User login

ESMO gets creative with guidelines for breast cancer care in the COVID-19 era

Like other agencies, the European Society for Medical Oncology has developed guidelines for managing breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, recommending when care should be prioritized, delayed, or modified.

ESMO’s breast cancer guidelines expand upon guidelines issued by other groups, addressing a broad spectrum of patient profiles and providing a creative array of treatment options in COVID-19–era clinical practice.

As with ESMO’s other disease-focused COVID-19 guidelines, the breast cancer guidelines are organized by priority levels – high, medium, and low – which are applied to several domains of diagnosis and treatment.

High-priority recommendations apply to patients whose condition is either clinically unstable or whose cancer burden is immediately life-threatening.

Medium-priority recommendations apply to patients for whom delaying care beyond 6 weeks would probably lower the likelihood of a significant benefit from the intervention.

Low-priority recommendations apply to patients for whom services can be delayed for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Personalized care and high-priority situations

ESMO’s guidelines suggest that multidisciplinary tumor boards should guide decisions about the urgency of care for individual patients, given the complexity of breast cancer biology, the multiplicity of evidence-based treatments, and the possibility of cure or durable high-quality remissions.

The guidelines deliver a clear message that prepandemic discussions about delivering personalized care are even more important now.

ESMO prioritizes investigating high-risk screening mammography results (i.e., BIRADS 5), lumps noted on breast self-examination, clinical evidence of local-regional recurrence, and breast cancer in pregnant women.

Making these scenarios “high priority” will facilitate the best long-term outcomes in time-sensitive scenarios and improve patient satisfaction with care.

Modifications to consider

ESMO provides explicit options for treatment of common breast cancer profiles in which short-term modifications of standard management strategies can safely be considered. Given the generally long natural history of most breast cancer subtypes, these temporary modifications are unlikely to compromise long-term outcomes.

For patients with a new diagnosis of localized breast cancer, the guidelines recommend neoadjuvant chemotherapy, targeted therapy, or hormonal therapy to achieve optimal breast cancer outcomes and safely delay surgery or radiotherapy.

In the metastatic setting, ESMO advises providers to consider:

- Symptom-oriented testing, recognizing the arguable benefit of frequent imaging or serum tumor marker measurement (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Aug 20;34[24]:2820-6).

- Drug holidays, de-escalated maintenance therapy, and protracted schedules of bone-modifying agents.

- Avoiding mTOR and PI3KCA inhibitors as an addition to standard hormonal therapy because of pneumonitis, hyperglycemia, and immunosuppression risks. The guidelines suggest careful thought about adding CDK4/6 inhibitors to standard hormonal therapy because of the added burden of remote safety monitoring with the biologic agents.

ESMO makes suggestions about trimming the duration of adjuvant trastuzumab to 6 months, as in the PERSEPHONE study (Lancet. 2019 Jun 29;393[10191]:2599-612), and modifying the schedule of luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone agonist administration, in an effort to reduce patient exposure to health care personnel (and vice versa).

The guidelines recommend continuing clinical trials if benefits to patients outweigh risks and trials can be modified to enhance patient safety while preserving study endpoint evaluations.

Lower-priority situations

ESMO pointedly assigns a low priority to follow-up of patients who are at high risk of relapse but lack signs or symptoms of relapse.

Like other groups, ESMO recommends that patients with equivocal (i.e., BIRADS 3) screening mammograms should have 6-month follow-up imaging in preference to immediate core needle biopsy of the area(s) of concern.

ESMO uses age to assign priority for postponing adjuvant breast radiation in patients with low- to moderate-risk lesions. However, the guidelines stop surprisingly short of recommending that adjuvant radiation be withheld for older patients with low-risk, stage I, hormonally sensitive, HER2-negative breast cancers who receive endocrine therapy.

Bottom line

The pragmatic adjustments ESMO suggests address the challenges of evaluating and treating breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. The guidelines protect each patient’s right to care and safety as well as protecting the safety of caregivers.

The guidelines will likely heighten patients’ satisfaction with care and decrease concern about adequacy of timely evaluation and treatment.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

Like other agencies, the European Society for Medical Oncology has developed guidelines for managing breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, recommending when care should be prioritized, delayed, or modified.

ESMO’s breast cancer guidelines expand upon guidelines issued by other groups, addressing a broad spectrum of patient profiles and providing a creative array of treatment options in COVID-19–era clinical practice.

As with ESMO’s other disease-focused COVID-19 guidelines, the breast cancer guidelines are organized by priority levels – high, medium, and low – which are applied to several domains of diagnosis and treatment.

High-priority recommendations apply to patients whose condition is either clinically unstable or whose cancer burden is immediately life-threatening.

Medium-priority recommendations apply to patients for whom delaying care beyond 6 weeks would probably lower the likelihood of a significant benefit from the intervention.

Low-priority recommendations apply to patients for whom services can be delayed for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Personalized care and high-priority situations

ESMO’s guidelines suggest that multidisciplinary tumor boards should guide decisions about the urgency of care for individual patients, given the complexity of breast cancer biology, the multiplicity of evidence-based treatments, and the possibility of cure or durable high-quality remissions.

The guidelines deliver a clear message that prepandemic discussions about delivering personalized care are even more important now.

ESMO prioritizes investigating high-risk screening mammography results (i.e., BIRADS 5), lumps noted on breast self-examination, clinical evidence of local-regional recurrence, and breast cancer in pregnant women.

Making these scenarios “high priority” will facilitate the best long-term outcomes in time-sensitive scenarios and improve patient satisfaction with care.

Modifications to consider

ESMO provides explicit options for treatment of common breast cancer profiles in which short-term modifications of standard management strategies can safely be considered. Given the generally long natural history of most breast cancer subtypes, these temporary modifications are unlikely to compromise long-term outcomes.

For patients with a new diagnosis of localized breast cancer, the guidelines recommend neoadjuvant chemotherapy, targeted therapy, or hormonal therapy to achieve optimal breast cancer outcomes and safely delay surgery or radiotherapy.

In the metastatic setting, ESMO advises providers to consider:

- Symptom-oriented testing, recognizing the arguable benefit of frequent imaging or serum tumor marker measurement (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Aug 20;34[24]:2820-6).

- Drug holidays, de-escalated maintenance therapy, and protracted schedules of bone-modifying agents.

- Avoiding mTOR and PI3KCA inhibitors as an addition to standard hormonal therapy because of pneumonitis, hyperglycemia, and immunosuppression risks. The guidelines suggest careful thought about adding CDK4/6 inhibitors to standard hormonal therapy because of the added burden of remote safety monitoring with the biologic agents.

ESMO makes suggestions about trimming the duration of adjuvant trastuzumab to 6 months, as in the PERSEPHONE study (Lancet. 2019 Jun 29;393[10191]:2599-612), and modifying the schedule of luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone agonist administration, in an effort to reduce patient exposure to health care personnel (and vice versa).

The guidelines recommend continuing clinical trials if benefits to patients outweigh risks and trials can be modified to enhance patient safety while preserving study endpoint evaluations.

Lower-priority situations

ESMO pointedly assigns a low priority to follow-up of patients who are at high risk of relapse but lack signs or symptoms of relapse.

Like other groups, ESMO recommends that patients with equivocal (i.e., BIRADS 3) screening mammograms should have 6-month follow-up imaging in preference to immediate core needle biopsy of the area(s) of concern.

ESMO uses age to assign priority for postponing adjuvant breast radiation in patients with low- to moderate-risk lesions. However, the guidelines stop surprisingly short of recommending that adjuvant radiation be withheld for older patients with low-risk, stage I, hormonally sensitive, HER2-negative breast cancers who receive endocrine therapy.

Bottom line

The pragmatic adjustments ESMO suggests address the challenges of evaluating and treating breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. The guidelines protect each patient’s right to care and safety as well as protecting the safety of caregivers.

The guidelines will likely heighten patients’ satisfaction with care and decrease concern about adequacy of timely evaluation and treatment.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

Like other agencies, the European Society for Medical Oncology has developed guidelines for managing breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, recommending when care should be prioritized, delayed, or modified.

