User login

Is mild cognitive impairment reversible?

new research shows.

The investigators found individuals with these factors, which are all markers of cognitive reserve, had a significantly greater chance of reversion from MCI to normal cognition (NC) than progression from MCI to dementia.

In a cohort study of more than 600 women aged 75 years or older, about a third of those with MCI reverted to NC at some point during follow-up, which sends “an encouraging message,” study author Suzanne Tyas, PhD, associate professor, University of Waterloo (Ont.), said in an interview.

“That’s a positive thing for people to keep in mind when they’re thinking about prognosis. Some of these novel characteristics we’ve identified might be useful in thinking about how likely a particular patient might be to improve versus decline cognitively,” Dr. Tyas added.

The findings were published online Feb. 4, 2022, in the journal Neurology.

Highly educated cohort

As the population ages, the number of individuals experiencing age-related conditions, including dementia, increases. There is no cure for most dementia types so prevention is key – and preventing dementia requires understanding its risk factors, Dr. Tyas noted.

The analysis included participants from the Nun Study, a longitudinal study of aging and cognition among members of the School Sisters of Notre Dame in the United States. All were 75 and older at baseline, which was from 1991 to 1993; about 14.5% were older than 90 years.

Participants were generally highly educated, with 84.5% attaining an undergraduate or graduate degree. They also had a similar socioeconomic status, level of social supports, marital and reproductive history, and alcohol and tobacco use.

Researchers examined cognitive function at baseline and then about annually until death or end of the 12th round of assessments. They used five measures from the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease neuropsychological battery to categorize subjects into NC, MCI, or dementia: Delayed Word Recall, Verbal Fluency, Boston Naming, Constructional Praxis, and the Mini-Mental State Exam.

The current analysis focused on the 619 participants with data on apolipoprotein E (apo E) epsilon-4 genotyping and education. From convent archives, investigators also had access to the nuns’ early high school academic performance in English, Latin, algebra, and geometry.

“Typically we only have data for [overall] education. But I know from teaching that there’s a difference between people who just pass my courses and graduate with a university degree versus those who really excel,” Dr. Tyas said.

The researchers also assessed handwriting samples from before the participants entered the religious order. From these, they scored “idea density,” which is the number of ideas contained in the writing and “grammatical complexity,” which includes structure, use of clauses, subclauses, and so on.

Dementia not inevitable

Results showed 472 of the 619 participants had MCI during the study period. About 30.3% of these showed at least one reverse transition from MCI to NC during a mean follow-up of 8.6 years; 83.9% went on to develop dementia.

This shows converting from MCI to NC occurs relatively frequently, Dr. Tyas noted.

“This is encouraging because some people think that if they have a diagnosis of MCI they are inevitably going to decline to dementia,” she added.

The researchers also used complicated modeling of transition rates over time between NC, MCI, and dementia and adjusted for participants who died. They estimated relative risk of reversion versus progression for age, apo E, and potential cognitive reserve indicators.

Not surprisingly, younger age (90 years or less) and absence of apo E epsilon-4 allele contributed to a significantly higher rate for reversion from MCI to NC versus progression from MCI to dementia.

However, although age and apo E are known risk factors for dementia, these have not been examined in the context of whether individuals with MCI are more likely to improve or decline, said Dr. Tyas.

Higher educational attainment, the traditional indicator of cognitive reserve, was associated with a significantly higher relative risk for reversion from MCI to NC versus progression from MCI to dementia (RR, 2.6) for a bachelor’s degree versus less education.

There was a greater RR for even higher education after adjusting for age and apo E epsilon-4 status.

Language skills key

Interestingly, the investigators also found a significant association with good grades in high school English but not other subjects (RR for higher vs. lower English grades, 1.83; 95% confidence interval, 1.07-3.14).

In addition, they found both characteristics of written language skills (idea density and grammatical complexity) were significant predictors of conversion to NC.

“Those with high levels of idea density were four times more likely to improve to normal cognition than progress to dementia, and the effect was even stronger for grammatical structure. Those individuals with higher levels were almost six times more likely to improve than decline,” Dr. Tyas reported.

The RR for higher versus lower idea density was 3.93 (95% CI, 1.3-11.9) and the RR for higher versus lower grammatical complexity was 5.78 (95% CI, 1.56-21.42).

These new results could be useful when planning future clinical trials, Dr. Tyas noted. “MCI in some people is going to improve even without any treatment, and this should be taken into consideration when recruiting participants to a study and when interpreting the results.

“You don’t want something to look like it’s a benefit of the treatment when in fact these individuals would have just reverted on their own,” she added.

Research implications

Commenting on the findings, Claire Sexton, DPhil, director of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, noted that, in “this study of highly educated, older women,” transitions from MCI to NC “were about equally common” as transitions from MCI to dementia.

“As advances are made in early detection of dementia, and treatments are developed and marketed for people living with MCI, this article’s findings are important to inform discussions of prognosis with patients and [to the] design of clinical trials,” Dr. Sexton said.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. Funding for the Nun Study at the University of Kentucky was provided by the U.S. National Institute of Aging and the Kleberg Foundation. Dr. Tyas has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research shows.

The investigators found individuals with these factors, which are all markers of cognitive reserve, had a significantly greater chance of reversion from MCI to normal cognition (NC) than progression from MCI to dementia.

In a cohort study of more than 600 women aged 75 years or older, about a third of those with MCI reverted to NC at some point during follow-up, which sends “an encouraging message,” study author Suzanne Tyas, PhD, associate professor, University of Waterloo (Ont.), said in an interview.

“That’s a positive thing for people to keep in mind when they’re thinking about prognosis. Some of these novel characteristics we’ve identified might be useful in thinking about how likely a particular patient might be to improve versus decline cognitively,” Dr. Tyas added.

The findings were published online Feb. 4, 2022, in the journal Neurology.

Highly educated cohort

As the population ages, the number of individuals experiencing age-related conditions, including dementia, increases. There is no cure for most dementia types so prevention is key – and preventing dementia requires understanding its risk factors, Dr. Tyas noted.

The analysis included participants from the Nun Study, a longitudinal study of aging and cognition among members of the School Sisters of Notre Dame in the United States. All were 75 and older at baseline, which was from 1991 to 1993; about 14.5% were older than 90 years.

Participants were generally highly educated, with 84.5% attaining an undergraduate or graduate degree. They also had a similar socioeconomic status, level of social supports, marital and reproductive history, and alcohol and tobacco use.

Researchers examined cognitive function at baseline and then about annually until death or end of the 12th round of assessments. They used five measures from the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease neuropsychological battery to categorize subjects into NC, MCI, or dementia: Delayed Word Recall, Verbal Fluency, Boston Naming, Constructional Praxis, and the Mini-Mental State Exam.

The current analysis focused on the 619 participants with data on apolipoprotein E (apo E) epsilon-4 genotyping and education. From convent archives, investigators also had access to the nuns’ early high school academic performance in English, Latin, algebra, and geometry.

“Typically we only have data for [overall] education. But I know from teaching that there’s a difference between people who just pass my courses and graduate with a university degree versus those who really excel,” Dr. Tyas said.

The researchers also assessed handwriting samples from before the participants entered the religious order. From these, they scored “idea density,” which is the number of ideas contained in the writing and “grammatical complexity,” which includes structure, use of clauses, subclauses, and so on.

Dementia not inevitable

Results showed 472 of the 619 participants had MCI during the study period. About 30.3% of these showed at least one reverse transition from MCI to NC during a mean follow-up of 8.6 years; 83.9% went on to develop dementia.

This shows converting from MCI to NC occurs relatively frequently, Dr. Tyas noted.

“This is encouraging because some people think that if they have a diagnosis of MCI they are inevitably going to decline to dementia,” she added.

The researchers also used complicated modeling of transition rates over time between NC, MCI, and dementia and adjusted for participants who died. They estimated relative risk of reversion versus progression for age, apo E, and potential cognitive reserve indicators.

Not surprisingly, younger age (90 years or less) and absence of apo E epsilon-4 allele contributed to a significantly higher rate for reversion from MCI to NC versus progression from MCI to dementia.

