User login

For SCC, legs are a high-risk anatomic site in women

When Maryam M. Asgari, MD, reviewed results from a large population-based study published in 2017, which found that a large proportion of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas were being detected on the lower extremities of women, it caused her to reflect on her own clinical practice as a Mohs surgeon.

“I was struck by the number of times I was seeing women present with lower extremity SCCs,” Dr. Asgari, professor of dermatology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, said during a virtual forum on cutaneous malignancies jointly presented by Postgraduate Institute for Medicine and Global Academy for Medical Education. “When female patients push you for a waist-up skin exam, try to convince them that the legs are an important area to look at as well.”

In an effort to ascertain if there are sex differences in the anatomic distribution of cutaneous SCC, she and her postdoctoral fellow, Yuhree Kim, MD, MPH, used an institutional registry to identify 618 non-Hispanic White patients diagnosed with 2,111 SCCs between 2000 and 2016. They found that men were more likely to have SCCs arise on the head and neck (52% vs. 21% among women, respectively), while women were more likely to have SCCs develop on the lower extremity (41% vs. 10% in men).

“When we looked at whether these tumors were in situ or invasive, in women, the majority of these weren’t just your run-of-the-mill in situ SCCs; 44% were actually invasive SCCs,” Dr. Asgari said. “What this is getting at is to make sure that you’re examining the lower extremities when you’re doing these skin exams. Many times, especially in colder weather, your patients will come in and request a waist-up exam. For women, you absolutely have to examine their lower extremities. That’s their high-risk area for SCCs.”

, she continued. According to 2020 data from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results SEER program, the incidence of KC in the United States is estimated to be 3.5 million cases per year, while all other cancers account for approximately 1.8 million cases per year.

To make matters worse, while the incidence of many other cancers have plateaued or even declined over time in the United States, data from a population-based cohort at Kaiser Permanente Northern California show that the incidence of BCCs rose between 1998 and 2012, estimated to occur in about 2 million Americans each year.

Dr. Asgari noted that the incidence of KCs can be difficult to quantify and study. “Part of the reason is that they’re not reported to traditional cancer registries like the SEER program,” she said. “You can imagine why. The sheer volume of KC dwarfs all other cancers, and oftentimes KCs are biopsied in dermatology offices. Sometimes, dermatologists even read their own biopsy specimens, so they don’t go to a central pathology repository like other cancers do.”

The best available research suggests that patients at the highest risk of KC include men and women between the ages of 60 and 89. Dr. Asgari said that she informs her patients that people in their 80s have about a 20-fold risk of BCC or SCC compared with people in their 30s. “I raise this because a lot of time the people who come in for skin cancer screenings are the ‘worried well,’ ” she said. “They can be at risk, but they’re not our highest risk subgroup. They come in proactively wanting to have those full skin screens done, but where we really need to be focusing is in people in their 60s to 80s.”

Risk factors can be shared or unique to each tumor type. Extrinsic factors include chronic UV exposure, ionizing radiation, and tanning bed use. “Acute UV exposures that give you a blistering sunburn puts you at risk for BCC, whereas chronic sun exposures puts you at risk for SCC,” she said. “Tanning bed use can increase the risk for both types, as can ionizing radiation, although it ups the risk for BCCs much more than it does for SCCs.” Intrinsic risk factors for both tumor types include fair skin, blue/green eyes, blond/red hair, male gender, having pigment gene variants, and being immunosuppressed.

By race/ethnicity, the highest risk for KC in the United States falls to non-Hispanic Whites (a rate of 150-360 per 100,000 individuals), while the rate among blacks is 3 per 100,000 individuals. “In darker skin phenotypes, sun exposure tends to be less of a risk factor,” Dr. Asgari said. “They can rise on sun-protected areas and are frequently associated with chronic inflammation, chronic wounds, or scarring.”

In a soon-to-be published study, Dr. Asgari and colleagues sought to examine the association between genetic ancestry and SCC risk. The found that people with northwestern European ancestry faced the highest risk of SCC, especially those with Irish/Scottish ancestry. Among people of Hispanic/Latino descent, the highest risk of SCC came in those who had the most European ancestry.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Asgari disclosed that she receives royalties from UpToDate.

When Maryam M. Asgari, MD, reviewed results from a large population-based study published in 2017, which found that a large proportion of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas were being detected on the lower extremities of women, it caused her to reflect on her own clinical practice as a Mohs surgeon.

“I was struck by the number of times I was seeing women present with lower extremity SCCs,” Dr. Asgari, professor of dermatology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, said during a virtual forum on cutaneous malignancies jointly presented by Postgraduate Institute for Medicine and Global Academy for Medical Education. “When female patients push you for a waist-up skin exam, try to convince them that the legs are an important area to look at as well.”

In an effort to ascertain if there are sex differences in the anatomic distribution of cutaneous SCC, she and her postdoctoral fellow, Yuhree Kim, MD, MPH, used an institutional registry to identify 618 non-Hispanic White patients diagnosed with 2,111 SCCs between 2000 and 2016. They found that men were more likely to have SCCs arise on the head and neck (52% vs. 21% among women, respectively), while women were more likely to have SCCs develop on the lower extremity (41% vs. 10% in men).

“When we looked at whether these tumors were in situ or invasive, in women, the majority of these weren’t just your run-of-the-mill in situ SCCs; 44% were actually invasive SCCs,” Dr. Asgari said. “What this is getting at is to make sure that you’re examining the lower extremities when you’re doing these skin exams. Many times, especially in colder weather, your patients will come in and request a waist-up exam. For women, you absolutely have to examine their lower extremities. That’s their high-risk area for SCCs.”

, she continued. According to 2020 data from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results SEER program, the incidence of KC in the United States is estimated to be 3.5 million cases per year, while all other cancers account for approximately 1.8 million cases per year.

To make matters worse, while the incidence of many other cancers have plateaued or even declined over time in the United States, data from a population-based cohort at Kaiser Permanente Northern California show that the incidence of BCCs rose between 1998 and 2012, estimated to occur in about 2 million Americans each year.

Dr. Asgari noted that the incidence of KCs can be difficult to quantify and study. “Part of the reason is that they’re not reported to traditional cancer registries like the SEER program,” she said. “You can imagine why. The sheer volume of KC dwarfs all other cancers, and oftentimes KCs are biopsied in dermatology offices. Sometimes, dermatologists even read their own biopsy specimens, so they don’t go to a central pathology repository like other cancers do.”

The best available research suggests that patients at the highest risk of KC include men and women between the ages of 60 and 89. Dr. Asgari said that she informs her patients that people in their 80s have about a 20-fold risk of BCC or SCC compared with people in their 30s. “I raise this because a lot of time the people who come in for skin cancer screenings are the ‘worried well,’ ” she said. “They can be at risk, but they’re not our highest risk subgroup. They come in proactively wanting to have those full skin screens done, but where we really need to be focusing is in people in their 60s to 80s.”

Risk factors can be shared or unique to each tumor type. Extrinsic factors include chronic UV exposure, ionizing radiation, and tanning bed use. “Acute UV exposures that give you a blistering sunburn puts you at risk for BCC, whereas chronic sun exposures puts you at risk for SCC,” she said. “Tanning bed use can increase the risk for both types, as can ionizing radiation, although it ups the risk for BCCs much more than it does for SCCs.” Intrinsic risk factors for both tumor types include fair skin, blue/green eyes, blond/red hair, male gender, having pigment gene variants, and being immunosuppressed.

By race/ethnicity, the highest risk for KC in the United States falls to non-Hispanic Whites (a rate of 150-360 per 100,000 individuals), while the rate among blacks is 3 per 100,000 individuals. “In darker skin phenotypes, sun exposure tends to be less of a risk factor,” Dr. Asgari said. “They can rise on sun-protected areas and are frequently associated with chronic inflammation, chronic wounds, or scarring.”

In a soon-to-be published study, Dr. Asgari and colleagues sought to examine the association between genetic ancestry and SCC risk. The found that people with northwestern European ancestry faced the highest risk of SCC, especially those with Irish/Scottish ancestry. Among people of Hispanic/Latino descent, the highest risk of SCC came in those who had the most European ancestry.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Asgari disclosed that she receives royalties from UpToDate.