ESMO’s breast cancer guidelines expand upon guidelines issued by other groups, addressing a broad spectrum of patient profiles and providing a creative array of treatment options in COVID-19–era clinical practice.

As with ESMO’s other disease-focused COVID-19 guidelines, the breast cancer guidelines are organized by priority levels – high, medium, and low – which are applied to several domains of diagnosis and treatment.

High-priority recommendations apply to patients whose condition is either clinically unstable or whose cancer burden is immediately life-threatening.

Medium-priority recommendations apply to patients for whom delaying care beyond 6 weeks would probably lower the likelihood of a significant benefit from the intervention.

Low-priority recommendations apply to patients for whom services can be delayed for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Personalized care and high-priority situations

ESMO’s guidelines suggest that multidisciplinary tumor boards should guide decisions about the urgency of care for individual patients, given the complexity of breast cancer biology, the multiplicity of evidence-based treatments, and the possibility of cure or durable high-quality remissions.

The guidelines deliver a clear message that prepandemic discussions about delivering personalized care are even more important now.

ESMO prioritizes investigating high-risk screening mammography results (i.e., BIRADS 5), lumps noted on breast self-examination, clinical evidence of local-regional recurrence, and breast cancer in pregnant women.

Making these scenarios “high priority” will facilitate the best long-term outcomes in time-sensitive scenarios and improve patient satisfaction with care.

Modifications to consider

ESMO provides explicit options for treatment of common breast cancer profiles in which short-term modifications of standard management strategies can safely be considered. Given the generally long natural history of most breast cancer subtypes, these temporary modifications are unlikely to compromise long-term outcomes.

For patients with a new diagnosis of localized breast cancer, the guidelines recommend neoadjuvant chemotherapy, targeted therapy, or hormonal therapy to achieve optimal breast cancer outcomes and safely delay surgery or radiotherapy.

In the metastatic setting, ESMO advises providers to consider:

- Symptom-oriented testing, recognizing the arguable benefit of frequent imaging or serum tumor marker measurement (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Aug 20;34[24]:2820-6).

- Drug holidays, de-escalated maintenance therapy, and protracted schedules of bone-modifying agents.

- Avoiding mTOR and PI3KCA inhibitors as an addition to standard hormonal therapy because of pneumonitis, hyperglycemia, and immunosuppression risks. The guidelines suggest careful thought about adding CDK4/6 inhibitors to standard hormonal therapy because of the added burden of remote safety monitoring with the biologic agents.

ESMO makes suggestions about trimming the duration of adjuvant trastuzumab to 6 months, as in the PERSEPHONE study (Lancet. 2019 Jun 29;393[10191]:2599-612), and modifying the schedule of luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone agonist administration, in an effort to reduce patient exposure to health care personnel (and vice versa).

The guidelines recommend continuing clinical trials if benefits to patients outweigh risks and trials can be modified to enhance patient safety while preserving study endpoint evaluations.

Lower-priority situations

ESMO pointedly assigns a low priority to follow-up of patients who are at high risk of relapse but lack signs or symptoms of relapse.

Like other groups, ESMO recommends that patients with equivocal (i.e., BIRADS 3) screening mammograms should have 6-month follow-up imaging in preference to immediate core needle biopsy of the area(s) of concern.

ESMO uses age to assign priority for postponing adjuvant breast radiation in patients with low- to moderate-risk lesions. However, the guidelines stop surprisingly short of recommending that adjuvant radiation be withheld for older patients with low-risk, stage I, hormonally sensitive, HER2-negative breast cancers who receive endocrine therapy.

Bottom line

The pragmatic adjustments ESMO suggests address the challenges of evaluating and treating breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. The guidelines protect each patient’s right to care and safety as well as protecting the safety of caregivers.

The guidelines will likely heighten patients’ satisfaction with care and decrease concern about adequacy of timely evaluation and treatment.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

EHA webinar addresses treating AML patients with COVID-19

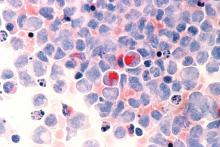

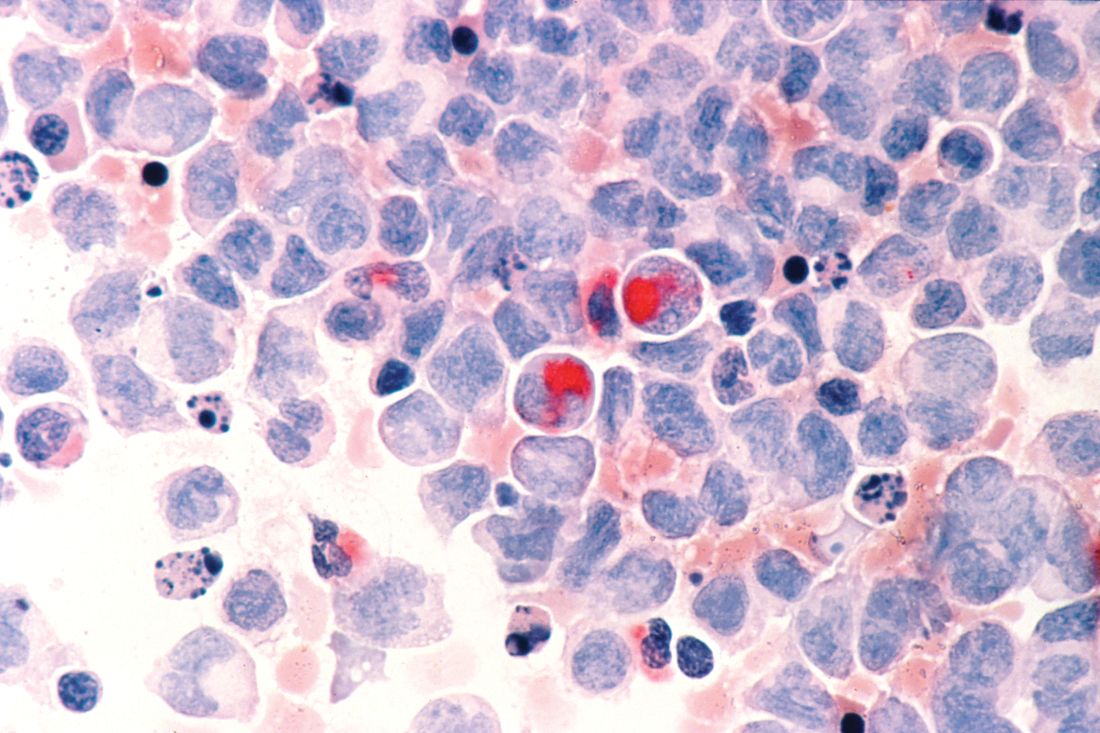

A hematologist in Italy shared his personal experience addressing the intersection of COVID-19 and the care of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients during a webinar hosted by the European Hematology Association (EHA).

Felicetto Ferrara, MD, of Cardarelli Hospital in Naples, Italy, discussed the main difficulties in administering optimal treatment for AML patients who become infected with SARS-CoV-2.

The major problems include the need to isolate patients while simultaneously allowing for collaboration with pulmonologists and intensivists, the delays in AML treatment caused by COVID-19, and the risk of drug-drug interactions while treating AML patients with COVID-19.

The need to isolate AML patients with COVID-19 is paramount, according to Dr. Ferrara. Isolation can be accomplished, ideally, by the creation of a dedicated COVID-19 unit or, alternatively, with the use of single-patient negative pressure rooms. Dr. Ferrara stressed that all patients with AML should be tested for COVID-19 before admission.

Delaying or reducing AML treatment

Treatment delays are of particular concern, according to Dr. Ferrara, and some patients may require dose reductions, especially for AML treatments that might have a detrimental effect on the immune system.

Decisions must be made as to whether planned approaches to induction or consolidation therapy should be changed, and special concern has to be paid to elderly AML patients, who have the highest risks of bad COVID-19 outcomes.

Specific attention should be paid to patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia as well, according to Dr. Ferrara. These patients are of concern in the COVID-19 era because of their risk of differentiation syndrome, which can induce respiratory distress.