However, although age and apo E are known risk factors for dementia, these have not been examined in the context of whether individuals with MCI are more likely to improve or decline, said Dr. Tyas.

Higher educational attainment, the traditional indicator of cognitive reserve, was associated with a significantly higher relative risk for reversion from MCI to NC versus progression from MCI to dementia (RR, 2.6) for a bachelor’s degree versus less education.

There was a greater RR for even higher education after adjusting for age and apo E epsilon-4 status.

Language skills key

Interestingly, the investigators also found a significant association with good grades in high school English but not other subjects (RR for higher vs. lower English grades, 1.83; 95% confidence interval, 1.07-3.14).

In addition, they found both characteristics of written language skills (idea density and grammatical complexity) were significant predictors of conversion to NC.

“Those with high levels of idea density were four times more likely to improve to normal cognition than progress to dementia, and the effect was even stronger for grammatical structure. Those individuals with higher levels were almost six times more likely to improve than decline,” Dr. Tyas reported.

The RR for higher versus lower idea density was 3.93 (95% CI, 1.3-11.9) and the RR for higher versus lower grammatical complexity was 5.78 (95% CI, 1.56-21.42).

These new results could be useful when planning future clinical trials, Dr. Tyas noted. “MCI in some people is going to improve even without any treatment, and this should be taken into consideration when recruiting participants to a study and when interpreting the results.

“You don’t want something to look like it’s a benefit of the treatment when in fact these individuals would have just reverted on their own,” she added.

Research implications

Commenting on the findings, Claire Sexton, DPhil, director of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, noted that, in “this study of highly educated, older women,” transitions from MCI to NC “were about equally common” as transitions from MCI to dementia.

“As advances are made in early detection of dementia, and treatments are developed and marketed for people living with MCI, this article’s findings are important to inform discussions of prognosis with patients and [to the] design of clinical trials,” Dr. Sexton said.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. Funding for the Nun Study at the University of Kentucky was provided by the U.S. National Institute of Aging and the Kleberg Foundation. Dr. Tyas has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research shows.

The investigators found individuals with these factors, which are all markers of cognitive reserve, had a significantly greater chance of reversion from MCI to normal cognition (NC) than progression from MCI to dementia.

In a cohort study of more than 600 women aged 75 years or older, about a third of those with MCI reverted to NC at some point during follow-up, which sends “an encouraging message,” study author Suzanne Tyas, PhD, associate professor, University of Waterloo (Ont.), said in an interview.

“That’s a positive thing for people to keep in mind when they’re thinking about prognosis. Some of these novel characteristics we’ve identified might be useful in thinking about how likely a particular patient might be to improve versus decline cognitively,” Dr. Tyas added.

The findings were published online Feb. 4, 2022, in the journal Neurology.

Highly educated cohort

As the population ages, the number of individuals experiencing age-related conditions, including dementia, increases. There is no cure for most dementia types so prevention is key – and preventing dementia requires understanding its risk factors, Dr. Tyas noted.

The analysis included participants from the Nun Study, a longitudinal study of aging and cognition among members of the School Sisters of Notre Dame in the United States. All were 75 and older at baseline, which was from 1991 to 1993; about 14.5% were older than 90 years.

Participants were generally highly educated, with 84.5% attaining an undergraduate or graduate degree. They also had a similar socioeconomic status, level of social supports, marital and reproductive history, and alcohol and tobacco use.

Researchers examined cognitive function at baseline and then about annually until death or end of the 12th round of assessments. They used five measures from the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease neuropsychological battery to categorize subjects into NC, MCI, or dementia: Delayed Word Recall, Verbal Fluency, Boston Naming, Constructional Praxis, and the Mini-Mental State Exam.

The current analysis focused on the 619 participants with data on apolipoprotein E (apo E) epsilon-4 genotyping and education. From convent archives, investigators also had access to the nuns’ early high school academic performance in English, Latin, algebra, and geometry.

“Typically we only have data for [overall] education. But I know from teaching that there’s a difference between people who just pass my courses and graduate with a university degree versus those who really excel,” Dr. Tyas said.

The researchers also assessed handwriting samples from before the participants entered the religious order. From these, they scored “idea density,” which is the number of ideas contained in the writing and “grammatical complexity,” which includes structure, use of clauses, subclauses, and so on.

Dementia not inevitable

Results showed 472 of the 619 participants had MCI during the study period. About 30.3% of these showed at least one reverse transition from MCI to NC during a mean follow-up of 8.6 years; 83.9% went on to develop dementia.

This shows converting from MCI to NC occurs relatively frequently, Dr. Tyas noted.

“This is encouraging because some people think that if they have a diagnosis of MCI they are inevitably going to decline to dementia,” she added.

The researchers also used complicated modeling of transition rates over time between NC, MCI, and dementia and adjusted for participants who died. They estimated relative risk of reversion versus progression for age, apo E, and potential cognitive reserve indicators.

Not surprisingly, younger age (90 years or less) and absence of apo E epsilon-4 allele contributed to a significantly higher rate for reversion from MCI to NC versus progression from MCI to dementia.

However, although age and apo E are known risk factors for dementia, these have not been examined in the context of whether individuals with MCI are more likely to improve or decline, said Dr. Tyas.

Higher educational attainment, the traditional indicator of cognitive reserve, was associated with a significantly higher relative risk for reversion from MCI to NC versus progression from MCI to dementia (RR, 2.6) for a bachelor’s degree versus less education.

There was a greater RR for even higher education after adjusting for age and apo E epsilon-4 status.

Language skills key

Interestingly, the investigators also found a significant association with good grades in high school English but not other subjects (RR for higher vs. lower English grades, 1.83; 95% confidence interval, 1.07-3.14).

In addition, they found both characteristics of written language skills (idea density and grammatical complexity) were significant predictors of conversion to NC.

“Those with high levels of idea density were four times more likely to improve to normal cognition than progress to dementia, and the effect was even stronger for grammatical structure. Those individuals with higher levels were almost six times more likely to improve than decline,” Dr. Tyas reported.

The RR for higher versus lower idea density was 3.93 (95% CI, 1.3-11.9) and the RR for higher versus lower grammatical complexity was 5.78 (95% CI, 1.56-21.42).

These new results could be useful when planning future clinical trials, Dr. Tyas noted. “MCI in some people is going to improve even without any treatment, and this should be taken into consideration when recruiting participants to a study and when interpreting the results.

“You don’t want something to look like it’s a benefit of the treatment when in fact these individuals would have just reverted on their own,” she added.

Research implications

Commenting on the findings, Claire Sexton, DPhil, director of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, noted that, in “this study of highly educated, older women,” transitions from MCI to NC “were about equally common” as transitions from MCI to dementia.

“As advances are made in early detection of dementia, and treatments are developed and marketed for people living with MCI, this article’s findings are important to inform discussions of prognosis with patients and [to the] design of clinical trials,” Dr. Sexton said.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. Funding for the Nun Study at the University of Kentucky was provided by the U.S. National Institute of Aging and the Kleberg Foundation. Dr. Tyas has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Seniors face higher risk of other medical conditions after COVID-19

The findings of the observational study, which were published in the BMJ, show the risk of a new condition being triggered by COVID is more than twice as high in seniors, compared with younger patients. Plus, the researchers observed an even higher risk among those who were hospitalized, with nearly half (46%) of patients having developed new conditions after the acute COVID-19 infection period.

Respiratory failure with shortness of breath was the most common postacute sequela, but a wide range of heart, kidney, lung, liver, cognitive, mental health, and other conditions were diagnosed at least 3 weeks after initial infection and persisted beyond 30 days.

This is one of the first studies to specifically describe the incidence and severity of new conditions triggered by COVID-19 infection in a general sample of older adults, said study author Ken Cohen MD, FACP, executive director of translational research at Optum Labs and national senior medical director at Optum Care.

“Much of what has been published on the postacute sequelae of COVID-19 has been predominantly from a younger population, and many of the patients had been hospitalized,” Dr. Cohen noted. “This was the first study to focus on a large population of seniors, most of whom did not require hospitalization.”

