User login

Lung disease raises mortality risk in older RA patients

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis–associated interstitial lung disease showed increases in overall mortality, respiratory mortality, and cancer mortality, compared with RA patients without interstitial lung disease, based on data from more than 500,000 patients in a nationwide cohort study.

RA-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) has been associated with worse survival rates as well as reduced quality of life, functional impairment, and increased health care use and costs, wrote Jeffrey A. Sparks, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues. However, data on the incidence and prevalence of RA-ILD have been inconsistent and large studies are lacking.

In a study published online in Rheumatology, the researchers identified 509,787 RA patients aged 65 years and older from Medicare claims data. The average age of the patients was 72.6 years, and 76.2% were women.

At baseline, 10,306 (2%) of the study population had RA-ILD, and 13,372 (2.7%) developed RA-ILD over an average of 3.8 years’ follow-up per person (total of 1,873,127 person-years of follow-up). The overall incidence of RA-ILD was 7.14 per 1,000 person-years.

Overall mortality was significantly higher among RA-ILD patients than in those with RA alone in a multivariate analysis (38.7% vs. 20.7%; hazard ratio, 1.66).

In addition, RA-ILD was associated with an increased risk of respiratory mortality (HR, 4.39) and cancer mortality (HR, 1.56), compared with RA without ILD. For these hazard regression analyses, the researchers used Fine and Gray subdistribution HRs “to handle competing risks of alternative causes of mortality. For example, the risk of respiratory mortality for patients with RA-ILD, compared with RA without ILD also accounted for the competing risk of cardiovascular, cancer, infection and other types of mortality.”

In another multivariate analysis, male gender, smoking, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, and medication use (specifically biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, targeted synthetic DMARDs, and glucocorticoids) were independently associated with increased incident RA-ILD at baseline. However, “the associations of RA-related medications with incident RA-ILD risk should be interpreted with caution since they may be explained by unmeasured factors, including RA disease activity, severity, comorbidities, and prior or concomitant medication use,” the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of data on disease activity, disease duration, disease severity, and RA-related autoantibodies, the researchers noted. However, the results support data from previous studies and were strengthened by the large sample size and data on demographics and health care use.

“Ours is the first to study the epidemiology and mortality outcomes of RA-ILD using a validated claims algorithm to identify RA and RA-ILD,” and “to quantify the mortality burden of RA-ILD and to identify a potentially novel association of RA-ILD with cancer mortality,” they noted.

The study was supported by an investigator-initiated grant from Bristol-Myers Squibb. Lead author Dr. Sparks disclosed support from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, the Brigham Research Institute, and the R. Bruce and Joan M. Mickey Research Scholar Fund. Dr. Sparks also disclosed serving as a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Inova Diagnostics, Janssen, Optum, and Pfizer for work unrelated to the current study. Other authors reported research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, involvement in a clinical trial funded by Genentech and Bristol-Myers Squibb, and receiving research support to Brigham and Women’s Hospital for other studies from AbbVie, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Vertex.

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis–associated interstitial lung disease showed increases in overall mortality, respiratory mortality, and cancer mortality, compared with RA patients without interstitial lung disease, based on data from more than 500,000 patients in a nationwide cohort study.

RA-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) has been associated with worse survival rates as well as reduced quality of life, functional impairment, and increased health care use and costs, wrote Jeffrey A. Sparks, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues. However, data on the incidence and prevalence of RA-ILD have been inconsistent and large studies are lacking.

In a study published online in Rheumatology, the researchers identified 509,787 RA patients aged 65 years and older from Medicare claims data. The average age of the patients was 72.6 years, and 76.2% were women.

At baseline, 10,306 (2%) of the study population had RA-ILD, and 13,372 (2.7%) developed RA-ILD over an average of 3.8 years’ follow-up per person (total of 1,873,127 person-years of follow-up). The overall incidence of RA-ILD was 7.14 per 1,000 person-years.

Overall mortality was significantly higher among RA-ILD patients than in those with RA alone in a multivariate analysis (38.7% vs. 20.7%; hazard ratio, 1.66).

In addition, RA-ILD was associated with an increased risk of respiratory mortality (HR, 4.39) and cancer mortality (HR, 1.56), compared with RA without ILD. For these hazard regression analyses, the researchers used Fine and Gray subdistribution HRs “to handle competing risks of alternative causes of mortality. For example, the risk of respiratory mortality for patients with RA-ILD, compared with RA without ILD also accounted for the competing risk of cardiovascular, cancer, infection and other types of mortality.”

In another multivariate analysis, male gender, smoking, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, and medication use (specifically biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, targeted synthetic DMARDs, and glucocorticoids) were independently associated with increased incident RA-ILD at baseline. However, “the associations of RA-related medications with incident RA-ILD risk should be interpreted with caution since they may be explained by unmeasured factors, including RA disease activity, severity, comorbidities, and prior or concomitant medication use,” the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of data on disease activity, disease duration, disease severity, and RA-related autoantibodies, the researchers noted. However, the results support data from previous studies and were strengthened by the large sample size and data on demographics and health care use.

“Ours is the first to study the epidemiology and mortality outcomes of RA-ILD using a validated claims algorithm to identify RA and RA-ILD,” and “to quantify the mortality burden of RA-ILD and to identify a potentially novel association of RA-ILD with cancer mortality,” they noted.

The study was supported by an investigator-initiated grant from Bristol-Myers Squibb. Lead author Dr. Sparks disclosed support from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, the Brigham Research Institute, and the R. Bruce and Joan M. Mickey Research Scholar Fund. Dr. Sparks also disclosed serving as a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Inova Diagnostics, Janssen, Optum, and Pfizer for work unrelated to the current study. Other authors reported research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, involvement in a clinical trial funded by Genentech and Bristol-Myers Squibb, and receiving research support to Brigham and Women’s Hospital for other studies from AbbVie, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Vertex.

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis–associated interstitial lung disease showed increases in overall mortality, respiratory mortality, and cancer mortality, compared with RA patients without interstitial lung disease, based on data from more than 500,000 patients in a nationwide cohort study.

RA-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) has been associated with worse survival rates as well as reduced quality of life, functional impairment, and increased health care use and costs, wrote Jeffrey A. Sparks, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues. However, data on the incidence and prevalence of RA-ILD have been inconsistent and large studies are lacking.

In a study published online in Rheumatology, the researchers identified 509,787 RA patients aged 65 years and older from Medicare claims data. The average age of the patients was 72.6 years, and 76.2% were women.

At baseline, 10,306 (2%) of the study population had RA-ILD, and 13,372 (2.7%) developed RA-ILD over an average of 3.8 years’ follow-up per person (total of 1,873,127 person-years of follow-up). The overall incidence of RA-ILD was 7.14 per 1,000 person-years.

Overall mortality was significantly higher among RA-ILD patients than in those with RA alone in a multivariate analysis (38.7% vs. 20.7%; hazard ratio, 1.66).

In addition, RA-ILD was associated with an increased risk of respiratory mortality (HR, 4.39) and cancer mortality (HR, 1.56), compared with RA without ILD. For these hazard regression analyses, the researchers used Fine and Gray subdistribution HRs “to handle competing risks of alternative causes of mortality. For example, the risk of respiratory mortality for patients with RA-ILD, compared with RA without ILD also accounted for the competing risk of cardiovascular, cancer, infection and other types of mortality.”

In another multivariate analysis, male gender, smoking, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, and medication use (specifically biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, targeted synthetic DMARDs, and glucocorticoids) were independently associated with increased incident RA-ILD at baseline. However, “the associations of RA-related medications with incident RA-ILD risk should be interpreted with caution since they may be explained by unmeasured factors, including RA disease activity, severity, comorbidities, and prior or concomitant medication use,” the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of data on disease activity, disease duration, disease severity, and RA-related autoantibodies, the researchers noted. However, the results support data from previous studies and were strengthened by the large sample size and data on demographics and health care use.

“Ours is the first to study the epidemiology and mortality outcomes of RA-ILD using a validated claims algorithm to identify RA and RA-ILD,” and “to quantify the mortality burden of RA-ILD and to identify a potentially novel association of RA-ILD with cancer mortality,” they noted.

The study was supported by an investigator-initiated grant from Bristol-Myers Squibb. Lead author Dr. Sparks disclosed support from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, the Brigham Research Institute, and the R. Bruce and Joan M. Mickey Research Scholar Fund. Dr. Sparks also disclosed serving as a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Inova Diagnostics, Janssen, Optum, and Pfizer for work unrelated to the current study. Other authors reported research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, involvement in a clinical trial funded by Genentech and Bristol-Myers Squibb, and receiving research support to Brigham and Women’s Hospital for other studies from AbbVie, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Vertex.

FROM RHEUMATOLOGY

A Preoperative Transthoracic Echocardiography Protocol to Reduce Time to Hip Fracture Surgery

From Dignity Health Methodist Hospital of Sacramento Family Medicine Residency Program, Sacramento, CA (Dr. Oldach); Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH (Dr. Irwin); OhioHealth Research Institute, Columbus, OH (Dr. Pershing); Department of Clinical Transformation, OhioHealth, Columbus, OH (Dr. Zigmont and Dr. Gascon); and Department of Geriatrics, OhioHealth, Columbus, OH (Dr. Skully).

Abstract

Objective: An interdisciplinary committee was formed to identify factors contributing to surgical delays in urgent hip fracture repair at an urban, level 1 trauma center, with the goal of reducing preoperative time to less than 24 hours. Surgical optimization was identified as a primary, modifiable factor, as surgeons were reluctant to clear patients for surgery without cardiac consultation. Preoperative transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) was recommended as a safe alternative to cardiac consultation in most patients.

Methods: A retrospective review was conducted for patients who underwent urgent hip fracture repair between January 2010 and April 2014 (n = 316). Time to medical optimization, time to surgery, hospital length of stay, and anesthesia induction were compared for 3 patient groups of interest: those who received (1) neither TTE nor cardiology consultation (ie, direct to surgery); (2) a preoperative TTE; or (3) preoperative cardiac consultation.

Results: There were significant between-group differences in medical optimization time (P = 0.001) and mean time to surgery (P < 0.001) when comparing the 3 groups of interest. Patients in the preoperative cardiac consult group had the longest times, followed by the TTE and direct-to-surgery groups. There were no differences in the type of induction agent used across treatment groups when stratifying by ejection fraction.