In all cases, autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplant should be deferred until confirmed COVID-19–negative test results are obtained.

Continuing AML treatment

Of particular concern is the fact that, without a standard therapy for COVID-19, many different drugs might be used in treatment efforts. This raises the potential for serious drug-drug interactions with the patient’s AML medications, so close attention should be paid to an individual patient’s medications.

In terms of continuing AML treatment for younger adults (less than 65 years) who are positive for COVID-19, symptomatic and asymptomatic patients should be treated differently, Dr. Ferarra said.

Symptomatic patients should be given hydroxyurea until symptom resolution, and unless urgent, any further AML treatments should be delayed. However, if treatment is needed immediately, it should be given in a COVID-19–dedicated unit.

The restrictions are much looser for young adult asymptomatic COVID-19 patients with AML. Standard induction therapy should be given, with intermediate-dose cytarabine used as consolidation therapy.

Therapy in elderly patients with AML and COVID-19 should be based on symptom status as well, said Dr. Ferrara.

Asymptomatic but otherwise fit elderly patients should have standard induction therapy if they are in the European Leukemia Network favorable genetic subgroup. Asymptomatic elderly patients with high-risk molecular disease can receive venetoclax with a hypomethylating agent.

Symptomatic elderly patients should continue with hydroxyurea until symptom resolution, and any other treatments should be delayed in nonemergency cases.

Relapsed AML patients with COVID-19 should have their treatments postponed until they obtain negative COVID-19 test results whenever possible, Dr. Ferarra said. However, if treatment is necessary, molecularly targeted therapies (gilteritinib, ivosidenib, and enasidenib) are preferable to high-dose chemotherapy.

In all cases, treatment decisions should be made in conjunction with pulmonologists and intensivists, Dr. Ferrera noted.

Webinar moderator Francesco Cerisoli, MD, head of research and mentoring at EHA, highlighted the fact that EHA has published specific recommendations for treating AML patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. The majority of these were discussed by and are aligned with the recommendations presented by Dr. Ferrara.

The EHA webinar contains a disclaimer that the content discussed was based on the personal experiences and opinions of the speakers and that no general, evidence-based guidance could be derived from the discussion. There were no disclosures given.

A hematologist in Italy shared his personal experience addressing the intersection of COVID-19 and the care of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients during a webinar hosted by the European Hematology Association (EHA).

Felicetto Ferrara, MD, of Cardarelli Hospital in Naples, Italy, discussed the main difficulties in administering optimal treatment for AML patients who become infected with SARS-CoV-2.

The major problems include the need to isolate patients while simultaneously allowing for collaboration with pulmonologists and intensivists, the delays in AML treatment caused by COVID-19, and the risk of drug-drug interactions while treating AML patients with COVID-19.

The need to isolate AML patients with COVID-19 is paramount, according to Dr. Ferrara. Isolation can be accomplished, ideally, by the creation of a dedicated COVID-19 unit or, alternatively, with the use of single-patient negative pressure rooms. Dr. Ferrara stressed that all patients with AML should be tested for COVID-19 before admission.

Delaying or reducing AML treatment

Treatment delays are of particular concern, according to Dr. Ferrara, and some patients may require dose reductions, especially for AML treatments that might have a detrimental effect on the immune system.

Decisions must be made as to whether planned approaches to induction or consolidation therapy should be changed, and special concern has to be paid to elderly AML patients, who have the highest risks of bad COVID-19 outcomes.

Specific attention should be paid to patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia as well, according to Dr. Ferrara. These patients are of concern in the COVID-19 era because of their risk of differentiation syndrome, which can induce respiratory distress.

In all cases, autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplant should be deferred until confirmed COVID-19–negative test results are obtained.

Continuing AML treatment

Of particular concern is the fact that, without a standard therapy for COVID-19, many different drugs might be used in treatment efforts. This raises the potential for serious drug-drug interactions with the patient’s AML medications, so close attention should be paid to an individual patient’s medications.

In terms of continuing AML treatment for younger adults (less than 65 years) who are positive for COVID-19, symptomatic and asymptomatic patients should be treated differently, Dr. Ferarra said.

Symptomatic patients should be given hydroxyurea until symptom resolution, and unless urgent, any further AML treatments should be delayed. However, if treatment is needed immediately, it should be given in a COVID-19–dedicated unit.

The restrictions are much looser for young adult asymptomatic COVID-19 patients with AML. Standard induction therapy should be given, with intermediate-dose cytarabine used as consolidation therapy.

Therapy in elderly patients with AML and COVID-19 should be based on symptom status as well, said Dr. Ferrara.

Asymptomatic but otherwise fit elderly patients should have standard induction therapy if they are in the European Leukemia Network favorable genetic subgroup. Asymptomatic elderly patients with high-risk molecular disease can receive venetoclax with a hypomethylating agent.

Symptomatic elderly patients should continue with hydroxyurea until symptom resolution, and any other treatments should be delayed in nonemergency cases.

Relapsed AML patients with COVID-19 should have their treatments postponed until they obtain negative COVID-19 test results whenever possible, Dr. Ferarra said. However, if treatment is necessary, molecularly targeted therapies (gilteritinib, ivosidenib, and enasidenib) are preferable to high-dose chemotherapy.

In all cases, treatment decisions should be made in conjunction with pulmonologists and intensivists, Dr. Ferrera noted.

Webinar moderator Francesco Cerisoli, MD, head of research and mentoring at EHA, highlighted the fact that EHA has published specific recommendations for treating AML patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. The majority of these were discussed by and are aligned with the recommendations presented by Dr. Ferrara.

The EHA webinar contains a disclaimer that the content discussed was based on the personal experiences and opinions of the speakers and that no general, evidence-based guidance could be derived from the discussion. There were no disclosures given.

A hematologist in Italy shared his personal experience addressing the intersection of COVID-19 and the care of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients during a webinar hosted by the European Hematology Association (EHA).

Felicetto Ferrara, MD, of Cardarelli Hospital in Naples, Italy, discussed the main difficulties in administering optimal treatment for AML patients who become infected with SARS-CoV-2.

The major problems include the need to isolate patients while simultaneously allowing for collaboration with pulmonologists and intensivists, the delays in AML treatment caused by COVID-19, and the risk of drug-drug interactions while treating AML patients with COVID-19.

The need to isolate AML patients with COVID-19 is paramount, according to Dr. Ferrara. Isolation can be accomplished, ideally, by the creation of a dedicated COVID-19 unit or, alternatively, with the use of single-patient negative pressure rooms. Dr. Ferrara stressed that all patients with AML should be tested for COVID-19 before admission.

Delaying or reducing AML treatment

Treatment delays are of particular concern, according to Dr. Ferrara, and some patients may require dose reductions, especially for AML treatments that might have a detrimental effect on the immune system.

Decisions must be made as to whether planned approaches to induction or consolidation therapy should be changed, and special concern has to be paid to elderly AML patients, who have the highest risks of bad COVID-19 outcomes.

Specific attention should be paid to patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia as well, according to Dr. Ferrara. These patients are of concern in the COVID-19 era because of their risk of differentiation syndrome, which can induce respiratory distress.

In all cases, autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplant should be deferred until confirmed COVID-19–negative test results are obtained.

Continuing AML treatment

Of particular concern is the fact that, without a standard therapy for COVID-19, many different drugs might be used in treatment efforts. This raises the potential for serious drug-drug interactions with the patient’s AML medications, so close attention should be paid to an individual patient’s medications.

In terms of continuing AML treatment for younger adults (less than 65 years) who are positive for COVID-19, symptomatic and asymptomatic patients should be treated differently, Dr. Ferarra said.

Symptomatic patients should be given hydroxyurea until symptom resolution, and unless urgent, any further AML treatments should be delayed. However, if treatment is needed immediately, it should be given in a COVID-19–dedicated unit.

The restrictions are much looser for young adult asymptomatic COVID-19 patients with AML. Standard induction therapy should be given, with intermediate-dose cytarabine used as consolidation therapy.

Therapy in elderly patients with AML and COVID-19 should be based on symptom status as well, said Dr. Ferrara.