Dr. Cohen and colleagues reviewed the health insurance records of more than 133,000 Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 or older who were diagnosed with COVID-19 before April 2020. They also matched individuals by age, race, sex, hospitalization status, and other factors to comparison groups without COVID-19 (one from 2020 and one from 2019), and to a group diagnosed with other lower respiratory tract viral infections before the pandemic.

Risk of developing new conditions was higher in hospitalized

After acute COVID-19 infection, 32% of seniors sought medical care for at least one new medical condition in 2020, compared with 21% of uninfected people in the same year.

The most commonly observed conditions included:

- Respiratory failure (7.55% higher risk).

- Fatigue (5.66% higher risk).

- High blood pressure (4.43% higher risk).

- Memory problems (2.63% higher risk).

- Kidney injury (2.59% higher risk).

- Mental health diagnoses (2.5% higher risk).

- Blood-clotting disorders (1.47 % higher risk).

- Heart rhythm disorders (2.9% higher risk).

The risk of developing new conditions was even higher among those 23,486 who were hospitalized in 2020. Those individuals showed a 23.6% higher risk for developing at least one new condition, compared with uninfected seniors in the same year. Also, patients older than 75 had a higher risk for neurological disorders, including dementia, encephalopathy, and memory problems. The researchers also found that respiratory failure and kidney injury were significantly more likely to affect men and Black patients.

When those who had COVID were compared with the group with other lower respiratory viral infections before the pandemic, only the risks of respiratory failure (2.39% higher), dementia (0.71% higher), and fatigue (0.18% higher) were higher.

Primary care providers can learn from these data to better evaluate and manage their geriatric patients with COVID-19 infection, said Amit Shah, MD, a geriatrician with the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, in an interview.

“We must assess older patients who have had COVID-19 for more than just improvement from the respiratory symptoms of COVID-19 in post-COVID follow-up visits,” he said. “Older individuals with frailty have vulnerability to subsequent complications from severe illnesses and it is common to see post-illness diagnoses, such as new diagnosis of delirium; dementia; or renal, respiratory, or cardiac issues that is precipitated by the original illness. This study confirms that this is likely the case with COVID-19 as well.

“Primary care physicians should be vigilant for these complications, including attention to the rehabilitation needs of older patients with longer-term postviral fatigue from COVID-19,” Dr. Shah added.

Data predates ‘Omicron wave’

It remains uncertain whether sequelae will differ with the Omicron variant, but the findings remain applicable, Dr. Cohen said.

“We know that illness from the Omicron variant is on average less severe in those that have been vaccinated. However, throughout the Omicron wave, individuals who have not been vaccinated continue to have significant rates of serious illness and hospitalization,” he said.

“Our findings showed that serious illness with hospitalization was associated with a higher rate of sequelae. It can therefore be inferred that the rates of sequelae seen in our study would continue to occur in unvaccinated individuals who contract Omicron, but might occur less frequently in vaccinated individuals who contract Omicron and have less severe illness.”

Dr. Cohen serves as a consultant for Pfizer. Dr. Shah has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

The findings of the observational study, which were published in the BMJ, show the risk of a new condition being triggered by COVID is more than twice as high in seniors, compared with younger patients. Plus, the researchers observed an even higher risk among those who were hospitalized, with nearly half (46%) of patients having developed new conditions after the acute COVID-19 infection period.

Respiratory failure with shortness of breath was the most common postacute sequela, but a wide range of heart, kidney, lung, liver, cognitive, mental health, and other conditions were diagnosed at least 3 weeks after initial infection and persisted beyond 30 days.

This is one of the first studies to specifically describe the incidence and severity of new conditions triggered by COVID-19 infection in a general sample of older adults, said study author Ken Cohen MD, FACP, executive director of translational research at Optum Labs and national senior medical director at Optum Care.

“Much of what has been published on the postacute sequelae of COVID-19 has been predominantly from a younger population, and many of the patients had been hospitalized,” Dr. Cohen noted. “This was the first study to focus on a large population of seniors, most of whom did not require hospitalization.”

Dr. Cohen and colleagues reviewed the health insurance records of more than 133,000 Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 or older who were diagnosed with COVID-19 before April 2020. They also matched individuals by age, race, sex, hospitalization status, and other factors to comparison groups without COVID-19 (one from 2020 and one from 2019), and to a group diagnosed with other lower respiratory tract viral infections before the pandemic.

Risk of developing new conditions was higher in hospitalized

After acute COVID-19 infection, 32% of seniors sought medical care for at least one new medical condition in 2020, compared with 21% of uninfected people in the same year.

The most commonly observed conditions included:

- Respiratory failure (7.55% higher risk).

- Fatigue (5.66% higher risk).

- High blood pressure (4.43% higher risk).

- Memory problems (2.63% higher risk).

- Kidney injury (2.59% higher risk).

- Mental health diagnoses (2.5% higher risk).

- Blood-clotting disorders (1.47 % higher risk).

- Heart rhythm disorders (2.9% higher risk).

The risk of developing new conditions was even higher among those 23,486 who were hospitalized in 2020. Those individuals showed a 23.6% higher risk for developing at least one new condition, compared with uninfected seniors in the same year. Also, patients older than 75 had a higher risk for neurological disorders, including dementia, encephalopathy, and memory problems. The researchers also found that respiratory failure and kidney injury were significantly more likely to affect men and Black patients.

When those who had COVID were compared with the group with other lower respiratory viral infections before the pandemic, only the risks of respiratory failure (2.39% higher), dementia (0.71% higher), and fatigue (0.18% higher) were higher.

Primary care providers can learn from these data to better evaluate and manage their geriatric patients with COVID-19 infection, said Amit Shah, MD, a geriatrician with the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, in an interview.

“We must assess older patients who have had COVID-19 for more than just improvement from the respiratory symptoms of COVID-19 in post-COVID follow-up visits,” he said. “Older individuals with frailty have vulnerability to subsequent complications from severe illnesses and it is common to see post-illness diagnoses, such as new diagnosis of delirium; dementia; or renal, respiratory, or cardiac issues that is precipitated by the original illness. This study confirms that this is likely the case with COVID-19 as well.

“Primary care physicians should be vigilant for these complications, including attention to the rehabilitation needs of older patients with longer-term postviral fatigue from COVID-19,” Dr. Shah added.

Data predates ‘Omicron wave’

It remains uncertain whether sequelae will differ with the Omicron variant, but the findings remain applicable, Dr. Cohen said.

“We know that illness from the Omicron variant is on average less severe in those that have been vaccinated. However, throughout the Omicron wave, individuals who have not been vaccinated continue to have significant rates of serious illness and hospitalization,” he said.

“Our findings showed that serious illness with hospitalization was associated with a higher rate of sequelae. It can therefore be inferred that the rates of sequelae seen in our study would continue to occur in unvaccinated individuals who contract Omicron, but might occur less frequently in vaccinated individuals who contract Omicron and have less severe illness.”

Dr. Cohen serves as a consultant for Pfizer. Dr. Shah has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

The findings of the observational study, which were published in the BMJ, show the risk of a new condition being triggered by COVID is more than twice as high in seniors, compared with younger patients. Plus, the researchers observed an even higher risk among those who were hospitalized, with nearly half (46%) of patients having developed new conditions after the acute COVID-19 infection period.

Respiratory failure with shortness of breath was the most common postacute sequela, but a wide range of heart, kidney, lung, liver, cognitive, mental health, and other conditions were diagnosed at least 3 weeks after initial infection and persisted beyond 30 days.

This is one of the first studies to specifically describe the incidence and severity of new conditions triggered by COVID-19 infection in a general sample of older adults, said study author Ken Cohen MD, FACP, executive director of translational research at Optum Labs and national senior medical director at Optum Care.

“Much of what has been published on the postacute sequelae of COVID-19 has been predominantly from a younger population, and many of the patients had been hospitalized,” Dr. Cohen noted. “This was the first study to focus on a large population of seniors, most of whom did not require hospitalization.”