When Maryam M. Asgari, MD, reviewed results from a large population-based study published in 2017, which found that a large proportion of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas were being detected on the lower extremities of women, it caused her to reflect on her own clinical practice as a Mohs surgeon.

“I was struck by the number of times I was seeing women present with lower extremity SCCs,” Dr. Asgari, professor of dermatology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, said during a virtual forum on cutaneous malignancies jointly presented by Postgraduate Institute for Medicine and Global Academy for Medical Education. “When female patients push you for a waist-up skin exam, try to convince them that the legs are an important area to look at as well.”

In an effort to ascertain if there are sex differences in the anatomic distribution of cutaneous SCC, she and her postdoctoral fellow, Yuhree Kim, MD, MPH, used an institutional registry to identify 618 non-Hispanic White patients diagnosed with 2,111 SCCs between 2000 and 2016. They found that men were more likely to have SCCs arise on the head and neck (52% vs. 21% among women, respectively), while women were more likely to have SCCs develop on the lower extremity (41% vs. 10% in men).

“When we looked at whether these tumors were in situ or invasive, in women, the majority of these weren’t just your run-of-the-mill in situ SCCs; 44% were actually invasive SCCs,” Dr. Asgari said. “What this is getting at is to make sure that you’re examining the lower extremities when you’re doing these skin exams. Many times, especially in colder weather, your patients will come in and request a waist-up exam. For women, you absolutely have to examine their lower extremities. That’s their high-risk area for SCCs.”

, she continued. According to 2020 data from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results SEER program, the incidence of KC in the United States is estimated to be 3.5 million cases per year, while all other cancers account for approximately 1.8 million cases per year.

To make matters worse, while the incidence of many other cancers have plateaued or even declined over time in the United States, data from a population-based cohort at Kaiser Permanente Northern California show that the incidence of BCCs rose between 1998 and 2012, estimated to occur in about 2 million Americans each year.

Dr. Asgari noted that the incidence of KCs can be difficult to quantify and study. “Part of the reason is that they’re not reported to traditional cancer registries like the SEER program,” she said. “You can imagine why. The sheer volume of KC dwarfs all other cancers, and oftentimes KCs are biopsied in dermatology offices. Sometimes, dermatologists even read their own biopsy specimens, so they don’t go to a central pathology repository like other cancers do.”

The best available research suggests that patients at the highest risk of KC include men and women between the ages of 60 and 89. Dr. Asgari said that she informs her patients that people in their 80s have about a 20-fold risk of BCC or SCC compared with people in their 30s. “I raise this because a lot of time the people who come in for skin cancer screenings are the ‘worried well,’ ” she said. “They can be at risk, but they’re not our highest risk subgroup. They come in proactively wanting to have those full skin screens done, but where we really need to be focusing is in people in their 60s to 80s.”

Risk factors can be shared or unique to each tumor type. Extrinsic factors include chronic UV exposure, ionizing radiation, and tanning bed use. “Acute UV exposures that give you a blistering sunburn puts you at risk for BCC, whereas chronic sun exposures puts you at risk for SCC,” she said. “Tanning bed use can increase the risk for both types, as can ionizing radiation, although it ups the risk for BCCs much more than it does for SCCs.” Intrinsic risk factors for both tumor types include fair skin, blue/green eyes, blond/red hair, male gender, having pigment gene variants, and being immunosuppressed.

By race/ethnicity, the highest risk for KC in the United States falls to non-Hispanic Whites (a rate of 150-360 per 100,000 individuals), while the rate among blacks is 3 per 100,000 individuals. “In darker skin phenotypes, sun exposure tends to be less of a risk factor,” Dr. Asgari said. “They can rise on sun-protected areas and are frequently associated with chronic inflammation, chronic wounds, or scarring.”

In a soon-to-be published study, Dr. Asgari and colleagues sought to examine the association between genetic ancestry and SCC risk. The found that people with northwestern European ancestry faced the highest risk of SCC, especially those with Irish/Scottish ancestry. Among people of Hispanic/Latino descent, the highest risk of SCC came in those who had the most European ancestry.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Asgari disclosed that she receives royalties from UpToDate.

FROM THE CUTANEOUS MALIGNANCIES FORUM

Keeping the Differential at Hand

ANSWER

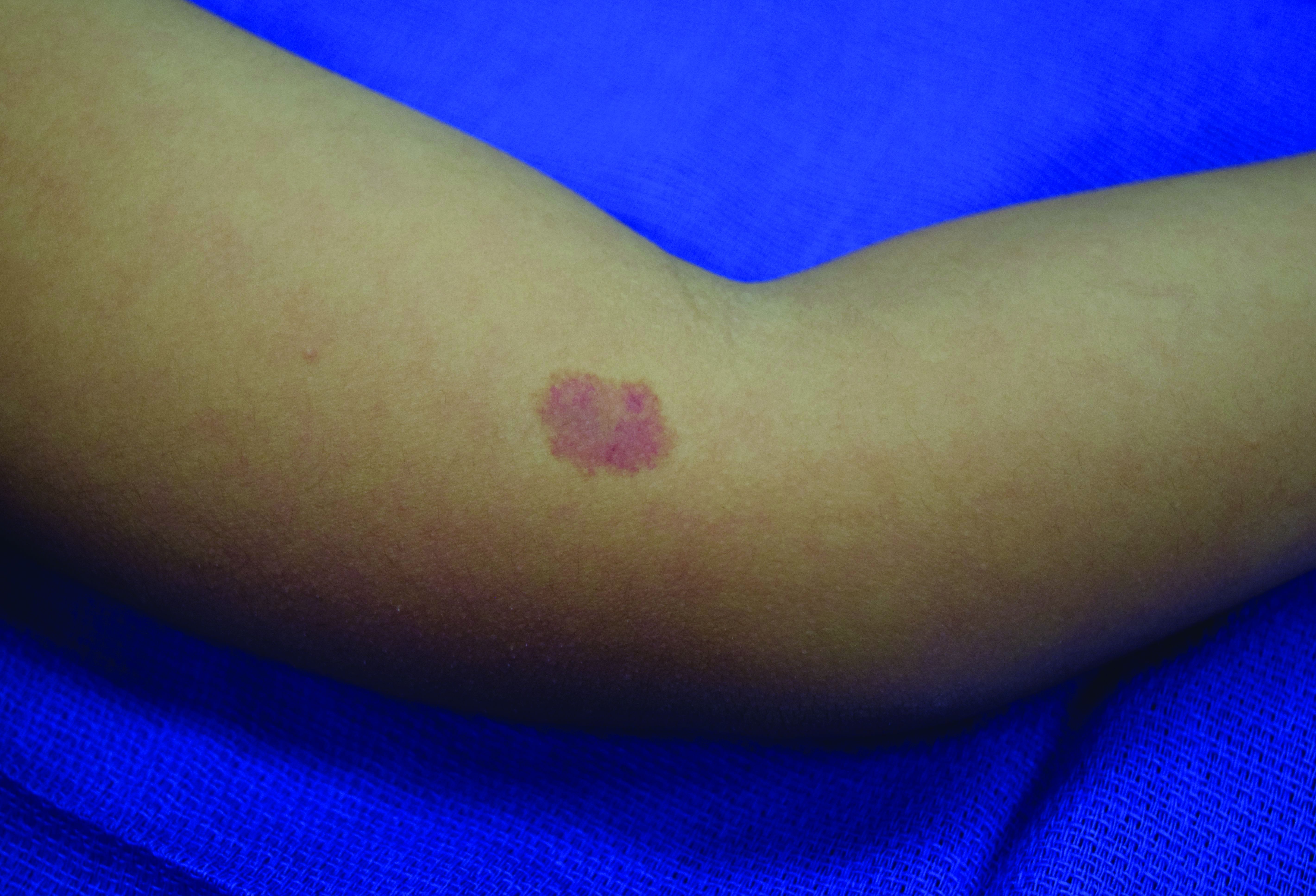

The correct answer is granuloma annulare (GA; choice “a”).

DISCUSSION

One of the most difficult concepts to grasp in dermatologic diagnosis is that almost all lesions and conditions—even the most common—have a broad range of morphologic presentations. These will often differ from the textbook photos. In this digital age, a simple Internet search will provide many results showing a diverse morphologic spectrum for many diseases, conditions, and lesions.