Asymptomatic but otherwise fit elderly patients should have standard induction therapy if they are in the European Leukemia Network favorable genetic subgroup. Asymptomatic elderly patients with high-risk molecular disease can receive venetoclax with a hypomethylating agent.

Symptomatic elderly patients should continue with hydroxyurea until symptom resolution, and any other treatments should be delayed in nonemergency cases.

Relapsed AML patients with COVID-19 should have their treatments postponed until they obtain negative COVID-19 test results whenever possible, Dr. Ferarra said. However, if treatment is necessary, molecularly targeted therapies (gilteritinib, ivosidenib, and enasidenib) are preferable to high-dose chemotherapy.

In all cases, treatment decisions should be made in conjunction with pulmonologists and intensivists, Dr. Ferrera noted.

Webinar moderator Francesco Cerisoli, MD, head of research and mentoring at EHA, highlighted the fact that EHA has published specific recommendations for treating AML patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. The majority of these were discussed by and are aligned with the recommendations presented by Dr. Ferrara.

The EHA webinar contains a disclaimer that the content discussed was based on the personal experiences and opinions of the speakers and that no general, evidence-based guidance could be derived from the discussion. There were no disclosures given.

COVID-19: Defer ‘bread and butter’ procedure for thyroid nodules

With a few notable exceptions, the majority of fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsies of thyroid nodules should be delayed until the risk of COVID-19, and the burden on resources, has lessened, according to expert consensus.

“Our group recommends that FNA biopsy of most asymptomatic thyroid nodules – taking into account the sonographic characteristics and patients’ clinical picture – be deferred to a later time, when risk of exposure to COVID-19 is more manageable and resource restriction is no longer a concern,” said the endocrinologists, writing in a guest editorial in Clinical Thyroidology.

All elective procedures have been canceled under guidance of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in conjunction with the U.S. surgeon general, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, thyroid nodule FNAs, though elective, fall into the category of being considered medically necessary and potentially prolonging life expectancy

Yet, with approximately 90% of asymptomatic thyroid nodules turning out to be benign and little evidence that early detection and treatment affects disease outcomes, there is a strong argument for deferral in most cases, stressed Ming Lee, MD, and colleagues, of the endocrinology division at Phoenix (Ariz.) Veterans Affairs Health Care System (PVAHCS), who convened a multidisciplinary meeting to address the urgent issue.

Patients should instead be interviewed by an endocrinologist (preferably via telehealth) to collect their clinical history as well as assess their perception of the disease and risk of malignancy, senior author S. Mitchell Harman, MD, chief of PVAHCS, said in an interview.

“The principal guiding factor should be the objectively assessed likelihood of malignancy of the individual patient’s nodule(s),” he said.

“In my opinion, we should also factor in the patient’s level of anxiety, since some patients are more sanguine about risk than others and our goal is to provide relief of anxiety as well as to determine need for, and course of, subsequent treatment,” Dr. Harman added.

Vast majority of malignant thyroid nodules are DTC, which is ‘indolent’

Dr. Lee and colleagues noted that, even of the 10% of thyroid nodules that do prove to be malignant, the vast majority of these (90%) are differentiated thyroid cancers (DTC). In general, patients with DTC “follow an indolent course and have excellent outcomes.”

“There is little evidence that early detection and treatment of DTC significantly alters disease outcomes as the overall mortality rate for DTC has remained low, at around 0.5%,” they wrote.

They also noted that ultrasound features of thyroid nodules can help guide priority for the future timing of an FNA procedure, but should not be the sole basis for deciding on immediate thyroid FNA or surgery.

Exceptions to the rule

Exceptions for considering FNA include more urgent thyroid disease diagnoses, including those that are symptomatic:

Suspected medullary thyroid cancer

“Regarding medullary thyroid cancer (MTC), early diagnosis and surgery do significantly improve outcomes, therefore, delaying FNA of nodules harboring MTC could be potentially injurious,” the authors said.

They suggested, however, measuring calcitonin levels instead, which they noted “is still controversial” in the United States, but “we feel it would be justified in patients with thyroid nodules that would usually be indicated for FNA.”

Those with a family history of MTC, or nodules located in the posterior upper third of lateral lobes (the usual location of MTC), should have calcitonin levels measured.

If calcitonin levels are above 10 pg/mL, “FNA should be offered as early as possible.”

“Significantly elevated serum calcitonin levels (e.g., > 100 pg/mL) should be considered an indication for surgery without cytologic confirmation by FNA,” they added.

Anaplastic thyroid cancer

Anaplastic thyroid cancer, though rare, “is one of the few occasions when thyroid surgery should be performed on an urgent basis, as this condition can worsen very rapidly.

“Patients typically present with a rapidly enlarging thyroid mass that is associated with compressive symptoms, such as dysphagia and dyspnea,” they observed.

In this instance, although FNA is part of the preoperative work-up, it is often nondiagnostic and could require additional sampling.

“At the time of this pandemic, it is reasonable that after a multidisciplinary discussion, such patients with the appropriate clinical scenario be referred for thyroid surgery, with or without prior FNA, based on the team’s judgment,” the authors recommended.

Long-standing thyroid masses

These are usually large and/or closely associated with vital structures, such as the trachea and esophagus, and when such masses cause compressive symptoms, thyroid surgery typically is warranted.

And although prior FNA is helpful to obtain a cytologic diagnosis, as this may change the extent of surgery, it may not always be essential.

Broadly, symptomatic patients with compressive symptoms threatening vital structures can be directly referred to a surgeon, with the timing for surgery jointly decided based on the severity of symptoms, rapidity of disease progression, local COVID-19 status, and available resources.

“During the pandemic, we believe that the vast majority of thyroid FNAs should be considered optional, and extent of surgery can be determined by pathological analysis of frozen sections intraoperatively,” they wrote.

“The value of FNA in these situations is less compelling in the current COVID-19 setting, as the basis of decision for surgery has been already determined,” the authors explained.

If urgent FNA needed, screen patient for COVID-19 and use PPE

Should the need for an urgent thyroid FNA occur, patients should be screened and tested for COVID-19 by a clinician wearing personal protective equipment (PPE), said Dr. Lee and colleagues.

“It is crucial to carefully weigh the risks of COVID-19 exposure, availability of resources, and urgency of these procedures for each patient in our individual practice settings,” they noted.

As restrictions eventually loosen, precautions will still be necessary to some degree, Dr. Harman said.

“I do not consider FNA a ‘high-risk’ procedure in the era of COVID-19, since it does not routinely result in profuse aerosolization of respiratory fluids,” he said in an interview.

“However, patients do sometimes cough or choke due to pressure on the neck and the operator is, of necessity, very close to the patient’s face. Therefore, when we resume FNA, patients will be screened for symptoms of COVID-19 infection and both the operator and the patient will be masked,” Dr. Harman continued.

“We routinely wear gloves, [and] whether the operator will wear a surgical or an N95 mask, disposable gown, etc, will depend on CDC guidance and guidance received from our VA infectious disease experts as it is applied specifically to each patient evaluation.”

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

With a few notable exceptions, the majority of fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsies of thyroid nodules should be delayed until the risk of COVID-19, and the burden on resources, has lessened, according to expert consensus.

“Our group recommends that FNA biopsy of most asymptomatic thyroid nodules – taking into account the sonographic characteristics and patients’ clinical picture – be deferred to a later time, when risk of exposure to COVID-19 is more manageable and resource restriction is no longer a concern,” said the endocrinologists, writing in a guest editorial in Clinical Thyroidology.

All elective procedures have been canceled under guidance of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in conjunction with the U.S. surgeon general, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, thyroid nodule FNAs, though elective, fall into the category of being considered medically necessary and potentially prolonging life expectancy

Yet, with approximately 90% of asymptomatic thyroid nodules turning out to be benign and little evidence that early detection and treatment affects disease outcomes, there is a strong argument for deferral in most cases, stressed Ming Lee, MD, and colleagues, of the endocrinology division at Phoenix (Ariz.) Veterans Affairs Health Care System (PVAHCS), who convened a multidisciplinary meeting to address the urgent issue.