Dr. Cohen and colleagues reviewed the health insurance records of more than 133,000 Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 or older who were diagnosed with COVID-19 before April 2020. They also matched individuals by age, race, sex, hospitalization status, and other factors to comparison groups without COVID-19 (one from 2020 and one from 2019), and to a group diagnosed with other lower respiratory tract viral infections before the pandemic.

Risk of developing new conditions was higher in hospitalized

After acute COVID-19 infection, 32% of seniors sought medical care for at least one new medical condition in 2020, compared with 21% of uninfected people in the same year.

The most commonly observed conditions included:

- Respiratory failure (7.55% higher risk).

- Fatigue (5.66% higher risk).

- High blood pressure (4.43% higher risk).

- Memory problems (2.63% higher risk).

- Kidney injury (2.59% higher risk).

- Mental health diagnoses (2.5% higher risk).

- Blood-clotting disorders (1.47 % higher risk).

- Heart rhythm disorders (2.9% higher risk).

The risk of developing new conditions was even higher among those 23,486 who were hospitalized in 2020. Those individuals showed a 23.6% higher risk for developing at least one new condition, compared with uninfected seniors in the same year. Also, patients older than 75 had a higher risk for neurological disorders, including dementia, encephalopathy, and memory problems. The researchers also found that respiratory failure and kidney injury were significantly more likely to affect men and Black patients.

When those who had COVID were compared with the group with other lower respiratory viral infections before the pandemic, only the risks of respiratory failure (2.39% higher), dementia (0.71% higher), and fatigue (0.18% higher) were higher.

Primary care providers can learn from these data to better evaluate and manage their geriatric patients with COVID-19 infection, said Amit Shah, MD, a geriatrician with the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, in an interview.

“We must assess older patients who have had COVID-19 for more than just improvement from the respiratory symptoms of COVID-19 in post-COVID follow-up visits,” he said. “Older individuals with frailty have vulnerability to subsequent complications from severe illnesses and it is common to see post-illness diagnoses, such as new diagnosis of delirium; dementia; or renal, respiratory, or cardiac issues that is precipitated by the original illness. This study confirms that this is likely the case with COVID-19 as well.

“Primary care physicians should be vigilant for these complications, including attention to the rehabilitation needs of older patients with longer-term postviral fatigue from COVID-19,” Dr. Shah added.

Data predates ‘Omicron wave’

It remains uncertain whether sequelae will differ with the Omicron variant, but the findings remain applicable, Dr. Cohen said.

“We know that illness from the Omicron variant is on average less severe in those that have been vaccinated. However, throughout the Omicron wave, individuals who have not been vaccinated continue to have significant rates of serious illness and hospitalization,” he said.

“Our findings showed that serious illness with hospitalization was associated with a higher rate of sequelae. It can therefore be inferred that the rates of sequelae seen in our study would continue to occur in unvaccinated individuals who contract Omicron, but might occur less frequently in vaccinated individuals who contract Omicron and have less severe illness.”

Dr. Cohen serves as a consultant for Pfizer. Dr. Shah has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

FROM BMJ

Structural Ableism: Defining Standards of Care Amid Crisis and Inequity

Equitable Standards for All Patients in a Crisis

Health care delivered during a pandemic instantiates medicine’s perspectives on the value of human life in clinical scenarios where resource allocation is limited. The COVID-19 pandemic has fostered dialogue and debate around the ethical principles that underly such resource allocation, which generally balance (1) utilitarian optimization of resources, (2) equality or equity in health access, (3) the instrumental value of individuals as agents in society, and (4) prioritizing the “worst off” in their natural history of disease.1,2 State legislatures and health systems have responded to the challeges posed by COVID-19 by considering both the scarcity of intensive care resources, such as mechanical ventilation and hemodialysis, and the clinical criteria to be used for determining which patients should receive said resources. These crisis guidelines have yielded several concerning themes vis-à-vis equitable distribution of health care resources, particularly when the disability status of patients is considered alongside life-expectancy or quality of life.3

Crisis standards of care (CSC) prioritize population-level health under a utilitarian paradigm, explicitly maximizing “life-years” within a population of patients rather than the life of any individual patient.4 Debated during initial COVID surges, these CSC guidelines have recently been enacted at the state level in several settings, including Alaska and Idaho.5 In a setting with scarce intensive care resources, balancing health equity in access to these resources against population-based survival metrics has been a challenge for commissions considering CSC.6,7 This need for balance has further promoted systemic views of “disability,” raising concern for structural “ableism” and highlighting the need for greater “ability awareness” in clinicians’ continued professional learning.

Structural Ableism: Defining Perspectives to Address Health Equity

Ableism has been defined as “a system that places value on people’s bodies and minds, based on societally constructed ideas of normalcy, intelligence, excellence, and productivity…[and] leads to people and society determining who is valuable and worthy based on their appearance and/or their ability to satisfactorily [re]produce, excel, and ‘behave.’”8 Regarding CSC, concerns about systemic bias in guideline design were raised early by disability advocacy groups during comment periods.9,10 More broadly, concerns about ableism sit alongside many deeply rooted societal perspectives of disabled individuals as pitiable or, conversely, heroic for having “overcome” their disability in some way. As a physician who sits in a manual wheelchair with paraplegia and mobility impairment, I have equally been subject to inappropriate bias and inappropriate praise for living in a wheelchair. I have also wondered, alongside my patients living with different levels of mobility or ability, why others often view us as “worse off.” Addressing directly whether disabled individuals are “worse off,” disability rights attorney and advocate Harriet McBryde Johnson has articulated a predominant sentiment among persons living with unique or different abilities:

Are we “worse off”? I don’t think so. Not in any meaningful way. There are too many variables. For those of us with congenital conditions, disability shapes all we are. Those disabled later in life adapt. We take constraints that no one would choose and build rich and satisfying lives within them. We enjoy pleasures other people enjoy and pleasures peculiarly our own. We have something the world needs.11

Many physician colleagues have common, invisible diseases such as diabetes and heart disease; fewer colleagues share conditions that are as visible as my spinal cord injury, as readily apparent to patients upon my entry to their hospital rooms. This simultaneous and inescapable identity as both patient and provider has afforded me wonderful doctor-patient interactions, particularly with those patients who appreciate how my patient experience impacts my ability to partially understand theirs. However, this simultaneous identity as doctor and patient also informed my personal and professional concerns regarding structural ableism as I considered scoring my own acutely ill hospital medicine patients with CSC triage scores in April 2020.

As a practicing hospital medicine physician, I have been emboldened by the efforts of my fellow clinicians amid COVID-19; their efforts have reaffirmed all the reasons I pursued a career in medicine. However, when I heard my clinical colleagues’ first explanation of the Massachusetts CSC guidelines in April 2020, I raised my hand to ask whether the “life-years” to which the guidelines referred were quality-adjusted. My concern regarding the implicit use of quality-adjusted life years (QALY) or disability-adjusted life years in clinical decision-making and implementation of these guidelines was validated when no clinical leaders could address this question directly. Sitting on the CSC committee for my hospital during this time was an honor. However, it was disconcerting to hear many clinicians’ unease when estimating mean survival for common chronic diseases, ranging from end-stage renal disease to advanced heart failure. If my expert colleagues, clinical specialists in kidney and heart disease, could not confidently apply mean survival estimates to multimorbid hospital patients, then idiosyncratic clinical judgment was sure to have a heavy hand in any calculation of “life-years.” Thus, my primary concern was that clinicians using triage heuristics would be subject to bias, regardless of their intention, and negatively adjust for the quality of a disabled life in their CSC triage scoring. My secondary concern was that the CSC guidelines themselves included systemic bias against disabled individuals.