Conclusion: Preoperative TTE allows for decreased preoperative time compared to a cardiology consultation. It provides an easily implemented inter-departmental, intra-institutional intervention to decrease preoperative time in patients presenting with hip fractures.

Keywords: surgical delay; preoperative risk stratification; process improvement.

Hip fractures are common, expensive, and associated with poor outcomes.1,2 Ample literature suggests that morbidity, mortality, and cost of care may be reduced by minimizing surgical delays.3-5 While individual reports indicate mixed evidence, in a 2010 meta-analysis, surgery within 72 hours was associated with significant reductions in pneumonia and pressure sores, as well as a 19% reduction in all-cause mortality through 1 year.6 Additional reviews suggest evidence of improved patient outcomes (pain, length of stay, non-union, and/or mortality) when surgery occurs early, within 12 to 72 hours after injury.4,6,7 Regardless of the definition of “early surgery” used, surgical delay remains a challenge, often due to organizational factors, including admission day of the week and hospital staffing, and patient characteristics, such as comorbidities, echocardiographic findings, age, and insurance status.7-9

Among factors that contribute to surgical delays, the need for preoperative cardiovascular risk stratification is significantly modifiable.10 The American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) Task Force risk stratification framework for preoperative cardiac testing assists clinicians in determining surgical urgency, active cardiac conditions, cardiovascular risk factors, and functional capacity of each patient, and is well established for low- or intermediate-risk patients.11 Specifically, metabolic equivalents (METs) measurements are used to identify medically stable patients with good or excellent functional capacity versus poor or unknown functional status. Patients with ≥ 4 METs may proceed to surgery without further testing; patients with < 4 METs may either proceed with planned surgery or undergo additional testing. Patients with a perceived increased risk profile who require urgent or semi-urgent hip fracture repair may be confounded by disagreement about required preoperative cardiac testing.

At OhioHealth Grant Medical Center (GMC), an urban, level 1 trauma center, the consideration of further preoperative noninvasive testing frequently contributed to surgical delays. In 2009, hip fracture patients arriving to the emergency department (ED) waited an average of 51 hours before being transferred to the operating room (OR) for surgery. Presuming prompt surgery is both desirable and feasible, the Grant Hip Fracture Management Committee (GHFMC) was developed in order to expedite surgeries in hip fracture patients. The GHFMC recommended a preoperative hip fracture protocol, and the outcomes from protocol implementation are described in this article.

Methods

This study was approved by the OhioHealth Institutional Review Board, with a waiver of the informed consent requirement. Medical records from patients treated at GMC during the time period between January 2010 and April 2014 (ie, following implementation of GHFMC recommendations) were retrospectively reviewed to identify the extent to which the use of preoperative transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) reduced average time to surgery and total length of stay, compared to cardiac consultation. This chart review included 316 participants and was used to identify primary induction agent utilized, time to medical optimization, time to surgery, and total length of hospital stay.

Intervention

The GHFMC conducted a 9-month quality improvement project to decrease ED-to-OR time to less than 24 hours for hip fracture patients. The multidisciplinary committee consisted of physicians from orthopedic surgery, anesthesia, hospital medicine, and geriatrics, along with key administrators and nurse outcomes managers. While there is lack of complete clarity surrounding optimal surgical timing, the committee decided that surgery within 24 hours would be beneficial for the majority of patients and therefore was considered a prudent goal.

Based on identified barriers that contributed to surgical delays, several process improvement strategies were implemented, including admitting patients to the hospitalist service, engaging the orthopedic trauma team, and implementing pre- and postoperative protocols and order sets (eg, ED and pain management order sets). Specific emphasis was placed on establishing guidelines for determining medical optimization. In the absence of established guidelines, medical optimization was determined at the discretion of the attending physician. The necessity of preoperative cardiac assessment was based, in part, on physician concerns about determining safe anesthesia protocols and hemodynamically managing patients who may have occult heart disease, specifically those patients with low functional capacity (< 4 METs) and/or inability to accurately communicate their medical history.

Many hip fractures result from a fall, and it may be unclear whether the fall causing a fracture was purely mechanical or indicative of a distinct acute or chronic illness. As a result, many patients received cardiac consultations, with or without pharmacologic stress testing, adding another 24 to 36 hours to preoperative time. As invasive preoperative cardiac procedures generally result in surgical delays without improving outcomes,11 the committee recommended that clinicians reserve preoperative cardiac consultation for patients with active cardiac conditions.

In lieu of cardiac consultation, the committee suggested preoperative TTE. While use of TTE has not been shown to improve preoperative risk stratification in routine noncardiac surgeries, it has been shown to provide clinically useful information in patients at high risk for cardiac complications.11 There was consensus for incorporating preoperative TTE for several reasons: (1) the patients with hip fractures were not “routine,” and often did not have a reliable medical history; (2) a large percentage of patients had cardiac risk factors; (3) patients with undiagnosed aortic stenosis, severe left ventricular dysfunction, or severe pulmonary hypertension would likely have altered intraoperative fluid management; and (4) in supplanting cardiac consultations, TTE would likely expedite patients’ ED-to-OR times. Therefore, the GHFMC created a recommendation of ordering urgent TTE for patients who were unable to exercise at ≥ 4 METs but needed urgent hip fracture surgery.

In order to evaluate the success of the new protocol, the ED-to-OR times were calculated for a cohort of patients who underwent surgery for hip fracture following algorithm implementation.

Participants

A chart review was conducted for patients admitted to GMC between January 2010 and April 2014 for operative treatment of a hip fracture. Exclusion criteria included lack of radiologist-diagnosed hip fracture, periprosthetic hip fracture, or multiple traumas. Electronic patient charts were reviewed by investigators (KI and BO) using a standardized, electronic abstraction form for 3 groups of patients who (1) proceeded directly to planned surgery without TTE or cardiac consultation (direct-to-surgery group); (2) received preoperative TTE but not a cardiac consultation (TTE-only group); or (3) received preoperative cardiac consultation (cardiac consult group).

Measures

Demographics, comorbid conditions, MET score, anesthesia protocol, and in-hospital morbidity and mortality were extracted from medical charts. Medical optimization time was determined by the latest time stamp of 1 of the following: time that the final consulting specialist stated that the patient was stable for surgery; time that the hospitalist described the patient as being ready for surgery; time that the TTE report was certified by the reading cardiologist; or time that the hospitalist described the outcome of completed preoperative risk stratification. Time elapsed prior to medical optimization, surgery, and discharge were calculated using differences between the patient’s arrival date and time at the ED, first recorded time of medical optimization, surgical start time (from the surgical report), and discharge time, respectively.

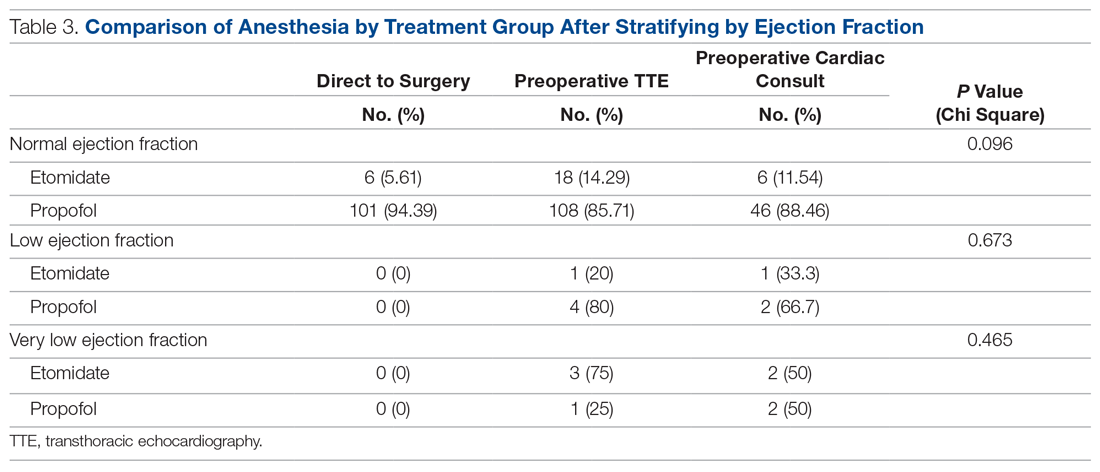

To assess whether the TTE protocol may have affected anesthesia selection, the induction agent (etomidate or propofol) was abstracted from anesthesia reports and stratified by the ejection fraction of each patient: very low (≤ 35%), low (36%–50%), or normal (> 50%). Patients without an echocardiogram report were assumed to have a normal ejection fraction for this analysis.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were produced using mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and frequency and percentage for categorical variables. To determine whether statistically significant differences existed between the 3 groups, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare skewed continuous variables, and Pearson’s chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. Due to differences in baseline patient characteristics across the 3 treatment groups, inverse probability weights were used to adjust for group differences (using a multinomial logit treatment model) while comparing differences in outcome variables. This modeling strategy does not rely on any assumptions for the distribution of the outcome variable. Covariates were considered for inclusion in the treatment or outcome model if they were significantly associated (P < 0.05) with the group variable. Additionally, anesthetic agent (etomidate or propofol) was compared across the treatment groups after stratifying by ejection fraction to identify whether any differences existed in anesthesia regimen. Patients who were prescribed more than 1 anesthetic agent (n = 2) or an agent that was not of interest were removed from the analysis (n = 13). Stata (version 14) was used for analysis. All other missing data with respect to the tested variables were omitted in the analysis for that variable. Any disagreements about abstraction were resolved through consensus between the investigators.