GA is a good example of how the presentation can vary. It has raised rolled margins and delled (gently concave) centers. The brownish red color is typical, but this patient showed a deeper red than most cases of GA. Occasionally, the red color is even deeper, with large patches of darkened skin and no palpable component.

Unfortunately, the misdiagnosis of fungal infection in this patient is typical. But dermatophytosis (otherwise known as “ringworm”)—the most common fungal skin infection—involves the epidermis. This means the patient would have scaly skin, probably with a well-defined margin—factors missing in this case. In addition, this patient reported no contact with sources of infection: animals, children, or immunosuppressive agents.

Ultimately, the most basic information that this patient's past providers neglected was a differential diagnosis. By establishing a differential, there was a clear decision to biopsy, which not only revealed the correct diagnosis but effectively ruled out the other options.

In defense of the patient’s other providers, I must admit that as a young primary care provider, I made this same mistake for exactly the same reasons.

TREATMENT

Most cases of GA are mild and self-limited, requiring no treatment. This is fortunate because no effective treatment exists. Topical steroids and cryotherapy will lighten the lesion, but GA nearly always resolves on its own.

ANSWER

The correct answer is granuloma annulare (GA; choice “a”).

DISCUSSION

One of the most difficult concepts to grasp in dermatologic diagnosis is that almost all lesions and conditions—even the most common—have a broad range of morphologic presentations. These will often differ from the textbook photos. In this digital age, a simple Internet search will provide many results showing a diverse morphologic spectrum for many diseases, conditions, and lesions.

GA is a good example of how the presentation can vary. It has raised rolled margins and delled (gently concave) centers. The brownish red color is typical, but this patient showed a deeper red than most cases of GA. Occasionally, the red color is even deeper, with large patches of darkened skin and no palpable component.

Unfortunately, the misdiagnosis of fungal infection in this patient is typical. But dermatophytosis (otherwise known as “ringworm”)—the most common fungal skin infection—involves the epidermis. This means the patient would have scaly skin, probably with a well-defined margin—factors missing in this case. In addition, this patient reported no contact with sources of infection: animals, children, or immunosuppressive agents.

Ultimately, the most basic information that this patient's past providers neglected was a differential diagnosis. By establishing a differential, there was a clear decision to biopsy, which not only revealed the correct diagnosis but effectively ruled out the other options.

In defense of the patient’s other providers, I must admit that as a young primary care provider, I made this same mistake for exactly the same reasons.

TREATMENT

Most cases of GA are mild and self-limited, requiring no treatment. This is fortunate because no effective treatment exists. Topical steroids and cryotherapy will lighten the lesion, but GA nearly always resolves on its own.

ANSWER

The correct answer is granuloma annulare (GA; choice “a”).

DISCUSSION

One of the most difficult concepts to grasp in dermatologic diagnosis is that almost all lesions and conditions—even the most common—have a broad range of morphologic presentations. These will often differ from the textbook photos. In this digital age, a simple Internet search will provide many results showing a diverse morphologic spectrum for many diseases, conditions, and lesions.

GA is a good example of how the presentation can vary. It has raised rolled margins and delled (gently concave) centers. The brownish red color is typical, but this patient showed a deeper red than most cases of GA. Occasionally, the red color is even deeper, with large patches of darkened skin and no palpable component.

Unfortunately, the misdiagnosis of fungal infection in this patient is typical. But dermatophytosis (otherwise known as “ringworm”)—the most common fungal skin infection—involves the epidermis. This means the patient would have scaly skin, probably with a well-defined margin—factors missing in this case. In addition, this patient reported no contact with sources of infection: animals, children, or immunosuppressive agents.

Ultimately, the most basic information that this patient's past providers neglected was a differential diagnosis. By establishing a differential, there was a clear decision to biopsy, which not only revealed the correct diagnosis but effectively ruled out the other options.

In defense of the patient’s other providers, I must admit that as a young primary care provider, I made this same mistake for exactly the same reasons.

TREATMENT

Most cases of GA are mild and self-limited, requiring no treatment. This is fortunate because no effective treatment exists. Topical steroids and cryotherapy will lighten the lesion, but GA nearly always resolves on its own.

Several months ago, an asymptomatic rash slowly manifested on a 60-year-old woman’s hand. The rash—diagnosed previously as a fungal infection—continues to grow despite application of multiple antifungal creams, including tolnaftate, clotrimazole, and terbinafine. In addition, she was treated with a 1-month course of oral terbinafine 250 mg/d. Unfortunately, no treatment has provided her relief.

The patient is in otherwise good health. She denies any injury to the area. She also reports no exposure to children or animals.

The rash is a reddish brown, annular patch of skin that covers most of the dorsum of her left hand. The borders are slightly raised and thickened. It is nontender and readily blanchable. It is intradermal, with no surface disturbance such as scaling.

Punch biopsy shows palisaded granulomatous features, with no epidermal changes. Stains for fungi and bacteria fail to demonstrate any organisms.

Painful pustules on hands

Close inspection of the plaques revealed multiple small pustules and mahogany colored macules on a broad, well-demarcated scaly red plaque. This pattern was consistent with palmoplantar pustular psoriasis.

Palmoplantar psoriasis is a chronic disease that may manifest at any age and in both sexes. The diagnosis may be clinical, as it was in this case. Bacterial culture of a pustule may demonstrate staphylococcus superinfection—a problem more likely to occur in smokers. More widespread disease, spiking fevers, or tachycardia could indicate a need for hospitalization for further work-up and management.

With disease localized to this patient’s hands and feet, the physician considered dyshidrotic eczema as part of the differential diagnosis. However dyshidrotic eczema, which presents with clear tapioca-like vesicles, is profoundly itchy; pustular psoriasis is often painful. Other differences: The vesicles in dyshidrotic eczema do not uniformly form pustules nor do they form brown macules upon healing, as occurs in palmoplantar pustular psoriasis.

Treatment for very limited disease includes topical ultrapotent steroids, topical retinoids, or phototherapy—either alone or in combination. However, more extensive disease, even if limited to hands and feet, merits systemic therapy with acitretin, methotrexate, or biologic agents. (Acitretin and methotrexate are reliable teratogens and should not be used in women who are, or may become, pregnant.) Individuals with known superinfection often benefit from antibiotic therapy, as well.

In this case, the patient had already undergone a tubal ligation for contraception. Therefore, she was started on acitretin 25 mg PO daily. Patients on systemic retinoids undergo laboratory surveillance for transaminitis and hypertriglyceridemia regularly. Adverse effects are generally well tolerated, but include photosensitivity and dry skin, lips, and eyes. The patient improved significantly on 25 mg/d and the dosage was reduced to 10 mg/d after 3 months. She currently remains clear on this regimen.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

Misiak-Galazka M, Zozula J, Rudnicka L. Palmoplantar pustulosis: recent advances in etiopathogenesis and emerging treatments. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:355-370.

Close inspection of the plaques revealed multiple small pustules and mahogany colored macules on a broad, well-demarcated scaly red plaque. This pattern was consistent with palmoplantar pustular psoriasis.

Palmoplantar psoriasis is a chronic disease that may manifest at any age and in both sexes. The diagnosis may be clinical, as it was in this case. Bacterial culture of a pustule may demonstrate staphylococcus superinfection—a problem more likely to occur in smokers. More widespread disease, spiking fevers, or tachycardia could indicate a need for hospitalization for further work-up and management.

With disease localized to this patient’s hands and feet, the physician considered dyshidrotic eczema as part of the differential diagnosis. However dyshidrotic eczema, which presents with clear tapioca-like vesicles, is profoundly itchy; pustular psoriasis is often painful. Other differences: The vesicles in dyshidrotic eczema do not uniformly form pustules nor do they form brown macules upon healing, as occurs in palmoplantar pustular psoriasis.

Treatment for very limited disease includes topical ultrapotent steroids, topical retinoids, or phototherapy—either alone or in combination. However, more extensive disease, even if limited to hands and feet, merits systemic therapy with acitretin, methotrexate, or biologic agents. (Acitretin and methotrexate are reliable teratogens and should not be used in women who are, or may become, pregnant.) Individuals with known superinfection often benefit from antibiotic therapy, as well.