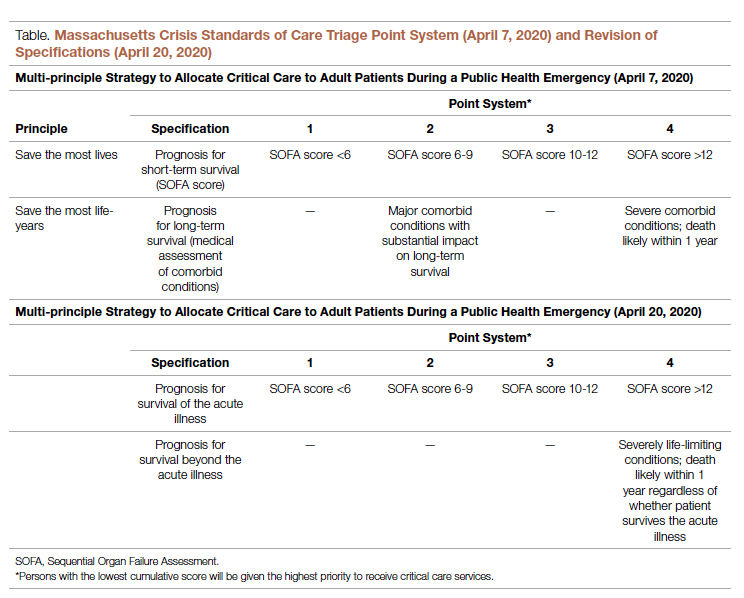

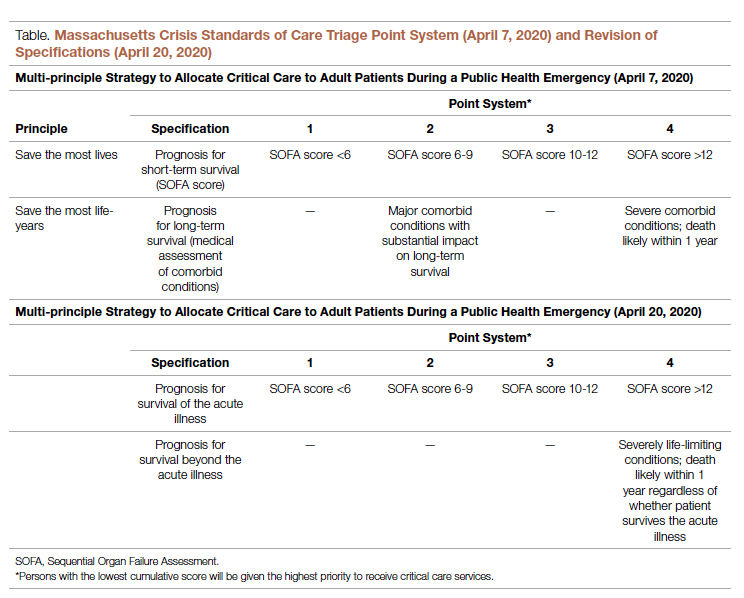

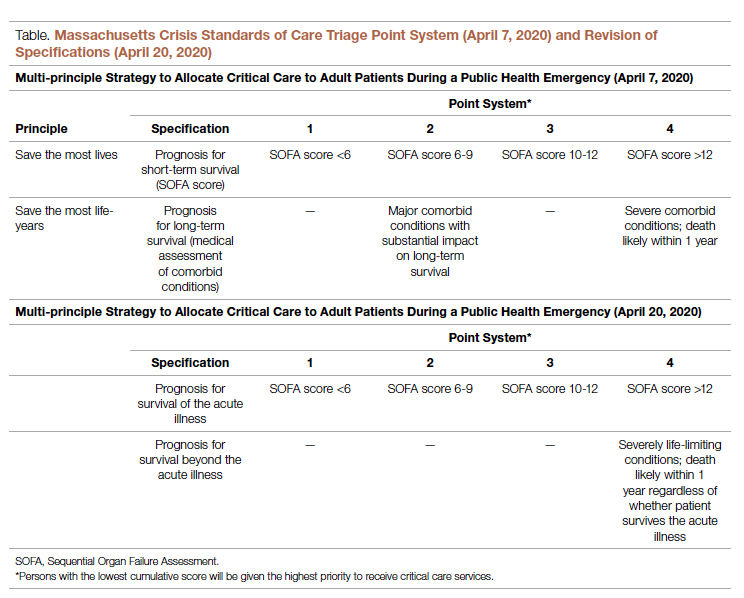

According to CSC schema, triage scores index heavily on Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores to define short-term survival; SOFA scores are partially driven by the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS). Following professional and public comment periods, CSC guidelines in Massachusetts were revised to, among other critical points of revision, change prognostic estimation via “life years” in favor of generic estimation of short-term survival (Table). I wondered, if I presented to an emergency department with severe COVID-19 and was scored with the GCS for the purpose of making a CSC ventilator triage decision, how would my complete paraplegia and lower-extremity motor impairment be accounted for by a clinician assessing “best motor response” in the GCS? The purpose of these scores is to act algorithmically, to guide clinicians whose cognitive load and time limitations may not allow for adjustment of these algorithms based on the individual patient in front of them. Individualization of clinical decisions is part of medicine’s art, but is difficult in the best of times and no easier during a crisis in care delivery. As CSC triage scores were amended and addended throughout 2020, I returned to the COVID wards, time and again wondering, “What have we learned about systemic bias and health inequity in the CSC process and the pandemic broadly, with specific regard to disability?”

Ability Awareness: Room for Our Improvement

Unfortunately, there is reason to believe that clinical judgment is impaired by structural ableism. In seminal work on this topic, Gerhart et al12 demonstrated that clinicians considered spinal cord injury (SCI) survivors to have low self-perceptions of worthiness, overall negative attitudes, and low self-esteem as compared to able-bodied individuals. However, surveyed SCI survivors generally had similar self-perceptions of worth and positivity as compared to ”able-bodied” clinicians.12 For providers who care for persons with disabilities, the majority (82.4%) have rated their disabled patients’ quality of life as worse.13 It is no wonder that patients with disabilities are more likely to feel that their doctor-patient relationship is impacted by lack of understanding, negative sentiment, or simple lack of listening.14 Generally, this poor doctor-patient relationship with disabled patients is exacerbated by poor exposure of medical trainees to disability education; only 34.2% of internal medicine residents recall any form of disability education in medical school, while only 52% of medical school deans report having disability educational content in their curricula.15,16 There is a similar lack of disability representation in the population of medical trainees themselves. While approximately 20% of the American population lives with a disability, less than 2% of American medical students have a disability.17-19

While representation of disabled populations in medical practice remains poor, disabled patients are generally less likely to receive age-appropriate prevention, appropriate access to care, and equal access to treatment.20-22 “Diagnostic overshadowing” refers to clinicians’ attribution of nonspecific signs or symptoms to a patient’s chronic disability as opposed to acute illness.23 This phenomenon has led to higher rates of preventable malignancy in disabled patients and misattribution of common somatic symptoms to intellectual disability.24,25 With this disparity in place as status quo for health care delivery to disabled populations, it is no surprise that certain portions of the disabled population have accounted for disproportionate mortality due to COVID-19.26,27Disability advocates have called for “nothing about us without us,” a phrase associated with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Understanding the profound neurodiversity among several forms of sensory and cognitive disabilities, as well as the functional difference between cognitive disabilities, mobility impairment, and inability to meet one’s instrumental activities of daily living independently, others have proposed a unique approach to certain disabled populations in COVID care.28 My own perspective is that definite progress may require a more general understanding of the prevalence of disability by clinicians, both via medical training and by directly addressing health equity for disabled populations in such calculations as the CSC. Systemic ableism is apparent in our most common clinical scoring systems, ranging from the GCS and Functional Assessment Staging Table to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group and Karnofsky Performance Status scales. I have reexamined these scoring systems in my own understanding given their general equation of ambulation with ability or normalcy. As a doctor in a manual wheelchair who values greatly my personal quality of life and professional contribution to patient care, I worry that these scoring systems inherently discount my own equitable access to care. Individualization of patients’ particular abilities in the context of these scales must occur alongside evidence-based, guideline-directed management via these scoring systems.