Results

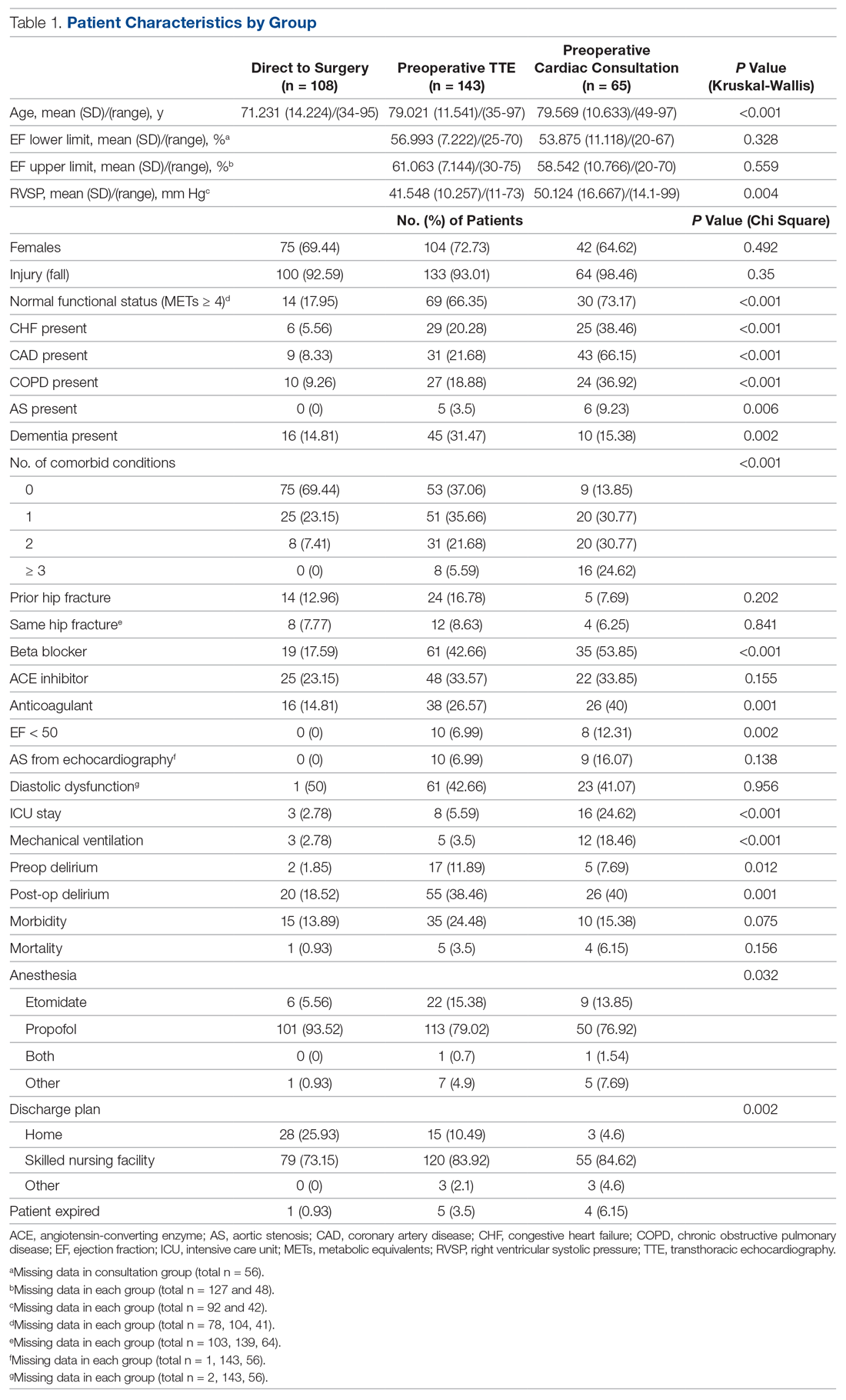

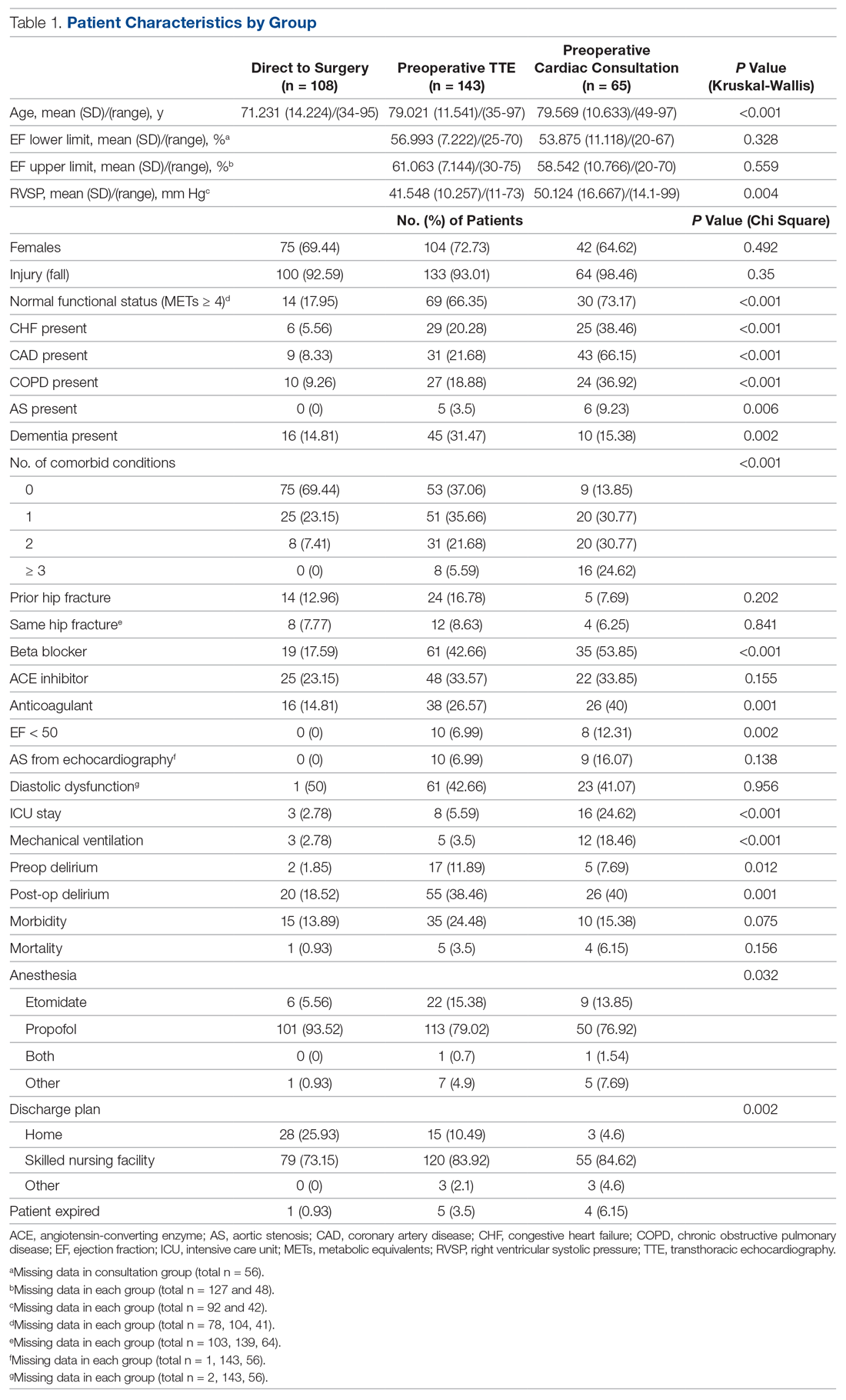

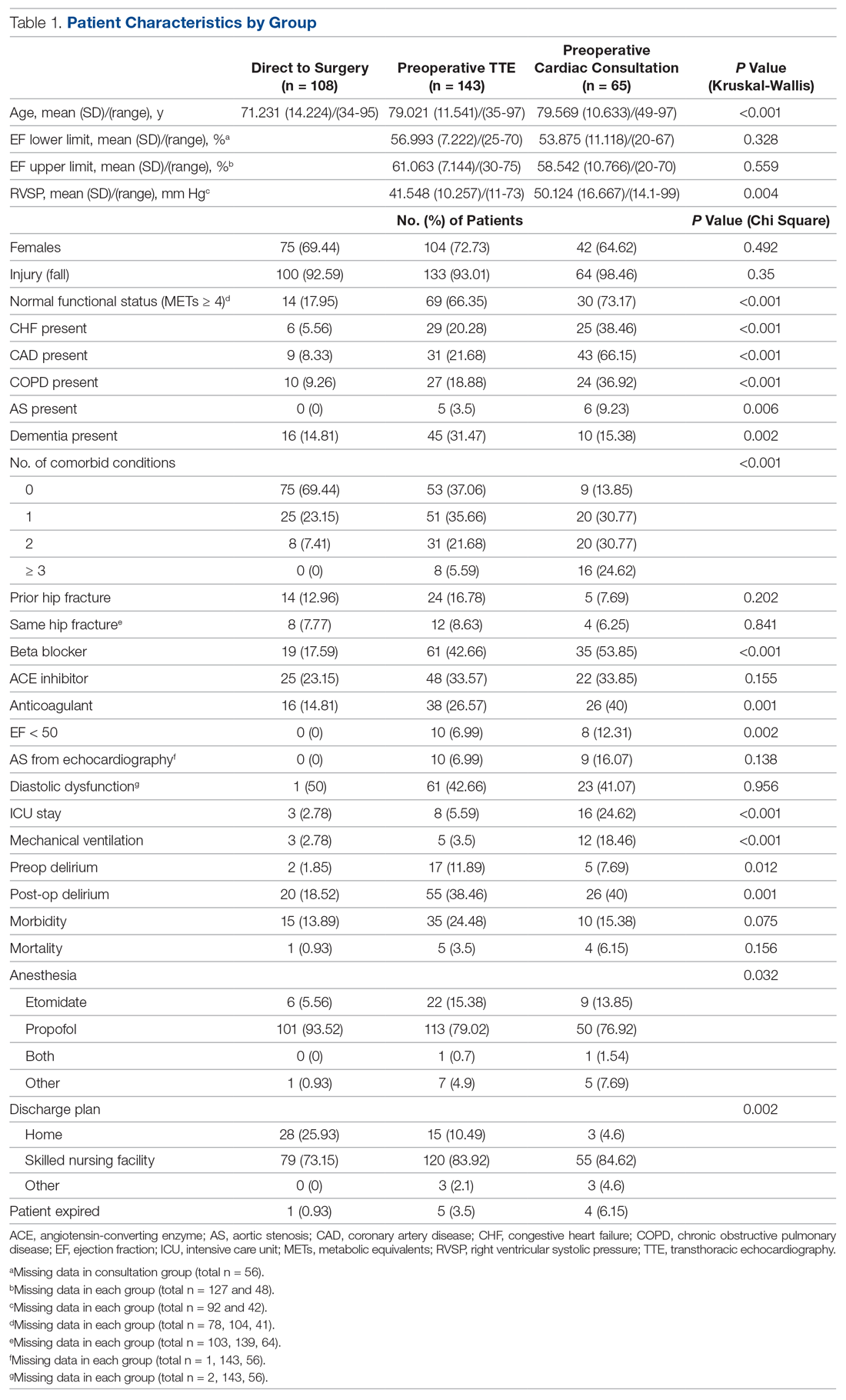

A total of 316 cases met inclusion criteria, including 108 direct-to-surgery patients, 143 preoperative TTE patients, and 65 cardiac consult patients. Patient demographics and preoperative characteristics are shown in Table 1. The average age for all patients was 76.5 years of age (SD, 12.89; IQR, 34-97); however, direct-to-surgery patients were significantly (P < 0.001) younger (71.2 years; SD, 14.2; interquartile range [IQR], 34-95 years) than TTE-only patients (79.0 years; SD, 11.5; IQR, 35-97 years) and cardiac consult patients (79.57 years; SD, 10.63; IQR, 49-97 years). The majority of patients were female (69.9%) and experienced a fall prior to admission (94%). Almost three-fourths of patients had 1 or more cardiac risk factors (73.7%), including history of congestive heart failure (CHF; 19%), coronary artery disease (CAD; 26.3%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD; 19.3%), or aortic stenosis (AS; 3.5%). Due to between-group differences in these comorbid conditions, confounding factors were adjusted for in subsequent analyses.

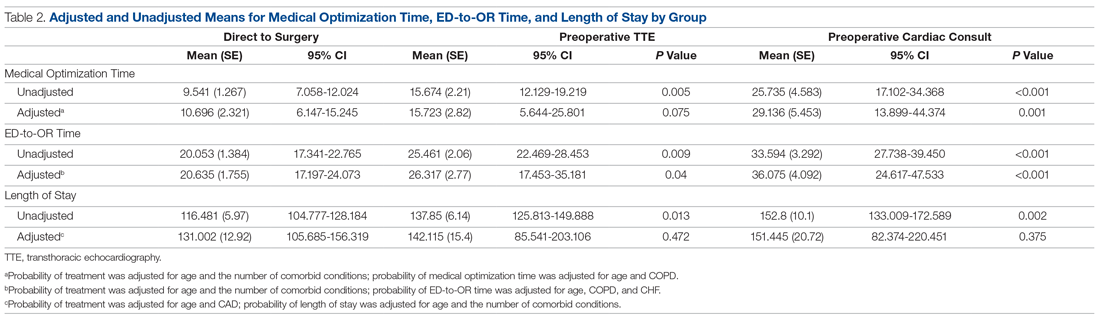

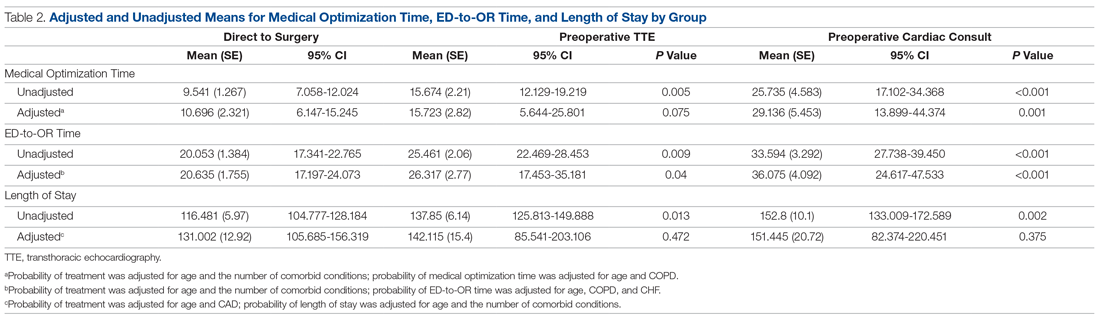

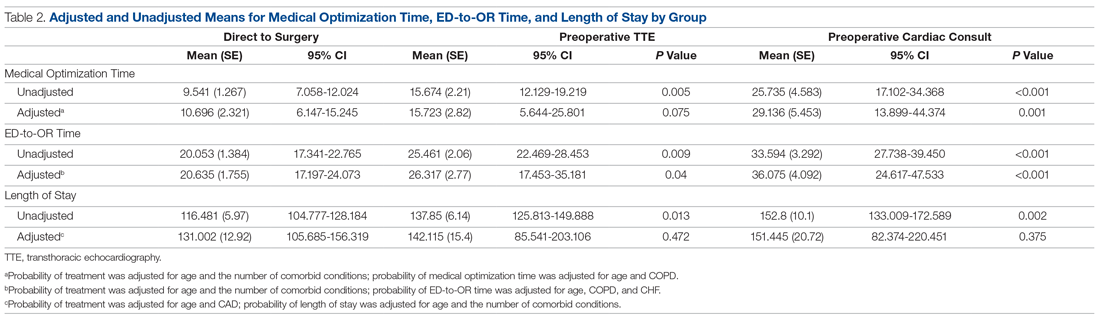

As shown in Table 2, before adjustment for confounding factors, there were significant between-group differences in medical optimization time for patients in all 3 groups. After adjustment for treatment differences using age and number of comorbid diseases, and medical optimization time differences using age and COPD, fewer between-group differences were statistically significant. Patients who received a cardiac consult had an 18.44-hour longer medical optimization time compared to patients who went directly to surgery (29.136 vs 10.696 hours; P = 0.001). Optimization remained approximately 5 hours longer for the TTE-only group than for the direct-to-surgery group; however, this difference was not significant (P = 0.075).