In this case, the patient had already undergone a tubal ligation for contraception. Therefore, she was started on acitretin 25 mg PO daily. Patients on systemic retinoids undergo laboratory surveillance for transaminitis and hypertriglyceridemia regularly. Adverse effects are generally well tolerated, but include photosensitivity and dry skin, lips, and eyes. The patient improved significantly on 25 mg/d and the dosage was reduced to 10 mg/d after 3 months. She currently remains clear on this regimen.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

Close inspection of the plaques revealed multiple small pustules and mahogany colored macules on a broad, well-demarcated scaly red plaque. This pattern was consistent with palmoplantar pustular psoriasis.

Palmoplantar psoriasis is a chronic disease that may manifest at any age and in both sexes. The diagnosis may be clinical, as it was in this case. Bacterial culture of a pustule may demonstrate staphylococcus superinfection—a problem more likely to occur in smokers. More widespread disease, spiking fevers, or tachycardia could indicate a need for hospitalization for further work-up and management.

With disease localized to this patient’s hands and feet, the physician considered dyshidrotic eczema as part of the differential diagnosis. However dyshidrotic eczema, which presents with clear tapioca-like vesicles, is profoundly itchy; pustular psoriasis is often painful. Other differences: The vesicles in dyshidrotic eczema do not uniformly form pustules nor do they form brown macules upon healing, as occurs in palmoplantar pustular psoriasis.

Treatment for very limited disease includes topical ultrapotent steroids, topical retinoids, or phototherapy—either alone or in combination. However, more extensive disease, even if limited to hands and feet, merits systemic therapy with acitretin, methotrexate, or biologic agents. (Acitretin and methotrexate are reliable teratogens and should not be used in women who are, or may become, pregnant.) Individuals with known superinfection often benefit from antibiotic therapy, as well.

In this case, the patient had already undergone a tubal ligation for contraception. Therefore, she was started on acitretin 25 mg PO daily. Patients on systemic retinoids undergo laboratory surveillance for transaminitis and hypertriglyceridemia regularly. Adverse effects are generally well tolerated, but include photosensitivity and dry skin, lips, and eyes. The patient improved significantly on 25 mg/d and the dosage was reduced to 10 mg/d after 3 months. She currently remains clear on this regimen.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

Misiak-Galazka M, Zozula J, Rudnicka L. Palmoplantar pustulosis: recent advances in etiopathogenesis and emerging treatments. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:355-370.

Misiak-Galazka M, Zozula J, Rudnicka L. Palmoplantar pustulosis: recent advances in etiopathogenesis and emerging treatments. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:355-370.

Poor image quality may limit televulvology care

Seeing patients with vulvar problems via telemedicine can lead to efficient and successful care, but there are challenges and limitations with this approach, doctors are finding.

Image quality is one key factor that determines whether a clinician can assess and manage a condition remotely, said Aruna Venkatesan, MD, chief of dermatology and director of the genital dermatology clinic at Santa Clara Valley Medical Center in San Jose, Calif. Other issues may be especially relevant to televulvology, including privacy concerns.

“Who is helping with the positioning? Who is the photographer? Is the patient comfortable with having photos taken of this part of their body and submitted, even if they know it is submitted securely? Because they might not be,” Dr. Venkatesan said in a lecture at a virtual conference on diseases of the vulva and vagina, hosted by the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease.

When quality photographs from referring providers are available, Dr. Venkatesan has conducted virtual new consultations. “But sometimes I will do a virtual telemedicine visit as the first visit and then figure out, okay, this isn’t really sufficient. I need to see them in person.”

Melissa Mauskar, MD, assistant professor of dermatology and obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, described a case early on during the COVID-19 pandemic that illustrates a limitation of virtual visits.

A patient sent in a photograph that appeared to show lichen sclerosus. “There looked like some classic lichen sclerosus changes,” Dr. Mauskar said during a discussion at the meeting. “But she was having a lot of pain, and after a week, her pain still was not better.”

Dr. Mauskar brought the patient into the office and ultimately diagnosed a squamous cell carcinoma. “What I thought was a normal erosion was actually an ulcerated plaque,” she said.

Like Dr. Venkatesan, Dr. Mauskar has found that image quality can be uneven. Photographs may be out of focus. Video visits have been a mixed bag. Some are successful. Other times, Dr. Mauskar has to tell the patient she needs to see her in the office.

Certain clinical scenarios require a vaginal exam, Dr. Venkatesan noted. Although some type of assessment may be possible if a patient is with a primary care provider during the telemedicine visit, the examination may not be equivalent. Doctors also should anticipate where a patient might go to have a biopsy if one is necessary.

Another telemedicine caveat pertains to patient counseling. When using store-and-forward telemedicine systems, advising patients in a written report can be challenging. “Is there an easy way ... to counsel patients how to apply their topical medications?” Dr. Venkatesan said.

Excellent care is possible

Vulvology is a small part of Dr. Venkatesan’s general dermatology practice, which has used telemedicine extensively since the pandemic.

In recent years, Dr. Venkatesan’s clinic began encouraging providers in their health system to submit photographs with referrals. “That has really paid off now because we have been able to help provide a lot of excellent quality care for patients without them having to come in,” she said. “We may be able to say: ‘These are excellent photos. We know what this patient has. We can manage it. They don’t need to come see us in person.’ ” That could be the case for certain types of acne, eczema, and psoriasis.

In other cases, they may be able to provide initial advice remotely but still want to see the patient. For a patient with severe acne, “I may be able to tell the referring doctor: ‘Please start the patient on these three medicines. It will take 2 months for those medicines to start working and then we will plan to have an in-person dermatology visit.’ ” In this case, telemedicine essentially replaces one in-person visit.

If photographs are poor, the differential diagnosis is broad, a procedure is required, the doctor needs to touch the lesion, or more involved history taking or counseling are required, the patient may need to go into the office.

Beyond its public health advantages during a pandemic, telemedicine can improve access for patients who live far away, lack transportation, or are unable to take time off from work. It also can decrease patient wait times. “Once we started doing some telemedicine work … we went from having a 5-month wait time for patients to see us in person to a 72-hour wait time for providing some care for patients if they had good photos as part of their referral,” Dr. Venkatesan said.

Telemedicine has been used in inpatient and outpatient dermatology settings. Primary care providers who consult with dermatologists using a store-and-forward telemedicine system may improve their dermatology knowledge and feel more confident in their ability to diagnose and manage dermatologic conditions, research indicates.

In obstetrics and gynecology, telemedicine may play a role in preconception, contraception, and medical abortion care, prenatal visits, well-woman exams, mental health, and pre- and postoperative counseling, a recent review suggests.

Image quality is key

“Quality of the image is so critical for being able to provide good care, especially in such a visual exam field as dermatology,” Dr. Venkatesan said.

To that end, doctors have offered recommendations on how to photograph skin conditions. A guide shared by the mobile telehealth system company ClickMedix suggests focusing on the area of importance, capturing the extent of involvement, and including involved and uninvolved areas.

Good lighting and checking the image resolution can help, Dr. Venkatesan offered. Nevertheless, patients may have difficulty photographing themselves. If a patient is with their primary care doctor, “we are much more likely to be able to get good quality photos,” she said.

Dr. Venkatesan is a paid consultant for DirectDerm, a store-and-forward teledermatology company. Dr. Mauskar had no relevant disclosures.

Seeing patients with vulvar problems via telemedicine can lead to efficient and successful care, but there are challenges and limitations with this approach, doctors are finding.

Image quality is one key factor that determines whether a clinician can assess and manage a condition remotely, said Aruna Venkatesan, MD, chief of dermatology and director of the genital dermatology clinic at Santa Clara Valley Medical Center in San Jose, Calif. Other issues may be especially relevant to televulvology, including privacy concerns.

“Who is helping with the positioning? Who is the photographer? Is the patient comfortable with having photos taken of this part of their body and submitted, even if they know it is submitted securely? Because they might not be,” Dr. Venkatesan said in a lecture at a virtual conference on diseases of the vulva and vagina, hosted by the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease.

When quality photographs from referring providers are available, Dr. Venkatesan has conducted virtual new consultations. “But sometimes I will do a virtual telemedicine visit as the first visit and then figure out, okay, this isn’t really sufficient. I need to see them in person.”