Conclusion: Future Orientation

Updated CSC guidelines have accounted for the unique considerations of disabled patients by effectively caveating their scoring algorithms, directing clinicians via disclaimers to uniquely consider their disabled patients in clinical judgement. This is a first step, but it is also one that erodes the value of algorithms, which generally obviate more deliberative thinking and individualization. For our patients who lack certain abilities, as CSC continue to be activated in several states, we have an opportunity to pursue more inherently equitable solutions before further suffering accrues.29 By way of example, adaptations to scoring systems that leverage QALYs for value-based drug pricing indices have been proposed by organizations like the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, which proposed the Equal-Value-of Life-Years-Gained framework to inform QALY-based arbitration of drug pricing.30 This is not a perfect rubric but instead represents an attempt to balance consideration of drugs, as has been done with ventilators during the pandemic, as a scare and expensive resource while addressing the just concerns of advocacy groups in structural ableism.

Resource stewardship during a crisis should not discount those states of human life that are perceived to be less desirable, particularly if they are not experienced as less desirable but are experienced uniquely. Instead, we should consider equitably measuring our intervention to match a patient’s needs, as we would dose-adjust a medication for renal function or consider minimally invasive procedures for multimorbid patients. COVID-19 has reflected our profession’s ethical adaptation during crisis as resources have become scarce; there is no better time to define solutions for health equity. We should now be concerned equally by the influence our personal biases have on our clinical practice and by the way in which these crisis standards will influence patients’ perception of and trust in their care providers during periods of perceived plentiful resources in the future. Health care resources are always limited, allocated according to societal values; if we value health equity for people of all abilities, then we will consider these abilities equitably as we pursue new standards for health care delivery.

Corresponding author: Gregory D. Snyder, MD, MBA, 2014 Washington Street, Newton, MA 02462; [email protected].

Disclosures: None.

1. Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, et al. Fair Allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):2049-2055. doi:10.1056/NEJMsb2005114

2. Savulescu J, Persson I, Wilkinson D. Utilitarianism and the pandemic. Bioethics. 2020;34(6):620-632. doi:10.1111/bioe.12771

3. Mello MM, Persad G, White DB. Respecting disability rights - toward improved crisis standards of care. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(5):e26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2011997

4. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts Executive Office of Health and Human Services Department of Public Health. Crisis Standards of Care Planning Guidance for the COVID-19 Pandemic. April 7, 2020. https://d279m997dpfwgl.cloudfront.net/wp/2020/04/CSC_April-7_2020.pdf

5. Knowles H. Hospitals overwhelmed by covid are turning to ‘crisis standards of care.’ What does that mean? The Washington Post. September 21, 2021. Accessed January 24, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2021/09/22/crisis-standards-of-care/

6. Hick JL, Hanfling D, Wynia MK, Toner E. Crisis standards of care and COVID-19: What did we learn? How do we ensure equity? What should we do? NAM Perspect. 2021;2021:10.31478/202108e. doi:10.31478/202108e

7. Cleveland Manchanda EC, Sanky C, Appel JM. Crisis standards of care in the USA: a systematic review and implications for equity amidst COVID-19. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;8(4):824-836. doi:10.1007/s40615-020-00840-5

8. Cleveland Manchanda EC, Sanky C, Appel JM. Crisis standards of care in the USA: a systematic review and implications for equity amidst COVID-19. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;8(4):824-836. doi:10.1007/s40615-020-00840-5

9. Kukla E. My life is more ‘disposable’ during this pandemic. The New York Times. March 19, 2020. Accessed January 24, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/19/opinion/coronavirus-disabled-health-care.html

10. CPR and Coalition Partners Secure Important Changes in Massachusetts’ Crisis Standards of Care. Center for Public Representation. December 1, 2020. Accessed January 24, 2022. https://www.centerforpublicrep.org/news/cpr-and-coalition-partners-secure-important-changes-in-massachusetts-crisis-standards-of-care/

11. Johnson HM. Unspeakable conversations. The New York Times. February 16, 2003. Accessed January 24, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2003/02/16/magazine/unspeakable-conversations.html

12. Gerhart KA, Koziol-McLain J, Lowenstein SR, Whiteneck GG. Quality of life following spinal cord injury: knowledge and attitudes of emergency care providers. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23(4):807-812. doi:10.1016/s0196-0644(94)70318-3

13. Iezzoni LI, Rao SR, Ressalam J, et al. Physicians’ perceptions of people with disability and their health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(2):297-306. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01452

14. Smith DL. Disparities in patient-physician communication for persons with a disability from the 2006 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). Disabil Health J. 2009;2(4):206-215. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2009.06.002

15. Stillman MD, Ankam N, Mallow M, Capron M, Williams S. A survey of internal and family medicine residents: Assessment of disability-specific education and knowledge. Disabil Health J. 2021;14(2):101011. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.101011

16. Seidel E, Crowe S. The state of disability awareness in American medical schools. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;96(9):673-676. doi:10.1097/PHM.0000000000000719

17. Okoro CA, Hollis ND, Cyrus AC, Griffin-Blake S. Prevalence of disabilities and health care access by disability status and type among adults - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(32):882-887. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6732a3

18. Peacock G, Iezzoni LI, Harkin TR. Health care for Americans with disabilities--25 years after the ADA. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(10):892-893. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1508854

19. DeLisa JA, Thomas P. Physicians with disabilities and the physician workforce: a need to reassess our policies. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84(1):5-11. doi:10.1097/01.phm.0000153323.28396.de

20. Disability and Health. Healthy People 2020. Accessed January 24, 2022. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/disability-and-health

21. Lagu T, Hannon NS, Rothberg MB, et al. Access to subspecialty care for patients with mobility impairment: a survey. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(6):441-446. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-6-201303190-00003

22. McCarthy EP, Ngo LH, Roetzheim RG, et al. Disparities in breast cancer treatment and survival for women with disabilities. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(9):637-645. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-9-200611070-00005

23. Javaid A, Nakata V, Michael D. Diagnostic overshadowing in learning disability: think beyond the disability. Prog Neurol Psychiatry. 2019;23:8-10.

24. Iezzoni LI, Rao SR, Agaronnik ND, El-Jawahri A. Cross-sectional analysis of the associations between four common cancers and disability. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18(8):1031-1044. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2020.7551

25. Sanders JS, Keller S, Aravamuthan BR. Caring for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities in the COVID-19 crisis. Neurol Clin Pract. 2021;11(2):e174-e178. doi:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000886

26. Landes SD, Turk MA, Formica MK, McDonald KE, Stevens JD. COVID-19 outcomes among people with intellectual and developmental disability living in residential group homes in New York State. Disabil Health J. 2020;13(4):100969. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.100969

27. Gleason J, Ross W, Fossi A, Blonksy H, Tobias J, Stephens M. The devastating impact of Covid-19 on individuals with intellectual disabilities in the United States. NEJM Catalyst. 2021.doi.org/10.1056/CAT.21.0051

28. Nankervis K, Chan J. Applying the CRPD to people with intellectual and developmental disability with behaviors of concern during COVID-19. J Policy Pract Intellect Disabil. 2021:10.1111/jppi.12374. doi:10.1111/jppi.12374

29. Alaska Department of Health and Social Services, Division of Public Health, Rural and Community Health Systems. Patient care strategies for scarce resource situations. Version 1. August 2021. Accessed November 11, 2021, https://dhss.alaska.gov/dph/Epi/id/SiteAssets/Pages/HumanCoV/SOA_DHSS_CrisisStandardsOfCare.pdf

30. Cost-effectiveness, the QALY, and the evlyg. ICER. May 21, 2021. Accessed January 24, 2022. https://icer.org/our-approach/methods-process/cost-effectiveness-the-qaly-and-the-evlyg/

Equitable Standards for All Patients in a Crisis

Health care delivered during a pandemic instantiates medicine’s perspectives on the value of human life in clinical scenarios where resource allocation is limited. The COVID-19 pandemic has fostered dialogue and debate around the ethical principles that underly such resource allocation, which generally balance (1) utilitarian optimization of resources, (2) equality or equity in health access, (3) the instrumental value of individuals as agents in society, and (4) prioritizing the “worst off” in their natural history of disease.1,2 State legislatures and health systems have responded to the challeges posed by COVID-19 by considering both the scarcity of intensive care resources, such as mechanical ventilation and hemodialysis, and the clinical criteria to be used for determining which patients should receive said resources. These crisis guidelines have yielded several concerning themes vis-à-vis equitable distribution of health care resources, particularly when the disability status of patients is considered alongside life-expectancy or quality of life.3

Crisis standards of care (CSC) prioritize population-level health under a utilitarian paradigm, explicitly maximizing “life-years” within a population of patients rather than the life of any individual patient.4 Debated during initial COVID surges, these CSC guidelines have recently been enacted at the state level in several settings, including Alaska and Idaho.5 In a setting with scarce intensive care resources, balancing health equity in access to these resources against population-based survival metrics has been a challenge for commissions considering CSC.6,7 This need for balance has further promoted systemic views of “disability,” raising concern for structural “ableism” and highlighting the need for greater “ability awareness” in clinicians’ continued professional learning.