When comparing differences in ED-to-OR time for the 3 groups after adjusting the probability of treatment for age and the number of comorbid conditions, and adjusting the probability of ED-to-OR time for age, COPD, and CHF, significant differences remained in ED-to-OR times across all groups. Specifically, patients in the direct-to-surgery group experienced the shortest time (mean, 20.64 hours), compared to patients in the TTE-only group (mean, 26.32; P = 0.04) or patients in the cardiac consult group (mean, 36.08; P < 0.001). TTE-only patients had a longer time of 5.68 hours, compared to the direct-to-surgery group, and patients in the preoperative cardiac consult group were on average 15.44 hours longer than the direct-to-surgery group.

When comparing differences in the length of stay for the 3 groups before statistical adjustments, differences were observed; however, after removing the confounding factors related to treatment (age and CAD) and the outcome (age and the number of comorbid conditions), there were no statistically significant differences in the length of stay for the 3 groups. Average length of stay was 131 hours for direct-to-surgery patients, 142 hours for TTE-only patients, and 141 hours for cardiac consult patients.

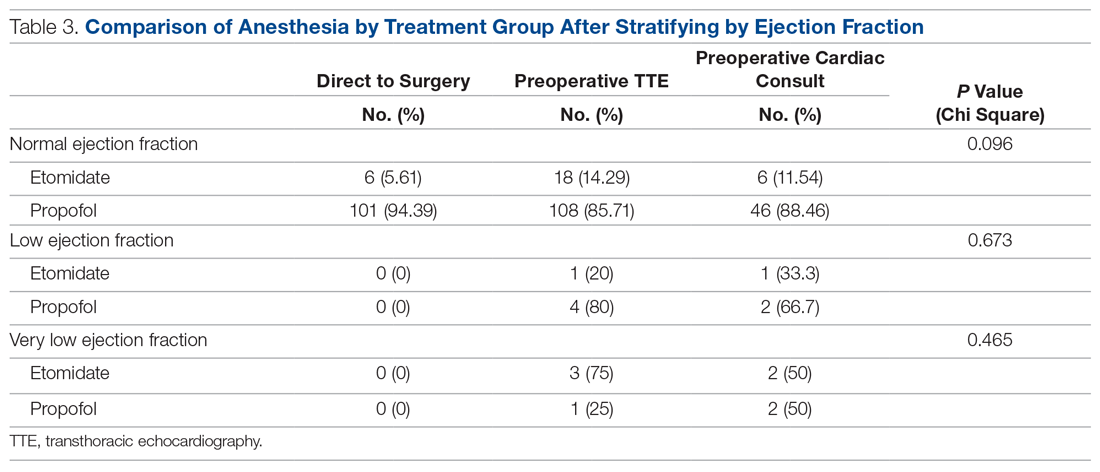

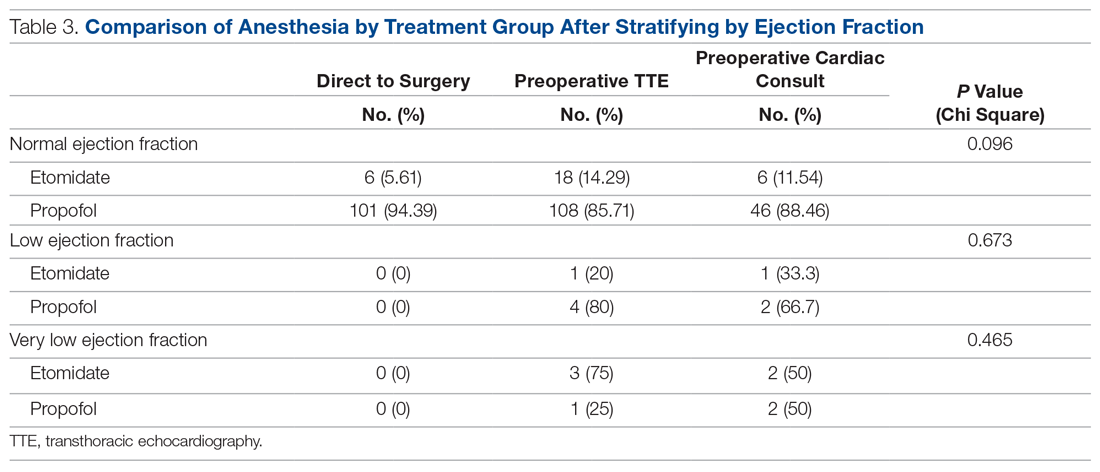

The use of different anesthetic agents was compared for patients in the 3 groups. The majority of patients in the study (87.7%) were given propofol, and there were no differences after stratifying by ejection fraction (Table 3).

