User login

Ventricular assist devices linked to sepsis

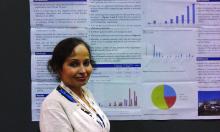

NEW ORLEANS – Back in 2008, there was only one case.

Since then, however, the number of patients with ventricular assist devices who developed sepsis while being treated in the cardiac unit at Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham, England, appeared to be noticeably growing. So, investigators launched a study to confirm their suspicions and to learn more about the underlying causes.

“Bloodstream infection is a serious infection, so I thought, ‘Let’s see what’s happening,’ ” explained Ira Das, MD, a consultant microbiologist at Queen Elizabeth Hospital.

Coagulase-negative staphylococci were the most common cause, present in 32% of the 25 cases. Sepsis was caused by Enterococcus faecium in 12%, Candida parapsilosis in 8%, and Staphylococcus aureus in 2%. Another 4% were either Enterococcus faecalis, Serratia marcescens, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, C. guilliermondii, or C. orthopsilosis. The remaining 16% of bloodstream infections were polymicrobial.

Less certain was the source of these infections.

“In the majority of cases, we didn’t know where it was coming from,” Dr. Das said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology. In 6 of the 25 cases, VAD was confirmed to be the focus of infection, either through imaging or because a failing component of the explanted device was examined later. An intravascular catheter was the source in another 5 patients, and in 14 cases, the source remained a mystery.

“Some of these infections just might have been hard to see,” Dr. Das said. “If the infection is inside the device, it’s not always easy to visualize.”

The study supports earlier findings from a review article that points to a significant infection risk associated with the implantation of VADs (Expert Rev Med Devices. 2011 Sep;8[5]:627-34). That article’s authors noted, “Despite recent improvements in outcomes, device-related infections remain a significant complication of LVAD [left ventricular assist device] therapy.”

In a previous study of people with end-stage heart failure, other investigators noted that, “despite the substantial survival benefit, the morbidity and mortality associated with the use of the left ventricular assist device were considerable. In particular, infection and mechanical failure of the device were major factors in the 2-year survival rate of only 23%” (N Engl J Med. 2001 Nov 15;345[20]:1435-43).

Similarly, in the current study, mortality was higher among those with sepsis and a VAD. Mortality was 39% – including eight patients who died with a VAD in situ and one following cardiac transplantation. However, Dr. Das cautioned, “It’s a small number, and there are other factors that could have contributed. They all go on anticoagulants so they have bleeding tendencies, and many of the patients are in the ICU with multiorgan failure.”

Infection prevention remains paramount to minimize mortality and other adverse events associated with a patient’s having a VAD. “We have to make sure that infection control procedures and our treatments are up to the optimal standard,” Dr. Das said. “It’s not easy to remove the device.”

Of the 129 VADs implanted, 68 were long-term LVADs, 11 were short-term LVADs, 15 were right ventricular devices, and 35 were biventricular devices.

The study is ongoing. The data presented at the meeting were collected up until December 2016.

“Since then, I’ve seen two more cases, and – very interestingly – one was Haemophilus influenzae,” Dr. Das said. “The patient was on the device, he was at home, and he came in with bacteremia.” Again, the source of infection proved elusive. “With H. influenzae, you would think it was coming from his chest, but the chest x-ray was normal.”

The second case, a patient with a coagulase-negative staphylococci bloodstream infection, was scheduled for a PET scan at the time of Dr. Das’ presentation to try to identify the source of infection.

Dr. Das had no relevant disclosures.

Modern technology saves our patients' lives, but there is always another side to the coin. Reports that LVAD devices are associated with a high incidence of bloodstream infections is important for future clinical practice. The fact that the causes and risk factors for these infections are unknown make this phenomena one of high interest.

Modern technology saves our patients' lives, but there is always another side to the coin. Reports that LVAD devices are associated with a high incidence of bloodstream infections is important for future clinical practice. The fact that the causes and risk factors for these infections are unknown make this phenomena one of high interest.

Modern technology saves our patients' lives, but there is always another side to the coin. Reports that LVAD devices are associated with a high incidence of bloodstream infections is important for future clinical practice. The fact that the causes and risk factors for these infections are unknown make this phenomena one of high interest.

NEW ORLEANS – Back in 2008, there was only one case.

Since then, however, the number of patients with ventricular assist devices who developed sepsis while being treated in the cardiac unit at Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham, England, appeared to be noticeably growing. So, investigators launched a study to confirm their suspicions and to learn more about the underlying causes.

“Bloodstream infection is a serious infection, so I thought, ‘Let’s see what’s happening,’ ” explained Ira Das, MD, a consultant microbiologist at Queen Elizabeth Hospital.

Coagulase-negative staphylococci were the most common cause, present in 32% of the 25 cases. Sepsis was caused by Enterococcus faecium in 12%, Candida parapsilosis in 8%, and Staphylococcus aureus in 2%. Another 4% were either Enterococcus faecalis, Serratia marcescens, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, C. guilliermondii, or C. orthopsilosis. The remaining 16% of bloodstream infections were polymicrobial.

Less certain was the source of these infections.

“In the majority of cases, we didn’t know where it was coming from,” Dr. Das said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology. In 6 of the 25 cases, VAD was confirmed to be the focus of infection, either through imaging or because a failing component of the explanted device was examined later. An intravascular catheter was the source in another 5 patients, and in 14 cases, the source remained a mystery.

“Some of these infections just might have been hard to see,” Dr. Das said. “If the infection is inside the device, it’s not always easy to visualize.”

The study supports earlier findings from a review article that points to a significant infection risk associated with the implantation of VADs (Expert Rev Med Devices. 2011 Sep;8[5]:627-34). That article’s authors noted, “Despite recent improvements in outcomes, device-related infections remain a significant complication of LVAD [left ventricular assist device] therapy.”

In a previous study of people with end-stage heart failure, other investigators noted that, “despite the substantial survival benefit, the morbidity and mortality associated with the use of the left ventricular assist device were considerable. In particular, infection and mechanical failure of the device were major factors in the 2-year survival rate of only 23%” (N Engl J Med. 2001 Nov 15;345[20]:1435-43).

Similarly, in the current study, mortality was higher among those with sepsis and a VAD. Mortality was 39% – including eight patients who died with a VAD in situ and one following cardiac transplantation. However, Dr. Das cautioned, “It’s a small number, and there are other factors that could have contributed. They all go on anticoagulants so they have bleeding tendencies, and many of the patients are in the ICU with multiorgan failure.”

Infection prevention remains paramount to minimize mortality and other adverse events associated with a patient’s having a VAD. “We have to make sure that infection control procedures and our treatments are up to the optimal standard,” Dr. Das said. “It’s not easy to remove the device.”

Of the 129 VADs implanted, 68 were long-term LVADs, 11 were short-term LVADs, 15 were right ventricular devices, and 35 were biventricular devices.

The study is ongoing. The data presented at the meeting were collected up until December 2016.

“Since then, I’ve seen two more cases, and – very interestingly – one was Haemophilus influenzae,” Dr. Das said. “The patient was on the device, he was at home, and he came in with bacteremia.” Again, the source of infection proved elusive. “With H. influenzae, you would think it was coming from his chest, but the chest x-ray was normal.”

The second case, a patient with a coagulase-negative staphylococci bloodstream infection, was scheduled for a PET scan at the time of Dr. Das’ presentation to try to identify the source of infection.

Dr. Das had no relevant disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Back in 2008, there was only one case.

Since then, however, the number of patients with ventricular assist devices who developed sepsis while being treated in the cardiac unit at Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham, England, appeared to be noticeably growing. So, investigators launched a study to confirm their suspicions and to learn more about the underlying causes.

“Bloodstream infection is a serious infection, so I thought, ‘Let’s see what’s happening,’ ” explained Ira Das, MD, a consultant microbiologist at Queen Elizabeth Hospital.

Coagulase-negative staphylococci were the most common cause, present in 32% of the 25 cases. Sepsis was caused by Enterococcus faecium in 12%, Candida parapsilosis in 8%, and Staphylococcus aureus in 2%. Another 4% were either Enterococcus faecalis, Serratia marcescens, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, C. guilliermondii, or C. orthopsilosis. The remaining 16% of bloodstream infections were polymicrobial.

Less certain was the source of these infections.

“In the majority of cases, we didn’t know where it was coming from,” Dr. Das said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology. In 6 of the 25 cases, VAD was confirmed to be the focus of infection, either through imaging or because a failing component of the explanted device was examined later. An intravascular catheter was the source in another 5 patients, and in 14 cases, the source remained a mystery.

“Some of these infections just might have been hard to see,” Dr. Das said. “If the infection is inside the device, it’s not always easy to visualize.”

The study supports earlier findings from a review article that points to a significant infection risk associated with the implantation of VADs (Expert Rev Med Devices. 2011 Sep;8[5]:627-34). That article’s authors noted, “Despite recent improvements in outcomes, device-related infections remain a significant complication of LVAD [left ventricular assist device] therapy.”