Melissa Mauskar, MD, assistant professor of dermatology and obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, described a case early on during the COVID-19 pandemic that illustrates a limitation of virtual visits.

A patient sent in a photograph that appeared to show lichen sclerosus. “There looked like some classic lichen sclerosus changes,” Dr. Mauskar said during a discussion at the meeting. “But she was having a lot of pain, and after a week, her pain still was not better.”

Dr. Mauskar brought the patient into the office and ultimately diagnosed a squamous cell carcinoma. “What I thought was a normal erosion was actually an ulcerated plaque,” she said.

Like Dr. Venkatesan, Dr. Mauskar has found that image quality can be uneven. Photographs may be out of focus. Video visits have been a mixed bag. Some are successful. Other times, Dr. Mauskar has to tell the patient she needs to see her in the office.

Certain clinical scenarios require a vaginal exam, Dr. Venkatesan noted. Although some type of assessment may be possible if a patient is with a primary care provider during the telemedicine visit, the examination may not be equivalent. Doctors also should anticipate where a patient might go to have a biopsy if one is necessary.

Another telemedicine caveat pertains to patient counseling. When using store-and-forward telemedicine systems, advising patients in a written report can be challenging. “Is there an easy way ... to counsel patients how to apply their topical medications?” Dr. Venkatesan said.

Excellent care is possible

Vulvology is a small part of Dr. Venkatesan’s general dermatology practice, which has used telemedicine extensively since the pandemic.

In recent years, Dr. Venkatesan’s clinic began encouraging providers in their health system to submit photographs with referrals. “That has really paid off now because we have been able to help provide a lot of excellent quality care for patients without them having to come in,” she said. “We may be able to say: ‘These are excellent photos. We know what this patient has. We can manage it. They don’t need to come see us in person.’ ” That could be the case for certain types of acne, eczema, and psoriasis.

In other cases, they may be able to provide initial advice remotely but still want to see the patient. For a patient with severe acne, “I may be able to tell the referring doctor: ‘Please start the patient on these three medicines. It will take 2 months for those medicines to start working and then we will plan to have an in-person dermatology visit.’ ” In this case, telemedicine essentially replaces one in-person visit.

If photographs are poor, the differential diagnosis is broad, a procedure is required, the doctor needs to touch the lesion, or more involved history taking or counseling are required, the patient may need to go into the office.

Beyond its public health advantages during a pandemic, telemedicine can improve access for patients who live far away, lack transportation, or are unable to take time off from work. It also can decrease patient wait times. “Once we started doing some telemedicine work … we went from having a 5-month wait time for patients to see us in person to a 72-hour wait time for providing some care for patients if they had good photos as part of their referral,” Dr. Venkatesan said.

Telemedicine has been used in inpatient and outpatient dermatology settings. Primary care providers who consult with dermatologists using a store-and-forward telemedicine system may improve their dermatology knowledge and feel more confident in their ability to diagnose and manage dermatologic conditions, research indicates.

In obstetrics and gynecology, telemedicine may play a role in preconception, contraception, and medical abortion care, prenatal visits, well-woman exams, mental health, and pre- and postoperative counseling, a recent review suggests.

Image quality is key

“Quality of the image is so critical for being able to provide good care, especially in such a visual exam field as dermatology,” Dr. Venkatesan said.

To that end, doctors have offered recommendations on how to photograph skin conditions. A guide shared by the mobile telehealth system company ClickMedix suggests focusing on the area of importance, capturing the extent of involvement, and including involved and uninvolved areas.

Good lighting and checking the image resolution can help, Dr. Venkatesan offered. Nevertheless, patients may have difficulty photographing themselves. If a patient is with their primary care doctor, “we are much more likely to be able to get good quality photos,” she said.

Dr. Venkatesan is a paid consultant for DirectDerm, a store-and-forward teledermatology company. Dr. Mauskar had no relevant disclosures.

Seeing patients with vulvar problems via telemedicine can lead to efficient and successful care, but there are challenges and limitations with this approach, doctors are finding.

Image quality is one key factor that determines whether a clinician can assess and manage a condition remotely, said Aruna Venkatesan, MD, chief of dermatology and director of the genital dermatology clinic at Santa Clara Valley Medical Center in San Jose, Calif. Other issues may be especially relevant to televulvology, including privacy concerns.

“Who is helping with the positioning? Who is the photographer? Is the patient comfortable with having photos taken of this part of their body and submitted, even if they know it is submitted securely? Because they might not be,” Dr. Venkatesan said in a lecture at a virtual conference on diseases of the vulva and vagina, hosted by the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease.

When quality photographs from referring providers are available, Dr. Venkatesan has conducted virtual new consultations. “But sometimes I will do a virtual telemedicine visit as the first visit and then figure out, okay, this isn’t really sufficient. I need to see them in person.”

Melissa Mauskar, MD, assistant professor of dermatology and obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, described a case early on during the COVID-19 pandemic that illustrates a limitation of virtual visits.

A patient sent in a photograph that appeared to show lichen sclerosus. “There looked like some classic lichen sclerosus changes,” Dr. Mauskar said during a discussion at the meeting. “But she was having a lot of pain, and after a week, her pain still was not better.”

Dr. Mauskar brought the patient into the office and ultimately diagnosed a squamous cell carcinoma. “What I thought was a normal erosion was actually an ulcerated plaque,” she said.

Like Dr. Venkatesan, Dr. Mauskar has found that image quality can be uneven. Photographs may be out of focus. Video visits have been a mixed bag. Some are successful. Other times, Dr. Mauskar has to tell the patient she needs to see her in the office.

Certain clinical scenarios require a vaginal exam, Dr. Venkatesan noted. Although some type of assessment may be possible if a patient is with a primary care provider during the telemedicine visit, the examination may not be equivalent. Doctors also should anticipate where a patient might go to have a biopsy if one is necessary.

Another telemedicine caveat pertains to patient counseling. When using store-and-forward telemedicine systems, advising patients in a written report can be challenging. “Is there an easy way ... to counsel patients how to apply their topical medications?” Dr. Venkatesan said.

Excellent care is possible

Vulvology is a small part of Dr. Venkatesan’s general dermatology practice, which has used telemedicine extensively since the pandemic.

In recent years, Dr. Venkatesan’s clinic began encouraging providers in their health system to submit photographs with referrals. “That has really paid off now because we have been able to help provide a lot of excellent quality care for patients without them having to come in,” she said. “We may be able to say: ‘These are excellent photos. We know what this patient has. We can manage it. They don’t need to come see us in person.’ ” That could be the case for certain types of acne, eczema, and psoriasis.

In other cases, they may be able to provide initial advice remotely but still want to see the patient. For a patient with severe acne, “I may be able to tell the referring doctor: ‘Please start the patient on these three medicines. It will take 2 months for those medicines to start working and then we will plan to have an in-person dermatology visit.’ ” In this case, telemedicine essentially replaces one in-person visit.

If photographs are poor, the differential diagnosis is broad, a procedure is required, the doctor needs to touch the lesion, or more involved history taking or counseling are required, the patient may need to go into the office.

Beyond its public health advantages during a pandemic, telemedicine can improve access for patients who live far away, lack transportation, or are unable to take time off from work. It also can decrease patient wait times. “Once we started doing some telemedicine work … we went from having a 5-month wait time for patients to see us in person to a 72-hour wait time for providing some care for patients if they had good photos as part of their referral,” Dr. Venkatesan said.

Telemedicine has been used in inpatient and outpatient dermatology settings. Primary care providers who consult with dermatologists using a store-and-forward telemedicine system may improve their dermatology knowledge and feel more confident in their ability to diagnose and manage dermatologic conditions, research indicates.

In obstetrics and gynecology, telemedicine may play a role in preconception, contraception, and medical abortion care, prenatal visits, well-woman exams, mental health, and pre- and postoperative counseling, a recent review suggests.

Image quality is key

“Quality of the image is so critical for being able to provide good care, especially in such a visual exam field as dermatology,” Dr. Venkatesan said.

To that end, doctors have offered recommendations on how to photograph skin conditions. A guide shared by the mobile telehealth system company ClickMedix suggests focusing on the area of importance, capturing the extent of involvement, and including involved and uninvolved areas.