Discussion

The GHFMC was created to reduce surgical delays for hip fracture. Medical optimization was considered a primary, modifiable factor given that surgeons were reluctant to proceed without a cardiac consult. To address this gap, the committee recommended a preoperative TTE for patients with low or unknown functional status. This threshold provides a quick and easy method for stratifying patients who previously required risk stratification by a cardiologist, which often resulted in surgery delays.

In their recommendations for implementation of hip fracture quality improvement projects, the Geriatric Fracture Center emphasizes the importance of multidisciplinary physician leadership along with standardization of approach across patients.12 This recommendation is supported by increasing evidence that orthogeriatric collaborations are associated with decreased mortality and length of stay.13 The GHFMC and subsequent interventions reflect this approach, allowing for collaboration to identify cross-disciplinary procedural barriers to care. In our institution, addressing identified procedural barriers to care was associated with a reduction in the average time to surgery from 51 hours to 25.3 hours.

Multiple approaches have been attempted to decrease presurgical time in hip fracture patients in various settings. Prehospital interventions, such as providing ambulances with checklists and ability to bypass the ED, have not been shown to decrease time to surgery for hip fracture patients, though similar strategies have been successful in other conditions, such as stroke.14,15 In-hospital procedures, such as implementation of a hip fracture protocol and reduction of preoperative interventions, have more consistently been found to decrease time to surgery and in-hospital mortality.16,17 However, reduced delays have not been found universally. Luttrell and Nana found that preoperative TTE resulted in approximately 30.8-hour delays from the ED to OR, compared to patients who did not receive a preoperative TTE.18 However, in that study hospitalists used TTE at their own discretion, and there may have been confounding factors contributing to delays. When used as part of a protocol targeting patients with poor or unknown functional capacity, we believe that preoperative TTE results in modest surgical delays yet provides clinically useful information about each patient.

ACC/AHA preoperative guidelines were updated after we implemented our intervention and now recommend that patients with poor or unknown functional capacity in whom stress testing will not influence care proceed to surgery “according to guideline-directed medical care.”11 While routine use of preoperative evaluation of left ventricular function is not recommended, assessing left ventricular function may be reasonable for patients with heart failure with a change in clinical status. Guidelines also recommend that patients with clinically suspected valvular stenosis undergo preoperative echocardiography.11

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, due to resource limitations, a substantial period of time elapsed between implementation of the new protocol and the analysis of the data set. That is, the hip fracture protocol assessed in this paper occurred from January 2010 through April 2014, and final analysis of the data set occurred in April 2020. This limitation precludes our ability to formally assess any pre- or post-protocol changes in patient outcomes. Second, randomization was not used to create groups that were balanced in differing health characteristics (ie, patients with noncardiac-related surgeries, patients in different age groups); however, the use of inverse probability treatment regression analysis was a way to statistically address these between-group differences. Moreover, this study is limited by the factors that were measured; unmeasured factors cannot be accounted for. Third, health care providers working at the hospital during this time were aware of the goal to decrease presurgical time, possibly creating exaggerated effects compared to a blinded trial. Finally, although this intervention is likely translatable to other centers, these results represent the experiences of a single level 1 trauma center and may not be replicable elsewhere.

Conclusion

Preoperative TTE in lieu of cardiac consultation has several advantages. First, it requires interdepartmental collaboration for implementation, but can be implemented through a single hospital or hospital system. Unlike prehospital interventions, preoperative urgent TTE for patients with low functional capacity does not require the support of emergency medical technicians, ambulance services, or other hospitals in the region. Second, while costs are associated with TTE, they are offset by a reduction in expensive consultations with specialists, surgical delays, and longer lengths of stay. Third, despite likely increased ED-to-OR times compared to no intervention, urgent TTE decreases time to surgery compared with cardiology consultation. Prior to the GHFMC, the ED-to-OR time at our institution was 51 hours. In contrast, the mean time following the GHFMC-led protocol was less than half that, at 25.3 hours (SD, 19.1 hours). In fact, nearly two-thirds (65.2%) of the patients evaluated in this study underwent surgery within 24 hours of admission. This improvement in presurgical time was attributed, in part, to the implementation of preoperative TTE over cardiology consultations.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Jenny Williams, RN, who was instrumental in obtaining the data set for analysis, and Shauna Ayres, MPH, from the OhioHealth Research Institute, who provided writing and technical assistance.

Corresponding author: Robert Skully, MD, OhioHealth Family Medicine Grant, 290 East Town St., Columbus, OH 43215; [email protected].

Funding: This work was supported by the OhioHealth Summer Research Externship Program.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Brauer CA, Coca-Perraillon M, Cutler DM, Rosen AB. Incidence and mortality of hip fractures in the United States. JAMA. 2009;302:1573-1579.

2. Lewiecki EM, Wright NC, Curtis JR, et al. Hip fracture trends in the United States 2002 to 2015. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29:717-722.

3. Colais P, Di Martino M, Fusco D, et al. The effect of early surgery after hip fracture on 1-year mortality. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:141.

4. Nyholm AM, Gromov K, Palm H, et al. Time to surgery is associated with thirty-day and ninety-day mortality after proximal femoral fracture: a retrospective observational study on prospectively collected data from the Danish Fracture Database Collaborators. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:1333-1339.

5. Judd KT, Christianson E. Expedited operative care of hip fractures results in significantly lower cost of treatment. Iowa Orthop J. 2015;35:62-64.

6. Simunovic N, Devereaux PJ, Sprague S, et al. Effect of early surgery after hip fracture on mortality and complications: systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2010;182:1609-1616.

7. Ryan DJ, Yoshihara H, Yoneoka D, et al. Delay in hip fracture surgery: an analysis of patient-specific and hospital-specific risk factors. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29:343-348.

8. Ricci WM, Brandt A, McAndrew C, Gardner MJ. Factors affecting delay to surgery and length of stay for patients with hip fracture. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29:e109-e114.

9. Hagino T, Ochiai S, Senga S, et al. Efficacy of early surgery and causes of surgical delay in patients with hip fracture. J Orthop. 2015;12:142-146.

10. Rafiq A, Sklyar E, Bella JN. Cardiac evaluation and monitoring of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Health Serv Insights. 2017;9:1178632916686074.

11. Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:e77-e137.

12. Basu N, Natour M, Mounasamy V, Kates SL. Geriatric hip fracture management: keys to providing a successful program. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2016;42:565-569.

13. Grigoryan KV, Javedan H, Rudolph JL. Orthogeriatric care models and outcomes in hip fracture patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28:e49-e55.

14. Tai YJ, Yan B. Minimising time to treatment: targeted strategies to minimise time to thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. Intern Med J. 2013;43:1176-1182.

15. Larsson G, Stromberg RU, Rogmark C, Nilsdotter A. Prehospital fast track care for patients with hip fracture: Impact on time to surgery, hospital stay, post-operative complications and mortality a randomised, controlled trial. Injury. 2016;47:881-886.

16. Bohm E, Loucks L, Wittmeier K, et al. Reduced time to surgery improves mortality and length of stay following hip fracture: results from an intervention study in a Canadian health authority. Can J Surg. 2015;58:257-263.

17. Ventura C, Trombetti S, Pioli G, et al. Impact of multidisciplinary hip fracture program on timing of surgery in elderly patients. Osteoporos Int J. 2014;25:2591-2597.

18. Luttrell K, Nana A. Effect of preoperative transthoracic echocardiogram on mortality and surgical timing in elderly adults with hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2505-2509.

From Dignity Health Methodist Hospital of Sacramento Family Medicine Residency Program, Sacramento, CA (Dr. Oldach); Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH (Dr. Irwin); OhioHealth Research Institute, Columbus, OH (Dr. Pershing); Department of Clinical Transformation, OhioHealth, Columbus, OH (Dr. Zigmont and Dr. Gascon); and Department of Geriatrics, OhioHealth, Columbus, OH (Dr. Skully).

Abstract

Objective: An interdisciplinary committee was formed to identify factors contributing to surgical delays in urgent hip fracture repair at an urban, level 1 trauma center, with the goal of reducing preoperative time to less than 24 hours. Surgical optimization was identified as a primary, modifiable factor, as surgeons were reluctant to clear patients for surgery without cardiac consultation. Preoperative transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) was recommended as a safe alternative to cardiac consultation in most patients.

Methods: A retrospective review was conducted for patients who underwent urgent hip fracture repair between January 2010 and April 2014 (n = 316). Time to medical optimization, time to surgery, hospital length of stay, and anesthesia induction were compared for 3 patient groups of interest: those who received (1) neither TTE nor cardiology consultation (ie, direct to surgery); (2) a preoperative TTE; or (3) preoperative cardiac consultation.

Results: There were significant between-group differences in medical optimization time (P = 0.001) and mean time to surgery (P < 0.001) when comparing the 3 groups of interest. Patients in the preoperative cardiac consult group had the longest times, followed by the TTE and direct-to-surgery groups. There were no differences in the type of induction agent used across treatment groups when stratifying by ejection fraction.

Conclusion: Preoperative TTE allows for decreased preoperative time compared to a cardiology consultation. It provides an easily implemented inter-departmental, intra-institutional intervention to decrease preoperative time in patients presenting with hip fractures.

Keywords: surgical delay; preoperative risk stratification; process improvement.

Hip fractures are common, expensive, and associated with poor outcomes.1,2 Ample literature suggests that morbidity, mortality, and cost of care may be reduced by minimizing surgical delays.3-5 While individual reports indicate mixed evidence, in a 2010 meta-analysis, surgery within 72 hours was associated with significant reductions in pneumonia and pressure sores, as well as a 19% reduction in all-cause mortality through 1 year.6 Additional reviews suggest evidence of improved patient outcomes (pain, length of stay, non-union, and/or mortality) when surgery occurs early, within 12 to 72 hours after injury.4,6,7 Regardless of the definition of “early surgery” used, surgical delay remains a challenge, often due to organizational factors, including admission day of the week and hospital staffing, and patient characteristics, such as comorbidities, echocardiographic findings, age, and insurance status.7-9

Among factors that contribute to surgical delays, the need for preoperative cardiovascular risk stratification is significantly modifiable.10 The American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) Task Force risk stratification framework for preoperative cardiac testing assists clinicians in determining surgical urgency, active cardiac conditions, cardiovascular risk factors, and functional capacity of each patient, and is well established for low- or intermediate-risk patients.11 Specifically, metabolic equivalents (METs) measurements are used to identify medically stable patients with good or excellent functional capacity versus poor or unknown functional status. Patients with ≥ 4 METs may proceed to surgery without further testing; patients with < 4 METs may either proceed with planned surgery or undergo additional testing. Patients with a perceived increased risk profile who require urgent or semi-urgent hip fracture repair may be confounded by disagreement about required preoperative cardiac testing.