Structural Ableism: Defining Perspectives to Address Health Equity

Ableism has been defined as “a system that places value on people’s bodies and minds, based on societally constructed ideas of normalcy, intelligence, excellence, and productivity…[and] leads to people and society determining who is valuable and worthy based on their appearance and/or their ability to satisfactorily [re]produce, excel, and ‘behave.’”8 Regarding CSC, concerns about systemic bias in guideline design were raised early by disability advocacy groups during comment periods.9,10 More broadly, concerns about ableism sit alongside many deeply rooted societal perspectives of disabled individuals as pitiable or, conversely, heroic for having “overcome” their disability in some way. As a physician who sits in a manual wheelchair with paraplegia and mobility impairment, I have equally been subject to inappropriate bias and inappropriate praise for living in a wheelchair. I have also wondered, alongside my patients living with different levels of mobility or ability, why others often view us as “worse off.” Addressing directly whether disabled individuals are “worse off,” disability rights attorney and advocate Harriet McBryde Johnson has articulated a predominant sentiment among persons living with unique or different abilities:

Are we “worse off”? I don’t think so. Not in any meaningful way. There are too many variables. For those of us with congenital conditions, disability shapes all we are. Those disabled later in life adapt. We take constraints that no one would choose and build rich and satisfying lives within them. We enjoy pleasures other people enjoy and pleasures peculiarly our own. We have something the world needs.11

Many physician colleagues have common, invisible diseases such as diabetes and heart disease; fewer colleagues share conditions that are as visible as my spinal cord injury, as readily apparent to patients upon my entry to their hospital rooms. This simultaneous and inescapable identity as both patient and provider has afforded me wonderful doctor-patient interactions, particularly with those patients who appreciate how my patient experience impacts my ability to partially understand theirs. However, this simultaneous identity as doctor and patient also informed my personal and professional concerns regarding structural ableism as I considered scoring my own acutely ill hospital medicine patients with CSC triage scores in April 2020.

As a practicing hospital medicine physician, I have been emboldened by the efforts of my fellow clinicians amid COVID-19; their efforts have reaffirmed all the reasons I pursued a career in medicine. However, when I heard my clinical colleagues’ first explanation of the Massachusetts CSC guidelines in April 2020, I raised my hand to ask whether the “life-years” to which the guidelines referred were quality-adjusted. My concern regarding the implicit use of quality-adjusted life years (QALY) or disability-adjusted life years in clinical decision-making and implementation of these guidelines was validated when no clinical leaders could address this question directly. Sitting on the CSC committee for my hospital during this time was an honor. However, it was disconcerting to hear many clinicians’ unease when estimating mean survival for common chronic diseases, ranging from end-stage renal disease to advanced heart failure. If my expert colleagues, clinical specialists in kidney and heart disease, could not confidently apply mean survival estimates to multimorbid hospital patients, then idiosyncratic clinical judgment was sure to have a heavy hand in any calculation of “life-years.” Thus, my primary concern was that clinicians using triage heuristics would be subject to bias, regardless of their intention, and negatively adjust for the quality of a disabled life in their CSC triage scoring. My secondary concern was that the CSC guidelines themselves included systemic bias against disabled individuals.

According to CSC schema, triage scores index heavily on Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores to define short-term survival; SOFA scores are partially driven by the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS). Following professional and public comment periods, CSC guidelines in Massachusetts were revised to, among other critical points of revision, change prognostic estimation via “life years” in favor of generic estimation of short-term survival (Table). I wondered, if I presented to an emergency department with severe COVID-19 and was scored with the GCS for the purpose of making a CSC ventilator triage decision, how would my complete paraplegia and lower-extremity motor impairment be accounted for by a clinician assessing “best motor response” in the GCS? The purpose of these scores is to act algorithmically, to guide clinicians whose cognitive load and time limitations may not allow for adjustment of these algorithms based on the individual patient in front of them. Individualization of clinical decisions is part of medicine’s art, but is difficult in the best of times and no easier during a crisis in care delivery. As CSC triage scores were amended and addended throughout 2020, I returned to the COVID wards, time and again wondering, “What have we learned about systemic bias and health inequity in the CSC process and the pandemic broadly, with specific regard to disability?”

Ability Awareness: Room for Our Improvement

Unfortunately, there is reason to believe that clinical judgment is impaired by structural ableism. In seminal work on this topic, Gerhart et al12 demonstrated that clinicians considered spinal cord injury (SCI) survivors to have low self-perceptions of worthiness, overall negative attitudes, and low self-esteem as compared to able-bodied individuals. However, surveyed SCI survivors generally had similar self-perceptions of worth and positivity as compared to ”able-bodied” clinicians.12 For providers who care for persons with disabilities, the majority (82.4%) have rated their disabled patients’ quality of life as worse.13 It is no wonder that patients with disabilities are more likely to feel that their doctor-patient relationship is impacted by lack of understanding, negative sentiment, or simple lack of listening.14 Generally, this poor doctor-patient relationship with disabled patients is exacerbated by poor exposure of medical trainees to disability education; only 34.2% of internal medicine residents recall any form of disability education in medical school, while only 52% of medical school deans report having disability educational content in their curricula.15,16 There is a similar lack of disability representation in the population of medical trainees themselves. While approximately 20% of the American population lives with a disability, less than 2% of American medical students have a disability.17-19

While representation of disabled populations in medical practice remains poor, disabled patients are generally less likely to receive age-appropriate prevention, appropriate access to care, and equal access to treatment.20-22 “Diagnostic overshadowing” refers to clinicians’ attribution of nonspecific signs or symptoms to a patient’s chronic disability as opposed to acute illness.23 This phenomenon has led to higher rates of preventable malignancy in disabled patients and misattribution of common somatic symptoms to intellectual disability.24,25 With this disparity in place as status quo for health care delivery to disabled populations, it is no surprise that certain portions of the disabled population have accounted for disproportionate mortality due to COVID-19.26,27Disability advocates have called for “nothing about us without us,” a phrase associated with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Understanding the profound neurodiversity among several forms of sensory and cognitive disabilities, as well as the functional difference between cognitive disabilities, mobility impairment, and inability to meet one’s instrumental activities of daily living independently, others have proposed a unique approach to certain disabled populations in COVID care.28 My own perspective is that definite progress may require a more general understanding of the prevalence of disability by clinicians, both via medical training and by directly addressing health equity for disabled populations in such calculations as the CSC. Systemic ableism is apparent in our most common clinical scoring systems, ranging from the GCS and Functional Assessment Staging Table to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group and Karnofsky Performance Status scales. I have reexamined these scoring systems in my own understanding given their general equation of ambulation with ability or normalcy. As a doctor in a manual wheelchair who values greatly my personal quality of life and professional contribution to patient care, I worry that these scoring systems inherently discount my own equitable access to care. Individualization of patients’ particular abilities in the context of these scales must occur alongside evidence-based, guideline-directed management via these scoring systems.