Good lighting and checking the image resolution can help, Dr. Venkatesan offered. Nevertheless, patients may have difficulty photographing themselves. If a patient is with their primary care doctor, “we are much more likely to be able to get good quality photos,” she said.

Dr. Venkatesan is a paid consultant for DirectDerm, a store-and-forward teledermatology company. Dr. Mauskar had no relevant disclosures.

FROM THE ISSVD BIENNIAL CONFERENCE

An 11-year-old female with a 3-year history of alopecia

Given the longstanding scarring alopecia, with negative fungal cultures and with perifollicular erythema and scaling, this diagnosis is most consistent with lichen planopilaris.

Lichen planopilaris (LPP) is considered one of the primary scarring alopecias, a group of diseases characterized by inflammation and subsequent irreversible hair loss.1 LPP specifically is believed to be caused by dysfunction of cell-mediated immunity, resulting in T lymphocytes attacking follicular hair stem cells.2 It typically presents with hair loss, pruritus, scaling, burning pain, and tenderness of the scalp when active,1,3 with exam showing perifollicular scale and erythema on the borders of the patches of alopecia.4,5 Over time, scarring of the scalp develops with loss of follicular ostia.1 Definitive diagnosis typically requires punch biopsy of the affected scalp, as such can determine the presence or absence of inflammation in affected areas of the scalp.1

What’s the treatment plan?

Given that LPP is an autoimmune inflammatory disease process, the goal of treatment is to calm down the inflammation of the scalp to prevent further progression of a patient’s hair loss. This is typically achieved with superpotent topical corticosteroids, such as clobetasol applied directly to the scalp, and/or intralesional corticosteroids, such as triamcinolone acetonide suspension injected directly to the affected scalp.3,6,7 Other treatment options include systemic agents, such as hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, pioglitazone, and doxycycline.3,6 Hair loss is not reversible as loss of follicular ostia and hair stem cells results in permanent scarring.1 Management often requires a referral to dermatology for aggressive treatment to prevent further hair loss.

What’s the differential diagnosis?

The differential diagnosis of lichen planopilaris includes other scarring alopecias, including central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, discoid lupus erythematosus, folliculitis decalvans. While nonscarring, alopecia areata, trichotillomania, and telogen effluvium are discussed below as well.

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia is very rare in pediatrics, and is a type of asymptomatic scarring alopecia that begins at the vertex of the scalp, spreading centrifugally and resulting in shiny plaque development. Treatment involves reduction of hair grooming as well as topical and intralesional steroids.

Discoid lupus erythematosus presents as scaling erythematous plaques on the face and scalp that result in skin pigment changes and atrophy over time. Scalp involvement results in scarring alopecia. Treatment includes the use of high-potency topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and hydroxychloroquine.

Folliculitis decalvans is another form of scarring alopecia believed to be caused by an inflammatory response to Staphylococcus aureus in the scalp, resulting in the formation of scarring of the scalp and perifollicular pustules. Treatment is topical antibiotics and intralesional steroids.

Alopecia areata is a form of nonscarring alopecia resulting in small round patches of partially reversible hair loss characterized by the pathognomonic finding of so-called exclamation point hairs that are broader distally and taper toward the scalp on physical exam. Considered an autoimmune disorder, it varies greatly in extent and course. While focal hair loss is the hallmark of this disease, usually hair follicles are present.

Trichotillosis, also known as trichotillomania (hair pulling), results in alopecia with irregular borders and broken hairs of different lengths secondary to the urge to remove or pull one’s own hair, resulting in nonscarring alopecia. It may be associated with stress or anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorders, or other repetitive body-altering behaviors. Treatments include reassurance and education as it can be self-limited in some, behavior modification, or systemic therapy including tricyclic antidepressants or SSRIs.

Our patient underwent scalp punch biopsy to confirm the diagnosis and was started on potent topical corticosteroids with good disease control.

Dr. Haft is a pediatric dermatology research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology, University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is the vice chair of the department of dermatology and a professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the university, and he is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the hospital. Neither of the doctors had any relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005 Jul. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.06.015.

2. J Pathol. 2013 Oct. doi: 10.1002/path.4233.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015 Sep-Oct. doi: 10.1111/pde.12624.

4. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.04.001.

5. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992 Dec. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70290-v.

6. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018 Feb 27. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S137870.

7. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009 Mar. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2008.12.006.

Given the longstanding scarring alopecia, with negative fungal cultures and with perifollicular erythema and scaling, this diagnosis is most consistent with lichen planopilaris.

Lichen planopilaris (LPP) is considered one of the primary scarring alopecias, a group of diseases characterized by inflammation and subsequent irreversible hair loss.1 LPP specifically is believed to be caused by dysfunction of cell-mediated immunity, resulting in T lymphocytes attacking follicular hair stem cells.2 It typically presents with hair loss, pruritus, scaling, burning pain, and tenderness of the scalp when active,1,3 with exam showing perifollicular scale and erythema on the borders of the patches of alopecia.4,5 Over time, scarring of the scalp develops with loss of follicular ostia.1 Definitive diagnosis typically requires punch biopsy of the affected scalp, as such can determine the presence or absence of inflammation in affected areas of the scalp.1

What’s the treatment plan?

Given that LPP is an autoimmune inflammatory disease process, the goal of treatment is to calm down the inflammation of the scalp to prevent further progression of a patient’s hair loss. This is typically achieved with superpotent topical corticosteroids, such as clobetasol applied directly to the scalp, and/or intralesional corticosteroids, such as triamcinolone acetonide suspension injected directly to the affected scalp.3,6,7 Other treatment options include systemic agents, such as hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, pioglitazone, and doxycycline.3,6 Hair loss is not reversible as loss of follicular ostia and hair stem cells results in permanent scarring.1 Management often requires a referral to dermatology for aggressive treatment to prevent further hair loss.

What’s the differential diagnosis?

The differential diagnosis of lichen planopilaris includes other scarring alopecias, including central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, discoid lupus erythematosus, folliculitis decalvans. While nonscarring, alopecia areata, trichotillomania, and telogen effluvium are discussed below as well.

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia is very rare in pediatrics, and is a type of asymptomatic scarring alopecia that begins at the vertex of the scalp, spreading centrifugally and resulting in shiny plaque development. Treatment involves reduction of hair grooming as well as topical and intralesional steroids.

Discoid lupus erythematosus presents as scaling erythematous plaques on the face and scalp that result in skin pigment changes and atrophy over time. Scalp involvement results in scarring alopecia. Treatment includes the use of high-potency topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and hydroxychloroquine.

Folliculitis decalvans is another form of scarring alopecia believed to be caused by an inflammatory response to Staphylococcus aureus in the scalp, resulting in the formation of scarring of the scalp and perifollicular pustules. Treatment is topical antibiotics and intralesional steroids.

Alopecia areata is a form of nonscarring alopecia resulting in small round patches of partially reversible hair loss characterized by the pathognomonic finding of so-called exclamation point hairs that are broader distally and taper toward the scalp on physical exam. Considered an autoimmune disorder, it varies greatly in extent and course. While focal hair loss is the hallmark of this disease, usually hair follicles are present.

Trichotillosis, also known as trichotillomania (hair pulling), results in alopecia with irregular borders and broken hairs of different lengths secondary to the urge to remove or pull one’s own hair, resulting in nonscarring alopecia. It may be associated with stress or anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorders, or other repetitive body-altering behaviors. Treatments include reassurance and education as it can be self-limited in some, behavior modification, or systemic therapy including tricyclic antidepressants or SSRIs.

Our patient underwent scalp punch biopsy to confirm the diagnosis and was started on potent topical corticosteroids with good disease control.

Dr. Haft is a pediatric dermatology research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology, University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is the vice chair of the department of dermatology and a professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the university, and he is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the hospital. Neither of the doctors had any relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005 Jul. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.06.015.

2. J Pathol. 2013 Oct. doi: 10.1002/path.4233.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015 Sep-Oct. doi: 10.1111/pde.12624.

4. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.04.001.

5. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992 Dec. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70290-v.

6. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018 Feb 27. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S137870.

7. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009 Mar. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2008.12.006.

Given the longstanding scarring alopecia, with negative fungal cultures and with perifollicular erythema and scaling, this diagnosis is most consistent with lichen planopilaris.