At OhioHealth Grant Medical Center (GMC), an urban, level 1 trauma center, the consideration of further preoperative noninvasive testing frequently contributed to surgical delays. In 2009, hip fracture patients arriving to the emergency department (ED) waited an average of 51 hours before being transferred to the operating room (OR) for surgery. Presuming prompt surgery is both desirable and feasible, the Grant Hip Fracture Management Committee (GHFMC) was developed in order to expedite surgeries in hip fracture patients. The GHFMC recommended a preoperative hip fracture protocol, and the outcomes from protocol implementation are described in this article.

Methods

This study was approved by the OhioHealth Institutional Review Board, with a waiver of the informed consent requirement. Medical records from patients treated at GMC during the time period between January 2010 and April 2014 (ie, following implementation of GHFMC recommendations) were retrospectively reviewed to identify the extent to which the use of preoperative transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) reduced average time to surgery and total length of stay, compared to cardiac consultation. This chart review included 316 participants and was used to identify primary induction agent utilized, time to medical optimization, time to surgery, and total length of hospital stay.

Intervention

The GHFMC conducted a 9-month quality improvement project to decrease ED-to-OR time to less than 24 hours for hip fracture patients. The multidisciplinary committee consisted of physicians from orthopedic surgery, anesthesia, hospital medicine, and geriatrics, along with key administrators and nurse outcomes managers. While there is lack of complete clarity surrounding optimal surgical timing, the committee decided that surgery within 24 hours would be beneficial for the majority of patients and therefore was considered a prudent goal.

Based on identified barriers that contributed to surgical delays, several process improvement strategies were implemented, including admitting patients to the hospitalist service, engaging the orthopedic trauma team, and implementing pre- and postoperative protocols and order sets (eg, ED and pain management order sets). Specific emphasis was placed on establishing guidelines for determining medical optimization. In the absence of established guidelines, medical optimization was determined at the discretion of the attending physician. The necessity of preoperative cardiac assessment was based, in part, on physician concerns about determining safe anesthesia protocols and hemodynamically managing patients who may have occult heart disease, specifically those patients with low functional capacity (< 4 METs) and/or inability to accurately communicate their medical history.

Many hip fractures result from a fall, and it may be unclear whether the fall causing a fracture was purely mechanical or indicative of a distinct acute or chronic illness. As a result, many patients received cardiac consultations, with or without pharmacologic stress testing, adding another 24 to 36 hours to preoperative time. As invasive preoperative cardiac procedures generally result in surgical delays without improving outcomes,11 the committee recommended that clinicians reserve preoperative cardiac consultation for patients with active cardiac conditions.

In lieu of cardiac consultation, the committee suggested preoperative TTE. While use of TTE has not been shown to improve preoperative risk stratification in routine noncardiac surgeries, it has been shown to provide clinically useful information in patients at high risk for cardiac complications.11 There was consensus for incorporating preoperative TTE for several reasons: (1) the patients with hip fractures were not “routine,” and often did not have a reliable medical history; (2) a large percentage of patients had cardiac risk factors; (3) patients with undiagnosed aortic stenosis, severe left ventricular dysfunction, or severe pulmonary hypertension would likely have altered intraoperative fluid management; and (4) in supplanting cardiac consultations, TTE would likely expedite patients’ ED-to-OR times. Therefore, the GHFMC created a recommendation of ordering urgent TTE for patients who were unable to exercise at ≥ 4 METs but needed urgent hip fracture surgery.

In order to evaluate the success of the new protocol, the ED-to-OR times were calculated for a cohort of patients who underwent surgery for hip fracture following algorithm implementation.

Participants

A chart review was conducted for patients admitted to GMC between January 2010 and April 2014 for operative treatment of a hip fracture. Exclusion criteria included lack of radiologist-diagnosed hip fracture, periprosthetic hip fracture, or multiple traumas. Electronic patient charts were reviewed by investigators (KI and BO) using a standardized, electronic abstraction form for 3 groups of patients who (1) proceeded directly to planned surgery without TTE or cardiac consultation (direct-to-surgery group); (2) received preoperative TTE but not a cardiac consultation (TTE-only group); or (3) received preoperative cardiac consultation (cardiac consult group).

Measures

Demographics, comorbid conditions, MET score, anesthesia protocol, and in-hospital morbidity and mortality were extracted from medical charts. Medical optimization time was determined by the latest time stamp of 1 of the following: time that the final consulting specialist stated that the patient was stable for surgery; time that the hospitalist described the patient as being ready for surgery; time that the TTE report was certified by the reading cardiologist; or time that the hospitalist described the outcome of completed preoperative risk stratification. Time elapsed prior to medical optimization, surgery, and discharge were calculated using differences between the patient’s arrival date and time at the ED, first recorded time of medical optimization, surgical start time (from the surgical report), and discharge time, respectively.

To assess whether the TTE protocol may have affected anesthesia selection, the induction agent (etomidate or propofol) was abstracted from anesthesia reports and stratified by the ejection fraction of each patient: very low (≤ 35%), low (36%–50%), or normal (> 50%). Patients without an echocardiogram report were assumed to have a normal ejection fraction for this analysis.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were produced using mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and frequency and percentage for categorical variables. To determine whether statistically significant differences existed between the 3 groups, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare skewed continuous variables, and Pearson’s chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. Due to differences in baseline patient characteristics across the 3 treatment groups, inverse probability weights were used to adjust for group differences (using a multinomial logit treatment model) while comparing differences in outcome variables. This modeling strategy does not rely on any assumptions for the distribution of the outcome variable. Covariates were considered for inclusion in the treatment or outcome model if they were significantly associated (P < 0.05) with the group variable. Additionally, anesthetic agent (etomidate or propofol) was compared across the treatment groups after stratifying by ejection fraction to identify whether any differences existed in anesthesia regimen. Patients who were prescribed more than 1 anesthetic agent (n = 2) or an agent that was not of interest were removed from the analysis (n = 13). Stata (version 14) was used for analysis. All other missing data with respect to the tested variables were omitted in the analysis for that variable. Any disagreements about abstraction were resolved through consensus between the investigators.

Results

A total of 316 cases met inclusion criteria, including 108 direct-to-surgery patients, 143 preoperative TTE patients, and 65 cardiac consult patients. Patient demographics and preoperative characteristics are shown in Table 1. The average age for all patients was 76.5 years of age (SD, 12.89; IQR, 34-97); however, direct-to-surgery patients were significantly (P < 0.001) younger (71.2 years; SD, 14.2; interquartile range [IQR], 34-95 years) than TTE-only patients (79.0 years; SD, 11.5; IQR, 35-97 years) and cardiac consult patients (79.57 years; SD, 10.63; IQR, 49-97 years). The majority of patients were female (69.9%) and experienced a fall prior to admission (94%). Almost three-fourths of patients had 1 or more cardiac risk factors (73.7%), including history of congestive heart failure (CHF; 19%), coronary artery disease (CAD; 26.3%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD; 19.3%), or aortic stenosis (AS; 3.5%). Due to between-group differences in these comorbid conditions, confounding factors were adjusted for in subsequent analyses.

As shown in Table 2, before adjustment for confounding factors, there were significant between-group differences in medical optimization time for patients in all 3 groups. After adjustment for treatment differences using age and number of comorbid diseases, and medical optimization time differences using age and COPD, fewer between-group differences were statistically significant. Patients who received a cardiac consult had an 18.44-hour longer medical optimization time compared to patients who went directly to surgery (29.136 vs 10.696 hours; P = 0.001). Optimization remained approximately 5 hours longer for the TTE-only group than for the direct-to-surgery group; however, this difference was not significant (P = 0.075).

When comparing differences in ED-to-OR time for the 3 groups after adjusting the probability of treatment for age and the number of comorbid conditions, and adjusting the probability of ED-to-OR time for age, COPD, and CHF, significant differences remained in ED-to-OR times across all groups. Specifically, patients in the direct-to-surgery group experienced the shortest time (mean, 20.64 hours), compared to patients in the TTE-only group (mean, 26.32; P = 0.04) or patients in the cardiac consult group (mean, 36.08; P < 0.001). TTE-only patients had a longer time of 5.68 hours, compared to the direct-to-surgery group, and patients in the preoperative cardiac consult group were on average 15.44 hours longer than the direct-to-surgery group.

When comparing differences in the length of stay for the 3 groups before statistical adjustments, differences were observed; however, after removing the confounding factors related to treatment (age and CAD) and the outcome (age and the number of comorbid conditions), there were no statistically significant differences in the length of stay for the 3 groups. Average length of stay was 131 hours for direct-to-surgery patients, 142 hours for TTE-only patients, and 141 hours for cardiac consult patients.

The use of different anesthetic agents was compared for patients in the 3 groups. The majority of patients in the study (87.7%) were given propofol, and there were no differences after stratifying by ejection fraction (Table 3).

Discussion

The GHFMC was created to reduce surgical delays for hip fracture. Medical optimization was considered a primary, modifiable factor given that surgeons were reluctant to proceed without a cardiac consult. To address this gap, the committee recommended a preoperative TTE for patients with low or unknown functional status. This threshold provides a quick and easy method for stratifying patients who previously required risk stratification by a cardiologist, which often resulted in surgery delays.

In their recommendations for implementation of hip fracture quality improvement projects, the Geriatric Fracture Center emphasizes the importance of multidisciplinary physician leadership along with standardization of approach across patients.12 This recommendation is supported by increasing evidence that orthogeriatric collaborations are associated with decreased mortality and length of stay.13 The GHFMC and subsequent interventions reflect this approach, allowing for collaboration to identify cross-disciplinary procedural barriers to care. In our institution, addressing identified procedural barriers to care was associated with a reduction in the average time to surgery from 51 hours to 25.3 hours.