Patients should instead be interviewed by an endocrinologist (preferably via telehealth) to collect their clinical history as well as assess their perception of the disease and risk of malignancy, senior author S. Mitchell Harman, MD, chief of PVAHCS, said in an interview.

“The principal guiding factor should be the objectively assessed likelihood of malignancy of the individual patient’s nodule(s),” he said.

“In my opinion, we should also factor in the patient’s level of anxiety, since some patients are more sanguine about risk than others and our goal is to provide relief of anxiety as well as to determine need for, and course of, subsequent treatment,” Dr. Harman added.

Vast majority of malignant thyroid nodules are DTC, which is ‘indolent’

Dr. Lee and colleagues noted that, even of the 10% of thyroid nodules that do prove to be malignant, the vast majority of these (90%) are differentiated thyroid cancers (DTC). In general, patients with DTC “follow an indolent course and have excellent outcomes.”

“There is little evidence that early detection and treatment of DTC significantly alters disease outcomes as the overall mortality rate for DTC has remained low, at around 0.5%,” they wrote.

They also noted that ultrasound features of thyroid nodules can help guide priority for the future timing of an FNA procedure, but should not be the sole basis for deciding on immediate thyroid FNA or surgery.

Exceptions to the rule

Exceptions for considering FNA include more urgent thyroid disease diagnoses, including those that are symptomatic:

Suspected medullary thyroid cancer

“Regarding medullary thyroid cancer (MTC), early diagnosis and surgery do significantly improve outcomes, therefore, delaying FNA of nodules harboring MTC could be potentially injurious,” the authors said.

They suggested, however, measuring calcitonin levels instead, which they noted “is still controversial” in the United States, but “we feel it would be justified in patients with thyroid nodules that would usually be indicated for FNA.”

Those with a family history of MTC, or nodules located in the posterior upper third of lateral lobes (the usual location of MTC), should have calcitonin levels measured.

If calcitonin levels are above 10 pg/mL, “FNA should be offered as early as possible.”

“Significantly elevated serum calcitonin levels (e.g., > 100 pg/mL) should be considered an indication for surgery without cytologic confirmation by FNA,” they added.

Anaplastic thyroid cancer

Anaplastic thyroid cancer, though rare, “is one of the few occasions when thyroid surgery should be performed on an urgent basis, as this condition can worsen very rapidly.

“Patients typically present with a rapidly enlarging thyroid mass that is associated with compressive symptoms, such as dysphagia and dyspnea,” they observed.

In this instance, although FNA is part of the preoperative work-up, it is often nondiagnostic and could require additional sampling.

“At the time of this pandemic, it is reasonable that after a multidisciplinary discussion, such patients with the appropriate clinical scenario be referred for thyroid surgery, with or without prior FNA, based on the team’s judgment,” the authors recommended.

Long-standing thyroid masses

These are usually large and/or closely associated with vital structures, such as the trachea and esophagus, and when such masses cause compressive symptoms, thyroid surgery typically is warranted.

And although prior FNA is helpful to obtain a cytologic diagnosis, as this may change the extent of surgery, it may not always be essential.

Broadly, symptomatic patients with compressive symptoms threatening vital structures can be directly referred to a surgeon, with the timing for surgery jointly decided based on the severity of symptoms, rapidity of disease progression, local COVID-19 status, and available resources.

“During the pandemic, we believe that the vast majority of thyroid FNAs should be considered optional, and extent of surgery can be determined by pathological analysis of frozen sections intraoperatively,” they wrote.

“The value of FNA in these situations is less compelling in the current COVID-19 setting, as the basis of decision for surgery has been already determined,” the authors explained.

If urgent FNA needed, screen patient for COVID-19 and use PPE

Should the need for an urgent thyroid FNA occur, patients should be screened and tested for COVID-19 by a clinician wearing personal protective equipment (PPE), said Dr. Lee and colleagues.

“It is crucial to carefully weigh the risks of COVID-19 exposure, availability of resources, and urgency of these procedures for each patient in our individual practice settings,” they noted.

As restrictions eventually loosen, precautions will still be necessary to some degree, Dr. Harman said.

“I do not consider FNA a ‘high-risk’ procedure in the era of COVID-19, since it does not routinely result in profuse aerosolization of respiratory fluids,” he said in an interview.

“However, patients do sometimes cough or choke due to pressure on the neck and the operator is, of necessity, very close to the patient’s face. Therefore, when we resume FNA, patients will be screened for symptoms of COVID-19 infection and both the operator and the patient will be masked,” Dr. Harman continued.

“We routinely wear gloves, [and] whether the operator will wear a surgical or an N95 mask, disposable gown, etc, will depend on CDC guidance and guidance received from our VA infectious disease experts as it is applied specifically to each patient evaluation.”

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

With a few notable exceptions, the majority of fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsies of thyroid nodules should be delayed until the risk of COVID-19, and the burden on resources, has lessened, according to expert consensus.

“Our group recommends that FNA biopsy of most asymptomatic thyroid nodules – taking into account the sonographic characteristics and patients’ clinical picture – be deferred to a later time, when risk of exposure to COVID-19 is more manageable and resource restriction is no longer a concern,” said the endocrinologists, writing in a guest editorial in Clinical Thyroidology.

All elective procedures have been canceled under guidance of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in conjunction with the U.S. surgeon general, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, thyroid nodule FNAs, though elective, fall into the category of being considered medically necessary and potentially prolonging life expectancy

Yet, with approximately 90% of asymptomatic thyroid nodules turning out to be benign and little evidence that early detection and treatment affects disease outcomes, there is a strong argument for deferral in most cases, stressed Ming Lee, MD, and colleagues, of the endocrinology division at Phoenix (Ariz.) Veterans Affairs Health Care System (PVAHCS), who convened a multidisciplinary meeting to address the urgent issue.

Patients should instead be interviewed by an endocrinologist (preferably via telehealth) to collect their clinical history as well as assess their perception of the disease and risk of malignancy, senior author S. Mitchell Harman, MD, chief of PVAHCS, said in an interview.

“The principal guiding factor should be the objectively assessed likelihood of malignancy of the individual patient’s nodule(s),” he said.

“In my opinion, we should also factor in the patient’s level of anxiety, since some patients are more sanguine about risk than others and our goal is to provide relief of anxiety as well as to determine need for, and course of, subsequent treatment,” Dr. Harman added.

Vast majority of malignant thyroid nodules are DTC, which is ‘indolent’

Dr. Lee and colleagues noted that, even of the 10% of thyroid nodules that do prove to be malignant, the vast majority of these (90%) are differentiated thyroid cancers (DTC). In general, patients with DTC “follow an indolent course and have excellent outcomes.”

“There is little evidence that early detection and treatment of DTC significantly alters disease outcomes as the overall mortality rate for DTC has remained low, at around 0.5%,” they wrote.

They also noted that ultrasound features of thyroid nodules can help guide priority for the future timing of an FNA procedure, but should not be the sole basis for deciding on immediate thyroid FNA or surgery.

Exceptions to the rule

Exceptions for considering FNA include more urgent thyroid disease diagnoses, including those that are symptomatic:

Suspected medullary thyroid cancer

“Regarding medullary thyroid cancer (MTC), early diagnosis and surgery do significantly improve outcomes, therefore, delaying FNA of nodules harboring MTC could be potentially injurious,” the authors said.

They suggested, however, measuring calcitonin levels instead, which they noted “is still controversial” in the United States, but “we feel it would be justified in patients with thyroid nodules that would usually be indicated for FNA.”

Those with a family history of MTC, or nodules located in the posterior upper third of lateral lobes (the usual location of MTC), should have calcitonin levels measured.

If calcitonin levels are above 10 pg/mL, “FNA should be offered as early as possible.”

“Significantly elevated serum calcitonin levels (e.g., > 100 pg/mL) should be considered an indication for surgery without cytologic confirmation by FNA,” they added.

Anaplastic thyroid cancer

Anaplastic thyroid cancer, though rare, “is one of the few occasions when thyroid surgery should be performed on an urgent basis, as this condition can worsen very rapidly.