In a previous study of people with end-stage heart failure, other investigators noted that, “despite the substantial survival benefit, the morbidity and mortality associated with the use of the left ventricular assist device were considerable. In particular, infection and mechanical failure of the device were major factors in the 2-year survival rate of only 23%” (N Engl J Med. 2001 Nov 15;345[20]:1435-43).

Similarly, in the current study, mortality was higher among those with sepsis and a VAD. Mortality was 39% – including eight patients who died with a VAD in situ and one following cardiac transplantation. However, Dr. Das cautioned, “It’s a small number, and there are other factors that could have contributed. They all go on anticoagulants so they have bleeding tendencies, and many of the patients are in the ICU with multiorgan failure.”

Infection prevention remains paramount to minimize mortality and other adverse events associated with a patient’s having a VAD. “We have to make sure that infection control procedures and our treatments are up to the optimal standard,” Dr. Das said. “It’s not easy to remove the device.”

Of the 129 VADs implanted, 68 were long-term LVADs, 11 were short-term LVADs, 15 were right ventricular devices, and 35 were biventricular devices.

The study is ongoing. The data presented at the meeting were collected up until December 2016.

“Since then, I’ve seen two more cases, and – very interestingly – one was Haemophilus influenzae,” Dr. Das said. “The patient was on the device, he was at home, and he came in with bacteremia.” Again, the source of infection proved elusive. “With H. influenzae, you would think it was coming from his chest, but the chest x-ray was normal.”

The second case, a patient with a coagulase-negative staphylococci bloodstream infection, was scheduled for a PET scan at the time of Dr. Das’ presentation to try to identify the source of infection.

Dr. Das had no relevant disclosures.

AT ASM MICROBE 2017

Key clinical point: There may be a significant rate of bloodstream infections among people with a ventricular assist device.

Major finding: A total of 20% of the 118 people with a VAD had a bloodstream infection.

Data source: A retrospective study of 129 ventricular assist devices placed in 118 people between 2008 and 2016.

Disclosures: Dr. Das had no relevant disclosures.

Expanded urine culture identified more pathogens

NEW ORLEANS – With the trade-off of an extra 24 hours for results, an enhanced protocol to culture clinically relevant urinary pathogens detected significantly more unique pathogens associated with urinary tract infection, compared with standard cultures, in a study of 150 women.

“What we were able to see is that for about 90% of the samples that were called negative by standard [approach], we were able to detect bacteria through our protocol,” said Travis K. Price, a PhD candidate in the department of microbiology and immunology at Loyola University, Chicago.

Typically, when a urine sample is cultured for a UTI at Loyola University Medical Center, the standard protocol is for the lab to test 1 mcL of urine using agar plates incubated aerobically for 24 hours, Mr. Price said. “When we’re testing the urinary microbiome, we expand on that protocol. We use 100 times more urine, different plates, different environmental conditions, and we hold them for 48 hours instead of 24.”

The investigators prospectively recruited 150 women coming in to the urogynecology clinic – half who felt they had a UTI that day, half who did not. “We wanted to understand if using our enhanced protocol was beneficial and essentially leading to better patient outcomes,” Mr. Price said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology.

“Among the women who felt they had a UTI, standard culture only picked up 50% of the pathogens we were picking up with our protocol,” Mr. Price said. “And when we looked closer, we realized most of that was Escherichia coli.” Excluding samples positive for E. coli, standard culture detected only 12% of UTI pathogens, he added, compared with 77% detected with the expanded quantitative protocol.

The expanded protocol detected significantly more unique pathogen species, 95, compared with 11 with standard cultures. In addition, of all the uropathogens detected by the new protocol, the standard protocol missed 67%, or 122 of the total 182.

In terms of clinical practicality, Mr. Price and his colleagues looked at “different conditions, multiple volumes of urine, different plates, 24 versus 48 hours – and at the end tried to figure out what is the least amount of work you can do to get the most information.” They then developed a streamlined protocol that involves 100 mcL of urine, a CNA agar plate that selects for gram-positive organisms, a MacConkey agar using 5% CO2, and 48 hours of incubation. “It’s easy to implement,” he added. “The only issue is the longer incubation time could lead to delayed treatment, potentially.”

The streamlined protocol detected more uropathogens – 152 of the 182, for an 84% detection rate – compared with standard cultures, which detected 60 of the 182, or 33%.

The streamlined protocol markedly improved uropathogen detection, the authors wrote. “These findings support the necessity for an immediate change in urine culture procedures.”

Another aim of the study was to evaluate the optimal threshold for UTI colony counts. Traditionally, the cutoff is set at 105 colonies or greater for diagnosis of a UTI, Mr. Price said. “We found there were always higher pathogen colony counts in people who thought they had a UTI. But there wasn’t one threshold that would have caught all of these.”

Next, the investigators looked for a correlation between the colony count cutoff and clinical outcomes. “For people who had a colony count greater than 105 – typically, it was a gram-negative organism – most people were treated with an antibiotic, and a week later most people, 62%, reported feeling better,” Mr. Price said. “But people who didn’t have a pathogen greater than 105, some were not treated, and when we called them a week later, most reported they were not feeling better. ... This suggests this threshold is not actually appropriate.”

Going forward, the investigators just started a clinical trial using the enhanced culture to confirm whether or not their protocol leads to better outcomes for women with UTIs.

Mr. Price did not have any relevant disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – With the trade-off of an extra 24 hours for results, an enhanced protocol to culture clinically relevant urinary pathogens detected significantly more unique pathogens associated with urinary tract infection, compared with standard cultures, in a study of 150 women.

“What we were able to see is that for about 90% of the samples that were called negative by standard [approach], we were able to detect bacteria through our protocol,” said Travis K. Price, a PhD candidate in the department of microbiology and immunology at Loyola University, Chicago.

Typically, when a urine sample is cultured for a UTI at Loyola University Medical Center, the standard protocol is for the lab to test 1 mcL of urine using agar plates incubated aerobically for 24 hours, Mr. Price said. “When we’re testing the urinary microbiome, we expand on that protocol. We use 100 times more urine, different plates, different environmental conditions, and we hold them for 48 hours instead of 24.”

The investigators prospectively recruited 150 women coming in to the urogynecology clinic – half who felt they had a UTI that day, half who did not. “We wanted to understand if using our enhanced protocol was beneficial and essentially leading to better patient outcomes,” Mr. Price said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology.

“Among the women who felt they had a UTI, standard culture only picked up 50% of the pathogens we were picking up with our protocol,” Mr. Price said. “And when we looked closer, we realized most of that was Escherichia coli.” Excluding samples positive for E. coli, standard culture detected only 12% of UTI pathogens, he added, compared with 77% detected with the expanded quantitative protocol.

The expanded protocol detected significantly more unique pathogen species, 95, compared with 11 with standard cultures. In addition, of all the uropathogens detected by the new protocol, the standard protocol missed 67%, or 122 of the total 182.

In terms of clinical practicality, Mr. Price and his colleagues looked at “different conditions, multiple volumes of urine, different plates, 24 versus 48 hours – and at the end tried to figure out what is the least amount of work you can do to get the most information.” They then developed a streamlined protocol that involves 100 mcL of urine, a CNA agar plate that selects for gram-positive organisms, a MacConkey agar using 5% CO2, and 48 hours of incubation. “It’s easy to implement,” he added. “The only issue is the longer incubation time could lead to delayed treatment, potentially.”

The streamlined protocol detected more uropathogens – 152 of the 182, for an 84% detection rate – compared with standard cultures, which detected 60 of the 182, or 33%.

The streamlined protocol markedly improved uropathogen detection, the authors wrote. “These findings support the necessity for an immediate change in urine culture procedures.”

Another aim of the study was to evaluate the optimal threshold for UTI colony counts. Traditionally, the cutoff is set at 105 colonies or greater for diagnosis of a UTI, Mr. Price said. “We found there were always higher pathogen colony counts in people who thought they had a UTI. But there wasn’t one threshold that would have caught all of these.”

Next, the investigators looked for a correlation between the colony count cutoff and clinical outcomes. “For people who had a colony count greater than 105 – typically, it was a gram-negative organism – most people were treated with an antibiotic, and a week later most people, 62%, reported feeling better,” Mr. Price said. “But people who didn’t have a pathogen greater than 105, some were not treated, and when we called them a week later, most reported they were not feeling better. ... This suggests this threshold is not actually appropriate.”

Going forward, the investigators just started a clinical trial using the enhanced culture to confirm whether or not their protocol leads to better outcomes for women with UTIs.

Mr. Price did not have any relevant disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – With the trade-off of an extra 24 hours for results, an enhanced protocol to culture clinically relevant urinary pathogens detected significantly more unique pathogens associated with urinary tract infection, compared with standard cultures, in a study of 150 women.

“What we were able to see is that for about 90% of the samples that were called negative by standard [approach], we were able to detect bacteria through our protocol,” said Travis K. Price, a PhD candidate in the department of microbiology and immunology at Loyola University, Chicago.

