredient in the contemporary perfume and cosmetics industries, vetiver, is the only grass cultivated throughout the world to retain its essential oil, which contains sesquiterpene alcohols and hydrocarbons.1-3 Field and glasshouse studies have revealed that vetiver grass can tolerate extreme variations in climate well, including protracted drought, floods, submergence, temperature, and soils high in acidity, alkalinity, and various heavy metals. Its heartiness may explain its continuing or even increasing use in fragrances and other products pertinent to skin health as humanity strives to adapt to climate change.4 In a 2017 review of various commercial essential oils as antimicrobial therapy for cutaneous disorders, Orchard and van Vuuren identified vetiver as warranting particular attention for its capacity to confer broad benefits to the skin in addressing acne, cuts, eczema, oiliness, sores, wounds, and aging skin.5 The focus of this column will be the dermatologic potential of vetiver.

Chemical constituents

Vetiver is thought to be one of the most complex of the essential oils owing to the hundreds of sesquiterpene derivatives with large structural diversity that contribute to its composition. 3

In a 2012 analysis of the components of South Indian vetiver oils, Mallavarapu et al. found an abundance of sesquiterpenes and oxygenated sesquiterpenes with cedrane, bisabolane, eudesmane, eremophilane, and zizaane skeletons. The primary constituents identified in the four oils evaluated included eudesma-4,6-diene (delta-selinene) + beta-vetispirene (3.9%-6.1%), beta-vetivenene (0.9%-9.4%), 13-nor-trans-eudesma-4(15),7-dien-11-one + amorph-4-en-10-ol (5.0%-6.4%), trans-eudesma-4(15),7-dien-12-ol (vetiselinenol) + (E)-opposita-4(15),7(11)-dien-12-ol (3.7%-5.9%), eremophila-1 (10),11-dien-2alpha-ol (nootkatol) + ziza-6(13)-en-12-ol (khusimol) (16.1%-19.2%), and eremophila-1(10),7(11)-dien-2alpha-ol (isonootkatol) + (E)-eremophila-1(10),7(11)-12-ol (isovalencenol) (5.6%-6.9%).6

Antimicrobial activity

In 2012, Saikia et al. assessed the antimycobacterial activity of Vetiveria zizanioides against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H(37)Rv and H(37)Ra strains. Their results showed that ethanolic extracts and hexane fractions displayed robust antimycobacterial properties, buttressing the traditional medical uses of the plant, as well as consideration of this agent as a modern antituberculosis agent.7

Two years later, Dos Santos et al. showed that Vetiveria zizanioides roots grown in Brazil exhibited notable antimicrobial effects against various pathogenic organisms.8In 2017, Burger et al. showed that vetiver essential oil primarily contributes its scent to cosmetic formulations but also displayed antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive bacterial strains, as well as one strain of Candida glabrata. They suggest that vetiver should be considered for its antimicrobial capacity as an added bonus to cosmetic formulations.2

In a 2018 study to ascertain the antimicrobial activity of 247 essential oil combinations against five reference strains of wound pathogens, Orchard et al. found that 26 combinations exhibited extensive antimicrobial activity. Sandalwood and vetiver were found to contribute most to antimicrobial function when used in combination. The investigators concluded that such combinations warrant consideration for wound therapy.9

Antiacne activity

In 2018, Orchard et al. conducted another study of the efficacy of commercial essential oil combinations against the two pathogens responsible for acne, Propionibacterium acnes and Staphlyococcus epidermidis. They investigated 408 combinations, of which 167 exhibited notable antimicrobial activity. They observed that the combination with the lowest minimum inhibitory concentration value against P. acnes and S. epidermidis was vetiver and cinnamon bark.10 This usage points to the potential of vetiver use as an antiacne ingredient.

Safety

The Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety (SCCS) offered a final opinion on the safety of the fragrance ingredient acetylated vetiver oil in 2019, declaring its use with 1% alpha-tocopherol in cosmetic leave-on and rinse-off products safe at proposed concentration levels. They noted that acetylated vetiver oil has been used for several years without provoking contact allergies.11

Conclusion

Much more research is necessary to determine just what kind of a role this perfumery powerhouse can play in dermatology.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Del Giudice L et al. Environ Microbiol. 2008 Oct;10(10):2824-41.

2. Burger P et al. Medicines (Basel). 2017 Jun 16;4(2):41.

3. Belhassen E et al. Chem Biodivers. 2014 Nov;11(11):1821–42.

4. Danh LT et al. Int J Phytoremediation. 2009 Oct-Dec;11(8):664–91.

5. Orchard A and van Vuuren S. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017;2017:4517971.

6. Mallavarapu GR et al. Nat Prod Commun. 2012 Feb;7(2):223–5.

7. Saikia D et al. Complement Ther Med. 2012 Dec;20(6):434–6.

8. Dos Santos DS et al. Acta Pharm. 2014 Dec;64(4):495-501.

9. Orchard A et al. Chem Biodivers. 2018 Dec;15(12):e1800405.

10. Orchard A et al. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2018 Mar 24. [Epub ahead of print].

11. SCCS members & External experts. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2019 Oct;107:104389.

Study highlights impact of acne in adult women on quality of life, mental health

results from a qualitative study demonstrated.