“Patients typically present with a rapidly enlarging thyroid mass that is associated with compressive symptoms, such as dysphagia and dyspnea,” they observed.

In this instance, although FNA is part of the preoperative work-up, it is often nondiagnostic and could require additional sampling.

“At the time of this pandemic, it is reasonable that after a multidisciplinary discussion, such patients with the appropriate clinical scenario be referred for thyroid surgery, with or without prior FNA, based on the team’s judgment,” the authors recommended.

Long-standing thyroid masses

These are usually large and/or closely associated with vital structures, such as the trachea and esophagus, and when such masses cause compressive symptoms, thyroid surgery typically is warranted.

And although prior FNA is helpful to obtain a cytologic diagnosis, as this may change the extent of surgery, it may not always be essential.

Broadly, symptomatic patients with compressive symptoms threatening vital structures can be directly referred to a surgeon, with the timing for surgery jointly decided based on the severity of symptoms, rapidity of disease progression, local COVID-19 status, and available resources.

“During the pandemic, we believe that the vast majority of thyroid FNAs should be considered optional, and extent of surgery can be determined by pathological analysis of frozen sections intraoperatively,” they wrote.

“The value of FNA in these situations is less compelling in the current COVID-19 setting, as the basis of decision for surgery has been already determined,” the authors explained.

If urgent FNA needed, screen patient for COVID-19 and use PPE

Should the need for an urgent thyroid FNA occur, patients should be screened and tested for COVID-19 by a clinician wearing personal protective equipment (PPE), said Dr. Lee and colleagues.

“It is crucial to carefully weigh the risks of COVID-19 exposure, availability of resources, and urgency of these procedures for each patient in our individual practice settings,” they noted.

As restrictions eventually loosen, precautions will still be necessary to some degree, Dr. Harman said.

“I do not consider FNA a ‘high-risk’ procedure in the era of COVID-19, since it does not routinely result in profuse aerosolization of respiratory fluids,” he said in an interview.

“However, patients do sometimes cough or choke due to pressure on the neck and the operator is, of necessity, very close to the patient’s face. Therefore, when we resume FNA, patients will be screened for symptoms of COVID-19 infection and both the operator and the patient will be masked,” Dr. Harman continued.

“We routinely wear gloves, [and] whether the operator will wear a surgical or an N95 mask, disposable gown, etc, will depend on CDC guidance and guidance received from our VA infectious disease experts as it is applied specifically to each patient evaluation.”

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 decimates outpatient visits

There has been a massive decline in outpatient office visits as patients have stayed home – likely deferring needed care – because of COVID-19, new research shows.

The number of visits to ambulatory practices dropped by a whopping 60% in mid-March, and continues to be down by at least 50% since early February, according to new data compiled and analyzed by Harvard University and Phreesia, a health care technology company.

Phreesia – which helps medical practices with patient registration, insurance verification, and payments – has data on 50,000 providers in all 50 states; in a typical year, Phreesia tracks 50 million outpatient visits.

The report was published online April 23 by the Commonwealth Fund.

The company captured data on visits from February 1 through April 16. The decline was greatest in New England and the Mid-Atlantic states, where, at the steepest end of the decline in late March, visits were down 66%.

They have rebounded slightly since then but are still down 64%. Practices in the mountain states had the smallest decline, but visits were down by 45% as of April 16.

Many practices have attempted to reach out to patients through telemedicine. As of April 16, about 30% of all visits tracked by Phreesia were provided via telemedicine – by phone or through video. That’s a monumental increase from mid-February, when zero visits were conducted virtually.

However, the Harvard researchers found that telemedicine visits barely made up for the huge decline in office visits.

Decline by specialty

Not surprisingly, declining visits have been steeper in procedure-oriented specialties.

Overall visits – including telemedicine – to ophthalmologists and otolaryngologists had declined by 79% and 75%, respectively, as of the week of April 5. Dermatology saw a 73% decline. Surgery, pulmonology, urology, orthopedics, cardiology, and gastroenterology all experienced declines ranging from 61% to 66%.

Primary care offices, oncology, endocrinology, and obstetrics/gynecology all fared slightly better, with visits down by half. Behavioral health experienced the lowest rate of decline (30%).

School-aged children were skipping care most often. The study showed a 71% drop in visits in 7- to 17-year-olds, and a 59% decline in visits by neonates, infants, and toddlers (up to age 6). Overall, pediatric practices experienced a 62% drop-off in visits.

Nearly two-thirds of Americans over age 65 also stayed away from their doctors. Only half of those aged 18 to 64 reduced their physician visits.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There has been a massive decline in outpatient office visits as patients have stayed home – likely deferring needed care – because of COVID-19, new research shows.

The number of visits to ambulatory practices dropped by a whopping 60% in mid-March, and continues to be down by at least 50% since early February, according to new data compiled and analyzed by Harvard University and Phreesia, a health care technology company.

Phreesia – which helps medical practices with patient registration, insurance verification, and payments – has data on 50,000 providers in all 50 states; in a typical year, Phreesia tracks 50 million outpatient visits.

The report was published online April 23 by the Commonwealth Fund.

The company captured data on visits from February 1 through April 16. The decline was greatest in New England and the Mid-Atlantic states, where, at the steepest end of the decline in late March, visits were down 66%.

They have rebounded slightly since then but are still down 64%. Practices in the mountain states had the smallest decline, but visits were down by 45% as of April 16.

Many practices have attempted to reach out to patients through telemedicine. As of April 16, about 30% of all visits tracked by Phreesia were provided via telemedicine – by phone or through video. That’s a monumental increase from mid-February, when zero visits were conducted virtually.

However, the Harvard researchers found that telemedicine visits barely made up for the huge decline in office visits.

Decline by specialty

Not surprisingly, declining visits have been steeper in procedure-oriented specialties.

Overall visits – including telemedicine – to ophthalmologists and otolaryngologists had declined by 79% and 75%, respectively, as of the week of April 5. Dermatology saw a 73% decline. Surgery, pulmonology, urology, orthopedics, cardiology, and gastroenterology all experienced declines ranging from 61% to 66%.

Primary care offices, oncology, endocrinology, and obstetrics/gynecology all fared slightly better, with visits down by half. Behavioral health experienced the lowest rate of decline (30%).

School-aged children were skipping care most often. The study showed a 71% drop in visits in 7- to 17-year-olds, and a 59% decline in visits by neonates, infants, and toddlers (up to age 6). Overall, pediatric practices experienced a 62% drop-off in visits.

Nearly two-thirds of Americans over age 65 also stayed away from their doctors. Only half of those aged 18 to 64 reduced their physician visits.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There has been a massive decline in outpatient office visits as patients have stayed home – likely deferring needed care – because of COVID-19, new research shows.

The number of visits to ambulatory practices dropped by a whopping 60% in mid-March, and continues to be down by at least 50% since early February, according to new data compiled and analyzed by Harvard University and Phreesia, a health care technology company.

Phreesia – which helps medical practices with patient registration, insurance verification, and payments – has data on 50,000 providers in all 50 states; in a typical year, Phreesia tracks 50 million outpatient visits.

The report was published online April 23 by the Commonwealth Fund.

The company captured data on visits from February 1 through April 16. The decline was greatest in New England and the Mid-Atlantic states, where, at the steepest end of the decline in late March, visits were down 66%.

They have rebounded slightly since then but are still down 64%. Practices in the mountain states had the smallest decline, but visits were down by 45% as of April 16.

Many practices have attempted to reach out to patients through telemedicine. As of April 16, about 30% of all visits tracked by Phreesia were provided via telemedicine – by phone or through video. That’s a monumental increase from mid-February, when zero visits were conducted virtually.

However, the Harvard researchers found that telemedicine visits barely made up for the huge decline in office visits.

Decline by specialty

Not surprisingly, declining visits have been steeper in procedure-oriented specialties.

Overall visits – including telemedicine – to ophthalmologists and otolaryngologists had declined by 79% and 75%, respectively, as of the week of April 5. Dermatology saw a 73% decline. Surgery, pulmonology, urology, orthopedics, cardiology, and gastroenterology all experienced declines ranging from 61% to 66%.