Multiple approaches have been attempted to decrease presurgical time in hip fracture patients in various settings. Prehospital interventions, such as providing ambulances with checklists and ability to bypass the ED, have not been shown to decrease time to surgery for hip fracture patients, though similar strategies have been successful in other conditions, such as stroke.14,15 In-hospital procedures, such as implementation of a hip fracture protocol and reduction of preoperative interventions, have more consistently been found to decrease time to surgery and in-hospital mortality.16,17 However, reduced delays have not been found universally. Luttrell and Nana found that preoperative TTE resulted in approximately 30.8-hour delays from the ED to OR, compared to patients who did not receive a preoperative TTE.18 However, in that study hospitalists used TTE at their own discretion, and there may have been confounding factors contributing to delays. When used as part of a protocol targeting patients with poor or unknown functional capacity, we believe that preoperative TTE results in modest surgical delays yet provides clinically useful information about each patient.

ACC/AHA preoperative guidelines were updated after we implemented our intervention and now recommend that patients with poor or unknown functional capacity in whom stress testing will not influence care proceed to surgery “according to guideline-directed medical care.”11 While routine use of preoperative evaluation of left ventricular function is not recommended, assessing left ventricular function may be reasonable for patients with heart failure with a change in clinical status. Guidelines also recommend that patients with clinically suspected valvular stenosis undergo preoperative echocardiography.11

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, due to resource limitations, a substantial period of time elapsed between implementation of the new protocol and the analysis of the data set. That is, the hip fracture protocol assessed in this paper occurred from January 2010 through April 2014, and final analysis of the data set occurred in April 2020. This limitation precludes our ability to formally assess any pre- or post-protocol changes in patient outcomes. Second, randomization was not used to create groups that were balanced in differing health characteristics (ie, patients with noncardiac-related surgeries, patients in different age groups); however, the use of inverse probability treatment regression analysis was a way to statistically address these between-group differences. Moreover, this study is limited by the factors that were measured; unmeasured factors cannot be accounted for. Third, health care providers working at the hospital during this time were aware of the goal to decrease presurgical time, possibly creating exaggerated effects compared to a blinded trial. Finally, although this intervention is likely translatable to other centers, these results represent the experiences of a single level 1 trauma center and may not be replicable elsewhere.

Conclusion

Preoperative TTE in lieu of cardiac consultation has several advantages. First, it requires interdepartmental collaboration for implementation, but can be implemented through a single hospital or hospital system. Unlike prehospital interventions, preoperative urgent TTE for patients with low functional capacity does not require the support of emergency medical technicians, ambulance services, or other hospitals in the region. Second, while costs are associated with TTE, they are offset by a reduction in expensive consultations with specialists, surgical delays, and longer lengths of stay. Third, despite likely increased ED-to-OR times compared to no intervention, urgent TTE decreases time to surgery compared with cardiology consultation. Prior to the GHFMC, the ED-to-OR time at our institution was 51 hours. In contrast, the mean time following the GHFMC-led protocol was less than half that, at 25.3 hours (SD, 19.1 hours). In fact, nearly two-thirds (65.2%) of the patients evaluated in this study underwent surgery within 24 hours of admission. This improvement in presurgical time was attributed, in part, to the implementation of preoperative TTE over cardiology consultations.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Jenny Williams, RN, who was instrumental in obtaining the data set for analysis, and Shauna Ayres, MPH, from the OhioHealth Research Institute, who provided writing and technical assistance.

Corresponding author: Robert Skully, MD, OhioHealth Family Medicine Grant, 290 East Town St., Columbus, OH 43215; [email protected].

Funding: This work was supported by the OhioHealth Summer Research Externship Program.

Financial disclosures: None.

From Dignity Health Methodist Hospital of Sacramento Family Medicine Residency Program, Sacramento, CA (Dr. Oldach); Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH (Dr. Irwin); OhioHealth Research Institute, Columbus, OH (Dr. Pershing); Department of Clinical Transformation, OhioHealth, Columbus, OH (Dr. Zigmont and Dr. Gascon); and Department of Geriatrics, OhioHealth, Columbus, OH (Dr. Skully).

Abstract

Objective: An interdisciplinary committee was formed to identify factors contributing to surgical delays in urgent hip fracture repair at an urban, level 1 trauma center, with the goal of reducing preoperative time to less than 24 hours. Surgical optimization was identified as a primary, modifiable factor, as surgeons were reluctant to clear patients for surgery without cardiac consultation. Preoperative transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) was recommended as a safe alternative to cardiac consultation in most patients.

Methods: A retrospective review was conducted for patients who underwent urgent hip fracture repair between January 2010 and April 2014 (n = 316). Time to medical optimization, time to surgery, hospital length of stay, and anesthesia induction were compared for 3 patient groups of interest: those who received (1) neither TTE nor cardiology consultation (ie, direct to surgery); (2) a preoperative TTE; or (3) preoperative cardiac consultation.

Results: There were significant between-group differences in medical optimization time (P = 0.001) and mean time to surgery (P < 0.001) when comparing the 3 groups of interest. Patients in the preoperative cardiac consult group had the longest times, followed by the TTE and direct-to-surgery groups. There were no differences in the type of induction agent used across treatment groups when stratifying by ejection fraction.

Conclusion: Preoperative TTE allows for decreased preoperative time compared to a cardiology consultation. It provides an easily implemented inter-departmental, intra-institutional intervention to decrease preoperative time in patients presenting with hip fractures.

Keywords: surgical delay; preoperative risk stratification; process improvement.

Hip fractures are common, expensive, and associated with poor outcomes.1,2 Ample literature suggests that morbidity, mortality, and cost of care may be reduced by minimizing surgical delays.3-5 While individual reports indicate mixed evidence, in a 2010 meta-analysis, surgery within 72 hours was associated with significant reductions in pneumonia and pressure sores, as well as a 19% reduction in all-cause mortality through 1 year.6 Additional reviews suggest evidence of improved patient outcomes (pain, length of stay, non-union, and/or mortality) when surgery occurs early, within 12 to 72 hours after injury.4,6,7 Regardless of the definition of “early surgery” used, surgical delay remains a challenge, often due to organizational factors, including admission day of the week and hospital staffing, and patient characteristics, such as comorbidities, echocardiographic findings, age, and insurance status.7-9

Among factors that contribute to surgical delays, the need for preoperative cardiovascular risk stratification is significantly modifiable.10 The American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) Task Force risk stratification framework for preoperative cardiac testing assists clinicians in determining surgical urgency, active cardiac conditions, cardiovascular risk factors, and functional capacity of each patient, and is well established for low- or intermediate-risk patients.11 Specifically, metabolic equivalents (METs) measurements are used to identify medically stable patients with good or excellent functional capacity versus poor or unknown functional status. Patients with ≥ 4 METs may proceed to surgery without further testing; patients with < 4 METs may either proceed with planned surgery or undergo additional testing. Patients with a perceived increased risk profile who require urgent or semi-urgent hip fracture repair may be confounded by disagreement about required preoperative cardiac testing.

At OhioHealth Grant Medical Center (GMC), an urban, level 1 trauma center, the consideration of further preoperative noninvasive testing frequently contributed to surgical delays. In 2009, hip fracture patients arriving to the emergency department (ED) waited an average of 51 hours before being transferred to the operating room (OR) for surgery. Presuming prompt surgery is both desirable and feasible, the Grant Hip Fracture Management Committee (GHFMC) was developed in order to expedite surgeries in hip fracture patients. The GHFMC recommended a preoperative hip fracture protocol, and the outcomes from protocol implementation are described in this article.

Methods

This study was approved by the OhioHealth Institutional Review Board, with a waiver of the informed consent requirement. Medical records from patients treated at GMC during the time period between January 2010 and April 2014 (ie, following implementation of GHFMC recommendations) were retrospectively reviewed to identify the extent to which the use of preoperative transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) reduced average time to surgery and total length of stay, compared to cardiac consultation. This chart review included 316 participants and was used to identify primary induction agent utilized, time to medical optimization, time to surgery, and total length of hospital stay.

Intervention

The GHFMC conducted a 9-month quality improvement project to decrease ED-to-OR time to less than 24 hours for hip fracture patients. The multidisciplinary committee consisted of physicians from orthopedic surgery, anesthesia, hospital medicine, and geriatrics, along with key administrators and nurse outcomes managers. While there is lack of complete clarity surrounding optimal surgical timing, the committee decided that surgery within 24 hours would be beneficial for the majority of patients and therefore was considered a prudent goal.

Based on identified barriers that contributed to surgical delays, several process improvement strategies were implemented, including admitting patients to the hospitalist service, engaging the orthopedic trauma team, and implementing pre- and postoperative protocols and order sets (eg, ED and pain management order sets). Specific emphasis was placed on establishing guidelines for determining medical optimization. In the absence of established guidelines, medical optimization was determined at the discretion of the attending physician. The necessity of preoperative cardiac assessment was based, in part, on physician concerns about determining safe anesthesia protocols and hemodynamically managing patients who may have occult heart disease, specifically those patients with low functional capacity (< 4 METs) and/or inability to accurately communicate their medical history.

Many hip fractures result from a fall, and it may be unclear whether the fall causing a fracture was purely mechanical or indicative of a distinct acute or chronic illness. As a result, many patients received cardiac consultations, with or without pharmacologic stress testing, adding another 24 to 36 hours to preoperative time. As invasive preoperative cardiac procedures generally result in surgical delays without improving outcomes,11 the committee recommended that clinicians reserve preoperative cardiac consultation for patients with active cardiac conditions.

In lieu of cardiac consultation, the committee suggested preoperative TTE. While use of TTE has not been shown to improve preoperative risk stratification in routine noncardiac surgeries, it has been shown to provide clinically useful information in patients at high risk for cardiac complications.11 There was consensus for incorporating preoperative TTE for several reasons: (1) the patients with hip fractures were not “routine,” and often did not have a reliable medical history; (2) a large percentage of patients had cardiac risk factors; (3) patients with undiagnosed aortic stenosis, severe left ventricular dysfunction, or severe pulmonary hypertension would likely have altered intraoperative fluid management; and (4) in supplanting cardiac consultations, TTE would likely expedite patients’ ED-to-OR times. Therefore, the GHFMC created a recommendation of ordering urgent TTE for patients who were unable to exercise at ≥ 4 METs but needed urgent hip fracture surgery.