Lichen planopilaris (LPP) is considered one of the primary scarring alopecias, a group of diseases characterized by inflammation and subsequent irreversible hair loss.1 LPP specifically is believed to be caused by dysfunction of cell-mediated immunity, resulting in T lymphocytes attacking follicular hair stem cells.2 It typically presents with hair loss, pruritus, scaling, burning pain, and tenderness of the scalp when active,1,3 with exam showing perifollicular scale and erythema on the borders of the patches of alopecia.4,5 Over time, scarring of the scalp develops with loss of follicular ostia.1 Definitive diagnosis typically requires punch biopsy of the affected scalp, as such can determine the presence or absence of inflammation in affected areas of the scalp.1

What’s the treatment plan?

Given that LPP is an autoimmune inflammatory disease process, the goal of treatment is to calm down the inflammation of the scalp to prevent further progression of a patient’s hair loss. This is typically achieved with superpotent topical corticosteroids, such as clobetasol applied directly to the scalp, and/or intralesional corticosteroids, such as triamcinolone acetonide suspension injected directly to the affected scalp.3,6,7 Other treatment options include systemic agents, such as hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, pioglitazone, and doxycycline.3,6 Hair loss is not reversible as loss of follicular ostia and hair stem cells results in permanent scarring.1 Management often requires a referral to dermatology for aggressive treatment to prevent further hair loss.

What’s the differential diagnosis?

The differential diagnosis of lichen planopilaris includes other scarring alopecias, including central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, discoid lupus erythematosus, folliculitis decalvans. While nonscarring, alopecia areata, trichotillomania, and telogen effluvium are discussed below as well.

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia is very rare in pediatrics, and is a type of asymptomatic scarring alopecia that begins at the vertex of the scalp, spreading centrifugally and resulting in shiny plaque development. Treatment involves reduction of hair grooming as well as topical and intralesional steroids.

Discoid lupus erythematosus presents as scaling erythematous plaques on the face and scalp that result in skin pigment changes and atrophy over time. Scalp involvement results in scarring alopecia. Treatment includes the use of high-potency topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and hydroxychloroquine.

Folliculitis decalvans is another form of scarring alopecia believed to be caused by an inflammatory response to Staphylococcus aureus in the scalp, resulting in the formation of scarring of the scalp and perifollicular pustules. Treatment is topical antibiotics and intralesional steroids.

Alopecia areata is a form of nonscarring alopecia resulting in small round patches of partially reversible hair loss characterized by the pathognomonic finding of so-called exclamation point hairs that are broader distally and taper toward the scalp on physical exam. Considered an autoimmune disorder, it varies greatly in extent and course. While focal hair loss is the hallmark of this disease, usually hair follicles are present.

Trichotillosis, also known as trichotillomania (hair pulling), results in alopecia with irregular borders and broken hairs of different lengths secondary to the urge to remove or pull one’s own hair, resulting in nonscarring alopecia. It may be associated with stress or anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorders, or other repetitive body-altering behaviors. Treatments include reassurance and education as it can be self-limited in some, behavior modification, or systemic therapy including tricyclic antidepressants or SSRIs.

Our patient underwent scalp punch biopsy to confirm the diagnosis and was started on potent topical corticosteroids with good disease control.

Dr. Haft is a pediatric dermatology research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology, University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is the vice chair of the department of dermatology and a professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the university, and he is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the hospital. Neither of the doctors had any relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005 Jul. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.06.015.

2. J Pathol. 2013 Oct. doi: 10.1002/path.4233.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015 Sep-Oct. doi: 10.1111/pde.12624.

4. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.04.001.

5. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992 Dec. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70290-v.

6. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018 Feb 27. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S137870.

7. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009 Mar. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2008.12.006.

An 11-year-old female is seen in clinic with a 3-year history of alopecia. The patient recently immigrated to the United States from Afghanistan. Prior to immigrating, she was evaluated for "scarring alopecia" and had been treated with oral and topical steroids as well as oral and topical antifungals. When active, she had itching and tenderness. She is not actively losing any hair at this time, but she has not regrown any of her hair. The patient has no family members with alopecia. She reports some burning pain and itching of her scalp, and denies any muscle pain or weakness or sun sensitivity.

On physical exam, you see 50% loss of hair on the superior scalp with preservation of the anterior hair line. Patches of hair can be seen throughout, with segments of smooth-skinned alopecia, without pustules. There is a loss of the follicle pattern in scarred areas, and magnification or "dermoscopy" shows perifollicular erythema and scaling at the border of the affected scalp. Labs are all within normal limits. Bacterial and fungal cultures of the scalp do not grow organisms.

Purple toe lesion

An excisional biopsy revealed that this was an eccrine poroma, a benign neoplasm of sweat gland tissue in the epidermis.

This lesion was clearly not a wart, as it lacked the common verrucous and keratotic features one would expect, and it did not respond to wart treatments. Other diagnoses that might be considered with a lesion like this include pyogenic granuloma, periungual fibroma, and squamous cell carcinoma.

Poromas are well demarcated papules that grow slowly or are stable in size. They are most commonly flesh colored and smooth, but poromas may also appear verrucous, pigmented, or ulcerated. They are usually found on acral skin—particularly the palms or soles. Due to their location, poromas bleed easily, which is what usually prompts patients to seek care. Friable lesions can mimic acral melanoma.

Poromas occur most often in patients over 40 years of age and are evenly distributed among sexes and skin types. Cases have been associated with trauma, radiation, and chemotherapy. Although exceedingly rare, malignant transformation can occur in the form of eccrine porocarcinoma—a larger tumor that can grow rapidly and that has metastatic potential.

Treatment is optional—but desirable—when lesions are painful or bleed easily. Surgical excision is curative. Shave biopsy or curettage coupled with electrocautery of the base is also curative. Recurrence rates are very low with either method of treatment.

In this case, an excisional biopsy of the lateral nail fold was both diagnostic and curative (second image). The patient remained clear 9 months after treatment.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

Sawaya JL, Khachemoune A. Poroma: a review of eccrine, apocrine, and malignant forms. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1053-1061.

An excisional biopsy revealed that this was an eccrine poroma, a benign neoplasm of sweat gland tissue in the epidermis.

This lesion was clearly not a wart, as it lacked the common verrucous and keratotic features one would expect, and it did not respond to wart treatments. Other diagnoses that might be considered with a lesion like this include pyogenic granuloma, periungual fibroma, and squamous cell carcinoma.

Poromas are well demarcated papules that grow slowly or are stable in size. They are most commonly flesh colored and smooth, but poromas may also appear verrucous, pigmented, or ulcerated. They are usually found on acral skin—particularly the palms or soles. Due to their location, poromas bleed easily, which is what usually prompts patients to seek care. Friable lesions can mimic acral melanoma.

Poromas occur most often in patients over 40 years of age and are evenly distributed among sexes and skin types. Cases have been associated with trauma, radiation, and chemotherapy. Although exceedingly rare, malignant transformation can occur in the form of eccrine porocarcinoma—a larger tumor that can grow rapidly and that has metastatic potential.

Treatment is optional—but desirable—when lesions are painful or bleed easily. Surgical excision is curative. Shave biopsy or curettage coupled with electrocautery of the base is also curative. Recurrence rates are very low with either method of treatment.

In this case, an excisional biopsy of the lateral nail fold was both diagnostic and curative (second image). The patient remained clear 9 months after treatment.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

An excisional biopsy revealed that this was an eccrine poroma, a benign neoplasm of sweat gland tissue in the epidermis.

This lesion was clearly not a wart, as it lacked the common verrucous and keratotic features one would expect, and it did not respond to wart treatments. Other diagnoses that might be considered with a lesion like this include pyogenic granuloma, periungual fibroma, and squamous cell carcinoma.

Poromas are well demarcated papules that grow slowly or are stable in size. They are most commonly flesh colored and smooth, but poromas may also appear verrucous, pigmented, or ulcerated. They are usually found on acral skin—particularly the palms or soles. Due to their location, poromas bleed easily, which is what usually prompts patients to seek care. Friable lesions can mimic acral melanoma.

Poromas occur most often in patients over 40 years of age and are evenly distributed among sexes and skin types. Cases have been associated with trauma, radiation, and chemotherapy. Although exceedingly rare, malignant transformation can occur in the form of eccrine porocarcinoma—a larger tumor that can grow rapidly and that has metastatic potential.