Primary care offices, oncology, endocrinology, and obstetrics/gynecology all fared slightly better, with visits down by half. Behavioral health experienced the lowest rate of decline (30%).

School-aged children were skipping care most often. The study showed a 71% drop in visits in 7- to 17-year-olds, and a 59% decline in visits by neonates, infants, and toddlers (up to age 6). Overall, pediatric practices experienced a 62% drop-off in visits.

Nearly two-thirds of Americans over age 65 also stayed away from their doctors. Only half of those aged 18 to 64 reduced their physician visits.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ASCO panel outlines cancer care challenges during COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to exact a heavy price on cancer patients, cancer care, and clinical trials, an expert panel reported during a presscast.

“Limited data available thus far are sobering: In Italy, about 20% of COVID-related deaths occurred in people with cancer, and, in China, COVID-19 patients who had cancer were about five times more likely than others to die or be placed on a ventilator in an intensive care unit,” said Howard A “Skip” Burris, MD, president of the American Society of Clinical Oncology and president and CEO of the Sarah Cannon Cancer Institute in Nashville, Tenn.

“We also have little evidence on returning COVID-19 patients with cancer. Physicians have to rely on limited data, anecdotal reports, and their own professional expertise” regarding the extent of increased risk to cancer patients with COVID-19, whether to interrupt or modify treatment, and the effects of cancer on recovery from COVID-19 infection, Dr. Burris said during the ASCO-sponsored online presscast.

Care of COVID-free patients

For cancer patients without COVID-19, the picture is equally dim, with the prospect of delayed surgery, chemotherapy, or screening; shortages of medications and equipment needed for critical care; the shift to telemedicine that may increase patient anxiety; and the potential loss of access to innovative therapies through clinical trials, Dr. Burris said.

“We’re concerned that some hospitals have effectively deemed all cancer surgeries to be elective, requiring them to be postponed. For patients with fast-moving or hard-to-treat cancer, this delay may be devastating,” he said.

Dr. Burris also cited concerns about delayed cancer diagnosis. “In a typical month, roughly 150,000 Americans are diagnosed with cancer. But right now, routine screening visits are postponed, and patients with pain or other warning signs may put off a doctor’s visit because of social distancing,” he said.

The pandemic has also exacerbated shortages of sedatives and opioid analgesics required for intubation and mechanical ventilation of patients.

Trials halted or slowed

Dr. Burris also briefly discussed results of a new survey, which were posted online ahead of publication in JCO Oncology Practice. The survey showed that, of 14 academic and 18 community-based cancer programs, 59.4% reported halting screening and/or enrollment for at least some clinical trials and suspending research-based clinical visits except for those where cancer treatment was delivered.

“Half of respondents reported ceasing research-only blood and/or tissue collections,” the authors of the article reported.

“Trial interruptions are devastating news for thousands of patients; in many cases, clinical trials are the best or only appropriate option for care,” Dr. Burris said.

The article authors, led by David Waterhouse, MD, of Oncology Hematology Care in Cincinnati, pointed to a silver lining in the pandemic cloud in the form of opportunities to improve clinical trials going forward.

“Nearly all respondents (90.3%) identified telehealth visits for participants as a potential improvement to clinical trial conduct, and more than three-quarters (77.4%) indicated that remote patient review of symptoms held similar potential,” the authors wrote.

Other potential improvements included remote site visits from trial sponsors and/or contract research organizations, more efficient study enrollment through secure electronic platforms, direct shipment of oral drugs to patients, remote assessments of adverse events, and streamlined data collection.

Lessons from the front lines

Another member of the presscast panel, Melissa Dillmon, MD, of the Harbin Clinic Cancer Center in Rome, Georgia, described the experience of community oncologists during the pandemic.

Her community, located in northeastern Georgia, experienced a COVID-19 outbreak in early March linked to services at two large churches. Community public health authorities issued a shelter-in-place order before the state government issued stay-at-home guidelines and shuttered all but essential business, some of which were allowed by state order to reopen as of April 24.

Dr. Dillmon’s center began screening patients for COVID-19 symptoms at the door, limited visitors or companions, instituted virtual visits and tumor boards, and set up a cancer treatment triage system that would allow essential surgeries to proceed and most infusions to continue, while delaying the start of chemotherapy when possible.

“We have encouraged patients to continue on treatment, especially if treatment is being given with curative intent, or if the cancer is responding well already to treatment,” she said.

The center, located in a community with a high prevalence of comorbidities and high incidence of lung cancer, has seen a sharp decline in colonoscopies, mammograms, and lung scans as patient shelter in place.

“We have great concerns about patients missing their screening lung scans, as this program has already proven to be finding earlier lung cancers that are curable,” Dr. Dillmon said.

A view from Washington state

Another panel member, Gary Lyman, MD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, described the response by the state of Washington, the initial epicenter of the COVID-19 outbreak in the United States.

Following identification of infections in hospitalized patients and at a nursing home in Kirkland, Washington, “our response, which began in early March and progressed through the second and third week in March at the state level, was to restrict large gatherings; progressively, schools were closed; larger businesses closed; and, by March 23, a stay-at-home policy was implemented, and all nonessential businesses were closed,” Dr. Lyman said.

“We believe, based on what has happened since that time, that this has considerably flattened the curve,” he continued.

Lessons from the Washington experience include the need to plan for a long-term disruption or alteration of cancer care, expand COVID-19 testing to all patients coming into hospitals or major clinics, institute aggressive supportive care measures, prepare for subsequent waves of infection, collect and share data, and, for remote or rural areas, identify lifelines to needed resources, Dr. Lyman said.

ASCO resources

Also speaking at the presscast, Jonathan Marron, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, outlined ASCO’s guidance on allocation of scarce resources during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Richard L. Schilsky, MD, ASCO chief medical officer and executive vice president, outlined community-wide collaborations, data initiatives, and online resources for both clinicians and patients.

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to exact a heavy price on cancer patients, cancer care, and clinical trials, an expert panel reported during a presscast.

“Limited data available thus far are sobering: In Italy, about 20% of COVID-related deaths occurred in people with cancer, and, in China, COVID-19 patients who had cancer were about five times more likely than others to die or be placed on a ventilator in an intensive care unit,” said Howard A “Skip” Burris, MD, president of the American Society of Clinical Oncology and president and CEO of the Sarah Cannon Cancer Institute in Nashville, Tenn.

“We also have little evidence on returning COVID-19 patients with cancer. Physicians have to rely on limited data, anecdotal reports, and their own professional expertise” regarding the extent of increased risk to cancer patients with COVID-19, whether to interrupt or modify treatment, and the effects of cancer on recovery from COVID-19 infection, Dr. Burris said during the ASCO-sponsored online presscast.

Care of COVID-free patients

For cancer patients without COVID-19, the picture is equally dim, with the prospect of delayed surgery, chemotherapy, or screening; shortages of medications and equipment needed for critical care; the shift to telemedicine that may increase patient anxiety; and the potential loss of access to innovative therapies through clinical trials, Dr. Burris said.

“We’re concerned that some hospitals have effectively deemed all cancer surgeries to be elective, requiring them to be postponed. For patients with fast-moving or hard-to-treat cancer, this delay may be devastating,” he said.

Dr. Burris also cited concerns about delayed cancer diagnosis. “In a typical month, roughly 150,000 Americans are diagnosed with cancer. But right now, routine screening visits are postponed, and patients with pain or other warning signs may put off a doctor’s visit because of social distancing,” he said.

The pandemic has also exacerbated shortages of sedatives and opioid analgesics required for intubation and mechanical ventilation of patients.

Trials halted or slowed

Dr. Burris also briefly discussed results of a new survey, which were posted online ahead of publication in JCO Oncology Practice. The survey showed that, of 14 academic and 18 community-based cancer programs, 59.4% reported halting screening and/or enrollment for at least some clinical trials and suspending research-based clinical visits except for those where cancer treatment was delivered.

“Half of respondents reported ceasing research-only blood and/or tissue collections,” the authors of the article reported.

“Trial interruptions are devastating news for thousands of patients; in many cases, clinical trials are the best or only appropriate option for care,” Dr. Burris said.