In order to evaluate the success of the new protocol, the ED-to-OR times were calculated for a cohort of patients who underwent surgery for hip fracture following algorithm implementation.

Participants

A chart review was conducted for patients admitted to GMC between January 2010 and April 2014 for operative treatment of a hip fracture. Exclusion criteria included lack of radiologist-diagnosed hip fracture, periprosthetic hip fracture, or multiple traumas. Electronic patient charts were reviewed by investigators (KI and BO) using a standardized, electronic abstraction form for 3 groups of patients who (1) proceeded directly to planned surgery without TTE or cardiac consultation (direct-to-surgery group); (2) received preoperative TTE but not a cardiac consultation (TTE-only group); or (3) received preoperative cardiac consultation (cardiac consult group).

Measures

Demographics, comorbid conditions, MET score, anesthesia protocol, and in-hospital morbidity and mortality were extracted from medical charts. Medical optimization time was determined by the latest time stamp of 1 of the following: time that the final consulting specialist stated that the patient was stable for surgery; time that the hospitalist described the patient as being ready for surgery; time that the TTE report was certified by the reading cardiologist; or time that the hospitalist described the outcome of completed preoperative risk stratification. Time elapsed prior to medical optimization, surgery, and discharge were calculated using differences between the patient’s arrival date and time at the ED, first recorded time of medical optimization, surgical start time (from the surgical report), and discharge time, respectively.

To assess whether the TTE protocol may have affected anesthesia selection, the induction agent (etomidate or propofol) was abstracted from anesthesia reports and stratified by the ejection fraction of each patient: very low (≤ 35%), low (36%–50%), or normal (> 50%). Patients without an echocardiogram report were assumed to have a normal ejection fraction for this analysis.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were produced using mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and frequency and percentage for categorical variables. To determine whether statistically significant differences existed between the 3 groups, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare skewed continuous variables, and Pearson’s chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. Due to differences in baseline patient characteristics across the 3 treatment groups, inverse probability weights were used to adjust for group differences (using a multinomial logit treatment model) while comparing differences in outcome variables. This modeling strategy does not rely on any assumptions for the distribution of the outcome variable. Covariates were considered for inclusion in the treatment or outcome model if they were significantly associated (P < 0.05) with the group variable. Additionally, anesthetic agent (etomidate or propofol) was compared across the treatment groups after stratifying by ejection fraction to identify whether any differences existed in anesthesia regimen. Patients who were prescribed more than 1 anesthetic agent (n = 2) or an agent that was not of interest were removed from the analysis (n = 13). Stata (version 14) was used for analysis. All other missing data with respect to the tested variables were omitted in the analysis for that variable. Any disagreements about abstraction were resolved through consensus between the investigators.

Results

A total of 316 cases met inclusion criteria, including 108 direct-to-surgery patients, 143 preoperative TTE patients, and 65 cardiac consult patients. Patient demographics and preoperative characteristics are shown in Table 1. The average age for all patients was 76.5 years of age (SD, 12.89; IQR, 34-97); however, direct-to-surgery patients were significantly (P < 0.001) younger (71.2 years; SD, 14.2; interquartile range [IQR], 34-95 years) than TTE-only patients (79.0 years; SD, 11.5; IQR, 35-97 years) and cardiac consult patients (79.57 years; SD, 10.63; IQR, 49-97 years). The majority of patients were female (69.9%) and experienced a fall prior to admission (94%). Almost three-fourths of patients had 1 or more cardiac risk factors (73.7%), including history of congestive heart failure (CHF; 19%), coronary artery disease (CAD; 26.3%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD; 19.3%), or aortic stenosis (AS; 3.5%). Due to between-group differences in these comorbid conditions, confounding factors were adjusted for in subsequent analyses.

As shown in Table 2, before adjustment for confounding factors, there were significant between-group differences in medical optimization time for patients in all 3 groups. After adjustment for treatment differences using age and number of comorbid diseases, and medical optimization time differences using age and COPD, fewer between-group differences were statistically significant. Patients who received a cardiac consult had an 18.44-hour longer medical optimization time compared to patients who went directly to surgery (29.136 vs 10.696 hours; P = 0.001). Optimization remained approximately 5 hours longer for the TTE-only group than for the direct-to-surgery group; however, this difference was not significant (P = 0.075).

When comparing differences in ED-to-OR time for the 3 groups after adjusting the probability of treatment for age and the number of comorbid conditions, and adjusting the probability of ED-to-OR time for age, COPD, and CHF, significant differences remained in ED-to-OR times across all groups. Specifically, patients in the direct-to-surgery group experienced the shortest time (mean, 20.64 hours), compared to patients in the TTE-only group (mean, 26.32; P = 0.04) or patients in the cardiac consult group (mean, 36.08; P < 0.001). TTE-only patients had a longer time of 5.68 hours, compared to the direct-to-surgery group, and patients in the preoperative cardiac consult group were on average 15.44 hours longer than the direct-to-surgery group.

When comparing differences in the length of stay for the 3 groups before statistical adjustments, differences were observed; however, after removing the confounding factors related to treatment (age and CAD) and the outcome (age and the number of comorbid conditions), there were no statistically significant differences in the length of stay for the 3 groups. Average length of stay was 131 hours for direct-to-surgery patients, 142 hours for TTE-only patients, and 141 hours for cardiac consult patients.

The use of different anesthetic agents was compared for patients in the 3 groups. The majority of patients in the study (87.7%) were given propofol, and there were no differences after stratifying by ejection fraction (Table 3).

Discussion

The GHFMC was created to reduce surgical delays for hip fracture. Medical optimization was considered a primary, modifiable factor given that surgeons were reluctant to proceed without a cardiac consult. To address this gap, the committee recommended a preoperative TTE for patients with low or unknown functional status. This threshold provides a quick and easy method for stratifying patients who previously required risk stratification by a cardiologist, which often resulted in surgery delays.

In their recommendations for implementation of hip fracture quality improvement projects, the Geriatric Fracture Center emphasizes the importance of multidisciplinary physician leadership along with standardization of approach across patients.12 This recommendation is supported by increasing evidence that orthogeriatric collaborations are associated with decreased mortality and length of stay.13 The GHFMC and subsequent interventions reflect this approach, allowing for collaboration to identify cross-disciplinary procedural barriers to care. In our institution, addressing identified procedural barriers to care was associated with a reduction in the average time to surgery from 51 hours to 25.3 hours.

Multiple approaches have been attempted to decrease presurgical time in hip fracture patients in various settings. Prehospital interventions, such as providing ambulances with checklists and ability to bypass the ED, have not been shown to decrease time to surgery for hip fracture patients, though similar strategies have been successful in other conditions, such as stroke.14,15 In-hospital procedures, such as implementation of a hip fracture protocol and reduction of preoperative interventions, have more consistently been found to decrease time to surgery and in-hospital mortality.16,17 However, reduced delays have not been found universally. Luttrell and Nana found that preoperative TTE resulted in approximately 30.8-hour delays from the ED to OR, compared to patients who did not receive a preoperative TTE.18 However, in that study hospitalists used TTE at their own discretion, and there may have been confounding factors contributing to delays. When used as part of a protocol targeting patients with poor or unknown functional capacity, we believe that preoperative TTE results in modest surgical delays yet provides clinically useful information about each patient.

ACC/AHA preoperative guidelines were updated after we implemented our intervention and now recommend that patients with poor or unknown functional capacity in whom stress testing will not influence care proceed to surgery “according to guideline-directed medical care.”11 While routine use of preoperative evaluation of left ventricular function is not recommended, assessing left ventricular function may be reasonable for patients with heart failure with a change in clinical status. Guidelines also recommend that patients with clinically suspected valvular stenosis undergo preoperative echocardiography.11

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, due to resource limitations, a substantial period of time elapsed between implementation of the new protocol and the analysis of the data set. That is, the hip fracture protocol assessed in this paper occurred from January 2010 through April 2014, and final analysis of the data set occurred in April 2020. This limitation precludes our ability to formally assess any pre- or post-protocol changes in patient outcomes. Second, randomization was not used to create groups that were balanced in differing health characteristics (ie, patients with noncardiac-related surgeries, patients in different age groups); however, the use of inverse probability treatment regression analysis was a way to statistically address these between-group differences. Moreover, this study is limited by the factors that were measured; unmeasured factors cannot be accounted for. Third, health care providers working at the hospital during this time were aware of the goal to decrease presurgical time, possibly creating exaggerated effects compared to a blinded trial. Finally, although this intervention is likely translatable to other centers, these results represent the experiences of a single level 1 trauma center and may not be replicable elsewhere.

Conclusion

Preoperative TTE in lieu of cardiac consultation has several advantages. First, it requires interdepartmental collaboration for implementation, but can be implemented through a single hospital or hospital system. Unlike prehospital interventions, preoperative urgent TTE for patients with low functional capacity does not require the support of emergency medical technicians, ambulance services, or other hospitals in the region. Second, while costs are associated with TTE, they are offset by a reduction in expensive consultations with specialists, surgical delays, and longer lengths of stay. Third, despite likely increased ED-to-OR times compared to no intervention, urgent TTE decreases time to surgery compared with cardiology consultation. Prior to the GHFMC, the ED-to-OR time at our institution was 51 hours. In contrast, the mean time following the GHFMC-led protocol was less than half that, at 25.3 hours (SD, 19.1 hours). In fact, nearly two-thirds (65.2%) of the patients evaluated in this study underwent surgery within 24 hours of admission. This improvement in presurgical time was attributed, in part, to the implementation of preoperative TTE over cardiology consultations.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Jenny Williams, RN, who was instrumental in obtaining the data set for analysis, and Shauna Ayres, MPH, from the OhioHealth Research Institute, who provided writing and technical assistance.

Corresponding author: Robert Skully, MD, OhioHealth Family Medicine Grant, 290 East Town St., Columbus, OH 43215; [email protected].