Typically, when a urine sample is cultured for a UTI at Loyola University Medical Center, the standard protocol is for the lab to test 1 mcL of urine using agar plates incubated aerobically for 24 hours, Mr. Price said. “When we’re testing the urinary microbiome, we expand on that protocol. We use 100 times more urine, different plates, different environmental conditions, and we hold them for 48 hours instead of 24.”

The investigators prospectively recruited 150 women coming in to the urogynecology clinic – half who felt they had a UTI that day, half who did not. “We wanted to understand if using our enhanced protocol was beneficial and essentially leading to better patient outcomes,” Mr. Price said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology.

“Among the women who felt they had a UTI, standard culture only picked up 50% of the pathogens we were picking up with our protocol,” Mr. Price said. “And when we looked closer, we realized most of that was Escherichia coli.” Excluding samples positive for E. coli, standard culture detected only 12% of UTI pathogens, he added, compared with 77% detected with the expanded quantitative protocol.

The expanded protocol detected significantly more unique pathogen species, 95, compared with 11 with standard cultures. In addition, of all the uropathogens detected by the new protocol, the standard protocol missed 67%, or 122 of the total 182.

In terms of clinical practicality, Mr. Price and his colleagues looked at “different conditions, multiple volumes of urine, different plates, 24 versus 48 hours – and at the end tried to figure out what is the least amount of work you can do to get the most information.” They then developed a streamlined protocol that involves 100 mcL of urine, a CNA agar plate that selects for gram-positive organisms, a MacConkey agar using 5% CO2, and 48 hours of incubation. “It’s easy to implement,” he added. “The only issue is the longer incubation time could lead to delayed treatment, potentially.”

The streamlined protocol detected more uropathogens – 152 of the 182, for an 84% detection rate – compared with standard cultures, which detected 60 of the 182, or 33%.

The streamlined protocol markedly improved uropathogen detection, the authors wrote. “These findings support the necessity for an immediate change in urine culture procedures.”

Another aim of the study was to evaluate the optimal threshold for UTI colony counts. Traditionally, the cutoff is set at 105 colonies or greater for diagnosis of a UTI, Mr. Price said. “We found there were always higher pathogen colony counts in people who thought they had a UTI. But there wasn’t one threshold that would have caught all of these.”

Next, the investigators looked for a correlation between the colony count cutoff and clinical outcomes. “For people who had a colony count greater than 105 – typically, it was a gram-negative organism – most people were treated with an antibiotic, and a week later most people, 62%, reported feeling better,” Mr. Price said. “But people who didn’t have a pathogen greater than 105, some were not treated, and when we called them a week later, most reported they were not feeling better. ... This suggests this threshold is not actually appropriate.”

Going forward, the investigators just started a clinical trial using the enhanced culture to confirm whether or not their protocol leads to better outcomes for women with UTIs.

Mr. Price did not have any relevant disclosures.

AT ASM MICROBE 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Standard cultures missed 67% (122 of 182) of the uropathogens identified with the expanded culture protocol.

Data source: A prospective study of 150 women comparing UTI pathogen detection between standard and expanded culture analysis.

Disclosures: Mr. Price did not have any relevant disclosures.

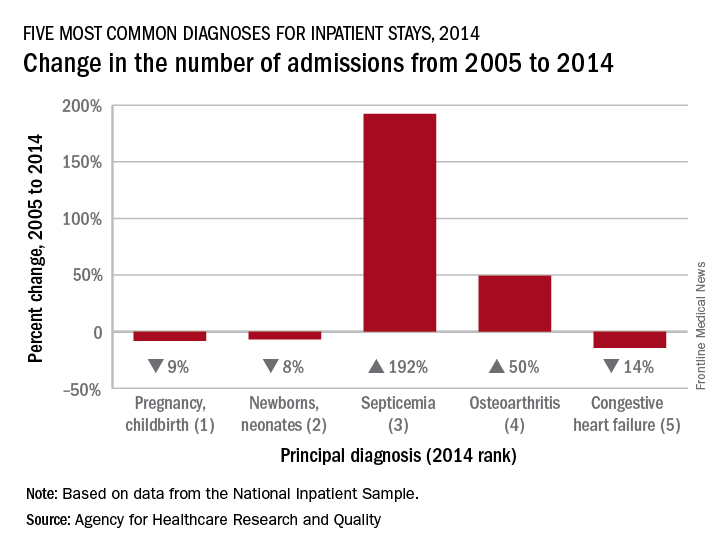

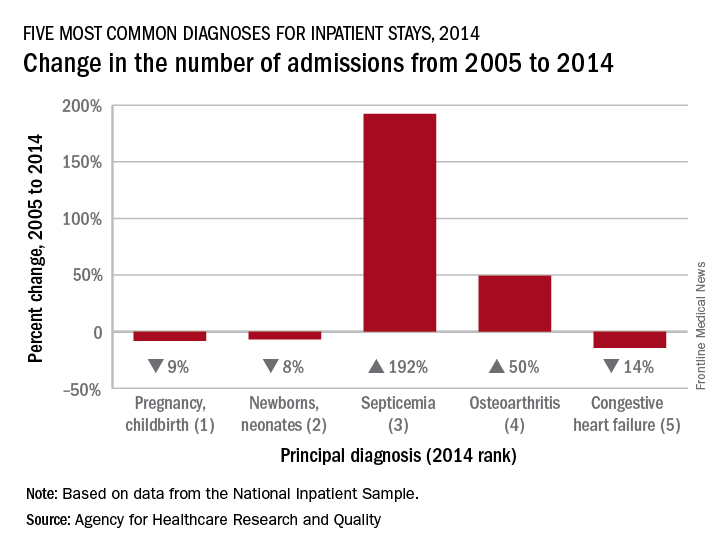

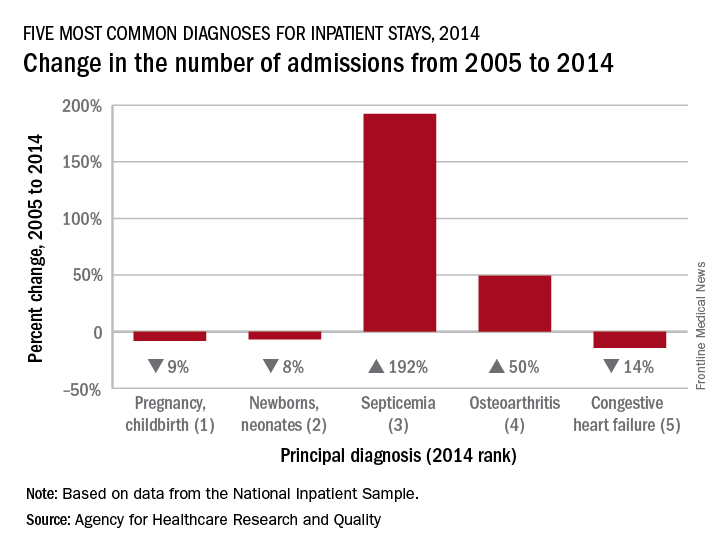

Septicemia admissions almost tripled from 2005 to 2014

Admissions for septicemia nearly tripled from 2005 to 2014, as it became the third most common diagnosis for hospital stays, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

There were over 1.5 million hospital stays with a principal diagnosis of septicemia in 2014, an increase of 192% over the 518,000 stays in 2005. The only diagnoses with more admissions in 2014 were pregnancy/childbirth with 4.1 million stays and newborns/neonates at almost 4 million, although both were down from 2005. That year, septicemia did not even rank among the top 10 diagnoses, the AHRQ reported.

Pneumonia, which was the third most common diagnosis in 2005, dropped by 32% and ended up in sixth place in 2014, while admissions for coronary atherosclerosis, which was fourth in 2005, decreased by 63%, dropping out of the top 10, by 2014, the AHRQ said.

Septicemia was the most common diagnosis for inpatient stays among those aged 75 years and older and the second most common for those aged 65-74 and 45-64. The leading nonmaternal, nonneonatal diagnosis in the two youngest age groups, 0-17 and 18-44 years, was mood disorders, and the most common cause of admissions for those aged 45-64 and 65-74 was osteoarthritis, the AHRQ reported.

Admissions for septicemia nearly tripled from 2005 to 2014, as it became the third most common diagnosis for hospital stays, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

There were over 1.5 million hospital stays with a principal diagnosis of septicemia in 2014, an increase of 192% over the 518,000 stays in 2005. The only diagnoses with more admissions in 2014 were pregnancy/childbirth with 4.1 million stays and newborns/neonates at almost 4 million, although both were down from 2005. That year, septicemia did not even rank among the top 10 diagnoses, the AHRQ reported.

Pneumonia, which was the third most common diagnosis in 2005, dropped by 32% and ended up in sixth place in 2014, while admissions for coronary atherosclerosis, which was fourth in 2005, decreased by 63%, dropping out of the top 10, by 2014, the AHRQ said.

Septicemia was the most common diagnosis for inpatient stays among those aged 75 years and older and the second most common for those aged 65-74 and 45-64. The leading nonmaternal, nonneonatal diagnosis in the two youngest age groups, 0-17 and 18-44 years, was mood disorders, and the most common cause of admissions for those aged 45-64 and 65-74 was osteoarthritis, the AHRQ reported.