Treatment is optional—but desirable—when lesions are painful or bleed easily. Surgical excision is curative. Shave biopsy or curettage coupled with electrocautery of the base is also curative. Recurrence rates are very low with either method of treatment.

In this case, an excisional biopsy of the lateral nail fold was both diagnostic and curative (second image). The patient remained clear 9 months after treatment.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

Sawaya JL, Khachemoune A. Poroma: a review of eccrine, apocrine, and malignant forms. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1053-1061.

Sawaya JL, Khachemoune A. Poroma: a review of eccrine, apocrine, and malignant forms. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1053-1061.

Tiny papules on trunk and genitals

The miniscule papules arising suddenly on the trunk and genitals with linear arrays and clusters are clinically consistent with lichen nitidus, an uncommon eruption without a clear etiology.

Presentations may be focal or widespread and range from mildly itchy to asymptomatic. Children and young adults are most often affected. Linear arrays may appear in response to the trauma of scratching, which is termed the Koebner phenomenon. The differential diagnosis includes molluscum contagiosum, lichen planus, and lichen spinulosis. Usually these conditions can be distinguished clinically, but a biopsy would differentiate them, if needed. It’s worth noting, too, that lichen nitidus papules are monomorphic and lack the umbilication that is seen with molluscum contagiosum.

Cases of lichen nitidus clear up spontaneously, although usually months to years after diagnosis. Lichen nitidus is not contagious. Reassurance is, however, important as many patients may have experienced misdiagnosis and have concerns about sexual transmission because of the location of the papules on their genitals.

Treatment is often unnecessary. However, if itching is problematic, topical steroids and other topical antipruritics may be used. Topical hydrocortisone 2.5% cream or ointment for skin folds and genitals may be safely used, as well as topical triamcinolone 0.1% for the trunk and extremities. Pramoxine lotion (Sarna) is an over-the-counter nonsteroidal antipruritic. Oral nonsedating antihistamines can also be used as an adjunct.

This patient was reassured that the lesions were not contagious. Due to the itching, he was started on the pramoxine lotion twice daily, as needed, and the lesions cleared in about 6 months.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

Al-Mutairi N, Hassanein A, Nour-Eldin O, et al. Generalized lichen nitidus. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:158-160.

The miniscule papules arising suddenly on the trunk and genitals with linear arrays and clusters are clinically consistent with lichen nitidus, an uncommon eruption without a clear etiology.

Presentations may be focal or widespread and range from mildly itchy to asymptomatic. Children and young adults are most often affected. Linear arrays may appear in response to the trauma of scratching, which is termed the Koebner phenomenon. The differential diagnosis includes molluscum contagiosum, lichen planus, and lichen spinulosis. Usually these conditions can be distinguished clinically, but a biopsy would differentiate them, if needed. It’s worth noting, too, that lichen nitidus papules are monomorphic and lack the umbilication that is seen with molluscum contagiosum.

Cases of lichen nitidus clear up spontaneously, although usually months to years after diagnosis. Lichen nitidus is not contagious. Reassurance is, however, important as many patients may have experienced misdiagnosis and have concerns about sexual transmission because of the location of the papules on their genitals.

Treatment is often unnecessary. However, if itching is problematic, topical steroids and other topical antipruritics may be used. Topical hydrocortisone 2.5% cream or ointment for skin folds and genitals may be safely used, as well as topical triamcinolone 0.1% for the trunk and extremities. Pramoxine lotion (Sarna) is an over-the-counter nonsteroidal antipruritic. Oral nonsedating antihistamines can also be used as an adjunct.

This patient was reassured that the lesions were not contagious. Due to the itching, he was started on the pramoxine lotion twice daily, as needed, and the lesions cleared in about 6 months.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

The miniscule papules arising suddenly on the trunk and genitals with linear arrays and clusters are clinically consistent with lichen nitidus, an uncommon eruption without a clear etiology.

Presentations may be focal or widespread and range from mildly itchy to asymptomatic. Children and young adults are most often affected. Linear arrays may appear in response to the trauma of scratching, which is termed the Koebner phenomenon. The differential diagnosis includes molluscum contagiosum, lichen planus, and lichen spinulosis. Usually these conditions can be distinguished clinically, but a biopsy would differentiate them, if needed. It’s worth noting, too, that lichen nitidus papules are monomorphic and lack the umbilication that is seen with molluscum contagiosum.

Cases of lichen nitidus clear up spontaneously, although usually months to years after diagnosis. Lichen nitidus is not contagious. Reassurance is, however, important as many patients may have experienced misdiagnosis and have concerns about sexual transmission because of the location of the papules on their genitals.

Treatment is often unnecessary. However, if itching is problematic, topical steroids and other topical antipruritics may be used. Topical hydrocortisone 2.5% cream or ointment for skin folds and genitals may be safely used, as well as topical triamcinolone 0.1% for the trunk and extremities. Pramoxine lotion (Sarna) is an over-the-counter nonsteroidal antipruritic. Oral nonsedating antihistamines can also be used as an adjunct.

This patient was reassured that the lesions were not contagious. Due to the itching, he was started on the pramoxine lotion twice daily, as needed, and the lesions cleared in about 6 months.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

Al-Mutairi N, Hassanein A, Nour-Eldin O, et al. Generalized lichen nitidus. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:158-160.

Al-Mutairi N, Hassanein A, Nour-Eldin O, et al. Generalized lichen nitidus. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:158-160.

What happened to melanoma care during COVID-19 sequestration

Initial evidence suggests that the , Rebecca I. Hartman, MD, MPH, said at a virtual forum on cutaneous malignancies jointly presented by Postgraduate Institute for Medicine and Global Academy for Medication Education.

This is not what National Comprehensive Cancer Network officials expected when they issued short-term recommendations on how to manage cutaneous melanoma during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Those recommendations for restriction of care, which Dr. Hartman characterized as “pretty significant changes from how we typically practice melanoma care in the U.S.,” came at a time when there was justifiable concern that the first COVID-19 surge would strain the U.S. health care system beyond the breaking point.

The rationale given for the NCCN recommendations was that most time-to-treat studies have shown no adverse patient outcomes for 90-day delays in treatment, even for thicker melanomas. But those studies, all retrospective, have been called into question. And the first real-world data on the impact of care restrictions during the lockdown, reported by Italian dermatologists, highlights adverse effects with potentially far-reaching consequences, noted Dr. Hartman, director of melanoma epidemiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a dermatologist, Harvard University, Boston.

Analysis of the impact of lockdown-induced delays in melanoma care is not merely an academic exercise, she added. While everyone hopes that the spring 2020 COVID-19 shelter-in-place was a once-in-a-lifetime event, there’s no guarantee that will be the case. Moreover, the lockdown provides a natural experiment addressing the possible consequences of melanoma care delays on patient outcomes, a topic that for ethical reasons could never be addressed in a randomized trial.

The short-term NCCN recommendations included the use of excisional biopsies for melanoma diagnosis whenever possible; and delay of up to 3 months for wide local excision of in situ melanoma, any invasive melanoma with negative margins, and even T1 melanomas with positive margins provided the bulk of the lesion had been excised. The guidance also suggested delaying sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), along with increased use of neoadjuvant therapy in patients with clinically palpable regional lymph nodes in order to delay surgery for up to 8 weeks. Single-agent systemic therapy at the least-frequent dosing was advised in order to minimize toxicity and reduce the need for additional health care resources: for example, nivolumab (Opdivo) at 480 mg every 4 weeks instead of every 2 weeks, and pembrolizumab (Keytruda) at 400 mg every 6 weeks, rather than every 3 weeks.

So, that’s what the NCCN recommended. Here’s what actually happened during shelter-in-place as captured in Dr. Hartman’s survey of 18 U.S. members of the Melanoma Prevention Working Group, all practicing dermatology in centers particularly hard-hit in the first wave of the pandemic: In-person new melanoma patient visits plunged from an average of 4.83 per week per provider to 0.83 per week. Telemedicine visits with new melanoma patients went from zero prepandemic to 0.67 visits per week per provider, which doesn’t come close to making up for the drop in in-person visits. Interestingly, two respondents reported turning to gene-expression profile testing for patient prognostication because of delays in SLNB.