Conclusion: Future Orientation

Updated CSC guidelines have accounted for the unique considerations of disabled patients by effectively caveating their scoring algorithms, directing clinicians via disclaimers to uniquely consider their disabled patients in clinical judgement. This is a first step, but it is also one that erodes the value of algorithms, which generally obviate more deliberative thinking and individualization. For our patients who lack certain abilities, as CSC continue to be activated in several states, we have an opportunity to pursue more inherently equitable solutions before further suffering accrues.29 By way of example, adaptations to scoring systems that leverage QALYs for value-based drug pricing indices have been proposed by organizations like the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, which proposed the Equal-Value-of Life-Years-Gained framework to inform QALY-based arbitration of drug pricing.30 This is not a perfect rubric but instead represents an attempt to balance consideration of drugs, as has been done with ventilators during the pandemic, as a scare and expensive resource while addressing the just concerns of advocacy groups in structural ableism.

Resource stewardship during a crisis should not discount those states of human life that are perceived to be less desirable, particularly if they are not experienced as less desirable but are experienced uniquely. Instead, we should consider equitably measuring our intervention to match a patient’s needs, as we would dose-adjust a medication for renal function or consider minimally invasive procedures for multimorbid patients. COVID-19 has reflected our profession’s ethical adaptation during crisis as resources have become scarce; there is no better time to define solutions for health equity. We should now be concerned equally by the influence our personal biases have on our clinical practice and by the way in which these crisis standards will influence patients’ perception of and trust in their care providers during periods of perceived plentiful resources in the future. Health care resources are always limited, allocated according to societal values; if we value health equity for people of all abilities, then we will consider these abilities equitably as we pursue new standards for health care delivery.

Corresponding author: Gregory D. Snyder, MD, MBA, 2014 Washington Street, Newton, MA 02462; [email protected].

Disclosures: None.

Equitable Standards for All Patients in a Crisis

Health care delivered during a pandemic instantiates medicine’s perspectives on the value of human life in clinical scenarios where resource allocation is limited. The COVID-19 pandemic has fostered dialogue and debate around the ethical principles that underly such resource allocation, which generally balance (1) utilitarian optimization of resources, (2) equality or equity in health access, (3) the instrumental value of individuals as agents in society, and (4) prioritizing the “worst off” in their natural history of disease.1,2 State legislatures and health systems have responded to the challeges posed by COVID-19 by considering both the scarcity of intensive care resources, such as mechanical ventilation and hemodialysis, and the clinical criteria to be used for determining which patients should receive said resources. These crisis guidelines have yielded several concerning themes vis-à-vis equitable distribution of health care resources, particularly when the disability status of patients is considered alongside life-expectancy or quality of life.3

Crisis standards of care (CSC) prioritize population-level health under a utilitarian paradigm, explicitly maximizing “life-years” within a population of patients rather than the life of any individual patient.4 Debated during initial COVID surges, these CSC guidelines have recently been enacted at the state level in several settings, including Alaska and Idaho.5 In a setting with scarce intensive care resources, balancing health equity in access to these resources against population-based survival metrics has been a challenge for commissions considering CSC.6,7 This need for balance has further promoted systemic views of “disability,” raising concern for structural “ableism” and highlighting the need for greater “ability awareness” in clinicians’ continued professional learning.

Structural Ableism: Defining Perspectives to Address Health Equity

Ableism has been defined as “a system that places value on people’s bodies and minds, based on societally constructed ideas of normalcy, intelligence, excellence, and productivity…[and] leads to people and society determining who is valuable and worthy based on their appearance and/or their ability to satisfactorily [re]produce, excel, and ‘behave.’”8 Regarding CSC, concerns about systemic bias in guideline design were raised early by disability advocacy groups during comment periods.9,10 More broadly, concerns about ableism sit alongside many deeply rooted societal perspectives of disabled individuals as pitiable or, conversely, heroic for having “overcome” their disability in some way. As a physician who sits in a manual wheelchair with paraplegia and mobility impairment, I have equally been subject to inappropriate bias and inappropriate praise for living in a wheelchair. I have also wondered, alongside my patients living with different levels of mobility or ability, why others often view us as “worse off.” Addressing directly whether disabled individuals are “worse off,” disability rights attorney and advocate Harriet McBryde Johnson has articulated a predominant sentiment among persons living with unique or different abilities:

Are we “worse off”? I don’t think so. Not in any meaningful way. There are too many variables. For those of us with congenital conditions, disability shapes all we are. Those disabled later in life adapt. We take constraints that no one would choose and build rich and satisfying lives within them. We enjoy pleasures other people enjoy and pleasures peculiarly our own. We have something the world needs.11

Many physician colleagues have common, invisible diseases such as diabetes and heart disease; fewer colleagues share conditions that are as visible as my spinal cord injury, as readily apparent to patients upon my entry to their hospital rooms. This simultaneous and inescapable identity as both patient and provider has afforded me wonderful doctor-patient interactions, particularly with those patients who appreciate how my patient experience impacts my ability to partially understand theirs. However, this simultaneous identity as doctor and patient also informed my personal and professional concerns regarding structural ableism as I considered scoring my own acutely ill hospital medicine patients with CSC triage scores in April 2020.

As a practicing hospital medicine physician, I have been emboldened by the efforts of my fellow clinicians amid COVID-19; their efforts have reaffirmed all the reasons I pursued a career in medicine. However, when I heard my clinical colleagues’ first explanation of the Massachusetts CSC guidelines in April 2020, I raised my hand to ask whether the “life-years” to which the guidelines referred were quality-adjusted. My concern regarding the implicit use of quality-adjusted life years (QALY) or disability-adjusted life years in clinical decision-making and implementation of these guidelines was validated when no clinical leaders could address this question directly. Sitting on the CSC committee for my hospital during this time was an honor. However, it was disconcerting to hear many clinicians’ unease when estimating mean survival for common chronic diseases, ranging from end-stage renal disease to advanced heart failure. If my expert colleagues, clinical specialists in kidney and heart disease, could not confidently apply mean survival estimates to multimorbid hospital patients, then idiosyncratic clinical judgment was sure to have a heavy hand in any calculation of “life-years.” Thus, my primary concern was that clinicians using triage heuristics would be subject to bias, regardless of their intention, and negatively adjust for the quality of a disabled life in their CSC triage scoring. My secondary concern was that the CSC guidelines themselves included systemic bias against disabled individuals.

According to CSC schema, triage scores index heavily on Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores to define short-term survival; SOFA scores are partially driven by the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS). Following professional and public comment periods, CSC guidelines in Massachusetts were revised to, among other critical points of revision, change prognostic estimation via “life years” in favor of generic estimation of short-term survival (Table). I wondered, if I presented to an emergency department with severe COVID-19 and was scored with the GCS for the purpose of making a CSC ventilator triage decision, how would my complete paraplegia and lower-extremity motor impairment be accounted for by a clinician assessing “best motor response” in the GCS? The purpose of these scores is to act algorithmically, to guide clinicians whose cognitive load and time limitations may not allow for adjustment of these algorithms based on the individual patient in front of them. Individualization of clinical decisions is part of medicine’s art, but is difficult in the best of times and no easier during a crisis in care delivery. As CSC triage scores were amended and addended throughout 2020, I returned to the COVID wards, time and again wondering, “What have we learned about systemic bias and health inequity in the CSC process and the pandemic broadly, with specific regard to disability?”

Ability Awareness: Room for Our Improvement

Unfortunately, there is reason to believe that clinical judgment is impaired by structural ableism. In seminal work on this topic, Gerhart et al12 demonstrated that clinicians considered spinal cord injury (SCI) survivors to have low self-perceptions of worthiness, overall negative attitudes, and low self-esteem as compared to able-bodied individuals. However, surveyed SCI survivors generally had similar self-perceptions of worth and positivity as compared to ”able-bodied” clinicians.12 For providers who care for persons with disabilities, the majority (82.4%) have rated their disabled patients’ quality of life as worse.13 It is no wonder that patients with disabilities are more likely to feel that their doctor-patient relationship is impacted by lack of understanding, negative sentiment, or simple lack of listening.14 Generally, this poor doctor-patient relationship with disabled patients is exacerbated by poor exposure of medical trainees to disability education; only 34.2% of internal medicine residents recall any form of disability education in medical school, while only 52% of medical school deans report having disability educational content in their curricula.15,16 There is a similar lack of disability representation in the population of medical trainees themselves. While approximately 20% of the American population lives with a disability, less than 2% of American medical students have a disability.17-19