Admissions for septicemia nearly tripled from 2005 to 2014, as it became the third most common diagnosis for hospital stays, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

There were over 1.5 million hospital stays with a principal diagnosis of septicemia in 2014, an increase of 192% over the 518,000 stays in 2005. The only diagnoses with more admissions in 2014 were pregnancy/childbirth with 4.1 million stays and newborns/neonates at almost 4 million, although both were down from 2005. That year, septicemia did not even rank among the top 10 diagnoses, the AHRQ reported.

Pneumonia, which was the third most common diagnosis in 2005, dropped by 32% and ended up in sixth place in 2014, while admissions for coronary atherosclerosis, which was fourth in 2005, decreased by 63%, dropping out of the top 10, by 2014, the AHRQ said.

Septicemia was the most common diagnosis for inpatient stays among those aged 75 years and older and the second most common for those aged 65-74 and 45-64. The leading nonmaternal, nonneonatal diagnosis in the two youngest age groups, 0-17 and 18-44 years, was mood disorders, and the most common cause of admissions for those aged 45-64 and 65-74 was osteoarthritis, the AHRQ reported.

Multiply recurrent C. difficile infection is on the rise

A retrospective cohort study of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI), the most common health care–associated infection, found that multiply recurrent CDI (mrCDI) is increasing in incidence, disproportionately to the overall increase in CDI.

Researchers from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, worked with a database of more than 38 million individuals with private health insurance between January 2001 and December 2012.

Cases of CDI and mrCDI in the study population were determined through ICD-9 diagnosis codes, and prescriptions for treatment. To meet the definition of mrCDI, there had to be at least three courses of treatment lasting at least 14 days each.

In the study population, 45,341 persons developed CDI, of whom 1,669 had mrCDI. The median age was 46 years, and 58.9% were female. Between 2001 and 2012, CDI incidence increased by 42.7% (P = .004), while mrCDI incidence increased by 188.8% (P less than .001).

With increases in CDI and mrCDI incidence, and with the effectiveness of standard antibiotic treatment decreasing with each recurrence, “demand for new antimicrobial therapies and FMT [fecal microbiota transplantation] can be expected to increase considerably in the coming years,” wrote Gene K. Ma, MD, and his coauthors.

As for FMT, the researchers noted that its likely greater demand in the future (as suggested by their study results) highlights the importance of establishing the long-term safety of the procedure (Ann Intern Med. 2017 Jul. doi: 10.7326/M16-2733).

The retrospective cohort study was based on administrative data rather than laboratory data, Sameer D. Saini, MD, MS, and Akbar K. Waljee, MD, noted in an editorial accompanying the study. Further, with Medicare patients excluded from the study (because Medicare data were not available for the full time period studied for private insurance data), the data may not be of relevance to patients older than age 65 years.

But the general conclusion that both CDI and mrCDI are on the rise is a crucial matter. “We must first have a better understanding of mrCDI, its scope and epidemiology, and its associated risk factors. The study by Ma and colleagues begins this important work. A better understanding of the epidemiology of mrCDI is a critical first step toward developing a sound strategy to address this growing public health challenge.”

Dr. Saini and Dr. Waljee are with the VA Ann Arbor (Michigan) Center for Clinical Management. Their editorial accompanied the study in Annals of Internal Medicine (2017 Jul. doi: 10.7326/M17-1565).

The retrospective cohort study was based on administrative data rather than laboratory data, Sameer D. Saini, MD, MS, and Akbar K. Waljee, MD, noted in an editorial accompanying the study. Further, with Medicare patients excluded from the study (because Medicare data were not available for the full time period studied for private insurance data), the data may not be of relevance to patients older than age 65 years.

But the general conclusion that both CDI and mrCDI are on the rise is a crucial matter. “We must first have a better understanding of mrCDI, its scope and epidemiology, and its associated risk factors. The study by Ma and colleagues begins this important work. A better understanding of the epidemiology of mrCDI is a critical first step toward developing a sound strategy to address this growing public health challenge.”

Dr. Saini and Dr. Waljee are with the VA Ann Arbor (Michigan) Center for Clinical Management. Their editorial accompanied the study in Annals of Internal Medicine (2017 Jul. doi: 10.7326/M17-1565).

The retrospective cohort study was based on administrative data rather than laboratory data, Sameer D. Saini, MD, MS, and Akbar K. Waljee, MD, noted in an editorial accompanying the study. Further, with Medicare patients excluded from the study (because Medicare data were not available for the full time period studied for private insurance data), the data may not be of relevance to patients older than age 65 years.

But the general conclusion that both CDI and mrCDI are on the rise is a crucial matter. “We must first have a better understanding of mrCDI, its scope and epidemiology, and its associated risk factors. The study by Ma and colleagues begins this important work. A better understanding of the epidemiology of mrCDI is a critical first step toward developing a sound strategy to address this growing public health challenge.”

Dr. Saini and Dr. Waljee are with the VA Ann Arbor (Michigan) Center for Clinical Management. Their editorial accompanied the study in Annals of Internal Medicine (2017 Jul. doi: 10.7326/M17-1565).

A retrospective cohort study of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI), the most common health care–associated infection, found that multiply recurrent CDI (mrCDI) is increasing in incidence, disproportionately to the overall increase in CDI.

Researchers from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, worked with a database of more than 38 million individuals with private health insurance between January 2001 and December 2012.

Cases of CDI and mrCDI in the study population were determined through ICD-9 diagnosis codes, and prescriptions for treatment. To meet the definition of mrCDI, there had to be at least three courses of treatment lasting at least 14 days each.

In the study population, 45,341 persons developed CDI, of whom 1,669 had mrCDI. The median age was 46 years, and 58.9% were female. Between 2001 and 2012, CDI incidence increased by 42.7% (P = .004), while mrCDI incidence increased by 188.8% (P less than .001).

With increases in CDI and mrCDI incidence, and with the effectiveness of standard antibiotic treatment decreasing with each recurrence, “demand for new antimicrobial therapies and FMT [fecal microbiota transplantation] can be expected to increase considerably in the coming years,” wrote Gene K. Ma, MD, and his coauthors.

As for FMT, the researchers noted that its likely greater demand in the future (as suggested by their study results) highlights the importance of establishing the long-term safety of the procedure (Ann Intern Med. 2017 Jul. doi: 10.7326/M16-2733).

A retrospective cohort study of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI), the most common health care–associated infection, found that multiply recurrent CDI (mrCDI) is increasing in incidence, disproportionately to the overall increase in CDI.

Researchers from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, worked with a database of more than 38 million individuals with private health insurance between January 2001 and December 2012.

Cases of CDI and mrCDI in the study population were determined through ICD-9 diagnosis codes, and prescriptions for treatment. To meet the definition of mrCDI, there had to be at least three courses of treatment lasting at least 14 days each.

In the study population, 45,341 persons developed CDI, of whom 1,669 had mrCDI. The median age was 46 years, and 58.9% were female. Between 2001 and 2012, CDI incidence increased by 42.7% (P = .004), while mrCDI incidence increased by 188.8% (P less than .001).

With increases in CDI and mrCDI incidence, and with the effectiveness of standard antibiotic treatment decreasing with each recurrence, “demand for new antimicrobial therapies and FMT [fecal microbiota transplantation] can be expected to increase considerably in the coming years,” wrote Gene K. Ma, MD, and his coauthors.

As for FMT, the researchers noted that its likely greater demand in the future (as suggested by their study results) highlights the importance of establishing the long-term safety of the procedure (Ann Intern Med. 2017 Jul. doi: 10.7326/M16-2733).

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

TB meningitis cases in U.S. are fewer but more complicated

BOSTON – The number of cases of meningitis caused by tuberculosis has fallen dramatically in the United States in recent decades as TB itself has become less common, according to findings from a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

However, these findings from patient hospitalizations during 1993-2013 in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database also indicate that neurologic complications from TB meningitis are on the rise.

The findings suggest that neurologists need to become involved whenever a patient with TB shows signs of neurologic problems, said study lead author Alexander E. Merkler, MD, of Cornell University, New York, in an interview. “They’re at high risk, and some complications can be life threatening.”

According to Dr. Merkler, TB meningitis occurs when a patient’s case of TB invades the meninges surrounding the brain. “It can lead to seizures, stroke, hydrocephalus, and death,” he said at the meeting.

TB meningitis can affect anyone with TB, he said, but those who are immunocompromised and those with diabetes are especially vulnerable.

For their current study, Dr. Merkler and his associates used the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database to track patients hospitalized in the United States with TB meningitis from 1993 to 2013. They found 16,196 new cases over the 20-year period and uncovered a dramatic decrease in the rate of hospitalizations: The incidence fell from 6.2 to 1.9 hospitalizations per million people (rate difference, 4.3; 95% confidence interval, 2.1-6.5; P less than .001), and mortality during index hospitalization fell from 17.6% (95% CI, 12.0%-23.2%) to 7.6%, (95% CI, 2.2%-13.0%).