“Nearly 50% of women experience acne in their 20s, and 35% experience acne in their 30s,” the study’s corresponding author, John S. Barbieri, MD, MBA, formerly of the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization. “While several qualitative studies have examined acne in adolescence, the lived experience of adult female acne has not been explored in detail and prior studies have included relatively few patients. As a result, we conducted a series of semistructured interviews among adult women with acne to examine the lived experience of adult acne and its treatment.”

For the study, published online July 28, 2021, in JAMA Dermatology, Dr. Barbieri and colleagues conducted voluntary, confidential phone interviews with 50 women aged between 18 and 40 years with moderate to severe acne who were recruited from the University of Pennsylvania Health System and from a private dermatology clinic in Cincinnati. They used free listing and open-ended, semistructured interviews to elicit opinions from the women on how acne affected their lives; their experience with acne treatments, dermatologists, and health care systems; as well as their views on treatment success.

The mean age of the participants was 28 years and 48% were white (10% were Black, 8% were Asian, 4% were more than one race, and the rest abstained from answering this question; 10% said they were Hispanic).

More than three-quarters (78%) reported prior treatment with topical retinoids, followed by spironolactone (70%), topical antibiotics (43%), combined oral contraceptives (43%), and isotretinoin (41%). During the free-listing part of interviews, where the women reported the first words that came to their mind when asked about success of treatment and adverse effects, the most important terms expressed related to treatment success were clear skin, no scarring, and no acne. The most important terms related to treatment adverse effects were dryness, redness, and burning.

In the semistructured interview portion of the study, the main themes expressed were acne-related concerns about appearance, including feeling less confident at work; mental and emotional health, including feelings of depression, anxiety, depression, and low self-worth during acne breakouts; and everyday life impact, including the notion that acne affected how other people perceived them. The other main themes included successful treatment, with clear skin and having a manageable number of lesions being desirable outcomes; and interactions with health care, including varied experiences with dermatologists. The researchers observed that most participants did not think oral antibiotics were appropriate treatments for their acne, specifically because of limited long-term effectiveness.

“Many patients described frustration with finding a dermatologist with whom they were comfortable and with identifying effective treatments for their acne,” the authors wrote. “In contrast, those who thought their dermatologist listened to their concerns and individualized their treatment plan reported higher levels of satisfaction.”

In an interview, Dr. Barbieri, who is now with the department of dermatology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said that he was surprised by how many patients expressed interest in nonantibiotic treatments for acne, “given that oral antibiotics are by far the most commonly prescribed systemic treatment for acne.”

Moreover, he added, “although I have experienced many patients being hesitant about isotretinoin, I was surprised by how strong patients’ concerns were about isotretinoin side effects. Unfortunately, there are many misconceptions about isotretinoin that limit use of this treatment that can be highly effective and safe for the appropriate patient.”

In an accompanying editorial, dermatologists Diane M. Thiboutot, MD and Andrea L. Zaenglein, MD, with Penn State University, Hershey, and Alison M. Layton, MB, ChB, with the Harrogate Foundation Trust, Harrogate, North Yorkshire, England, wrote that the findings from the study “resonate with those recently reported in several international studies that examine the impacts of acne, how patients assess treatment success, and what is important to measure from a patient and health care professional perspective in a clinical trial for acne.”

A large systematic review on the impact of acne on patients, conducted by the Acne Core Outcomes Research Network (ACORN), found that “appearance-related concerns and negative psychosocial effects were found to be a major impact of acne,” they noted. “Surprisingly, only 22 of the 473 studies identified in this review included qualitative data gathered from patient interviews. It is encouraging to see the concordance between the concerns voiced by the participants in the current study and those identified from the literature review, wherein a variety of methods were used to assess acne impacts.”

For his part, Dr. Barbieri said that the study findings “justify the importance of having a discussion with patients about their unique lived experience of acne and individualizing treatment to their specific needs. Patient reported outcome measures could be a useful adjunctive tool to capture these impacts on quality of life.”

This study was funded by grant from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Barbieri disclosed that he received partial salary support through a Pfizer Fellowship in Dermatology Patient Oriented Research grant to the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Thiboutot reported receiving consultant fees from Galderma and Novartis outside the submitted work. Dr. Layton reported receiving unrestricted educational presentation, advisory board, and consultancy fees from Galderma Honoraria; unrestricted educational presentation and advisory board honoraria from Leo; advisory board honoraria from Novartis and Mylan; consultancy honoraria from Procter and Gamble and Meda; grants from Galderma; and consultancy and advisory board honoraria from Origimm outside the submitted work.

results from a qualitative study demonstrated.