The article authors, led by David Waterhouse, MD, of Oncology Hematology Care in Cincinnati, pointed to a silver lining in the pandemic cloud in the form of opportunities to improve clinical trials going forward.

“Nearly all respondents (90.3%) identified telehealth visits for participants as a potential improvement to clinical trial conduct, and more than three-quarters (77.4%) indicated that remote patient review of symptoms held similar potential,” the authors wrote.

Other potential improvements included remote site visits from trial sponsors and/or contract research organizations, more efficient study enrollment through secure electronic platforms, direct shipment of oral drugs to patients, remote assessments of adverse events, and streamlined data collection.

Lessons from the front lines

Another member of the presscast panel, Melissa Dillmon, MD, of the Harbin Clinic Cancer Center in Rome, Georgia, described the experience of community oncologists during the pandemic.

Her community, located in northeastern Georgia, experienced a COVID-19 outbreak in early March linked to services at two large churches. Community public health authorities issued a shelter-in-place order before the state government issued stay-at-home guidelines and shuttered all but essential business, some of which were allowed by state order to reopen as of April 24.

Dr. Dillmon’s center began screening patients for COVID-19 symptoms at the door, limited visitors or companions, instituted virtual visits and tumor boards, and set up a cancer treatment triage system that would allow essential surgeries to proceed and most infusions to continue, while delaying the start of chemotherapy when possible.

“We have encouraged patients to continue on treatment, especially if treatment is being given with curative intent, or if the cancer is responding well already to treatment,” she said.

The center, located in a community with a high prevalence of comorbidities and high incidence of lung cancer, has seen a sharp decline in colonoscopies, mammograms, and lung scans as patient shelter in place.

“We have great concerns about patients missing their screening lung scans, as this program has already proven to be finding earlier lung cancers that are curable,” Dr. Dillmon said.

A view from Washington state

Another panel member, Gary Lyman, MD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, described the response by the state of Washington, the initial epicenter of the COVID-19 outbreak in the United States.

Following identification of infections in hospitalized patients and at a nursing home in Kirkland, Washington, “our response, which began in early March and progressed through the second and third week in March at the state level, was to restrict large gatherings; progressively, schools were closed; larger businesses closed; and, by March 23, a stay-at-home policy was implemented, and all nonessential businesses were closed,” Dr. Lyman said.

“We believe, based on what has happened since that time, that this has considerably flattened the curve,” he continued.

Lessons from the Washington experience include the need to plan for a long-term disruption or alteration of cancer care, expand COVID-19 testing to all patients coming into hospitals or major clinics, institute aggressive supportive care measures, prepare for subsequent waves of infection, collect and share data, and, for remote or rural areas, identify lifelines to needed resources, Dr. Lyman said.

ASCO resources

Also speaking at the presscast, Jonathan Marron, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, outlined ASCO’s guidance on allocation of scarce resources during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Richard L. Schilsky, MD, ASCO chief medical officer and executive vice president, outlined community-wide collaborations, data initiatives, and online resources for both clinicians and patients.

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to exact a heavy price on cancer patients, cancer care, and clinical trials, an expert panel reported during a presscast.

“Limited data available thus far are sobering: In Italy, about 20% of COVID-related deaths occurred in people with cancer, and, in China, COVID-19 patients who had cancer were about five times more likely than others to die or be placed on a ventilator in an intensive care unit,” said Howard A “Skip” Burris, MD, president of the American Society of Clinical Oncology and president and CEO of the Sarah Cannon Cancer Institute in Nashville, Tenn.

“We also have little evidence on returning COVID-19 patients with cancer. Physicians have to rely on limited data, anecdotal reports, and their own professional expertise” regarding the extent of increased risk to cancer patients with COVID-19, whether to interrupt or modify treatment, and the effects of cancer on recovery from COVID-19 infection, Dr. Burris said during the ASCO-sponsored online presscast.

Care of COVID-free patients

For cancer patients without COVID-19, the picture is equally dim, with the prospect of delayed surgery, chemotherapy, or screening; shortages of medications and equipment needed for critical care; the shift to telemedicine that may increase patient anxiety; and the potential loss of access to innovative therapies through clinical trials, Dr. Burris said.

“We’re concerned that some hospitals have effectively deemed all cancer surgeries to be elective, requiring them to be postponed. For patients with fast-moving or hard-to-treat cancer, this delay may be devastating,” he said.

Dr. Burris also cited concerns about delayed cancer diagnosis. “In a typical month, roughly 150,000 Americans are diagnosed with cancer. But right now, routine screening visits are postponed, and patients with pain or other warning signs may put off a doctor’s visit because of social distancing,” he said.

The pandemic has also exacerbated shortages of sedatives and opioid analgesics required for intubation and mechanical ventilation of patients.

Trials halted or slowed

Dr. Burris also briefly discussed results of a new survey, which were posted online ahead of publication in JCO Oncology Practice. The survey showed that, of 14 academic and 18 community-based cancer programs, 59.4% reported halting screening and/or enrollment for at least some clinical trials and suspending research-based clinical visits except for those where cancer treatment was delivered.

“Half of respondents reported ceasing research-only blood and/or tissue collections,” the authors of the article reported.

“Trial interruptions are devastating news for thousands of patients; in many cases, clinical trials are the best or only appropriate option for care,” Dr. Burris said.

The article authors, led by David Waterhouse, MD, of Oncology Hematology Care in Cincinnati, pointed to a silver lining in the pandemic cloud in the form of opportunities to improve clinical trials going forward.

“Nearly all respondents (90.3%) identified telehealth visits for participants as a potential improvement to clinical trial conduct, and more than three-quarters (77.4%) indicated that remote patient review of symptoms held similar potential,” the authors wrote.

Other potential improvements included remote site visits from trial sponsors and/or contract research organizations, more efficient study enrollment through secure electronic platforms, direct shipment of oral drugs to patients, remote assessments of adverse events, and streamlined data collection.

Lessons from the front lines

Another member of the presscast panel, Melissa Dillmon, MD, of the Harbin Clinic Cancer Center in Rome, Georgia, described the experience of community oncologists during the pandemic.

Her community, located in northeastern Georgia, experienced a COVID-19 outbreak in early March linked to services at two large churches. Community public health authorities issued a shelter-in-place order before the state government issued stay-at-home guidelines and shuttered all but essential business, some of which were allowed by state order to reopen as of April 24.

Dr. Dillmon’s center began screening patients for COVID-19 symptoms at the door, limited visitors or companions, instituted virtual visits and tumor boards, and set up a cancer treatment triage system that would allow essential surgeries to proceed and most infusions to continue, while delaying the start of chemotherapy when possible.

“We have encouraged patients to continue on treatment, especially if treatment is being given with curative intent, or if the cancer is responding well already to treatment,” she said.

The center, located in a community with a high prevalence of comorbidities and high incidence of lung cancer, has seen a sharp decline in colonoscopies, mammograms, and lung scans as patient shelter in place.

“We have great concerns about patients missing their screening lung scans, as this program has already proven to be finding earlier lung cancers that are curable,” Dr. Dillmon said.

A view from Washington state

Another panel member, Gary Lyman, MD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, described the response by the state of Washington, the initial epicenter of the COVID-19 outbreak in the United States.

Following identification of infections in hospitalized patients and at a nursing home in Kirkland, Washington, “our response, which began in early March and progressed through the second and third week in March at the state level, was to restrict large gatherings; progressively, schools were closed; larger businesses closed; and, by March 23, a stay-at-home policy was implemented, and all nonessential businesses were closed,” Dr. Lyman said.

“We believe, based on what has happened since that time, that this has considerably flattened the curve,” he continued.

Lessons from the Washington experience include the need to plan for a long-term disruption or alteration of cancer care, expand COVID-19 testing to all patients coming into hospitals or major clinics, institute aggressive supportive care measures, prepare for subsequent waves of infection, collect and share data, and, for remote or rural areas, identify lifelines to needed resources, Dr. Lyman said.

ASCO resources

Also speaking at the presscast, Jonathan Marron, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, outlined ASCO’s guidance on allocation of scarce resources during the COVID-19 pandemic.