Dr. Merkler said that mortality appears to have declined as TB itself has become less common. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the number of reported TB cases nationally was 9,557 in 2015, a rate of 3.0 cases per 100,000 persons. The total number of annual cases fell each year from 1993 to 2014, the CDC reported, although the rate leveled off at around 3.0/100,000 from 2013 to 2015.

“The fewer people have lung TB, the less they’ll have it going into meningitis and the brain,” Dr. Merkler said. “In terms of mortality, it is going down because we have better supportive care. We’re better at keeping these patients alive and giving them antibiotics sooner.”

However, the study found that the rates of the following complications in hospitalized TB meningitis patients rose over the 20-year period:

• Hydrocephalus, from 2.3% (95% confidence interval, 0.5%-4.2%) to 5.4% (95% CI, 2.3%-10.0%).

• Seizure, from 2.9% (95% CI, 0.3%-5.4%) to 14.1% (95% CI, 7.3%-21.0%).

• Stroke, from 2.9% (95% CI, 0.6%-5.3%) to 13.0% (95% CI, 6.3%-19.8%).

• Vision and hearing impairment, from 8.2% (95% CI, 4.8%-11.6%) to 10.9% (95% CI, 4.1%-17.6%), and from 1.1% (95% CI, 0.0%-2.3%) to 3.3% (95% CI, 0.0%-6.9%), respectively.

Dr. Merkler said it’s not clear why these rates are going up, but it may be because patients have more complications as a result of living longer. Another theory is that a form of drug-resistant TB is boosting the level of these complications, Dr. Merkler said, but he’s skeptical of that idea: “I don’t know why drug resistance would lead to more neurological complications.”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the Michael Goldberg Stroke Research Fund. Dr. Merkler reported no relevant financial disclosures.

BOSTON – The number of cases of meningitis caused by tuberculosis has fallen dramatically in the United States in recent decades as TB itself has become less common, according to findings from a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

However, these findings from patient hospitalizations during 1993-2013 in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database also indicate that neurologic complications from TB meningitis are on the rise.

The findings suggest that neurologists need to become involved whenever a patient with TB shows signs of neurologic problems, said study lead author Alexander E. Merkler, MD, of Cornell University, New York, in an interview. “They’re at high risk, and some complications can be life threatening.”

According to Dr. Merkler, TB meningitis occurs when a patient’s case of TB invades the meninges surrounding the brain. “It can lead to seizures, stroke, hydrocephalus, and death,” he said at the meeting.

TB meningitis can affect anyone with TB, he said, but those who are immunocompromised and those with diabetes are especially vulnerable.

For their current study, Dr. Merkler and his associates used the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database to track patients hospitalized in the United States with TB meningitis from 1993 to 2013. They found 16,196 new cases over the 20-year period and uncovered a dramatic decrease in the rate of hospitalizations: The incidence fell from 6.2 to 1.9 hospitalizations per million people (rate difference, 4.3; 95% confidence interval, 2.1-6.5; P less than .001), and mortality during index hospitalization fell from 17.6% (95% CI, 12.0%-23.2%) to 7.6%, (95% CI, 2.2%-13.0%).

Dr. Merkler said that mortality appears to have declined as TB itself has become less common. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the number of reported TB cases nationally was 9,557 in 2015, a rate of 3.0 cases per 100,000 persons. The total number of annual cases fell each year from 1993 to 2014, the CDC reported, although the rate leveled off at around 3.0/100,000 from 2013 to 2015.

“The fewer people have lung TB, the less they’ll have it going into meningitis and the brain,” Dr. Merkler said. “In terms of mortality, it is going down because we have better supportive care. We’re better at keeping these patients alive and giving them antibiotics sooner.”

However, the study found that the rates of the following complications in hospitalized TB meningitis patients rose over the 20-year period:

• Hydrocephalus, from 2.3% (95% confidence interval, 0.5%-4.2%) to 5.4% (95% CI, 2.3%-10.0%).

• Seizure, from 2.9% (95% CI, 0.3%-5.4%) to 14.1% (95% CI, 7.3%-21.0%).

• Stroke, from 2.9% (95% CI, 0.6%-5.3%) to 13.0% (95% CI, 6.3%-19.8%).

• Vision and hearing impairment, from 8.2% (95% CI, 4.8%-11.6%) to 10.9% (95% CI, 4.1%-17.6%), and from 1.1% (95% CI, 0.0%-2.3%) to 3.3% (95% CI, 0.0%-6.9%), respectively.

Dr. Merkler said it’s not clear why these rates are going up, but it may be because patients have more complications as a result of living longer. Another theory is that a form of drug-resistant TB is boosting the level of these complications, Dr. Merkler said, but he’s skeptical of that idea: “I don’t know why drug resistance would lead to more neurological complications.”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the Michael Goldberg Stroke Research Fund. Dr. Merkler reported no relevant financial disclosures.

BOSTON – The number of cases of meningitis caused by tuberculosis has fallen dramatically in the United States in recent decades as TB itself has become less common, according to findings from a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

However, these findings from patient hospitalizations during 1993-2013 in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database also indicate that neurologic complications from TB meningitis are on the rise.

The findings suggest that neurologists need to become involved whenever a patient with TB shows signs of neurologic problems, said study lead author Alexander E. Merkler, MD, of Cornell University, New York, in an interview. “They’re at high risk, and some complications can be life threatening.”

According to Dr. Merkler, TB meningitis occurs when a patient’s case of TB invades the meninges surrounding the brain. “It can lead to seizures, stroke, hydrocephalus, and death,” he said at the meeting.

TB meningitis can affect anyone with TB, he said, but those who are immunocompromised and those with diabetes are especially vulnerable.

For their current study, Dr. Merkler and his associates used the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database to track patients hospitalized in the United States with TB meningitis from 1993 to 2013. They found 16,196 new cases over the 20-year period and uncovered a dramatic decrease in the rate of hospitalizations: The incidence fell from 6.2 to 1.9 hospitalizations per million people (rate difference, 4.3; 95% confidence interval, 2.1-6.5; P less than .001), and mortality during index hospitalization fell from 17.6% (95% CI, 12.0%-23.2%) to 7.6%, (95% CI, 2.2%-13.0%).

Dr. Merkler said that mortality appears to have declined as TB itself has become less common. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the number of reported TB cases nationally was 9,557 in 2015, a rate of 3.0 cases per 100,000 persons. The total number of annual cases fell each year from 1993 to 2014, the CDC reported, although the rate leveled off at around 3.0/100,000 from 2013 to 2015.

“The fewer people have lung TB, the less they’ll have it going into meningitis and the brain,” Dr. Merkler said. “In terms of mortality, it is going down because we have better supportive care. We’re better at keeping these patients alive and giving them antibiotics sooner.”

However, the study found that the rates of the following complications in hospitalized TB meningitis patients rose over the 20-year period:

• Hydrocephalus, from 2.3% (95% confidence interval, 0.5%-4.2%) to 5.4% (95% CI, 2.3%-10.0%).

• Seizure, from 2.9% (95% CI, 0.3%-5.4%) to 14.1% (95% CI, 7.3%-21.0%).

• Stroke, from 2.9% (95% CI, 0.6%-5.3%) to 13.0% (95% CI, 6.3%-19.8%).

• Vision and hearing impairment, from 8.2% (95% CI, 4.8%-11.6%) to 10.9% (95% CI, 4.1%-17.6%), and from 1.1% (95% CI, 0.0%-2.3%) to 3.3% (95% CI, 0.0%-6.9%), respectively.

Dr. Merkler said it’s not clear why these rates are going up, but it may be because patients have more complications as a result of living longer. Another theory is that a form of drug-resistant TB is boosting the level of these complications, Dr. Merkler said, but he’s skeptical of that idea: “I don’t know why drug resistance would lead to more neurological complications.”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the Michael Goldberg Stroke Research Fund. Dr. Merkler reported no relevant financial disclosures.

AT AAN 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The rate of TB meningitis hospitalizations fell from 6.2 to 1.9 per million people (rate difference, 4.3; 95% CI, 2.1-6.5; P less than .001).

Data source: The Nationwide Inpatient Sample database, which revealed 16,196 new cases of TB meningitis from 1993 to 2013.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the Michael Goldberg Stroke Research Fund. Dr. Merkler reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Bilateral cellulitis on legs? Think venous stasis dermatitis

SAN FRANCISCO – If a patient presents with bilateral cellulitis on both legs, think venous stasis dermatitis, which is the number one misdiagnosis of cellulitis and a frequent cause of unnecessary hospitalization for so-called “red leg,” according to Kanade Shinkai, MD, PhD.

“It’s easy to make that mistake, because you have a red, hot leg that’s painful, and the patient is having difficulty walking,” Dr. Shinkai said at the UCSF Annual Advances in Internal Medicine meeting. “Venous stasis dermatitis is one of the things you want to learn to recognize, as hospitalization is typically not needed.”