“Nearly 50% of women experience acne in their 20s, and 35% experience acne in their 30s,” the study’s corresponding author, John S. Barbieri, MD, MBA, formerly of the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization. “While several qualitative studies have examined acne in adolescence, the lived experience of adult female acne has not been explored in detail and prior studies have included relatively few patients. As a result, we conducted a series of semistructured interviews among adult women with acne to examine the lived experience of adult acne and its treatment.”

For the study, published online July 28, 2021, in JAMA Dermatology, Dr. Barbieri and colleagues conducted voluntary, confidential phone interviews with 50 women aged between 18 and 40 years with moderate to severe acne who were recruited from the University of Pennsylvania Health System and from a private dermatology clinic in Cincinnati. They used free listing and open-ended, semistructured interviews to elicit opinions from the women on how acne affected their lives; their experience with acne treatments, dermatologists, and health care systems; as well as their views on treatment success.

The mean age of the participants was 28 years and 48% were white (10% were Black, 8% were Asian, 4% were more than one race, and the rest abstained from answering this question; 10% said they were Hispanic).

More than three-quarters (78%) reported prior treatment with topical retinoids, followed by spironolactone (70%), topical antibiotics (43%), combined oral contraceptives (43%), and isotretinoin (41%). During the free-listing part of interviews, where the women reported the first words that came to their mind when asked about success of treatment and adverse effects, the most important terms expressed related to treatment success were clear skin, no scarring, and no acne. The most important terms related to treatment adverse effects were dryness, redness, and burning.

In the semistructured interview portion of the study, the main themes expressed were acne-related concerns about appearance, including feeling less confident at work; mental and emotional health, including feelings of depression, anxiety, depression, and low self-worth during acne breakouts; and everyday life impact, including the notion that acne affected how other people perceived them. The other main themes included successful treatment, with clear skin and having a manageable number of lesions being desirable outcomes; and interactions with health care, including varied experiences with dermatologists. The researchers observed that most participants did not think oral antibiotics were appropriate treatments for their acne, specifically because of limited long-term effectiveness.

“Many patients described frustration with finding a dermatologist with whom they were comfortable and with identifying effective treatments for their acne,” the authors wrote. “In contrast, those who thought their dermatologist listened to their concerns and individualized their treatment plan reported higher levels of satisfaction.”

In an interview, Dr. Barbieri, who is now with the department of dermatology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said that he was surprised by how many patients expressed interest in nonantibiotic treatments for acne, “given that oral antibiotics are by far the most commonly prescribed systemic treatment for acne.”

Moreover, he added, “although I have experienced many patients being hesitant about isotretinoin, I was surprised by how strong patients’ concerns were about isotretinoin side effects. Unfortunately, there are many misconceptions about isotretinoin that limit use of this treatment that can be highly effective and safe for the appropriate patient.”

In an accompanying editorial, dermatologists Diane M. Thiboutot, MD and Andrea L. Zaenglein, MD, with Penn State University, Hershey, and Alison M. Layton, MB, ChB, with the Harrogate Foundation Trust, Harrogate, North Yorkshire, England, wrote that the findings from the study “resonate with those recently reported in several international studies that examine the impacts of acne, how patients assess treatment success, and what is important to measure from a patient and health care professional perspective in a clinical trial for acne.”

A large systematic review on the impact of acne on patients, conducted by the Acne Core Outcomes Research Network (ACORN), found that “appearance-related concerns and negative psychosocial effects were found to be a major impact of acne,” they noted. “Surprisingly, only 22 of the 473 studies identified in this review included qualitative data gathered from patient interviews. It is encouraging to see the concordance between the concerns voiced by the participants in the current study and those identified from the literature review, wherein a variety of methods were used to assess acne impacts.”

For his part, Dr. Barbieri said that the study findings “justify the importance of having a discussion with patients about their unique lived experience of acne and individualizing treatment to their specific needs. Patient reported outcome measures could be a useful adjunctive tool to capture these impacts on quality of life.”

This study was funded by grant from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Barbieri disclosed that he received partial salary support through a Pfizer Fellowship in Dermatology Patient Oriented Research grant to the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Thiboutot reported receiving consultant fees from Galderma and Novartis outside the submitted work. Dr. Layton reported receiving unrestricted educational presentation, advisory board, and consultancy fees from Galderma Honoraria; unrestricted educational presentation and advisory board honoraria from Leo; advisory board honoraria from Novartis and Mylan; consultancy honoraria from Procter and Gamble and Meda; grants from Galderma; and consultancy and advisory board honoraria from Origimm outside the submitted work.

results from a qualitative study demonstrated.

“Nearly 50% of women experience acne in their 20s, and 35% experience acne in their 30s,” the study’s corresponding author, John S. Barbieri, MD, MBA, formerly of the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization. “While several qualitative studies have examined acne in adolescence, the lived experience of adult female acne has not been explored in detail and prior studies have included relatively few patients. As a result, we conducted a series of semistructured interviews among adult women with acne to examine the lived experience of adult acne and its treatment.”