“That has to do with the venous return back to the heart,” said Dr. Shinkai, a dermatologist at UCSF Medical Center. “If it’s unilateral, it’s almost always on the left side.”

Patients often have features of venous insufficiency that cause stasis, including varicose veins and brawny hyperpigmentation on the medial aspects of the ankles. “They have almost no systemic features: no fever, no white count, no lymphadenopathy,” she said. “These patients need some kind of anti-inflammatory medication because the skin is very inflamed. If you happened to take a biopsy, you would see inflammation as well as lymphatic congestion.”

Dr. Shinkai recommends that patients apply a midpotency topical steroid such as triamcinolone to the affected area, followed by compression, ideally antiembolism stockings (TED hose) – but that can be a hard sell.

“When your legs are that swollen, they’re really painful to wear,” she said. “Patients will say, ‘Don’t you come near me with those TED hose.’ If you’re in that situation, tell them to use an Ace wrap with light compression and each day tighten the Ace wrap a little more until they are able to use TED hose with minimal discomfort.”

The differential diagnosis for venous stasis dermatitis includes cellulitis (which rarely presents bilaterally), deep vein thrombosis, asteatotic dermatitis, erysipelas (more superficial cellulitis that results in elevated, shiny plaques), pyomyositis, necrotizing fasciitis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and allergic contact dermatitis.

Dr. Shinkai reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – If a patient presents with bilateral cellulitis on both legs, think venous stasis dermatitis, which is the number one misdiagnosis of cellulitis and a frequent cause of unnecessary hospitalization for so-called “red leg,” according to Kanade Shinkai, MD, PhD.

“It’s easy to make that mistake, because you have a red, hot leg that’s painful, and the patient is having difficulty walking,” Dr. Shinkai said at the UCSF Annual Advances in Internal Medicine meeting. “Venous stasis dermatitis is one of the things you want to learn to recognize, as hospitalization is typically not needed.”

“That has to do with the venous return back to the heart,” said Dr. Shinkai, a dermatologist at UCSF Medical Center. “If it’s unilateral, it’s almost always on the left side.”

Patients often have features of venous insufficiency that cause stasis, including varicose veins and brawny hyperpigmentation on the medial aspects of the ankles. “They have almost no systemic features: no fever, no white count, no lymphadenopathy,” she said. “These patients need some kind of anti-inflammatory medication because the skin is very inflamed. If you happened to take a biopsy, you would see inflammation as well as lymphatic congestion.”

Dr. Shinkai recommends that patients apply a midpotency topical steroid such as triamcinolone to the affected area, followed by compression, ideally antiembolism stockings (TED hose) – but that can be a hard sell.

“When your legs are that swollen, they’re really painful to wear,” she said. “Patients will say, ‘Don’t you come near me with those TED hose.’ If you’re in that situation, tell them to use an Ace wrap with light compression and each day tighten the Ace wrap a little more until they are able to use TED hose with minimal discomfort.”

The differential diagnosis for venous stasis dermatitis includes cellulitis (which rarely presents bilaterally), deep vein thrombosis, asteatotic dermatitis, erysipelas (more superficial cellulitis that results in elevated, shiny plaques), pyomyositis, necrotizing fasciitis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and allergic contact dermatitis.

Dr. Shinkai reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – If a patient presents with bilateral cellulitis on both legs, think venous stasis dermatitis, which is the number one misdiagnosis of cellulitis and a frequent cause of unnecessary hospitalization for so-called “red leg,” according to Kanade Shinkai, MD, PhD.

“It’s easy to make that mistake, because you have a red, hot leg that’s painful, and the patient is having difficulty walking,” Dr. Shinkai said at the UCSF Annual Advances in Internal Medicine meeting. “Venous stasis dermatitis is one of the things you want to learn to recognize, as hospitalization is typically not needed.”

“That has to do with the venous return back to the heart,” said Dr. Shinkai, a dermatologist at UCSF Medical Center. “If it’s unilateral, it’s almost always on the left side.”

Patients often have features of venous insufficiency that cause stasis, including varicose veins and brawny hyperpigmentation on the medial aspects of the ankles. “They have almost no systemic features: no fever, no white count, no lymphadenopathy,” she said. “These patients need some kind of anti-inflammatory medication because the skin is very inflamed. If you happened to take a biopsy, you would see inflammation as well as lymphatic congestion.”

Dr. Shinkai recommends that patients apply a midpotency topical steroid such as triamcinolone to the affected area, followed by compression, ideally antiembolism stockings (TED hose) – but that can be a hard sell.

“When your legs are that swollen, they’re really painful to wear,” she said. “Patients will say, ‘Don’t you come near me with those TED hose.’ If you’re in that situation, tell them to use an Ace wrap with light compression and each day tighten the Ace wrap a little more until they are able to use TED hose with minimal discomfort.”

The differential diagnosis for venous stasis dermatitis includes cellulitis (which rarely presents bilaterally), deep vein thrombosis, asteatotic dermatitis, erysipelas (more superficial cellulitis that results in elevated, shiny plaques), pyomyositis, necrotizing fasciitis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and allergic contact dermatitis.

Dr. Shinkai reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE ANNUAL ADVANCES IN INTERNAL MEDICINE

U.S. malaria cases dipped slightly in 2014

The number of confirmed malaria cases reported in the United States in 2014 is the fourth highest annual total since 1973, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, but the 2014 number of 1,724 cases is down slightly from 1,741 – the previous year’s number of confirmed cases.

The CDC monitors malaria cases in part to identify any instances of local, rather than imported, transmission. For 2014, no cases of local transmission were reported.

Of the imported transmission cases for which the region of acquisition was known, 1,383 (82.1%) came from Africa and 160 (9.5%) from Asia, making up all but 62 of the imported cases. The four leading countries of origin in Africa were Nigeria, Ghana, Sierra Leone, and Liberia (346, 153, 133, and 125 cases, respectively). Most of the cases from Asia came from India, which accounted for 100 of the 160 cases.

Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea were the countries primarily affected by the Ebola virus disease outbreak in 2014 and into 2015. The study authors, Kimberly E. Mace, PhD, and Paul M. Arguin, MD, noted in the May 26 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report that “Ebola negatively impacted the delivery of malaria care and prevention services in the Ebola-affected countries, which could have increased malaria morbidity and mortality” (MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66[12]:1-24).

“Despite progress in reducing global prevalence of malaria, the disease remains endemic in many regions and use of appropriate prevention measures by travelers is still inadequate,” they added.

Among all cases, 17% were classified as severe illness, including five deaths (a decrease from 10 deaths in 2013). All five patients who died reported not taking chemoprophylaxis during their travel. More than half (57.5%) of the patients reported that the purpose of their travel was to visit friends and relatives.

“Health care providers should talk to their patients, especially those who would travel to countries where malaria is endemic to visit friends and relatives, about upcoming travel plans and offer education and medicines to prevent malaria,” the authors wrote.

The number of confirmed malaria cases reported in the United States in 2014 is the fourth highest annual total since 1973, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, but the 2014 number of 1,724 cases is down slightly from 1,741 – the previous year’s number of confirmed cases.

The CDC monitors malaria cases in part to identify any instances of local, rather than imported, transmission. For 2014, no cases of local transmission were reported.

Of the imported transmission cases for which the region of acquisition was known, 1,383 (82.1%) came from Africa and 160 (9.5%) from Asia, making up all but 62 of the imported cases. The four leading countries of origin in Africa were Nigeria, Ghana, Sierra Leone, and Liberia (346, 153, 133, and 125 cases, respectively). Most of the cases from Asia came from India, which accounted for 100 of the 160 cases.

Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea were the countries primarily affected by the Ebola virus disease outbreak in 2014 and into 2015. The study authors, Kimberly E. Mace, PhD, and Paul M. Arguin, MD, noted in the May 26 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report that “Ebola negatively impacted the delivery of malaria care and prevention services in the Ebola-affected countries, which could have increased malaria morbidity and mortality” (MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66[12]:1-24).

“Despite progress in reducing global prevalence of malaria, the disease remains endemic in many regions and use of appropriate prevention measures by travelers is still inadequate,” they added.

Among all cases, 17% were classified as severe illness, including five deaths (a decrease from 10 deaths in 2013). All five patients who died reported not taking chemoprophylaxis during their travel. More than half (57.5%) of the patients reported that the purpose of their travel was to visit friends and relatives.

“Health care providers should talk to their patients, especially those who would travel to countries where malaria is endemic to visit friends and relatives, about upcoming travel plans and offer education and medicines to prevent malaria,” the authors wrote.

The number of confirmed malaria cases reported in the United States in 2014 is the fourth highest annual total since 1973, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, but the 2014 number of 1,724 cases is down slightly from 1,741 – the previous year’s number of confirmed cases.

The CDC monitors malaria cases in part to identify any instances of local, rather than imported, transmission. For 2014, no cases of local transmission were reported.

Of the imported transmission cases for which the region of acquisition was known, 1,383 (82.1%) came from Africa and 160 (9.5%) from Asia, making up all but 62 of the imported cases. The four leading countries of origin in Africa were Nigeria, Ghana, Sierra Leone, and Liberia (346, 153, 133, and 125 cases, respectively). Most of the cases from Asia came from India, which accounted for 100 of the 160 cases.

Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea were the countries primarily affected by the Ebola virus disease outbreak in 2014 and into 2015. The study authors, Kimberly E. Mace, PhD, and Paul M. Arguin, MD, noted in the May 26 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report that “Ebola negatively impacted the delivery of malaria care and prevention services in the Ebola-affected countries, which could have increased malaria morbidity and mortality” (MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66[12]:1-24).

“Despite progress in reducing global prevalence of malaria, the disease remains endemic in many regions and use of appropriate prevention measures by travelers is still inadequate,” they added.

Among all cases, 17% were classified as severe illness, including five deaths (a decrease from 10 deaths in 2013). All five patients who died reported not taking chemoprophylaxis during their travel. More than half (57.5%) of the patients reported that the purpose of their travel was to visit friends and relatives.

“Health care providers should talk to their patients, especially those who would travel to countries where malaria is endemic to visit friends and relatives, about upcoming travel plans and offer education and medicines to prevent malaria,” the authors wrote.

FROM MMWR

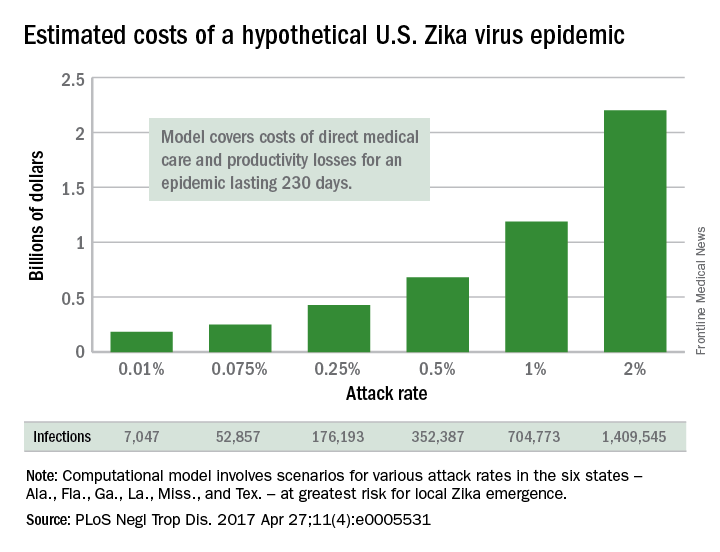

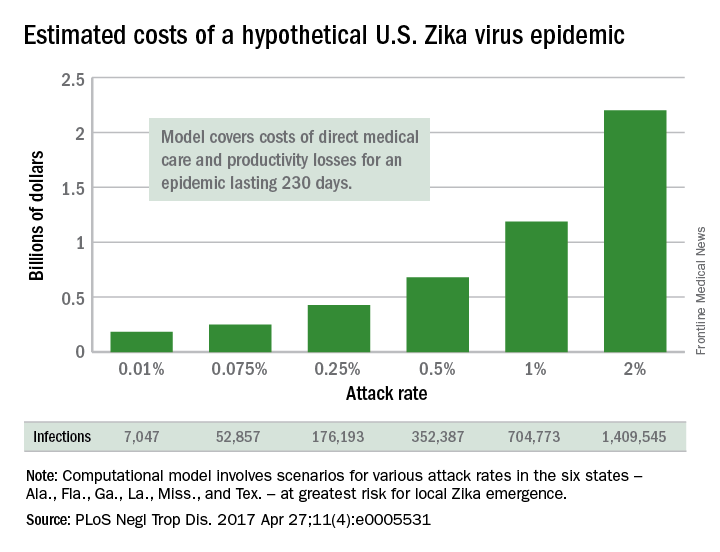

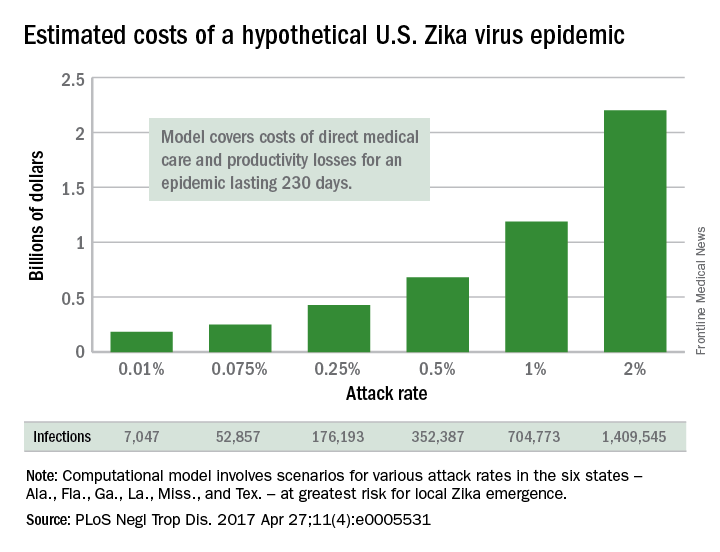

U.S. Zika epidemic could cost billions, or less

A Zika virus epidemic could cost the United States $183 million … or $680 million … or $2.2 billion, according to a new computational model developed to estimate Zika’s economic impact.

The model’s seeming lack of conviction comes from its options for an attack rate – the percentage of the population infected by the virus. An epidemic with a low attack rate of 0.01% would be expected to result in over 7,000 symptomatic cases and cost $183 million in direct medical costs and losses in productivity, said Bruce Y. Lee, MD, of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and his associates (PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017 Apr 27;11[4]:e0005531).

The investigators based their model on the six states at the highest risk for local Zika emergence: Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas. The hypothetical epidemic lasts 230 days, which is equivalent to the Zika-related microcephaly outbreak in Brazil in 2015.

The National Institutes of Health, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the United States Agency for International Development funded the study. The authors declared that no competing interests exist.

A Zika virus epidemic could cost the United States $183 million … or $680 million … or $2.2 billion, according to a new computational model developed to estimate Zika’s economic impact.

The model’s seeming lack of conviction comes from its options for an attack rate – the percentage of the population infected by the virus. An epidemic with a low attack rate of 0.01% would be expected to result in over 7,000 symptomatic cases and cost $183 million in direct medical costs and losses in productivity, said Bruce Y. Lee, MD, of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and his associates (PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017 Apr 27;11[4]:e0005531).

The investigators based their model on the six states at the highest risk for local Zika emergence: Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas. The hypothetical epidemic lasts 230 days, which is equivalent to the Zika-related microcephaly outbreak in Brazil in 2015.

The National Institutes of Health, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the United States Agency for International Development funded the study. The authors declared that no competing interests exist.

A Zika virus epidemic could cost the United States $183 million … or $680 million … or $2.2 billion, according to a new computational model developed to estimate Zika’s economic impact.

The model’s seeming lack of conviction comes from its options for an attack rate – the percentage of the population infected by the virus. An epidemic with a low attack rate of 0.01% would be expected to result in over 7,000 symptomatic cases and cost $183 million in direct medical costs and losses in productivity, said Bruce Y. Lee, MD, of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and his associates (PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017 Apr 27;11[4]:e0005531).

The investigators based their model on the six states at the highest risk for local Zika emergence: Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas. The hypothetical epidemic lasts 230 days, which is equivalent to the Zika-related microcephaly outbreak in Brazil in 2015.

The National Institutes of Health, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the United States Agency for International Development funded the study. The authors declared that no competing interests exist.

FROM PLOS NEGLECTED TROPICAL DISEASES

After the epidemic, Ebola’s destructive power still haunts survivors

VIENNA – The Ebola crisis may be over in Sierra Leone, but the suffering is not.

The last patient from the epidemic was discharged in February 2016, but 78% of survivors now appear to have one or more sequelae of the infection. Some problems are mild, but some are so debilitating that life may never be the same.

Janet Scott, MD, of the University of Liverpool (England), heads a task force studying Ebola’s lingering aftereffects. These fall into four categories, Dr. Scott said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress: musculoskeletal pain, headache, eye problems, and psychological disorders.

They add up to an enormous risk of disability – survivors are more than 200 times more likely than controls to express at least moderate disability.

Dr. Scott and her team of researchers are partnering with clinicians and data managers in the Ebola treatment unit in the 34th Regimental Military Hospital (MH34) in Freetown, Sierra Leone. In Sierra Leone alone, she said, there were nearly 9,000 cases and 3,500 deaths from the virus; about 5,000 patients survived. So far, Dr. Scott and her team have collected data on about 500 patients for whom they also provide free health care.

The project has six arms, each headed by an expert: clinical care, data collection, disability, neurology, ophthalmology, and psychiatry.

The team sees patients in a large tent sectioned by a plywood wall*. Wireless Internet access, which she said is “enormously expensive” in Sierra Leone, has been donated by Omline Business Communications*. It’s the team’s lifeline, allowing them to transmit data between Freetown and participating units around the world. Members also Skype regularly, talking with patients and with each other.

All patients who come into the clinic have an initial visit that includes collection of demographics, their Ebola and clinical history (including an exploration of comorbidities), a maternal health screening for women, vital signs and symptom assessment, medication dispensing, and a treatment plan.

Then they visit the specialists, either onsite or through local referral*. These specialist modules include joints, eyes, headache, ears, neurology, cardiac, respiratory, gastrointestinal, renal and urologic, reproductive health for both genders, and psychiatry.

Last year, Dr. Scott published initial data on 44 patients. At ECCMID 2017, she expanded that report to include 203 survivors. They spanned all ages, but about 67% were in their most productive adult years, aged 20-39 years.

Her findings are striking: About 78% report musculoskeletal pain, with many saying they have trouble walking even short distances, climbing stairs, or picking up their children.

Headache was the next most common problem, reported by nearly 40%. About 15% report ocular problems, which include anterior uveitis, cataracts – even in very young children – and retinal lesions. Abdominal and chest pain affect about 10% of the survivors.

Although she didn’t present specific numbers, Dr. Scott also said that many of the survivors experience psychological sequelae, including insomnia, anxiety, and depression. Whether this is related to viral pathology isn’t clear; it could be a not-unexpected response to the trauma of living through the epidemic.

“Many of these people have lost their entire family, and those that are left now shun them,” she said in a live video interview on Facebook. “It’s almost like a post-traumatic stress reaction.”

The other symptoms probably are related to the disease pathology, she observed. “Unfortunately, we don’t have all the clinical details of the acute phase for everyone, but for those for whom we do have details, we are seeing correlation between some of the problems with viral loads at admission, and even episodes of becoming unconscious during the acute illness.”

Patrick Howlett, MD, of the King’s Sierra Leone Partnership, Freetown, leads the neurology study. So far, the researchers have collected data on 19 patients with severe neurological consequences. Of those, 12 (63%) experienced a period of unconsciousness during their acute Ebola episode. In a comparator group of 21 with nonsevere neurologic sequelae, 33% had experienced unconsciousness.

Headache was present in nine (47%) of the patients. Migraine was the most common diagnosis. “We don’t have money for migraine medications, but fortunately, most of our migraine patients seem to be doing well on beta blockers,” Dr. Scott said.

CT scans were performed on 17 patients: three showed cerebral or cerebellar atrophy and two had confirmed stroke.

The brain injuries were severe in two, including a 42-year-old with extensive gliosis in the left middle cerebral artery region and a dilated left ventricle secondary to loss of volume in that hemisphere. A 12-year-old girl showed extensive parietal and temporal lobe atrophy. She is now so disabled that her family can’t care for her at home.

Other neurological problems include peripheral neuropathy, brachial plexus neuropathy, and asymmetric lower limb muscular atrophy.

Paul Steptoe, MD, an ophthalmic registrar from St. Paul’s Eye Unit at the Royal Liverpool Hospital, heads the eye study. He has observed dense cataracts, even in children, and anterior uveitis that has blinded some patients. There is concern about live virus persisting in vitreal fluid, but two eye taps have been negative, Dr. Scott said.

The most exciting recent finding, however, was made possible by the donation of a digital retinal camera, which “enabled us to get dozens of amazing images,” Dr. Scott said. With it, Dr. Steptoe conducted a case-control study of 81 Ebola survivors and 106 community controls. The findings of this study are potentially very, very important, Dr. Scott said.

“The first thing we found out is that retinal scarring is pervasive in our control patients,” she said. “There is just a lot of it out here in the community. But more interesting is that Dr. Steptoe seems to have identified a characteristic retinal lesion seen only in our survivors. It could be evidence of neurotropic aspects of the Ebola virus.”

The lesions occurred in 12 (15%) of the survivors and none of the controls. They are of a striking and consistent shape: straight-edged and sharply angulated. The lesions are only on the surface of the retina and do not penetrate into deeper levels. Nor do they interfere with vision. Dr. Steptoe has proposed that they take their angular shape from the retina’s underlying structures. His paper documenting this finding has been accepted and will be published shortly in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases.

All of the post-Ebola sequelae add up to general disability for survivors, Dr. Scott said. Soushieta Jagadesh, of the* Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, is conducting a disability survey. The comparison between 27 survivors and 54 community controls employed the Washington Group extended disability questionnaire. “We noted major limitations 1 year after discharge in mobility, vision, cognition, and affect,” Dr. Scott said.

The hazard ratios for these issues are enormous: Overall, compared with controls, survivors were 23 times more likely to have some level of disability. They were 94 times more likely to have walking limitations and 65 times more likely to have problems with stairs. Survivors were over 200 times more likely to have moderate disability than were their unaffected neighbors.

If funding for the project is renewed – and Dr. Scott admitted this is an “if,” not a “when” – caring for and studying these survivors will continue. Just in this one city, she said, the need is huge.

According to data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 17,000 patients in Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea survived the 2014 Ebola outbreak.

If the assessments of Freetown survivors hold true across this population, thousands of survivors face life-limiting sequelae of the disease.

“We still have patients walk in every day with musculoskeletal pain, headaches, and ocular issues,” Dr. Scott said. “At the beginning of the epidemic, we were just focusing on containing it and reducing transmission. Now, we are faced with the long-term consequences.”

The Wellcome Trust supported the study. The authors have been awarded a grant from the Enhancing Research Activity in Epidemic Situations (ERAES) program, funded by the Wellcome Trust to support further research into the sequelae of Ebola virus disease.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

*This story was updated May 2, 2017.

VIENNA – The Ebola crisis may be over in Sierra Leone, but the suffering is not.

The last patient from the epidemic was discharged in February 2016, but 78% of survivors now appear to have one or more sequelae of the infection. Some problems are mild, but some are so debilitating that life may never be the same.

Janet Scott, MD, of the University of Liverpool (England), heads a task force studying Ebola’s lingering aftereffects. These fall into four categories, Dr. Scott said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress: musculoskeletal pain, headache, eye problems, and psychological disorders.

They add up to an enormous risk of disability – survivors are more than 200 times more likely than controls to express at least moderate disability.

Dr. Scott and her team of researchers are partnering with clinicians and data managers in the Ebola treatment unit in the 34th Regimental Military Hospital (MH34) in Freetown, Sierra Leone. In Sierra Leone alone, she said, there were nearly 9,000 cases and 3,500 deaths from the virus; about 5,000 patients survived. So far, Dr. Scott and her team have collected data on about 500 patients for whom they also provide free health care.

The project has six arms, each headed by an expert: clinical care, data collection, disability, neurology, ophthalmology, and psychiatry.

The team sees patients in a large tent sectioned by a plywood wall*. Wireless Internet access, which she said is “enormously expensive” in Sierra Leone, has been donated by Omline Business Communications*. It’s the team’s lifeline, allowing them to transmit data between Freetown and participating units around the world. Members also Skype regularly, talking with patients and with each other.

All patients who come into the clinic have an initial visit that includes collection of demographics, their Ebola and clinical history (including an exploration of comorbidities), a maternal health screening for women, vital signs and symptom assessment, medication dispensing, and a treatment plan.

Then they visit the specialists, either onsite or through local referral*. These specialist modules include joints, eyes, headache, ears, neurology, cardiac, respiratory, gastrointestinal, renal and urologic, reproductive health for both genders, and psychiatry.

Last year, Dr. Scott published initial data on 44 patients. At ECCMID 2017, she expanded that report to include 203 survivors. They spanned all ages, but about 67% were in their most productive adult years, aged 20-39 years.

Her findings are striking: About 78% report musculoskeletal pain, with many saying they have trouble walking even short distances, climbing stairs, or picking up their children.

Headache was the next most common problem, reported by nearly 40%. About 15% report ocular problems, which include anterior uveitis, cataracts – even in very young children – and retinal lesions. Abdominal and chest pain affect about 10% of the survivors.

Although she didn’t present specific numbers, Dr. Scott also said that many of the survivors experience psychological sequelae, including insomnia, anxiety, and depression. Whether this is related to viral pathology isn’t clear; it could be a not-unexpected response to the trauma of living through the epidemic.

“Many of these people have lost their entire family, and those that are left now shun them,” she said in a live video interview on Facebook. “It’s almost like a post-traumatic stress reaction.”

The other symptoms probably are related to the disease pathology, she observed. “Unfortunately, we don’t have all the clinical details of the acute phase for everyone, but for those for whom we do have details, we are seeing correlation between some of the problems with viral loads at admission, and even episodes of becoming unconscious during the acute illness.”

Patrick Howlett, MD, of the King’s Sierra Leone Partnership, Freetown, leads the neurology study. So far, the researchers have collected data on 19 patients with severe neurological consequences. Of those, 12 (63%) experienced a period of unconsciousness during their acute Ebola episode. In a comparator group of 21 with nonsevere neurologic sequelae, 33% had experienced unconsciousness.

Headache was present in nine (47%) of the patients. Migraine was the most common diagnosis. “We don’t have money for migraine medications, but fortunately, most of our migraine patients seem to be doing well on beta blockers,” Dr. Scott said.